User login

Diabetic dyslipidemia with eruptive xanthoma

A workup for secondary causes of hypertriglyceridemia was negative for hypothyroidism and nephrotic syndrome. She was currently taking no medications. She had no family history of dyslipidemia, and she denied alcohol consumption.

Based on the patient’s presentation, history, and the results of laboratory testing and skin biopsy, the diagnosis was eruptive xanthoma.

A RESULT OF ELEVATED TRIGLYCERIDES

Eruptive xanthoma is associated with elevation of chylomicrons and triglycerides.1 Hyperlipidemia that causes eruptive xanthoma may be familial (ie, due to a primary genetic defect) or secondary to another disease, or both.

Types of primary hypertriglyceridemia include elevated chylomicrons (Frederickson classification type I), elevated very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) (Frederickson type IV), and elevation of both chylomicrons and VLDL (Frederickson type V).2,3 Hypertriglyceridemia may also be secondary to obesity, diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, nephrotic syndrome, liver cirrhosis, excess ethanol ingestion, and medicines such as retinoids and estrogens.2,3

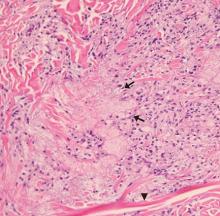

Lesions of eruptive xanthoma are yellowish papules 2 to 5 mm in diameter surrounded by an erythematous border. They are formed by clusters of foamy cells caused by phagocytosis of macrophages as a consequence of increased accumulations of intracellular lipids. The most common sites are the buttocks, extensor surfaces of the arms, and the back.4

Eruptive xanthoma occurs with markedly elevated triglyceride levels (ie, > 1,000 mg/dL),5 with an estimated prevalence of 18 cases per 100,000 people (< 0.02%).6 Diagnosis is usually established through the clinical history, physical examination, and prompt laboratory confirmation of hypertriglyceridemia. Skin biopsy is rarely if ever needed.

RECOGNIZE AND TREAT PROMPTLY TO AVOID FURTHER COMPLICATIONS

Severe hypertriglyceridemia poses an increased risk of acute pancreatitis. Early recognition and medical treatment in our patient prevented serious complications.

Treatment of eruptive xanthoma includes identifying the underlying cause of hypertriglyceridemia and commencing lifestyle modifications that include weight reduction, aerobic exercise, a strict low-fat diet with avoidance of simple carbohydrates and alcohol,7 and drug therapy.

The patient’s treatment plan

Although HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) have a modest triglyceride-lowering effect and are useful to modify cardiovascular risk, fibric acid derivatives (eg, gemfibrozil, fenofibrate) are the first-line therapy.8 Omega-3 fatty acids, statins, or niacin may be added if necessary.8

Our patient’s uncontrolled glycemia caused marked hypertriglyceridemia, perhaps from a decrease in lipoprotein lipase activity in adipose tissue and muscle. Lifestyle modifications, glucose-lowering agents (metformin, glimepiride), and fenofibrate were prescribed. She was also advised to seek medical attention if she developed upper-abdominal pain, which could be a symptom of pancreatitis.

- Flynn PD, Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C. Xanthomas and abnormalities of lipid metabolism and storage. In: Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 2010.

- Breckenridge WC, Alaupovic P, Cox DW, Little JA. Apolipoprotein and lipoprotein concentrations in familial apolipoprotein C-II deficiency. Atherosclerosis 1982; 44(2):223–235. pmid:7138621

- Santamarina-Fojo S. The familial chylomicronemia syndrome. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 1998; 27(3):551–567. pmid:9785052

- Melmed S, Polonsky KS, Larsen PR, Kronenberg H. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. 13th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2016.

- Zak A, Zeman M, Slaby A, Vecka M. Xanthomas: clinical and pathophysiological relations. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub 2014; 158(2):181–188. doi:10.5507/bp.2014.016

- Leaf DA. Chylomicronemia and the chylomicronemia syndrome: a practical approach to management. Am J Med 2008; 121(1):10–12. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.10.004

- Hegele RA, Ginsberg HN, Chapman MJ, et al; European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel. The polygenic nature of hypertriglyceridaemia: implications for definition, diagnosis, and management. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2014; 2(8):655–666. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70191-8

- Berglund L, Brunzell JD, Goldberg AC, et al; Endocrine Society. Evaluation and treatment of hypertriglyceridemia: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012; 97(9):2969–2989. doi:10.1210/jc.2011-3213

A workup for secondary causes of hypertriglyceridemia was negative for hypothyroidism and nephrotic syndrome. She was currently taking no medications. She had no family history of dyslipidemia, and she denied alcohol consumption.

Based on the patient’s presentation, history, and the results of laboratory testing and skin biopsy, the diagnosis was eruptive xanthoma.

A RESULT OF ELEVATED TRIGLYCERIDES

Eruptive xanthoma is associated with elevation of chylomicrons and triglycerides.1 Hyperlipidemia that causes eruptive xanthoma may be familial (ie, due to a primary genetic defect) or secondary to another disease, or both.

Types of primary hypertriglyceridemia include elevated chylomicrons (Frederickson classification type I), elevated very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) (Frederickson type IV), and elevation of both chylomicrons and VLDL (Frederickson type V).2,3 Hypertriglyceridemia may also be secondary to obesity, diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, nephrotic syndrome, liver cirrhosis, excess ethanol ingestion, and medicines such as retinoids and estrogens.2,3

Lesions of eruptive xanthoma are yellowish papules 2 to 5 mm in diameter surrounded by an erythematous border. They are formed by clusters of foamy cells caused by phagocytosis of macrophages as a consequence of increased accumulations of intracellular lipids. The most common sites are the buttocks, extensor surfaces of the arms, and the back.4

Eruptive xanthoma occurs with markedly elevated triglyceride levels (ie, > 1,000 mg/dL),5 with an estimated prevalence of 18 cases per 100,000 people (< 0.02%).6 Diagnosis is usually established through the clinical history, physical examination, and prompt laboratory confirmation of hypertriglyceridemia. Skin biopsy is rarely if ever needed.

RECOGNIZE AND TREAT PROMPTLY TO AVOID FURTHER COMPLICATIONS

Severe hypertriglyceridemia poses an increased risk of acute pancreatitis. Early recognition and medical treatment in our patient prevented serious complications.

Treatment of eruptive xanthoma includes identifying the underlying cause of hypertriglyceridemia and commencing lifestyle modifications that include weight reduction, aerobic exercise, a strict low-fat diet with avoidance of simple carbohydrates and alcohol,7 and drug therapy.

The patient’s treatment plan

Although HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) have a modest triglyceride-lowering effect and are useful to modify cardiovascular risk, fibric acid derivatives (eg, gemfibrozil, fenofibrate) are the first-line therapy.8 Omega-3 fatty acids, statins, or niacin may be added if necessary.8

Our patient’s uncontrolled glycemia caused marked hypertriglyceridemia, perhaps from a decrease in lipoprotein lipase activity in adipose tissue and muscle. Lifestyle modifications, glucose-lowering agents (metformin, glimepiride), and fenofibrate were prescribed. She was also advised to seek medical attention if she developed upper-abdominal pain, which could be a symptom of pancreatitis.

A workup for secondary causes of hypertriglyceridemia was negative for hypothyroidism and nephrotic syndrome. She was currently taking no medications. She had no family history of dyslipidemia, and she denied alcohol consumption.

Based on the patient’s presentation, history, and the results of laboratory testing and skin biopsy, the diagnosis was eruptive xanthoma.

A RESULT OF ELEVATED TRIGLYCERIDES

Eruptive xanthoma is associated with elevation of chylomicrons and triglycerides.1 Hyperlipidemia that causes eruptive xanthoma may be familial (ie, due to a primary genetic defect) or secondary to another disease, or both.

