User login

Nonfatal opioid overdose rises in teen girls

More adolescent girls than boys experienced nonfatal opioid overdose and reported baseline levels of anxiety, depression, and self-harm, according to data from a retrospective cohort study of more than 20,000 youth in the United States.

Previous studies have identified sex-based differences in opioid overdose such as a higher prevalence of co-occurring psychiatric disorders in women compared with men, wrote Sarah M. Bagley, MD, of Boston University, and colleagues. “However, few studies have examined whether such sex-based differences in opioid overdose risk extend to the population of adolescents and young adults,” they said.

In a retrospective cohort study published in JAMA Network Open, the researchers identified 20,312 commercially insured youth aged 11-24 years who experienced a nonfatal opioid overdose between Jan. 1, 2006, and Dec. 31, 2017, and reviewed data using the IBM MarketScan Commercial Database. The average age of the study population was 20 years and approximately 42% were female.

Females aged 11-16 years had a significantly higher incidence of nonfatal opioid overdose (60%) compared with males, but this trend reversed at age 17 years, after which the incidence of nonfatal opioid overdose became significantly higher in males. “Our finding that females younger than 17 years had a higher incidence of NFOD is consistent with epidemiologic data that have indicated changes in alcohol and drug prevalence among female youths,” the researchers wrote.

Overall, 57.8% of the cohort had mood and anxiety disorders, 12.8% had trauma- or stress-related disorders, and 11.7% had attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

When analyzed by sex, females had a significantly higher prevalence than that of males of mood or anxiety disorders (65.5% vs. 51.9%) trauma or stress-related disorders (16.4% vs. 10.1%) and attempts at suicide or self-harm (14.6% vs. 9.9%). Males had significantly higher prevalence than that of females of opioid use disorder (44.7% vs. 29.2%), cannabis use disorder (18.3% vs. 11.3%), and alcohol use disorder (20.3% vs. 14.4%).

“Although in our study, female youths had a lower prevalence of all substance use disorders, including OUD [opioid use disorder], and a higher prevalence of mood and trauma-associated disorders, both male and female youths had a higher prevalence of psychiatric illness and substance use disorder than youths in the general population,” the researchers noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the inclusion only of youth with commercial insurance, with no uninsured or publicly insured youth, and only those youth who sought health care after a nonfatal opioid overdose, the researchers noted. The prevalence of substance use and mental health disorders may be over- or underdiagnosed, and race was not included as a variable because of unreliable data, they added. The database also did not allow for gender identity beyond sex as listed by the insurance carrier, they said.

However, the results indicate significant differences in the incidence of nonfatal opioid overdose and accompanying mental health and substance use disorders based on age and sex, they said.

“These differences may have important implications for developing effective interventions to prevent first-time NFOD and to engage youths in care after an NFOD,” they concluded.

The study was supported by grants to several researchers from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health, and the Charles A. King Trust. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

More adolescent girls than boys experienced nonfatal opioid overdose and reported baseline levels of anxiety, depression, and self-harm, according to data from a retrospective cohort study of more than 20,000 youth in the United States.

Previous studies have identified sex-based differences in opioid overdose such as a higher prevalence of co-occurring psychiatric disorders in women compared with men, wrote Sarah M. Bagley, MD, of Boston University, and colleagues. “However, few studies have examined whether such sex-based differences in opioid overdose risk extend to the population of adolescents and young adults,” they said.

In a retrospective cohort study published in JAMA Network Open, the researchers identified 20,312 commercially insured youth aged 11-24 years who experienced a nonfatal opioid overdose between Jan. 1, 2006, and Dec. 31, 2017, and reviewed data using the IBM MarketScan Commercial Database. The average age of the study population was 20 years and approximately 42% were female.

Females aged 11-16 years had a significantly higher incidence of nonfatal opioid overdose (60%) compared with males, but this trend reversed at age 17 years, after which the incidence of nonfatal opioid overdose became significantly higher in males. “Our finding that females younger than 17 years had a higher incidence of NFOD is consistent with epidemiologic data that have indicated changes in alcohol and drug prevalence among female youths,” the researchers wrote.

Overall, 57.8% of the cohort had mood and anxiety disorders, 12.8% had trauma- or stress-related disorders, and 11.7% had attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

When analyzed by sex, females had a significantly higher prevalence than that of males of mood or anxiety disorders (65.5% vs. 51.9%) trauma or stress-related disorders (16.4% vs. 10.1%) and attempts at suicide or self-harm (14.6% vs. 9.9%). Males had significantly higher prevalence than that of females of opioid use disorder (44.7% vs. 29.2%), cannabis use disorder (18.3% vs. 11.3%), and alcohol use disorder (20.3% vs. 14.4%).

“Although in our study, female youths had a lower prevalence of all substance use disorders, including OUD [opioid use disorder], and a higher prevalence of mood and trauma-associated disorders, both male and female youths had a higher prevalence of psychiatric illness and substance use disorder than youths in the general population,” the researchers noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the inclusion only of youth with commercial insurance, with no uninsured or publicly insured youth, and only those youth who sought health care after a nonfatal opioid overdose, the researchers noted. The prevalence of substance use and mental health disorders may be over- or underdiagnosed, and race was not included as a variable because of unreliable data, they added. The database also did not allow for gender identity beyond sex as listed by the insurance carrier, they said.

However, the results indicate significant differences in the incidence of nonfatal opioid overdose and accompanying mental health and substance use disorders based on age and sex, they said.

“These differences may have important implications for developing effective interventions to prevent first-time NFOD and to engage youths in care after an NFOD,” they concluded.

The study was supported by grants to several researchers from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health, and the Charles A. King Trust. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

More adolescent girls than boys experienced nonfatal opioid overdose and reported baseline levels of anxiety, depression, and self-harm, according to data from a retrospective cohort study of more than 20,000 youth in the United States.

Previous studies have identified sex-based differences in opioid overdose such as a higher prevalence of co-occurring psychiatric disorders in women compared with men, wrote Sarah M. Bagley, MD, of Boston University, and colleagues. “However, few studies have examined whether such sex-based differences in opioid overdose risk extend to the population of adolescents and young adults,” they said.

In a retrospective cohort study published in JAMA Network Open, the researchers identified 20,312 commercially insured youth aged 11-24 years who experienced a nonfatal opioid overdose between Jan. 1, 2006, and Dec. 31, 2017, and reviewed data using the IBM MarketScan Commercial Database. The average age of the study population was 20 years and approximately 42% were female.

Females aged 11-16 years had a significantly higher incidence of nonfatal opioid overdose (60%) compared with males, but this trend reversed at age 17 years, after which the incidence of nonfatal opioid overdose became significantly higher in males. “Our finding that females younger than 17 years had a higher incidence of NFOD is consistent with epidemiologic data that have indicated changes in alcohol and drug prevalence among female youths,” the researchers wrote.

Overall, 57.8% of the cohort had mood and anxiety disorders, 12.8% had trauma- or stress-related disorders, and 11.7% had attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

When analyzed by sex, females had a significantly higher prevalence than that of males of mood or anxiety disorders (65.5% vs. 51.9%) trauma or stress-related disorders (16.4% vs. 10.1%) and attempts at suicide or self-harm (14.6% vs. 9.9%). Males had significantly higher prevalence than that of females of opioid use disorder (44.7% vs. 29.2%), cannabis use disorder (18.3% vs. 11.3%), and alcohol use disorder (20.3% vs. 14.4%).

“Although in our study, female youths had a lower prevalence of all substance use disorders, including OUD [opioid use disorder], and a higher prevalence of mood and trauma-associated disorders, both male and female youths had a higher prevalence of psychiatric illness and substance use disorder than youths in the general population,” the researchers noted.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the inclusion only of youth with commercial insurance, with no uninsured or publicly insured youth, and only those youth who sought health care after a nonfatal opioid overdose, the researchers noted. The prevalence of substance use and mental health disorders may be over- or underdiagnosed, and race was not included as a variable because of unreliable data, they added. The database also did not allow for gender identity beyond sex as listed by the insurance carrier, they said.

However, the results indicate significant differences in the incidence of nonfatal opioid overdose and accompanying mental health and substance use disorders based on age and sex, they said.

“These differences may have important implications for developing effective interventions to prevent first-time NFOD and to engage youths in care after an NFOD,” they concluded.

The study was supported by grants to several researchers from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health, and the Charles A. King Trust. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Daily Recap: Hospitalized COVID patients need MRIs; Americans vote for face masks

Here are the stories our MDedge editors across specialties think you need to know about today:

Three stages to COVID-19 brain damage, new review suggests

A new review outlined a three-stage classification of the impact of COVID-19 on the central nervous system and recommended all hospitalized patients with the virus undergo MRI to flag potential neurologic damage and inform postdischarge monitoring.

