User login

FDA panels back brexanolone infusion for postpartum depression

A joint panel of the Food and Drug Administration voted Nov. 2 in support of brexanolone infusion as a treatment for postpartum depression.

The 17-1 vote by members of the Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee and the Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committee was based primarily on data from three studies, including 247 women aged 18-44 years with postpartum depression; 140 received brexanolone and 107 received placebo. Effectiveness was assessed based on the Hamilton Depression Scale (HAM-D) at the end of the infusion (hour 60).

In all three studies, patients given brexanolone showed significantly improved HAM-D scores, compared with placebo. The patients experienced significant differences at hour 24, which illustrated the rapid response. “The individual item scores of the HAM-D consistently favored brexanolone IV over placebo, confirming an overall antidepressant effect of the drug,” according to the briefing document of Sage Therapeutics, developer of the drug. In addition, more than 80% of the patients in the treatment and placebo groups sustained their improvement in symptoms at 30 days after the end of the infusion.

“[Postpartum depression] is symptomatically indistinguishable from an episode of major depression,” the FDA briefing document said. “However, the timing of its onset has led to its recognition as a potentially unique illness. There are no drugs specifically approved to treat [postpartum depression].”

Some clinicians use drugs approved for major depression to treat postpartum depression, but the effectiveness of these drugs is limited, the agency said. Other interventions, such as electroconvulsive therapy, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, and psychotherapy also are used, but they can take several weeks to show results.

Recent estimates of postpartum depression in the United States range from about 8% to 20%, according to the FDA document. and both the FDA and Sage Therapeutics agreed on the need for additional treatment options for women with postpartum depression. , according to Sage.

The treatment protocol for brexanolone involves a single 60-hour continuous infusion with a recommended maximum dose of 90 µg/kg/h, referred to as a “90 dose regimen.” The patient receives a single infusion per episode of postpartum depression. The infusion includes three dosing phases: titration at 30 μg/kg/h for 4 hours followed by 60 μg/kg/h for 20 hours (hour 0-24), maintenance at 90 μg/kg/h for 28 hours (hour 24-52), and taper at 60 μg/kg/h for 4 hours – followed by 30 μg/kg/h for 4 hours (hour 52-60).

Brexanolone is an allosteric modulator of GABAA receptors and “a new molecular entity not currently marketed anywhere in the world for any indication,” according to the FDA document. The drug originally was studied as a treatment for seizure patients before its antidepressant properties were discovered.

Adverse reactions observed in 3% or more of the brexanolone patients during the 60-hour treatment and 4-week follow-up included dry mouth, infusion site pain, fatigue, headache, sedation/somnolence, dizziness/vertigo, and loss of consciousness.

Of those reactions, loss of consciousness was the issue of greatest concern to the committee members and informed their discussion of the strict Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy protocol that would be needed to accompany approval of the drug. The details of the REMS will be determined, but the basics of the FDA’s proposed REMS to mitigate the risk of loss of consciousness include administration of the drug only in medically supervised settings by an authorized representative.

In addition, the proposed REMS states that the authorized representative must “establish policies and procedures to ensure that 1) all staff are trained on the risks and 2) the product is not dispensed for use outside the health care setting.”

The proposed REMS also stated that, “Patients must be continuously monitored for the duration of the infusion and 12 hours after, by health care provider who can intervene if the patient experiences excessive sedation or loss of consciousness.”

Despite those concerns, which most committee members thought could be addressed by the REMS, the overall impression of the committees’ members was that brexanolone could have a significant impact on postpartum depression. According to one member, brexanolone is mechanistically “groundbreaking” and “could be a tremendous help in changing the trajectory of postpartum depression.”

The FDA usually follows its panels’ recommendations, which are not binding.

A joint panel of the Food and Drug Administration voted Nov. 2 in support of brexanolone infusion as a treatment for postpartum depression.

The 17-1 vote by members of the Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee and the Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committee was based primarily on data from three studies, including 247 women aged 18-44 years with postpartum depression; 140 received brexanolone and 107 received placebo. Effectiveness was assessed based on the Hamilton Depression Scale (HAM-D) at the end of the infusion (hour 60).

In all three studies, patients given brexanolone showed significantly improved HAM-D scores, compared with placebo. The patients experienced significant differences at hour 24, which illustrated the rapid response. “The individual item scores of the HAM-D consistently favored brexanolone IV over placebo, confirming an overall antidepressant effect of the drug,” according to the briefing document of Sage Therapeutics, developer of the drug. In addition, more than 80% of the patients in the treatment and placebo groups sustained their improvement in symptoms at 30 days after the end of the infusion.

“[Postpartum depression] is symptomatically indistinguishable from an episode of major depression,” the FDA briefing document said. “However, the timing of its onset has led to its recognition as a potentially unique illness. There are no drugs specifically approved to treat [postpartum depression].”

Some clinicians use drugs approved for major depression to treat postpartum depression, but the effectiveness of these drugs is limited, the agency said. Other interventions, such as electroconvulsive therapy, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, and psychotherapy also are used, but they can take several weeks to show results.

Recent estimates of postpartum depression in the United States range from about 8% to 20%, according to the FDA document. and both the FDA and Sage Therapeutics agreed on the need for additional treatment options for women with postpartum depression. , according to Sage.

The treatment protocol for brexanolone involves a single 60-hour continuous infusion with a recommended maximum dose of 90 µg/kg/h, referred to as a “90 dose regimen.” The patient receives a single infusion per episode of postpartum depression. The infusion includes three dosing phases: titration at 30 μg/kg/h for 4 hours followed by 60 μg/kg/h for 20 hours (hour 0-24), maintenance at 90 μg/kg/h for 28 hours (hour 24-52), and taper at 60 μg/kg/h for 4 hours – followed by 30 μg/kg/h for 4 hours (hour 52-60).

Brexanolone is an allosteric modulator of GABAA receptors and “a new molecular entity not currently marketed anywhere in the world for any indication,” according to the FDA document. The drug originally was studied as a treatment for seizure patients before its antidepressant properties were discovered.

Adverse reactions observed in 3% or more of the brexanolone patients during the 60-hour treatment and 4-week follow-up included dry mouth, infusion site pain, fatigue, headache, sedation/somnolence, dizziness/vertigo, and loss of consciousness.

Of those reactions, loss of consciousness was the issue of greatest concern to the committee members and informed their discussion of the strict Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy protocol that would be needed to accompany approval of the drug. The details of the REMS will be determined, but the basics of the FDA’s proposed REMS to mitigate the risk of loss of consciousness include administration of the drug only in medically supervised settings by an authorized representative.

In addition, the proposed REMS states that the authorized representative must “establish policies and procedures to ensure that 1) all staff are trained on the risks and 2) the product is not dispensed for use outside the health care setting.”

The proposed REMS also stated that, “Patients must be continuously monitored for the duration of the infusion and 12 hours after, by health care provider who can intervene if the patient experiences excessive sedation or loss of consciousness.”

Despite those concerns, which most committee members thought could be addressed by the REMS, the overall impression of the committees’ members was that brexanolone could have a significant impact on postpartum depression. According to one member, brexanolone is mechanistically “groundbreaking” and “could be a tremendous help in changing the trajectory of postpartum depression.”

The FDA usually follows its panels’ recommendations, which are not binding.

A joint panel of the Food and Drug Administration voted Nov. 2 in support of brexanolone infusion as a treatment for postpartum depression.

The 17-1 vote by members of the Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee and the Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committee was based primarily on data from three studies, including 247 women aged 18-44 years with postpartum depression; 140 received brexanolone and 107 received placebo. Effectiveness was assessed based on the Hamilton Depression Scale (HAM-D) at the end of the infusion (hour 60).

In all three studies, patients given brexanolone showed significantly improved HAM-D scores, compared with placebo. The patients experienced significant differences at hour 24, which illustrated the rapid response. “The individual item scores of the HAM-D consistently favored brexanolone IV over placebo, confirming an overall antidepressant effect of the drug,” according to the briefing document of Sage Therapeutics, developer of the drug. In addition, more than 80% of the patients in the treatment and placebo groups sustained their improvement in symptoms at 30 days after the end of the infusion.

“[Postpartum depression] is symptomatically indistinguishable from an episode of major depression,” the FDA briefing document said. “However, the timing of its onset has led to its recognition as a potentially unique illness. There are no drugs specifically approved to treat [postpartum depression].”

