User login

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Update 2018

Subclinical Hypothyroidism in Pregnancy

ACOG: First gynecologist visit between ages 13 and 15

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends that girls receive their first reproductive health visit between the ages of 13 and 15 years to discuss healthy relationships in addition to general reproductive health, according to a new committee opinion.

The recommendation, published online Oct. 24, emphasizes that such early visits provide opportunities for ob.gyns. to educate teenage girls and their guardians about age-appropriate health issues, such as sexual relationships, dating violence, and sexual coercion. Between the ages of 13 years and 15 years is an ideal window because middle school is a time that some adolescents develop their first romantic and sexual relationships (Obstet Gynecol. 2018; 132[5]:1317-18 doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002946).

“Creating a nonjudgmental environment and educating staff on the unique concerns of adolescents are helpful ways to provide effective and appropriate care to this group of patients,” the authors wrote.

Ob.gyns. can use the early meeting to discuss key aspects of a healthy relationship with patients, including communication, self-respect, and mutual respect, while helping adolescents identify the characteristics of an unhealthy relationships such as dishonesty, intimidation, disrespect, and abuse, according to the opinion. As part of the discussion, ob.gyns. also may counsel patients to define their current relationship and their expectations for future relationships. Both relationships with and without sexual intimacy should be discussed, the opinion advises.

The recommendation reminds health care professionals to be mindful of federal and state confidentiality laws and that they be aware of mandatory reporting laws when intimate partner violence, teen dating violence, or statutory rape is suspected. In addition, the opinion notes that pregnant and parenting adolescents; lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, or questioning (LGBTQ) individuals; and adolescents with physical and mental disabilities are at particular risk of disparities in the health care system.

“The promotion of healthy relationships in these groups requires the obstetrician-gynecologist to be aware of the unique barriers and hurdles to sexual and nonsexual expression, as well as to health care,” the opinion states. “Interventions to promote healthy relationships and a strong sexual health framework are more effective when started early and can affect indicators of long-term individual health and public health.”

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that the first reproductive health visit occur between the ages of 13 and 15, and I agree with them. Often patients attending this appointment don’t have physical complaints, and we can focus on prevention and education. The visit can be about building the provider-patient relationship and may serve to ease fears and develop trust before visits for problem management.

There are a number of important health education topics to cover from puberty and menses to confidentiality and minor-access laws. Because many young people will begin to initiate romantic relationships during middle school, the topic of healthy relationships is critical. Unhealthy relationships, in their many forms, can have far reaching impacts on a young person’s health and wellness. For years, we’ve been talking with young people about preventing STIs or preventing unwanted pregnancy, but we’ve spent less energy working towards something.

I’m excited to see these recommendations and look forward to helping my younger patients think through relationships as important aspects of life and health, what they want from them, and how they can work towards them.

Melissa Kottke , MD is an obstetrician-gynecologist specializing in family planning and adolescent reproductive health at Emory University in Atlanta.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that the first reproductive health visit occur between the ages of 13 and 15, and I agree with them. Often patients attending this appointment don’t have physical complaints, and we can focus on prevention and education. The visit can be about building the provider-patient relationship and may serve to ease fears and develop trust before visits for problem management.

There are a number of important health education topics to cover from puberty and menses to confidentiality and minor-access laws. Because many young people will begin to initiate romantic relationships during middle school, the topic of healthy relationships is critical. Unhealthy relationships, in their many forms, can have far reaching impacts on a young person’s health and wellness. For years, we’ve been talking with young people about preventing STIs or preventing unwanted pregnancy, but we’ve spent less energy working towards something.

I’m excited to see these recommendations and look forward to helping my younger patients think through relationships as important aspects of life and health, what they want from them, and how they can work towards them.

Melissa Kottke , MD is an obstetrician-gynecologist specializing in family planning and adolescent reproductive health at Emory University in Atlanta.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that the first reproductive health visit occur between the ages of 13 and 15, and I agree with them. Often patients attending this appointment don’t have physical complaints, and we can focus on prevention and education. The visit can be about building the provider-patient relationship and may serve to ease fears and develop trust before visits for problem management.

There are a number of important health education topics to cover from puberty and menses to confidentiality and minor-access laws. Because many young people will begin to initiate romantic relationships during middle school, the topic of healthy relationships is critical. Unhealthy relationships, in their many forms, can have far reaching impacts on a young person’s health and wellness. For years, we’ve been talking with young people about preventing STIs or preventing unwanted pregnancy, but we’ve spent less energy working towards something.

I’m excited to see these recommendations and look forward to helping my younger patients think through relationships as important aspects of life and health, what they want from them, and how they can work towards them.

Melissa Kottke , MD is an obstetrician-gynecologist specializing in family planning and adolescent reproductive health at Emory University in Atlanta.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends that girls receive their first reproductive health visit between the ages of 13 and 15 years to discuss healthy relationships in addition to general reproductive health, according to a new committee opinion.

The recommendation, published online Oct. 24, emphasizes that such early visits provide opportunities for ob.gyns. to educate teenage girls and their guardians about age-appropriate health issues, such as sexual relationships, dating violence, and sexual coercion. Between the ages of 13 years and 15 years is an ideal window because middle school is a time that some adolescents develop their first romantic and sexual relationships (Obstet Gynecol. 2018; 132[5]:1317-18 doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002946).

“Creating a nonjudgmental environment and educating staff on the unique concerns of adolescents are helpful ways to provide effective and appropriate care to this group of patients,” the authors wrote.

Ob.gyns. can use the early meeting to discuss key aspects of a healthy relationship with patients, including communication, self-respect, and mutual respect, while helping adolescents identify the characteristics of an unhealthy relationships such as dishonesty, intimidation, disrespect, and abuse, according to the opinion. As part of the discussion, ob.gyns. also may counsel patients to define their current relationship and their expectations for future relationships. Both relationships with and without sexual intimacy should be discussed, the opinion advises.

The recommendation reminds health care professionals to be mindful of federal and state confidentiality laws and that they be aware of mandatory reporting laws when intimate partner violence, teen dating violence, or statutory rape is suspected. In addition, the opinion notes that pregnant and parenting adolescents; lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, or questioning (LGBTQ) individuals; and adolescents with physical and mental disabilities are at particular risk of disparities in the health care system.

“The promotion of healthy relationships in these groups requires the obstetrician-gynecologist to be aware of the unique barriers and hurdles to sexual and nonsexual expression, as well as to health care,” the opinion states. “Interventions to promote healthy relationships and a strong sexual health framework are more effective when started early and can affect indicators of long-term individual health and public health.”

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends that girls receive their first reproductive health visit between the ages of 13 and 15 years to discuss healthy relationships in addition to general reproductive health, according to a new committee opinion.

The recommendation, published online Oct. 24, emphasizes that such early visits provide opportunities for ob.gyns. to educate teenage girls and their guardians about age-appropriate health issues, such as sexual relationships, dating violence, and sexual coercion. Between the ages of 13 years and 15 years is an ideal window because middle school is a time that some adolescents develop their first romantic and sexual relationships (Obstet Gynecol. 2018; 132[5]:1317-18 doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002946).

“Creating a nonjudgmental environment and educating staff on the unique concerns of adolescents are helpful ways to provide effective and appropriate care to this group of patients,” the authors wrote.

Ob.gyns. can use the early meeting to discuss key aspects of a healthy relationship with patients, including communication, self-respect, and mutual respect, while helping adolescents identify the characteristics of an unhealthy relationships such as dishonesty, intimidation, disrespect, and abuse, according to the opinion. As part of the discussion, ob.gyns. also may counsel patients to define their current relationship and their expectations for future relationships. Both relationships with and without sexual intimacy should be discussed, the opinion advises.

The recommendation reminds health care professionals to be mindful of federal and state confidentiality laws and that they be aware of mandatory reporting laws when intimate partner violence, teen dating violence, or statutory rape is suspected. In addition, the opinion notes that pregnant and parenting adolescents; lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, or questioning (LGBTQ) individuals; and adolescents with physical and mental disabilities are at particular risk of disparities in the health care system.

“The promotion of healthy relationships in these groups requires the obstetrician-gynecologist to be aware of the unique barriers and hurdles to sexual and nonsexual expression, as well as to health care,” the opinion states. “Interventions to promote healthy relationships and a strong sexual health framework are more effective when started early and can affect indicators of long-term individual health and public health.”

