User login

Darkening and Eruptive Nevi During Treatment With Erlotinib

To the Editor:

Erlotinib is a small-molecule selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor that functions by blocking the intracellular portion of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)1,2; EGFR normally is expressed in the basal layer of the epidermis, sweat glands, and hair follicles, and is overexpressed in some cancers.1,3 Normal activation of EGFR leads to signal transduction through the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway, which stimulates cell survival and proliferation.4,5 Erlotinib-induced inhibition of EGFR prevents tyrosine kinase phosphorylation and aims to decrease cell proliferation in these tumors.

Erlotinib is indicated as once-daily oral monotherapy for the treatment of advanced-stage non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLCA) and in combination with gemcitabine for treatment of advanced-stage pancreatic cancer.1 A number of cutaneous side effects have been reported, including acneform eruption, xerosis, paronychia, and pruritus.6 Other tyrosine kinase inhibitors, which also decrease signal transduction through the MAPK pathway, have some overlapping side effects; among these are vemurafenib, a selective BRAF inhibitor, and sorafenib, a multikinase inhibitor.7,8

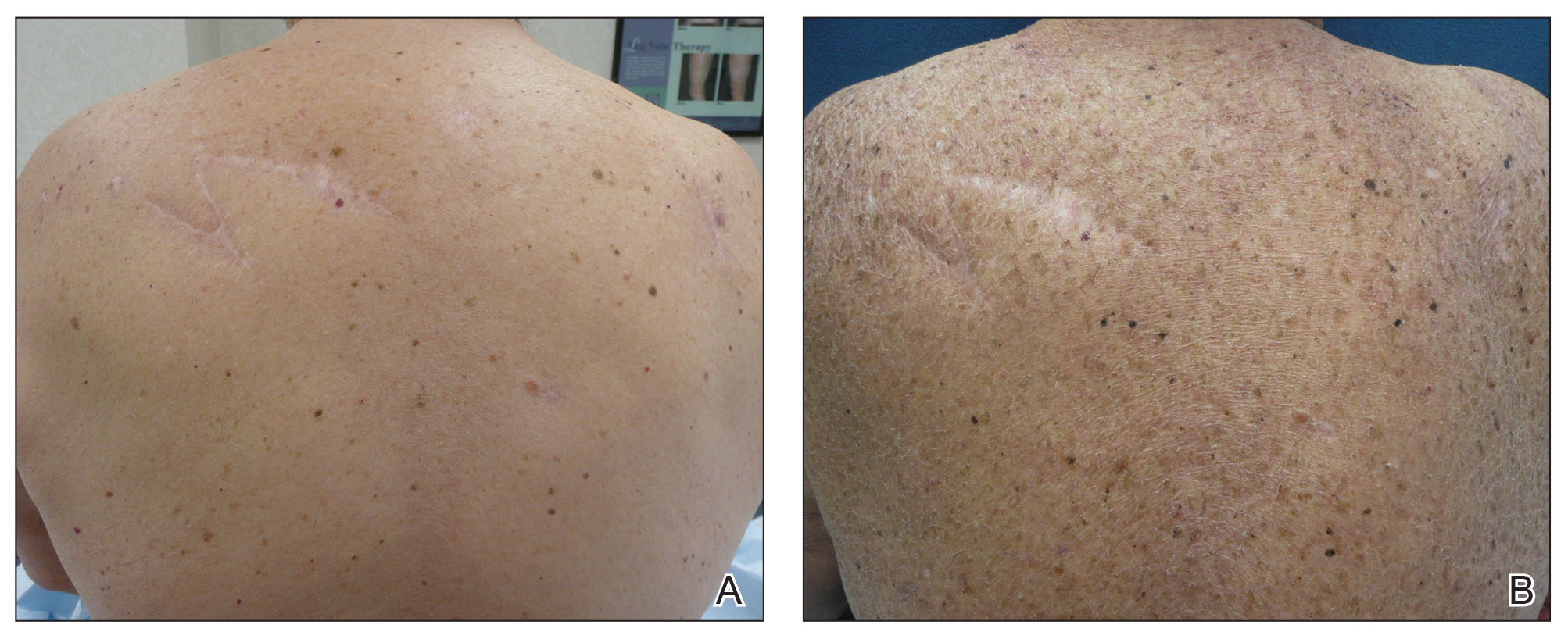

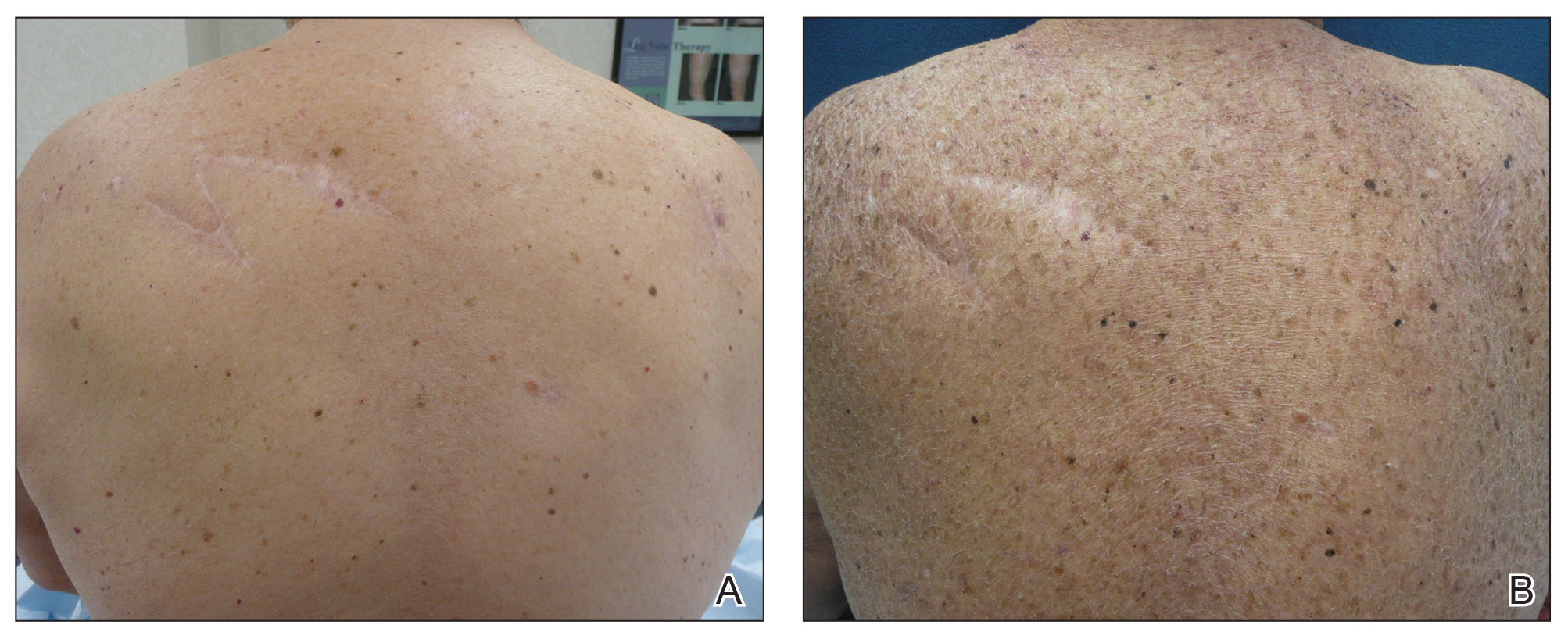

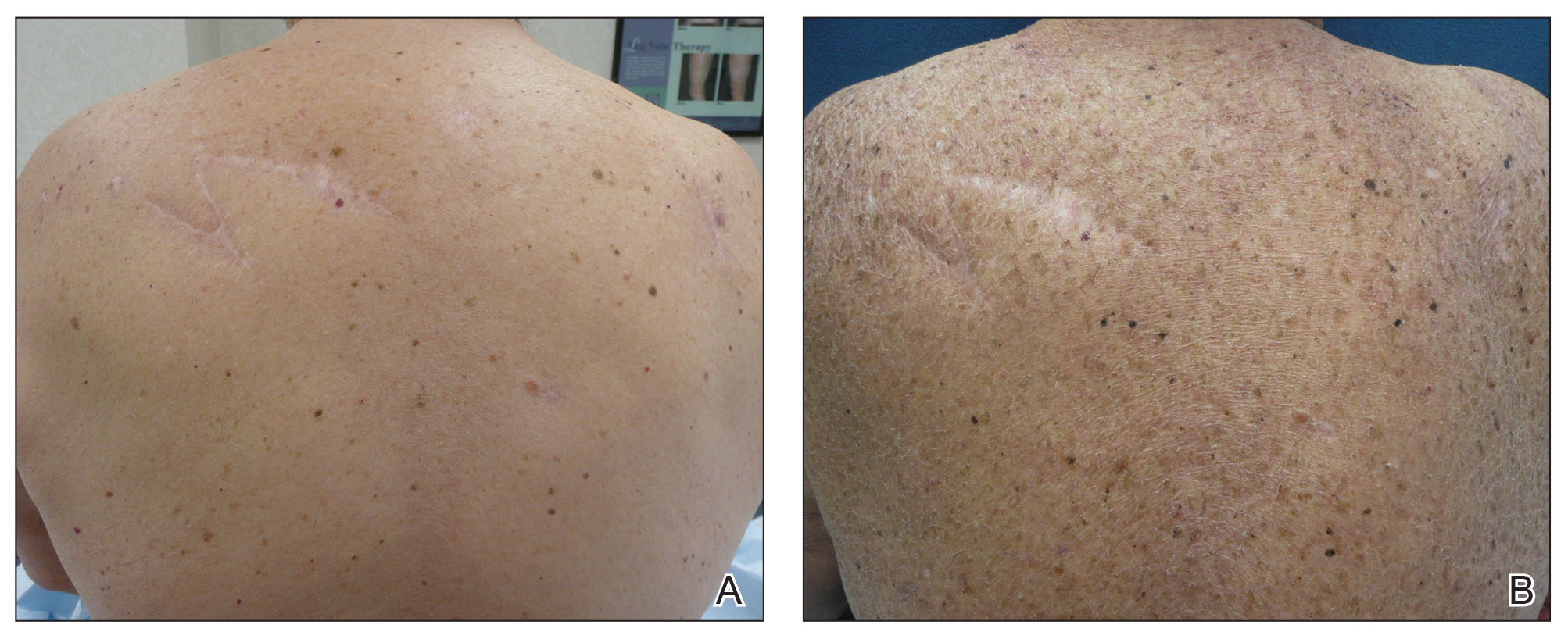

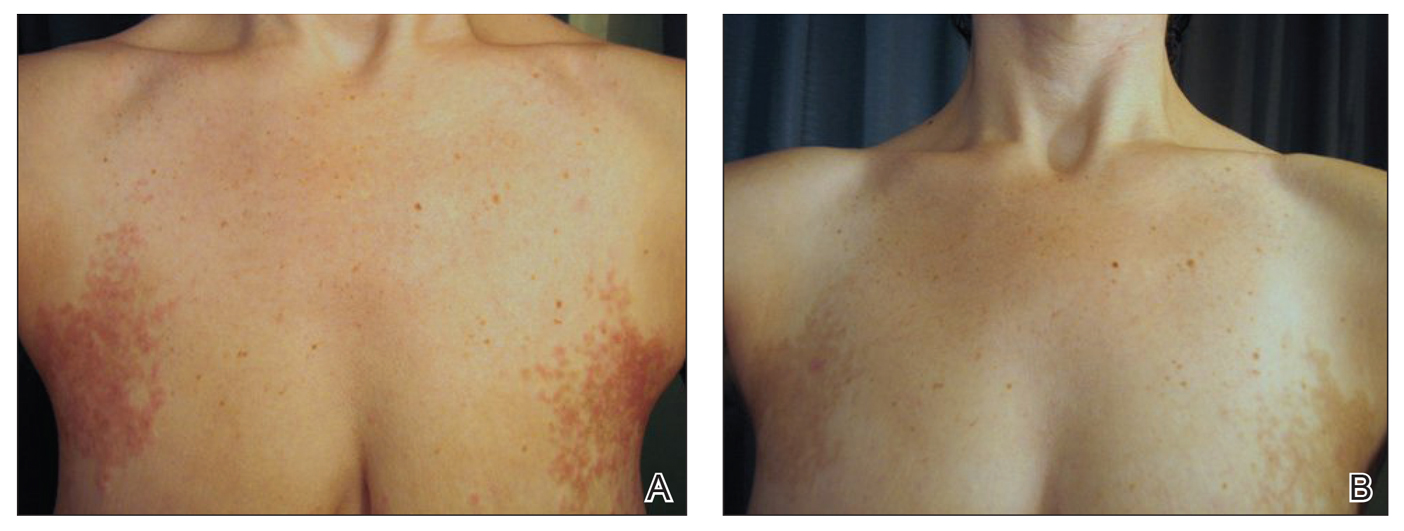

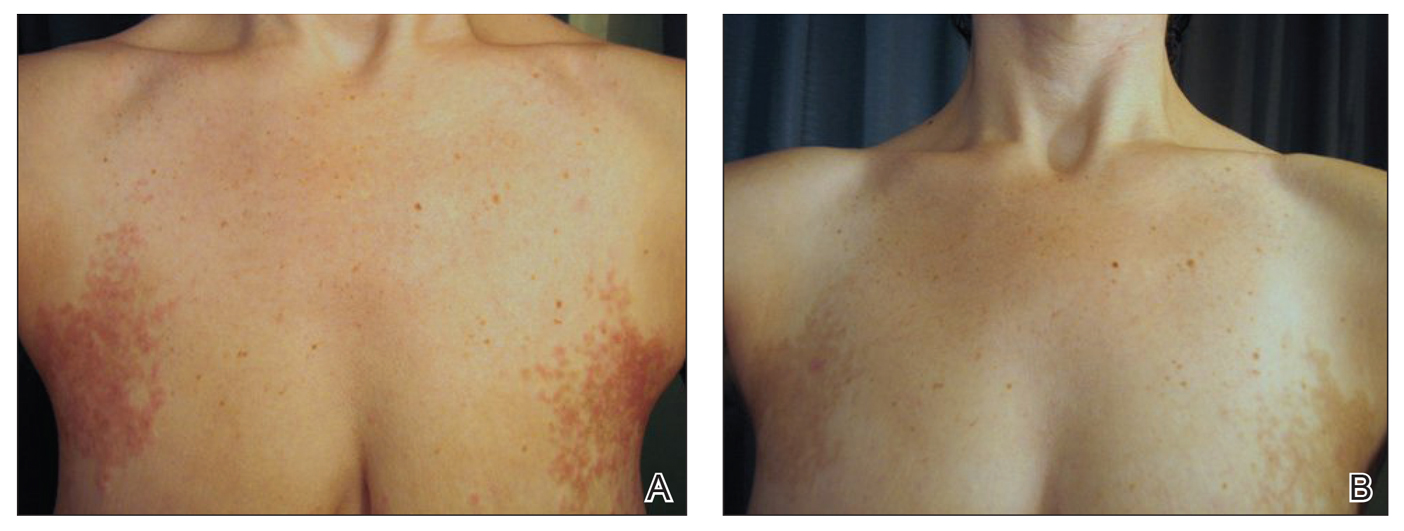

A 70-year-old man with NSCLCA presented with eruptive nevi and darkening of existing nevi 3 months after starting monotherapy with erlotinib. Physical examination demonstrated the simultaneous appearance of scattered acneform papules and pustules; diffuse xerosis; and numerous dark brown to black nevi on the trunk, arms, and legs. Compared to prior clinical photographs taken in our office, darkening of existing medium brown nevi was noted, and new nevi developed in areas where no prior nevi had been visible (Figure 1).

The patient’s medical history included 3 invasive melanomas, all of which were diagnosed at least 7 years prior to the initiation of erlotinib and were treated by surgical excision alone. Prior treatment of NSCLCA consisted of a left lower lobectomy followed by docetaxel, carboplatin, pegfilgrastim, dexamethasone, and pemetrexed. A thorough review of all of the patient’s medications revealed no associations with changes in nevi.

A review of the patient’s treatment timeline revealed that all other chemotherapeutic medications had been discontinued a minimum of 5 weeks before starting erlotinib. A complete cutaneous examination performed in our office after completion of these chemotherapeutic agents and prior to initiation of erlotinib was unremarkable for abnormally dark or eruptive nevi.

Since starting erlotinib treatment, the patient underwent 10 biopsies of clinically suspicious dark nevi performed by a dermatologist in our office. Two of these were diagnosed as melanoma in situ and one as an atypical nevus. A temporal association of the darkening and eruptive nevi with erlotinib treatment was established; however, because erlotinib was essential to his NSCLCA treatment, he continued erlotinib with frequent complete cutaneous examinations.

A number of cutaneous side effects have been described during treatment with erlotinib, the most common being acneform eruption.6 The incidence and severity of acneform eruptions have been positively correlated to survival in patients with NSCLCA.3,5,6 Other common side effects include xerosis, paronychia, and pruritus.1,5,6 Less common side effects include periungual pyogenic granulomas and hair growth abnormalities.1

Eruptive nevi previously were reported in a patient who was treated with erlotinib.1 Other tyrosine kinase inhibitors that also decrease signal transduction through the MAPK pathway, including sorafenib and vemurafenib, have been reported to cause eruptive nevi. There are 7 reports of eruptive nevi with sorafenib and 5 reports with vemurafenib.7-9 Development of nevi were noted within a few months of initiating treatment with these medications.7

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms erlotinib and melanoma and erlotinib and nevi yielded no prior reports of darkening of existing nevi or the development of melanoma during treatment with erlotinib. However, vemurafenib has been reported to cause dysplastic nevi, melanomas, and darkening of existing nevi, in addition to eruptive nevi.8-10 The side effects of vemurafenib have been ascribed to a paradoxical upregulation of MAPK in BRAF wild-type cells. This effect has been well documented and demonstrated in vivo.8,10 Perhaps erlotinib has a similar potential to paradoxically upregulate the MAPK pathway, thus stimulating cellular proliferation and survival.

Another tyrosine kinase receptor, c-KIT, is found on the cell membrane of melanocytes along with EGFR.11,12 The c-KIT receptor also activates the MAPK pathway and is critical to the development, migration, and survival of melanocytes.11,13 Stimulation of the c-KIT tyrosine kinase receptor also can induce melanocyte proliferation and melanogenesis.11 The c-KIT receptor is encoded by the KIT gene (KIT proto-oncogene receptor tyrosine kinase). Mutations in this gene are associated with melanocytic disorders. Inherited KIT mutation leading to c-KIT receptor deficiency is associated with piebaldism. Acquired activating KIT mutations increasing c-KIT expression are associated with acral and mucosal melanomas as well as melanomas in chronically sun-damaged skin.13

