User login

Obesity, hypoxia predict severity in children with COVID-19

based on data from 281 patients at 8 locations.

Manifestations of COVID-19 in children include respiratory disease similar to that seen in adults, but the full spectrum of disease in children has been studied mainly in single settings or with a focus on one clinical manifestation, wrote Danielle M. Fernandes, MD, of Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, and colleagues.

In a study published in the Journal of Pediatrics, the researchers identified 281 children hospitalized with COVID-19 and/or multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) at 8 sites in Connecticut, New Jersey, and New York. A total of 143 (51%) had respiratory disease, 69 (25%) had MIS-C, and 69 (25%) had other manifestations of illness including 32 patients with gastrointestinal problems, 21 infants with fever, 6 cases of neurologic disease, 6 cases of diabetic ketoacidosis, and 4 patients with other indications. The median age of the patients was 10 years, 60% were male, 51% were Hispanic, and 23% were non-Hispanic Black. The most common comorbidities were obesity (34%) and asthma (14%).

Independent predictors of disease severity in children found

After controlling for multiple variables, obesity and hypoxia at hospital admission were significant independent predictors of severe respiratory disease, with odds ratios of 3.39 and 4.01, respectively. In addition, lower absolute lymphocyte count (OR, 8.33 per unit decrease in 109 cells/L) and higher C-reactive protein (OR, 1.06 per unit increase in mg/dL) were significantly predictive of severe MIS-C (P = .001 and P = .017, respectively).

“The association between weight and severe respiratory COVID-19 is consistent with the adult literature; however, the mechanisms of this association require further study,” Dr. Fernandes and associates noted.

Overall, children with MIS-C were significantly more likely to be non-Hispanic Black, compared with children with respiratory disease, an 18% difference. However, neither race/ethnicity nor socioeconomic status were significant predictors of disease severity, the researchers wrote.

During the study period, 7 patients (2%) died and 114 (41%) were admitted to the ICU.

“We found a wide array of clinical manifestations in children and youth hospitalized with SARS-CoV-2,” Dr. Fernandes and associates wrote. Notably, gastrointestinal symptoms, ocular symptoms, and dermatologic symptoms have rarely been noted in adults with COVID-19, but occurred in more than 30% of the pediatric patients.

“We also found that SARS-CoV-2 can be an incidental finding in a substantial number of hospitalized pediatric patients,” the researchers said.

The findings were limited by several factors including a population of patients only from Connecticut, New Jersey, and New York, and the possibility that decisions on hospital and ICU admission may have varied by location, the researchers said. In addition, approaches may have varied in the absence of data on the optimal treatment of MIS-C.

“This study builds on the growing body of evidence showing that mortality in hospitalized pediatric patients is low, compared with adults,” Dr. Fernandes and associates said. “However, it highlights that the young population is not universally spared from morbidity, and that even previously healthy children and youth can develop severe disease requiring supportive therapy.”

Findings confirm other clinical experience

The study was important to show that, “although most children are spared severe illness from COVID-19, some children are hospitalized both with acute COVID-19 respiratory disease, with MIS-C and with a range of other complications,” Adrienne Randolph, MD, of Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in an interview.

Dr. Randolph said she was not surprised by the study findings, “as we are also seeing these types of complications at Boston Children’s Hospital where I work.”

Additional research is needed on the outcomes of these patients, “especially the longer-term sequelae of having COVID-19 or MIS-C early in life,” she emphasized.

The take-home message to clinicians from the findings at this time is to be aware that children and adolescents can become severely ill from COVID-19–related complications, said Dr. Randolph. “Some of the laboratory values on presentation appear to be associated with disease severity.”

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Randolph disclosed funding from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to lead the Overcoming COVID-19 Study in U.S. Children and Adults.

SOURCE: Fernandes DM et al. J Pediatr. 2020 Nov 13. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.11.016.

based on data from 281 patients at 8 locations.

Manifestations of COVID-19 in children include respiratory disease similar to that seen in adults, but the full spectrum of disease in children has been studied mainly in single settings or with a focus on one clinical manifestation, wrote Danielle M. Fernandes, MD, of Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, and colleagues.

In a study published in the Journal of Pediatrics, the researchers identified 281 children hospitalized with COVID-19 and/or multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) at 8 sites in Connecticut, New Jersey, and New York. A total of 143 (51%) had respiratory disease, 69 (25%) had MIS-C, and 69 (25%) had other manifestations of illness including 32 patients with gastrointestinal problems, 21 infants with fever, 6 cases of neurologic disease, 6 cases of diabetic ketoacidosis, and 4 patients with other indications. The median age of the patients was 10 years, 60% were male, 51% were Hispanic, and 23% were non-Hispanic Black. The most common comorbidities were obesity (34%) and asthma (14%).

Independent predictors of disease severity in children found

After controlling for multiple variables, obesity and hypoxia at hospital admission were significant independent predictors of severe respiratory disease, with odds ratios of 3.39 and 4.01, respectively. In addition, lower absolute lymphocyte count (OR, 8.33 per unit decrease in 109 cells/L) and higher C-reactive protein (OR, 1.06 per unit increase in mg/dL) were significantly predictive of severe MIS-C (P = .001 and P = .017, respectively).

“The association between weight and severe respiratory COVID-19 is consistent with the adult literature; however, the mechanisms of this association require further study,” Dr. Fernandes and associates noted.

Overall, children with MIS-C were significantly more likely to be non-Hispanic Black, compared with children with respiratory disease, an 18% difference. However, neither race/ethnicity nor socioeconomic status were significant predictors of disease severity, the researchers wrote.

During the study period, 7 patients (2%) died and 114 (41%) were admitted to the ICU.

“We found a wide array of clinical manifestations in children and youth hospitalized with SARS-CoV-2,” Dr. Fernandes and associates wrote. Notably, gastrointestinal symptoms, ocular symptoms, and dermatologic symptoms have rarely been noted in adults with COVID-19, but occurred in more than 30% of the pediatric patients.

“We also found that SARS-CoV-2 can be an incidental finding in a substantial number of hospitalized pediatric patients,” the researchers said.

The findings were limited by several factors including a population of patients only from Connecticut, New Jersey, and New York, and the possibility that decisions on hospital and ICU admission may have varied by location, the researchers said. In addition, approaches may have varied in the absence of data on the optimal treatment of MIS-C.

“This study builds on the growing body of evidence showing that mortality in hospitalized pediatric patients is low, compared with adults,” Dr. Fernandes and associates said. “However, it highlights that the young population is not universally spared from morbidity, and that even previously healthy children and youth can develop severe disease requiring supportive therapy.”

Findings confirm other clinical experience

The study was important to show that, “although most children are spared severe illness from COVID-19, some children are hospitalized both with acute COVID-19 respiratory disease, with MIS-C and with a range of other complications,” Adrienne Randolph, MD, of Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in an interview.

Dr. Randolph said she was not surprised by the study findings, “as we are also seeing these types of complications at Boston Children’s Hospital where I work.”

Additional research is needed on the outcomes of these patients, “especially the longer-term sequelae of having COVID-19 or MIS-C early in life,” she emphasized.

The take-home message to clinicians from the findings at this time is to be aware that children and adolescents can become severely ill from COVID-19–related complications, said Dr. Randolph. “Some of the laboratory values on presentation appear to be associated with disease severity.”

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Randolph disclosed funding from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to lead the Overcoming COVID-19 Study in U.S. Children and Adults.

SOURCE: Fernandes DM et al. J Pediatr. 2020 Nov 13. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.11.016.

based on data from 281 patients at 8 locations.

Manifestations of COVID-19 in children include respiratory disease similar to that seen in adults, but the full spectrum of disease in children has been studied mainly in single settings or with a focus on one clinical manifestation, wrote Danielle M. Fernandes, MD, of Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, and colleagues.

In a study published in the Journal of Pediatrics, the researchers identified 281 children hospitalized with COVID-19 and/or multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) at 8 sites in Connecticut, New Jersey, and New York. A total of 143 (51%) had respiratory disease, 69 (25%) had MIS-C, and 69 (25%) had other manifestations of illness including 32 patients with gastrointestinal problems, 21 infants with fever, 6 cases of neurologic disease, 6 cases of diabetic ketoacidosis, and 4 patients with other indications. The median age of the patients was 10 years, 60% were male, 51% were Hispanic, and 23% were non-Hispanic Black. The most common comorbidities were obesity (34%) and asthma (14%).

Independent predictors of disease severity in children found

After controlling for multiple variables, obesity and hypoxia at hospital admission were significant independent predictors of severe respiratory disease, with odds ratios of 3.39 and 4.01, respectively. In addition, lower absolute lymphocyte count (OR, 8.33 per unit decrease in 109 cells/L) and higher C-reactive protein (OR, 1.06 per unit increase in mg/dL) were significantly predictive of severe MIS-C (P = .001 and P = .017, respectively).

“The association between weight and severe respiratory COVID-19 is consistent with the adult literature; however, the mechanisms of this association require further study,” Dr. Fernandes and associates noted.

Overall, children with MIS-C were significantly more likely to be non-Hispanic Black, compared with children with respiratory disease, an 18% difference. However, neither race/ethnicity nor socioeconomic status were significant predictors of disease severity, the researchers wrote.

