User login

FDA expands Essure’s postmarketing surveillance study

The study, ordered in 2016, will now run 5 years instead of 3, and the cohort will be enlarged to add any women who elect implantation while the device is still on the market, FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, announced in a press statement. The agency also added a key biological measure: All patients with Essure will undergo regular blood work to evaluate proinflammatory markers that could be device related.

“We’re requiring additional blood testing of patients enrolled in follow-up visits during the study to learn more about patients’ levels of certain inflammatory markers that can be indicators of increased inflammation,” Dr. Gottlieb said. “This could help us better evaluate potential immune reactions to the device and whether these findings are associated with symptoms that patients have reported related to Essure.”

The device has been associated with severe problems in some patients, he noted.

“I personally had the opportunity to meet with women who have been adversely affected by Essure to listen and learn about their concerns. Some of the women I spoke with developed significant medical problems that they ascribe to their use of the product. We remain committed to these women and to improving how we monitor the safety of medical devices, including those related to women’s health.”

The study expansion comes as Bayer is facing more than 16,000 lawsuits over adverse events associated with Essure implantation.

Since its approval, Essure is estimated to have been used by more than 750,000 patients worldwide. Bayer claims the device is 99% effective in preventing pregnancy, but it’s also been associated with some serious risks, including persistent pain, perforation of the uterus and fallopian tubes, and migration of the coils into the pelvis or abdomen. In view of these – and more than 15,000 adverse events reported to the FDA – the agency announced new restrictions on Essure earlier this year. Those restrictions, plus a prior boxed warning on the label, contributed to about a 70% decline in U.S. sales, which Bayer says prompted the discontinuation.

The open-label prospective observational study will compare women who have the Essure device to a matched cohort that underwent laparoscopic tubal ligation. The main safety endpoints are chronic pelvic pain and abnormal uterine bleeding, as well as the new measure of inflammatory markers. As of Dec. 3, 791 patients have been enrolled (293 in the Essure arm and 498 in the laparoscopic tubal ligation arm).

Women who have the implant now and remain free of any adverse events should probably keep the device, Dr. Gottlieb advised.

“We believe women who’ve been using Essure successfully to prevent pregnancy can and should continue to do so. Women who suspect the device may be related to symptoms they are experiencing, such as persistent pain, should talk to their doctor on what steps may be appropriate. Device removal has its own risks. Patients should discuss the benefits and risks of any procedure with their health care providers before deciding on the best option for them.”

The study, ordered in 2016, will now run 5 years instead of 3, and the cohort will be enlarged to add any women who elect implantation while the device is still on the market, FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, announced in a press statement. The agency also added a key biological measure: All patients with Essure will undergo regular blood work to evaluate proinflammatory markers that could be device related.

“We’re requiring additional blood testing of patients enrolled in follow-up visits during the study to learn more about patients’ levels of certain inflammatory markers that can be indicators of increased inflammation,” Dr. Gottlieb said. “This could help us better evaluate potential immune reactions to the device and whether these findings are associated with symptoms that patients have reported related to Essure.”

The device has been associated with severe problems in some patients, he noted.

“I personally had the opportunity to meet with women who have been adversely affected by Essure to listen and learn about their concerns. Some of the women I spoke with developed significant medical problems that they ascribe to their use of the product. We remain committed to these women and to improving how we monitor the safety of medical devices, including those related to women’s health.”

The study expansion comes as Bayer is facing more than 16,000 lawsuits over adverse events associated with Essure implantation.

Since its approval, Essure is estimated to have been used by more than 750,000 patients worldwide. Bayer claims the device is 99% effective in preventing pregnancy, but it’s also been associated with some serious risks, including persistent pain, perforation of the uterus and fallopian tubes, and migration of the coils into the pelvis or abdomen. In view of these – and more than 15,000 adverse events reported to the FDA – the agency announced new restrictions on Essure earlier this year. Those restrictions, plus a prior boxed warning on the label, contributed to about a 70% decline in U.S. sales, which Bayer says prompted the discontinuation.

The open-label prospective observational study will compare women who have the Essure device to a matched cohort that underwent laparoscopic tubal ligation. The main safety endpoints are chronic pelvic pain and abnormal uterine bleeding, as well as the new measure of inflammatory markers. As of Dec. 3, 791 patients have been enrolled (293 in the Essure arm and 498 in the laparoscopic tubal ligation arm).

Women who have the implant now and remain free of any adverse events should probably keep the device, Dr. Gottlieb advised.

“We believe women who’ve been using Essure successfully to prevent pregnancy can and should continue to do so. Women who suspect the device may be related to symptoms they are experiencing, such as persistent pain, should talk to their doctor on what steps may be appropriate. Device removal has its own risks. Patients should discuss the benefits and risks of any procedure with their health care providers before deciding on the best option for them.”

The study, ordered in 2016, will now run 5 years instead of 3, and the cohort will be enlarged to add any women who elect implantation while the device is still on the market, FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, announced in a press statement. The agency also added a key biological measure: All patients with Essure will undergo regular blood work to evaluate proinflammatory markers that could be device related.

“We’re requiring additional blood testing of patients enrolled in follow-up visits during the study to learn more about patients’ levels of certain inflammatory markers that can be indicators of increased inflammation,” Dr. Gottlieb said. “This could help us better evaluate potential immune reactions to the device and whether these findings are associated with symptoms that patients have reported related to Essure.”

The device has been associated with severe problems in some patients, he noted.

“I personally had the opportunity to meet with women who have been adversely affected by Essure to listen and learn about their concerns. Some of the women I spoke with developed significant medical problems that they ascribe to their use of the product. We remain committed to these women and to improving how we monitor the safety of medical devices, including those related to women’s health.”

The study expansion comes as Bayer is facing more than 16,000 lawsuits over adverse events associated with Essure implantation.

Since its approval, Essure is estimated to have been used by more than 750,000 patients worldwide. Bayer claims the device is 99% effective in preventing pregnancy, but it’s also been associated with some serious risks, including persistent pain, perforation of the uterus and fallopian tubes, and migration of the coils into the pelvis or abdomen. In view of these – and more than 15,000 adverse events reported to the FDA – the agency announced new restrictions on Essure earlier this year. Those restrictions, plus a prior boxed warning on the label, contributed to about a 70% decline in U.S. sales, which Bayer says prompted the discontinuation.

The open-label prospective observational study will compare women who have the Essure device to a matched cohort that underwent laparoscopic tubal ligation. The main safety endpoints are chronic pelvic pain and abnormal uterine bleeding, as well as the new measure of inflammatory markers. As of Dec. 3, 791 patients have been enrolled (293 in the Essure arm and 498 in the laparoscopic tubal ligation arm).

Women who have the implant now and remain free of any adverse events should probably keep the device, Dr. Gottlieb advised.

“We believe women who’ve been using Essure successfully to prevent pregnancy can and should continue to do so. Women who suspect the device may be related to symptoms they are experiencing, such as persistent pain, should talk to their doctor on what steps may be appropriate. Device removal has its own risks. Patients should discuss the benefits and risks of any procedure with their health care providers before deciding on the best option for them.”

Beware “The Great Mimicker” that can lurk in the vulva

LAS VEGAS – Officially a type of precancerous lesion is known as vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN); unofficially, an obstetrician-gynecologist calls it something else: “The Great Mimicker.” That’s because symptoms of VIN can fool physicians into thinking they’re seeing other vulvar conditions. The good news: A biopsy can offer crucial insight and should be performed on any dysplastic or unusual lesion on the vulva.

Amanda Nickles Fader, MD, of Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, offered this advice and other tips about this type of precancerous vulvar lesion in a presentation at the Pelvic Anatomy and Gynecologic Surgery Symposium.

According to Dr. Nickles Fader, vulvar cancer accounts for 5% of all gynecologic malignancies, and it appears most in women aged 65-75 years. However, about 15% of all vulvar cancers appear in women under the age of 40 years. “We’re seeing a greater number of premenopausal women with this condition, probably due to HPV [human papillomavirus],” she said, adding that HPV vaccines are crucial to prevention.

The VIN form of precancerous lesion is most common in premenopausal women (75%) and – like vulvar cancer – is linked to HPV infection, HIV infection, cigarette smoking, and weakened or suppressed immune systems, Dr. Nickles Faber said at the meeting jointly provided by Global Academy for Medical Education and the University of Cincinnati. Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same company.

