User login

Collagen filler succeeds against acne scars

SAN DIEGO – An injectable collagen-based filler significantly outperformed saline placebo for treating acne scars, with durable effects at 12 months, according to a randomized, double-blind crossover trial of 147 adults.

The study “successfully demonstrates the effectiveness and safety of polymethylmethacrylate in atrophic acne scars,” said Dr. James Spencer, who conducted the research while at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York. Dr. Spencer is now in private practice in St. Petersburg, Fla.

Six months after treatment, 64% of patients who received the polymethylmethacrylate-collagen filler (or PMMA) had at least half their scars improve by at least 2 points on an acne rating scale, Dr. Spencer and his associates said at the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery. Only 32% of the control group achieved that result (P = .0005). Response rates for the filler were 61% at 9 months and 70% at 12 months, and “crossover subjects subsequently treated with PMMA collagen showed similar response levels,” they said.

The PMMA-collagen filler is easy to administer; “works well on deep, severe scars; and should also work very well on shallow scars,” the researchers noted. The treatment “may enable practitioners to effectively treat acne scarring with no need for capital equipment expenditure or the risks associated with resurfacing procedures,” they said.

About 61% of patients in the study were female, participants averaged 44 years of age, and 20% were Fitzpatrick skin type V or VI. To enter the study, participants had to have at least four facial acne scars that were soft contoured, rolling, distensible, and rated moderate to severe (3-4) on a 4-point acne rating scale.

The patients were treated every 2 weeks for a month, and again at months 3 and 6. At 6 months, patients in the placebo group crossed over and received the filler, and all patients were followed for another 6 months.

Adverse effects were uncommon and included mild transient pain at the injection site, swelling, bruising, and acne, the researchers said. “There was no evidence of granulomas, changes in pigmentation, or hypertrophic scarring,” they added.

No funding source was reported for the study. Dr. Spencer and his coauthors reported financial relationships with Photomedex, Genentech, and Leo Pharma.

SAN DIEGO – An injectable collagen-based filler significantly outperformed saline placebo for treating acne scars, with durable effects at 12 months, according to a randomized, double-blind crossover trial of 147 adults.

The study “successfully demonstrates the effectiveness and safety of polymethylmethacrylate in atrophic acne scars,” said Dr. James Spencer, who conducted the research while at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York. Dr. Spencer is now in private practice in St. Petersburg, Fla.

Six months after treatment, 64% of patients who received the polymethylmethacrylate-collagen filler (or PMMA) had at least half their scars improve by at least 2 points on an acne rating scale, Dr. Spencer and his associates said at the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery. Only 32% of the control group achieved that result (P = .0005). Response rates for the filler were 61% at 9 months and 70% at 12 months, and “crossover subjects subsequently treated with PMMA collagen showed similar response levels,” they said.

The PMMA-collagen filler is easy to administer; “works well on deep, severe scars; and should also work very well on shallow scars,” the researchers noted. The treatment “may enable practitioners to effectively treat acne scarring with no need for capital equipment expenditure or the risks associated with resurfacing procedures,” they said.

About 61% of patients in the study were female, participants averaged 44 years of age, and 20% were Fitzpatrick skin type V or VI. To enter the study, participants had to have at least four facial acne scars that were soft contoured, rolling, distensible, and rated moderate to severe (3-4) on a 4-point acne rating scale.

The patients were treated every 2 weeks for a month, and again at months 3 and 6. At 6 months, patients in the placebo group crossed over and received the filler, and all patients were followed for another 6 months.

Adverse effects were uncommon and included mild transient pain at the injection site, swelling, bruising, and acne, the researchers said. “There was no evidence of granulomas, changes in pigmentation, or hypertrophic scarring,” they added.

No funding source was reported for the study. Dr. Spencer and his coauthors reported financial relationships with Photomedex, Genentech, and Leo Pharma.

SAN DIEGO – An injectable collagen-based filler significantly outperformed saline placebo for treating acne scars, with durable effects at 12 months, according to a randomized, double-blind crossover trial of 147 adults.

The study “successfully demonstrates the effectiveness and safety of polymethylmethacrylate in atrophic acne scars,” said Dr. James Spencer, who conducted the research while at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York. Dr. Spencer is now in private practice in St. Petersburg, Fla.

Six months after treatment, 64% of patients who received the polymethylmethacrylate-collagen filler (or PMMA) had at least half their scars improve by at least 2 points on an acne rating scale, Dr. Spencer and his associates said at the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery. Only 32% of the control group achieved that result (P = .0005). Response rates for the filler were 61% at 9 months and 70% at 12 months, and “crossover subjects subsequently treated with PMMA collagen showed similar response levels,” they said.

The PMMA-collagen filler is easy to administer; “works well on deep, severe scars; and should also work very well on shallow scars,” the researchers noted. The treatment “may enable practitioners to effectively treat acne scarring with no need for capital equipment expenditure or the risks associated with resurfacing procedures,” they said.

About 61% of patients in the study were female, participants averaged 44 years of age, and 20% were Fitzpatrick skin type V or VI. To enter the study, participants had to have at least four facial acne scars that were soft contoured, rolling, distensible, and rated moderate to severe (3-4) on a 4-point acne rating scale.

The patients were treated every 2 weeks for a month, and again at months 3 and 6. At 6 months, patients in the placebo group crossed over and received the filler, and all patients were followed for another 6 months.

Adverse effects were uncommon and included mild transient pain at the injection site, swelling, bruising, and acne, the researchers said. “There was no evidence of granulomas, changes in pigmentation, or hypertrophic scarring,” they added.

No funding source was reported for the study. Dr. Spencer and his coauthors reported financial relationships with Photomedex, Genentech, and Leo Pharma.

Key clinical point: A collagen-based filler significantly improved the appearance of acne scars in adults, with persistent improvement at 12 months.

Major finding: At 6-month evaluation, 64% of the intervention group were considered responders, compared with 32% of the control group (P = .0005).

Data source: A prospective, randomized, double-blind, controlled, multicenter crossover study of 147 adults with acne scars.

Disclosures: The researchers did not report funding sources. Dr. Spencer and his coauthors reported financial relationships with Photomedex, Genentech, and Leo Pharma.

Fractional laser technology reduces facial acne scarring

Fractional laser technology, often used in the removal of unwanted tattoos, can improve the appearance and texture of facial acne scars, based on data published online Nov.19 in JAMA Dermatology.

“The evolution from traditional nanosecond to picosecond lasers has been observed to produce a photomechanical effect that causes fragmentation of tattoo ink or pigment,” wrote Dr. Jeremy A. Brauer, a dermatologist in group practice in New York, and his coinvestigators. “An innovative optical attachment for the picosecond laser, a diffractive lens array, has been developed that gauges distribution of energy to the treatment area. This specialized optic affects more surface area, has a greater pattern density per pulse, and may improve the appearance of acne scars,” they reported.

In a single-center, prospective study, Dr. Brauer and his associates enrolled 20 patients – 15 women and 5 men – based on screenings to ensure no history of skin cancer, keloidal scarring, localized or active infection, immunodeficiency disorders, and light hypersensitivity or use of medications with known phototoxic effects. Of that initial group, 17 completed all six treatments and presented for follow-up visits at 1 and 3 months. Patients were aged 27-66 (mean age, 44 years), and included Fitzpatrick skin types I (one patient), II (seven patients), III (six patients), and IV (three patients).

Subjects mostly had rolling-type scars, boxcar scars, and icepick lesions related to acne. Each subject underwent six treatments with a 755-nanometer alexandrite picosecond laser with a diffractive lens array; each treatment occurred every 4-8 weeks.

Subjects also provided a subjective score for pain experienced during each treatment on a scale of 0 (no pain) to 10 (extreme pain). The patients also used a scale of 0-4 to indicate their satisfaction with improvement of overall skin appearance and texture prior to their final treatment, at the 1-month follow-up, and at the 3-month follow-up (with 0 being total dissatisfaction and 4 total satisfaction).

At the 1-month and 3-month follow-ups, three independent dermatologists gave masked evaluations of each patient’s improvement on a 4-point scale, with 0 = 0%-25%, 1 = 26%-50%, 3 = 51%-75%, and 4 = 76%-100%.

All patients were either “satisfied” or “extremely satisfied” with the appearance and texture of their facial skin after receiving the full treatment regimen, and recorded an average pain score of 2.83 out of 10. The masked assessment scores also were favorable, averaging 1.5 of 3 and 1.4 of 3 at the 1-month and 3-month follow-ups, with a score of 0 indicating 0-25% improvement and a score of 3, greater than 75% improvement, the researchers reported.

Dr. Brauer and his associates also evaluated three-dimensional volumetric data for each subject, which showed an average of 24.0% improvement in scar volume at the 1-month follow-up and 27.2% at the 3-month follow-up. Furthermore, histologic analysis revealed elongation and increased density of elastic fibers, as well as an increase in dermal collagen and mucin.

