User login

‘Deeper dive’ into opioid overdose deaths during COVID pandemic

Opioid overdose deaths were significantly higher during 2020, but occurrences were not homogeneous across nine states. Male deaths were higher than in the 2 previous years in two states, according to a new, granular examination of data collected by researchers at the Massachusetts General Hospital (Mass General), Boston.

The analysis also showed that synthetic opioids such as fentanyl played an outsized role in most of the states that were reviewed. Additional drugs of abuse found in decedents, such as cocaine and psychostimulants, were more prevalent in some states than in others.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention used provisional death data in its recent report. It found that opioid-related deaths substantially rose in 2020 and that synthetic opioids were a primary driver.

The current Mass General analysis provides a more timely and detailed dive, senior author Mohammad Jalali, PhD, who is a senior scientist at Mass General’s Institute for Technology Assessment, told this news organization.

The findings, which have not yet been peer reviewed, were published in MedRxiv.

Shifting sands of opioid use disorder

to analyze and project trends and also to be better prepared to address the shifting sands of opioid use disorder in the United States.

They attempted to collect data on confirmed opioid overdose deaths from all 50 states and Washington, D.C. to assess what might have changed during the COVID-19 pandemic. Only nine states provided enough data for the analysis, which has been submitted to a peer reviewed publication.

These states were Alaska, Connecticut, Indiana, Massachusetts, North Carolina, Rhode Island, Colorado, Utah, and Wyoming.

“Drug overdose data are collected and reported more slowly than COVID-19 data,” Dr. Jalali said in a press release. The data reflected a lag time of about 4 to 8 months in Massachusetts and North Carolina to more than a year in Maryland and Ohio, he noted.

The reporting lag “has clouded the understanding of the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on opioid-related overdose deaths,” said Dr. Jalali.

Commenting on the findings, Brandon Marshall, PhD, associate professor of epidemiology at Brown University, Providence, R.I, said that “the overall pattern of what’s being reported here is not surprising,” given the national trends seen in the CDC data.

“This paper adds a deeper dive into some of the sociodemographic trends that we’re starting to observe in specific states,” Dr. Marshall said.

Also commenting for this news organization, Brian Fuehrlein, MD, PhD, director of the psychiatric emergency department at the VA Connecticut Healthcare System in West Haven, Connecticut, noted that the current study “highlights things that we are currently seeing at VA Connecticut.”

Decrease in heroin, rise in fentanyl

The investigators found a significant reduction in overdose deaths that involved heroin in Alaska, Connecticut, Indiana, Massachusetts, North Carolina, and Rhode Island. That was a new trend for Alaska, Indiana, and Rhode Island, although with only 3 years of data, it’s hard to say whether it will continue, Dr. Jalali noted.

The decrease in heroin involvement seemed to continue a trend previously observed in Colorado, Connecticut, Massachusetts, and North Carolina.

In Connecticut, heroin was involved in 36% of deaths in 2018, 30% in 2019, and 16% in 2020, according to the study.

“We have begun seeing more and more heroin-negative, fentanyl-positive drug screens,” said Dr. Fuehrlein, who is also associate professor of psychiatry at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

“There is a shift from fentanyl being an adulterant to fentanyl being what is sold and used exclusively,” he added.

In 2020, 92% (n = 887) of deaths in Connecticut involved synthetic opioids, continuing a trend. In Alaska, however, synthetic opioids were involved in 60% (44) of deaths, which is a big jump from 23% (9) in 2018.

Synthetic opioids were involved in the largest percentage of overdoses in all of the states studied. The fewest deaths, 17 (49%), occurred in Wyoming.

Cocaine is also increasingly found in addition to other substances in decedents. In Alaska, about 14% of individuals who overdosed in 2020 also had cocaine in their system, which was a jump from 2% in the prior year.

In Colorado, 19% (94) of those who died also had taken cocaine, up from 13% in 2019. Cocaine was also frequently found in those who died in the northeast: 39% (467) of those who died in Massachusetts, 29% (280) in Connecticut, and 47% (109) in Rhode Island.

There was also an increase in psychostimulants found in those who had died in Massachusetts in 2020.

More male overdoses in 2020

Results also showed that, compared to 2019, significantly more men died from overdoses in 2020 in Colorado (61% vs. 70%, P = .017) and Indiana (62% vs. 70%, P = .026).

This finding was unexpected, said Dr. Marshall, who has observed the same phenomenon in Rhode Island. He is the scientific director of PreventOverdoseRI, Rhode Island’s drug overdose surveillance and information dashboard.

Dr. Marshall and his colleagues conducted a study that also found disproportionate increases in overdoses among men. The findings of that study will be published in September.

“We’re still trying to wrap our head around why that is,” he said. He added that a deeper dive into the Rhode Island data showed that the deaths were increased especially among middle-aged men who had been diagnosed with depression and anxiety.

The same patterns were not seen among women in either Dr. Jalali’s study or his own analysis of the Rhode Island data, said Dr. Marshall.

“That suggests the COVID-19 pandemic impacted men who are at risk for overdose in some particularly severe way,” he noted.

Dr. Fuehrlein said he believes a variety of factors have led to an increase in overdose deaths during the pandemic, including the fact that many patients who would normally seek help avoided care or dropped out of treatment because of COVID fears. In addition, other support systems, such as group therapy and Narcotics Anonymous, were unavailable.

The pandemic increased stress, which can lead to worsening substance use, said Dr. Fuehrlein. He also noted that regular opioid suppliers were often not available, which led some to buy from different dealers, “which can lead to overdose if the fentanyl content is different.”

Identifying at-risk individuals

Dr. Jalali and colleagues note that clinicians and policymakers could use the new study to help identify and treat at-risk individuals.

“Practitioners and policy makers can use our findings to help them anticipate which groups of people might be most affected by opioid overdose and which types of policy interventions might be most effective given each state’s unique situation,” said lead study author Gian-Gabriel P. Garcia, PhD, in a press release. At the time of the study, Dr. Garcia was a postdoctoral fellow at Mass General and Harvard Medical School. He is currently an assistant professor at Georgia Tech, Atlanta.

Dr. Marshall pointed out that Dr. Jalali’s study is also relevant for emergency departments.

ED clinicians “are and will be seeing patients coming in who have no idea they were exposed to an opioid, nevermind fentanyl,” he said. ED clinicians can discuss with patients various harm reduction techniques, including the use of naloxone as well as test strips that can detect fentanyl in the drug supply, he added.

“Given the increasing use of fentanyl, which is very dangerous in overdose, clinicians need to be well versed in a harm reduction/overdose prevention approach to patient care,” Dr. Fuehrlein agreed.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Opioid overdose deaths were significantly higher during 2020, but occurrences were not homogeneous across nine states. Male deaths were higher than in the 2 previous years in two states, according to a new, granular examination of data collected by researchers at the Massachusetts General Hospital (Mass General), Boston.

The analysis also showed that synthetic opioids such as fentanyl played an outsized role in most of the states that were reviewed. Additional drugs of abuse found in decedents, such as cocaine and psychostimulants, were more prevalent in some states than in others.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention used provisional death data in its recent report. It found that opioid-related deaths substantially rose in 2020 and that synthetic opioids were a primary driver.

The current Mass General analysis provides a more timely and detailed dive, senior author Mohammad Jalali, PhD, who is a senior scientist at Mass General’s Institute for Technology Assessment, told this news organization.

The findings, which have not yet been peer reviewed, were published in MedRxiv.

Shifting sands of opioid use disorder

to analyze and project trends and also to be better prepared to address the shifting sands of opioid use disorder in the United States.

They attempted to collect data on confirmed opioid overdose deaths from all 50 states and Washington, D.C. to assess what might have changed during the COVID-19 pandemic. Only nine states provided enough data for the analysis, which has been submitted to a peer reviewed publication.

These states were Alaska, Connecticut, Indiana, Massachusetts, North Carolina, Rhode Island, Colorado, Utah, and Wyoming.

“Drug overdose data are collected and reported more slowly than COVID-19 data,” Dr. Jalali said in a press release. The data reflected a lag time of about 4 to 8 months in Massachusetts and North Carolina to more than a year in Maryland and Ohio, he noted.

The reporting lag “has clouded the understanding of the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on opioid-related overdose deaths,” said Dr. Jalali.

Commenting on the findings, Brandon Marshall, PhD, associate professor of epidemiology at Brown University, Providence, R.I, said that “the overall pattern of what’s being reported here is not surprising,” given the national trends seen in the CDC data.

“This paper adds a deeper dive into some of the sociodemographic trends that we’re starting to observe in specific states,” Dr. Marshall said.

