User login

Traumatic Fractures Should Trigger Osteoporosis Assessment in Postmenopausal Women

Study Overview

Objective. To compare the risk of subsequent fractures after an initial traumatic or nontraumatic fracture in postmenopausal women.

Design. A prospective observational study utilizing data from the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) Study, WHI Clinical Trials (WHI-CT), and WHI Bone Density Substudy to evaluate rates at which patients who suffered a traumatic fracture vs nontraumatic fracture develop a subsequent fracture.

Setting and participants. The WHI study, implemented at 40 United States clinical sites, enrolled 161 808 postmenopausal women aged 50 to 79 years at baseline between 1993 and 1998. The study cohort consisted of 75 335 patients who had self-reported fractures from September 1994 to December 1998 that were confirmed by the WHI Bone Density Substudy and WHI-CT. Of these participants, 253 (0.3%) were excluded because of a lack of follow-up information regarding incident fractures, and 8208 (10.9%) were excluded due to incomplete information on covariates, thus resulting in an analytic sample of 66 874 (88.8%) participants. Prospective fracture ascertainment with participants was conducted at least annually and the mechanism of fracture was assessed to differentiate traumatic vs nontraumatic incident fractures. Traumatic fractures were defined as fractures caused by motor vehicle collisions, falls from a height, falls downstairs, or sports injury. Nontraumatic fractures were defined as fractures caused by a trip and fall.

Main outcome measures. The primary outcome was an incident fracture at an anatomically distinct body part. Fractures were classified as upper extremity (carpal, elbow, lower or upper end of humerus, shaft of humerus, upper radius/ulna, or radius/ulna), lower extremity (ankle, hip, patella, pelvis, shaft of femur, tibia/fibula, or tibial plateau), or spine (lumbar and/or thoracic spine). Self-reported fractures were verified via medical chart review by WHI study physicians; hip fractures were confirmed by review of written reports of radiographic studies; and nonhip fractures were confirmed by review of radiography reports or clinical documentations.

Main results. In total, 66 874 women in the study (mean [SD] age) 63.1 (7.0) years without clinical fracture and 65.3 (7.2) years with clinical fracture at baseline were followed for 8.1 (1.6) years. Of these participants, 7142 (10.7%) experienced incident fracture during the study follow-up period (13.9 per 1000 person-years), and 721 (10.1%) of whom had a subsequent fracture. The adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) of subsequent fracture after an initial fracture was 1.49 (95% CI, 1.38-1.61, P < .001). Covariates adjusted were age, race, ethnicity, body mass index, treated diabetes, frequency of falls in the previous year, and physical function and activity. In women with initial traumatic fracture, the association between initial and subsequent fracture was increased (aHR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.06-1.48, P = .01). Among women with initial nontraumatic fracture, the association between initial and subsequent fracture was also increased (aHR, 1.52; 95% CI, 1.37-1.68, P < .001). The confidence intervals for the 2 preceding associations for traumatic and nontraumatic initial fracture strata were overlapping.

Conclusion. Fractures, regardless of mechanism of injury, are similarly associated with an increased risk of subsequent fractures in postmenopausal women aged 50 years and older. Findings from this study provide evidence to support reevaluation of current clinical guidelines to include traumatic fracture as a trigger for osteoporosis screening.

Commentary

Osteoporosis is one of the most common age-associated disease that affects 1 in 4 women and 1 in 20 men over the age of 65.1 It increases the risk of fracture, and its clinical sequelae include reduced mobility, health decline, and increased all-cause mortality. The high prevalence of osteoporosis poses a clinical challenge as the global population continues to age. Pharmacological treatments such as bisphosphonates are highly effective in preventing or slowing bone mineral density (BMD) loss and reducing risk of fragility fractures (eg, nontraumatic fractures of the vertebra, hip, and femur) and are commonly used to mitigate adverse effects of degenerative bone changes secondary to osteoporosis.1

The high prevalence of osteoporosis and effectiveness of bisphosphonates raises the question of how to optimally identify adults at risk for osteoporosis so that pharmacologic therapy can be promptly initiated to prevent disease progression. Multiple osteoporosis screening guidelines, including those from the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), American Association of Family Physicians, and National Osteoporosis Foundation, are widely used in the clinical setting to address this important clinical question. In general, the prevailing wisdom is to screen osteoporosis in postmenopausal women over the age of 65, women under the age of 65 who have a significant 10-year fracture risk, or women over the age of 50 who have experienced a fragility fracture.1 In the study reported by Crandall et al, it was shown that the risks of having subsequent fractures were similar after an initial traumatic or nontraumatic (fragility) fracture in postmenopausal women aged 50 years and older.2 This finding brings into question whether traumatic fractures should be viewed any differently than nontraumatic fractures in women over the age of 50 in light of evaluation for osteoporosis. Furthermore, these results suggest that most fractures in postmenopausal women may indicate decreased bone integrity, thus adding to the rationale that osteoporosis screening needs to be considered and expanded to include postmenopausal women under the age of 65 who endured a traumatic fracture.

Per current guidelines, a woman under the age of 65 is recommended for osteoporosis screening only if she has an increased 10-year fracture risk compared to women aged 65 years and older. This risk is calculated based on the World Health Organization fracture-risk algorithm (WHO FRAX) tool which uses multiple factors such as age, weight, and history of fragility fractures to predict whether an individual is at risk of developing a fracture in the next 10 years. The WHO FRAX tool does not include traumatic fractures in its risk calculation and current clinical guidelines do not account for traumatic fractures as a red flag to initiate osteoporosis screening. Therefore, postmenopausal women under the age of 65 are less likely to be screened for osteoporosis when they experience a traumatic fracture compared to a fragility fracture, despite being at a demonstrably higher risk for subsequent fracture. As an unintended consequence, this may lead to the under diagnosis of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women under the age of 65. Thus, Crandall et al conclude that a fracture due to any cause warrants follow up evaluation for osteoporosis including BMD testing in women older than 50 years of age.

Older men constitute another population who are commonly under screened for osteoporosis. The current USPSTF guidelines indicate that there is an insufficient body of evidence to screen men for osteoporosis given its lower prevalence.1 However, it is important to note that men have significantly increased mortality after a hip fracture, are less likely to be on pharmacological treatment for osteoporosis, and are under diagnosed for osteoporosis.3 Consistent with findings from the current study, Leslie et al showed that high-trauma and low-trauma fractures have similarly elevated subsequent fracture risk in both men and women over the age of 40 in a Canadian study.4 Moreover, in the same study, BMD was decreased in both men and women who suffered a fracture regardless of the injury mechanism. This finding further underscores a need to consider traumatic fractures as a risk factor for osteoporosis. Taken together, given that men are under screened and treated for osteoporosis but have increased mortality post-fracture, considerations to initiate osteoporosis evaluation should be similarly given to men who endured a traumatic fracture.

The study conducted by Crandall et al has several strengths. It is noteworthy for the large size of the WHI cohort with participants from across the United States which enables the capture of a wider range of age groups as women under the age of 65 are not common participants of osteoporosis studies. Additionally, data ascertainment and outcome adjudication utilizing medical records and physician review assure data quality. A limitation of the study is that the study cohort consists exclusively of women and therefore the findings are not generalizable to men. However, findings from this study echo those from other studies that investigate the relationship between fracture mechanisms and subsequent fracture risk in men and women.3,4 Collectively, these comparable findings highlight the need for additional research to validate traumatic fracture as a risk factor for osteoporosis and to incorporate it into clinical guidelines for osteoporosis screening.

Applications for Clinical Practice

The findings from the current study indicate that traumatic and fragility fractures may be more alike than previously recognized in regards to bone health and subsequent fracture prevention in postmenopausal women. If validated, these results may lead to changes in clinical practice whereby all fractures in postmenopausal women could trigger osteoporosis screening, assessment, and treatment if indicated for the secondary prevention of fractures.

1. US Preventive Services Task Force, Curry SJ, Krist Ah, et al. Screening for Osteoporosis to Prevent Fractures: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2018;319(24):2521–2531. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.7498

2. Crandall CJ, Larson JC, LaCroix AZ, et al. Risk of Subsequent Fractures in Postmenopausal Women After Nontraumatic vs Traumatic Fractures. JAMA Intern Med. Published online June 7, 2021. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.2617

3. Mackey DC, Lui L, Cawthon PM, et al. High-Trauma Fractures and Low Bone Mineral Density in Older Women and Men. JAMA. 2007;298(20):2381–2388. doi:10.1001/jama.298.20.2381

4. Leslie WD, Schousboe JT, Morin SN, et al. Fracture risk following high-trauma versus low-trauma fracture: a registry-based cohort study. Osteoporos Int. 2020;31(6):1059–1067. doi:10.1007/s00198-019-05274-2

Study Overview

Objective. To compare the risk of subsequent fractures after an initial traumatic or nontraumatic fracture in postmenopausal women.

Design. A prospective observational study utilizing data from the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) Study, WHI Clinical Trials (WHI-CT), and WHI Bone Density Substudy to evaluate rates at which patients who suffered a traumatic fracture vs nontraumatic fracture develop a subsequent fracture.

Setting and participants. The WHI study, implemented at 40 United States clinical sites, enrolled 161 808 postmenopausal women aged 50 to 79 years at baseline between 1993 and 1998. The study cohort consisted of 75 335 patients who had self-reported fractures from September 1994 to December 1998 that were confirmed by the WHI Bone Density Substudy and WHI-CT. Of these participants, 253 (0.3%) were excluded because of a lack of follow-up information regarding incident fractures, and 8208 (10.9%) were excluded due to incomplete information on covariates, thus resulting in an analytic sample of 66 874 (88.8%) participants. Prospective fracture ascertainment with participants was conducted at least annually and the mechanism of fracture was assessed to differentiate traumatic vs nontraumatic incident fractures. Traumatic fractures were defined as fractures caused by motor vehicle collisions, falls from a height, falls downstairs, or sports injury. Nontraumatic fractures were defined as fractures caused by a trip and fall.

