User login

Is fructose all to blame for obesity?

A recent article hypothesized that fructose causes more metabolic disease than does sucrose when overfed in the human diet. Fructose intake as high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS) has risen since its use in soft drinks in the United States and parallels the increase in the prevalence of obesity.

The newest hypothesis regarding fructose invokes a genetic survival of the fittest rationale for how fructose-enhanced fat deposition exacerbates the increased caloric consumption from the Western diet to promote metabolic disease especially in our adolescent and young adult population. This theory suggests that fructose consumption causes low adenosine triphosphate, which stimulates energy intake causing an imbalance of energy regulation.

Ongoing interest in the association between the increased use of HFCS and the prevalence of obesity in the United States continues. The use of HFCS in sugary sweetened beverages (SSBs) has reduced the cost of these beverages because of technology in preparing HFCS from corn and the substitution of the cheaper HFCS for sugar in SSBs. Although SSBs haven’t been proven to cause obesity, there has been an increase in the risk for type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease (CVD), nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), and even cancer. Research in HFCS, weight gain, and metabolic disease continues despite little definitive evidence of causation.

The relationship between SSBs consumption and obesity has been attributed to the increase in overall total caloric intake of the diet. These liquid calories do not suppress the intake of other foods to equalize the total amount of calories ingested. This knowledge has been gleaned from work performed by R. Mattes and B. Rolls in the 1990s through the early 2000s.

This research and the current work on HFCS and metabolic disease is important because there are adolescents and young adults in the United States and globally that ingest a large amount of SSBs and therefore are at risk for metabolic disease, type 2 diabetes, NAFLD, and CVD at an early age.

, around 1970-1980.

Researchers noted the association and began to focus on potential reasons to pinpoint HFCS or fructose itself so we have a mechanism of action specific to fructose. Therefore, the public could be warned about the risk of drinking SSBs due to the HFCS and fructose ingested and the possibility of metabolic disease. Perhaps, there is a method to remove harmful HFCS from the food supply much like what has happened with industrially produced trans fatty acids. In 2018, the World Health Organization called for a total ban on trans fats due to causation of 500 million early deaths per year globally.

Similar to the process of making HFCS, most trans fats are formed through an industrial process that alters vegetable oil and creates a shelf stable inexpensive partially hydrogenated oil. Trans fats have been shown to increase low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and decrease high-density lipoprotein (HDL) increasing the risk for myocardial infarction and stroke.

What was the pivotal moment for the ban on trans fats? It was tough convincing the scientific community and certainly the industry that trans fats were especially harmful. This is because of the dogma that margarine and Crisco oils were somehow better for you than were lard and butter. The evidence kept coming in from epidemiological studies showing that people who ate more trans fats had increased levels of LDL and decreased levels of HDL, and the dogma that saturated fat was the villain in heart disease was reinforced. Maybe that pivotal moment was when a researcher with experience testing trans fat deposition in cadavers and pigs sued the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for not acting on cumulative evidence sooner.

Do we have this kind of evidence to make a claim for the FDA to ban HFCS? What we have is the time course of HFCS entry into the food supply which occurred in 1970. This coincided with the growing prevalence of obesity between 1960 and 2000.

The excess energy in SSBs can provide a hedonic stimulus that overcomes the natural energy balance regulatory mechanism because SSBs excess energy comes in liquid form and may bypass the satiety signal in the hypothalamus.

We still have to prove this.

Blaming fructose in HFCS as the sole cause for the increase obesity will be much tougher than blaming trans fats for an increase in LDL cholesterol and a decrease in HDL cholesterol.

The prevalence of obesity has increased worldwide, even in countries where SSBs do not contain HFCS.

Still, the proof that HFCS can override the satiety pathway and cause excess calorie intake is intriguing and may have teeth if we can pinpoint the increase in prevalence of obesity in children and adolescents on increased ingestion of HFCS in SSBs. There is no reason nutritionally to add sugar or HFCS to liquids. Plus, if HFCS has a metabolic disadvantage then all the more reason to ban it. Then, it becomes like trans fats: a toxin in the food supply.

Dr. Apovian is a Faculty Member, Department of Medicine; Co-Director, Center for Weight Management and Wellness, Section of Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Hypertension, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts. She has disclosed financial relationships with Altimmune, Inc; Cowen and Company, LLC; Currax Pharmaceuticals, LLC; EPG Communication Holdings, Ltd; Gelesis, Srl; L-Nutra, Inc; NeuroBo Pharmaceuticals; and Novo Nordisk, Inc. She has received research grants from the National Institutes of Health; Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute; GI Dynamics, Inc.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

A recent article hypothesized that fructose causes more metabolic disease than does sucrose when overfed in the human diet. Fructose intake as high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS) has risen since its use in soft drinks in the United States and parallels the increase in the prevalence of obesity.

The newest hypothesis regarding fructose invokes a genetic survival of the fittest rationale for how fructose-enhanced fat deposition exacerbates the increased caloric consumption from the Western diet to promote metabolic disease especially in our adolescent and young adult population. This theory suggests that fructose consumption causes low adenosine triphosphate, which stimulates energy intake causing an imbalance of energy regulation.