Also commenting for this news organization, Brian Fuehrlein, MD, PhD, director of the psychiatric emergency department at the VA Connecticut Healthcare System in West Haven, Connecticut, noted that the current study “highlights things that we are currently seeing at VA Connecticut.”

Decrease in heroin, rise in fentanyl

The investigators found a significant reduction in overdose deaths that involved heroin in Alaska, Connecticut, Indiana, Massachusetts, North Carolina, and Rhode Island. That was a new trend for Alaska, Indiana, and Rhode Island, although with only 3 years of data, it’s hard to say whether it will continue, Dr. Jalali noted.

The decrease in heroin involvement seemed to continue a trend previously observed in Colorado, Connecticut, Massachusetts, and North Carolina.

In Connecticut, heroin was involved in 36% of deaths in 2018, 30% in 2019, and 16% in 2020, according to the study.

“We have begun seeing more and more heroin-negative, fentanyl-positive drug screens,” said Dr. Fuehrlein, who is also associate professor of psychiatry at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

“There is a shift from fentanyl being an adulterant to fentanyl being what is sold and used exclusively,” he added.

In 2020, 92% (n = 887) of deaths in Connecticut involved synthetic opioids, continuing a trend. In Alaska, however, synthetic opioids were involved in 60% (44) of deaths, which is a big jump from 23% (9) in 2018.

Synthetic opioids were involved in the largest percentage of overdoses in all of the states studied. The fewest deaths, 17 (49%), occurred in Wyoming.

Cocaine is also increasingly found in addition to other substances in decedents. In Alaska, about 14% of individuals who overdosed in 2020 also had cocaine in their system, which was a jump from 2% in the prior year.

In Colorado, 19% (94) of those who died also had taken cocaine, up from 13% in 2019. Cocaine was also frequently found in those who died in the northeast: 39% (467) of those who died in Massachusetts, 29% (280) in Connecticut, and 47% (109) in Rhode Island.

There was also an increase in psychostimulants found in those who had died in Massachusetts in 2020.

More male overdoses in 2020

Results also showed that, compared to 2019, significantly more men died from overdoses in 2020 in Colorado (61% vs. 70%, P = .017) and Indiana (62% vs. 70%, P = .026).

This finding was unexpected, said Dr. Marshall, who has observed the same phenomenon in Rhode Island. He is the scientific director of PreventOverdoseRI, Rhode Island’s drug overdose surveillance and information dashboard.

Dr. Marshall and his colleagues conducted a study that also found disproportionate increases in overdoses among men. The findings of that study will be published in September.

“We’re still trying to wrap our head around why that is,” he said. He added that a deeper dive into the Rhode Island data showed that the deaths were increased especially among middle-aged men who had been diagnosed with depression and anxiety.

The same patterns were not seen among women in either Dr. Jalali’s study or his own analysis of the Rhode Island data, said Dr. Marshall.

“That suggests the COVID-19 pandemic impacted men who are at risk for overdose in some particularly severe way,” he noted.

Dr. Fuehrlein said he believes a variety of factors have led to an increase in overdose deaths during the pandemic, including the fact that many patients who would normally seek help avoided care or dropped out of treatment because of COVID fears. In addition, other support systems, such as group therapy and Narcotics Anonymous, were unavailable.

The pandemic increased stress, which can lead to worsening substance use, said Dr. Fuehrlein. He also noted that regular opioid suppliers were often not available, which led some to buy from different dealers, “which can lead to overdose if the fentanyl content is different.”

Identifying at-risk individuals

Dr. Jalali and colleagues note that clinicians and policymakers could use the new study to help identify and treat at-risk individuals.

“Practitioners and policy makers can use our findings to help them anticipate which groups of people might be most affected by opioid overdose and which types of policy interventions might be most effective given each state’s unique situation,” said lead study author Gian-Gabriel P. Garcia, PhD, in a press release. At the time of the study, Dr. Garcia was a postdoctoral fellow at Mass General and Harvard Medical School. He is currently an assistant professor at Georgia Tech, Atlanta.

Dr. Marshall pointed out that Dr. Jalali’s study is also relevant for emergency departments.

ED clinicians “are and will be seeing patients coming in who have no idea they were exposed to an opioid, nevermind fentanyl,” he said. ED clinicians can discuss with patients various harm reduction techniques, including the use of naloxone as well as test strips that can detect fentanyl in the drug supply, he added.

“Given the increasing use of fentanyl, which is very dangerous in overdose, clinicians need to be well versed in a harm reduction/overdose prevention approach to patient care,” Dr. Fuehrlein agreed.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Opioid overdose deaths were significantly higher during 2020, but occurrences were not homogeneous across nine states. Male deaths were higher than in the 2 previous years in two states, according to a new, granular examination of data collected by researchers at the Massachusetts General Hospital (Mass General), Boston.

The analysis also showed that synthetic opioids such as fentanyl played an outsized role in most of the states that were reviewed. Additional drugs of abuse found in decedents, such as cocaine and psychostimulants, were more prevalent in some states than in others.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention used provisional death data in its recent report. It found that opioid-related deaths substantially rose in 2020 and that synthetic opioids were a primary driver.

The current Mass General analysis provides a more timely and detailed dive, senior author Mohammad Jalali, PhD, who is a senior scientist at Mass General’s Institute for Technology Assessment, told this news organization.

The findings, which have not yet been peer reviewed, were published in MedRxiv.

Shifting sands of opioid use disorder

to analyze and project trends and also to be better prepared to address the shifting sands of opioid use disorder in the United States.

They attempted to collect data on confirmed opioid overdose deaths from all 50 states and Washington, D.C. to assess what might have changed during the COVID-19 pandemic. Only nine states provided enough data for the analysis, which has been submitted to a peer reviewed publication.

These states were Alaska, Connecticut, Indiana, Massachusetts, North Carolina, Rhode Island, Colorado, Utah, and Wyoming.

“Drug overdose data are collected and reported more slowly than COVID-19 data,” Dr. Jalali said in a press release. The data reflected a lag time of about 4 to 8 months in Massachusetts and North Carolina to more than a year in Maryland and Ohio, he noted.

The reporting lag “has clouded the understanding of the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on opioid-related overdose deaths,” said Dr. Jalali.

Commenting on the findings, Brandon Marshall, PhD, associate professor of epidemiology at Brown University, Providence, R.I, said that “the overall pattern of what’s being reported here is not surprising,” given the national trends seen in the CDC data.

“This paper adds a deeper dive into some of the sociodemographic trends that we’re starting to observe in specific states,” Dr. Marshall said.

Also commenting for this news organization, Brian Fuehrlein, MD, PhD, director of the psychiatric emergency department at the VA Connecticut Healthcare System in West Haven, Connecticut, noted that the current study “highlights things that we are currently seeing at VA Connecticut.”

Decrease in heroin, rise in fentanyl

The investigators found a significant reduction in overdose deaths that involved heroin in Alaska, Connecticut, Indiana, Massachusetts, North Carolina, and Rhode Island. That was a new trend for Alaska, Indiana, and Rhode Island, although with only 3 years of data, it’s hard to say whether it will continue, Dr. Jalali noted.

The decrease in heroin involvement seemed to continue a trend previously observed in Colorado, Connecticut, Massachusetts, and North Carolina.

In Connecticut, heroin was involved in 36% of deaths in 2018, 30% in 2019, and 16% in 2020, according to the study.

“We have begun seeing more and more heroin-negative, fentanyl-positive drug screens,” said Dr. Fuehrlein, who is also associate professor of psychiatry at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

“There is a shift from fentanyl being an adulterant to fentanyl being what is sold and used exclusively,” he added.

In 2020, 92% (n = 887) of deaths in Connecticut involved synthetic opioids, continuing a trend. In Alaska, however, synthetic opioids were involved in 60% (44) of deaths, which is a big jump from 23% (9) in 2018.

Synthetic opioids were involved in the largest percentage of overdoses in all of the states studied. The fewest deaths, 17 (49%), occurred in Wyoming.

Cocaine is also increasingly found in addition to other substances in decedents. In Alaska, about 14% of individuals who overdosed in 2020 also had cocaine in their system, which was a jump from 2% in the prior year.

In Colorado, 19% (94) of those who died also had taken cocaine, up from 13% in 2019. Cocaine was also frequently found in those who died in the northeast: 39% (467) of those who died in Massachusetts, 29% (280) in Connecticut, and 47% (109) in Rhode Island.

There was also an increase in psychostimulants found in those who had died in Massachusetts in 2020.

More male overdoses in 2020

Results also showed that, compared to 2019, significantly more men died from overdoses in 2020 in Colorado (61% vs. 70%, P = .017) and Indiana (62% vs. 70%, P = .026).

