User login

How to have ‘the talk’ with vaccine skeptics

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – An effective strategy in helping vaccine skeptics to come around to accepting immunizations for their children is to pivot the conversation away from vaccine safety and focus instead on the disease itself and its potential consequences, Saad B. Omer, MBBS, PhD, asserted at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

“Why do we cede ground by focusing too much on the vaccine itself? I call it the disease salience approach,” said Dr. Omer, professor of global health, epidemiology, and pediatrics at Emory University in Atlanta.

It’s a strategy guided by developments in social psychology, persuasion theory, and communication theory. But if applied incorrectly, the disease salience approach can backfire, causing behavioral paralysis and an inability to act, he cautioned.

Dr. Omer explained that it’s a matter of framing.

“Always include a solution to promote self-efficacy and response-efficacy. After you inform parents of disease risks, provide them with actions they can take. Now readdress the vaccine, pointing out that this is the single best way to protect yourself and your baby,” he said. “The lesson is that since vaccines are a social norm, reframe nonvaccination as an active act, rather than vaccination as an active act.”

Don’t attempt to wow parents with statistics on how vaccine complication rates are dwarfed by the disease risk if left unvaccinated, he advised. Studies have shown that‘s generally not effective. What actually works is to provide narratives of disease severity.

“We are excellent linguists, but really, really poor statisticians,” Dr. Omer observed.

Is it ethical to talk to parents about disease risks to influence their behavior? Absolutely, in his view.

“We’re not selling toothpaste. We are in the business of life-saving vaccines. And I would submit that if it’s done correctly it’s entirely ethical to talk about the disease, and sometimes even the severe risks of the disease, instead of the vaccine,” said Dr. Omer.

If parents cite a myth about vaccines, it’s necessary to address it head on without lingering on it. But debunking a myth is tricky because people tend to remember negative information they received earlier.

“If you’re going to debunk a myth, clearly label it as a myth in the headline as you introduce it. State why it’s not true. Replace the myth with the best alternative explanation. Think of it like a blank space where the myth used to reside. That space needs to be filled with an alternative explanation or the myth will come back,” Dr. Omer said.

He is a coauthor of a book titled, ‘The Clinician’s Vaccine Safety Resource Guide: Optimizing Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases Across the Lifespan.’

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – An effective strategy in helping vaccine skeptics to come around to accepting immunizations for their children is to pivot the conversation away from vaccine safety and focus instead on the disease itself and its potential consequences, Saad B. Omer, MBBS, PhD, asserted at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

“Why do we cede ground by focusing too much on the vaccine itself? I call it the disease salience approach,” said Dr. Omer, professor of global health, epidemiology, and pediatrics at Emory University in Atlanta.

It’s a strategy guided by developments in social psychology, persuasion theory, and communication theory. But if applied incorrectly, the disease salience approach can backfire, causing behavioral paralysis and an inability to act, he cautioned.

Dr. Omer explained that it’s a matter of framing.

“Always include a solution to promote self-efficacy and response-efficacy. After you inform parents of disease risks, provide them with actions they can take. Now readdress the vaccine, pointing out that this is the single best way to protect yourself and your baby,” he said. “The lesson is that since vaccines are a social norm, reframe nonvaccination as an active act, rather than vaccination as an active act.”

Don’t attempt to wow parents with statistics on how vaccine complication rates are dwarfed by the disease risk if left unvaccinated, he advised. Studies have shown that‘s generally not effective. What actually works is to provide narratives of disease severity.

“We are excellent linguists, but really, really poor statisticians,” Dr. Omer observed.

Is it ethical to talk to parents about disease risks to influence their behavior? Absolutely, in his view.

“We’re not selling toothpaste. We are in the business of life-saving vaccines. And I would submit that if it’s done correctly it’s entirely ethical to talk about the disease, and sometimes even the severe risks of the disease, instead of the vaccine,” said Dr. Omer.

If parents cite a myth about vaccines, it’s necessary to address it head on without lingering on it. But debunking a myth is tricky because people tend to remember negative information they received earlier.

“If you’re going to debunk a myth, clearly label it as a myth in the headline as you introduce it. State why it’s not true. Replace the myth with the best alternative explanation. Think of it like a blank space where the myth used to reside. That space needs to be filled with an alternative explanation or the myth will come back,” Dr. Omer said.

He is a coauthor of a book titled, ‘The Clinician’s Vaccine Safety Resource Guide: Optimizing Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases Across the Lifespan.’

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – An effective strategy in helping vaccine skeptics to come around to accepting immunizations for their children is to pivot the conversation away from vaccine safety and focus instead on the disease itself and its potential consequences, Saad B. Omer, MBBS, PhD, asserted at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

“Why do we cede ground by focusing too much on the vaccine itself? I call it the disease salience approach,” said Dr. Omer, professor of global health, epidemiology, and pediatrics at Emory University in Atlanta.

It’s a strategy guided by developments in social psychology, persuasion theory, and communication theory. But if applied incorrectly, the disease salience approach can backfire, causing behavioral paralysis and an inability to act, he cautioned.

Dr. Omer explained that it’s a matter of framing.

“Always include a solution to promote self-efficacy and response-efficacy. After you inform parents of disease risks, provide them with actions they can take. Now readdress the vaccine, pointing out that this is the single best way to protect yourself and your baby,” he said. “The lesson is that since vaccines are a social norm, reframe nonvaccination as an active act, rather than vaccination as an active act.”

Don’t attempt to wow parents with statistics on how vaccine complication rates are dwarfed by the disease risk if left unvaccinated, he advised. Studies have shown that‘s generally not effective. What actually works is to provide narratives of disease severity.

“We are excellent linguists, but really, really poor statisticians,” Dr. Omer observed.

Is it ethical to talk to parents about disease risks to influence their behavior? Absolutely, in his view.

“We’re not selling toothpaste. We are in the business of life-saving vaccines. And I would submit that if it’s done correctly it’s entirely ethical to talk about the disease, and sometimes even the severe risks of the disease, instead of the vaccine,” said Dr. Omer.

If parents cite a myth about vaccines, it’s necessary to address it head on without lingering on it. But debunking a myth is tricky because people tend to remember negative information they received earlier.

“If you’re going to debunk a myth, clearly label it as a myth in the headline as you introduce it. State why it’s not true. Replace the myth with the best alternative explanation. Think of it like a blank space where the myth used to reside. That space needs to be filled with an alternative explanation or the myth will come back,” Dr. Omer said.

He is a coauthor of a book titled, ‘The Clinician’s Vaccine Safety Resource Guide: Optimizing Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases Across the Lifespan.’

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM ESPID 2019

Scabies rates plummeted with community mass drug administration

MILAN – In a region where scabies is endemic, a , findings that may have implications for future treatment of scabies or other infestations in other regions, dermatologist Margot Whitfield, MD, said at the World Congress of Dermatology.

“Mass drug administration is highly effective and safe in the treatment of endemic scabies,” she said.

Using a strategy of directly observed treatment (DOT) with oral ivermectin or topical permethrin for all residents of two separate island groups in Fiji, Dr. Whitfield, together with epidemiologist Lucia Romani, PhD, both of the University of New South Wales, Sydney, and coinvestigators, demonstrated large and sustained decreases in the rates of scabies and impetigo (N Engl J Med. 2015 Dec 10;373[24]:2305-13).

Across study arms, which included a usual care arm, the baseline rate for scabies ranged from 30% to 40%. With usual care, the rate dropped from 36.6% to 18.8% at the end of 12 months, a relative reduction of 49%. However, the 15.8% prevalence rate 12 months after permethrin DOT (from 41.7%), and the 1.9% rate 12 months after ivermectin DOT (from 32.1%) – reductions of 62% and 94%, respectively – represented much larger decreases, “especially since these reductions were seen without any further interventions,” Dr. Whitfield said. “This was extremely exciting, and a game-changer as far as the management of endemic scabies is concerned.”

At baseline, impetigo rates hovered around 20%-25%, and usual care resulted in a 32% reduction at 12 months. With permethrin DOT, the impetigo rate dropped by 54%; with ivermectin DOT, the impetigo rate dropped by 67%. “The community level of impetigo went down, purely as a result of treating the scabies,” Dr. Whitfield said.

The outcomes of this study, she noted, “have contributed to the global discussion of the treatment of scabies.”

Two years after the mass drug administration (MDA) campaign, scabies prevalence remained much lower than at baseline, with clinical scabies diagnosed in 15.2% of the usual care group, 13.5% of the permethrin group, and just 3.6% of the ivermectin group. “The exciting thing for us was that these levels ... were able to be sustained at 2 years,” Dr. Whitfield noted.