Types of primary hypertriglyceridemia include elevated chylomicrons (Frederickson classification type I), elevated very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) (Frederickson type IV), and elevation of both chylomicrons and VLDL (Frederickson type V).2,3 Hypertriglyceridemia may also be secondary to obesity, diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, nephrotic syndrome, liver cirrhosis, excess ethanol ingestion, and medicines such as retinoids and estrogens.2,3

Lesions of eruptive xanthoma are yellowish papules 2 to 5 mm in diameter surrounded by an erythematous border. They are formed by clusters of foamy cells caused by phagocytosis of macrophages as a consequence of increased accumulations of intracellular lipids. The most common sites are the buttocks, extensor surfaces of the arms, and the back.4

Eruptive xanthoma occurs with markedly elevated triglyceride levels (ie, > 1,000 mg/dL),5 with an estimated prevalence of 18 cases per 100,000 people (< 0.02%).6 Diagnosis is usually established through the clinical history, physical examination, and prompt laboratory confirmation of hypertriglyceridemia. Skin biopsy is rarely if ever needed.

RECOGNIZE AND TREAT PROMPTLY TO AVOID FURTHER COMPLICATIONS

Severe hypertriglyceridemia poses an increased risk of acute pancreatitis. Early recognition and medical treatment in our patient prevented serious complications.

Treatment of eruptive xanthoma includes identifying the underlying cause of hypertriglyceridemia and commencing lifestyle modifications that include weight reduction, aerobic exercise, a strict low-fat diet with avoidance of simple carbohydrates and alcohol,7 and drug therapy.

The patient’s treatment plan

Although HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) have a modest triglyceride-lowering effect and are useful to modify cardiovascular risk, fibric acid derivatives (eg, gemfibrozil, fenofibrate) are the first-line therapy.8 Omega-3 fatty acids, statins, or niacin may be added if necessary.8

Our patient’s uncontrolled glycemia caused marked hypertriglyceridemia, perhaps from a decrease in lipoprotein lipase activity in adipose tissue and muscle. Lifestyle modifications, glucose-lowering agents (metformin, glimepiride), and fenofibrate were prescribed. She was also advised to seek medical attention if she developed upper-abdominal pain, which could be a symptom of pancreatitis.

- Flynn PD, Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C. Xanthomas and abnormalities of lipid metabolism and storage. In: Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 2010.

- Breckenridge WC, Alaupovic P, Cox DW, Little JA. Apolipoprotein and lipoprotein concentrations in familial apolipoprotein C-II deficiency. Atherosclerosis 1982; 44(2):223–235. pmid:7138621

- Santamarina-Fojo S. The familial chylomicronemia syndrome. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 1998; 27(3):551–567. pmid:9785052

- Melmed S, Polonsky KS, Larsen PR, Kronenberg H. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. 13th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2016.

- Zak A, Zeman M, Slaby A, Vecka M. Xanthomas: clinical and pathophysiological relations. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub 2014; 158(2):181–188. doi:10.5507/bp.2014.016

- Leaf DA. Chylomicronemia and the chylomicronemia syndrome: a practical approach to management. Am J Med 2008; 121(1):10–12. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.10.004

- Hegele RA, Ginsberg HN, Chapman MJ, et al; European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel. The polygenic nature of hypertriglyceridaemia: implications for definition, diagnosis, and management. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2014; 2(8):655–666. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70191-8

- Berglund L, Brunzell JD, Goldberg AC, et al; Endocrine Society. Evaluation and treatment of hypertriglyceridemia: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012; 97(9):2969–2989. doi:10.1210/jc.2011-3213

- Flynn PD, Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C. Xanthomas and abnormalities of lipid metabolism and storage. In: Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 2010.

- Breckenridge WC, Alaupovic P, Cox DW, Little JA. Apolipoprotein and lipoprotein concentrations in familial apolipoprotein C-II deficiency. Atherosclerosis 1982; 44(2):223–235. pmid:7138621

- Santamarina-Fojo S. The familial chylomicronemia syndrome. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 1998; 27(3):551–567. pmid:9785052

- Melmed S, Polonsky KS, Larsen PR, Kronenberg H. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. 13th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2016.

- Zak A, Zeman M, Slaby A, Vecka M. Xanthomas: clinical and pathophysiological relations. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub 2014; 158(2):181–188. doi:10.5507/bp.2014.016

- Leaf DA. Chylomicronemia and the chylomicronemia syndrome: a practical approach to management. Am J Med 2008; 121(1):10–12. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.10.004

- Hegele RA, Ginsberg HN, Chapman MJ, et al; European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel. The polygenic nature of hypertriglyceridaemia: implications for definition, diagnosis, and management. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2014; 2(8):655–666. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70191-8

- Berglund L, Brunzell JD, Goldberg AC, et al; Endocrine Society. Evaluation and treatment of hypertriglyceridemia: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012; 97(9):2969–2989. doi:10.1210/jc.2011-3213

Click for Credit: Fasting rules for surgery; Biomarkers for PSA vs OA; more

Here are 5 articles from the September issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. No birth rate gains from levothyroxine in pregnancy

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2ZoXzK8

Expires March 23, 2020

2. Simple screening for risk of falling in elderly can guide prevention

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2NKXxu3

Expires March 24, 2020

3. Time to revisit fasting rules for surgery patients

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2HHwHiD

Expires March 26, 2020

4. Four biomarkers could distinguish psoriatic arthritis from osteoarthritis

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/344WPNS

Expires March 28, 2020

5. More chest compression–only CPR leads to increased survival rates

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/30CahGF

Expires April 1, 2020

Here are 5 articles from the September issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. No birth rate gains from levothyroxine in pregnancy

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2ZoXzK8

Expires March 23, 2020

2. Simple screening for risk of falling in elderly can guide prevention

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2NKXxu3

Expires March 24, 2020

3. Time to revisit fasting rules for surgery patients

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2HHwHiD

Expires March 26, 2020

4. Four biomarkers could distinguish psoriatic arthritis from osteoarthritis

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/344WPNS

Expires March 28, 2020

5. More chest compression–only CPR leads to increased survival rates

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/30CahGF

Expires April 1, 2020

Here are 5 articles from the September issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. No birth rate gains from levothyroxine in pregnancy

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2ZoXzK8

Expires March 23, 2020

2. Simple screening for risk of falling in elderly can guide prevention

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2NKXxu3

Expires March 24, 2020

3. Time to revisit fasting rules for surgery patients

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2HHwHiD

Expires March 26, 2020

4. Four biomarkers could distinguish psoriatic arthritis from osteoarthritis

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/344WPNS

Expires March 28, 2020

5. More chest compression–only CPR leads to increased survival rates

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/30CahGF

Expires April 1, 2020

ACIP issues 2 new recs on HPV vaccination

References

1. Markowitz L. Overview and background (HPV). CDC Web site. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2019-02/HPV-2-Markowitz-508.pdf. Presented February 27, 2019. Accessed August 1, 2019.

2. Brisson M, Laprise J-F. Cost-effectiveness of extending HPV vaccination above age 26 years in the U.S. CDC Web site. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2019-02/HPV-3-Brisson-508.pdf. Presented February 2019. Accessed August 1, 2019.

3. Markowitz L. Recommendations for mid-adult HPV vaccination work group considerations. CDC Web site. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2019-02/HPV-7-Markowitz-508.pdf, Presented February 27, 2019. Accessed August 1, 2019.

4. Meites E, Szilagyi PG, Chesson HW, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination for adults: updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:698-702.

References

1. Markowitz L. Overview and background (HPV). CDC Web site. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2019-02/HPV-2-Markowitz-508.pdf. Presented February 27, 2019. Accessed August 1, 2019.

2. Brisson M, Laprise J-F. Cost-effectiveness of extending HPV vaccination above age 26 years in the U.S. CDC Web site. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2019-02/HPV-3-Brisson-508.pdf. Presented February 2019. Accessed August 1, 2019.

3. Markowitz L. Recommendations for mid-adult HPV vaccination work group considerations. CDC Web site. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2019-02/HPV-7-Markowitz-508.pdf, Presented February 27, 2019. Accessed August 1, 2019.

4. Meites E, Szilagyi PG, Chesson HW, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination for adults: updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:698-702.

References

1. Markowitz L. Overview and background (HPV). CDC Web site. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2019-02/HPV-2-Markowitz-508.pdf. Presented February 27, 2019. Accessed August 1, 2019.

2. Brisson M, Laprise J-F. Cost-effectiveness of extending HPV vaccination above age 26 years in the U.S. CDC Web site. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2019-02/HPV-3-Brisson-508.pdf. Presented February 2019. Accessed August 1, 2019.

