User login

Gender, racial, socioeconomic differences found in obesity-depression link

Association holds for white women across income levels, black men with incomes of $100,000 or higher.

Among white women, obesity is positively associated with depressive symptoms across all income levels. However, among black women, no such associations are found – regardless of income. Meanwhile, among men, the link between obesity and depression appears strong for black men with high household incomes, a cross-sectional analysis of 12,220 adults suggests.

“This work underscores the importance of disentangling the association of race and [socioeconomic status] to gain a better understanding of how each operates to impact health outcomes,” wrote Caryn N. Bell, PhD, and her associates. The report is in Preventive Medicine.

The study comprised 3,755 black subjects, 55.5% of whom were women, and 8,465 white subjects, 51.8% of whom were women. They completed a detailed questionnaire as part of the 2007-2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey and had a physical exam. Depressive symptoms were measured by the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), and obesity was defined as a body mass index of 30 kg/m2 or higher. About 1% of both black and white subjects had severe depressive symptoms, meaning a PHQ-9 score ranging from 20 to 27 points.

A greater percentage of black participants were obese (47.3% vs. 34.4%), and black participants were less likely to live in a household earning $100,000 per year or more (10.9% vs. 28.3%). Black participants were a bit younger (mean age 44.8 years vs. 49.2 years), and less likely to be currently married, college graduates, insured, and physically active. A higher percentage reported fair to poor health (23.9% vs. 14.6%). The differences were statistically significant.

For white women, the association between obesity and depression held across all income levels. For black women, this association was not found at any income level. For black men, the link between obesity and depression was limited to those with a household income of $100,000 or more (odds ratio, 4.65; 95% confidence interval, 1.48-14.59). And for white men, the association was limited to those with a household income of $35,000-$74,999 (OR, 1.44; 95% CI, 1.02-2.03).

The effect of race on obesity and depression has been well studied – it’s known, for instance, that the association between obesity and depression is strongest among white women – but the role of income as a modifier has not been well addressed, wrote Dr. Bell, an assistant professor in the department of African American studies at the University of Maryland, College Park, and her associates.

Dr. Bell and her associates wrote.

As for explanations, the authors suggested that strong, antiobesity stigma “may be present among white women at all income levels,” and may drive depression regardless of how much they make.

The prevalence of depressive symptoms at specific income levels among men suggests that something other than stigma is at work. Depression among obese, middle-income white men might be tied to “an unmeasured factor like subjective social status.” Meanwhile, obese black men with high household incomes “have less income and wealth than their white counterparts” because “of various forms of structural racism. ... This may be manifested with higher rates of depression through obesity-related factors like unhealthy coping behaviors and stress,” the investigators said.

Dr. Bell and her associates cited a few limitations. One is that the study looked only at those factors among black and white people. “Results could differ with other ethnic groups,” they wrote. In addition, income was self-reported, and three-way interactions – which are tough to interpret – were used. Nevertheless, they said, the study results have key public health implications.

The study had no financial disclosures, and the investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Bell CN et al. Prev Med. 2018 Dec 3. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.11.024.

Association holds for white women across income levels, black men with incomes of $100,000 or higher.

Association holds for white women across income levels, black men with incomes of $100,000 or higher.

Among white women, obesity is positively associated with depressive symptoms across all income levels. However, among black women, no such associations are found – regardless of income. Meanwhile, among men, the link between obesity and depression appears strong for black men with high household incomes, a cross-sectional analysis of 12,220 adults suggests.

“This work underscores the importance of disentangling the association of race and [socioeconomic status] to gain a better understanding of how each operates to impact health outcomes,” wrote Caryn N. Bell, PhD, and her associates. The report is in Preventive Medicine.

The study comprised 3,755 black subjects, 55.5% of whom were women, and 8,465 white subjects, 51.8% of whom were women. They completed a detailed questionnaire as part of the 2007-2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey and had a physical exam. Depressive symptoms were measured by the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), and obesity was defined as a body mass index of 30 kg/m2 or higher. About 1% of both black and white subjects had severe depressive symptoms, meaning a PHQ-9 score ranging from 20 to 27 points.

A greater percentage of black participants were obese (47.3% vs. 34.4%), and black participants were less likely to live in a household earning $100,000 per year or more (10.9% vs. 28.3%). Black participants were a bit younger (mean age 44.8 years vs. 49.2 years), and less likely to be currently married, college graduates, insured, and physically active. A higher percentage reported fair to poor health (23.9% vs. 14.6%). The differences were statistically significant.

For white women, the association between obesity and depression held across all income levels. For black women, this association was not found at any income level. For black men, the link between obesity and depression was limited to those with a household income of $100,000 or more (odds ratio, 4.65; 95% confidence interval, 1.48-14.59). And for white men, the association was limited to those with a household income of $35,000-$74,999 (OR, 1.44; 95% CI, 1.02-2.03).

The effect of race on obesity and depression has been well studied – it’s known, for instance, that the association between obesity and depression is strongest among white women – but the role of income as a modifier has not been well addressed, wrote Dr. Bell, an assistant professor in the department of African American studies at the University of Maryland, College Park, and her associates.

Dr. Bell and her associates wrote.

As for explanations, the authors suggested that strong, antiobesity stigma “may be present among white women at all income levels,” and may drive depression regardless of how much they make.

The prevalence of depressive symptoms at specific income levels among men suggests that something other than stigma is at work. Depression among obese, middle-income white men might be tied to “an unmeasured factor like subjective social status.” Meanwhile, obese black men with high household incomes “have less income and wealth than their white counterparts” because “of various forms of structural racism. ... This may be manifested with higher rates of depression through obesity-related factors like unhealthy coping behaviors and stress,” the investigators said.

Dr. Bell and her associates cited a few limitations. One is that the study looked only at those factors among black and white people. “Results could differ with other ethnic groups,” they wrote. In addition, income was self-reported, and three-way interactions – which are tough to interpret – were used. Nevertheless, they said, the study results have key public health implications.

The study had no financial disclosures, and the investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Bell CN et al. Prev Med. 2018 Dec 3. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.11.024.

Among white women, obesity is positively associated with depressive symptoms across all income levels. However, among black women, no such associations are found – regardless of income. Meanwhile, among men, the link between obesity and depression appears strong for black men with high household incomes, a cross-sectional analysis of 12,220 adults suggests.

“This work underscores the importance of disentangling the association of race and [socioeconomic status] to gain a better understanding of how each operates to impact health outcomes,” wrote Caryn N. Bell, PhD, and her associates. The report is in Preventive Medicine.

The study comprised 3,755 black subjects, 55.5% of whom were women, and 8,465 white subjects, 51.8% of whom were women. They completed a detailed questionnaire as part of the 2007-2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey and had a physical exam. Depressive symptoms were measured by the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), and obesity was defined as a body mass index of 30 kg/m2 or higher. About 1% of both black and white subjects had severe depressive symptoms, meaning a PHQ-9 score ranging from 20 to 27 points.

A greater percentage of black participants were obese (47.3% vs. 34.4%), and black participants were less likely to live in a household earning $100,000 per year or more (10.9% vs. 28.3%). Black participants were a bit younger (mean age 44.8 years vs. 49.2 years), and less likely to be currently married, college graduates, insured, and physically active. A higher percentage reported fair to poor health (23.9% vs. 14.6%). The differences were statistically significant.

For white women, the association between obesity and depression held across all income levels. For black women, this association was not found at any income level. For black men, the link between obesity and depression was limited to those with a household income of $100,000 or more (odds ratio, 4.65; 95% confidence interval, 1.48-14.59). And for white men, the association was limited to those with a household income of $35,000-$74,999 (OR, 1.44; 95% CI, 1.02-2.03).

The effect of race on obesity and depression has been well studied – it’s known, for instance, that the association between obesity and depression is strongest among white women – but the role of income as a modifier has not been well addressed, wrote Dr. Bell, an assistant professor in the department of African American studies at the University of Maryland, College Park, and her associates.

Dr. Bell and her associates wrote.