“This is the first study, to our knowledge, that demonstrates favorable clinical outcomes in acne scar management with the 755[-nm] picosecond laser and diffractive lens array,” the researchers noted. “Observed improvement in pigmentation and texture of the surrounding skin suggests that there may be benefits for indications beyond scarring,” they wrote.

The authors disclosed that funding for this study was provided in part by Cynosure, manufacturer of the Food and Drug Administration–approved 755-nm picosecond alexandrite laser used in the study, and noted that “Cynosure had a role in the design of the study but not the conduct, collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of data. They approved the manuscript but did not prepare or decide to submit.” Dr. Brauer disclosed receiving honoraria from Cynosure/Palomar Medical Technologies and consulting for Miramar. Several other coauthors disclosed financial relationships with multiple companies, including Cynosure/Palomar Medical Technologies.

Fractional laser technology, often used in the removal of unwanted tattoos, can improve the appearance and texture of facial acne scars, based on data published online Nov.19 in JAMA Dermatology.

“The evolution from traditional nanosecond to picosecond lasers has been observed to produce a photomechanical effect that causes fragmentation of tattoo ink or pigment,” wrote Dr. Jeremy A. Brauer, a dermatologist in group practice in New York, and his coinvestigators. “An innovative optical attachment for the picosecond laser, a diffractive lens array, has been developed that gauges distribution of energy to the treatment area. This specialized optic affects more surface area, has a greater pattern density per pulse, and may improve the appearance of acne scars,” they reported.

In a single-center, prospective study, Dr. Brauer and his associates enrolled 20 patients – 15 women and 5 men – based on screenings to ensure no history of skin cancer, keloidal scarring, localized or active infection, immunodeficiency disorders, and light hypersensitivity or use of medications with known phototoxic effects. Of that initial group, 17 completed all six treatments and presented for follow-up visits at 1 and 3 months. Patients were aged 27-66 (mean age, 44 years), and included Fitzpatrick skin types I (one patient), II (seven patients), III (six patients), and IV (three patients).

Subjects mostly had rolling-type scars, boxcar scars, and icepick lesions related to acne. Each subject underwent six treatments with a 755-nanometer alexandrite picosecond laser with a diffractive lens array; each treatment occurred every 4-8 weeks.

Subjects also provided a subjective score for pain experienced during each treatment on a scale of 0 (no pain) to 10 (extreme pain). The patients also used a scale of 0-4 to indicate their satisfaction with improvement of overall skin appearance and texture prior to their final treatment, at the 1-month follow-up, and at the 3-month follow-up (with 0 being total dissatisfaction and 4 total satisfaction).

At the 1-month and 3-month follow-ups, three independent dermatologists gave masked evaluations of each patient’s improvement on a 4-point scale, with 0 = 0%-25%, 1 = 26%-50%, 3 = 51%-75%, and 4 = 76%-100%.

All patients were either “satisfied” or “extremely satisfied” with the appearance and texture of their facial skin after receiving the full treatment regimen, and recorded an average pain score of 2.83 out of 10. The masked assessment scores also were favorable, averaging 1.5 of 3 and 1.4 of 3 at the 1-month and 3-month follow-ups, with a score of 0 indicating 0-25% improvement and a score of 3, greater than 75% improvement, the researchers reported.

Dr. Brauer and his associates also evaluated three-dimensional volumetric data for each subject, which showed an average of 24.0% improvement in scar volume at the 1-month follow-up and 27.2% at the 3-month follow-up. Furthermore, histologic analysis revealed elongation and increased density of elastic fibers, as well as an increase in dermal collagen and mucin.

“This is the first study, to our knowledge, that demonstrates favorable clinical outcomes in acne scar management with the 755[-nm] picosecond laser and diffractive lens array,” the researchers noted. “Observed improvement in pigmentation and texture of the surrounding skin suggests that there may be benefits for indications beyond scarring,” they wrote.

The authors disclosed that funding for this study was provided in part by Cynosure, manufacturer of the Food and Drug Administration–approved 755-nm picosecond alexandrite laser used in the study, and noted that “Cynosure had a role in the design of the study but not the conduct, collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of data. They approved the manuscript but did not prepare or decide to submit.” Dr. Brauer disclosed receiving honoraria from Cynosure/Palomar Medical Technologies and consulting for Miramar. Several other coauthors disclosed financial relationships with multiple companies, including Cynosure/Palomar Medical Technologies.

Fractional laser technology, often used in the removal of unwanted tattoos, can improve the appearance and texture of facial acne scars, based on data published online Nov.19 in JAMA Dermatology.

“The evolution from traditional nanosecond to picosecond lasers has been observed to produce a photomechanical effect that causes fragmentation of tattoo ink or pigment,” wrote Dr. Jeremy A. Brauer, a dermatologist in group practice in New York, and his coinvestigators. “An innovative optical attachment for the picosecond laser, a diffractive lens array, has been developed that gauges distribution of energy to the treatment area. This specialized optic affects more surface area, has a greater pattern density per pulse, and may improve the appearance of acne scars,” they reported.

In a single-center, prospective study, Dr. Brauer and his associates enrolled 20 patients – 15 women and 5 men – based on screenings to ensure no history of skin cancer, keloidal scarring, localized or active infection, immunodeficiency disorders, and light hypersensitivity or use of medications with known phototoxic effects. Of that initial group, 17 completed all six treatments and presented for follow-up visits at 1 and 3 months. Patients were aged 27-66 (mean age, 44 years), and included Fitzpatrick skin types I (one patient), II (seven patients), III (six patients), and IV (three patients).

Subjects mostly had rolling-type scars, boxcar scars, and icepick lesions related to acne. Each subject underwent six treatments with a 755-nanometer alexandrite picosecond laser with a diffractive lens array; each treatment occurred every 4-8 weeks.

Subjects also provided a subjective score for pain experienced during each treatment on a scale of 0 (no pain) to 10 (extreme pain). The patients also used a scale of 0-4 to indicate their satisfaction with improvement of overall skin appearance and texture prior to their final treatment, at the 1-month follow-up, and at the 3-month follow-up (with 0 being total dissatisfaction and 4 total satisfaction).

At the 1-month and 3-month follow-ups, three independent dermatologists gave masked evaluations of each patient’s improvement on a 4-point scale, with 0 = 0%-25%, 1 = 26%-50%, 3 = 51%-75%, and 4 = 76%-100%.

All patients were either “satisfied” or “extremely satisfied” with the appearance and texture of their facial skin after receiving the full treatment regimen, and recorded an average pain score of 2.83 out of 10. The masked assessment scores also were favorable, averaging 1.5 of 3 and 1.4 of 3 at the 1-month and 3-month follow-ups, with a score of 0 indicating 0-25% improvement and a score of 3, greater than 75% improvement, the researchers reported.

Dr. Brauer and his associates also evaluated three-dimensional volumetric data for each subject, which showed an average of 24.0% improvement in scar volume at the 1-month follow-up and 27.2% at the 3-month follow-up. Furthermore, histologic analysis revealed elongation and increased density of elastic fibers, as well as an increase in dermal collagen and mucin.

“This is the first study, to our knowledge, that demonstrates favorable clinical outcomes in acne scar management with the 755[-nm] picosecond laser and diffractive lens array,” the researchers noted. “Observed improvement in pigmentation and texture of the surrounding skin suggests that there may be benefits for indications beyond scarring,” they wrote.

The authors disclosed that funding for this study was provided in part by Cynosure, manufacturer of the Food and Drug Administration–approved 755-nm picosecond alexandrite laser used in the study, and noted that “Cynosure had a role in the design of the study but not the conduct, collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of data. They approved the manuscript but did not prepare or decide to submit.” Dr. Brauer disclosed receiving honoraria from Cynosure/Palomar Medical Technologies and consulting for Miramar. Several other coauthors disclosed financial relationships with multiple companies, including Cynosure/Palomar Medical Technologies.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Treatment of facial acne scars with a diffractive lens array and a picosecond 755-nm alexandrite laser improves the appearance and texture of skin within 3 months.

Major finding: Masked assessments by a dermatologist found a 25%-50% global improvement at the 1-month postoperation follow-up visit, which was maintained at the 3-month follow-up.

Data source: A single-center, prospective study of 20 patients.

Disclosures: This study was supported in part by Cynosure. The authors disclosed several potential conflicts of interest.

VIDEO: Dr. Sheila F. Friedlander discusses when and why to worry about acne in young children

NEWPORT BEACH, CALIF.– “The group we worry about are the 1- to 7-year-olds,” when it comes to new-onset acne, Dr. Sheila Fallon Friedlander said at Skin Disease Education Foundation’s Women’s & Pediatric Dermatology Seminar.

In an interview at the meeting, Dr. Friedlander, a professor at the University of California, San Diego, explained the additional clinical signs that can indicate a serious problem, and what questions to ask parents.