Main outcome measures. The primary outcome was an incident fracture at an anatomically distinct body part. Fractures were classified as upper extremity (carpal, elbow, lower or upper end of humerus, shaft of humerus, upper radius/ulna, or radius/ulna), lower extremity (ankle, hip, patella, pelvis, shaft of femur, tibia/fibula, or tibial plateau), or spine (lumbar and/or thoracic spine). Self-reported fractures were verified via medical chart review by WHI study physicians; hip fractures were confirmed by review of written reports of radiographic studies; and nonhip fractures were confirmed by review of radiography reports or clinical documentations.

Main results. In total, 66 874 women in the study (mean [SD] age) 63.1 (7.0) years without clinical fracture and 65.3 (7.2) years with clinical fracture at baseline were followed for 8.1 (1.6) years. Of these participants, 7142 (10.7%) experienced incident fracture during the study follow-up period (13.9 per 1000 person-years), and 721 (10.1%) of whom had a subsequent fracture. The adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) of subsequent fracture after an initial fracture was 1.49 (95% CI, 1.38-1.61, P < .001). Covariates adjusted were age, race, ethnicity, body mass index, treated diabetes, frequency of falls in the previous year, and physical function and activity. In women with initial traumatic fracture, the association between initial and subsequent fracture was increased (aHR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.06-1.48, P = .01). Among women with initial nontraumatic fracture, the association between initial and subsequent fracture was also increased (aHR, 1.52; 95% CI, 1.37-1.68, P < .001). The confidence intervals for the 2 preceding associations for traumatic and nontraumatic initial fracture strata were overlapping.

Conclusion. Fractures, regardless of mechanism of injury, are similarly associated with an increased risk of subsequent fractures in postmenopausal women aged 50 years and older. Findings from this study provide evidence to support reevaluation of current clinical guidelines to include traumatic fracture as a trigger for osteoporosis screening.

Commentary

Osteoporosis is one of the most common age-associated disease that affects 1 in 4 women and 1 in 20 men over the age of 65.1 It increases the risk of fracture, and its clinical sequelae include reduced mobility, health decline, and increased all-cause mortality. The high prevalence of osteoporosis poses a clinical challenge as the global population continues to age. Pharmacological treatments such as bisphosphonates are highly effective in preventing or slowing bone mineral density (BMD) loss and reducing risk of fragility fractures (eg, nontraumatic fractures of the vertebra, hip, and femur) and are commonly used to mitigate adverse effects of degenerative bone changes secondary to osteoporosis.1

The high prevalence of osteoporosis and effectiveness of bisphosphonates raises the question of how to optimally identify adults at risk for osteoporosis so that pharmacologic therapy can be promptly initiated to prevent disease progression. Multiple osteoporosis screening guidelines, including those from the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), American Association of Family Physicians, and National Osteoporosis Foundation, are widely used in the clinical setting to address this important clinical question. In general, the prevailing wisdom is to screen osteoporosis in postmenopausal women over the age of 65, women under the age of 65 who have a significant 10-year fracture risk, or women over the age of 50 who have experienced a fragility fracture.1 In the study reported by Crandall et al, it was shown that the risks of having subsequent fractures were similar after an initial traumatic or nontraumatic (fragility) fracture in postmenopausal women aged 50 years and older.2 This finding brings into question whether traumatic fractures should be viewed any differently than nontraumatic fractures in women over the age of 50 in light of evaluation for osteoporosis. Furthermore, these results suggest that most fractures in postmenopausal women may indicate decreased bone integrity, thus adding to the rationale that osteoporosis screening needs to be considered and expanded to include postmenopausal women under the age of 65 who endured a traumatic fracture.

Per current guidelines, a woman under the age of 65 is recommended for osteoporosis screening only if she has an increased 10-year fracture risk compared to women aged 65 years and older. This risk is calculated based on the World Health Organization fracture-risk algorithm (WHO FRAX) tool which uses multiple factors such as age, weight, and history of fragility fractures to predict whether an individual is at risk of developing a fracture in the next 10 years. The WHO FRAX tool does not include traumatic fractures in its risk calculation and current clinical guidelines do not account for traumatic fractures as a red flag to initiate osteoporosis screening. Therefore, postmenopausal women under the age of 65 are less likely to be screened for osteoporosis when they experience a traumatic fracture compared to a fragility fracture, despite being at a demonstrably higher risk for subsequent fracture. As an unintended consequence, this may lead to the under diagnosis of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women under the age of 65. Thus, Crandall et al conclude that a fracture due to any cause warrants follow up evaluation for osteoporosis including BMD testing in women older than 50 years of age.

Older men constitute another population who are commonly under screened for osteoporosis. The current USPSTF guidelines indicate that there is an insufficient body of evidence to screen men for osteoporosis given its lower prevalence.1 However, it is important to note that men have significantly increased mortality after a hip fracture, are less likely to be on pharmacological treatment for osteoporosis, and are under diagnosed for osteoporosis.3 Consistent with findings from the current study, Leslie et al showed that high-trauma and low-trauma fractures have similarly elevated subsequent fracture risk in both men and women over the age of 40 in a Canadian study.4 Moreover, in the same study, BMD was decreased in both men and women who suffered a fracture regardless of the injury mechanism. This finding further underscores a need to consider traumatic fractures as a risk factor for osteoporosis. Taken together, given that men are under screened and treated for osteoporosis but have increased mortality post-fracture, considerations to initiate osteoporosis evaluation should be similarly given to men who endured a traumatic fracture.

The study conducted by Crandall et al has several strengths. It is noteworthy for the large size of the WHI cohort with participants from across the United States which enables the capture of a wider range of age groups as women under the age of 65 are not common participants of osteoporosis studies. Additionally, data ascertainment and outcome adjudication utilizing medical records and physician review assure data quality. A limitation of the study is that the study cohort consists exclusively of women and therefore the findings are not generalizable to men. However, findings from this study echo those from other studies that investigate the relationship between fracture mechanisms and subsequent fracture risk in men and women.3,4 Collectively, these comparable findings highlight the need for additional research to validate traumatic fracture as a risk factor for osteoporosis and to incorporate it into clinical guidelines for osteoporosis screening.

Applications for Clinical Practice

The findings from the current study indicate that traumatic and fragility fractures may be more alike than previously recognized in regards to bone health and subsequent fracture prevention in postmenopausal women. If validated, these results may lead to changes in clinical practice whereby all fractures in postmenopausal women could trigger osteoporosis screening, assessment, and treatment if indicated for the secondary prevention of fractures.

Study Overview

Objective. To compare the risk of subsequent fractures after an initial traumatic or nontraumatic fracture in postmenopausal women.

Design. A prospective observational study utilizing data from the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) Study, WHI Clinical Trials (WHI-CT), and WHI Bone Density Substudy to evaluate rates at which patients who suffered a traumatic fracture vs nontraumatic fracture develop a subsequent fracture.

Setting and participants. The WHI study, implemented at 40 United States clinical sites, enrolled 161 808 postmenopausal women aged 50 to 79 years at baseline between 1993 and 1998. The study cohort consisted of 75 335 patients who had self-reported fractures from September 1994 to December 1998 that were confirmed by the WHI Bone Density Substudy and WHI-CT. Of these participants, 253 (0.3%) were excluded because of a lack of follow-up information regarding incident fractures, and 8208 (10.9%) were excluded due to incomplete information on covariates, thus resulting in an analytic sample of 66 874 (88.8%) participants. Prospective fracture ascertainment with participants was conducted at least annually and the mechanism of fracture was assessed to differentiate traumatic vs nontraumatic incident fractures. Traumatic fractures were defined as fractures caused by motor vehicle collisions, falls from a height, falls downstairs, or sports injury. Nontraumatic fractures were defined as fractures caused by a trip and fall.

Main outcome measures. The primary outcome was an incident fracture at an anatomically distinct body part. Fractures were classified as upper extremity (carpal, elbow, lower or upper end of humerus, shaft of humerus, upper radius/ulna, or radius/ulna), lower extremity (ankle, hip, patella, pelvis, shaft of femur, tibia/fibula, or tibial plateau), or spine (lumbar and/or thoracic spine). Self-reported fractures were verified via medical chart review by WHI study physicians; hip fractures were confirmed by review of written reports of radiographic studies; and nonhip fractures were confirmed by review of radiography reports or clinical documentations.

Main results. In total, 66 874 women in the study (mean [SD] age) 63.1 (7.0) years without clinical fracture and 65.3 (7.2) years with clinical fracture at baseline were followed for 8.1 (1.6) years. Of these participants, 7142 (10.7%) experienced incident fracture during the study follow-up period (13.9 per 1000 person-years), and 721 (10.1%) of whom had a subsequent fracture. The adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) of subsequent fracture after an initial fracture was 1.49 (95% CI, 1.38-1.61, P < .001). Covariates adjusted were age, race, ethnicity, body mass index, treated diabetes, frequency of falls in the previous year, and physical function and activity. In women with initial traumatic fracture, the association between initial and subsequent fracture was increased (aHR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.06-1.48, P = .01). Among women with initial nontraumatic fracture, the association between initial and subsequent fracture was also increased (aHR, 1.52; 95% CI, 1.37-1.68, P < .001). The confidence intervals for the 2 preceding associations for traumatic and nontraumatic initial fracture strata were overlapping.

Conclusion. Fractures, regardless of mechanism of injury, are similarly associated with an increased risk of subsequent fractures in postmenopausal women aged 50 years and older. Findings from this study provide evidence to support reevaluation of current clinical guidelines to include traumatic fracture as a trigger for osteoporosis screening.