Ongoing interest in the association between the increased use of HFCS and the prevalence of obesity in the United States continues. The use of HFCS in sugary sweetened beverages (SSBs) has reduced the cost of these beverages because of technology in preparing HFCS from corn and the substitution of the cheaper HFCS for sugar in SSBs. Although SSBs haven’t been proven to cause obesity, there has been an increase in the risk for type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease (CVD), nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), and even cancer. Research in HFCS, weight gain, and metabolic disease continues despite little definitive evidence of causation.

The relationship between SSBs consumption and obesity has been attributed to the increase in overall total caloric intake of the diet. These liquid calories do not suppress the intake of other foods to equalize the total amount of calories ingested. This knowledge has been gleaned from work performed by R. Mattes and B. Rolls in the 1990s through the early 2000s.

This research and the current work on HFCS and metabolic disease is important because there are adolescents and young adults in the United States and globally that ingest a large amount of SSBs and therefore are at risk for metabolic disease, type 2 diabetes, NAFLD, and CVD at an early age.

, around 1970-1980.

Researchers noted the association and began to focus on potential reasons to pinpoint HFCS or fructose itself so we have a mechanism of action specific to fructose. Therefore, the public could be warned about the risk of drinking SSBs due to the HFCS and fructose ingested and the possibility of metabolic disease. Perhaps, there is a method to remove harmful HFCS from the food supply much like what has happened with industrially produced trans fatty acids. In 2018, the World Health Organization called for a total ban on trans fats due to causation of 500 million early deaths per year globally.

Similar to the process of making HFCS, most trans fats are formed through an industrial process that alters vegetable oil and creates a shelf stable inexpensive partially hydrogenated oil. Trans fats have been shown to increase low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and decrease high-density lipoprotein (HDL) increasing the risk for myocardial infarction and stroke.

What was the pivotal moment for the ban on trans fats? It was tough convincing the scientific community and certainly the industry that trans fats were especially harmful. This is because of the dogma that margarine and Crisco oils were somehow better for you than were lard and butter. The evidence kept coming in from epidemiological studies showing that people who ate more trans fats had increased levels of LDL and decreased levels of HDL, and the dogma that saturated fat was the villain in heart disease was reinforced. Maybe that pivotal moment was when a researcher with experience testing trans fat deposition in cadavers and pigs sued the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for not acting on cumulative evidence sooner.

Do we have this kind of evidence to make a claim for the FDA to ban HFCS? What we have is the time course of HFCS entry into the food supply which occurred in 1970. This coincided with the growing prevalence of obesity between 1960 and 2000.

The excess energy in SSBs can provide a hedonic stimulus that overcomes the natural energy balance regulatory mechanism because SSBs excess energy comes in liquid form and may bypass the satiety signal in the hypothalamus.

We still have to prove this.

Blaming fructose in HFCS as the sole cause for the increase obesity will be much tougher than blaming trans fats for an increase in LDL cholesterol and a decrease in HDL cholesterol.

The prevalence of obesity has increased worldwide, even in countries where SSBs do not contain HFCS.

Still, the proof that HFCS can override the satiety pathway and cause excess calorie intake is intriguing and may have teeth if we can pinpoint the increase in prevalence of obesity in children and adolescents on increased ingestion of HFCS in SSBs. There is no reason nutritionally to add sugar or HFCS to liquids. Plus, if HFCS has a metabolic disadvantage then all the more reason to ban it. Then, it becomes like trans fats: a toxin in the food supply.

Dr. Apovian is a Faculty Member, Department of Medicine; Co-Director, Center for Weight Management and Wellness, Section of Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Hypertension, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts. She has disclosed financial relationships with Altimmune, Inc; Cowen and Company, LLC; Currax Pharmaceuticals, LLC; EPG Communication Holdings, Ltd; Gelesis, Srl; L-Nutra, Inc; NeuroBo Pharmaceuticals; and Novo Nordisk, Inc. She has received research grants from the National Institutes of Health; Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute; GI Dynamics, Inc.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

A recent article hypothesized that fructose causes more metabolic disease than does sucrose when overfed in the human diet. Fructose intake as high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS) has risen since its use in soft drinks in the United States and parallels the increase in the prevalence of obesity.

The newest hypothesis regarding fructose invokes a genetic survival of the fittest rationale for how fructose-enhanced fat deposition exacerbates the increased caloric consumption from the Western diet to promote metabolic disease especially in our adolescent and young adult population. This theory suggests that fructose consumption causes low adenosine triphosphate, which stimulates energy intake causing an imbalance of energy regulation.

Ongoing interest in the association between the increased use of HFCS and the prevalence of obesity in the United States continues. The use of HFCS in sugary sweetened beverages (SSBs) has reduced the cost of these beverages because of technology in preparing HFCS from corn and the substitution of the cheaper HFCS for sugar in SSBs. Although SSBs haven’t been proven to cause obesity, there has been an increase in the risk for type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease (CVD), nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), and even cancer. Research in HFCS, weight gain, and metabolic disease continues despite little definitive evidence of causation.

The relationship between SSBs consumption and obesity has been attributed to the increase in overall total caloric intake of the diet. These liquid calories do not suppress the intake of other foods to equalize the total amount of calories ingested. This knowledge has been gleaned from work performed by R. Mattes and B. Rolls in the 1990s through the early 2000s.

This research and the current work on HFCS and metabolic disease is important because there are adolescents and young adults in the United States and globally that ingest a large amount of SSBs and therefore are at risk for metabolic disease, type 2 diabetes, NAFLD, and CVD at an early age.

, around 1970-1980.

