User login

Intent to vaccinate kids against COVID higher among vaccinated parents

“Parental vaccine hesitancy is a major issue for schools resuming in-person instruction, potentially requiring regular testing, strict mask wearing, and physical distancing for safe operation,” wrote lead author Madhura S. Rane, PhD, from the City University of New York in New York City, and colleagues in their paper, published online in JAMA Pediatrics.

The survey was conducted in June 2021 of 1,162 parents with children ranging in age from 2 to 17 years. The majority of parents (74.4%) were already vaccinated/vaccine-willing ,while 25.6% were vaccine hesitant. The study cohort, including both 1,652 children and their parents, was part of the nationwide CHASING COVID.

Vaccinated parents overall were more willing to vaccinate or had already vaccinated their eligible children when compared with vaccine-hesitant parents: 64.9% vs. 8.3% for children 2-4 years of age; 77.6% vs. 12.1% for children 5-11 years of age; 81.3% vs. 13.9% for children 12-15 years of age; and 86.4% vs. 12.7% for children 16-17 years of age; P < .001.

The researchers found greater hesitancy among Black and Hispanic parents, compared with parents who were non-Hispanic White, women, younger, and did not have a college education. Parents of children who were currently attending school remotely or only partially, were found to be more willing to vaccinate their children when compared to parents of children who were attending school fully in person.

The authors also found that parents who knew someone who had died of COVID-19 or had experienced a prior COVID-19 infection, were more willing to vaccinate their children.

Hesitance in vaccinated parents

Interestingly, 10% of COVID-vaccinated parents said they were still hesitant to vaccinate their kids because of concern for long-term adverse effects of the vaccine.

“These data point out that vaccine concerns may exist even among vaccinated or vaccine-favorable parents, so we should ask any parent who has not vaccinated their child whether we can discuss their concerns and perhaps move their opinions,” said William T. Basco Jr, MD, MS, a professor of pediatrics at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, and director of the division of general pediatrics.

In an interview, when asked whether recent approval of the vaccine for children aged 5-11 will likely aid in overcoming parental hesitancy, Dr. Basco replied: “Absolutely. As more children get the vaccine and people know a neighbor or nephew or cousin, etc., who received the vaccine and did fine, it will engender greater comfort and allow parents to feel better about having their own child receive the vaccine.”

Advice for clinicians from outside expert

“We can always start by asking parents if we can help them understand the vaccine and the need for it. The tidal wave of disinformation is huge, but we can, on a daily basis, offer to help families navigate this decision,” concluded Dr. Basco, who was not involved with the new paper.

Funding for this study was provided through grants from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the CUNY Institute of Implementation Science in Population Health, and the COVID-19 Grant Program of the CUNY Graduate School of Public Health and Health Policy. The authors and Dr. Basco have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

“Parental vaccine hesitancy is a major issue for schools resuming in-person instruction, potentially requiring regular testing, strict mask wearing, and physical distancing for safe operation,” wrote lead author Madhura S. Rane, PhD, from the City University of New York in New York City, and colleagues in their paper, published online in JAMA Pediatrics.

The survey was conducted in June 2021 of 1,162 parents with children ranging in age from 2 to 17 years. The majority of parents (74.4%) were already vaccinated/vaccine-willing ,while 25.6% were vaccine hesitant. The study cohort, including both 1,652 children and their parents, was part of the nationwide CHASING COVID.

Vaccinated parents overall were more willing to vaccinate or had already vaccinated their eligible children when compared with vaccine-hesitant parents: 64.9% vs. 8.3% for children 2-4 years of age; 77.6% vs. 12.1% for children 5-11 years of age; 81.3% vs. 13.9% for children 12-15 years of age; and 86.4% vs. 12.7% for children 16-17 years of age; P < .001.

The researchers found greater hesitancy among Black and Hispanic parents, compared with parents who were non-Hispanic White, women, younger, and did not have a college education. Parents of children who were currently attending school remotely or only partially, were found to be more willing to vaccinate their children when compared to parents of children who were attending school fully in person.

The authors also found that parents who knew someone who had died of COVID-19 or had experienced a prior COVID-19 infection, were more willing to vaccinate their children.

Hesitance in vaccinated parents

Interestingly, 10% of COVID-vaccinated parents said they were still hesitant to vaccinate their kids because of concern for long-term adverse effects of the vaccine.

“These data point out that vaccine concerns may exist even among vaccinated or vaccine-favorable parents, so we should ask any parent who has not vaccinated their child whether we can discuss their concerns and perhaps move their opinions,” said William T. Basco Jr, MD, MS, a professor of pediatrics at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, and director of the division of general pediatrics.

In an interview, when asked whether recent approval of the vaccine for children aged 5-11 will likely aid in overcoming parental hesitancy, Dr. Basco replied: “Absolutely. As more children get the vaccine and people know a neighbor or nephew or cousin, etc., who received the vaccine and did fine, it will engender greater comfort and allow parents to feel better about having their own child receive the vaccine.”

Advice for clinicians from outside expert

“We can always start by asking parents if we can help them understand the vaccine and the need for it. The tidal wave of disinformation is huge, but we can, on a daily basis, offer to help families navigate this decision,” concluded Dr. Basco, who was not involved with the new paper.

Funding for this study was provided through grants from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the CUNY Institute of Implementation Science in Population Health, and the COVID-19 Grant Program of the CUNY Graduate School of Public Health and Health Policy. The authors and Dr. Basco have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

“Parental vaccine hesitancy is a major issue for schools resuming in-person instruction, potentially requiring regular testing, strict mask wearing, and physical distancing for safe operation,” wrote lead author Madhura S. Rane, PhD, from the City University of New York in New York City, and colleagues in their paper, published online in JAMA Pediatrics.

The survey was conducted in June 2021 of 1,162 parents with children ranging in age from 2 to 17 years. The majority of parents (74.4%) were already vaccinated/vaccine-willing ,while 25.6% were vaccine hesitant. The study cohort, including both 1,652 children and their parents, was part of the nationwide CHASING COVID.

Vaccinated parents overall were more willing to vaccinate or had already vaccinated their eligible children when compared with vaccine-hesitant parents: 64.9% vs. 8.3% for children 2-4 years of age; 77.6% vs. 12.1% for children 5-11 years of age; 81.3% vs. 13.9% for children 12-15 years of age; and 86.4% vs. 12.7% for children 16-17 years of age; P < .001.

The researchers found greater hesitancy among Black and Hispanic parents, compared with parents who were non-Hispanic White, women, younger, and did not have a college education. Parents of children who were currently attending school remotely or only partially, were found to be more willing to vaccinate their children when compared to parents of children who were attending school fully in person.

The authors also found that parents who knew someone who had died of COVID-19 or had experienced a prior COVID-19 infection, were more willing to vaccinate their children.

Hesitance in vaccinated parents

Interestingly, 10% of COVID-vaccinated parents said they were still hesitant to vaccinate their kids because of concern for long-term adverse effects of the vaccine.

“These data point out that vaccine concerns may exist even among vaccinated or vaccine-favorable parents, so we should ask any parent who has not vaccinated their child whether we can discuss their concerns and perhaps move their opinions,” said William T. Basco Jr, MD, MS, a professor of pediatrics at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, and director of the division of general pediatrics.

In an interview, when asked whether recent approval of the vaccine for children aged 5-11 will likely aid in overcoming parental hesitancy, Dr. Basco replied: “Absolutely. As more children get the vaccine and people know a neighbor or nephew or cousin, etc., who received the vaccine and did fine, it will engender greater comfort and allow parents to feel better about having their own child receive the vaccine.”

Advice for clinicians from outside expert

“We can always start by asking parents if we can help them understand the vaccine and the need for it. The tidal wave of disinformation is huge, but we can, on a daily basis, offer to help families navigate this decision,” concluded Dr. Basco, who was not involved with the new paper.

Funding for this study was provided through grants from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the CUNY Institute of Implementation Science in Population Health, and the COVID-19 Grant Program of the CUNY Graduate School of Public Health and Health Policy. The authors and Dr. Basco have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

Children and COVID-19: 7 million cases and still counting

Total COVID-19 cases in children surpassed the 7-million mark as new cases rose slightly after the previous week’s decline, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report. New cases had dropped the previous week after 3 straight weeks of increases since late October.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention puts the total number of child COVID-19 cases at 6.2 million, but both estimates are based on all-age totals – 40 million for the CDC and 41 million for the AAP/CHA – that are well short of the CDC’s latest cumulative figure, which is now just over 49 million, so the actual figures are undoubtedly higher.

Meanwhile, the 1-month anniversary of 5- to 11-year-olds’ vaccine eligibility brought many completions: 923,000 received their second dose during the week ending Dec. 6, compared with 405,000 the previous week. About 16.9% (4.9 million) of children aged 5-11 have gotten at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine thus far, of whom almost 1.5 million children (5.1% of the age group) are now fully vaccinated, the CDC said on its COVID-19 Data Tracker.

The pace of vaccinations, however, is much lower for older children. Weekly numbers for all COVID-19 vaccinations, both first and second doses, dropped from 84,000 (Nov. 23-29) to 70,000 (Nov. 30 to Dec. 6), for those aged 12-17 years. In that group, 61.6% have received at least one dose and 51.8% are fully vaccinated, the CDC said.

The pace of vaccinations varies for younger children as well, when geography is considered. The AAP analyzed the CDC’s data and found that 42% of all 5- to 11-year-olds in Vermont had received at least one dose as of Dec. 1, followed by Massachusetts (33%), Maine (30%), and Rhode Island (28%). At the other end of the vaccination scale are Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, and West Virginia, all with 4%, the AAP reported.

As the United States puts 7 million children infected with COVID-19 in its rear view mirror, another milestone is looming ahead: The CDC’s current count of deaths in children is 974.

Total COVID-19 cases in children surpassed the 7-million mark as new cases rose slightly after the previous week’s decline, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report. New cases had dropped the previous week after 3 straight weeks of increases since late October.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention puts the total number of child COVID-19 cases at 6.2 million, but both estimates are based on all-age totals – 40 million for the CDC and 41 million for the AAP/CHA – that are well short of the CDC’s latest cumulative figure, which is now just over 49 million, so the actual figures are undoubtedly higher.

Meanwhile, the 1-month anniversary of 5- to 11-year-olds’ vaccine eligibility brought many completions: 923,000 received their second dose during the week ending Dec. 6, compared with 405,000 the previous week. About 16.9% (4.9 million) of children aged 5-11 have gotten at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine thus far, of whom almost 1.5 million children (5.1% of the age group) are now fully vaccinated, the CDC said on its COVID-19 Data Tracker.

The pace of vaccinations, however, is much lower for older children. Weekly numbers for all COVID-19 vaccinations, both first and second doses, dropped from 84,000 (Nov. 23-29) to 70,000 (Nov. 30 to Dec. 6), for those aged 12-17 years. In that group, 61.6% have received at least one dose and 51.8% are fully vaccinated, the CDC said.

The pace of vaccinations varies for younger children as well, when geography is considered. The AAP analyzed the CDC’s data and found that 42% of all 5- to 11-year-olds in Vermont had received at least one dose as of Dec. 1, followed by Massachusetts (33%), Maine (30%), and Rhode Island (28%). At the other end of the vaccination scale are Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, and West Virginia, all with 4%, the AAP reported.

As the United States puts 7 million children infected with COVID-19 in its rear view mirror, another milestone is looming ahead: The CDC’s current count of deaths in children is 974.

Total COVID-19 cases in children surpassed the 7-million mark as new cases rose slightly after the previous week’s decline, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report. New cases had dropped the previous week after 3 straight weeks of increases since late October.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention puts the total number of child COVID-19 cases at 6.2 million, but both estimates are based on all-age totals – 40 million for the CDC and 41 million for the AAP/CHA – that are well short of the CDC’s latest cumulative figure, which is now just over 49 million, so the actual figures are undoubtedly higher.

Meanwhile, the 1-month anniversary of 5- to 11-year-olds’ vaccine eligibility brought many completions: 923,000 received their second dose during the week ending Dec. 6, compared with 405,000 the previous week. About 16.9% (4.9 million) of children aged 5-11 have gotten at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine thus far, of whom almost 1.5 million children (5.1% of the age group) are now fully vaccinated, the CDC said on its COVID-19 Data Tracker.

The pace of vaccinations, however, is much lower for older children. Weekly numbers for all COVID-19 vaccinations, both first and second doses, dropped from 84,000 (Nov. 23-29) to 70,000 (Nov. 30 to Dec. 6), for those aged 12-17 years. In that group, 61.6% have received at least one dose and 51.8% are fully vaccinated, the CDC said.

The pace of vaccinations varies for younger children as well, when geography is considered. The AAP analyzed the CDC’s data and found that 42% of all 5- to 11-year-olds in Vermont had received at least one dose as of Dec. 1, followed by Massachusetts (33%), Maine (30%), and Rhode Island (28%). At the other end of the vaccination scale are Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, and West Virginia, all with 4%, the AAP reported.

As the United States puts 7 million children infected with COVID-19 in its rear view mirror, another milestone is looming ahead: The CDC’s current count of deaths in children is 974.

Does inadequate sleep increase obesity risk in children?

Evidence summary

Multiple analyses suggest short sleep increases obesity risk

Three recent, large systematic reviews of prospective cohort studies with meta-analyses in infants, children, and adolescents all found associations between short sleep at intake and later excessive weight.