VIN presents with symptoms such as pruritus, altered vulvar appearance at the site of the lesion, palpable abnormality, and perineal pain or burning. About 40% of cases do not show symptoms and are diagnosed by gynecologists at annual visits.

It’s important to biopsy these lesions, she said, because they can mimic other conditions such as vulvar cancer, condyloma acuminatum (genital warts), lichen sclerosus, lichen planus, and condyloma latum (a lesion linked to syphilis).

“Biopsy, biopsy, biopsy,” she urged.

In fact, one form of VIN – differentiated VIN – is associated with dermatologic conditions such as lichen sclerosus, and treatment of these conditions can prevent development of this VIN type.

As for treatment, Dr. Nickles Faber said surgery is the mainstay. About 90% of the time, wide local excision is the “go-to” approach, although the skinning vulvectomy procedure may be appropriate in lesions that are more extensive or multifocal and confluent. “It’s a lot more disfiguring.”

Laser ablation is a “very reasonable” option when cancer has been eliminated as a possibility, she said. It may be appropriate in multifocal or extensive lesions and can have important cosmetic advantages when excision would be inappropriate.

Off-label use of imiquimod 5%, a topical immune response modifier, can be appropriate in multifocal high-grade VINs, but it’s crucial to exclude invasive squamous cell carcinoma. As she noted, imiquimod is Food and Drug Administration–approved for anogenital warts but not for VIN. Beware of toxicity over the long term.

Dr. Nickles Fader reported no relevant financial disclosures.

LAS VEGAS – Officially a type of precancerous lesion is known as vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN); unofficially, an obstetrician-gynecologist calls it something else: “The Great Mimicker.” That’s because symptoms of VIN can fool physicians into thinking they’re seeing other vulvar conditions. The good news: A biopsy can offer crucial insight and should be performed on any dysplastic or unusual lesion on the vulva.

Amanda Nickles Fader, MD, of Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, offered this advice and other tips about this type of precancerous vulvar lesion in a presentation at the Pelvic Anatomy and Gynecologic Surgery Symposium.

According to Dr. Nickles Fader, vulvar cancer accounts for 5% of all gynecologic malignancies, and it appears most in women aged 65-75 years. However, about 15% of all vulvar cancers appear in women under the age of 40 years. “We’re seeing a greater number of premenopausal women with this condition, probably due to HPV [human papillomavirus],” she said, adding that HPV vaccines are crucial to prevention.

The VIN form of precancerous lesion is most common in premenopausal women (75%) and – like vulvar cancer – is linked to HPV infection, HIV infection, cigarette smoking, and weakened or suppressed immune systems, Dr. Nickles Faber said at the meeting jointly provided by Global Academy for Medical Education and the University of Cincinnati. Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same company.

VIN presents with symptoms such as pruritus, altered vulvar appearance at the site of the lesion, palpable abnormality, and perineal pain or burning. About 40% of cases do not show symptoms and are diagnosed by gynecologists at annual visits.

It’s important to biopsy these lesions, she said, because they can mimic other conditions such as vulvar cancer, condyloma acuminatum (genital warts), lichen sclerosus, lichen planus, and condyloma latum (a lesion linked to syphilis).

“Biopsy, biopsy, biopsy,” she urged.

In fact, one form of VIN – differentiated VIN – is associated with dermatologic conditions such as lichen sclerosus, and treatment of these conditions can prevent development of this VIN type.

As for treatment, Dr. Nickles Faber said surgery is the mainstay. About 90% of the time, wide local excision is the “go-to” approach, although the skinning vulvectomy procedure may be appropriate in lesions that are more extensive or multifocal and confluent. “It’s a lot more disfiguring.”

Laser ablation is a “very reasonable” option when cancer has been eliminated as a possibility, she said. It may be appropriate in multifocal or extensive lesions and can have important cosmetic advantages when excision would be inappropriate.

Off-label use of imiquimod 5%, a topical immune response modifier, can be appropriate in multifocal high-grade VINs, but it’s crucial to exclude invasive squamous cell carcinoma. As she noted, imiquimod is Food and Drug Administration–approved for anogenital warts but not for VIN. Beware of toxicity over the long term.

Dr. Nickles Fader reported no relevant financial disclosures.

LAS VEGAS – Officially a type of precancerous lesion is known as vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN); unofficially, an obstetrician-gynecologist calls it something else: “The Great Mimicker.” That’s because symptoms of VIN can fool physicians into thinking they’re seeing other vulvar conditions. The good news: A biopsy can offer crucial insight and should be performed on any dysplastic or unusual lesion on the vulva.

Amanda Nickles Fader, MD, of Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, offered this advice and other tips about this type of precancerous vulvar lesion in a presentation at the Pelvic Anatomy and Gynecologic Surgery Symposium.

According to Dr. Nickles Fader, vulvar cancer accounts for 5% of all gynecologic malignancies, and it appears most in women aged 65-75 years. However, about 15% of all vulvar cancers appear in women under the age of 40 years. “We’re seeing a greater number of premenopausal women with this condition, probably due to HPV [human papillomavirus],” she said, adding that HPV vaccines are crucial to prevention.

The VIN form of precancerous lesion is most common in premenopausal women (75%) and – like vulvar cancer – is linked to HPV infection, HIV infection, cigarette smoking, and weakened or suppressed immune systems, Dr. Nickles Faber said at the meeting jointly provided by Global Academy for Medical Education and the University of Cincinnati. Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same company.

VIN presents with symptoms such as pruritus, altered vulvar appearance at the site of the lesion, palpable abnormality, and perineal pain or burning. About 40% of cases do not show symptoms and are diagnosed by gynecologists at annual visits.

It’s important to biopsy these lesions, she said, because they can mimic other conditions such as vulvar cancer, condyloma acuminatum (genital warts), lichen sclerosus, lichen planus, and condyloma latum (a lesion linked to syphilis).

“Biopsy, biopsy, biopsy,” she urged.

In fact, one form of VIN – differentiated VIN – is associated with dermatologic conditions such as lichen sclerosus, and treatment of these conditions can prevent development of this VIN type.

As for treatment, Dr. Nickles Faber said surgery is the mainstay. About 90% of the time, wide local excision is the “go-to” approach, although the skinning vulvectomy procedure may be appropriate in lesions that are more extensive or multifocal and confluent. “It’s a lot more disfiguring.”

Laser ablation is a “very reasonable” option when cancer has been eliminated as a possibility, she said. It may be appropriate in multifocal or extensive lesions and can have important cosmetic advantages when excision would be inappropriate.

Off-label use of imiquimod 5%, a topical immune response modifier, can be appropriate in multifocal high-grade VINs, but it’s crucial to exclude invasive squamous cell carcinoma. As she noted, imiquimod is Food and Drug Administration–approved for anogenital warts but not for VIN. Beware of toxicity over the long term.

Dr. Nickles Fader reported no relevant financial disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM PAGS

Pregnant women commonly refuse the influenza vaccine

Pregnant women commonly refuse vaccines, and refusal of influenza vaccine is more common than refusal of Tdap vaccine, according to a nationally representative survey of obstetrician/gynecologists.

“It appears vaccine refusal among pregnant women may be more common than parental refusal of childhood vaccines,” Sean T. O’Leary, MD, MPH, director of the Colorado Children’s Outcomes Network at the University of Colorado in Aurora, and his coauthors wrote in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

The survey was sent to 477 ob.gyns. via both email and mail between March and June 2016. The response rate was 69%, and almost all respondents reported recommending both influenza (97%) and Tdap (95%) vaccines to pregnant women.

However, respondents also reported that refusal of both vaccines was common, with more refusals of influenza vaccine than Tdap vaccine. Of ob.gyns. who responded, 62% reported that 10% or greater of their pregnant patients refused the influenza vaccine, compared with 32% reporting this for Tdap vaccine (P greater than .001; x2, less than 10% vs. 10% or greater). Of those refusing the vaccine, 48% believed influenza vaccine would make them sick; 38% felt they were unlikely to get a vaccine-preventable disease; and 32% had general worries about vaccines overall. In addition, the only strategy perceived as “very effective” in convincing a vaccine refuser to choose otherwise was “explaining that not getting the vaccine puts the fetus or newborn at risk.”