Tune in for her tips on how to evaluate children aged 1-7 years with acne.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by Frontline Medical Communications.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

NEWPORT BEACH, CALIF.– “The group we worry about are the 1- to 7-year-olds,” when it comes to new-onset acne, Dr. Sheila Fallon Friedlander said at Skin Disease Education Foundation’s Women’s & Pediatric Dermatology Seminar.

In an interview at the meeting, Dr. Friedlander, a professor at the University of California, San Diego, explained the additional clinical signs that can indicate a serious problem, and what questions to ask parents.

Tune in for her tips on how to evaluate children aged 1-7 years with acne.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by Frontline Medical Communications.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

NEWPORT BEACH, CALIF.– “The group we worry about are the 1- to 7-year-olds,” when it comes to new-onset acne, Dr. Sheila Fallon Friedlander said at Skin Disease Education Foundation’s Women’s & Pediatric Dermatology Seminar.

In an interview at the meeting, Dr. Friedlander, a professor at the University of California, San Diego, explained the additional clinical signs that can indicate a serious problem, and what questions to ask parents.

Tune in for her tips on how to evaluate children aged 1-7 years with acne.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by Frontline Medical Communications.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AT SDEF WOMEN’S & PEDIATRIC DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

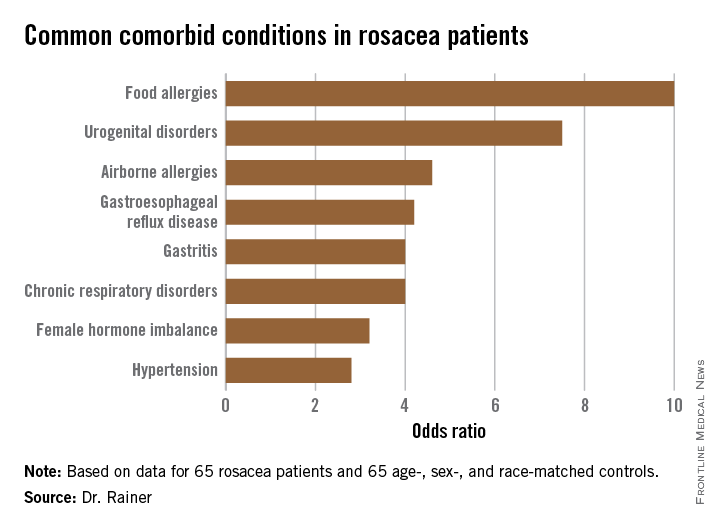

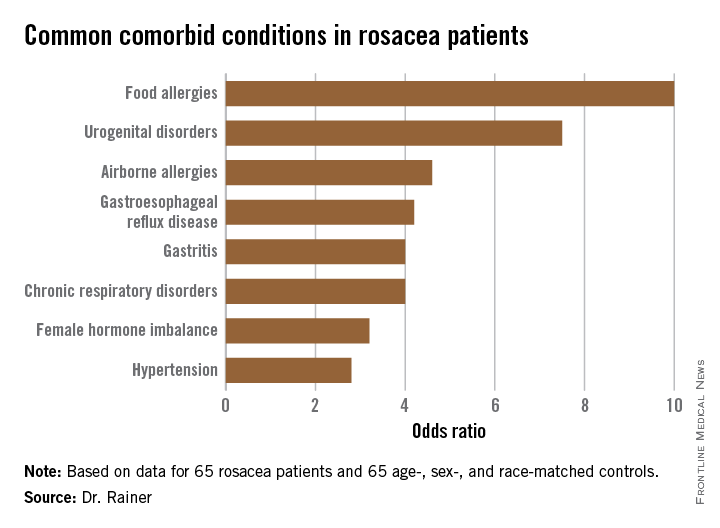

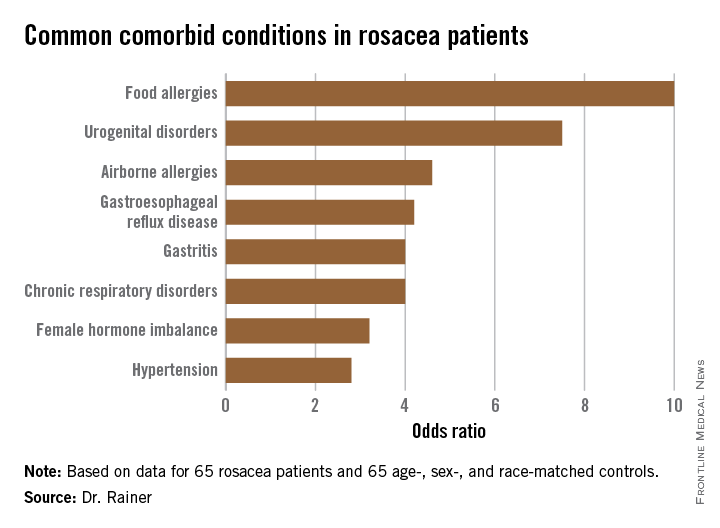

Rosacea’s comorbidities are more than skin deep

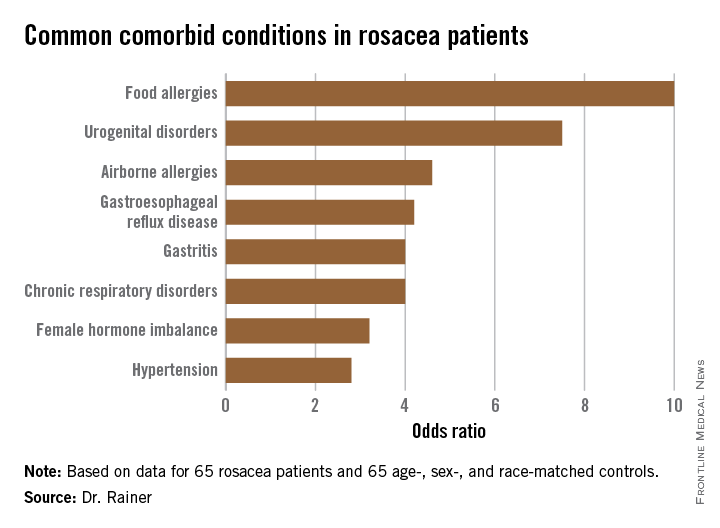

AMSTERDAM – Rosacea is associated with increased risk of a range of chronic systemic diseases, including allergies and urogential disorders, a case-control study showed.

The common denominator among this linked diverse collection of diseases is probably underlying systemic inflammation, Dr. Barbara M. Rainer explained at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. But regardless of the pathophysiologic mechanisms at work, the important thing is that physicians be on the lookout for these comorbid conditions in their patients with rosacea.

Dr. Rainer of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore presented a case-control study involving 130 subjects: 65 rosacea patients and an equal number of controls matched for age, sex, and race.

The most common comorbidity was food allergies (odds ratio, 10), followed by urogenital disorders (OR, 7.5).

The rosacea patients averaged 50 years of age and had a mean 11.8-year history of their skin disease. Body mass index, smoking status, alcohol intake, and coffee consumption were similar in cases and controls. Two-thirds of subjects were women. Relative risks for comorbid conditions were calculated using logistic regression analysis.

Dr. Rainer reported no relevant financial conflicts.

AMSTERDAM – Rosacea is associated with increased risk of a range of chronic systemic diseases, including allergies and urogential disorders, a case-control study showed.

The common denominator among this linked diverse collection of diseases is probably underlying systemic inflammation, Dr. Barbara M. Rainer explained at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. But regardless of the pathophysiologic mechanisms at work, the important thing is that physicians be on the lookout for these comorbid conditions in their patients with rosacea.

Dr. Rainer of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore presented a case-control study involving 130 subjects: 65 rosacea patients and an equal number of controls matched for age, sex, and race.

The most common comorbidity was food allergies (odds ratio, 10), followed by urogenital disorders (OR, 7.5).

The rosacea patients averaged 50 years of age and had a mean 11.8-year history of their skin disease. Body mass index, smoking status, alcohol intake, and coffee consumption were similar in cases and controls. Two-thirds of subjects were women. Relative risks for comorbid conditions were calculated using logistic regression analysis.

Dr. Rainer reported no relevant financial conflicts.

AMSTERDAM – Rosacea is associated with increased risk of a range of chronic systemic diseases, including allergies and urogential disorders, a case-control study showed.

The common denominator among this linked diverse collection of diseases is probably underlying systemic inflammation, Dr. Barbara M. Rainer explained at the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. But regardless of the pathophysiologic mechanisms at work, the important thing is that physicians be on the lookout for these comorbid conditions in their patients with rosacea.

Dr. Rainer of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore presented a case-control study involving 130 subjects: 65 rosacea patients and an equal number of controls matched for age, sex, and race.

The most common comorbidity was food allergies (odds ratio, 10), followed by urogenital disorders (OR, 7.5).

The rosacea patients averaged 50 years of age and had a mean 11.8-year history of their skin disease. Body mass index, smoking status, alcohol intake, and coffee consumption were similar in cases and controls. Two-thirds of subjects were women. Relative risks for comorbid conditions were calculated using logistic regression analysis.

