User login

Frail elders at high mortality risk in the year following surgery

SAN DIEGO – Frail elderly patients face a significantly increased risk of mortality in the year after undergoing major elective noncardiac surgery, a large study from Canada showed.

“The current literature on perioperative frailty clearly shows that being frail before surgery substantially increases your risk of adverse postoperative outcomes,” Dr. Daniel I. McIsaac said in an interview prior to the annual meeting of the American Society of Anesthesiologists, where the study was presented. “In fact, frailty may underlie a lot of the associations between advanced age and adverse postoperative outcomes. Frailty increases in prevalence with increasing age, and as we all know, the population is aging. Therefore, we expect to see an increasing number of frail patients coming for surgery.”

In an effort to determine the risk of 1-year mortality in frail elderly patients having major elective surgery, the researchers used population-based health administrative data in Ontario, to identify 202,811 patients over the age of 65 who had intermediate- to high-risk elective noncardiac surgery between 2002 and 2012. They used the Johns Hopkins Adjusted Clinical Groups (ACG) frailty indicator and captured all deaths that occurred within 1 year of surgery. Proportional hazards regression models adjusted for age, gender, and socioeconomic status were used to evaluate the impact of frailty on 1-year postoperative mortality.

Of the 202,811 patients, 6,289 (3.1%) were frail, reported Dr. McIsaac of the department of anesthesiology at the University of Ottawa. The 1-year postoperative mortality was 13.6% among frail patients, compared with 4.8% of nonfrail patients, for an adjusted hazard ratio of 2.23. Mortality was higher among frail patients for all types of surgery, compared with their nonfrail counterparts, with the exception of pancreaticoduodenectomy. Frailty had the strongest impact on the risk of mortality after total joint arthroplasty (adjusted hazard ratio of 3.79 for hip replacement and adjusted HR of 2.68 for knee replacement).

The risk of postoperative mortality for frail patients was much higher than for nonfrail patients in the early time period after surgery, especially during the first postoperative week. “Depending on how you control for other variables, a frail patient was 13-35 times more likely to die in the week after surgery than a nonfrail patient of the same age having the same surgery,” said Dr. McIsaac, who is also a staff anesthesiologist at the Ottawa Hospital. “This makes a lot of sense; frail patients are vulnerable to stressors, and surgery puts an enormous physiological stress on even healthy patients. Future work clearly needs to focus [on] addressing this high-risk time in the immediate postoperative period.”

He acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its reliance on health administrative data and the fact that frailty “is a challenging exposure to study because there are a plethora of instruments that can be used to call someone frail. We used a validated set of frailty-defining diagnoses that have been shown to identify people with multidimensional frailty. That said, you can’t necessarily generalize our findings to patients identified as frail using other instruments.”

The findings, Dr. McIsaac concluded, suggest that clinicians should focus on identifying frail patients prior to surgery, “support them to ensure that they are more likely to derive benefit from surgery than harm, and focus on optimizing their care after surgery to address this early mortality risk.”

The study was funded by departments of anesthesiology at the University of Ottawa and at the Ottawa Hospital. Dr. McIsaac reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Frail elderly patients face a significantly increased risk of mortality in the year after undergoing major elective noncardiac surgery, a large study from Canada showed.

“The current literature on perioperative frailty clearly shows that being frail before surgery substantially increases your risk of adverse postoperative outcomes,” Dr. Daniel I. McIsaac said in an interview prior to the annual meeting of the American Society of Anesthesiologists, where the study was presented. “In fact, frailty may underlie a lot of the associations between advanced age and adverse postoperative outcomes. Frailty increases in prevalence with increasing age, and as we all know, the population is aging. Therefore, we expect to see an increasing number of frail patients coming for surgery.”

In an effort to determine the risk of 1-year mortality in frail elderly patients having major elective surgery, the researchers used population-based health administrative data in Ontario, to identify 202,811 patients over the age of 65 who had intermediate- to high-risk elective noncardiac surgery between 2002 and 2012. They used the Johns Hopkins Adjusted Clinical Groups (ACG) frailty indicator and captured all deaths that occurred within 1 year of surgery. Proportional hazards regression models adjusted for age, gender, and socioeconomic status were used to evaluate the impact of frailty on 1-year postoperative mortality.

Of the 202,811 patients, 6,289 (3.1%) were frail, reported Dr. McIsaac of the department of anesthesiology at the University of Ottawa. The 1-year postoperative mortality was 13.6% among frail patients, compared with 4.8% of nonfrail patients, for an adjusted hazard ratio of 2.23. Mortality was higher among frail patients for all types of surgery, compared with their nonfrail counterparts, with the exception of pancreaticoduodenectomy. Frailty had the strongest impact on the risk of mortality after total joint arthroplasty (adjusted hazard ratio of 3.79 for hip replacement and adjusted HR of 2.68 for knee replacement).

The risk of postoperative mortality for frail patients was much higher than for nonfrail patients in the early time period after surgery, especially during the first postoperative week. “Depending on how you control for other variables, a frail patient was 13-35 times more likely to die in the week after surgery than a nonfrail patient of the same age having the same surgery,” said Dr. McIsaac, who is also a staff anesthesiologist at the Ottawa Hospital. “This makes a lot of sense; frail patients are vulnerable to stressors, and surgery puts an enormous physiological stress on even healthy patients. Future work clearly needs to focus [on] addressing this high-risk time in the immediate postoperative period.”

He acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its reliance on health administrative data and the fact that frailty “is a challenging exposure to study because there are a plethora of instruments that can be used to call someone frail. We used a validated set of frailty-defining diagnoses that have been shown to identify people with multidimensional frailty. That said, you can’t necessarily generalize our findings to patients identified as frail using other instruments.”

The findings, Dr. McIsaac concluded, suggest that clinicians should focus on identifying frail patients prior to surgery, “support them to ensure that they are more likely to derive benefit from surgery than harm, and focus on optimizing their care after surgery to address this early mortality risk.”

The study was funded by departments of anesthesiology at the University of Ottawa and at the Ottawa Hospital. Dr. McIsaac reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Frail elderly patients face a significantly increased risk of mortality in the year after undergoing major elective noncardiac surgery, a large study from Canada showed.

“The current literature on perioperative frailty clearly shows that being frail before surgery substantially increases your risk of adverse postoperative outcomes,” Dr. Daniel I. McIsaac said in an interview prior to the annual meeting of the American Society of Anesthesiologists, where the study was presented. “In fact, frailty may underlie a lot of the associations between advanced age and adverse postoperative outcomes. Frailty increases in prevalence with increasing age, and as we all know, the population is aging. Therefore, we expect to see an increasing number of frail patients coming for surgery.”

In an effort to determine the risk of 1-year mortality in frail elderly patients having major elective surgery, the researchers used population-based health administrative data in Ontario, to identify 202,811 patients over the age of 65 who had intermediate- to high-risk elective noncardiac surgery between 2002 and 2012. They used the Johns Hopkins Adjusted Clinical Groups (ACG) frailty indicator and captured all deaths that occurred within 1 year of surgery. Proportional hazards regression models adjusted for age, gender, and socioeconomic status were used to evaluate the impact of frailty on 1-year postoperative mortality.

Of the 202,811 patients, 6,289 (3.1%) were frail, reported Dr. McIsaac of the department of anesthesiology at the University of Ottawa. The 1-year postoperative mortality was 13.6% among frail patients, compared with 4.8% of nonfrail patients, for an adjusted hazard ratio of 2.23. Mortality was higher among frail patients for all types of surgery, compared with their nonfrail counterparts, with the exception of pancreaticoduodenectomy. Frailty had the strongest impact on the risk of mortality after total joint arthroplasty (adjusted hazard ratio of 3.79 for hip replacement and adjusted HR of 2.68 for knee replacement).

The risk of postoperative mortality for frail patients was much higher than for nonfrail patients in the early time period after surgery, especially during the first postoperative week. “Depending on how you control for other variables, a frail patient was 13-35 times more likely to die in the week after surgery than a nonfrail patient of the same age having the same surgery,” said Dr. McIsaac, who is also a staff anesthesiologist at the Ottawa Hospital. “This makes a lot of sense; frail patients are vulnerable to stressors, and surgery puts an enormous physiological stress on even healthy patients. Future work clearly needs to focus [on] addressing this high-risk time in the immediate postoperative period.”

He acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its reliance on health administrative data and the fact that frailty “is a challenging exposure to study because there are a plethora of instruments that can be used to call someone frail. We used a validated set of frailty-defining diagnoses that have been shown to identify people with multidimensional frailty. That said, you can’t necessarily generalize our findings to patients identified as frail using other instruments.”

The findings, Dr. McIsaac concluded, suggest that clinicians should focus on identifying frail patients prior to surgery, “support them to ensure that they are more likely to derive benefit from surgery than harm, and focus on optimizing their care after surgery to address this early mortality risk.”

The study was funded by departments of anesthesiology at the University of Ottawa and at the Ottawa Hospital. Dr. McIsaac reported having no financial disclosures.

AT THE ASA ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Frail elderly patients face an increased risk of mortality within 1 year of undergoing noncardiac surgery.

Major finding: The 1-year postoperative mortality was 13.6% among frail patients, compared with 4.8% of nonfrail patients, for an adjusted hazard ratio of 2.23.

Data source: A study of 202,811 patients over the age of 65 years who underwent noncardiac surgery between 2002 and 2012.

Disclosures: The study was funded by departments of anesthesiology at the University of Ottawa and at The Ottawa Hospital. Dr. McIsaac reported having no financial disclosures.

Benefits, risks of total knee replacement for OA illuminated in trial

Total knee replacement was superior to nonsurgical treatment in relieving pain, restoring function, and improving quality of life for patients with moderate to severe knee osteoarthritis, according to a report published online Oct. 22 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Even though the number of total knee replacements performed each year is large and steadily increasing – with more than 670,000 done in 2012 in the United States alone – no high-quality randomized, controlled trials have ever compared the effectiveness of the procedure against nonsurgical treatment, said Søren T. Skou, Ph.D., of the Research Unit for Musculoskeletal Function and Physiotherapy, Institute of Sports Science and Clinical Biomechanics, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, and his associates.

Dr. Skou and his colleagues remedied that situation by randomly assigning 100 adults (mean age, 66 years) who were eligible for unilateral total knee replacement to either undergo the procedure and then receive a comprehensive nonsurgical intervention (50 patients) or receive the comprehensive nonsurgical intervention alone (50 patients) at two specialized university clinics in Denmark. The 12-week nonsurgical intervention comprised a twice-weekly group exercise program to restore neutral, functional realignment of the legs; two 1-hour education sessions regarding osteoarthritis characteristics, treatments, and self-help strategies; a dietary (weight-loss) program; provision of individually fitted insoles with medial arch support and a lateral wedge if patients had knee-lateral-to-foot positioning; and as-needed pain medication for pain – acetaminophen and ibuprofen – and pantoprazole, a proton-pump inhibitor.

The primary outcome measure in the trial was the between-group difference at 1 year in improvement on four subscales of the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Scores (KOOS) for pain, symptoms, activities of daily living, and quality of life. The surgical group showed a significantly greater improvement (32.5 out of a possible 100 points) than the nonsurgical group (16.0 points) in this outcome. The surgical group also showed significantly greater improvements in all five individual subscales and in a timed chair-rising test, a timed 20-meter walk test, and on a quality-of-life index, the investigators said (N Engl J Med. 2015 373;17:1597-606).

However, it is important to note that patients who had only the nonsurgical intervention showed clinically relevant improvements, and only 26% of them chose to have the surgery after the conclusion of the study. As expected, the surgical group had more serious adverse events than did the nonsurgical group (24 vs. 6), including three cases of deep venous thrombosis and three cases of knee stiffness requiring brisement forcé while the patient was anesthetized, Dr. Skou and his associates said.

This study was supported by the Obel Family Foundation, the Danish Rheumatism Association, the Health Science Foundation of the North Denmark Region, Foot Science International, Spar Nord Foundation, the Bevica Foundation, the Association of Danish Physiotherapists Research Fund, the Medical Specialist Heinrich Kopp’s Grant, and the Danish Medical Association Research Fund. Dr. Skou and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

|

Dr. Jeffrey N. Katz |

This study provides the first rigorously controlled data to inform discussions about whether patients should undergo total knee replacement or opt for comprehensive nonsurgical treatment. Surgery proved markedly superior in this trial, with 85% of surgical patients reporting a clinically important improvement in pain and function at 1 year, compared with 68% of nonsurgical patients.

But surgery was associated with several severe adverse events, including deep venous thrombosis, deep wound infection, supracondylar fracture, and stiffness requiring treatment under general anesthesia. Each patient must weigh these considerations; each physician should present the relevant data to their patients and then listen carefully to their preferences.

Dr. Jeffrey N. Katz is in the departments of medicine and orthopedic surgery at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard University, Boston. He reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Katz made these remarks in an editorial accompanying Dr. Skou’s report (N Engl J Med. 2015 373;17:1668-9).

|

Dr. Jeffrey N. Katz |

This study provides the first rigorously controlled data to inform discussions about whether patients should undergo total knee replacement or opt for comprehensive nonsurgical treatment. Surgery proved markedly superior in this trial, with 85% of surgical patients reporting a clinically important improvement in pain and function at 1 year, compared with 68% of nonsurgical patients.

But surgery was associated with several severe adverse events, including deep venous thrombosis, deep wound infection, supracondylar fracture, and stiffness requiring treatment under general anesthesia. Each patient must weigh these considerations; each physician should present the relevant data to their patients and then listen carefully to their preferences.

Dr. Jeffrey N. Katz is in the departments of medicine and orthopedic surgery at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard University, Boston. He reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Katz made these remarks in an editorial accompanying Dr. Skou’s report (N Engl J Med. 2015 373;17:1668-9).

|

Dr. Jeffrey N. Katz |

This study provides the first rigorously controlled data to inform discussions about whether patients should undergo total knee replacement or opt for comprehensive nonsurgical treatment. Surgery proved markedly superior in this trial, with 85% of surgical patients reporting a clinically important improvement in pain and function at 1 year, compared with 68% of nonsurgical patients.

But surgery was associated with several severe adverse events, including deep venous thrombosis, deep wound infection, supracondylar fracture, and stiffness requiring treatment under general anesthesia. Each patient must weigh these considerations; each physician should present the relevant data to their patients and then listen carefully to their preferences.

Dr. Jeffrey N. Katz is in the departments of medicine and orthopedic surgery at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard University, Boston. He reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Katz made these remarks in an editorial accompanying Dr. Skou’s report (N Engl J Med. 2015 373;17:1668-9).

Total knee replacement was superior to nonsurgical treatment in relieving pain, restoring function, and improving quality of life for patients with moderate to severe knee osteoarthritis, according to a report published online Oct. 22 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Even though the number of total knee replacements performed each year is large and steadily increasing – with more than 670,000 done in 2012 in the United States alone – no high-quality randomized, controlled trials have ever compared the effectiveness of the procedure against nonsurgical treatment, said Søren T. Skou, Ph.D., of the Research Unit for Musculoskeletal Function and Physiotherapy, Institute of Sports Science and Clinical Biomechanics, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, and his associates.

Dr. Skou and his colleagues remedied that situation by randomly assigning 100 adults (mean age, 66 years) who were eligible for unilateral total knee replacement to either undergo the procedure and then receive a comprehensive nonsurgical intervention (50 patients) or receive the comprehensive nonsurgical intervention alone (50 patients) at two specialized university clinics in Denmark. The 12-week nonsurgical intervention comprised a twice-weekly group exercise program to restore neutral, functional realignment of the legs; two 1-hour education sessions regarding osteoarthritis characteristics, treatments, and self-help strategies; a dietary (weight-loss) program; provision of individually fitted insoles with medial arch support and a lateral wedge if patients had knee-lateral-to-foot positioning; and as-needed pain medication for pain – acetaminophen and ibuprofen – and pantoprazole, a proton-pump inhibitor.