In stage 1, viral damage is limited to epithelial cells of the nose and mouth, and in stage 2 blood clots that form in the lungs may travel to the brain, leading to stroke. In stage 3, the virus crosses the blood-brain barrier and invades the brain.

“Our major take-home points are that patients with COVID-19 symptoms, such as shortness of breath, headache, or dizziness, may have neurological symptoms that, at the time of hospitalization, might not be noticed or prioritized, or whose neurological symptoms may become apparent only after they leave the hospital,” said lead author Majid Fotuhi, MD, PhD. The review was published online in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. Read more.

Topline results for novel intranasal med to treat opioid overdose

Topline results show positive results for the experimental intranasal nalmefene product OX125 for opioid overdose reversal, Orexo, the drug’s manufacturer, announced.

A crossover, comparative bioavailability study was conducted in healthy volunteers to assess nalmefene absorption of three development formulations of OX125. Preliminary results showed “extensive and rapid absorption” across all three formulations versus an intramuscular injection of nalmefene, Orexo reported.

“As the U.S. heroin crisis has developed to a fentanyl crisis, the medical need for novel and more powerful opioid rescue medications is vast,” Nikolaj Sørensen, president and CEO of Orexo, said in a press release. Read more.

Republican or Democrat, Americans vote for face masks

Most Americans support the required use of face masks in public, along with universal COVID-19 testing, to provide a safe work environment during the pandemic, according to a new report from the Commonwealth Fund.

Results of a recent survey show that 85% of adults believe that it is very or somewhat important to require everyone to wear a face mask “at work, when shopping, and on public transportation,” said Sara R. Collins, PhD, vice president for health care coverage and access at the fund, and associates.

Regarding regular testing, 66% of Republicans and those leaning Republican said that such testing was very/somewhat important to ensure a safe work environment, as did 91% on the Democratic side. Read more.

Weight loss failures drive bariatric surgery regrets

Not all weight loss surgery patients “live happily ever after,” according to Daniel B. Jones, MD.

A 2014 study of 22 women who underwent weight loss surgery reported lower energy, worse quality of life, and persistent eating disorders.

Of gastric band patients, “almost 20% did not think they made the right decision,” he said. As for RYGP patients, 13% of patients at 1 year and 4 years reported that weight loss surgery caused “some” or “a lot” of negative effects. Read more.

For more on COVID-19, visit our Resource Center. All of our latest news is available on MDedge.com.

Here are the stories our MDedge editors across specialties think you need to know about today:

Three stages to COVID-19 brain damage, new review suggests

A new review outlined a three-stage classification of the impact of COVID-19 on the central nervous system and recommended all hospitalized patients with the virus undergo MRI to flag potential neurologic damage and inform postdischarge monitoring.

In stage 1, viral damage is limited to epithelial cells of the nose and mouth, and in stage 2 blood clots that form in the lungs may travel to the brain, leading to stroke. In stage 3, the virus crosses the blood-brain barrier and invades the brain.

“Our major take-home points are that patients with COVID-19 symptoms, such as shortness of breath, headache, or dizziness, may have neurological symptoms that, at the time of hospitalization, might not be noticed or prioritized, or whose neurological symptoms may become apparent only after they leave the hospital,” said lead author Majid Fotuhi, MD, PhD. The review was published online in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. Read more.

Topline results for novel intranasal med to treat opioid overdose

Topline results show positive results for the experimental intranasal nalmefene product OX125 for opioid overdose reversal, Orexo, the drug’s manufacturer, announced.

A crossover, comparative bioavailability study was conducted in healthy volunteers to assess nalmefene absorption of three development formulations of OX125. Preliminary results showed “extensive and rapid absorption” across all three formulations versus an intramuscular injection of nalmefene, Orexo reported.

“As the U.S. heroin crisis has developed to a fentanyl crisis, the medical need for novel and more powerful opioid rescue medications is vast,” Nikolaj Sørensen, president and CEO of Orexo, said in a press release. Read more.

Republican or Democrat, Americans vote for face masks

Most Americans support the required use of face masks in public, along with universal COVID-19 testing, to provide a safe work environment during the pandemic, according to a new report from the Commonwealth Fund.

Results of a recent survey show that 85% of adults believe that it is very or somewhat important to require everyone to wear a face mask “at work, when shopping, and on public transportation,” said Sara R. Collins, PhD, vice president for health care coverage and access at the fund, and associates.

Regarding regular testing, 66% of Republicans and those leaning Republican said that such testing was very/somewhat important to ensure a safe work environment, as did 91% on the Democratic side. Read more.

Weight loss failures drive bariatric surgery regrets

Not all weight loss surgery patients “live happily ever after,” according to Daniel B. Jones, MD.

A 2014 study of 22 women who underwent weight loss surgery reported lower energy, worse quality of life, and persistent eating disorders.

Of gastric band patients, “almost 20% did not think they made the right decision,” he said. As for RYGP patients, 13% of patients at 1 year and 4 years reported that weight loss surgery caused “some” or “a lot” of negative effects. Read more.

For more on COVID-19, visit our Resource Center. All of our latest news is available on MDedge.com.

Here are the stories our MDedge editors across specialties think you need to know about today:

Three stages to COVID-19 brain damage, new review suggests

A new review outlined a three-stage classification of the impact of COVID-19 on the central nervous system and recommended all hospitalized patients with the virus undergo MRI to flag potential neurologic damage and inform postdischarge monitoring.

In stage 1, viral damage is limited to epithelial cells of the nose and mouth, and in stage 2 blood clots that form in the lungs may travel to the brain, leading to stroke. In stage 3, the virus crosses the blood-brain barrier and invades the brain.

“Our major take-home points are that patients with COVID-19 symptoms, such as shortness of breath, headache, or dizziness, may have neurological symptoms that, at the time of hospitalization, might not be noticed or prioritized, or whose neurological symptoms may become apparent only after they leave the hospital,” said lead author Majid Fotuhi, MD, PhD. The review was published online in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. Read more.

Topline results for novel intranasal med to treat opioid overdose

Topline results show positive results for the experimental intranasal nalmefene product OX125 for opioid overdose reversal, Orexo, the drug’s manufacturer, announced.

A crossover, comparative bioavailability study was conducted in healthy volunteers to assess nalmefene absorption of three development formulations of OX125. Preliminary results showed “extensive and rapid absorption” across all three formulations versus an intramuscular injection of nalmefene, Orexo reported.

“As the U.S. heroin crisis has developed to a fentanyl crisis, the medical need for novel and more powerful opioid rescue medications is vast,” Nikolaj Sørensen, president and CEO of Orexo, said in a press release. Read more.

Republican or Democrat, Americans vote for face masks

Most Americans support the required use of face masks in public, along with universal COVID-19 testing, to provide a safe work environment during the pandemic, according to a new report from the Commonwealth Fund.

Results of a recent survey show that 85% of adults believe that it is very or somewhat important to require everyone to wear a face mask “at work, when shopping, and on public transportation,” said Sara R. Collins, PhD, vice president for health care coverage and access at the fund, and associates.

Regarding regular testing, 66% of Republicans and those leaning Republican said that such testing was very/somewhat important to ensure a safe work environment, as did 91% on the Democratic side. Read more.

Weight loss failures drive bariatric surgery regrets

Not all weight loss surgery patients “live happily ever after,” according to Daniel B. Jones, MD.

A 2014 study of 22 women who underwent weight loss surgery reported lower energy, worse quality of life, and persistent eating disorders.

Of gastric band patients, “almost 20% did not think they made the right decision,” he said. As for RYGP patients, 13% of patients at 1 year and 4 years reported that weight loss surgery caused “some” or “a lot” of negative effects. Read more.

For more on COVID-19, visit our Resource Center. All of our latest news is available on MDedge.com.

Kratom: Botanical with opiate-like effects increasingly blamed for liver injury

BOSTON – Kratom, a botanical product with opioid-like activity, is increasingly responsible for cases of liver injury in the United States, according to investigators.

Kratom-associated liver damage involves a mixed pattern of hepatocellular and cholestatic injury that typically occurs after about 2-6 weeks of use, reported lead author Victor J. Navarro, MD, division head of gastroenterology at Einstein Healthcare Network in Philadelphia, and colleagues.

“I think it’s important for clinicians to have heightened awareness of the abuse potential [of kratom], because it is an opioid agonist and [because of] its capacity to cause liver injury,” Dr. Navarro said.

Kratom acts as a stimulant at low doses, while higher doses have sedating and narcotic properties. These effects are attributed to several alkaloids found in kratom’s source plant, Mitragyna speciose, of which mitragynine, a suspected opioid agonist, is most common.