Dr. Rainer reported no relevant financial conflicts.

AT THE EADV CONGRESS

Key clinical point: Rosacea patients are at increased risk for an eclectic variety of chronic systemic comorbid conditions.

Major finding: The strongest associations seen with rosacea were for food allergies, with a 10-fold increased risk, and urogenital disorders, with a 7.5-fold relative risk.

Data source: A case-control study including 65 rosacea patients and an equal number of matched controls.

Disclosures: Dr. Rainer reported no relevant financial conflicts.

VIDEO: What’s unique about treating acne in adult women

NEWPORT BEACH, CALIF. – Do more women today really have acne? Or are they simply more likely to seek help because they learn of new and better medications?

Acne often causes more psychosocial and psychological stress in adult women than in men or adolescents, Dr. Hilary Baldwin of SUNY Downstate Medical Center, Brooklyn, N.Y., said at Skin Disease Education Foundation’s Women’s & Pediatric Dermatology Seminar.

In an interview at the meeting, Dr. Baldwin explained what makes the treatment of acne in adult women distinct from acne treatment for men and adolescents, and what underused medications can yield success.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by Frontline Medical Communications.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

NEWPORT BEACH, CALIF. – Do more women today really have acne? Or are they simply more likely to seek help because they learn of new and better medications?

Acne often causes more psychosocial and psychological stress in adult women than in men or adolescents, Dr. Hilary Baldwin of SUNY Downstate Medical Center, Brooklyn, N.Y., said at Skin Disease Education Foundation’s Women’s & Pediatric Dermatology Seminar.

In an interview at the meeting, Dr. Baldwin explained what makes the treatment of acne in adult women distinct from acne treatment for men and adolescents, and what underused medications can yield success.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by Frontline Medical Communications.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

NEWPORT BEACH, CALIF. – Do more women today really have acne? Or are they simply more likely to seek help because they learn of new and better medications?

Acne often causes more psychosocial and psychological stress in adult women than in men or adolescents, Dr. Hilary Baldwin of SUNY Downstate Medical Center, Brooklyn, N.Y., said at Skin Disease Education Foundation’s Women’s & Pediatric Dermatology Seminar.

In an interview at the meeting, Dr. Baldwin explained what makes the treatment of acne in adult women distinct from acne treatment for men and adolescents, and what underused medications can yield success.

SDEF and this news organization are owned by Frontline Medical Communications.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AT THE SDEF WOMEN’S & PEDIATRIC DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

Acne and rosacea management for men

In a report released March 2014 by the American Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, the top five surgical procedures for men were liposuction, eyelid surgery, rhinoplasty, male breast reduction, and ear surgery. However, the rate of noninvasive cosmetic procedures and sales of men’s grooming products is one of the leading segments of the beauty industry.

Although most scientific research and media are focused on the female aesthetic, understanding the specific needs of your male patients is key to patient satisfaction. Most men are generally less aware than are women of the treatment options and risks and benefits of procedures. Men also prefer treatments with less downtime and natural-looking results. This column continues our miniseries on aesthetic dermatology for the male patient.

In a general dermatology practice, there are several skin concerns often identified by male patients, and acne and rosacea are among them.

Acne: Men generally have thicker, more sebaceous skin than that of women. Although acne is a very common problem in teens and young men, there is a growing trend of cases of cystic acne in adult men who consume popular protein meal replacement or muscle enhancing shakes that contain whey protein. Whey is a protein derived from cow’s milk. Milk and dairy products act by increasing insulin-like growth factor 1, which has been linked to acne. Although few case reports have shown a link between dietary whey supplementation and acne, in my practice, men with cystic acne who report using whey supplementation products have had almost complete resolution of their acne without medical intervention after discontinuing these products.

Rosacea: Men have a higher density of facial blood vessels than women do, and often seek treatment for telangiectasias and overall facial erythema. For papulopustular rosacea, common treatments include oral antibiotics, topical antibiotics, topical azaleic acid, and topical anti-inflammatory medications. For erythematotelangiectatic rosacea, Mirvaso (brimonidine), a topical vasoconstrictor, can be applied to the skin for 8-12 hours of marked reduction in facial erythema. Although theoretically a great option for patients suffering from erythema, the effects of topical brimonidine are transient, and the gel requires daily application with no long-term benefit. Vascular laser treatments are effective for telangiectasias for both men and women. However, men with more granulomatous or phymatous rosacea often need a combination of treatments including antibiotics, oral isotretinoin and fractional ablative lasers.

Resources:

American Society for Plastic Surgery 2012 statistics.

“Whey protein precipitating moderate to severe acne flares in 5 teenaged athletes,” Cutis 2012;90:70-2.

Dr. Talakoub and Dr. Wesley are cocontributors to a monthly Aesthetic Dermatology column in Skin & Allergy News. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub.

In a report released March 2014 by the American Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, the top five surgical procedures for men were liposuction, eyelid surgery, rhinoplasty, male breast reduction, and ear surgery. However, the rate of noninvasive cosmetic procedures and sales of men’s grooming products is one of the leading segments of the beauty industry.

Although most scientific research and media are focused on the female aesthetic, understanding the specific needs of your male patients is key to patient satisfaction. Most men are generally less aware than are women of the treatment options and risks and benefits of procedures. Men also prefer treatments with less downtime and natural-looking results. This column continues our miniseries on aesthetic dermatology for the male patient.

In a general dermatology practice, there are several skin concerns often identified by male patients, and acne and rosacea are among them.

Acne: Men generally have thicker, more sebaceous skin than that of women. Although acne is a very common problem in teens and young men, there is a growing trend of cases of cystic acne in adult men who consume popular protein meal replacement or muscle enhancing shakes that contain whey protein. Whey is a protein derived from cow’s milk. Milk and dairy products act by increasing insulin-like growth factor 1, which has been linked to acne. Although few case reports have shown a link between dietary whey supplementation and acne, in my practice, men with cystic acne who report using whey supplementation products have had almost complete resolution of their acne without medical intervention after discontinuing these products.

Rosacea: Men have a higher density of facial blood vessels than women do, and often seek treatment for telangiectasias and overall facial erythema. For papulopustular rosacea, common treatments include oral antibiotics, topical antibiotics, topical azaleic acid, and topical anti-inflammatory medications. For erythematotelangiectatic rosacea, Mirvaso (brimonidine), a topical vasoconstrictor, can be applied to the skin for 8-12 hours of marked reduction in facial erythema. Although theoretically a great option for patients suffering from erythema, the effects of topical brimonidine are transient, and the gel requires daily application with no long-term benefit. Vascular laser treatments are effective for telangiectasias for both men and women. However, men with more granulomatous or phymatous rosacea often need a combination of treatments including antibiotics, oral isotretinoin and fractional ablative lasers.

Resources:

American Society for Plastic Surgery 2012 statistics.

“Whey protein precipitating moderate to severe acne flares in 5 teenaged athletes,” Cutis 2012;90:70-2.

Dr. Talakoub and Dr. Wesley are cocontributors to a monthly Aesthetic Dermatology column in Skin & Allergy News. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub.

In a report released March 2014 by the American Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, the top five surgical procedures for men were liposuction, eyelid surgery, rhinoplasty, male breast reduction, and ear surgery. However, the rate of noninvasive cosmetic procedures and sales of men’s grooming products is one of the leading segments of the beauty industry.

Although most scientific research and media are focused on the female aesthetic, understanding the specific needs of your male patients is key to patient satisfaction. Most men are generally less aware than are women of the treatment options and risks and benefits of procedures. Men also prefer treatments with less downtime and natural-looking results. This column continues our miniseries on aesthetic dermatology for the male patient.

In a general dermatology practice, there are several skin concerns often identified by male patients, and acne and rosacea are among them.

Acne: Men generally have thicker, more sebaceous skin than that of women. Although acne is a very common problem in teens and young men, there is a growing trend of cases of cystic acne in adult men who consume popular protein meal replacement or muscle enhancing shakes that contain whey protein. Whey is a protein derived from cow’s milk. Milk and dairy products act by increasing insulin-like growth factor 1, which has been linked to acne. Although few case reports have shown a link between dietary whey supplementation and acne, in my practice, men with cystic acne who report using whey supplementation products have had almost complete resolution of their acne without medical intervention after discontinuing these products.

Rosacea: Men have a higher density of facial blood vessels than women do, and often seek treatment for telangiectasias and overall facial erythema. For papulopustular rosacea, common treatments include oral antibiotics, topical antibiotics, topical azaleic acid, and topical anti-inflammatory medications. For erythematotelangiectatic rosacea, Mirvaso (brimonidine), a topical vasoconstrictor, can be applied to the skin for 8-12 hours of marked reduction in facial erythema. Although theoretically a great option for patients suffering from erythema, the effects of topical brimonidine are transient, and the gel requires daily application with no long-term benefit. Vascular laser treatments are effective for telangiectasias for both men and women. However, men with more granulomatous or phymatous rosacea often need a combination of treatments including antibiotics, oral isotretinoin and fractional ablative lasers.

