User login

Children with uncontrolled asthma at higher risk of being bullied

The risk of bullying and teasing is higher in children and young people with poorer asthma control, an international study reported. Published online in the Archives of Disease in Childhood, the Room to Breathe survey of 943 children in six countries found 9.9% had experienced asthma-related bullying or teasing (n = 93).

Children with well-controlled disease, however, were less likely to report being victimized by asthma-related bullying/teasing: odds ratio, 0.51; 95% confidence interval, 0.23-0.84; P = .006).

“It’s important for pediatricians to recognize that children and young people with asthma commonly report bullying or teasing as a result of their condition,” Will Carroll, MD, of the Paediatric Respiratory Service at Staffordshire Children’s Hospital at Royal Stoke, Stoke-on-Trent, England, told this news organization. “Pediatricians should talk to children themselves with asthma about this and not just their parents, and efforts should be made to improve asthma control whenever possible.”

Though common and potentially long-lasting in its effects, bullying is rarely addressed by health care professionals, the U.K. authors said.

But things may differ in the United States. According to Mark Welles, MD, a pediatrician at Cohen Children’s Medical Center at Northwell Health in Queen’s, N.Y., and regional cochair of the American Academy of Pediatrics antibullying committee, young doctors here are trained to ask about bullying when seeing a child, no matter what the reason for the visit. “It’s important to build a rapport with the child, and you need to ask about the disease they may have but also generally ask, ‘How are things at school? Is everyone nice to you?’ It is becoming more common practice to ask this,” said Dr. Welles, who was not involved with the U.K. research.

The U.K. study drew on unpublished data from the Room to Breathe survey conducted by Dr. Carroll’s group during 2008-2009 in Canada, the United Kingdom, Greece, Hungary, South Africa, and the Netherlands. Only 358 of 930 (38.5%) children were found to be well controlled according to current Global Initiative for Asthma symptom-control criteria.

The analysis also found a highly significant association (P < .0001) between Childhood Asthma Control Test (C-ACT) score and reported bullying/teasing, with bullied children having lower scores. C-ACT–defined controlled asthma scores of 20 or higher were significantly associated with a lower risk of bullying (OR, 0.46; 95% CI, 0.28-0.76; P = .001).

In other study findings, harassment was more common in children whose asthma was serious enough to entail activity restriction (OR, 1.74; 95% CI, 1.11-2.75; P = .010) and who described their asthma as “bad” (OR, 3.02; 95% CI, 1.86-4.85; P < .001), as well as those whose parents reported ongoing asthma-related health worries (OR, 1.64; 95% CI, 1.04-2.58; P = .024).

“When a child is clearly different from others, such as having bad asthma or being limited in activities due to asthma, they stand out more and are more frequently bullied,” said Tracy Evian Waasdorp, PhD, MSEd, director of research for school-based bullying and social-emotional learning at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and also not a participant in the U.K. study.

In contrast to the 10% bullying rate in Dr. Carroll’s study, Dr. Waasdorp referred to a CHOP analysis of more than 64,000 youth from a Northeastern state in which those with asthma were 40% more likely to be victims of in-person bullying and 70% were more likely to be cyberbullied than youth without asthma. “Having a medical condition can therefore put you at risk of being bullied regardless of what country you live in,” she said.

CHOP policy encourages practitioners to routinely ask about bullying and to provide handouts and resources for parents, she added.

Interestingly, the U.K. investigators found that open public use of spacers was not associated with asthma-related bullying, nor was parental worry at diagnosis or parental concern about steroid use.

But according to Dr. Welles, “Kids may be using the inhaler in front of other kids, and they may be embarrassed and not want to be seen as different. So they may not use the inhaler when needed for gym class or sports, forcing them to sit out and then potentially be bullied again. It’s a vicious cycle.”

Previous research has identified the bullying and teasing of children with food allergies.

Behaviors have included allergy-specific harassment such as smearing peanut butter on a youngster’s forehead or putting peanut butter cookie crumbs in a child’s lunch box.

“In our survey we asked the question ‘Have you been teased or bullied because of your asthma?’ but we didn’t ask what form this took,” Dr. Carroll said. “But we were surprised at just how many children said yes. It’s time for more research, I think.”

“There are never enough studies around this,” added Dr. Welles. “Bullying, whether because of asthma or otherwise, has the potential for long-term effects well into adulthood.”

In the meantime, asthma consultations should incorporate specific questions about bullying. They should also be child focused in order to gain a representative appreciation of asthma control and its effect on the child’s life.

“As pediatricians, we need to be continuously supporting parents and find the help they need to address any mental health issues,” Dr. Welles said. “Every pediatrician and parent needs to be aware and recognize when something is different in their child’s life. Please don’t ignore it.”

Dr. Waasdorp stressed that school and other communities should be aware that children with asthma may be at increased risk for aggression and harmful interactions related to their asthma. “Programming to reduce bullying should focus broadly on shifting the climate so that bullying is not perceived to be normative and on improving ‘upstander,’ or positive bystander, responses.” she said.

The original survey was funded by Nycomed (Zurich). No additional funding was requested for the current analysis. Dr. Carroll reported personal fees from GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, and Trudell Medical International outside the submitted work. Dr. Welles and Dr. Waasdorp disclosed no competing interests relevant to their comments.

The risk of bullying and teasing is higher in children and young people with poorer asthma control, an international study reported. Published online in the Archives of Disease in Childhood, the Room to Breathe survey of 943 children in six countries found 9.9% had experienced asthma-related bullying or teasing (n = 93).

Children with well-controlled disease, however, were less likely to report being victimized by asthma-related bullying/teasing: odds ratio, 0.51; 95% confidence interval, 0.23-0.84; P = .006).

“It’s important for pediatricians to recognize that children and young people with asthma commonly report bullying or teasing as a result of their condition,” Will Carroll, MD, of the Paediatric Respiratory Service at Staffordshire Children’s Hospital at Royal Stoke, Stoke-on-Trent, England, told this news organization. “Pediatricians should talk to children themselves with asthma about this and not just their parents, and efforts should be made to improve asthma control whenever possible.”

Though common and potentially long-lasting in its effects, bullying is rarely addressed by health care professionals, the U.K. authors said.

But things may differ in the United States. According to Mark Welles, MD, a pediatrician at Cohen Children’s Medical Center at Northwell Health in Queen’s, N.Y., and regional cochair of the American Academy of Pediatrics antibullying committee, young doctors here are trained to ask about bullying when seeing a child, no matter what the reason for the visit. “It’s important to build a rapport with the child, and you need to ask about the disease they may have but also generally ask, ‘How are things at school? Is everyone nice to you?’ It is becoming more common practice to ask this,” said Dr. Welles, who was not involved with the U.K. research.

The U.K. study drew on unpublished data from the Room to Breathe survey conducted by Dr. Carroll’s group during 2008-2009 in Canada, the United Kingdom, Greece, Hungary, South Africa, and the Netherlands. Only 358 of 930 (38.5%) children were found to be well controlled according to current Global Initiative for Asthma symptom-control criteria.

The analysis also found a highly significant association (P < .0001) between Childhood Asthma Control Test (C-ACT) score and reported bullying/teasing, with bullied children having lower scores. C-ACT–defined controlled asthma scores of 20 or higher were significantly associated with a lower risk of bullying (OR, 0.46; 95% CI, 0.28-0.76; P = .001).

In other study findings, harassment was more common in children whose asthma was serious enough to entail activity restriction (OR, 1.74; 95% CI, 1.11-2.75; P = .010) and who described their asthma as “bad” (OR, 3.02; 95% CI, 1.86-4.85; P < .001), as well as those whose parents reported ongoing asthma-related health worries (OR, 1.64; 95% CI, 1.04-2.58; P = .024).

“When a child is clearly different from others, such as having bad asthma or being limited in activities due to asthma, they stand out more and are more frequently bullied,” said Tracy Evian Waasdorp, PhD, MSEd, director of research for school-based bullying and social-emotional learning at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and also not a participant in the U.K. study.