Researchers noted the association and began to focus on potential reasons to pinpoint HFCS or fructose itself so we have a mechanism of action specific to fructose. Therefore, the public could be warned about the risk of drinking SSBs due to the HFCS and fructose ingested and the possibility of metabolic disease. Perhaps, there is a method to remove harmful HFCS from the food supply much like what has happened with industrially produced trans fatty acids. In 2018, the World Health Organization called for a total ban on trans fats due to causation of 500 million early deaths per year globally.

Similar to the process of making HFCS, most trans fats are formed through an industrial process that alters vegetable oil and creates a shelf stable inexpensive partially hydrogenated oil. Trans fats have been shown to increase low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and decrease high-density lipoprotein (HDL) increasing the risk for myocardial infarction and stroke.

What was the pivotal moment for the ban on trans fats? It was tough convincing the scientific community and certainly the industry that trans fats were especially harmful. This is because of the dogma that margarine and Crisco oils were somehow better for you than were lard and butter. The evidence kept coming in from epidemiological studies showing that people who ate more trans fats had increased levels of LDL and decreased levels of HDL, and the dogma that saturated fat was the villain in heart disease was reinforced. Maybe that pivotal moment was when a researcher with experience testing trans fat deposition in cadavers and pigs sued the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for not acting on cumulative evidence sooner.

Do we have this kind of evidence to make a claim for the FDA to ban HFCS? What we have is the time course of HFCS entry into the food supply which occurred in 1970. This coincided with the growing prevalence of obesity between 1960 and 2000.

The excess energy in SSBs can provide a hedonic stimulus that overcomes the natural energy balance regulatory mechanism because SSBs excess energy comes in liquid form and may bypass the satiety signal in the hypothalamus.

We still have to prove this.

Blaming fructose in HFCS as the sole cause for the increase obesity will be much tougher than blaming trans fats for an increase in LDL cholesterol and a decrease in HDL cholesterol.

The prevalence of obesity has increased worldwide, even in countries where SSBs do not contain HFCS.

Still, the proof that HFCS can override the satiety pathway and cause excess calorie intake is intriguing and may have teeth if we can pinpoint the increase in prevalence of obesity in children and adolescents on increased ingestion of HFCS in SSBs. There is no reason nutritionally to add sugar or HFCS to liquids. Plus, if HFCS has a metabolic disadvantage then all the more reason to ban it. Then, it becomes like trans fats: a toxin in the food supply.

Dr. Apovian is a Faculty Member, Department of Medicine; Co-Director, Center for Weight Management and Wellness, Section of Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Hypertension, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts. She has disclosed financial relationships with Altimmune, Inc; Cowen and Company, LLC; Currax Pharmaceuticals, LLC; EPG Communication Holdings, Ltd; Gelesis, Srl; L-Nutra, Inc; NeuroBo Pharmaceuticals; and Novo Nordisk, Inc. She has received research grants from the National Institutes of Health; Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute; GI Dynamics, Inc.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Making an impact beyond medicine

across all career stages and practice settings, highlight the diversity of our membership, and build a sense of community by learning more about one another.

As physicians, we are fortunate to have the opportunity to meaningfully impact the lives of our patients through the practice of clinical medicine, or by spearheading groundbreaking research that improves patient outcomes. However, some physicians arguably make their greatest mark outside of medicine.

To close out the inaugural year of our Member Spotlight feature, we introduce you to gastroenterologist Eric Esrailian, MD, MPH, chair of the division of gastroenterology at UCLA. He is an Emmy-nominated film producer and distinguished human rights advocate. His story is inspirational, and poignantly highlights how one’s impact as a physician can extend far beyond the walls of the hospital. We hope to continue to feature exceptional individuals like Dr. Esrailian who leverage their unique talents for societal good. We appreciate your continued nominations as we plan our 2024 coverage.

Also in the December issue, we summarize the results of a pivotal, head-to-head trial of risankizumab (Skyrizi) and ustekinumab (Stelara) for Crohn’s disease, which was presented in October at United European Gastroenterology (UEG) Week in Copenhagen.

We also highlight the FDA’s recent approval of vonoprazan, a new pharmacologic treatment for erosive esophagitis expected to be available in the U.S. sometime this month. Finally, Dr. Lauren Feld explains how gastroenterologists can advocate for more robust parental leave and return to work policies at their institutions and why it matters.

We wish you all a wonderful holiday season and look forward to seeing you again in the New Year.

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

across all career stages and practice settings, highlight the diversity of our membership, and build a sense of community by learning more about one another.

As physicians, we are fortunate to have the opportunity to meaningfully impact the lives of our patients through the practice of clinical medicine, or by spearheading groundbreaking research that improves patient outcomes. However, some physicians arguably make their greatest mark outside of medicine.

To close out the inaugural year of our Member Spotlight feature, we introduce you to gastroenterologist Eric Esrailian, MD, MPH, chair of the division of gastroenterology at UCLA. He is an Emmy-nominated film producer and distinguished human rights advocate. His story is inspirational, and poignantly highlights how one’s impact as a physician can extend far beyond the walls of the hospital. We hope to continue to feature exceptional individuals like Dr. Esrailian who leverage their unique talents for societal good. We appreciate your continued nominations as we plan our 2024 coverage.

