User login

Artificial pancreas improved glycemia after islet cell transplant

A closed-loop insulin pump with continuous glucose monitor produced significantly better blood glucose control in patients who have received islet cell transplants after pancreatectomy, compared with regular insulin injections, a pilot study has found.

Fourteen adults who received auto-islet transplants after pancreatectomy for chronic pancreatitis were randomized either to receive a closed-loop insulin pump system or the usual treatment of multiple insulin injections for 72 hours after transition from intravenous to subcutaneous insulin following surgery.

Researchers observed a significantly lower mean serum glucose in the insulin pump group, compared with the control group, with the highest average serum glucose level in individual patients in the pump group still being lower than the lowest average in the control group.

These improvements in glycemia were not associated with an increased risk of hypoglycemia in the closed-loop pump group and patients in the closed-loop pump group also required a significantly lower total daily insulin dose than did the control group, according to a paper published Nov. 20 in the American Journal of Transplantation.

“Success of islet engraftment is heavily dependent on maintenance of narrow-range euglycemia in the post-transplant period,” wrote Dr. Gregory P. Forlenza of the University of Minnesota Medical Center, Minneapolis, and his coauthors (Am J Transplant. 2015 Nov 20. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13539).

“This technology was shown in this study to provide some statistically and clinically significant improvements in glycemic parameters in adults after TP [total pancreatectomy] with IAT [intraportal islet autotransplantation] without producing associated increased episodes of hypoglycemia or adverse events.”

The study was funded by the Vikings Children’s Research Fund and the University of Minnesota. Medtronic Diabetes provided supplies as part of an investigator-initiated grant. No conflicts of interest were declared.

A closed-loop insulin pump with continuous glucose monitor produced significantly better blood glucose control in patients who have received islet cell transplants after pancreatectomy, compared with regular insulin injections, a pilot study has found.

Fourteen adults who received auto-islet transplants after pancreatectomy for chronic pancreatitis were randomized either to receive a closed-loop insulin pump system or the usual treatment of multiple insulin injections for 72 hours after transition from intravenous to subcutaneous insulin following surgery.

Researchers observed a significantly lower mean serum glucose in the insulin pump group, compared with the control group, with the highest average serum glucose level in individual patients in the pump group still being lower than the lowest average in the control group.

These improvements in glycemia were not associated with an increased risk of hypoglycemia in the closed-loop pump group and patients in the closed-loop pump group also required a significantly lower total daily insulin dose than did the control group, according to a paper published Nov. 20 in the American Journal of Transplantation.

“Success of islet engraftment is heavily dependent on maintenance of narrow-range euglycemia in the post-transplant period,” wrote Dr. Gregory P. Forlenza of the University of Minnesota Medical Center, Minneapolis, and his coauthors (Am J Transplant. 2015 Nov 20. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13539).

“This technology was shown in this study to provide some statistically and clinically significant improvements in glycemic parameters in adults after TP [total pancreatectomy] with IAT [intraportal islet autotransplantation] without producing associated increased episodes of hypoglycemia or adverse events.”

The study was funded by the Vikings Children’s Research Fund and the University of Minnesota. Medtronic Diabetes provided supplies as part of an investigator-initiated grant. No conflicts of interest were declared.

A closed-loop insulin pump with continuous glucose monitor produced significantly better blood glucose control in patients who have received islet cell transplants after pancreatectomy, compared with regular insulin injections, a pilot study has found.

Fourteen adults who received auto-islet transplants after pancreatectomy for chronic pancreatitis were randomized either to receive a closed-loop insulin pump system or the usual treatment of multiple insulin injections for 72 hours after transition from intravenous to subcutaneous insulin following surgery.

Researchers observed a significantly lower mean serum glucose in the insulin pump group, compared with the control group, with the highest average serum glucose level in individual patients in the pump group still being lower than the lowest average in the control group.

These improvements in glycemia were not associated with an increased risk of hypoglycemia in the closed-loop pump group and patients in the closed-loop pump group also required a significantly lower total daily insulin dose than did the control group, according to a paper published Nov. 20 in the American Journal of Transplantation.

“Success of islet engraftment is heavily dependent on maintenance of narrow-range euglycemia in the post-transplant period,” wrote Dr. Gregory P. Forlenza of the University of Minnesota Medical Center, Minneapolis, and his coauthors (Am J Transplant. 2015 Nov 20. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13539).

“This technology was shown in this study to provide some statistically and clinically significant improvements in glycemic parameters in adults after TP [total pancreatectomy] with IAT [intraportal islet autotransplantation] without producing associated increased episodes of hypoglycemia or adverse events.”

The study was funded by the Vikings Children’s Research Fund and the University of Minnesota. Medtronic Diabetes provided supplies as part of an investigator-initiated grant. No conflicts of interest were declared.

FROM THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF TRANSPLANTATION

Key clinical point: A closed-loop insulin pump with a continuous glucose monitor offers significantly better blood glucose control in patients who have received islet cell transplants after pancreatectomy.

Major finding: Closed-loop insulin pumps were associated with a significantly lower mean serum glucose, compared with multiple daily insulin injections.

Data source: Randomized, controlled pilot study in 14 patients receiving auto-islet transplants after pancreatectomy.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the Vikings Children’s Research Fund and the University of Minnesota. Medtronic Diabetes provided supplies as part of an investigator-initiated grant. No conflicts of interest were declared.

Complications climb with revisional surgery after adjustable gastric banding

LOS ANGELES – Revisional surgery after failed adjustable gastric banding (AGB) is associated with an increased risk of adverse events and resource utilization, according to Dr. Steven Poplawski, medical director for Barix Clinics in Ypsilanti, Mich.

His conclusion is based on safety outcomes at 30 days for 55,237 patients who underwent primary bariatric surgery and 1,417 patients who underwent AGB revision between June 2006 and July 2015 in the Michigan Bariatric Surgery Collaborative. Patients were excluded from the retrospective evaluation if they had urgent/emergent procedures or more than one previous bariatric operation.

The primary bariatric surgery was Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) in 43%, sleeve gastrectomy in 37%, AGB in 19%, and biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch (BPD/DS) in 1%.

The patients turned to AGB revision for the same reasons that have prompted its dramatic decline in utilization: weight loss failure (38%), band complications (33%), or both (29%). AGB revisional procedures were sleeve gastrectomy in 54%, RYGB in 35%, AGB in 9%, and BPD/DS in 2%.

Patients undergoing band-to-RYGB conversions had significantly more serious complications, compared with primary RYGB procedures (10.2% vs. 4.4%; P less than .0001), reoperations (5.1% vs. 2.3%; P = .0001), and hospital readmissions (10% vs. 7.3%; P = .0064), and a nonsignificant trend toward more leaks (1.3% vs. 0.7%; P = .13), Dr. Poplawski reported.

Patients undergoing band-to-sleeve conversions had significantly more serious complications when compared with primary sleeve gastrectomy (5% vs. 1.8%; P less than .0001), reoperations (3.3% vs. 1%; P less than .0001), and leaks (1.5% vs. 0.5%; P = .0001), and a nonsignificant trend toward more readmissions (7.7% vs. 4.6%; P = .0685).

Outcomes were not reported for the smaller number of patients undergoing AGB-to-AGB or AGB-to-BPD/DS conversions.

A secondary analysis was performed examining a one-stage versus a two-stage procedure in 525 patients undergoing revisional surgery for weight loss failure only. The only safety outcome to show a significant difference at 30 days was hospital readmissions in the RYGB-conversion group, favoring the one-stage over the two-stage procedure (7.1% vs. 11.5%; P = .0164).

“Clearly, the benefit of a one-stage procedure versus a two-stage procedure is unclear in the way it was studied here,” Dr. Poplawski said at Obesity Week 2015, presented by the Obesity Society and the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

“You can read in some reports that [surgeons] do all [of these procedures as] two-stage because they think it’s safer, but I don’t know that there’s much support for that here. I think it’s reasonable to get most of them done in one stage because there’s also two hospitalizations, two periods of convalescence, and when we talk about the complications of the two-stage operation we aren’t even including the costs to remove the initial band, which are not insignificant,” he noted.

Dr. Raul Rosenthal of the Cleveland Clinic in Weston, Fla., who comoderated the session, said the takeaway message is that “reoperative surgery pays a price. No matter how you look at it, one stage, two stages, with bands or sleeve, you’re going to get in trouble.”

