User login

Food insecurity called urgent issue you must address

and advocate on behalf of those experiencing or at risk of food insecurity, according to Kofi Essel, MD, MPH, a pediatrician at Children’s National Hospital in Washington.

More than one in four adults are dealing with food access hardships during the pandemic, Dr. Essel said at the virtual annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics. Food insecurity is often interchangeable with hunger and refers to limited or uncertain availability of foods that are nutritious and safe.

“Food insecurity is as much about the threat of deprivation as it is about deprivation itself: A food-insecure life means a life lived in fear of hunger, and the psychological toll that takes,” according to a 2020 New York Times photo feature on food insecurity by Brenda Ann Kenneally that Dr. Essel quoted.

The lived experience of food insecure households includes food anxiety, a preoccupation with being able to get enough food that takes up cognitive bandwidth and prevents people from being able to focus on other important things. Another feature of food-insecure homes is a monotony of diet, which often involves an increase in caloric density and decrease in nutritional quality. As food insecurity grows more dire, adults’ food intake decreases, and then children’s intake decreases as adults seek out any way to get food, including “socially unacceptable” ways, which can include food pantries and bartering for food.

Food insecurity is associated with a wide range of negative outcomes even after accounting for other confounders, including decreased overall health, mental health, and educational outcomes. It’s also associated with an increase in developmental delays, hospitalizations, iron deficiency, asthma, and birth defects, among other problems. Somewhat paradoxically, it’s associated with both an increase and a decrease in obesity in the research.

Megan J. Gray, MD, MPH, assistant professor of pediatrics and population health at Dell Medical School at the The University of Texas at Austin, attended Dr. Essel’s session because food insecurity during COVID-19 now affects about half her patients, according to screening research she’s conducted.

“I wanted to learn more about the nuances of screening and using language and talking points that are helpful with families and with staff in building a culture of discussing food insecurity in our clinics,” Dr. Gray said in an interview. “What I’ve learned in my clinic is that if we don’t ask about it, families aren’t telling us – food insecurity is hiding in plain sight.”

She particularly appreciated Dr. Essel’s slides on the progression of food insecurity and how they acknowledged the mental health burden of food insecurity among parents.

“Right now during COVID-19, I see more patients I would call ‘socially complex’ rather than ‘medically complex,’ ” she said. “We all need to get a crash course in social work and Dr. Essel’s presentation is a great starting place.”

Screening for food insecurity

Beginning in 2015, an AAP policy statement charged pediatricians to “screen and intervene” with regard to food insecurity and their patients, Dr. Essel said. The statement also called for pediatricians to advocate for programs and policies that end childhood food insecurity.

The policy statement recommended a validated two-question screening tool called the Hunger Vital Sign:

1. “Within the past 12 months, we worried whether our food would run out before we got money to buy more.”

2. “Within the past 12 months, the food that we bought just didn’t last and we didn’t have money to get more.”

But in screening, you need to be conscious of how dignity intersects with food insecurity concerns, Dr. Essel said.

“We need to create dignity for our families,” he said. “We need to create a safe environment for our families and use appropriate tools when necessary to be able to identify families that are struggling with food insecurity.”

That need is seen in research on food screening. The Hunger Vital Signs questions can be asked with a dichotomous variable, as a yes/no question, or on a Likert scale, though the latter is a more complex way to ask.

A 2017 study found, however, that asking with “yes/no” answers missed more than a quarter of at-risk families. In the AAP survey using “yes/no” answers, 31% of families screened positive for being at risk of food insecurity, compared with 46% when the same question was asked on a Likert scale. It seems the ability to answer with “sometimes” feels “safer” than answering “yes,” Dr. Essel said.

Another factor that potentially affects answers is how doctors ask. In a March 2020 study at a single primary care practice, 16% of families screened positive with yes/no responses to a food insecurity screen when the questions were written, compared with 10% of positive screens with verbal responses (P < .001).

Epidemiology of food insecurity

The most updated United States Department of Agriculture report on food insecurity released in September shows the United States finally reached prerecession levels in 2019, with 11% of families designated as “food insecure.” But 2019 data cannot show what has occurred since the pandemic.

Further, the numbers are higher in households with children: Fourteen percent, or one in seven households with children, are experiencing food insecurity. Racial and ethnic disparities in food insecurity have remained consistent over the past 2 decades, with about twice as many Black and Hispanic homes experiencing food insecurity as White homes.

More recent research using Census Household Pulse Surveys has found a tremendous increase in food insecurity for children in 2020. One in three Black children and one in four Hispanic children are food insecure, according to these surveys. The rates are one in six for Asian households and one in ten for White households.

“The disparity is consistent,” Dr. Essel said. “We see what COVID has done. We once may have described it as a great equalizer – everyone is touched in the same way – but the reality is, this is actually a great magnifier. It’s revealing to us and magnifying disparities that have existed for far too long and has really allowed us to see it in a new way.”

A big part of disparities in food insecurity is disparities in wealth, “the safety net or cushion for families when things go wrong,” Dr. Essel said. The median wealth of White Americans in 2016 was $171,000, compared to $20,700 among Latinx Americans and $17,600 among Black Americans, according to the Federal Reserve Board Survey of Consumer Finances.

Food insecurity interventions

Federal nutrition programs – such as Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), and school meal programs – are key to addressing food insecurity, Dr. Essel said.

“They have a long track record of rescuing families out of poverty, of rescuing families from food security and improving overall health of families,” he said.

But emergency food relief programs are important as well. Four in 10 families currently coming into food pantries are new recipients, and these resources have seen a 60% increase in clients, he said.

“This is utterly unreasonable for them to be able to manage,” he said. “Food pantries are essential but inadequate to compensate for large numbers of families,” even while they also may be the only option for families unable or unwilling to access federal programs. For example, for every one meal that food banks can provide, SNAP can provide nine meals, Dr. Essel said. Further, during times of economic downtown, every SNAP $1 spent generates $1.50 to $2 in economic activity.

Currently, the Pandemic Electronic Benefit Transfer (P-EBT) program provides benefits to families for school breakfast and lunch and has been extended through December 2021. Another federal pandemic response was to increase SNAP to the maximum household benefit for families, about $646 for a family of four, although 40% of households were already receiving the maximum benefit.

Food insecurity advocacy

You can advocate for any one of multiple pillars when it comes to food insecurity, Dr. Essel said. “Food cannot solve food insecurity by itself,” he said. “We have to think about root causes – systemic causes – and think about unemployment, livable wage, systemic racism, oppression, an inequitable food system. All of these things are pillars that any of you can advocate for when recognizing a family that is struggling with food insecurity.”

He offered several suggestions for advocacy:

- Join your local AAP chapter and prioritize food insecurity.

- Join a local antihunger task force.

- Make your clinical environment as safe as possible for families to respond to questions about food insecurity.

- Know what’s happening in your community immigrant populations.

- Provide up-to-date information to families about eligibility for federal programs.

- Share stories through op-eds and letters to the editor, and by contacting congressional representatives and providing expert testimony to school boards and city councils.

- Educate others about food insecurity through the above channels and on social media.

Jessica Lazerov, MD, a general pediatrician at Children’s National Anacostia and assistant professor of pediatrics at George Washington University, Washington, said the session was fantastic.

“Dr. Essel went beyond the basics of food insecurity, delving into the root causes, potential solutions, and important considerations when screening for food insecurity in practice,” Dr. Lazerov said in an interview. “I enjoyed his focus on advocacy, as well as the fact that he spent a bit of time reviewing how the COVID pandemic has affected food insecurity. I truly felt empowered to take my advocacy efforts a step further as Dr. Essel laid out concrete, actionable next steps, as well as a review of the most relevant and current information about food insecurity.”

Dr. Essel, Dr. Lazerov, and Dr. Gray have no relevant financial disclosures.

and advocate on behalf of those experiencing or at risk of food insecurity, according to Kofi Essel, MD, MPH, a pediatrician at Children’s National Hospital in Washington.

More than one in four adults are dealing with food access hardships during the pandemic, Dr. Essel said at the virtual annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics. Food insecurity is often interchangeable with hunger and refers to limited or uncertain availability of foods that are nutritious and safe.

