User login

Surgical principles of vaginal cuff dehiscence repair

Additional videos from SGS are available here, including these recent offerings:

Strategies for safe dissection of cervical fibroids during hysterectomy

Concomitant laparoscopic and vaginal excision of duplicated collecting system

Additional videos from SGS are available here, including these recent offerings:

Strategies for safe dissection of cervical fibroids during hysterectomy

Concomitant laparoscopic and vaginal excision of duplicated collecting system

Additional videos from SGS are available here, including these recent offerings:

Strategies for safe dissection of cervical fibroids during hysterectomy

Concomitant laparoscopic and vaginal excision of duplicated collecting system

WPATH draft on gender dysphoria ‘skewed and misses urgent issues’

New draft guidance from the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) is raising serious concerns among professionals caring for people with gender dysphoria, prompting claims that WPATH is an organization “captured by activists.”

Experts in adolescent and child psychology, as well as pediatric health, have expressed dismay that the WPATH Standards of Care (SOC) 8 appear to miss some of the most urgent issues in the field of transgender medicine and are considered to express a radical and unreserved leaning towards “gender-affirmation.”

The WPATH SOC 8 document is available for view and comment until Dec. 16 until 11.59 PM EST, after which time revisions will be made and the final version published.

Despite repeated attempts by this news organization to seek clarification on certain aspects of the guidance from members of the WPATH SOC 8 committee, requests were declined “until the guidance is finalized.”

According to the WPATH website, the SOC 8 aims to provide “clinical guidance for health professionals to assist transgender and gender diverse people with safe and effective pathways” to manage their gender dysphoria and potentially transition.

Such pathways may relate to primary care, gynecologic and urologic care, reproductive options, voice and communication therapy, mental health services, and hormonal or surgical treatments, among others.

WPATH adds that it was felt necessary to revise the existing SOC 7 (published in 2012) because of recent “globally unprecedented increase and visibility of transgender and gender-diverse people seeking support and gender-affirming medical treatment.”

Gender-affirming medical treatment means different things at different ages. In the case of kids with gender dysphoria who have not yet entered puberty associated with their birth sex, this might include prescribing so-called “puberty blockers” to delay natural puberty – gonadotrophin-releasing hormone analogs that are licensed for use in precocious puberty in children. Such agents have not been licensed for use in children with gender dysphoria, however, so any use for this purpose is off-label.

Following puberty blockade – or in cases where adolescents have already undergone natural puberty – the next step is to begin cross-sex hormones. So, for a female patient who wants to transition to male (FTM), that would be lifelong testosterone, and for a male who wants to be female (MTF), it involves lifelong estrogen. Again, use of such hormones in transgender individuals is entirely off-label.

Just last month, two of America’s leading experts on transgender medicine, both psychologists – including one who is transgender – told this news organization they were concerned that the quality of the evaluations of youth with gender dysphoria are being stifled by activists who are worried that open discussions will further stigmatize trans individuals.

They subsequently wrote an op-ed on the topic entitled, “The mental health establishment is failing trans kids,” which was finally published in the Washington Post on Nov. 24, after numerous other mainstream U.S. media outlets had rejected it.

New SOC 8 ‘is not evidence based,’ should not be new ‘gold standard’

One expert says the draft SOC 8 lacks balance and does not address certain issues, while paying undue attention to others that detract from real questions facing the field of transgender medicine, both in the United States and around the world.

Julia Mason, MD, is a pediatrician based in Gresham, Oregon, with a special interest in children and adolescents experiencing gender dysphoria. “The SOC 8 shows us that WPATH remains captured by activists,” she asserts.

Dr. Mason questions the integrity of WPATH based on what she has read in the draft SOC 8.

“We need a serious organization to take a sober look at the evidence, and that is why we have established the Society for Evidence-Based Gender Medicine [SEGM],” she noted. “This is what we do – we are looking at all of the evidence.”

Dr. Mason is a clinical advisor to SEGM, an organization set-up to evaluate current interventions and evidence on gender dysphoria.

The pediatrician has particular concerns regarding the child and adolescent chapters in the draft SOC 8. The adolescent chapter states: “Guidelines are meant to provide a gold standard based on the available evidence at this moment of time.”

Dr. Mason disputes this assertion. “This document should not be the new gold standard going forward, primarily because it is not evidence based.”

In an interview, Dr. Mason explained that WPATH say they used the “Delphi consensus process” to determine their recommendations, but “this process is designed for use with a panel of experts when evidence is lacking. I would say they didn’t have a panel of experts. They largely had a panel of activists, with a few experts.”

There is no mention, for example, of England’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) evidence reviews on puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones from earlier this year. These reviews determined that no studies have compared cross-sex hormones or puberty blockers with a control group and all follow-up periods for cross-sex hormones were relatively short.

This disappoints Dr. Mason: “These are significant; they are important documents.”

And much of the evidence quoted comes from the well-known and often-quoted “Dutch-protocol” study of 2011, in which the children studied were much younger at the time of their gender dysphoria, compared with the many adolescents who make up the current surge in presentation at gender clinics worldwide, she adds.

Rapid-onset GD: adolescents presenting late with little history

Dr. Mason also stresses that the SOC 8 does not address the most urgent issues in transgender medicine today, mainly because it does not address rapid-onset gender dysphoria (ROGD): “This is the dilemma of the 21st century; it’s new.”

ROGD – a term first coined in 2018 by researcher Lisa Littman, MD, MPH, now president of the Institute for Comprehensive Gender Dysphoria Research (ICGDR) – refers to the phenomena of adolescents expressing a desire to transition from their birth sex after little or no apparent previous indication.

However, the SOC 8 does make reference to aspects of adolescent development that might impact their decision-making processes around gender identity during teen years. The chapter on adolescents reads: “... adolescence is also often associated with increased risk-taking behaviors. Along with these notable changes ... individuation from parents ... [there is] often a heightened focus on peer relationships, which can be both positive and detrimental.”

The guidance goes on to point out that “it is critical to understand how all of these aspects of development may impact the decision-making for a given young person within their specific cultural context.”

Desistance and detransitioning not adequately addressed

Dr. Mason also says there is little mention “about detransitioning in this SOC [8], and ‘gender dysphoria’ and ‘trans’ are terms that are not defined.”

Likewise, there is no mention of desistance, she highlights, which is when individuals naturally resolve their dysphoria around their birth sex as they grow older.

The most recent published data seen by this news organization relates to a study from March 2021 that showed nearly 88% of boys who struggled with gender identity in childhood (approximate mean age 8 years and follow-up at approximate mean age 20 years) desisted. It reads: “Of the 139 participants, 17 (12.2%) were classified as ‘persisters’ and the remaining 122 (87.8%) were classified as desisters.”

“Most children with gender dysphoria will desist and lose their concept of themselves as being the opposite gender,” Dr. Mason explains. “This is the safest path for a child – desistance.”

“Transition can turn a healthy young person into a lifelong medical patient and has significant health risks,” she emphasizes, stressing that transition has not been shown to decrease the probability of suicide, or attempts at suicide, despite myriad claims saying otherwise.

“Before we were routinely transitioning kids at school, the vast majority of children grew out of their gender dysphoria. This history is not recognized at all in these SOC [8],” she maintains.

Ken Zucker, PhD, CPsych, an author of the study of desistance in boys, says the terms desistence and persistence of gender dysphoria have caused some consternation in certain circles.

An editor of the Archives of Sexual Behavior and professor in the department of psychiatry, University of Toronto, Dr. Zucker has published widely on the topic.

He told this news organization: “The terms persistence and desistance have become verboten among the WPATH cognoscenti. Perhaps the contributors to SOC 8 have come up with alternative descriptors.”

“The term ‘desistance’ is particularly annoying to some of the gender-affirming clinicians, because they don’t believe that desistance is bona fide,” Dr. Zucker points out.

“The desistance resisters are like anti-vaxxers – nothing one can provide as evidence for the efficacy of vaccines is sufficient. There will always be a new objection.”

Other mental health issues, in particular ADHD and autism

It is also widely acknowledged that there is a higher rate of neurodevelopmental and psychiatric diagnoses in individuals with gender dysphoria. For example, one 2020 study found that transgender people were three to six times as likely to be autistic as cisgender people (those whose gender is aligned with their birth sex).

Statement one in the chapter on adolescents in draft WPATH SOC 8 does give a nod to this, pointing out that health professionals working with gender diverse adolescents “should receive training and develop expertise in autism spectrum disorders and other neurodiversity conditions.”