The largest meta-analysis included 42 prospective studies with 75,499 patients ranging in age from infancy to adolescence and with follow-up ranging from 1 to 27 years. In a pooled analysis, short sleep—variously defined across trials and mostly assessed by parental report—was associated with an increased risk of obesity or overweight (relative risk [RR] = 1.58; 95% CI, 1.35-1.85; I2= 92%), compared to normal and long sleep. When the authors adjusted for suspected publication bias using a “trim and fill” method, short sleep remained associated with later overweight or obesity (RR = 1.42; 95% CI, 1.12-1.81). Short sleep was associated with later unhealthy weight status in all age groups: 0 to < 3 years (RR = 1.4; 95% CI, 1.19-1.65); 3 to < 9 years (RR = 1.57; 95% CI, 1.4-1.76);9 to < 12 years (RR = 2.23; 95% CI, 2.18-2.27); and 12 to 18 years (RR = 1.3; 95% CI, 1.11-1.53). In addition to high heterogeneity, limitations of the review included variability in the definition of short sleep, use of parent- or self-reported sleep duration, and variability in classification of overweight and obesity in primary studies.1

A second systematic review and meta-analysis included 25 longitudinal studies (20 of which overlapped with the previously discussed meta-analysis) of children and adolescents (N = 56,584). Patients ranged in age from infancy to 16 years, and follow-up ranged from 6 months to 10 years (mean, 3.4 years). Children and adolescents with the shortest sleep duration were more likely to be overweight or obese at follow-up (pooled odds ratio [OR] = 1.76; 95% CI, 1.39-2.23; I2 = 70.5%) than those with the longest sleep duration. Due to the overlap in studies, the limitations of this analysis were similar to those already mentioned. Lack of a linear association between sleep duration and weight was cited as evidence of possible publication bias; the authors did not attempt to correct for it.2

The third systematic review and meta-analysis included 22 longitudinal studies (18 overlapped with first meta-analysis and 17 with the second) of children and adolescents (N = 24,821) ages 6 months to 18 years. Follow-up ranged from 1 to 27 years. This meta-analysis standardized the categories of sleep duration using recommendations from the Sleep Health Foundation. Patients with short sleep duration had an increased risk of overweight or obesity compared with patients sleeping “normal” or “longer than normal” durations (pooled OR = 2.15; 95% CI, 1.64-2.81; I2 = 67%). The authors indicated that their analysis could have been more robust if information about daytime sleep (ie, napping) had been available, but it was not collected in many of the included studies.3

Accelerometer data quantify the sleep/obesity association

A subsequent cohort study (N = 202) sought to better examine the association between sleep characteristics and adiposity by measuring sleep duration using accelerometers. Toddlers (ages 12 to 26 months) without previous medical history were recruited from early childhood education centers. Patients wore accelerometers for 7 consecutive days and then returned to the clinic after 12 months for collection of biometric information. Researchers measured body morphology with the BMI z-score (ie, the number of standard deviations from the mean). Every additional hour of total sleep time was associated with a 0.12-unit lower BMI z-score (95% CI, –0.23 to –0.01) at 1 year. However, every hour increase in nap duration was associated with a 0.41-unit higher BMI z-score (95% CI, 0.14-0.68).4

Recommendations from others

In 2016, the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) recommended the following sleep durations (per 24 hours): infants ages 4 to 12 months, 12-16 hours; children 1 to 2 years, 11-14 hours; children 3 to 5 years, 10-13 hours; children 6 to 12 years, 9-12 hours; and teenagers 13 to 18 years, 8-10 hours. The AASM further stated that sleeping the recommended number of hours was associated with better health outcomes, and that sleeping too few hours increased the risk of various health conditions, including obesity.5 In 2015, the American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Nutrition acknowledged the association between obesity and short sleep duration and recommended that health care professionals counsel parents about age-appropriate sleep guidelines.6

Editor’s takeaway

Studies demonstrate that short sleep duration in pediatric patients is associated with later weight gain. However, associations do not prove a causal link, and other factors may contribute to both weight gain and poor sleep.

1. Miller MA, Kruisbrink M, Wallace J, et al. Sleep duration and incidence of obesity in infants, children, and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Sleep. 2018;41:1-19. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsy018

2. Ruan H, Xun P, Cai W, et al. Habitual sleep duration and risk of childhood obesity: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Sci Rep. 2015;5:16160. doi: 10.1038/srep16160

3. Fatima Y, Doi SA, Mamun AA. Longitudinal impact of sleep on overweight and obesity in children and adolescents: a systematic review and bias-adjusted meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2015;16:137-149. doi: 10.1111/obr.12245

4. Zhang Z, Pereira JR, Sousa-Sá E, et al. The cross‐sectional and prospective associations between sleep characteristics and adiposity in toddlers: results from the GET UP! study. Pediatr Obes. 2019;14:e1255. doi: 10.1111/ijpo.12557

5. Paruthi S, Brooks LJ, D’Ambrosio C, et al. Recommended amount of sleep for pediatric populations: a consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. J Clin Sleep Med. 2016;12:785-786. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.5866

6. Daniels SR, Hassink SG; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Nutrition. The role of the pediatrician in primary prevention of obesity. Pediatrics 2015;136:e275-e292. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-1558

Evidence summary

Multiple analyses suggest short sleep increases obesity risk

Three recent, large systematic reviews of prospective cohort studies with meta-analyses in infants, children, and adolescents all found associations between short sleep at intake and later excessive weight.

The largest meta-analysis included 42 prospective studies with 75,499 patients ranging in age from infancy to adolescence and with follow-up ranging from 1 to 27 years. In a pooled analysis, short sleep—variously defined across trials and mostly assessed by parental report—was associated with an increased risk of obesity or overweight (relative risk [RR] = 1.58; 95% CI, 1.35-1.85; I2= 92%), compared to normal and long sleep. When the authors adjusted for suspected publication bias using a “trim and fill” method, short sleep remained associated with later overweight or obesity (RR = 1.42; 95% CI, 1.12-1.81). Short sleep was associated with later unhealthy weight status in all age groups: 0 to < 3 years (RR = 1.4; 95% CI, 1.19-1.65); 3 to < 9 years (RR = 1.57; 95% CI, 1.4-1.76);9 to < 12 years (RR = 2.23; 95% CI, 2.18-2.27); and 12 to 18 years (RR = 1.3; 95% CI, 1.11-1.53). In addition to high heterogeneity, limitations of the review included variability in the definition of short sleep, use of parent- or self-reported sleep duration, and variability in classification of overweight and obesity in primary studies.1

A second systematic review and meta-analysis included 25 longitudinal studies (20 of which overlapped with the previously discussed meta-analysis) of children and adolescents (N = 56,584). Patients ranged in age from infancy to 16 years, and follow-up ranged from 6 months to 10 years (mean, 3.4 years). Children and adolescents with the shortest sleep duration were more likely to be overweight or obese at follow-up (pooled odds ratio [OR] = 1.76; 95% CI, 1.39-2.23; I2 = 70.5%) than those with the longest sleep duration. Due to the overlap in studies, the limitations of this analysis were similar to those already mentioned. Lack of a linear association between sleep duration and weight was cited as evidence of possible publication bias; the authors did not attempt to correct for it.2

The third systematic review and meta-analysis included 22 longitudinal studies (18 overlapped with first meta-analysis and 17 with the second) of children and adolescents (N = 24,821) ages 6 months to 18 years. Follow-up ranged from 1 to 27 years. This meta-analysis standardized the categories of sleep duration using recommendations from the Sleep Health Foundation. Patients with short sleep duration had an increased risk of overweight or obesity compared with patients sleeping “normal” or “longer than normal” durations (pooled OR = 2.15; 95% CI, 1.64-2.81; I2 = 67%). The authors indicated that their analysis could have been more robust if information about daytime sleep (ie, napping) had been available, but it was not collected in many of the included studies.3

Accelerometer data quantify the sleep/obesity association

A subsequent cohort study (N = 202) sought to better examine the association between sleep characteristics and adiposity by measuring sleep duration using accelerometers. Toddlers (ages 12 to 26 months) without previous medical history were recruited from early childhood education centers. Patients wore accelerometers for 7 consecutive days and then returned to the clinic after 12 months for collection of biometric information. Researchers measured body morphology with the BMI z-score (ie, the number of standard deviations from the mean). Every additional hour of total sleep time was associated with a 0.12-unit lower BMI z-score (95% CI, –0.23 to –0.01) at 1 year. However, every hour increase in nap duration was associated with a 0.41-unit higher BMI z-score (95% CI, 0.14-0.68).4

Recommendations from others

In 2016, the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) recommended the following sleep durations (per 24 hours): infants ages 4 to 12 months, 12-16 hours; children 1 to 2 years, 11-14 hours; children 3 to 5 years, 10-13 hours; children 6 to 12 years, 9-12 hours; and teenagers 13 to 18 years, 8-10 hours. The AASM further stated that sleeping the recommended number of hours was associated with better health outcomes, and that sleeping too few hours increased the risk of various health conditions, including obesity.5 In 2015, the American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Nutrition acknowledged the association between obesity and short sleep duration and recommended that health care professionals counsel parents about age-appropriate sleep guidelines.6

Editor’s takeaway

Studies demonstrate that short sleep duration in pediatric patients is associated with later weight gain. However, associations do not prove a causal link, and other factors may contribute to both weight gain and poor sleep.

Evidence summary

Multiple analyses suggest short sleep increases obesity risk

Three recent, large systematic reviews of prospective cohort studies with meta-analyses in infants, children, and adolescents all found associations between short sleep at intake and later excessive weight.

The largest meta-analysis included 42 prospective studies with 75,499 patients ranging in age from infancy to adolescence and with follow-up ranging from 1 to 27 years. In a pooled analysis, short sleep—variously defined across trials and mostly assessed by parental report—was associated with an increased risk of obesity or overweight (relative risk [RR] = 1.58; 95% CI, 1.35-1.85; I2= 92%), compared to normal and long sleep. When the authors adjusted for suspected publication bias using a “trim and fill” method, short sleep remained associated with later overweight or obesity (RR = 1.42; 95% CI, 1.12-1.81). Short sleep was associated with later unhealthy weight status in all age groups: 0 to < 3 years (RR = 1.4; 95% CI, 1.19-1.65); 3 to < 9 years (RR = 1.57; 95% CI, 1.4-1.76);9 to < 12 years (RR = 2.23; 95% CI, 2.18-2.27); and 12 to 18 years (RR = 1.3; 95% CI, 1.11-1.53). In addition to high heterogeneity, limitations of the review included variability in the definition of short sleep, use of parent- or self-reported sleep duration, and variability in classification of overweight and obesity in primary studies.1

A second systematic review and meta-analysis included 25 longitudinal studies (20 of which overlapped with the previously discussed meta-analysis) of children and adolescents (N = 56,584). Patients ranged in age from infancy to 16 years, and follow-up ranged from 6 months to 10 years (mean, 3.4 years). Children and adolescents with the shortest sleep duration were more likely to be overweight or obese at follow-up (pooled odds ratio [OR] = 1.76; 95% CI, 1.39-2.23; I2 = 70.5%) than those with the longest sleep duration. Due to the overlap in studies, the limitations of this analysis were similar to those already mentioned. Lack of a linear association between sleep duration and weight was cited as evidence of possible publication bias; the authors did not attempt to correct for it.2

The third systematic review and meta-analysis included 22 longitudinal studies (18 overlapped with first meta-analysis and 17 with the second) of children and adolescents (N = 24,821) ages 6 months to 18 years. Follow-up ranged from 1 to 27 years. This meta-analysis standardized the categories of sleep duration using recommendations from the Sleep Health Foundation. Patients with short sleep duration had an increased risk of overweight or obesity compared with patients sleeping “normal” or “longer than normal” durations (pooled OR = 2.15; 95% CI, 1.64-2.81; I2 = 67%). The authors indicated that their analysis could have been more robust if information about daytime sleep (ie, napping) had been available, but it was not collected in many of the included studies.3

Accelerometer data quantify the sleep/obesity association

A subsequent cohort study (N = 202) sought to better examine the association between sleep characteristics and adiposity by measuring sleep duration using accelerometers. Toddlers (ages 12 to 26 months) without previous medical history were recruited from early childhood education centers. Patients wore accelerometers for 7 consecutive days and then returned to the clinic after 12 months for collection of biometric information. Researchers measured body morphology with the BMI z-score (ie, the number of standard deviations from the mean). Every additional hour of total sleep time was associated with a 0.12-unit lower BMI z-score (95% CI, –0.23 to –0.01) at 1 year. However, every hour increase in nap duration was associated with a 0.41-unit higher BMI z-score (95% CI, 0.14-0.68).4

Recommendations from others

In 2016, the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) recommended the following sleep durations (per 24 hours): infants ages 4 to 12 months, 12-16 hours; children 1 to 2 years, 11-14 hours; children 3 to 5 years, 10-13 hours; children 6 to 12 years, 9-12 hours; and teenagers 13 to 18 years, 8-10 hours. The AASM further stated that sleeping the recommended number of hours was associated with better health outcomes, and that sleeping too few hours increased the risk of various health conditions, including obesity.5 In 2015, the American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Nutrition acknowledged the association between obesity and short sleep duration and recommended that health care professionals counsel parents about age-appropriate sleep guidelines.6

Editor’s takeaway

Studies demonstrate that short sleep duration in pediatric patients is associated with later weight gain. However, associations do not prove a causal link, and other factors may contribute to both weight gain and poor sleep.