As for explanations, the authors suggested that strong, antiobesity stigma “may be present among white women at all income levels,” and may drive depression regardless of how much they make.

The prevalence of depressive symptoms at specific income levels among men suggests that something other than stigma is at work. Depression among obese, middle-income white men might be tied to “an unmeasured factor like subjective social status.” Meanwhile, obese black men with high household incomes “have less income and wealth than their white counterparts” because “of various forms of structural racism. ... This may be manifested with higher rates of depression through obesity-related factors like unhealthy coping behaviors and stress,” the investigators said.

Dr. Bell and her associates cited a few limitations. One is that the study looked only at those factors among black and white people. “Results could differ with other ethnic groups,” they wrote. In addition, income was self-reported, and three-way interactions – which are tough to interpret – were used. Nevertheless, they said, the study results have key public health implications.

The study had no financial disclosures, and the investigators reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Bell CN et al. Prev Med. 2018 Dec 3. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.11.024.

FROM PREVENTIVE MEDICINE

For pelvic pain, think outside the lower body

LAS VEGAS – An estimated 15%-25% of women aged 18-50 years suffer from chronic pelvic pain, a condition that commonly leads to sick days, reduced activity, and higher medication use. Treatments like surgery and opioids may seem feasible, but an obstetrician-gynecologist who studies pain urged colleagues to think twice.

In some cases, pelvic pain patients may suffer from centralized pain syndromes, conditions linked to the central nervous system that may not respond well to those common treatments, said Sawsan As-Sanie, MD, MPH, director of the University of Michigan Endometriosis Center, Ann Arbor.

“If we have laser vision on the pelvis, we may help some patients, but many of us will do harm,” said Dr. As-Sanie, who spoke at the Pelvic Anatomy and Gynecologic Surgery Symposium.

Endometriosis is frequently linked to pelvic pain. But, she said, the link between the two is fuzzier than has been assumed.

“It would make sense that endometriosis or pelvic adhesions would activate nociceptive pain, and [there are] a lot of data to support that this is, in part, how endometriosis causes pain,” she said. “But I would argue it really isn’t that simple because the relationship between endometriosis and pelvic pain is very complex and not explained entirely by the lesion.” For example, “we know that pain recurs after medical and surgical therapy, often without evidence of recurrent endometriosis.” And, there’s little relationship between pain symptoms and the location or extent of endometriosis.

What’s going on? Dr. As-Sanie suggested central pain syndromes can play a significant role in pelvic pain. These syndromes are 1.5-2 times more common in women than men, and are triggered or exacerbated by stressors.

She also emphasized the wide-ranging effects of these syndromes. “We focus on pain, but it’s clearly not a just a pain disorder,” noting that patients can report fatigue, poor sleep, greater sensitivity to light and sound, and memory difficulties that produce “fibromyalgia fog.”

Research suggests that patients with central pain syndromes experience changes in both brain structure and function, she said. As for pelvic pain specifically, studies have linked it to increased pain sensitivity and altered central nervous system structure and function regardless of whether endometriosis is present.

How should patients with pelvic pain be treated in light of this information? Dr. As-Sanie suggests first trying “gold standard” approaches to treat contributing factors whether they’re gynecologic, urologic, gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal or nerve related.

If those strategies don’t work, she said, “consider treating centralized pain” with a blend of approaches: behavioral (such as diet and cognitive-behavior therapy), medical (such as hormone modulation), and interventional (such as physical therapy and surgery).

Also consider pharmacologic therapies, said Dr. As-Sanie, who identified dual reuptake inhibitors (venlafaxine [Effexor] and duloxetine [Cymbalta] are a class of antidepressants that block the reuptake of both serotonin and norepinephrine) and anticonvulsants as drugs with strong evidence as treatments for central pain syndromes.

“Start at low doses and titrate up,” she advised, and “if at any point a given medication doesn’t work, we should try another.”

The Pelvic Anatomy and Gynecologic Surgery Symposium was jointly provided by Global Academy for Medical Education and the University of Cincinnati. Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same company.

Dr. As-Sanie discloses she is a consultant for AbbVie and Myovant.

LAS VEGAS – An estimated 15%-25% of women aged 18-50 years suffer from chronic pelvic pain, a condition that commonly leads to sick days, reduced activity, and higher medication use. Treatments like surgery and opioids may seem feasible, but an obstetrician-gynecologist who studies pain urged colleagues to think twice.

In some cases, pelvic pain patients may suffer from centralized pain syndromes, conditions linked to the central nervous system that may not respond well to those common treatments, said Sawsan As-Sanie, MD, MPH, director of the University of Michigan Endometriosis Center, Ann Arbor.

“If we have laser vision on the pelvis, we may help some patients, but many of us will do harm,” said Dr. As-Sanie, who spoke at the Pelvic Anatomy and Gynecologic Surgery Symposium.

Endometriosis is frequently linked to pelvic pain. But, she said, the link between the two is fuzzier than has been assumed.

“It would make sense that endometriosis or pelvic adhesions would activate nociceptive pain, and [there are] a lot of data to support that this is, in part, how endometriosis causes pain,” she said. “But I would argue it really isn’t that simple because the relationship between endometriosis and pelvic pain is very complex and not explained entirely by the lesion.” For example, “we know that pain recurs after medical and surgical therapy, often without evidence of recurrent endometriosis.” And, there’s little relationship between pain symptoms and the location or extent of endometriosis.

What’s going on? Dr. As-Sanie suggested central pain syndromes can play a significant role in pelvic pain. These syndromes are 1.5-2 times more common in women than men, and are triggered or exacerbated by stressors.

She also emphasized the wide-ranging effects of these syndromes. “We focus on pain, but it’s clearly not a just a pain disorder,” noting that patients can report fatigue, poor sleep, greater sensitivity to light and sound, and memory difficulties that produce “fibromyalgia fog.”

Research suggests that patients with central pain syndromes experience changes in both brain structure and function, she said. As for pelvic pain specifically, studies have linked it to increased pain sensitivity and altered central nervous system structure and function regardless of whether endometriosis is present.

How should patients with pelvic pain be treated in light of this information? Dr. As-Sanie suggests first trying “gold standard” approaches to treat contributing factors whether they’re gynecologic, urologic, gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal or nerve related.

If those strategies don’t work, she said, “consider treating centralized pain” with a blend of approaches: behavioral (such as diet and cognitive-behavior therapy), medical (such as hormone modulation), and interventional (such as physical therapy and surgery).

Also consider pharmacologic therapies, said Dr. As-Sanie, who identified dual reuptake inhibitors (venlafaxine [Effexor] and duloxetine [Cymbalta] are a class of antidepressants that block the reuptake of both serotonin and norepinephrine) and anticonvulsants as drugs with strong evidence as treatments for central pain syndromes.

“Start at low doses and titrate up,” she advised, and “if at any point a given medication doesn’t work, we should try another.”

The Pelvic Anatomy and Gynecologic Surgery Symposium was jointly provided by Global Academy for Medical Education and the University of Cincinnati. Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same company.

Dr. As-Sanie discloses she is a consultant for AbbVie and Myovant.

LAS VEGAS – An estimated 15%-25% of women aged 18-50 years suffer from chronic pelvic pain, a condition that commonly leads to sick days, reduced activity, and higher medication use. Treatments like surgery and opioids may seem feasible, but an obstetrician-gynecologist who studies pain urged colleagues to think twice.

In some cases, pelvic pain patients may suffer from centralized pain syndromes, conditions linked to the central nervous system that may not respond well to those common treatments, said Sawsan As-Sanie, MD, MPH, director of the University of Michigan Endometriosis Center, Ann Arbor.

“If we have laser vision on the pelvis, we may help some patients, but many of us will do harm,” said Dr. As-Sanie, who spoke at the Pelvic Anatomy and Gynecologic Surgery Symposium.

Endometriosis is frequently linked to pelvic pain. But, she said, the link between the two is fuzzier than has been assumed.

