User login

Diffuse Dermal Angiomatosis

Diffuse dermal angiomatosis (DDA) is a rare acquired, cutaneous, reactive, vascular disorder that was originally thought to be a variant of cutaneous reactive angiomatosis (CREA) but is now considered to be on the spectrum of CREA. This article will focus on DDA and review the literature of prior case reports with brief descriptions of the differential diagnosis.

Case Report

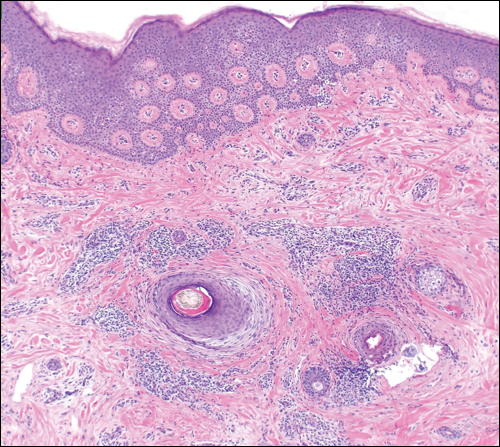

A 43-year-old Haitian man presented to the clinic with a lesion on the left buttock that had developed over the last 6 years. The patient stated the lesion had been enlarging over the last several months. Upon examination, there was a large (15-cm diameter), indurated, hyperpigmented plaque covering the left buttock (Figure 1). The patient reported no medical or contributory family history. Upon review of systems, he described a burning sensation sometimes in the area of the lesion that would develop randomly throughout the year.

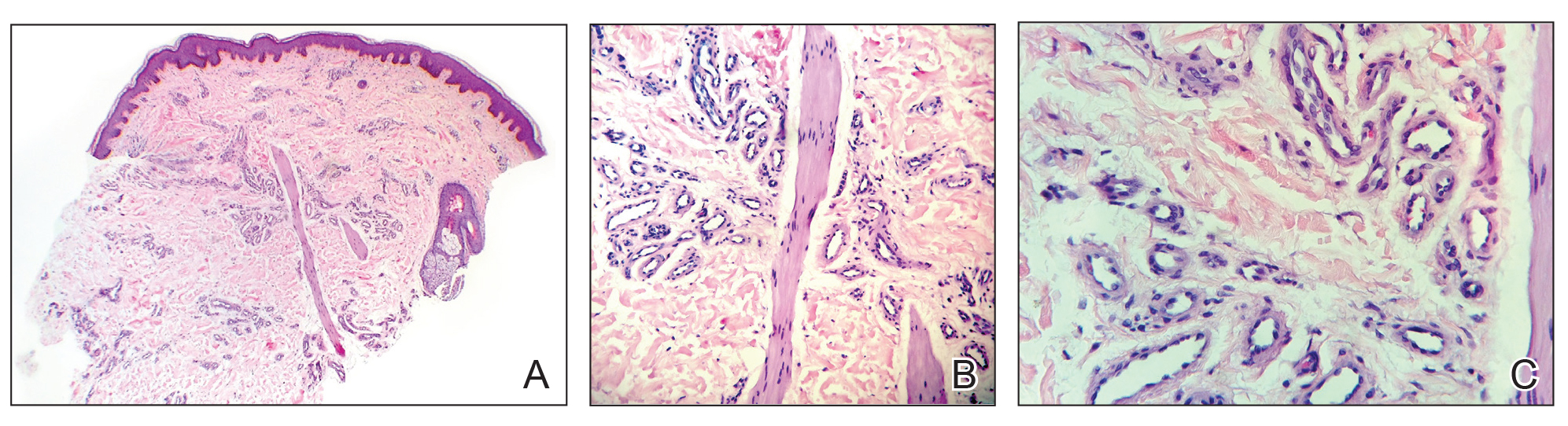

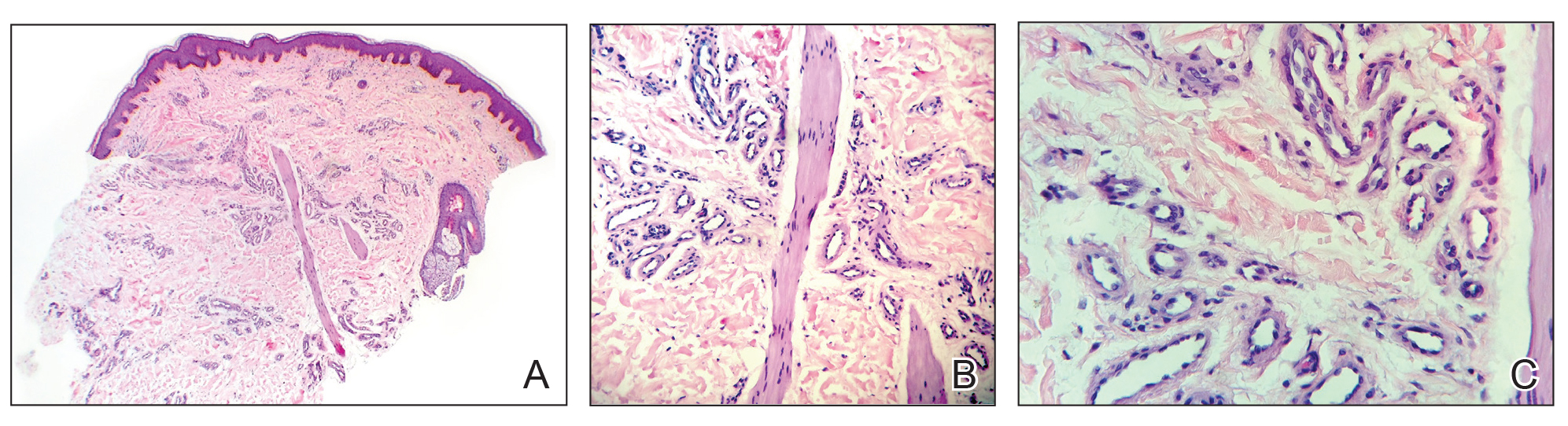

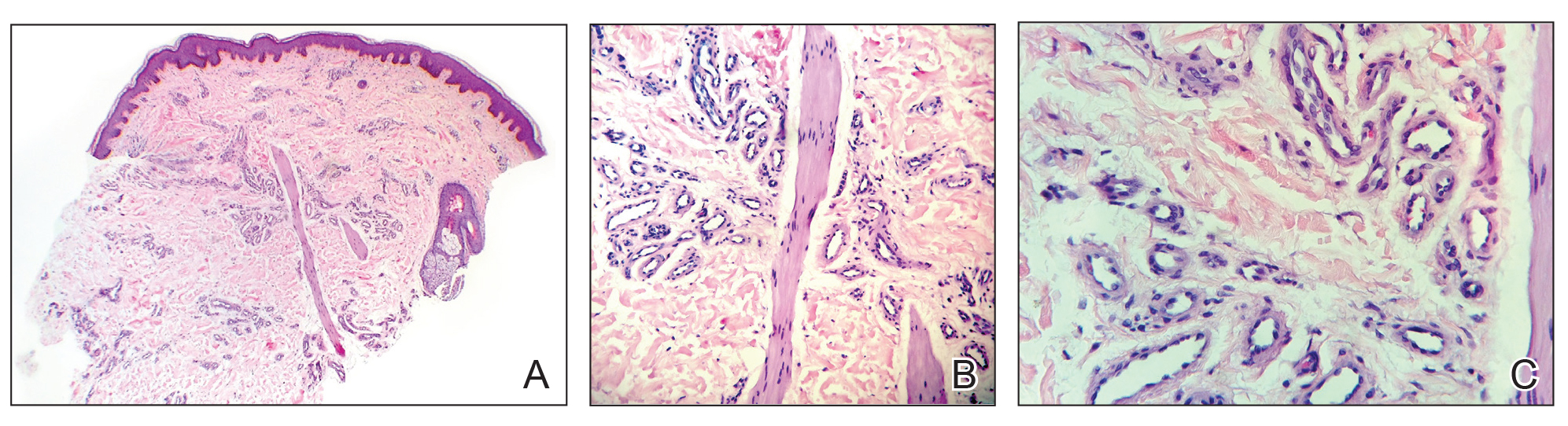

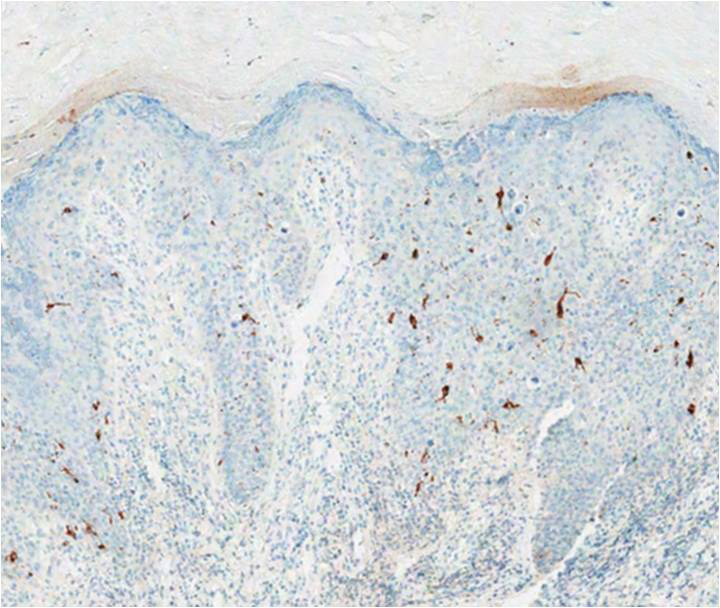

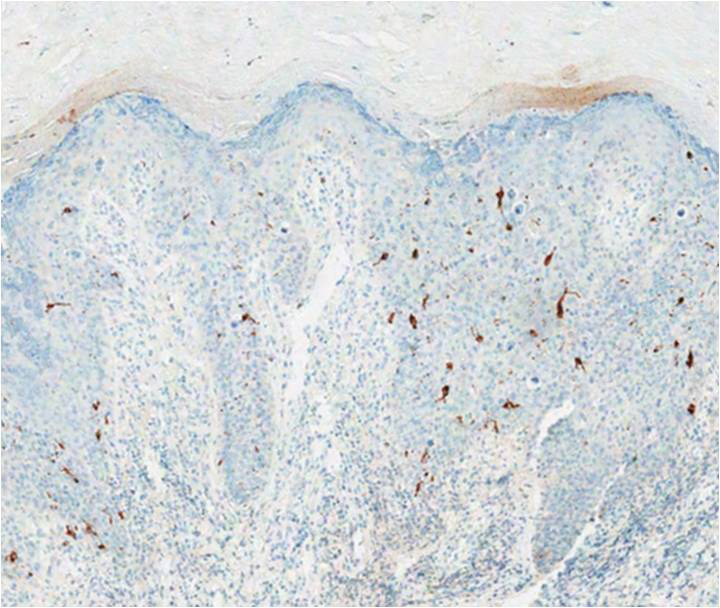

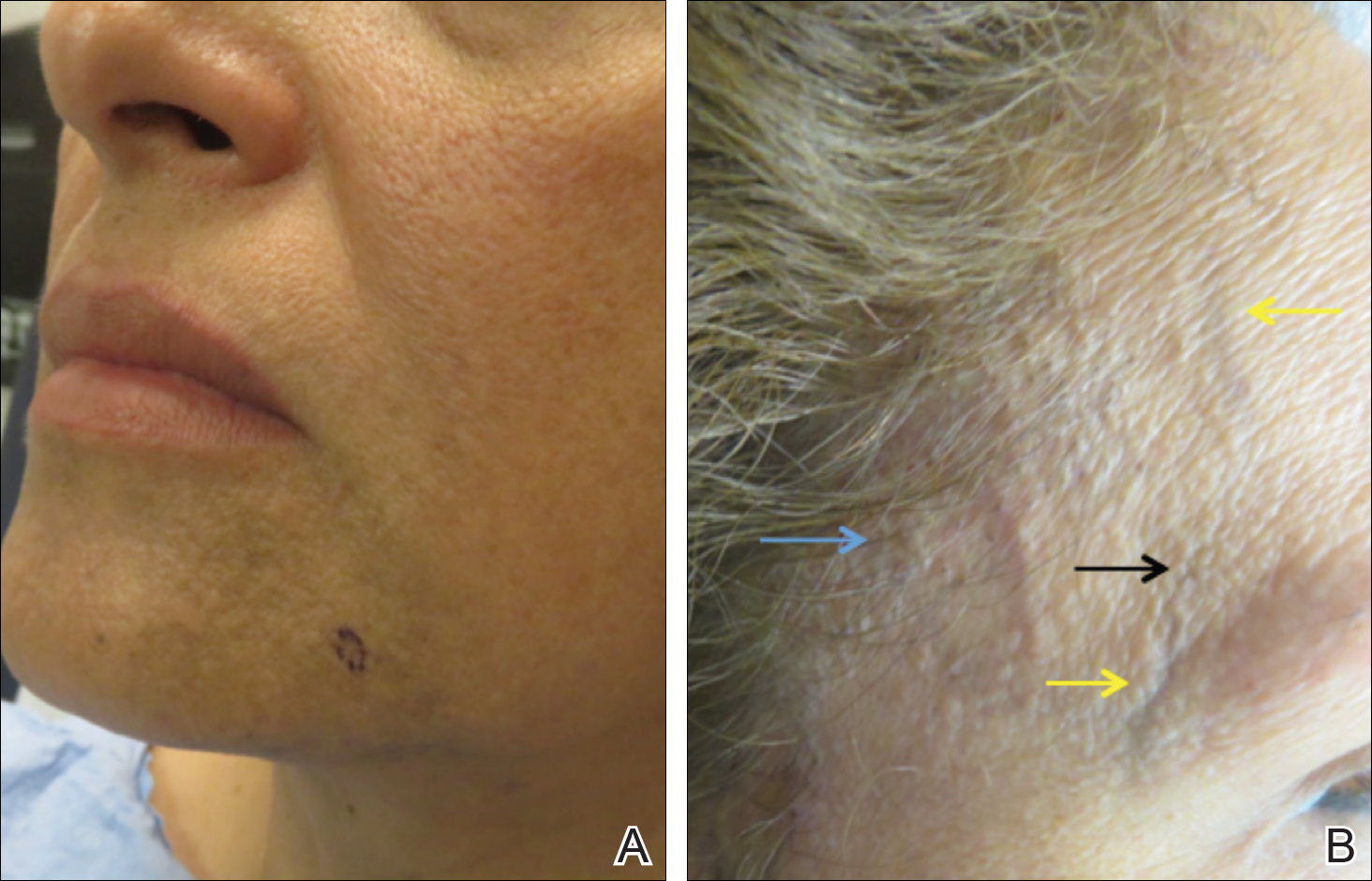

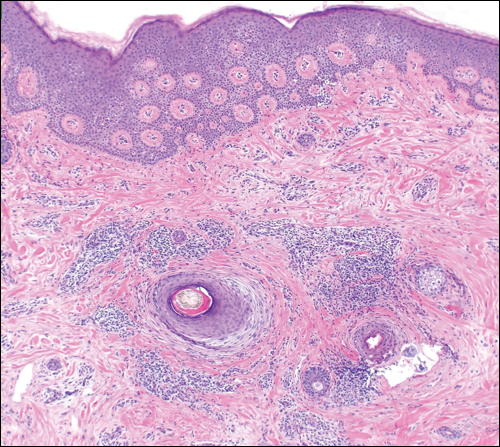

Three biopsies were performed, which revealed a collection of slightly dilated blood vessels with normal-appearing endothelial cells occupying the mid dermis and deep dermis (Figure 2). Immunohistochemical stains with antibodies were directed against human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8), CD31, CD34, the cell surface glycoprotein podoplanin, Ki-67, and smooth muscle actin antigens, with appropriate controls. The vessel walls were positive for CD31, CD34, and smooth muscle actin, and negative for HHV-8 and podoplanin; Ki-67 was not increased. These histologic findings were consistent with a diagnosis of DDA. A detailed history was taken. The cause of DDA in our patient was uncertain.

