User login

Adolescent immunizations and protecting our children from COVID-19

I began thinking of a topic for this column weeks ago determined to discuss anything except COVID-19. Yet, news reports from all sources blasted daily reminders of rising COVID-19 cases overall and specifically in children.

In August, school resumed for many of our patients and the battle over mandating masks for school attendance was in full swing. The fact that it is a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendation supported by both the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Pediatric Infectious Disease Society fell on deaf ears. One day, I heard a report that over 25,000 students attending Texas public schools were diagnosed with COVID-19 between Aug. 23 and Aug. 29. This peak in activity occurred just 2 weeks after the start of school and led to the closure of 45 school districts. Texas does not have a monopoly on these rising cases. Delta, a more contagious variant, began circulating in June 2021 and by July it was the most predominant. Emergency department visits and hospitalizations have increased nationwide. During the latter 2 weeks of August 2021, COVID-19–related ED visits and hospitalizations for persons aged 0-17 years were 3.4 and 3.7 times higher in states with the lowest vaccination coverage, compared with states with high vaccination coverage (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:1249-54). Specifically, the rates of hospitalization the week ending Aug. 14, 2021, were nearly 5 times the rates for the week ending June 26, 2021, for 0- to 17-year-olds and nearly 10 times the rates for children 0-4 years of age. Hospitalization rates were 10.1 times higher for unimmunized adolescents than for fully vaccinated ones (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:1255-60).

Multiple elected state leaders have opposed interventions such as mandating masks in school, and our children are paying for it. These leaders have relinquished their responsibility to local school boards. Several have reinforced the no-mask mandate while others have had the courage and insight to ignore state government leaders and have established mask mandates.

How is this lack of enforcement of national recommendations affecting our patients? Let’s look at two neighboring school districts in Texas. School districts have COVID-19 dashboards that are updated daily and accessible to the general public. School District A requires masks for school entry. It serves 196,171 students and has 27,195 teachers and staff. Since school opened in August, 1,606 cumulative cases of COVID-19 in students (0.8%) and 282 in staff (1%) have been reported. Fifty-five percent of the student cases occurred in elementary schools. In contrast, School District B located in the adjacent county serves 64,517 students and has 3,906 teachers and staff with no mask mandate. Since August, there have been 4,506 cumulative COVID-19 cases in students (6.9%) and 578 (14.7%) in staff. Information regarding the specific school type was not provided; however, the dashboard indicates that 2,924 cases (64.8%) occurred in children younger than 11 years of age. County data indicate 62% of those older than 12 years of age were fully vaccinated in District A, compared with 54% of persons older than 12 years in District B. The county COVID-19 positivity rate in District A is 17.6% and in District B it is 20%. Both counties are experiencing increased COVID-19 activity yet have had strikingly different outcomes in the student/staff population. While supporting the case for wearing masks to prevent disease transmission, one can’t ignore the adolescents who were infected and vaccine eligible (District A: 706; District B: 1,582). Their vaccination status could not be determined.

As pediatricians we have played an integral part in the elimination of diseases through educating and administering vaccinations. Adolescents are relatively healthy, thus limiting the number of encounters with them. The majority complete the 11-year visit; however, many fail to return for the 16- to 18-year visit.

So how are we doing? CDC data from 10 U.S. jurisdictions demonstrated a substantial decrease in vaccine administration between March and May of 2020, compared with the same period in 2018 and 2019. A decline was anticipated because of the nationwide lockdown. Doses of HPV administered declined almost 64% and 71% for 9- to 12-year-olds and 13- to 17-year-olds, respectively. Tdap administration declined 66% and 61% for the same respective age groups. Although administered doses increased between June and September of 2020, it was not sufficient to achieve catch-up coverage. Compared to the same period in 2018-2019, administration of the HPV vaccine declined 12.8% and 28% (ages 9-12 and ages 13-17) and for Tdap it was 21% and 30% lower (ages 9-12 and ages 13-17) (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:840-5).

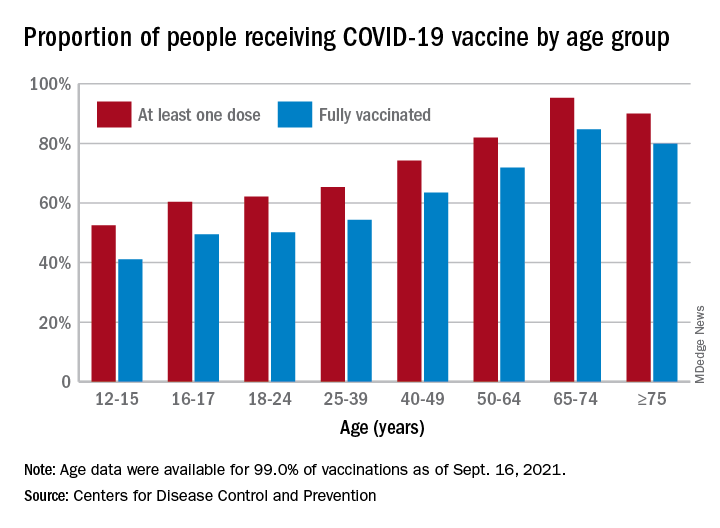

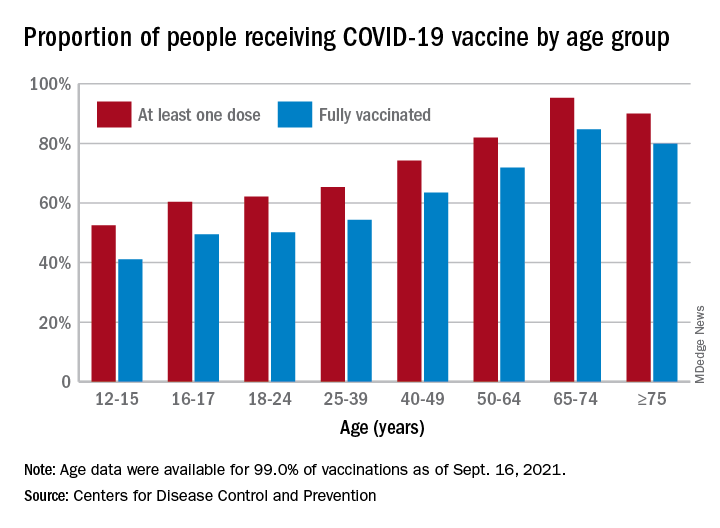

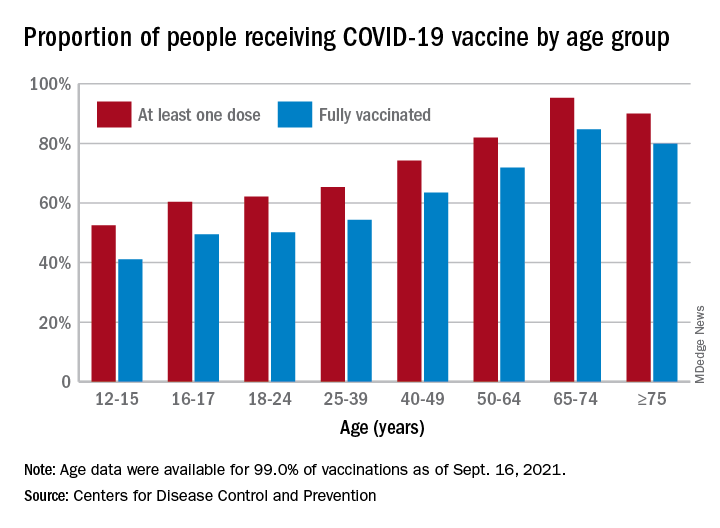

Now, we have another adolescent vaccine to discuss and encourage our patients to receive. We also need to address their concerns and/or to at least direct them to a reliable source to obtain accurate information. For the first time, a recommended vaccine may not be available at their medical home. Many don’t know where to go to receive it (http://www.vaccines.gov). Results of a Kaiser Family Foundation COVID-19 survey (August 2021) indicated that parents trusted their pediatricians most often (78%) for vaccine advice. The respondents voiced concern about trusting the location where the child would be immunized and long-term effects especially related to fertility. Parents who received communications regarding the benefits of vaccination were twice as likely to have their adolescents immunized. Finally, remember: Like parent, like child. An immunized parent is more likely to immunize the adolescent. (See Fig. 1.)

