User login

Rapidly Growing Cutaneous Nodules on the Scalp

The Diagnosis: B-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia

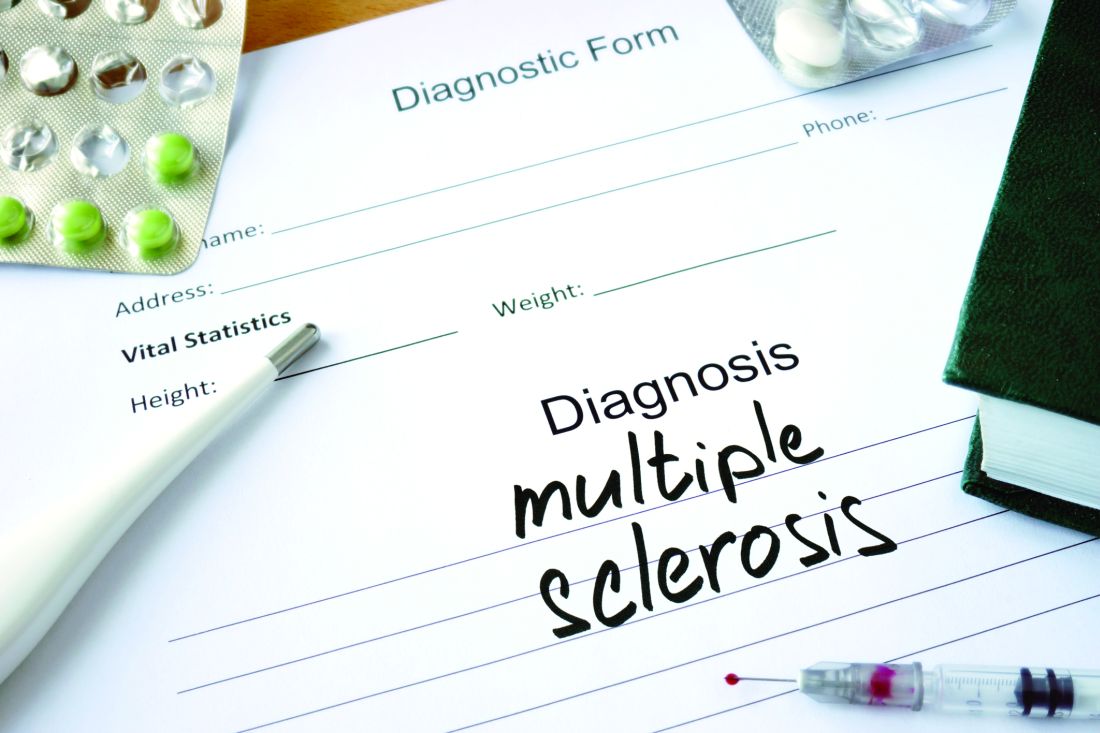

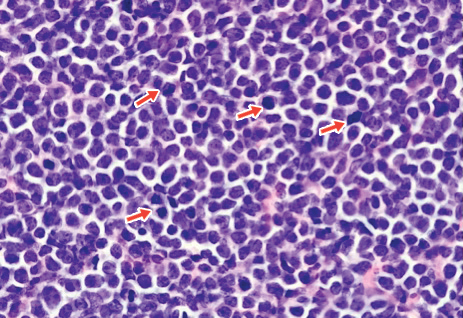

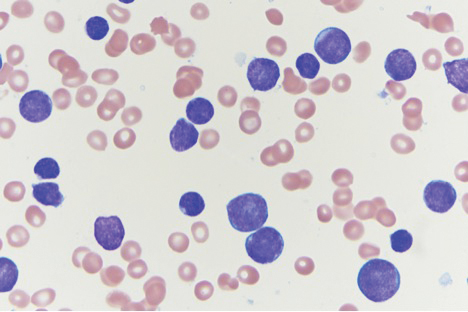

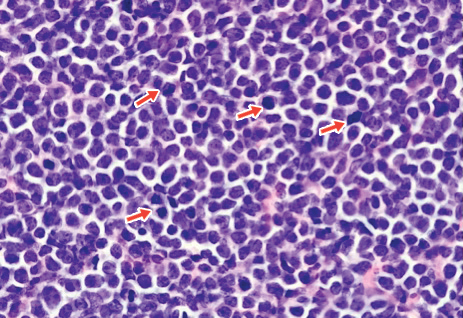

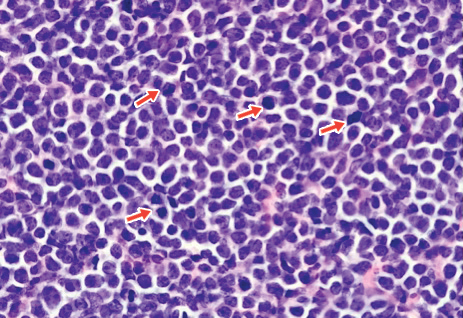

A 4-mm punch biopsy of one of the scalp lesions showed a diffuse infiltrate of intermediately sized cells with variably mature chromatin and irregular nuclear contours, consistent with a neoplastic process. Numerous mitotic figures were present, indicating a high proliferation rate (Figure 1). At that time there was no evidence of systemic involvement. A repeat biopsy with concurrent bone marrow biopsy was scheduled 10 days after the patient's initial presentation for further classification. Laboratory studies at that time revealed leukocytosis with elevated neutrophils and lymphocytes as well as a high absolute blast count.

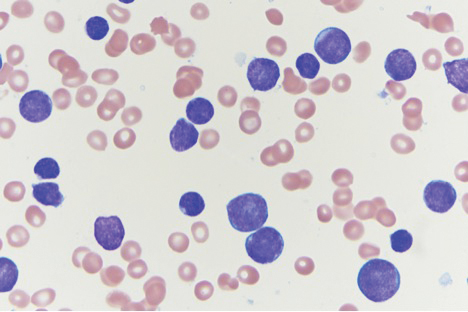

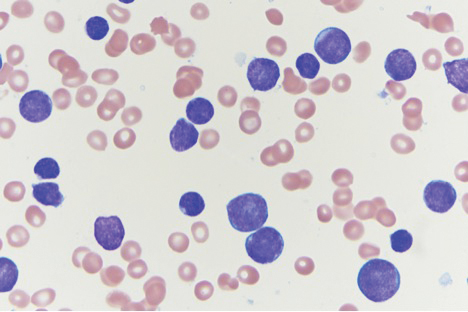

On immunohistochemical staining, the neoplastic cells were positive for CD45, which indicated the neoplasm was hematopoietic, as well as CD10 and the B-cell antigens PAX-5 and CD79a. The cells were negative for CD20, which also is a B-cell marker, but this marker is only expressed in approximately half of pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) cases with B-cell precursor origin.1 Markers that typically are expressed in B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL)--CD34 and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase--were both negative. These results were somewhat contradictory, and the differential remained open to both B-ALL and mature B-cell lymphoma. A bone marrow biopsy showed approximately 65% blasts or leukemic cells (Figure 2). Flow cytometry showed the cells were positive for CD10, CD19, weak CD79a, and variable lambda surface antigen expression. The cells were negative for expression of CD20, CD34, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase, myeloid antigens, and CD3. Ultimately, the morphology and immunophenotype were most consistent with a diagnosis of B-ALL. Fluorescence in situ hybridization revealed mixed lineage leukemia, MLL, gene rearrangements.

In general, when considering the differential diagnosis of superficial nodules, 5 elements are helpful to consider: the number of nodules (single vs multiple); the location; and the presence or absence of tenderness, pigmentation or erythema, and firmness.2 Our patient had multiple nodules on the scalp, which were erythematous to slightly purple and firm. The differential diagnosis can be categorized into malignant; infectious; and benign inflammatory, vascular, and fibrous tumors.

Potential oncologic processes include leukemia cutis, lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, and rhabdomyosarcoma. Initial laboratory test results were reassuring. Infectious processes in the differential include deep fungal infections such as coccidioidomycosis and nontuberculous mycobacterial infections. Coccidioidomycosis was the most likely to cause skin lesions or masses in our patient; however, it was considered less likely because the patient's family had not traveled or been exposed to an endemic area.3

Benign tumors in the differential include deep hemangioma, which was deemed less likely in our patient because most hemangiomas reach 80% of their maximum size by 5 months of age.4 Another possible benign tumor is infantile myofibromatosis, which is rare but is the most common fibrous tumor of infancy.5

Early-onset childhood sarcoidosis also has been shown to produce multiple nontender firm nodules.2 This process was considered unlikely in our patient because not only is the disease relatively rare in the pediatric population, but most reported childhood cases have occurred in patients aged 13 to 15 years.6 Additionally, no uveitis or arthritis was observed in this case.

