User login

Doctors’ offices may be hot spot for transmission of respiratory infections

Prior research has examined the issue of hospital-acquired infections. A 2014 study published in the New England Journal of Medicine, for example, found that 4% of hospitalized patients acquired a health care–associated infection during their stay. Furthermore, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that, on any given day, one in 31 hospital patients has at least one health care–associated infection. However, researchers for the new study, published in Health Affairs, said evidence about the risk of acquiring respiratory viral infections in medical office settings is limited.

“Hospital-acquired infections has been a problem for a while,” study author Hannah Neprash, PhD, of the department of health policy and management at the University of Minnesota School of Public Health, Minneapolis, said in an interview. “However, there’s never been a similar study of whether a similar phenomenon happens in physician offices. This is especially relevant now when we’re dealing with respiratory infections.”

Methods and results

For the new study, Dr. Neprash and her colleagues analyzed deidentified billing and scheduling data from 2016-2017 for 105,462,600 outpatient visits that occurred at 6,709 office-based primary care practices. They used the World Health Organization case definition for influenzalike illness “to capture cases in which the physician may suspect this illness even if a specific diagnosis code was not present.” Their control conditions included exposure to urinary tract infections and back pain.

Doctor visits were considered unexposed if they were scheduled to start at least 90 minutes before the first influenzalike illness visit of the day. They were considered exposed if they were scheduled to start at the same time or after the first influenzalike illness visit of the day at that practice.

Researchers quantified whether exposed patients were more likely to return with a similar illness in the next 2 weeks, compared with nonexposed patients seen earlier in the day

They found that 2.7 patients per 1,000 returned within 2 weeks with an influenzalike illness.

Patients were more likely to return with influenzalike illness if their visit occurred after an influenzalike illness visit versus before, the researchers said.

The authors of the paper said their new research highlights the importance of infection control in health care settings, including outpatient offices.

Where did the exposure occur?

Diego Hijano, MD, MSc, pediatric infectious disease specialist at St. Jude’s Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, Tenn., said he was not surprised by the findings, but noted that it’s hard to say if the exposure to influenzalike illnesses happened in the office or in the community.

“If you start to see individuals with influenza in your office it’s because [there’s influenza] in the community,” Dr. Hijano explained. “So that means that you will have more patients coming in with influenza.”

To reduce the transmission of infections, Dr. Neprash suggested that doctors’ offices follow the CDC guidelines for indoor conduct, which include masking, washing hands, and “taking appropriate infection control measures.”

So potentially masking within offices is a way to minimize transmission between whatever people are there to be seen when it’s contagious, Dr. Neprash said.

“Telehealth really took off in 2020 and it’s unclear what the state of telehealth will be going forward. [These findings] suggest that there’s a patient safety argument for continuing to enable primary care physicians to provide visits either by phone or by video,” he added.

Dr. Hijano thinks it would be helpful for doctors to separate patients with respiratory illnesses from those without respiratory illnesses.

Driver of transmissions

Dr. Neprash suggested that another driver of these transmissions could be doctors not washing their hands, which is a “notorious issue,” and Dr. Hijano agreed with that statement.

“We did know that the hands of physicians and nurses and care providers are the main driver of infections in the health care setting,” Dr. Hijano explained. “I mean, washing your hands properly between encounters is the single best way that any given health care provider can prevent the spread of infections.”

“We have a unique opportunity with COVID-19 to change how these clinics are operating now,” Dr. Hijano said. “Many clinics are actually asking patients to call ahead of time if you have symptoms of a respiratory illness that could be contagious, and those who are not are still mandating the use of mask and physical distance in the waiting areas and limiting the amount of number of patients in any given hour. So I think that those are really big practices that would kind of make an impact in respiratory illness in terms of decreasing transmission in clinics.”

The authors, who had no conflicts of interest said their hope is that their study will help inform policy for reopening outpatient care settings. Dr. Hijano, who was not involved in the study also had no conflicts.

Prior research has examined the issue of hospital-acquired infections. A 2014 study published in the New England Journal of Medicine, for example, found that 4% of hospitalized patients acquired a health care–associated infection during their stay. Furthermore, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that, on any given day, one in 31 hospital patients has at least one health care–associated infection. However, researchers for the new study, published in Health Affairs, said evidence about the risk of acquiring respiratory viral infections in medical office settings is limited.

“Hospital-acquired infections has been a problem for a while,” study author Hannah Neprash, PhD, of the department of health policy and management at the University of Minnesota School of Public Health, Minneapolis, said in an interview. “However, there’s never been a similar study of whether a similar phenomenon happens in physician offices. This is especially relevant now when we’re dealing with respiratory infections.”

Methods and results

For the new study, Dr. Neprash and her colleagues analyzed deidentified billing and scheduling data from 2016-2017 for 105,462,600 outpatient visits that occurred at 6,709 office-based primary care practices. They used the World Health Organization case definition for influenzalike illness “to capture cases in which the physician may suspect this illness even if a specific diagnosis code was not present.” Their control conditions included exposure to urinary tract infections and back pain.

Doctor visits were considered unexposed if they were scheduled to start at least 90 minutes before the first influenzalike illness visit of the day. They were considered exposed if they were scheduled to start at the same time or after the first influenzalike illness visit of the day at that practice.

Researchers quantified whether exposed patients were more likely to return with a similar illness in the next 2 weeks, compared with nonexposed patients seen earlier in the day

They found that 2.7 patients per 1,000 returned within 2 weeks with an influenzalike illness.

Patients were more likely to return with influenzalike illness if their visit occurred after an influenzalike illness visit versus before, the researchers said.

The authors of the paper said their new research highlights the importance of infection control in health care settings, including outpatient offices.

Where did the exposure occur?

Diego Hijano, MD, MSc, pediatric infectious disease specialist at St. Jude’s Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, Tenn., said he was not surprised by the findings, but noted that it’s hard to say if the exposure to influenzalike illnesses happened in the office or in the community.

“If you start to see individuals with influenza in your office it’s because [there’s influenza] in the community,” Dr. Hijano explained. “So that means that you will have more patients coming in with influenza.”

To reduce the transmission of infections, Dr. Neprash suggested that doctors’ offices follow the CDC guidelines for indoor conduct, which include masking, washing hands, and “taking appropriate infection control measures.”

So potentially masking within offices is a way to minimize transmission between whatever people are there to be seen when it’s contagious, Dr. Neprash said.

“Telehealth really took off in 2020 and it’s unclear what the state of telehealth will be going forward. [These findings] suggest that there’s a patient safety argument for continuing to enable primary care physicians to provide visits either by phone or by video,” he added.

Dr. Hijano thinks it would be helpful for doctors to separate patients with respiratory illnesses from those without respiratory illnesses.

Driver of transmissions

Dr. Neprash suggested that another driver of these transmissions could be doctors not washing their hands, which is a “notorious issue,” and Dr. Hijano agreed with that statement.

“We did know that the hands of physicians and nurses and care providers are the main driver of infections in the health care setting,” Dr. Hijano explained. “I mean, washing your hands properly between encounters is the single best way that any given health care provider can prevent the spread of infections.”

“We have a unique opportunity with COVID-19 to change how these clinics are operating now,” Dr. Hijano said. “Many clinics are actually asking patients to call ahead of time if you have symptoms of a respiratory illness that could be contagious, and those who are not are still mandating the use of mask and physical distance in the waiting areas and limiting the amount of number of patients in any given hour. So I think that those are really big practices that would kind of make an impact in respiratory illness in terms of decreasing transmission in clinics.”

The authors, who had no conflicts of interest said their hope is that their study will help inform policy for reopening outpatient care settings. Dr. Hijano, who was not involved in the study also had no conflicts.

Prior research has examined the issue of hospital-acquired infections. A 2014 study published in the New England Journal of Medicine, for example, found that 4% of hospitalized patients acquired a health care–associated infection during their stay. Furthermore, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that, on any given day, one in 31 hospital patients has at least one health care–associated infection. However, researchers for the new study, published in Health Affairs, said evidence about the risk of acquiring respiratory viral infections in medical office settings is limited.

“Hospital-acquired infections has been a problem for a while,” study author Hannah Neprash, PhD, of the department of health policy and management at the University of Minnesota School of Public Health, Minneapolis, said in an interview. “However, there’s never been a similar study of whether a similar phenomenon happens in physician offices. This is especially relevant now when we’re dealing with respiratory infections.”

Methods and results

For the new study, Dr. Neprash and her colleagues analyzed deidentified billing and scheduling data from 2016-2017 for 105,462,600 outpatient visits that occurred at 6,709 office-based primary care practices. They used the World Health Organization case definition for influenzalike illness “to capture cases in which the physician may suspect this illness even if a specific diagnosis code was not present.” Their control conditions included exposure to urinary tract infections and back pain.

Doctor visits were considered unexposed if they were scheduled to start at least 90 minutes before the first influenzalike illness visit of the day. They were considered exposed if they were scheduled to start at the same time or after the first influenzalike illness visit of the day at that practice.

Researchers quantified whether exposed patients were more likely to return with a similar illness in the next 2 weeks, compared with nonexposed patients seen earlier in the day

They found that 2.7 patients per 1,000 returned within 2 weeks with an influenzalike illness.