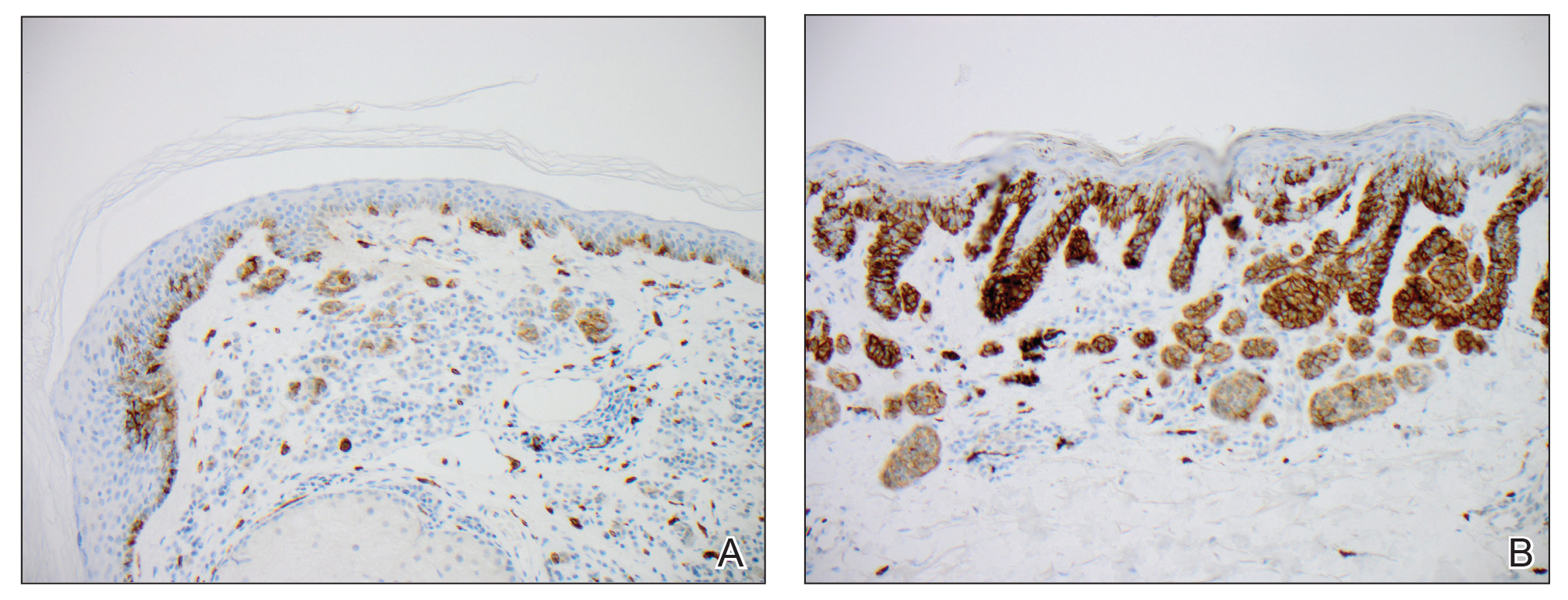

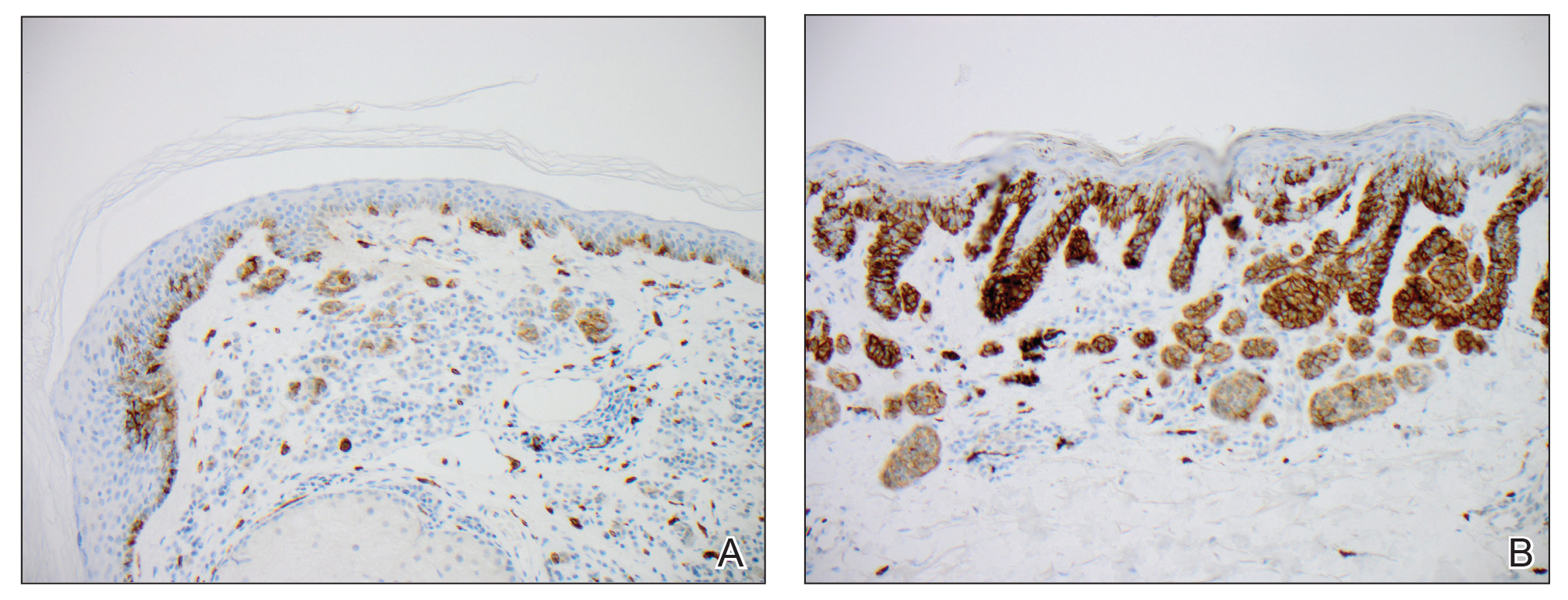

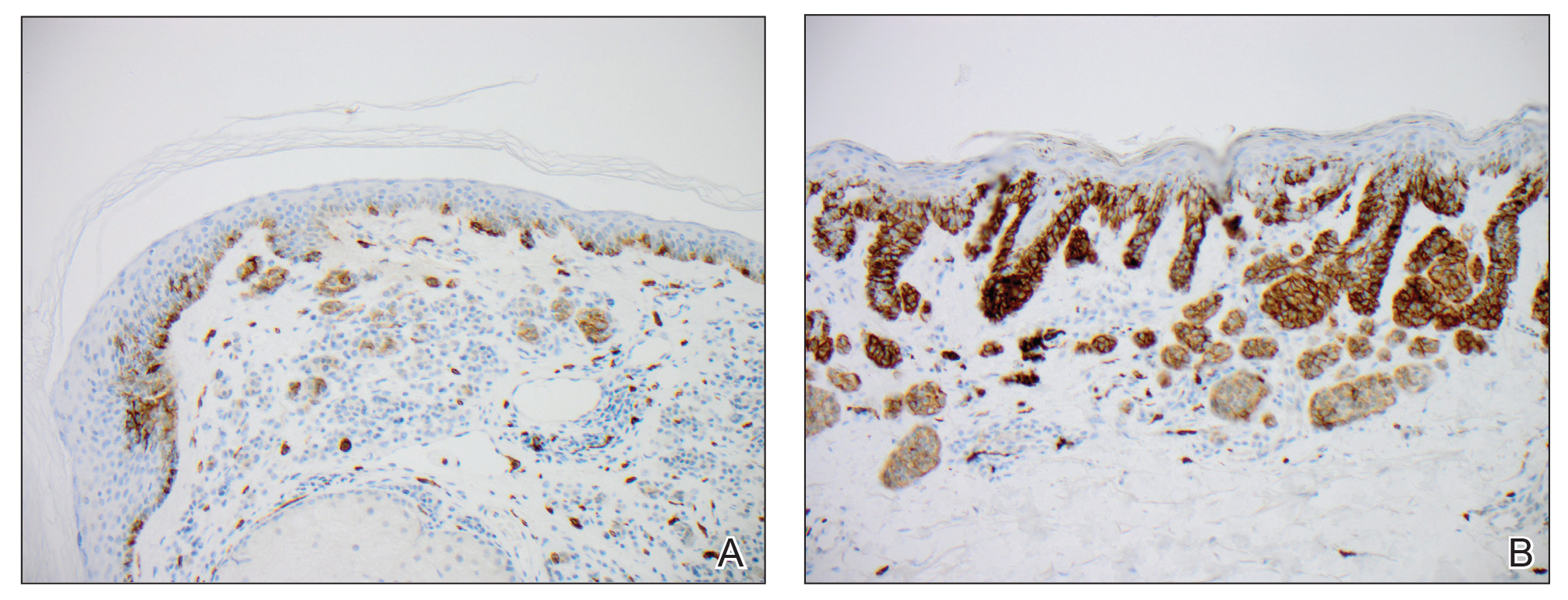

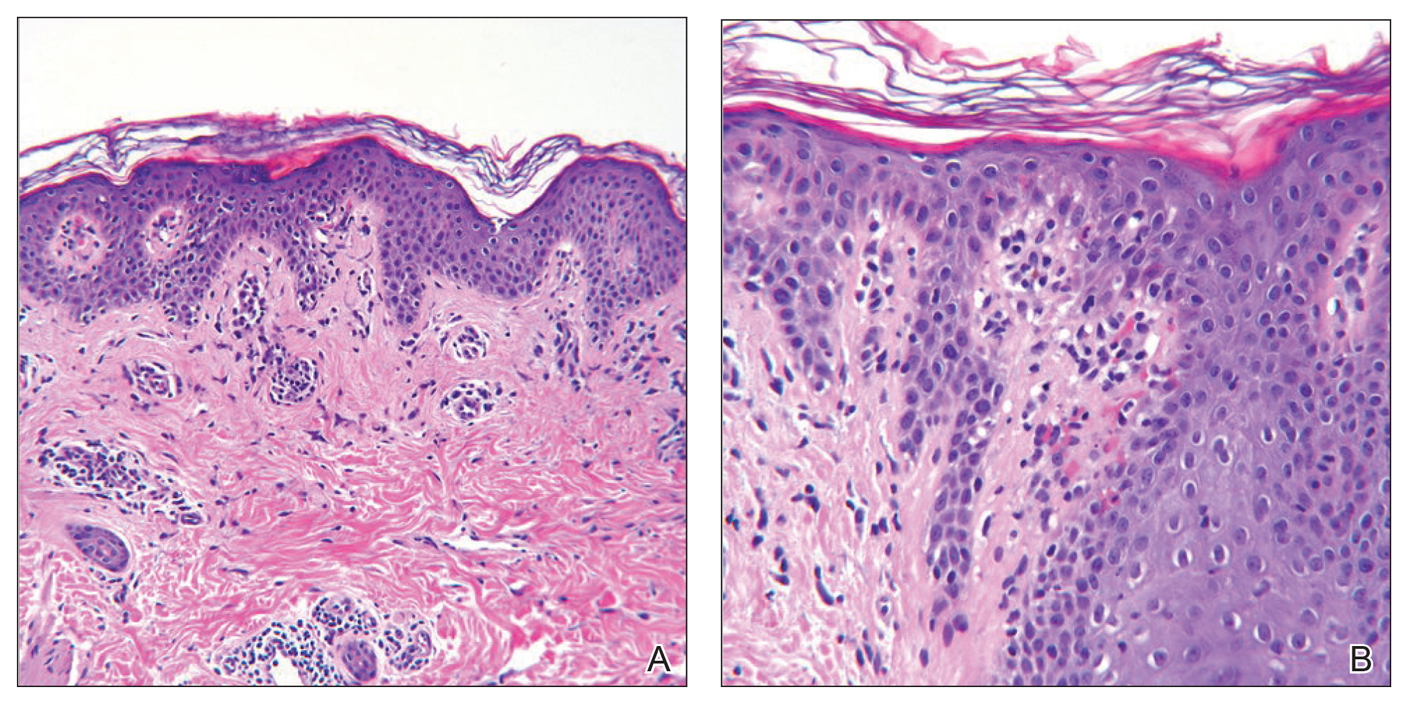

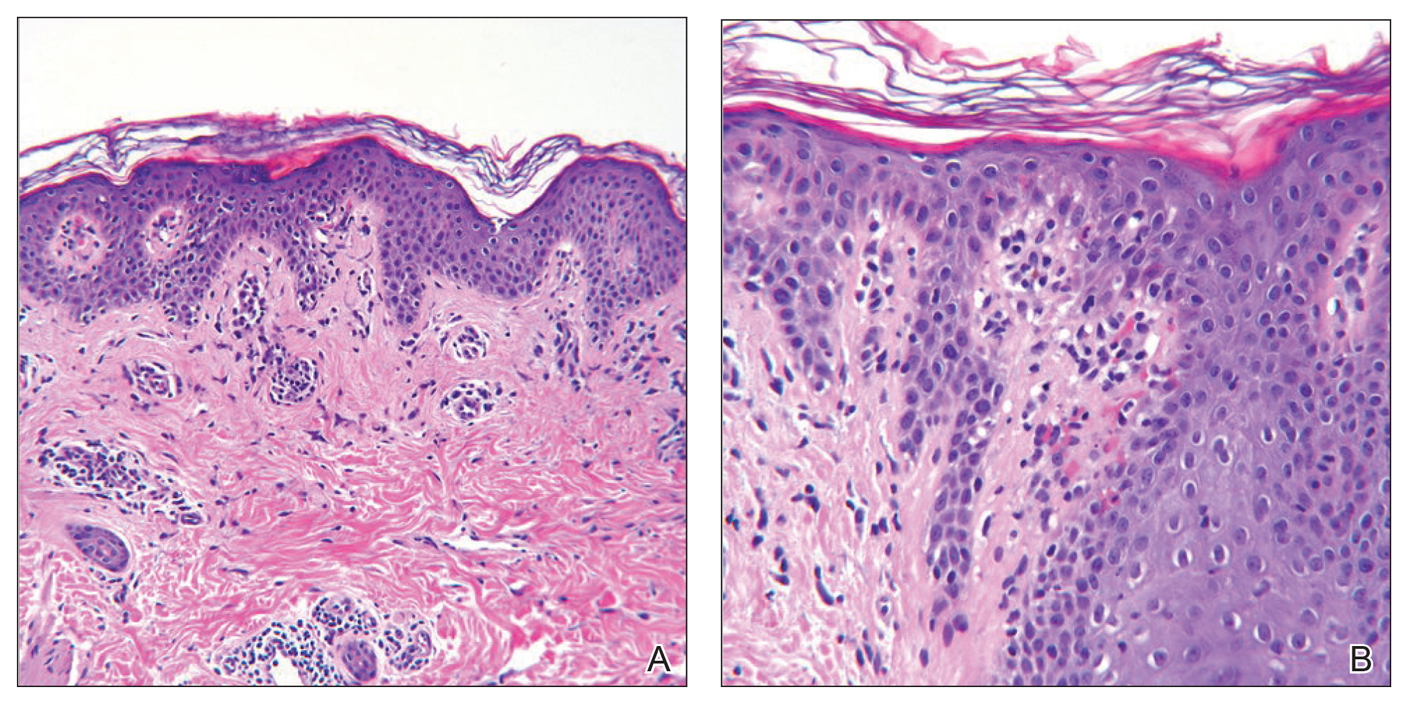

We hypothesized that erlotinib-induced inhibition of the MAPK pathway could lead to a reactive increase in expression of c-KIT and thus stimulate melanocyte proliferation and pigment production. Similar feedback upregulation of an MAPK pathway stimulating receptor during downstream MAPK inhibition has been demonstrated in colon adenocarcinoma; in this setting, BRAF inhibitors blocking the MAPK pathway leads to upregulation of EGFR.14 In our patient, c-KIT immunostaining revealed a mild to moderate increase in intensity (ie, the darkness of the staining) in nevi and melanomas during treatment with erlotinib compared to nevi biopsied before erlotinib treatment (Figure 2). The increased intensity of c-KIT immunostaining was further confirmed via semiquantitative digital image analysis. Using this method, a darkened nevus biopsied during treatment with erlotinib demonstrated 43.16% of cells (N=31,451) had very strong c-KIT staining, while a nevus biopsied before treatment with erlotinib demonstrated only 3.32% of cells (N=7507) with very strong c-KIT staining. Increased expression of c-KIT, possibly reactive to downstream inhibition the MAPK pathway from erlotinib, could be implicated in our case of eruptive nevi.

In summary, we report a rare case of darkening of existing nevi and development of melanoma in situ during treatment with erlotinib. The patient’s therapeutic timeline and concurrence of other well-documented side effects provided support for erlotinib as the causative agent in our patient. Additional support is provided through reports of other medications affecting the same pathway as erlotinib causing eruptive nevi, darkening of existing nevi, and melanoma in situ.7-10 Through c-KIT immunostaining, we demonstrated that increased expression of c-KIT might be responsible for the changes in nevi in our patient. We, therefore, suggest frequent full-body skin examinations in patients treated with erlotinib to monitor for the possible development of malignant melanomas.

- Santiago F, Goncalo M, Reis J, et al. Adverse cutaneous reactions to epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors: a study of 14 patients. An Bras Dermatol 2011;86:483-490.

- Lubbe J, Masouye I, Dietrich P. Generalized xerotic dermatitis with neutrophilic spongiosis induced by erlotinib (Tarceva). Dermatology. 2008;216:247-249.

- Dessinioti C, Antoniou C, Katsambas A. Acneiform eruptions. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:24-34.