“It would make sense that endometriosis or pelvic adhesions would activate nociceptive pain, and [there are] a lot of data to support that this is, in part, how endometriosis causes pain,” she said. “But I would argue it really isn’t that simple because the relationship between endometriosis and pelvic pain is very complex and not explained entirely by the lesion.” For example, “we know that pain recurs after medical and surgical therapy, often without evidence of recurrent endometriosis.” And, there’s little relationship between pain symptoms and the location or extent of endometriosis.

What’s going on? Dr. As-Sanie suggested central pain syndromes can play a significant role in pelvic pain. These syndromes are 1.5-2 times more common in women than men, and are triggered or exacerbated by stressors.

She also emphasized the wide-ranging effects of these syndromes. “We focus on pain, but it’s clearly not a just a pain disorder,” noting that patients can report fatigue, poor sleep, greater sensitivity to light and sound, and memory difficulties that produce “fibromyalgia fog.”

Research suggests that patients with central pain syndromes experience changes in both brain structure and function, she said. As for pelvic pain specifically, studies have linked it to increased pain sensitivity and altered central nervous system structure and function regardless of whether endometriosis is present.

How should patients with pelvic pain be treated in light of this information? Dr. As-Sanie suggests first trying “gold standard” approaches to treat contributing factors whether they’re gynecologic, urologic, gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal or nerve related.

If those strategies don’t work, she said, “consider treating centralized pain” with a blend of approaches: behavioral (such as diet and cognitive-behavior therapy), medical (such as hormone modulation), and interventional (such as physical therapy and surgery).

Also consider pharmacologic therapies, said Dr. As-Sanie, who identified dual reuptake inhibitors (venlafaxine [Effexor] and duloxetine [Cymbalta] are a class of antidepressants that block the reuptake of both serotonin and norepinephrine) and anticonvulsants as drugs with strong evidence as treatments for central pain syndromes.

“Start at low doses and titrate up,” she advised, and “if at any point a given medication doesn’t work, we should try another.”

The Pelvic Anatomy and Gynecologic Surgery Symposium was jointly provided by Global Academy for Medical Education and the University of Cincinnati. Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same company.

Dr. As-Sanie discloses she is a consultant for AbbVie and Myovant.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM PAGS

Poor-prognosis cancers linked to highest suicide risk in first year

Suicide risk significantly increases within the first year of a cancer diagnosis, with risk varying by type of cancer, according to investigators who conducted a retrospective analysis representing nearly 4.7 million patients.

Risk of suicide in that first year after diagnosis was especially high in pancreatic and lung cancers, while by contrast, breast and prostate cancer did not increase suicide risk, reported the researchers, led by Hesham Hamoda, MD, MPH, of Boston Children’s Hospital/Harvard Medical School, and Ahmad Alfaar, MBBCh, MSc, of Charité–Universitätsmedizin Berlin.

That variation in suicide risk by cancer type suggests that prognosis and 5-year relative survival play a role in increasing suicide rates, according to Dr. Hamoda, Dr. Alfaar, and their coauthors.

“After the diagnosis, it is important that health care providers be vigilant in screening for suicide and ensuring that patients have access to social and emotional support,” they wrote in a report published in Cancer. Their analysis was based on 4,671,989 patients with a diagnosis of cancer in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database between 2000 and 2014. Out of 1,005,825 of those patients who died within the first year of diagnosis, the cause of death was suicide for 1,585, or 0.16%.

Overall, the risk of suicide increased significantly among cancer patients versus the general population, with an observed-to-expected (O/E) ratio of 2.51 per 10,000 person-years, the investigators found. The risk was highest in the first 6 months, with an O/E mortality of 3.13 versus 1.8 in the latter 6 months.

The highest ratios were seen for pancreatic cancer, with an O/E ratio of 8.01, and lung cancer, with a ratio of 6.05, the researchers found in further analysis.

Significant increases in suicide risk were also seen for colorectal cancer (2.08) and melanoma (1.45), though rates were not significantly different versus the general population for breast (1.23) and prostate (0.99), according to the reported data.

Suicide risk was relatively high for any cancer with distant metastases (5.63), though still significantly higher at 1.65 in persons with localized/regional disease, the data show.

The increased suicide risk persisted more than 1 year after the cancer diagnosis, though not to the degree observed within that first year, they added.

Most patients with suicide as a cause of death were white (90.2%) and male (87%). Nearly 60% were between the ages of 65 and 84 at the time of suicide.

Social support plays an integral role in suicide prevention among cancer patients, the researchers noted.

Previous studies suggest that support programs may decrease suicide risk by making patients better aware of their prognosis, receptive to decreased social stigma, or less likely to have stress related to cost of care, they said.

“Discussing the quality of life after diagnosis, the effectiveness of therapy, and the prognosis of the disease and maintaining a trusting relationship with health care professionals all decrease the likelihood of suicide immediately after a diagnosis of cancer,” they said.

Dr. Hamoda, Dr. Alfaar, and their coauthors reported no conflicts of interest. Funding for the study came in part from the German Academic Exchange Service (Dr. Alfaar).

SOURCE: Saad AM, et al. Cancer 2019 Jan 7. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31876.

Suicide risk significantly increases within the first year of a cancer diagnosis, with risk varying by type of cancer, according to investigators who conducted a retrospective analysis representing nearly 4.7 million patients.

Risk of suicide in that first year after diagnosis was especially high in pancreatic and lung cancers, while by contrast, breast and prostate cancer did not increase suicide risk, reported the researchers, led by Hesham Hamoda, MD, MPH, of Boston Children’s Hospital/Harvard Medical School, and Ahmad Alfaar, MBBCh, MSc, of Charité–Universitätsmedizin Berlin.

That variation in suicide risk by cancer type suggests that prognosis and 5-year relative survival play a role in increasing suicide rates, according to Dr. Hamoda, Dr. Alfaar, and their coauthors.

“After the diagnosis, it is important that health care providers be vigilant in screening for suicide and ensuring that patients have access to social and emotional support,” they wrote in a report published in Cancer. Their analysis was based on 4,671,989 patients with a diagnosis of cancer in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database between 2000 and 2014. Out of 1,005,825 of those patients who died within the first year of diagnosis, the cause of death was suicide for 1,585, or 0.16%.

Overall, the risk of suicide increased significantly among cancer patients versus the general population, with an observed-to-expected (O/E) ratio of 2.51 per 10,000 person-years, the investigators found. The risk was highest in the first 6 months, with an O/E mortality of 3.13 versus 1.8 in the latter 6 months.

The highest ratios were seen for pancreatic cancer, with an O/E ratio of 8.01, and lung cancer, with a ratio of 6.05, the researchers found in further analysis.

Significant increases in suicide risk were also seen for colorectal cancer (2.08) and melanoma (1.45), though rates were not significantly different versus the general population for breast (1.23) and prostate (0.99), according to the reported data.

Suicide risk was relatively high for any cancer with distant metastases (5.63), though still significantly higher at 1.65 in persons with localized/regional disease, the data show.

The increased suicide risk persisted more than 1 year after the cancer diagnosis, though not to the degree observed within that first year, they added.

Most patients with suicide as a cause of death were white (90.2%) and male (87%). Nearly 60% were between the ages of 65 and 84 at the time of suicide.

Social support plays an integral role in suicide prevention among cancer patients, the researchers noted.

Previous studies suggest that support programs may decrease suicide risk by making patients better aware of their prognosis, receptive to decreased social stigma, or less likely to have stress related to cost of care, they said.

“Discussing the quality of life after diagnosis, the effectiveness of therapy, and the prognosis of the disease and maintaining a trusting relationship with health care professionals all decrease the likelihood of suicide immediately after a diagnosis of cancer,” they said.

Dr. Hamoda, Dr. Alfaar, and their coauthors reported no conflicts of interest. Funding for the study came in part from the German Academic Exchange Service (Dr. Alfaar).

SOURCE: Saad AM, et al. Cancer 2019 Jan 7. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31876.