LOS ANGELES – Revisional surgery after failed adjustable gastric banding (AGB) is associated with an increased risk of adverse events and resource utilization, according to Dr. Steven Poplawski, medical director for Barix Clinics in Ypsilanti, Mich.

His conclusion is based on safety outcomes at 30 days for 55,237 patients who underwent primary bariatric surgery and 1,417 patients who underwent AGB revision between June 2006 and July 2015 in the Michigan Bariatric Surgery Collaborative. Patients were excluded from the retrospective evaluation if they had urgent/emergent procedures or more than one previous bariatric operation.

The primary bariatric surgery was Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) in 43%, sleeve gastrectomy in 37%, AGB in 19%, and biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch (BPD/DS) in 1%.

The patients turned to AGB revision for the same reasons that have prompted its dramatic decline in utilization: weight loss failure (38%), band complications (33%), or both (29%). AGB revisional procedures were sleeve gastrectomy in 54%, RYGB in 35%, AGB in 9%, and BPD/DS in 2%.

Patients undergoing band-to-RYGB conversions had significantly more serious complications, compared with primary RYGB procedures (10.2% vs. 4.4%; P less than .0001), reoperations (5.1% vs. 2.3%; P = .0001), and hospital readmissions (10% vs. 7.3%; P = .0064), and a nonsignificant trend toward more leaks (1.3% vs. 0.7%; P = .13), Dr. Poplawski reported.

Patients undergoing band-to-sleeve conversions had significantly more serious complications when compared with primary sleeve gastrectomy (5% vs. 1.8%; P less than .0001), reoperations (3.3% vs. 1%; P less than .0001), and leaks (1.5% vs. 0.5%; P = .0001), and a nonsignificant trend toward more readmissions (7.7% vs. 4.6%; P = .0685).

Outcomes were not reported for the smaller number of patients undergoing AGB-to-AGB or AGB-to-BPD/DS conversions.

A secondary analysis was performed examining a one-stage versus a two-stage procedure in 525 patients undergoing revisional surgery for weight loss failure only. The only safety outcome to show a significant difference at 30 days was hospital readmissions in the RYGB-conversion group, favoring the one-stage over the two-stage procedure (7.1% vs. 11.5%; P = .0164).

“Clearly, the benefit of a one-stage procedure versus a two-stage procedure is unclear in the way it was studied here,” Dr. Poplawski said at Obesity Week 2015, presented by the Obesity Society and the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

“You can read in some reports that [surgeons] do all [of these procedures as] two-stage because they think it’s safer, but I don’t know that there’s much support for that here. I think it’s reasonable to get most of them done in one stage because there’s also two hospitalizations, two periods of convalescence, and when we talk about the complications of the two-stage operation we aren’t even including the costs to remove the initial band, which are not insignificant,” he noted.

Dr. Raul Rosenthal of the Cleveland Clinic in Weston, Fla., who comoderated the session, said the takeaway message is that “reoperative surgery pays a price. No matter how you look at it, one stage, two stages, with bands or sleeve, you’re going to get in trouble.”

LOS ANGELES – Revisional surgery after failed adjustable gastric banding (AGB) is associated with an increased risk of adverse events and resource utilization, according to Dr. Steven Poplawski, medical director for Barix Clinics in Ypsilanti, Mich.

His conclusion is based on safety outcomes at 30 days for 55,237 patients who underwent primary bariatric surgery and 1,417 patients who underwent AGB revision between June 2006 and July 2015 in the Michigan Bariatric Surgery Collaborative. Patients were excluded from the retrospective evaluation if they had urgent/emergent procedures or more than one previous bariatric operation.

The primary bariatric surgery was Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) in 43%, sleeve gastrectomy in 37%, AGB in 19%, and biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch (BPD/DS) in 1%.

The patients turned to AGB revision for the same reasons that have prompted its dramatic decline in utilization: weight loss failure (38%), band complications (33%), or both (29%). AGB revisional procedures were sleeve gastrectomy in 54%, RYGB in 35%, AGB in 9%, and BPD/DS in 2%.

Patients undergoing band-to-RYGB conversions had significantly more serious complications, compared with primary RYGB procedures (10.2% vs. 4.4%; P less than .0001), reoperations (5.1% vs. 2.3%; P = .0001), and hospital readmissions (10% vs. 7.3%; P = .0064), and a nonsignificant trend toward more leaks (1.3% vs. 0.7%; P = .13), Dr. Poplawski reported.

Patients undergoing band-to-sleeve conversions had significantly more serious complications when compared with primary sleeve gastrectomy (5% vs. 1.8%; P less than .0001), reoperations (3.3% vs. 1%; P less than .0001), and leaks (1.5% vs. 0.5%; P = .0001), and a nonsignificant trend toward more readmissions (7.7% vs. 4.6%; P = .0685).

Outcomes were not reported for the smaller number of patients undergoing AGB-to-AGB or AGB-to-BPD/DS conversions.

A secondary analysis was performed examining a one-stage versus a two-stage procedure in 525 patients undergoing revisional surgery for weight loss failure only. The only safety outcome to show a significant difference at 30 days was hospital readmissions in the RYGB-conversion group, favoring the one-stage over the two-stage procedure (7.1% vs. 11.5%; P = .0164).

“Clearly, the benefit of a one-stage procedure versus a two-stage procedure is unclear in the way it was studied here,” Dr. Poplawski said at Obesity Week 2015, presented by the Obesity Society and the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

“You can read in some reports that [surgeons] do all [of these procedures as] two-stage because they think it’s safer, but I don’t know that there’s much support for that here. I think it’s reasonable to get most of them done in one stage because there’s also two hospitalizations, two periods of convalescence, and when we talk about the complications of the two-stage operation we aren’t even including the costs to remove the initial band, which are not insignificant,” he noted.

Dr. Raul Rosenthal of the Cleveland Clinic in Weston, Fla., who comoderated the session, said the takeaway message is that “reoperative surgery pays a price. No matter how you look at it, one stage, two stages, with bands or sleeve, you’re going to get in trouble.”

AT OBESITY WEEK 2015

Key clinical point: Conversions of adjustable gastric bands are associated with more 30-day adverse events.

Major finding: Serious complications were higher in AGB–to–Roux-en-Y gastric bypass conversions than in primary RYGB (10.2% vs. 4.4%; P less than .0001) and in AGB-to-sleeve gastrectomy conversions, compared with primary sleeves (5% vs. 1.8%; P less than .0001).

Data source: Retrospective study of 55,237 patients who underwent primary bariatric surgery and 1,417 patients who underwent adjustable gastric band revision.

Disclosures: Dr. Poplawski reported having no disclosures.

Steroids did not reduce kidney injury in CABG

SAN DIEGO – Among patients undergoing cardiac bypass surgery, perioperative use of corticosteroids did not alter the risk of acute kidney injury, results from a large randomized trial showed.

“Worldwide, over 20 million cardiac surgeries are done each year, but 4 million are complicated by acute kidney injury, and 200,000 are complicated by severe kidney injury treated with dialysis,” Dr. Amit X. Garg said during a press briefing at the annual meeting of the American Society of Nephrology. “So certainly people would benefit from a therapy to prevent acute kidney injury (AKI) and improve the safety of surgery.”

Dr. Garg, a nephrologist at the London Health Sciences Centre in London, Ontario, Canada, noted that cardiopulmonary bypass initiates a systemic inflammatory response syndrome, “which activates complement, inflammatory cytokines, and other inflammatory mediators, which in turn increases endothelial permeability, organ damage, and increased morbidity and mortality, including acute kidney injury.” Researchers are interested in corticosteroids, “because they suppress this inflammatory response. In other settings, such as acute glomerulonephritis, we successfully use corticosteroids to treat acute inflammation in the kidney,” he said.

In a study known as the Steroids in caRdiac Surgery Trial (SIRS), researchers at 79 centers in 18 countries set out to investigate if methylprednisolone alters the risk of acute kidney injury in patients undergoing cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass. Between June 2007 and December 2013, 7,286 patients were randomized to intravenous methylprednisolone 250 mg at anesthetic induction and 250 mg at initiation of coronary bypass, or placebo.

