User login

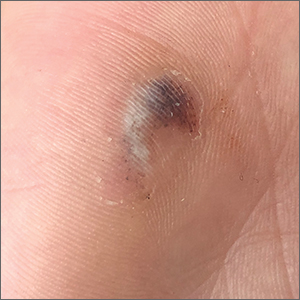

Hyperpigmented lesion on palm

This patient had a posttraumatic tache noir (also known as talon noir on the volar aspect of the feet); it is a subcorneal hematoma. The diagnosis is made clinically. Dermoscopic evaluation of tache/talon noir will reveal “pebbles on a ridge” or “satellite globules.” Confirmation of tache/talon noir can be made by paring the corneum with a #15 blade, which will reveal blood in the shavings and punctate lesions.1

This patient noted that the knob of his baseball bat rubbed the hypothenar eminence of his nondominant hand when he took a swing. The sheer force of the knob led to the subcorneal hematoma. Tache noir was high on the differential due to his physician’s clinical experience with similar cases. Tache noir occurs predominantly in people ages 12 to 24 years, without regard to gender.2 The condition is commonly found in athletes who participate in baseball, cricket, racquet sports, weightlifting, and rock climbing.2-4

Talon noir occurs most commonly in athletes who are frequently jumping, turning, and pivoting, as in football, basketball, tennis, and lacrosse.

Tache noir can be differentiated from other conditions by the presence of preserved architecture of the skin surface and punctate capillaries beneath the stratum corneum. The differential diagnosis includes verruca vulgaris, acral melanoma, and a traumatic tattoo.

Talon/tache noir are benign conditions that do not require treatment and do not affect sports performance. The lesion will usually self-resolve within a matter of weeks from onset or can even be gently scraped with a sterile needle or blade.

This patient was advised that the lesion would resolve on its own. His knee pain was determined to be a simple case of patellofemoral syndrome or “runner’s knee” and he opted to complete a home exercise program to obtain relief.

This case was adapted from: Warden D. Hyperpigmented lesion on left palm. J Fam Pract. 2021;70:459-460. Photos courtesy of Daniel Warden, MD

1. Googe AB, Schulmeier JS, Jackson AR, et al. Talon noir: paring can eliminate the need for biopsy. Postgrad Med J. 2014;90:730-731. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2014-132996

2. Burkhart C, Nguyen N. Talon noire. Dermatology Advisor. Accessed October 19, 2021. www.dermatologyadvisor.com/home/decision-support-in-medicine/dermatology/talon-noire-black-heel-calcaneal-petechiae-runners-heel-basketball-heel-tennis-heel-hyperkeratosis-hemorrhagica-pseudochromhidrosis-plantaris-chromidrose-plantaire-eccrine-intracorne/

3. Talon noir. Primary Care Dermatology Society. Updated August 1, 2021. Accessed October 19, 2021. www.pcds.org.uk/clinical-guidance/talon-noir

4. Birrer RB, Griesemer BA, Cataletto MB, eds. Pediatric Sports Medicine for Primary Care. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2002.

This patient had a posttraumatic tache noir (also known as talon noir on the volar aspect of the feet); it is a subcorneal hematoma. The diagnosis is made clinically. Dermoscopic evaluation of tache/talon noir will reveal “pebbles on a ridge” or “satellite globules.” Confirmation of tache/talon noir can be made by paring the corneum with a #15 blade, which will reveal blood in the shavings and punctate lesions.1

This patient noted that the knob of his baseball bat rubbed the hypothenar eminence of his nondominant hand when he took a swing. The sheer force of the knob led to the subcorneal hematoma. Tache noir was high on the differential due to his physician’s clinical experience with similar cases. Tache noir occurs predominantly in people ages 12 to 24 years, without regard to gender.2 The condition is commonly found in athletes who participate in baseball, cricket, racquet sports, weightlifting, and rock climbing.2-4

Talon noir occurs most commonly in athletes who are frequently jumping, turning, and pivoting, as in football, basketball, tennis, and lacrosse.

Tache noir can be differentiated from other conditions by the presence of preserved architecture of the skin surface and punctate capillaries beneath the stratum corneum. The differential diagnosis includes verruca vulgaris, acral melanoma, and a traumatic tattoo.

Talon/tache noir are benign conditions that do not require treatment and do not affect sports performance. The lesion will usually self-resolve within a matter of weeks from onset or can even be gently scraped with a sterile needle or blade.

This patient was advised that the lesion would resolve on its own. His knee pain was determined to be a simple case of patellofemoral syndrome or “runner’s knee” and he opted to complete a home exercise program to obtain relief.

This case was adapted from: Warden D. Hyperpigmented lesion on left palm. J Fam Pract. 2021;70:459-460. Photos courtesy of Daniel Warden, MD

This patient had a posttraumatic tache noir (also known as talon noir on the volar aspect of the feet); it is a subcorneal hematoma. The diagnosis is made clinically. Dermoscopic evaluation of tache/talon noir will reveal “pebbles on a ridge” or “satellite globules.” Confirmation of tache/talon noir can be made by paring the corneum with a #15 blade, which will reveal blood in the shavings and punctate lesions.1

This patient noted that the knob of his baseball bat rubbed the hypothenar eminence of his nondominant hand when he took a swing. The sheer force of the knob led to the subcorneal hematoma. Tache noir was high on the differential due to his physician’s clinical experience with similar cases. Tache noir occurs predominantly in people ages 12 to 24 years, without regard to gender.2 The condition is commonly found in athletes who participate in baseball, cricket, racquet sports, weightlifting, and rock climbing.2-4

Talon noir occurs most commonly in athletes who are frequently jumping, turning, and pivoting, as in football, basketball, tennis, and lacrosse.

Tache noir can be differentiated from other conditions by the presence of preserved architecture of the skin surface and punctate capillaries beneath the stratum corneum. The differential diagnosis includes verruca vulgaris, acral melanoma, and a traumatic tattoo.

Talon/tache noir are benign conditions that do not require treatment and do not affect sports performance. The lesion will usually self-resolve within a matter of weeks from onset or can even be gently scraped with a sterile needle or blade.

This patient was advised that the lesion would resolve on its own. His knee pain was determined to be a simple case of patellofemoral syndrome or “runner’s knee” and he opted to complete a home exercise program to obtain relief.

This case was adapted from: Warden D. Hyperpigmented lesion on left palm. J Fam Pract. 2021;70:459-460. Photos courtesy of Daniel Warden, MD

1. Googe AB, Schulmeier JS, Jackson AR, et al. Talon noir: paring can eliminate the need for biopsy. Postgrad Med J. 2014;90:730-731. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2014-132996

2. Burkhart C, Nguyen N. Talon noire. Dermatology Advisor. Accessed October 19, 2021. www.dermatologyadvisor.com/home/decision-support-in-medicine/dermatology/talon-noire-black-heel-calcaneal-petechiae-runners-heel-basketball-heel-tennis-heel-hyperkeratosis-hemorrhagica-pseudochromhidrosis-plantaris-chromidrose-plantaire-eccrine-intracorne/

3. Talon noir. Primary Care Dermatology Society. Updated August 1, 2021. Accessed October 19, 2021. www.pcds.org.uk/clinical-guidance/talon-noir

4. Birrer RB, Griesemer BA, Cataletto MB, eds. Pediatric Sports Medicine for Primary Care. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2002.

1. Googe AB, Schulmeier JS, Jackson AR, et al. Talon noir: paring can eliminate the need for biopsy. Postgrad Med J. 2014;90:730-731. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2014-132996

2. Burkhart C, Nguyen N. Talon noire. Dermatology Advisor. Accessed October 19, 2021. www.dermatologyadvisor.com/home/decision-support-in-medicine/dermatology/talon-noire-black-heel-calcaneal-petechiae-runners-heel-basketball-heel-tennis-heel-hyperkeratosis-hemorrhagica-pseudochromhidrosis-plantaris-chromidrose-plantaire-eccrine-intracorne/

3. Talon noir. Primary Care Dermatology Society. Updated August 1, 2021. Accessed October 19, 2021. www.pcds.org.uk/clinical-guidance/talon-noir

4. Birrer RB, Griesemer BA, Cataletto MB, eds. Pediatric Sports Medicine for Primary Care. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2002.