It also notes that in some cases “a more extended assessment process may be useful, such as for youth with more complex presentations (e.g., complicated mental health histories, co-occurring autism spectrum characteristics in particular) and an absence of experienced childhood gender incongruence.”

However, Dr. Mason stresses that underlying mental health issues are central to addressing how to manage a significant number of these patients.

“If a young person has ADHD or autism, they are not ready to make decisions about the rest of their life at age 18. Even a neurotypical young person is still developing their frontal cortex in their early 20s, and it takes longer for those with ADHD or on the autism spectrum.”

She firmly believes that the guidance does not give sufficient consideration to comorbidities in people over the age of 18.

According to their [SOC 8] guidelines, “once someone is 18 they are ready for anything,” says Dr. Mason.

Offering some explanation for the increased prevalence of ADHD and autism in those with gender dysphoria, Dr. Mason notes that children can have “hyperfocus” and those with autism will fixate on a particular area of interest. “If a child is unhappy in their life, and this can be more likely if someone is neuro-atypical, then it is likely that the individual might go online and find this one solution [for example, a transgender identity] that seems to fix everything.”

Perceptions of femininity and masculinity can also be extra challenging for a child with autism, Dr. Mason says. “It is relatively easy for an autistic girl to feel like she should be a boy because the rules of femininity are composed of nonverbal, subtle behaviors that can be difficult to pick up on,” she points out. “An autistic child who isn’t particularly good at nonverbal communication might not pick up on these and thus feel they are not very ‘female.’”

“There’s a whole lot of grass-is-greener-type thinking. Girls think boys have an easier life, and boys think girls have an easier life. I know some detransitioners who have spoken eloquently about realizing their mistake on this,” she adds.

Other parts of the SOC 8 that Dr. Mason disagrees with include the recommendation in the adolescent chapter that 14-year-olds are mature enough to start cross-sex hormones, that is, giving testosterone to a female who wants to transition to male or estrogen to a male who wishes to transition to female. “I think that’s far too young,” she asserts.

And she points out that the document states 17-year-olds are ready for genital reassignment surgery. Again, she believes this is far too young.

“Also, the SOC 8 document does not clarify who is appropriate for surgery. Whenever surgery is discussed, it becomes very vague,” she said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New draft guidance from the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) is raising serious concerns among professionals caring for people with gender dysphoria, prompting claims that WPATH is an organization “captured by activists.”

Experts in adolescent and child psychology, as well as pediatric health, have expressed dismay that the WPATH Standards of Care (SOC) 8 appear to miss some of the most urgent issues in the field of transgender medicine and are considered to express a radical and unreserved leaning towards “gender-affirmation.”

The WPATH SOC 8 document is available for view and comment until Dec. 16 until 11.59 PM EST, after which time revisions will be made and the final version published.

Despite repeated attempts by this news organization to seek clarification on certain aspects of the guidance from members of the WPATH SOC 8 committee, requests were declined “until the guidance is finalized.”

According to the WPATH website, the SOC 8 aims to provide “clinical guidance for health professionals to assist transgender and gender diverse people with safe and effective pathways” to manage their gender dysphoria and potentially transition.

Such pathways may relate to primary care, gynecologic and urologic care, reproductive options, voice and communication therapy, mental health services, and hormonal or surgical treatments, among others.

WPATH adds that it was felt necessary to revise the existing SOC 7 (published in 2012) because of recent “globally unprecedented increase and visibility of transgender and gender-diverse people seeking support and gender-affirming medical treatment.”

Gender-affirming medical treatment means different things at different ages. In the case of kids with gender dysphoria who have not yet entered puberty associated with their birth sex, this might include prescribing so-called “puberty blockers” to delay natural puberty – gonadotrophin-releasing hormone analogs that are licensed for use in precocious puberty in children. Such agents have not been licensed for use in children with gender dysphoria, however, so any use for this purpose is off-label.

Following puberty blockade – or in cases where adolescents have already undergone natural puberty – the next step is to begin cross-sex hormones. So, for a female patient who wants to transition to male (FTM), that would be lifelong testosterone, and for a male who wants to be female (MTF), it involves lifelong estrogen. Again, use of such hormones in transgender individuals is entirely off-label.

Just last month, two of America’s leading experts on transgender medicine, both psychologists – including one who is transgender – told this news organization they were concerned that the quality of the evaluations of youth with gender dysphoria are being stifled by activists who are worried that open discussions will further stigmatize trans individuals.

They subsequently wrote an op-ed on the topic entitled, “The mental health establishment is failing trans kids,” which was finally published in the Washington Post on Nov. 24, after numerous other mainstream U.S. media outlets had rejected it.

New SOC 8 ‘is not evidence based,’ should not be new ‘gold standard’

One expert says the draft SOC 8 lacks balance and does not address certain issues, while paying undue attention to others that detract from real questions facing the field of transgender medicine, both in the United States and around the world.

Julia Mason, MD, is a pediatrician based in Gresham, Oregon, with a special interest in children and adolescents experiencing gender dysphoria. “The SOC 8 shows us that WPATH remains captured by activists,” she asserts.

Dr. Mason questions the integrity of WPATH based on what she has read in the draft SOC 8.

“We need a serious organization to take a sober look at the evidence, and that is why we have established the Society for Evidence-Based Gender Medicine [SEGM],” she noted. “This is what we do – we are looking at all of the evidence.”

Dr. Mason is a clinical advisor to SEGM, an organization set-up to evaluate current interventions and evidence on gender dysphoria.

The pediatrician has particular concerns regarding the child and adolescent chapters in the draft SOC 8. The adolescent chapter states: “Guidelines are meant to provide a gold standard based on the available evidence at this moment of time.”

Dr. Mason disputes this assertion. “This document should not be the new gold standard going forward, primarily because it is not evidence based.”

In an interview, Dr. Mason explained that WPATH say they used the “Delphi consensus process” to determine their recommendations, but “this process is designed for use with a panel of experts when evidence is lacking. I would say they didn’t have a panel of experts. They largely had a panel of activists, with a few experts.”

There is no mention, for example, of England’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) evidence reviews on puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones from earlier this year. These reviews determined that no studies have compared cross-sex hormones or puberty blockers with a control group and all follow-up periods for cross-sex hormones were relatively short.

This disappoints Dr. Mason: “These are significant; they are important documents.”

And much of the evidence quoted comes from the well-known and often-quoted “Dutch-protocol” study of 2011, in which the children studied were much younger at the time of their gender dysphoria, compared with the many adolescents who make up the current surge in presentation at gender clinics worldwide, she adds.

Rapid-onset GD: adolescents presenting late with little history

Dr. Mason also stresses that the SOC 8 does not address the most urgent issues in transgender medicine today, mainly because it does not address rapid-onset gender dysphoria (ROGD): “This is the dilemma of the 21st century; it’s new.”

ROGD – a term first coined in 2018 by researcher Lisa Littman, MD, MPH, now president of the Institute for Comprehensive Gender Dysphoria Research (ICGDR) – refers to the phenomena of adolescents expressing a desire to transition from their birth sex after little or no apparent previous indication.

However, the SOC 8 does make reference to aspects of adolescent development that might impact their decision-making processes around gender identity during teen years. The chapter on adolescents reads: “... adolescence is also often associated with increased risk-taking behaviors. Along with these notable changes ... individuation from parents ... [there is] often a heightened focus on peer relationships, which can be both positive and detrimental.”

The guidance goes on to point out that “it is critical to understand how all of these aspects of development may impact the decision-making for a given young person within their specific cultural context.”

Desistance and detransitioning not adequately addressed

Dr. Mason also says there is little mention “about detransitioning in this SOC [8], and ‘gender dysphoria’ and ‘trans’ are terms that are not defined.”

Likewise, there is no mention of desistance, she highlights, which is when individuals naturally resolve their dysphoria around their birth sex as they grow older.

The most recent published data seen by this news organization relates to a study from March 2021 that showed nearly 88% of boys who struggled with gender identity in childhood (approximate mean age 8 years and follow-up at approximate mean age 20 years) desisted. It reads: “Of the 139 participants, 17 (12.2%) were classified as ‘persisters’ and the remaining 122 (87.8%) were classified as desisters.”

“Most children with gender dysphoria will desist and lose their concept of themselves as being the opposite gender,” Dr. Mason explains. “This is the safest path for a child – desistance.”