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Vaccine protects against flu-related hospitalizations in pregnancy

A review of more than 1,000 hospitalizations revealed a 40% influenza vaccine effectiveness against laboratory-confirmed influenza-associated hospitalizations during pregnancy, Mark Thompson, MD, said at a meeting of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices in Atlanta.

To date, no study has examined influenza vaccine effectiveness (IVE) against hospitalizations among pregnant women, said Dr. Thompson, of the CDC’s influenza division.

He presented results of a study based on data from the Pregnancy Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network (PREVENT), which included public health or health care systems with integrated laboratory, medical, and vaccination records in Australia, Canada (Alberta and Ontario), Israel, and three states (California, Oregon, and Washington). The study included women aged 18-50 years who were pregnant during local influenza seasons from 2010 to 2016. Most of the women were older than 35 years (79%), and in the third trimester (65%), and had no high risk medical conditions (66%). The study was published in Clinical Infectious Diseases (2018 Oct 11. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy737).

The researchers identified 19,450 hospitalizations with an acute respiratory or febrile illness discharge diagnosis and clinician-ordered real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) testing for flu viruses. Of these, 1,030 (6%) of the women underwent rRT-PCR testing, 54% were diagnosed with either influenza or pneumonia, and 58% had detectable influenza A or B virus infections.

Overall, the adjusted IVE was 40%; 13% of rRT-PCR-confirmed influenza-positive pregnant women and 22% of influenza-negative pregnant women were vaccinated; IVE was adjusted for site, season, season timing, and high-risk medical conditions.

“The takeaway is this is the average performance of the vaccine across multiple countries and different seasons,” and the vaccine effectiveness appeared stable across high-risk medical conditions and trimesters of pregnancy, Dr. Thompson said.

The generalizability of the study findings was limited by the lack of data from low- to middle-income countries, he said during the meeting discussion. However, the ICU admission rate is “what we would expect” and similar to results from previous studies. The consistent results showed the need to increase flu vaccination for pregnant women worldwide and to include study populations from lower-income countries in future research.

Dr. Thompson had no financial conflicts to disclose.

A review of more than 1,000 hospitalizations revealed a 40% influenza vaccine effectiveness against laboratory-confirmed influenza-associated hospitalizations during pregnancy, Mark Thompson, MD, said at a meeting of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices in Atlanta.

To date, no study has examined influenza vaccine effectiveness (IVE) against hospitalizations among pregnant women, said Dr. Thompson, of the CDC’s influenza division.

He presented results of a study based on data from the Pregnancy Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network (PREVENT), which included public health or health care systems with integrated laboratory, medical, and vaccination records in Australia, Canada (Alberta and Ontario), Israel, and three states (California, Oregon, and Washington). The study included women aged 18-50 years who were pregnant during local influenza seasons from 2010 to 2016. Most of the women were older than 35 years (79%), and in the third trimester (65%), and had no high risk medical conditions (66%). The study was published in Clinical Infectious Diseases (2018 Oct 11. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy737).

The researchers identified 19,450 hospitalizations with an acute respiratory or febrile illness discharge diagnosis and clinician-ordered real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) testing for flu viruses. Of these, 1,030 (6%) of the women underwent rRT-PCR testing, 54% were diagnosed with either influenza or pneumonia, and 58% had detectable influenza A or B virus infections.

Overall, the adjusted IVE was 40%; 13% of rRT-PCR-confirmed influenza-positive pregnant women and 22% of influenza-negative pregnant women were vaccinated; IVE was adjusted for site, season, season timing, and high-risk medical conditions.

“The takeaway is this is the average performance of the vaccine across multiple countries and different seasons,” and the vaccine effectiveness appeared stable across high-risk medical conditions and trimesters of pregnancy, Dr. Thompson said.

The generalizability of the study findings was limited by the lack of data from low- to middle-income countries, he said during the meeting discussion. However, the ICU admission rate is “what we would expect” and similar to results from previous studies. The consistent results showed the need to increase flu vaccination for pregnant women worldwide and to include study populations from lower-income countries in future research.

Dr. Thompson had no financial conflicts to disclose.

A review of more than 1,000 hospitalizations revealed a 40% influenza vaccine effectiveness against laboratory-confirmed influenza-associated hospitalizations during pregnancy, Mark Thompson, MD, said at a meeting of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices in Atlanta.

To date, no study has examined influenza vaccine effectiveness (IVE) against hospitalizations among pregnant women, said Dr. Thompson, of the CDC’s influenza division.

He presented results of a study based on data from the Pregnancy Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network (PREVENT), which included public health or health care systems with integrated laboratory, medical, and vaccination records in Australia, Canada (Alberta and Ontario), Israel, and three states (California, Oregon, and Washington). The study included women aged 18-50 years who were pregnant during local influenza seasons from 2010 to 2016. Most of the women were older than 35 years (79%), and in the third trimester (65%), and had no high risk medical conditions (66%). The study was published in Clinical Infectious Diseases (2018 Oct 11. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy737).

The researchers identified 19,450 hospitalizations with an acute respiratory or febrile illness discharge diagnosis and clinician-ordered real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) testing for flu viruses. Of these, 1,030 (6%) of the women underwent rRT-PCR testing, 54% were diagnosed with either influenza or pneumonia, and 58% had detectable influenza A or B virus infections.

Overall, the adjusted IVE was 40%; 13% of rRT-PCR-confirmed influenza-positive pregnant women and 22% of influenza-negative pregnant women were vaccinated; IVE was adjusted for site, season, season timing, and high-risk medical conditions.

“The takeaway is this is the average performance of the vaccine across multiple countries and different seasons,” and the vaccine effectiveness appeared stable across high-risk medical conditions and trimesters of pregnancy, Dr. Thompson said.

The generalizability of the study findings was limited by the lack of data from low- to middle-income countries, he said during the meeting discussion. However, the ICU admission rate is “what we would expect” and similar to results from previous studies. The consistent results showed the need to increase flu vaccination for pregnant women worldwide and to include study populations from lower-income countries in future research.

Dr. Thompson had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM AN ACIP MEETING

Shorter interpregnancy intervals may increase risk of adverse outcomes

Short interpregnancy intervals carry an increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes for women of all ages and increased adverse fetal and infant outcome risks for women between 20 and 34 years old, according to research published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

“This finding may be reassuring particularly for older women who must weigh the competing risks of increasing maternal age with longer interpregnancy intervals (including infertility and chromosomal anomalies) against the risks of short interpregnancy intervals,” wrote Laura Schummers, SD, of the department of epidemiology at Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, and her colleagues.

The researchers examined 148,544 pregnancies of women in British Columbia who were younger than 20 years old at the index (5%), 20-34 years at the index birth (83%), and 35 years or older (12%). The women had two or more consecutive singleton pregnancies that resulted in a live birth between 2004 and 2014 and were recorded in the British Columbia Perinatal Data Registry. There was a lower number of short interpregnancy intervals, defined as less than 6 months between the index and second pregnancy, among women in the 35-years-or-older group, compared with the 20- to 34-year-old group (4.4% vs. 5.5%); the 35-years-or-older group instead had a higher number of interpregnancy intervals between 6 and 11 months and between 12 and 17 months, compared with the 20- to 34-year-old group (17.7% vs. 16.6%, and 25.2% vs. 22.5%, respectively).

The risk for maternal mortality or severe morbidity was higher in women who were a minimum 35 years old with 6 months between pregnancies (0.62%), compared with women who had 18 months (0.26%) between pregnancies (adjusted relative risk [aRR], 2.39). There was no significant increase in those aged between 20 and 34 years at 6 months, compared with 18 months (0.23% vs. 0.25%; aRR, 0.92). However, the 20- to 34-year-old group did have an increased risk of fetal and infant adverse outcomes at 6 months, compared with 18 months (2.0% vs. 1.4%; aRR, 1.42) and compared with women in the 35-years-or-older group at 6 months and 18 months (2.1% vs. 1.8%; aRR, 1.15).

There was a 5.3% increased risk at 6 months and a 3.2% increased risk at 18 months of spontaneous preterm delivery in the 20- to 34-year-old group (aRR, 1.65), compared with a 5.0% risk at 6 months and 3.6% at 18 months in the 35-years-or-older group (aRR, 1.40). The researchers noted “modest increases” in newborns who were born small for their gestational age and indicated preterm delivery at short intervals that did not differ by age group.