In contrast to the 10% bullying rate in Dr. Carroll’s study, Dr. Waasdorp referred to a CHOP analysis of more than 64,000 youth from a Northeastern state in which those with asthma were 40% more likely to be victims of in-person bullying and 70% were more likely to be cyberbullied than youth without asthma. “Having a medical condition can therefore put you at risk of being bullied regardless of what country you live in,” she said.

CHOP policy encourages practitioners to routinely ask about bullying and to provide handouts and resources for parents, she added.

Interestingly, the U.K. investigators found that open public use of spacers was not associated with asthma-related bullying, nor was parental worry at diagnosis or parental concern about steroid use.

But according to Dr. Welles, “Kids may be using the inhaler in front of other kids, and they may be embarrassed and not want to be seen as different. So they may not use the inhaler when needed for gym class or sports, forcing them to sit out and then potentially be bullied again. It’s a vicious cycle.”

Previous research has identified the bullying and teasing of children with food allergies.

Behaviors have included allergy-specific harassment such as smearing peanut butter on a youngster’s forehead or putting peanut butter cookie crumbs in a child’s lunch box.

“In our survey we asked the question ‘Have you been teased or bullied because of your asthma?’ but we didn’t ask what form this took,” Dr. Carroll said. “But we were surprised at just how many children said yes. It’s time for more research, I think.”

“There are never enough studies around this,” added Dr. Welles. “Bullying, whether because of asthma or otherwise, has the potential for long-term effects well into adulthood.”

In the meantime, asthma consultations should incorporate specific questions about bullying. They should also be child focused in order to gain a representative appreciation of asthma control and its effect on the child’s life.

“As pediatricians, we need to be continuously supporting parents and find the help they need to address any mental health issues,” Dr. Welles said. “Every pediatrician and parent needs to be aware and recognize when something is different in their child’s life. Please don’t ignore it.”

Dr. Waasdorp stressed that school and other communities should be aware that children with asthma may be at increased risk for aggression and harmful interactions related to their asthma. “Programming to reduce bullying should focus broadly on shifting the climate so that bullying is not perceived to be normative and on improving ‘upstander,’ or positive bystander, responses.” she said.

The original survey was funded by Nycomed (Zurich). No additional funding was requested for the current analysis. Dr. Carroll reported personal fees from GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, and Trudell Medical International outside the submitted work. Dr. Welles and Dr. Waasdorp disclosed no competing interests relevant to their comments.

The risk of bullying and teasing is higher in children and young people with poorer asthma control, an international study reported. Published online in the Archives of Disease in Childhood, the Room to Breathe survey of 943 children in six countries found 9.9% had experienced asthma-related bullying or teasing (n = 93).

Children with well-controlled disease, however, were less likely to report being victimized by asthma-related bullying/teasing: odds ratio, 0.51; 95% confidence interval, 0.23-0.84; P = .006).

“It’s important for pediatricians to recognize that children and young people with asthma commonly report bullying or teasing as a result of their condition,” Will Carroll, MD, of the Paediatric Respiratory Service at Staffordshire Children’s Hospital at Royal Stoke, Stoke-on-Trent, England, told this news organization. “Pediatricians should talk to children themselves with asthma about this and not just their parents, and efforts should be made to improve asthma control whenever possible.”

Though common and potentially long-lasting in its effects, bullying is rarely addressed by health care professionals, the U.K. authors said.

But things may differ in the United States. According to Mark Welles, MD, a pediatrician at Cohen Children’s Medical Center at Northwell Health in Queen’s, N.Y., and regional cochair of the American Academy of Pediatrics antibullying committee, young doctors here are trained to ask about bullying when seeing a child, no matter what the reason for the visit. “It’s important to build a rapport with the child, and you need to ask about the disease they may have but also generally ask, ‘How are things at school? Is everyone nice to you?’ It is becoming more common practice to ask this,” said Dr. Welles, who was not involved with the U.K. research.

The U.K. study drew on unpublished data from the Room to Breathe survey conducted by Dr. Carroll’s group during 2008-2009 in Canada, the United Kingdom, Greece, Hungary, South Africa, and the Netherlands. Only 358 of 930 (38.5%) children were found to be well controlled according to current Global Initiative for Asthma symptom-control criteria.

The analysis also found a highly significant association (P < .0001) between Childhood Asthma Control Test (C-ACT) score and reported bullying/teasing, with bullied children having lower scores. C-ACT–defined controlled asthma scores of 20 or higher were significantly associated with a lower risk of bullying (OR, 0.46; 95% CI, 0.28-0.76; P = .001).

In other study findings, harassment was more common in children whose asthma was serious enough to entail activity restriction (OR, 1.74; 95% CI, 1.11-2.75; P = .010) and who described their asthma as “bad” (OR, 3.02; 95% CI, 1.86-4.85; P < .001), as well as those whose parents reported ongoing asthma-related health worries (OR, 1.64; 95% CI, 1.04-2.58; P = .024).

“When a child is clearly different from others, such as having bad asthma or being limited in activities due to asthma, they stand out more and are more frequently bullied,” said Tracy Evian Waasdorp, PhD, MSEd, director of research for school-based bullying and social-emotional learning at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and also not a participant in the U.K. study.

In contrast to the 10% bullying rate in Dr. Carroll’s study, Dr. Waasdorp referred to a CHOP analysis of more than 64,000 youth from a Northeastern state in which those with asthma were 40% more likely to be victims of in-person bullying and 70% were more likely to be cyberbullied than youth without asthma. “Having a medical condition can therefore put you at risk of being bullied regardless of what country you live in,” she said.

CHOP policy encourages practitioners to routinely ask about bullying and to provide handouts and resources for parents, she added.

Interestingly, the U.K. investigators found that open public use of spacers was not associated with asthma-related bullying, nor was parental worry at diagnosis or parental concern about steroid use.

But according to Dr. Welles, “Kids may be using the inhaler in front of other kids, and they may be embarrassed and not want to be seen as different. So they may not use the inhaler when needed for gym class or sports, forcing them to sit out and then potentially be bullied again. It’s a vicious cycle.”

Previous research has identified the bullying and teasing of children with food allergies.

Behaviors have included allergy-specific harassment such as smearing peanut butter on a youngster’s forehead or putting peanut butter cookie crumbs in a child’s lunch box.

“In our survey we asked the question ‘Have you been teased or bullied because of your asthma?’ but we didn’t ask what form this took,” Dr. Carroll said. “But we were surprised at just how many children said yes. It’s time for more research, I think.”

“There are never enough studies around this,” added Dr. Welles. “Bullying, whether because of asthma or otherwise, has the potential for long-term effects well into adulthood.”

In the meantime, asthma consultations should incorporate specific questions about bullying. They should also be child focused in order to gain a representative appreciation of asthma control and its effect on the child’s life.

“As pediatricians, we need to be continuously supporting parents and find the help they need to address any mental health issues,” Dr. Welles said. “Every pediatrician and parent needs to be aware and recognize when something is different in their child’s life. Please don’t ignore it.”

Dr. Waasdorp stressed that school and other communities should be aware that children with asthma may be at increased risk for aggression and harmful interactions related to their asthma. “Programming to reduce bullying should focus broadly on shifting the climate so that bullying is not perceived to be normative and on improving ‘upstander,’ or positive bystander, responses.” she said.

The original survey was funded by Nycomed (Zurich). No additional funding was requested for the current analysis. Dr. Carroll reported personal fees from GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, and Trudell Medical International outside the submitted work. Dr. Welles and Dr. Waasdorp disclosed no competing interests relevant to their comments.

