User login

Chronic inflammatory diseases vary widely in CHD risk

Not all chronic systemic inflammatory diseases are equal enhancers of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk, according to a large case-control study.

Current AHA/American College of Cardiology guidelines cite three chronic inflammatory diseases as atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk enhancers: rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, and HIV infection. But this study of those three diseases, along with three others marked by elevated high sensitivity C-reactive protein (systemic sclerosis, inflammatory bowel disease, and systemic lupus erythematosus [SLE]), showed that chronic inflammatory diseases are not monolithic in terms of their associated risk of incident coronary heart disease (CHD).

Indeed, two of the six inflammatory diseases – psoriasis and inflammatory bowel disease – turned out to be not at all associated with increased cardiovascular risk in the 37,117-patient study. The highest-risk disease was SLE, not specifically mentioned in the guidelines, Arjun Sinha, MD, a cardiology fellow at Northwestern University, Chicago, noted in his presentation at the virtual American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The study included 18,129 patients with one of the six chronic inflammatory diseases and 18,988 matched controls, none with CHD at baseline. All regularly received outpatient care at Northwestern during 2000-2019. There were 1,011 incident CHD events during a median of 3.5 years of follow-up.

In a Cox proportional hazards analysis adjusted for demographics, insurance status, hypertension, diabetes, current smoking, total cholesterol, and estimated glomerular filtration rate, here’s how the chronic inflammatory diseases stacked up in terms of incident CHD and MI risks:

- SLE: hazard ratio for CHD, 2.85; for MI, 4.76.

- Systemic sclerosis: HR for CHD, 2.14; for MI, 3.19.

- HIV: HR for CHD, 1.38; for MI, 1.69.

- Rheumatoid arthritis: HR for CHD, 1.22; for MI, 1.45.

- Psoriasis: no significant increase.

- Inflammatory bowel disease: no significant increase.

In an exploratory analysis, Dr. Sinha and coinvestigators evaluated the risk of incident CHD stratified by disease severity. For lack of standardized disease severity scales, the investigators relied upon tertiles of CD4 T cell count in the HIV group and CRP in the others. The HR for new-onset CHD in the more than 5,000 patients with psoriasis didn’t vary by CRP tertile. However, there was a nonsignificant trend for greater disease severity, as reflected by CRP tertile, to be associated with increased incident CHD risk in the HIV and inflammatory bowel disease groups.

In contrast, patients with rheumatoid arthritis or systemic sclerosis who were in the top CRP tertile had a significantly greater risk of developing CHD than that of controls, with HRs of 2.11 in the rheumatoid arthritis group and 4.59 with systemic sclerosis, although patients in the other two tertiles weren’t at significantly increased risk. But all three tertiles of CRP in patients with SLE were associated with significantly increased CHD risk: 3.17-fold in the lowest tertile of lupus severity, 5.38-fold in the middle tertile, and 4.04-fold in the top tertile for inflammation.

These findings could be used in clinical practice to fine-tune atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk assessment based upon chronic inflammatory disease type and severity. That’s information which in turn can help guide the timing and intensity of preventive therapy for patients with each disease type.

But studying the association between chronic systemic inflammatory diseases and CHD risk can be useful in additional ways, according to Dr. Sinha. These inflammatory diseases can serve as models of atherosclerosis that shed light on the non–lipid-related mechanisms involved in cardiovascular disease.

“The gradient in risk may be hypothesis-generating with respect to which specific inflammatory pathways may contribute to CHD,” he explained.

Each of these six chronic inflammatory diseases is characterized by a different form of major immune dysfunction, Dr. Sinha continued. A case in point is SLE, the inflammatory disease associated with the highest risk of CHD and MI. Lupus is characterized by a form of neutrophil dysfunction marked by increased formation and reduced degradation of neutrophil extracellular traps, or NETs, as well as by an increase in autoreactive B cells and dysfunctional CD4+ T helper cells. The increase in NETs of of particular interest because NETs have also been shown to contribute to the development of atherosclerosis, endothelial dysfunction, plaque erosion, and thrombosis.

In another exploratory analysis, Dr. Sinha and coworkers found that SLE patients with a neutrophil count above the median level were twice as likely to develop CHD than were those with a neutrophil count below the median.

A better understanding of the upstream pathways linking NET formation in SLE and atherosclerosis could lead to development of new or repurposed medications that target immune dysfunction in order to curb atherosclerosis, said Dr. Sinha, whose study won the AHA’s Samuel A. Levine Early Career Clinical Investigator Award.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study.

Not all chronic systemic inflammatory diseases are equal enhancers of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk, according to a large case-control study.

Current AHA/American College of Cardiology guidelines cite three chronic inflammatory diseases as atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk enhancers: rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, and HIV infection. But this study of those three diseases, along with three others marked by elevated high sensitivity C-reactive protein (systemic sclerosis, inflammatory bowel disease, and systemic lupus erythematosus [SLE]), showed that chronic inflammatory diseases are not monolithic in terms of their associated risk of incident coronary heart disease (CHD).

Indeed, two of the six inflammatory diseases – psoriasis and inflammatory bowel disease – turned out to be not at all associated with increased cardiovascular risk in the 37,117-patient study. The highest-risk disease was SLE, not specifically mentioned in the guidelines, Arjun Sinha, MD, a cardiology fellow at Northwestern University, Chicago, noted in his presentation at the virtual American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The study included 18,129 patients with one of the six chronic inflammatory diseases and 18,988 matched controls, none with CHD at baseline. All regularly received outpatient care at Northwestern during 2000-2019. There were 1,011 incident CHD events during a median of 3.5 years of follow-up.

In a Cox proportional hazards analysis adjusted for demographics, insurance status, hypertension, diabetes, current smoking, total cholesterol, and estimated glomerular filtration rate, here’s how the chronic inflammatory diseases stacked up in terms of incident CHD and MI risks:

- SLE: hazard ratio for CHD, 2.85; for MI, 4.76.

- Systemic sclerosis: HR for CHD, 2.14; for MI, 3.19.

- HIV: HR for CHD, 1.38; for MI, 1.69.

- Rheumatoid arthritis: HR for CHD, 1.22; for MI, 1.45.

- Psoriasis: no significant increase.

- Inflammatory bowel disease: no significant increase.

In an exploratory analysis, Dr. Sinha and coinvestigators evaluated the risk of incident CHD stratified by disease severity. For lack of standardized disease severity scales, the investigators relied upon tertiles of CD4 T cell count in the HIV group and CRP in the others. The HR for new-onset CHD in the more than 5,000 patients with psoriasis didn’t vary by CRP tertile. However, there was a nonsignificant trend for greater disease severity, as reflected by CRP tertile, to be associated with increased incident CHD risk in the HIV and inflammatory bowel disease groups.

In contrast, patients with rheumatoid arthritis or systemic sclerosis who were in the top CRP tertile had a significantly greater risk of developing CHD than that of controls, with HRs of 2.11 in the rheumatoid arthritis group and 4.59 with systemic sclerosis, although patients in the other two tertiles weren’t at significantly increased risk. But all three tertiles of CRP in patients with SLE were associated with significantly increased CHD risk: 3.17-fold in the lowest tertile of lupus severity, 5.38-fold in the middle tertile, and 4.04-fold in the top tertile for inflammation.

These findings could be used in clinical practice to fine-tune atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk assessment based upon chronic inflammatory disease type and severity. That’s information which in turn can help guide the timing and intensity of preventive therapy for patients with each disease type.

But studying the association between chronic systemic inflammatory diseases and CHD risk can be useful in additional ways, according to Dr. Sinha. These inflammatory diseases can serve as models of atherosclerosis that shed light on the non–lipid-related mechanisms involved in cardiovascular disease.

“The gradient in risk may be hypothesis-generating with respect to which specific inflammatory pathways may contribute to CHD,” he explained.

Each of these six chronic inflammatory diseases is characterized by a different form of major immune dysfunction, Dr. Sinha continued. A case in point is SLE, the inflammatory disease associated with the highest risk of CHD and MI. Lupus is characterized by a form of neutrophil dysfunction marked by increased formation and reduced degradation of neutrophil extracellular traps, or NETs, as well as by an increase in autoreactive B cells and dysfunctional CD4+ T helper cells. The increase in NETs of of particular interest because NETs have also been shown to contribute to the development of atherosclerosis, endothelial dysfunction, plaque erosion, and thrombosis.

In another exploratory analysis, Dr. Sinha and coworkers found that SLE patients with a neutrophil count above the median level were twice as likely to develop CHD than were those with a neutrophil count below the median.

A better understanding of the upstream pathways linking NET formation in SLE and atherosclerosis could lead to development of new or repurposed medications that target immune dysfunction in order to curb atherosclerosis, said Dr. Sinha, whose study won the AHA’s Samuel A. Levine Early Career Clinical Investigator Award.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study.

Not all chronic systemic inflammatory diseases are equal enhancers of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk, according to a large case-control study.

Current AHA/American College of Cardiology guidelines cite three chronic inflammatory diseases as atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk enhancers: rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, and HIV infection. But this study of those three diseases, along with three others marked by elevated high sensitivity C-reactive protein (systemic sclerosis, inflammatory bowel disease, and systemic lupus erythematosus [SLE]), showed that chronic inflammatory diseases are not monolithic in terms of their associated risk of incident coronary heart disease (CHD).

Indeed, two of the six inflammatory diseases – psoriasis and inflammatory bowel disease – turned out to be not at all associated with increased cardiovascular risk in the 37,117-patient study. The highest-risk disease was SLE, not specifically mentioned in the guidelines, Arjun Sinha, MD, a cardiology fellow at Northwestern University, Chicago, noted in his presentation at the virtual American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The study included 18,129 patients with one of the six chronic inflammatory diseases and 18,988 matched controls, none with CHD at baseline. All regularly received outpatient care at Northwestern during 2000-2019. There were 1,011 incident CHD events during a median of 3.5 years of follow-up.

In a Cox proportional hazards analysis adjusted for demographics, insurance status, hypertension, diabetes, current smoking, total cholesterol, and estimated glomerular filtration rate, here’s how the chronic inflammatory diseases stacked up in terms of incident CHD and MI risks:

- SLE: hazard ratio for CHD, 2.85; for MI, 4.76.

- Systemic sclerosis: HR for CHD, 2.14; for MI, 3.19.

- HIV: HR for CHD, 1.38; for MI, 1.69.

- Rheumatoid arthritis: HR for CHD, 1.22; for MI, 1.45.

- Psoriasis: no significant increase.

- Inflammatory bowel disease: no significant increase.

In an exploratory analysis, Dr. Sinha and coinvestigators evaluated the risk of incident CHD stratified by disease severity. For lack of standardized disease severity scales, the investigators relied upon tertiles of CD4 T cell count in the HIV group and CRP in the others. The HR for new-onset CHD in the more than 5,000 patients with psoriasis didn’t vary by CRP tertile. However, there was a nonsignificant trend for greater disease severity, as reflected by CRP tertile, to be associated with increased incident CHD risk in the HIV and inflammatory bowel disease groups.

In contrast, patients with rheumatoid arthritis or systemic sclerosis who were in the top CRP tertile had a significantly greater risk of developing CHD than that of controls, with HRs of 2.11 in the rheumatoid arthritis group and 4.59 with systemic sclerosis, although patients in the other two tertiles weren’t at significantly increased risk. But all three tertiles of CRP in patients with SLE were associated with significantly increased CHD risk: 3.17-fold in the lowest tertile of lupus severity, 5.38-fold in the middle tertile, and 4.04-fold in the top tertile for inflammation.

These findings could be used in clinical practice to fine-tune atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk assessment based upon chronic inflammatory disease type and severity. That’s information which in turn can help guide the timing and intensity of preventive therapy for patients with each disease type.

But studying the association between chronic systemic inflammatory diseases and CHD risk can be useful in additional ways, according to Dr. Sinha. These inflammatory diseases can serve as models of atherosclerosis that shed light on the non–lipid-related mechanisms involved in cardiovascular disease.

“The gradient in risk may be hypothesis-generating with respect to which specific inflammatory pathways may contribute to CHD,” he explained.