“Food insecurity is as much about the threat of deprivation as it is about deprivation itself: A food-insecure life means a life lived in fear of hunger, and the psychological toll that takes,” according to a 2020 New York Times photo feature on food insecurity by Brenda Ann Kenneally that Dr. Essel quoted.

The lived experience of food insecure households includes food anxiety, a preoccupation with being able to get enough food that takes up cognitive bandwidth and prevents people from being able to focus on other important things. Another feature of food-insecure homes is a monotony of diet, which often involves an increase in caloric density and decrease in nutritional quality. As food insecurity grows more dire, adults’ food intake decreases, and then children’s intake decreases as adults seek out any way to get food, including “socially unacceptable” ways, which can include food pantries and bartering for food.

Food insecurity is associated with a wide range of negative outcomes even after accounting for other confounders, including decreased overall health, mental health, and educational outcomes. It’s also associated with an increase in developmental delays, hospitalizations, iron deficiency, asthma, and birth defects, among other problems. Somewhat paradoxically, it’s associated with both an increase and a decrease in obesity in the research.

Megan J. Gray, MD, MPH, assistant professor of pediatrics and population health at Dell Medical School at the The University of Texas at Austin, attended Dr. Essel’s session because food insecurity during COVID-19 now affects about half her patients, according to screening research she’s conducted.

“I wanted to learn more about the nuances of screening and using language and talking points that are helpful with families and with staff in building a culture of discussing food insecurity in our clinics,” Dr. Gray said in an interview. “What I’ve learned in my clinic is that if we don’t ask about it, families aren’t telling us – food insecurity is hiding in plain sight.”

She particularly appreciated Dr. Essel’s slides on the progression of food insecurity and how they acknowledged the mental health burden of food insecurity among parents.

“Right now during COVID-19, I see more patients I would call ‘socially complex’ rather than ‘medically complex,’ ” she said. “We all need to get a crash course in social work and Dr. Essel’s presentation is a great starting place.”

Screening for food insecurity

Beginning in 2015, an AAP policy statement charged pediatricians to “screen and intervene” with regard to food insecurity and their patients, Dr. Essel said. The statement also called for pediatricians to advocate for programs and policies that end childhood food insecurity.

The policy statement recommended a validated two-question screening tool called the Hunger Vital Sign:

1. “Within the past 12 months, we worried whether our food would run out before we got money to buy more.”

2. “Within the past 12 months, the food that we bought just didn’t last and we didn’t have money to get more.”

But in screening, you need to be conscious of how dignity intersects with food insecurity concerns, Dr. Essel said.

“We need to create dignity for our families,” he said. “We need to create a safe environment for our families and use appropriate tools when necessary to be able to identify families that are struggling with food insecurity.”

That need is seen in research on food screening. The Hunger Vital Signs questions can be asked with a dichotomous variable, as a yes/no question, or on a Likert scale, though the latter is a more complex way to ask.

A 2017 study found, however, that asking with “yes/no” answers missed more than a quarter of at-risk families. In the AAP survey using “yes/no” answers, 31% of families screened positive for being at risk of food insecurity, compared with 46% when the same question was asked on a Likert scale. It seems the ability to answer with “sometimes” feels “safer” than answering “yes,” Dr. Essel said.

Another factor that potentially affects answers is how doctors ask. In a March 2020 study at a single primary care practice, 16% of families screened positive with yes/no responses to a food insecurity screen when the questions were written, compared with 10% of positive screens with verbal responses (P < .001).

Epidemiology of food insecurity

The most updated United States Department of Agriculture report on food insecurity released in September shows the United States finally reached prerecession levels in 2019, with 11% of families designated as “food insecure.” But 2019 data cannot show what has occurred since the pandemic.

Further, the numbers are higher in households with children: Fourteen percent, or one in seven households with children, are experiencing food insecurity. Racial and ethnic disparities in food insecurity have remained consistent over the past 2 decades, with about twice as many Black and Hispanic homes experiencing food insecurity as White homes.

More recent research using Census Household Pulse Surveys has found a tremendous increase in food insecurity for children in 2020. One in three Black children and one in four Hispanic children are food insecure, according to these surveys. The rates are one in six for Asian households and one in ten for White households.

“The disparity is consistent,” Dr. Essel said. “We see what COVID has done. We once may have described it as a great equalizer – everyone is touched in the same way – but the reality is, this is actually a great magnifier. It’s revealing to us and magnifying disparities that have existed for far too long and has really allowed us to see it in a new way.”

A big part of disparities in food insecurity is disparities in wealth, “the safety net or cushion for families when things go wrong,” Dr. Essel said. The median wealth of White Americans in 2016 was $171,000, compared to $20,700 among Latinx Americans and $17,600 among Black Americans, according to the Federal Reserve Board Survey of Consumer Finances.

Food insecurity interventions

Federal nutrition programs – such as Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), and school meal programs – are key to addressing food insecurity, Dr. Essel said.

“They have a long track record of rescuing families out of poverty, of rescuing families from food security and improving overall health of families,” he said.

But emergency food relief programs are important as well. Four in 10 families currently coming into food pantries are new recipients, and these resources have seen a 60% increase in clients, he said.

“This is utterly unreasonable for them to be able to manage,” he said. “Food pantries are essential but inadequate to compensate for large numbers of families,” even while they also may be the only option for families unable or unwilling to access federal programs. For example, for every one meal that food banks can provide, SNAP can provide nine meals, Dr. Essel said. Further, during times of economic downtown, every SNAP $1 spent generates $1.50 to $2 in economic activity.

Currently, the Pandemic Electronic Benefit Transfer (P-EBT) program provides benefits to families for school breakfast and lunch and has been extended through December 2021. Another federal pandemic response was to increase SNAP to the maximum household benefit for families, about $646 for a family of four, although 40% of households were already receiving the maximum benefit.

Food insecurity advocacy

You can advocate for any one of multiple pillars when it comes to food insecurity, Dr. Essel said. “Food cannot solve food insecurity by itself,” he said. “We have to think about root causes – systemic causes – and think about unemployment, livable wage, systemic racism, oppression, an inequitable food system. All of these things are pillars that any of you can advocate for when recognizing a family that is struggling with food insecurity.”

He offered several suggestions for advocacy:

- Join your local AAP chapter and prioritize food insecurity.

- Join a local antihunger task force.

- Make your clinical environment as safe as possible for families to respond to questions about food insecurity.

- Know what’s happening in your community immigrant populations.

- Provide up-to-date information to families about eligibility for federal programs.

- Share stories through op-eds and letters to the editor, and by contacting congressional representatives and providing expert testimony to school boards and city councils.

- Educate others about food insecurity through the above channels and on social media.

Jessica Lazerov, MD, a general pediatrician at Children’s National Anacostia and assistant professor of pediatrics at George Washington University, Washington, said the session was fantastic.

“Dr. Essel went beyond the basics of food insecurity, delving into the root causes, potential solutions, and important considerations when screening for food insecurity in practice,” Dr. Lazerov said in an interview. “I enjoyed his focus on advocacy, as well as the fact that he spent a bit of time reviewing how the COVID pandemic has affected food insecurity. I truly felt empowered to take my advocacy efforts a step further as Dr. Essel laid out concrete, actionable next steps, as well as a review of the most relevant and current information about food insecurity.”

Dr. Essel, Dr. Lazerov, and Dr. Gray have no relevant financial disclosures.

and advocate on behalf of those experiencing or at risk of food insecurity, according to Kofi Essel, MD, MPH, a pediatrician at Children’s National Hospital in Washington.

More than one in four adults are dealing with food access hardships during the pandemic, Dr. Essel said at the virtual annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics. Food insecurity is often interchangeable with hunger and refers to limited or uncertain availability of foods that are nutritious and safe.

“Food insecurity is as much about the threat of deprivation as it is about deprivation itself: A food-insecure life means a life lived in fear of hunger, and the psychological toll that takes,” according to a 2020 New York Times photo feature on food insecurity by Brenda Ann Kenneally that Dr. Essel quoted.

The lived experience of food insecure households includes food anxiety, a preoccupation with being able to get enough food that takes up cognitive bandwidth and prevents people from being able to focus on other important things. Another feature of food-insecure homes is a monotony of diet, which often involves an increase in caloric density and decrease in nutritional quality. As food insecurity grows more dire, adults’ food intake decreases, and then children’s intake decreases as adults seek out any way to get food, including “socially unacceptable” ways, which can include food pantries and bartering for food.