Commentary

Osteoporosis is one of the most common age-associated disease that affects 1 in 4 women and 1 in 20 men over the age of 65.1 It increases the risk of fracture, and its clinical sequelae include reduced mobility, health decline, and increased all-cause mortality. The high prevalence of osteoporosis poses a clinical challenge as the global population continues to age. Pharmacological treatments such as bisphosphonates are highly effective in preventing or slowing bone mineral density (BMD) loss and reducing risk of fragility fractures (eg, nontraumatic fractures of the vertebra, hip, and femur) and are commonly used to mitigate adverse effects of degenerative bone changes secondary to osteoporosis.1

The high prevalence of osteoporosis and effectiveness of bisphosphonates raises the question of how to optimally identify adults at risk for osteoporosis so that pharmacologic therapy can be promptly initiated to prevent disease progression. Multiple osteoporosis screening guidelines, including those from the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), American Association of Family Physicians, and National Osteoporosis Foundation, are widely used in the clinical setting to address this important clinical question. In general, the prevailing wisdom is to screen osteoporosis in postmenopausal women over the age of 65, women under the age of 65 who have a significant 10-year fracture risk, or women over the age of 50 who have experienced a fragility fracture.1 In the study reported by Crandall et al, it was shown that the risks of having subsequent fractures were similar after an initial traumatic or nontraumatic (fragility) fracture in postmenopausal women aged 50 years and older.2 This finding brings into question whether traumatic fractures should be viewed any differently than nontraumatic fractures in women over the age of 50 in light of evaluation for osteoporosis. Furthermore, these results suggest that most fractures in postmenopausal women may indicate decreased bone integrity, thus adding to the rationale that osteoporosis screening needs to be considered and expanded to include postmenopausal women under the age of 65 who endured a traumatic fracture.

Per current guidelines, a woman under the age of 65 is recommended for osteoporosis screening only if she has an increased 10-year fracture risk compared to women aged 65 years and older. This risk is calculated based on the World Health Organization fracture-risk algorithm (WHO FRAX) tool which uses multiple factors such as age, weight, and history of fragility fractures to predict whether an individual is at risk of developing a fracture in the next 10 years. The WHO FRAX tool does not include traumatic fractures in its risk calculation and current clinical guidelines do not account for traumatic fractures as a red flag to initiate osteoporosis screening. Therefore, postmenopausal women under the age of 65 are less likely to be screened for osteoporosis when they experience a traumatic fracture compared to a fragility fracture, despite being at a demonstrably higher risk for subsequent fracture. As an unintended consequence, this may lead to the under diagnosis of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women under the age of 65. Thus, Crandall et al conclude that a fracture due to any cause warrants follow up evaluation for osteoporosis including BMD testing in women older than 50 years of age.

Older men constitute another population who are commonly under screened for osteoporosis. The current USPSTF guidelines indicate that there is an insufficient body of evidence to screen men for osteoporosis given its lower prevalence.1 However, it is important to note that men have significantly increased mortality after a hip fracture, are less likely to be on pharmacological treatment for osteoporosis, and are under diagnosed for osteoporosis.3 Consistent with findings from the current study, Leslie et al showed that high-trauma and low-trauma fractures have similarly elevated subsequent fracture risk in both men and women over the age of 40 in a Canadian study.4 Moreover, in the same study, BMD was decreased in both men and women who suffered a fracture regardless of the injury mechanism. This finding further underscores a need to consider traumatic fractures as a risk factor for osteoporosis. Taken together, given that men are under screened and treated for osteoporosis but have increased mortality post-fracture, considerations to initiate osteoporosis evaluation should be similarly given to men who endured a traumatic fracture.

The study conducted by Crandall et al has several strengths. It is noteworthy for the large size of the WHI cohort with participants from across the United States which enables the capture of a wider range of age groups as women under the age of 65 are not common participants of osteoporosis studies. Additionally, data ascertainment and outcome adjudication utilizing medical records and physician review assure data quality. A limitation of the study is that the study cohort consists exclusively of women and therefore the findings are not generalizable to men. However, findings from this study echo those from other studies that investigate the relationship between fracture mechanisms and subsequent fracture risk in men and women.3,4 Collectively, these comparable findings highlight the need for additional research to validate traumatic fracture as a risk factor for osteoporosis and to incorporate it into clinical guidelines for osteoporosis screening.

Applications for Clinical Practice

The findings from the current study indicate that traumatic and fragility fractures may be more alike than previously recognized in regards to bone health and subsequent fracture prevention in postmenopausal women. If validated, these results may lead to changes in clinical practice whereby all fractures in postmenopausal women could trigger osteoporosis screening, assessment, and treatment if indicated for the secondary prevention of fractures.

1. US Preventive Services Task Force, Curry SJ, Krist Ah, et al. Screening for Osteoporosis to Prevent Fractures: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2018;319(24):2521–2531. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.7498

2. Crandall CJ, Larson JC, LaCroix AZ, et al. Risk of Subsequent Fractures in Postmenopausal Women After Nontraumatic vs Traumatic Fractures. JAMA Intern Med. Published online June 7, 2021. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.2617

3. Mackey DC, Lui L, Cawthon PM, et al. High-Trauma Fractures and Low Bone Mineral Density in Older Women and Men. JAMA. 2007;298(20):2381–2388. doi:10.1001/jama.298.20.2381

4. Leslie WD, Schousboe JT, Morin SN, et al. Fracture risk following high-trauma versus low-trauma fracture: a registry-based cohort study. Osteoporos Int. 2020;31(6):1059–1067. doi:10.1007/s00198-019-05274-2

1. US Preventive Services Task Force, Curry SJ, Krist Ah, et al. Screening for Osteoporosis to Prevent Fractures: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2018;319(24):2521–2531. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.7498

2. Crandall CJ, Larson JC, LaCroix AZ, et al. Risk of Subsequent Fractures in Postmenopausal Women After Nontraumatic vs Traumatic Fractures. JAMA Intern Med. Published online June 7, 2021. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.2617

3. Mackey DC, Lui L, Cawthon PM, et al. High-Trauma Fractures and Low Bone Mineral Density in Older Women and Men. JAMA. 2007;298(20):2381–2388. doi:10.1001/jama.298.20.2381

4. Leslie WD, Schousboe JT, Morin SN, et al. Fracture risk following high-trauma versus low-trauma fracture: a registry-based cohort study. Osteoporos Int. 2020;31(6):1059–1067. doi:10.1007/s00198-019-05274-2

Occipital nerve stimulation offers relief for patients with intractable chronic cluster headache

Occipital nerve stimulation may help safely prevent attacks of medically intractable chronic cluster headache, according to a new study.

Medically intractable chronic cluster headaches are unilateral headaches that cause excruciating pain during attacks, which may happen as frequently as eight times per day. They are refractory to, or intolerant of, preventive medications typically used in chronic cluster headaches.

“ONS was associated with a major, rapid, and sustained improvement of severe and long-lasting medically intractable chronic cluster headache, both at high and low intensity,” Leopoldine A. Wilbrink, MD, of Leiden (the Netherlands) University Medical Centre, and coauthors wrote in their paper.

The findings were published online.

The multicenter, randomized, double-blind, phase 3 clinical trial was carried out at seven hospitals in the Netherlands, Belgium, Germany, and Hungary. A total of 150 patients with suspected medically intractable chronic cluster headache were enrolled between October 2010 and December 2017, and observed for 12 weeks at baseline. Of those initially enrolled, 131 patients with at least four medically intractable chronic cluster headache attacks per week and a history of nonresponsiveness to at least three standard preventive medications were randomly allocated to one of two groups: Sixty-five patients received 24 weeks of ONS at high intensity (100% intensity, or the intensity 10% below the threshold of discomfort as reported by the patient) while 66 received low-intensity (30%) ONS. At 25-48 weeks, the patients received open-label ONS.

Safe and well tolerated

“Because ONS causes paraesthesia, preventing masked comparison versus placebo, we compared high-intensity versus low-intensity ONS, which are hypothesised to cause similar paraesthesia, but with different efficacy,” wrote Dr. Wilbrink and colleagues.

From baseline to weeks 21-24, the median weekly mean attack frequencies decreased to 7.38 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 2.5-18.5, P < .0001). A median decrease in 5.21 attacks per week (–11.18 to –0.19, P < .0001) was observed.

The 100% ONS group saw a decrease in mean attack frequency from 17.58 at baseline (range, 9.83-29.33) to 9.5 (3-21.25) at 21-24 weeks with a median change of –4.08 (–11.92 to –0.25). In the 30% ONS group, the mean attack frequency decreased from 15 (9.25 to 22.33) to 6.75 (1.5-16.5) with a median change of –6.5 (–10.83 to –0.08).

At weeks 21-24, the difference in median weekly mean attack frequency between the groups was –2.42 (–5.17 to 3.33).

The authors stated that, in both groups, ONS was “safe and well tolerated.” A total of 129 adverse events were reported in the 100% ONS group and 95 in the 30% ONS group, of which 17 and 9 were considered serious, respectively. The serious adverse events required a short hospital stay to resolve minor hardware issues. The adverse events most frequently observed were local pain, impaired wound healing, neck stiffness, and hardware damage.

Low intensity stimulation may be best

“The main limitation of the study comes from the difficulty in defining the electrical dose, which was not constant across patients within each group, but individually adjusted depending on the perception of the ONS-induced paraesthesia,” Denys Fontaine, MD, and Michel Lanteri-Minet, MD, both from Université Cote D’Azur in France, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

Given that the primary outcome did not differ significantly between the treatment groups, the editorialists stated that “the lowest stimulation intensity that induces paraesthesia is sufficient to obtain an effect in the patients who respond. Increasing the electrical dose or intensity does not seem to bring better efficacy and might even induce discomfort (painful paraesthesia or shock-like sensations) that might substantially reduce the tolerance of this approach.”

While the trial did not provide convincing evidence of high intensity ONS in medically intractable chronic cluster headache, the editorialists are otherwise optimistic about the findings: “… considering the significant difference between baseline and the end of the randomised stimulation phase in both groups (about half of the patients showed a 50% decrease in attack frequency), the findings of this study support the favourable results of previous real-world studies, and indicate that a substantial proportion of patients with intractable chronic cluster headache, although not all, could have their condition substantially improved by ONS.” Dr. Fontaine and Dr. Lanteri-Minet added that they hope that “these data will help health authorities to recognise the efficacy of ONS and consider its approval for use in patients with intractable chronic cluster headache.”

