User login

COVID-19 cases in children nearly doubled in just 4 weeks

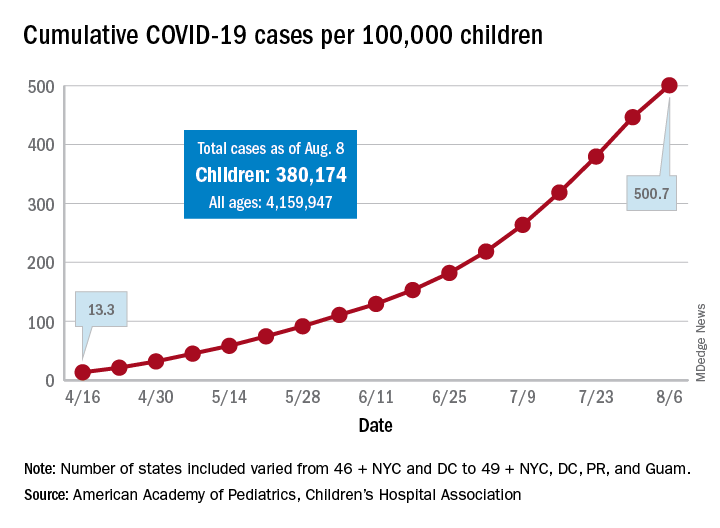

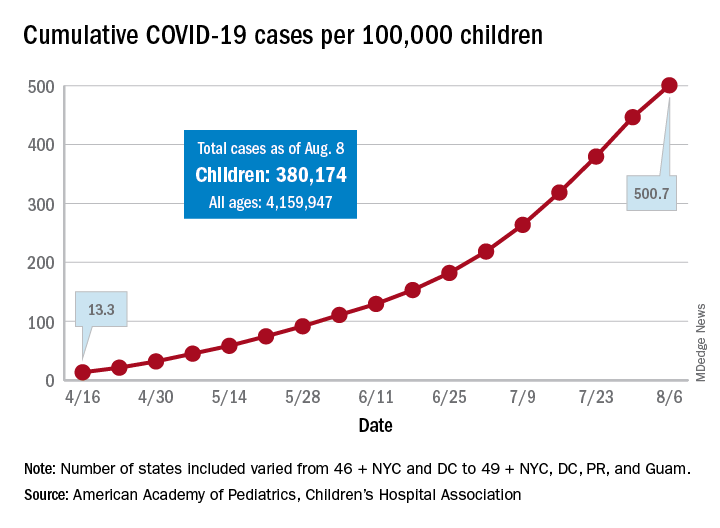

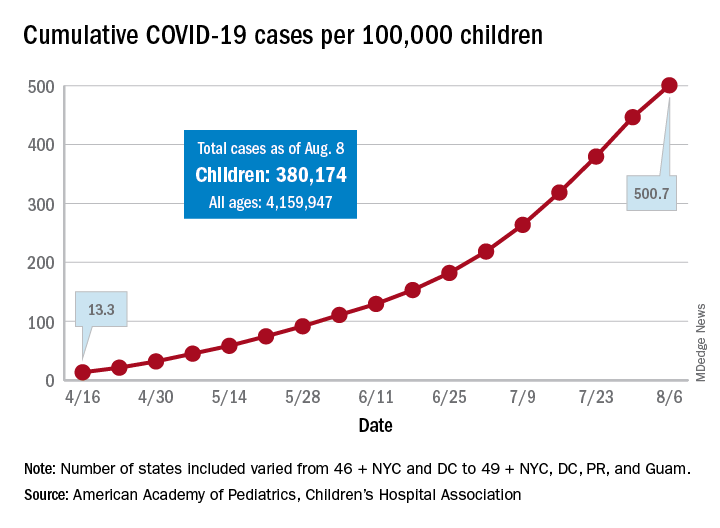

The cumulative number of new COVID-19 cases among children in the United States jumped by 90% during a recent 4-week period, according to a report that confirms children are not immune to the coronavirus.

“In areas with rapid community spread, it’s likely that more children will also be infected, and these data show that,” Sally Goza, MD, president of the American Academy of Pediatrics, said in a written statement. “I urge people to wear cloth face coverings and be diligent in social distancing and hand-washing. It is up to us to make the difference, community by community.”

The joint report from the AAP and the Children’s Hospital Association draws on data from state and local health departments in 49 states, New York City, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

The cumulative number of COVID-19 cases in children as of Aug. 6, 2020, was 380,174, and that number is 90% higher – an increase of 179,990 cases – than the total on July 9, just 4 weeks earlier, the two organizations said in the report.

and 27 states out of 47 with available data now report that over 10% of their cases were children, with Wyoming the highest at 16.5% and New Jersey the lowest at 2.9%, the report data show.

Alabama has a higher percentage of 22.5%, but the state has been reporting cases in individuals aged 0-24 years as child cases since May 7. The report’s findings are somewhat limited by differences in reporting among the states and by “gaps in the data they are reporting [that affect] how the data can be interpreted,” the AAP said in its statement.

The cumulative number of cases per 100,000 children has risen from 13.3 in mid-April, when the total number was 9,259 cases, to 500.7 per 100,000 as of Aug. 6, and there are now 21 states, along with the District of Columbia, reporting a rate of over 500 cases per 100,000 children. Arizona has the highest rate at 1,206.4, followed by South Carolina (1,074.4) and Tennessee (1,050.8), the AAP and the CHA said.

In New York City, the early epicenter of the pandemic, the 390.5 cases per 100,000 children have been reported, and in New Jersey, which joined New York in the initial surge of cases, the number is 269.5. As of Aug. 6, Hawaii had the fewest cases of any state at 91.2 per 100,000, according to the report.

Children continue to represent a very low proportion of COVID-19 deaths, “but as case counts rise across the board, that is likely to impact more children with severe illness as well,” Sean O’Leary, MD, MPH, vice chair of the AAP’s committee on infectious diseases, said in the AAP statement.

It is possible that “some of the increase in numbers of cases in children could be due to more testing. Early in the pandemic, testing only occurred for the sickest individuals. Now that there is more testing capacity … the numbers reflect a broader slice of the population, including children who may have mild or few symptoms,” the AAP suggested.

This article was updated on 8/17/2020.

The cumulative number of new COVID-19 cases among children in the United States jumped by 90% during a recent 4-week period, according to a report that confirms children are not immune to the coronavirus.

“In areas with rapid community spread, it’s likely that more children will also be infected, and these data show that,” Sally Goza, MD, president of the American Academy of Pediatrics, said in a written statement. “I urge people to wear cloth face coverings and be diligent in social distancing and hand-washing. It is up to us to make the difference, community by community.”

The joint report from the AAP and the Children’s Hospital Association draws on data from state and local health departments in 49 states, New York City, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

The cumulative number of COVID-19 cases in children as of Aug. 6, 2020, was 380,174, and that number is 90% higher – an increase of 179,990 cases – than the total on July 9, just 4 weeks earlier, the two organizations said in the report.

and 27 states out of 47 with available data now report that over 10% of their cases were children, with Wyoming the highest at 16.5% and New Jersey the lowest at 2.9%, the report data show.

Alabama has a higher percentage of 22.5%, but the state has been reporting cases in individuals aged 0-24 years as child cases since May 7. The report’s findings are somewhat limited by differences in reporting among the states and by “gaps in the data they are reporting [that affect] how the data can be interpreted,” the AAP said in its statement.

The cumulative number of cases per 100,000 children has risen from 13.3 in mid-April, when the total number was 9,259 cases, to 500.7 per 100,000 as of Aug. 6, and there are now 21 states, along with the District of Columbia, reporting a rate of over 500 cases per 100,000 children. Arizona has the highest rate at 1,206.4, followed by South Carolina (1,074.4) and Tennessee (1,050.8), the AAP and the CHA said.

In New York City, the early epicenter of the pandemic, the 390.5 cases per 100,000 children have been reported, and in New Jersey, which joined New York in the initial surge of cases, the number is 269.5. As of Aug. 6, Hawaii had the fewest cases of any state at 91.2 per 100,000, according to the report.