Presenting at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, Dr. Navarro cited figures from the National Poison Data System that suggest an upward trend in kratom usage in the United States, from very little use in 2011 to 1 exposure per million people in 2014 and more recently to slightly more than 2.5 exposures per million people in 2017, predominantly among individuals aged 20 years and older. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, more than 90 kratom-associated deaths occurred between July 2016 and December 2017. Because of growing concerns, the Food and Drug Administration has issued multiple public warnings about kratom, ranging from products contaminated with Salmonella and heavy metals, to adverse effects such as seizures and liver toxicity.

The present study aimed to characterize kratom-associated liver injury through a case series analysis. First, the investigators reviewed 404 cases of herbal and dietary supplement-associated liver injury from the Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network prospective study. They found 11 suspected cases of kratom-related liver injury, with an upward trend in recent years. At this time, seven of the cases have been adjudicated by an expert panel and confirmed to be highly likely or probably associated with kratom.

Of these seven cases, all patients were hospitalized, although all recovered without need for liver transplant. Patients presented after a median of 15 days of kratom use, with a 28-day symptom latency period. However, Dr. Navarro noted that some cases presented after just 5 days of use. The most common presenting symptom was itching (86%), followed by jaundice (71%), abdominal pain (71%), nausea (57%), and fever (43%). Blood work revealed a mixed hepatocellular and cholestatic pattern. Median peak ALT was 362 U/L, peak alkaline phosphatase was 294 U/L, and peak total bilirubin was 20.1 mg/dL. Despite these changes, patients did not have significant liver dysfunction, such as coagulopathy.

Following this clinical characterization, Dr. Navarro reviewed existing toxicity data. Rat studies suggest that kratom is safe at doses between 1-10 mg/kg, while toxicity occurs after prolonged exposure to more than 100 mg/kg. A cross-sectional human study reported that kratom was safe at doses up to 75 mg/day. However, in the present case series, some patients presented after ingesting as little as 0.66 mg/day, and Dr. Navarro pointed out wide variations in product concentrations of mitragynine.

“Certainly, we need more human toxicity studies to determine what a safe dose really is, because this product is not going away,” Dr. Navarro said.

The investigators disclosed relationships with Gilead, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Sanofi, and others.

SOURCE: Navarro VJ et al. The Liver Meeting 2019, Abstract 212.

BOSTON – Kratom, a botanical product with opioid-like activity, is increasingly responsible for cases of liver injury in the United States, according to investigators.

Kratom-associated liver damage involves a mixed pattern of hepatocellular and cholestatic injury that typically occurs after about 2-6 weeks of use, reported lead author Victor J. Navarro, MD, division head of gastroenterology at Einstein Healthcare Network in Philadelphia, and colleagues.

“I think it’s important for clinicians to have heightened awareness of the abuse potential [of kratom], because it is an opioid agonist and [because of] its capacity to cause liver injury,” Dr. Navarro said.

Kratom acts as a stimulant at low doses, while higher doses have sedating and narcotic properties. These effects are attributed to several alkaloids found in kratom’s source plant, Mitragyna speciose, of which mitragynine, a suspected opioid agonist, is most common.

Presenting at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, Dr. Navarro cited figures from the National Poison Data System that suggest an upward trend in kratom usage in the United States, from very little use in 2011 to 1 exposure per million people in 2014 and more recently to slightly more than 2.5 exposures per million people in 2017, predominantly among individuals aged 20 years and older. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, more than 90 kratom-associated deaths occurred between July 2016 and December 2017. Because of growing concerns, the Food and Drug Administration has issued multiple public warnings about kratom, ranging from products contaminated with Salmonella and heavy metals, to adverse effects such as seizures and liver toxicity.

The present study aimed to characterize kratom-associated liver injury through a case series analysis. First, the investigators reviewed 404 cases of herbal and dietary supplement-associated liver injury from the Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network prospective study. They found 11 suspected cases of kratom-related liver injury, with an upward trend in recent years. At this time, seven of the cases have been adjudicated by an expert panel and confirmed to be highly likely or probably associated with kratom.

Of these seven cases, all patients were hospitalized, although all recovered without need for liver transplant. Patients presented after a median of 15 days of kratom use, with a 28-day symptom latency period. However, Dr. Navarro noted that some cases presented after just 5 days of use. The most common presenting symptom was itching (86%), followed by jaundice (71%), abdominal pain (71%), nausea (57%), and fever (43%). Blood work revealed a mixed hepatocellular and cholestatic pattern. Median peak ALT was 362 U/L, peak alkaline phosphatase was 294 U/L, and peak total bilirubin was 20.1 mg/dL. Despite these changes, patients did not have significant liver dysfunction, such as coagulopathy.

Following this clinical characterization, Dr. Navarro reviewed existing toxicity data. Rat studies suggest that kratom is safe at doses between 1-10 mg/kg, while toxicity occurs after prolonged exposure to more than 100 mg/kg. A cross-sectional human study reported that kratom was safe at doses up to 75 mg/day. However, in the present case series, some patients presented after ingesting as little as 0.66 mg/day, and Dr. Navarro pointed out wide variations in product concentrations of mitragynine.

“Certainly, we need more human toxicity studies to determine what a safe dose really is, because this product is not going away,” Dr. Navarro said.

The investigators disclosed relationships with Gilead, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Sanofi, and others.

SOURCE: Navarro VJ et al. The Liver Meeting 2019, Abstract 212.

BOSTON – Kratom, a botanical product with opioid-like activity, is increasingly responsible for cases of liver injury in the United States, according to investigators.

Kratom-associated liver damage involves a mixed pattern of hepatocellular and cholestatic injury that typically occurs after about 2-6 weeks of use, reported lead author Victor J. Navarro, MD, division head of gastroenterology at Einstein Healthcare Network in Philadelphia, and colleagues.

“I think it’s important for clinicians to have heightened awareness of the abuse potential [of kratom], because it is an opioid agonist and [because of] its capacity to cause liver injury,” Dr. Navarro said.

Kratom acts as a stimulant at low doses, while higher doses have sedating and narcotic properties. These effects are attributed to several alkaloids found in kratom’s source plant, Mitragyna speciose, of which mitragynine, a suspected opioid agonist, is most common.

Presenting at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, Dr. Navarro cited figures from the National Poison Data System that suggest an upward trend in kratom usage in the United States, from very little use in 2011 to 1 exposure per million people in 2014 and more recently to slightly more than 2.5 exposures per million people in 2017, predominantly among individuals aged 20 years and older. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, more than 90 kratom-associated deaths occurred between July 2016 and December 2017. Because of growing concerns, the Food and Drug Administration has issued multiple public warnings about kratom, ranging from products contaminated with Salmonella and heavy metals, to adverse effects such as seizures and liver toxicity.

The present study aimed to characterize kratom-associated liver injury through a case series analysis. First, the investigators reviewed 404 cases of herbal and dietary supplement-associated liver injury from the Drug-Induced Liver Injury Network prospective study. They found 11 suspected cases of kratom-related liver injury, with an upward trend in recent years. At this time, seven of the cases have been adjudicated by an expert panel and confirmed to be highly likely or probably associated with kratom.

Of these seven cases, all patients were hospitalized, although all recovered without need for liver transplant. Patients presented after a median of 15 days of kratom use, with a 28-day symptom latency period. However, Dr. Navarro noted that some cases presented after just 5 days of use. The most common presenting symptom was itching (86%), followed by jaundice (71%), abdominal pain (71%), nausea (57%), and fever (43%). Blood work revealed a mixed hepatocellular and cholestatic pattern. Median peak ALT was 362 U/L, peak alkaline phosphatase was 294 U/L, and peak total bilirubin was 20.1 mg/dL. Despite these changes, patients did not have significant liver dysfunction, such as coagulopathy.

Following this clinical characterization, Dr. Navarro reviewed existing toxicity data. Rat studies suggest that kratom is safe at doses between 1-10 mg/kg, while toxicity occurs after prolonged exposure to more than 100 mg/kg. A cross-sectional human study reported that kratom was safe at doses up to 75 mg/day. However, in the present case series, some patients presented after ingesting as little as 0.66 mg/day, and Dr. Navarro pointed out wide variations in product concentrations of mitragynine.

“Certainly, we need more human toxicity studies to determine what a safe dose really is, because this product is not going away,” Dr. Navarro said.

The investigators disclosed relationships with Gilead, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Sanofi, and others.

SOURCE: Navarro VJ et al. The Liver Meeting 2019, Abstract 212.