Patients were more likely to return with influenzalike illness if their visit occurred after an influenzalike illness visit versus before, the researchers said.

The authors of the paper said their new research highlights the importance of infection control in health care settings, including outpatient offices.

Where did the exposure occur?

Diego Hijano, MD, MSc, pediatric infectious disease specialist at St. Jude’s Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, Tenn., said he was not surprised by the findings, but noted that it’s hard to say if the exposure to influenzalike illnesses happened in the office or in the community.

“If you start to see individuals with influenza in your office it’s because [there’s influenza] in the community,” Dr. Hijano explained. “So that means that you will have more patients coming in with influenza.”

To reduce the transmission of infections, Dr. Neprash suggested that doctors’ offices follow the CDC guidelines for indoor conduct, which include masking, washing hands, and “taking appropriate infection control measures.”

So potentially masking within offices is a way to minimize transmission between whatever people are there to be seen when it’s contagious, Dr. Neprash said.

“Telehealth really took off in 2020 and it’s unclear what the state of telehealth will be going forward. [These findings] suggest that there’s a patient safety argument for continuing to enable primary care physicians to provide visits either by phone or by video,” he added.

Dr. Hijano thinks it would be helpful for doctors to separate patients with respiratory illnesses from those without respiratory illnesses.

Driver of transmissions

Dr. Neprash suggested that another driver of these transmissions could be doctors not washing their hands, which is a “notorious issue,” and Dr. Hijano agreed with that statement.

“We did know that the hands of physicians and nurses and care providers are the main driver of infections in the health care setting,” Dr. Hijano explained. “I mean, washing your hands properly between encounters is the single best way that any given health care provider can prevent the spread of infections.”

“We have a unique opportunity with COVID-19 to change how these clinics are operating now,” Dr. Hijano said. “Many clinics are actually asking patients to call ahead of time if you have symptoms of a respiratory illness that could be contagious, and those who are not are still mandating the use of mask and physical distance in the waiting areas and limiting the amount of number of patients in any given hour. So I think that those are really big practices that would kind of make an impact in respiratory illness in terms of decreasing transmission in clinics.”

The authors, who had no conflicts of interest said their hope is that their study will help inform policy for reopening outpatient care settings. Dr. Hijano, who was not involved in the study also had no conflicts.

FROM HEALTH AFFAIRS

Bronchitis the leader at putting children in the hospital

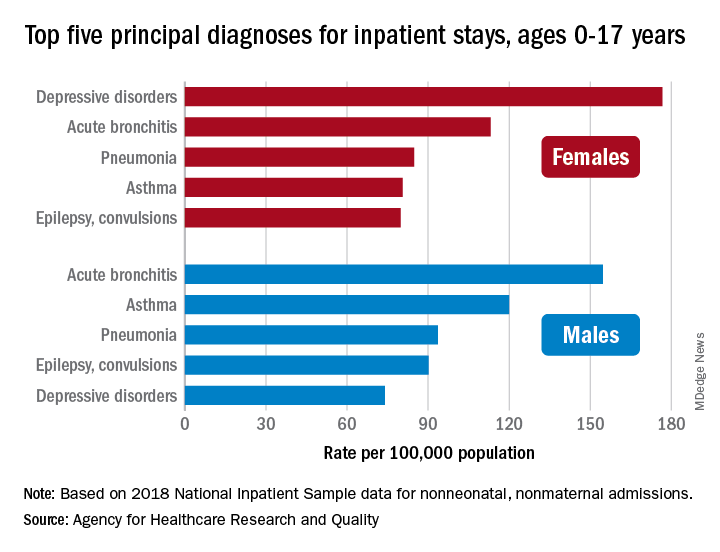

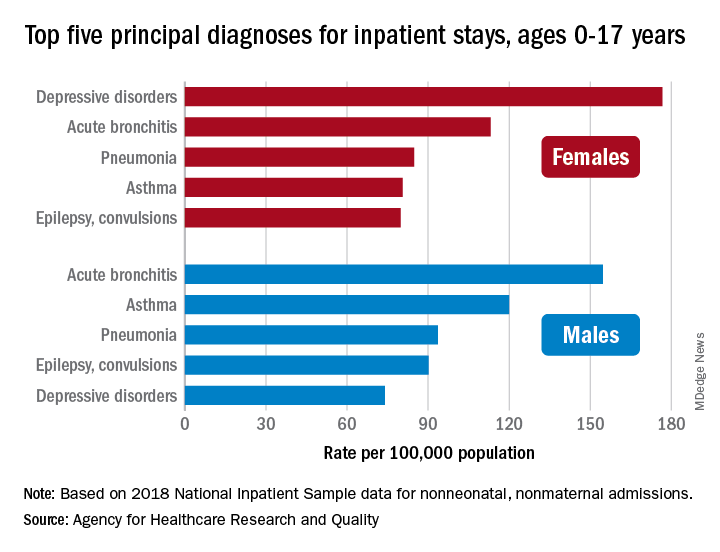

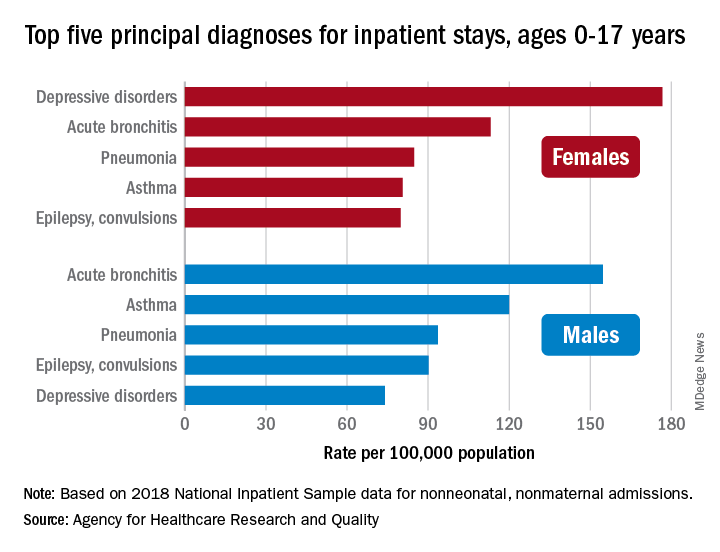

About 7% (99,000) of the 1.47 million nonmaternal, nonneonatal hospital stays in children aged 0-17 years involved a primary diagnosis of acute bronchitis in 2018, representing the leading cause of admissions in boys (154.7 stays per 100,000 population) and the second-leading diagnosis in girls (113.1 stays per 100,000), Kimberly W. McDermott, PhD, and Marc Roemer, MS, said in a statistical brief.

Depressive disorders were the most common primary diagnosis in girls, with a rate of 176.7 stays per 100,000, and the second-leading diagnosis overall, although the rate was less than half that (74.0 per 100,000) in boys. Two other respiratory conditions, asthma and pneumonia, were among the top five for both girls and boys, as was epilepsy, they reported.

The combined rate for all diagnoses was slightly higher for boys, 2,051 per 100,000, compared with 1,922 for girls, they said based on data from the National Inpatient Sample.

“Identifying the most frequent primary conditions for which patients are admitted to the hospital is important to the implementation and improvement of health care delivery, quality initiatives, and health policy,” said Dr. McDermott of IBM Watson Health and Mr. Roemer of the AHRQ.

About 7% (99,000) of the 1.47 million nonmaternal, nonneonatal hospital stays in children aged 0-17 years involved a primary diagnosis of acute bronchitis in 2018, representing the leading cause of admissions in boys (154.7 stays per 100,000 population) and the second-leading diagnosis in girls (113.1 stays per 100,000), Kimberly W. McDermott, PhD, and Marc Roemer, MS, said in a statistical brief.

Depressive disorders were the most common primary diagnosis in girls, with a rate of 176.7 stays per 100,000, and the second-leading diagnosis overall, although the rate was less than half that (74.0 per 100,000) in boys. Two other respiratory conditions, asthma and pneumonia, were among the top five for both girls and boys, as was epilepsy, they reported.

The combined rate for all diagnoses was slightly higher for boys, 2,051 per 100,000, compared with 1,922 for girls, they said based on data from the National Inpatient Sample.

“Identifying the most frequent primary conditions for which patients are admitted to the hospital is important to the implementation and improvement of health care delivery, quality initiatives, and health policy,” said Dr. McDermott of IBM Watson Health and Mr. Roemer of the AHRQ.

About 7% (99,000) of the 1.47 million nonmaternal, nonneonatal hospital stays in children aged 0-17 years involved a primary diagnosis of acute bronchitis in 2018, representing the leading cause of admissions in boys (154.7 stays per 100,000 population) and the second-leading diagnosis in girls (113.1 stays per 100,000), Kimberly W. McDermott, PhD, and Marc Roemer, MS, said in a statistical brief.

Depressive disorders were the most common primary diagnosis in girls, with a rate of 176.7 stays per 100,000, and the second-leading diagnosis overall, although the rate was less than half that (74.0 per 100,000) in boys. Two other respiratory conditions, asthma and pneumonia, were among the top five for both girls and boys, as was epilepsy, they reported.