Priorities for future research in this area should “focus on optimising stimulation protocols and disentangling the underlying mechanism of action,” Dr. Wilbrink and colleagues wrote.

The study was funded by the Spinoza 2009 Lifetime Scientific Research Achievement Premium, the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research, the Dutch Ministry of Health (as part of a national provisional reimbursement program for promising new treatments), the NutsOhra Foundation from the Dutch Health Insurance Companies, and an unrestricted grant from Medtronic, all to Dr. Ferrari.

Occipital nerve stimulation may help safely prevent attacks of medically intractable chronic cluster headache, according to a new study.

Medically intractable chronic cluster headaches are unilateral headaches that cause excruciating pain during attacks, which may happen as frequently as eight times per day. They are refractory to, or intolerant of, preventive medications typically used in chronic cluster headaches.

“ONS was associated with a major, rapid, and sustained improvement of severe and long-lasting medically intractable chronic cluster headache, both at high and low intensity,” Leopoldine A. Wilbrink, MD, of Leiden (the Netherlands) University Medical Centre, and coauthors wrote in their paper.

The findings were published online.

The multicenter, randomized, double-blind, phase 3 clinical trial was carried out at seven hospitals in the Netherlands, Belgium, Germany, and Hungary. A total of 150 patients with suspected medically intractable chronic cluster headache were enrolled between October 2010 and December 2017, and observed for 12 weeks at baseline. Of those initially enrolled, 131 patients with at least four medically intractable chronic cluster headache attacks per week and a history of nonresponsiveness to at least three standard preventive medications were randomly allocated to one of two groups: Sixty-five patients received 24 weeks of ONS at high intensity (100% intensity, or the intensity 10% below the threshold of discomfort as reported by the patient) while 66 received low-intensity (30%) ONS. At 25-48 weeks, the patients received open-label ONS.

Safe and well tolerated

“Because ONS causes paraesthesia, preventing masked comparison versus placebo, we compared high-intensity versus low-intensity ONS, which are hypothesised to cause similar paraesthesia, but with different efficacy,” wrote Dr. Wilbrink and colleagues.

From baseline to weeks 21-24, the median weekly mean attack frequencies decreased to 7.38 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 2.5-18.5, P < .0001). A median decrease in 5.21 attacks per week (–11.18 to –0.19, P < .0001) was observed.

The 100% ONS group saw a decrease in mean attack frequency from 17.58 at baseline (range, 9.83-29.33) to 9.5 (3-21.25) at 21-24 weeks with a median change of –4.08 (–11.92 to –0.25). In the 30% ONS group, the mean attack frequency decreased from 15 (9.25 to 22.33) to 6.75 (1.5-16.5) with a median change of –6.5 (–10.83 to –0.08).

At weeks 21-24, the difference in median weekly mean attack frequency between the groups was –2.42 (–5.17 to 3.33).

The authors stated that, in both groups, ONS was “safe and well tolerated.” A total of 129 adverse events were reported in the 100% ONS group and 95 in the 30% ONS group, of which 17 and 9 were considered serious, respectively. The serious adverse events required a short hospital stay to resolve minor hardware issues. The adverse events most frequently observed were local pain, impaired wound healing, neck stiffness, and hardware damage.

Low intensity stimulation may be best

“The main limitation of the study comes from the difficulty in defining the electrical dose, which was not constant across patients within each group, but individually adjusted depending on the perception of the ONS-induced paraesthesia,” Denys Fontaine, MD, and Michel Lanteri-Minet, MD, both from Université Cote D’Azur in France, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

Given that the primary outcome did not differ significantly between the treatment groups, the editorialists stated that “the lowest stimulation intensity that induces paraesthesia is sufficient to obtain an effect in the patients who respond. Increasing the electrical dose or intensity does not seem to bring better efficacy and might even induce discomfort (painful paraesthesia or shock-like sensations) that might substantially reduce the tolerance of this approach.”

While the trial did not provide convincing evidence of high intensity ONS in medically intractable chronic cluster headache, the editorialists are otherwise optimistic about the findings: “… considering the significant difference between baseline and the end of the randomised stimulation phase in both groups (about half of the patients showed a 50% decrease in attack frequency), the findings of this study support the favourable results of previous real-world studies, and indicate that a substantial proportion of patients with intractable chronic cluster headache, although not all, could have their condition substantially improved by ONS.” Dr. Fontaine and Dr. Lanteri-Minet added that they hope that “these data will help health authorities to recognise the efficacy of ONS and consider its approval for use in patients with intractable chronic cluster headache.”

Priorities for future research in this area should “focus on optimising stimulation protocols and disentangling the underlying mechanism of action,” Dr. Wilbrink and colleagues wrote.

The study was funded by the Spinoza 2009 Lifetime Scientific Research Achievement Premium, the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research, the Dutch Ministry of Health (as part of a national provisional reimbursement program for promising new treatments), the NutsOhra Foundation from the Dutch Health Insurance Companies, and an unrestricted grant from Medtronic, all to Dr. Ferrari.

Occipital nerve stimulation may help safely prevent attacks of medically intractable chronic cluster headache, according to a new study.

Medically intractable chronic cluster headaches are unilateral headaches that cause excruciating pain during attacks, which may happen as frequently as eight times per day. They are refractory to, or intolerant of, preventive medications typically used in chronic cluster headaches.

“ONS was associated with a major, rapid, and sustained improvement of severe and long-lasting medically intractable chronic cluster headache, both at high and low intensity,” Leopoldine A. Wilbrink, MD, of Leiden (the Netherlands) University Medical Centre, and coauthors wrote in their paper.

The findings were published online.

The multicenter, randomized, double-blind, phase 3 clinical trial was carried out at seven hospitals in the Netherlands, Belgium, Germany, and Hungary. A total of 150 patients with suspected medically intractable chronic cluster headache were enrolled between October 2010 and December 2017, and observed for 12 weeks at baseline. Of those initially enrolled, 131 patients with at least four medically intractable chronic cluster headache attacks per week and a history of nonresponsiveness to at least three standard preventive medications were randomly allocated to one of two groups: Sixty-five patients received 24 weeks of ONS at high intensity (100% intensity, or the intensity 10% below the threshold of discomfort as reported by the patient) while 66 received low-intensity (30%) ONS. At 25-48 weeks, the patients received open-label ONS.

Safe and well tolerated

“Because ONS causes paraesthesia, preventing masked comparison versus placebo, we compared high-intensity versus low-intensity ONS, which are hypothesised to cause similar paraesthesia, but with different efficacy,” wrote Dr. Wilbrink and colleagues.

From baseline to weeks 21-24, the median weekly mean attack frequencies decreased to 7.38 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 2.5-18.5, P < .0001). A median decrease in 5.21 attacks per week (–11.18 to –0.19, P < .0001) was observed.

The 100% ONS group saw a decrease in mean attack frequency from 17.58 at baseline (range, 9.83-29.33) to 9.5 (3-21.25) at 21-24 weeks with a median change of –4.08 (–11.92 to –0.25). In the 30% ONS group, the mean attack frequency decreased from 15 (9.25 to 22.33) to 6.75 (1.5-16.5) with a median change of –6.5 (–10.83 to –0.08).

At weeks 21-24, the difference in median weekly mean attack frequency between the groups was –2.42 (–5.17 to 3.33).

The authors stated that, in both groups, ONS was “safe and well tolerated.” A total of 129 adverse events were reported in the 100% ONS group and 95 in the 30% ONS group, of which 17 and 9 were considered serious, respectively. The serious adverse events required a short hospital stay to resolve minor hardware issues. The adverse events most frequently observed were local pain, impaired wound healing, neck stiffness, and hardware damage.

Low intensity stimulation may be best

“The main limitation of the study comes from the difficulty in defining the electrical dose, which was not constant across patients within each group, but individually adjusted depending on the perception of the ONS-induced paraesthesia,” Denys Fontaine, MD, and Michel Lanteri-Minet, MD, both from Université Cote D’Azur in France, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

Given that the primary outcome did not differ significantly between the treatment groups, the editorialists stated that “the lowest stimulation intensity that induces paraesthesia is sufficient to obtain an effect in the patients who respond. Increasing the electrical dose or intensity does not seem to bring better efficacy and might even induce discomfort (painful paraesthesia or shock-like sensations) that might substantially reduce the tolerance of this approach.”

While the trial did not provide convincing evidence of high intensity ONS in medically intractable chronic cluster headache, the editorialists are otherwise optimistic about the findings: “… considering the significant difference between baseline and the end of the randomised stimulation phase in both groups (about half of the patients showed a 50% decrease in attack frequency), the findings of this study support the favourable results of previous real-world studies, and indicate that a substantial proportion of patients with intractable chronic cluster headache, although not all, could have their condition substantially improved by ONS.” Dr. Fontaine and Dr. Lanteri-Minet added that they hope that “these data will help health authorities to recognise the efficacy of ONS and consider its approval for use in patients with intractable chronic cluster headache.”

Priorities for future research in this area should “focus on optimising stimulation protocols and disentangling the underlying mechanism of action,” Dr. Wilbrink and colleagues wrote.

The study was funded by the Spinoza 2009 Lifetime Scientific Research Achievement Premium, the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research, the Dutch Ministry of Health (as part of a national provisional reimbursement program for promising new treatments), the NutsOhra Foundation from the Dutch Health Insurance Companies, and an unrestricted grant from Medtronic, all to Dr. Ferrari.

