User login

Changing Public Perception of Vitiligo

Bilateral Brown Plaques Behind the Ears

The Diagnosis: Terra Firma-Forme Dermatosis

Terra firma-forme dermatosis (TFFD), also known as Duncan dirty dermatosis, is an idiopathic benign cutaneous condition that is easily misdiagnosed or mismanaged. In 1987, Duncan et al1 first described the condition in children who had mothers that lamented over dirty skin spots that could not be washed off. The term terra firma translates in Latin to solid ground, which describes the characteristic dirtlike appearance of these lesions.

Terra firma-forme dermatosis most commonly affects children and young adults, though it can present in patients of any age without any known predisposing risk factors.1-4 The lesions have a predilection for the face, neck, shoulders, trunk, and ankles. Terra firma-forme dermatosis has no association with bathing and hygiene habits, and most patients describe unsuccessful removal of the lesions, even after vigorous scrubbing with soaps and detergents at home. The lesions are asymptomatic, and many patients present to dermatology for cosmetic concerns.1-8

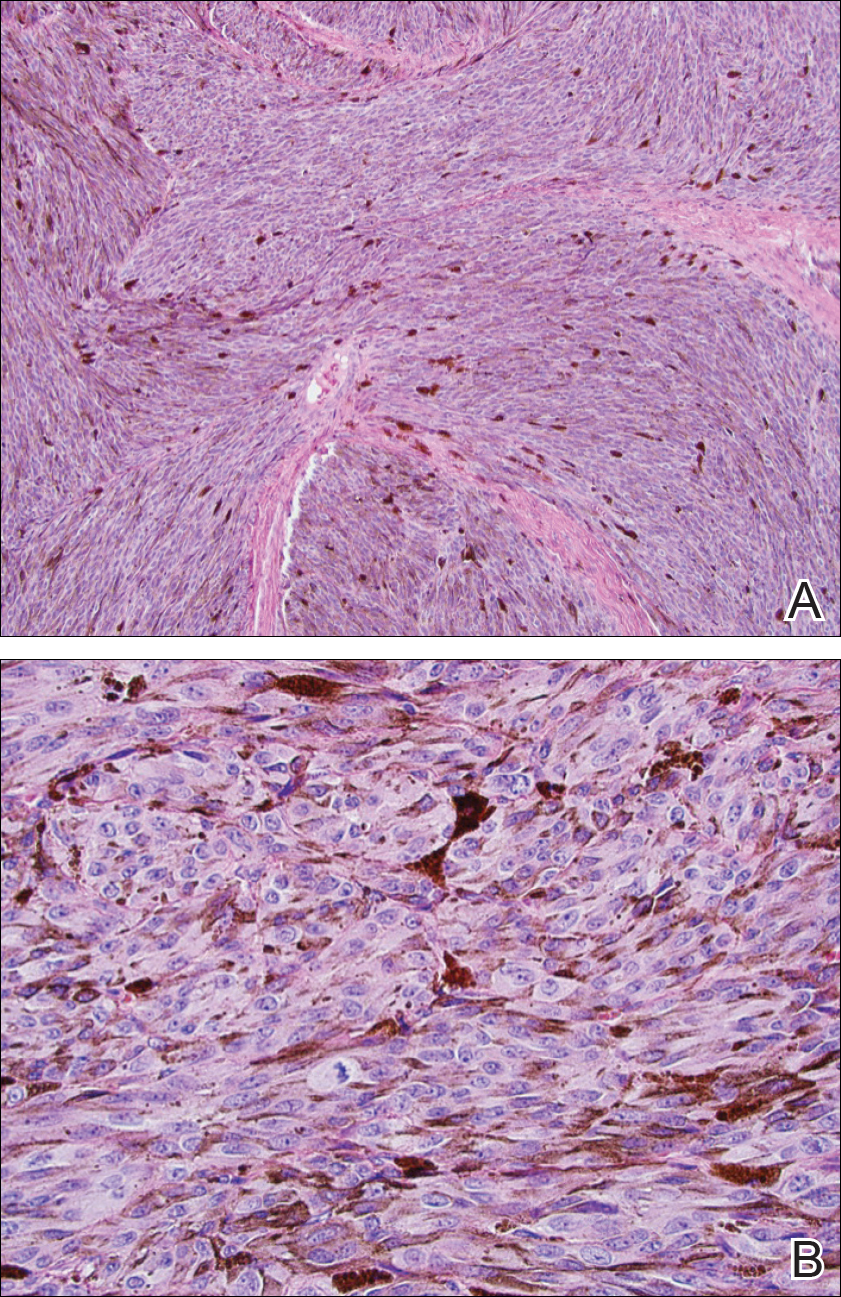

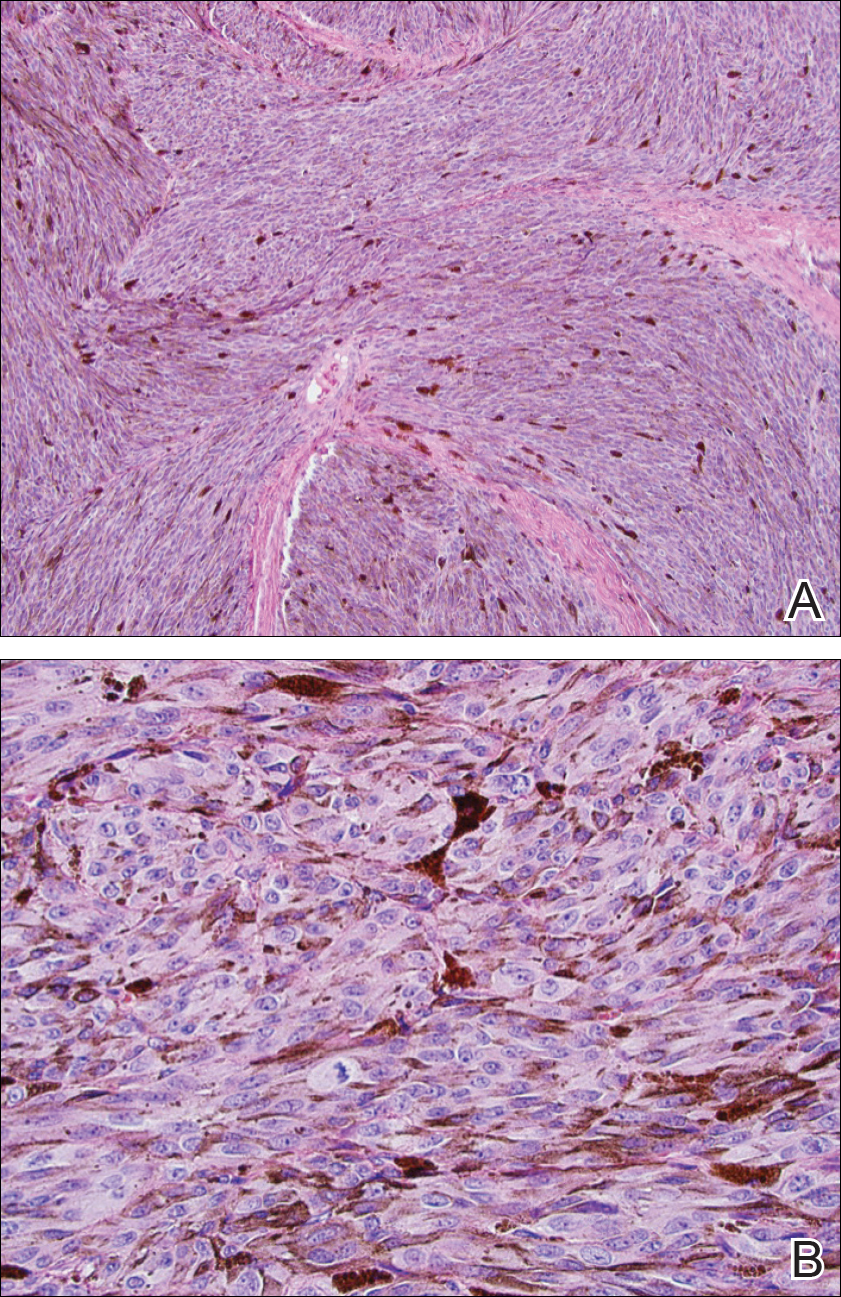

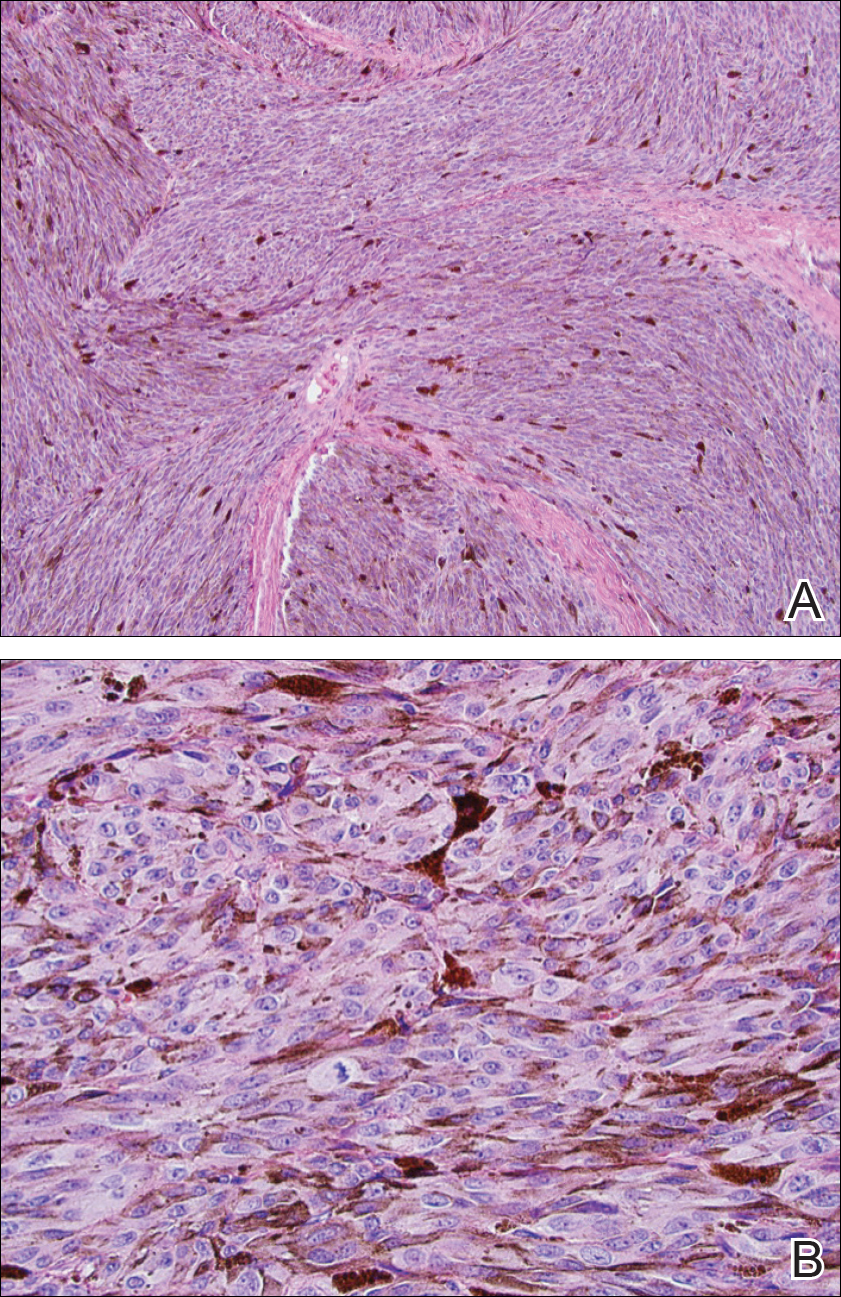

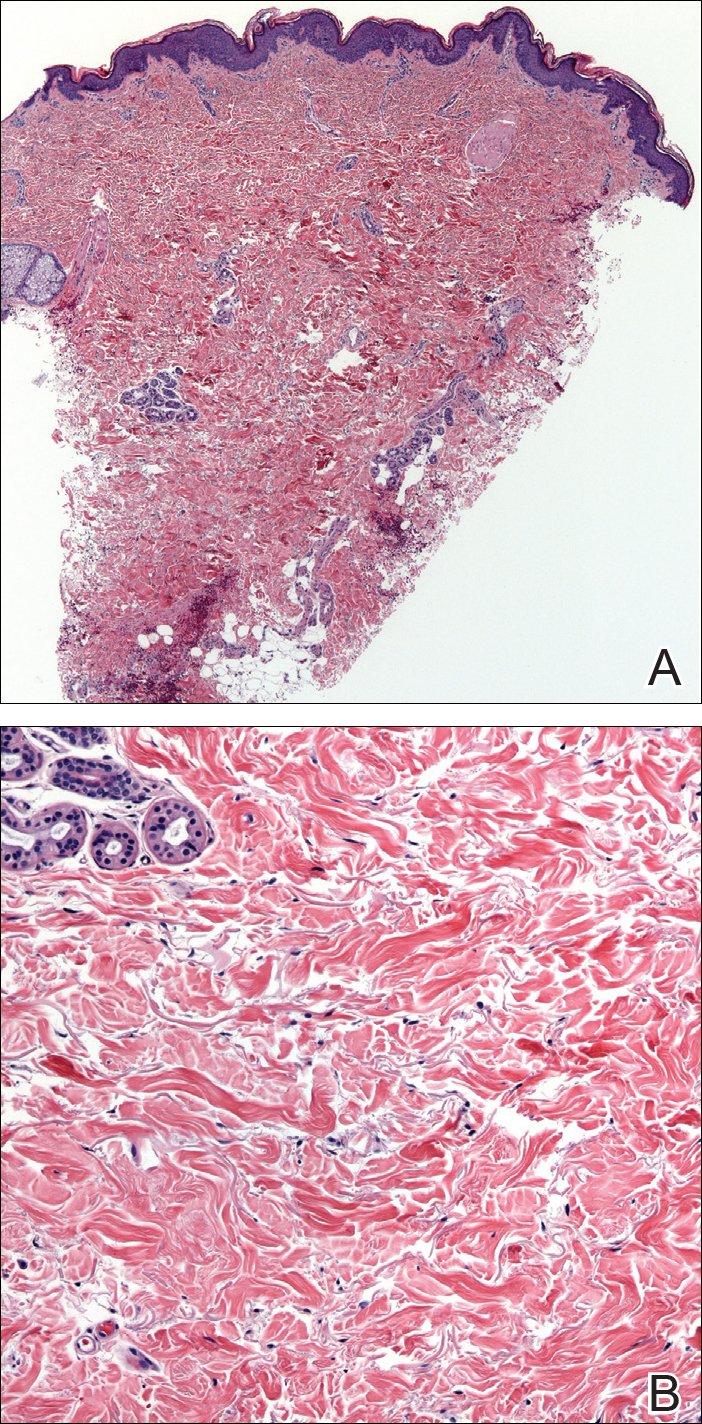

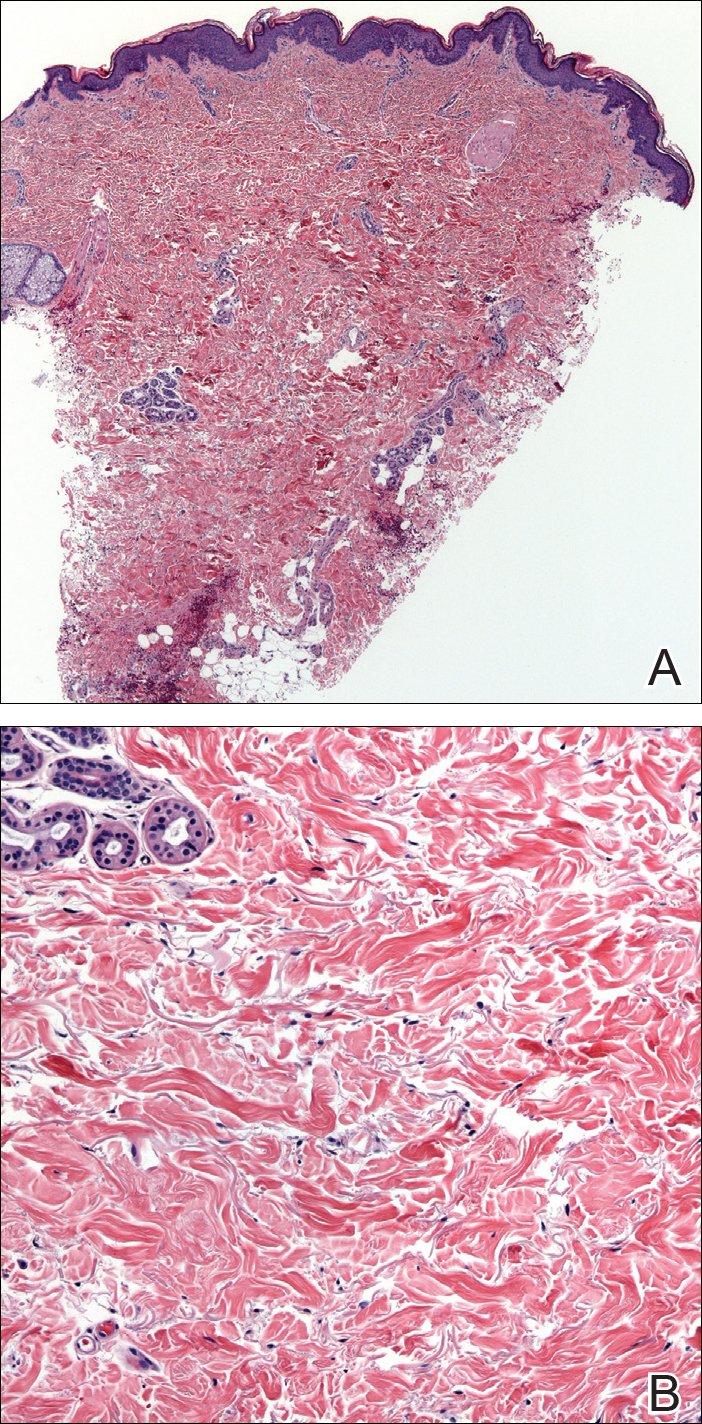

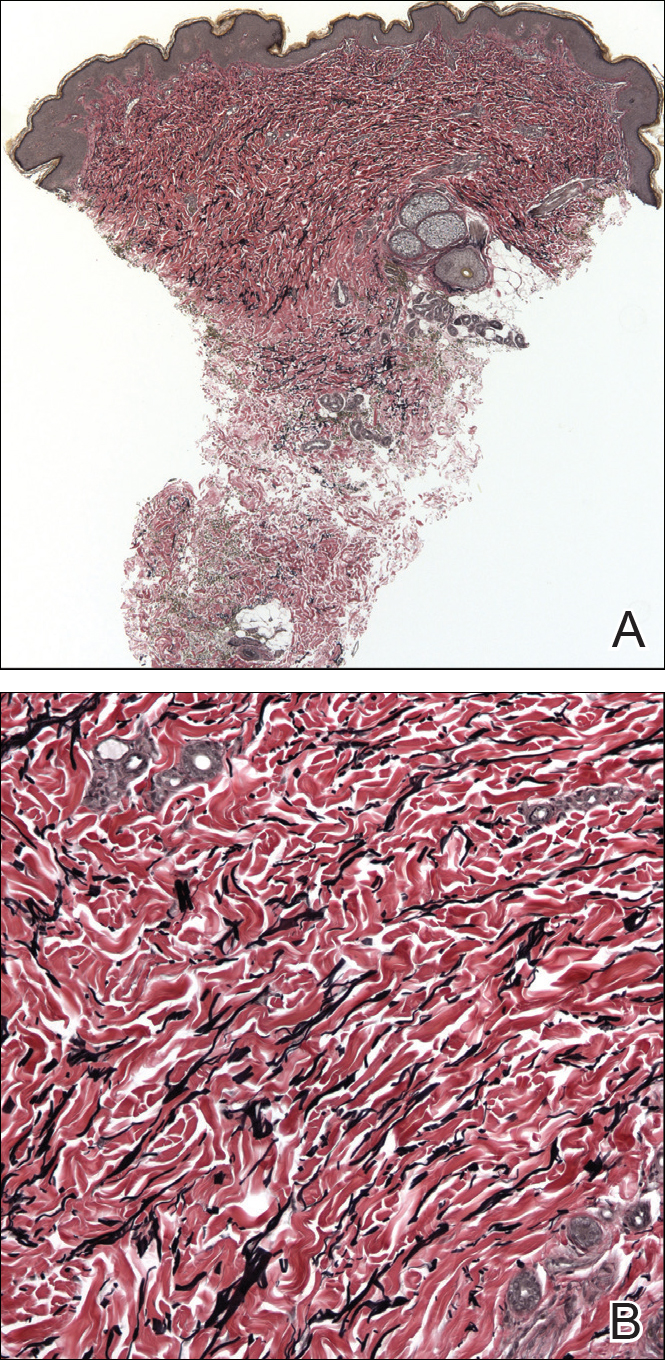

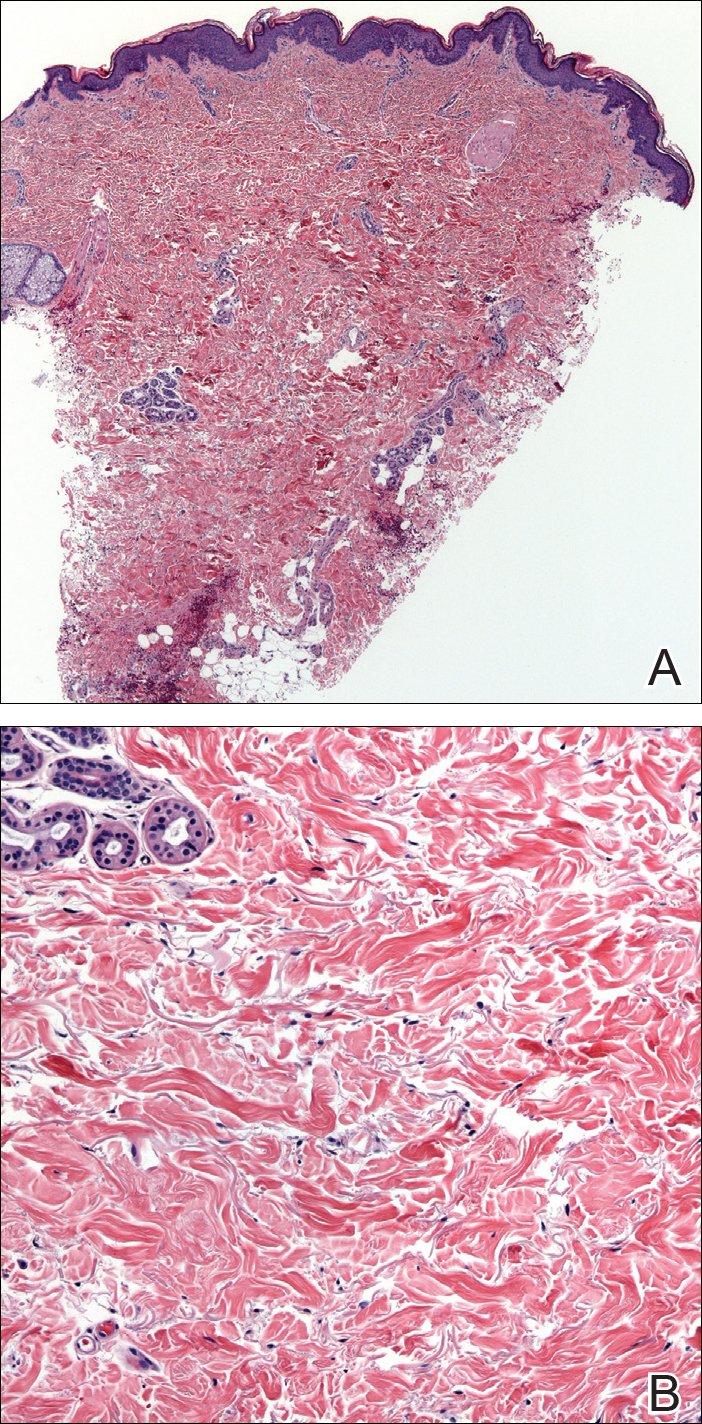

The etiology of TFFD is not well understood and is considered a retention hyperkeratosis. Duncan et al1 postulated that TFFD is the result of partial or improper maturation of keratinocytes leading to keratinocyte and melanin retention. Hematoxylin and eosin stains demonstrate lamellar hyperkeratosis of the stratum corneum without parakeratosis as well as keratin pearls scattered throughout. Mild acanthosis and papillomatosis also have been reported.1,5-7 Fontana-Masson stain shows excess melanin in these lesions, extending from the basal layer to the stratum corneum. Fungal and bacterial stains as well as cultures often have no notable findings.1,7 Similarly, histopathologic examination of our patient's biopsy with hematoxylin and eosin stain revealed hyperorthokeratosis with scattered naked vellus hair shafts and incidental yeast forms (Figure 1).

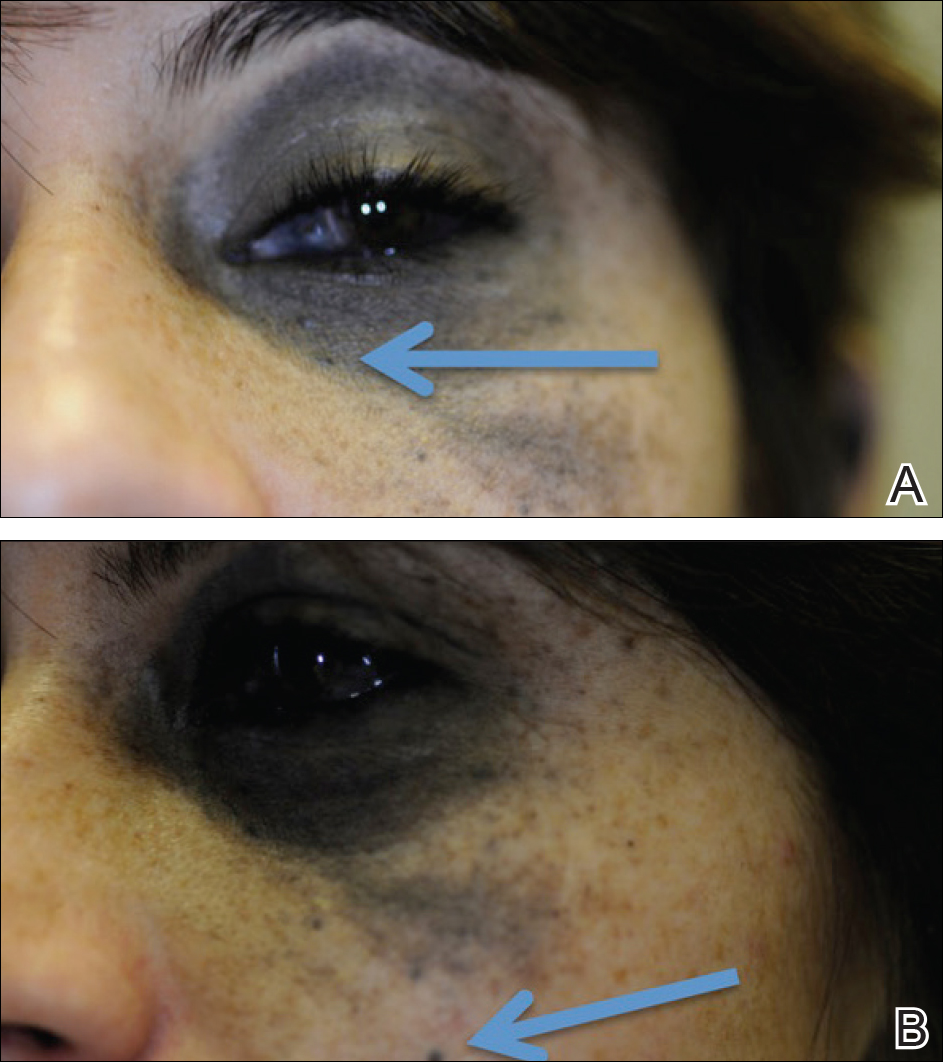