Each of these six chronic inflammatory diseases is characterized by a different form of major immune dysfunction, Dr. Sinha continued. A case in point is SLE, the inflammatory disease associated with the highest risk of CHD and MI. Lupus is characterized by a form of neutrophil dysfunction marked by increased formation and reduced degradation of neutrophil extracellular traps, or NETs, as well as by an increase in autoreactive B cells and dysfunctional CD4+ T helper cells. The increase in NETs of of particular interest because NETs have also been shown to contribute to the development of atherosclerosis, endothelial dysfunction, plaque erosion, and thrombosis.

In another exploratory analysis, Dr. Sinha and coworkers found that SLE patients with a neutrophil count above the median level were twice as likely to develop CHD than were those with a neutrophil count below the median.

A better understanding of the upstream pathways linking NET formation in SLE and atherosclerosis could lead to development of new or repurposed medications that target immune dysfunction in order to curb atherosclerosis, said Dr. Sinha, whose study won the AHA’s Samuel A. Levine Early Career Clinical Investigator Award.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study.

FROM AHA 2020

Methotrexate users need tuberculosis tests in high-TB areas

People taking even low-dose methotrexate need tuberculosis screening and ongoing clinical care if they live in areas where TB is common, results of a study presented at the virtual annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology suggest.

Coauthor Carol Hitchon, MD, MSc, a rheumatologist with the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg, who presented the findings, warned that methotrexate (MTX) users who also take corticosteroids or other immunosuppressants are at particular risk and need TB screening.

Current management guidelines for rheumatic disease address TB in relation to biologics, but not in relation to methotrexate, Dr. Hitchon said.

“We know that methotrexate is the foundational DMARD [disease-modifying antirheumatic drug] for many rheumatic diseases, especially rheumatoid arthritis,” Dr. Hitchon noted at a press conference. “It’s safe and effective when dosed properly. However, methotrexate does have the potential for significant liver toxicity as well as infection, particularly for infectious organisms that are targeted by cell-mediated immunity, and TB is one of those agents.”

Using multiple databases, researchers conducted a systematic review of the literature published from 1990 to 2018 on TB rates among people who take less than 30 mg of methotrexate a week. Of the 4,700 studies they examined, 31 fit the criteria for this analysis.

They collected data on tuberculosis incidence or new TB diagnoses vs. reactivation of latent TB infection as well as TB outcomes, such as pulmonary symptoms, dissemination, and mortality.

They found a modest increase in the risk of TB infections in the setting of low-dose methotrexate. In addition, rates of TB in people with rheumatic disease who are treated with either methotrexate or biologics are generally higher than in the general population.

They also found that methotrexate users had higher rates of the type of TB that spreads beyond a patient’s lungs, compared with the general population.

Safety of INH with methotrexate

Researchers also looked at the safety of isoniazid (INH), the antibiotic used to treat TB, and found that isoniazid-related liver toxicity and neutropenia were more common when people took the antibiotic along with methotrexate, but those effects were usually reversible.

TB is endemic in various regions around the world. Historically there hasn’t been much rheumatology capacity in many of these areas, but as that capacity increases more people who are at high risk for developing or reactivating TB will be receiving methotrexate for rheumatic diseases, Dr. Hitchon said.

“It’s prudent for people managing patients who may be at higher risk for TB either from where they live or from where they travel that we should have a high suspicion for TB and consider screening as part of our workup in the course of initiating treatment like methotrexate,” she said.

Narender Annapureddy, MD, a rheumatologist at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., who was not involved in the research, pointed out that a limitation of the work is that only 27% of the studies are from developing countries, which are more likely to have endemic TB, and those studies had very few cases.

“This finding needs to be studied in larger populations in TB-endemic areas and in high-risk populations,” he said in an interview.

As for practice implications in the United States, Dr. Annapureddy noted that TB is rare in the United States and most of the cases occur in people born in other countries.

“This population may be at risk for TB and should probably be screened for TB before initiating methotrexate,” he said. “Since biologics are usually the next step, especially in RA after patients fail methotrexate, having information on TB status may also help guide management options after MTX failure.

“Since high-dose steroids are another important risk factor for TB activation,” Dr. Annapureddy continued, “rheumatologists should likely consider screening patients who are going to be on moderate to high doses of steroids with MTX.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

People taking even low-dose methotrexate need tuberculosis screening and ongoing clinical care if they live in areas where TB is common, results of a study presented at the virtual annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology suggest.

Coauthor Carol Hitchon, MD, MSc, a rheumatologist with the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg, who presented the findings, warned that methotrexate (MTX) users who also take corticosteroids or other immunosuppressants are at particular risk and need TB screening.

Current management guidelines for rheumatic disease address TB in relation to biologics, but not in relation to methotrexate, Dr. Hitchon said.

“We know that methotrexate is the foundational DMARD [disease-modifying antirheumatic drug] for many rheumatic diseases, especially rheumatoid arthritis,” Dr. Hitchon noted at a press conference. “It’s safe and effective when dosed properly. However, methotrexate does have the potential for significant liver toxicity as well as infection, particularly for infectious organisms that are targeted by cell-mediated immunity, and TB is one of those agents.”

Using multiple databases, researchers conducted a systematic review of the literature published from 1990 to 2018 on TB rates among people who take less than 30 mg of methotrexate a week. Of the 4,700 studies they examined, 31 fit the criteria for this analysis.

They collected data on tuberculosis incidence or new TB diagnoses vs. reactivation of latent TB infection as well as TB outcomes, such as pulmonary symptoms, dissemination, and mortality.

They found a modest increase in the risk of TB infections in the setting of low-dose methotrexate. In addition, rates of TB in people with rheumatic disease who are treated with either methotrexate or biologics are generally higher than in the general population.

They also found that methotrexate users had higher rates of the type of TB that spreads beyond a patient’s lungs, compared with the general population.

Safety of INH with methotrexate

Researchers also looked at the safety of isoniazid (INH), the antibiotic used to treat TB, and found that isoniazid-related liver toxicity and neutropenia were more common when people took the antibiotic along with methotrexate, but those effects were usually reversible.

TB is endemic in various regions around the world. Historically there hasn’t been much rheumatology capacity in many of these areas, but as that capacity increases more people who are at high risk for developing or reactivating TB will be receiving methotrexate for rheumatic diseases, Dr. Hitchon said.

“It’s prudent for people managing patients who may be at higher risk for TB either from where they live or from where they travel that we should have a high suspicion for TB and consider screening as part of our workup in the course of initiating treatment like methotrexate,” she said.

Narender Annapureddy, MD, a rheumatologist at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., who was not involved in the research, pointed out that a limitation of the work is that only 27% of the studies are from developing countries, which are more likely to have endemic TB, and those studies had very few cases.

“This finding needs to be studied in larger populations in TB-endemic areas and in high-risk populations,” he said in an interview.

As for practice implications in the United States, Dr. Annapureddy noted that TB is rare in the United States and most of the cases occur in people born in other countries.

“This population may be at risk for TB and should probably be screened for TB before initiating methotrexate,” he said. “Since biologics are usually the next step, especially in RA after patients fail methotrexate, having information on TB status may also help guide management options after MTX failure.

“Since high-dose steroids are another important risk factor for TB activation,” Dr. Annapureddy continued, “rheumatologists should likely consider screening patients who are going to be on moderate to high doses of steroids with MTX.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

People taking even low-dose methotrexate need tuberculosis screening and ongoing clinical care if they live in areas where TB is common, results of a study presented at the virtual annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology suggest.

Coauthor Carol Hitchon, MD, MSc, a rheumatologist with the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg, who presented the findings, warned that methotrexate (MTX) users who also take corticosteroids or other immunosuppressants are at particular risk and need TB screening.

Current management guidelines for rheumatic disease address TB in relation to biologics, but not in relation to methotrexate, Dr. Hitchon said.

“We know that methotrexate is the foundational DMARD [disease-modifying antirheumatic drug] for many rheumatic diseases, especially rheumatoid arthritis,” Dr. Hitchon noted at a press conference. “It’s safe and effective when dosed properly. However, methotrexate does have the potential for significant liver toxicity as well as infection, particularly for infectious organisms that are targeted by cell-mediated immunity, and TB is one of those agents.”

Using multiple databases, researchers conducted a systematic review of the literature published from 1990 to 2018 on TB rates among people who take less than 30 mg of methotrexate a week. Of the 4,700 studies they examined, 31 fit the criteria for this analysis.

They collected data on tuberculosis incidence or new TB diagnoses vs. reactivation of latent TB infection as well as TB outcomes, such as pulmonary symptoms, dissemination, and mortality.

They found a modest increase in the risk of TB infections in the setting of low-dose methotrexate. In addition, rates of TB in people with rheumatic disease who are treated with either methotrexate or biologics are generally higher than in the general population.

They also found that methotrexate users had higher rates of the type of TB that spreads beyond a patient’s lungs, compared with the general population.

Safety of INH with methotrexate

Researchers also looked at the safety of isoniazid (INH), the antibiotic used to treat TB, and found that isoniazid-related liver toxicity and neutropenia were more common when people took the antibiotic along with methotrexate, but those effects were usually reversible.

TB is endemic in various regions around the world. Historically there hasn’t been much rheumatology capacity in many of these areas, but as that capacity increases more people who are at high risk for developing or reactivating TB will be receiving methotrexate for rheumatic diseases, Dr. Hitchon said.

“It’s prudent for people managing patients who may be at higher risk for TB either from where they live or from where they travel that we should have a high suspicion for TB and consider screening as part of our workup in the course of initiating treatment like methotrexate,” she said.

Narender Annapureddy, MD, a rheumatologist at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., who was not involved in the research, pointed out that a limitation of the work is that only 27% of the studies are from developing countries, which are more likely to have endemic TB, and those studies had very few cases.

“This finding needs to be studied in larger populations in TB-endemic areas and in high-risk populations,” he said in an interview.

As for practice implications in the United States, Dr. Annapureddy noted that TB is rare in the United States and most of the cases occur in people born in other countries.

“This population may be at risk for TB and should probably be screened for TB before initiating methotrexate,” he said. “Since biologics are usually the next step, especially in RA after patients fail methotrexate, having information on TB status may also help guide management options after MTX failure.

“Since high-dose steroids are another important risk factor for TB activation,” Dr. Annapureddy continued, “rheumatologists should likely consider screening patients who are going to be on moderate to high doses of steroids with MTX.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Topical tapinarof effective in pivotal psoriasis trials

in two identical pivotal phase 3, randomized trials, Mark G. Lebwohl, MD, reported at the virtual annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

“Tapinarof cream has the potential to be a first-in-class topical therapeutic aryl hydrocarbon receptor modulating agent and will provide physicians and patients with a novel nonsteroidal topical treatment option that’s effective and well tolerated,” predicted Dr. Lebwohl, professor and chair of the department of dermatology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

Dermavant Sciences, the company developing topical tapinarof for treatment of atopic dermatitis as well as psoriasis, announced that upon completion of an ongoing long-term extension study the company plans to file for approval of the drug for psoriasis in 2021.

The two pivotal phase 3 trials, PSOARING 1 and PSOARING 2, randomized a total of 1,025 patients with plaque psoriasis to once-daily tapinarof cream 1% or its vehicle. “This was a fairly difficult group of patients,” Dr. Lebwohl said. Roughly 80% had moderate psoriasis as defined by a baseline Physician Global Assessment (PGA) score of 3, with the remainder split evenly between mild and severe disease. Participants averaged 8% body surface area involvement. Body mass index was on average greater than 31 kg/m2.

The primary efficacy endpoint was a PGA score of 0 or 1 – that is, clear or almost clear – plus at least a 2-grade improvement in PGA from baseline at week 12. This was achieved in 35.4% of patients on tapinarof cream once daily in PSOARING 1 and 40.2% in PSOARING 2, compared with 6.0% and 6.3% of vehicle-treated controls, a highly significant difference (both P < .0001).

The prespecified secondary endpoint was a 75% improvement in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score from baseline to week 12. The PASI 75 rates were 36.1% and 47.6% with tapinarof, significantly better than the 10.2% and 6.9% rates in controls.