Resources:

American Society for Plastic Surgery 2012 statistics.

“Whey protein precipitating moderate to severe acne flares in 5 teenaged athletes,” Cutis 2012;90:70-2.

Dr. Talakoub and Dr. Wesley are cocontributors to a monthly Aesthetic Dermatology column in Skin & Allergy News. Dr. Talakoub is in private practice in McLean, Va. Dr. Wesley practices dermatology in Beverly Hills, Calif. This month’s column is by Dr. Talakoub.

Best Practices in Pulsed Dye Laser Treatment

For more information, access Dr. Ezra's article from the August 2014 issue, "Linear Scarring Following Treatment With a 595-nm Pulsed Dye Laser."

For more information, access Dr. Ezra's article from the August 2014 issue, "Linear Scarring Following Treatment With a 595-nm Pulsed Dye Laser."

For more information, access Dr. Ezra's article from the August 2014 issue, "Linear Scarring Following Treatment With a 595-nm Pulsed Dye Laser."

Pros and Cons of Devices for Rosacea

For more information, access Dr. Goldenberg's article from the July 2014 issue, "Devices and Topical Agents for Rosacea Management."

For more information, access Dr. Goldenberg's article from the July 2014 issue, "Devices and Topical Agents for Rosacea Management."

For more information, access Dr. Goldenberg's article from the July 2014 issue, "Devices and Topical Agents for Rosacea Management."

Devices and Topical Agents for Rosacea Management

Rosacea is a common chronic inflammatory disease that typically affects centrofacial skin, particularly the convexities of the forehead, nose, cheeks, and chin. Occasionally, involvement of the scalp, neck, or upper trunk can occur.1 Rosacea is more common in light-skinned individuals and has been called the “curse of the Celts,”2 but it also can affect Asian individuals and patients of African descent. Although rosacea affects women more frequently, men are more likely to develop severe disease with complications such as rhinophyma. Diagnosis is made on clinical grounds, and histologic confirmation rarely is necessary.

Despite its high incidence and recent advances, the pathogenesis of rosacea is still poorly understood. A combination of factors, such as aberrations in innate immunity,3 neurovascular dysregulation, dilated blood and lymphatic vessels, and a possible genetic predisposition seem to be involved.4 Presence of commensal Demodex folliculorum mites may be a contributing factor for papulopustular disease.

Patients can present with a range of clinical features, such as transient or persistent facial erythema, telangiectasia, papules, pustules, edema, thickening, plaque formation, and ocular manifestations. Associated burning and stinging also may occur. Rosacea-related erythema (eg, lesional and perilesional erythema) can be caused by inflammatory lesions or can present independent of lesions in the case of diffuse facial erythema. Due to the diversity of clinical signs and limited knowledge regarding its etiology, rosacea is best regarded as a syndrome and has been classified into 4 subtypes—erythematotelangiectatic, papulopustular, phymatous, and ocular—and 1 variant (granulomatous rosacea).5 The most common phymatous changes affect the nose, with hypertrophy and lymphedema of subcutaneous tissues. Other sites that can be affected are the ears, forehead, and chin. Ocular manifestations affect approximately 50% of rosacea patients,6 ranging from conjunctivitis and blepharitis to keratitis and corneal ulceration, thereby requiring ophthalmologic assessment.

Because rosacea affects facial appearance, it can have a devastating impact on the patient’s quality of life, leading to social isolation. Although there is no cure available for rosacea, lifestyle modification and treatment can reduce or control its features, which tend to exacerbate and remit. There are a number of possible triggers for rosacea that ideally should be avoided such as sun exposure, hot or cold weather, heavy exercise, emotional stress, and consumption of alcohol and spicy foods. It is essential to consider disease subtype as well as the signs and symptoms presenting in each individual patient when approaching therapy selection. Most well-established US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved treatments of rosacea target the papulopustular aspect of disease, including the erythema associated with the lesions. These treatments include topical and systemic antibiotics and azelaic acid. Non–FDA-approved agents such as topical and systemic retinoids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, and topical benzoyl peroxide also are used, though there is limited evidence of their efficacy.7

Management options for diffuse facial erythema and telangiectasia, however, are limited. Standard rosacea treatments often are not efficacious in treating these aspects of the disease, thereby requiring an alternative approach. This article reviews devices and topical agents currently available for the management of rosacea.

Skin Care

The skin of rosacea patients often is sensitive and prone to irritation; therefore, a good skin care regimen is an integral part of disease management and should include a gentle cleanser, moisturizer, and sunscreen.8 Lipid-free liquid cleansers or synthetic detergent (syndet) cleansers with a neutral to slightly acidic pH (ie, similar to the pH of normal skin) are ideal.9 Following cleansing, the skin should be gently dried. It may be beneficial to wait up to 30 minutes before application of a moisturizer to avoid irritation. Hydrating moisturizers should be free of irritants or abrasives, allowing maintenance of stratum corneum pH in an acid range of 4 to 6. Green-tinted makeup can be a useful tool in covering areas of erythema.

Devices

A variety of devices targeting hemoglobin are reported to be effective for the management of erythema and telangiectasia in rosacea patients, including the 595-nm pulsed dye laser (PDL), the potassium titanyl phosphate (KTP) laser, the 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser, and noncoherent intense pulsed light (IPL) sources.

The major chromophore in blood vessels is oxyhemoglobin, with 2 major absorption bands in the visible light spectrum at 542 and 577 nm. There also is notable albeit lesser absorption in the near-infrared range from 700 to 1100 nm.10 Following absorption by oxyhemoglobin, light energy is converted to thermal energy, which diffuses in the blood vessel causing photocoagulation, mechanical injury, and finally thrombosis.

Pulsed Dye Laser (585–595 nm)

Among the vascular lasers, the PDL has a long safety record. It was the first laser that used the concept of selective photothermolysis for treatment of vascular lesions.11,12 The first PDLs had a wavelength of 577 nm, while current PDLs have wavelengths of 585 or 595 nm with longer pulse durations and circular or oval spot sizes that are ideal for treatment of dermal vessels. The main disadvantage of PDLs is the development of posttreatment purpura. The longer pulse durations of KTP lasers avoid damage to cutaneous vasculature and eliminate the risk for bruising. Nonetheless, the wavelength of the PDL provides a greater depth of penetration due to its substantial absorption by cutaneous vasculature compared to the shorter wavelength of the KTP laser.

Although newer-generation PDLs still have the potential to cause purpura, various attempts have been made to minimize this risk, such as the use of longer pulse durations, multiple minipulses or “pulselets,”13 and multiple passes. Separate parameters may need to be used when treating linear vessels and diffuse erythema, with longer pulse durations required for larger vessels. The Figure shows a rosacea patient with facial telangiectasia before and after 1 treatment with a PDL.

According to Alam et al,14 purpuric settings were more efficacious in a comparison of variable-pulsed PDLs for facial telangiectasia. In 82% (9/11) of cases, greater reduction in telangiectasia density was noted on the side of the face that had been treated with purpuric settings versus the other side of the face.14 Purpuric settings are particularly effective in treating larger vessels, while finer telangiectatic vessels may respond to purpura-free settings.

In a study of 12 participants treated with a 595-nm PDL at a pulse duration of 6 ms and fluences from 7 to 9 J/cm2, no lasting purpura was seen; however, while 9 participants achieved more than 25% improvement after a single treatment, only 2 participants achieved more than 75% improvement.15 Nonetheless, some patients may prefer this potentially less effective treatment method to avoid the socially embarrassing side effect of purpura.

In a study of 12 rosacea patients, a 75% reduction in telangiectasia scores was noted after a mean of 3 treatments with the 585-nm PDL using 450-ms pulse durations. Purpura occurred in all patients.16 In another study by Madan and Ferguson,17 18 participants with nasal telangiectasia that had been resistant to the traditional round spot, 595-nm PDL and/or 532-nm KTP laser were treated with a 3x10-mm elliptical spot, ultra-long pulse, 595-nm PDL with a 40-ms pulse duration and double passes. Complete clearance was seen in 10 (55.6%) participants and 8 (44.4%) showed more than 80% improvement. No purpura was associated with the treatment.17

Further studies comparing the efficacy of nonpurpuric and purpuric settings in the same patient would allow us to determine the most effective option for future treatment.