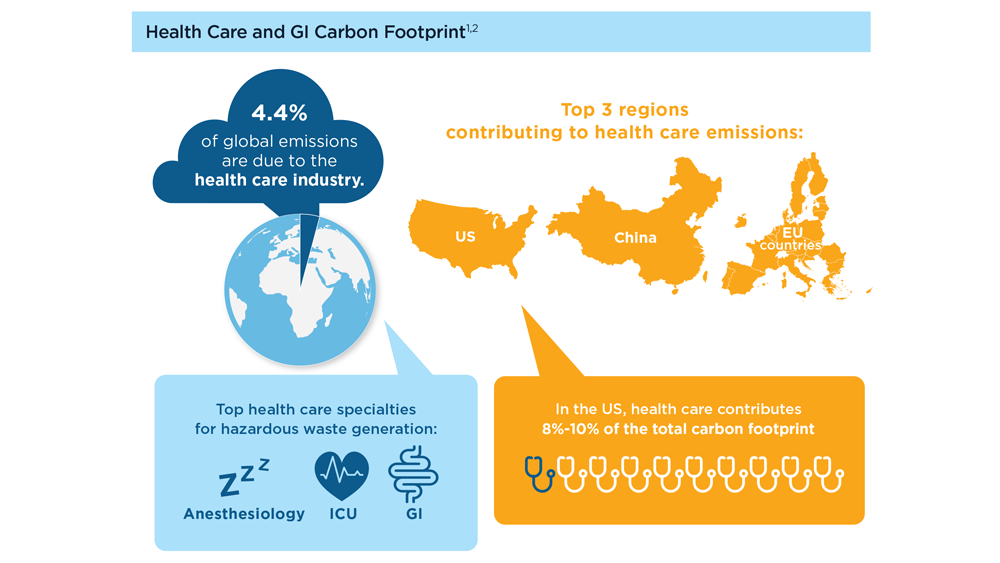

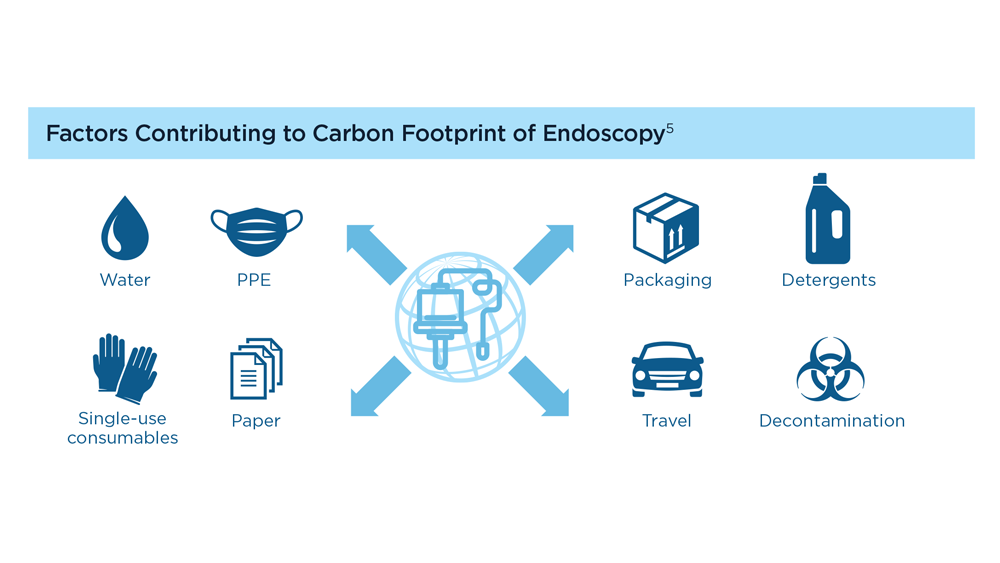

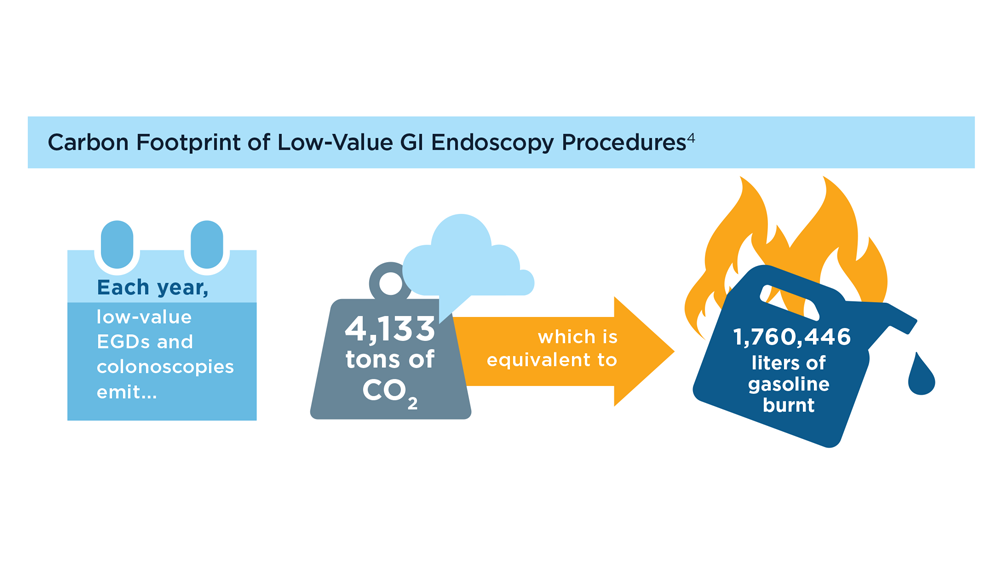

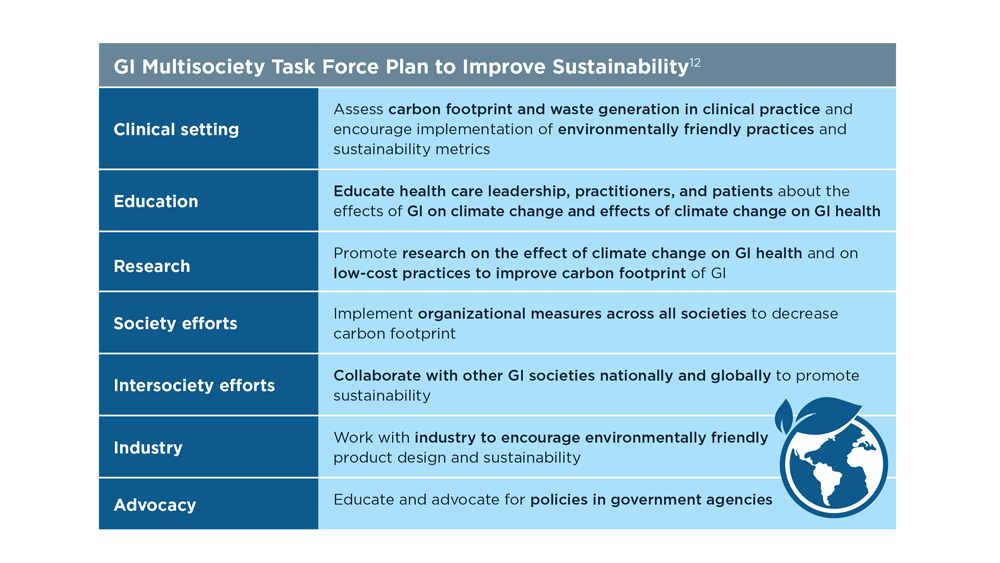

Gastroenterology and Climate Change: Assessing and Mitigating Impacts

- Karliner J et al. Eur J Public Health. 2020;30(suppl 5):v311. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckaa165.843

- Vaccari M et al. Waste Manag Res. 2018;36(1):39-47. doi:10.1177/0734242X17739968

- Peery AF et al. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(1):254-272.e11. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2018.08.063

- Sorge A et al. Endoscopy. 2023;55(suppl 2):S72-S73. https://www.esge.com/assets/downloads/pdfs/guidelines/ESGE_Days_2023.pdf

- Maurice JB et al. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5(7):636-638. doi:10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30157-6

- Gayam S. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115(12):1931-1932. doi:10.14309/ajg.0000000000001005

- Siau K et al. Tech Innov Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;23(4):344-352. doi:10.1016/j.tige.2021.06.005

- Namburar S et al. Gut. 2022;71(7):1326-1331. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2021-324729

- Haddock R et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117(3):394-400. doi:10.14309/ajg.0000000000001604

- Donnelly MC et al. J Hepatol. 2022;76(5):995-1000. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2022.02.01

- Leddin D, Macrae F. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2020;54(5):393-397. doi:10.1097/MCG.0000000000001336