- Herbst R, Fukuoka M, Baselga J. Gefitinib—a novel targeted approach to treating cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:979-987.

- Brodell L, Hepper D, Lind A, et al. Histopathology of acneiform eruptions in patients treated with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:865-870.

- Kiyohara Y, Yamazaki N, Kishi A. Erlotinib-related skin toxicities: treatment strategies in patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. J Am Acad Dermatol 2013;69:463-472.

- Uhlenhake E, Watson A, Aronson P. Sorafenib induced eruptive melanocytic lesions. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:181-84.

- Chu E, Wanat K, Miller C, et al. Diverse cutaneous side effects associated with BRAF inhibitor therapy: a clinicopathologic study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2012;67:1265-1272.

- Boussemart L, Routier E, Mateus C, et al. Prospective study of cutaneous side-effects associated with the BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib: a study of 42 patients. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:1691-1697.

- Cohen P, Bedikian A, Kim K. Appearance of new vemurafenib-associated melanocytic nevi on normal-appearing skin: case series and a review of changing or new pigmented lesions in patients with metastatic malignant melanoma after initiating treatment with vemurafenib. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:27-37.

- Longley B, Tyrrell L, Lu S, et al. Somatic c-KIT activating mutation in urticaria pigmentosa and aggressive mastocytosis: establishment of clonality in a human mast cell neoplasm. Nat Genet. 1996;12:312-314.

- Yun W, Bang S, Min K, et al. Epidermal growth factor and epidermal growth factor signaling attenuate laser-induced melanogenesis. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:1903-1911.

- Swick J, Maize J. Molecular biology of melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:1049-1054.

- Sun C, Wang L, Huang S, et al. Reversible and adaptive resistance to BRAF(V600E) inhibition in melanoma. Nature. 2014;508:118-122.

To the Editor:

Erlotinib is a small-molecule selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor that functions by blocking the intracellular portion of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)1,2; EGFR normally is expressed in the basal layer of the epidermis, sweat glands, and hair follicles, and is overexpressed in some cancers.1,3 Normal activation of EGFR leads to signal transduction through the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway, which stimulates cell survival and proliferation.4,5 Erlotinib-induced inhibition of EGFR prevents tyrosine kinase phosphorylation and aims to decrease cell proliferation in these tumors.