Food insecurity is associated with a wide range of negative outcomes even after accounting for other confounders, including decreased overall health, mental health, and educational outcomes. It’s also associated with an increase in developmental delays, hospitalizations, iron deficiency, asthma, and birth defects, among other problems. Somewhat paradoxically, it’s associated with both an increase and a decrease in obesity in the research.

Megan J. Gray, MD, MPH, assistant professor of pediatrics and population health at Dell Medical School at the The University of Texas at Austin, attended Dr. Essel’s session because food insecurity during COVID-19 now affects about half her patients, according to screening research she’s conducted.

“I wanted to learn more about the nuances of screening and using language and talking points that are helpful with families and with staff in building a culture of discussing food insecurity in our clinics,” Dr. Gray said in an interview. “What I’ve learned in my clinic is that if we don’t ask about it, families aren’t telling us – food insecurity is hiding in plain sight.”

She particularly appreciated Dr. Essel’s slides on the progression of food insecurity and how they acknowledged the mental health burden of food insecurity among parents.

“Right now during COVID-19, I see more patients I would call ‘socially complex’ rather than ‘medically complex,’ ” she said. “We all need to get a crash course in social work and Dr. Essel’s presentation is a great starting place.”

Screening for food insecurity

Beginning in 2015, an AAP policy statement charged pediatricians to “screen and intervene” with regard to food insecurity and their patients, Dr. Essel said. The statement also called for pediatricians to advocate for programs and policies that end childhood food insecurity.

The policy statement recommended a validated two-question screening tool called the Hunger Vital Sign:

1. “Within the past 12 months, we worried whether our food would run out before we got money to buy more.”

2. “Within the past 12 months, the food that we bought just didn’t last and we didn’t have money to get more.”

But in screening, you need to be conscious of how dignity intersects with food insecurity concerns, Dr. Essel said.

“We need to create dignity for our families,” he said. “We need to create a safe environment for our families and use appropriate tools when necessary to be able to identify families that are struggling with food insecurity.”

That need is seen in research on food screening. The Hunger Vital Signs questions can be asked with a dichotomous variable, as a yes/no question, or on a Likert scale, though the latter is a more complex way to ask.

A 2017 study found, however, that asking with “yes/no” answers missed more than a quarter of at-risk families. In the AAP survey using “yes/no” answers, 31% of families screened positive for being at risk of food insecurity, compared with 46% when the same question was asked on a Likert scale. It seems the ability to answer with “sometimes” feels “safer” than answering “yes,” Dr. Essel said.

Another factor that potentially affects answers is how doctors ask. In a March 2020 study at a single primary care practice, 16% of families screened positive with yes/no responses to a food insecurity screen when the questions were written, compared with 10% of positive screens with verbal responses (P < .001).

Epidemiology of food insecurity

The most updated United States Department of Agriculture report on food insecurity released in September shows the United States finally reached prerecession levels in 2019, with 11% of families designated as “food insecure.” But 2019 data cannot show what has occurred since the pandemic.

Further, the numbers are higher in households with children: Fourteen percent, or one in seven households with children, are experiencing food insecurity. Racial and ethnic disparities in food insecurity have remained consistent over the past 2 decades, with about twice as many Black and Hispanic homes experiencing food insecurity as White homes.

More recent research using Census Household Pulse Surveys has found a tremendous increase in food insecurity for children in 2020. One in three Black children and one in four Hispanic children are food insecure, according to these surveys. The rates are one in six for Asian households and one in ten for White households.

“The disparity is consistent,” Dr. Essel said. “We see what COVID has done. We once may have described it as a great equalizer – everyone is touched in the same way – but the reality is, this is actually a great magnifier. It’s revealing to us and magnifying disparities that have existed for far too long and has really allowed us to see it in a new way.”

A big part of disparities in food insecurity is disparities in wealth, “the safety net or cushion for families when things go wrong,” Dr. Essel said. The median wealth of White Americans in 2016 was $171,000, compared to $20,700 among Latinx Americans and $17,600 among Black Americans, according to the Federal Reserve Board Survey of Consumer Finances.

Food insecurity interventions

Federal nutrition programs – such as Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), and school meal programs – are key to addressing food insecurity, Dr. Essel said.

“They have a long track record of rescuing families out of poverty, of rescuing families from food security and improving overall health of families,” he said.

But emergency food relief programs are important as well. Four in 10 families currently coming into food pantries are new recipients, and these resources have seen a 60% increase in clients, he said.

“This is utterly unreasonable for them to be able to manage,” he said. “Food pantries are essential but inadequate to compensate for large numbers of families,” even while they also may be the only option for families unable or unwilling to access federal programs. For example, for every one meal that food banks can provide, SNAP can provide nine meals, Dr. Essel said. Further, during times of economic downtown, every SNAP $1 spent generates $1.50 to $2 in economic activity.

Currently, the Pandemic Electronic Benefit Transfer (P-EBT) program provides benefits to families for school breakfast and lunch and has been extended through December 2021. Another federal pandemic response was to increase SNAP to the maximum household benefit for families, about $646 for a family of four, although 40% of households were already receiving the maximum benefit.

Food insecurity advocacy

You can advocate for any one of multiple pillars when it comes to food insecurity, Dr. Essel said. “Food cannot solve food insecurity by itself,” he said. “We have to think about root causes – systemic causes – and think about unemployment, livable wage, systemic racism, oppression, an inequitable food system. All of these things are pillars that any of you can advocate for when recognizing a family that is struggling with food insecurity.”

He offered several suggestions for advocacy:

- Join your local AAP chapter and prioritize food insecurity.

- Join a local antihunger task force.

- Make your clinical environment as safe as possible for families to respond to questions about food insecurity.

- Know what’s happening in your community immigrant populations.

- Provide up-to-date information to families about eligibility for federal programs.

- Share stories through op-eds and letters to the editor, and by contacting congressional representatives and providing expert testimony to school boards and city councils.

- Educate others about food insecurity through the above channels and on social media.

Jessica Lazerov, MD, a general pediatrician at Children’s National Anacostia and assistant professor of pediatrics at George Washington University, Washington, said the session was fantastic.

“Dr. Essel went beyond the basics of food insecurity, delving into the root causes, potential solutions, and important considerations when screening for food insecurity in practice,” Dr. Lazerov said in an interview. “I enjoyed his focus on advocacy, as well as the fact that he spent a bit of time reviewing how the COVID pandemic has affected food insecurity. I truly felt empowered to take my advocacy efforts a step further as Dr. Essel laid out concrete, actionable next steps, as well as a review of the most relevant and current information about food insecurity.”

Dr. Essel, Dr. Lazerov, and Dr. Gray have no relevant financial disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM AAP 2020

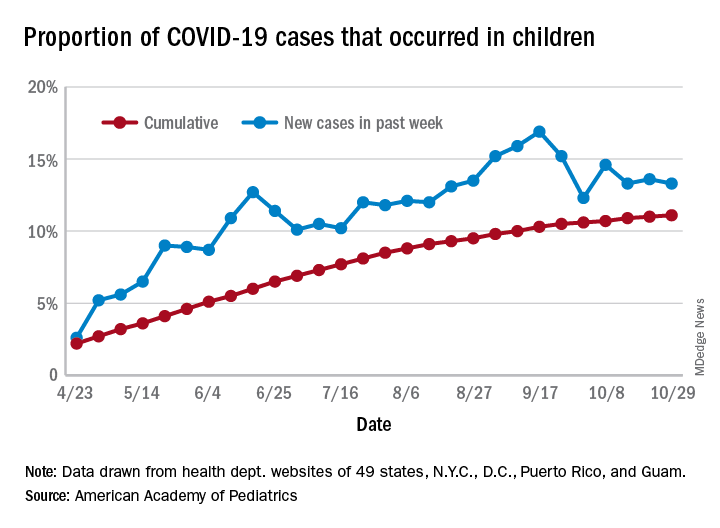

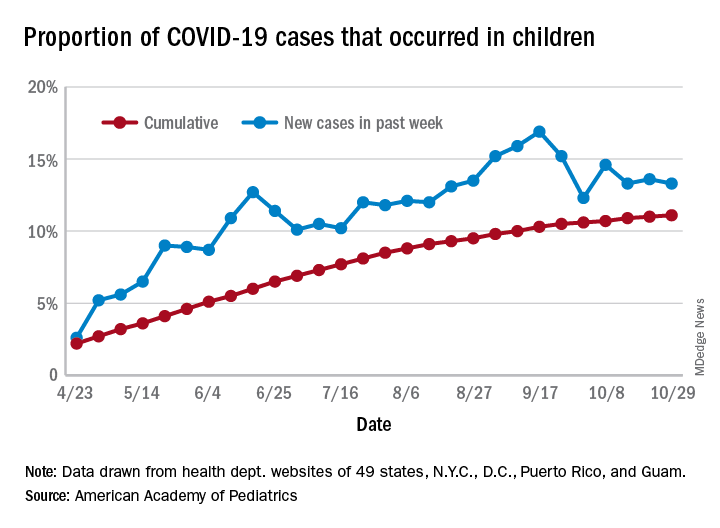

COVID-19: U.S. sets new weekly high in children

the American Academy of Pediatrics announced Nov. 2.

