User login

Polio in 2022: Some concerns but vaccine still works

Who would have thought we would need to refresh our knowledge on polio virus in 2022? Fate seems cruel to add this concern on the heels of SARS-CoV-2, monkeypox, abnormal seasons for RSV, acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) linked to enteroviruses, and a summer of parechovirus causing infant meningitis. But confirmation that indeed an adult had polio with paralytic disease raises concerns among public health groups and ordinary citizens alike, particularly those who remember polio in its heyday.

History: In the summer of 1952, polio was among the most feared diseases on the planet. Families were advised to not allow children to congregate in groups or use public swimming pools; little league baseball games were being canceled and there was talk of not opening schools for the fall. Every parent’s nightmare seemed to be the nonspecific febrile summer illness that led to paralytic sequelae. TV news included videos of the iron lung wards in hospitals across the country. Medical providers felt powerless, only able to give nonspecific preventive advice. There was no specific antiviral (there still isn’t) and vaccines seemed a long way off.

Then came the news that Dr. Jonas Salk’s group had gotten an inactivated polio vaccine (IPV) approved for general use in 1955. Families were excited to have their children vaccinated. Paralytic polio cases dropped like a rock from approximately 22,000/year in 1952 to approximately 2,200 in 1956. A surge to near 6,000 cases in 1959 led to Dr. Albert Sabin’s oral polio vaccine (OPV), which supplanted IPV in 1961. OPV had the advantages of: 1) Inducing mucosal as well as serum antibodies, 2) more durable responses, and 3) immunity in unvaccinated persons exposed to vaccine virus that had been shed in stools into wastewater and rivers.

By 1964, polio had nearly disappeared. The last wild-type indigenous U.S. case was in 1979. By 1994, all the Americas were declared polio free. Because the only U.S. paralytic polio cases thereafter were foreign imports or were associated with oral vaccine strains (so-called vaccine-associated paralytic polio [VAPP]), OPV was replaced by an enhanced IPV in 2000 to prevent further VAPP.

Polio facts: Polio is asymptomatic in about 70% of infections. Among the 30% with symptoms, paralysis occurs infrequently, with the overall rate of paralytic infections being 0.5% (rate varies by virus type with type 3 having the highest rate).1 Why then was the world so afraid of polio? If every person in a U.S. birth cohort (about 3.7 million) was unvaccinated and became infected with poliovirus, more than 18,000 would get paralytic polio and almost 1,300 would die. Of note, adults have a higher chance of paralytic polio after infection than children.

Concerns in 2022: Persons vaccinated with at least three doses of either IPV or OPV have historically been protected from paralytic polio (99% protection). But are we sure that the United States remains protected against polio after 2 decades of IPV being the only vaccine? Polio could be reintroduced at any time to the United States from countries with reported cases that likely arose because of low vaccination rates related to war, famine, or political upheavals (Malawi, Mozambique, Nigeria, Pakistan, and Afghanistan).2 The proof? The recent confirmed New York case.

International efforts resulted in global eradication of two polio wild-types viruses (type 2 in 2015 and type 3 in 2019). Nevertheless, vaccine-derived, virulent polio virus (VDPV) type 2 and VDPV-3 still circulate in some areas, particularly Africa (VDPV-2) and Israel (VDPV-3). The above-mentioned U.S. case is an unvaccinated adult traveler who went to an area where VDPV-2 circulates and developed disease after returning home.3 So, it was not an indigenous reappearance in the United States and it was not a breakthrough case in a vaccinated person. But it is sobering to realize that all who are unvaccinated remain at risk for paralytic polio in 2022, particularly because vaccination rates declined nearly everywhere during the initial COVID-19 pandemic. We are still catching up, with vaccination rates under 50% in some ZIP codes.4

Are VDPVs circulating in some parts of the United States? Interestingly, wastewater surveillance programs may be the most economical and practical way to perform polio surveillance. Such a program detected polio virus in London wastewater in June 2022.5 New York has recently detected polio in wastewater during testing begun because of the recent case.6

Good news: For paralytic polio, seropositivity at any titer indicates protection, so U.S. serosurveillance data would also be informative. How durable is polio protection in the IPV era? Available data suggest that even though we have used only IPV these past 20 years, seropositivity rates among vaccinees with at least three doses of either IPV or OPV should persist for decades and likely for life. Even before polio became a concern this year, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, being proactive, wanted to ensure that the enhanced IPV was producing durable immunity and that persons of all ages remained seropositive to the three polio virus types over 10 years after discontinuing OPV use in 2012.

The CDC collaborated with investigators in Kansas City, Mo., to evaluate titers and seropositivity to all three types in a 2- to 85-year-old otherwise healthy cohort with demographics that mirrored the 2010 census for the Kansas City region, which in turn mirrored the national 2021 census data.7 There were approximately 100 persons in each age cohort, with 200 below age 11 years (the cohort that had received only IPV). Serology was performed at the CDC.

Overall seropositivity rates were high, but lower for type 3 (83.3%) and type 2 (90.7%) than type 1 (94.4%). Of note, most of those seronegative for one or more types were among 2- to 3-year-olds who had not completed their full IPV series, with most seronegative results being against polio types 1 and 3. Further, five, who were confirmed as having received no polio vaccine, were seronegative for all three types. Two with no available vaccine records (over 18 years old) were also seronegative for all three types.

So, regardless of the era in which one got polio vaccine, vaccine protection appears to persist indefinitely after three doses. Even 80-year-olds were still seropositive if they had three doses. We can confidently reassure our patients that the vaccine still works; the persons who need to fear polio in 2022 are those who are not vaccinated or have had fewer than three doses, particularly if they travel to areas of persistent polio. Wild type 1 virus persists in a few countries as does VDPV type 2 and VDPV type 3. Importantly, wild type 2 and wild type 3 (with the lowest seropositivity in 2012 study) have been eliminated globally so the only circulating type 2 and type 3 polio virus is VDPV in a few countries. Travel to these countries warrants review of polio vaccine records and CDC or WHO current recommendations for travelers to those countries.

Dr. Harrison is a professor, University of Missouri Kansas City School of Medicine, department of medicine, infectious diseases section, Kansas City. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. Poliomyelitis. World Health Organization fact sheet, 2022 Jul 4..

2. Franco-Paredes C et al. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022 Aug 16. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00548-5.

3. Link-Gelles R et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022 Aug 19;71(33):1065-8.

4. “Polio vaccination rate for 2-year-olds is as low as 37% in parts of N.Y. county where paralysis case was found,” NBC News, Erika Edwards, 2022 Aug 16. 5. Vaccine-derived poliovirus type 2 (VDPV2) detected in environmental samples in London. Polioeradication.org. 2022 Jun 22.

6. “NYSDOH and NYCDOHMH wastewater monitoring identifies polio in New York City and urges unvaccinated New Yorkers to get vaccinated now,” nyc.gov. 2022 Aug 12.

7. Wallace GS et al. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017;13(4):776-83.

Who would have thought we would need to refresh our knowledge on polio virus in 2022? Fate seems cruel to add this concern on the heels of SARS-CoV-2, monkeypox, abnormal seasons for RSV, acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) linked to enteroviruses, and a summer of parechovirus causing infant meningitis. But confirmation that indeed an adult had polio with paralytic disease raises concerns among public health groups and ordinary citizens alike, particularly those who remember polio in its heyday.

History: In the summer of 1952, polio was among the most feared diseases on the planet. Families were advised to not allow children to congregate in groups or use public swimming pools; little league baseball games were being canceled and there was talk of not opening schools for the fall. Every parent’s nightmare seemed to be the nonspecific febrile summer illness that led to paralytic sequelae. TV news included videos of the iron lung wards in hospitals across the country. Medical providers felt powerless, only able to give nonspecific preventive advice. There was no specific antiviral (there still isn’t) and vaccines seemed a long way off.

Then came the news that Dr. Jonas Salk’s group had gotten an inactivated polio vaccine (IPV) approved for general use in 1955. Families were excited to have their children vaccinated. Paralytic polio cases dropped like a rock from approximately 22,000/year in 1952 to approximately 2,200 in 1956. A surge to near 6,000 cases in 1959 led to Dr. Albert Sabin’s oral polio vaccine (OPV), which supplanted IPV in 1961. OPV had the advantages of: 1) Inducing mucosal as well as serum antibodies, 2) more durable responses, and 3) immunity in unvaccinated persons exposed to vaccine virus that had been shed in stools into wastewater and rivers.

By 1964, polio had nearly disappeared. The last wild-type indigenous U.S. case was in 1979. By 1994, all the Americas were declared polio free. Because the only U.S. paralytic polio cases thereafter were foreign imports or were associated with oral vaccine strains (so-called vaccine-associated paralytic polio [VAPP]), OPV was replaced by an enhanced IPV in 2000 to prevent further VAPP.

Polio facts: Polio is asymptomatic in about 70% of infections. Among the 30% with symptoms, paralysis occurs infrequently, with the overall rate of paralytic infections being 0.5% (rate varies by virus type with type 3 having the highest rate).1 Why then was the world so afraid of polio? If every person in a U.S. birth cohort (about 3.7 million) was unvaccinated and became infected with poliovirus, more than 18,000 would get paralytic polio and almost 1,300 would die. Of note, adults have a higher chance of paralytic polio after infection than children.