Comment

Classification and Epidemiology

Diffuse dermal angiomatosis is a rare acquired, cutaneous, reactive, vascular disorder first described by Krell et al1 in 1994. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis is benign and is classified in the group of cutaneous reactive angiomatoses,2 which are benign vascular disorders marked by intravascular and extravascular hyperplasia of endothelial cells that may or may not include pericytes.2 Diffuse dermal angiomatosis was originally described as a variant of CREA, which is characterized by hyperplasia of endothelial dermal cells and intravascular proliferation.3 However, DDA has more recently been identified as a distinct disorder on the spectrum of CREA rather than as a variant of CREA.2 Given the recent reclassification, not all physicians make this distinction. However, as more case reports of DDA are published, physicians continue to support this change.4 Nevertheless, DDA has been an established disorder since 1994.1

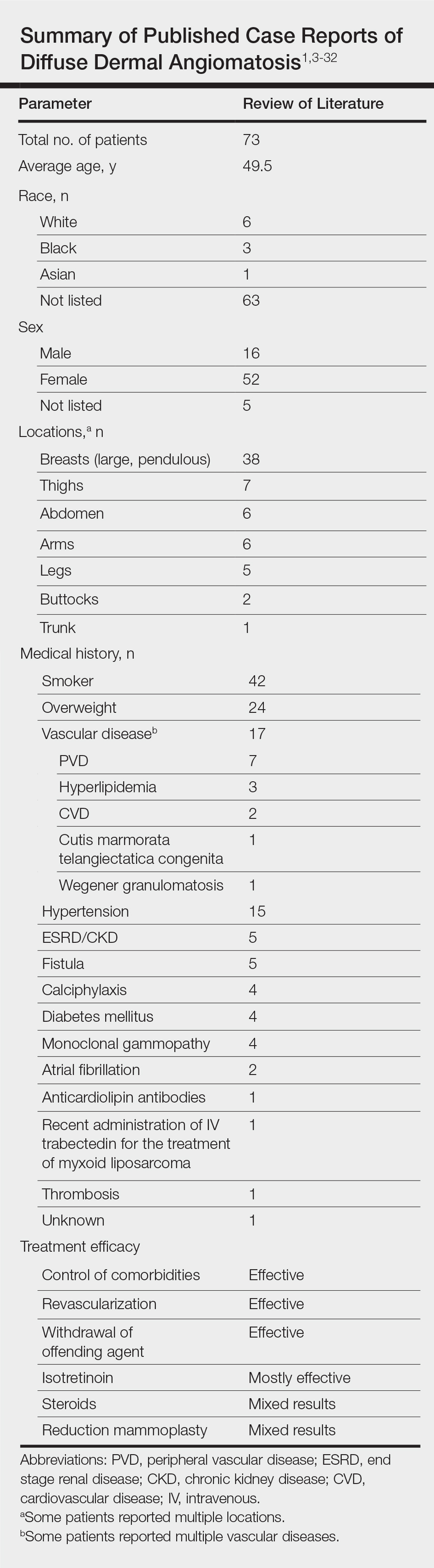

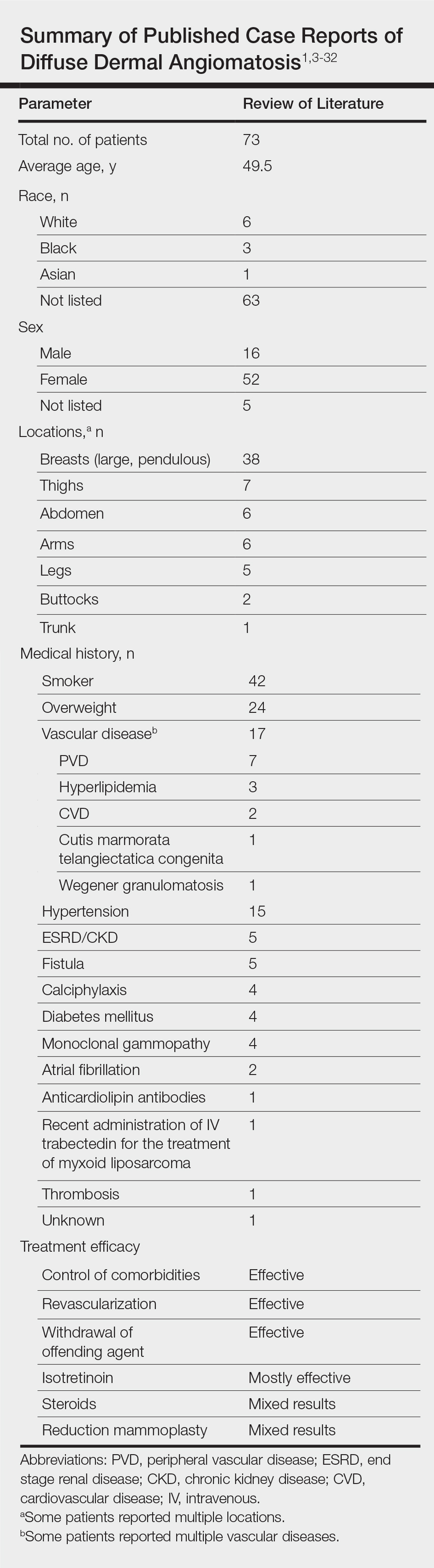

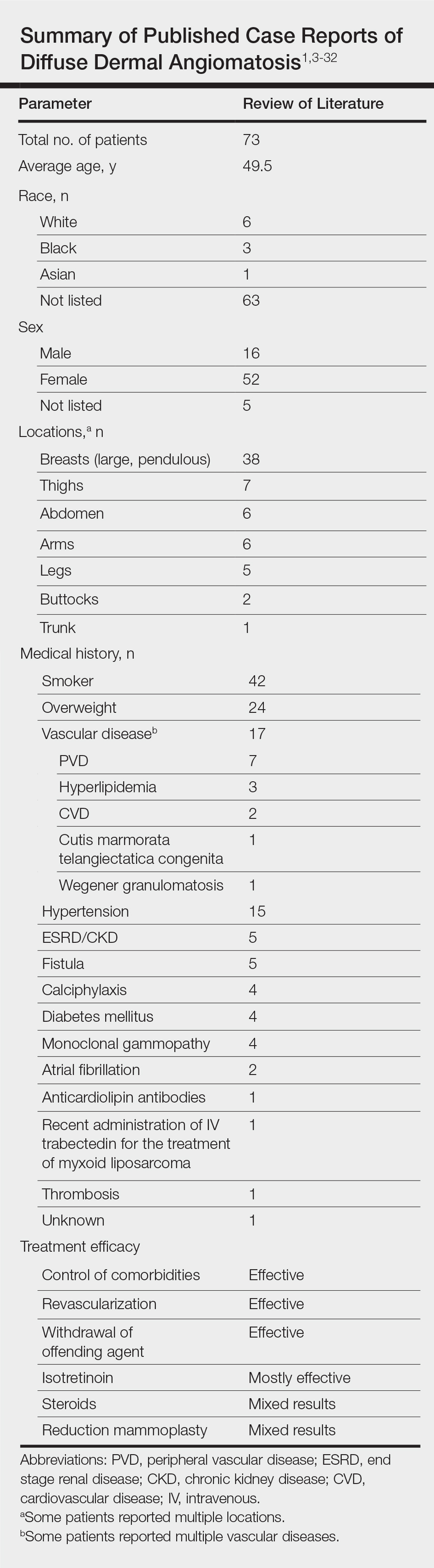

Vascular proliferation in DDA is hypothesized to stem from ischemia or inflammation.5 Peripheral vascular atherosclerosis has been associated with DDA.6 The epidemiology of DDA is not well known because of the rarity of the disease. We performed a more specific review of the literature by limiting the PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE to the term diffuse dermal angiomatosis rather than a broader search including all reactive angioendotheliomatoses. Only 31 case reports have been published1,3-32; of them, only adults were affected. Most reported cases were in middle-aged females. A summary of the demographics of DDA is provided in the Table.1,3-32

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of DDA remains unclear. It has been hypothesized that ischemia or inflammation creates local hypoxia, leading to an increase in vascular endothelial growth factor with subsequent endothelial proliferation and neovascularization.5 Rongioletti and Robora2 supported this hypothesis, proposing that occlusion or inflammation of the vasculature creates microthrombi and thus hypoxia. Afterward, histiocytes are recruited to reabsorb the microthrombi while hyperplasia of endothelial cells and pericytes ensues.7 Complete resolution of skin lesions following revascularization provides support for this theory.8

Etiology

Diffuse dermal angiomatosis is a rare complication of ischemia that may be secondary to atherosclerosis, arteriovenous fistula, or macromastia.9-11 In DDA of the breasts, ulcerations of fatty tissue occur due to trauma in these patients who have large pendulous breasts, causing angiogenesis resembling DDA histologically.2 One case of DDA was reported secondary to relative ischemia from cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita,12 whereas another case highlighted Wegener granulomatosis as the cause of ischemia.7 There also have been reported cases associated with calciphylaxis and anticardiolipin antibiodies.13 In general, any medical condition that can lead to ischemia can cause DDA. Comorbid conditions for DDA include cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and most often severe peripheral vascular disease. Many patients also have a history of smoking.14 Diffuse dermal angiomatosis rarely presents without underlying comorbidity, with only 1 case report of unknown cause (Table).

Presentation, Histopathology, and Differential Diagnosis

Cutaneous reactive angiomatosis disorders present the same clinically, with multiple erythematous to violaceous purpuric patches and plaques that can progress to necrosis and ulceration. Lesions are widely distributed but are predisposed to the upper and lower extremities.2 The differential diagnosis of DDA includes CREA, acroangiodermatitis (pseudo–Kaposi sarcoma), or vascular malignancies such as Kaposi sarcoma and low-grade angiosarcoma.7

In DDA, lesions may be painful and sometimes have a central ulceration.15 They often are associated with notable peripheral vascular atherosclerotic disease and are mainly found on the lower extremities.12,16 Histologically, DDA presents as a diffuse proliferation of endothelial cells between collagen bundles. The endothelial cells are distributed throughout the papillary and reticular dermis and develop into vascular lumina.17 Furthermore, the proliferating endothelial cells are spindle shaped and contain vacuolated cytoplasm.14

Acroangiodermatitis, or pseudo–Kaposi sarcoma, presents as slow-growing, erythematous to violaceous, brown, or dusky macules, papules, or plaques of the legs.14 Histologically, acroangiodermatitis presents with relatively less proliferation of endothelial cells found intravascularly rather than extravascularly, as in DDA, forming new thick-walled vessels in a lobular pattern in the papillary dermis.14

Vascular malignancies, such as Kaposi sarcoma and angiosarcoma, may present similarly to DDA. Kaposi sarcoma, for example, presents as erythematous to violaceous patches, plaques, or nodules found mostly on the extremities.7 Histologically, spindle cells and vascular structures also are found but in a clefting pattern representative of Kaposi sarcoma (so-called vascular slits).7 Diffuse dermal angiomatosis and vascular malignancies can further be distinguished based on atypia of the proliferations and staining for HHV-8.7,14 Lastly, DDA differs from vascular tumors in that vascular tumors are reactive to locations of occluded vessels, with vascular proliferation ceasing once the underlying cause of hypoxia is removed.2

Treatment

There is no standard treatment of DDA.7 Treatment of the underlying cause of ischemia is the primary goal, which will cause the DDA to resolve in most cases. Stenting, removal of an arteriovenous fistula, or other forms of revascularization may be warranted.1,5,6,10,17,29,30

Reported medical therapies for DDA include systemic or topical corticosteroids used for their antiangiogenic properties with varying results.7 Isotretinoin also has been used, which has been found to be effective in several cases of DDA of the breast, though 1 study reported a subsequent elevated lipid profile, requiring a decrease in dosage.14,15,27,31

Most interestingly, a study by Sanz-Motilva et al16 demonstrated that control of comorbidities, especially smoking cessation, led to improvement, which highlights the importance of incorporating nonpharmacotherapy rather than initiating treatment solely with medication. The Table summarizes treatments used and their efficacy.

Conclusion

Diffuse dermal angiomatosis is associated with medical conditions that predispose an individual to ischemia. Although rare, DDA can present as painful and visibly disturbing lesions that can affect the daily life of afflicted patients. By reporting the few cases that do arise and reviewing prior cases and their treatments, physicians can consider DDA within the differential diagnosis and identify which treatment is most efficient for a given patient. For all DDA patients, strict control of comorbidities, especially smoking cessation, should be incorporated into the treatment plan. When DDA affects the breasts, isotretinoin appears to provide the best relief. Otherwise, treatment of the underlying cause, revascularization, withdrawal of the offending agent, or steroids seem to be the best treatment options.

- Krell JM, Sanchez RL, Solomon AR. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis: a variant of reactive cutaneous angioendotheliomatosis. J Cutan Pathol. 1994;21:363-370.

- Rongioletti F, Robora A. Cutaneous reactive angiomatoses: patterns and classification of reactive vascular proliferation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:887-896.

- Crickx E, Saussine A, Vignon-Pennamen MD, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis associated with severe atherosclerosis: two cases and review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:521-524.

- Reusche R, Winocour S, Degnim A, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis of the breast: a series of 22 cases from a single institution. Gland Surg. 2015;4:554-560.

- Sriphojanart T, Vachiramon V. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis: a clue to the diagnosis of atherosclerotic vascular disease. Case Rep Dermatol. 2015;7:100-106.

- Kimyai-Asadi A, Nousari HC, Ketabchi N, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis: a variant of reactive angioendotheliomatosis associated with atherosclerosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:257-259.

- Bassi A, Arunachalam M, Maio V, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis in a patient with an iatrogenic arterio-venous fistula and Wegener’s granulomatosis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2013;93:93-94.

- Ormerod E, Miller K, Kennedy C. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis: a contributory factor to ulceration in a patient with renal transplant. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:48-51.

- Kim S, Elenitsas R, James WD. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis: a variant of reactive angioendotheliomatosis associated with peripheral vascular atherosclerosis. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:456-458.

- Requena L, Fariña MC, Renedo G, et al. Intravascular and diffuse dermal reactive angioendotheliomatosis secondary to iatrogenic arteriovenous fistulas. J Cutan Pathol. 1999;26:159-164.

- Villa MT, White LE, Petronic-Rosic V, et al. The treatment of diffuse dermal angiomatosis of the breast with reduction mammoplasty. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:693-694.

- Halbesleben JJ, Cleveland MG, Stone MS. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis arising in cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1311-1313.

- Ferreli C, Atzori L, Pinna AL, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis: a clinical mimicker of vasculitis associated with calciphylaxis and monoclonal gammopathy. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2015;150:115-121.

- Yang H, Ahmed I, Mathew V, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis of the breast. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:343-347.

- Steele KT, Sullivan BJ, Wanat KA, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis associated with calciphylaxis in a patient with end-stage renal disease.J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:829-832.

- Sanz-Motilva V, Martorell-Calatayud A, Rongioletti F, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis of the breast: clinical and histopathological features. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:445-449.

- Kirkland CR, Hawayek LH, Mutasim DF. Atherosclerosis-induced diffuse dermal angiomatosis with fatal outcome. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:684-685.

- Sommer S, Merchant WJ, Wilson CL. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis due to an iatrogenic arteriovenous fistula. Acta Derm Venereol. 2004;84:251-252.

- Corti MA, Rongioletti F, Borradori L, et al. Cutaneous reactive angiomatosis with combined histological pattern mimicking a cellulitis. Dermatology. 2013;227:226-230.

- Tollefson MM, McEvoy MT, Torgerson RR, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis of the breast: clinicopathologic study of 5 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:1212-1217.

- Walton K, Liggett J. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis: a case report. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66(suppl 1):AB49.

- Mayor-Ibarguren A, Gómez-Fernández C, Beato-Merino MJ, et al. Diffuse reactive angioendotheliomatosis secondary to the administration of trabectedin and pegfilgrastim. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:581-584.

- Lora V, Cota C, Cerroni L. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis of the abdomen. Eur J Dermatol. 2015;25:350-352.

- Pichardo RO, Lu D, Sangueza OP, et al. What is your diagnosis? diffuse dermal angiomatosis secondary to anticardiolipin antibodies. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:502.

- Kutzner H, Requena L, Mentzel T, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis. Hautarzt. 2002;53:808-812.

- McLaughlin ER, Morris R, Weiss SW, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis of the breast: response to isotretinoin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:462-465.

- Prinz Vavricka BM, Barry C, Victor T, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis associated with calciphylaxis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:653-657.

- Müller CS, Wagner A, Pföhler C, et al. Cup-shaped painful ulcer of abdominal wall. Hautarzt. 2008;59:656-658.

- Draper BK, Boyd AS. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:646-648.

- Adams BJ, Goldberg S, Massey HD, et al. A cause of unbearably painful breast, diffuse dermal angiomatosis. Gland Surg. 2012;1. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2227-684X.2012.07.02.

- Quatresooz P, Fumal I, Willemaers V, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis: a previously undescribed pattern of immunoglobulin and complement deposits in two cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:150-154.

- Morimoto K, Ioka H, Asada H, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2011;42:381-383.

Diffuse dermal angiomatosis (DDA) is a rare acquired, cutaneous, reactive, vascular disorder that was originally thought to be a variant of cutaneous reactive angiomatosis (CREA) but is now considered to be on the spectrum of CREA. This article will focus on DDA and review the literature of prior case reports with brief descriptions of the differential diagnosis.

Case Report

A 43-year-old Haitian man presented to the clinic with a lesion on the left buttock that had developed over the last 6 years. The patient stated the lesion had been enlarging over the last several months. Upon examination, there was a large (15-cm diameter), indurated, hyperpigmented plaque covering the left buttock (Figure 1). The patient reported no medical or contributory family history. Upon review of systems, he described a burning sensation sometimes in the area of the lesion that would develop randomly throughout the year.

Three biopsies were performed, which revealed a collection of slightly dilated blood vessels with normal-appearing endothelial cells occupying the mid dermis and deep dermis (Figure 2). Immunohistochemical stains with antibodies were directed against human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8), CD31, CD34, the cell surface glycoprotein podoplanin, Ki-67, and smooth muscle actin antigens, with appropriate controls. The vessel walls were positive for CD31, CD34, and smooth muscle actin, and negative for HHV-8 and podoplanin; Ki-67 was not increased. These histologic findings were consistent with a diagnosis of DDA. A detailed history was taken. The cause of DDA in our patient was uncertain.

Comment

Classification and Epidemiology

Diffuse dermal angiomatosis is a rare acquired, cutaneous, reactive, vascular disorder first described by Krell et al1 in 1994. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis is benign and is classified in the group of cutaneous reactive angiomatoses,2 which are benign vascular disorders marked by intravascular and extravascular hyperplasia of endothelial cells that may or may not include pericytes.2 Diffuse dermal angiomatosis was originally described as a variant of CREA, which is characterized by hyperplasia of endothelial dermal cells and intravascular proliferation.3 However, DDA has more recently been identified as a distinct disorder on the spectrum of CREA rather than as a variant of CREA.2 Given the recent reclassification, not all physicians make this distinction. However, as more case reports of DDA are published, physicians continue to support this change.4 Nevertheless, DDA has been an established disorder since 1994.1

Vascular proliferation in DDA is hypothesized to stem from ischemia or inflammation.5 Peripheral vascular atherosclerosis has been associated with DDA.6 The epidemiology of DDA is not well known because of the rarity of the disease. We performed a more specific review of the literature by limiting the PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE to the term diffuse dermal angiomatosis rather than a broader search including all reactive angioendotheliomatoses. Only 31 case reports have been published1,3-32; of them, only adults were affected. Most reported cases were in middle-aged females. A summary of the demographics of DDA is provided in the Table.1,3-32

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of DDA remains unclear. It has been hypothesized that ischemia or inflammation creates local hypoxia, leading to an increase in vascular endothelial growth factor with subsequent endothelial proliferation and neovascularization.5 Rongioletti and Robora2 supported this hypothesis, proposing that occlusion or inflammation of the vasculature creates microthrombi and thus hypoxia. Afterward, histiocytes are recruited to reabsorb the microthrombi while hyperplasia of endothelial cells and pericytes ensues.7 Complete resolution of skin lesions following revascularization provides support for this theory.8

Etiology

Diffuse dermal angiomatosis is a rare complication of ischemia that may be secondary to atherosclerosis, arteriovenous fistula, or macromastia.9-11 In DDA of the breasts, ulcerations of fatty tissue occur due to trauma in these patients who have large pendulous breasts, causing angiogenesis resembling DDA histologically.2 One case of DDA was reported secondary to relative ischemia from cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita,12 whereas another case highlighted Wegener granulomatosis as the cause of ischemia.7 There also have been reported cases associated with calciphylaxis and anticardiolipin antibiodies.13 In general, any medical condition that can lead to ischemia can cause DDA. Comorbid conditions for DDA include cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and most often severe peripheral vascular disease. Many patients also have a history of smoking.14 Diffuse dermal angiomatosis rarely presents without underlying comorbidity, with only 1 case report of unknown cause (Table).