KTP Laser (532 nm)

Potassium titanyl phosphate lasers have the disadvantage of higher melanin absorption, which can lead to epidermal damage with postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Their use is limited to lighter skin types. Because of its shorter wavelength, the KTP laser is best used to treat superficial telangiectasia. The absence of posttreatment purpura can make KTP lasers a popular alternative to PDLs.17 Uebelhoer et al18 performed a split-face study in 15 participants to compare the 595-nm PDL and 532-nm KTP laser. Although both treatments were effective, the KTP laser achieved 62% clearance after the first treatment and 85% clearance 3 weeks after the third treatment compared to 49% and 75%, respectively, for the PDL. Interestingly, the degree of swelling and erythema posttreatment were greater on the KTP laser–treated side.18

Nd:YAG (1064 nm)

The wavelength of the Nd:YAG laser targets the lower absorption peak of oxyhemoglobin. In a study of 15 participants with facial telangiectasia who were treated with a 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser at day 0 and day 30 using a 3-mm spot size, a fluence of 120 to 170 J/cm,2 and 5- to 40-ms pulse durations, 73% (11/15) showed moderate to significant improvement at day 0 and day 30 and 80% improvement at 3 months’ follow-up.19 In a split-face study of 14 patients, treatment with the 595-nm PDL with a fluence of 7.5 J/cm2, pulse duration of 6 ms, and spot size of 10 mm was compared with the 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser with a fluence of 6 J/cm2, pulse duration of 0.3 ms, and spot size of 8 mm.20 Erythema improved by 6.4% from baseline on the side treated with the PDL. Although participants rated the Nd:YAG laser treatment as less painful, they were more satisfied with the results of the PDL treatment.20 In another split-face study comparing the 595-nm PDL and 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser, greater improvement was reported with the Nd:YAG laser, though the results were not statistically significant.21

Intense Pulsed Light

While lasers use selective photothermolysis, IPL devices emit noncoherent light at a wavelength of 500 to 1200 nm. Cutoff filters allow for selective tissue damage depending on the absorption spectra of the tissue. Longer wavelengths are effective for the treatment of deeper vessels, while shorter wavelengths target more superficial vessels; however, the shorter wavelengths can interact with melanin and should be avoided in darker skin types. In a phase 3 open trial, 34 participants were treated with IPL with a 560-nm cutoff filter and fluences of 24 to 32 J/cm2. The mean reduction of erythema following 4 treatments was 39% on the cheeks and 22% on the chin; side effects were minimal.22

Photodynamic Therapy

Photodynamic therapy is an effective and widely used treatment method for a number of skin conditions. Following its success in the treatment of acne, it also has been used in the management of rosacea, though the exact mechanism of action remains unclear.

Photodynamic therapy involves topical application of a photosensitizing agent (eg, 5-aminolevulinic acid, methyl aminolevulinate [MAL]) followed by exposure to red or blue light. The photosensitizing agent accumulates semiselectively in abnormal skin tissue and is converted to protoporphyrin IX, which induces a toxic skin reaction through reactive oxygen radicals in the presence of visible light.23 Photodynamic therapy generally is well tolerated. The primary side effects are pain, burning, and stinging.

In 3 of 4 (75%) patients treated with MAL and red light, rosacea clearance was noted after 2 to 3 sessions. Remission lasted for 3 months in 2 (66.7%) participants and for 9 months in 1 (33.3%) participant.24 In another study, 17 patients were treated with MAL and red light. Results were good in 10 participants (58.8%), fair in 4 (23.5%), and poor in 3 (17.6%).23

ALPHA-Adrenergic Receptor Agonists

Recently, the α-adrenergic receptor agonists brimonidine tartrate and oxymetazoline have been found to be effective in controlling diffuse facial erythema of rosacea, which is thought to arise from vasomotor instability and abnormal vasodilation of the superficial cutaneous vasculature. Brimonidine tartrate is a potent α2-agonist that is mainly used for treatment of open-angle glaucoma. In 2 phase 3 controlled studies, once-daily application of brimonidine tartrate gel 0.5% was found to be effective and safe in reducing the erythema of rosacea.25 Brimonidine tartrate gel is the first FDA-approved treatment of facial erythema associated with rosacea. Possible side effects are erythema worse than baseline (4%), flushing (3%), and burning (2%).26 Oxymetazoline is a potent α1- and partial α2-agonist that is available as a nasal decongestant. Oxymetazoline solution 0.05% used once daily has been shown in case reports to reduce rosacea-associated erythema for several hours.27

Nicotinamide

Nicotinamide is the amide form of niacin, which has both anti-inflammatory properties and a stabilizing effect on epidermal barrier function.28 Although topical application of nicotinamide has been used in the treatment of inflammatory dermatoses such as rosacea,28,29 niacin can lead to cutaneous vasodilation and thus flushing. It has been hypothesized to potentially enhance the effect of PDL if used as pretreatment for rosacea-associated erythema.30

Conclusion

Rosacea can have a substantial impact on patient quality of life. Recent advances in treatment options and rapidly advancing knowledge of laser therapy are providing dermatologists with powerful tools for rosacea clearance. Lasers and IPL are effective treatments of the erythematotelangiectatic aspect of the disease, and careful selection of devices and treatment parameters can reduce unwanted side effects.

- Ayres S Jr. Extrafacial rosacea is rare but does exist. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:391-392.

- Jansen T, Plewig G. Rosacea: classification and treatment. J R Soc Med. 1997;90:144-150.

- Yamasaki K, Gallo RL. Rosacea as a disease of cathelicidins and skin innate immunity. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2011;15:12-15.

- Steinhoff M, Schauber J, Leyden JJ. New insights into rosacea pathophysiology: a review of recent findings. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(6, suppl 1):S15-S26.

- Wilkin J, Dahl M, Detmar M, et al; National Rosacea Society Expert Committee. Standard classification of rosacea: report of the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee on the classification and staging of rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:584-587.

- Webster G, Schaller M. Ocular rosacea: a dermatologic perspective. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(6, suppl 1):S42-S43.

- Del Rosso JQ, Thiboutot D, Gallo R, et al. Consensus recommendations from the American Acne & Rosacea Society on the management of rosacea, part 2: a status report on topical agents. Cutis. 2013;92:277-284.

- Levin J, Miller R. A guide to the ingredients and potential benefits of over-the-counter cleansers and moisturizers for rosacea patients. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2011;4:31-49.

- Draelos ZD. The effect of Cetaphil gentle skin cleanser on the skin barrier of patients with rosacea. Cutis. 2006;77:27-33.

- Hare McCoppin HH, Goldberg DJ. Laser treatment of facial telangiectases: an update. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1221-1230.

- Garden JM, Polla LL, Tan OT. The treatment of port-wine stains by the pulsed dye laser. analysis of pulse duration and long-term therapy. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:889-896.

- Anderson RR, Parrish JA. Microvasculature can be selectively damaged using dye lasers: a basic theory and experimental evidence in human skin. Lasers Surg Med. 1981;1:263-276.

- Bernstein EF, Kligman A. Rosacea treatment using the new-generation, high-energy, 595 nm, long pulse-duration pulsed-dye laser. Lasers Surg Med. 2008;40:233-239.

- Alam M, Dover JS, Arndt KA. Treatment of facial telangiectasia with variable-pulse high-fluence pulsed-dye laser: comparison of efficacy with fluences immediately above and below the purpura threshold. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:681-684.

- Jasim ZF, Woo WK, Handley JM. Long-pulsed (6-ms) pulsed dye laser treatment of rosacea-associated telangiectasia using subpurpuric clinical threshold. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:37-40.

- Clark SM, Lanigan SW, Marks R. Laser treatment of erythema and telangiectasia associated with rosacea. Lasers Med Sci. 2002;17:26-33.

- Madan V, Ferguson J. Using the ultra-long pulse width pulsed dye laser and elliptical spot to treat resistant nasal telangiectasia. Lasers Med Sci. 2010;25:151-154.

- Uebelhoer NS, Bogle MA, Stewart B, et al. A split-face comparison study of pulsed 532-nm KTP laser and 595-nm pulsed dye laser in the treatment of facial telangiectases and diffuse telangiectatic facial erythema. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:441-448.

- Sarradet DM, Hussain M, Goldberg DJ. Millisecond 1064-nm neodymium:YAG laser treatment of facial telangiectases. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:56-58.

- Alam M, Voravutinon N, Warycha M, et al. Comparative effectiveness of nonpurpuragenic 595-nm pulsed dye laser and microsecond 1064-nm neodymium:yttrium-aluminum-garnet laser for treatment of diffuse facial erythema: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:438-443.

- Salem SA, Abdel Fattah NS, Tantawy SM, et al. Neodymium-yttrium aluminum garnet laser versus pulsed dye laser in erythemato-telangiectatic rosacea:comparison of clinical efficacy and effect on cutaneoussubstance (P) expression. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2013;12:187-194.

- Papageorgiou P, Clayton W, Norwood S, et al. Treatment of rosacea with intense pulsed light: significant improvement and long-lasting results. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:628-632.

- Bryld LE, Jemec GB. Photodynamic therapy in a series of rosacea patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:1199-1202.

- Nybaek H, Jemec GB. Photodynamic therapy in the treatment of rosacea. Dermatology. 2005;211:135-138.

- Fowler J, Jackson M, Moore A, et al. Efficacy and safety of once-daily topical brimonidine tartrate gel 0.5% for the treatment of moderate to severe facial erythema of rosacea: results of two randomized, double-blind, and vehicle-controlled pivotal studies. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:650-656.