AKI was defined as a 0.3 mg/dL increase or greater in postoperative serum creatinine concentration from the preoperative concentration within 14 days following surgery, or a 50% increase from the preoperative value within 14 days following surgery. Secondary outcomes included different stages of AKI and receipt of acute dialysis in the 30 days following surgery. Patients, caregivers, and researchers were blinded to the treatment allocation.

Of the 7,286 patients, 3,647 received methylprednisolone and 3,639 received placebo. The mean age of patients was 60 years, 60% were men, 26% were diabetic, and 25% of patients had combined CABG and valve surgery.

The SIRS Investigators reported that the risk of AKI was similar among patients who received methylprednisolone and those who received placebo (40.9% vs. 39.5%, respectively; relative risk 1.03). Results were similar across multiple categorical definitions of AKI, including AKI or death (41.5% vs 40.2%; RR 1.03); AKI stage of 2 or greater (9.9% vs 9.9%; RR 1.01); AKI stage of 3 or greater (4% vs. 4.5%; RR .89), and being on acute dialysis (2.6% vs. 2.4%; RR 1.08).

“There was no benefit of steroids on the risk of AKI in those with or without preoperative chronic kidney disease,” Dr. Garg said. “The result was also not different in the subpopulation of patients with AKI as defined by Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes.” Results from SIRS “would suggest that patients undergoing cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass should not use prophylactic steroids to prevent AKI. When we consider the side effect profile, the most clinically relevant outcomes, and apply the GRADE framework [the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation] to the available evidence, we would recommend that steroids not be used in this way, with a grade 1B recommendation.”

The study was sponsored by the Population Health Research Institute in Hamilton, Ontario and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Garg reported having no relevant financial disclosures for this study.

SAN DIEGO – Among patients undergoing cardiac bypass surgery, perioperative use of corticosteroids did not alter the risk of acute kidney injury, results from a large randomized trial showed.

“Worldwide, over 20 million cardiac surgeries are done each year, but 4 million are complicated by acute kidney injury, and 200,000 are complicated by severe kidney injury treated with dialysis,” Dr. Amit X. Garg said during a press briefing at the annual meeting of the American Society of Nephrology. “So certainly people would benefit from a therapy to prevent acute kidney injury (AKI) and improve the safety of surgery.”

Dr. Garg, a nephrologist at the London Health Sciences Centre in London, Ontario, Canada, noted that cardiopulmonary bypass initiates a systemic inflammatory response syndrome, “which activates complement, inflammatory cytokines, and other inflammatory mediators, which in turn increases endothelial permeability, organ damage, and increased morbidity and mortality, including acute kidney injury.” Researchers are interested in corticosteroids, “because they suppress this inflammatory response. In other settings, such as acute glomerulonephritis, we successfully use corticosteroids to treat acute inflammation in the kidney,” he said.

In a study known as the Steroids in caRdiac Surgery Trial (SIRS), researchers at 79 centers in 18 countries set out to investigate if methylprednisolone alters the risk of acute kidney injury in patients undergoing cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass. Between June 2007 and December 2013, 7,286 patients were randomized to intravenous methylprednisolone 250 mg at anesthetic induction and 250 mg at initiation of coronary bypass, or placebo.

AKI was defined as a 0.3 mg/dL increase or greater in postoperative serum creatinine concentration from the preoperative concentration within 14 days following surgery, or a 50% increase from the preoperative value within 14 days following surgery. Secondary outcomes included different stages of AKI and receipt of acute dialysis in the 30 days following surgery. Patients, caregivers, and researchers were blinded to the treatment allocation.

Of the 7,286 patients, 3,647 received methylprednisolone and 3,639 received placebo. The mean age of patients was 60 years, 60% were men, 26% were diabetic, and 25% of patients had combined CABG and valve surgery.

The SIRS Investigators reported that the risk of AKI was similar among patients who received methylprednisolone and those who received placebo (40.9% vs. 39.5%, respectively; relative risk 1.03). Results were similar across multiple categorical definitions of AKI, including AKI or death (41.5% vs 40.2%; RR 1.03); AKI stage of 2 or greater (9.9% vs 9.9%; RR 1.01); AKI stage of 3 or greater (4% vs. 4.5%; RR .89), and being on acute dialysis (2.6% vs. 2.4%; RR 1.08).

“There was no benefit of steroids on the risk of AKI in those with or without preoperative chronic kidney disease,” Dr. Garg said. “The result was also not different in the subpopulation of patients with AKI as defined by Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes.” Results from SIRS “would suggest that patients undergoing cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass should not use prophylactic steroids to prevent AKI. When we consider the side effect profile, the most clinically relevant outcomes, and apply the GRADE framework [the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation] to the available evidence, we would recommend that steroids not be used in this way, with a grade 1B recommendation.”

The study was sponsored by the Population Health Research Institute in Hamilton, Ontario and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Garg reported having no relevant financial disclosures for this study.

SAN DIEGO – Among patients undergoing cardiac bypass surgery, perioperative use of corticosteroids did not alter the risk of acute kidney injury, results from a large randomized trial showed.

“Worldwide, over 20 million cardiac surgeries are done each year, but 4 million are complicated by acute kidney injury, and 200,000 are complicated by severe kidney injury treated with dialysis,” Dr. Amit X. Garg said during a press briefing at the annual meeting of the American Society of Nephrology. “So certainly people would benefit from a therapy to prevent acute kidney injury (AKI) and improve the safety of surgery.”

Dr. Garg, a nephrologist at the London Health Sciences Centre in London, Ontario, Canada, noted that cardiopulmonary bypass initiates a systemic inflammatory response syndrome, “which activates complement, inflammatory cytokines, and other inflammatory mediators, which in turn increases endothelial permeability, organ damage, and increased morbidity and mortality, including acute kidney injury.” Researchers are interested in corticosteroids, “because they suppress this inflammatory response. In other settings, such as acute glomerulonephritis, we successfully use corticosteroids to treat acute inflammation in the kidney,” he said.

In a study known as the Steroids in caRdiac Surgery Trial (SIRS), researchers at 79 centers in 18 countries set out to investigate if methylprednisolone alters the risk of acute kidney injury in patients undergoing cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass. Between June 2007 and December 2013, 7,286 patients were randomized to intravenous methylprednisolone 250 mg at anesthetic induction and 250 mg at initiation of coronary bypass, or placebo.

AKI was defined as a 0.3 mg/dL increase or greater in postoperative serum creatinine concentration from the preoperative concentration within 14 days following surgery, or a 50% increase from the preoperative value within 14 days following surgery. Secondary outcomes included different stages of AKI and receipt of acute dialysis in the 30 days following surgery. Patients, caregivers, and researchers were blinded to the treatment allocation.

Of the 7,286 patients, 3,647 received methylprednisolone and 3,639 received placebo. The mean age of patients was 60 years, 60% were men, 26% were diabetic, and 25% of patients had combined CABG and valve surgery.

The SIRS Investigators reported that the risk of AKI was similar among patients who received methylprednisolone and those who received placebo (40.9% vs. 39.5%, respectively; relative risk 1.03). Results were similar across multiple categorical definitions of AKI, including AKI or death (41.5% vs 40.2%; RR 1.03); AKI stage of 2 or greater (9.9% vs 9.9%; RR 1.01); AKI stage of 3 or greater (4% vs. 4.5%; RR .89), and being on acute dialysis (2.6% vs. 2.4%; RR 1.08).

“There was no benefit of steroids on the risk of AKI in those with or without preoperative chronic kidney disease,” Dr. Garg said. “The result was also not different in the subpopulation of patients with AKI as defined by Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes.” Results from SIRS “would suggest that patients undergoing cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass should not use prophylactic steroids to prevent AKI. When we consider the side effect profile, the most clinically relevant outcomes, and apply the GRADE framework [the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation] to the available evidence, we would recommend that steroids not be used in this way, with a grade 1B recommendation.”

The study was sponsored by the Population Health Research Institute in Hamilton, Ontario and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Garg reported having no relevant financial disclosures for this study.

AT KIDNEY WEEK 2015

Key clinical point: Perioperative use of steroids did not affect the risk of acute kidney injury (AKI) in patients undergoing coronary bypass surgery.

Major finding: The risk of AKI was similar among patients who received methylprednisolone and those who received placebo (40.9% vs. 39.5%, respectively; relative risk 1.03).