Presentation, Histopathology, and Differential Diagnosis

Cutaneous reactive angiomatosis disorders present the same clinically, with multiple erythematous to violaceous purpuric patches and plaques that can progress to necrosis and ulceration. Lesions are widely distributed but are predisposed to the upper and lower extremities.2 The differential diagnosis of DDA includes CREA, acroangiodermatitis (pseudo–Kaposi sarcoma), or vascular malignancies such as Kaposi sarcoma and low-grade angiosarcoma.7

In DDA, lesions may be painful and sometimes have a central ulceration.15 They often are associated with notable peripheral vascular atherosclerotic disease and are mainly found on the lower extremities.12,16 Histologically, DDA presents as a diffuse proliferation of endothelial cells between collagen bundles. The endothelial cells are distributed throughout the papillary and reticular dermis and develop into vascular lumina.17 Furthermore, the proliferating endothelial cells are spindle shaped and contain vacuolated cytoplasm.14

Acroangiodermatitis, or pseudo–Kaposi sarcoma, presents as slow-growing, erythematous to violaceous, brown, or dusky macules, papules, or plaques of the legs.14 Histologically, acroangiodermatitis presents with relatively less proliferation of endothelial cells found intravascularly rather than extravascularly, as in DDA, forming new thick-walled vessels in a lobular pattern in the papillary dermis.14

Vascular malignancies, such as Kaposi sarcoma and angiosarcoma, may present similarly to DDA. Kaposi sarcoma, for example, presents as erythematous to violaceous patches, plaques, or nodules found mostly on the extremities.7 Histologically, spindle cells and vascular structures also are found but in a clefting pattern representative of Kaposi sarcoma (so-called vascular slits).7 Diffuse dermal angiomatosis and vascular malignancies can further be distinguished based on atypia of the proliferations and staining for HHV-8.7,14 Lastly, DDA differs from vascular tumors in that vascular tumors are reactive to locations of occluded vessels, with vascular proliferation ceasing once the underlying cause of hypoxia is removed.2

Treatment

There is no standard treatment of DDA.7 Treatment of the underlying cause of ischemia is the primary goal, which will cause the DDA to resolve in most cases. Stenting, removal of an arteriovenous fistula, or other forms of revascularization may be warranted.1,5,6,10,17,29,30

Reported medical therapies for DDA include systemic or topical corticosteroids used for their antiangiogenic properties with varying results.7 Isotretinoin also has been used, which has been found to be effective in several cases of DDA of the breast, though 1 study reported a subsequent elevated lipid profile, requiring a decrease in dosage.14,15,27,31

Most interestingly, a study by Sanz-Motilva et al16 demonstrated that control of comorbidities, especially smoking cessation, led to improvement, which highlights the importance of incorporating nonpharmacotherapy rather than initiating treatment solely with medication. The Table summarizes treatments used and their efficacy.

Conclusion

Diffuse dermal angiomatosis is associated with medical conditions that predispose an individual to ischemia. Although rare, DDA can present as painful and visibly disturbing lesions that can affect the daily life of afflicted patients. By reporting the few cases that do arise and reviewing prior cases and their treatments, physicians can consider DDA within the differential diagnosis and identify which treatment is most efficient for a given patient. For all DDA patients, strict control of comorbidities, especially smoking cessation, should be incorporated into the treatment plan. When DDA affects the breasts, isotretinoin appears to provide the best relief. Otherwise, treatment of the underlying cause, revascularization, withdrawal of the offending agent, or steroids seem to be the best treatment options.

Diffuse dermal angiomatosis (DDA) is a rare acquired, cutaneous, reactive, vascular disorder that was originally thought to be a variant of cutaneous reactive angiomatosis (CREA) but is now considered to be on the spectrum of CREA. This article will focus on DDA and review the literature of prior case reports with brief descriptions of the differential diagnosis.

Case Report

A 43-year-old Haitian man presented to the clinic with a lesion on the left buttock that had developed over the last 6 years. The patient stated the lesion had been enlarging over the last several months. Upon examination, there was a large (15-cm diameter), indurated, hyperpigmented plaque covering the left buttock (Figure 1). The patient reported no medical or contributory family history. Upon review of systems, he described a burning sensation sometimes in the area of the lesion that would develop randomly throughout the year.

Three biopsies were performed, which revealed a collection of slightly dilated blood vessels with normal-appearing endothelial cells occupying the mid dermis and deep dermis (Figure 2). Immunohistochemical stains with antibodies were directed against human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8), CD31, CD34, the cell surface glycoprotein podoplanin, Ki-67, and smooth muscle actin antigens, with appropriate controls. The vessel walls were positive for CD31, CD34, and smooth muscle actin, and negative for HHV-8 and podoplanin; Ki-67 was not increased. These histologic findings were consistent with a diagnosis of DDA. A detailed history was taken. The cause of DDA in our patient was uncertain.

Comment

Classification and Epidemiology

Diffuse dermal angiomatosis is a rare acquired, cutaneous, reactive, vascular disorder first described by Krell et al1 in 1994. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis is benign and is classified in the group of cutaneous reactive angiomatoses,2 which are benign vascular disorders marked by intravascular and extravascular hyperplasia of endothelial cells that may or may not include pericytes.2 Diffuse dermal angiomatosis was originally described as a variant of CREA, which is characterized by hyperplasia of endothelial dermal cells and intravascular proliferation.3 However, DDA has more recently been identified as a distinct disorder on the spectrum of CREA rather than as a variant of CREA.2 Given the recent reclassification, not all physicians make this distinction. However, as more case reports of DDA are published, physicians continue to support this change.4 Nevertheless, DDA has been an established disorder since 1994.1

Vascular proliferation in DDA is hypothesized to stem from ischemia or inflammation.5 Peripheral vascular atherosclerosis has been associated with DDA.6 The epidemiology of DDA is not well known because of the rarity of the disease. We performed a more specific review of the literature by limiting the PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE to the term diffuse dermal angiomatosis rather than a broader search including all reactive angioendotheliomatoses. Only 31 case reports have been published1,3-32; of them, only adults were affected. Most reported cases were in middle-aged females. A summary of the demographics of DDA is provided in the Table.1,3-32

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of DDA remains unclear. It has been hypothesized that ischemia or inflammation creates local hypoxia, leading to an increase in vascular endothelial growth factor with subsequent endothelial proliferation and neovascularization.5 Rongioletti and Robora2 supported this hypothesis, proposing that occlusion or inflammation of the vasculature creates microthrombi and thus hypoxia. Afterward, histiocytes are recruited to reabsorb the microthrombi while hyperplasia of endothelial cells and pericytes ensues.7 Complete resolution of skin lesions following revascularization provides support for this theory.8

Etiology

Diffuse dermal angiomatosis is a rare complication of ischemia that may be secondary to atherosclerosis, arteriovenous fistula, or macromastia.9-11 In DDA of the breasts, ulcerations of fatty tissue occur due to trauma in these patients who have large pendulous breasts, causing angiogenesis resembling DDA histologically.2 One case of DDA was reported secondary to relative ischemia from cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita,12 whereas another case highlighted Wegener granulomatosis as the cause of ischemia.7 There also have been reported cases associated with calciphylaxis and anticardiolipin antibiodies.13 In general, any medical condition that can lead to ischemia can cause DDA. Comorbid conditions for DDA include cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and most often severe peripheral vascular disease. Many patients also have a history of smoking.14 Diffuse dermal angiomatosis rarely presents without underlying comorbidity, with only 1 case report of unknown cause (Table).

Presentation, Histopathology, and Differential Diagnosis

Cutaneous reactive angiomatosis disorders present the same clinically, with multiple erythematous to violaceous purpuric patches and plaques that can progress to necrosis and ulceration. Lesions are widely distributed but are predisposed to the upper and lower extremities.2 The differential diagnosis of DDA includes CREA, acroangiodermatitis (pseudo–Kaposi sarcoma), or vascular malignancies such as Kaposi sarcoma and low-grade angiosarcoma.7

In DDA, lesions may be painful and sometimes have a central ulceration.15 They often are associated with notable peripheral vascular atherosclerotic disease and are mainly found on the lower extremities.12,16 Histologically, DDA presents as a diffuse proliferation of endothelial cells between collagen bundles. The endothelial cells are distributed throughout the papillary and reticular dermis and develop into vascular lumina.17 Furthermore, the proliferating endothelial cells are spindle shaped and contain vacuolated cytoplasm.14

Acroangiodermatitis, or pseudo–Kaposi sarcoma, presents as slow-growing, erythematous to violaceous, brown, or dusky macules, papules, or plaques of the legs.14 Histologically, acroangiodermatitis presents with relatively less proliferation of endothelial cells found intravascularly rather than extravascularly, as in DDA, forming new thick-walled vessels in a lobular pattern in the papillary dermis.14

Vascular malignancies, such as Kaposi sarcoma and angiosarcoma, may present similarly to DDA. Kaposi sarcoma, for example, presents as erythematous to violaceous patches, plaques, or nodules found mostly on the extremities.7 Histologically, spindle cells and vascular structures also are found but in a clefting pattern representative of Kaposi sarcoma (so-called vascular slits).7 Diffuse dermal angiomatosis and vascular malignancies can further be distinguished based on atypia of the proliferations and staining for HHV-8.7,14 Lastly, DDA differs from vascular tumors in that vascular tumors are reactive to locations of occluded vessels, with vascular proliferation ceasing once the underlying cause of hypoxia is removed.2

Treatment

There is no standard treatment of DDA.7 Treatment of the underlying cause of ischemia is the primary goal, which will cause the DDA to resolve in most cases. Stenting, removal of an arteriovenous fistula, or other forms of revascularization may be warranted.1,5,6,10,17,29,30

Reported medical therapies for DDA include systemic or topical corticosteroids used for their antiangiogenic properties with varying results.7 Isotretinoin also has been used, which has been found to be effective in several cases of DDA of the breast, though 1 study reported a subsequent elevated lipid profile, requiring a decrease in dosage.14,15,27,31

Most interestingly, a study by Sanz-Motilva et al16 demonstrated that control of comorbidities, especially smoking cessation, led to improvement, which highlights the importance of incorporating nonpharmacotherapy rather than initiating treatment solely with medication. The Table summarizes treatments used and their efficacy.

Conclusion

Diffuse dermal angiomatosis is associated with medical conditions that predispose an individual to ischemia. Although rare, DDA can present as painful and visibly disturbing lesions that can affect the daily life of afflicted patients. By reporting the few cases that do arise and reviewing prior cases and their treatments, physicians can consider DDA within the differential diagnosis and identify which treatment is most efficient for a given patient. For all DDA patients, strict control of comorbidities, especially smoking cessation, should be incorporated into the treatment plan. When DDA affects the breasts, isotretinoin appears to provide the best relief. Otherwise, treatment of the underlying cause, revascularization, withdrawal of the offending agent, or steroids seem to be the best treatment options.

- Krell JM, Sanchez RL, Solomon AR. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis: a variant of reactive cutaneous angioendotheliomatosis. J Cutan Pathol. 1994;21:363-370.

- Rongioletti F, Robora A. Cutaneous reactive angiomatoses: patterns and classification of reactive vascular proliferation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:887-896.

- Crickx E, Saussine A, Vignon-Pennamen MD, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis associated with severe atherosclerosis: two cases and review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:521-524.

- Reusche R, Winocour S, Degnim A, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis of the breast: a series of 22 cases from a single institution. Gland Surg. 2015;4:554-560.

- Sriphojanart T, Vachiramon V. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis: a clue to the diagnosis of atherosclerotic vascular disease. Case Rep Dermatol. 2015;7:100-106.

- Kimyai-Asadi A, Nousari HC, Ketabchi N, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis: a variant of reactive angioendotheliomatosis associated with atherosclerosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:257-259.

- Bassi A, Arunachalam M, Maio V, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis in a patient with an iatrogenic arterio-venous fistula and Wegener’s granulomatosis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2013;93:93-94.

- Ormerod E, Miller K, Kennedy C. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis: a contributory factor to ulceration in a patient with renal transplant. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:48-51.

- Kim S, Elenitsas R, James WD. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis: a variant of reactive angioendotheliomatosis associated with peripheral vascular atherosclerosis. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:456-458.

- Requena L, Fariña MC, Renedo G, et al. Intravascular and diffuse dermal reactive angioendotheliomatosis secondary to iatrogenic arteriovenous fistulas. J Cutan Pathol. 1999;26:159-164.

- Villa MT, White LE, Petronic-Rosic V, et al. The treatment of diffuse dermal angiomatosis of the breast with reduction mammoplasty. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:693-694.

- Halbesleben JJ, Cleveland MG, Stone MS. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis arising in cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1311-1313.

- Ferreli C, Atzori L, Pinna AL, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis: a clinical mimicker of vasculitis associated with calciphylaxis and monoclonal gammopathy. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2015;150:115-121.

- Yang H, Ahmed I, Mathew V, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis of the breast. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:343-347.

- Steele KT, Sullivan BJ, Wanat KA, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis associated with calciphylaxis in a patient with end-stage renal disease.J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:829-832.

- Sanz-Motilva V, Martorell-Calatayud A, Rongioletti F, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis of the breast: clinical and histopathological features. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:445-449.

- Kirkland CR, Hawayek LH, Mutasim DF. Atherosclerosis-induced diffuse dermal angiomatosis with fatal outcome. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:684-685.

- Sommer S, Merchant WJ, Wilson CL. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis due to an iatrogenic arteriovenous fistula. Acta Derm Venereol. 2004;84:251-252.

- Corti MA, Rongioletti F, Borradori L, et al. Cutaneous reactive angiomatosis with combined histological pattern mimicking a cellulitis. Dermatology. 2013;227:226-230.

- Tollefson MM, McEvoy MT, Torgerson RR, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis of the breast: clinicopathologic study of 5 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:1212-1217.

- Walton K, Liggett J. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis: a case report. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66(suppl 1):AB49.

- Mayor-Ibarguren A, Gómez-Fernández C, Beato-Merino MJ, et al. Diffuse reactive angioendotheliomatosis secondary to the administration of trabectedin and pegfilgrastim. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:581-584.

- Lora V, Cota C, Cerroni L. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis of the abdomen. Eur J Dermatol. 2015;25:350-352.

- Pichardo RO, Lu D, Sangueza OP, et al. What is your diagnosis? diffuse dermal angiomatosis secondary to anticardiolipin antibodies. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:502.

- Kutzner H, Requena L, Mentzel T, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis. Hautarzt. 2002;53:808-812.

- McLaughlin ER, Morris R, Weiss SW, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis of the breast: response to isotretinoin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:462-465.

- Prinz Vavricka BM, Barry C, Victor T, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis associated with calciphylaxis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:653-657.

- Müller CS, Wagner A, Pföhler C, et al. Cup-shaped painful ulcer of abdominal wall. Hautarzt. 2008;59:656-658.

- Draper BK, Boyd AS. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:646-648.

- Adams BJ, Goldberg S, Massey HD, et al. A cause of unbearably painful breast, diffuse dermal angiomatosis. Gland Surg. 2012;1. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2227-684X.2012.07.02.

- Quatresooz P, Fumal I, Willemaers V, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis: a previously undescribed pattern of immunoglobulin and complement deposits in two cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:150-154.

- Morimoto K, Ioka H, Asada H, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2011;42:381-383.

- Krell JM, Sanchez RL, Solomon AR. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis: a variant of reactive cutaneous angioendotheliomatosis. J Cutan Pathol. 1994;21:363-370.

- Rongioletti F, Robora A. Cutaneous reactive angiomatoses: patterns and classification of reactive vascular proliferation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:887-896.

- Crickx E, Saussine A, Vignon-Pennamen MD, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis associated with severe atherosclerosis: two cases and review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:521-524.

- Reusche R, Winocour S, Degnim A, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis of the breast: a series of 22 cases from a single institution. Gland Surg. 2015;4:554-560.

- Sriphojanart T, Vachiramon V. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis: a clue to the diagnosis of atherosclerotic vascular disease. Case Rep Dermatol. 2015;7:100-106.

- Kimyai-Asadi A, Nousari HC, Ketabchi N, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis: a variant of reactive angioendotheliomatosis associated with atherosclerosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:257-259.

- Bassi A, Arunachalam M, Maio V, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis in a patient with an iatrogenic arterio-venous fistula and Wegener’s granulomatosis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2013;93:93-94.

- Ormerod E, Miller K, Kennedy C. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis: a contributory factor to ulceration in a patient with renal transplant. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:48-51.

- Kim S, Elenitsas R, James WD. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis: a variant of reactive angioendotheliomatosis associated with peripheral vascular atherosclerosis. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:456-458.

- Requena L, Fariña MC, Renedo G, et al. Intravascular and diffuse dermal reactive angioendotheliomatosis secondary to iatrogenic arteriovenous fistulas. J Cutan Pathol. 1999;26:159-164.

- Villa MT, White LE, Petronic-Rosic V, et al. The treatment of diffuse dermal angiomatosis of the breast with reduction mammoplasty. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:693-694.

- Halbesleben JJ, Cleveland MG, Stone MS. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis arising in cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1311-1313.

- Ferreli C, Atzori L, Pinna AL, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis: a clinical mimicker of vasculitis associated with calciphylaxis and monoclonal gammopathy. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2015;150:115-121.

- Yang H, Ahmed I, Mathew V, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis of the breast. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:343-347.

- Steele KT, Sullivan BJ, Wanat KA, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis associated with calciphylaxis in a patient with end-stage renal disease.J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:829-832.

- Sanz-Motilva V, Martorell-Calatayud A, Rongioletti F, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis of the breast: clinical and histopathological features. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:445-449.

- Kirkland CR, Hawayek LH, Mutasim DF. Atherosclerosis-induced diffuse dermal angiomatosis with fatal outcome. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:684-685.

- Sommer S, Merchant WJ, Wilson CL. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis due to an iatrogenic arteriovenous fistula. Acta Derm Venereol. 2004;84:251-252.

- Corti MA, Rongioletti F, Borradori L, et al. Cutaneous reactive angiomatosis with combined histological pattern mimicking a cellulitis. Dermatology. 2013;227:226-230.

- Tollefson MM, McEvoy MT, Torgerson RR, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis of the breast: clinicopathologic study of 5 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:1212-1217.

- Walton K, Liggett J. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis: a case report. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66(suppl 1):AB49.

- Mayor-Ibarguren A, Gómez-Fernández C, Beato-Merino MJ, et al. Diffuse reactive angioendotheliomatosis secondary to the administration of trabectedin and pegfilgrastim. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:581-584.

- Lora V, Cota C, Cerroni L. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis of the abdomen. Eur J Dermatol. 2015;25:350-352.

- Pichardo RO, Lu D, Sangueza OP, et al. What is your diagnosis? diffuse dermal angiomatosis secondary to anticardiolipin antibodies. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:502.

- Kutzner H, Requena L, Mentzel T, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis. Hautarzt. 2002;53:808-812.

- McLaughlin ER, Morris R, Weiss SW, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis of the breast: response to isotretinoin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:462-465.

- Prinz Vavricka BM, Barry C, Victor T, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis associated with calciphylaxis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:653-657.

- Müller CS, Wagner A, Pföhler C, et al. Cup-shaped painful ulcer of abdominal wall. Hautarzt. 2008;59:656-658.

- Draper BK, Boyd AS. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:646-648.

