User login

Gout flares linked to transient jump in MI, stroke risk

There is evidence that gout and heart disease are mechanistically linked by inflammation and patients with gout are at elevated risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD). But do gout flares, on their own, affect short-term risk for CV events? A new analysis based on records from British medical practices suggests that might be the case.

Risk for myocardial infarction or stroke climbed in the weeks after individual gout flare-ups in the study’s more than 60,000 patients with a recent gout diagnosis. The jump in risk, significant but small in absolute terms, held for about 4 months in the case-control study before going away.

A sensitivity analysis that excluded patients who already had CVD when their gout was diagnosed yielded similar results.

The observational study isn’t able to show that gout flares themselves transiently raise the risk for MI or stroke, but it’s enough to send a cautionary message to physicians who care for patients with gout, rheumatologist Abhishek Abhishek, PhD, Nottingham (England) City Hospital, said in an interview.

In such patients who also have conditions like hypertension, diabetes, or dyslipidemia, or a history of heart disease, he said, it’s important “to manage risk factors really aggressively, knowing that when these patients have a gout flare, there’s a temporary increase in risk of a cardiovascular event.”

Managing their absolute CV risk – whether with drug therapy, lifestyle changes, or other interventions – should help limit the transient jump in risk for MI or stroke following a gout flare, proposed Dr. Abhishek, who is senior author on the study published in JAMA, with lead author Edoardo Cipolletta, MD, also from Nottingham City Hospital.

First robust evidence

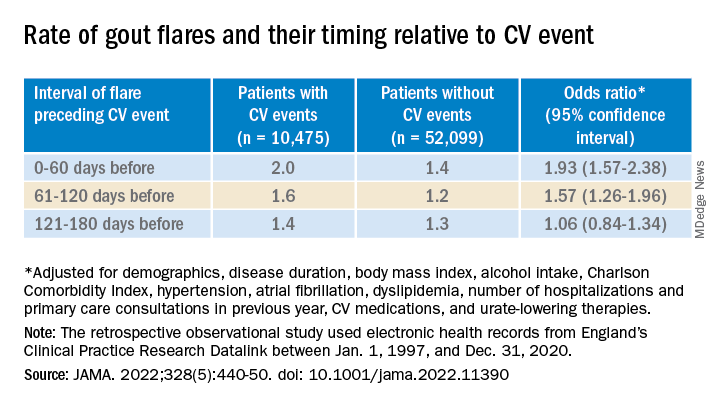

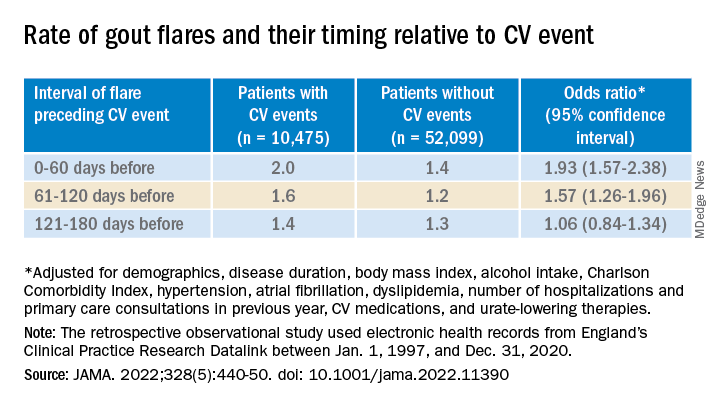

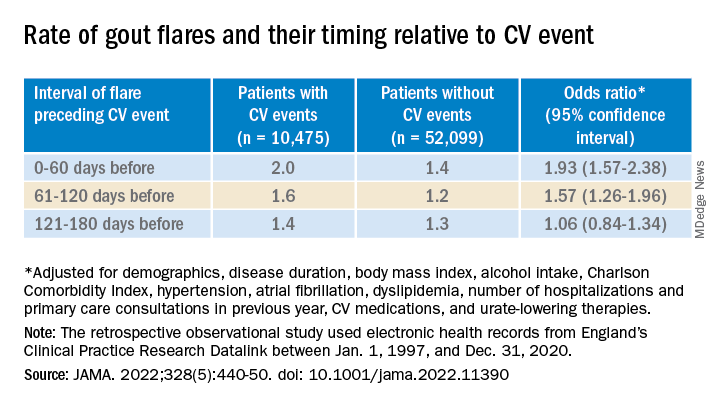

The case-control study, which involved more than 60,000 patients with a recent gout diagnosis, some who went on to have MI or stroke, looked at rates of such events at different time intervals after gout flares. Those who experienced such events showed a more than 90% increased likelihood of a gout flare-up in the preceding 60 days, a greater than 50% chance of a flare between 60 and 120 days before the event, but no increased likelihood prior to 120 days before the event.

Such a link between gout flares and CV events “has been suspected but never proven,” observed rheumatologist Hyon K. Choi, MD, Harvard Medical School, Boston, who was not associated with the analysis. “This is the first time it has actually been shown in a robust way,” he said in an interview.

The study suggests a “likely causative relationship” between gout flares and CV events, but – as the published report noted – has limitations like any observational study, said Dr. Choi, who also directs the Gout & Crystal Arthropathy Center at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. “Hopefully, this can be replicated in other cohorts.”

The analysis controlled for a number of relevant potential confounders, he noted, but couldn’t account for all issues that could argue against gout flares as a direct cause of the MIs and strokes.

Gout attacks are a complex experience with a range of potential indirect effects on CV risk, Dr. Choi observed. They can immobilize patients, possibly raising their risk for thrombotic events, for example. They can be exceptionally painful, which causes stress and can lead to frequent or chronic use of glucocorticoids or NSAIDs, all of which can exacerbate high blood pressure and possibly worsen CV risk.

A unique insight

The timing of gout flares relative to acute vascular events hasn’t been fully explored, observed an accompanying editorial. The current study’s “unique insight,” it stated, “is that disease activity from gout was associated with an incremental increase in risk for acute vascular events during the time period immediately following the gout flare.”

Although the study is observational, a “large body of evidence from animal and human research, mechanistic insights, and clinical interventions” support an association between flares and vascular events and “make a causal link eminently reasonable,” stated the editorialists, Jeffrey L. Anderson, MD, and Kirk U. Knowlton, MD, both with Intermountain Medical Center, Salt Lake City, Utah.

The findings, they wrote, “should alert clinicians and patients to the increased cardiovascular risk in the weeks beginning after a gout flare and should focus attention on optimizing preventive measures.” Those can include “lifestyle measures and standard risk-factor control including adherence to diet, statins, anti-inflammatory drugs (e.g., aspirin, colchicine), smoking cessation, diabetic and blood pressure control, and antithrombotic medications as indicated.”

Dr. Choi said the current results argue for more liberal use of colchicine, and for preferring colchicine over other anti-inflammatories, in patients with gout and traditional CV risk factors, given multiple randomized trials supporting the drug’s use in such cases. “If you use colchicine, you are covering their heart disease risk as well as their gout. It’s two birds with one stone.”

Nested case-control study

The investigators accessed electronic health records from 96,153 patients with recently diagnosed gout in England from 1997 to 2020; the cohort’s mean age was about 76 years, and 69% of participants were men. They matched 10,475 patients with at least one CV event to 52,099 others who didn’t have such an event by age, sex, and time from gout diagnosis. In each matched set of patients, those not experiencing a CV event were assigned a flare-to-event interval based on their matching with patients who did experience such an event.

Those with CV events, compared with patients without an event, had a greater than 90% increased likelihood of experiencing a gout flare-up in the 60 days preceding the event, a more than 50% greater chance of a flare-up 60-120 days before the CV event, but no increased likelihood more than 120 days before the event.

A self-controlled case series based on the same overall cohort with gout yielded similar results while sidestepping any potential for residual confounding, an inherent concern with any case–control analysis, the report notes. It involved 1,421 patients with one or more gout flare and at least one MI or stroke after the diagnosis of gout.

Among that cohort, the CV-event incidence rate ratio, adjusted for age and season of the year, by time interval after a gout flare, was 1.89 (95% confidence interval, 1.54-2.30) at 0-60 days, 1.64 (95% CI, 1.45-1.86) at 61-120 days, and1.29 (95% CI, 1.02-1.64) at 121-180 days.