Children continue to represent a very low proportion of COVID-19 deaths, “but as case counts rise across the board, that is likely to impact more children with severe illness as well,” Sean O’Leary, MD, MPH, vice chair of the AAP’s committee on infectious diseases, said in the AAP statement.

It is possible that “some of the increase in numbers of cases in children could be due to more testing. Early in the pandemic, testing only occurred for the sickest individuals. Now that there is more testing capacity … the numbers reflect a broader slice of the population, including children who may have mild or few symptoms,” the AAP suggested.

This article was updated on 8/17/2020.

The cumulative number of new COVID-19 cases among children in the United States jumped by 90% during a recent 4-week period, according to a report that confirms children are not immune to the coronavirus.

“In areas with rapid community spread, it’s likely that more children will also be infected, and these data show that,” Sally Goza, MD, president of the American Academy of Pediatrics, said in a written statement. “I urge people to wear cloth face coverings and be diligent in social distancing and hand-washing. It is up to us to make the difference, community by community.”

The joint report from the AAP and the Children’s Hospital Association draws on data from state and local health departments in 49 states, New York City, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

The cumulative number of COVID-19 cases in children as of Aug. 6, 2020, was 380,174, and that number is 90% higher – an increase of 179,990 cases – than the total on July 9, just 4 weeks earlier, the two organizations said in the report.

and 27 states out of 47 with available data now report that over 10% of their cases were children, with Wyoming the highest at 16.5% and New Jersey the lowest at 2.9%, the report data show.

Alabama has a higher percentage of 22.5%, but the state has been reporting cases in individuals aged 0-24 years as child cases since May 7. The report’s findings are somewhat limited by differences in reporting among the states and by “gaps in the data they are reporting [that affect] how the data can be interpreted,” the AAP said in its statement.

The cumulative number of cases per 100,000 children has risen from 13.3 in mid-April, when the total number was 9,259 cases, to 500.7 per 100,000 as of Aug. 6, and there are now 21 states, along with the District of Columbia, reporting a rate of over 500 cases per 100,000 children. Arizona has the highest rate at 1,206.4, followed by South Carolina (1,074.4) and Tennessee (1,050.8), the AAP and the CHA said.

In New York City, the early epicenter of the pandemic, the 390.5 cases per 100,000 children have been reported, and in New Jersey, which joined New York in the initial surge of cases, the number is 269.5. As of Aug. 6, Hawaii had the fewest cases of any state at 91.2 per 100,000, according to the report.

Children continue to represent a very low proportion of COVID-19 deaths, “but as case counts rise across the board, that is likely to impact more children with severe illness as well,” Sean O’Leary, MD, MPH, vice chair of the AAP’s committee on infectious diseases, said in the AAP statement.

It is possible that “some of the increase in numbers of cases in children could be due to more testing. Early in the pandemic, testing only occurred for the sickest individuals. Now that there is more testing capacity … the numbers reflect a broader slice of the population, including children who may have mild or few symptoms,” the AAP suggested.

This article was updated on 8/17/2020.

Telehealth in the COVID-19 era: The New York experience

Big data scientists and health-care experts have tried preparing physicians and patients for the arrival of telemedicine for years. Health tracking applications are on our smartphones. Compact ambulatory devices diagnose hypertension and atrial fibrillation. Advanced imaging modalities make the stethoscope more of a neck accessory than a practical tool. Despite these efficient technologic advancements, the idea of making the sacred in-person office visit remote and through a screen appealed to few. In fact, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, only 15% of medical practices offered telehealth services and 8% of Americans joined in remote visits annually (Mann DM et al. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2019 Feb 1;26[2]:106-114).

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit New York City and admissions for hypoxemic respiratory failure skyrocketed, ED and in-person clinic visits for other acute and chronic conditions plummeted. Prior to clinics officially closing their doors, doctors in New York City asked their patients to reserve office visits for emergency issues only ,with most patients willingly staying home to avoid exposure to the virus. Suddenly, after years of disinterest in adopting telehealth, hospitals and clinics were catapulted into a full-on need for this technology. Overnight, our division’s secretaries and medical assistants became IT support staff. We all learned together what worked, what didn’t work, and how to adapt our workflow to meet everyone’s needs.

Previously, longstanding issues with accessibility and reimbursement presented barriers to widespread adoption of telemedicine. Once the pandemic hit, though, many regulatory changes were quickly made to accommodate telehealth.

Three such changes are worth highlighting (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. COVID-19 emergency declaration blanket waivers for health care providers. March 30, 2020).

First, patient privacy rules became more lenient. Prior to the pandemic, HIPAA mandated that both doctor and patient use embedded video interfaces with high levels of security. Now, health-care providers can use commonplace video chat applications such as FaceTime, Google Hangouts, Zoom, or Skype to provide telehealth without risk of penalty for HIPAA noncompliance. When connectivity concerns arose with our EMR’s embedded telehealth application, a quick transition to one of these platforms mitigated patient and provider frustration.

Second, prior to the pandemic, some private insurance providers reimbursed for televisits, but there were stipulations on how the visit could be conducted. Now, many of the commercial insurers plus Medicare and Medicaid in New York State reimburse the same amount for televisits as in-person visits (fee-for-service rate). Reimbursement rates of audio-only encounters were increased. If these changes are continued postpandemic, it will have an expansive impact on the future of an outpatient practice.

Third, restrictive government regulations relaxed with regard to telehealth deployment. Gone are the demands on providers and patients to be physically face-to-face. Many colleagues worked from home, safely social distancing.

Even though remote medical visits were a crucial part of flattening the curve during the peak of the pandemic in New York City, the telehealth experience is not without flaws.

An informal survey of providers in our own division garnered diverse and spirited viewpoints about seeing patients remotely. Instead of using a stethoscope to pick up a subtle finding, telehealth visits require the use of our eyes to scan a patient’s home environment for insights explaining their chronic cough (Where is the mold? Where is the water damage? Where is the bird?). We use our ears to hear the intonation of our patient’s voice to know when he or she is concerned, anxious, or are at their baselines. We would implore patients to put on their pulse oximeter and perform activities of daily living and/or exertion. On multiple occasions, patients would perform their own, unsolicited walks about their home to show us what they could and couldn’t do, where they place their concentrators, and where they are likely to trip over oxygen tubing. We learned to depend on them to reach the conclusion that they were at their normal state of health.

For straight-forward encounters with existing patients, most of our colleagues appreciated the simplicity and efficiency of telemedicine. But when it came to new patients, some colleagues struggled with whether they should see them for the first time over video. Universally, providers felt feelings of inadequacy without an in-person examination and review of diagnostic information.

Along those lines, many of our colleagues worried about their ability to perform the most fundamental role of a physician over the phone/internet for all patients: building trust with a patient. Eye contact, the physical exam, and verbal and nonv

Providers also noted that telehealth implementation is not the same for all individuals. Just as COVID-19 disproportionately affects the most vulnerable populations (NYC Health. COVID-19: data. Accessed July 1, 2020. https://www1.nyc.gov/site/doh/covid/covid-19-data.page), practicing telehealth has uncovered more ways in which racial/ethnic minorities, low income communities, and older patients are at a disadvantage (Garg S, et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69[15]:458). The relatively quick transition to telemedicine revealed that many of our patients don’t have emails or home computers to connect with online platforms. Similarly, some do not have smart phones with internet capabilities. Many do not speak English and cannot partake in video visits since translators are not yet embedded into the EMR’s video system. Elderly patients were frequently very anxious with telemedicine because of unfamiliarity with the technology, and many preferred a phone conversation. Thus, while more fortunate patients get to use a video interface and its association with higher patient understanding and satisfaction, our most vulnerable populations are often denied the same access to such care (Voils CI et al. J Genet Couns. 2018;27[2]:339).