- Adams BJ, Goldberg S, Massey HD, et al. A cause of unbearably painful breast, diffuse dermal angiomatosis. Gland Surg. 2012;1. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2227-684X.2012.07.02.

- Quatresooz P, Fumal I, Willemaers V, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis: a previously undescribed pattern of immunoglobulin and complement deposits in two cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:150-154.

- Morimoto K, Ioka H, Asada H, et al. Diffuse dermal angiomatosis. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2011;42:381-383.

Practice Points

- Diffuse dermal angiomatosis is commonly reported in patients with hypoxic comorbidities such as smoking or vascular disease as well as in women with large pendulous breasts.

- Effective treatments include control of comorbidities, revascularization, withdrawal of the offending agent, steroids, and isotretinoin.

Depigmentation therapy may be appropriate for patients with vitiligo

WASHINGTON – Seemal Desai, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Depigmentation therapy is “an underutilized resource for those patients who have recalcitrant disease or whose disease is so bad that you have not been able to improve their clinical, visible outcome,” said Dr. Desai, clinical assistant professor of dermatology at the University of Texas, Dallas. “Some of these patients simply desire to be one uniform color.”

Therapy is administered through medications that destroy residual melanocytes with the goal of achieving a uniform appearance of the skin. Monobenzyl ether of hydroquinone (MBEH) is the most common drug used in depigmentation therapy, according to Dr. Desai. It is available in concentrations of 20% and 40% and can be compounded in other concentrations. At first, patients should apply MBEH to a nickel-sized area of the skin (such as the forearm, the back of the hand, or the thigh) for 3 or 4 days. Treatment is administered in the morning and evening, but not at bedtime. A common side effect is irritant contact dermatitis.

When the patient is able to tolerate the medication in the first area, he or she can apply it to larger areas of the skin. Parts of the body are treated one at a time, and successful treatment takes time, he noted. Hair may become depigmented, but patients can be assured that the eyes will not.

Repigmentation has been reported after sun exposure. For all patients undergoing depigmentation therapy, dermatologists should provide extensive counseling about the need for lifelong photoprotection, said Dr. Desai. Protective measures can include wide-brimmed hats and broad-spectrum sunscreen. Paradoxical repigmentation can be treated with a stronger concentration of MBEH, liquid nitrogen therapy, microdermabrasion, and peels.

For patients with vitiligo, which results from the immune-mediated destruction of melanocytes, dermatologists should assess the patient’s psychological status and discuss “the impact that the disease has on not only the patient, but also the family,” Dr. Desai said. “The psychological trauma from this disease, especially for our patients who have rapidly progressing vitiligo or who have failed multiple therapies, is something that we cannot discount.”

Patients with vitiligo often have comorbid depression, and evening of the skin tone that depigmentation provides can benefit the patient’s mental state, he observed. Patients with severe depression related to vitiligo should be referred to a psychologist or psychiatrist. Finally, counseling and appropriate patient selection for depigmentation is of paramount importance.

During the presentation, he noted that hair dyes, resin products and adhesives, detergents, and leather preservatives have been associated with vitiligo. Dermatologic drugs such as imiquimod, chemotherapeutic agents, and interferon also may cause the condition.

He referred to the thousands of reported cases of vitiligo related to rhododenol, a phenolic compound that has been used in cosmetics and topical products. Most cases resolved when those affected stopped using the product, but some developed vitiligo vulgaris. Cosmetics containing rhododenol have been recalled in Japan since 2013, but over-the-counter products in Asia and Africa have been found to contain similar compounds, so dermatologists should ask patients about their travel history and about what products they are using for their skin, Dr. Desai advised.

He reported receiving grants and research funding from AbbVie, Dermira, Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories, and Menlo Therapeutics and serving as a consultant for several pharmaceutical companies.

WASHINGTON – Seemal Desai, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Depigmentation therapy is “an underutilized resource for those patients who have recalcitrant disease or whose disease is so bad that you have not been able to improve their clinical, visible outcome,” said Dr. Desai, clinical assistant professor of dermatology at the University of Texas, Dallas. “Some of these patients simply desire to be one uniform color.”

Therapy is administered through medications that destroy residual melanocytes with the goal of achieving a uniform appearance of the skin. Monobenzyl ether of hydroquinone (MBEH) is the most common drug used in depigmentation therapy, according to Dr. Desai. It is available in concentrations of 20% and 40% and can be compounded in other concentrations. At first, patients should apply MBEH to a nickel-sized area of the skin (such as the forearm, the back of the hand, or the thigh) for 3 or 4 days. Treatment is administered in the morning and evening, but not at bedtime. A common side effect is irritant contact dermatitis.

When the patient is able to tolerate the medication in the first area, he or she can apply it to larger areas of the skin. Parts of the body are treated one at a time, and successful treatment takes time, he noted. Hair may become depigmented, but patients can be assured that the eyes will not.

Repigmentation has been reported after sun exposure. For all patients undergoing depigmentation therapy, dermatologists should provide extensive counseling about the need for lifelong photoprotection, said Dr. Desai. Protective measures can include wide-brimmed hats and broad-spectrum sunscreen. Paradoxical repigmentation can be treated with a stronger concentration of MBEH, liquid nitrogen therapy, microdermabrasion, and peels.

For patients with vitiligo, which results from the immune-mediated destruction of melanocytes, dermatologists should assess the patient’s psychological status and discuss “the impact that the disease has on not only the patient, but also the family,” Dr. Desai said. “The psychological trauma from this disease, especially for our patients who have rapidly progressing vitiligo or who have failed multiple therapies, is something that we cannot discount.”

Patients with vitiligo often have comorbid depression, and evening of the skin tone that depigmentation provides can benefit the patient’s mental state, he observed. Patients with severe depression related to vitiligo should be referred to a psychologist or psychiatrist. Finally, counseling and appropriate patient selection for depigmentation is of paramount importance.

During the presentation, he noted that hair dyes, resin products and adhesives, detergents, and leather preservatives have been associated with vitiligo. Dermatologic drugs such as imiquimod, chemotherapeutic agents, and interferon also may cause the condition.

He referred to the thousands of reported cases of vitiligo related to rhododenol, a phenolic compound that has been used in cosmetics and topical products. Most cases resolved when those affected stopped using the product, but some developed vitiligo vulgaris. Cosmetics containing rhododenol have been recalled in Japan since 2013, but over-the-counter products in Asia and Africa have been found to contain similar compounds, so dermatologists should ask patients about their travel history and about what products they are using for their skin, Dr. Desai advised.

He reported receiving grants and research funding from AbbVie, Dermira, Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories, and Menlo Therapeutics and serving as a consultant for several pharmaceutical companies.

WASHINGTON – Seemal Desai, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Depigmentation therapy is “an underutilized resource for those patients who have recalcitrant disease or whose disease is so bad that you have not been able to improve their clinical, visible outcome,” said Dr. Desai, clinical assistant professor of dermatology at the University of Texas, Dallas. “Some of these patients simply desire to be one uniform color.”

Therapy is administered through medications that destroy residual melanocytes with the goal of achieving a uniform appearance of the skin. Monobenzyl ether of hydroquinone (MBEH) is the most common drug used in depigmentation therapy, according to Dr. Desai. It is available in concentrations of 20% and 40% and can be compounded in other concentrations. At first, patients should apply MBEH to a nickel-sized area of the skin (such as the forearm, the back of the hand, or the thigh) for 3 or 4 days. Treatment is administered in the morning and evening, but not at bedtime. A common side effect is irritant contact dermatitis.

When the patient is able to tolerate the medication in the first area, he or she can apply it to larger areas of the skin. Parts of the body are treated one at a time, and successful treatment takes time, he noted. Hair may become depigmented, but patients can be assured that the eyes will not.

Repigmentation has been reported after sun exposure. For all patients undergoing depigmentation therapy, dermatologists should provide extensive counseling about the need for lifelong photoprotection, said Dr. Desai. Protective measures can include wide-brimmed hats and broad-spectrum sunscreen. Paradoxical repigmentation can be treated with a stronger concentration of MBEH, liquid nitrogen therapy, microdermabrasion, and peels.

For patients with vitiligo, which results from the immune-mediated destruction of melanocytes, dermatologists should assess the patient’s psychological status and discuss “the impact that the disease has on not only the patient, but also the family,” Dr. Desai said. “The psychological trauma from this disease, especially for our patients who have rapidly progressing vitiligo or who have failed multiple therapies, is something that we cannot discount.”

Patients with vitiligo often have comorbid depression, and evening of the skin tone that depigmentation provides can benefit the patient’s mental state, he observed. Patients with severe depression related to vitiligo should be referred to a psychologist or psychiatrist. Finally, counseling and appropriate patient selection for depigmentation is of paramount importance.

During the presentation, he noted that hair dyes, resin products and adhesives, detergents, and leather preservatives have been associated with vitiligo. Dermatologic drugs such as imiquimod, chemotherapeutic agents, and interferon also may cause the condition.

He referred to the thousands of reported cases of vitiligo related to rhododenol, a phenolic compound that has been used in cosmetics and topical products. Most cases resolved when those affected stopped using the product, but some developed vitiligo vulgaris. Cosmetics containing rhododenol have been recalled in Japan since 2013, but over-the-counter products in Asia and Africa have been found to contain similar compounds, so dermatologists should ask patients about their travel history and about what products they are using for their skin, Dr. Desai advised.

He reported receiving grants and research funding from AbbVie, Dermira, Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories, and Menlo Therapeutics and serving as a consultant for several pharmaceutical companies.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM AAD 2019

Trametinib effectively treats case of giant congenital melanocytic nevus

according to a case report presented in Pediatrics.

Her nevus covered most of her back and much of her torso and had thickened significantly over the years since initial presentation to the point of disfigurement, even invading the fascia and musculature of the trunk and pelvis, reported Adnan Mir, MD, PhD, of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, and his coauthors. Furthermore, she presented with intractable pruritus and pain that interfered with sleep and responded minimally to treatments. Although initial immunohistochemical staining and gene sequencing did not reveal any mutations, such as BRAF V600E, further testing uncovered an AKAP9-BRAF fusion.

There are few if any effective ways of treating GCMNs. With that knowledge, as well as general theories of the mechanism GCMNs in mind, the patient’s health care team decided to try a 0.5-mg daily dose of trametinib when she was 7 years old. Her pruritus and pain resolved completely, and after 6 months of treatment with trametinib, repeat MRI “revealed decreased thickening of the dermis and near resolutions of muscular invasion.” According to the patient’s family, her quality of life improved dramatically.

SOURCE: Mir A et al. Pediatrics. 2019;143(3):e20182469.

according to a case report presented in Pediatrics.

Her nevus covered most of her back and much of her torso and had thickened significantly over the years since initial presentation to the point of disfigurement, even invading the fascia and musculature of the trunk and pelvis, reported Adnan Mir, MD, PhD, of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, and his coauthors. Furthermore, she presented with intractable pruritus and pain that interfered with sleep and responded minimally to treatments. Although initial immunohistochemical staining and gene sequencing did not reveal any mutations, such as BRAF V600E, further testing uncovered an AKAP9-BRAF fusion.

There are few if any effective ways of treating GCMNs. With that knowledge, as well as general theories of the mechanism GCMNs in mind, the patient’s health care team decided to try a 0.5-mg daily dose of trametinib when she was 7 years old. Her pruritus and pain resolved completely, and after 6 months of treatment with trametinib, repeat MRI “revealed decreased thickening of the dermis and near resolutions of muscular invasion.” According to the patient’s family, her quality of life improved dramatically.

SOURCE: Mir A et al. Pediatrics. 2019;143(3):e20182469.

according to a case report presented in Pediatrics.

Her nevus covered most of her back and much of her torso and had thickened significantly over the years since initial presentation to the point of disfigurement, even invading the fascia and musculature of the trunk and pelvis, reported Adnan Mir, MD, PhD, of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, and his coauthors. Furthermore, she presented with intractable pruritus and pain that interfered with sleep and responded minimally to treatments. Although initial immunohistochemical staining and gene sequencing did not reveal any mutations, such as BRAF V600E, further testing uncovered an AKAP9-BRAF fusion.

There are few if any effective ways of treating GCMNs. With that knowledge, as well as general theories of the mechanism GCMNs in mind, the patient’s health care team decided to try a 0.5-mg daily dose of trametinib when she was 7 years old. Her pruritus and pain resolved completely, and after 6 months of treatment with trametinib, repeat MRI “revealed decreased thickening of the dermis and near resolutions of muscular invasion.” According to the patient’s family, her quality of life improved dramatically.

SOURCE: Mir A et al. Pediatrics. 2019;143(3):e20182469.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Irregularly Hyperpigmented Plaque on the Right Heel

