User login

Empowering Culture Change and Safety on the Journey to Zero Harm With Huddle Cards

Empowering Culture Change and Safety on the Journey to Zero Harm With Huddle Cards

Safety event reporting plays a vital role in fostering a culture of safety within a health care organization. The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has shifted its focus from eradicating medical errors to minimizing or eliminating harm to patients.1 The National Center for Patient Safety’s objective is to prevent recurring errors by identifying and addressing systemic problems that may have been overlooked.2

Taking inspiration from industries known for high reliability, such as aviation and nuclear power, the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) patient safety program aims to identify and eliminate system vulnerabilities, such as medical errors. Learning from near misses, which occur more frequently than actual adverse events, is a crucial part of this process.3 By addressing these issues, the VHA can establish safer systems and encourage continuous identification of potential problems with proactive resolution.

All staff should participate actively in event reporting, which involves documenting and communicating details, outcomes, and relevant data about an event to understand what occurred, evaluate success, identify areas for improvement, and inform future decisions. This helps identify system weaknesses, create opportunities to standardize procedures and enhance patient care.

At the high complexity Central Texas Veterans Health Care System (CTVHCS), the fiscal year (FY) 2023 All Employee Survey (AES) found that staff members require additional education and awareness regarding the reporting of patient safety concerns.4 The survey highlighted areas such as lack of education on reporting, doubts about the effectiveness of reporting, confusion about the process after a report is made, and insufficient feedback.

BACKGROUND

To improve the culture of safety and address deficiencies noted in the AES, the CTVHCS patient safety (PS) and high reliability organization (HRO) teams partnered to develop a quality improvement initiative to increase staff understanding of safety event reporting and strengthen the safety culture. The PS and HRO teams developed an innovative education model that integrates Joint Patient Safety Reporting System (JPSR) education into huddles.

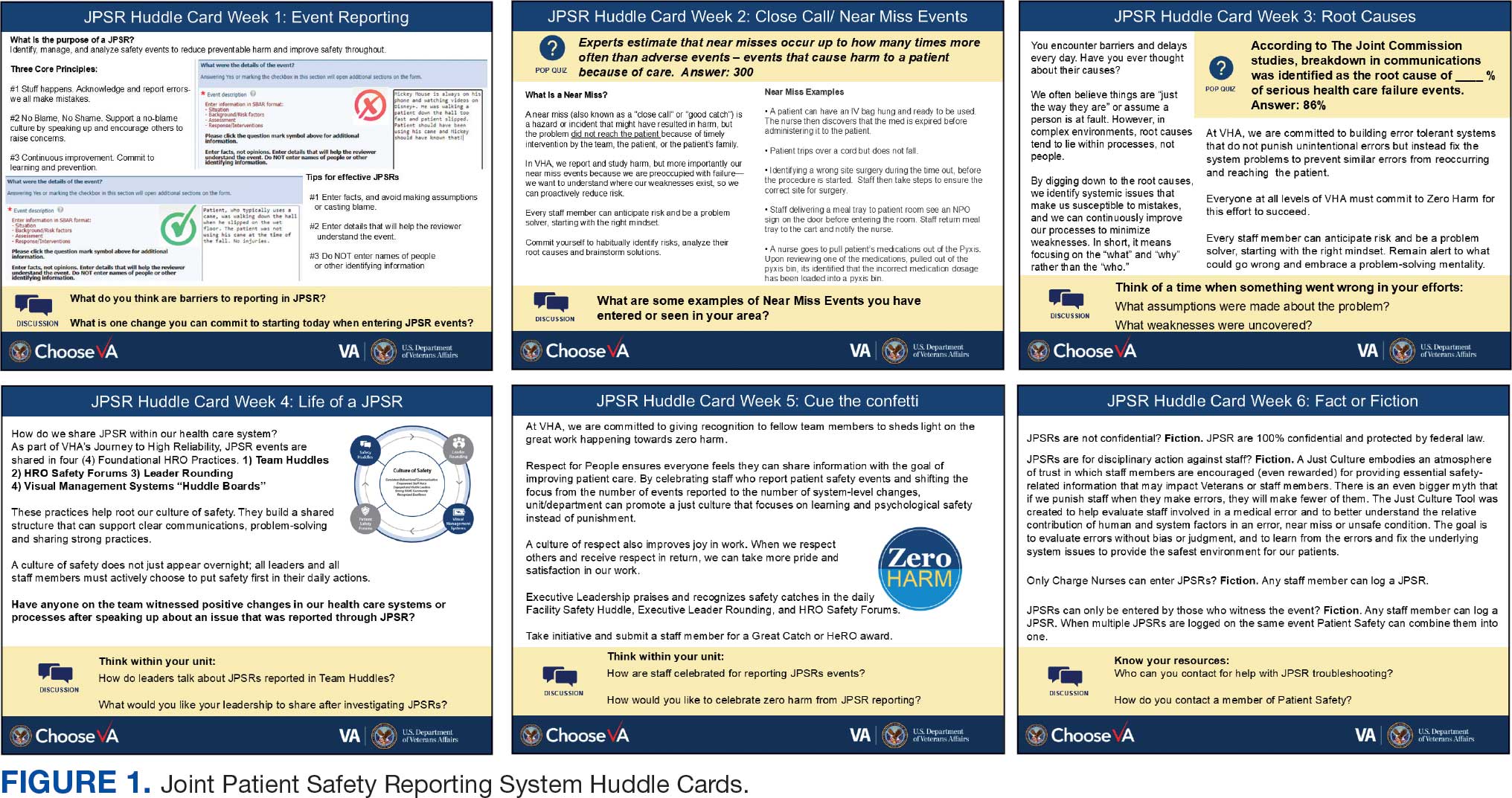

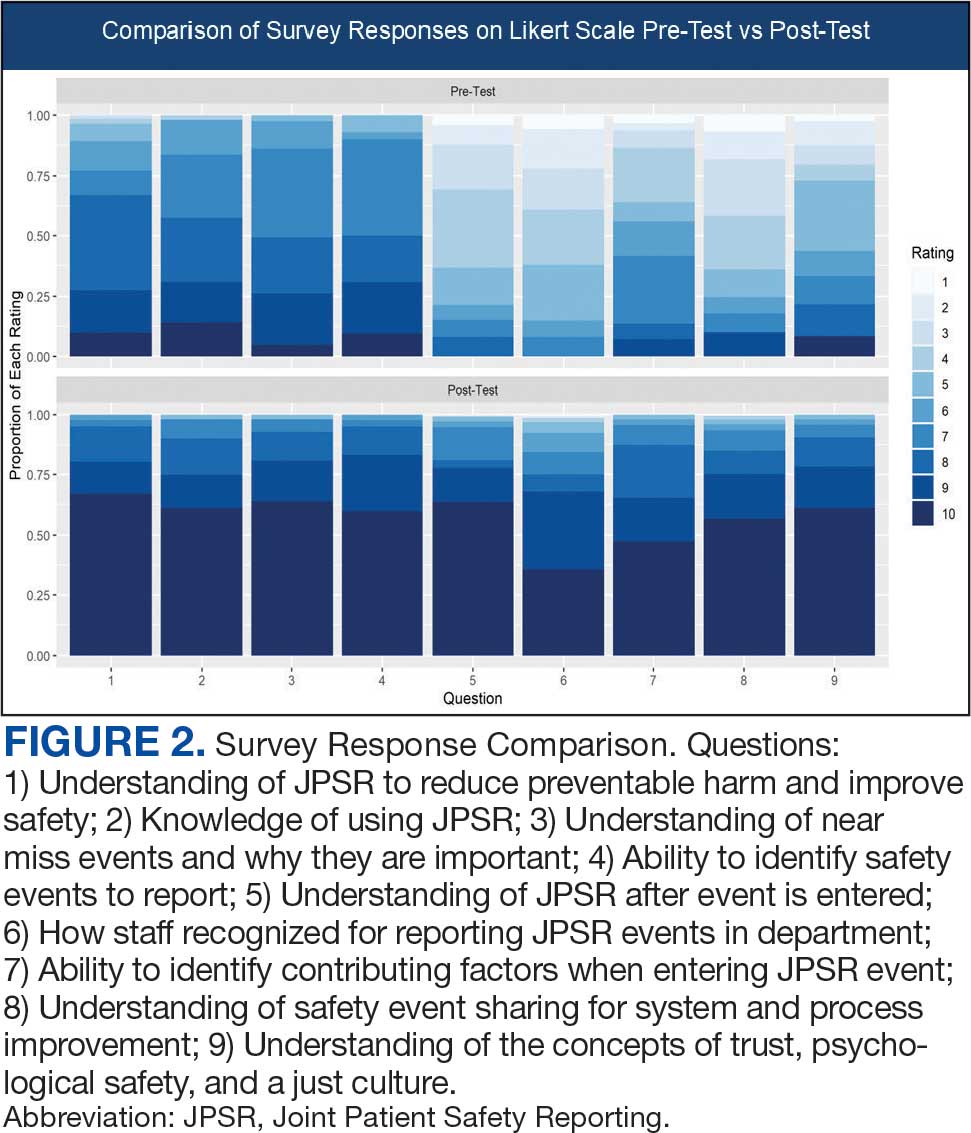

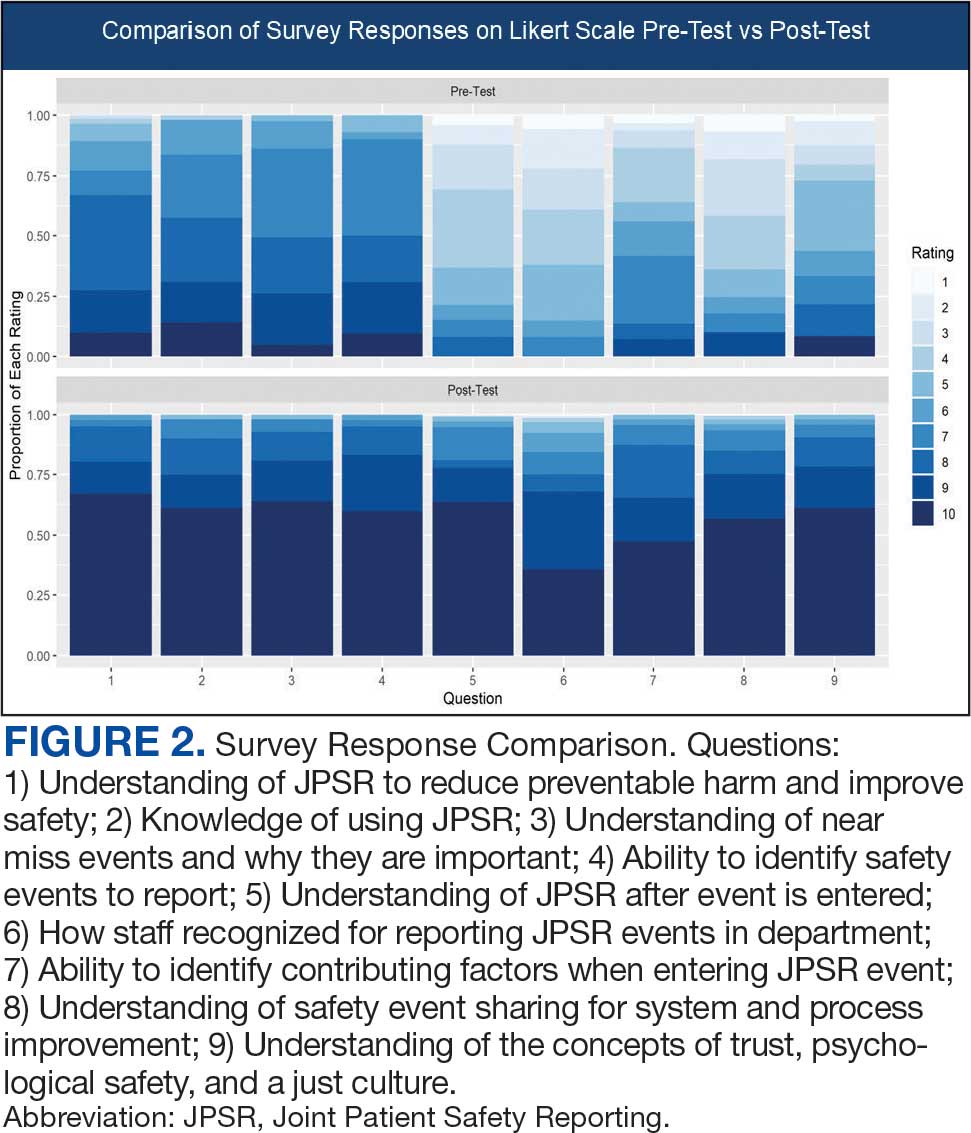

This initiative, called the JPSR Huddle Card Toolkit, sought to assess the impact of the toolkit on staff knowledge and behaviors related to patient safety event reporting. The toolkit consisted of educational materials encompassing 6 key areas: (1) reporting incidents; (2) close calls and near misses; (3) identification of root causes; (4) understanding the life cycle of a JPSR; (5) celebrating achievements; and (6) distinguishing between facts and fiction. Each JPSR huddle card included discussion points for the facilitator and was formatted on a 5 × 7-inch card (Figure 1). Topics were addressed during weekly safety huddles conducted in the pilot unit over a 6-week period. To evaluate its effectiveness, a pilot unit was selected and distributed an anonymous questionnaire paired with the JPSR huddle card toolkit to measure staff responses.

The pilot was conducted from November 2023 to January 2024. The participating pilot unit was a 10-bed critical care unit with 42 full-time employees. Nursing leadership, quality safety, and value personnel, and the Veterans Integrated Services Network (VISN) PS Team reviewed and approved the pilot.

Reporting of adverse events and near misses provides an opportunity to learn about latent systems errors.2 In 2018, the VHA began using the JPSR to standardize the capture and data management on medical errors and close calls across the Defense Health Administration (DHA) and VHA.1 The JPSR software is a joint application of the VHA and DHA. It improves the identification and documentation of patient safety-related events for VA medical centers, military hospitals and clinics, active-duty personnel, veterans and their families.

Event reporting is a key element in advancing high reliability and achieving zero preventable harm.1 Teams use these data to identify organizational patient safety trends and preempt common safety issues. All data are protected under 38 USC §5705 and 10 USC §1102.5 The JPSR single-source system standardizes the collection of core data points and increases collaboration between the DHA and VHA. This partnership increases insight into safety-related incidents, allowing for earlier detection and prevention of patient harm or injury incidents.

Numerous studies consistently commend huddles for their effectiveness in promoting teamwork and their positive impact on patient safety.6-8 Huddles facilitate connections between employees who may not typically interact, provide opportunities for discussions, and serve as a platform to encourage employees to voice their opinions. By fostering these interactions, huddles empower employees and create an environment for shared understanding, building trust, and promoting continuous learning.8

OBSERVATIONS

The JPSR huddle card initiative aimed to improve understanding of the JPSR process and promote knowledge and attitudes about patient safety and event reporting, while emphasizing shared responsibility. The goals focused on effective communication, respect for expertise, awareness of operational nuances, voicing concerns, and ensuring zero harm.

The facilitator initiated huddles by announcing their start to cultivate a constructive outcome.8 The JPSR huddle cards used a structured format designed to foster engagement and understanding of the topic. Each card begins with a factual statement or an open-ended question to gauge participants’ awareness or understanding. It then provides essential facts, principles, and relevant information to deepen knowledge. The card concludes with a discussion question, allowing facilitators to assess shared learning and encourage group reflection. This format promotes active participation and ensures that key concepts are both introduced and reinforced through dialogue.

The PS team standardized the format for all huddle cards, allowing 5 to 10 minutes for discussing training materials, receiving feedback, and concluding with a discussion question and call to action. Prior to each huddle, the facilitator would read a scripted remark that reviewed the objectives and ground rules for an effective huddle.

The PS and HRO teams promoted interactive discussions and welcomed ongoing feedback. Huddles provided a psychologically safe environment where individuals were encouraged to voice their thoughts and ideas.

Each weekly huddle card addressed a different patient safety topic. The Week 1 huddle card focuses on event reporting for safety improvement. The card outlines the purpose of JPSR as a tool to identify, manage, and analyze safety events to reduce preventable harm. The card emphasizes 3 core principles: (1) acknowledging mistakes, recognizing that errors happen; (2) no blame, no shame (encouraging a no-blame just culture to raise concerns); and (3) continuous improvement (committing to ongoing learning and prevention). It provides guidance on event details entry, advising staff to include facts in an SBAR (Situation, Background, Assessment, Response) format, avoid assumptions, and exclude personal identifiers. Tips include entering only relevant facts to help reviewers understand the incident. The card ends with discussion questions on reporting barriers and potential improvements in event reporting practices.

The Week 2 huddle card focuses on understanding and reporting near miss events, also known as close calls or good catches. A near miss is an incident where a potential hazard was identified and prevented before it reached the patient, avoiding harm due to timely intervention. The card emphasizes the importance of identifying these events to understand weaknesses and proactively reduce risks. Examples of near misses include discovering expired medication before use, catching a potential wrong-site surgery, and noticing incorrect medication dosages. Staff are encouraged to develop a mindset for anticipating and solving risks. The card ends with a discussion asking participants to share examples of near misses in their area.

The Week 3 huddle card covers root causes in preventing errors. The card highlights that errors in health care often stem from flawed processes rather than individual faults. By identifying root causes, systemic weaknesses can be addressed to reduce mistakes and build more error-tolerant and robust systems. All staff are advised to adopt a mindset of continuous improvement, error trapping behaviors and problem-solving. It concludes with discussion questions prompting reflection on assumptions and identifying weaknesses when something goes wrong.

The Week 4 huddle card covers the life of a JPSR, detailing that after entry JPSR events are viewed by the highest leadership levels at the morning report, and that lessons learned are distributed through frontline managers and chiefs in a monthly report to be shared with frontline staff. Additionally, JPSR trends are shared during monthly HRO safety forums. These practices promote a culture of safety through open communication and problem-solving. Staff and leaders are encouraged to prioritize safety daily. Discussion prompts ask team members if they had seen positive changes from JPSR reporting and what they would like leadership to communicate after investigations.

The Week 5 huddle card covers celebrating safety event reporting called Cue the Confetti. The VHA emphasizes recognizing staff who report safety events as part of their commitment to zero harm. By celebrating these contributions, the VHA fosters respect, joy, and satisfaction in the work. Staff are encouraged to nominate colleagues for recognition, reinforcing a supportive environment. Prompts invite teams to discuss how they celebrate JPSR reporting and how they’d like to enhance this culture of appreciation.

The Week 6 huddle card covers common misconceptions about JPSR. Key facts include that JPSRs are confidential, not for disciplinary action, and can be submitted by any staff member at any time. Only PS can view reporter identities for clarification purposes. The card concludes with prompts to ensure staff know how to access JPSR support and resources.