Also similar, the report noted, were results of several sensitivity analyses, including one that excluded patients with confirmed CVD before their gout diagnosis; another that left out patients at low to moderate CV risk; and one that considered only gout flares treated with colchicine, corticosteroids, or NSAIDs.

The incremental CV event risks observed after flares in the study were small, which “has implications for both cost effectiveness and clinical relevance,” observed Dr. Anderson and Dr. Knowlton.

“An alternative to universal augmentation of cardiovascular risk prevention with therapies among patients with gout flares,” they wrote, would be “to further stratify risk by defining a group at highest near-term risk.” Such interventions could potentially be guided by markers of CV risk such as, for example, levels of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein or lipoprotein(a), or plaque burden on coronary-artery calcium scans.

Dr. Abhishek, Dr. Cipolletta, and the other authors reported no competing interests. Dr. Choi disclosed research support from Ironwood and Horizon; and consulting fees from Ironwood, Selecta, Horizon, Takeda, Kowa, and Vaxart. Dr. Anderson disclosed receiving grants to his institution from Novartis and Milestone.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

There is evidence that gout and heart disease are mechanistically linked by inflammation and patients with gout are at elevated risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD). But do gout flares, on their own, affect short-term risk for CV events? A new analysis based on records from British medical practices suggests that might be the case.

Risk for myocardial infarction or stroke climbed in the weeks after individual gout flare-ups in the study’s more than 60,000 patients with a recent gout diagnosis. The jump in risk, significant but small in absolute terms, held for about 4 months in the case-control study before going away.

A sensitivity analysis that excluded patients who already had CVD when their gout was diagnosed yielded similar results.

The observational study isn’t able to show that gout flares themselves transiently raise the risk for MI or stroke, but it’s enough to send a cautionary message to physicians who care for patients with gout, rheumatologist Abhishek Abhishek, PhD, Nottingham (England) City Hospital, said in an interview.

In such patients who also have conditions like hypertension, diabetes, or dyslipidemia, or a history of heart disease, he said, it’s important “to manage risk factors really aggressively, knowing that when these patients have a gout flare, there’s a temporary increase in risk of a cardiovascular event.”

Managing their absolute CV risk – whether with drug therapy, lifestyle changes, or other interventions – should help limit the transient jump in risk for MI or stroke following a gout flare, proposed Dr. Abhishek, who is senior author on the study published in JAMA, with lead author Edoardo Cipolletta, MD, also from Nottingham City Hospital.

First robust evidence

The case-control study, which involved more than 60,000 patients with a recent gout diagnosis, some who went on to have MI or stroke, looked at rates of such events at different time intervals after gout flares. Those who experienced such events showed a more than 90% increased likelihood of a gout flare-up in the preceding 60 days, a greater than 50% chance of a flare between 60 and 120 days before the event, but no increased likelihood prior to 120 days before the event.

Such a link between gout flares and CV events “has been suspected but never proven,” observed rheumatologist Hyon K. Choi, MD, Harvard Medical School, Boston, who was not associated with the analysis. “This is the first time it has actually been shown in a robust way,” he said in an interview.

The study suggests a “likely causative relationship” between gout flares and CV events, but – as the published report noted – has limitations like any observational study, said Dr. Choi, who also directs the Gout & Crystal Arthropathy Center at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. “Hopefully, this can be replicated in other cohorts.”

The analysis controlled for a number of relevant potential confounders, he noted, but couldn’t account for all issues that could argue against gout flares as a direct cause of the MIs and strokes.

Gout attacks are a complex experience with a range of potential indirect effects on CV risk, Dr. Choi observed. They can immobilize patients, possibly raising their risk for thrombotic events, for example. They can be exceptionally painful, which causes stress and can lead to frequent or chronic use of glucocorticoids or NSAIDs, all of which can exacerbate high blood pressure and possibly worsen CV risk.

A unique insight

The timing of gout flares relative to acute vascular events hasn’t been fully explored, observed an accompanying editorial. The current study’s “unique insight,” it stated, “is that disease activity from gout was associated with an incremental increase in risk for acute vascular events during the time period immediately following the gout flare.”

Although the study is observational, a “large body of evidence from animal and human research, mechanistic insights, and clinical interventions” support an association between flares and vascular events and “make a causal link eminently reasonable,” stated the editorialists, Jeffrey L. Anderson, MD, and Kirk U. Knowlton, MD, both with Intermountain Medical Center, Salt Lake City, Utah.

The findings, they wrote, “should alert clinicians and patients to the increased cardiovascular risk in the weeks beginning after a gout flare and should focus attention on optimizing preventive measures.” Those can include “lifestyle measures and standard risk-factor control including adherence to diet, statins, anti-inflammatory drugs (e.g., aspirin, colchicine), smoking cessation, diabetic and blood pressure control, and antithrombotic medications as indicated.”

Dr. Choi said the current results argue for more liberal use of colchicine, and for preferring colchicine over other anti-inflammatories, in patients with gout and traditional CV risk factors, given multiple randomized trials supporting the drug’s use in such cases. “If you use colchicine, you are covering their heart disease risk as well as their gout. It’s two birds with one stone.”

Nested case-control study

The investigators accessed electronic health records from 96,153 patients with recently diagnosed gout in England from 1997 to 2020; the cohort’s mean age was about 76 years, and 69% of participants were men. They matched 10,475 patients with at least one CV event to 52,099 others who didn’t have such an event by age, sex, and time from gout diagnosis. In each matched set of patients, those not experiencing a CV event were assigned a flare-to-event interval based on their matching with patients who did experience such an event.

Those with CV events, compared with patients without an event, had a greater than 90% increased likelihood of experiencing a gout flare-up in the 60 days preceding the event, a more than 50% greater chance of a flare-up 60-120 days before the CV event, but no increased likelihood more than 120 days before the event.

A self-controlled case series based on the same overall cohort with gout yielded similar results while sidestepping any potential for residual confounding, an inherent concern with any case–control analysis, the report notes. It involved 1,421 patients with one or more gout flare and at least one MI or stroke after the diagnosis of gout.

Among that cohort, the CV-event incidence rate ratio, adjusted for age and season of the year, by time interval after a gout flare, was 1.89 (95% confidence interval, 1.54-2.30) at 0-60 days, 1.64 (95% CI, 1.45-1.86) at 61-120 days, and1.29 (95% CI, 1.02-1.64) at 121-180 days.

Also similar, the report noted, were results of several sensitivity analyses, including one that excluded patients with confirmed CVD before their gout diagnosis; another that left out patients at low to moderate CV risk; and one that considered only gout flares treated with colchicine, corticosteroids, or NSAIDs.

The incremental CV event risks observed after flares in the study were small, which “has implications for both cost effectiveness and clinical relevance,” observed Dr. Anderson and Dr. Knowlton.

“An alternative to universal augmentation of cardiovascular risk prevention with therapies among patients with gout flares,” they wrote, would be “to further stratify risk by defining a group at highest near-term risk.” Such interventions could potentially be guided by markers of CV risk such as, for example, levels of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein or lipoprotein(a), or plaque burden on coronary-artery calcium scans.

Dr. Abhishek, Dr. Cipolletta, and the other authors reported no competing interests. Dr. Choi disclosed research support from Ironwood and Horizon; and consulting fees from Ironwood, Selecta, Horizon, Takeda, Kowa, and Vaxart. Dr. Anderson disclosed receiving grants to his institution from Novartis and Milestone.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

There is evidence that gout and heart disease are mechanistically linked by inflammation and patients with gout are at elevated risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD). But do gout flares, on their own, affect short-term risk for CV events? A new analysis based on records from British medical practices suggests that might be the case.

Risk for myocardial infarction or stroke climbed in the weeks after individual gout flare-ups in the study’s more than 60,000 patients with a recent gout diagnosis. The jump in risk, significant but small in absolute terms, held for about 4 months in the case-control study before going away.

A sensitivity analysis that excluded patients who already had CVD when their gout was diagnosed yielded similar results.

The observational study isn’t able to show that gout flares themselves transiently raise the risk for MI or stroke, but it’s enough to send a cautionary message to physicians who care for patients with gout, rheumatologist Abhishek Abhishek, PhD, Nottingham (England) City Hospital, said in an interview.

In such patients who also have conditions like hypertension, diabetes, or dyslipidemia, or a history of heart disease, he said, it’s important “to manage risk factors really aggressively, knowing that when these patients have a gout flare, there’s a temporary increase in risk of a cardiovascular event.”