FROM LANCET NEUROLOGY

Hand ulceration

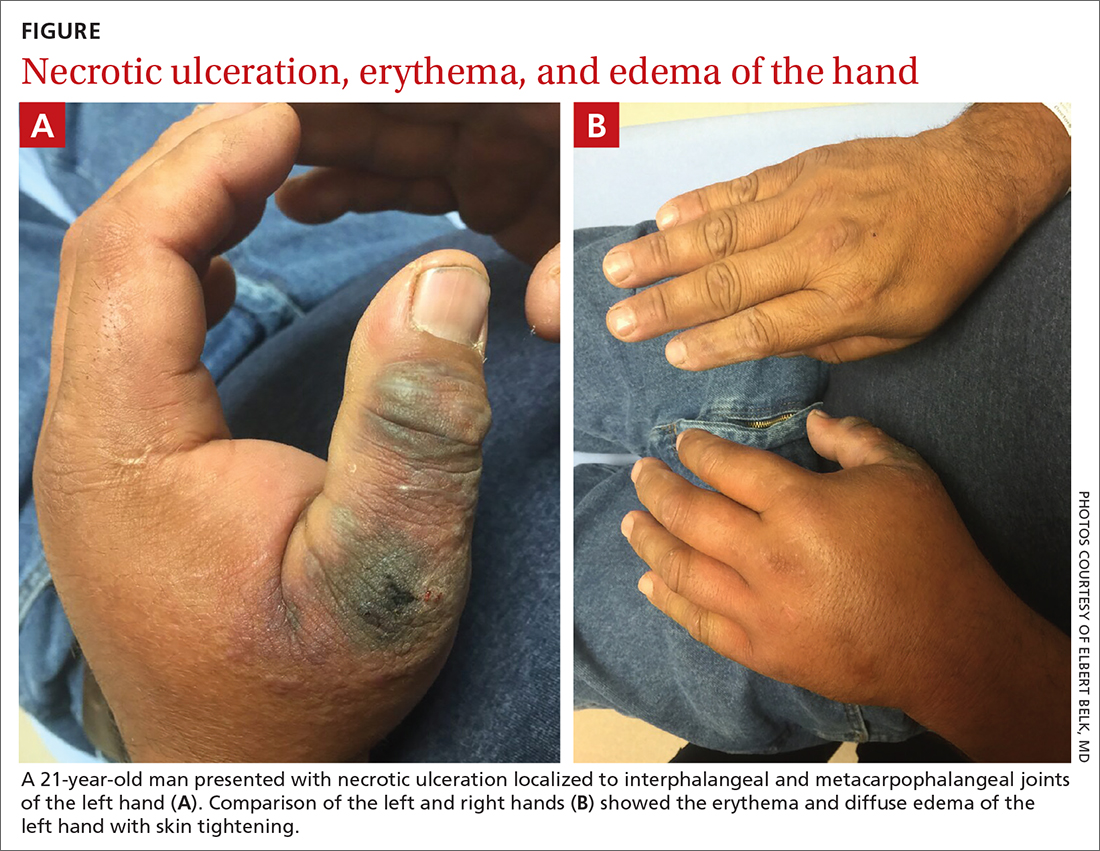

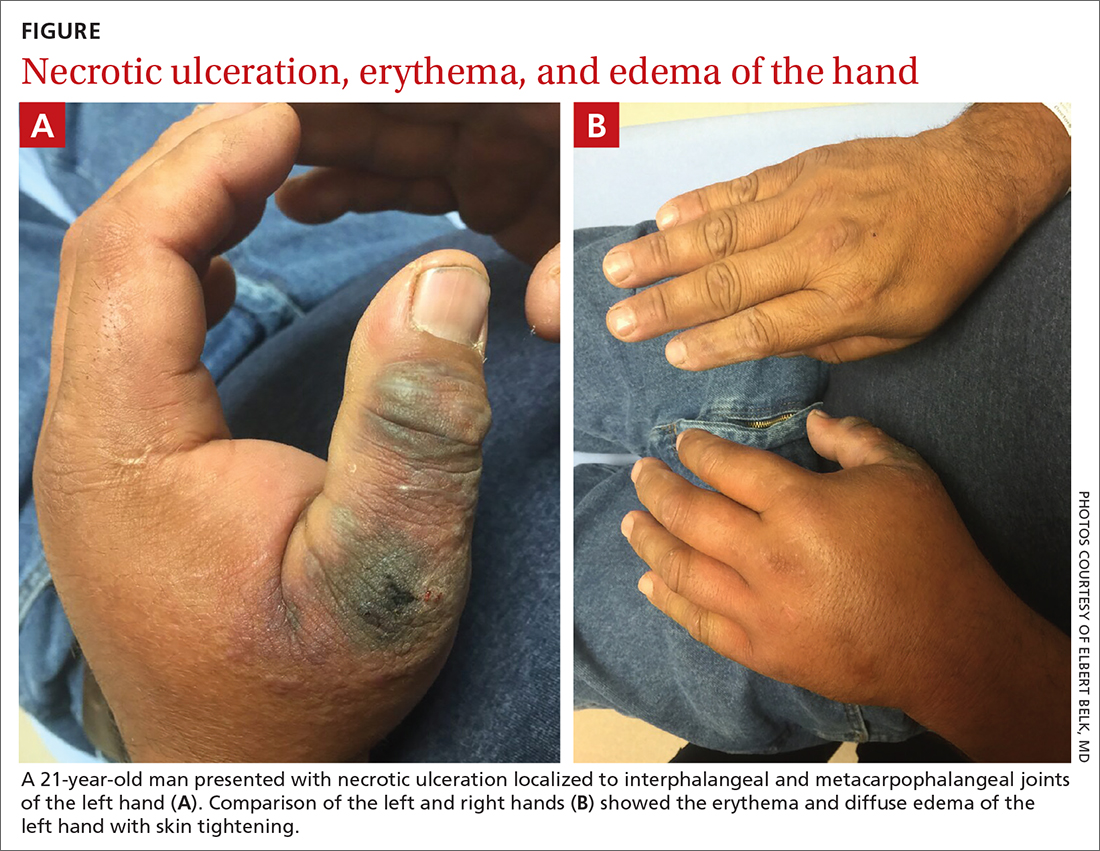

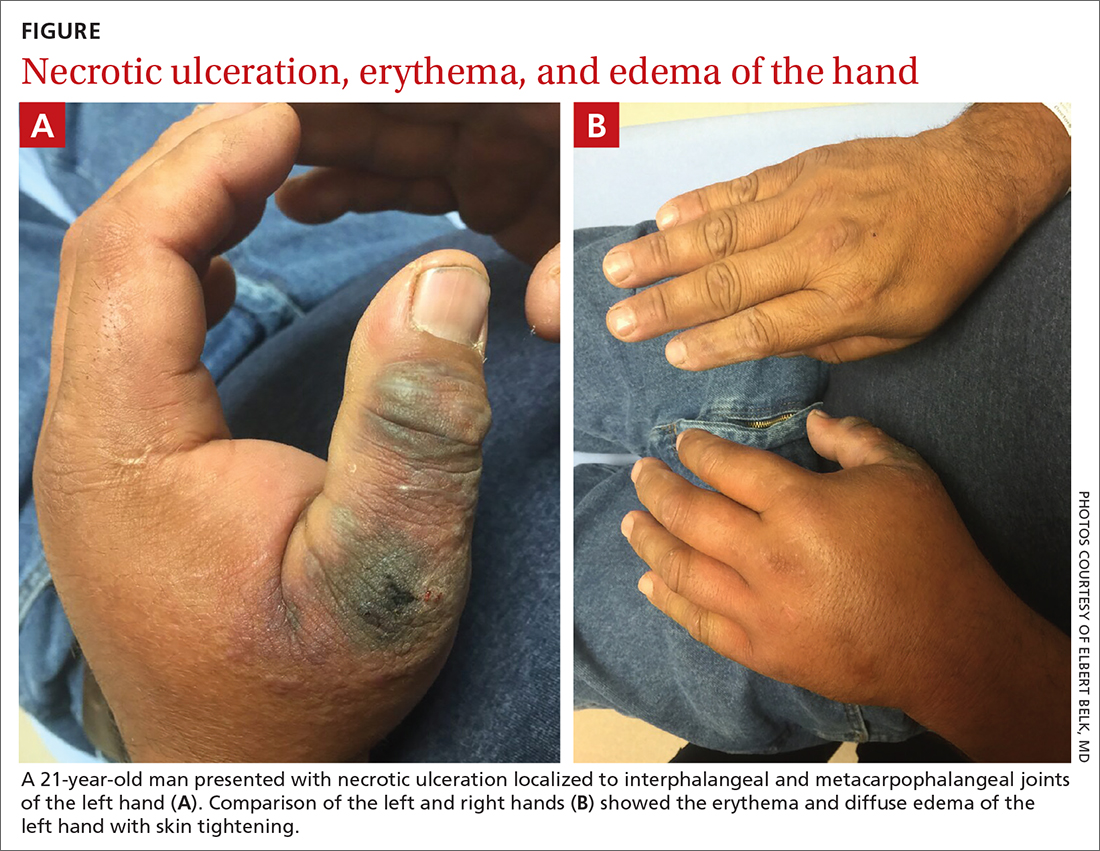

A 45-year-old man presented to a south Texas emergency department with a red, tender, edematous left hand. Earlier that day, he had been working in an oil field when his hand suddenly began to hurt.

On physical exam, puncture wounds were visible at the metacarpophalangeal joint of the thumb and the interphalangeal joint, dorsal aspect; the area was surrounded by necrotic black tissue (FIGURE). Additionally, erythema with extensive edema extended distally to the proximal interphalangeal joints of each digit. Upon palpation, the area was warm, firm, and tender, with the edema tracking proximally to his mid-forearm.

The patient had a temperature of 99.5 °F; his other vital signs were normal. His past medical history included hypertension.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Cellulitis, compartment syndrome by scorpion sting

Based on the necrotic puncture wounds, unilateral distribution of the swelling, and the patient’s acknowledgement that he’d seen a scorpion in his work environment prior to symptom onset, he was given a diagnosis of cellulitis with secondary compartment syndrome following a scorpion sting.