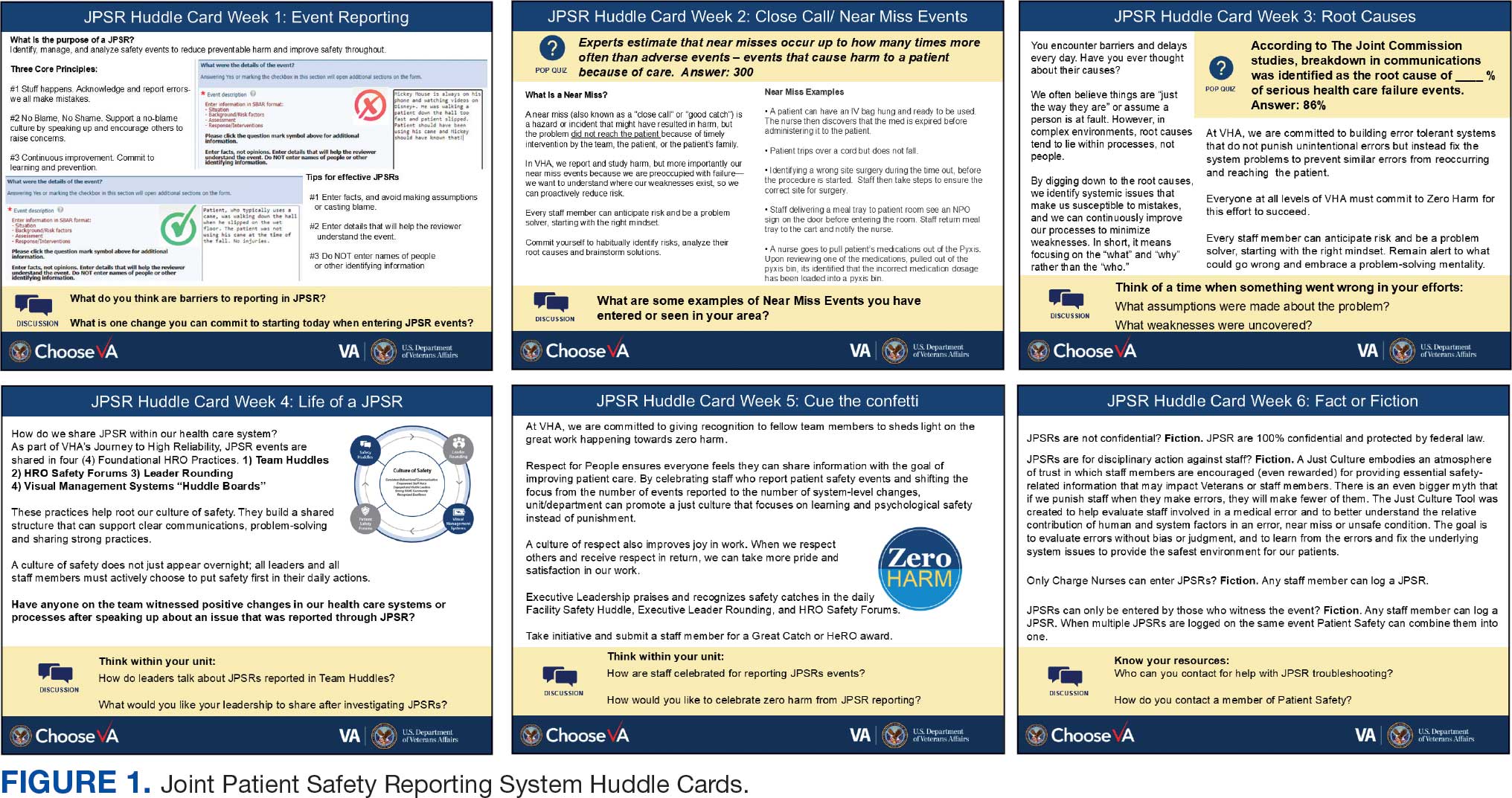

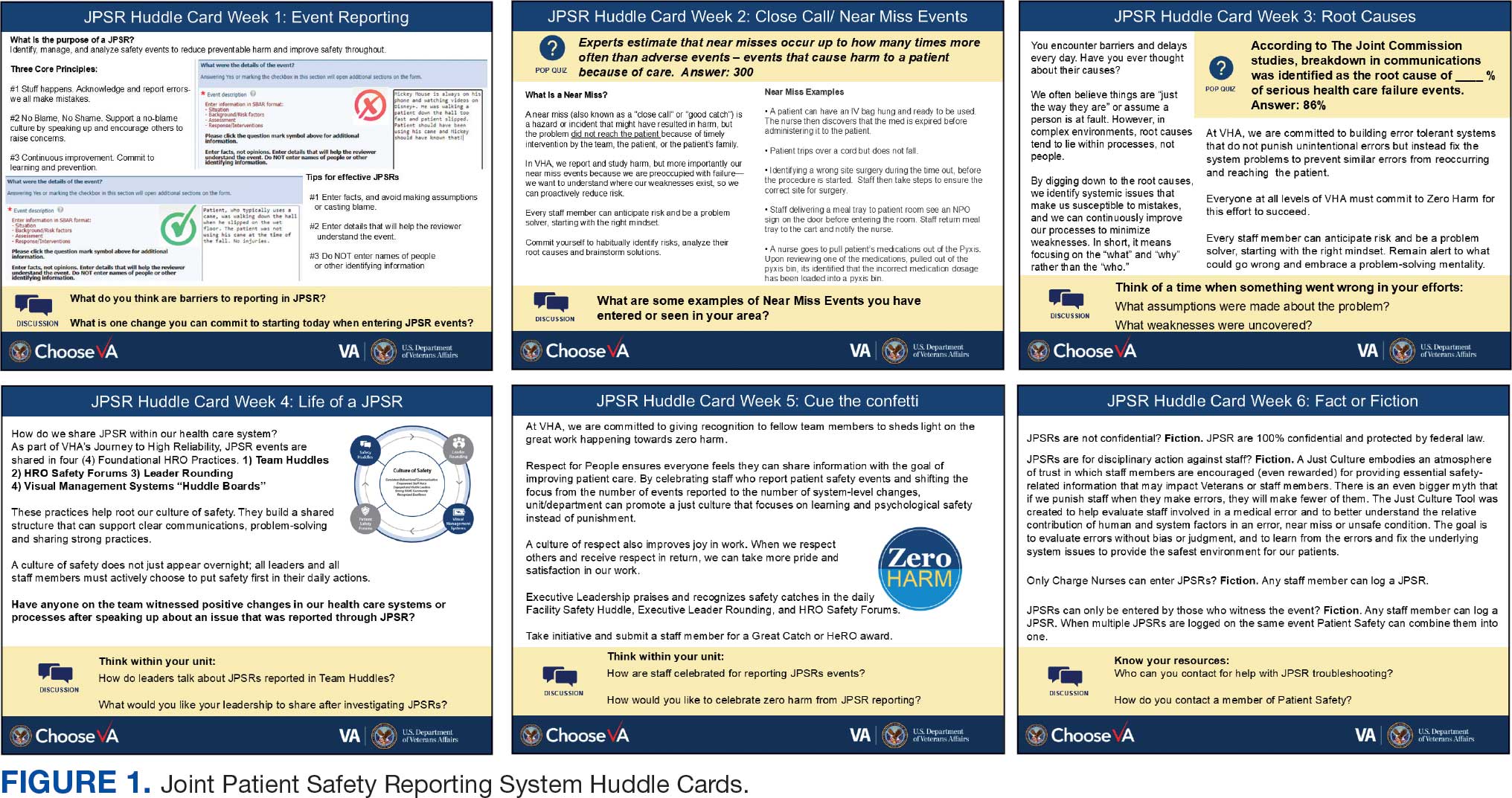

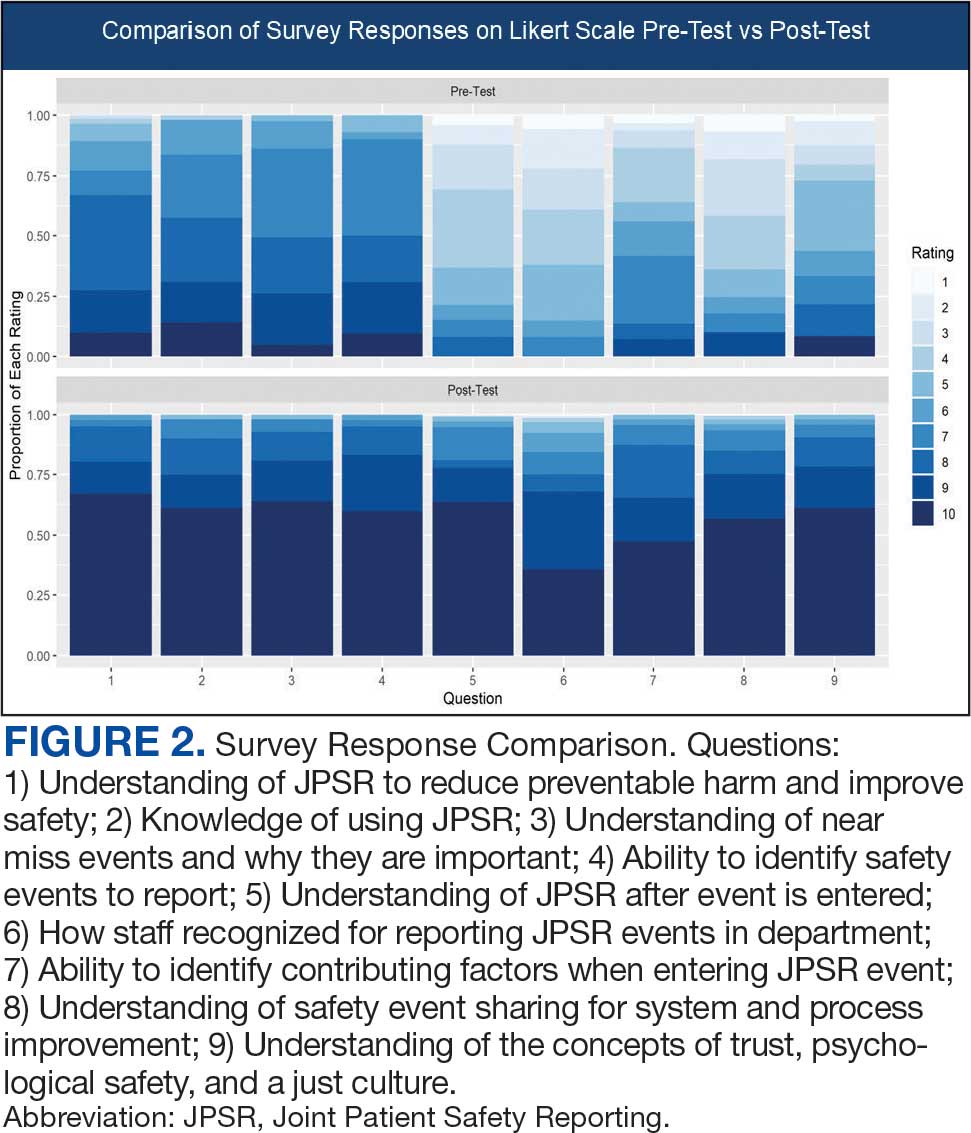

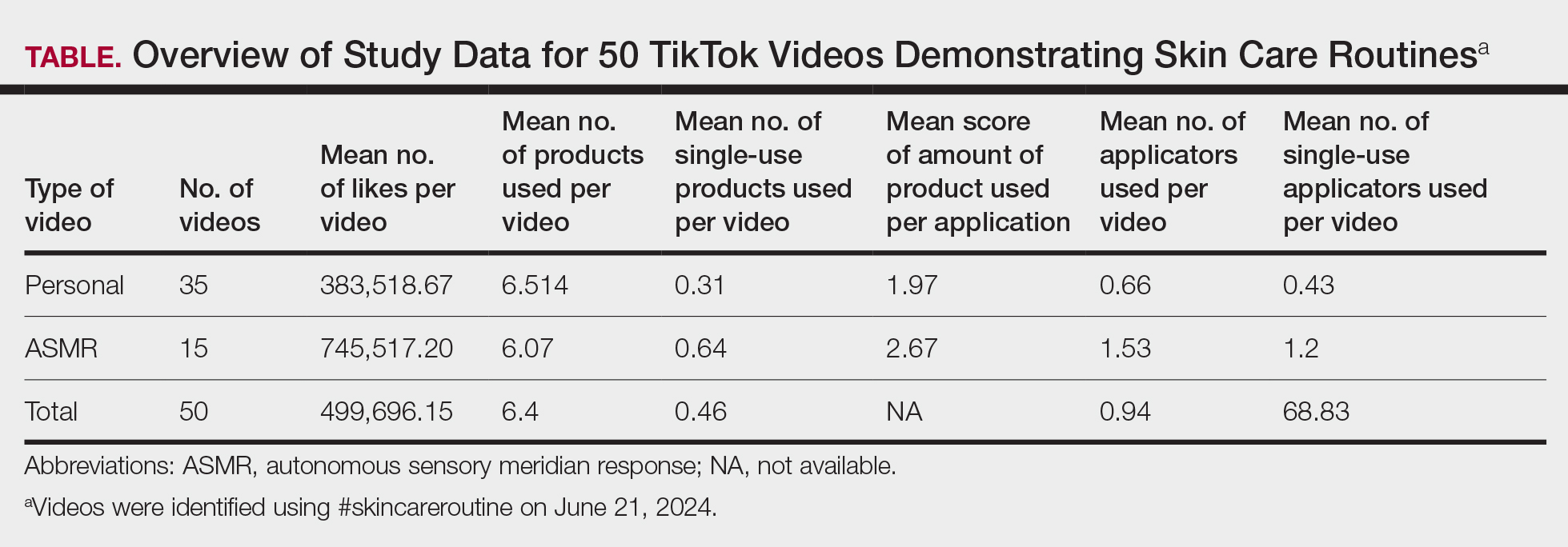

Measuring the impact on staff was essential to assess effectiveness and gather data for program improvement. To evaluate the impact of the huddle cards on the staff, the team provided a voluntary and anonymous 9 question survey (Figure 2). The survey was completed before the pilot began and again at the end of Week 6.

Questions 1 through 5 and 7 through 9 pertained to participants’ perceived knowledge and understanding of aspects of the JPSR. Perceived improvement among intensive care unit (ICU) participants ranged from 15% to 53%. There was a positive increase associated with every question with the top improvements: question 8, “How do you rate your understanding of how we share safety events for system and process improvement?” (53.4% increase); question 5, “How do you rate your understanding of what happens to a JPSR after it is entered?” (51.9% increase), and question 9, “How do you rate your understanding of the concepts of trust, psychological safety and a just culture?” (47.8% increase).

The survey analysis was not able to track individual changes. As a result, the findings reflect an overall change for the entire study group. Moreover, the questions assessed participants’ perceived knowledge rather than actual knowledge gained. It is important to note that there may be a significant gap between the actual knowledge gained and how participants perceive it. Additionally, improvement in knowledge and comprehension does not necessarily translate into behavior changes.

CONCLUSIONS

The use of JPSR huddle cards and direct engagement with staff during safety huddles yielded positive outcomes. On average, participants demonstrated higher scores in posttest questions compared to pretest questions. The posttest scores were consistently higher than the pretest scores, showing an average increase of around 2 standard deviations across all questions. This indicates an improvement in participants’ perceived knowledge and comprehension of the JPSR material.

During the pilot implementation of the huddle cards, there was a notable improvement in team member engagement. The structured format of the cards facilitated focused and meaningful discussions during safety huddles, encouraging open dialogue and fostering a culture of safety. Team members actively participated in identifying potential risks, sharing observations, and proposing actionable solutions, which reflected an enhanced sense of ownership regarding safety practices.

The support dialogue facilitated by the huddle cards highlighted the significance of mutual accountability and a collective commitment to achieving zero harm. This collaborative environment strengthened trust among team members and underscored the importance of shared vigilance in preventing adverse events. The pilot demonstrated the potential of huddle cards as an essential tool for enhancing team-based safety initiatives and promoting a culture of high reliability within the organization.

The total number of JPSR events in the ICU rose from 156 in FY 23 to 170 in FY 24. Adverse events increased from 19 to 31, while close calls saw a slight uptick from 137 to 139. Despite the overall rise in adverse events, a detailed analysis indicated that incidents of moderate harm decreased from 4 in FY 23 to 2 in FY 24. Furthermore, there was 1 reported case of death or severe harm in FY 23, which decreased to 0 in FY 24. This trend is consistent with the overarching objective of a high-reliability organization to achieve zero harm.

The next step is to expand this initiative across CTVHCS. This initiative aims to make this an annual education for all areas. The JPSR huddle card toolkit will be formatted by the media department for easy printing and retrieval. Leaders within units, clinics, and services will be empowered to facilitate the sessions in their safety huddles and reap the same outcomes as in the pilot. CTVHCS PS will monitor the effectiveness of this through ongoing CTVHCS patient safety rounding and future AES.

- Essen K, Villalobos C, Sculli GL, Steinbach L. Establishing a just culture: implications for the Veterans Health Administration journey to high reliability. Fed Pract. 2024;41:290-297. doi:10.12788/fp.0512

- Louis MY, Hussain LR, Dhanraj DN, et al. Improving patient safety event reporting among residents and teaching faculty. Ochsner J. 2016;16:73-80.

- Pimental CB, Snow AL, Carnes SL, et al. Huddles and their effectiveness at the frontlines of clinical care: a scoping review. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36:2772-2783. doi:10.1007/s11606-021-06632-9

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Appendix C: Nature of Veterans Health Administration Facilities Management (Engineering) Tasks and Staffing. Facilities Staffing Requirements for the Veterans Health Administration-Resource Planning and Methodology for the Future. National Academies Press. 2020:105-116. Accessed August 11, 2025. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/read/25454/chapter/11

- Woodier N, Burnett C, Moppett I. The value of learning from near misses to improve patient safety: a scoping review. J Patient Saf. 2023;19:42-47. doi:10.1097/pts.0000000000001078

- Ismail A, Khalid SNM. Patient safety culture and its determinants among healthcare professionals at a cluster hospital in Malaysia: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2022;12:e060546. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-060546

- Ngo J, Lau D, Ploquin J, Receveur T, Stassen K, Del Castilho C. Improving incident reporting among physicians at south health campus hospital. BMJ Open Qual. 2022;11:e001945. doi:10.1136/bmjoq-2022-001945

- Oweidat I, Al-Mugheed K, Alsenany SA, et al. Awareness of reporting practices and barriers to incident reporting among nurses. BMC Nurs. 2023;22:231. doi:10.1186/s12912-023-01376-9

Safety event reporting plays a vital role in fostering a culture of safety within a health care organization. The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has shifted its focus from eradicating medical errors to minimizing or eliminating harm to patients.1 The National Center for Patient Safety’s objective is to prevent recurring errors by identifying and addressing systemic problems that may have been overlooked.2

Taking inspiration from industries known for high reliability, such as aviation and nuclear power, the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) patient safety program aims to identify and eliminate system vulnerabilities, such as medical errors. Learning from near misses, which occur more frequently than actual adverse events, is a crucial part of this process.3 By addressing these issues, the VHA can establish safer systems and encourage continuous identification of potential problems with proactive resolution.

All staff should participate actively in event reporting, which involves documenting and communicating details, outcomes, and relevant data about an event to understand what occurred, evaluate success, identify areas for improvement, and inform future decisions. This helps identify system weaknesses, create opportunities to standardize procedures and enhance patient care.

At the high complexity Central Texas Veterans Health Care System (CTVHCS), the fiscal year (FY) 2023 All Employee Survey (AES) found that staff members require additional education and awareness regarding the reporting of patient safety concerns.4 The survey highlighted areas such as lack of education on reporting, doubts about the effectiveness of reporting, confusion about the process after a report is made, and insufficient feedback.

BACKGROUND

To improve the culture of safety and address deficiencies noted in the AES, the CTVHCS patient safety (PS) and high reliability organization (HRO) teams partnered to develop a quality improvement initiative to increase staff understanding of safety event reporting and strengthen the safety culture. The PS and HRO teams developed an innovative education model that integrates Joint Patient Safety Reporting System (JPSR) education into huddles.

This initiative, called the JPSR Huddle Card Toolkit, sought to assess the impact of the toolkit on staff knowledge and behaviors related to patient safety event reporting. The toolkit consisted of educational materials encompassing 6 key areas: (1) reporting incidents; (2) close calls and near misses; (3) identification of root causes; (4) understanding the life cycle of a JPSR; (5) celebrating achievements; and (6) distinguishing between facts and fiction. Each JPSR huddle card included discussion points for the facilitator and was formatted on a 5 × 7-inch card (Figure 1). Topics were addressed during weekly safety huddles conducted in the pilot unit over a 6-week period. To evaluate its effectiveness, a pilot unit was selected and distributed an anonymous questionnaire paired with the JPSR huddle card toolkit to measure staff responses.

The pilot was conducted from November 2023 to January 2024. The participating pilot unit was a 10-bed critical care unit with 42 full-time employees. Nursing leadership, quality safety, and value personnel, and the Veterans Integrated Services Network (VISN) PS Team reviewed and approved the pilot.

Reporting of adverse events and near misses provides an opportunity to learn about latent systems errors.2 In 2018, the VHA began using the JPSR to standardize the capture and data management on medical errors and close calls across the Defense Health Administration (DHA) and VHA.1 The JPSR software is a joint application of the VHA and DHA. It improves the identification and documentation of patient safety-related events for VA medical centers, military hospitals and clinics, active-duty personnel, veterans and their families.

Event reporting is a key element in advancing high reliability and achieving zero preventable harm.1 Teams use these data to identify organizational patient safety trends and preempt common safety issues. All data are protected under 38 USC §5705 and 10 USC §1102.5 The JPSR single-source system standardizes the collection of core data points and increases collaboration between the DHA and VHA. This partnership increases insight into safety-related incidents, allowing for earlier detection and prevention of patient harm or injury incidents.

Numerous studies consistently commend huddles for their effectiveness in promoting teamwork and their positive impact on patient safety.6-8 Huddles facilitate connections between employees who may not typically interact, provide opportunities for discussions, and serve as a platform to encourage employees to voice their opinions. By fostering these interactions, huddles empower employees and create an environment for shared understanding, building trust, and promoting continuous learning.8

OBSERVATIONS

The JPSR huddle card initiative aimed to improve understanding of the JPSR process and promote knowledge and attitudes about patient safety and event reporting, while emphasizing shared responsibility. The goals focused on effective communication, respect for expertise, awareness of operational nuances, voicing concerns, and ensuring zero harm.

The facilitator initiated huddles by announcing their start to cultivate a constructive outcome.8 The JPSR huddle cards used a structured format designed to foster engagement and understanding of the topic. Each card begins with a factual statement or an open-ended question to gauge participants’ awareness or understanding. It then provides essential facts, principles, and relevant information to deepen knowledge. The card concludes with a discussion question, allowing facilitators to assess shared learning and encourage group reflection. This format promotes active participation and ensures that key concepts are both introduced and reinforced through dialogue.

The PS team standardized the format for all huddle cards, allowing 5 to 10 minutes for discussing training materials, receiving feedback, and concluding with a discussion question and call to action. Prior to each huddle, the facilitator would read a scripted remark that reviewed the objectives and ground rules for an effective huddle.

The PS and HRO teams promoted interactive discussions and welcomed ongoing feedback. Huddles provided a psychologically safe environment where individuals were encouraged to voice their thoughts and ideas.

Each weekly huddle card addressed a different patient safety topic. The Week 1 huddle card focuses on event reporting for safety improvement. The card outlines the purpose of JPSR as a tool to identify, manage, and analyze safety events to reduce preventable harm. The card emphasizes 3 core principles: (1) acknowledging mistakes, recognizing that errors happen; (2) no blame, no shame (encouraging a no-blame just culture to raise concerns); and (3) continuous improvement (committing to ongoing learning and prevention). It provides guidance on event details entry, advising staff to include facts in an SBAR (Situation, Background, Assessment, Response) format, avoid assumptions, and exclude personal identifiers. Tips include entering only relevant facts to help reviewers understand the incident. The card ends with discussion questions on reporting barriers and potential improvements in event reporting practices.