This finding was unexpected, said Dr. Marshall, who has observed the same phenomenon in Rhode Island. He is the scientific director of PreventOverdoseRI, Rhode Island’s drug overdose surveillance and information dashboard.

Dr. Marshall and his colleagues conducted a study that also found disproportionate increases in overdoses among men. The findings of that study will be published in September.

“We’re still trying to wrap our head around why that is,” he said. He added that a deeper dive into the Rhode Island data showed that the deaths were increased especially among middle-aged men who had been diagnosed with depression and anxiety.

The same patterns were not seen among women in either Dr. Jalali’s study or his own analysis of the Rhode Island data, said Dr. Marshall.

“That suggests the COVID-19 pandemic impacted men who are at risk for overdose in some particularly severe way,” he noted.

Dr. Fuehrlein said he believes a variety of factors have led to an increase in overdose deaths during the pandemic, including the fact that many patients who would normally seek help avoided care or dropped out of treatment because of COVID fears. In addition, other support systems, such as group therapy and Narcotics Anonymous, were unavailable.

The pandemic increased stress, which can lead to worsening substance use, said Dr. Fuehrlein. He also noted that regular opioid suppliers were often not available, which led some to buy from different dealers, “which can lead to overdose if the fentanyl content is different.”

Identifying at-risk individuals

Dr. Jalali and colleagues note that clinicians and policymakers could use the new study to help identify and treat at-risk individuals.

“Practitioners and policy makers can use our findings to help them anticipate which groups of people might be most affected by opioid overdose and which types of policy interventions might be most effective given each state’s unique situation,” said lead study author Gian-Gabriel P. Garcia, PhD, in a press release. At the time of the study, Dr. Garcia was a postdoctoral fellow at Mass General and Harvard Medical School. He is currently an assistant professor at Georgia Tech, Atlanta.

Dr. Marshall pointed out that Dr. Jalali’s study is also relevant for emergency departments.

ED clinicians “are and will be seeing patients coming in who have no idea they were exposed to an opioid, nevermind fentanyl,” he said. ED clinicians can discuss with patients various harm reduction techniques, including the use of naloxone as well as test strips that can detect fentanyl in the drug supply, he added.

“Given the increasing use of fentanyl, which is very dangerous in overdose, clinicians need to be well versed in a harm reduction/overdose prevention approach to patient care,” Dr. Fuehrlein agreed.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

EDs saw more benzodiazepine overdoses, but fewer patients overall, in 2020

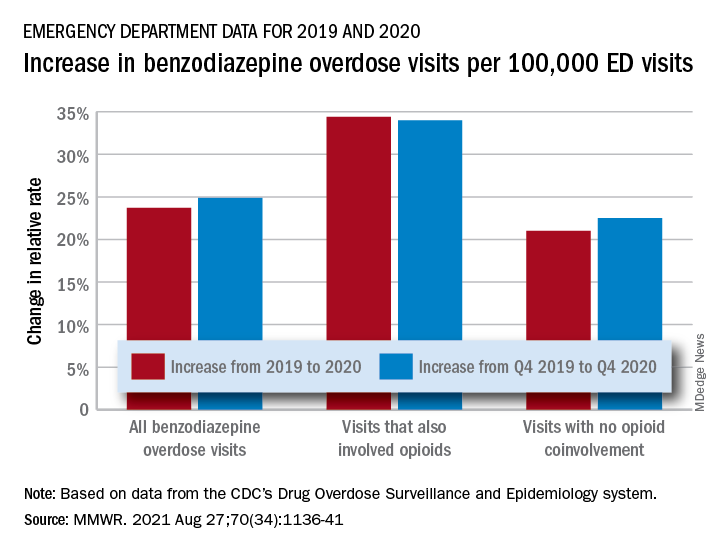

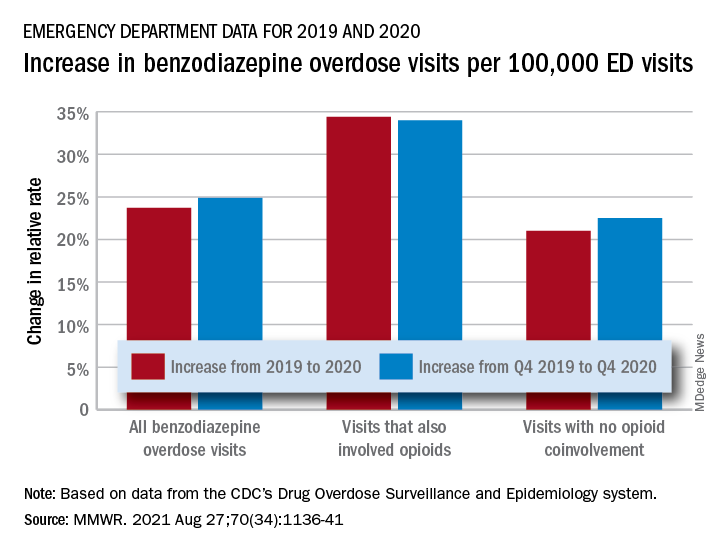

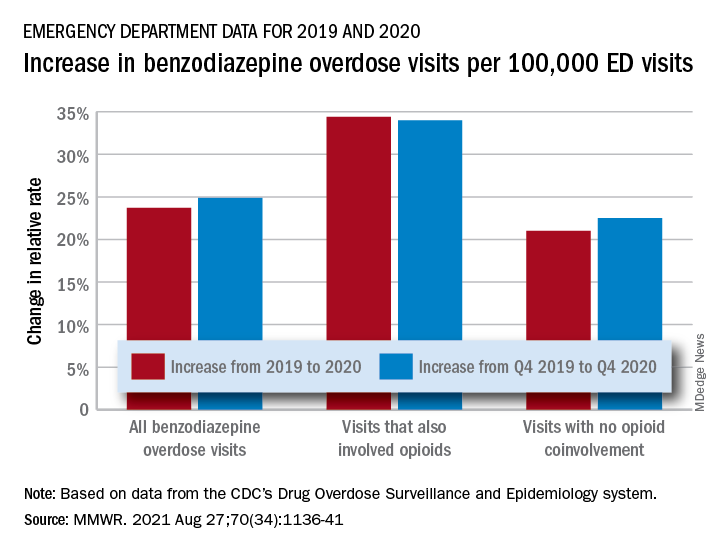

In a year when emergency department visits dropped by almost 18%, visits for benzodiazepine overdoses did the opposite, according to a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The actual increase in the number of overdose visits for benzodiazepine overdoses was quite small – from 15,547 in 2019 to 15,830 in 2020 (1.8%) – but the 11 million fewer ED visits magnified its effect, Stephen Liu, PhD, and associates said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The rate of benzodiazepine overdose visits to all visits increased by 23.7% from 2019 (24.22 per 100,000 ED visits) to 2020 (29.97 per 100,000), with the larger share going to those involving opioids, which were up by 34.4%, compared with overdose visits not involving opioids (21.0%), the investigators said, based on data reported by 32 states and the District of Columbia to the CDC’s Drug Overdose Surveillance and Epidemiology system. All of the rate changes are statistically significant.

The number of overdose visits without opioid coinvolvement actually dropped, from 2019 (12,276) to 2020 (12,218), but not by enough to offset the decline in total visits, noted Dr. Liu, of the CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control and associates.

The number of deaths from benzodiazepine overdose, on the other hand, did not drop in 2020. Those data, coming from 23 states participating in the CDC’s State Unintentional Drug Overdose Reporting System, were available only for the first half of the year.

In those 6 months, The first quarter of 2020 also showed an increase, but exact numbers were not provided in the report. Overdose deaths rose by 22% for prescription forms of benzodiazepine and 520% for illicit forms in Q2 of 2020, compared with 2019, the researchers said.

Almost all of the benzodiazepine deaths (93%) in the first half of 2020 also involved opioids, mostly in the form of illicitly manufactured fentanyls (67% of all deaths). Between Q2 of 2019 and Q2 of 2020, involvement of illicit fentanyls in benzodiazepine overdose deaths increased from almost 57% to 71%, Dr. Liu and associates reported.

“Despite progress in reducing coprescribing [of opioids and benzodiazepines] before 2019, this study suggests a reversal in the decline in benzodiazepine deaths from 2017 to 2019, driven in part by increasing involvement of [illicitly manufactured fentanyls] in benzodiazepine deaths and influxes of illicit benzodiazepines,” they wrote.