The authors shared potential limitations of their study, including the fact that they examined reported practices and perceptions, not observed practices, along with the potential that the attitudes and practices of respondents may differ from those of nonrespondents. However, they noted that this is unlikely given prior work and that next steps should consider responses to refusal while also sympathizing with the patients’ concerns. “Future work should focus on testing evidence-based strategies for addressing vaccine refusal in the obstetric setting and understanding how the unique concerns of pregnant women influence the effectiveness of such strategies,” they wrote.

The study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. No conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: O’Leary ST et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Dec. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003005.

Pregnant women make up 1% of the population but accounted for 5% of all influenza deaths during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, which makes the common vaccine refusals reported by the nation’s ob.gyns. all the more serious, according to Sonja A. Rasmussen, MD, MS, of the University of Florida in Gainesville and Denise J. Jamieson, MD, MPH, of Emory University in Atlanta.

After the 2009 pandemic, vaccination coverage for pregnant woman during flu season leapt from less than 30% to 54%, according to data from a 2016-2017 Internet panel survey. This was in large part because of the committed work of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, who emphasized the importance of the influenza vaccine. But coverage rates have stagnated since then, and these two coauthors wrote that “the 2017-2018 severe influenza season was a stern reminder that influenza should not be underestimated.”

These last 2 years saw the highest-documented rate of hospitalizations for influenza since 2005-2006, but given that there’s been very little specific information available on hospitalizations of pregnant women, Dr. Rasmussen and Dr. Jamieson fear the onset of “complacency among health care providers, pregnant women, and the general public” when it comes to the effects of influenza.

They insisted that, as 2009 drifts even further into memory, “obstetric providers should not become complacent regarding influenza.” Strategies to improve coverage are necessary to break that 50% barrier, and “pregnant women and their infants deserve our best efforts to protect them from influenza.”

These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Dec. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003040). No conflicts of interest were reported.

Pregnant women make up 1% of the population but accounted for 5% of all influenza deaths during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, which makes the common vaccine refusals reported by the nation’s ob.gyns. all the more serious, according to Sonja A. Rasmussen, MD, MS, of the University of Florida in Gainesville and Denise J. Jamieson, MD, MPH, of Emory University in Atlanta.

After the 2009 pandemic, vaccination coverage for pregnant woman during flu season leapt from less than 30% to 54%, according to data from a 2016-2017 Internet panel survey. This was in large part because of the committed work of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, who emphasized the importance of the influenza vaccine. But coverage rates have stagnated since then, and these two coauthors wrote that “the 2017-2018 severe influenza season was a stern reminder that influenza should not be underestimated.”

These last 2 years saw the highest-documented rate of hospitalizations for influenza since 2005-2006, but given that there’s been very little specific information available on hospitalizations of pregnant women, Dr. Rasmussen and Dr. Jamieson fear the onset of “complacency among health care providers, pregnant women, and the general public” when it comes to the effects of influenza.

They insisted that, as 2009 drifts even further into memory, “obstetric providers should not become complacent regarding influenza.” Strategies to improve coverage are necessary to break that 50% barrier, and “pregnant women and their infants deserve our best efforts to protect them from influenza.”

These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Dec. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003040). No conflicts of interest were reported.

Pregnant women make up 1% of the population but accounted for 5% of all influenza deaths during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, which makes the common vaccine refusals reported by the nation’s ob.gyns. all the more serious, according to Sonja A. Rasmussen, MD, MS, of the University of Florida in Gainesville and Denise J. Jamieson, MD, MPH, of Emory University in Atlanta.

After the 2009 pandemic, vaccination coverage for pregnant woman during flu season leapt from less than 30% to 54%, according to data from a 2016-2017 Internet panel survey. This was in large part because of the committed work of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, who emphasized the importance of the influenza vaccine. But coverage rates have stagnated since then, and these two coauthors wrote that “the 2017-2018 severe influenza season was a stern reminder that influenza should not be underestimated.”

These last 2 years saw the highest-documented rate of hospitalizations for influenza since 2005-2006, but given that there’s been very little specific information available on hospitalizations of pregnant women, Dr. Rasmussen and Dr. Jamieson fear the onset of “complacency among health care providers, pregnant women, and the general public” when it comes to the effects of influenza.

They insisted that, as 2009 drifts even further into memory, “obstetric providers should not become complacent regarding influenza.” Strategies to improve coverage are necessary to break that 50% barrier, and “pregnant women and their infants deserve our best efforts to protect them from influenza.”

These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Dec. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003040). No conflicts of interest were reported.

Pregnant women commonly refuse vaccines, and refusal of influenza vaccine is more common than refusal of Tdap vaccine, according to a nationally representative survey of obstetrician/gynecologists.

“It appears vaccine refusal among pregnant women may be more common than parental refusal of childhood vaccines,” Sean T. O’Leary, MD, MPH, director of the Colorado Children’s Outcomes Network at the University of Colorado in Aurora, and his coauthors wrote in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

The survey was sent to 477 ob.gyns. via both email and mail between March and June 2016. The response rate was 69%, and almost all respondents reported recommending both influenza (97%) and Tdap (95%) vaccines to pregnant women.

However, respondents also reported that refusal of both vaccines was common, with more refusals of influenza vaccine than Tdap vaccine. Of ob.gyns. who responded, 62% reported that 10% or greater of their pregnant patients refused the influenza vaccine, compared with 32% reporting this for Tdap vaccine (P greater than .001; x2, less than 10% vs. 10% or greater). Of those refusing the vaccine, 48% believed influenza vaccine would make them sick; 38% felt they were unlikely to get a vaccine-preventable disease; and 32% had general worries about vaccines overall. In addition, the only strategy perceived as “very effective” in convincing a vaccine refuser to choose otherwise was “explaining that not getting the vaccine puts the fetus or newborn at risk.”

The authors shared potential limitations of their study, including the fact that they examined reported practices and perceptions, not observed practices, along with the potential that the attitudes and practices of respondents may differ from those of nonrespondents. However, they noted that this is unlikely given prior work and that next steps should consider responses to refusal while also sympathizing with the patients’ concerns. “Future work should focus on testing evidence-based strategies for addressing vaccine refusal in the obstetric setting and understanding how the unique concerns of pregnant women influence the effectiveness of such strategies,” they wrote.

The study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. No conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: O’Leary ST et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Dec. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003005.

Pregnant women commonly refuse vaccines, and refusal of influenza vaccine is more common than refusal of Tdap vaccine, according to a nationally representative survey of obstetrician/gynecologists.

“It appears vaccine refusal among pregnant women may be more common than parental refusal of childhood vaccines,” Sean T. O’Leary, MD, MPH, director of the Colorado Children’s Outcomes Network at the University of Colorado in Aurora, and his coauthors wrote in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

The survey was sent to 477 ob.gyns. via both email and mail between March and June 2016. The response rate was 69%, and almost all respondents reported recommending both influenza (97%) and Tdap (95%) vaccines to pregnant women.

However, respondents also reported that refusal of both vaccines was common, with more refusals of influenza vaccine than Tdap vaccine. Of ob.gyns. who responded, 62% reported that 10% or greater of their pregnant patients refused the influenza vaccine, compared with 32% reporting this for Tdap vaccine (P greater than .001; x2, less than 10% vs. 10% or greater). Of those refusing the vaccine, 48% believed influenza vaccine would make them sick; 38% felt they were unlikely to get a vaccine-preventable disease; and 32% had general worries about vaccines overall. In addition, the only strategy perceived as “very effective” in convincing a vaccine refuser to choose otherwise was “explaining that not getting the vaccine puts the fetus or newborn at risk.”

The authors shared potential limitations of their study, including the fact that they examined reported practices and perceptions, not observed practices, along with the potential that the attitudes and practices of respondents may differ from those of nonrespondents. However, they noted that this is unlikely given prior work and that next steps should consider responses to refusal while also sympathizing with the patients’ concerns. “Future work should focus on testing evidence-based strategies for addressing vaccine refusal in the obstetric setting and understanding how the unique concerns of pregnant women influence the effectiveness of such strategies,” they wrote.

The study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. No conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: O’Leary ST et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Dec. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003005.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Key clinical point: Although almost all ob.gyns. recommend the influenza and Tdap vaccines for pregnant women, both commonly are refused.