Suicide risk significantly increases within the first year of a cancer diagnosis, with risk varying by type of cancer, according to investigators who conducted a retrospective analysis representing nearly 4.7 million patients.

Risk of suicide in that first year after diagnosis was especially high in pancreatic and lung cancers, while by contrast, breast and prostate cancer did not increase suicide risk, reported the researchers, led by Hesham Hamoda, MD, MPH, of Boston Children’s Hospital/Harvard Medical School, and Ahmad Alfaar, MBBCh, MSc, of Charité–Universitätsmedizin Berlin.

That variation in suicide risk by cancer type suggests that prognosis and 5-year relative survival play a role in increasing suicide rates, according to Dr. Hamoda, Dr. Alfaar, and their coauthors.

“After the diagnosis, it is important that health care providers be vigilant in screening for suicide and ensuring that patients have access to social and emotional support,” they wrote in a report published in Cancer. Their analysis was based on 4,671,989 patients with a diagnosis of cancer in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database between 2000 and 2014. Out of 1,005,825 of those patients who died within the first year of diagnosis, the cause of death was suicide for 1,585, or 0.16%.

Overall, the risk of suicide increased significantly among cancer patients versus the general population, with an observed-to-expected (O/E) ratio of 2.51 per 10,000 person-years, the investigators found. The risk was highest in the first 6 months, with an O/E mortality of 3.13 versus 1.8 in the latter 6 months.

The highest ratios were seen for pancreatic cancer, with an O/E ratio of 8.01, and lung cancer, with a ratio of 6.05, the researchers found in further analysis.

Significant increases in suicide risk were also seen for colorectal cancer (2.08) and melanoma (1.45), though rates were not significantly different versus the general population for breast (1.23) and prostate (0.99), according to the reported data.

Suicide risk was relatively high for any cancer with distant metastases (5.63), though still significantly higher at 1.65 in persons with localized/regional disease, the data show.

The increased suicide risk persisted more than 1 year after the cancer diagnosis, though not to the degree observed within that first year, they added.

Most patients with suicide as a cause of death were white (90.2%) and male (87%). Nearly 60% were between the ages of 65 and 84 at the time of suicide.

Social support plays an integral role in suicide prevention among cancer patients, the researchers noted.

Previous studies suggest that support programs may decrease suicide risk by making patients better aware of their prognosis, receptive to decreased social stigma, or less likely to have stress related to cost of care, they said.

“Discussing the quality of life after diagnosis, the effectiveness of therapy, and the prognosis of the disease and maintaining a trusting relationship with health care professionals all decrease the likelihood of suicide immediately after a diagnosis of cancer,” they said.

Dr. Hamoda, Dr. Alfaar, and their coauthors reported no conflicts of interest. Funding for the study came in part from the German Academic Exchange Service (Dr. Alfaar).

SOURCE: Saad AM, et al. Cancer 2019 Jan 7. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31876.

FROM CANCER

Key clinical point: A cancer diagnosis significantly increases risk of suicide in comparison to the general population, particularly for poorer-prognosis cancers.

Major finding: The observed-to-expected mortality ratio was substantially higher for pancreatic cancer (8.01), and lung cancer (6.05), but not significantly increased for breast (1.23) and prostate (0.99).

Study details: A retrospective population-based study of 4,671,989 cancer patients.

Disclosures: The authors reported no conflicts of interest. Funding for the study came in part from the German Academic Exchange Service.

Source: Saad AM et al. Cancer. 2019 Jan 7. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31876.

Cerebral small vessel and cognitive impairment

Also today, antidepressants are tied to greater hip fracture incidence, a hospital readmission reduction program may be doing more harm than good, and the flu season rages on with 19 states showing high activity in the final week of 2018.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Also today, antidepressants are tied to greater hip fracture incidence, a hospital readmission reduction program may be doing more harm than good, and the flu season rages on with 19 states showing high activity in the final week of 2018.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Also today, antidepressants are tied to greater hip fracture incidence, a hospital readmission reduction program may be doing more harm than good, and the flu season rages on with 19 states showing high activity in the final week of 2018.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Click for Credit: STIs on the rise; psoriasis & cardiac risk; more

Here are 5 articles from the January issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. Can ultrasound screening improve survival in ovarian cancer?

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2Vtuc8F

Expires October 17, 2019

2. Higher BMI associated with greater loss of gray matter volume in MS

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2ArvFDp

Expires October 29, 2019

3. Psoriasis adds to increased risk of cardiovascular procedures, surgery in patients with hypertension

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2sbnkiS

Expires October 31, 2019

4. Fever, intestinal symptoms may delay diagnosis of Kawasaki disease in children

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2RdPoBi

Expires October 31, 2019

5. Rate of STIs is rising, and many U.S. teens are sexually active

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2CPuYFW

Expires November 8, 2019

Here are 5 articles from the January issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. Can ultrasound screening improve survival in ovarian cancer?

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2Vtuc8F

Expires October 17, 2019

2. Higher BMI associated with greater loss of gray matter volume in MS

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2ArvFDp

Expires October 29, 2019

3. Psoriasis adds to increased risk of cardiovascular procedures, surgery in patients with hypertension

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2sbnkiS

Expires October 31, 2019

4. Fever, intestinal symptoms may delay diagnosis of Kawasaki disease in children

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2RdPoBi

Expires October 31, 2019

5. Rate of STIs is rising, and many U.S. teens are sexually active

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2CPuYFW

Expires November 8, 2019

Here are 5 articles from the January issue of Clinician Reviews (individual articles are valid for one year from date of publication—expiration dates below):

1. Can ultrasound screening improve survival in ovarian cancer?

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2Vtuc8F

Expires October 17, 2019

2. Higher BMI associated with greater loss of gray matter volume in MS

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2ArvFDp

Expires October 29, 2019

3. Psoriasis adds to increased risk of cardiovascular procedures, surgery in patients with hypertension

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2sbnkiS

Expires October 31, 2019

4. Fever, intestinal symptoms may delay diagnosis of Kawasaki disease in children

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2RdPoBi

Expires October 31, 2019

5. Rate of STIs is rising, and many U.S. teens are sexually active

To take the posttest, go to: https://bit.ly/2CPuYFW

Expires November 8, 2019

Endometriosis surgery: Women can expect years-long benefits

LAS VEGAS – according to a survey study from the University of Pittsburgh.

The work was likely the first to assess long-term outcomes after laparoscopic endometriosis excision with a disease-specific questionnaire, the Endometriosis Health Profile-30 (EHP-30). The findings should reassure both surgeons and patients. “I really feel these results can help us as endometriosis providers” to counsel women, said lead investigator Nicole M. Donnellan, MD, a gynecologic surgeon at the University of Pittsburgh.

Surgery “offers lasting improvement in all quality of life domains ... measured by the EHP-30”: pain; control/powerlessness; emotional well-being; social support; and self-image, with supplemental questions about work, sexual function, and other matters. Because “definitive surgery was not associated with improved outcomes when compared with fertility-sparing surgery ... fertility preservation should continue to be offered as first-line surgery for treatment of symptomatic disease,” Dr. Donnellan and her team concluded at a meeting sponsored by AAGL.

Surgery is the gold standard for endometriosis, but there just hasn’t been much data on long-term outcomes until now, especially with a potent questionnaire like the EHP-30. The gap left surgeons in the lurch on what to tell women how they’ll do, especially because results from previous, shorter, and less-rigorous studies have been mixed. The Pittsburgh results mean that competent surgeons can breathe easier and be confident in telling women what to expect.

The team administered EHP-30 to 61 women before surgery and at 4 weeks postoperatively; 45 patients (74%) had fertility-sparing excisions, 7 (11%) had hysterectomy with adnexa preservation, and 9 (15%) had hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. The women were contacted again in 2017 to fill out the survey anywhere from 3 to 7 years after their operation; 45 women agreed, a response rate of 74%.

There was a definitive, statistically significant reduction in scores across all five domains of the survey, both at 4 weeks and out to 7 years, and the improvements did not vary by endometriosis stage or the type of surgery women had.

