User login

Early Hospital Discharge Following PCI for Patients With STEMI

Study Overview

Objective: To assess the safety and efficacy of early hospital discharge (EHD) for selected low-risk patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) after primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

Design: Single-center retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data.

Setting and participants: An EHD group comprised of 600 patients who were discharged at <48 hours between April 2020 and June 2021 was compared to a control group of 700 patients who met EHD criteria but were discharged at >48 hour between October 2018 and June 2021. Patients were selected into the EHD group based on the following criteria, in accordance with recommendations from the European Society of Cardiology, and all patients had close follow-up with a combination of structured telephone follow-up at 48 hours post discharge and virtual visits at 2, 6, and 8 weeks and at 3 months:

- Left ventricular ejection fraction ≥40%

- Successful primary PCI (that achieved thrombolysis in myocardial infarction flow grade 3)

- Absence of severe nonculprit disease requiring further inpatient revascularization

- Absence of ischemic symptoms post PCI

- Absence of heart failure or hemodynamic instability

- Absence of significant arrhythmia (ventricular fibrillation, ventricular tachycardia, or atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter requiring prolonged stay)

- Mobility with suitable social circumstances for discharge

Main outcome measures: The outcomes measured were length of hospitalization and a composite primary endpoint of cardiovascular mortality and major adverse cardiovascular event (MACE) rates, defined as a composite of all-cause mortality, recurrent MI, and target lesion revascularization.

Main results: The median length of stay of hospitalization in the EHD group was 24.6 hours compared to 56.1 hours in the >48-hour historical control group. On median follow-up of 271 days, the EHD group demonstrated 0% cardiovascular mortality and a MACE rate of 1.2%. This was shown to be noninferior compared to the >48-hour historical control group, which had mortality of 0.7% and a MACE rate of 1.9%.

Conclusion: Selected low-risk STEMI patients can be safely discharged early with appropriate follow-up after primary PCI.

Commentary

Patients with STEMI have a higher risk of postprocedural adverse events such as MI, arrhythmia, or acute heart failure compared to patients with stable ischemic heart disease, and thus are monitored after primary PCI. Although patients were traditionally monitored for 5 to 7 days a few decades ago,1 with improvements in PCI techniques, devices, and pharmacotherapy as well as in door-to-balloon time, the in-hospital complication rates for patients with STEMI have been decreasing, leading to earlier discharge. Currently in the United States, patients are most commonly monitored for 48 to 72 hours post PCI.2 The current guidelines support this practice, recommending early discharge within 48 to 72 hours in selected low-risk patients if adequate follow-up and rehabilitation are arranged.3

Given the COVID-19 pandemic and decreased hospital bed availability, Rathod et al took one step further on the question of whether low-risk STEMI patients with primary PCI can be discharged safely within 48 hours with adequate follow-up. They found that at a median follow-up of 271 days, EHD patients had 2 COVID-related deaths, with 0% cardiovascular mortality and a MACE rate of 1.2%, including deaths, MI, and ischemic revascularization. The median time to discharge was 25 hours. This was noninferior to the >48-hour historical control group, which had mortality of 0.7% (P = 0.349) and a MACE rate of 1.9% (P = .674). The results remained similar after propensity matching for mortality (0.34% vs 0.69%, P = .410) or MACE (1.2% vs 1.9%, P = .342).

This is the first prospective study to systematically assess the safety and feasibility of discharge of low-risk STEMI patients with primary PCI within 48 hours. This study is unique in that it involved the use of telemedicine, including a virtual platform to collect data such as heart rate, blood pressure, and blood glucose, and virtual visits to facilitate follow-up and reduce clinic travel, cost, and potential COVID-19 exposure. The investigators’ protocol included virtual follow-up by cardiology advanced practitioners at 2, 6, and 8 weeks and by an interventional cardiologist at 12 weeks. This protocol led to an increase in patient satisfaction. The study’s main limitation is that it is a single-center trial with a smaller sample size. Further studies are necessary to confirm the safety and feasibility of this approach. In addition, further refinement of the patient selection criteria for EHD should be considered.

Applications for Clinical Practice

In low-risk STEMI patients after primary PCI, discharge within 48 hours may be considered if close follow-up is arranged. However, further studies are necessary to confirm this finding.

—Thai Nguyen, MD, Albert Chan, MD, and Taishi Hirai MD

1. Grines CL, Marsalese DL, Brodie B, et al. Safety and cost-effectiveness of early discharge after primary angioplasty in low risk patients with acute myocardial infarction. PAMI-II Investigators. Primary Angioplasty in Myocardial Infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;31:967-72. doi:10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00031-x

2. Seto AH, Shroff A, Abu-Fadel M, et al. Length of stay following percutaneous coronary intervention: An expert consensus document update from the society for cardiovascular angiography and interventions. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;92:717-731. doi:10.1002/ccd.27637

3. Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, et al. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:119-177. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehx393

Study Overview

Objective: To assess the safety and efficacy of early hospital discharge (EHD) for selected low-risk patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) after primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

Design: Single-center retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data.

Setting and participants: An EHD group comprised of 600 patients who were discharged at <48 hours between April 2020 and June 2021 was compared to a control group of 700 patients who met EHD criteria but were discharged at >48 hour between October 2018 and June 2021. Patients were selected into the EHD group based on the following criteria, in accordance with recommendations from the European Society of Cardiology, and all patients had close follow-up with a combination of structured telephone follow-up at 48 hours post discharge and virtual visits at 2, 6, and 8 weeks and at 3 months:

- Left ventricular ejection fraction ≥40%

- Successful primary PCI (that achieved thrombolysis in myocardial infarction flow grade 3)

- Absence of severe nonculprit disease requiring further inpatient revascularization

- Absence of ischemic symptoms post PCI

- Absence of heart failure or hemodynamic instability

- Absence of significant arrhythmia (ventricular fibrillation, ventricular tachycardia, or atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter requiring prolonged stay)

- Mobility with suitable social circumstances for discharge

Main outcome measures: The outcomes measured were length of hospitalization and a composite primary endpoint of cardiovascular mortality and major adverse cardiovascular event (MACE) rates, defined as a composite of all-cause mortality, recurrent MI, and target lesion revascularization.

Main results: The median length of stay of hospitalization in the EHD group was 24.6 hours compared to 56.1 hours in the >48-hour historical control group. On median follow-up of 271 days, the EHD group demonstrated 0% cardiovascular mortality and a MACE rate of 1.2%. This was shown to be noninferior compared to the >48-hour historical control group, which had mortality of 0.7% and a MACE rate of 1.9%.

Conclusion: Selected low-risk STEMI patients can be safely discharged early with appropriate follow-up after primary PCI.

Commentary

Patients with STEMI have a higher risk of postprocedural adverse events such as MI, arrhythmia, or acute heart failure compared to patients with stable ischemic heart disease, and thus are monitored after primary PCI. Although patients were traditionally monitored for 5 to 7 days a few decades ago,1 with improvements in PCI techniques, devices, and pharmacotherapy as well as in door-to-balloon time, the in-hospital complication rates for patients with STEMI have been decreasing, leading to earlier discharge. Currently in the United States, patients are most commonly monitored for 48 to 72 hours post PCI.2 The current guidelines support this practice, recommending early discharge within 48 to 72 hours in selected low-risk patients if adequate follow-up and rehabilitation are arranged.3

Given the COVID-19 pandemic and decreased hospital bed availability, Rathod et al took one step further on the question of whether low-risk STEMI patients with primary PCI can be discharged safely within 48 hours with adequate follow-up. They found that at a median follow-up of 271 days, EHD patients had 2 COVID-related deaths, with 0% cardiovascular mortality and a MACE rate of 1.2%, including deaths, MI, and ischemic revascularization. The median time to discharge was 25 hours. This was noninferior to the >48-hour historical control group, which had mortality of 0.7% (P = 0.349) and a MACE rate of 1.9% (P = .674). The results remained similar after propensity matching for mortality (0.34% vs 0.69%, P = .410) or MACE (1.2% vs 1.9%, P = .342).

This is the first prospective study to systematically assess the safety and feasibility of discharge of low-risk STEMI patients with primary PCI within 48 hours. This study is unique in that it involved the use of telemedicine, including a virtual platform to collect data such as heart rate, blood pressure, and blood glucose, and virtual visits to facilitate follow-up and reduce clinic travel, cost, and potential COVID-19 exposure. The investigators’ protocol included virtual follow-up by cardiology advanced practitioners at 2, 6, and 8 weeks and by an interventional cardiologist at 12 weeks. This protocol led to an increase in patient satisfaction. The study’s main limitation is that it is a single-center trial with a smaller sample size. Further studies are necessary to confirm the safety and feasibility of this approach. In addition, further refinement of the patient selection criteria for EHD should be considered.

Applications for Clinical Practice

In low-risk STEMI patients after primary PCI, discharge within 48 hours may be considered if close follow-up is arranged. However, further studies are necessary to confirm this finding.

—Thai Nguyen, MD, Albert Chan, MD, and Taishi Hirai MD

Study Overview

Objective: To assess the safety and efficacy of early hospital discharge (EHD) for selected low-risk patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) after primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

Design: Single-center retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data.