Also in the December issue, we summarize the results of a pivotal, head-to-head trial of risankizumab (Skyrizi) and ustekinumab (Stelara) for Crohn’s disease, which was presented in October at United European Gastroenterology (UEG) Week in Copenhagen.

We also highlight the FDA’s recent approval of vonoprazan, a new pharmacologic treatment for erosive esophagitis expected to be available in the U.S. sometime this month. Finally, Dr. Lauren Feld explains how gastroenterologists can advocate for more robust parental leave and return to work policies at their institutions and why it matters.

We wish you all a wonderful holiday season and look forward to seeing you again in the New Year.

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

across all career stages and practice settings, highlight the diversity of our membership, and build a sense of community by learning more about one another.

As physicians, we are fortunate to have the opportunity to meaningfully impact the lives of our patients through the practice of clinical medicine, or by spearheading groundbreaking research that improves patient outcomes. However, some physicians arguably make their greatest mark outside of medicine.

To close out the inaugural year of our Member Spotlight feature, we introduce you to gastroenterologist Eric Esrailian, MD, MPH, chair of the division of gastroenterology at UCLA. He is an Emmy-nominated film producer and distinguished human rights advocate. His story is inspirational, and poignantly highlights how one’s impact as a physician can extend far beyond the walls of the hospital. We hope to continue to feature exceptional individuals like Dr. Esrailian who leverage their unique talents for societal good. We appreciate your continued nominations as we plan our 2024 coverage.

Also in the December issue, we summarize the results of a pivotal, head-to-head trial of risankizumab (Skyrizi) and ustekinumab (Stelara) for Crohn’s disease, which was presented in October at United European Gastroenterology (UEG) Week in Copenhagen.

We also highlight the FDA’s recent approval of vonoprazan, a new pharmacologic treatment for erosive esophagitis expected to be available in the U.S. sometime this month. Finally, Dr. Lauren Feld explains how gastroenterologists can advocate for more robust parental leave and return to work policies at their institutions and why it matters.

We wish you all a wonderful holiday season and look forward to seeing you again in the New Year.

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

In general, I’m happy

I’m a general neurologist. I consider myself a jack of all (or at least most) trades in my field, and a master of none.

In the April 2023 issue of JAMA Neurology there was an editorial about neurology training, with general neurology being renamed “comprehensive neurology” and a fellowship offered in practicing general neurology.

This seems rather silly to me. If 4 years of residency (1 of internship and 3 of neurology) don’t prepare you to practice general neurology, then what’s the point of residency at all? For that matter, what difference will renaming it do?

Imagine completing a 3-year internal medicine residency, then being told you need to do a fellowship in “comprehensive medicine” in order to practice. Or at least so you can add the word “comprehensive” to your shingle.

The authors bemoan the increasing number of neurology residents wanting to do fellowships and subspecialize, a situation that mirrors the general trend of people away from general medicine toward specialties.

While I agree we do need subspecialists in neurology (and currently there are at least 31 recognized, which is way more than I would have guessed), the fact is that patients, and sometimes their internists, aren’t going to be the best judge of who does or doesn’t need to see one, compared with a general neurologist.

Most of us general people can handle straightforward Parkinson’s disease, epilepsy, migraines, etc. Certainly, there are times where the condition is refractory to our care, or there’s something unusual about the case, that leads us to refer them to someone with more expertise. But isn’t that how it’s supposed to work? Like medicine in general, we need more general people than subspecialists.

Honestly, I can’t claim to be any different. Twenty-six years ago, when I finished residency, I did a clinical neurophysiology fellowship. From a practical view it was an epilepsy fellowship at my program. Some of this was an interest at the time in subspecializing, some of it was me putting off joining the “real world” of having to find a job for a year.

When I hung up my own shingle, my business card listed a subspecialty in epilepsy. Looking back years later, this wasn’t the best move. In solo practice I had no access to an epilepsy monitoring unit, vagus nerve stimulation capabilities, or epilepsy surgery at the hospital I rounded at. Not only that, I discovered it put me at a disadvantage, as internists were referring only epilepsy patients to me, and all the other stuff (which is the majority of patients) to the general (or comprehensive) neurologists around me. Which, financially, wasn’t a good thing when you’re young and starting out.

Not only that, but I discovered that I didn’t like only seeing one thing. I found it boring, and not for me.

So after a year or so, I took the word “epilepsy” off my card, left it at “general neurology,” and sent out letters reminding my referral base that I was willing to see the majority of things in my field (rare diseases, even today, I won’t attempt to handle).

So now my days are a mix of things, which I like. Neurology is enough of a specialty for me without going further up the pyramid. Having sub (and even sub-sub) specialists is important to maintain medical excellence, but we still need people willing to do general neurology, and I’m happy there.

Changing my title to “comprehensive” is unnecessary. I’m happy with what I am.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I’m a general neurologist. I consider myself a jack of all (or at least most) trades in my field, and a master of none.

In the April 2023 issue of JAMA Neurology there was an editorial about neurology training, with general neurology being renamed “comprehensive neurology” and a fellowship offered in practicing general neurology.

This seems rather silly to me. If 4 years of residency (1 of internship and 3 of neurology) don’t prepare you to practice general neurology, then what’s the point of residency at all? For that matter, what difference will renaming it do?

Imagine completing a 3-year internal medicine residency, then being told you need to do a fellowship in “comprehensive medicine” in order to practice. Or at least so you can add the word “comprehensive” to your shingle.