The primary outcome measure in the trial was the between-group difference at 1 year in improvement on four subscales of the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Scores (KOOS) for pain, symptoms, activities of daily living, and quality of life. The surgical group showed a significantly greater improvement (32.5 out of a possible 100 points) than the nonsurgical group (16.0 points) in this outcome. The surgical group also showed significantly greater improvements in all five individual subscales and in a timed chair-rising test, a timed 20-meter walk test, and on a quality-of-life index, the investigators said (N Engl J Med. 2015 373;17:1597-606).

However, it is important to note that patients who had only the nonsurgical intervention showed clinically relevant improvements, and only 26% of them chose to have the surgery after the conclusion of the study. As expected, the surgical group had more serious adverse events than did the nonsurgical group (24 vs. 6), including three cases of deep venous thrombosis and three cases of knee stiffness requiring brisement forcé while the patient was anesthetized, Dr. Skou and his associates said.

This study was supported by the Obel Family Foundation, the Danish Rheumatism Association, the Health Science Foundation of the North Denmark Region, Foot Science International, Spar Nord Foundation, the Bevica Foundation, the Association of Danish Physiotherapists Research Fund, the Medical Specialist Heinrich Kopp’s Grant, and the Danish Medical Association Research Fund. Dr. Skou and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Total knee replacement was superior to nonsurgical treatment in relieving pain, restoring function, and improving quality of life for patients with moderate to severe knee osteoarthritis, according to a report published online Oct. 22 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Even though the number of total knee replacements performed each year is large and steadily increasing – with more than 670,000 done in 2012 in the United States alone – no high-quality randomized, controlled trials have ever compared the effectiveness of the procedure against nonsurgical treatment, said Søren T. Skou, Ph.D., of the Research Unit for Musculoskeletal Function and Physiotherapy, Institute of Sports Science and Clinical Biomechanics, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, and his associates.

Dr. Skou and his colleagues remedied that situation by randomly assigning 100 adults (mean age, 66 years) who were eligible for unilateral total knee replacement to either undergo the procedure and then receive a comprehensive nonsurgical intervention (50 patients) or receive the comprehensive nonsurgical intervention alone (50 patients) at two specialized university clinics in Denmark. The 12-week nonsurgical intervention comprised a twice-weekly group exercise program to restore neutral, functional realignment of the legs; two 1-hour education sessions regarding osteoarthritis characteristics, treatments, and self-help strategies; a dietary (weight-loss) program; provision of individually fitted insoles with medial arch support and a lateral wedge if patients had knee-lateral-to-foot positioning; and as-needed pain medication for pain – acetaminophen and ibuprofen – and pantoprazole, a proton-pump inhibitor.

The primary outcome measure in the trial was the between-group difference at 1 year in improvement on four subscales of the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Scores (KOOS) for pain, symptoms, activities of daily living, and quality of life. The surgical group showed a significantly greater improvement (32.5 out of a possible 100 points) than the nonsurgical group (16.0 points) in this outcome. The surgical group also showed significantly greater improvements in all five individual subscales and in a timed chair-rising test, a timed 20-meter walk test, and on a quality-of-life index, the investigators said (N Engl J Med. 2015 373;17:1597-606).

However, it is important to note that patients who had only the nonsurgical intervention showed clinically relevant improvements, and only 26% of them chose to have the surgery after the conclusion of the study. As expected, the surgical group had more serious adverse events than did the nonsurgical group (24 vs. 6), including three cases of deep venous thrombosis and three cases of knee stiffness requiring brisement forcé while the patient was anesthetized, Dr. Skou and his associates said.

This study was supported by the Obel Family Foundation, the Danish Rheumatism Association, the Health Science Foundation of the North Denmark Region, Foot Science International, Spar Nord Foundation, the Bevica Foundation, the Association of Danish Physiotherapists Research Fund, the Medical Specialist Heinrich Kopp’s Grant, and the Danish Medical Association Research Fund. Dr. Skou and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Total knee replacement is superior to nonsurgical treatment in decreasing pain and improving function and quality of life.

Major finding: The surgical group showed a significantly greater improvement 1 year from baseline (32.5 out of a possible 100 points) than did the nonsurgical group (16.0 points) in mean Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Scores (KOOS) for pain, symptoms, activities of daily living, and quality of life.

Data source: A randomized, controlled trial comparing 1-year outcomes after total knee replacement (50 patients) vs. nonsurgical treatment (50 patients) for osteoarthritis.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Obel Family Foundation, the Danish Rheumatism Association, the Health Science Foundation of the North Denmark Region, Foot Science International, Spar Nord Foundation, the Bevica Foundation, the Association of Danish Physiotherapists Research Fund, the Medical Specialist Heinrich Kopp’s Grant, and the Danish Medical Association Research Fund. Dr. Skou and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Changing Paradigms in Short Stay Total Joint Arthroplasty

Reflections on My VA Experience and Why I See the Proverbial Glass as Half Full

Veterans Health Administration (VA) hospitals have received notoriety due to episodes of misdiagnosis, poor management, and negligent care described in many recent reports and news articles.1-3 While veterans are appropriately the primary focus of these investigative reports, physicians are also challenged in this setting, as they often meet resistance when advocating for patients and attempting to improve a flawed system.2 Although my residency training includes 6 months at a VA hospital mired in controversy, the hospital has played a critical role in my training.3

Despite my many frustrations with the VA and the daily stresses incurred because of barriers impeding the timing and quality of care, I have several reasons to see the glass as “half full” when reflecting on my experiences as an orthopedic surgery resident at a VA medical center. This editorial will focus on the most important of these reasons—the special opportunity and pride associated with caring for veterans and these patients’ extremely appreciative nature.

The VA is one of the largest integrated health care systems in the United States, offering both inpatient and outpatient care to eligible veterans. Although eligibility has historically been based on military service–related medical conditions, disability, and financial need, reforms from 1996 to 2002 expanded enrollment to veteran populations previously deemed ineligible for VA care.4,5 Despite this, studies suggest that some uninsured veterans do not seek VA care, even when eligible for VA coverage. This troubling notion is further complicated by research suggesting that veterans who use the VA for all of their health care are more likely to be from poor, less-educated, and minority populations, and are more likely to report fair or poor health and seek more disability days.6

Such disheartening realities can mask the most important attributes of VA patients, which pertain to their selfless commitment to our country. Orthopedic surgery residents must appreciate these attributes as well as the tremendous need for musculoskeletal care in this setting, as musculoskeletal conditions are some of the most common reasons for patient visits at the VA.7 Although combat-related high-energy blast injuries and the reconstructive procedures used to treat them have received a lot of attention, it is the more common musculoskeletal disorders that are most responsible for the tremendous burden of musculoskeletal disease in the VA. In a study by Dominick and colleagues,8 veterans had significantly greater odds of reporting doctor-diagnosed arthritis compared with nonveterans. Furthermore, veterans are also more vulnerable to overuse injuries, a finding attributed to the intense physical activity associated with military training and service.9

The busy orthopedic surgery clinic at my VA hospital is a fulfilling experience and a reminder of the large demand for musculoskeletal care. However, it is the patient population that makes it most gratifying. Most of the veterans seeking care are appreciative, regularly expressing their gratitude. They view me and the other residents as their physicians, not simply as doctors in training, like so many other non-VA patients do. Despite the fact that VA patients sometimes have to wait several hours to be seen in clinic and several months for surgery, I have never been subjected to their inevitable disdain or frustration. This is true in even the most trying and infuriating times, such as when an operation is cancelled on the day of surgery for reasons that many surgeons in non-VA hospitals would consider trivial. And even when witness to my visible irritation with the VA system, the veterans remain respectful and understanding; if they ever share similar feelings, they most certainly never voice them to me.

I cannot refute the notion that the VA must change and that the veterans deserve an improved health care system. However, this editorial is not written as a call to action. Instead, I hope it helps to humanize the patients of the VA, serving as a reminder to residents and other providers that the VA is a unique and extraordinary opportunity to give back and say thank you to veterans.