The overall score – a combination of the five domains – fell from a preoperative median of 50 points out of a possible 100, with 100 being the worst possible score, to a median of about 20 points 4 weeks after surgery, and a median of about 10 points at long-term follow-up. Pain scores fell about the same amount; the greatest improvements were on questions that focused on sense of control and empowerment.

At long-term follow-up, overall scores improved a median of 43 points in women with American Society for Reproductive Medicine stage 1 endometriosis and 28 points among women with stage 4 disease (P = .705). Although the differences were not statistically significant, women with stage 1 disease generally reported the greatest improvements, except on the control and empowerment scale, where women reported the same improvement across all four stages, about 50 points out of 100.

Long-term score improvements were pretty much identical among women who had fertility-sparing surgery and those who had hysterectomies, with, for instance, both groups reporting about a 33-point improvement in pain scores. The two groups separated out only on emotional well-being scores, a 38-point improvement in the hysterectomy group versus 21 points, but the difference was not statistically significant (P = .525).

The long-term results remained the same when eight women who had subsequent gynecologic surgery were excluded.

In the end, the take home is that “all of these women improved,” Dr. Donnellan said.

The investigators didn’t report any disclosures.

SOURCE: Donnellan NM et al. 2018 AAGL Global Congress, Abstract 82.

LAS VEGAS – according to a survey study from the University of Pittsburgh.

The work was likely the first to assess long-term outcomes after laparoscopic endometriosis excision with a disease-specific questionnaire, the Endometriosis Health Profile-30 (EHP-30). The findings should reassure both surgeons and patients. “I really feel these results can help us as endometriosis providers” to counsel women, said lead investigator Nicole M. Donnellan, MD, a gynecologic surgeon at the University of Pittsburgh.

Surgery “offers lasting improvement in all quality of life domains ... measured by the EHP-30”: pain; control/powerlessness; emotional well-being; social support; and self-image, with supplemental questions about work, sexual function, and other matters. Because “definitive surgery was not associated with improved outcomes when compared with fertility-sparing surgery ... fertility preservation should continue to be offered as first-line surgery for treatment of symptomatic disease,” Dr. Donnellan and her team concluded at a meeting sponsored by AAGL.

Surgery is the gold standard for endometriosis, but there just hasn’t been much data on long-term outcomes until now, especially with a potent questionnaire like the EHP-30. The gap left surgeons in the lurch on what to tell women how they’ll do, especially because results from previous, shorter, and less-rigorous studies have been mixed. The Pittsburgh results mean that competent surgeons can breathe easier and be confident in telling women what to expect.

The team administered EHP-30 to 61 women before surgery and at 4 weeks postoperatively; 45 patients (74%) had fertility-sparing excisions, 7 (11%) had hysterectomy with adnexa preservation, and 9 (15%) had hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. The women were contacted again in 2017 to fill out the survey anywhere from 3 to 7 years after their operation; 45 women agreed, a response rate of 74%.

There was a definitive, statistically significant reduction in scores across all five domains of the survey, both at 4 weeks and out to 7 years, and the improvements did not vary by endometriosis stage or the type of surgery women had.

The overall score – a combination of the five domains – fell from a preoperative median of 50 points out of a possible 100, with 100 being the worst possible score, to a median of about 20 points 4 weeks after surgery, and a median of about 10 points at long-term follow-up. Pain scores fell about the same amount; the greatest improvements were on questions that focused on sense of control and empowerment.

At long-term follow-up, overall scores improved a median of 43 points in women with American Society for Reproductive Medicine stage 1 endometriosis and 28 points among women with stage 4 disease (P = .705). Although the differences were not statistically significant, women with stage 1 disease generally reported the greatest improvements, except on the control and empowerment scale, where women reported the same improvement across all four stages, about 50 points out of 100.

Long-term score improvements were pretty much identical among women who had fertility-sparing surgery and those who had hysterectomies, with, for instance, both groups reporting about a 33-point improvement in pain scores. The two groups separated out only on emotional well-being scores, a 38-point improvement in the hysterectomy group versus 21 points, but the difference was not statistically significant (P = .525).

The long-term results remained the same when eight women who had subsequent gynecologic surgery were excluded.

In the end, the take home is that “all of these women improved,” Dr. Donnellan said.

The investigators didn’t report any disclosures.

SOURCE: Donnellan NM et al. 2018 AAGL Global Congress, Abstract 82.

LAS VEGAS – according to a survey study from the University of Pittsburgh.

The work was likely the first to assess long-term outcomes after laparoscopic endometriosis excision with a disease-specific questionnaire, the Endometriosis Health Profile-30 (EHP-30). The findings should reassure both surgeons and patients. “I really feel these results can help us as endometriosis providers” to counsel women, said lead investigator Nicole M. Donnellan, MD, a gynecologic surgeon at the University of Pittsburgh.

Surgery “offers lasting improvement in all quality of life domains ... measured by the EHP-30”: pain; control/powerlessness; emotional well-being; social support; and self-image, with supplemental questions about work, sexual function, and other matters. Because “definitive surgery was not associated with improved outcomes when compared with fertility-sparing surgery ... fertility preservation should continue to be offered as first-line surgery for treatment of symptomatic disease,” Dr. Donnellan and her team concluded at a meeting sponsored by AAGL.

Surgery is the gold standard for endometriosis, but there just hasn’t been much data on long-term outcomes until now, especially with a potent questionnaire like the EHP-30. The gap left surgeons in the lurch on what to tell women how they’ll do, especially because results from previous, shorter, and less-rigorous studies have been mixed. The Pittsburgh results mean that competent surgeons can breathe easier and be confident in telling women what to expect.

The team administered EHP-30 to 61 women before surgery and at 4 weeks postoperatively; 45 patients (74%) had fertility-sparing excisions, 7 (11%) had hysterectomy with adnexa preservation, and 9 (15%) had hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. The women were contacted again in 2017 to fill out the survey anywhere from 3 to 7 years after their operation; 45 women agreed, a response rate of 74%.

There was a definitive, statistically significant reduction in scores across all five domains of the survey, both at 4 weeks and out to 7 years, and the improvements did not vary by endometriosis stage or the type of surgery women had.

The overall score – a combination of the five domains – fell from a preoperative median of 50 points out of a possible 100, with 100 being the worst possible score, to a median of about 20 points 4 weeks after surgery, and a median of about 10 points at long-term follow-up. Pain scores fell about the same amount; the greatest improvements were on questions that focused on sense of control and empowerment.

At long-term follow-up, overall scores improved a median of 43 points in women with American Society for Reproductive Medicine stage 1 endometriosis and 28 points among women with stage 4 disease (P = .705). Although the differences were not statistically significant, women with stage 1 disease generally reported the greatest improvements, except on the control and empowerment scale, where women reported the same improvement across all four stages, about 50 points out of 100.

Long-term score improvements were pretty much identical among women who had fertility-sparing surgery and those who had hysterectomies, with, for instance, both groups reporting about a 33-point improvement in pain scores. The two groups separated out only on emotional well-being scores, a 38-point improvement in the hysterectomy group versus 21 points, but the difference was not statistically significant (P = .525).

The long-term results remained the same when eight women who had subsequent gynecologic surgery were excluded.

In the end, the take home is that “all of these women improved,” Dr. Donnellan said.

The investigators didn’t report any disclosures.

SOURCE: Donnellan NM et al. 2018 AAGL Global Congress, Abstract 82.

REPORTING FROM THE AAGL GLOBAL CONGRESS

Key clinical point: Endometriosis excision improves quality of life for at least 7 years, even when women have conservative, fertility-sparing surgery.

Major finding: The overall score on the Endometriosis Health Profile-30 fell from a preoperative median of 50 points out of a possible 100, with 100 being the worst possible score, to a median of about 20 points 4 weeks after surgery, and a median of about 10 points at the 7-year follow-up.

Study details: A review of 61 cases

Disclosures: The investigators didn’t report any disclosures.

Source: Donnellan NM et al. 2018 AAGL Global Congress, Abstract 82.