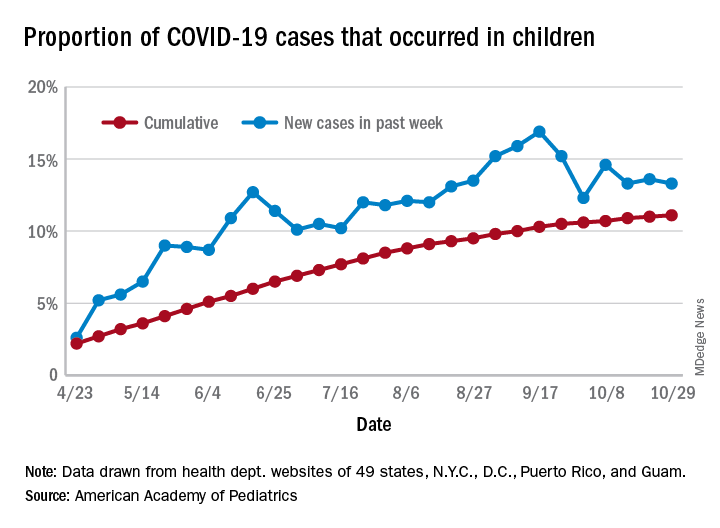

For the week, over 61,000 cases were reported in children, bringing the number of COVID-19 cases for the month of October to nearly 200,000 and the total since the start of the pandemic to over 853,000, the AAP and the Children’s Hospital Association said in their weekly report.

“These numbers reflect a disturbing increase in cases throughout most of the United States in all populations, especially among young adults,” Yvonne Maldonado, MD, chair of the AAP Committee on Infectious Diseases, said in a separate statement. “We are entering a heightened wave of infections around the country. We would encourage family holiday gatherings to be avoided if possible, especially if there are high-risk individuals in the household.”

For the week ending Oct. 29, children represented 13.3% of all cases, possibly constituting a minitrend of stability over the past 3 weeks. For the full length of the pandemic, 11.1% of all COVID-19 cases have occurred in children, although severe illness is much less common: 1.7% of all hospitalizations (data from 24 states and New York City) and 0.06% of all deaths (data from 42 states and New York City), the AAP and CHA report said.

Other data show that 1,134 per 100,000 children in the United States have been infected by the coronavirus, up from 1,053 the previous week, with state rates ranging from 221 per 100,000 in Vermont to 3,321 in North Dakota. In Wyoming, 25.5% of all COVID-19 cases have occurred in children, the highest of any state, while New Jersey has the lowest rate at 4.9%, the AAP/CHA report showed.

In the 10 states making testing data available, children represent the lowest percentage of tests in Iowa (5.0%) and the highest in Indiana (16.9%). Iowa, however, has the highest positivity rate for children at 14.6%, along with Nevada, while West Virginia has the lowest at 3.6%, the AAP and CHA said in the report.

These numbers, however, may not be telling the whole story. “The number of reported COVID-19 cases in children is likely an undercount because children’s symptoms are often mild and they may not be tested for every illness,” the AAP said in its statement.

“We urge policy makers to listen to doctors and public health experts rather than level baseless accusations against them. Physicians, nurses and other health care professionals have put their lives on the line to protect our communities. We can all do our part to protect them, and our communities, by wearing masks, practicing physical distancing, and getting our flu immunizations,” AAP President Sally Goza, MD, said in the AAP statement.

the American Academy of Pediatrics announced Nov. 2.

For the week, over 61,000 cases were reported in children, bringing the number of COVID-19 cases for the month of October to nearly 200,000 and the total since the start of the pandemic to over 853,000, the AAP and the Children’s Hospital Association said in their weekly report.

“These numbers reflect a disturbing increase in cases throughout most of the United States in all populations, especially among young adults,” Yvonne Maldonado, MD, chair of the AAP Committee on Infectious Diseases, said in a separate statement. “We are entering a heightened wave of infections around the country. We would encourage family holiday gatherings to be avoided if possible, especially if there are high-risk individuals in the household.”

For the week ending Oct. 29, children represented 13.3% of all cases, possibly constituting a minitrend of stability over the past 3 weeks. For the full length of the pandemic, 11.1% of all COVID-19 cases have occurred in children, although severe illness is much less common: 1.7% of all hospitalizations (data from 24 states and New York City) and 0.06% of all deaths (data from 42 states and New York City), the AAP and CHA report said.

Other data show that 1,134 per 100,000 children in the United States have been infected by the coronavirus, up from 1,053 the previous week, with state rates ranging from 221 per 100,000 in Vermont to 3,321 in North Dakota. In Wyoming, 25.5% of all COVID-19 cases have occurred in children, the highest of any state, while New Jersey has the lowest rate at 4.9%, the AAP/CHA report showed.

In the 10 states making testing data available, children represent the lowest percentage of tests in Iowa (5.0%) and the highest in Indiana (16.9%). Iowa, however, has the highest positivity rate for children at 14.6%, along with Nevada, while West Virginia has the lowest at 3.6%, the AAP and CHA said in the report.

These numbers, however, may not be telling the whole story. “The number of reported COVID-19 cases in children is likely an undercount because children’s symptoms are often mild and they may not be tested for every illness,” the AAP said in its statement.

“We urge policy makers to listen to doctors and public health experts rather than level baseless accusations against them. Physicians, nurses and other health care professionals have put their lives on the line to protect our communities. We can all do our part to protect them, and our communities, by wearing masks, practicing physical distancing, and getting our flu immunizations,” AAP President Sally Goza, MD, said in the AAP statement.

the American Academy of Pediatrics announced Nov. 2.

For the week, over 61,000 cases were reported in children, bringing the number of COVID-19 cases for the month of October to nearly 200,000 and the total since the start of the pandemic to over 853,000, the AAP and the Children’s Hospital Association said in their weekly report.

“These numbers reflect a disturbing increase in cases throughout most of the United States in all populations, especially among young adults,” Yvonne Maldonado, MD, chair of the AAP Committee on Infectious Diseases, said in a separate statement. “We are entering a heightened wave of infections around the country. We would encourage family holiday gatherings to be avoided if possible, especially if there are high-risk individuals in the household.”

For the week ending Oct. 29, children represented 13.3% of all cases, possibly constituting a minitrend of stability over the past 3 weeks. For the full length of the pandemic, 11.1% of all COVID-19 cases have occurred in children, although severe illness is much less common: 1.7% of all hospitalizations (data from 24 states and New York City) and 0.06% of all deaths (data from 42 states and New York City), the AAP and CHA report said.

Other data show that 1,134 per 100,000 children in the United States have been infected by the coronavirus, up from 1,053 the previous week, with state rates ranging from 221 per 100,000 in Vermont to 3,321 in North Dakota. In Wyoming, 25.5% of all COVID-19 cases have occurred in children, the highest of any state, while New Jersey has the lowest rate at 4.9%, the AAP/CHA report showed.

In the 10 states making testing data available, children represent the lowest percentage of tests in Iowa (5.0%) and the highest in Indiana (16.9%). Iowa, however, has the highest positivity rate for children at 14.6%, along with Nevada, while West Virginia has the lowest at 3.6%, the AAP and CHA said in the report.

These numbers, however, may not be telling the whole story. “The number of reported COVID-19 cases in children is likely an undercount because children’s symptoms are often mild and they may not be tested for every illness,” the AAP said in its statement.