“Transition can turn a healthy young person into a lifelong medical patient and has significant health risks,” she emphasizes, stressing that transition has not been shown to decrease the probability of suicide, or attempts at suicide, despite myriad claims saying otherwise.

“Before we were routinely transitioning kids at school, the vast majority of children grew out of their gender dysphoria. This history is not recognized at all in these SOC [8],” she maintains.

Ken Zucker, PhD, CPsych, an author of the study of desistance in boys, says the terms desistence and persistence of gender dysphoria have caused some consternation in certain circles.

An editor of the Archives of Sexual Behavior and professor in the department of psychiatry, University of Toronto, Dr. Zucker has published widely on the topic.

He told this news organization: “The terms persistence and desistance have become verboten among the WPATH cognoscenti. Perhaps the contributors to SOC 8 have come up with alternative descriptors.”

“The term ‘desistance’ is particularly annoying to some of the gender-affirming clinicians, because they don’t believe that desistance is bona fide,” Dr. Zucker points out.

“The desistance resisters are like anti-vaxxers – nothing one can provide as evidence for the efficacy of vaccines is sufficient. There will always be a new objection.”

Other mental health issues, in particular ADHD and autism

It is also widely acknowledged that there is a higher rate of neurodevelopmental and psychiatric diagnoses in individuals with gender dysphoria. For example, one 2020 study found that transgender people were three to six times as likely to be autistic as cisgender people (those whose gender is aligned with their birth sex).

Statement one in the chapter on adolescents in draft WPATH SOC 8 does give a nod to this, pointing out that health professionals working with gender diverse adolescents “should receive training and develop expertise in autism spectrum disorders and other neurodiversity conditions.”

It also notes that in some cases “a more extended assessment process may be useful, such as for youth with more complex presentations (e.g., complicated mental health histories, co-occurring autism spectrum characteristics in particular) and an absence of experienced childhood gender incongruence.”

However, Dr. Mason stresses that underlying mental health issues are central to addressing how to manage a significant number of these patients.

“If a young person has ADHD or autism, they are not ready to make decisions about the rest of their life at age 18. Even a neurotypical young person is still developing their frontal cortex in their early 20s, and it takes longer for those with ADHD or on the autism spectrum.”

She firmly believes that the guidance does not give sufficient consideration to comorbidities in people over the age of 18.

According to their [SOC 8] guidelines, “once someone is 18 they are ready for anything,” says Dr. Mason.

Offering some explanation for the increased prevalence of ADHD and autism in those with gender dysphoria, Dr. Mason notes that children can have “hyperfocus” and those with autism will fixate on a particular area of interest. “If a child is unhappy in their life, and this can be more likely if someone is neuro-atypical, then it is likely that the individual might go online and find this one solution [for example, a transgender identity] that seems to fix everything.”

Perceptions of femininity and masculinity can also be extra challenging for a child with autism, Dr. Mason says. “It is relatively easy for an autistic girl to feel like she should be a boy because the rules of femininity are composed of nonverbal, subtle behaviors that can be difficult to pick up on,” she points out. “An autistic child who isn’t particularly good at nonverbal communication might not pick up on these and thus feel they are not very ‘female.’”

“There’s a whole lot of grass-is-greener-type thinking. Girls think boys have an easier life, and boys think girls have an easier life. I know some detransitioners who have spoken eloquently about realizing their mistake on this,” she adds.

Other parts of the SOC 8 that Dr. Mason disagrees with include the recommendation in the adolescent chapter that 14-year-olds are mature enough to start cross-sex hormones, that is, giving testosterone to a female who wants to transition to male or estrogen to a male who wishes to transition to female. “I think that’s far too young,” she asserts.

And she points out that the document states 17-year-olds are ready for genital reassignment surgery. Again, she believes this is far too young.

“Also, the SOC 8 document does not clarify who is appropriate for surgery. Whenever surgery is discussed, it becomes very vague,” she said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New draft guidance from the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) is raising serious concerns among professionals caring for people with gender dysphoria, prompting claims that WPATH is an organization “captured by activists.”

Experts in adolescent and child psychology, as well as pediatric health, have expressed dismay that the WPATH Standards of Care (SOC) 8 appear to miss some of the most urgent issues in the field of transgender medicine and are considered to express a radical and unreserved leaning towards “gender-affirmation.”

The WPATH SOC 8 document is available for view and comment until Dec. 16 until 11.59 PM EST, after which time revisions will be made and the final version published.

Despite repeated attempts by this news organization to seek clarification on certain aspects of the guidance from members of the WPATH SOC 8 committee, requests were declined “until the guidance is finalized.”

According to the WPATH website, the SOC 8 aims to provide “clinical guidance for health professionals to assist transgender and gender diverse people with safe and effective pathways” to manage their gender dysphoria and potentially transition.

Such pathways may relate to primary care, gynecologic and urologic care, reproductive options, voice and communication therapy, mental health services, and hormonal or surgical treatments, among others.

WPATH adds that it was felt necessary to revise the existing SOC 7 (published in 2012) because of recent “globally unprecedented increase and visibility of transgender and gender-diverse people seeking support and gender-affirming medical treatment.”

Gender-affirming medical treatment means different things at different ages. In the case of kids with gender dysphoria who have not yet entered puberty associated with their birth sex, this might include prescribing so-called “puberty blockers” to delay natural puberty – gonadotrophin-releasing hormone analogs that are licensed for use in precocious puberty in children. Such agents have not been licensed for use in children with gender dysphoria, however, so any use for this purpose is off-label.

Following puberty blockade – or in cases where adolescents have already undergone natural puberty – the next step is to begin cross-sex hormones. So, for a female patient who wants to transition to male (FTM), that would be lifelong testosterone, and for a male who wants to be female (MTF), it involves lifelong estrogen. Again, use of such hormones in transgender individuals is entirely off-label.

Just last month, two of America’s leading experts on transgender medicine, both psychologists – including one who is transgender – told this news organization they were concerned that the quality of the evaluations of youth with gender dysphoria are being stifled by activists who are worried that open discussions will further stigmatize trans individuals.

They subsequently wrote an op-ed on the topic entitled, “The mental health establishment is failing trans kids,” which was finally published in the Washington Post on Nov. 24, after numerous other mainstream U.S. media outlets had rejected it.

New SOC 8 ‘is not evidence based,’ should not be new ‘gold standard’

One expert says the draft SOC 8 lacks balance and does not address certain issues, while paying undue attention to others that detract from real questions facing the field of transgender medicine, both in the United States and around the world.

Julia Mason, MD, is a pediatrician based in Gresham, Oregon, with a special interest in children and adolescents experiencing gender dysphoria. “The SOC 8 shows us that WPATH remains captured by activists,” she asserts.

Dr. Mason questions the integrity of WPATH based on what she has read in the draft SOC 8.

“We need a serious organization to take a sober look at the evidence, and that is why we have established the Society for Evidence-Based Gender Medicine [SEGM],” she noted. “This is what we do – we are looking at all of the evidence.”

Dr. Mason is a clinical advisor to SEGM, an organization set-up to evaluate current interventions and evidence on gender dysphoria.

The pediatrician has particular concerns regarding the child and adolescent chapters in the draft SOC 8. The adolescent chapter states: “Guidelines are meant to provide a gold standard based on the available evidence at this moment of time.”

Dr. Mason disputes this assertion. “This document should not be the new gold standard going forward, primarily because it is not evidence based.”

In an interview, Dr. Mason explained that WPATH say they used the “Delphi consensus process” to determine their recommendations, but “this process is designed for use with a panel of experts when evidence is lacking. I would say they didn’t have a panel of experts. They largely had a panel of activists, with a few experts.”

There is no mention, for example, of England’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) evidence reviews on puberty blockers and cross-sex hormones from earlier this year. These reviews determined that no studies have compared cross-sex hormones or puberty blockers with a control group and all follow-up periods for cross-sex hormones were relatively short.

This disappoints Dr. Mason: “These are significant; they are important documents.”

And much of the evidence quoted comes from the well-known and often-quoted “Dutch-protocol” study of 2011, in which the children studied were much younger at the time of their gender dysphoria, compared with the many adolescents who make up the current surge in presentation at gender clinics worldwide, she adds.

Rapid-onset GD: adolescents presenting late with little history

Dr. Mason also stresses that the SOC 8 does not address the most urgent issues in transgender medicine today, mainly because it does not address rapid-onset gender dysphoria (ROGD): “This is the dilemma of the 21st century; it’s new.”