Erlotinib is indicated as once-daily oral monotherapy for the treatment of advanced-stage non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLCA) and in combination with gemcitabine for treatment of advanced-stage pancreatic cancer.1 A number of cutaneous side effects have been reported, including acneform eruption, xerosis, paronychia, and pruritus.6 Other tyrosine kinase inhibitors, which also decrease signal transduction through the MAPK pathway, have some overlapping side effects; among these are vemurafenib, a selective BRAF inhibitor, and sorafenib, a multikinase inhibitor.7,8

A 70-year-old man with NSCLCA presented with eruptive nevi and darkening of existing nevi 3 months after starting monotherapy with erlotinib. Physical examination demonstrated the simultaneous appearance of scattered acneform papules and pustules; diffuse xerosis; and numerous dark brown to black nevi on the trunk, arms, and legs. Compared to prior clinical photographs taken in our office, darkening of existing medium brown nevi was noted, and new nevi developed in areas where no prior nevi had been visible (Figure 1).

The patient’s medical history included 3 invasive melanomas, all of which were diagnosed at least 7 years prior to the initiation of erlotinib and were treated by surgical excision alone. Prior treatment of NSCLCA consisted of a left lower lobectomy followed by docetaxel, carboplatin, pegfilgrastim, dexamethasone, and pemetrexed. A thorough review of all of the patient’s medications revealed no associations with changes in nevi.

A review of the patient’s treatment timeline revealed that all other chemotherapeutic medications had been discontinued a minimum of 5 weeks before starting erlotinib. A complete cutaneous examination performed in our office after completion of these chemotherapeutic agents and prior to initiation of erlotinib was unremarkable for abnormally dark or eruptive nevi.

Since starting erlotinib treatment, the patient underwent 10 biopsies of clinically suspicious dark nevi performed by a dermatologist in our office. Two of these were diagnosed as melanoma in situ and one as an atypical nevus. A temporal association of the darkening and eruptive nevi with erlotinib treatment was established; however, because erlotinib was essential to his NSCLCA treatment, he continued erlotinib with frequent complete cutaneous examinations.

A number of cutaneous side effects have been described during treatment with erlotinib, the most common being acneform eruption.6 The incidence and severity of acneform eruptions have been positively correlated to survival in patients with NSCLCA.3,5,6 Other common side effects include xerosis, paronychia, and pruritus.1,5,6 Less common side effects include periungual pyogenic granulomas and hair growth abnormalities.1

Eruptive nevi previously were reported in a patient who was treated with erlotinib.1 Other tyrosine kinase inhibitors that also decrease signal transduction through the MAPK pathway, including sorafenib and vemurafenib, have been reported to cause eruptive nevi. There are 7 reports of eruptive nevi with sorafenib and 5 reports with vemurafenib.7-9 Development of nevi were noted within a few months of initiating treatment with these medications.7

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms erlotinib and melanoma and erlotinib and nevi yielded no prior reports of darkening of existing nevi or the development of melanoma during treatment with erlotinib. However, vemurafenib has been reported to cause dysplastic nevi, melanomas, and darkening of existing nevi, in addition to eruptive nevi.8-10 The side effects of vemurafenib have been ascribed to a paradoxical upregulation of MAPK in BRAF wild-type cells. This effect has been well documented and demonstrated in vivo.8,10 Perhaps erlotinib has a similar potential to paradoxically upregulate the MAPK pathway, thus stimulating cellular proliferation and survival.

Another tyrosine kinase receptor, c-KIT, is found on the cell membrane of melanocytes along with EGFR.11,12 The c-KIT receptor also activates the MAPK pathway and is critical to the development, migration, and survival of melanocytes.11,13 Stimulation of the c-KIT tyrosine kinase receptor also can induce melanocyte proliferation and melanogenesis.11 The c-KIT receptor is encoded by the KIT gene (KIT proto-oncogene receptor tyrosine kinase). Mutations in this gene are associated with melanocytic disorders. Inherited KIT mutation leading to c-KIT receptor deficiency is associated with piebaldism. Acquired activating KIT mutations increasing c-KIT expression are associated with acral and mucosal melanomas as well as melanomas in chronically sun-damaged skin.13

We hypothesized that erlotinib-induced inhibition of the MAPK pathway could lead to a reactive increase in expression of c-KIT and thus stimulate melanocyte proliferation and pigment production. Similar feedback upregulation of an MAPK pathway stimulating receptor during downstream MAPK inhibition has been demonstrated in colon adenocarcinoma; in this setting, BRAF inhibitors blocking the MAPK pathway leads to upregulation of EGFR.14 In our patient, c-KIT immunostaining revealed a mild to moderate increase in intensity (ie, the darkness of the staining) in nevi and melanomas during treatment with erlotinib compared to nevi biopsied before erlotinib treatment (Figure 2). The increased intensity of c-KIT immunostaining was further confirmed via semiquantitative digital image analysis. Using this method, a darkened nevus biopsied during treatment with erlotinib demonstrated 43.16% of cells (N=31,451) had very strong c-KIT staining, while a nevus biopsied before treatment with erlotinib demonstrated only 3.32% of cells (N=7507) with very strong c-KIT staining. Increased expression of c-KIT, possibly reactive to downstream inhibition the MAPK pathway from erlotinib, could be implicated in our case of eruptive nevi.

In summary, we report a rare case of darkening of existing nevi and development of melanoma in situ during treatment with erlotinib. The patient’s therapeutic timeline and concurrence of other well-documented side effects provided support for erlotinib as the causative agent in our patient. Additional support is provided through reports of other medications affecting the same pathway as erlotinib causing eruptive nevi, darkening of existing nevi, and melanoma in situ.7-10 Through c-KIT immunostaining, we demonstrated that increased expression of c-KIT might be responsible for the changes in nevi in our patient. We, therefore, suggest frequent full-body skin examinations in patients treated with erlotinib to monitor for the possible development of malignant melanomas.

To the Editor:

Erlotinib is a small-molecule selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor that functions by blocking the intracellular portion of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)1,2; EGFR normally is expressed in the basal layer of the epidermis, sweat glands, and hair follicles, and is overexpressed in some cancers.1,3 Normal activation of EGFR leads to signal transduction through the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway, which stimulates cell survival and proliferation.4,5 Erlotinib-induced inhibition of EGFR prevents tyrosine kinase phosphorylation and aims to decrease cell proliferation in these tumors.

Erlotinib is indicated as once-daily oral monotherapy for the treatment of advanced-stage non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLCA) and in combination with gemcitabine for treatment of advanced-stage pancreatic cancer.1 A number of cutaneous side effects have been reported, including acneform eruption, xerosis, paronychia, and pruritus.6 Other tyrosine kinase inhibitors, which also decrease signal transduction through the MAPK pathway, have some overlapping side effects; among these are vemurafenib, a selective BRAF inhibitor, and sorafenib, a multikinase inhibitor.7,8

A 70-year-old man with NSCLCA presented with eruptive nevi and darkening of existing nevi 3 months after starting monotherapy with erlotinib. Physical examination demonstrated the simultaneous appearance of scattered acneform papules and pustules; diffuse xerosis; and numerous dark brown to black nevi on the trunk, arms, and legs. Compared to prior clinical photographs taken in our office, darkening of existing medium brown nevi was noted, and new nevi developed in areas where no prior nevi had been visible (Figure 1).

The patient’s medical history included 3 invasive melanomas, all of which were diagnosed at least 7 years prior to the initiation of erlotinib and were treated by surgical excision alone. Prior treatment of NSCLCA consisted of a left lower lobectomy followed by docetaxel, carboplatin, pegfilgrastim, dexamethasone, and pemetrexed. A thorough review of all of the patient’s medications revealed no associations with changes in nevi.

A review of the patient’s treatment timeline revealed that all other chemotherapeutic medications had been discontinued a minimum of 5 weeks before starting erlotinib. A complete cutaneous examination performed in our office after completion of these chemotherapeutic agents and prior to initiation of erlotinib was unremarkable for abnormally dark or eruptive nevi.

Since starting erlotinib treatment, the patient underwent 10 biopsies of clinically suspicious dark nevi performed by a dermatologist in our office. Two of these were diagnosed as melanoma in situ and one as an atypical nevus. A temporal association of the darkening and eruptive nevi with erlotinib treatment was established; however, because erlotinib was essential to his NSCLCA treatment, he continued erlotinib with frequent complete cutaneous examinations.

A number of cutaneous side effects have been described during treatment with erlotinib, the most common being acneform eruption.6 The incidence and severity of acneform eruptions have been positively correlated to survival in patients with NSCLCA.3,5,6 Other common side effects include xerosis, paronychia, and pruritus.1,5,6 Less common side effects include periungual pyogenic granulomas and hair growth abnormalities.1

Eruptive nevi previously were reported in a patient who was treated with erlotinib.1 Other tyrosine kinase inhibitors that also decrease signal transduction through the MAPK pathway, including sorafenib and vemurafenib, have been reported to cause eruptive nevi. There are 7 reports of eruptive nevi with sorafenib and 5 reports with vemurafenib.7-9 Development of nevi were noted within a few months of initiating treatment with these medications.7

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms erlotinib and melanoma and erlotinib and nevi yielded no prior reports of darkening of existing nevi or the development of melanoma during treatment with erlotinib. However, vemurafenib has been reported to cause dysplastic nevi, melanomas, and darkening of existing nevi, in addition to eruptive nevi.8-10 The side effects of vemurafenib have been ascribed to a paradoxical upregulation of MAPK in BRAF wild-type cells. This effect has been well documented and demonstrated in vivo.8,10 Perhaps erlotinib has a similar potential to paradoxically upregulate the MAPK pathway, thus stimulating cellular proliferation and survival.

Another tyrosine kinase receptor, c-KIT, is found on the cell membrane of melanocytes along with EGFR.11,12 The c-KIT receptor also activates the MAPK pathway and is critical to the development, migration, and survival of melanocytes.11,13 Stimulation of the c-KIT tyrosine kinase receptor also can induce melanocyte proliferation and melanogenesis.11 The c-KIT receptor is encoded by the KIT gene (KIT proto-oncogene receptor tyrosine kinase). Mutations in this gene are associated with melanocytic disorders. Inherited KIT mutation leading to c-KIT receptor deficiency is associated with piebaldism. Acquired activating KIT mutations increasing c-KIT expression are associated with acral and mucosal melanomas as well as melanomas in chronically sun-damaged skin.13

We hypothesized that erlotinib-induced inhibition of the MAPK pathway could lead to a reactive increase in expression of c-KIT and thus stimulate melanocyte proliferation and pigment production. Similar feedback upregulation of an MAPK pathway stimulating receptor during downstream MAPK inhibition has been demonstrated in colon adenocarcinoma; in this setting, BRAF inhibitors blocking the MAPK pathway leads to upregulation of EGFR.14 In our patient, c-KIT immunostaining revealed a mild to moderate increase in intensity (ie, the darkness of the staining) in nevi and melanomas during treatment with erlotinib compared to nevi biopsied before erlotinib treatment (Figure 2). The increased intensity of c-KIT immunostaining was further confirmed via semiquantitative digital image analysis. Using this method, a darkened nevus biopsied during treatment with erlotinib demonstrated 43.16% of cells (N=31,451) had very strong c-KIT staining, while a nevus biopsied before treatment with erlotinib demonstrated only 3.32% of cells (N=7507) with very strong c-KIT staining. Increased expression of c-KIT, possibly reactive to downstream inhibition the MAPK pathway from erlotinib, could be implicated in our case of eruptive nevi.

In summary, we report a rare case of darkening of existing nevi and development of melanoma in situ during treatment with erlotinib. The patient’s therapeutic timeline and concurrence of other well-documented side effects provided support for erlotinib as the causative agent in our patient. Additional support is provided through reports of other medications affecting the same pathway as erlotinib causing eruptive nevi, darkening of existing nevi, and melanoma in situ.7-10 Through c-KIT immunostaining, we demonstrated that increased expression of c-KIT might be responsible for the changes in nevi in our patient. We, therefore, suggest frequent full-body skin examinations in patients treated with erlotinib to monitor for the possible development of malignant melanomas.

- Santiago F, Goncalo M, Reis J, et al. Adverse cutaneous reactions to epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors: a study of 14 patients. An Bras Dermatol 2011;86:483-490.

- Lubbe J, Masouye I, Dietrich P. Generalized xerotic dermatitis with neutrophilic spongiosis induced by erlotinib (Tarceva). Dermatology. 2008;216:247-249.

- Dessinioti C, Antoniou C, Katsambas A. Acneiform eruptions. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:24-34.

- Herbst R, Fukuoka M, Baselga J. Gefitinib—a novel targeted approach to treating cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:979-987.

- Brodell L, Hepper D, Lind A, et al. Histopathology of acneiform eruptions in patients treated with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:865-870.

- Kiyohara Y, Yamazaki N, Kishi A. Erlotinib-related skin toxicities: treatment strategies in patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. J Am Acad Dermatol 2013;69:463-472.