Telemedicine will continue to have a significant impact on the future of health care long after the COVID-19 pandemic abates. There will be growing pains, refinement of technology, improvements in policy, and an ongoing general evolution of the system. Patients and providers will grow together as its utilization continues. We suspect patient surveys about their attitudes and preferences for telemedicine will be as varied as the providers surveyed here. A recent survey of 1000 patients about their telehealth experiences during the pandemic reported that over 75% were very or completely satisfied with their virtual care experiences and over 50% indicated they would be willing to switch providers to have virtual visits on a regular basis (Patient Perspectives on Virtual Care Report, Accessed July 7, 2020, https://www.kyruus.com/2020-virtual-care-report).

One hopes that with time and on-going feedback, the fundamental purpose of the physician-patient relationship can be maintained and both sides can still appreciate the conveniences and power of telehealth technology.

Dr. Fedyna and Dr. McGroder are affiliated with the Division of Pulmonary, Allergy, and Critical Care Medicine, Columbia University Medical Center, New York, NY.

Big data scientists and health-care experts have tried preparing physicians and patients for the arrival of telemedicine for years. Health tracking applications are on our smartphones. Compact ambulatory devices diagnose hypertension and atrial fibrillation. Advanced imaging modalities make the stethoscope more of a neck accessory than a practical tool. Despite these efficient technologic advancements, the idea of making the sacred in-person office visit remote and through a screen appealed to few. In fact, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, only 15% of medical practices offered telehealth services and 8% of Americans joined in remote visits annually (Mann DM et al. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2019 Feb 1;26[2]:106-114).

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit New York City and admissions for hypoxemic respiratory failure skyrocketed, ED and in-person clinic visits for other acute and chronic conditions plummeted. Prior to clinics officially closing their doors, doctors in New York City asked their patients to reserve office visits for emergency issues only ,with most patients willingly staying home to avoid exposure to the virus. Suddenly, after years of disinterest in adopting telehealth, hospitals and clinics were catapulted into a full-on need for this technology. Overnight, our division’s secretaries and medical assistants became IT support staff. We all learned together what worked, what didn’t work, and how to adapt our workflow to meet everyone’s needs.

Previously, longstanding issues with accessibility and reimbursement presented barriers to widespread adoption of telemedicine. Once the pandemic hit, though, many regulatory changes were quickly made to accommodate telehealth.

Three such changes are worth highlighting (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. COVID-19 emergency declaration blanket waivers for health care providers. March 30, 2020).

First, patient privacy rules became more lenient. Prior to the pandemic, HIPAA mandated that both doctor and patient use embedded video interfaces with high levels of security. Now, health-care providers can use commonplace video chat applications such as FaceTime, Google Hangouts, Zoom, or Skype to provide telehealth without risk of penalty for HIPAA noncompliance. When connectivity concerns arose with our EMR’s embedded telehealth application, a quick transition to one of these platforms mitigated patient and provider frustration.

Second, prior to the pandemic, some private insurance providers reimbursed for televisits, but there were stipulations on how the visit could be conducted. Now, many of the commercial insurers plus Medicare and Medicaid in New York State reimburse the same amount for televisits as in-person visits (fee-for-service rate). Reimbursement rates of audio-only encounters were increased. If these changes are continued postpandemic, it will have an expansive impact on the future of an outpatient practice.

Third, restrictive government regulations relaxed with regard to telehealth deployment. Gone are the demands on providers and patients to be physically face-to-face. Many colleagues worked from home, safely social distancing.

Even though remote medical visits were a crucial part of flattening the curve during the peak of the pandemic in New York City, the telehealth experience is not without flaws.

An informal survey of providers in our own division garnered diverse and spirited viewpoints about seeing patients remotely. Instead of using a stethoscope to pick up a subtle finding, telehealth visits require the use of our eyes to scan a patient’s home environment for insights explaining their chronic cough (Where is the mold? Where is the water damage? Where is the bird?). We use our ears to hear the intonation of our patient’s voice to know when he or she is concerned, anxious, or are at their baselines. We would implore patients to put on their pulse oximeter and perform activities of daily living and/or exertion. On multiple occasions, patients would perform their own, unsolicited walks about their home to show us what they could and couldn’t do, where they place their concentrators, and where they are likely to trip over oxygen tubing. We learned to depend on them to reach the conclusion that they were at their normal state of health.

For straight-forward encounters with existing patients, most of our colleagues appreciated the simplicity and efficiency of telemedicine. But when it came to new patients, some colleagues struggled with whether they should see them for the first time over video. Universally, providers felt feelings of inadequacy without an in-person examination and review of diagnostic information.

Along those lines, many of our colleagues worried about their ability to perform the most fundamental role of a physician over the phone/internet for all patients: building trust with a patient. Eye contact, the physical exam, and verbal and nonv

Providers also noted that telehealth implementation is not the same for all individuals. Just as COVID-19 disproportionately affects the most vulnerable populations (NYC Health. COVID-19: data. Accessed July 1, 2020. https://www1.nyc.gov/site/doh/covid/covid-19-data.page), practicing telehealth has uncovered more ways in which racial/ethnic minorities, low income communities, and older patients are at a disadvantage (Garg S, et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69[15]:458). The relatively quick transition to telemedicine revealed that many of our patients don’t have emails or home computers to connect with online platforms. Similarly, some do not have smart phones with internet capabilities. Many do not speak English and cannot partake in video visits since translators are not yet embedded into the EMR’s video system. Elderly patients were frequently very anxious with telemedicine because of unfamiliarity with the technology, and many preferred a phone conversation. Thus, while more fortunate patients get to use a video interface and its association with higher patient understanding and satisfaction, our most vulnerable populations are often denied the same access to such care (Voils CI et al. J Genet Couns. 2018;27[2]:339).

Telemedicine will continue to have a significant impact on the future of health care long after the COVID-19 pandemic abates. There will be growing pains, refinement of technology, improvements in policy, and an ongoing general evolution of the system. Patients and providers will grow together as its utilization continues. We suspect patient surveys about their attitudes and preferences for telemedicine will be as varied as the providers surveyed here. A recent survey of 1000 patients about their telehealth experiences during the pandemic reported that over 75% were very or completely satisfied with their virtual care experiences and over 50% indicated they would be willing to switch providers to have virtual visits on a regular basis (Patient Perspectives on Virtual Care Report, Accessed July 7, 2020, https://www.kyruus.com/2020-virtual-care-report).

One hopes that with time and on-going feedback, the fundamental purpose of the physician-patient relationship can be maintained and both sides can still appreciate the conveniences and power of telehealth technology.

Dr. Fedyna and Dr. McGroder are affiliated with the Division of Pulmonary, Allergy, and Critical Care Medicine, Columbia University Medical Center, New York, NY.

Big data scientists and health-care experts have tried preparing physicians and patients for the arrival of telemedicine for years. Health tracking applications are on our smartphones. Compact ambulatory devices diagnose hypertension and atrial fibrillation. Advanced imaging modalities make the stethoscope more of a neck accessory than a practical tool. Despite these efficient technologic advancements, the idea of making the sacred in-person office visit remote and through a screen appealed to few. In fact, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, only 15% of medical practices offered telehealth services and 8% of Americans joined in remote visits annually (Mann DM et al. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2019 Feb 1;26[2]:106-114).

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit New York City and admissions for hypoxemic respiratory failure skyrocketed, ED and in-person clinic visits for other acute and chronic conditions plummeted. Prior to clinics officially closing their doors, doctors in New York City asked their patients to reserve office visits for emergency issues only ,with most patients willingly staying home to avoid exposure to the virus. Suddenly, after years of disinterest in adopting telehealth, hospitals and clinics were catapulted into a full-on need for this technology. Overnight, our division’s secretaries and medical assistants became IT support staff. We all learned together what worked, what didn’t work, and how to adapt our workflow to meet everyone’s needs.

Previously, longstanding issues with accessibility and reimbursement presented barriers to widespread adoption of telemedicine. Once the pandemic hit, though, many regulatory changes were quickly made to accommodate telehealth.