Ultimately, histopathology and bone marrow biopsy were necessary to determine the diagnosis of B-ALL. Although uncommon, cutaneous involvement can be an early sign of ALL in children.7 Thus, neoplastic etiologies should be considered in the workup of cutaneous nodules in children, especially when these nodules are hard, rapidly growing, ulcerated, fixed, and/or vascular.8 Once the diagnosis is established, initial workup of ALL in children should include complete blood cell count with manual differential, prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, electrolytes, uric acid, and renal and liver function tests. Often, baseline viral titers such as cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B virus, and varicella-zoster virus also are included. Patients are risk stratified to the appropriate level of treatment based on tumor immunophenotype, cytogenetic findings, patient age, white blood cell count at the time of diagnosis, and response to initial therapy. Treatment typically is comprised of a multidrug regimen divided into several phases--induction, consolidation, and maintenance--as well as therapy directed to the central nervous system. Treatment protocols usually take 2 to 3 years to complete.

Our patient was treated with 1 dose of intrathecal methotrexate before starting the Interfant-06 protocol with a 7-day methylprednisolone prophase. The patient's nodules shrank over time and were no longer present after 14 days of treatment.

- Dworzak MN, Schumich A, Printz D, et al. CD20 up-regulation in pediatric B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia during induction treatment: setting the stage for anti-CD20 directed immunotherapy. Blood. 2008;112:3982-3988.

- Whelan JP, Zembowicz A. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. case 19-2006. a 22-month-old boy with the rapid growth of subcutaneous nodules. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2697-2704.

- Malo J, Luraschi-Monjagatta C, Wolk DM, et al. Update on the diagnosis of pulmonary coccidioidomycosis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11:243-253.

- Chang LC, Haggstrom AN, Drolet BA, et al. Growth characteristics of infantile hemangiomas: implications for management. Pediatrics. 2008;122:360-367.

- Schurr P, Moulsdale W. Infantile myofibroma. Adv Neonatal Care. 2008;8:13-20.

- Shetty AK, Gedalia A. Childhood sarcoidosis: a rare but fascinating disorder. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2008;6:16.

- Millot F, Robert A, Bertrand Y, et al. Cutaneous involvement in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia or lymphoblastic lymphoma. The Children's Leukemia Cooperative Group of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Pediatrics. 1997;100:60-64.

- Fogelson S, Dohil M. Papular and nodular skin lesions in children. Semin Plast Surg. 2006;20:180-191.

The Diagnosis: B-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia

A 4-mm punch biopsy of one of the scalp lesions showed a diffuse infiltrate of intermediately sized cells with variably mature chromatin and irregular nuclear contours, consistent with a neoplastic process. Numerous mitotic figures were present, indicating a high proliferation rate (Figure 1). At that time there was no evidence of systemic involvement. A repeat biopsy with concurrent bone marrow biopsy was scheduled 10 days after the patient's initial presentation for further classification. Laboratory studies at that time revealed leukocytosis with elevated neutrophils and lymphocytes as well as a high absolute blast count.

On immunohistochemical staining, the neoplastic cells were positive for CD45, which indicated the neoplasm was hematopoietic, as well as CD10 and the B-cell antigens PAX-5 and CD79a. The cells were negative for CD20, which also is a B-cell marker, but this marker is only expressed in approximately half of pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) cases with B-cell precursor origin.1 Markers that typically are expressed in B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL)--CD34 and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase--were both negative. These results were somewhat contradictory, and the differential remained open to both B-ALL and mature B-cell lymphoma. A bone marrow biopsy showed approximately 65% blasts or leukemic cells (Figure 2). Flow cytometry showed the cells were positive for CD10, CD19, weak CD79a, and variable lambda surface antigen expression. The cells were negative for expression of CD20, CD34, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase, myeloid antigens, and CD3. Ultimately, the morphology and immunophenotype were most consistent with a diagnosis of B-ALL. Fluorescence in situ hybridization revealed mixed lineage leukemia, MLL, gene rearrangements.

In general, when considering the differential diagnosis of superficial nodules, 5 elements are helpful to consider: the number of nodules (single vs multiple); the location; and the presence or absence of tenderness, pigmentation or erythema, and firmness.2 Our patient had multiple nodules on the scalp, which were erythematous to slightly purple and firm. The differential diagnosis can be categorized into malignant; infectious; and benign inflammatory, vascular, and fibrous tumors.

Potential oncologic processes include leukemia cutis, lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, and rhabdomyosarcoma. Initial laboratory test results were reassuring. Infectious processes in the differential include deep fungal infections such as coccidioidomycosis and nontuberculous mycobacterial infections. Coccidioidomycosis was the most likely to cause skin lesions or masses in our patient; however, it was considered less likely because the patient's family had not traveled or been exposed to an endemic area.3

Benign tumors in the differential include deep hemangioma, which was deemed less likely in our patient because most hemangiomas reach 80% of their maximum size by 5 months of age.4 Another possible benign tumor is infantile myofibromatosis, which is rare but is the most common fibrous tumor of infancy.5

Early-onset childhood sarcoidosis also has been shown to produce multiple nontender firm nodules.2 This process was considered unlikely in our patient because not only is the disease relatively rare in the pediatric population, but most reported childhood cases have occurred in patients aged 13 to 15 years.6 Additionally, no uveitis or arthritis was observed in this case.

Ultimately, histopathology and bone marrow biopsy were necessary to determine the diagnosis of B-ALL. Although uncommon, cutaneous involvement can be an early sign of ALL in children.7 Thus, neoplastic etiologies should be considered in the workup of cutaneous nodules in children, especially when these nodules are hard, rapidly growing, ulcerated, fixed, and/or vascular.8 Once the diagnosis is established, initial workup of ALL in children should include complete blood cell count with manual differential, prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, electrolytes, uric acid, and renal and liver function tests. Often, baseline viral titers such as cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B virus, and varicella-zoster virus also are included. Patients are risk stratified to the appropriate level of treatment based on tumor immunophenotype, cytogenetic findings, patient age, white blood cell count at the time of diagnosis, and response to initial therapy. Treatment typically is comprised of a multidrug regimen divided into several phases--induction, consolidation, and maintenance--as well as therapy directed to the central nervous system. Treatment protocols usually take 2 to 3 years to complete.

Our patient was treated with 1 dose of intrathecal methotrexate before starting the Interfant-06 protocol with a 7-day methylprednisolone prophase. The patient's nodules shrank over time and were no longer present after 14 days of treatment.

The Diagnosis: B-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia

A 4-mm punch biopsy of one of the scalp lesions showed a diffuse infiltrate of intermediately sized cells with variably mature chromatin and irregular nuclear contours, consistent with a neoplastic process. Numerous mitotic figures were present, indicating a high proliferation rate (Figure 1). At that time there was no evidence of systemic involvement. A repeat biopsy with concurrent bone marrow biopsy was scheduled 10 days after the patient's initial presentation for further classification. Laboratory studies at that time revealed leukocytosis with elevated neutrophils and lymphocytes as well as a high absolute blast count.

On immunohistochemical staining, the neoplastic cells were positive for CD45, which indicated the neoplasm was hematopoietic, as well as CD10 and the B-cell antigens PAX-5 and CD79a. The cells were negative for CD20, which also is a B-cell marker, but this marker is only expressed in approximately half of pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) cases with B-cell precursor origin.1 Markers that typically are expressed in B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL)--CD34 and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase--were both negative. These results were somewhat contradictory, and the differential remained open to both B-ALL and mature B-cell lymphoma. A bone marrow biopsy showed approximately 65% blasts or leukemic cells (Figure 2). Flow cytometry showed the cells were positive for CD10, CD19, weak CD79a, and variable lambda surface antigen expression. The cells were negative for expression of CD20, CD34, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase, myeloid antigens, and CD3. Ultimately, the morphology and immunophenotype were most consistent with a diagnosis of B-ALL. Fluorescence in situ hybridization revealed mixed lineage leukemia, MLL, gene rearrangements.

In general, when considering the differential diagnosis of superficial nodules, 5 elements are helpful to consider: the number of nodules (single vs multiple); the location; and the presence or absence of tenderness, pigmentation or erythema, and firmness.2 Our patient had multiple nodules on the scalp, which were erythematous to slightly purple and firm. The differential diagnosis can be categorized into malignant; infectious; and benign inflammatory, vascular, and fibrous tumors.