Some clinicians use drugs approved for major depression to treat postpartum depression, but the effectiveness of these drugs is limited, the agency said. Other interventions, such as electroconvulsive therapy, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, and psychotherapy also are used, but they can take several weeks to show results.

Recent estimates of postpartum depression in the United States range from about 8% to 20%, according to the FDA document. and both the FDA and Sage Therapeutics agreed on the need for additional treatment options for women with postpartum depression. , according to Sage.

The treatment protocol for brexanolone involves a single 60-hour continuous infusion with a recommended maximum dose of 90 µg/kg/h, referred to as a “90 dose regimen.” The patient receives a single infusion per episode of postpartum depression. The infusion includes three dosing phases: titration at 30 μg/kg/h for 4 hours followed by 60 μg/kg/h for 20 hours (hour 0-24), maintenance at 90 μg/kg/h for 28 hours (hour 24-52), and taper at 60 μg/kg/h for 4 hours – followed by 30 μg/kg/h for 4 hours (hour 52-60).

Brexanolone is an allosteric modulator of GABAA receptors and “a new molecular entity not currently marketed anywhere in the world for any indication,” according to the FDA document. The drug originally was studied as a treatment for seizure patients before its antidepressant properties were discovered.

Adverse reactions observed in 3% or more of the brexanolone patients during the 60-hour treatment and 4-week follow-up included dry mouth, infusion site pain, fatigue, headache, sedation/somnolence, dizziness/vertigo, and loss of consciousness.

Of those reactions, loss of consciousness was the issue of greatest concern to the committee members and informed their discussion of the strict Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy protocol that would be needed to accompany approval of the drug. The details of the REMS will be determined, but the basics of the FDA’s proposed REMS to mitigate the risk of loss of consciousness include administration of the drug only in medically supervised settings by an authorized representative.

In addition, the proposed REMS states that the authorized representative must “establish policies and procedures to ensure that 1) all staff are trained on the risks and 2) the product is not dispensed for use outside the health care setting.”

The proposed REMS also stated that, “Patients must be continuously monitored for the duration of the infusion and 12 hours after, by health care provider who can intervene if the patient experiences excessive sedation or loss of consciousness.”

Despite those concerns, which most committee members thought could be addressed by the REMS, the overall impression of the committees’ members was that brexanolone could have a significant impact on postpartum depression. According to one member, brexanolone is mechanistically “groundbreaking” and “could be a tremendous help in changing the trajectory of postpartum depression.”

The FDA usually follows its panels’ recommendations, which are not binding.

Hospitals could reduce maternal mortality with four achievable steps

rate in the United States, according to a new perspective from leading obstetricians published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The authors, including Kimberlee McKay, MD, president of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), also call for collaboration with family physicians to increase access to obstetric care in rural areas.

The president of the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), John S. Cullen, MD, in a separate statement, welcomed the opportunity for collaboration in addressing the maternal mortality crisis. However, some distance still lies between the finer points of how the two organizations see family physicians helping curb the crisis.

“Women in the United States are more likely to die from childbirth- or pregnancy-related causes than women in any other high-income country, and black women die at a rate three to four times that of white women,” noted Susan Mann, MD, along with her coauthors of the obstetric perspective, calling increasing maternal mortality a “tragedy.”

In an interview, Dr. Cullen concurred, calling the current situation “unconscionable.” One of the primary reasons he sought AAFP leadership, he said, was to bring experiences learned during his 25 years of obstetric practice in rural Alaska to bear on the current crisis.

A set of maternal care bundles created by the Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health (AIM) provides the framework for the first action recommended by Dr. Mann and her coauthors. The AIM bundles focus on protocols that improve readiness, recognition, response, and reporting in maternal care. The protocols are institution specific. For example, the authors noted, antihypertensive medications should be readily available around the clock, because not all facilities will have a pharmacist in-house at all times, and hypertensive emergencies are among the gravest obstetric complications.

“Although management may vary from institution to institution, each unit can be required to demonstrate readiness to deal with emergencies 24/7,” said Dr. Mann, a physician in private practice in Boston, and her coauthors.

The second recommended action revolves around multidisciplinary staff meetings to perform individual assessments for each woman’s obstetric risk factors. These huddles should include assessing hemorrhage risk by using the California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative guidelines, and briefings with the full care team to “develop shared understandings of the patient and the procedure” before elective or nonurgent cesarean deliveries, said Dr. Mann and her colleagues. Patients should be informed of any safety concerns, and caregivers should use shared decision-making moving forward.

“Approximately 50% of U.S. hospitals provide care for three or fewer deliveries per day, but the need to identify women at risk is equally important for these small obstetrics services,” Dr. Mann and her coauthors noted.

Third, simulation of obstetric emergencies lets all members of the team understand the speed at which decisions must be made and actions taken when minutes, or even seconds, count. Dr. Mann and her coauthors pointed out that logistics problems come out during a well-run simulation, giving such examples as a lag in receiving blood products or a poorly placed hemorrhage cart.

Drawing an analogy to the extensive time pilots spend in flight simulators, Dr. Mann and her coauthors noted that “because severe maternity-related events are rare and often unpredictable, and because members of the care team may not know each other, it is important to train for low-probability but high-risk events.”

Using the Maternal Health Compact will help ensure that lower-resource hospitals have a relationship in place with a facility that can provide a higher level of maternal care when needed, they said.

This fourth action means that there’s a connection that “can be activated by lower-resource hospitals to get immediate consultation in the event of an unexpected obstetrical emergency whose care demands exceed their resources,” said Dr. Mann and her coauthors. When transport is necessary, it too can be facilitated if a compact is already in place.

The final, broader, recommendation from the obstetricians is that ACOG and AAFP collaborate “on an additional year of comprehensive training for family medicine physicians who are considering practicing obstetrics in rural areas.” The fourth year of training for these family physicians could help address widespread shortages of obstetricians and midwives in rural communities, Dr. Mann and her coauthors wrote. They observed that “pregnant women who live in rural areas may need to travel hundreds of miles to obtain routine prenatal care or consultation with an obstetrical specialist.”

Dr. Cullen, whose practice is in Valdez, Alaska, said he happily reciprocates the desire for collaboration. In his inaugural blog post after assuming the AAFP presidency in October, 2018, he extended warm thanks to his obstetrician and perinatologist colleagues. “The relationship between family physicians and obstetricians is vital in rural communities like mine. The training I received has saved lives and prevented catastrophe,” he wrote.

At the same time, Dr. Cullen said that he believes family physicians are the best hope for quality obstetrical care in rural communities. Dr. Cullen’s own training, he said, was structured to involve significant obstetric experience with obstetrician mentorship. “A 3-year residency left me very comfortable with fairly sophisticated obstetric management at graduation,” he added.

In his practice, Dr. Cullen said, a family physician hired a decade ago after a 3-year residency came with excellent obstetric skills, which have been further honed during the succeeding years of rural practice. During a 3-year residency, “family physicians receive training and demonstrate the skills and competencies required to deliver high-quality maternity care in any community, including those in rural settings,” he said in his statement.

“The bigger issue is really the closure of obstetric units in rural hospitals,” said Dr. Cullen. He pointed out that although obstetric services may have left a community, that rural hospital will still have miscarrying patients with hemorrhage, patients in preterm labor, and other obstetric emergencies arriving at the doorstep. These and other instances often “represent true emergencies without possibility of transfer, requiring immediate and effective response,” he wrote.

“We would encourage the authors to ensure an equal focus on improving care at all levels and in all hospitals, as well as relying on transfer as appropriate,” Dr. Cullen said in his statement.

Such mutual support can be bolstered by new technology, wrote Dr. Mann and her coauthors, because “telehealth and collaborations and consultation with clinics and regional hospitals can help increase the availability of maternity care in the United States.”

For Dr. Cullen also, the way forward is together. In his blog, he wrote: “As family physicians, we can only deliver obstetrical care to our patients with the cooperation of obstetricians and perinatologists. Conversely, obstetricians can only improve maternal and infant mortality rates, especially in rural areas, with the help of family physicians.”

SOURCE: Mann S et al. N Engl J Med 2018;379:1689-91.

rate in the United States, according to a new perspective from leading obstetricians published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The authors, including Kimberlee McKay, MD, president of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), also call for collaboration with family physicians to increase access to obstetric care in rural areas.