FROM ARCHIVES OF DISEASE IN CHILDHOOD

DRESS Syndrome Due to Cefdinir Mimicking Superinfected Eczema in a Pediatric Patient

To the Editor:

Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome, or drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome, is a serious and potentially fatal multiorgan drug hypersensitivity reaction. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms syndrome shares many clinical features with viral exanthems and may be difficult to diagnose in the setting of atopic dermatitis (AD) in which children may have baseline eosinophilia from an atopic diathesis. The cutaneous exanthema also may be variable in presentation, further complicating diagnosis.1,2

A 3-year-old boy with AD since infancy and a history of anaphylaxis to peanuts presented to the emergency department with reported fever, rash, sore throat, and decreased oral intake. Ten days prior, the patient was treated for cellulitis of the left foot with a 7-day course of cefdinir with complete resolution of symptoms. Four days prior to admission, the patient started developing “bumps” on the face and fevers. He was seen at an outside facility, where a rapid test for Streptococcus was negative, and the patient was treated with ibuprofen and fluids for a presumed viral exanthem. The rash subsequently spread to involve the trunk and extremities. On the day of admission, the patient had a positive rapid test for Streptococcus and was referred to the emergency department with concern for superinfected eczema and eczema herpeticum. The patient recently traveled to Puerto Rico, where he had contact with an aunt with active herpes zoster but no other sick contacts. The patient’s immunizations were reported to be up-to-date.

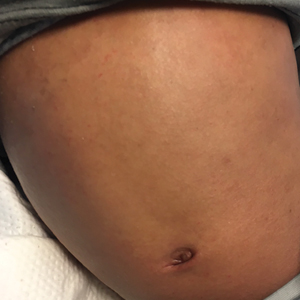

Physical examination revealed the patient was afebrile but irritable and had erythematous crusted papules and patches on the face, arms, and legs, as well as erythematous dry patches on the chest, abdomen, and back (Figure). There were no conjunctival erythematous or oral erosions. The patient was admitted to the hospital for presumed superinfected AD and possible eczema herpeticum. He was started on intravenous clindamycin and acyclovir.

The following day, the patient had new facial edema and fever (temperature, 102.8 °F [39.36 °C]) in addition to palpable mobile cervical, axillary, and inguinal lymphadenopathy. He also was noted to have notably worsening eosinophilia from 1288 (14%) to 2570 (29.2%) cells/µL (reference range, 0%–5%) and new-onset transaminitis. Herpes and varicella-zoster direct fluorescent antibody tests, culture, and serum polymerase chain reaction were all negative, and acyclovir was discontinued. Repeat laboratory tests 12 hours later showed a continued uptrend in transaminitis. Serologies for acute and chronic cytomegalovirus; Epstein-Barr virus; and hepatitis A, B, and C were all nonreactive. The patient was started on intravenous methylprednisolone 1 mg/kg daily for suspected DRESS syndrome likely due to cefdinir.

The patient’s eosinophilia completely resolved (from approximately 2600 to 100 cells/µL) after 1 dose of steroids, and his transaminitis trended down over the next few days. He remained afebrile for the remainder of his admission, and his facial swelling and rash continued to improve. Bacterial culture from the skin grew oxacillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus and group A Streptococcus pyogenes. A blood culture was negative. The patient was discharged home to complete a 10-day course of clindamycin and was given topical steroids for the eczema. He continued on oral prednisolone 1 mg/kg daily for 10 days, after which the dose was tapered down for a total 1-month course of systemic corticosteroids. At 1-month follow-up after completing the course of steroids, he was doing well with normal hepatic enzyme levels and no recurrence of fever, facial edema, or rash. He continues to be followed for management of the AD.

Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms syndrome is a serious systemic adverse drug reaction, with high morbidity and even mortality, estimated at 10% in the adult population, though more specific pediatric mortality data are not available.1,2 The exact pathogenesis of DRESS syndrome has not been elucidated. Certain human leukocyte antigen class I alleles are predisposed to the development of DRESS syndrome, but there has not been a human leukocyte antigen subtype identified with beta-lactam–associated DRESS syndrome. Some studies have demonstrated a reactivation of human herpesvirus 6, human herpesvirus 7, and Epstein-Barr virus.3 One study involving 40 patients with DRESS syndrome identified viremia in 76% (29/38) of patients and identified CD8+ T-cell populations directed toward viral epitopes.3 Finally, DRESS syndrome may be related to the slow detoxification and elimination of intermediary products of offending medications that serve as an immunogenic stimulus for the inflammatory cascade.2

In adults, DRESS syndrome was first identified in association with phenytoin, but more recently other drugs have been identified, including other aromatic anticonvulsants (ie, lamotrigine, phenobarbital, carbamazepine), allopurinol, sulfonamides, antiretrovirals (particularly abacavir), and minocycline.2 In a 3-year pediatric prospective study, 11 cases of DRESS syndrome were identified: 4 cases due to lamotrigine, and 3 caused by penicillins.4 The trigger in our patient’s case was the beta-lactam, third-generation cephalosporin cefdinir, and his symptoms developed within 6 days of starting the medication. Many articles report that beta-lactams are a rare cause of DRESS syndrome, with only a handful of cases reported.1,5,6

The diagnosis of DRESS syndrome often can be delayed, as children present acutely febrile and toxic appearing. Unlike many adverse drug reactions, DRESS syndrome does not show rapid resolution with withdrawal of the causative agent, further complicating the diagnosis. The typical onset of DRESS syndrome generally ranges from 2 to 6 weeks after the initiation of the offending drug; however, faster onset of symptoms, similar to our case, has been noted in antibiotic-triggered cases. In the prospective pediatric series by Sasidharanpillai et al,4 the average time to onset among 3 antibiotic-triggered DRESS cases was 5.8 days vs 23.9 days among the 4 cases of lamotrigine-associated DRESS syndrome.

Our patient demonstrated the classic features of DRESS syndrome, including fever, rash, lymphadenopathy, facial edema, peripheral eosinophilia, atypical lymphocytosis, and hepatitis. Based on the proposed RegiSCAR scoring system, our patient was classified as a “definite” case of DRESS syndrome.1,7 Other hematologic findings in DRESS syndrome may include thrombocytopenia and anemia. The liver is the most commonly affected internal organ in DRESS syndrome, with pneumonitis, carditis, and nephritis reported less frequently.1 The pattern of liver injury in our patient was mixed (hepatocellular and cholestatic), the second most common pattern in patients with DRESS syndrome (the cholestatic pattern is most common).8

The exanthem of DRESS syndrome can vary in morphology, with up to 7% of patients reported to have eczemalike lesions in the multinational prospective RegiSCAR study.1 Other entities in the differential diagnosis for our patient included Kawasaki disease, where conjunctivitis and strawberry tongue are classically present, as well as erythrodermic AD, where internal organ involvement is not common.2 Our patient’s exanthem initially was considered to be a flare of AD with superimposed bacterial infection and possible eczema herpeticum. Although bacterial cultures did grow Staphylococcus and Streptococcus, viral studies were all negative, and this alone would not have explained the facial edema, rapidly rising eosinophil count, and transaminitis. The dramatic drop in his eosinophil count and decrease in hepatic enzymes after 1 dose of intravenous methylprednisolone also supported the diagnosis of DRESS syndrome.

Treatment recommendations remain largely anecdotal. Early systemic steroids generally are accepted as the first line of therapy, with a slow taper. Although the average required duration of systemic steroids in 1 series of adults was reported at 50.1 days,9 the duration was shorter (21–35 days) in a series of pediatric patients.4 Our patient’s clinical symptoms and laboratory values normalized after completing a 1-month steroid taper. Other therapies have been tried for recalcitrant cases, including intravenous immunoglobulin, plasmapheresis, rituximab, and valganciclovir.2

Early clinical recognition of the signs and symptoms of DRESS syndrome in the setting of a new medication can decrease morbidity and mortality. Although DRESS syndrome in pediatric patients presents with many similar clinical features as in adults, it may be a greater diagnostic challenge. As in adult cases, timely administration of systemic corticosteroids and tapering based on clinical signs and symptoms can lead to resolution of the hypersensitivity syndrome.

- Kardaun SH, Sekula P, Valeyrie-Allanore L, et al. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS): an original multisystem adverse drug reaction. results from the prospective RegiSCAR study. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:1071-1080.

- Fernando SL. Drug-reaction eosinophilia and systemic symptoms and drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome. Australas J Dermatol. 2014;55:15-23.

- Picard D, Janela B, Descamps V, et al. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS): a multiorgan antiviral T cell response. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:46ra62.

- Sasidharanpillai S, Sabitha S, Riyaz N, et al. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms in children: a prospective study. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:E162-E165.