This editorial is dedicated to CPT David Huskie, USAR (Ret.), a veteran of Operation Desert Storm and orthopedic nurse at my VA hospital. It was he who first reminded me, and the other orthopedic residents, of the importance of our time at the VA. The Figure depicts the letter he gives to orthopedic residents at our program, along with a pewter coin, after their first VA rotation.

1. Pearson M. The VA’s troubled history. Cable News Network (CNN) website. http://www.cnn.com/2014/05/23/politics/va-scandals-timeline. Updated May 30, 2014. Accessed August 28, 2015.

2. Scherz H. Doctors’ war stories from VA hospitals. The Wall Street Journal website. http://www.wsj.com/articles/hal-scherz-doctors-war-stories-from-va-hospitals-1401233147. Published May 27, 2014. Accessed August 28, 2015.

3. Riviello V. Nurse exposes VA hospital: stolen drugs, tortured veterans. New York Post website. http://nypost.com/2014/07/12/nurse-exposes-va-hospital-stolen-drugs-tortured-veterans. Published July 12, 2014. Accessed August 28, 2015.

4. Enrollment—provision of hospital and outpatient care to veterans—VA. Proposed rule. Fed Regist. 1998;63(132):37299-37307.

5. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Assistant Deputy Under Secretary for Health for Policy and Planning. 2003 Survey of Veteran Enrollees’ Health and Reliance Upon VA With Selected Comparisons to the 1999 and 2002 Surveys. US Department of Veterans Affairs website. www.va.gov/healthpolicyplanning/Docs/SOE2003_Report.pdf. Published December 2004. Accessed August 28, 2015.

6. Nelson KM, Starkebaum GA, Reiber GE. Veterans using and uninsured veterans not using Veterans Affairs (VA) health care. Public Health Rep. 2007;122(1):93-100.

7. Wasserman GM, Martin BL, Hyams KC, Merrill BR, Oaks HG, McAdoo HA. A survey of outpatient visits in a United States Army forward unit during Operation Desert Shield. Mil Med. 1997;162(6):374-379.

8. Dominick KL, Golightly YM, Jackson GL. Arthritis prevalence and symptoms among US non-veterans, veterans, and veterans receiving Department of Veterans Affairs Healthcare. J Rheumatol. 2006;33(2):348-354.

9. West SG. Rheumatic disorders during Operation Desert Storm. Arthritis Rheum. 1993;36(10):1487-1488.

Veterans Health Administration (VA) hospitals have received notoriety due to episodes of misdiagnosis, poor management, and negligent care described in many recent reports and news articles.1-3 While veterans are appropriately the primary focus of these investigative reports, physicians are also challenged in this setting, as they often meet resistance when advocating for patients and attempting to improve a flawed system.2 Although my residency training includes 6 months at a VA hospital mired in controversy, the hospital has played a critical role in my training.3

Despite my many frustrations with the VA and the daily stresses incurred because of barriers impeding the timing and quality of care, I have several reasons to see the glass as “half full” when reflecting on my experiences as an orthopedic surgery resident at a VA medical center. This editorial will focus on the most important of these reasons—the special opportunity and pride associated with caring for veterans and these patients’ extremely appreciative nature.

The VA is one of the largest integrated health care systems in the United States, offering both inpatient and outpatient care to eligible veterans. Although eligibility has historically been based on military service–related medical conditions, disability, and financial need, reforms from 1996 to 2002 expanded enrollment to veteran populations previously deemed ineligible for VA care.4,5 Despite this, studies suggest that some uninsured veterans do not seek VA care, even when eligible for VA coverage. This troubling notion is further complicated by research suggesting that veterans who use the VA for all of their health care are more likely to be from poor, less-educated, and minority populations, and are more likely to report fair or poor health and seek more disability days.6

Such disheartening realities can mask the most important attributes of VA patients, which pertain to their selfless commitment to our country. Orthopedic surgery residents must appreciate these attributes as well as the tremendous need for musculoskeletal care in this setting, as musculoskeletal conditions are some of the most common reasons for patient visits at the VA.7 Although combat-related high-energy blast injuries and the reconstructive procedures used to treat them have received a lot of attention, it is the more common musculoskeletal disorders that are most responsible for the tremendous burden of musculoskeletal disease in the VA. In a study by Dominick and colleagues,8 veterans had significantly greater odds of reporting doctor-diagnosed arthritis compared with nonveterans. Furthermore, veterans are also more vulnerable to overuse injuries, a finding attributed to the intense physical activity associated with military training and service.9

The busy orthopedic surgery clinic at my VA hospital is a fulfilling experience and a reminder of the large demand for musculoskeletal care. However, it is the patient population that makes it most gratifying. Most of the veterans seeking care are appreciative, regularly expressing their gratitude. They view me and the other residents as their physicians, not simply as doctors in training, like so many other non-VA patients do. Despite the fact that VA patients sometimes have to wait several hours to be seen in clinic and several months for surgery, I have never been subjected to their inevitable disdain or frustration. This is true in even the most trying and infuriating times, such as when an operation is cancelled on the day of surgery for reasons that many surgeons in non-VA hospitals would consider trivial. And even when witness to my visible irritation with the VA system, the veterans remain respectful and understanding; if they ever share similar feelings, they most certainly never voice them to me.

I cannot refute the notion that the VA must change and that the veterans deserve an improved health care system. However, this editorial is not written as a call to action. Instead, I hope it helps to humanize the patients of the VA, serving as a reminder to residents and other providers that the VA is a unique and extraordinary opportunity to give back and say thank you to veterans.

This editorial is dedicated to CPT David Huskie, USAR (Ret.), a veteran of Operation Desert Storm and orthopedic nurse at my VA hospital. It was he who first reminded me, and the other orthopedic residents, of the importance of our time at the VA. The Figure depicts the letter he gives to orthopedic residents at our program, along with a pewter coin, after their first VA rotation.

Veterans Health Administration (VA) hospitals have received notoriety due to episodes of misdiagnosis, poor management, and negligent care described in many recent reports and news articles.1-3 While veterans are appropriately the primary focus of these investigative reports, physicians are also challenged in this setting, as they often meet resistance when advocating for patients and attempting to improve a flawed system.2 Although my residency training includes 6 months at a VA hospital mired in controversy, the hospital has played a critical role in my training.3

Despite my many frustrations with the VA and the daily stresses incurred because of barriers impeding the timing and quality of care, I have several reasons to see the glass as “half full” when reflecting on my experiences as an orthopedic surgery resident at a VA medical center. This editorial will focus on the most important of these reasons—the special opportunity and pride associated with caring for veterans and these patients’ extremely appreciative nature.

The VA is one of the largest integrated health care systems in the United States, offering both inpatient and outpatient care to eligible veterans. Although eligibility has historically been based on military service–related medical conditions, disability, and financial need, reforms from 1996 to 2002 expanded enrollment to veteran populations previously deemed ineligible for VA care.4,5 Despite this, studies suggest that some uninsured veterans do not seek VA care, even when eligible for VA coverage. This troubling notion is further complicated by research suggesting that veterans who use the VA for all of their health care are more likely to be from poor, less-educated, and minority populations, and are more likely to report fair or poor health and seek more disability days.6

Such disheartening realities can mask the most important attributes of VA patients, which pertain to their selfless commitment to our country. Orthopedic surgery residents must appreciate these attributes as well as the tremendous need for musculoskeletal care in this setting, as musculoskeletal conditions are some of the most common reasons for patient visits at the VA.7 Although combat-related high-energy blast injuries and the reconstructive procedures used to treat them have received a lot of attention, it is the more common musculoskeletal disorders that are most responsible for the tremendous burden of musculoskeletal disease in the VA. In a study by Dominick and colleagues,8 veterans had significantly greater odds of reporting doctor-diagnosed arthritis compared with nonveterans. Furthermore, veterans are also more vulnerable to overuse injuries, a finding attributed to the intense physical activity associated with military training and service.9

The busy orthopedic surgery clinic at my VA hospital is a fulfilling experience and a reminder of the large demand for musculoskeletal care. However, it is the patient population that makes it most gratifying. Most of the veterans seeking care are appreciative, regularly expressing their gratitude. They view me and the other residents as their physicians, not simply as doctors in training, like so many other non-VA patients do. Despite the fact that VA patients sometimes have to wait several hours to be seen in clinic and several months for surgery, I have never been subjected to their inevitable disdain or frustration. This is true in even the most trying and infuriating times, such as when an operation is cancelled on the day of surgery for reasons that many surgeons in non-VA hospitals would consider trivial. And even when witness to my visible irritation with the VA system, the veterans remain respectful and understanding; if they ever share similar feelings, they most certainly never voice them to me.