The authors reported no conflicts of interest. Dr Schummers was supported a National Research Service Award from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and received a grant from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research and the Public Health Agency of Canada Family Planning Public Health Chair Seed Grant. Two of her coauthors were supported by various other awards.

SOURCE: Schummers L et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Oct 29. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4696.

While the findings of Schummers et al. appear to encourage pregnancy spacing among women of all ages, women who are 35 or older should be counseled differently than women aged 20-34 years, Stephanie B. Teal, MD, MPH, and Jeanelle Sheeder, MSPH, PhD, wrote in a related editorial.

“Clinicians should understand that women delivering at age 35 years or later may desire more children and may wish to conceive sooner than recommended,” the authors wrote.

Women who are 35 years old or older may not have 6-12 months to delay pregnancy, the authors explained, and thus should be counseled differently than younger patients. Delaying pregnancy in older women may increase the risk of miscarriage and chromosomal abnormalities, and may cause families to miss out on their desired family size. In addition, spacing out births up to 24 months apart does not significantly diminish the risk of fetal or infant risk among women 35 years and older as it does for younger women, which may make short interpregnancy intervals in this group a “rational choice.”

“Simply telling older women to delay conception is not likely to improve health outcomes, as women are aware of their ‘biological clocks’ and many will value their desire for another child over their physician’s warnings,” Dr. Teal and Dr. Sheeder noted. “Clinicians should use patient-centered counseling and shared decision-making strategies that respect women’s desires for pregnancy, possibly at short intervals in women 35 years or older, and adequately discuss fetal, infant, and maternal risks in this context.”

Dr. Teal and Dr. Sheeder are in the division of family planning in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Colorado in Aurora. Their their comments were made in an editorial in JAMA Internal Medicine (2018 Oct 29. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4734 ). They reported no conflicts of interest.

While the findings of Schummers et al. appear to encourage pregnancy spacing among women of all ages, women who are 35 or older should be counseled differently than women aged 20-34 years, Stephanie B. Teal, MD, MPH, and Jeanelle Sheeder, MSPH, PhD, wrote in a related editorial.

“Clinicians should understand that women delivering at age 35 years or later may desire more children and may wish to conceive sooner than recommended,” the authors wrote.

Women who are 35 years old or older may not have 6-12 months to delay pregnancy, the authors explained, and thus should be counseled differently than younger patients. Delaying pregnancy in older women may increase the risk of miscarriage and chromosomal abnormalities, and may cause families to miss out on their desired family size. In addition, spacing out births up to 24 months apart does not significantly diminish the risk of fetal or infant risk among women 35 years and older as it does for younger women, which may make short interpregnancy intervals in this group a “rational choice.”

“Simply telling older women to delay conception is not likely to improve health outcomes, as women are aware of their ‘biological clocks’ and many will value their desire for another child over their physician’s warnings,” Dr. Teal and Dr. Sheeder noted. “Clinicians should use patient-centered counseling and shared decision-making strategies that respect women’s desires for pregnancy, possibly at short intervals in women 35 years or older, and adequately discuss fetal, infant, and maternal risks in this context.”

Dr. Teal and Dr. Sheeder are in the division of family planning in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Colorado in Aurora. Their their comments were made in an editorial in JAMA Internal Medicine (2018 Oct 29. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4734 ). They reported no conflicts of interest.

While the findings of Schummers et al. appear to encourage pregnancy spacing among women of all ages, women who are 35 or older should be counseled differently than women aged 20-34 years, Stephanie B. Teal, MD, MPH, and Jeanelle Sheeder, MSPH, PhD, wrote in a related editorial.

“Clinicians should understand that women delivering at age 35 years or later may desire more children and may wish to conceive sooner than recommended,” the authors wrote.

Women who are 35 years old or older may not have 6-12 months to delay pregnancy, the authors explained, and thus should be counseled differently than younger patients. Delaying pregnancy in older women may increase the risk of miscarriage and chromosomal abnormalities, and may cause families to miss out on their desired family size. In addition, spacing out births up to 24 months apart does not significantly diminish the risk of fetal or infant risk among women 35 years and older as it does for younger women, which may make short interpregnancy intervals in this group a “rational choice.”

“Simply telling older women to delay conception is not likely to improve health outcomes, as women are aware of their ‘biological clocks’ and many will value their desire for another child over their physician’s warnings,” Dr. Teal and Dr. Sheeder noted. “Clinicians should use patient-centered counseling and shared decision-making strategies that respect women’s desires for pregnancy, possibly at short intervals in women 35 years or older, and adequately discuss fetal, infant, and maternal risks in this context.”

Dr. Teal and Dr. Sheeder are in the division of family planning in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Colorado in Aurora. Their their comments were made in an editorial in JAMA Internal Medicine (2018 Oct 29. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4734 ). They reported no conflicts of interest.

Short interpregnancy intervals carry an increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes for women of all ages and increased adverse fetal and infant outcome risks for women between 20 and 34 years old, according to research published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

“This finding may be reassuring particularly for older women who must weigh the competing risks of increasing maternal age with longer interpregnancy intervals (including infertility and chromosomal anomalies) against the risks of short interpregnancy intervals,” wrote Laura Schummers, SD, of the department of epidemiology at Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, and her colleagues.

The researchers examined 148,544 pregnancies of women in British Columbia who were younger than 20 years old at the index (5%), 20-34 years at the index birth (83%), and 35 years or older (12%). The women had two or more consecutive singleton pregnancies that resulted in a live birth between 2004 and 2014 and were recorded in the British Columbia Perinatal Data Registry. There was a lower number of short interpregnancy intervals, defined as less than 6 months between the index and second pregnancy, among women in the 35-years-or-older group, compared with the 20- to 34-year-old group (4.4% vs. 5.5%); the 35-years-or-older group instead had a higher number of interpregnancy intervals between 6 and 11 months and between 12 and 17 months, compared with the 20- to 34-year-old group (17.7% vs. 16.6%, and 25.2% vs. 22.5%, respectively).

The risk for maternal mortality or severe morbidity was higher in women who were a minimum 35 years old with 6 months between pregnancies (0.62%), compared with women who had 18 months (0.26%) between pregnancies (adjusted relative risk [aRR], 2.39). There was no significant increase in those aged between 20 and 34 years at 6 months, compared with 18 months (0.23% vs. 0.25%; aRR, 0.92). However, the 20- to 34-year-old group did have an increased risk of fetal and infant adverse outcomes at 6 months, compared with 18 months (2.0% vs. 1.4%; aRR, 1.42) and compared with women in the 35-years-or-older group at 6 months and 18 months (2.1% vs. 1.8%; aRR, 1.15).

There was a 5.3% increased risk at 6 months and a 3.2% increased risk at 18 months of spontaneous preterm delivery in the 20- to 34-year-old group (aRR, 1.65), compared with a 5.0% risk at 6 months and 3.6% at 18 months in the 35-years-or-older group (aRR, 1.40). The researchers noted “modest increases” in newborns who were born small for their gestational age and indicated preterm delivery at short intervals that did not differ by age group.

The authors reported no conflicts of interest. Dr Schummers was supported a National Research Service Award from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and received a grant from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research and the Public Health Agency of Canada Family Planning Public Health Chair Seed Grant. Two of her coauthors were supported by various other awards.

SOURCE: Schummers L et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Oct 29. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4696.

Short interpregnancy intervals carry an increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes for women of all ages and increased adverse fetal and infant outcome risks for women between 20 and 34 years old, according to research published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

“This finding may be reassuring particularly for older women who must weigh the competing risks of increasing maternal age with longer interpregnancy intervals (including infertility and chromosomal anomalies) against the risks of short interpregnancy intervals,” wrote Laura Schummers, SD, of the department of epidemiology at Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, and her colleagues.

