User login

Delayed first contraception use raises unwanted pregnancy risk

Young women who delay starting contraception when they start sexual activity are at increased risk of unwanted pregnancy, according to data from a cross-sectional study of more than 26,000 women in the United States.

Unintended pregnancy in the United States is associated with delayed prenatal care, premature birth, and low birth weight and remains more common among African American and Hispanic women than among white women, and it also is more common among low-income women than among high income women, wrote Mara E. Murray Horwitz, MD, of Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute in Boston and her colleagues.

“Reducing unintended pregnancy and the associated socioeconomic disparities is a national public health priority,” they wrote.

In a study published in Pediatrics, the researchers reviewed data from four cycles of the National Survey of Family Growth between 2002 and 2015. They examined self-reported responses from 26,359 women aged 15-44 years with sexual debuts during 1970-2014, including the dates of sexual debut, initiation of contraceptives, and rates of unwanted pregnancy. Timely contraceptive initiation was defined as use within a month of starting sexual activity.

Overall, one in five women reported delayed initiation of contraception. This delay was significantly associated with an increased unwanted pregnancy risk within 3 months of starting sexual activity, compared with timely use of contraception (adjusted risk ratio, 3.7). The average age of sexual debut was 17 years.

When the researchers examined subgroups, they found that one in four respondents who were African American, Hispanic, or low income reported delayed contraceptive initiation.

No association with unwanted pregnancy was found between effective versus less effective contraception methods. Timely contraceptive use increased during the study period from less than 10% in the 1970s to more than 25% in the 2000s, but condoms accounted for most of this increase. Use of other methods including long-acting reversible and short-acting hormonal options was low, especially among African American, Hispanic, and low-income women, Dr. Murray Horwitz and her colleagues noted.

The study was limited by several factors including the use of self-reports, lack of data on the exact start of contraceptive initiation, and the lack of association between contraceptive method and unwanted pregnancy, the researchers noted. However, the findings suggest that clinicians can help by intervening with young patients and educating them about early adoption of pregnancy prevention strategies.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health; Dr. Murray Horwitz was supported by an award from the NIH and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute. Another researcher received support from Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute to provide mentorship for the study. The remaining researcher had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Murray Horwitz M et al. Pediatrics. 2019;143(2):e20182463.

Despite a declining teen birth rate in the last several decades, the United States has the highest teen birth rate among industrialized nations. While many factors play into this rate, we know that, in many European countries with low teen birth rates, adolescents often initiate contraceptive methods before their sexual debut. As we often tell teenagers, they can become pregnant the “first time,” which makes initiating contraception early – and preferably before sexual debut – an important strategy to preventing unplanned pregnancy.

This study identifies the trends over time in the initiation of contraception in relationship to sexual debut and examines its effects on unplanned teen pregnancy. Understanding these trends can help clinicians more effectively target teen pregnancy.

I was pleasantly surprised to see that rates of timely contraceptive initiation have increased since 1970. Sadly, this rise is largely because of condom use. Use of effective forms of contraception – especially long-acting reversible forms of contraception (LARC), such as the IUD or the etonogestrel rod – still remain low at the time of sexual debut. While we continue to encourage LARCs as first line for pregnancy prevention, many patients are not getting the message about these highly effective, safe methods. Unsurprisingly, there are significant differences based on race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status on timely initiation of contraceptive methods, especially highly effective methods. This supports prior research which has shown significant barriers in access to contraception to these groups, which leads to higher rates of unplanned pregnancies.

Dr. Kelly Curran, MD, specializes in adolescent medicine at the University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma City. She is a member of the Pediatric News editorial advisory board and was asked to comment on the study by Murray Horwitz et al. Dr. Curran had no relevant financial disclosures.

Despite a declining teen birth rate in the last several decades, the United States has the highest teen birth rate among industrialized nations. While many factors play into this rate, we know that, in many European countries with low teen birth rates, adolescents often initiate contraceptive methods before their sexual debut. As we often tell teenagers, they can become pregnant the “first time,” which makes initiating contraception early – and preferably before sexual debut – an important strategy to preventing unplanned pregnancy.

This study identifies the trends over time in the initiation of contraception in relationship to sexual debut and examines its effects on unplanned teen pregnancy. Understanding these trends can help clinicians more effectively target teen pregnancy.

I was pleasantly surprised to see that rates of timely contraceptive initiation have increased since 1970. Sadly, this rise is largely because of condom use. Use of effective forms of contraception – especially long-acting reversible forms of contraception (LARC), such as the IUD or the etonogestrel rod – still remain low at the time of sexual debut. While we continue to encourage LARCs as first line for pregnancy prevention, many patients are not getting the message about these highly effective, safe methods. Unsurprisingly, there are significant differences based on race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status on timely initiation of contraceptive methods, especially highly effective methods. This supports prior research which has shown significant barriers in access to contraception to these groups, which leads to higher rates of unplanned pregnancies.

Dr. Kelly Curran, MD, specializes in adolescent medicine at the University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma City. She is a member of the Pediatric News editorial advisory board and was asked to comment on the study by Murray Horwitz et al. Dr. Curran had no relevant financial disclosures.

Despite a declining teen birth rate in the last several decades, the United States has the highest teen birth rate among industrialized nations. While many factors play into this rate, we know that, in many European countries with low teen birth rates, adolescents often initiate contraceptive methods before their sexual debut. As we often tell teenagers, they can become pregnant the “first time,” which makes initiating contraception early – and preferably before sexual debut – an important strategy to preventing unplanned pregnancy.

This study identifies the trends over time in the initiation of contraception in relationship to sexual debut and examines its effects on unplanned teen pregnancy. Understanding these trends can help clinicians more effectively target teen pregnancy.

I was pleasantly surprised to see that rates of timely contraceptive initiation have increased since 1970. Sadly, this rise is largely because of condom use. Use of effective forms of contraception – especially long-acting reversible forms of contraception (LARC), such as the IUD or the etonogestrel rod – still remain low at the time of sexual debut. While we continue to encourage LARCs as first line for pregnancy prevention, many patients are not getting the message about these highly effective, safe methods. Unsurprisingly, there are significant differences based on race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status on timely initiation of contraceptive methods, especially highly effective methods. This supports prior research which has shown significant barriers in access to contraception to these groups, which leads to higher rates of unplanned pregnancies.

Dr. Kelly Curran, MD, specializes in adolescent medicine at the University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma City. She is a member of the Pediatric News editorial advisory board and was asked to comment on the study by Murray Horwitz et al. Dr. Curran had no relevant financial disclosures.

Young women who delay starting contraception when they start sexual activity are at increased risk of unwanted pregnancy, according to data from a cross-sectional study of more than 26,000 women in the United States.

Unintended pregnancy in the United States is associated with delayed prenatal care, premature birth, and low birth weight and remains more common among African American and Hispanic women than among white women, and it also is more common among low-income women than among high income women, wrote Mara E. Murray Horwitz, MD, of Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute in Boston and her colleagues.

“Reducing unintended pregnancy and the associated socioeconomic disparities is a national public health priority,” they wrote.

In a study published in Pediatrics, the researchers reviewed data from four cycles of the National Survey of Family Growth between 2002 and 2015. They examined self-reported responses from 26,359 women aged 15-44 years with sexual debuts during 1970-2014, including the dates of sexual debut, initiation of contraceptives, and rates of unwanted pregnancy. Timely contraceptive initiation was defined as use within a month of starting sexual activity.

Overall, one in five women reported delayed initiation of contraception. This delay was significantly associated with an increased unwanted pregnancy risk within 3 months of starting sexual activity, compared with timely use of contraception (adjusted risk ratio, 3.7). The average age of sexual debut was 17 years.

When the researchers examined subgroups, they found that one in four respondents who were African American, Hispanic, or low income reported delayed contraceptive initiation.

No association with unwanted pregnancy was found between effective versus less effective contraception methods. Timely contraceptive use increased during the study period from less than 10% in the 1970s to more than 25% in the 2000s, but condoms accounted for most of this increase. Use of other methods including long-acting reversible and short-acting hormonal options was low, especially among African American, Hispanic, and low-income women, Dr. Murray Horwitz and her colleagues noted.