I cannot refute the notion that the VA must change and that the veterans deserve an improved health care system. However, this editorial is not written as a call to action. Instead, I hope it helps to humanize the patients of the VA, serving as a reminder to residents and other providers that the VA is a unique and extraordinary opportunity to give back and say thank you to veterans.

This editorial is dedicated to CPT David Huskie, USAR (Ret.), a veteran of Operation Desert Storm and orthopedic nurse at my VA hospital. It was he who first reminded me, and the other orthopedic residents, of the importance of our time at the VA. The Figure depicts the letter he gives to orthopedic residents at our program, along with a pewter coin, after their first VA rotation.

1. Pearson M. The VA’s troubled history. Cable News Network (CNN) website. http://www.cnn.com/2014/05/23/politics/va-scandals-timeline. Updated May 30, 2014. Accessed August 28, 2015.

2. Scherz H. Doctors’ war stories from VA hospitals. The Wall Street Journal website. http://www.wsj.com/articles/hal-scherz-doctors-war-stories-from-va-hospitals-1401233147. Published May 27, 2014. Accessed August 28, 2015.

3. Riviello V. Nurse exposes VA hospital: stolen drugs, tortured veterans. New York Post website. http://nypost.com/2014/07/12/nurse-exposes-va-hospital-stolen-drugs-tortured-veterans. Published July 12, 2014. Accessed August 28, 2015.

4. Enrollment—provision of hospital and outpatient care to veterans—VA. Proposed rule. Fed Regist. 1998;63(132):37299-37307.

5. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Assistant Deputy Under Secretary for Health for Policy and Planning. 2003 Survey of Veteran Enrollees’ Health and Reliance Upon VA With Selected Comparisons to the 1999 and 2002 Surveys. US Department of Veterans Affairs website. www.va.gov/healthpolicyplanning/Docs/SOE2003_Report.pdf. Published December 2004. Accessed August 28, 2015.

6. Nelson KM, Starkebaum GA, Reiber GE. Veterans using and uninsured veterans not using Veterans Affairs (VA) health care. Public Health Rep. 2007;122(1):93-100.

7. Wasserman GM, Martin BL, Hyams KC, Merrill BR, Oaks HG, McAdoo HA. A survey of outpatient visits in a United States Army forward unit during Operation Desert Shield. Mil Med. 1997;162(6):374-379.

8. Dominick KL, Golightly YM, Jackson GL. Arthritis prevalence and symptoms among US non-veterans, veterans, and veterans receiving Department of Veterans Affairs Healthcare. J Rheumatol. 2006;33(2):348-354.

9. West SG. Rheumatic disorders during Operation Desert Storm. Arthritis Rheum. 1993;36(10):1487-1488.

1. Pearson M. The VA’s troubled history. Cable News Network (CNN) website. http://www.cnn.com/2014/05/23/politics/va-scandals-timeline. Updated May 30, 2014. Accessed August 28, 2015.

2. Scherz H. Doctors’ war stories from VA hospitals. The Wall Street Journal website. http://www.wsj.com/articles/hal-scherz-doctors-war-stories-from-va-hospitals-1401233147. Published May 27, 2014. Accessed August 28, 2015.

3. Riviello V. Nurse exposes VA hospital: stolen drugs, tortured veterans. New York Post website. http://nypost.com/2014/07/12/nurse-exposes-va-hospital-stolen-drugs-tortured-veterans. Published July 12, 2014. Accessed August 28, 2015.

4. Enrollment—provision of hospital and outpatient care to veterans—VA. Proposed rule. Fed Regist. 1998;63(132):37299-37307.

5. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Assistant Deputy Under Secretary for Health for Policy and Planning. 2003 Survey of Veteran Enrollees’ Health and Reliance Upon VA With Selected Comparisons to the 1999 and 2002 Surveys. US Department of Veterans Affairs website. www.va.gov/healthpolicyplanning/Docs/SOE2003_Report.pdf. Published December 2004. Accessed August 28, 2015.

6. Nelson KM, Starkebaum GA, Reiber GE. Veterans using and uninsured veterans not using Veterans Affairs (VA) health care. Public Health Rep. 2007;122(1):93-100.

7. Wasserman GM, Martin BL, Hyams KC, Merrill BR, Oaks HG, McAdoo HA. A survey of outpatient visits in a United States Army forward unit during Operation Desert Shield. Mil Med. 1997;162(6):374-379.

8. Dominick KL, Golightly YM, Jackson GL. Arthritis prevalence and symptoms among US non-veterans, veterans, and veterans receiving Department of Veterans Affairs Healthcare. J Rheumatol. 2006;33(2):348-354.

9. West SG. Rheumatic disorders during Operation Desert Storm. Arthritis Rheum. 1993;36(10):1487-1488.

Is Skin Tenting Secondary to Displaced Clavicle Fracture More Than a Theoretical Risk? A Report of 2 Adolescent Cases

Fractures of the clavicle, which account for 2.6% of all fractures, are displaced in 70% of cases and are mid-diaphyseal in 80% of cases.1-3 Historically, both displaced and nondisplaced fractures were treated nonoperatively with excellent outcomes reported in the majority of patients.1-3 Traditionally, the indications for surgical fixation of a clavicular fracture include open fractures, which occur infrequently, accounting for only 3.2% of clavicle fractures.4 Other indications include floating shoulder girdle or scapulothoracic dissociation, neurovascular injury, and skin “tenting” by the fracture fragments.3,5 Recently, both meta-analyses and randomized clinical trials have reported reduced malunion rates and improved patient outcomes with open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF).6-9 Consequently, operative fixation could be considered in patients with 100% displacement or greater than 1.5 cm shortening.6-9 Open reduction and internal fixation of the clavicle has been demonstrated to have excellent outcomes in pediatric populations as well.10

The clavicle is subcutaneous for much of its length and, thus, displaced clavicular fractures often result in a visible deformity with a stretch of the soft-tissue envelope over the fracture. While this has been suggested as an operative indication, several recent sources indicate that this concern may only be theoretical. According to the fourth edition of Skeletal Trauma, “It is often stated that open reduction and internal fixation should be considered if the skin is threatened by pressure from a prominent clavicle fracture fragment; however, it is extremely rare of the skin to be perforated from within.”5 The most recent Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery Current Concepts Review on the subject stated that “open fractures or soft-tissue tenting sufficient to produce skin necrosis is uncommon.”3 To the best of our knowledge, there is no reported case of a displaced midshaft clavicle fracture with secondary skin necrosis and conversion into an open fracture, validating the conclusion that this complication may be only theoretical. Given that surgical fixation carries a risk of complications including wound complications, infection, nonunion, malunion, and damage to the nearby neurovascular structures and pleural apices,11 some surgeons may be uncertain how to proceed in cases at risk for disturbance of the soft tissues.

We report 2 adolescent cases of displaced, comminuted clavicle fractures in which the skin was initially intact. Both were managed nonoperatively and both secondarily presented with open lesions at the fracture site requiring urgent irrigation and débridement (I&D) and ORIF. The patients and their guardians provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of these case reports.

Case Reports

Case 1

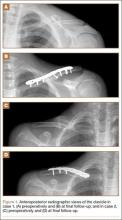

A 15-year-old boy with no significant medical or surgical history flipped over the handlebars of his bicycle the day prior to presentation and sustained a clavicle fracture on his left nondominant upper extremity. This was an isolated injury. On examination, his skin was intact with an area of tender mild osseous protuberance at the midclavicle with associated surrounding edema. He was neurovascularly intact. Radiographs showed a displaced fracture of the midshaft of the clavicle with 20% shortening with a vertically angulated piece of comminution (Figure 1A). After a discussion of the treatment options with the family, the decision was made to pursue nonoperative treatment with sling immobilization as needed and restriction from gym and sports.