The authors bemoan the increasing number of neurology residents wanting to do fellowships and subspecialize, a situation that mirrors the general trend of people away from general medicine toward specialties.

While I agree we do need subspecialists in neurology (and currently there are at least 31 recognized, which is way more than I would have guessed), the fact is that patients, and sometimes their internists, aren’t going to be the best judge of who does or doesn’t need to see one, compared with a general neurologist.

Most of us general people can handle straightforward Parkinson’s disease, epilepsy, migraines, etc. Certainly, there are times where the condition is refractory to our care, or there’s something unusual about the case, that leads us to refer them to someone with more expertise. But isn’t that how it’s supposed to work? Like medicine in general, we need more general people than subspecialists.

Honestly, I can’t claim to be any different. Twenty-six years ago, when I finished residency, I did a clinical neurophysiology fellowship. From a practical view it was an epilepsy fellowship at my program. Some of this was an interest at the time in subspecializing, some of it was me putting off joining the “real world” of having to find a job for a year.

When I hung up my own shingle, my business card listed a subspecialty in epilepsy. Looking back years later, this wasn’t the best move. In solo practice I had no access to an epilepsy monitoring unit, vagus nerve stimulation capabilities, or epilepsy surgery at the hospital I rounded at. Not only that, I discovered it put me at a disadvantage, as internists were referring only epilepsy patients to me, and all the other stuff (which is the majority of patients) to the general (or comprehensive) neurologists around me. Which, financially, wasn’t a good thing when you’re young and starting out.

Not only that, but I discovered that I didn’t like only seeing one thing. I found it boring, and not for me.

So after a year or so, I took the word “epilepsy” off my card, left it at “general neurology,” and sent out letters reminding my referral base that I was willing to see the majority of things in my field (rare diseases, even today, I won’t attempt to handle).

So now my days are a mix of things, which I like. Neurology is enough of a specialty for me without going further up the pyramid. Having sub (and even sub-sub) specialists is important to maintain medical excellence, but we still need people willing to do general neurology, and I’m happy there.

Changing my title to “comprehensive” is unnecessary. I’m happy with what I am.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I’m a general neurologist. I consider myself a jack of all (or at least most) trades in my field, and a master of none.

In the April 2023 issue of JAMA Neurology there was an editorial about neurology training, with general neurology being renamed “comprehensive neurology” and a fellowship offered in practicing general neurology.

This seems rather silly to me. If 4 years of residency (1 of internship and 3 of neurology) don’t prepare you to practice general neurology, then what’s the point of residency at all? For that matter, what difference will renaming it do?

Imagine completing a 3-year internal medicine residency, then being told you need to do a fellowship in “comprehensive medicine” in order to practice. Or at least so you can add the word “comprehensive” to your shingle.

The authors bemoan the increasing number of neurology residents wanting to do fellowships and subspecialize, a situation that mirrors the general trend of people away from general medicine toward specialties.

While I agree we do need subspecialists in neurology (and currently there are at least 31 recognized, which is way more than I would have guessed), the fact is that patients, and sometimes their internists, aren’t going to be the best judge of who does or doesn’t need to see one, compared with a general neurologist.

Most of us general people can handle straightforward Parkinson’s disease, epilepsy, migraines, etc. Certainly, there are times where the condition is refractory to our care, or there’s something unusual about the case, that leads us to refer them to someone with more expertise. But isn’t that how it’s supposed to work? Like medicine in general, we need more general people than subspecialists.

Honestly, I can’t claim to be any different. Twenty-six years ago, when I finished residency, I did a clinical neurophysiology fellowship. From a practical view it was an epilepsy fellowship at my program. Some of this was an interest at the time in subspecializing, some of it was me putting off joining the “real world” of having to find a job for a year.

When I hung up my own shingle, my business card listed a subspecialty in epilepsy. Looking back years later, this wasn’t the best move. In solo practice I had no access to an epilepsy monitoring unit, vagus nerve stimulation capabilities, or epilepsy surgery at the hospital I rounded at. Not only that, I discovered it put me at a disadvantage, as internists were referring only epilepsy patients to me, and all the other stuff (which is the majority of patients) to the general (or comprehensive) neurologists around me. Which, financially, wasn’t a good thing when you’re young and starting out.

Not only that, but I discovered that I didn’t like only seeing one thing. I found it boring, and not for me.

So after a year or so, I took the word “epilepsy” off my card, left it at “general neurology,” and sent out letters reminding my referral base that I was willing to see the majority of things in my field (rare diseases, even today, I won’t attempt to handle).

So now my days are a mix of things, which I like. Neurology is enough of a specialty for me without going further up the pyramid. Having sub (and even sub-sub) specialists is important to maintain medical excellence, but we still need people willing to do general neurology, and I’m happy there.

Changing my title to “comprehensive” is unnecessary. I’m happy with what I am.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Quitting medical school

A few weeks ago I shared by concerns about the dwindling numbers of primary care physicians. The early exodus of practicing providers and an obvious disinterest by future physicians in what they see as the unpalatable work/life balance of frontline hands-on medicine are among the causes.

A recent study published in the journal Pediatrics highlights personal finance as a contributor to the drain on the primary care workforce. The investigators found “high self-reported educational debt ($200,000 to < $300,000) was positively associated with training in a positive lifetime earnings potential subspecialty.” In other words, why would a physician who was burdened with student loans enter a subspecialty that would limit his or her ability to pay it off? I suspect that money has always been a factor in career selection, but the ballooning cost of college and medical school has certainly not nudged graduates toward the low lifetime earnings potential of primary care pediatrics.