The most common adverse event associated with tapinarof was folliculitis, which occurred in 20.6% of treated patients in PSOARING 1 and in 15.7% in PSOARING 2. More than 98% of cases were mild or moderate. The folliculitis led to study discontinuation in only 1.8% and 0.9% of subjects in the two trials.

The other noteworthy adverse event was contact dermatitis. It occurred in 3.8% and 4.7% of tapinarof-treated patients, again with low study discontinuation rates of 1.5% and 2.2%.

During the audience discussion, Linda Stein Gold, MD, lead investigator for PSOARING 2, was asked about this folliculitis. She said the mechanism is unclear, as is the best management. She encountered it in patients, didn’t treat it, and it went away on its own. It’s not a bacterial folliculitis; when cultured it invariably proved culture negative, she noted.

The comparative efficacy of tapinarof cream versus the potent and superpotent topical corticosteroids commonly used in the treatment of psoriasis hasn’t been evaluated in head-to-head studies. Her experience and that of the other investigators has been that tapinarof’s efficacy is comparably strong, “but we don’t have the steroid side effects,” said Dr. Stein Gold, director of dermatology clinical research at Henry Ford Health System in Detroit.

In an interview, Dr. Lebwohl said tapinarof, if approved, could help meet a major unmet need for new and better topical therapies for psoriasis.

“You keep hearing about all these biologic agents and small-molecule pills coming out, but the majority of patients still only need topical therapy,” he observed.

Moreover, even when patients with more severe disease achieve a PASI 75 or PASI 90 response with systemic therapy, they usually still need supplemental topical therapy to get them closer to the goal of clear skin.

The superpotent steroids that are the current mainstay of topical therapy come with predictable side effects that dictate a 2- to 4-week limit on their approved use. Also, they’re not supposed to be applied to the face or to intertriginous sites, including the groin, axillae, and under the breasts. In contrast, tapinarof has proved safe and effective in these sensitive areas.

Asked to predict how tapinarof is likely to be used in clinical practice, Dr. Lebwohl replied: “The efficacy was equivalent to strong topical steroids, so I think it could be used first line in place of topical steroids. And in particular, in patients with psoriasis at facial and intertriginous sites, I think an argument can be made for insisting that it be first line.”

He also expects that physicians will end up utilizing tapinarof for a varied group of steroid-responsive dermatoses beyond psoriasis and atopic dermatitis.

“It clearly reduces inflammation, which is why I would expect it would work well for those,” the dermatologist said.

The mechanism of action of tapinarof has been worked out. The drug enters the cell and binds to the aryl hydrocarbon receptor, forming a complex that enters the nucleus. There it joins with the aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator, which regulates gene expression so as to reduce production of inflammatory cytokines while promoting an increase in skin barrier proteins, which is why tapinarof is also being developed as an atopic dermatitis therapy.

Dr. Lebwohl and Dr. Stein Gold reported receiving research funds from and serving as consultants to Dermavant Sciences as well as numerous other pharmaceutical companies.

in two identical pivotal phase 3, randomized trials, Mark G. Lebwohl, MD, reported at the virtual annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

“Tapinarof cream has the potential to be a first-in-class topical therapeutic aryl hydrocarbon receptor modulating agent and will provide physicians and patients with a novel nonsteroidal topical treatment option that’s effective and well tolerated,” predicted Dr. Lebwohl, professor and chair of the department of dermatology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

Dermavant Sciences, the company developing topical tapinarof for treatment of atopic dermatitis as well as psoriasis, announced that upon completion of an ongoing long-term extension study the company plans to file for approval of the drug for psoriasis in 2021.

The two pivotal phase 3 trials, PSOARING 1 and PSOARING 2, randomized a total of 1,025 patients with plaque psoriasis to once-daily tapinarof cream 1% or its vehicle. “This was a fairly difficult group of patients,” Dr. Lebwohl said. Roughly 80% had moderate psoriasis as defined by a baseline Physician Global Assessment (PGA) score of 3, with the remainder split evenly between mild and severe disease. Participants averaged 8% body surface area involvement. Body mass index was on average greater than 31 kg/m2.

The primary efficacy endpoint was a PGA score of 0 or 1 – that is, clear or almost clear – plus at least a 2-grade improvement in PGA from baseline at week 12. This was achieved in 35.4% of patients on tapinarof cream once daily in PSOARING 1 and 40.2% in PSOARING 2, compared with 6.0% and 6.3% of vehicle-treated controls, a highly significant difference (both P < .0001).

The prespecified secondary endpoint was a 75% improvement in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score from baseline to week 12. The PASI 75 rates were 36.1% and 47.6% with tapinarof, significantly better than the 10.2% and 6.9% rates in controls.

The most common adverse event associated with tapinarof was folliculitis, which occurred in 20.6% of treated patients in PSOARING 1 and in 15.7% in PSOARING 2. More than 98% of cases were mild or moderate. The folliculitis led to study discontinuation in only 1.8% and 0.9% of subjects in the two trials.

The other noteworthy adverse event was contact dermatitis. It occurred in 3.8% and 4.7% of tapinarof-treated patients, again with low study discontinuation rates of 1.5% and 2.2%.

During the audience discussion, Linda Stein Gold, MD, lead investigator for PSOARING 2, was asked about this folliculitis. She said the mechanism is unclear, as is the best management. She encountered it in patients, didn’t treat it, and it went away on its own. It’s not a bacterial folliculitis; when cultured it invariably proved culture negative, she noted.

The comparative efficacy of tapinarof cream versus the potent and superpotent topical corticosteroids commonly used in the treatment of psoriasis hasn’t been evaluated in head-to-head studies. Her experience and that of the other investigators has been that tapinarof’s efficacy is comparably strong, “but we don’t have the steroid side effects,” said Dr. Stein Gold, director of dermatology clinical research at Henry Ford Health System in Detroit.

In an interview, Dr. Lebwohl said tapinarof, if approved, could help meet a major unmet need for new and better topical therapies for psoriasis.

“You keep hearing about all these biologic agents and small-molecule pills coming out, but the majority of patients still only need topical therapy,” he observed.

Moreover, even when patients with more severe disease achieve a PASI 75 or PASI 90 response with systemic therapy, they usually still need supplemental topical therapy to get them closer to the goal of clear skin.

The superpotent steroids that are the current mainstay of topical therapy come with predictable side effects that dictate a 2- to 4-week limit on their approved use. Also, they’re not supposed to be applied to the face or to intertriginous sites, including the groin, axillae, and under the breasts. In contrast, tapinarof has proved safe and effective in these sensitive areas.

Asked to predict how tapinarof is likely to be used in clinical practice, Dr. Lebwohl replied: “The efficacy was equivalent to strong topical steroids, so I think it could be used first line in place of topical steroids. And in particular, in patients with psoriasis at facial and intertriginous sites, I think an argument can be made for insisting that it be first line.”

He also expects that physicians will end up utilizing tapinarof for a varied group of steroid-responsive dermatoses beyond psoriasis and atopic dermatitis.

“It clearly reduces inflammation, which is why I would expect it would work well for those,” the dermatologist said.

The mechanism of action of tapinarof has been worked out. The drug enters the cell and binds to the aryl hydrocarbon receptor, forming a complex that enters the nucleus. There it joins with the aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator, which regulates gene expression so as to reduce production of inflammatory cytokines while promoting an increase in skin barrier proteins, which is why tapinarof is also being developed as an atopic dermatitis therapy.

Dr. Lebwohl and Dr. Stein Gold reported receiving research funds from and serving as consultants to Dermavant Sciences as well as numerous other pharmaceutical companies.

in two identical pivotal phase 3, randomized trials, Mark G. Lebwohl, MD, reported at the virtual annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

“Tapinarof cream has the potential to be a first-in-class topical therapeutic aryl hydrocarbon receptor modulating agent and will provide physicians and patients with a novel nonsteroidal topical treatment option that’s effective and well tolerated,” predicted Dr. Lebwohl, professor and chair of the department of dermatology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

Dermavant Sciences, the company developing topical tapinarof for treatment of atopic dermatitis as well as psoriasis, announced that upon completion of an ongoing long-term extension study the company plans to file for approval of the drug for psoriasis in 2021.

The two pivotal phase 3 trials, PSOARING 1 and PSOARING 2, randomized a total of 1,025 patients with plaque psoriasis to once-daily tapinarof cream 1% or its vehicle. “This was a fairly difficult group of patients,” Dr. Lebwohl said. Roughly 80% had moderate psoriasis as defined by a baseline Physician Global Assessment (PGA) score of 3, with the remainder split evenly between mild and severe disease. Participants averaged 8% body surface area involvement. Body mass index was on average greater than 31 kg/m2.

The primary efficacy endpoint was a PGA score of 0 or 1 – that is, clear or almost clear – plus at least a 2-grade improvement in PGA from baseline at week 12. This was achieved in 35.4% of patients on tapinarof cream once daily in PSOARING 1 and 40.2% in PSOARING 2, compared with 6.0% and 6.3% of vehicle-treated controls, a highly significant difference (both P < .0001).

The prespecified secondary endpoint was a 75% improvement in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score from baseline to week 12. The PASI 75 rates were 36.1% and 47.6% with tapinarof, significantly better than the 10.2% and 6.9% rates in controls.

The most common adverse event associated with tapinarof was folliculitis, which occurred in 20.6% of treated patients in PSOARING 1 and in 15.7% in PSOARING 2. More than 98% of cases were mild or moderate. The folliculitis led to study discontinuation in only 1.8% and 0.9% of subjects in the two trials.

The other noteworthy adverse event was contact dermatitis. It occurred in 3.8% and 4.7% of tapinarof-treated patients, again with low study discontinuation rates of 1.5% and 2.2%.

During the audience discussion, Linda Stein Gold, MD, lead investigator for PSOARING 2, was asked about this folliculitis. She said the mechanism is unclear, as is the best management. She encountered it in patients, didn’t treat it, and it went away on its own. It’s not a bacterial folliculitis; when cultured it invariably proved culture negative, she noted.

The comparative efficacy of tapinarof cream versus the potent and superpotent topical corticosteroids commonly used in the treatment of psoriasis hasn’t been evaluated in head-to-head studies. Her experience and that of the other investigators has been that tapinarof’s efficacy is comparably strong, “but we don’t have the steroid side effects,” said Dr. Stein Gold, director of dermatology clinical research at Henry Ford Health System in Detroit.

In an interview, Dr. Lebwohl said tapinarof, if approved, could help meet a major unmet need for new and better topical therapies for psoriasis.

“You keep hearing about all these biologic agents and small-molecule pills coming out, but the majority of patients still only need topical therapy,” he observed.

Moreover, even when patients with more severe disease achieve a PASI 75 or PASI 90 response with systemic therapy, they usually still need supplemental topical therapy to get them closer to the goal of clear skin.

The superpotent steroids that are the current mainstay of topical therapy come with predictable side effects that dictate a 2- to 4-week limit on their approved use. Also, they’re not supposed to be applied to the face or to intertriginous sites, including the groin, axillae, and under the breasts. In contrast, tapinarof has proved safe and effective in these sensitive areas.

Asked to predict how tapinarof is likely to be used in clinical practice, Dr. Lebwohl replied: “The efficacy was equivalent to strong topical steroids, so I think it could be used first line in place of topical steroids. And in particular, in patients with psoriasis at facial and intertriginous sites, I think an argument can be made for insisting that it be first line.”

He also expects that physicians will end up utilizing tapinarof for a varied group of steroid-responsive dermatoses beyond psoriasis and atopic dermatitis.

“It clearly reduces inflammation, which is why I would expect it would work well for those,” the dermatologist said.

The mechanism of action of tapinarof has been worked out. The drug enters the cell and binds to the aryl hydrocarbon receptor, forming a complex that enters the nucleus. There it joins with the aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator, which regulates gene expression so as to reduce production of inflammatory cytokines while promoting an increase in skin barrier proteins, which is why tapinarof is also being developed as an atopic dermatitis therapy.