The combined rate for all diagnoses was slightly higher for boys, 2,051 per 100,000, compared with 1,922 for girls, they said based on data from the National Inpatient Sample.

“Identifying the most frequent primary conditions for which patients are admitted to the hospital is important to the implementation and improvement of health care delivery, quality initiatives, and health policy,” said Dr. McDermott of IBM Watson Health and Mr. Roemer of the AHRQ.

Unclear benefit to home NIPPV in COPD

Background: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a prevalent condition that is associated with significant mortality, morbidity, and health care utilization. Use of noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation (NIPPV) in acute hypercapnic respiratory failure caused by COPD exacerbations is well established. However, the benefits of in-home NIPPV for COPD with chronic hypercapnia is unclear.

Study design: Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Setting: Multicenter catchment of 21 randomized control trials (RCTs) and 12 observational studies involving more than 51,000 patients during 1995-2019.

Synopsis: Patients included were those with COPD and hypercapnia who used NIPPV for more than 1 month. Home bilevel positive airway pressure (BiPAP), compared to no device use was associated with lower risk of mortality, all-cause hospital admission, and intubation, but no significant difference in quality of life. Noninvasive home mechanical ventilation, compared with no device was significantly associated with lower risk of hospital admission, but not a significant difference in mortality. Of note, there was no statistically significant difference in any outcome for either BiPAP or home mechanical ventilation if evidence was limited to RCTs. Importantly, on rigorous measure, the evidence was low to moderate quality or insufficient, and some outcomes analysis was based on small numbers of studies.

Bottom line: While there is suggestion of benefit on some measures with the use of home NIPPV, the evidence is not robust enough to clearly guide use.

Citation: Wilson et al. Association of home noninvasive positive pressure ventilation with clinical outcomes in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. JAMA. 2020 Feb 4;323(5):455-65.

Dr. Sneed is assistant professor of medicine, section of hospital medicine, at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville.

Background: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a prevalent condition that is associated with significant mortality, morbidity, and health care utilization. Use of noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation (NIPPV) in acute hypercapnic respiratory failure caused by COPD exacerbations is well established. However, the benefits of in-home NIPPV for COPD with chronic hypercapnia is unclear.

Study design: Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Setting: Multicenter catchment of 21 randomized control trials (RCTs) and 12 observational studies involving more than 51,000 patients during 1995-2019.

Synopsis: Patients included were those with COPD and hypercapnia who used NIPPV for more than 1 month. Home bilevel positive airway pressure (BiPAP), compared to no device use was associated with lower risk of mortality, all-cause hospital admission, and intubation, but no significant difference in quality of life. Noninvasive home mechanical ventilation, compared with no device was significantly associated with lower risk of hospital admission, but not a significant difference in mortality. Of note, there was no statistically significant difference in any outcome for either BiPAP or home mechanical ventilation if evidence was limited to RCTs. Importantly, on rigorous measure, the evidence was low to moderate quality or insufficient, and some outcomes analysis was based on small numbers of studies.

Bottom line: While there is suggestion of benefit on some measures with the use of home NIPPV, the evidence is not robust enough to clearly guide use.

Citation: Wilson et al. Association of home noninvasive positive pressure ventilation with clinical outcomes in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. JAMA. 2020 Feb 4;323(5):455-65.

Dr. Sneed is assistant professor of medicine, section of hospital medicine, at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville.

Background: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a prevalent condition that is associated with significant mortality, morbidity, and health care utilization. Use of noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation (NIPPV) in acute hypercapnic respiratory failure caused by COPD exacerbations is well established. However, the benefits of in-home NIPPV for COPD with chronic hypercapnia is unclear.

Study design: Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Setting: Multicenter catchment of 21 randomized control trials (RCTs) and 12 observational studies involving more than 51,000 patients during 1995-2019.

Synopsis: Patients included were those with COPD and hypercapnia who used NIPPV for more than 1 month. Home bilevel positive airway pressure (BiPAP), compared to no device use was associated with lower risk of mortality, all-cause hospital admission, and intubation, but no significant difference in quality of life. Noninvasive home mechanical ventilation, compared with no device was significantly associated with lower risk of hospital admission, but not a significant difference in mortality. Of note, there was no statistically significant difference in any outcome for either BiPAP or home mechanical ventilation if evidence was limited to RCTs. Importantly, on rigorous measure, the evidence was low to moderate quality or insufficient, and some outcomes analysis was based on small numbers of studies.

Bottom line: While there is suggestion of benefit on some measures with the use of home NIPPV, the evidence is not robust enough to clearly guide use.

Citation: Wilson et al. Association of home noninvasive positive pressure ventilation with clinical outcomes in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. JAMA. 2020 Feb 4;323(5):455-65.

Dr. Sneed is assistant professor of medicine, section of hospital medicine, at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville.

Reducing air pollution is linked to slowed brain aging and lower dementia risk

, new research reveals. The findings have implications for individual behaviors, such as avoiding areas with poor air quality, but they also have implications for public policy, said study investigator, Xinhui Wang, PhD, assistant professor of research neurology, department of neurology, University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

“Controlling air quality has great benefits not only for the short-term, for example for pulmonary function or very broadly mortality, but can impact brain function and slow memory function decline and in the long run may reduce dementia cases.”

The findings were presented at the 2021 Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

New approach

Previous research examining the impact of reducing air pollution, which has primarily examined respiratory illnesses and mortality, showed it is beneficial. However, no previous studies have examined the impact of improved air quality on cognitive function.

The current study used a subset of participants from the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study-Epidemiology of Cognitive Health Outcomes (WHIMS-ECHO), which evaluated whether postmenopausal women derive cognitive benefit from hormone therapy.

The analysis included 2,232 community-dwelling older women aged 74-92 (mean age, 81.5 years) who did not have dementia at study enrollment.

Researchers obtained measures of participants’ annual cognitive function from 2008 to 2018. These measures included general cognitive status assessed using the Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status-modified (TICSm) and episodic memory assessed by the telephone-based California Verbal Learning Test (CVLT).

The investigators used complex geographical covariates to estimate exposure to fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and nitrogen dioxide (NO2), in areas where individual participants lived from 1996 to 2012. The investigators averaged measures over 3-year periods immediately preceding (recent exposure) and 10 years prior to (remote exposure) enrollment, then calculated individual-level improvements in air quality as the reduction from remote to recent exposures.

The researchers examined pollution exposure and cognitive outcomes at different times to determine causation.

“Maybe the relationship isn’t causal and is just an association, so we tried to separate the timeframe for exposure and outcome and make sure the exposure was before we measured the outcome,” said Dr. Wang.

The investigators adjusted for multiple sociodemographic, lifestyle, and clinical characteristics.

Reduced dementia risk

The analysis showed air quality improved significantly for both PM2.5 and NO2 before study enrollment. “For almost 95% of the subjects in our study, air quality improved over the 10 years,” said Dr. Wang.

During a median follow-up of 6.2 years, there was a significant decline in cognitive status and episodic memory in study participants, which makes sense, said Dr. Wang, because cognitive function naturally declines with age.

However, a 10% improvement in air quality PM2.5 and NO2 resulted in a respective 14% and 26% decreased risk for dementia. This translates into a level of risk seen in women 2 to 3 years younger.

Greater air quality improvement was associated with slower decline in both general cognitive status and episodic memory.

“Participants all declined in cognitive function, but living in areas with the greatest air quality improvement slowed this decline,” said Dr. Wang.

“Whether you look at global cognitive function or memory-specific function, and whether you look at PM2.5 or NO2, slower decline was in the range of someone who is 1-2 years younger.”

The associations did not significantly differ by age, region, education, APOE ε4 genotypes, or cardiovascular risk factors.

Patients concerned about cognitive decline can take steps to avoid exposure to pollution by wearing a mask; avoiding heavy traffic, fires, and smoke; or moving to an area with better air quality, said Dr. Wang.

“But our study mainly tried to provide some evidence for policymakers and regulators,” she added.

Another study carried out by the same investigators suggests pollution may affect various cognitive functions differently. This analysis used the same cohort, timeframe, and air quality improvement indicators as the first study but examined the association with specific cognitive domains, including episodic memory, working memory, attention/executive function, and language.

The investigators found women living in locations with greater PM2.5 improvement performed better on tests of episodic memory (P = .002), working memory (P = .01) and attention/executive function (P = .01), but not language. Findings were similar for improved NO2.

When looking at air quality improvement and trajectory slopes of decline across cognitive functions, only the association between improved NO2 and slower episodic memory decline was statistically significant (P < 0.001). “The other domains were marginal or not significant,” said Dr. Wang.

“This suggests that brain regions are impacted differently,” she said, adding that various brain areas oversee different cognitive functions.

Important policy implications

Commenting on the research, Rebecca Edelmayer, PhD, senior director of scientific engagement, Alzheimer’s Association, said she welcomes new research on environmental factors that affect Alzheimer’s disease.

Whereas previous studies have linked longterm air pollution exposure to accumulation of Alzheimer’s disease-related brain plaques and increased risk of dementia, “these newer studies provide some of the first evidence to suggest that actually reducing pollution is associated with lower risk of all-cause dementia,” said Dr. Edelmayer.