- Aouam K, Chaabane A, Toumi A, et al. Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) probably induced by cefotaxime: a report of two cases. Clin Med Res. 2012;10:32-35.

- Guleria VS, Dhillon M, Gill S, et al. Ceftriaxone induced drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms. J Res Pharm Pract. 2014;3:72-74.

- Kardaun SH, Sidoroff A, Valeyrie-Allanore L, et al. Variability in the clinical pattern of cutaneous side-effects of drugs with systemic symptoms: does a DRESS syndrome really exist? Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:609-611.

- Lin IC, Yang HC, Strong C, et al. Liver injury in patients with DRESS: a clinical study of 72 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:984-991.

- Ang CC, Wang YS, Yoosuff EL, et al. Retrospective analysis of drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome: a study of 27 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:219-227.

To the Editor:

Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome, or drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome, is a serious and potentially fatal multiorgan drug hypersensitivity reaction. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms syndrome shares many clinical features with viral exanthems and may be difficult to diagnose in the setting of atopic dermatitis (AD) in which children may have baseline eosinophilia from an atopic diathesis. The cutaneous exanthema also may be variable in presentation, further complicating diagnosis.1,2

A 3-year-old boy with AD since infancy and a history of anaphylaxis to peanuts presented to the emergency department with reported fever, rash, sore throat, and decreased oral intake. Ten days prior, the patient was treated for cellulitis of the left foot with a 7-day course of cefdinir with complete resolution of symptoms. Four days prior to admission, the patient started developing “bumps” on the face and fevers. He was seen at an outside facility, where a rapid test for Streptococcus was negative, and the patient was treated with ibuprofen and fluids for a presumed viral exanthem. The rash subsequently spread to involve the trunk and extremities. On the day of admission, the patient had a positive rapid test for Streptococcus and was referred to the emergency department with concern for superinfected eczema and eczema herpeticum. The patient recently traveled to Puerto Rico, where he had contact with an aunt with active herpes zoster but no other sick contacts. The patient’s immunizations were reported to be up-to-date.

Physical examination revealed the patient was afebrile but irritable and had erythematous crusted papules and patches on the face, arms, and legs, as well as erythematous dry patches on the chest, abdomen, and back (Figure). There were no conjunctival erythematous or oral erosions. The patient was admitted to the hospital for presumed superinfected AD and possible eczema herpeticum. He was started on intravenous clindamycin and acyclovir.

The following day, the patient had new facial edema and fever (temperature, 102.8 °F [39.36 °C]) in addition to palpable mobile cervical, axillary, and inguinal lymphadenopathy. He also was noted to have notably worsening eosinophilia from 1288 (14%) to 2570 (29.2%) cells/µL (reference range, 0%–5%) and new-onset transaminitis. Herpes and varicella-zoster direct fluorescent antibody tests, culture, and serum polymerase chain reaction were all negative, and acyclovir was discontinued. Repeat laboratory tests 12 hours later showed a continued uptrend in transaminitis. Serologies for acute and chronic cytomegalovirus; Epstein-Barr virus; and hepatitis A, B, and C were all nonreactive. The patient was started on intravenous methylprednisolone 1 mg/kg daily for suspected DRESS syndrome likely due to cefdinir.

The patient’s eosinophilia completely resolved (from approximately 2600 to 100 cells/µL) after 1 dose of steroids, and his transaminitis trended down over the next few days. He remained afebrile for the remainder of his admission, and his facial swelling and rash continued to improve. Bacterial culture from the skin grew oxacillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus and group A Streptococcus pyogenes. A blood culture was negative. The patient was discharged home to complete a 10-day course of clindamycin and was given topical steroids for the eczema. He continued on oral prednisolone 1 mg/kg daily for 10 days, after which the dose was tapered down for a total 1-month course of systemic corticosteroids. At 1-month follow-up after completing the course of steroids, he was doing well with normal hepatic enzyme levels and no recurrence of fever, facial edema, or rash. He continues to be followed for management of the AD.

Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms syndrome is a serious systemic adverse drug reaction, with high morbidity and even mortality, estimated at 10% in the adult population, though more specific pediatric mortality data are not available.1,2 The exact pathogenesis of DRESS syndrome has not been elucidated. Certain human leukocyte antigen class I alleles are predisposed to the development of DRESS syndrome, but there has not been a human leukocyte antigen subtype identified with beta-lactam–associated DRESS syndrome. Some studies have demonstrated a reactivation of human herpesvirus 6, human herpesvirus 7, and Epstein-Barr virus.3 One study involving 40 patients with DRESS syndrome identified viremia in 76% (29/38) of patients and identified CD8+ T-cell populations directed toward viral epitopes.3 Finally, DRESS syndrome may be related to the slow detoxification and elimination of intermediary products of offending medications that serve as an immunogenic stimulus for the inflammatory cascade.2

In adults, DRESS syndrome was first identified in association with phenytoin, but more recently other drugs have been identified, including other aromatic anticonvulsants (ie, lamotrigine, phenobarbital, carbamazepine), allopurinol, sulfonamides, antiretrovirals (particularly abacavir), and minocycline.2 In a 3-year pediatric prospective study, 11 cases of DRESS syndrome were identified: 4 cases due to lamotrigine, and 3 caused by penicillins.4 The trigger in our patient’s case was the beta-lactam, third-generation cephalosporin cefdinir, and his symptoms developed within 6 days of starting the medication. Many articles report that beta-lactams are a rare cause of DRESS syndrome, with only a handful of cases reported.1,5,6

The diagnosis of DRESS syndrome often can be delayed, as children present acutely febrile and toxic appearing. Unlike many adverse drug reactions, DRESS syndrome does not show rapid resolution with withdrawal of the causative agent, further complicating the diagnosis. The typical onset of DRESS syndrome generally ranges from 2 to 6 weeks after the initiation of the offending drug; however, faster onset of symptoms, similar to our case, has been noted in antibiotic-triggered cases. In the prospective pediatric series by Sasidharanpillai et al,4 the average time to onset among 3 antibiotic-triggered DRESS cases was 5.8 days vs 23.9 days among the 4 cases of lamotrigine-associated DRESS syndrome.

Our patient demonstrated the classic features of DRESS syndrome, including fever, rash, lymphadenopathy, facial edema, peripheral eosinophilia, atypical lymphocytosis, and hepatitis. Based on the proposed RegiSCAR scoring system, our patient was classified as a “definite” case of DRESS syndrome.1,7 Other hematologic findings in DRESS syndrome may include thrombocytopenia and anemia. The liver is the most commonly affected internal organ in DRESS syndrome, with pneumonitis, carditis, and nephritis reported less frequently.1 The pattern of liver injury in our patient was mixed (hepatocellular and cholestatic), the second most common pattern in patients with DRESS syndrome (the cholestatic pattern is most common).8

The exanthem of DRESS syndrome can vary in morphology, with up to 7% of patients reported to have eczemalike lesions in the multinational prospective RegiSCAR study.1 Other entities in the differential diagnosis for our patient included Kawasaki disease, where conjunctivitis and strawberry tongue are classically present, as well as erythrodermic AD, where internal organ involvement is not common.2 Our patient’s exanthem initially was considered to be a flare of AD with superimposed bacterial infection and possible eczema herpeticum. Although bacterial cultures did grow Staphylococcus and Streptococcus, viral studies were all negative, and this alone would not have explained the facial edema, rapidly rising eosinophil count, and transaminitis. The dramatic drop in his eosinophil count and decrease in hepatic enzymes after 1 dose of intravenous methylprednisolone also supported the diagnosis of DRESS syndrome.

Treatment recommendations remain largely anecdotal. Early systemic steroids generally are accepted as the first line of therapy, with a slow taper. Although the average required duration of systemic steroids in 1 series of adults was reported at 50.1 days,9 the duration was shorter (21–35 days) in a series of pediatric patients.4 Our patient’s clinical symptoms and laboratory values normalized after completing a 1-month steroid taper. Other therapies have been tried for recalcitrant cases, including intravenous immunoglobulin, plasmapheresis, rituximab, and valganciclovir.2

Early clinical recognition of the signs and symptoms of DRESS syndrome in the setting of a new medication can decrease morbidity and mortality. Although DRESS syndrome in pediatric patients presents with many similar clinical features as in adults, it may be a greater diagnostic challenge. As in adult cases, timely administration of systemic corticosteroids and tapering based on clinical signs and symptoms can lead to resolution of the hypersensitivity syndrome.