During the study period, 7 patients (2%) died and 114 (41%) were admitted to the ICU.

“We found a wide array of clinical manifestations in children and youth hospitalized with SARS-CoV-2,” Dr. Fernandes and associates wrote. Notably, gastrointestinal symptoms, ocular symptoms, and dermatologic symptoms have rarely been noted in adults with COVID-19, but occurred in more than 30% of the pediatric patients.

“We also found that SARS-CoV-2 can be an incidental finding in a substantial number of hospitalized pediatric patients,” the researchers said.

The findings were limited by several factors including a population of patients only from Connecticut, New Jersey, and New York, and the possibility that decisions on hospital and ICU admission may have varied by location, the researchers said. In addition, approaches may have varied in the absence of data on the optimal treatment of MIS-C.

“This study builds on the growing body of evidence showing that mortality in hospitalized pediatric patients is low, compared with adults,” Dr. Fernandes and associates said. “However, it highlights that the young population is not universally spared from morbidity, and that even previously healthy children and youth can develop severe disease requiring supportive therapy.”

Findings confirm other clinical experience

The study was important to show that, “although most children are spared severe illness from COVID-19, some children are hospitalized both with acute COVID-19 respiratory disease, with MIS-C and with a range of other complications,” Adrienne Randolph, MD, of Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in an interview.

Dr. Randolph said she was not surprised by the study findings, “as we are also seeing these types of complications at Boston Children’s Hospital where I work.”

Additional research is needed on the outcomes of these patients, “especially the longer-term sequelae of having COVID-19 or MIS-C early in life,” she emphasized.

The take-home message to clinicians from the findings at this time is to be aware that children and adolescents can become severely ill from COVID-19–related complications, said Dr. Randolph. “Some of the laboratory values on presentation appear to be associated with disease severity.”

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Randolph disclosed funding from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to lead the Overcoming COVID-19 Study in U.S. Children and Adults.

SOURCE: Fernandes DM et al. J Pediatr. 2020 Nov 13. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.11.016.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF PEDIATRICS

Cervical cancer recurrence patterns differ after laparoscopic and open hysterectomy

When cervical cancer recurs after radical hysterectomy, the likelihood of recurrence at certain sites and the timing of recurrence may be associated with the surgical approach, according to a retrospective study.

according to a propensity-matched analysis of data from 105 patients with recurrence.

And recurrence in the pelvic cavity and peritoneal carcinomatosis were more common after laparoscopic hysterectomy than after open surgery. Overall survival was similar between the groups, however.

The different patterns of recurrence may relate to dissemination of the disease during colpotomy, but the reasons are unknown, study author Giorgio Bogani, MD, PhD, said at the meeting sponsored by AAGL.

To examine patterns of recurrence after laparoscopic and open abdominal radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer, Dr. Bogani of the department of gynecologic surgery at the National Cancer Institute in Milan and colleagues analyzed data from patients with cervical cancer who developed recurrence after surgery at two oncologic referral centers between 1990 and 2018 (Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2020 Jul. doi: 10.1136/ijgc-2020-001381).

The investigators applied a propensity-matching algorithm to reduce possible confounding factors. They matched 35 patients who had recurrence after laparoscopic hysterectomy to 70 patients who had recurrence after open surgery. The groups had similar baseline characteristics.

As in the Laparoscopic Approach to Cervical Cancer (LACC) trial, patients who had minimally invasive surgery were more likely to have a worse disease-free survival, compared with patients who had open surgery, Dr. Bogani said. Patients who underwent laparoscopic radical hysterectomy had a median progression-free survival of 8 months, whereas patients who underwent open abdominal procedures had a median progression-free survival of 15.8 months.

Although vaginal, lymphatic, and distant recurrences were similar between the groups, a greater percentage of patients in the laparoscopic hysterectomy group had recurrence in the pelvic cavity (74% vs. 34%) and peritoneal carcinomatosis (17% vs. 1.5%).

The LACC trial, which found significantly lower disease-free and overall survival with laparoscopic hysterectomy, sent a “shockwave through the gynecologic oncology community” when it was published in 2018, said Masoud Azodi, MD, in a discussion following Dr. Bogani’s presentation.

Researchers have raised questions about that trial’s design and validity, noted Dr. Azodi, director of minimally invasive and robotic surgery at Yale University in New Haven, Conn.

It could be that local recurrences are attributable to surgical technique, rather than to the minimally invasive approach in itself, Dr. Azodi said. Prior studies of laparoscopic hysterectomy for cervical cancer had indicated better surgical outcomes and equivalent oncologic results, relative to open surgery.

Before the LACC trial, Dr. Bogani used the minimally invasive approach for almost all surgeries. Since then, he has performed open surgeries. If he were to use a minimally invasive approach now, it would be in the context of a clinical trial, Dr. Bogani said.

Dr. Bogani and Dr. Azodi had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Bogani G et al. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020 Nov. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2020.08.069.

When cervical cancer recurs after radical hysterectomy, the likelihood of recurrence at certain sites and the timing of recurrence may be associated with the surgical approach, according to a retrospective study.

according to a propensity-matched analysis of data from 105 patients with recurrence.

And recurrence in the pelvic cavity and peritoneal carcinomatosis were more common after laparoscopic hysterectomy than after open surgery. Overall survival was similar between the groups, however.

The different patterns of recurrence may relate to dissemination of the disease during colpotomy, but the reasons are unknown, study author Giorgio Bogani, MD, PhD, said at the meeting sponsored by AAGL.

To examine patterns of recurrence after laparoscopic and open abdominal radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer, Dr. Bogani of the department of gynecologic surgery at the National Cancer Institute in Milan and colleagues analyzed data from patients with cervical cancer who developed recurrence after surgery at two oncologic referral centers between 1990 and 2018 (Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2020 Jul. doi: 10.1136/ijgc-2020-001381).

The investigators applied a propensity-matching algorithm to reduce possible confounding factors. They matched 35 patients who had recurrence after laparoscopic hysterectomy to 70 patients who had recurrence after open surgery. The groups had similar baseline characteristics.

As in the Laparoscopic Approach to Cervical Cancer (LACC) trial, patients who had minimally invasive surgery were more likely to have a worse disease-free survival, compared with patients who had open surgery, Dr. Bogani said. Patients who underwent laparoscopic radical hysterectomy had a median progression-free survival of 8 months, whereas patients who underwent open abdominal procedures had a median progression-free survival of 15.8 months.

Although vaginal, lymphatic, and distant recurrences were similar between the groups, a greater percentage of patients in the laparoscopic hysterectomy group had recurrence in the pelvic cavity (74% vs. 34%) and peritoneal carcinomatosis (17% vs. 1.5%).

The LACC trial, which found significantly lower disease-free and overall survival with laparoscopic hysterectomy, sent a “shockwave through the gynecologic oncology community” when it was published in 2018, said Masoud Azodi, MD, in a discussion following Dr. Bogani’s presentation.

Researchers have raised questions about that trial’s design and validity, noted Dr. Azodi, director of minimally invasive and robotic surgery at Yale University in New Haven, Conn.

It could be that local recurrences are attributable to surgical technique, rather than to the minimally invasive approach in itself, Dr. Azodi said. Prior studies of laparoscopic hysterectomy for cervical cancer had indicated better surgical outcomes and equivalent oncologic results, relative to open surgery.

Before the LACC trial, Dr. Bogani used the minimally invasive approach for almost all surgeries. Since then, he has performed open surgeries. If he were to use a minimally invasive approach now, it would be in the context of a clinical trial, Dr. Bogani said.

Dr. Bogani and Dr. Azodi had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Bogani G et al. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020 Nov. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2020.08.069.

When cervical cancer recurs after radical hysterectomy, the likelihood of recurrence at certain sites and the timing of recurrence may be associated with the surgical approach, according to a retrospective study.

according to a propensity-matched analysis of data from 105 patients with recurrence.

And recurrence in the pelvic cavity and peritoneal carcinomatosis were more common after laparoscopic hysterectomy than after open surgery. Overall survival was similar between the groups, however.

The different patterns of recurrence may relate to dissemination of the disease during colpotomy, but the reasons are unknown, study author Giorgio Bogani, MD, PhD, said at the meeting sponsored by AAGL.

To examine patterns of recurrence after laparoscopic and open abdominal radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer, Dr. Bogani of the department of gynecologic surgery at the National Cancer Institute in Milan and colleagues analyzed data from patients with cervical cancer who developed recurrence after surgery at two oncologic referral centers between 1990 and 2018 (Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2020 Jul. doi: 10.1136/ijgc-2020-001381).

The investigators applied a propensity-matching algorithm to reduce possible confounding factors. They matched 35 patients who had recurrence after laparoscopic hysterectomy to 70 patients who had recurrence after open surgery. The groups had similar baseline characteristics.

As in the Laparoscopic Approach to Cervical Cancer (LACC) trial, patients who had minimally invasive surgery were more likely to have a worse disease-free survival, compared with patients who had open surgery, Dr. Bogani said. Patients who underwent laparoscopic radical hysterectomy had a median progression-free survival of 8 months, whereas patients who underwent open abdominal procedures had a median progression-free survival of 15.8 months.