ROGD – a term first coined in 2018 by researcher Lisa Littman, MD, MPH, now president of the Institute for Comprehensive Gender Dysphoria Research (ICGDR) – refers to the phenomena of adolescents expressing a desire to transition from their birth sex after little or no apparent previous indication.

However, the SOC 8 does make reference to aspects of adolescent development that might impact their decision-making processes around gender identity during teen years. The chapter on adolescents reads: “... adolescence is also often associated with increased risk-taking behaviors. Along with these notable changes ... individuation from parents ... [there is] often a heightened focus on peer relationships, which can be both positive and detrimental.”

The guidance goes on to point out that “it is critical to understand how all of these aspects of development may impact the decision-making for a given young person within their specific cultural context.”

Desistance and detransitioning not adequately addressed

Dr. Mason also says there is little mention “about detransitioning in this SOC [8], and ‘gender dysphoria’ and ‘trans’ are terms that are not defined.”

Likewise, there is no mention of desistance, she highlights, which is when individuals naturally resolve their dysphoria around their birth sex as they grow older.

The most recent published data seen by this news organization relates to a study from March 2021 that showed nearly 88% of boys who struggled with gender identity in childhood (approximate mean age 8 years and follow-up at approximate mean age 20 years) desisted. It reads: “Of the 139 participants, 17 (12.2%) were classified as ‘persisters’ and the remaining 122 (87.8%) were classified as desisters.”

“Most children with gender dysphoria will desist and lose their concept of themselves as being the opposite gender,” Dr. Mason explains. “This is the safest path for a child – desistance.”

“Transition can turn a healthy young person into a lifelong medical patient and has significant health risks,” she emphasizes, stressing that transition has not been shown to decrease the probability of suicide, or attempts at suicide, despite myriad claims saying otherwise.

“Before we were routinely transitioning kids at school, the vast majority of children grew out of their gender dysphoria. This history is not recognized at all in these SOC [8],” she maintains.

Ken Zucker, PhD, CPsych, an author of the study of desistance in boys, says the terms desistence and persistence of gender dysphoria have caused some consternation in certain circles.

An editor of the Archives of Sexual Behavior and professor in the department of psychiatry, University of Toronto, Dr. Zucker has published widely on the topic.

He told this news organization: “The terms persistence and desistance have become verboten among the WPATH cognoscenti. Perhaps the contributors to SOC 8 have come up with alternative descriptors.”

“The term ‘desistance’ is particularly annoying to some of the gender-affirming clinicians, because they don’t believe that desistance is bona fide,” Dr. Zucker points out.

“The desistance resisters are like anti-vaxxers – nothing one can provide as evidence for the efficacy of vaccines is sufficient. There will always be a new objection.”

Other mental health issues, in particular ADHD and autism

It is also widely acknowledged that there is a higher rate of neurodevelopmental and psychiatric diagnoses in individuals with gender dysphoria. For example, one 2020 study found that transgender people were three to six times as likely to be autistic as cisgender people (those whose gender is aligned with their birth sex).

Statement one in the chapter on adolescents in draft WPATH SOC 8 does give a nod to this, pointing out that health professionals working with gender diverse adolescents “should receive training and develop expertise in autism spectrum disorders and other neurodiversity conditions.”

It also notes that in some cases “a more extended assessment process may be useful, such as for youth with more complex presentations (e.g., complicated mental health histories, co-occurring autism spectrum characteristics in particular) and an absence of experienced childhood gender incongruence.”

However, Dr. Mason stresses that underlying mental health issues are central to addressing how to manage a significant number of these patients.

“If a young person has ADHD or autism, they are not ready to make decisions about the rest of their life at age 18. Even a neurotypical young person is still developing their frontal cortex in their early 20s, and it takes longer for those with ADHD or on the autism spectrum.”

She firmly believes that the guidance does not give sufficient consideration to comorbidities in people over the age of 18.

According to their [SOC 8] guidelines, “once someone is 18 they are ready for anything,” says Dr. Mason.

Offering some explanation for the increased prevalence of ADHD and autism in those with gender dysphoria, Dr. Mason notes that children can have “hyperfocus” and those with autism will fixate on a particular area of interest. “If a child is unhappy in their life, and this can be more likely if someone is neuro-atypical, then it is likely that the individual might go online and find this one solution [for example, a transgender identity] that seems to fix everything.”

Perceptions of femininity and masculinity can also be extra challenging for a child with autism, Dr. Mason says. “It is relatively easy for an autistic girl to feel like she should be a boy because the rules of femininity are composed of nonverbal, subtle behaviors that can be difficult to pick up on,” she points out. “An autistic child who isn’t particularly good at nonverbal communication might not pick up on these and thus feel they are not very ‘female.’”

“There’s a whole lot of grass-is-greener-type thinking. Girls think boys have an easier life, and boys think girls have an easier life. I know some detransitioners who have spoken eloquently about realizing their mistake on this,” she adds.

Other parts of the SOC 8 that Dr. Mason disagrees with include the recommendation in the adolescent chapter that 14-year-olds are mature enough to start cross-sex hormones, that is, giving testosterone to a female who wants to transition to male or estrogen to a male who wishes to transition to female. “I think that’s far too young,” she asserts.

And she points out that the document states 17-year-olds are ready for genital reassignment surgery. Again, she believes this is far too young.

“Also, the SOC 8 document does not clarify who is appropriate for surgery. Whenever surgery is discussed, it becomes very vague,” she said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Average-risk women with dense breasts—What breast screening is appropriate?

Text copyright DenseBreast-info.org.

Answer

A. For women with extremely dense breasts who are not otherwise at increased risk for breast cancer, screening magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is preferred, plus her mammogram or tomosynthesis. If MRI is not an option, consider ultrasonography or contrast-enhanced mammography.

The same screening considerations apply to women with heterogeneously dense breasts; however, there is limited capacity for MRI or even ultrasound screening at many facilities. Research supports MRI in dense breasts, and abbreviated, lower-cost protocols have been validated that address some of the barriers to MRI.1 Although not yet widely available, abbreviated MRI will likely have a greater role in screening women with dense breasts who are not high risk. It is important to note that preauthorization from insurance may be required for screening MRI, and in most US states, deductibles and copays apply.

The exam

Contrast-enhanced MRI requires IV injection of gadolinium-based contrast to look at the anatomy and blood flow patterns of the breast tissue. The patient lies face down with the breasts placed in two rectangular openings, or “coils.” The exam takes place inside the tunnel of the scanner, with the head facing out.After initial images are obtained, the contrast agent is injected into a vein in the arm, and additional images are taken, which will show areas of enhancement. The exam takes about 20 to 40 minutes. An “abbreviated” MRI can be performed for screening in some centers, which uses fewer sequences and takes about 10 minutes.

Benefits

At least 40% of cancers are missed on mammography in women with dense breasts.2 MRI is the most widely studied technique using a contrast agent, and it produces the highest additional cancer detection of all the supplemental technologies to date, yielding, in the first year, 10-16 additional cancers per 1,000 women screened after mammography/tomosynthesis (reviewed in Berg et al.3). The cancer-detection benefit is seen across all breast density categories, even among average-risk women.4 There is no ionizing radiation, and it has been shown to reduce the rate of interval cancers (those detected due to symptoms after a negative screening mammogram), as well as the rate of late-stage disease. Axillary lymph nodes can be examined at the same screening exam.