- Pohl H et al. Hepatology. 2022;76(6):1836-1844. doi:10.1002/hep.32810

- Rodríguez de Santiago E et al. Endoscopy. 2022;54(8):797-826. doi:10.1055/a-1859-3726

- Sebastian S et al. Gut. 2023;72(1):12-26. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2022-328460

- Cunha Neves JA et al. Gut. 2023;72(2):306-313. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2022-327005

- Kaplan S et al. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund). 2012;29:1-14. PMID:23214181

- López-Muñoz P et al. Gut. 2023;gutjnl-2023-329544. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2023-329544

- Karliner J et al. Eur J Public Health. 2020;30(suppl 5):v311. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckaa165.843

- Vaccari M et al. Waste Manag Res. 2018;36(1):39-47. doi:10.1177/0734242X17739968

- Peery AF et al. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(1):254-272.e11. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2018.08.063

- Sorge A et al. Endoscopy. 2023;55(suppl 2):S72-S73. https://www.esge.com/assets/downloads/pdfs/guidelines/ESGE_Days_2023.pdf

- Maurice JB et al. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5(7):636-638. doi:10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30157-6

- Gayam S. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115(12):1931-1932. doi:10.14309/ajg.0000000000001005

- Siau K et al. Tech Innov Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;23(4):344-352. doi:10.1016/j.tige.2021.06.005

- Namburar S et al. Gut. 2022;71(7):1326-1331. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2021-324729

- Haddock R et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117(3):394-400. doi:10.14309/ajg.0000000000001604

- Donnelly MC et al. J Hepatol. 2022;76(5):995-1000. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2022.02.01

- Leddin D, Macrae F. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2020;54(5):393-397. doi:10.1097/MCG.0000000000001336

- Pohl H et al. Hepatology. 2022;76(6):1836-1844. doi:10.1002/hep.32810

- Rodríguez de Santiago E et al. Endoscopy. 2022;54(8):797-826. doi:10.1055/a-1859-3726

- Sebastian S et al. Gut. 2023;72(1):12-26. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2022-328460

- Cunha Neves JA et al. Gut. 2023;72(2):306-313. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2022-327005

- Kaplan S et al. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund). 2012;29:1-14. PMID:23214181

- López-Muñoz P et al. Gut. 2023;gutjnl-2023-329544. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2023-329544

- Karliner J et al. Eur J Public Health. 2020;30(suppl 5):v311. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckaa165.843

- Vaccari M et al. Waste Manag Res. 2018;36(1):39-47. doi:10.1177/0734242X17739968

- Peery AF et al. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(1):254-272.e11. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2018.08.063

- Sorge A et al. Endoscopy. 2023;55(suppl 2):S72-S73. https://www.esge.com/assets/downloads/pdfs/guidelines/ESGE_Days_2023.pdf

- Maurice JB et al. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5(7):636-638. doi:10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30157-6

- Gayam S. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115(12):1931-1932. doi:10.14309/ajg.0000000000001005

- Siau K et al. Tech Innov Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;23(4):344-352. doi:10.1016/j.tige.2021.06.005

- Namburar S et al. Gut. 2022;71(7):1326-1331. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2021-324729

- Haddock R et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117(3):394-400. doi:10.14309/ajg.0000000000001604

- Donnelly MC et al. J Hepatol. 2022;76(5):995-1000. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2022.02.01

- Leddin D, Macrae F. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2020;54(5):393-397. doi:10.1097/MCG.0000000000001336

- Pohl H et al. Hepatology. 2022;76(6):1836-1844. doi:10.1002/hep.32810

- Rodríguez de Santiago E et al. Endoscopy. 2022;54(8):797-826. doi:10.1055/a-1859-3726

- Sebastian S et al. Gut. 2023;72(1):12-26. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2022-328460

- Cunha Neves JA et al. Gut. 2023;72(2):306-313. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2022-327005

- Kaplan S et al. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund). 2012;29:1-14. PMID:23214181

- López-Muñoz P et al. Gut. 2023;gutjnl-2023-329544. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2023-329544

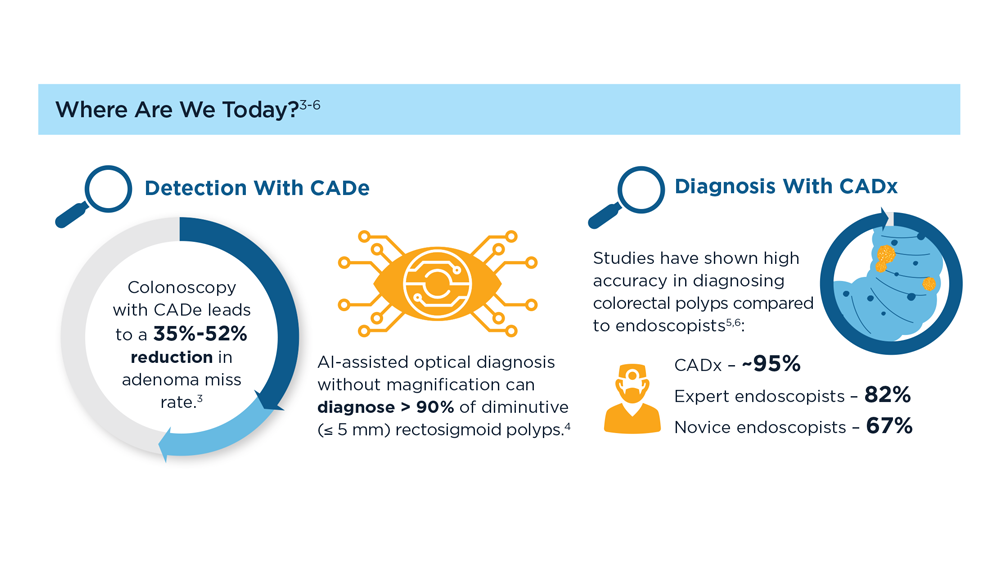

Harnessing the Power of AI to Enhance Endoscopy: Promises and Pitfalls

- Jin Z et al. BioMed Eng OnLine. 2022;21(1):12. doi:10.1186/s12938-022-00979-

- Buendgens L, Cifci D, Ghaffari Laleh N, et al. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):4829. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-08773-1

- Uche-Anya EN, Berzin TM. Artificial intelligence applications in colonoscopy. GI & Hepatology News. January 24, 2023. https://www.mdedge.com/gihepnews/article/260769/mixed-topics/artificial-intelligence-applications-colonoscopy

- Rondonotti E et al. Endoscopy. 2023;55(1):14-22. doi:10.1055/a-1852-0330

- Antonelli G et al. Ann Gastroenterol. 2023;36(2):114-122. doi:10.20524/aog.2023.0781

- van der Zander QEW et al. Endoscopy. 2021;53(12):1219-1226. doi:10.1055/a-1343-159

- Areia PM et al. Lancet Digital Health. 2022;4(6):e436-e444. doi:10.1016/S2589-7500(22)00042-5

- Sumiyama K et al. Dig Endosc. 2021;33(2):218-230. doi:10.1111/den.13837

- Berzin TM et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;92(4):951-959. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2020.06.035

- Mori Y et al. Dig Endosc. 2023;35(4):422-429. doi:10.1111/den.14531

- Uche-Anya E et al. Gut. 2022;71(9):1909-1915. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2021-326271

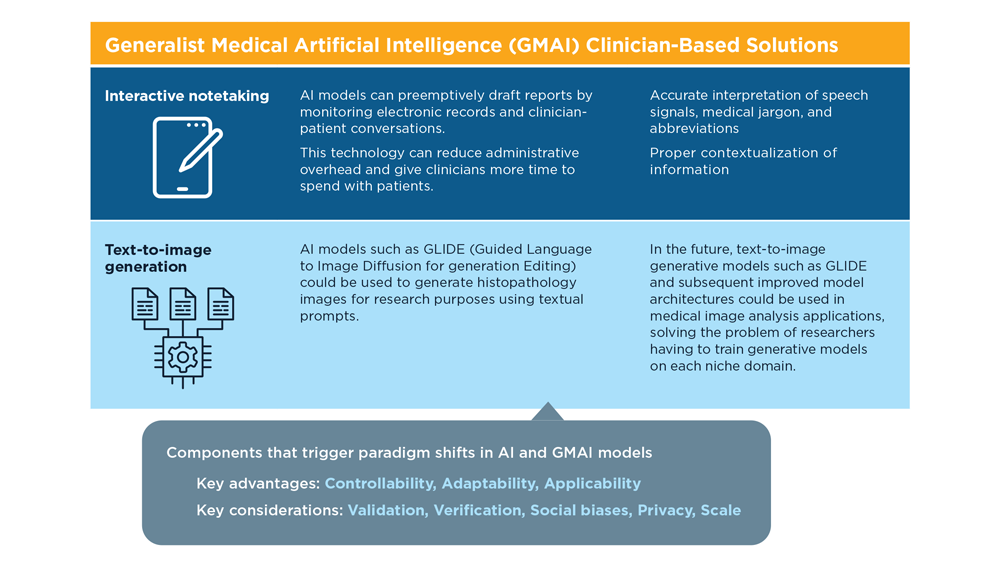

- Moor M et al. Nature. 2023;616(7956):259-265. 10.1038/s41586-023-05881-4

- Kather JN et al. NPJ Digit Med. 2022;5(1):90. doi:10.1038/s41746-022-00634-5

- Jin Z et al. BioMed Eng OnLine. 2022;21(1):12. doi:10.1186/s12938-022-00979-

- Buendgens L, Cifci D, Ghaffari Laleh N, et al. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):4829. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-08773-1