1. Miller MA, Kruisbrink M, Wallace J, et al. Sleep duration and incidence of obesity in infants, children, and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Sleep. 2018;41:1-19. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsy018

2. Ruan H, Xun P, Cai W, et al. Habitual sleep duration and risk of childhood obesity: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Sci Rep. 2015;5:16160. doi: 10.1038/srep16160

3. Fatima Y, Doi SA, Mamun AA. Longitudinal impact of sleep on overweight and obesity in children and adolescents: a systematic review and bias-adjusted meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2015;16:137-149. doi: 10.1111/obr.12245

4. Zhang Z, Pereira JR, Sousa-Sá E, et al. The cross‐sectional and prospective associations between sleep characteristics and adiposity in toddlers: results from the GET UP! study. Pediatr Obes. 2019;14:e1255. doi: 10.1111/ijpo.12557

5. Paruthi S, Brooks LJ, D’Ambrosio C, et al. Recommended amount of sleep for pediatric populations: a consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. J Clin Sleep Med. 2016;12:785-786. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.5866

6. Daniels SR, Hassink SG; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Nutrition. The role of the pediatrician in primary prevention of obesity. Pediatrics 2015;136:e275-e292. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-1558

1. Miller MA, Kruisbrink M, Wallace J, et al. Sleep duration and incidence of obesity in infants, children, and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Sleep. 2018;41:1-19. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsy018

2. Ruan H, Xun P, Cai W, et al. Habitual sleep duration and risk of childhood obesity: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Sci Rep. 2015;5:16160. doi: 10.1038/srep16160

3. Fatima Y, Doi SA, Mamun AA. Longitudinal impact of sleep on overweight and obesity in children and adolescents: a systematic review and bias-adjusted meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2015;16:137-149. doi: 10.1111/obr.12245

4. Zhang Z, Pereira JR, Sousa-Sá E, et al. The cross‐sectional and prospective associations between sleep characteristics and adiposity in toddlers: results from the GET UP! study. Pediatr Obes. 2019;14:e1255. doi: 10.1111/ijpo.12557

5. Paruthi S, Brooks LJ, D’Ambrosio C, et al. Recommended amount of sleep for pediatric populations: a consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. J Clin Sleep Med. 2016;12:785-786. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.5866

6. Daniels SR, Hassink SG; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Nutrition. The role of the pediatrician in primary prevention of obesity. Pediatrics 2015;136:e275-e292. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-1558

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Yes, a link has been established but not a cause-effect relationship. Shorter reported sleep duration in childhood is associated with an increased risk of overweight or obesity years later (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, meta-analyses of prospective cohort trials with high heterogeneity). In toddlers, accelerometer documentation of short sleep duration is associated with elevation of body mass index (BMI) at 1-year follow-up (SOR: B, prospective cohort). Adequate sleep is recommended to help prevent excessive weight gain in children (SOR: C, expert opinion).

Dust mite immunotherapy may help some with eczema

, but improvement in the primary outcome was not significant, new data show.

Results of the small, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial were published recently in The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice.

Lead author Sarah Sella Langer, MD, of the department of medicine, Ribeirão Preto (Brazil) Medical School, University of São Paulo, and colleagues said their results suggest HDM SLIT is safe and effective as an add-on treatment.

The dust mite extract therapy had no major side effects after 18 months of treatment, the authors reported.

The researchers included data from 66 patients who completed the study. The participants were at least 3 years old, registered at least 15 on the SCORing Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD) measure, and had a skin prick test and/or immunoglobulin E (IgE) test for sensitization to dust mites.

Patients were grouped by age (younger than 12 years or 12 years and older) to receive HDM SLIT (n = 35) or placebo (n = 31) 3 days a week for the study period – between May 2018 and June 2020 – at the Clinical Research Unit of Ribeirão Preto Medical School Hospital.

At baseline, the mean SCORAD was 46.9 (range, 17-87).

After 18 months, 74.2% and 58% of patients in HDM SLIT and placebo groups, respectively, showed at least a15-point decrease in SCORAD (relative risk, 1.28; 95% confidence interval, 0.89-1.83). However, those primary outcome results did not reach statistical significance.

On the other hand, some secondary outcomes did show significant results.

At 95% CI, the researchers reported significant objective-SCORAD decreases of 56.8% and 34.9% in HDM SLIT and placebo groups (average difference, 21.3). Significantly more patients had a score of 0 or 1 on the 5-point Investigator’s Global Assessment scale in the intervention group than in the placebo group (14/35 vs. 5/31; RR, 2.63).

There were no significant changes in the Eczema Area and Severity Index, the visual analogue scale for symptoms, the pruritus scale, or the Dermatology Life Quality Index.

Patients in the trial, most of whom had moderate to severe disease, continued to be treated with usual, individualized therapy for AD, in accordance with current guidelines and experts’ recommendations.

Tina Sindher, MD, an allergist with the Sean N. Parker Center for Allergy and Asthma Research at Stanford (Calif.) University, , told this news organization that the results are not robust enough to recommend the immunotherapy widely.

She pointed out that even in the placebo group, more than half the patients met the primary endpoint.

However, she did say HDM SLIT could be considered as an add-on treatment for the right patients, especially since risk for an allergic reaction or other adverse condition is small. The most common adverse effects were headache and abdominal pain, and they were reported in both the treatment and placebo groups.

With AD, she said, “there is no one drug that’s right for everyone,” because genetics and environment make the kind of symptoms and severity and duration different for each patient.

It all comes down to risk and benefits, she said.

She said if she had a patient with an environmental allergy who’s trying to manage nasal congestion and also happened to have eczema, “I think they’re a great candidate for sublingual dust mite therapy because then not only am I treating their nasal congestions, their other symptoms, it may also help their eczema,” Dr. Sindher said.

Without those concurrent conditions, she said, the benefits of dust mite immunotherapy would not outweigh the risks or the potential burden on the patient of having to take the SLIT.

She said she would present the choice to the patient, and if other treatments haven’t been successful and the patient wants to try it, she would be open to a trial period.

The study was supported by the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development, the Institute of Investigation in Immunology, the National Institutes of Science and Technology, the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development, and the São Paulo Research Foundation. The mite extract for immunotherapy was provided by the laboratory IPI-ASAC Brasil/ASAC Pharma Brasil. Dr. Langer received a doctoral scholarship from the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – Brasil (CAPES). Dr. Sindher reported no relevant financial relationships.

Commentary by Lawrence F. Eichenfield, MD

Environmental triggers of atopic dermatitis (AD) may be difficult to assess, especially as children with AD commonly develop “overlap” conditions of allergic rhinitis, food allergy, and asthma. The place of immunotherapy in treatment of AD has been controversial over the years, with mixed results from studies on its effect on eczema in different subpopulations. However, a holistic view of allergy care makes consideration of environmental allergies reasonable. The study by Dr. Langer and colleagues was a well-designed double-blind placebo-controlled trial of house dust mite sublingual immunotherapy in mite-sensitized AD patients aged 3 and older with at least mild AD, though the mean eczema severity was severe. After 18 months, there was an impressive 74% decrease in eczema score (SCORAD), but also a 58% decrease in the placebo group. While the primary outcome measure wasn’t statistically significant, some secondary ones were. I agree with the commentary in the article that the data doesn’t support immunotherapy being advised to everyone, while its use as an add-on treatment for certain patients in whom the eczema may overlap with other allergic manifestations is reasonable. For several years at Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego, we have run a multidisciplinary atopic dermatitis program where patients are comanaged by dermatology and allergy. We have learned to appreciate that a broad perspective on managing comorbid conditions in children with AD really helps the patients and families to understand the many effects of inflammatory and allergic conditions, with improved outcomes and quality of life.

Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children's Hospital-San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. He disclosed that he has served as an investigator and/or consultant to AbbVie, Lilly, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sanofi-Genzyme, and Verrica.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This article was updated 6/18/22.

, but improvement in the primary outcome was not significant, new data show.

Results of the small, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial were published recently in The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice.

Lead author Sarah Sella Langer, MD, of the department of medicine, Ribeirão Preto (Brazil) Medical School, University of São Paulo, and colleagues said their results suggest HDM SLIT is safe and effective as an add-on treatment.

The dust mite extract therapy had no major side effects after 18 months of treatment, the authors reported.

The researchers included data from 66 patients who completed the study. The participants were at least 3 years old, registered at least 15 on the SCORing Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD) measure, and had a skin prick test and/or immunoglobulin E (IgE) test for sensitization to dust mites.

Patients were grouped by age (younger than 12 years or 12 years and older) to receive HDM SLIT (n = 35) or placebo (n = 31) 3 days a week for the study period – between May 2018 and June 2020 – at the Clinical Research Unit of Ribeirão Preto Medical School Hospital.

At baseline, the mean SCORAD was 46.9 (range, 17-87).

After 18 months, 74.2% and 58% of patients in HDM SLIT and placebo groups, respectively, showed at least a15-point decrease in SCORAD (relative risk, 1.28; 95% confidence interval, 0.89-1.83). However, those primary outcome results did not reach statistical significance.

On the other hand, some secondary outcomes did show significant results.

At 95% CI, the researchers reported significant objective-SCORAD decreases of 56.8% and 34.9% in HDM SLIT and placebo groups (average difference, 21.3). Significantly more patients had a score of 0 or 1 on the 5-point Investigator’s Global Assessment scale in the intervention group than in the placebo group (14/35 vs. 5/31; RR, 2.63).

There were no significant changes in the Eczema Area and Severity Index, the visual analogue scale for symptoms, the pruritus scale, or the Dermatology Life Quality Index.

Patients in the trial, most of whom had moderate to severe disease, continued to be treated with usual, individualized therapy for AD, in accordance with current guidelines and experts’ recommendations.

Tina Sindher, MD, an allergist with the Sean N. Parker Center for Allergy and Asthma Research at Stanford (Calif.) University, , told this news organization that the results are not robust enough to recommend the immunotherapy widely.

She pointed out that even in the placebo group, more than half the patients met the primary endpoint.

However, she did say HDM SLIT could be considered as an add-on treatment for the right patients, especially since risk for an allergic reaction or other adverse condition is small. The most common adverse effects were headache and abdominal pain, and they were reported in both the treatment and placebo groups.

With AD, she said, “there is no one drug that’s right for everyone,” because genetics and environment make the kind of symptoms and severity and duration different for each patient.

It all comes down to risk and benefits, she said.

She said if she had a patient with an environmental allergy who’s trying to manage nasal congestion and also happened to have eczema, “I think they’re a great candidate for sublingual dust mite therapy because then not only am I treating their nasal congestions, their other symptoms, it may also help their eczema,” Dr. Sindher said.

Without those concurrent conditions, she said, the benefits of dust mite immunotherapy would not outweigh the risks or the potential burden on the patient of having to take the SLIT.

She said she would present the choice to the patient, and if other treatments haven’t been successful and the patient wants to try it, she would be open to a trial period.

The study was supported by the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development, the Institute of Investigation in Immunology, the National Institutes of Science and Technology, the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development, and the São Paulo Research Foundation. The mite extract for immunotherapy was provided by the laboratory IPI-ASAC Brasil/ASAC Pharma Brasil. Dr. Langer received a doctoral scholarship from the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – Brasil (CAPES). Dr. Sindher reported no relevant financial relationships.

Commentary by Lawrence F. Eichenfield, MD

Environmental triggers of atopic dermatitis (AD) may be difficult to assess, especially as children with AD commonly develop “overlap” conditions of allergic rhinitis, food allergy, and asthma. The place of immunotherapy in treatment of AD has been controversial over the years, with mixed results from studies on its effect on eczema in different subpopulations. However, a holistic view of allergy care makes consideration of environmental allergies reasonable. The study by Dr. Langer and colleagues was a well-designed double-blind placebo-controlled trial of house dust mite sublingual immunotherapy in mite-sensitized AD patients aged 3 and older with at least mild AD, though the mean eczema severity was severe. After 18 months, there was an impressive 74% decrease in eczema score (SCORAD), but also a 58% decrease in the placebo group. While the primary outcome measure wasn’t statistically significant, some secondary ones were. I agree with the commentary in the article that the data doesn’t support immunotherapy being advised to everyone, while its use as an add-on treatment for certain patients in whom the eczema may overlap with other allergic manifestations is reasonable. For several years at Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego, we have run a multidisciplinary atopic dermatitis program where patients are comanaged by dermatology and allergy. We have learned to appreciate that a broad perspective on managing comorbid conditions in children with AD really helps the patients and families to understand the many effects of inflammatory and allergic conditions, with improved outcomes and quality of life.

Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children's Hospital-San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. He disclosed that he has served as an investigator and/or consultant to AbbVie, Lilly, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sanofi-Genzyme, and Verrica.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This article was updated 6/18/22.

, but improvement in the primary outcome was not significant, new data show.

Results of the small, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial were published recently in The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice.

Lead author Sarah Sella Langer, MD, of the department of medicine, Ribeirão Preto (Brazil) Medical School, University of São Paulo, and colleagues said their results suggest HDM SLIT is safe and effective as an add-on treatment.

The dust mite extract therapy had no major side effects after 18 months of treatment, the authors reported.

The researchers included data from 66 patients who completed the study. The participants were at least 3 years old, registered at least 15 on the SCORing Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD) measure, and had a skin prick test and/or immunoglobulin E (IgE) test for sensitization to dust mites.

Patients were grouped by age (younger than 12 years or 12 years and older) to receive HDM SLIT (n = 35) or placebo (n = 31) 3 days a week for the study period – between May 2018 and June 2020 – at the Clinical Research Unit of Ribeirão Preto Medical School Hospital.

At baseline, the mean SCORAD was 46.9 (range, 17-87).

After 18 months, 74.2% and 58% of patients in HDM SLIT and placebo groups, respectively, showed at least a15-point decrease in SCORAD (relative risk, 1.28; 95% confidence interval, 0.89-1.83). However, those primary outcome results did not reach statistical significance.