Setting and participants: An EHD group comprised of 600 patients who were discharged at <48 hours between April 2020 and June 2021 was compared to a control group of 700 patients who met EHD criteria but were discharged at >48 hour between October 2018 and June 2021. Patients were selected into the EHD group based on the following criteria, in accordance with recommendations from the European Society of Cardiology, and all patients had close follow-up with a combination of structured telephone follow-up at 48 hours post discharge and virtual visits at 2, 6, and 8 weeks and at 3 months:

- Left ventricular ejection fraction ≥40%

- Successful primary PCI (that achieved thrombolysis in myocardial infarction flow grade 3)

- Absence of severe nonculprit disease requiring further inpatient revascularization

- Absence of ischemic symptoms post PCI

- Absence of heart failure or hemodynamic instability

- Absence of significant arrhythmia (ventricular fibrillation, ventricular tachycardia, or atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter requiring prolonged stay)

- Mobility with suitable social circumstances for discharge

Main outcome measures: The outcomes measured were length of hospitalization and a composite primary endpoint of cardiovascular mortality and major adverse cardiovascular event (MACE) rates, defined as a composite of all-cause mortality, recurrent MI, and target lesion revascularization.

Main results: The median length of stay of hospitalization in the EHD group was 24.6 hours compared to 56.1 hours in the >48-hour historical control group. On median follow-up of 271 days, the EHD group demonstrated 0% cardiovascular mortality and a MACE rate of 1.2%. This was shown to be noninferior compared to the >48-hour historical control group, which had mortality of 0.7% and a MACE rate of 1.9%.

Conclusion: Selected low-risk STEMI patients can be safely discharged early with appropriate follow-up after primary PCI.

Commentary

Patients with STEMI have a higher risk of postprocedural adverse events such as MI, arrhythmia, or acute heart failure compared to patients with stable ischemic heart disease, and thus are monitored after primary PCI. Although patients were traditionally monitored for 5 to 7 days a few decades ago,1 with improvements in PCI techniques, devices, and pharmacotherapy as well as in door-to-balloon time, the in-hospital complication rates for patients with STEMI have been decreasing, leading to earlier discharge. Currently in the United States, patients are most commonly monitored for 48 to 72 hours post PCI.2 The current guidelines support this practice, recommending early discharge within 48 to 72 hours in selected low-risk patients if adequate follow-up and rehabilitation are arranged.3

Given the COVID-19 pandemic and decreased hospital bed availability, Rathod et al took one step further on the question of whether low-risk STEMI patients with primary PCI can be discharged safely within 48 hours with adequate follow-up. They found that at a median follow-up of 271 days, EHD patients had 2 COVID-related deaths, with 0% cardiovascular mortality and a MACE rate of 1.2%, including deaths, MI, and ischemic revascularization. The median time to discharge was 25 hours. This was noninferior to the >48-hour historical control group, which had mortality of 0.7% (P = 0.349) and a MACE rate of 1.9% (P = .674). The results remained similar after propensity matching for mortality (0.34% vs 0.69%, P = .410) or MACE (1.2% vs 1.9%, P = .342).

This is the first prospective study to systematically assess the safety and feasibility of discharge of low-risk STEMI patients with primary PCI within 48 hours. This study is unique in that it involved the use of telemedicine, including a virtual platform to collect data such as heart rate, blood pressure, and blood glucose, and virtual visits to facilitate follow-up and reduce clinic travel, cost, and potential COVID-19 exposure. The investigators’ protocol included virtual follow-up by cardiology advanced practitioners at 2, 6, and 8 weeks and by an interventional cardiologist at 12 weeks. This protocol led to an increase in patient satisfaction. The study’s main limitation is that it is a single-center trial with a smaller sample size. Further studies are necessary to confirm the safety and feasibility of this approach. In addition, further refinement of the patient selection criteria for EHD should be considered.

Applications for Clinical Practice

In low-risk STEMI patients after primary PCI, discharge within 48 hours may be considered if close follow-up is arranged. However, further studies are necessary to confirm this finding.

—Thai Nguyen, MD, Albert Chan, MD, and Taishi Hirai MD

1. Grines CL, Marsalese DL, Brodie B, et al. Safety and cost-effectiveness of early discharge after primary angioplasty in low risk patients with acute myocardial infarction. PAMI-II Investigators. Primary Angioplasty in Myocardial Infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;31:967-72. doi:10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00031-x

2. Seto AH, Shroff A, Abu-Fadel M, et al. Length of stay following percutaneous coronary intervention: An expert consensus document update from the society for cardiovascular angiography and interventions. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;92:717-731. doi:10.1002/ccd.27637

3. Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, et al. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:119-177. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehx393

1. Grines CL, Marsalese DL, Brodie B, et al. Safety and cost-effectiveness of early discharge after primary angioplasty in low risk patients with acute myocardial infarction. PAMI-II Investigators. Primary Angioplasty in Myocardial Infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;31:967-72. doi:10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00031-x

2. Seto AH, Shroff A, Abu-Fadel M, et al. Length of stay following percutaneous coronary intervention: An expert consensus document update from the society for cardiovascular angiography and interventions. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;92:717-731. doi:10.1002/ccd.27637

3. Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, et al. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:119-177. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehx393

Elective surgery should be delayed 7 weeks after COVID-19 infection for unvaccinated patients, statement recommends

.

For patients fully vaccinated against COVID-19 with breakthrough infections, there is no consensus on how vaccination affects the time between COVID-19 infection and elective surgery. Clinicians should use their clinical judgment to schedule procedures, said Randall M. Clark, MD, president of the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA). “We need all physicians, anesthesiologists, surgeons, and others to base their decision to go ahead with elective surgery on the patient’s symptoms, their need for the procedure, and whether delays could cause other problems with their health,” he said in an interview.

Prior to these updated recommendations, which were published Feb. 22, the ASA and the APSF recommended a 4-week gap between COVID-19 diagnosis and elective surgery for asymptomatic or mild cases, regardless of a patient’s vaccination status.

Extending the wait time from 4 to 7 weeks was based on a multination study conducted in October 2020 following more than 140,000 surgical patients. Patients with previous COVID-19 infection had an increased risk for complications and death in elective surgery for up to 6 weeks following their diagnosis, compared with patients without COVID-19. Additional research in the United States found that patients with a preoperative COVID diagnosis were at higher risk for postoperative complications of respiratory failure for up to 4 weeks after diagnosis and postoperative pneumonia complications for up to 8 weeks after diagnosis.

Because these studies were conducted in unvaccinated populations or those with low vaccination rates, and preliminary data suggest vaccinated patients with breakthrough infections may have a lower risk for complications and death postinfection, “we felt that it was prudent to just make recommendations specific to unvaccinated patients,” Dr. Clark added.

Although this guidance is “very helpful” in that it summarizes the currently available research to give evidence-based recommendations, the 7-week wait time is a “very conservative estimate,” Brent Matthews, MD, surgeon-in-chief of the surgery care division of Atrium Health, Charlotte, N.C., told this news organization. At Atrium Health, surgery is scheduled at least 21 days after a patient’s COVID-19 diagnosis, regardless of their vaccination status, Dr. Matthews said.

The studies currently available were conducted earlier in the pandemic, when a different variant was prevalent, Dr. Matthews explained. The Omicron variant is currently the most prevalent COVID-19 variant and is less virulent than earlier strains of the virus. The joint statement does note that there is currently “no robust data” on patients infected with the Delta or Omicron variants of COVID-19, and that “the Omicron variant causes less severe disease and is more likely to reside in the oro- and nasopharynx without infiltration and damage to the lungs.”

Still, the new recommendations are a reminder to re-evaluate the potential complications from surgery for previously infected patients and to consider what comorbidities might make them more vulnerable, Dr. Matthews said. “The real power of the joint statement is to get people to ensure that they make an assessment of every patient that comes in front of them who has had a recent positive COVID test.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

.

For patients fully vaccinated against COVID-19 with breakthrough infections, there is no consensus on how vaccination affects the time between COVID-19 infection and elective surgery. Clinicians should use their clinical judgment to schedule procedures, said Randall M. Clark, MD, president of the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA). “We need all physicians, anesthesiologists, surgeons, and others to base their decision to go ahead with elective surgery on the patient’s symptoms, their need for the procedure, and whether delays could cause other problems with their health,” he said in an interview.

Prior to these updated recommendations, which were published Feb. 22, the ASA and the APSF recommended a 4-week gap between COVID-19 diagnosis and elective surgery for asymptomatic or mild cases, regardless of a patient’s vaccination status.

Extending the wait time from 4 to 7 weeks was based on a multination study conducted in October 2020 following more than 140,000 surgical patients. Patients with previous COVID-19 infection had an increased risk for complications and death in elective surgery for up to 6 weeks following their diagnosis, compared with patients without COVID-19. Additional research in the United States found that patients with a preoperative COVID diagnosis were at higher risk for postoperative complications of respiratory failure for up to 4 weeks after diagnosis and postoperative pneumonia complications for up to 8 weeks after diagnosis.

Because these studies were conducted in unvaccinated populations or those with low vaccination rates, and preliminary data suggest vaccinated patients with breakthrough infections may have a lower risk for complications and death postinfection, “we felt that it was prudent to just make recommendations specific to unvaccinated patients,” Dr. Clark added.

Although this guidance is “very helpful” in that it summarizes the currently available research to give evidence-based recommendations, the 7-week wait time is a “very conservative estimate,” Brent Matthews, MD, surgeon-in-chief of the surgery care division of Atrium Health, Charlotte, N.C., told this news organization. At Atrium Health, surgery is scheduled at least 21 days after a patient’s COVID-19 diagnosis, regardless of their vaccination status, Dr. Matthews said.