Managing their absolute CV risk – whether with drug therapy, lifestyle changes, or other interventions – should help limit the transient jump in risk for MI or stroke following a gout flare, proposed Dr. Abhishek, who is senior author on the study published in JAMA, with lead author Edoardo Cipolletta, MD, also from Nottingham City Hospital.

First robust evidence

The case-control study, which involved more than 60,000 patients with a recent gout diagnosis, some who went on to have MI or stroke, looked at rates of such events at different time intervals after gout flares. Those who experienced such events showed a more than 90% increased likelihood of a gout flare-up in the preceding 60 days, a greater than 50% chance of a flare between 60 and 120 days before the event, but no increased likelihood prior to 120 days before the event.

Such a link between gout flares and CV events “has been suspected but never proven,” observed rheumatologist Hyon K. Choi, MD, Harvard Medical School, Boston, who was not associated with the analysis. “This is the first time it has actually been shown in a robust way,” he said in an interview.

The study suggests a “likely causative relationship” between gout flares and CV events, but – as the published report noted – has limitations like any observational study, said Dr. Choi, who also directs the Gout & Crystal Arthropathy Center at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. “Hopefully, this can be replicated in other cohorts.”

The analysis controlled for a number of relevant potential confounders, he noted, but couldn’t account for all issues that could argue against gout flares as a direct cause of the MIs and strokes.

Gout attacks are a complex experience with a range of potential indirect effects on CV risk, Dr. Choi observed. They can immobilize patients, possibly raising their risk for thrombotic events, for example. They can be exceptionally painful, which causes stress and can lead to frequent or chronic use of glucocorticoids or NSAIDs, all of which can exacerbate high blood pressure and possibly worsen CV risk.

A unique insight

The timing of gout flares relative to acute vascular events hasn’t been fully explored, observed an accompanying editorial. The current study’s “unique insight,” it stated, “is that disease activity from gout was associated with an incremental increase in risk for acute vascular events during the time period immediately following the gout flare.”

Although the study is observational, a “large body of evidence from animal and human research, mechanistic insights, and clinical interventions” support an association between flares and vascular events and “make a causal link eminently reasonable,” stated the editorialists, Jeffrey L. Anderson, MD, and Kirk U. Knowlton, MD, both with Intermountain Medical Center, Salt Lake City, Utah.

The findings, they wrote, “should alert clinicians and patients to the increased cardiovascular risk in the weeks beginning after a gout flare and should focus attention on optimizing preventive measures.” Those can include “lifestyle measures and standard risk-factor control including adherence to diet, statins, anti-inflammatory drugs (e.g., aspirin, colchicine), smoking cessation, diabetic and blood pressure control, and antithrombotic medications as indicated.”

Dr. Choi said the current results argue for more liberal use of colchicine, and for preferring colchicine over other anti-inflammatories, in patients with gout and traditional CV risk factors, given multiple randomized trials supporting the drug’s use in such cases. “If you use colchicine, you are covering their heart disease risk as well as their gout. It’s two birds with one stone.”

Nested case-control study

The investigators accessed electronic health records from 96,153 patients with recently diagnosed gout in England from 1997 to 2020; the cohort’s mean age was about 76 years, and 69% of participants were men. They matched 10,475 patients with at least one CV event to 52,099 others who didn’t have such an event by age, sex, and time from gout diagnosis. In each matched set of patients, those not experiencing a CV event were assigned a flare-to-event interval based on their matching with patients who did experience such an event.

Those with CV events, compared with patients without an event, had a greater than 90% increased likelihood of experiencing a gout flare-up in the 60 days preceding the event, a more than 50% greater chance of a flare-up 60-120 days before the CV event, but no increased likelihood more than 120 days before the event.

A self-controlled case series based on the same overall cohort with gout yielded similar results while sidestepping any potential for residual confounding, an inherent concern with any case–control analysis, the report notes. It involved 1,421 patients with one or more gout flare and at least one MI or stroke after the diagnosis of gout.

Among that cohort, the CV-event incidence rate ratio, adjusted for age and season of the year, by time interval after a gout flare, was 1.89 (95% confidence interval, 1.54-2.30) at 0-60 days, 1.64 (95% CI, 1.45-1.86) at 61-120 days, and1.29 (95% CI, 1.02-1.64) at 121-180 days.

Also similar, the report noted, were results of several sensitivity analyses, including one that excluded patients with confirmed CVD before their gout diagnosis; another that left out patients at low to moderate CV risk; and one that considered only gout flares treated with colchicine, corticosteroids, or NSAIDs.

The incremental CV event risks observed after flares in the study were small, which “has implications for both cost effectiveness and clinical relevance,” observed Dr. Anderson and Dr. Knowlton.

“An alternative to universal augmentation of cardiovascular risk prevention with therapies among patients with gout flares,” they wrote, would be “to further stratify risk by defining a group at highest near-term risk.” Such interventions could potentially be guided by markers of CV risk such as, for example, levels of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein or lipoprotein(a), or plaque burden on coronary-artery calcium scans.

Dr. Abhishek, Dr. Cipolletta, and the other authors reported no competing interests. Dr. Choi disclosed research support from Ironwood and Horizon; and consulting fees from Ironwood, Selecta, Horizon, Takeda, Kowa, and Vaxart. Dr. Anderson disclosed receiving grants to his institution from Novartis and Milestone.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA

‘Striking’ disparities in CVD deaths persist across COVID waves

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality rose significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic and persists more than 2 years on and, once again, Blacks and African Americans have been disproportionately affected, an analysis of death certificates shows.

The findings “suggest that the pandemic may reverse years or decades of work aimed at reducing gaps in cardiovascular outcomes,” Sadeer G. Al-Kindi, MD, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, said in an interview.

Although the disparities are in line with previous research, he said, “what was surprising is the persistence of excess cardiovascular mortality approximately 2 years after the pandemic started, even during a period of low COVID-19 mortality.”

“This suggests that the pandemic resulted in a disruption of health care access and, along with disparities in COVID-19 infection and its complications, he said, “may have a long-lasting effect on health care disparities, especially among vulnerable populations.”

The study was published online in Mayo Clinic Proceedings with lead author Scott E. Janus, MD, also of Case Western Reserve University.

Impact consistently greater for Blacks

Dr. Al-Kindi and colleagues used 3,598,352 U.S. death files to investigate trends in deaths caused specifically by CVD as well as its subtypes myocardial infarction, stroke, and heart failure (HF) in 2018 and 2019 (prepandemic) and the pandemic years 2020 and 2021. Baseline demographics showed a higher percentage of older, female, and Black individuals among the CVD subtypes of interest.

Overall, there was an excess CVD mortality of 6.7% during the pandemic, compared with prepandemic years, including a 2.5% rise in MI deaths and an 8.5% rise in stroke deaths. HF mortality remained relatively steady, rising only 0.1%.

Subgroup analyses revealed “striking differences” in excess mortality between Blacks and Whites, the authors noted. Blacks had an overall excess mortality of 13.8% versus 5.1% for Whites, compared with the prepandemic years. The differences were consistent across subtypes: MI (9.6% vs. 1.0%); stroke (14.5% vs. 6.9%); and HF (5.1% vs. –1.2%; P value for all < .001).

When the investigators looked at deaths on a yearly basis with 2018 as the baseline, they found CVD deaths increased by 1.5% in 2019, 15.8% in 2020, and 13.5% in 2021 among Black Americans, compared with 0.5%, 5.1%, and 5.7%, respectively, among White Americans.

Excess deaths from MI rose by 9.5% in 2020 and by 6.7% in 2021 among Blacks but fell by 1.2% in 2020 and by 1.0% in 2021 among Whites.

Disparities in excess HF mortality were similar, rising 9.1% and 4.1% in 2020 and 2021 among Blacks, while dipping 0.1% and 0.8% in 2020 and 2021 among Whites.

The “most striking difference” was in excess stroke mortality, which doubled among Blacks compared with whites in 2020 (14.9% vs. 6.7%) and in 2021 (17.5% vs. 8.1%), according to the authors.

Awareness urged

Although the disparities were expected, “there is clear value in documenting and quantifying the magnitude of these disparities,” Amil M. Shah, MD, MPH, of Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston, said in an interview.