The differential diagnosis for TFFD may include pityriasis versicolor, confluent and reticulated papillomatosis, acanthosis nigricans, ichthyosis, malignant melanoma, and seborrheic keratosis. All of these diagnoses can be ruled out by the easy removal of the lesions with isopropyl alcohol 70%, which was performed on our patient by scrubbing the lesions with soaked gauze (Figure 2). Indeed, removal with isopropyl alcohol 70% is both the therapeutic and diagnostic procedure for TFFD.1-8 Of note, dermatitis neglecta is histologically and clinically identical to TFFD, albeit with a history of uncleanly habits or exposure to dirty environments.

The diagnosis of TFFD often is discovered incidentally as physicians wipe the area with alcohol to prepare for biopsy.1 Occasionally, vigorous scrubbing is needed to completely remove the lesions, and without this effort the lesions may be easily mistaken for another cutaneous process.3 Failure to consider TFFD as a diagnosis has led to unnecessary endocrine workups and invasive biopsies.4 Therefore, physicians should have early clinical suspicion of TFFD and be aware of the bedside diagnostic procedure using isopropyl alcohol.

- Duncan WC, Tschen JA, Knox JM. Terra firma-forme dermatosis. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:567-569.

- Greywal T, Cohen PR. Terra firma-forme dermatosis: a report of ten individuals with Duncan's dirty dermatosis and literature review. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2015;5:29-33.

- Moon J, Kim MW, Yoon HS, et al. A case of terra firma-forme dermatosis: differentiation from other dirty-appearing diseases. Ann Dermatol. 2016;28:413-415.

- Berk DR. Terra firma-forme dermatosis: a retrospective review of 31 patients. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:297-300.

- Akkash L, Badran D, Al-Omari AQ. Terra firma forme dermatosis. case series and review of the literature. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2009;7:102-107.

- Ashique KT, Kaliyadan F, Goyal T. Terra firma-forme dermatosis: report of a series of 11 cases and a brief review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:769-774.

- Chun SW, Lee SY, Kim JB, et al. A case of terra firma-forme dermatosis treated with salicylic acid alcohol peeling. Ann Dermatol. 2017;29:83-85.

- Aslan NC, Guler S, Demirci K, et al. Features of terra firma-forme dermatosis. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16:52-54.

The Diagnosis: Terra Firma-Forme Dermatosis

Terra firma-forme dermatosis (TFFD), also known as Duncan dirty dermatosis, is an idiopathic benign cutaneous condition that is easily misdiagnosed or mismanaged. In 1987, Duncan et al1 first described the condition in children who had mothers that lamented over dirty skin spots that could not be washed off. The term terra firma translates in Latin to solid ground, which describes the characteristic dirtlike appearance of these lesions.