REPORTING FROM THE LIVER MEETING 2019

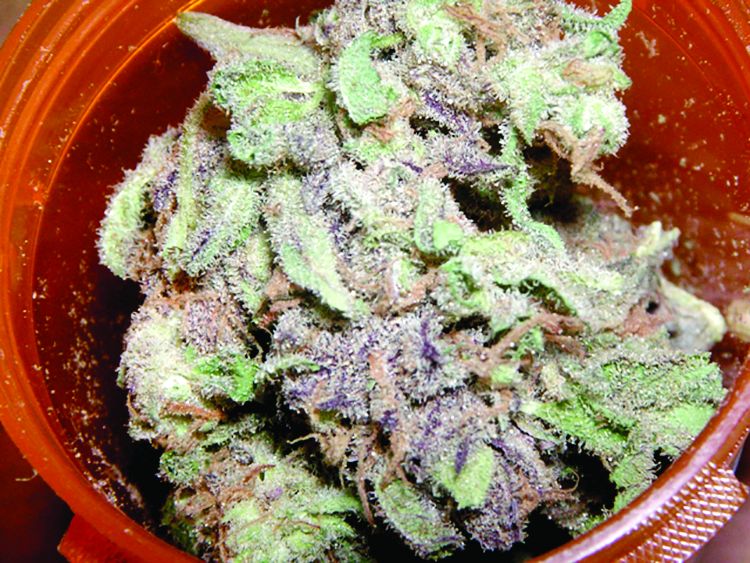

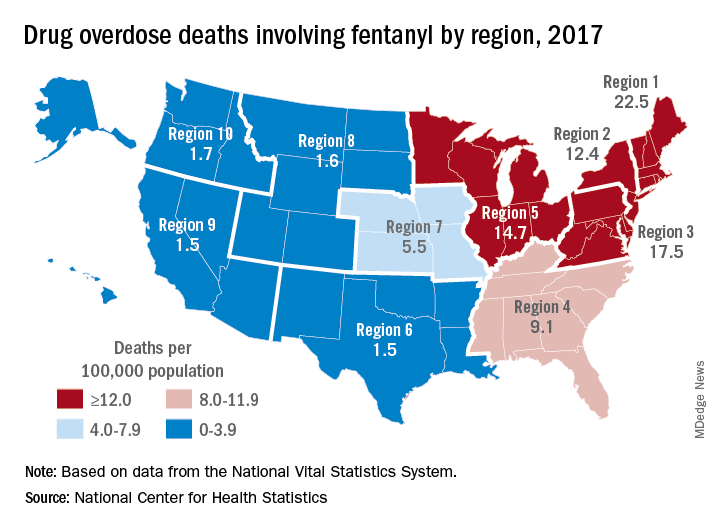

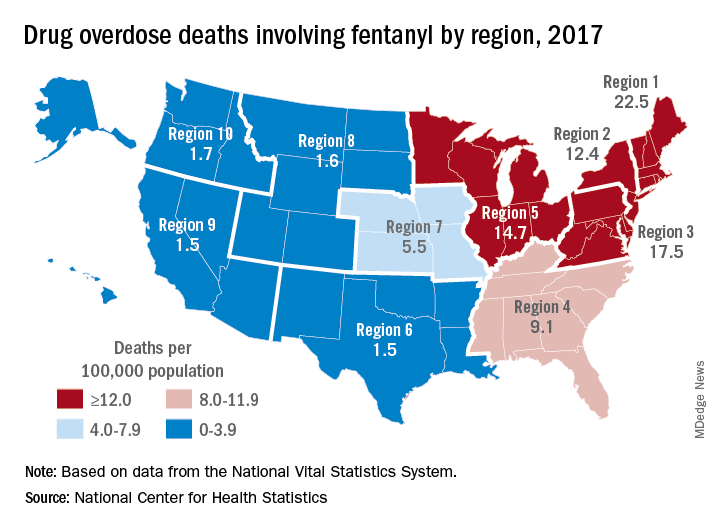

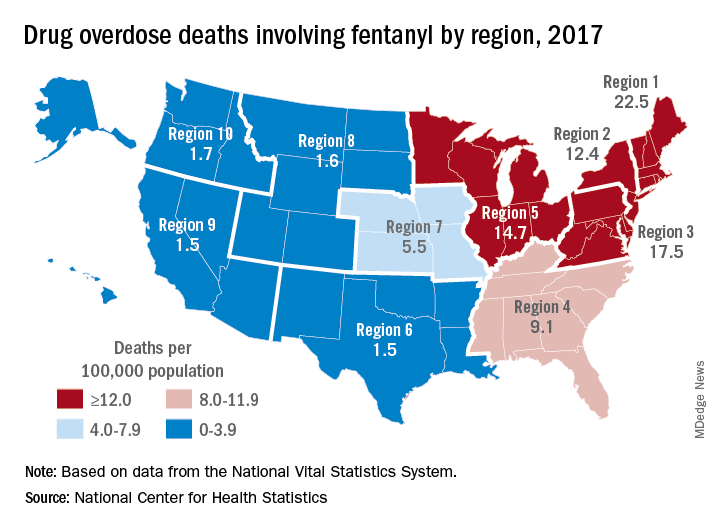

Fentanyl-related deaths show strong regional pattern

Fentanyl was involved in more overdose deaths than any other drug in 2017, and the death rate in New England was 15 times higher than in regions of the Midwest and West, according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

Nationally, fentanyl was involved in 39% of all drug overdose deaths and had an age-adjusted death rate of 8.7/100,000 standard population in 2017. In 2016, when fentanyl also was the most involved drug in the United States, the corresponding figures were 29% and 5.9/100,000, the agency said in a recent report.

Fentanyl was the most involved drug in overdose deaths for 6 of the country’s 10 public health regions in 2017, with a clear pattern of decreasing use from east to west. The highest death rate (22.5/100,000) occurred in Region 1 (New England) and the lowest rates (1.5/100,000) came in Region 6 (Arkansas, Louisiana, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Texas) and Region 9 (Arizona, California, Hawaii, and Nevada), the researchers said.

A somewhat similar pattern was seen for heroin, which was second nationally on the list of drugs most frequently involved in overdose deaths (23%), except that New England was somewhat below three other regions in the East and upper Midwest. The highest heroin death rate (8.6/100,000) was seen in Region 2 (New Jersey and New York) and the lowest (2.2) occurred in Region 9, they said, based on data from the National Vital Statistics System’s mortality files.

The fentanyl pattern was even more closely repeated with cocaine, third in involvement nationally at 21% of overdose deaths in 2017. The high in overdose deaths (9.5/100,000) came in Region 1 again, and the low in Region 9 (1.3), along with Region 7 (Iowa, Kansas, Missouri, and Nebraska) and Region 10 (Alaska, Idaho, Oregon, and Washington), the report showed.

The regional pattern of overdose deaths for methamphetamine, which was fourth nationally in involvement (13.3%), basically reversed the other three drugs: highest in the West and lowest in the Northeast. Region 9 had the highest death rate (5.2/100,000) and Region 2 the lowest (0.4), with Region 1 just ahead at 0.6.

Fentanyl was involved in more overdose deaths than any other drug in 2017, and the death rate in New England was 15 times higher than in regions of the Midwest and West, according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

Nationally, fentanyl was involved in 39% of all drug overdose deaths and had an age-adjusted death rate of 8.7/100,000 standard population in 2017. In 2016, when fentanyl also was the most involved drug in the United States, the corresponding figures were 29% and 5.9/100,000, the agency said in a recent report.

Fentanyl was the most involved drug in overdose deaths for 6 of the country’s 10 public health regions in 2017, with a clear pattern of decreasing use from east to west. The highest death rate (22.5/100,000) occurred in Region 1 (New England) and the lowest rates (1.5/100,000) came in Region 6 (Arkansas, Louisiana, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Texas) and Region 9 (Arizona, California, Hawaii, and Nevada), the researchers said.

A somewhat similar pattern was seen for heroin, which was second nationally on the list of drugs most frequently involved in overdose deaths (23%), except that New England was somewhat below three other regions in the East and upper Midwest. The highest heroin death rate (8.6/100,000) was seen in Region 2 (New Jersey and New York) and the lowest (2.2) occurred in Region 9, they said, based on data from the National Vital Statistics System’s mortality files.

The fentanyl pattern was even more closely repeated with cocaine, third in involvement nationally at 21% of overdose deaths in 2017. The high in overdose deaths (9.5/100,000) came in Region 1 again, and the low in Region 9 (1.3), along with Region 7 (Iowa, Kansas, Missouri, and Nebraska) and Region 10 (Alaska, Idaho, Oregon, and Washington), the report showed.