- Uche-Anya EN, Berzin TM. Artificial intelligence applications in colonoscopy. GI & Hepatology News. January 24, 2023. https://www.mdedge.com/gihepnews/article/260769/mixed-topics/artificial-intelligence-applications-colonoscopy

- Rondonotti E et al. Endoscopy. 2023;55(1):14-22. doi:10.1055/a-1852-0330

- Antonelli G et al. Ann Gastroenterol. 2023;36(2):114-122. doi:10.20524/aog.2023.0781

- van der Zander QEW et al. Endoscopy. 2021;53(12):1219-1226. doi:10.1055/a-1343-159

- Areia PM et al. Lancet Digital Health. 2022;4(6):e436-e444. doi:10.1016/S2589-7500(22)00042-5

- Sumiyama K et al. Dig Endosc. 2021;33(2):218-230. doi:10.1111/den.13837

- Berzin TM et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;92(4):951-959. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2020.06.035

- Mori Y et al. Dig Endosc. 2023;35(4):422-429. doi:10.1111/den.14531

- Uche-Anya E et al. Gut. 2022;71(9):1909-1915. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2021-326271

- Moor M et al. Nature. 2023;616(7956):259-265. 10.1038/s41586-023-05881-4

- Kather JN et al. NPJ Digit Med. 2022;5(1):90. doi:10.1038/s41746-022-00634-5

- Jin Z et al. BioMed Eng OnLine. 2022;21(1):12. doi:10.1186/s12938-022-00979-

- Buendgens L, Cifci D, Ghaffari Laleh N, et al. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):4829. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-08773-1

- Uche-Anya EN, Berzin TM. Artificial intelligence applications in colonoscopy. GI & Hepatology News. January 24, 2023. https://www.mdedge.com/gihepnews/article/260769/mixed-topics/artificial-intelligence-applications-colonoscopy

- Rondonotti E et al. Endoscopy. 2023;55(1):14-22. doi:10.1055/a-1852-0330

- Antonelli G et al. Ann Gastroenterol. 2023;36(2):114-122. doi:10.20524/aog.2023.0781

- van der Zander QEW et al. Endoscopy. 2021;53(12):1219-1226. doi:10.1055/a-1343-159

- Areia PM et al. Lancet Digital Health. 2022;4(6):e436-e444. doi:10.1016/S2589-7500(22)00042-5

- Sumiyama K et al. Dig Endosc. 2021;33(2):218-230. doi:10.1111/den.13837

- Berzin TM et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;92(4):951-959. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2020.06.035

- Mori Y et al. Dig Endosc. 2023;35(4):422-429. doi:10.1111/den.14531

- Uche-Anya E et al. Gut. 2022;71(9):1909-1915. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2021-326271

- Moor M et al. Nature. 2023;616(7956):259-265. 10.1038/s41586-023-05881-4

- Kather JN et al. NPJ Digit Med. 2022;5(1):90. doi:10.1038/s41746-022-00634-5

Evolution of Targeted Therapies for C difficile

- Di Bella S et al. Toxins (Basel). 2016;8(5):134. doi:10.3390/toxins8050134

- Turner NA, Anderson DJ. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2020;33(2):98-108. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1701234

- Czepiel J et al. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2019;38(7):1211-1221. doi:10.1007/s10096-019-03539-6

- Sekirov I et al. Gut microbiota in health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2012;90(3):859-904. doi:10.1152/physrev.00045.2009

- Posteraro B et al. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2018;18(4):469-476. doi:10.1080/14712598.2018.1452908

- Khanna S. J Intern Med. 2021;290(2):294-309. doi:10.1111/joim.13290

- Seekatz AM et al . Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2022;15:17562848221134396. doi:10.1177/17562848221134396

- Federal Drug Administration. FDA approves first fecal microbiota product: Rebyota approved for the prevention of recurrence of Clostridioides difficile infection in adults [press release]. Published November 30, 2022. Accessed July 14, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-fecal-microbiota-product

- Bafeta A et al. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(1):34-39. doi:10.7326/M16-2810

- Guh AY et al; Emerging Infections Program Clostridioides difficile Infection Working Group. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(14):1320-1330. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1910215

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. What is C. diff? Last reviewed September 7, 2022. Accessed July 14, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/cdiff/what-is.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Patients and families: be antibiotics aware. C. diff infection—Am I at risk? Accessed July 14, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/cdiff/pdf/FS-Cdiff-PatientsFamilies-508.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2019 annual report for the emerging infections program for Clostridioides difficile infection. Last reviewed February 1, 2023. Accessed July 14, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/hai/eip/Annual-CDI-Report-2019.html

- Kelly CR et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116(6):1124-1147. doi:10.14309/ajg.0000000000001278

- Tariq R et al. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2021;14:1756284821994046. doi:10.1177/1756284821994046

- McDonald LC et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66(7):e1-e48. doi:10.1093/cid/cix1085

- Wilcox MH et al. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(4):305-317. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1602615

- Guilleman MM et al. Gene Ther. 2023;30:455-462. doi:10.1038/s41434-021-00236-y

- Sims MD et al; ECOSPOR IV Investigators. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(2):e2255758. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.55758

- Microbiota Restoration Therapy for Recurrent Clostridium Difficile Infection (PUNCHCD2). ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02299570. Updated January 2021. Accessed August 2023. https://classic.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/results/NCT02299570

- Khanna S et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73(7):e1613-e1620. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa1430

- Di Bella S et al. Toxins (Basel). 2016;8(5):134. doi:10.3390/toxins8050134

- Turner NA, Anderson DJ. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2020;33(2):98-108. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1701234

- Czepiel J et al. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2019;38(7):1211-1221. doi:10.1007/s10096-019-03539-6

- Sekirov I et al. Gut microbiota in health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2012;90(3):859-904. doi:10.1152/physrev.00045.2009

- Posteraro B et al. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2018;18(4):469-476. doi:10.1080/14712598.2018.1452908

- Khanna S. J Intern Med. 2021;290(2):294-309. doi:10.1111/joim.13290

- Seekatz AM et al . Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2022;15:17562848221134396. doi:10.1177/17562848221134396

- Federal Drug Administration. FDA approves first fecal microbiota product: Rebyota approved for the prevention of recurrence of Clostridioides difficile infection in adults [press release]. Published November 30, 2022. Accessed July 14, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-fecal-microbiota-product

- Bafeta A et al. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(1):34-39. doi:10.7326/M16-2810

- Guh AY et al; Emerging Infections Program Clostridioides difficile Infection Working Group. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(14):1320-1330. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1910215

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. What is C. diff? Last reviewed September 7, 2022. Accessed July 14, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/cdiff/what-is.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Patients and families: be antibiotics aware. C. diff infection—Am I at risk? Accessed July 14, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/cdiff/pdf/FS-Cdiff-PatientsFamilies-508.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2019 annual report for the emerging infections program for Clostridioides difficile infection. Last reviewed February 1, 2023. Accessed July 14, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/hai/eip/Annual-CDI-Report-2019.html

- Kelly CR et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116(6):1124-1147. doi:10.14309/ajg.0000000000001278

- Tariq R et al. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2021;14:1756284821994046. doi:10.1177/1756284821994046

- McDonald LC et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66(7):e1-e48. doi:10.1093/cid/cix1085

- Wilcox MH et al. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(4):305-317. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1602615

- Guilleman MM et al. Gene Ther. 2023;30:455-462. doi:10.1038/s41434-021-00236-y

- Sims MD et al; ECOSPOR IV Investigators. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(2):e2255758. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.55758