The studies currently available were conducted earlier in the pandemic, when a different variant was prevalent, Dr. Matthews explained. The Omicron variant is currently the most prevalent COVID-19 variant and is less virulent than earlier strains of the virus. The joint statement does note that there is currently “no robust data” on patients infected with the Delta or Omicron variants of COVID-19, and that “the Omicron variant causes less severe disease and is more likely to reside in the oro- and nasopharynx without infiltration and damage to the lungs.”

Still, the new recommendations are a reminder to re-evaluate the potential complications from surgery for previously infected patients and to consider what comorbidities might make them more vulnerable, Dr. Matthews said. “The real power of the joint statement is to get people to ensure that they make an assessment of every patient that comes in front of them who has had a recent positive COVID test.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

.

For patients fully vaccinated against COVID-19 with breakthrough infections, there is no consensus on how vaccination affects the time between COVID-19 infection and elective surgery. Clinicians should use their clinical judgment to schedule procedures, said Randall M. Clark, MD, president of the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA). “We need all physicians, anesthesiologists, surgeons, and others to base their decision to go ahead with elective surgery on the patient’s symptoms, their need for the procedure, and whether delays could cause other problems with their health,” he said in an interview.

Prior to these updated recommendations, which were published Feb. 22, the ASA and the APSF recommended a 4-week gap between COVID-19 diagnosis and elective surgery for asymptomatic or mild cases, regardless of a patient’s vaccination status.

Extending the wait time from 4 to 7 weeks was based on a multination study conducted in October 2020 following more than 140,000 surgical patients. Patients with previous COVID-19 infection had an increased risk for complications and death in elective surgery for up to 6 weeks following their diagnosis, compared with patients without COVID-19. Additional research in the United States found that patients with a preoperative COVID diagnosis were at higher risk for postoperative complications of respiratory failure for up to 4 weeks after diagnosis and postoperative pneumonia complications for up to 8 weeks after diagnosis.

Because these studies were conducted in unvaccinated populations or those with low vaccination rates, and preliminary data suggest vaccinated patients with breakthrough infections may have a lower risk for complications and death postinfection, “we felt that it was prudent to just make recommendations specific to unvaccinated patients,” Dr. Clark added.

Although this guidance is “very helpful” in that it summarizes the currently available research to give evidence-based recommendations, the 7-week wait time is a “very conservative estimate,” Brent Matthews, MD, surgeon-in-chief of the surgery care division of Atrium Health, Charlotte, N.C., told this news organization. At Atrium Health, surgery is scheduled at least 21 days after a patient’s COVID-19 diagnosis, regardless of their vaccination status, Dr. Matthews said.

The studies currently available were conducted earlier in the pandemic, when a different variant was prevalent, Dr. Matthews explained. The Omicron variant is currently the most prevalent COVID-19 variant and is less virulent than earlier strains of the virus. The joint statement does note that there is currently “no robust data” on patients infected with the Delta or Omicron variants of COVID-19, and that “the Omicron variant causes less severe disease and is more likely to reside in the oro- and nasopharynx without infiltration and damage to the lungs.”

Still, the new recommendations are a reminder to re-evaluate the potential complications from surgery for previously infected patients and to consider what comorbidities might make them more vulnerable, Dr. Matthews said. “The real power of the joint statement is to get people to ensure that they make an assessment of every patient that comes in front of them who has had a recent positive COVID test.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Left upper quadrant entry is often a reliable alternative to umbilicus