On the other hand, some secondary outcomes did show significant results.

At 95% CI, the researchers reported significant objective-SCORAD decreases of 56.8% and 34.9% in HDM SLIT and placebo groups (average difference, 21.3). Significantly more patients had a score of 0 or 1 on the 5-point Investigator’s Global Assessment scale in the intervention group than in the placebo group (14/35 vs. 5/31; RR, 2.63).

There were no significant changes in the Eczema Area and Severity Index, the visual analogue scale for symptoms, the pruritus scale, or the Dermatology Life Quality Index.

Patients in the trial, most of whom had moderate to severe disease, continued to be treated with usual, individualized therapy for AD, in accordance with current guidelines and experts’ recommendations.

Tina Sindher, MD, an allergist with the Sean N. Parker Center for Allergy and Asthma Research at Stanford (Calif.) University, , told this news organization that the results are not robust enough to recommend the immunotherapy widely.

She pointed out that even in the placebo group, more than half the patients met the primary endpoint.

However, she did say HDM SLIT could be considered as an add-on treatment for the right patients, especially since risk for an allergic reaction or other adverse condition is small. The most common adverse effects were headache and abdominal pain, and they were reported in both the treatment and placebo groups.

With AD, she said, “there is no one drug that’s right for everyone,” because genetics and environment make the kind of symptoms and severity and duration different for each patient.

It all comes down to risk and benefits, she said.

She said if she had a patient with an environmental allergy who’s trying to manage nasal congestion and also happened to have eczema, “I think they’re a great candidate for sublingual dust mite therapy because then not only am I treating their nasal congestions, their other symptoms, it may also help their eczema,” Dr. Sindher said.

Without those concurrent conditions, she said, the benefits of dust mite immunotherapy would not outweigh the risks or the potential burden on the patient of having to take the SLIT.

She said she would present the choice to the patient, and if other treatments haven’t been successful and the patient wants to try it, she would be open to a trial period.

The study was supported by the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development, the Institute of Investigation in Immunology, the National Institutes of Science and Technology, the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development, and the São Paulo Research Foundation. The mite extract for immunotherapy was provided by the laboratory IPI-ASAC Brasil/ASAC Pharma Brasil. Dr. Langer received a doctoral scholarship from the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – Brasil (CAPES). Dr. Sindher reported no relevant financial relationships.

Commentary by Lawrence F. Eichenfield, MD

Environmental triggers of atopic dermatitis (AD) may be difficult to assess, especially as children with AD commonly develop “overlap” conditions of allergic rhinitis, food allergy, and asthma. The place of immunotherapy in treatment of AD has been controversial over the years, with mixed results from studies on its effect on eczema in different subpopulations. However, a holistic view of allergy care makes consideration of environmental allergies reasonable. The study by Dr. Langer and colleagues was a well-designed double-blind placebo-controlled trial of house dust mite sublingual immunotherapy in mite-sensitized AD patients aged 3 and older with at least mild AD, though the mean eczema severity was severe. After 18 months, there was an impressive 74% decrease in eczema score (SCORAD), but also a 58% decrease in the placebo group. While the primary outcome measure wasn’t statistically significant, some secondary ones were. I agree with the commentary in the article that the data doesn’t support immunotherapy being advised to everyone, while its use as an add-on treatment for certain patients in whom the eczema may overlap with other allergic manifestations is reasonable. For several years at Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego, we have run a multidisciplinary atopic dermatitis program where patients are comanaged by dermatology and allergy. We have learned to appreciate that a broad perspective on managing comorbid conditions in children with AD really helps the patients and families to understand the many effects of inflammatory and allergic conditions, with improved outcomes and quality of life.

Dr. Eichenfield is chief of pediatric and adolescent dermatology at Rady Children's Hospital-San Diego. He is vice chair of the department of dermatology and professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. He disclosed that he has served as an investigator and/or consultant to AbbVie, Lilly, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sanofi-Genzyme, and Verrica.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This article was updated 6/18/22.

Tender Subcutaneous Nodule in a Prepubescent Boy

The Diagnosis: Dermatomyofibroma

Dermatomyofibroma is an uncommon, benign, cutaneous mesenchymal neoplasm composed of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts.1-3 This skin tumor was first described in 1991 by Hugel4 in the German literature as plaquelike fibromatosis. Pediatric dermatomyofibromas are exceedingly rare, with pediatric patients ranging in age from infants to teenagers.1

Clinically, dermatomyofibromas appear as long-standing, isolated, ill-demarcated, flesh-colored, slightly hyperpigmented or erythematous nodules or plaques that may be raised or indurated.1 Dermatomyofibromas may present with constant mild pain or pruritus, though in most cases the lesions are asymptomatic.1,3 The clinical presentation of dermatomyofibroma has a few distinct differences in children compared to adults. In adulthood, dermatomyofibroma has a strong female predominance and most commonly is located on the shoulder and adjacent upper body regions, including the axilla, neck, upper arm, and upper trunk.1-3 In childhood, the majority of dermatomyofibromas occur in young boys and usually are located on the neck with other upper body regions occurring less frequently.1,2 A shared characteristic includes the tendency for dermatomyofibromas to have an initial period of enlargement followed by stabilization or slow growth.1 Reported pediatric lesions have ranged in size from 4 to 60 mm with an average size of 14.9 mm (median, 12 mm).2

The diagnosis of dermatomyofibroma is based on histopathologic features in addition to clinical presentation. Histology from punch biopsy usually reveals a noninvasive dermal proliferation of bland, uniform, slender spindle cells oriented parallel to the overlying epidermis with increased and fragmented elastic fibers.1,3 Infiltration into the mid or deep dermis is common. The adnexal structures usually are spared; the stroma contains collagen and increased small blood vessels; and there typically is no inflammatory infiltrate, except for occasional scattered mast cells.2 Cytologically, the monomorphic spindleshaped tumor cells have an ill-defined, pale, eosinophilic cytoplasm and nuclei that are elongated with tapered edges.3 Dermatomyofibroma has a variable immunohistochemical profile, as it may stain focally positive for CD34 or smooth muscle actin, with occasional staining of factor XIIIa, desmin, calponin, or vimentin.1-3 Normal to increased levels of often fragmented elastic fibers is a helpful clue in distinguishing dermatomyofibroma from dermatofibroma, hypertrophic scar, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, and pilar leiomyoma, in which elastic fibers typically are reduced.3 Differential diagnoses of mesenchymal tumors in children include desmoid fibromatosis, connective tissue nevus, myofibromatosis, and smooth muscle hamartoma.1

A punch biopsy with clinical observation and followup is recommended for the management of lesions in cosmetically sensitive areas or in very young children who may not tolerate surgery. In symptomatic or cosmetically unappealing cases of dermatomyofibroma, simple surgical excision remains a viable treatment option. Recurrence is uncommon, even if only partially excised, and no instances of metastasis have been reported.1-5