The islands that had received ivermectin saw a continued decline in impetigo prevalence as well: By 24 months, impetigo was seen in 2.6% of participants in that arm.

Scabies is a neglected – but highly treatable – tropical disease, she noted. It is associated with intense pruritus, which results in reduced quality of life, and excoriations predispose those affected to bacterial superinfections, commonly impetigo in the young.

In Fiji, the scabies mite infests nearly 40% of those aged 5-9 years, and over one-third of those younger than 5 years. Rates drop steeply with increasing age and then climb again for the elderly; still, prevalence tops 10% for all Fijian age groups, Dr. Whitfield pointed out. Overall, scabies prevalence is 23% in Fiji, with resultant impetigo affecting 19% of the population.

Providing more details about the study, she said that she and her collaborators – working in conjunction with the Fijian Ministry of Health – took advantage of the geography of the island country, whose 850,000 residents live on 300 islands, to compare mass drug treatment with either ivermectin or permethrin with usual care. “We actually didn’t look for ‘infected scabies,’ ” she explained. “We looked for scabies as one outcome, and infection as another.”

The study was designed to take advantage of lessons from previous public health work addressing filariasis and soil-transmitted helminths, and addressed the following question: In Fiji, could a single round of MDA for scabies control lead to sustained reductions in scabies and impetigo prevalence 12 months later, compared with standard care?

The study applied standard-of-care scabies treatment to residents of one island; here, all residents of the island were assessed for scabies, and those who received a clinical diagnosis of scabies, along with family members and close contacts, were treated. Another group of three small islands received permethrin MDA. A third pair of neighboring islands received ivermectin MDA.

For one MDA arm, island residents received oral ivermectin via DOT. A second DOT dose was administered for those with clinically diagnosed scabies. For pregnant and breastfeeding women, children weighing less than 15 kg, and those with ivermectin hypersensitivity, permethrin was used, Dr. Whitfield said.

The individuals in the permethrin MDA arm received one topical dose via DOT, with a second round of topical permethrin for those with topical scabies.

In all, 803 Fijians were assigned to receive standard of care, 532 permethrin MDA, and 716 ivermectin MDA. Of these, 623 received ivermectin DOT, and 93 received permethrin. In all, DOT was achieved for 96% of those receiving the first dose. At baseline, 230 patients had scabies, with 200 receiving ivermectin and 30 permethrin; the DOT rate was 100% for the second dose.

For the permethrin arm, just 307 of 532 participants (58%) had DOT, though all were given permethrin. Scabies was present at baseline for 222 participants, and of these, 181 had DOT. “It’s much easier to do the direct observed therapy with an oral medication than with a cream,” Dr. Whitfield said. Data were not collected for the Fijians who received usual care at community health centers.

Outcomes were clinically determined via the child skin assessment algorithm of the World Health Organization’s International Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI) guidelines.

Dr. Whitfield acknowledged that the study was not a true cluster-randomized trial, and differences existed between the communities studies. Also, “dermatoscopy was not a practical option” for this real-world trial in a resource-limited setting, but validated clinical criteria were used, she said.

Going forward, she and her colleagues are continuing to track durability of reduced scabies rates, as well as downstream sequelae such as impetigo and septicemia. Also, “we need to see whether this community- and island-based project could be scaled up to a national or regional level,” she said.

The burden of disease from scabies globally is probably underestimated, and changing migration patterns may bring endemic scabies to the doorsteps of more developed nations, prompting consideration of MDA as a strategy in expanded circumstances.

Dr. Whitfield reported that she had no relevant conflicts of interest.

MILAN – In a region where scabies is endemic, a , findings that may have implications for future treatment of scabies or other infestations in other regions, dermatologist Margot Whitfield, MD, said at the World Congress of Dermatology.

“Mass drug administration is highly effective and safe in the treatment of endemic scabies,” she said.

Using a strategy of directly observed treatment (DOT) with oral ivermectin or topical permethrin for all residents of two separate island groups in Fiji, Dr. Whitfield, together with epidemiologist Lucia Romani, PhD, both of the University of New South Wales, Sydney, and coinvestigators, demonstrated large and sustained decreases in the rates of scabies and impetigo (N Engl J Med. 2015 Dec 10;373[24]:2305-13).

Across study arms, which included a usual care arm, the baseline rate for scabies ranged from 30% to 40%. With usual care, the rate dropped from 36.6% to 18.8% at the end of 12 months, a relative reduction of 49%. However, the 15.8% prevalence rate 12 months after permethrin DOT (from 41.7%), and the 1.9% rate 12 months after ivermectin DOT (from 32.1%) – reductions of 62% and 94%, respectively – represented much larger decreases, “especially since these reductions were seen without any further interventions,” Dr. Whitfield said. “This was extremely exciting, and a game-changer as far as the management of endemic scabies is concerned.”

At baseline, impetigo rates hovered around 20%-25%, and usual care resulted in a 32% reduction at 12 months. With permethrin DOT, the impetigo rate dropped by 54%; with ivermectin DOT, the impetigo rate dropped by 67%. “The community level of impetigo went down, purely as a result of treating the scabies,” Dr. Whitfield said.

The outcomes of this study, she noted, “have contributed to the global discussion of the treatment of scabies.”

Two years after the mass drug administration (MDA) campaign, scabies prevalence remained much lower than at baseline, with clinical scabies diagnosed in 15.2% of the usual care group, 13.5% of the permethrin group, and just 3.6% of the ivermectin group. “The exciting thing for us was that these levels ... were able to be sustained at 2 years,” Dr. Whitfield noted.

The islands that had received ivermectin saw a continued decline in impetigo prevalence as well: By 24 months, impetigo was seen in 2.6% of participants in that arm.

Scabies is a neglected – but highly treatable – tropical disease, she noted. It is associated with intense pruritus, which results in reduced quality of life, and excoriations predispose those affected to bacterial superinfections, commonly impetigo in the young.

In Fiji, the scabies mite infests nearly 40% of those aged 5-9 years, and over one-third of those younger than 5 years. Rates drop steeply with increasing age and then climb again for the elderly; still, prevalence tops 10% for all Fijian age groups, Dr. Whitfield pointed out. Overall, scabies prevalence is 23% in Fiji, with resultant impetigo affecting 19% of the population.

Providing more details about the study, she said that she and her collaborators – working in conjunction with the Fijian Ministry of Health – took advantage of the geography of the island country, whose 850,000 residents live on 300 islands, to compare mass drug treatment with either ivermectin or permethrin with usual care. “We actually didn’t look for ‘infected scabies,’ ” she explained. “We looked for scabies as one outcome, and infection as another.”

The study was designed to take advantage of lessons from previous public health work addressing filariasis and soil-transmitted helminths, and addressed the following question: In Fiji, could a single round of MDA for scabies control lead to sustained reductions in scabies and impetigo prevalence 12 months later, compared with standard care?

The study applied standard-of-care scabies treatment to residents of one island; here, all residents of the island were assessed for scabies, and those who received a clinical diagnosis of scabies, along with family members and close contacts, were treated. Another group of three small islands received permethrin MDA. A third pair of neighboring islands received ivermectin MDA.

For one MDA arm, island residents received oral ivermectin via DOT. A second DOT dose was administered for those with clinically diagnosed scabies. For pregnant and breastfeeding women, children weighing less than 15 kg, and those with ivermectin hypersensitivity, permethrin was used, Dr. Whitfield said.

The individuals in the permethrin MDA arm received one topical dose via DOT, with a second round of topical permethrin for those with topical scabies.

In all, 803 Fijians were assigned to receive standard of care, 532 permethrin MDA, and 716 ivermectin MDA. Of these, 623 received ivermectin DOT, and 93 received permethrin. In all, DOT was achieved for 96% of those receiving the first dose. At baseline, 230 patients had scabies, with 200 receiving ivermectin and 30 permethrin; the DOT rate was 100% for the second dose.

For the permethrin arm, just 307 of 532 participants (58%) had DOT, though all were given permethrin. Scabies was present at baseline for 222 participants, and of these, 181 had DOT. “It’s much easier to do the direct observed therapy with an oral medication than with a cream,” Dr. Whitfield said. Data were not collected for the Fijians who received usual care at community health centers.

Outcomes were clinically determined via the child skin assessment algorithm of the World Health Organization’s International Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI) guidelines.

Dr. Whitfield acknowledged that the study was not a true cluster-randomized trial, and differences existed between the communities studies. Also, “dermatoscopy was not a practical option” for this real-world trial in a resource-limited setting, but validated clinical criteria were used, she said.