While tomosynthesis improves cancer detection in women with fatty breasts, scattered fibroglandular breast tissue, and heterogeneously dense breasts, it does not significantly improve cancer detection in women with extremely dense breasts.5,6 Current American Cancer Society and National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend annual screening MRI for women at high risk for breast cancer (regardless of breast density); however, increasingly, research supports the effectiveness of MRI in women with dense breasts who are otherwise considered average risk. A large randomized controlled trial in the Netherlands compared outcomes in women with extremely dense breasts invited to have screening MRI after negative mammography to those assigned to continue receiving screening mammography only. The incremental cancer detection rate was 16.5 per 1,000 (79/4,783) women screened with MRI in the first round7 and 6 per 1,000 women screened in the second round 2 years later.8 The interval cancer rate was 0.8 per 1,000 (4/4,783) women screened with MRI, compared with 4.9 per 1,000 (16/3,278) women who declined MRI and received mammography only.7

Screening ultrasound will show up to 3 additional cancers per 1,000 women screened after mammography/tomosynthesis (reviewed in Vourtsis and Berg9 and Berg and Vourtsis10), far lower than the added cancer-detection rate of MRI. Consider screening ultrasound for women who cannot tolerate or access screening MRI.11 Contrast-enhanced mammography (CEM) uses iodinated contrast (as in computed tomography). CEM is not widely available but appears to show cancer-detection similar to MRI. For further discussion, see Berg et al’s 2021 review.3

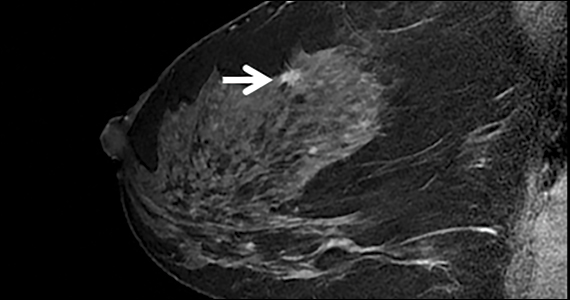

The FIGURE shows an example of an invasive cancer depicted on contrast-enhanced MRI in a 53-year-old woman with dense breasts and a family history of breast cancer that was not visible on tomosynthesis, even in retrospect, due to masking by dense tissue.

Considerations

Breast MRI increases callbacks even after mammography and ultrasound; however, such false alarms are reduced in subsequent screening rounds. MRI cannot be performed in women who have certain metal implants— some pacemakers or spinal fixation rods—and is not recommended for pregnant women. Claustrophobia may be an issue for some women. MRI is expensive and requires IV contrast. Gadolinium is known to accumulate in the brain, although the long-term effects of this are unknown and no harm has been shown.●

For more information, visit medically sourced DenseBreast-info.org. Comprehensive resources include a free CME opportunity, Dense Breasts and Supplemental Screening.

- Comstock CE, Gatsonis C, Newstead GM, et al. Comparison of abbreviated breast MRI vs digital breast tomosynthesis for breast cancer detection among women with dense breasts undergoing screening. JAMA. 2020;323:746-756. doi: 10.1001 /jama.2020.0572

- Kerlikowske K, Zhu W, Tosteson AN, et al. Identifying women with dense breasts at high risk for interval cancer: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:673-681. doi: 10.7326/M14-1465.

- Berg WA, Rafferty EA, Friedewald SM, Hruska CB, Rahbar H. Screening Algorithms in Dense Breasts: AJR Expert Panel Narrative Review. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2021;216:275-294. doi: 10.2214/AJR.20.24436.

- Kuhl CK, Strobel K, Bieling H, et al. Supplemental breast MR imaging screening of women with average risk of breast cancer. Radiology. 2017;283:361-370. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2016161444.

- Rafferty EA, Durand MA, Conant EF, et al. Breast cancer screening using tomosynthesis and digital mammography in dense and nondense breasts. JAMA. 2016;315:1784-1786. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.1708.

- Osteras BH, Martinsen ACT, Gullien R, et al. Digital mammography versus breast tomosynthesis: impact of breast density on diagnostic performance in population-based screening. Radiology. 2019;293:60-68. doi: 10.1148 /radiol.2019190425.

- Bakker MF, de Lange SV, Pijnappel RM, et al. Supplemental MRI screening for women with extremely dense breast tissue. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2091-2102. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1903986.

- Veenhuizen SGA, de Lange SV, Bakker MF, et al. Supplemental breast MRI for women with extremely dense breasts: results of the second screening round of the DENSE trial. Radiology. 2021;299:278-286. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2021203633.

- Vourtsis A, Berg WA. Breast density implications and supplemental screening. Eur Radiol. 2019;29:1762-1777. doi: 10.1007/s00330-018-5668-8.

- Berg WA, Vourtsis A. Screening ultrasound using handheld or automated technique in women with dense breasts. J Breast Imaging. 2019;1:283-296.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Breast Cancer Screening and Diagnosis (Version 1.2021). https://www.nccn. org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast-screening.pdf. Accessed November 18, 2021.

Text copyright DenseBreast-info.org.

Answer

A. For women with extremely dense breasts who are not otherwise at increased risk for breast cancer, screening magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is preferred, plus her mammogram or tomosynthesis. If MRI is not an option, consider ultrasonography or contrast-enhanced mammography.

The same screening considerations apply to women with heterogeneously dense breasts; however, there is limited capacity for MRI or even ultrasound screening at many facilities. Research supports MRI in dense breasts, and abbreviated, lower-cost protocols have been validated that address some of the barriers to MRI.1 Although not yet widely available, abbreviated MRI will likely have a greater role in screening women with dense breasts who are not high risk. It is important to note that preauthorization from insurance may be required for screening MRI, and in most US states, deductibles and copays apply.

The exam

Contrast-enhanced MRI requires IV injection of gadolinium-based contrast to look at the anatomy and blood flow patterns of the breast tissue. The patient lies face down with the breasts placed in two rectangular openings, or “coils.” The exam takes place inside the tunnel of the scanner, with the head facing out.After initial images are obtained, the contrast agent is injected into a vein in the arm, and additional images are taken, which will show areas of enhancement. The exam takes about 20 to 40 minutes. An “abbreviated” MRI can be performed for screening in some centers, which uses fewer sequences and takes about 10 minutes.

Benefits

At least 40% of cancers are missed on mammography in women with dense breasts.2 MRI is the most widely studied technique using a contrast agent, and it produces the highest additional cancer detection of all the supplemental technologies to date, yielding, in the first year, 10-16 additional cancers per 1,000 women screened after mammography/tomosynthesis (reviewed in Berg et al.3). The cancer-detection benefit is seen across all breast density categories, even among average-risk women.4 There is no ionizing radiation, and it has been shown to reduce the rate of interval cancers (those detected due to symptoms after a negative screening mammogram), as well as the rate of late-stage disease. Axillary lymph nodes can be examined at the same screening exam.

While tomosynthesis improves cancer detection in women with fatty breasts, scattered fibroglandular breast tissue, and heterogeneously dense breasts, it does not significantly improve cancer detection in women with extremely dense breasts.5,6 Current American Cancer Society and National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend annual screening MRI for women at high risk for breast cancer (regardless of breast density); however, increasingly, research supports the effectiveness of MRI in women with dense breasts who are otherwise considered average risk. A large randomized controlled trial in the Netherlands compared outcomes in women with extremely dense breasts invited to have screening MRI after negative mammography to those assigned to continue receiving screening mammography only. The incremental cancer detection rate was 16.5 per 1,000 (79/4,783) women screened with MRI in the first round7 and 6 per 1,000 women screened in the second round 2 years later.8 The interval cancer rate was 0.8 per 1,000 (4/4,783) women screened with MRI, compared with 4.9 per 1,000 (16/3,278) women who declined MRI and received mammography only.7

Screening ultrasound will show up to 3 additional cancers per 1,000 women screened after mammography/tomosynthesis (reviewed in Vourtsis and Berg9 and Berg and Vourtsis10), far lower than the added cancer-detection rate of MRI. Consider screening ultrasound for women who cannot tolerate or access screening MRI.11 Contrast-enhanced mammography (CEM) uses iodinated contrast (as in computed tomography). CEM is not widely available but appears to show cancer-detection similar to MRI. For further discussion, see Berg et al’s 2021 review.3

The FIGURE shows an example of an invasive cancer depicted on contrast-enhanced MRI in a 53-year-old woman with dense breasts and a family history of breast cancer that was not visible on tomosynthesis, even in retrospect, due to masking by dense tissue.

Considerations

Breast MRI increases callbacks even after mammography and ultrasound; however, such false alarms are reduced in subsequent screening rounds. MRI cannot be performed in women who have certain metal implants— some pacemakers or spinal fixation rods—and is not recommended for pregnant women. Claustrophobia may be an issue for some women. MRI is expensive and requires IV contrast. Gadolinium is known to accumulate in the brain, although the long-term effects of this are unknown and no harm has been shown.●

For more information, visit medically sourced DenseBreast-info.org. Comprehensive resources include a free CME opportunity, Dense Breasts and Supplemental Screening.

Text copyright DenseBreast-info.org.

Answer

A. For women with extremely dense breasts who are not otherwise at increased risk for breast cancer, screening magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is preferred, plus her mammogram or tomosynthesis. If MRI is not an option, consider ultrasonography or contrast-enhanced mammography.