To the Editor:

Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome, or drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome, is a serious and potentially fatal multiorgan drug hypersensitivity reaction. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms syndrome shares many clinical features with viral exanthems and may be difficult to diagnose in the setting of atopic dermatitis (AD) in which children may have baseline eosinophilia from an atopic diathesis. The cutaneous exanthema also may be variable in presentation, further complicating diagnosis.1,2

A 3-year-old boy with AD since infancy and a history of anaphylaxis to peanuts presented to the emergency department with reported fever, rash, sore throat, and decreased oral intake. Ten days prior, the patient was treated for cellulitis of the left foot with a 7-day course of cefdinir with complete resolution of symptoms. Four days prior to admission, the patient started developing “bumps” on the face and fevers. He was seen at an outside facility, where a rapid test for Streptococcus was negative, and the patient was treated with ibuprofen and fluids for a presumed viral exanthem. The rash subsequently spread to involve the trunk and extremities. On the day of admission, the patient had a positive rapid test for Streptococcus and was referred to the emergency department with concern for superinfected eczema and eczema herpeticum. The patient recently traveled to Puerto Rico, where he had contact with an aunt with active herpes zoster but no other sick contacts. The patient’s immunizations were reported to be up-to-date.

Physical examination revealed the patient was afebrile but irritable and had erythematous crusted papules and patches on the face, arms, and legs, as well as erythematous dry patches on the chest, abdomen, and back (Figure). There were no conjunctival erythematous or oral erosions. The patient was admitted to the hospital for presumed superinfected AD and possible eczema herpeticum. He was started on intravenous clindamycin and acyclovir.

The following day, the patient had new facial edema and fever (temperature, 102.8 °F [39.36 °C]) in addition to palpable mobile cervical, axillary, and inguinal lymphadenopathy. He also was noted to have notably worsening eosinophilia from 1288 (14%) to 2570 (29.2%) cells/µL (reference range, 0%–5%) and new-onset transaminitis. Herpes and varicella-zoster direct fluorescent antibody tests, culture, and serum polymerase chain reaction were all negative, and acyclovir was discontinued. Repeat laboratory tests 12 hours later showed a continued uptrend in transaminitis. Serologies for acute and chronic cytomegalovirus; Epstein-Barr virus; and hepatitis A, B, and C were all nonreactive. The patient was started on intravenous methylprednisolone 1 mg/kg daily for suspected DRESS syndrome likely due to cefdinir.

The patient’s eosinophilia completely resolved (from approximately 2600 to 100 cells/µL) after 1 dose of steroids, and his transaminitis trended down over the next few days. He remained afebrile for the remainder of his admission, and his facial swelling and rash continued to improve. Bacterial culture from the skin grew oxacillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus and group A Streptococcus pyogenes. A blood culture was negative. The patient was discharged home to complete a 10-day course of clindamycin and was given topical steroids for the eczema. He continued on oral prednisolone 1 mg/kg daily for 10 days, after which the dose was tapered down for a total 1-month course of systemic corticosteroids. At 1-month follow-up after completing the course of steroids, he was doing well with normal hepatic enzyme levels and no recurrence of fever, facial edema, or rash. He continues to be followed for management of the AD.

Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms syndrome is a serious systemic adverse drug reaction, with high morbidity and even mortality, estimated at 10% in the adult population, though more specific pediatric mortality data are not available.1,2 The exact pathogenesis of DRESS syndrome has not been elucidated. Certain human leukocyte antigen class I alleles are predisposed to the development of DRESS syndrome, but there has not been a human leukocyte antigen subtype identified with beta-lactam–associated DRESS syndrome. Some studies have demonstrated a reactivation of human herpesvirus 6, human herpesvirus 7, and Epstein-Barr virus.3 One study involving 40 patients with DRESS syndrome identified viremia in 76% (29/38) of patients and identified CD8+ T-cell populations directed toward viral epitopes.3 Finally, DRESS syndrome may be related to the slow detoxification and elimination of intermediary products of offending medications that serve as an immunogenic stimulus for the inflammatory cascade.2

In adults, DRESS syndrome was first identified in association with phenytoin, but more recently other drugs have been identified, including other aromatic anticonvulsants (ie, lamotrigine, phenobarbital, carbamazepine), allopurinol, sulfonamides, antiretrovirals (particularly abacavir), and minocycline.2 In a 3-year pediatric prospective study, 11 cases of DRESS syndrome were identified: 4 cases due to lamotrigine, and 3 caused by penicillins.4 The trigger in our patient’s case was the beta-lactam, third-generation cephalosporin cefdinir, and his symptoms developed within 6 days of starting the medication. Many articles report that beta-lactams are a rare cause of DRESS syndrome, with only a handful of cases reported.1,5,6

The diagnosis of DRESS syndrome often can be delayed, as children present acutely febrile and toxic appearing. Unlike many adverse drug reactions, DRESS syndrome does not show rapid resolution with withdrawal of the causative agent, further complicating the diagnosis. The typical onset of DRESS syndrome generally ranges from 2 to 6 weeks after the initiation of the offending drug; however, faster onset of symptoms, similar to our case, has been noted in antibiotic-triggered cases. In the prospective pediatric series by Sasidharanpillai et al,4 the average time to onset among 3 antibiotic-triggered DRESS cases was 5.8 days vs 23.9 days among the 4 cases of lamotrigine-associated DRESS syndrome.

Our patient demonstrated the classic features of DRESS syndrome, including fever, rash, lymphadenopathy, facial edema, peripheral eosinophilia, atypical lymphocytosis, and hepatitis. Based on the proposed RegiSCAR scoring system, our patient was classified as a “definite” case of DRESS syndrome.1,7 Other hematologic findings in DRESS syndrome may include thrombocytopenia and anemia. The liver is the most commonly affected internal organ in DRESS syndrome, with pneumonitis, carditis, and nephritis reported less frequently.1 The pattern of liver injury in our patient was mixed (hepatocellular and cholestatic), the second most common pattern in patients with DRESS syndrome (the cholestatic pattern is most common).8

The exanthem of DRESS syndrome can vary in morphology, with up to 7% of patients reported to have eczemalike lesions in the multinational prospective RegiSCAR study.1 Other entities in the differential diagnosis for our patient included Kawasaki disease, where conjunctivitis and strawberry tongue are classically present, as well as erythrodermic AD, where internal organ involvement is not common.2 Our patient’s exanthem initially was considered to be a flare of AD with superimposed bacterial infection and possible eczema herpeticum. Although bacterial cultures did grow Staphylococcus and Streptococcus, viral studies were all negative, and this alone would not have explained the facial edema, rapidly rising eosinophil count, and transaminitis. The dramatic drop in his eosinophil count and decrease in hepatic enzymes after 1 dose of intravenous methylprednisolone also supported the diagnosis of DRESS syndrome.

Treatment recommendations remain largely anecdotal. Early systemic steroids generally are accepted as the first line of therapy, with a slow taper. Although the average required duration of systemic steroids in 1 series of adults was reported at 50.1 days,9 the duration was shorter (21–35 days) in a series of pediatric patients.4 Our patient’s clinical symptoms and laboratory values normalized after completing a 1-month steroid taper. Other therapies have been tried for recalcitrant cases, including intravenous immunoglobulin, plasmapheresis, rituximab, and valganciclovir.2

Early clinical recognition of the signs and symptoms of DRESS syndrome in the setting of a new medication can decrease morbidity and mortality. Although DRESS syndrome in pediatric patients presents with many similar clinical features as in adults, it may be a greater diagnostic challenge. As in adult cases, timely administration of systemic corticosteroids and tapering based on clinical signs and symptoms can lead to resolution of the hypersensitivity syndrome.

- Kardaun SH, Sekula P, Valeyrie-Allanore L, et al. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS): an original multisystem adverse drug reaction. results from the prospective RegiSCAR study. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:1071-1080.