Although vaginal, lymphatic, and distant recurrences were similar between the groups, a greater percentage of patients in the laparoscopic hysterectomy group had recurrence in the pelvic cavity (74% vs. 34%) and peritoneal carcinomatosis (17% vs. 1.5%).

The LACC trial, which found significantly lower disease-free and overall survival with laparoscopic hysterectomy, sent a “shockwave through the gynecologic oncology community” when it was published in 2018, said Masoud Azodi, MD, in a discussion following Dr. Bogani’s presentation.

Researchers have raised questions about that trial’s design and validity, noted Dr. Azodi, director of minimally invasive and robotic surgery at Yale University in New Haven, Conn.

It could be that local recurrences are attributable to surgical technique, rather than to the minimally invasive approach in itself, Dr. Azodi said. Prior studies of laparoscopic hysterectomy for cervical cancer had indicated better surgical outcomes and equivalent oncologic results, relative to open surgery.

Before the LACC trial, Dr. Bogani used the minimally invasive approach for almost all surgeries. Since then, he has performed open surgeries. If he were to use a minimally invasive approach now, it would be in the context of a clinical trial, Dr. Bogani said.

Dr. Bogani and Dr. Azodi had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Bogani G et al. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2020 Nov. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2020.08.069.

FROM AAGL GLOBAL CONGRESS

Challenges in the Management of Peptic Ulcer Disease

From the University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL.

Abstract

Objective: To review current challenges in the management of peptic ulcer disease.

Methods: Review of the literature.

Results: Peptic ulcer disease affects 5% to 10% of the population worldwide, with recent decreases in lifetime prevalence in high-income countries. Helicobacter pylori infection and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use are the most important drivers of peptic ulcer disease. Current management strategies for peptic ulcer disease focus on ulcer healing; management of complications such as bleeding, perforation, and obstruction; and prevention of ulcer recurrence. Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are the cornerstone of medical therapy for peptic ulcers, and complement testing for and treatment of H. pylori infection as well as elimination of NSAID use. Although advances have been made in the medical and endoscopic treatment of peptic ulcer disease and the management of ulcer complications, such as bleeding and obstruction, challenges remain.

Conclusion: Peptic ulcer disease is a common health problem globally, with persistent challenges related to refractory ulcers, antiplatelet and anticoagulant use, and continued bleeding in the face of endoscopic therapy. These challenges should be met with PPI therapy of adequate frequency and duration, vigilant attention to and treatment of ulcer etiology, evidence-based handling of antiplatelet and anticoagulant medications, and utilization of novel endoscopic tools to obtain improved clinical outcomes.

Keywords: H. pylori; nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; NSAIDs; proton pump inhibitor; PPI; bleeding; perforation; obstruction; refractory ulcer; salvage endoscopic therapy; transcatheter angiographic embolization.

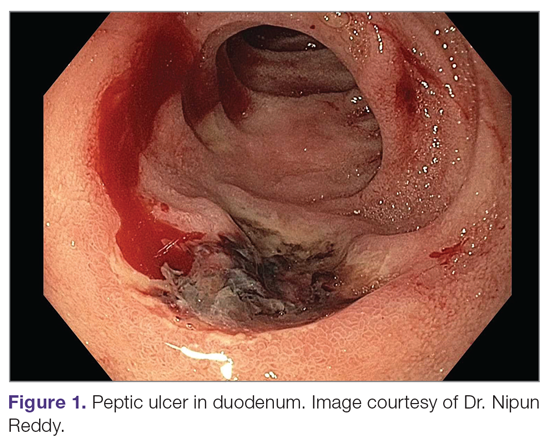

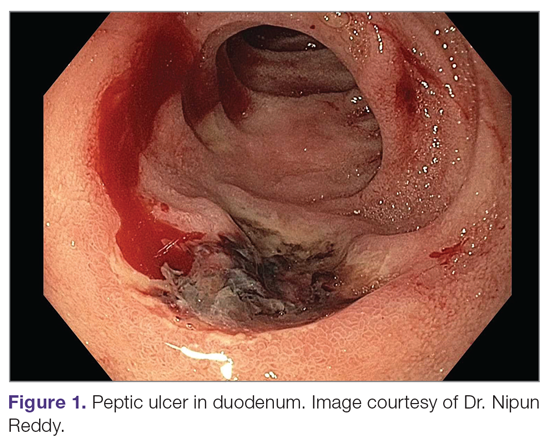

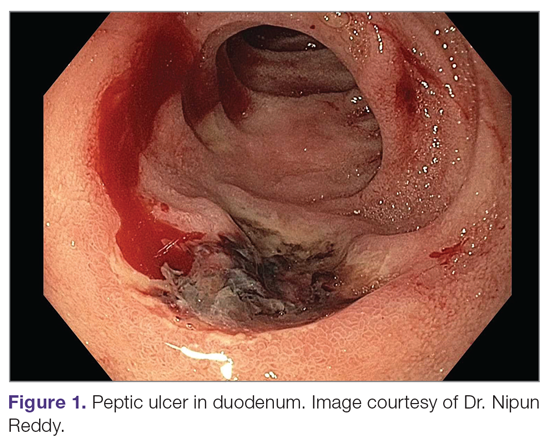

A peptic ulcer is a fibrin-covered break in the mucosa of the digestive tract extending to the submucosa that is caused by acid injury (Figure 1). Most peptic ulcers occur in the stomach or proximal duodenum, though they may also occur in the esophagus or, less frequently, in a Meckel’s diverticulum.1,2 The estimated worldwide prevalence of peptic ulcer disease is 5% to 10%, with an annual incidence of 0.1% to 0.3%1; both rates are declining.3 The annual incidence of peptic ulcer disease requiring medical or surgical treatment is also declining, and currently is estimated to be 0.1% to 0.2%.4 The lifetime prevalence of peptic ulcers has been decreasing in high-income countries since the mid-20th century due to both the widespread use of medications that suppress gastric acid secretion and the declining prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection.1,3

Peptic ulcer disease in most individuals results from H. pylori infection, chronic use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), including aspirin, or both. A combination of H. pylori factors and host factors lead to mucosal disruption in infected individuals who develop peptic ulcers. H. pylori–specific factors include the expression of virulence factors such as CagA and VacA, which interact with the host inflammatory response to cause mucosal injury. The mucosal inflammatory response is at least partially determined by polymorphisms in the host’s cytokine genes.1,4 NSAIDs inhibit the production of cyclooxygenase-1-derived prostaglandins, with subsequent decreases in epithelial mucous formation, bicarbonate secretion, cell proliferation, and mucosal blood flow, all of which are key elements in the maintenance of mucosal integrity.1,5 Less common causes of peptic ulcers include gastrinoma, adenocarcinoma, idiopathic ulcers, use of sympathomimetic drugs (eg, cocaine or methamphetamine), certain anticancer agents, and bariatric surgery.4,6

This article provides an overview of current management principles for peptic ulcer disease and discusses current challenges in peptic ulcer management, including proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy, refractory ulcers, handling of antiplatelet and anticoagulants during and after peptic ulcer bleeding, and ulcer bleeding that continues despite salvage endoscopic therapy.

Methods

We searched MEDLINE using the term peptic ulcer disease in combination with the terms current challenges, epidemiology, bleeding, anticoagulant, antiplatelet, PPI potency, etiology, treatment, management, and refractory. We selected publications from the past 35 years that we judged to be relevant.

Current Management

The goals of peptic ulcer disease management are ulcer healing and prevention of recurrence. The primary interventions used in the management of peptic ulcer disease are medical therapy and implementation of measures that address the underlying etiology of the disease.

Medical Therapy

Introduced in the late 1980s, PPIs are the cornerstone of medical therapy for peptic ulcer disease.6 These agents irreversibly inhibit the H+/K+-ATPase pump in the gastric mucosa and thereby inhibit gastric acid secretion, promoting ulcer healing. PPIs improve rates of ulcer healing compared to H2-receptor antagonists.4,7

Underlying Causes

The underlying cause of peptic ulcer disease should be addressed, in addition to initiating medical therapy. A detailed history of NSAID use should be obtained, and patients with peptic ulcers caused by NSAIDs should be counseled to avoid them, if possible. Patients with peptic ulcer disease who require long-term use of NSAIDs should be placed on long-term PPI therapy.6 Any patient with peptic ulcer disease, regardless of any history of H. pylori infection or treatment, should be tested for infection. Tests that identify active infection, such as urea breath test, stool antigen assay, or mucosal biopsy–based testing, are preferred to IgG antibody testing, although the latter is acceptable in the context of peptic ulcer disease with a high pretest probability of infection.8 Any evidence of active infection warrants appropriate treatment to allow ulcer healing and prevent recurrence.1H. pylori infection is most often treated with clarithromycin triple therapy or bismuth quadruple therapy for 14 days, with regimens selected based on the presence or absence of penicillin allergy, prior antibiotic exposure, and local clarithromycin resistance rates, when known.4,8

Managing Complications

An additional aspect of care in peptic ulcer disease is managing the complications of bleeding, perforation, and gastric outlet obstruction. Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding (GIB) is the most common complication of peptic ulcer disease, which accounts for 40% to 60% of nonvariceal acute upper GIB.1,6 The first step in the management of acute GIB from a peptic ulcer is fluid resuscitation to ensure hemodynamic stability. If there is associated anemia with a hemoglobin level < 8 g/dL, blood transfusion should be undertaken to target a hemoglobin level > 8 g/dL. In patients with peptic ulcer disease–related acute upper GIB and comorbid cardiovascular disease, the transfusion threshold is higher, with the specific cutoff depending on clinical status, type and severity of cardiovascular disease, and degree of bleeding. Endoscopic management should generally be undertaken within 24 hours of presentation and should not be delayed in patients taking anticoagulants.9 Combination endoscopic treatment with through-the-scope clips plus thermocoagulation or sclerosant injection is recommended for acutely bleeding peptic ulcers with high-risk stigmata.