Three such changes are worth highlighting (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. COVID-19 emergency declaration blanket waivers for health care providers. March 30, 2020).

First, patient privacy rules became more lenient. Prior to the pandemic, HIPAA mandated that both doctor and patient use embedded video interfaces with high levels of security. Now, health-care providers can use commonplace video chat applications such as FaceTime, Google Hangouts, Zoom, or Skype to provide telehealth without risk of penalty for HIPAA noncompliance. When connectivity concerns arose with our EMR’s embedded telehealth application, a quick transition to one of these platforms mitigated patient and provider frustration.

Second, prior to the pandemic, some private insurance providers reimbursed for televisits, but there were stipulations on how the visit could be conducted. Now, many of the commercial insurers plus Medicare and Medicaid in New York State reimburse the same amount for televisits as in-person visits (fee-for-service rate). Reimbursement rates of audio-only encounters were increased. If these changes are continued postpandemic, it will have an expansive impact on the future of an outpatient practice.

Third, restrictive government regulations relaxed with regard to telehealth deployment. Gone are the demands on providers and patients to be physically face-to-face. Many colleagues worked from home, safely social distancing.

Even though remote medical visits were a crucial part of flattening the curve during the peak of the pandemic in New York City, the telehealth experience is not without flaws.

An informal survey of providers in our own division garnered diverse and spirited viewpoints about seeing patients remotely. Instead of using a stethoscope to pick up a subtle finding, telehealth visits require the use of our eyes to scan a patient’s home environment for insights explaining their chronic cough (Where is the mold? Where is the water damage? Where is the bird?). We use our ears to hear the intonation of our patient’s voice to know when he or she is concerned, anxious, or are at their baselines. We would implore patients to put on their pulse oximeter and perform activities of daily living and/or exertion. On multiple occasions, patients would perform their own, unsolicited walks about their home to show us what they could and couldn’t do, where they place their concentrators, and where they are likely to trip over oxygen tubing. We learned to depend on them to reach the conclusion that they were at their normal state of health.

For straight-forward encounters with existing patients, most of our colleagues appreciated the simplicity and efficiency of telemedicine. But when it came to new patients, some colleagues struggled with whether they should see them for the first time over video. Universally, providers felt feelings of inadequacy without an in-person examination and review of diagnostic information.

Along those lines, many of our colleagues worried about their ability to perform the most fundamental role of a physician over the phone/internet for all patients: building trust with a patient. Eye contact, the physical exam, and verbal and nonv

Providers also noted that telehealth implementation is not the same for all individuals. Just as COVID-19 disproportionately affects the most vulnerable populations (NYC Health. COVID-19: data. Accessed July 1, 2020. https://www1.nyc.gov/site/doh/covid/covid-19-data.page), practicing telehealth has uncovered more ways in which racial/ethnic minorities, low income communities, and older patients are at a disadvantage (Garg S, et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69[15]:458). The relatively quick transition to telemedicine revealed that many of our patients don’t have emails or home computers to connect with online platforms. Similarly, some do not have smart phones with internet capabilities. Many do not speak English and cannot partake in video visits since translators are not yet embedded into the EMR’s video system. Elderly patients were frequently very anxious with telemedicine because of unfamiliarity with the technology, and many preferred a phone conversation. Thus, while more fortunate patients get to use a video interface and its association with higher patient understanding and satisfaction, our most vulnerable populations are often denied the same access to such care (Voils CI et al. J Genet Couns. 2018;27[2]:339).

Telemedicine will continue to have a significant impact on the future of health care long after the COVID-19 pandemic abates. There will be growing pains, refinement of technology, improvements in policy, and an ongoing general evolution of the system. Patients and providers will grow together as its utilization continues. We suspect patient surveys about their attitudes and preferences for telemedicine will be as varied as the providers surveyed here. A recent survey of 1000 patients about their telehealth experiences during the pandemic reported that over 75% were very or completely satisfied with their virtual care experiences and over 50% indicated they would be willing to switch providers to have virtual visits on a regular basis (Patient Perspectives on Virtual Care Report, Accessed July 7, 2020, https://www.kyruus.com/2020-virtual-care-report).

One hopes that with time and on-going feedback, the fundamental purpose of the physician-patient relationship can be maintained and both sides can still appreciate the conveniences and power of telehealth technology.

Dr. Fedyna and Dr. McGroder are affiliated with the Division of Pulmonary, Allergy, and Critical Care Medicine, Columbia University Medical Center, New York, NY.

Studies gauge role of schools, kids in spread of COVID-19

When officials closed U.S. schools in March to limit the spread of COVID-19, they may have prevented more than 1 million cases over a 26-day period, a new estimate published online July 29 in JAMA suggests.

But school closures also left blind spots in understanding how children and schools affect disease transmission.

“School closures early in pandemic responses thwarted larger-scale investigations of schools as a source of community transmission,” researchers noted in a separate study, published online July 30 in JAMA Pediatrics, that examined levels of viral RNA in children and adults with COVID-19.

“Our analyses suggest children younger than 5 years with mild to moderate COVID-19 have high amounts of SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA in their nasopharynx, compared with older children and adults,” reported Taylor Heald-Sargent, MD, PhD, and colleagues. “Thus, young children can potentially be important drivers of SARS-CoV-2 spread in the general population, as has been demonstrated with respiratory syncytial virus, where children with high viral loads are more likely to transmit.”

Although the study “was not designed to prove that younger children spread COVID-19 as much as adults,” it is a possibility, Dr. Heald-Sargent, a pediatric infectious diseases specialist at Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital and assistant professor of pediatrics at Northwestern University, Chicago, said in a related news release. “We need to take that into account in efforts to reduce transmission as we continue to learn more about this virus.”.

The study included 145 patients with mild or moderate illness who were within 1 week of symptom onset. The researchers used reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (rt-PCR) on nasopharyngeal swabs collected at inpatient, outpatient, emergency department, or drive-through testing sites to measure SARS-CoV-2 levels. The investigators compared PCR amplification cycle threshold (CT) values for children younger than 5 years (n = 46), children aged 5-17 years (n = 51), and adults aged 18-65 years (n = 48); lower CT values indicate higher amounts of viral nucleic acid.

Median CT values for older children and adults were similar (about 11), whereas the median CT value for young children was significantly lower (6.5). The differences between young children and adults “approximate a 10-fold to 100-fold greater amount of SARS-CoV-2 in the upper respiratory tract of young children,” the researchers wrote.

“Behavioral habits of young children and close quarters in school and day care settings raise concern for SARS-CoV-2 amplification in this population as public health restrictions are eased,” they write.

Modeling the impact of school closures

In the JAMA study, Katherine A. Auger, MD, of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, and colleagues examined at the U.S. population level whether closing schools, as all 50 states did in March, was associated with relative decreases in COVID-19 incidence and mortality.

To isolate the effect of school closures, the researchers used an interrupted time series analysis and included other state-level nonpharmaceutical interventions and variables in their regression models.

“Per week, the incidence was estimated to have been 39% of what it would have been had schools remained open,” Dr. Auger and colleagues wrote. “Extrapolating the absolute differences of 423.9 cases and 12.6 deaths per 100,000 to 322.2 million residents nationally suggests that school closure may have been associated with approximately 1.37 million fewer cases of COVID-19 over a 26-day period and 40,600 fewer deaths over a 16-day period; however, these figures do not account for uncertainty in the model assumptions and the resulting estimates.”

Relative reductions in incidence and mortality were largest in states that closed schools when the incidence of COVID-19 was low, the authors found.

Decisions with high stakes

In an accompanying editorial, Julie M. Donohue, PhD, and Elizabeth Miller, MD, PhD, both affiliated with the University of Pittsburgh, emphasized that the results are estimates. “School closures were enacted in close proximity ... to other physical distancing measures, such as nonessential business closures and stay-at-home orders, making it difficult to disentangle the potential effect of each intervention.”