The president of the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), John S. Cullen, MD, in a separate statement, welcomed the opportunity for collaboration in addressing the maternal mortality crisis. However, some distance still lies between the finer points of how the two organizations see family physicians helping curb the crisis.

“Women in the United States are more likely to die from childbirth- or pregnancy-related causes than women in any other high-income country, and black women die at a rate three to four times that of white women,” noted Susan Mann, MD, along with her coauthors of the obstetric perspective, calling increasing maternal mortality a “tragedy.”

In an interview, Dr. Cullen concurred, calling the current situation “unconscionable.” One of the primary reasons he sought AAFP leadership, he said, was to bring experiences learned during his 25 years of obstetric practice in rural Alaska to bear on the current crisis.

A set of maternal care bundles created by the Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health (AIM) provides the framework for the first action recommended by Dr. Mann and her coauthors. The AIM bundles focus on protocols that improve readiness, recognition, response, and reporting in maternal care. The protocols are institution specific. For example, the authors noted, antihypertensive medications should be readily available around the clock, because not all facilities will have a pharmacist in-house at all times, and hypertensive emergencies are among the gravest obstetric complications.

“Although management may vary from institution to institution, each unit can be required to demonstrate readiness to deal with emergencies 24/7,” said Dr. Mann, a physician in private practice in Boston, and her coauthors.

The second recommended action revolves around multidisciplinary staff meetings to perform individual assessments for each woman’s obstetric risk factors. These huddles should include assessing hemorrhage risk by using the California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative guidelines, and briefings with the full care team to “develop shared understandings of the patient and the procedure” before elective or nonurgent cesarean deliveries, said Dr. Mann and her colleagues. Patients should be informed of any safety concerns, and caregivers should use shared decision-making moving forward.

“Approximately 50% of U.S. hospitals provide care for three or fewer deliveries per day, but the need to identify women at risk is equally important for these small obstetrics services,” Dr. Mann and her coauthors noted.

Third, simulation of obstetric emergencies lets all members of the team understand the speed at which decisions must be made and actions taken when minutes, or even seconds, count. Dr. Mann and her coauthors pointed out that logistics problems come out during a well-run simulation, giving such examples as a lag in receiving blood products or a poorly placed hemorrhage cart.

Drawing an analogy to the extensive time pilots spend in flight simulators, Dr. Mann and her coauthors noted that “because severe maternity-related events are rare and often unpredictable, and because members of the care team may not know each other, it is important to train for low-probability but high-risk events.”

Using the Maternal Health Compact will help ensure that lower-resource hospitals have a relationship in place with a facility that can provide a higher level of maternal care when needed, they said.

This fourth action means that there’s a connection that “can be activated by lower-resource hospitals to get immediate consultation in the event of an unexpected obstetrical emergency whose care demands exceed their resources,” said Dr. Mann and her coauthors. When transport is necessary, it too can be facilitated if a compact is already in place.

The final, broader, recommendation from the obstetricians is that ACOG and AAFP collaborate “on an additional year of comprehensive training for family medicine physicians who are considering practicing obstetrics in rural areas.” The fourth year of training for these family physicians could help address widespread shortages of obstetricians and midwives in rural communities, Dr. Mann and her coauthors wrote. They observed that “pregnant women who live in rural areas may need to travel hundreds of miles to obtain routine prenatal care or consultation with an obstetrical specialist.”

Dr. Cullen, whose practice is in Valdez, Alaska, said he happily reciprocates the desire for collaboration. In his inaugural blog post after assuming the AAFP presidency in October, 2018, he extended warm thanks to his obstetrician and perinatologist colleagues. “The relationship between family physicians and obstetricians is vital in rural communities like mine. The training I received has saved lives and prevented catastrophe,” he wrote.

At the same time, Dr. Cullen said that he believes family physicians are the best hope for quality obstetrical care in rural communities. Dr. Cullen’s own training, he said, was structured to involve significant obstetric experience with obstetrician mentorship. “A 3-year residency left me very comfortable with fairly sophisticated obstetric management at graduation,” he added.

In his practice, Dr. Cullen said, a family physician hired a decade ago after a 3-year residency came with excellent obstetric skills, which have been further honed during the succeeding years of rural practice. During a 3-year residency, “family physicians receive training and demonstrate the skills and competencies required to deliver high-quality maternity care in any community, including those in rural settings,” he said in his statement.

“The bigger issue is really the closure of obstetric units in rural hospitals,” said Dr. Cullen. He pointed out that although obstetric services may have left a community, that rural hospital will still have miscarrying patients with hemorrhage, patients in preterm labor, and other obstetric emergencies arriving at the doorstep. These and other instances often “represent true emergencies without possibility of transfer, requiring immediate and effective response,” he wrote.

“We would encourage the authors to ensure an equal focus on improving care at all levels and in all hospitals, as well as relying on transfer as appropriate,” Dr. Cullen said in his statement.

Such mutual support can be bolstered by new technology, wrote Dr. Mann and her coauthors, because “telehealth and collaborations and consultation with clinics and regional hospitals can help increase the availability of maternity care in the United States.”

For Dr. Cullen also, the way forward is together. In his blog, he wrote: “As family physicians, we can only deliver obstetrical care to our patients with the cooperation of obstetricians and perinatologists. Conversely, obstetricians can only improve maternal and infant mortality rates, especially in rural areas, with the help of family physicians.”

SOURCE: Mann S et al. N Engl J Med 2018;379:1689-91.

rate in the United States, according to a new perspective from leading obstetricians published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The authors, including Kimberlee McKay, MD, president of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), also call for collaboration with family physicians to increase access to obstetric care in rural areas.

The president of the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), John S. Cullen, MD, in a separate statement, welcomed the opportunity for collaboration in addressing the maternal mortality crisis. However, some distance still lies between the finer points of how the two organizations see family physicians helping curb the crisis.

“Women in the United States are more likely to die from childbirth- or pregnancy-related causes than women in any other high-income country, and black women die at a rate three to four times that of white women,” noted Susan Mann, MD, along with her coauthors of the obstetric perspective, calling increasing maternal mortality a “tragedy.”

In an interview, Dr. Cullen concurred, calling the current situation “unconscionable.” One of the primary reasons he sought AAFP leadership, he said, was to bring experiences learned during his 25 years of obstetric practice in rural Alaska to bear on the current crisis.

A set of maternal care bundles created by the Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health (AIM) provides the framework for the first action recommended by Dr. Mann and her coauthors. The AIM bundles focus on protocols that improve readiness, recognition, response, and reporting in maternal care. The protocols are institution specific. For example, the authors noted, antihypertensive medications should be readily available around the clock, because not all facilities will have a pharmacist in-house at all times, and hypertensive emergencies are among the gravest obstetric complications.

“Although management may vary from institution to institution, each unit can be required to demonstrate readiness to deal with emergencies 24/7,” said Dr. Mann, a physician in private practice in Boston, and her coauthors.

The second recommended action revolves around multidisciplinary staff meetings to perform individual assessments for each woman’s obstetric risk factors. These huddles should include assessing hemorrhage risk by using the California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative guidelines, and briefings with the full care team to “develop shared understandings of the patient and the procedure” before elective or nonurgent cesarean deliveries, said Dr. Mann and her colleagues. Patients should be informed of any safety concerns, and caregivers should use shared decision-making moving forward.

“Approximately 50% of U.S. hospitals provide care for three or fewer deliveries per day, but the need to identify women at risk is equally important for these small obstetrics services,” Dr. Mann and her coauthors noted.

Third, simulation of obstetric emergencies lets all members of the team understand the speed at which decisions must be made and actions taken when minutes, or even seconds, count. Dr. Mann and her coauthors pointed out that logistics problems come out during a well-run simulation, giving such examples as a lag in receiving blood products or a poorly placed hemorrhage cart.

Drawing an analogy to the extensive time pilots spend in flight simulators, Dr. Mann and her coauthors noted that “because severe maternity-related events are rare and often unpredictable, and because members of the care team may not know each other, it is important to train for low-probability but high-risk events.”

Using the Maternal Health Compact will help ensure that lower-resource hospitals have a relationship in place with a facility that can provide a higher level of maternal care when needed, they said.