The Week 2 huddle card focuses on understanding and reporting near miss events, also known as close calls or good catches. A near miss is an incident where a potential hazard was identified and prevented before it reached the patient, avoiding harm due to timely intervention. The card emphasizes the importance of identifying these events to understand weaknesses and proactively reduce risks. Examples of near misses include discovering expired medication before use, catching a potential wrong-site surgery, and noticing incorrect medication dosages. Staff are encouraged to develop a mindset for anticipating and solving risks. The card ends with a discussion asking participants to share examples of near misses in their area.

The Week 3 huddle card covers root causes in preventing errors. The card highlights that errors in health care often stem from flawed processes rather than individual faults. By identifying root causes, systemic weaknesses can be addressed to reduce mistakes and build more error-tolerant and robust systems. All staff are advised to adopt a mindset of continuous improvement, error trapping behaviors and problem-solving. It concludes with discussion questions prompting reflection on assumptions and identifying weaknesses when something goes wrong.

The Week 4 huddle card covers the life of a JPSR, detailing that after entry JPSR events are viewed by the highest leadership levels at the morning report, and that lessons learned are distributed through frontline managers and chiefs in a monthly report to be shared with frontline staff. Additionally, JPSR trends are shared during monthly HRO safety forums. These practices promote a culture of safety through open communication and problem-solving. Staff and leaders are encouraged to prioritize safety daily. Discussion prompts ask team members if they had seen positive changes from JPSR reporting and what they would like leadership to communicate after investigations.

The Week 5 huddle card covers celebrating safety event reporting called Cue the Confetti. The VHA emphasizes recognizing staff who report safety events as part of their commitment to zero harm. By celebrating these contributions, the VHA fosters respect, joy, and satisfaction in the work. Staff are encouraged to nominate colleagues for recognition, reinforcing a supportive environment. Prompts invite teams to discuss how they celebrate JPSR reporting and how they’d like to enhance this culture of appreciation.

The Week 6 huddle card covers common misconceptions about JPSR. Key facts include that JPSRs are confidential, not for disciplinary action, and can be submitted by any staff member at any time. Only PS can view reporter identities for clarification purposes. The card concludes with prompts to ensure staff know how to access JPSR support and resources.

Measuring the impact on staff was essential to assess effectiveness and gather data for program improvement. To evaluate the impact of the huddle cards on the staff, the team provided a voluntary and anonymous 9 question survey (Figure 2). The survey was completed before the pilot began and again at the end of Week 6.

Questions 1 through 5 and 7 through 9 pertained to participants’ perceived knowledge and understanding of aspects of the JPSR. Perceived improvement among intensive care unit (ICU) participants ranged from 15% to 53%. There was a positive increase associated with every question with the top improvements: question 8, “How do you rate your understanding of how we share safety events for system and process improvement?” (53.4% increase); question 5, “How do you rate your understanding of what happens to a JPSR after it is entered?” (51.9% increase), and question 9, “How do you rate your understanding of the concepts of trust, psychological safety and a just culture?” (47.8% increase).

The survey analysis was not able to track individual changes. As a result, the findings reflect an overall change for the entire study group. Moreover, the questions assessed participants’ perceived knowledge rather than actual knowledge gained. It is important to note that there may be a significant gap between the actual knowledge gained and how participants perceive it. Additionally, improvement in knowledge and comprehension does not necessarily translate into behavior changes.

CONCLUSIONS

The use of JPSR huddle cards and direct engagement with staff during safety huddles yielded positive outcomes. On average, participants demonstrated higher scores in posttest questions compared to pretest questions. The posttest scores were consistently higher than the pretest scores, showing an average increase of around 2 standard deviations across all questions. This indicates an improvement in participants’ perceived knowledge and comprehension of the JPSR material.

During the pilot implementation of the huddle cards, there was a notable improvement in team member engagement. The structured format of the cards facilitated focused and meaningful discussions during safety huddles, encouraging open dialogue and fostering a culture of safety. Team members actively participated in identifying potential risks, sharing observations, and proposing actionable solutions, which reflected an enhanced sense of ownership regarding safety practices.

The support dialogue facilitated by the huddle cards highlighted the significance of mutual accountability and a collective commitment to achieving zero harm. This collaborative environment strengthened trust among team members and underscored the importance of shared vigilance in preventing adverse events. The pilot demonstrated the potential of huddle cards as an essential tool for enhancing team-based safety initiatives and promoting a culture of high reliability within the organization.

The total number of JPSR events in the ICU rose from 156 in FY 23 to 170 in FY 24. Adverse events increased from 19 to 31, while close calls saw a slight uptick from 137 to 139. Despite the overall rise in adverse events, a detailed analysis indicated that incidents of moderate harm decreased from 4 in FY 23 to 2 in FY 24. Furthermore, there was 1 reported case of death or severe harm in FY 23, which decreased to 0 in FY 24. This trend is consistent with the overarching objective of a high-reliability organization to achieve zero harm.

The next step is to expand this initiative across CTVHCS. This initiative aims to make this an annual education for all areas. The JPSR huddle card toolkit will be formatted by the media department for easy printing and retrieval. Leaders within units, clinics, and services will be empowered to facilitate the sessions in their safety huddles and reap the same outcomes as in the pilot. CTVHCS PS will monitor the effectiveness of this through ongoing CTVHCS patient safety rounding and future AES.

Safety event reporting plays a vital role in fostering a culture of safety within a health care organization. The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has shifted its focus from eradicating medical errors to minimizing or eliminating harm to patients.1 The National Center for Patient Safety’s objective is to prevent recurring errors by identifying and addressing systemic problems that may have been overlooked.2

Taking inspiration from industries known for high reliability, such as aviation and nuclear power, the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) patient safety program aims to identify and eliminate system vulnerabilities, such as medical errors. Learning from near misses, which occur more frequently than actual adverse events, is a crucial part of this process.3 By addressing these issues, the VHA can establish safer systems and encourage continuous identification of potential problems with proactive resolution.

All staff should participate actively in event reporting, which involves documenting and communicating details, outcomes, and relevant data about an event to understand what occurred, evaluate success, identify areas for improvement, and inform future decisions. This helps identify system weaknesses, create opportunities to standardize procedures and enhance patient care.

At the high complexity Central Texas Veterans Health Care System (CTVHCS), the fiscal year (FY) 2023 All Employee Survey (AES) found that staff members require additional education and awareness regarding the reporting of patient safety concerns.4 The survey highlighted areas such as lack of education on reporting, doubts about the effectiveness of reporting, confusion about the process after a report is made, and insufficient feedback.

BACKGROUND

To improve the culture of safety and address deficiencies noted in the AES, the CTVHCS patient safety (PS) and high reliability organization (HRO) teams partnered to develop a quality improvement initiative to increase staff understanding of safety event reporting and strengthen the safety culture. The PS and HRO teams developed an innovative education model that integrates Joint Patient Safety Reporting System (JPSR) education into huddles.

This initiative, called the JPSR Huddle Card Toolkit, sought to assess the impact of the toolkit on staff knowledge and behaviors related to patient safety event reporting. The toolkit consisted of educational materials encompassing 6 key areas: (1) reporting incidents; (2) close calls and near misses; (3) identification of root causes; (4) understanding the life cycle of a JPSR; (5) celebrating achievements; and (6) distinguishing between facts and fiction. Each JPSR huddle card included discussion points for the facilitator and was formatted on a 5 × 7-inch card (Figure 1). Topics were addressed during weekly safety huddles conducted in the pilot unit over a 6-week period. To evaluate its effectiveness, a pilot unit was selected and distributed an anonymous questionnaire paired with the JPSR huddle card toolkit to measure staff responses.

The pilot was conducted from November 2023 to January 2024. The participating pilot unit was a 10-bed critical care unit with 42 full-time employees. Nursing leadership, quality safety, and value personnel, and the Veterans Integrated Services Network (VISN) PS Team reviewed and approved the pilot.

Reporting of adverse events and near misses provides an opportunity to learn about latent systems errors.2 In 2018, the VHA began using the JPSR to standardize the capture and data management on medical errors and close calls across the Defense Health Administration (DHA) and VHA.1 The JPSR software is a joint application of the VHA and DHA. It improves the identification and documentation of patient safety-related events for VA medical centers, military hospitals and clinics, active-duty personnel, veterans and their families.

Event reporting is a key element in advancing high reliability and achieving zero preventable harm.1 Teams use these data to identify organizational patient safety trends and preempt common safety issues. All data are protected under 38 USC §5705 and 10 USC §1102.5 The JPSR single-source system standardizes the collection of core data points and increases collaboration between the DHA and VHA. This partnership increases insight into safety-related incidents, allowing for earlier detection and prevention of patient harm or injury incidents.

Numerous studies consistently commend huddles for their effectiveness in promoting teamwork and their positive impact on patient safety.6-8 Huddles facilitate connections between employees who may not typically interact, provide opportunities for discussions, and serve as a platform to encourage employees to voice their opinions. By fostering these interactions, huddles empower employees and create an environment for shared understanding, building trust, and promoting continuous learning.8

OBSERVATIONS

The JPSR huddle card initiative aimed to improve understanding of the JPSR process and promote knowledge and attitudes about patient safety and event reporting, while emphasizing shared responsibility. The goals focused on effective communication, respect for expertise, awareness of operational nuances, voicing concerns, and ensuring zero harm.

The facilitator initiated huddles by announcing their start to cultivate a constructive outcome.8 The JPSR huddle cards used a structured format designed to foster engagement and understanding of the topic. Each card begins with a factual statement or an open-ended question to gauge participants’ awareness or understanding. It then provides essential facts, principles, and relevant information to deepen knowledge. The card concludes with a discussion question, allowing facilitators to assess shared learning and encourage group reflection. This format promotes active participation and ensures that key concepts are both introduced and reinforced through dialogue.

The PS team standardized the format for all huddle cards, allowing 5 to 10 minutes for discussing training materials, receiving feedback, and concluding with a discussion question and call to action. Prior to each huddle, the facilitator would read a scripted remark that reviewed the objectives and ground rules for an effective huddle.

The PS and HRO teams promoted interactive discussions and welcomed ongoing feedback. Huddles provided a psychologically safe environment where individuals were encouraged to voice their thoughts and ideas.

Each weekly huddle card addressed a different patient safety topic. The Week 1 huddle card focuses on event reporting for safety improvement. The card outlines the purpose of JPSR as a tool to identify, manage, and analyze safety events to reduce preventable harm. The card emphasizes 3 core principles: (1) acknowledging mistakes, recognizing that errors happen; (2) no blame, no shame (encouraging a no-blame just culture to raise concerns); and (3) continuous improvement (committing to ongoing learning and prevention). It provides guidance on event details entry, advising staff to include facts in an SBAR (Situation, Background, Assessment, Response) format, avoid assumptions, and exclude personal identifiers. Tips include entering only relevant facts to help reviewers understand the incident. The card ends with discussion questions on reporting barriers and potential improvements in event reporting practices.

The Week 2 huddle card focuses on understanding and reporting near miss events, also known as close calls or good catches. A near miss is an incident where a potential hazard was identified and prevented before it reached the patient, avoiding harm due to timely intervention. The card emphasizes the importance of identifying these events to understand weaknesses and proactively reduce risks. Examples of near misses include discovering expired medication before use, catching a potential wrong-site surgery, and noticing incorrect medication dosages. Staff are encouraged to develop a mindset for anticipating and solving risks. The card ends with a discussion asking participants to share examples of near misses in their area.

The Week 3 huddle card covers root causes in preventing errors. The card highlights that errors in health care often stem from flawed processes rather than individual faults. By identifying root causes, systemic weaknesses can be addressed to reduce mistakes and build more error-tolerant and robust systems. All staff are advised to adopt a mindset of continuous improvement, error trapping behaviors and problem-solving. It concludes with discussion questions prompting reflection on assumptions and identifying weaknesses when something goes wrong.

The Week 4 huddle card covers the life of a JPSR, detailing that after entry JPSR events are viewed by the highest leadership levels at the morning report, and that lessons learned are distributed through frontline managers and chiefs in a monthly report to be shared with frontline staff. Additionally, JPSR trends are shared during monthly HRO safety forums. These practices promote a culture of safety through open communication and problem-solving. Staff and leaders are encouraged to prioritize safety daily. Discussion prompts ask team members if they had seen positive changes from JPSR reporting and what they would like leadership to communicate after investigations.

The Week 5 huddle card covers celebrating safety event reporting called Cue the Confetti. The VHA emphasizes recognizing staff who report safety events as part of their commitment to zero harm. By celebrating these contributions, the VHA fosters respect, joy, and satisfaction in the work. Staff are encouraged to nominate colleagues for recognition, reinforcing a supportive environment. Prompts invite teams to discuss how they celebrate JPSR reporting and how they’d like to enhance this culture of appreciation.

The Week 6 huddle card covers common misconceptions about JPSR. Key facts include that JPSRs are confidential, not for disciplinary action, and can be submitted by any staff member at any time. Only PS can view reporter identities for clarification purposes. The card concludes with prompts to ensure staff know how to access JPSR support and resources.

Measuring the impact on staff was essential to assess effectiveness and gather data for program improvement. To evaluate the impact of the huddle cards on the staff, the team provided a voluntary and anonymous 9 question survey (Figure 2). The survey was completed before the pilot began and again at the end of Week 6.

Questions 1 through 5 and 7 through 9 pertained to participants’ perceived knowledge and understanding of aspects of the JPSR. Perceived improvement among intensive care unit (ICU) participants ranged from 15% to 53%. There was a positive increase associated with every question with the top improvements: question 8, “How do you rate your understanding of how we share safety events for system and process improvement?” (53.4% increase); question 5, “How do you rate your understanding of what happens to a JPSR after it is entered?” (51.9% increase), and question 9, “How do you rate your understanding of the concepts of trust, psychological safety and a just culture?” (47.8% increase).

The survey analysis was not able to track individual changes. As a result, the findings reflect an overall change for the entire study group. Moreover, the questions assessed participants’ perceived knowledge rather than actual knowledge gained. It is important to note that there may be a significant gap between the actual knowledge gained and how participants perceive it. Additionally, improvement in knowledge and comprehension does not necessarily translate into behavior changes.

CONCLUSIONS

The use of JPSR huddle cards and direct engagement with staff during safety huddles yielded positive outcomes. On average, participants demonstrated higher scores in posttest questions compared to pretest questions. The posttest scores were consistently higher than the pretest scores, showing an average increase of around 2 standard deviations across all questions. This indicates an improvement in participants’ perceived knowledge and comprehension of the JPSR material.

During the pilot implementation of the huddle cards, there was a notable improvement in team member engagement. The structured format of the cards facilitated focused and meaningful discussions during safety huddles, encouraging open dialogue and fostering a culture of safety. Team members actively participated in identifying potential risks, sharing observations, and proposing actionable solutions, which reflected an enhanced sense of ownership regarding safety practices.

The support dialogue facilitated by the huddle cards highlighted the significance of mutual accountability and a collective commitment to achieving zero harm. This collaborative environment strengthened trust among team members and underscored the importance of shared vigilance in preventing adverse events. The pilot demonstrated the potential of huddle cards as an essential tool for enhancing team-based safety initiatives and promoting a culture of high reliability within the organization.

The total number of JPSR events in the ICU rose from 156 in FY 23 to 170 in FY 24. Adverse events increased from 19 to 31, while close calls saw a slight uptick from 137 to 139. Despite the overall rise in adverse events, a detailed analysis indicated that incidents of moderate harm decreased from 4 in FY 23 to 2 in FY 24. Furthermore, there was 1 reported case of death or severe harm in FY 23, which decreased to 0 in FY 24. This trend is consistent with the overarching objective of a high-reliability organization to achieve zero harm.

The next step is to expand this initiative across CTVHCS. This initiative aims to make this an annual education for all areas. The JPSR huddle card toolkit will be formatted by the media department for easy printing and retrieval. Leaders within units, clinics, and services will be empowered to facilitate the sessions in their safety huddles and reap the same outcomes as in the pilot. CTVHCS PS will monitor the effectiveness of this through ongoing CTVHCS patient safety rounding and future AES.

- Essen K, Villalobos C, Sculli GL, Steinbach L. Establishing a just culture: implications for the Veterans Health Administration journey to high reliability. Fed Pract. 2024;41:290-297. doi:10.12788/fp.0512

- Louis MY, Hussain LR, Dhanraj DN, et al. Improving patient safety event reporting among residents and teaching faculty. Ochsner J. 2016;16:73-80.

- Pimental CB, Snow AL, Carnes SL, et al. Huddles and their effectiveness at the frontlines of clinical care: a scoping review. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36:2772-2783. doi:10.1007/s11606-021-06632-9

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Appendix C: Nature of Veterans Health Administration Facilities Management (Engineering) Tasks and Staffing. Facilities Staffing Requirements for the Veterans Health Administration-Resource Planning and Methodology for the Future. National Academies Press. 2020:105-116. Accessed August 11, 2025. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/read/25454/chapter/11

- Woodier N, Burnett C, Moppett I. The value of learning from near misses to improve patient safety: a scoping review. J Patient Saf. 2023;19:42-47. doi:10.1097/pts.0000000000001078

- Ismail A, Khalid SNM. Patient safety culture and its determinants among healthcare professionals at a cluster hospital in Malaysia: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2022;12:e060546. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-060546

- Ngo J, Lau D, Ploquin J, Receveur T, Stassen K, Del Castilho C. Improving incident reporting among physicians at south health campus hospital. BMJ Open Qual. 2022;11:e001945. doi:10.1136/bmjoq-2022-001945

- Oweidat I, Al-Mugheed K, Alsenany SA, et al. Awareness of reporting practices and barriers to incident reporting among nurses. BMC Nurs. 2023;22:231. doi:10.1186/s12912-023-01376-9

- Essen K, Villalobos C, Sculli GL, Steinbach L. Establishing a just culture: implications for the Veterans Health Administration journey to high reliability. Fed Pract. 2024;41:290-297. doi:10.12788/fp.0512

- Louis MY, Hussain LR, Dhanraj DN, et al. Improving patient safety event reporting among residents and teaching faculty. Ochsner J. 2016;16:73-80.

- Pimental CB, Snow AL, Carnes SL, et al. Huddles and their effectiveness at the frontlines of clinical care: a scoping review. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36:2772-2783. doi:10.1007/s11606-021-06632-9

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Appendix C: Nature of Veterans Health Administration Facilities Management (Engineering) Tasks and Staffing. Facilities Staffing Requirements for the Veterans Health Administration-Resource Planning and Methodology for the Future. National Academies Press. 2020:105-116. Accessed August 11, 2025. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/read/25454/chapter/11

- Woodier N, Burnett C, Moppett I. The value of learning from near misses to improve patient safety: a scoping review. J Patient Saf. 2023;19:42-47. doi:10.1097/pts.0000000000001078

- Ismail A, Khalid SNM. Patient safety culture and its determinants among healthcare professionals at a cluster hospital in Malaysia: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2022;12:e060546. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2021-060546

- Ngo J, Lau D, Ploquin J, Receveur T, Stassen K, Del Castilho C. Improving incident reporting among physicians at south health campus hospital. BMJ Open Qual. 2022;11:e001945. doi:10.1136/bmjoq-2022-001945

- Oweidat I, Al-Mugheed K, Alsenany SA, et al. Awareness of reporting practices and barriers to incident reporting among nurses. BMC Nurs. 2023;22:231. doi:10.1186/s12912-023-01376-9

Empowering Culture Change and Safety on the Journey to Zero Harm With Huddle Cards

Empowering Culture Change and Safety on the Journey to Zero Harm With Huddle Cards

Advanced Imaging Techniques Use in Giant Cell Arteritis Diagnosis: The Experience at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center

Advanced Imaging Techniques Use in Giant Cell Arteritis Diagnosis: The Experience at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center

Giant cell arteritis (GCA), the most commonly diagnosed systemic vasculitis, is a large- and medium-vessel vasculitis that can lead to significant morbidity due to aneurysm formation or vascular occlusion if not diagnosed in a timely manner.1,2 Diagnosis is typically based on clinical history and inflammatory markers. Laboratory inflammatory markers may be normal in the early stages of GCA but can be abnormal due to other unrelated reasons leading to a false positive diagnosis.3 Delayed treatment may lead to visual loss, jaw or limb claudication, or ischemic stroke.2 Initial treatment typically includes high-dose steroids that can lead to significant adverse reactions such as hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysfunction, metabolic syndrome, premature atherosclerosis, and increased risk of infection.4-6