3. Markowitz L. Recommendations for mid-adult HPV vaccination work group considerations. CDC Web site. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2019-02/HPV-7-Markowitz-508.pdf, Presented February 27, 2019. Accessed August 1, 2019.

4. Meites E, Szilagyi PG, Chesson HW, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination for adults: updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:698-702.

Zoledronate maintains bone loss after denosumab discontinuation

Women with postmenopausal osteoporosis who discontinued denosumab treatment after achieving osteopenia maintained bone mineral density at the spine and hip with a single infusion of zoledronate given 6 months after the last infusion of denosumab, according to results from a small, multicenter, randomized trial published in the Journal of Bone and Mineral Research.

The cessation of the monoclonal antibody denosumab is typically followed by a “rebound phenomenon” often attributed to an increase in bone turnover above pretreatment values caused by the up-regulation of osteoclastogenesis, according to Athanasios D. Anastasilakis, MD, of 424 General Military Hospital, Thessaloníki, Greece, and colleagues. Guidelines recommend that patients take a bisphosphonate to prevent this effect, but the optimal bisphosphonate regimen is unknown and evidence is inconsistent.

To address this question, the investigators randomized 57 postmenopausal women with osteoporosis who had received six monthly injections of denosumab (for an average of 2.2 years) and had achieved nonosteoporotic bone mineral density (BMD) T scores greater than –2.5 but no greater than –1 at the hip or the spine. A total of 27 received a single IV infusion of zoledronate 5 mg given 6 months after the last denosumab injection with a 3-week window, and 30 continued denosumab and received two additional monthly 60-mg injections. Following either the zoledronate infusion or the last denosumab injection, all women received no treatment and were followed until 2 years from randomization. All women were given vitamin D supplements and were seen in clinic appointments at baseline, 6, 12, 15, 18, and 24 months.

Areal BMD of the lumbar spine and femoral neck of the nondominant hip were measured at baseline, 12, and 24 months by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry, and least significant changes were 5% or less at the spine and 4% or less at the femoral neck, based on proposals from the International Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation USA.

At 24 months, lumbar spine BMD (LS‐BMD) returned to baseline in the zoledronate group, but decreased in the denosumab group by 4.82% from the 12‐month value (P less than .001).

The difference in LS-BMD changes between the two groups from month 12 to 24, the primary endpoint of the study, was statistically significant (–0.018 with zoledronate vs. –0.045 with denosumab; P = .025). Differences in changes of femoral neck BMD were also statistically significant (–0.004 with zoledronate vs. –0.038 with denosumab; P = .005), the researchers reported.

The differences in BMD changes between the two groups 24 and 12 months after discontinuation of denosumab (6 months after the last injection) for the zoledronate and denosumab group respectively were also statistically significant both at the lumbar spine (–0.002 with zoledronate vs. –0.045 with denosumab; P = .03) and at the femoral neck (–0.004 with zoledronate vs. –0.038 with denosumab; P = .007).

The authors observed no relationship between the number of denosumab injections and LS-BMD changes in either group of women; however, they noted that responses of individual patients to zoledronate were variable. For example, three women who took zoledronate experienced decreases of LS-BMD greater than the least significant change observed at 24 months, a finding which could not be explained by the timing of the infusion, baseline rate of bone turnover, or baseline BMD.

“It appears that intrinsic factors that still need to be defined may affect the response of a few individuals,” they wrote.

This was further illustrated by one patient in the zoledronate group who sustained clinical vertebral fractures associated with significant, unexplained decreases of BMD that could not be prevented with the zoledronate infusion.

“In clinical practice, it is, therefore, advisable to measure BMD at 12 months after the zoledronate infusion and decide whether additional treatment may be required,” the authors wrote.

Another significant finding reported by the authors was that neither baseline nor 12‐month bone turnover marker (BTM) values were associated with BMD changes in either group of women during the entire study period.

“Particularly important for clinical practice was the lack of a relationship in zoledronate-treated women; even when women were divided according to baseline median BTM values (below or above) there were no significant difference in BMD changes at 12 or 24 months,” they wrote.

“In a substantial number of women in the denosumab group BTMs were still above the upper limit of normal of the postmenopausal age 18 months after the last Dmab [denosumab] injection but also in 7.4% of patients treated with zoledronate at 2 years,” they added.

“Whether in the latter patients BTMs were also increased before the start of Dmab treatment, as it is known to occur in some patients with osteoporosis, or are due to a prolonged effect of Dmab withdrawal on bone metabolism could not be prevented by zoledronate, is not known because pretreatment data were not available,” the study authors noted.

For adverse events, in addition to the one patient in the zoledronate group with clinical vertebral fractures, three patients in the denosumab group sustained vertebral fractures.

“Prevalent vertebral fractures have been previously reported as the most important risk factor for clinical vertebral fractures following cessation of Dmab therapy [which] strongly suggest that spine x-rays should be performed in all patients in whom discontinuation of Dmab treatment is considered,” the authors wrote.

“In most women with postmenopausal osteoporosis treated with [denosumab] in whom discontinuation of treatment is considered when a nonosteoporotic BMD is achieved, a single intravenous infusion of zoledronate 5 mg given 6 months after the last Dmab injection prevents bone loss for at least 2 years independently of the rate of bone turnover. Follow-up is recommended, as in a few patients treatment might not have the expected effect at 2 years for currently unknown reasons,” they concluded.

The study was funded by institutional funds and the Hellenic Endocrine Society. Several authors reported receiving consulting or lecture fees from Amgen, which markets denosumab, as well as other pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Anastasilakis A et al. J Bone Miner Res. 2019 Aug 21. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3853.

Women with postmenopausal osteoporosis who discontinued denosumab treatment after achieving osteopenia maintained bone mineral density at the spine and hip with a single infusion of zoledronate given 6 months after the last infusion of denosumab, according to results from a small, multicenter, randomized trial published in the Journal of Bone and Mineral Research.

The cessation of the monoclonal antibody denosumab is typically followed by a “rebound phenomenon” often attributed to an increase in bone turnover above pretreatment values caused by the up-regulation of osteoclastogenesis, according to Athanasios D. Anastasilakis, MD, of 424 General Military Hospital, Thessaloníki, Greece, and colleagues. Guidelines recommend that patients take a bisphosphonate to prevent this effect, but the optimal bisphosphonate regimen is unknown and evidence is inconsistent.

To address this question, the investigators randomized 57 postmenopausal women with osteoporosis who had received six monthly injections of denosumab (for an average of 2.2 years) and had achieved nonosteoporotic bone mineral density (BMD) T scores greater than –2.5 but no greater than –1 at the hip or the spine. A total of 27 received a single IV infusion of zoledronate 5 mg given 6 months after the last denosumab injection with a 3-week window, and 30 continued denosumab and received two additional monthly 60-mg injections. Following either the zoledronate infusion or the last denosumab injection, all women received no treatment and were followed until 2 years from randomization. All women were given vitamin D supplements and were seen in clinic appointments at baseline, 6, 12, 15, 18, and 24 months.

Areal BMD of the lumbar spine and femoral neck of the nondominant hip were measured at baseline, 12, and 24 months by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry, and least significant changes were 5% or less at the spine and 4% or less at the femoral neck, based on proposals from the International Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation USA.

At 24 months, lumbar spine BMD (LS‐BMD) returned to baseline in the zoledronate group, but decreased in the denosumab group by 4.82% from the 12‐month value (P less than .001).

The difference in LS-BMD changes between the two groups from month 12 to 24, the primary endpoint of the study, was statistically significant (–0.018 with zoledronate vs. –0.045 with denosumab; P = .025). Differences in changes of femoral neck BMD were also statistically significant (–0.004 with zoledronate vs. –0.038 with denosumab; P = .005), the researchers reported.

The differences in BMD changes between the two groups 24 and 12 months after discontinuation of denosumab (6 months after the last injection) for the zoledronate and denosumab group respectively were also statistically significant both at the lumbar spine (–0.002 with zoledronate vs. –0.045 with denosumab; P = .03) and at the femoral neck (–0.004 with zoledronate vs. –0.038 with denosumab; P = .007).