Dr. Lebwohl and Dr. Stein Gold reported receiving research funds from and serving as consultants to Dermavant Sciences as well as numerous other pharmaceutical companies.

FROM THE EADV CONGRESS

Translating the 2019 AAD-NPF Guidelines of Care for the Management of Psoriasis in Pediatric Patients

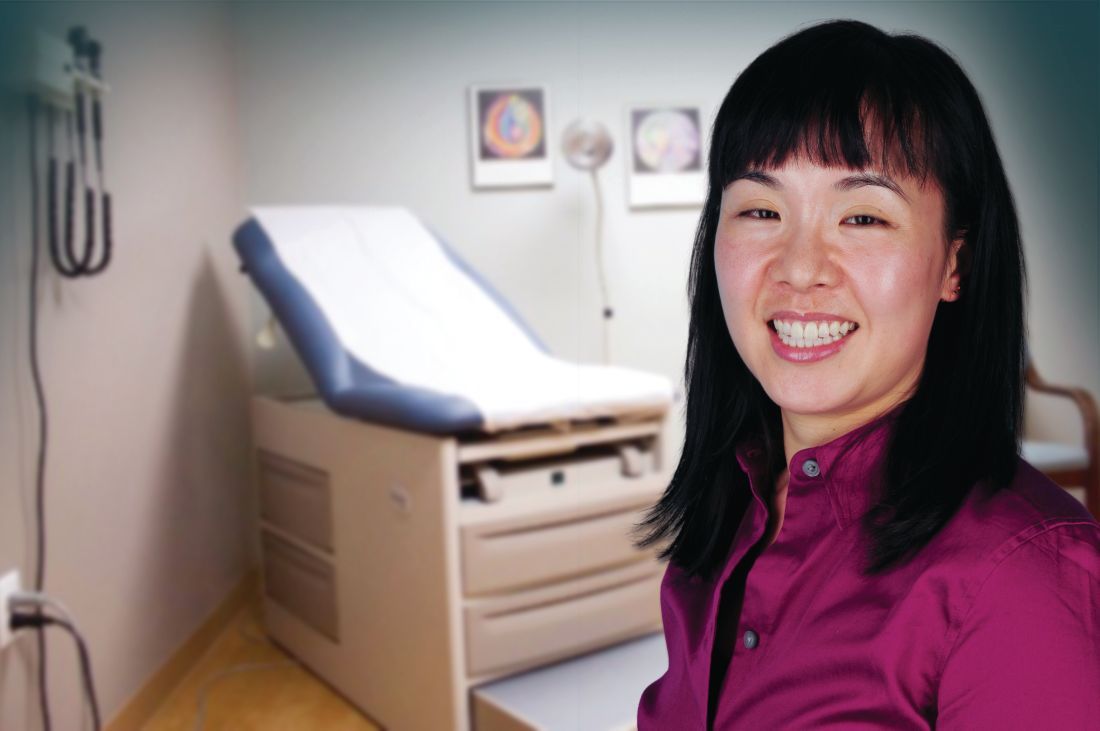

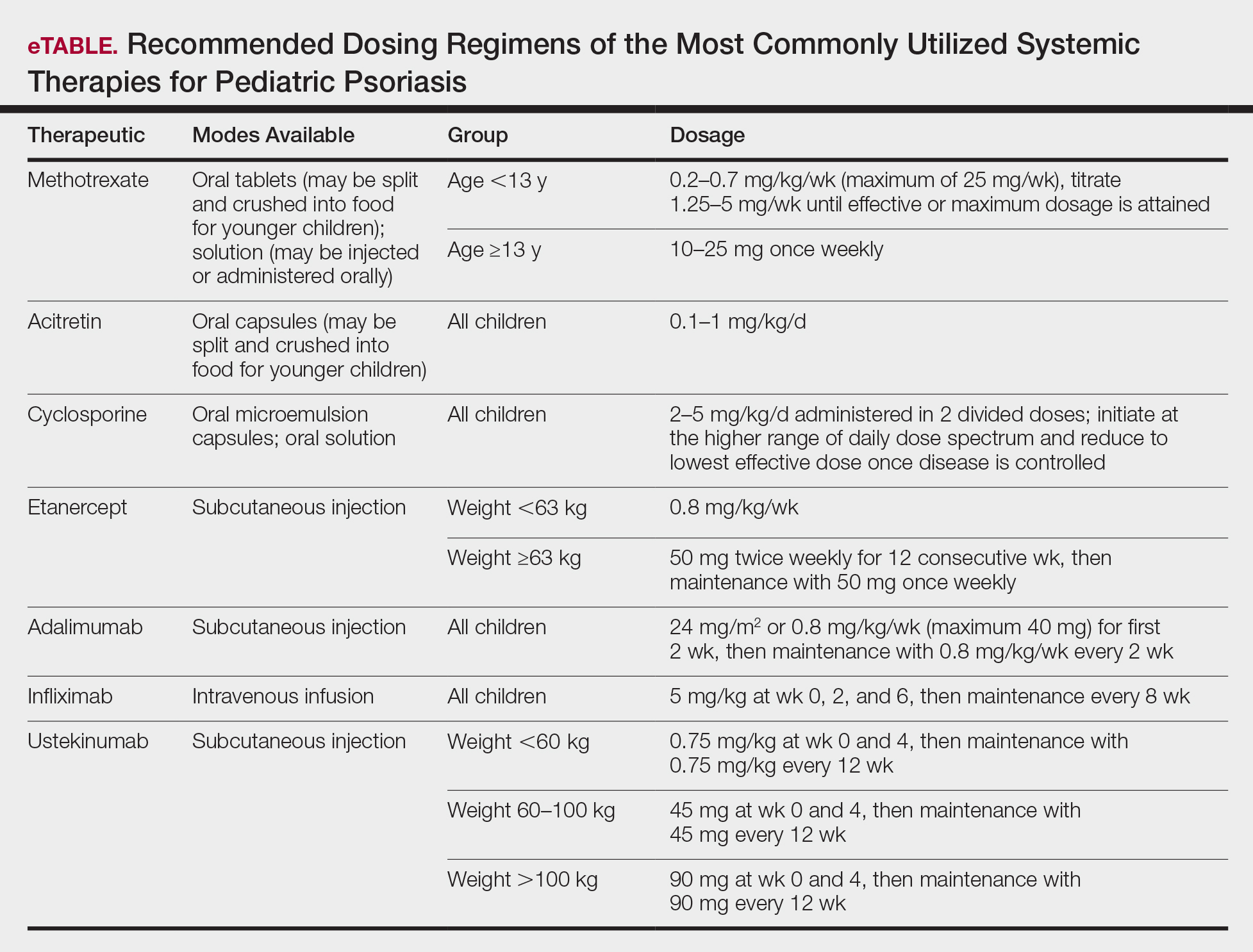

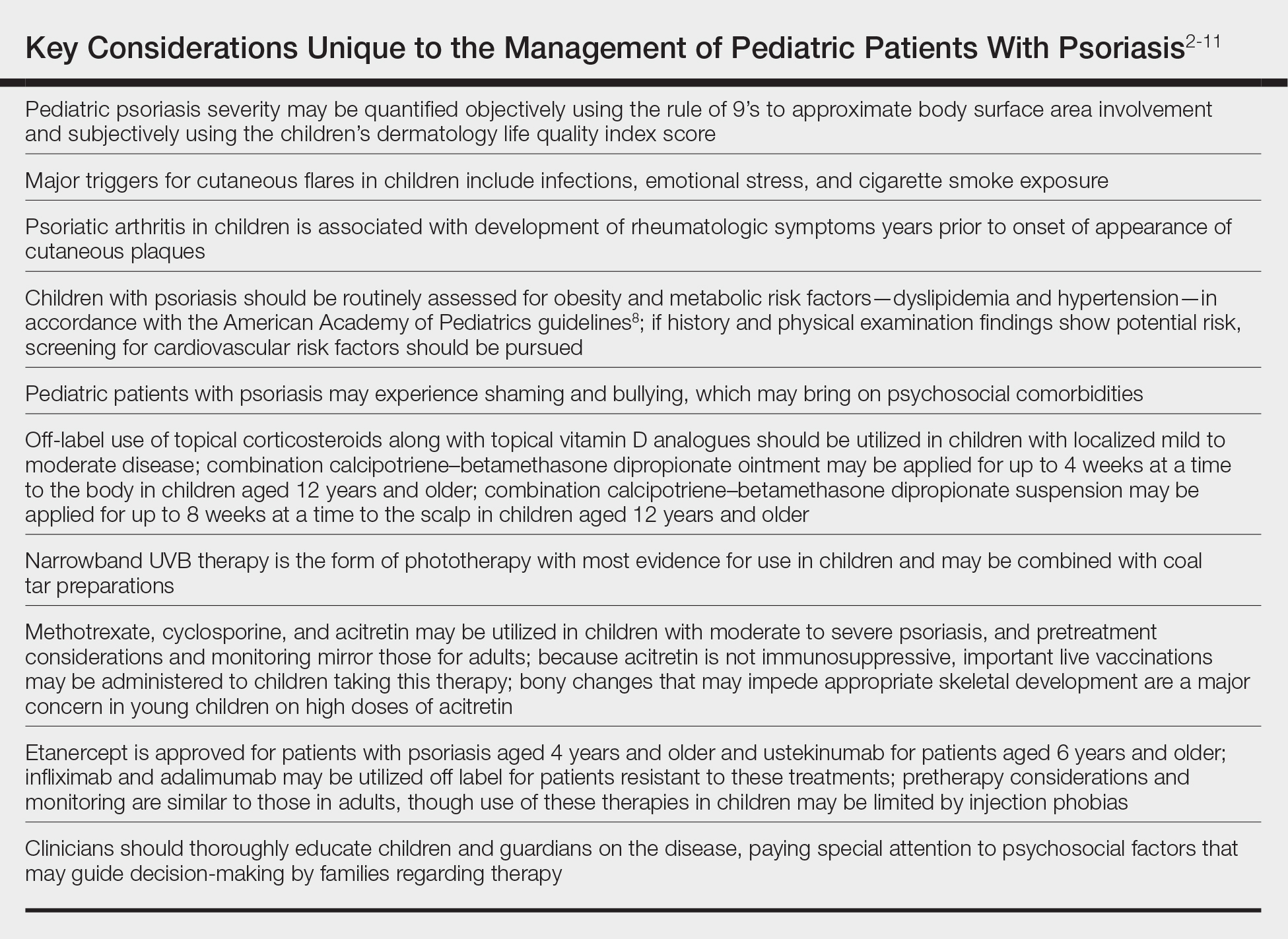

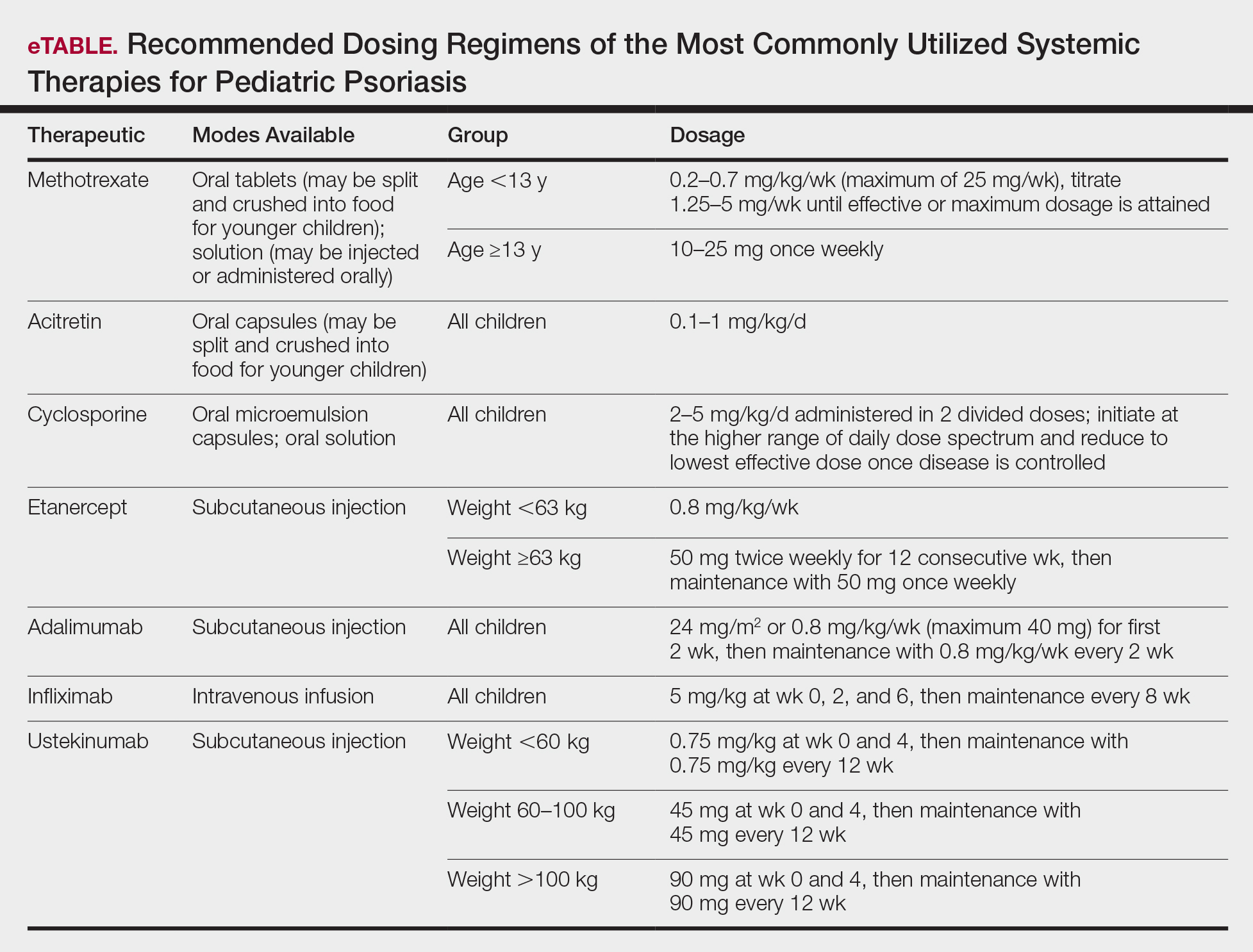

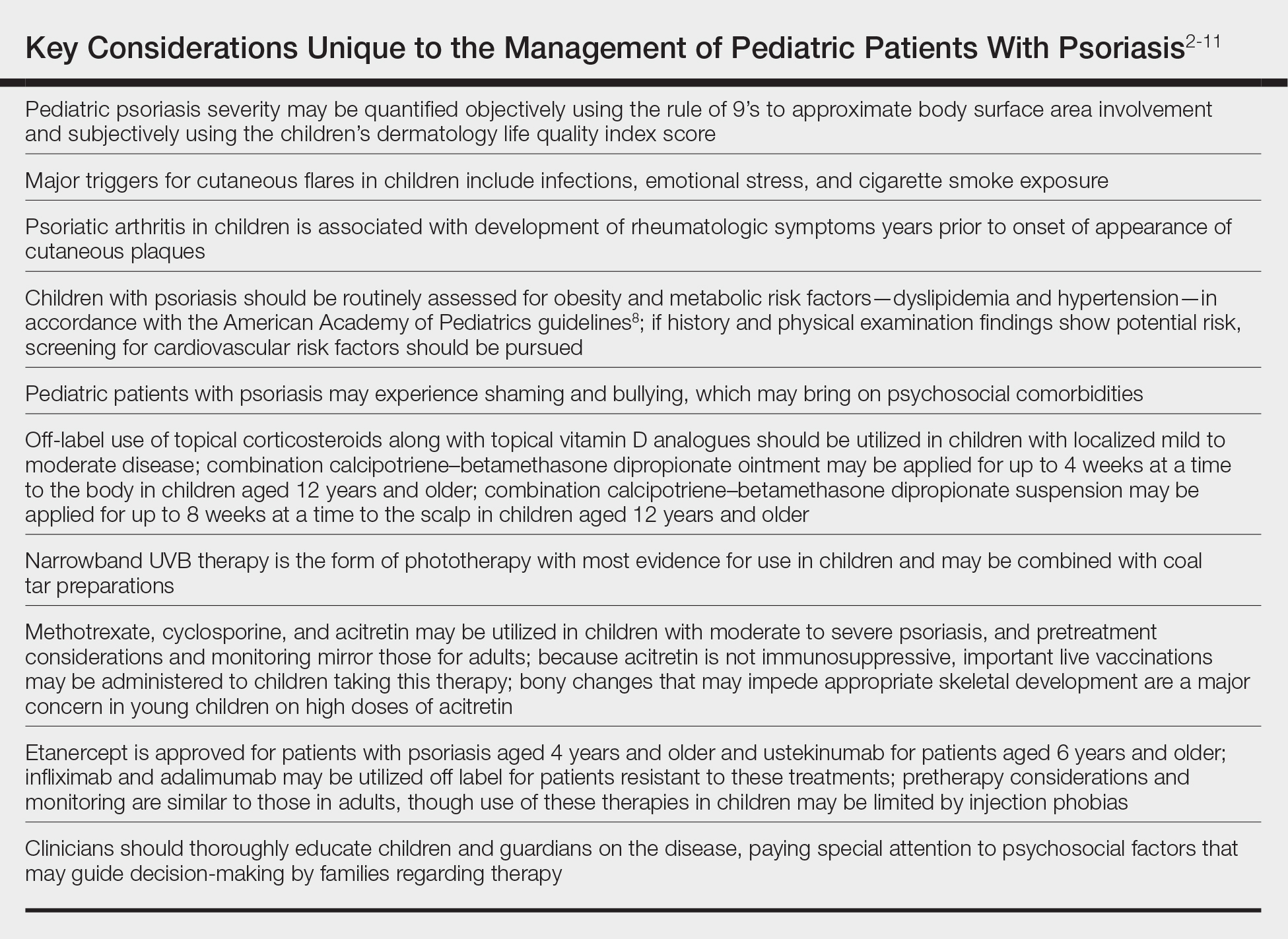

In November 2019, the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) and the National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) released their first set of recommendations for the management of pediatric psoriasis.1 The pediatric guidelines discuss methods of quantifying disease severity in children, triggers and comorbidities, and the efficacy and safety of various therapeutic agents. This review aims to discuss, in a condensed form, special considerations unique to the management of children with psoriasis as presented in the guidelines as well as grade A– and grade B–level treatment recommendations (Table).

Quantifying Psoriasis Severity in Children

Percentage body surface area (BSA) involvement is the most common mode of grading psoriasis severity, with less than 3% BSA involvement being considered mild, 3% to 10% BSA moderate, and more than 10% severe disease. In children, the standard method of measuring BSA is the rule of 9’s: the head and each arm make up 9% of the total BSA, each leg and the front and back of the torso respectively each make up 18%, and the genitalia make up 1%. It also is important to consider impact on quality of life, which may be remarkable in spite of limited BSA involvement. The children’s dermatology life quality index score may be utilized in combination with affected BSA to determine the burden of psoriasis in context of impact on daily life. This metric is available in both written and cartoon form, and it consists of 10 questions that include variables such as severity of itch, impact on social life, and effects on sleep. Most notably, this tool incorporates pruritus,2 which generally is addressed inadequately in pediatric psoriasis.

Triggers and Comorbidities in Pediatric Patients

In children, it is important to identify and eliminate modifiable factors that may prompt psoriasis flares. Infections, particularly group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal infections, are a major trigger in neonates and infants. Other exacerbating factors in children include emotional stress, secondhand cigarette smoke, Kawasaki disease, and withdrawal from systemic corticosteroids.

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a burdensome comorbidity affecting children with psoriasis. The prevalence of joint disease is 15-times greater in children with psoriasis vs those without,3 and 80% of children with PsA develop rheumatologic symptoms, which typically include oligoarticular disease and dactylitis in infants and girls and enthesitis and axial joint involvement in boys and older children, years prior to the onset of cutaneous disease.4 Uveitis often occurs in children with psoriasis and PsA but not in those with isolated cutaneous disease.

Compared to unaffected children, pediatric patients with psoriasis have greater prevalence of metabolic and cardiovascular risk factors during childhood, including central obesity, hypertension, hypertriglyceridemia, hypercholesterolemia, insulin resistance, atherosclerosis, arrythmia, and valvular heart disease. Family history of obesity increases the risk for early-onset development of cutaneous lesions,5,6 and weight reduction may alleviate severity of psoriasis lesions.7 In the United States, many of the metabolic associations observed are particularly robust in Black and Hispanic children vs those of other races. Furthermore, the prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease is 3- to 4-times higher in children with psoriasis compared to those without.