Terra firma-forme dermatosis most commonly affects children and young adults, though it can present in patients of any age without any known predisposing risk factors.1-4 The lesions have a predilection for the face, neck, shoulders, trunk, and ankles. Terra firma-forme dermatosis has no association with bathing and hygiene habits, and most patients describe unsuccessful removal of the lesions, even after vigorous scrubbing with soaps and detergents at home. The lesions are asymptomatic, and many patients present to dermatology for cosmetic concerns.1-8

The etiology of TFFD is not well understood and is considered a retention hyperkeratosis. Duncan et al1 postulated that TFFD is the result of partial or improper maturation of keratinocytes leading to keratinocyte and melanin retention. Hematoxylin and eosin stains demonstrate lamellar hyperkeratosis of the stratum corneum without parakeratosis as well as keratin pearls scattered throughout. Mild acanthosis and papillomatosis also have been reported.1,5-7 Fontana-Masson stain shows excess melanin in these lesions, extending from the basal layer to the stratum corneum. Fungal and bacterial stains as well as cultures often have no notable findings.1,7 Similarly, histopathologic examination of our patient's biopsy with hematoxylin and eosin stain revealed hyperorthokeratosis with scattered naked vellus hair shafts and incidental yeast forms (Figure 1).

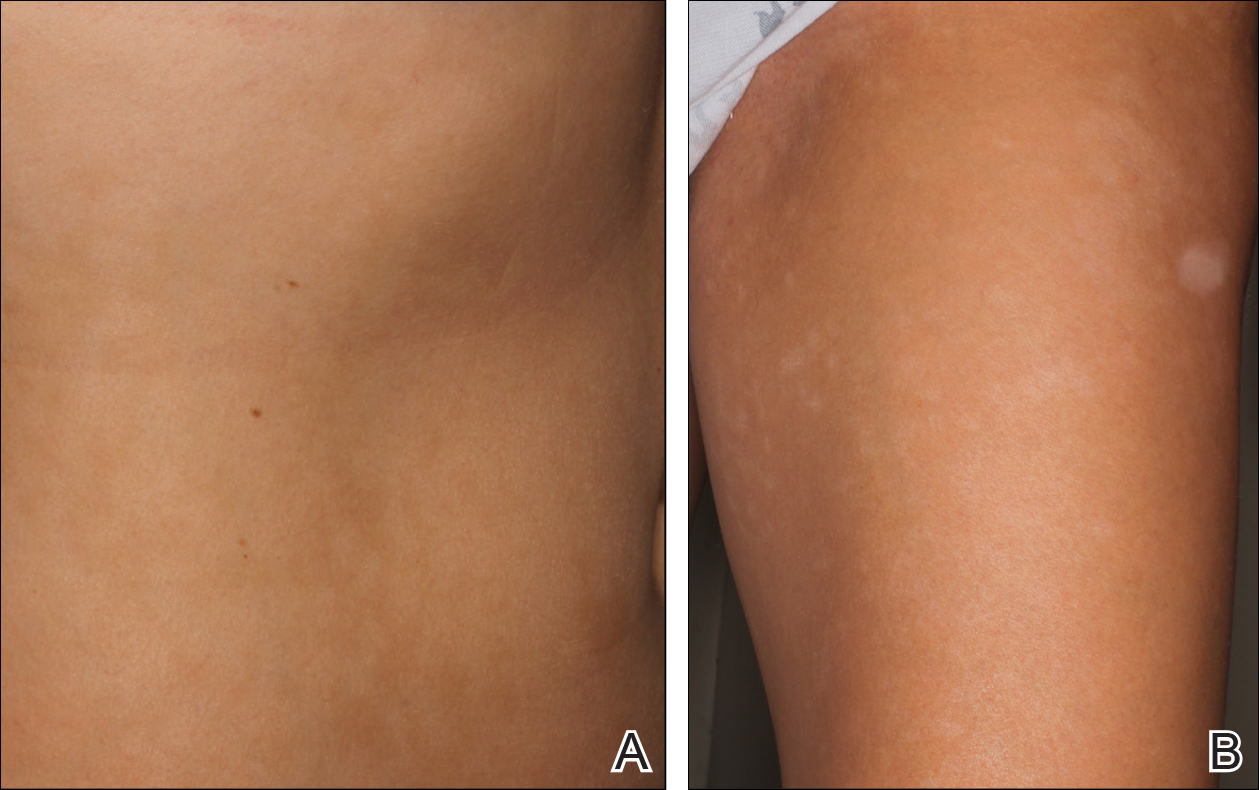

The differential diagnosis for TFFD may include pityriasis versicolor, confluent and reticulated papillomatosis, acanthosis nigricans, ichthyosis, malignant melanoma, and seborrheic keratosis. All of these diagnoses can be ruled out by the easy removal of the lesions with isopropyl alcohol 70%, which was performed on our patient by scrubbing the lesions with soaked gauze (Figure 2). Indeed, removal with isopropyl alcohol 70% is both the therapeutic and diagnostic procedure for TFFD.1-8 Of note, dermatitis neglecta is histologically and clinically identical to TFFD, albeit with a history of uncleanly habits or exposure to dirty environments.

The diagnosis of TFFD often is discovered incidentally as physicians wipe the area with alcohol to prepare for biopsy.1 Occasionally, vigorous scrubbing is needed to completely remove the lesions, and without this effort the lesions may be easily mistaken for another cutaneous process.3 Failure to consider TFFD as a diagnosis has led to unnecessary endocrine workups and invasive biopsies.4 Therefore, physicians should have early clinical suspicion of TFFD and be aware of the bedside diagnostic procedure using isopropyl alcohol.

The Diagnosis: Terra Firma-Forme Dermatosis

Terra firma-forme dermatosis (TFFD), also known as Duncan dirty dermatosis, is an idiopathic benign cutaneous condition that is easily misdiagnosed or mismanaged. In 1987, Duncan et al1 first described the condition in children who had mothers that lamented over dirty skin spots that could not be washed off. The term terra firma translates in Latin to solid ground, which describes the characteristic dirtlike appearance of these lesions.

Terra firma-forme dermatosis most commonly affects children and young adults, though it can present in patients of any age without any known predisposing risk factors.1-4 The lesions have a predilection for the face, neck, shoulders, trunk, and ankles. Terra firma-forme dermatosis has no association with bathing and hygiene habits, and most patients describe unsuccessful removal of the lesions, even after vigorous scrubbing with soaps and detergents at home. The lesions are asymptomatic, and many patients present to dermatology for cosmetic concerns.1-8

The etiology of TFFD is not well understood and is considered a retention hyperkeratosis. Duncan et al1 postulated that TFFD is the result of partial or improper maturation of keratinocytes leading to keratinocyte and melanin retention. Hematoxylin and eosin stains demonstrate lamellar hyperkeratosis of the stratum corneum without parakeratosis as well as keratin pearls scattered throughout. Mild acanthosis and papillomatosis also have been reported.1,5-7 Fontana-Masson stain shows excess melanin in these lesions, extending from the basal layer to the stratum corneum. Fungal and bacterial stains as well as cultures often have no notable findings.1,7 Similarly, histopathologic examination of our patient's biopsy with hematoxylin and eosin stain revealed hyperorthokeratosis with scattered naked vellus hair shafts and incidental yeast forms (Figure 1).

The differential diagnosis for TFFD may include pityriasis versicolor, confluent and reticulated papillomatosis, acanthosis nigricans, ichthyosis, malignant melanoma, and seborrheic keratosis. All of these diagnoses can be ruled out by the easy removal of the lesions with isopropyl alcohol 70%, which was performed on our patient by scrubbing the lesions with soaked gauze (Figure 2). Indeed, removal with isopropyl alcohol 70% is both the therapeutic and diagnostic procedure for TFFD.1-8 Of note, dermatitis neglecta is histologically and clinically identical to TFFD, albeit with a history of uncleanly habits or exposure to dirty environments.

The diagnosis of TFFD often is discovered incidentally as physicians wipe the area with alcohol to prepare for biopsy.1 Occasionally, vigorous scrubbing is needed to completely remove the lesions, and without this effort the lesions may be easily mistaken for another cutaneous process.3 Failure to consider TFFD as a diagnosis has led to unnecessary endocrine workups and invasive biopsies.4 Therefore, physicians should have early clinical suspicion of TFFD and be aware of the bedside diagnostic procedure using isopropyl alcohol.

- Duncan WC, Tschen JA, Knox JM. Terra firma-forme dermatosis. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:567-569.

- Greywal T, Cohen PR. Terra firma-forme dermatosis: a report of ten individuals with Duncan's dirty dermatosis and literature review. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2015;5:29-33.

- Moon J, Kim MW, Yoon HS, et al. A case of terra firma-forme dermatosis: differentiation from other dirty-appearing diseases. Ann Dermatol. 2016;28:413-415.

- Berk DR. Terra firma-forme dermatosis: a retrospective review of 31 patients. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:297-300.

- Akkash L, Badran D, Al-Omari AQ. Terra firma forme dermatosis. case series and review of the literature. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2009;7:102-107.

- Ashique KT, Kaliyadan F, Goyal T. Terra firma-forme dermatosis: report of a series of 11 cases and a brief review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:769-774.

- Chun SW, Lee SY, Kim JB, et al. A case of terra firma-forme dermatosis treated with salicylic acid alcohol peeling. Ann Dermatol. 2017;29:83-85.

- Aslan NC, Guler S, Demirci K, et al. Features of terra firma-forme dermatosis. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16:52-54.

- Duncan WC, Tschen JA, Knox JM. Terra firma-forme dermatosis. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:567-569.

- Greywal T, Cohen PR. Terra firma-forme dermatosis: a report of ten individuals with Duncan's dirty dermatosis and literature review. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2015;5:29-33.

- Moon J, Kim MW, Yoon HS, et al. A case of terra firma-forme dermatosis: differentiation from other dirty-appearing diseases. Ann Dermatol. 2016;28:413-415.

- Berk DR. Terra firma-forme dermatosis: a retrospective review of 31 patients. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:297-300.

- Akkash L, Badran D, Al-Omari AQ. Terra firma forme dermatosis. case series and review of the literature. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2009;7:102-107.

- Ashique KT, Kaliyadan F, Goyal T. Terra firma-forme dermatosis: report of a series of 11 cases and a brief review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:769-774.

- Chun SW, Lee SY, Kim JB, et al. A case of terra firma-forme dermatosis treated with salicylic acid alcohol peeling. Ann Dermatol. 2017;29:83-85.

- Aslan NC, Guler S, Demirci K, et al. Features of terra firma-forme dermatosis. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16:52-54.

A 94-year-old woman was referred to the dermatology department for biopsy of pigmented tumors behind the ears of unknown duration. The growths were asymptomatic. Her medical history included the early stages of Alzheimer disease. On physical examination dark brown, smooth, coalescing papules and plaques were noted extending from the posterior neck to the conchal bowls and ear folds bilaterally. The nodules were removed by scrubbing with isopropyl alcohol 70%. A nodule was submitted for histopathologic review.

Is Vitiligo in Vogue? The Changing Face of Vitiligo

Vitiligo is a disfiguring skin condition that is thought to result from autoimmune destruction of melanocytes in the skin, leading to patchy depigmentation. The prevalence of vitiligo is estimated at 1% worldwide.1 Once seen as merely a cosmetic disorder, it is increasingly recognized for its devastating psychological effects. As skin quality, texture, and color are a few of the first things people notice about others, skin plays a major role in our daily interactions with the world. Vitiligo often affects the face and other visible areas of the body; thus, it is associated with impaired quality of life, and affected individuals often experience psychosocial impairment including anxiety, depression, stigmatization, and self-harm ideation.2 Indeed, vitiligo is a condition with not only a visible skin component but a deeper psychological component that also is important to recognize and address. However, due in large part to recent exposure to vitiligo through mainstream media, general understanding about and attitudes toward this condition are changing. As a result, vitiligo has seen a surge in outreach by those affected by the disease.

Perhaps the most well-known current face of vitiligo is Chantelle Brown-Young, a black fashion model, activist, and vitiligo spokesperson known professionally as Winnie Harlow. Diagnosed with vitiligo in childhood, she revealed she was teased and bullied and at one point contemplated suicide. “The continuous harassment and the despair that [vitiligo] brought on my life was so unbearably dehumanizing that I wanted to kill myself,” she disclosed.3 After competing on America’s Next Top Model in 2014, Winnie Harlow became a household name for redefining global standards of beauty and, in her own words, accepting the differences that make us unique and authentic.4 She went on to speak at the Dove Self-Esteem Project panel at the 2015 Women in the World London Summit and was presented with the Role Model award at the Portuguese GQ Men of the Year event that same year.5

More recently, Amy Deanna, a model with vitiligo, was featured in videos for CoverGirl’s 2018 “I Am What I Make Up” campaign in which she is shown enhancing her various skin tones rather than hiding them by applying both light and dark shades of makeup on her face. In a press release she stated, “Vitiligo awareness is something that is very important to me. Being given a platform to [raise awareness] means so much.”6

Additionally, Brock Elbank, a London-based photographer, recently launched a photograph series of men and women with vitiligo on the digital platform Instagram.7 In a recent interview he stated, “I see beauty in what many see as different. Unique individuals who stand out from the crowd are what inspire me to do what I do.”7

Lee Thomas, a television broadcaster and author of the book Turning White: A Memoir of Change is yet another example of a vitiligo patient who recently stopped hiding his condition. He admitted he has had people refuse to shake his hand due to his condition but has used the experience to educate others. He stated, “Because I’m in this position, I think this is where my next thing is supposed to be. It’s supposed to be about sharing and helping, and hopefully leaving the planet a little better for everybody else who comes along with vitiligo.”8 Thomas is dedicated to inspiring others with the condition and started the Clarity Lee Thomas Foundation to provide emotional and mental support to those with vitiligo.

Critics may say this vitiligo movement is merely another example of exploitation of what is unique or different by mainstream media and the fashion industry, similar to prior movements for plus-sized models, natural hairstyles in black women, and transgender identification. Even if partially true, the ultimate effect has been an increase in attention and representation of individuals with vitiligo in mainstream media. At the time this article was being published (September 2018), an Instagram search for #vitiligo yielded approximately 226,000 posts. For comparison with other much more common dermatologic conditions, #eczema returned approximately 958,000 results, #moles returned approximately 65,000 results, and #skincancer returned approximately 104,000 results. Additionally, the Vitiligo Research Foundation currently has more than 5000 followers on Instagram, which is as many as the Melanoma Research Foundation and almost twice as many as the Skin Cancer Foundation, supporting the idea that mainstream representation of individuals with vitiligo is contributing to raising awareness and backing of organizations aimed at making advancements in this area of dermatology.

As more individuals gain an understanding and curiosity about this disease, perhaps more research and investigation will be done to improve treatment options and outcomes for patients with vitiligo. With this movement, perhaps vitiligo patients will feel more comfortable and confident in their skin.

- Ezzedine K, Eleftheriadou V, Whitton M, et al. Vitiligo. Lancet. 2015;386:74-84.

- Tomas‐Aragones L, Marron SE. Body image and body dysmorphic concerns. Acta Derm Venereol. 2016;96:47-50.

- Rodney D. From suicide thoughts to finalist in America’s Next Top Model. The Gleaner. February 25, 2014. http://jamaica-gleaner.com/gleaner/20140225/news/news1.html. Accessed September 7, 2018.

- Keyes-Bevan B. Winnie Harlow: her emotional story with vitiligo. Personal Health News website. http://www.personalhealthnews.ca/prevention-and-treatment/her-emotional-story-with-vitiligo. Accessed September 7, 2018.

- Giles K, Davidson R. ‘I think I’m beautiful’: model Winnie Harlow, who suffers from rare vitiligo skin condition, gives empowering talk at Women in the World event. Daily Mail. October 9, 2015. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/tvshowbiz/article-3266579/I-think-m-beautiful-Model-Winnie-Harlow-suffers-rare-Vitiligo-skin-condition-gives-empowering-talk-Women-World-event.html. Updated October 13, 2015. Accessed September 7, 2018.