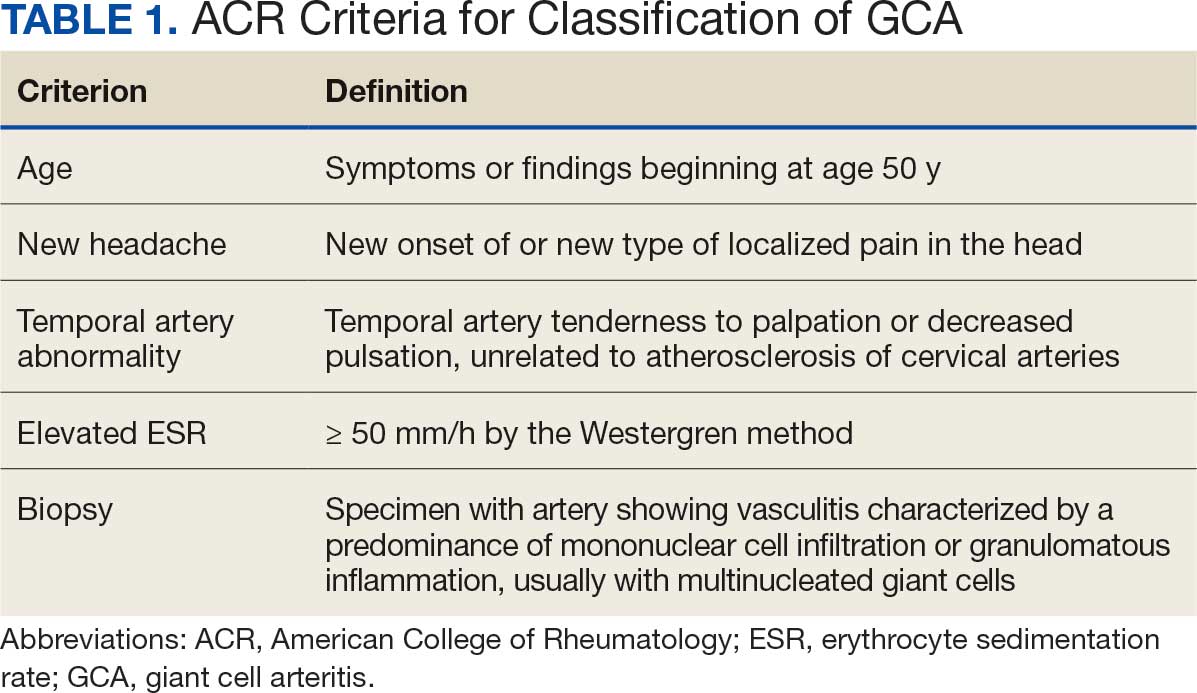

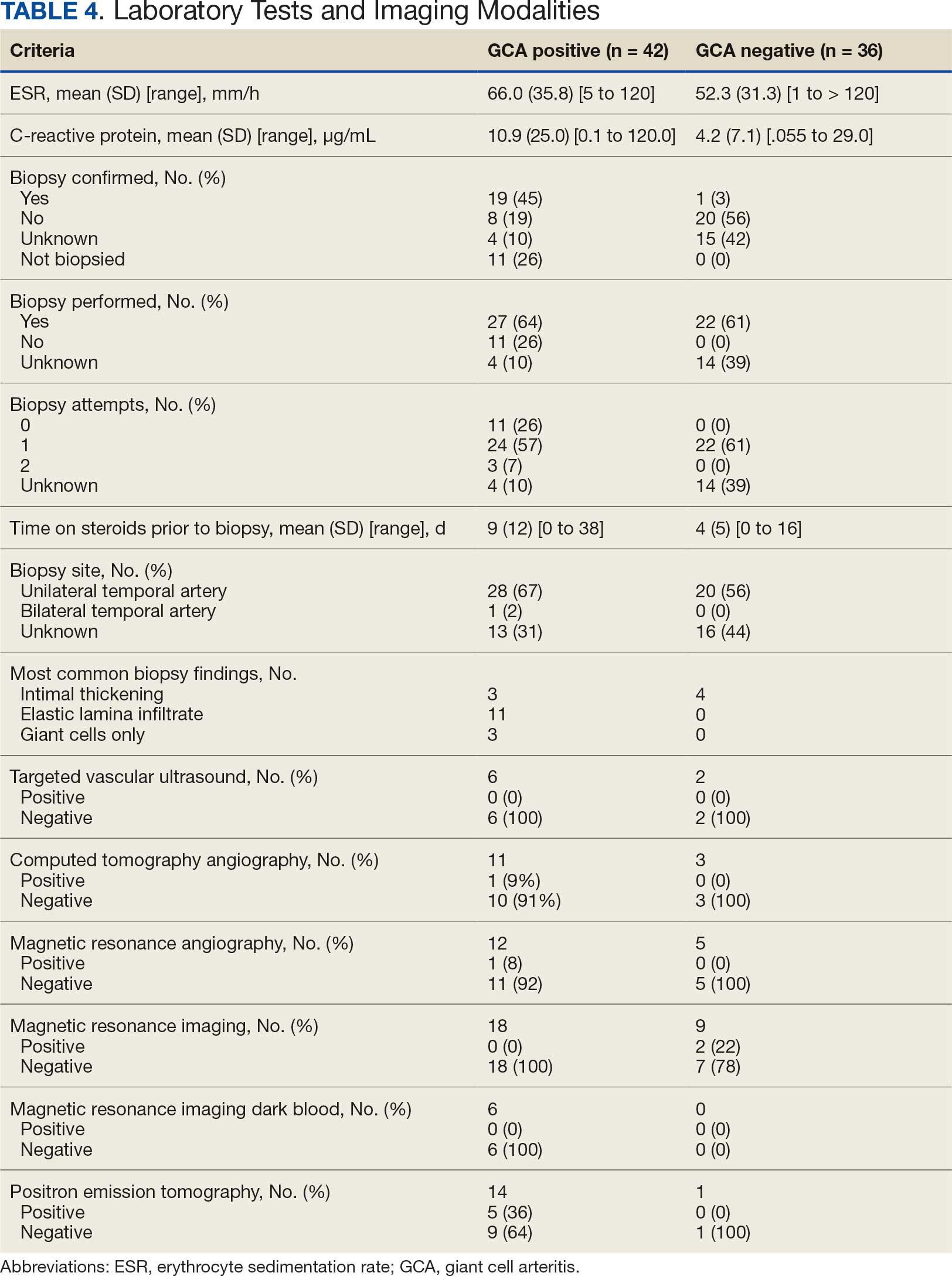

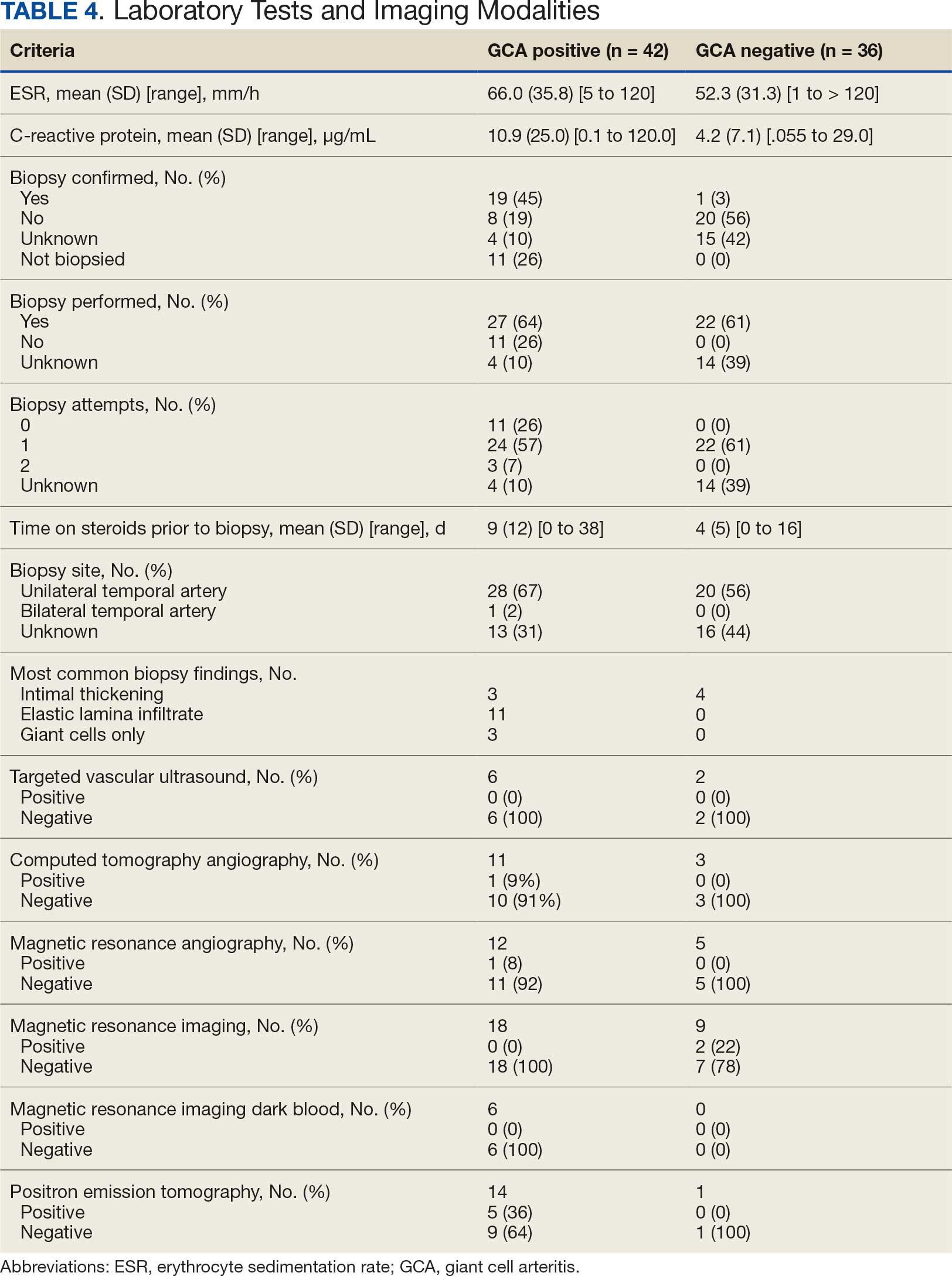

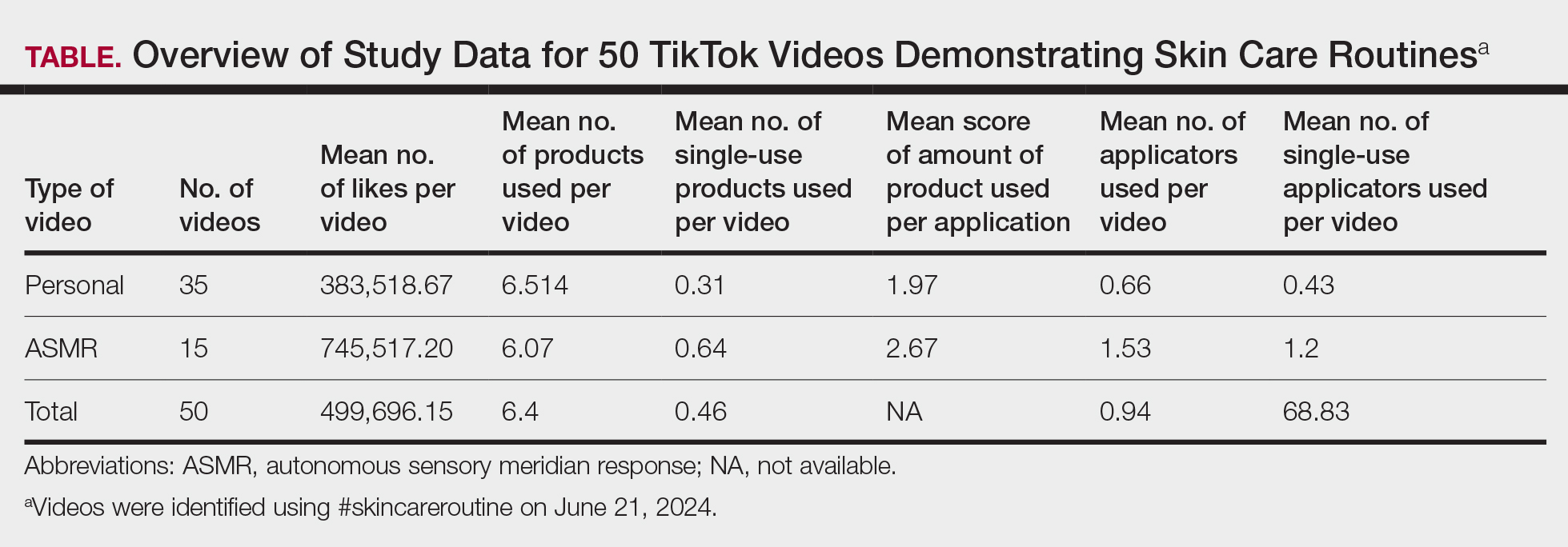

The 1990 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria for GCA are widely recognized (Table 1).7 The criteria focuses on clinical manifestations, including new onset headache, temporal artery tenderness, age ≥ 50 years, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) ≥ 50 mm/hr, and temporal artery biopsy with positive anatomical findings.8 When 3 of the 5 1990 ACR criteria are present, the sensitivity and specificity is estimated to be > 90% for GCA vs alternative vasculitides.7

Although the 1990 ACR criteria do not include imaging, modalities such as ultrasound, computed tomography angiography (CTA), 18F-FDG positron emission tomography (PET), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)/magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) may be used in GCA diagnosis.8-10 These imaging modalities have been added to the proposed ACR classification criteria for GCA.11 For this updated point system standard, age ≥ 50 years is a requirement and includes a positive temporal artery biopsy or temporal artery halo sign on ultrasound (+5 points), an ESR ≥ 50 mm/h or C-reactive protein (CRP) ≥ 10 mg/L (+3 points), or sudden visual loss (+3 points). Scalp tenderness, jaw or tongue claudication, new temporal headache, morning stiffness in shoulders or neck, temporal artery abnormality on vascular examination, bilateral axillary vessel involvement on imaging, and 18F-FDG PET activity throughout the aorta are scored +2 points each. With these new criteria, a cumulative score ≥ 6 is classified as GCA. Diagnostic accuracy is further improved with imaging: ultrasonography (sensitivity 55% and specificity 95%) and 18F-FDG PET (sensitivity 69% and specificity 92%), CTA (sensitivity 71% and specificity 86%), and MRI/MRA (sensitivity 73% and specificity 88%).12-15

In recent years, clinicians have reported increased glucose uptake in arteries observed on PET imaging that suggests GCA.9,10,16-20 18F-FDG accumulates in cells with high metabolic activity rates, such as areas of inflammation. In assessing temporal arteries or other involved vasculature (eg, axillary or great vessels) for GCA, this modality indicates increased glucose uptake in the lining of vessel walls. The inflammation of vessel walls can then be visualized with PET. 18F-FDG PET presents a noninvasive imaging technique for evaluating GCA but its use has been limited in the United States due to its high cost.

Methods

Approval for a retrospective chart review of patients evaluated for suspected GCA was obtained from the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (WRNMMC) Institutional Review Board. The review included patients who underwent diagnostic procedures such as ultrasound, MRI, CT angiogram, and PET studies from 2016 through 2022. International Classification of Diseases codes used for case identification included: M31.6, M31.5, I77.6, I77.8, I77.89, I67.7, and I68.2. The Current Procedural Terminology code used for temporal artery biopsy is 37609.