Another recently released survey adds the perspective of current medical school students to the murky future of the primary health care workforce. The Clinician of the Future 2023: Education Edition, published by Elsevier Health, reports on insights of more than 2,000 nursing and medical school student from around the world. The headline shocker was that while across the board a not surprising 12% of medical students were considering quitting their studies, in the United States this number was 25%.

Overall, more than 60% of the students worried about their future income, how workforce shortages would effect them and whether they would join the ranks of those clinicians suffering from burnout. While the students surveyed acknowledged that artificial intelligence could have some negative repercussions, 62% were excited about its use in their education. Similarly, they anticipated the positive contribution of digital technology while acknowledging its potential downsides.

Given the current mental health climate in this country, I was not surprised that almost a quarter of medical students in this country are considering quitting school. I would like to see a larger sample surveyed and repeated over time. But, the discrepancy between the United States and the rest of the world is troubling.

The number that really jumped out at me was that 54% of medical students (nurses, 62%) viewed “ their current studies as a stepping-stone toward a broader career in health care.” As an example, the authors quoted one medical student who plans to “look for other possibilities where I don’t directly treat patients.”

Whether this disinterest in direct patient care is an attitude that preceded their entry into medical school or a change reflecting a major reversal induced by the realty of face-to-face patient encounters in school was not addressed in the survey. I think the general population would be surprised and maybe disappointed to learn that half the students in medical school weren’t planning on seeing patients.

I went off to medical school with a rather naive Norman Rockwellian view of a physician. I was a little surprised that a few of my classmates seemed to be gravitating toward administrative and research careers, but by far most of us were heading toward opportunities that would place us face to face with patients. Some would become specialists but primary care still had an appeal for many of us.

In my last letter about primary care training, I suggested that traditional medical school was probably a poor investment for the person who shares a bit of my old-school image of the primary care physician. In addition to cost and the time invested, the curriculum would likely be overly broad and deep and not terribly applicable to the patient mix he or she would eventually be seeing. This global survey may suggest that medical students have already discovered, or are just now discovering, this mismatch between medical school and the realities of primary care.

Our challenge is to first deal with deterrent of student debt and then to develop a new, affordable and efficient pathway to primary care that attracts those people who are looking for a face to face style of medicine on the front line. The patients know we need specialists and administrators but they also want a bit more of Norman Rockwell.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

A few weeks ago I shared by concerns about the dwindling numbers of primary care physicians. The early exodus of practicing providers and an obvious disinterest by future physicians in what they see as the unpalatable work/life balance of frontline hands-on medicine are among the causes.

A recent study published in the journal Pediatrics highlights personal finance as a contributor to the drain on the primary care workforce. The investigators found “high self-reported educational debt ($200,000 to < $300,000) was positively associated with training in a positive lifetime earnings potential subspecialty.” In other words, why would a physician who was burdened with student loans enter a subspecialty that would limit his or her ability to pay it off? I suspect that money has always been a factor in career selection, but the ballooning cost of college and medical school has certainly not nudged graduates toward the low lifetime earnings potential of primary care pediatrics.

Another recently released survey adds the perspective of current medical school students to the murky future of the primary health care workforce. The Clinician of the Future 2023: Education Edition, published by Elsevier Health, reports on insights of more than 2,000 nursing and medical school student from around the world. The headline shocker was that while across the board a not surprising 12% of medical students were considering quitting their studies, in the United States this number was 25%.

Overall, more than 60% of the students worried about their future income, how workforce shortages would effect them and whether they would join the ranks of those clinicians suffering from burnout. While the students surveyed acknowledged that artificial intelligence could have some negative repercussions, 62% were excited about its use in their education. Similarly, they anticipated the positive contribution of digital technology while acknowledging its potential downsides.

Given the current mental health climate in this country, I was not surprised that almost a quarter of medical students in this country are considering quitting school. I would like to see a larger sample surveyed and repeated over time. But, the discrepancy between the United States and the rest of the world is troubling.

The number that really jumped out at me was that 54% of medical students (nurses, 62%) viewed “ their current studies as a stepping-stone toward a broader career in health care.” As an example, the authors quoted one medical student who plans to “look for other possibilities where I don’t directly treat patients.”

Whether this disinterest in direct patient care is an attitude that preceded their entry into medical school or a change reflecting a major reversal induced by the realty of face-to-face patient encounters in school was not addressed in the survey. I think the general population would be surprised and maybe disappointed to learn that half the students in medical school weren’t planning on seeing patients.

I went off to medical school with a rather naive Norman Rockwellian view of a physician. I was a little surprised that a few of my classmates seemed to be gravitating toward administrative and research careers, but by far most of us were heading toward opportunities that would place us face to face with patients. Some would become specialists but primary care still had an appeal for many of us.

In my last letter about primary care training, I suggested that traditional medical school was probably a poor investment for the person who shares a bit of my old-school image of the primary care physician. In addition to cost and the time invested, the curriculum would likely be overly broad and deep and not terribly applicable to the patient mix he or she would eventually be seeing. This global survey may suggest that medical students have already discovered, or are just now discovering, this mismatch between medical school and the realities of primary care.