In a year when emergency department visits dropped by almost 18%, visits for benzodiazepine overdoses did the opposite, according to a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The actual increase in the number of overdose visits for benzodiazepine overdoses was quite small – from 15,547 in 2019 to 15,830 in 2020 (1.8%) – but the 11 million fewer ED visits magnified its effect, Stephen Liu, PhD, and associates said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The rate of benzodiazepine overdose visits to all visits increased by 23.7% from 2019 (24.22 per 100,000 ED visits) to 2020 (29.97 per 100,000), with the larger share going to those involving opioids, which were up by 34.4%, compared with overdose visits not involving opioids (21.0%), the investigators said, based on data reported by 32 states and the District of Columbia to the CDC’s Drug Overdose Surveillance and Epidemiology system. All of the rate changes are statistically significant.

The number of overdose visits without opioid coinvolvement actually dropped, from 2019 (12,276) to 2020 (12,218), but not by enough to offset the decline in total visits, noted Dr. Liu, of the CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control and associates.

The number of deaths from benzodiazepine overdose, on the other hand, did not drop in 2020. Those data, coming from 23 states participating in the CDC’s State Unintentional Drug Overdose Reporting System, were available only for the first half of the year.

In those 6 months, The first quarter of 2020 also showed an increase, but exact numbers were not provided in the report. Overdose deaths rose by 22% for prescription forms of benzodiazepine and 520% for illicit forms in Q2 of 2020, compared with 2019, the researchers said.

Almost all of the benzodiazepine deaths (93%) in the first half of 2020 also involved opioids, mostly in the form of illicitly manufactured fentanyls (67% of all deaths). Between Q2 of 2019 and Q2 of 2020, involvement of illicit fentanyls in benzodiazepine overdose deaths increased from almost 57% to 71%, Dr. Liu and associates reported.

“Despite progress in reducing coprescribing [of opioids and benzodiazepines] before 2019, this study suggests a reversal in the decline in benzodiazepine deaths from 2017 to 2019, driven in part by increasing involvement of [illicitly manufactured fentanyls] in benzodiazepine deaths and influxes of illicit benzodiazepines,” they wrote.

In a year when emergency department visits dropped by almost 18%, visits for benzodiazepine overdoses did the opposite, according to a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The actual increase in the number of overdose visits for benzodiazepine overdoses was quite small – from 15,547 in 2019 to 15,830 in 2020 (1.8%) – but the 11 million fewer ED visits magnified its effect, Stephen Liu, PhD, and associates said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The rate of benzodiazepine overdose visits to all visits increased by 23.7% from 2019 (24.22 per 100,000 ED visits) to 2020 (29.97 per 100,000), with the larger share going to those involving opioids, which were up by 34.4%, compared with overdose visits not involving opioids (21.0%), the investigators said, based on data reported by 32 states and the District of Columbia to the CDC’s Drug Overdose Surveillance and Epidemiology system. All of the rate changes are statistically significant.

The number of overdose visits without opioid coinvolvement actually dropped, from 2019 (12,276) to 2020 (12,218), but not by enough to offset the decline in total visits, noted Dr. Liu, of the CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control and associates.

The number of deaths from benzodiazepine overdose, on the other hand, did not drop in 2020. Those data, coming from 23 states participating in the CDC’s State Unintentional Drug Overdose Reporting System, were available only for the first half of the year.

In those 6 months, The first quarter of 2020 also showed an increase, but exact numbers were not provided in the report. Overdose deaths rose by 22% for prescription forms of benzodiazepine and 520% for illicit forms in Q2 of 2020, compared with 2019, the researchers said.

Almost all of the benzodiazepine deaths (93%) in the first half of 2020 also involved opioids, mostly in the form of illicitly manufactured fentanyls (67% of all deaths). Between Q2 of 2019 and Q2 of 2020, involvement of illicit fentanyls in benzodiazepine overdose deaths increased from almost 57% to 71%, Dr. Liu and associates reported.

“Despite progress in reducing coprescribing [of opioids and benzodiazepines] before 2019, this study suggests a reversal in the decline in benzodiazepine deaths from 2017 to 2019, driven in part by increasing involvement of [illicitly manufactured fentanyls] in benzodiazepine deaths and influxes of illicit benzodiazepines,” they wrote.

FROM MMWR

PA gets prison time for knowingly prescribing unneeded addictive drugs

A U.S. District Judge sentenced William Soyke, 68, of Hanover, Penn., for acting outside the scope of professional practice and not for a legitimate medical purpose, according to the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Maryland. The 37-month prison term will be followed by 3 years of supervised release.

According to the plea agreement, Mr. Soyke worked as a physician assistant with Rosen-Hoffberg Rehabilitation and Pain Management from 2011 to 2018, where he treated patients during follow-up doctor appointments. As a physician assistant, Mr. Soyke had privileges to prescribe controlled substance medications, but was required to operate under a delegation agreement with the Rosen-Hoffberg owners.

In his plea, Mr. Soyke said that he believed the owners, Norman Rosen, MD, and Howard Hoffberg, MD, prescribed excessive levels of opioids. Despite Mr. Soyke’s attempts to lower patient’s prescription doses, both doctors overruled the PA’s opinion, according to the plea agreement. Also, if another health care provider within the practice declined to treat a patient because of the patient’s aberrant behavior – such as failing a drug screening test for illicit drugs or selling their prescriptions – Dr. Rosen and Dr. Hoffberg would assume that patient’s care, the report continued.

As stated in the plea agreement, Mr. Sokye was aware that many of the patients presenting to Rosen-Hoffberg Rehabilitation and Pain Management did not have a legitimate medical need for the oxycodone, fentanyl, alprazolam, and methadone they were being prescribed. Nevertheless, Mr. Soyke issued prescriptions for these drugs to patients without a legitimate medical need and outside the bounds of acceptable medical practice, according to the release.

Mr. Soyke also admitted that in several instances he engaged in sexual, physical contact with female patients who were attempting to get prescriptions, the plea agreement stated. Specifically, Mr. Soyke asked some female customers to engage in a range of motion test, and while they were bending over, he would position himself behind them such that his genitalia would rub against the customers’ buttocks through their clothes. These patients often submitted to this sexual abuse for fear of not getting the medications to which they were addicted, according to the press release.

Although the female patients complained to Dr. Rosen and Dr. Hoffberg about Mr. Soyke’s behavior, the doctors did not fire Mr. Soyke because the PA saw the largest number of patients at the practice and generated significant revenue, according to federal officials.

Dr. Hoffberg, the associate medical director and part-owner of the practice, pleaded guilty in June to accepting kickbacks from pharmaceutical company Insys Therapeutics in exchange for prescribing an opioid drug called Subsys (a fentanyl sublingual spray) marketed by Insys for breakthrough pain in cancer patients for off-label purposes. He will be sentenced in September and faces a maximum of 5 years in federal prison.

Mr. Soyke pled guilty to a federal drug charge in July 2019. In announcing the guilty plea then, U.S. Attorney Robert Hur said, “Opioid overdoses are killing thousands of Marylanders each year, and opioid addiction is fueled by health care providers who prescribe drugs for people without a legitimate medical need. Doctors and other medical professionals who irresponsibly write opioid prescriptions are acting like street-corner drug pushers.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A U.S. District Judge sentenced William Soyke, 68, of Hanover, Penn., for acting outside the scope of professional practice and not for a legitimate medical purpose, according to the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Maryland. The 37-month prison term will be followed by 3 years of supervised release.

According to the plea agreement, Mr. Soyke worked as a physician assistant with Rosen-Hoffberg Rehabilitation and Pain Management from 2011 to 2018, where he treated patients during follow-up doctor appointments. As a physician assistant, Mr. Soyke had privileges to prescribe controlled substance medications, but was required to operate under a delegation agreement with the Rosen-Hoffberg owners.

In his plea, Mr. Soyke said that he believed the owners, Norman Rosen, MD, and Howard Hoffberg, MD, prescribed excessive levels of opioids. Despite Mr. Soyke’s attempts to lower patient’s prescription doses, both doctors overruled the PA’s opinion, according to the plea agreement. Also, if another health care provider within the practice declined to treat a patient because of the patient’s aberrant behavior – such as failing a drug screening test for illicit drugs or selling their prescriptions – Dr. Rosen and Dr. Hoffberg would assume that patient’s care, the report continued.

As stated in the plea agreement, Mr. Sokye was aware that many of the patients presenting to Rosen-Hoffberg Rehabilitation and Pain Management did not have a legitimate medical need for the oxycodone, fentanyl, alprazolam, and methadone they were being prescribed. Nevertheless, Mr. Soyke issued prescriptions for these drugs to patients without a legitimate medical need and outside the bounds of acceptable medical practice, according to the release.

Mr. Soyke also admitted that in several instances he engaged in sexual, physical contact with female patients who were attempting to get prescriptions, the plea agreement stated. Specifically, Mr. Soyke asked some female customers to engage in a range of motion test, and while they were bending over, he would position himself behind them such that his genitalia would rub against the customers’ buttocks through their clothes. These patients often submitted to this sexual abuse for fear of not getting the medications to which they were addicted, according to the press release.