The Diagnosis: Pigmented Bowen Disease

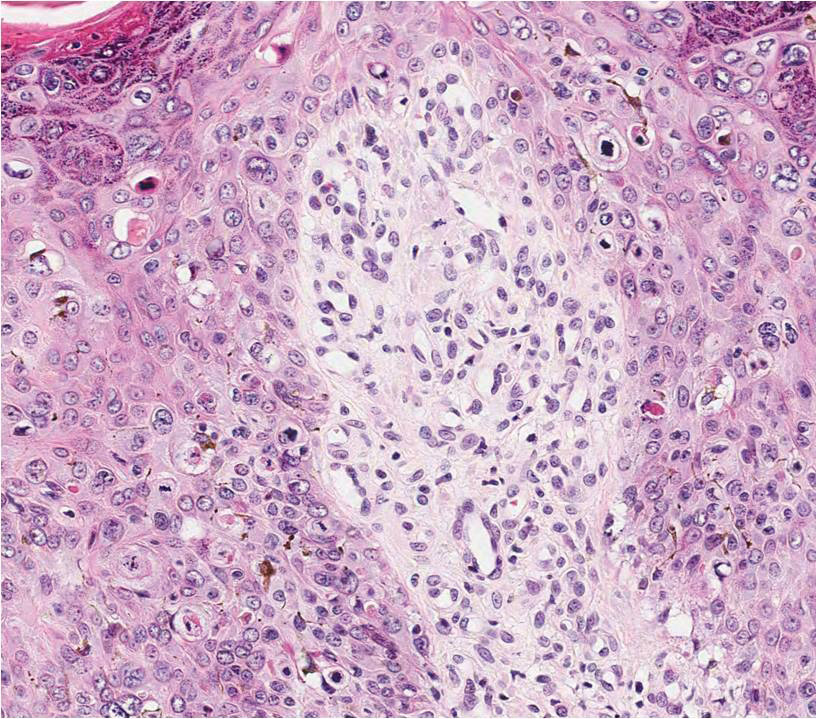

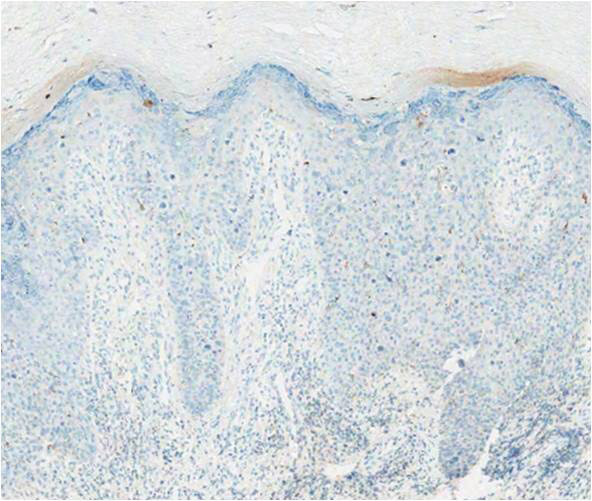

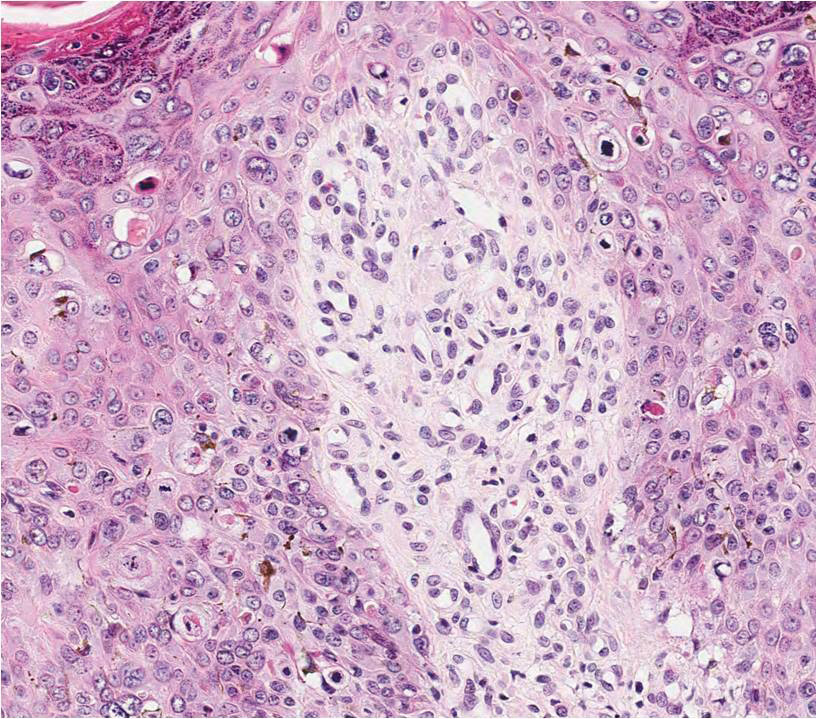

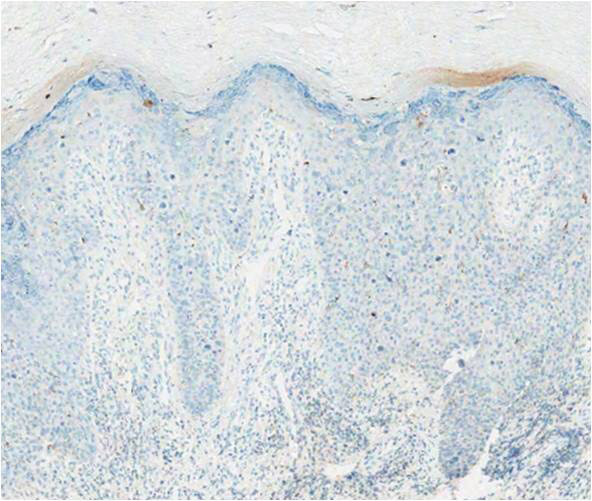

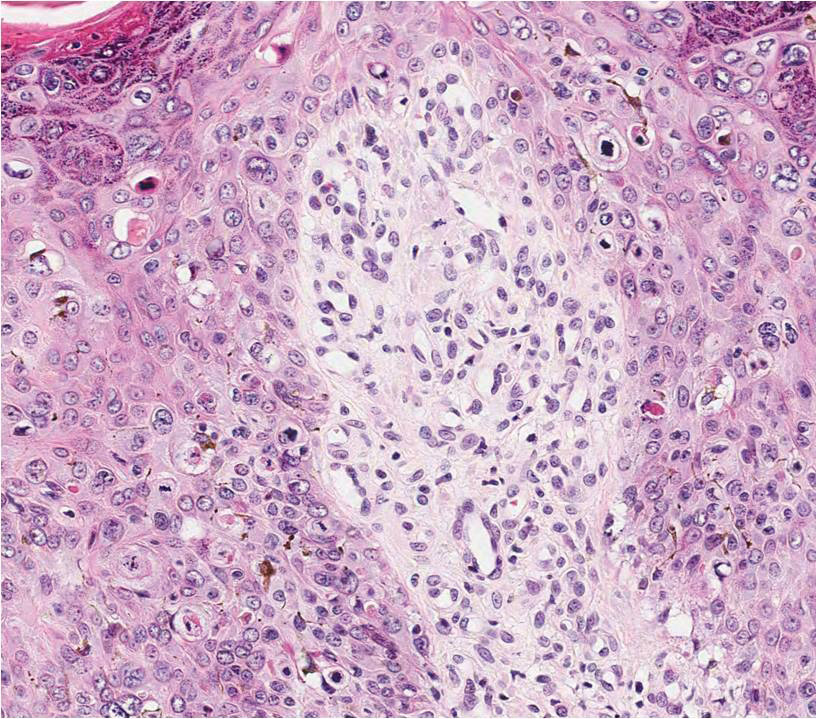

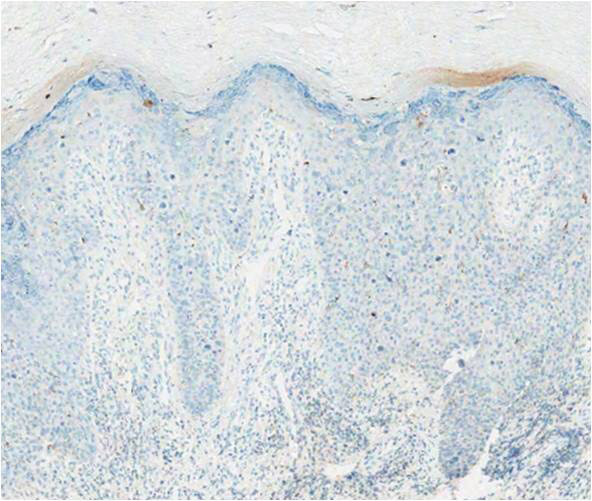

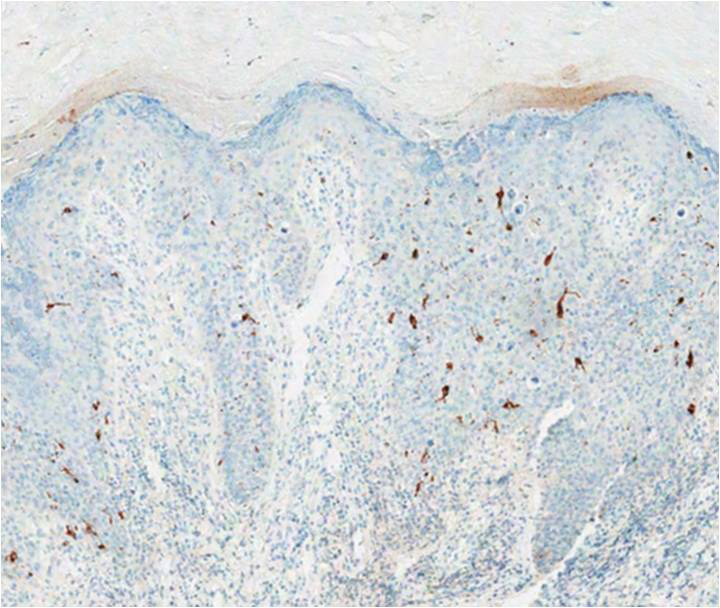

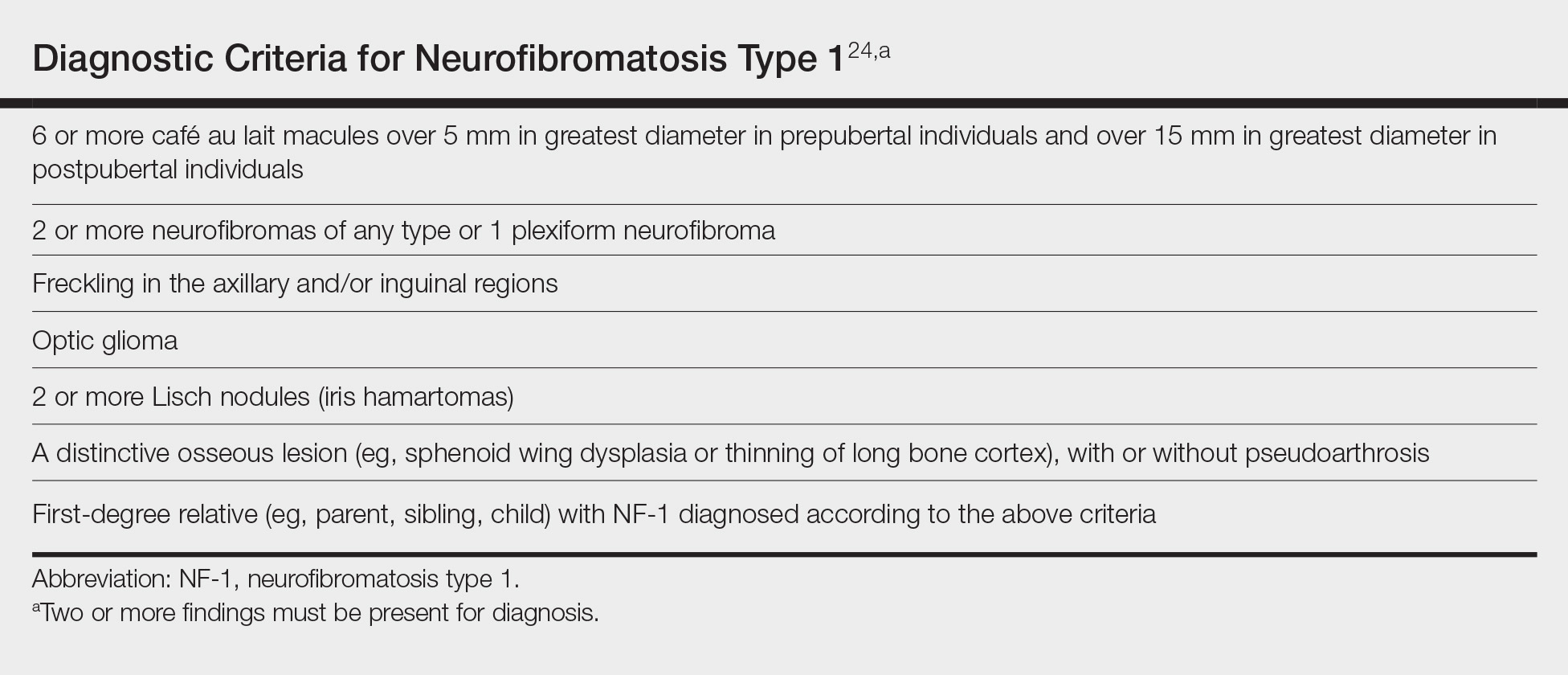

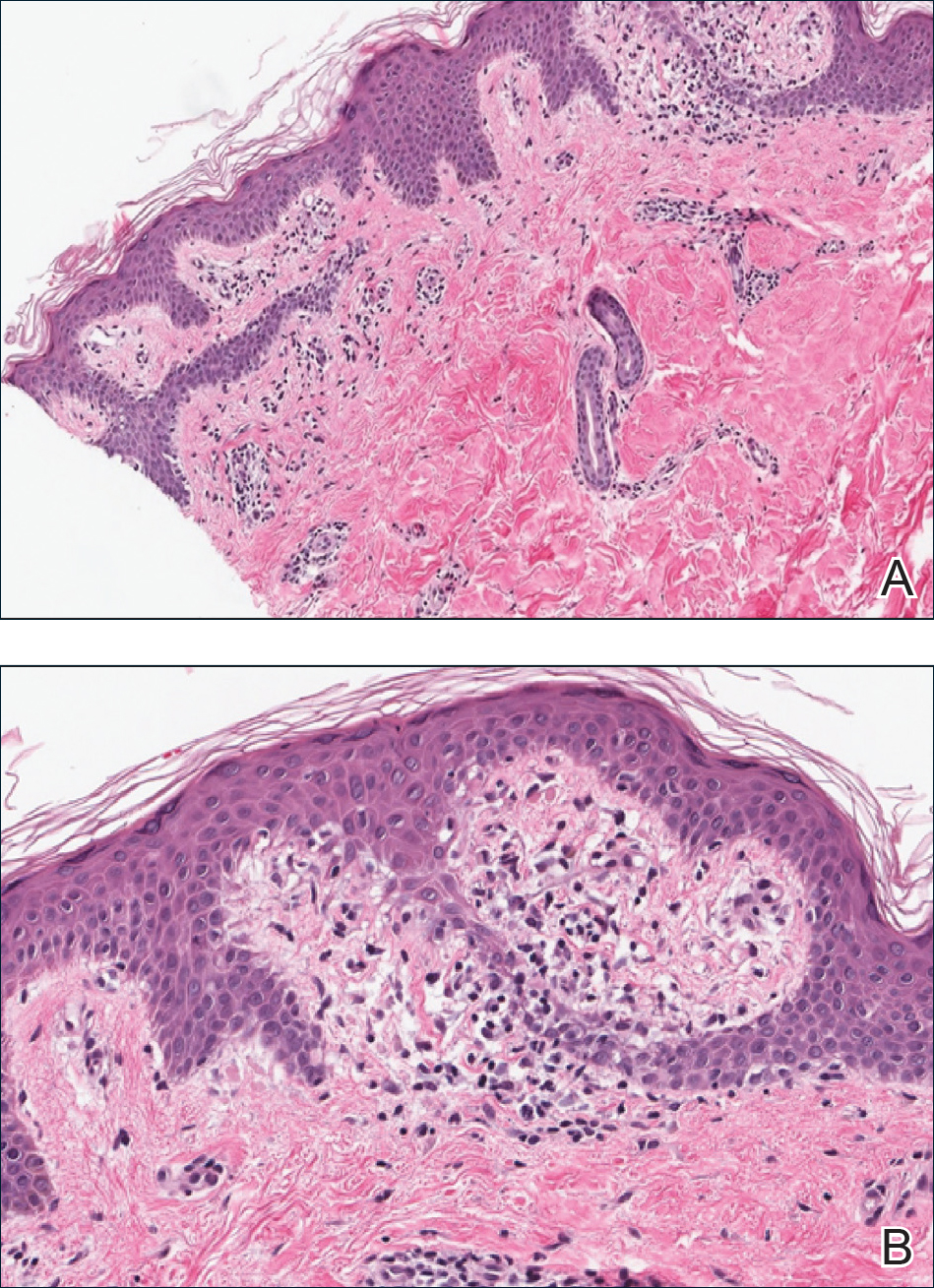

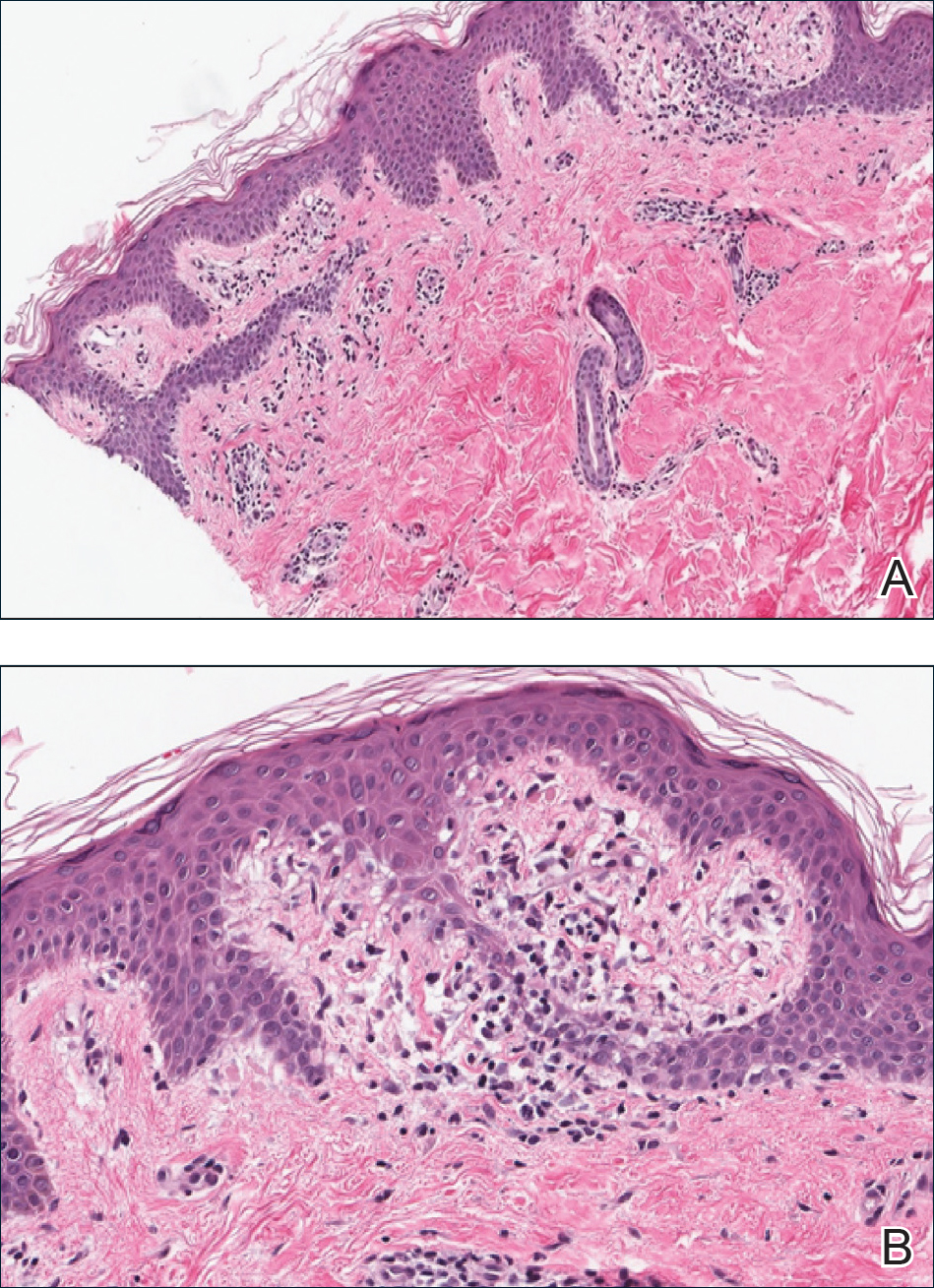

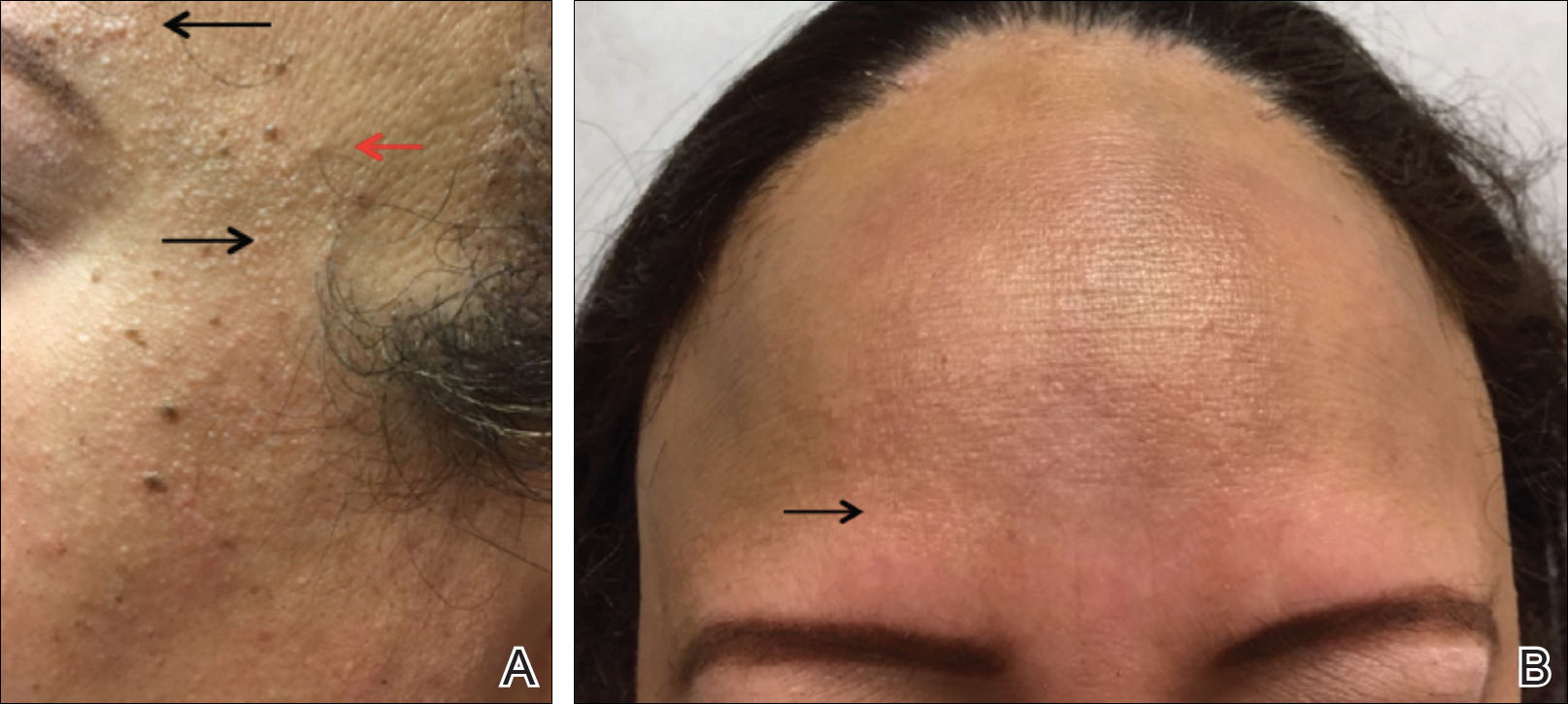

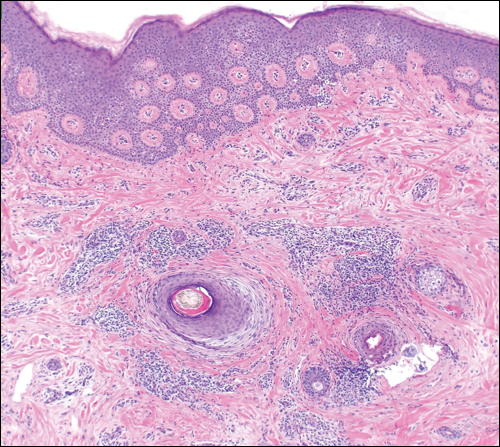

A biopsy of the lesion was performed for suspected acral malignant melanoma. Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed acanthosis, elongation of rete ridges, and keratinocytes in complete disorder with atypical mitoses and pleomorphism affecting the full layer of the epidermis (Figure 1). The basement membrane was intact. Melanin pigmentation was increased in the lower epidermis and the upper dermis, and a lymphohistiocytic inflammatory infiltrate was present in the dermis. Staining for carcinoembryonic antigen (Figure 2) and melanoma

antigen (Figure 3) recognized by T cells (melan-A) both revealed negative results. Histopathologic findings led to the diagnosis of pigmented Bowen disease (BD).