Potential oncologic processes include leukemia cutis, lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, and rhabdomyosarcoma. Initial laboratory test results were reassuring. Infectious processes in the differential include deep fungal infections such as coccidioidomycosis and nontuberculous mycobacterial infections. Coccidioidomycosis was the most likely to cause skin lesions or masses in our patient; however, it was considered less likely because the patient's family had not traveled or been exposed to an endemic area.3

Benign tumors in the differential include deep hemangioma, which was deemed less likely in our patient because most hemangiomas reach 80% of their maximum size by 5 months of age.4 Another possible benign tumor is infantile myofibromatosis, which is rare but is the most common fibrous tumor of infancy.5

Early-onset childhood sarcoidosis also has been shown to produce multiple nontender firm nodules.2 This process was considered unlikely in our patient because not only is the disease relatively rare in the pediatric population, but most reported childhood cases have occurred in patients aged 13 to 15 years.6 Additionally, no uveitis or arthritis was observed in this case.

Ultimately, histopathology and bone marrow biopsy were necessary to determine the diagnosis of B-ALL. Although uncommon, cutaneous involvement can be an early sign of ALL in children.7 Thus, neoplastic etiologies should be considered in the workup of cutaneous nodules in children, especially when these nodules are hard, rapidly growing, ulcerated, fixed, and/or vascular.8 Once the diagnosis is established, initial workup of ALL in children should include complete blood cell count with manual differential, prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, electrolytes, uric acid, and renal and liver function tests. Often, baseline viral titers such as cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B virus, and varicella-zoster virus also are included. Patients are risk stratified to the appropriate level of treatment based on tumor immunophenotype, cytogenetic findings, patient age, white blood cell count at the time of diagnosis, and response to initial therapy. Treatment typically is comprised of a multidrug regimen divided into several phases--induction, consolidation, and maintenance--as well as therapy directed to the central nervous system. Treatment protocols usually take 2 to 3 years to complete.

Our patient was treated with 1 dose of intrathecal methotrexate before starting the Interfant-06 protocol with a 7-day methylprednisolone prophase. The patient's nodules shrank over time and were no longer present after 14 days of treatment.

- Dworzak MN, Schumich A, Printz D, et al. CD20 up-regulation in pediatric B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia during induction treatment: setting the stage for anti-CD20 directed immunotherapy. Blood. 2008;112:3982-3988.

- Whelan JP, Zembowicz A. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. case 19-2006. a 22-month-old boy with the rapid growth of subcutaneous nodules. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2697-2704.

- Malo J, Luraschi-Monjagatta C, Wolk DM, et al. Update on the diagnosis of pulmonary coccidioidomycosis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11:243-253.

- Chang LC, Haggstrom AN, Drolet BA, et al. Growth characteristics of infantile hemangiomas: implications for management. Pediatrics. 2008;122:360-367.

- Schurr P, Moulsdale W. Infantile myofibroma. Adv Neonatal Care. 2008;8:13-20.

- Shetty AK, Gedalia A. Childhood sarcoidosis: a rare but fascinating disorder. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2008;6:16.

- Millot F, Robert A, Bertrand Y, et al. Cutaneous involvement in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia or lymphoblastic lymphoma. The Children's Leukemia Cooperative Group of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Pediatrics. 1997;100:60-64.

- Fogelson S, Dohil M. Papular and nodular skin lesions in children. Semin Plast Surg. 2006;20:180-191.

- Dworzak MN, Schumich A, Printz D, et al. CD20 up-regulation in pediatric B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia during induction treatment: setting the stage for anti-CD20 directed immunotherapy. Blood. 2008;112:3982-3988.

- Whelan JP, Zembowicz A. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. case 19-2006. a 22-month-old boy with the rapid growth of subcutaneous nodules. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2697-2704.

- Malo J, Luraschi-Monjagatta C, Wolk DM, et al. Update on the diagnosis of pulmonary coccidioidomycosis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11:243-253.

- Chang LC, Haggstrom AN, Drolet BA, et al. Growth characteristics of infantile hemangiomas: implications for management. Pediatrics. 2008;122:360-367.

- Schurr P, Moulsdale W. Infantile myofibroma. Adv Neonatal Care. 2008;8:13-20.

- Shetty AK, Gedalia A. Childhood sarcoidosis: a rare but fascinating disorder. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2008;6:16.

- Millot F, Robert A, Bertrand Y, et al. Cutaneous involvement in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia or lymphoblastic lymphoma. The Children's Leukemia Cooperative Group of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Pediatrics. 1997;100:60-64.

- Fogelson S, Dohil M. Papular and nodular skin lesions in children. Semin Plast Surg. 2006;20:180-191.

An 8-month-old infant girl presented with rapidly growing cutaneous nodules on the scalp of 1 month's duration. Her parents reported that she disliked lying flat but was otherwise growing and developing normally. Nondiagnostic ultrasonography of the head and brain had been performed as well as a skull radiograph, which found no evidence of lytic lesions. On physical examination, 3 erythematous to violaceous, subcutaneous, firm, fixed nodules were observed on the scalp. Notable cervical lymphadenopathy with several distinct, fixed, firm, subcutaneous nodules in the postauricular lymph chains also were noted. The patient had no pertinent medical history and was born via normal spontaneous vaginal delivery to healthy parents. The remainder of the physical examination and review of systems was negative.

Liraglutide indication expanded to include children

according to a news release from the agency. The approval comes after granting the application Priority Review, which means the FDA aimed to take action on it within 6 months instead of the usual 10 months seen with a Standard Review.

Liraglutide injection has been approved for treatment of adults with type 2 diabetes since 2010, but this is the first noninsulin treatment for pediatric patients since metformin received approval for this population in 2000.

“The expanded indication provides an additional treatment option at a time when an increasing number of children are being diagnosed with [type 2 diabetes],” said Lisa Yanoff, MD, acting director of the division of metabolism and endocrinology products in the agency’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.

The approval is based on efficacy and safety results from several placebo-controlled trials in adults, and one trial in 134 pediatric patients aged 10 years or older. In the latter trial, which ran for more than 26 weeks, hemoglobin A1c levels fell below 7% in approximately 64% of patients treated with liraglutide injection, compared with 37% of those who received placebo. Those results were seen regardless of whether patients concomitantly used insulin.

Although an increase in hypoglycemia risk has sometimes been seen in adult patients taking liraglutide injection with insulin or other drugs that raise insulin production, this heightened risk was seen in the pediatric patients regardless of whether they took other therapies for diabetes.

Liraglutide injection carries a Boxed Warning, the FDA’s strongest warning, for heightened risk of thyroid C-cell tumors. Therefore, the agency recommends against patients with history or family members with history of medullary thyroid carcinoma or multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 2 using this treatment. Among its other warnings are those pertaining to patients with renal impairment or kidney failure, pancreatitis, and/or acute gallbladder disease.

The most common side effects are nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, decreased appetite, indigestion, and constipation. The full prescribing information can be found on the FDA website.

according to a news release from the agency. The approval comes after granting the application Priority Review, which means the FDA aimed to take action on it within 6 months instead of the usual 10 months seen with a Standard Review.

Liraglutide injection has been approved for treatment of adults with type 2 diabetes since 2010, but this is the first noninsulin treatment for pediatric patients since metformin received approval for this population in 2000.

“The expanded indication provides an additional treatment option at a time when an increasing number of children are being diagnosed with [type 2 diabetes],” said Lisa Yanoff, MD, acting director of the division of metabolism and endocrinology products in the agency’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.

The approval is based on efficacy and safety results from several placebo-controlled trials in adults, and one trial in 134 pediatric patients aged 10 years or older. In the latter trial, which ran for more than 26 weeks, hemoglobin A1c levels fell below 7% in approximately 64% of patients treated with liraglutide injection, compared with 37% of those who received placebo. Those results were seen regardless of whether patients concomitantly used insulin.

Although an increase in hypoglycemia risk has sometimes been seen in adult patients taking liraglutide injection with insulin or other drugs that raise insulin production, this heightened risk was seen in the pediatric patients regardless of whether they took other therapies for diabetes.

Liraglutide injection carries a Boxed Warning, the FDA’s strongest warning, for heightened risk of thyroid C-cell tumors. Therefore, the agency recommends against patients with history or family members with history of medullary thyroid carcinoma or multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 2 using this treatment. Among its other warnings are those pertaining to patients with renal impairment or kidney failure, pancreatitis, and/or acute gallbladder disease.

The most common side effects are nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, decreased appetite, indigestion, and constipation. The full prescribing information can be found on the FDA website.

according to a news release from the agency. The approval comes after granting the application Priority Review, which means the FDA aimed to take action on it within 6 months instead of the usual 10 months seen with a Standard Review.

Liraglutide injection has been approved for treatment of adults with type 2 diabetes since 2010, but this is the first noninsulin treatment for pediatric patients since metformin received approval for this population in 2000.