Data source: A study of 7,286 patients undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass surgery who were randomized to intravenous methylprednisolone 250 mg at anesthetic induction and 250 mg at initiation of coronary bypass, or placebo.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by the Population Health Research Institute in Hamilton, Ontario and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Garg reported having no relevant financial disclosures for this study.

Short-term adverse events modest after bariatric surgery in slimmer diabetics

LOS ANGELES – A nationwide analysis shows modest early morbidity and low mortality following bariatric surgery in patients with type 2 diabetes who are not morbidly obese.

At 30 days’ follow-up among 1,003 patients, the composite complication rate, defined as the presence of any of 16 adverse events, was 4.2%; the reoperation rate was 1.6%; and two patients (0.2%) died.

“A 2-hour surgical procedure requiring a 2-day hospital stay that is associated with low morbidity and mortality can lead to remission of a chronic, progressive, and disabling disease,” lead author Dr. Ali Aminian of the Cleveland Clinic said at Obesity Week 2015.

“Based on these findings, bariatric surgery can be considered a relatively safe option for managing type 2 diabetes in patients with mild obesity.”

The analysis included adults with a body mass index of at least 25 kg/m2, but less than 35 kg/m2 (mean, 33 kg/m2).

These data are important because most patients with type 2 diabetes fall into this BMI category, he said.

Most of the patients were women (74.3%), 40% were using insulin, 78% had hypertension, and 9% had cardiac disease, according to the analysis, drawn from the American College of Surgery National Surgical Quality Improvement Program 2005-2013 database.

Roux-en-Y bypass was performed in 574 patients, adjustable gastric banding in 227, sleeve gastrectomy in 189, and duodenal switch in 13.

The most common adverse events overall were blood transfusion and reoperation (both 1.6%), a hospital stay longer than 7 days (0.6%), and organ space surgical-site infection (0.5%).

Composite morbidity and mortality was highest in the Roux-en-Y bypass group, compared with the adjustable banding and sleeve groups (5% vs. 3.1% vs. 3.2%, respectively), Dr. Aminian said at the meeting, presented by the Obesity Society and the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

Only 3 of 46 patients with a BMI of less than 30 kg/m2 had an adverse event.

Available randomized controlled trials can’t clearly resolve the safety concerns of bariatric surgery in the subgroup of patients with type 2 diabetes who are overweight and mildly obese because such small trials are unlikely to reveal uncommon but clinically serious complications, Dr. Aminian said. In addition, many of the trials have screened out low-BMI and high-risk patients.

Those in attendance at the presentation, however, weren’t entirely convinced the current analysis could allay all safety concerns.

Session comoderator Dr. Daniel Cottam, a bariatric surgeon in group practice in Salt Lake City, said, “I like the summary; however, the use of the word ‘safe’ can be taken to mean a lot of things. It’s one of those squishy words.”

Though the authors have shown that bariatric surgery can be performed in diabetics with a low BMI, in order to say it is safe, the comparison needs to be drawn to the all-cause mortality for these patients in the general population and with other surgical procedures.

“That would be useful in the manuscript because as we approach our patients, we want to be able to say, ‘Listen, if you live with diabetes and a BMI of 25-35 for 5 years, this is your all-cause mortality, and surgery is going to save your life, not hurt it,’ ” Dr. Cottam said.

Along the same lines, Dr. Harvey Sugerman emeritus professor of surgery at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, commented, “Like the old days of routinely operating on any patient with diabetes and gallstones, the data were that just having one death in a young person and the quality-of-life-years lost, it would take you thousands of gallbladders to make up for that one death.”

Dr. Sugarmen also asked for details on the deaths including where they occurred, in whom, and whether the centers were inexperienced.

Dr. Aminian could not recall at the time, but in an interview with this news organization said one death was in a 61-year-old with a history of cardiac disease and chronic kidney failure secondary to insulin-dependent diabetes who developed postop bleeding after gastric bypass. The second was in a 59-year-old patient, again on insulin, who was discharged without problems after gastric bypass, but died within 30 days after surgery.

Although most serious complications occur in this period, the main limitation of the study is that the dataset does not capture adverse events beyond 30 days after surgery, which can lead to underestimation of real risk, Dr. Aminian told the crowd.

“Further large clinical studies on long-term safety and efficacy outcomes of bariatric surgery in patients with type 2 diabetes and low BMI are warranted,” he said.

LOS ANGELES – A nationwide analysis shows modest early morbidity and low mortality following bariatric surgery in patients with type 2 diabetes who are not morbidly obese.

At 30 days’ follow-up among 1,003 patients, the composite complication rate, defined as the presence of any of 16 adverse events, was 4.2%; the reoperation rate was 1.6%; and two patients (0.2%) died.

“A 2-hour surgical procedure requiring a 2-day hospital stay that is associated with low morbidity and mortality can lead to remission of a chronic, progressive, and disabling disease,” lead author Dr. Ali Aminian of the Cleveland Clinic said at Obesity Week 2015.

“Based on these findings, bariatric surgery can be considered a relatively safe option for managing type 2 diabetes in patients with mild obesity.”

The analysis included adults with a body mass index of at least 25 kg/m2, but less than 35 kg/m2 (mean, 33 kg/m2).

These data are important because most patients with type 2 diabetes fall into this BMI category, he said.

Most of the patients were women (74.3%), 40% were using insulin, 78% had hypertension, and 9% had cardiac disease, according to the analysis, drawn from the American College of Surgery National Surgical Quality Improvement Program 2005-2013 database.

Roux-en-Y bypass was performed in 574 patients, adjustable gastric banding in 227, sleeve gastrectomy in 189, and duodenal switch in 13.

The most common adverse events overall were blood transfusion and reoperation (both 1.6%), a hospital stay longer than 7 days (0.6%), and organ space surgical-site infection (0.5%).

Composite morbidity and mortality was highest in the Roux-en-Y bypass group, compared with the adjustable banding and sleeve groups (5% vs. 3.1% vs. 3.2%, respectively), Dr. Aminian said at the meeting, presented by the Obesity Society and the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

Only 3 of 46 patients with a BMI of less than 30 kg/m2 had an adverse event.

Available randomized controlled trials can’t clearly resolve the safety concerns of bariatric surgery in the subgroup of patients with type 2 diabetes who are overweight and mildly obese because such small trials are unlikely to reveal uncommon but clinically serious complications, Dr. Aminian said. In addition, many of the trials have screened out low-BMI and high-risk patients.

Those in attendance at the presentation, however, weren’t entirely convinced the current analysis could allay all safety concerns.

Session comoderator Dr. Daniel Cottam, a bariatric surgeon in group practice in Salt Lake City, said, “I like the summary; however, the use of the word ‘safe’ can be taken to mean a lot of things. It’s one of those squishy words.”

Though the authors have shown that bariatric surgery can be performed in diabetics with a low BMI, in order to say it is safe, the comparison needs to be drawn to the all-cause mortality for these patients in the general population and with other surgical procedures.

“That would be useful in the manuscript because as we approach our patients, we want to be able to say, ‘Listen, if you live with diabetes and a BMI of 25-35 for 5 years, this is your all-cause mortality, and surgery is going to save your life, not hurt it,’ ” Dr. Cottam said.

Along the same lines, Dr. Harvey Sugerman emeritus professor of surgery at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, commented, “Like the old days of routinely operating on any patient with diabetes and gallstones, the data were that just having one death in a young person and the quality-of-life-years lost, it would take you thousands of gallbladders to make up for that one death.”

Dr. Sugarmen also asked for details on the deaths including where they occurred, in whom, and whether the centers were inexperienced.

Dr. Aminian could not recall at the time, but in an interview with this news organization said one death was in a 61-year-old with a history of cardiac disease and chronic kidney failure secondary to insulin-dependent diabetes who developed postop bleeding after gastric bypass. The second was in a 59-year-old patient, again on insulin, who was discharged without problems after gastric bypass, but died within 30 days after surgery.

Although most serious complications occur in this period, the main limitation of the study is that the dataset does not capture adverse events beyond 30 days after surgery, which can lead to underestimation of real risk, Dr. Aminian told the crowd.

“Further large clinical studies on long-term safety and efficacy outcomes of bariatric surgery in patients with type 2 diabetes and low BMI are warranted,” he said.