The researchers examined 148,544 pregnancies of women in British Columbia who were younger than 20 years old at the index (5%), 20-34 years at the index birth (83%), and 35 years or older (12%). The women had two or more consecutive singleton pregnancies that resulted in a live birth between 2004 and 2014 and were recorded in the British Columbia Perinatal Data Registry. There was a lower number of short interpregnancy intervals, defined as less than 6 months between the index and second pregnancy, among women in the 35-years-or-older group, compared with the 20- to 34-year-old group (4.4% vs. 5.5%); the 35-years-or-older group instead had a higher number of interpregnancy intervals between 6 and 11 months and between 12 and 17 months, compared with the 20- to 34-year-old group (17.7% vs. 16.6%, and 25.2% vs. 22.5%, respectively).

The risk for maternal mortality or severe morbidity was higher in women who were a minimum 35 years old with 6 months between pregnancies (0.62%), compared with women who had 18 months (0.26%) between pregnancies (adjusted relative risk [aRR], 2.39). There was no significant increase in those aged between 20 and 34 years at 6 months, compared with 18 months (0.23% vs. 0.25%; aRR, 0.92). However, the 20- to 34-year-old group did have an increased risk of fetal and infant adverse outcomes at 6 months, compared with 18 months (2.0% vs. 1.4%; aRR, 1.42) and compared with women in the 35-years-or-older group at 6 months and 18 months (2.1% vs. 1.8%; aRR, 1.15).

There was a 5.3% increased risk at 6 months and a 3.2% increased risk at 18 months of spontaneous preterm delivery in the 20- to 34-year-old group (aRR, 1.65), compared with a 5.0% risk at 6 months and 3.6% at 18 months in the 35-years-or-older group (aRR, 1.40). The researchers noted “modest increases” in newborns who were born small for their gestational age and indicated preterm delivery at short intervals that did not differ by age group.

The authors reported no conflicts of interest. Dr Schummers was supported a National Research Service Award from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and received a grant from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research and the Public Health Agency of Canada Family Planning Public Health Chair Seed Grant. Two of her coauthors were supported by various other awards.

SOURCE: Schummers L et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Oct 29. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4696.

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The risk for maternal mortality or severe morbidity was higher in women who were a minimum 35 years old with 6 months between pregnancies (0.62%), compared with women who had 18 months (0.26%) between pregnancies (adjusted relative risk, 2.39).

Study details: A cohort study of 148,544 pregnancies in Canada between 2004 and 2014.

Disclosures: The authors reported no conflicts of interest. Dr Schummers was supported a National Research Service Award from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and received a grant from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research and the Public Health Agency of Canada Family Planning Public Health Chair Seed Grant. Two of her coauthors were supported by other awards.

Source: Schummers L et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Oct 29. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4696.

‘Woeful lack of awareness’ leads to delayed diagnoses for women with ovarian cancer

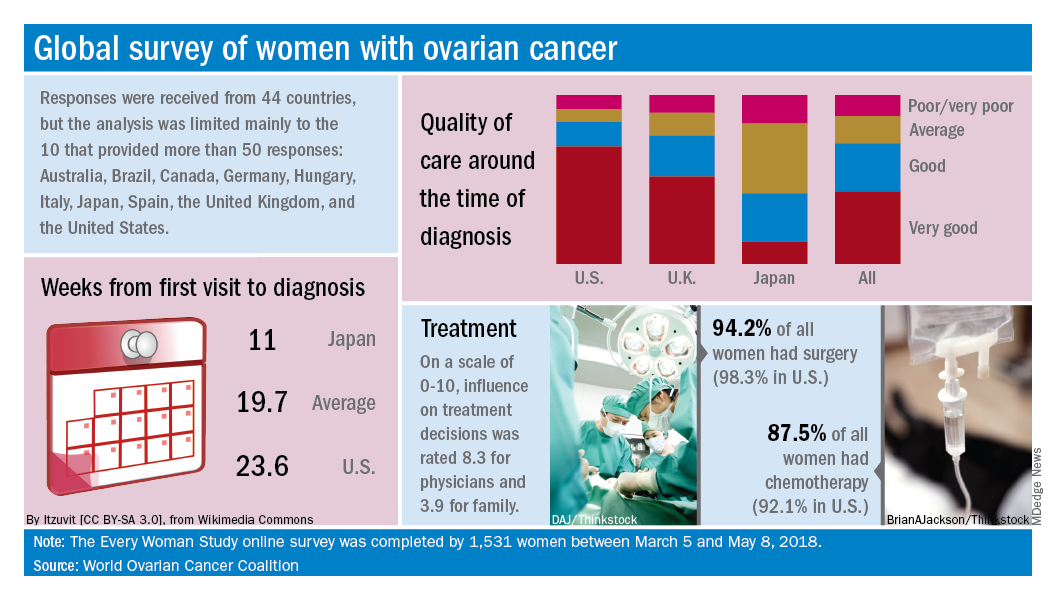

Lack of knowledge about ovarian cancer prevents many women from seeking medical attention, which delays diagnosis and treatment and may prove increasingly dangerous as incidence rises by an expected 55% over the next 2 decades, according to the World Ovarian Cancer Coalition.

Data from the coalition’s 2018 survey of women with ovarian cancer show that 18% had never heard of the disease before their diagnosis and 51% had heard of it but did not know anything about it. The Every Women Study survey, completed by 1,531 women in 44 countries, also reveals that nine out of ten had experienced symptoms prior to diagnosis but fewer than half saw a physician within a month of noticing those symptoms, the coalition said.

“This study, for the first time, provides powerful evidence of the challenges faced by women diagnosed with ovarian cancer across the world and sets an agenda for global change. We were especially shocked by the widespread, woeful lack of awareness of ovarian cancer,” Annwen Jones, coalition vice-chair and cochair of the study, said in a separate written statement.

Results varied considerably by country, and only 10 countries provided enough responses to allow comparisons: Australia (120), Brazil (52), Canada (167), Germany (141), Hungary (58), Italy (92), Japan (250), Spain (70), the United Kingdom (176), and the United States (248).

Among those comparisons, women in Germany (5.5 weeks) and Spain (7.9 weeks) were the first to visit a physician after first experiencing symptoms, while those in Italy (15.2 weeks) and the United States (12.9 weeks) were last. The United States was also longest in time from first visit to diagnosis (23.6 weeks), and Japan was the shortest (11 weeks). Despite that world-longest time to diagnosis, however, over 69% of U.S. women said that their care around the time of diagnosis was very good, which was higher than any other country, the coalition reported.

Surgery statistics were closer among countries, with an average of 94% of all women undergoing surgery to treat their ovarian cancer. The United States, at 98.3%, was second to Spain’s 98.5%, and Hungary was the largest outlier on the low side at 59%. Over 87% of all women reported having chemotherapy to treat or control their cancer, and 9.8% of women said that they had received intraperitoneal chemotherapy. In the United States, 22.5% of women received intraperitoneal therapy, compared with 0.7% for the United Kingdom.

“No one country has all the answers, and whilst there is still an urgent need for a step-change in the level of investment in research for better treatments and tools for early diagnosis, there are significant opportunities to improve survival and quality of life for women in the immediate and short term to make a series of marginal gains if these variations are addressed by individual countries,” the coalition said in the report.

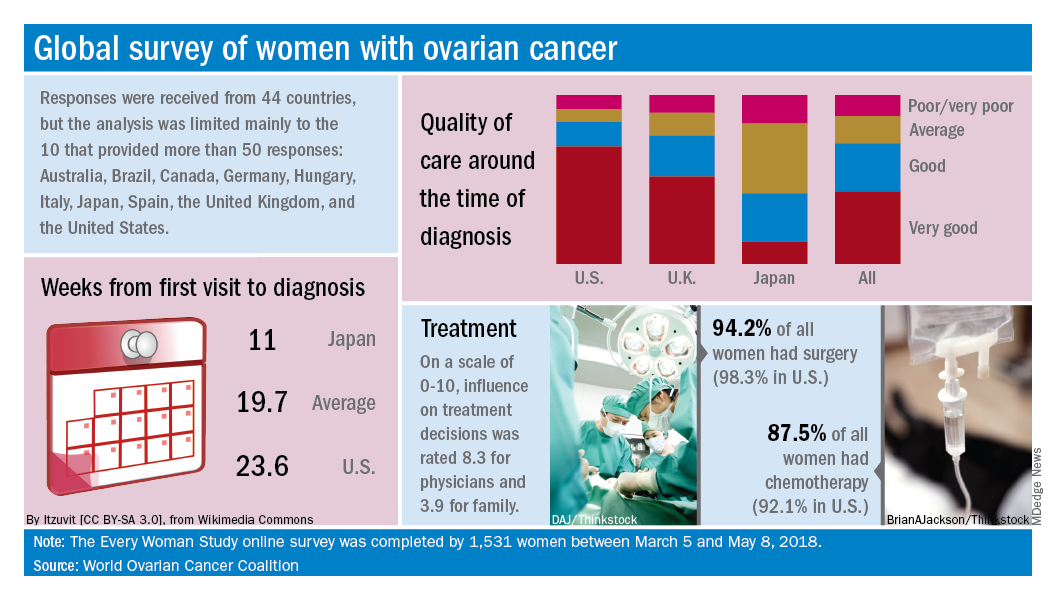

Lack of knowledge about ovarian cancer prevents many women from seeking medical attention, which delays diagnosis and treatment and may prove increasingly dangerous as incidence rises by an expected 55% over the next 2 decades, according to the World Ovarian Cancer Coalition.