Pharmacologic management of patients with bleeding peptic ulcers with high-risk stigmata includes PPI therapy, with an 80 mg intravenous (IV) loading dose followed by continuous infusion of 8 mg/hr for 72 hours to reduce rebleeding and mortality. Following completion of IV therapy, oral PPI therapy should be continued twice daily for 14 days, followed by once-daily dosing thereafter.9Patients with peptic ulcer perforation present with sudden-onset epigastric abdominal pain and have tenderness to palpation, guarding, and rigidity on examination, often along with tachycardia and hypotension.1,4 Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen is 98% sensitive for identifying and localizing a perforation. Most perforations occur in the duodenum or antrum.

Management of a peptic ulcer perforation requires consultation with a surgeon to determine whether a nonoperative approach may be employed (eg, a stable patient with a contained perforation), or if surgery is indicated. The surgical approach to peptic ulcer perforation has been impacted by the clinical success of gastric acid suppression with PPIs and H. pylori eradication, but a range of surgical approaches are still used to repair perforations, from omental patch repair with peritoneal drain placement, to more extensive surgeries such as wedge resection or partial gastrectomy.4 Perforation carries a high mortality risk, up to 20% to 30%, and is the leading cause of death in patients with peptic ulcer disease.1,4

Gastric outlet obstruction, a rare complication of peptic ulcer disease, results from recurrent ulcer formation and scarring. Obstruction often presents with hypovolemia and metabolic alkalosis from prolonged vomiting. CT imaging with oral contrast is often the first diagnostic test employed to demonstrate obstruction. Upper endoscopy should be performed to evaluate the appearance and degree of obstruction as well as to obtain biopsies to evaluate for a malignant etiology of the ulcer disease. Endoscopic balloon dilation has become the cornerstone of initial therapy for obstruction from peptic ulcer disease, especially in the case of ulcers due to reversible causes. Surgery is now typically reserved for cases of refractory obstruction, after repeated endoscopic balloon dilation has failed to remove the obstruction. However, because nearly all patients with gastric outlet obstruction present with malnutrition, nutritional deficiencies should be addressed prior to the patient undergoing surgical intervention. Surgical options include pyloroplasty, antrectomy, and gastrojejunostomy.4

Current Challenges

Rapid Metabolism of PPIs

High-dose PPI therapy is a key component of therapy for peptic ulcer healing. PPIs are metabolized by the cytochrome P450 system, which is comprised of multiple isoenzymes. CYP2C19, an isoenzyme involved in PPI metabolism, has 21 polymorphisms, which have variable effects leading to ultra-rapid, extensive, intermediate, or poor metabolism of PPIs.10 With rapid metabolism of PPIs, standard dosing can result in inadequate suppression of acid secretion. Despite this knowledge, routine testing of CYP2C19 phenotype is not recommended due to the cost of testing. Instead, inadequate ulcer healing should prompt consideration of increased PPI dosing to 80 mg orally twice daily, which may be sufficient to overcome rapid PPI metabolism.11

Relative Potency of PPIs

In addition to variation in PPI metabolism, the relative potency of various PPIs has been questioned. A review of all available clinical studies of the effects of PPIs on mean 24-hour intragastric pH reported a quantitative difference in the potency of 5 PPIs, with omeprazole as the reference standard. Potencies ranged from 0.23 omeprazole equivalents for pantoprazole to 1.82 omeprazole equivalents for rabeprazole.12 An additional study of data from 56 randomized clinical trials confirmed that PPIs vary in potency, which was measured as time that gastric pH is less than 4. A linear increase in intragastric pH time less than 4 was observed from 9 to 64 mg omeprazole equivalents; higher doses yielded no additional benefit. An increase in PPI dosing from once daily to twice daily also increased the duration of intragastric pH time less than 4 from 15 to 21 hours.13 Earlier modeling of the relationship between duodenal ulcer healing and antisecretory therapy showed a strong correlation of ulcer healing with the duration of acid suppression, length of therapy, and the degree of acid suppression. Additional benefit was not observed after intragastric pH rose above 3.14 Thus, as the frequency and duration of acid suppression therapy are more important than PPI potency, PPIs can be used interchangeably.13,14

Addressing Underlying Causes

Continued NSAID Use. Refractory peptic ulcers are defined as those that do not heal despite adherence to 8 to 12 weeks of standard acid-suppression therapy. A cause of refractory peptic ulcer disease that must be considered is continued NSAID use.1,15 In a study of patients with refractory peptic ulcers, 27% of patients continued NSAID use, as determined by eventual disclosure by the patients or platelet cyclooxygenase activity assay, despite extensive counseling to avoid NSAIDs at the time of the diagnosis of their refractory ulcer and at subsequent visits.16 Pain may make NSAID cessation difficult for some patients, while others do not realize that over-the-counter preparations they take contain NSAIDs.15

Another group of patients with continued NSAID exposure are those who require long-term NSAID therapy for control of arthritis or the management of cardiovascular conditions. If NSAID therapy cannot be discontinued, the risk of NSAID-related gastrointestinal injury can be assessed based on the presence of multiple risk factors, including age > 65 years, high-dose NSAID therapy, a history of peptic ulcer, and concurrent use of aspirin, corticosteroids, or anticoagulants. Individuals with 3 or more of the preceding risk factors or a history of a peptic ulcer with a complication, especially if recent, are considered to be at high risk of developing an NSAID-related ulcer and possible subsequent complications.17 In these individuals, NSAID therapy should be continued with agents that have the lowest risk for gastrointestinal toxicity and at the lowest possible dose. A meta-analysis comparing nonselective NSAIDs to placebo demonstrated naproxen to have the highest risk of gastrointestinal complications, including GIB, perforation, and obstruction (adjusted rate ratio, 4.2), while diclofenac demonstrated the lowest risk (adjusted rate ratio, 1.89). High-dose NSAID therapy demonstrated a 2-fold increase in risk of peptic ulcer formation as compared to low-dose therapy.18

In addition to selecting the NSAID with the least gastrointestinal toxicity at the lowest possible dose, additional strategies to prevent peptic ulcer disease and its complications in chronic NSAID users include co-administration of a PPI and substitution of a COX-2 selective NSAID for nonselective NSAIDs.1,9 Prior double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized, multicenter trials with patients requiring daily NSAIDs demonstrated an up to 15% absolute reduction in the risk of developing peptic ulcers over 6 months while taking esomeprazole.19

Persistent Infection. Persistent H. pylori infection, due either to initial false-negative testing or ongoing infection despite first-line therapy, is another cause of refractory peptic ulcer disease.1,15 Because antibiotics and PPIs can reduce the number of H. pylori bacteria, use of these medications concurrent with H. pylori testing can lead to false-negative results with several testing modalities. When suspicion for H. pylori is high, 2 or more diagnostic tests may be needed to effectively rule out infection.15

When H. pylori is detected, successful eradication is becoming more difficult due to an increasing prevalence of antibiotic resistance, leading to persistent infection in many cases and maintained risk of peptic ulcer disease, despite appropriate first-line therapy.8 Options for salvage therapy for persistent H. pylori, as well as information on the role and best timing of susceptibility testing, are beyond the scope of this review, but are reviewed by Lanas and Chan1 and in the American College of Gastroenterology guideline on the treatment of H. pylori infection.8

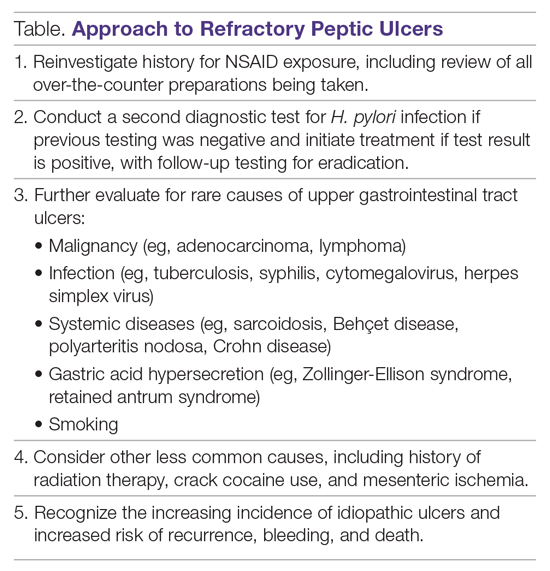

Other Causes. In a meta-analysis of rigorously designed studies from North America, 20% of patients experienced ulcer recurrence at 6 months, despite successful H. pylori eradication and no NSAID use.20 In addition, as H. pylori prevalence is decreasing, idiopathic ulcers are increasingly being diagnosed, and such ulcers may be associated with high rates of GIB and mortality.1 In this subset of patients with non-H. pylori, non-NSAID ulcers, increased effort is required to further evaluate the differential diagnosis for rarer causes of upper GI tract ulcer disease (Table). Certain malignancies, including adenocarcinoma and lymphoma, can cause ulcer formation and should be considered in refractory cases. Repeat biopsy at follow-up endoscopy for persistent ulcers should always be obtained to further evaluate for malignancy.1,15 Infectious diseases other than H. pylori infection, such as tuberculosis, syphilis, cytomegalovirus, and herpes simplex virus, are also reported as etiologies of refractory ulcers, and require specific antimicrobial treatment over and above PPI monotherapy. Special attention in biopsy sampling and sample processing is often required when infectious etiologies are being considered, as specific histologic stains and cultures may be needed for identification.15