LOS ANGELES – A nationwide analysis shows modest early morbidity and low mortality following bariatric surgery in patients with type 2 diabetes who are not morbidly obese.

At 30 days’ follow-up among 1,003 patients, the composite complication rate, defined as the presence of any of 16 adverse events, was 4.2%; the reoperation rate was 1.6%; and two patients (0.2%) died.

“A 2-hour surgical procedure requiring a 2-day hospital stay that is associated with low morbidity and mortality can lead to remission of a chronic, progressive, and disabling disease,” lead author Dr. Ali Aminian of the Cleveland Clinic said at Obesity Week 2015.

“Based on these findings, bariatric surgery can be considered a relatively safe option for managing type 2 diabetes in patients with mild obesity.”

The analysis included adults with a body mass index of at least 25 kg/m2, but less than 35 kg/m2 (mean, 33 kg/m2).

These data are important because most patients with type 2 diabetes fall into this BMI category, he said.

Most of the patients were women (74.3%), 40% were using insulin, 78% had hypertension, and 9% had cardiac disease, according to the analysis, drawn from the American College of Surgery National Surgical Quality Improvement Program 2005-2013 database.

Roux-en-Y bypass was performed in 574 patients, adjustable gastric banding in 227, sleeve gastrectomy in 189, and duodenal switch in 13.

The most common adverse events overall were blood transfusion and reoperation (both 1.6%), a hospital stay longer than 7 days (0.6%), and organ space surgical-site infection (0.5%).

Composite morbidity and mortality was highest in the Roux-en-Y bypass group, compared with the adjustable banding and sleeve groups (5% vs. 3.1% vs. 3.2%, respectively), Dr. Aminian said at the meeting, presented by the Obesity Society and the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

Only 3 of 46 patients with a BMI of less than 30 kg/m2 had an adverse event.

Available randomized controlled trials can’t clearly resolve the safety concerns of bariatric surgery in the subgroup of patients with type 2 diabetes who are overweight and mildly obese because such small trials are unlikely to reveal uncommon but clinically serious complications, Dr. Aminian said. In addition, many of the trials have screened out low-BMI and high-risk patients.

Those in attendance at the presentation, however, weren’t entirely convinced the current analysis could allay all safety concerns.

Session comoderator Dr. Daniel Cottam, a bariatric surgeon in group practice in Salt Lake City, said, “I like the summary; however, the use of the word ‘safe’ can be taken to mean a lot of things. It’s one of those squishy words.”

Though the authors have shown that bariatric surgery can be performed in diabetics with a low BMI, in order to say it is safe, the comparison needs to be drawn to the all-cause mortality for these patients in the general population and with other surgical procedures.

“That would be useful in the manuscript because as we approach our patients, we want to be able to say, ‘Listen, if you live with diabetes and a BMI of 25-35 for 5 years, this is your all-cause mortality, and surgery is going to save your life, not hurt it,’ ” Dr. Cottam said.

Along the same lines, Dr. Harvey Sugerman emeritus professor of surgery at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, commented, “Like the old days of routinely operating on any patient with diabetes and gallstones, the data were that just having one death in a young person and the quality-of-life-years lost, it would take you thousands of gallbladders to make up for that one death.”

Dr. Sugarmen also asked for details on the deaths including where they occurred, in whom, and whether the centers were inexperienced.

Dr. Aminian could not recall at the time, but in an interview with this news organization said one death was in a 61-year-old with a history of cardiac disease and chronic kidney failure secondary to insulin-dependent diabetes who developed postop bleeding after gastric bypass. The second was in a 59-year-old patient, again on insulin, who was discharged without problems after gastric bypass, but died within 30 days after surgery.

Although most serious complications occur in this period, the main limitation of the study is that the dataset does not capture adverse events beyond 30 days after surgery, which can lead to underestimation of real risk, Dr. Aminian told the crowd.

“Further large clinical studies on long-term safety and efficacy outcomes of bariatric surgery in patients with type 2 diabetes and low BMI are warranted,” he said.

AT OBESITY WEEK 2015

Key clinical point: Short-term outcomes suggest that bariatric surgery may be safe in patients with type 2 diabetes who are not morbidly obese.

Major finding: The composite complication rate was 4.2%, 1.6% required reoperation, and two patients (0.2%) died.

Data source: An ACS-NSQIP safety analysis of 1,003 diabetics undergoing bariatric surgery.

Disclosures: The authors reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

Pain a common cause of revisits after same-day surgery

SAN DIEGO – Nearly one-third of pain-related emergency room visits or hospital readmissions following same-day surgery were attributable to inadequate pain management in the peridischarge period, a large single-center analysis demonstrated.

“Pain management in the perioperative period is largely an anesthesiologist responsibility, but maybe it would be helpful if it was a little bit more multispecialty, if we had more communication,” study author Dr. Martha O. Herbst said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Society of Anesthesiologists.

“There were some patients who came back for pain because they didn’t even receive prescriptions from their surgeon. Maybe a little better communication between the anesthesiologist and the surgeon on how to optimize specific patients and prevent those readmissions for pain would help,” she said.

Inspired by a similar study published in 2002 (J Clin Anesth. 2002;14[5]:349-53), Dr. Herbst, a fourth-year anesthesiology resident at Beaumont Hospital in Royal Oak, Mich., and her associates retrospectively evaluated the number of readmissions or revisits that occurred among 28,647 patients who underwent same-day surgery in the Beaumont Health system in 2012. A total of 1,559 revisits occurred during the study period. Of these, 621 (39.8%) were revisits related to the surgical procedure and 145 (9.3% overall and 23.3% of readmissions) were due to pain.

The researchers then stratified patients into one of six categories for readmission. These included all-cause pain (16%); surgical-related issues such as wound opening or reinfection (21%); medical issues such as exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (43%); bleeding complications such as hematuria, hemodialysis, and surgical site bleeding (6%); adverse medical reactions (2%); and other (12%).

Of the 145 patients who were readmitted for pain from the same-day surgery, 71% were deemed to have no pre-existing risk for readmission while 29% had at least one risk factor for readmission. These included opioid monotherapy during the procedure (11%), history of chronic pain (9%), no pain medication given during the procedure (4%), inadequate doses of analgesics used (3%), and discharge without a prescription for an analgesic (2%).

“There were people who got tiny doses of pain medications after a huge, painful procedure, so that was surprising,” Dr. Herbst said. “Maybe they weren’t optimally managed at the time of surgery.”

The findings, she concluded, underscore the need for a team-based approach to pain management in the same-day surgery population, with discharge planning focused on patient education, expectation management, multimodal analgesia optimization, and pain risk assessment.

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Nearly one-third of pain-related emergency room visits or hospital readmissions following same-day surgery were attributable to inadequate pain management in the peridischarge period, a large single-center analysis demonstrated.

“Pain management in the perioperative period is largely an anesthesiologist responsibility, but maybe it would be helpful if it was a little bit more multispecialty, if we had more communication,” study author Dr. Martha O. Herbst said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Society of Anesthesiologists.

“There were some patients who came back for pain because they didn’t even receive prescriptions from their surgeon. Maybe a little better communication between the anesthesiologist and the surgeon on how to optimize specific patients and prevent those readmissions for pain would help,” she said.

Inspired by a similar study published in 2002 (J Clin Anesth. 2002;14[5]:349-53), Dr. Herbst, a fourth-year anesthesiology resident at Beaumont Hospital in Royal Oak, Mich., and her associates retrospectively evaluated the number of readmissions or revisits that occurred among 28,647 patients who underwent same-day surgery in the Beaumont Health system in 2012. A total of 1,559 revisits occurred during the study period. Of these, 621 (39.8%) were revisits related to the surgical procedure and 145 (9.3% overall and 23.3% of readmissions) were due to pain.

The researchers then stratified patients into one of six categories for readmission. These included all-cause pain (16%); surgical-related issues such as wound opening or reinfection (21%); medical issues such as exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (43%); bleeding complications such as hematuria, hemodialysis, and surgical site bleeding (6%); adverse medical reactions (2%); and other (12%).

Of the 145 patients who were readmitted for pain from the same-day surgery, 71% were deemed to have no pre-existing risk for readmission while 29% had at least one risk factor for readmission. These included opioid monotherapy during the procedure (11%), history of chronic pain (9%), no pain medication given during the procedure (4%), inadequate doses of analgesics used (3%), and discharge without a prescription for an analgesic (2%).