- Uhlenhake E, Watson A, Aronson P. Sorafenib induced eruptive melanocytic lesions. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:181-84.

- Chu E, Wanat K, Miller C, et al. Diverse cutaneous side effects associated with BRAF inhibitor therapy: a clinicopathologic study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2012;67:1265-1272.

- Boussemart L, Routier E, Mateus C, et al. Prospective study of cutaneous side-effects associated with the BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib: a study of 42 patients. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:1691-1697.

- Cohen P, Bedikian A, Kim K. Appearance of new vemurafenib-associated melanocytic nevi on normal-appearing skin: case series and a review of changing or new pigmented lesions in patients with metastatic malignant melanoma after initiating treatment with vemurafenib. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:27-37.

- Longley B, Tyrrell L, Lu S, et al. Somatic c-KIT activating mutation in urticaria pigmentosa and aggressive mastocytosis: establishment of clonality in a human mast cell neoplasm. Nat Genet. 1996;12:312-314.

- Yun W, Bang S, Min K, et al. Epidermal growth factor and epidermal growth factor signaling attenuate laser-induced melanogenesis. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:1903-1911.

- Swick J, Maize J. Molecular biology of melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:1049-1054.

- Sun C, Wang L, Huang S, et al. Reversible and adaptive resistance to BRAF(V600E) inhibition in melanoma. Nature. 2014;508:118-122.

- Santiago F, Goncalo M, Reis J, et al. Adverse cutaneous reactions to epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors: a study of 14 patients. An Bras Dermatol 2011;86:483-490.

- Lubbe J, Masouye I, Dietrich P. Generalized xerotic dermatitis with neutrophilic spongiosis induced by erlotinib (Tarceva). Dermatology. 2008;216:247-249.

- Dessinioti C, Antoniou C, Katsambas A. Acneiform eruptions. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:24-34.

- Herbst R, Fukuoka M, Baselga J. Gefitinib—a novel targeted approach to treating cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:979-987.

- Brodell L, Hepper D, Lind A, et al. Histopathology of acneiform eruptions in patients treated with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:865-870.

- Kiyohara Y, Yamazaki N, Kishi A. Erlotinib-related skin toxicities: treatment strategies in patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. J Am Acad Dermatol 2013;69:463-472.

- Uhlenhake E, Watson A, Aronson P. Sorafenib induced eruptive melanocytic lesions. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:181-84.

- Chu E, Wanat K, Miller C, et al. Diverse cutaneous side effects associated with BRAF inhibitor therapy: a clinicopathologic study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2012;67:1265-1272.

- Boussemart L, Routier E, Mateus C, et al. Prospective study of cutaneous side-effects associated with the BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib: a study of 42 patients. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:1691-1697.

- Cohen P, Bedikian A, Kim K. Appearance of new vemurafenib-associated melanocytic nevi on normal-appearing skin: case series and a review of changing or new pigmented lesions in patients with metastatic malignant melanoma after initiating treatment with vemurafenib. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:27-37.

- Longley B, Tyrrell L, Lu S, et al. Somatic c-KIT activating mutation in urticaria pigmentosa and aggressive mastocytosis: establishment of clonality in a human mast cell neoplasm. Nat Genet. 1996;12:312-314.

- Yun W, Bang S, Min K, et al. Epidermal growth factor and epidermal growth factor signaling attenuate laser-induced melanogenesis. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:1903-1911.

- Swick J, Maize J. Molecular biology of melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:1049-1054.

- Sun C, Wang L, Huang S, et al. Reversible and adaptive resistance to BRAF(V600E) inhibition in melanoma. Nature. 2014;508:118-122.

Practice Points

- Cutaneous side effects of erlotinib include acneform eruption, xerosis, paronychia, and pruritus.

- Clinicians should monitor patients for darkening and/or eruptive nevi as well as melanoma during treatment with erlotinib.

Topical ruxolitinib looks good for facial vitiligo, in phase 2 study

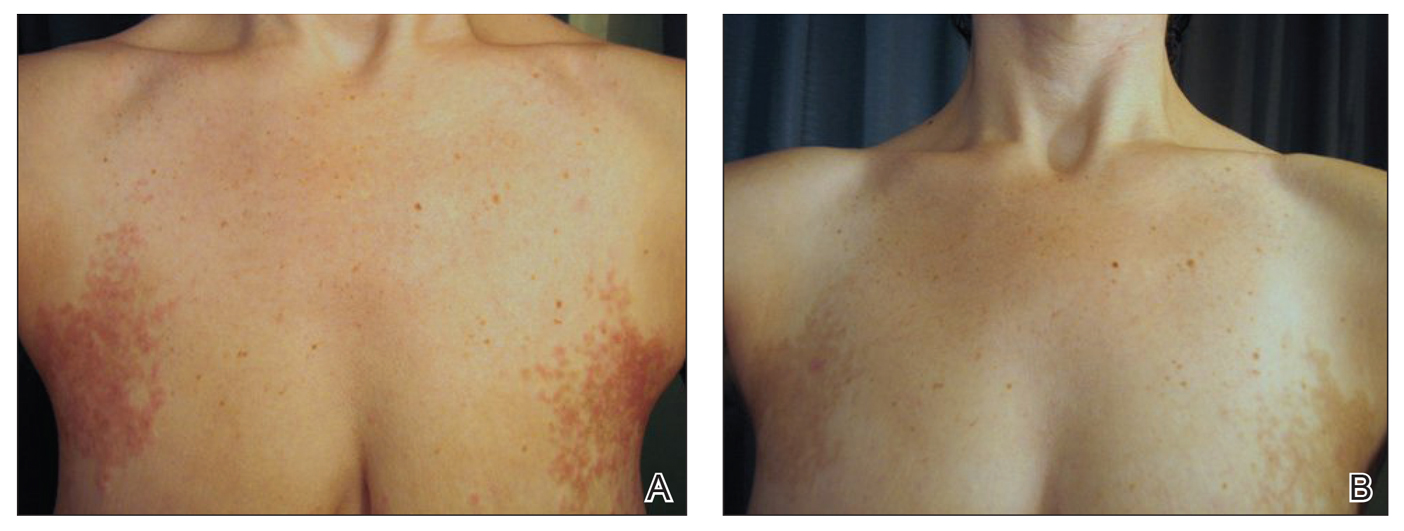

MILAN – Targeting the Janus kinase (JAK) 1 and 2 pathways in vitiligo resulted in significant reduction of facial depigmentation after 24 weeks of treatment, in a phase 2b trial of topical ruxolitinib cream.

compared with vehicle alone, said David Rosmarin, MD, speaking in a late-breaking abstracts session at the World Congress of Dermatology.

The highest response rate was seen with a higher dose: Among patients receiving ruxolitinib cream 1.5% once daily, 50% met the 50% clearing mark at 24 weeks, as did 45.5% of those with twice-daily 1.5% dosing of the 1.5% formulation. At 24 weeks, 3.1% of those receiving vehicle had 50% facial vitiligo resolution (P less than .0001, compared with vehicle for both doses).

Vitiligo affects about 3,000,000 people in the United States, and it is a plausible treatment target for the JAK inhibitor ruxolitinib, explained Dr. Rosmarin, a dermatologist at Tufts University, Boston. “Interferon-gamma, signaling through JAK1 and JAK2, is central to the pathogenesis of vitiligo,” he said. “Ruxolitinib is a potent inhibitor of JAK1 and JAK2, so it made sense to investigate it as a treatment for vitiligo.”

The 24-month randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled phase 2 study of ruxolitinib cream for vitiligo compared the vehicle to four different concentrations of ruxolitinib during the first phase of the study. For the first 24 weeks, patients were randomized to receive vehicle twice daily, or various doses of ruxolitinib ranging from 0.15% once daily to 1.5% twice daily.

At this point, the study’s primary endpoint was assessed, with investigators comparing the proportion of patients treated with ruxolitinib who had at least 50% improvement in facial repigmentation from baseline on the Facial Vitiligo Area Scoring Index (F-VASI50) compared with those who received vehicle. A secondary endpoint, also assessed at week 24, was the proportion of patients who were clear, or almost clear, of facial vitiligo; safety and tolerability were also assessed.

In addition to the F-VASI50 measure, Dr. Rosmarin and his coinvestigators also tracked 75% facial clearing (F-VASI75). Here, the 1.5% twice daily regimen topped the others, with 30% of those receiving that dose achieving F-VASI75, compared with almost 10%-17% of those on other doses.

Using another measure, More than one-third of patients using ruxolitinib (35.3%) had clear (no signs of vitiligo) or almost clear (only specks of depigmentation) facial skin at week 24, according to a clinician assessment tool. No patients on placebo had clear or almost clear facial skin at that point. “It is my hope that with continued use beyond week 24, more patients will meet this very stringent endpoint,” Dr. Rosmarin said.

The safety profile was good, with no serious treatment-related adverse events, and no application site reactions that reached clinical significance, although numerically more patients reported acne with ruxolitinib than with vehicle alone.

In the trial, patients aged 18-75 years with vitiligo were eligible if they had facial depigmentation that constituted at least half of their body surface area (BSA), as well as depigmentation of at least 3% of BSA on nonfacial areas. Patients were excluded if they had another dermatologic disease, infection, prior JAK inhibitor therapy, or recent use of biologic or experimental drugs, laser or light-based treatments, or immunomodulators. Of the 157 patients who were randomized, 18 patients (11.5%) had discontinued treatment by week 24, with 3 patients stopping for adverse events, 3 for protocol deviation or noncompliance, and 10 withdrawals. Two patients were lost to follow-up; all patients were included in analysis of the primary and secondary endpoints.

In the second year of the study, investigators rerandomized patients who had been receiving vehicle to an active arm of the study, and patients who had less than 25% improvement on a facial vitiligo scoring scale were rerandomized to one of the different doses. Twenty-eight weeks after rerandomization, all participants were given the opportunity to participate in a year-long open-label extension, receiving 1.5% ruxolitinib cream twice daily. Phototherapy was allowed in the extension arm, but not in the first year of the study.

Data beyond 24 weeks have not yet been reported, and the 2-year study plan acknowledged that “repigmentation takes a while,” Dr. Rosmarin said. He added that patients were allowed to use the study drug on body vitiligo as well, and many saw improvement there, although these results weren’t tracked in the study. “This isn’t a drug that’s meant just for the face,” he said.

Dr. Rosmarin and his coauthors reported financial arrangements with several pharmaceutical companies, including Incyte, which funded the study. An oral formulation of ruxolitinib (Jakafi), marketed by Incyte, was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2011, for myelofibrosis, and was recently approved for steroid-refractory acute graft-versus-host disease in adults and children aged 12 years and older.

MILAN – Targeting the Janus kinase (JAK) 1 and 2 pathways in vitiligo resulted in significant reduction of facial depigmentation after 24 weeks of treatment, in a phase 2b trial of topical ruxolitinib cream.

compared with vehicle alone, said David Rosmarin, MD, speaking in a late-breaking abstracts session at the World Congress of Dermatology.

The highest response rate was seen with a higher dose: Among patients receiving ruxolitinib cream 1.5% once daily, 50% met the 50% clearing mark at 24 weeks, as did 45.5% of those with twice-daily 1.5% dosing of the 1.5% formulation. At 24 weeks, 3.1% of those receiving vehicle had 50% facial vitiligo resolution (P less than .0001, compared with vehicle for both doses).

Vitiligo affects about 3,000,000 people in the United States, and it is a plausible treatment target for the JAK inhibitor ruxolitinib, explained Dr. Rosmarin, a dermatologist at Tufts University, Boston. “Interferon-gamma, signaling through JAK1 and JAK2, is central to the pathogenesis of vitiligo,” he said. “Ruxolitinib is a potent inhibitor of JAK1 and JAK2, so it made sense to investigate it as a treatment for vitiligo.”

The 24-month randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled phase 2 study of ruxolitinib cream for vitiligo compared the vehicle to four different concentrations of ruxolitinib during the first phase of the study. For the first 24 weeks, patients were randomized to receive vehicle twice daily, or various doses of ruxolitinib ranging from 0.15% once daily to 1.5% twice daily.

At this point, the study’s primary endpoint was assessed, with investigators comparing the proportion of patients treated with ruxolitinib who had at least 50% improvement in facial repigmentation from baseline on the Facial Vitiligo Area Scoring Index (F-VASI50) compared with those who received vehicle. A secondary endpoint, also assessed at week 24, was the proportion of patients who were clear, or almost clear, of facial vitiligo; safety and tolerability were also assessed.

In addition to the F-VASI50 measure, Dr. Rosmarin and his coinvestigators also tracked 75% facial clearing (F-VASI75). Here, the 1.5% twice daily regimen topped the others, with 30% of those receiving that dose achieving F-VASI75, compared with almost 10%-17% of those on other doses.

Using another measure, More than one-third of patients using ruxolitinib (35.3%) had clear (no signs of vitiligo) or almost clear (only specks of depigmentation) facial skin at week 24, according to a clinician assessment tool. No patients on placebo had clear or almost clear facial skin at that point. “It is my hope that with continued use beyond week 24, more patients will meet this very stringent endpoint,” Dr. Rosmarin said.