Systemic conditions, including sarcoidosis,21 Behçet disease,22 and polyarteritis nodosa,15,23 can also cause refractory ulcers. Approximately 15% of patients with Crohn disease have gastroduodenal involvement, which may include ulcers of variable sizes.1,15,24 The increased gastric acid production seen in Zollinger-Ellison syndrome commonly presents as refractory peptic ulcers in the duodenum beyond the bulb that do not heal with standard doses of PPIs.1,15 More rare causes of acid hypersecretion leading to refractory ulcers include idiopathic gastric acid hypersecretion and retained gastric antrum syndrome after partial gastrectomy with Billroth II anastomosis.15 Smoking is a known risk factor for impaired tissue healing throughout the body, and can contribute to impaired healing of peptic ulcers through decreased prostaglandin synthesis25 and reduced gastric mucosal blood flow.26 Smoking should always be addressed in patients with refractory peptic ulcers, and cessation should be strongly encouraged. Other less common causes of refractory upper GI tract ulcers include radiation therapy, crack cocaine use, and mesenteric ischemia.15

Managing Antiplatelet and Anticoagulant Medications

Use of antiplatelets and anticoagulants, alone or in combination, increases the risk of peptic ulcer bleeding. In patients who continue to take aspirin after a peptic ulcer bleed, recurrent bleeding occurs in up to 300 cases per 1000 person-years. The rate of GIB associated with aspirin use ranges from 1.1% to 2.5%, depending on the dose. Prior peptic ulcer disease, age greater than 70 years, and concurrent NSAID, steroid, anticoagulant, or dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) use increase the risk of bleeding while on aspirin. The rate of GIB while taking a thienopyridine alone is slightly less than that when taking aspirin, ranging from 0.5% to 1.6%. Studies to date have yielded mixed estimates of the effect of DAPT on the risk of GIB. Estimates of the risk of GIB with DAPT range from an odds ratio for serious GIB of 7.4 to an absolute risk increase of only 1.3% when compared to clopidogrel alone.27

Many patients are also on warfarin or a direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC). In a study from the United Kingdom, the adjusted rate ratio of GIB with warfarin alone was 1.94, and this increased to 6.48 when warfarin was used with aspirin.28 The use of warfarin and DAPT, often called triple therapy, further increases the risk of GIB, with a hazard ratio of 5.0 compared to DAPT alone, and 5.38 when compared to warfarin alone. DOACs are increasingly prescribed for the treatment and prevention of thromboembolism, and by 2014 were prescribed as often as warfarin for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation in the United States. A meta-analysis showed the risk of major GIB did not differ between DOACs and warfarin or low-molecular-weight heparin, but among DOACs factor Xa inhibitors showed a reduced risk of GIB compared with dabigatran, a direct thrombin inhibitor.29

The use of antiplatelets and anticoagulants in the context of peptic ulcer bleeding is a current management challenge. Data to guide decision-making in patients on antiplatelet and/or anticoagulant therapy who experience peptic ulcer bleeding are scarce. Decision-making in this group of patients requires balancing the severity and risk of bleeding with the risk of thromboembolism.1,27 In patients on antiplatelet therapy for primary prophylaxis of atherothrombosis who develop bleeding from a peptic ulcer, the antiplatelet should generally be held and the indication for the medication reassessed. In patients on antiplatelet therapy for secondary prevention, the agent may be immediately resumed after endoscopy if bleeding is found to be due to an ulcer with low-risk stigmata. With bleeding resulting from an ulcer with high-risk stigmata, antiplatelet agents employed for secondary prevention may be held initially, with consideration given to early reintroduction, as early as day 3 after endoscopy.1 In patients at high risk for atherothrombotic events, including those on aspirin for secondary prophylaxis, withholding aspirin leads to a 3-fold increase in the risk of a major adverse cardiac event, with events occurring as early as 5 days after aspirin cessation in some cases.27 A randomized controlled trial of continuing low-dose aspirin versus withholding it for 8 weeks in patients on aspirin for secondary prophylaxis of cardiovascular events who experienced peptic ulcer bleeding that required endoscopic therapy demonstrated lower all-cause mortality (1.3% vs 12.9%), including death from cardiovascular or cerebrovascular events, among those who continued aspirin therapy, with a small increased risk of recurrent ulcer bleeding (10.3% vs 5.4%).30 Thus, it is recommended that antiplatelet therapy, when held, be resumed as early as possible when the risk of a cardiovascular or cerebrovascular event is considered to be higher than the risk of bleeding.27

When patients are on DAPT for a history of drug-eluting stent placement, withholding both antiplatelet medications should be avoided, even for a brief period of time, given the risk of in-stent thrombosis. When DAPT is employed for other reasons, it should be continued, if indicated, after bleeding that is found to be due to peptic ulcers with low-risk stigmata. If bleeding is due to a peptic ulcer with high-risk stigmata at endoscopy, then aspirin monotherapy should be continued and consultation should be obtained with a cardiologist to determine optimal timing to resume the second antiplatelet agent.1 In patients on anticoagulants, anticoagulation should be resumed once hemostasis is achieved when the risk of withholding anticoagulation is thought to be greater than the risk of rebleeding. For example, anticoagulation should be resumed early in a patient with a mechanical heart valve to prevent thrombosis.1,27 Following upper GIB from peptic ulcer disease, patients who will require long-term aspirin, DAPT, or anticoagulation with either warfarin or DOACs should be maintained on long-term PPI therapy to reduce the risk of recurrent bleeding.9,27

Failure of Endoscopic Therapy to Control Peptic Ulcer Bleeding

Bleeding recurs in as many as 10% to 20% of patients after initial endoscopic control of peptic ulcer bleeding.4,31 In this context, repeat upper endoscopy for hemostasis is preferred to surgery, as it leads to less morbidity while providing long-term control of bleeding in more than 70% of cases.31,32 Two potential endoscopic rescue therapies that may be employed are over-the-scope clips (OTSCs) and hemostatic powder.32,33

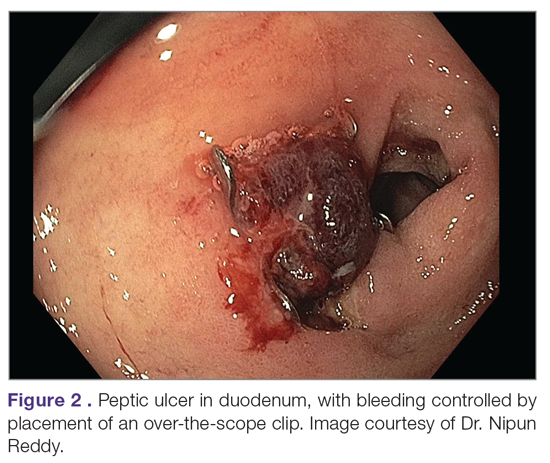

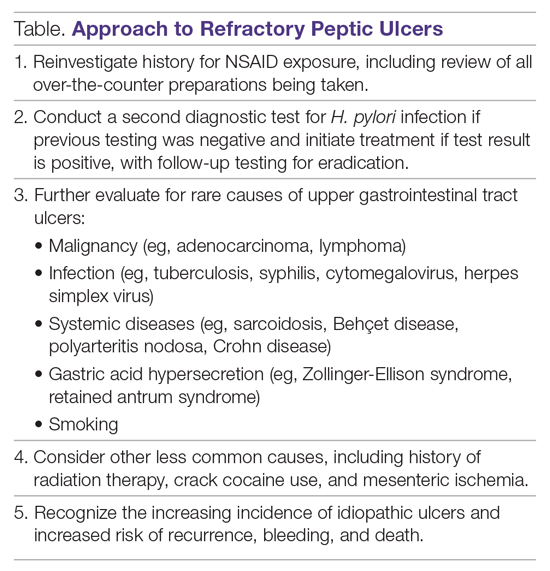

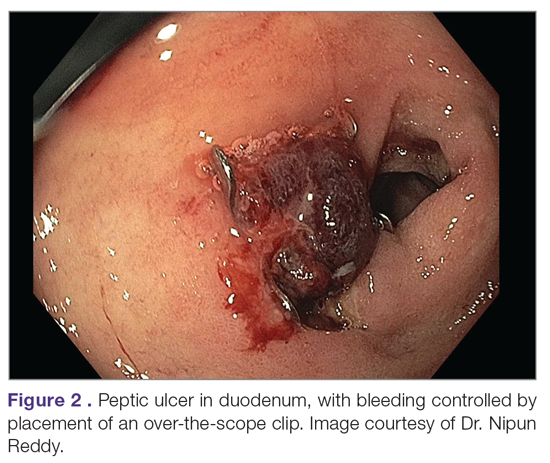

While through-the-scope (TTS) hemostatic clips are often used during endoscopy to control active peptic ulcer bleeding, their use may be limited in large or fibrotic ulcers due to the smaller size of the clips and method of application. OTSCs have several advantages over TTS clips; notably, their larger size allows the endoscopist to achieve deeper mucosal or submucosal clip attachment via suction of the targeted tissue into the endoscopic cap (Figure 2). In a systematic review of OTSCs, successful hemostasis was achieved in 84% of 761 lesions, including 75% of lesions due to peptic ulcer disease.34 Some have argued that OTSCs may be preferred as first-line therapy over epinephrine with TTS clips for hemostasis in bleeding from high-risk peptic ulcers (ie, those with visualized arterial bleeding or a visible vessel) given observed decreases in rebleeding events.35