The study was limited by several factors including the use of self-reports, lack of data on the exact start of contraceptive initiation, and the lack of association between contraceptive method and unwanted pregnancy, the researchers noted. However, the findings suggest that clinicians can help by intervening with young patients and educating them about early adoption of pregnancy prevention strategies.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health; Dr. Murray Horwitz was supported by an award from the NIH and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute. Another researcher received support from Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute to provide mentorship for the study. The remaining researcher had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Murray Horwitz M et al. Pediatrics. 2019;143(2):e20182463.

Young women who delay starting contraception when they start sexual activity are at increased risk of unwanted pregnancy, according to data from a cross-sectional study of more than 26,000 women in the United States.

Unintended pregnancy in the United States is associated with delayed prenatal care, premature birth, and low birth weight and remains more common among African American and Hispanic women than among white women, and it also is more common among low-income women than among high income women, wrote Mara E. Murray Horwitz, MD, of Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute in Boston and her colleagues.

“Reducing unintended pregnancy and the associated socioeconomic disparities is a national public health priority,” they wrote.

In a study published in Pediatrics, the researchers reviewed data from four cycles of the National Survey of Family Growth between 2002 and 2015. They examined self-reported responses from 26,359 women aged 15-44 years with sexual debuts during 1970-2014, including the dates of sexual debut, initiation of contraceptives, and rates of unwanted pregnancy. Timely contraceptive initiation was defined as use within a month of starting sexual activity.

Overall, one in five women reported delayed initiation of contraception. This delay was significantly associated with an increased unwanted pregnancy risk within 3 months of starting sexual activity, compared with timely use of contraception (adjusted risk ratio, 3.7). The average age of sexual debut was 17 years.

When the researchers examined subgroups, they found that one in four respondents who were African American, Hispanic, or low income reported delayed contraceptive initiation.

No association with unwanted pregnancy was found between effective versus less effective contraception methods. Timely contraceptive use increased during the study period from less than 10% in the 1970s to more than 25% in the 2000s, but condoms accounted for most of this increase. Use of other methods including long-acting reversible and short-acting hormonal options was low, especially among African American, Hispanic, and low-income women, Dr. Murray Horwitz and her colleagues noted.

The study was limited by several factors including the use of self-reports, lack of data on the exact start of contraceptive initiation, and the lack of association between contraceptive method and unwanted pregnancy, the researchers noted. However, the findings suggest that clinicians can help by intervening with young patients and educating them about early adoption of pregnancy prevention strategies.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health; Dr. Murray Horwitz was supported by an award from the NIH and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute. Another researcher received support from Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute to provide mentorship for the study. The remaining researcher had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Murray Horwitz M et al. Pediatrics. 2019;143(2):e20182463.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: Women who delayed using contraception were significantly more likely to become pregnant within 3 months of starting sexual activity than were those who had initiated contraception use, especially black, Hispanic, and low-income women.

Major finding: Unwanted pregnancy within 3 months of sexual debut was 3.7 times more likely in women who delayed initial contraception use, compared with those who had timely initiation.

Study details: The data come from a cross-sectional study including 26,359 women with sexual debuts between 1970 and 2014.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health; Dr. Murray Horwitz was supported by an award from the NIH and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute. Another researcher received support from Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute to provide mentorship for the study. The remaining researcher had no relevant financial disclosures.

Source: Horwitz M et al. Pediatrics. 2019;143(2):e20182463.

SMFM and ACOG team up for interpregnancy care guidance

A new consensus statement places renewed focus on maternal interpregnancy care, with a goal of extending care past the postpartum period to provide a wellness-maximizing continuum of care.

The document, developed by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM), recognizes that pregnancy is part of the lifelong continuum of health and wellness. Although not all women will go on to have another pregnancy, the concept of interpregnancy care recognizes that ob.gyns. have a vital role that extends past the postpartum period.

“This is a shift in what we used to think was our job. We used to think that our job ended when the baby came out,” said the first author of the obstetric care consensus statement, Judette Marie Louis, MD, an ob.gyn. faculty member at the University of South Florida, Tampa, and a SMFM board member. “For too long, our focus was just the baby; we need to tell women, ‘You’re important too,’ ” she said in an interview.

“The interpregnancy period is an opportunity to address these complications of medical issues that have developed during pregnancy, to assess a woman’s mental and physical well-being, and to optimize her health along her life course,” Dr. Louis and her coauthors wrote in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

Conceptually, the opportunity for interpregnancy care arises after any pregnancy, no matter the outcome, and is part of the continuum of care for women of reproductive age. For women who do not intend a future pregnancy, well-woman care is the focus, while women who currently intend to become pregnant again receive interpregnancy care. Women may move from one arm of the continuum to the other if their intentions change or if they become pregnant, explained Dr. Louis and her coauthors.

Birth spacing

The new consensus document includes an emphasis on long-term health outcomes as well as maternal and neonatal outcomes in future pregnancies. Although the evidence is of no more than moderate quality, women should be advised to have an interpregnancy interval of at least 6 months and offered counseling about family planning before delivery. Risks and benefits of an interpregnancy interval of less than 18 months should be reviewed as well.

For women with a history of preterm birth and those who have had a prior cesarean delivery and desire a subsequent trial of labor, birth spacing is particularly important, noted Dr. Louis and her colleagues. There is higher-risk evidence for uterine rupture after cesarean delivery if delivery-to-delivery intervals are 18-24 months or less.

Recommendations regarding the length of the interpregnancy interval generally should not be affected by a history of prior infertility.

Other recommendations

High-quality evidence supports breast feeding’s salutary effects on maternal and child health, so women should receive anticipatory support and guidance to enable breastfeeding, according to the document.

In accordance with other guidelines, the document recommends that all women be screened for depression post partum and as part of well-woman care in the interpregnancy interval. Procedures for effective diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up should accompany the screening.

Best practices dictate that women are asked about alcohol, prescription, and nonprescription drug use as a routine matter. High-quality evidence supports offering smoking cessation support to women who smoke and giving specific advice about nutrition and physical activity that’s based on “proven behavioral techniques.”

Evidence is of moderate quality that women should be encouraged to reach their prepregnancy weight by a year after delivery, with the ultimate goal of having a body mass index of 18.5-24.9.

High-quality evidence backs encouragement to engage in safe sex practices, with care providers also advised to facilitate partner screening and treatment for STIs.

Screening for STIs should follow guidance put forward by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and should be offered to women at high risk for STIs; those with a history of STI should have a careful history taken to determine risks for current or repeat infections, wrote Dr. Louis and her coauthors. These strong recommendations have high-quality evidence behind them.

The consensus statement recommends screening women for intimate partner violence, with moderate-quality evidence to support the recommendation. Patient navigators, expert medical interpretation, and other health educators can be offered to women with health literacy or language and communication challenges, but the evidence backing the recommendation is of low quality.

A subset of the interpregnancy care recommendations gives additional guidance regarding women with a history of high-risk pregnancy. All women planning pregnancy – or who could become pregnant – should take 500 mcg of folic acid daily beginning 1 month before fertilization and continuing through the 12th week of pregnancy. Folic acid supplementation for women who have had children with neural tube defects should begin at least 3 months before fertilization and continue through 12 weeks of pregnancy, at a dose of 400 mg.

All prescription and nonprescription medications, as well as potential environmental teratogens, should be reviewed before a repeat pregnancy. This, as well as the folic acid recommendations, are strong recommendations backed by high-quality evidence.

When appropriate, genetic counseling should be offered to women who have had prior pregnancies with genetic disorders or congenital anomalies. Asymptomatic genitourinary infections should not be treated in women with a history of preterm birth during the interpregnancy interval. These are strong recommendations, but are backed by low to moderate quality evidence, wrote Dr. Louis and her colleagues.

Another section of the consensus document specifically addresses specific health conditions, including diabetes, gestational diabetes, gestational and chronic hypertension, and preeclampsia, as well as mental health disorders and overweight or obesity.