“We urge policy makers to listen to doctors and public health experts rather than level baseless accusations against them. Physicians, nurses and other health care professionals have put their lives on the line to protect our communities. We can all do our part to protect them, and our communities, by wearing masks, practicing physical distancing, and getting our flu immunizations,” AAP President Sally Goza, MD, said in the AAP statement.

Surgery for adhesive small-bowel obstruction linked with lower risk of recurrence

Background: Guidelines recommend nonoperative monitoring for aSBO; however, long-term association of operative versus nonoperative management and aSBO recurrence is poorly understood.

Study design: Longitudinal, retrospective cohort.

Setting: Hospitals in Ontario.

Synopsis: Administrative data for 2005-2014 was used to identify 27,904 adults hospitalized for an initial episode of aSBO who did not have known inflammatory bowel disease, history of radiotherapy, malignancy, ileus, impaction, or anatomical obstruction. Approximately 22% of patients were managed surgically during the index admission. Patients were followed for a median of 3.6 years. Overall, 19.6% of patients experienced at least one admission for recurrence of aSBO during the study period. With each recurrence, the probability of subsequent recurrence increased, the time between episodes decreased, and the probability of being treated surgically decreased.

Patients were then matched into operative (n = 6,160) and nonoperative (n = 6,160) cohorts based on a propensity score which incorporated comorbidity burden, age, gender, and socioeconomic status. Patients who underwent operative management during their index admission for aSBO had a lower overall risk of recurrence compared to patients managed nonoperatively (13.0% vs. 21.3%; P less than .001). Operative intervention was associated with lower hazards of recurrence even when accounting for death. Additionally, surgical intervention after any episode was associated with a significantly lower risk of recurrence, compared with nonoperative management.

Bottom line: Contrary to surgical dogma, surgical intervention is associated with reduced risk of recurrent aSBO in patients without complicating factors. Hospitalists should consider recurrence risk when managing these patients nonoperatively.

Citation: Behman R et al. Association of surgical intervention for adhesive small-bowel obstruction with the risk of recurrence. JAMA Surg. 2019 May 1;154(5):413-20.

Dr. Liu is a hospitalist at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn.

Background: Guidelines recommend nonoperative monitoring for aSBO; however, long-term association of operative versus nonoperative management and aSBO recurrence is poorly understood.

Study design: Longitudinal, retrospective cohort.

Setting: Hospitals in Ontario.

Synopsis: Administrative data for 2005-2014 was used to identify 27,904 adults hospitalized for an initial episode of aSBO who did not have known inflammatory bowel disease, history of radiotherapy, malignancy, ileus, impaction, or anatomical obstruction. Approximately 22% of patients were managed surgically during the index admission. Patients were followed for a median of 3.6 years. Overall, 19.6% of patients experienced at least one admission for recurrence of aSBO during the study period. With each recurrence, the probability of subsequent recurrence increased, the time between episodes decreased, and the probability of being treated surgically decreased.

Patients were then matched into operative (n = 6,160) and nonoperative (n = 6,160) cohorts based on a propensity score which incorporated comorbidity burden, age, gender, and socioeconomic status. Patients who underwent operative management during their index admission for aSBO had a lower overall risk of recurrence compared to patients managed nonoperatively (13.0% vs. 21.3%; P less than .001). Operative intervention was associated with lower hazards of recurrence even when accounting for death. Additionally, surgical intervention after any episode was associated with a significantly lower risk of recurrence, compared with nonoperative management.

Bottom line: Contrary to surgical dogma, surgical intervention is associated with reduced risk of recurrent aSBO in patients without complicating factors. Hospitalists should consider recurrence risk when managing these patients nonoperatively.

Citation: Behman R et al. Association of surgical intervention for adhesive small-bowel obstruction with the risk of recurrence. JAMA Surg. 2019 May 1;154(5):413-20.

Dr. Liu is a hospitalist at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn.

Background: Guidelines recommend nonoperative monitoring for aSBO; however, long-term association of operative versus nonoperative management and aSBO recurrence is poorly understood.

Study design: Longitudinal, retrospective cohort.

Setting: Hospitals in Ontario.

Synopsis: Administrative data for 2005-2014 was used to identify 27,904 adults hospitalized for an initial episode of aSBO who did not have known inflammatory bowel disease, history of radiotherapy, malignancy, ileus, impaction, or anatomical obstruction. Approximately 22% of patients were managed surgically during the index admission. Patients were followed for a median of 3.6 years. Overall, 19.6% of patients experienced at least one admission for recurrence of aSBO during the study period. With each recurrence, the probability of subsequent recurrence increased, the time between episodes decreased, and the probability of being treated surgically decreased.

Patients were then matched into operative (n = 6,160) and nonoperative (n = 6,160) cohorts based on a propensity score which incorporated comorbidity burden, age, gender, and socioeconomic status. Patients who underwent operative management during their index admission for aSBO had a lower overall risk of recurrence compared to patients managed nonoperatively (13.0% vs. 21.3%; P less than .001). Operative intervention was associated with lower hazards of recurrence even when accounting for death. Additionally, surgical intervention after any episode was associated with a significantly lower risk of recurrence, compared with nonoperative management.

Bottom line: Contrary to surgical dogma, surgical intervention is associated with reduced risk of recurrent aSBO in patients without complicating factors. Hospitalists should consider recurrence risk when managing these patients nonoperatively.

Citation: Behman R et al. Association of surgical intervention for adhesive small-bowel obstruction with the risk of recurrence. JAMA Surg. 2019 May 1;154(5):413-20.

Dr. Liu is a hospitalist at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn.

Chinese American families suffer discrimination related to COVID-19

according to results from a survey study.

In the United States, where public officials continue to refer to SARS-CoV-2 as the “China virus” and have often sought to draw attention to its origins in Wuhan, China, “the associations between discrimination triggered by the racialization of this acute public health crisis and mental health are unknown,” Charissa S.L. Cheah, PhD, of the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, and colleagues wrote.

For their research published Oct. 29 in Pediatrics, Dr. Cheah and colleagues recruited a cohort of 543 Chinese American parents of school-age children, and 230 of their children aged 10-18 years, to complete online surveys between mid-March and late May 2020. Parents in the cohort were largely foreign born, with all identifying as ethnically Chinese, while their children were mostly U.S. born.

Evidence of discrimination against Chinese Americans

Half of parents and their children (51% of parents and 50% of youth) reported experiencing at least one in-person incident of direct discrimination (assessed using questions derived from a validated scale of racial aggression) related to the pandemic. Dr. Cheah and colleagues also reported a high incidence of direct discrimination online (32% of parents and 46% of youth). Additionally, the researchers measured reports of vicarious or indirect discrimination – such as hearing jokes or disparaging remarks about one’s ethnic group – which they used a different adapted scale to capture. More than three-quarters of the cohort reported such experiences.

The experiences of discrimination likely bore on the mental health of both parents and youth. Using a series of instruments designed to measure overall psychological well-being as well as symptoms of depression, anxiety, and certain emotional and behavioral outcomes, Dr. Cheah and colleagues reported significant negative associations between direct online or in-person discrimination and psychological health. For parents and children alike, anxiety and depressive symptoms were positively associated with all varieties of discrimination experiences measured in the study.

About a fifth of the youth in the study were deemed, based on the symptom scales used in the study, to have an elevated risk of clinically significant mental health problems, higher than the 10%-15% that would be expected for these age groups in the United States.

“This study revealed that a high percentage of Chinese American parents and their children personally experienced or witnessed anti-Chinese or anti–Asian American racial discrimination both online and in person due to the COVID-19 pandemic,” the investigators wrote. “Most respondents reported directly experiencing or witnessing racial discrimination against other Chinese or Asian American individuals due to COVID-19 at least once.”

Dr. Cheah and colleagues noted that their cross-sectional study did not lend itself to causal interpretations and was vulnerable to certain types of reporting bias. Nonetheless, they argued, as the pandemic continues, “pediatricians should be sensitive to the potential mental health needs of Chinese American youth and their parents related to various forms of racism, in addition to other stressors, as the foundations of perceptions of racial-ethnic discrimination and their consequences may be set during this period.”