The regional pattern of overdose deaths for methamphetamine, which was fourth nationally in involvement (13.3%), basically reversed the other three drugs: highest in the West and lowest in the Northeast. Region 9 had the highest death rate (5.2/100,000) and Region 2 the lowest (0.4), with Region 1 just ahead at 0.6.

Fentanyl was involved in more overdose deaths than any other drug in 2017, and the death rate in New England was 15 times higher than in regions of the Midwest and West, according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

Nationally, fentanyl was involved in 39% of all drug overdose deaths and had an age-adjusted death rate of 8.7/100,000 standard population in 2017. In 2016, when fentanyl also was the most involved drug in the United States, the corresponding figures were 29% and 5.9/100,000, the agency said in a recent report.

Fentanyl was the most involved drug in overdose deaths for 6 of the country’s 10 public health regions in 2017, with a clear pattern of decreasing use from east to west. The highest death rate (22.5/100,000) occurred in Region 1 (New England) and the lowest rates (1.5/100,000) came in Region 6 (Arkansas, Louisiana, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Texas) and Region 9 (Arizona, California, Hawaii, and Nevada), the researchers said.

A somewhat similar pattern was seen for heroin, which was second nationally on the list of drugs most frequently involved in overdose deaths (23%), except that New England was somewhat below three other regions in the East and upper Midwest. The highest heroin death rate (8.6/100,000) was seen in Region 2 (New Jersey and New York) and the lowest (2.2) occurred in Region 9, they said, based on data from the National Vital Statistics System’s mortality files.

The fentanyl pattern was even more closely repeated with cocaine, third in involvement nationally at 21% of overdose deaths in 2017. The high in overdose deaths (9.5/100,000) came in Region 1 again, and the low in Region 9 (1.3), along with Region 7 (Iowa, Kansas, Missouri, and Nebraska) and Region 10 (Alaska, Idaho, Oregon, and Washington), the report showed.

The regional pattern of overdose deaths for methamphetamine, which was fourth nationally in involvement (13.3%), basically reversed the other three drugs: highest in the West and lowest in the Northeast. Region 9 had the highest death rate (5.2/100,000) and Region 2 the lowest (0.4), with Region 1 just ahead at 0.6.

Self-harm with bupropion linked to greater risk compared to SSRIs

Adolescents who attempt self-harm using bupropion are at a significantly higher risk of serious morbidity and poor outcomes, compared with those who attempt self-harm with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), according to Adam Overberg, PharmD, of the Indiana Poison Center in Indianapolis and associates.

In a study published in Pediatrics, the researchers analyzed 30,026 cases that were coded as “suspected suicide” and were reported to the National Poison Data System between June 2013 and December 2017. All cases were in adolescents aged 10-19 years. A total of 3,504 cases were exposures to bupropion; the rest were exposures to SSRIs.

Cases involving SSRIs were significantly more likely to result in either minor or no outcomes, compared with bupropion (68.0% vs 33.2%); cases resulting in moderate or major outcomes were much more likely to involve bupropion, compared with SSRIs (58.1% vs 19.0%). Among the 10 most common effects in cases with a moderate or major outcome, bupropion was more likely to cause tachycardia (83.7% vs. 59.9%), vomiting (24.8% vs. 20.6%), cardiac conduction disturbances (20.0% vs. 17.1%), agitation (20.2% vs. 11.7%), seizures (27.0% vs. 8.5%), and hallucinations (28.6% vs. 4.3%). Cases involving SSRIs were more likely to cause hypertension (25.3% vs. 17.6%). Eight deaths were reported in the study population; all were caused by bupropion ingestion.

Medical therapies that were more common with bupropion overdose included intubation (4.9% vs. 0.3%), vasopressor use (1.1% vs. 0.2%), benzodiazepine administration (34.2% vs. 5.4%), supplemental oxygen requirement (8.2% vs. 0.8%), and CPR (0.5% vs. 0.01%); three patients in the bupropion group required extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, compared with none in the SSRI group.

“Suicidal ingestions are increasing steadily, as are the numbers of adolescents treated with medication for depression. In light of bupropion’s disproportionately significant morbidity and mortality risk, it would be prudent for practitioners to avoid the use of this medication in adolescents that are at risk for self-harm,” the investigators concluded.

The study investigators reported that there were no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Overberg A et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Jul 5. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3295.

Adolescents who attempt self-harm using bupropion are at a significantly higher risk of serious morbidity and poor outcomes, compared with those who attempt self-harm with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), according to Adam Overberg, PharmD, of the Indiana Poison Center in Indianapolis and associates.

In a study published in Pediatrics, the researchers analyzed 30,026 cases that were coded as “suspected suicide” and were reported to the National Poison Data System between June 2013 and December 2017. All cases were in adolescents aged 10-19 years. A total of 3,504 cases were exposures to bupropion; the rest were exposures to SSRIs.

Cases involving SSRIs were significantly more likely to result in either minor or no outcomes, compared with bupropion (68.0% vs 33.2%); cases resulting in moderate or major outcomes were much more likely to involve bupropion, compared with SSRIs (58.1% vs 19.0%). Among the 10 most common effects in cases with a moderate or major outcome, bupropion was more likely to cause tachycardia (83.7% vs. 59.9%), vomiting (24.8% vs. 20.6%), cardiac conduction disturbances (20.0% vs. 17.1%), agitation (20.2% vs. 11.7%), seizures (27.0% vs. 8.5%), and hallucinations (28.6% vs. 4.3%). Cases involving SSRIs were more likely to cause hypertension (25.3% vs. 17.6%). Eight deaths were reported in the study population; all were caused by bupropion ingestion.

Medical therapies that were more common with bupropion overdose included intubation (4.9% vs. 0.3%), vasopressor use (1.1% vs. 0.2%), benzodiazepine administration (34.2% vs. 5.4%), supplemental oxygen requirement (8.2% vs. 0.8%), and CPR (0.5% vs. 0.01%); three patients in the bupropion group required extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, compared with none in the SSRI group.

“Suicidal ingestions are increasing steadily, as are the numbers of adolescents treated with medication for depression. In light of bupropion’s disproportionately significant morbidity and mortality risk, it would be prudent for practitioners to avoid the use of this medication in adolescents that are at risk for self-harm,” the investigators concluded.

The study investigators reported that there were no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Overberg A et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Jul 5. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3295.

Adolescents who attempt self-harm using bupropion are at a significantly higher risk of serious morbidity and poor outcomes, compared with those who attempt self-harm with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), according to Adam Overberg, PharmD, of the Indiana Poison Center in Indianapolis and associates.

In a study published in Pediatrics, the researchers analyzed 30,026 cases that were coded as “suspected suicide” and were reported to the National Poison Data System between June 2013 and December 2017. All cases were in adolescents aged 10-19 years. A total of 3,504 cases were exposures to bupropion; the rest were exposures to SSRIs.

Cases involving SSRIs were significantly more likely to result in either minor or no outcomes, compared with bupropion (68.0% vs 33.2%); cases resulting in moderate or major outcomes were much more likely to involve bupropion, compared with SSRIs (58.1% vs 19.0%). Among the 10 most common effects in cases with a moderate or major outcome, bupropion was more likely to cause tachycardia (83.7% vs. 59.9%), vomiting (24.8% vs. 20.6%), cardiac conduction disturbances (20.0% vs. 17.1%), agitation (20.2% vs. 11.7%), seizures (27.0% vs. 8.5%), and hallucinations (28.6% vs. 4.3%). Cases involving SSRIs were more likely to cause hypertension (25.3% vs. 17.6%). Eight deaths were reported in the study population; all were caused by bupropion ingestion.

Medical therapies that were more common with bupropion overdose included intubation (4.9% vs. 0.3%), vasopressor use (1.1% vs. 0.2%), benzodiazepine administration (34.2% vs. 5.4%), supplemental oxygen requirement (8.2% vs. 0.8%), and CPR (0.5% vs. 0.01%); three patients in the bupropion group required extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, compared with none in the SSRI group.

“Suicidal ingestions are increasing steadily, as are the numbers of adolescents treated with medication for depression. In light of bupropion’s disproportionately significant morbidity and mortality risk, it would be prudent for practitioners to avoid the use of this medication in adolescents that are at risk for self-harm,” the investigators concluded.

The study investigators reported that there were no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Overberg A et al. Pediatrics. 2019 Jul 5. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3295.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Medical cannabis laws appear no longer tied to drop in opioid overdose mortality

Correlations do not hold when analysis is expanded to 2017

Contrary to previous research indicating that medical cannabis laws reduced opioid overdose mortality, the association between these two has reversed, with opioid overdose mortality increased in states with comprehensive medical cannabis laws, according to Chelsea L. Shover, PhD, and associates.