It is beyond the scope of this column to discuss the psychosocial aspects of this disease: children experiencing the death of teachers, classmates, family members, and those viewing the vitriol between pro- and antimask proponents often exhibited on school premises. And let’s not forget the child who wants to wear a mask but may be ostracized or bullied for doing so.

Our job is to do our very best to advocate for and to protect our patients by promoting mandatory masks at schools and encouraging vaccination of adolescents as we patiently wait for vaccines to become available for all of our children.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

I began thinking of a topic for this column weeks ago determined to discuss anything except COVID-19. Yet, news reports from all sources blasted daily reminders of rising COVID-19 cases overall and specifically in children.

In August, school resumed for many of our patients and the battle over mandating masks for school attendance was in full swing. The fact that it is a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendation supported by both the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Pediatric Infectious Disease Society fell on deaf ears. One day, I heard a report that over 25,000 students attending Texas public schools were diagnosed with COVID-19 between Aug. 23 and Aug. 29. This peak in activity occurred just 2 weeks after the start of school and led to the closure of 45 school districts. Texas does not have a monopoly on these rising cases. Delta, a more contagious variant, began circulating in June 2021 and by July it was the most predominant. Emergency department visits and hospitalizations have increased nationwide. During the latter 2 weeks of August 2021, COVID-19–related ED visits and hospitalizations for persons aged 0-17 years were 3.4 and 3.7 times higher in states with the lowest vaccination coverage, compared with states with high vaccination coverage (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:1249-54). Specifically, the rates of hospitalization the week ending Aug. 14, 2021, were nearly 5 times the rates for the week ending June 26, 2021, for 0- to 17-year-olds and nearly 10 times the rates for children 0-4 years of age. Hospitalization rates were 10.1 times higher for unimmunized adolescents than for fully vaccinated ones (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:1255-60).

Multiple elected state leaders have opposed interventions such as mandating masks in school, and our children are paying for it. These leaders have relinquished their responsibility to local school boards. Several have reinforced the no-mask mandate while others have had the courage and insight to ignore state government leaders and have established mask mandates.

How is this lack of enforcement of national recommendations affecting our patients? Let’s look at two neighboring school districts in Texas. School districts have COVID-19 dashboards that are updated daily and accessible to the general public. School District A requires masks for school entry. It serves 196,171 students and has 27,195 teachers and staff. Since school opened in August, 1,606 cumulative cases of COVID-19 in students (0.8%) and 282 in staff (1%) have been reported. Fifty-five percent of the student cases occurred in elementary schools. In contrast, School District B located in the adjacent county serves 64,517 students and has 3,906 teachers and staff with no mask mandate. Since August, there have been 4,506 cumulative COVID-19 cases in students (6.9%) and 578 (14.7%) in staff. Information regarding the specific school type was not provided; however, the dashboard indicates that 2,924 cases (64.8%) occurred in children younger than 11 years of age. County data indicate 62% of those older than 12 years of age were fully vaccinated in District A, compared with 54% of persons older than 12 years in District B. The county COVID-19 positivity rate in District A is 17.6% and in District B it is 20%. Both counties are experiencing increased COVID-19 activity yet have had strikingly different outcomes in the student/staff population. While supporting the case for wearing masks to prevent disease transmission, one can’t ignore the adolescents who were infected and vaccine eligible (District A: 706; District B: 1,582). Their vaccination status could not be determined.

As pediatricians we have played an integral part in the elimination of diseases through educating and administering vaccinations. Adolescents are relatively healthy, thus limiting the number of encounters with them. The majority complete the 11-year visit; however, many fail to return for the 16- to 18-year visit.

So how are we doing? CDC data from 10 U.S. jurisdictions demonstrated a substantial decrease in vaccine administration between March and May of 2020, compared with the same period in 2018 and 2019. A decline was anticipated because of the nationwide lockdown. Doses of HPV administered declined almost 64% and 71% for 9- to 12-year-olds and 13- to 17-year-olds, respectively. Tdap administration declined 66% and 61% for the same respective age groups. Although administered doses increased between June and September of 2020, it was not sufficient to achieve catch-up coverage. Compared to the same period in 2018-2019, administration of the HPV vaccine declined 12.8% and 28% (ages 9-12 and ages 13-17) and for Tdap it was 21% and 30% lower (ages 9-12 and ages 13-17) (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:840-5).

Now, we have another adolescent vaccine to discuss and encourage our patients to receive. We also need to address their concerns and/or to at least direct them to a reliable source to obtain accurate information. For the first time, a recommended vaccine may not be available at their medical home. Many don’t know where to go to receive it (http://www.vaccines.gov). Results of a Kaiser Family Foundation COVID-19 survey (August 2021) indicated that parents trusted their pediatricians most often (78%) for vaccine advice. The respondents voiced concern about trusting the location where the child would be immunized and long-term effects especially related to fertility. Parents who received communications regarding the benefits of vaccination were twice as likely to have their adolescents immunized. Finally, remember: Like parent, like child. An immunized parent is more likely to immunize the adolescent. (See Fig. 1.)

It is beyond the scope of this column to discuss the psychosocial aspects of this disease: children experiencing the death of teachers, classmates, family members, and those viewing the vitriol between pro- and antimask proponents often exhibited on school premises. And let’s not forget the child who wants to wear a mask but may be ostracized or bullied for doing so.

Our job is to do our very best to advocate for and to protect our patients by promoting mandatory masks at schools and encouraging vaccination of adolescents as we patiently wait for vaccines to become available for all of our children.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

I began thinking of a topic for this column weeks ago determined to discuss anything except COVID-19. Yet, news reports from all sources blasted daily reminders of rising COVID-19 cases overall and specifically in children.

In August, school resumed for many of our patients and the battle over mandating masks for school attendance was in full swing. The fact that it is a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendation supported by both the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Pediatric Infectious Disease Society fell on deaf ears. One day, I heard a report that over 25,000 students attending Texas public schools were diagnosed with COVID-19 between Aug. 23 and Aug. 29. This peak in activity occurred just 2 weeks after the start of school and led to the closure of 45 school districts. Texas does not have a monopoly on these rising cases. Delta, a more contagious variant, began circulating in June 2021 and by July it was the most predominant. Emergency department visits and hospitalizations have increased nationwide. During the latter 2 weeks of August 2021, COVID-19–related ED visits and hospitalizations for persons aged 0-17 years were 3.4 and 3.7 times higher in states with the lowest vaccination coverage, compared with states with high vaccination coverage (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:1249-54). Specifically, the rates of hospitalization the week ending Aug. 14, 2021, were nearly 5 times the rates for the week ending June 26, 2021, for 0- to 17-year-olds and nearly 10 times the rates for children 0-4 years of age. Hospitalization rates were 10.1 times higher for unimmunized adolescents than for fully vaccinated ones (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:1255-60).

Multiple elected state leaders have opposed interventions such as mandating masks in school, and our children are paying for it. These leaders have relinquished their responsibility to local school boards. Several have reinforced the no-mask mandate while others have had the courage and insight to ignore state government leaders and have established mask mandates.