Concerns in 2022: Persons vaccinated with at least three doses of either IPV or OPV have historically been protected from paralytic polio (99% protection). But are we sure that the United States remains protected against polio after 2 decades of IPV being the only vaccine? Polio could be reintroduced at any time to the United States from countries with reported cases that likely arose because of low vaccination rates related to war, famine, or political upheavals (Malawi, Mozambique, Nigeria, Pakistan, and Afghanistan).2 The proof? The recent confirmed New York case.

International efforts resulted in global eradication of two polio wild-types viruses (type 2 in 2015 and type 3 in 2019). Nevertheless, vaccine-derived, virulent polio virus (VDPV) type 2 and VDPV-3 still circulate in some areas, particularly Africa (VDPV-2) and Israel (VDPV-3). The above-mentioned U.S. case is an unvaccinated adult traveler who went to an area where VDPV-2 circulates and developed disease after returning home.3 So, it was not an indigenous reappearance in the United States and it was not a breakthrough case in a vaccinated person. But it is sobering to realize that all who are unvaccinated remain at risk for paralytic polio in 2022, particularly because vaccination rates declined nearly everywhere during the initial COVID-19 pandemic. We are still catching up, with vaccination rates under 50% in some ZIP codes.4

Are VDPVs circulating in some parts of the United States? Interestingly, wastewater surveillance programs may be the most economical and practical way to perform polio surveillance. Such a program detected polio virus in London wastewater in June 2022.5 New York has recently detected polio in wastewater during testing begun because of the recent case.6

Good news: For paralytic polio, seropositivity at any titer indicates protection, so U.S. serosurveillance data would also be informative. How durable is polio protection in the IPV era? Available data suggest that even though we have used only IPV these past 20 years, seropositivity rates among vaccinees with at least three doses of either IPV or OPV should persist for decades and likely for life. Even before polio became a concern this year, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, being proactive, wanted to ensure that the enhanced IPV was producing durable immunity and that persons of all ages remained seropositive to the three polio virus types over 10 years after discontinuing OPV use in 2012.

The CDC collaborated with investigators in Kansas City, Mo., to evaluate titers and seropositivity to all three types in a 2- to 85-year-old otherwise healthy cohort with demographics that mirrored the 2010 census for the Kansas City region, which in turn mirrored the national 2021 census data.7 There were approximately 100 persons in each age cohort, with 200 below age 11 years (the cohort that had received only IPV). Serology was performed at the CDC.

Overall seropositivity rates were high, but lower for type 3 (83.3%) and type 2 (90.7%) than type 1 (94.4%). Of note, most of those seronegative for one or more types were among 2- to 3-year-olds who had not completed their full IPV series, with most seronegative results being against polio types 1 and 3. Further, five, who were confirmed as having received no polio vaccine, were seronegative for all three types. Two with no available vaccine records (over 18 years old) were also seronegative for all three types.

So, regardless of the era in which one got polio vaccine, vaccine protection appears to persist indefinitely after three doses. Even 80-year-olds were still seropositive if they had three doses. We can confidently reassure our patients that the vaccine still works; the persons who need to fear polio in 2022 are those who are not vaccinated or have had fewer than three doses, particularly if they travel to areas of persistent polio. Wild type 1 virus persists in a few countries as does VDPV type 2 and VDPV type 3. Importantly, wild type 2 and wild type 3 (with the lowest seropositivity in 2012 study) have been eliminated globally so the only circulating type 2 and type 3 polio virus is VDPV in a few countries. Travel to these countries warrants review of polio vaccine records and CDC or WHO current recommendations for travelers to those countries.

Dr. Harrison is a professor, University of Missouri Kansas City School of Medicine, department of medicine, infectious diseases section, Kansas City. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. Poliomyelitis. World Health Organization fact sheet, 2022 Jul 4..

2. Franco-Paredes C et al. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022 Aug 16. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00548-5.

3. Link-Gelles R et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022 Aug 19;71(33):1065-8.

4. “Polio vaccination rate for 2-year-olds is as low as 37% in parts of N.Y. county where paralysis case was found,” NBC News, Erika Edwards, 2022 Aug 16. 5. Vaccine-derived poliovirus type 2 (VDPV2) detected in environmental samples in London. Polioeradication.org. 2022 Jun 22.

6. “NYSDOH and NYCDOHMH wastewater monitoring identifies polio in New York City and urges unvaccinated New Yorkers to get vaccinated now,” nyc.gov. 2022 Aug 12.

7. Wallace GS et al. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017;13(4):776-83.

Who would have thought we would need to refresh our knowledge on polio virus in 2022? Fate seems cruel to add this concern on the heels of SARS-CoV-2, monkeypox, abnormal seasons for RSV, acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) linked to enteroviruses, and a summer of parechovirus causing infant meningitis. But confirmation that indeed an adult had polio with paralytic disease raises concerns among public health groups and ordinary citizens alike, particularly those who remember polio in its heyday.

History: In the summer of 1952, polio was among the most feared diseases on the planet. Families were advised to not allow children to congregate in groups or use public swimming pools; little league baseball games were being canceled and there was talk of not opening schools for the fall. Every parent’s nightmare seemed to be the nonspecific febrile summer illness that led to paralytic sequelae. TV news included videos of the iron lung wards in hospitals across the country. Medical providers felt powerless, only able to give nonspecific preventive advice. There was no specific antiviral (there still isn’t) and vaccines seemed a long way off.

Then came the news that Dr. Jonas Salk’s group had gotten an inactivated polio vaccine (IPV) approved for general use in 1955. Families were excited to have their children vaccinated. Paralytic polio cases dropped like a rock from approximately 22,000/year in 1952 to approximately 2,200 in 1956. A surge to near 6,000 cases in 1959 led to Dr. Albert Sabin’s oral polio vaccine (OPV), which supplanted IPV in 1961. OPV had the advantages of: 1) Inducing mucosal as well as serum antibodies, 2) more durable responses, and 3) immunity in unvaccinated persons exposed to vaccine virus that had been shed in stools into wastewater and rivers.

By 1964, polio had nearly disappeared. The last wild-type indigenous U.S. case was in 1979. By 1994, all the Americas were declared polio free. Because the only U.S. paralytic polio cases thereafter were foreign imports or were associated with oral vaccine strains (so-called vaccine-associated paralytic polio [VAPP]), OPV was replaced by an enhanced IPV in 2000 to prevent further VAPP.

Polio facts: Polio is asymptomatic in about 70% of infections. Among the 30% with symptoms, paralysis occurs infrequently, with the overall rate of paralytic infections being 0.5% (rate varies by virus type with type 3 having the highest rate).1 Why then was the world so afraid of polio? If every person in a U.S. birth cohort (about 3.7 million) was unvaccinated and became infected with poliovirus, more than 18,000 would get paralytic polio and almost 1,300 would die. Of note, adults have a higher chance of paralytic polio after infection than children.

Concerns in 2022: Persons vaccinated with at least three doses of either IPV or OPV have historically been protected from paralytic polio (99% protection). But are we sure that the United States remains protected against polio after 2 decades of IPV being the only vaccine? Polio could be reintroduced at any time to the United States from countries with reported cases that likely arose because of low vaccination rates related to war, famine, or political upheavals (Malawi, Mozambique, Nigeria, Pakistan, and Afghanistan).2 The proof? The recent confirmed New York case.

International efforts resulted in global eradication of two polio wild-types viruses (type 2 in 2015 and type 3 in 2019). Nevertheless, vaccine-derived, virulent polio virus (VDPV) type 2 and VDPV-3 still circulate in some areas, particularly Africa (VDPV-2) and Israel (VDPV-3). The above-mentioned U.S. case is an unvaccinated adult traveler who went to an area where VDPV-2 circulates and developed disease after returning home.3 So, it was not an indigenous reappearance in the United States and it was not a breakthrough case in a vaccinated person. But it is sobering to realize that all who are unvaccinated remain at risk for paralytic polio in 2022, particularly because vaccination rates declined nearly everywhere during the initial COVID-19 pandemic. We are still catching up, with vaccination rates under 50% in some ZIP codes.4

Are VDPVs circulating in some parts of the United States? Interestingly, wastewater surveillance programs may be the most economical and practical way to perform polio surveillance. Such a program detected polio virus in London wastewater in June 2022.5 New York has recently detected polio in wastewater during testing begun because of the recent case.6

Good news: For paralytic polio, seropositivity at any titer indicates protection, so U.S. serosurveillance data would also be informative. How durable is polio protection in the IPV era? Available data suggest that even though we have used only IPV these past 20 years, seropositivity rates among vaccinees with at least three doses of either IPV or OPV should persist for decades and likely for life. Even before polio became a concern this year, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, being proactive, wanted to ensure that the enhanced IPV was producing durable immunity and that persons of all ages remained seropositive to the three polio virus types over 10 years after discontinuing OPV use in 2012.

The CDC collaborated with investigators in Kansas City, Mo., to evaluate titers and seropositivity to all three types in a 2- to 85-year-old otherwise healthy cohort with demographics that mirrored the 2010 census for the Kansas City region, which in turn mirrored the national 2021 census data.7 There were approximately 100 persons in each age cohort, with 200 below age 11 years (the cohort that had received only IPV). Serology was performed at the CDC.