As with other cutaneous diseases, it is important to be aware of social and mental health concerns in children with psoriasis. The majority of pediatric patients with psoriasis experience name-calling, shaming, or bullying, and many have concerns from skin shedding and malodor. Independent risk for depression after the onset of psoriasis is high. Affected older children and adolescents are at increased risk for alcohol and drug abuse as well as eating disorders.

Despite these identified comorbidities, there are no unique screening recommendations for arthritis, ophthalmologic disease, metabolic disease, cardiovascular disease, gastrointestinal tract disease, or mental health issues in children with psoriasis. Rather, these patients should be monitored according to the American Academy of Pediatrics or American Diabetes Association guidelines for all pediatric patients.8,9 Nonetheless, educating patients and guardians about these potential issues may be warranted.

Topical Therapies

For children with mild to moderate psoriasis, topical therapies are first line. Despite being off label, topical corticosteroids are the mainstay of therapy for localized psoriatic plaques in children. Topical vitamin D analogues—calcitriol and calcipotriol/calcipotriene—are highly effective and well tolerated, and they frequently are used in combination with topical corticosteroids. Topical calcineurin inhibitors, namely tacrolimus, also are used off label but are considered first line for sensitive regions of the skin in children, including the face, genitalia, and body folds. There currently is limited evidence for supporting the use of the topical vitamin A analogue tazarotene in children with psoriasis, though some consider its off-label use effective for pediatric nail psoriasis. It also may be used as an adjunct to topical corticosteroids to minimize irritation.

Although there is no gold standard topical regimen, combination therapy with a high-potency topical steroid and topical vitamin D analogue commonly is used to minimize steroid-induced side effects. For the first 2 weeks of treatment, they each may be applied once daily or mixed together and applied twice daily. For subsequent maintenance, topical calcipotriene may be applied on weekdays and topical steroids only on weekends. Combination calcipotriol–betamethasone dipropionate also is available as cream, ointment, foam, and suspension vehicles for use on the body and scalp in children aged 12 years and older. Tacrolimus ointment 0.1% may be applied in a thin layer up to twice daily. Concurrent emollient use also is recommended with these therapies.

Health care providers should educate patients and guardians about the potential side effects of topical therapies. They also should provide explicit instructions for amount, site, frequency, and duration of application. Topical corticosteroids commonly result in burning on application and may potentially cause skin thinning and striae with overuse. Topical vitamin D analogues may result in local irritation that may be improved by concurrent emollient use, and they generally should be avoided on sensitive sites. Topical calcineurin inhibitors are associated with burning, stinging, and pruritus, and the US Food and Drug Administration has issued a black-box warning related to risk for lymphoma with their chronic intermittent use. However, it was based on rare reports of lymphoma in transplant patients taking oral calcineurin inhibitors; no clinical trials to date in humans have demonstrated an increased risk for malignancy with topical calcineurin inhibitors.10 Tazarotene should be used cautiously in females of childbearing age given its teratogenic potential.

Children younger than 7 years are especially prone to suppression of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis from topical corticosteroid therapy and theoretically hypercalcemia and hypervitaminosis D from topical vitamin D analogues, as their high BSA-to-volume ratio increases potential for systemic absorption. Children should avoid occlusive application of topical vitamin D analogues to large areas of the skin. Monitoring of vitamin D metabolites in the serum may be considered if calcipotriene or calcipotriol application to a large BSA is warranted.