This fourth action means that there’s a connection that “can be activated by lower-resource hospitals to get immediate consultation in the event of an unexpected obstetrical emergency whose care demands exceed their resources,” said Dr. Mann and her coauthors. When transport is necessary, it too can be facilitated if a compact is already in place.

The final, broader, recommendation from the obstetricians is that ACOG and AAFP collaborate “on an additional year of comprehensive training for family medicine physicians who are considering practicing obstetrics in rural areas.” The fourth year of training for these family physicians could help address widespread shortages of obstetricians and midwives in rural communities, Dr. Mann and her coauthors wrote. They observed that “pregnant women who live in rural areas may need to travel hundreds of miles to obtain routine prenatal care or consultation with an obstetrical specialist.”

Dr. Cullen, whose practice is in Valdez, Alaska, said he happily reciprocates the desire for collaboration. In his inaugural blog post after assuming the AAFP presidency in October, 2018, he extended warm thanks to his obstetrician and perinatologist colleagues. “The relationship between family physicians and obstetricians is vital in rural communities like mine. The training I received has saved lives and prevented catastrophe,” he wrote.

At the same time, Dr. Cullen said that he believes family physicians are the best hope for quality obstetrical care in rural communities. Dr. Cullen’s own training, he said, was structured to involve significant obstetric experience with obstetrician mentorship. “A 3-year residency left me very comfortable with fairly sophisticated obstetric management at graduation,” he added.

In his practice, Dr. Cullen said, a family physician hired a decade ago after a 3-year residency came with excellent obstetric skills, which have been further honed during the succeeding years of rural practice. During a 3-year residency, “family physicians receive training and demonstrate the skills and competencies required to deliver high-quality maternity care in any community, including those in rural settings,” he said in his statement.

“The bigger issue is really the closure of obstetric units in rural hospitals,” said Dr. Cullen. He pointed out that although obstetric services may have left a community, that rural hospital will still have miscarrying patients with hemorrhage, patients in preterm labor, and other obstetric emergencies arriving at the doorstep. These and other instances often “represent true emergencies without possibility of transfer, requiring immediate and effective response,” he wrote.

“We would encourage the authors to ensure an equal focus on improving care at all levels and in all hospitals, as well as relying on transfer as appropriate,” Dr. Cullen said in his statement.

Such mutual support can be bolstered by new technology, wrote Dr. Mann and her coauthors, because “telehealth and collaborations and consultation with clinics and regional hospitals can help increase the availability of maternity care in the United States.”

For Dr. Cullen also, the way forward is together. In his blog, he wrote: “As family physicians, we can only deliver obstetrical care to our patients with the cooperation of obstetricians and perinatologists. Conversely, obstetricians can only improve maternal and infant mortality rates, especially in rural areas, with the help of family physicians.”

SOURCE: Mann S et al. N Engl J Med 2018;379:1689-91.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Yoga feasible, provides modest benefits for women with urinary incontinence

according to Alison J. Huang, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, and her associates.

In a small study published in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 28 women enrolled in a 3-month yoga intervention program and 28 were enrolled in a control program consisting of nonspecific muscle stretching and strengthening. The mean age was 65 years, baseline urinary incontinence was 3.5 episodes/day, and 37 women had urgency-predominant incontinence.

Of those who completed the study, 89% of 27 patients in the yoga group attended at least 80% of classes, compared with 87% in the control group; over 90% of women in the yoga group completed at least 9 home practice hours.

Overall incontinence frequency was reduced by 76% in the yoga group and by 56% in the control group. Incontinence caused by stress was significantly reduced in the yoga group, compared with the control group (61% vs. 35%; P = .045), but the rate of incontinence caused by urgency did not noticeably differ. A total of 48 nonserious adverse events were reported over the 3-month period (23 in the yoga and 25 in the control group), but none were associated with either yoga or control treatment.

“Yoga may be useful for incontinent women in the community who lack access to incontinence specialists, are unable to use clinical therapies, or wish to enhance conventional care. Since yoga can be practiced in a group setting without continuous supervision by health care specialists, it offers a potentially cost-effective, community-based self-management strategy for incontinence, provided that it can be taught with appropriate attention to safety and to patients’ clinical needs,” the authors noted.

The study was supported with grants from the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Medicine and the UCSF Osher Center for Integrative Medicine’s Bradley fund. One of the authors received a grant from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disorders. Two study authors reported receiving funding from Pfizer and Astellas to conduct research unrelated to the current study.

SOURCE: Huang AJ et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Oct 26. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.10.031.

according to Alison J. Huang, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, and her associates.

In a small study published in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 28 women enrolled in a 3-month yoga intervention program and 28 were enrolled in a control program consisting of nonspecific muscle stretching and strengthening. The mean age was 65 years, baseline urinary incontinence was 3.5 episodes/day, and 37 women had urgency-predominant incontinence.

Of those who completed the study, 89% of 27 patients in the yoga group attended at least 80% of classes, compared with 87% in the control group; over 90% of women in the yoga group completed at least 9 home practice hours.

Overall incontinence frequency was reduced by 76% in the yoga group and by 56% in the control group. Incontinence caused by stress was significantly reduced in the yoga group, compared with the control group (61% vs. 35%; P = .045), but the rate of incontinence caused by urgency did not noticeably differ. A total of 48 nonserious adverse events were reported over the 3-month period (23 in the yoga and 25 in the control group), but none were associated with either yoga or control treatment.

“Yoga may be useful for incontinent women in the community who lack access to incontinence specialists, are unable to use clinical therapies, or wish to enhance conventional care. Since yoga can be practiced in a group setting without continuous supervision by health care specialists, it offers a potentially cost-effective, community-based self-management strategy for incontinence, provided that it can be taught with appropriate attention to safety and to patients’ clinical needs,” the authors noted.

The study was supported with grants from the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Medicine and the UCSF Osher Center for Integrative Medicine’s Bradley fund. One of the authors received a grant from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disorders. Two study authors reported receiving funding from Pfizer and Astellas to conduct research unrelated to the current study.

SOURCE: Huang AJ et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Oct 26. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.10.031.

according to Alison J. Huang, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, and her associates.

In a small study published in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 28 women enrolled in a 3-month yoga intervention program and 28 were enrolled in a control program consisting of nonspecific muscle stretching and strengthening. The mean age was 65 years, baseline urinary incontinence was 3.5 episodes/day, and 37 women had urgency-predominant incontinence.

Of those who completed the study, 89% of 27 patients in the yoga group attended at least 80% of classes, compared with 87% in the control group; over 90% of women in the yoga group completed at least 9 home practice hours.

Overall incontinence frequency was reduced by 76% in the yoga group and by 56% in the control group. Incontinence caused by stress was significantly reduced in the yoga group, compared with the control group (61% vs. 35%; P = .045), but the rate of incontinence caused by urgency did not noticeably differ. A total of 48 nonserious adverse events were reported over the 3-month period (23 in the yoga and 25 in the control group), but none were associated with either yoga or control treatment.

“Yoga may be useful for incontinent women in the community who lack access to incontinence specialists, are unable to use clinical therapies, or wish to enhance conventional care. Since yoga can be practiced in a group setting without continuous supervision by health care specialists, it offers a potentially cost-effective, community-based self-management strategy for incontinence, provided that it can be taught with appropriate attention to safety and to patients’ clinical needs,” the authors noted.

The study was supported with grants from the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Medicine and the UCSF Osher Center for Integrative Medicine’s Bradley fund. One of the authors received a grant from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disorders. Two study authors reported receiving funding from Pfizer and Astellas to conduct research unrelated to the current study.

SOURCE: Huang AJ et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Oct 26. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.10.031.

FROM THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF OBSTETRICS AND GYNECOLOGY

Estetrol safely limited menopause symptoms in a phase 2b study

Estetrol (Donesta) relieved vasomotor menopausal symptoms without stimulating breast tenderness or raising triglyceride levels in a dose-finding study of the investigational drug presented at the annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society.

Estetrol (E4), an estrogen produced by the fetal liver, is the first native estrogen acting selectively in tissues. Since it crosses the placenta, estetrol is present in maternal urine at about 9 weeks’ gestation. In fetal plasma, it circulates at concentrations about 12 times higher than maternal estetrol levels. The hormone has a half-life of 28-32 hours, longer than the half-life of most other estrogens.