- Fernando SL. Drug-reaction eosinophilia and systemic symptoms and drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome. Australas J Dermatol. 2014;55:15-23.

- Picard D, Janela B, Descamps V, et al. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS): a multiorgan antiviral T cell response. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:46ra62.

- Sasidharanpillai S, Sabitha S, Riyaz N, et al. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms in children: a prospective study. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:E162-E165.

- Aouam K, Chaabane A, Toumi A, et al. Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) probably induced by cefotaxime: a report of two cases. Clin Med Res. 2012;10:32-35.

- Guleria VS, Dhillon M, Gill S, et al. Ceftriaxone induced drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms. J Res Pharm Pract. 2014;3:72-74.

- Kardaun SH, Sidoroff A, Valeyrie-Allanore L, et al. Variability in the clinical pattern of cutaneous side-effects of drugs with systemic symptoms: does a DRESS syndrome really exist? Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:609-611.

- Lin IC, Yang HC, Strong C, et al. Liver injury in patients with DRESS: a clinical study of 72 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:984-991.

- Ang CC, Wang YS, Yoosuff EL, et al. Retrospective analysis of drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome: a study of 27 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:219-227.

- Kardaun SH, Sekula P, Valeyrie-Allanore L, et al. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS): an original multisystem adverse drug reaction. results from the prospective RegiSCAR study. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:1071-1080.

- Fernando SL. Drug-reaction eosinophilia and systemic symptoms and drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome. Australas J Dermatol. 2014;55:15-23.

- Picard D, Janela B, Descamps V, et al. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS): a multiorgan antiviral T cell response. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:46ra62.

- Sasidharanpillai S, Sabitha S, Riyaz N, et al. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms in children: a prospective study. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:E162-E165.

- Aouam K, Chaabane A, Toumi A, et al. Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) probably induced by cefotaxime: a report of two cases. Clin Med Res. 2012;10:32-35.

- Guleria VS, Dhillon M, Gill S, et al. Ceftriaxone induced drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms. J Res Pharm Pract. 2014;3:72-74.

- Kardaun SH, Sidoroff A, Valeyrie-Allanore L, et al. Variability in the clinical pattern of cutaneous side-effects of drugs with systemic symptoms: does a DRESS syndrome really exist? Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:609-611.

- Lin IC, Yang HC, Strong C, et al. Liver injury in patients with DRESS: a clinical study of 72 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:984-991.

- Ang CC, Wang YS, Yoosuff EL, et al. Retrospective analysis of drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome: a study of 27 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:219-227.

Practice Points

- Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome shares many clinical features with viral exanthems and may be difficult to diagnose in the setting of atopic dermatitis in which children may have baseline eosinophilia from an atopic diathesis.

- Early clinical recognition of the signs and symptoms of DRESS syndrome in the setting of a new medication can decrease morbidity and mortality.

Genomic screening of healthy newborns gets more popular

Even before their baby is born, parents face some tough questions: Home birth or hospital? Cloth or disposable diapers? Breast, bottle, or both? But advances in genetic sequencing technology mean that parents will soon face yet another choice: whether to sequence their newborn’s DNA for an overview of the baby’s entire genome.

Genetic testing has been used for decades to diagnose conditions even before birth. But DNA sequencing technologies, once expensive and tough to access, are now rapid and cheap enough that doctors could order genomic screening for any infant, regardless of health status.

The possibility has raised many questions about the ethical, legal, and social repercussions of doing so. One of the biggest sticking points of sequencing newborns is the potential psychosocial fallout for families of such wide-scale use of genetic screening.

“There’s a narrative of catastrophic distress,” says Robert Green, MD, a geneticist at Harvard Medical School and lead investigator on the BabySeq study, which is evaluating the medical, social, and economic consequences of newborn genetic screening. The concern is that parents learning that their child carries a gene variant related to cancer or heart disease will become “incredibly anxious and distressed,” he says. “And it’s not an unreasonable speculation.”

But Dr. Green’s team found no evidence of such anxiety in the results from a randomized trial it conducted, published in JAMA Pediatrics. In the meantime, Genomics England announced it would begin a pilot study involving whole-genome sequencing of up to 200,000 babies. The first goal is to identify severe disease that starts in childhood, but the information would also be stored and used to detect drug sensitivities and conditions that come up later in life.

The large U.K. project is a bold move, according to David Amor, PhD, a pediatric geneticist at Murdoch Children’s Research Institute in Australia, who says its time has come. Geneticists have been accused of thinking their field involves unique pitfalls, compared with the rest of medicine, he points out, and that doctors need to protect patients and families from the potential harm genetic testing poses.

“But it is becoming apparent that that’s not really the case,” he says, and “maybe there’s not a whole lot special about genetics – it’s just medicine.”

When a first-draft copy of the human genome was published in 2001, scientists and doctors hailed the start of a new era of precision medicine. Knowing our genome sequence was expected to lead to a better grasp on our individual disease risks. Yet even as technologies advanced, clinical genetics remained focused on diagnosis rather than screening, according to Lilian Downie, a clinical genetics PhD candidate at the University of Melbourne. She calls the difference subtle but important.

Diagnostic genetic testing confirms whether a person has a specific condition, whereas genetic screening tests evaluate someone’s risk of getting an illness. Both approaches use sequencing, but they answer different questions, explains Ms. Downie.

Diagnosing disease versus predicting future illness

Genetic testing is on the upswing for both purposes, whether clinically for diagnosis or through direct-to-consumer screening-oriented services like 23andMe. Scientists began to note that many people carried disease-related genetic variants without having signs of disease. In some cases, a variant that is mathematically linked to a disease simply doesn’t cause it. In other cases, though, even if the gene variant contributes to a disease, not everyone who carries the genetic change will get the condition.

This potential disconnect between having a variant and developing the condition is a big problem, says Katie Stoll, a genetic counselor and executive director of the Genetic Support Foundation in Olympia, WA.

“It’s more complicated than just looking at one gene variant and one outcome,” she says. Without a sure link between the two, this information could unnecessarily entail “some pretty big emotional and financial costs.”

Ms. Stoll and others in the genetics field who share similar concerns are one reason the BabySeq project was first funded back in 2015. Although the overall aim of the initiative is to answer questions about the value of genomic sequencing in newborn screening, the media and scientific attention has focused on the psychosocial impact of healthy newborn sequencing, says Dr. Green. In the study published in JAMA Pediatrics, his group focused on these issues, too.

For that randomized trial, they enrolled 325 families, 257 with healthy babies and 68 whose babies had spent time in neonatal intensive care. Enrolled infants were randomly given standard care alone or standard care with genomic sequencing added on. The genomic sequencing report contained information about the presence of genetic variants associated with disease that start in childhood. Parents also could choose whether to learn about genetic risks for conditions that start in adulthood, such as cancer.

Boston-based Tina Moniz was one of those parents. When her first daughter was born in Jan. 2016, someone from the BabySeq study asked her and her husband if they would like to take part. The decision was simple for the couple.

“I didn’t hesitate,” she says. “To me, knowledge is power.”

Using screening tools for parental and marital distress and parent-child bonding, the research evaluated BabySeq families at 3 and 10 months after parents received the sequencing results. The investigators found no significant differences in any of these measures between screened and unscreened families. Ms. Moniz learned that her daughter’s only concerning result was being a carrier for cystic fibrosis. Rather than finding this information anxiety-provoking, Ms. Moniz considered it to be reassuring.

“My mom brain worries about so many things, but at least I know I don’t have to add genetic disease to the list,” she says.

But Ms. Stoll, who wasn’t involved in the BabySeq study, isn’t as convinced. She says that less than 10% of the families approached about the trial ultimately agreed to take part, suggesting potential bias in the selection process. Most participants were white, well-educated, and well-off, making it hard to generalize the study’s results.

What’s more, the standard care involved meeting with a genetic counselor and giving a detailed family history, neither of which is routinely offered to new parents, Ms. Stoll says. These study features leave her unconvinced that healthy newborn genetic screening is beneficial.