Going forward, she and her colleagues are continuing to track durability of reduced scabies rates, as well as downstream sequelae such as impetigo and septicemia. Also, “we need to see whether this community- and island-based project could be scaled up to a national or regional level,” she said.

The burden of disease from scabies globally is probably underestimated, and changing migration patterns may bring endemic scabies to the doorsteps of more developed nations, prompting consideration of MDA as a strategy in expanded circumstances.

Dr. Whitfield reported that she had no relevant conflicts of interest.

MILAN – In a region where scabies is endemic, a , findings that may have implications for future treatment of scabies or other infestations in other regions, dermatologist Margot Whitfield, MD, said at the World Congress of Dermatology.

“Mass drug administration is highly effective and safe in the treatment of endemic scabies,” she said.

Using a strategy of directly observed treatment (DOT) with oral ivermectin or topical permethrin for all residents of two separate island groups in Fiji, Dr. Whitfield, together with epidemiologist Lucia Romani, PhD, both of the University of New South Wales, Sydney, and coinvestigators, demonstrated large and sustained decreases in the rates of scabies and impetigo (N Engl J Med. 2015 Dec 10;373[24]:2305-13).

Across study arms, which included a usual care arm, the baseline rate for scabies ranged from 30% to 40%. With usual care, the rate dropped from 36.6% to 18.8% at the end of 12 months, a relative reduction of 49%. However, the 15.8% prevalence rate 12 months after permethrin DOT (from 41.7%), and the 1.9% rate 12 months after ivermectin DOT (from 32.1%) – reductions of 62% and 94%, respectively – represented much larger decreases, “especially since these reductions were seen without any further interventions,” Dr. Whitfield said. “This was extremely exciting, and a game-changer as far as the management of endemic scabies is concerned.”

At baseline, impetigo rates hovered around 20%-25%, and usual care resulted in a 32% reduction at 12 months. With permethrin DOT, the impetigo rate dropped by 54%; with ivermectin DOT, the impetigo rate dropped by 67%. “The community level of impetigo went down, purely as a result of treating the scabies,” Dr. Whitfield said.

The outcomes of this study, she noted, “have contributed to the global discussion of the treatment of scabies.”

Two years after the mass drug administration (MDA) campaign, scabies prevalence remained much lower than at baseline, with clinical scabies diagnosed in 15.2% of the usual care group, 13.5% of the permethrin group, and just 3.6% of the ivermectin group. “The exciting thing for us was that these levels ... were able to be sustained at 2 years,” Dr. Whitfield noted.

The islands that had received ivermectin saw a continued decline in impetigo prevalence as well: By 24 months, impetigo was seen in 2.6% of participants in that arm.

Scabies is a neglected – but highly treatable – tropical disease, she noted. It is associated with intense pruritus, which results in reduced quality of life, and excoriations predispose those affected to bacterial superinfections, commonly impetigo in the young.

In Fiji, the scabies mite infests nearly 40% of those aged 5-9 years, and over one-third of those younger than 5 years. Rates drop steeply with increasing age and then climb again for the elderly; still, prevalence tops 10% for all Fijian age groups, Dr. Whitfield pointed out. Overall, scabies prevalence is 23% in Fiji, with resultant impetigo affecting 19% of the population.

Providing more details about the study, she said that she and her collaborators – working in conjunction with the Fijian Ministry of Health – took advantage of the geography of the island country, whose 850,000 residents live on 300 islands, to compare mass drug treatment with either ivermectin or permethrin with usual care. “We actually didn’t look for ‘infected scabies,’ ” she explained. “We looked for scabies as one outcome, and infection as another.”

The study was designed to take advantage of lessons from previous public health work addressing filariasis and soil-transmitted helminths, and addressed the following question: In Fiji, could a single round of MDA for scabies control lead to sustained reductions in scabies and impetigo prevalence 12 months later, compared with standard care?

The study applied standard-of-care scabies treatment to residents of one island; here, all residents of the island were assessed for scabies, and those who received a clinical diagnosis of scabies, along with family members and close contacts, were treated. Another group of three small islands received permethrin MDA. A third pair of neighboring islands received ivermectin MDA.

For one MDA arm, island residents received oral ivermectin via DOT. A second DOT dose was administered for those with clinically diagnosed scabies. For pregnant and breastfeeding women, children weighing less than 15 kg, and those with ivermectin hypersensitivity, permethrin was used, Dr. Whitfield said.

The individuals in the permethrin MDA arm received one topical dose via DOT, with a second round of topical permethrin for those with topical scabies.

In all, 803 Fijians were assigned to receive standard of care, 532 permethrin MDA, and 716 ivermectin MDA. Of these, 623 received ivermectin DOT, and 93 received permethrin. In all, DOT was achieved for 96% of those receiving the first dose. At baseline, 230 patients had scabies, with 200 receiving ivermectin and 30 permethrin; the DOT rate was 100% for the second dose.

For the permethrin arm, just 307 of 532 participants (58%) had DOT, though all were given permethrin. Scabies was present at baseline for 222 participants, and of these, 181 had DOT. “It’s much easier to do the direct observed therapy with an oral medication than with a cream,” Dr. Whitfield said. Data were not collected for the Fijians who received usual care at community health centers.

Outcomes were clinically determined via the child skin assessment algorithm of the World Health Organization’s International Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI) guidelines.

Dr. Whitfield acknowledged that the study was not a true cluster-randomized trial, and differences existed between the communities studies. Also, “dermatoscopy was not a practical option” for this real-world trial in a resource-limited setting, but validated clinical criteria were used, she said.

Going forward, she and her colleagues are continuing to track durability of reduced scabies rates, as well as downstream sequelae such as impetigo and septicemia. Also, “we need to see whether this community- and island-based project could be scaled up to a national or regional level,” she said.

The burden of disease from scabies globally is probably underestimated, and changing migration patterns may bring endemic scabies to the doorsteps of more developed nations, prompting consideration of MDA as a strategy in expanded circumstances.

Dr. Whitfield reported that she had no relevant conflicts of interest.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM WCD2019

In MS, children aren’t just little adults

SEATTLE – Multiple sclerosis (MS) presents quite differently in children than adults, a neurologist told colleagues, but many treatments are the same.

“We need to treat them when they’re young, perhaps, to prevent disability later on,” said Jennifer Graves, MD, PhD, director of neuroimmunology research at the University of California, San Diego, and director of the Rady Children’s Pediatric MS Clinic.

Fortunately, “they tend to respond to any DMT [disease-modifying therapy] you give them,” said Dr. Graves, who spoke at the annual meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers.

Unlike the adult version, pediatric MS is almost never progressive, she said, and the relapsing form affects 85%-99% of those with the condition.

And children with MS suffer from high relapse rates. “In some of the more recent studies, the annual relapse rates have been two to even five to six times higher than in adults,” she related.

For acute relapses, Dr. Graves recommends IV methylprednisolone as a first-line treatment. High-dose oral steroids can be appropriate in teenagers, and plasma exchange is a second-line option.

DMT does work in children. “They’re just so inflammatory, having so much activity, that they tend to respond to anything,” she noted.

With few exceptions, DMTs have been tested in children, she said. But the trials in children have tended to be small, and only fingolimod (Gilenya) is Food and Drug Administration–approved for pediatric patients (aged 10-18 years).

What’s the best DMT for kids? “There is evidence that the higher-potency drugs may work better in some patients,” Dr. Graves said. “I diagnosed a 4 year old with MS. With an annual relapse rate of 6, I had no hesitancy about jumping to the highest-potency agent I had available.”

She cautioned, however, that there may never be deep insight into the best choices because of it is not feasible to study all the available DMTs in children.

Dr. Graves offered these tips about treating children with MS:

- Be prepared to spend long periods educating children and their parents. “You think you spend a long time with your adult patients? Double it,” she said. “Most new patient appointments will be 90 minutes at least. Negotiate that time for the patients in your clinic who are very young.”

- Don’t separate kids from parents. “I discourage parents from asking their children to leave the room. Everyone should know what the choices are as much as possible and having the children on the same page can help with compliance,” Dr. Graves said.

- Consider unique safety considerations. “Children are less likely to be JC [John Cunningham] virus antibody-positive than adults, and we can feel more confident with agents that cause PML [progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy],” she said. “But they’re more likely to convert on our watch.”