Overall seropositivity rates were high, but lower for type 3 (83.3%) and type 2 (90.7%) than type 1 (94.4%). Of note, most of those seronegative for one or more types were among 2- to 3-year-olds who had not completed their full IPV series, with most seronegative results being against polio types 1 and 3. Further, five, who were confirmed as having received no polio vaccine, were seronegative for all three types. Two with no available vaccine records (over 18 years old) were also seronegative for all three types.

So, regardless of the era in which one got polio vaccine, vaccine protection appears to persist indefinitely after three doses. Even 80-year-olds were still seropositive if they had three doses. We can confidently reassure our patients that the vaccine still works; the persons who need to fear polio in 2022 are those who are not vaccinated or have had fewer than three doses, particularly if they travel to areas of persistent polio. Wild type 1 virus persists in a few countries as does VDPV type 2 and VDPV type 3. Importantly, wild type 2 and wild type 3 (with the lowest seropositivity in 2012 study) have been eliminated globally so the only circulating type 2 and type 3 polio virus is VDPV in a few countries. Travel to these countries warrants review of polio vaccine records and CDC or WHO current recommendations for travelers to those countries.

Dr. Harrison is a professor, University of Missouri Kansas City School of Medicine, department of medicine, infectious diseases section, Kansas City. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. Poliomyelitis. World Health Organization fact sheet, 2022 Jul 4..

2. Franco-Paredes C et al. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022 Aug 16. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00548-5.

3. Link-Gelles R et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022 Aug 19;71(33):1065-8.

4. “Polio vaccination rate for 2-year-olds is as low as 37% in parts of N.Y. county where paralysis case was found,” NBC News, Erika Edwards, 2022 Aug 16. 5. Vaccine-derived poliovirus type 2 (VDPV2) detected in environmental samples in London. Polioeradication.org. 2022 Jun 22.

6. “NYSDOH and NYCDOHMH wastewater monitoring identifies polio in New York City and urges unvaccinated New Yorkers to get vaccinated now,” nyc.gov. 2022 Aug 12.

7. Wallace GS et al. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017;13(4):776-83.

Improving Inpatient COVID-19 Vaccination Rates Among Adult Patients at a Tertiary Academic Medical Center

From the Department of Medicine, The George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Washington, DC.

Abstract

Objective: Inpatient vaccination initiatives are well described in the literature. During the COVID-19 pandemic, hospitals began administering COVID-19 vaccines to hospitalized patients. Although vaccination rates increased, there remained many unvaccinated patients despite community efforts. This quality improvement project aimed to increase the COVID-19 vaccination rates of hospitalized patients on the medicine service at the George Washington University Hospital (GWUH).

Methods: From November 2021 through February 2022, we conducted a Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycle with 3 phases. Initial steps included gathering baseline data from the electronic health record and consulting stakeholders. The first 2 phases focused on educating housestaff on the availability, ordering process, and administration of the Pfizer vaccine. The third phase consisted of developing educational pamphlets for patients to be included in their admission packets.

Results: The baseline mean COVID-19 vaccination rate (August to October 2021) of eligible patients on the medicine service was 10.7%. In the months after we implemented the PDSA cycle (November 2021 to February 2022), the mean vaccination rate increased to 15.4%.

Conclusion: This quality improvement project implemented measures to increase administration of the Pfizer vaccine to eligible patients admitted to the medicine service at GWUH. The mean vaccination rate increased from 10.7% in the 3 months prior to implementation to 15.4% during the 4 months post implementation. Other measures to consider in the future include increasing the availability of other COVID-19 vaccines at our hospital and incorporating the vaccine into the admission order set to help facilitate vaccination early in the hospital course.

Keywords: housestaff, quality improvement, PDSA, COVID-19, BNT162b2 vaccine, patient education

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, case rates in the United States have fluctuated considerably, corresponding to epidemic waves. In 2021, US daily cases of COVID-19 peaked at nearly 300,000 in early January and reached a nadir of 8000 cases in mid-June.1 In September 2021, new cases had increased to 200,000 per day due to the prevalence of the Delta variant.1 Particularly with the emergence of new variants of SARS-CoV-2, vaccination efforts to limit the spread of infection and severity of illness are critical. Data have shown that 2 doses of the BNT162b2 vaccine (Pfizer-BioNTech) were largely protective against severe infection for approximately 6 months.2,3 When we began this quality improvement (QI) project in September 2021, only 179 million Americans had been fully vaccinated, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which is just over half of the US population.4 An electronic survey conducted in the United States with more than 5 million responses found that, of those who were hesitant about receiving the vaccine, 49% reported a fear of adverse effects and 48% reported a lack of trust in the vaccine.5

This QI project sought to target unvaccinated individuals admitted to the internal medicine inpatient service. Vaccinating hospitalized patients is especially important since they are sicker than the general population and at higher risk of having poor outcomes from COVID-19. Inpatient vaccine initiatives, such as administering influenza vaccine prior to discharge, have been successfully implemented in the past.6 One large COVID-19 vaccination program featured an admission order set to increase the rates of vaccination among hospitalized patients.7 Our QI project piloted a multidisciplinary approach involving the nursing staff, pharmacy, information technology (IT) department, and internal medicine housestaff to increase COVID-19 vaccination rates among hospitalized patients on the medical service. This project aimed to increase inpatient vaccination rates through interventions targeting both primary providers as well as the patients themselves.

Methods

Setting and Interventions

This project was conducted at the George Washington University Hospital (GWUH) in Washington, DC. The clinicians involved in the study were the internal medicine housestaff, and the patients included were adults admitted to the resident medicine ward teams. The project was exempt by the institutional review board and did not require informed consent.

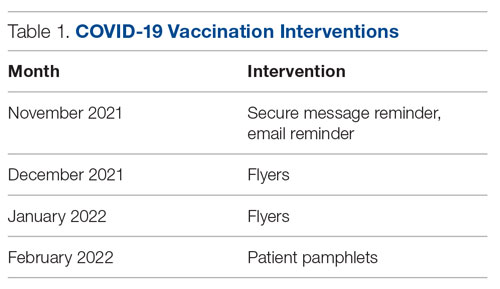

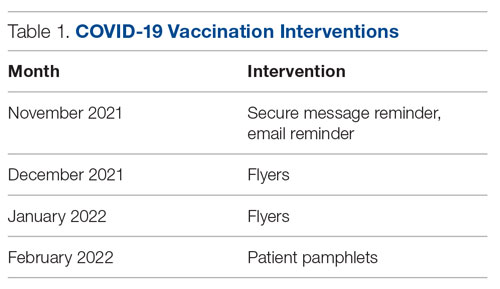

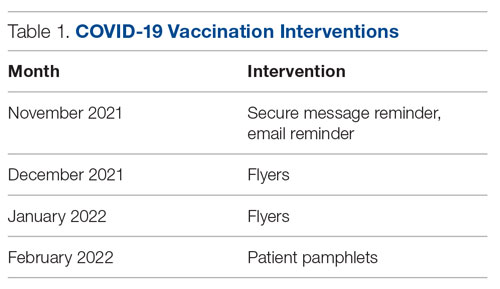

The quality improvement initiative had 3 phases, each featuring a different intervention (Table 1). The first phase involved sending a weekly announcement (via email and a secure health care messaging app) to current residents rotating on the inpatient medicine service. The announcement contained information regarding COVID-19 vaccine availability at the hospital, instructions on ordering the vaccine, and the process of coordinating with pharmacy to facilitate vaccine administration. Thereafter, residents were educated on the process of giving a COVID-19 vaccine to a patient from start to finish. Due to the nature of the residency schedule, different housestaff members rotated in and out of the medicine wards during the intervention periods. The weekly email was sent to the entire internal medicine housestaff, informing all residents about the QI project, while the weekly secure messages served as reminders and were only sent to residents currently on the medicine wards.

In the second phase, we posted paper flyers throughout the hospital to remind housestaff to give the vaccine and again educate them on the process of ordering the vaccine. For the third intervention, a COVID-19 vaccine educational pamphlet was developed for distribution to inpatients at GWUH. The pamphlet included information on vaccine efficacy, safety, side effects, and eligibility. The pamphlet was incorporated in the admission packet that every patient receives upon admission to the hospital. The patients reviewed the pamphlets with nursing staff, who would answer any questions, with residents available to discuss any outstanding concerns.

Measures and Data Gathering

The primary endpoint of the study was inpatient vaccination rate, defined as the number of COVID-19 vaccines administered divided by the number of patients eligible to receive a vaccine (not fully vaccinated). During initial triage, nursing staff documented vaccination status in the electronic health record (EHR), checking a box in a data entry form if a patient had received 0, 1, or 2 doses of the COVID-19 vaccine. The GWUH IT department generated data from this form to determine the number of patients eligible to receive a COVID-19 vaccine. Data were extracted from the medication administration record in the EHR to determine the number of vaccines that were administered to patients during their hospitalization on the inpatient medical service. Each month, the IT department extracted data for the number of eligible patients and the number of vaccines administered. This yielded the monthly vaccination rates. The monthly vaccination rates in the period prior to starting the QI initiative were compared to the rates in the period after the interventions were implemented.