“We can’t assume these psychosocial consequences will be true for everyone,” she says.

Follow-up and treatment needed

Traditional newborn screening relies on blood biochemical tests to detect and diagnose metabolic diseases. This approach still outperforms DNA sequencing in trials, says Cynthia Powell, MD, a pediatric geneticist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, who wasn’t involved with the BabySeq study. Despite the enthusiasm for genomics, this kind of screening won’t replace newborn biochemical screening anytime soon, she says.

“There are some states that have only one geneticist available, so should we really be doing this if we can’t provide the necessary follow-up and treatment for these babies?” she asks.

Still, Dr. Powell says, the BabySeq study helps advance understanding of what the infrastructure needs are for widespread use of DNA sequencing in newborns. She says those needs include appropriate consent processes, access to genetic counselors to discuss testing, and referrals for further testing and treatment in those babies with concerning results.

The BabySeq program will also guide new initiatives, like the pilot program that Genomics England launched in Sept. 2021. As part of that project, the U.K. group intends to look into how practical whole-genome sequencing for newborn screening would be and look at the risks, benefits, and limits of its widespread use.

“For the first time, we’re putting real data into these questions that people have basically just speculated and hypothesized and created narratives about,” Dr. Green says.

But for now, the findings on the psychosocial effects of general newborn genomic screening show that “we should consider genetics to be just one more arrow in our medical quiver.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Even before their baby is born, parents face some tough questions: Home birth or hospital? Cloth or disposable diapers? Breast, bottle, or both? But advances in genetic sequencing technology mean that parents will soon face yet another choice: whether to sequence their newborn’s DNA for an overview of the baby’s entire genome.

Genetic testing has been used for decades to diagnose conditions even before birth. But DNA sequencing technologies, once expensive and tough to access, are now rapid and cheap enough that doctors could order genomic screening for any infant, regardless of health status.

The possibility has raised many questions about the ethical, legal, and social repercussions of doing so. One of the biggest sticking points of sequencing newborns is the potential psychosocial fallout for families of such wide-scale use of genetic screening.

“There’s a narrative of catastrophic distress,” says Robert Green, MD, a geneticist at Harvard Medical School and lead investigator on the BabySeq study, which is evaluating the medical, social, and economic consequences of newborn genetic screening. The concern is that parents learning that their child carries a gene variant related to cancer or heart disease will become “incredibly anxious and distressed,” he says. “And it’s not an unreasonable speculation.”

But Dr. Green’s team found no evidence of such anxiety in the results from a randomized trial it conducted, published in JAMA Pediatrics. In the meantime, Genomics England announced it would begin a pilot study involving whole-genome sequencing of up to 200,000 babies. The first goal is to identify severe disease that starts in childhood, but the information would also be stored and used to detect drug sensitivities and conditions that come up later in life.

The large U.K. project is a bold move, according to David Amor, PhD, a pediatric geneticist at Murdoch Children’s Research Institute in Australia, who says its time has come. Geneticists have been accused of thinking their field involves unique pitfalls, compared with the rest of medicine, he points out, and that doctors need to protect patients and families from the potential harm genetic testing poses.

“But it is becoming apparent that that’s not really the case,” he says, and “maybe there’s not a whole lot special about genetics – it’s just medicine.”

When a first-draft copy of the human genome was published in 2001, scientists and doctors hailed the start of a new era of precision medicine. Knowing our genome sequence was expected to lead to a better grasp on our individual disease risks. Yet even as technologies advanced, clinical genetics remained focused on diagnosis rather than screening, according to Lilian Downie, a clinical genetics PhD candidate at the University of Melbourne. She calls the difference subtle but important.

Diagnostic genetic testing confirms whether a person has a specific condition, whereas genetic screening tests evaluate someone’s risk of getting an illness. Both approaches use sequencing, but they answer different questions, explains Ms. Downie.

Diagnosing disease versus predicting future illness

Genetic testing is on the upswing for both purposes, whether clinically for diagnosis or through direct-to-consumer screening-oriented services like 23andMe. Scientists began to note that many people carried disease-related genetic variants without having signs of disease. In some cases, a variant that is mathematically linked to a disease simply doesn’t cause it. In other cases, though, even if the gene variant contributes to a disease, not everyone who carries the genetic change will get the condition.

This potential disconnect between having a variant and developing the condition is a big problem, says Katie Stoll, a genetic counselor and executive director of the Genetic Support Foundation in Olympia, WA.

“It’s more complicated than just looking at one gene variant and one outcome,” she says. Without a sure link between the two, this information could unnecessarily entail “some pretty big emotional and financial costs.”

Ms. Stoll and others in the genetics field who share similar concerns are one reason the BabySeq project was first funded back in 2015. Although the overall aim of the initiative is to answer questions about the value of genomic sequencing in newborn screening, the media and scientific attention has focused on the psychosocial impact of healthy newborn sequencing, says Dr. Green. In the study published in JAMA Pediatrics, his group focused on these issues, too.

For that randomized trial, they enrolled 325 families, 257 with healthy babies and 68 whose babies had spent time in neonatal intensive care. Enrolled infants were randomly given standard care alone or standard care with genomic sequencing added on. The genomic sequencing report contained information about the presence of genetic variants associated with disease that start in childhood. Parents also could choose whether to learn about genetic risks for conditions that start in adulthood, such as cancer.

Boston-based Tina Moniz was one of those parents. When her first daughter was born in Jan. 2016, someone from the BabySeq study asked her and her husband if they would like to take part. The decision was simple for the couple.

“I didn’t hesitate,” she says. “To me, knowledge is power.”

Using screening tools for parental and marital distress and parent-child bonding, the research evaluated BabySeq families at 3 and 10 months after parents received the sequencing results. The investigators found no significant differences in any of these measures between screened and unscreened families. Ms. Moniz learned that her daughter’s only concerning result was being a carrier for cystic fibrosis. Rather than finding this information anxiety-provoking, Ms. Moniz considered it to be reassuring.

“My mom brain worries about so many things, but at least I know I don’t have to add genetic disease to the list,” she says.

But Ms. Stoll, who wasn’t involved in the BabySeq study, isn’t as convinced. She says that less than 10% of the families approached about the trial ultimately agreed to take part, suggesting potential bias in the selection process. Most participants were white, well-educated, and well-off, making it hard to generalize the study’s results.

What’s more, the standard care involved meeting with a genetic counselor and giving a detailed family history, neither of which is routinely offered to new parents, Ms. Stoll says. These study features leave her unconvinced that healthy newborn genetic screening is beneficial.

“We can’t assume these psychosocial consequences will be true for everyone,” she says.

Follow-up and treatment needed

Traditional newborn screening relies on blood biochemical tests to detect and diagnose metabolic diseases. This approach still outperforms DNA sequencing in trials, says Cynthia Powell, MD, a pediatric geneticist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, who wasn’t involved with the BabySeq study. Despite the enthusiasm for genomics, this kind of screening won’t replace newborn biochemical screening anytime soon, she says.

“There are some states that have only one geneticist available, so should we really be doing this if we can’t provide the necessary follow-up and treatment for these babies?” she asks.

Still, Dr. Powell says, the BabySeq study helps advance understanding of what the infrastructure needs are for widespread use of DNA sequencing in newborns. She says those needs include appropriate consent processes, access to genetic counselors to discuss testing, and referrals for further testing and treatment in those babies with concerning results.

The BabySeq program will also guide new initiatives, like the pilot program that Genomics England launched in Sept. 2021. As part of that project, the U.K. group intends to look into how practical whole-genome sequencing for newborn screening would be and look at the risks, benefits, and limits of its widespread use.

“For the first time, we’re putting real data into these questions that people have basically just speculated and hypothesized and created narratives about,” Dr. Green says.

But for now, the findings on the psychosocial effects of general newborn genomic screening show that “we should consider genetics to be just one more arrow in our medical quiver.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Even before their baby is born, parents face some tough questions: Home birth or hospital? Cloth or disposable diapers? Breast, bottle, or both? But advances in genetic sequencing technology mean that parents will soon face yet another choice: whether to sequence their newborn’s DNA for an overview of the baby’s entire genome.