- Consider mentioning sexual function to teens. As adolescents, “they’re unsure of sexual function to begin with, and they often don’t know if they’re normal in terms of sexual function.” Don’t forget that contraceptives may be appropriate because some MS drugs are teratogenic. “Have a lengthy and realistic conversation about birth control,” Dr. Graves said, “and maybe ask the parents to leave the room.”

Dr. Graves disclosed receiving speaking honoraria from Novartis and Sanofi Genzyme, and grants from Biogen and Genentech.

SEATTLE – Multiple sclerosis (MS) presents quite differently in children than adults, a neurologist told colleagues, but many treatments are the same.

“We need to treat them when they’re young, perhaps, to prevent disability later on,” said Jennifer Graves, MD, PhD, director of neuroimmunology research at the University of California, San Diego, and director of the Rady Children’s Pediatric MS Clinic.

Fortunately, “they tend to respond to any DMT [disease-modifying therapy] you give them,” said Dr. Graves, who spoke at the annual meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers.

Unlike the adult version, pediatric MS is almost never progressive, she said, and the relapsing form affects 85%-99% of those with the condition.

And children with MS suffer from high relapse rates. “In some of the more recent studies, the annual relapse rates have been two to even five to six times higher than in adults,” she related.

For acute relapses, Dr. Graves recommends IV methylprednisolone as a first-line treatment. High-dose oral steroids can be appropriate in teenagers, and plasma exchange is a second-line option.

DMT does work in children. “They’re just so inflammatory, having so much activity, that they tend to respond to anything,” she noted.

With few exceptions, DMTs have been tested in children, she said. But the trials in children have tended to be small, and only fingolimod (Gilenya) is Food and Drug Administration–approved for pediatric patients (aged 10-18 years).

What’s the best DMT for kids? “There is evidence that the higher-potency drugs may work better in some patients,” Dr. Graves said. “I diagnosed a 4 year old with MS. With an annual relapse rate of 6, I had no hesitancy about jumping to the highest-potency agent I had available.”

She cautioned, however, that there may never be deep insight into the best choices because of it is not feasible to study all the available DMTs in children.

Dr. Graves offered these tips about treating children with MS:

- Be prepared to spend long periods educating children and their parents. “You think you spend a long time with your adult patients? Double it,” she said. “Most new patient appointments will be 90 minutes at least. Negotiate that time for the patients in your clinic who are very young.”

- Don’t separate kids from parents. “I discourage parents from asking their children to leave the room. Everyone should know what the choices are as much as possible and having the children on the same page can help with compliance,” Dr. Graves said.

- Consider unique safety considerations. “Children are less likely to be JC [John Cunningham] virus antibody-positive than adults, and we can feel more confident with agents that cause PML [progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy],” she said. “But they’re more likely to convert on our watch.”

- Consider mentioning sexual function to teens. As adolescents, “they’re unsure of sexual function to begin with, and they often don’t know if they’re normal in terms of sexual function.” Don’t forget that contraceptives may be appropriate because some MS drugs are teratogenic. “Have a lengthy and realistic conversation about birth control,” Dr. Graves said, “and maybe ask the parents to leave the room.”

Dr. Graves disclosed receiving speaking honoraria from Novartis and Sanofi Genzyme, and grants from Biogen and Genentech.

SEATTLE – Multiple sclerosis (MS) presents quite differently in children than adults, a neurologist told colleagues, but many treatments are the same.

“We need to treat them when they’re young, perhaps, to prevent disability later on,” said Jennifer Graves, MD, PhD, director of neuroimmunology research at the University of California, San Diego, and director of the Rady Children’s Pediatric MS Clinic.

Fortunately, “they tend to respond to any DMT [disease-modifying therapy] you give them,” said Dr. Graves, who spoke at the annual meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers.

Unlike the adult version, pediatric MS is almost never progressive, she said, and the relapsing form affects 85%-99% of those with the condition.

And children with MS suffer from high relapse rates. “In some of the more recent studies, the annual relapse rates have been two to even five to six times higher than in adults,” she related.

For acute relapses, Dr. Graves recommends IV methylprednisolone as a first-line treatment. High-dose oral steroids can be appropriate in teenagers, and plasma exchange is a second-line option.

DMT does work in children. “They’re just so inflammatory, having so much activity, that they tend to respond to anything,” she noted.

With few exceptions, DMTs have been tested in children, she said. But the trials in children have tended to be small, and only fingolimod (Gilenya) is Food and Drug Administration–approved for pediatric patients (aged 10-18 years).

What’s the best DMT for kids? “There is evidence that the higher-potency drugs may work better in some patients,” Dr. Graves said. “I diagnosed a 4 year old with MS. With an annual relapse rate of 6, I had no hesitancy about jumping to the highest-potency agent I had available.”

She cautioned, however, that there may never be deep insight into the best choices because of it is not feasible to study all the available DMTs in children.

Dr. Graves offered these tips about treating children with MS:

- Be prepared to spend long periods educating children and their parents. “You think you spend a long time with your adult patients? Double it,” she said. “Most new patient appointments will be 90 minutes at least. Negotiate that time for the patients in your clinic who are very young.”

- Don’t separate kids from parents. “I discourage parents from asking their children to leave the room. Everyone should know what the choices are as much as possible and having the children on the same page can help with compliance,” Dr. Graves said.

- Consider unique safety considerations. “Children are less likely to be JC [John Cunningham] virus antibody-positive than adults, and we can feel more confident with agents that cause PML [progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy],” she said. “But they’re more likely to convert on our watch.”

- Consider mentioning sexual function to teens. As adolescents, “they’re unsure of sexual function to begin with, and they often don’t know if they’re normal in terms of sexual function.” Don’t forget that contraceptives may be appropriate because some MS drugs are teratogenic. “Have a lengthy and realistic conversation about birth control,” Dr. Graves said, “and maybe ask the parents to leave the room.”

Dr. Graves disclosed receiving speaking honoraria from Novartis and Sanofi Genzyme, and grants from Biogen and Genentech.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM CMSC 2019

Reducing pediatric RSV burden is top priority

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – Prevention or early effective treatment of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection in infants and small children holds the promise of sharply reduced burdens of both acute otitis media (AOM) and pneumonia, Terho Heikkinen, MD, PhD, predicted in the Bill Marshall Award Lecture presented at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases (ESPID).

RSV is by far the hottest virus in the world,” declared Dr. Heikkinen, professor of pediatrics at the University of Turku (Finland).

“A lot of progress is being made with respect to RSV. This increased understanding holds great promise for new interventions,” he explained. “Lots of different types of vaccines are being developed, monoclonal antibodies, antivirals. So

Today influenza is the only respiratory viral infection that’s preventable via vaccine or effectively treatable using antiviral drugs. That situation has to change, as Dr. Heikkinen demonstrated early in his career; RSV is the respiratory virus that’s most likely to invade the middle ear during AOM. It’s much more ototropic than influenza, parainfluenza, enteroviruses, or adenoviruses (N Engl J Med. 1999 Jan 28;340[4]:260-4), he noted.

The Bill Marshall Award and Lecture, ESPID’s most prestigious award, is given annually to an individual recognized as having significantly advanced the field of pediatric infectious diseases. Dr. Heikkinen was singled out for his decades of work establishing that viruses, including RSV, play a key role in AOM, which had traditionally been regarded as a bacterial infection. He and his coinvestigators demonstrated that in about two-thirds of cases, AOM is actually caused by a combination of bacteria and viruses, which explains why patients’ clinical response to antibiotic therapy for AOM often is poor. They also described the chain of events whereby viral infection of the upper airway epithelium triggers an inflammatory response in the nasopharynx, with resultant Eustachian tube dysfunction and negative middle ear pressure, which in turn encourages microbial invasion of the middle ear. Moreover, they showed that the peak incidence of AOM isn’t on day 1 after onset of upper respiratory infection symptoms, but on day 3 or 4.

“What this tells us is that, once a child has a viral respiratory infection, there is a certain window of opportunity to try to prevent the development of the complication if we have the right tools in place,” Dr. Heikkinen said.

He and his colleagues put this lesson to good use nearly a decade ago in a randomized, double-blind trial in which they showed that giving oseltamivir (Tamiflu) within 12 hours after onset of influenza symptoms in children aged 1-3 years reduced the subsequent incidence of AOM by 85%, compared with placebo (Clin Infect Dis. 2010 Oct 15;51[8]:887-94).

These observations paved the way for the ongoing intensive research effort exploring ways of preventing AOM through interventions at two different levels: by developing viral vaccines to prevent a healthy child from contracting the viral upper respiratory infection that precedes AOM and by coming up with antiviral drugs or bacterial vaccines to prevent a upper respiratory infection from evolving into AOM.