Of note, during the course of this project, patients became eligible for a third COVID-19 vaccine (booster). We decided to continue with the original aim of vaccinating adults who had only received 0 or 1 dose of the vaccine. Therefore, the eligibility criteria remained the same throughout the study. We obtained retrospective data to ensure that the vaccines being counted toward the vaccination rate were vaccines given to patients not yet fully vaccinated and not vaccines given as boosters.

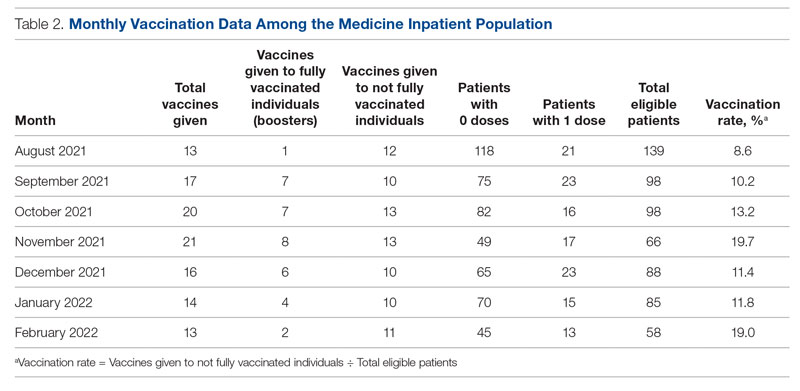

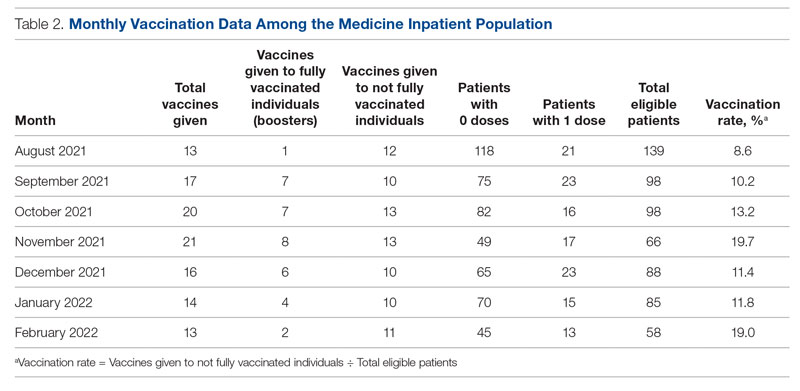

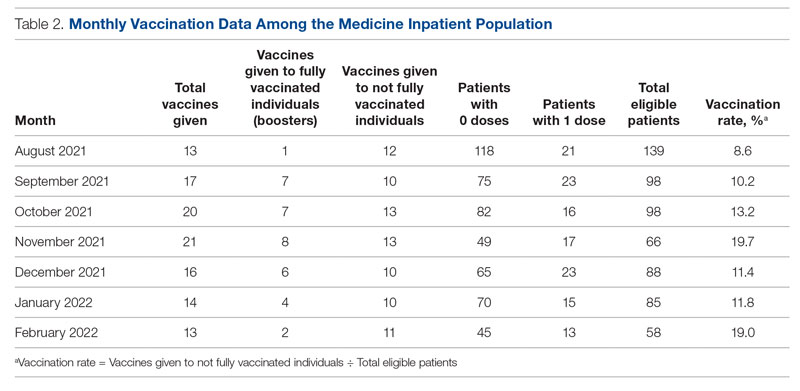

Results

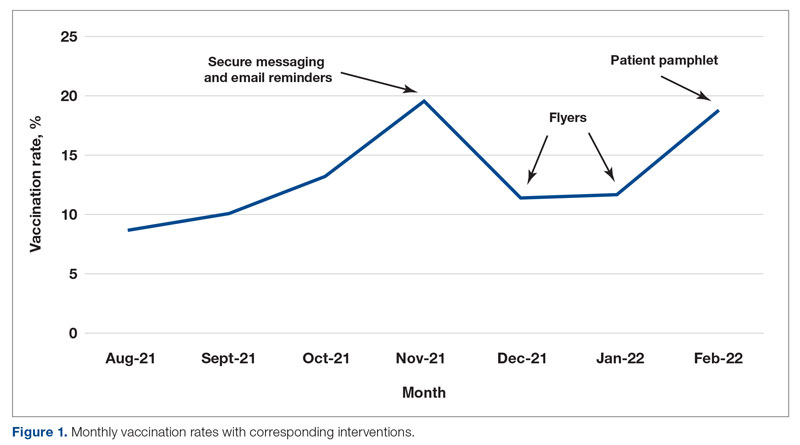

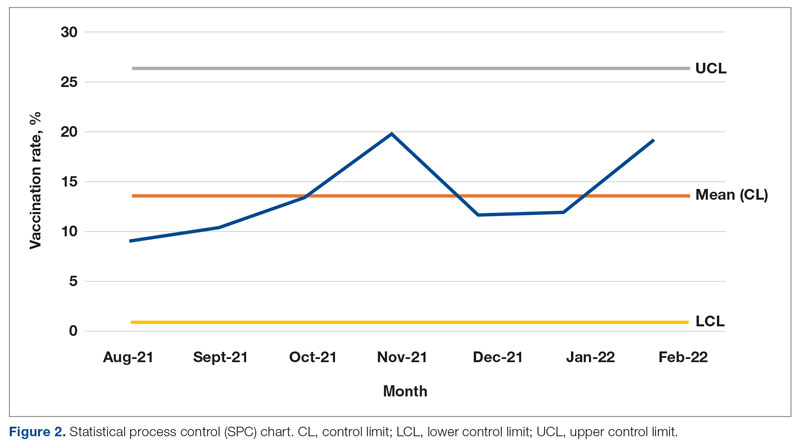

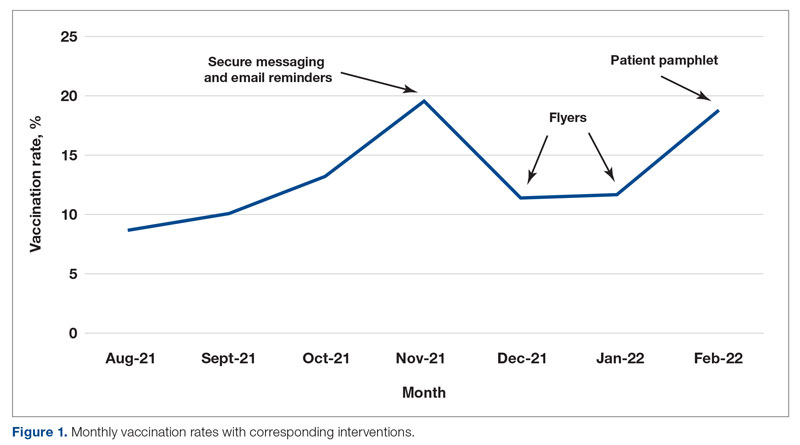

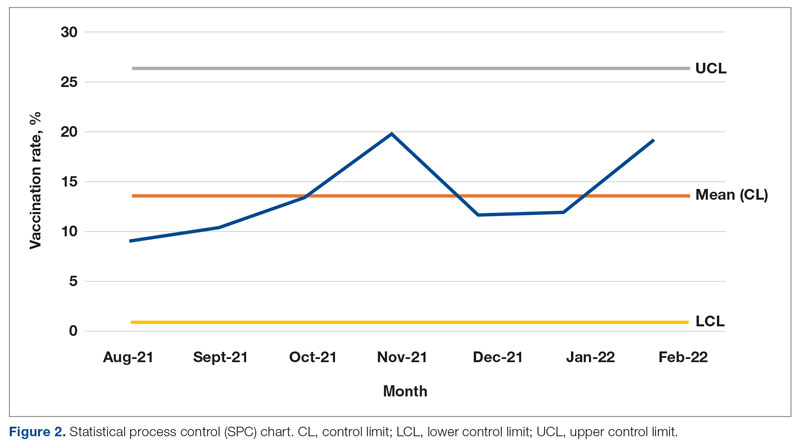

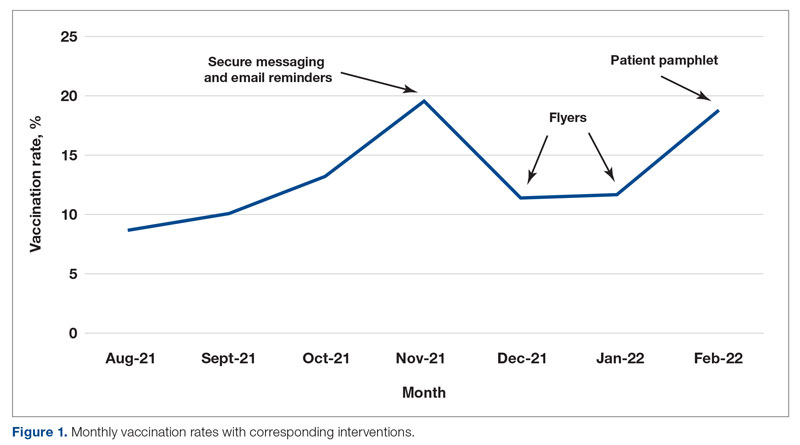

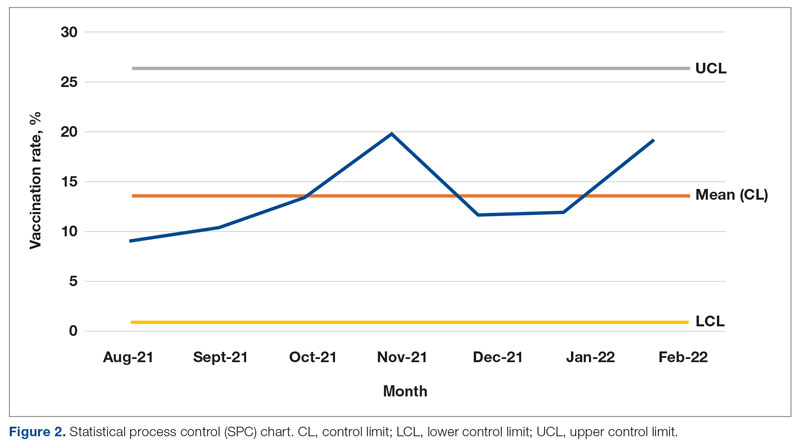

From August to October 2021, the baseline average monthly vaccination rate of patients on the medicine service who were eligible to receive a COVID-19 vaccine was 10.7%. After the first intervention, the vaccination rate increased to 19.7% in November 2021 (Table 2). The second intervention yielded vaccination rates of 11.4% and 11.8% in December 2021 and January 2022, respectively. During the final phase in February 2022, the vaccination rate was 19.0%. At the conclusion of the study, the mean vaccination rate for the intervention months was 15.4% (Figure 1). Process stability and variation are demonstrated with a statistical process control chart (Figure 2).

Discussion

For this housestaff-driven QI project, we implemented an inpatient COVID-19 vaccination campaign consisting of 3 phases that targeted both providers and patients. During the intervention period, we observed an increased vaccination rate compared to the period just prior to implementation of the QI project. While our interventions may certainly have boosted vaccination rates, we understand other variables could have contributed to increased rates as well. The emergence of variants in the United States, such as omicron in December 2021,8 could have precipitated a demand for vaccinations among patients. Holidays in November and December may also have increased patients’ desire to get vaccinated before travel.

We encountered a number of roadblocks that challenged our project, including difficulty identifying patients who were eligible for the vaccine, logistical vaccine administration challenges, and hesitancy among the inpatient population. Accurately identifying patients who were eligible for a vaccine in the EHR was especially challenging in the setting of rapidly changing guidelines regarding COVID-19 vaccination. In September 2021, the US Food and Drug Administration authorized the Pfizer booster for certain populations and later, in November 2021, for all adults. This meant that some fully vaccinated hospitalized patients (those with 2 doses) then qualified for an additional dose of the vaccine and received a dose during hospitalization. To determine the true vaccination rate, we obtained retrospective data that allowed us to track each vaccine administered. If a patient had already received 2 doses of the COVID-19 vaccine, the vaccine administered was counted as a booster and excluded from the calculation of the vaccination rate. Future PDSA cycles could include updating the EHR to capture the whole range of COVID-19 vaccination status (unvaccinated, partially vaccinated, fully vaccinated, fully vaccinated with 1 booster, fully vaccinated with 2 boosters).

We also encountered logistical challenges with the administration of the COVID-19 vaccine to hospitalized patients. During the intervention period, our pharmacy department required 5 COVID-19 vaccination orders before opening a vial and administering the vaccine doses in order to reduce waste. This policy may have limited our ability to vaccinate eligible inpatients because we were not always able to identify 5 patients simultaneously on the service who were eligible and consented to the vaccine.

The majority of patients who were interested in receiving COVID-19 vaccination had already been vaccinated in the outpatient setting. This fact made the inpatient internal medicine subset of patients a particularly challenging population to target, given their possible hesitancy regarding vaccination. By utilizing a multidisciplinary team and increasing communication of providers and nursing staff, we helped to increase the COVID-19 vaccination rates at our hospital from 10.7% to 15.4%.

Future Directions

Future interventions to consider include increasing the availability of other approved COVID-19 vaccines at our hospital besides the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine. Furthermore, incorporating the vaccine into the admission order set would help initiate the vaccination process early in the hospital course. We encourage other institutions to utilize similar approaches to not only remind providers about inpatient vaccination, but also educate and encourage patients to receive the vaccine. These measures will help institutions increase inpatient COVID-19 vaccination rates in a high-risk population.

Corresponding author: Anna Rubin, MD, Department of Medicine, The George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Washington, DC; [email protected]

Disclosures: None reported.

1. Trends in number of COVID-19 cases and deaths in the US reported to CDC, by state/territory. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed February 25, 2022. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#trends_dailycases

2. Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162B2 MRNA COVID-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(27):2603-2615. doi:10.1056/nejmoa2034577