A geographic problem

In the United States, there are approximately 17,000 reported cases of scorpion stings every year, with fewer than 11 related deaths reported between 1999 and 2014.1 These cases tend to follow a geographic distribution along the American Southwest, with the highest incidence occurring in Arizona, followed by Texas; the majority of cases occur during the summer months.1

The most clinically relevant scorpion in the United States is the Centruroides sculpturatus, also known as the Arizona bark scorpion.2Centruroides spp can be recognized by a slender, yellow to light brown or tan body measuring 1.3 cm to 7.6 cm in length. There is a tubercule at the base of the stringer, a defining characteristic of the species.3

Urgent care is necessary for more severe symptoms

The most common complaint following a scorpion sting tends to be pain (88.7%), followed by numbness, edema, and erythema.1 Other signs and symptoms include muscle spasms, hypertension, and salivation. Symptoms can persist for 10 to 48 hours. Cardiovascular collapse and disseminated intravascular coagulation are 2 potentially fatal complications of a scorpion sting.

The diagnosis is made clinically based on history and physical exam findings; a complete blood count, coagulation panel, and creatine kinase and amylase/lipase bloodwork may be ordered to assess for end-organ complications. Local serious complications, such as compartment syndrome, should be urgently referred for surgical management.

Continue to: Signs of compartment syndrome...

Signs of compartment syndrome include tense, swollen compartments and pain with passive stretching of muscles within the compartment. Rapid progression of symptoms, as seen in this case, is also a red flag.

Differential diagnosis includes necrotizing fasciitis

The differential diagnosis includes uncomplicated cellulitis, as well as necrotizing fasciitis and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) cellulitis.

Necrotizing fasciitis. The lack of subcutaneous crackles and pain that is out of proportion to touch, as well as relatively normal vital signs, ruled out a diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis in this case.

Community-acquired MRSA is seen with purulent cellulitis. However, this patient had no purulent discharge.

Antivenom is only needed for severe cases

Treatment is primarily supportive; all patients should have the wound thoroughly cleaned, and pain can be controlled using nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or opioid therapy.2 Tetanus prophylaxis should be given. The Centruroides antivenom, Anascorp, should be considered for patients with severe symptoms, including loss of muscle control, roving or abnormal eye movements, slurred speech, respiratory distress, excessive salivation, frothing at the mouth, and vomiting.4 In most cases, local poison control centers should be consulted for advice on management and to answer questions about antivenom availability.

Our patient was admitted to the hospital and an urgent surgery consult was obtained. The surgeon performed a fasciotomy to treat the compartment syndrome, and the patient survived without loss of his hand or arm.

1. Kang AM, Brooks DE. Nationwide scorpion exposures reported to US poison control centers from 2005 to 2015. J Med Toxicol. 2017;13:158-165. doi: 10.1007/s13181-016-0594-0

2. Barish RA, Arnold T. Scorpion Stings. Merck Manual. Updated April 2020. Accessed June 26, 2021. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/injuries-poisoning/bites-and-stings/scorpion-stings

3. González-Santillán E, Possani LD. North American scorpion species of public health importance with reappraisal of historical epidemiology. Acta Trop. 2018;187:264-274. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2018.08.002

4. Anascorp. Package insert. Accredo Health Group, Inc; 2011.

A 45-year-old man presented to a south Texas emergency department with a red, tender, edematous left hand. Earlier that day, he had been working in an oil field when his hand suddenly began to hurt.

On physical exam, puncture wounds were visible at the metacarpophalangeal joint of the thumb and the interphalangeal joint, dorsal aspect; the area was surrounded by necrotic black tissue (FIGURE). Additionally, erythema with extensive edema extended distally to the proximal interphalangeal joints of each digit. Upon palpation, the area was warm, firm, and tender, with the edema tracking proximally to his mid-forearm.

The patient had a temperature of 99.5 °F; his other vital signs were normal. His past medical history included hypertension.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Cellulitis, compartment syndrome by scorpion sting

Based on the necrotic puncture wounds, unilateral distribution of the swelling, and the patient’s acknowledgement that he’d seen a scorpion in his work environment prior to symptom onset, he was given a diagnosis of cellulitis with secondary compartment syndrome following a scorpion sting.

A geographic problem

In the United States, there are approximately 17,000 reported cases of scorpion stings every year, with fewer than 11 related deaths reported between 1999 and 2014.1 These cases tend to follow a geographic distribution along the American Southwest, with the highest incidence occurring in Arizona, followed by Texas; the majority of cases occur during the summer months.1

The most clinically relevant scorpion in the United States is the Centruroides sculpturatus, also known as the Arizona bark scorpion.2Centruroides spp can be recognized by a slender, yellow to light brown or tan body measuring 1.3 cm to 7.6 cm in length. There is a tubercule at the base of the stringer, a defining characteristic of the species.3

Urgent care is necessary for more severe symptoms

The most common complaint following a scorpion sting tends to be pain (88.7%), followed by numbness, edema, and erythema.1 Other signs and symptoms include muscle spasms, hypertension, and salivation. Symptoms can persist for 10 to 48 hours. Cardiovascular collapse and disseminated intravascular coagulation are 2 potentially fatal complications of a scorpion sting.

The diagnosis is made clinically based on history and physical exam findings; a complete blood count, coagulation panel, and creatine kinase and amylase/lipase bloodwork may be ordered to assess for end-organ complications. Local serious complications, such as compartment syndrome, should be urgently referred for surgical management.

Continue to: Signs of compartment syndrome...

Signs of compartment syndrome include tense, swollen compartments and pain with passive stretching of muscles within the compartment. Rapid progression of symptoms, as seen in this case, is also a red flag.

Differential diagnosis includes necrotizing fasciitis

The differential diagnosis includes uncomplicated cellulitis, as well as necrotizing fasciitis and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) cellulitis.

Necrotizing fasciitis. The lack of subcutaneous crackles and pain that is out of proportion to touch, as well as relatively normal vital signs, ruled out a diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis in this case.

Community-acquired MRSA is seen with purulent cellulitis. However, this patient had no purulent discharge.

Antivenom is only needed for severe cases

Treatment is primarily supportive; all patients should have the wound thoroughly cleaned, and pain can be controlled using nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or opioid therapy.2 Tetanus prophylaxis should be given. The Centruroides antivenom, Anascorp, should be considered for patients with severe symptoms, including loss of muscle control, roving or abnormal eye movements, slurred speech, respiratory distress, excessive salivation, frothing at the mouth, and vomiting.4 In most cases, local poison control centers should be consulted for advice on management and to answer questions about antivenom availability.

Our patient was admitted to the hospital and an urgent surgery consult was obtained. The surgeon performed a fasciotomy to treat the compartment syndrome, and the patient survived without loss of his hand or arm.

A 45-year-old man presented to a south Texas emergency department with a red, tender, edematous left hand. Earlier that day, he had been working in an oil field when his hand suddenly began to hurt.

On physical exam, puncture wounds were visible at the metacarpophalangeal joint of the thumb and the interphalangeal joint, dorsal aspect; the area was surrounded by necrotic black tissue (FIGURE). Additionally, erythema with extensive edema extended distally to the proximal interphalangeal joints of each digit. Upon palpation, the area was warm, firm, and tender, with the edema tracking proximally to his mid-forearm.

The patient had a temperature of 99.5 °F; his other vital signs were normal. His past medical history included hypertension.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Cellulitis, compartment syndrome by scorpion sting

Based on the necrotic puncture wounds, unilateral distribution of the swelling, and the patient’s acknowledgement that he’d seen a scorpion in his work environment prior to symptom onset, he was given a diagnosis of cellulitis with secondary compartment syndrome following a scorpion sting.

A geographic problem

In the United States, there are approximately 17,000 reported cases of scorpion stings every year, with fewer than 11 related deaths reported between 1999 and 2014.1 These cases tend to follow a geographic distribution along the American Southwest, with the highest incidence occurring in Arizona, followed by Texas; the majority of cases occur during the summer months.1

The most clinically relevant scorpion in the United States is the Centruroides sculpturatus, also known as the Arizona bark scorpion.2Centruroides spp can be recognized by a slender, yellow to light brown or tan body measuring 1.3 cm to 7.6 cm in length. There is a tubercule at the base of the stringer, a defining characteristic of the species.3

Urgent care is necessary for more severe symptoms

The most common complaint following a scorpion sting tends to be pain (88.7%), followed by numbness, edema, and erythema.1 Other signs and symptoms include muscle spasms, hypertension, and salivation. Symptoms can persist for 10 to 48 hours. Cardiovascular collapse and disseminated intravascular coagulation are 2 potentially fatal complications of a scorpion sting.

The diagnosis is made clinically based on history and physical exam findings; a complete blood count, coagulation panel, and creatine kinase and amylase/lipase bloodwork may be ordered to assess for end-organ complications. Local serious complications, such as compartment syndrome, should be urgently referred for surgical management.

Continue to: Signs of compartment syndrome...

Signs of compartment syndrome include tense, swollen compartments and pain with passive stretching of muscles within the compartment. Rapid progression of symptoms, as seen in this case, is also a red flag.

Differential diagnosis includes necrotizing fasciitis

The differential diagnosis includes uncomplicated cellulitis, as well as necrotizing fasciitis and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) cellulitis.

Necrotizing fasciitis. The lack of subcutaneous crackles and pain that is out of proportion to touch, as well as relatively normal vital signs, ruled out a diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis in this case.

Community-acquired MRSA is seen with purulent cellulitis. However, this patient had no purulent discharge.

Antivenom is only needed for severe cases

Treatment is primarily supportive; all patients should have the wound thoroughly cleaned, and pain can be controlled using nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or opioid therapy.2 Tetanus prophylaxis should be given. The Centruroides antivenom, Anascorp, should be considered for patients with severe symptoms, including loss of muscle control, roving or abnormal eye movements, slurred speech, respiratory distress, excessive salivation, frothing at the mouth, and vomiting.4 In most cases, local poison control centers should be consulted for advice on management and to answer questions about antivenom availability.

Our patient was admitted to the hospital and an urgent surgery consult was obtained. The surgeon performed a fasciotomy to treat the compartment syndrome, and the patient survived without loss of his hand or arm.