Despite the advantages of OTSCs, endoscopists should be mindful of the potential complications of OTSC use, including luminal obstruction, particularly in the duodenum, and perforation, which occurs in 0.3% to 2% of cases. Additionally, retrieval of misplaced OTSCs presents a significant challenge. Careful decision-making with consideration of the location, size, and depth of lesions is required when deciding on OTSC placement.34,36

A newer endoscopic tool developed for refractory bleeding from peptic ulcers and other causes is hemostatic powder. Hemostatic powders accelerate the coagulation cascade, leading to shortened coagulation times and enhanced clot formation.37 A recent meta-analysis showed that immediate hemostasis could be achieved in 95% of cases of bleeding, including in 96% of cases of bleeding from peptic ulcer disease.38 The primary limitation of hemostatic powders is the temporary nature of hemostasis, which requires the underlying etiology of bleeding to be addressed in order to provide long-term hemostasis. In the above meta-analysis, rebleeding occurred in 17% of cases after 30 days.38

Hypotension and ulcer diameter ≥ 2 cm are independent predictors of failure of endoscopic salvage therapy.31 When severe bleeding is not controlled with initial endoscopic therapy or bleeding recurs despite salvage endoscopic therapy, transcatheter angiographic embolization (TAE) is the treatment of choice.4 Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that compared TAE to surgery have shown that the rate of rebleeding may be higher with TAE, but with less morbidity and either decreased or equivalent rates of mortality, with no increased need for additional interventions.4,32 In a case series examining 5 years of experience at a single medical center in China, massive GIB from duodenal ulcers was successfully treated with TAE in 27 of 29 cases (93% clinical success rate), with no mucosal ischemic necrosis observed.39

If repeated endoscopic therapy has not led to hemostasis of a bleeding peptic ulcer and TAE is not available, then surgery is the next best option. Bleeding gastric ulcers may be excised, wedge resected, or oversewn after an anterior gastrostomy. Bleeding duodenal ulcers may require use of a Kocher maneuver and linear incision of the anterior duodenum followed by ligation of the gastroduodenal artery. Fortunately, such surgical management is rarely necessary given the availability of TAE at most centers.4

Conclusion

Peptic ulcer disease is a common health problem globally, with persistent challenges related to refractory ulcers, antiplatelet and anticoagulant use, and continued bleeding in the face of endoscopic therapy. These challenges should be met with adequate frequency and duration of PPI therapy, vigilant attention to and treatment of ulcer etiology, evidence-based handling of antiplatelet and anticoagulant medications, and utilization of novel endoscopic tools to obtain improved clinical outcomes.

Acknowledgment: We thank Dr. Nipun Reddy from our institution for providing the endoscopic images used in this article.

Corresponding author: Adam L. Edwards, MD, MS; [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Lanas A, Chan FKL. Peptic ulcer disease. Lancet. 2017;390:613-624.

2. Malfertheiner P, Chan FK, McColl KE. Peptic ulcer disease. Lancet. 2009;374:1449-1461.

3. Roberts-Thomson IC. Rise and fall of peptic ulceration: A disease of civilization? J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;33:1321-1326.

4. Kempenich JW, Sirinek KR. Acid peptic disease. Surg Clin North Am. 2018;98:933-944.

5. Cryer B, Feldman M. Effects of very low dose daily, long-term aspirin therapy on gastric, duodenal, and rectal prostaglandin levels and on mucosal injury in healthy humans. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:17-25.

6. Kavitt RT, Lipowska AM, Anyane-Yeboa A, Gralnek IM. Diagnosis and treatment of peptic ulcer disease. Am J Med. 2019;132:447-456.

7. Walan A, Bader JP, Classen M, et al. Effect of omeprazole and ranitidine on ulcer healing and relapse rates in patients with benign gastric ulcer. New Engl J Med. 1989;320:69-75.

8. Chey WD, Leontiadis GI, Howden CW, Moss SF. ACG Clinical Guideline: Treatment of Helicobacter pylori Infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:212-239.

9. Barkun AN, Almadi M, Kuipers EJ, et al. Management of nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding: Guideline recommendations from the International Consensus Group. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171:805-822.

10. Arevalo Galvis A, Trespalacios Rangel AA, Otero Regino W. Personalized therapy for Helicobacter pylori: CYP2C19 genotype effect on first-line triple therapy. Helicobacter. 2019;24:e12574.

11. Furuta T, Ohashi K, Kamata T, et al. Effect of genetic differences in omeprazole metabolism on cure rates for Helicobacter pylori infection and peptic ulcer. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:1027-1030.

12. Kirchheiner J, Glatt S, Fuhr U, et al. Relative potency of proton-pump inhibitors-comparison of effects on intragastric pH. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;65:19-31.

13. Graham DY, Tansel A. Interchangeable use of proton pump inhibitors based on relative potency. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:800-808.e7.

14. Burget DW, Chiverton SG, Hunt RH. Is there an optimal degree of acid suppression for healing of duodenal ulcers? A model of the relationship between ulcer healing and acid suppression. Gastroenterology. 1990;99:345-351.

15. Kim HU. Diagnostic and treatment approaches for refractory peptic ulcers. Clin Endosc. 2015;48:285-290.

16. Lanas AI, Remacha B, Esteva F, Sainz R. Risk factors associated with refractory peptic ulcers. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:124-133.

17. Lanza FL, Chan FK, Quigley EM. Guidelines for prevention of NSAID-related ulcer complications. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:728-738.

18. Richy F, Bruyere O, Ethgen O, et al. Time dependent risk of gastrointestinal complications induced by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use: a consensus statement using a meta-analytic approach. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63:759-766.

19. Scheiman JM, Yeomans ND, Talley NJ, et al. Prevention of ulcers by esomeprazole in at-risk patients using non-selective NSAIDs and COX-2 inhibitors. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:701-710.

20. Laine L, Hopkins RJ, Girardi LS. Has the impact of Helicobacter pylori therapy on ulcer recurrence in the United States been overstated? A meta-analysis of rigorously designed trials. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1409-1415.

21. Akiyama T, Endo H, Inamori M, et al. Symptomatic gastric sarcoidosis with multiple antral ulcers. Endoscopy. 2009;41 Suppl 2:E159.

22. Sonoda A, Ogawa R, Mizukami K, et al. Marked improvement in gastric involvement in Behcet’s disease with adalimumab treatment. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2017;28:405-407.

23. Saikia N, Talukdar R, Mazumder S, et al. Polyarteritis nodosa presenting as massive upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:868-870.

24. Annunziata ML, Caviglia R, Papparella LG, Cicala M. Upper gastrointestinal involvement of Crohn’s disease: a prospective study on the role of upper endoscopy in the diagnostic work-up. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:1618-1623.

25. Quimby GF, Bonnice CA, Burstein SH, Eastwood GL. Active smoking depresses prostaglandin synthesis in human gastric mucosa. Ann Intern Med. 1986;104:616-619.

26. Iwao T, Toyonaga A, Ikegami M, et al. Gastric mucosal blood flow after smoking in healthy human beings assessed by laser Doppler flowmetry. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993;39:400-403.

27. Almadi MA, Barkun A, Brophy J. Antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy in patients with gastrointestinal bleeding: an 86-year-old woman with peptic ulcer disease. JAMA. 2011;306:2367-2374.

28. Delaney JA, Opatrny L, Brophy JM, Suissa S. Drug drug interactions between antithrombotic medications and the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding. CMAJ. 2007;177:347-351.

29. Burr N, Lummis K, Sood R, et al. Risk of gastrointestinal bleeding with direct oral anticoagulants: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2:85-93.

30. Sung JJ, Lau JY, Ching JY, et al. Continuation of low-dose aspirin therapy in peptic ulcer bleeding: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:1-9.

31. Lau JY, Sung JJ, Lam YH, et al. Endoscopic retreatment compared with surgery in patients with recurrent bleeding after initial endoscopic control of bleeding ulcers. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:751-756.

32. Gralnek IM, Dumonceau JM, Kuipers EJ, et al. Diagnosis and management of nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy. 2015;47:a1-46.

33. Skinner M, Gutierrez JP, Neumann H, et al. Over-the-scope clip placement is effective rescue therapy for severe acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Endosc Int Open. 2014;2:E37-40.