- Microbiota Restoration Therapy for Recurrent Clostridium Difficile Infection (PUNCHCD2). ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02299570. Updated January 2021. Accessed August 2023. https://classic.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/results/NCT02299570

- Khanna S et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73(7):e1613-e1620. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa1430

- Di Bella S et al. Toxins (Basel). 2016;8(5):134. doi:10.3390/toxins8050134

- Turner NA, Anderson DJ. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2020;33(2):98-108. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1701234

- Czepiel J et al. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2019;38(7):1211-1221. doi:10.1007/s10096-019-03539-6

- Sekirov I et al. Gut microbiota in health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2012;90(3):859-904. doi:10.1152/physrev.00045.2009

- Posteraro B et al. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2018;18(4):469-476. doi:10.1080/14712598.2018.1452908

- Khanna S. J Intern Med. 2021;290(2):294-309. doi:10.1111/joim.13290

- Seekatz AM et al . Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2022;15:17562848221134396. doi:10.1177/17562848221134396

- Federal Drug Administration. FDA approves first fecal microbiota product: Rebyota approved for the prevention of recurrence of Clostridioides difficile infection in adults [press release]. Published November 30, 2022. Accessed July 14, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-fecal-microbiota-product

- Bafeta A et al. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(1):34-39. doi:10.7326/M16-2810

- Guh AY et al; Emerging Infections Program Clostridioides difficile Infection Working Group. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(14):1320-1330. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1910215

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. What is C. diff? Last reviewed September 7, 2022. Accessed July 14, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/cdiff/what-is.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Patients and families: be antibiotics aware. C. diff infection—Am I at risk? Accessed July 14, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/cdiff/pdf/FS-Cdiff-PatientsFamilies-508.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2019 annual report for the emerging infections program for Clostridioides difficile infection. Last reviewed February 1, 2023. Accessed July 14, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/hai/eip/Annual-CDI-Report-2019.html

- Kelly CR et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116(6):1124-1147. doi:10.14309/ajg.0000000000001278

- Tariq R et al. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2021;14:1756284821994046. doi:10.1177/1756284821994046

- McDonald LC et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66(7):e1-e48. doi:10.1093/cid/cix1085

- Wilcox MH et al. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(4):305-317. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1602615

- Guilleman MM et al. Gene Ther. 2023;30:455-462. doi:10.1038/s41434-021-00236-y

- Sims MD et al; ECOSPOR IV Investigators. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(2):e2255758. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.55758

- Microbiota Restoration Therapy for Recurrent Clostridium Difficile Infection (PUNCHCD2). ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02299570. Updated January 2021. Accessed August 2023. https://classic.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/results/NCT02299570

- Khanna S et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73(7):e1613-e1620. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa1430

Gastroenterology Data Trends 2023

GI&Hepatology News and the American Gastroenterological Association present the 2023 issue of Gastroenterology Data Trends, a special report on hot topics in gastroenterology told through original infographics and visual storytelling.

In this issue:

- Gastroenterology and Climate Change: Assessing and Mitigating Impacts

Swapna Gayam, MD, FACG - MASLD/MASH and Weight Loss

Arpan Mohanty, MD, MSc - Digital Tools in the Management of IBS/Functional GI Disorders

Eric D. Shah, MD, MBA, FACG - Long COVID and the Gastrointestinal System: Emerging Evidence

Daniel E. Freedberg, MD, MS, and Lin Chang, MD, AGAF - Germline Genetic Testing in CRC: Implications for Familial and Population-Based Testing

Fay Kastrinos, MD, MPH - Evolution of Targeted Therapies for C difficile

Sahil Khanna, MBBS, MS, FACG, AGAF - Harnessing the Power of AI to Enhance Endoscopy: Promises and Pitfalls

Eugenia Uche-Anya, MD, MPH - The Evolving Role of Surgery for IBD

Julie K.M. Thacker, MD, FACS, FASCRS

GI&Hepatology News and the American Gastroenterological Association present the 2023 issue of Gastroenterology Data Trends, a special report on hot topics in gastroenterology told through original infographics and visual storytelling.

In this issue:

- Gastroenterology and Climate Change: Assessing and Mitigating Impacts

Swapna Gayam, MD, FACG - MASLD/MASH and Weight Loss

Arpan Mohanty, MD, MSc - Digital Tools in the Management of IBS/Functional GI Disorders

Eric D. Shah, MD, MBA, FACG - Long COVID and the Gastrointestinal System: Emerging Evidence

Daniel E. Freedberg, MD, MS, and Lin Chang, MD, AGAF - Germline Genetic Testing in CRC: Implications for Familial and Population-Based Testing

Fay Kastrinos, MD, MPH - Evolution of Targeted Therapies for C difficile

Sahil Khanna, MBBS, MS, FACG, AGAF - Harnessing the Power of AI to Enhance Endoscopy: Promises and Pitfalls

Eugenia Uche-Anya, MD, MPH - The Evolving Role of Surgery for IBD

Julie K.M. Thacker, MD, FACS, FASCRS

GI&Hepatology News and the American Gastroenterological Association present the 2023 issue of Gastroenterology Data Trends, a special report on hot topics in gastroenterology told through original infographics and visual storytelling.

In this issue:

- Gastroenterology and Climate Change: Assessing and Mitigating Impacts

Swapna Gayam, MD, FACG - MASLD/MASH and Weight Loss

Arpan Mohanty, MD, MSc - Digital Tools in the Management of IBS/Functional GI Disorders

Eric D. Shah, MD, MBA, FACG - Long COVID and the Gastrointestinal System: Emerging Evidence

Daniel E. Freedberg, MD, MS, and Lin Chang, MD, AGAF - Germline Genetic Testing in CRC: Implications for Familial and Population-Based Testing

Fay Kastrinos, MD, MPH - Evolution of Targeted Therapies for C difficile

Sahil Khanna, MBBS, MS, FACG, AGAF - Harnessing the Power of AI to Enhance Endoscopy: Promises and Pitfalls

Eugenia Uche-Anya, MD, MPH - The Evolving Role of Surgery for IBD

Julie K.M. Thacker, MD, FACS, FASCRS

Germline Genetic Testing in CRC: Implications for Familial and Population-Based Testing

- Weiss JM et al. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2021;19(10):1122-1132. doi:10.1164/jnccn.2021.0048

- Samadder NJ et al. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(2):230-237. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.6252

- Pearlman R et al; Ohio Colorectal Cancer Prevention Initiative Study Group. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(4):464-471. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.5194

- Stoffel EM et al. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(4):897-905.e1. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2017.11.004

- Stoffel EM, Murphy CC. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(2):341-353. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2019.07.055

- Cavestro GM et al; Associazione Italiana Familiarità Ereditarietà Tumori; Collaborative Group of the Americas on Inherited Gastrointestinal Cancer; European Hereditary Tumour Group, and the International Society for Gastrointestinal Hereditary Tumours. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;21(3):581-603.e33. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2022.12.006

- Gupta S et al. Cancer. 2020;126(13):3013-3020. doi:10.1002/cncr.32851

- Stanich PP et al. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(5):1850-1852. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2020.12.009

- Rustgi S et al. Universal screening strategies for the identification of Lynch syndrome in colorectal cancer patients and at-risk relatives. Research forum lecture #263 presented at: Digestive Disease Week (DDW) 2023; May 6-9, 2023; Chicago, IL.

- Tier 1 genomic applications and their importance to public health. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reviewed March 6, 2014. Accessed August 15, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/genomics/implementation/toolkit/tier1.htm

- Win AK et al. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017;26(3):404-412. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-16-0693

- Yurgelun MB et al. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(10):1086-1095. doi:10.1200/JCO.2016.71.0012

- Pearlman R et al. JCO Precis Oncol. 2021;5:PO.20.00525. doi:10.1200/PO.20.00525

- Patel R, Hyer W. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2019;10(4):379-387. doi:10.1136/flgastro-2018-101053

- Weiss JM et al. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2021;19(10):1122-1132. doi:10.1164/jnccn.2021.0048

- Samadder NJ et al. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(2):230-237. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.6252

- Pearlman R et al; Ohio Colorectal Cancer Prevention Initiative Study Group. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(4):464-471. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.5194

- Stoffel EM et al. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(4):897-905.e1. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2017.11.004

- Stoffel EM, Murphy CC. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(2):341-353. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2019.07.055

- Cavestro GM et al; Associazione Italiana Familiarità Ereditarietà Tumori; Collaborative Group of the Americas on Inherited Gastrointestinal Cancer; European Hereditary Tumour Group, and the International Society for Gastrointestinal Hereditary Tumours. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;21(3):581-603.e33. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2022.12.006

- Gupta S et al. Cancer. 2020;126(13):3013-3020. doi:10.1002/cncr.32851

- Stanich PP et al. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(5):1850-1852. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2020.12.009

- Rustgi S et al. Universal screening strategies for the identification of Lynch syndrome in colorectal cancer patients and at-risk relatives. Research forum lecture #263 presented at: Digestive Disease Week (DDW) 2023; May 6-9, 2023; Chicago, IL.