Major finding: A total of 62% of ob.gyns. reported that 10% or greater of their pregnant patients refused the influenza vaccine; 32% reported this for Tdap vaccine.

Study details: An email and mail survey sent to a national network of ob.gyns. between March and June 2016.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. No conflicts of interest were reported.

Source: O’Leary ST et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Dec. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003005.

QOL is poorer for young women after mastectomy than BCS

SAN ANTONIO – , according to investigators for a multicenter cross-sectional cohort study reported at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

Women aged 40 or younger make up about 7% of all newly diagnosed cases of breast cancer in the United States, according to lead author, Laura S. Dominici, MD, of Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center and Harvard Medical School, Boston.

“Despite the fact that there is equivalent local-regional control with breast conservation and mastectomy, the rates of mastectomy and particularly bilateral mastectomy are increasing in young women, with a 10-fold increase seen from 1998 to 2011,” she noted in a press conference. “Young women are at particular risk for poorer psychosocial outcomes following a breast cancer diagnosis and in survivorship. However, little is known about the impact of surgery, particularly in the era of increasing bilateral mastectomy, on the quality of life of young survivors.”

Nearly three-fourths of the 560 young breast cancer survivors studied had undergone mastectomy, usually with some kind of reconstruction. Roughly 6 years later, compared with peers who had undergone breast-conserving surgery, women who had undergone unilateral or bilateral mastectomy had significantly poorer adjusted BREAST-Q scores for satisfaction with the appearance and feel of their breasts (beta, –8.7 and –9.3 points) and psychosocial well-being (–8.3 and –10.5 points). The latter also had poorer adjusted scores for sexual well-being (–8.1 points). Physical well-being, which captures aspects such as pain and range of motion, did not differ significantly by type of surgery.

“Local therapy decisions are associated with a persistent impact on quality of life in young breast cancer survivors,” Dr. Dominici concluded. “Knowledge of the potential long-term impact of surgery and quality of life is of critical importance for counseling young women about surgical decisions.”

Moving away from mastectomy

“The data are, to me anyway, more disconcerting when you consider the high mastectomy rate in this country relative to Europe, and this urge to have bilateral mastectomies, which, pardon the expression, is ridiculous in some cases because it doesn’t improve your outcome. And yet, it does have deleterious effects that last for years psychologically,” commented SABCS codirector and press conference moderator C. Kent Osborne, MD, who is director of the Dan L. Duncan Cancer Center at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston. “What can we do about that?” he asked.

“It’s a really challenging problem,” Dr. Dominici replied. “Part of what we are missing in the conversation that we have with our patients is this kind of information. We can certainly tell patients that the outcomes are equivalent, but if they don’t know that the long-term [quality of life] impact is potentially worse, then that may not affect their decision. The more prospective data that we generate to help us figure out which patients are going to have better or worse outcomes with these different types of surgery, the better we will be able to counsel patients with things that will be meaningful to them in the long run.”

The study was not designed to tease out the specific role of anxiety about a recurrence or a new breast cancer, which is a major driver of the decision to have mastectomy and also needs to be addressed during counseling, Dr. Dominici and Dr. Osborne agreed. “I think I spend more time talking patients out of bilateral mastectomy or mastectomy at all than anything,” he commented.

Study details

The women studied were participants in the prospective Young Women’s Breast Cancer Study (YWS) and had a mean age of 37 years at diagnosis. Most (86%) had stage 0-2 breast cancer. (Those with metastatic disease at diagnosis or a recurrence during follow-up were excluded.)

Overall, 52% of the women underwent bilateral mastectomy, 20% underwent unilateral mastectomy, and 28% underwent breast-conserving surgery, Dr. Dominici reported. Within the mastectomy group, most underwent implant-based reconstruction (69%) or flap reconstruction (12%), while some opted for no reconstruction (11%).

Multivariate analyses showed that, in addition to mastectomy, other significant predictors of poorer breast satisfaction were receipt of radiation therapy (beta, –7.5 points) and having a financially uncomfortable status as compared with a comfortable one (–5.4 points).

Additional significant predictors of poorer psychosocial well-being were receiving radiation (beta, –6.0 points), being financially uncomfortable (–7 points), and being overweight or obese (–4.2 points), and additional significant predictors of poorer sexual well-being were being financially uncomfortable (–6.8 points), being overweight or obese (–5.3 points), and having lymphedema a year after diagnosis (–3.8 points).

The only significant predictors of poorer physical health were financially uncomfortable status (beta, –4.8 points) and lymphedema (–6.4 points), whereas longer time since surgery (more than 5 years) predicted better physical health (+6.0 points), according to Dr. Dominici.

Age, race, marital status, work status, education level, disease stage, chemotherapy, and endocrine therapy did not significantly predict any of the outcomes studied.

“This was a one-time survey of women who were enrolled in an observational cohort study, and we know that preoperative quality of life likely drives surgical choices,” she commented, addressing the study’s limitations. “Our findings may have limited generalizability to a more diverse population in that the majority of our participants were white and of high socioeconomic status.”

Dr. Dominici disclosed that she had no conflicts of interest. The study was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Susan G. Komen, the Breast Cancer Research Foundation, and The Pink Agenda.

SOURCE: Dominici LS et al. SABCS 2018, Abstract GS6-06,

SAN ANTONIO – , according to investigators for a multicenter cross-sectional cohort study reported at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

Women aged 40 or younger make up about 7% of all newly diagnosed cases of breast cancer in the United States, according to lead author, Laura S. Dominici, MD, of Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center and Harvard Medical School, Boston.

“Despite the fact that there is equivalent local-regional control with breast conservation and mastectomy, the rates of mastectomy and particularly bilateral mastectomy are increasing in young women, with a 10-fold increase seen from 1998 to 2011,” she noted in a press conference. “Young women are at particular risk for poorer psychosocial outcomes following a breast cancer diagnosis and in survivorship. However, little is known about the impact of surgery, particularly in the era of increasing bilateral mastectomy, on the quality of life of young survivors.”

Nearly three-fourths of the 560 young breast cancer survivors studied had undergone mastectomy, usually with some kind of reconstruction. Roughly 6 years later, compared with peers who had undergone breast-conserving surgery, women who had undergone unilateral or bilateral mastectomy had significantly poorer adjusted BREAST-Q scores for satisfaction with the appearance and feel of their breasts (beta, –8.7 and –9.3 points) and psychosocial well-being (–8.3 and –10.5 points). The latter also had poorer adjusted scores for sexual well-being (–8.1 points). Physical well-being, which captures aspects such as pain and range of motion, did not differ significantly by type of surgery.

“Local therapy decisions are associated with a persistent impact on quality of life in young breast cancer survivors,” Dr. Dominici concluded. “Knowledge of the potential long-term impact of surgery and quality of life is of critical importance for counseling young women about surgical decisions.”

Moving away from mastectomy

“The data are, to me anyway, more disconcerting when you consider the high mastectomy rate in this country relative to Europe, and this urge to have bilateral mastectomies, which, pardon the expression, is ridiculous in some cases because it doesn’t improve your outcome. And yet, it does have deleterious effects that last for years psychologically,” commented SABCS codirector and press conference moderator C. Kent Osborne, MD, who is director of the Dan L. Duncan Cancer Center at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston. “What can we do about that?” he asked.

“It’s a really challenging problem,” Dr. Dominici replied. “Part of what we are missing in the conversation that we have with our patients is this kind of information. We can certainly tell patients that the outcomes are equivalent, but if they don’t know that the long-term [quality of life] impact is potentially worse, then that may not affect their decision. The more prospective data that we generate to help us figure out which patients are going to have better or worse outcomes with these different types of surgery, the better we will be able to counsel patients with things that will be meaningful to them in the long run.”

The study was not designed to tease out the specific role of anxiety about a recurrence or a new breast cancer, which is a major driver of the decision to have mastectomy and also needs to be addressed during counseling, Dr. Dominici and Dr. Osborne agreed. “I think I spend more time talking patients out of bilateral mastectomy or mastectomy at all than anything,” he commented.

Study details

The women studied were participants in the prospective Young Women’s Breast Cancer Study (YWS) and had a mean age of 37 years at diagnosis. Most (86%) had stage 0-2 breast cancer. (Those with metastatic disease at diagnosis or a recurrence during follow-up were excluded.)