- Routt ET, Levitt JO. Rebound erythema and burning sensation from a new topical brimonidine tartrate gel 0.33%. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:E37-E38.

- Shanler SD, Ondo AL. Successful treatment of the erythema and flushing of rosacea using a topically applied selective alpha1-adrenergic receptor agonist, oxymetazoline. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:1369-1371.

- Draelos ZD, Ertel K, Berge C. Niacinamide-containing facial moisturizer improves skin barrier and benefits subjects with rosacea. Cutis. 2005;76:135-141.

- Draelos ZD, Ertel KD, Berge CA. Facilitating facial retinization through barrier improvement. Cutis. 2006;78:275-281.

- Kim TG, Roh HJ, Cho SB, et al. Enhancing effect of pretreatment with topical niacin in the treatment of rosacea-associated erythema by 585-nm pulsed dye laser in Koreans: a randomized, prospective, split-face trial. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:573-579.

Rosacea is a common chronic inflammatory disease that typically affects centrofacial skin, particularly the convexities of the forehead, nose, cheeks, and chin. Occasionally, involvement of the scalp, neck, or upper trunk can occur.1 Rosacea is more common in light-skinned individuals and has been called the “curse of the Celts,”2 but it also can affect Asian individuals and patients of African descent. Although rosacea affects women more frequently, men are more likely to develop severe disease with complications such as rhinophyma. Diagnosis is made on clinical grounds, and histologic confirmation rarely is necessary.

Despite its high incidence and recent advances, the pathogenesis of rosacea is still poorly understood. A combination of factors, such as aberrations in innate immunity,3 neurovascular dysregulation, dilated blood and lymphatic vessels, and a possible genetic predisposition seem to be involved.4 Presence of commensal Demodex folliculorum mites may be a contributing factor for papulopustular disease.

Patients can present with a range of clinical features, such as transient or persistent facial erythema, telangiectasia, papules, pustules, edema, thickening, plaque formation, and ocular manifestations. Associated burning and stinging also may occur. Rosacea-related erythema (eg, lesional and perilesional erythema) can be caused by inflammatory lesions or can present independent of lesions in the case of diffuse facial erythema. Due to the diversity of clinical signs and limited knowledge regarding its etiology, rosacea is best regarded as a syndrome and has been classified into 4 subtypes—erythematotelangiectatic, papulopustular, phymatous, and ocular—and 1 variant (granulomatous rosacea).5 The most common phymatous changes affect the nose, with hypertrophy and lymphedema of subcutaneous tissues. Other sites that can be affected are the ears, forehead, and chin. Ocular manifestations affect approximately 50% of rosacea patients,6 ranging from conjunctivitis and blepharitis to keratitis and corneal ulceration, thereby requiring ophthalmologic assessment.

Because rosacea affects facial appearance, it can have a devastating impact on the patient’s quality of life, leading to social isolation. Although there is no cure available for rosacea, lifestyle modification and treatment can reduce or control its features, which tend to exacerbate and remit. There are a number of possible triggers for rosacea that ideally should be avoided such as sun exposure, hot or cold weather, heavy exercise, emotional stress, and consumption of alcohol and spicy foods. It is essential to consider disease subtype as well as the signs and symptoms presenting in each individual patient when approaching therapy selection. Most well-established US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved treatments of rosacea target the papulopustular aspect of disease, including the erythema associated with the lesions. These treatments include topical and systemic antibiotics and azelaic acid. Non–FDA-approved agents such as topical and systemic retinoids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, and topical benzoyl peroxide also are used, though there is limited evidence of their efficacy.7

Management options for diffuse facial erythema and telangiectasia, however, are limited. Standard rosacea treatments often are not efficacious in treating these aspects of the disease, thereby requiring an alternative approach. This article reviews devices and topical agents currently available for the management of rosacea.

Skin Care

The skin of rosacea patients often is sensitive and prone to irritation; therefore, a good skin care regimen is an integral part of disease management and should include a gentle cleanser, moisturizer, and sunscreen.8 Lipid-free liquid cleansers or synthetic detergent (syndet) cleansers with a neutral to slightly acidic pH (ie, similar to the pH of normal skin) are ideal.9 Following cleansing, the skin should be gently dried. It may be beneficial to wait up to 30 minutes before application of a moisturizer to avoid irritation. Hydrating moisturizers should be free of irritants or abrasives, allowing maintenance of stratum corneum pH in an acid range of 4 to 6. Green-tinted makeup can be a useful tool in covering areas of erythema.

Devices

A variety of devices targeting hemoglobin are reported to be effective for the management of erythema and telangiectasia in rosacea patients, including the 595-nm pulsed dye laser (PDL), the potassium titanyl phosphate (KTP) laser, the 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser, and noncoherent intense pulsed light (IPL) sources.

The major chromophore in blood vessels is oxyhemoglobin, with 2 major absorption bands in the visible light spectrum at 542 and 577 nm. There also is notable albeit lesser absorption in the near-infrared range from 700 to 1100 nm.10 Following absorption by oxyhemoglobin, light energy is converted to thermal energy, which diffuses in the blood vessel causing photocoagulation, mechanical injury, and finally thrombosis.

Pulsed Dye Laser (585–595 nm)

Among the vascular lasers, the PDL has a long safety record. It was the first laser that used the concept of selective photothermolysis for treatment of vascular lesions.11,12 The first PDLs had a wavelength of 577 nm, while current PDLs have wavelengths of 585 or 595 nm with longer pulse durations and circular or oval spot sizes that are ideal for treatment of dermal vessels. The main disadvantage of PDLs is the development of posttreatment purpura. The longer pulse durations of KTP lasers avoid damage to cutaneous vasculature and eliminate the risk for bruising. Nonetheless, the wavelength of the PDL provides a greater depth of penetration due to its substantial absorption by cutaneous vasculature compared to the shorter wavelength of the KTP laser.

Although newer-generation PDLs still have the potential to cause purpura, various attempts have been made to minimize this risk, such as the use of longer pulse durations, multiple minipulses or “pulselets,”13 and multiple passes. Separate parameters may need to be used when treating linear vessels and diffuse erythema, with longer pulse durations required for larger vessels. The Figure shows a rosacea patient with facial telangiectasia before and after 1 treatment with a PDL.

According to Alam et al,14 purpuric settings were more efficacious in a comparison of variable-pulsed PDLs for facial telangiectasia. In 82% (9/11) of cases, greater reduction in telangiectasia density was noted on the side of the face that had been treated with purpuric settings versus the other side of the face.14 Purpuric settings are particularly effective in treating larger vessels, while finer telangiectatic vessels may respond to purpura-free settings.

In a study of 12 participants treated with a 595-nm PDL at a pulse duration of 6 ms and fluences from 7 to 9 J/cm2, no lasting purpura was seen; however, while 9 participants achieved more than 25% improvement after a single treatment, only 2 participants achieved more than 75% improvement.15 Nonetheless, some patients may prefer this potentially less effective treatment method to avoid the socially embarrassing side effect of purpura.

In a study of 12 rosacea patients, a 75% reduction in telangiectasia scores was noted after a mean of 3 treatments with the 585-nm PDL using 450-ms pulse durations. Purpura occurred in all patients.16 In another study by Madan and Ferguson,17 18 participants with nasal telangiectasia that had been resistant to the traditional round spot, 595-nm PDL and/or 532-nm KTP laser were treated with a 3x10-mm elliptical spot, ultra-long pulse, 595-nm PDL with a 40-ms pulse duration and double passes. Complete clearance was seen in 10 (55.6%) participants and 8 (44.4%) showed more than 80% improvement. No purpura was associated with the treatment.17

Further studies comparing the efficacy of nonpurpuric and purpuric settings in the same patient would allow us to determine the most effective option for future treatment.