1. Kang AM, Brooks DE. Nationwide scorpion exposures reported to US poison control centers from 2005 to 2015. J Med Toxicol. 2017;13:158-165. doi: 10.1007/s13181-016-0594-0

2. Barish RA, Arnold T. Scorpion Stings. Merck Manual. Updated April 2020. Accessed June 26, 2021. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/injuries-poisoning/bites-and-stings/scorpion-stings

3. González-Santillán E, Possani LD. North American scorpion species of public health importance with reappraisal of historical epidemiology. Acta Trop. 2018;187:264-274. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2018.08.002

4. Anascorp. Package insert. Accredo Health Group, Inc; 2011.

1. Kang AM, Brooks DE. Nationwide scorpion exposures reported to US poison control centers from 2005 to 2015. J Med Toxicol. 2017;13:158-165. doi: 10.1007/s13181-016-0594-0

2. Barish RA, Arnold T. Scorpion Stings. Merck Manual. Updated April 2020. Accessed June 26, 2021. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/injuries-poisoning/bites-and-stings/scorpion-stings

3. González-Santillán E, Possani LD. North American scorpion species of public health importance with reappraisal of historical epidemiology. Acta Trop. 2018;187:264-274. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2018.08.002

4. Anascorp. Package insert. Accredo Health Group, Inc; 2011.

Moving patients beyond injury and back to work

This month, JFP tackles a topic—work disability—that might, at first, seem a bit outside our usual wheelhouse of clinical review articles. Work disability is, however, a very important topic. The authors point out that “... primary care clinicians are asked to provide guidance about work activities in nearly 10% of their patient encounters; however, 25% of those clinicians thought they had little influence over work disability outcomes.” This statement suggests that we need to learn more about managing work-related disability and how to influence patients’ outcomes in a positive manner.

I suspect that we tend to be pessimistic about our ability to influence patient outcomes because we are uncertain about the best course of action. The authors of this article provide excellent information about how we can—and should—help ill and injured patients return to work.

As I read the article, I reflected on my own experience providing patients with advice about returning to work. Two points, in particular, struck a chord with me.

1. Many factors in the process are beyond our control. The physician’s role in helping patients return to work after an injury or illness is limited. The authors remind us that there are many patient and employer factors that are beyond our control and that influence patients’ successful return to work. Patient factors include motivation, mental health, and job satisfaction. Employer factors include job flexibility and disability benefits and policies. And of course, there are system factors that include laws governing work-related disability.

2. Our role, while limited, is important. By putting forth a positive attitude toward recovery and providing encouragement to patients, we can facilitate an earlier return to work.

I am cognizant of the pivotal role we can play with back injuries, a frequent cause of work disability. A great deal of excellent research over the past 20 years guides us regarding treatment and prognosis. Most back injuries are due to musculoskeletal injury and improve quickly during the first week, no matter what the therapy. By steering these patients clear of narcotics, telling them to remain as physically active as their pain will allow, and letting them know they will recover, we can pave the way for an early return to work.

Let us all take full advantage, then, of these important conversations with our patients. Armed with the strategies in this month’s article, we can increase the likelihood of our patients’ success.

This month, JFP tackles a topic—work disability—that might, at first, seem a bit outside our usual wheelhouse of clinical review articles. Work disability is, however, a very important topic. The authors point out that “... primary care clinicians are asked to provide guidance about work activities in nearly 10% of their patient encounters; however, 25% of those clinicians thought they had little influence over work disability outcomes.” This statement suggests that we need to learn more about managing work-related disability and how to influence patients’ outcomes in a positive manner.

I suspect that we tend to be pessimistic about our ability to influence patient outcomes because we are uncertain about the best course of action. The authors of this article provide excellent information about how we can—and should—help ill and injured patients return to work.

As I read the article, I reflected on my own experience providing patients with advice about returning to work. Two points, in particular, struck a chord with me.

1. Many factors in the process are beyond our control. The physician’s role in helping patients return to work after an injury or illness is limited. The authors remind us that there are many patient and employer factors that are beyond our control and that influence patients’ successful return to work. Patient factors include motivation, mental health, and job satisfaction. Employer factors include job flexibility and disability benefits and policies. And of course, there are system factors that include laws governing work-related disability.

2. Our role, while limited, is important. By putting forth a positive attitude toward recovery and providing encouragement to patients, we can facilitate an earlier return to work.

I am cognizant of the pivotal role we can play with back injuries, a frequent cause of work disability. A great deal of excellent research over the past 20 years guides us regarding treatment and prognosis. Most back injuries are due to musculoskeletal injury and improve quickly during the first week, no matter what the therapy. By steering these patients clear of narcotics, telling them to remain as physically active as their pain will allow, and letting them know they will recover, we can pave the way for an early return to work.

Let us all take full advantage, then, of these important conversations with our patients. Armed with the strategies in this month’s article, we can increase the likelihood of our patients’ success.

This month, JFP tackles a topic—work disability—that might, at first, seem a bit outside our usual wheelhouse of clinical review articles. Work disability is, however, a very important topic. The authors point out that “... primary care clinicians are asked to provide guidance about work activities in nearly 10% of their patient encounters; however, 25% of those clinicians thought they had little influence over work disability outcomes.” This statement suggests that we need to learn more about managing work-related disability and how to influence patients’ outcomes in a positive manner.

I suspect that we tend to be pessimistic about our ability to influence patient outcomes because we are uncertain about the best course of action. The authors of this article provide excellent information about how we can—and should—help ill and injured patients return to work.

As I read the article, I reflected on my own experience providing patients with advice about returning to work. Two points, in particular, struck a chord with me.

1. Many factors in the process are beyond our control. The physician’s role in helping patients return to work after an injury or illness is limited. The authors remind us that there are many patient and employer factors that are beyond our control and that influence patients’ successful return to work. Patient factors include motivation, mental health, and job satisfaction. Employer factors include job flexibility and disability benefits and policies. And of course, there are system factors that include laws governing work-related disability.

2. Our role, while limited, is important. By putting forth a positive attitude toward recovery and providing encouragement to patients, we can facilitate an earlier return to work.

I am cognizant of the pivotal role we can play with back injuries, a frequent cause of work disability. A great deal of excellent research over the past 20 years guides us regarding treatment and prognosis. Most back injuries are due to musculoskeletal injury and improve quickly during the first week, no matter what the therapy. By steering these patients clear of narcotics, telling them to remain as physically active as their pain will allow, and letting them know they will recover, we can pave the way for an early return to work.

Let us all take full advantage, then, of these important conversations with our patients. Armed with the strategies in this month’s article, we can increase the likelihood of our patients’ success.

Managing work disability to help patients return to the job

All clinicians who have patients who are employed play an essential role in work disability programs—whether or not those clinicians have received formal training in occupational health. A study found that primary care clinicians are asked to provide guidance about work activities in nearly 10% of their patient encounters; however, 25% of those clinicians thought they had little influence over work disability outcomes.1

In this article, we explain why it is important for family physicians to better manage work disability at the point of care, to help patients return to their pre-injury or pre-illness level of activity.

Why managing the duration of work disability matters

Each year, millions of American workers leave their jobs—temporarily or permanently—because of illness, injury, or the effects of a chronic condition.2 It is estimated that 893 million workdays are lost annually due to a new medical problem; an additional 527 million workdays are lost due to the impact of chronic health conditions on the ability to perform at work.3 The great majority of these lost workdays are the result of personal health conditions, not work-related problems; patients must therefore cope with the accompanying disruption of life and work.

Significant injury and illness can create a life crisis, especially when there is uncertainty about future livelihood, such as an income shortfall during a lengthy recovery. Only 40% of the US workforce is covered by a short-term disability insurance program; only 10% of low-wage and low-skill workers have this type of coverage.4 Benefits rarely replace loss of income entirely, and worker compensation insurance programs provide only partial wage replacement.

In short, work disability is destabilizing and can threaten overall well-being.5

Furthermore, the longer a person remains on temporary disability, the more likely that person is to move to a publicly funded disability program or leave the workforce entirely—thus, potentially losing future earnings and self-identity related to being a working member of society.6-8

Most of the annual cost of poor health for US employers derives from medical and wage benefits ($226 billion) and impaired or reduced employee performance ($223 billion).3 In addition, temporarily disabled workers likely account for a disproportionate share of health care costs: A study found that one-half of medical and pharmacy payments were paid out to the one-quarter of employees requiring disability benefits.9

Continue to: Benefits of staying on the job

Benefits of staying on the job. Research shows that there are physical and mental health benefits to remaining at, or returning to, work after an injury or illness.10,11 For example, in a longitudinal cohort of people with low back pain, immediate or early return to work (in 1-7 days) was associated with reduced pain and improved functioning at 3 months.12 Physicians who can guide patients safely back to normal activities, including work, minimize the physical and mental health impact of the injury or illness and avoid chronicity.13

Emphasizing the importance of health, not disease or injury

Health researchers have found that diagnosis, cause, and extent of morbidity do not adequately explain observed variability in the impact of health conditions, utilization of resources, or need for services. A wider view of the functional implications of an injury or illness is therefore required for physicians to effectively recommend disability duration.

The World Health Organization recommends a shift toward a more holistic view of health, impairment, and disability, including an emphasis on functional ability, intrinsic capacity, and environmental context.14 The American Medical Association, American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, and Canadian Medical Association emphasize that prolonged absence from one’s normal role can be detrimental to mental, physical, and social well-being.8 These advisory groups recommend that physicians encourage patients who are unable to work to (1) focus on restoring the rhythm of their everyday life in a stepwise fashion and (2) resume their usual responsibilities as soon as possible.

Advising a patient to focus on “what you can do,” not “what you can’t do,” might make all the difference in their return to productivity. Keeping the patient’s—as well as your own—attention focused on the positive process of recovery and documenting evidence of functional progress is an important addition to (or substitute for) detailed inquiries about pain and dysfunction.

Why does duration of disability vary so much from case to case?