E4 “has been shown to have a remarkably safe profile and I like to describe it as the first natural oral estrogen with the safety profile of a transdermal estrogen,” said Wulf H. Utian, MD, the Arthur H. Bill Professor of Obstetrics & Gynecology at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland. Estetrol uniquely activates nuclear estrogen receptor–alpha, while antagonizing membrane estrogen receptor-alpha. These properties give E4 selective tissue action, with low breast stimulation meaning less breast tenderness and “low carcinogenic impact.”

Additionally, triglyceride levels are minimally affected, and serum markers for venous thromboembolism generally remain unchanged with E4 exposure, he said.

In a phase 2b dose-finding study, a variety of estetrol doses were compared with placebo to treat vasomotor symptoms in postmenopausal women aged 40-65 years with at least 7 moderate to severe hot flashes daily, or at least 50 moderate to severe hot flashes in the week before randomization. The multicenter, double-blind randomized controlled trial took place in five European countries, with 200 women overall completing the study. The study design excluded women with personal histories of malignancy, thromboembolism, or coagulopathy, and women with diabetes and poor glycemic control. Women with a uterus who had current or past endometrial hyperplasia, polyps, or an abnormal cervical smear were also excluded.

Women who had an intact uterus were included if transvaginal ultrasound showed endometrial thickness of 5 mm or less. Participants were randomized 1:1:1:1 to receive four different E4 doses: 2.5 mg, 5 mg, 10 mg, or 15 mg.

At the highest dose of 15 mg, E4 significantly reduced the frequency of vasomotor symptoms compared with placebo by study week 4 and throughout the 12-week study period (P less than .05).

This high dose also resulted in a 28% reduction in vasomotor symptom severity, compared with placebo by study week 12, with a significant separation from placebo by week 12.

In terms of the number of women who experienced at least a 50% drop in severe vasomotor symptoms, the 15-mg E4 dose also bested placebo (P less than .01). Among the group taking the 15 mg dose, significantly more also saw at least a 75% drop in frequency of severe vasomotor symptom (P less than .001).

Vaginal cytology showed that by week 12 all doses of E4 significantly increased the vaginal maturation index from baseline, a finding that corresponds with less thinning of vaginal tissues (P less than .001, compared with placebo for all doses).

The safety profile of E4 was good, Dr. Utian said. Coagulation markers were unaffected, and most lipid and blood glucose markers were also unchanged. There were “small but potentially beneficial changes in HDL-C [HDL cholesterol levels] and HbA1c values [hemoglobin A1c]” in groups taking the two highest doses of E4.

Also, C-telopeptide of type 1 collagen and osteocalcin values were reduced, “suggesting reduction in bone resorption,” he said.

According to Dr. Utian, those taking the two highest doses also saw a “slight though significant increase” from baseline in sex hormone–binding globulin levels, “indicating that the E4 estrogenic effect was mild and dose dependent.”

Endometrial biopsies showed no hyperplasia. In those taking the 15-mg E4 dose, mean endometrial thickness did increase from a mean 2 mm at baseline to 6 mm at 12 weeks. However, endometrial thickness returned to baseline after progestin therapy, said Dr. Utian. There were no unexpected adverse events during the study.

Dr. Utian reported consultant relationships with Mithra, the maker of estetrol; AMAG; Pharmavite; and Endoceutics. The study was funded by Mithra.

SOURCE: Utian W. NAMS 2018, Friday concurrent session 1.

Estetrol (Donesta) relieved vasomotor menopausal symptoms without stimulating breast tenderness or raising triglyceride levels in a dose-finding study of the investigational drug presented at the annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society.

Estetrol (E4), an estrogen produced by the fetal liver, is the first native estrogen acting selectively in tissues. Since it crosses the placenta, estetrol is present in maternal urine at about 9 weeks’ gestation. In fetal plasma, it circulates at concentrations about 12 times higher than maternal estetrol levels. The hormone has a half-life of 28-32 hours, longer than the half-life of most other estrogens.

E4 “has been shown to have a remarkably safe profile and I like to describe it as the first natural oral estrogen with the safety profile of a transdermal estrogen,” said Wulf H. Utian, MD, the Arthur H. Bill Professor of Obstetrics & Gynecology at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland. Estetrol uniquely activates nuclear estrogen receptor–alpha, while antagonizing membrane estrogen receptor-alpha. These properties give E4 selective tissue action, with low breast stimulation meaning less breast tenderness and “low carcinogenic impact.”

Additionally, triglyceride levels are minimally affected, and serum markers for venous thromboembolism generally remain unchanged with E4 exposure, he said.

In a phase 2b dose-finding study, a variety of estetrol doses were compared with placebo to treat vasomotor symptoms in postmenopausal women aged 40-65 years with at least 7 moderate to severe hot flashes daily, or at least 50 moderate to severe hot flashes in the week before randomization. The multicenter, double-blind randomized controlled trial took place in five European countries, with 200 women overall completing the study. The study design excluded women with personal histories of malignancy, thromboembolism, or coagulopathy, and women with diabetes and poor glycemic control. Women with a uterus who had current or past endometrial hyperplasia, polyps, or an abnormal cervical smear were also excluded.

Women who had an intact uterus were included if transvaginal ultrasound showed endometrial thickness of 5 mm or less. Participants were randomized 1:1:1:1 to receive four different E4 doses: 2.5 mg, 5 mg, 10 mg, or 15 mg.

At the highest dose of 15 mg, E4 significantly reduced the frequency of vasomotor symptoms compared with placebo by study week 4 and throughout the 12-week study period (P less than .05).

This high dose also resulted in a 28% reduction in vasomotor symptom severity, compared with placebo by study week 12, with a significant separation from placebo by week 12.

In terms of the number of women who experienced at least a 50% drop in severe vasomotor symptoms, the 15-mg E4 dose also bested placebo (P less than .01). Among the group taking the 15 mg dose, significantly more also saw at least a 75% drop in frequency of severe vasomotor symptom (P less than .001).

Vaginal cytology showed that by week 12 all doses of E4 significantly increased the vaginal maturation index from baseline, a finding that corresponds with less thinning of vaginal tissues (P less than .001, compared with placebo for all doses).

The safety profile of E4 was good, Dr. Utian said. Coagulation markers were unaffected, and most lipid and blood glucose markers were also unchanged. There were “small but potentially beneficial changes in HDL-C [HDL cholesterol levels] and HbA1c values [hemoglobin A1c]” in groups taking the two highest doses of E4.

Also, C-telopeptide of type 1 collagen and osteocalcin values were reduced, “suggesting reduction in bone resorption,” he said.

According to Dr. Utian, those taking the two highest doses also saw a “slight though significant increase” from baseline in sex hormone–binding globulin levels, “indicating that the E4 estrogenic effect was mild and dose dependent.”

Endometrial biopsies showed no hyperplasia. In those taking the 15-mg E4 dose, mean endometrial thickness did increase from a mean 2 mm at baseline to 6 mm at 12 weeks. However, endometrial thickness returned to baseline after progestin therapy, said Dr. Utian. There were no unexpected adverse events during the study.

Dr. Utian reported consultant relationships with Mithra, the maker of estetrol; AMAG; Pharmavite; and Endoceutics. The study was funded by Mithra.

SOURCE: Utian W. NAMS 2018, Friday concurrent session 1.

Estetrol (Donesta) relieved vasomotor menopausal symptoms without stimulating breast tenderness or raising triglyceride levels in a dose-finding study of the investigational drug presented at the annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society.

Estetrol (E4), an estrogen produced by the fetal liver, is the first native estrogen acting selectively in tissues. Since it crosses the placenta, estetrol is present in maternal urine at about 9 weeks’ gestation. In fetal plasma, it circulates at concentrations about 12 times higher than maternal estetrol levels. The hormone has a half-life of 28-32 hours, longer than the half-life of most other estrogens.

E4 “has been shown to have a remarkably safe profile and I like to describe it as the first natural oral estrogen with the safety profile of a transdermal estrogen,” said Wulf H. Utian, MD, the Arthur H. Bill Professor of Obstetrics & Gynecology at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland. Estetrol uniquely activates nuclear estrogen receptor–alpha, while antagonizing membrane estrogen receptor-alpha. These properties give E4 selective tissue action, with low breast stimulation meaning less breast tenderness and “low carcinogenic impact.”

Additionally, triglyceride levels are minimally affected, and serum markers for venous thromboembolism generally remain unchanged with E4 exposure, he said.