- Tier 1 genomic applications and their importance to public health. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reviewed March 6, 2014. Accessed August 15, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/genomics/implementation/toolkit/tier1.htm

- Win AK et al. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017;26(3):404-412. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-16-0693

- Yurgelun MB et al. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(10):1086-1095. doi:10.1200/JCO.2016.71.0012

- Pearlman R et al. JCO Precis Oncol. 2021;5:PO.20.00525. doi:10.1200/PO.20.00525

- Patel R, Hyer W. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2019;10(4):379-387. doi:10.1136/flgastro-2018-101053

- Weiss JM et al. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2021;19(10):1122-1132. doi:10.1164/jnccn.2021.0048

- Samadder NJ et al. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(2):230-237. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.6252

- Pearlman R et al; Ohio Colorectal Cancer Prevention Initiative Study Group. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(4):464-471. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.5194

- Stoffel EM et al. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(4):897-905.e1. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2017.11.004

- Stoffel EM, Murphy CC. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(2):341-353. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2019.07.055

- Cavestro GM et al; Associazione Italiana Familiarità Ereditarietà Tumori; Collaborative Group of the Americas on Inherited Gastrointestinal Cancer; European Hereditary Tumour Group, and the International Society for Gastrointestinal Hereditary Tumours. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;21(3):581-603.e33. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2022.12.006

- Gupta S et al. Cancer. 2020;126(13):3013-3020. doi:10.1002/cncr.32851

- Stanich PP et al. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(5):1850-1852. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2020.12.009

- Rustgi S et al. Universal screening strategies for the identification of Lynch syndrome in colorectal cancer patients and at-risk relatives. Research forum lecture #263 presented at: Digestive Disease Week (DDW) 2023; May 6-9, 2023; Chicago, IL.

- Tier 1 genomic applications and their importance to public health. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reviewed March 6, 2014. Accessed August 15, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/genomics/implementation/toolkit/tier1.htm

- Win AK et al. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017;26(3):404-412. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-16-0693

- Yurgelun MB et al. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(10):1086-1095. doi:10.1200/JCO.2016.71.0012

- Pearlman R et al. JCO Precis Oncol. 2021;5:PO.20.00525. doi:10.1200/PO.20.00525

- Patel R, Hyer W. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2019;10(4):379-387. doi:10.1136/flgastro-2018-101053

AVAHO Shines Spotlight on Health Literacy

At a glance, “health literacy” sounds like it has something specifically to do with the ability to read. Mary Laudon Thomas, MS, CNS, AOCN, a former president of Association of VA Hematology/Oncology, knows better.

“It’s not the same as reading level, and it’s not the same as educational level,” Thomas told Federal Practitioner. “Even educated people can think men can’t get breast cancer or misunderstand how to properly take their medications.”

Instead, health literacy is a broader topic: Do patients understand what’s going on when they get medical care? Can they use the information they get to make informed decisions about their health? Low health literacy is associated with lower use of preventative care of poorer adherence, poorer ability to navigate the health system and contributes to social inequities. In cancer care, low health literacy is associated with lower levels of screening, longer lag times in symptom identification, impairments in risk perception, fewer questions, lower perceived quality of life, and less follow-up.

Thomas and colleagues explored strategies to improve health literacy in cancer care during a half-day session on September 28th, kicking off the AVAHO 2023 annual meeting in Chicago.

There are countless examples of patients who fail to understand aspects of their care, said Thomas, a retired clinical nurse specialist in hematology at California’s VA Palo Alto Health Care System who now serves as cochair of the AVAHO education committee. A patient may not realize that high blood pressure and hypertension are the same thing, for instance, or not understand that they need to go to the radiology department for a computed tomography.

“That’s our problem,” Thomas said. “We’re so fluent in our medical-speak that we forget we’re speaking a foreign language to other people.”

The goal of the AVAHO 2023 workshop is to “help people develop awareness of the scope of the problem and give them tools they can use to simplify how they speak to patients, teach patients and inform patients,” Thomas said.

In the first segment of the program, Angela Kumar, MPH, national program manager for Veterans Health Education and Information, discussed the VA organizational approach to health literacy. She noted that building a health-literate care organization aligns with the VA goal to be a high reliability organization. Veterans who have questions and concerns will need additional information throughout their cancer journey. The role for VA clinicians is to help answer veterans’ questions. “Rather than assume patients know what we are talking about, we have to make sure they understand,” Kumar explained. Institutional support will lead to better health outcomes and patient satisfaction throughout the system. VA is in the process of creating a patient centered learning program, Kumar noted. The program will be open to veterans, their families, caregivers, and provide training for VA health care professionals.

In the workshop’s 2 other sessions Janet Papadakos, PhD, MEd, a scientist at the University of Toronto’s Institute for Education Research, discussed the impact of health literacy on cancer treatment and outcomes and Fatemeh Youssefi, PhD, RN, OCN, director at large and committee member of the Oncology Nursing Society, discussed the roles of health literacy and patient education in empowering patients. Both speakers noted that patients with cancer are undergoing intense emotional stress, which can significantly impact their ability to understanding their treatment. Importantly, Papadakos explained, people can change and improve their health literacy, so clinicians have an opportunity to help influence and improve comprehension for their patient, by taking basic steps shown to improve health literacy.

“We know that in general, people with low health literacy report worse health, and they also have historically have poor outcomes,” Thomas said. Indeed, a 2021 systematic review of 66 papers found that “lower health literacy was associated with greater difficulties understanding and processing cancer related information, poorer quality of life and poorer experience of care.” Just 12% of US adults have proficient health literacy and one-third of adults have difficulty with common health tasks.

Papadakos and Youssefi provided some guidance for better communication with patients. Teach back, for example, is a tool to ensure patients understand topics when discussed. The key, Papadakos explained, is that it is not a test of the patient but rather a test of how well the information was communicated. Youssefi and Papadakos also emphasized the importance of using plain language. Clear and precise words that avoid technical terms avoid miscommunication and confusion. Finally, they urged clinicians to never assume health literacy and to approach all patients using clear language to ensure that they understand and can provide back the content covered.

Thomas said 3 more virtual sessions about health literacy will be offered over the coming year. Organizers will develop the specific topics after engaging in a discussion with attendees at the end of the AVAHO session. Meanwhile, advocates are developing a section of the AVAHO website that will be devoted to health literacy.

The workshop received support from Genentech.

At a glance, “health literacy” sounds like it has something specifically to do with the ability to read. Mary Laudon Thomas, MS, CNS, AOCN, a former president of Association of VA Hematology/Oncology, knows better.

“It’s not the same as reading level, and it’s not the same as educational level,” Thomas told Federal Practitioner. “Even educated people can think men can’t get breast cancer or misunderstand how to properly take their medications.”

Instead, health literacy is a broader topic: Do patients understand what’s going on when they get medical care? Can they use the information they get to make informed decisions about their health? Low health literacy is associated with lower use of preventative care of poorer adherence, poorer ability to navigate the health system and contributes to social inequities. In cancer care, low health literacy is associated with lower levels of screening, longer lag times in symptom identification, impairments in risk perception, fewer questions, lower perceived quality of life, and less follow-up.

Thomas and colleagues explored strategies to improve health literacy in cancer care during a half-day session on September 28th, kicking off the AVAHO 2023 annual meeting in Chicago.

There are countless examples of patients who fail to understand aspects of their care, said Thomas, a retired clinical nurse specialist in hematology at California’s VA Palo Alto Health Care System who now serves as cochair of the AVAHO education committee. A patient may not realize that high blood pressure and hypertension are the same thing, for instance, or not understand that they need to go to the radiology department for a computed tomography.

“That’s our problem,” Thomas said. “We’re so fluent in our medical-speak that we forget we’re speaking a foreign language to other people.”

The goal of the AVAHO 2023 workshop is to “help people develop awareness of the scope of the problem and give them tools they can use to simplify how they speak to patients, teach patients and inform patients,” Thomas said.