Although the findings “suggest a role for school closures in virus mitigation, school and health officials must balance this with academic, health, and economic consequences,” Dr. Donohue and Dr. Miller added. “Given the strong connection between education, income, and life expectancy, school closures could have long-term deleterious consequences for child health, likely reaching into adulthood.” Schools provide “meals and nutrition, health care including behavioral health supports, physical activity, social interaction, supports for students with special education needs and disabilities, and other vital resources for healthy development.”

In a viewpoint article also published in JAMA, authors involved in the creation of a National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine reported on the reopening of schools recommend that districts “make every effort to prioritize reopening with an emphasis on providing in-person instruction for students in kindergarten through grade 5 as well as those students with special needs who might be best served by in-person instruction.

“To reopen safely, school districts are encouraged to ensure ventilation and air filtration, clean surfaces frequently, provide facilities for regular handwashing, and provide space for physical distancing,” write Kenne A. Dibner, PhD, of the NASEM in Washington, D.C., and coauthors.

Furthermore, districts “need to consider transparent communication of the reality that while measures can be implemented to lower the risk of transmitting COVID-19 when schools reopen, there is no way to eliminate that risk entirely. It is critical to share both the risks and benefits of different scenarios,” they wrote.

The JAMA modeling study received funding from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and the National Institutes of Health. The NASEM report was funded by the Brady Education Foundation and the Spencer Foundation. The authors disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this story originally appeared on Medscape.com.

When officials closed U.S. schools in March to limit the spread of COVID-19, they may have prevented more than 1 million cases over a 26-day period, a new estimate published online July 29 in JAMA suggests.

But school closures also left blind spots in understanding how children and schools affect disease transmission.

“School closures early in pandemic responses thwarted larger-scale investigations of schools as a source of community transmission,” researchers noted in a separate study, published online July 30 in JAMA Pediatrics, that examined levels of viral RNA in children and adults with COVID-19.

“Our analyses suggest children younger than 5 years with mild to moderate COVID-19 have high amounts of SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA in their nasopharynx, compared with older children and adults,” reported Taylor Heald-Sargent, MD, PhD, and colleagues. “Thus, young children can potentially be important drivers of SARS-CoV-2 spread in the general population, as has been demonstrated with respiratory syncytial virus, where children with high viral loads are more likely to transmit.”

Although the study “was not designed to prove that younger children spread COVID-19 as much as adults,” it is a possibility, Dr. Heald-Sargent, a pediatric infectious diseases specialist at Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital and assistant professor of pediatrics at Northwestern University, Chicago, said in a related news release. “We need to take that into account in efforts to reduce transmission as we continue to learn more about this virus.”.

The study included 145 patients with mild or moderate illness who were within 1 week of symptom onset. The researchers used reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (rt-PCR) on nasopharyngeal swabs collected at inpatient, outpatient, emergency department, or drive-through testing sites to measure SARS-CoV-2 levels. The investigators compared PCR amplification cycle threshold (CT) values for children younger than 5 years (n = 46), children aged 5-17 years (n = 51), and adults aged 18-65 years (n = 48); lower CT values indicate higher amounts of viral nucleic acid.

Median CT values for older children and adults were similar (about 11), whereas the median CT value for young children was significantly lower (6.5). The differences between young children and adults “approximate a 10-fold to 100-fold greater amount of SARS-CoV-2 in the upper respiratory tract of young children,” the researchers wrote.

“Behavioral habits of young children and close quarters in school and day care settings raise concern for SARS-CoV-2 amplification in this population as public health restrictions are eased,” they write.

Modeling the impact of school closures

In the JAMA study, Katherine A. Auger, MD, of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, and colleagues examined at the U.S. population level whether closing schools, as all 50 states did in March, was associated with relative decreases in COVID-19 incidence and mortality.

To isolate the effect of school closures, the researchers used an interrupted time series analysis and included other state-level nonpharmaceutical interventions and variables in their regression models.

“Per week, the incidence was estimated to have been 39% of what it would have been had schools remained open,” Dr. Auger and colleagues wrote. “Extrapolating the absolute differences of 423.9 cases and 12.6 deaths per 100,000 to 322.2 million residents nationally suggests that school closure may have been associated with approximately 1.37 million fewer cases of COVID-19 over a 26-day period and 40,600 fewer deaths over a 16-day period; however, these figures do not account for uncertainty in the model assumptions and the resulting estimates.”

Relative reductions in incidence and mortality were largest in states that closed schools when the incidence of COVID-19 was low, the authors found.

Decisions with high stakes

In an accompanying editorial, Julie M. Donohue, PhD, and Elizabeth Miller, MD, PhD, both affiliated with the University of Pittsburgh, emphasized that the results are estimates. “School closures were enacted in close proximity ... to other physical distancing measures, such as nonessential business closures and stay-at-home orders, making it difficult to disentangle the potential effect of each intervention.”

Although the findings “suggest a role for school closures in virus mitigation, school and health officials must balance this with academic, health, and economic consequences,” Dr. Donohue and Dr. Miller added. “Given the strong connection between education, income, and life expectancy, school closures could have long-term deleterious consequences for child health, likely reaching into adulthood.” Schools provide “meals and nutrition, health care including behavioral health supports, physical activity, social interaction, supports for students with special education needs and disabilities, and other vital resources for healthy development.”

In a viewpoint article also published in JAMA, authors involved in the creation of a National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine reported on the reopening of schools recommend that districts “make every effort to prioritize reopening with an emphasis on providing in-person instruction for students in kindergarten through grade 5 as well as those students with special needs who might be best served by in-person instruction.

“To reopen safely, school districts are encouraged to ensure ventilation and air filtration, clean surfaces frequently, provide facilities for regular handwashing, and provide space for physical distancing,” write Kenne A. Dibner, PhD, of the NASEM in Washington, D.C., and coauthors.

Furthermore, districts “need to consider transparent communication of the reality that while measures can be implemented to lower the risk of transmitting COVID-19 when schools reopen, there is no way to eliminate that risk entirely. It is critical to share both the risks and benefits of different scenarios,” they wrote.

The JAMA modeling study received funding from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and the National Institutes of Health. The NASEM report was funded by the Brady Education Foundation and the Spencer Foundation. The authors disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this story originally appeared on Medscape.com.

When officials closed U.S. schools in March to limit the spread of COVID-19, they may have prevented more than 1 million cases over a 26-day period, a new estimate published online July 29 in JAMA suggests.

But school closures also left blind spots in understanding how children and schools affect disease transmission.

“School closures early in pandemic responses thwarted larger-scale investigations of schools as a source of community transmission,” researchers noted in a separate study, published online July 30 in JAMA Pediatrics, that examined levels of viral RNA in children and adults with COVID-19.

“Our analyses suggest children younger than 5 years with mild to moderate COVID-19 have high amounts of SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA in their nasopharynx, compared with older children and adults,” reported Taylor Heald-Sargent, MD, PhD, and colleagues. “Thus, young children can potentially be important drivers of SARS-CoV-2 spread in the general population, as has been demonstrated with respiratory syncytial virus, where children with high viral loads are more likely to transmit.”

Although the study “was not designed to prove that younger children spread COVID-19 as much as adults,” it is a possibility, Dr. Heald-Sargent, a pediatric infectious diseases specialist at Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital and assistant professor of pediatrics at Northwestern University, Chicago, said in a related news release. “We need to take that into account in efforts to reduce transmission as we continue to learn more about this virus.”.

The study included 145 patients with mild or moderate illness who were within 1 week of symptom onset. The researchers used reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (rt-PCR) on nasopharyngeal swabs collected at inpatient, outpatient, emergency department, or drive-through testing sites to measure SARS-CoV-2 levels. The investigators compared PCR amplification cycle threshold (CT) values for children younger than 5 years (n = 46), children aged 5-17 years (n = 51), and adults aged 18-65 years (n = 48); lower CT values indicate higher amounts of viral nucleic acid.

Median CT values for older children and adults were similar (about 11), whereas the median CT value for young children was significantly lower (6.5). The differences between young children and adults “approximate a 10-fold to 100-fold greater amount of SARS-CoV-2 in the upper respiratory tract of young children,” the researchers wrote.