The authors observed no relationship between the number of denosumab injections and LS-BMD changes in either group of women; however, they noted that responses of individual patients to zoledronate were variable. For example, three women who took zoledronate experienced decreases of LS-BMD greater than the least significant change observed at 24 months, a finding which could not be explained by the timing of the infusion, baseline rate of bone turnover, or baseline BMD.

“It appears that intrinsic factors that still need to be defined may affect the response of a few individuals,” they wrote.

This was further illustrated by one patient in the zoledronate group who sustained clinical vertebral fractures associated with significant, unexplained decreases of BMD that could not be prevented with the zoledronate infusion.

“In clinical practice, it is, therefore, advisable to measure BMD at 12 months after the zoledronate infusion and decide whether additional treatment may be required,” the authors wrote.

Another significant finding reported by the authors was that neither baseline nor 12‐month bone turnover marker (BTM) values were associated with BMD changes in either group of women during the entire study period.

“Particularly important for clinical practice was the lack of a relationship in zoledronate-treated women; even when women were divided according to baseline median BTM values (below or above) there were no significant difference in BMD changes at 12 or 24 months,” they wrote.

“In a substantial number of women in the denosumab group BTMs were still above the upper limit of normal of the postmenopausal age 18 months after the last Dmab [denosumab] injection but also in 7.4% of patients treated with zoledronate at 2 years,” they added.

“Whether in the latter patients BTMs were also increased before the start of Dmab treatment, as it is known to occur in some patients with osteoporosis, or are due to a prolonged effect of Dmab withdrawal on bone metabolism could not be prevented by zoledronate, is not known because pretreatment data were not available,” the study authors noted.

For adverse events, in addition to the one patient in the zoledronate group with clinical vertebral fractures, three patients in the denosumab group sustained vertebral fractures.

“Prevalent vertebral fractures have been previously reported as the most important risk factor for clinical vertebral fractures following cessation of Dmab therapy [which] strongly suggest that spine x-rays should be performed in all patients in whom discontinuation of Dmab treatment is considered,” the authors wrote.

“In most women with postmenopausal osteoporosis treated with [denosumab] in whom discontinuation of treatment is considered when a nonosteoporotic BMD is achieved, a single intravenous infusion of zoledronate 5 mg given 6 months after the last Dmab injection prevents bone loss for at least 2 years independently of the rate of bone turnover. Follow-up is recommended, as in a few patients treatment might not have the expected effect at 2 years for currently unknown reasons,” they concluded.

The study was funded by institutional funds and the Hellenic Endocrine Society. Several authors reported receiving consulting or lecture fees from Amgen, which markets denosumab, as well as other pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Anastasilakis A et al. J Bone Miner Res. 2019 Aug 21. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3853.

Women with postmenopausal osteoporosis who discontinued denosumab treatment after achieving osteopenia maintained bone mineral density at the spine and hip with a single infusion of zoledronate given 6 months after the last infusion of denosumab, according to results from a small, multicenter, randomized trial published in the Journal of Bone and Mineral Research.

The cessation of the monoclonal antibody denosumab is typically followed by a “rebound phenomenon” often attributed to an increase in bone turnover above pretreatment values caused by the up-regulation of osteoclastogenesis, according to Athanasios D. Anastasilakis, MD, of 424 General Military Hospital, Thessaloníki, Greece, and colleagues. Guidelines recommend that patients take a bisphosphonate to prevent this effect, but the optimal bisphosphonate regimen is unknown and evidence is inconsistent.

To address this question, the investigators randomized 57 postmenopausal women with osteoporosis who had received six monthly injections of denosumab (for an average of 2.2 years) and had achieved nonosteoporotic bone mineral density (BMD) T scores greater than –2.5 but no greater than –1 at the hip or the spine. A total of 27 received a single IV infusion of zoledronate 5 mg given 6 months after the last denosumab injection with a 3-week window, and 30 continued denosumab and received two additional monthly 60-mg injections. Following either the zoledronate infusion or the last denosumab injection, all women received no treatment and were followed until 2 years from randomization. All women were given vitamin D supplements and were seen in clinic appointments at baseline, 6, 12, 15, 18, and 24 months.

Areal BMD of the lumbar spine and femoral neck of the nondominant hip were measured at baseline, 12, and 24 months by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry, and least significant changes were 5% or less at the spine and 4% or less at the femoral neck, based on proposals from the International Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation USA.

At 24 months, lumbar spine BMD (LS‐BMD) returned to baseline in the zoledronate group, but decreased in the denosumab group by 4.82% from the 12‐month value (P less than .001).

The difference in LS-BMD changes between the two groups from month 12 to 24, the primary endpoint of the study, was statistically significant (–0.018 with zoledronate vs. –0.045 with denosumab; P = .025). Differences in changes of femoral neck BMD were also statistically significant (–0.004 with zoledronate vs. –0.038 with denosumab; P = .005), the researchers reported.

The differences in BMD changes between the two groups 24 and 12 months after discontinuation of denosumab (6 months after the last injection) for the zoledronate and denosumab group respectively were also statistically significant both at the lumbar spine (–0.002 with zoledronate vs. –0.045 with denosumab; P = .03) and at the femoral neck (–0.004 with zoledronate vs. –0.038 with denosumab; P = .007).

The authors observed no relationship between the number of denosumab injections and LS-BMD changes in either group of women; however, they noted that responses of individual patients to zoledronate were variable. For example, three women who took zoledronate experienced decreases of LS-BMD greater than the least significant change observed at 24 months, a finding which could not be explained by the timing of the infusion, baseline rate of bone turnover, or baseline BMD.

“It appears that intrinsic factors that still need to be defined may affect the response of a few individuals,” they wrote.

This was further illustrated by one patient in the zoledronate group who sustained clinical vertebral fractures associated with significant, unexplained decreases of BMD that could not be prevented with the zoledronate infusion.

“In clinical practice, it is, therefore, advisable to measure BMD at 12 months after the zoledronate infusion and decide whether additional treatment may be required,” the authors wrote.

Another significant finding reported by the authors was that neither baseline nor 12‐month bone turnover marker (BTM) values were associated with BMD changes in either group of women during the entire study period.

“Particularly important for clinical practice was the lack of a relationship in zoledronate-treated women; even when women were divided according to baseline median BTM values (below or above) there were no significant difference in BMD changes at 12 or 24 months,” they wrote.

“In a substantial number of women in the denosumab group BTMs were still above the upper limit of normal of the postmenopausal age 18 months after the last Dmab [denosumab] injection but also in 7.4% of patients treated with zoledronate at 2 years,” they added.

“Whether in the latter patients BTMs were also increased before the start of Dmab treatment, as it is known to occur in some patients with osteoporosis, or are due to a prolonged effect of Dmab withdrawal on bone metabolism could not be prevented by zoledronate, is not known because pretreatment data were not available,” the study authors noted.

For adverse events, in addition to the one patient in the zoledronate group with clinical vertebral fractures, three patients in the denosumab group sustained vertebral fractures.

“Prevalent vertebral fractures have been previously reported as the most important risk factor for clinical vertebral fractures following cessation of Dmab therapy [which] strongly suggest that spine x-rays should be performed in all patients in whom discontinuation of Dmab treatment is considered,” the authors wrote.

“In most women with postmenopausal osteoporosis treated with [denosumab] in whom discontinuation of treatment is considered when a nonosteoporotic BMD is achieved, a single intravenous infusion of zoledronate 5 mg given 6 months after the last Dmab injection prevents bone loss for at least 2 years independently of the rate of bone turnover. Follow-up is recommended, as in a few patients treatment might not have the expected effect at 2 years for currently unknown reasons,” they concluded.

The study was funded by institutional funds and the Hellenic Endocrine Society. Several authors reported receiving consulting or lecture fees from Amgen, which markets denosumab, as well as other pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Anastasilakis A et al. J Bone Miner Res. 2019 Aug 21. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3853.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF BONE AND MINERAL RESEARCH

ACOG advises bleeding disorder screening for teens with heavy menstruation

Adolescent girls with heavy menstrual bleeding should be assessed for bleeding disorders, according to a Committee Opinion issued by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

A bleeding disorder is secondary only to anovulation as a cause of heavy menstrual bleeding in adolescents.