Data from the coalition’s 2018 survey of women with ovarian cancer show that 18% had never heard of the disease before their diagnosis and 51% had heard of it but did not know anything about it. The Every Women Study survey, completed by 1,531 women in 44 countries, also reveals that nine out of ten had experienced symptoms prior to diagnosis but fewer than half saw a physician within a month of noticing those symptoms, the coalition said.

“This study, for the first time, provides powerful evidence of the challenges faced by women diagnosed with ovarian cancer across the world and sets an agenda for global change. We were especially shocked by the widespread, woeful lack of awareness of ovarian cancer,” Annwen Jones, coalition vice-chair and cochair of the study, said in a separate written statement.

Results varied considerably by country, and only 10 countries provided enough responses to allow comparisons: Australia (120), Brazil (52), Canada (167), Germany (141), Hungary (58), Italy (92), Japan (250), Spain (70), the United Kingdom (176), and the United States (248).

Among those comparisons, women in Germany (5.5 weeks) and Spain (7.9 weeks) were the first to visit a physician after first experiencing symptoms, while those in Italy (15.2 weeks) and the United States (12.9 weeks) were last. The United States was also longest in time from first visit to diagnosis (23.6 weeks), and Japan was the shortest (11 weeks). Despite that world-longest time to diagnosis, however, over 69% of U.S. women said that their care around the time of diagnosis was very good, which was higher than any other country, the coalition reported.

Surgery statistics were closer among countries, with an average of 94% of all women undergoing surgery to treat their ovarian cancer. The United States, at 98.3%, was second to Spain’s 98.5%, and Hungary was the largest outlier on the low side at 59%. Over 87% of all women reported having chemotherapy to treat or control their cancer, and 9.8% of women said that they had received intraperitoneal chemotherapy. In the United States, 22.5% of women received intraperitoneal therapy, compared with 0.7% for the United Kingdom.

“No one country has all the answers, and whilst there is still an urgent need for a step-change in the level of investment in research for better treatments and tools for early diagnosis, there are significant opportunities to improve survival and quality of life for women in the immediate and short term to make a series of marginal gains if these variations are addressed by individual countries,” the coalition said in the report.

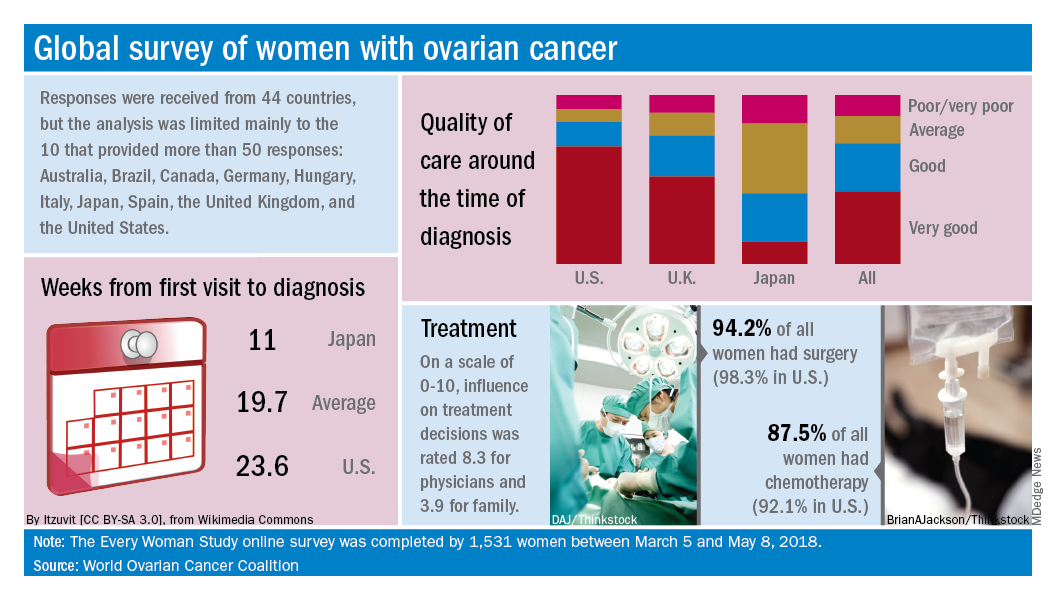

Lack of knowledge about ovarian cancer prevents many women from seeking medical attention, which delays diagnosis and treatment and may prove increasingly dangerous as incidence rises by an expected 55% over the next 2 decades, according to the World Ovarian Cancer Coalition.

Data from the coalition’s 2018 survey of women with ovarian cancer show that 18% had never heard of the disease before their diagnosis and 51% had heard of it but did not know anything about it. The Every Women Study survey, completed by 1,531 women in 44 countries, also reveals that nine out of ten had experienced symptoms prior to diagnosis but fewer than half saw a physician within a month of noticing those symptoms, the coalition said.

“This study, for the first time, provides powerful evidence of the challenges faced by women diagnosed with ovarian cancer across the world and sets an agenda for global change. We were especially shocked by the widespread, woeful lack of awareness of ovarian cancer,” Annwen Jones, coalition vice-chair and cochair of the study, said in a separate written statement.

Results varied considerably by country, and only 10 countries provided enough responses to allow comparisons: Australia (120), Brazil (52), Canada (167), Germany (141), Hungary (58), Italy (92), Japan (250), Spain (70), the United Kingdom (176), and the United States (248).

Among those comparisons, women in Germany (5.5 weeks) and Spain (7.9 weeks) were the first to visit a physician after first experiencing symptoms, while those in Italy (15.2 weeks) and the United States (12.9 weeks) were last. The United States was also longest in time from first visit to diagnosis (23.6 weeks), and Japan was the shortest (11 weeks). Despite that world-longest time to diagnosis, however, over 69% of U.S. women said that their care around the time of diagnosis was very good, which was higher than any other country, the coalition reported.

Surgery statistics were closer among countries, with an average of 94% of all women undergoing surgery to treat their ovarian cancer. The United States, at 98.3%, was second to Spain’s 98.5%, and Hungary was the largest outlier on the low side at 59%. Over 87% of all women reported having chemotherapy to treat or control their cancer, and 9.8% of women said that they had received intraperitoneal chemotherapy. In the United States, 22.5% of women received intraperitoneal therapy, compared with 0.7% for the United Kingdom.

“No one country has all the answers, and whilst there is still an urgent need for a step-change in the level of investment in research for better treatments and tools for early diagnosis, there are significant opportunities to improve survival and quality of life for women in the immediate and short term to make a series of marginal gains if these variations are addressed by individual countries,” the coalition said in the report.

ACR readies first-ever guidelines on managing reproductive health in rheumatology

CHICAGO – Help is on the way for rheumatologists who may feel out of their depth regarding reproductive health issues in their patients.

for internal review in draft form. Lisa R. Sammaritano, MD, a leader of the expert panel that developed the evidence-based recommendations, shared highlights of the forthcoming guidelines at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

“Our patients, fortunately, are pursuing pregnancy more often now than in years past. One of the key messages of the guidelines is that patients really do want to discuss these topics with their rheumatologist, even though that often does not happen now. What patients told us [in the guideline-development process] is their rheumatologist knows them better than their gynecologist or any of their other doctors because we have followed them for a long period of time and we understand their disease and their symptoms. They really want our input on questions about contraception, when to plan a pregnancy, and medication use,” said Dr. Sammaritano of the Hospital for Special Surgery and Cornell University in New York.