Genetic testing has been used for decades to diagnose conditions even before birth. But DNA sequencing technologies, once expensive and tough to access, are now rapid and cheap enough that doctors could order genomic screening for any infant, regardless of health status.

The possibility has raised many questions about the ethical, legal, and social repercussions of doing so. One of the biggest sticking points of sequencing newborns is the potential psychosocial fallout for families of such wide-scale use of genetic screening.

“There’s a narrative of catastrophic distress,” says Robert Green, MD, a geneticist at Harvard Medical School and lead investigator on the BabySeq study, which is evaluating the medical, social, and economic consequences of newborn genetic screening. The concern is that parents learning that their child carries a gene variant related to cancer or heart disease will become “incredibly anxious and distressed,” he says. “And it’s not an unreasonable speculation.”

But Dr. Green’s team found no evidence of such anxiety in the results from a randomized trial it conducted, published in JAMA Pediatrics. In the meantime, Genomics England announced it would begin a pilot study involving whole-genome sequencing of up to 200,000 babies. The first goal is to identify severe disease that starts in childhood, but the information would also be stored and used to detect drug sensitivities and conditions that come up later in life.

The large U.K. project is a bold move, according to David Amor, PhD, a pediatric geneticist at Murdoch Children’s Research Institute in Australia, who says its time has come. Geneticists have been accused of thinking their field involves unique pitfalls, compared with the rest of medicine, he points out, and that doctors need to protect patients and families from the potential harm genetic testing poses.

“But it is becoming apparent that that’s not really the case,” he says, and “maybe there’s not a whole lot special about genetics – it’s just medicine.”

When a first-draft copy of the human genome was published in 2001, scientists and doctors hailed the start of a new era of precision medicine. Knowing our genome sequence was expected to lead to a better grasp on our individual disease risks. Yet even as technologies advanced, clinical genetics remained focused on diagnosis rather than screening, according to Lilian Downie, a clinical genetics PhD candidate at the University of Melbourne. She calls the difference subtle but important.

Diagnostic genetic testing confirms whether a person has a specific condition, whereas genetic screening tests evaluate someone’s risk of getting an illness. Both approaches use sequencing, but they answer different questions, explains Ms. Downie.

Diagnosing disease versus predicting future illness

Genetic testing is on the upswing for both purposes, whether clinically for diagnosis or through direct-to-consumer screening-oriented services like 23andMe. Scientists began to note that many people carried disease-related genetic variants without having signs of disease. In some cases, a variant that is mathematically linked to a disease simply doesn’t cause it. In other cases, though, even if the gene variant contributes to a disease, not everyone who carries the genetic change will get the condition.

This potential disconnect between having a variant and developing the condition is a big problem, says Katie Stoll, a genetic counselor and executive director of the Genetic Support Foundation in Olympia, WA.

“It’s more complicated than just looking at one gene variant and one outcome,” she says. Without a sure link between the two, this information could unnecessarily entail “some pretty big emotional and financial costs.”

Ms. Stoll and others in the genetics field who share similar concerns are one reason the BabySeq project was first funded back in 2015. Although the overall aim of the initiative is to answer questions about the value of genomic sequencing in newborn screening, the media and scientific attention has focused on the psychosocial impact of healthy newborn sequencing, says Dr. Green. In the study published in JAMA Pediatrics, his group focused on these issues, too.

For that randomized trial, they enrolled 325 families, 257 with healthy babies and 68 whose babies had spent time in neonatal intensive care. Enrolled infants were randomly given standard care alone or standard care with genomic sequencing added on. The genomic sequencing report contained information about the presence of genetic variants associated with disease that start in childhood. Parents also could choose whether to learn about genetic risks for conditions that start in adulthood, such as cancer.

Boston-based Tina Moniz was one of those parents. When her first daughter was born in Jan. 2016, someone from the BabySeq study asked her and her husband if they would like to take part. The decision was simple for the couple.

“I didn’t hesitate,” she says. “To me, knowledge is power.”

Using screening tools for parental and marital distress and parent-child bonding, the research evaluated BabySeq families at 3 and 10 months after parents received the sequencing results. The investigators found no significant differences in any of these measures between screened and unscreened families. Ms. Moniz learned that her daughter’s only concerning result was being a carrier for cystic fibrosis. Rather than finding this information anxiety-provoking, Ms. Moniz considered it to be reassuring.

“My mom brain worries about so many things, but at least I know I don’t have to add genetic disease to the list,” she says.

But Ms. Stoll, who wasn’t involved in the BabySeq study, isn’t as convinced. She says that less than 10% of the families approached about the trial ultimately agreed to take part, suggesting potential bias in the selection process. Most participants were white, well-educated, and well-off, making it hard to generalize the study’s results.

What’s more, the standard care involved meeting with a genetic counselor and giving a detailed family history, neither of which is routinely offered to new parents, Ms. Stoll says. These study features leave her unconvinced that healthy newborn genetic screening is beneficial.

“We can’t assume these psychosocial consequences will be true for everyone,” she says.

Follow-up and treatment needed

Traditional newborn screening relies on blood biochemical tests to detect and diagnose metabolic diseases. This approach still outperforms DNA sequencing in trials, says Cynthia Powell, MD, a pediatric geneticist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, who wasn’t involved with the BabySeq study. Despite the enthusiasm for genomics, this kind of screening won’t replace newborn biochemical screening anytime soon, she says.

“There are some states that have only one geneticist available, so should we really be doing this if we can’t provide the necessary follow-up and treatment for these babies?” she asks.

Still, Dr. Powell says, the BabySeq study helps advance understanding of what the infrastructure needs are for widespread use of DNA sequencing in newborns. She says those needs include appropriate consent processes, access to genetic counselors to discuss testing, and referrals for further testing and treatment in those babies with concerning results.

The BabySeq program will also guide new initiatives, like the pilot program that Genomics England launched in Sept. 2021. As part of that project, the U.K. group intends to look into how practical whole-genome sequencing for newborn screening would be and look at the risks, benefits, and limits of its widespread use.

“For the first time, we’re putting real data into these questions that people have basically just speculated and hypothesized and created narratives about,” Dr. Green says.

But for now, the findings on the psychosocial effects of general newborn genomic screening show that “we should consider genetics to be just one more arrow in our medical quiver.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Expert shares top five atopic dermatitis–related questions he fields

Will my child outgrow the eczema?

That is perhaps the No. 1 atopic dermatitis–related question that Lawrence F. Eichenfield, MD, fields from parents in his role as chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady’s Children’s Hospital, San Diego.

The answer “is pretty tricky,” he said during MedscapeLive’s annual Las Vegas Dermatology Seminar. “We used to say, ‘yeah, your kid will probably outgrow the disease,’ but we now have good data that show there are variable courses.”

Using data from the birth study cohort known as the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children, researchers in the United Kingdom investigated the existence of different longitudinal phenotypes of AD among 9,894 children. They found that 58% of the children in the cohort were unaffected or had transient AD, while 12.9% had early-onset/early-resolving AD. The remaining AD phenotypes consisted of 7%-8% patients each (early-onset persistent, early-onset late-resolving, mid-onset resolving, and late-onset resolving).

“There have been several studies that looked at the natural course of AD,” said Dr. Eichenfield, distinguished professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. “A cohort study from Thailand showed that 50% of patients with childhood AD lost their AD diagnosis about 5 years into it, while there was an increase in allergic rhino-conjunctivitis and asthma, similar to what’s been seen in atopic march studies,” he noted.

A separate group of investigators analyzed records from The Health Improvement Network in the UK to determine the prevalence of AD among more than 8 million patients seen in primary care between 1994 and 2013. They found that the cumulative lifetime prevalence of atopic eczema was 9.9% and the highest rates of active disease were among children and older adults. “The takeaway was markedly inconsistent in terms of whether AD went away over time or increased over time, so it’s really not especially helpful prevalence data,” Dr. Eichenfield said. “Overall, you have a high prevalence in the first years of life, it decreases, and it may increase again when people are 60 years and older. Whether that’s truly AD or xerotic eczema isn’t known in this data set.”