For each, Dr. Louis and her coauthors recommend counseling that reviews complications and risk for future disease; for example, not only does prior preeclampsia increase risk for that complication in future pregnancies, risk for later cardiovascular disease is also doubled. The document outlines recommended interpregnancy testing, management considerations and medications of concern for health care providers caring for women with these conditions, and condition-specific goals.

Of the association between gestational diabetes, hypertension, and preeclampsia with later disease, Dr. Louis said in the interview, “We don’t know. ... It may be that pregnancy accelerates these diseases. We do know that normal changes in pregnancy stress your body, and that preeclampsia damages your vessels. Pregnancy can give you a warning, but we don’t have enough information to predict the outcome” in later life. “We do know there is some advice we can give: stop smoking and maintain a normal body weight.”

Other conditions such as HIV, renal disease, epilepsy, autoimmune and thyroid disease, and thrombophilias and antiphospholipid antibody syndrome are also addressed in this section of the consensus document.

Specific attention also is given to psychosocial risks, such as socioeconomic disadvantages and being a member of a racial or ethnic minority. Social determinants of health are complex, said Dr. Louis, but socioeconomic and racial stressors can include the added burden of caring for loved ones with constrained resources. Additionally, there can be access issues: Women can get emergent care by presenting to the ED but receiving continued primary and specialty care can be much more of a challenge.

Regarding racism, Dr. Louis said, “We all come into caring for these women with certain ideas.” For example, it’s not enough to say of a patient, “She’s noncompliant. You need to ask why.” When the “why” question is asked, then you may discover, “there’s something you can help the patient with,” she said. “We need to ask why, and then take steps to help our patients.”

Document building

The working group for the consensus document felt it was important to include nonphysicians who care for women, Dr. Louis said, so drafts were reviewed by and input received from the American College of Nurse-Midwives and the National Association of Nurse Practitioners in Women’s Health. Both groups endorsed the document.

The collaborative process of putting drafts together and then reviewing and revising the document was a big part of the reason it took 2 years to produce the interpregnancy care consensus statement. “It was the equivalent of two full gestations with a short interpregnancy interval!” said Dr. Louis, laughing. But seeking input from all stakeholders strengthened the final product.

Dr. Louis reported no conflicts of interest and no outside sources of funding were reported.

SOURCE: Louis JM et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:e51-72.

A new consensus statement places renewed focus on maternal interpregnancy care, with a goal of extending care past the postpartum period to provide a wellness-maximizing continuum of care.

The document, developed by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM), recognizes that pregnancy is part of the lifelong continuum of health and wellness. Although not all women will go on to have another pregnancy, the concept of interpregnancy care recognizes that ob.gyns. have a vital role that extends past the postpartum period.

“This is a shift in what we used to think was our job. We used to think that our job ended when the baby came out,” said the first author of the obstetric care consensus statement, Judette Marie Louis, MD, an ob.gyn. faculty member at the University of South Florida, Tampa, and a SMFM board member. “For too long, our focus was just the baby; we need to tell women, ‘You’re important too,’ ” she said in an interview.

“The interpregnancy period is an opportunity to address these complications of medical issues that have developed during pregnancy, to assess a woman’s mental and physical well-being, and to optimize her health along her life course,” Dr. Louis and her coauthors wrote in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

Conceptually, the opportunity for interpregnancy care arises after any pregnancy, no matter the outcome, and is part of the continuum of care for women of reproductive age. For women who do not intend a future pregnancy, well-woman care is the focus, while women who currently intend to become pregnant again receive interpregnancy care. Women may move from one arm of the continuum to the other if their intentions change or if they become pregnant, explained Dr. Louis and her coauthors.

Birth spacing

The new consensus document includes an emphasis on long-term health outcomes as well as maternal and neonatal outcomes in future pregnancies. Although the evidence is of no more than moderate quality, women should be advised to have an interpregnancy interval of at least 6 months and offered counseling about family planning before delivery. Risks and benefits of an interpregnancy interval of less than 18 months should be reviewed as well.

For women with a history of preterm birth and those who have had a prior cesarean delivery and desire a subsequent trial of labor, birth spacing is particularly important, noted Dr. Louis and her colleagues. There is higher-risk evidence for uterine rupture after cesarean delivery if delivery-to-delivery intervals are 18-24 months or less.

Recommendations regarding the length of the interpregnancy interval generally should not be affected by a history of prior infertility.

Other recommendations

High-quality evidence supports breast feeding’s salutary effects on maternal and child health, so women should receive anticipatory support and guidance to enable breastfeeding, according to the document.

In accordance with other guidelines, the document recommends that all women be screened for depression post partum and as part of well-woman care in the interpregnancy interval. Procedures for effective diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up should accompany the screening.

Best practices dictate that women are asked about alcohol, prescription, and nonprescription drug use as a routine matter. High-quality evidence supports offering smoking cessation support to women who smoke and giving specific advice about nutrition and physical activity that’s based on “proven behavioral techniques.”

Evidence is of moderate quality that women should be encouraged to reach their prepregnancy weight by a year after delivery, with the ultimate goal of having a body mass index of 18.5-24.9.

High-quality evidence backs encouragement to engage in safe sex practices, with care providers also advised to facilitate partner screening and treatment for STIs.

Screening for STIs should follow guidance put forward by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and should be offered to women at high risk for STIs; those with a history of STI should have a careful history taken to determine risks for current or repeat infections, wrote Dr. Louis and her coauthors. These strong recommendations have high-quality evidence behind them.

The consensus statement recommends screening women for intimate partner violence, with moderate-quality evidence to support the recommendation. Patient navigators, expert medical interpretation, and other health educators can be offered to women with health literacy or language and communication challenges, but the evidence backing the recommendation is of low quality.

A subset of the interpregnancy care recommendations gives additional guidance regarding women with a history of high-risk pregnancy. All women planning pregnancy – or who could become pregnant – should take 500 mcg of folic acid daily beginning 1 month before fertilization and continuing through the 12th week of pregnancy. Folic acid supplementation for women who have had children with neural tube defects should begin at least 3 months before fertilization and continue through 12 weeks of pregnancy, at a dose of 400 mg.

All prescription and nonprescription medications, as well as potential environmental teratogens, should be reviewed before a repeat pregnancy. This, as well as the folic acid recommendations, are strong recommendations backed by high-quality evidence.

When appropriate, genetic counseling should be offered to women who have had prior pregnancies with genetic disorders or congenital anomalies. Asymptomatic genitourinary infections should not be treated in women with a history of preterm birth during the interpregnancy interval. These are strong recommendations, but are backed by low to moderate quality evidence, wrote Dr. Louis and her colleagues.

Another section of the consensus document specifically addresses specific health conditions, including diabetes, gestational diabetes, gestational and chronic hypertension, and preeclampsia, as well as mental health disorders and overweight or obesity.

For each, Dr. Louis and her coauthors recommend counseling that reviews complications and risk for future disease; for example, not only does prior preeclampsia increase risk for that complication in future pregnancies, risk for later cardiovascular disease is also doubled. The document outlines recommended interpregnancy testing, management considerations and medications of concern for health care providers caring for women with these conditions, and condition-specific goals.

Of the association between gestational diabetes, hypertension, and preeclampsia with later disease, Dr. Louis said in the interview, “We don’t know. ... It may be that pregnancy accelerates these diseases. We do know that normal changes in pregnancy stress your body, and that preeclampsia damages your vessels. Pregnancy can give you a warning, but we don’t have enough information to predict the outcome” in later life. “We do know there is some advice we can give: stop smoking and maintain a normal body weight.”

Other conditions such as HIV, renal disease, epilepsy, autoimmune and thyroid disease, and thrombophilias and antiphospholipid antibody syndrome are also addressed in this section of the consensus document.

Specific attention also is given to psychosocial risks, such as socioeconomic disadvantages and being a member of a racial or ethnic minority. Social determinants of health are complex, said Dr. Louis, but socioeconomic and racial stressors can include the added burden of caring for loved ones with constrained resources. Additionally, there can be access issues: Women can get emergent care by presenting to the ED but receiving continued primary and specialty care can be much more of a challenge.