Overall, 52% of the women underwent bilateral mastectomy, 20% underwent unilateral mastectomy, and 28% underwent breast-conserving surgery, Dr. Dominici reported. Within the mastectomy group, most underwent implant-based reconstruction (69%) or flap reconstruction (12%), while some opted for no reconstruction (11%).

Multivariate analyses showed that, in addition to mastectomy, other significant predictors of poorer breast satisfaction were receipt of radiation therapy (beta, –7.5 points) and having a financially uncomfortable status as compared with a comfortable one (–5.4 points).

Additional significant predictors of poorer psychosocial well-being were receiving radiation (beta, –6.0 points), being financially uncomfortable (–7 points), and being overweight or obese (–4.2 points), and additional significant predictors of poorer sexual well-being were being financially uncomfortable (–6.8 points), being overweight or obese (–5.3 points), and having lymphedema a year after diagnosis (–3.8 points).

The only significant predictors of poorer physical health were financially uncomfortable status (beta, –4.8 points) and lymphedema (–6.4 points), whereas longer time since surgery (more than 5 years) predicted better physical health (+6.0 points), according to Dr. Dominici.

Age, race, marital status, work status, education level, disease stage, chemotherapy, and endocrine therapy did not significantly predict any of the outcomes studied.

“This was a one-time survey of women who were enrolled in an observational cohort study, and we know that preoperative quality of life likely drives surgical choices,” she commented, addressing the study’s limitations. “Our findings may have limited generalizability to a more diverse population in that the majority of our participants were white and of high socioeconomic status.”

Dr. Dominici disclosed that she had no conflicts of interest. The study was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Susan G. Komen, the Breast Cancer Research Foundation, and The Pink Agenda.

SOURCE: Dominici LS et al. SABCS 2018, Abstract GS6-06,

SAN ANTONIO – , according to investigators for a multicenter cross-sectional cohort study reported at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

Women aged 40 or younger make up about 7% of all newly diagnosed cases of breast cancer in the United States, according to lead author, Laura S. Dominici, MD, of Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center and Harvard Medical School, Boston.

“Despite the fact that there is equivalent local-regional control with breast conservation and mastectomy, the rates of mastectomy and particularly bilateral mastectomy are increasing in young women, with a 10-fold increase seen from 1998 to 2011,” she noted in a press conference. “Young women are at particular risk for poorer psychosocial outcomes following a breast cancer diagnosis and in survivorship. However, little is known about the impact of surgery, particularly in the era of increasing bilateral mastectomy, on the quality of life of young survivors.”

Nearly three-fourths of the 560 young breast cancer survivors studied had undergone mastectomy, usually with some kind of reconstruction. Roughly 6 years later, compared with peers who had undergone breast-conserving surgery, women who had undergone unilateral or bilateral mastectomy had significantly poorer adjusted BREAST-Q scores for satisfaction with the appearance and feel of their breasts (beta, –8.7 and –9.3 points) and psychosocial well-being (–8.3 and –10.5 points). The latter also had poorer adjusted scores for sexual well-being (–8.1 points). Physical well-being, which captures aspects such as pain and range of motion, did not differ significantly by type of surgery.

“Local therapy decisions are associated with a persistent impact on quality of life in young breast cancer survivors,” Dr. Dominici concluded. “Knowledge of the potential long-term impact of surgery and quality of life is of critical importance for counseling young women about surgical decisions.”

Moving away from mastectomy

“The data are, to me anyway, more disconcerting when you consider the high mastectomy rate in this country relative to Europe, and this urge to have bilateral mastectomies, which, pardon the expression, is ridiculous in some cases because it doesn’t improve your outcome. And yet, it does have deleterious effects that last for years psychologically,” commented SABCS codirector and press conference moderator C. Kent Osborne, MD, who is director of the Dan L. Duncan Cancer Center at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston. “What can we do about that?” he asked.

“It’s a really challenging problem,” Dr. Dominici replied. “Part of what we are missing in the conversation that we have with our patients is this kind of information. We can certainly tell patients that the outcomes are equivalent, but if they don’t know that the long-term [quality of life] impact is potentially worse, then that may not affect their decision. The more prospective data that we generate to help us figure out which patients are going to have better or worse outcomes with these different types of surgery, the better we will be able to counsel patients with things that will be meaningful to them in the long run.”

The study was not designed to tease out the specific role of anxiety about a recurrence or a new breast cancer, which is a major driver of the decision to have mastectomy and also needs to be addressed during counseling, Dr. Dominici and Dr. Osborne agreed. “I think I spend more time talking patients out of bilateral mastectomy or mastectomy at all than anything,” he commented.

Study details

The women studied were participants in the prospective Young Women’s Breast Cancer Study (YWS) and had a mean age of 37 years at diagnosis. Most (86%) had stage 0-2 breast cancer. (Those with metastatic disease at diagnosis or a recurrence during follow-up were excluded.)

Overall, 52% of the women underwent bilateral mastectomy, 20% underwent unilateral mastectomy, and 28% underwent breast-conserving surgery, Dr. Dominici reported. Within the mastectomy group, most underwent implant-based reconstruction (69%) or flap reconstruction (12%), while some opted for no reconstruction (11%).

Multivariate analyses showed that, in addition to mastectomy, other significant predictors of poorer breast satisfaction were receipt of radiation therapy (beta, –7.5 points) and having a financially uncomfortable status as compared with a comfortable one (–5.4 points).

Additional significant predictors of poorer psychosocial well-being were receiving radiation (beta, –6.0 points), being financially uncomfortable (–7 points), and being overweight or obese (–4.2 points), and additional significant predictors of poorer sexual well-being were being financially uncomfortable (–6.8 points), being overweight or obese (–5.3 points), and having lymphedema a year after diagnosis (–3.8 points).

The only significant predictors of poorer physical health were financially uncomfortable status (beta, –4.8 points) and lymphedema (–6.4 points), whereas longer time since surgery (more than 5 years) predicted better physical health (+6.0 points), according to Dr. Dominici.

Age, race, marital status, work status, education level, disease stage, chemotherapy, and endocrine therapy did not significantly predict any of the outcomes studied.

“This was a one-time survey of women who were enrolled in an observational cohort study, and we know that preoperative quality of life likely drives surgical choices,” she commented, addressing the study’s limitations. “Our findings may have limited generalizability to a more diverse population in that the majority of our participants were white and of high socioeconomic status.”

Dr. Dominici disclosed that she had no conflicts of interest. The study was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Susan G. Komen, the Breast Cancer Research Foundation, and The Pink Agenda.

SOURCE: Dominici LS et al. SABCS 2018, Abstract GS6-06,

REPORTING FROM SABCS 2018

Key clinical point: More extensive breast surgery has a long-term negative impact on QOL for young breast cancer survivors.

Major finding: Compared with peers who underwent breast-conserving surgery, young women who underwent unilateral or bilateral mastectomy had significantly poorer adjusted scores for breast satisfaction (beta, –8.7 and –9.3 points) and psychosocial well-being (beta, –8.3 and –10.5 points).

Study details: A multicenter cross-sectional cohort study of 560 women with a mean age of 37 years at breast cancer diagnosis who completed the BREAST-Q questionnaire a median of 5.8 years later.

Disclosures: Dr. Dominici disclosed that she had no conflicts of interest. The study was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Susan G. Komen, the Breast Cancer Research Foundation, and The Pink Agenda.

Source: Dominici LS et al. SABCS 2018, Abstract GS6-06.