3. Hall V, Foulkes S, Insalata F, et al. Protection against SARS-COV-2 after covid-19 vaccination and previous infection. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(13):1207-1220. doi:10.1056/nejmoa2118691

4. Trends in number of COVID-19 vaccinations in the US. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed February 25, 2022. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#vaccination-trends_vacctrends-fully-cum

5. King WC, Rubinstein M, Reinhart A, Mejia R. Time trends, factors associated with, and reasons for covid-19 vaccine hesitancy: A massive online survey of US adults from January-May 2021. PLOS ONE. 2021;16(12). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0260731

6. Cohen ES, Ogrinc G, Taylor T, et al. Influenza vaccination rates for hospitalised patients: A multiyear quality improvement effort. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24(3):221-227. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2014-003556

7. Berger RE, Diaz DC, Chacko S, et al. Implementation of an inpatient covid-19 vaccination program. NEJM Catalyst. 2021;2(10). doi:10.1056/cat.21.0235

8. CDC COVID-19 Response Team. SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.529 (Omicron) Variant - United States, December 1-8, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(50):1731-1734. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7050e1

From the Department of Medicine, The George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Washington, DC.

Abstract

Objective: Inpatient vaccination initiatives are well described in the literature. During the COVID-19 pandemic, hospitals began administering COVID-19 vaccines to hospitalized patients. Although vaccination rates increased, there remained many unvaccinated patients despite community efforts. This quality improvement project aimed to increase the COVID-19 vaccination rates of hospitalized patients on the medicine service at the George Washington University Hospital (GWUH).

Methods: From November 2021 through February 2022, we conducted a Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycle with 3 phases. Initial steps included gathering baseline data from the electronic health record and consulting stakeholders. The first 2 phases focused on educating housestaff on the availability, ordering process, and administration of the Pfizer vaccine. The third phase consisted of developing educational pamphlets for patients to be included in their admission packets.

Results: The baseline mean COVID-19 vaccination rate (August to October 2021) of eligible patients on the medicine service was 10.7%. In the months after we implemented the PDSA cycle (November 2021 to February 2022), the mean vaccination rate increased to 15.4%.

Conclusion: This quality improvement project implemented measures to increase administration of the Pfizer vaccine to eligible patients admitted to the medicine service at GWUH. The mean vaccination rate increased from 10.7% in the 3 months prior to implementation to 15.4% during the 4 months post implementation. Other measures to consider in the future include increasing the availability of other COVID-19 vaccines at our hospital and incorporating the vaccine into the admission order set to help facilitate vaccination early in the hospital course.

Keywords: housestaff, quality improvement, PDSA, COVID-19, BNT162b2 vaccine, patient education

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, case rates in the United States have fluctuated considerably, corresponding to epidemic waves. In 2021, US daily cases of COVID-19 peaked at nearly 300,000 in early January and reached a nadir of 8000 cases in mid-June.1 In September 2021, new cases had increased to 200,000 per day due to the prevalence of the Delta variant.1 Particularly with the emergence of new variants of SARS-CoV-2, vaccination efforts to limit the spread of infection and severity of illness are critical. Data have shown that 2 doses of the BNT162b2 vaccine (Pfizer-BioNTech) were largely protective against severe infection for approximately 6 months.2,3 When we began this quality improvement (QI) project in September 2021, only 179 million Americans had been fully vaccinated, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which is just over half of the US population.4 An electronic survey conducted in the United States with more than 5 million responses found that, of those who were hesitant about receiving the vaccine, 49% reported a fear of adverse effects and 48% reported a lack of trust in the vaccine.5

This QI project sought to target unvaccinated individuals admitted to the internal medicine inpatient service. Vaccinating hospitalized patients is especially important since they are sicker than the general population and at higher risk of having poor outcomes from COVID-19. Inpatient vaccine initiatives, such as administering influenza vaccine prior to discharge, have been successfully implemented in the past.6 One large COVID-19 vaccination program featured an admission order set to increase the rates of vaccination among hospitalized patients.7 Our QI project piloted a multidisciplinary approach involving the nursing staff, pharmacy, information technology (IT) department, and internal medicine housestaff to increase COVID-19 vaccination rates among hospitalized patients on the medical service. This project aimed to increase inpatient vaccination rates through interventions targeting both primary providers as well as the patients themselves.

Methods

Setting and Interventions

This project was conducted at the George Washington University Hospital (GWUH) in Washington, DC. The clinicians involved in the study were the internal medicine housestaff, and the patients included were adults admitted to the resident medicine ward teams. The project was exempt by the institutional review board and did not require informed consent.