The same applies to pneumonia. Other investigators showed years ago that both respiratory viruses and bacteria were present in two-thirds of sputum samples obtained from children with community-acquired pneumonia (Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012 Mar;18[3]:300-7).

RSV is the top cause of hospitalization for acute respiratory infection – pneumonia and bronchiolitis – in infants. Worldwide, it’s estimated that RSV accounts for more than 33 million episodes of pneumonia annually, with 3.2 million hospitalizations and 118,200 deaths.

Beyond the hospital, however, Dr. Heikkinen and colleagues conducted a prospective cohort study in Turku over the course of two consecutive respiratory infection seasons in which they captured the huge burden of RSV as an outpatient illness. It hit hardest in children younger than 3 years, in whom the average annual incidence of RSV infection was 275 cases per 1,000 children. In that youngest age population, RSV upper respiratory infection was followed by AOM 58% of the time, with antibiotics prescribed in 66% of the cases of this complication of RSV illness. The mean duration of RSV illness was greatest in this young age group, at 13 days, and it was associated with parental absenteeism from work at a rate of 136 days per 100 children with RSV illness.

Moreover, while AOM occurred less frequently in children aged 3-6 years, 46% of the cases were attributed to a preceding RSV infection, which led to antibiotic treatment nearly half of the time (J Infect Dis. 2017 Jan 1;215[1]:17-23). This documentation has spurred further efforts to develop RSV vaccines and antivirals.

He reported serving as a consultant to a half-dozen pharmaceutical companies, as well as having received research funding from Janssen, GlaxoSmithKline, and Novavax.

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – Prevention or early effective treatment of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection in infants and small children holds the promise of sharply reduced burdens of both acute otitis media (AOM) and pneumonia, Terho Heikkinen, MD, PhD, predicted in the Bill Marshall Award Lecture presented at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases (ESPID).

RSV is by far the hottest virus in the world,” declared Dr. Heikkinen, professor of pediatrics at the University of Turku (Finland).

“A lot of progress is being made with respect to RSV. This increased understanding holds great promise for new interventions,” he explained. “Lots of different types of vaccines are being developed, monoclonal antibodies, antivirals. So

Today influenza is the only respiratory viral infection that’s preventable via vaccine or effectively treatable using antiviral drugs. That situation has to change, as Dr. Heikkinen demonstrated early in his career; RSV is the respiratory virus that’s most likely to invade the middle ear during AOM. It’s much more ototropic than influenza, parainfluenza, enteroviruses, or adenoviruses (N Engl J Med. 1999 Jan 28;340[4]:260-4), he noted.

The Bill Marshall Award and Lecture, ESPID’s most prestigious award, is given annually to an individual recognized as having significantly advanced the field of pediatric infectious diseases. Dr. Heikkinen was singled out for his decades of work establishing that viruses, including RSV, play a key role in AOM, which had traditionally been regarded as a bacterial infection. He and his coinvestigators demonstrated that in about two-thirds of cases, AOM is actually caused by a combination of bacteria and viruses, which explains why patients’ clinical response to antibiotic therapy for AOM often is poor. They also described the chain of events whereby viral infection of the upper airway epithelium triggers an inflammatory response in the nasopharynx, with resultant Eustachian tube dysfunction and negative middle ear pressure, which in turn encourages microbial invasion of the middle ear. Moreover, they showed that the peak incidence of AOM isn’t on day 1 after onset of upper respiratory infection symptoms, but on day 3 or 4.

“What this tells us is that, once a child has a viral respiratory infection, there is a certain window of opportunity to try to prevent the development of the complication if we have the right tools in place,” Dr. Heikkinen said.

He and his colleagues put this lesson to good use nearly a decade ago in a randomized, double-blind trial in which they showed that giving oseltamivir (Tamiflu) within 12 hours after onset of influenza symptoms in children aged 1-3 years reduced the subsequent incidence of AOM by 85%, compared with placebo (Clin Infect Dis. 2010 Oct 15;51[8]:887-94).

These observations paved the way for the ongoing intensive research effort exploring ways of preventing AOM through interventions at two different levels: by developing viral vaccines to prevent a healthy child from contracting the viral upper respiratory infection that precedes AOM and by coming up with antiviral drugs or bacterial vaccines to prevent a upper respiratory infection from evolving into AOM.

The same applies to pneumonia. Other investigators showed years ago that both respiratory viruses and bacteria were present in two-thirds of sputum samples obtained from children with community-acquired pneumonia (Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012 Mar;18[3]:300-7).

RSV is the top cause of hospitalization for acute respiratory infection – pneumonia and bronchiolitis – in infants. Worldwide, it’s estimated that RSV accounts for more than 33 million episodes of pneumonia annually, with 3.2 million hospitalizations and 118,200 deaths.

Beyond the hospital, however, Dr. Heikkinen and colleagues conducted a prospective cohort study in Turku over the course of two consecutive respiratory infection seasons in which they captured the huge burden of RSV as an outpatient illness. It hit hardest in children younger than 3 years, in whom the average annual incidence of RSV infection was 275 cases per 1,000 children. In that youngest age population, RSV upper respiratory infection was followed by AOM 58% of the time, with antibiotics prescribed in 66% of the cases of this complication of RSV illness. The mean duration of RSV illness was greatest in this young age group, at 13 days, and it was associated with parental absenteeism from work at a rate of 136 days per 100 children with RSV illness.

Moreover, while AOM occurred less frequently in children aged 3-6 years, 46% of the cases were attributed to a preceding RSV infection, which led to antibiotic treatment nearly half of the time (J Infect Dis. 2017 Jan 1;215[1]:17-23). This documentation has spurred further efforts to develop RSV vaccines and antivirals.

He reported serving as a consultant to a half-dozen pharmaceutical companies, as well as having received research funding from Janssen, GlaxoSmithKline, and Novavax.

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – Prevention or early effective treatment of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection in infants and small children holds the promise of sharply reduced burdens of both acute otitis media (AOM) and pneumonia, Terho Heikkinen, MD, PhD, predicted in the Bill Marshall Award Lecture presented at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases (ESPID).

RSV is by far the hottest virus in the world,” declared Dr. Heikkinen, professor of pediatrics at the University of Turku (Finland).

“A lot of progress is being made with respect to RSV. This increased understanding holds great promise for new interventions,” he explained. “Lots of different types of vaccines are being developed, monoclonal antibodies, antivirals. So

Today influenza is the only respiratory viral infection that’s preventable via vaccine or effectively treatable using antiviral drugs. That situation has to change, as Dr. Heikkinen demonstrated early in his career; RSV is the respiratory virus that’s most likely to invade the middle ear during AOM. It’s much more ototropic than influenza, parainfluenza, enteroviruses, or adenoviruses (N Engl J Med. 1999 Jan 28;340[4]:260-4), he noted.

The Bill Marshall Award and Lecture, ESPID’s most prestigious award, is given annually to an individual recognized as having significantly advanced the field of pediatric infectious diseases. Dr. Heikkinen was singled out for his decades of work establishing that viruses, including RSV, play a key role in AOM, which had traditionally been regarded as a bacterial infection. He and his coinvestigators demonstrated that in about two-thirds of cases, AOM is actually caused by a combination of bacteria and viruses, which explains why patients’ clinical response to antibiotic therapy for AOM often is poor. They also described the chain of events whereby viral infection of the upper airway epithelium triggers an inflammatory response in the nasopharynx, with resultant Eustachian tube dysfunction and negative middle ear pressure, which in turn encourages microbial invasion of the middle ear. Moreover, they showed that the peak incidence of AOM isn’t on day 1 after onset of upper respiratory infection symptoms, but on day 3 or 4.

“What this tells us is that, once a child has a viral respiratory infection, there is a certain window of opportunity to try to prevent the development of the complication if we have the right tools in place,” Dr. Heikkinen said.

He and his colleagues put this lesson to good use nearly a decade ago in a randomized, double-blind trial in which they showed that giving oseltamivir (Tamiflu) within 12 hours after onset of influenza symptoms in children aged 1-3 years reduced the subsequent incidence of AOM by 85%, compared with placebo (Clin Infect Dis. 2010 Oct 15;51[8]:887-94).

These observations paved the way for the ongoing intensive research effort exploring ways of preventing AOM through interventions at two different levels: by developing viral vaccines to prevent a healthy child from contracting the viral upper respiratory infection that precedes AOM and by coming up with antiviral drugs or bacterial vaccines to prevent a upper respiratory infection from evolving into AOM.