- Ruffo J. CoverGirl’s first model with vitiligo stars in new campaign: ‘w

e have to be more inclusive.’ People. February 20, 2018. https://people.com/style/covergirl-first-model-with-vitiligo-interview/. Accessed September 25, 2018. - Blair O. This vitiligo photo series is absolutely breathtaking. Cosmopolitan. March 23, 2018. https://www.cosmopolitan.com/uk/beauty-hair/a19494259/vitiligo-photo-series-instagram/. Accessed September 7, 2018.

- Broadcaster opens up about living with vitiligo. People. February 20, 2018. http://people.com/health/lee-thomas-tv-reporter-on-his-vitiligo/. Accessed April 1, 2018.

Vitiligo is a disfiguring skin condition that is thought to result from autoimmune destruction of melanocytes in the skin, leading to patchy depigmentation. The prevalence of vitiligo is estimated at 1% worldwide.1 Once seen as merely a cosmetic disorder, it is increasingly recognized for its devastating psychological effects. As skin quality, texture, and color are a few of the first things people notice about others, skin plays a major role in our daily interactions with the world. Vitiligo often affects the face and other visible areas of the body; thus, it is associated with impaired quality of life, and affected individuals often experience psychosocial impairment including anxiety, depression, stigmatization, and self-harm ideation.2 Indeed, vitiligo is a condition with not only a visible skin component but a deeper psychological component that also is important to recognize and address. However, due in large part to recent exposure to vitiligo through mainstream media, general understanding about and attitudes toward this condition are changing. As a result, vitiligo has seen a surge in outreach by those affected by the disease.

Perhaps the most well-known current face of vitiligo is Chantelle Brown-Young, a black fashion model, activist, and vitiligo spokesperson known professionally as Winnie Harlow. Diagnosed with vitiligo in childhood, she revealed she was teased and bullied and at one point contemplated suicide. “The continuous harassment and the despair that [vitiligo] brought on my life was so unbearably dehumanizing that I wanted to kill myself,” she disclosed.3 After competing on America’s Next Top Model in 2014, Winnie Harlow became a household name for redefining global standards of beauty and, in her own words, accepting the differences that make us unique and authentic.4 She went on to speak at the Dove Self-Esteem Project panel at the 2015 Women in the World London Summit and was presented with the Role Model award at the Portuguese GQ Men of the Year event that same year.5

More recently, Amy Deanna, a model with vitiligo, was featured in videos for CoverGirl’s 2018 “I Am What I Make Up” campaign in which she is shown enhancing her various skin tones rather than hiding them by applying both light and dark shades of makeup on her face. In a press release she stated, “Vitiligo awareness is something that is very important to me. Being given a platform to [raise awareness] means so much.”6

Additionally, Brock Elbank, a London-based photographer, recently launched a photograph series of men and women with vitiligo on the digital platform Instagram.7 In a recent interview he stated, “I see beauty in what many see as different. Unique individuals who stand out from the crowd are what inspire me to do what I do.”7

Lee Thomas, a television broadcaster and author of the book Turning White: A Memoir of Change is yet another example of a vitiligo patient who recently stopped hiding his condition. He admitted he has had people refuse to shake his hand due to his condition but has used the experience to educate others. He stated, “Because I’m in this position, I think this is where my next thing is supposed to be. It’s supposed to be about sharing and helping, and hopefully leaving the planet a little better for everybody else who comes along with vitiligo.”8 Thomas is dedicated to inspiring others with the condition and started the Clarity Lee Thomas Foundation to provide emotional and mental support to those with vitiligo.

Critics may say this vitiligo movement is merely another example of exploitation of what is unique or different by mainstream media and the fashion industry, similar to prior movements for plus-sized models, natural hairstyles in black women, and transgender identification. Even if partially true, the ultimate effect has been an increase in attention and representation of individuals with vitiligo in mainstream media. At the time this article was being published (September 2018), an Instagram search for #vitiligo yielded approximately 226,000 posts. For comparison with other much more common dermatologic conditions, #eczema returned approximately 958,000 results, #moles returned approximately 65,000 results, and #skincancer returned approximately 104,000 results. Additionally, the Vitiligo Research Foundation currently has more than 5000 followers on Instagram, which is as many as the Melanoma Research Foundation and almost twice as many as the Skin Cancer Foundation, supporting the idea that mainstream representation of individuals with vitiligo is contributing to raising awareness and backing of organizations aimed at making advancements in this area of dermatology.

As more individuals gain an understanding and curiosity about this disease, perhaps more research and investigation will be done to improve treatment options and outcomes for patients with vitiligo. With this movement, perhaps vitiligo patients will feel more comfortable and confident in their skin.

Vitiligo is a disfiguring skin condition that is thought to result from autoimmune destruction of melanocytes in the skin, leading to patchy depigmentation. The prevalence of vitiligo is estimated at 1% worldwide.1 Once seen as merely a cosmetic disorder, it is increasingly recognized for its devastating psychological effects. As skin quality, texture, and color are a few of the first things people notice about others, skin plays a major role in our daily interactions with the world. Vitiligo often affects the face and other visible areas of the body; thus, it is associated with impaired quality of life, and affected individuals often experience psychosocial impairment including anxiety, depression, stigmatization, and self-harm ideation.2 Indeed, vitiligo is a condition with not only a visible skin component but a deeper psychological component that also is important to recognize and address. However, due in large part to recent exposure to vitiligo through mainstream media, general understanding about and attitudes toward this condition are changing. As a result, vitiligo has seen a surge in outreach by those affected by the disease.

Perhaps the most well-known current face of vitiligo is Chantelle Brown-Young, a black fashion model, activist, and vitiligo spokesperson known professionally as Winnie Harlow. Diagnosed with vitiligo in childhood, she revealed she was teased and bullied and at one point contemplated suicide. “The continuous harassment and the despair that [vitiligo] brought on my life was so unbearably dehumanizing that I wanted to kill myself,” she disclosed.3 After competing on America’s Next Top Model in 2014, Winnie Harlow became a household name for redefining global standards of beauty and, in her own words, accepting the differences that make us unique and authentic.4 She went on to speak at the Dove Self-Esteem Project panel at the 2015 Women in the World London Summit and was presented with the Role Model award at the Portuguese GQ Men of the Year event that same year.5

More recently, Amy Deanna, a model with vitiligo, was featured in videos for CoverGirl’s 2018 “I Am What I Make Up” campaign in which she is shown enhancing her various skin tones rather than hiding them by applying both light and dark shades of makeup on her face. In a press release she stated, “Vitiligo awareness is something that is very important to me. Being given a platform to [raise awareness] means so much.”6

Additionally, Brock Elbank, a London-based photographer, recently launched a photograph series of men and women with vitiligo on the digital platform Instagram.7 In a recent interview he stated, “I see beauty in what many see as different. Unique individuals who stand out from the crowd are what inspire me to do what I do.”7

Lee Thomas, a television broadcaster and author of the book Turning White: A Memoir of Change is yet another example of a vitiligo patient who recently stopped hiding his condition. He admitted he has had people refuse to shake his hand due to his condition but has used the experience to educate others. He stated, “Because I’m in this position, I think this is where my next thing is supposed to be. It’s supposed to be about sharing and helping, and hopefully leaving the planet a little better for everybody else who comes along with vitiligo.”8 Thomas is dedicated to inspiring others with the condition and started the Clarity Lee Thomas Foundation to provide emotional and mental support to those with vitiligo.

Critics may say this vitiligo movement is merely another example of exploitation of what is unique or different by mainstream media and the fashion industry, similar to prior movements for plus-sized models, natural hairstyles in black women, and transgender identification. Even if partially true, the ultimate effect has been an increase in attention and representation of individuals with vitiligo in mainstream media. At the time this article was being published (September 2018), an Instagram search for #vitiligo yielded approximately 226,000 posts. For comparison with other much more common dermatologic conditions, #eczema returned approximately 958,000 results, #moles returned approximately 65,000 results, and #skincancer returned approximately 104,000 results. Additionally, the Vitiligo Research Foundation currently has more than 5000 followers on Instagram, which is as many as the Melanoma Research Foundation and almost twice as many as the Skin Cancer Foundation, supporting the idea that mainstream representation of individuals with vitiligo is contributing to raising awareness and backing of organizations aimed at making advancements in this area of dermatology.

As more individuals gain an understanding and curiosity about this disease, perhaps more research and investigation will be done to improve treatment options and outcomes for patients with vitiligo. With this movement, perhaps vitiligo patients will feel more comfortable and confident in their skin.

- Ezzedine K, Eleftheriadou V, Whitton M, et al. Vitiligo. Lancet. 2015;386:74-84.

- Tomas‐Aragones L, Marron SE. Body image and body dysmorphic concerns. Acta Derm Venereol. 2016;96:47-50.

- Rodney D. From suicide thoughts to finalist in America’s Next Top Model. The Gleaner. February 25, 2014. http://jamaica-gleaner.com/gleaner/20140225/news/news1.html. Accessed September 7, 2018.

- Keyes-Bevan B. Winnie Harlow: her emotional story with vitiligo. Personal Health News website. http://www.personalhealthnews.ca/prevention-and-treatment/her-emotional-story-with-vitiligo. Accessed September 7, 2018.

- Giles K, Davidson R. ‘I think I’m beautiful’: model Winnie Harlow, who suffers from rare vitiligo skin condition, gives empowering talk at Women in the World event. Daily Mail. October 9, 2015. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/tvshowbiz/article-3266579/I-think-m-beautiful-Model-Winnie-Harlow-suffers-rare-Vitiligo-skin-condition-gives-empowering-talk-Women-World-event.html. Updated October 13, 2015. Accessed September 7, 2018.

- Ruffo J. CoverGirl’s first model with vitiligo stars in new campaign: ‘w

e have to be more inclusive.’ People. February 20, 2018. https://people.com/style/covergirl-first-model-with-vitiligo-interview/. Accessed September 25, 2018. - Blair O. This vitiligo photo series is absolutely breathtaking. Cosmopolitan. March 23, 2018. https://www.cosmopolitan.com/uk/beauty-hair/a19494259/vitiligo-photo-series-instagram/. Accessed September 7, 2018.

- Broadcaster opens up about living with vitiligo. People. February 20, 2018. http://people.com/health/lee-thomas-tv-reporter-on-his-vitiligo/. Accessed April 1, 2018.

- Ezzedine K, Eleftheriadou V, Whitton M, et al. Vitiligo. Lancet. 2015;386:74-84.

- Tomas‐Aragones L, Marron SE. Body image and body dysmorphic concerns. Acta Derm Venereol. 2016;96:47-50.

- Rodney D. From suicide thoughts to finalist in America’s Next Top Model. The Gleaner. February 25, 2014. http://jamaica-gleaner.com/gleaner/20140225/news/news1.html. Accessed September 7, 2018.

- Keyes-Bevan B. Winnie Harlow: her emotional story with vitiligo. Personal Health News website. http://www.personalhealthnews.ca/prevention-and-treatment/her-emotional-story-with-vitiligo. Accessed September 7, 2018.

- Giles K, Davidson R. ‘I think I’m beautiful’: model Winnie Harlow, who suffers from rare vitiligo skin condition, gives empowering talk at Women in the World event. Daily Mail. October 9, 2015. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/tvshowbiz/article-3266579/I-think-m-beautiful-Model-Winnie-Harlow-suffers-rare-Vitiligo-skin-condition-gives-empowering-talk-Women-World-event.html. Updated October 13, 2015. Accessed September 7, 2018.

- Ruffo J. CoverGirl’s first model with vitiligo stars in new campaign: ‘w

e have to be more inclusive.’ People. February 20, 2018. https://people.com/style/covergirl-first-model-with-vitiligo-interview/. Accessed September 25, 2018. - Blair O. This vitiligo photo series is absolutely breathtaking. Cosmopolitan. March 23, 2018. https://www.cosmopolitan.com/uk/beauty-hair/a19494259/vitiligo-photo-series-instagram/. Accessed September 7, 2018.

- Broadcaster opens up about living with vitiligo. People. February 20, 2018. http://people.com/health/lee-thomas-tv-reporter-on-his-vitiligo/. Accessed April 1, 2018.

Nevus of Ota Associated With a Primary Uveal Melanoma and Intracranial Melanoma Metastasis

Nevus of Ota, originally referred to as nevus fusco-caeruleus ophthalmomaxillaris, initially was described in 1939 by Ota and Tanino.1 It is a dermal melanocytic hamartoma arising from incomplete migration of neural crest melanocytes to the epidermis during embryogenesis, resulting in nesting of subtle bands of dendritic melanocytes in the upper dermis. More common in Asians, Native Americans, and females, this hyperpigmented dermatosis most often is unilaterally distributed along the ophthalmic (V1) and maxillary (V2) branches of the trigeminal nerve.2 In some patients, nevus of Ota also is associated with ocular, orbital, and leptomeningeal melanocytosis. Approximately 15% of nevi of Ota have an activating guanine nucleotide-binding protein G(q) subunit alpha (GNAQ) or G protein subunit alpha 11 (GNAQ) mutation; 85% of uveal melanomas harbor one of these mutations.3 Although uncommon, neoplastic transformation with extension or metastasis to the brain has been reported in patients with nevus of Ota.4

We report the case of a 29-year-old woman with a long-standing history of nevus of Ota who presented acutely with an intracranial melanoma as an extension of a primary uveal melanoma.