The quality improvement initiative had 3 phases, each featuring a different intervention (Table 1). The first phase involved sending a weekly announcement (via email and a secure health care messaging app) to current residents rotating on the inpatient medicine service. The announcement contained information regarding COVID-19 vaccine availability at the hospital, instructions on ordering the vaccine, and the process of coordinating with pharmacy to facilitate vaccine administration. Thereafter, residents were educated on the process of giving a COVID-19 vaccine to a patient from start to finish. Due to the nature of the residency schedule, different housestaff members rotated in and out of the medicine wards during the intervention periods. The weekly email was sent to the entire internal medicine housestaff, informing all residents about the QI project, while the weekly secure messages served as reminders and were only sent to residents currently on the medicine wards.

In the second phase, we posted paper flyers throughout the hospital to remind housestaff to give the vaccine and again educate them on the process of ordering the vaccine. For the third intervention, a COVID-19 vaccine educational pamphlet was developed for distribution to inpatients at GWUH. The pamphlet included information on vaccine efficacy, safety, side effects, and eligibility. The pamphlet was incorporated in the admission packet that every patient receives upon admission to the hospital. The patients reviewed the pamphlets with nursing staff, who would answer any questions, with residents available to discuss any outstanding concerns.

Measures and Data Gathering

The primary endpoint of the study was inpatient vaccination rate, defined as the number of COVID-19 vaccines administered divided by the number of patients eligible to receive a vaccine (not fully vaccinated). During initial triage, nursing staff documented vaccination status in the electronic health record (EHR), checking a box in a data entry form if a patient had received 0, 1, or 2 doses of the COVID-19 vaccine. The GWUH IT department generated data from this form to determine the number of patients eligible to receive a COVID-19 vaccine. Data were extracted from the medication administration record in the EHR to determine the number of vaccines that were administered to patients during their hospitalization on the inpatient medical service. Each month, the IT department extracted data for the number of eligible patients and the number of vaccines administered. This yielded the monthly vaccination rates. The monthly vaccination rates in the period prior to starting the QI initiative were compared to the rates in the period after the interventions were implemented.

Of note, during the course of this project, patients became eligible for a third COVID-19 vaccine (booster). We decided to continue with the original aim of vaccinating adults who had only received 0 or 1 dose of the vaccine. Therefore, the eligibility criteria remained the same throughout the study. We obtained retrospective data to ensure that the vaccines being counted toward the vaccination rate were vaccines given to patients not yet fully vaccinated and not vaccines given as boosters.

Results

From August to October 2021, the baseline average monthly vaccination rate of patients on the medicine service who were eligible to receive a COVID-19 vaccine was 10.7%. After the first intervention, the vaccination rate increased to 19.7% in November 2021 (Table 2). The second intervention yielded vaccination rates of 11.4% and 11.8% in December 2021 and January 2022, respectively. During the final phase in February 2022, the vaccination rate was 19.0%. At the conclusion of the study, the mean vaccination rate for the intervention months was 15.4% (Figure 1). Process stability and variation are demonstrated with a statistical process control chart (Figure 2).

Discussion

For this housestaff-driven QI project, we implemented an inpatient COVID-19 vaccination campaign consisting of 3 phases that targeted both providers and patients. During the intervention period, we observed an increased vaccination rate compared to the period just prior to implementation of the QI project. While our interventions may certainly have boosted vaccination rates, we understand other variables could have contributed to increased rates as well. The emergence of variants in the United States, such as omicron in December 2021,8 could have precipitated a demand for vaccinations among patients. Holidays in November and December may also have increased patients’ desire to get vaccinated before travel.

We encountered a number of roadblocks that challenged our project, including difficulty identifying patients who were eligible for the vaccine, logistical vaccine administration challenges, and hesitancy among the inpatient population. Accurately identifying patients who were eligible for a vaccine in the EHR was especially challenging in the setting of rapidly changing guidelines regarding COVID-19 vaccination. In September 2021, the US Food and Drug Administration authorized the Pfizer booster for certain populations and later, in November 2021, for all adults. This meant that some fully vaccinated hospitalized patients (those with 2 doses) then qualified for an additional dose of the vaccine and received a dose during hospitalization. To determine the true vaccination rate, we obtained retrospective data that allowed us to track each vaccine administered. If a patient had already received 2 doses of the COVID-19 vaccine, the vaccine administered was counted as a booster and excluded from the calculation of the vaccination rate. Future PDSA cycles could include updating the EHR to capture the whole range of COVID-19 vaccination status (unvaccinated, partially vaccinated, fully vaccinated, fully vaccinated with 1 booster, fully vaccinated with 2 boosters).

We also encountered logistical challenges with the administration of the COVID-19 vaccine to hospitalized patients. During the intervention period, our pharmacy department required 5 COVID-19 vaccination orders before opening a vial and administering the vaccine doses in order to reduce waste. This policy may have limited our ability to vaccinate eligible inpatients because we were not always able to identify 5 patients simultaneously on the service who were eligible and consented to the vaccine.

The majority of patients who were interested in receiving COVID-19 vaccination had already been vaccinated in the outpatient setting. This fact made the inpatient internal medicine subset of patients a particularly challenging population to target, given their possible hesitancy regarding vaccination. By utilizing a multidisciplinary team and increasing communication of providers and nursing staff, we helped to increase the COVID-19 vaccination rates at our hospital from 10.7% to 15.4%.

Future Directions

Future interventions to consider include increasing the availability of other approved COVID-19 vaccines at our hospital besides the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine. Furthermore, incorporating the vaccine into the admission order set would help initiate the vaccination process early in the hospital course. We encourage other institutions to utilize similar approaches to not only remind providers about inpatient vaccination, but also educate and encourage patients to receive the vaccine. These measures will help institutions increase inpatient COVID-19 vaccination rates in a high-risk population.

Corresponding author: Anna Rubin, MD, Department of Medicine, The George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Washington, DC; [email protected]

Disclosures: None reported.

From the Department of Medicine, The George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Washington, DC.

Abstract

Objective: Inpatient vaccination initiatives are well described in the literature. During the COVID-19 pandemic, hospitals began administering COVID-19 vaccines to hospitalized patients. Although vaccination rates increased, there remained many unvaccinated patients despite community efforts. This quality improvement project aimed to increase the COVID-19 vaccination rates of hospitalized patients on the medicine service at the George Washington University Hospital (GWUH).

Methods: From November 2021 through February 2022, we conducted a Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycle with 3 phases. Initial steps included gathering baseline data from the electronic health record and consulting stakeholders. The first 2 phases focused on educating housestaff on the availability, ordering process, and administration of the Pfizer vaccine. The third phase consisted of developing educational pamphlets for patients to be included in their admission packets.

Results: The baseline mean COVID-19 vaccination rate (August to October 2021) of eligible patients on the medicine service was 10.7%. In the months after we implemented the PDSA cycle (November 2021 to February 2022), the mean vaccination rate increased to 15.4%.

Conclusion: This quality improvement project implemented measures to increase administration of the Pfizer vaccine to eligible patients admitted to the medicine service at GWUH. The mean vaccination rate increased from 10.7% in the 3 months prior to implementation to 15.4% during the 4 months post implementation. Other measures to consider in the future include increasing the availability of other COVID-19 vaccines at our hospital and incorporating the vaccine into the admission order set to help facilitate vaccination early in the hospital course.

Keywords: housestaff, quality improvement, PDSA, COVID-19, BNT162b2 vaccine, patient education

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, case rates in the United States have fluctuated considerably, corresponding to epidemic waves. In 2021, US daily cases of COVID-19 peaked at nearly 300,000 in early January and reached a nadir of 8000 cases in mid-June.1 In September 2021, new cases had increased to 200,000 per day due to the prevalence of the Delta variant.1 Particularly with the emergence of new variants of SARS-CoV-2, vaccination efforts to limit the spread of infection and severity of illness are critical. Data have shown that 2 doses of the BNT162b2 vaccine (Pfizer-BioNTech) were largely protective against severe infection for approximately 6 months.2,3 When we began this quality improvement (QI) project in September 2021, only 179 million Americans had been fully vaccinated, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which is just over half of the US population.4 An electronic survey conducted in the United States with more than 5 million responses found that, of those who were hesitant about receiving the vaccine, 49% reported a fear of adverse effects and 48% reported a lack of trust in the vaccine.5

This QI project sought to target unvaccinated individuals admitted to the internal medicine inpatient service. Vaccinating hospitalized patients is especially important since they are sicker than the general population and at higher risk of having poor outcomes from COVID-19. Inpatient vaccine initiatives, such as administering influenza vaccine prior to discharge, have been successfully implemented in the past.6 One large COVID-19 vaccination program featured an admission order set to increase the rates of vaccination among hospitalized patients.7 Our QI project piloted a multidisciplinary approach involving the nursing staff, pharmacy, information technology (IT) department, and internal medicine housestaff to increase COVID-19 vaccination rates among hospitalized patients on the medical service. This project aimed to increase inpatient vaccination rates through interventions targeting both primary providers as well as the patients themselves.

Methods

Setting and Interventions

This project was conducted at the George Washington University Hospital (GWUH) in Washington, DC. The clinicians involved in the study were the internal medicine housestaff, and the patients included were adults admitted to the resident medicine ward teams. The project was exempt by the institutional review board and did not require informed consent.