Bleeding disorders affect 1%-2% of the general population, but are “found in approximately 20% of adolescent girls who present for evaluation of heavy menstrual bleeding and in 33% of adolescent girls hospitalized for heavy menstrual bleeding,” wrote Oluyemisi Adeyemi-Fowode, MD, and Judith Simms-Cendan, MD, and members of the ACOG Committee on Adolescent Health Care in the opinion, published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

The committee advised that physical examination of teens with acute heavy menstrual bleeding should include assessment of hemodynamic stability with orthostatic blood pressure and pulse measurements. A speculum exam is not usually needed in teen girls with heavy menstrual bleeding. Evaluation should include screening for anemia attributable to blood loss with serum ferritin, endocrine disorders, and bleeding disorders. In suspected cases of bleeding disorders, laboratory evaluation and medical management should be done in consultation with a hematologist.

Those who are actively bleeding or hemodynamically unstable should be hospitalized for medical management, they said.

Ultrasonography is not necessary for an initial work-up of teens with heavy menstrual bleeding, but could be useful in patients who fail to respond to medical management.

Adolescent girls without contraindications to estrogen can be treated with hormone therapy in various forms including intravenous conjugated estrogen every 4-6 hours or oral 30-50 mg ethinyl estradiol every 6-8 hours until cessation of bleeding. Antifibrinolytics also can be used to stop bleeding.

Maintenance therapy after correction of acute heavy bleeding can include a combination of treatments such as hormonal contraceptives, oral and injectable progestins, and levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine devices, the committee wrote. They also recommended oral iron replacement therapy for all women of reproductive age with anemia caused by menstrual bleeding.

If a patient fails to respond to medical therapy, nonmedical options or surgery may be considered, according to the committee. In addition, all teen girls with bleeding disorders should be advised about safe medication use, including the use of aspirin or NSAIDs only on the recommendation of a hematologist.

Patients and their families need education on menstrual issues including possible options for surgery in the future if heavy menstruation does not resolve. If a patient has a known bleeding disorder and is considering surgery, preoperative evaluation should include a consultation with a hematologist and an anesthesiologist, the committee noted.

Melissa Kottke, MD, MPH, said in an interview, “Every ob.gyn. will see a young patient with ‘heavy menstrual bleeding.’ And it becomes part of the art and challenge to work with the patient and family to collectively explore if this is, indeed, ‘heavy’ and of concern … or is it is a ‘normal’ menstrual period and simply reflects a newer life experience that would benefit from some education? And the stakes are high. Young people who have heavy menstrual cycles are much more likely to have an underlying bleeding disorder than the general population (20% vs. 1%-2%), and 75%-80% of adolescents with bleeding disorders report heavy menses as the most common clinical manifestation of their disorder.

“Fortunately, Committee Opinion 785, ‘Screening and Management of Bleeding Disorders in Adolescents with Heavy Menstrual Bleeding’ from the ACOG Committee on Adolescent Health Care is detailed and pragmatic. It outlines how to translate everyday conversations with young people about their menses into a quantifiable estimate of bleeding, including a very teen-friendly Pictorial Blood Loss Assessment Chart. It also gives ob.gyns. ever-important guidance about what to do next for evaluation and diagnosis. This committee opinion nicely outlines how to help manage heavy bleeding in an adolescent with a detailed algorithm. And very importantly, it gives clear management guidance and encourages ob.gyns. to avoid frequently unnecessary (speculum exams and ultrasounds) and excessive (early transfusion or surgical interventions) approaches to management for the young patient. I think it will be a great resource for any provider who is taking care of heavy menstrual bleeding for a young person,” said Dr. Kottke, who is director of the Jane Fonda Center for Adolescent Reproductive Health and associate professor of gynecology and obstetrics, both at Emory University, Atlanta. Dr. Kottke is not a member of the ACOG Committee on Adolescent Health and was asked to comment on the opinion.*

The complete opinion, ACOG Committee Opinion number 785, includes recommended laboratory tests, an eight-question screening tool, and a management algorithm.

The committee members had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Kottke said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Adeyemi-Fowode O and Simms-Cendan J. Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Sep. 134:e71-83.

*This article was updated on 9/9/2019.

Adolescent girls with heavy menstrual bleeding should be assessed for bleeding disorders, according to a Committee Opinion issued by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

A bleeding disorder is secondary only to anovulation as a cause of heavy menstrual bleeding in adolescents.

Bleeding disorders affect 1%-2% of the general population, but are “found in approximately 20% of adolescent girls who present for evaluation of heavy menstrual bleeding and in 33% of adolescent girls hospitalized for heavy menstrual bleeding,” wrote Oluyemisi Adeyemi-Fowode, MD, and Judith Simms-Cendan, MD, and members of the ACOG Committee on Adolescent Health Care in the opinion, published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

The committee advised that physical examination of teens with acute heavy menstrual bleeding should include assessment of hemodynamic stability with orthostatic blood pressure and pulse measurements. A speculum exam is not usually needed in teen girls with heavy menstrual bleeding. Evaluation should include screening for anemia attributable to blood loss with serum ferritin, endocrine disorders, and bleeding disorders. In suspected cases of bleeding disorders, laboratory evaluation and medical management should be done in consultation with a hematologist.

Those who are actively bleeding or hemodynamically unstable should be hospitalized for medical management, they said.

Ultrasonography is not necessary for an initial work-up of teens with heavy menstrual bleeding, but could be useful in patients who fail to respond to medical management.

Adolescent girls without contraindications to estrogen can be treated with hormone therapy in various forms including intravenous conjugated estrogen every 4-6 hours or oral 30-50 mg ethinyl estradiol every 6-8 hours until cessation of bleeding. Antifibrinolytics also can be used to stop bleeding.

Maintenance therapy after correction of acute heavy bleeding can include a combination of treatments such as hormonal contraceptives, oral and injectable progestins, and levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine devices, the committee wrote. They also recommended oral iron replacement therapy for all women of reproductive age with anemia caused by menstrual bleeding.

If a patient fails to respond to medical therapy, nonmedical options or surgery may be considered, according to the committee. In addition, all teen girls with bleeding disorders should be advised about safe medication use, including the use of aspirin or NSAIDs only on the recommendation of a hematologist.

Patients and their families need education on menstrual issues including possible options for surgery in the future if heavy menstruation does not resolve. If a patient has a known bleeding disorder and is considering surgery, preoperative evaluation should include a consultation with a hematologist and an anesthesiologist, the committee noted.

Melissa Kottke, MD, MPH, said in an interview, “Every ob.gyn. will see a young patient with ‘heavy menstrual bleeding.’ And it becomes part of the art and challenge to work with the patient and family to collectively explore if this is, indeed, ‘heavy’ and of concern … or is it is a ‘normal’ menstrual period and simply reflects a newer life experience that would benefit from some education? And the stakes are high. Young people who have heavy menstrual cycles are much more likely to have an underlying bleeding disorder than the general population (20% vs. 1%-2%), and 75%-80% of adolescents with bleeding disorders report heavy menses as the most common clinical manifestation of their disorder.

“Fortunately, Committee Opinion 785, ‘Screening and Management of Bleeding Disorders in Adolescents with Heavy Menstrual Bleeding’ from the ACOG Committee on Adolescent Health Care is detailed and pragmatic. It outlines how to translate everyday conversations with young people about their menses into a quantifiable estimate of bleeding, including a very teen-friendly Pictorial Blood Loss Assessment Chart. It also gives ob.gyns. ever-important guidance about what to do next for evaluation and diagnosis. This committee opinion nicely outlines how to help manage heavy bleeding in an adolescent with a detailed algorithm. And very importantly, it gives clear management guidance and encourages ob.gyns. to avoid frequently unnecessary (speculum exams and ultrasounds) and excessive (early transfusion or surgical interventions) approaches to management for the young patient. I think it will be a great resource for any provider who is taking care of heavy menstrual bleeding for a young person,” said Dr. Kottke, who is director of the Jane Fonda Center for Adolescent Reproductive Health and associate professor of gynecology and obstetrics, both at Emory University, Atlanta. Dr. Kottke is not a member of the ACOG Committee on Adolescent Health and was asked to comment on the opinion.*

The complete opinion, ACOG Committee Opinion number 785, includes recommended laboratory tests, an eight-question screening tool, and a management algorithm.