Although the female patients complained to Dr. Rosen and Dr. Hoffberg about Mr. Soyke’s behavior, the doctors did not fire Mr. Soyke because the PA saw the largest number of patients at the practice and generated significant revenue, according to federal officials.

Dr. Hoffberg, the associate medical director and part-owner of the practice, pleaded guilty in June to accepting kickbacks from pharmaceutical company Insys Therapeutics in exchange for prescribing an opioid drug called Subsys (a fentanyl sublingual spray) marketed by Insys for breakthrough pain in cancer patients for off-label purposes. He will be sentenced in September and faces a maximum of 5 years in federal prison.

Mr. Soyke pled guilty to a federal drug charge in July 2019. In announcing the guilty plea then, U.S. Attorney Robert Hur said, “Opioid overdoses are killing thousands of Marylanders each year, and opioid addiction is fueled by health care providers who prescribe drugs for people without a legitimate medical need. Doctors and other medical professionals who irresponsibly write opioid prescriptions are acting like street-corner drug pushers.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A U.S. District Judge sentenced William Soyke, 68, of Hanover, Penn., for acting outside the scope of professional practice and not for a legitimate medical purpose, according to the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Maryland. The 37-month prison term will be followed by 3 years of supervised release.

According to the plea agreement, Mr. Soyke worked as a physician assistant with Rosen-Hoffberg Rehabilitation and Pain Management from 2011 to 2018, where he treated patients during follow-up doctor appointments. As a physician assistant, Mr. Soyke had privileges to prescribe controlled substance medications, but was required to operate under a delegation agreement with the Rosen-Hoffberg owners.

In his plea, Mr. Soyke said that he believed the owners, Norman Rosen, MD, and Howard Hoffberg, MD, prescribed excessive levels of opioids. Despite Mr. Soyke’s attempts to lower patient’s prescription doses, both doctors overruled the PA’s opinion, according to the plea agreement. Also, if another health care provider within the practice declined to treat a patient because of the patient’s aberrant behavior – such as failing a drug screening test for illicit drugs or selling their prescriptions – Dr. Rosen and Dr. Hoffberg would assume that patient’s care, the report continued.

As stated in the plea agreement, Mr. Sokye was aware that many of the patients presenting to Rosen-Hoffberg Rehabilitation and Pain Management did not have a legitimate medical need for the oxycodone, fentanyl, alprazolam, and methadone they were being prescribed. Nevertheless, Mr. Soyke issued prescriptions for these drugs to patients without a legitimate medical need and outside the bounds of acceptable medical practice, according to the release.

Mr. Soyke also admitted that in several instances he engaged in sexual, physical contact with female patients who were attempting to get prescriptions, the plea agreement stated. Specifically, Mr. Soyke asked some female customers to engage in a range of motion test, and while they were bending over, he would position himself behind them such that his genitalia would rub against the customers’ buttocks through their clothes. These patients often submitted to this sexual abuse for fear of not getting the medications to which they were addicted, according to the press release.

Although the female patients complained to Dr. Rosen and Dr. Hoffberg about Mr. Soyke’s behavior, the doctors did not fire Mr. Soyke because the PA saw the largest number of patients at the practice and generated significant revenue, according to federal officials.

Dr. Hoffberg, the associate medical director and part-owner of the practice, pleaded guilty in June to accepting kickbacks from pharmaceutical company Insys Therapeutics in exchange for prescribing an opioid drug called Subsys (a fentanyl sublingual spray) marketed by Insys for breakthrough pain in cancer patients for off-label purposes. He will be sentenced in September and faces a maximum of 5 years in federal prison.

Mr. Soyke pled guilty to a federal drug charge in July 2019. In announcing the guilty plea then, U.S. Attorney Robert Hur said, “Opioid overdoses are killing thousands of Marylanders each year, and opioid addiction is fueled by health care providers who prescribe drugs for people without a legitimate medical need. Doctors and other medical professionals who irresponsibly write opioid prescriptions are acting like street-corner drug pushers.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Atogepant reduces migraine days: ADVANCE trial results published

full results from a phase 3 trial suggest.

AbbVie, the company developing the oral therapy, announced topline results of the ADVANCE trial of atogepant last year. Safety results were presented in April at the 2021 annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

The full results were published online Aug. 19 in the New England Journal of Medicine ahead of the upcoming target action date of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

The multicenter study included nearly 900 patients who were randomly assigned to receive either placebo or one of three doses of atogepant for 12 weeks. The mean number of monthly migraine days decreased by about 4 for all three doses of the active treatment, compared with a reduction of 2.5 days with placebo.

“Overall, this study showed us that atogepant was safe and surprisingly seems to be pretty effective regardless of the dose,” said lead author Jessica Ailani, MD, director of MedStar Georgetown Headache Center and associate professor of neurology at Georgetown University, Washington.

All doses effective

The study included 873 patients with episodic migraine with or without aura. Patients who were not assigned to the placebo control group received either 10 mg, 30 mg, or 60 mg of atogepant once daily.

After a 4-week screening period, all patients received treatment for 12 weeks and then entered a 4-week safety follow-up period. In total, the participants completed eight scheduled clinical visits.

The mean reduction from baseline in the mean number of migraine days per month was 3.7 with the 10-mg dose of atogepant, 3.9 with the 30-mg dose, 4.2 with the 60-mg dose, and 2.5 with placebo. The differences between each active dose and placebo was statistically significant (P < .001).

Treatment with the CGRP inhibitor was also associated with a reduction in the mean number of headache days per month. The mean reduction from baseline was 3.9 days for the 10-mg dose, 4.0 days for the 30-mg dose, 4.2 days for the 60-mg dose, and 2.5 days for placebo (P < .001 for all comparisons with placebo).

In addition, for 55.6% of the 10-mg group, 58.7% of the 30-mg group, 60.8% of the 60-mg group, and 29.0% of the control group, there was a reduction of at least 50% in the 3-month average number of migraine days per month (P < .001 for each vs. placebo).

The most commonly reported adverse events (AEs) among patients who received atogepant were constipation (6.9%-7.7% across doses), nausea (4.4%-6.1%), and upper respiratory tract infection (1.4%-3.9%). Frequency of AEs did not differ between the active-treatment groups and the control group, and no relationships between AEs and atogepant dose were observed.

Multidose flexibility

“Side effects were pretty even across the board,” said Dr. Ailani. She noted that the reported AEs were expected because of atogepant’s mechanism of action. In addition, the rate of discontinuation in the study was low.

The proportion of participants who experienced a reduction in monthly migraine days of at least 50% grew as time passed. “By the end of this study, your chance of having a greater than 50% response is about 75%,” Dr. Ailani said.

“Imagine telling your patient, ‘You stick on this drug for 3 months, and I can almost guarantee you that you’re going to get better,’” she added.

Although the treatment has no drug-drug contraindications, drug-drug interactions may occur. “The availability of various doses would allow clinicians to adjust treatment to avoid potential drug-drug interactions,” said Dr. Ailani. “That multidose flexibility is very important.”

An FDA decision on atogepant could be made in the coming months. “I’m hopeful, as a clinician, that it is positive news, because we really have waited a long time for something like this,” Dr. Ailani said.

“You can easily identify patients who would do well on this medication,” she added.

In a different study of atogepant among patients with chronic migraine, there were recruitment delays because of the pandemic. That study is now almost complete, Dr. Ailani reported.

“Well-conducted study”

Commenting on the findings, Kathleen B. Digre, MD, chief of the division of headache and neuro-ophthalmology at the University of Utah Health, Salt Lake City, expressed enthusiasm for the experimental drug. “I’m excited to see another treatment modality for migraine,” said Dr. Digre, who was not involved with the research. “It was a very well-conducted study,” she added.

The treatment arms were almost identical in regard to disease severity, and all the doses showed an effect. Although the difference in reduction of monthly migraine days in comparison with placebo was numerically small, “for people who have frequent migraine, it’s important,” Dr. Digre said.

The results for atogepant should be viewed in a larger context, however. “Even though it’s a treatment that works better than placebo for well-matched controls, it may not be a medication that everybody’s going to respond to,” she noted. “And we can’t generalize it for some of the most disabled people, which is for chronic migraine,” she said.

It is significant that the study was published in the New England Journal of Medicine, Dr. Digre noted. “Sometimes migraine is dismissed as not important and not affecting people’s lives,” she said. “That makes me very happy to see migraine being taken seriously by our major journals.”

In addition, she noted that the prospects for FDA approval of atogepant seem favorable. “I’m hopeful that they will approve it, because it’s got a low side-effect profile, plus it’s effective.”