“The expanded indication provides an additional treatment option at a time when an increasing number of children are being diagnosed with [type 2 diabetes],” said Lisa Yanoff, MD, acting director of the division of metabolism and endocrinology products in the agency’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.

The approval is based on efficacy and safety results from several placebo-controlled trials in adults, and one trial in 134 pediatric patients aged 10 years or older. In the latter trial, which ran for more than 26 weeks, hemoglobin A1c levels fell below 7% in approximately 64% of patients treated with liraglutide injection, compared with 37% of those who received placebo. Those results were seen regardless of whether patients concomitantly used insulin.

Although an increase in hypoglycemia risk has sometimes been seen in adult patients taking liraglutide injection with insulin or other drugs that raise insulin production, this heightened risk was seen in the pediatric patients regardless of whether they took other therapies for diabetes.

Liraglutide injection carries a Boxed Warning, the FDA’s strongest warning, for heightened risk of thyroid C-cell tumors. Therefore, the agency recommends against patients with history or family members with history of medullary thyroid carcinoma or multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 2 using this treatment. Among its other warnings are those pertaining to patients with renal impairment or kidney failure, pancreatitis, and/or acute gallbladder disease.

The most common side effects are nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, decreased appetite, indigestion, and constipation. The full prescribing information can be found on the FDA website.

Obesity and overweight declined among lower-income kids

The combined rate of , according to a study in JAMA.

Liping Pan, MD, MPH, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and colleagues used data from the WIC Participant and Program Characteristics survey from 2010, 2012, 2014, and 2016 for 12,403,629 children aged 2-4 years from 50 states, Washington, D.C., and 5 territories. In addition to a –3.2% change (95% confidence interval, –3.3% to –3.2%) in adjusted prevalence difference for the combined rate of obesity and overweight seen between 2010 and 2016, the researchers found the crude prevalence decreased from 32.5% to 29.1%. A decrease was also seen for obesity alone (crude prevalence, 15.9% to 13.9%; adjusted prevalence difference, –1.9%; 95% CI, –1.9% to –1.8%).

One of the limitations of the study is that the characteristics of enrolled children might differ from those of children not enrolled in this WIC program; however, the researchers noted that they accounted for many demographic characteristics in the trend analyses.

“Reasons for the declines in obesity among young children in WIC remain undetermined but may include WIC food package revisions and local, state, and national initiatives,” they wrote.

SOURCE: Pan L et al. JAMA. 2019 Jun 18;321(23):2364-6.

The combined rate of , according to a study in JAMA.

Liping Pan, MD, MPH, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and colleagues used data from the WIC Participant and Program Characteristics survey from 2010, 2012, 2014, and 2016 for 12,403,629 children aged 2-4 years from 50 states, Washington, D.C., and 5 territories. In addition to a –3.2% change (95% confidence interval, –3.3% to –3.2%) in adjusted prevalence difference for the combined rate of obesity and overweight seen between 2010 and 2016, the researchers found the crude prevalence decreased from 32.5% to 29.1%. A decrease was also seen for obesity alone (crude prevalence, 15.9% to 13.9%; adjusted prevalence difference, –1.9%; 95% CI, –1.9% to –1.8%).

One of the limitations of the study is that the characteristics of enrolled children might differ from those of children not enrolled in this WIC program; however, the researchers noted that they accounted for many demographic characteristics in the trend analyses.

“Reasons for the declines in obesity among young children in WIC remain undetermined but may include WIC food package revisions and local, state, and national initiatives,” they wrote.

SOURCE: Pan L et al. JAMA. 2019 Jun 18;321(23):2364-6.

The combined rate of , according to a study in JAMA.

Liping Pan, MD, MPH, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and colleagues used data from the WIC Participant and Program Characteristics survey from 2010, 2012, 2014, and 2016 for 12,403,629 children aged 2-4 years from 50 states, Washington, D.C., and 5 territories. In addition to a –3.2% change (95% confidence interval, –3.3% to –3.2%) in adjusted prevalence difference for the combined rate of obesity and overweight seen between 2010 and 2016, the researchers found the crude prevalence decreased from 32.5% to 29.1%. A decrease was also seen for obesity alone (crude prevalence, 15.9% to 13.9%; adjusted prevalence difference, –1.9%; 95% CI, –1.9% to –1.8%).

One of the limitations of the study is that the characteristics of enrolled children might differ from those of children not enrolled in this WIC program; however, the researchers noted that they accounted for many demographic characteristics in the trend analyses.

“Reasons for the declines in obesity among young children in WIC remain undetermined but may include WIC food package revisions and local, state, and national initiatives,” they wrote.

SOURCE: Pan L et al. JAMA. 2019 Jun 18;321(23):2364-6.

FROM JAMA

Suicide rates rise in U.S. adolescents and young adults

Suicides in teens and young adults reached 6,241 in 2017, the highest since 2000, according to data from a review of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Underlying Cause of Death database.

The suicide rate overall was 12 per 100,000 in 2017 for 15-19 year olds.

Although suicide rates have increased across all age groups in the United States since 2000, “adolescents are of particular concern, with increases in social media use, anxiety, depression, and self-inflicted injuries,” wrote Oren Miron of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and colleagues.

In a research letter published in JAMA, the researchers analyzed trends in teen and young adult suicides from 2000 to 2017. The combined suicide rate for males and females aged 15-19 years in 2000 was 8 per 100,000 with no significant changes until 2007, followed by an annual percentage change (APC) of 3% from 2007 to 2014 and 10% from 2014 to 2017.

When the data were broken out by gender, Of note, these young men showed a decreasing trend in APC of –2% from 2000 to 2007 before increasing.

Among females aged 15-19 years, no increase was noted until 2010, then researchers identified an APC of 8% from 2010 to 2017.

For ages 20-24 years, the combined suicide rate for males and females was 13 per 100,000 in 2000, which rose to 17 per 100,000 in 2017. The APC in the older group was 1% from 2000 to 2013 and 6% from 2013 to 2017. Increasing trends were observed for both males and females over the study period.

The study was limited by the potential inaccuracy in cause of death listed on death certificates, such as mistaking a suicide for an accidental overdose, and the increased suicide rate could reflect more accurate reporting, the researchers noted.

Nonetheless, the results support the need for more studies of contributing factors to teen and young adult suicides to help develop prevention strategies and analysis of factors that may have contributed to declines in suicide rates in the past, they said.

Coauthor Dr. Yu was supported by the Harvard Data Science Fellowship. The researchers had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Miron O et al. JAMA. 2019 Jun 28;321:2362-4.

Suicides in teens and young adults reached 6,241 in 2017, the highest since 2000, according to data from a review of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Underlying Cause of Death database.

The suicide rate overall was 12 per 100,000 in 2017 for 15-19 year olds.

Although suicide rates have increased across all age groups in the United States since 2000, “adolescents are of particular concern, with increases in social media use, anxiety, depression, and self-inflicted injuries,” wrote Oren Miron of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and colleagues.

In a research letter published in JAMA, the researchers analyzed trends in teen and young adult suicides from 2000 to 2017. The combined suicide rate for males and females aged 15-19 years in 2000 was 8 per 100,000 with no significant changes until 2007, followed by an annual percentage change (APC) of 3% from 2007 to 2014 and 10% from 2014 to 2017.

When the data were broken out by gender, Of note, these young men showed a decreasing trend in APC of –2% from 2000 to 2007 before increasing.

Among females aged 15-19 years, no increase was noted until 2010, then researchers identified an APC of 8% from 2010 to 2017.

For ages 20-24 years, the combined suicide rate for males and females was 13 per 100,000 in 2000, which rose to 17 per 100,000 in 2017. The APC in the older group was 1% from 2000 to 2013 and 6% from 2013 to 2017. Increasing trends were observed for both males and females over the study period.

The study was limited by the potential inaccuracy in cause of death listed on death certificates, such as mistaking a suicide for an accidental overdose, and the increased suicide rate could reflect more accurate reporting, the researchers noted.

Nonetheless, the results support the need for more studies of contributing factors to teen and young adult suicides to help develop prevention strategies and analysis of factors that may have contributed to declines in suicide rates in the past, they said.

Coauthor Dr. Yu was supported by the Harvard Data Science Fellowship. The researchers had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Miron O et al. JAMA. 2019 Jun 28;321:2362-4.

Suicides in teens and young adults reached 6,241 in 2017, the highest since 2000, according to data from a review of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Underlying Cause of Death database.

The suicide rate overall was 12 per 100,000 in 2017 for 15-19 year olds.