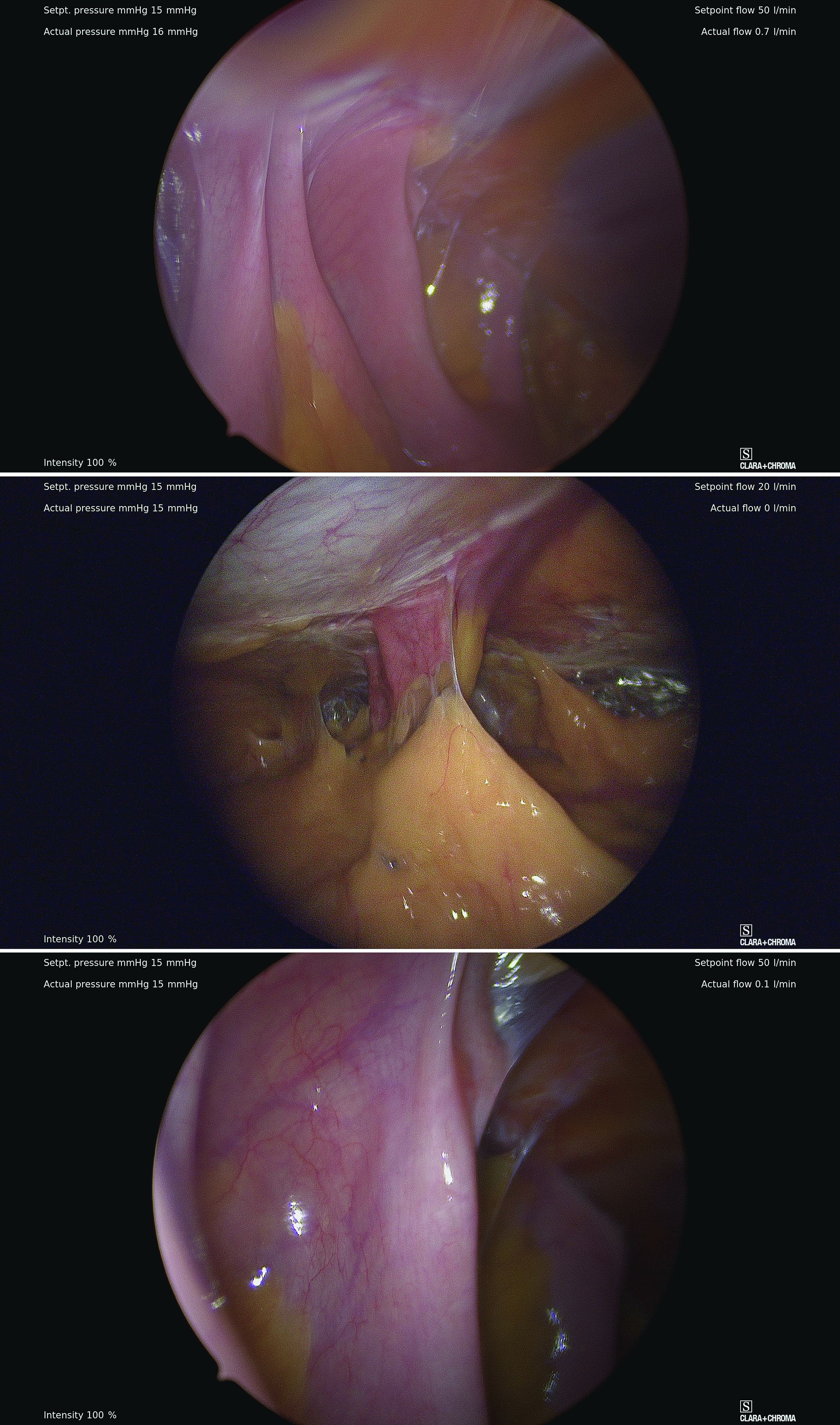

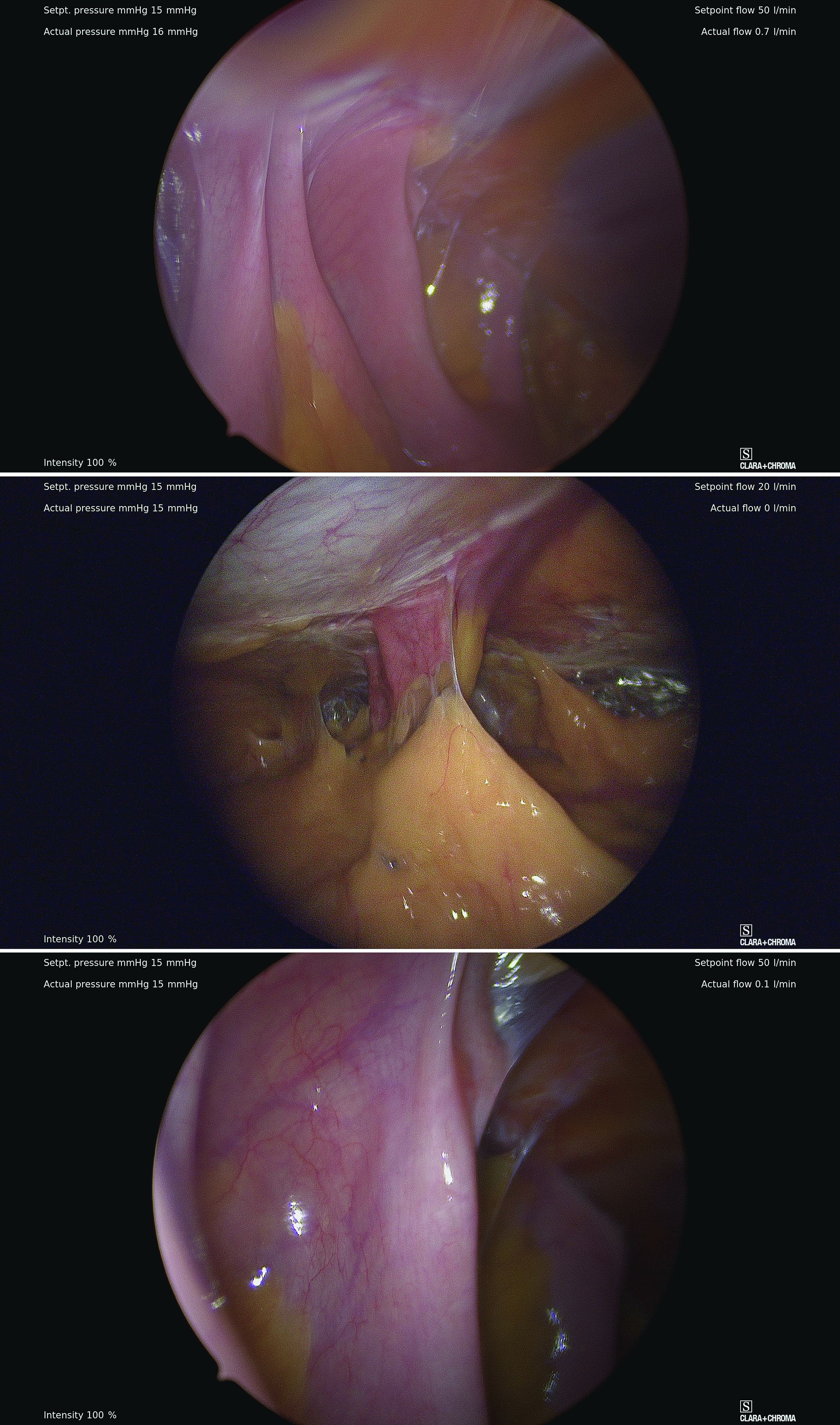

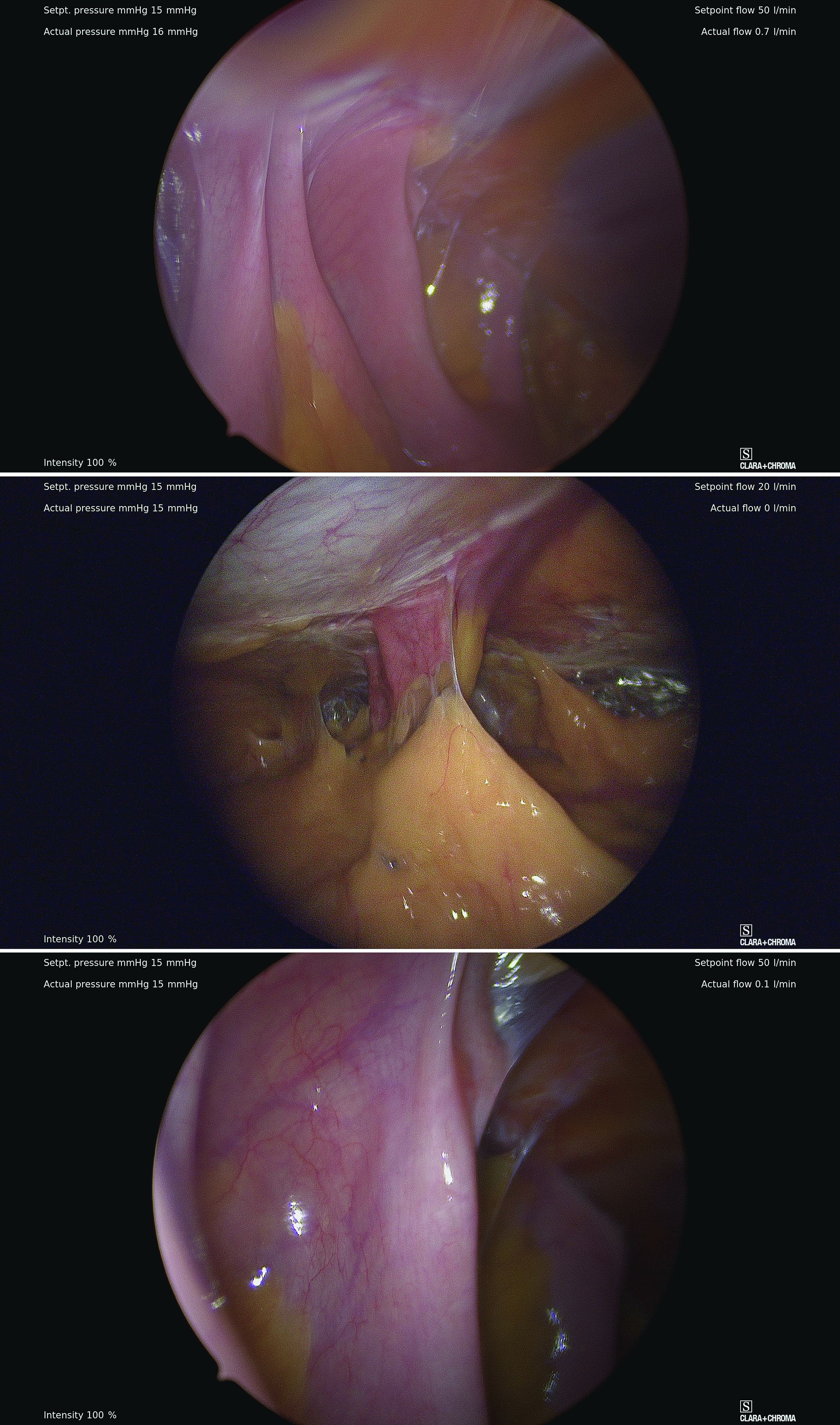

The choice of entry point for gynecologic laparoscopy is critical, considering that most laparoscopic injuries occur during initial entry into the abdomen. In addition, different abdominal access points may have differing utility and efficacy depending on the patient. (The overall rate of injuries to abdominal viscera and blood vessels at the time of entry is an estimated 1 per 1,000 cases.1)

The most conventional entry point for gynecologic laparoscopic surgeries has been the umbilicus, but there are contraindications to this choice and situations in which it may not be the best access site. It is important to have knowledge of alternate entry points and techniques that consider the patient’s current pathology, anatomy, and most importantly, surgical history to better facilitate a safe initial entry.

The left upper quadrant (LUQ) has been described as a preferred alternate site to the umbilicus, and some gynecologic surgeons even consider it as a routine mode of entry.2 In our practice, LUQ entry is a safe and commonly used technique that is chosen primarily based on a patient’s history of a midline vertical incision, the presence of abdominal mesh from a prior umbilical hernia repair, or repeated cesarean sections.

Our technique for LUQ entry is a modification of the traditional approach that employs Palmer’s point – the entry point described by Raoul Palmer, MD, in 1974 as 3-4 cm below the left subcostal margin at the midclavicular line.3 We choose to enter at the midclavicular level and directly under the last rib.

When the umbilicus is problematic

The umbilicus is a favored entry point not only for its operative access to pelvic structures but also because – in the absence of obesity – it has no or little subcutaneous fat and, therefore, provides the shortest distance from skin to peritoneum.

However, adhesive disease from a prior laparotomy involving the umbilicus is a risk factor for bowel injury during umbilical entry (direct trocar, Veress needle, or open technique). In a 1995 review of 360 women undergoing operative laparoscopy after a previous laparotomy, Brill et al. reported umbilical adhesions in 27% of those with prior horizontal suprapubic (Pfannenstiel) incisions, in 55% of those with prior incisions in the midline below the umbilicus, and 67% of those with prior midline incisions above the umbilicus.4

Of the 259 patients whose prior laparotomy was for gynecologic surgery (as opposed to obstetric or general surgery) adhesions were present in 70% of those who had midline incisions. (Direct injury to adherent omentum and bowel occurred during laparoscopic procedures in 21% of all women.)

Since the Brill paper, other studies have similarly reported significant adhesion rate, especially after midline incisions. For instance, one French study of patients undergoing laparoscopy reported umbilical adhesions in 51.7% of 89 patients who had previous laparotomy with a midline incision.5

Prior umbilical laparoscopy is not a risk factor for umbilical entry unless a hernia repair with mesh was performed at the umbilicus. Umbilical adhesions have been reported to occur in up to 15% of women who have had prior laparoscopic surgery, with more adhesions associated with larger trocar use (specifically 12-mm trocars).1 Still, the rate of those adhesions was very low.

Obesity is not necessarily a contraindication to umbilical entry; however, it can make successful entry more difficult, particularly in those with central obesity and a thicker layer of subcutaneous fat. It can be difficult in such cases to know when peritoneal access is achieved. Extra-long Veress needles or trocars may be needed, and it is important to enter the abdomen at a 90° angle to minimize risk to the great vessel vasculature.

LUQ entry is often a reliable alternative when central obesity is significant or when umbilical access proves to be difficult. Certainly, the subcutaneous fat layer is thinner at the LUQ than at the umbilicus, and in patients whose umbilicus is pulled very caudal because of a large pannus, the LUQ will also provide a better location for visualization of pelvic anatomy and for easier entry.

We still use umbilical entry in most patients with obesity, but if we are unsuccessful after two to three attempts, we proceed to the LUQ (barring any contraindications to this site).

LUQ entry: Our approach, contraindications

By entering at the midclavicular level and directly under the bottom of the rib cage, rather than 2-3 cm below the last rib as in traditional Palmer’s point LUQ entry, we benefit from the tenting up of the peritoneum by the last rib. Having space between the peritoneum and underlying omentum and stomach can facilitate an easier entry, as shown in the video.