In a phase 2b dose-finding study, a variety of estetrol doses were compared with placebo to treat vasomotor symptoms in postmenopausal women aged 40-65 years with at least 7 moderate to severe hot flashes daily, or at least 50 moderate to severe hot flashes in the week before randomization. The multicenter, double-blind randomized controlled trial took place in five European countries, with 200 women overall completing the study. The study design excluded women with personal histories of malignancy, thromboembolism, or coagulopathy, and women with diabetes and poor glycemic control. Women with a uterus who had current or past endometrial hyperplasia, polyps, or an abnormal cervical smear were also excluded.

Women who had an intact uterus were included if transvaginal ultrasound showed endometrial thickness of 5 mm or less. Participants were randomized 1:1:1:1 to receive four different E4 doses: 2.5 mg, 5 mg, 10 mg, or 15 mg.

At the highest dose of 15 mg, E4 significantly reduced the frequency of vasomotor symptoms compared with placebo by study week 4 and throughout the 12-week study period (P less than .05).

This high dose also resulted in a 28% reduction in vasomotor symptom severity, compared with placebo by study week 12, with a significant separation from placebo by week 12.

In terms of the number of women who experienced at least a 50% drop in severe vasomotor symptoms, the 15-mg E4 dose also bested placebo (P less than .01). Among the group taking the 15 mg dose, significantly more also saw at least a 75% drop in frequency of severe vasomotor symptom (P less than .001).

Vaginal cytology showed that by week 12 all doses of E4 significantly increased the vaginal maturation index from baseline, a finding that corresponds with less thinning of vaginal tissues (P less than .001, compared with placebo for all doses).

The safety profile of E4 was good, Dr. Utian said. Coagulation markers were unaffected, and most lipid and blood glucose markers were also unchanged. There were “small but potentially beneficial changes in HDL-C [HDL cholesterol levels] and HbA1c values [hemoglobin A1c]” in groups taking the two highest doses of E4.

Also, C-telopeptide of type 1 collagen and osteocalcin values were reduced, “suggesting reduction in bone resorption,” he said.

According to Dr. Utian, those taking the two highest doses also saw a “slight though significant increase” from baseline in sex hormone–binding globulin levels, “indicating that the E4 estrogenic effect was mild and dose dependent.”

Endometrial biopsies showed no hyperplasia. In those taking the 15-mg E4 dose, mean endometrial thickness did increase from a mean 2 mm at baseline to 6 mm at 12 weeks. However, endometrial thickness returned to baseline after progestin therapy, said Dr. Utian. There were no unexpected adverse events during the study.

Dr. Utian reported consultant relationships with Mithra, the maker of estetrol; AMAG; Pharmavite; and Endoceutics. The study was funded by Mithra.

SOURCE: Utian W. NAMS 2018, Friday concurrent session 1.

FROM NAMS 2018

Key clinical point: Estetrol relieved hot flashes without adversely affecting lipid markers.

Major finding: Estetrol 15 mg reduced vasomotor symptom severity by 28%.

Study details: Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2b dose-finding study of 200 women.

Disclosures: Dr. Utian reported financial relationships with several pharmaceutical companies, including Mithra, the sponsor of the study.

Source: Utian WH. NAMS 2018, Friday concurrent session 1.

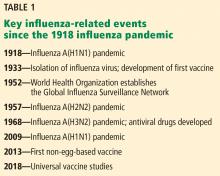

Influenza update 2018–2019: 100 years after the great pandemic

This centennial year update focuses primarily on immunization, but also reviews epidemiology, transmission, and treatment.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

2017–2018 was a bad season

The 2017–2018 influenza epidemic was memorable, dominated by influenza A(H3N2) viruses with morbidity and mortality rates approaching pandemic numbers. It lasted 19 weeks, killed more people than any other epidemic since 2010, particularly children, and was associated with 30,453 hospitalizations—almost twice the previous season high in some parts of the United States.2

Regrettably, 171 unvaccinated children died during 2017–2018, accounting for almost 80% of deaths.2 The mean age of the children who died was 7.1 years; 51% had at least 1 underlying medical condition placing them at risk for influenza-related complications, and 57% died after hospitalization.2

Recent estimates of the incidence of symptomatic influenza among all ages ranged from 3% to 11%, which is slightly lower than historical estimates. The rates were higher for children under age 18 than for adults.3 Interestingly, influenza A(H3N2) accounted for 50% of cases of non-mumps viral parotitis during the 2014–2015 influenza season in the United States.4

Influenza C exists but is rare

Influenza A and B account for almost all influenza-related outpatient visits and hospitalizations. Surveillance data from May 2013 through December 2016 showed that influenza C accounts for 0.5% of influenza-related outpatient visits and hospitalizations, particularly affecting children ages 6 to 24 months. Medical comorbidities and copathogens were seen in all patients requiring intensive care and in most hospitalizations.5 Diagnostic tests for influenza C are not widely available.

Dogs and cats: Factories for new flu strains?

While pigs and birds are the major reservoirs of influenza viral genetic diversity from which infection is transmitted to humans, dogs and cats have recently emerged as possible sources of novel reassortant influenza A.6 With their frequent close contact with humans, our pets may prove to pose a significant threat.

Obesity a risk factor for influenza

Obesity emerged as a risk factor for severe influenza in the 2009 pandemic. Recent data also showed that obesity increases the duration of influenza A virus shedding, thus increasing duration of contagiousness.7

Influenza a cardiovascular risk factor

Previous data showed that influenza was a risk factor for cardiovascular events. Two recent epidemiologic studies from the United Kingdom showed that laboratory-confirmed influenza was associated with higher rates of myocardial infarction and stroke for up to 4 weeks.8,9

Which strain is the biggest threat?

Predicting which emerging influenza serotype may cause the next pandemic is difficult, but influenza A(H7N9), which had not infected humans until 2013 but has since infected about 1,600 people in China and killed 37% of them, appears to have the greatest potential.10

National influenza surveillance programs and influenza-related social media applications have been developed and may get a boost from technology. A smartphone equipped with a temperature sensor can instantly detect one’s temperature with great precision. A 2018 study suggested that a smartphone-driven thermometry application correlated well with national influenza-like illness activity and improved its forecast in real time and up to 3 weeks in advance.11

TRANSMISSION

Humidity may not block transmission

Animal studies have suggested that humidity in the air interferes with transmission of airborne influenza virus, partially from biologic inactivation. But when a recent study used humidity-controlled chambers to investigate the stability of the 2009 influenza A(H1N1) virus in suspended aerosols and stationary droplets, the virus remained infectious in aerosols across a wide range of relative humidities, challenging the common belief that humidity destabilizes respiratory viruses in aerosols.12

One sick passenger may not infect the whole plane

Transmission of respiratory viruses on airplane flights has long been considered a potential avenue for spreading influenza. However, a recent study that monitored movements of individuals on 10 transcontinental US flights and simulated inflight transmission based on these data showed a low probability of direct transmission, except for passengers seated in close proximity to an infectious passenger.13

WHAT’S IN THE NEW FLU SHOT?

The 2018–2019 quadrivalent vaccine for the Northern Hemisphere14 contains the following strains:

- A/Michigan/45/2015 A(H1N1)pdm09-like virus

- A/Singapore/INFIMH-16-0019/2016 (H3N2)-like virus

- B/Colorado/06/2017-like virus (Victoria lineage)

- B/Phuket/3073/2013-like virus (Yamagata lineage).

The A(H3N2) (Singapore) and B/Victoria lineage components are new this year. The A(H3N2) strain was the main cause of the 2018 influenza epidemic in the Southern Hemisphere.

The quadrivalent live-attenuated vaccine, which was not recommended during the 2016–2017 and 2017–2018 influenza seasons, has made a comeback and is recommended for the 2018–2019 season in people for whom it is appropriate based on age and comorbidities.15 Although it was effective against influenza B and A(H3N2) viruses, it was less effective against the influenza A(H1N1)pdm09-like viruses during the 2013–2014 and 2015–2016 seasons.

A/Slovenia/2903/2015, the new A(H1N1)pdm09-like virus included in the 2018–2019 quadrivalent live-attenuated vaccine, is significantly more immunogenic than its predecessor, A/Bolivia/559/2013, but its clinical effectiveness remains to be seen.