The same applies to pneumonia. Other investigators showed years ago that both respiratory viruses and bacteria were present in two-thirds of sputum samples obtained from children with community-acquired pneumonia (Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012 Mar;18[3]:300-7).

RSV is the top cause of hospitalization for acute respiratory infection – pneumonia and bronchiolitis – in infants. Worldwide, it’s estimated that RSV accounts for more than 33 million episodes of pneumonia annually, with 3.2 million hospitalizations and 118,200 deaths.

Beyond the hospital, however, Dr. Heikkinen and colleagues conducted a prospective cohort study in Turku over the course of two consecutive respiratory infection seasons in which they captured the huge burden of RSV as an outpatient illness. It hit hardest in children younger than 3 years, in whom the average annual incidence of RSV infection was 275 cases per 1,000 children. In that youngest age population, RSV upper respiratory infection was followed by AOM 58% of the time, with antibiotics prescribed in 66% of the cases of this complication of RSV illness. The mean duration of RSV illness was greatest in this young age group, at 13 days, and it was associated with parental absenteeism from work at a rate of 136 days per 100 children with RSV illness.

Moreover, while AOM occurred less frequently in children aged 3-6 years, 46% of the cases were attributed to a preceding RSV infection, which led to antibiotic treatment nearly half of the time (J Infect Dis. 2017 Jan 1;215[1]:17-23). This documentation has spurred further efforts to develop RSV vaccines and antivirals.

He reported serving as a consultant to a half-dozen pharmaceutical companies, as well as having received research funding from Janssen, GlaxoSmithKline, and Novavax.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM ESPID 2019

Waning pertussis immunity may be linked to acellular vaccine

A large Kaiser Permanente study paints a nuanced picture of the acellular pertussis vaccine, with more cases occurring in fully vaccinated children, but the highest risk of disease occurring among the under- and unvaccinated.

Among nearly half a million children, the unvaccinated were 13 times more likely to develop pertussis than fully vaccinated children, Ousseny Zerbo, PhD, of Kaiser Permanente Northern California in Oakland and colleagues wrote in Pediatrics. But 82% of cases occurred in fully vaccinated children and just 5% in undervaccinated children – and rates increased in both groups the farther they were in time from the last vaccination.

“Within our study population, greater than 80% of pertussis cases occurred among age-appropriately vaccinated children,” the team wrote. “Children who were further away from their last DTaP dose were at increased risk of pertussis, even after controlling for undervaccination. Our results suggest that, in this population, possibly in conjunction with other factors not addressed in this study, suboptimal vaccine efficacy and waning [immunity] played a major role in recent pertussis epidemics.”

The results are consistent with several prior studies, including one finding that the odds of the disease increased by 33% for every additional year after the third or fifth DTaP dose (Pediatrics. 2015;135[2]:331-43).

The current study comprised 469,982 children aged between 3 months and 11 years, who were followed for a mean of 4.6 years. Over the entire study period, there were 738 lab-confirmed pertussis cases. Most of these (515; 70%) occurred in fully vaccinated children. Another 99 (13%) occurred in unvaccinated children, 36 (5%) in undervaccinated children, and 88 (12%) in fully vaccinated plus one dose.

In a multivariate analysis, the risk of pertussis was 13 times higher among the unvaccinated (adjusted hazard ratio, 13) and almost 2 times higher among the undervaccinated (aHR, 1.9), compared with fully vaccinated children. Those who had been fully vaccinated and received a booster had the lowest risk, about half that of fully vaccinated children (aHR, 0.48).

Risk varied according to age, but also was significantly higher among unvaccinated children at each time point. Risk ranged from 4 times higher among those aged 3-5 months to 23 times higher among those aged 19-84 months. Undervaccinated children aged 5-7 months and 19-84 months also were at significantly increased risk for pertussis, compared with fully vaccinated children. Children who were fully vaccinated plus one dose had a significantly reduced risk at 7-19 months and at 19-84 months, compared with the fully vaccinated reference group.

“Across all follow-up and all age groups, VE [vaccine effectiveness] was 86% ... for undervaccinated children, compared with unvaccinated children,” Dr. Zerbo and associates wrote. “VE was even higher for fully vaccinated children [93%] and for those who were fully vaccinated plus one dose [96%].”

But VE waned as time progressed farther from the last DTaP dose. The multivariate model found more than a 100% increased risk for those whose last DTaP was at least 3 years past, compared with less than 1 year past (aHR, 2.58).

The model also found time-bound risk increases among fully vaccinated children, with a more than 300% increased risk among those at least 6 years out from the last DTaP dose, compared with 3 years out (aHR, 4.66).

The results indicate that other factors besides adherence to the recommended vaccine schedule may be at work in recent pertussis outbreaks.

“Although waning immunity is clearly an important factor driving pertussis epidemics in recent years, other factors that we did not evaluate in this study might also contribute to pertussis epidemics individually or in synergy,” Dr. Zerbo and associates wrote. “Results from studies in baboons suggest that the acellular pertussis vaccines are unable to prevent colonization, carriage, and transmission. If this is also true for humans, this could contribute to pertussis epidemics. The causes of recent pertussis epidemics are complex, and we were only able to address some aspects in our study.”

The study was funded by Kaiser Permanente Northern California, the National Institutes of Health, and in part by a National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grant. One coauthor reported receiving research grant support from Sanofi Pasteur, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, MedImmune, Pfizer, and Dynavax for unrelated studies; the other authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Zerbo O et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Jun 10. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3466.

Fixing one problem with the pertussis vaccine seemed to have created another, Kathryn M. Edwards, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

The current acellular vaccine was approved in 1997. It was considered a less reactive substitute for the previous whole-cell vaccine, which was associated with injection site pain, swelling, fever, and febrile seizures, Dr. Edwards wrote. “For about a decade, all seemed to be going well with pertussis control. Serological methods were employed to diagnose pertussis infections in adolescents and adults, and polymerase chain reaction methods were devised to more accurately detect pertussis organisms. Thus, the burden of pertussis disease was increasingly appreciated as the diagnostic methods improved.”

But things soon changed. There were pertussis outbreaks, some of them quite large. The increasing disease rates showed that protection conferred by the acellular vaccine waned much more quickly than that conferred by the whole-cell vaccine. “In the current study, Zerbo et al. add to the body of evidence documenting the increase in pertussis risk with time after DTaP vaccination,” she noted.

This has several practical implications, Dr. Edwards wrote.

“First, given the markedly increased risk of pertussis in unvaccinated and undervaccinated children, universal DTaP vaccination should be strongly recommended. Second, the addition of maternal Tdap vaccination administered during pregnancy has been shown to significantly reduce infant disease before primary immunization and should remain the standard,” Dr. Edwards wrote.

More problematic is how to address the waning DTaP immunity now seen. “One option presented [at an international meeting] was a live-attenuated pertussis vaccine administered intranasally that would stimulate local immune responses and prevent colonization with pertussis organisms. This vaccine is currently being studied in adults and might provide a solution for waning immunity seen with DTaP vaccine,” she noted.

Another possibility is adding the live vaccine to the current DTaP, which should, in theory, stimulate more long-lasting immunity. But numerous safety studies in young children would be necessary before adopting such an approach, Dr. Edwards wrote.

Adding more antigens to the acellular vaccine also might work, and investigational vaccines like this are in development.

Studies in animals and humans show that acellular vaccines “generate functionally different T-cell responses than those seen after whole-cell vaccines, with the whole cell vaccines generating more protective T-cell responses. Studies are ongoing to determine if adjuvants can be added to acellular vaccines to modify their T-cell responses to a more protective immune response or whether the T-cell response remains fixed once primed with DTaP vaccine,” she wrote.

Dr. Edwards is a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn. She wrote an editorial to accompany Zerbo et al (Pediatrics. 2019. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1276). She reported no financial disclosures, and received no funding to write the editorial.

Fixing one problem with the pertussis vaccine seemed to have created another, Kathryn M. Edwards, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

The current acellular vaccine was approved in 1997. It was considered a less reactive substitute for the previous whole-cell vaccine, which was associated with injection site pain, swelling, fever, and febrile seizures, Dr. Edwards wrote. “For about a decade, all seemed to be going well with pertussis control. Serological methods were employed to diagnose pertussis infections in adolescents and adults, and polymerase chain reaction methods were devised to more accurately detect pertussis organisms. Thus, the burden of pertussis disease was increasingly appreciated as the diagnostic methods improved.”