34. Zhong C, Tan S, Ren Y, et al. Clinical outcomes of over-the-scope-clip system for the treatment of acute upper non-variceal gastrointestinal bleeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2019;19:225.

35. Mangiafico S, Pigo F, Bertani H, et al. Over-the-scope clip vs epinephrine with clip for first-line hemostasis in non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding: a propensity score match analysis. Endosc Int Open. 2020;8:E50-e8.

36. Wedi E, Gonzalez S, Menke D, et al. One hundred and one over-the-scope-clip applications for severe gastrointestinal bleeding, leaks and fistulas. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:1844-1853.

37. Holster IL, van Beusekom HM, Kuipers EJ, et al. Effects of a hemostatic powder hemospray on coagulation and clot formation. Endoscopy. 2015;47:638-645.

38. Facciorusso A, Straus Takahashi M, et al. Efficacy of hemostatic powders in upper gastrointestinal bleeding: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dig Liver Dis. 2019;51:1633-1640.

39. Wang YL, Cheng YS, et al. Emergency transcatheter arterial embolization for patients with acute massive duodenal ulcer hemorrhage. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:4765-4770.

From the University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL.

Abstract

Objective: To review current challenges in the management of peptic ulcer disease.

Methods: Review of the literature.

Results: Peptic ulcer disease affects 5% to 10% of the population worldwide, with recent decreases in lifetime prevalence in high-income countries. Helicobacter pylori infection and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use are the most important drivers of peptic ulcer disease. Current management strategies for peptic ulcer disease focus on ulcer healing; management of complications such as bleeding, perforation, and obstruction; and prevention of ulcer recurrence. Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are the cornerstone of medical therapy for peptic ulcers, and complement testing for and treatment of H. pylori infection as well as elimination of NSAID use. Although advances have been made in the medical and endoscopic treatment of peptic ulcer disease and the management of ulcer complications, such as bleeding and obstruction, challenges remain.

Conclusion: Peptic ulcer disease is a common health problem globally, with persistent challenges related to refractory ulcers, antiplatelet and anticoagulant use, and continued bleeding in the face of endoscopic therapy. These challenges should be met with PPI therapy of adequate frequency and duration, vigilant attention to and treatment of ulcer etiology, evidence-based handling of antiplatelet and anticoagulant medications, and utilization of novel endoscopic tools to obtain improved clinical outcomes.

Keywords: H. pylori; nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; NSAIDs; proton pump inhibitor; PPI; bleeding; perforation; obstruction; refractory ulcer; salvage endoscopic therapy; transcatheter angiographic embolization.

A peptic ulcer is a fibrin-covered break in the mucosa of the digestive tract extending to the submucosa that is caused by acid injury (Figure 1). Most peptic ulcers occur in the stomach or proximal duodenum, though they may also occur in the esophagus or, less frequently, in a Meckel’s diverticulum.1,2 The estimated worldwide prevalence of peptic ulcer disease is 5% to 10%, with an annual incidence of 0.1% to 0.3%1; both rates are declining.3 The annual incidence of peptic ulcer disease requiring medical or surgical treatment is also declining, and currently is estimated to be 0.1% to 0.2%.4 The lifetime prevalence of peptic ulcers has been decreasing in high-income countries since the mid-20th century due to both the widespread use of medications that suppress gastric acid secretion and the declining prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection.1,3

Peptic ulcer disease in most individuals results from H. pylori infection, chronic use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), including aspirin, or both. A combination of H. pylori factors and host factors lead to mucosal disruption in infected individuals who develop peptic ulcers. H. pylori–specific factors include the expression of virulence factors such as CagA and VacA, which interact with the host inflammatory response to cause mucosal injury. The mucosal inflammatory response is at least partially determined by polymorphisms in the host’s cytokine genes.1,4 NSAIDs inhibit the production of cyclooxygenase-1-derived prostaglandins, with subsequent decreases in epithelial mucous formation, bicarbonate secretion, cell proliferation, and mucosal blood flow, all of which are key elements in the maintenance of mucosal integrity.1,5 Less common causes of peptic ulcers include gastrinoma, adenocarcinoma, idiopathic ulcers, use of sympathomimetic drugs (eg, cocaine or methamphetamine), certain anticancer agents, and bariatric surgery.4,6

This article provides an overview of current management principles for peptic ulcer disease and discusses current challenges in peptic ulcer management, including proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy, refractory ulcers, handling of antiplatelet and anticoagulants during and after peptic ulcer bleeding, and ulcer bleeding that continues despite salvage endoscopic therapy.

Methods

We searched MEDLINE using the term peptic ulcer disease in combination with the terms current challenges, epidemiology, bleeding, anticoagulant, antiplatelet, PPI potency, etiology, treatment, management, and refractory. We selected publications from the past 35 years that we judged to be relevant.

Current Management

The goals of peptic ulcer disease management are ulcer healing and prevention of recurrence. The primary interventions used in the management of peptic ulcer disease are medical therapy and implementation of measures that address the underlying etiology of the disease.

Medical Therapy

Introduced in the late 1980s, PPIs are the cornerstone of medical therapy for peptic ulcer disease.6 These agents irreversibly inhibit the H+/K+-ATPase pump in the gastric mucosa and thereby inhibit gastric acid secretion, promoting ulcer healing. PPIs improve rates of ulcer healing compared to H2-receptor antagonists.4,7

Underlying Causes

The underlying cause of peptic ulcer disease should be addressed, in addition to initiating medical therapy. A detailed history of NSAID use should be obtained, and patients with peptic ulcers caused by NSAIDs should be counseled to avoid them, if possible. Patients with peptic ulcer disease who require long-term use of NSAIDs should be placed on long-term PPI therapy.6 Any patient with peptic ulcer disease, regardless of any history of H. pylori infection or treatment, should be tested for infection. Tests that identify active infection, such as urea breath test, stool antigen assay, or mucosal biopsy–based testing, are preferred to IgG antibody testing, although the latter is acceptable in the context of peptic ulcer disease with a high pretest probability of infection.8 Any evidence of active infection warrants appropriate treatment to allow ulcer healing and prevent recurrence.1H. pylori infection is most often treated with clarithromycin triple therapy or bismuth quadruple therapy for 14 days, with regimens selected based on the presence or absence of penicillin allergy, prior antibiotic exposure, and local clarithromycin resistance rates, when known.4,8

Managing Complications

An additional aspect of care in peptic ulcer disease is managing the complications of bleeding, perforation, and gastric outlet obstruction. Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding (GIB) is the most common complication of peptic ulcer disease, which accounts for 40% to 60% of nonvariceal acute upper GIB.1,6 The first step in the management of acute GIB from a peptic ulcer is fluid resuscitation to ensure hemodynamic stability. If there is associated anemia with a hemoglobin level < 8 g/dL, blood transfusion should be undertaken to target a hemoglobin level > 8 g/dL. In patients with peptic ulcer disease–related acute upper GIB and comorbid cardiovascular disease, the transfusion threshold is higher, with the specific cutoff depending on clinical status, type and severity of cardiovascular disease, and degree of bleeding. Endoscopic management should generally be undertaken within 24 hours of presentation and should not be delayed in patients taking anticoagulants.9 Combination endoscopic treatment with through-the-scope clips plus thermocoagulation or sclerosant injection is recommended for acutely bleeding peptic ulcers with high-risk stigmata.

Pharmacologic management of patients with bleeding peptic ulcers with high-risk stigmata includes PPI therapy, with an 80 mg intravenous (IV) loading dose followed by continuous infusion of 8 mg/hr for 72 hours to reduce rebleeding and mortality. Following completion of IV therapy, oral PPI therapy should be continued twice daily for 14 days, followed by once-daily dosing thereafter.9Patients with peptic ulcer perforation present with sudden-onset epigastric abdominal pain and have tenderness to palpation, guarding, and rigidity on examination, often along with tachycardia and hypotension.1,4 Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen is 98% sensitive for identifying and localizing a perforation. Most perforations occur in the duodenum or antrum.