Regarding racism, Dr. Louis said, “We all come into caring for these women with certain ideas.” For example, it’s not enough to say of a patient, “She’s noncompliant. You need to ask why.” When the “why” question is asked, then you may discover, “there’s something you can help the patient with,” she said. “We need to ask why, and then take steps to help our patients.”

Document building

The working group for the consensus document felt it was important to include nonphysicians who care for women, Dr. Louis said, so drafts were reviewed by and input received from the American College of Nurse-Midwives and the National Association of Nurse Practitioners in Women’s Health. Both groups endorsed the document.

The collaborative process of putting drafts together and then reviewing and revising the document was a big part of the reason it took 2 years to produce the interpregnancy care consensus statement. “It was the equivalent of two full gestations with a short interpregnancy interval!” said Dr. Louis, laughing. But seeking input from all stakeholders strengthened the final product.

Dr. Louis reported no conflicts of interest and no outside sources of funding were reported.

SOURCE: Louis JM et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:e51-72.

A new consensus statement places renewed focus on maternal interpregnancy care, with a goal of extending care past the postpartum period to provide a wellness-maximizing continuum of care.

The document, developed by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM), recognizes that pregnancy is part of the lifelong continuum of health and wellness. Although not all women will go on to have another pregnancy, the concept of interpregnancy care recognizes that ob.gyns. have a vital role that extends past the postpartum period.

“This is a shift in what we used to think was our job. We used to think that our job ended when the baby came out,” said the first author of the obstetric care consensus statement, Judette Marie Louis, MD, an ob.gyn. faculty member at the University of South Florida, Tampa, and a SMFM board member. “For too long, our focus was just the baby; we need to tell women, ‘You’re important too,’ ” she said in an interview.

“The interpregnancy period is an opportunity to address these complications of medical issues that have developed during pregnancy, to assess a woman’s mental and physical well-being, and to optimize her health along her life course,” Dr. Louis and her coauthors wrote in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

Conceptually, the opportunity for interpregnancy care arises after any pregnancy, no matter the outcome, and is part of the continuum of care for women of reproductive age. For women who do not intend a future pregnancy, well-woman care is the focus, while women who currently intend to become pregnant again receive interpregnancy care. Women may move from one arm of the continuum to the other if their intentions change or if they become pregnant, explained Dr. Louis and her coauthors.

Birth spacing

The new consensus document includes an emphasis on long-term health outcomes as well as maternal and neonatal outcomes in future pregnancies. Although the evidence is of no more than moderate quality, women should be advised to have an interpregnancy interval of at least 6 months and offered counseling about family planning before delivery. Risks and benefits of an interpregnancy interval of less than 18 months should be reviewed as well.

For women with a history of preterm birth and those who have had a prior cesarean delivery and desire a subsequent trial of labor, birth spacing is particularly important, noted Dr. Louis and her colleagues. There is higher-risk evidence for uterine rupture after cesarean delivery if delivery-to-delivery intervals are 18-24 months or less.

Recommendations regarding the length of the interpregnancy interval generally should not be affected by a history of prior infertility.

Other recommendations

High-quality evidence supports breast feeding’s salutary effects on maternal and child health, so women should receive anticipatory support and guidance to enable breastfeeding, according to the document.

In accordance with other guidelines, the document recommends that all women be screened for depression post partum and as part of well-woman care in the interpregnancy interval. Procedures for effective diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up should accompany the screening.

Best practices dictate that women are asked about alcohol, prescription, and nonprescription drug use as a routine matter. High-quality evidence supports offering smoking cessation support to women who smoke and giving specific advice about nutrition and physical activity that’s based on “proven behavioral techniques.”

Evidence is of moderate quality that women should be encouraged to reach their prepregnancy weight by a year after delivery, with the ultimate goal of having a body mass index of 18.5-24.9.

High-quality evidence backs encouragement to engage in safe sex practices, with care providers also advised to facilitate partner screening and treatment for STIs.

Screening for STIs should follow guidance put forward by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and should be offered to women at high risk for STIs; those with a history of STI should have a careful history taken to determine risks for current or repeat infections, wrote Dr. Louis and her coauthors. These strong recommendations have high-quality evidence behind them.

The consensus statement recommends screening women for intimate partner violence, with moderate-quality evidence to support the recommendation. Patient navigators, expert medical interpretation, and other health educators can be offered to women with health literacy or language and communication challenges, but the evidence backing the recommendation is of low quality.

A subset of the interpregnancy care recommendations gives additional guidance regarding women with a history of high-risk pregnancy. All women planning pregnancy – or who could become pregnant – should take 500 mcg of folic acid daily beginning 1 month before fertilization and continuing through the 12th week of pregnancy. Folic acid supplementation for women who have had children with neural tube defects should begin at least 3 months before fertilization and continue through 12 weeks of pregnancy, at a dose of 400 mg.

All prescription and nonprescription medications, as well as potential environmental teratogens, should be reviewed before a repeat pregnancy. This, as well as the folic acid recommendations, are strong recommendations backed by high-quality evidence.

When appropriate, genetic counseling should be offered to women who have had prior pregnancies with genetic disorders or congenital anomalies. Asymptomatic genitourinary infections should not be treated in women with a history of preterm birth during the interpregnancy interval. These are strong recommendations, but are backed by low to moderate quality evidence, wrote Dr. Louis and her colleagues.

Another section of the consensus document specifically addresses specific health conditions, including diabetes, gestational diabetes, gestational and chronic hypertension, and preeclampsia, as well as mental health disorders and overweight or obesity.

For each, Dr. Louis and her coauthors recommend counseling that reviews complications and risk for future disease; for example, not only does prior preeclampsia increase risk for that complication in future pregnancies, risk for later cardiovascular disease is also doubled. The document outlines recommended interpregnancy testing, management considerations and medications of concern for health care providers caring for women with these conditions, and condition-specific goals.

Of the association between gestational diabetes, hypertension, and preeclampsia with later disease, Dr. Louis said in the interview, “We don’t know. ... It may be that pregnancy accelerates these diseases. We do know that normal changes in pregnancy stress your body, and that preeclampsia damages your vessels. Pregnancy can give you a warning, but we don’t have enough information to predict the outcome” in later life. “We do know there is some advice we can give: stop smoking and maintain a normal body weight.”

Other conditions such as HIV, renal disease, epilepsy, autoimmune and thyroid disease, and thrombophilias and antiphospholipid antibody syndrome are also addressed in this section of the consensus document.

Specific attention also is given to psychosocial risks, such as socioeconomic disadvantages and being a member of a racial or ethnic minority. Social determinants of health are complex, said Dr. Louis, but socioeconomic and racial stressors can include the added burden of caring for loved ones with constrained resources. Additionally, there can be access issues: Women can get emergent care by presenting to the ED but receiving continued primary and specialty care can be much more of a challenge.

Regarding racism, Dr. Louis said, “We all come into caring for these women with certain ideas.” For example, it’s not enough to say of a patient, “She’s noncompliant. You need to ask why.” When the “why” question is asked, then you may discover, “there’s something you can help the patient with,” she said. “We need to ask why, and then take steps to help our patients.”

Document building

The working group for the consensus document felt it was important to include nonphysicians who care for women, Dr. Louis said, so drafts were reviewed by and input received from the American College of Nurse-Midwives and the National Association of Nurse Practitioners in Women’s Health. Both groups endorsed the document.

The collaborative process of putting drafts together and then reviewing and revising the document was a big part of the reason it took 2 years to produce the interpregnancy care consensus statement. “It was the equivalent of two full gestations with a short interpregnancy interval!” said Dr. Louis, laughing. But seeking input from all stakeholders strengthened the final product.

Dr. Louis reported no conflicts of interest and no outside sources of funding were reported.