The same screening considerations apply to women with heterogeneously dense breasts; however, there is limited capacity for MRI or even ultrasound screening at many facilities. Research supports MRI in dense breasts, and abbreviated, lower-cost protocols have been validated that address some of the barriers to MRI.1 Although not yet widely available, abbreviated MRI will likely have a greater role in screening women with dense breasts who are not high risk. It is important to note that preauthorization from insurance may be required for screening MRI, and in most US states, deductibles and copays apply.

The exam

Contrast-enhanced MRI requires IV injection of gadolinium-based contrast to look at the anatomy and blood flow patterns of the breast tissue. The patient lies face down with the breasts placed in two rectangular openings, or “coils.” The exam takes place inside the tunnel of the scanner, with the head facing out.After initial images are obtained, the contrast agent is injected into a vein in the arm, and additional images are taken, which will show areas of enhancement. The exam takes about 20 to 40 minutes. An “abbreviated” MRI can be performed for screening in some centers, which uses fewer sequences and takes about 10 minutes.

Benefits

At least 40% of cancers are missed on mammography in women with dense breasts.2 MRI is the most widely studied technique using a contrast agent, and it produces the highest additional cancer detection of all the supplemental technologies to date, yielding, in the first year, 10-16 additional cancers per 1,000 women screened after mammography/tomosynthesis (reviewed in Berg et al.3). The cancer-detection benefit is seen across all breast density categories, even among average-risk women.4 There is no ionizing radiation, and it has been shown to reduce the rate of interval cancers (those detected due to symptoms after a negative screening mammogram), as well as the rate of late-stage disease. Axillary lymph nodes can be examined at the same screening exam.

While tomosynthesis improves cancer detection in women with fatty breasts, scattered fibroglandular breast tissue, and heterogeneously dense breasts, it does not significantly improve cancer detection in women with extremely dense breasts.5,6 Current American Cancer Society and National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend annual screening MRI for women at high risk for breast cancer (regardless of breast density); however, increasingly, research supports the effectiveness of MRI in women with dense breasts who are otherwise considered average risk. A large randomized controlled trial in the Netherlands compared outcomes in women with extremely dense breasts invited to have screening MRI after negative mammography to those assigned to continue receiving screening mammography only. The incremental cancer detection rate was 16.5 per 1,000 (79/4,783) women screened with MRI in the first round7 and 6 per 1,000 women screened in the second round 2 years later.8 The interval cancer rate was 0.8 per 1,000 (4/4,783) women screened with MRI, compared with 4.9 per 1,000 (16/3,278) women who declined MRI and received mammography only.7

Screening ultrasound will show up to 3 additional cancers per 1,000 women screened after mammography/tomosynthesis (reviewed in Vourtsis and Berg9 and Berg and Vourtsis10), far lower than the added cancer-detection rate of MRI. Consider screening ultrasound for women who cannot tolerate or access screening MRI.11 Contrast-enhanced mammography (CEM) uses iodinated contrast (as in computed tomography). CEM is not widely available but appears to show cancer-detection similar to MRI. For further discussion, see Berg et al’s 2021 review.3

The FIGURE shows an example of an invasive cancer depicted on contrast-enhanced MRI in a 53-year-old woman with dense breasts and a family history of breast cancer that was not visible on tomosynthesis, even in retrospect, due to masking by dense tissue.

Considerations

Breast MRI increases callbacks even after mammography and ultrasound; however, such false alarms are reduced in subsequent screening rounds. MRI cannot be performed in women who have certain metal implants— some pacemakers or spinal fixation rods—and is not recommended for pregnant women. Claustrophobia may be an issue for some women. MRI is expensive and requires IV contrast. Gadolinium is known to accumulate in the brain, although the long-term effects of this are unknown and no harm has been shown.●

For more information, visit medically sourced DenseBreast-info.org. Comprehensive resources include a free CME opportunity, Dense Breasts and Supplemental Screening.

- Comstock CE, Gatsonis C, Newstead GM, et al. Comparison of abbreviated breast MRI vs digital breast tomosynthesis for breast cancer detection among women with dense breasts undergoing screening. JAMA. 2020;323:746-756. doi: 10.1001 /jama.2020.0572

- Kerlikowske K, Zhu W, Tosteson AN, et al. Identifying women with dense breasts at high risk for interval cancer: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:673-681. doi: 10.7326/M14-1465.

- Berg WA, Rafferty EA, Friedewald SM, Hruska CB, Rahbar H. Screening Algorithms in Dense Breasts: AJR Expert Panel Narrative Review. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2021;216:275-294. doi: 10.2214/AJR.20.24436.

- Kuhl CK, Strobel K, Bieling H, et al. Supplemental breast MR imaging screening of women with average risk of breast cancer. Radiology. 2017;283:361-370. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2016161444.

- Rafferty EA, Durand MA, Conant EF, et al. Breast cancer screening using tomosynthesis and digital mammography in dense and nondense breasts. JAMA. 2016;315:1784-1786. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.1708.

- Osteras BH, Martinsen ACT, Gullien R, et al. Digital mammography versus breast tomosynthesis: impact of breast density on diagnostic performance in population-based screening. Radiology. 2019;293:60-68. doi: 10.1148 /radiol.2019190425.

- Bakker MF, de Lange SV, Pijnappel RM, et al. Supplemental MRI screening for women with extremely dense breast tissue. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2091-2102. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1903986.

- Veenhuizen SGA, de Lange SV, Bakker MF, et al. Supplemental breast MRI for women with extremely dense breasts: results of the second screening round of the DENSE trial. Radiology. 2021;299:278-286. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2021203633.

- Vourtsis A, Berg WA. Breast density implications and supplemental screening. Eur Radiol. 2019;29:1762-1777. doi: 10.1007/s00330-018-5668-8.

- Berg WA, Vourtsis A. Screening ultrasound using handheld or automated technique in women with dense breasts. J Breast Imaging. 2019;1:283-296.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Breast Cancer Screening and Diagnosis (Version 1.2021). https://www.nccn. org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast-screening.pdf. Accessed November 18, 2021.

- Comstock CE, Gatsonis C, Newstead GM, et al. Comparison of abbreviated breast MRI vs digital breast tomosynthesis for breast cancer detection among women with dense breasts undergoing screening. JAMA. 2020;323:746-756. doi: 10.1001 /jama.2020.0572

- Kerlikowske K, Zhu W, Tosteson AN, et al. Identifying women with dense breasts at high risk for interval cancer: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:673-681. doi: 10.7326/M14-1465.

- Berg WA, Rafferty EA, Friedewald SM, Hruska CB, Rahbar H. Screening Algorithms in Dense Breasts: AJR Expert Panel Narrative Review. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2021;216:275-294. doi: 10.2214/AJR.20.24436.

- Kuhl CK, Strobel K, Bieling H, et al. Supplemental breast MR imaging screening of women with average risk of breast cancer. Radiology. 2017;283:361-370. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2016161444.

- Rafferty EA, Durand MA, Conant EF, et al. Breast cancer screening using tomosynthesis and digital mammography in dense and nondense breasts. JAMA. 2016;315:1784-1786. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.1708.

- Osteras BH, Martinsen ACT, Gullien R, et al. Digital mammography versus breast tomosynthesis: impact of breast density on diagnostic performance in population-based screening. Radiology. 2019;293:60-68. doi: 10.1148 /radiol.2019190425.

- Bakker MF, de Lange SV, Pijnappel RM, et al. Supplemental MRI screening for women with extremely dense breast tissue. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2091-2102. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1903986.

- Veenhuizen SGA, de Lange SV, Bakker MF, et al. Supplemental breast MRI for women with extremely dense breasts: results of the second screening round of the DENSE trial. Radiology. 2021;299:278-286. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2021203633.

- Vourtsis A, Berg WA. Breast density implications and supplemental screening. Eur Radiol. 2019;29:1762-1777. doi: 10.1007/s00330-018-5668-8.

- Berg WA, Vourtsis A. Screening ultrasound using handheld or automated technique in women with dense breasts. J Breast Imaging. 2019;1:283-296.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Breast Cancer Screening and Diagnosis (Version 1.2021). https://www.nccn. org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast-screening.pdf. Accessed November 18, 2021.