Results

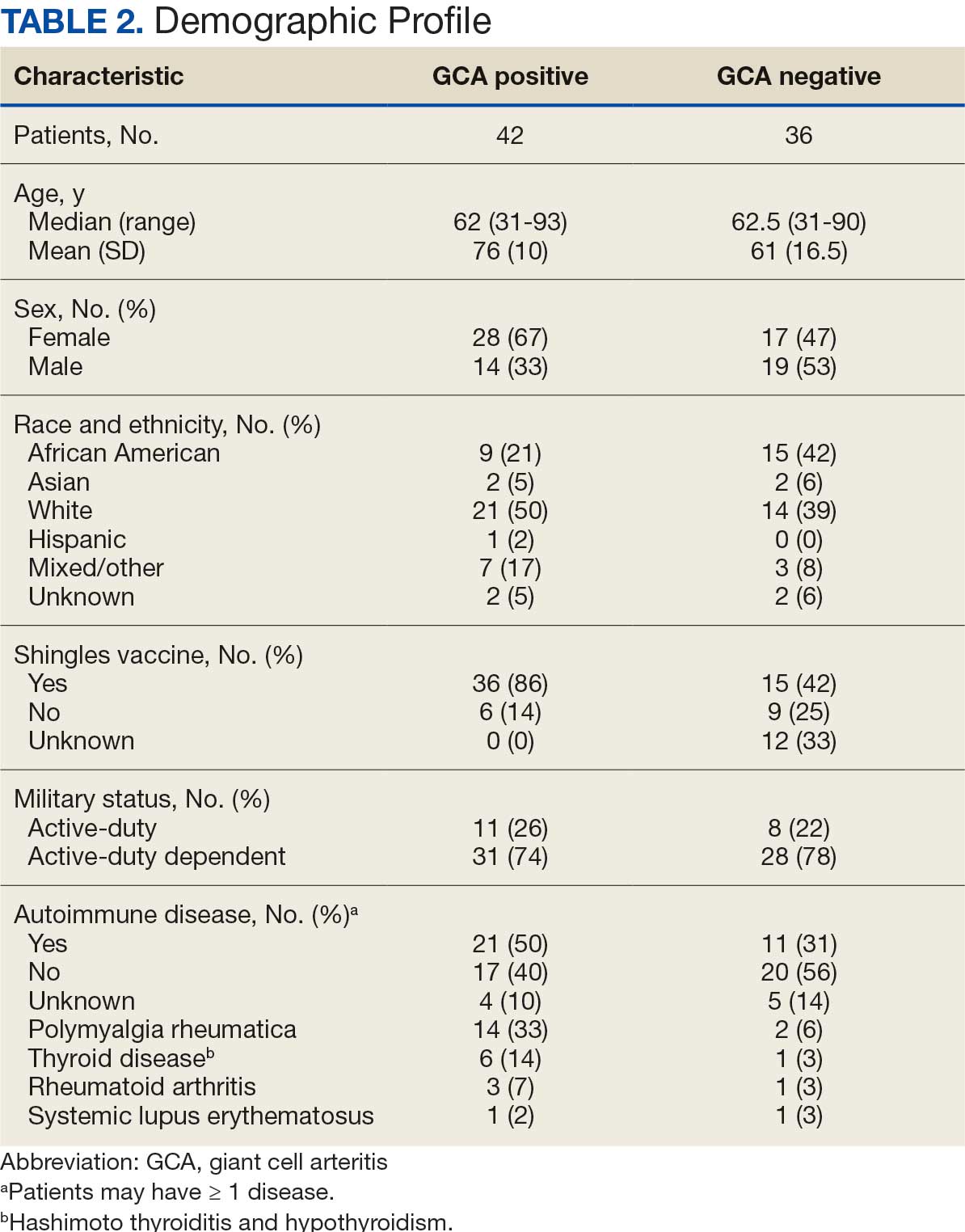

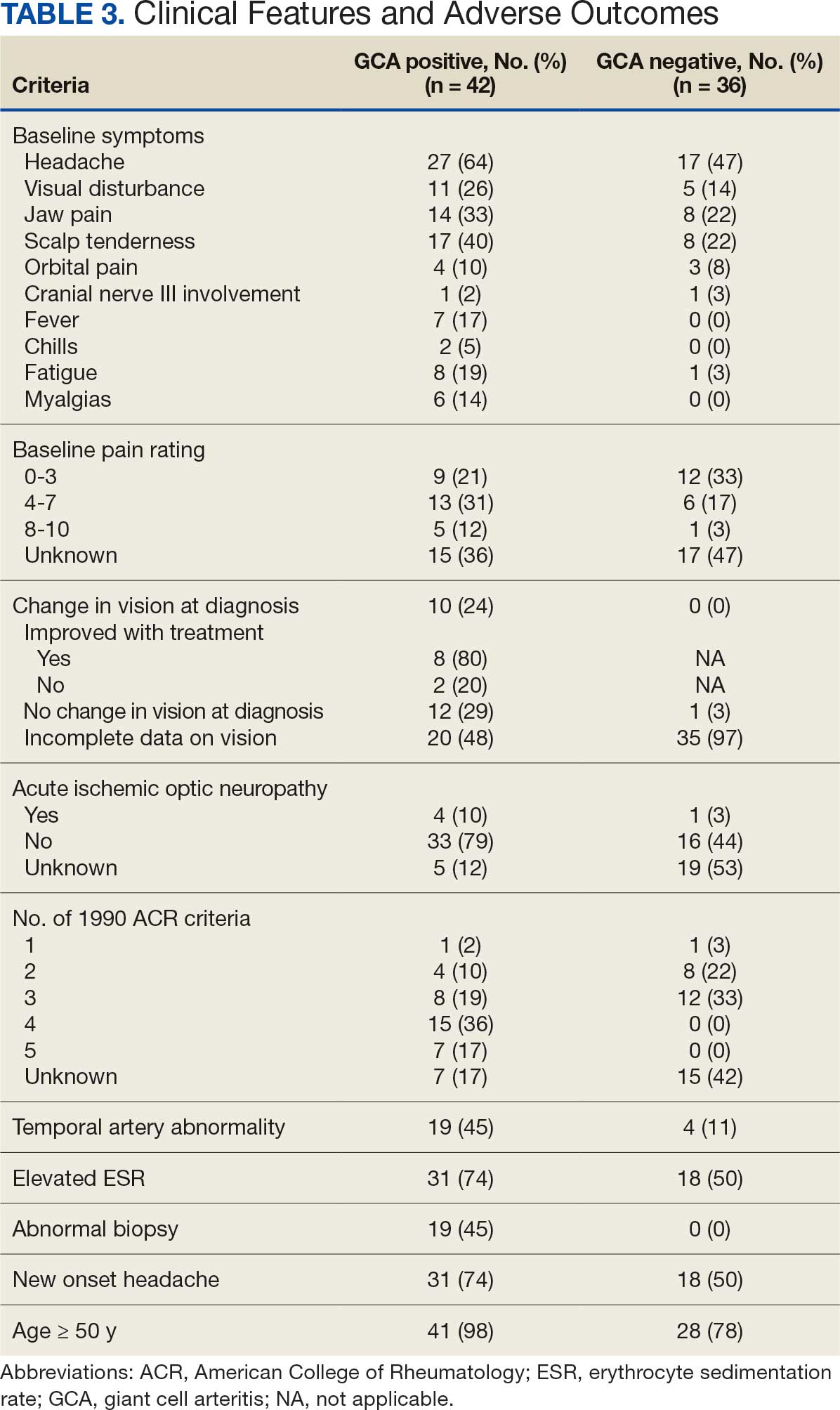

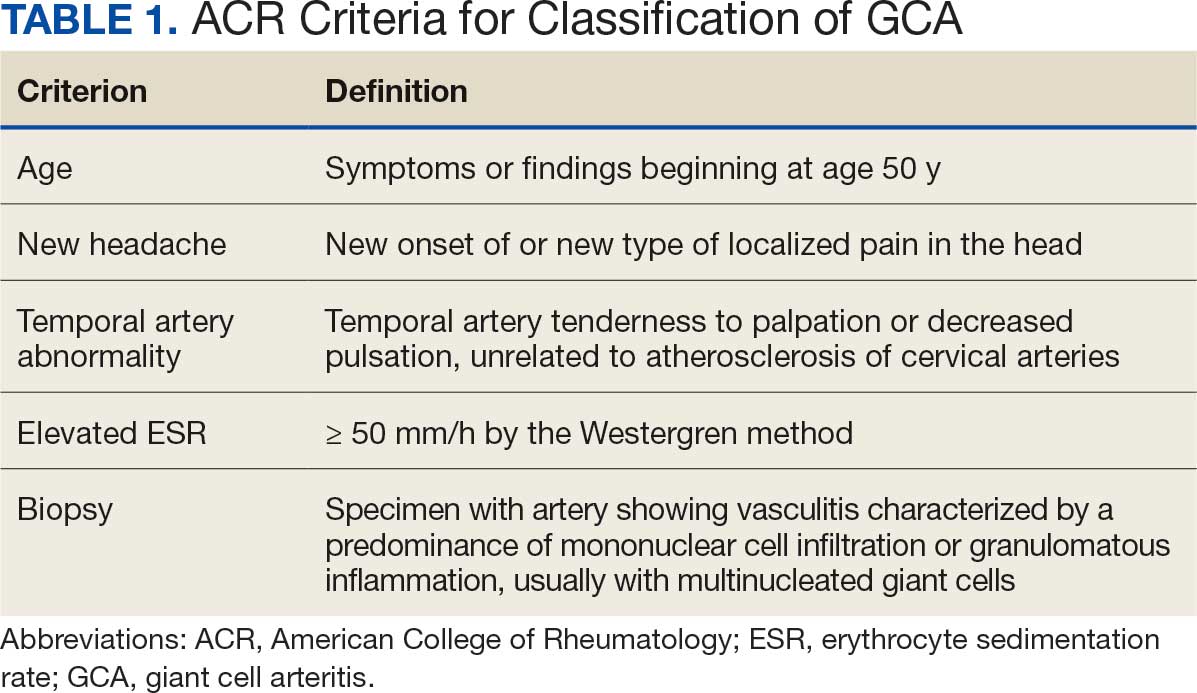

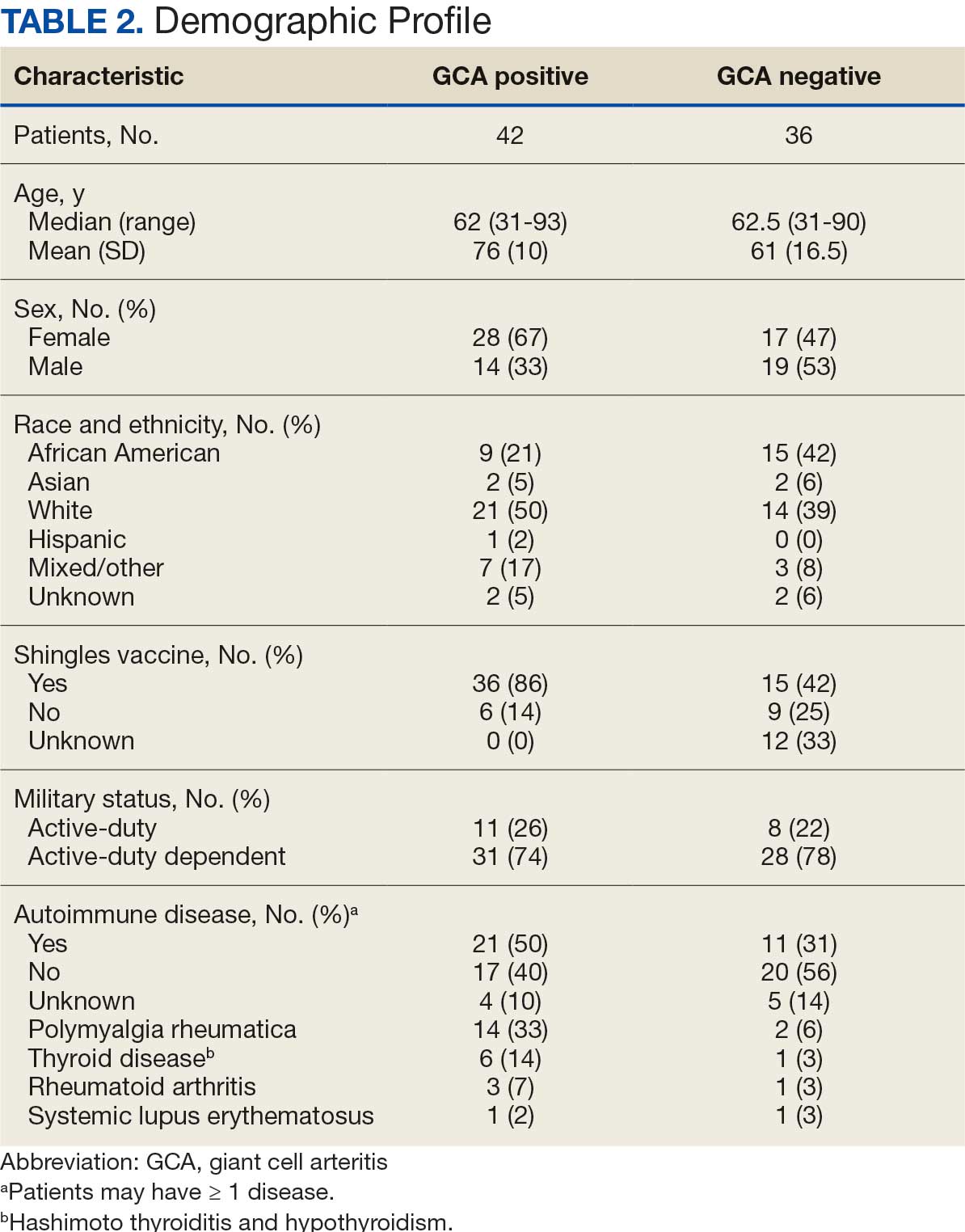

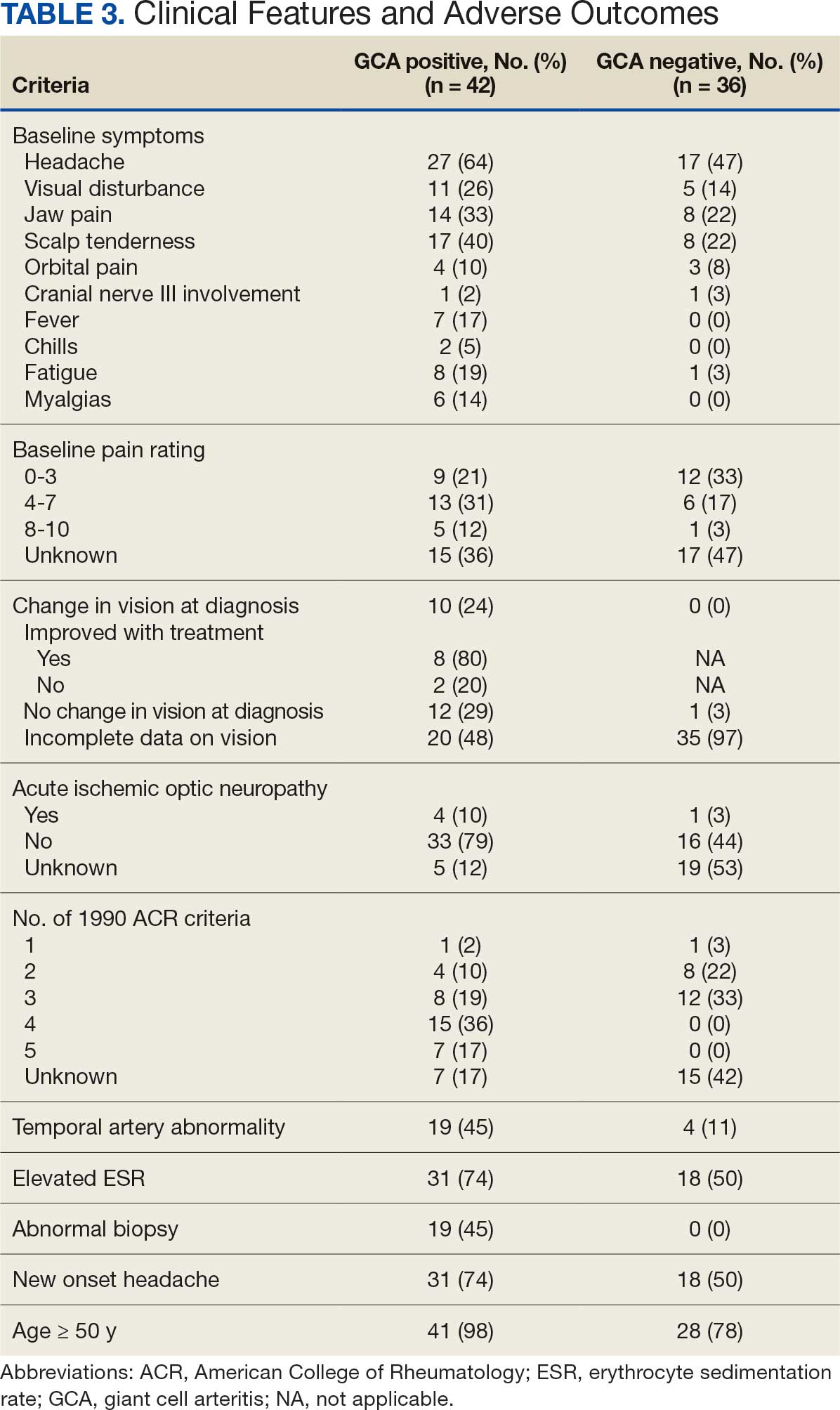

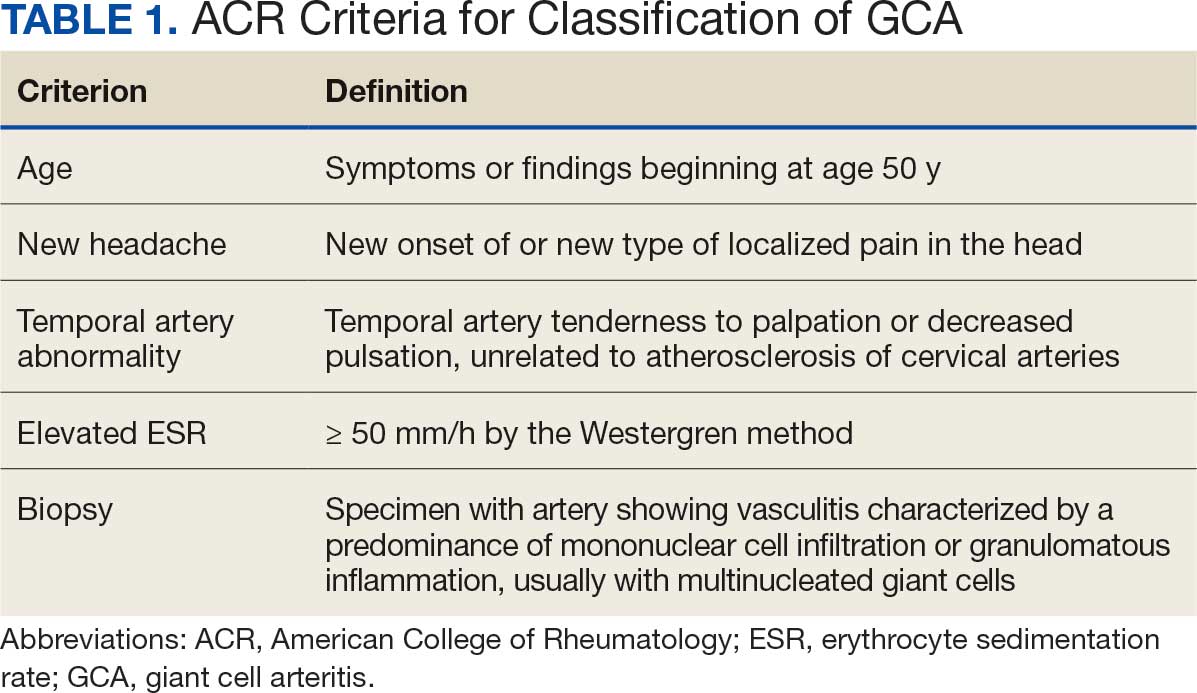

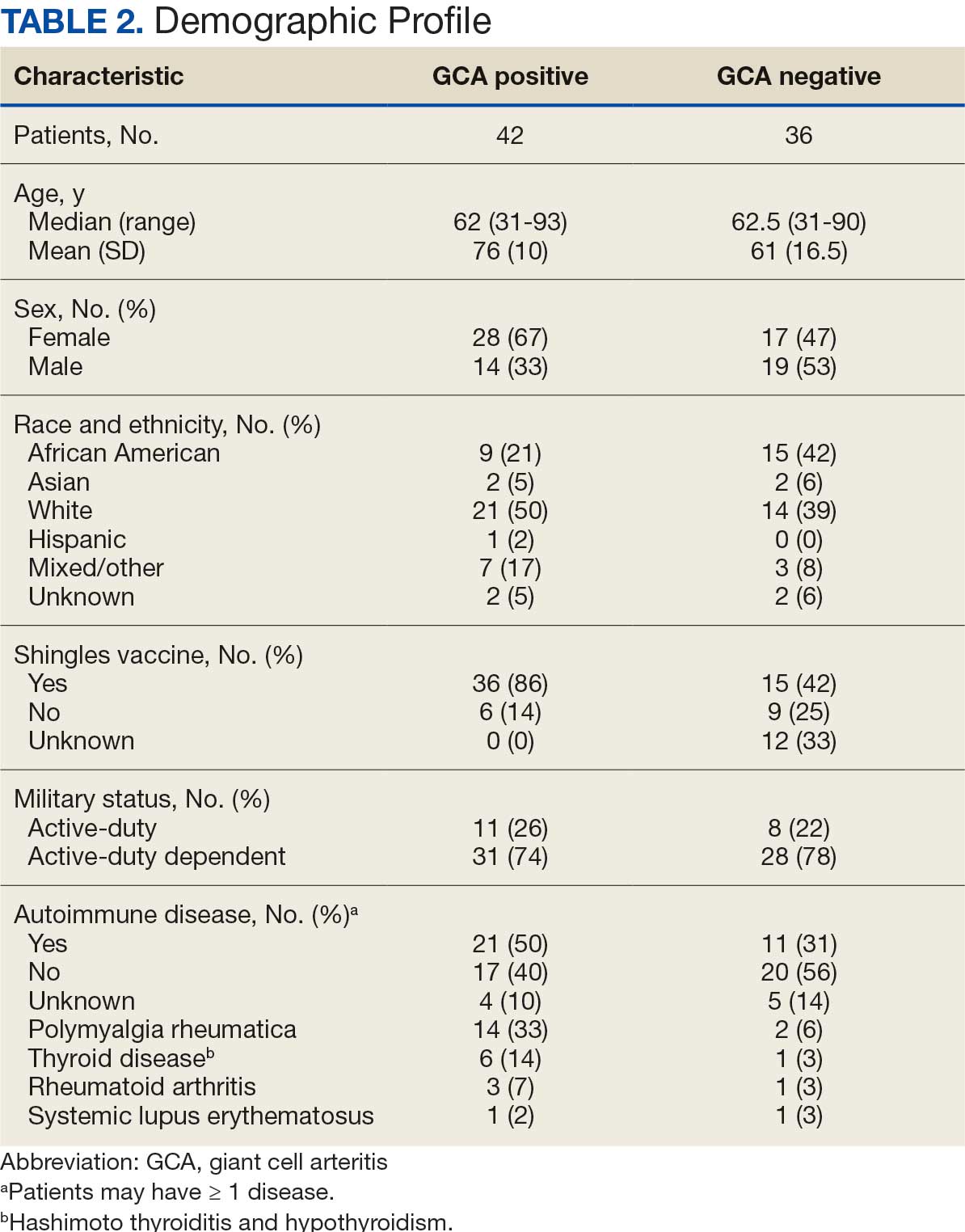

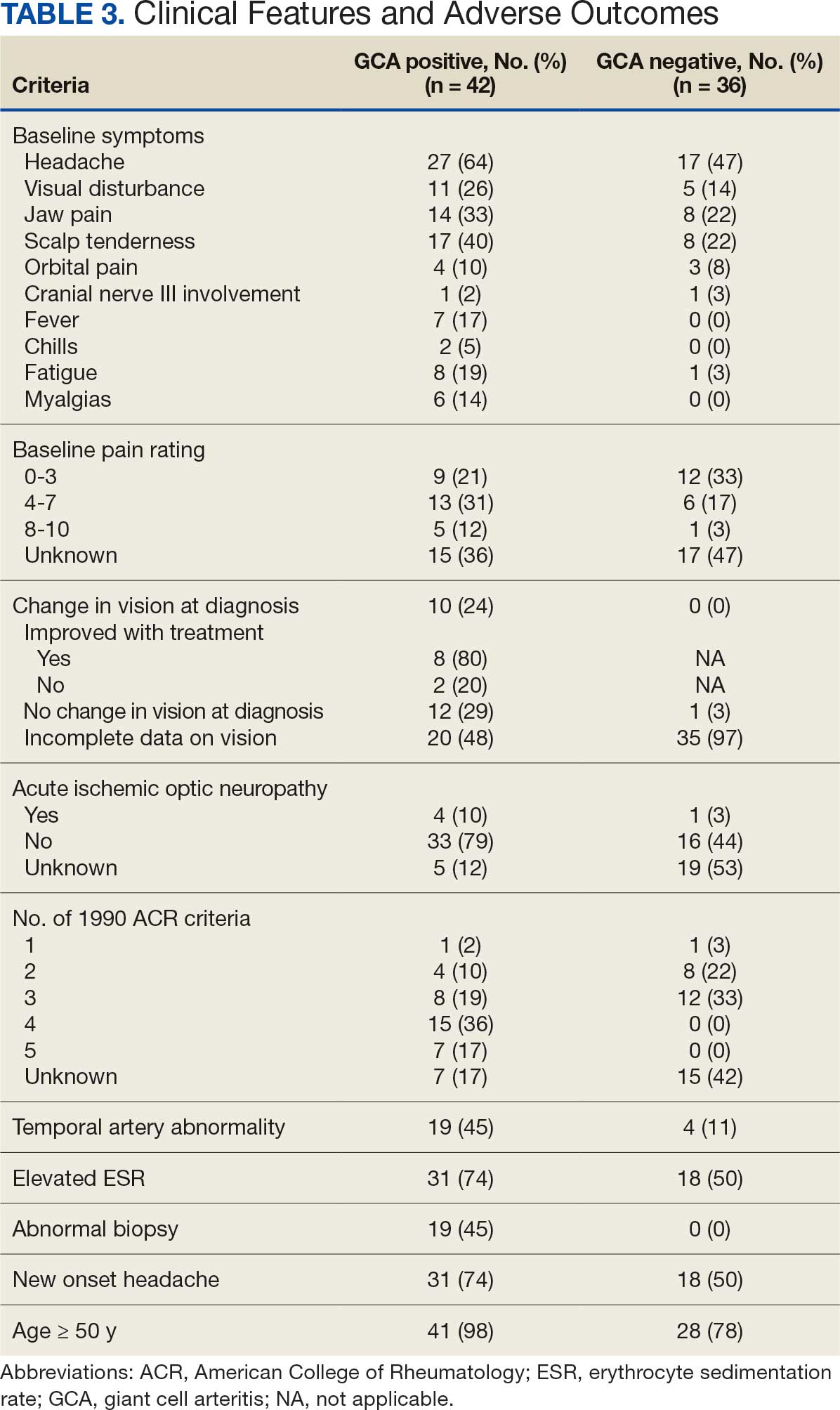

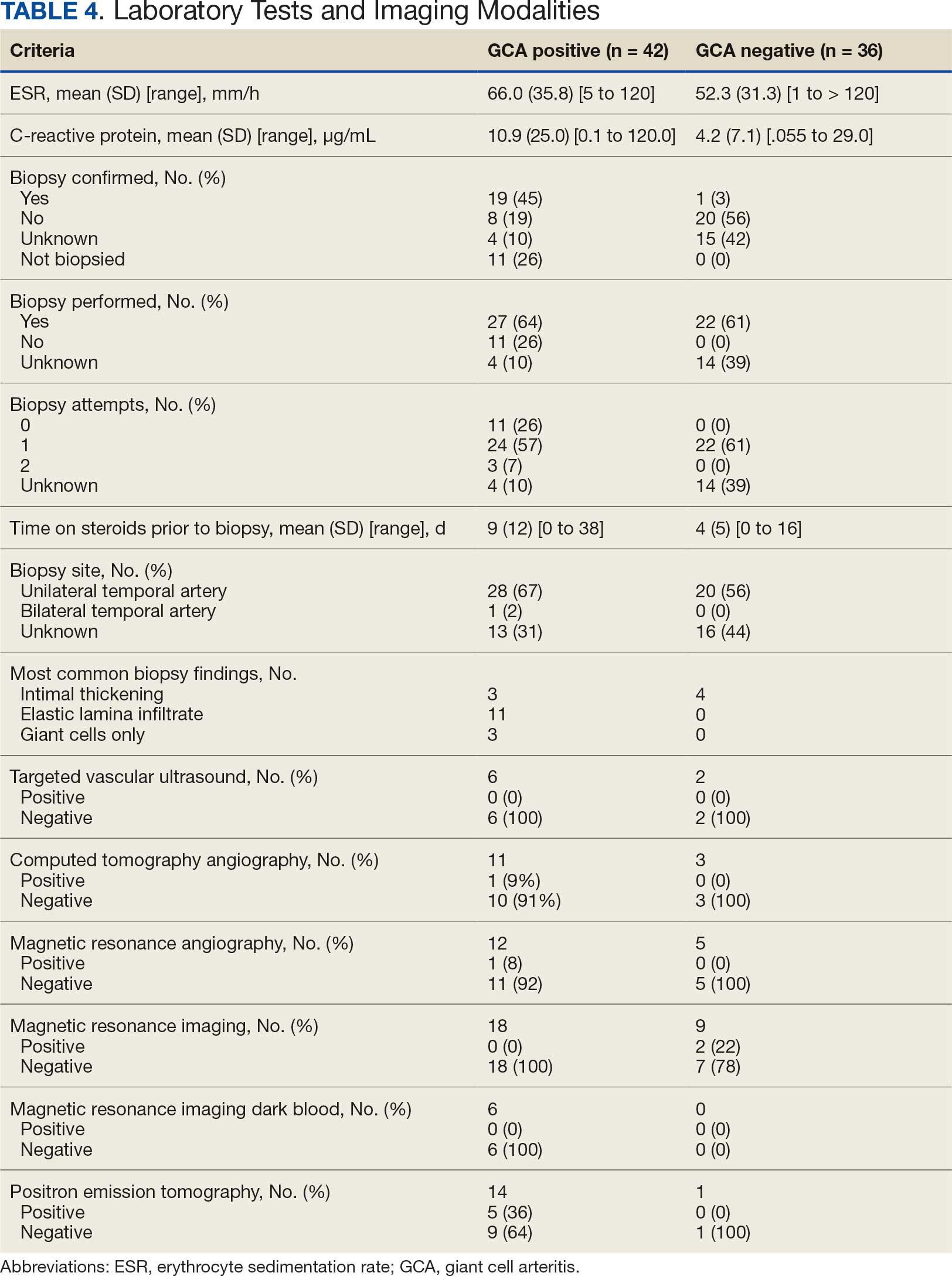

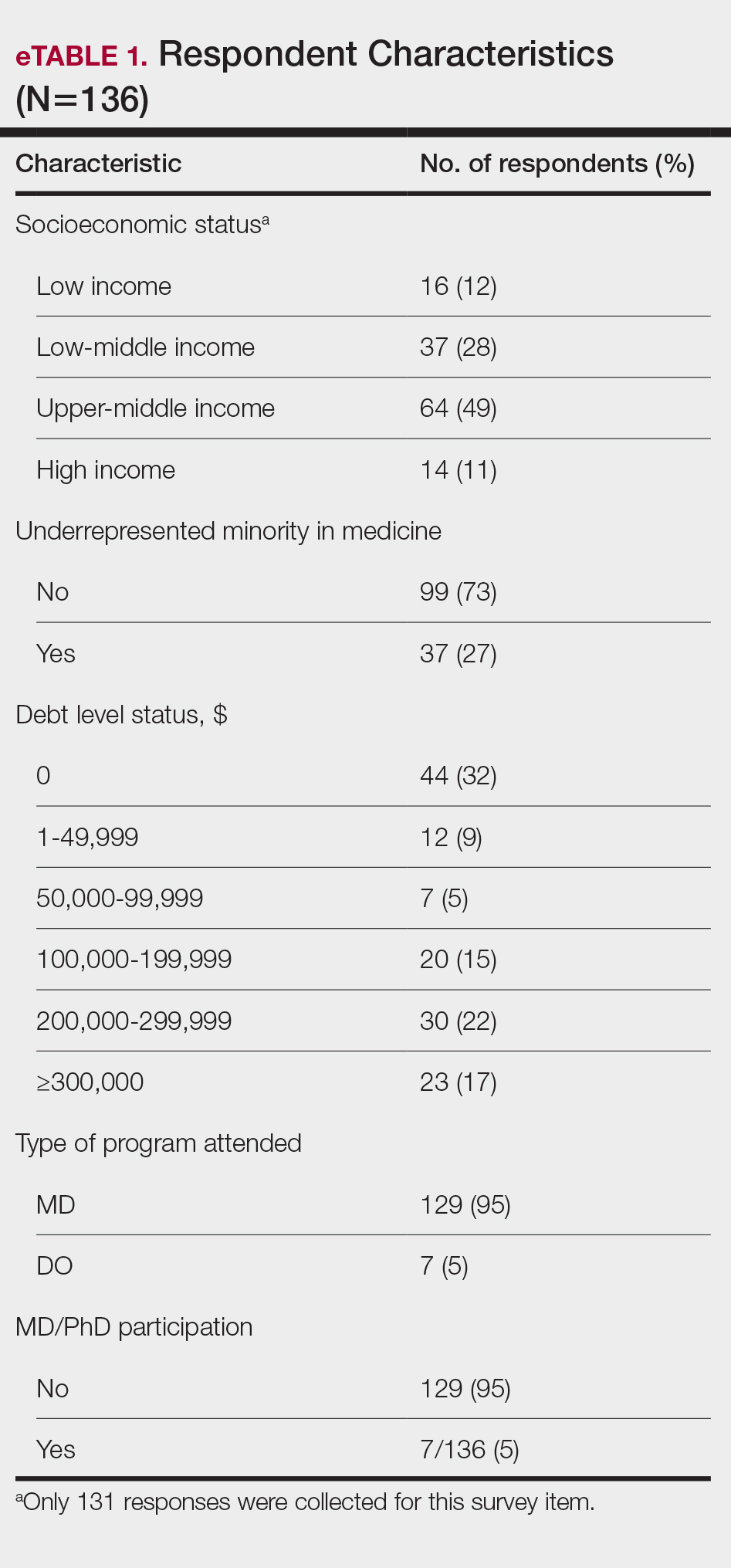

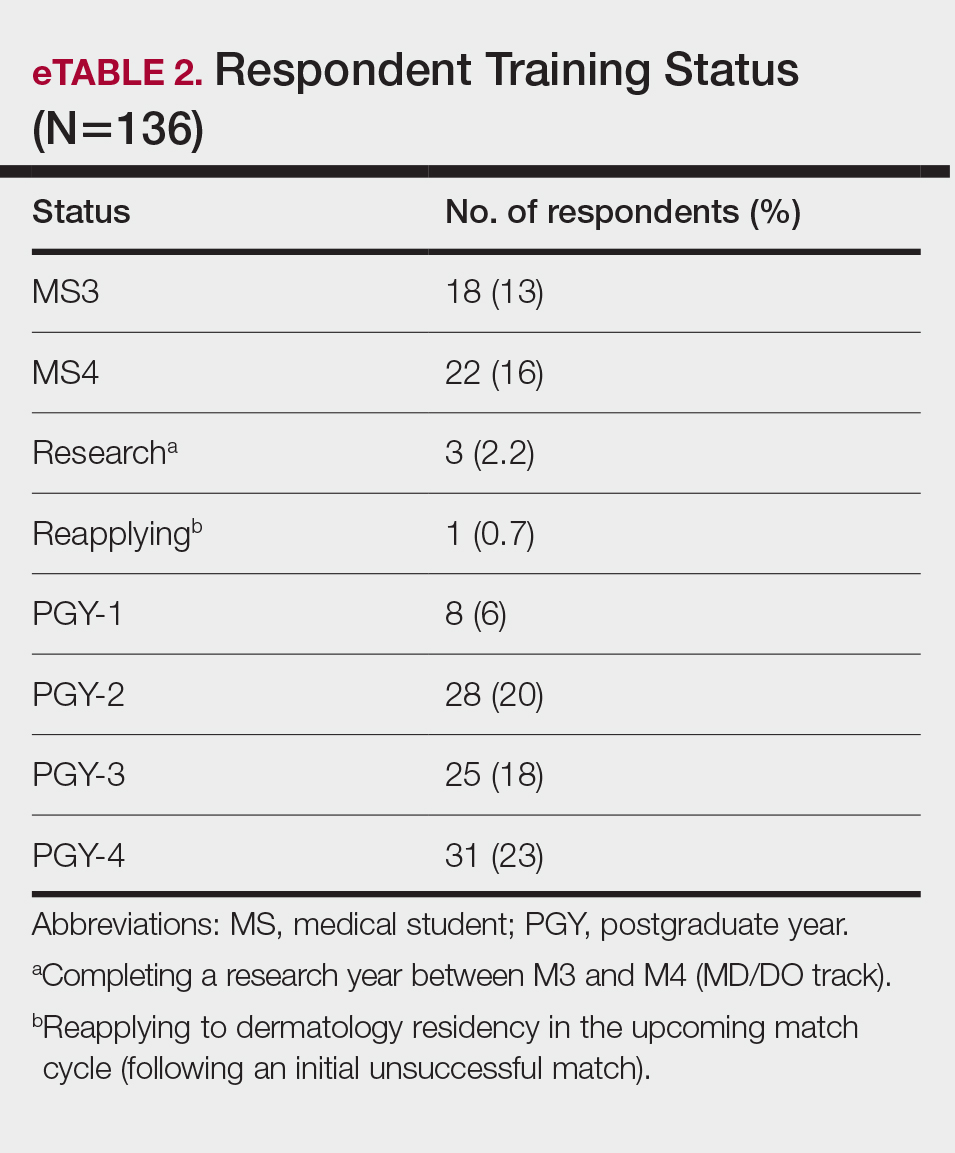

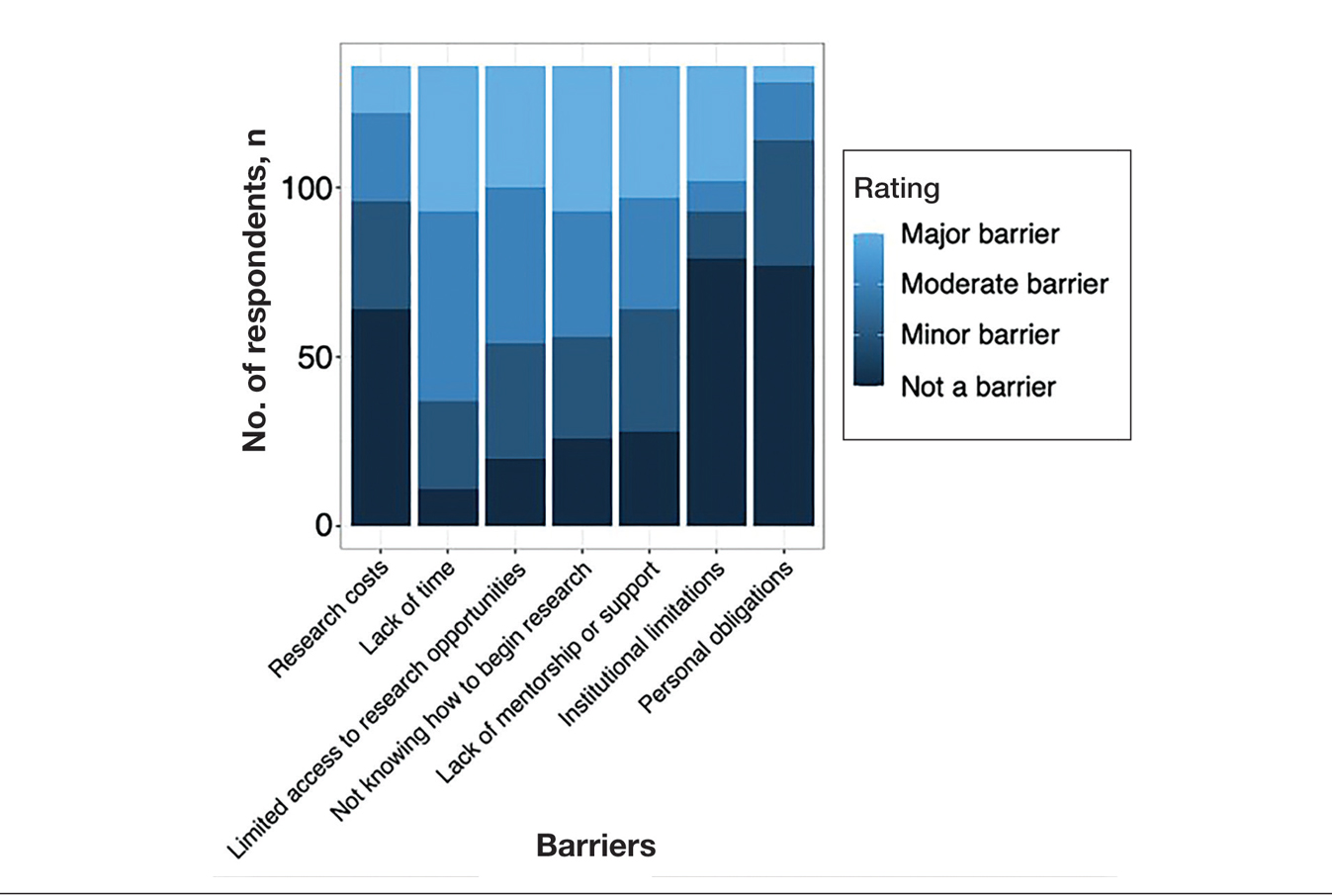

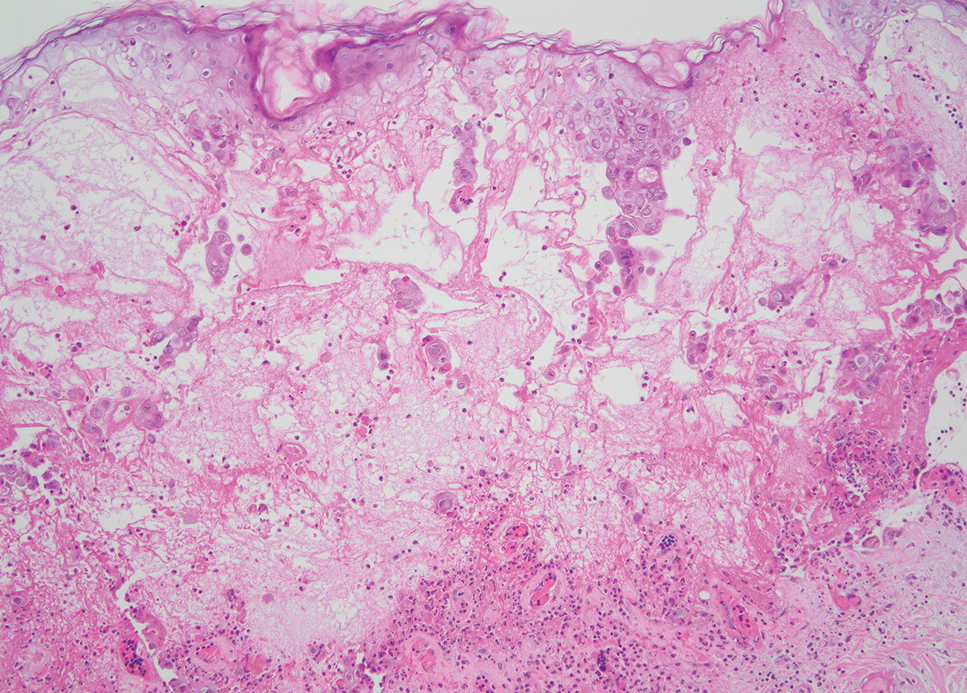

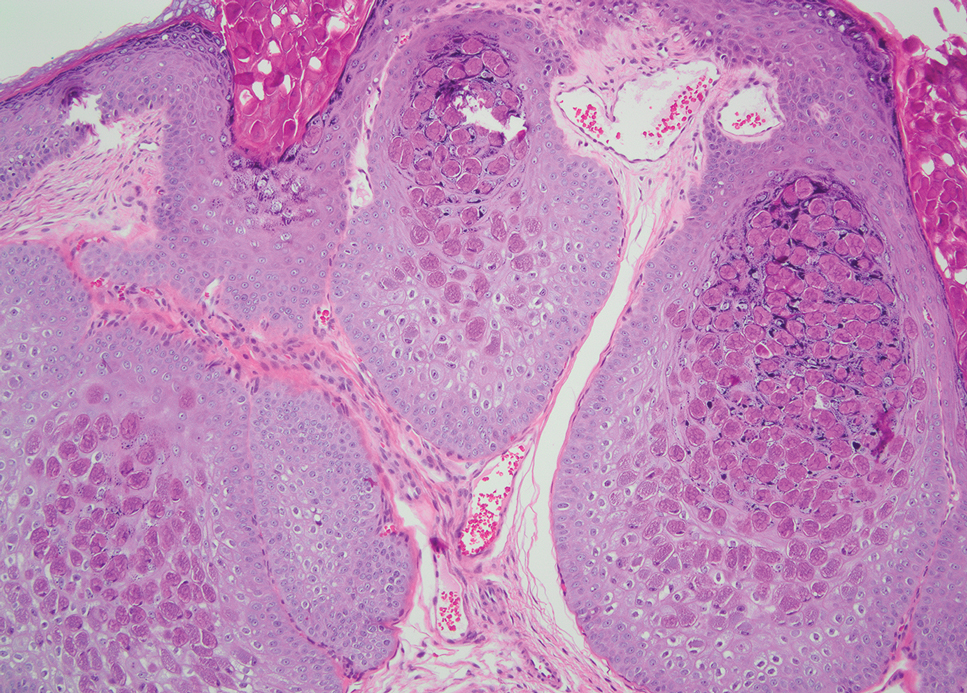

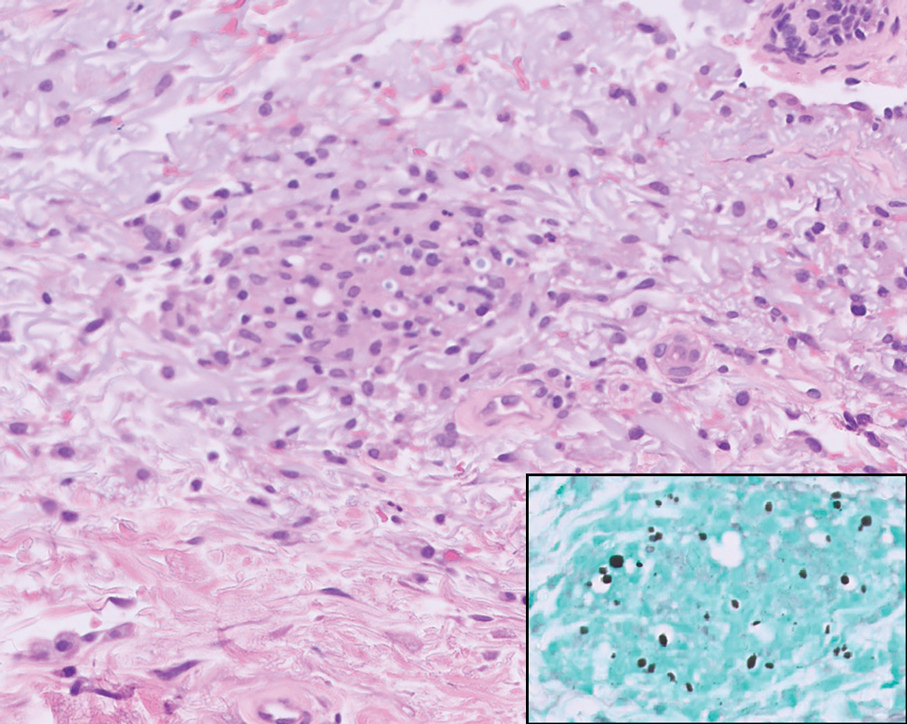

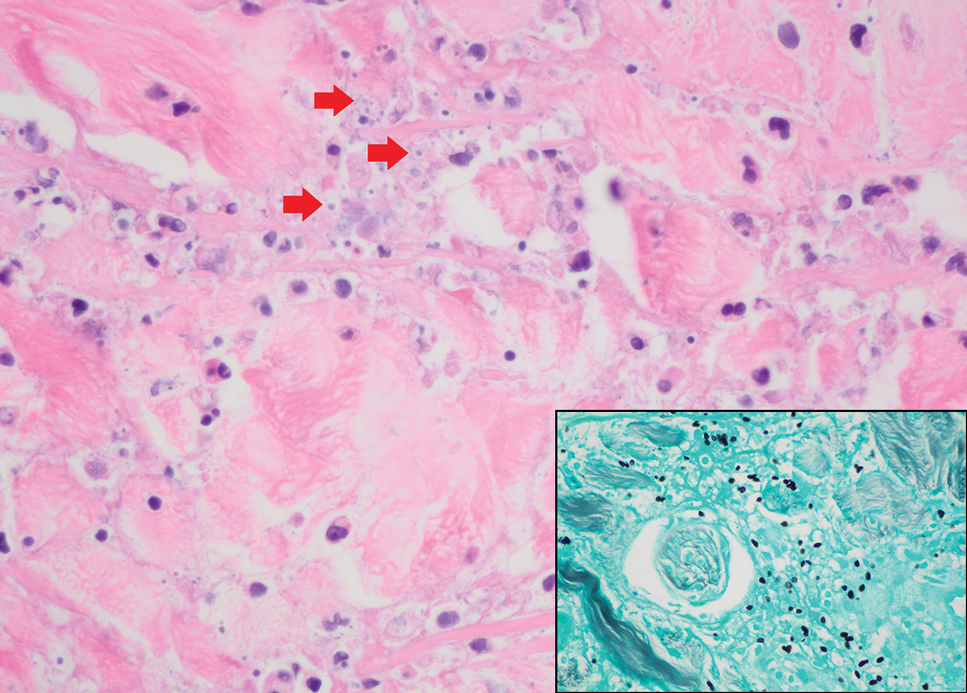

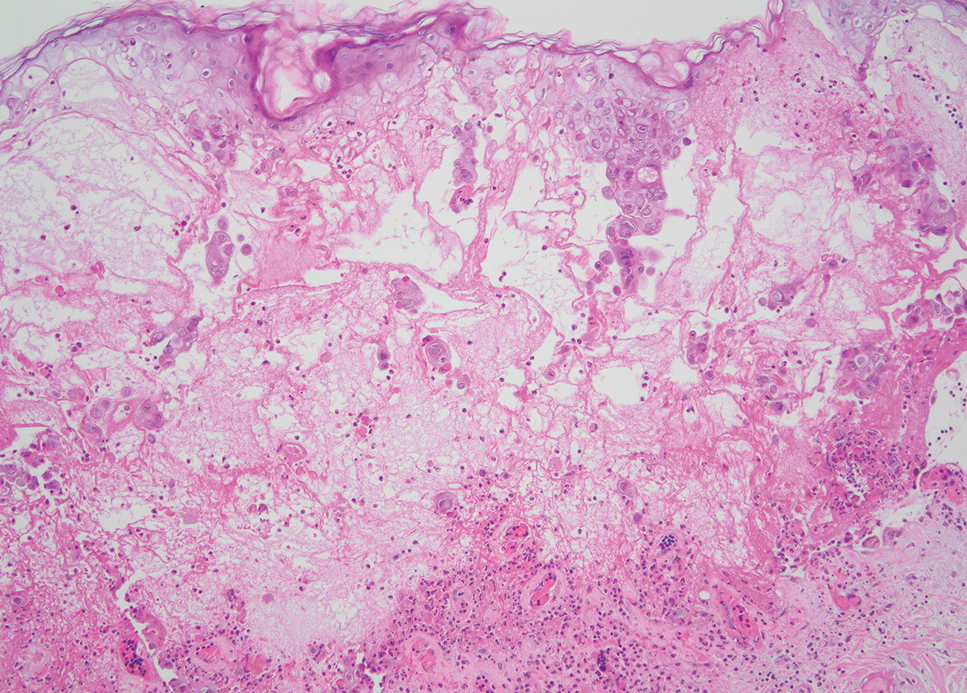

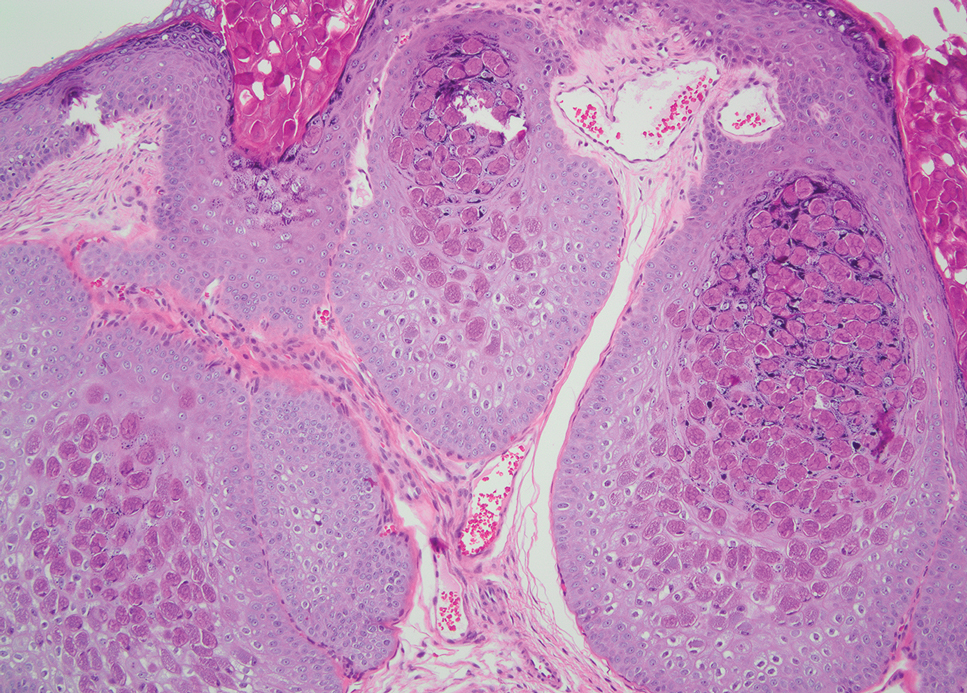

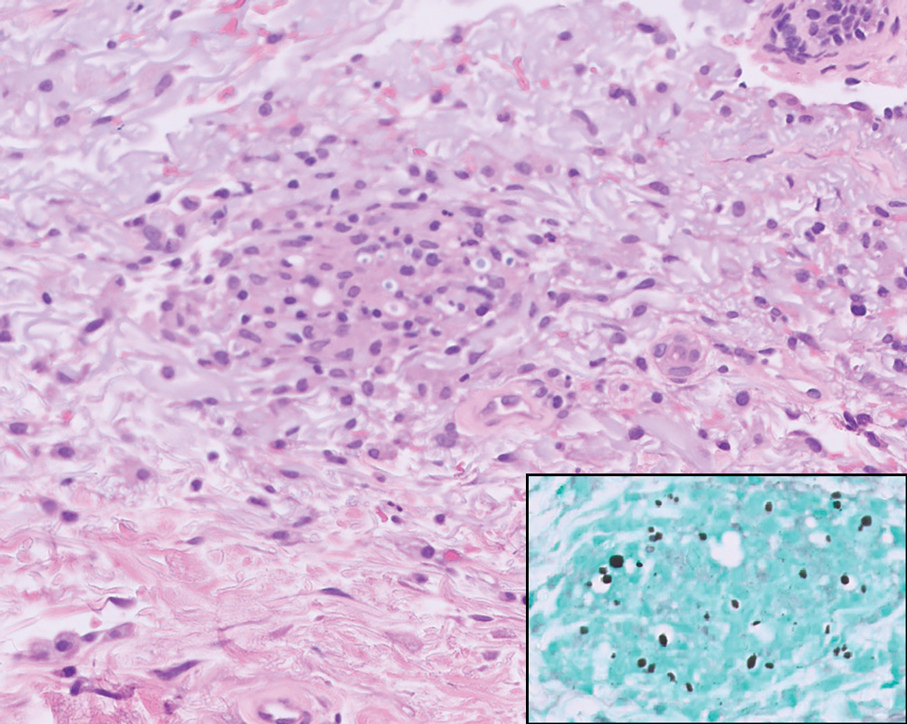

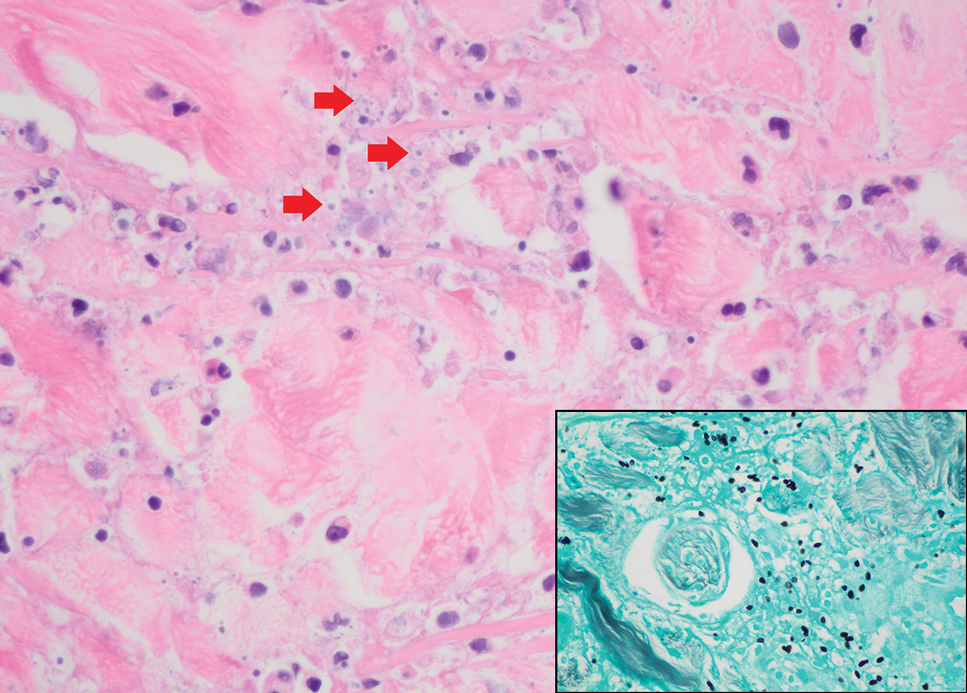

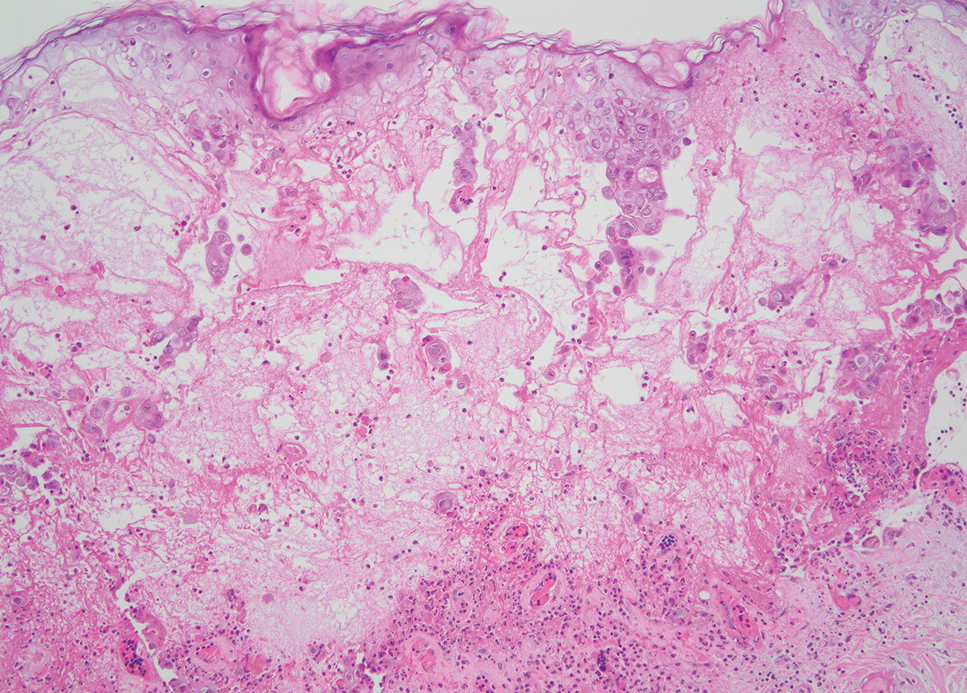

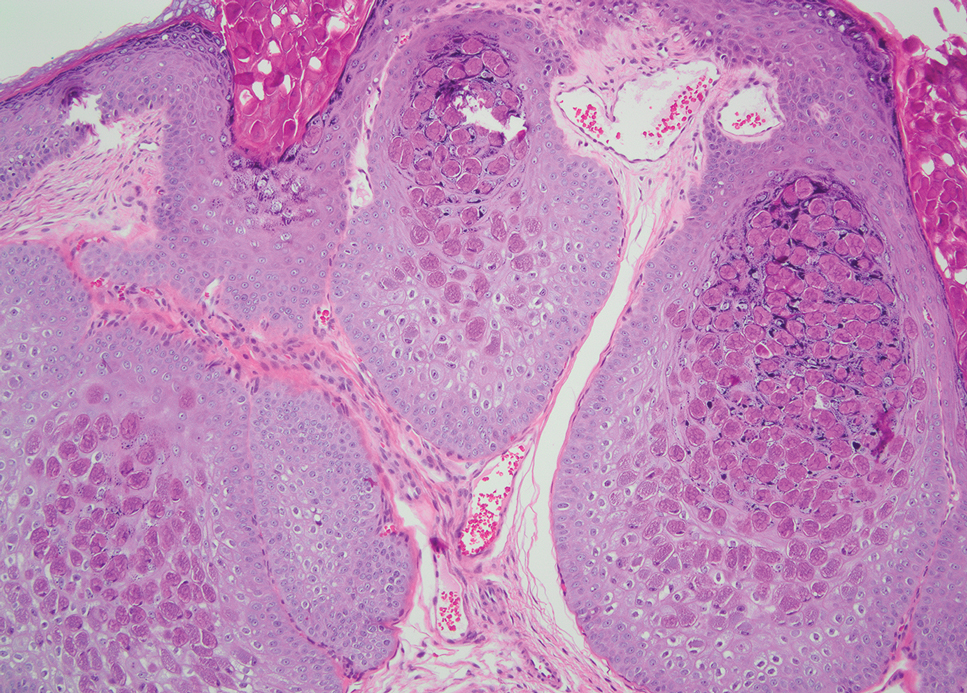

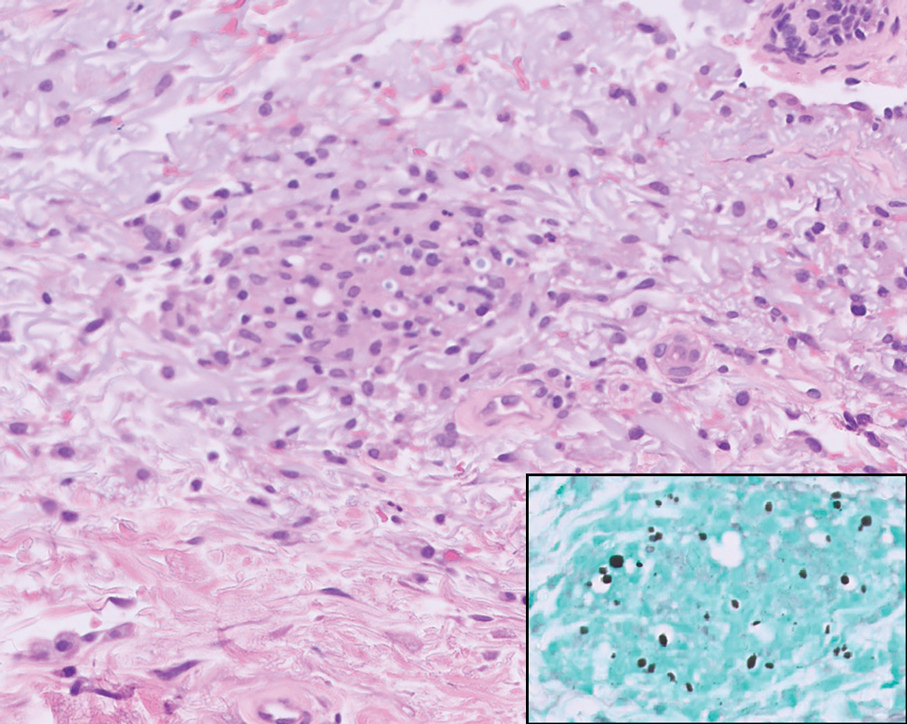

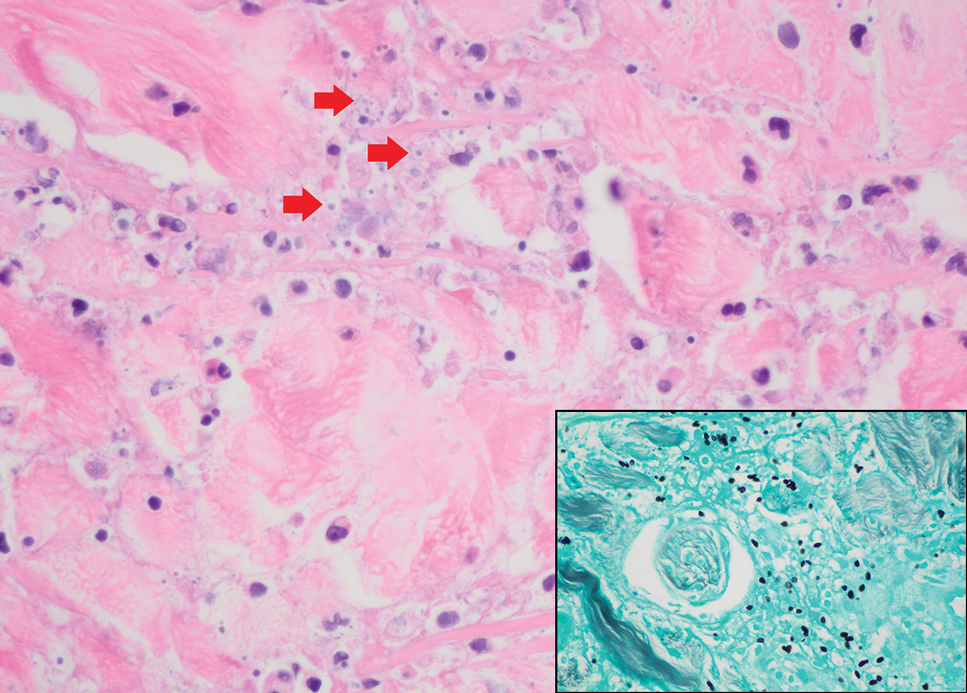

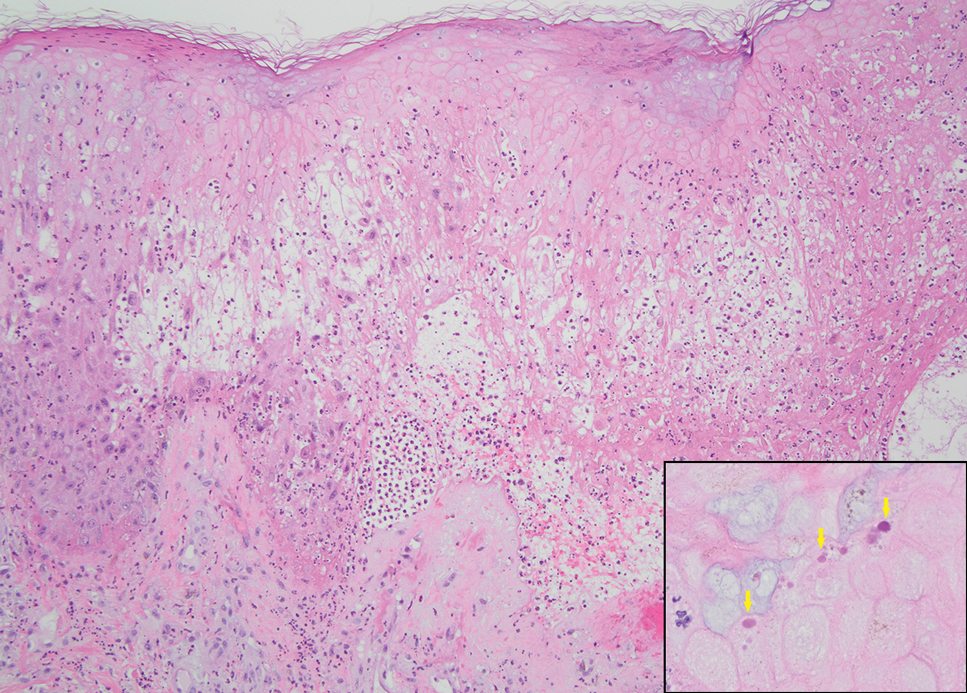