The safety profile was good, with no serious treatment-related adverse events, and no application site reactions that reached clinical significance, although numerically more patients reported acne with ruxolitinib than with vehicle alone.

In the trial, patients aged 18-75 years with vitiligo were eligible if they had facial depigmentation that constituted at least half of their body surface area (BSA), as well as depigmentation of at least 3% of BSA on nonfacial areas. Patients were excluded if they had another dermatologic disease, infection, prior JAK inhibitor therapy, or recent use of biologic or experimental drugs, laser or light-based treatments, or immunomodulators. Of the 157 patients who were randomized, 18 patients (11.5%) had discontinued treatment by week 24, with 3 patients stopping for adverse events, 3 for protocol deviation or noncompliance, and 10 withdrawals. Two patients were lost to follow-up; all patients were included in analysis of the primary and secondary endpoints.

In the second year of the study, investigators rerandomized patients who had been receiving vehicle to an active arm of the study, and patients who had less than 25% improvement on a facial vitiligo scoring scale were rerandomized to one of the different doses. Twenty-eight weeks after rerandomization, all participants were given the opportunity to participate in a year-long open-label extension, receiving 1.5% ruxolitinib cream twice daily. Phototherapy was allowed in the extension arm, but not in the first year of the study.

Data beyond 24 weeks have not yet been reported, and the 2-year study plan acknowledged that “repigmentation takes a while,” Dr. Rosmarin said. He added that patients were allowed to use the study drug on body vitiligo as well, and many saw improvement there, although these results weren’t tracked in the study. “This isn’t a drug that’s meant just for the face,” he said.

Dr. Rosmarin and his coauthors reported financial arrangements with several pharmaceutical companies, including Incyte, which funded the study. An oral formulation of ruxolitinib (Jakafi), marketed by Incyte, was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2011, for myelofibrosis, and was recently approved for steroid-refractory acute graft-versus-host disease in adults and children aged 12 years and older.

MILAN – Targeting the Janus kinase (JAK) 1 and 2 pathways in vitiligo resulted in significant reduction of facial depigmentation after 24 weeks of treatment, in a phase 2b trial of topical ruxolitinib cream.

compared with vehicle alone, said David Rosmarin, MD, speaking in a late-breaking abstracts session at the World Congress of Dermatology.

The highest response rate was seen with a higher dose: Among patients receiving ruxolitinib cream 1.5% once daily, 50% met the 50% clearing mark at 24 weeks, as did 45.5% of those with twice-daily 1.5% dosing of the 1.5% formulation. At 24 weeks, 3.1% of those receiving vehicle had 50% facial vitiligo resolution (P less than .0001, compared with vehicle for both doses).

Vitiligo affects about 3,000,000 people in the United States, and it is a plausible treatment target for the JAK inhibitor ruxolitinib, explained Dr. Rosmarin, a dermatologist at Tufts University, Boston. “Interferon-gamma, signaling through JAK1 and JAK2, is central to the pathogenesis of vitiligo,” he said. “Ruxolitinib is a potent inhibitor of JAK1 and JAK2, so it made sense to investigate it as a treatment for vitiligo.”

The 24-month randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled phase 2 study of ruxolitinib cream for vitiligo compared the vehicle to four different concentrations of ruxolitinib during the first phase of the study. For the first 24 weeks, patients were randomized to receive vehicle twice daily, or various doses of ruxolitinib ranging from 0.15% once daily to 1.5% twice daily.

At this point, the study’s primary endpoint was assessed, with investigators comparing the proportion of patients treated with ruxolitinib who had at least 50% improvement in facial repigmentation from baseline on the Facial Vitiligo Area Scoring Index (F-VASI50) compared with those who received vehicle. A secondary endpoint, also assessed at week 24, was the proportion of patients who were clear, or almost clear, of facial vitiligo; safety and tolerability were also assessed.

In addition to the F-VASI50 measure, Dr. Rosmarin and his coinvestigators also tracked 75% facial clearing (F-VASI75). Here, the 1.5% twice daily regimen topped the others, with 30% of those receiving that dose achieving F-VASI75, compared with almost 10%-17% of those on other doses.

Using another measure, More than one-third of patients using ruxolitinib (35.3%) had clear (no signs of vitiligo) or almost clear (only specks of depigmentation) facial skin at week 24, according to a clinician assessment tool. No patients on placebo had clear or almost clear facial skin at that point. “It is my hope that with continued use beyond week 24, more patients will meet this very stringent endpoint,” Dr. Rosmarin said.

The safety profile was good, with no serious treatment-related adverse events, and no application site reactions that reached clinical significance, although numerically more patients reported acne with ruxolitinib than with vehicle alone.

In the trial, patients aged 18-75 years with vitiligo were eligible if they had facial depigmentation that constituted at least half of their body surface area (BSA), as well as depigmentation of at least 3% of BSA on nonfacial areas. Patients were excluded if they had another dermatologic disease, infection, prior JAK inhibitor therapy, or recent use of biologic or experimental drugs, laser or light-based treatments, or immunomodulators. Of the 157 patients who were randomized, 18 patients (11.5%) had discontinued treatment by week 24, with 3 patients stopping for adverse events, 3 for protocol deviation or noncompliance, and 10 withdrawals. Two patients were lost to follow-up; all patients were included in analysis of the primary and secondary endpoints.

In the second year of the study, investigators rerandomized patients who had been receiving vehicle to an active arm of the study, and patients who had less than 25% improvement on a facial vitiligo scoring scale were rerandomized to one of the different doses. Twenty-eight weeks after rerandomization, all participants were given the opportunity to participate in a year-long open-label extension, receiving 1.5% ruxolitinib cream twice daily. Phototherapy was allowed in the extension arm, but not in the first year of the study.

Data beyond 24 weeks have not yet been reported, and the 2-year study plan acknowledged that “repigmentation takes a while,” Dr. Rosmarin said. He added that patients were allowed to use the study drug on body vitiligo as well, and many saw improvement there, although these results weren’t tracked in the study. “This isn’t a drug that’s meant just for the face,” he said.

Dr. Rosmarin and his coauthors reported financial arrangements with several pharmaceutical companies, including Incyte, which funded the study. An oral formulation of ruxolitinib (Jakafi), marketed by Incyte, was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2011, for myelofibrosis, and was recently approved for steroid-refractory acute graft-versus-host disease in adults and children aged 12 years and older.

REPORTING FROM WCD2019

Visual examinations yield signs to guide vitiligo treatment

MILAN – Subtle signs beyond depigmentation alone can guide management of vitiligo, Michelle Rodrigues, MBBS, said at the World Congress of Dermatology.

Signs of high disease activity can be visually observed and, when found, can compel urgent treatment, Dr. Rodrigues said. “If we identify and understand these [signs, they] can change our management plan, and the patient’s outcomes ... picking these up quickly, getting the best response you can, can help our patients tremendously.”

To assess clinical signs of severity in vitiligo, “use the tools that you have in your practice – your dermatoscope, your Wood’s lamp.”

Showing an image of the leg of a patient with vitiligo, Dr. Rodrigues said, “I know this patient’s vitiligo is very, very active. Why?” Clues come when there are areas of hypopigmentation at the rim of lesions, with depigmentation at the center. The presence of pigmentation, hypopigmentation, and depigmentation within the same lesion indicates high disease activity. This finding is the trichrome sign, also called the “blurry borders” sign in some regions, said Dr. Rodrigues, a dermatologist in Melbourne and the founder of Chroma Dermatology, which specializes in treating pigment problems and diagnosing and managing skin conditions in patients with skin of color.

Next, Dr. Rodrigues said, look at hair growth within the vitiliginous area. “If you’re unable to see that clinically, it’s really important to get that dermatoscope onto the patient, and look within a patch, to see whether or not you can actually see white hairs or normal colored hairs,” she said. This finding will help to determine both treatment plan and prognosis, since leukotrichia is a marker of disease severity in vitiligo.

Be alert to Koebnerization, said Dr. Rodrigues; the presentation may be subtle. As an example, she shared an image of a patient with depigmented patches on the dorsum of each foot. It wasn’t until the patient removed her foot gear – rubber slide-type sandals with a single broad strap over the dorsum – that Dr. Rodrigues recognized that “there was clear Koebnerization from the constant friction as a result of the wearing of the shoes.

“This can also be seen when patients scratch themselves, as can be seen with the itch that vitiligo can sometimes cause,” she said.

She noted that about 10% of patients with vitiligo have pruritus as a prominent symptom. Here, she said, is where a Wood’s lamp can be helpful as well. “Sometimes we can’t appreciate the very, very subtle Koebnerization, especially in patients with lighter skin. Getting out that Wood’s lamp and looking at other areas of involvement is really important,” she said. Areas of high disease activity and signs of progression that might otherwise be missed will be more obvious under the ultraviolet light.

It’s important to look beyond the obvious patches of vitiligo to examine the surrounding skin. Searching for “confetti depigmentation” – tiny white dots of depigmentation scattered over the otherwise normally pigmented skin – also marks high disease activity. An area with these dots – each often only a few millimeters in diameter – is likely destined for rapid depigmentation unless aggressive treatment is started. “We know that without treating these areas there will be very, very rapid and aggressive depigmentation. And remember that in areas that have a paucity of hair follicles, it might be irreversible ... so recognizing these signs is absolutely critical.”

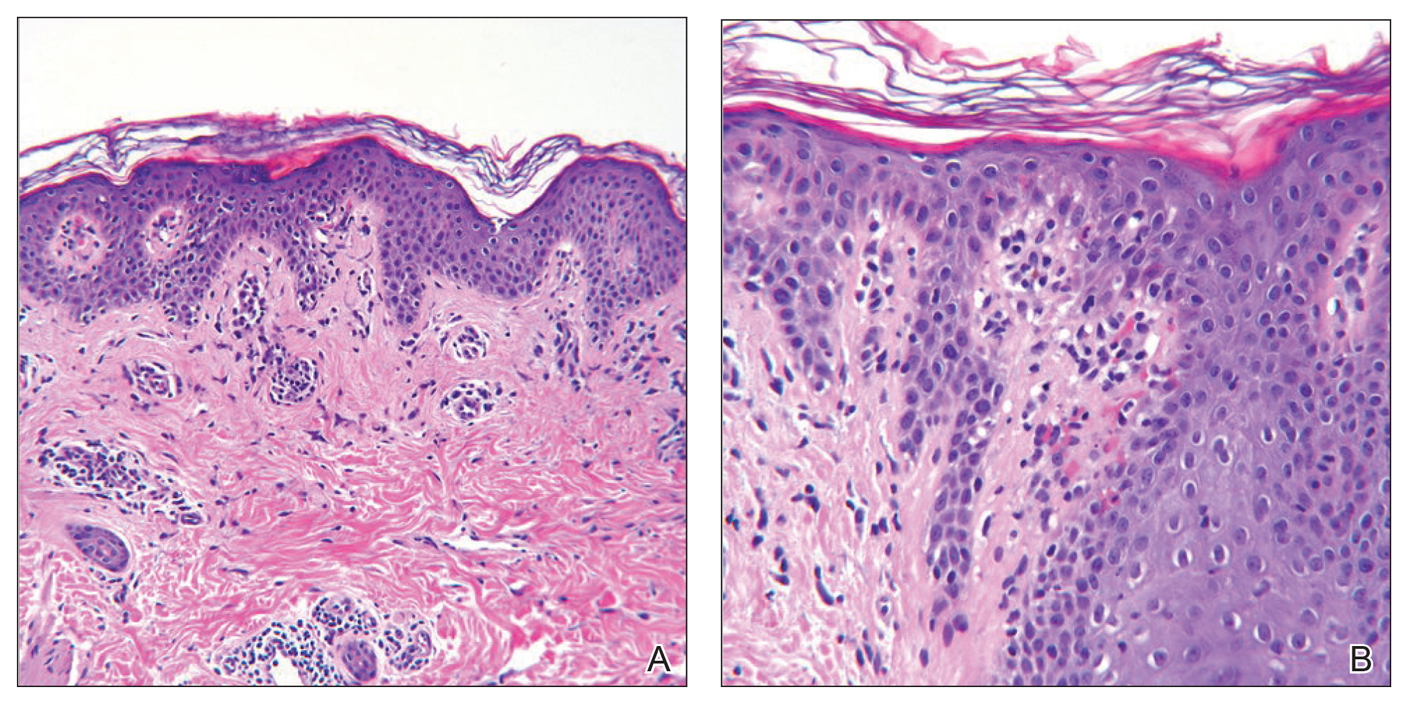

The final clue to highly active disease that’s likely to move quickly without intervention can be found at the border of a vitiligo lesion. Look for a fine rim of erythema and some scale, Dr. Rodrigues said. This sign is common, and often seen early in the disease course. When this erythematous region is biopsied, ”You’ll see an intense inflammatory response, with an interface dermatitis. Again, this tells us that the patient may have a poorer prognosis if we don’t commence treatment early on.”