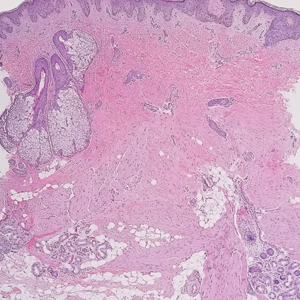

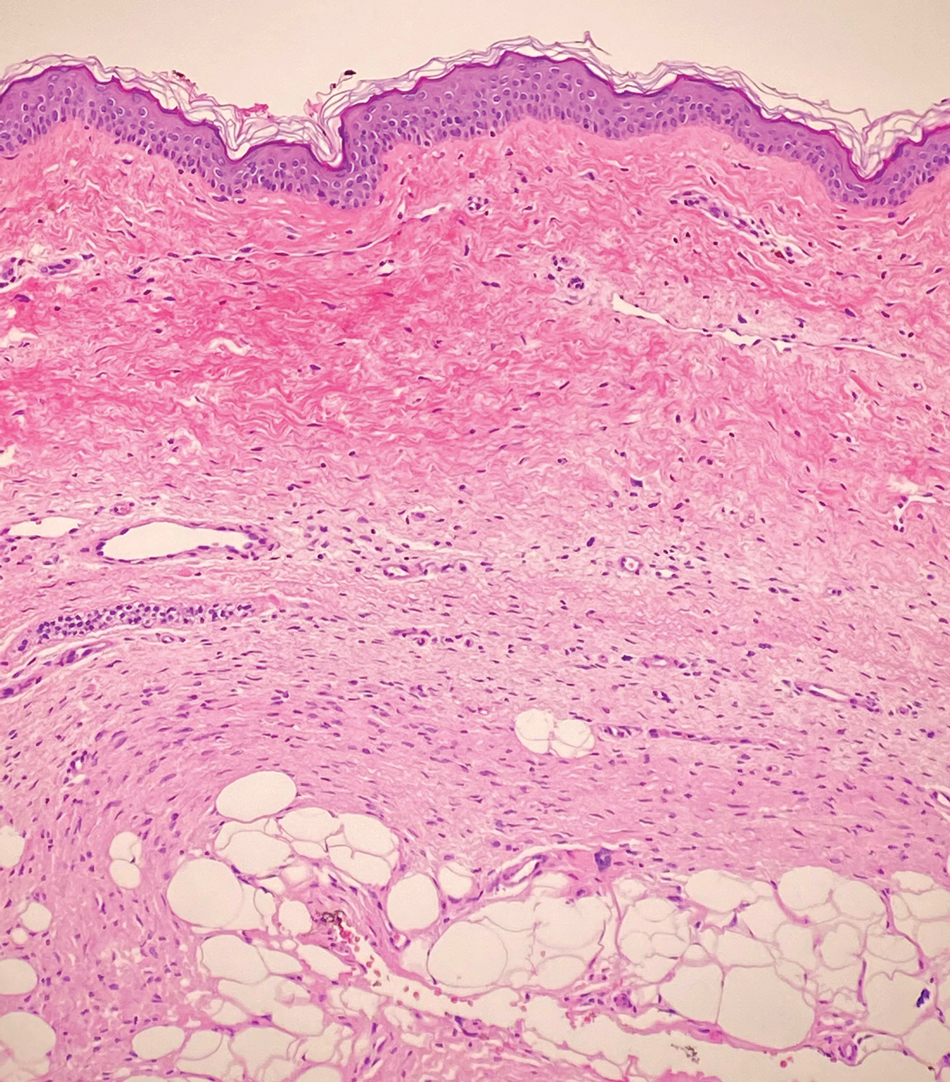

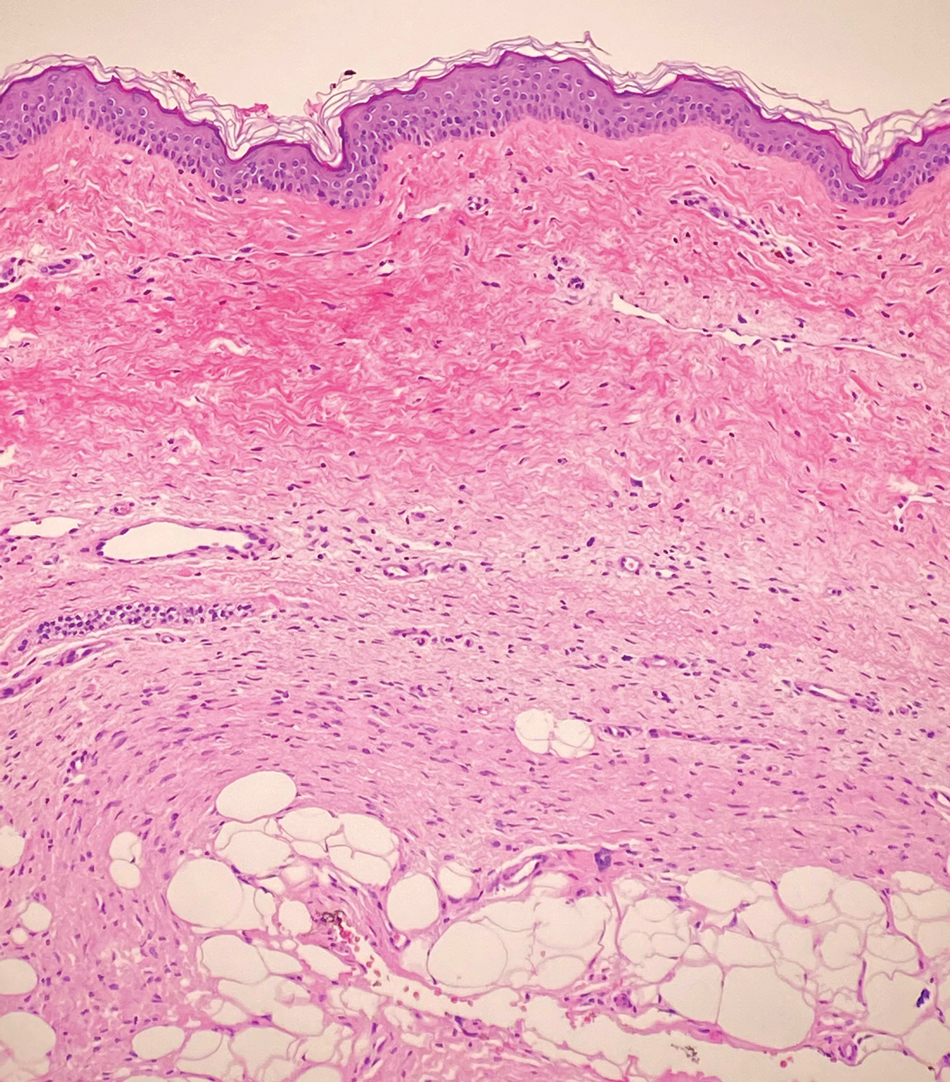

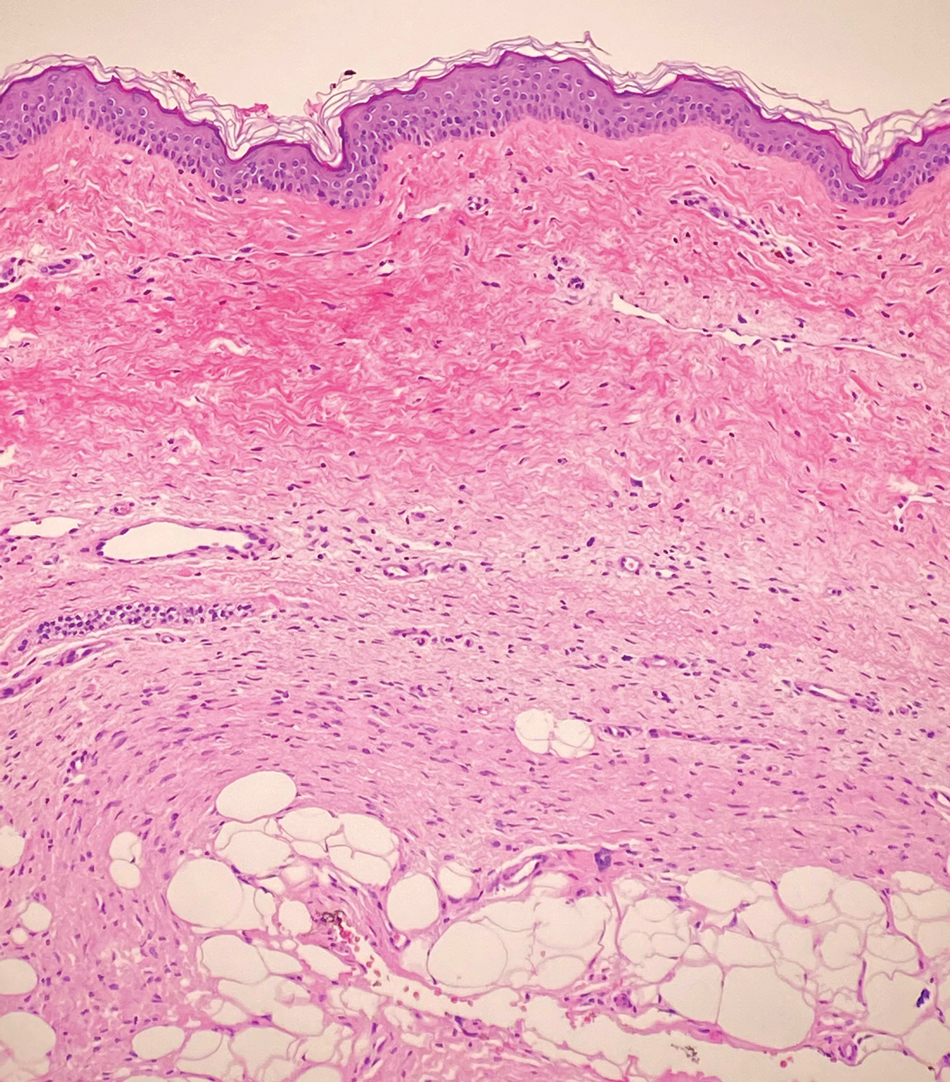

Dermatomyofibromas may be mistaken for several other entities both benign and malignant. For example, the benign dermatofibroma is the second most common fibrohistiocytic tumor of the skin and presents as a firm, nontender, minimally elevated to dome-shaped papule that usually measures less than or equal to 1 cm in diameter with or without overlying skin changes.5,6 It primarily is seen in adults with a slight female predominance and favors the lower extremities.5 Patients usually are asymptomatic but often report a history of local trauma at the lesion site.6 Histologically, dermatofibroma is characterized by a nodular dermal proliferation of spindleshaped fibrous cells and histiocytes in a storiform pattern (Figure 1).6 Epidermal induction with acanthosis overlying the tumor often is found with occasional basilar hyperpigmentation.5 Dermatofibroma also characteristically has trapped collagen (“collagen balls”) seen at the periphery.5,6