Two and a half weeks later, the patient presented at follow-up with significant reduction but persistence of his pain and a new complaint of drainage from the area of the fracture. On examination, he was found to have a puncture wound of the skin with exposed clavicle protruding through the wound with a 1-cm circumferential area of erythema without purulence present or expressible. The patient denied reinjury and endorsed compliance with sling immobilization. He was taken for urgent I&D and ORIF. After excision of the eschar surrounding the open lesion and full I&D of the soft tissues, the protruding spike was partially excised and the fracture site was débrided. The fracture was reduced and fixated with a lag screw and neutralization plate technique using an anatomically contoured locking clavicle plate (Synthes). Vancomycin powder was sprinkled into the wound at the completion of the procedure to reduce the chance of infection.12

Postoperatively, the patient was prescribed oral clindamycin but was subsequently switched to oral cephalexin because of mild signs of an allergic reaction, for a total course of antibiotics of 1 week. The patient was immobilized in a sling for comfort for the first 9 weeks postoperatively until radiographic union occurred. The patient’s wound healed uneventfully and with acceptable cosmesis. He was released to full activities at 10 weeks postoperatively. At final follow-up 6 months after surgery, the patient had returned to all of his regular activities without pain, and with full range of motion and no demonstrable deficits with radiographic union (Figure 1B).

Case 2

An 11-year-old boy with no significant medical or surgical history fell onto his right dominant upper extremity while doing a jump on his dirt bike 1 week prior to presentation, sustaining a clavicle fracture. This was an isolated injury. He was seen and evaluated by an outside orthopedist who noted that the soft-tissue envelope was intact and the patient was neurovascularly intact. Radiographs showed a displaced fracture of the midshaft of the clavicle with 15% shortening and with a vertically angulated piece of comminution (Figure 1C). Nonoperative treatment with a figure-of-8 brace was recommended. The patient’s discomfort completely resolved.

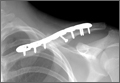

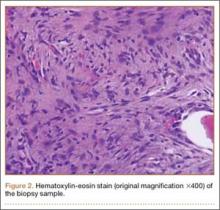

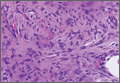

One week later, when he presented to the outside orthopedist for follow-up, the development of a wound overlying the fracture site was noted, and the patient was started on oral trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole and referred to our office for treatment (Figure 1D). The patient denied reinjury and endorsed compliance with brace immobilization. On examination, the patient was afebrile and was noted to have a puncture wound at the fracture site with a protruding spike of bone and surrounding erythema but without present or expressible discharge (Figure 2). The patient was taken urgently for I&D and ORIF, using a similar technique to case 1, except that no lag screw was employed.

Postoperatively, the patient did well with no complications; he was prescribed oral cephalexin for 1 week. The patient was immobilized in a sling for the first 5 weeks after surgery until radiographic union had occurred, after which the sling was discontinued. The patient’s wound healed uneventfully and with acceptable cosmesis. The patient was released from activity restrictions at 6 weeks postoperatively. At final follow-up 5 weeks after surgery, the patient had full painless range of motion, no tenderness at the fracture site, no signs of infection on examination, and radiographic union (Figure 1D).

Discussion

Optimal treatment of displaced clavicle fractures is controversial. While nonoperative treatment has been recommended,1-3 especially in skeletally immature populations with a capacity for remodeling,7-9 2 recent randomized clinical trials have demonstrated improved patient outcomes with ORIF.6,8,9 Traditionally, ORIF was recommended with tenting of the skin because of concern for an impending open fracture. However, recent review materials have implied that this complication may only be theoretical.3,5 Indeed, in 2 randomized trials, sufficient displacement to cause concern for impending violation of the skin envelope was not listed as an exclusion criteria.8,9 We report 2 cases of displaced comminuted clavicle fractures that were initially managed nonoperatively but developed open lesions at the fracture site. This complication, while rare, is possible, and surgeons must consider it as a possibility when assessing patients with displaced clavicle fractures. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, no guidelines exist to direct antibiotic choice and duration in secondarily open fractures.

These 2 cases have several features in common that may serve as risk factors for impending violation of the skin envelope. Both fractures had a vertically angulated segmental piece of comminution with a sharp spike. This feature has been identified as a potential risk factor for subsequent development of an open fracture in a case report of fragment excision without reduction or fixation to allow rapid return to play in a professional jockey.13 Both patients in these cases presented with high-velocity mechanisms of injury and significant displacement, both of which may serve as risk factors. In the only similar case the authors could identify, Strauss and colleagues14 described a distal clavicle fracture with significant displacement and with secondary ulceration of the skin complicated by infection presenting with purulent discharge, cultured positive for methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus, requiring management with an external fixator and 6 weeks of intravenous antibiotics. Because both cases presented here occurred in healthy adolescent patients who were taken urgently for I&D and ORIF as soon as the wound was discovered, deep infection was avoided in these cases. Finally, in 1 case, a figure-of-8 brace was employed, which may also have placed pressure on the skin overlying the fracture and may have predisposed this patient to this complication.

Conclusion

In displaced midshaft clavicle fractures, tenting of the skin sufficient to cause subsequent violation of the soft-tissue envelope is possible and is more than a theoretical risk. At-risk patients, ie, those with a vertically angulated sharp fragment of comminution, should be counseled appropriately and observed closely or considered for primary ORIF.

1. Neer CS 2nd. Nonunion of the clavicle. J Am Med Assoc. 1960;172:1006-1011.

2. Robinson CM. Fractures of the clavicle in the adult. Epidemiology and classification. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1998;80(3):476-484.

3. Khan LA, Bradnock TJ, Scott C, Robinson CM. Fractures of the clavicle. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(2):447-460.

4. Gottschalk HP, Dumont G, Khanani S, Browne RH, Starr AJ. Open clavicle fractures: patterns of trauma and associated injuries. J Orthop Trauma. 2012;26(2):107-109.

5. Ring D, Jupiter JB. Injuries to the shoulder girdle. In: Browner BD, Jupiter JB, eds. Skeletal Trauma. 4th ed. New York, NY: Elsevier; 2009:1755–1778.

6. McKee RC, Whelan DB, Schemitsch EH, McKee MD. Operative versus nonoperative care of displaced midshaft clavicular fractures: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(8):675-684.

7. Zlowodzki M, Zelle BA, Cole PA, Jeray K, McKee MD; Evidence-Based Orthopaedic Trauma Working Group. Treatment of acute midshaft clavicle fractures: systematic review of 2144 fractures: on behalf of the Evidence-Based Orthopaedic Trauma Working Group. J Orthop Trauma. 2005;19(7):504-507.

8. Robinson CM, Goudie EB, Murray IR, et al. Open reduction and plate fixation versus nonoperative treatment for displaced midshaft clavicular fractures: a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(17):1576-1584.

9. Canadian Orthopaedic Trauma Society. Nonoperative treatment compared with plate fixation of displaced midshaft clavicular fractures. A multicenter, randomized clinical trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(1):1-10.

10. Mehlman CT, Yihua G, Bochang C, Zhigang W. Operative treatment of completely displaced clavicle shaft fractures in children. J Pediatr Orthop. 2009;29(8):851-855.

11. Gross CE, Chalmers PN, Ellman M, Fernandez JJ, Verma NN. Acute brachial plexopathy after clavicular open reduction and internal fixation. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(5):e6-e9.

12. Pahys JM, Pahys JR, Cho SK, et al. Methods to decrease postoperative infections following posterior cervical spine surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(6):549-554.

13. Mandalia V, Shivshanker V, Foy MA. Excision of a bony spike without fixation of the fractured clavicle in a jockey. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;(409):275-277.

14. Strauss EJ, Kaplan KM, Paksima N, Bosco JA. Treatment of an open infected type IIB distal clavicle fracture: case report and review of the literature. Bull NYU Hosp Jt Dis. 2008;66(2):129-133.