SOURCE: Louis JM et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:e51-72.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

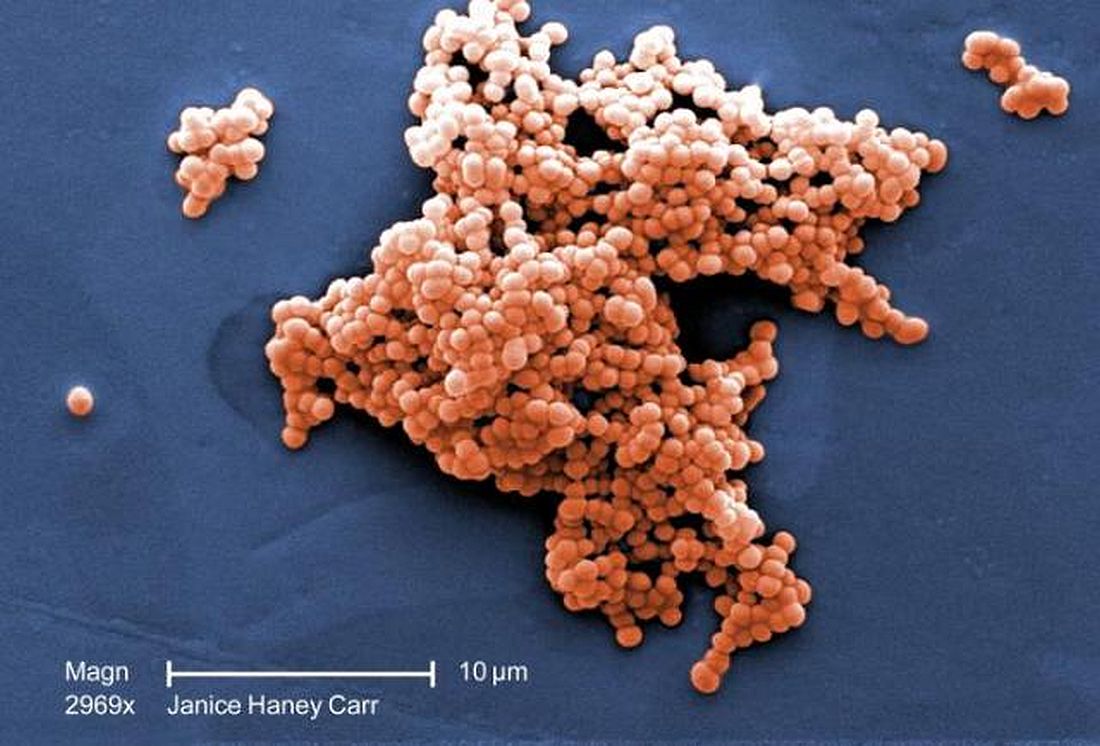

Incidence of late-onset GBS cases are higher than early-onset disease

according to a multistate study of invasive group B streptococcal disease published in JAMA Pediatrics.

Using data from the Active Bacterial Core surveillance (ABCs) program, Srinivas Acharya Nanduri, MD, MPH, at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and colleagues performed an analysis of early-onset disease (EOD) and late-onset disease (LOD) cases of group B Streptococcus (GBS) in infants from 10 different states between 2006 and 2015, and whether mothers of infants with EOD received intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis (IAP). EOD was defined as between 0 and 6 days old, while LOD occurred between 7 days and 89 days old.

They found 1,277 cases of EOD and 1,387 cases of LOD in total, with a decrease in incidence of EOD from 0.37 per 1,000 live births in 2006 to 0.23 per 1,000 live births in 2015 (P less than .001); LOD incidence remained stable at a mean 0.31 per 1,000 live births during the same time period.

In 2015, the national burden for EOD and LOD was estimated at 840 and 1,265 cases, respectively. Mothers of infants with EOD did not have indications for and did not receive IAP in 617 cases (48%) and did not receive IAP despite indications in 278 (22%) cases.

“While the current culture-based screening strategy has been highly successful in reducing EOD burden, our data show that almost half of remaining infants with EOD were born to mothers with no indication for receiving IAP,” Dr. Nanduri and colleagues wrote.

Because there currently is no effective prevention strategy against LOS GBS, the investigators wrote that a maternal vaccine against the most common serotypes “holds promise to prevent a substantial portion of this remaining burden,” and noted several GBS candidate vaccines were in advanced stages of development.

The researchers also looked at GBS serotype data in 1,743 patients from seven different centers. The most commonly found serotype isolates of 887 EOD cases were Ia (242 cases, 27%) and III (242 cases, 27%) overall. Serotype III was most common for LOD cases (481 cases, 56%) and increased in incidence from 0.12 per 1,000 live births to 0.20 per 1,000 live births during the study period (P less than .001), while serotype IV was responsible for 53 cases (6%) of both EOD and LOD.

Dr. Nanduri and associates wrote that over 99% of the serotyped EOD (881 cases) and serotyped LOD (853 cases) cases were caused by serotypes Ia, Ib, II, III, IV, and V. With regard to antimicrobial resistance, there were no cases of beta-lactam resistance, but there was constitutive clindamycin resistance in 359 isolate test results (21%).

The researchers noted that they were limited in the study by 1 year of whole-genome sequencing data, the ABCs capturing only 10% of live birth data in the United States, and conclusions on EOD prevention restricted to data from labor and delivery records.

This study was funded in part by the CDC. Paula S. Vagnone received grants from the CDC, while William S. Schaffner, MD, received grants from the CDC and personal fees from Pfizer, Merck, SutroVax, Shionogi, Dynavax, and Seqirus outside of the study. The other authors reported no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Nanduri SA et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Jan 14. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4826.

Perinatal group B Streptococcus (GBS) disease prevention guidelines are credited for the low rate of early-onset disease (EOD) cases of GBS in the United States, but the practice of intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis (IAP) remains controversial in places like the United Kingdom where the National Health Service does not recommend screening-based IAP for GBS, Sagori Mukhopadhyay, MD, MMSc, and Karen M. Puopolo, MD, PhD, wrote in a related editorial.

One reason for concern about GBS IAP policies is that, despite the decreased number of EOD cases after implementation of IAP, the rate of late-onset disease (LOD) cases remain the same, the authors wrote. And implementation of IAP is not perfect: In some cases IAP was used for less than the recommended duration, used less effective drugs, or given too late so fetal infections were already established.

In addition, some may be uncomfortable with increased perinatal exposure to antibiotics – “a long-held concern about the extent to which widespread perinatal antibiotic use may contribute to the emergence and expansion of antibiotic-resistant GBS,” they added. However, despite the concern, the fatality ratio for EOD was 7% in the study by Nanduri et al., and one complication of GBS in survivors is neurodevelopmental impairment, according to a meta-analysis of 18 studies.

One solution that could address both EOD and LOD cases of GBS is the development of a GBS vaccine. Although there is reluctance to vaccinate pregnant women, recent studies have shown success in vaccinating women for influenza, tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis; these recent efforts have “reinvigorated” academia’s interest in vaccine research for this population.

“Vaccination certainly could be a first step to eliminating neonatal GBS disease in the United States and may be the only available approach to addressing the substantial international burden of GBS-associated stillbirth, preterm birth, and neonatal disease morbidity and mortality,” the authors wrote. “But for now, while GBS IAP may be imperfect, it is the success we have.”

Dr. Mukhopadhyay and Dr. Puopolo are from the division of neonatology at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Dr. Mukhopadhyay and Dr. Puopolo commented on the study by Nanduri et al. in an accompanying editorial (Mukhopadhyay et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4824). They reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Perinatal group B Streptococcus (GBS) disease prevention guidelines are credited for the low rate of early-onset disease (EOD) cases of GBS in the United States, but the practice of intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis (IAP) remains controversial in places like the United Kingdom where the National Health Service does not recommend screening-based IAP for GBS, Sagori Mukhopadhyay, MD, MMSc, and Karen M. Puopolo, MD, PhD, wrote in a related editorial.

One reason for concern about GBS IAP policies is that, despite the decreased number of EOD cases after implementation of IAP, the rate of late-onset disease (LOD) cases remain the same, the authors wrote. And implementation of IAP is not perfect: In some cases IAP was used for less than the recommended duration, used less effective drugs, or given too late so fetal infections were already established.