In addition to being observational, the main limitation of the study, he noted, is the quality and resolution of the death certificate data, which may limit the accuracy of the cause of death ascertainment and classification of race or ethnicity. “However, I think these potential inaccuracies are unlikely to materially impact the overall study findings.”

Dr. Shah, who was not involved in the study, said he would like to see additional research into the diversity and heterogeneity in risk among Black communities. “Understanding the environmental, social, and health care factors – both harmful and protective – that influence risk for CVD morbidity and mortality among Black individuals and communities offers the promise to provide actionable insights to mitigate these disparities.”

“Intervention studies testing approaches to mitigate disparities based on race/ethnicity” are also needed, he added. These may be at the policy, community, health system, or individual level, and community involvement in phases will be essential.”

Meanwhile, both Dr. Al-Kindi and Dr. Shah urged clinicians to be aware of the disparities and the need to improve access to care and address social determinants of health in vulnerable populations.

These disparities “are driven by structural factors, and are reinforced by individual behaviors. In this context, implicit bias training is important to help clinicians recognize and mitigate bias in their own practice,” Dr. Shah said. “Supporting diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts, and advocating for anti-racist policies and practices in their health systems” can also help.

Dr. Al-Kindi and Dr. Shah disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality rose significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic and persists more than 2 years on and, once again, Blacks and African Americans have been disproportionately affected, an analysis of death certificates shows.

The findings “suggest that the pandemic may reverse years or decades of work aimed at reducing gaps in cardiovascular outcomes,” Sadeer G. Al-Kindi, MD, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, said in an interview.

Although the disparities are in line with previous research, he said, “what was surprising is the persistence of excess cardiovascular mortality approximately 2 years after the pandemic started, even during a period of low COVID-19 mortality.”

“This suggests that the pandemic resulted in a disruption of health care access and, along with disparities in COVID-19 infection and its complications, he said, “may have a long-lasting effect on health care disparities, especially among vulnerable populations.”

The study was published online in Mayo Clinic Proceedings with lead author Scott E. Janus, MD, also of Case Western Reserve University.

Impact consistently greater for Blacks

Dr. Al-Kindi and colleagues used 3,598,352 U.S. death files to investigate trends in deaths caused specifically by CVD as well as its subtypes myocardial infarction, stroke, and heart failure (HF) in 2018 and 2019 (prepandemic) and the pandemic years 2020 and 2021. Baseline demographics showed a higher percentage of older, female, and Black individuals among the CVD subtypes of interest.

Overall, there was an excess CVD mortality of 6.7% during the pandemic, compared with prepandemic years, including a 2.5% rise in MI deaths and an 8.5% rise in stroke deaths. HF mortality remained relatively steady, rising only 0.1%.

Subgroup analyses revealed “striking differences” in excess mortality between Blacks and Whites, the authors noted. Blacks had an overall excess mortality of 13.8% versus 5.1% for Whites, compared with the prepandemic years. The differences were consistent across subtypes: MI (9.6% vs. 1.0%); stroke (14.5% vs. 6.9%); and HF (5.1% vs. –1.2%; P value for all < .001).

When the investigators looked at deaths on a yearly basis with 2018 as the baseline, they found CVD deaths increased by 1.5% in 2019, 15.8% in 2020, and 13.5% in 2021 among Black Americans, compared with 0.5%, 5.1%, and 5.7%, respectively, among White Americans.

Excess deaths from MI rose by 9.5% in 2020 and by 6.7% in 2021 among Blacks but fell by 1.2% in 2020 and by 1.0% in 2021 among Whites.

Disparities in excess HF mortality were similar, rising 9.1% and 4.1% in 2020 and 2021 among Blacks, while dipping 0.1% and 0.8% in 2020 and 2021 among Whites.

The “most striking difference” was in excess stroke mortality, which doubled among Blacks compared with whites in 2020 (14.9% vs. 6.7%) and in 2021 (17.5% vs. 8.1%), according to the authors.

Awareness urged

Although the disparities were expected, “there is clear value in documenting and quantifying the magnitude of these disparities,” Amil M. Shah, MD, MPH, of Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston, said in an interview.

In addition to being observational, the main limitation of the study, he noted, is the quality and resolution of the death certificate data, which may limit the accuracy of the cause of death ascertainment and classification of race or ethnicity. “However, I think these potential inaccuracies are unlikely to materially impact the overall study findings.”

Dr. Shah, who was not involved in the study, said he would like to see additional research into the diversity and heterogeneity in risk among Black communities. “Understanding the environmental, social, and health care factors – both harmful and protective – that influence risk for CVD morbidity and mortality among Black individuals and communities offers the promise to provide actionable insights to mitigate these disparities.”

“Intervention studies testing approaches to mitigate disparities based on race/ethnicity” are also needed, he added. These may be at the policy, community, health system, or individual level, and community involvement in phases will be essential.”

Meanwhile, both Dr. Al-Kindi and Dr. Shah urged clinicians to be aware of the disparities and the need to improve access to care and address social determinants of health in vulnerable populations.

These disparities “are driven by structural factors, and are reinforced by individual behaviors. In this context, implicit bias training is important to help clinicians recognize and mitigate bias in their own practice,” Dr. Shah said. “Supporting diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts, and advocating for anti-racist policies and practices in their health systems” can also help.

Dr. Al-Kindi and Dr. Shah disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality rose significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic and persists more than 2 years on and, once again, Blacks and African Americans have been disproportionately affected, an analysis of death certificates shows.

The findings “suggest that the pandemic may reverse years or decades of work aimed at reducing gaps in cardiovascular outcomes,” Sadeer G. Al-Kindi, MD, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, said in an interview.

Although the disparities are in line with previous research, he said, “what was surprising is the persistence of excess cardiovascular mortality approximately 2 years after the pandemic started, even during a period of low COVID-19 mortality.”

“This suggests that the pandemic resulted in a disruption of health care access and, along with disparities in COVID-19 infection and its complications, he said, “may have a long-lasting effect on health care disparities, especially among vulnerable populations.”

The study was published online in Mayo Clinic Proceedings with lead author Scott E. Janus, MD, also of Case Western Reserve University.

Impact consistently greater for Blacks

Dr. Al-Kindi and colleagues used 3,598,352 U.S. death files to investigate trends in deaths caused specifically by CVD as well as its subtypes myocardial infarction, stroke, and heart failure (HF) in 2018 and 2019 (prepandemic) and the pandemic years 2020 and 2021. Baseline demographics showed a higher percentage of older, female, and Black individuals among the CVD subtypes of interest.

Overall, there was an excess CVD mortality of 6.7% during the pandemic, compared with prepandemic years, including a 2.5% rise in MI deaths and an 8.5% rise in stroke deaths. HF mortality remained relatively steady, rising only 0.1%.

Subgroup analyses revealed “striking differences” in excess mortality between Blacks and Whites, the authors noted. Blacks had an overall excess mortality of 13.8% versus 5.1% for Whites, compared with the prepandemic years. The differences were consistent across subtypes: MI (9.6% vs. 1.0%); stroke (14.5% vs. 6.9%); and HF (5.1% vs. –1.2%; P value for all < .001).

When the investigators looked at deaths on a yearly basis with 2018 as the baseline, they found CVD deaths increased by 1.5% in 2019, 15.8% in 2020, and 13.5% in 2021 among Black Americans, compared with 0.5%, 5.1%, and 5.7%, respectively, among White Americans.

Excess deaths from MI rose by 9.5% in 2020 and by 6.7% in 2021 among Blacks but fell by 1.2% in 2020 and by 1.0% in 2021 among Whites.

Disparities in excess HF mortality were similar, rising 9.1% and 4.1% in 2020 and 2021 among Blacks, while dipping 0.1% and 0.8% in 2020 and 2021 among Whites.

The “most striking difference” was in excess stroke mortality, which doubled among Blacks compared with whites in 2020 (14.9% vs. 6.7%) and in 2021 (17.5% vs. 8.1%), according to the authors.

Awareness urged

Although the disparities were expected, “there is clear value in documenting and quantifying the magnitude of these disparities,” Amil M. Shah, MD, MPH, of Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston, said in an interview.

In addition to being observational, the main limitation of the study, he noted, is the quality and resolution of the death certificate data, which may limit the accuracy of the cause of death ascertainment and classification of race or ethnicity. “However, I think these potential inaccuracies are unlikely to materially impact the overall study findings.”