The committee members had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Kottke said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Adeyemi-Fowode O and Simms-Cendan J. Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Sep. 134:e71-83.

*This article was updated on 9/9/2019.

Adolescent girls with heavy menstrual bleeding should be assessed for bleeding disorders, according to a Committee Opinion issued by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

A bleeding disorder is secondary only to anovulation as a cause of heavy menstrual bleeding in adolescents.

Bleeding disorders affect 1%-2% of the general population, but are “found in approximately 20% of adolescent girls who present for evaluation of heavy menstrual bleeding and in 33% of adolescent girls hospitalized for heavy menstrual bleeding,” wrote Oluyemisi Adeyemi-Fowode, MD, and Judith Simms-Cendan, MD, and members of the ACOG Committee on Adolescent Health Care in the opinion, published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

The committee advised that physical examination of teens with acute heavy menstrual bleeding should include assessment of hemodynamic stability with orthostatic blood pressure and pulse measurements. A speculum exam is not usually needed in teen girls with heavy menstrual bleeding. Evaluation should include screening for anemia attributable to blood loss with serum ferritin, endocrine disorders, and bleeding disorders. In suspected cases of bleeding disorders, laboratory evaluation and medical management should be done in consultation with a hematologist.

Those who are actively bleeding or hemodynamically unstable should be hospitalized for medical management, they said.

Ultrasonography is not necessary for an initial work-up of teens with heavy menstrual bleeding, but could be useful in patients who fail to respond to medical management.

Adolescent girls without contraindications to estrogen can be treated with hormone therapy in various forms including intravenous conjugated estrogen every 4-6 hours or oral 30-50 mg ethinyl estradiol every 6-8 hours until cessation of bleeding. Antifibrinolytics also can be used to stop bleeding.

Maintenance therapy after correction of acute heavy bleeding can include a combination of treatments such as hormonal contraceptives, oral and injectable progestins, and levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine devices, the committee wrote. They also recommended oral iron replacement therapy for all women of reproductive age with anemia caused by menstrual bleeding.

If a patient fails to respond to medical therapy, nonmedical options or surgery may be considered, according to the committee. In addition, all teen girls with bleeding disorders should be advised about safe medication use, including the use of aspirin or NSAIDs only on the recommendation of a hematologist.

Patients and their families need education on menstrual issues including possible options for surgery in the future if heavy menstruation does not resolve. If a patient has a known bleeding disorder and is considering surgery, preoperative evaluation should include a consultation with a hematologist and an anesthesiologist, the committee noted.

Melissa Kottke, MD, MPH, said in an interview, “Every ob.gyn. will see a young patient with ‘heavy menstrual bleeding.’ And it becomes part of the art and challenge to work with the patient and family to collectively explore if this is, indeed, ‘heavy’ and of concern … or is it is a ‘normal’ menstrual period and simply reflects a newer life experience that would benefit from some education? And the stakes are high. Young people who have heavy menstrual cycles are much more likely to have an underlying bleeding disorder than the general population (20% vs. 1%-2%), and 75%-80% of adolescents with bleeding disorders report heavy menses as the most common clinical manifestation of their disorder.

“Fortunately, Committee Opinion 785, ‘Screening and Management of Bleeding Disorders in Adolescents with Heavy Menstrual Bleeding’ from the ACOG Committee on Adolescent Health Care is detailed and pragmatic. It outlines how to translate everyday conversations with young people about their menses into a quantifiable estimate of bleeding, including a very teen-friendly Pictorial Blood Loss Assessment Chart. It also gives ob.gyns. ever-important guidance about what to do next for evaluation and diagnosis. This committee opinion nicely outlines how to help manage heavy bleeding in an adolescent with a detailed algorithm. And very importantly, it gives clear management guidance and encourages ob.gyns. to avoid frequently unnecessary (speculum exams and ultrasounds) and excessive (early transfusion or surgical interventions) approaches to management for the young patient. I think it will be a great resource for any provider who is taking care of heavy menstrual bleeding for a young person,” said Dr. Kottke, who is director of the Jane Fonda Center for Adolescent Reproductive Health and associate professor of gynecology and obstetrics, both at Emory University, Atlanta. Dr. Kottke is not a member of the ACOG Committee on Adolescent Health and was asked to comment on the opinion.*

The complete opinion, ACOG Committee Opinion number 785, includes recommended laboratory tests, an eight-question screening tool, and a management algorithm.

The committee members had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Kottke said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Adeyemi-Fowode O and Simms-Cendan J. Obstet Gynecol. 2019 Sep. 134:e71-83.

*This article was updated on 9/9/2019.

FROM OBSTETRICS AND GYNECOLOGY

High-dose vitamin D for bone health may do more harm than good

In fact, rather than a hypothesized increase in volumetric bone mineral density (BMD) with doses well above the recommended dietary allowance, a negative dose-response relationship was observed, Lauren A. Burt, PhD, of the McCaig Institute for Bone and Joint Health at the University of Calgary (Alta.) and colleagues found.

The total volumetric radial BMD was significantly lower in 101 and 97 study participants randomized to receive daily vitamin D3 doses of 10,000 IU or 4,000 IU for 3 years, respectively (–7.5 and –3.9 mg of calcium hydroxyapatite [HA] per cm3), compared with 105 participants randomized to a reference group that received 400 IU (mean percent changes, –3.5%, –2.4%, and –1.2%, respectively). Total volumetric tibial BMD was also significantly lower in the 10,000 IU arm, compared with the reference arm (–4.1 mg HA per cm3; mean percent change –1.7% vs. –0.4%), the investigators reported Aug. 27 in JAMA.

There also were no significant differences seen between the three groups for the coprimary endpoint of bone strength at either the radius or tibia.

Participants in the double-blind trial were community-dwelling healthy men and women aged 55-70 years (mean age, 62.2 years) without osteoporosis and with baseline levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) of 30-125 nmol/L. They were enrolled from a single center between August 2013 and December 2017 and treated with daily oral vitamin D3 drops at the assigned dosage for 3 years and with calcium supplementation if dietary calcium intake was less than 1,200 mg daily.

Mean supplementation adherence was 99% among the 303 participants who completed the trial (out of 311 enrolled), and adherence was similar across the groups.

Baseline 25(OH)D levels in the 400 IU group were 76.3 nmol/L at baseline, 76.7 nmol/L at 3 months, and 77.4 nmol/L at 3 years. The corresponding measures for the 4,000 IU group were 81.3, 115.3, and 132.2 nmol/L, and for the 10,000 IU group, they were 78.4, 188.0, and 144.4, the investigators said, noting that significant group-by-time interactions were noted for volumetric BMD.

Bone strength decreased over time, but group-by-time interactions for that measure were not statistically significant, they said.

A total of 44 serious adverse events occurred in 38 participants (12.2%), and one death from presumed myocardial infarction occurred in the 400 IU group. Of eight prespecified adverse events, only hypercalcemia and hypercalciuria had significant dose-response effects; all episodes of hypercalcemia were mild and had resolved at follow-up, and the two hypercalcemia events, which occurred in one participant in the 10,000 IU group, were also transient. No significant difference in fall rates was seen in the three groups, they noted.

Vitamin D is considered beneficial for preventing and treating osteoporosis, and data support supplementation in individuals with 25(OH)D levels less than 30 nmol/L, but recent meta-analyses did not find a major treatment benefit for osteoporosis or for preventing falls and fractures, the investigators said.

Further, while most supplementation recommendations call for 400-2,000 IU daily, with a tolerable upper intake level of 4,000-10,000 IU, 3% of U.S. adults in 2013-2014 reported intake of at least 4,000 IU per day, but few studies have assessed the effects of doses at or above the upper intake level for 12 months or longer, they noted, adding that this study was “motivated by the prevalence of high-dose vitamin D supplementation among healthy adults.”

“It was hypothesized that a higher dose of vitamin D has a positive effect on high-resolution peripheral quantitative CT measures of volumetric density and strength, perhaps via suppression of parathyroid hormone (PTH)–mediated bone turnover,” they wrote.