Pigmented BD is a rare variant that accounts for 1.7% (N=420) to 5.5% (N=951) of all cases of BD.1,2 It is reported to affect men more than women and to be more prevalent in individuals with higher Fitzpatrick skin types.3 Furthermore, exposure to UV radiation, chemicals (eg, arsenic), or human papillomavirus, as well as immunosuppression, are known to be related to pigmented BD.2,4 Clinically, pigmented BD commonly involves nonexposed areas such as the anogenital area, trunk, and extremities, unlike typical BD that involves sun-exposed areas.5 In addition, it most frequently presents as a well-delineated, irregularly pigmented, asymptomatic

plaque and not as a scaly erythematous plaque. Therefore, the clinical diagnosis may be challenging. The differential diagnosis includes malignant melanoma, pigmented extramammary Paget disease, pigmented basal cell carcinoma, seborrheic keratosis, pigmented actinic keratosis, solar lentigo, and melanocytic nevi.

Histopathologically, a varying amount of melanin deposit is noted on hematoxylin and eosin staining, along with features of BD, including disarrayed atypical keratinocytes involving the full epidermis but not the basement membrane, with atypical individual cell keratinization.3,5,6 Pigmented extramammary Paget disease can mimic pigmented BD clinically and pathologically, but Paget cells stain positive for anticytokeratin (CAM 5.2), carcinoembryonic antigen, and mucicarmine, whereas cells in pigmented BD stain negative.7 Moreover, negative staining for human melanoma black, melan-A, and S-100 helps differentiate malignant melanoma from pigmented BD.8

The prognosis of pigmented BD is similar to classic BD and is independent of the presence of melanin pigment.6 Therefore, the treatment options do not differ from those for typical BD and include surgical excision, cryotherapy, laser ablation, topical imiquimod or 5-fluorouracil, curettage, electrosurgery, and photodynamic therapy (PDT).

In our case, the patient and her family did not want surgical removal; therefore, 1 course of fractional laser-assisted PDT and 2 courses of ablative laser-assisted PDT were performed. Unfortunately, the lesion persisted, possibly because it was too large and pigmented. Two months later, ingenol mebutate gel 0.05% was applied (4 courses) after using an ablative laser over 3 consecutive days with a 1-month interval between courses. The lesion resolved without any adverse events.

- Cameron A, Rosendahl C, Tschandl P, et al. Dermatoscopy of pigmented Bowen’s disease [published online January 15, 2010]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:597-604.

- Ragi G, Turner MS, Klein LE, et al. Pigmented Bowen’s disease and review of 420 Bowen’s disease lesions. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1988;14:765-769.

- Hernandez C, Ivkovic A, Fowler A. Growing plaque on foot. J Fam Pract. 2008;57:603-605.

- Hwang SW, Kim JW, Park SW, et al. Two cases of pigmented Bowen’s disease. Ann Dermatol 2002;14:127-129.

- Wilmer EM, Lee KC, Higgins W 2nd, et al. Hyperpigmented palmar plaque: an unexpected diagnosis of Bowen disease. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:18573.

- Brinca A, Teixeira V, Gonçalo M, et al. A large pigmented lesion mimicking malignant melanoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:817-884.

- Hilliard NJ, Huang C, Andea A. Pigmented extramammary Paget’s disease of the axilla mimicking melanoma: case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:995-1000.

- Öztürk Durmaz E, Dog˘ an Ekici I, Ozian F, et al. Pigmented Bowen’s disease of the genitalia masquerading as malignant melanoma. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2015;23:130-133.

The Diagnosis: Pigmented Bowen Disease

A biopsy of the lesion was performed for suspected acral malignant melanoma. Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed acanthosis, elongation of rete ridges, and keratinocytes in complete disorder with atypical mitoses and pleomorphism affecting the full layer of the epidermis (Figure 1). The basement membrane was intact. Melanin pigmentation was increased in the lower epidermis and the upper dermis, and a lymphohistiocytic inflammatory infiltrate was present in the dermis. Staining for carcinoembryonic antigen (Figure 2) and melanoma

antigen (Figure 3) recognized by T cells (melan-A) both revealed negative results. Histopathologic findings led to the diagnosis of pigmented Bowen disease (BD).

Pigmented BD is a rare variant that accounts for 1.7% (N=420) to 5.5% (N=951) of all cases of BD.1,2 It is reported to affect men more than women and to be more prevalent in individuals with higher Fitzpatrick skin types.3 Furthermore, exposure to UV radiation, chemicals (eg, arsenic), or human papillomavirus, as well as immunosuppression, are known to be related to pigmented BD.2,4 Clinically, pigmented BD commonly involves nonexposed areas such as the anogenital area, trunk, and extremities, unlike typical BD that involves sun-exposed areas.5 In addition, it most frequently presents as a well-delineated, irregularly pigmented, asymptomatic

plaque and not as a scaly erythematous plaque. Therefore, the clinical diagnosis may be challenging. The differential diagnosis includes malignant melanoma, pigmented extramammary Paget disease, pigmented basal cell carcinoma, seborrheic keratosis, pigmented actinic keratosis, solar lentigo, and melanocytic nevi.

Histopathologically, a varying amount of melanin deposit is noted on hematoxylin and eosin staining, along with features of BD, including disarrayed atypical keratinocytes involving the full epidermis but not the basement membrane, with atypical individual cell keratinization.3,5,6 Pigmented extramammary Paget disease can mimic pigmented BD clinically and pathologically, but Paget cells stain positive for anticytokeratin (CAM 5.2), carcinoembryonic antigen, and mucicarmine, whereas cells in pigmented BD stain negative.7 Moreover, negative staining for human melanoma black, melan-A, and S-100 helps differentiate malignant melanoma from pigmented BD.8

The prognosis of pigmented BD is similar to classic BD and is independent of the presence of melanin pigment.6 Therefore, the treatment options do not differ from those for typical BD and include surgical excision, cryotherapy, laser ablation, topical imiquimod or 5-fluorouracil, curettage, electrosurgery, and photodynamic therapy (PDT).

In our case, the patient and her family did not want surgical removal; therefore, 1 course of fractional laser-assisted PDT and 2 courses of ablative laser-assisted PDT were performed. Unfortunately, the lesion persisted, possibly because it was too large and pigmented. Two months later, ingenol mebutate gel 0.05% was applied (4 courses) after using an ablative laser over 3 consecutive days with a 1-month interval between courses. The lesion resolved without any adverse events.

The Diagnosis: Pigmented Bowen Disease

A biopsy of the lesion was performed for suspected acral malignant melanoma. Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed acanthosis, elongation of rete ridges, and keratinocytes in complete disorder with atypical mitoses and pleomorphism affecting the full layer of the epidermis (Figure 1). The basement membrane was intact. Melanin pigmentation was increased in the lower epidermis and the upper dermis, and a lymphohistiocytic inflammatory infiltrate was present in the dermis. Staining for carcinoembryonic antigen (Figure 2) and melanoma

antigen (Figure 3) recognized by T cells (melan-A) both revealed negative results. Histopathologic findings led to the diagnosis of pigmented Bowen disease (BD).

Pigmented BD is a rare variant that accounts for 1.7% (N=420) to 5.5% (N=951) of all cases of BD.1,2 It is reported to affect men more than women and to be more prevalent in individuals with higher Fitzpatrick skin types.3 Furthermore, exposure to UV radiation, chemicals (eg, arsenic), or human papillomavirus, as well as immunosuppression, are known to be related to pigmented BD.2,4 Clinically, pigmented BD commonly involves nonexposed areas such as the anogenital area, trunk, and extremities, unlike typical BD that involves sun-exposed areas.5 In addition, it most frequently presents as a well-delineated, irregularly pigmented, asymptomatic

plaque and not as a scaly erythematous plaque. Therefore, the clinical diagnosis may be challenging. The differential diagnosis includes malignant melanoma, pigmented extramammary Paget disease, pigmented basal cell carcinoma, seborrheic keratosis, pigmented actinic keratosis, solar lentigo, and melanocytic nevi.

Histopathologically, a varying amount of melanin deposit is noted on hematoxylin and eosin staining, along with features of BD, including disarrayed atypical keratinocytes involving the full epidermis but not the basement membrane, with atypical individual cell keratinization.3,5,6 Pigmented extramammary Paget disease can mimic pigmented BD clinically and pathologically, but Paget cells stain positive for anticytokeratin (CAM 5.2), carcinoembryonic antigen, and mucicarmine, whereas cells in pigmented BD stain negative.7 Moreover, negative staining for human melanoma black, melan-A, and S-100 helps differentiate malignant melanoma from pigmented BD.8

The prognosis of pigmented BD is similar to classic BD and is independent of the presence of melanin pigment.6 Therefore, the treatment options do not differ from those for typical BD and include surgical excision, cryotherapy, laser ablation, topical imiquimod or 5-fluorouracil, curettage, electrosurgery, and photodynamic therapy (PDT).

In our case, the patient and her family did not want surgical removal; therefore, 1 course of fractional laser-assisted PDT and 2 courses of ablative laser-assisted PDT were performed. Unfortunately, the lesion persisted, possibly because it was too large and pigmented. Two months later, ingenol mebutate gel 0.05% was applied (4 courses) after using an ablative laser over 3 consecutive days with a 1-month interval between courses. The lesion resolved without any adverse events.

- Cameron A, Rosendahl C, Tschandl P, et al. Dermatoscopy of pigmented Bowen’s disease [published online January 15, 2010]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:597-604.

- Ragi G, Turner MS, Klein LE, et al. Pigmented Bowen’s disease and review of 420 Bowen’s disease lesions. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1988;14:765-769.

- Hernandez C, Ivkovic A, Fowler A. Growing plaque on foot. J Fam Pract. 2008;57:603-605.

- Hwang SW, Kim JW, Park SW, et al. Two cases of pigmented Bowen’s disease. Ann Dermatol 2002;14:127-129.

- Wilmer EM, Lee KC, Higgins W 2nd, et al. Hyperpigmented palmar plaque: an unexpected diagnosis of Bowen disease. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:18573.

- Brinca A, Teixeira V, Gonçalo M, et al. A large pigmented lesion mimicking malignant melanoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:817-884.

- Hilliard NJ, Huang C, Andea A. Pigmented extramammary Paget’s disease of the axilla mimicking melanoma: case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:995-1000.

- Öztürk Durmaz E, Dog˘ an Ekici I, Ozian F, et al. Pigmented Bowen’s disease of the genitalia masquerading as malignant melanoma. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2015;23:130-133.

- Cameron A, Rosendahl C, Tschandl P, et al. Dermatoscopy of pigmented Bowen’s disease [published online January 15, 2010]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:597-604.

- Ragi G, Turner MS, Klein LE, et al. Pigmented Bowen’s disease and review of 420 Bowen’s disease lesions. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1988;14:765-769.

- Hernandez C, Ivkovic A, Fowler A. Growing plaque on foot. J Fam Pract. 2008;57:603-605.

- Hwang SW, Kim JW, Park SW, et al. Two cases of pigmented Bowen’s disease. Ann Dermatol 2002;14:127-129.

- Wilmer EM, Lee KC, Higgins W 2nd, et al. Hyperpigmented palmar plaque: an unexpected diagnosis of Bowen disease. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:18573.

- Brinca A, Teixeira V, Gonçalo M, et al. A large pigmented lesion mimicking malignant melanoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:817-884.

- Hilliard NJ, Huang C, Andea A. Pigmented extramammary Paget’s disease of the axilla mimicking melanoma: case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:995-1000.

- Öztürk Durmaz E, Dog˘ an Ekici I, Ozian F, et al. Pigmented Bowen’s disease of the genitalia masquerading as malignant melanoma. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2015;23:130-133.

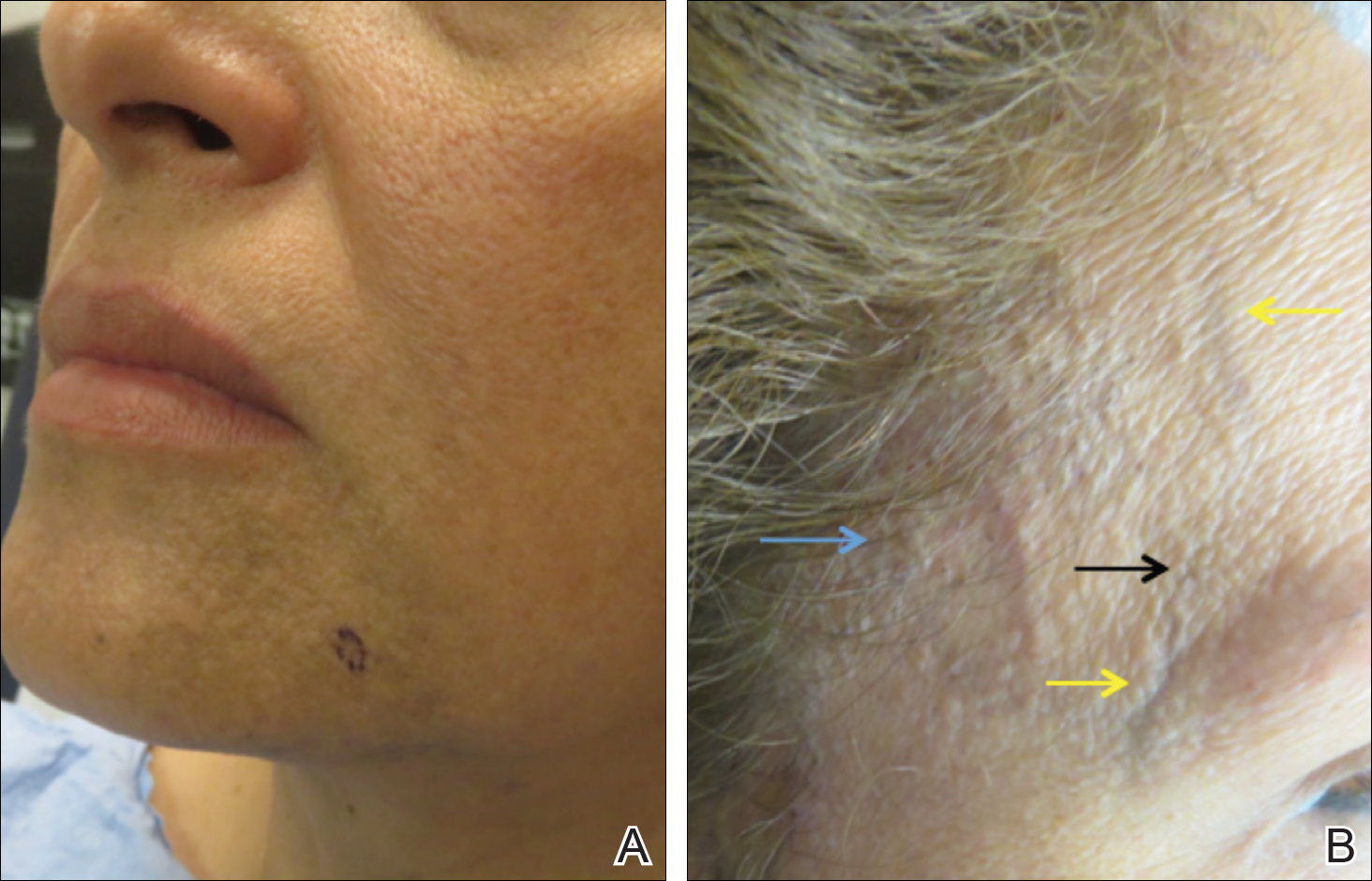

A 56-year-old woman presented with an asymptomatic plaque on the right heel that had grown

steadily over the last year. Pigmented lesions were not appreciated on other sites, and lymph nodes were not enlarged. Her medical history was otherwise normal, except for bilateral hearing loss due to encephalitis at the age of 5 years. None of her family members had similar symptoms. Physical examination revealed a well-defined, irregularly hyperpigmented plaque on the right heel.

Neurofibromatosis Type 1 in the Setting of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

To the Editor:

Patients with concurrent neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF-1) and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) rarely have been reported in the literature. Neurofibromatosis type 1 is one of the most common genetic disorders, with a worldwide birth incidence of 1 in 2500 individuals and prevalence of 1 in 4000 individuals.1 The incidence and prevalence of SLE varies widely depending on race and geographic location. Estimated incidence rates for SLE range from 1 to 25 per 100,000 individuals annually in North America, South America, Europe, and Asia.2,3 The reported worldwide prevalence is 20 to 150 cases per 100,000 individuals annually.2,4,5

Given the high prevalence of both conditions, the association between SLE and NF-1 likely is underrecognized; therefore, identifying more patients with concurrent SLE and NF-1 and describing the interplay between the 2 conditions may have important therapeutic implications. We present the case of a middle-aged woman with a history of SLE who had cutaneous lesions characteristic of NF-1 to further the understanding of these concurrent conditions.