Dr. Shah, who was not involved in the study, said he would like to see additional research into the diversity and heterogeneity in risk among Black communities. “Understanding the environmental, social, and health care factors – both harmful and protective – that influence risk for CVD morbidity and mortality among Black individuals and communities offers the promise to provide actionable insights to mitigate these disparities.”

“Intervention studies testing approaches to mitigate disparities based on race/ethnicity” are also needed, he added. These may be at the policy, community, health system, or individual level, and community involvement in phases will be essential.”

Meanwhile, both Dr. Al-Kindi and Dr. Shah urged clinicians to be aware of the disparities and the need to improve access to care and address social determinants of health in vulnerable populations.

These disparities “are driven by structural factors, and are reinforced by individual behaviors. In this context, implicit bias training is important to help clinicians recognize and mitigate bias in their own practice,” Dr. Shah said. “Supporting diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts, and advocating for anti-racist policies and practices in their health systems” can also help.

Dr. Al-Kindi and Dr. Shah disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM MAYO CLINIC PROCEEDINGS

‘Case closed’: Bridging thrombolysis remains ‘gold standard’ in stroke thrombectomy

Two new noninferiority trials address the controversial question of whether thrombolytic therapy can be omitted for acute ischemic stroke in patients undergoing endovascular thrombectomy for large-vessel occlusion.

Both trials show better outcomes when standard bridging thrombolytic therapy is used before thrombectomy, with comparable safety.

The results of SWIFT-DIRECT and DIRECT-SAFE were published online June 22 in The Lancet.

“The case appears closed. Bypass intravenous thrombolysis is highly unlikely to be noninferior to standard care by a clinically acceptable margin for most patients,” writes Pooja Khatri, MD, MSc, department of neurology, University of Cincinnati, in a linked comment.

SWIFT-DIRECT

SWIFT-DIRECT enrolled 408 patients (median age 72; 51% women) with acute stroke due to large vessel occlusion admitted to stroke centers in Europe and Canada. Half were randomly allocated to thrombectomy alone and half to intravenous alteplase and thrombectomy.

Successful reperfusion was less common in patients who had thrombectomy alone (91% vs. 96%; risk difference −5.1%; 95% confidence interval, −10.2 to 0.0, P = .047).

With combination therapy, more patients achieved functional independence with a modified Rankin scale score of 0-2 at 90 days (65% vs. 57%; adjusted risk difference −7.3%; 95% CI, −16·6 to 2·1, lower limit of one-sided 95% CI, −15·1%, crossing the noninferiority margin of −12%).

“Despite a very liberal noninferiority margin and strict inclusion and exclusion criteria aimed at studying a population most likely to benefit from thrombectomy alone, point estimates directionally favored intravenous thrombolysis plus thrombectomy,” Urs Fischer, MD, cochair of the Stroke Center, University Hospital Basel, Switzerland, told this news organization.

“Furthermore, we could demonstrate that overall reperfusion rates were extremely high and yet significantly better in patients receiving intravenous thrombolysis plus thrombectomy than in patients treated with thrombectomy alone, a finding which has not been shown before,” Dr. Fischer said.

There was no significant difference in the risk of symptomatic intracranial bleeding (3% with combination therapy and 2% with thrombectomy alone).

Based on the results, in patients suitable for thrombolysis, skipping it before thrombectomy “is not justified,” the study team concludes.

DIRECT-SAFE

DIRECT-SAFE enrolled 295 patients (median age 69; 43% women) with stroke and large vessel occlusion from Australia, New Zealand, China, and Vietnam, with half undergoing direct thrombectomy and half bridging therapy first.

Functional independence (modified Rankin Scale 0-2 or return to baseline at 90 days) was more common in the bridging group (61% vs. 55%).

Safety outcomes were similar between groups. Symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage occurred in 2 (1%) patients in the direct group and 1 (1%) patient in the bridging group. There were 22 (15%) deaths in the direct group and 24 in the bridging group.

“There has been concern across the world regarding cost of treatment, together with fears of increasing bleeding risk or clot migration with intravenous thrombolytic,” lead investigator Peter Mitchell, MBBS, director, NeuroIntervention Service, The Royal Melbourne Hospital, Parkville, Victoria, Australia, told this news organization.

“We showed that patients in the bridging treatment arm had better outcomes across the entire study, especially in Asian region patients” and therefore remains “the gold standard,” Dr. Mitchell said.

To date, six published trials have addressed this question of endovascular therapy alone or with thrombolysis – SKIP, DIRECT-MT, MR CLEAN NO IV, SWIFT-DIRECT, and DIRECT-SAFE.

Dr. Fischer said the SWIFT-DIRECT study group plans to perform an individual participant data meta-analysis known as Improving Reperfusion Strategies in Ischemic Stroke (IRIS) of all six trials to see whether there are subgroups of patients in whom thrombectomy alone is as effective as thrombolysis plus thrombectomy.

Subgroups of interest, he said, include patients with early ischemic signs on imaging, those at increased risk for hemorrhagic complications, and patients with a high clot burden.

SWIFT-DIRECT was funding by Medtronic and University Hospital Bern. DIRECT-SAFE was funded by Australian National Health and Medical Research Council and Stryker USA. A complete list of author disclosures is available with the original articles.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Two new noninferiority trials address the controversial question of whether thrombolytic therapy can be omitted for acute ischemic stroke in patients undergoing endovascular thrombectomy for large-vessel occlusion.

Both trials show better outcomes when standard bridging thrombolytic therapy is used before thrombectomy, with comparable safety.

The results of SWIFT-DIRECT and DIRECT-SAFE were published online June 22 in The Lancet.

“The case appears closed. Bypass intravenous thrombolysis is highly unlikely to be noninferior to standard care by a clinically acceptable margin for most patients,” writes Pooja Khatri, MD, MSc, department of neurology, University of Cincinnati, in a linked comment.

SWIFT-DIRECT

SWIFT-DIRECT enrolled 408 patients (median age 72; 51% women) with acute stroke due to large vessel occlusion admitted to stroke centers in Europe and Canada. Half were randomly allocated to thrombectomy alone and half to intravenous alteplase and thrombectomy.

Successful reperfusion was less common in patients who had thrombectomy alone (91% vs. 96%; risk difference −5.1%; 95% confidence interval, −10.2 to 0.0, P = .047).

With combination therapy, more patients achieved functional independence with a modified Rankin scale score of 0-2 at 90 days (65% vs. 57%; adjusted risk difference −7.3%; 95% CI, −16·6 to 2·1, lower limit of one-sided 95% CI, −15·1%, crossing the noninferiority margin of −12%).

“Despite a very liberal noninferiority margin and strict inclusion and exclusion criteria aimed at studying a population most likely to benefit from thrombectomy alone, point estimates directionally favored intravenous thrombolysis plus thrombectomy,” Urs Fischer, MD, cochair of the Stroke Center, University Hospital Basel, Switzerland, told this news organization.

“Furthermore, we could demonstrate that overall reperfusion rates were extremely high and yet significantly better in patients receiving intravenous thrombolysis plus thrombectomy than in patients treated with thrombectomy alone, a finding which has not been shown before,” Dr. Fischer said.

There was no significant difference in the risk of symptomatic intracranial bleeding (3% with combination therapy and 2% with thrombectomy alone).

Based on the results, in patients suitable for thrombolysis, skipping it before thrombectomy “is not justified,” the study team concludes.

DIRECT-SAFE

DIRECT-SAFE enrolled 295 patients (median age 69; 43% women) with stroke and large vessel occlusion from Australia, New Zealand, China, and Vietnam, with half undergoing direct thrombectomy and half bridging therapy first.

Functional independence (modified Rankin Scale 0-2 or return to baseline at 90 days) was more common in the bridging group (61% vs. 55%).

Safety outcomes were similar between groups. Symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage occurred in 2 (1%) patients in the direct group and 1 (1%) patient in the bridging group. There were 22 (15%) deaths in the direct group and 24 in the bridging group.

“There has been concern across the world regarding cost of treatment, together with fears of increasing bleeding risk or clot migration with intravenous thrombolytic,” lead investigator Peter Mitchell, MBBS, director, NeuroIntervention Service, The Royal Melbourne Hospital, Parkville, Victoria, Australia, told this news organization.