The guidelines were created over the course of a year and a half with extensive input from ob.gyns., as well as a patient panel. The project included a systematic review of more than 300 published studies in which guideline panelists attempt to find answers to an initial list of 370 questions. Dr. Sammaritano predicted that the guidelines will prove to be useful not only for rheumatologists, but for their colleagues in ob.gyn. as well. Just as rheumatologists likely haven’t kept up with the sea changes that have occurred in ob.gyn. since their medical school days, most ob.gyns. know little about rheumatic diseases.

“There’s room for education on both sides,” she observed in an interview. “I have had to write letters to gynecologists to get them to put my patients with antiphospholipid antibodies on a contraceptive that includes a progestin because the labeling says, ‘May increase risk of thrombosis.’ And yet if you look at the literature, most of the progestins do not increase the risk of thrombosis, even in patients who are already at increased risk because of a genetic prothrombotic abnormality. I practically had to sign my life away to get a gynecologist to put a progestin-containing IUD in my patient, whereas the risk of thrombosis to my patient with an unplanned pregnancy would have been 10-fold or 100-fold higher. Unplanned pregnancy is dangerous for patients with our diseases.”

And yet, she noted, half of all pregnancies in the United States are unplanned. Among women with rheumatic diseases, the proportion may well be even higher in light of their documented low rate of utilization of effective contraception.

A publication date for the guidelines won’t be set until the review is completed, but the plan is to issue three separate documents. One will address reproductive health outside of pregnancy, with key topics to include contraception, fertility preservation, menopause, and hormone replacement therapy. The second document will focus on pregnancy management, with special attention devoted to women with lupus or antiphospholipid antibodies because they are at particularly high risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. The third document will be devoted to medications, covering issues including which medications can be continued during pregnancy and when to safely stop the ones that can’t. This section will address both maternal and paternal use of rheumatologic medications, the latter being a topic below the radar of ob.gyns.

The three medications whose paternal use in pregnancy generate the most questions in clinical practice are methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, and sulfasalazine.

“I cannot tell you how many times I’ve been asked whether male patients with rheumatic diseases need to stop their methotrexate before they plan to father a child – that’s been a big one. The answer is they don’t need to stop, but that’s a conditional recommendation because the product label still says to stop it 3 months before. But that’s based on theoretical concerns, and all the data support a lack of teratogenicity for men using methotrexate prior to and during pregnancy,” Dr. Sammaritano said.

Men on cyclophosphamide absolutely have to stop the drug 3 months before pregnancy because the drug causes DNA fragmentation in the sperm. Sulfasalazine is known to impair male fertility. The ACR guidelines will recommend that men continue the drug, but if pregnancy doesn’t occur within a reasonable time, then it’s appropriate to get a semen analysis rather than stopping sulfasalazine unnecessarily.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists guidelines now recommend long-acting reversible contraception, including IUDs and progestin implants, as first-line contraception for all women. The ACR draft guidelines strongly recommend the same.

“That is new. The use of this form of contraception in women with rheumatic diseases is quite low. In general, our patients don’t use contraception as often as other women, and when they do, they don’t use effective contraception. There are many theories as to why that may be: perhaps it’s a focus on the more immediate issues of their rheumatic disease that doesn’t allow their rheumatologist to get to the point of discussing contraception,” according to Dr. Sammaritano.

Many rheumatologists will be pleasantly surprised to learn that the problem of increased risk of pelvic inflammatory disease associated with earlier-generation IUDs is no longer an issue with the current devices. And contrary to a misconception among some ob.gyns., autoimmune disease will not cause a woman to reject her IUD.

The ACR guidelines recommend continuing hydroxychloroquine in lupus patients during pregnancy – and considering starting the drug in those not already on it – because of strong evidence supporting both safety and benefit for mother and baby.

“We are recommending the use of low-dose aspirin for patients with lupus and antiphospholipid antibodies because those two conditions increase the risk for preeclampsia, and the ob.gyns. routinely use low-dose aspirin starting toward the end of the first trimester as preventive therapy. Large studies show that it reduces the risk,” she continued.

Dr. Sammaritano cautioned that the literature on the use of rheumatologic medications in pregnancy and breast feeding is generally weak – and in the case of the new oral small molecule JAK inhibitors, essentially nonexistent.

“A lot of our recommendations are conditional because we did not feel that the data support a strong recommendation. But you have to do something. As long as you communicate the idea that we’re doing the best we can with what information is available, I think patients will respond to that,” the rheumatologist said.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her presentation.

CHICAGO – Help is on the way for rheumatologists who may feel out of their depth regarding reproductive health issues in their patients.

for internal review in draft form. Lisa R. Sammaritano, MD, a leader of the expert panel that developed the evidence-based recommendations, shared highlights of the forthcoming guidelines at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

“Our patients, fortunately, are pursuing pregnancy more often now than in years past. One of the key messages of the guidelines is that patients really do want to discuss these topics with their rheumatologist, even though that often does not happen now. What patients told us [in the guideline-development process] is their rheumatologist knows them better than their gynecologist or any of their other doctors because we have followed them for a long period of time and we understand their disease and their symptoms. They really want our input on questions about contraception, when to plan a pregnancy, and medication use,” said Dr. Sammaritano of the Hospital for Special Surgery and Cornell University in New York.

The guidelines were created over the course of a year and a half with extensive input from ob.gyns., as well as a patient panel. The project included a systematic review of more than 300 published studies in which guideline panelists attempt to find answers to an initial list of 370 questions. Dr. Sammaritano predicted that the guidelines will prove to be useful not only for rheumatologists, but for their colleagues in ob.gyn. as well. Just as rheumatologists likely haven’t kept up with the sea changes that have occurred in ob.gyn. since their medical school days, most ob.gyns. know little about rheumatic diseases.

“There’s room for education on both sides,” she observed in an interview. “I have had to write letters to gynecologists to get them to put my patients with antiphospholipid antibodies on a contraceptive that includes a progestin because the labeling says, ‘May increase risk of thrombosis.’ And yet if you look at the literature, most of the progestins do not increase the risk of thrombosis, even in patients who are already at increased risk because of a genetic prothrombotic abnormality. I practically had to sign my life away to get a gynecologist to put a progestin-containing IUD in my patient, whereas the risk of thrombosis to my patient with an unplanned pregnancy would have been 10-fold or 100-fold higher. Unplanned pregnancy is dangerous for patients with our diseases.”

And yet, she noted, half of all pregnancies in the United States are unplanned. Among women with rheumatic diseases, the proportion may well be even higher in light of their documented low rate of utilization of effective contraception.

A publication date for the guidelines won’t be set until the review is completed, but the plan is to issue three separate documents. One will address reproductive health outside of pregnancy, with key topics to include contraception, fertility preservation, menopause, and hormone replacement therapy. The second document will focus on pregnancy management, with special attention devoted to women with lupus or antiphospholipid antibodies because they are at particularly high risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. The third document will be devoted to medications, covering issues including which medications can be continued during pregnancy and when to safely stop the ones that can’t. This section will address both maternal and paternal use of rheumatologic medications, the latter being a topic below the radar of ob.gyns.

The three medications whose paternal use in pregnancy generate the most questions in clinical practice are methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, and sulfasalazine.

“I cannot tell you how many times I’ve been asked whether male patients with rheumatic diseases need to stop their methotrexate before they plan to father a child – that’s been a big one. The answer is they don’t need to stop, but that’s a conditional recommendation because the product label still says to stop it 3 months before. But that’s based on theoretical concerns, and all the data support a lack of teratogenicity for men using methotrexate prior to and during pregnancy,” Dr. Sammaritano said.

Men on cyclophosphamide absolutely have to stop the drug 3 months before pregnancy because the drug causes DNA fragmentation in the sperm. Sulfasalazine is known to impair male fertility. The ACR guidelines will recommend that men continue the drug, but if pregnancy doesn’t occur within a reasonable time, then it’s appropriate to get a semen analysis rather than stopping sulfasalazine unnecessarily.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists guidelines now recommend long-acting reversible contraception, including IUDs and progestin implants, as first-line contraception for all women. The ACR draft guidelines strongly recommend the same.