“There were people who got tiny doses of pain medications after a huge, painful procedure, so that was surprising,” Dr. Herbst said. “Maybe they weren’t optimally managed at the time of surgery.”

The findings, she concluded, underscore the need for a team-based approach to pain management in the same-day surgery population, with discharge planning focused on patient education, expectation management, multimodal analgesia optimization, and pain risk assessment.

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Nearly one-third of pain-related emergency room visits or hospital readmissions following same-day surgery were attributable to inadequate pain management in the peridischarge period, a large single-center analysis demonstrated.

“Pain management in the perioperative period is largely an anesthesiologist responsibility, but maybe it would be helpful if it was a little bit more multispecialty, if we had more communication,” study author Dr. Martha O. Herbst said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Society of Anesthesiologists.

“There were some patients who came back for pain because they didn’t even receive prescriptions from their surgeon. Maybe a little better communication between the anesthesiologist and the surgeon on how to optimize specific patients and prevent those readmissions for pain would help,” she said.

Inspired by a similar study published in 2002 (J Clin Anesth. 2002;14[5]:349-53), Dr. Herbst, a fourth-year anesthesiology resident at Beaumont Hospital in Royal Oak, Mich., and her associates retrospectively evaluated the number of readmissions or revisits that occurred among 28,647 patients who underwent same-day surgery in the Beaumont Health system in 2012. A total of 1,559 revisits occurred during the study period. Of these, 621 (39.8%) were revisits related to the surgical procedure and 145 (9.3% overall and 23.3% of readmissions) were due to pain.

The researchers then stratified patients into one of six categories for readmission. These included all-cause pain (16%); surgical-related issues such as wound opening or reinfection (21%); medical issues such as exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (43%); bleeding complications such as hematuria, hemodialysis, and surgical site bleeding (6%); adverse medical reactions (2%); and other (12%).

Of the 145 patients who were readmitted for pain from the same-day surgery, 71% were deemed to have no pre-existing risk for readmission while 29% had at least one risk factor for readmission. These included opioid monotherapy during the procedure (11%), history of chronic pain (9%), no pain medication given during the procedure (4%), inadequate doses of analgesics used (3%), and discharge without a prescription for an analgesic (2%).

“There were people who got tiny doses of pain medications after a huge, painful procedure, so that was surprising,” Dr. Herbst said. “Maybe they weren’t optimally managed at the time of surgery.”

The findings, she concluded, underscore the need for a team-based approach to pain management in the same-day surgery population, with discharge planning focused on patient education, expectation management, multimodal analgesia optimization, and pain risk assessment.

The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

AT THE ASA ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Among patients who underwent same-day surgery, pain was a significant cause of readmissions or revisits.

Major finding: Of 145 patients who were readmitted for pain following same-day surgery, 71% were deemed to have no pre-existing risk for readmission, while 29% had at least one risk factor for readmission.

Data source: A retrospective evaluation of the number of readmissions or revisits that occurred among 28,647 patients who underwent same-day surgery at a single health system in 2012.

Disclosures: The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

AHA: Mixed results for mitral valve replacement vs. repair

Patients undergoing mitral valve replacement had a lower risk of regurgitation and heart failure–related adverse events at 2 years than those undergoing valve repair, according to the results of a trial presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions and published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The results of the trial appear to associate mitral valve replacement with clinical advantages over mitral valve repair after 2 years of follow-up. However, replacement held no significant advantages over repair in the primary endpoint of left ventricular end-systolic volume index (LVESVI) or in overall survival, said Dr. Daniel Goldstein of the department of cardiothoracic surgery at Montefiore Medical Center, New York.

In the trial conducted by the Cardiothoracic Surgical Trials Network (CTSN), 251 patients with chronic severe ischemic mitral regurgitation were randomly assigned to undergo surgical repair of the mitral valve or to receive a mitral valve replacement with a prosthetic and procedure selected at the discretion of the surgeon.

In addition to the primary endpoint of LVESVI, the two approaches were also compared for survival, regurgitation recurrence, and heart failure events.

At 2 years, the mean change from baseline in LVESVI, a measure of remodeling, did not differ significantly between the repair and replacement arms (–9.0 vs. –6.5 mL/m2, respectively). In addition, although the 2-year mortality rate was numerically lower in the repair arm relative to the replacement arm (19% vs. 23.2%, respectively), it was also not statistically different (P = .39).

However, the rate of recurrence of moderate or severe mitral regurgitation favored replacement over repair and was significant (3.8% vs. 58.8%, respectively; P less than .001). In addition, the rate of cardiovascular readmissions was significantly lower in the replacement group (P = .01).

For those in the repair group, there were significant trends for more serious adverse events related to heart failure (P = .05) and for a lower quality of life improvement (P = .07) on the Minnesota Living With Heart Failure questionnaire. There were no significant differences in rates of all serious adverse events or overall readmissions.

All of the differences between groups observed at 2 years amplify differences previously reported after 12 months (N Engl J Med. 2014 Jan 2;370[1]:23-32). For example, the difference in the rate of moderate to severe regurgitation favoring replacement over repair was already significant at that time (2.3% vs. 32.6%, respectively; P less than .001), even though the mortality rates were then, as now, numerically lower in the repair group versus the replacement group (14.3% vs. 17.6%, respectively; P = .45).

Dr. Goldstein reported no relevant financial relationships.

Patients undergoing mitral valve replacement had a lower risk of regurgitation and heart failure–related adverse events at 2 years than those undergoing valve repair, according to the results of a trial presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions and published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The results of the trial appear to associate mitral valve replacement with clinical advantages over mitral valve repair after 2 years of follow-up. However, replacement held no significant advantages over repair in the primary endpoint of left ventricular end-systolic volume index (LVESVI) or in overall survival, said Dr. Daniel Goldstein of the department of cardiothoracic surgery at Montefiore Medical Center, New York.

In the trial conducted by the Cardiothoracic Surgical Trials Network (CTSN), 251 patients with chronic severe ischemic mitral regurgitation were randomly assigned to undergo surgical repair of the mitral valve or to receive a mitral valve replacement with a prosthetic and procedure selected at the discretion of the surgeon.

In addition to the primary endpoint of LVESVI, the two approaches were also compared for survival, regurgitation recurrence, and heart failure events.

At 2 years, the mean change from baseline in LVESVI, a measure of remodeling, did not differ significantly between the repair and replacement arms (–9.0 vs. –6.5 mL/m2, respectively). In addition, although the 2-year mortality rate was numerically lower in the repair arm relative to the replacement arm (19% vs. 23.2%, respectively), it was also not statistically different (P = .39).

However, the rate of recurrence of moderate or severe mitral regurgitation favored replacement over repair and was significant (3.8% vs. 58.8%, respectively; P less than .001). In addition, the rate of cardiovascular readmissions was significantly lower in the replacement group (P = .01).

For those in the repair group, there were significant trends for more serious adverse events related to heart failure (P = .05) and for a lower quality of life improvement (P = .07) on the Minnesota Living With Heart Failure questionnaire. There were no significant differences in rates of all serious adverse events or overall readmissions.

All of the differences between groups observed at 2 years amplify differences previously reported after 12 months (N Engl J Med. 2014 Jan 2;370[1]:23-32). For example, the difference in the rate of moderate to severe regurgitation favoring replacement over repair was already significant at that time (2.3% vs. 32.6%, respectively; P less than .001), even though the mortality rates were then, as now, numerically lower in the repair group versus the replacement group (14.3% vs. 17.6%, respectively; P = .45).

Dr. Goldstein reported no relevant financial relationships.

Patients undergoing mitral valve replacement had a lower risk of regurgitation and heart failure–related adverse events at 2 years than those undergoing valve repair, according to the results of a trial presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions and published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The results of the trial appear to associate mitral valve replacement with clinical advantages over mitral valve repair after 2 years of follow-up. However, replacement held no significant advantages over repair in the primary endpoint of left ventricular end-systolic volume index (LVESVI) or in overall survival, said Dr. Daniel Goldstein of the department of cardiothoracic surgery at Montefiore Medical Center, New York.

In the trial conducted by the Cardiothoracic Surgical Trials Network (CTSN), 251 patients with chronic severe ischemic mitral regurgitation were randomly assigned to undergo surgical repair of the mitral valve or to receive a mitral valve replacement with a prosthetic and procedure selected at the discretion of the surgeon.