COVID-19 didn’t only bring infection

In an accompanying editorial, Tina L. Cheng, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and her daughter Alison M. Conca-Cheng, a medical student at Brown University, Providence, R.I., remarked that the study’s findings were consistent with recent research that found “4 in 10 Americans reported that it has become more common since COVID-19 for people to express racist views about Asian Americans,” and also described an increase in complaints of discriminatory experiences by Asian Americans.

In this context, a link to poor mental health “should be no surprise,” Dr. Cheng and Ms. Conca-Cheng argued, and urged pediatricians to consult the American Academy of Pediatrics’ 2019 policy statement on racism and on child and adolescent health. “It calls for us to optimize clinical practice, improve workforce development and professional education, strengthen research, and deploy systems through community engagement, advocacy, and public policy.”

David Rettew, MD, a child and adolescent psychiatrist and associate professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at the University of Vermont, Burlington, called the study’s main points “clear and disturbing.”

“While it is difficult to find much in the way here of a silver lining, these alarming reports have helped people working in health care and mental health to understand racism as another form of trauma and abuse which, like other types, can have real negative effects on health,” Dr. Rettew said in an interview. “The more we as mental health professions ask about racism and offer resources for people who have experienced it, just as we would people who have endured other types of trauma, the more we can help people heal. That said, it would be better just to stop this from happening in the first place.”

Dr. Cheah and colleagues’ study was supported by a National Science Foundation grant. The investigators disclosed no conflicts of interest. Dr. Cheng and Ms. Conca-Cheng disclosed no financial conflicts of interest related to their editorial. Dr. Rettew said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Cheah CSL et al. Pediatrics. 2020;146(5):e2020021816.

according to results from a survey study.

In the United States, where public officials continue to refer to SARS-CoV-2 as the “China virus” and have often sought to draw attention to its origins in Wuhan, China, “the associations between discrimination triggered by the racialization of this acute public health crisis and mental health are unknown,” Charissa S.L. Cheah, PhD, of the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, and colleagues wrote.

For their research published Oct. 29 in Pediatrics, Dr. Cheah and colleagues recruited a cohort of 543 Chinese American parents of school-age children, and 230 of their children aged 10-18 years, to complete online surveys between mid-March and late May 2020. Parents in the cohort were largely foreign born, with all identifying as ethnically Chinese, while their children were mostly U.S. born.

Evidence of discrimination against Chinese Americans

Half of parents and their children (51% of parents and 50% of youth) reported experiencing at least one in-person incident of direct discrimination (assessed using questions derived from a validated scale of racial aggression) related to the pandemic. Dr. Cheah and colleagues also reported a high incidence of direct discrimination online (32% of parents and 46% of youth). Additionally, the researchers measured reports of vicarious or indirect discrimination – such as hearing jokes or disparaging remarks about one’s ethnic group – which they used a different adapted scale to capture. More than three-quarters of the cohort reported such experiences.

The experiences of discrimination likely bore on the mental health of both parents and youth. Using a series of instruments designed to measure overall psychological well-being as well as symptoms of depression, anxiety, and certain emotional and behavioral outcomes, Dr. Cheah and colleagues reported significant negative associations between direct online or in-person discrimination and psychological health. For parents and children alike, anxiety and depressive symptoms were positively associated with all varieties of discrimination experiences measured in the study.

About a fifth of the youth in the study were deemed, based on the symptom scales used in the study, to have an elevated risk of clinically significant mental health problems, higher than the 10%-15% that would be expected for these age groups in the United States.

“This study revealed that a high percentage of Chinese American parents and their children personally experienced or witnessed anti-Chinese or anti–Asian American racial discrimination both online and in person due to the COVID-19 pandemic,” the investigators wrote. “Most respondents reported directly experiencing or witnessing racial discrimination against other Chinese or Asian American individuals due to COVID-19 at least once.”

Dr. Cheah and colleagues noted that their cross-sectional study did not lend itself to causal interpretations and was vulnerable to certain types of reporting bias. Nonetheless, they argued, as the pandemic continues, “pediatricians should be sensitive to the potential mental health needs of Chinese American youth and their parents related to various forms of racism, in addition to other stressors, as the foundations of perceptions of racial-ethnic discrimination and their consequences may be set during this period.”

COVID-19 didn’t only bring infection

In an accompanying editorial, Tina L. Cheng, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and her daughter Alison M. Conca-Cheng, a medical student at Brown University, Providence, R.I., remarked that the study’s findings were consistent with recent research that found “4 in 10 Americans reported that it has become more common since COVID-19 for people to express racist views about Asian Americans,” and also described an increase in complaints of discriminatory experiences by Asian Americans.

In this context, a link to poor mental health “should be no surprise,” Dr. Cheng and Ms. Conca-Cheng argued, and urged pediatricians to consult the American Academy of Pediatrics’ 2019 policy statement on racism and on child and adolescent health. “It calls for us to optimize clinical practice, improve workforce development and professional education, strengthen research, and deploy systems through community engagement, advocacy, and public policy.”

David Rettew, MD, a child and adolescent psychiatrist and associate professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at the University of Vermont, Burlington, called the study’s main points “clear and disturbing.”

“While it is difficult to find much in the way here of a silver lining, these alarming reports have helped people working in health care and mental health to understand racism as another form of trauma and abuse which, like other types, can have real negative effects on health,” Dr. Rettew said in an interview. “The more we as mental health professions ask about racism and offer resources for people who have experienced it, just as we would people who have endured other types of trauma, the more we can help people heal. That said, it would be better just to stop this from happening in the first place.”

Dr. Cheah and colleagues’ study was supported by a National Science Foundation grant. The investigators disclosed no conflicts of interest. Dr. Cheng and Ms. Conca-Cheng disclosed no financial conflicts of interest related to their editorial. Dr. Rettew said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Cheah CSL et al. Pediatrics. 2020;146(5):e2020021816.

according to results from a survey study.

In the United States, where public officials continue to refer to SARS-CoV-2 as the “China virus” and have often sought to draw attention to its origins in Wuhan, China, “the associations between discrimination triggered by the racialization of this acute public health crisis and mental health are unknown,” Charissa S.L. Cheah, PhD, of the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, and colleagues wrote.

For their research published Oct. 29 in Pediatrics, Dr. Cheah and colleagues recruited a cohort of 543 Chinese American parents of school-age children, and 230 of their children aged 10-18 years, to complete online surveys between mid-March and late May 2020. Parents in the cohort were largely foreign born, with all identifying as ethnically Chinese, while their children were mostly U.S. born.

Evidence of discrimination against Chinese Americans

Half of parents and their children (51% of parents and 50% of youth) reported experiencing at least one in-person incident of direct discrimination (assessed using questions derived from a validated scale of racial aggression) related to the pandemic. Dr. Cheah and colleagues also reported a high incidence of direct discrimination online (32% of parents and 46% of youth). Additionally, the researchers measured reports of vicarious or indirect discrimination – such as hearing jokes or disparaging remarks about one’s ethnic group – which they used a different adapted scale to capture. More than three-quarters of the cohort reported such experiences.

The experiences of discrimination likely bore on the mental health of both parents and youth. Using a series of instruments designed to measure overall psychological well-being as well as symptoms of depression, anxiety, and certain emotional and behavioral outcomes, Dr. Cheah and colleagues reported significant negative associations between direct online or in-person discrimination and psychological health. For parents and children alike, anxiety and depressive symptoms were positively associated with all varieties of discrimination experiences measured in the study.

About a fifth of the youth in the study were deemed, based on the symptom scales used in the study, to have an elevated risk of clinically significant mental health problems, higher than the 10%-15% that would be expected for these age groups in the United States.

“This study revealed that a high percentage of Chinese American parents and their children personally experienced or witnessed anti-Chinese or anti–Asian American racial discrimination both online and in person due to the COVID-19 pandemic,” the investigators wrote. “Most respondents reported directly experiencing or witnessing racial discrimination against other Chinese or Asian American individuals due to COVID-19 at least once.”

Dr. Cheah and colleagues noted that their cross-sectional study did not lend itself to causal interpretations and was vulnerable to certain types of reporting bias. Nonetheless, they argued, as the pandemic continues, “pediatricians should be sensitive to the potential mental health needs of Chinese American youth and their parents related to various forms of racism, in addition to other stressors, as the foundations of perceptions of racial-ethnic discrimination and their consequences may be set during this period.”