Seventy-eight charts were reviewed and 42 patients (54%) were diagnosed with GCA (Table 2). This study sample had a much higher proportion of African American subjects (31%) when compared with the civilian population, likely reflecting the higher representation of African Americans in the armed forces. Twenty-eight females (67%) were GCA positive. The most common presenting symptoms included 27 patients (64%) with headache, 17 (40%) with scalp tenderness, and 14 (33%) with jaw pain. The mean 1990 ACR score was 3.8 (range, 2-5). With respect to the score criteria: 41 patients (98%) were aged ≥ 50 years, 31 (74%) had new onset headache, and 31 (74%) had elevated ESR (Table 3). Acute ischemic optic neuropathy was documented in 4 patients (10%) with confirmed GCA. The mean ESR and CRP values at diagnosis were 66.2 mm/h (range, 7-122 mm/h) and 8.711 μg/mL (range, 0.054 – 92.690 μg/mL), respectively. Twenty-seven patients (64%) underwent biopsy: 24 (89%) were unilateral and 3 (11%) were bilateral (Table 4). Four patients with GCA (10%) were missing biopsy data. Nineteen patients with GCA (70%) had biopsies with pathologic findings consistent with GCA.

Twenty-five patients with GCA (60%) received ≥ 1 imaging modality. The most common imaging modality was MRI, which was used for 18 (43%) patients. Fourteen patients (33%) had 18F-FDG PET, 12 patients (29%) had MRA, and 11 patients (26%) had CTA. The small number of patients who underwent point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS), brain MRI, or dark blood MRI were negative for disease. Five patients who underwent 18F-FDG PET had findings consistent with GCA. One patient with GCA had CTA of the head and neck with radiographic findings supportive of GCA.

Discussion

The available evidence supports the use of additional screening tests to increase the temporal artery biopsy yield for GCA. Inflammatory laboratory markers demonstrate some sensitivity but are nonspecific for GCA. In this study, only 60% of patients with GCA underwent diagnostic imaging as part of the workup. There are multiple factors that may contribute to the underutilization of advanced imaging in the diagnosis of GCA, including outdated standardized diagnostic criteria, limited resources (direct access to modalities), and lack of clinician awareness of diagnostic testing options. In this retrospective review, 30 patients (71%) were diagnosed with GCA with a 1990 ACR GCA score ≤ 3. Of these 30 patients, 19 underwent confirmatory biopsy followed by prolonged courses of steroid therapy. In addition, only 25 patients underwent advanced imaging to increase diagnostic accuracy of the suspected syndrome.