“We showed that patients in the bridging treatment arm had better outcomes across the entire study, especially in Asian region patients” and therefore remains “the gold standard,” Dr. Mitchell said.

To date, six published trials have addressed this question of endovascular therapy alone or with thrombolysis – SKIP, DIRECT-MT, MR CLEAN NO IV, SWIFT-DIRECT, and DIRECT-SAFE.

Dr. Fischer said the SWIFT-DIRECT study group plans to perform an individual participant data meta-analysis known as Improving Reperfusion Strategies in Ischemic Stroke (IRIS) of all six trials to see whether there are subgroups of patients in whom thrombectomy alone is as effective as thrombolysis plus thrombectomy.

Subgroups of interest, he said, include patients with early ischemic signs on imaging, those at increased risk for hemorrhagic complications, and patients with a high clot burden.

SWIFT-DIRECT was funding by Medtronic and University Hospital Bern. DIRECT-SAFE was funded by Australian National Health and Medical Research Council and Stryker USA. A complete list of author disclosures is available with the original articles.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Two new noninferiority trials address the controversial question of whether thrombolytic therapy can be omitted for acute ischemic stroke in patients undergoing endovascular thrombectomy for large-vessel occlusion.

Both trials show better outcomes when standard bridging thrombolytic therapy is used before thrombectomy, with comparable safety.

The results of SWIFT-DIRECT and DIRECT-SAFE were published online June 22 in The Lancet.

“The case appears closed. Bypass intravenous thrombolysis is highly unlikely to be noninferior to standard care by a clinically acceptable margin for most patients,” writes Pooja Khatri, MD, MSc, department of neurology, University of Cincinnati, in a linked comment.

SWIFT-DIRECT

SWIFT-DIRECT enrolled 408 patients (median age 72; 51% women) with acute stroke due to large vessel occlusion admitted to stroke centers in Europe and Canada. Half were randomly allocated to thrombectomy alone and half to intravenous alteplase and thrombectomy.

Successful reperfusion was less common in patients who had thrombectomy alone (91% vs. 96%; risk difference −5.1%; 95% confidence interval, −10.2 to 0.0, P = .047).

With combination therapy, more patients achieved functional independence with a modified Rankin scale score of 0-2 at 90 days (65% vs. 57%; adjusted risk difference −7.3%; 95% CI, −16·6 to 2·1, lower limit of one-sided 95% CI, −15·1%, crossing the noninferiority margin of −12%).

“Despite a very liberal noninferiority margin and strict inclusion and exclusion criteria aimed at studying a population most likely to benefit from thrombectomy alone, point estimates directionally favored intravenous thrombolysis plus thrombectomy,” Urs Fischer, MD, cochair of the Stroke Center, University Hospital Basel, Switzerland, told this news organization.

“Furthermore, we could demonstrate that overall reperfusion rates were extremely high and yet significantly better in patients receiving intravenous thrombolysis plus thrombectomy than in patients treated with thrombectomy alone, a finding which has not been shown before,” Dr. Fischer said.

There was no significant difference in the risk of symptomatic intracranial bleeding (3% with combination therapy and 2% with thrombectomy alone).

Based on the results, in patients suitable for thrombolysis, skipping it before thrombectomy “is not justified,” the study team concludes.

DIRECT-SAFE

DIRECT-SAFE enrolled 295 patients (median age 69; 43% women) with stroke and large vessel occlusion from Australia, New Zealand, China, and Vietnam, with half undergoing direct thrombectomy and half bridging therapy first.

Functional independence (modified Rankin Scale 0-2 or return to baseline at 90 days) was more common in the bridging group (61% vs. 55%).

Safety outcomes were similar between groups. Symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage occurred in 2 (1%) patients in the direct group and 1 (1%) patient in the bridging group. There were 22 (15%) deaths in the direct group and 24 in the bridging group.

“There has been concern across the world regarding cost of treatment, together with fears of increasing bleeding risk or clot migration with intravenous thrombolytic,” lead investigator Peter Mitchell, MBBS, director, NeuroIntervention Service, The Royal Melbourne Hospital, Parkville, Victoria, Australia, told this news organization.

“We showed that patients in the bridging treatment arm had better outcomes across the entire study, especially in Asian region patients” and therefore remains “the gold standard,” Dr. Mitchell said.

To date, six published trials have addressed this question of endovascular therapy alone or with thrombolysis – SKIP, DIRECT-MT, MR CLEAN NO IV, SWIFT-DIRECT, and DIRECT-SAFE.

Dr. Fischer said the SWIFT-DIRECT study group plans to perform an individual participant data meta-analysis known as Improving Reperfusion Strategies in Ischemic Stroke (IRIS) of all six trials to see whether there are subgroups of patients in whom thrombectomy alone is as effective as thrombolysis plus thrombectomy.

Subgroups of interest, he said, include patients with early ischemic signs on imaging, those at increased risk for hemorrhagic complications, and patients with a high clot burden.

SWIFT-DIRECT was funding by Medtronic and University Hospital Bern. DIRECT-SAFE was funded by Australian National Health and Medical Research Council and Stryker USA. A complete list of author disclosures is available with the original articles.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE LANCET

Nurses’ cohort study: Endometriosis elevates stroke risk

Women who’ve had endometriosis carry an elevated risk of stroke with them for the rest of their lives, with the greatest risk found in women who’ve had a hysterectomy with an oophorectomy, according to a cohort study of the Nurses’ Health Study.

“This is yet additional evidence that those girls and women with endometriosis are having effects across their lives and in multiple aspects of their health and well-being,” senior study author Stacey A. Missmer, ScD, of the Michigan State University, East Lansing, said in an interview. “This is not, in quotes ‘just a gynecologic condition,’ ” Dr. Missmer added. “It is not strictly about the pelvic pain or infertility, but it really is about the whole health across the life course.”

The study included 112,056 women in the NHSII cohort study who were followed from 1989 to June 2017, documenting 893 incident cases of stroke among them – an incidence of less than 1%. Endometriosis was reported in 5,244 women, and 93% of the cohort were White.

Multivariate adjusted models showed that women who had laparoscopically confirmed endometriosis had a 34% greater risk of stroke than women without a history of endometriosis. Leslie V. Farland, ScD, of the University of Arizona, Tucson, was lead author of the study.

While previous studies have demonstrated an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, heart attack, angina, and atherosclerosis in women who’ve had endometriosis, this is the first study that has confirmed an additional increased risk of stroke, Dr. Missmer said.

Another novel finding, Dr. Missmer said, is that while the CVD risks for these women “seem to peak at an earlier age,” the study found no age differences for stroke risk. “That also reinforces that these stroke events are often happening in an age range typical for stroke, which is further removed from when women are thinking about their gynecologic health specifically.”

These findings don’t translate into a significantly greater risk for stroke overall in women who’ve had endometriosis, Dr. Missmer said. She characterized the risk as “not negligible, but it’s not a huge increased risk.” The absolute risk is still fairly low, she said.

“We don’t want to give the impression that all women with endometriosis need to be panicked or fearful about stroke, she said. “Rather, the messaging is that this yet another bit of evidence that whole health care for those with endometriosis is important.”

Women who’ve had endometriosis and their primary care providers need to be attuned to stroke risk, she said. “This is a critical condition that primary care physicians need to engage around, and perhaps if symptoms related to cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease emerge in their patients, they need to be engaging cardiology and similar types of support. This is not just about the gynecologists.”

The study also explored other factors that may contribute to stroke risk, with the most significant being hysterectomy with bilateral oophorectomy, Dr. Missmer said.

This study was unique because it used laparoscopically confirmed rather than self-reported endometriosis, said Louise D. McCullough, MD, neurology chair at the University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston. Another strength of the study she noted was its longitudinal design, although the cohort study design yielded a low number of stroke patients.

“Regardless, I do think it was a very important study because we have a growing recognition about how women’s health and factors such as pregnancy, infertility, parity, complications, and gonadal hormones such as estrogen can influence a woman’s stroke risk much later in life,” Dr. McCullough said in an interview.

Future studies into the relationship between endometriosis and CVD and stroke risk should focus on the mechanism behind the inflammation that occurs in endometriosis, Dr. McCullough said. “Part of it is probably the loss of hormones if a patient has to have an oophorectomy, but part of it is just what do these diseases do for a woman’s later risk – and for primary care physicians, ob.gyns., and stroke neurologists to recognize that these are questions we should ask: Have you ever had eclampsia or preeclampsia? Did you have endometriosis? Have you had miscarriages?”