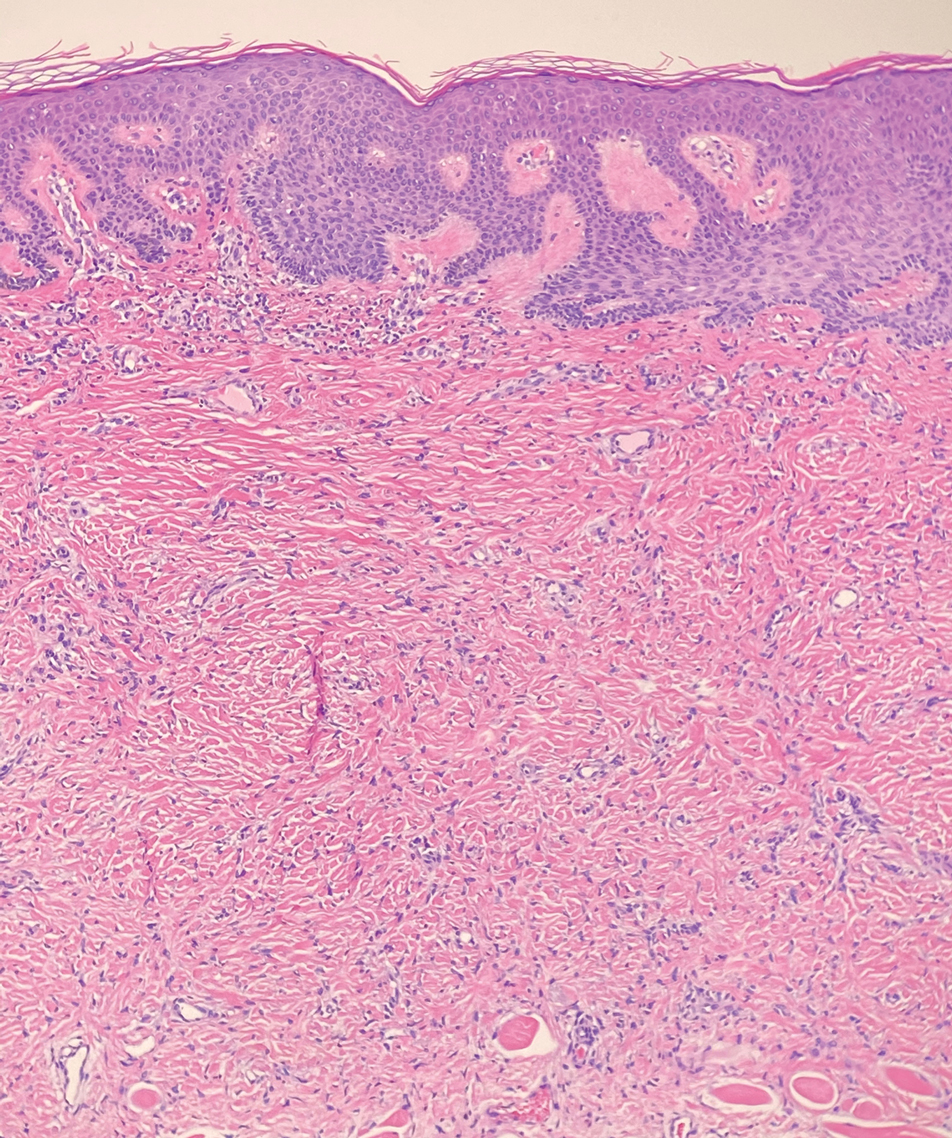

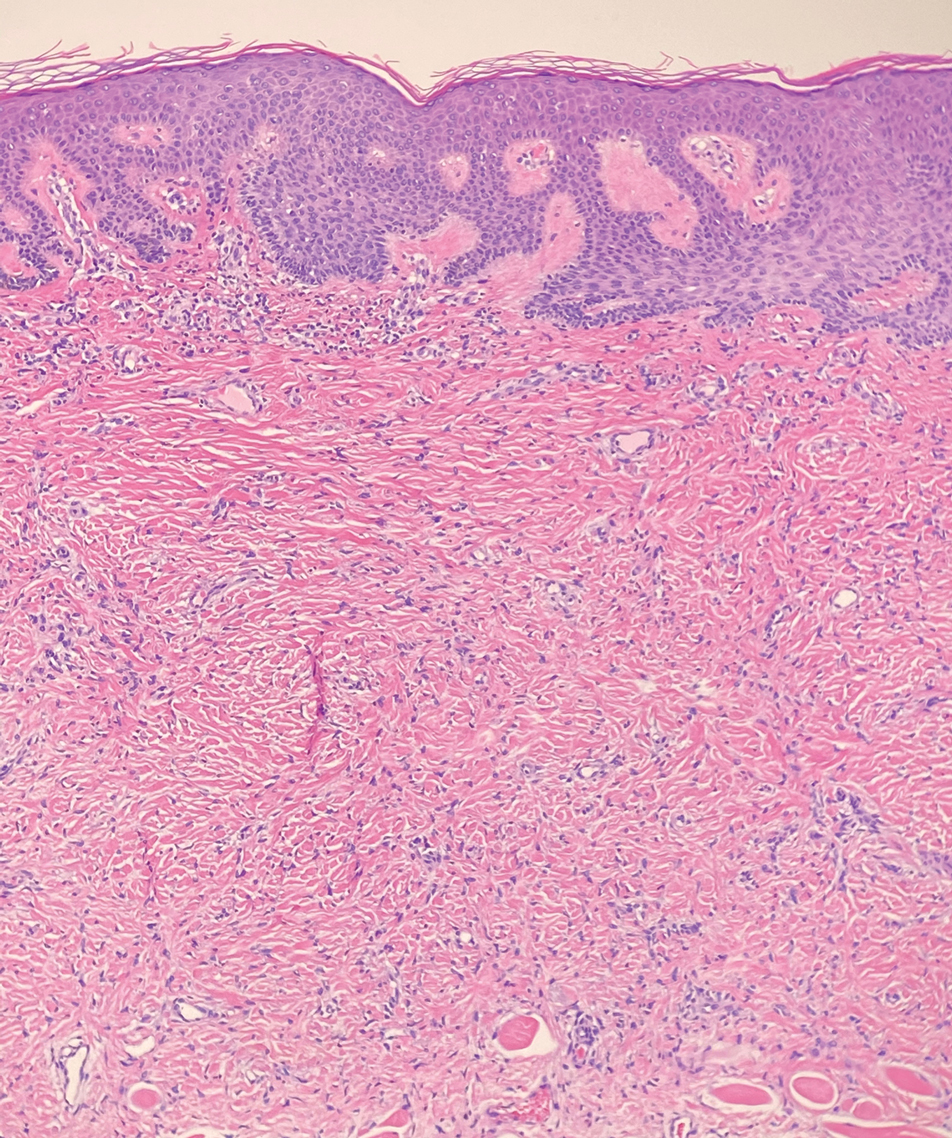

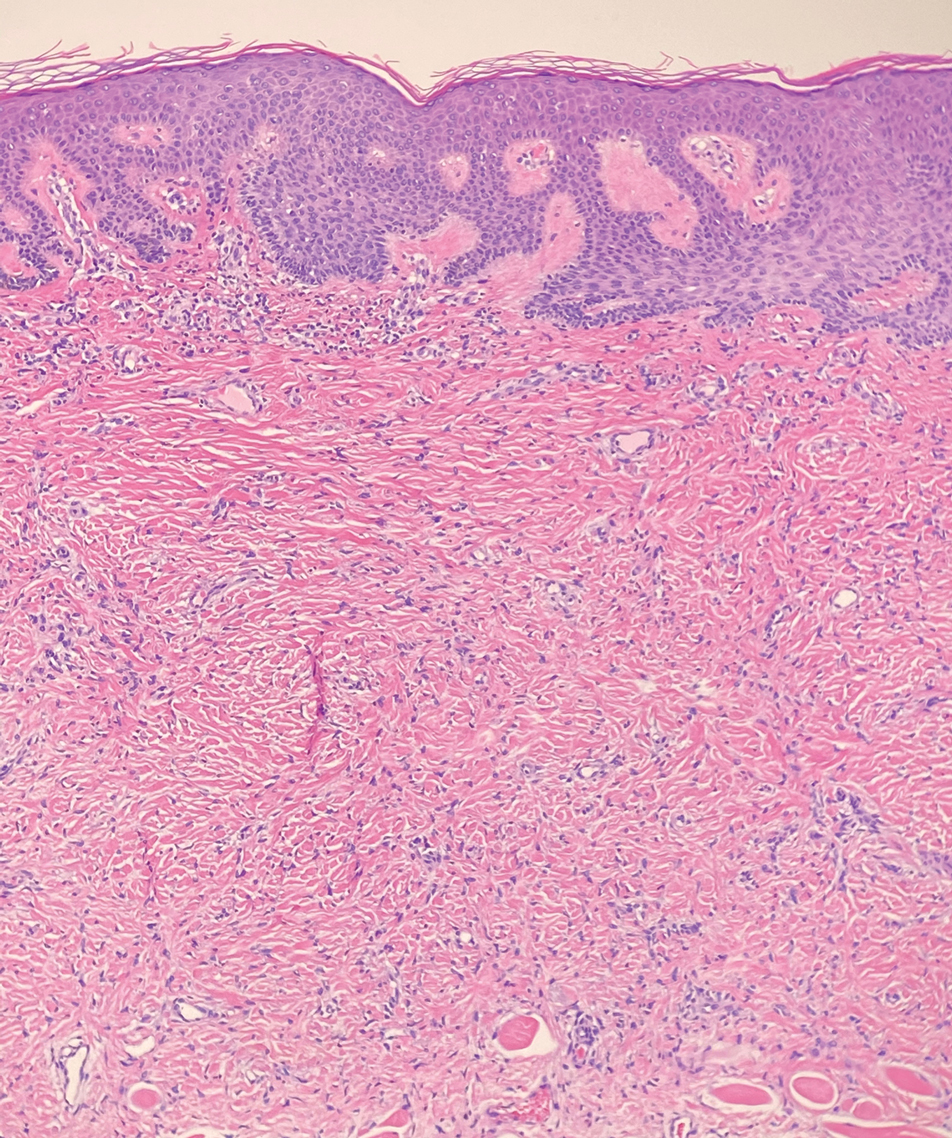

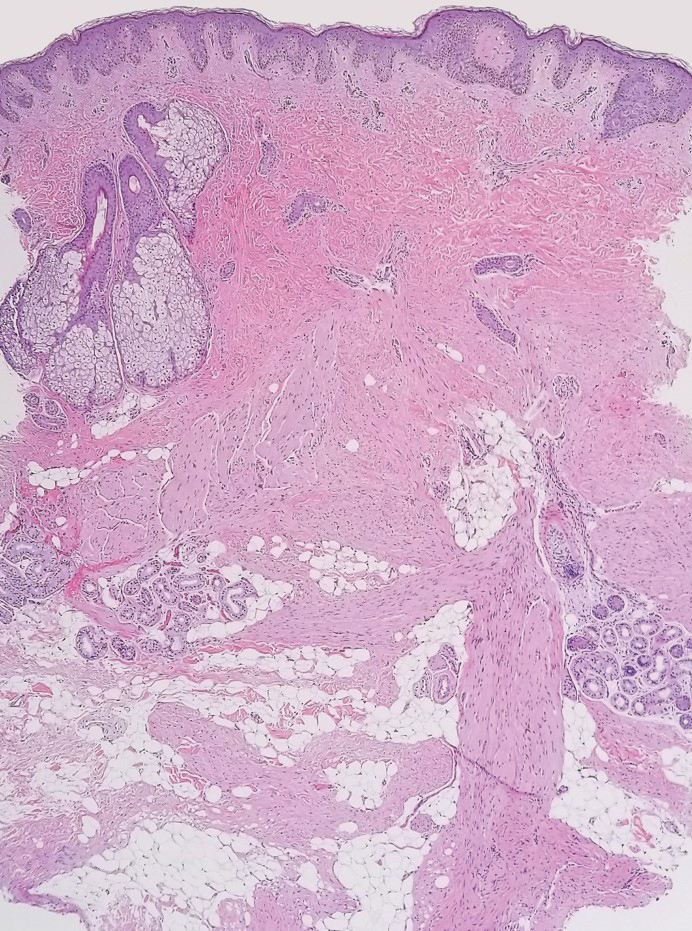

Piloleiomyomas are benign smooth muscle tumors arising from arrector pili muscles that may be solitary or multiple.5 Clinically, they typically present as firm, reddish-brown to flesh-colored papules or nodules that develop more commonly in adulthood.5,7 Piloleiomyomas favor the extremities and trunk, particularly the shoulder, and can be associated with spontaneous or induced pain. Histologically, piloleiomyomas are well circumscribed and centered within the reticular dermis situated closely to hair follicles (Figure 2).5 They are composed of numerous interlacing fascicles or whorls of smooth muscle cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and blunt-ended, cigar-shaped nuclei.5,7

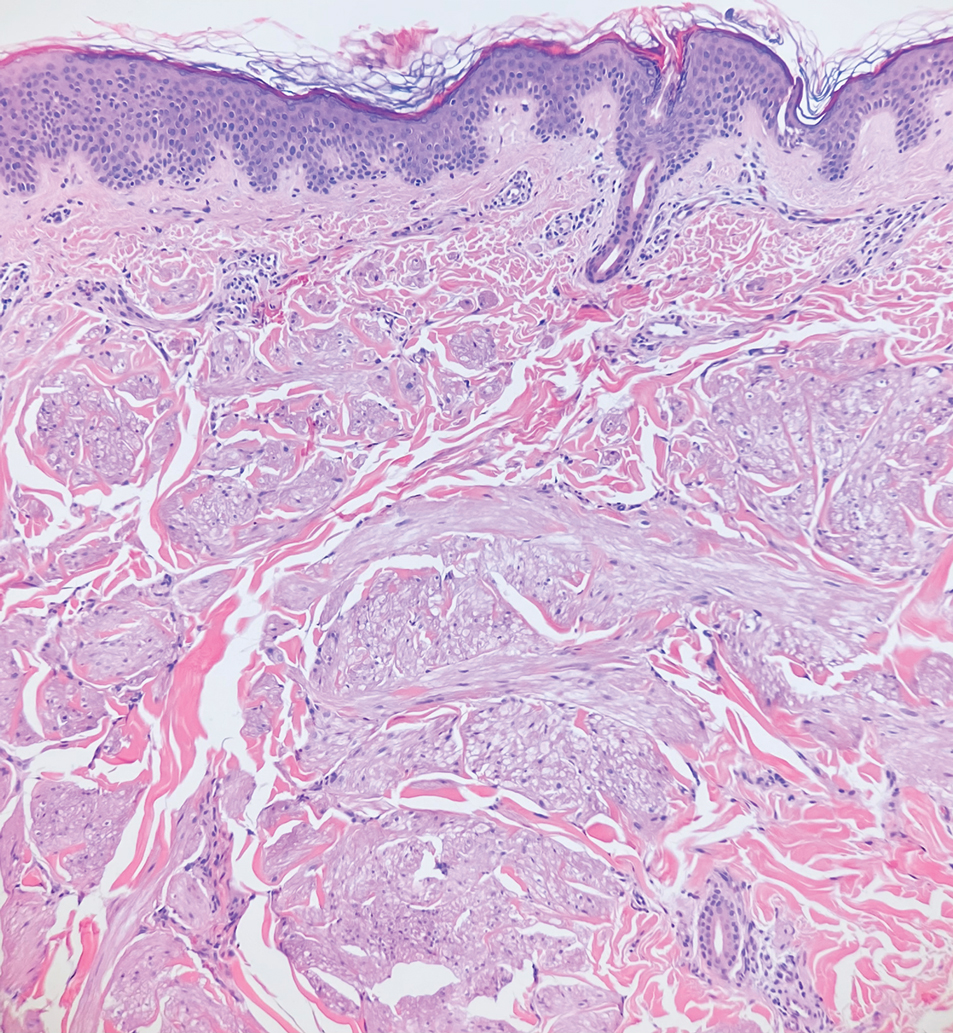

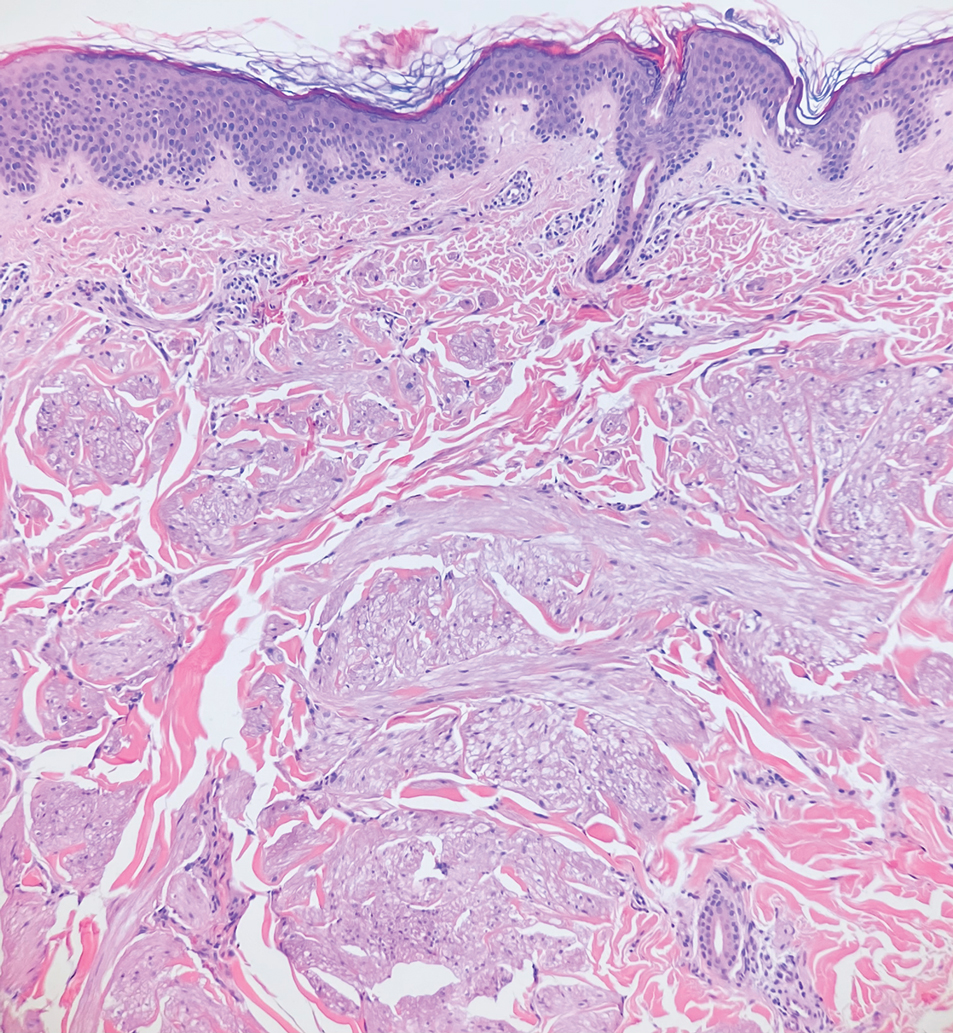

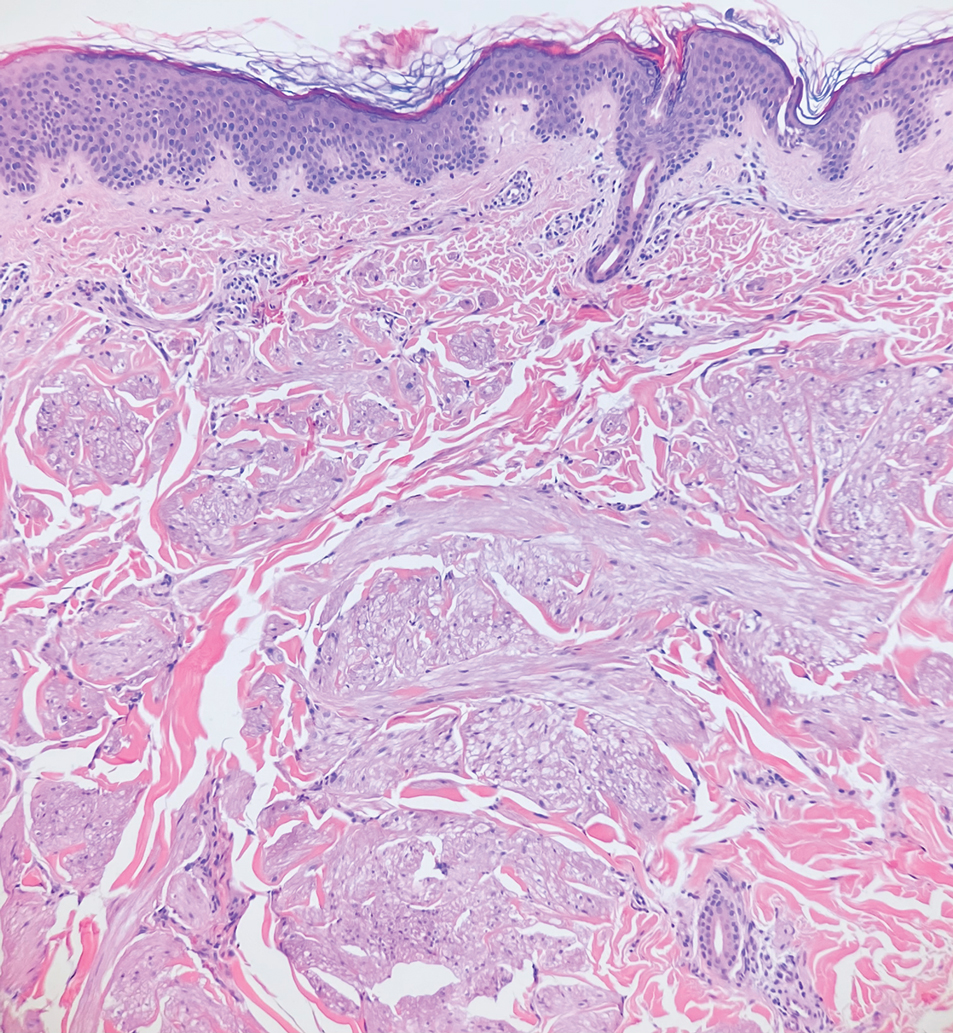

Solitary cutaneous myofibroma is a benign fibrous tumor found in adolescents and adults and is the counterpart to infantile myofibromatosis.8 Clinically, myofibromas typically present as painless, slow-growing, firm nodules with an occasional bluish hue. Histologically, solitary cutaneous myofibromas appear in a biphasic pattern, with hemangiopericytomatous components as well as spindle cells arranged in short bundles and fascicles resembling leiomyoma (Figure 3). The spindle cells also have abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm with short plump nuclei; the random, irregularly intersecting angles can be used to help differentiate myofibromas from smooth muscle lesions.8 Solitary cutaneous myofibroma is in the differential diagnosis for dermatomyofibroma because of their shared myofibroblastic nature.9