Hypertension guidelines: Treat patients, not numbers

When treating high blood pressure, how low should we try to go? Debate continues about optimal blood pressure goals after publication of guidelines from the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) in 2017 that set or permitted a treatment goal of less than 130 mm Hg, depending on the population.1

In this article, we summarize the evolution of hypertension guidelines and the evidence behind them.

HOW THE GOALS EVOLVED

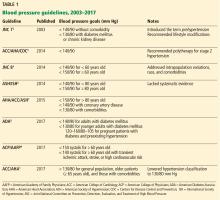

JNC 7, 2003: 140/90 or 130/80

The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 7),2 published in 2003, specified treatment goals of:

- < 140/90 mm Hg for most patients

- < 130/80 mm Hg for those with diabetes or chronic kidney disease.

JNC 7 provided much-needed clarity and uniformity to managing hypertension. Since then, various scientific groups have published their own guidelines (Table 1).1–9

ACC/AHA/CDC 2014: 140/90

In 2014, the ACC, AHA, and US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published an evidence-based algorithm for hypertension management.3 As in JNC 7, they suggested a blood pressure goal of less than 140/90 mm Hg, lifestyle modification, and polytherapy, eg, a thiazide diuretic for stage 1 hypertension (< 160/100 mm Hg) and combination therapy with a thiazide diuretic and an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor, angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB), or calcium channel blocker for stage 2 hypertension (≥ 160/100 mm Hg).

JNC 8 2014: 140/90 or 150/90

Soon after, the much-anticipated report of the panel members appointed to the eighth JNC (JNC 8) was published.4 Previous JNC reports were written and published under the auspices of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, but while the JNC 8 report was being prepared, this government body announced it would no longer publish guidelines.

In contrast to JNC 7, the JNC 8 panel based its recommendations on a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. However, the process and methodology were controversial, especially as the panel excluded some important clinical trials from the analysis.

JNC 8 relaxed the targets in several subgroups, such as patients over age 60 and those with diabetes and chronic kidney disease, due to a lack of definitive evidence on the impact of blood pressure targets lower than 140/90 mm Hg in these groups. Thus, their goals were:

- < 140/90 mm Hg for patients under age 60

- < 150/90 mm Hg for patients age 60 and older.

Of note, a minority of the JNC 8 panel disagreed with the new targets and provided evidence for keeping the systolic blood pressure target below 140 mm Hg for patients 60 and older.5 Further, the JNC 8 report was not endorsed by several important societies, ie, the AHA, ACC, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, and American Society of Hypertension (ASH). These issues compromised the acceptance and applicability of the guidelines.

ASH/ISH 2014: 140/90 or 150/90

Also in 2014, the ASH and the International Society of Hypertension released their own report.6 Their goals:

- < 140/90 mm Hg for most patients

- < 150/90 mm Hg for patients age 80 and older.

AHA/ACC/ASH 2015: Goals in subgroups

In 2015, the AHA, ACC, and ASH released a joint scientific statement outlining hypertension goals for specific patient populations7:

- < 150/90 mm Hg for those age 80 and older

- < 140/90 mm Hg for those with coronary artery disease

- < 130/80 mm Hg for those with comorbidities such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

ADA 2016: Goals for patients with diabetes

In 2016, the American Diabetes Association (ADA) set the following blood pressure goals for patients with diabetes8:

- < 140/90 mm Hg for adults with diabetes

- < 130/80 mm Hg for younger adults with diabetes and adults with a high risk of cardiovascular disease

- 120–160/80–105 mm Hg for pregnant patients with diabetes and preexisting hypertension who are treated with antihypertensive therapy.

ACP/AAFP 2017: Systolic 150 or 130

In 2017, the American College of Physicians (ACP) and the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) recommended a relaxed systolic blood pressure target, ie, below 150 mm Hg, for adults over age 60, but a tighter goal of less than 140 mm Hg for the same age group if they have transient ischemic attack, stroke, or high cardiovascular risk.9

ACC/AHA 2017: 130/80

The 2017 ACC/AHA guidelines recommended a more aggressive goal of below 130/80 for all, including patients age 65 and older.1

This is a class I (strong) recommendation for patients with known cardiovascular disease or a 10-year risk of a cardiovascular event of 10% or higher, with a B-R level of evidence for the systolic goal (ie, moderate-quality, based on systematic review of randomized controlled trials) and a C-EO level of evidence for the diastolic goal (ie, based on expert opinion).

For patients who do not have cardiovascular disease and who are at lower risk of it, this is a class IIb (weak) recommendation, ie, it “may be reasonable,” with a B-NR level of evidence (moderate-quality, based on nonrandomized studies) for the systolic goal and C-EO (expert opinion) for the diastolic goal.

For many patients, this involves drug treatment. For those with known cardiovascular disease or a 10-year risk of an atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease event of 10% or higher, the ACC/AHA guidelines say that drug treatment “is recommended” if their average blood pressure is 130/80 mm Hg or higher (class I recommendation, based on strong evidence for the systolic threshold and expert option for the diastolic). For those without cardiovascular disease and at lower risk, drug treatment is recommended if their average blood pressure is 140/90 mm Hg or higher (also class I, but based on limited data).

EVERYONE AGREES ON LIFESTYLE

Although the guidelines differ in their blood pressure targets, they consistently recommend lifestyle modifications.

Lifestyle modifications, first described in JNC 7, included weight loss, sodium restriction, and the DASH diet, which is rich in fruits, vegetables, low-fat dairy products, whole grains, poultry, and fish, and low in red meat, sweets, cholesterol, and total and saturated fat.2

These recommendations were based on results from 3 large randomized controlled trials in patients with and without hypertension.10–12 In patients with no history of hypertension, interventions to promote weight loss and sodium restriction significantly reduced blood pressure and the incidence of hypertension (the latter by as much as 77%) compared with usual care.10,11

In patients with and without hypertension, lowering sodium intake in conjunction with the DASH diet was associated with substantially larger reductions in systolic blood pressure.12

The recommendation to lower sodium intake has not changed in the guideline revisions. Meanwhile, other modifications have been added, such as incorporating both aerobic and resistance exercise and moderating alcohol intake. These recommendations have a class I level of evidence (ie, strongest level) in the 2017 ACC/AHA guidelines.1

HYPERTENSION BEGINS AT 130/80

The definition of hypertension changed in the 2017 ACC/AHA guidelines1: previously set at 140/90 mm Hg or higher, it is now 130/80 mm Hg or higher for all age groups. Adults with systolic blood pressure of 130 to 139 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure of 80 to 89 mm Hg are now classified as having stage 1 hypertension.

Under the new definition, the number of US adults who have hypertension expanded to 45.6% of the general population,13 up from 31.9% under the JNC 7 definition. Thus, overall, 103.3 million US adults now have hypertension, compared with 72.2 million under the JNC 7 criteria.

In addition, the new guidelines expanded the population of adults for whom antihypertensive drug treatment is recommended to 36.2% (81.9 million). However, this represents only a 1.9% absolute increase over the JNC 7 recommendations (34.3%) and a 5.1% absolute increase over the JNC 8 recommendations.14

SPRINT: INTENSIVE TREATMENT IS BENEFICIAL

The new ACC/AHA guidelines1 were based on evidence from several trials, including the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT).15

This multicenter trial investigated the effect of intensive blood pressure treatment on cardiovascular disease risk.16 The primary outcome was a composite of myocardial infarction, acute coronary syndrome, stroke, and heart failure.

The trial enrolled 9,361 participants at least 50 years of age with systolic blood pressure 130 mm Hg or higher and at least 1 additional risk factor for cardiovascular disease. It excluded anyone with a history of diabetes mellitus, stroke, symptomatic heart failure, or end-stage renal disease.

Two interventions were compared:

- Intensive treatment, with a systolic blood pressure goal of less than 120 mm Hg: the protocol called for polytherapy, even for participants who were 75 or older if their blood pressure was 140 mm Hg or higher

- Standard treatment, with a systolic blood pressure goal of less than 140 mm Hg: it used polytherapy for patients whose systolic blood pressure was 160 mm Hg or higher.