Individuals can control some factors that contribute to dementia risk, such as exercise, diet, and physical activity, but it’s more difficult for them to control exposure to smog and pollution, she said.

“This is probably going to require changes to policy from federal and local governments and businesses, to start addressing the need to improve air quality to help reduce risk for dementia.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research reveals. The findings have implications for individual behaviors, such as avoiding areas with poor air quality, but they also have implications for public policy, said study investigator, Xinhui Wang, PhD, assistant professor of research neurology, department of neurology, University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

“Controlling air quality has great benefits not only for the short-term, for example for pulmonary function or very broadly mortality, but can impact brain function and slow memory function decline and in the long run may reduce dementia cases.”

The findings were presented at the 2021 Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

New approach

Previous research examining the impact of reducing air pollution, which has primarily examined respiratory illnesses and mortality, showed it is beneficial. However, no previous studies have examined the impact of improved air quality on cognitive function.

The current study used a subset of participants from the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study-Epidemiology of Cognitive Health Outcomes (WHIMS-ECHO), which evaluated whether postmenopausal women derive cognitive benefit from hormone therapy.

The analysis included 2,232 community-dwelling older women aged 74-92 (mean age, 81.5 years) who did not have dementia at study enrollment.

Researchers obtained measures of participants’ annual cognitive function from 2008 to 2018. These measures included general cognitive status assessed using the Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status-modified (TICSm) and episodic memory assessed by the telephone-based California Verbal Learning Test (CVLT).

The investigators used complex geographical covariates to estimate exposure to fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and nitrogen dioxide (NO2), in areas where individual participants lived from 1996 to 2012. The investigators averaged measures over 3-year periods immediately preceding (recent exposure) and 10 years prior to (remote exposure) enrollment, then calculated individual-level improvements in air quality as the reduction from remote to recent exposures.

The researchers examined pollution exposure and cognitive outcomes at different times to determine causation.

“Maybe the relationship isn’t causal and is just an association, so we tried to separate the timeframe for exposure and outcome and make sure the exposure was before we measured the outcome,” said Dr. Wang.

The investigators adjusted for multiple sociodemographic, lifestyle, and clinical characteristics.

Reduced dementia risk

The analysis showed air quality improved significantly for both PM2.5 and NO2 before study enrollment. “For almost 95% of the subjects in our study, air quality improved over the 10 years,” said Dr. Wang.

During a median follow-up of 6.2 years, there was a significant decline in cognitive status and episodic memory in study participants, which makes sense, said Dr. Wang, because cognitive function naturally declines with age.

However, a 10% improvement in air quality PM2.5 and NO2 resulted in a respective 14% and 26% decreased risk for dementia. This translates into a level of risk seen in women 2 to 3 years younger.

Greater air quality improvement was associated with slower decline in both general cognitive status and episodic memory.

“Participants all declined in cognitive function, but living in areas with the greatest air quality improvement slowed this decline,” said Dr. Wang.

“Whether you look at global cognitive function or memory-specific function, and whether you look at PM2.5 or NO2, slower decline was in the range of someone who is 1-2 years younger.”

The associations did not significantly differ by age, region, education, APOE ε4 genotypes, or cardiovascular risk factors.

Patients concerned about cognitive decline can take steps to avoid exposure to pollution by wearing a mask; avoiding heavy traffic, fires, and smoke; or moving to an area with better air quality, said Dr. Wang.

“But our study mainly tried to provide some evidence for policymakers and regulators,” she added.

Another study carried out by the same investigators suggests pollution may affect various cognitive functions differently. This analysis used the same cohort, timeframe, and air quality improvement indicators as the first study but examined the association with specific cognitive domains, including episodic memory, working memory, attention/executive function, and language.

The investigators found women living in locations with greater PM2.5 improvement performed better on tests of episodic memory (P = .002), working memory (P = .01) and attention/executive function (P = .01), but not language. Findings were similar for improved NO2.

When looking at air quality improvement and trajectory slopes of decline across cognitive functions, only the association between improved NO2 and slower episodic memory decline was statistically significant (P < 0.001). “The other domains were marginal or not significant,” said Dr. Wang.

“This suggests that brain regions are impacted differently,” she said, adding that various brain areas oversee different cognitive functions.

Important policy implications

Commenting on the research, Rebecca Edelmayer, PhD, senior director of scientific engagement, Alzheimer’s Association, said she welcomes new research on environmental factors that affect Alzheimer’s disease.

Whereas previous studies have linked longterm air pollution exposure to accumulation of Alzheimer’s disease-related brain plaques and increased risk of dementia, “these newer studies provide some of the first evidence to suggest that actually reducing pollution is associated with lower risk of all-cause dementia,” said Dr. Edelmayer.

Individuals can control some factors that contribute to dementia risk, such as exercise, diet, and physical activity, but it’s more difficult for them to control exposure to smog and pollution, she said.

“This is probably going to require changes to policy from federal and local governments and businesses, to start addressing the need to improve air quality to help reduce risk for dementia.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research reveals. The findings have implications for individual behaviors, such as avoiding areas with poor air quality, but they also have implications for public policy, said study investigator, Xinhui Wang, PhD, assistant professor of research neurology, department of neurology, University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

“Controlling air quality has great benefits not only for the short-term, for example for pulmonary function or very broadly mortality, but can impact brain function and slow memory function decline and in the long run may reduce dementia cases.”

The findings were presented at the 2021 Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

New approach

Previous research examining the impact of reducing air pollution, which has primarily examined respiratory illnesses and mortality, showed it is beneficial. However, no previous studies have examined the impact of improved air quality on cognitive function.

The current study used a subset of participants from the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study-Epidemiology of Cognitive Health Outcomes (WHIMS-ECHO), which evaluated whether postmenopausal women derive cognitive benefit from hormone therapy.

The analysis included 2,232 community-dwelling older women aged 74-92 (mean age, 81.5 years) who did not have dementia at study enrollment.

Researchers obtained measures of participants’ annual cognitive function from 2008 to 2018. These measures included general cognitive status assessed using the Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status-modified (TICSm) and episodic memory assessed by the telephone-based California Verbal Learning Test (CVLT).

The investigators used complex geographical covariates to estimate exposure to fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and nitrogen dioxide (NO2), in areas where individual participants lived from 1996 to 2012. The investigators averaged measures over 3-year periods immediately preceding (recent exposure) and 10 years prior to (remote exposure) enrollment, then calculated individual-level improvements in air quality as the reduction from remote to recent exposures.

The researchers examined pollution exposure and cognitive outcomes at different times to determine causation.

“Maybe the relationship isn’t causal and is just an association, so we tried to separate the timeframe for exposure and outcome and make sure the exposure was before we measured the outcome,” said Dr. Wang.

The investigators adjusted for multiple sociodemographic, lifestyle, and clinical characteristics.

Reduced dementia risk

The analysis showed air quality improved significantly for both PM2.5 and NO2 before study enrollment. “For almost 95% of the subjects in our study, air quality improved over the 10 years,” said Dr. Wang.

During a median follow-up of 6.2 years, there was a significant decline in cognitive status and episodic memory in study participants, which makes sense, said Dr. Wang, because cognitive function naturally declines with age.

However, a 10% improvement in air quality PM2.5 and NO2 resulted in a respective 14% and 26% decreased risk for dementia. This translates into a level of risk seen in women 2 to 3 years younger.

Greater air quality improvement was associated with slower decline in both general cognitive status and episodic memory.

“Participants all declined in cognitive function, but living in areas with the greatest air quality improvement slowed this decline,” said Dr. Wang.

“Whether you look at global cognitive function or memory-specific function, and whether you look at PM2.5 or NO2, slower decline was in the range of someone who is 1-2 years younger.”

The associations did not significantly differ by age, region, education, APOE ε4 genotypes, or cardiovascular risk factors.

Patients concerned about cognitive decline can take steps to avoid exposure to pollution by wearing a mask; avoiding heavy traffic, fires, and smoke; or moving to an area with better air quality, said Dr. Wang.

“But our study mainly tried to provide some evidence for policymakers and regulators,” she added.

Another study carried out by the same investigators suggests pollution may affect various cognitive functions differently. This analysis used the same cohort, timeframe, and air quality improvement indicators as the first study but examined the association with specific cognitive domains, including episodic memory, working memory, attention/executive function, and language.

The investigators found women living in locations with greater PM2.5 improvement performed better on tests of episodic memory (P = .002), working memory (P = .01) and attention/executive function (P = .01), but not language. Findings were similar for improved NO2.

When looking at air quality improvement and trajectory slopes of decline across cognitive functions, only the association between improved NO2 and slower episodic memory decline was statistically significant (P < 0.001). “The other domains were marginal or not significant,” said Dr. Wang.

“This suggests that brain regions are impacted differently,” she said, adding that various brain areas oversee different cognitive functions.

Important policy implications

Commenting on the research, Rebecca Edelmayer, PhD, senior director of scientific engagement, Alzheimer’s Association, said she welcomes new research on environmental factors that affect Alzheimer’s disease.