COVID-19 didn’t only bring infection

In an accompanying editorial, Tina L. Cheng, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and her daughter Alison M. Conca-Cheng, a medical student at Brown University, Providence, R.I., remarked that the study’s findings were consistent with recent research that found “4 in 10 Americans reported that it has become more common since COVID-19 for people to express racist views about Asian Americans,” and also described an increase in complaints of discriminatory experiences by Asian Americans.

In this context, a link to poor mental health “should be no surprise,” Dr. Cheng and Ms. Conca-Cheng argued, and urged pediatricians to consult the American Academy of Pediatrics’ 2019 policy statement on racism and on child and adolescent health. “It calls for us to optimize clinical practice, improve workforce development and professional education, strengthen research, and deploy systems through community engagement, advocacy, and public policy.”

David Rettew, MD, a child and adolescent psychiatrist and associate professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at the University of Vermont, Burlington, called the study’s main points “clear and disturbing.”

“While it is difficult to find much in the way here of a silver lining, these alarming reports have helped people working in health care and mental health to understand racism as another form of trauma and abuse which, like other types, can have real negative effects on health,” Dr. Rettew said in an interview. “The more we as mental health professions ask about racism and offer resources for people who have experienced it, just as we would people who have endured other types of trauma, the more we can help people heal. That said, it would be better just to stop this from happening in the first place.”

Dr. Cheah and colleagues’ study was supported by a National Science Foundation grant. The investigators disclosed no conflicts of interest. Dr. Cheng and Ms. Conca-Cheng disclosed no financial conflicts of interest related to their editorial. Dr. Rettew said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Cheah CSL et al. Pediatrics. 2020;146(5):e2020021816.

FROM PEDIATRICS

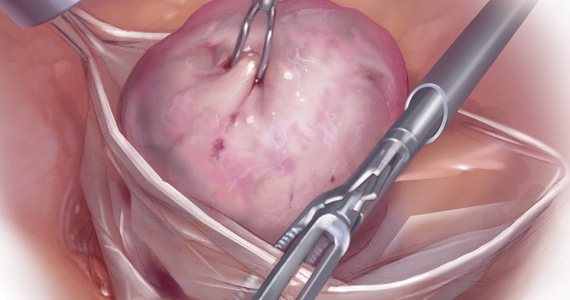

Are uterine manipulators safe for gynecologic cancer surgery?

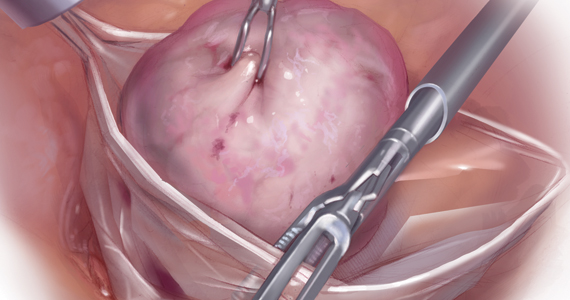

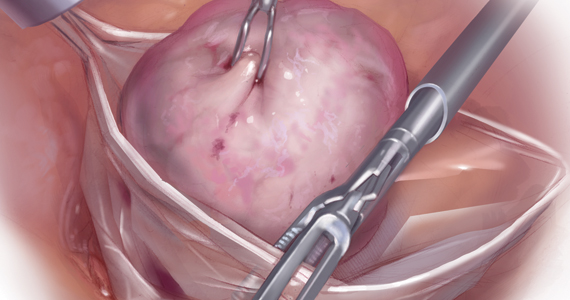

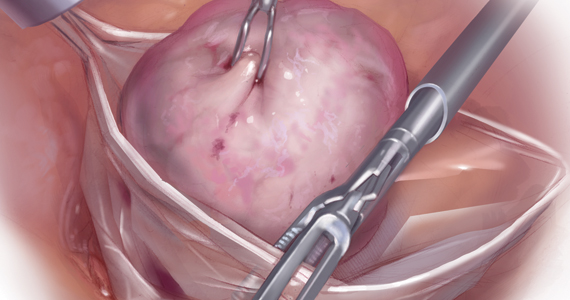

Over the past 4 decades there has been increasing use of minimally invasive surgery (MIS) for gynecologic cancer, particularly endometrial and cervical cancers. Uterine manipulators are a device inserted into the uterine cavity during MIS approaches to aid in directing the uterus within the pelvis, facilitating access to the uterine blood supply, defining the cardinal ligaments, lateralizing the ureters, and delineating the cervicovaginal junction. However, concerns have been raised regarding whether these devices are safe to use when the uterine corpus or cervix contains cancer.

In 2018, the LACC trial was published and demonstrated decreased survival for patients with cervical cancer who had undergone radical hysterectomy via a minimally invasive route.1 Several hypotheses were proposed to explain this finding including possible tumor disruption from use of a uterine manipulator. Regrettably, this study did not document manipulator use, and therefore its influence on outcomes could not be measured. However, since that time there has been honed interest into the potential negative influence of uterine manipulators on endometrial and cervical cancer surgery.

Uterine manipulators typically are inserted through the uterine cervix and reside in the endometrial cavity. It is often an inflated balloon which stabilizes the device within the cavity. Hypotheses for how they may contribute to the spread of malignancy include the massage of endometrial tumor from the pressure of the inflated balloon, facilitation of tumor dissemination through cervical lymphatics or vasculature as the manipulator traverses or punctures a cervical cancer, and possibly perforation of the uterine cavity during placement of the manipulator, and in doing so, contaminating the peritoneal cavity with endometrial or cervical cancer cells that have been dragged through with the device.

Interestingly, uterine manipulator placement is not the only time during which endometrial or cervical cancers may be disturbed prior to resection. Many diagnostic procedures such as cervical excisional procedures (loop electrosurgical excision procedure and conizations) or hysteroscopic resections cause significant intentional disruption of tumor. In the case of hysteroscopy for endometrial cancer, endometrial cancer cells have been detected in the peritoneal washings of endometrial cancer patients who have undergone this procedure, however, no worse outcomes have been associated when hysteroscopy was included as part of the diagnostic work-up, suggesting that more than simply efflux into the peritoneal cavity is necessary for those tumor cells to have metastatic potential.2

Indeed the data is mixed regarding oncologic outcomes with uterine manipulator use, especially for endometrial cancer. In one recent study the outcomes of 951 patients with endometrial cancer from seven Italian centers were evaluated.3 There was no difference in recurrence rates or disease-specific survival between the 579 patients in whom manipulators were used and the 372 patients in which surgery was performed without manipulators. More recently a Spanish study reported retrospectively on 2,661 patients at 15 centers and determined that use of a uterine manipulator (two-thirds of the cohort) was associated with a hazard ratio of 1.74 (95% confidence interval, 1.07-2.83) for risk of death.4 Unfortunately, in this study there were substantial differences between sites that used manipulators and those that did not. Additionally, while one would expect different patterns of recurrence if the manipulator was introducing a unique mechanism for metastasis, this was not observed between the manipulator and nonmanipulator arms. Finally, the groups were intrinsically different with respect to important risk factors such as lymphovascular space invasion, which might have contributed to the observed outcomes. It is important to recognize that, in both the LAP-2 and LACE trials, minimally invasive hysterectomy for endometrial cancer had been shown to have noninferior survival outcomes, compared with open hysterectomy.5,6 While these large randomized, controlled trials did not capture uterine manipulator usage, presumably it was utilized in at least some or most cases, and without apparent significant negative effect.

In cervical cancer, there is more competing data raising concern regarding manipulator use. The SUCCOR study was completed in 2020 and included a retrospective evaluation of 1,272 patients who had undergone open or MIS radical hysterectomy for early stage cervical cancer across 126 European centers during 2013-2014.7 They were able to evaluate for variables, such as uterine manipulator use. While they found that recurrence was higher for patients who had MIS hysterectomy, the HR (2.07) was similar to the HR for recurrence (2.76) among those who had uterine manipulator use. Conversely, the hazard ratio for recurrence following MIS radical hysterectomy without a manipulator was comparable with the superior rates seen with open surgery. This study was retrospective and therefore is largely hypothesis generating, however it does raise the question of whether the technique of MIS radical hysterectomy can be performed safely if particular steps, such as avoidance of a uterine manipulator, are followed. We await definitive results from prospective trials to determine this.