The study received funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Dr. Missmer disclosed relationships with Shanghai Huilun Biotechnology, Roche, and AbbVie. Dr. McCullough has no relevant disclosures.

Women who’ve had endometriosis carry an elevated risk of stroke with them for the rest of their lives, with the greatest risk found in women who’ve had a hysterectomy with an oophorectomy, according to a cohort study of the Nurses’ Health Study.

“This is yet additional evidence that those girls and women with endometriosis are having effects across their lives and in multiple aspects of their health and well-being,” senior study author Stacey A. Missmer, ScD, of the Michigan State University, East Lansing, said in an interview. “This is not, in quotes ‘just a gynecologic condition,’ ” Dr. Missmer added. “It is not strictly about the pelvic pain or infertility, but it really is about the whole health across the life course.”

The study included 112,056 women in the NHSII cohort study who were followed from 1989 to June 2017, documenting 893 incident cases of stroke among them – an incidence of less than 1%. Endometriosis was reported in 5,244 women, and 93% of the cohort were White.

Multivariate adjusted models showed that women who had laparoscopically confirmed endometriosis had a 34% greater risk of stroke than women without a history of endometriosis. Leslie V. Farland, ScD, of the University of Arizona, Tucson, was lead author of the study.

While previous studies have demonstrated an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, heart attack, angina, and atherosclerosis in women who’ve had endometriosis, this is the first study that has confirmed an additional increased risk of stroke, Dr. Missmer said.

Another novel finding, Dr. Missmer said, is that while the CVD risks for these women “seem to peak at an earlier age,” the study found no age differences for stroke risk. “That also reinforces that these stroke events are often happening in an age range typical for stroke, which is further removed from when women are thinking about their gynecologic health specifically.”

These findings don’t translate into a significantly greater risk for stroke overall in women who’ve had endometriosis, Dr. Missmer said. She characterized the risk as “not negligible, but it’s not a huge increased risk.” The absolute risk is still fairly low, she said.

“We don’t want to give the impression that all women with endometriosis need to be panicked or fearful about stroke, she said. “Rather, the messaging is that this yet another bit of evidence that whole health care for those with endometriosis is important.”

Women who’ve had endometriosis and their primary care providers need to be attuned to stroke risk, she said. “This is a critical condition that primary care physicians need to engage around, and perhaps if symptoms related to cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease emerge in their patients, they need to be engaging cardiology and similar types of support. This is not just about the gynecologists.”

The study also explored other factors that may contribute to stroke risk, with the most significant being hysterectomy with bilateral oophorectomy, Dr. Missmer said.

This study was unique because it used laparoscopically confirmed rather than self-reported endometriosis, said Louise D. McCullough, MD, neurology chair at the University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston. Another strength of the study she noted was its longitudinal design, although the cohort study design yielded a low number of stroke patients.

“Regardless, I do think it was a very important study because we have a growing recognition about how women’s health and factors such as pregnancy, infertility, parity, complications, and gonadal hormones such as estrogen can influence a woman’s stroke risk much later in life,” Dr. McCullough said in an interview.

Future studies into the relationship between endometriosis and CVD and stroke risk should focus on the mechanism behind the inflammation that occurs in endometriosis, Dr. McCullough said. “Part of it is probably the loss of hormones if a patient has to have an oophorectomy, but part of it is just what do these diseases do for a woman’s later risk – and for primary care physicians, ob.gyns., and stroke neurologists to recognize that these are questions we should ask: Have you ever had eclampsia or preeclampsia? Did you have endometriosis? Have you had miscarriages?”

The study received funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Dr. Missmer disclosed relationships with Shanghai Huilun Biotechnology, Roche, and AbbVie. Dr. McCullough has no relevant disclosures.

Women who’ve had endometriosis carry an elevated risk of stroke with them for the rest of their lives, with the greatest risk found in women who’ve had a hysterectomy with an oophorectomy, according to a cohort study of the Nurses’ Health Study.

“This is yet additional evidence that those girls and women with endometriosis are having effects across their lives and in multiple aspects of their health and well-being,” senior study author Stacey A. Missmer, ScD, of the Michigan State University, East Lansing, said in an interview. “This is not, in quotes ‘just a gynecologic condition,’ ” Dr. Missmer added. “It is not strictly about the pelvic pain or infertility, but it really is about the whole health across the life course.”

The study included 112,056 women in the NHSII cohort study who were followed from 1989 to June 2017, documenting 893 incident cases of stroke among them – an incidence of less than 1%. Endometriosis was reported in 5,244 women, and 93% of the cohort were White.

Multivariate adjusted models showed that women who had laparoscopically confirmed endometriosis had a 34% greater risk of stroke than women without a history of endometriosis. Leslie V. Farland, ScD, of the University of Arizona, Tucson, was lead author of the study.

While previous studies have demonstrated an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, heart attack, angina, and atherosclerosis in women who’ve had endometriosis, this is the first study that has confirmed an additional increased risk of stroke, Dr. Missmer said.

Another novel finding, Dr. Missmer said, is that while the CVD risks for these women “seem to peak at an earlier age,” the study found no age differences for stroke risk. “That also reinforces that these stroke events are often happening in an age range typical for stroke, which is further removed from when women are thinking about their gynecologic health specifically.”

These findings don’t translate into a significantly greater risk for stroke overall in women who’ve had endometriosis, Dr. Missmer said. She characterized the risk as “not negligible, but it’s not a huge increased risk.” The absolute risk is still fairly low, she said.

“We don’t want to give the impression that all women with endometriosis need to be panicked or fearful about stroke, she said. “Rather, the messaging is that this yet another bit of evidence that whole health care for those with endometriosis is important.”

Women who’ve had endometriosis and their primary care providers need to be attuned to stroke risk, she said. “This is a critical condition that primary care physicians need to engage around, and perhaps if symptoms related to cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease emerge in their patients, they need to be engaging cardiology and similar types of support. This is not just about the gynecologists.”

The study also explored other factors that may contribute to stroke risk, with the most significant being hysterectomy with bilateral oophorectomy, Dr. Missmer said.

This study was unique because it used laparoscopically confirmed rather than self-reported endometriosis, said Louise D. McCullough, MD, neurology chair at the University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston. Another strength of the study she noted was its longitudinal design, although the cohort study design yielded a low number of stroke patients.

“Regardless, I do think it was a very important study because we have a growing recognition about how women’s health and factors such as pregnancy, infertility, parity, complications, and gonadal hormones such as estrogen can influence a woman’s stroke risk much later in life,” Dr. McCullough said in an interview.

Future studies into the relationship between endometriosis and CVD and stroke risk should focus on the mechanism behind the inflammation that occurs in endometriosis, Dr. McCullough said. “Part of it is probably the loss of hormones if a patient has to have an oophorectomy, but part of it is just what do these diseases do for a woman’s later risk – and for primary care physicians, ob.gyns., and stroke neurologists to recognize that these are questions we should ask: Have you ever had eclampsia or preeclampsia? Did you have endometriosis? Have you had miscarriages?”

The study received funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke. Dr. Missmer disclosed relationships with Shanghai Huilun Biotechnology, Roche, and AbbVie. Dr. McCullough has no relevant disclosures.

FROM STROKE

Moderate drinking shows more benefit for older vs. younger adults

The health risks and benefits of moderate alcohol consumption are complex and remain a hot topic of debate. The data suggest that small amounts of alcohol may reduce the risk of certain health outcomes over time, but increase the risk of others, wrote Dana Bryazka, MS, a researcher at the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) at the University of Washington, Seattle, and colleagues, in a paper published in the Lancet.

“The amount of alcohol that minimizes health loss is likely to depend on the distribution of underlying causes of disease burden in a given population. Since this distribution varies widely by geography, age, sex, and time, the level of alcohol consumption associated with the lowest risk to health would depend on the age structure and disease composition of that population,” the researchers wrote.

“We estimate that 1.78 million people worldwide died due to alcohol use in 2020,” Ms. Bryazka said in an interview. “It is important that alcohol consumption guidelines and policies are updated to minimize this harm, particularly in the populations at greatest risk,” she said.