Migraine-specific preventive therapy has emerged only in the past few years. “I’m so excited to see this surge of preventive medicine for migraine,” Dr. Digre said. “It’s so important, because we see so many people who are disabled by migraine,” she added.

The study was funded by Allergan before atogepant was acquired by AbbVie. Dr. Ailani has received honoraria from AbbVie for consulting, has received compensation from Allergan and AbbVie for participating in a speakers’ bureau, and has received clinical trial grants from Allergan. Dr. Digre has reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

full results from a phase 3 trial suggest.

AbbVie, the company developing the oral therapy, announced topline results of the ADVANCE trial of atogepant last year. Safety results were presented in April at the 2021 annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

The full results were published online Aug. 19 in the New England Journal of Medicine ahead of the upcoming target action date of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

The multicenter study included nearly 900 patients who were randomly assigned to receive either placebo or one of three doses of atogepant for 12 weeks. The mean number of monthly migraine days decreased by about 4 for all three doses of the active treatment, compared with a reduction of 2.5 days with placebo.

“Overall, this study showed us that atogepant was safe and surprisingly seems to be pretty effective regardless of the dose,” said lead author Jessica Ailani, MD, director of MedStar Georgetown Headache Center and associate professor of neurology at Georgetown University, Washington.

All doses effective

The study included 873 patients with episodic migraine with or without aura. Patients who were not assigned to the placebo control group received either 10 mg, 30 mg, or 60 mg of atogepant once daily.

After a 4-week screening period, all patients received treatment for 12 weeks and then entered a 4-week safety follow-up period. In total, the participants completed eight scheduled clinical visits.

The mean reduction from baseline in the mean number of migraine days per month was 3.7 with the 10-mg dose of atogepant, 3.9 with the 30-mg dose, 4.2 with the 60-mg dose, and 2.5 with placebo. The differences between each active dose and placebo was statistically significant (P < .001).

Treatment with the CGRP inhibitor was also associated with a reduction in the mean number of headache days per month. The mean reduction from baseline was 3.9 days for the 10-mg dose, 4.0 days for the 30-mg dose, 4.2 days for the 60-mg dose, and 2.5 days for placebo (P < .001 for all comparisons with placebo).

In addition, for 55.6% of the 10-mg group, 58.7% of the 30-mg group, 60.8% of the 60-mg group, and 29.0% of the control group, there was a reduction of at least 50% in the 3-month average number of migraine days per month (P < .001 for each vs. placebo).

The most commonly reported adverse events (AEs) among patients who received atogepant were constipation (6.9%-7.7% across doses), nausea (4.4%-6.1%), and upper respiratory tract infection (1.4%-3.9%). Frequency of AEs did not differ between the active-treatment groups and the control group, and no relationships between AEs and atogepant dose were observed.

Multidose flexibility

“Side effects were pretty even across the board,” said Dr. Ailani. She noted that the reported AEs were expected because of atogepant’s mechanism of action. In addition, the rate of discontinuation in the study was low.

The proportion of participants who experienced a reduction in monthly migraine days of at least 50% grew as time passed. “By the end of this study, your chance of having a greater than 50% response is about 75%,” Dr. Ailani said.

“Imagine telling your patient, ‘You stick on this drug for 3 months, and I can almost guarantee you that you’re going to get better,’” she added.

Although the treatment has no drug-drug contraindications, drug-drug interactions may occur. “The availability of various doses would allow clinicians to adjust treatment to avoid potential drug-drug interactions,” said Dr. Ailani. “That multidose flexibility is very important.”

An FDA decision on atogepant could be made in the coming months. “I’m hopeful, as a clinician, that it is positive news, because we really have waited a long time for something like this,” Dr. Ailani said.

“You can easily identify patients who would do well on this medication,” she added.

In a different study of atogepant among patients with chronic migraine, there were recruitment delays because of the pandemic. That study is now almost complete, Dr. Ailani reported.

“Well-conducted study”

Commenting on the findings, Kathleen B. Digre, MD, chief of the division of headache and neuro-ophthalmology at the University of Utah Health, Salt Lake City, expressed enthusiasm for the experimental drug. “I’m excited to see another treatment modality for migraine,” said Dr. Digre, who was not involved with the research. “It was a very well-conducted study,” she added.

The treatment arms were almost identical in regard to disease severity, and all the doses showed an effect. Although the difference in reduction of monthly migraine days in comparison with placebo was numerically small, “for people who have frequent migraine, it’s important,” Dr. Digre said.

The results for atogepant should be viewed in a larger context, however. “Even though it’s a treatment that works better than placebo for well-matched controls, it may not be a medication that everybody’s going to respond to,” she noted. “And we can’t generalize it for some of the most disabled people, which is for chronic migraine,” she said.

It is significant that the study was published in the New England Journal of Medicine, Dr. Digre noted. “Sometimes migraine is dismissed as not important and not affecting people’s lives,” she said. “That makes me very happy to see migraine being taken seriously by our major journals.”

In addition, she noted that the prospects for FDA approval of atogepant seem favorable. “I’m hopeful that they will approve it, because it’s got a low side-effect profile, plus it’s effective.”

Migraine-specific preventive therapy has emerged only in the past few years. “I’m so excited to see this surge of preventive medicine for migraine,” Dr. Digre said. “It’s so important, because we see so many people who are disabled by migraine,” she added.

The study was funded by Allergan before atogepant was acquired by AbbVie. Dr. Ailani has received honoraria from AbbVie for consulting, has received compensation from Allergan and AbbVie for participating in a speakers’ bureau, and has received clinical trial grants from Allergan. Dr. Digre has reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

full results from a phase 3 trial suggest.

AbbVie, the company developing the oral therapy, announced topline results of the ADVANCE trial of atogepant last year. Safety results were presented in April at the 2021 annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology.

The full results were published online Aug. 19 in the New England Journal of Medicine ahead of the upcoming target action date of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

The multicenter study included nearly 900 patients who were randomly assigned to receive either placebo or one of three doses of atogepant for 12 weeks. The mean number of monthly migraine days decreased by about 4 for all three doses of the active treatment, compared with a reduction of 2.5 days with placebo.

“Overall, this study showed us that atogepant was safe and surprisingly seems to be pretty effective regardless of the dose,” said lead author Jessica Ailani, MD, director of MedStar Georgetown Headache Center and associate professor of neurology at Georgetown University, Washington.

All doses effective

The study included 873 patients with episodic migraine with or without aura. Patients who were not assigned to the placebo control group received either 10 mg, 30 mg, or 60 mg of atogepant once daily.

After a 4-week screening period, all patients received treatment for 12 weeks and then entered a 4-week safety follow-up period. In total, the participants completed eight scheduled clinical visits.

The mean reduction from baseline in the mean number of migraine days per month was 3.7 with the 10-mg dose of atogepant, 3.9 with the 30-mg dose, 4.2 with the 60-mg dose, and 2.5 with placebo. The differences between each active dose and placebo was statistically significant (P < .001).

Treatment with the CGRP inhibitor was also associated with a reduction in the mean number of headache days per month. The mean reduction from baseline was 3.9 days for the 10-mg dose, 4.0 days for the 30-mg dose, 4.2 days for the 60-mg dose, and 2.5 days for placebo (P < .001 for all comparisons with placebo).

In addition, for 55.6% of the 10-mg group, 58.7% of the 30-mg group, 60.8% of the 60-mg group, and 29.0% of the control group, there was a reduction of at least 50% in the 3-month average number of migraine days per month (P < .001 for each vs. placebo).

The most commonly reported adverse events (AEs) among patients who received atogepant were constipation (6.9%-7.7% across doses), nausea (4.4%-6.1%), and upper respiratory tract infection (1.4%-3.9%). Frequency of AEs did not differ between the active-treatment groups and the control group, and no relationships between AEs and atogepant dose were observed.

Multidose flexibility

“Side effects were pretty even across the board,” said Dr. Ailani. She noted that the reported AEs were expected because of atogepant’s mechanism of action. In addition, the rate of discontinuation in the study was low.

The proportion of participants who experienced a reduction in monthly migraine days of at least 50% grew as time passed. “By the end of this study, your chance of having a greater than 50% response is about 75%,” Dr. Ailani said.

“Imagine telling your patient, ‘You stick on this drug for 3 months, and I can almost guarantee you that you’re going to get better,’” she added.

Although the treatment has no drug-drug contraindications, drug-drug interactions may occur. “The availability of various doses would allow clinicians to adjust treatment to avoid potential drug-drug interactions,” said Dr. Ailani. “That multidose flexibility is very important.”

An FDA decision on atogepant could be made in the coming months. “I’m hopeful, as a clinician, that it is positive news, because we really have waited a long time for something like this,” Dr. Ailani said.