PROMOTING VACCINATION

How effective is it?

Influenza vaccine effectiveness in the 2017–2018 influenza season was 36% overall, 67% against A(H1N1), 42% against influenza B, and 25% against A(H3N2).16 It is estimated that influenza vaccine prevents 300 to 4,000 deaths annually in the United States alone.17

A 2018 Cochrane review17 concluded that vaccination reduced the incidence of influenza by about half, with 2.3% of the population contracting the flu without vaccination compared with 0.9% with vaccination (risk ratio 0.41, 95% confidence interval 0.36–0.47). The same review found that 71 healthy adults need to be vaccinated to prevent 1 from experiencing influenza, and 29 to prevent 1 influenza-like illness.

Several recent studies showed that influenza vaccine effectiveness varied based on age and influenza serotype, with higher effectiveness in people ages 5 to 17 and ages 18 to 64 than in those age 65 and older.18–20 A mathematical model of influenza transmission and vaccination in the United States determined that even relatively low-efficacy influenza vaccines can be very useful if optimally distributed across age groups.21

Vaccination rates are low, and ‘antivaxxers’ are on the rise

Although the influenza vaccine is recommended in the United States for all people age 6 months and older regardless of the state of their health, vaccination rates remain low. In 2016, only 37% of employed adults were vaccinated. The highest rate was for government employees (45%), followed by private employees (36%), followed by the self-employed (30%).22

A national goal is to immunize 80% of all Americans and 90% of at-risk populations (which include children and the elderly).23 The number of US hospitals that require their employees to be vaccinated increased from 37.1% in 2013 to 61.4% in 2017.24 Regrettably, as of March 2018, 14 lawsuits addressing religious objections to hospital influenza vaccination mandates have been filed.25

Despite hundreds of studies demonstrating the efficacy, safety, and cost savings of influenza vaccination, the antivaccine movement has been growing in the United States and worldwide.26 All US states except West Virginia, Mississippi, and California allow nonmedical exemptions from vaccination based on religious or personal belief.27 Several US metropolitan areas represent “hot spots” for these exemptions.28 This may render such areas vulnerable to vaccine-preventable diseases, including influenza.

Herd immunity: We’re all in this together

Some argue that the potential adverse effects and the cost of vaccination outweigh the benefits, but the protective benefits of herd immunity are significant for those with comorbidities or compromised immunity.

Educating the public about herd immunity and local influenza vaccination uptake increases people’s willingness to be vaccinated.29 A key educational point is that at least 70% of a community needs to be vaccinated to prevent community outbreaks; this protects everyone, including those who do not mount a protective antibody response to influenza vaccination and those who are not vaccinated.

DOES ANNUAL VACCINATION BLUNT ITS EFFECTIVENESS?

Some studies from the 1970s and 1980s raised concern over a possible negative effect of annual influenza vaccination on vaccine effectiveness. The “antigenic distance hypothesis” holds that vaccine effectiveness is influenced by antigenic similarity between the previous season’s vaccine serotypes and the epidemic serotypes, as well as the antigenic similarity between the serotypes of the current and previous seasons.

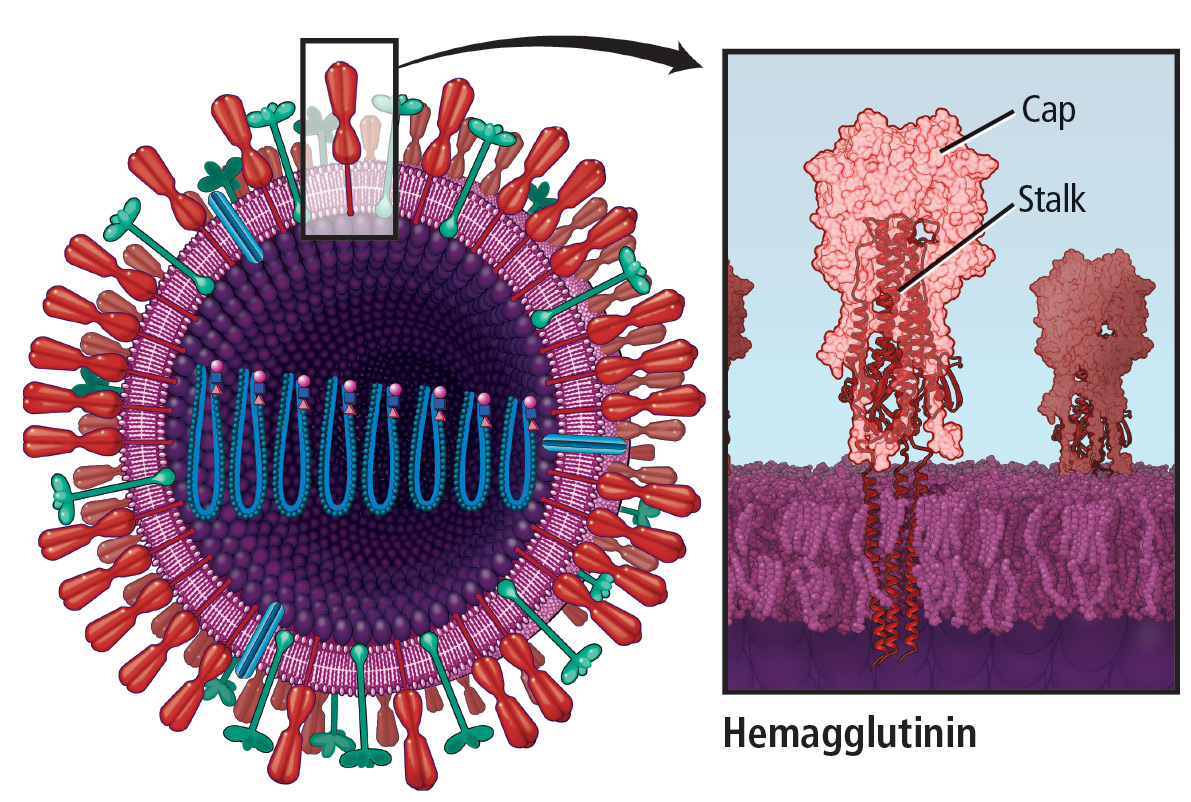

A meta-analysis of studies from 2010 through 2015 showed significant inconsistencies in repeat vaccination effects within and between seasons and serotypes. It also showed that vaccine effectiveness may be influenced by more than 1 previous season, particularly for influenza A(H3N2), in which repeated vaccination can blunt the hemagglutinin antibody response.30

A study from Japan showed that people who needed medical attention for influenza in the previous season were at lower risk of a similar event in the current season.31 Prior-season influenza vaccination reduced current-season vaccine effectiveness only in those who did not have medically attended influenza in the prior season. This suggests that infection is more immunogenic than vaccination, but only against the serotype causing the infection and not the other serotypes included in the vaccine.

An Australian study showed that annual influenza vaccination did not decrease vaccine effectiveness against influenza-associated hospitalization. Rather, effectiveness increased by about 15% in those vaccinated in both current and previous seasons compared with those vaccinated in either season alone.32

European investigators showed that repeated seasonal influenza vaccination in the elderly prevented the need for hospitalization due to influenza A(H3N2) and B, but not A(H1N1)pdm09.33

VACCINATION IN SPECIAL POPULATIONS

High-dose vaccine for older adults

The high-dose influenza vaccine has been licensed since 2009 for use in the United States for people ages 65 and older.

Recent studies confirmed that high-dose vaccine is more effective than standard-dose vaccine in veterans34 and US Medicare beneficiaries.35

The high-dose vaccine is rapidly becoming the primary vaccine given to people ages 65 and older in retail pharmacies, where vaccination begins earlier in the season than in providers’ offices.36 Some studies have shown that the standard-dose vaccine wanes in effectiveness toward the end of the influenza season (particularly if the season is long) if it is given very early. It remains to be seen whether the same applies to the high-dose influenza vaccine.

Some advocate twice-annual influenza vaccination, particularly for older adults living in tropical and subtropical areas, where influenza seasons are more prolonged. However, a recently published study observed reductions in influenza-specific hemagglutination inhibition and cell-mediated immunity after twice-annual vaccination.37

Vaccination is beneficial during pregnancy

Many studies have shown the value of influenza vaccination during pregnancy for both mothers and their infants.