In the first segment of the program, Angela Kumar, MPH, national program manager for Veterans Health Education and Information, discussed the VA organizational approach to health literacy. She noted that building a health-literate care organization aligns with the VA goal to be a high reliability organization. Veterans who have questions and concerns will need additional information throughout their cancer journey. The role for VA clinicians is to help answer veterans’ questions. “Rather than assume patients know what we are talking about, we have to make sure they understand,” Kumar explained. Institutional support will lead to better health outcomes and patient satisfaction throughout the system. VA is in the process of creating a patient centered learning program, Kumar noted. The program will be open to veterans, their families, caregivers, and provide training for VA health care professionals.

In the workshop’s 2 other sessions Janet Papadakos, PhD, MEd, a scientist at the University of Toronto’s Institute for Education Research, discussed the impact of health literacy on cancer treatment and outcomes and Fatemeh Youssefi, PhD, RN, OCN, director at large and committee member of the Oncology Nursing Society, discussed the roles of health literacy and patient education in empowering patients. Both speakers noted that patients with cancer are undergoing intense emotional stress, which can significantly impact their ability to understanding their treatment. Importantly, Papadakos explained, people can change and improve their health literacy, so clinicians have an opportunity to help influence and improve comprehension for their patient, by taking basic steps shown to improve health literacy.

“We know that in general, people with low health literacy report worse health, and they also have historically have poor outcomes,” Thomas said. Indeed, a 2021 systematic review of 66 papers found that “lower health literacy was associated with greater difficulties understanding and processing cancer related information, poorer quality of life and poorer experience of care.” Just 12% of US adults have proficient health literacy and one-third of adults have difficulty with common health tasks.

Papadakos and Youssefi provided some guidance for better communication with patients. Teach back, for example, is a tool to ensure patients understand topics when discussed. The key, Papadakos explained, is that it is not a test of the patient but rather a test of how well the information was communicated. Youssefi and Papadakos also emphasized the importance of using plain language. Clear and precise words that avoid technical terms avoid miscommunication and confusion. Finally, they urged clinicians to never assume health literacy and to approach all patients using clear language to ensure that they understand and can provide back the content covered.

Thomas said 3 more virtual sessions about health literacy will be offered over the coming year. Organizers will develop the specific topics after engaging in a discussion with attendees at the end of the AVAHO session. Meanwhile, advocates are developing a section of the AVAHO website that will be devoted to health literacy.

The workshop received support from Genentech.

At a glance, “health literacy” sounds like it has something specifically to do with the ability to read. Mary Laudon Thomas, MS, CNS, AOCN, a former president of Association of VA Hematology/Oncology, knows better.

“It’s not the same as reading level, and it’s not the same as educational level,” Thomas told Federal Practitioner. “Even educated people can think men can’t get breast cancer or misunderstand how to properly take their medications.”

Instead, health literacy is a broader topic: Do patients understand what’s going on when they get medical care? Can they use the information they get to make informed decisions about their health? Low health literacy is associated with lower use of preventative care of poorer adherence, poorer ability to navigate the health system and contributes to social inequities. In cancer care, low health literacy is associated with lower levels of screening, longer lag times in symptom identification, impairments in risk perception, fewer questions, lower perceived quality of life, and less follow-up.

Thomas and colleagues explored strategies to improve health literacy in cancer care during a half-day session on September 28th, kicking off the AVAHO 2023 annual meeting in Chicago.

There are countless examples of patients who fail to understand aspects of their care, said Thomas, a retired clinical nurse specialist in hematology at California’s VA Palo Alto Health Care System who now serves as cochair of the AVAHO education committee. A patient may not realize that high blood pressure and hypertension are the same thing, for instance, or not understand that they need to go to the radiology department for a computed tomography.

“That’s our problem,” Thomas said. “We’re so fluent in our medical-speak that we forget we’re speaking a foreign language to other people.”

The goal of the AVAHO 2023 workshop is to “help people develop awareness of the scope of the problem and give them tools they can use to simplify how they speak to patients, teach patients and inform patients,” Thomas said.

In the first segment of the program, Angela Kumar, MPH, national program manager for Veterans Health Education and Information, discussed the VA organizational approach to health literacy. She noted that building a health-literate care organization aligns with the VA goal to be a high reliability organization. Veterans who have questions and concerns will need additional information throughout their cancer journey. The role for VA clinicians is to help answer veterans’ questions. “Rather than assume patients know what we are talking about, we have to make sure they understand,” Kumar explained. Institutional support will lead to better health outcomes and patient satisfaction throughout the system. VA is in the process of creating a patient centered learning program, Kumar noted. The program will be open to veterans, their families, caregivers, and provide training for VA health care professionals.

In the workshop’s 2 other sessions Janet Papadakos, PhD, MEd, a scientist at the University of Toronto’s Institute for Education Research, discussed the impact of health literacy on cancer treatment and outcomes and Fatemeh Youssefi, PhD, RN, OCN, director at large and committee member of the Oncology Nursing Society, discussed the roles of health literacy and patient education in empowering patients. Both speakers noted that patients with cancer are undergoing intense emotional stress, which can significantly impact their ability to understanding their treatment. Importantly, Papadakos explained, people can change and improve their health literacy, so clinicians have an opportunity to help influence and improve comprehension for their patient, by taking basic steps shown to improve health literacy.

“We know that in general, people with low health literacy report worse health, and they also have historically have poor outcomes,” Thomas said. Indeed, a 2021 systematic review of 66 papers found that “lower health literacy was associated with greater difficulties understanding and processing cancer related information, poorer quality of life and poorer experience of care.” Just 12% of US adults have proficient health literacy and one-third of adults have difficulty with common health tasks.

Papadakos and Youssefi provided some guidance for better communication with patients. Teach back, for example, is a tool to ensure patients understand topics when discussed. The key, Papadakos explained, is that it is not a test of the patient but rather a test of how well the information was communicated. Youssefi and Papadakos also emphasized the importance of using plain language. Clear and precise words that avoid technical terms avoid miscommunication and confusion. Finally, they urged clinicians to never assume health literacy and to approach all patients using clear language to ensure that they understand and can provide back the content covered.

Thomas said 3 more virtual sessions about health literacy will be offered over the coming year. Organizers will develop the specific topics after engaging in a discussion with attendees at the end of the AVAHO session. Meanwhile, advocates are developing a section of the AVAHO website that will be devoted to health literacy.

The workshop received support from Genentech.

Fremanezumab reduces medication overuse in chronic migraine

Key clinical point: Fremanezumab was effective as a preventive treatment in patients with chronic migraine (CM) with or without medication overuse (MO) and showed potential benefits in reducing MO.

Major finding: During a 12-week follow-up period, the administration of monthly and quarterly fremanezumab vs placebo led to significantly reduced average number of monthly headache days of moderate or greater severity in patients with MO (monthly: mean change [∆] −2.0, P = .0012; and quarterly: ∆ −1.8, P = .0042) and without MO (monthly: ∆ −1.6, P = .0437; and quarterly: ∆ −1.5, P = .0441). A greater proportion of patients receiving fremanezumab vs placebo reverted to no MO (P ≤ .05).

Study details: This post hoc analysis of a phase 2b/3 trial included 479 Japanese patients with CM who were randomly assigned to receive monthly fremanezumab (n = 159), quarterly fremanezumab (n = 159), or placebo (n = 161), and of whom 320 patients reported MO.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Several authors declared being full-time employees of Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., and N Imai declared ties with various other sources.

Source: Imai N et al. Effects of fremanezumab on medication overuse in Japanese chronic migraine patients: Post hoc analysis of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Neurol Ther. 2023 (Sep 11). doi: 10.1007/s40120-023-00531-3

Key clinical point: Fremanezumab was effective as a preventive treatment in patients with chronic migraine (CM) with or without medication overuse (MO) and showed potential benefits in reducing MO.

Major finding: During a 12-week follow-up period, the administration of monthly and quarterly fremanezumab vs placebo led to significantly reduced average number of monthly headache days of moderate or greater severity in patients with MO (monthly: mean change [∆] −2.0, P = .0012; and quarterly: ∆ −1.8, P = .0042) and without MO (monthly: ∆ −1.6, P = .0437; and quarterly: ∆ −1.5, P = .0441). A greater proportion of patients receiving fremanezumab vs placebo reverted to no MO (P ≤ .05).