Case Report

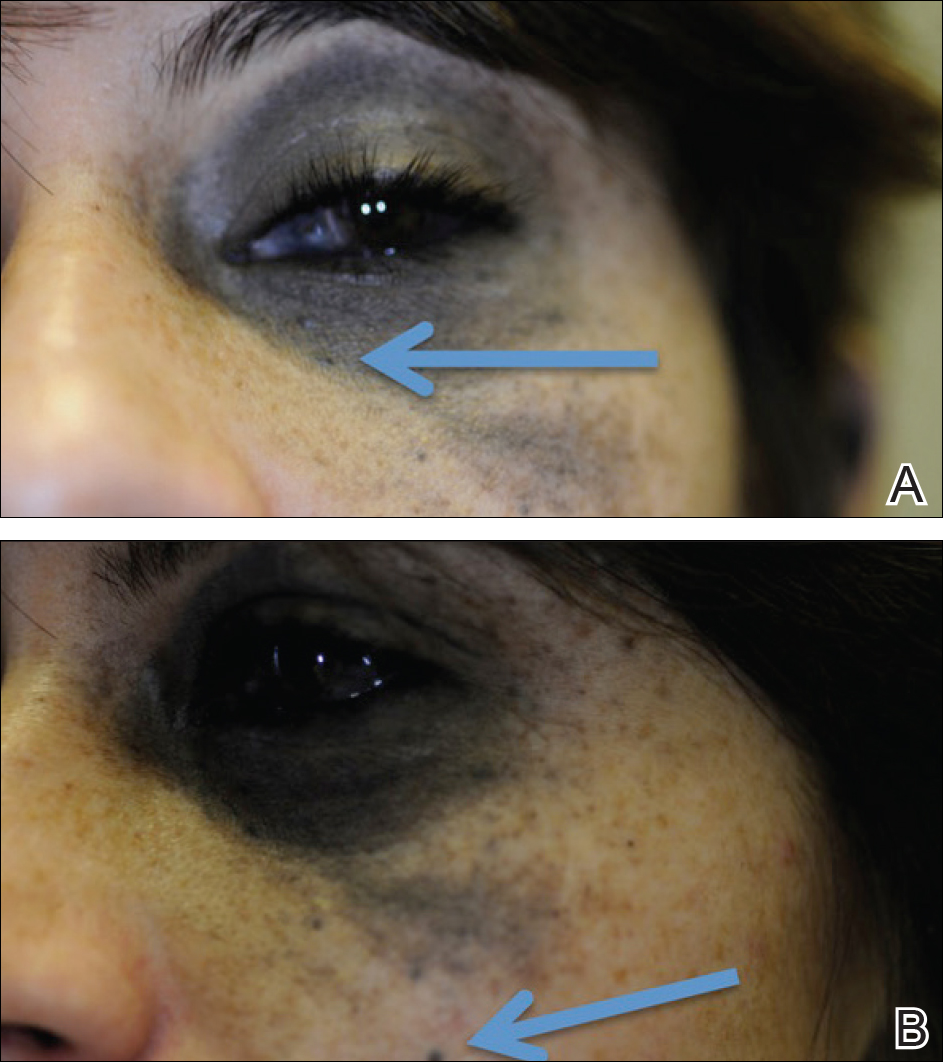

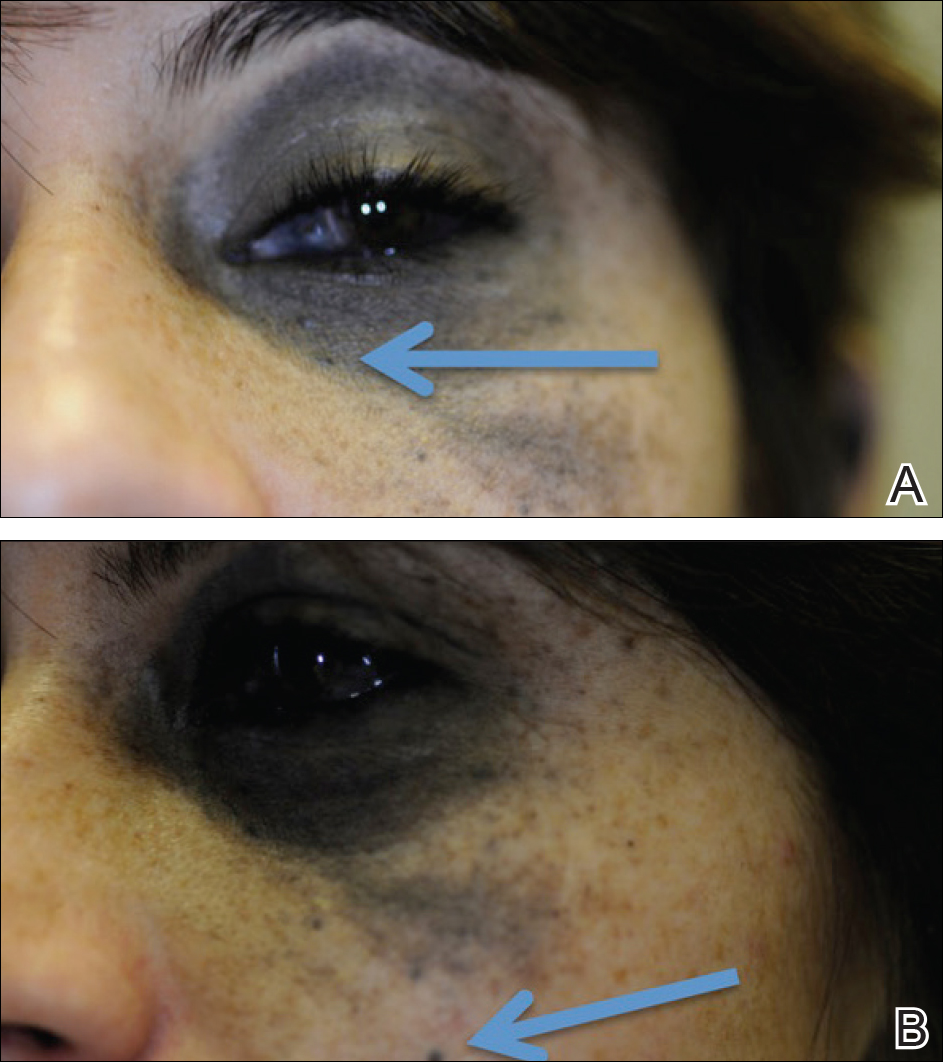

A 29-year-old woman with a history of a nevus of Ota involving the left inner canthus, eyelids, sclera, and superior malar cheek that had been present since birth presented to the emergency department with an acute onset of severe headache, blurred vision, and vomiting. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging of the brain revealed a hemorrhagic mass in the left frontal lobe. Subsequent frontal craniotomy and resection revealed an intracranial melanoma.

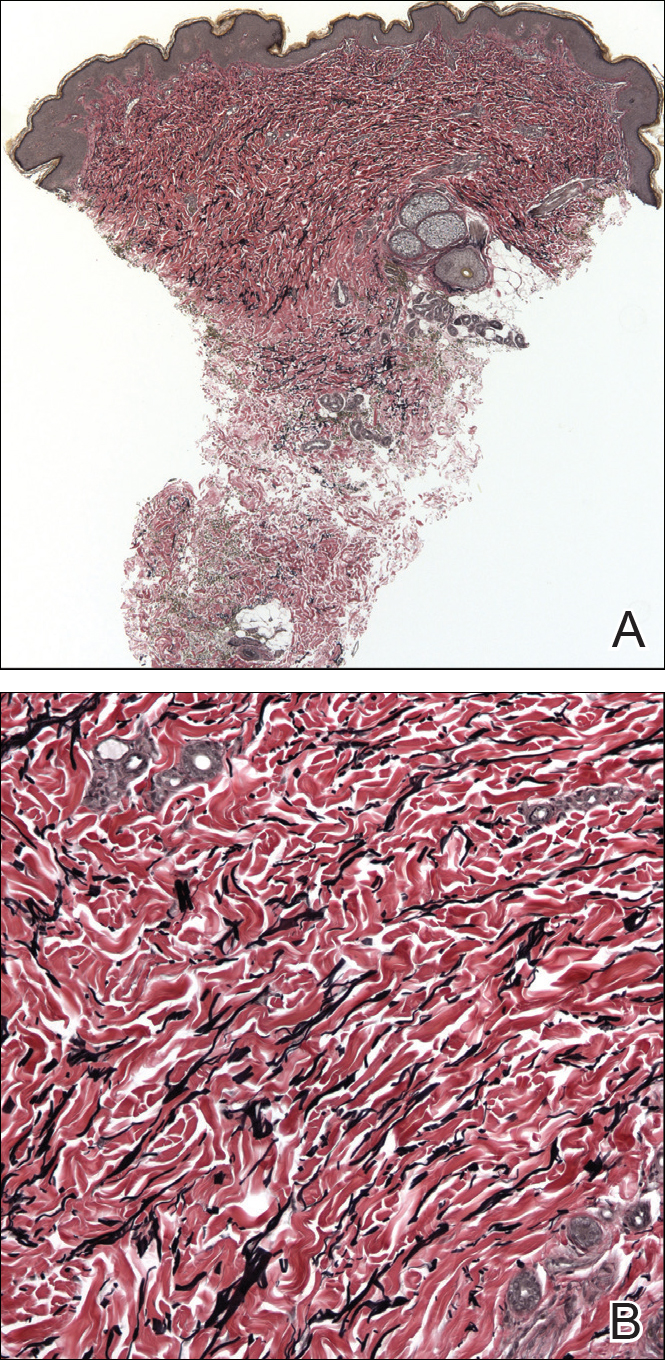

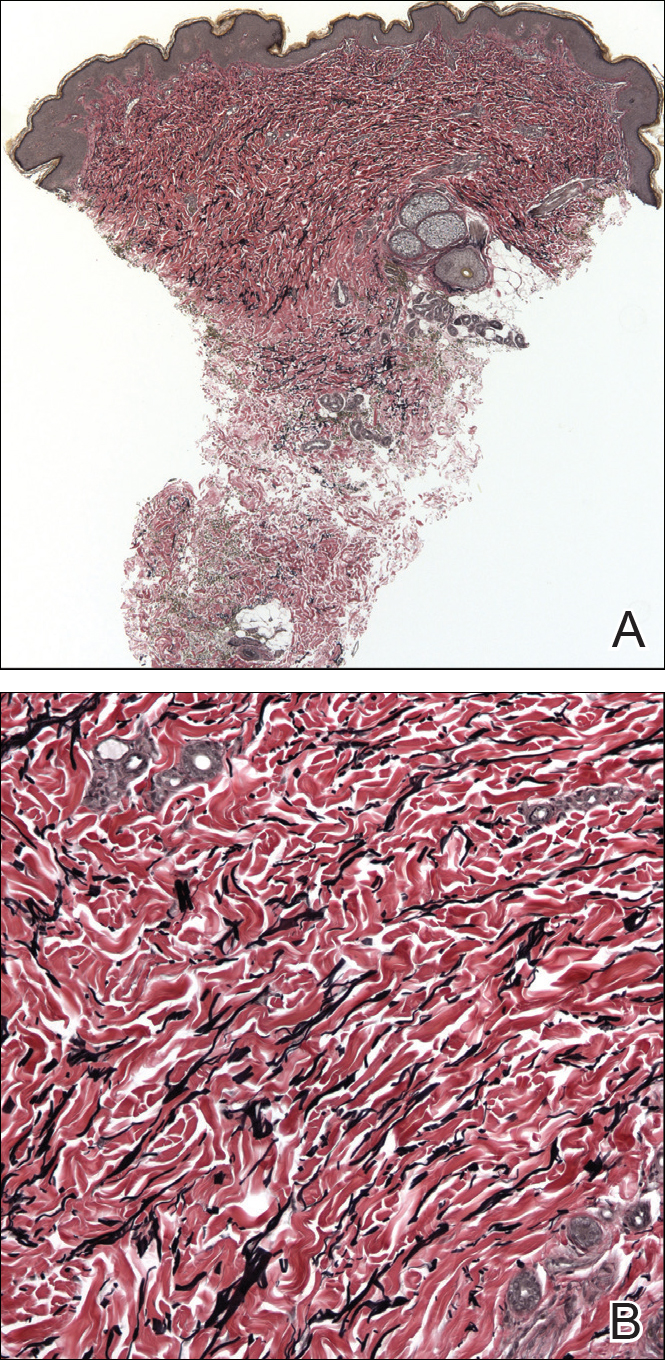

Two weeks following surgery, the patient underwent magnetic resonance imaging and combined positron emission tomography and CT scans that demonstrated a fluorodeoxyglucose-avid left retro-orbital mass. Histopathology of a biopsy from the left retro-orbital mass that had been obtained intraoperatively demonstrated a pigmented, spindled to epithelioid neoplasm with areas of marked atypia and a high mitotic rate that was compatible with malignant melanoma (Figure 1). Intracranial biopsies were sent for genetic study and were found to harbor GNAQ (Q209P) and BRCA1-associated protein 1 (BAP1)(p.P324fs*11) mutations.

The patient was referred to dermatology by neurosurgery for evaluation of a suspected primary cutaneous melanoma.

The patient entered a clinical trial at an outside institution several weeks after initial presentation to our institution for treatment with a mitogen-activated protein kinase MEK1 inhibitor as well as radiation therapy. The patient was lost to follow-up.

Comment

It has been demonstrated that homozygous loss of BAP1, located on the chromosome 3p21.1 locus, allows for progression to metastatic disease in uveal melanoma. The BAP1 gene codes for ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase 7, which is involved in the removal of ubiquitin from proteins. This enzyme binds to BRCA1 (BRCA1, DNA repair associated) via the RING (Really Interesting New Gene) finger domain and acts as a tumor suppressor.5 Biallelic BAP1 mutations allow the transition to malignancy in concert with other mutations, such as GNAQ. Identification of a BAP1 mutation may serve as a valuable diagnostic and future therapeutic target in uveal melanoma.

Currently, there are no drugs that directly target mutated GNA11 and GNAQ proteins. Because aberrant GNA11 and GNAQ proteins activate MEK1, several MEK1 inhibitors are being tested with the hope of achieving indirect suppression of GNA11/GNAQ.6

We present a rare case of BAP1 and GNAQ mutations in intracranial melanoma associated with nevus of Ota. Although the uveal melanoma was not confirmed on histopathology, the clear mention of foci within the eye by ophthalmology, positron emission tomography–CT scan showing a fluorodeoxyglucose-avid left retro-orbital mass, and genetic studies of the intracranial biopsies were highly suggestive of a primary uveal melanoma.

Our case highlights the importance of ongoing ocular screening in patients with nevus of Ota, noting the possibility of malignant transformation. Furthermore, patients with nevus of Ota with ocular involvement may benefit from testing of BAP1 protein expression by immunohistochemistry.7 Identification of BAP1 and GNAQ mutations in patients with nevus of Ota place them at markedly higher risk for malignant melanoma. Therefore, dermatologic evaluation of patients with nevus of Ota should include a thorough review of the patient’s history and skin examination as well as referral for ophthalmologic evaluation.

- Ota M, Tanino H. A variety of nevus, frequently encountered in Japan, nevus fusco-caeruleus ophthalmomaxillaris and its relationship to pigmentary changes in the eye. Tokyo Med J. 1939;63:1243-1244.

- Swann PG, Kwong E. The naevus of Ota. Clin Exp Optom. 2010;93:264-267.

- Van Raamsdonk CD, Griewank KG, Crosby MB, et al. Mutations in GNA11 in uveal melanoma [published online November 17, 2010]. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2191-2199.

- Nitta K, Kashima T, Mayuzumi H, et al. Animal-type malignancy melanoma associated with nevus of Ota in the orbit of a Japanese woman: a case report. Melanoma Res. 2014;24:286-289.

- Harbour JW, Onken MD, Roberson ED, et al. Frequent mutation of BAP1 in metastasizing uveal melanomas [published online November 4, 2010]. Science. 2010;330:1410-1413.

- Chen X, Wu Q, Tan L, et al. Combined PKC and MEK inhibition in uveal melanoma with GNAQ and GNA11 mutations. Oncogene. 2014;33:4724-4734.

- Kalirai H, Dodson A, Faqir S, et al. Lack of BAP1 protein expression in uveal melanoma is associated with increased metastatic risk and has utility in routine prognostic testing [published online July 24, 2010]. Br J Cancer. 2014;111:1373-1380.

Nevus of Ota, originally referred to as nevus fusco-caeruleus ophthalmomaxillaris, initially was described in 1939 by Ota and Tanino.1 It is a dermal melanocytic hamartoma arising from incomplete migration of neural crest melanocytes to the epidermis during embryogenesis, resulting in nesting of subtle bands of dendritic melanocytes in the upper dermis. More common in Asians, Native Americans, and females, this hyperpigmented dermatosis most often is unilaterally distributed along the ophthalmic (V1) and maxillary (V2) branches of the trigeminal nerve.2 In some patients, nevus of Ota also is associated with ocular, orbital, and leptomeningeal melanocytosis. Approximately 15% of nevi of Ota have an activating guanine nucleotide-binding protein G(q) subunit alpha (GNAQ) or G protein subunit alpha 11 (GNAQ) mutation; 85% of uveal melanomas harbor one of these mutations.3 Although uncommon, neoplastic transformation with extension or metastasis to the brain has been reported in patients with nevus of Ota.4

We report the case of a 29-year-old woman with a long-standing history of nevus of Ota who presented acutely with an intracranial melanoma as an extension of a primary uveal melanoma.

Case Report

A 29-year-old woman with a history of a nevus of Ota involving the left inner canthus, eyelids, sclera, and superior malar cheek that had been present since birth presented to the emergency department with an acute onset of severe headache, blurred vision, and vomiting. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging of the brain revealed a hemorrhagic mass in the left frontal lobe. Subsequent frontal craniotomy and resection revealed an intracranial melanoma.