Light-Based Therapy

In children with widespread psoriasis or those refractory to topical therapy, phototherapy may be considered. Narrowband UVB (311- to 313-nm wavelength) therapy is considered a first-line form of phototherapy in pediatric psoriasis. Mineral oil or emollient pretreatment to affected areas may augment the efficacy of UV-based treatments.11 Excimer laser and UVA also may be efficacious, though evidence is limited in children. Treatment is recommended to start at 3 days a week, and once improvement is seen, the frequency can be decreased to 2 days a week. Once desired clearance is achieved, maintenance therapy can be continued at even longer intervals. Adjunctive use of tar preparations may potentiate the efficacy of phototherapy, though there is a theoretical increased risk for carcinogenicity with prolonged use of coal tar. Side effects of phototherapy include erythema, blistering hyperpigmentation, and pruritus. Psoralen is contraindicated in children younger than 12 years. All forms of phototherapy are contraindicated in children with generalized erythroderma and cutaneous cancer syndromes. Other important pediatric-specific considerations include anxiety that may be provoked by UV light machines and inconvenience of frequent appointments.

Nonbiologic Systemic Therapies

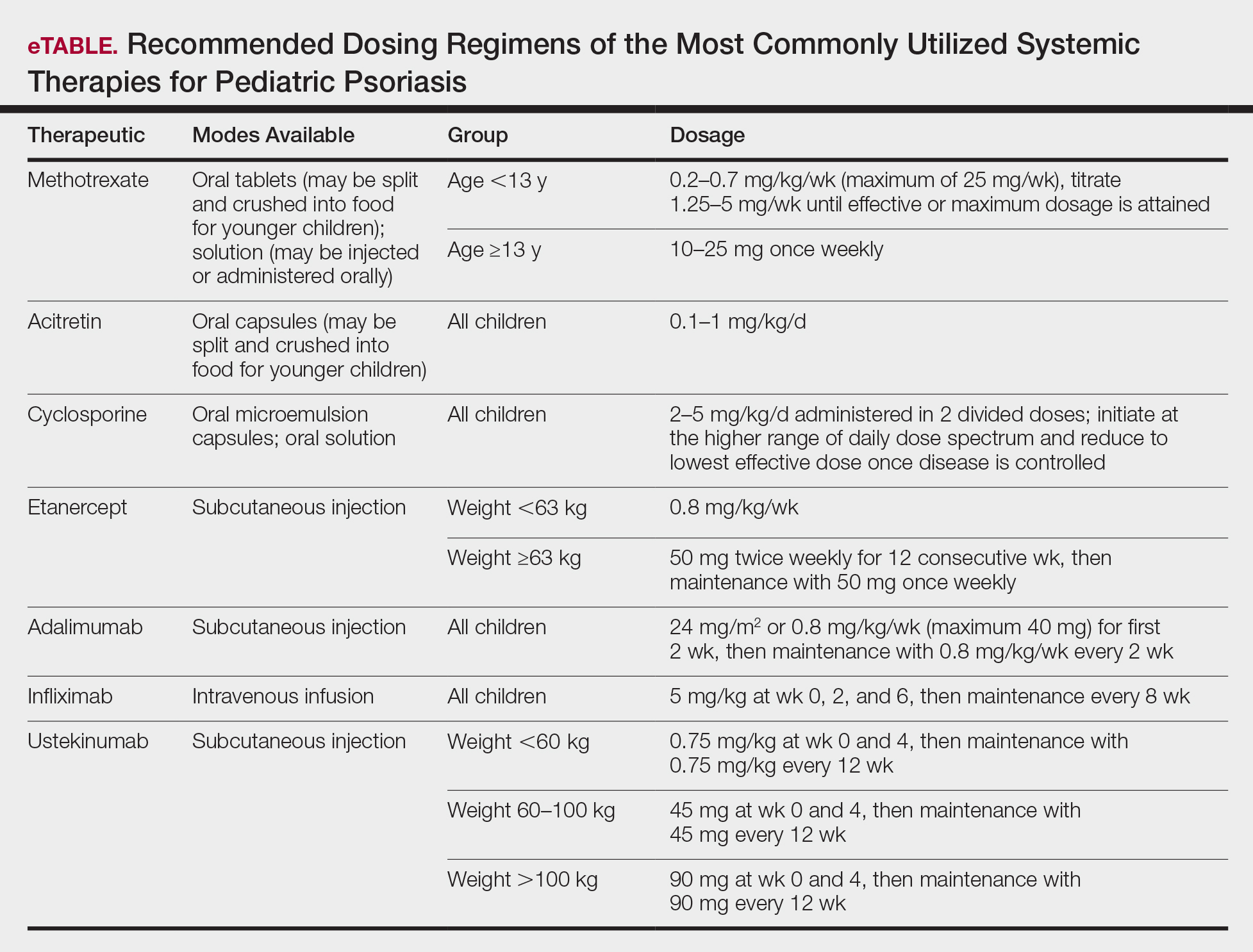

Systemic therapies may be considered in children with recalcitrant, widespread, or rapidly progressing psoriasis, particularly if the disease is accompanied by severe emotional and psychological burden. These drugs, which include methotrexate, cyclosporine, and acitretin (see eTable for recommended dosing), are advantageous in that they may be combined with other therapies; however, they have potential for dangerous toxicities.

Methotrexate is the most frequently utilized systemic therapy for psoriasis worldwide in children because of its low cost, once-weekly dosing, and the substantial amount of long-term efficacy and safety data available in the pediatric population. It is slow acting initially but has excellent long-term efficacy for nearly every subtype of psoriasis. The most common side effect of methotrexate is gastrointestinal tract intolerance. Nonetheless, adverse events are rare in children without prior history, with 1 large study (N=289) reporting no adverse events in more than 90% of patients aged 9 to 14 years treated with methotrexate.12 Current guidelines recommend monitoring for bone marrow suppression and elevated transaminase levels 4 to 6 days after initiating treatment.1 The absolute contraindications for methotrexate are pregnancy and liver disease, and caution should be taken in children with metabolic risk factors. Adolescents must be counseled regarding the elevated risk for hepatotoxicity associated with alcohol ingestion. Methotrexate therapy also requires 1 mg folic acid supplementation 6 to 7 days a week, which decreases the risk for developing folic acid deficiency and may decrease gastrointestinal tract intolerance and hepatic side effects that may result from therapy.

Cyclosporine is an effective and well-tolerated option for rapid control of severe psoriasis in children. It is useful for various types of psoriasis but generally is reserved for more severe subtypes, such as generalized pustular psoriasis, erythrodermic psoriasis, and uncontrolled plaque psoriasis. Long-term use of cyclosporine may result in renal toxicity and hypertension, and this therapy is absolutely contraindicated in children with kidney disease or hypertension at baseline. It is strongly recommended to evaluate blood pressure every week for the first month of therapy and at every subsequent follow-up visit, which may occur at variable intervals based on the judgement of the provider. Evaluation before and during treatment with cyclosporine also should include a complete blood cell count, complete metabolic panel, and lipid panel.

Systemic retinoids have a unique advantage over methotrexate and cyclosporine in that they are not immunosuppressive and therefore are not contraindicated in children who are very young or immunosuppressed. Children receiving systemic retinoids also can receive routine live vaccines—measles-mumps-rubella, varicella zoster, and rotavirus—that are contraindicated with other systemic therapies. Acitretin is particularly effective in pediatric patients with diffuse guttate psoriasis, pustular psoriasis, and palmoplantar psoriasis. Narrowband UVB therapy has been shown to augment the effectiveness of acitretin in children, which may allow for reduced acitretin dosing. Pustular psoriasis may respond as quickly as 3 weeks after initiation, whereas it may take 2 to 3 months before improvement is noticed in plaque psoriasis. Side effects of retinoids include skin dryness, hyperlipidemia, and gastrointestinal tract upset. The most severe long-term concern is skeletal toxicity, including premature epiphyseal closure, hyperostosis, periosteal bone formation, and decreased bone mineral density.1 Vitamin A derivatives also are known teratogens and should be avoided in females of childbearing potential. Lipids and transaminases should be monitored routinely, and screening for depression and psychiatric symptoms should be performed frequently.1

When utilizing systemic therapies, the objective should be to control the disease, maintain stability, and ultimately taper to the lowest effective dose or transition to a topical therapy, if feasible. Although no particular systemic therapy is recommended as first line for children with psoriasis, it is important to consider comorbidities, contraindications, monitoring frequency, mode of administration (injectable therapies elicit more psychological trauma in children than oral therapies), and expense when determining the best choice.