Whereas previous studies have linked longterm air pollution exposure to accumulation of Alzheimer’s disease-related brain plaques and increased risk of dementia, “these newer studies provide some of the first evidence to suggest that actually reducing pollution is associated with lower risk of all-cause dementia,” said Dr. Edelmayer.

Individuals can control some factors that contribute to dementia risk, such as exercise, diet, and physical activity, but it’s more difficult for them to control exposure to smog and pollution, she said.

“This is probably going to require changes to policy from federal and local governments and businesses, to start addressing the need to improve air quality to help reduce risk for dementia.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

From AAIC 2021

Empirical anti-MRSA therapy does not improve mortality in patients with pneumonia

Background: Empirical broad-spectrum antibiotics including anti-MRSA therapy are often selected because of concerns for resistant organisms. However, the outcomes of empirical anti-MRSA therapy among patients with pneumonia are unknown.

Study design: A national retrospective multicenter cohort study of hospitalizations for pneumonia.

Setting: This cohort study included 88,605 hospitalizations for pneumonia in the Veterans Health Administration health care system during 2008-2013, in which patients received either anti-MRSA or standard therapy for community-onset pneumonia.

Synopsis: Among 88,605 hospitalizations for pneumonia, 38% of the patients received empirical anti-MRSA therapy within the first day of hospitalization and vancomycin accounted for 98% of the therapy. The primary outcome was 30-day all-cause mortality after adjustment for patient comorbidities, vital signs, and laboratory results. Three treatment groups were studied: patients receiving anti-MRSA therapy (vancomycin hydrochloride or linezolid) plus guideline-recommended standard antibiotics (beta-lactam and macrolide or tetracycline hydrochloride, or fluoroquinolone); patients receiving anti-MRSA therapy without standard antibiotics; and patients receiving standard therapy alone. There was no mortality benefit of empirical anti-MRSA therapy versus standard antibiotics, even in those with risk factors for MRSA or in those whose clinical severity warranted admission to the ICU. Empirical anti-MRSA treatment was associated with greater 30-day mortality compared with standard therapy alone, with an adjusted risk ratio of 1.4 (95% confidence interval, 1.3-1.5) versus empirical anti-MRSA treatment plus standard therapy and 1.5 (1.4-1.6) versus empirical anti-MRSA treatment without standard therapy.

Bottom line: Empirical anti-MRSA therapy does not improve mortality and should not be routinely used in patients hospitalized for community-onset pneumonia, even in those with MRSA risk factors.

Citation: Jones BE et al. Empirical anti-MRSA vs. standard antibiotic therapy and risk of 30-day mortality in patients hospitalized for pneumonia. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 Feb 17;180(4):552-60.

Dr. Li is assistant professor of medicine, section of hospital medicine, at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville.

Background: Empirical broad-spectrum antibiotics including anti-MRSA therapy are often selected because of concerns for resistant organisms. However, the outcomes of empirical anti-MRSA therapy among patients with pneumonia are unknown.

Study design: A national retrospective multicenter cohort study of hospitalizations for pneumonia.

Setting: This cohort study included 88,605 hospitalizations for pneumonia in the Veterans Health Administration health care system during 2008-2013, in which patients received either anti-MRSA or standard therapy for community-onset pneumonia.

Synopsis: Among 88,605 hospitalizations for pneumonia, 38% of the patients received empirical anti-MRSA therapy within the first day of hospitalization and vancomycin accounted for 98% of the therapy. The primary outcome was 30-day all-cause mortality after adjustment for patient comorbidities, vital signs, and laboratory results. Three treatment groups were studied: patients receiving anti-MRSA therapy (vancomycin hydrochloride or linezolid) plus guideline-recommended standard antibiotics (beta-lactam and macrolide or tetracycline hydrochloride, or fluoroquinolone); patients receiving anti-MRSA therapy without standard antibiotics; and patients receiving standard therapy alone. There was no mortality benefit of empirical anti-MRSA therapy versus standard antibiotics, even in those with risk factors for MRSA or in those whose clinical severity warranted admission to the ICU. Empirical anti-MRSA treatment was associated with greater 30-day mortality compared with standard therapy alone, with an adjusted risk ratio of 1.4 (95% confidence interval, 1.3-1.5) versus empirical anti-MRSA treatment plus standard therapy and 1.5 (1.4-1.6) versus empirical anti-MRSA treatment without standard therapy.

Bottom line: Empirical anti-MRSA therapy does not improve mortality and should not be routinely used in patients hospitalized for community-onset pneumonia, even in those with MRSA risk factors.

Citation: Jones BE et al. Empirical anti-MRSA vs. standard antibiotic therapy and risk of 30-day mortality in patients hospitalized for pneumonia. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 Feb 17;180(4):552-60.

Dr. Li is assistant professor of medicine, section of hospital medicine, at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville.

Background: Empirical broad-spectrum antibiotics including anti-MRSA therapy are often selected because of concerns for resistant organisms. However, the outcomes of empirical anti-MRSA therapy among patients with pneumonia are unknown.

Study design: A national retrospective multicenter cohort study of hospitalizations for pneumonia.

Setting: This cohort study included 88,605 hospitalizations for pneumonia in the Veterans Health Administration health care system during 2008-2013, in which patients received either anti-MRSA or standard therapy for community-onset pneumonia.

Synopsis: Among 88,605 hospitalizations for pneumonia, 38% of the patients received empirical anti-MRSA therapy within the first day of hospitalization and vancomycin accounted for 98% of the therapy. The primary outcome was 30-day all-cause mortality after adjustment for patient comorbidities, vital signs, and laboratory results. Three treatment groups were studied: patients receiving anti-MRSA therapy (vancomycin hydrochloride or linezolid) plus guideline-recommended standard antibiotics (beta-lactam and macrolide or tetracycline hydrochloride, or fluoroquinolone); patients receiving anti-MRSA therapy without standard antibiotics; and patients receiving standard therapy alone. There was no mortality benefit of empirical anti-MRSA therapy versus standard antibiotics, even in those with risk factors for MRSA or in those whose clinical severity warranted admission to the ICU. Empirical anti-MRSA treatment was associated with greater 30-day mortality compared with standard therapy alone, with an adjusted risk ratio of 1.4 (95% confidence interval, 1.3-1.5) versus empirical anti-MRSA treatment plus standard therapy and 1.5 (1.4-1.6) versus empirical anti-MRSA treatment without standard therapy.

Bottom line: Empirical anti-MRSA therapy does not improve mortality and should not be routinely used in patients hospitalized for community-onset pneumonia, even in those with MRSA risk factors.

Citation: Jones BE et al. Empirical anti-MRSA vs. standard antibiotic therapy and risk of 30-day mortality in patients hospitalized for pneumonia. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 Feb 17;180(4):552-60.

Dr. Li is assistant professor of medicine, section of hospital medicine, at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville.

Long COVID seen in patients with severe and mild disease

Findings from the cohort, composed of 113 COVID-19 survivors who developed ARDS after admission to a single center before to April 16, 2020, were presented online at the 31st European Congress of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases by Judit Aranda, MD, from Complex Hospitalari Moisés Broggi in Barcelona.

Median age of the participants was 64 years, and 70% were male. At least one persistent symptom was experienced during follow-up by 81% of the cohort, with 45% reporting shortness of breath, 50% reporting muscle pain, 43% reporting memory impairment, and 46% reporting physical weakness of at least 5 on a 10-point scale.

Of the 104 participants who completed a 6-minute walk test, 30% had a decrease in oxygen saturation level of at least 4%, and 5% had an initial or final level below 88%. Of the 46 participants who underwent a pulmonary function test, 15% had a forced expiratory volume in 1 second below 70%.

And of the 49% of participants with pathologic findings on chest x-ray, most were bilateral interstitial infiltrates (88%).

In addition, more than 90% of participants developed depression, anxiety, or PTSD, Dr. Aranda reported.

Not the whole picture

This study shows that sicker people – “those in intensive care units with acute respiratory distress syndrome” – are “more likely to be struggling with more severe symptoms,” said Christopher Terndrup, MD, from the division of general internal medicine and geriatrics at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland.

But a Swiss study, also presented at the meeting, “shows how even mild COVID cases can lead to debilitating symptoms,” Dr. Terndrup said in an interview.

The investigation of long-term COVID symptoms in outpatients was presented online by Florian Desgranges, MD, from Lausanne (Switzerland) University Hospital. He and his colleagues found that more than half of those with a mild to moderate disease had persistent symptoms at least 3 months after diagnosis.

The prevalence of long COVID has varied in previous research, from 15% in a study of health care workers, to 46% in a study of patients with mild COVID, 52% in a study of young COVID outpatients, and 76% in a study of patients hospitalized with COVID.

Dr. Desgranges and colleagues evaluated patients seen in an ED or outpatient clinic from February to April 2020.

The 418 patients with a confirmed COVID-19 diagnosis were compared with a control group of 89 patients who presented to the same centers during the same time frame with similar symptoms – cough, shortness of breath, or fever – but had a negative SARS-CoV-2 test.