How is this lack of enforcement of national recommendations affecting our patients? Let’s look at two neighboring school districts in Texas. School districts have COVID-19 dashboards that are updated daily and accessible to the general public. School District A requires masks for school entry. It serves 196,171 students and has 27,195 teachers and staff. Since school opened in August, 1,606 cumulative cases of COVID-19 in students (0.8%) and 282 in staff (1%) have been reported. Fifty-five percent of the student cases occurred in elementary schools. In contrast, School District B located in the adjacent county serves 64,517 students and has 3,906 teachers and staff with no mask mandate. Since August, there have been 4,506 cumulative COVID-19 cases in students (6.9%) and 578 (14.7%) in staff. Information regarding the specific school type was not provided; however, the dashboard indicates that 2,924 cases (64.8%) occurred in children younger than 11 years of age. County data indicate 62% of those older than 12 years of age were fully vaccinated in District A, compared with 54% of persons older than 12 years in District B. The county COVID-19 positivity rate in District A is 17.6% and in District B it is 20%. Both counties are experiencing increased COVID-19 activity yet have had strikingly different outcomes in the student/staff population. While supporting the case for wearing masks to prevent disease transmission, one can’t ignore the adolescents who were infected and vaccine eligible (District A: 706; District B: 1,582). Their vaccination status could not be determined.

As pediatricians we have played an integral part in the elimination of diseases through educating and administering vaccinations. Adolescents are relatively healthy, thus limiting the number of encounters with them. The majority complete the 11-year visit; however, many fail to return for the 16- to 18-year visit.

So how are we doing? CDC data from 10 U.S. jurisdictions demonstrated a substantial decrease in vaccine administration between March and May of 2020, compared with the same period in 2018 and 2019. A decline was anticipated because of the nationwide lockdown. Doses of HPV administered declined almost 64% and 71% for 9- to 12-year-olds and 13- to 17-year-olds, respectively. Tdap administration declined 66% and 61% for the same respective age groups. Although administered doses increased between June and September of 2020, it was not sufficient to achieve catch-up coverage. Compared to the same period in 2018-2019, administration of the HPV vaccine declined 12.8% and 28% (ages 9-12 and ages 13-17) and for Tdap it was 21% and 30% lower (ages 9-12 and ages 13-17) (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:840-5).

Now, we have another adolescent vaccine to discuss and encourage our patients to receive. We also need to address their concerns and/or to at least direct them to a reliable source to obtain accurate information. For the first time, a recommended vaccine may not be available at their medical home. Many don’t know where to go to receive it (http://www.vaccines.gov). Results of a Kaiser Family Foundation COVID-19 survey (August 2021) indicated that parents trusted their pediatricians most often (78%) for vaccine advice. The respondents voiced concern about trusting the location where the child would be immunized and long-term effects especially related to fertility. Parents who received communications regarding the benefits of vaccination were twice as likely to have their adolescents immunized. Finally, remember: Like parent, like child. An immunized parent is more likely to immunize the adolescent. (See Fig. 1.)

It is beyond the scope of this column to discuss the psychosocial aspects of this disease: children experiencing the death of teachers, classmates, family members, and those viewing the vitriol between pro- and antimask proponents often exhibited on school premises. And let’s not forget the child who wants to wear a mask but may be ostracized or bullied for doing so.

Our job is to do our very best to advocate for and to protect our patients by promoting mandatory masks at schools and encouraging vaccination of adolescents as we patiently wait for vaccines to become available for all of our children.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

Moderna vaccine more effective than Pfizer and J&J

the Centers for Disease Control and Protection has said.

“Among U.S. adults without immunocompromising conditions, vaccine effectiveness against COVID-19 hospitalization during March 11–Aug. 15, 2021, was higher for the Moderna vaccine (93%) than the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine (88%) and the Janssen vaccine (71%),” the agency’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report said. Janssen refers to the Johnson & Johnson vaccine.

The CDC said the data could help people make informed decisions.

“Understanding differences in VE [vaccine effectiveness] by vaccine product can guide individual choices and policy recommendations regarding vaccine boosters. All Food and Drug Administration–approved or authorized COVID-19 vaccines provide substantial protection against COVID-19 hospitalization,” the report said.

The study also broke down effectiveness for longer periods. Moderna came out on top again.

After 120 days, the Moderna vaccine provided 92% effectiveness against hospitalization, whereas the Pfizer vaccine’s effectiveness dropped to 77%, the CDC said. There was no similar calculation for the Johnson & Johnson vaccine.

The CDC studied 3,689 adults at 21 hospitals in 18 states who got the two-shot Pfizer or Moderna vaccine or the one-shot Johnson & Johnson vaccine between March and August.

The agency noted some factors that could have come into play.

“Differences in vaccine effectiveness between the Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine might be due to higher mRNA content in the Moderna vaccine, differences in timing between doses (3 weeks for Pfizer-BioNTech vs. 4 weeks for Moderna), or possible differences between groups that received each vaccine that were not accounted for in the analysis,” the report said.

The CDC noted limitations in the findings. Children, immunocompromised adults, and vaccine effectiveness against COVID-19 that did not result in hospitalization were not studied.

Other studies have shown all three U.S. vaccines provide a high rate of protection against coronavirus.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

the Centers for Disease Control and Protection has said.

“Among U.S. adults without immunocompromising conditions, vaccine effectiveness against COVID-19 hospitalization during March 11–Aug. 15, 2021, was higher for the Moderna vaccine (93%) than the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine (88%) and the Janssen vaccine (71%),” the agency’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report said. Janssen refers to the Johnson & Johnson vaccine.

The CDC said the data could help people make informed decisions.

“Understanding differences in VE [vaccine effectiveness] by vaccine product can guide individual choices and policy recommendations regarding vaccine boosters. All Food and Drug Administration–approved or authorized COVID-19 vaccines provide substantial protection against COVID-19 hospitalization,” the report said.

The study also broke down effectiveness for longer periods. Moderna came out on top again.

After 120 days, the Moderna vaccine provided 92% effectiveness against hospitalization, whereas the Pfizer vaccine’s effectiveness dropped to 77%, the CDC said. There was no similar calculation for the Johnson & Johnson vaccine.

The CDC studied 3,689 adults at 21 hospitals in 18 states who got the two-shot Pfizer or Moderna vaccine or the one-shot Johnson & Johnson vaccine between March and August.

The agency noted some factors that could have come into play.

“Differences in vaccine effectiveness between the Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine might be due to higher mRNA content in the Moderna vaccine, differences in timing between doses (3 weeks for Pfizer-BioNTech vs. 4 weeks for Moderna), or possible differences between groups that received each vaccine that were not accounted for in the analysis,” the report said.

The CDC noted limitations in the findings. Children, immunocompromised adults, and vaccine effectiveness against COVID-19 that did not result in hospitalization were not studied.

Other studies have shown all three U.S. vaccines provide a high rate of protection against coronavirus.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

the Centers for Disease Control and Protection has said.

“Among U.S. adults without immunocompromising conditions, vaccine effectiveness against COVID-19 hospitalization during March 11–Aug. 15, 2021, was higher for the Moderna vaccine (93%) than the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine (88%) and the Janssen vaccine (71%),” the agency’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report said. Janssen refers to the Johnson & Johnson vaccine.

The CDC said the data could help people make informed decisions.

“Understanding differences in VE [vaccine effectiveness] by vaccine product can guide individual choices and policy recommendations regarding vaccine boosters. All Food and Drug Administration–approved or authorized COVID-19 vaccines provide substantial protection against COVID-19 hospitalization,” the report said.

The study also broke down effectiveness for longer periods. Moderna came out on top again.

After 120 days, the Moderna vaccine provided 92% effectiveness against hospitalization, whereas the Pfizer vaccine’s effectiveness dropped to 77%, the CDC said. There was no similar calculation for the Johnson & Johnson vaccine.

The CDC studied 3,689 adults at 21 hospitals in 18 states who got the two-shot Pfizer or Moderna vaccine or the one-shot Johnson & Johnson vaccine between March and August.

The agency noted some factors that could have come into play.

“Differences in vaccine effectiveness between the Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine might be due to higher mRNA content in the Moderna vaccine, differences in timing between doses (3 weeks for Pfizer-BioNTech vs. 4 weeks for Moderna), or possible differences between groups that received each vaccine that were not accounted for in the analysis,” the report said.

The CDC noted limitations in the findings. Children, immunocompromised adults, and vaccine effectiveness against COVID-19 that did not result in hospitalization were not studied.