In addition to the primary endpoint of LVESVI, the two approaches were also compared for survival, regurgitation recurrence, and heart failure events.

At 2 years, the mean change from baseline in LVESVI, a measure of remodeling, did not differ significantly between the repair and replacement arms (–9.0 vs. –6.5 mL/m2, respectively). In addition, although the 2-year mortality rate was numerically lower in the repair arm relative to the replacement arm (19% vs. 23.2%, respectively), it was also not statistically different (P = .39).

However, the rate of recurrence of moderate or severe mitral regurgitation favored replacement over repair and was significant (3.8% vs. 58.8%, respectively; P less than .001). In addition, the rate of cardiovascular readmissions was significantly lower in the replacement group (P = .01).

For those in the repair group, there were significant trends for more serious adverse events related to heart failure (P = .05) and for a lower quality of life improvement (P = .07) on the Minnesota Living With Heart Failure questionnaire. There were no significant differences in rates of all serious adverse events or overall readmissions.

All of the differences between groups observed at 2 years amplify differences previously reported after 12 months (N Engl J Med. 2014 Jan 2;370[1]:23-32). For example, the difference in the rate of moderate to severe regurgitation favoring replacement over repair was already significant at that time (2.3% vs. 32.6%, respectively; P less than .001), even though the mortality rates were then, as now, numerically lower in the repair group versus the replacement group (14.3% vs. 17.6%, respectively; P = .45).

Dr. Goldstein reported no relevant financial relationships.

FROM THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: Mitral valve replacement reduced regurgitation better than valve repair, but it didn’t significantly improve left ventricular function or survival.

Major finding: In patients with severe ischemic mitral regurgitation, regurgitation occurred more frequently after mitral valve repair than after valve replacement (58.8% vs. 3.8%; P less than .001), but left ventricular end-systolic volume indexes and survival rates were not significantly different.

Data source: A randomized, multicenter trial with 251 patients.

Disclosures: Dr. Goldstein reported no relevant financial relationships.

CDC to celebrate best blood clot prevention strategies

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has launched a program to honor hospitals, health systems, and managed care organizations that have implemented effective strategies to prevent health care–associated blood clots.

The HA-VTE Prevention Challenge invites provider organizations around the world to submit evidence of demonstrated successful use of venous thromboembolism (VTE) prevention strategies and interventions. VTE leads to approximately 100,000 premature deaths in the United States every year, according to the CDC, yet as many as 70% of HA-VTEs are preventable, although fewer than half of hospital patients receive appropriate prevention. Indeed, about half of all blood clots happen after a recent hospital stay or surgery.

“Doctors and nurses in hospitals and other health care settings can save lives by implementing the best practices discovered through this challenge,” Dr. Tom Frieden, CDC director, said in a statement. “Tell us about what you are doing and what’s helping prevent blood clots, so we can advance science and save lives together.”

The purpose of the challenge is to highlight the systems, processes, and staffing that contribute to exceptional VTE prevention, according to the CDC. Processes may include the implementation of protocols, risk assessments, and the use of health information technology and clinical decision support tools. Seven of the highest scoring U.S. non-federal hospitals, multihospital systems, hospital networks, and managed care organizations will be recognized as HA-VTE Prevention Champions and will receive a cash award of $10,000 each. Winning submissions from U.S. federal and international entities will be eligible for nonmonetary recognition.

The CDC will accept submissions from Nov. 2, 2015, until Jan. 10, 2016. Winners will be announced in March 2016.

For more information, visit the HA-VTE Prevention Challenge website.

On Twitter: @richpizzi

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has launched a program to honor hospitals, health systems, and managed care organizations that have implemented effective strategies to prevent health care–associated blood clots.

The HA-VTE Prevention Challenge invites provider organizations around the world to submit evidence of demonstrated successful use of venous thromboembolism (VTE) prevention strategies and interventions. VTE leads to approximately 100,000 premature deaths in the United States every year, according to the CDC, yet as many as 70% of HA-VTEs are preventable, although fewer than half of hospital patients receive appropriate prevention. Indeed, about half of all blood clots happen after a recent hospital stay or surgery.

“Doctors and nurses in hospitals and other health care settings can save lives by implementing the best practices discovered through this challenge,” Dr. Tom Frieden, CDC director, said in a statement. “Tell us about what you are doing and what’s helping prevent blood clots, so we can advance science and save lives together.”

The purpose of the challenge is to highlight the systems, processes, and staffing that contribute to exceptional VTE prevention, according to the CDC. Processes may include the implementation of protocols, risk assessments, and the use of health information technology and clinical decision support tools. Seven of the highest scoring U.S. non-federal hospitals, multihospital systems, hospital networks, and managed care organizations will be recognized as HA-VTE Prevention Champions and will receive a cash award of $10,000 each. Winning submissions from U.S. federal and international entities will be eligible for nonmonetary recognition.

The CDC will accept submissions from Nov. 2, 2015, until Jan. 10, 2016. Winners will be announced in March 2016.

For more information, visit the HA-VTE Prevention Challenge website.

On Twitter: @richpizzi

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has launched a program to honor hospitals, health systems, and managed care organizations that have implemented effective strategies to prevent health care–associated blood clots.

The HA-VTE Prevention Challenge invites provider organizations around the world to submit evidence of demonstrated successful use of venous thromboembolism (VTE) prevention strategies and interventions. VTE leads to approximately 100,000 premature deaths in the United States every year, according to the CDC, yet as many as 70% of HA-VTEs are preventable, although fewer than half of hospital patients receive appropriate prevention. Indeed, about half of all blood clots happen after a recent hospital stay or surgery.

“Doctors and nurses in hospitals and other health care settings can save lives by implementing the best practices discovered through this challenge,” Dr. Tom Frieden, CDC director, said in a statement. “Tell us about what you are doing and what’s helping prevent blood clots, so we can advance science and save lives together.”

The purpose of the challenge is to highlight the systems, processes, and staffing that contribute to exceptional VTE prevention, according to the CDC. Processes may include the implementation of protocols, risk assessments, and the use of health information technology and clinical decision support tools. Seven of the highest scoring U.S. non-federal hospitals, multihospital systems, hospital networks, and managed care organizations will be recognized as HA-VTE Prevention Champions and will receive a cash award of $10,000 each. Winning submissions from U.S. federal and international entities will be eligible for nonmonetary recognition.

The CDC will accept submissions from Nov. 2, 2015, until Jan. 10, 2016. Winners will be announced in March 2016.

For more information, visit the HA-VTE Prevention Challenge website.

On Twitter: @richpizzi

Study: High rate of medical errors in postop drug administrations

Medication errors or adverse drug events after surgery occur in as many as one in twenty perioperative medication administrations, according to data published online in the journal Anesthesiology.

A prospective observational study of 277 surgical operations and 3,671 medication administrations found 193 cases (5.3%) involved a medication error or adverse drug event, nearly four-fifths (79.3%) of which were preventable and 68.9% of which were serious (Anesthesiology. 2015 Oct. doi:10.1097/ALN.0000000000000904).

Among the 51 medication errors that led to adverse reactions, nearly half were the result of inappropriate medication doses and 31.4% were due to omitted medications or failure to act, but the most common overall error type was a labeling error.

The medications most commonly associated with errors were propofol, phenylephrine, and fentanyl, and operations greater than 6 hours in duration or with 13 or more medication administrations were associated with a significantly greater risk of errors.

“Examples of technology-based interventions [to minimize perioperative MEs and/or ADEs] include bar code–assisted syringe labeling systems, point-of-care bar code–assisted anesthesia documentation systems, specific drug decision support, and alerts,” wrote the study’s lead author Dr. Karen C. Nanji of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, and her coauthors.

The study was supported by the Doctors Company Foundation and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health. One coauthor – Dr. David Bates – declared financial interests in medical decision support software, as well as funding and positions with a variety of medical technology companies.

Medication errors or adverse drug events after surgery occur in as many as one in twenty perioperative medication administrations, according to data published online in the journal Anesthesiology.

A prospective observational study of 277 surgical operations and 3,671 medication administrations found 193 cases (5.3%) involved a medication error or adverse drug event, nearly four-fifths (79.3%) of which were preventable and 68.9% of which were serious (Anesthesiology. 2015 Oct. doi:10.1097/ALN.0000000000000904).