We primarily utilize the Veress needle for entry. The needle is inserted directly perpendicular to the fascia, or at a slight angle toward the umbilicus. After the abdomen is insufflated to 15 mm Hg, we proceed with a visual peritoneal entry using a 5-mm trocar with a clear tip, which allows us to visualize both layers of fascia, and subsequently the peritoneum, as the trocar is advanced.

The fascia is not fused, so we can expect to feel three “pops” as the needle (or trocar) passes through the aponeuroses of the internal and external obliques, the aponeuroses of the internal oblique and transversus, and the peritoneum.

While successful peritoneal entry with umbilical access is generally confirmed with an intraperitoneal pressure measuring less than 7 mm Hg (which varies depending on abdominal wall thickness and adiposity), we have found that the opening pressure with LUQ entry is slightly higher. A recently published Canadian guideline for gynecologic laparoscopic entry recommends that an initial Veress intraperitoneal pressure of 10 mm Hg or below be considered an indicator of successful entry, regardless of the patient’s body habitus.1

LUQ entry can be helpful for surgeries involving large pelvic masses, for which there is little or no space to enter at the umbilicus or to optimally view the pathology. Utilizing the LUQ not only allows for an unobstructed entry and optimal viewing but also may become an extra operative port that can be used for the camera, allowing both surgeons to operate with two hands – a four-port technique. It also allows the surgeon to use a larger diameter port at the umbilicus without concern for cosmetics.

Additionally, there is a school of thought that LUQ entry is overall more successful, requiring less conversion to alternative sites and fewer attempts. This success may result from the presence of less adhesive disease in the LUQ, as well as clearer visualization of the anatomy while entering and confidence in entering the intraperitoneal space.

A prerequisite for LUQ entry is that the stomach be decompressed through placement of an oral gastric or nasogastric tube and suctioning of all gastric contents. An inability to decompress the stomach is a contraindication to LUQ entry, as is a history of splenectomy, an enlarged liver, gastric bypass surgery, or upper abdominal surgery.

Entry techniques, alternate sites

No single entry site or technique has been proven to be universally safer than another. A 2019 Cochrane review of laparoscopic entry techniques noted an advantage of direct trocar entry over Veress-needle entry for failed entry but concluded that, overall, evidence was insufficient to support the use of one entry technique over another to decrease complication rates.6

A more recently published review of randomized controlled trials, Cochrane reviews, and older descriptive accounts similarly concluded that, between the Veress needle (the oldest described technique), direct trocar insertion, and open entry (Hasson), there is no good evidence to suggest that any of these methods is universally superior.2 Surgeon comfort is, therefore, an important factor.

Regarding entry sites, we advocate use of the LUQ as an advantageous alternative site for access, but there are several other approaches described in the literature. These include right upper quadrant entry; the Lee Huang point, which is about 10 cm below the xiphoid; and uncommonly, vaginal, either posterior to the uterus into the pouch of Douglas or through the uterine fundus.2

The right upper quadrant approach is included in a recent video review in the Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology of safe entry techniques, along with umbilicus, LUQ, and supraumbilical entry.7

Another described entry site is the “Jain point,” located at the intersection of a vertical line drawn 2.5 cm medial to the anterior superior iliac spine, up to the level of the umbilicus, and a horizontal line at the upper margin of the umbilicus. In a retrospective study of 7,802 cases involving this method, the authors reported only one significant entry complication. Patients in the study had a wide range of BMIs and previous surgeries.8

With respect to entry techniques, we facilitate the Veress entry technique described by Frank E. Loeffler, MD, in the mid-1970s, unless there are contraindications such as second-trimester pregnancy. For umbilical entry, we first use a Kocher clamp to grasp the base of the umbilicus and then evert it. Using two towel clips, the surgeon and assistant apply countertraction by grasping the skin and fat on either side of the umbilicus. A horizontal incision is then made directly on the base of the umbilicus. The towel clips are used to elevate the anterior abdominal wall, and the Veress needle is attached to insufflation tubing, then inserted into the abdomen.

Alternatively, direct entry involves incising the skin, placing a laparoscope in a visual entry trocar, and directly visualizing each layer as the abdomen is entered. Once the trocar is intraperitoneal, insufflation is started.

In open laparoscopic/Hasson entry, the umbilical skin is incised, and the subcutaneous fat is dissected down until the rectal fascia is visualized. The fascia is then incised, the peritoneum is entered bluntly, and the Hasson trocar is placed. Insufflation is attached, and the laparoscope is inserted.

Dr. Sasaki is a partner, and Dr. McKenna is an AAGL MIGS fellow, in the private practice of Charles E. Miller, MD, & Associates in Chicago. They reported that they have no disclosures.

References

1. Vilos GA et al. J Obstet Gyneacol Can. 2021;43(3):376-89.

2. Recknagel JD and Goodman LR. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28(3):467-74.

3. Palmer R. J Reprod Med. 1974;13:1-5.

4. Brill AI et al. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85(2):269-72.

5. Audebert AJ and Gomel V. Fertil Steril. 2000;73(3):631-5.

6. Ahmad G et al. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019;1:CD006583.

7. Patzkowsky KE et al. J. Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28(3):386.

8. Nutan J et al. Updates in Surgery. 2021;73(6):2321-9.

The choice of entry point for gynecologic laparoscopy is critical, considering that most laparoscopic injuries occur during initial entry into the abdomen. In addition, different abdominal access points may have differing utility and efficacy depending on the patient. (The overall rate of injuries to abdominal viscera and blood vessels at the time of entry is an estimated 1 per 1,000 cases.1)

The most conventional entry point for gynecologic laparoscopic surgeries has been the umbilicus, but there are contraindications to this choice and situations in which it may not be the best access site. It is important to have knowledge of alternate entry points and techniques that consider the patient’s current pathology, anatomy, and most importantly, surgical history to better facilitate a safe initial entry.

The left upper quadrant (LUQ) has been described as a preferred alternate site to the umbilicus, and some gynecologic surgeons even consider it as a routine mode of entry.2 In our practice, LUQ entry is a safe and commonly used technique that is chosen primarily based on a patient’s history of a midline vertical incision, the presence of abdominal mesh from a prior umbilical hernia repair, or repeated cesarean sections.

Our technique for LUQ entry is a modification of the traditional approach that employs Palmer’s point – the entry point described by Raoul Palmer, MD, in 1974 as 3-4 cm below the left subcostal margin at the midclavicular line.3 We choose to enter at the midclavicular level and directly under the last rib.

When the umbilicus is problematic

The umbilicus is a favored entry point not only for its operative access to pelvic structures but also because – in the absence of obesity – it has no or little subcutaneous fat and, therefore, provides the shortest distance from skin to peritoneum.

However, adhesive disease from a prior laparotomy involving the umbilicus is a risk factor for bowel injury during umbilical entry (direct trocar, Veress needle, or open technique). In a 1995 review of 360 women undergoing operative laparoscopy after a previous laparotomy, Brill et al. reported umbilical adhesions in 27% of those with prior horizontal suprapubic (Pfannenstiel) incisions, in 55% of those with prior incisions in the midline below the umbilicus, and 67% of those with prior midline incisions above the umbilicus.4

Of the 259 patients whose prior laparotomy was for gynecologic surgery (as opposed to obstetric or general surgery) adhesions were present in 70% of those who had midline incisions. (Direct injury to adherent omentum and bowel occurred during laparoscopic procedures in 21% of all women.)

Since the Brill paper, other studies have similarly reported significant adhesion rate, especially after midline incisions. For instance, one French study of patients undergoing laparoscopy reported umbilical adhesions in 51.7% of 89 patients who had previous laparotomy with a midline incision.5

Prior umbilical laparoscopy is not a risk factor for umbilical entry unless a hernia repair with mesh was performed at the umbilicus. Umbilical adhesions have been reported to occur in up to 15% of women who have had prior laparoscopic surgery, with more adhesions associated with larger trocar use (specifically 12-mm trocars).1 Still, the rate of those adhesions was very low.

Obesity is not necessarily a contraindication to umbilical entry; however, it can make successful entry more difficult, particularly in those with central obesity and a thicker layer of subcutaneous fat. It can be difficult in such cases to know when peritoneal access is achieved. Extra-long Veress needles or trocars may be needed, and it is important to enter the abdomen at a 90° angle to minimize risk to the great vessel vasculature.

LUQ entry is often a reliable alternative when central obesity is significant or when umbilical access proves to be difficult. Certainly, the subcutaneous fat layer is thinner at the LUQ than at the umbilicus, and in patients whose umbilicus is pulled very caudal because of a large pannus, the LUQ will also provide a better location for visualization of pelvic anatomy and for easier entry.

We still use umbilical entry in most patients with obesity, but if we are unsuccessful after two to three attempts, we proceed to the LUQ (barring any contraindications to this site).

LUQ entry: Our approach, contraindications

By entering at the midclavicular level and directly under the bottom of the rib cage, rather than 2-3 cm below the last rib as in traditional Palmer’s point LUQ entry, we benefit from the tenting up of the peritoneum by the last rib. Having space between the peritoneum and underlying omentum and stomach can facilitate an easier entry, as shown in the video.