Although suicide rates have increased across all age groups in the United States since 2000, “adolescents are of particular concern, with increases in social media use, anxiety, depression, and self-inflicted injuries,” wrote Oren Miron of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and colleagues.

In a research letter published in JAMA, the researchers analyzed trends in teen and young adult suicides from 2000 to 2017. The combined suicide rate for males and females aged 15-19 years in 2000 was 8 per 100,000 with no significant changes until 2007, followed by an annual percentage change (APC) of 3% from 2007 to 2014 and 10% from 2014 to 2017.

When the data were broken out by gender, Of note, these young men showed a decreasing trend in APC of –2% from 2000 to 2007 before increasing.

Among females aged 15-19 years, no increase was noted until 2010, then researchers identified an APC of 8% from 2010 to 2017.

For ages 20-24 years, the combined suicide rate for males and females was 13 per 100,000 in 2000, which rose to 17 per 100,000 in 2017. The APC in the older group was 1% from 2000 to 2013 and 6% from 2013 to 2017. Increasing trends were observed for both males and females over the study period.

The study was limited by the potential inaccuracy in cause of death listed on death certificates, such as mistaking a suicide for an accidental overdose, and the increased suicide rate could reflect more accurate reporting, the researchers noted.

Nonetheless, the results support the need for more studies of contributing factors to teen and young adult suicides to help develop prevention strategies and analysis of factors that may have contributed to declines in suicide rates in the past, they said.

Coauthor Dr. Yu was supported by the Harvard Data Science Fellowship. The researchers had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Miron O et al. JAMA. 2019 Jun 28;321:2362-4.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: Suicide rates in U.S. adolescents and young adults have increased since 2000.

Major finding: The combined suicide rate for males and females aged 15-19 years underwent an annual percentage change of 3% from 2007 to 2014 and 10% from 2014 to 2017.

Study details: The data come from the CDC Underlying Cause of Death database.

Disclosures: Coauthor Dr. Yu was supported by the Harvard Data Science Fellowship. The researchers had no relevant financial disclosures.

Source: Miron O et al. JAMA. 2019 Jun 28;321:2362-4.

Pediatric-onset MS may slow information processing in adulthood

independent of age or disease duration, according to a study published in JAMA Neurology.

Information-processing efficiency as measured by the Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT) may decrease more rapidly in patients with pediatric-onset multiple sclerosis (MS).

“Children and adolescents who develop [MS] should be monitored closely for cognitive changes and helped to manage the potential challenges that early-onset multiple sclerosis poses for cognitive abilities later in life,” Kyla A. McKay, PhD, a researcher at Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, and colleagues wrote.

Prior research has found that an SDMT score of 55 may be a point at which a person with MS is “employed but work challenged.” In the present study, patients with pediatric-onset MS reached this threshold at about age 34 years, whereas patients with adult-onset MS reached it at approximately 50 years. These findings suggest that the groups’ different cognitive outcomes “may be meaningful,” the researchers wrote.

Onset of MS before age 18 years occurs in 2%-10% of cases, but few studies have looked at cognitive outcomes of patients with pediatric-onset MS in adulthood. Cognitive impairment is common in patients with MS and may affect quality of life, social functioning, and employment.

To compare changes in cognitive function over time in adults with pediatric-onset MS versus adults with adult-onset MS, Dr. McKay and colleagues conducted a population-based, longitudinal cohort study using data from more than 5,700 patients in the Swedish Multiple Sclerosis Registry. The registry includes information from all neurology clinics in Sweden, and the researchers examined data collected between April 2006 and April 2018.

SDMT scores range from 0 to 120, and higher scores indicate greater information-processing efficiency.

The researchers classified patients with MS onset at younger than 18 years as pediatric-onset MS. The researchers excluded patients with fewer than two SDMT scores, patients younger than 18 years or older than 55 years at the time of testing, and patients with disease duration of 30 years or more.

The researchers included 5,704 patients, 300 of whom had pediatric-onset MS (5.3%). About 70% of the patients were female, and 98% had a relapsing-onset disease course. The pediatric-onset MS group had a younger median age at baseline than the adult-onset group did (26 years vs. 38 years). The patients had more than 46,000 SDMT scores, with an average baseline SDMT of 51; the median follow-up time was 3 years.

Patients with pediatric-onset MS had significantly lower SDMT scores (beta coefficient, –3.59), after adjusting for sex, age, disease duration, disease course, total number of SDMTs completed, oral or visual SDMT form, and exposure to disease-modifying therapy. Their scores also declined faster than those of patients with adult-onset MS (beta coefficient, –0.30; 95% confidence interval, –5.56 to –1.54), and they were more likely to ever have cognitive impairment (odds ratio, 1.44).

“At younger than 30 years, SDMT scores between the ... groups were comparable; but after 30 years of age the trajectories began to diverge,” Dr. McKay and associates wrote. At age 35 years, the mean SDMT score for patients with adult-onset MS was 61, whereas for patients with pediatric-onset MS it was 51. By age 40 years, the mean score was 58 for adult-onset MS versus 46 for pediatric-onset MS.

The study was supported by the Swedish Research Council and the Swedish Brain Foundation and by postdoctoral awards from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research to Dr. McKay and European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis to Dr. McKay. Coauthors reported receiving honoraria for speaking and serving on advisory boards for various pharmaceutical companies, as well as receiving research funding from agencies, foundations, and pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: McKay KA et al. JAMA Neurol. 2019 Jun 17. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.1546.

The study by McKay et al. indicates that onset of multiple sclerosis (MS) during childhood or adolescence has long-term effects, Lauren B. Krupp, MD, and Leigh E. Charvet, PhD, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

In early adulthood, patients with pediatric-onset MS initially may perform better on the Symbol Digit Modalities Test, compared with patients with adult-onset MS. “However, the two groups diverged by the time the [pediatric-onset MS] patients reached 30 years of age, with slower performance in the [pediatric-onset MS] group relative to the [adult-onset MS] group, a difference that persisted over time,” Dr. Krupp and Dr. Charvet wrote. The findings remained even when the researchers adjusted for disease duration.

“Despite initial resiliency and age-based advantages, the study’s findings suggest greater deleterious long-term consequences from developing MS during a period of ongoing brain development,” they wrote.

The effect of slowed cognitive processing on quality of life is unclear, however. “The key question for future research is whether those with [pediatric-onset MS] attain their anticipated educational and occupational achievements in a manner comparable to those with [adult-onset MS],” Dr. Krupp and Dr. Charvet concluded.

Dr. Krupp and Dr. Charvet are affiliated with the Multiple Sclerosis Comprehensive Care Center at New York University. These comments are adapted from an editorial accompanying the article by McKay et al. ( JAMA Neurol. 2019 Jun 17. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.1546 ). Dr. Krupp reported receiving grants from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society; grants and personal fees from Biogen; and personal fees from Novartis, Sanofi Aventis, Sanofi Genzyme, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Roche, and RedHill Biopharma outside the submitted work. Dr. Charvet reported receiving grants and personal fees from Biogen, grants from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society, and research funding from Novartis and Biogen outside the submitted work.

The study by McKay et al. indicates that onset of multiple sclerosis (MS) during childhood or adolescence has long-term effects, Lauren B. Krupp, MD, and Leigh E. Charvet, PhD, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

In early adulthood, patients with pediatric-onset MS initially may perform better on the Symbol Digit Modalities Test, compared with patients with adult-onset MS. “However, the two groups diverged by the time the [pediatric-onset MS] patients reached 30 years of age, with slower performance in the [pediatric-onset MS] group relative to the [adult-onset MS] group, a difference that persisted over time,” Dr. Krupp and Dr. Charvet wrote. The findings remained even when the researchers adjusted for disease duration.

“Despite initial resiliency and age-based advantages, the study’s findings suggest greater deleterious long-term consequences from developing MS during a period of ongoing brain development,” they wrote.

The effect of slowed cognitive processing on quality of life is unclear, however. “The key question for future research is whether those with [pediatric-onset MS] attain their anticipated educational and occupational achievements in a manner comparable to those with [adult-onset MS],” Dr. Krupp and Dr. Charvet concluded.

Dr. Krupp and Dr. Charvet are affiliated with the Multiple Sclerosis Comprehensive Care Center at New York University. These comments are adapted from an editorial accompanying the article by McKay et al. ( JAMA Neurol. 2019 Jun 17. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.1546 ). Dr. Krupp reported receiving grants from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society; grants and personal fees from Biogen; and personal fees from Novartis, Sanofi Aventis, Sanofi Genzyme, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Roche, and RedHill Biopharma outside the submitted work. Dr. Charvet reported receiving grants and personal fees from Biogen, grants from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society, and research funding from Novartis and Biogen outside the submitted work.