As a final clinical tip, Dr. Rodrigues reminded attendees that when one sign of disease activity is seen, others are often present. A thorough clinical examination is needed to document aggressive disease. “Please make sure that if you find one, you’re looking for other signs of disease severity as well.”

Dr. Rodrigues reported that she had no disclosures relevant to her presentation.

MILAN – Subtle signs beyond depigmentation alone can guide management of vitiligo, Michelle Rodrigues, MBBS, said at the World Congress of Dermatology.

Signs of high disease activity can be visually observed and, when found, can compel urgent treatment, Dr. Rodrigues said. “If we identify and understand these [signs, they] can change our management plan, and the patient’s outcomes ... picking these up quickly, getting the best response you can, can help our patients tremendously.”

To assess clinical signs of severity in vitiligo, “use the tools that you have in your practice – your dermatoscope, your Wood’s lamp.”

Showing an image of the leg of a patient with vitiligo, Dr. Rodrigues said, “I know this patient’s vitiligo is very, very active. Why?” Clues come when there are areas of hypopigmentation at the rim of lesions, with depigmentation at the center. The presence of pigmentation, hypopigmentation, and depigmentation within the same lesion indicates high disease activity. This finding is the trichrome sign, also called the “blurry borders” sign in some regions, said Dr. Rodrigues, a dermatologist in Melbourne and the founder of Chroma Dermatology, which specializes in treating pigment problems and diagnosing and managing skin conditions in patients with skin of color.

Next, Dr. Rodrigues said, look at hair growth within the vitiliginous area. “If you’re unable to see that clinically, it’s really important to get that dermatoscope onto the patient, and look within a patch, to see whether or not you can actually see white hairs or normal colored hairs,” she said. This finding will help to determine both treatment plan and prognosis, since leukotrichia is a marker of disease severity in vitiligo.

Be alert to Koebnerization, said Dr. Rodrigues; the presentation may be subtle. As an example, she shared an image of a patient with depigmented patches on the dorsum of each foot. It wasn’t until the patient removed her foot gear – rubber slide-type sandals with a single broad strap over the dorsum – that Dr. Rodrigues recognized that “there was clear Koebnerization from the constant friction as a result of the wearing of the shoes.

“This can also be seen when patients scratch themselves, as can be seen with the itch that vitiligo can sometimes cause,” she said.

She noted that about 10% of patients with vitiligo have pruritus as a prominent symptom. Here, she said, is where a Wood’s lamp can be helpful as well. “Sometimes we can’t appreciate the very, very subtle Koebnerization, especially in patients with lighter skin. Getting out that Wood’s lamp and looking at other areas of involvement is really important,” she said. Areas of high disease activity and signs of progression that might otherwise be missed will be more obvious under the ultraviolet light.

It’s important to look beyond the obvious patches of vitiligo to examine the surrounding skin. Searching for “confetti depigmentation” – tiny white dots of depigmentation scattered over the otherwise normally pigmented skin – also marks high disease activity. An area with these dots – each often only a few millimeters in diameter – is likely destined for rapid depigmentation unless aggressive treatment is started. “We know that without treating these areas there will be very, very rapid and aggressive depigmentation. And remember that in areas that have a paucity of hair follicles, it might be irreversible ... so recognizing these signs is absolutely critical.”

The final clue to highly active disease that’s likely to move quickly without intervention can be found at the border of a vitiligo lesion. Look for a fine rim of erythema and some scale, Dr. Rodrigues said. This sign is common, and often seen early in the disease course. When this erythematous region is biopsied, ”You’ll see an intense inflammatory response, with an interface dermatitis. Again, this tells us that the patient may have a poorer prognosis if we don’t commence treatment early on.”

As a final clinical tip, Dr. Rodrigues reminded attendees that when one sign of disease activity is seen, others are often present. A thorough clinical examination is needed to document aggressive disease. “Please make sure that if you find one, you’re looking for other signs of disease severity as well.”

Dr. Rodrigues reported that she had no disclosures relevant to her presentation.

MILAN – Subtle signs beyond depigmentation alone can guide management of vitiligo, Michelle Rodrigues, MBBS, said at the World Congress of Dermatology.

Signs of high disease activity can be visually observed and, when found, can compel urgent treatment, Dr. Rodrigues said. “If we identify and understand these [signs, they] can change our management plan, and the patient’s outcomes ... picking these up quickly, getting the best response you can, can help our patients tremendously.”

To assess clinical signs of severity in vitiligo, “use the tools that you have in your practice – your dermatoscope, your Wood’s lamp.”

Showing an image of the leg of a patient with vitiligo, Dr. Rodrigues said, “I know this patient’s vitiligo is very, very active. Why?” Clues come when there are areas of hypopigmentation at the rim of lesions, with depigmentation at the center. The presence of pigmentation, hypopigmentation, and depigmentation within the same lesion indicates high disease activity. This finding is the trichrome sign, also called the “blurry borders” sign in some regions, said Dr. Rodrigues, a dermatologist in Melbourne and the founder of Chroma Dermatology, which specializes in treating pigment problems and diagnosing and managing skin conditions in patients with skin of color.

Next, Dr. Rodrigues said, look at hair growth within the vitiliginous area. “If you’re unable to see that clinically, it’s really important to get that dermatoscope onto the patient, and look within a patch, to see whether or not you can actually see white hairs or normal colored hairs,” she said. This finding will help to determine both treatment plan and prognosis, since leukotrichia is a marker of disease severity in vitiligo.

Be alert to Koebnerization, said Dr. Rodrigues; the presentation may be subtle. As an example, she shared an image of a patient with depigmented patches on the dorsum of each foot. It wasn’t until the patient removed her foot gear – rubber slide-type sandals with a single broad strap over the dorsum – that Dr. Rodrigues recognized that “there was clear Koebnerization from the constant friction as a result of the wearing of the shoes.

“This can also be seen when patients scratch themselves, as can be seen with the itch that vitiligo can sometimes cause,” she said.

She noted that about 10% of patients with vitiligo have pruritus as a prominent symptom. Here, she said, is where a Wood’s lamp can be helpful as well. “Sometimes we can’t appreciate the very, very subtle Koebnerization, especially in patients with lighter skin. Getting out that Wood’s lamp and looking at other areas of involvement is really important,” she said. Areas of high disease activity and signs of progression that might otherwise be missed will be more obvious under the ultraviolet light.

It’s important to look beyond the obvious patches of vitiligo to examine the surrounding skin. Searching for “confetti depigmentation” – tiny white dots of depigmentation scattered over the otherwise normally pigmented skin – also marks high disease activity. An area with these dots – each often only a few millimeters in diameter – is likely destined for rapid depigmentation unless aggressive treatment is started. “We know that without treating these areas there will be very, very rapid and aggressive depigmentation. And remember that in areas that have a paucity of hair follicles, it might be irreversible ... so recognizing these signs is absolutely critical.”

The final clue to highly active disease that’s likely to move quickly without intervention can be found at the border of a vitiligo lesion. Look for a fine rim of erythema and some scale, Dr. Rodrigues said. This sign is common, and often seen early in the disease course. When this erythematous region is biopsied, ”You’ll see an intense inflammatory response, with an interface dermatitis. Again, this tells us that the patient may have a poorer prognosis if we don’t commence treatment early on.”

As a final clinical tip, Dr. Rodrigues reminded attendees that when one sign of disease activity is seen, others are often present. A thorough clinical examination is needed to document aggressive disease. “Please make sure that if you find one, you’re looking for other signs of disease severity as well.”

Dr. Rodrigues reported that she had no disclosures relevant to her presentation.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM WCD2019

Timolol shortens propranolol use in infantile hemangioma

according to a study published in Pediatric Dermatology.

Diana B. Mannschreck, BSN, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and colleagues performed a retrospective chart review of 559 patients with infantile hemangioma seen in the dermatology clinic at Johns Hopkins between December 2008 and January 2018. Patients received any of five courses of treatment, including oral propranolol followed by topical timolol, propranolol only, and timolol only. Of the courses evaluated, propranolol followed by timolol had the shortest duration of propranolol therapy – a median of 2.2 months shorter than propranolol-only therapy (P = .0006). This sequential regimen also was associated with no reinitiations of propranolol therapy following tapering, whereas 13% of those receiving propranolol alone had to reinitiate it after tapering.

This is of interest because oral beta-blockers, including propranolol, have been associated with rare but serious adverse events, such as bronchospasm, hypotension, and hypoglycemia.

Limitations of the study include its retrospective and single-center nature. There was no funding or disclosure information given.

SOURCE: Mannschreck DB et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019 Apr 9. doi: 10.1111/pde.13816.

according to a study published in Pediatric Dermatology.

Diana B. Mannschreck, BSN, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and colleagues performed a retrospective chart review of 559 patients with infantile hemangioma seen in the dermatology clinic at Johns Hopkins between December 2008 and January 2018. Patients received any of five courses of treatment, including oral propranolol followed by topical timolol, propranolol only, and timolol only. Of the courses evaluated, propranolol followed by timolol had the shortest duration of propranolol therapy – a median of 2.2 months shorter than propranolol-only therapy (P = .0006). This sequential regimen also was associated with no reinitiations of propranolol therapy following tapering, whereas 13% of those receiving propranolol alone had to reinitiate it after tapering.

This is of interest because oral beta-blockers, including propranolol, have been associated with rare but serious adverse events, such as bronchospasm, hypotension, and hypoglycemia.

Limitations of the study include its retrospective and single-center nature. There was no funding or disclosure information given.

SOURCE: Mannschreck DB et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019 Apr 9. doi: 10.1111/pde.13816.

according to a study published in Pediatric Dermatology.

Diana B. Mannschreck, BSN, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and colleagues performed a retrospective chart review of 559 patients with infantile hemangioma seen in the dermatology clinic at Johns Hopkins between December 2008 and January 2018. Patients received any of five courses of treatment, including oral propranolol followed by topical timolol, propranolol only, and timolol only. Of the courses evaluated, propranolol followed by timolol had the shortest duration of propranolol therapy – a median of 2.2 months shorter than propranolol-only therapy (P = .0006). This sequential regimen also was associated with no reinitiations of propranolol therapy following tapering, whereas 13% of those receiving propranolol alone had to reinitiate it after tapering.

This is of interest because oral beta-blockers, including propranolol, have been associated with rare but serious adverse events, such as bronchospasm, hypotension, and hypoglycemia.

Limitations of the study include its retrospective and single-center nature. There was no funding or disclosure information given.

SOURCE: Mannschreck DB et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019 Apr 9. doi: 10.1111/pde.13816.

FROM PEDIATRIC DERMATOLOGY

Topical calcineurin inhibitors prove beneficial for patients with vitiligo

Though responses to topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCIs) plus phototherapy were found to be higher than TCI monotherapy, a meta-analysis of studies on TCI therapy found that both should be used in treatment for patients with vitiligo.

“In addition, the proactive use of TCIs to maintain remission of vitiligo could be promising, considering its high recurrence rate,” wrote Ji Hae Lee, MD, PhD, of the Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, and coauthors in JAMA Dermatology.

To assess TCIs as treatment for vitiligo, the researchers undertook a systematic review and analysis of 56 relevant studies. Eleven of the studies were on the TCI mechanism; 36 were on TCI monotherapy; 12 were on TCI plus phototherapy; and 1 was on TCI maintenance therapy. Treatment responses for each study were measured via the degree of repigmentation on a quartile scale: an at least mild response (25% or greater repigmentation), at least moderate response (50% or greater repigmentation), and marked response (75% or greater repigmentation).

In regard to TCI monotherapy, an at least mild response was achieved in 55% (95% confidence interval, 42.2%-67.8%) of 560 patients in 21 studies. An at least moderate response was achieved in 38.5% (95% CI, 28.2%-48.8%) of 619 patients in 23 studies, and there was a marked response in 18.1% (95% CI, 13.2%-23.1%) of 520 patients in 19 studies.

For TCI plus phototherapy, an at least mild response was achieved in 89.5% (95% CI, 81.1%-97.9%) of 433 patients in eight studies. An at least moderate response was achieved in 72.9% (95% CI, 57.6%-88.2%) of 486 patients in 10 studies, and a marked response was achieved in 47.5% (95% CI, 30.6%-64.4%) of 490 patients in 9 studies.

The authors noted several limitations with their review, including a level of heterogeneity in the study designs, characteristics of the patients, and protocols. They also acknowledged that the quartile scale may be somewhat arbitrary in nature, though they added that it has been the “most commonly used measure and would have been one of the best estimates of the treatment response at this time.”

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Lee JH et al. Jama Dermatol. 2019 May 29. doi: 10.1001/Jamadermatol.2019.0696.

Though responses to topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCIs) plus phototherapy were found to be higher than TCI monotherapy, a meta-analysis of studies on TCI therapy found that both should be used in treatment for patients with vitiligo.