The number of patients with comorbidities was similar in the COVID and control groups (34% vs. 36%), as was median age (41 vs. 36 years) and the prevalence of women (62% vs 64%), but the proportion of health care workers was lower in the COVID group (64% vs 82%; P =.006).

Symptoms that persisted for at least 3 months were more common in the COVID than in the control group (53% vs. 37%). And patients in the COVID group reported more symptoms than those in the control group after adjustment for age, gender, smoking status, comorbidities, and timing of the survey phone call.

Levels of sleeping problems and headache were similar in the two groups.

“We have to remember that with COVID-19 came the psychosocial changes of the pandemic situation” Dr. Desgranges said.

This study suggests that some long-COVID symptoms – such as the fatigue, headache, and sleep disorders reported in the control group – could be related to the pandemic itself, which has caused psychosocial distress, Dr. Terndrup said.

Another study that looked at outpatients “has some fantastic long-term follow-up data, and shows that many patients are still engaging in rehabilitation programs nearly a year after their diagnosis,” he explained.

The COVID HOME study

That prospective longitudinal COVID HOME study, which assessed long-term symptoms in people who were never hospitalized for COVID, was presented online by Adriana Tami, MD, PhD, from the University Medical Center Groningen (the Netherlands).

The researchers visited the homes of patients to collect data, blood samples, and perform polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing 1, 2, and 3 weeks after a diagnosis of COVID-19. If their PCR test was still positive, testing continued until week 6 or a negative test. In addition, participants completed questionnaires at week 2 and at months 3, 6 and 12 to assess fatigue, quality of life, and symptoms of depression and anxiety.

Three-month follow-up data were available for 134 of the 276 people initially enrolled in the study. Questionnaires were completed by 85 participants at 3 months, 62 participants at 6 months, and 10 participants at 12 months.

At least 40% of participants reported long-lasting symptoms at some point during follow-up, and at least 30% said they didn’t feel fully recovered at 12 months. The most common symptom was persistent fatigue, reported at 3, 6, and 12 months by at least 44% of participants. Other common symptoms – reported by at least 20% of respondents at 3, 6, and 12 months – were headache, mental or neurologic symptoms, and sleep disorders, shortness of breath, lack of smell or taste, and severe fatigue.

“We have a high proportion of nonhospitalized individuals who suffer from long COVID after more than 12 months,” Dr. Tami concluded, adding that the study is ongoing. “We have other variables that we want to look at, including duration viral shedding and serological results and variants.”

“These cohort studies are very helpful, but they can lead to inaccurate conclusions,” Dr. Terndrup cautioned.

They only provide pieces of the big picture, but they “do add to a growing body of knowledge about a significant portion of COVID patients still struggling with symptoms long after their initial infection. The symptoms can be quite variable but are dominated by both physical and mental fatigue, and tend to be worse in patients who were sicker at initial infection,” he said in an interview.

As a whole, these studies reinforce the need for treatment programs to help patients who suffer from long COVID, he added, but “I advise caution to folks suffering out there who seek ‘miracle cures’; across the world, we are collaborating to find solutions that are safe and effective.”

We are in desperate need of an equity lens in these studies.

“There is still a great deal to learn about long COVID,” said Dr. Terndrup. Data on underrepresented populations – such as Black, Indigenous, and people of color – are lacking from these and others studies, he explained. “We are in desperate need of an equity lens in these studies,” particularly in the United States, where there are “significant disparities” in the treatment of different populations.

However, “I do hope that this work can lead to a better understanding of how other viral infections can cause long-lasting symptoms,” said Dr. Terndrup.

“We have long proposed that after acute presentation, some microbes can cause chronic symptoms, like fatigue and widespread pain. Perhaps we can learn how to better care for these patients after learning from COVID’s significant impact on our societies across the globe.”

Dr. Aranda and Dr. Desgranges have disclosed no relevant financial relationships or study funding. The study by Dr. Tami’s team was funded by the University Medical Center Groningen Organization for Health Research and Development, and Connecting European Cohorts to Increase Common and Effective Response to SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic. Dr. Terndrup disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Findings from the cohort, composed of 113 COVID-19 survivors who developed ARDS after admission to a single center before to April 16, 2020, were presented online at the 31st European Congress of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases by Judit Aranda, MD, from Complex Hospitalari Moisés Broggi in Barcelona.

Median age of the participants was 64 years, and 70% were male. At least one persistent symptom was experienced during follow-up by 81% of the cohort, with 45% reporting shortness of breath, 50% reporting muscle pain, 43% reporting memory impairment, and 46% reporting physical weakness of at least 5 on a 10-point scale.

Of the 104 participants who completed a 6-minute walk test, 30% had a decrease in oxygen saturation level of at least 4%, and 5% had an initial or final level below 88%. Of the 46 participants who underwent a pulmonary function test, 15% had a forced expiratory volume in 1 second below 70%.

And of the 49% of participants with pathologic findings on chest x-ray, most were bilateral interstitial infiltrates (88%).

In addition, more than 90% of participants developed depression, anxiety, or PTSD, Dr. Aranda reported.

Not the whole picture

This study shows that sicker people – “those in intensive care units with acute respiratory distress syndrome” – are “more likely to be struggling with more severe symptoms,” said Christopher Terndrup, MD, from the division of general internal medicine and geriatrics at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland.

But a Swiss study, also presented at the meeting, “shows how even mild COVID cases can lead to debilitating symptoms,” Dr. Terndrup said in an interview.