“You can easily identify patients who would do well on this medication,” she added.

In a different study of atogepant among patients with chronic migraine, there were recruitment delays because of the pandemic. That study is now almost complete, Dr. Ailani reported.

“Well-conducted study”

Commenting on the findings, Kathleen B. Digre, MD, chief of the division of headache and neuro-ophthalmology at the University of Utah Health, Salt Lake City, expressed enthusiasm for the experimental drug. “I’m excited to see another treatment modality for migraine,” said Dr. Digre, who was not involved with the research. “It was a very well-conducted study,” she added.

The treatment arms were almost identical in regard to disease severity, and all the doses showed an effect. Although the difference in reduction of monthly migraine days in comparison with placebo was numerically small, “for people who have frequent migraine, it’s important,” Dr. Digre said.

The results for atogepant should be viewed in a larger context, however. “Even though it’s a treatment that works better than placebo for well-matched controls, it may not be a medication that everybody’s going to respond to,” she noted. “And we can’t generalize it for some of the most disabled people, which is for chronic migraine,” she said.

It is significant that the study was published in the New England Journal of Medicine, Dr. Digre noted. “Sometimes migraine is dismissed as not important and not affecting people’s lives,” she said. “That makes me very happy to see migraine being taken seriously by our major journals.”

In addition, she noted that the prospects for FDA approval of atogepant seem favorable. “I’m hopeful that they will approve it, because it’s got a low side-effect profile, plus it’s effective.”

Migraine-specific preventive therapy has emerged only in the past few years. “I’m so excited to see this surge of preventive medicine for migraine,” Dr. Digre said. “It’s so important, because we see so many people who are disabled by migraine,” she added.

The study was funded by Allergan before atogepant was acquired by AbbVie. Dr. Ailani has received honoraria from AbbVie for consulting, has received compensation from Allergan and AbbVie for participating in a speakers’ bureau, and has received clinical trial grants from Allergan. Dr. Digre has reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Doctor wins restraining order against CVS after prescription ban

In an Aug. 11 decision, District Court Judge William Bertelsman ordered CVS to stop refusing prescriptions written by Kendall E. Hansen, MD. Judge Bertelsman ruled that Dr. Hansen is likely to succeed in his claim that CVS barred his prescriptions without evidence that he violated any law or professional protocol. The restraining order will remain in place while Dr. Hansen’s lawsuit against CVS Pharmacy proceeds.

Ronald W. Chapman II, an attorney representing Dr. Hansen, said the order is groundbreaking and that, to his knowledge, it’s the first time a federal court has overturned a pharmacy’s decision to block a prescriber.

“We believe that CVS’ decision was based solely on algorithms they use to analyze prescriber practices and not an any individual review of patient records,” Mr. Chapman said. “In fact, we invited CVS to come out to Dr. Hansen’s practice and look at how he was treating patients and ensure things were compliant, but they refused. Instead, they had a phone call with him then cut his patients off.”

Michael DeAngelis, a spokesman for CVS, said the court’s order illustrates the proverbial rock and hard place that pharmacies are placed between in the country’s fight against the misuse of prescription opioids.

“It is alleged in many lawsuits that pharmacies fill too many opioid prescriptions and should operate programs that use data to block prescriptions written by some doctors,” Mr. DeAngelis told this news organization. “And yet other lawsuits, including this one, argue that we should not operate programs that may block prescriptions. Such contradictions are grossly unfair to the pharmacy profession.”

Mr. DeAngelis declined to comment about Dr. Hansen’s claims or specify what led CVS to refuse his prescriptions.

Dr. Hansen declined to comment for this story through his attorney.

Dr. Hansen is no stranger to the spotlight. The Northern Kentucky pain doctor made headlines in 2012 when two of his horses, Fast and Accurate, and Hansen, ran in the Kentucky Derby. In February 2019, he drew media attention when his practice, Interventional Pain Specialists in Crestview Hills, Ky., was raided by federal agents. Dr. Hansen owns and operates the facility, which serves patients in Kentucky, Ohio, and Indiana.

The search yielded no findings, and no charges were filed, according to Mr. Chapman. Scott Hardcorn, director of the Northern Kentucky Drug Strike Force, confirmed that his agency assisted in the operation but said he was unaware of the outcome and that his officers generated no reports from the investigation. A spokesperson for the Drug Enforcement Administration would not comment about the investigation and directed a reporter for this news organization to the DEA website where enforcement actions are listed. No records or actions against Dr. Hansen can be found.

The CVS complaint stems from actions taken by the pharmacy against Dr. Hansen earlier this year. In June, a pharmacy representative allegedly contacted Dr. Hansen by phone and asked him questions about his practice and his prescribing practices, according to his lawsuit filed in U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Kentucky. During the call, the representative did not inform Dr. Hansen that any of his prescriptions were in question or were suspected of being medically unnecessary, the complaint alleges.

On July 28, 2021, CVS sent Dr. Hansen a letter announcing that its pharmacies would no longer be honoring his prescriptions. The letter, entered as an exhibit in the lawsuit, states that CVS contacted Dr. Hansen twice in 2021 about his prescribing practices, once in May and again in June.

“Despite our attempts to resolve the concerns with your controlled substance prescribing patterns, these concerns persist,” Kahra Lutkiewicz, director of CVS’ retail pharmacy professional practice, wrote in the letter. “Thus, we are writing to inform you that effective Aug. 5, 2021, CVS/pharmacy stores will no longer be able to fill prescriptions that you write for controlled substances. We take our compliance obligations very seriously, and after careful consideration, find it necessary to take this action.”

The letter does not explain the details behind CVS’ concerns.

Dr. Hansen sued CVS on Aug. 4 for tortious interference with a business relationship and defamation, among other claims. His complaint alleges that Dr. Hansen and his patients will suffer irreparable injury if the prescription decision stands. More than 250 of Dr. Hansen’s patients use CVS pharmacies for their prescriptions, and some are locked into using the pharmacy because of insurance contracts, Mr. Chapman said.

“There really is nowhere else for these patients to go,” Mr. Chapman said. “They would have to go to a new doctor and establish a new relationship, and obviously that has devastating consequences when we’re talking about people who need their medication.”

CVS has not yet issued a written response to the lawsuit. In his order, Judge Bertelsman stated that a preliminary conference was held in which all parties were represented and stated their positions to the judge.

“Plaintiffs are likely to succeed on the merits of their claims that defendant has interfered with plaintiffs’ relationships with their patients by refusing to fill prescriptions written by plaintiffs, and defendant has done so without evidence that plaintiffs have violated any law or professional protocol related to such prescriptions,” Judge Bertelsman wrote. “The balance of the hardships between the parties weighs in favor of issuing a temporary restraining order inasmuch as defendant’s actions pose a threat to plaintiffs’ professional reputation and livelihood and ... because plaintiffs’ patients’ medical care is implicated by defendant’s actions, the public interest weighs in favor of issuance of the temporary restraining order.”

Dr. Hansen is currently embroiled in several other legal battles as both a plaintiff and a defendant.

In 2019, a patient sued him for negligence and fraud for allegedly performing medically unnecessary and excessive injection therapy. The suit claims the patient was required to undergo injection therapy on a continuing basis in order to receive her narcotic pain medication, according to the lawsuit filed in Kenton Circuit Court. The complaint alleges that Dr. Hansen made false representations to the patient and to her insurers that the injections were necessary for the treatment of the patient’s chronic pain.

The federal government is not involved in the case.

The negligence lawsuit is in the discovery stage, and attorneys plan to collect Dr. Hansen’s deposition soon, said Eric Deters, a spokesman for Deters Law, a law firm based in Independence, Ky., that is representing the patient.

“The crux is that he performs unnecessary pain procedures and forces you to get an unnecessary procedure before giving you your medication,” Mr. Deters said.

However, Dr. Hansen’s and Mr. Deters’ history together includes a recent riff, according to an August 2021 lawsuit filed by Dr. Hansen against the law firm. Dr. Hansen was a former medical expert in cases for Deters and Associates, but the relationship turned sour when attorneys believed Dr. Hansen was retained as an expert in a case against their clients, according to Dr. Hansen’s suit. Dr. Hansen claims that as retribution, Deters and Associates issued a medical malpractice lawsuit against him in 2020, even though attorneys allegedly knew the statute of limitations had run out. A trial court dismissed the 2020 lawsuit against Dr. Hansen as being untimely filed. Dr. Hansen’s lawsuit alleges wrongful use of civil proceedings and requests compensatory, punitive damages and court costs from the law firm.