Carol Bernstein Part II

New syphilis cases for pregnant women rose 61% over 5 years

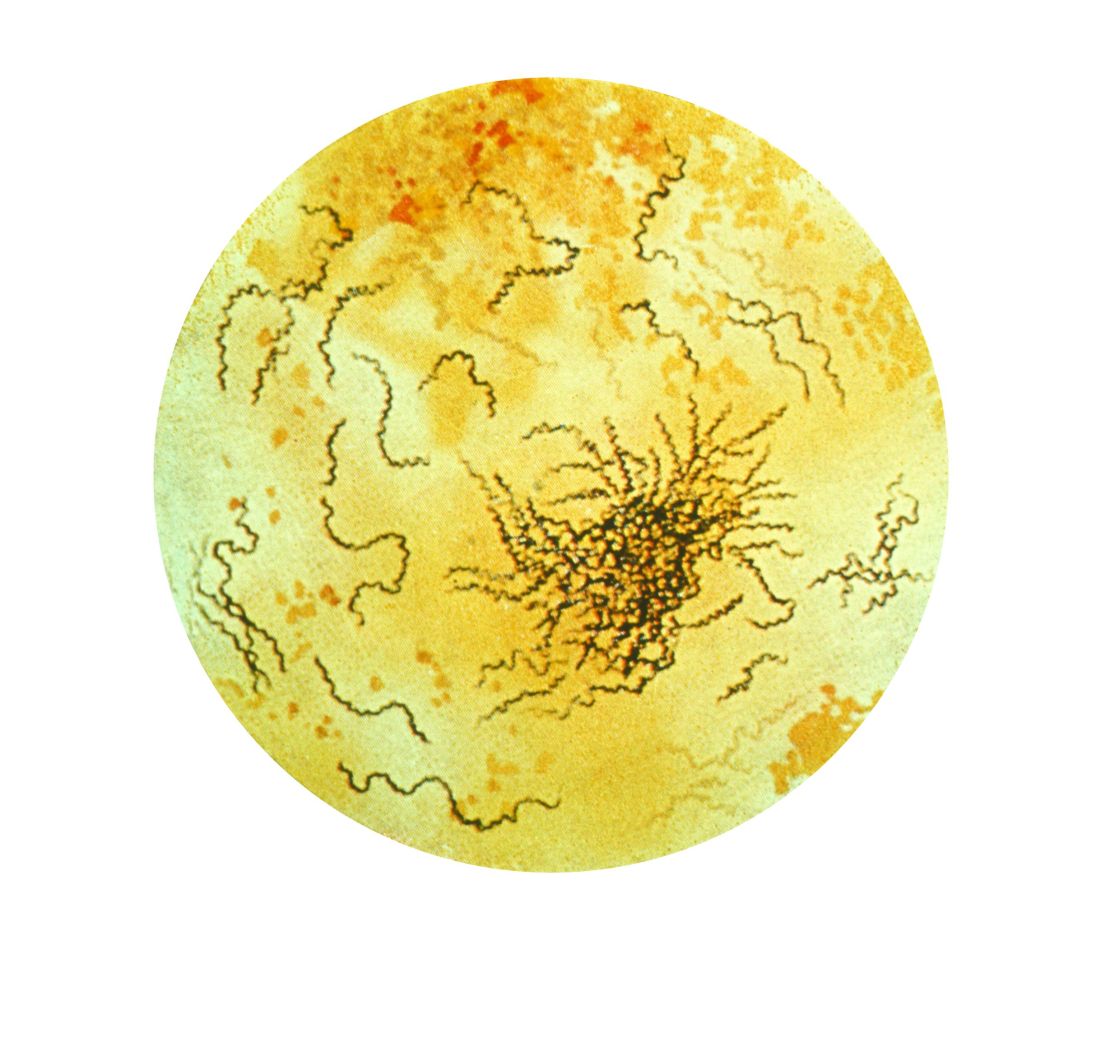

Syphilis cases increased by 61% between 2012 and 2016 among pregnant women, and the proportion of syphilis cases was higher for women who were non-Hispanic black race and Hispanic ethnicity, according to research in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

“These findings support current recommendations for universal syphilis screening at the first prenatal visit and indicate that it may be necessary to include population context when determining whether to implement repeat screening during pregnancy,” Shivika Trivedi, MD, MSc, of the CDC Foundation and the Division of STD Prevention at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and colleagues wrote.

Dr. Trivedi and colleagues identified 9,883 pregnant women with reported syphilis in the CDC National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System during 2012-2016. During that time, there was an increase in the number of female syphilis cases from 9,551 cases in 2012 to 14,838 cases in 2016 (55%), while there was an increase in the number of syphilis cases for pregnant women from 1,561 cases in 2012 to 2,508 cases in 2016 (61%). Of the risk factors reported for syphilis, 49% reported no risk factors within 12 priors before diagnosis, 43% said they had had at least one sexually transmitted disease, and 30% reported more than one sexual partner within the last year.

The greatest prevalence for syphilis was among women who were in their 20s (59%), located in the South (56%), and were non-Hispanic black (49%) or Hispanic (28%). However, researchers noted the rates of syphilis increased among all women between 18 years and 45 years and in every race and ethnicity group between 2012 and 2016. Early syphilis cases increased from 35% in 2012 to 58% in 2016, while late latent cases decreased from 65% in 2012 to 42% in 2016.

Researchers noted several limitations in the study, including case-based surveillance data, which potentially underreported the rates of syphilis, and a lack of pregnancy outcomes for pregnant women with syphilitic infections. However, they noted the data do show a trend of syphilis infections in pregnant women because the live birth rate “was relatively stable and did not fluctuate more than” 1.5% between 2012 and 2016.

“Through an increased awareness of the rising syphilis cases among pregnant women as well as these trend data, health care providers can be better informed to ensure they are following national guidelines and state policies for syphilis screening in pregnancy,” Dr. Trivedi and colleagues concluded.

The authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Trivedi S et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2018. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003000.

I think this is an important topic of which pregnant women and their providers should be aware. It is possible the rising incidence is a result of increased screening and awareness; however, regardless of whether this is the case, it is important to identify the cases of congenital syphilis as preventable.

It is important for providers to be aware of their local syphilis prevalence and regulations on prenatal syphilis screening because given the effects of congenital syphilis and the ease of treatment.

Martina L. Badell, MD, is an assistant professor in the department of gynecology and obstetrics and maternal-fetal medicine at Emory University in Atlanta. She reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

I think this is an important topic of which pregnant women and their providers should be aware. It is possible the rising incidence is a result of increased screening and awareness; however, regardless of whether this is the case, it is important to identify the cases of congenital syphilis as preventable.

It is important for providers to be aware of their local syphilis prevalence and regulations on prenatal syphilis screening because given the effects of congenital syphilis and the ease of treatment.

Martina L. Badell, MD, is an assistant professor in the department of gynecology and obstetrics and maternal-fetal medicine at Emory University in Atlanta. She reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

I think this is an important topic of which pregnant women and their providers should be aware. It is possible the rising incidence is a result of increased screening and awareness; however, regardless of whether this is the case, it is important to identify the cases of congenital syphilis as preventable.

It is important for providers to be aware of their local syphilis prevalence and regulations on prenatal syphilis screening because given the effects of congenital syphilis and the ease of treatment.

Martina L. Badell, MD, is an assistant professor in the department of gynecology and obstetrics and maternal-fetal medicine at Emory University in Atlanta. She reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Syphilis cases increased by 61% between 2012 and 2016 among pregnant women, and the proportion of syphilis cases was higher for women who were non-Hispanic black race and Hispanic ethnicity, according to research in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

“These findings support current recommendations for universal syphilis screening at the first prenatal visit and indicate that it may be necessary to include population context when determining whether to implement repeat screening during pregnancy,” Shivika Trivedi, MD, MSc, of the CDC Foundation and the Division of STD Prevention at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and colleagues wrote.

Dr. Trivedi and colleagues identified 9,883 pregnant women with reported syphilis in the CDC National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System during 2012-2016. During that time, there was an increase in the number of female syphilis cases from 9,551 cases in 2012 to 14,838 cases in 2016 (55%), while there was an increase in the number of syphilis cases for pregnant women from 1,561 cases in 2012 to 2,508 cases in 2016 (61%). Of the risk factors reported for syphilis, 49% reported no risk factors within 12 priors before diagnosis, 43% said they had had at least one sexually transmitted disease, and 30% reported more than one sexual partner within the last year.

The greatest prevalence for syphilis was among women who were in their 20s (59%), located in the South (56%), and were non-Hispanic black (49%) or Hispanic (28%). However, researchers noted the rates of syphilis increased among all women between 18 years and 45 years and in every race and ethnicity group between 2012 and 2016. Early syphilis cases increased from 35% in 2012 to 58% in 2016, while late latent cases decreased from 65% in 2012 to 42% in 2016.

Researchers noted several limitations in the study, including case-based surveillance data, which potentially underreported the rates of syphilis, and a lack of pregnancy outcomes for pregnant women with syphilitic infections. However, they noted the data do show a trend of syphilis infections in pregnant women because the live birth rate “was relatively stable and did not fluctuate more than” 1.5% between 2012 and 2016.