We primarily utilize the Veress needle for entry. The needle is inserted directly perpendicular to the fascia, or at a slight angle toward the umbilicus. After the abdomen is insufflated to 15 mm Hg, we proceed with a visual peritoneal entry using a 5-mm trocar with a clear tip, which allows us to visualize both layers of fascia, and subsequently the peritoneum, as the trocar is advanced.

The fascia is not fused, so we can expect to feel three “pops” as the needle (or trocar) passes through the aponeuroses of the internal and external obliques, the aponeuroses of the internal oblique and transversus, and the peritoneum.

While successful peritoneal entry with umbilical access is generally confirmed with an intraperitoneal pressure measuring less than 7 mm Hg (which varies depending on abdominal wall thickness and adiposity), we have found that the opening pressure with LUQ entry is slightly higher. A recently published Canadian guideline for gynecologic laparoscopic entry recommends that an initial Veress intraperitoneal pressure of 10 mm Hg or below be considered an indicator of successful entry, regardless of the patient’s body habitus.1

LUQ entry can be helpful for surgeries involving large pelvic masses, for which there is little or no space to enter at the umbilicus or to optimally view the pathology. Utilizing the LUQ not only allows for an unobstructed entry and optimal viewing but also may become an extra operative port that can be used for the camera, allowing both surgeons to operate with two hands – a four-port technique. It also allows the surgeon to use a larger diameter port at the umbilicus without concern for cosmetics.

Additionally, there is a school of thought that LUQ entry is overall more successful, requiring less conversion to alternative sites and fewer attempts. This success may result from the presence of less adhesive disease in the LUQ, as well as clearer visualization of the anatomy while entering and confidence in entering the intraperitoneal space.

A prerequisite for LUQ entry is that the stomach be decompressed through placement of an oral gastric or nasogastric tube and suctioning of all gastric contents. An inability to decompress the stomach is a contraindication to LUQ entry, as is a history of splenectomy, an enlarged liver, gastric bypass surgery, or upper abdominal surgery.

Entry techniques, alternate sites

No single entry site or technique has been proven to be universally safer than another. A 2019 Cochrane review of laparoscopic entry techniques noted an advantage of direct trocar entry over Veress-needle entry for failed entry but concluded that, overall, evidence was insufficient to support the use of one entry technique over another to decrease complication rates.6

A more recently published review of randomized controlled trials, Cochrane reviews, and older descriptive accounts similarly concluded that, between the Veress needle (the oldest described technique), direct trocar insertion, and open entry (Hasson), there is no good evidence to suggest that any of these methods is universally superior.2 Surgeon comfort is, therefore, an important factor.

Regarding entry sites, we advocate use of the LUQ as an advantageous alternative site for access, but there are several other approaches described in the literature. These include right upper quadrant entry; the Lee Huang point, which is about 10 cm below the xiphoid; and uncommonly, vaginal, either posterior to the uterus into the pouch of Douglas or through the uterine fundus.2

The right upper quadrant approach is included in a recent video review in the Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology of safe entry techniques, along with umbilicus, LUQ, and supraumbilical entry.7

Another described entry site is the “Jain point,” located at the intersection of a vertical line drawn 2.5 cm medial to the anterior superior iliac spine, up to the level of the umbilicus, and a horizontal line at the upper margin of the umbilicus. In a retrospective study of 7,802 cases involving this method, the authors reported only one significant entry complication. Patients in the study had a wide range of BMIs and previous surgeries.8

With respect to entry techniques, we facilitate the Veress entry technique described by Frank E. Loeffler, MD, in the mid-1970s, unless there are contraindications such as second-trimester pregnancy. For umbilical entry, we first use a Kocher clamp to grasp the base of the umbilicus and then evert it. Using two towel clips, the surgeon and assistant apply countertraction by grasping the skin and fat on either side of the umbilicus. A horizontal incision is then made directly on the base of the umbilicus. The towel clips are used to elevate the anterior abdominal wall, and the Veress needle is attached to insufflation tubing, then inserted into the abdomen.

Alternatively, direct entry involves incising the skin, placing a laparoscope in a visual entry trocar, and directly visualizing each layer as the abdomen is entered. Once the trocar is intraperitoneal, insufflation is started.

In open laparoscopic/Hasson entry, the umbilical skin is incised, and the subcutaneous fat is dissected down until the rectal fascia is visualized. The fascia is then incised, the peritoneum is entered bluntly, and the Hasson trocar is placed. Insufflation is attached, and the laparoscope is inserted.

Dr. Sasaki is a partner, and Dr. McKenna is an AAGL MIGS fellow, in the private practice of Charles E. Miller, MD, & Associates in Chicago. They reported that they have no disclosures.

References

1. Vilos GA et al. J Obstet Gyneacol Can. 2021;43(3):376-89.

2. Recknagel JD and Goodman LR. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28(3):467-74.

3. Palmer R. J Reprod Med. 1974;13:1-5.

4. Brill AI et al. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85(2):269-72.

5. Audebert AJ and Gomel V. Fertil Steril. 2000;73(3):631-5.

6. Ahmad G et al. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019;1:CD006583.

7. Patzkowsky KE et al. J. Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28(3):386.

8. Nutan J et al. Updates in Surgery. 2021;73(6):2321-9.

The choice of entry point for gynecologic laparoscopy is critical, considering that most laparoscopic injuries occur during initial entry into the abdomen. In addition, different abdominal access points may have differing utility and efficacy depending on the patient. (The overall rate of injuries to abdominal viscera and blood vessels at the time of entry is an estimated 1 per 1,000 cases.1)

The most conventional entry point for gynecologic laparoscopic surgeries has been the umbilicus, but there are contraindications to this choice and situations in which it may not be the best access site. It is important to have knowledge of alternate entry points and techniques that consider the patient’s current pathology, anatomy, and most importantly, surgical history to better facilitate a safe initial entry.

The left upper quadrant (LUQ) has been described as a preferred alternate site to the umbilicus, and some gynecologic surgeons even consider it as a routine mode of entry.2 In our practice, LUQ entry is a safe and commonly used technique that is chosen primarily based on a patient’s history of a midline vertical incision, the presence of abdominal mesh from a prior umbilical hernia repair, or repeated cesarean sections.

Our technique for LUQ entry is a modification of the traditional approach that employs Palmer’s point – the entry point described by Raoul Palmer, MD, in 1974 as 3-4 cm below the left subcostal margin at the midclavicular line.3 We choose to enter at the midclavicular level and directly under the last rib.

When the umbilicus is problematic

The umbilicus is a favored entry point not only for its operative access to pelvic structures but also because – in the absence of obesity – it has no or little subcutaneous fat and, therefore, provides the shortest distance from skin to peritoneum.

However, adhesive disease from a prior laparotomy involving the umbilicus is a risk factor for bowel injury during umbilical entry (direct trocar, Veress needle, or open technique). In a 1995 review of 360 women undergoing operative laparoscopy after a previous laparotomy, Brill et al. reported umbilical adhesions in 27% of those with prior horizontal suprapubic (Pfannenstiel) incisions, in 55% of those with prior incisions in the midline below the umbilicus, and 67% of those with prior midline incisions above the umbilicus.4

Of the 259 patients whose prior laparotomy was for gynecologic surgery (as opposed to obstetric or general surgery) adhesions were present in 70% of those who had midline incisions. (Direct injury to adherent omentum and bowel occurred during laparoscopic procedures in 21% of all women.)

Since the Brill paper, other studies have similarly reported significant adhesion rate, especially after midline incisions. For instance, one French study of patients undergoing laparoscopy reported umbilical adhesions in 51.7% of 89 patients who had previous laparotomy with a midline incision.5

Prior umbilical laparoscopy is not a risk factor for umbilical entry unless a hernia repair with mesh was performed at the umbilicus. Umbilical adhesions have been reported to occur in up to 15% of women who have had prior laparoscopic surgery, with more adhesions associated with larger trocar use (specifically 12-mm trocars).1 Still, the rate of those adhesions was very low.

Obesity is not necessarily a contraindication to umbilical entry; however, it can make successful entry more difficult, particularly in those with central obesity and a thicker layer of subcutaneous fat. It can be difficult in such cases to know when peritoneal access is achieved. Extra-long Veress needles or trocars may be needed, and it is important to enter the abdomen at a 90° angle to minimize risk to the great vessel vasculature.

LUQ entry is often a reliable alternative when central obesity is significant or when umbilical access proves to be difficult. Certainly, the subcutaneous fat layer is thinner at the LUQ than at the umbilicus, and in patients whose umbilicus is pulled very caudal because of a large pannus, the LUQ will also provide a better location for visualization of pelvic anatomy and for easier entry.

We still use umbilical entry in most patients with obesity, but if we are unsuccessful after two to three attempts, we proceed to the LUQ (barring any contraindications to this site).

LUQ entry: Our approach, contraindications

By entering at the midclavicular level and directly under the bottom of the rib cage, rather than 2-3 cm below the last rib as in traditional Palmer’s point LUQ entry, we benefit from the tenting up of the peritoneum by the last rib. Having space between the peritoneum and underlying omentum and stomach can facilitate an easier entry, as shown in the video.

We primarily utilize the Veress needle for entry. The needle is inserted directly perpendicular to the fascia, or at a slight angle toward the umbilicus. After the abdomen is insufflated to 15 mm Hg, we proceed with a visual peritoneal entry using a 5-mm trocar with a clear tip, which allows us to visualize both layers of fascia, and subsequently the peritoneum, as the trocar is advanced.