However, based on the significantly lower radial BMD seen with both 4,000 and 10,000 IU, compared with 400 IU; the lower tibial BMD with 10,000 IU, compared with 400 IU; and the lack of a difference in bone strength at the radius and tibia, the findings do not support a benefit of high-dose vitamin D supplementation for bone health, they said, noting that additional study is needed to determine whether such doses are harmful.

“Because these results are in the opposite direction of the research hypothesis, this evidence of high-dose vitamin D having a negative effect on bone should be regarded as hypothesis generating, requiring confirmation with further research,” they concluded.

SOURCE: Burt L et al. JAMA. 2019 Aug 27;322(8):736-45.

In fact, rather than a hypothesized increase in volumetric bone mineral density (BMD) with doses well above the recommended dietary allowance, a negative dose-response relationship was observed, Lauren A. Burt, PhD, of the McCaig Institute for Bone and Joint Health at the University of Calgary (Alta.) and colleagues found.

The total volumetric radial BMD was significantly lower in 101 and 97 study participants randomized to receive daily vitamin D3 doses of 10,000 IU or 4,000 IU for 3 years, respectively (–7.5 and –3.9 mg of calcium hydroxyapatite [HA] per cm3), compared with 105 participants randomized to a reference group that received 400 IU (mean percent changes, –3.5%, –2.4%, and –1.2%, respectively). Total volumetric tibial BMD was also significantly lower in the 10,000 IU arm, compared with the reference arm (–4.1 mg HA per cm3; mean percent change –1.7% vs. –0.4%), the investigators reported Aug. 27 in JAMA.

There also were no significant differences seen between the three groups for the coprimary endpoint of bone strength at either the radius or tibia.

Participants in the double-blind trial were community-dwelling healthy men and women aged 55-70 years (mean age, 62.2 years) without osteoporosis and with baseline levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) of 30-125 nmol/L. They were enrolled from a single center between August 2013 and December 2017 and treated with daily oral vitamin D3 drops at the assigned dosage for 3 years and with calcium supplementation if dietary calcium intake was less than 1,200 mg daily.

Mean supplementation adherence was 99% among the 303 participants who completed the trial (out of 311 enrolled), and adherence was similar across the groups.

Baseline 25(OH)D levels in the 400 IU group were 76.3 nmol/L at baseline, 76.7 nmol/L at 3 months, and 77.4 nmol/L at 3 years. The corresponding measures for the 4,000 IU group were 81.3, 115.3, and 132.2 nmol/L, and for the 10,000 IU group, they were 78.4, 188.0, and 144.4, the investigators said, noting that significant group-by-time interactions were noted for volumetric BMD.

Bone strength decreased over time, but group-by-time interactions for that measure were not statistically significant, they said.

A total of 44 serious adverse events occurred in 38 participants (12.2%), and one death from presumed myocardial infarction occurred in the 400 IU group. Of eight prespecified adverse events, only hypercalcemia and hypercalciuria had significant dose-response effects; all episodes of hypercalcemia were mild and had resolved at follow-up, and the two hypercalcemia events, which occurred in one participant in the 10,000 IU group, were also transient. No significant difference in fall rates was seen in the three groups, they noted.

Vitamin D is considered beneficial for preventing and treating osteoporosis, and data support supplementation in individuals with 25(OH)D levels less than 30 nmol/L, but recent meta-analyses did not find a major treatment benefit for osteoporosis or for preventing falls and fractures, the investigators said.

Further, while most supplementation recommendations call for 400-2,000 IU daily, with a tolerable upper intake level of 4,000-10,000 IU, 3% of U.S. adults in 2013-2014 reported intake of at least 4,000 IU per day, but few studies have assessed the effects of doses at or above the upper intake level for 12 months or longer, they noted, adding that this study was “motivated by the prevalence of high-dose vitamin D supplementation among healthy adults.”

“It was hypothesized that a higher dose of vitamin D has a positive effect on high-resolution peripheral quantitative CT measures of volumetric density and strength, perhaps via suppression of parathyroid hormone (PTH)–mediated bone turnover,” they wrote.

However, based on the significantly lower radial BMD seen with both 4,000 and 10,000 IU, compared with 400 IU; the lower tibial BMD with 10,000 IU, compared with 400 IU; and the lack of a difference in bone strength at the radius and tibia, the findings do not support a benefit of high-dose vitamin D supplementation for bone health, they said, noting that additional study is needed to determine whether such doses are harmful.

“Because these results are in the opposite direction of the research hypothesis, this evidence of high-dose vitamin D having a negative effect on bone should be regarded as hypothesis generating, requiring confirmation with further research,” they concluded.

SOURCE: Burt L et al. JAMA. 2019 Aug 27;322(8):736-45.

In fact, rather than a hypothesized increase in volumetric bone mineral density (BMD) with doses well above the recommended dietary allowance, a negative dose-response relationship was observed, Lauren A. Burt, PhD, of the McCaig Institute for Bone and Joint Health at the University of Calgary (Alta.) and colleagues found.

The total volumetric radial BMD was significantly lower in 101 and 97 study participants randomized to receive daily vitamin D3 doses of 10,000 IU or 4,000 IU for 3 years, respectively (–7.5 and –3.9 mg of calcium hydroxyapatite [HA] per cm3), compared with 105 participants randomized to a reference group that received 400 IU (mean percent changes, –3.5%, –2.4%, and –1.2%, respectively). Total volumetric tibial BMD was also significantly lower in the 10,000 IU arm, compared with the reference arm (–4.1 mg HA per cm3; mean percent change –1.7% vs. –0.4%), the investigators reported Aug. 27 in JAMA.

There also were no significant differences seen between the three groups for the coprimary endpoint of bone strength at either the radius or tibia.

Participants in the double-blind trial were community-dwelling healthy men and women aged 55-70 years (mean age, 62.2 years) without osteoporosis and with baseline levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) of 30-125 nmol/L. They were enrolled from a single center between August 2013 and December 2017 and treated with daily oral vitamin D3 drops at the assigned dosage for 3 years and with calcium supplementation if dietary calcium intake was less than 1,200 mg daily.

Mean supplementation adherence was 99% among the 303 participants who completed the trial (out of 311 enrolled), and adherence was similar across the groups.

Baseline 25(OH)D levels in the 400 IU group were 76.3 nmol/L at baseline, 76.7 nmol/L at 3 months, and 77.4 nmol/L at 3 years. The corresponding measures for the 4,000 IU group were 81.3, 115.3, and 132.2 nmol/L, and for the 10,000 IU group, they were 78.4, 188.0, and 144.4, the investigators said, noting that significant group-by-time interactions were noted for volumetric BMD.

Bone strength decreased over time, but group-by-time interactions for that measure were not statistically significant, they said.

A total of 44 serious adverse events occurred in 38 participants (12.2%), and one death from presumed myocardial infarction occurred in the 400 IU group. Of eight prespecified adverse events, only hypercalcemia and hypercalciuria had significant dose-response effects; all episodes of hypercalcemia were mild and had resolved at follow-up, and the two hypercalcemia events, which occurred in one participant in the 10,000 IU group, were also transient. No significant difference in fall rates was seen in the three groups, they noted.

Vitamin D is considered beneficial for preventing and treating osteoporosis, and data support supplementation in individuals with 25(OH)D levels less than 30 nmol/L, but recent meta-analyses did not find a major treatment benefit for osteoporosis or for preventing falls and fractures, the investigators said.

Further, while most supplementation recommendations call for 400-2,000 IU daily, with a tolerable upper intake level of 4,000-10,000 IU, 3% of U.S. adults in 2013-2014 reported intake of at least 4,000 IU per day, but few studies have assessed the effects of doses at or above the upper intake level for 12 months or longer, they noted, adding that this study was “motivated by the prevalence of high-dose vitamin D supplementation among healthy adults.”

“It was hypothesized that a higher dose of vitamin D has a positive effect on high-resolution peripheral quantitative CT measures of volumetric density and strength, perhaps via suppression of parathyroid hormone (PTH)–mediated bone turnover,” they wrote.