The study by McKay et al. indicates that onset of multiple sclerosis (MS) during childhood or adolescence has long-term effects, Lauren B. Krupp, MD, and Leigh E. Charvet, PhD, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

In early adulthood, patients with pediatric-onset MS initially may perform better on the Symbol Digit Modalities Test, compared with patients with adult-onset MS. “However, the two groups diverged by the time the [pediatric-onset MS] patients reached 30 years of age, with slower performance in the [pediatric-onset MS] group relative to the [adult-onset MS] group, a difference that persisted over time,” Dr. Krupp and Dr. Charvet wrote. The findings remained even when the researchers adjusted for disease duration.

“Despite initial resiliency and age-based advantages, the study’s findings suggest greater deleterious long-term consequences from developing MS during a period of ongoing brain development,” they wrote.

The effect of slowed cognitive processing on quality of life is unclear, however. “The key question for future research is whether those with [pediatric-onset MS] attain their anticipated educational and occupational achievements in a manner comparable to those with [adult-onset MS],” Dr. Krupp and Dr. Charvet concluded.

Dr. Krupp and Dr. Charvet are affiliated with the Multiple Sclerosis Comprehensive Care Center at New York University. These comments are adapted from an editorial accompanying the article by McKay et al. ( JAMA Neurol. 2019 Jun 17. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.1546 ). Dr. Krupp reported receiving grants from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society; grants and personal fees from Biogen; and personal fees from Novartis, Sanofi Aventis, Sanofi Genzyme, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Roche, and RedHill Biopharma outside the submitted work. Dr. Charvet reported receiving grants and personal fees from Biogen, grants from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society, and research funding from Novartis and Biogen outside the submitted work.

independent of age or disease duration, according to a study published in JAMA Neurology.

Information-processing efficiency as measured by the Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT) may decrease more rapidly in patients with pediatric-onset multiple sclerosis (MS).

“Children and adolescents who develop [MS] should be monitored closely for cognitive changes and helped to manage the potential challenges that early-onset multiple sclerosis poses for cognitive abilities later in life,” Kyla A. McKay, PhD, a researcher at Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, and colleagues wrote.

Prior research has found that an SDMT score of 55 may be a point at which a person with MS is “employed but work challenged.” In the present study, patients with pediatric-onset MS reached this threshold at about age 34 years, whereas patients with adult-onset MS reached it at approximately 50 years. These findings suggest that the groups’ different cognitive outcomes “may be meaningful,” the researchers wrote.

Onset of MS before age 18 years occurs in 2%-10% of cases, but few studies have looked at cognitive outcomes of patients with pediatric-onset MS in adulthood. Cognitive impairment is common in patients with MS and may affect quality of life, social functioning, and employment.

To compare changes in cognitive function over time in adults with pediatric-onset MS versus adults with adult-onset MS, Dr. McKay and colleagues conducted a population-based, longitudinal cohort study using data from more than 5,700 patients in the Swedish Multiple Sclerosis Registry. The registry includes information from all neurology clinics in Sweden, and the researchers examined data collected between April 2006 and April 2018.

SDMT scores range from 0 to 120, and higher scores indicate greater information-processing efficiency.

The researchers classified patients with MS onset at younger than 18 years as pediatric-onset MS. The researchers excluded patients with fewer than two SDMT scores, patients younger than 18 years or older than 55 years at the time of testing, and patients with disease duration of 30 years or more.

The researchers included 5,704 patients, 300 of whom had pediatric-onset MS (5.3%). About 70% of the patients were female, and 98% had a relapsing-onset disease course. The pediatric-onset MS group had a younger median age at baseline than the adult-onset group did (26 years vs. 38 years). The patients had more than 46,000 SDMT scores, with an average baseline SDMT of 51; the median follow-up time was 3 years.

Patients with pediatric-onset MS had significantly lower SDMT scores (beta coefficient, –3.59), after adjusting for sex, age, disease duration, disease course, total number of SDMTs completed, oral or visual SDMT form, and exposure to disease-modifying therapy. Their scores also declined faster than those of patients with adult-onset MS (beta coefficient, –0.30; 95% confidence interval, –5.56 to –1.54), and they were more likely to ever have cognitive impairment (odds ratio, 1.44).

“At younger than 30 years, SDMT scores between the ... groups were comparable; but after 30 years of age the trajectories began to diverge,” Dr. McKay and associates wrote. At age 35 years, the mean SDMT score for patients with adult-onset MS was 61, whereas for patients with pediatric-onset MS it was 51. By age 40 years, the mean score was 58 for adult-onset MS versus 46 for pediatric-onset MS.

The study was supported by the Swedish Research Council and the Swedish Brain Foundation and by postdoctoral awards from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research to Dr. McKay and European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis to Dr. McKay. Coauthors reported receiving honoraria for speaking and serving on advisory boards for various pharmaceutical companies, as well as receiving research funding from agencies, foundations, and pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: McKay KA et al. JAMA Neurol. 2019 Jun 17. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.1546.

independent of age or disease duration, according to a study published in JAMA Neurology.

Information-processing efficiency as measured by the Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT) may decrease more rapidly in patients with pediatric-onset multiple sclerosis (MS).

“Children and adolescents who develop [MS] should be monitored closely for cognitive changes and helped to manage the potential challenges that early-onset multiple sclerosis poses for cognitive abilities later in life,” Kyla A. McKay, PhD, a researcher at Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, and colleagues wrote.

Prior research has found that an SDMT score of 55 may be a point at which a person with MS is “employed but work challenged.” In the present study, patients with pediatric-onset MS reached this threshold at about age 34 years, whereas patients with adult-onset MS reached it at approximately 50 years. These findings suggest that the groups’ different cognitive outcomes “may be meaningful,” the researchers wrote.

Onset of MS before age 18 years occurs in 2%-10% of cases, but few studies have looked at cognitive outcomes of patients with pediatric-onset MS in adulthood. Cognitive impairment is common in patients with MS and may affect quality of life, social functioning, and employment.

To compare changes in cognitive function over time in adults with pediatric-onset MS versus adults with adult-onset MS, Dr. McKay and colleagues conducted a population-based, longitudinal cohort study using data from more than 5,700 patients in the Swedish Multiple Sclerosis Registry. The registry includes information from all neurology clinics in Sweden, and the researchers examined data collected between April 2006 and April 2018.

SDMT scores range from 0 to 120, and higher scores indicate greater information-processing efficiency.

The researchers classified patients with MS onset at younger than 18 years as pediatric-onset MS. The researchers excluded patients with fewer than two SDMT scores, patients younger than 18 years or older than 55 years at the time of testing, and patients with disease duration of 30 years or more.

The researchers included 5,704 patients, 300 of whom had pediatric-onset MS (5.3%). About 70% of the patients were female, and 98% had a relapsing-onset disease course. The pediatric-onset MS group had a younger median age at baseline than the adult-onset group did (26 years vs. 38 years). The patients had more than 46,000 SDMT scores, with an average baseline SDMT of 51; the median follow-up time was 3 years.

Patients with pediatric-onset MS had significantly lower SDMT scores (beta coefficient, –3.59), after adjusting for sex, age, disease duration, disease course, total number of SDMTs completed, oral or visual SDMT form, and exposure to disease-modifying therapy. Their scores also declined faster than those of patients with adult-onset MS (beta coefficient, –0.30; 95% confidence interval, –5.56 to –1.54), and they were more likely to ever have cognitive impairment (odds ratio, 1.44).

“At younger than 30 years, SDMT scores between the ... groups were comparable; but after 30 years of age the trajectories began to diverge,” Dr. McKay and associates wrote. At age 35 years, the mean SDMT score for patients with adult-onset MS was 61, whereas for patients with pediatric-onset MS it was 51. By age 40 years, the mean score was 58 for adult-onset MS versus 46 for pediatric-onset MS.

The study was supported by the Swedish Research Council and the Swedish Brain Foundation and by postdoctoral awards from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research to Dr. McKay and European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis to Dr. McKay. Coauthors reported receiving honoraria for speaking and serving on advisory boards for various pharmaceutical companies, as well as receiving research funding from agencies, foundations, and pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: McKay KA et al. JAMA Neurol. 2019 Jun 17. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.1546.

FROM JAMA NEUROLOGY

U.S. travelers to Europe need up to date measles immunization

researchers at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend in a Pediatrics special report.

More than 41,000 measles cases and 37 deaths – primarily due to low immunization coverage – were reported in the World Health Organization European Region in the first 6 months of 2018, the highest incidence since the 1990s. Typical case counts since 2010 have ranged from 5,000 to 24,000 in this region, wrote Kristina M. Angelo, DO, MPH, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Travelers’ Health Branch in Atlanta, and associates.