Our challenge is to first deal with deterrent of student debt and then to develop a new, affordable and efficient pathway to primary care that attracts those people who are looking for a face to face style of medicine on the front line. The patients know we need specialists and administrators but they also want a bit more of Norman Rockwell.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

A few weeks ago I shared by concerns about the dwindling numbers of primary care physicians. The early exodus of practicing providers and an obvious disinterest by future physicians in what they see as the unpalatable work/life balance of frontline hands-on medicine are among the causes.

A recent study published in the journal Pediatrics highlights personal finance as a contributor to the drain on the primary care workforce. The investigators found “high self-reported educational debt ($200,000 to < $300,000) was positively associated with training in a positive lifetime earnings potential subspecialty.” In other words, why would a physician who was burdened with student loans enter a subspecialty that would limit his or her ability to pay it off? I suspect that money has always been a factor in career selection, but the ballooning cost of college and medical school has certainly not nudged graduates toward the low lifetime earnings potential of primary care pediatrics.

Another recently released survey adds the perspective of current medical school students to the murky future of the primary health care workforce. The Clinician of the Future 2023: Education Edition, published by Elsevier Health, reports on insights of more than 2,000 nursing and medical school student from around the world. The headline shocker was that while across the board a not surprising 12% of medical students were considering quitting their studies, in the United States this number was 25%.

Overall, more than 60% of the students worried about their future income, how workforce shortages would effect them and whether they would join the ranks of those clinicians suffering from burnout. While the students surveyed acknowledged that artificial intelligence could have some negative repercussions, 62% were excited about its use in their education. Similarly, they anticipated the positive contribution of digital technology while acknowledging its potential downsides.

Given the current mental health climate in this country, I was not surprised that almost a quarter of medical students in this country are considering quitting school. I would like to see a larger sample surveyed and repeated over time. But, the discrepancy between the United States and the rest of the world is troubling.

The number that really jumped out at me was that 54% of medical students (nurses, 62%) viewed “ their current studies as a stepping-stone toward a broader career in health care.” As an example, the authors quoted one medical student who plans to “look for other possibilities where I don’t directly treat patients.”

Whether this disinterest in direct patient care is an attitude that preceded their entry into medical school or a change reflecting a major reversal induced by the realty of face-to-face patient encounters in school was not addressed in the survey. I think the general population would be surprised and maybe disappointed to learn that half the students in medical school weren’t planning on seeing patients.

I went off to medical school with a rather naive Norman Rockwellian view of a physician. I was a little surprised that a few of my classmates seemed to be gravitating toward administrative and research careers, but by far most of us were heading toward opportunities that would place us face to face with patients. Some would become specialists but primary care still had an appeal for many of us.

In my last letter about primary care training, I suggested that traditional medical school was probably a poor investment for the person who shares a bit of my old-school image of the primary care physician. In addition to cost and the time invested, the curriculum would likely be overly broad and deep and not terribly applicable to the patient mix he or she would eventually be seeing. This global survey may suggest that medical students have already discovered, or are just now discovering, this mismatch between medical school and the realities of primary care.

Our challenge is to first deal with deterrent of student debt and then to develop a new, affordable and efficient pathway to primary care that attracts those people who are looking for a face to face style of medicine on the front line. The patients know we need specialists and administrators but they also want a bit more of Norman Rockwell.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

Is air filtration the best public health intervention against respiratory viruses?

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

When it comes to the public health fight against respiratory viruses – COVID, flu, RSV, and so on – it has always struck me as strange how staunchly basically any intervention is opposed. Masking was, of course, the prototypical entrenched warfare of opposing ideologies, with advocates pointing to studies suggesting the efficacy of masking to prevent transmission and advocating for broad masking recommendations, and detractors citing studies that suggested masks were ineffective and characterizing masking policies as fascist overreach. I’ll admit that I was always perplexed by this a bit, as that particular intervention seemed so benign – a bit annoying, I guess, but not crazy.

I have come to appreciate what I call status quo bias, which is the tendency to reject any policy, advice, or intervention that would force you, as an individual, to change your usual behavior. We just don’t like to do that. It has made me think that the most successful public health interventions might be the ones that take the individual out of the loop. And air quality control seems an ideal fit here. Here is a potential intervention where you, the individual, have to do precisely nothing. The status quo is preserved. We just, you know, have cleaner indoor air.

But even the suggestion of air treatment systems as a bulwark against respiratory virus transmission has been met with not just skepticism but cynicism, and perhaps even defeatism. It seems that there are those out there who think there really is nothing we can do. Sickness is interpreted in a Calvinistic framework: You become ill because it is your pre-destiny. But maybe air treatment could actually work. It seems like it might, if a new paper from PLOS One is to be believed.