In addition, some may be uncomfortable with increased perinatal exposure to antibiotics – “a long-held concern about the extent to which widespread perinatal antibiotic use may contribute to the emergence and expansion of antibiotic-resistant GBS,” they added. However, despite the concern, the fatality ratio for EOD was 7% in the study by Nanduri et al., and one complication of GBS in survivors is neurodevelopmental impairment, according to a meta-analysis of 18 studies.

One solution that could address both EOD and LOD cases of GBS is the development of a GBS vaccine. Although there is reluctance to vaccinate pregnant women, recent studies have shown success in vaccinating women for influenza, tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis; these recent efforts have “reinvigorated” academia’s interest in vaccine research for this population.

“Vaccination certainly could be a first step to eliminating neonatal GBS disease in the United States and may be the only available approach to addressing the substantial international burden of GBS-associated stillbirth, preterm birth, and neonatal disease morbidity and mortality,” the authors wrote. “But for now, while GBS IAP may be imperfect, it is the success we have.”

Dr. Mukhopadhyay and Dr. Puopolo are from the division of neonatology at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Dr. Mukhopadhyay and Dr. Puopolo commented on the study by Nanduri et al. in an accompanying editorial (Mukhopadhyay et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4824). They reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Perinatal group B Streptococcus (GBS) disease prevention guidelines are credited for the low rate of early-onset disease (EOD) cases of GBS in the United States, but the practice of intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis (IAP) remains controversial in places like the United Kingdom where the National Health Service does not recommend screening-based IAP for GBS, Sagori Mukhopadhyay, MD, MMSc, and Karen M. Puopolo, MD, PhD, wrote in a related editorial.

One reason for concern about GBS IAP policies is that, despite the decreased number of EOD cases after implementation of IAP, the rate of late-onset disease (LOD) cases remain the same, the authors wrote. And implementation of IAP is not perfect: In some cases IAP was used for less than the recommended duration, used less effective drugs, or given too late so fetal infections were already established.

In addition, some may be uncomfortable with increased perinatal exposure to antibiotics – “a long-held concern about the extent to which widespread perinatal antibiotic use may contribute to the emergence and expansion of antibiotic-resistant GBS,” they added. However, despite the concern, the fatality ratio for EOD was 7% in the study by Nanduri et al., and one complication of GBS in survivors is neurodevelopmental impairment, according to a meta-analysis of 18 studies.

One solution that could address both EOD and LOD cases of GBS is the development of a GBS vaccine. Although there is reluctance to vaccinate pregnant women, recent studies have shown success in vaccinating women for influenza, tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis; these recent efforts have “reinvigorated” academia’s interest in vaccine research for this population.

“Vaccination certainly could be a first step to eliminating neonatal GBS disease in the United States and may be the only available approach to addressing the substantial international burden of GBS-associated stillbirth, preterm birth, and neonatal disease morbidity and mortality,” the authors wrote. “But for now, while GBS IAP may be imperfect, it is the success we have.”

Dr. Mukhopadhyay and Dr. Puopolo are from the division of neonatology at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Dr. Mukhopadhyay and Dr. Puopolo commented on the study by Nanduri et al. in an accompanying editorial (Mukhopadhyay et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4824). They reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

according to a multistate study of invasive group B streptococcal disease published in JAMA Pediatrics.

Using data from the Active Bacterial Core surveillance (ABCs) program, Srinivas Acharya Nanduri, MD, MPH, at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and colleagues performed an analysis of early-onset disease (EOD) and late-onset disease (LOD) cases of group B Streptococcus (GBS) in infants from 10 different states between 2006 and 2015, and whether mothers of infants with EOD received intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis (IAP). EOD was defined as between 0 and 6 days old, while LOD occurred between 7 days and 89 days old.

They found 1,277 cases of EOD and 1,387 cases of LOD in total, with a decrease in incidence of EOD from 0.37 per 1,000 live births in 2006 to 0.23 per 1,000 live births in 2015 (P less than .001); LOD incidence remained stable at a mean 0.31 per 1,000 live births during the same time period.

In 2015, the national burden for EOD and LOD was estimated at 840 and 1,265 cases, respectively. Mothers of infants with EOD did not have indications for and did not receive IAP in 617 cases (48%) and did not receive IAP despite indications in 278 (22%) cases.

“While the current culture-based screening strategy has been highly successful in reducing EOD burden, our data show that almost half of remaining infants with EOD were born to mothers with no indication for receiving IAP,” Dr. Nanduri and colleagues wrote.

Because there currently is no effective prevention strategy against LOS GBS, the investigators wrote that a maternal vaccine against the most common serotypes “holds promise to prevent a substantial portion of this remaining burden,” and noted several GBS candidate vaccines were in advanced stages of development.

The researchers also looked at GBS serotype data in 1,743 patients from seven different centers. The most commonly found serotype isolates of 887 EOD cases were Ia (242 cases, 27%) and III (242 cases, 27%) overall. Serotype III was most common for LOD cases (481 cases, 56%) and increased in incidence from 0.12 per 1,000 live births to 0.20 per 1,000 live births during the study period (P less than .001), while serotype IV was responsible for 53 cases (6%) of both EOD and LOD.

Dr. Nanduri and associates wrote that over 99% of the serotyped EOD (881 cases) and serotyped LOD (853 cases) cases were caused by serotypes Ia, Ib, II, III, IV, and V. With regard to antimicrobial resistance, there were no cases of beta-lactam resistance, but there was constitutive clindamycin resistance in 359 isolate test results (21%).

The researchers noted that they were limited in the study by 1 year of whole-genome sequencing data, the ABCs capturing only 10% of live birth data in the United States, and conclusions on EOD prevention restricted to data from labor and delivery records.

This study was funded in part by the CDC. Paula S. Vagnone received grants from the CDC, while William S. Schaffner, MD, received grants from the CDC and personal fees from Pfizer, Merck, SutroVax, Shionogi, Dynavax, and Seqirus outside of the study. The other authors reported no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Nanduri SA et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Jan 14. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4826.

according to a multistate study of invasive group B streptococcal disease published in JAMA Pediatrics.

Using data from the Active Bacterial Core surveillance (ABCs) program, Srinivas Acharya Nanduri, MD, MPH, at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and colleagues performed an analysis of early-onset disease (EOD) and late-onset disease (LOD) cases of group B Streptococcus (GBS) in infants from 10 different states between 2006 and 2015, and whether mothers of infants with EOD received intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis (IAP). EOD was defined as between 0 and 6 days old, while LOD occurred between 7 days and 89 days old.

They found 1,277 cases of EOD and 1,387 cases of LOD in total, with a decrease in incidence of EOD from 0.37 per 1,000 live births in 2006 to 0.23 per 1,000 live births in 2015 (P less than .001); LOD incidence remained stable at a mean 0.31 per 1,000 live births during the same time period.

In 2015, the national burden for EOD and LOD was estimated at 840 and 1,265 cases, respectively. Mothers of infants with EOD did not have indications for and did not receive IAP in 617 cases (48%) and did not receive IAP despite indications in 278 (22%) cases.

“While the current culture-based screening strategy has been highly successful in reducing EOD burden, our data show that almost half of remaining infants with EOD were born to mothers with no indication for receiving IAP,” Dr. Nanduri and colleagues wrote.

Because there currently is no effective prevention strategy against LOS GBS, the investigators wrote that a maternal vaccine against the most common serotypes “holds promise to prevent a substantial portion of this remaining burden,” and noted several GBS candidate vaccines were in advanced stages of development.

The researchers also looked at GBS serotype data in 1,743 patients from seven different centers. The most commonly found serotype isolates of 887 EOD cases were Ia (242 cases, 27%) and III (242 cases, 27%) overall. Serotype III was most common for LOD cases (481 cases, 56%) and increased in incidence from 0.12 per 1,000 live births to 0.20 per 1,000 live births during the study period (P less than .001), while serotype IV was responsible for 53 cases (6%) of both EOD and LOD.

Dr. Nanduri and associates wrote that over 99% of the serotyped EOD (881 cases) and serotyped LOD (853 cases) cases were caused by serotypes Ia, Ib, II, III, IV, and V. With regard to antimicrobial resistance, there were no cases of beta-lactam resistance, but there was constitutive clindamycin resistance in 359 isolate test results (21%).