Fractures of the clavicle, which account for 2.6% of all fractures, are displaced in 70% of cases and are mid-diaphyseal in 80% of cases.1-3 Historically, both displaced and nondisplaced fractures were treated nonoperatively with excellent outcomes reported in the majority of patients.1-3 Traditionally, the indications for surgical fixation of a clavicular fracture include open fractures, which occur infrequently, accounting for only 3.2% of clavicle fractures.4 Other indications include floating shoulder girdle or scapulothoracic dissociation, neurovascular injury, and skin “tenting” by the fracture fragments.3,5 Recently, both meta-analyses and randomized clinical trials have reported reduced malunion rates and improved patient outcomes with open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF).6-9 Consequently, operative fixation could be considered in patients with 100% displacement or greater than 1.5 cm shortening.6-9 Open reduction and internal fixation of the clavicle has been demonstrated to have excellent outcomes in pediatric populations as well.10

The clavicle is subcutaneous for much of its length and, thus, displaced clavicular fractures often result in a visible deformity with a stretch of the soft-tissue envelope over the fracture. While this has been suggested as an operative indication, several recent sources indicate that this concern may only be theoretical. According to the fourth edition of Skeletal Trauma, “It is often stated that open reduction and internal fixation should be considered if the skin is threatened by pressure from a prominent clavicle fracture fragment; however, it is extremely rare of the skin to be perforated from within.”5 The most recent Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery Current Concepts Review on the subject stated that “open fractures or soft-tissue tenting sufficient to produce skin necrosis is uncommon.”3 To the best of our knowledge, there is no reported case of a displaced midshaft clavicle fracture with secondary skin necrosis and conversion into an open fracture, validating the conclusion that this complication may be only theoretical. Given that surgical fixation carries a risk of complications including wound complications, infection, nonunion, malunion, and damage to the nearby neurovascular structures and pleural apices,11 some surgeons may be uncertain how to proceed in cases at risk for disturbance of the soft tissues.

We report 2 adolescent cases of displaced, comminuted clavicle fractures in which the skin was initially intact. Both were managed nonoperatively and both secondarily presented with open lesions at the fracture site requiring urgent irrigation and débridement (I&D) and ORIF. The patients and their guardians provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of these case reports.

Case Reports

Case 1

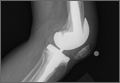

A 15-year-old boy with no significant medical or surgical history flipped over the handlebars of his bicycle the day prior to presentation and sustained a clavicle fracture on his left nondominant upper extremity. This was an isolated injury. On examination, his skin was intact with an area of tender mild osseous protuberance at the midclavicle with associated surrounding edema. He was neurovascularly intact. Radiographs showed a displaced fracture of the midshaft of the clavicle with 20% shortening with a vertically angulated piece of comminution (Figure 1A). After a discussion of the treatment options with the family, the decision was made to pursue nonoperative treatment with sling immobilization as needed and restriction from gym and sports.

Two and a half weeks later, the patient presented at follow-up with significant reduction but persistence of his pain and a new complaint of drainage from the area of the fracture. On examination, he was found to have a puncture wound of the skin with exposed clavicle protruding through the wound with a 1-cm circumferential area of erythema without purulence present or expressible. The patient denied reinjury and endorsed compliance with sling immobilization. He was taken for urgent I&D and ORIF. After excision of the eschar surrounding the open lesion and full I&D of the soft tissues, the protruding spike was partially excised and the fracture site was débrided. The fracture was reduced and fixated with a lag screw and neutralization plate technique using an anatomically contoured locking clavicle plate (Synthes). Vancomycin powder was sprinkled into the wound at the completion of the procedure to reduce the chance of infection.12

Postoperatively, the patient was prescribed oral clindamycin but was subsequently switched to oral cephalexin because of mild signs of an allergic reaction, for a total course of antibiotics of 1 week. The patient was immobilized in a sling for comfort for the first 9 weeks postoperatively until radiographic union occurred. The patient’s wound healed uneventfully and with acceptable cosmesis. He was released to full activities at 10 weeks postoperatively. At final follow-up 6 months after surgery, the patient had returned to all of his regular activities without pain, and with full range of motion and no demonstrable deficits with radiographic union (Figure 1B).

Case 2

An 11-year-old boy with no significant medical or surgical history fell onto his right dominant upper extremity while doing a jump on his dirt bike 1 week prior to presentation, sustaining a clavicle fracture. This was an isolated injury. He was seen and evaluated by an outside orthopedist who noted that the soft-tissue envelope was intact and the patient was neurovascularly intact. Radiographs showed a displaced fracture of the midshaft of the clavicle with 15% shortening and with a vertically angulated piece of comminution (Figure 1C). Nonoperative treatment with a figure-of-8 brace was recommended. The patient’s discomfort completely resolved.

One week later, when he presented to the outside orthopedist for follow-up, the development of a wound overlying the fracture site was noted, and the patient was started on oral trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole and referred to our office for treatment (Figure 1D). The patient denied reinjury and endorsed compliance with brace immobilization. On examination, the patient was afebrile and was noted to have a puncture wound at the fracture site with a protruding spike of bone and surrounding erythema but without present or expressible discharge (Figure 2). The patient was taken urgently for I&D and ORIF, using a similar technique to case 1, except that no lag screw was employed.

Postoperatively, the patient did well with no complications; he was prescribed oral cephalexin for 1 week. The patient was immobilized in a sling for the first 5 weeks after surgery until radiographic union had occurred, after which the sling was discontinued. The patient’s wound healed uneventfully and with acceptable cosmesis. The patient was released from activity restrictions at 6 weeks postoperatively. At final follow-up 5 weeks after surgery, the patient had full painless range of motion, no tenderness at the fracture site, no signs of infection on examination, and radiographic union (Figure 1D).

Discussion

Optimal treatment of displaced clavicle fractures is controversial. While nonoperative treatment has been recommended,1-3 especially in skeletally immature populations with a capacity for remodeling,7-9 2 recent randomized clinical trials have demonstrated improved patient outcomes with ORIF.6,8,9 Traditionally, ORIF was recommended with tenting of the skin because of concern for an impending open fracture. However, recent review materials have implied that this complication may only be theoretical.3,5 Indeed, in 2 randomized trials, sufficient displacement to cause concern for impending violation of the skin envelope was not listed as an exclusion criteria.8,9 We report 2 cases of displaced comminuted clavicle fractures that were initially managed nonoperatively but developed open lesions at the fracture site. This complication, while rare, is possible, and surgeons must consider it as a possibility when assessing patients with displaced clavicle fractures. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, no guidelines exist to direct antibiotic choice and duration in secondarily open fractures.

These 2 cases have several features in common that may serve as risk factors for impending violation of the skin envelope. Both fractures had a vertically angulated segmental piece of comminution with a sharp spike. This feature has been identified as a potential risk factor for subsequent development of an open fracture in a case report of fragment excision without reduction or fixation to allow rapid return to play in a professional jockey.13 Both patients in these cases presented with high-velocity mechanisms of injury and significant displacement, both of which may serve as risk factors. In the only similar case the authors could identify, Strauss and colleagues14 described a distal clavicle fracture with significant displacement and with secondary ulceration of the skin complicated by infection presenting with purulent discharge, cultured positive for methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus, requiring management with an external fixator and 6 weeks of intravenous antibiotics. Because both cases presented here occurred in healthy adolescent patients who were taken urgently for I&D and ORIF as soon as the wound was discovered, deep infection was avoided in these cases. Finally, in 1 case, a figure-of-8 brace was employed, which may also have placed pressure on the skin overlying the fracture and may have predisposed this patient to this complication.

Conclusion

In displaced midshaft clavicle fractures, tenting of the skin sufficient to cause subsequent violation of the soft-tissue envelope is possible and is more than a theoretical risk. At-risk patients, ie, those with a vertically angulated sharp fragment of comminution, should be counseled appropriately and observed closely or considered for primary ORIF.