The original research by Marcus A. Bachhuber, MD, and associates showed that the introduction of state medical cannabis laws was associated with a 24.8% reduction in opioid overdose deaths per 100,000 population between 1999 and 2010. In contrast, the new research – which looked at a longer time period than the original research did – found that the association between state medical cannabis laws and opioid overdose mortality reversed direction, from –21% to +23%.

“We find it unlikely that medical cannabis – used by about 2.5% of the U.S. population – has exerted large conflicting effects on opioid overdose mortality,” wrote Dr. Shover, of the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford (Calif.) University, and associates. “A more plausible interpretation is that this association is spurious.” Their study was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

To conduct their analysis, Dr. Shover and associates extended the timeline reviewed by Dr. Bachhuber and associates to 2017. During 2010-2017, 32 states enacted medical cannabis laws, including 17 allowing only medical cannabis with low levels of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), and 8 legalized recreational marijuana. In the expanded timeline during 1999-2017, states possessing a comprehensive medical marijuana law saw an increase in opioid overdose mortality of 28.2%. Meanwhile, states with recreational marijuana laws saw a decrease of 14.7% in opioid overdose mortality, and states with low-THC medical cannabis laws saw a decrease of 7.1%. However, the investigators noted that those values had wide confidence intervals, which indicates “compatibility with large range of true associations.”

Corporate actors with deep pockets have substantial ability to promote congenial results, and suffering people are desperate for effective solutions. Cannabinoids have demonstrated therapeutic benefits, but reducing population-level opioid overdose mortality does not appear to be among them,” Dr. Shover and associates noted.

Dr. Shover reported receiving support from National Institute on Drug Abuse and the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute. Another coauthor received support from the Veterans Health Administration, Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute, and the Esther Ting Memorial Professorship at Stanford.

SOURCE: Shover CL et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019 Jun 10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1903434116.

Correlations do not hold when analysis is expanded to 2017

Correlations do not hold when analysis is expanded to 2017

Contrary to previous research indicating that medical cannabis laws reduced opioid overdose mortality, the association between these two has reversed, with opioid overdose mortality increased in states with comprehensive medical cannabis laws, according to Chelsea L. Shover, PhD, and associates.

The original research by Marcus A. Bachhuber, MD, and associates showed that the introduction of state medical cannabis laws was associated with a 24.8% reduction in opioid overdose deaths per 100,000 population between 1999 and 2010. In contrast, the new research – which looked at a longer time period than the original research did – found that the association between state medical cannabis laws and opioid overdose mortality reversed direction, from –21% to +23%.

“We find it unlikely that medical cannabis – used by about 2.5% of the U.S. population – has exerted large conflicting effects on opioid overdose mortality,” wrote Dr. Shover, of the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford (Calif.) University, and associates. “A more plausible interpretation is that this association is spurious.” Their study was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

To conduct their analysis, Dr. Shover and associates extended the timeline reviewed by Dr. Bachhuber and associates to 2017. During 2010-2017, 32 states enacted medical cannabis laws, including 17 allowing only medical cannabis with low levels of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), and 8 legalized recreational marijuana. In the expanded timeline during 1999-2017, states possessing a comprehensive medical marijuana law saw an increase in opioid overdose mortality of 28.2%. Meanwhile, states with recreational marijuana laws saw a decrease of 14.7% in opioid overdose mortality, and states with low-THC medical cannabis laws saw a decrease of 7.1%. However, the investigators noted that those values had wide confidence intervals, which indicates “compatibility with large range of true associations.”

Corporate actors with deep pockets have substantial ability to promote congenial results, and suffering people are desperate for effective solutions. Cannabinoids have demonstrated therapeutic benefits, but reducing population-level opioid overdose mortality does not appear to be among them,” Dr. Shover and associates noted.

Dr. Shover reported receiving support from National Institute on Drug Abuse and the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute. Another coauthor received support from the Veterans Health Administration, Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute, and the Esther Ting Memorial Professorship at Stanford.

SOURCE: Shover CL et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019 Jun 10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1903434116.

Contrary to previous research indicating that medical cannabis laws reduced opioid overdose mortality, the association between these two has reversed, with opioid overdose mortality increased in states with comprehensive medical cannabis laws, according to Chelsea L. Shover, PhD, and associates.

The original research by Marcus A. Bachhuber, MD, and associates showed that the introduction of state medical cannabis laws was associated with a 24.8% reduction in opioid overdose deaths per 100,000 population between 1999 and 2010. In contrast, the new research – which looked at a longer time period than the original research did – found that the association between state medical cannabis laws and opioid overdose mortality reversed direction, from –21% to +23%.

“We find it unlikely that medical cannabis – used by about 2.5% of the U.S. population – has exerted large conflicting effects on opioid overdose mortality,” wrote Dr. Shover, of the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford (Calif.) University, and associates. “A more plausible interpretation is that this association is spurious.” Their study was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

To conduct their analysis, Dr. Shover and associates extended the timeline reviewed by Dr. Bachhuber and associates to 2017. During 2010-2017, 32 states enacted medical cannabis laws, including 17 allowing only medical cannabis with low levels of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), and 8 legalized recreational marijuana. In the expanded timeline during 1999-2017, states possessing a comprehensive medical marijuana law saw an increase in opioid overdose mortality of 28.2%. Meanwhile, states with recreational marijuana laws saw a decrease of 14.7% in opioid overdose mortality, and states with low-THC medical cannabis laws saw a decrease of 7.1%. However, the investigators noted that those values had wide confidence intervals, which indicates “compatibility with large range of true associations.”

Corporate actors with deep pockets have substantial ability to promote congenial results, and suffering people are desperate for effective solutions. Cannabinoids have demonstrated therapeutic benefits, but reducing population-level opioid overdose mortality does not appear to be among them,” Dr. Shover and associates noted.

Dr. Shover reported receiving support from National Institute on Drug Abuse and the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute. Another coauthor received support from the Veterans Health Administration, Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute, and the Esther Ting Memorial Professorship at Stanford.

SOURCE: Shover CL et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019 Jun 10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1903434116.

FROM PROCEEDINGS OF THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES

Synthetic drugs pose regulatory, diagnostic challenges

SAN FRANCISCO – Designer drugs, especially synthetic opioids and cannabinoids, are presenting increasing challenges to psychiatrists treating patients with overdoses or psychiatric adverse effects. In 2017, synthetic opioids caused more than 28,000 deaths in the United States, more than any other type. Some of these drugs are technically legal, because their modified chemical structures aren’t covered as legal definitions struggle to keep up with street drug identities.

... people are using drugs and they don’t even know what they’re using,” Vanessa Torres-Llenza, MD, assistant professor of psychiatry at George Washington University, Washington, said in an interview. Dr. Torres-Llenza moderated a session on synthetic opioids at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association.

Of particular concern is the synthetic opioid fentanyl, which has a potency about 50 times that of heroin, and 100 times that of morphine. It is a legal pharmaceutical drug for use in severe pain, but it can be made illicitly, and it is frequently mixed with heroin or cocaine and put into counterfeit pills. The user often is not even aware of its presence. Another derivative, carfentanil, is even more dangerous. Used as a large-animal tranquilizer, and illegal for human use, carfentanil is about 100 times more potent than fentanyl.

These developments may require reconsideration of treatment using the opioid antagonist naloxone and similar drugs. The current guidance for naloxone is a 0.4- to 2-mg dose, followed by repeat dose at 2- to 3-minute intervals as needed. Considering the increasing presence of more potent drugs, “there may not be time to wait,” Dr. Torres-Llenza said.

Another concern is illicit manufacturing: By making even slight modifications to legal drugs, illegal operations can stay a step ahead of regulators because these derivatives are completely legal until legislation is passed to ban them. Estimates peg the number of such new derivatives at about 250 per year.

The recent history of the Food Drug Administration’s regulation of synthetic opioids, presented during the session by Gowri Ramachandran, MD, a resident at George Washington University, illustrates the challenges. The Controlled Substances Act of 1970 assigned every regulated drug into one of five classes based on medical use, and potential for abuse and dependence. Schedule I substances are flagged for a high potential of abuse, having no medical use in the United States, and a lack of accepted safety data for use under medical supervision. Schedule II substances have accepted medical uses.

In 2012, the Synthetic Drug Abuse Prevention Act amended the earlier legislation, declaring that any chemical or related derivative with cannabimimetic properties, as well as some other hallucinogenic molecules and their close relatives, were included as schedule I controlled substances.

The amended legislation also extended the potential length of temporary schedule I status, from 1 year with a 6-month extension, to 2 years with a 1-year extension, to give regulators more time to catch up with both legal and illegal synthetic changes to determine if a drug should be schedule I or II.