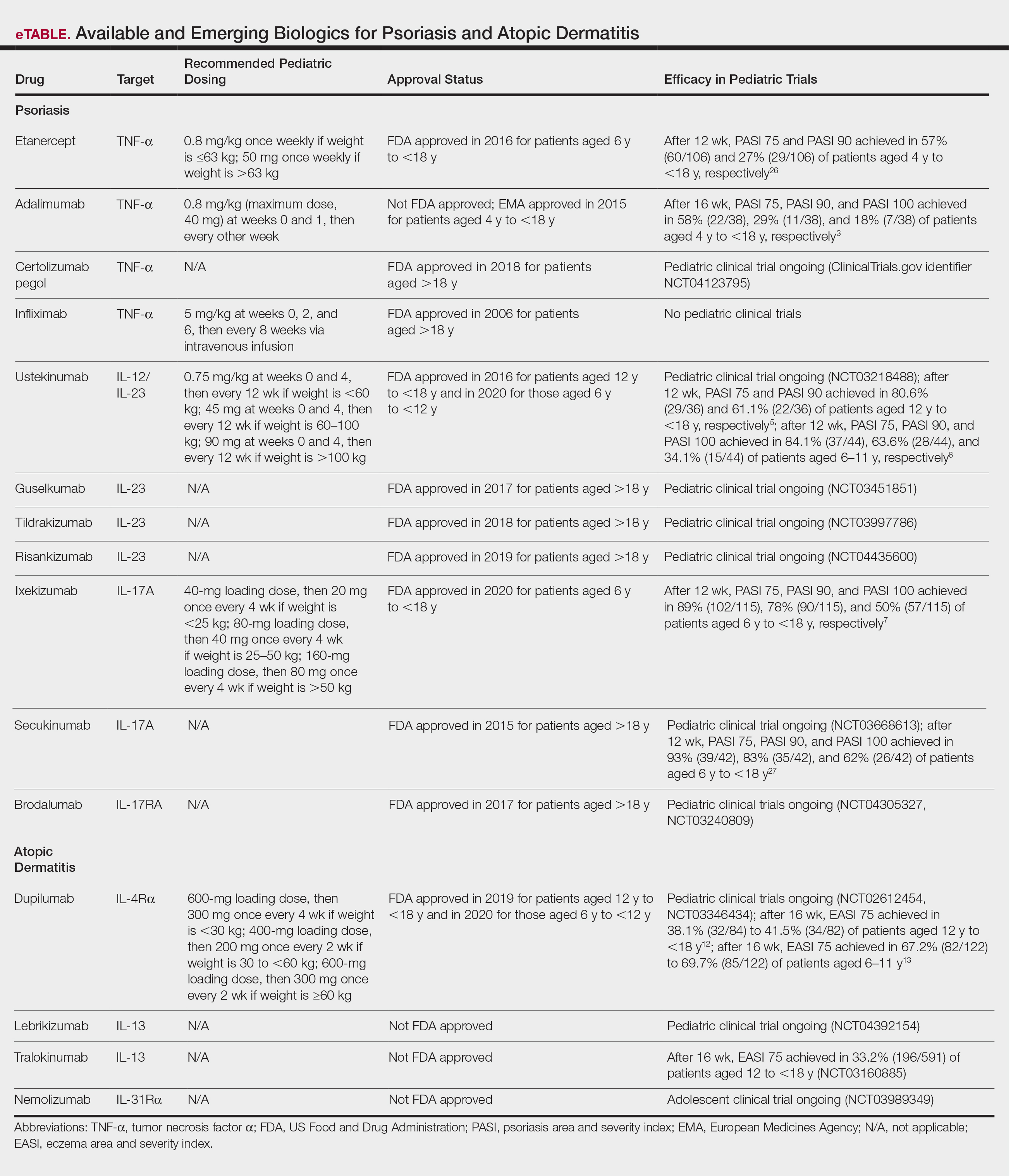

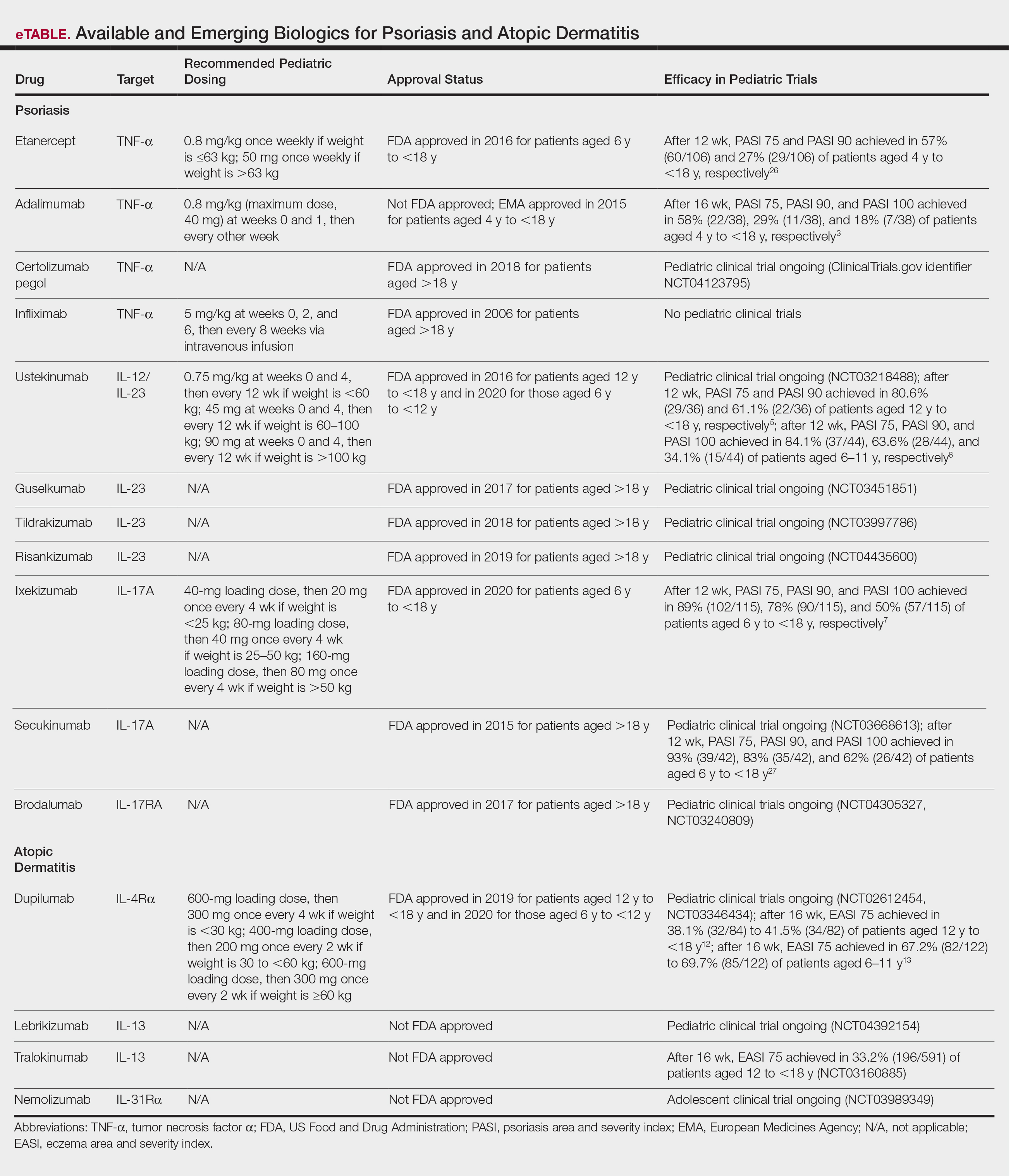

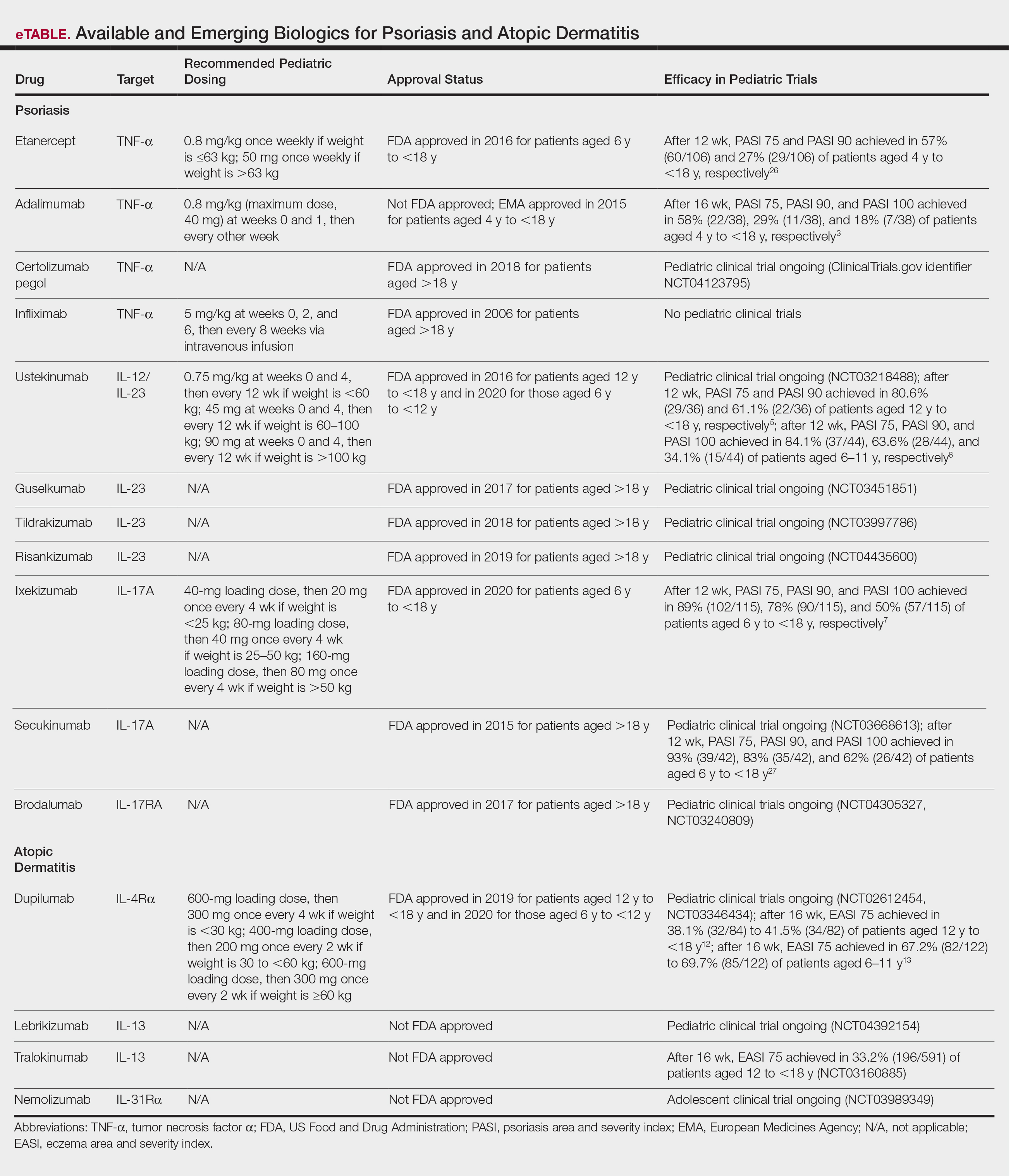

Biologics

Biologic agents are associated with very high to total psoriatic plaque clearance rates and require infrequent dosing and monitoring. However, their use may be limited by cost and injection phobias in children as well as limited evidence for their efficacy and safety in pediatric psoriasis. Several studies have established the safety and effectiveness of biologics in children with plaque psoriasis (see eTable for recommended dosing), whereas the evidence supporting their use in treating pustular and erythrodermic variants are limited to case reports and case series. The tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) inhibitor etanercept has been approved for use in children aged 4 years and older, and the IL-12/IL-23 inhibitor ustekinumab is approved in children aged 6 years and older. Other TNF-α inhibitors, namely infliximab and adalimumab, commonly are utilized off label for pediatric psoriasis. The most common side effect of biologic therapies in pediatric patients is injection-site reactions.1 Prior to initiating therapy, children must undergo tuberculosis screening either by purified protein derivative testing or IFN-γ release assay. Testing should be repeated annually in individuals taking TNF-α inhibitors, though the utility of repeat testing when taking biologics in other classes is not clear. High-risk patients also should be screened for human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis. Follow-up frequency may range from every 3 months to annually, based on judgement of the provider. In children who develop loss of response to biologics, methotrexate can be added to the regimen to attenuate formation of efficacy-reducing antidrug antibodies.

Final Thoughts

When managing children with psoriasis, it is important for dermatologists to appropriately educate guardians and children on the disease course, as well as consider the psychological, emotional, social, and financial factors that may direct decision-making regarding optimal therapeutics. Dermatologists should consider collaboration with the child’s primary care physician and other specialists to ensure that all needs are met.

These guidelines provide a framework agreed upon by numerous experts in pediatric psoriasis, but they are limited by gaps in the research. There still is much to be learned regarding the pathophysiology of psoriasis; the risk for developing comorbidities during adulthood; and the efficacy and safety of certain therapeutics, particularly biologics, in pediatric patients with psoriasis.

- Menter A, Cordoro KM, Davis DMR, et al. Joint American Academy of Dermatology–National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis in pediatric patients [published online November 5, 2019]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:161-201.

- Lewis-Jones MS, Finlay AY. The Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI): initial validation and practical use. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:942-949.

- Augustin M, Radtke MA, Glaeske G, et al. Epidemiology and comorbidity in children with psoriasis and atopic eczema. Dermatology. 2015;231:35-40.

- Osier E, Wang AS, Tollefson MM, et al. Pediatric psoriasis comorbidity screening guidelines. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:698-704.

- Boccardi D, Menni S, La Vecchia C, et al. Overweight and childhood psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:484-486.

- Becker L, Tom WL, Eshagh K, et al. Excess adiposity preceding pediatric psoriasis. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:573-574.

- Alotaibi HA. Effects of weight loss on psoriasis: a review of clinical trials. Cureus. 2018;10:E3491.

- Guidelines summaries—American Academy of Pediatrics. Guideline Central

website. https://www.guidelinecentral.com/summaries/organizations/american-academy-of-pediatrics/2019. Accessed October 27, 2020. - Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes. American Diabetes Association website. https://care.diabetesjournals.org/content/43/Supplement_1. Published January 1, 2020. Accessed May 8, 2020.

- Siegfried EC, Jaworski JC, Hebert AA. Topical calcineurin inhibitors and lymphoma risk: evidence update with implications for daily practice. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:163-178.

- Jain VK, Bansal A, Aggarwal K, et al. Enhanced response of childhood psoriasis to narrow-band UV-B phototherapy with preirradiation use of mineral oil. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25:559-564.

- Ergun T, Seckin Gencosmanoglu D, Alpsoy E, et al. Efficacy, safety and drug survival of conventional agents in pediatric psoriasis: a multicenter, cohort study. J Dermatol. 2017;44:630-634.

In November 2019, the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) and the National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) released their first set of recommendations for the management of pediatric psoriasis.1 The pediatric guidelines discuss methods of quantifying disease severity in children, triggers and comorbidities, and the efficacy and safety of various therapeutic agents. This review aims to discuss, in a condensed form, special considerations unique to the management of children with psoriasis as presented in the guidelines as well as grade A– and grade B–level treatment recommendations (Table).