Other studies have shown all three U.S. vaccines provide a high rate of protection against coronavirus.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

COVID vaccine is safe, effective for children aged 5-11, Pfizer says

With record numbers of COVID-19 cases being reported in kids, Pfizer and its partner BioNTech have announced that their mRNA vaccine for COVID-19 is safe and appears to generate a protective immune response in children as young as 5.

The companies have been testing a lower dose of the vaccine -- just 10 milligrams -- in children between the ages of 5 and 11. That’s one-third the dose given to adults.

In a clinical trial that included more than 2,200 children, Pfizer says two doses of the vaccines given 3 weeks apart generated a high level of neutralizing antibodies, comparable to the level seen in older children who get a higher dose of the vaccine.

On the advice of its vaccine advisory committee, the Food and Drug Administration asked vaccine makers to include more children in these studies earlier this year.

Rather than testing whether the vaccines are preventing COVID-19 illness in children, as they did in adults, the pharmaceutical companies that make the COVID-19 vaccines are looking at the antibody levels generated by the vaccines instead. The FDA has approved the approach in hopes of speeding vaccines to children, who are now back in school full time in most parts of the United States.

With that in mind, Evan Anderson, MD, a doctor with Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta who is an investigator for the trial — and is therefore kept in the dark about its results — said it’s important to keep in mind that the company didn’t share any efficacy data today.

“We don’t know whether there were cases of COVID-19 among children that were enrolled in the study and how those compared in those who received placebo versus those that received vaccine,” he said.

The company says side effects seen in the trial are comparable to those seen in older children. The company said there were no cases of heart inflammation called myocarditis observed. Pfizer says they plan to send their data to the FDA as soon as possible.

The company says side effects seen in the trial are comparable to those seen in older children. Pfizer says they plan to send their data to the FDA as soon as possible.

“We are pleased to be able to submit data to regulatory authorities for this group of school-aged children before the start of the winter season,” Ugur Sahin, MD, CEO and co-founder of BioNTech, said in a news release. “The safety profile and immunogenicity data in children aged 5 to 11 years vaccinated at a lower dose are consistent with those we have observed with our vaccine in other older populations at a higher dose.”

When asked how soon the FDA might act on Pfizer’s application, Anderson said others had speculated about timelines of 4 to 6 weeks, but he also noted that the FDA could still exercise its authority to ask the company for more information, which could slow the process down.

“As a parent myself, I would love to see that timeline occurring quickly. However, I do want the FDA to fully review the data and ask the necessary questions,” he said. “It’s a little speculative to get too definitive with timelines.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

With record numbers of COVID-19 cases being reported in kids, Pfizer and its partner BioNTech have announced that their mRNA vaccine for COVID-19 is safe and appears to generate a protective immune response in children as young as 5.

The companies have been testing a lower dose of the vaccine -- just 10 milligrams -- in children between the ages of 5 and 11. That’s one-third the dose given to adults.

In a clinical trial that included more than 2,200 children, Pfizer says two doses of the vaccines given 3 weeks apart generated a high level of neutralizing antibodies, comparable to the level seen in older children who get a higher dose of the vaccine.

On the advice of its vaccine advisory committee, the Food and Drug Administration asked vaccine makers to include more children in these studies earlier this year.

Rather than testing whether the vaccines are preventing COVID-19 illness in children, as they did in adults, the pharmaceutical companies that make the COVID-19 vaccines are looking at the antibody levels generated by the vaccines instead. The FDA has approved the approach in hopes of speeding vaccines to children, who are now back in school full time in most parts of the United States.

With that in mind, Evan Anderson, MD, a doctor with Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta who is an investigator for the trial — and is therefore kept in the dark about its results — said it’s important to keep in mind that the company didn’t share any efficacy data today.

“We don’t know whether there were cases of COVID-19 among children that were enrolled in the study and how those compared in those who received placebo versus those that received vaccine,” he said.

The company says side effects seen in the trial are comparable to those seen in older children. The company said there were no cases of heart inflammation called myocarditis observed. Pfizer says they plan to send their data to the FDA as soon as possible.

The company says side effects seen in the trial are comparable to those seen in older children. Pfizer says they plan to send their data to the FDA as soon as possible.

“We are pleased to be able to submit data to regulatory authorities for this group of school-aged children before the start of the winter season,” Ugur Sahin, MD, CEO and co-founder of BioNTech, said in a news release. “The safety profile and immunogenicity data in children aged 5 to 11 years vaccinated at a lower dose are consistent with those we have observed with our vaccine in other older populations at a higher dose.”

When asked how soon the FDA might act on Pfizer’s application, Anderson said others had speculated about timelines of 4 to 6 weeks, but he also noted that the FDA could still exercise its authority to ask the company for more information, which could slow the process down.

“As a parent myself, I would love to see that timeline occurring quickly. However, I do want the FDA to fully review the data and ask the necessary questions,” he said. “It’s a little speculative to get too definitive with timelines.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

With record numbers of COVID-19 cases being reported in kids, Pfizer and its partner BioNTech have announced that their mRNA vaccine for COVID-19 is safe and appears to generate a protective immune response in children as young as 5.

The companies have been testing a lower dose of the vaccine -- just 10 milligrams -- in children between the ages of 5 and 11. That’s one-third the dose given to adults.

In a clinical trial that included more than 2,200 children, Pfizer says two doses of the vaccines given 3 weeks apart generated a high level of neutralizing antibodies, comparable to the level seen in older children who get a higher dose of the vaccine.

On the advice of its vaccine advisory committee, the Food and Drug Administration asked vaccine makers to include more children in these studies earlier this year.

Rather than testing whether the vaccines are preventing COVID-19 illness in children, as they did in adults, the pharmaceutical companies that make the COVID-19 vaccines are looking at the antibody levels generated by the vaccines instead. The FDA has approved the approach in hopes of speeding vaccines to children, who are now back in school full time in most parts of the United States.

With that in mind, Evan Anderson, MD, a doctor with Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta who is an investigator for the trial — and is therefore kept in the dark about its results — said it’s important to keep in mind that the company didn’t share any efficacy data today.

“We don’t know whether there were cases of COVID-19 among children that were enrolled in the study and how those compared in those who received placebo versus those that received vaccine,” he said.

The company says side effects seen in the trial are comparable to those seen in older children. The company said there were no cases of heart inflammation called myocarditis observed. Pfizer says they plan to send their data to the FDA as soon as possible.

The company says side effects seen in the trial are comparable to those seen in older children. Pfizer says they plan to send their data to the FDA as soon as possible.

“We are pleased to be able to submit data to regulatory authorities for this group of school-aged children before the start of the winter season,” Ugur Sahin, MD, CEO and co-founder of BioNTech, said in a news release. “The safety profile and immunogenicity data in children aged 5 to 11 years vaccinated at a lower dose are consistent with those we have observed with our vaccine in other older populations at a higher dose.”

When asked how soon the FDA might act on Pfizer’s application, Anderson said others had speculated about timelines of 4 to 6 weeks, but he also noted that the FDA could still exercise its authority to ask the company for more information, which could slow the process down.

“As a parent myself, I would love to see that timeline occurring quickly. However, I do want the FDA to fully review the data and ask the necessary questions,” he said. “It’s a little speculative to get too definitive with timelines.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

FDA panel backs Pfizer's COVID booster for 65 and older, those at high risk

An expert panel that advises the Food and Drug Administration on its regulatory decisions voted Sept. 17 against recommending third doses of Pfizer’s COVID-19 vaccine for younger Americans.

But they didn’t kill the idea of booster shots completely.

In a dramatic, last-minute pivot, the 18 members of the FDA’s Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee unanimously voted to recommend the FDA make boosters available for seniors and others at high risk of severe outcomes from COVID-19, including health care workers.

The 16-2 vote was a rebuttal to Pfizer’s initial request. The company had asked the FDA to allow it to offer third doses to all Americans over the age of 16 at least six months after their second shot.