Quiz developed in collaboration with

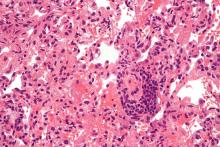

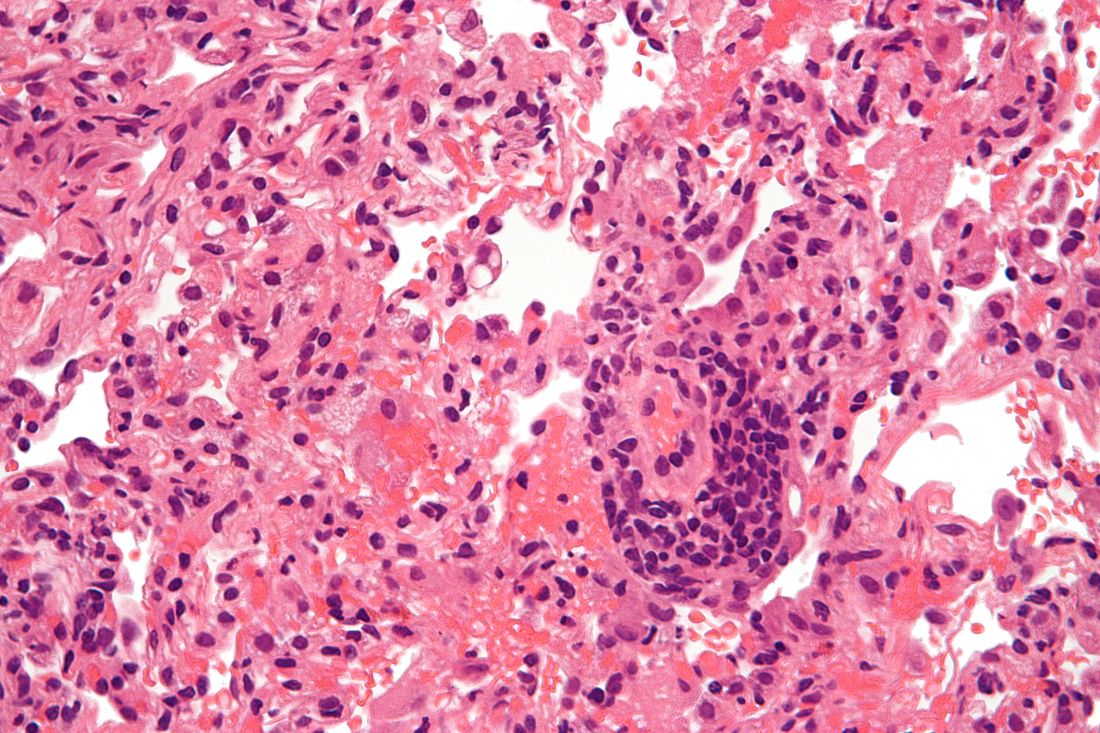

Lung transplantation in the era of COVID-19: New issues and paradigms

Data is sparse thus far, but there is concern in lung transplant medicine about the long-term risk of chronic lung allograft dysfunction (CLAD) and a potentially shortened longevity of transplanted lungs in recipients who become ill with COVID-19.

“My fear is that we’re potentially sitting on this iceberg worth of people who, come 6 months or a year from [the acute phase of] their COVID illness, will in fact have earlier and progressive, chronic rejection,” said Cameron R. Wolfe, MBBS, MPH, associate professor of medicine in transplant infectious disease at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

Lower respiratory viral infections have long been concerning for lung transplant recipients given their propensity to cause scarring, a decline in lung function, and a heightened risk of allograft rejection. Time will tell whether lung transplant recipients who survive COVID-19 follow a similar path, or one that is worse, he said.

Short-term data

Outcomes beyond hospitalization and acute illness for lung transplant recipients affected by COVID-19 have been reported in the literature by only a few lung transplant programs. These reports – as well as anecdotal experiences being informally shared among transplant programs – have raised the specter of more severe dysfunction following the acute phase and more early CLAD, said Tathagat Narula, MD, assistant professor of medicine at the Mayo Medical School, Rochester, Minn., and a consultant in lung transplantation at the Mayo Clinic’s Jacksonville program.

“The available data cover only 3-6 months out. We don’t know what will happen in the next 6 months and beyond,” Dr. Narula said in an interview.

The risks of COVID-19 in already-transplanted patients and issues relating to the inadequate antibody responses to vaccination are just some of the challenges of lung transplant medicine in the era of SARS-CoV-2. “COVID-19,” said Dr. Narula, “has completely changed the way we practice lung transplant medicine – the way we’re looking both at our recipients and our donors.”

Potential donors are being evaluated with lower respiratory SARS-CoV-2 testing and an abundance of caution. And patients with severe COVID-19 affecting their own lungs are roundly expected to drive up lung transplant volume in the near future. “The whole paradigm has changed,” Dr. Narula said.

Post-acute trajectories

A chart review study published in October by the lung transplant team at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, covered 44 consecutive survivors at a median follow-up of 4.5 months from hospital discharge or acute illness (the survival rate was 83.3%). Patients had significantly impaired functional status, and 18 of the 44 (40.9%) had a significant and persistent loss of forced vital capacity or forced expiratory volume in 1 second (>10% from pre–COVID-19 baseline).

Three patients met the criteria for new CLAD after COVID-19 infection, with all three classified as restrictive allograft syndrome (RAS) phenotype.

Moreover, the majority of COVID-19 survivors who had CT chest scans (22 of 28) showed persistent parenchymal opacities – a finding that, regardless of symptomatology, suggests persistent allograft injury, said Amit Banga, MD, associate professor of medicine and medical director of the ex vivo lung perfusion program in UT Southwestern’s lung transplant program.

“The implication is that there may be long-term consequences of COVID-19, perhaps related to some degree of ongoing inflammation and damage,” said Dr. Banga, a coauthor of the postinfection outcomes paper.

The UT Southwestern lung transplant program, which normally performs 60-80 transplants a year, began routine CT scanning 4-5 months into the pandemic, after “stumbling into a few patients who had no symptoms indicative of COVID pneumonia and no changes on an x-ray but significant involvement on a CT,” he said.

Without routine scanning in the general population of COVID-19 patients, Dr. Banga noted, “we’re limited in convincingly saying that COVID is uniquely doing this to lung transplant recipients.” Nor can they conclude that SARS-CoV-2 is unique from other respiratory viruses such as respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) in this regard. (The program has added CT scanning to its protocol for lung transplant recipients afflicted with other respiratory viruses to learn more.)

However, in the big picture, COVID-19 has proven to be far worse for lung transplant recipients than illness with other respiratory viruses, including RSV. “Patients have more frequent and greater loss of lung function, and worse debility from the acute illness,” Dr. Banga said.

“The cornerstones of treatment of both these viruses are very similar, but both the in-hospital course and the postdischarge outcomes are significantly different.”

In an initial paper published in September 2021, Dr. Banga and colleagues compared their first 25 lung transplant patients testing positive for SARS-CoV-2 with a historical cohort of 36 patients with RSV treated during 2016-2018.

Patients with COVID-19 had significantly worse morbidity and mortality, including worse postinfection lung function loss, functional decline, and 3-month survival.

More time, he said, will shed light on the risks of CLAD and the long-term potential for recovery of lung function. Currently, at UT Southwestern, it appears that patients who survive acute illness and the “first 3-6 months after COVID-19, when we’re seeing all the postinfection morbidity, may [enter] a period of stability,” Dr. Banga said.

Overall, he said, patients in their initial cohort are “holding steady” without unusual morbidity, readmissions, or “other setbacks to their allografts.”

At the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, which normally performs 40-50 lung transplants a year, transplant physicians have similarly observed significant declines in lung function beyond the acute phase of COVID-19. “Anecdotally, we’re seeing that some patients are beginning to recover some of their lung function, while others have not,” said Dr. Narula. “And we don’t have predictors as to who will progress to CLAD. It’s a big knowledge gap.”

Dr. Narula noted that patients with restrictive allograft syndrome, such as those reported by the UT Southwestern team, “have scarring of the lung and a much worse prognosis than the obstructive type of chronic rejection.” Whether there’s a role for antifibrotic therapy is a question worthy of research.

In UT Southwestern’s analysis, persistently lower absolute lymphocyte counts (< 600/dL) and higher ferritin levels (>150 ng/mL) at the time of hospital discharge were independently associated with significant lung function loss. This finding, reported in their October paper, has helped guide their management practices, Dr. Banga said.

“Persistently elevated ferritin may indicate ongoing inflammation at the allograft level,” he said. “We now send [such patients] home on a longer course of oral corticosteroids.”