The researchers noted that they were limited in the study by 1 year of whole-genome sequencing data, the ABCs capturing only 10% of live birth data in the United States, and conclusions on EOD prevention restricted to data from labor and delivery records.

This study was funded in part by the CDC. Paula S. Vagnone received grants from the CDC, while William S. Schaffner, MD, received grants from the CDC and personal fees from Pfizer, Merck, SutroVax, Shionogi, Dynavax, and Seqirus outside of the study. The other authors reported no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Nanduri SA et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Jan 14. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4826.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: Between 2006 and 2015, early-onset disease cases of group B Streptococcus (GBS) declined, while the incidence of late-onset cases did not change.

Major finding: The rate of early-onset GBS declined from 0.37 to 0.23 per 1,000 live births and the rate of late-onset GBS cases remained at a mean 0.31 per 1,000 live births.

Study details: A population-based study of infants with early-onset disease and late-onset disease GBS from 10 different states in the Active Bacterial Core surveillance program between 2006 and 2015.

Disclosures: This study was funded in part by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Paula S. Vagnone received grants from the CDC, while William S. Schaffner, MD, received grants from the CDC and personal fees from Pfizer, Merck, SutroVax, Shionogi, Dynavax, and Seqirus outside of the study. The other authors reported no relevant disclosures.

Source: Nanduri SA et al. JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Jan 14. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4826.

Soy didn’t up all-cause mortality in breast cancer survivors

A cohort of Chinese women who are breast cancer survivors had no increased mortality from soy intake, according to a new study.

The work adds to the existing body of evidence that women with breast cancer, or risk for breast cancer, don’t need to modify their soy intake to mitigate risk, said the study’s first author, Suzanne C. Ho, PhD.

Speaking at the annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society, Dr. Ho noted that the combination of increasing breast cancer incidence and improved outcome has resulted in larger numbers of breast cancer survivors in Hong Kong, where she is professor emerita at the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

The prospective, ongoing study examines the association between soy intake pre- and postdiagnosis and total mortality for Chinese women who are breast cancer survivors. Dr. Ho said that she and her colleagues hypothesized that they would not see higher mortality among women who had higher soy intake – and this was the case.

Of 1,497 breast cancer survivors drawn from two facilities in Hong Kong, those who consumed higher quantities of dietary soy did not have increased risk of all-cause mortality, compared with those in the lowest tertile of soy consumption.

There are theoretical underpinnings for thinking that soy could be a player in cancer risk, but the biochemistry and epidemiology behind the studies are complicated. Estrogen plays a role in human breast cancer, and many modern breast cancer treatments actually dampen endogenous estrogens.

However, epidemiologic data have shown that consumption of soy-based foods – which contain phytoestrogens, primarily in the form of isoflavones – is inversely associated with developing breast cancer.

This is all part of why soy-based foods have been thought of as a mixed bag with regard to breast cancer: Soy isoflavones are, said Dr. Ho, “Natural estrogen receptor modulators that possess both estrogenlike and antiestrogenic properties.”

Other chemicals contained in soy may fight cancer, with effects that are antioxidative and strengthen immune response. Soy constituents also inhibit DNA topoisomerase I and II, proteases, tyrosine kinases, and inositol phosphate, effects that can slow tumor growth. Still, one soy isoflavone, genistein, actually can promote growth of estrogen-dependent tumors in rats, said Dr. Ho

Dr. Ho and her colleagues enrolled Hong Kong residents for the study of mortality among breast cancer survivors. Participants were included if they were Chinese, female, aged 24-77 years, and had their first primary breast cancer histologically confirmed within 12 months of entering the study. Cancer had to be graded below stage III.

Using a 109-item validated food questionnaire, investigators gathered information about participants’ soy intake and general diet for the year prior to breast cancer diagnosis. Other patient characteristics, relevant prognostic information from medical records, and anthropometric data were collected at baseline, and repeated at 18, 36, and 60 months.

The primary outcome measure – all-cause mortality during the follow-up period – was tracked for a mean 50.9 months, with a 78% retention rate for study participants, said Dr. Ho. In total, 96 patients died during follow-up, making up 5.9% of the premenopausal and 7% of the postmenopausal participants.

Statistical analysis corrected for potential confounders, including patient and disease characteristics and treatment modalities, as well as overall energy consumption.

Patients were evenly divided into tertiles of soy isoflavone intake, with cutpoints of 3.77 mg/1,000 kcal and 10.05 mg/1,000 kcal for the lower limit of the two higher tertiles. For the highest tertile, though, mean isoflavone intake was actually 20.87 mg/1,000 kcal.

Patient, disease, and treatment characteristics did not differ significantly among the tertiles.

An adjusted statistical analysis looked at pre- and postmenopausal women separately by tertile of soy isoflavone consumption, setting the hazard ratio for all-cause mortality at 1.00 for women in the lowest tertile of soy consumption.

For premenopausal women in the middle tertile, the HR was 0.45 (95% confidence interval, 0.20-1.00), and 0.86 for those in the highest tertile (95% CI, 0.43-1.72); 782 participants, in all, were premenopausal.

For the 715 postmenopausal women, the HR for those in the middle tertile of soy consumption was 0.94 (95% CI, 0.43-2.05), and 1.11 in the highest (95% CI, 0.54-2.29).

Taking all pre- and postmenopausal participants together, those in the middle tertile of soy isoflavone intake had an all-cause mortality HR of 0.63 (95% CI, 0.37-1.09). For the highest tertile of the full cohort, the HR was 0.95 (95% CI, 0.58-1.55).

Confidence intervals were wide in these findings, but Dr. Ho noted that “moderate soy food intake might be associated with better survival.”

“Prediagnosis soy intake did not increase the risk of all-cause mortality in breast cancer survivors,” said Dr. Ho, findings she called “consistent with the literature that soy consumption does not adversely effect breast cancer survival.”

The study is ongoing, she explained, and “longer follow-up will provide further evidence on the effect of pre- and postdiagnosis soy intake on breast cancer outcomes.”

The study had a homogeneous population of southern Chinese women, with fairly good retention and robust statistical adjustment for confounders. However, it wasn’t possible to assess bioavailability of isoflavones and their metabolites, which can vary according to individual microbiota. Also, researchers did not track whether patients used traditional Chinese medicine.

The World Cancer Research Fund International supported the study. Dr. Ho reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Ho S et al. NAMS 2018, Abstract S-23.

A cohort of Chinese women who are breast cancer survivors had no increased mortality from soy intake, according to a new study.

The work adds to the existing body of evidence that women with breast cancer, or risk for breast cancer, don’t need to modify their soy intake to mitigate risk, said the study’s first author, Suzanne C. Ho, PhD.

Speaking at the annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society, Dr. Ho noted that the combination of increasing breast cancer incidence and improved outcome has resulted in larger numbers of breast cancer survivors in Hong Kong, where she is professor emerita at the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

The prospective, ongoing study examines the association between soy intake pre- and postdiagnosis and total mortality for Chinese women who are breast cancer survivors. Dr. Ho said that she and her colleagues hypothesized that they would not see higher mortality among women who had higher soy intake – and this was the case.

Of 1,497 breast cancer survivors drawn from two facilities in Hong Kong, those who consumed higher quantities of dietary soy did not have increased risk of all-cause mortality, compared with those in the lowest tertile of soy consumption.

There are theoretical underpinnings for thinking that soy could be a player in cancer risk, but the biochemistry and epidemiology behind the studies are complicated. Estrogen plays a role in human breast cancer, and many modern breast cancer treatments actually dampen endogenous estrogens.

However, epidemiologic data have shown that consumption of soy-based foods – which contain phytoestrogens, primarily in the form of isoflavones – is inversely associated with developing breast cancer.

This is all part of why soy-based foods have been thought of as a mixed bag with regard to breast cancer: Soy isoflavones are, said Dr. Ho, “Natural estrogen receptor modulators that possess both estrogenlike and antiestrogenic properties.”