The law firm has faced trouble in the past. In August 2021, the Ohio Supreme Court ordered that Mr. Deters pay a $6,500 fine for engaging in the unauthorized practice of law. Mr. Deters’ Kentucky law license has been suspended since 2013 for ethics infractions, according to court records. He retired from law in 2014 and now acts as a spokesperson and office manager for the law firm. The fine resulted from legal advice given by Mr. Deters to two clients at the law firm, according to the Ohio Supreme Court decision.

As for the CVS lawsuit, an upcoming hearing will determine whether the federal court issues a permanent injunction against CVS’s actions. CVS officials have not said whether they will fight the temporary restraining order or the withdrawal of their prescription ban against Dr. Hansen.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In an Aug. 11 decision, District Court Judge William Bertelsman ordered CVS to stop refusing prescriptions written by Kendall E. Hansen, MD. Judge Bertelsman ruled that Dr. Hansen is likely to succeed in his claim that CVS barred his prescriptions without evidence that he violated any law or professional protocol. The restraining order will remain in place while Dr. Hansen’s lawsuit against CVS Pharmacy proceeds.

Ronald W. Chapman II, an attorney representing Dr. Hansen, said the order is groundbreaking and that, to his knowledge, it’s the first time a federal court has overturned a pharmacy’s decision to block a prescriber.

“We believe that CVS’ decision was based solely on algorithms they use to analyze prescriber practices and not an any individual review of patient records,” Mr. Chapman said. “In fact, we invited CVS to come out to Dr. Hansen’s practice and look at how he was treating patients and ensure things were compliant, but they refused. Instead, they had a phone call with him then cut his patients off.”

Michael DeAngelis, a spokesman for CVS, said the court’s order illustrates the proverbial rock and hard place that pharmacies are placed between in the country’s fight against the misuse of prescription opioids.

“It is alleged in many lawsuits that pharmacies fill too many opioid prescriptions and should operate programs that use data to block prescriptions written by some doctors,” Mr. DeAngelis told this news organization. “And yet other lawsuits, including this one, argue that we should not operate programs that may block prescriptions. Such contradictions are grossly unfair to the pharmacy profession.”

Mr. DeAngelis declined to comment about Dr. Hansen’s claims or specify what led CVS to refuse his prescriptions.

Dr. Hansen declined to comment for this story through his attorney.

Dr. Hansen is no stranger to the spotlight. The Northern Kentucky pain doctor made headlines in 2012 when two of his horses, Fast and Accurate, and Hansen, ran in the Kentucky Derby. In February 2019, he drew media attention when his practice, Interventional Pain Specialists in Crestview Hills, Ky., was raided by federal agents. Dr. Hansen owns and operates the facility, which serves patients in Kentucky, Ohio, and Indiana.

The search yielded no findings, and no charges were filed, according to Mr. Chapman. Scott Hardcorn, director of the Northern Kentucky Drug Strike Force, confirmed that his agency assisted in the operation but said he was unaware of the outcome and that his officers generated no reports from the investigation. A spokesperson for the Drug Enforcement Administration would not comment about the investigation and directed a reporter for this news organization to the DEA website where enforcement actions are listed. No records or actions against Dr. Hansen can be found.

The CVS complaint stems from actions taken by the pharmacy against Dr. Hansen earlier this year. In June, a pharmacy representative allegedly contacted Dr. Hansen by phone and asked him questions about his practice and his prescribing practices, according to his lawsuit filed in U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Kentucky. During the call, the representative did not inform Dr. Hansen that any of his prescriptions were in question or were suspected of being medically unnecessary, the complaint alleges.

On July 28, 2021, CVS sent Dr. Hansen a letter announcing that its pharmacies would no longer be honoring his prescriptions. The letter, entered as an exhibit in the lawsuit, states that CVS contacted Dr. Hansen twice in 2021 about his prescribing practices, once in May and again in June.

“Despite our attempts to resolve the concerns with your controlled substance prescribing patterns, these concerns persist,” Kahra Lutkiewicz, director of CVS’ retail pharmacy professional practice, wrote in the letter. “Thus, we are writing to inform you that effective Aug. 5, 2021, CVS/pharmacy stores will no longer be able to fill prescriptions that you write for controlled substances. We take our compliance obligations very seriously, and after careful consideration, find it necessary to take this action.”

The letter does not explain the details behind CVS’ concerns.

Dr. Hansen sued CVS on Aug. 4 for tortious interference with a business relationship and defamation, among other claims. His complaint alleges that Dr. Hansen and his patients will suffer irreparable injury if the prescription decision stands. More than 250 of Dr. Hansen’s patients use CVS pharmacies for their prescriptions, and some are locked into using the pharmacy because of insurance contracts, Mr. Chapman said.

“There really is nowhere else for these patients to go,” Mr. Chapman said. “They would have to go to a new doctor and establish a new relationship, and obviously that has devastating consequences when we’re talking about people who need their medication.”

CVS has not yet issued a written response to the lawsuit. In his order, Judge Bertelsman stated that a preliminary conference was held in which all parties were represented and stated their positions to the judge.

“Plaintiffs are likely to succeed on the merits of their claims that defendant has interfered with plaintiffs’ relationships with their patients by refusing to fill prescriptions written by plaintiffs, and defendant has done so without evidence that plaintiffs have violated any law or professional protocol related to such prescriptions,” Judge Bertelsman wrote. “The balance of the hardships between the parties weighs in favor of issuing a temporary restraining order inasmuch as defendant’s actions pose a threat to plaintiffs’ professional reputation and livelihood and ... because plaintiffs’ patients’ medical care is implicated by defendant’s actions, the public interest weighs in favor of issuance of the temporary restraining order.”

Dr. Hansen is currently embroiled in several other legal battles as both a plaintiff and a defendant.

In 2019, a patient sued him for negligence and fraud for allegedly performing medically unnecessary and excessive injection therapy. The suit claims the patient was required to undergo injection therapy on a continuing basis in order to receive her narcotic pain medication, according to the lawsuit filed in Kenton Circuit Court. The complaint alleges that Dr. Hansen made false representations to the patient and to her insurers that the injections were necessary for the treatment of the patient’s chronic pain.

The federal government is not involved in the case.

The negligence lawsuit is in the discovery stage, and attorneys plan to collect Dr. Hansen’s deposition soon, said Eric Deters, a spokesman for Deters Law, a law firm based in Independence, Ky., that is representing the patient.

“The crux is that he performs unnecessary pain procedures and forces you to get an unnecessary procedure before giving you your medication,” Mr. Deters said.

However, Dr. Hansen’s and Mr. Deters’ history together includes a recent riff, according to an August 2021 lawsuit filed by Dr. Hansen against the law firm. Dr. Hansen was a former medical expert in cases for Deters and Associates, but the relationship turned sour when attorneys believed Dr. Hansen was retained as an expert in a case against their clients, according to Dr. Hansen’s suit. Dr. Hansen claims that as retribution, Deters and Associates issued a medical malpractice lawsuit against him in 2020, even though attorneys allegedly knew the statute of limitations had run out. A trial court dismissed the 2020 lawsuit against Dr. Hansen as being untimely filed. Dr. Hansen’s lawsuit alleges wrongful use of civil proceedings and requests compensatory, punitive damages and court costs from the law firm.

The law firm has faced trouble in the past. In August 2021, the Ohio Supreme Court ordered that Mr. Deters pay a $6,500 fine for engaging in the unauthorized practice of law. Mr. Deters’ Kentucky law license has been suspended since 2013 for ethics infractions, according to court records. He retired from law in 2014 and now acts as a spokesperson and office manager for the law firm. The fine resulted from legal advice given by Mr. Deters to two clients at the law firm, according to the Ohio Supreme Court decision.

As for the CVS lawsuit, an upcoming hearing will determine whether the federal court issues a permanent injunction against CVS’s actions. CVS officials have not said whether they will fight the temporary restraining order or the withdrawal of their prescription ban against Dr. Hansen.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In an Aug. 11 decision, District Court Judge William Bertelsman ordered CVS to stop refusing prescriptions written by Kendall E. Hansen, MD. Judge Bertelsman ruled that Dr. Hansen is likely to succeed in his claim that CVS barred his prescriptions without evidence that he violated any law or professional protocol. The restraining order will remain in place while Dr. Hansen’s lawsuit against CVS Pharmacy proceeds.

Ronald W. Chapman II, an attorney representing Dr. Hansen, said the order is groundbreaking and that, to his knowledge, it’s the first time a federal court has overturned a pharmacy’s decision to block a prescriber.

“We believe that CVS’ decision was based solely on algorithms they use to analyze prescriber practices and not an any individual review of patient records,” Mr. Chapman said. “In fact, we invited CVS to come out to Dr. Hansen’s practice and look at how he was treating patients and ensure things were compliant, but they refused. Instead, they had a phone call with him then cut his patients off.”