Fractures of the clavicle, which account for 2.6% of all fractures, are displaced in 70% of cases and are mid-diaphyseal in 80% of cases.1-3 Historically, both displaced and nondisplaced fractures were treated nonoperatively with excellent outcomes reported in the majority of patients.1-3 Traditionally, the indications for surgical fixation of a clavicular fracture include open fractures, which occur infrequently, accounting for only 3.2% of clavicle fractures.4 Other indications include floating shoulder girdle or scapulothoracic dissociation, neurovascular injury, and skin “tenting” by the fracture fragments.3,5 Recently, both meta-analyses and randomized clinical trials have reported reduced malunion rates and improved patient outcomes with open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF).6-9 Consequently, operative fixation could be considered in patients with 100% displacement or greater than 1.5 cm shortening.6-9 Open reduction and internal fixation of the clavicle has been demonstrated to have excellent outcomes in pediatric populations as well.10

The clavicle is subcutaneous for much of its length and, thus, displaced clavicular fractures often result in a visible deformity with a stretch of the soft-tissue envelope over the fracture. While this has been suggested as an operative indication, several recent sources indicate that this concern may only be theoretical. According to the fourth edition of Skeletal Trauma, “It is often stated that open reduction and internal fixation should be considered if the skin is threatened by pressure from a prominent clavicle fracture fragment; however, it is extremely rare of the skin to be perforated from within.”5 The most recent Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery Current Concepts Review on the subject stated that “open fractures or soft-tissue tenting sufficient to produce skin necrosis is uncommon.”3 To the best of our knowledge, there is no reported case of a displaced midshaft clavicle fracture with secondary skin necrosis and conversion into an open fracture, validating the conclusion that this complication may be only theoretical. Given that surgical fixation carries a risk of complications including wound complications, infection, nonunion, malunion, and damage to the nearby neurovascular structures and pleural apices,11 some surgeons may be uncertain how to proceed in cases at risk for disturbance of the soft tissues.

We report 2 adolescent cases of displaced, comminuted clavicle fractures in which the skin was initially intact. Both were managed nonoperatively and both secondarily presented with open lesions at the fracture site requiring urgent irrigation and débridement (I&D) and ORIF. The patients and their guardians provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of these case reports.

Case Reports

Case 1

A 15-year-old boy with no significant medical or surgical history flipped over the handlebars of his bicycle the day prior to presentation and sustained a clavicle fracture on his left nondominant upper extremity. This was an isolated injury. On examination, his skin was intact with an area of tender mild osseous protuberance at the midclavicle with associated surrounding edema. He was neurovascularly intact. Radiographs showed a displaced fracture of the midshaft of the clavicle with 20% shortening with a vertically angulated piece of comminution (Figure 1A). After a discussion of the treatment options with the family, the decision was made to pursue nonoperative treatment with sling immobilization as needed and restriction from gym and sports.

Two and a half weeks later, the patient presented at follow-up with significant reduction but persistence of his pain and a new complaint of drainage from the area of the fracture. On examination, he was found to have a puncture wound of the skin with exposed clavicle protruding through the wound with a 1-cm circumferential area of erythema without purulence present or expressible. The patient denied reinjury and endorsed compliance with sling immobilization. He was taken for urgent I&D and ORIF. After excision of the eschar surrounding the open lesion and full I&D of the soft tissues, the protruding spike was partially excised and the fracture site was débrided. The fracture was reduced and fixated with a lag screw and neutralization plate technique using an anatomically contoured locking clavicle plate (Synthes). Vancomycin powder was sprinkled into the wound at the completion of the procedure to reduce the chance of infection.12

Postoperatively, the patient was prescribed oral clindamycin but was subsequently switched to oral cephalexin because of mild signs of an allergic reaction, for a total course of antibiotics of 1 week. The patient was immobilized in a sling for comfort for the first 9 weeks postoperatively until radiographic union occurred. The patient’s wound healed uneventfully and with acceptable cosmesis. He was released to full activities at 10 weeks postoperatively. At final follow-up 6 months after surgery, the patient had returned to all of his regular activities without pain, and with full range of motion and no demonstrable deficits with radiographic union (Figure 1B).

Case 2

An 11-year-old boy with no significant medical or surgical history fell onto his right dominant upper extremity while doing a jump on his dirt bike 1 week prior to presentation, sustaining a clavicle fracture. This was an isolated injury. He was seen and evaluated by an outside orthopedist who noted that the soft-tissue envelope was intact and the patient was neurovascularly intact. Radiographs showed a displaced fracture of the midshaft of the clavicle with 15% shortening and with a vertically angulated piece of comminution (Figure 1C). Nonoperative treatment with a figure-of-8 brace was recommended. The patient’s discomfort completely resolved.

One week later, when he presented to the outside orthopedist for follow-up, the development of a wound overlying the fracture site was noted, and the patient was started on oral trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole and referred to our office for treatment (Figure 1D). The patient denied reinjury and endorsed compliance with brace immobilization. On examination, the patient was afebrile and was noted to have a puncture wound at the fracture site with a protruding spike of bone and surrounding erythema but without present or expressible discharge (Figure 2). The patient was taken urgently for I&D and ORIF, using a similar technique to case 1, except that no lag screw was employed.

Postoperatively, the patient did well with no complications; he was prescribed oral cephalexin for 1 week. The patient was immobilized in a sling for the first 5 weeks after surgery until radiographic union had occurred, after which the sling was discontinued. The patient’s wound healed uneventfully and with acceptable cosmesis. The patient was released from activity restrictions at 6 weeks postoperatively. At final follow-up 5 weeks after surgery, the patient had full painless range of motion, no tenderness at the fracture site, no signs of infection on examination, and radiographic union (Figure 1D).

Discussion

Optimal treatment of displaced clavicle fractures is controversial. While nonoperative treatment has been recommended,1-3 especially in skeletally immature populations with a capacity for remodeling,7-9 2 recent randomized clinical trials have demonstrated improved patient outcomes with ORIF.6,8,9 Traditionally, ORIF was recommended with tenting of the skin because of concern for an impending open fracture. However, recent review materials have implied that this complication may only be theoretical.3,5 Indeed, in 2 randomized trials, sufficient displacement to cause concern for impending violation of the skin envelope was not listed as an exclusion criteria.8,9 We report 2 cases of displaced comminuted clavicle fractures that were initially managed nonoperatively but developed open lesions at the fracture site. This complication, while rare, is possible, and surgeons must consider it as a possibility when assessing patients with displaced clavicle fractures. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, no guidelines exist to direct antibiotic choice and duration in secondarily open fractures.

These 2 cases have several features in common that may serve as risk factors for impending violation of the skin envelope. Both fractures had a vertically angulated segmental piece of comminution with a sharp spike. This feature has been identified as a potential risk factor for subsequent development of an open fracture in a case report of fragment excision without reduction or fixation to allow rapid return to play in a professional jockey.13 Both patients in these cases presented with high-velocity mechanisms of injury and significant displacement, both of which may serve as risk factors. In the only similar case the authors could identify, Strauss and colleagues14 described a distal clavicle fracture with significant displacement and with secondary ulceration of the skin complicated by infection presenting with purulent discharge, cultured positive for methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus, requiring management with an external fixator and 6 weeks of intravenous antibiotics. Because both cases presented here occurred in healthy adolescent patients who were taken urgently for I&D and ORIF as soon as the wound was discovered, deep infection was avoided in these cases. Finally, in 1 case, a figure-of-8 brace was employed, which may also have placed pressure on the skin overlying the fracture and may have predisposed this patient to this complication.

Conclusion

In displaced midshaft clavicle fractures, tenting of the skin sufficient to cause subsequent violation of the soft-tissue envelope is possible and is more than a theoretical risk. At-risk patients, ie, those with a vertically angulated sharp fragment of comminution, should be counseled appropriately and observed closely or considered for primary ORIF.

1. Neer CS 2nd. Nonunion of the clavicle. J Am Med Assoc. 1960;172:1006-1011.

2. Robinson CM. Fractures of the clavicle in the adult. Epidemiology and classification. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1998;80(3):476-484.

3. Khan LA, Bradnock TJ, Scott C, Robinson CM. Fractures of the clavicle. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(2):447-460.

4. Gottschalk HP, Dumont G, Khanani S, Browne RH, Starr AJ. Open clavicle fractures: patterns of trauma and associated injuries. J Orthop Trauma. 2012;26(2):107-109.