The quality improvement initiative had 3 phases, each featuring a different intervention (Table 1). The first phase involved sending a weekly announcement (via email and a secure health care messaging app) to current residents rotating on the inpatient medicine service. The announcement contained information regarding COVID-19 vaccine availability at the hospital, instructions on ordering the vaccine, and the process of coordinating with pharmacy to facilitate vaccine administration. Thereafter, residents were educated on the process of giving a COVID-19 vaccine to a patient from start to finish. Due to the nature of the residency schedule, different housestaff members rotated in and out of the medicine wards during the intervention periods. The weekly email was sent to the entire internal medicine housestaff, informing all residents about the QI project, while the weekly secure messages served as reminders and were only sent to residents currently on the medicine wards.

In the second phase, we posted paper flyers throughout the hospital to remind housestaff to give the vaccine and again educate them on the process of ordering the vaccine. For the third intervention, a COVID-19 vaccine educational pamphlet was developed for distribution to inpatients at GWUH. The pamphlet included information on vaccine efficacy, safety, side effects, and eligibility. The pamphlet was incorporated in the admission packet that every patient receives upon admission to the hospital. The patients reviewed the pamphlets with nursing staff, who would answer any questions, with residents available to discuss any outstanding concerns.

Measures and Data Gathering

The primary endpoint of the study was inpatient vaccination rate, defined as the number of COVID-19 vaccines administered divided by the number of patients eligible to receive a vaccine (not fully vaccinated). During initial triage, nursing staff documented vaccination status in the electronic health record (EHR), checking a box in a data entry form if a patient had received 0, 1, or 2 doses of the COVID-19 vaccine. The GWUH IT department generated data from this form to determine the number of patients eligible to receive a COVID-19 vaccine. Data were extracted from the medication administration record in the EHR to determine the number of vaccines that were administered to patients during their hospitalization on the inpatient medical service. Each month, the IT department extracted data for the number of eligible patients and the number of vaccines administered. This yielded the monthly vaccination rates. The monthly vaccination rates in the period prior to starting the QI initiative were compared to the rates in the period after the interventions were implemented.

Of note, during the course of this project, patients became eligible for a third COVID-19 vaccine (booster). We decided to continue with the original aim of vaccinating adults who had only received 0 or 1 dose of the vaccine. Therefore, the eligibility criteria remained the same throughout the study. We obtained retrospective data to ensure that the vaccines being counted toward the vaccination rate were vaccines given to patients not yet fully vaccinated and not vaccines given as boosters.

Results

From August to October 2021, the baseline average monthly vaccination rate of patients on the medicine service who were eligible to receive a COVID-19 vaccine was 10.7%. After the first intervention, the vaccination rate increased to 19.7% in November 2021 (Table 2). The second intervention yielded vaccination rates of 11.4% and 11.8% in December 2021 and January 2022, respectively. During the final phase in February 2022, the vaccination rate was 19.0%. At the conclusion of the study, the mean vaccination rate for the intervention months was 15.4% (Figure 1). Process stability and variation are demonstrated with a statistical process control chart (Figure 2).

Discussion

For this housestaff-driven QI project, we implemented an inpatient COVID-19 vaccination campaign consisting of 3 phases that targeted both providers and patients. During the intervention period, we observed an increased vaccination rate compared to the period just prior to implementation of the QI project. While our interventions may certainly have boosted vaccination rates, we understand other variables could have contributed to increased rates as well. The emergence of variants in the United States, such as omicron in December 2021,8 could have precipitated a demand for vaccinations among patients. Holidays in November and December may also have increased patients’ desire to get vaccinated before travel.

We encountered a number of roadblocks that challenged our project, including difficulty identifying patients who were eligible for the vaccine, logistical vaccine administration challenges, and hesitancy among the inpatient population. Accurately identifying patients who were eligible for a vaccine in the EHR was especially challenging in the setting of rapidly changing guidelines regarding COVID-19 vaccination. In September 2021, the US Food and Drug Administration authorized the Pfizer booster for certain populations and later, in November 2021, for all adults. This meant that some fully vaccinated hospitalized patients (those with 2 doses) then qualified for an additional dose of the vaccine and received a dose during hospitalization. To determine the true vaccination rate, we obtained retrospective data that allowed us to track each vaccine administered. If a patient had already received 2 doses of the COVID-19 vaccine, the vaccine administered was counted as a booster and excluded from the calculation of the vaccination rate. Future PDSA cycles could include updating the EHR to capture the whole range of COVID-19 vaccination status (unvaccinated, partially vaccinated, fully vaccinated, fully vaccinated with 1 booster, fully vaccinated with 2 boosters).

We also encountered logistical challenges with the administration of the COVID-19 vaccine to hospitalized patients. During the intervention period, our pharmacy department required 5 COVID-19 vaccination orders before opening a vial and administering the vaccine doses in order to reduce waste. This policy may have limited our ability to vaccinate eligible inpatients because we were not always able to identify 5 patients simultaneously on the service who were eligible and consented to the vaccine.

The majority of patients who were interested in receiving COVID-19 vaccination had already been vaccinated in the outpatient setting. This fact made the inpatient internal medicine subset of patients a particularly challenging population to target, given their possible hesitancy regarding vaccination. By utilizing a multidisciplinary team and increasing communication of providers and nursing staff, we helped to increase the COVID-19 vaccination rates at our hospital from 10.7% to 15.4%.

Future Directions

Future interventions to consider include increasing the availability of other approved COVID-19 vaccines at our hospital besides the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine. Furthermore, incorporating the vaccine into the admission order set would help initiate the vaccination process early in the hospital course. We encourage other institutions to utilize similar approaches to not only remind providers about inpatient vaccination, but also educate and encourage patients to receive the vaccine. These measures will help institutions increase inpatient COVID-19 vaccination rates in a high-risk population.

Corresponding author: Anna Rubin, MD, Department of Medicine, The George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Washington, DC; [email protected]

Disclosures: None reported.

1. Trends in number of COVID-19 cases and deaths in the US reported to CDC, by state/territory. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed February 25, 2022. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#trends_dailycases

2. Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162B2 MRNA COVID-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(27):2603-2615. doi:10.1056/nejmoa2034577

3. Hall V, Foulkes S, Insalata F, et al. Protection against SARS-COV-2 after covid-19 vaccination and previous infection. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(13):1207-1220. doi:10.1056/nejmoa2118691

4. Trends in number of COVID-19 vaccinations in the US. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed February 25, 2022. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#vaccination-trends_vacctrends-fully-cum

5. King WC, Rubinstein M, Reinhart A, Mejia R. Time trends, factors associated with, and reasons for covid-19 vaccine hesitancy: A massive online survey of US adults from January-May 2021. PLOS ONE. 2021;16(12). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0260731

6. Cohen ES, Ogrinc G, Taylor T, et al. Influenza vaccination rates for hospitalised patients: A multiyear quality improvement effort. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24(3):221-227. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2014-003556

7. Berger RE, Diaz DC, Chacko S, et al. Implementation of an inpatient covid-19 vaccination program. NEJM Catalyst. 2021;2(10). doi:10.1056/cat.21.0235

8. CDC COVID-19 Response Team. SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.529 (Omicron) Variant - United States, December 1-8, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(50):1731-1734. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7050e1

1. Trends in number of COVID-19 cases and deaths in the US reported to CDC, by state/territory. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed February 25, 2022. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#trends_dailycases

2. Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162B2 MRNA COVID-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(27):2603-2615. doi:10.1056/nejmoa2034577

3. Hall V, Foulkes S, Insalata F, et al. Protection against SARS-COV-2 after covid-19 vaccination and previous infection. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(13):1207-1220. doi:10.1056/nejmoa2118691

4. Trends in number of COVID-19 vaccinations in the US. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed February 25, 2022. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#vaccination-trends_vacctrends-fully-cum

5. King WC, Rubinstein M, Reinhart A, Mejia R. Time trends, factors associated with, and reasons for covid-19 vaccine hesitancy: A massive online survey of US adults from January-May 2021. PLOS ONE. 2021;16(12). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0260731

6. Cohen ES, Ogrinc G, Taylor T, et al. Influenza vaccination rates for hospitalised patients: A multiyear quality improvement effort. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24(3):221-227. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2014-003556

7. Berger RE, Diaz DC, Chacko S, et al. Implementation of an inpatient covid-19 vaccination program. NEJM Catalyst. 2021;2(10). doi:10.1056/cat.21.0235

8. CDC COVID-19 Response Team. SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.529 (Omicron) Variant - United States, December 1-8, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(50):1731-1734. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7050e1

N.Y. governor declares state disaster emergency to boost polio vaccination

New York Governor Kathy Hochul declared a state disaster emergency on Sept. 9 after the polio virus has been detected in another county. The order allows EMS workers, midwives, and pharmacists to administer the vaccine and permits physicians and nurse practitioners to issue standing orders for polio vaccines.

“On polio, we simply cannot roll the dice,” New York State Health Commissioner Dr. Mary T. Bassett said in a news release. “If you or your child are unvaccinated or not up to date with vaccinations, the risk of paralytic disease is real. I urge New Yorkers to not accept any risk at all.”

In July, an unvaccinated adult man in Rockland County, which is north of New York City, was diagnosed with polio virus. It was the first confirmed case of the virus in the United States since 2013.