At the front end of care for infected lung transplant recipients, Dr. Banga said that his team and physicians at other lung transplant programs are holding the cell-cycle inhibitor component of patients’ maintenance immunosuppression therapy (commonly mycophenolate or azathioprine) once infection is diagnosed to maximize chances of a better outcome.

“There may be variation on how long [the regimens are adjusted],” he said. “We changed our duration from 4 weeks to 2 due to patients developing a rebound worsening in the third and fourth week of acute illness.”

There is significant variation from institution to institution in how viral infections are managed in lung transplant recipients, he and Dr. Narula said. “Our numbers are so small in lung transplant, and we don’t have standardized protocols – it’s one of the biggest challenges in our field,” said Dr. Narula.

Vaccination issues, evaluation of donors

Whether or not immunosuppression regimens should be adjusted prior to vaccination is a controversial question, but is “an absolutely valid one” and is currently being studied in at least one National Institutes of Health–funded trial involving solid organ transplant recipients, said Dr. Wolfe.

“Some have jumped to the conclusion [based on some earlier data] that they should reduce immunosuppression regimens for everyone at the time of vaccination ... but I don’t know the answer yet,” he said. “Balancing staying rejection free with potentially gaining more immune response is complicated ... and it may depend on where the pandemic is going in your area and other factors.”

Reductions aside, Dr. Wolfe tells lung transplant recipients that, based on his approximation of a number of different studies in solid organ transplant recipients, approximately 40%-50% of patients who are immunized with two doses of the COVID-19 mRNA vaccines will develop meaningful antibody levels – and that this rises to 50%-60% after a third dose.

It is difficult to glean from available studies the level of vaccine response for lung transplant recipients specifically. But given that their level of maintenance immunosuppression is higher than for recipients of other donor organs, “as a broad sweep, lung transplant recipients tend to be lower in the pecking order of response,” he said.

Still, “there’s a lot to gain,” he said, pointing to a recent study from the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (2021 Nov 5. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7044e3) showing that effectiveness of mRNA vaccination against COVID-19–associated hospitalization was 77% among immunocompromised adults (compared with 90% in immunocompetent adults).

“This is good vindication to keep vaccinating,” he said, “and perhaps speaks to how difficult it is to assess the vaccine response [through measurement of antibody only].”

Neither Duke University’s transplant program, which performed 100-120 lung transplants a year pre-COVID, nor the programs at UT Southwestern or the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville require that solid organ transplant candidates be vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2 in order to receive transplants, as some other transplant programs have done. (When asked about the issue, Dr. Banga and Dr. Narula each said that they have had no or little trouble convincing patients awaiting lung transplants of the need for COVID-19 vaccination.)

In an August statement, the American Society of Transplantation recommended vaccination for all solid organ transplant recipients, preferably prior to transplantation, and said that it “support[s] the development of institutional policies regarding pretransplant vaccination.”

The Society is not tracking centers’ vaccination policies. But Kaiser Health News reported in October that a growing number of transplant programs, such as UCHealth in Denver and UW Medicine in Seattle, have decided to either bar patients who refuse to be vaccinated from receiving transplants or give them lower priority on waitlists.

Potential lung donors, meanwhile, must be evaluated with lower respiratory COVID-19 testing, with results available prior to transplantation, according to policy developed by the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network and effective in May 2021. The policy followed three published cases of donor-derived COVID-19 in lung transplant recipients, said Dr. Wolfe, who wrote about use of COVID-positive donors in an editorial published in October.

In each case, the donor had a negative COVID-19 nasopharyngeal swab at the time of organ procurement but was later found to have the virus on bronchoalveolar lavage, he said.

(The use of other organs from COVID-positive donors is appearing thus far to be safe, Dr. Wolfe noted. In the editorial, he references 13 cases of solid organ transplantation from SARS-CoV-2–infected donors into noninfected recipients; none of the 13 transplant recipients developed COVID-19).

Some questions remain, such as how many lower respiratory tests should be run, and how donors should be evaluated in cases of discordant results. Dr. Banga shared the case of a donor with one positive lower respiratory test result followed by two negative results. After internal debate, and consideration of potential false positives and other issues, the team at UT Southwestern decided to decline the donor, Dr. Banga said.

Other programs are likely making similar, appropriately cautious decisions, said Dr. Wolfe. “There’s no way in real-time donor evaluation to know whether the positive test is active virus that could infect the recipient and replicate ... or whether it’s [picking up] inactive or dead fragments of virus that was there several weeks ago. Our tests don’t differentiate that.”

Transplants in COVID-19 patients

Decision-making about lung transplant candidacy among patients with COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome is complex and in need of a new paradigm.

“Some of these patients have the potential to recover, and they’re going to recover way later than what we’re used to,” said Dr. Banga. “We can’t extrapolate for COVID ARDS what we’ve learned for any other virus-related ARDS.”

Dr. Narula also has recently seen at least one COVID-19 patient on ECMO and under evaluation for transplantation recover. “We do not want to transplant too early,” he said, noting that there is consensus that lung transplant should be pursued only when the damage is deemed irreversible clinically and radiologically in the best judgment of the team. Still, “for many of these patients the only exit route will be lung transplants. For the next 12-24 months, a significant proportion of our lung transplant patients will have had post-COVID–related lung damage.”

As of October 2021, 233 lung transplants had been performed in the United States in recipients whose primary diagnosis was reported as COVID related, said Anne Paschke, media relations specialist with the United Network for Organ Sharing.

Dr. Banga, Dr. Wolfe, and Dr. Narula reported that they have no relevant disclosures.

Data is sparse thus far, but there is concern in lung transplant medicine about the long-term risk of chronic lung allograft dysfunction (CLAD) and a potentially shortened longevity of transplanted lungs in recipients who become ill with COVID-19.

“My fear is that we’re potentially sitting on this iceberg worth of people who, come 6 months or a year from [the acute phase of] their COVID illness, will in fact have earlier and progressive, chronic rejection,” said Cameron R. Wolfe, MBBS, MPH, associate professor of medicine in transplant infectious disease at Duke University, Durham, N.C.

Lower respiratory viral infections have long been concerning for lung transplant recipients given their propensity to cause scarring, a decline in lung function, and a heightened risk of allograft rejection. Time will tell whether lung transplant recipients who survive COVID-19 follow a similar path, or one that is worse, he said.

Short-term data

Outcomes beyond hospitalization and acute illness for lung transplant recipients affected by COVID-19 have been reported in the literature by only a few lung transplant programs. These reports – as well as anecdotal experiences being informally shared among transplant programs – have raised the specter of more severe dysfunction following the acute phase and more early CLAD, said Tathagat Narula, MD, assistant professor of medicine at the Mayo Medical School, Rochester, Minn., and a consultant in lung transplantation at the Mayo Clinic’s Jacksonville program.

“The available data cover only 3-6 months out. We don’t know what will happen in the next 6 months and beyond,” Dr. Narula said in an interview.

The risks of COVID-19 in already-transplanted patients and issues relating to the inadequate antibody responses to vaccination are just some of the challenges of lung transplant medicine in the era of SARS-CoV-2. “COVID-19,” said Dr. Narula, “has completely changed the way we practice lung transplant medicine – the way we’re looking both at our recipients and our donors.”

Potential donors are being evaluated with lower respiratory SARS-CoV-2 testing and an abundance of caution. And patients with severe COVID-19 affecting their own lungs are roundly expected to drive up lung transplant volume in the near future. “The whole paradigm has changed,” Dr. Narula said.

Post-acute trajectories

A chart review study published in October by the lung transplant team at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, covered 44 consecutive survivors at a median follow-up of 4.5 months from hospital discharge or acute illness (the survival rate was 83.3%). Patients had significantly impaired functional status, and 18 of the 44 (40.9%) had a significant and persistent loss of forced vital capacity or forced expiratory volume in 1 second (>10% from pre–COVID-19 baseline).

Three patients met the criteria for new CLAD after COVID-19 infection, with all three classified as restrictive allograft syndrome (RAS) phenotype.

Moreover, the majority of COVID-19 survivors who had CT chest scans (22 of 28) showed persistent parenchymal opacities – a finding that, regardless of symptomatology, suggests persistent allograft injury, said Amit Banga, MD, associate professor of medicine and medical director of the ex vivo lung perfusion program in UT Southwestern’s lung transplant program.

“The implication is that there may be long-term consequences of COVID-19, perhaps related to some degree of ongoing inflammation and damage,” said Dr. Banga, a coauthor of the postinfection outcomes paper.