As mentioned earlier, the uterine manipulator is an important safety and feasibility tool for MIS hysterectomy. When not utilized, surgeons may need to add additional ports and instrumentation to maneuver the uterus and may have difficulty completing hysterectomy via a MIS approach for obese patients. There are additional urologic safety concerns when uterine elevation and cervicovaginal delineation is missing. Therefore, While the wealth of prospective data suggests that manipulators are most likely safe in hysterectomy for endometrial cancer, they should be avoided if a minimally invasive approach to cervical cancer is employed.

Dr. Rossi is assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She has no conflicts of interest to report. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. N Engl J Med. 2018 Nov 15. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1806395.

2. Fertil Steril. 2011 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.07.1146.

3. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Jun. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.01.027.

4. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Jul 18. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.07.025.

5. J Clin Oncol. 2009 Nov 10. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.3248.

6. JAMA. 2017 Mar 28. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.2068.

7. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2020. doi: 10.1136/ijgc-2020-001506.

Over the past 4 decades there has been increasing use of minimally invasive surgery (MIS) for gynecologic cancer, particularly endometrial and cervical cancers. Uterine manipulators are a device inserted into the uterine cavity during MIS approaches to aid in directing the uterus within the pelvis, facilitating access to the uterine blood supply, defining the cardinal ligaments, lateralizing the ureters, and delineating the cervicovaginal junction. However, concerns have been raised regarding whether these devices are safe to use when the uterine corpus or cervix contains cancer.

In 2018, the LACC trial was published and demonstrated decreased survival for patients with cervical cancer who had undergone radical hysterectomy via a minimally invasive route.1 Several hypotheses were proposed to explain this finding including possible tumor disruption from use of a uterine manipulator. Regrettably, this study did not document manipulator use, and therefore its influence on outcomes could not be measured. However, since that time there has been honed interest into the potential negative influence of uterine manipulators on endometrial and cervical cancer surgery.

Uterine manipulators typically are inserted through the uterine cervix and reside in the endometrial cavity. It is often an inflated balloon which stabilizes the device within the cavity. Hypotheses for how they may contribute to the spread of malignancy include the massage of endometrial tumor from the pressure of the inflated balloon, facilitation of tumor dissemination through cervical lymphatics or vasculature as the manipulator traverses or punctures a cervical cancer, and possibly perforation of the uterine cavity during placement of the manipulator, and in doing so, contaminating the peritoneal cavity with endometrial or cervical cancer cells that have been dragged through with the device.

Interestingly, uterine manipulator placement is not the only time during which endometrial or cervical cancers may be disturbed prior to resection. Many diagnostic procedures such as cervical excisional procedures (loop electrosurgical excision procedure and conizations) or hysteroscopic resections cause significant intentional disruption of tumor. In the case of hysteroscopy for endometrial cancer, endometrial cancer cells have been detected in the peritoneal washings of endometrial cancer patients who have undergone this procedure, however, no worse outcomes have been associated when hysteroscopy was included as part of the diagnostic work-up, suggesting that more than simply efflux into the peritoneal cavity is necessary for those tumor cells to have metastatic potential.2

Indeed the data is mixed regarding oncologic outcomes with uterine manipulator use, especially for endometrial cancer. In one recent study the outcomes of 951 patients with endometrial cancer from seven Italian centers were evaluated.3 There was no difference in recurrence rates or disease-specific survival between the 579 patients in whom manipulators were used and the 372 patients in which surgery was performed without manipulators. More recently a Spanish study reported retrospectively on 2,661 patients at 15 centers and determined that use of a uterine manipulator (two-thirds of the cohort) was associated with a hazard ratio of 1.74 (95% confidence interval, 1.07-2.83) for risk of death.4 Unfortunately, in this study there were substantial differences between sites that used manipulators and those that did not. Additionally, while one would expect different patterns of recurrence if the manipulator was introducing a unique mechanism for metastasis, this was not observed between the manipulator and nonmanipulator arms. Finally, the groups were intrinsically different with respect to important risk factors such as lymphovascular space invasion, which might have contributed to the observed outcomes. It is important to recognize that, in both the LAP-2 and LACE trials, minimally invasive hysterectomy for endometrial cancer had been shown to have noninferior survival outcomes, compared with open hysterectomy.5,6 While these large randomized, controlled trials did not capture uterine manipulator usage, presumably it was utilized in at least some or most cases, and without apparent significant negative effect.

In cervical cancer, there is more competing data raising concern regarding manipulator use. The SUCCOR study was completed in 2020 and included a retrospective evaluation of 1,272 patients who had undergone open or MIS radical hysterectomy for early stage cervical cancer across 126 European centers during 2013-2014.7 They were able to evaluate for variables, such as uterine manipulator use. While they found that recurrence was higher for patients who had MIS hysterectomy, the HR (2.07) was similar to the HR for recurrence (2.76) among those who had uterine manipulator use. Conversely, the hazard ratio for recurrence following MIS radical hysterectomy without a manipulator was comparable with the superior rates seen with open surgery. This study was retrospective and therefore is largely hypothesis generating, however it does raise the question of whether the technique of MIS radical hysterectomy can be performed safely if particular steps, such as avoidance of a uterine manipulator, are followed. We await definitive results from prospective trials to determine this.

As mentioned earlier, the uterine manipulator is an important safety and feasibility tool for MIS hysterectomy. When not utilized, surgeons may need to add additional ports and instrumentation to maneuver the uterus and may have difficulty completing hysterectomy via a MIS approach for obese patients. There are additional urologic safety concerns when uterine elevation and cervicovaginal delineation is missing. Therefore, While the wealth of prospective data suggests that manipulators are most likely safe in hysterectomy for endometrial cancer, they should be avoided if a minimally invasive approach to cervical cancer is employed.

Dr. Rossi is assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She has no conflicts of interest to report. Email her at [email protected].

References

1. N Engl J Med. 2018 Nov 15. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1806395.

2. Fertil Steril. 2011 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.07.1146.

3. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Jun. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.01.027.

4. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Jul 18. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.07.025.

5. J Clin Oncol. 2009 Nov 10. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.3248.

6. JAMA. 2017 Mar 28. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.2068.

7. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2020. doi: 10.1136/ijgc-2020-001506.

Over the past 4 decades there has been increasing use of minimally invasive surgery (MIS) for gynecologic cancer, particularly endometrial and cervical cancers. Uterine manipulators are a device inserted into the uterine cavity during MIS approaches to aid in directing the uterus within the pelvis, facilitating access to the uterine blood supply, defining the cardinal ligaments, lateralizing the ureters, and delineating the cervicovaginal junction. However, concerns have been raised regarding whether these devices are safe to use when the uterine corpus or cervix contains cancer.

In 2018, the LACC trial was published and demonstrated decreased survival for patients with cervical cancer who had undergone radical hysterectomy via a minimally invasive route.1 Several hypotheses were proposed to explain this finding including possible tumor disruption from use of a uterine manipulator. Regrettably, this study did not document manipulator use, and therefore its influence on outcomes could not be measured. However, since that time there has been honed interest into the potential negative influence of uterine manipulators on endometrial and cervical cancer surgery.

Uterine manipulators typically are inserted through the uterine cervix and reside in the endometrial cavity. It is often an inflated balloon which stabilizes the device within the cavity. Hypotheses for how they may contribute to the spread of malignancy include the massage of endometrial tumor from the pressure of the inflated balloon, facilitation of tumor dissemination through cervical lymphatics or vasculature as the manipulator traverses or punctures a cervical cancer, and possibly perforation of the uterine cavity during placement of the manipulator, and in doing so, contaminating the peritoneal cavity with endometrial or cervical cancer cells that have been dragged through with the device.

Interestingly, uterine manipulator placement is not the only time during which endometrial or cervical cancers may be disturbed prior to resection. Many diagnostic procedures such as cervical excisional procedures (loop electrosurgical excision procedure and conizations) or hysteroscopic resections cause significant intentional disruption of tumor. In the case of hysteroscopy for endometrial cancer, endometrial cancer cells have been detected in the peritoneal washings of endometrial cancer patients who have undergone this procedure, however, no worse outcomes have been associated when hysteroscopy was included as part of the diagnostic work-up, suggesting that more than simply efflux into the peritoneal cavity is necessary for those tumor cells to have metastatic potential.2