The trial was intended to last 5 years but was stopped early at a median of 3.26 years owing to a significantly lower rate of the primary composite outcome in the intensive-treatment group: 1.65% per year vs 2.19%, a 25% relative risk reduction (P < .001) or a 0.54% absolute risk reduction. We calculate the number needed to treat (NNT) for 1 year to prevent 1 event as 185, and over the 3.26 years of the trial, the investigators calculated the NNT as 61. Similarly, the rate of death from any cause was also lower with intensive treatment, 1.03% per year vs 1.40% per year, a 27% relative risk reduction (P = .003) or a 0.37% absolute risk reduction, NNT 270.

Using these findings, Bress et al16 estimated that implementing intensive blood pressure goals could prevent 107,500 deaths annually.

The downside is adverse effects. In SPRINT,15 the intensive-treatment group experienced significantly higher rates of serious adverse effects than the standard-treatment group, ie:

- Hypotension 2.4% vs 1.4%, P = .001

- Syncope 2.3% vs 1.7%, P = .05

- Electrolyte abnormalities 3.1% vs 2.3%, P = .02)

- Acute kidney injury or kidney failure 4.1% vs 2.5%, P < .001

- Any treatment-related adverse event 4.7% vs 2.5%, P = .001.

Thus, Bress et al16 estimated that fully implementing the intensive-treatment goals could cause an additional 56,100 episodes of hypotension per year, 34,400 cases of syncope, 43,400 serious electrolyte disorders, and 88,700 cases of acute kidney injury. All told, about 3 million Americans could suffer a serious adverse effect under the intensive-treatment goals.

SPRINT caveats and limitations

SPRINT15 was stopped early, after 3.26 years instead of the planned 5 years. The true risk-benefit ratio may have been different if the trial had been extended longer.

In addition, SPRINT used automated office blood pressure measurements in which patients were seated alone and a device (Model 907, Omron Healthcare) took 3 blood pressure measurements at 1-minute intervals after 5 minutes of quiet rest. This was designed to reduce elevated blood pressure readings in the presence of a healthcare professional in a medical setting (ie, “white coat” hypertension).

Many physicians are still taking blood pressure manually, which tends to give higher readings. Therefore, if they aim for a lower goal, they may risk overtreating the patient.

About 50% of patients did not achieve the target systolic blood pressure (< 120 mm Hg) despite receiving an average of 2.8 antihypertensive medications in the intensive-treatment group and 1.8 in the standard-treatment group. The use of antihypertensive medications, however, was not a controlled variable in the trial, and practitioners chose the appropriate drugs for their patients.

Diastolic pressure, which can be markedly lower in older hypertensive patients, was largely ignored, although lower diastolic pressure may have contributed to higher syncope rates in response to alpha blockers and calcium blockers.

Moreover, the trial excluded those with significant comorbidities and those younger than 50 (the mean age was 67.9), which limits the generalizability of the results.

JNC 8 VS SPRINT GOALS: WHAT'S THE EFFECT ON OUTCOMES?

JNC 84 recommended a relaxed target of less than 140/90 mm Hg for adults younger than 60, including those with chronic kidney disease or diabetes, and less than 150/90 mm Hg for adults 60 and older. The SPRINT findings upended those recommendations, showing that intensive treatment in adults age 75 or older significantly improved the composite cardiovascular disease outcome (2.59 vs 3.85 events per year; P < .001) and all-cause mortality (1.78 vs 2.63 events per year; P < .05) compared with standard treatment.17 Also, a subset review of SPRINT trial data found no difference in benefit based on chronic kidney disease status.18

A meta-analysis of 74 clinical trials (N = 306,273) offers a compromise between the SPRINT findings and the JNC 8 recommendations.19 It found that the beneficial effect of blood pressure treatment depended on the patient’s baseline systolic blood pressure. In those with a baseline systolic pressure of 160 mm Hg or higher, treatment reduced cardiovascular mortality by about 15% (relative risk [RR] 0.85; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.77–0.95). In patients with systolic pressure below 140 mm Hg, treatment effects were neutral (RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.87–1.20) and not associated with any benefit as primary prevention, although data suggest it may reduce the risk of adverse outcomes in patients with coronary heart disease.

OTHER TRIALS THAT INFLUENCED THE GUIDELINES

SHEP and HYVET (the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program20 and the Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial)21 supported intensive blood pressure treatment for older patients by reporting a reduction in fatal and nonfatal stroke risks for those with a systolic blood pressure above 160 mm Hg.

FEVER (the Felodipine Event Reduction study)22 found that treatment with a calcium channel blocker in even a low dose can significantly decrease cardiovascular events, cardiovascular disease, and heart failure compared with no treatment.

JATOS and VALISH (the Japanese Trial to Assess Optimal Systolic Blood Pressure in Elderly Hypertensive Patients23 and the Valsartan in Elderly Isolated Systolic Hypertension study)24 found that outcomes were similar with intensive vs standard treatment.

Ettehad et al25 performed a meta-analysis of 123 studies with more than 600,000 participants that provided strong evidence supporting blood pressure treatment goals below 130/90 mm Hg, in line with the SPRINT trial results.

BLOOD PRESSURE ISN’T EVERYTHING

Other trials remind us that although blood pressure is important, it is not the only factor affecting cardiovascular risk.

HOPE (the Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation)26 investigated the use of ramipril (an ACE inhibitor) in preventing myocardial infarction, stroke, or cardiovascular death in patients at high risk of cardiovascular events. The study included 9,297 participants over age 55 (mean age 66) with a baseline blood pressure 139/79 mm Hg. Follow-up was 4.5 years.

Ramipril was better than placebo, with significantly fewer patients experiencing adverse end points in the ramipril group compared with the placebo group:

- Myocardial infarction 9.9% vs 12.3%, RR 0.80, P < .001

- Cardiovascular death 6.1% vs 8.1%, RR 0.74, P < .001

- Stroke 3.4% vs 4.9%, RR = .68, P < .001

- The composite end point 14.0% vs 17.8%, RR 0.78, P < .001).

Results were even better in the subset of patients who had diabetes.27 However, the decrease in blood pressure attributable to antihypertensive therapy with ramipril was minimal (3–4 mm Hg systolic and 1–2 mm Hg diastolic). This slight change should not have been enough to produce significant differences in clinical outcomes, a major limitation of this trial. The investigators speculated that the positive results may be due to a class effect of ACE inhibitors.26

HOPE 328–30 explored the effect of blood pressure- and cholesterol-controlling drugs on the same primary end points but in patients at intermediate risk of major cardiovascular events. Investigators randomized the 12,705 patients to 4 treatment groups:

- Blood pressure control with candesartan (an ARB) plus hydrochlorothiazide (a thiazide diuretic)

- Cholesterol control with rosuvastatin (a statin)

- Blood pressure plus cholesterol control

- Placebo.

Therapy was started at a systolic blood pressure above 140 mm Hg.

Compared with placebo, the rate of composite events was significantly reduced in the rosuvastatin group (3.7% vs 4.8%, HR 0.76, P = .002)28 and the candesartan-hydrochlorothiazide-rosuvastatin group (3.6% vs 5.0%, HR 0.71; P = .005)29 but not in the candesartan-hydrochlorothiazide group (4.1% vs 4.4%; HR 0.93; P = .40).30

In addition, a subgroup analysis comparing active treatment vs placebo found a significant reduction in major cardiovascular events for treated patients whose baseline systolic blood pressure was in the upper third (> 143.5 mm Hg, mean 154.1 mm Hg), while treated patients in the lower middle and lower thirds had no significant reduction.30

These results suggest that intensive treatment to achieve a systolic blood pressure below 140 mm Hg in patients at intermediate risk may not be helpful. Nevertheless, there seems to be agreement that intensive treatment generally leads to a reduction in cardiovascular events. The results also show the benefit of lowering cholesterol.