However, based on the significantly lower radial BMD seen with both 4,000 and 10,000 IU, compared with 400 IU; the lower tibial BMD with 10,000 IU, compared with 400 IU; and the lack of a difference in bone strength at the radius and tibia, the findings do not support a benefit of high-dose vitamin D supplementation for bone health, they said, noting that additional study is needed to determine whether such doses are harmful.

“Because these results are in the opposite direction of the research hypothesis, this evidence of high-dose vitamin D having a negative effect on bone should be regarded as hypothesis generating, requiring confirmation with further research,” they concluded.

SOURCE: Burt L et al. JAMA. 2019 Aug 27;322(8):736-45.

FROM JAMA

Predictive model estimates likelihood of failing induction of labor in obese patients

reported researchers from the University of Cincinnati and Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

The ten variables included in the model were prior vaginal delivery; prior cesarean delivery; maternal height, age, and weight at delivery; parity; gestational weight gain; Medicaid insurance; pregestational diabetes; and chronic hypertension, said Robert M. Rossi, MD, of the university and associates, who developed the model.

“Our hope is that this model may be useful as a tool to estimate an individualized risk based on commonly available prenatal factors that may assist in delivery planning and allocation of appropriate resources,” the investigators said in a study summarizing their findings, published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

The researchers conducted a population-based, retrospective cohort study of delivery records from 1,098,981 obese women in a National Center for Health Statistics birth-death cohort database who underwent induction of labor between 2012 and 2016. Of these women, 825,797 (75%) women succeeded in delivering after induction, while 273,184 (25%) women failed to deliver after induction of labor and instead underwent cesarean section. The women included in the study had a body mass index of 30 or higher and underwent induction between 37 weeks and 44 weeks of gestation.

The class of obesity prior to pregnancy impacted the rate of induction failure, as patients with class I obesity had a rate of cesarean section of 21.6% (95% confidence interval, 21.4%-21.7%), while women with class II obesity had a rate of 25% (95% CI, 24.8%-25.2%) and women with class III obesity had a rate of 31% (95% CI, 30.8%-31.3%). Women also were more likely to fail induction if they had received fertility treatment, if they were older than 35 years, if they were of non-Hispanic black race, if they had gestational weight gain or maternal weight gain, if they had pregestational diabetes or gestational diabetes, or if they had gestational hypertension or preeclampsia (all P less than .001). Factors that made a woman less likely to undergo cesarean delivery were Medicaid insurance status or receiving Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infant and Children (SNAP WIC) support.

Under the predictive model, the receiver operator characteristic curve (ROC) had an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.79 (95% CI, 0.78-0.79), and subsequent validation of the model using a different external U.S. birth cohort dataset showed an AUC of 0.77 (95% CI, 0.76-0.77). In both datasets, the model was calibrated to predict failure of induction of labor up to 75%, at which point the model overestimated the risk in patients, Dr. Rossi and associates said.

“Although we do not stipulate that an elective cesarean delivery should be offered for ‘high risk’ obese women, this tool may allow the provider to have a heightened awareness and prepare accordingly with timing of delivery, increased staffing, and anesthesia presence, particularly given the higher rates of maternal and neonatal adverse outcomes after a failed induction of labor,” said Dr. Rossi and colleagues.

Martina Louise Badell, MD, commented in an interview, “This is well-designed, large, population-based cohort study of more than 1 million obese women with a singleton pregnancy who underwent induction of labor. To determine the chance of successful induction of labor, a 10-variable model was created. This model achieved an AUC of 0.79, which is fairly good accuracy.

“They created an easy-to-use risk calculator as a tool to help identify chance of successful induction of labor in obese women. Similar to the VBAC [vaginal birth after cesarean] calculator, this calculator may help clinicians with patient-specific counseling, risk stratifying, and delivery planning,” said Dr. Badell, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist who is director of the Emory Perinatal Center at Emory University, Atlanta. Dr. Badell, who was not a coauthor of this study, was asked to comment on the study’s merit.

The authors reported no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Badell had no relevant financial disclosures. There was no external funding.

SOURCE: Rossi R et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2019. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003377.

reported researchers from the University of Cincinnati and Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

The ten variables included in the model were prior vaginal delivery; prior cesarean delivery; maternal height, age, and weight at delivery; parity; gestational weight gain; Medicaid insurance; pregestational diabetes; and chronic hypertension, said Robert M. Rossi, MD, of the university and associates, who developed the model.

“Our hope is that this model may be useful as a tool to estimate an individualized risk based on commonly available prenatal factors that may assist in delivery planning and allocation of appropriate resources,” the investigators said in a study summarizing their findings, published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

The researchers conducted a population-based, retrospective cohort study of delivery records from 1,098,981 obese women in a National Center for Health Statistics birth-death cohort database who underwent induction of labor between 2012 and 2016. Of these women, 825,797 (75%) women succeeded in delivering after induction, while 273,184 (25%) women failed to deliver after induction of labor and instead underwent cesarean section. The women included in the study had a body mass index of 30 or higher and underwent induction between 37 weeks and 44 weeks of gestation.

The class of obesity prior to pregnancy impacted the rate of induction failure, as patients with class I obesity had a rate of cesarean section of 21.6% (95% confidence interval, 21.4%-21.7%), while women with class II obesity had a rate of 25% (95% CI, 24.8%-25.2%) and women with class III obesity had a rate of 31% (95% CI, 30.8%-31.3%). Women also were more likely to fail induction if they had received fertility treatment, if they were older than 35 years, if they were of non-Hispanic black race, if they had gestational weight gain or maternal weight gain, if they had pregestational diabetes or gestational diabetes, or if they had gestational hypertension or preeclampsia (all P less than .001). Factors that made a woman less likely to undergo cesarean delivery were Medicaid insurance status or receiving Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infant and Children (SNAP WIC) support.

Under the predictive model, the receiver operator characteristic curve (ROC) had an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.79 (95% CI, 0.78-0.79), and subsequent validation of the model using a different external U.S. birth cohort dataset showed an AUC of 0.77 (95% CI, 0.76-0.77). In both datasets, the model was calibrated to predict failure of induction of labor up to 75%, at which point the model overestimated the risk in patients, Dr. Rossi and associates said.

“Although we do not stipulate that an elective cesarean delivery should be offered for ‘high risk’ obese women, this tool may allow the provider to have a heightened awareness and prepare accordingly with timing of delivery, increased staffing, and anesthesia presence, particularly given the higher rates of maternal and neonatal adverse outcomes after a failed induction of labor,” said Dr. Rossi and colleagues.

Martina Louise Badell, MD, commented in an interview, “This is well-designed, large, population-based cohort study of more than 1 million obese women with a singleton pregnancy who underwent induction of labor. To determine the chance of successful induction of labor, a 10-variable model was created. This model achieved an AUC of 0.79, which is fairly good accuracy.

“They created an easy-to-use risk calculator as a tool to help identify chance of successful induction of labor in obese women. Similar to the VBAC [vaginal birth after cesarean] calculator, this calculator may help clinicians with patient-specific counseling, risk stratifying, and delivery planning,” said Dr. Badell, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist who is director of the Emory Perinatal Center at Emory University, Atlanta. Dr. Badell, who was not a coauthor of this study, was asked to comment on the study’s merit.

The authors reported no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Badell had no relevant financial disclosures. There was no external funding.

SOURCE: Rossi R et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2019. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003377.

reported researchers from the University of Cincinnati and Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

The ten variables included in the model were prior vaginal delivery; prior cesarean delivery; maternal height, age, and weight at delivery; parity; gestational weight gain; Medicaid insurance; pregestational diabetes; and chronic hypertension, said Robert M. Rossi, MD, of the university and associates, who developed the model.

“Our hope is that this model may be useful as a tool to estimate an individualized risk based on commonly available prenatal factors that may assist in delivery planning and allocation of appropriate resources,” the investigators said in a study summarizing their findings, published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

The researchers conducted a population-based, retrospective cohort study of delivery records from 1,098,981 obese women in a National Center for Health Statistics birth-death cohort database who underwent induction of labor between 2012 and 2016. Of these women, 825,797 (75%) women succeeded in delivering after induction, while 273,184 (25%) women failed to deliver after induction of labor and instead underwent cesarean section. The women included in the study had a body mass index of 30 or higher and underwent induction between 37 weeks and 44 weeks of gestation.