Study details: This post hoc analysis of a phase 2b/3 trial included 479 Japanese patients with CM who were randomly assigned to receive monthly fremanezumab (n = 159), quarterly fremanezumab (n = 159), or placebo (n = 161), and of whom 320 patients reported MO.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Several authors declared being full-time employees of Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., and N Imai declared ties with various other sources.

Source: Imai N et al. Effects of fremanezumab on medication overuse in Japanese chronic migraine patients: Post hoc analysis of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Neurol Ther. 2023 (Sep 11). doi: 10.1007/s40120-023-00531-3

Key clinical point: Fremanezumab was effective as a preventive treatment in patients with chronic migraine (CM) with or without medication overuse (MO) and showed potential benefits in reducing MO.

Major finding: During a 12-week follow-up period, the administration of monthly and quarterly fremanezumab vs placebo led to significantly reduced average number of monthly headache days of moderate or greater severity in patients with MO (monthly: mean change [∆] −2.0, P = .0012; and quarterly: ∆ −1.8, P = .0042) and without MO (monthly: ∆ −1.6, P = .0437; and quarterly: ∆ −1.5, P = .0441). A greater proportion of patients receiving fremanezumab vs placebo reverted to no MO (P ≤ .05).

Study details: This post hoc analysis of a phase 2b/3 trial included 479 Japanese patients with CM who were randomly assigned to receive monthly fremanezumab (n = 159), quarterly fremanezumab (n = 159), or placebo (n = 161), and of whom 320 patients reported MO.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Several authors declared being full-time employees of Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., and N Imai declared ties with various other sources.

Source: Imai N et al. Effects of fremanezumab on medication overuse in Japanese chronic migraine patients: Post hoc analysis of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Neurol Ther. 2023 (Sep 11). doi: 10.1007/s40120-023-00531-3

Responders to anti-CGRP mAb show improvement in migraine-attack-associated symptoms

Key clinical point: Patients with migraine who achieved ≥ 50% reduction in headache days at 6 months (responders) with anti-calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) monoclonal antibodies (mAb) showed an even greater reduction in the number of days per month with photophobia, phonophobia, and aura ratios.

Major finding: Monthly headache days reduced significantly by 9.4 days/month (P < .001) and 2.2 days/month (P = .004) among responders and non-responders, respectively, with responders having additional significant reductions in photophobia (−19.5%; P < .001), phonophobia (−12.1%; P = .010), and aura (−25.1%; P = .008) ratios. Higher basal photophobia ratios were predictors of increased response rates between months 3 and 6 (incidence risk ratio 0.928; P = .040).

Study details: This prospective observational study included 158 patients with migraine treated with anti-CGRP mAb, of whom 43.7% were responders.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. A Alpuente, E Caronna, M Torres-Ferrús, and P Pozo-Rosich declared receiving honoraria as consultants or speakers from various sources.

Source: Alpuente A et al. Impact of anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies on migraine attack accompanying symptoms: A real-world evidence study. Cephalalgia. 2023;43(8):3331024231177636 (Aug 9). doi: 10.1177/03331024231177636

Key clinical point: Patients with migraine who achieved ≥ 50% reduction in headache days at 6 months (responders) with anti-calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) monoclonal antibodies (mAb) showed an even greater reduction in the number of days per month with photophobia, phonophobia, and aura ratios.

Major finding: Monthly headache days reduced significantly by 9.4 days/month (P < .001) and 2.2 days/month (P = .004) among responders and non-responders, respectively, with responders having additional significant reductions in photophobia (−19.5%; P < .001), phonophobia (−12.1%; P = .010), and aura (−25.1%; P = .008) ratios. Higher basal photophobia ratios were predictors of increased response rates between months 3 and 6 (incidence risk ratio 0.928; P = .040).

Study details: This prospective observational study included 158 patients with migraine treated with anti-CGRP mAb, of whom 43.7% were responders.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. A Alpuente, E Caronna, M Torres-Ferrús, and P Pozo-Rosich declared receiving honoraria as consultants or speakers from various sources.

Source: Alpuente A et al. Impact of anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies on migraine attack accompanying symptoms: A real-world evidence study. Cephalalgia. 2023;43(8):3331024231177636 (Aug 9). doi: 10.1177/03331024231177636

Key clinical point: Patients with migraine who achieved ≥ 50% reduction in headache days at 6 months (responders) with anti-calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) monoclonal antibodies (mAb) showed an even greater reduction in the number of days per month with photophobia, phonophobia, and aura ratios.

Major finding: Monthly headache days reduced significantly by 9.4 days/month (P < .001) and 2.2 days/month (P = .004) among responders and non-responders, respectively, with responders having additional significant reductions in photophobia (−19.5%; P < .001), phonophobia (−12.1%; P = .010), and aura (−25.1%; P = .008) ratios. Higher basal photophobia ratios were predictors of increased response rates between months 3 and 6 (incidence risk ratio 0.928; P = .040).

Study details: This prospective observational study included 158 patients with migraine treated with anti-CGRP mAb, of whom 43.7% were responders.

Disclosures: This study did not receive any funding. A Alpuente, E Caronna, M Torres-Ferrús, and P Pozo-Rosich declared receiving honoraria as consultants or speakers from various sources.

Source: Alpuente A et al. Impact of anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies on migraine attack accompanying symptoms: A real-world evidence study. Cephalalgia. 2023;43(8):3331024231177636 (Aug 9). doi: 10.1177/03331024231177636

Migraine history and COVID-19 risk in older women: Is there a link?

Key clinical point: No appreciable association was observed between a history of migraine or its subtypes and an increase in the risk for COVID-19, including hospitalization for COVID-19, in older women.

Major finding: No significant association was observed between a history of migraine and the risk of developing COVID-19 (odds ratio [OR] 1.08; 95% CI 0.95-1.22) or being hospitalized for COVID-19 (OR 1.20; 95% CI 0.86-1.68) among older women. Similarly, other migraine statuses, including migraine with aura, showed no association with the risk for COVID-19.

Study details: This prospective cohort study included 16,492 women (age ≥ 45 years) enrolled in the Women’s Health Study, of whom 28.9% had a history of migraine and 7.7% reported positive SARS-CoV-2 test results, a diagnosis of COVID-19, or hospitalization for COVID-19.

Disclosures: The Women’s Health Study was funded by grants from the US National Cancer Institute and the US National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. T Kurth declared receiving research grants and personal compensation from various sources. The other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Rist PM et al. History of migraine and risk of COVID-19: A cohort study. Am J Med. 2023 (Aug 18). doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2023.07.021

Key clinical point: No appreciable association was observed between a history of migraine or its subtypes and an increase in the risk for COVID-19, including hospitalization for COVID-19, in older women.

Major finding: No significant association was observed between a history of migraine and the risk of developing COVID-19 (odds ratio [OR] 1.08; 95% CI 0.95-1.22) or being hospitalized for COVID-19 (OR 1.20; 95% CI 0.86-1.68) among older women. Similarly, other migraine statuses, including migraine with aura, showed no association with the risk for COVID-19.

Study details: This prospective cohort study included 16,492 women (age ≥ 45 years) enrolled in the Women’s Health Study, of whom 28.9% had a history of migraine and 7.7% reported positive SARS-CoV-2 test results, a diagnosis of COVID-19, or hospitalization for COVID-19.

Disclosures: The Women’s Health Study was funded by grants from the US National Cancer Institute and the US National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. T Kurth declared receiving research grants and personal compensation from various sources. The other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Rist PM et al. History of migraine and risk of COVID-19: A cohort study. Am J Med. 2023 (Aug 18). doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2023.07.021

Key clinical point: No appreciable association was observed between a history of migraine or its subtypes and an increase in the risk for COVID-19, including hospitalization for COVID-19, in older women.

Major finding: No significant association was observed between a history of migraine and the risk of developing COVID-19 (odds ratio [OR] 1.08; 95% CI 0.95-1.22) or being hospitalized for COVID-19 (OR 1.20; 95% CI 0.86-1.68) among older women. Similarly, other migraine statuses, including migraine with aura, showed no association with the risk for COVID-19.

Study details: This prospective cohort study included 16,492 women (age ≥ 45 years) enrolled in the Women’s Health Study, of whom 28.9% had a history of migraine and 7.7% reported positive SARS-CoV-2 test results, a diagnosis of COVID-19, or hospitalization for COVID-19.

Disclosures: The Women’s Health Study was funded by grants from the US National Cancer Institute and the US National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. T Kurth declared receiving research grants and personal compensation from various sources. The other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Rist PM et al. History of migraine and risk of COVID-19: A cohort study. Am J Med. 2023 (Aug 18). doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2023.07.021