Among the 51 medication errors that led to adverse reactions, nearly half were the result of inappropriate medication doses and 31.4% were due to omitted medications or failure to act, but the most common overall error type was a labeling error.

The medications most commonly associated with errors were propofol, phenylephrine, and fentanyl, and operations greater than 6 hours in duration or with 13 or more medication administrations were associated with a significantly greater risk of errors.

“Examples of technology-based interventions [to minimize perioperative MEs and/or ADEs] include bar code–assisted syringe labeling systems, point-of-care bar code–assisted anesthesia documentation systems, specific drug decision support, and alerts,” wrote the study’s lead author Dr. Karen C. Nanji of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, and her coauthors.

The study was supported by the Doctors Company Foundation and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health. One coauthor – Dr. David Bates – declared financial interests in medical decision support software, as well as funding and positions with a variety of medical technology companies.

Medication errors or adverse drug events after surgery occur in as many as one in twenty perioperative medication administrations, according to data published online in the journal Anesthesiology.

A prospective observational study of 277 surgical operations and 3,671 medication administrations found 193 cases (5.3%) involved a medication error or adverse drug event, nearly four-fifths (79.3%) of which were preventable and 68.9% of which were serious (Anesthesiology. 2015 Oct. doi:10.1097/ALN.0000000000000904).

Among the 51 medication errors that led to adverse reactions, nearly half were the result of inappropriate medication doses and 31.4% were due to omitted medications or failure to act, but the most common overall error type was a labeling error.

The medications most commonly associated with errors were propofol, phenylephrine, and fentanyl, and operations greater than 6 hours in duration or with 13 or more medication administrations were associated with a significantly greater risk of errors.

“Examples of technology-based interventions [to minimize perioperative MEs and/or ADEs] include bar code–assisted syringe labeling systems, point-of-care bar code–assisted anesthesia documentation systems, specific drug decision support, and alerts,” wrote the study’s lead author Dr. Karen C. Nanji of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, and her coauthors.

The study was supported by the Doctors Company Foundation and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health. One coauthor – Dr. David Bates – declared financial interests in medical decision support software, as well as funding and positions with a variety of medical technology companies.

FROM ANESTHESIOLOGY

Key clinical point: One in twenty perioperative medication administrations may involve a medication error and/or adverse drug event.

Major finding: Nearly four-fifths of perioperative medication errors or adverse events are preventable.

Data source: A prospective observational study of 277 surgical operations and 3,671 medication administrations.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the Doctors Company Foundation and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health. One coauthor – Dr. David Bates – declared financial interests in medical decision support software, as well as funding and positions with a variety of medical technology companies.

Concurrent mesh herniorrhaphy with bowel surgery doesn’t up morbidity

Concurrent colorectal surgery and mesh herniorrhaphy can be done safely, according to findings from a case-matched study based on American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program data.

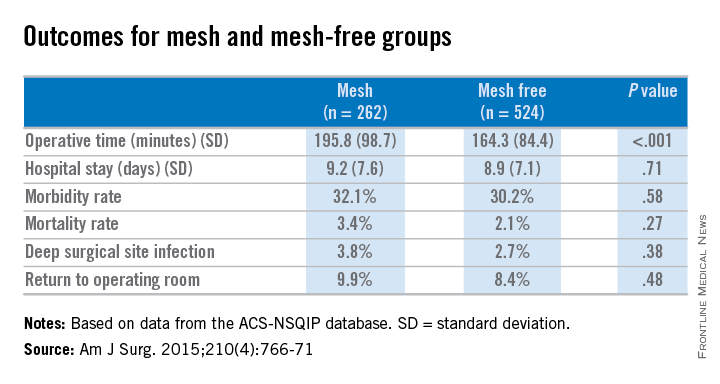

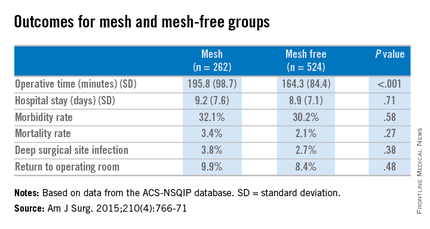

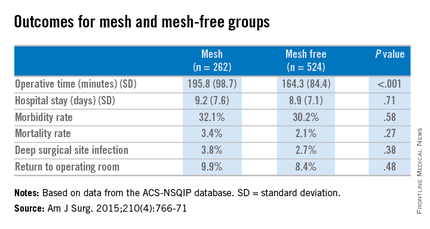

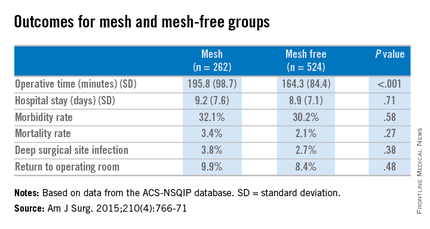

“Our study suggests that mesh repair for [ventral hernia] in the setting of [colorectal surgery] does not worsen 30-day postoperative outcomes,” wrote Dr. Cigdem Benlice and colleagues of the Cleveland Clinic. The study was published in the American Journal of Surgery (2015; 210[4]:766-771]

These two operations are undertaken concurrently in part to save patients from further procedures and anesthesia, but the practice is limited by safety concerns. The complications anticipated include intra-abdominal adhesions, chronic draining sinus, chronic enteric fistula, chronic wound infection, and mesh migration. Any one of these complications could entail further surgical interventions.

Dr. Benlice and her colleagues used the national, validated, risk-adjusted American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS-NSQIP) database to look at short-term outcomes after concurrent ventral hernia repair (VHR) and colorectal surgery (CS), and the risk factors associated with complications. Data on 2,250 patients having CS and VHR operations simultaneously from 2005 to 2010 were reviewed. Patients having simultaneous VHR with mesh and CS (262) were matched closely with those having both procedures but without mesh (524). The case-matching criteria included diagnosis, type of bowel procedure, and American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) class, and follow-up was limited to 30 days.

In a comparison of the mesh and nonmesh groups, morbidity rates were found to be similar (32% vs. 30%, P = .58) as were mortality rates (3.4% vs. 2.1%, P = .27). The rate of deep surgical site infections (3.8% vs. 2.7%, P = .38) were similar between the two groups, and wound disruptions (3.1% vs. 3.1%) rates were the same. The length of hospital stay was also comparable. Mean operating time, however, proved longer in patients who had hernia repair using mesh (196 minutes vs. 164 minutes, P less than .001).

A multivariate analysis showed that open colorectal procedures, III or IV ASA class, smoking, and preoperative open wound or wound infection were significant and independent risk factors (odds ratios, 2.67, 2.51, 2.06, and 2.27, respectively) for surgical site infection.

The limitations of this study reflect some of the limitations of the ACS-NSQIP database. Long-term follow-up, hernia size, type of mesh used, and type of technique used in the operation could not be assessed using the available data. In addition, further analysis of the subgroups of patients with surgical site infections would be needed to examine the impact of mesh (and types of mesh) use on clean-contaminated cases. Researchers noted that at the Cleveland Clinic, type of mesh (biologic vs. nonbiologic) used has been found to have no impact on rates of wound and mesh infection and hernia recurrence, but they were unable to do this kind of analysis with the available data for simultaneous bowel and hernia repair surgery.

The researchers concluded, “the large cohort and strict inclusion, exclusion, and case-matching criteria strengthen the clinical value of this study. When performed simultaneously with CS, VHR with mesh can be performed without increasing perioperative and short-term postoperative morbidity.”

The researchers had no relevant disclosures.

Concurrent colorectal surgery and mesh herniorrhaphy can be done safely, according to findings from a case-matched study based on American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program data.

“Our study suggests that mesh repair for [ventral hernia] in the setting of [colorectal surgery] does not worsen 30-day postoperative outcomes,” wrote Dr. Cigdem Benlice and colleagues of the Cleveland Clinic. The study was published in the American Journal of Surgery (2015; 210[4]:766-771]

These two operations are undertaken concurrently in part to save patients from further procedures and anesthesia, but the practice is limited by safety concerns. The complications anticipated include intra-abdominal adhesions, chronic draining sinus, chronic enteric fistula, chronic wound infection, and mesh migration. Any one of these complications could entail further surgical interventions.