“Behavioral habits of young children and close quarters in school and day care settings raise concern for SARS-CoV-2 amplification in this population as public health restrictions are eased,” they write.

Modeling the impact of school closures

In the JAMA study, Katherine A. Auger, MD, of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, and colleagues examined at the U.S. population level whether closing schools, as all 50 states did in March, was associated with relative decreases in COVID-19 incidence and mortality.

To isolate the effect of school closures, the researchers used an interrupted time series analysis and included other state-level nonpharmaceutical interventions and variables in their regression models.

“Per week, the incidence was estimated to have been 39% of what it would have been had schools remained open,” Dr. Auger and colleagues wrote. “Extrapolating the absolute differences of 423.9 cases and 12.6 deaths per 100,000 to 322.2 million residents nationally suggests that school closure may have been associated with approximately 1.37 million fewer cases of COVID-19 over a 26-day period and 40,600 fewer deaths over a 16-day period; however, these figures do not account for uncertainty in the model assumptions and the resulting estimates.”

Relative reductions in incidence and mortality were largest in states that closed schools when the incidence of COVID-19 was low, the authors found.

Decisions with high stakes

In an accompanying editorial, Julie M. Donohue, PhD, and Elizabeth Miller, MD, PhD, both affiliated with the University of Pittsburgh, emphasized that the results are estimates. “School closures were enacted in close proximity ... to other physical distancing measures, such as nonessential business closures and stay-at-home orders, making it difficult to disentangle the potential effect of each intervention.”

Although the findings “suggest a role for school closures in virus mitigation, school and health officials must balance this with academic, health, and economic consequences,” Dr. Donohue and Dr. Miller added. “Given the strong connection between education, income, and life expectancy, school closures could have long-term deleterious consequences for child health, likely reaching into adulthood.” Schools provide “meals and nutrition, health care including behavioral health supports, physical activity, social interaction, supports for students with special education needs and disabilities, and other vital resources for healthy development.”

In a viewpoint article also published in JAMA, authors involved in the creation of a National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine reported on the reopening of schools recommend that districts “make every effort to prioritize reopening with an emphasis on providing in-person instruction for students in kindergarten through grade 5 as well as those students with special needs who might be best served by in-person instruction.

“To reopen safely, school districts are encouraged to ensure ventilation and air filtration, clean surfaces frequently, provide facilities for regular handwashing, and provide space for physical distancing,” write Kenne A. Dibner, PhD, of the NASEM in Washington, D.C., and coauthors.

Furthermore, districts “need to consider transparent communication of the reality that while measures can be implemented to lower the risk of transmitting COVID-19 when schools reopen, there is no way to eliminate that risk entirely. It is critical to share both the risks and benefits of different scenarios,” they wrote.

The JAMA modeling study received funding from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and the National Institutes of Health. The NASEM report was funded by the Brady Education Foundation and the Spencer Foundation. The authors disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this story originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Telemedicine in primary care

How to effectively utilize this tool

By now it is well known that the COVID-19 pandemic has significantly disrupted primary care. Office visits and revenues have precipitously dropped as physicians and patients alike fear in-person visits may increase their risks of contracting the virus. However, telemedicine has emerged as a lifeline of sorts for many practices, enabling them to conduct visits and maintain contact with patients.

Telemedicine is likely to continue to serve as a tool for primary care providers to improve access to convenient, cost-effective, high-quality care after the pandemic. Another benefit of telemedicine is it can help maintain a portion of a practice’s revenue stream for physicians during uncertain times.

Indeed, the nation has seen recent progress toward telemedicine parity, which refers to the concept of reimbursing providers’ telehealth visits at the same rates as similar in-person visits.

A challenge to adopting telemedicine is that it calls for adjusting established workflows for in-person encounters. A practice cannot simply replicate in-person processes to work for telehealth. While both in-person and virtual visits require adherence to HIPAA, for example, how you actually protect patient privacy will call for different measures. Harking back to the early days of EMR implementation, one does not need to like the telemedicine platform or process, but come to terms with the fact that it is a tool that is here to stay to deliver patient care.

Treat your practice like a laboratory

Adoption may vary between practices depending on many factors, including clinicians’ comfort with technology, clinical tolerance and triage rules for nontouch encounters, state regulations, and more. Every provider group should begin experimenting with telemedicine in specific ways that make sense for them.

One physician may practice telemedicine full-time while the rest abstain, or perhaps the practice prefers to offer telemedicine services during specific hours on specific days. Don’t be afraid to start slowly when you’re trying something new – but do get started with telehealth. It will increasingly be a mainstream medium and more patients will come to expect it.

Train the entire team

Many primary care practices do not enjoy the resources of an information technology team, so all team members essentially need to learn the new skill of telemedicine usage, in addition to assisting patients. That can’t happen without staff buy-in, so it is essential that everyone from the office manager to medical assistants have the training they need to make the technology work. Juggling schedules for telehealth and in-office, activating an account through email, starting and joining a telehealth meeting, and preparing a patient for a visit are just a handful of basic tasks your staff should be trained to do to contribute to the successful integration of telehealth.

Educate and encourage patients to use telehealth

While unfamiliarity with technology may represent a roadblock for some patients, others resist telemedicine simply because no one has explained to them why it’s so important and the benefits it can hold for them. Education and communication are critical, including the sometimes painstaking work of slowly walking patients through the process of performing important functions on the telemedicine app. By providing them with some friendly coaching, patients won’t feel lost or abandoned during what for some may be an unfamiliar and frustrating process.

Manage more behavioral health

Different states and health plans incentivize primary practices for integrating behavioral health into their offerings. Rather than dismiss this addition to your own practice as too cumbersome to take on, I would recommend using telehealth to expand behavioral health care services.

If your practice is working toward a team-based, interdisciplinary approach to care delivery, behavioral health is a critical component. While other elements of this “whole person” health care may be better suited for an office visit, the vast majority of behavioral health services can be delivered virtually.

To decide if your patient may benefit from behavioral health care, the primary care provider (PCP) can conduct a screening via telehealth. Once the screening is complete, the PCP can discuss results and refer the patient to a mental health professional – all via telehealth. While patients may be reluctant to receive behavioral health treatment, perhaps because of stigma or inexperience, they may appreciate the telemedicine option as they can remain in the comfort and familiarity of their homes.

Collaborative Care is both an in-person and virtual model that allows PCP practices to offer behavioral health services in a cost effective way by utilizing a psychiatrist as a “consultant” to the practice as opposed to hiring a full-time psychiatrist. All services within the Collaborative Care Model can be offered via telehealth, and all major insurance providers reimburse primary care providers for delivering Collaborative Care.

When PCPs provide behavioral health treatment as an “extension” of the primary care service offerings, the stigma is reduced and more patients are willing to accept the care they need.

Many areas of the country suffer from a lack of access to behavioral health specialists. In rural counties, for example, the nearest therapist may be located over an hour away. By integrating behavioral telehealth services into your practice’s offerings, you can remove geographic and transportation obstacles to care for your patient population.

Doing this can lead to providing more culturally competent care. It’s important that you’re able to offer mental health services to your patients from a professional with a similar ethnic or racial background. Language barriers and cultural differences may limit a provider’s ability to treat a patient, particularly if the patient faces health disparities related to race or ethnicity. If your practice needs to look outside of your community to tap into a more diverse pool of providers to better meet your patients’ needs, telehealth makes it easier to do that.

Adopting telemedicine for consultative patient visits offers primary care a path toward restoring patient volume and hope for a postpandemic future.

Mark Stephan, MD, is chief medical officer at Equality Health, a whole-health delivery system. He practiced family medicine for 19 years, including hospital medicine and obstetrics in rural and urban settings. Dr. Stephan has no conflicts related to the content of this piece.