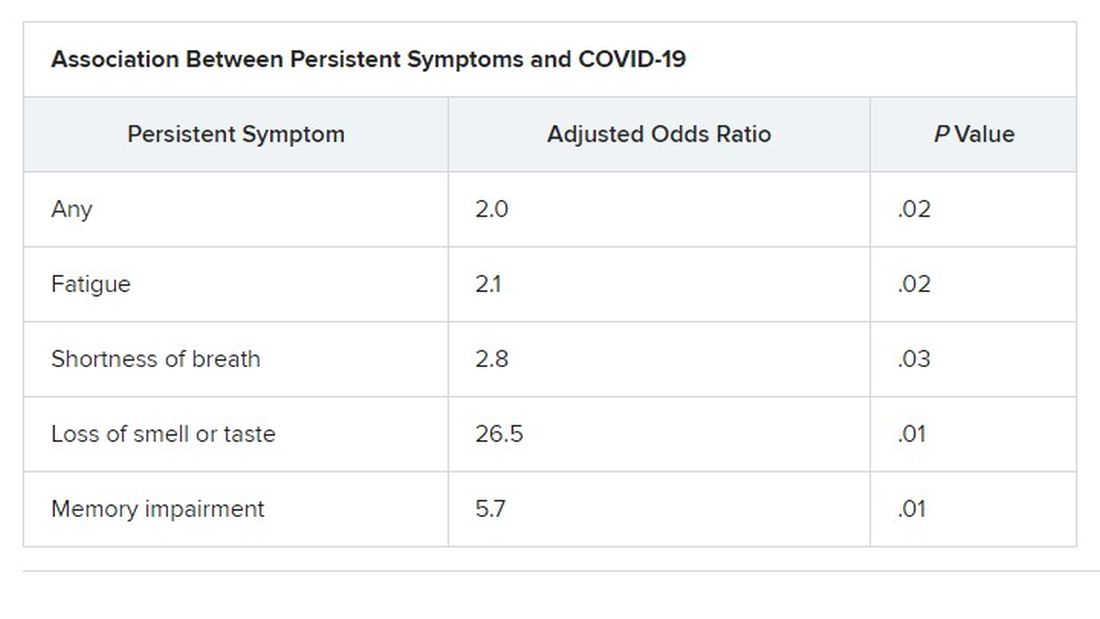

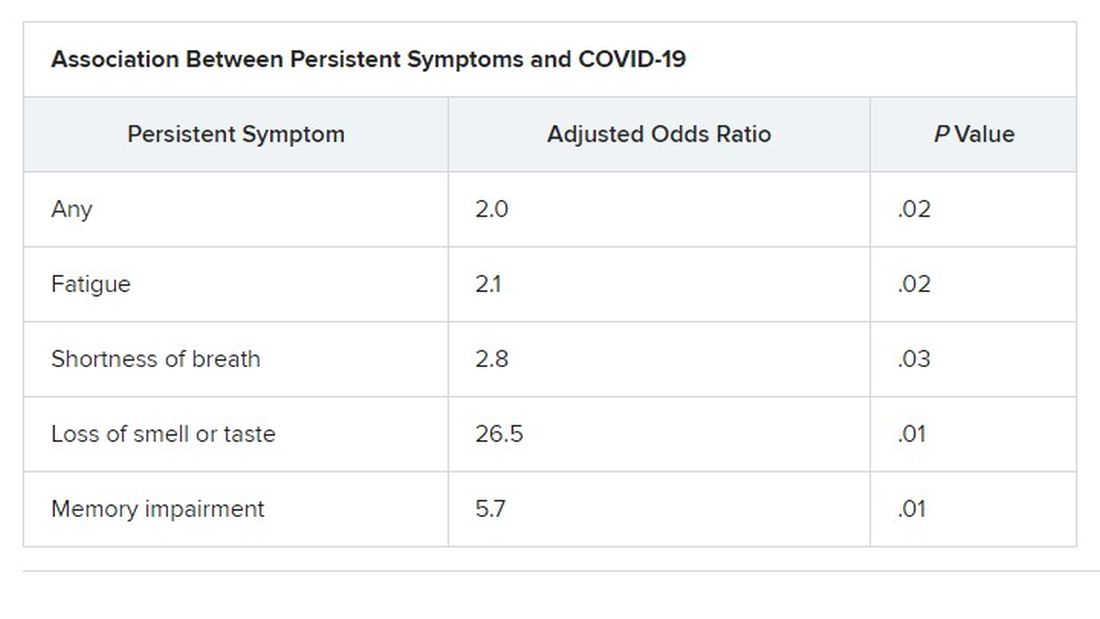

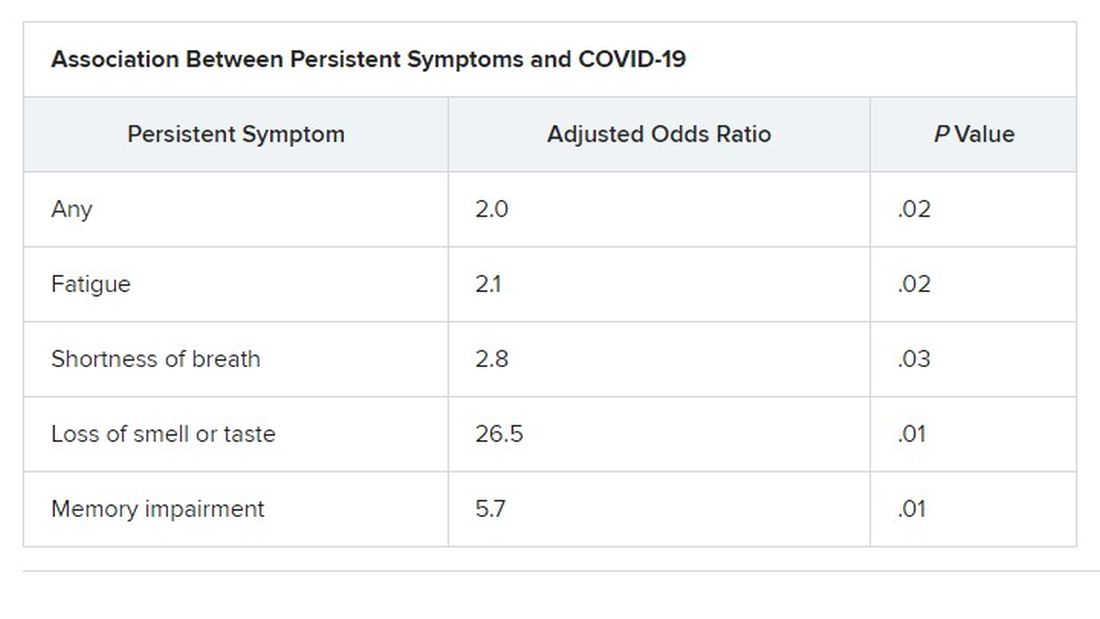

The investigation of long-term COVID symptoms in outpatients was presented online by Florian Desgranges, MD, from Lausanne (Switzerland) University Hospital. He and his colleagues found that more than half of those with a mild to moderate disease had persistent symptoms at least 3 months after diagnosis.

The prevalence of long COVID has varied in previous research, from 15% in a study of health care workers, to 46% in a study of patients with mild COVID, 52% in a study of young COVID outpatients, and 76% in a study of patients hospitalized with COVID.

Dr. Desgranges and colleagues evaluated patients seen in an ED or outpatient clinic from February to April 2020.

The 418 patients with a confirmed COVID-19 diagnosis were compared with a control group of 89 patients who presented to the same centers during the same time frame with similar symptoms – cough, shortness of breath, or fever – but had a negative SARS-CoV-2 test.

The number of patients with comorbidities was similar in the COVID and control groups (34% vs. 36%), as was median age (41 vs. 36 years) and the prevalence of women (62% vs 64%), but the proportion of health care workers was lower in the COVID group (64% vs 82%; P =.006).

Symptoms that persisted for at least 3 months were more common in the COVID than in the control group (53% vs. 37%). And patients in the COVID group reported more symptoms than those in the control group after adjustment for age, gender, smoking status, comorbidities, and timing of the survey phone call.

Levels of sleeping problems and headache were similar in the two groups.

“We have to remember that with COVID-19 came the psychosocial changes of the pandemic situation” Dr. Desgranges said.

This study suggests that some long-COVID symptoms – such as the fatigue, headache, and sleep disorders reported in the control group – could be related to the pandemic itself, which has caused psychosocial distress, Dr. Terndrup said.

Another study that looked at outpatients “has some fantastic long-term follow-up data, and shows that many patients are still engaging in rehabilitation programs nearly a year after their diagnosis,” he explained.

The COVID HOME study

That prospective longitudinal COVID HOME study, which assessed long-term symptoms in people who were never hospitalized for COVID, was presented online by Adriana Tami, MD, PhD, from the University Medical Center Groningen (the Netherlands).

The researchers visited the homes of patients to collect data, blood samples, and perform polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing 1, 2, and 3 weeks after a diagnosis of COVID-19. If their PCR test was still positive, testing continued until week 6 or a negative test. In addition, participants completed questionnaires at week 2 and at months 3, 6 and 12 to assess fatigue, quality of life, and symptoms of depression and anxiety.

Three-month follow-up data were available for 134 of the 276 people initially enrolled in the study. Questionnaires were completed by 85 participants at 3 months, 62 participants at 6 months, and 10 participants at 12 months.

At least 40% of participants reported long-lasting symptoms at some point during follow-up, and at least 30% said they didn’t feel fully recovered at 12 months. The most common symptom was persistent fatigue, reported at 3, 6, and 12 months by at least 44% of participants. Other common symptoms – reported by at least 20% of respondents at 3, 6, and 12 months – were headache, mental or neurologic symptoms, and sleep disorders, shortness of breath, lack of smell or taste, and severe fatigue.

“We have a high proportion of nonhospitalized individuals who suffer from long COVID after more than 12 months,” Dr. Tami concluded, adding that the study is ongoing. “We have other variables that we want to look at, including duration viral shedding and serological results and variants.”

“These cohort studies are very helpful, but they can lead to inaccurate conclusions,” Dr. Terndrup cautioned.

They only provide pieces of the big picture, but they “do add to a growing body of knowledge about a significant portion of COVID patients still struggling with symptoms long after their initial infection. The symptoms can be quite variable but are dominated by both physical and mental fatigue, and tend to be worse in patients who were sicker at initial infection,” he said in an interview.

As a whole, these studies reinforce the need for treatment programs to help patients who suffer from long COVID, he added, but “I advise caution to folks suffering out there who seek ‘miracle cures’; across the world, we are collaborating to find solutions that are safe and effective.”

We are in desperate need of an equity lens in these studies.

“There is still a great deal to learn about long COVID,” said Dr. Terndrup. Data on underrepresented populations – such as Black, Indigenous, and people of color – are lacking from these and others studies, he explained. “We are in desperate need of an equity lens in these studies,” particularly in the United States, where there are “significant disparities” in the treatment of different populations.

However, “I do hope that this work can lead to a better understanding of how other viral infections can cause long-lasting symptoms,” said Dr. Terndrup.

“We have long proposed that after acute presentation, some microbes can cause chronic symptoms, like fatigue and widespread pain. Perhaps we can learn how to better care for these patients after learning from COVID’s significant impact on our societies across the globe.”

Dr. Aranda and Dr. Desgranges have disclosed no relevant financial relationships or study funding. The study by Dr. Tami’s team was funded by the University Medical Center Groningen Organization for Health Research and Development, and Connecting European Cohorts to Increase Common and Effective Response to SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic. Dr. Terndrup disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Findings from the cohort, composed of 113 COVID-19 survivors who developed ARDS after admission to a single center before to April 16, 2020, were presented online at the 31st European Congress of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases by Judit Aranda, MD, from Complex Hospitalari Moisés Broggi in Barcelona.

Median age of the participants was 64 years, and 70% were male. At least one persistent symptom was experienced during follow-up by 81% of the cohort, with 45% reporting shortness of breath, 50% reporting muscle pain, 43% reporting memory impairment, and 46% reporting physical weakness of at least 5 on a 10-point scale.

Of the 104 participants who completed a 6-minute walk test, 30% had a decrease in oxygen saturation level of at least 4%, and 5% had an initial or final level below 88%. Of the 46 participants who underwent a pulmonary function test, 15% had a forced expiratory volume in 1 second below 70%.

And of the 49% of participants with pathologic findings on chest x-ray, most were bilateral interstitial infiltrates (88%).

In addition, more than 90% of participants developed depression, anxiety, or PTSD, Dr. Aranda reported.

Not the whole picture

This study shows that sicker people – “those in intensive care units with acute respiratory distress syndrome” – are “more likely to be struggling with more severe symptoms,” said Christopher Terndrup, MD, from the division of general internal medicine and geriatrics at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland.