KTP Laser (532 nm)

Potassium titanyl phosphate lasers have the disadvantage of higher melanin absorption, which can lead to epidermal damage with postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Their use is limited to lighter skin types. Because of its shorter wavelength, the KTP laser is best used to treat superficial telangiectasia. The absence of posttreatment purpura can make KTP lasers a popular alternative to PDLs.17 Uebelhoer et al18 performed a split-face study in 15 participants to compare the 595-nm PDL and 532-nm KTP laser. Although both treatments were effective, the KTP laser achieved 62% clearance after the first treatment and 85% clearance 3 weeks after the third treatment compared to 49% and 75%, respectively, for the PDL. Interestingly, the degree of swelling and erythema posttreatment were greater on the KTP laser–treated side.18

Nd:YAG (1064 nm)

The wavelength of the Nd:YAG laser targets the lower absorption peak of oxyhemoglobin. In a study of 15 participants with facial telangiectasia who were treated with a 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser at day 0 and day 30 using a 3-mm spot size, a fluence of 120 to 170 J/cm,2 and 5- to 40-ms pulse durations, 73% (11/15) showed moderate to significant improvement at day 0 and day 30 and 80% improvement at 3 months’ follow-up.19 In a split-face study of 14 patients, treatment with the 595-nm PDL with a fluence of 7.5 J/cm2, pulse duration of 6 ms, and spot size of 10 mm was compared with the 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser with a fluence of 6 J/cm2, pulse duration of 0.3 ms, and spot size of 8 mm.20 Erythema improved by 6.4% from baseline on the side treated with the PDL. Although participants rated the Nd:YAG laser treatment as less painful, they were more satisfied with the results of the PDL treatment.20 In another split-face study comparing the 595-nm PDL and 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser, greater improvement was reported with the Nd:YAG laser, though the results were not statistically significant.21

Intense Pulsed Light

While lasers use selective photothermolysis, IPL devices emit noncoherent light at a wavelength of 500 to 1200 nm. Cutoff filters allow for selective tissue damage depending on the absorption spectra of the tissue. Longer wavelengths are effective for the treatment of deeper vessels, while shorter wavelengths target more superficial vessels; however, the shorter wavelengths can interact with melanin and should be avoided in darker skin types. In a phase 3 open trial, 34 participants were treated with IPL with a 560-nm cutoff filter and fluences of 24 to 32 J/cm2. The mean reduction of erythema following 4 treatments was 39% on the cheeks and 22% on the chin; side effects were minimal.22

Photodynamic Therapy

Photodynamic therapy is an effective and widely used treatment method for a number of skin conditions. Following its success in the treatment of acne, it also has been used in the management of rosacea, though the exact mechanism of action remains unclear.

Photodynamic therapy involves topical application of a photosensitizing agent (eg, 5-aminolevulinic acid, methyl aminolevulinate [MAL]) followed by exposure to red or blue light. The photosensitizing agent accumulates semiselectively in abnormal skin tissue and is converted to protoporphyrin IX, which induces a toxic skin reaction through reactive oxygen radicals in the presence of visible light.23 Photodynamic therapy generally is well tolerated. The primary side effects are pain, burning, and stinging.

In 3 of 4 (75%) patients treated with MAL and red light, rosacea clearance was noted after 2 to 3 sessions. Remission lasted for 3 months in 2 (66.7%) participants and for 9 months in 1 (33.3%) participant.24 In another study, 17 patients were treated with MAL and red light. Results were good in 10 participants (58.8%), fair in 4 (23.5%), and poor in 3 (17.6%).23

ALPHA-Adrenergic Receptor Agonists

Recently, the α-adrenergic receptor agonists brimonidine tartrate and oxymetazoline have been found to be effective in controlling diffuse facial erythema of rosacea, which is thought to arise from vasomotor instability and abnormal vasodilation of the superficial cutaneous vasculature. Brimonidine tartrate is a potent α2-agonist that is mainly used for treatment of open-angle glaucoma. In 2 phase 3 controlled studies, once-daily application of brimonidine tartrate gel 0.5% was found to be effective and safe in reducing the erythema of rosacea.25 Brimonidine tartrate gel is the first FDA-approved treatment of facial erythema associated with rosacea. Possible side effects are erythema worse than baseline (4%), flushing (3%), and burning (2%).26 Oxymetazoline is a potent α1- and partial α2-agonist that is available as a nasal decongestant. Oxymetazoline solution 0.05% used once daily has been shown in case reports to reduce rosacea-associated erythema for several hours.27

Nicotinamide

Nicotinamide is the amide form of niacin, which has both anti-inflammatory properties and a stabilizing effect on epidermal barrier function.28 Although topical application of nicotinamide has been used in the treatment of inflammatory dermatoses such as rosacea,28,29 niacin can lead to cutaneous vasodilation and thus flushing. It has been hypothesized to potentially enhance the effect of PDL if used as pretreatment for rosacea-associated erythema.30

Conclusion

Rosacea can have a substantial impact on patient quality of life. Recent advances in treatment options and rapidly advancing knowledge of laser therapy are providing dermatologists with powerful tools for rosacea clearance. Lasers and IPL are effective treatments of the erythematotelangiectatic aspect of the disease, and careful selection of devices and treatment parameters can reduce unwanted side effects.

Rosacea is a common chronic inflammatory disease that typically affects centrofacial skin, particularly the convexities of the forehead, nose, cheeks, and chin. Occasionally, involvement of the scalp, neck, or upper trunk can occur.1 Rosacea is more common in light-skinned individuals and has been called the “curse of the Celts,”2 but it also can affect Asian individuals and patients of African descent. Although rosacea affects women more frequently, men are more likely to develop severe disease with complications such as rhinophyma. Diagnosis is made on clinical grounds, and histologic confirmation rarely is necessary.

Despite its high incidence and recent advances, the pathogenesis of rosacea is still poorly understood. A combination of factors, such as aberrations in innate immunity,3 neurovascular dysregulation, dilated blood and lymphatic vessels, and a possible genetic predisposition seem to be involved.4 Presence of commensal Demodex folliculorum mites may be a contributing factor for papulopustular disease.

Patients can present with a range of clinical features, such as transient or persistent facial erythema, telangiectasia, papules, pustules, edema, thickening, plaque formation, and ocular manifestations. Associated burning and stinging also may occur. Rosacea-related erythema (eg, lesional and perilesional erythema) can be caused by inflammatory lesions or can present independent of lesions in the case of diffuse facial erythema. Due to the diversity of clinical signs and limited knowledge regarding its etiology, rosacea is best regarded as a syndrome and has been classified into 4 subtypes—erythematotelangiectatic, papulopustular, phymatous, and ocular—and 1 variant (granulomatous rosacea).5 The most common phymatous changes affect the nose, with hypertrophy and lymphedema of subcutaneous tissues. Other sites that can be affected are the ears, forehead, and chin. Ocular manifestations affect approximately 50% of rosacea patients,6 ranging from conjunctivitis and blepharitis to keratitis and corneal ulceration, thereby requiring ophthalmologic assessment.

Because rosacea affects facial appearance, it can have a devastating impact on the patient’s quality of life, leading to social isolation. Although there is no cure available for rosacea, lifestyle modification and treatment can reduce or control its features, which tend to exacerbate and remit. There are a number of possible triggers for rosacea that ideally should be avoided such as sun exposure, hot or cold weather, heavy exercise, emotional stress, and consumption of alcohol and spicy foods. It is essential to consider disease subtype as well as the signs and symptoms presenting in each individual patient when approaching therapy selection. Most well-established US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved treatments of rosacea target the papulopustular aspect of disease, including the erythema associated with the lesions. These treatments include topical and systemic antibiotics and azelaic acid. Non–FDA-approved agents such as topical and systemic retinoids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, and topical benzoyl peroxide also are used, though there is limited evidence of their efficacy.7

Management options for diffuse facial erythema and telangiectasia, however, are limited. Standard rosacea treatments often are not efficacious in treating these aspects of the disease, thereby requiring an alternative approach. This article reviews devices and topical agents currently available for the management of rosacea.

Skin Care

The skin of rosacea patients often is sensitive and prone to irritation; therefore, a good skin care regimen is an integral part of disease management and should include a gentle cleanser, moisturizer, and sunscreen.8 Lipid-free liquid cleansers or synthetic detergent (syndet) cleansers with a neutral to slightly acidic pH (ie, similar to the pH of normal skin) are ideal.9 Following cleansing, the skin should be gently dried. It may be beneficial to wait up to 30 minutes before application of a moisturizer to avoid irritation. Hydrating moisturizers should be free of irritants or abrasives, allowing maintenance of stratum corneum pH in an acid range of 4 to 6. Green-tinted makeup can be a useful tool in covering areas of erythema.

Devices

A variety of devices targeting hemoglobin are reported to be effective for the management of erythema and telangiectasia in rosacea patients, including the 595-nm pulsed dye laser (PDL), the potassium titanyl phosphate (KTP) laser, the 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser, and noncoherent intense pulsed light (IPL) sources.

The major chromophore in blood vessels is oxyhemoglobin, with 2 major absorption bands in the visible light spectrum at 542 and 577 nm. There also is notable albeit lesser absorption in the near-infrared range from 700 to 1100 nm.10 Following absorption by oxyhemoglobin, light energy is converted to thermal energy, which diffuses in the blood vessel causing photocoagulation, mechanical injury, and finally thrombosis.

Pulsed Dye Laser (585–595 nm)

Among the vascular lasers, the PDL has a long safety record. It was the first laser that used the concept of selective photothermolysis for treatment of vascular lesions.11,12 The first PDLs had a wavelength of 577 nm, while current PDLs have wavelengths of 585 or 595 nm with longer pulse durations and circular or oval spot sizes that are ideal for treatment of dermal vessels. The main disadvantage of PDLs is the development of posttreatment purpura. The longer pulse durations of KTP lasers avoid damage to cutaneous vasculature and eliminate the risk for bruising. Nonetheless, the wavelength of the PDL provides a greater depth of penetration due to its substantial absorption by cutaneous vasculature compared to the shorter wavelength of the KTP laser.