Two weeks following surgery, the patient underwent magnetic resonance imaging and combined positron emission tomography and CT scans that demonstrated a fluorodeoxyglucose-avid left retro-orbital mass. Histopathology of a biopsy from the left retro-orbital mass that had been obtained intraoperatively demonstrated a pigmented, spindled to epithelioid neoplasm with areas of marked atypia and a high mitotic rate that was compatible with malignant melanoma (Figure 1). Intracranial biopsies were sent for genetic study and were found to harbor GNAQ (Q209P) and BRCA1-associated protein 1 (BAP1)(p.P324fs*11) mutations.

The patient was referred to dermatology by neurosurgery for evaluation of a suspected primary cutaneous melanoma.

The patient entered a clinical trial at an outside institution several weeks after initial presentation to our institution for treatment with a mitogen-activated protein kinase MEK1 inhibitor as well as radiation therapy. The patient was lost to follow-up.

Comment

It has been demonstrated that homozygous loss of BAP1, located on the chromosome 3p21.1 locus, allows for progression to metastatic disease in uveal melanoma. The BAP1 gene codes for ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase 7, which is involved in the removal of ubiquitin from proteins. This enzyme binds to BRCA1 (BRCA1, DNA repair associated) via the RING (Really Interesting New Gene) finger domain and acts as a tumor suppressor.5 Biallelic BAP1 mutations allow the transition to malignancy in concert with other mutations, such as GNAQ. Identification of a BAP1 mutation may serve as a valuable diagnostic and future therapeutic target in uveal melanoma.

Currently, there are no drugs that directly target mutated GNA11 and GNAQ proteins. Because aberrant GNA11 and GNAQ proteins activate MEK1, several MEK1 inhibitors are being tested with the hope of achieving indirect suppression of GNA11/GNAQ.6

We present a rare case of BAP1 and GNAQ mutations in intracranial melanoma associated with nevus of Ota. Although the uveal melanoma was not confirmed on histopathology, the clear mention of foci within the eye by ophthalmology, positron emission tomography–CT scan showing a fluorodeoxyglucose-avid left retro-orbital mass, and genetic studies of the intracranial biopsies were highly suggestive of a primary uveal melanoma.

Our case highlights the importance of ongoing ocular screening in patients with nevus of Ota, noting the possibility of malignant transformation. Furthermore, patients with nevus of Ota with ocular involvement may benefit from testing of BAP1 protein expression by immunohistochemistry.7 Identification of BAP1 and GNAQ mutations in patients with nevus of Ota place them at markedly higher risk for malignant melanoma. Therefore, dermatologic evaluation of patients with nevus of Ota should include a thorough review of the patient’s history and skin examination as well as referral for ophthalmologic evaluation.

Nevus of Ota, originally referred to as nevus fusco-caeruleus ophthalmomaxillaris, initially was described in 1939 by Ota and Tanino.1 It is a dermal melanocytic hamartoma arising from incomplete migration of neural crest melanocytes to the epidermis during embryogenesis, resulting in nesting of subtle bands of dendritic melanocytes in the upper dermis. More common in Asians, Native Americans, and females, this hyperpigmented dermatosis most often is unilaterally distributed along the ophthalmic (V1) and maxillary (V2) branches of the trigeminal nerve.2 In some patients, nevus of Ota also is associated with ocular, orbital, and leptomeningeal melanocytosis. Approximately 15% of nevi of Ota have an activating guanine nucleotide-binding protein G(q) subunit alpha (GNAQ) or G protein subunit alpha 11 (GNAQ) mutation; 85% of uveal melanomas harbor one of these mutations.3 Although uncommon, neoplastic transformation with extension or metastasis to the brain has been reported in patients with nevus of Ota.4

We report the case of a 29-year-old woman with a long-standing history of nevus of Ota who presented acutely with an intracranial melanoma as an extension of a primary uveal melanoma.

Case Report

A 29-year-old woman with a history of a nevus of Ota involving the left inner canthus, eyelids, sclera, and superior malar cheek that had been present since birth presented to the emergency department with an acute onset of severe headache, blurred vision, and vomiting. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging of the brain revealed a hemorrhagic mass in the left frontal lobe. Subsequent frontal craniotomy and resection revealed an intracranial melanoma.

Two weeks following surgery, the patient underwent magnetic resonance imaging and combined positron emission tomography and CT scans that demonstrated a fluorodeoxyglucose-avid left retro-orbital mass. Histopathology of a biopsy from the left retro-orbital mass that had been obtained intraoperatively demonstrated a pigmented, spindled to epithelioid neoplasm with areas of marked atypia and a high mitotic rate that was compatible with malignant melanoma (Figure 1). Intracranial biopsies were sent for genetic study and were found to harbor GNAQ (Q209P) and BRCA1-associated protein 1 (BAP1)(p.P324fs*11) mutations.

The patient was referred to dermatology by neurosurgery for evaluation of a suspected primary cutaneous melanoma.

The patient entered a clinical trial at an outside institution several weeks after initial presentation to our institution for treatment with a mitogen-activated protein kinase MEK1 inhibitor as well as radiation therapy. The patient was lost to follow-up.

Comment

It has been demonstrated that homozygous loss of BAP1, located on the chromosome 3p21.1 locus, allows for progression to metastatic disease in uveal melanoma. The BAP1 gene codes for ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase 7, which is involved in the removal of ubiquitin from proteins. This enzyme binds to BRCA1 (BRCA1, DNA repair associated) via the RING (Really Interesting New Gene) finger domain and acts as a tumor suppressor.5 Biallelic BAP1 mutations allow the transition to malignancy in concert with other mutations, such as GNAQ. Identification of a BAP1 mutation may serve as a valuable diagnostic and future therapeutic target in uveal melanoma.

Currently, there are no drugs that directly target mutated GNA11 and GNAQ proteins. Because aberrant GNA11 and GNAQ proteins activate MEK1, several MEK1 inhibitors are being tested with the hope of achieving indirect suppression of GNA11/GNAQ.6

We present a rare case of BAP1 and GNAQ mutations in intracranial melanoma associated with nevus of Ota. Although the uveal melanoma was not confirmed on histopathology, the clear mention of foci within the eye by ophthalmology, positron emission tomography–CT scan showing a fluorodeoxyglucose-avid left retro-orbital mass, and genetic studies of the intracranial biopsies were highly suggestive of a primary uveal melanoma.

Our case highlights the importance of ongoing ocular screening in patients with nevus of Ota, noting the possibility of malignant transformation. Furthermore, patients with nevus of Ota with ocular involvement may benefit from testing of BAP1 protein expression by immunohistochemistry.7 Identification of BAP1 and GNAQ mutations in patients with nevus of Ota place them at markedly higher risk for malignant melanoma. Therefore, dermatologic evaluation of patients with nevus of Ota should include a thorough review of the patient’s history and skin examination as well as referral for ophthalmologic evaluation.

- Ota M, Tanino H. A variety of nevus, frequently encountered in Japan, nevus fusco-caeruleus ophthalmomaxillaris and its relationship to pigmentary changes in the eye. Tokyo Med J. 1939;63:1243-1244.

- Swann PG, Kwong E. The naevus of Ota. Clin Exp Optom. 2010;93:264-267.

- Van Raamsdonk CD, Griewank KG, Crosby MB, et al. Mutations in GNA11 in uveal melanoma [published online November 17, 2010]. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2191-2199.

- Nitta K, Kashima T, Mayuzumi H, et al. Animal-type malignancy melanoma associated with nevus of Ota in the orbit of a Japanese woman: a case report. Melanoma Res. 2014;24:286-289.

- Harbour JW, Onken MD, Roberson ED, et al. Frequent mutation of BAP1 in metastasizing uveal melanomas [published online November 4, 2010]. Science. 2010;330:1410-1413.

- Chen X, Wu Q, Tan L, et al. Combined PKC and MEK inhibition in uveal melanoma with GNAQ and GNA11 mutations. Oncogene. 2014;33:4724-4734.

- Kalirai H, Dodson A, Faqir S, et al. Lack of BAP1 protein expression in uveal melanoma is associated with increased metastatic risk and has utility in routine prognostic testing [published online July 24, 2010]. Br J Cancer. 2014;111:1373-1380.

- Ota M, Tanino H. A variety of nevus, frequently encountered in Japan, nevus fusco-caeruleus ophthalmomaxillaris and its relationship to pigmentary changes in the eye. Tokyo Med J. 1939;63:1243-1244.

- Swann PG, Kwong E. The naevus of Ota. Clin Exp Optom. 2010;93:264-267.

- Van Raamsdonk CD, Griewank KG, Crosby MB, et al. Mutations in GNA11 in uveal melanoma [published online November 17, 2010]. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2191-2199.

- Nitta K, Kashima T, Mayuzumi H, et al. Animal-type malignancy melanoma associated with nevus of Ota in the orbit of a Japanese woman: a case report. Melanoma Res. 2014;24:286-289.

- Harbour JW, Onken MD, Roberson ED, et al. Frequent mutation of BAP1 in metastasizing uveal melanomas [published online November 4, 2010]. Science. 2010;330:1410-1413.

- Chen X, Wu Q, Tan L, et al. Combined PKC and MEK inhibition in uveal melanoma with GNAQ and GNA11 mutations. Oncogene. 2014;33:4724-4734.

- Kalirai H, Dodson A, Faqir S, et al. Lack of BAP1 protein expression in uveal melanoma is associated with increased metastatic risk and has utility in routine prognostic testing [published online July 24, 2010]. Br J Cancer. 2014;111:1373-1380.

Practice Points

- Nevus of Ota is a hyperpigmented dermatosis that typically is distributed along the ophthalmic (V1) and maxillary (V2) branches of the trigeminal nerve.

- GNAQ and BAP1 mutations in patients with nevus of Ota confer a greater risk for malignant melanoma and metastatic progression.

- Ongoing ophthalmologic screening is paramount in patients with nevus of Ota and may prevent devastating sequelae.

Many devices optimal for treating vascular skin lesions

SAN DIEGO – According to J. Stuart Nelson, MD, PhD,

“You’re going to be using wavelengths of light generally in the green and yellow portion of the spectrum,” Dr. Nelson, professor of surgery and biomedical engineering at the Beckman Laser Institute and Medical Clinic at the University of California, Irvine, said at the annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium. “Blue light is highly absorbed by hemoglobin but unfortunately, blue light is highly scattered by human skin, so it won’t penetrate deep enough into the dermis. So primarily, we’re targeting hemoglobin using green and yellow light sources.”

The second principle is to match the pulse width with the vessel size, while the third is to give sufficient energy to irreversibly injure vessels based on selective photothermolysis.

Next, he advised clinicians to ask themselves three questions: What is the vessel size? “The larger the vessel, the longer the thermal relaxation time,” he said. What is the vessel depth? Deeper vessels require longer wavelengths of light and larger spot sizes. What is the patient’s skin phototype? Darker skin contains more epidermal melanin and requires extra caution during treatment.

Dr. Nelson listed seven optimal devices for the treatment of vascular skin lesions: intense pulsed light (IPL) with wavelengths of 515-1,200 nm and pulse durations of 1-10 ms, pulsed green light with a wavelength of 532 nm and pulse durations of 1-50 ms, pulsed dye yellow light with wavelengths of 585-600 nm and pulse durations of 0.5-40 ms, pulsed dye plus Nd:YAG with wavelengths of 595 and 1,064 nm and pulse durations of 0.5-40 ms, alexandrite laser with a wavelength of 755 nm and pulse durations of 0.25-100 ms, diode laser with a wavelength of 940 nm and pulse durations of 5-100 ms, and the pulsed Nd:YAG laser with a wavelength of 1,064 nm and pulse durations of 0.25-100 ms.

“You can get good results with every one of these devices,” Dr. Nelson said. “What you need to do is pick one and become what R. Rox Anderson, MD, calls an ‘endpointologist,’ so you can understand the clinical endpoints. Do not use a cookbook approach by trying to memorize treatment settings.”

Pulsed dye lasers with a wavelength of 585-600 nm have been the standard of care for years, he said, and is the treatment of choice for port wine stains in infants and young children. Upsides include the ability to treat large areas quickly and the ability to use two to three separate passes. It also induces diminution in diffuse redness and telangiectasia. Drawbacks include its potential to cause purpura when short pulse durations are used, it requires several treatments, it can be painful, and it causes considerable edema and erythema.

Millisecond green lasers at a wavelength of 532 nm are also effective for treating vascular skin lesions. “The nice thing about these devices is that you can focus them down to very small spots, so you can literally trace out individual blood vessels,” Dr. Nelson said. Other upsides include the fact that it can be performed without producing purpura, only transient erythema if few areas are treated. Drawbacks are that it’s moderately painful and may cause considerable edema. It also causes significant melanin absorption so is not advised for use in tanned and darker-skinned individuals. For all patients, contact cooling must be assured.

IPL, meanwhile, “can be very useful for treating not only vascular lesions, but also concurrently pigmented lesions such as poikiloderma of Civatte,” Dr. Nelson said. Potential drawbacks to IPL therapy are that the spectrum of light emitted and the pulse duration characteristics vary between devices and multiple treatments are required.

Finally, in the millisecond domain, the pulsed alexandrite 755-nm and Nd:YAG 1,064-nm lasers “are very good when trying to target something very deep in the skin like a vein,” he said. “But when you’re using those devices, you’re coagulating a large volume of tissue, so you need to be very careful about the amount of heat that you’re generating deep in the skin.”

When consulting with patients who have rosacea or telangiectasia, Dr. Nelson tells them multiple treatments will be required. “These are chronic conditions, and they may need ongoing maintenance treatments. The nice thing about all these procedures you’re doing for rosacea and telangiectasia is that they can be combined with all of your FDA [Food and Drug Administration]-approved topical and oral treatment protocols. All of these drugs you have at your disposal to medically treat rosacea can be all used concurrently with your laser treatment. When you see a patient you need to emphasize to them: ‘I’m not treating your rosacea with the laser. I’m treating a symptom of your rosacea with the laser.’ ”

Dr. Nelson closed his presentation by offering basic principles for success, the first being do no harm. “That’s the single most important thing you want to remember. No one will get mad if the blood vessel’s still there, but they’ll get very mad if something bad happens. You also want to underpromise and overdeliver. I always tell patients it’s going to require two to four treatments. When in doubt, don’t treat or undertreat. You can always treat again.”

If you’re concerned, perform a test spot. “There’s nothing wrong with that, particularly in a patient where you’re not sure what the outcome will be,” he said. “Check for any unusual skin reaction and for potential success of the procedure. Finally, don’t treat patients who are tanned.”

Dr. Nelson reported having intellectual property rights with Syneron Candela.

SAN DIEGO – According to J. Stuart Nelson, MD, PhD,

“You’re going to be using wavelengths of light generally in the green and yellow portion of the spectrum,” Dr. Nelson, professor of surgery and biomedical engineering at the Beckman Laser Institute and Medical Clinic at the University of California, Irvine, said at the annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium. “Blue light is highly absorbed by hemoglobin but unfortunately, blue light is highly scattered by human skin, so it won’t penetrate deep enough into the dermis. So primarily, we’re targeting hemoglobin using green and yellow light sources.”

The second principle is to match the pulse width with the vessel size, while the third is to give sufficient energy to irreversibly injure vessels based on selective photothermolysis.

Next, he advised clinicians to ask themselves three questions: What is the vessel size? “The larger the vessel, the longer the thermal relaxation time,” he said. What is the vessel depth? Deeper vessels require longer wavelengths of light and larger spot sizes. What is the patient’s skin phototype? Darker skin contains more epidermal melanin and requires extra caution during treatment.