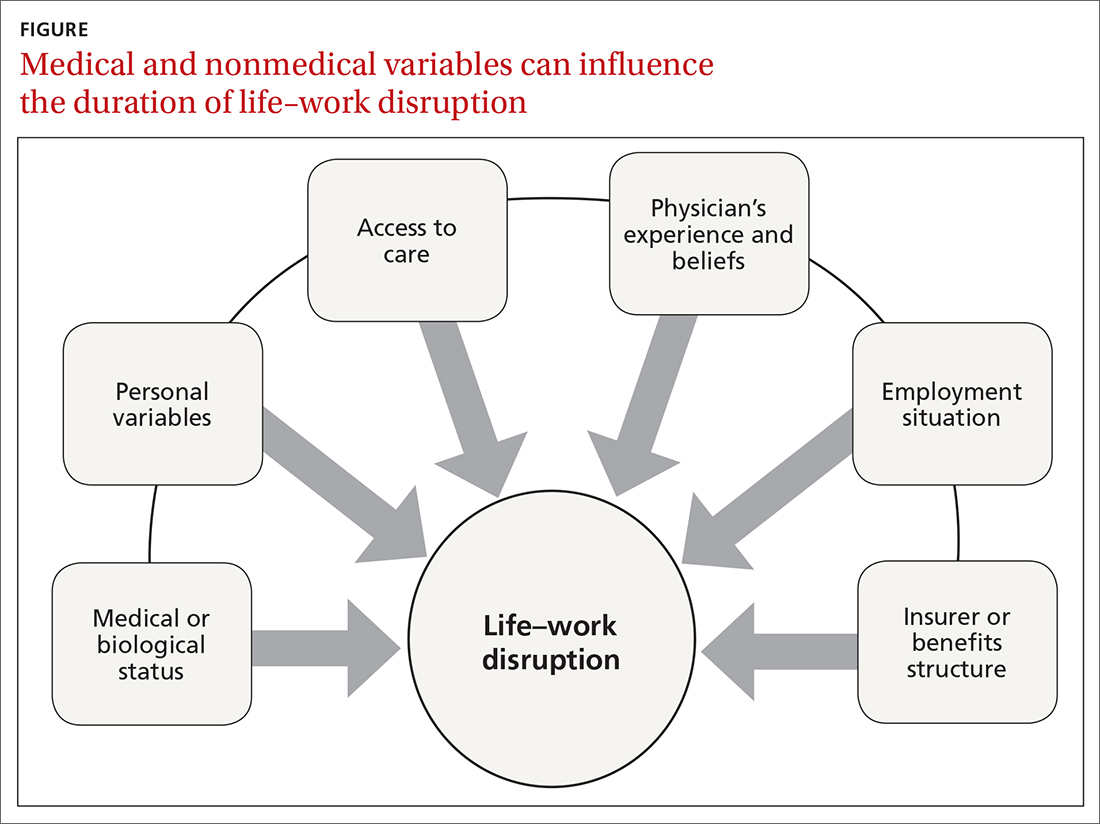

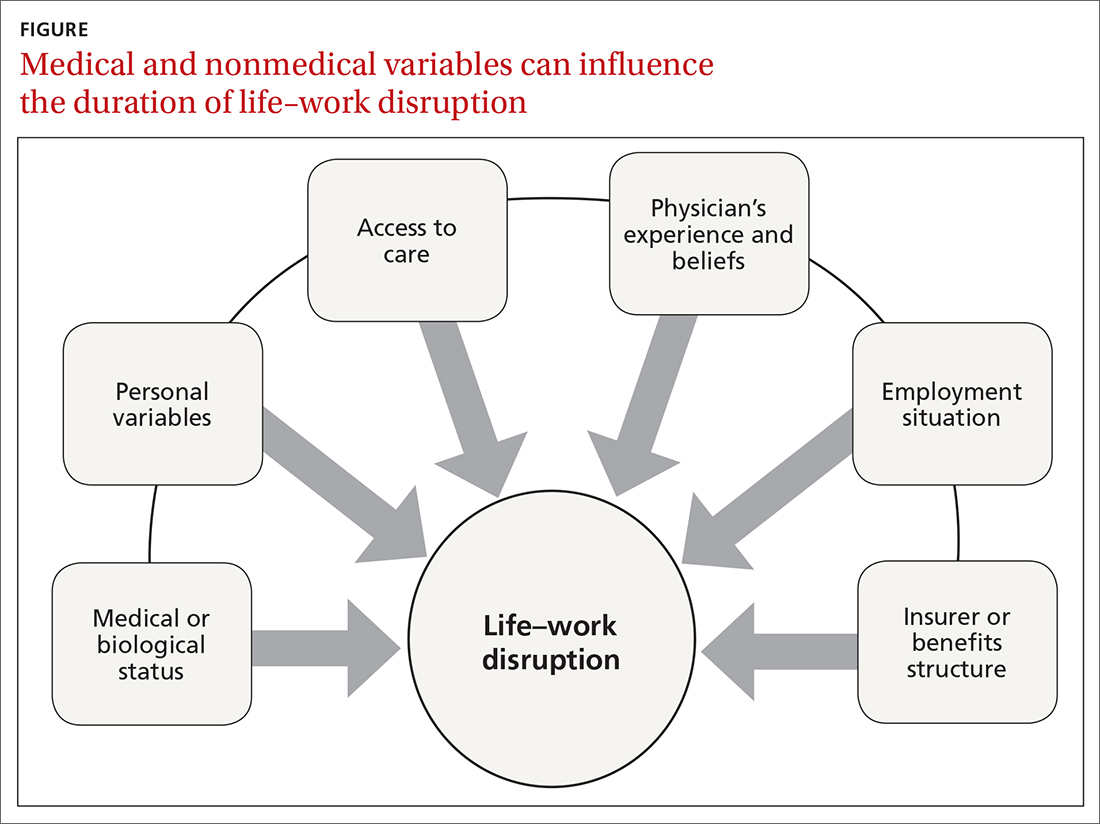

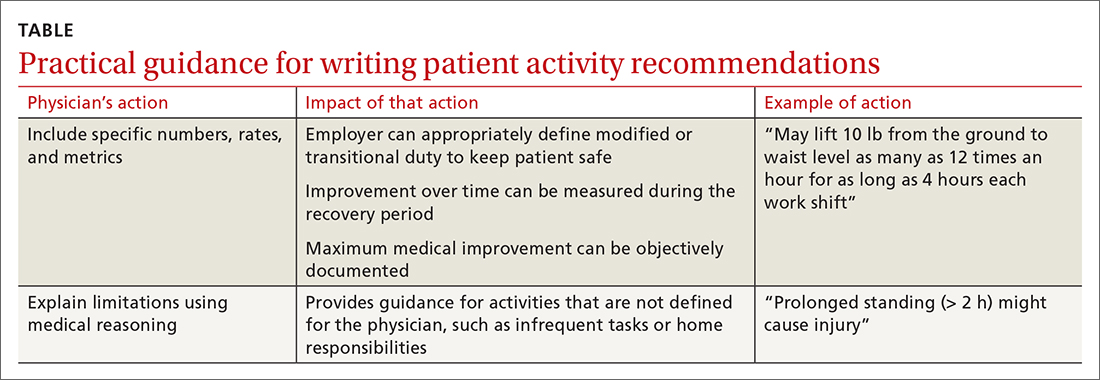

Disability duration is influenced by the individual patient, employer, physician, jurisdiction, insurer or benefits structure, and access to care.15 For you to effectively manage a patient who is out of work for a medical reason, it is important to understand how nonmedical variables often influence the pace of recovery and the timing of return to work (FIGURE).

Continue to: Deficient communication

Deficient communication. Often, employers, insurers, third-party administrators, and clinicians—each a key stakeholder in disability care—are disconnected from one another, resulting in poor communication with the injured worker. Such fragmented communication can delay treatment and recovery.16 Data systems are not designed to measure the duration of disability or provide proactive notification for key stakeholders who might intervene to facilitate a patient’s recovery.

Alternatively, a collaborative approach to disability management has been shown to improve outcomes.17,18 Communication among the various professionals involved can be coordinated and expedited by a case manager or disability manager hired by the medical practice, the employer, or the insurance company.

Psychosocial and economic influences can radically affect the time it takes to return to pre-injury or pre-illness functional status. Demographic variables (age, sex, income, education, and support system) influence how a person responds to a debilitating injury or illness.19 Fear of re-injury, anxiety over the intensity of pain upon movement, worry over dependency on others, and resiliency play an important role when a patient is attempting to return to full activity.20,21

Job satisfaction has been identified as the most significant variable associated with prompt return to work.15 Work has many health-enhancing aspects, including socioeconomic status, psychosocial support, and self-identity22; however, not everyone wants, or feels ready, to go back to work even once they are physically able. Workplace variables, such as the patient–employee’s dislike of the position, coworkers, or manager, have been cited by physicians as leading barriers to returning to work at an appropriate time.23,24

Other external variables. Physicians should formulate activity prescriptions and medical restrictions based on the impact the medical condition has on the usual ability to function, as well as the anticipated impact of specific activities on the body’s natural healing process. However, Rainville and colleagues found that external variables—patient requests, employer characteristics, and jurisdiction issues—considerably influence physicians’ recommendations.20 For example, benefit structure might influence how long a patient wants to remain out of work—thus altering the requests they make to their physician. Jurisdictional characteristics, such as health care systems, state workers’ compensation departments, and payer systems, all influence a patient’s recovery timeline and time away from work.25

Continue to: What does your patient need so that they can recover?

What does your patient need so that they can recover? Individual and systemic factors must be appropriately addressed to minimize the impact that recovery from a disability has on a person’s life. Successful functional recovery enables the person to self-manage symptoms, reduce disruption-associated stress, preserve mental health, and maintain healthy relationships at home and work. An example is the patient who has successfully coped with the entire predicament that their medical condition posed and resumed their usual daily routine and responsibilities at home and at work—albeit sometimes with temporary or permanent modification necessitated by their specific condition.

Strategies that help patients stay at, or return to, their job

Physicians who anticipate, monitor, and actively manage the duration of a work disability can improve patient outcomes by minimizing life disruption, avoiding unnecessary medical care, and shortening the period of absence from work.