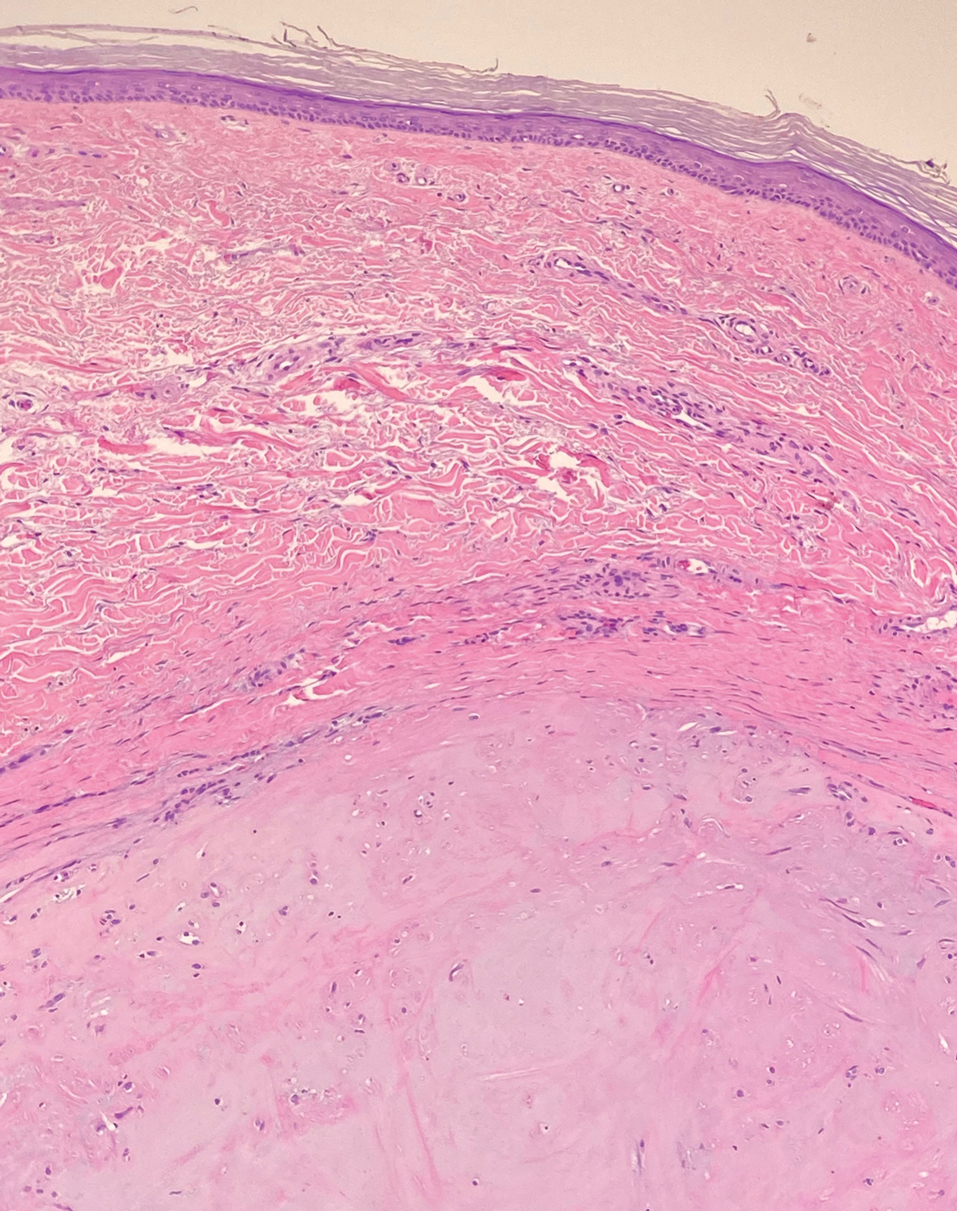

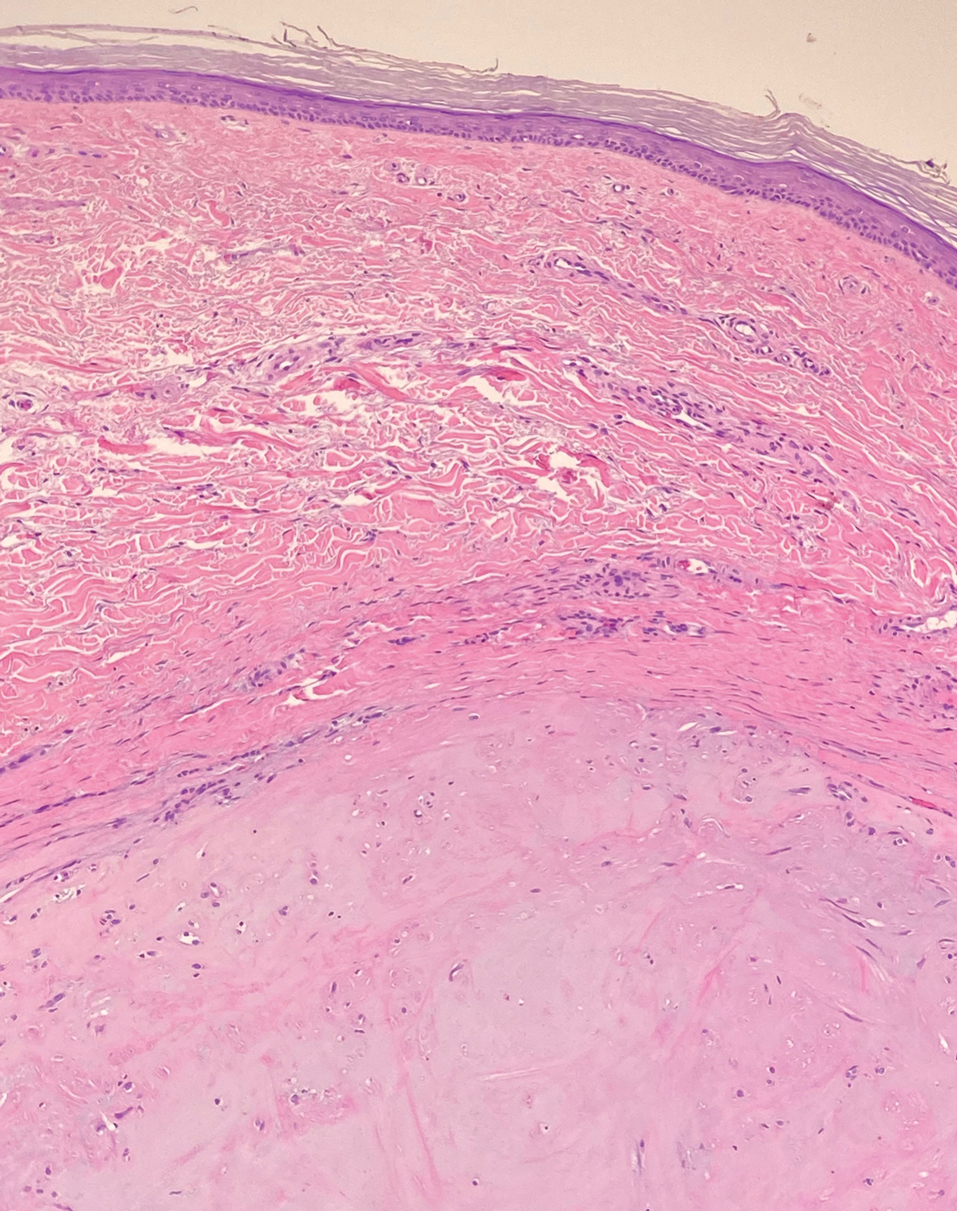

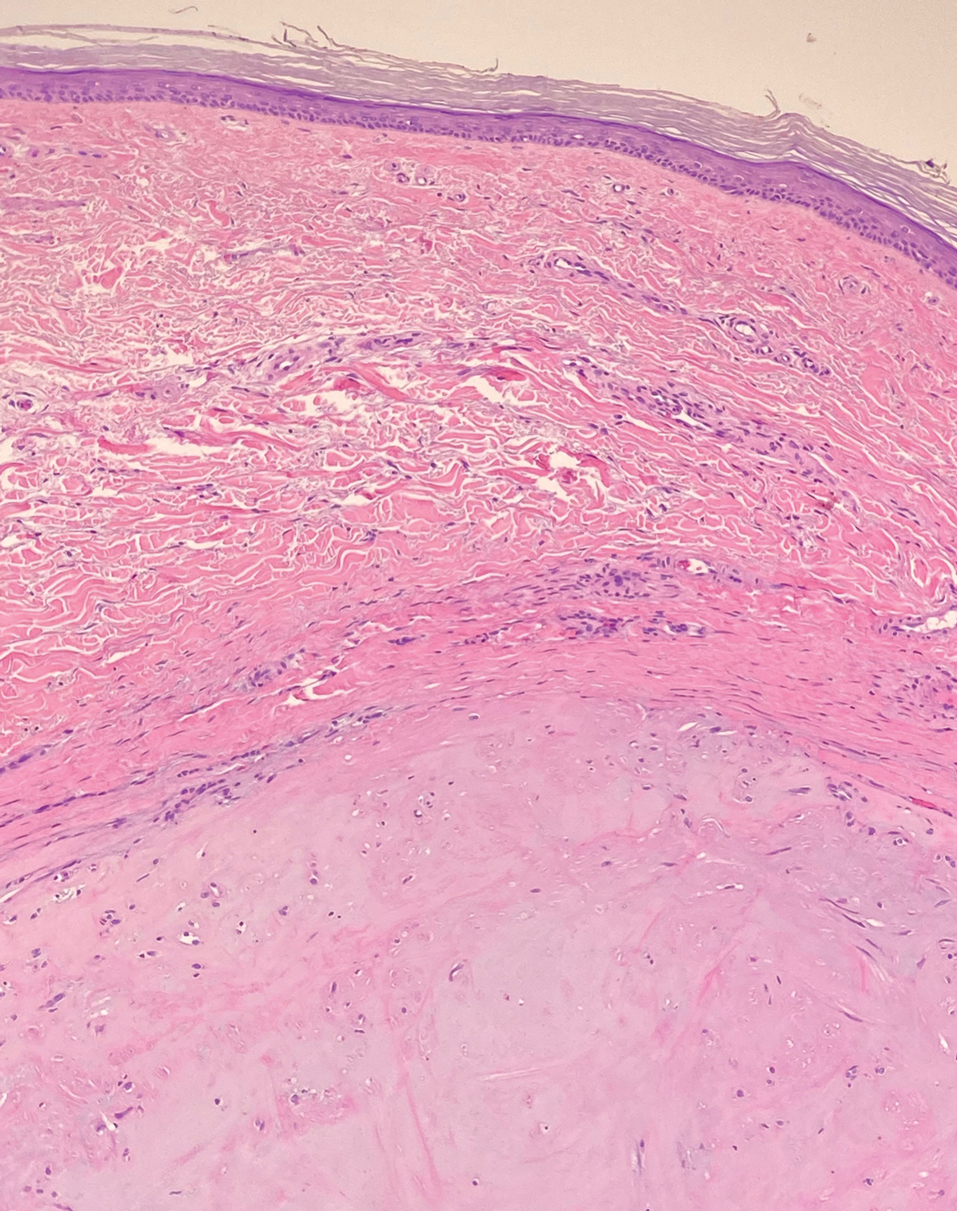

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP) is an uncommon, locally invasive sarcoma with a high recurrence rate that favors young to middle-aged adults, with rare childhood onset reported.5,10,11 Clinically, DFSP typically presents as an asymptomatic, slow-growing, firm, flesh-colored, indurated plaque that develops into a violaceous to reddish-brown nodule.5 The atrophic variant of DFSP is characterized by a nonprotuberant lesion and can be especially difficult to distinguish from other entities such as dermatomyofibroma.11 The majority of DFSP lesions occur on the trunk, particularly in the shoulder or pelvic region.5 Histologically, early plaque lesions are comprised of monomorphic spindle cells arranged in long fascicles (parallel to the skin surface), infiltrating adnexal structures, and subcutaneous adipocytes in a multilayered honeycomb pattern; the spindle cells of late nodular lesions are arranged in short fascicles in a matted or storiform pattern (Figure 4).5,10 Early stages of DFSP as well as variations in childhood-onset DFSP can easily be misdiagnosed and incompletely excised.5

- Ma JE, Wieland CN, Tollefson MM. Dermatomyofibromas arising in children: report of two new cases and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34:347-351.

- Tardio JC, Azorin D, Hernandez-Nunez A, et al. Dermatomyofibromas presenting in pediatric patients: clinicopathologic characteristics and differential diagnosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:967-972.

- Mentzel T, Kutzner H. Dermatomyofibroma: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 56 cases and reappraisal of a rare and distinct cutaneous neoplasm. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:44-49.

- Hugel H. Plaque-like dermal fibromatosis. Hautarzt. 1991;42:223-226.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. WB Saunders Co; 2012.

- Myers DJ, Fillman EP. Dermatofibroma. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2020.

- Dilek N, Yuksel D, Sehitoglu I, et al. Cutaneous leiomyoma in a child: a case report. Oncol Lett. 2013;5:1163-1164.

- Roh HS, Paek JO, Yu HJ, et al. Solitary cutaneous myofibroma on the sole: an unusual localization. Ann Dermatol. 2012;24:220-222.