Quantifying Psoriasis Severity in Children

Percentage body surface area (BSA) involvement is the most common mode of grading psoriasis severity, with less than 3% BSA involvement being considered mild, 3% to 10% BSA moderate, and more than 10% severe disease. In children, the standard method of measuring BSA is the rule of 9’s: the head and each arm make up 9% of the total BSA, each leg and the front and back of the torso respectively each make up 18%, and the genitalia make up 1%. It also is important to consider impact on quality of life, which may be remarkable in spite of limited BSA involvement. The children’s dermatology life quality index score may be utilized in combination with affected BSA to determine the burden of psoriasis in context of impact on daily life. This metric is available in both written and cartoon form, and it consists of 10 questions that include variables such as severity of itch, impact on social life, and effects on sleep. Most notably, this tool incorporates pruritus,2 which generally is addressed inadequately in pediatric psoriasis.

Triggers and Comorbidities in Pediatric Patients

In children, it is important to identify and eliminate modifiable factors that may prompt psoriasis flares. Infections, particularly group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal infections, are a major trigger in neonates and infants. Other exacerbating factors in children include emotional stress, secondhand cigarette smoke, Kawasaki disease, and withdrawal from systemic corticosteroids.

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a burdensome comorbidity affecting children with psoriasis. The prevalence of joint disease is 15-times greater in children with psoriasis vs those without,3 and 80% of children with PsA develop rheumatologic symptoms, which typically include oligoarticular disease and dactylitis in infants and girls and enthesitis and axial joint involvement in boys and older children, years prior to the onset of cutaneous disease.4 Uveitis often occurs in children with psoriasis and PsA but not in those with isolated cutaneous disease.

Compared to unaffected children, pediatric patients with psoriasis have greater prevalence of metabolic and cardiovascular risk factors during childhood, including central obesity, hypertension, hypertriglyceridemia, hypercholesterolemia, insulin resistance, atherosclerosis, arrythmia, and valvular heart disease. Family history of obesity increases the risk for early-onset development of cutaneous lesions,5,6 and weight reduction may alleviate severity of psoriasis lesions.7 In the United States, many of the metabolic associations observed are particularly robust in Black and Hispanic children vs those of other races. Furthermore, the prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease is 3- to 4-times higher in children with psoriasis compared to those without.

As with other cutaneous diseases, it is important to be aware of social and mental health concerns in children with psoriasis. The majority of pediatric patients with psoriasis experience name-calling, shaming, or bullying, and many have concerns from skin shedding and malodor. Independent risk for depression after the onset of psoriasis is high. Affected older children and adolescents are at increased risk for alcohol and drug abuse as well as eating disorders.

Despite these identified comorbidities, there are no unique screening recommendations for arthritis, ophthalmologic disease, metabolic disease, cardiovascular disease, gastrointestinal tract disease, or mental health issues in children with psoriasis. Rather, these patients should be monitored according to the American Academy of Pediatrics or American Diabetes Association guidelines for all pediatric patients.8,9 Nonetheless, educating patients and guardians about these potential issues may be warranted.

Topical Therapies

For children with mild to moderate psoriasis, topical therapies are first line. Despite being off label, topical corticosteroids are the mainstay of therapy for localized psoriatic plaques in children. Topical vitamin D analogues—calcitriol and calcipotriol/calcipotriene—are highly effective and well tolerated, and they frequently are used in combination with topical corticosteroids. Topical calcineurin inhibitors, namely tacrolimus, also are used off label but are considered first line for sensitive regions of the skin in children, including the face, genitalia, and body folds. There currently is limited evidence for supporting the use of the topical vitamin A analogue tazarotene in children with psoriasis, though some consider its off-label use effective for pediatric nail psoriasis. It also may be used as an adjunct to topical corticosteroids to minimize irritation.

Although there is no gold standard topical regimen, combination therapy with a high-potency topical steroid and topical vitamin D analogue commonly is used to minimize steroid-induced side effects. For the first 2 weeks of treatment, they each may be applied once daily or mixed together and applied twice daily. For subsequent maintenance, topical calcipotriene may be applied on weekdays and topical steroids only on weekends. Combination calcipotriol–betamethasone dipropionate also is available as cream, ointment, foam, and suspension vehicles for use on the body and scalp in children aged 12 years and older. Tacrolimus ointment 0.1% may be applied in a thin layer up to twice daily. Concurrent emollient use also is recommended with these therapies.

Health care providers should educate patients and guardians about the potential side effects of topical therapies. They also should provide explicit instructions for amount, site, frequency, and duration of application. Topical corticosteroids commonly result in burning on application and may potentially cause skin thinning and striae with overuse. Topical vitamin D analogues may result in local irritation that may be improved by concurrent emollient use, and they generally should be avoided on sensitive sites. Topical calcineurin inhibitors are associated with burning, stinging, and pruritus, and the US Food and Drug Administration has issued a black-box warning related to risk for lymphoma with their chronic intermittent use. However, it was based on rare reports of lymphoma in transplant patients taking oral calcineurin inhibitors; no clinical trials to date in humans have demonstrated an increased risk for malignancy with topical calcineurin inhibitors.10 Tazarotene should be used cautiously in females of childbearing age given its teratogenic potential.

Children younger than 7 years are especially prone to suppression of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis from topical corticosteroid therapy and theoretically hypercalcemia and hypervitaminosis D from topical vitamin D analogues, as their high BSA-to-volume ratio increases potential for systemic absorption. Children should avoid occlusive application of topical vitamin D analogues to large areas of the skin. Monitoring of vitamin D metabolites in the serum may be considered if calcipotriene or calcipotriol application to a large BSA is warranted.

Light-Based Therapy

In children with widespread psoriasis or those refractory to topical therapy, phototherapy may be considered. Narrowband UVB (311- to 313-nm wavelength) therapy is considered a first-line form of phototherapy in pediatric psoriasis. Mineral oil or emollient pretreatment to affected areas may augment the efficacy of UV-based treatments.11 Excimer laser and UVA also may be efficacious, though evidence is limited in children. Treatment is recommended to start at 3 days a week, and once improvement is seen, the frequency can be decreased to 2 days a week. Once desired clearance is achieved, maintenance therapy can be continued at even longer intervals. Adjunctive use of tar preparations may potentiate the efficacy of phototherapy, though there is a theoretical increased risk for carcinogenicity with prolonged use of coal tar. Side effects of phototherapy include erythema, blistering hyperpigmentation, and pruritus. Psoralen is contraindicated in children younger than 12 years. All forms of phototherapy are contraindicated in children with generalized erythroderma and cutaneous cancer syndromes. Other important pediatric-specific considerations include anxiety that may be provoked by UV light machines and inconvenience of frequent appointments.

Nonbiologic Systemic Therapies

Systemic therapies may be considered in children with recalcitrant, widespread, or rapidly progressing psoriasis, particularly if the disease is accompanied by severe emotional and psychological burden. These drugs, which include methotrexate, cyclosporine, and acitretin (see eTable for recommended dosing), are advantageous in that they may be combined with other therapies; however, they have potential for dangerous toxicities.

Methotrexate is the most frequently utilized systemic therapy for psoriasis worldwide in children because of its low cost, once-weekly dosing, and the substantial amount of long-term efficacy and safety data available in the pediatric population. It is slow acting initially but has excellent long-term efficacy for nearly every subtype of psoriasis. The most common side effect of methotrexate is gastrointestinal tract intolerance. Nonetheless, adverse events are rare in children without prior history, with 1 large study (N=289) reporting no adverse events in more than 90% of patients aged 9 to 14 years treated with methotrexate.12 Current guidelines recommend monitoring for bone marrow suppression and elevated transaminase levels 4 to 6 days after initiating treatment.1 The absolute contraindications for methotrexate are pregnancy and liver disease, and caution should be taken in children with metabolic risk factors. Adolescents must be counseled regarding the elevated risk for hepatotoxicity associated with alcohol ingestion. Methotrexate therapy also requires 1 mg folic acid supplementation 6 to 7 days a week, which decreases the risk for developing folic acid deficiency and may decrease gastrointestinal tract intolerance and hepatic side effects that may result from therapy.

Cyclosporine is an effective and well-tolerated option for rapid control of severe psoriasis in children. It is useful for various types of psoriasis but generally is reserved for more severe subtypes, such as generalized pustular psoriasis, erythrodermic psoriasis, and uncontrolled plaque psoriasis. Long-term use of cyclosporine may result in renal toxicity and hypertension, and this therapy is absolutely contraindicated in children with kidney disease or hypertension at baseline. It is strongly recommended to evaluate blood pressure every week for the first month of therapy and at every subsequent follow-up visit, which may occur at variable intervals based on the judgement of the provider. Evaluation before and during treatment with cyclosporine also should include a complete blood cell count, complete metabolic panel, and lipid panel.

Systemic retinoids have a unique advantage over methotrexate and cyclosporine in that they are not immunosuppressive and therefore are not contraindicated in children who are very young or immunosuppressed. Children receiving systemic retinoids also can receive routine live vaccines—measles-mumps-rubella, varicella zoster, and rotavirus—that are contraindicated with other systemic therapies. Acitretin is particularly effective in pediatric patients with diffuse guttate psoriasis, pustular psoriasis, and palmoplantar psoriasis. Narrowband UVB therapy has been shown to augment the effectiveness of acitretin in children, which may allow for reduced acitretin dosing. Pustular psoriasis may respond as quickly as 3 weeks after initiation, whereas it may take 2 to 3 months before improvement is noticed in plaque psoriasis. Side effects of retinoids include skin dryness, hyperlipidemia, and gastrointestinal tract upset. The most severe long-term concern is skeletal toxicity, including premature epiphyseal closure, hyperostosis, periosteal bone formation, and decreased bone mineral density.1 Vitamin A derivatives also are known teratogens and should be avoided in females of childbearing potential. Lipids and transaminases should be monitored routinely, and screening for depression and psychiatric symptoms should be performed frequently.1

When utilizing systemic therapies, the objective should be to control the disease, maintain stability, and ultimately taper to the lowest effective dose or transition to a topical therapy, if feasible. Although no particular systemic therapy is recommended as first line for children with psoriasis, it is important to consider comorbidities, contraindications, monitoring frequency, mode of administration (injectable therapies elicit more psychological trauma in children than oral therapies), and expense when determining the best choice.

Biologics

Biologic agents are associated with very high to total psoriatic plaque clearance rates and require infrequent dosing and monitoring. However, their use may be limited by cost and injection phobias in children as well as limited evidence for their efficacy and safety in pediatric psoriasis. Several studies have established the safety and effectiveness of biologics in children with plaque psoriasis (see eTable for recommended dosing), whereas the evidence supporting their use in treating pustular and erythrodermic variants are limited to case reports and case series. The tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) inhibitor etanercept has been approved for use in children aged 4 years and older, and the IL-12/IL-23 inhibitor ustekinumab is approved in children aged 6 years and older. Other TNF-α inhibitors, namely infliximab and adalimumab, commonly are utilized off label for pediatric psoriasis. The most common side effect of biologic therapies in pediatric patients is injection-site reactions.1 Prior to initiating therapy, children must undergo tuberculosis screening either by purified protein derivative testing or IFN-γ release assay. Testing should be repeated annually in individuals taking TNF-α inhibitors, though the utility of repeat testing when taking biologics in other classes is not clear. High-risk patients also should be screened for human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis. Follow-up frequency may range from every 3 months to annually, based on judgement of the provider. In children who develop loss of response to biologics, methotrexate can be added to the regimen to attenuate formation of efficacy-reducing antidrug antibodies.

Final Thoughts

When managing children with psoriasis, it is important for dermatologists to appropriately educate guardians and children on the disease course, as well as consider the psychological, emotional, social, and financial factors that may direct decision-making regarding optimal therapeutics. Dermatologists should consider collaboration with the child’s primary care physician and other specialists to ensure that all needs are met.

These guidelines provide a framework agreed upon by numerous experts in pediatric psoriasis, but they are limited by gaps in the research. There still is much to be learned regarding the pathophysiology of psoriasis; the risk for developing comorbidities during adulthood; and the efficacy and safety of certain therapeutics, particularly biologics, in pediatric patients with psoriasis.