“Through an increased awareness of the rising syphilis cases among pregnant women as well as these trend data, health care providers can be better informed to ensure they are following national guidelines and state policies for syphilis screening in pregnancy,” Dr. Trivedi and colleagues concluded.

The authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Trivedi S et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2018. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003000.

Syphilis cases increased by 61% between 2012 and 2016 among pregnant women, and the proportion of syphilis cases was higher for women who were non-Hispanic black race and Hispanic ethnicity, according to research in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

“These findings support current recommendations for universal syphilis screening at the first prenatal visit and indicate that it may be necessary to include population context when determining whether to implement repeat screening during pregnancy,” Shivika Trivedi, MD, MSc, of the CDC Foundation and the Division of STD Prevention at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and colleagues wrote.

Dr. Trivedi and colleagues identified 9,883 pregnant women with reported syphilis in the CDC National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System during 2012-2016. During that time, there was an increase in the number of female syphilis cases from 9,551 cases in 2012 to 14,838 cases in 2016 (55%), while there was an increase in the number of syphilis cases for pregnant women from 1,561 cases in 2012 to 2,508 cases in 2016 (61%). Of the risk factors reported for syphilis, 49% reported no risk factors within 12 priors before diagnosis, 43% said they had had at least one sexually transmitted disease, and 30% reported more than one sexual partner within the last year.

The greatest prevalence for syphilis was among women who were in their 20s (59%), located in the South (56%), and were non-Hispanic black (49%) or Hispanic (28%). However, researchers noted the rates of syphilis increased among all women between 18 years and 45 years and in every race and ethnicity group between 2012 and 2016. Early syphilis cases increased from 35% in 2012 to 58% in 2016, while late latent cases decreased from 65% in 2012 to 42% in 2016.

Researchers noted several limitations in the study, including case-based surveillance data, which potentially underreported the rates of syphilis, and a lack of pregnancy outcomes for pregnant women with syphilitic infections. However, they noted the data do show a trend of syphilis infections in pregnant women because the live birth rate “was relatively stable and did not fluctuate more than” 1.5% between 2012 and 2016.

“Through an increased awareness of the rising syphilis cases among pregnant women as well as these trend data, health care providers can be better informed to ensure they are following national guidelines and state policies for syphilis screening in pregnancy,” Dr. Trivedi and colleagues concluded.

The authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Trivedi S et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2018. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003000.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Key clinical point: Syphilis rates rose more in pregnant women between 2012 and 2016, compared with women in the general population.

Major finding: There was an increase of syphilis cases by 61% among pregnant women, compared with a 55% increase among women overall.

Study details: A study of national case report data from 9,883 pregnant women with reported syphilis during 2012-2016.

Disclosures: The authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Source: Trivedi S et al. Obstet Gynecol. 2018. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003000.

Brazil sees first live birth from deceased-donor uterus transplant

The healthy 2,550-g infant girl was born in December 2017 via a planned cesarean delivery at about 36 weeks’ gestation. Her mother, the transplant recipient, has congenital absence of the uterus from Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser (MRKH) syndrome. Removal of the transplanted uterus at the time of delivery allowed the woman to stop taking the immunosuppressive medications that she’d been on since the transplantation, which had been performed less than a year and a half previously.

The uterus had been retrieved from a 45-year-old donor who experienced a subarachnoid hemorrhage and subsequent brain death. The donor had three vaginal deliveries, and no history of reproductive issues or sexually transmitted infection, wrote Dani Ejzenberg, MD, and his colleagues at the University of São Paolo, Brazil.

The retrieval and transplantation procedures were done at the university’s hospital, in accordance with a research protocol approved by the university, a Brazilian national ethics committee, and the country’s national transplantation system. Thorough psychological evaluation was part of the research protocol, and the patient and her partner had monthly psychological counseling from therapists with expertise in transplant and fertility, wrote Dr. Ejzenberg and his colleagues.

In preparation for the transplantation, which occurred when the recipient was 32 years old, she had in vitro fertilization several months before the procedure. Eight “good-quality” blastocysts were retrieved and cryopreserved, said Dr. Ejzenberg and his coauthors. The recipient’s menstrual cycle resumed 37 days after transplantation, and one of the cryopreserved embryos was transferred about 7 months after the uterine transplantation procedure, resulting in the pregnancy.

The donor and recipient were matched only by ABO blood type, with no further tissue typing being done, wrote Dr. Ejzenberg and his colleagues. The immunosuppressive regimen paralleled that used in previous successful uterine transplantations from live donors in Sweden, with induction via 1 g intraoperative methylprednisolone and 1.5 mg/kg of thymoglobulin. Thereafter, the recipient received tacrolimus titrated to a trough of 8-10 ng/mL, along with mycophenolate mofetil 720 mg twice daily. Five months after her transplantation, the mycophenolate mofetil was replaced with 100 mg azathioprine and 10 mg prednisone daily, a regimen that she stayed on until cesarean delivery.

Broad-spectrum antibiotics, antifungals, and anthelmintics were administered during the patient’s hospital stay. Prophylactic antibiotics were continued for 6 months, and antiviral medication was given prophylactically for 3 months. The recipient had one episode of vaginal discharge, treated with antifungal medication, and one episode of pyelonephritis during pregnancy, treated during a brief inpatient stay.

Enoxaparin and aspirin were used for inpatient venous thromboembolism prophylaxis, and heparin and aspirin thereafter. Aspirin was discontinued at 34 weeks, and heparin the day before delivery.

Swedish and American teams involved in uterine transplantation are working to develop standardization of surgical techniques, immunosuppression protocol, and methods to monitor rejection.

However, pointed out Dr. Ejzenberg and his coauthors, some technical aspects were unique to the deceased donor transplantation. These included managing total ischemic time for the donor tissue because heart, liver, and kidney retrieval all were given priority.

One downstream effect of this was longer-than-expected procedure and anesthesia time for the recipient, because coordinating donor uterus retrieval and preparation of the surgical bed in the live recipient was tricky; surgery time was about 10.5 hours. Also, there was prolonged warm-ischemia time because six small-vessel anastomoses needed to be performed, wrote the investigators.

After reperfusion of the implanted uterus, there was brisk bleeding from a number of small vessels that had not been ligated on retrieval because of concerns about ischemic time. These were identified and sutured or cauterized, but the total estimated blood loss during the procedures was 1,200 mL, with most of that coming from the uterus, said Dr. Ejzenberg and his coauthors.

The donor uterus had a total of almost 8 hours of ischemic time, exceeding the previously published live donor maximum uterine ischemic time of 3 hours, 25 minutes. This experience can inform surgical teams considering future uterine transplantations.

Dr. Ejzenberg and his colleagues also said that they cast a broad net with immunosuppression, erring on the side of caution. With more experience may come the ability to scale back immunosuppressive regimens, they noted.

The explantation of the uterus and associated blood vessels after delivery afforded the opportunity for pathological examination of the uterus and other tissues, which showed no signs of rejection. The uterine arteries did have mild intimal fibrous hyperplasia that was likely related to the age of the donor, said Dr. Ejzenberg and his coauthors.

This successful completion of a deceased-donor uterine transplantation demonstrates the feasibility of accessing “a much wider potential donor population, as the numbers of people willing and committed to donate organs upon their own deaths are far larger than those of potential live donors,” wrote Dr. Ejzenberg and his colleagues. “Further incidental but substantial benefits of the use of deceased donors include lower costs and avoidance of live donors’ surgical risks.”

In 2011, a uterine transplantation from a deceased donor resulted in pregnancy, but ended in miscarriage.

Funding was provided by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo and the Hospital das Clínicas of University of São Paulo School of Medicine. Dr. Ejzenberg and his colleagues reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Ejzenberg D. et al. Lancet. 2018 Dec. doi: 10.1015/S0140-6736(18)31766-5.

Among the advances seen in this deceased-donor uterus transplant is a demonstration that ischemic time of nearly 8 hours – four times the average seen in live donation – does not preclude a successful transplantation.

Also, the timetable for transplantation seen here did not involve the year-long waiting period between transplantation and pregnancy that has been the norm in live uterine transplantation.