The company requested an amendment to the full approval the FDA granted in August. That is the typical way boosters are authorized in the U.S., but it requires a higher bar of evidence and more regulatory scrutiny than the agency had been able to give since Pfizer filed for the change just days after its vaccine was granted full approval.

The committee’s actions were also a rebuff to the Biden administration, which announced before the FDA approved them that boosters would be rolled out to the general public Sept. 20. The announcement triggered the resignations of two of the agency’s top vaccine reviewers, who both participated in the Sept. 17 meeting.

After initially voting against Pfizer’s request to amend its license, the committee then worked on the fly with FDA officials to craft a strategy that would allow third doses to be offered under an emergency use authorization (EUA).

An EUA requires a lower standard of evidence and is more specific. It will restrict third doses to a more defined population than a change to the license would. It will also require Pfizer to continue to monitor the safety of third doses as they begin to be administered.

“This should demonstrate to the public that the members of this committee are independent of the FDA and that we do, in fact, bring our voices to the table when we are asked to serve on this committee,” said Archana Chattergee, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist who is dean of the Chicago Medical School at Rosalind Franklin University in Illinois.

The FDA doesn’t have to follow the committee’s recommendation, but almost certainly will, though regulators said they may still make some changes.

“We are not bound at FDA by your vote, we can tweak this,” said Peter Marks, MD, director of the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research at the FDA. Dr. Marks participated in the meeting and helped to draft the revised proposal.

If the FDA issues the recommended EUA, a council of independent advisors to the CDC will make specific recommendations about how the third doses should be given. After the CDC director weighs in, boosters will begin rolling out to the public.

Moderna submitted data to the FDA on Sept. 1 in support of adding a booster dose to its regimen. The agency has not yet scheduled a public review of that data.

The Biden administration is prepared to administer shots as soon as they get the green light, Surgeon General Vivek Murthy, MD, said at a White House briefing earlier Sept. 17.

"This process is consistent with what we outlined in August where our goals were to stay ahead of the virus," Dr. Murthy said. "Our goal then and now is to protect the health and well-being of the public. As soon as the FDA and CDC complete their evaluations, we will be ready to move forward accordingly."

He added, "We've used this time since our August announcement to communicate and coordinate with pharmacy partners, nursing homes, states, and localities."

White House COVID-19 Response Coordinator Jeff Zients said vaccine supply is "in good shape for all Americans to get boosters as recommended."

Taking cues from Israel

In considering Pfizer’s original request, the committee overwhelmingly felt that they didn’t have enough information to say that the benefits of an additional dose of vaccine in 16- and 17-year-olds would outweigh its risk. Teens have the highest risk of rare heart inflammation after vaccination, a side effect known as myocarditis. It is not known how the vaccines are causing these cases of heart swelling. Most who have been diagnosed with the condition have recovered, though some have needed hospital care.

Pfizer didn’t include 16- and 17-year-olds in its studies of boosters, which included about 300 people between the ages of 18 and 55. The company acknowledged that gap in its data but pointed to FDA guidance that said evidence from adults could be extrapolated to teens.

“We don’t know that much about risks,” said committee member Eric Rubin, MD, who is editor-in-chief of the New England Journal of Medicine.

Much of the data on the potential benefits and harms of third Pfizer doses comes from Israel, which first began rolling out boosters to older adults in July.

In a highly anticipated presentation, Sharon Alroy-Preis, Israel’s director of public health services, joined the meeting to describe Israel’s experience with boosters.

Israel began to see a third surge of COVID-19 cases in December.

“This was after having two waves and two lockdowns,” Ms. Alroy-Preis said. By the third surge, she said, Israelis were tired.

“We decided on a lockdown, but the compliance of the public wasn’t as it was in the previous two waves,” she said.

Then the vaccine arrived. Israel started vaccinations as soon as the FDA approved it, and they quickly vaccinated a high percentage of their population, about 3 months faster than the rest of the world.

All vaccinations are reported and tracked by the Ministry of Health, so the country is able to keep close tabs on how well the shots are working.

As vaccines rolled out, cases fell dramatically. The pandemic seemed to be behind them. Delta arrived in March. By June, their cases were doubling every 10 days, despite about 80% of their most vulnerable adults being fully vaccinated, she said.

Most concerning was that about 60% of severe cases were breakthrough cases in fully vaccinated individuals.

“We had to stop and figure out, was this a Delta issue,” she said. “Or was this a waning immunity issue.”

“We had some clue that it might not be the Delta variant, at least not alone,” she said.

People who had originally been first in line for the vaccines, seniors and health care workers, were having the highest rates of breakthrough infections. People further away from their second dose were more likely to get a breakthrough infection.

Ms. Alroy-Preis said that if they had not started booster doses in July, their hospitals would have been overwhelmed. They had projected that they would have 2,000 cases in the hospital each day.

Boosters have helped to flatten the curve, though they are still seeing a significant number of infections.

Data from Israel presented at the meeting show boosters are largely safe and effective at reducing severe outcomes in seniors. Israeli experience also showed that third doses, which generate very high levels of neutralizing antibodies—the first and fastest line of the body’s immune defense - -may also slow transmission of the virus.

Key differences in the U.S.

The benefit of slowing down the explosive spread of a highly contagious virus was tantalizing, but many members noted that circumstances in Israel are very different than in the United States. Israel went into its current Delta surge already having high levels of vaccination in its population. They also relied on the Pfizer vaccine almost exclusively for their campaign.

The United States used a different mix of vaccines – Pfizer, Moderna, and Johnson & Johnson -- and doesn’t have the same high level of vaccination coverage of its population.

In the United States, transmission is mainly being driven by unvaccinated people, Dr. Rubin noted.

“That really means the primary benefit is going to be in reducing disease,” he said, “And we know the people who are going to benefit from that … and those are the kinds of people the FDA has already approved a third dose for,” he said, referring to those with underlying health conditions.

But Israel only began vaccinating younger people a few weeks ago. Most are still within a window where rare risks like myocarditis could appear, Rubin noted.

He and other members of the committee said they wished they had more information about the safety of third doses in younger adults.

“We don’t have that right now, and I don’t think I would be comfortable giving it to a 16-year-old,” he said.

At the same time, the primary benefit for third doses would be in preventing severe disease, and overall, data from the United States and other countries show that two doses of the vaccines remain highly effective at preventing hospitalization and death.

Asked why Israel began to see more severe cases in fully vaccinated people, the CDC’s Sara Oliver, MD, a disease detective with the CDC, said it was probably due to a mix of factors including the fact that Israel defines severe cases a little differently.

In the United States, a severe case is generally a person who has to be hospitalized or who has died from the infection. In Israel, a person with a severe case is someone who has an elevated respiratory rate and someone who has a blood oxygen level less than 94%. In the United States, that kind of patient wouldn’t necessarily be hospitalized.

In the end, one of the two committee members who wanted full approval for Pfizer’s third doses said he was satisfied with the outcome.

Mark Sawyer, MD, a professor of pediatrics and infectious disease at the University of California at San Diego, said he voted yes on the first question because he thought full approval was the best way to give doctors the flexibility to prescribe the shots to vulnerable individuals.

“I’m really glad we authorized a vaccine for a third dose, and I plan to go out and get my vaccine this afternoon,” Dr. Sawyer said, noting that he was at high risk as a health care provider.

This article was updated 9/19/21.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

An expert panel that advises the Food and Drug Administration on its regulatory decisions voted Sept. 17 against recommending third doses of Pfizer’s COVID-19 vaccine for younger Americans.

But they didn’t kill the idea of booster shots completely.

In a dramatic, last-minute pivot, the 18 members of the FDA’s Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee unanimously voted to recommend the FDA make boosters available for seniors and others at high risk of severe outcomes from COVID-19, including health care workers.

The 16-2 vote was a rebuttal to Pfizer’s initial request. The company had asked the FDA to allow it to offer third doses to all Americans over the age of 16 at least six months after their second shot.