A large meta-analysis demonstrated a sensitivity of 77.3% (95% CI, 71.8-81.9%) for temporal artery biopsy.21 The overall yield was 40% in the meta-analysis. Advanced noninvasive imaging represents an appropriate method of evaluating GCA.8-20 In our study, 18F-FDG PET demonstrated the highest sensitivity (36%) for the diagnosis of GCA. Ultrasonography is recommended as an initial screening tool to identify the noncompressible halo sign (a hypoechoic circumferential wall thickening due to edema) as a cost-effective and widely available technology.22 Other research has corroborated the beneficial use of ultrasonography in improving diagnostic accuracy by detecting the noncompressible halo sign in temporal arteries.22,23 GCA diagnostic performance has been significantly improved with the use of B-mode probes ≥ 15 MHz as well as proposals to incorporate a compression sign or interrogating the axillary vessels, showing a sensitivity of 54% to 77%.23,24

POCUS may reduce the risk of a false-negative biopsy and improve yield with more frequent utilization. However, ultrasonography may be limited by operator skills and visualization of the great vessels. The accuracy of ultrasonography is dependent on the experience and adeptness of the operator. Additional studies are needed to establish a systematic standard for POCUS training to ensure accurate interpretation and uniform interrogation procedure.24 Artificial intelligence (AI) may aid in interpreting results of POCUS and bridging the operator skill gap among operators.25,26 AI and machine learning techniques can assist in detecting the noncompressible halo sign and compression sign in temporal arteries and other affected vessels.

In comparing the WRNMMC patient population with other US civilian GCA cohorts, there are some differences and similarities. There was a high representation of African American patients in the study, which may reflect a greater severity of autoimmune disease expression in this population.27 We also observed a higher number of females and an association with polymyalgia rheumatica in the data, consistent with previous reports.28,29 The females in this study were primarily civilians and therefore more similar to the general population of individuals with GCA. In contrast, male patients were more likely to be active-duty service members or have prior service experience with increased exposure to novel environmental factors linked to increased risk of autoimmune disease. This includes an increased risk of Guillain-Barré syndrome and Graves disease among Vietnam veterans exposed to Agent Orange.30,31 Other studies have found that veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder are at increased risk for severe autoimmune diseases.32,33 As more women join the active-duty military, the impact of autoimmune disease in the military service population is expected to grow, requiring further research.

Conclusions

Early diagnosis and treatment of GCA are critical to preventing serious outcomes, such as visual loss, jaw or limb claudication, or ischemic stroke. The incidence of autoimmune disease is expected to rise in the armed forces and veteran populations due to exposure to novel environmental factors and the increasing representation of women in the military. The use of additional screening tools can aid in earlier diagnosis of GCA. The 2022 ACR classification criteria for GCA represent significant updates to the 1990 criteria, incorporating ancillary tests such as the temporal artery halo sign on ultrasound, bilateral axillary vessel screening on imaging, and 18F-FDG PET activity throughout the aorta. The updated criteria require further validation and supports the adoption of a multidisciplinary approach that includes ultrasonography, vascular MRI/CT, and 18F-FDG PET. Furthermore, AI may play a future key role in ultrasound interpretation and study interrogation procedure. Ultimately, ultrasonography is a noninvasive and promising technique for the early diagnosis of GCA. A target goal is to increase the yield of positive temporal artery biopsies to ≥ 70%.

- Jennette JC. Overview of the 2012 revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference nomenclature of vasculitides. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2013;17:603-606. doi:10.1007/s10157-013-0869-6

- Kale N, Eggenberger E. Diagnosis and management of giant cell arteritis: a review. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2010;21:417-422. doi:10.1097/ICU.0b013e32833eae8b

- Smetana GW, Shmerling RH. Does this patient have temporal arteritis? JAMA. 2002;287:92-101.

- Schäcke H, Döcke WD, Asadullah K. Mechanisms involved in the side effects of glucocorticoids. Pharmacol Ther. 2002;96:23-43. doi:10.1016/s0163-7258(02)00297-8

- Curtis JR, Patkar N, Xie A, et al. Risk of serious bacterial infections among rheumatoid arthritis patients exposed to tumor necrosis factor alpha antagonists. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:1125-1133. doi:10.1002/art.22504

- Hoes JN, van der Goes MC, van Raalte DH, et al. Glucose tolerance, insulin sensitivity and ß-cell function in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with or without low-to-medium dose glucocorticoids. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:1887-1894. doi:10.1136/ard.2011.151464

- Hunder GG, Bloch DA, Michel BA, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of giant cell arteritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33:1122-1128. doi:10.1002/art.1780330810

- Dejaco C, Duftner C, Buttgereit F, Matteson EL, Dasgupta B. The spectrum of giant cell arteritis and polymyalgia rheumatica: revisiting the concept of the disease. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2017;56:506-515. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/kew273

- Slart RHJ, Nienhuis PH, Glaudemans AWJM, et al. Role of 18F-FDG PET/CT in large vessel vasculitis and polymyalgia rheumatica. J Nucl Med. 2023;64:515-521. doi:10.2967/jnumed.122.265016

- Shimol JB, Amital H, Lidar M, Domachevsky L, Shoenfeld Y, Davidson T. The utility of PET/CT in large vessel vasculitis. Sci Rep. 2020;10:17709. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-73818-2

- Ponte C, Grayson PC, Robson JC, et al. 2022 American College of Rheumatology/EULAR Classification Criteria for Giant Cell Arteritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2022;74:1881-1889. doi:10.1002/art.42325

- He J, Williamson L, Ng B, et al. The diagnostic accuracy of temporal artery ultrasound and temporal artery biopsy in giant cell arteritis: a single center Australian experience over 10 years. Int J Rheum Dis. 2022;25:447-453. doi:10.1111/1756-185X.14288

- Stellingwerff MD, Brouwer E, Lensen KDF, et al. Different scoring methods of FDG PET/CT in giant cell arteritis: need for standardization. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e1542. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000001542

- Conway R, Smyth AE, Kavanagh RG, et al. Diagnostic utility of computed tomographic angiography in giant-cell arteritis. Stroke. 2018;49:2233-2236. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.021995

- Duftner C, Dejaco C, Sepriano A, et al. Imaging in diagnosis, outcome prediction and monitoring of large vessel vasculitis: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis informing the EULAR recommendations. RMD Open. 2018;4:e000612. doi:10.1136/rmdopen-2017-000612

- Rehak Z, Vasina J, Ptacek J, et al. PET/CT in giant cell arteritis: high 18F-FDG uptake in the temporal, occipital and vertebral arteries. Rev Esp Med Nucl Imagen Mol. 2016;35:398-401. doi:10.1016/j.remn.2016.03.007

- Salvarani C, Soriano A, Muratore F, et al. Is PET/CT essential in the diagnosis and follow-up of temporal arteritis? Autoimmun Rev. 2017;16:1125-1130. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2017.09.007

- Brodmann M, Lipp RW, Passath A, et al. The role of 2-18F-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography in the diagnosis of giant cell arteritis of the temporal arteries. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2004;43:241-242. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/keh025

- Flaus A, Granjon D, Habouzit V, Gaultier JB, Prevot-Bitot N. Unusual and diffuse hypermetabolism in routine 18F-FDG PET/CT of the supra-aortic vessels in biopsy-positive giant cell arteritis. Clin Nucl Med. 2018;43:e336-e337. doi:10.1097/RLU.0000000000002198

- Berger CT, Sommer G, Aschwanden M, et al. The clinical benefit of imaging in the diagnosis and treatment of giant cell arteritis. Swiss Med Wkly. 2018;148:w14661. doi:10.4414/smw.2018.14661

- Rubenstein E, Maldini C, Gonzalez-Chiappe S, et al. Sensitivity of temporal artery biopsy in the diagnosis of giant cell arteritis: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2020;59:1011-1020. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/kez385

- Tsivgoulis G, Heliopoulos I, Vadikolias K, et al. Teaching neuroimages: ultrasound findings in giant-cell arteritis. Neurology. 2010;75:e67-e68. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181f881e9

- Nakajima E, Moon FH, Canvas Jr N, et al. Accuracy of Doppler ultrasound in the diagnosis of giant cell arteritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Adv Rheumatol. 2023;63:5. doi:10.1186/s42358-023-00286-3

- Naumegni SR, Hoffmann C, Cornec D, et al. Temporal artery ultrasound to diagnose giant cell arteritis: a practical guide. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2021;47:201-213. doi:10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2020.10.004

- Kim YH. Artificial intelligence in medical ultrasonography: driving on an unpaved road. Ultrasonography. 2021;40:313-317. doi:10.14366/usg.21031

- Sultan LR, Mohamed MH, Andronikou S. ChatGPT-4: a breakthrough in ultrasound image analysis. Radiol Adv. 2024;1:umae006. doi:10.1093/radadv/umae006

- Cipriani VP, Klein S. Clinical characteristics of multiple sclerosis in African-Americans. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2019;19:87. doi:10.1007/s11910-019-1000-5

- Sturm A, Dechant C, Proft F, et al. Gender differences in giant cell arteritis: a case-control study. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2016;34:S70-72.

- Li KJ, Semenov D, Turk M, et al. A meta-analysis of the epidemiology of giant cell arteritis across time and space. Arthritis Res Ther. 2021;23:82. doi:10.1186/s13075-021-02450-w

- Nelson L, Gormley R, Riddle MS, Tribble DR, Porter CK. The epidemiology of Guillain-Barré syndrome in U.S. military personnel: a case-control study. BMC Res Notes. 2009;2:171. doi:10.1186/1756-0500-2-171

- Spaulding SW. The possible roles of environmental factors and the aryl hydrocarbon receptor in the prevalence of thyroid diseases in Vietnam era veterans. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2011;18:315-320.

- O’Donovan A, Cohen BE, Seal KH, et al. Elevated risk for autoimmune disorders in Iraq and Afghanistan veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;77:365-374. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.06.015

- Bookwalter DB, Roenfeldt KA, LeardMann CA, Kong SY, Riddle MS, Rull RP. Posttraumatic stress disorder and risk of selected autoimmune diseases among US military personnel. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20:23. doi:10.1186/s12888-020-2432-9

Giant cell arteritis (GCA), the most commonly diagnosed systemic vasculitis, is a large- and medium-vessel vasculitis that can lead to significant morbidity due to aneurysm formation or vascular occlusion if not diagnosed in a timely manner.1,2 Diagnosis is typically based on clinical history and inflammatory markers. Laboratory inflammatory markers may be normal in the early stages of GCA but can be abnormal due to other unrelated reasons leading to a false positive diagnosis.3 Delayed treatment may lead to visual loss, jaw or limb claudication, or ischemic stroke.2 Initial treatment typically includes high-dose steroids that can lead to significant adverse reactions such as hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysfunction, metabolic syndrome, premature atherosclerosis, and increased risk of infection.4-6

The 1990 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria for GCA are widely recognized (Table 1).7 The criteria focuses on clinical manifestations, including new onset headache, temporal artery tenderness, age ≥ 50 years, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) ≥ 50 mm/hr, and temporal artery biopsy with positive anatomical findings.8 When 3 of the 5 1990 ACR criteria are present, the sensitivity and specificity is estimated to be > 90% for GCA vs alternative vasculitides.7

Although the 1990 ACR criteria do not include imaging, modalities such as ultrasound, computed tomography angiography (CTA), 18F-FDG positron emission tomography (PET), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)/magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) may be used in GCA diagnosis.8-10 These imaging modalities have been added to the proposed ACR classification criteria for GCA.11 For this updated point system standard, age ≥ 50 years is a requirement and includes a positive temporal artery biopsy or temporal artery halo sign on ultrasound (+5 points), an ESR ≥ 50 mm/h or C-reactive protein (CRP) ≥ 10 mg/L (+3 points), or sudden visual loss (+3 points). Scalp tenderness, jaw or tongue claudication, new temporal headache, morning stiffness in shoulders or neck, temporal artery abnormality on vascular examination, bilateral axillary vessel involvement on imaging, and 18F-FDG PET activity throughout the aorta are scored +2 points each. With these new criteria, a cumulative score ≥ 6 is classified as GCA. Diagnostic accuracy is further improved with imaging: ultrasonography (sensitivity 55% and specificity 95%) and 18F-FDG PET (sensitivity 69% and specificity 92%), CTA (sensitivity 71% and specificity 86%), and MRI/MRA (sensitivity 73% and specificity 88%).12-15

In recent years, clinicians have reported increased glucose uptake in arteries observed on PET imaging that suggests GCA.9,10,16-20 18F-FDG accumulates in cells with high metabolic activity rates, such as areas of inflammation. In assessing temporal arteries or other involved vasculature (eg, axillary or great vessels) for GCA, this modality indicates increased glucose uptake in the lining of vessel walls. The inflammation of vessel walls can then be visualized with PET. 18F-FDG PET presents a noninvasive imaging technique for evaluating GCA but its use has been limited in the United States due to its high cost.

Methods

Approval for a retrospective chart review of patients evaluated for suspected GCA was obtained from the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (WRNMMC) Institutional Review Board. The review included patients who underwent diagnostic procedures such as ultrasound, MRI, CT angiogram, and PET studies from 2016 through 2022. International Classification of Diseases codes used for case identification included: M31.6, M31.5, I77.6, I77.8, I77.89, I67.7, and I68.2. The Current Procedural Terminology code used for temporal artery biopsy is 37609.

Results

Seventy-eight charts were reviewed and 42 patients (54%) were diagnosed with GCA (Table 2). This study sample had a much higher proportion of African American subjects (31%) when compared with the civilian population, likely reflecting the higher representation of African Americans in the armed forces. Twenty-eight females (67%) were GCA positive. The most common presenting symptoms included 27 patients (64%) with headache, 17 (40%) with scalp tenderness, and 14 (33%) with jaw pain. The mean 1990 ACR score was 3.8 (range, 2-5). With respect to the score criteria: 41 patients (98%) were aged ≥ 50 years, 31 (74%) had new onset headache, and 31 (74%) had elevated ESR (Table 3). Acute ischemic optic neuropathy was documented in 4 patients (10%) with confirmed GCA. The mean ESR and CRP values at diagnosis were 66.2 mm/h (range, 7-122 mm/h) and 8.711 μg/mL (range, 0.054 – 92.690 μg/mL), respectively. Twenty-seven patients (64%) underwent biopsy: 24 (89%) were unilateral and 3 (11%) were bilateral (Table 4). Four patients with GCA (10%) were missing biopsy data. Nineteen patients with GCA (70%) had biopsies with pathologic findings consistent with GCA.

Twenty-five patients with GCA (60%) received ≥ 1 imaging modality. The most common imaging modality was MRI, which was used for 18 (43%) patients. Fourteen patients (33%) had 18F-FDG PET, 12 patients (29%) had MRA, and 11 patients (26%) had CTA. The small number of patients who underwent point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS), brain MRI, or dark blood MRI were negative for disease. Five patients who underwent 18F-FDG PET had findings consistent with GCA. One patient with GCA had CTA of the head and neck with radiographic findings supportive of GCA.

Discussion

The available evidence supports the use of additional screening tests to increase the temporal artery biopsy yield for GCA. Inflammatory laboratory markers demonstrate some sensitivity but are nonspecific for GCA. In this study, only 60% of patients with GCA underwent diagnostic imaging as part of the workup. There are multiple factors that may contribute to the underutilization of advanced imaging in the diagnosis of GCA, including outdated standardized diagnostic criteria, limited resources (direct access to modalities), and lack of clinician awareness of diagnostic testing options. In this retrospective review, 30 patients (71%) were diagnosed with GCA with a 1990 ACR GCA score ≤ 3. Of these 30 patients, 19 underwent confirmatory biopsy followed by prolonged courses of steroid therapy. In addition, only 25 patients underwent advanced imaging to increase diagnostic accuracy of the suspected syndrome.

A large meta-analysis demonstrated a sensitivity of 77.3% (95% CI, 71.8-81.9%) for temporal artery biopsy.21 The overall yield was 40% in the meta-analysis. Advanced noninvasive imaging represents an appropriate method of evaluating GCA.8-20 In our study, 18F-FDG PET demonstrated the highest sensitivity (36%) for the diagnosis of GCA. Ultrasonography is recommended as an initial screening tool to identify the noncompressible halo sign (a hypoechoic circumferential wall thickening due to edema) as a cost-effective and widely available technology.22 Other research has corroborated the beneficial use of ultrasonography in improving diagnostic accuracy by detecting the noncompressible halo sign in temporal arteries.22,23 GCA diagnostic performance has been significantly improved with the use of B-mode probes ≥ 15 MHz as well as proposals to incorporate a compression sign or interrogating the axillary vessels, showing a sensitivity of 54% to 77%.23,24

POCUS may reduce the risk of a false-negative biopsy and improve yield with more frequent utilization. However, ultrasonography may be limited by operator skills and visualization of the great vessels. The accuracy of ultrasonography is dependent on the experience and adeptness of the operator. Additional studies are needed to establish a systematic standard for POCUS training to ensure accurate interpretation and uniform interrogation procedure.24 Artificial intelligence (AI) may aid in interpreting results of POCUS and bridging the operator skill gap among operators.25,26 AI and machine learning techniques can assist in detecting the noncompressible halo sign and compression sign in temporal arteries and other affected vessels.

In comparing the WRNMMC patient population with other US civilian GCA cohorts, there are some differences and similarities. There was a high representation of African American patients in the study, which may reflect a greater severity of autoimmune disease expression in this population.27 We also observed a higher number of females and an association with polymyalgia rheumatica in the data, consistent with previous reports.28,29 The females in this study were primarily civilians and therefore more similar to the general population of individuals with GCA. In contrast, male patients were more likely to be active-duty service members or have prior service experience with increased exposure to novel environmental factors linked to increased risk of autoimmune disease. This includes an increased risk of Guillain-Barré syndrome and Graves disease among Vietnam veterans exposed to Agent Orange.30,31 Other studies have found that veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder are at increased risk for severe autoimmune diseases.32,33 As more women join the active-duty military, the impact of autoimmune disease in the military service population is expected to grow, requiring further research.

Conclusions

Early diagnosis and treatment of GCA are critical to preventing serious outcomes, such as visual loss, jaw or limb claudication, or ischemic stroke. The incidence of autoimmune disease is expected to rise in the armed forces and veteran populations due to exposure to novel environmental factors and the increasing representation of women in the military. The use of additional screening tools can aid in earlier diagnosis of GCA. The 2022 ACR classification criteria for GCA represent significant updates to the 1990 criteria, incorporating ancillary tests such as the temporal artery halo sign on ultrasound, bilateral axillary vessel screening on imaging, and 18F-FDG PET activity throughout the aorta. The updated criteria require further validation and supports the adoption of a multidisciplinary approach that includes ultrasonography, vascular MRI/CT, and 18F-FDG PET. Furthermore, AI may play a future key role in ultrasound interpretation and study interrogation procedure. Ultimately, ultrasonography is a noninvasive and promising technique for the early diagnosis of GCA. A target goal is to increase the yield of positive temporal artery biopsies to ≥ 70%.

Giant cell arteritis (GCA), the most commonly diagnosed systemic vasculitis, is a large- and medium-vessel vasculitis that can lead to significant morbidity due to aneurysm formation or vascular occlusion if not diagnosed in a timely manner.1,2 Diagnosis is typically based on clinical history and inflammatory markers. Laboratory inflammatory markers may be normal in the early stages of GCA but can be abnormal due to other unrelated reasons leading to a false positive diagnosis.3 Delayed treatment may lead to visual loss, jaw or limb claudication, or ischemic stroke.2 Initial treatment typically includes high-dose steroids that can lead to significant adverse reactions such as hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysfunction, metabolic syndrome, premature atherosclerosis, and increased risk of infection.4-6

The 1990 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria for GCA are widely recognized (Table 1).7 The criteria focuses on clinical manifestations, including new onset headache, temporal artery tenderness, age ≥ 50 years, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) ≥ 50 mm/hr, and temporal artery biopsy with positive anatomical findings.8 When 3 of the 5 1990 ACR criteria are present, the sensitivity and specificity is estimated to be > 90% for GCA vs alternative vasculitides.7

Although the 1990 ACR criteria do not include imaging, modalities such as ultrasound, computed tomography angiography (CTA), 18F-FDG positron emission tomography (PET), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)/magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) may be used in GCA diagnosis.8-10 These imaging modalities have been added to the proposed ACR classification criteria for GCA.11 For this updated point system standard, age ≥ 50 years is a requirement and includes a positive temporal artery biopsy or temporal artery halo sign on ultrasound (+5 points), an ESR ≥ 50 mm/h or C-reactive protein (CRP) ≥ 10 mg/L (+3 points), or sudden visual loss (+3 points). Scalp tenderness, jaw or tongue claudication, new temporal headache, morning stiffness in shoulders or neck, temporal artery abnormality on vascular examination, bilateral axillary vessel involvement on imaging, and 18F-FDG PET activity throughout the aorta are scored +2 points each. With these new criteria, a cumulative score ≥ 6 is classified as GCA. Diagnostic accuracy is further improved with imaging: ultrasonography (sensitivity 55% and specificity 95%) and 18F-FDG PET (sensitivity 69% and specificity 92%), CTA (sensitivity 71% and specificity 86%), and MRI/MRA (sensitivity 73% and specificity 88%).12-15