“That is new. The use of this form of contraception in women with rheumatic diseases is quite low. In general, our patients don’t use contraception as often as other women, and when they do, they don’t use effective contraception. There are many theories as to why that may be: perhaps it’s a focus on the more immediate issues of their rheumatic disease that doesn’t allow their rheumatologist to get to the point of discussing contraception,” according to Dr. Sammaritano.

Many rheumatologists will be pleasantly surprised to learn that the problem of increased risk of pelvic inflammatory disease associated with earlier-generation IUDs is no longer an issue with the current devices. And contrary to a misconception among some ob.gyns., autoimmune disease will not cause a woman to reject her IUD.

The ACR guidelines recommend continuing hydroxychloroquine in lupus patients during pregnancy – and considering starting the drug in those not already on it – because of strong evidence supporting both safety and benefit for mother and baby.

“We are recommending the use of low-dose aspirin for patients with lupus and antiphospholipid antibodies because those two conditions increase the risk for preeclampsia, and the ob.gyns. routinely use low-dose aspirin starting toward the end of the first trimester as preventive therapy. Large studies show that it reduces the risk,” she continued.

Dr. Sammaritano cautioned that the literature on the use of rheumatologic medications in pregnancy and breast feeding is generally weak – and in the case of the new oral small molecule JAK inhibitors, essentially nonexistent.

“A lot of our recommendations are conditional because we did not feel that the data support a strong recommendation. But you have to do something. As long as you communicate the idea that we’re doing the best we can with what information is available, I think patients will respond to that,” the rheumatologist said.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her presentation.

CHICAGO – Help is on the way for rheumatologists who may feel out of their depth regarding reproductive health issues in their patients.

for internal review in draft form. Lisa R. Sammaritano, MD, a leader of the expert panel that developed the evidence-based recommendations, shared highlights of the forthcoming guidelines at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

“Our patients, fortunately, are pursuing pregnancy more often now than in years past. One of the key messages of the guidelines is that patients really do want to discuss these topics with their rheumatologist, even though that often does not happen now. What patients told us [in the guideline-development process] is their rheumatologist knows them better than their gynecologist or any of their other doctors because we have followed them for a long period of time and we understand their disease and their symptoms. They really want our input on questions about contraception, when to plan a pregnancy, and medication use,” said Dr. Sammaritano of the Hospital for Special Surgery and Cornell University in New York.

The guidelines were created over the course of a year and a half with extensive input from ob.gyns., as well as a patient panel. The project included a systematic review of more than 300 published studies in which guideline panelists attempt to find answers to an initial list of 370 questions. Dr. Sammaritano predicted that the guidelines will prove to be useful not only for rheumatologists, but for their colleagues in ob.gyn. as well. Just as rheumatologists likely haven’t kept up with the sea changes that have occurred in ob.gyn. since their medical school days, most ob.gyns. know little about rheumatic diseases.

“There’s room for education on both sides,” she observed in an interview. “I have had to write letters to gynecologists to get them to put my patients with antiphospholipid antibodies on a contraceptive that includes a progestin because the labeling says, ‘May increase risk of thrombosis.’ And yet if you look at the literature, most of the progestins do not increase the risk of thrombosis, even in patients who are already at increased risk because of a genetic prothrombotic abnormality. I practically had to sign my life away to get a gynecologist to put a progestin-containing IUD in my patient, whereas the risk of thrombosis to my patient with an unplanned pregnancy would have been 10-fold or 100-fold higher. Unplanned pregnancy is dangerous for patients with our diseases.”

And yet, she noted, half of all pregnancies in the United States are unplanned. Among women with rheumatic diseases, the proportion may well be even higher in light of their documented low rate of utilization of effective contraception.

A publication date for the guidelines won’t be set until the review is completed, but the plan is to issue three separate documents. One will address reproductive health outside of pregnancy, with key topics to include contraception, fertility preservation, menopause, and hormone replacement therapy. The second document will focus on pregnancy management, with special attention devoted to women with lupus or antiphospholipid antibodies because they are at particularly high risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. The third document will be devoted to medications, covering issues including which medications can be continued during pregnancy and when to safely stop the ones that can’t. This section will address both maternal and paternal use of rheumatologic medications, the latter being a topic below the radar of ob.gyns.

The three medications whose paternal use in pregnancy generate the most questions in clinical practice are methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, and sulfasalazine.

“I cannot tell you how many times I’ve been asked whether male patients with rheumatic diseases need to stop their methotrexate before they plan to father a child – that’s been a big one. The answer is they don’t need to stop, but that’s a conditional recommendation because the product label still says to stop it 3 months before. But that’s based on theoretical concerns, and all the data support a lack of teratogenicity for men using methotrexate prior to and during pregnancy,” Dr. Sammaritano said.

Men on cyclophosphamide absolutely have to stop the drug 3 months before pregnancy because the drug causes DNA fragmentation in the sperm. Sulfasalazine is known to impair male fertility. The ACR guidelines will recommend that men continue the drug, but if pregnancy doesn’t occur within a reasonable time, then it’s appropriate to get a semen analysis rather than stopping sulfasalazine unnecessarily.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists guidelines now recommend long-acting reversible contraception, including IUDs and progestin implants, as first-line contraception for all women. The ACR draft guidelines strongly recommend the same.

“That is new. The use of this form of contraception in women with rheumatic diseases is quite low. In general, our patients don’t use contraception as often as other women, and when they do, they don’t use effective contraception. There are many theories as to why that may be: perhaps it’s a focus on the more immediate issues of their rheumatic disease that doesn’t allow their rheumatologist to get to the point of discussing contraception,” according to Dr. Sammaritano.

Many rheumatologists will be pleasantly surprised to learn that the problem of increased risk of pelvic inflammatory disease associated with earlier-generation IUDs is no longer an issue with the current devices. And contrary to a misconception among some ob.gyns., autoimmune disease will not cause a woman to reject her IUD.

The ACR guidelines recommend continuing hydroxychloroquine in lupus patients during pregnancy – and considering starting the drug in those not already on it – because of strong evidence supporting both safety and benefit for mother and baby.

“We are recommending the use of low-dose aspirin for patients with lupus and antiphospholipid antibodies because those two conditions increase the risk for preeclampsia, and the ob.gyns. routinely use low-dose aspirin starting toward the end of the first trimester as preventive therapy. Large studies show that it reduces the risk,” she continued.

Dr. Sammaritano cautioned that the literature on the use of rheumatologic medications in pregnancy and breast feeding is generally weak – and in the case of the new oral small molecule JAK inhibitors, essentially nonexistent.

“A lot of our recommendations are conditional because we did not feel that the data support a strong recommendation. But you have to do something. As long as you communicate the idea that we’re doing the best we can with what information is available, I think patients will respond to that,” the rheumatologist said.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her presentation.

REPORTING FROM THE ACR ANNUAL MEETING

Understanding hypertensive disorders in pregnancy

Preeclampsia is one of the most significant medical complications in pregnancy because of the acute onset it can have in so many affected patients. This acute onset may then rapidly progress to eclampsia and to severe consequences, including maternal death. In addition, the disorder can occur as early as the late second trimester and can thus impact the timing of delivery and fetal age at birth.

It is an obstetrical syndrome with serious implications for the fetus, the infant at birth, and the mother, and it is one whose incidence has been increasing. A full knowledge of the disease state – its pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and various therapeutic options, both medical and surgical – is critical for the health and well-being of both the mother and fetus.

A new classification system introduced in 2013 by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Task Force Report on Hypertension in Pregnancy has added further complexity to an already complicated disease. On one hand, attempting to precisely achieve a diagnosis with such an imprecise and insidious disease seems ill advised. On the other hand, it is important to achieve some level of clarity with respect to diagnosis and management. In doing so, we must lean toward overdiagnosis and maintain a low threshold for treatment and intervention in the interest of the mother and infant.

I have engaged Baha M. Sibai, MD, professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Texas McGovern Medical School, Houston, to introduce a practical approach for interpreting and utilizing the ACOG report. This installment is the first of a two-part series in which we hope to provide practical clinical strategies for this complex disease.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. He is the medical editor of this column. Contact him at [email protected].