New York state health officials have not announced any additional polio cases. Since as early as April, polio has also been detected in wastewater samples in New York City and in Rockland, Orange, and Sullivan counties. In August, the virus was detected in wastewater from Nassau County on Long Island.

New York’s statewide polio vaccination rate is 79%, and the New York State Department of Health is aiming for a rate over 90%, the announcement said. In some counties, vaccination rates are far below the state average, including Rockland County (60%), Orange County (59%), and Sullivan County (62%). Nassau County’s polio vaccination rate is similar to the state average.

“Polio immunization is safe and effective – protecting nearly all people against disease who receive the recommended doses,” Dr. Basset said; “Do not wait to vaccinate.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New York Governor Kathy Hochul declared a state disaster emergency on Sept. 9 after the polio virus has been detected in another county. The order allows EMS workers, midwives, and pharmacists to administer the vaccine and permits physicians and nurse practitioners to issue standing orders for polio vaccines.

“On polio, we simply cannot roll the dice,” New York State Health Commissioner Dr. Mary T. Bassett said in a news release. “If you or your child are unvaccinated or not up to date with vaccinations, the risk of paralytic disease is real. I urge New Yorkers to not accept any risk at all.”

In July, an unvaccinated adult man in Rockland County, which is north of New York City, was diagnosed with polio virus. It was the first confirmed case of the virus in the United States since 2013.

New York state health officials have not announced any additional polio cases. Since as early as April, polio has also been detected in wastewater samples in New York City and in Rockland, Orange, and Sullivan counties. In August, the virus was detected in wastewater from Nassau County on Long Island.

New York’s statewide polio vaccination rate is 79%, and the New York State Department of Health is aiming for a rate over 90%, the announcement said. In some counties, vaccination rates are far below the state average, including Rockland County (60%), Orange County (59%), and Sullivan County (62%). Nassau County’s polio vaccination rate is similar to the state average.

“Polio immunization is safe and effective – protecting nearly all people against disease who receive the recommended doses,” Dr. Basset said; “Do not wait to vaccinate.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New York Governor Kathy Hochul declared a state disaster emergency on Sept. 9 after the polio virus has been detected in another county. The order allows EMS workers, midwives, and pharmacists to administer the vaccine and permits physicians and nurse practitioners to issue standing orders for polio vaccines.

“On polio, we simply cannot roll the dice,” New York State Health Commissioner Dr. Mary T. Bassett said in a news release. “If you or your child are unvaccinated or not up to date with vaccinations, the risk of paralytic disease is real. I urge New Yorkers to not accept any risk at all.”

In July, an unvaccinated adult man in Rockland County, which is north of New York City, was diagnosed with polio virus. It was the first confirmed case of the virus in the United States since 2013.

New York state health officials have not announced any additional polio cases. Since as early as April, polio has also been detected in wastewater samples in New York City and in Rockland, Orange, and Sullivan counties. In August, the virus was detected in wastewater from Nassau County on Long Island.

New York’s statewide polio vaccination rate is 79%, and the New York State Department of Health is aiming for a rate over 90%, the announcement said. In some counties, vaccination rates are far below the state average, including Rockland County (60%), Orange County (59%), and Sullivan County (62%). Nassau County’s polio vaccination rate is similar to the state average.

“Polio immunization is safe and effective – protecting nearly all people against disease who receive the recommended doses,” Dr. Basset said; “Do not wait to vaccinate.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Congenital cytomegalovirus declined in wake of COVID-19

Congenital cytomegalovirus cases declined significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic, compared with a period before the pandemic, based on data from nearly 20,000 newborns.

A study originated to explore racial and ethnic differences in congenital cytomegalovirus (cCMV) began in 2016, but was halted in April 2020 because of the COVID-19 pandemic, wrote Mark R. Schleiss, MD, of the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and colleagues. The study resumed for a period from August 2020 to December 2021, and the researchers compared data on cCMV before and during the pandemic. The prepandemic period included data from April 2016 to March 2020.

“We have been screening for congenital CMV infection in Minnesota for 6 years as a part of a multicenter collaborative study that I lead as the primary investigator,” Dr. Schleiss said in an interview. “Our efforts have contributed to the decision, vetted through the Minnesota Legislature and signed into law in 2021 (the “Vivian Act”), to begin universal screening for all newborns in Minnesota in 2023. In the context of this ongoing screening/surveillance study, it was important and scientifically very interesting to examine the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the risk of congenital CMV infection,” he explained.

The findings were published in a research letter in JAMA Network Open. A total of 15,697 newborns were screened before the pandemic and 4,222 were screened during the pandemic period at six hospitals. The majority of the mothers participating during the prepandemic and pandemic periods were non-Hispanic White (71% and 60%, respectively).

Overall, the percentage screened prevalence for cCMV was 79% in the prepandemic period and 21% during the pandemic, with rates of 4.5 per 1,000 and 1.4 per 1,000, respectively.

Although the highest percentage of cCMV cases occurred in newborns of mothers aged 25 years and older (86%), the prevalence was highest among newborns of mothers aged 24 years and younger (6.0 per 1,000). The prevalence of cCMV overall was higher in infants of non-Hispanic Black mothers vs. non-Hispanic White mothers, but not significantly different (5.1 per 1,000 vs. 4.6 per 1,000) and among second newborns vs. first newborns (6.0 vs. 3.2 per 1,000, respectively).

Factors related to COVID-19, including reduced day care attendance, behavioral changes, and mitigation measures at childcare facilities such as smaller classes and increased hand hygiene and disinfection may have contributed to this decrease in cCMV in the pandemic period, the researchers wrote in their discussion.

The comparable prevalence in newborns of non-Hispanic Black and White mothers contrasts with previous studies showing a higher prevalence in children of non-Hispanic Black mothers, the researchers noted in their discussion.

The study was limited by several factors, including the variation in time points for enrollment at different sites and the exclusion of families in the newborn nursery with positive COVID-19 results during the pandemic, they wrote. More research is needed on the potential effects of behavioral interventions to reduce CMV risk during pregnancy, as well as future CMV vaccination for childbearing-aged women and young children, they concluded.

However, the researchers were surprised by the impact of COVID-19 on the prevalence of cCMV, Dr. Schleiss said in an interview. “We have had the knowledge for many years that CMV infections in young women are commonly acquired through interactions with their toddlers. These interactions – sharing food, wiping drool and nasal discharge from the toddler’s nose, changing diapers, kissing the child on the mouth – can transmit CMV,” he said. In addition, toddlers may acquire CMV from group day care; the child then sheds CMV and transmits the virus to their pregnant mother, who then transmits the virus across the placenta, leading to cCMV infection in the newborn, Dr. Schleiss explained.

Although the researchers expected a decrease in CMV in the wake of closures of group day care, increased home schooling, decreased interactions among children, hygienic precautions, and social isolation, the decrease exceeded their expectations, said Dr. Schleiss. “Our previous work showed that in the 5-year period leading up to the pandemic, about one baby in every 200 births was born with CMV. Between August 2020 and December 2021, the number decreased to one baby in every 1,000 births,” a difference he and his team found striking.

The message from the study is that CMV can be prevented, said Dr. Schleiss. “Hygienic precautions during pregnancy had a big impact. Since congenital CMV infection is the most common congenital infection in the United States, and probably globally, that causes disabilities in children, the implications are highly significant,” he said. “The hygienic precautions we all have engaged in during the pandemic, such as masking, handwashing, and infection prevention behaviors, were almost certainly responsible for the reduction in CMV transmission, which in turn protected mothers and newborns from the potentially devastating effects of the CMV virus,” he noted.

Looking ahead, “Vaccines are moving forward in clinical trials that aim to confer immunity on young women of childbearing age to protect future pregnancies against transmission of CMV to the newborn infant; it would be very important to examine in future studies whether hygienic precautions would have the same impact as a potential vaccine,” Dr. Schleiss said. More research is needed to examine the effect of education of women about CMV transmission, he added. “We think it is very important to share this knowledge from our study with the pediatric community, since pediatricians can be important in counseling women about future pregnancies and the risks of CMV acquisition and transmission,” he noted.

Implications for other viruses

Although CMV poses minimal risk for healthy populations, irreversible complications for infants born with congenital CMV, especially hearing loss, are very concerning, said Catherine Haut, DNP, CPNP-AC/PC, a pediatric nurse practitioner in Rehoboth Beach, Del., in an interview.

“The study of viral transmission during a time of isolation, masking, and other mitigation procedures for COVID-19 assists in awareness that other viruses may also be limited with the use of these measures,” she said.

Dr. Haut was not surprised by the findings, given that CMV is transmitted primarily through direct contact with body fluids and that more than 50% of American adults have been infected by age 40, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, she said.

The take-home message for pediatricians, Dr. Haut said, is measures to prevent transmission of viral infection can yield significant positive health outcomes for the pediatric population; however, the effect of isolation, which has been associated with a higher rate of mental health problems, should not be ignored.

“Despite appropriate statistical analyses and presentation of findings in this study, the population sampled during the pandemic was less than 30% of the pre-COVID sampling, representing a study limitation,” and conducting research in a single state limits generalizability, Dr. Haut noted. “I agree with the authors that additional study is necessary to better understand prevention measures and apply these methods to reduce CMV transmission. Pursuit of CMV immunization opportunities is also needed,” she said.