A recent example of this problem is bath salts, which are far more powerful, synthetic versions of a stimulant derived from the khat plant that is grown in East Africa and southern Arabia. Bath salts can produce hallucinogenic and euphoric effects similar to methamphetamine and ecstasy, but they are readily available online and in retail stores, labeled as “not for human use” and marketed as “bath salts,” “plant food,” “jewelry cleaner,” or “phone screen cleaner.”

Another concern is synthetic cannabinoids, which resemble the 100 or so cannabinoids found in marijuana, tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), and cannabidiol (CBD) being the most well-known examples. These began to appear in recreational use in 2005, representing legal forms of marijuana and sold with names like K2, Spice, and Kronic. They are sold in tobacco shops, again labeled “not for human consumption,” trumpeted instead as a “harmless incense blend” or “natural herbs.” Manufacture and content of these derivatives are completely unregulated, according to Dr. Ramachandran.

Like other drug classes, synthetic cannabinoids – many related to THC – have been structurally altered in recent years, posing challenges to regulation and even detection. This is especially concerning because a synthetic cannabinoid product could contain a potpourri of other drugs such as opioids or herbs, leading to unpredictable effects. It’s also nearly impossible to identify everything in a patient’s system, Dr. Torrez-Llenza said.

That makes diagnosis challenging given that synthetic cannabinoids can cause a wide range of symptoms, commonly violence, agitation, panic attacks, hallucinations, hyperglycemia, hyperkalemia, and tachycardia.

Synthetic cannabinoids usually do not contain CBD, which has some antipsychotic and anxiolytic effects. Instead they are generally derived from THC, which is associated with psychosis, and they are 40-660 times more potent than natural THC. This suggests that synthetic versions may pose a greater psychosis risk than natural cannabis. However, only case reports have examined the existence of an association between synthetic cannabinoids and psychosis, and it is difficult to distinguish a toxic syndrome from exacerbation of a previous prodromal syndrome, or new-onset illness.

Acute reactions can occur within minutes of use and last 2-5 hours or more. But this is all very unpredictable as it depends on the specific mixture used.

In the emergency department, agitation, aggression, and impulsive behaviors may signal exposure to synthetic cannabinoids. Most patients can be treated in the ED with antipsychotics or benzodiazepines to manage symptoms. There could be regional toxidromes that arise from local distribution of specific synthetic cannabinoid combinations.

While testing for synthetic cannabinoids remains challenging, Quest Diagnostics has a urine-based panel that includes them, and the company says it is working with information from the National Forensic Laboratory Information System, the Drug Enforcement Agency, industry sources, and the scientific literature to periodically update its standard panel.

Dr. Torres-Llenza had no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN FRANCISCO – Designer drugs, especially synthetic opioids and cannabinoids, are presenting increasing challenges to psychiatrists treating patients with overdoses or psychiatric adverse effects. In 2017, synthetic opioids caused more than 28,000 deaths in the United States, more than any other type. Some of these drugs are technically legal, because their modified chemical structures aren’t covered as legal definitions struggle to keep up with street drug identities.

... people are using drugs and they don’t even know what they’re using,” Vanessa Torres-Llenza, MD, assistant professor of psychiatry at George Washington University, Washington, said in an interview. Dr. Torres-Llenza moderated a session on synthetic opioids at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association.

Of particular concern is the synthetic opioid fentanyl, which has a potency about 50 times that of heroin, and 100 times that of morphine. It is a legal pharmaceutical drug for use in severe pain, but it can be made illicitly, and it is frequently mixed with heroin or cocaine and put into counterfeit pills. The user often is not even aware of its presence. Another derivative, carfentanil, is even more dangerous. Used as a large-animal tranquilizer, and illegal for human use, carfentanil is about 100 times more potent than fentanyl.

These developments may require reconsideration of treatment using the opioid antagonist naloxone and similar drugs. The current guidance for naloxone is a 0.4- to 2-mg dose, followed by repeat dose at 2- to 3-minute intervals as needed. Considering the increasing presence of more potent drugs, “there may not be time to wait,” Dr. Torres-Llenza said.

Another concern is illicit manufacturing: By making even slight modifications to legal drugs, illegal operations can stay a step ahead of regulators because these derivatives are completely legal until legislation is passed to ban them. Estimates peg the number of such new derivatives at about 250 per year.

The recent history of the Food Drug Administration’s regulation of synthetic opioids, presented during the session by Gowri Ramachandran, MD, a resident at George Washington University, illustrates the challenges. The Controlled Substances Act of 1970 assigned every regulated drug into one of five classes based on medical use, and potential for abuse and dependence. Schedule I substances are flagged for a high potential of abuse, having no medical use in the United States, and a lack of accepted safety data for use under medical supervision. Schedule II substances have accepted medical uses.

In 2012, the Synthetic Drug Abuse Prevention Act amended the earlier legislation, declaring that any chemical or related derivative with cannabimimetic properties, as well as some other hallucinogenic molecules and their close relatives, were included as schedule I controlled substances.

The amended legislation also extended the potential length of temporary schedule I status, from 1 year with a 6-month extension, to 2 years with a 1-year extension, to give regulators more time to catch up with both legal and illegal synthetic changes to determine if a drug should be schedule I or II.

A recent example of this problem is bath salts, which are far more powerful, synthetic versions of a stimulant derived from the khat plant that is grown in East Africa and southern Arabia. Bath salts can produce hallucinogenic and euphoric effects similar to methamphetamine and ecstasy, but they are readily available online and in retail stores, labeled as “not for human use” and marketed as “bath salts,” “plant food,” “jewelry cleaner,” or “phone screen cleaner.”

Another concern is synthetic cannabinoids, which resemble the 100 or so cannabinoids found in marijuana, tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), and cannabidiol (CBD) being the most well-known examples. These began to appear in recreational use in 2005, representing legal forms of marijuana and sold with names like K2, Spice, and Kronic. They are sold in tobacco shops, again labeled “not for human consumption,” trumpeted instead as a “harmless incense blend” or “natural herbs.” Manufacture and content of these derivatives are completely unregulated, according to Dr. Ramachandran.

Like other drug classes, synthetic cannabinoids – many related to THC – have been structurally altered in recent years, posing challenges to regulation and even detection. This is especially concerning because a synthetic cannabinoid product could contain a potpourri of other drugs such as opioids or herbs, leading to unpredictable effects. It’s also nearly impossible to identify everything in a patient’s system, Dr. Torrez-Llenza said.

That makes diagnosis challenging given that synthetic cannabinoids can cause a wide range of symptoms, commonly violence, agitation, panic attacks, hallucinations, hyperglycemia, hyperkalemia, and tachycardia.

Synthetic cannabinoids usually do not contain CBD, which has some antipsychotic and anxiolytic effects. Instead they are generally derived from THC, which is associated with psychosis, and they are 40-660 times more potent than natural THC. This suggests that synthetic versions may pose a greater psychosis risk than natural cannabis. However, only case reports have examined the existence of an association between synthetic cannabinoids and psychosis, and it is difficult to distinguish a toxic syndrome from exacerbation of a previous prodromal syndrome, or new-onset illness.

Acute reactions can occur within minutes of use and last 2-5 hours or more. But this is all very unpredictable as it depends on the specific mixture used.

In the emergency department, agitation, aggression, and impulsive behaviors may signal exposure to synthetic cannabinoids. Most patients can be treated in the ED with antipsychotics or benzodiazepines to manage symptoms. There could be regional toxidromes that arise from local distribution of specific synthetic cannabinoid combinations.

While testing for synthetic cannabinoids remains challenging, Quest Diagnostics has a urine-based panel that includes them, and the company says it is working with information from the National Forensic Laboratory Information System, the Drug Enforcement Agency, industry sources, and the scientific literature to periodically update its standard panel.

Dr. Torres-Llenza had no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN FRANCISCO – Designer drugs, especially synthetic opioids and cannabinoids, are presenting increasing challenges to psychiatrists treating patients with overdoses or psychiatric adverse effects. In 2017, synthetic opioids caused more than 28,000 deaths in the United States, more than any other type. Some of these drugs are technically legal, because their modified chemical structures aren’t covered as legal definitions struggle to keep up with street drug identities.

... people are using drugs and they don’t even know what they’re using,” Vanessa Torres-Llenza, MD, assistant professor of psychiatry at George Washington University, Washington, said in an interview. Dr. Torres-Llenza moderated a session on synthetic opioids at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association.

Of particular concern is the synthetic opioid fentanyl, which has a potency about 50 times that of heroin, and 100 times that of morphine. It is a legal pharmaceutical drug for use in severe pain, but it can be made illicitly, and it is frequently mixed with heroin or cocaine and put into counterfeit pills. The user often is not even aware of its presence. Another derivative, carfentanil, is even more dangerous. Used as a large-animal tranquilizer, and illegal for human use, carfentanil is about 100 times more potent than fentanyl.