Management of a peptic ulcer perforation requires consultation with a surgeon to determine whether a nonoperative approach may be employed (eg, a stable patient with a contained perforation), or if surgery is indicated. The surgical approach to peptic ulcer perforation has been impacted by the clinical success of gastric acid suppression with PPIs and H. pylori eradication, but a range of surgical approaches are still used to repair perforations, from omental patch repair with peritoneal drain placement, to more extensive surgeries such as wedge resection or partial gastrectomy.4 Perforation carries a high mortality risk, up to 20% to 30%, and is the leading cause of death in patients with peptic ulcer disease.1,4

Gastric outlet obstruction, a rare complication of peptic ulcer disease, results from recurrent ulcer formation and scarring. Obstruction often presents with hypovolemia and metabolic alkalosis from prolonged vomiting. CT imaging with oral contrast is often the first diagnostic test employed to demonstrate obstruction. Upper endoscopy should be performed to evaluate the appearance and degree of obstruction as well as to obtain biopsies to evaluate for a malignant etiology of the ulcer disease. Endoscopic balloon dilation has become the cornerstone of initial therapy for obstruction from peptic ulcer disease, especially in the case of ulcers due to reversible causes. Surgery is now typically reserved for cases of refractory obstruction, after repeated endoscopic balloon dilation has failed to remove the obstruction. However, because nearly all patients with gastric outlet obstruction present with malnutrition, nutritional deficiencies should be addressed prior to the patient undergoing surgical intervention. Surgical options include pyloroplasty, antrectomy, and gastrojejunostomy.4

Current Challenges

Rapid Metabolism of PPIs

High-dose PPI therapy is a key component of therapy for peptic ulcer healing. PPIs are metabolized by the cytochrome P450 system, which is comprised of multiple isoenzymes. CYP2C19, an isoenzyme involved in PPI metabolism, has 21 polymorphisms, which have variable effects leading to ultra-rapid, extensive, intermediate, or poor metabolism of PPIs.10 With rapid metabolism of PPIs, standard dosing can result in inadequate suppression of acid secretion. Despite this knowledge, routine testing of CYP2C19 phenotype is not recommended due to the cost of testing. Instead, inadequate ulcer healing should prompt consideration of increased PPI dosing to 80 mg orally twice daily, which may be sufficient to overcome rapid PPI metabolism.11

Relative Potency of PPIs

In addition to variation in PPI metabolism, the relative potency of various PPIs has been questioned. A review of all available clinical studies of the effects of PPIs on mean 24-hour intragastric pH reported a quantitative difference in the potency of 5 PPIs, with omeprazole as the reference standard. Potencies ranged from 0.23 omeprazole equivalents for pantoprazole to 1.82 omeprazole equivalents for rabeprazole.12 An additional study of data from 56 randomized clinical trials confirmed that PPIs vary in potency, which was measured as time that gastric pH is less than 4. A linear increase in intragastric pH time less than 4 was observed from 9 to 64 mg omeprazole equivalents; higher doses yielded no additional benefit. An increase in PPI dosing from once daily to twice daily also increased the duration of intragastric pH time less than 4 from 15 to 21 hours.13 Earlier modeling of the relationship between duodenal ulcer healing and antisecretory therapy showed a strong correlation of ulcer healing with the duration of acid suppression, length of therapy, and the degree of acid suppression. Additional benefit was not observed after intragastric pH rose above 3.14 Thus, as the frequency and duration of acid suppression therapy are more important than PPI potency, PPIs can be used interchangeably.13,14

Addressing Underlying Causes

Continued NSAID Use. Refractory peptic ulcers are defined as those that do not heal despite adherence to 8 to 12 weeks of standard acid-suppression therapy. A cause of refractory peptic ulcer disease that must be considered is continued NSAID use.1,15 In a study of patients with refractory peptic ulcers, 27% of patients continued NSAID use, as determined by eventual disclosure by the patients or platelet cyclooxygenase activity assay, despite extensive counseling to avoid NSAIDs at the time of the diagnosis of their refractory ulcer and at subsequent visits.16 Pain may make NSAID cessation difficult for some patients, while others do not realize that over-the-counter preparations they take contain NSAIDs.15

Another group of patients with continued NSAID exposure are those who require long-term NSAID therapy for control of arthritis or the management of cardiovascular conditions. If NSAID therapy cannot be discontinued, the risk of NSAID-related gastrointestinal injury can be assessed based on the presence of multiple risk factors, including age > 65 years, high-dose NSAID therapy, a history of peptic ulcer, and concurrent use of aspirin, corticosteroids, or anticoagulants. Individuals with 3 or more of the preceding risk factors or a history of a peptic ulcer with a complication, especially if recent, are considered to be at high risk of developing an NSAID-related ulcer and possible subsequent complications.17 In these individuals, NSAID therapy should be continued with agents that have the lowest risk for gastrointestinal toxicity and at the lowest possible dose. A meta-analysis comparing nonselective NSAIDs to placebo demonstrated naproxen to have the highest risk of gastrointestinal complications, including GIB, perforation, and obstruction (adjusted rate ratio, 4.2), while diclofenac demonstrated the lowest risk (adjusted rate ratio, 1.89). High-dose NSAID therapy demonstrated a 2-fold increase in risk of peptic ulcer formation as compared to low-dose therapy.18

In addition to selecting the NSAID with the least gastrointestinal toxicity at the lowest possible dose, additional strategies to prevent peptic ulcer disease and its complications in chronic NSAID users include co-administration of a PPI and substitution of a COX-2 selective NSAID for nonselective NSAIDs.1,9 Prior double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized, multicenter trials with patients requiring daily NSAIDs demonstrated an up to 15% absolute reduction in the risk of developing peptic ulcers over 6 months while taking esomeprazole.19

Persistent Infection. Persistent H. pylori infection, due either to initial false-negative testing or ongoing infection despite first-line therapy, is another cause of refractory peptic ulcer disease.1,15 Because antibiotics and PPIs can reduce the number of H. pylori bacteria, use of these medications concurrent with H. pylori testing can lead to false-negative results with several testing modalities. When suspicion for H. pylori is high, 2 or more diagnostic tests may be needed to effectively rule out infection.15

When H. pylori is detected, successful eradication is becoming more difficult due to an increasing prevalence of antibiotic resistance, leading to persistent infection in many cases and maintained risk of peptic ulcer disease, despite appropriate first-line therapy.8 Options for salvage therapy for persistent H. pylori, as well as information on the role and best timing of susceptibility testing, are beyond the scope of this review, but are reviewed by Lanas and Chan1 and in the American College of Gastroenterology guideline on the treatment of H. pylori infection.8

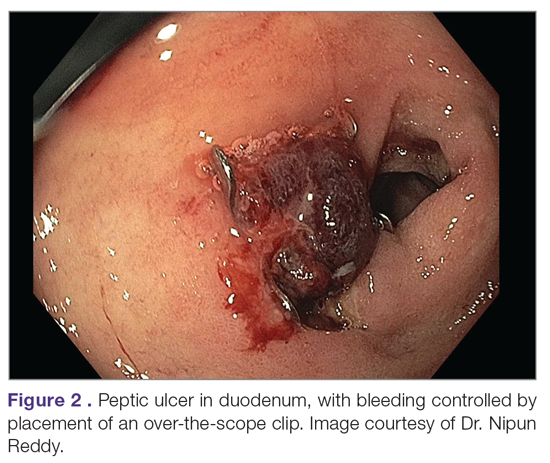

Other Causes. In a meta-analysis of rigorously designed studies from North America, 20% of patients experienced ulcer recurrence at 6 months, despite successful H. pylori eradication and no NSAID use.20 In addition, as H. pylori prevalence is decreasing, idiopathic ulcers are increasingly being diagnosed, and such ulcers may be associated with high rates of GIB and mortality.1 In this subset of patients with non-H. pylori, non-NSAID ulcers, increased effort is required to further evaluate the differential diagnosis for rarer causes of upper GI tract ulcer disease (Table). Certain malignancies, including adenocarcinoma and lymphoma, can cause ulcer formation and should be considered in refractory cases. Repeat biopsy at follow-up endoscopy for persistent ulcers should always be obtained to further evaluate for malignancy.1,15 Infectious diseases other than H. pylori infection, such as tuberculosis, syphilis, cytomegalovirus, and herpes simplex virus, are also reported as etiologies of refractory ulcers, and require specific antimicrobial treatment over and above PPI monotherapy. Special attention in biopsy sampling and sample processing is often required when infectious etiologies are being considered, as specific histologic stains and cultures may be needed for identification.15

Systemic conditions, including sarcoidosis,21 Behçet disease,22 and polyarteritis nodosa,15,23 can also cause refractory ulcers. Approximately 15% of patients with Crohn disease have gastroduodenal involvement, which may include ulcers of variable sizes.1,15,24 The increased gastric acid production seen in Zollinger-Ellison syndrome commonly presents as refractory peptic ulcers in the duodenum beyond the bulb that do not heal with standard doses of PPIs.1,15 More rare causes of acid hypersecretion leading to refractory ulcers include idiopathic gastric acid hypersecretion and retained gastric antrum syndrome after partial gastrectomy with Billroth II anastomosis.15 Smoking is a known risk factor for impaired tissue healing throughout the body, and can contribute to impaired healing of peptic ulcers through decreased prostaglandin synthesis25 and reduced gastric mucosal blood flow.26 Smoking should always be addressed in patients with refractory peptic ulcers, and cessation should be strongly encouraged. Other less common causes of refractory upper GI tract ulcers include radiation therapy, crack cocaine use, and mesenteric ischemia.15

Managing Antiplatelet and Anticoagulant Medications

Use of antiplatelets and anticoagulants, alone or in combination, increases the risk of peptic ulcer bleeding. In patients who continue to take aspirin after a peptic ulcer bleed, recurrent bleeding occurs in up to 300 cases per 1000 person-years. The rate of GIB associated with aspirin use ranges from 1.1% to 2.5%, depending on the dose. Prior peptic ulcer disease, age greater than 70 years, and concurrent NSAID, steroid, anticoagulant, or dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) use increase the risk of bleeding while on aspirin. The rate of GIB while taking a thienopyridine alone is slightly less than that when taking aspirin, ranging from 0.5% to 1.6%. Studies to date have yielded mixed estimates of the effect of DAPT on the risk of GIB. Estimates of the risk of GIB with DAPT range from an odds ratio for serious GIB of 7.4 to an absolute risk increase of only 1.3% when compared to clopidogrel alone.27