The company requested an amendment to the full approval the FDA granted in August. That is the typical way boosters are authorized in the U.S., but it requires a higher bar of evidence and more regulatory scrutiny than the agency had been able to give since Pfizer filed for the change just days after its vaccine was granted full approval.

The committee’s actions were also a rebuff to the Biden administration, which announced before the FDA approved them that boosters would be rolled out to the general public Sept. 20. The announcement triggered the resignations of two of the agency’s top vaccine reviewers, who both participated in the Sept. 17 meeting.

After initially voting against Pfizer’s request to amend its license, the committee then worked on the fly with FDA officials to craft a strategy that would allow third doses to be offered under an emergency use authorization (EUA).

An EUA requires a lower standard of evidence and is more specific. It will restrict third doses to a more defined population than a change to the license would. It will also require Pfizer to continue to monitor the safety of third doses as they begin to be administered.

“This should demonstrate to the public that the members of this committee are independent of the FDA and that we do, in fact, bring our voices to the table when we are asked to serve on this committee,” said Archana Chattergee, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist who is dean of the Chicago Medical School at Rosalind Franklin University in Illinois.

The FDA doesn’t have to follow the committee’s recommendation, but almost certainly will, though regulators said they may still make some changes.

“We are not bound at FDA by your vote, we can tweak this,” said Peter Marks, MD, director of the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research at the FDA. Dr. Marks participated in the meeting and helped to draft the revised proposal.

If the FDA issues the recommended EUA, a council of independent advisors to the CDC will make specific recommendations about how the third doses should be given. After the CDC director weighs in, boosters will begin rolling out to the public.

Moderna submitted data to the FDA on Sept. 1 in support of adding a booster dose to its regimen. The agency has not yet scheduled a public review of that data.

The Biden administration is prepared to administer shots as soon as they get the green light, Surgeon General Vivek Murthy, MD, said at a White House briefing earlier Sept. 17.

"This process is consistent with what we outlined in August where our goals were to stay ahead of the virus," Dr. Murthy said. "Our goal then and now is to protect the health and well-being of the public. As soon as the FDA and CDC complete their evaluations, we will be ready to move forward accordingly."

He added, "We've used this time since our August announcement to communicate and coordinate with pharmacy partners, nursing homes, states, and localities."

White House COVID-19 Response Coordinator Jeff Zients said vaccine supply is "in good shape for all Americans to get boosters as recommended."

Taking cues from Israel

In considering Pfizer’s original request, the committee overwhelmingly felt that they didn’t have enough information to say that the benefits of an additional dose of vaccine in 16- and 17-year-olds would outweigh its risk. Teens have the highest risk of rare heart inflammation after vaccination, a side effect known as myocarditis. It is not known how the vaccines are causing these cases of heart swelling. Most who have been diagnosed with the condition have recovered, though some have needed hospital care.

Pfizer didn’t include 16- and 17-year-olds in its studies of boosters, which included about 300 people between the ages of 18 and 55. The company acknowledged that gap in its data but pointed to FDA guidance that said evidence from adults could be extrapolated to teens.

“We don’t know that much about risks,” said committee member Eric Rubin, MD, who is editor-in-chief of the New England Journal of Medicine.

Much of the data on the potential benefits and harms of third Pfizer doses comes from Israel, which first began rolling out boosters to older adults in July.

In a highly anticipated presentation, Sharon Alroy-Preis, Israel’s director of public health services, joined the meeting to describe Israel’s experience with boosters.

Israel began to see a third surge of COVID-19 cases in December.

“This was after having two waves and two lockdowns,” Ms. Alroy-Preis said. By the third surge, she said, Israelis were tired.

“We decided on a lockdown, but the compliance of the public wasn’t as it was in the previous two waves,” she said.

Then the vaccine arrived. Israel started vaccinations as soon as the FDA approved it, and they quickly vaccinated a high percentage of their population, about 3 months faster than the rest of the world.

All vaccinations are reported and tracked by the Ministry of Health, so the country is able to keep close tabs on how well the shots are working.

As vaccines rolled out, cases fell dramatically. The pandemic seemed to be behind them. Delta arrived in March. By June, their cases were doubling every 10 days, despite about 80% of their most vulnerable adults being fully vaccinated, she said.

Most concerning was that about 60% of severe cases were breakthrough cases in fully vaccinated individuals.

“We had to stop and figure out, was this a Delta issue,” she said. “Or was this a waning immunity issue.”

“We had some clue that it might not be the Delta variant, at least not alone,” she said.

People who had originally been first in line for the vaccines, seniors and health care workers, were having the highest rates of breakthrough infections. People further away from their second dose were more likely to get a breakthrough infection.

Ms. Alroy-Preis said that if they had not started booster doses in July, their hospitals would have been overwhelmed. They had projected that they would have 2,000 cases in the hospital each day.

Boosters have helped to flatten the curve, though they are still seeing a significant number of infections.

Data from Israel presented at the meeting show boosters are largely safe and effective at reducing severe outcomes in seniors. Israeli experience also showed that third doses, which generate very high levels of neutralizing antibodies—the first and fastest line of the body’s immune defense - -may also slow transmission of the virus.

Key differences in the U.S.

The benefit of slowing down the explosive spread of a highly contagious virus was tantalizing, but many members noted that circumstances in Israel are very different than in the United States. Israel went into its current Delta surge already having high levels of vaccination in its population. They also relied on the Pfizer vaccine almost exclusively for their campaign.

The United States used a different mix of vaccines – Pfizer, Moderna, and Johnson & Johnson -- and doesn’t have the same high level of vaccination coverage of its population.

In the United States, transmission is mainly being driven by unvaccinated people, Dr. Rubin noted.

“That really means the primary benefit is going to be in reducing disease,” he said, “And we know the people who are going to benefit from that … and those are the kinds of people the FDA has already approved a third dose for,” he said, referring to those with underlying health conditions.

But Israel only began vaccinating younger people a few weeks ago. Most are still within a window where rare risks like myocarditis could appear, Rubin noted.

He and other members of the committee said they wished they had more information about the safety of third doses in younger adults.

“We don’t have that right now, and I don’t think I would be comfortable giving it to a 16-year-old,” he said.

At the same time, the primary benefit for third doses would be in preventing severe disease, and overall, data from the United States and other countries show that two doses of the vaccines remain highly effective at preventing hospitalization and death.

Asked why Israel began to see more severe cases in fully vaccinated people, the CDC’s Sara Oliver, MD, a disease detective with the CDC, said it was probably due to a mix of factors including the fact that Israel defines severe cases a little differently.

In the United States, a severe case is generally a person who has to be hospitalized or who has died from the infection. In Israel, a person with a severe case is someone who has an elevated respiratory rate and someone who has a blood oxygen level less than 94%. In the United States, that kind of patient wouldn’t necessarily be hospitalized.

In the end, one of the two committee members who wanted full approval for Pfizer’s third doses said he was satisfied with the outcome.

Mark Sawyer, MD, a professor of pediatrics and infectious disease at the University of California at San Diego, said he voted yes on the first question because he thought full approval was the best way to give doctors the flexibility to prescribe the shots to vulnerable individuals.

“I’m really glad we authorized a vaccine for a third dose, and I plan to go out and get my vaccine this afternoon,” Dr. Sawyer said, noting that he was at high risk as a health care provider.

This article was updated 9/19/21.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

An expert panel that advises the Food and Drug Administration on its regulatory decisions voted Sept. 17 against recommending third doses of Pfizer’s COVID-19 vaccine for younger Americans.

But they didn’t kill the idea of booster shots completely.

In a dramatic, last-minute pivot, the 18 members of the FDA’s Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee unanimously voted to recommend the FDA make boosters available for seniors and others at high risk of severe outcomes from COVID-19, including health care workers.

The 16-2 vote was a rebuttal to Pfizer’s initial request. The company had asked the FDA to allow it to offer third doses to all Americans over the age of 16 at least six months after their second shot.