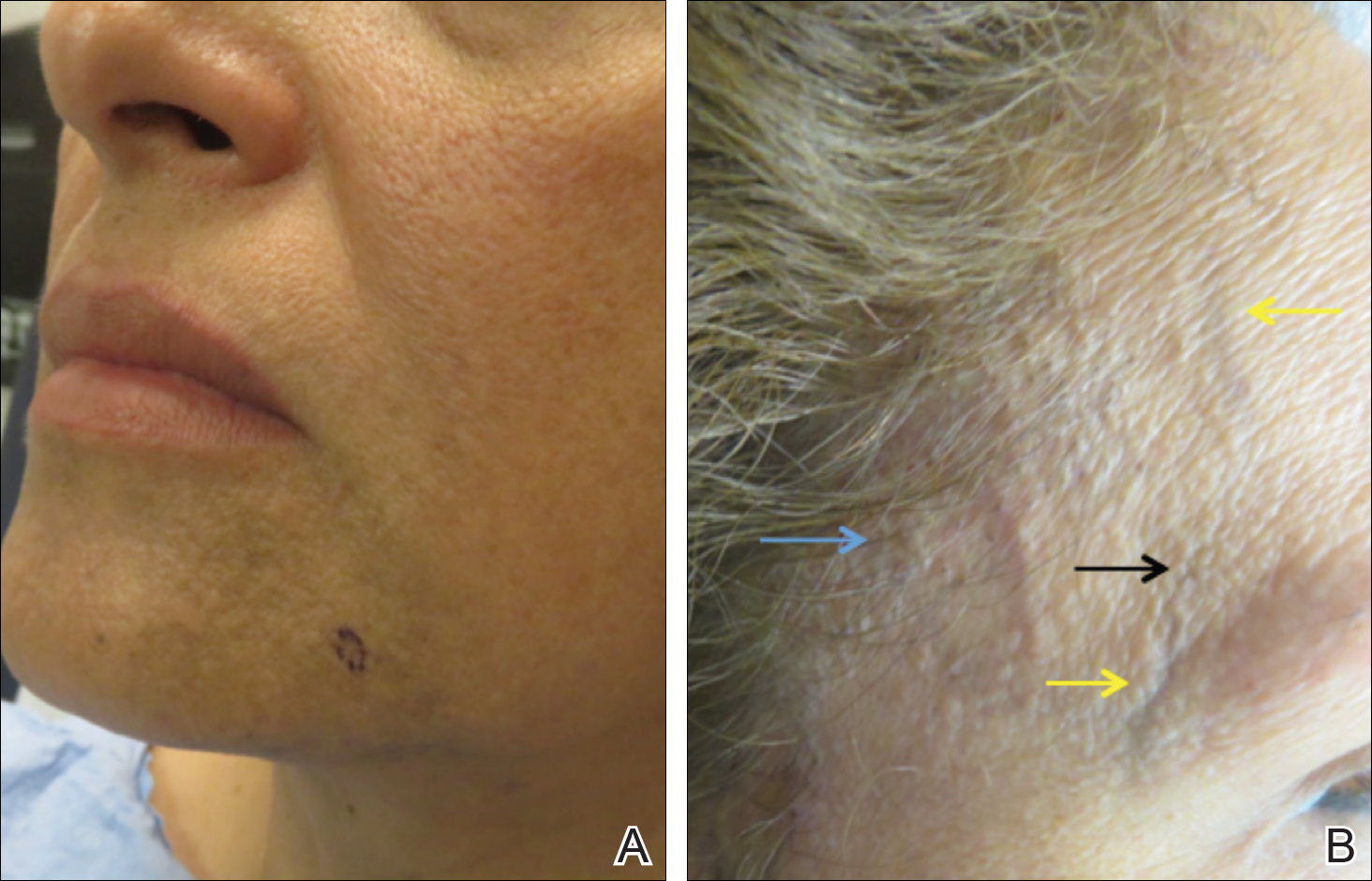

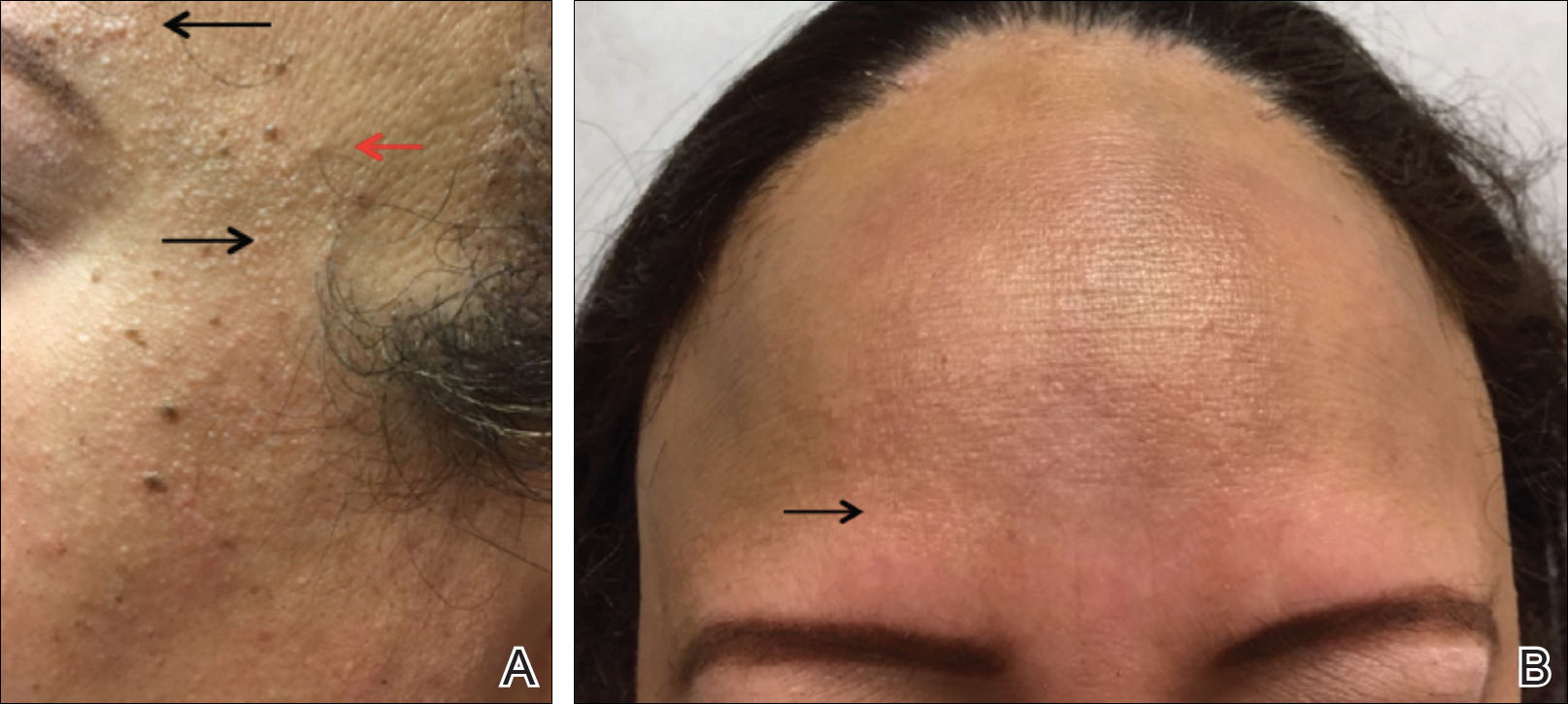

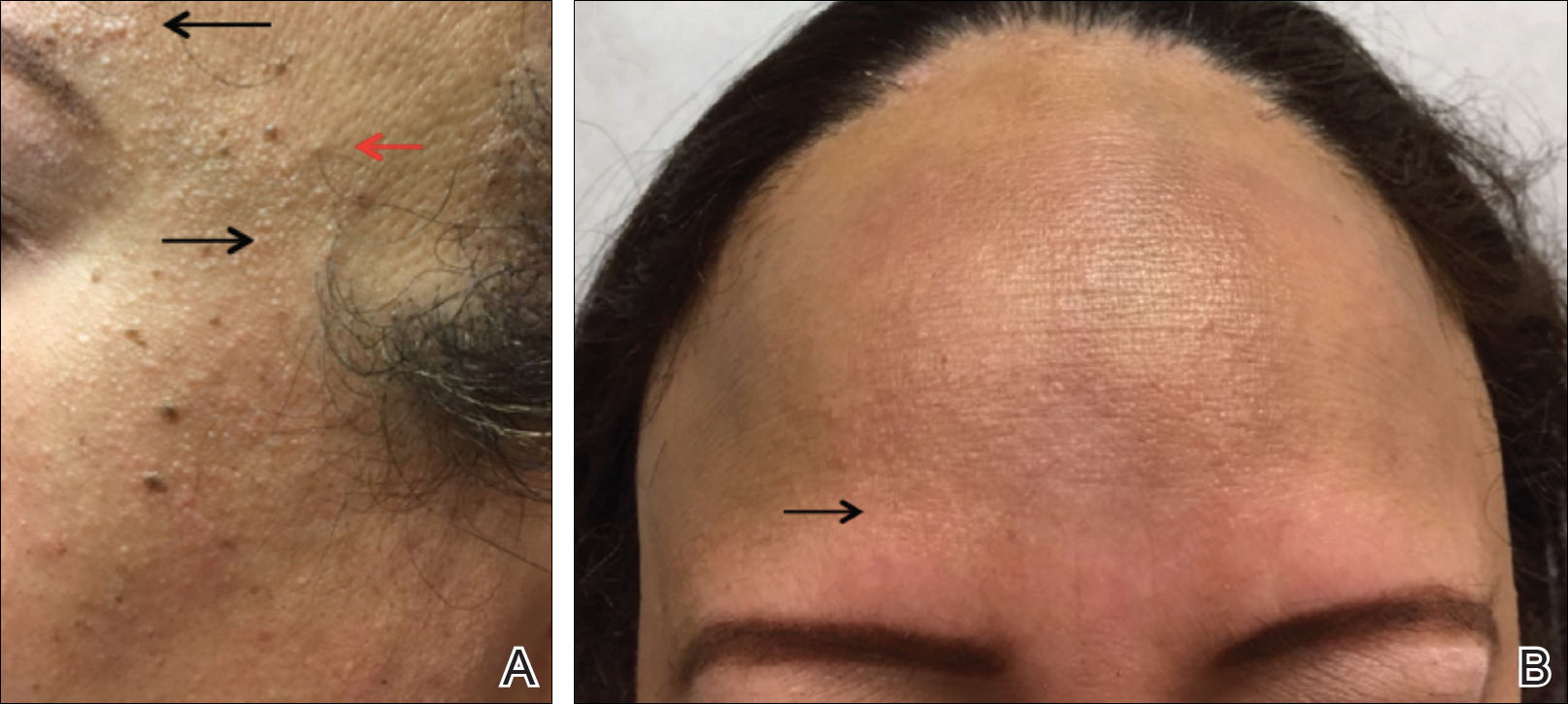

A middle-aged woman presented to our academic dermatology clinic for evaluation and removal of dark spots that had been present diffusely on the trunk and extremities since birth. She reported a history of SLE with lupus nephritis, hypertension, and a nodular goiter following a partial thyroidectomy. She noted that she did not seek treatment for the skin findings sooner because she was more concerned about her other medical conditions; however, because she felt these conditions were now stable, she decided to seek treatment for the “rash.” Physical examination revealed hundreds of café au lait macules and numerous neurofibromas diffusely distributed on the trunk and extremities (Figure 1) as well as bilateral axillary freckling. A clinical diagnosis of NF-1 was made.

When questioned, the patient reported that she may have been diagnosed with NF-1 in the past by another physician, but she did not recall it specifically. The patient was advised that there were no treatments for the café au lait macules. We notified her other physicians of the NF-1 diagnosis so she could be monitored for systemic conditions related to NF-1, including optic gliomas, pheochromocytoma, renal artery stenosis, and internal neurofibromas. We also referred the patient for genetic counseling; of note, the patient reported she had 4 children without any evidence of similar skin lesions or chronic health problems.