But a Swiss study, also presented at the meeting, “shows how even mild COVID cases can lead to debilitating symptoms,” Dr. Terndrup said in an interview.

The investigation of long-term COVID symptoms in outpatients was presented online by Florian Desgranges, MD, from Lausanne (Switzerland) University Hospital. He and his colleagues found that more than half of those with a mild to moderate disease had persistent symptoms at least 3 months after diagnosis.

The prevalence of long COVID has varied in previous research, from 15% in a study of health care workers, to 46% in a study of patients with mild COVID, 52% in a study of young COVID outpatients, and 76% in a study of patients hospitalized with COVID.

Dr. Desgranges and colleagues evaluated patients seen in an ED or outpatient clinic from February to April 2020.

The 418 patients with a confirmed COVID-19 diagnosis were compared with a control group of 89 patients who presented to the same centers during the same time frame with similar symptoms – cough, shortness of breath, or fever – but had a negative SARS-CoV-2 test.

The number of patients with comorbidities was similar in the COVID and control groups (34% vs. 36%), as was median age (41 vs. 36 years) and the prevalence of women (62% vs 64%), but the proportion of health care workers was lower in the COVID group (64% vs 82%; P =.006).

Symptoms that persisted for at least 3 months were more common in the COVID than in the control group (53% vs. 37%). And patients in the COVID group reported more symptoms than those in the control group after adjustment for age, gender, smoking status, comorbidities, and timing of the survey phone call.

Levels of sleeping problems and headache were similar in the two groups.

“We have to remember that with COVID-19 came the psychosocial changes of the pandemic situation” Dr. Desgranges said.

This study suggests that some long-COVID symptoms – such as the fatigue, headache, and sleep disorders reported in the control group – could be related to the pandemic itself, which has caused psychosocial distress, Dr. Terndrup said.

Another study that looked at outpatients “has some fantastic long-term follow-up data, and shows that many patients are still engaging in rehabilitation programs nearly a year after their diagnosis,” he explained.

The COVID HOME study

That prospective longitudinal COVID HOME study, which assessed long-term symptoms in people who were never hospitalized for COVID, was presented online by Adriana Tami, MD, PhD, from the University Medical Center Groningen (the Netherlands).

The researchers visited the homes of patients to collect data, blood samples, and perform polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing 1, 2, and 3 weeks after a diagnosis of COVID-19. If their PCR test was still positive, testing continued until week 6 or a negative test. In addition, participants completed questionnaires at week 2 and at months 3, 6 and 12 to assess fatigue, quality of life, and symptoms of depression and anxiety.

Three-month follow-up data were available for 134 of the 276 people initially enrolled in the study. Questionnaires were completed by 85 participants at 3 months, 62 participants at 6 months, and 10 participants at 12 months.

At least 40% of participants reported long-lasting symptoms at some point during follow-up, and at least 30% said they didn’t feel fully recovered at 12 months. The most common symptom was persistent fatigue, reported at 3, 6, and 12 months by at least 44% of participants. Other common symptoms – reported by at least 20% of respondents at 3, 6, and 12 months – were headache, mental or neurologic symptoms, and sleep disorders, shortness of breath, lack of smell or taste, and severe fatigue.

“We have a high proportion of nonhospitalized individuals who suffer from long COVID after more than 12 months,” Dr. Tami concluded, adding that the study is ongoing. “We have other variables that we want to look at, including duration viral shedding and serological results and variants.”

“These cohort studies are very helpful, but they can lead to inaccurate conclusions,” Dr. Terndrup cautioned.

They only provide pieces of the big picture, but they “do add to a growing body of knowledge about a significant portion of COVID patients still struggling with symptoms long after their initial infection. The symptoms can be quite variable but are dominated by both physical and mental fatigue, and tend to be worse in patients who were sicker at initial infection,” he said in an interview.

As a whole, these studies reinforce the need for treatment programs to help patients who suffer from long COVID, he added, but “I advise caution to folks suffering out there who seek ‘miracle cures’; across the world, we are collaborating to find solutions that are safe and effective.”

We are in desperate need of an equity lens in these studies.

“There is still a great deal to learn about long COVID,” said Dr. Terndrup. Data on underrepresented populations – such as Black, Indigenous, and people of color – are lacking from these and others studies, he explained. “We are in desperate need of an equity lens in these studies,” particularly in the United States, where there are “significant disparities” in the treatment of different populations.

However, “I do hope that this work can lead to a better understanding of how other viral infections can cause long-lasting symptoms,” said Dr. Terndrup.

“We have long proposed that after acute presentation, some microbes can cause chronic symptoms, like fatigue and widespread pain. Perhaps we can learn how to better care for these patients after learning from COVID’s significant impact on our societies across the globe.”

Dr. Aranda and Dr. Desgranges have disclosed no relevant financial relationships or study funding. The study by Dr. Tami’s team was funded by the University Medical Center Groningen Organization for Health Research and Development, and Connecting European Cohorts to Increase Common and Effective Response to SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic. Dr. Terndrup disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM EUROPEAN CONGRESS OF CLINICAL MICROBIOLOGY & INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Resistant TB: Adjustments to BPaL regimen reduce AEs, not efficacy

Lower doses of linezolid in the BPaL drug regimen (bedaquiline, pretomanid, and linezolid) significantly reduce the adverse events associated with the treatment for patients with highly drug-resistant tuberculosis (TB) without compromising its high efficacy, new research shows.

“The ZeNix trial shows that reduced doses and/or shorter durations of linezolid appear to have high efficacy and improved safety,” said first author Francesca Conradie, MB, BCh, of the clinical HIV research unit, faculty of health sciences, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa, in presenting the findings at the virtual meeting of the International AIDS Society conference.

As recently reported in the pivotal Nix-TB trial, the BPaL regimen yielded a 90% treatment success rate among people with highly drug-resistant forms of TB.

However, a 6-month regimen that included linezolid 1,200 mg resulted in toxic effects: 81% of patients in the study experienced peripheral neuropathy, and myelosuppression occurred in 48%. These effects often led to dose reductions or treatment interruption.

Adjustments in the dose of linezolid in the new ZeNix trial substantially reduced peripheral neuropathy to 13% and myelosuppression to 7%, with no significant reduction in the treatment response.

Importantly, the results were similar among patients with and those without HIV. This is of note because TB is the leading cause of death among patients with HIV.

“In the ZeNix trial, only 20% of patients were HIV infected, but in the [previous] Nix-TB trial, 30% were infected, so we have experience now in about 70 patients who were infected, and the outcomes were no different,” Dr. Conradie said in an interview.

Experts say the findings represent an important turn in the steep challenge of tackling highly resistant TB.

“In our opinion, these are exciting results that could change treatment guidelines for highly drug-resistant tuberculosis, with real benefits for the patients,” said Hendrik Streeck, MD, International AIDS Society cochair and director of the Institute of Virology and the Institute for HIV Research at the University Bonn (Germany), in a press conference.

Payam Nahid, MD, MPH, director of the Center for Tuberculosis at theUniversity of California, San Francisco, agreed.

“The results of this trial will impact global practices in treating drug-resistant TB as well as the design and conduct of future TB clinical trials,” Dr. Nahid said in an interview.

ZeNix trial

The phase 3 ZeNix trial included 181 patients with highly resistant TB in South Africa, Russia, Georgia, and Moldova. The mean age of the patients was 37 years; 67.4% were men, 63.5% were White, and 19.9% were HIV positive.

All patients were treated for 6 months with bedaquiline 200 mg daily for 8 weeks followed by 100 mg daily for 18 weeks, as well as pretomanid 200 mg daily.

The patients were randomly assigned to receive one of four daily doses of linezolid: 1,200 mg for 6 months (the original dose from the Nix-TB trial; n = 45) or 2 months (n = 46), or 600 mg for 6 or 2 months (45 patients each).

Percentages of patients with HIV were equal among the four groups, at about 20% each.

The primary outcomes – resolution of clinical disease and a negative culture status after 6 months – were observed across all linezolid dose groups. The success rate was 93% for those receiving 1,200 mg for 6 months, 89% for those receiving 1,200 mg for 2 months, 91% for those receiving 600 mg for 6 months, and 84% for those receiving 600 mg for 2 months.

With regard to the key adverse events of peripheral neuropathy and myelosuppression, manifested as anemia, the highest rates were among those who received linezolid 1,200 mg for 6 month, at 38% and 22%, respectively, compared with 24% and 17.4% among those who received 1,200 mg for 2 months, 24% and 2% among those who received 600 mg for 6 months, and 13% and 6.7% among those who received 600 mg for 2 months.

Four cases of optic neuropathy occurred among those who received 1,200 mg for 6 months; all cases resolved.

Patients who received 1,200 mg for 6 months required the highest number of linezolid dose modifications; 51% required changes that included reduction, interruption, or discontinuation, compared with 28% among those who received 1,200 mg for 2 months and 13% each in the other two groups.

On the basis of these results, “my personal opinion is that 600 mg at 6 months [of linezolid] is most likely the best strategy for the treatment of this highly resistant treatment population group,” Dr. Conradie told this news organization.

Findings represent ‘great news’ in addressing concerns