The company requested an amendment to the full approval the FDA granted in August. That is the typical way boosters are authorized in the U.S., but it requires a higher bar of evidence and more regulatory scrutiny than the agency had been able to give since Pfizer filed for the change just days after its vaccine was granted full approval.

The committee’s actions were also a rebuff to the Biden administration, which announced before the FDA approved them that boosters would be rolled out to the general public Sept. 20. The announcement triggered the resignations of two of the agency’s top vaccine reviewers, who both participated in the Sept. 17 meeting.

After initially voting against Pfizer’s request to amend its license, the committee then worked on the fly with FDA officials to craft a strategy that would allow third doses to be offered under an emergency use authorization (EUA).

An EUA requires a lower standard of evidence and is more specific. It will restrict third doses to a more defined population than a change to the license would. It will also require Pfizer to continue to monitor the safety of third doses as they begin to be administered.

“This should demonstrate to the public that the members of this committee are independent of the FDA and that we do, in fact, bring our voices to the table when we are asked to serve on this committee,” said Archana Chattergee, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist who is dean of the Chicago Medical School at Rosalind Franklin University in Illinois.

The FDA doesn’t have to follow the committee’s recommendation, but almost certainly will, though regulators said they may still make some changes.

“We are not bound at FDA by your vote, we can tweak this,” said Peter Marks, MD, director of the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research at the FDA. Dr. Marks participated in the meeting and helped to draft the revised proposal.

If the FDA issues the recommended EUA, a council of independent advisors to the CDC will make specific recommendations about how the third doses should be given. After the CDC director weighs in, boosters will begin rolling out to the public.

Moderna submitted data to the FDA on Sept. 1 in support of adding a booster dose to its regimen. The agency has not yet scheduled a public review of that data.

The Biden administration is prepared to administer shots as soon as they get the green light, Surgeon General Vivek Murthy, MD, said at a White House briefing earlier Sept. 17.

"This process is consistent with what we outlined in August where our goals were to stay ahead of the virus," Dr. Murthy said. "Our goal then and now is to protect the health and well-being of the public. As soon as the FDA and CDC complete their evaluations, we will be ready to move forward accordingly."

He added, "We've used this time since our August announcement to communicate and coordinate with pharmacy partners, nursing homes, states, and localities."

White House COVID-19 Response Coordinator Jeff Zients said vaccine supply is "in good shape for all Americans to get boosters as recommended."

Taking cues from Israel

In considering Pfizer’s original request, the committee overwhelmingly felt that they didn’t have enough information to say that the benefits of an additional dose of vaccine in 16- and 17-year-olds would outweigh its risk. Teens have the highest risk of rare heart inflammation after vaccination, a side effect known as myocarditis. It is not known how the vaccines are causing these cases of heart swelling. Most who have been diagnosed with the condition have recovered, though some have needed hospital care.

Pfizer didn’t include 16- and 17-year-olds in its studies of boosters, which included about 300 people between the ages of 18 and 55. The company acknowledged that gap in its data but pointed to FDA guidance that said evidence from adults could be extrapolated to teens.

“We don’t know that much about risks,” said committee member Eric Rubin, MD, who is editor-in-chief of the New England Journal of Medicine.

Much of the data on the potential benefits and harms of third Pfizer doses comes from Israel, which first began rolling out boosters to older adults in July.

In a highly anticipated presentation, Sharon Alroy-Preis, Israel’s director of public health services, joined the meeting to describe Israel’s experience with boosters.

Israel began to see a third surge of COVID-19 cases in December.

“This was after having two waves and two lockdowns,” Ms. Alroy-Preis said. By the third surge, she said, Israelis were tired.

“We decided on a lockdown, but the compliance of the public wasn’t as it was in the previous two waves,” she said.

Then the vaccine arrived. Israel started vaccinations as soon as the FDA approved it, and they quickly vaccinated a high percentage of their population, about 3 months faster than the rest of the world.

All vaccinations are reported and tracked by the Ministry of Health, so the country is able to keep close tabs on how well the shots are working.

As vaccines rolled out, cases fell dramatically. The pandemic seemed to be behind them. Delta arrived in March. By June, their cases were doubling every 10 days, despite about 80% of their most vulnerable adults being fully vaccinated, she said.

Most concerning was that about 60% of severe cases were breakthrough cases in fully vaccinated individuals.

“We had to stop and figure out, was this a Delta issue,” she said. “Or was this a waning immunity issue.”

“We had some clue that it might not be the Delta variant, at least not alone,” she said.

People who had originally been first in line for the vaccines, seniors and health care workers, were having the highest rates of breakthrough infections. People further away from their second dose were more likely to get a breakthrough infection.

Ms. Alroy-Preis said that if they had not started booster doses in July, their hospitals would have been overwhelmed. They had projected that they would have 2,000 cases in the hospital each day.

Boosters have helped to flatten the curve, though they are still seeing a significant number of infections.

Data from Israel presented at the meeting show boosters are largely safe and effective at reducing severe outcomes in seniors. Israeli experience also showed that third doses, which generate very high levels of neutralizing antibodies—the first and fastest line of the body’s immune defense - -may also slow transmission of the virus.

Key differences in the U.S.

The benefit of slowing down the explosive spread of a highly contagious virus was tantalizing, but many members noted that circumstances in Israel are very different than in the United States. Israel went into its current Delta surge already having high levels of vaccination in its population. They also relied on the Pfizer vaccine almost exclusively for their campaign.

The United States used a different mix of vaccines – Pfizer, Moderna, and Johnson & Johnson -- and doesn’t have the same high level of vaccination coverage of its population.

In the United States, transmission is mainly being driven by unvaccinated people, Dr. Rubin noted.

“That really means the primary benefit is going to be in reducing disease,” he said, “And we know the people who are going to benefit from that … and those are the kinds of people the FDA has already approved a third dose for,” he said, referring to those with underlying health conditions.

But Israel only began vaccinating younger people a few weeks ago. Most are still within a window where rare risks like myocarditis could appear, Rubin noted.

He and other members of the committee said they wished they had more information about the safety of third doses in younger adults.

“We don’t have that right now, and I don’t think I would be comfortable giving it to a 16-year-old,” he said.

At the same time, the primary benefit for third doses would be in preventing severe disease, and overall, data from the United States and other countries show that two doses of the vaccines remain highly effective at preventing hospitalization and death.

Asked why Israel began to see more severe cases in fully vaccinated people, the CDC’s Sara Oliver, MD, a disease detective with the CDC, said it was probably due to a mix of factors including the fact that Israel defines severe cases a little differently.

In the United States, a severe case is generally a person who has to be hospitalized or who has died from the infection. In Israel, a person with a severe case is someone who has an elevated respiratory rate and someone who has a blood oxygen level less than 94%. In the United States, that kind of patient wouldn’t necessarily be hospitalized.

In the end, one of the two committee members who wanted full approval for Pfizer’s third doses said he was satisfied with the outcome.

Mark Sawyer, MD, a professor of pediatrics and infectious disease at the University of California at San Diego, said he voted yes on the first question because he thought full approval was the best way to give doctors the flexibility to prescribe the shots to vulnerable individuals.

“I’m really glad we authorized a vaccine for a third dose, and I plan to go out and get my vaccine this afternoon,” Dr. Sawyer said, noting that he was at high risk as a health care provider.

This article was updated 9/19/21.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Pandemic goal deficiency disorder

In August I shared with you my observations on two opposing op-ed pieces from two major newspapers, one was in favor of masking mandates for public schools, the other against. (Masking in school: A battle of the op-eds. MDedge Pediatrics. Letters from Maine, 2021 Aug 12). Neither group of authors could offer us evidence from controlled studies to support their views. However, both agreed that returning children to school deserves a high priority. But neither the authors nor I treaded into the uncharted waters of exactly how masking fits into our national goals for managing the pandemic because ... no one in this country has articulated what these goals should be. A third op-ed appearing 3 weeks later suggests why we are floundering in this goal-deficient limbo.