“In addition, the proactive use of TCIs to maintain remission of vitiligo could be promising, considering its high recurrence rate,” wrote Ji Hae Lee, MD, PhD, of the Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, and coauthors in JAMA Dermatology.

To assess TCIs as treatment for vitiligo, the researchers undertook a systematic review and analysis of 56 relevant studies. Eleven of the studies were on the TCI mechanism; 36 were on TCI monotherapy; 12 were on TCI plus phototherapy; and 1 was on TCI maintenance therapy. Treatment responses for each study were measured via the degree of repigmentation on a quartile scale: an at least mild response (25% or greater repigmentation), at least moderate response (50% or greater repigmentation), and marked response (75% or greater repigmentation).

In regard to TCI monotherapy, an at least mild response was achieved in 55% (95% confidence interval, 42.2%-67.8%) of 560 patients in 21 studies. An at least moderate response was achieved in 38.5% (95% CI, 28.2%-48.8%) of 619 patients in 23 studies, and there was a marked response in 18.1% (95% CI, 13.2%-23.1%) of 520 patients in 19 studies.

For TCI plus phototherapy, an at least mild response was achieved in 89.5% (95% CI, 81.1%-97.9%) of 433 patients in eight studies. An at least moderate response was achieved in 72.9% (95% CI, 57.6%-88.2%) of 486 patients in 10 studies, and a marked response was achieved in 47.5% (95% CI, 30.6%-64.4%) of 490 patients in 9 studies.

The authors noted several limitations with their review, including a level of heterogeneity in the study designs, characteristics of the patients, and protocols. They also acknowledged that the quartile scale may be somewhat arbitrary in nature, though they added that it has been the “most commonly used measure and would have been one of the best estimates of the treatment response at this time.”

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Lee JH et al. Jama Dermatol. 2019 May 29. doi: 10.1001/Jamadermatol.2019.0696.

Though responses to topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCIs) plus phototherapy were found to be higher than TCI monotherapy, a meta-analysis of studies on TCI therapy found that both should be used in treatment for patients with vitiligo.

“In addition, the proactive use of TCIs to maintain remission of vitiligo could be promising, considering its high recurrence rate,” wrote Ji Hae Lee, MD, PhD, of the Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, and coauthors in JAMA Dermatology.

To assess TCIs as treatment for vitiligo, the researchers undertook a systematic review and analysis of 56 relevant studies. Eleven of the studies were on the TCI mechanism; 36 were on TCI monotherapy; 12 were on TCI plus phototherapy; and 1 was on TCI maintenance therapy. Treatment responses for each study were measured via the degree of repigmentation on a quartile scale: an at least mild response (25% or greater repigmentation), at least moderate response (50% or greater repigmentation), and marked response (75% or greater repigmentation).

In regard to TCI monotherapy, an at least mild response was achieved in 55% (95% confidence interval, 42.2%-67.8%) of 560 patients in 21 studies. An at least moderate response was achieved in 38.5% (95% CI, 28.2%-48.8%) of 619 patients in 23 studies, and there was a marked response in 18.1% (95% CI, 13.2%-23.1%) of 520 patients in 19 studies.

For TCI plus phototherapy, an at least mild response was achieved in 89.5% (95% CI, 81.1%-97.9%) of 433 patients in eight studies. An at least moderate response was achieved in 72.9% (95% CI, 57.6%-88.2%) of 486 patients in 10 studies, and a marked response was achieved in 47.5% (95% CI, 30.6%-64.4%) of 490 patients in 9 studies.

The authors noted several limitations with their review, including a level of heterogeneity in the study designs, characteristics of the patients, and protocols. They also acknowledged that the quartile scale may be somewhat arbitrary in nature, though they added that it has been the “most commonly used measure and would have been one of the best estimates of the treatment response at this time.”

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Lee JH et al. Jama Dermatol. 2019 May 29. doi: 10.1001/Jamadermatol.2019.0696.

FROM JAMA Dermatology

Leukemia Cutis–Associated Leonine Facies and Eyebrow Loss

To the Editor:

I read with interest the informative Cutis case report by Krooks and Weatherall1 in which the authors not only described the case of a 66-year-old man whose diagnosis of bone marrow biopsy–confirmed acute myeloid leukemia (AML) presented concurrently with skin biopsy–confirmed leukemia cutis but also discussed the poor prognosis of individuals with acute myelogenous leukemia cutis. Their patient died within 5 weeks of establishing the diagnosis. In addition, lateral and frontal photographs of the patient’s face demonstrated diffuse infiltrative plaques of leukemia cutis; he had swollen eyelids and lips with distortion of the nose secondary to dermal infiltration of leukemic myeloid cells.1 Although not emphasized by the authors, the patient appeared to have a leonine facies and at least partial loss of the lateral eyebrows.

Malignancy-associated leonine facies resulting from infiltration of the skin by neoplastic cells has been reported in a patient with metastatic breast carcinoma.2,3 However, it predominantly occurs in patients with hematologic dyscrasias such as leukemia cutis, lymphoma (ie, cutaneous B cell, cutaneous T cell, Hodgkin), plasmacytoma, and systemic mastocytosis.3,4 The report by Krooks and Weatherall1 adds AML-associated leukemia cutis to the previously observed types of leukemia cutis–related leonine facies in patients with acute lymphocytic leukemia, acute myelomonocytic leukemia, and chronic lymphocytic leukemia.3,4

Partial or complete loss of eyebrows in the setting of leonine facies has a limited differential diagnosis.3,5 In addition to cancer, the associated disorders include adnexal mucin deposition (alopecia mucinosis), granulomatous conditions (sarcoidosis), infectious diseases (leprosy), inherited syndromes (Setleis syndrome), photoallergic dermatoses (actinic reticuloid), and viral conditions (viral-associated trichodysplasia).3-9 Neoplasms associated with leonine facies and eyebrow loss include lymphomas (mycosis fungoides and unspecified cutaneous T-cell lymphoma), systemic mastocytosis and leukemia cutis secondary to acute lymphocytic leukemia, acute myelomonocytic leukemia, and now AML.1,3-5

The eyebrow loss associated with leonine facies often is not reversible once the causative cell of the associated condition (eg, granulomas of mycobacteria-infected histiocytes in leprosy, neoplastic lymphocytes in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma) has infiltrated the area of the eyebrows and abolished the preexisting hair follicles; however, follow-up descriptions of patients after treatment of other conditions that cause eyebrow loss usually are not reported. Indeed, there was partial reappearance of the eyebrows in a woman with systemic mastocytosis–associated loss of the eyebrows after malignancy-related treatment was reinitiated and the infiltrative facial plaques that had created her leonine facies had decreased in size.5 It is reasonable to speculate that the eyebrows may have reappeared in the patient reported by Krooks and Weatherall1 and his leonine facies–associated facial plaques may have resolved if he had underwent and responded to treatment with antineoplastic chemotherapy.

- Krooks JA, Weatherall AG. Leukemia cutis in acute myeloid leukemia signifies a poor prognosis. Cutis. 2018;102:266, 271-272.

- Jin CC, Martinelli PT, Cohen PR. What are these erythematous skin lesions? leukemia cutis. The Dermatologist. 2012;20:46-50.

- Chodkiewicz HM, Cohen PR. Systemic mastocytosis-associated leonine facies and eyebrow loss. South Med J. 2011;104:236-238.

- Cohen PR, Rapini RP, Beran M. Infiltrated blue-gray plaques in a patient with leukemia. Chloroma (granulocytic sarcoma). Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:251, 254.

- Cohen PR. Leonine facies associated with eyebrow loss. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:e148-e149.

- Ravic-Nikolic A, Milicic V, Ristic G, et al. Actinic reticuloid presented as facies leonine. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:234-236.

- Jacob Raja SA, Raja JJ, Vijayashree R, et al. Evaluation of oral and periodontal status of leprosy patients in Dindigul district. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2016;8(suppl 1):S119-S121.

- McGaughran J, Aftimos S. Setleis syndrome: three new cases and a review of the literature. Am J Med Genet. 2002;111:376-380.

- Benoit T, Bacelieri R, Morrell DS, et al. Viral-associated trichodysplasia of immunosuppression: report of a pediatric patient with response to oral valganciclovir. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:871-874.

To the Editor:

I read with interest the informative Cutis case report by Krooks and Weatherall1 in which the authors not only described the case of a 66-year-old man whose diagnosis of bone marrow biopsy–confirmed acute myeloid leukemia (AML) presented concurrently with skin biopsy–confirmed leukemia cutis but also discussed the poor prognosis of individuals with acute myelogenous leukemia cutis. Their patient died within 5 weeks of establishing the diagnosis. In addition, lateral and frontal photographs of the patient’s face demonstrated diffuse infiltrative plaques of leukemia cutis; he had swollen eyelids and lips with distortion of the nose secondary to dermal infiltration of leukemic myeloid cells.1 Although not emphasized by the authors, the patient appeared to have a leonine facies and at least partial loss of the lateral eyebrows.

Malignancy-associated leonine facies resulting from infiltration of the skin by neoplastic cells has been reported in a patient with metastatic breast carcinoma.2,3 However, it predominantly occurs in patients with hematologic dyscrasias such as leukemia cutis, lymphoma (ie, cutaneous B cell, cutaneous T cell, Hodgkin), plasmacytoma, and systemic mastocytosis.3,4 The report by Krooks and Weatherall1 adds AML-associated leukemia cutis to the previously observed types of leukemia cutis–related leonine facies in patients with acute lymphocytic leukemia, acute myelomonocytic leukemia, and chronic lymphocytic leukemia.3,4

Partial or complete loss of eyebrows in the setting of leonine facies has a limited differential diagnosis.3,5 In addition to cancer, the associated disorders include adnexal mucin deposition (alopecia mucinosis), granulomatous conditions (sarcoidosis), infectious diseases (leprosy), inherited syndromes (Setleis syndrome), photoallergic dermatoses (actinic reticuloid), and viral conditions (viral-associated trichodysplasia).3-9 Neoplasms associated with leonine facies and eyebrow loss include lymphomas (mycosis fungoides and unspecified cutaneous T-cell lymphoma), systemic mastocytosis and leukemia cutis secondary to acute lymphocytic leukemia, acute myelomonocytic leukemia, and now AML.1,3-5

The eyebrow loss associated with leonine facies often is not reversible once the causative cell of the associated condition (eg, granulomas of mycobacteria-infected histiocytes in leprosy, neoplastic lymphocytes in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma) has infiltrated the area of the eyebrows and abolished the preexisting hair follicles; however, follow-up descriptions of patients after treatment of other conditions that cause eyebrow loss usually are not reported. Indeed, there was partial reappearance of the eyebrows in a woman with systemic mastocytosis–associated loss of the eyebrows after malignancy-related treatment was reinitiated and the infiltrative facial plaques that had created her leonine facies had decreased in size.5 It is reasonable to speculate that the eyebrows may have reappeared in the patient reported by Krooks and Weatherall1 and his leonine facies–associated facial plaques may have resolved if he had underwent and responded to treatment with antineoplastic chemotherapy.

To the Editor:

I read with interest the informative Cutis case report by Krooks and Weatherall1 in which the authors not only described the case of a 66-year-old man whose diagnosis of bone marrow biopsy–confirmed acute myeloid leukemia (AML) presented concurrently with skin biopsy–confirmed leukemia cutis but also discussed the poor prognosis of individuals with acute myelogenous leukemia cutis. Their patient died within 5 weeks of establishing the diagnosis. In addition, lateral and frontal photographs of the patient’s face demonstrated diffuse infiltrative plaques of leukemia cutis; he had swollen eyelids and lips with distortion of the nose secondary to dermal infiltration of leukemic myeloid cells.1 Although not emphasized by the authors, the patient appeared to have a leonine facies and at least partial loss of the lateral eyebrows.

Malignancy-associated leonine facies resulting from infiltration of the skin by neoplastic cells has been reported in a patient with metastatic breast carcinoma.2,3 However, it predominantly occurs in patients with hematologic dyscrasias such as leukemia cutis, lymphoma (ie, cutaneous B cell, cutaneous T cell, Hodgkin), plasmacytoma, and systemic mastocytosis.3,4 The report by Krooks and Weatherall1 adds AML-associated leukemia cutis to the previously observed types of leukemia cutis–related leonine facies in patients with acute lymphocytic leukemia, acute myelomonocytic leukemia, and chronic lymphocytic leukemia.3,4

Partial or complete loss of eyebrows in the setting of leonine facies has a limited differential diagnosis.3,5 In addition to cancer, the associated disorders include adnexal mucin deposition (alopecia mucinosis), granulomatous conditions (sarcoidosis), infectious diseases (leprosy), inherited syndromes (Setleis syndrome), photoallergic dermatoses (actinic reticuloid), and viral conditions (viral-associated trichodysplasia).3-9 Neoplasms associated with leonine facies and eyebrow loss include lymphomas (mycosis fungoides and unspecified cutaneous T-cell lymphoma), systemic mastocytosis and leukemia cutis secondary to acute lymphocytic leukemia, acute myelomonocytic leukemia, and now AML.1,3-5