- Weedon D, Strutton G, Rubin AI, et al. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2010.

- Mendenhall WM, Zlotecki RA, Scarborough MT. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Cancer. 2004;101:2503-2508.

- Akay BN, Unlu E, Erdem C, et al. Dermatoscopic findings of atrophic dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2015;5:71-73.

The Diagnosis: Dermatomyofibroma

Dermatomyofibroma is an uncommon, benign, cutaneous mesenchymal neoplasm composed of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts.1-3 This skin tumor was first described in 1991 by Hugel4 in the German literature as plaquelike fibromatosis. Pediatric dermatomyofibromas are exceedingly rare, with pediatric patients ranging in age from infants to teenagers.1

Clinically, dermatomyofibromas appear as long-standing, isolated, ill-demarcated, flesh-colored, slightly hyperpigmented or erythematous nodules or plaques that may be raised or indurated.1 Dermatomyofibromas may present with constant mild pain or pruritus, though in most cases the lesions are asymptomatic.1,3 The clinical presentation of dermatomyofibroma has a few distinct differences in children compared to adults. In adulthood, dermatomyofibroma has a strong female predominance and most commonly is located on the shoulder and adjacent upper body regions, including the axilla, neck, upper arm, and upper trunk.1-3 In childhood, the majority of dermatomyofibromas occur in young boys and usually are located on the neck with other upper body regions occurring less frequently.1,2 A shared characteristic includes the tendency for dermatomyofibromas to have an initial period of enlargement followed by stabilization or slow growth.1 Reported pediatric lesions have ranged in size from 4 to 60 mm with an average size of 14.9 mm (median, 12 mm).2

The diagnosis of dermatomyofibroma is based on histopathologic features in addition to clinical presentation. Histology from punch biopsy usually reveals a noninvasive dermal proliferation of bland, uniform, slender spindle cells oriented parallel to the overlying epidermis with increased and fragmented elastic fibers.1,3 Infiltration into the mid or deep dermis is common. The adnexal structures usually are spared; the stroma contains collagen and increased small blood vessels; and there typically is no inflammatory infiltrate, except for occasional scattered mast cells.2 Cytologically, the monomorphic spindleshaped tumor cells have an ill-defined, pale, eosinophilic cytoplasm and nuclei that are elongated with tapered edges.3 Dermatomyofibroma has a variable immunohistochemical profile, as it may stain focally positive for CD34 or smooth muscle actin, with occasional staining of factor XIIIa, desmin, calponin, or vimentin.1-3 Normal to increased levels of often fragmented elastic fibers is a helpful clue in distinguishing dermatomyofibroma from dermatofibroma, hypertrophic scar, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, and pilar leiomyoma, in which elastic fibers typically are reduced.3 Differential diagnoses of mesenchymal tumors in children include desmoid fibromatosis, connective tissue nevus, myofibromatosis, and smooth muscle hamartoma.1

A punch biopsy with clinical observation and followup is recommended for the management of lesions in cosmetically sensitive areas or in very young children who may not tolerate surgery. In symptomatic or cosmetically unappealing cases of dermatomyofibroma, simple surgical excision remains a viable treatment option. Recurrence is uncommon, even if only partially excised, and no instances of metastasis have been reported.1-5

Dermatomyofibromas may be mistaken for several other entities both benign and malignant. For example, the benign dermatofibroma is the second most common fibrohistiocytic tumor of the skin and presents as a firm, nontender, minimally elevated to dome-shaped papule that usually measures less than or equal to 1 cm in diameter with or without overlying skin changes.5,6 It primarily is seen in adults with a slight female predominance and favors the lower extremities.5 Patients usually are asymptomatic but often report a history of local trauma at the lesion site.6 Histologically, dermatofibroma is characterized by a nodular dermal proliferation of spindleshaped fibrous cells and histiocytes in a storiform pattern (Figure 1).6 Epidermal induction with acanthosis overlying the tumor often is found with occasional basilar hyperpigmentation.5 Dermatofibroma also characteristically has trapped collagen (“collagen balls”) seen at the periphery.5,6

Piloleiomyomas are benign smooth muscle tumors arising from arrector pili muscles that may be solitary or multiple.5 Clinically, they typically present as firm, reddish-brown to flesh-colored papules or nodules that develop more commonly in adulthood.5,7 Piloleiomyomas favor the extremities and trunk, particularly the shoulder, and can be associated with spontaneous or induced pain. Histologically, piloleiomyomas are well circumscribed and centered within the reticular dermis situated closely to hair follicles (Figure 2).5 They are composed of numerous interlacing fascicles or whorls of smooth muscle cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and blunt-ended, cigar-shaped nuclei.5,7

Solitary cutaneous myofibroma is a benign fibrous tumor found in adolescents and adults and is the counterpart to infantile myofibromatosis.8 Clinically, myofibromas typically present as painless, slow-growing, firm nodules with an occasional bluish hue. Histologically, solitary cutaneous myofibromas appear in a biphasic pattern, with hemangiopericytomatous components as well as spindle cells arranged in short bundles and fascicles resembling leiomyoma (Figure 3). The spindle cells also have abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm with short plump nuclei; the random, irregularly intersecting angles can be used to help differentiate myofibromas from smooth muscle lesions.8 Solitary cutaneous myofibroma is in the differential diagnosis for dermatomyofibroma because of their shared myofibroblastic nature.9

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP) is an uncommon, locally invasive sarcoma with a high recurrence rate that favors young to middle-aged adults, with rare childhood onset reported.5,10,11 Clinically, DFSP typically presents as an asymptomatic, slow-growing, firm, flesh-colored, indurated plaque that develops into a violaceous to reddish-brown nodule.5 The atrophic variant of DFSP is characterized by a nonprotuberant lesion and can be especially difficult to distinguish from other entities such as dermatomyofibroma.11 The majority of DFSP lesions occur on the trunk, particularly in the shoulder or pelvic region.5 Histologically, early plaque lesions are comprised of monomorphic spindle cells arranged in long fascicles (parallel to the skin surface), infiltrating adnexal structures, and subcutaneous adipocytes in a multilayered honeycomb pattern; the spindle cells of late nodular lesions are arranged in short fascicles in a matted or storiform pattern (Figure 4).5,10 Early stages of DFSP as well as variations in childhood-onset DFSP can easily be misdiagnosed and incompletely excised.5

The Diagnosis: Dermatomyofibroma

Dermatomyofibroma is an uncommon, benign, cutaneous mesenchymal neoplasm composed of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts.1-3 This skin tumor was first described in 1991 by Hugel4 in the German literature as plaquelike fibromatosis. Pediatric dermatomyofibromas are exceedingly rare, with pediatric patients ranging in age from infants to teenagers.1

Clinically, dermatomyofibromas appear as long-standing, isolated, ill-demarcated, flesh-colored, slightly hyperpigmented or erythematous nodules or plaques that may be raised or indurated.1 Dermatomyofibromas may present with constant mild pain or pruritus, though in most cases the lesions are asymptomatic.1,3 The clinical presentation of dermatomyofibroma has a few distinct differences in children compared to adults. In adulthood, dermatomyofibroma has a strong female predominance and most commonly is located on the shoulder and adjacent upper body regions, including the axilla, neck, upper arm, and upper trunk.1-3 In childhood, the majority of dermatomyofibromas occur in young boys and usually are located on the neck with other upper body regions occurring less frequently.1,2 A shared characteristic includes the tendency for dermatomyofibromas to have an initial period of enlargement followed by stabilization or slow growth.1 Reported pediatric lesions have ranged in size from 4 to 60 mm with an average size of 14.9 mm (median, 12 mm).2

The diagnosis of dermatomyofibroma is based on histopathologic features in addition to clinical presentation. Histology from punch biopsy usually reveals a noninvasive dermal proliferation of bland, uniform, slender spindle cells oriented parallel to the overlying epidermis with increased and fragmented elastic fibers.1,3 Infiltration into the mid or deep dermis is common. The adnexal structures usually are spared; the stroma contains collagen and increased small blood vessels; and there typically is no inflammatory infiltrate, except for occasional scattered mast cells.2 Cytologically, the monomorphic spindleshaped tumor cells have an ill-defined, pale, eosinophilic cytoplasm and nuclei that are elongated with tapered edges.3 Dermatomyofibroma has a variable immunohistochemical profile, as it may stain focally positive for CD34 or smooth muscle actin, with occasional staining of factor XIIIa, desmin, calponin, or vimentin.1-3 Normal to increased levels of often fragmented elastic fibers is a helpful clue in distinguishing dermatomyofibroma from dermatofibroma, hypertrophic scar, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, and pilar leiomyoma, in which elastic fibers typically are reduced.3 Differential diagnoses of mesenchymal tumors in children include desmoid fibromatosis, connective tissue nevus, myofibromatosis, and smooth muscle hamartoma.1

A punch biopsy with clinical observation and followup is recommended for the management of lesions in cosmetically sensitive areas or in very young children who may not tolerate surgery. In symptomatic or cosmetically unappealing cases of dermatomyofibroma, simple surgical excision remains a viable treatment option. Recurrence is uncommon, even if only partially excised, and no instances of metastasis have been reported.1-5

Dermatomyofibromas may be mistaken for several other entities both benign and malignant. For example, the benign dermatofibroma is the second most common fibrohistiocytic tumor of the skin and presents as a firm, nontender, minimally elevated to dome-shaped papule that usually measures less than or equal to 1 cm in diameter with or without overlying skin changes.5,6 It primarily is seen in adults with a slight female predominance and favors the lower extremities.5 Patients usually are asymptomatic but often report a history of local trauma at the lesion site.6 Histologically, dermatofibroma is characterized by a nodular dermal proliferation of spindleshaped fibrous cells and histiocytes in a storiform pattern (Figure 1).6 Epidermal induction with acanthosis overlying the tumor often is found with occasional basilar hyperpigmentation.5 Dermatofibroma also characteristically has trapped collagen (“collagen balls”) seen at the periphery.5,6

Piloleiomyomas are benign smooth muscle tumors arising from arrector pili muscles that may be solitary or multiple.5 Clinically, they typically present as firm, reddish-brown to flesh-colored papules or nodules that develop more commonly in adulthood.5,7 Piloleiomyomas favor the extremities and trunk, particularly the shoulder, and can be associated with spontaneous or induced pain. Histologically, piloleiomyomas are well circumscribed and centered within the reticular dermis situated closely to hair follicles (Figure 2).5 They are composed of numerous interlacing fascicles or whorls of smooth muscle cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and blunt-ended, cigar-shaped nuclei.5,7

Solitary cutaneous myofibroma is a benign fibrous tumor found in adolescents and adults and is the counterpart to infantile myofibromatosis.8 Clinically, myofibromas typically present as painless, slow-growing, firm nodules with an occasional bluish hue. Histologically, solitary cutaneous myofibromas appear in a biphasic pattern, with hemangiopericytomatous components as well as spindle cells arranged in short bundles and fascicles resembling leiomyoma (Figure 3). The spindle cells also have abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm with short plump nuclei; the random, irregularly intersecting angles can be used to help differentiate myofibromas from smooth muscle lesions.8 Solitary cutaneous myofibroma is in the differential diagnosis for dermatomyofibroma because of their shared myofibroblastic nature.9

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP) is an uncommon, locally invasive sarcoma with a high recurrence rate that favors young to middle-aged adults, with rare childhood onset reported.5,10,11 Clinically, DFSP typically presents as an asymptomatic, slow-growing, firm, flesh-colored, indurated plaque that develops into a violaceous to reddish-brown nodule.5 The atrophic variant of DFSP is characterized by a nonprotuberant lesion and can be especially difficult to distinguish from other entities such as dermatomyofibroma.11 The majority of DFSP lesions occur on the trunk, particularly in the shoulder or pelvic region.5 Histologically, early plaque lesions are comprised of monomorphic spindle cells arranged in long fascicles (parallel to the skin surface), infiltrating adnexal structures, and subcutaneous adipocytes in a multilayered honeycomb pattern; the spindle cells of late nodular lesions are arranged in short fascicles in a matted or storiform pattern (Figure 4).5,10 Early stages of DFSP as well as variations in childhood-onset DFSP can easily be misdiagnosed and incompletely excised.5

- Ma JE, Wieland CN, Tollefson MM. Dermatomyofibromas arising in children: report of two new cases and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34:347-351.

- Tardio JC, Azorin D, Hernandez-Nunez A, et al. Dermatomyofibromas presenting in pediatric patients: clinicopathologic characteristics and differential diagnosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:967-972.

- Mentzel T, Kutzner H. Dermatomyofibroma: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 56 cases and reappraisal of a rare and distinct cutaneous neoplasm. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:44-49.

- Hugel H. Plaque-like dermal fibromatosis. Hautarzt. 1991;42:223-226.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. WB Saunders Co; 2012.

- Myers DJ, Fillman EP. Dermatofibroma. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2020.

- Dilek N, Yuksel D, Sehitoglu I, et al. Cutaneous leiomyoma in a child: a case report. Oncol Lett. 2013;5:1163-1164.

- Roh HS, Paek JO, Yu HJ, et al. Solitary cutaneous myofibroma on the sole: an unusual localization. Ann Dermatol. 2012;24:220-222.

- Weedon D, Strutton G, Rubin AI, et al. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2010.

- Mendenhall WM, Zlotecki RA, Scarborough MT. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Cancer. 2004;101:2503-2508.

- Akay BN, Unlu E, Erdem C, et al. Dermatoscopic findings of atrophic dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2015;5:71-73.