Dr. Nelson listed seven optimal devices for the treatment of vascular skin lesions: intense pulsed light (IPL) with wavelengths of 515-1,200 nm and pulse durations of 1-10 ms, pulsed green light with a wavelength of 532 nm and pulse durations of 1-50 ms, pulsed dye yellow light with wavelengths of 585-600 nm and pulse durations of 0.5-40 ms, pulsed dye plus Nd:YAG with wavelengths of 595 and 1,064 nm and pulse durations of 0.5-40 ms, alexandrite laser with a wavelength of 755 nm and pulse durations of 0.25-100 ms, diode laser with a wavelength of 940 nm and pulse durations of 5-100 ms, and the pulsed Nd:YAG laser with a wavelength of 1,064 nm and pulse durations of 0.25-100 ms.

“You can get good results with every one of these devices,” Dr. Nelson said. “What you need to do is pick one and become what R. Rox Anderson, MD, calls an ‘endpointologist,’ so you can understand the clinical endpoints. Do not use a cookbook approach by trying to memorize treatment settings.”

Pulsed dye lasers with a wavelength of 585-600 nm have been the standard of care for years, he said, and is the treatment of choice for port wine stains in infants and young children. Upsides include the ability to treat large areas quickly and the ability to use two to three separate passes. It also induces diminution in diffuse redness and telangiectasia. Drawbacks include its potential to cause purpura when short pulse durations are used, it requires several treatments, it can be painful, and it causes considerable edema and erythema.

Millisecond green lasers at a wavelength of 532 nm are also effective for treating vascular skin lesions. “The nice thing about these devices is that you can focus them down to very small spots, so you can literally trace out individual blood vessels,” Dr. Nelson said. Other upsides include the fact that it can be performed without producing purpura, only transient erythema if few areas are treated. Drawbacks are that it’s moderately painful and may cause considerable edema. It also causes significant melanin absorption so is not advised for use in tanned and darker-skinned individuals. For all patients, contact cooling must be assured.

IPL, meanwhile, “can be very useful for treating not only vascular lesions, but also concurrently pigmented lesions such as poikiloderma of Civatte,” Dr. Nelson said. Potential drawbacks to IPL therapy are that the spectrum of light emitted and the pulse duration characteristics vary between devices and multiple treatments are required.

Finally, in the millisecond domain, the pulsed alexandrite 755-nm and Nd:YAG 1,064-nm lasers “are very good when trying to target something very deep in the skin like a vein,” he said. “But when you’re using those devices, you’re coagulating a large volume of tissue, so you need to be very careful about the amount of heat that you’re generating deep in the skin.”

When consulting with patients who have rosacea or telangiectasia, Dr. Nelson tells them multiple treatments will be required. “These are chronic conditions, and they may need ongoing maintenance treatments. The nice thing about all these procedures you’re doing for rosacea and telangiectasia is that they can be combined with all of your FDA [Food and Drug Administration]-approved topical and oral treatment protocols. All of these drugs you have at your disposal to medically treat rosacea can be all used concurrently with your laser treatment. When you see a patient you need to emphasize to them: ‘I’m not treating your rosacea with the laser. I’m treating a symptom of your rosacea with the laser.’ ”

Dr. Nelson closed his presentation by offering basic principles for success, the first being do no harm. “That’s the single most important thing you want to remember. No one will get mad if the blood vessel’s still there, but they’ll get very mad if something bad happens. You also want to underpromise and overdeliver. I always tell patients it’s going to require two to four treatments. When in doubt, don’t treat or undertreat. You can always treat again.”

If you’re concerned, perform a test spot. “There’s nothing wrong with that, particularly in a patient where you’re not sure what the outcome will be,” he said. “Check for any unusual skin reaction and for potential success of the procedure. Finally, don’t treat patients who are tanned.”

Dr. Nelson reported having intellectual property rights with Syneron Candela.

SAN DIEGO – According to J. Stuart Nelson, MD, PhD,

“You’re going to be using wavelengths of light generally in the green and yellow portion of the spectrum,” Dr. Nelson, professor of surgery and biomedical engineering at the Beckman Laser Institute and Medical Clinic at the University of California, Irvine, said at the annual Masters of Aesthetics Symposium. “Blue light is highly absorbed by hemoglobin but unfortunately, blue light is highly scattered by human skin, so it won’t penetrate deep enough into the dermis. So primarily, we’re targeting hemoglobin using green and yellow light sources.”

The second principle is to match the pulse width with the vessel size, while the third is to give sufficient energy to irreversibly injure vessels based on selective photothermolysis.

Next, he advised clinicians to ask themselves three questions: What is the vessel size? “The larger the vessel, the longer the thermal relaxation time,” he said. What is the vessel depth? Deeper vessels require longer wavelengths of light and larger spot sizes. What is the patient’s skin phototype? Darker skin contains more epidermal melanin and requires extra caution during treatment.

Dr. Nelson listed seven optimal devices for the treatment of vascular skin lesions: intense pulsed light (IPL) with wavelengths of 515-1,200 nm and pulse durations of 1-10 ms, pulsed green light with a wavelength of 532 nm and pulse durations of 1-50 ms, pulsed dye yellow light with wavelengths of 585-600 nm and pulse durations of 0.5-40 ms, pulsed dye plus Nd:YAG with wavelengths of 595 and 1,064 nm and pulse durations of 0.5-40 ms, alexandrite laser with a wavelength of 755 nm and pulse durations of 0.25-100 ms, diode laser with a wavelength of 940 nm and pulse durations of 5-100 ms, and the pulsed Nd:YAG laser with a wavelength of 1,064 nm and pulse durations of 0.25-100 ms.

“You can get good results with every one of these devices,” Dr. Nelson said. “What you need to do is pick one and become what R. Rox Anderson, MD, calls an ‘endpointologist,’ so you can understand the clinical endpoints. Do not use a cookbook approach by trying to memorize treatment settings.”

Pulsed dye lasers with a wavelength of 585-600 nm have been the standard of care for years, he said, and is the treatment of choice for port wine stains in infants and young children. Upsides include the ability to treat large areas quickly and the ability to use two to three separate passes. It also induces diminution in diffuse redness and telangiectasia. Drawbacks include its potential to cause purpura when short pulse durations are used, it requires several treatments, it can be painful, and it causes considerable edema and erythema.

Millisecond green lasers at a wavelength of 532 nm are also effective for treating vascular skin lesions. “The nice thing about these devices is that you can focus them down to very small spots, so you can literally trace out individual blood vessels,” Dr. Nelson said. Other upsides include the fact that it can be performed without producing purpura, only transient erythema if few areas are treated. Drawbacks are that it’s moderately painful and may cause considerable edema. It also causes significant melanin absorption so is not advised for use in tanned and darker-skinned individuals. For all patients, contact cooling must be assured.

IPL, meanwhile, “can be very useful for treating not only vascular lesions, but also concurrently pigmented lesions such as poikiloderma of Civatte,” Dr. Nelson said. Potential drawbacks to IPL therapy are that the spectrum of light emitted and the pulse duration characteristics vary between devices and multiple treatments are required.

Finally, in the millisecond domain, the pulsed alexandrite 755-nm and Nd:YAG 1,064-nm lasers “are very good when trying to target something very deep in the skin like a vein,” he said. “But when you’re using those devices, you’re coagulating a large volume of tissue, so you need to be very careful about the amount of heat that you’re generating deep in the skin.”

When consulting with patients who have rosacea or telangiectasia, Dr. Nelson tells them multiple treatments will be required. “These are chronic conditions, and they may need ongoing maintenance treatments. The nice thing about all these procedures you’re doing for rosacea and telangiectasia is that they can be combined with all of your FDA [Food and Drug Administration]-approved topical and oral treatment protocols. All of these drugs you have at your disposal to medically treat rosacea can be all used concurrently with your laser treatment. When you see a patient you need to emphasize to them: ‘I’m not treating your rosacea with the laser. I’m treating a symptom of your rosacea with the laser.’ ”

Dr. Nelson closed his presentation by offering basic principles for success, the first being do no harm. “That’s the single most important thing you want to remember. No one will get mad if the blood vessel’s still there, but they’ll get very mad if something bad happens. You also want to underpromise and overdeliver. I always tell patients it’s going to require two to four treatments. When in doubt, don’t treat or undertreat. You can always treat again.”

If you’re concerned, perform a test spot. “There’s nothing wrong with that, particularly in a patient where you’re not sure what the outcome will be,” he said. “Check for any unusual skin reaction and for potential success of the procedure. Finally, don’t treat patients who are tanned.”

Dr. Nelson reported having intellectual property rights with Syneron Candela.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM MOAS 2018

Terra Firma-Forme Dermatosis Mimicking Livedo Racemosa

To the Editor:

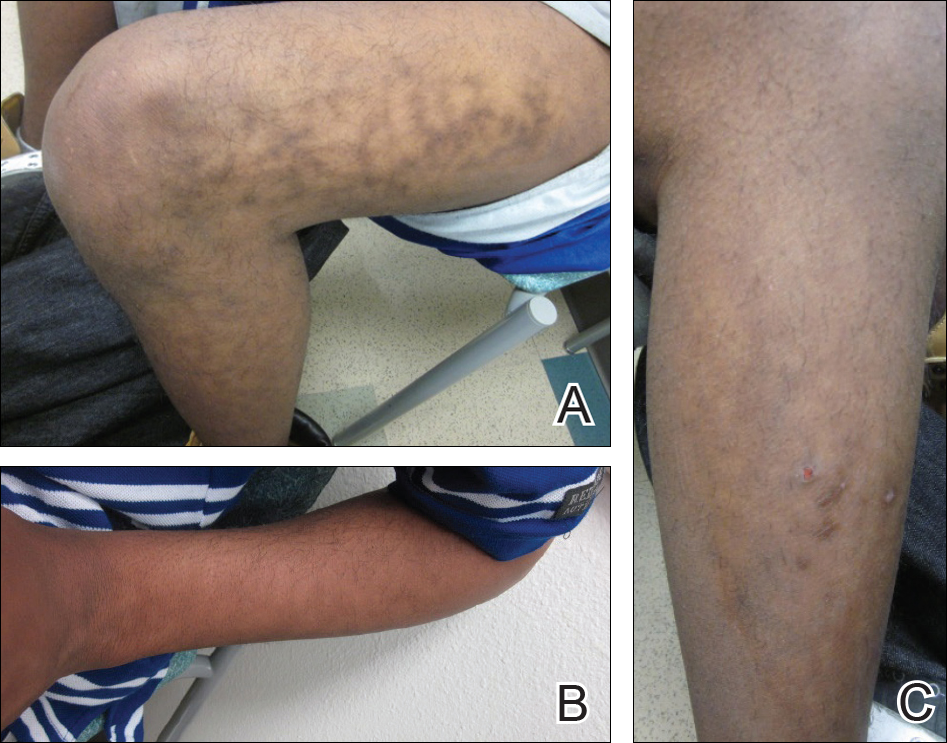

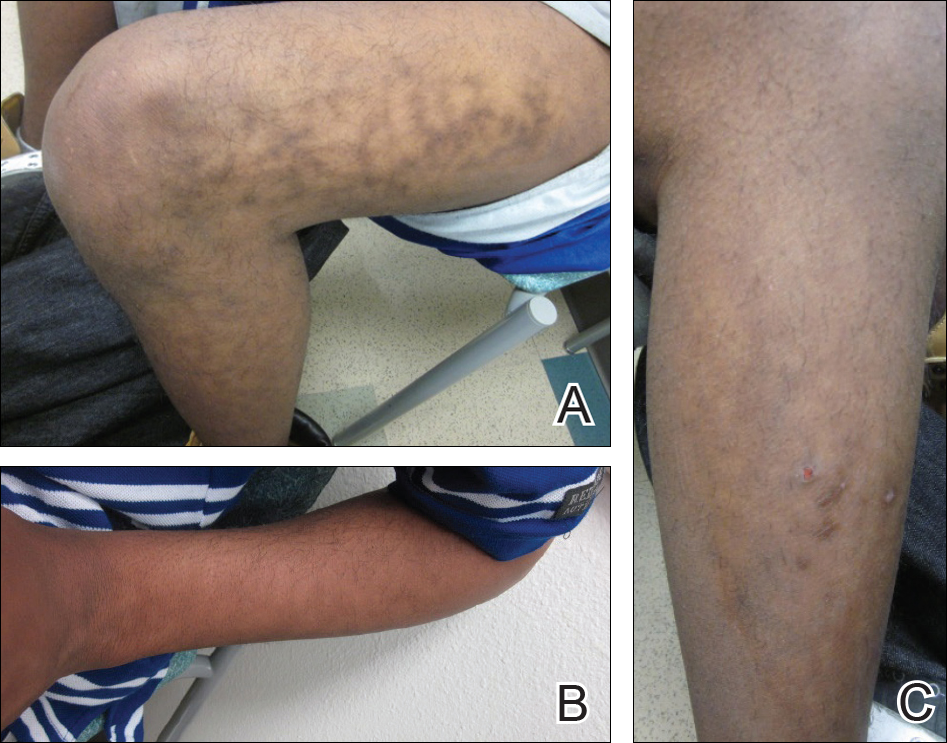

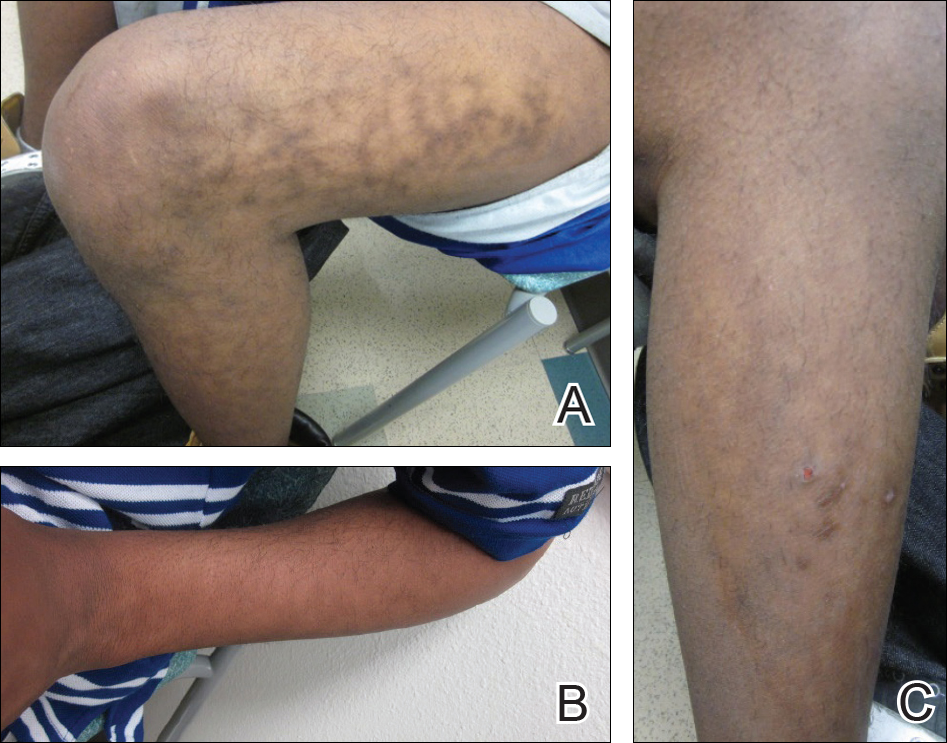

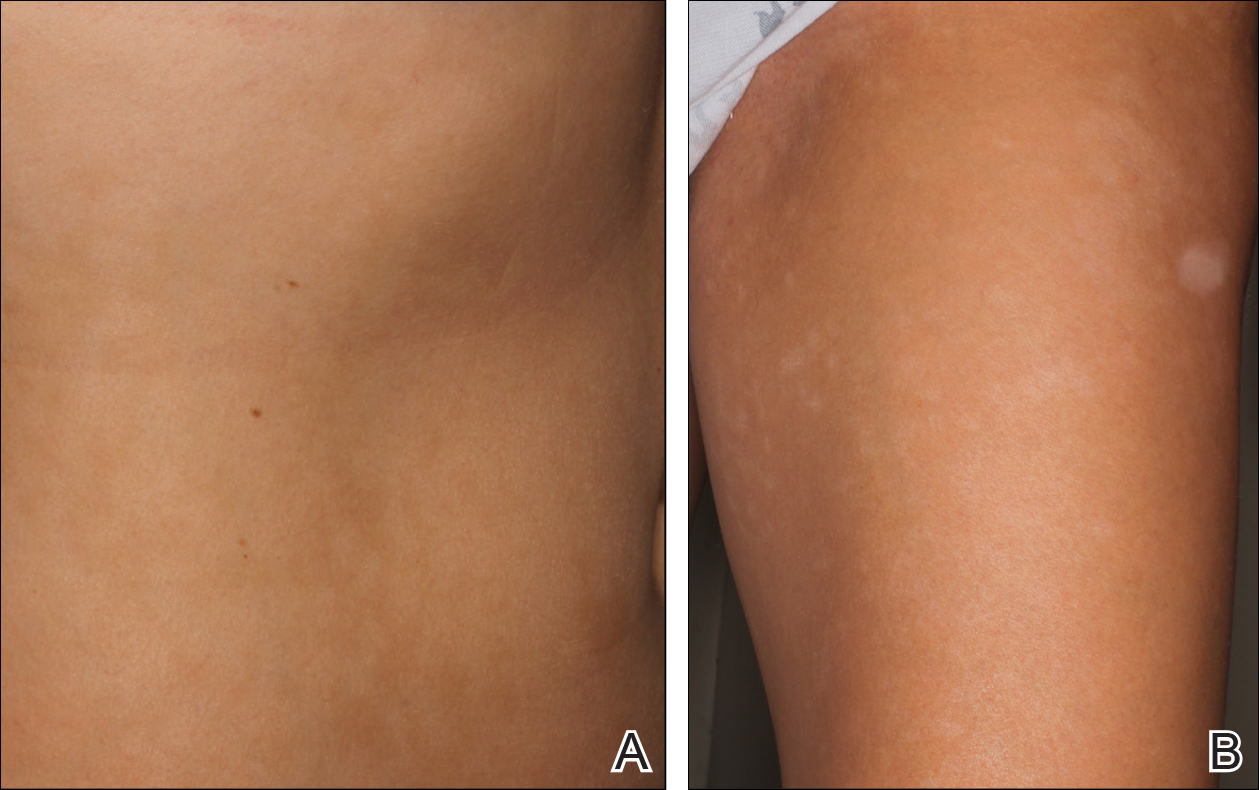

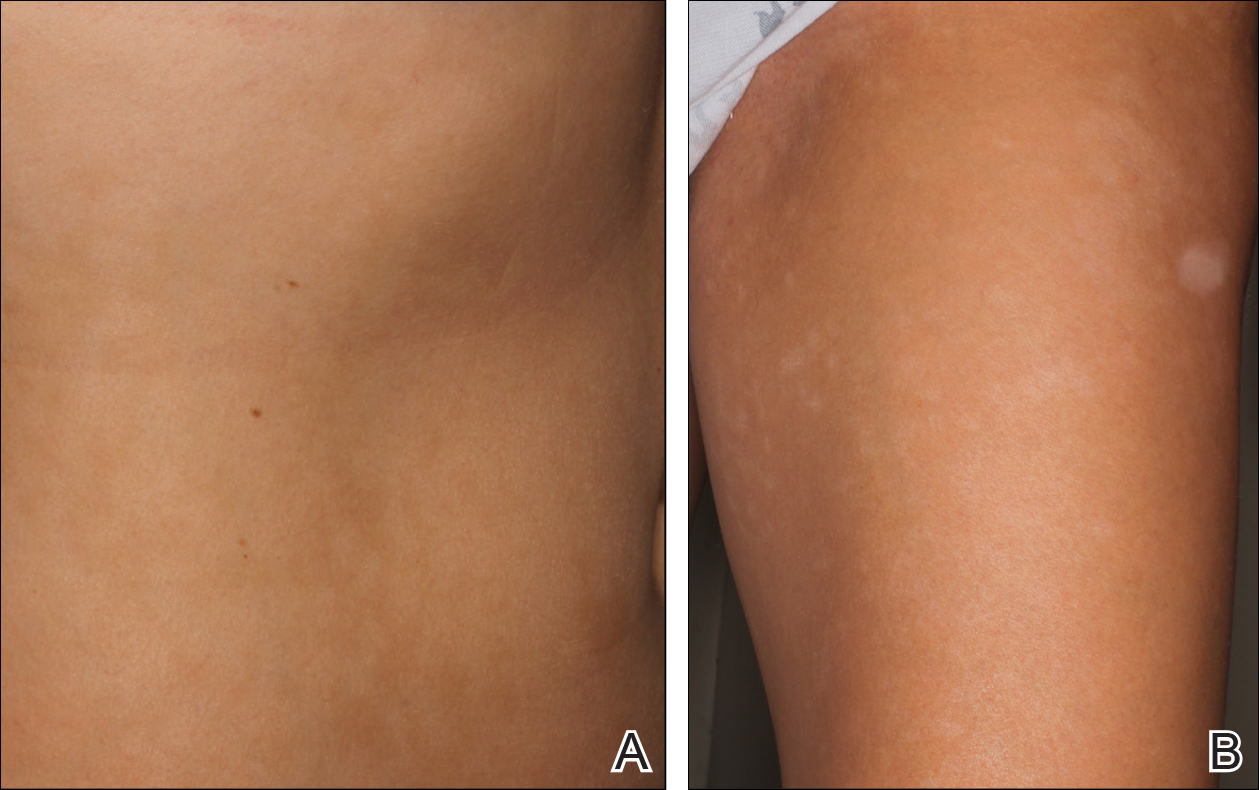

A 17-year-old adolescent boy presented with dark spots on the legs and back of 2 months’ duration. He was not taking any medications and the spots could not be washed away by scrubbing with soap and water. He denied symptoms, except occasional itching. Family history revealed a maternal uncle with protein C deficiency and a maternal grandmother with systemic lupus erythematosus. Review of systems was negative; the patient denied joint pain and contact with heating pads or laptop computers. Based on the initial presentation, an underlying systemic condition was suspected. Physical examination revealed reticulate, nonblanching, brown patches on the bilateral arms, legs, and back in an apparent livedoid pattern (Figure). The patient’s history and physical examination suggested terra firma-forme dermatosis, livedo racemosa, or another vasculopathic process. However, gentle rubbing of the skin with an alcohol swab removed the discoloration completely, leading to the diagnosis of terra firma-forme dermatosis.

Livedo racemosa appears as an irregular, focal, reticulated discoloration of the skin.1 The reticulated pattern of livedo racemosa has a branched or broken-up appearance.2 Livedo racemosa indicates a disruption in the vasculature due to inflammation or occlusion.1 The change is pathologic and does not blanch or resolve with warming.1,2 The condition can progress to pigmentation and ulceration.1 Livedo racemosa is a cutaneous manifestation of underlying vascular pathology. Due to a variety of causes, skin biopsy is nondiagnostic. Livedo racemosa can be caused by conditions such as systemic lupus erythematosus, syphilis, tuberculosis, polycythemia rubra vera, and Sneddon syndrome, among others.3-5

Terra firma-forme dermatosis was reported in 1987 by Duncan et al.6 The condition classically presents with an exasperated mother who is unable to clean the “dirt” off her child’s skin despite multiple vigorous scrubbing attempts. The condition most commonly occurs in the summer months on the neck, face, and ankles.7,8 Duncan et al6 reported that when the affected area was prepared for a biopsy, clean skin was revealed after wiping with an alcohol swab. No other cleansing agent has been reported to effectively remove the discoloration of terra firma-forme dermatosis. Hoping to elucidate a cause, Duncan et al6 performed both bacteriologic and fungal studies. The bacterial skin culture grew only normal flora, and fungal culture grew only normal contaminants consistent with the potassium hydroxide preparation of skin scraping. Histopathologic examination showed hyperkeratosis and orthokeratosis but not parakeratosis. Staining revealed melanin in the hyperkeratotic areas.6 Although the cause of this condition largely is unknown, it is thought that the epidermis in the affected areas could undergo altered maturation, resulting in trapping melanin that causes the skin to appear hyperkeratotic and hyperpigmented.1 In our case, wiping the skin revealed the unsuspected diagnosis of terra firma-forme dermatosis displaying an unusual pseudolivedoid pattern. With apparently hyperpigmented processes, rubbing the skin with alcohol may help avoid unnecessary aggressive workup.

- Parsi K, Partsch H, Rabe E, et al. Reticulate eruptions: part 2. historical perspectives, morphology, terminology and classification. Australas J Dermatol. 2011;52:237-244.

- Ehrmann S. A new vascular symptom in syphilis [in German]. Wien Med Wochenschr. 1907;57:777-782.

- Sneddon IB. Cerebrovascular lesions and livedo reticularis. Br J Dermatol. 1965;77:180-185.

- Golden RL. Livedo reticularis in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol. 1963;87:299-301.

- Lyell A, Church R. The cutaneous manifestations of polyarteritis nodosa. Br J Dermatol. 1954;66:335-343.

- Duncan WC, Tschen JA, Knox JM. Terra firma-forme dermatosis. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:567-569.

- Berk DR. Terra firma-forme dermatosis: a retrospective review of 31 patients. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;23:297-300.

- Guarneri C, Guarneri F, Cannavò SP. Terra firma-forme dermatosis. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:482-484.

To the Editor:

A 17-year-old adolescent boy presented with dark spots on the legs and back of 2 months’ duration. He was not taking any medications and the spots could not be washed away by scrubbing with soap and water. He denied symptoms, except occasional itching. Family history revealed a maternal uncle with protein C deficiency and a maternal grandmother with systemic lupus erythematosus. Review of systems was negative; the patient denied joint pain and contact with heating pads or laptop computers. Based on the initial presentation, an underlying systemic condition was suspected. Physical examination revealed reticulate, nonblanching, brown patches on the bilateral arms, legs, and back in an apparent livedoid pattern (Figure). The patient’s history and physical examination suggested terra firma-forme dermatosis, livedo racemosa, or another vasculopathic process. However, gentle rubbing of the skin with an alcohol swab removed the discoloration completely, leading to the diagnosis of terra firma-forme dermatosis.

Livedo racemosa appears as an irregular, focal, reticulated discoloration of the skin.1 The reticulated pattern of livedo racemosa has a branched or broken-up appearance.2 Livedo racemosa indicates a disruption in the vasculature due to inflammation or occlusion.1 The change is pathologic and does not blanch or resolve with warming.1,2 The condition can progress to pigmentation and ulceration.1 Livedo racemosa is a cutaneous manifestation of underlying vascular pathology. Due to a variety of causes, skin biopsy is nondiagnostic. Livedo racemosa can be caused by conditions such as systemic lupus erythematosus, syphilis, tuberculosis, polycythemia rubra vera, and Sneddon syndrome, among others.3-5

Terra firma-forme dermatosis was reported in 1987 by Duncan et al.6 The condition classically presents with an exasperated mother who is unable to clean the “dirt” off her child’s skin despite multiple vigorous scrubbing attempts. The condition most commonly occurs in the summer months on the neck, face, and ankles.7,8 Duncan et al6 reported that when the affected area was prepared for a biopsy, clean skin was revealed after wiping with an alcohol swab. No other cleansing agent has been reported to effectively remove the discoloration of terra firma-forme dermatosis. Hoping to elucidate a cause, Duncan et al6 performed both bacteriologic and fungal studies. The bacterial skin culture grew only normal flora, and fungal culture grew only normal contaminants consistent with the potassium hydroxide preparation of skin scraping. Histopathologic examination showed hyperkeratosis and orthokeratosis but not parakeratosis. Staining revealed melanin in the hyperkeratotic areas.6 Although the cause of this condition largely is unknown, it is thought that the epidermis in the affected areas could undergo altered maturation, resulting in trapping melanin that causes the skin to appear hyperkeratotic and hyperpigmented.1 In our case, wiping the skin revealed the unsuspected diagnosis of terra firma-forme dermatosis displaying an unusual pseudolivedoid pattern. With apparently hyperpigmented processes, rubbing the skin with alcohol may help avoid unnecessary aggressive workup.

To the Editor:

A 17-year-old adolescent boy presented with dark spots on the legs and back of 2 months’ duration. He was not taking any medications and the spots could not be washed away by scrubbing with soap and water. He denied symptoms, except occasional itching. Family history revealed a maternal uncle with protein C deficiency and a maternal grandmother with systemic lupus erythematosus. Review of systems was negative; the patient denied joint pain and contact with heating pads or laptop computers. Based on the initial presentation, an underlying systemic condition was suspected. Physical examination revealed reticulate, nonblanching, brown patches on the bilateral arms, legs, and back in an apparent livedoid pattern (Figure). The patient’s history and physical examination suggested terra firma-forme dermatosis, livedo racemosa, or another vasculopathic process. However, gentle rubbing of the skin with an alcohol swab removed the discoloration completely, leading to the diagnosis of terra firma-forme dermatosis.

Livedo racemosa appears as an irregular, focal, reticulated discoloration of the skin.1 The reticulated pattern of livedo racemosa has a branched or broken-up appearance.2 Livedo racemosa indicates a disruption in the vasculature due to inflammation or occlusion.1 The change is pathologic and does not blanch or resolve with warming.1,2 The condition can progress to pigmentation and ulceration.1 Livedo racemosa is a cutaneous manifestation of underlying vascular pathology. Due to a variety of causes, skin biopsy is nondiagnostic. Livedo racemosa can be caused by conditions such as systemic lupus erythematosus, syphilis, tuberculosis, polycythemia rubra vera, and Sneddon syndrome, among others.3-5

Terra firma-forme dermatosis was reported in 1987 by Duncan et al.6 The condition classically presents with an exasperated mother who is unable to clean the “dirt” off her child’s skin despite multiple vigorous scrubbing attempts. The condition most commonly occurs in the summer months on the neck, face, and ankles.7,8 Duncan et al6 reported that when the affected area was prepared for a biopsy, clean skin was revealed after wiping with an alcohol swab. No other cleansing agent has been reported to effectively remove the discoloration of terra firma-forme dermatosis. Hoping to elucidate a cause, Duncan et al6 performed both bacteriologic and fungal studies. The bacterial skin culture grew only normal flora, and fungal culture grew only normal contaminants consistent with the potassium hydroxide preparation of skin scraping. Histopathologic examination showed hyperkeratosis and orthokeratosis but not parakeratosis. Staining revealed melanin in the hyperkeratotic areas.6 Although the cause of this condition largely is unknown, it is thought that the epidermis in the affected areas could undergo altered maturation, resulting in trapping melanin that causes the skin to appear hyperkeratotic and hyperpigmented.1 In our case, wiping the skin revealed the unsuspected diagnosis of terra firma-forme dermatosis displaying an unusual pseudolivedoid pattern. With apparently hyperpigmented processes, rubbing the skin with alcohol may help avoid unnecessary aggressive workup.

- Parsi K, Partsch H, Rabe E, et al. Reticulate eruptions: part 2. historical perspectives, morphology, terminology and classification. Australas J Dermatol. 2011;52:237-244.