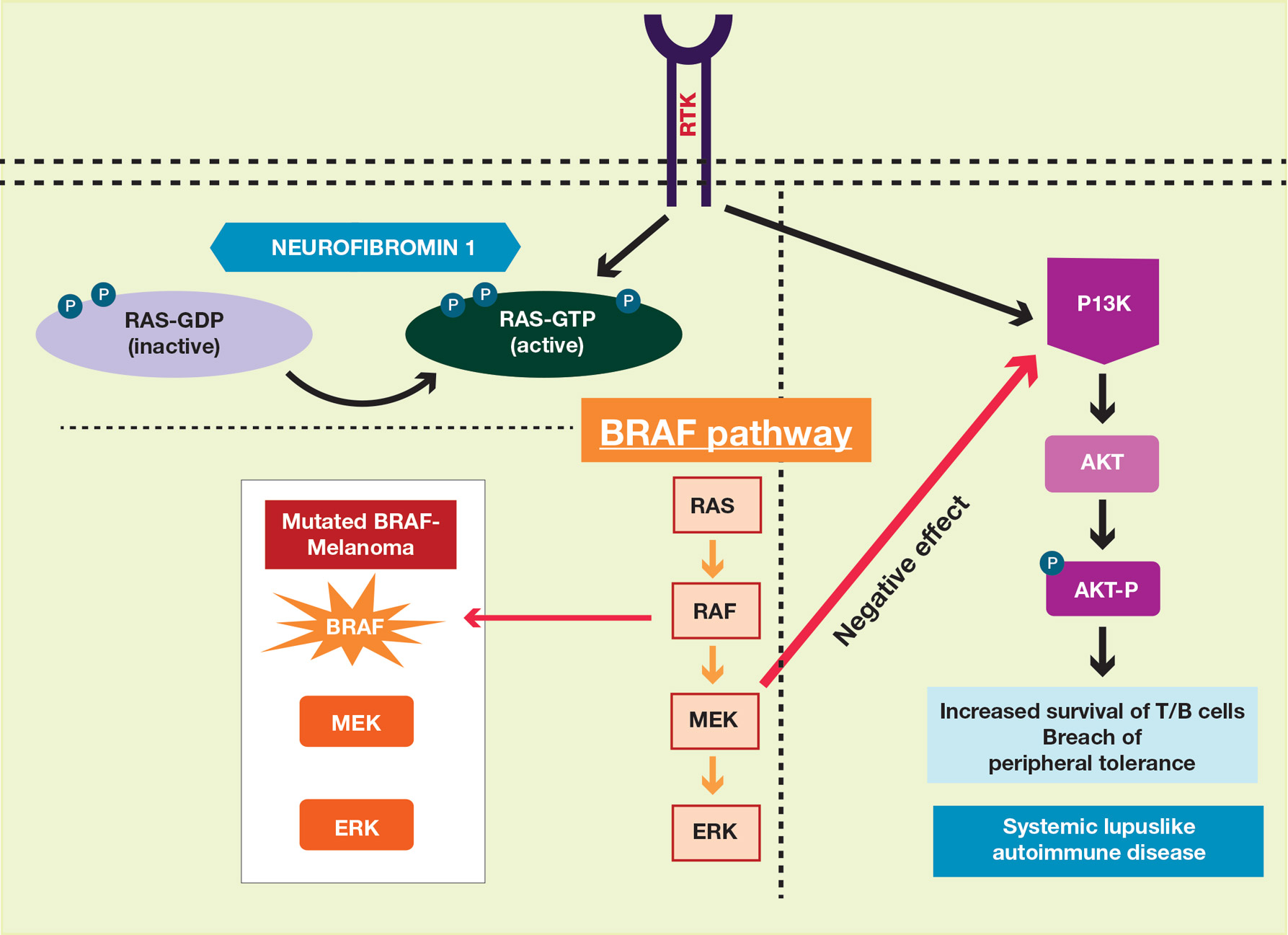

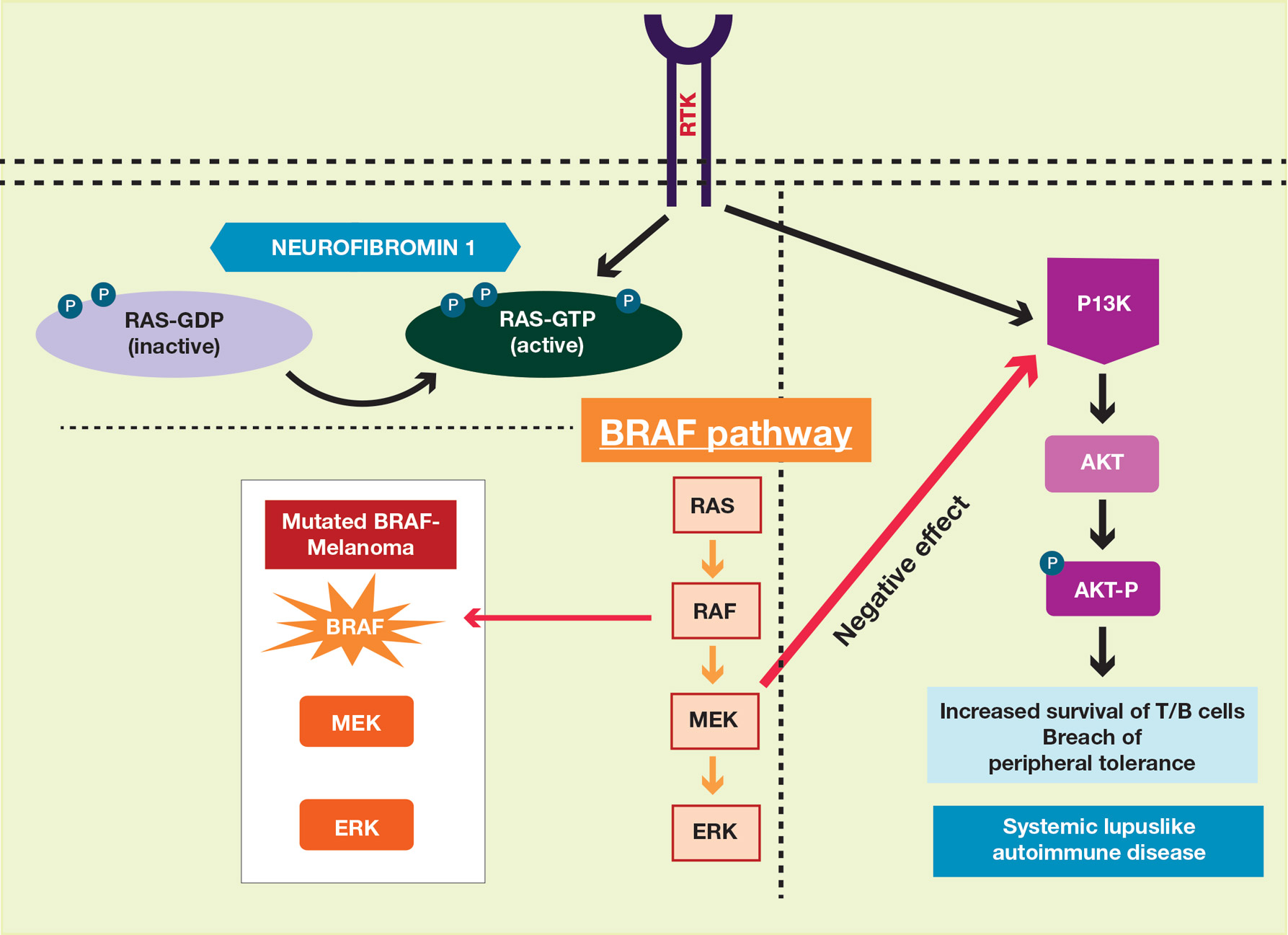

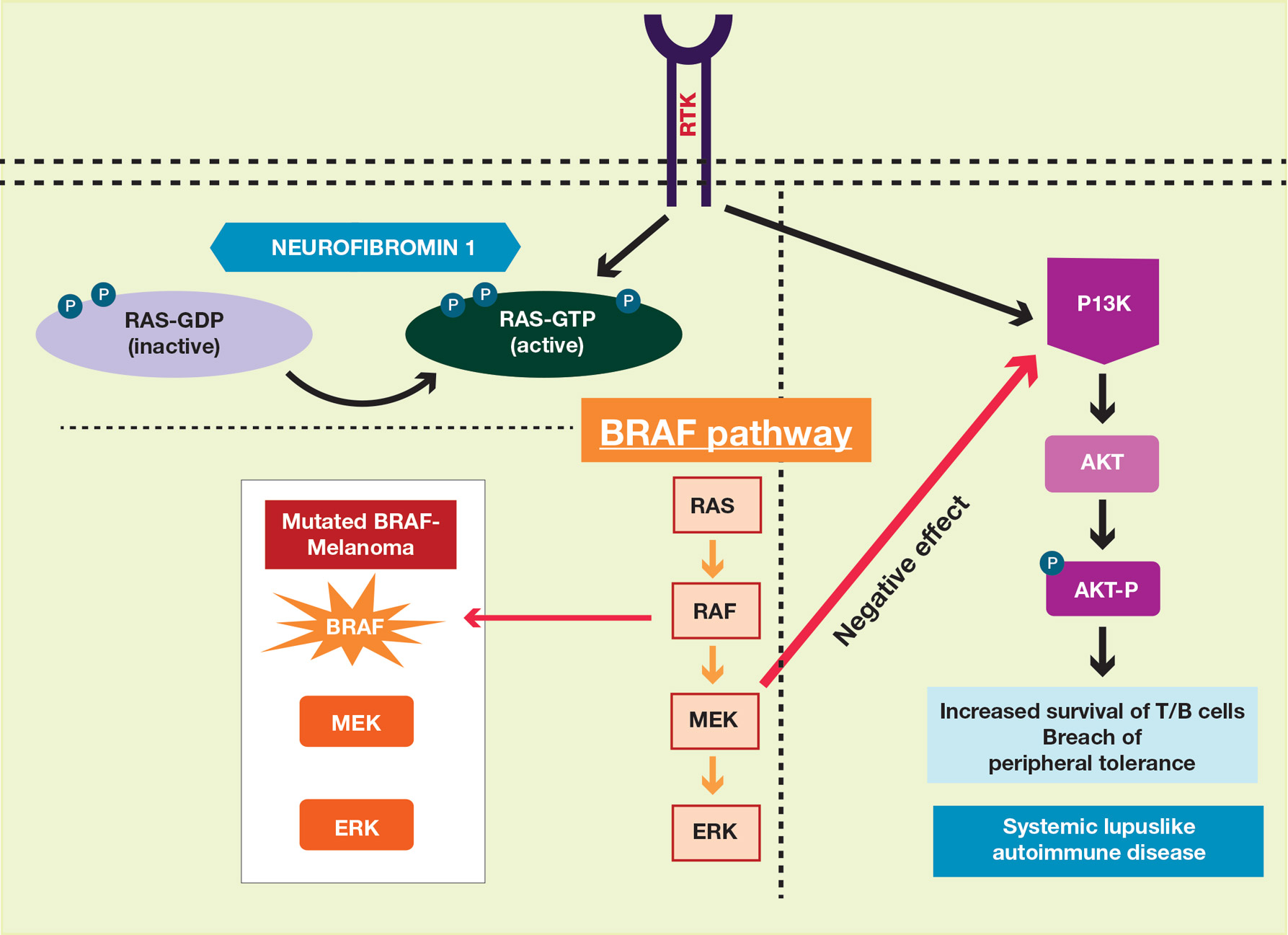

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms systemic lupus and neurofibromatosis yielded 8 cases of patients having both SLE and NF-1 (including our case).6-11 Our patient reported having multiple lesions since birth, decades before the onset and diagnosis of SLE. In 3 other cases, patients were diagnosed with SLE and then presented with neurofibromas, leading to NF-1 diagnosis.In the discussion of those 3 cases, it was proposed that immune system alterations caused by SLE leading to viral illness may have predisposed the patients to the development of tumors and other collagen diseases, or it could be coincidental.6,7 In another case, a patient with NF-1 developed SLE, which was thought to be coincidental.8 Akyuz et al9 described the case of a pediatric patient with NF-1 who subsequently was diagnosed with SLE. The authors suggested that the lack of neurofibromin contributed to the development of SLE, an autoimmune condition. Under normal circumstances, neurofibromin acts as a guanosine triphosphatase–activating protein for RAS in T cells.10 CD8+ T-cell function also is impaired in patients with SLE.9 Additionally, it has been reported that anti–double-stranded DNA antibodies and immune complexes were present in NF-1 patients, even though there were low titers.12 Thus, the authors proposed that the lack of neurofibromin led to dysregulation of the RAS pathway and impairment of T cells, creating an immune milieu that predisposed the patient to development of SLE. Our case gives additional credence to this theory, as our patient had a similar clinical course: the café au lait macules were present since birth and the symptoms of SLE surfaced much later in her late 20s and 30s. Another case by Makino and Tampo10 described a patient with a history of SLE who was later diagnosed with NF-1 based on choroidal findings highly specific for NF-1 but did not have other classic findings of NF-1. The authors mentioned that there might be a potential relationship between these two disorders but did not speculate any theory in particular for their case.10

The interplay between an autoimmune condition such as SLE and NF-1, a condition traditionally thought to be due to a genetic mutation, may have greater clinical and therapeutic implications beyond just these two disorders. Although it is well established that RAS pathway disruption causes NF-1, it has been uncovered that dysfunction in the RAS pathway also can contribute to melanoma oncogenesis.13,14 These insights have led to the development of and approval of targeted drugs designed to inhibit the RAS pathway (eg, vemurafenib, dabrafenib, trametinib).14-17 Melanoma also is considered a “model” tumor for studying the relationship between the immune system and cancer.18

Our case also is instructive in another point: our patient had never sought treatment for her skin lesions, as she said she had other more serious health conditions. Closer evaluation of her skin condition may have led to earlier diagnosis of NF-1, which has important health implications. The average lifespan of patients with NF-1 is 10 to 15 years lower than the general population, with cancer being the leading cause of death.20 Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors are the most common malignant tumors observed in such patients.21-23 Other cancers that are associated with NF-1 include rhabdomyosarcomas, gastrointestinal stromal tumors, neuroectodermal tumors, pheochromocytomas, and breast carcinomas.23

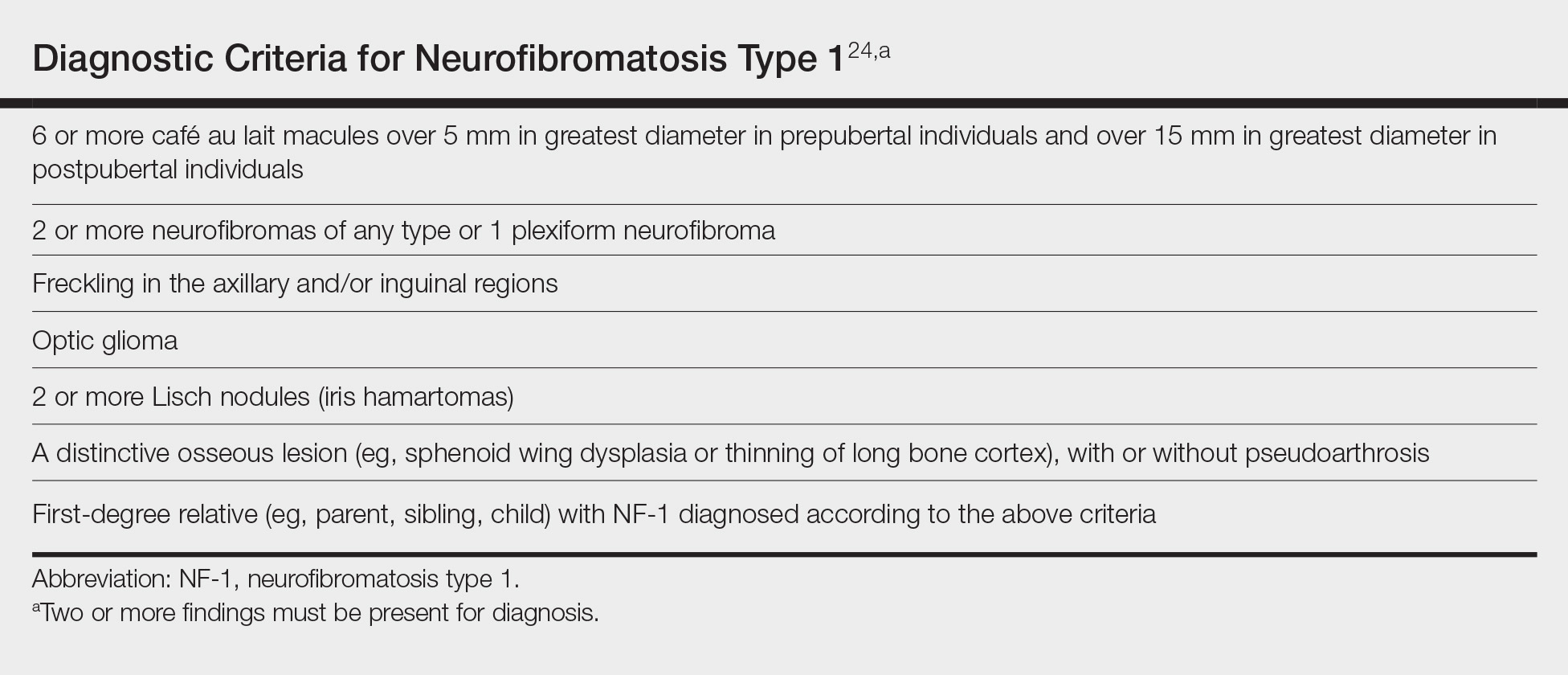

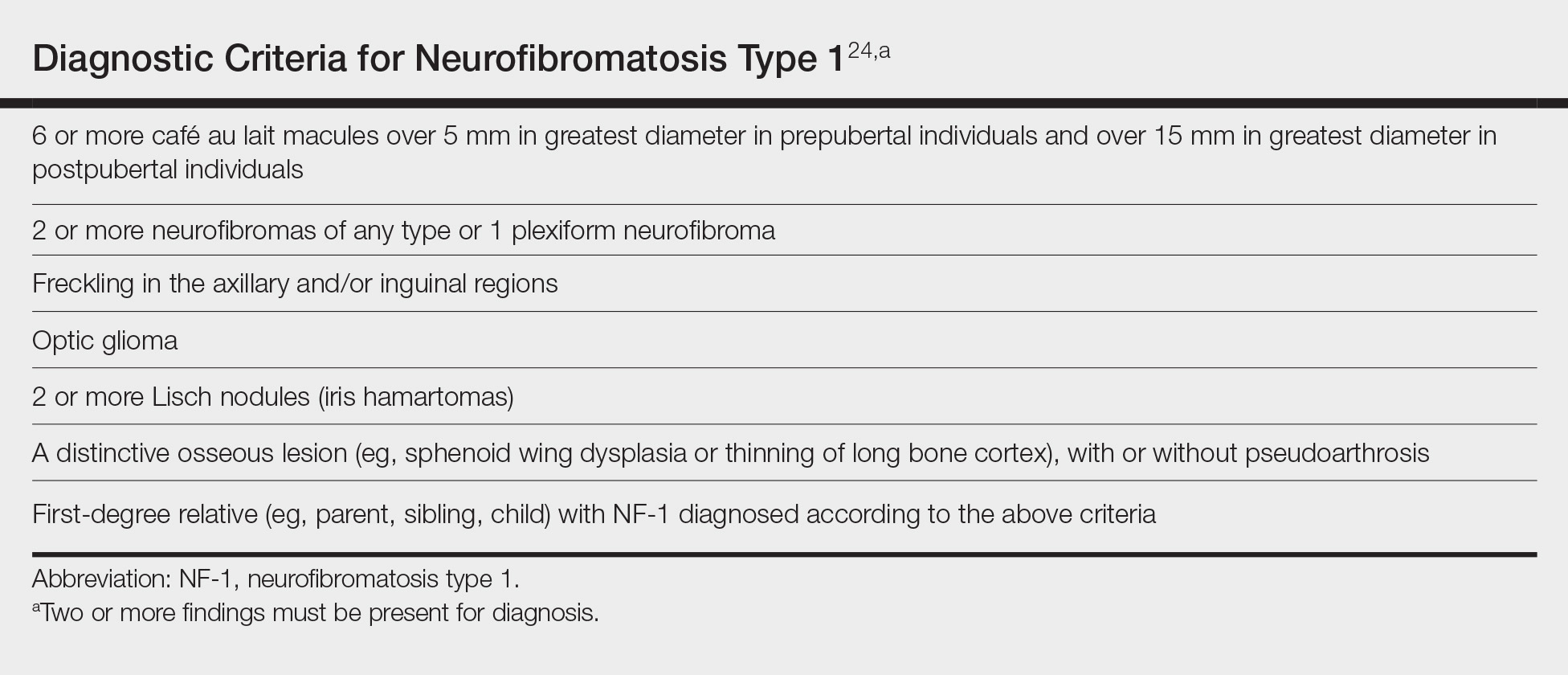

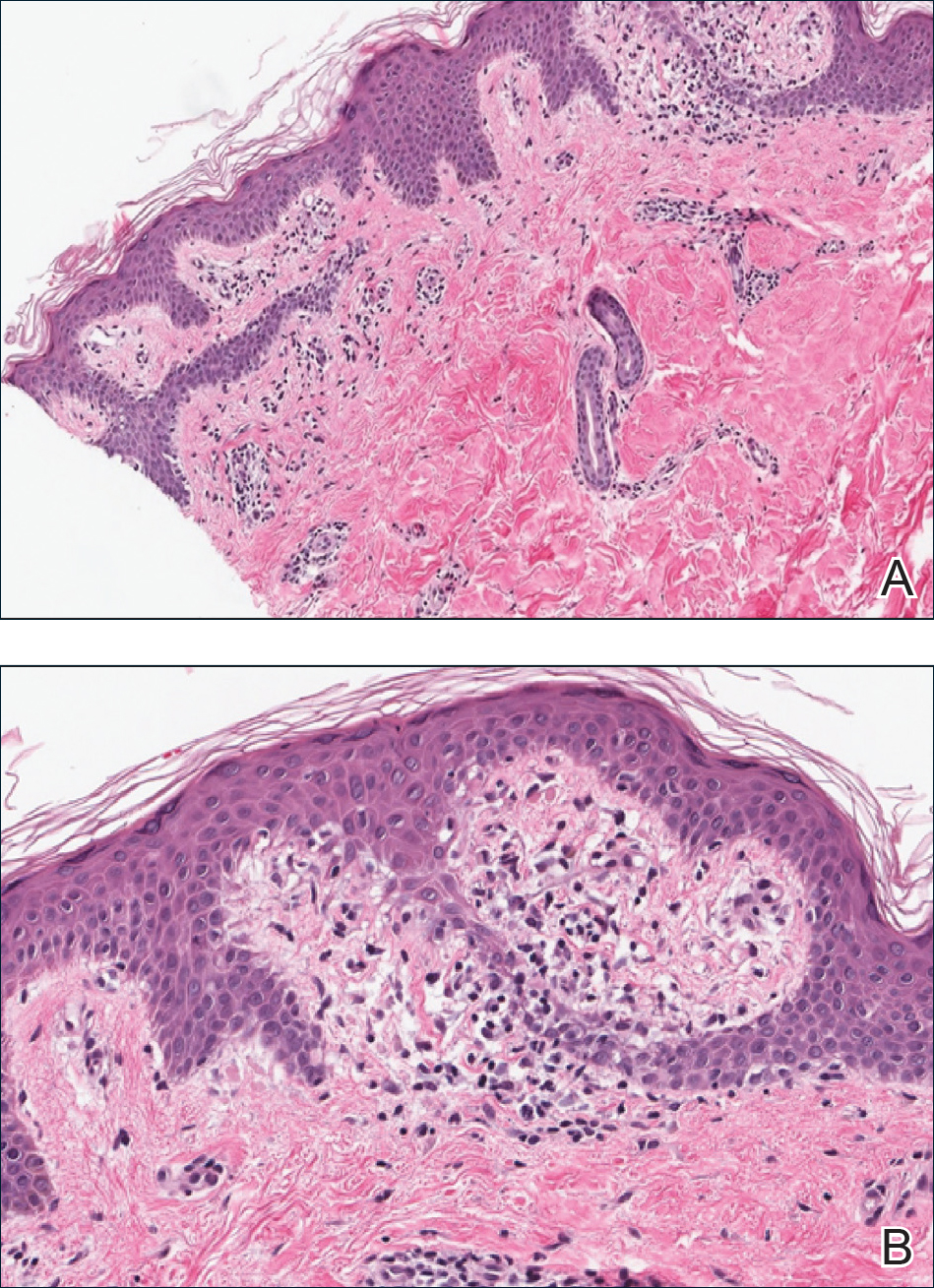

To make a clinical diagnosis of NF-1, a patient must have 2 of 7 cardinal clinical features as defined by the National Institutes of Health (Table).24 In our patient with hundreds of café au lait macules and dozens of neurofibromas, the diagnosis was clear; however, in other patients, the skin findings of NF-1 may not be as prominent. A patient could meet criteria for NF-1 diagnosis with the inconspicuous presentation of 6 café au lait macules and either 1 plexiform neurofibroma or 2 neurofibromas (of any type) on the entire body.

We recommend that patients with SLE undergo skin examinations to look for more subtle presentations of NF-1. Earlier diagnosis will help to initiate close monitoring of the disorder’s associated systemic health risks. In addition, the identification of more patients with both NF-1 and SLE may help shed light on the etiology of both conditions.

- Carey JC, Baty BJ, Johnson JP, et al. The genetic aspects of neurofibromatosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1986;486:45-56.

- Pons-Estel GJ, Alarcón GS, Scofield L, et al. Understanding the epidemiology and progression of systemic lupus erythematosus. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2010;39:257-268.

- Danchenko N, Satia JA, Anthony MS. Epidemiology of systemic lupus erythematosus: a comparison of worldwide disease burden. Lupus. 2006;15:308-318.

- Lawrence RC, Helmick CG, Arnett FC, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and selected musculoskeletal disorders in the United States. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:778-799.

- Chakravarty EF, Bush TM, Manzi S, et al. Prevalence of adult systemic lupus erythematosus in California and Pennsylvania in 2000: estimates obtained using hospitalization data. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:2092-2094.