The fascia is not fused, so we can expect to feel three “pops” as the needle (or trocar) passes through the aponeuroses of the internal and external obliques, the aponeuroses of the internal oblique and transversus, and the peritoneum.

While successful peritoneal entry with umbilical access is generally confirmed with an intraperitoneal pressure measuring less than 7 mm Hg (which varies depending on abdominal wall thickness and adiposity), we have found that the opening pressure with LUQ entry is slightly higher. A recently published Canadian guideline for gynecologic laparoscopic entry recommends that an initial Veress intraperitoneal pressure of 10 mm Hg or below be considered an indicator of successful entry, regardless of the patient’s body habitus.1

LUQ entry can be helpful for surgeries involving large pelvic masses, for which there is little or no space to enter at the umbilicus or to optimally view the pathology. Utilizing the LUQ not only allows for an unobstructed entry and optimal viewing but also may become an extra operative port that can be used for the camera, allowing both surgeons to operate with two hands – a four-port technique. It also allows the surgeon to use a larger diameter port at the umbilicus without concern for cosmetics.

Additionally, there is a school of thought that LUQ entry is overall more successful, requiring less conversion to alternative sites and fewer attempts. This success may result from the presence of less adhesive disease in the LUQ, as well as clearer visualization of the anatomy while entering and confidence in entering the intraperitoneal space.

A prerequisite for LUQ entry is that the stomach be decompressed through placement of an oral gastric or nasogastric tube and suctioning of all gastric contents. An inability to decompress the stomach is a contraindication to LUQ entry, as is a history of splenectomy, an enlarged liver, gastric bypass surgery, or upper abdominal surgery.

Entry techniques, alternate sites

No single entry site or technique has been proven to be universally safer than another. A 2019 Cochrane review of laparoscopic entry techniques noted an advantage of direct trocar entry over Veress-needle entry for failed entry but concluded that, overall, evidence was insufficient to support the use of one entry technique over another to decrease complication rates.6

A more recently published review of randomized controlled trials, Cochrane reviews, and older descriptive accounts similarly concluded that, between the Veress needle (the oldest described technique), direct trocar insertion, and open entry (Hasson), there is no good evidence to suggest that any of these methods is universally superior.2 Surgeon comfort is, therefore, an important factor.

Regarding entry sites, we advocate use of the LUQ as an advantageous alternative site for access, but there are several other approaches described in the literature. These include right upper quadrant entry; the Lee Huang point, which is about 10 cm below the xiphoid; and uncommonly, vaginal, either posterior to the uterus into the pouch of Douglas or through the uterine fundus.2

The right upper quadrant approach is included in a recent video review in the Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology of safe entry techniques, along with umbilicus, LUQ, and supraumbilical entry.7

Another described entry site is the “Jain point,” located at the intersection of a vertical line drawn 2.5 cm medial to the anterior superior iliac spine, up to the level of the umbilicus, and a horizontal line at the upper margin of the umbilicus. In a retrospective study of 7,802 cases involving this method, the authors reported only one significant entry complication. Patients in the study had a wide range of BMIs and previous surgeries.8

With respect to entry techniques, we facilitate the Veress entry technique described by Frank E. Loeffler, MD, in the mid-1970s, unless there are contraindications such as second-trimester pregnancy. For umbilical entry, we first use a Kocher clamp to grasp the base of the umbilicus and then evert it. Using two towel clips, the surgeon and assistant apply countertraction by grasping the skin and fat on either side of the umbilicus. A horizontal incision is then made directly on the base of the umbilicus. The towel clips are used to elevate the anterior abdominal wall, and the Veress needle is attached to insufflation tubing, then inserted into the abdomen.

Alternatively, direct entry involves incising the skin, placing a laparoscope in a visual entry trocar, and directly visualizing each layer as the abdomen is entered. Once the trocar is intraperitoneal, insufflation is started.

In open laparoscopic/Hasson entry, the umbilical skin is incised, and the subcutaneous fat is dissected down until the rectal fascia is visualized. The fascia is then incised, the peritoneum is entered bluntly, and the Hasson trocar is placed. Insufflation is attached, and the laparoscope is inserted.

Dr. Sasaki is a partner, and Dr. McKenna is an AAGL MIGS fellow, in the private practice of Charles E. Miller, MD, & Associates in Chicago. They reported that they have no disclosures.

References

1. Vilos GA et al. J Obstet Gyneacol Can. 2021;43(3):376-89.

2. Recknagel JD and Goodman LR. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28(3):467-74.

3. Palmer R. J Reprod Med. 1974;13:1-5.

4. Brill AI et al. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85(2):269-72.

5. Audebert AJ and Gomel V. Fertil Steril. 2000;73(3):631-5.

6. Ahmad G et al. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019;1:CD006583.

7. Patzkowsky KE et al. J. Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2021;28(3):386.

8. Nutan J et al. Updates in Surgery. 2021;73(6):2321-9.

Safe abdominal laparoscopic entry

There are few procedures in gynecologic surgery that are blind. We can readily name dilatation and uterine curettage, but even the dreaded suction curettage can be performed under ultrasound guidance. Laparoscopy with direct insertion or with use of a Veress needle remain two of the few blind procedures in our specialty.

The reality that we all face as minimally invasive gynecologic surgeons is that, as Javier F. Magrina, MD, showed in 2002, more than 50% of injuries to the gastrointestinal tract and major blood vessels occur at entry, prior to the start of the intended surgery, with the majority occurring at the time of the primary umbilical trocar placement. In his study of over 1.5 million gynecologic patients, Dr. Magrina also noted that 20% to 25% of complications were not recognized until the postoperative period.

Interestingly, while some have recommended the open Hasson technique pioneered by Harrith M. Hasson, MD, over the blind Veress needle or direct insertion, there is no evidence to suggest it is safer. Use of shielded trocars have not been shown to decrease entry injuries; that is, visceral or vascular injuries have not been shown to decrease. Finally, at present, data do not support the recommendation that visual entry cannulas offer increased safety, although additional studies are recommended.

It is a pleasure to welcome my partner and former AAGL MIGS fellow, Kirsten J. Sasaki, MD, as well as my current AAGL MIGS fellow, Mary (Molly) McKenna, MD, to this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery.

Dr. Miller is a clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois in Chicago and past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in metropolitan Chicago and the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill. He has no disclosures relevant to this Master Class.

Reference

Magrina JF. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2002 Jun;45(2):469-80.

There are few procedures in gynecologic surgery that are blind. We can readily name dilatation and uterine curettage, but even the dreaded suction curettage can be performed under ultrasound guidance. Laparoscopy with direct insertion or with use of a Veress needle remain two of the few blind procedures in our specialty.

The reality that we all face as minimally invasive gynecologic surgeons is that, as Javier F. Magrina, MD, showed in 2002, more than 50% of injuries to the gastrointestinal tract and major blood vessels occur at entry, prior to the start of the intended surgery, with the majority occurring at the time of the primary umbilical trocar placement. In his study of over 1.5 million gynecologic patients, Dr. Magrina also noted that 20% to 25% of complications were not recognized until the postoperative period.

Interestingly, while some have recommended the open Hasson technique pioneered by Harrith M. Hasson, MD, over the blind Veress needle or direct insertion, there is no evidence to suggest it is safer. Use of shielded trocars have not been shown to decrease entry injuries; that is, visceral or vascular injuries have not been shown to decrease. Finally, at present, data do not support the recommendation that visual entry cannulas offer increased safety, although additional studies are recommended.

It is a pleasure to welcome my partner and former AAGL MIGS fellow, Kirsten J. Sasaki, MD, as well as my current AAGL MIGS fellow, Mary (Molly) McKenna, MD, to this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery.

Dr. Miller is a clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois in Chicago and past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in metropolitan Chicago and the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill. He has no disclosures relevant to this Master Class.

Reference

Magrina JF. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2002 Jun;45(2):469-80.

There are few procedures in gynecologic surgery that are blind. We can readily name dilatation and uterine curettage, but even the dreaded suction curettage can be performed under ultrasound guidance. Laparoscopy with direct insertion or with use of a Veress needle remain two of the few blind procedures in our specialty.

The reality that we all face as minimally invasive gynecologic surgeons is that, as Javier F. Magrina, MD, showed in 2002, more than 50% of injuries to the gastrointestinal tract and major blood vessels occur at entry, prior to the start of the intended surgery, with the majority occurring at the time of the primary umbilical trocar placement. In his study of over 1.5 million gynecologic patients, Dr. Magrina also noted that 20% to 25% of complications were not recognized until the postoperative period.

Interestingly, while some have recommended the open Hasson technique pioneered by Harrith M. Hasson, MD, over the blind Veress needle or direct insertion, there is no evidence to suggest it is safer. Use of shielded trocars have not been shown to decrease entry injuries; that is, visceral or vascular injuries have not been shown to decrease. Finally, at present, data do not support the recommendation that visual entry cannulas offer increased safety, although additional studies are recommended.

It is a pleasure to welcome my partner and former AAGL MIGS fellow, Kirsten J. Sasaki, MD, as well as my current AAGL MIGS fellow, Mary (Molly) McKenna, MD, to this edition of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery.

Dr. Miller is a clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois in Chicago and past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in metropolitan Chicago and the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill. He has no disclosures relevant to this Master Class.

Reference

Magrina JF. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2002 Jun;45(2):469-80.