How to effectively utilize this tool

How to effectively utilize this tool

By now it is well known that the COVID-19 pandemic has significantly disrupted primary care. Office visits and revenues have precipitously dropped as physicians and patients alike fear in-person visits may increase their risks of contracting the virus. However, telemedicine has emerged as a lifeline of sorts for many practices, enabling them to conduct visits and maintain contact with patients.

Telemedicine is likely to continue to serve as a tool for primary care providers to improve access to convenient, cost-effective, high-quality care after the pandemic. Another benefit of telemedicine is it can help maintain a portion of a practice’s revenue stream for physicians during uncertain times.

Indeed, the nation has seen recent progress toward telemedicine parity, which refers to the concept of reimbursing providers’ telehealth visits at the same rates as similar in-person visits.

A challenge to adopting telemedicine is that it calls for adjusting established workflows for in-person encounters. A practice cannot simply replicate in-person processes to work for telehealth. While both in-person and virtual visits require adherence to HIPAA, for example, how you actually protect patient privacy will call for different measures. Harking back to the early days of EMR implementation, one does not need to like the telemedicine platform or process, but come to terms with the fact that it is a tool that is here to stay to deliver patient care.

Treat your practice like a laboratory

Adoption may vary between practices depending on many factors, including clinicians’ comfort with technology, clinical tolerance and triage rules for nontouch encounters, state regulations, and more. Every provider group should begin experimenting with telemedicine in specific ways that make sense for them.

One physician may practice telemedicine full-time while the rest abstain, or perhaps the practice prefers to offer telemedicine services during specific hours on specific days. Don’t be afraid to start slowly when you’re trying something new – but do get started with telehealth. It will increasingly be a mainstream medium and more patients will come to expect it.

Train the entire team

Many primary care practices do not enjoy the resources of an information technology team, so all team members essentially need to learn the new skill of telemedicine usage, in addition to assisting patients. That can’t happen without staff buy-in, so it is essential that everyone from the office manager to medical assistants have the training they need to make the technology work. Juggling schedules for telehealth and in-office, activating an account through email, starting and joining a telehealth meeting, and preparing a patient for a visit are just a handful of basic tasks your staff should be trained to do to contribute to the successful integration of telehealth.

Educate and encourage patients to use telehealth

While unfamiliarity with technology may represent a roadblock for some patients, others resist telemedicine simply because no one has explained to them why it’s so important and the benefits it can hold for them. Education and communication are critical, including the sometimes painstaking work of slowly walking patients through the process of performing important functions on the telemedicine app. By providing them with some friendly coaching, patients won’t feel lost or abandoned during what for some may be an unfamiliar and frustrating process.

Manage more behavioral health

Different states and health plans incentivize primary practices for integrating behavioral health into their offerings. Rather than dismiss this addition to your own practice as too cumbersome to take on, I would recommend using telehealth to expand behavioral health care services.

If your practice is working toward a team-based, interdisciplinary approach to care delivery, behavioral health is a critical component. While other elements of this “whole person” health care may be better suited for an office visit, the vast majority of behavioral health services can be delivered virtually.

To decide if your patient may benefit from behavioral health care, the primary care provider (PCP) can conduct a screening via telehealth. Once the screening is complete, the PCP can discuss results and refer the patient to a mental health professional – all via telehealth. While patients may be reluctant to receive behavioral health treatment, perhaps because of stigma or inexperience, they may appreciate the telemedicine option as they can remain in the comfort and familiarity of their homes.

Collaborative Care is both an in-person and virtual model that allows PCP practices to offer behavioral health services in a cost effective way by utilizing a psychiatrist as a “consultant” to the practice as opposed to hiring a full-time psychiatrist. All services within the Collaborative Care Model can be offered via telehealth, and all major insurance providers reimburse primary care providers for delivering Collaborative Care.

When PCPs provide behavioral health treatment as an “extension” of the primary care service offerings, the stigma is reduced and more patients are willing to accept the care they need.

Many areas of the country suffer from a lack of access to behavioral health specialists. In rural counties, for example, the nearest therapist may be located over an hour away. By integrating behavioral telehealth services into your practice’s offerings, you can remove geographic and transportation obstacles to care for your patient population.

Doing this can lead to providing more culturally competent care. It’s important that you’re able to offer mental health services to your patients from a professional with a similar ethnic or racial background. Language barriers and cultural differences may limit a provider’s ability to treat a patient, particularly if the patient faces health disparities related to race or ethnicity. If your practice needs to look outside of your community to tap into a more diverse pool of providers to better meet your patients’ needs, telehealth makes it easier to do that.

Adopting telemedicine for consultative patient visits offers primary care a path toward restoring patient volume and hope for a postpandemic future.

Mark Stephan, MD, is chief medical officer at Equality Health, a whole-health delivery system. He practiced family medicine for 19 years, including hospital medicine and obstetrics in rural and urban settings. Dr. Stephan has no conflicts related to the content of this piece.

By now it is well known that the COVID-19 pandemic has significantly disrupted primary care. Office visits and revenues have precipitously dropped as physicians and patients alike fear in-person visits may increase their risks of contracting the virus. However, telemedicine has emerged as a lifeline of sorts for many practices, enabling them to conduct visits and maintain contact with patients.

Telemedicine is likely to continue to serve as a tool for primary care providers to improve access to convenient, cost-effective, high-quality care after the pandemic. Another benefit of telemedicine is it can help maintain a portion of a practice’s revenue stream for physicians during uncertain times.

Indeed, the nation has seen recent progress toward telemedicine parity, which refers to the concept of reimbursing providers’ telehealth visits at the same rates as similar in-person visits.

A challenge to adopting telemedicine is that it calls for adjusting established workflows for in-person encounters. A practice cannot simply replicate in-person processes to work for telehealth. While both in-person and virtual visits require adherence to HIPAA, for example, how you actually protect patient privacy will call for different measures. Harking back to the early days of EMR implementation, one does not need to like the telemedicine platform or process, but come to terms with the fact that it is a tool that is here to stay to deliver patient care.

Treat your practice like a laboratory

Adoption may vary between practices depending on many factors, including clinicians’ comfort with technology, clinical tolerance and triage rules for nontouch encounters, state regulations, and more. Every provider group should begin experimenting with telemedicine in specific ways that make sense for them.

One physician may practice telemedicine full-time while the rest abstain, or perhaps the practice prefers to offer telemedicine services during specific hours on specific days. Don’t be afraid to start slowly when you’re trying something new – but do get started with telehealth. It will increasingly be a mainstream medium and more patients will come to expect it.

Train the entire team

Many primary care practices do not enjoy the resources of an information technology team, so all team members essentially need to learn the new skill of telemedicine usage, in addition to assisting patients. That can’t happen without staff buy-in, so it is essential that everyone from the office manager to medical assistants have the training they need to make the technology work. Juggling schedules for telehealth and in-office, activating an account through email, starting and joining a telehealth meeting, and preparing a patient for a visit are just a handful of basic tasks your staff should be trained to do to contribute to the successful integration of telehealth.

Educate and encourage patients to use telehealth

While unfamiliarity with technology may represent a roadblock for some patients, others resist telemedicine simply because no one has explained to them why it’s so important and the benefits it can hold for them. Education and communication are critical, including the sometimes painstaking work of slowly walking patients through the process of performing important functions on the telemedicine app. By providing them with some friendly coaching, patients won’t feel lost or abandoned during what for some may be an unfamiliar and frustrating process.

Manage more behavioral health

Different states and health plans incentivize primary practices for integrating behavioral health into their offerings. Rather than dismiss this addition to your own practice as too cumbersome to take on, I would recommend using telehealth to expand behavioral health care services.

If your practice is working toward a team-based, interdisciplinary approach to care delivery, behavioral health is a critical component. While other elements of this “whole person” health care may be better suited for an office visit, the vast majority of behavioral health services can be delivered virtually.

To decide if your patient may benefit from behavioral health care, the primary care provider (PCP) can conduct a screening via telehealth. Once the screening is complete, the PCP can discuss results and refer the patient to a mental health professional – all via telehealth. While patients may be reluctant to receive behavioral health treatment, perhaps because of stigma or inexperience, they may appreciate the telemedicine option as they can remain in the comfort and familiarity of their homes.