These developments may require reconsideration of treatment using the opioid antagonist naloxone and similar drugs. The current guidance for naloxone is a 0.4- to 2-mg dose, followed by repeat dose at 2- to 3-minute intervals as needed. Considering the increasing presence of more potent drugs, “there may not be time to wait,” Dr. Torres-Llenza said.

Another concern is illicit manufacturing: By making even slight modifications to legal drugs, illegal operations can stay a step ahead of regulators because these derivatives are completely legal until legislation is passed to ban them. Estimates peg the number of such new derivatives at about 250 per year.

The recent history of the Food Drug Administration’s regulation of synthetic opioids, presented during the session by Gowri Ramachandran, MD, a resident at George Washington University, illustrates the challenges. The Controlled Substances Act of 1970 assigned every regulated drug into one of five classes based on medical use, and potential for abuse and dependence. Schedule I substances are flagged for a high potential of abuse, having no medical use in the United States, and a lack of accepted safety data for use under medical supervision. Schedule II substances have accepted medical uses.

In 2012, the Synthetic Drug Abuse Prevention Act amended the earlier legislation, declaring that any chemical or related derivative with cannabimimetic properties, as well as some other hallucinogenic molecules and their close relatives, were included as schedule I controlled substances.

The amended legislation also extended the potential length of temporary schedule I status, from 1 year with a 6-month extension, to 2 years with a 1-year extension, to give regulators more time to catch up with both legal and illegal synthetic changes to determine if a drug should be schedule I or II.

A recent example of this problem is bath salts, which are far more powerful, synthetic versions of a stimulant derived from the khat plant that is grown in East Africa and southern Arabia. Bath salts can produce hallucinogenic and euphoric effects similar to methamphetamine and ecstasy, but they are readily available online and in retail stores, labeled as “not for human use” and marketed as “bath salts,” “plant food,” “jewelry cleaner,” or “phone screen cleaner.”

Another concern is synthetic cannabinoids, which resemble the 100 or so cannabinoids found in marijuana, tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), and cannabidiol (CBD) being the most well-known examples. These began to appear in recreational use in 2005, representing legal forms of marijuana and sold with names like K2, Spice, and Kronic. They are sold in tobacco shops, again labeled “not for human consumption,” trumpeted instead as a “harmless incense blend” or “natural herbs.” Manufacture and content of these derivatives are completely unregulated, according to Dr. Ramachandran.

Like other drug classes, synthetic cannabinoids – many related to THC – have been structurally altered in recent years, posing challenges to regulation and even detection. This is especially concerning because a synthetic cannabinoid product could contain a potpourri of other drugs such as opioids or herbs, leading to unpredictable effects. It’s also nearly impossible to identify everything in a patient’s system, Dr. Torrez-Llenza said.

That makes diagnosis challenging given that synthetic cannabinoids can cause a wide range of symptoms, commonly violence, agitation, panic attacks, hallucinations, hyperglycemia, hyperkalemia, and tachycardia.

Synthetic cannabinoids usually do not contain CBD, which has some antipsychotic and anxiolytic effects. Instead they are generally derived from THC, which is associated with psychosis, and they are 40-660 times more potent than natural THC. This suggests that synthetic versions may pose a greater psychosis risk than natural cannabis. However, only case reports have examined the existence of an association between synthetic cannabinoids and psychosis, and it is difficult to distinguish a toxic syndrome from exacerbation of a previous prodromal syndrome, or new-onset illness.

Acute reactions can occur within minutes of use and last 2-5 hours or more. But this is all very unpredictable as it depends on the specific mixture used.

In the emergency department, agitation, aggression, and impulsive behaviors may signal exposure to synthetic cannabinoids. Most patients can be treated in the ED with antipsychotics or benzodiazepines to manage symptoms. There could be regional toxidromes that arise from local distribution of specific synthetic cannabinoid combinations.

While testing for synthetic cannabinoids remains challenging, Quest Diagnostics has a urine-based panel that includes them, and the company says it is working with information from the National Forensic Laboratory Information System, the Drug Enforcement Agency, industry sources, and the scientific literature to periodically update its standard panel.

Dr. Torres-Llenza had no relevant financial disclosures.

REPORTING FROM APA 2019

Button batteries that pass to the stomach may warrant rapid endoscopic removal

SAN DIEGO – A button battery lodged in a child’s esophagus is an acknowledged emergency, but there is less evidence about retrieval of button batteries that have passed to the stomach. Observation alone has been recommended when an x-ray determines that the button battery has passed to the stomach within 2 hours of ingestion, when the battery is less than 20 mm, and the child is aged at least 5 years.

At the annual Digestive Disease Week, Racha Khalaf, MD, and Thomas Walker, MD, both of Children’s Hospital Colorado, Aurora, presented data that call this approach into question. Their retrospective cohort study of 4 years’ worth of records from four pediatric centers in the United States identified 68 cases in which a pediatric gastroenterologist had endoscopically removed the button battery. In 60% of those cases, the battery had already caused mucosal damage varying from minor to deep necrosis and perforation.

Further, the degree of injury was not correlated with symptoms, strengthening the recommendation for retrieving the button battery from the stomach.

In our exclusive video interview, Dr. Khalaf and Dr. Walker discussed the impact of their findings for guidelines for pediatric gastroenterologists and Poison Control Center advice to parents about ingestion of button batteries.

Their study was partly supported by a Cystic Fibrosis Foundational Grant Award and by National Institutes of Health Training Grants.

SAN DIEGO – A button battery lodged in a child’s esophagus is an acknowledged emergency, but there is less evidence about retrieval of button batteries that have passed to the stomach. Observation alone has been recommended when an x-ray determines that the button battery has passed to the stomach within 2 hours of ingestion, when the battery is less than 20 mm, and the child is aged at least 5 years.

At the annual Digestive Disease Week, Racha Khalaf, MD, and Thomas Walker, MD, both of Children’s Hospital Colorado, Aurora, presented data that call this approach into question. Their retrospective cohort study of 4 years’ worth of records from four pediatric centers in the United States identified 68 cases in which a pediatric gastroenterologist had endoscopically removed the button battery. In 60% of those cases, the battery had already caused mucosal damage varying from minor to deep necrosis and perforation.

Further, the degree of injury was not correlated with symptoms, strengthening the recommendation for retrieving the button battery from the stomach.

In our exclusive video interview, Dr. Khalaf and Dr. Walker discussed the impact of their findings for guidelines for pediatric gastroenterologists and Poison Control Center advice to parents about ingestion of button batteries.

Their study was partly supported by a Cystic Fibrosis Foundational Grant Award and by National Institutes of Health Training Grants.

SAN DIEGO – A button battery lodged in a child’s esophagus is an acknowledged emergency, but there is less evidence about retrieval of button batteries that have passed to the stomach. Observation alone has been recommended when an x-ray determines that the button battery has passed to the stomach within 2 hours of ingestion, when the battery is less than 20 mm, and the child is aged at least 5 years.

At the annual Digestive Disease Week, Racha Khalaf, MD, and Thomas Walker, MD, both of Children’s Hospital Colorado, Aurora, presented data that call this approach into question. Their retrospective cohort study of 4 years’ worth of records from four pediatric centers in the United States identified 68 cases in which a pediatric gastroenterologist had endoscopically removed the button battery. In 60% of those cases, the battery had already caused mucosal damage varying from minor to deep necrosis and perforation.

Further, the degree of injury was not correlated with symptoms, strengthening the recommendation for retrieving the button battery from the stomach.

In our exclusive video interview, Dr. Khalaf and Dr. Walker discussed the impact of their findings for guidelines for pediatric gastroenterologists and Poison Control Center advice to parents about ingestion of button batteries.

Their study was partly supported by a Cystic Fibrosis Foundational Grant Award and by National Institutes of Health Training Grants.

REPORTING FROM DDW 2019

Only 1.5% of individuals at high risk of opioid overdose receive naloxone

The vast majority of individuals at high risk for opioid overdose do not receive naloxone, despite numerous opportunities, according to Sarah Follman and associates from the University of Chicago.

In a retrospective study published in JAMA Network Open, the study authors analyzed data from individuals in the Truven Health MarketScan Research Database who had ICD-10 codes related to opioid use, misuse, dependence, and overdose. Data from Oct. 1, 2015, through Dec. 31, 2016, were included; a total of 138,108 high-risk individuals were identified as interacting with the health care system nearly 1.2 million times (88,618 hospitalizations, 229,680 ED visits, 298,058 internal medicine visits, and 568,448 family practice visits).