Preeclampsia is one of the most significant medical complications in pregnancy because of the acute onset it can have in so many affected patients. This acute onset may then rapidly progress to eclampsia and to severe consequences, including maternal death. In addition, the disorder can occur as early as the late second trimester and can thus impact the timing of delivery and fetal age at birth.

It is an obstetrical syndrome with serious implications for the fetus, the infant at birth, and the mother, and it is one whose incidence has been increasing. A full knowledge of the disease state – its pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and various therapeutic options, both medical and surgical – is critical for the health and well-being of both the mother and fetus.

A new classification system introduced in 2013 by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Task Force Report on Hypertension in Pregnancy has added further complexity to an already complicated disease. On one hand, attempting to precisely achieve a diagnosis with such an imprecise and insidious disease seems ill advised. On the other hand, it is important to achieve some level of clarity with respect to diagnosis and management. In doing so, we must lean toward overdiagnosis and maintain a low threshold for treatment and intervention in the interest of the mother and infant.

I have engaged Baha M. Sibai, MD, professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Texas McGovern Medical School, Houston, to introduce a practical approach for interpreting and utilizing the ACOG report. This installment is the first of a two-part series in which we hope to provide practical clinical strategies for this complex disease.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. He is the medical editor of this column. Contact him at [email protected].

Preeclampsia is one of the most significant medical complications in pregnancy because of the acute onset it can have in so many affected patients. This acute onset may then rapidly progress to eclampsia and to severe consequences, including maternal death. In addition, the disorder can occur as early as the late second trimester and can thus impact the timing of delivery and fetal age at birth.

It is an obstetrical syndrome with serious implications for the fetus, the infant at birth, and the mother, and it is one whose incidence has been increasing. A full knowledge of the disease state – its pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and various therapeutic options, both medical and surgical – is critical for the health and well-being of both the mother and fetus.

A new classification system introduced in 2013 by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Task Force Report on Hypertension in Pregnancy has added further complexity to an already complicated disease. On one hand, attempting to precisely achieve a diagnosis with such an imprecise and insidious disease seems ill advised. On the other hand, it is important to achieve some level of clarity with respect to diagnosis and management. In doing so, we must lean toward overdiagnosis and maintain a low threshold for treatment and intervention in the interest of the mother and infant.

I have engaged Baha M. Sibai, MD, professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the University of Texas McGovern Medical School, Houston, to introduce a practical approach for interpreting and utilizing the ACOG report. This installment is the first of a two-part series in which we hope to provide practical clinical strategies for this complex disease.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures. He is the medical editor of this column. Contact him at [email protected].

Clarifying the categories of hypertensive disorders in pregnancy

Prenatal care always has been in part about identifying women with medical complications including preeclampsia. We have long measured blood pressure, checked the urine for high levels of protein, and monitored weight gain. We still do.

However, over the years, the diagnostic criteria for preeclampsia have evolved, first with the exclusion of edema and more recently with the exclusion of proteinuria as a necessary element of the diagnosis. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Task Force Report, Hypertension in Pregnancy, published in 2013, concluded that while preeclampsia may still be defined by the occurrence of hypertension with proteinuria, it also may be diagnosed when hypertension occurs in association with other multisystemic signs indicative of disease severity. The change came based on evidence that some women develop eclampsia, HELLP syndrome, and other serious complications in the absence of proteinuria.

The 2013 document also attempted to review and clarify various issues relating to the classifications, diagnosis, prediction and prevention, and management of hypertension during pregnancy, including the postpartum period. In many respects, it was successful in doing so. However, there is still much confusion regarding the diagnosis of certain categories of hypertensive disorders – particularly preeclampsia with severe features and superimposed preeclampsia with or without severe features.

While it is difficult to establish precise definitions given the often insidious nature of preeclampsia, it still is important to achieve a higher level of clarity with respect to these categories. Overdiagnosis may be preferable. However, improper classification also may influence management decisions that could prove detrimental to the fetus.

Severe gestational hypertension

ACOG’s 2013 Report on Hypertension in Pregnancy classifies hypertensive disorders of pregnancy into these categories: Gestational hypertension (GHTN), preeclampsia, preeclampsia with severe features (this includes HELLP), chronic hypertension (CHTN), superimposed preeclampsia with or without severe features, and eclampsia.

Some of the definitions and diagnostic criteria are clear. For instance, GHTN is defined as the new onset of hypertension after 20 weeks’ gestation in the absence of proteinuria or systemic findings such as thrombocytopenia or impaired liver function. CHTN is defined as hypertension that predates conception or is detected before 20 weeks’ gestation. In both cases there should be elevated blood pressure on two occasions at least 4 hours apart.

A major omission is the lack of a definition for severe GHTN. Removal of this previously well-understood classification category combined with unclear statements regarding preeclampsia with or without severe features has made it difficult for physicians to know in some cases of severe hypertension only what diagnosis a woman should receive and how she should be managed.

I recommend that we maintain the category of severe GHTN, and that it be defined as a systolic blood pressure (BP) greater than or equal to 160 mm Hg and/or diastolic BP greater than or equal to 110 mm Hg on at least two occasions at least 4 hours apart when antihypertensive medications have not been initiated. There should be no proteinuria or severe features such as thrombocytopenia or impaired liver function.

The physician may elect in these cases to administer antihypertensive medication and observe the patient in the hospital. An individualized decision can then be made regarding how the patient should be managed, including whether she should be admitted and whether the pregnancy should continue beyond 34 weeks. Blood pressure, gestational age at diagnosis, the presence or absence of symptoms, and laboratory tests all should be taken into consideration.

Preeclampsia with or without severe features

We need to clarify and simplify how we think about GHTN and preeclampsia with or without severe features.

Most cases of preeclampsia will involve new-onset proteinuria, with proteinuria being defined as greater than or equal to 300 mg/day or a protein-creatinine ratio of greater than or equal to 0.3 mg/dL. In cases in which a dipstick test must be used, proteinuria is suggested by a urine protein reading of 1+. (It is important to note that dipstick readings should be taken on two separate occasions.) According to the report, preeclampsia also may be established by the presence of GHTN in association with any one of a list of features that are generally referred to as “severe features.”

Various boxes and textual descriptions in the report offer a sometimes confusing picture, however, of the terms preeclampsia and preeclampsia with severe features and their differences. For clarification, I recommend that we define preeclampsia with severe features as GHTN (mild or severe) in association with any one of the severe features.

Severe features of preeclampsia

- Platelet count less than 100,000/microliter.

- Elevated hepatic transaminases greater than two times the upper limit of normal for specific laboratory adult reference ranges.

- Severe persistent right upper quadrant abdominal pain or epigastric pain unresponsive to analgesics and unexplained by other etiology.

- Serum creatinine greater than 1.1 mg/dL.

- Pulmonary edema.

- Persistent cerebral disturbances such as severe persistent new-onset headaches unresponsive to nonnarcotic analgesics, altered mental status or other neurologic deficits.

- Visual disturbances such as blurred vision, scotomata, photophobia, or loss of vision.

I also suggest that we think of “mild” GHTN (systolic BP of 140-159 mm Hg or diastolic BP 90-109 mm Hg) and preeclampsia without severe features as one in the same, and that we manage them similarly. The presence or absence of proteinuria is currently the only difference diagnostically. The only difference with respect to management – aside from a weekly urine protein check in the case of GHTN – is the frequency of nonstress testing (NST) and amniotic fluid index (AFI) measurement (currently once a week for GHTN and twice a week for preeclampsia).

Given that unnecessary time and energy may be spent differentiating the two when management is essentially the same, I suggest that preeclampsia be diagnosed in any patient with GHTN with or without proteinuria. All patients can then be managed with blood pressure checks twice a week; symptoms and kick count daily; NST and AFI twice a week; estimated fetal weight by ultrasound every third week; lab tests (CBC, liver enzymes, and creatinine) once a week, and delivery at 37 weeks.

Superimposed preeclampsia with or without severe features

As the report states, the recognition of preeclampsia superimposed on chronic hypertension is “perhaps the greatest challenge” in the diagnosis and management of hypertensive disorders in pregnancy. Overdiagnosis “may be preferable,” the report says, given the high risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes with superimposed preeclampsia. On the other hand, it says, a “more stratified approach based on severity and predictors of adverse outcome may be useful” in avoiding unnecessary preterm births.