“Existing alcohol consumption guidelines frequently vary by sex, with higher consumption thresholds set for males compared to females. Interestingly, with the currently available data we do not see evidence that risk of alcohol use varies by sex,” she noted.

Methods and results

In the study, the researchers conducted a systematic analysis of burden-weighted dose-response relative risk curves across 22 health outcomes. They used disease rates from the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study (GBD) 2020 for the years 1990-2020 for 21 regions, including 204 countries and territories. The data were analyzed by 5-year age group, sex, and year for individuals aged 15-95 years and older. The researchers estimated the theoretical minimum risk exposure level (TMREL) and nondrinker equivalent (NDE), meaning the amount of alcohol at which the health risk equals that of a nondrinker.

One standard drink was defined as 10 g of pure alcohol, equivalent to a small glass of red wine (100 mL or 3.4 fluid ounces) at 13% alcohol by volume, a can or bottle of beer (375 mL or 12 fluid ounces) at 3.5% alcohol by volume, or a shot of whiskey or other spirits (30 mL or 1.0 fluid ounces) at 40% alcohol by volume.

Overall, the TMREL was low regardless of age, sex, time, or geography, and varied from 0 to 1.87 standard drinks per day. However, it was lowest for males aged 15-39 years (0.136 drinks per day) and only slightly higher for females aged 15-39 (0.273), representing 1-2 tenths of a standard drink.

For adults aged 40 and older without any underlying health conditions, drinking a small amount of alcohol may provide some benefits, such as reducing the risk of ischemic heart disease, stroke, and diabetes, the researchers noted. In general, for individuals aged 40-64 years, TMRELs ranged from about half a standard drink per day (0.527 drinks for males and 0.562 standard drinks per day for females) to almost two standard drinks (1.69 standard drinks per day for males and 1.82 for females). For those older than 65 years, the TMRELs represented just over 3 standard drinks per day (3.19 for males and 3.51 for females). For individuals aged 40 years and older, the distribution of disease burden varied by region, but was J-shaped across all regions, the researchers noted.

The researchers also found that those individuals consuming harmful amounts of alcohol were most likely to be aged 15-39 (59.1%) and male (76.9%).

The study findings were limited by several factors including the observational design and lack of data on drinking patterns, such as binge drinking, the researchers noted. Other limitations include the lack of data reflecting patterns of alcohol consumption during the COVID-19 pandemic, and exclusion of outcomes often associated with alcohol use, such as depression, anxiety, and dementia, that might reduce estimates of TMREL and NDE.

However, the results add to the ongoing discussion of the relationship between moderate alcohol consumption and health, the researchers said.

“The findings of this study support the development of tailored guidelines and recommendations on alcohol consumption by age and across regions and highlight that existing low consumption thresholds are too high for younger populations in all regions,” they concluded.

Consider individual factors when counseling patients

The takeaway message for primary care is that alcohol consumed in moderation can reduce the risk of ischemic heart disease, stroke, and diabetes, Ms. Bryazka noted. “However, it also increases the risk of many cancers, intentional and unintentional injuries, and infectious diseases like tuberculosis,” she said. “Of these health outcomes, young people are most likely to experience injuries, and as a result, we find that there are significant health risks associated with consuming alcohol for young people. Among older individuals, the relative proportions of these outcomes vary by geography, and so do the risks associated with consuming alcohol,” she explained.

“Importantly, our analysis was conducted at the population level; when evaluating risk at the individual level, it is also important to consider other factors such as the presence of comorbidities and interactions between alcohol and medications,” she emphasized.

Health and alcohol interaction is complicated

“These findings seemingly contradict a previous [Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study] estimate published in The Lancet, which emphasized that any alcohol use, regardless of amount, leads to health loss across populations,” wrote Robyn Burton, PhD, and Nick Sheron, MD, both of King’s College, London, in an accompanying comment.

However, the novel methods of weighting relative risk curves according to levels of underlying disease drive the difference in results, along with disaggregated estimates by age, sex, and region, they said.

“Across most geographical regions in this latest analysis, injuries accounted for most alcohol-related harm in younger age groups. This led to a minimum risk level of zero, or very close to zero, among individuals aged 15-39 years across all geographical regions,” which is lower than the level for older adults because of the shift in alcohol-related disease burden towards cardiovascular disease and cancers, they said. “This highlights the need to consider existing rates of disease in a population when trying to determine the total harm posed by alcohol,” the commentators wrote.

In an additional commentary, Tony Rao, MD, a visiting clinical research fellow in psychiatry at King’s College, London, noted that “the elephant in the room with this study is the interpretation of risk based on outcomes for cardiovascular disease – particularly in older people. We know that any purported health benefits from alcohol on the heart and circulation are balanced out by the increased risk from other conditions such as cancer, liver disease, and mental disorders such as depression and dementia,” Dr. Rao said. “If we are to simply draw the conclusion that older people should continue or start drinking small amounts because it protects against diseases affecting heart and circulation – which still remains controversial – other lifestyle changes or the use of drugs targeted at individual cardiovascular disorders seem like a less harmful way of improving health and wellbeing.”

Data can guide clinical practice

No previous study has examined the effect of the theoretical minimum risk of alcohol consumption by geography, age, sex, and time in the context of background disease rates, said Noel Deep, MD, in an interview.

“This study enabled the researchers to quantify the proportion of the population that consumed alcohol in amounts that exceeded the thresholds by location, age, sex, and year, and this can serve as a guide in our efforts to target the control of alcohol intake by individuals,” said Dr. Deep, a general internist in private practice in Antigo, Wisc. He also serves as chief medical officer and a staff physician at Aspirus Langlade Hospital in Antigo.

The first take-home message for clinicians is that even low levels of alcohol consumption can have deleterious effects on the health of patients, and patients should be advised accordingly based on the prevalence of diseases in that community and geographic area, Dr. Deep said. “Secondly, clinicians should also consider the risk of alcohol consumption on all forms of health impacts in a given population rather than just focusing on alcohol-related health conditions,” he added.

“This study provides us with the data to tailor our efforts in educating the clinicians and the public about the relationship between alcohol consumption and disease outcomes based on the observed disease rates in each population,” Dr. Deep explained. “The data should provide another reason for physicians to advise their younger patients, especially the younger males, to avoid or minimize alcohol use,” he said. The data also can help clinicians formulate public health messaging and community education to reduce harmful alcohol use, he added.

As for additional research, Dr. Deep said he would like to see data on the difference in the health-related effects of alcohol in binge-drinkers vs. those who regularly consume alcohol on a daily basis. “It would probably also be helpful to figure out what type of alcohol is being studied and the quality of the alcohol,” he said.

The study was supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Ms. Bryazka and colleagues had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Burton disclosed serving as a consultant to the World Health Organization European Office for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases. Dr. Sheron had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Deep had no financial conflicts to disclose, but serves on the Editorial Advisory Board of Internal Medicine News.

The study was supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

The health risks and benefits of moderate alcohol consumption are complex and remain a hot topic of debate. The data suggest that small amounts of alcohol may reduce the risk of certain health outcomes over time, but increase the risk of others, wrote Dana Bryazka, MS, a researcher at the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) at the University of Washington, Seattle, and colleagues, in a paper published in the Lancet.

“The amount of alcohol that minimizes health loss is likely to depend on the distribution of underlying causes of disease burden in a given population. Since this distribution varies widely by geography, age, sex, and time, the level of alcohol consumption associated with the lowest risk to health would depend on the age structure and disease composition of that population,” the researchers wrote.

“We estimate that 1.78 million people worldwide died due to alcohol use in 2020,” Ms. Bryazka said in an interview. “It is important that alcohol consumption guidelines and policies are updated to minimize this harm, particularly in the populations at greatest risk,” she said.

“Existing alcohol consumption guidelines frequently vary by sex, with higher consumption thresholds set for males compared to females. Interestingly, with the currently available data we do not see evidence that risk of alcohol use varies by sex,” she noted.

Methods and results

In the study, the researchers conducted a systematic analysis of burden-weighted dose-response relative risk curves across 22 health outcomes. They used disease rates from the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study (GBD) 2020 for the years 1990-2020 for 21 regions, including 204 countries and territories. The data were analyzed by 5-year age group, sex, and year for individuals aged 15-95 years and older. The researchers estimated the theoretical minimum risk exposure level (TMREL) and nondrinker equivalent (NDE), meaning the amount of alcohol at which the health risk equals that of a nondrinker.