But things soon changed. There were pertussis outbreaks, some of them quite large. The increasing disease rates showed that protection conferred by the acellular vaccine waned much more quickly than that conferred by the whole-cell vaccine. “In the current study, Zerbo et al. add to the body of evidence documenting the increase in pertussis risk with time after DTaP vaccination,” she noted.

This has several practical implications, Dr. Edwards wrote.

“First, given the markedly increased risk of pertussis in unvaccinated and undervaccinated children, universal DTaP vaccination should be strongly recommended. Second, the addition of maternal Tdap vaccination administered during pregnancy has been shown to significantly reduce infant disease before primary immunization and should remain the standard,” Dr. Edwards wrote.

More problematic is how to address the waning DTaP immunity now seen. “One option presented [at an international meeting] was a live-attenuated pertussis vaccine administered intranasally that would stimulate local immune responses and prevent colonization with pertussis organisms. This vaccine is currently being studied in adults and might provide a solution for waning immunity seen with DTaP vaccine,” she noted.

Another possibility is adding the live vaccine to the current DTaP, which should, in theory, stimulate more long-lasting immunity. But numerous safety studies in young children would be necessary before adopting such an approach, Dr. Edwards wrote.

Adding more antigens to the acellular vaccine also might work, and investigational vaccines like this are in development.

Studies in animals and humans show that acellular vaccines “generate functionally different T-cell responses than those seen after whole-cell vaccines, with the whole cell vaccines generating more protective T-cell responses. Studies are ongoing to determine if adjuvants can be added to acellular vaccines to modify their T-cell responses to a more protective immune response or whether the T-cell response remains fixed once primed with DTaP vaccine,” she wrote.

Dr. Edwards is a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn. She wrote an editorial to accompany Zerbo et al (Pediatrics. 2019. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1276). She reported no financial disclosures, and received no funding to write the editorial.

Fixing one problem with the pertussis vaccine seemed to have created another, Kathryn M. Edwards, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

The current acellular vaccine was approved in 1997. It was considered a less reactive substitute for the previous whole-cell vaccine, which was associated with injection site pain, swelling, fever, and febrile seizures, Dr. Edwards wrote. “For about a decade, all seemed to be going well with pertussis control. Serological methods were employed to diagnose pertussis infections in adolescents and adults, and polymerase chain reaction methods were devised to more accurately detect pertussis organisms. Thus, the burden of pertussis disease was increasingly appreciated as the diagnostic methods improved.”

But things soon changed. There were pertussis outbreaks, some of them quite large. The increasing disease rates showed that protection conferred by the acellular vaccine waned much more quickly than that conferred by the whole-cell vaccine. “In the current study, Zerbo et al. add to the body of evidence documenting the increase in pertussis risk with time after DTaP vaccination,” she noted.

This has several practical implications, Dr. Edwards wrote.

“First, given the markedly increased risk of pertussis in unvaccinated and undervaccinated children, universal DTaP vaccination should be strongly recommended. Second, the addition of maternal Tdap vaccination administered during pregnancy has been shown to significantly reduce infant disease before primary immunization and should remain the standard,” Dr. Edwards wrote.

More problematic is how to address the waning DTaP immunity now seen. “One option presented [at an international meeting] was a live-attenuated pertussis vaccine administered intranasally that would stimulate local immune responses and prevent colonization with pertussis organisms. This vaccine is currently being studied in adults and might provide a solution for waning immunity seen with DTaP vaccine,” she noted.

Another possibility is adding the live vaccine to the current DTaP, which should, in theory, stimulate more long-lasting immunity. But numerous safety studies in young children would be necessary before adopting such an approach, Dr. Edwards wrote.

Adding more antigens to the acellular vaccine also might work, and investigational vaccines like this are in development.

Studies in animals and humans show that acellular vaccines “generate functionally different T-cell responses than those seen after whole-cell vaccines, with the whole cell vaccines generating more protective T-cell responses. Studies are ongoing to determine if adjuvants can be added to acellular vaccines to modify their T-cell responses to a more protective immune response or whether the T-cell response remains fixed once primed with DTaP vaccine,” she wrote.

Dr. Edwards is a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn. She wrote an editorial to accompany Zerbo et al (Pediatrics. 2019. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1276). She reported no financial disclosures, and received no funding to write the editorial.

A large Kaiser Permanente study paints a nuanced picture of the acellular pertussis vaccine, with more cases occurring in fully vaccinated children, but the highest risk of disease occurring among the under- and unvaccinated.

Among nearly half a million children, the unvaccinated were 13 times more likely to develop pertussis than fully vaccinated children, Ousseny Zerbo, PhD, of Kaiser Permanente Northern California in Oakland and colleagues wrote in Pediatrics. But 82% of cases occurred in fully vaccinated children and just 5% in undervaccinated children – and rates increased in both groups the farther they were in time from the last vaccination.

“Within our study population, greater than 80% of pertussis cases occurred among age-appropriately vaccinated children,” the team wrote. “Children who were further away from their last DTaP dose were at increased risk of pertussis, even after controlling for undervaccination. Our results suggest that, in this population, possibly in conjunction with other factors not addressed in this study, suboptimal vaccine efficacy and waning [immunity] played a major role in recent pertussis epidemics.”

The results are consistent with several prior studies, including one finding that the odds of the disease increased by 33% for every additional year after the third or fifth DTaP dose (Pediatrics. 2015;135[2]:331-43).

The current study comprised 469,982 children aged between 3 months and 11 years, who were followed for a mean of 4.6 years. Over the entire study period, there were 738 lab-confirmed pertussis cases. Most of these (515; 70%) occurred in fully vaccinated children. Another 99 (13%) occurred in unvaccinated children, 36 (5%) in undervaccinated children, and 88 (12%) in fully vaccinated plus one dose.

In a multivariate analysis, the risk of pertussis was 13 times higher among the unvaccinated (adjusted hazard ratio, 13) and almost 2 times higher among the undervaccinated (aHR, 1.9), compared with fully vaccinated children. Those who had been fully vaccinated and received a booster had the lowest risk, about half that of fully vaccinated children (aHR, 0.48).

Risk varied according to age, but also was significantly higher among unvaccinated children at each time point. Risk ranged from 4 times higher among those aged 3-5 months to 23 times higher among those aged 19-84 months. Undervaccinated children aged 5-7 months and 19-84 months also were at significantly increased risk for pertussis, compared with fully vaccinated children. Children who were fully vaccinated plus one dose had a significantly reduced risk at 7-19 months and at 19-84 months, compared with the fully vaccinated reference group.

“Across all follow-up and all age groups, VE [vaccine effectiveness] was 86% ... for undervaccinated children, compared with unvaccinated children,” Dr. Zerbo and associates wrote. “VE was even higher for fully vaccinated children [93%] and for those who were fully vaccinated plus one dose [96%].”

But VE waned as time progressed farther from the last DTaP dose. The multivariate model found more than a 100% increased risk for those whose last DTaP was at least 3 years past, compared with less than 1 year past (aHR, 2.58).

The model also found time-bound risk increases among fully vaccinated children, with a more than 300% increased risk among those at least 6 years out from the last DTaP dose, compared with 3 years out (aHR, 4.66).

The results indicate that other factors besides adherence to the recommended vaccine schedule may be at work in recent pertussis outbreaks.

“Although waning immunity is clearly an important factor driving pertussis epidemics in recent years, other factors that we did not evaluate in this study might also contribute to pertussis epidemics individually or in synergy,” Dr. Zerbo and associates wrote. “Results from studies in baboons suggest that the acellular pertussis vaccines are unable to prevent colonization, carriage, and transmission. If this is also true for humans, this could contribute to pertussis epidemics. The causes of recent pertussis epidemics are complex, and we were only able to address some aspects in our study.”

The study was funded by Kaiser Permanente Northern California, the National Institutes of Health, and in part by a National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grant. One coauthor reported receiving research grant support from Sanofi Pasteur, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, MedImmune, Pfizer, and Dynavax for unrelated studies; the other authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Zerbo O et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Jun 10. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3466.

A large Kaiser Permanente study paints a nuanced picture of the acellular pertussis vaccine, with more cases occurring in fully vaccinated children, but the highest risk of disease occurring among the under- and unvaccinated.

Among nearly half a million children, the unvaccinated were 13 times more likely to develop pertussis than fully vaccinated children, Ousseny Zerbo, PhD, of Kaiser Permanente Northern California in Oakland and colleagues wrote in Pediatrics. But 82% of cases occurred in fully vaccinated children and just 5% in undervaccinated children – and rates increased in both groups the farther they were in time from the last vaccination.