Collaborative Care is both an in-person and virtual model that allows PCP practices to offer behavioral health services in a cost effective way by utilizing a psychiatrist as a “consultant” to the practice as opposed to hiring a full-time psychiatrist. All services within the Collaborative Care Model can be offered via telehealth, and all major insurance providers reimburse primary care providers for delivering Collaborative Care.

When PCPs provide behavioral health treatment as an “extension” of the primary care service offerings, the stigma is reduced and more patients are willing to accept the care they need.

Many areas of the country suffer from a lack of access to behavioral health specialists. In rural counties, for example, the nearest therapist may be located over an hour away. By integrating behavioral telehealth services into your practice’s offerings, you can remove geographic and transportation obstacles to care for your patient population.

Doing this can lead to providing more culturally competent care. It’s important that you’re able to offer mental health services to your patients from a professional with a similar ethnic or racial background. Language barriers and cultural differences may limit a provider’s ability to treat a patient, particularly if the patient faces health disparities related to race or ethnicity. If your practice needs to look outside of your community to tap into a more diverse pool of providers to better meet your patients’ needs, telehealth makes it easier to do that.

Adopting telemedicine for consultative patient visits offers primary care a path toward restoring patient volume and hope for a postpandemic future.

Mark Stephan, MD, is chief medical officer at Equality Health, a whole-health delivery system. He practiced family medicine for 19 years, including hospital medicine and obstetrics in rural and urban settings. Dr. Stephan has no conflicts related to the content of this piece.

Educational intervention curbs use of antibiotics for respiratory infections

A clinician education program significantly reduced overall antibiotic prescribing during pediatric visits for acute respiratory tract infections, according to data from 57 clinicians who participated in an intervention.

In a study published in Pediatrics, Matthew P. Kronman, MD, of the University of Washington, Seattle, and associates randomized 57 clinicians at 19 pediatric practices to a stepped-wedge clinical trial. The study included visits for acute otitis media, bronchitis, pharyngitis, sinusitis, and upper respiratory infections (defined as ARTI visits) for children aged 6 months to less than 11 years, for a total of 72,723 ARTI visits by 29,762 patients. The primary outcome was overall antibiotic prescribing for ARTI visits.

For the intervention, known as the Dialogue Around Respiratory Illness Treatment (DART) quality improvement (QI) program, clinicians received three program modules containing online tutorials and webinars. These professionally-produced modules included a combination of evidence-based communication strategies and antibiotic prescribing, booster video vignettes, and individualized antibiotic prescribing feedback reports over 11 months.

Overall, the probability of antibiotic prescribing for ARTI visits decreased by 7% (adjusted relative risk 0.93) from baseline to a 2- to 8-month postintervention in an adjusted intent-to-treat analysis.

Analysis of secondary outcomes revealed that prescribing any antibiotics for viral ARTI decreased by 40% during the postintervention period compared to baseline (aRR 0.60).

In addition, second-line antibiotic prescribing decreased from baseline by 34% for streptococcal pharyngitis (aRR 0.66), and by 41% for sinusitis (aRR 0.59); however there was no significant change in prescribing for acute otitis media, the researchers said.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the potential for biased results because of the randomization of clinicians from multiple practices and the potential for clinicians to change their prescribing habits after the start of the study, Dr. Kronman and colleagues noted.

In addition, the study did not include complete data on rapid streptococcal antigen testing, which might eliminate some children from the study population, and the relatively short postintervention period “may not represent the true long-term intervention durability may not represent the true long-term intervention durability,” they said.

However, the results support the potential of the DART program. “The 7% reduction in antibiotic prescribing for all ARTIs, if extrapolated to all ambulatory ARTI visits to pediatricians nationally, would represent 1.5 million fewer antibiotic prescriptions for children with ARTI annually,” they wrote.

“Providing online communication training and evidence-based antibiotic prescribing education in combination with individualized antibiotic prescribing feedback reports may help achieve national goals of reducing unnecessary outpatient antibiotic prescribing for children,” Dr. Kronman and associates concluded.

Combining interventions are key to reducing unnecessary antibiotics use in pediatric ambulatory care, Rana F. Hamdy, MD, MPH, of Children’s National Hospital, Washington, , and Sophie E. Katz, MD, of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., wrote in an accompanying editorial (Pediatrics. 2020 Aug 3. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-012922).

The researchers in the current study “seem to recognize that clinicians are adult learners, and they combine interventions to implement these adult learning theory tenets to improve appropriate antibiotic prescribing,” they wrote. The DART intervention combined best practices training, communications training, and individualized antibiotic prescribing feedback reports to improve communication between providers and families “especially when faced with a situation in which a parent or guardian might expect an antibiotic prescription but the provider does not think one is necessary,” Dr. Hamdy and Dr. Katz said.

Overall, the findings suggest that the interventions work best in combination vs. being used alone, although the study did not evaluate the separate contributions of each intervention, the editorialists wrote.

“In the current study, nonengaged physicians had an increase in second-line antibiotic prescribing, whereas the engaged physicians had a decrease in second-line antibiotic prescribing,” they noted. “This suggests that the addition of communications training could mitigate the undesirable effects that may result from solely using feedback reports.”

“Each year, U.S. children are prescribed as many as 10 million unnecessary antibiotic courses for acute respiratory tract infections,” Kristina A. Bryant, MD, of the University of Louisville, Ky., said in an interview. “Some of these prescriptions result in side effects or allergic reactions, and they contribute to growing antibiotic resistance. We need effective interventions to reduce antibiotic prescribing.”

Although the DART modules are free and available online, busy clinicians might struggle to find time to view them consistently, said Dr. Bryant.

“One advantage of the study design was that information was pushed to clinicians along with communication booster videos,” she said. “We know that education and reinforcement over time works better than a one and done approach.

“Study participants also received feedback over time about their prescribing habits, which can be a powerful motivator for change, although not all clinicians may have easy access to these reports,” she noted.

To overcome some of the barriers to using the modules, clinicians who are “interested in improving their prescribing could work with their office managers to develop antibiotic prescribing reports and schedule reminders to review them,” said Dr. Bryant.

“An individual could commit to education and review of his or her own prescribing patterns, but support from one’s partners and shared accountability is likely to be even more effective,” she said. “Sharing data within a practice and exploring differences in prescribing patterns can drive improvement.

“Spaced education and regular feedback about prescribing patterns can improve antibiotic prescribing for pharyngitis and sinusitis, and reduce antibiotic prescriptions for ARTIs,” Dr. Bryant said. The take-home from the study is that it should prompt anyone who prescribes antibiotics for children to ask themselves how they can improve their own prescribing habits.

“In this study, prescribing for viral ARTIs was reduced but not eliminated. We need additional studies to further reduce unnecessary antibiotic use,” Dr. Bryant said.

In addition, areas for future research could include longer-term follow-up. “Study participants were followed for 2 to 8 months after the intervention ended in June 2018. It would be interesting to know about their prescribing practices now, and if the changes observed in the study were durable,” she concluded.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health, along with additional infrastructure funding from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Health Resources and Services Administration of the Department of Health and Human Services. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Dr. Hamdy and Dr. Katz had no financial conflicts to disclose, but Dr. Katz disclosed grant support through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as a recipient of the Leadership in Epidemiology, Antimicrobial Stewardship, and Public Health fellowship, sponsored by the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, Infectious Diseases Society of America, and Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society.

Dr. Bryant disclosed serving as an investigator on multicenter clinical vaccine trials funded by Pfizer (but not in the last year). She also serves as the current president of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society, but the opinions expressed here are her own and do not necessarily reflect the views of PIDS.

SOURCE: Kronman MP et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Aug 3. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0038.

A clinician education program significantly reduced overall antibiotic prescribing during pediatric visits for acute respiratory tract infections, according to data from 57 clinicians who participated in an intervention.