One recently published study showed that 18% of infants who developed influenza required hospitalization.38 In that study, prenatal and postpartum maternal influenza vaccination decreased the odds of influenza in infants by 61% and 53%, respectively.

Another study showed that vaccine effectiveness did not vary by gestational age at vaccination.39

Some studies have shown that influenza virus infection can increase susceptibility to certain bacterial infections. A post hoc analysis of an influenza vaccination study in pregnant women suggested that the vaccine was also associated with decreased rates of pertussis in these women.40

Factors that make vaccination less effective

Several factors including age-related frailty and iatrogenic and disease-related immunosuppression can affect vaccine effectiveness.

Frailty. A recent study showed that vaccine effectiveness was 77.6% in nonfrail older adults but only 58.7% in frail older adults.41

Immunosuppression. Temporary discontinuation of methotrexate for 2 weeks after influenza vaccination in patients with rheumatoid arthritis improves vaccine immunogenicity without precipitating disease flare.42 Solid-organ and hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients who received influenza vaccine were less likely to develop pneumonia and require intensive care unit admission.43

The high-dose influenza vaccine is more immunogenic than the standard-dose vaccine in solid-organ transplant recipients.44

Statins are widely prescribed and have recently been associated with reduced influenza vaccine effectiveness against medically attended acute respiratory illness, but their benefits in preventing cardiovascular events outweigh this risk.45

FUTURE VACCINE CONSIDERATIONS

Moving away from eggs

During the annual egg-based production process, which takes several months, the influenza vaccine acquires antigenic changes that allow replication in eggs, particularly in the hemagglutinin protein, which mediates receptor binding. This process of egg adaptation may cause antigenic changes that decrease vaccine effectiveness against circulating viruses.

The cell-based baculovirus influenza vaccine grown in dog kidney cells has higher antigenic content and is not subject to the limitations of egg-based vaccine, although it still requires annual updates. A recombinant influenza vaccine reduces the probability of influenza-like illness by 30% compared with the egg-based influenza vaccine, but also still requires annual updates.46 The market share of these non-egg-based vaccines is small, and thus their effectiveness has yet to be demonstrated.

The US Department of Defense administered the cell-based influenza vaccine to about one-third of Armed Forces personnel, their families, and retirees in the 2017–2018 influenza seasons, and data on its effectiveness are expected in the near future.47

A universal vaccine would be ideal

The quest continues for a universal influenza vaccine, one that remains protective for several years and does not require annual updates.48 Such a vaccine would protect against seasonal epidemic influenza drift variants and pandemic strains. More people could likely be persuaded to be vaccinated once rather than every year.

An ideal universal vaccine would be suitable for all age groups, at least 75% effective against symptomatic influenza virus infection, protective against all influenza A viruses (influenza A, not B, causes pandemics and seasonal epidemics), and durable through multiple influenza seasons.51

Research and production of such a vaccine are expected to require funding of about $1 billion over the next 5 years.

Boosting effectiveness

Estimates of influenza vaccine effectiveness range from 40% to 60% in years when the vaccine viruses closely match the circulating viruses, and variably lower when they do not match. The efficacy of most other vaccines given to prevent other infections is much higher.

New technologies to improve influenza vaccine effectiveness are needed, particularly for influenza A(H3N2) viruses, which are rapidly evolving and are highly susceptible to egg-adaptive mutations in the manufacturing process.

In one study, a nanoparticle vaccine formulated with a saponin-based adjuvant induced hemagglutination inhibition responses that were even greater than those induced by the high-dose vaccine.52

Immunoglobulin A (IgA) may be a more effective vaccine target than traditional influenza vaccines that target IgG, since different parts of IgA may engage the influenza virus simultaneously.53

Vaccines can be developed more quickly than in the past. The timeline from viral sequencing to human studies with deoxyribonucleic acid plasmid vaccines decreased from 20 months in 2003 for the severe acquired respiratory syndrome coronavirus to 11 months in 2006 for influenza A/Indonesia/2006 (H5), to 4 months in 2009 for influenza A/California/2009 (H1), to 3.5 months in 2016 for Zika virus.54 This is because it is possible today to sequence a virus and insert the genetic material into a vaccine platform without ever having to grow the virus.

TREATMENT

Numerous studies have found anti-influenza medications to be effective. Nevertheless, in an analysis of the 2011–2016 influenza seasons, only 15% of high-risk patients were prescribed anti-influenza medications within 2 days of symptom onset, including 37% in those with laboratory-confirmed influenza.55 Fever was associated with an increased rate of antiviral treatment, but 25% of high-risk outpatients were afebrile. Empiric treatment of 4 high-risk outpatients with acute respiratory illness was needed to treat 1 patient with influenza.55

Treatment with a neuraminidase inhibitor within 2 days of illness has recently been shown to improve survival and shorten duration of viral shedding in patients with avian influenza A(H7N9) infection.56 Antiviral treatment within 2 days of illness is associated with improved outcomes in transplant recipients57 and with a lower risk of otitis media in children.58

Appropriate anti-influenza treatment is as important as avoiding unnecessary antibiotics. Regrettably, as many as one-third of patients with laboratory-confirmed influenza are prescribed antibiotics.59

The US Food and Drug Administration warns against fraudulent unapproved over-the-counter influenza products.60

Baloxavir marboxil

Baloxavir marboxil is a new anti-influenza medication approved in Japan in February 2018 and anticipated to be available in the United States sometime in 2019.

This prodrug is hydrolyzed in vivo to the active metabolite, which selectively inhibits cap-dependent endonuclease enzyme, a key enzyme in initiation of messenger ribonucleic acid synthesis required for influenza viral replication.61

In a double-blind phase 3 trial, the median time to alleviation of influenza symptoms is 26.5 hours shorter with baloxavir marboxil than with placebo. One tablet was as effective as 5 days of the neuraminidase inhibitor oseltamivir and was associated with greater reduction in viral load 1 day after initiation, and similar side effects.62 Of concern is the emergence of nucleic acid substitutions conferring resistance to baloxavir; this occurred in 2.2% and 9.7% of baloxavir recipients in the phase 2 and 3 trials, respectively.

CLOSING THE GAPS

Several gaps in the management of influenza persist since the 1918 pandemic.1 These include gaps in epidemiology, prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis.

- Global networks wider than current ones are needed to address this global disease and to prioritize coordination efforts.

- Establishing and strengthening clinical capacity is needed in limited resource settings. New technologies are needed to expedite vaccine development and to achieve progress toward a universal vaccine.

- Current diagnostic tests do not distinguish between seasonal and novel influenza A viruses of zoonotic origin, which are expected to cause the next pandemic.

- Current antivirals have been shown to shorten duration of illness in outpatients with uncomplicated influenza, but the benefit in hospitalized patients has been less well established.

- In 2007, resistance of seasonal influenza A(H1N1) to oseltamivir became widespread. In 2009, pandemic influenza A(H1N1), which is highly susceptible to oseltamivir, replaced the seasonal virus and remains the predominantly circulating A(H1N1) strain.

- A small-molecule fragment, N-cyclohexyaltaurine, binds to the conserved hemagglutinin receptor-binding site in a manner that mimics the binding mode of the natural receptor sialic acid. This can serve as a template to guide the development of novel broad-spectrum small-molecule anti-influenza drugs.63

- Biomarkers that can accurately predict development of severe disease in patients with influenza are needed.

- Uyeki TM, Fowler RA, Fischer WA. Gaps in the clinical management of influenza: a century since the 1918 pandemic. JAMA 2018; 320(8):755–756. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.8113

- Garten R, Blanton L, Elal AI, et al. Update: influenza activity in the United States during the 2017–18 season and composition of the 2018–19 influenza vaccine. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018; 67(22):634–642. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6722a4

- Tokars JI, Olsen SJ, Reed C. Seasonal incidence of symptomatic influenza in the United States. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 66(10):1511–1518. doi:10.1093/cid/cix1060

- Elbadawi LI, Talley P, Rolfes MA, et al. Non-mumps viral parotitis during the 2014–2015 influenza season in the United States. Clin Infect Dis 2018. Epub ahead of print. doi:10.1093/cid/ciy137

- Thielen BK, Friedlander H, Bistodeau S, et al. Detection of influenza C viruses among outpatients and patients hospitalized for severe acute respiratory infection, Minnesota, 2013–2016. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 66(7):1092–1098. doi:10.1093/cid/cix931