“Within our study population, greater than 80% of pertussis cases occurred among age-appropriately vaccinated children,” the team wrote. “Children who were further away from their last DTaP dose were at increased risk of pertussis, even after controlling for undervaccination. Our results suggest that, in this population, possibly in conjunction with other factors not addressed in this study, suboptimal vaccine efficacy and waning [immunity] played a major role in recent pertussis epidemics.”

The results are consistent with several prior studies, including one finding that the odds of the disease increased by 33% for every additional year after the third or fifth DTaP dose (Pediatrics. 2015;135[2]:331-43).

The current study comprised 469,982 children aged between 3 months and 11 years, who were followed for a mean of 4.6 years. Over the entire study period, there were 738 lab-confirmed pertussis cases. Most of these (515; 70%) occurred in fully vaccinated children. Another 99 (13%) occurred in unvaccinated children, 36 (5%) in undervaccinated children, and 88 (12%) in fully vaccinated plus one dose.

In a multivariate analysis, the risk of pertussis was 13 times higher among the unvaccinated (adjusted hazard ratio, 13) and almost 2 times higher among the undervaccinated (aHR, 1.9), compared with fully vaccinated children. Those who had been fully vaccinated and received a booster had the lowest risk, about half that of fully vaccinated children (aHR, 0.48).

Risk varied according to age, but also was significantly higher among unvaccinated children at each time point. Risk ranged from 4 times higher among those aged 3-5 months to 23 times higher among those aged 19-84 months. Undervaccinated children aged 5-7 months and 19-84 months also were at significantly increased risk for pertussis, compared with fully vaccinated children. Children who were fully vaccinated plus one dose had a significantly reduced risk at 7-19 months and at 19-84 months, compared with the fully vaccinated reference group.

“Across all follow-up and all age groups, VE [vaccine effectiveness] was 86% ... for undervaccinated children, compared with unvaccinated children,” Dr. Zerbo and associates wrote. “VE was even higher for fully vaccinated children [93%] and for those who were fully vaccinated plus one dose [96%].”

But VE waned as time progressed farther from the last DTaP dose. The multivariate model found more than a 100% increased risk for those whose last DTaP was at least 3 years past, compared with less than 1 year past (aHR, 2.58).

The model also found time-bound risk increases among fully vaccinated children, with a more than 300% increased risk among those at least 6 years out from the last DTaP dose, compared with 3 years out (aHR, 4.66).

The results indicate that other factors besides adherence to the recommended vaccine schedule may be at work in recent pertussis outbreaks.

“Although waning immunity is clearly an important factor driving pertussis epidemics in recent years, other factors that we did not evaluate in this study might also contribute to pertussis epidemics individually or in synergy,” Dr. Zerbo and associates wrote. “Results from studies in baboons suggest that the acellular pertussis vaccines are unable to prevent colonization, carriage, and transmission. If this is also true for humans, this could contribute to pertussis epidemics. The causes of recent pertussis epidemics are complex, and we were only able to address some aspects in our study.”

The study was funded by Kaiser Permanente Northern California, the National Institutes of Health, and in part by a National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grant. One coauthor reported receiving research grant support from Sanofi Pasteur, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, MedImmune, Pfizer, and Dynavax for unrelated studies; the other authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Zerbo O et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Jun 10. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3466.

FROM PEDIATRICS

United States now over 1,000 measles cases this year

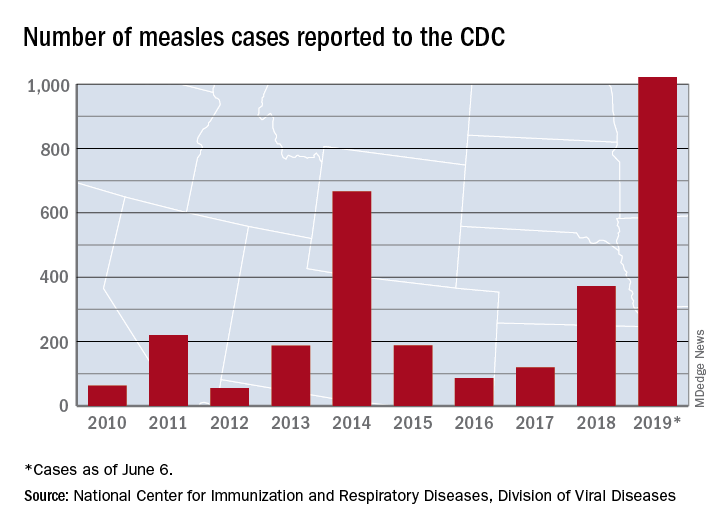

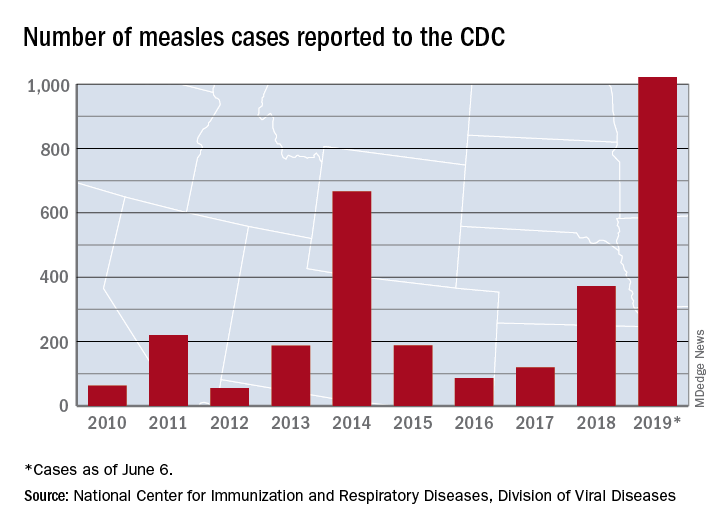

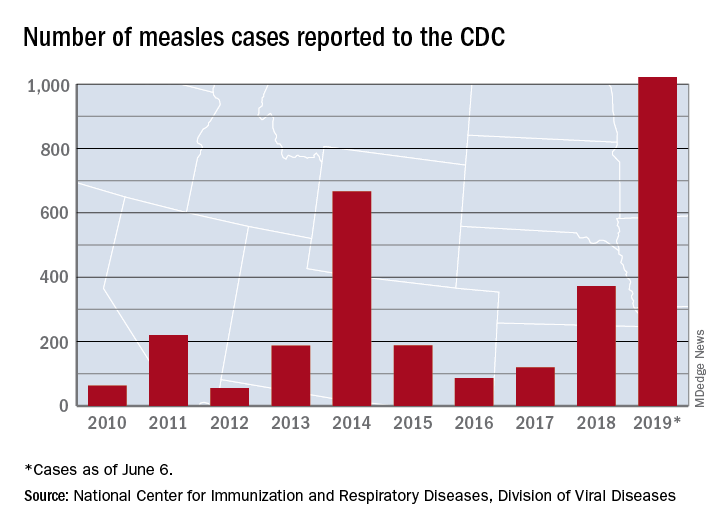

The 41 new cases reported for the week ending June 6 bring the total for the year to 1,022, the CDC reported June 10, and that is more than any year since 1992, when there were 2,237 cases.

Idaho and Virginia reported their first cases of 2019, which makes a total of 28 states with measles cases this year. The Idaho case was reported in Latah County and is the state’s first since 2001. In Virginia, health officials are investigating possible contacts with an infected individual at Dulles International Airport and two other locations on June 2 and 4.

Outbreaks in Georgia, Maryland, and Michigan have ended, while seven others continue in California (Butte, Los Angeles, and Sacramento Counties), New York (Rockland County and New York City), Pennsylvania, and Washington, the CDC said. New York City has the largest outbreak this year with 509 cases through June 3, most of them occurring in Brooklyn.

The 41 new cases reported for the week ending June 6 bring the total for the year to 1,022, the CDC reported June 10, and that is more than any year since 1992, when there were 2,237 cases.

Idaho and Virginia reported their first cases of 2019, which makes a total of 28 states with measles cases this year. The Idaho case was reported in Latah County and is the state’s first since 2001. In Virginia, health officials are investigating possible contacts with an infected individual at Dulles International Airport and two other locations on June 2 and 4.

Outbreaks in Georgia, Maryland, and Michigan have ended, while seven others continue in California (Butte, Los Angeles, and Sacramento Counties), New York (Rockland County and New York City), Pennsylvania, and Washington, the CDC said. New York City has the largest outbreak this year with 509 cases through June 3, most of them occurring in Brooklyn.