France, Italy and Greece – all particularly popular countries for U.S. vacationers to visit – have particularly high numbers of cases, as do Georgia, Russia, Serbia and, comprising the majority of cases, Ukraine. Italy, for example, is the 10th most popular destination worldwide for Americans, with an estimated 2.5 million American visitors in 2015.

“The large number of measles infections in the WHO European Region ... is a global concern because the European continent is the most common travel destination worldwide,” but is not perceived as a place with infectious disease risk. So travelers may not consider the need of a pretravel health consultation, including vaccination, they said.

But they need to, Dr. Angelo and associates state, and health care providers should be vigilant about checking for symptoms of measles among those who have recently returned from overseas. Given how highly contagious measles is, unvaccinated and under vaccinated travelers to Europe are susceptible to infection, as are any people they encounter back in the United States if the travelers come home sick.

Measles was eliminated in the United States in 2000, but that status is in jeopardy, CDC officials recently warned. The number of domestic measles cases has exceeded 1,000 just halfway through 2019, the highest count since 1992, nearly a decade before elimination.

“Avoiding international travel with nonimmune infants and performing early vaccination at 6 to 12 months of age per the ACIP [Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices] recommendations if travel is unavoidable are of utmost importance,” Dr. Angelo and colleagues advised. “Other at-risk populations (e.g., immunocompromised individuals and pregnant women), for whom vaccination against the measles virus is contraindicated, may consider alternative destinations or delay travel to measles-endemic destinations or areas with known, ongoing measles outbreaks.”

“Presumptive immunity to measles is defined as 1 or more of the following: birth before 1957, laboratory evidence of immunity or infection, 1 or more doses of a measles containing vaccine administered for preschool-aged children and low-risk adults, or 2 doses of measles vaccine among school-aged children and high-risk adults, including international travelers,” they explained.

In Europe, measles remains endemic in Belgium, Bosnia and Herzegovina, France, Georgia, Germany, Italy, Romania, the Russian Federation, Serbia and the Ukraine, the authors wrote.

“As long as measles remains endemic in other countries, the United States will be challenged by measles importations,” the authors wrote. Yet at least one past study in 2017 revealed a third of U.S. travelers to Europe left the country without being fully vaccinated against measles, most often due to vaccine refusal.

“The reason one-third of travelers to Europe missed an opportunity for measles vaccination remains unclear,” the authors wrote. “It may represent a lack of concern or awareness on the part of travelers and the health care providers about acquiring measles in Europe.”

Dr. Angelo and colleagues also emphasized the importance of returning U.S. travelers seeking health care if they have symptoms of measles, including fever and a rash.

Health care providers should ask all patients about recent international travel, they stated. “If measles is suspected, health care providers should isolate travelers immediately, placing them on airborne precautions until day 4 of the rash.” Providers may consider administering immunoglobulin for unvaccinated and undervaccinated travelers and monitor them for 21 days for development of measles symptoms.

The statement was funded by the CDC. The authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Angelo KM et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Jun 17. doi: /10.1542/peds.2019-0414.

researchers at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend in a Pediatrics special report.

More than 41,000 measles cases and 37 deaths – primarily due to low immunization coverage – were reported in the World Health Organization European Region in the first 6 months of 2018, the highest incidence since the 1990s. Typical case counts since 2010 have ranged from 5,000 to 24,000 in this region, wrote Kristina M. Angelo, DO, MPH, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Travelers’ Health Branch in Atlanta, and associates.

France, Italy and Greece – all particularly popular countries for U.S. vacationers to visit – have particularly high numbers of cases, as do Georgia, Russia, Serbia and, comprising the majority of cases, Ukraine. Italy, for example, is the 10th most popular destination worldwide for Americans, with an estimated 2.5 million American visitors in 2015.

“The large number of measles infections in the WHO European Region ... is a global concern because the European continent is the most common travel destination worldwide,” but is not perceived as a place with infectious disease risk. So travelers may not consider the need of a pretravel health consultation, including vaccination, they said.

But they need to, Dr. Angelo and associates state, and health care providers should be vigilant about checking for symptoms of measles among those who have recently returned from overseas. Given how highly contagious measles is, unvaccinated and under vaccinated travelers to Europe are susceptible to infection, as are any people they encounter back in the United States if the travelers come home sick.

Measles was eliminated in the United States in 2000, but that status is in jeopardy, CDC officials recently warned. The number of domestic measles cases has exceeded 1,000 just halfway through 2019, the highest count since 1992, nearly a decade before elimination.

“Avoiding international travel with nonimmune infants and performing early vaccination at 6 to 12 months of age per the ACIP [Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices] recommendations if travel is unavoidable are of utmost importance,” Dr. Angelo and colleagues advised. “Other at-risk populations (e.g., immunocompromised individuals and pregnant women), for whom vaccination against the measles virus is contraindicated, may consider alternative destinations or delay travel to measles-endemic destinations or areas with known, ongoing measles outbreaks.”

“Presumptive immunity to measles is defined as 1 or more of the following: birth before 1957, laboratory evidence of immunity or infection, 1 or more doses of a measles containing vaccine administered for preschool-aged children and low-risk adults, or 2 doses of measles vaccine among school-aged children and high-risk adults, including international travelers,” they explained.

In Europe, measles remains endemic in Belgium, Bosnia and Herzegovina, France, Georgia, Germany, Italy, Romania, the Russian Federation, Serbia and the Ukraine, the authors wrote.

“As long as measles remains endemic in other countries, the United States will be challenged by measles importations,” the authors wrote. Yet at least one past study in 2017 revealed a third of U.S. travelers to Europe left the country without being fully vaccinated against measles, most often due to vaccine refusal.

“The reason one-third of travelers to Europe missed an opportunity for measles vaccination remains unclear,” the authors wrote. “It may represent a lack of concern or awareness on the part of travelers and the health care providers about acquiring measles in Europe.”

Dr. Angelo and colleagues also emphasized the importance of returning U.S. travelers seeking health care if they have symptoms of measles, including fever and a rash.

Health care providers should ask all patients about recent international travel, they stated. “If measles is suspected, health care providers should isolate travelers immediately, placing them on airborne precautions until day 4 of the rash.” Providers may consider administering immunoglobulin for unvaccinated and undervaccinated travelers and monitor them for 21 days for development of measles symptoms.

The statement was funded by the CDC. The authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Angelo KM et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Jun 17. doi: /10.1542/peds.2019-0414.

researchers at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend in a Pediatrics special report.

More than 41,000 measles cases and 37 deaths – primarily due to low immunization coverage – were reported in the World Health Organization European Region in the first 6 months of 2018, the highest incidence since the 1990s. Typical case counts since 2010 have ranged from 5,000 to 24,000 in this region, wrote Kristina M. Angelo, DO, MPH, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Travelers’ Health Branch in Atlanta, and associates.

France, Italy and Greece – all particularly popular countries for U.S. vacationers to visit – have particularly high numbers of cases, as do Georgia, Russia, Serbia and, comprising the majority of cases, Ukraine. Italy, for example, is the 10th most popular destination worldwide for Americans, with an estimated 2.5 million American visitors in 2015.

“The large number of measles infections in the WHO European Region ... is a global concern because the European continent is the most common travel destination worldwide,” but is not perceived as a place with infectious disease risk. So travelers may not consider the need of a pretravel health consultation, including vaccination, they said.

But they need to, Dr. Angelo and associates state, and health care providers should be vigilant about checking for symptoms of measles among those who have recently returned from overseas. Given how highly contagious measles is, unvaccinated and under vaccinated travelers to Europe are susceptible to infection, as are any people they encounter back in the United States if the travelers come home sick.

Measles was eliminated in the United States in 2000, but that status is in jeopardy, CDC officials recently warned. The number of domestic measles cases has exceeded 1,000 just halfway through 2019, the highest count since 1992, nearly a decade before elimination.

“Avoiding international travel with nonimmune infants and performing early vaccination at 6 to 12 months of age per the ACIP [Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices] recommendations if travel is unavoidable are of utmost importance,” Dr. Angelo and colleagues advised. “Other at-risk populations (e.g., immunocompromised individuals and pregnant women), for whom vaccination against the measles virus is contraindicated, may consider alternative destinations or delay travel to measles-endemic destinations or areas with known, ongoing measles outbreaks.”

“Presumptive immunity to measles is defined as 1 or more of the following: birth before 1957, laboratory evidence of immunity or infection, 1 or more doses of a measles containing vaccine administered for preschool-aged children and low-risk adults, or 2 doses of measles vaccine among school-aged children and high-risk adults, including international travelers,” they explained.