Ear tubes not recommended for recurrent AOM without effusion, ENTs maintain

A practice guideline update from the ENT community on tympanostomy tubes in children reaffirms that tube insertion should not be considered in cases of otitis media with effusion (OME) lasting less than 3 months, or in children with recurrent acute otitis media (AOM) without middle ear effusion at the time of assessment for the procedure.

New in the update from the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery Foundation (AAO-HNSF) is a strong recommendation for timely follow-up after surgery and recommendations against both routine use of prophylactic antibiotic ear drops after surgery and the initial use of long-term tubes except when there are specific reasons for doing so.

The update also expands the list of risk factors that place children with OME at increased risk of developmental difficulties – and often in need of timely ear tube placement – to include intellectual disability, learning disorder, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

“Most of what we said in the 2013 [original] guideline was good and still valid ... and [important for] pediatricians, who are the key players” in managing otitis media, Jesse Hackell, MD, one of two general pediatricians who served on the Academy’s guideline update committee, said in an interview.

OME spontaneously clears up to 90% of the time within 3 months, said Dr. Hackell, of Pomona (New York) Pediatrics, and chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine.

The updated guideline, for children 6 months to 12 years, reaffirms a recommendation that tube insertion be offered to children with “bilateral OME for 3 months or longer AND documented hearing difficulties.”

It also reaffirms “options” (a lesser quality of evidence) that in the absence of hearing difficulties, surgery may be performed for children with chronic OME (3 months or longer) in one or both ears if 1) they are at increased risk of developmental difficulties from OME or 2) effusion is likely contributing to balance problems, poor school performance, behavioral problems, ear discomfort, or reduced quality of life.

Children with chronic OME who do not undergo surgery should be reevaluated at 3- to 6-month intervals and monitored until effusion is no longer present, significant hearing loss is detected, or structural abnormalities of the tympanic membrane or middle ear are detected, the update again recommends.

Tympanostomy tube placement is the most common ambulatory surgery performed on children in the United States, the guideline authors say. In 2014, about 9% of children had undergone the surgery, they wrote, noting also that “tubes were placed in 25%-30% of children with frequent ear infections.”

Recurrent AOM

The AAO-HNSF guidance regarding tympanostomy tubes for OME is similar overall to management guidance issued by the AAP in its clinical practice guideline on OME.

The organizations differ, however, on their guidance for tube insertion for recurrent AOM. In its 2013 clinical practice guideline on AOM, the AAP recommends that clinicians may offer tube insertion for recurrent AOM, with no mention of the presence or absence of persistent fluid as a consideration.

According to the AAO-HNSF update, grade A evidence, including some research published since its original 2013 guideline, has shown little benefit to tube insertion in reducing the incidence of AOM in otherwise healthy children who don’t have middle ear effusion.

One study published in 2019 assessed outcomes after watchful waiting and found that only one-third of 123 children eventually went on to tympanostomy tube placement, noted Richard M. Rosenfeld, MD, distinguished professor and chairman of otolaryngology at SUNY Downstate Health Sciences University in Brooklyn, N.Y., and lead author of the original and updated guidelines.

In practice, “the real question [for the ENT] is the future. If the ears are perfectly clear, will tubes really reduce the frequency of infections going forward?” Dr. Rosenfeld said in an interview. “All the evidence seems to say no, it doesn’t make much of a difference.”

Dr. Hackell said he’s confident that the question “is settled enough.” While there “could be stronger research and higher quality studies, the evidence is still pretty good to suggest you gain little to no benefit with tubes when you’re dealing with recurrent AOM without effusion,” he said.

Asked to comment on the ENT update and its guidance on tympanostomy tubes for children with recurrent AOM, an AAP spokesperson said the “issue is under review” and that the AAP did not currently have a statement.

At-risk children

The AAO-HNSF update renews a recommendation to evaluate children with either recurrent AOM or OME of any duration for increased risk for speech, language, or learning problems from OME because of baseline factors (sensory, physical, cognitive, or behavioral).

When OME becomes chronic – or when a tympanogram gives a flat-line reading – OME is likely to persist, and families of at-risk children especially should be encouraged to pursue tube placement, Dr. Rosenfeld said.

Despite prior guidance to this effect, he said, ear tubes are being underutilized in at-risk children, with effusion being missed in primary care and with ENTs not expediting tube placement upon referral.

“These children have learning issues, cognitive issues, developmental issues,” he said in the interview. “It’s a population that does very poorly with ears full of fluid ... and despite guidance suggesting these children should be prioritized with tubes, it doesn’t seem to be happening enough.”

Formulating guidelines for at-risk children is challenging because they are often excluded from trials, Dr. Rosenfeld said, which limits evidence about the benefits of tubes and limits the strength of recommendations.

The addition of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, intellectual disability, and learning disorder to the list of risk factors is notable, Dr. Hackell said. (The list includes autism spectrum disorder, developmental delay, and suspected or confirmed speech and language delay or disorder.)

“We know that kids with ADHD take in and process information a little differently ... it may be harder to get their attention with auditory stimulation,” he said. “So anything that would impact the taking in of information even for a short period of time increases their risk.”

Surgical practice

ENTs are advised in the new guidance to use long-term tubes and perioperative antibiotic ear drops more judiciously. “Long-term tubes have a role, but there are some doctors who routinely use them, even for a first-time surgery,” said Dr. Rosenfeld.

Overuse of long-term tubes results in a higher incidence of tympanic membrane perforation, chronic drainage, and other complications, as well as greater need for long-term follow-up. “There needs to be a reason – something to justify the need for prolonged ventilation,” he said.

Perioperative antibiotic ear drops are often administered during surgery and then prescribed routinely for all children afterward, but research has shown that saline irrigation during surgery and a single application of antibiotic/steroid drops is similarly efficacious in preventing otorrhea, the guideline says. Antibiotic ear drops are also “expensive,” noted Dr. Hackell. “There’s not enough benefit to justify it.”

The update also more explicitly advises selective use of adenoidectomy. A new option says that clinicians may perform the procedure as an adjunct to tube insertion for children 4 years or older to potentially reduce the future incidence of recurrent OME or the need for repeat surgery.

However, in younger children, it should not be offered unless there are symptoms directly related to adenoid infection or nasal obstruction. “Under 4 years, there’s no primary benefit for the ears,” said Dr. Rosenfeld.

Follow-up with the surgeon after tympanostomy tube insertion should occur within 3 months to assess outcomes and educate the family, the update strongly recommends.

And pediatricians should know, Dr. Hackell notes, that clinical evidence continues to show that earplugs and other water precautions are not routinely needed for children who have tubes in place. A good approach, the guideline says, is to “first avoid water precautions and instead reserve them for children with recurrent or persistent tympanostomy tube otorrhea.”

Asked to comment on the guideline update, Tim Joos, MD, MPH, who practices combined internal medicine/pediatrics in Seattle and is an editorial advisory board member of Pediatric News, noted the inclusion of patient information sheets with frequently asked questions – resources that can be useful for guiding parents through what’s often a shared decision-making process.

Neither Dr. Rosenfeld nor Dr. Hackell reported any disclosures. Other members of the guideline update committee reported various book royalties, consulting fees, and other disclosures. Dr. Joos reported he has no connections to the guideline authors.

A practice guideline update from the ENT community on tympanostomy tubes in children reaffirms that tube insertion should not be considered in cases of otitis media with effusion (OME) lasting less than 3 months, or in children with recurrent acute otitis media (AOM) without middle ear effusion at the time of assessment for the procedure.

New in the update from the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery Foundation (AAO-HNSF) is a strong recommendation for timely follow-up after surgery and recommendations against both routine use of prophylactic antibiotic ear drops after surgery and the initial use of long-term tubes except when there are specific reasons for doing so.

The update also expands the list of risk factors that place children with OME at increased risk of developmental difficulties – and often in need of timely ear tube placement – to include intellectual disability, learning disorder, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

“Most of what we said in the 2013 [original] guideline was good and still valid ... and [important for] pediatricians, who are the key players” in managing otitis media, Jesse Hackell, MD, one of two general pediatricians who served on the Academy’s guideline update committee, said in an interview.

OME spontaneously clears up to 90% of the time within 3 months, said Dr. Hackell, of Pomona (New York) Pediatrics, and chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine.

The updated guideline, for children 6 months to 12 years, reaffirms a recommendation that tube insertion be offered to children with “bilateral OME for 3 months or longer AND documented hearing difficulties.”

It also reaffirms “options” (a lesser quality of evidence) that in the absence of hearing difficulties, surgery may be performed for children with chronic OME (3 months or longer) in one or both ears if 1) they are at increased risk of developmental difficulties from OME or 2) effusion is likely contributing to balance problems, poor school performance, behavioral problems, ear discomfort, or reduced quality of life.

Children with chronic OME who do not undergo surgery should be reevaluated at 3- to 6-month intervals and monitored until effusion is no longer present, significant hearing loss is detected, or structural abnormalities of the tympanic membrane or middle ear are detected, the update again recommends.

Tympanostomy tube placement is the most common ambulatory surgery performed on children in the United States, the guideline authors say. In 2014, about 9% of children had undergone the surgery, they wrote, noting also that “tubes were placed in 25%-30% of children with frequent ear infections.”

Recurrent AOM

The AAO-HNSF guidance regarding tympanostomy tubes for OME is similar overall to management guidance issued by the AAP in its clinical practice guideline on OME.