However, uterine transplantation, whether from a living or deceased donor, is still in its early stages. Among the many unsettled questions are whether live or deceased donor transplantations yield superior results. Additional technical aspects to be further studied include best surgical approach for the donor uterus, best anastomosis technique, and optimal immunosuppression and antimicrobial/antifungal/antiviral regimens.

Continued work needs to be done to standardize these and other aspects of the peri- and postoperative care of women undergoing uterine transplantation.

In addition, long-term tracking of children born from transplanted uteri is needed, so outcomes can be assessed over the lifespan.

Going forward, it could be that uterine transplantation may be offered to an expanded cohort of women, including those with bulky, nonoperable uterine fibroids, those who have received pelvic radiotherapy, and even those who have had multiple unexplained problems with implantation during fertility treatments. In all cases, researchers should work toward achieving the highest live birth rate at the lowest risk to donors and patients, while also working to make more organs available; establishing registries, and encouraging prospective registration and transparent reporting of uterus transplantation procedures.

Cesar Diaz-Garcia, MD, is medical director of IVI-London, and Antonio Pellicer, MD, is professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Valencia, Spain. These remarks were drawn from their editorial accompanying the report by Ejzenberg et al. (Lancet. 2018 Dec. doi: 10.1016/50140-6736(18)32106-8).

Among the advances seen in this deceased-donor uterus transplant is a demonstration that ischemic time of nearly 8 hours – four times the average seen in live donation – does not preclude a successful transplantation.

Also, the timetable for transplantation seen here did not involve the year-long waiting period between transplantation and pregnancy that has been the norm in live uterine transplantation.

However, uterine transplantation, whether from a living or deceased donor, is still in its early stages. Among the many unsettled questions are whether live or deceased donor transplantations yield superior results. Additional technical aspects to be further studied include best surgical approach for the donor uterus, best anastomosis technique, and optimal immunosuppression and antimicrobial/antifungal/antiviral regimens.

Continued work needs to be done to standardize these and other aspects of the peri- and postoperative care of women undergoing uterine transplantation.

In addition, long-term tracking of children born from transplanted uteri is needed, so outcomes can be assessed over the lifespan.

Going forward, it could be that uterine transplantation may be offered to an expanded cohort of women, including those with bulky, nonoperable uterine fibroids, those who have received pelvic radiotherapy, and even those who have had multiple unexplained problems with implantation during fertility treatments. In all cases, researchers should work toward achieving the highest live birth rate at the lowest risk to donors and patients, while also working to make more organs available; establishing registries, and encouraging prospective registration and transparent reporting of uterus transplantation procedures.

Cesar Diaz-Garcia, MD, is medical director of IVI-London, and Antonio Pellicer, MD, is professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Valencia, Spain. These remarks were drawn from their editorial accompanying the report by Ejzenberg et al. (Lancet. 2018 Dec. doi: 10.1016/50140-6736(18)32106-8).

Among the advances seen in this deceased-donor uterus transplant is a demonstration that ischemic time of nearly 8 hours – four times the average seen in live donation – does not preclude a successful transplantation.

Also, the timetable for transplantation seen here did not involve the year-long waiting period between transplantation and pregnancy that has been the norm in live uterine transplantation.

However, uterine transplantation, whether from a living or deceased donor, is still in its early stages. Among the many unsettled questions are whether live or deceased donor transplantations yield superior results. Additional technical aspects to be further studied include best surgical approach for the donor uterus, best anastomosis technique, and optimal immunosuppression and antimicrobial/antifungal/antiviral regimens.

Continued work needs to be done to standardize these and other aspects of the peri- and postoperative care of women undergoing uterine transplantation.

In addition, long-term tracking of children born from transplanted uteri is needed, so outcomes can be assessed over the lifespan.

Going forward, it could be that uterine transplantation may be offered to an expanded cohort of women, including those with bulky, nonoperable uterine fibroids, those who have received pelvic radiotherapy, and even those who have had multiple unexplained problems with implantation during fertility treatments. In all cases, researchers should work toward achieving the highest live birth rate at the lowest risk to donors and patients, while also working to make more organs available; establishing registries, and encouraging prospective registration and transparent reporting of uterus transplantation procedures.

Cesar Diaz-Garcia, MD, is medical director of IVI-London, and Antonio Pellicer, MD, is professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Valencia, Spain. These remarks were drawn from their editorial accompanying the report by Ejzenberg et al. (Lancet. 2018 Dec. doi: 10.1016/50140-6736(18)32106-8).

The healthy 2,550-g infant girl was born in December 2017 via a planned cesarean delivery at about 36 weeks’ gestation. Her mother, the transplant recipient, has congenital absence of the uterus from Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser (MRKH) syndrome. Removal of the transplanted uterus at the time of delivery allowed the woman to stop taking the immunosuppressive medications that she’d been on since the transplantation, which had been performed less than a year and a half previously.

The uterus had been retrieved from a 45-year-old donor who experienced a subarachnoid hemorrhage and subsequent brain death. The donor had three vaginal deliveries, and no history of reproductive issues or sexually transmitted infection, wrote Dani Ejzenberg, MD, and his colleagues at the University of São Paolo, Brazil.

The retrieval and transplantation procedures were done at the university’s hospital, in accordance with a research protocol approved by the university, a Brazilian national ethics committee, and the country’s national transplantation system. Thorough psychological evaluation was part of the research protocol, and the patient and her partner had monthly psychological counseling from therapists with expertise in transplant and fertility, wrote Dr. Ejzenberg and his colleagues.

In preparation for the transplantation, which occurred when the recipient was 32 years old, she had in vitro fertilization several months before the procedure. Eight “good-quality” blastocysts were retrieved and cryopreserved, said Dr. Ejzenberg and his coauthors. The recipient’s menstrual cycle resumed 37 days after transplantation, and one of the cryopreserved embryos was transferred about 7 months after the uterine transplantation procedure, resulting in the pregnancy.

The donor and recipient were matched only by ABO blood type, with no further tissue typing being done, wrote Dr. Ejzenberg and his colleagues. The immunosuppressive regimen paralleled that used in previous successful uterine transplantations from live donors in Sweden, with induction via 1 g intraoperative methylprednisolone and 1.5 mg/kg of thymoglobulin. Thereafter, the recipient received tacrolimus titrated to a trough of 8-10 ng/mL, along with mycophenolate mofetil 720 mg twice daily. Five months after her transplantation, the mycophenolate mofetil was replaced with 100 mg azathioprine and 10 mg prednisone daily, a regimen that she stayed on until cesarean delivery.

Broad-spectrum antibiotics, antifungals, and anthelmintics were administered during the patient’s hospital stay. Prophylactic antibiotics were continued for 6 months, and antiviral medication was given prophylactically for 3 months. The recipient had one episode of vaginal discharge, treated with antifungal medication, and one episode of pyelonephritis during pregnancy, treated during a brief inpatient stay.

Enoxaparin and aspirin were used for inpatient venous thromboembolism prophylaxis, and heparin and aspirin thereafter. Aspirin was discontinued at 34 weeks, and heparin the day before delivery.

Swedish and American teams involved in uterine transplantation are working to develop standardization of surgical techniques, immunosuppression protocol, and methods to monitor rejection.

However, pointed out Dr. Ejzenberg and his coauthors, some technical aspects were unique to the deceased donor transplantation. These included managing total ischemic time for the donor tissue because heart, liver, and kidney retrieval all were given priority.

One downstream effect of this was longer-than-expected procedure and anesthesia time for the recipient, because coordinating donor uterus retrieval and preparation of the surgical bed in the live recipient was tricky; surgery time was about 10.5 hours. Also, there was prolonged warm-ischemia time because six small-vessel anastomoses needed to be performed, wrote the investigators.

After reperfusion of the implanted uterus, there was brisk bleeding from a number of small vessels that had not been ligated on retrieval because of concerns about ischemic time. These were identified and sutured or cauterized, but the total estimated blood loss during the procedures was 1,200 mL, with most of that coming from the uterus, said Dr. Ejzenberg and his coauthors.

The donor uterus had a total of almost 8 hours of ischemic time, exceeding the previously published live donor maximum uterine ischemic time of 3 hours, 25 minutes. This experience can inform surgical teams considering future uterine transplantations.

Dr. Ejzenberg and his colleagues also said that they cast a broad net with immunosuppression, erring on the side of caution. With more experience may come the ability to scale back immunosuppressive regimens, they noted.