In Europe, measles remains endemic in Belgium, Bosnia and Herzegovina, France, Georgia, Germany, Italy, Romania, the Russian Federation, Serbia and the Ukraine, the authors wrote.

“As long as measles remains endemic in other countries, the United States will be challenged by measles importations,” the authors wrote. Yet at least one past study in 2017 revealed a third of U.S. travelers to Europe left the country without being fully vaccinated against measles, most often due to vaccine refusal.

“The reason one-third of travelers to Europe missed an opportunity for measles vaccination remains unclear,” the authors wrote. “It may represent a lack of concern or awareness on the part of travelers and the health care providers about acquiring measles in Europe.”

Dr. Angelo and colleagues also emphasized the importance of returning U.S. travelers seeking health care if they have symptoms of measles, including fever and a rash.

Health care providers should ask all patients about recent international travel, they stated. “If measles is suspected, health care providers should isolate travelers immediately, placing them on airborne precautions until day 4 of the rash.” Providers may consider administering immunoglobulin for unvaccinated and undervaccinated travelers and monitor them for 21 days for development of measles symptoms.

The statement was funded by the CDC. The authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Angelo KM et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Jun 17. doi: /10.1542/peds.2019-0414.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Booster vaccines found largely safe in children on immunosuppressive drugs

MADRID – Administration of live attenuated booster of the MMR vaccine with or without varicella (MMR/V) was not associated with serious adverse events in children on immunosuppressive therapy for a rheumatic disease, according to data presented at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

“The study implies that patients can receive booster vaccinations regardless of age, diagnosis, or therapy,” reported Veronica Bergonzo Moshe, MD, a pediatric rheumatologist at Meir Medical Center, Kfar Saba, Israel.

In the absence of safety data, the vaccination of children with rheumatic diseases taking immunosuppressive therapies has been controversial. Although these children face communicable and sometimes life-threatening diseases without vaccination, many clinicians are not offering this protection because they fear adverse consequences.

Current Paediatric Rheumatology European Society (PReS) guidelines have been equivocal, recommending that vaccines be considered on a “case-by-case basis” in children with a rheumatic disease if they are taking high doses of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), glucocorticoids, or any dose of biologics.

“The fear is that a state of immune suppression might decrease response to the vaccine or lead to a flare of the rheumatologic disease,” Dr. Moshe said.

In the retrospective study presented by Dr. Moshe, data were collected on 234 children with rheumatic diseases who received a live attenuated MMR/V booster. The children were drawn from 12 pediatric rheumatology centers in 10 countries.

In this relatively large series, 82% of the children had oligoarticular or polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA). A range of other rheumatic diseases, including juvenile dermatomyositis, localized scleroderma, and isolated idiopathic uveitis were represented among the remaining patients. All were taking medication, and 48% were in remission.

When broken down by therapy, there were three localized reactions in 110 (2.7%) children who received the booster while on methotrexate. No other adverse events, including disease flare, were observed.

Similarly, six of the seven adverse events observed in 76 (8%) patients who were taking methotrexate plus a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor biologic at the time of vaccination were local reactions. Fever was reported in one patient. All of these events were transient.

In the 39 patients taking a TNF inhibitor alone, there was a single case of transient fever. There were no adverse events reported in the three patients vaccinated while on tocilizumab, seven patients while on anakinra, or five patients while on canakinumab.

Following vaccination, there were no signs of symptoms of the diseases that the vaccines are designed to prevent. In the minority of patients who did develop localized reactions or fever in this series, there was no apparent relationship with disease activity, age, or sex when compared to those who did not develop an adverse event.

These retrospective data are not definitive, but they are reassuring, according to Dr. Moshe. A larger prospective study by the PReS vaccination study group is now planned. The issue of leaving children unvaccinated is topical due to the recent outbreaks of measles in the United States.

“We must have clear guidelines on how to deal with the administration of live vaccines in this patient population so that we can provide the safest and most effective practice,” Dr. Moshe said.

These data are a first step.

“This large retrospective study demonstrates that live attenuated booster vaccine is probably safe in children with rheumatic diseases,” said Dr. Moshe, but she deferred to the PReS guidelines in suggesting that the decision to vaccinate still might best be performed on a case-by-case basis.

MADRID – Administration of live attenuated booster of the MMR vaccine with or without varicella (MMR/V) was not associated with serious adverse events in children on immunosuppressive therapy for a rheumatic disease, according to data presented at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

“The study implies that patients can receive booster vaccinations regardless of age, diagnosis, or therapy,” reported Veronica Bergonzo Moshe, MD, a pediatric rheumatologist at Meir Medical Center, Kfar Saba, Israel.

In the absence of safety data, the vaccination of children with rheumatic diseases taking immunosuppressive therapies has been controversial. Although these children face communicable and sometimes life-threatening diseases without vaccination, many clinicians are not offering this protection because they fear adverse consequences.

Current Paediatric Rheumatology European Society (PReS) guidelines have been equivocal, recommending that vaccines be considered on a “case-by-case basis” in children with a rheumatic disease if they are taking high doses of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), glucocorticoids, or any dose of biologics.

“The fear is that a state of immune suppression might decrease response to the vaccine or lead to a flare of the rheumatologic disease,” Dr. Moshe said.

In the retrospective study presented by Dr. Moshe, data were collected on 234 children with rheumatic diseases who received a live attenuated MMR/V booster. The children were drawn from 12 pediatric rheumatology centers in 10 countries.

In this relatively large series, 82% of the children had oligoarticular or polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA). A range of other rheumatic diseases, including juvenile dermatomyositis, localized scleroderma, and isolated idiopathic uveitis were represented among the remaining patients. All were taking medication, and 48% were in remission.

When broken down by therapy, there were three localized reactions in 110 (2.7%) children who received the booster while on methotrexate. No other adverse events, including disease flare, were observed.

Similarly, six of the seven adverse events observed in 76 (8%) patients who were taking methotrexate plus a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor biologic at the time of vaccination were local reactions. Fever was reported in one patient. All of these events were transient.

In the 39 patients taking a TNF inhibitor alone, there was a single case of transient fever. There were no adverse events reported in the three patients vaccinated while on tocilizumab, seven patients while on anakinra, or five patients while on canakinumab.

Following vaccination, there were no signs of symptoms of the diseases that the vaccines are designed to prevent. In the minority of patients who did develop localized reactions or fever in this series, there was no apparent relationship with disease activity, age, or sex when compared to those who did not develop an adverse event.

These retrospective data are not definitive, but they are reassuring, according to Dr. Moshe. A larger prospective study by the PReS vaccination study group is now planned. The issue of leaving children unvaccinated is topical due to the recent outbreaks of measles in the United States.

“We must have clear guidelines on how to deal with the administration of live vaccines in this patient population so that we can provide the safest and most effective practice,” Dr. Moshe said.

These data are a first step.

“This large retrospective study demonstrates that live attenuated booster vaccine is probably safe in children with rheumatic diseases,” said Dr. Moshe, but she deferred to the PReS guidelines in suggesting that the decision to vaccinate still might best be performed on a case-by-case basis.

MADRID – Administration of live attenuated booster of the MMR vaccine with or without varicella (MMR/V) was not associated with serious adverse events in children on immunosuppressive therapy for a rheumatic disease, according to data presented at the European Congress of Rheumatology.

“The study implies that patients can receive booster vaccinations regardless of age, diagnosis, or therapy,” reported Veronica Bergonzo Moshe, MD, a pediatric rheumatologist at Meir Medical Center, Kfar Saba, Israel.

In the absence of safety data, the vaccination of children with rheumatic diseases taking immunosuppressive therapies has been controversial. Although these children face communicable and sometimes life-threatening diseases without vaccination, many clinicians are not offering this protection because they fear adverse consequences.

Current Paediatric Rheumatology European Society (PReS) guidelines have been equivocal, recommending that vaccines be considered on a “case-by-case basis” in children with a rheumatic disease if they are taking high doses of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), glucocorticoids, or any dose of biologics.

“The fear is that a state of immune suppression might decrease response to the vaccine or lead to a flare of the rheumatologic disease,” Dr. Moshe said.

In the retrospective study presented by Dr. Moshe, data were collected on 234 children with rheumatic diseases who received a live attenuated MMR/V booster. The children were drawn from 12 pediatric rheumatology centers in 10 countries.

In this relatively large series, 82% of the children had oligoarticular or polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA). A range of other rheumatic diseases, including juvenile dermatomyositis, localized scleroderma, and isolated idiopathic uveitis were represented among the remaining patients. All were taking medication, and 48% were in remission.

When broken down by therapy, there were three localized reactions in 110 (2.7%) children who received the booster while on methotrexate. No other adverse events, including disease flare, were observed.