Other chemicals contained in soy may fight cancer, with effects that are antioxidative and strengthen immune response. Soy constituents also inhibit DNA topoisomerase I and II, proteases, tyrosine kinases, and inositol phosphate, effects that can slow tumor growth. Still, one soy isoflavone, genistein, actually can promote growth of estrogen-dependent tumors in rats, said Dr. Ho

Dr. Ho and her colleagues enrolled Hong Kong residents for the study of mortality among breast cancer survivors. Participants were included if they were Chinese, female, aged 24-77 years, and had their first primary breast cancer histologically confirmed within 12 months of entering the study. Cancer had to be graded below stage III.

Using a 109-item validated food questionnaire, investigators gathered information about participants’ soy intake and general diet for the year prior to breast cancer diagnosis. Other patient characteristics, relevant prognostic information from medical records, and anthropometric data were collected at baseline, and repeated at 18, 36, and 60 months.

The primary outcome measure – all-cause mortality during the follow-up period – was tracked for a mean 50.9 months, with a 78% retention rate for study participants, said Dr. Ho. In total, 96 patients died during follow-up, making up 5.9% of the premenopausal and 7% of the postmenopausal participants.

Statistical analysis corrected for potential confounders, including patient and disease characteristics and treatment modalities, as well as overall energy consumption.

Patients were evenly divided into tertiles of soy isoflavone intake, with cutpoints of 3.77 mg/1,000 kcal and 10.05 mg/1,000 kcal for the lower limit of the two higher tertiles. For the highest tertile, though, mean isoflavone intake was actually 20.87 mg/1,000 kcal.

Patient, disease, and treatment characteristics did not differ significantly among the tertiles.

An adjusted statistical analysis looked at pre- and postmenopausal women separately by tertile of soy isoflavone consumption, setting the hazard ratio for all-cause mortality at 1.00 for women in the lowest tertile of soy consumption.

For premenopausal women in the middle tertile, the HR was 0.45 (95% confidence interval, 0.20-1.00), and 0.86 for those in the highest tertile (95% CI, 0.43-1.72); 782 participants, in all, were premenopausal.

For the 715 postmenopausal women, the HR for those in the middle tertile of soy consumption was 0.94 (95% CI, 0.43-2.05), and 1.11 in the highest (95% CI, 0.54-2.29).

Taking all pre- and postmenopausal participants together, those in the middle tertile of soy isoflavone intake had an all-cause mortality HR of 0.63 (95% CI, 0.37-1.09). For the highest tertile of the full cohort, the HR was 0.95 (95% CI, 0.58-1.55).

Confidence intervals were wide in these findings, but Dr. Ho noted that “moderate soy food intake might be associated with better survival.”

“Prediagnosis soy intake did not increase the risk of all-cause mortality in breast cancer survivors,” said Dr. Ho, findings she called “consistent with the literature that soy consumption does not adversely effect breast cancer survival.”

The study is ongoing, she explained, and “longer follow-up will provide further evidence on the effect of pre- and postdiagnosis soy intake on breast cancer outcomes.”

The study had a homogeneous population of southern Chinese women, with fairly good retention and robust statistical adjustment for confounders. However, it wasn’t possible to assess bioavailability of isoflavones and their metabolites, which can vary according to individual microbiota. Also, researchers did not track whether patients used traditional Chinese medicine.

The World Cancer Research Fund International supported the study. Dr. Ho reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Ho S et al. NAMS 2018, Abstract S-23.

A cohort of Chinese women who are breast cancer survivors had no increased mortality from soy intake, according to a new study.

The work adds to the existing body of evidence that women with breast cancer, or risk for breast cancer, don’t need to modify their soy intake to mitigate risk, said the study’s first author, Suzanne C. Ho, PhD.

Speaking at the annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society, Dr. Ho noted that the combination of increasing breast cancer incidence and improved outcome has resulted in larger numbers of breast cancer survivors in Hong Kong, where she is professor emerita at the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

The prospective, ongoing study examines the association between soy intake pre- and postdiagnosis and total mortality for Chinese women who are breast cancer survivors. Dr. Ho said that she and her colleagues hypothesized that they would not see higher mortality among women who had higher soy intake – and this was the case.

Of 1,497 breast cancer survivors drawn from two facilities in Hong Kong, those who consumed higher quantities of dietary soy did not have increased risk of all-cause mortality, compared with those in the lowest tertile of soy consumption.

There are theoretical underpinnings for thinking that soy could be a player in cancer risk, but the biochemistry and epidemiology behind the studies are complicated. Estrogen plays a role in human breast cancer, and many modern breast cancer treatments actually dampen endogenous estrogens.

However, epidemiologic data have shown that consumption of soy-based foods – which contain phytoestrogens, primarily in the form of isoflavones – is inversely associated with developing breast cancer.

This is all part of why soy-based foods have been thought of as a mixed bag with regard to breast cancer: Soy isoflavones are, said Dr. Ho, “Natural estrogen receptor modulators that possess both estrogenlike and antiestrogenic properties.”

Other chemicals contained in soy may fight cancer, with effects that are antioxidative and strengthen immune response. Soy constituents also inhibit DNA topoisomerase I and II, proteases, tyrosine kinases, and inositol phosphate, effects that can slow tumor growth. Still, one soy isoflavone, genistein, actually can promote growth of estrogen-dependent tumors in rats, said Dr. Ho

Dr. Ho and her colleagues enrolled Hong Kong residents for the study of mortality among breast cancer survivors. Participants were included if they were Chinese, female, aged 24-77 years, and had their first primary breast cancer histologically confirmed within 12 months of entering the study. Cancer had to be graded below stage III.

Using a 109-item validated food questionnaire, investigators gathered information about participants’ soy intake and general diet for the year prior to breast cancer diagnosis. Other patient characteristics, relevant prognostic information from medical records, and anthropometric data were collected at baseline, and repeated at 18, 36, and 60 months.

The primary outcome measure – all-cause mortality during the follow-up period – was tracked for a mean 50.9 months, with a 78% retention rate for study participants, said Dr. Ho. In total, 96 patients died during follow-up, making up 5.9% of the premenopausal and 7% of the postmenopausal participants.

Statistical analysis corrected for potential confounders, including patient and disease characteristics and treatment modalities, as well as overall energy consumption.

Patients were evenly divided into tertiles of soy isoflavone intake, with cutpoints of 3.77 mg/1,000 kcal and 10.05 mg/1,000 kcal for the lower limit of the two higher tertiles. For the highest tertile, though, mean isoflavone intake was actually 20.87 mg/1,000 kcal.

Patient, disease, and treatment characteristics did not differ significantly among the tertiles.

An adjusted statistical analysis looked at pre- and postmenopausal women separately by tertile of soy isoflavone consumption, setting the hazard ratio for all-cause mortality at 1.00 for women in the lowest tertile of soy consumption.

For premenopausal women in the middle tertile, the HR was 0.45 (95% confidence interval, 0.20-1.00), and 0.86 for those in the highest tertile (95% CI, 0.43-1.72); 782 participants, in all, were premenopausal.

For the 715 postmenopausal women, the HR for those in the middle tertile of soy consumption was 0.94 (95% CI, 0.43-2.05), and 1.11 in the highest (95% CI, 0.54-2.29).

Taking all pre- and postmenopausal participants together, those in the middle tertile of soy isoflavone intake had an all-cause mortality HR of 0.63 (95% CI, 0.37-1.09). For the highest tertile of the full cohort, the HR was 0.95 (95% CI, 0.58-1.55).

Confidence intervals were wide in these findings, but Dr. Ho noted that “moderate soy food intake might be associated with better survival.”

“Prediagnosis soy intake did not increase the risk of all-cause mortality in breast cancer survivors,” said Dr. Ho, findings she called “consistent with the literature that soy consumption does not adversely effect breast cancer survival.”

The study is ongoing, she explained, and “longer follow-up will provide further evidence on the effect of pre- and postdiagnosis soy intake on breast cancer outcomes.”

The study had a homogeneous population of southern Chinese women, with fairly good retention and robust statistical adjustment for confounders. However, it wasn’t possible to assess bioavailability of isoflavones and their metabolites, which can vary according to individual microbiota. Also, researchers did not track whether patients used traditional Chinese medicine.