Bundy et al31 performed a meta-analysis that provides support for intensive antihypertensive treatment. Reviewing 42 clinical trials in more than 144,000 patients, they found that treating to reach a target systolic blood pressure of 120 to 124 mm Hg can reduce cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality.

The trade-off is a minimal increase in the risk of adverse events. Also, the risk-benefit ratio of intensive treatment seems to vary in different patient subgroups.

WHAT ABOUT PATIENTS WITH COMORBIDITIES?

The debate over intensive vs standard treatment in blood pressure management extends beyond hypertension and includes important comorbidities such as diabetes, stroke, and renal disease. Patients with a history of stroke or end-stage renal disease have only a minimal mention in the AHA/ACC guidelines.

Diabetes

Emdin et al,32 in a meta-analysis of 40 trials that included more than 100,000 patients with diabetes, concluded that a 10-mm Hg lowering of systolic blood pressure significantly reduces the rates of all-cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, coronary heart disease, stroke, albuminuria, and retinopathy. Stratifying the results according to the systolic blood pressure achieved (≥ 130 or < 130 mm Hg), the relative risks of mortality, coronary heart disease, cardiovascular disease, heart failure, and albuminuria were actually lower in the higher stratum than in the lower.

ACCORD (the Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes)33 study provides contrary results. It examined intensive and standard blood pressure control targets in patients with type 2 diabetes at high risk of cardiovascular events, using primary outcome measures similar to those in SPRINT. It found no significant difference in fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular events between the intensive and standard blood pressure target arms.

Despite those results, the ACC/AHA guidelines still advocate for more intensive treatment (goal < 130/80 mm Hg) in all patients, including those with diabetes.1

The ADA position statement (September 2017) recommended a target below 140/90 mm Hg in patients with diabetes and hypertension.8 However, they also noted that lower systolic and diastolic blood pressure targets, such as below 130/80 mm Hg, may be appropriate for patients at high risk of cardiovascular disease “if they can be achieved without undue treatment burden.”8 Thus, it is not clear which blood pressure targets in patients with diabetes are the best.

Stroke

In patients with stroke, AHA/ACC guidelines1 recommend treatment if the blood pressure is 140/90 mm Hg or higher because antihypertensive therapy has been associated with a decrease in the recurrence of transient ischemic attack and stroke. The ideal target blood pressure is not known, but a goal of less than 130/80 mm Hg may be reasonable.

In the Secondary Prevention of Small Subcortical Strokes (SPS3) trial, a retrospective open-label trial, a target blood pressure below 130/80 mm Hg in patients with a history of lacunar stroke was associated with a lower risk of intracranial hemorrhage, but the difference was not statistically significant.34 For this reason, the ACC/AHA guidelines consider it reasonable to aim for a systolic blood pressure below 130 mm Hg in these patients.1

Renal disease

The ACC/AHA guidelines do not address how to manage hypertension in patients with end-stage renal disease, but for patients with chronic kidney disease they recommend a blood pressure target below 130/80 mm Hg.1 This recommendation is derived from the SPRINT trial,15 in which patients with stage 3 or 4 chronic kidney disease accounted for 28% of the study population. In that subgroup, intensive blood pressure control seemed to provide the same benefits for reduction in cardiovascular death and all-cause mortality.

TREAT PATIENTS, NOT NUMBERS

Blood pressure targets should be applied in the appropriate clinical context and on a patient-by-patient basis. In clinical practice, one size does not always fit all, as special cases exist.

For example, blood pressure can oscillate widely in patients with autonomic nerve disorders, making it difficult to strive for a specific target, especially an intensive one. Thus, it may be necessary to allow higher systolic blood pressure in these patients. Similarly, patients with diabetes or chronic kidney disease may be at higher risk of kidney injury with more intensive blood pressure management.

Treating numbers rather than patients may result in unbalanced patient care. The optimal approach to blood pressure management relies on a comprehensive risk factor assessment and shared decision-making with the patient before setting specific blood pressure targets.

OUR APPROACH

We aim for a blood pressure goal below 130/80 mm Hg for all patients with cardiovascular disease, according to the AHA/ACC guidelines. We aim for that same target in patients without cardiovascular disease but who have an elevated estimated cardiovascular risk (> 10%) over the next 10 years.

We recognize, however, that the benefits of aggressive blood pressure reduction may not be as clear in all patients, such as those with diabetes. We also recognize that some patient subgroups are at high risk of adverse events, including those with low diastolic pressure, chronic kidney disease, a history of falls, and older age. In those patients, we are extremely judicious when titrating antihypertensive medications. We often make smaller titrations, at longer intervals, and with more frequent laboratory testing and in-office follow-up.

Our process of managing hypertension through intensive blood pressure control to achieve lower systolic blood pressure targets requires a concerted effort among healthcare providers at all levels. It especially requires more involvement and investment from primary care providers to individualize treatment in their patients. This process has helped us to reach our treatment goals while limiting adverse effects of lower blood pressure targets.

MOVING FORWARD

Hypertension is a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease, and intensive blood pressure control has the potential to significantly reduce rates of morbidity and death associated with cardiovascular disease. Thus, a general consensus on the definition of hypertension and treatment goals is essential to reduce the risk of cardiovascular events in this large patient population.

Intensive blood pressure treatment has shown efficacy, but it has a small accompanying risk of adverse events, which varies in patient subgroups and affects the benefit-risk ratio of this therapy. For example, the cardiovascular benefit of intensive treatment is less clear in diabetic patients, and the risk of adverse events may be higher in older patients with chronic kidney disease.

Moving forward, more research is needed into the effects of intensive and standard treatment on patients of all ages, those with common comorbid conditions, and those with other important factors such as diastolic hypertension.

Finally, the various medical societies should collaborate on hypertension guideline development. This would require considerable planning and coordination but would ultimately be useful in creating a generalizable approach to hypertension management.

- Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018; 71(19):e127–e248. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.006

- Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA 2003; 289(19):2560–2572. doi:10.1001/jama.289.19.2560

- Go AS, Bauman MA, King SM, et al. An effective approach to high blood pressure control: a science advisory from the American Heart Association, the American College of Cardiology, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hypertension 2014; 63(4):878–885. doi:10.1161/HYP.0000000000000003

- James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA 2014; 311(5):507–520. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.284427

- Wright JT Jr, Fine LJ, Lackland DT, Ogedegbe G, Dennison Himmelfarb CR. Evidence supporting a systolic blood pressure goal of less than 150 mm Hg in patients aged 60 years or older: the minority view. Ann Intern Med 2014; 160(7):499–503. doi:10.7326/M13-2981

- Weber MA, Schiffrin EL, White WB, et al. Notice of duplicate publication [duplicate publication of Weber MA, Schiffrin EL, White WB, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of hypertension in the community: a statement by the American Society of Hypertension and the International Society of Hypertension. J Clin Hypertens 2014; 16(1):14–26. doi:10.1111/jch.12237] J Hypertens 2014; 32(1):3–15. doi:10.1097/HJH.0000000000000065

- Rosendorff C, Lackland DT, Allison M, et al. Treatment of hypertension in patients with coronary artery disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, and American Society of Hypertension. J Am Soc Hypertens 2015; 9(6):453–498. doi:10.1016/j.jash.2015.03.002

- de Boer IH, Bangalore S, Benetos A, et al. Diabetes and hypertension: a position statement by the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2017; 40(9):1273–1284. doi:10.2337/dci17-0026

- Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Rich R, Humphrey LL, Frost J, Forciea MA. Pharmacologic treatment of hypertension in adults aged 60 years or older to higher versus lower blood pressure targets: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Academy of Family Physicians. Ann Intern Med 2017; 166(6):430–437. doi:10.7326/M16-1785

- The Trials of Hypertension Prevention Collaborative Research Group. Effects of weight loss and sodium reduction intervention on blood pressure and hypertension incidence in over-weight people with high normal blood pressure: the Trials of Hypertension Prevention, phase II. Arch Intern Med 1997; 157(6):657–667. pmid:9080920