Writing in the New York Times, two epidemiologists in Boston ask the simple question: “What are we actually trying to achieve in the United States?” when it comes to the pandemic. (Allen AG and Jenkins H. The Hard Covid-19 Questions We’re Not Asking. 2021 Aug 30). Is our goal zero infections? Is it hammering on the virus until we can treat it like the seasonal flu? We do seem to agree that not having kids in school has been a disaster economically, educationally, and psychologically. But, where does the goal of getting them back in school fit into a larger and as yet undefined national goal? Without that target we have little idea of what compromises and risks we should be willing to accept.

How much serious pediatric disease is acceptable? It appears that the number of fatal complications in the pediatric population is very small in comparison with other demographic groups. Although few in number, there have been and there will continue to be pediatric deaths because of COVID. Is our goal zero pediatric deaths? If it is then this dictates a level of response that ripples back upstream to every child in every classroom and could threaten our overarching goal of returning children to school. Because none of us likes the thought of a child dying, some of us may be hesitant to even consider a strategy that doesn’t include zero pediatric deaths as a goal.

Are we looking to have zero serious pediatric infections? Achieving this goal is unlikely. Even if we develop a pediatric vaccine in the near future it probably won’t be in the arms of enough children by the end of this school year to make a significant dent in the number of serious pediatric infections. Waiting until an optimal number of children are immunized doesn’t feel like it will achieve a primary goal of getting kids back in school if we continue to focus on driving the level of serious pediatric infections to zero. We have already endured a year in which many communities made decisions that seemed to have prioritized an unstated goal of no school exposure–related educator deaths. Again, a goal based on little if any evidence.

The problem we face in this country is that our response to the pandemic has been nonuniform. Here in Brunswick, Maine, 99% of the eligible adults have been vaccinated. Even with the recent surge, we may be ready for a strategy that avoids wholesale quarantining. A targeted and robust antibody testing system might work for us and make an unproven and unpopular masking mandate unnecessary. Britain seems to be moving in a similar direction to meet its goal of keeping children in school.

However, there are large population groups in regions of this country that have stumbled at taking the initial steps to get the pandemic under control. Articulating a national goal that covers both communities where the response to the pandemic has been less thoughtful and robust along with states that have been more successful is going to be difficult. But it must be done.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

In August I shared with you my observations on two opposing op-ed pieces from two major newspapers, one was in favor of masking mandates for public schools, the other against. (Masking in school: A battle of the op-eds. MDedge Pediatrics. Letters from Maine, 2021 Aug 12). Neither group of authors could offer us evidence from controlled studies to support their views. However, both agreed that returning children to school deserves a high priority. But neither the authors nor I treaded into the uncharted waters of exactly how masking fits into our national goals for managing the pandemic because ... no one in this country has articulated what these goals should be. A third op-ed appearing 3 weeks later suggests why we are floundering in this goal-deficient limbo.

Writing in the New York Times, two epidemiologists in Boston ask the simple question: “What are we actually trying to achieve in the United States?” when it comes to the pandemic. (Allen AG and Jenkins H. The Hard Covid-19 Questions We’re Not Asking. 2021 Aug 30). Is our goal zero infections? Is it hammering on the virus until we can treat it like the seasonal flu? We do seem to agree that not having kids in school has been a disaster economically, educationally, and psychologically. But, where does the goal of getting them back in school fit into a larger and as yet undefined national goal? Without that target we have little idea of what compromises and risks we should be willing to accept.

How much serious pediatric disease is acceptable? It appears that the number of fatal complications in the pediatric population is very small in comparison with other demographic groups. Although few in number, there have been and there will continue to be pediatric deaths because of COVID. Is our goal zero pediatric deaths? If it is then this dictates a level of response that ripples back upstream to every child in every classroom and could threaten our overarching goal of returning children to school. Because none of us likes the thought of a child dying, some of us may be hesitant to even consider a strategy that doesn’t include zero pediatric deaths as a goal.

Are we looking to have zero serious pediatric infections? Achieving this goal is unlikely. Even if we develop a pediatric vaccine in the near future it probably won’t be in the arms of enough children by the end of this school year to make a significant dent in the number of serious pediatric infections. Waiting until an optimal number of children are immunized doesn’t feel like it will achieve a primary goal of getting kids back in school if we continue to focus on driving the level of serious pediatric infections to zero. We have already endured a year in which many communities made decisions that seemed to have prioritized an unstated goal of no school exposure–related educator deaths. Again, a goal based on little if any evidence.

The problem we face in this country is that our response to the pandemic has been nonuniform. Here in Brunswick, Maine, 99% of the eligible adults have been vaccinated. Even with the recent surge, we may be ready for a strategy that avoids wholesale quarantining. A targeted and robust antibody testing system might work for us and make an unproven and unpopular masking mandate unnecessary. Britain seems to be moving in a similar direction to meet its goal of keeping children in school.

However, there are large population groups in regions of this country that have stumbled at taking the initial steps to get the pandemic under control. Articulating a national goal that covers both communities where the response to the pandemic has been less thoughtful and robust along with states that have been more successful is going to be difficult. But it must be done.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

In August I shared with you my observations on two opposing op-ed pieces from two major newspapers, one was in favor of masking mandates for public schools, the other against. (Masking in school: A battle of the op-eds. MDedge Pediatrics. Letters from Maine, 2021 Aug 12). Neither group of authors could offer us evidence from controlled studies to support their views. However, both agreed that returning children to school deserves a high priority. But neither the authors nor I treaded into the uncharted waters of exactly how masking fits into our national goals for managing the pandemic because ... no one in this country has articulated what these goals should be. A third op-ed appearing 3 weeks later suggests why we are floundering in this goal-deficient limbo.

Writing in the New York Times, two epidemiologists in Boston ask the simple question: “What are we actually trying to achieve in the United States?” when it comes to the pandemic. (Allen AG and Jenkins H. The Hard Covid-19 Questions We’re Not Asking. 2021 Aug 30). Is our goal zero infections? Is it hammering on the virus until we can treat it like the seasonal flu? We do seem to agree that not having kids in school has been a disaster economically, educationally, and psychologically. But, where does the goal of getting them back in school fit into a larger and as yet undefined national goal? Without that target we have little idea of what compromises and risks we should be willing to accept.

How much serious pediatric disease is acceptable? It appears that the number of fatal complications in the pediatric population is very small in comparison with other demographic groups. Although few in number, there have been and there will continue to be pediatric deaths because of COVID. Is our goal zero pediatric deaths? If it is then this dictates a level of response that ripples back upstream to every child in every classroom and could threaten our overarching goal of returning children to school. Because none of us likes the thought of a child dying, some of us may be hesitant to even consider a strategy that doesn’t include zero pediatric deaths as a goal.

Are we looking to have zero serious pediatric infections? Achieving this goal is unlikely. Even if we develop a pediatric vaccine in the near future it probably won’t be in the arms of enough children by the end of this school year to make a significant dent in the number of serious pediatric infections. Waiting until an optimal number of children are immunized doesn’t feel like it will achieve a primary goal of getting kids back in school if we continue to focus on driving the level of serious pediatric infections to zero. We have already endured a year in which many communities made decisions that seemed to have prioritized an unstated goal of no school exposure–related educator deaths. Again, a goal based on little if any evidence.

The problem we face in this country is that our response to the pandemic has been nonuniform. Here in Brunswick, Maine, 99% of the eligible adults have been vaccinated. Even with the recent surge, we may be ready for a strategy that avoids wholesale quarantining. A targeted and robust antibody testing system might work for us and make an unproven and unpopular masking mandate unnecessary. Britain seems to be moving in a similar direction to meet its goal of keeping children in school.

However, there are large population groups in regions of this country that have stumbled at taking the initial steps to get the pandemic under control. Articulating a national goal that covers both communities where the response to the pandemic has been less thoughtful and robust along with states that have been more successful is going to be difficult. But it must be done.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

HPV infection during pregnancy ups risk of premature birth

Persistent human papillomavirus (HPV) 16 and HPV 18 during a pregnancy may be associated with an increased risk of premature birth.