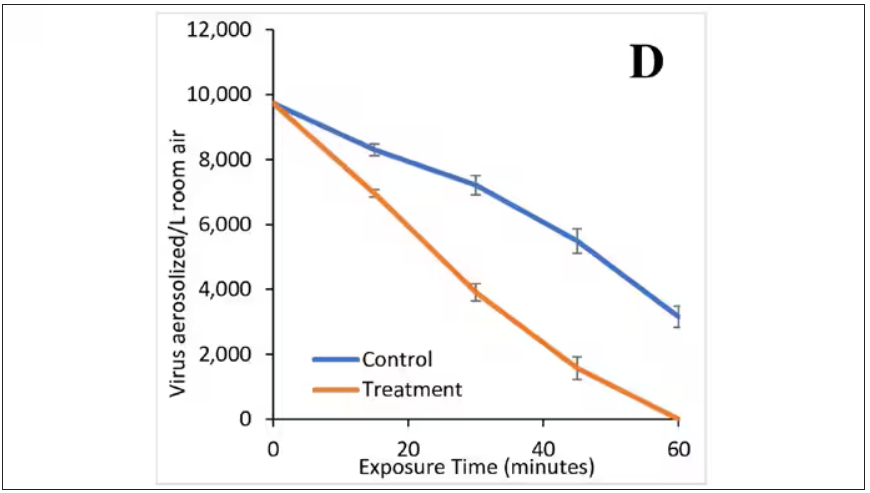

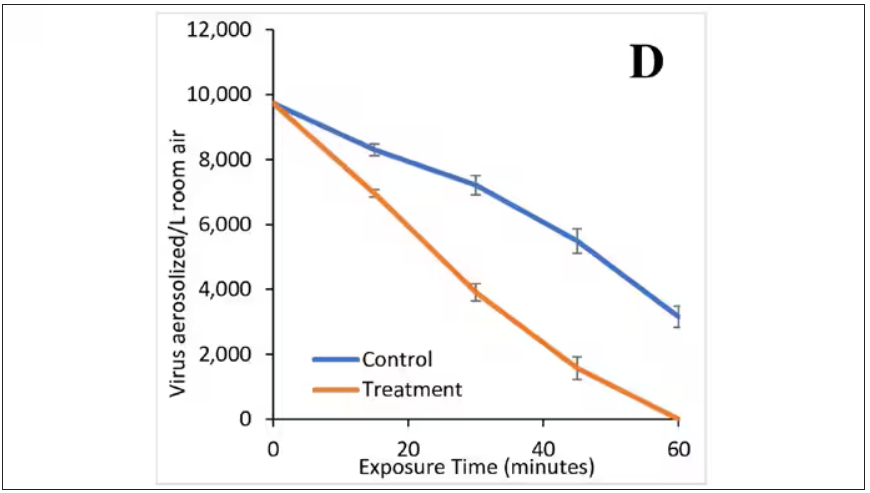

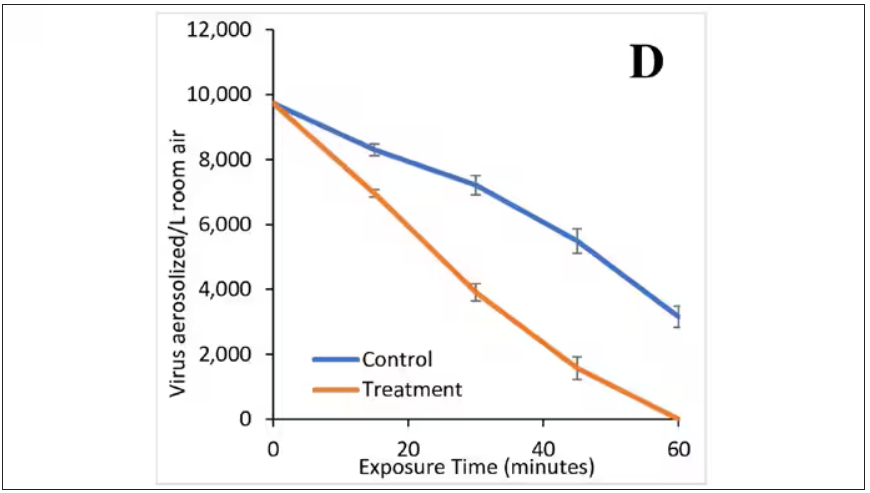

What we’re talking about is a study titled “Bipolar Ionization Rapidly Inactivates Real-World, Airborne Concentrations of Infective Respiratory Viruses” – a highly controlled, laboratory-based analysis of a bipolar ionization system which seems to rapidly reduce viral counts in the air.

The proposed mechanism of action is pretty simple. The ionization system – which, don’t worry, has been shown not to produce ozone – spits out positively and negatively charged particles, which float around the test chamber, designed to look like a pretty standard room that you might find in an office or a school.

Virus is then injected into the chamber through an aerosolization machine, to achieve concentrations on the order of what you might get standing within 6 feet or so of someone actively infected with COVID while they are breathing and talking.

The idea is that those ions stick to the virus particles, similar to how a balloon sticks to the wall after you rub it on your hair, and that tends to cause them to clump together and settle on surfaces more rapidly, and thus get farther away from their ports of entry to the human system: nose, mouth, and eyes. But the ions may also interfere with viruses’ ability to bind to cellular receptors, even in the air.

To quantify viral infectivity, the researchers used a biological system. Basically, you take air samples and expose a petri dish of cells to them and see how many cells die. Fewer cells dying, less infective. Under control conditions, you can see that virus infectivity does decrease over time. Time zero here is the end of a SARS-CoV-2 aerosolization.

This may simply reflect the fact that virus particles settle out of the air. But As you can see, within about an hour, you have almost no infective virus detectable. That’s fairly impressive.

Now, I’m not saying that this is a panacea, but it is certainly worth considering the use of technologies like these if we are going to revamp the infrastructure of our offices and schools. And, of course, it would be nice to see this tested in a rigorous clinical trial with actual infected people, not cells, as the outcome. But I continue to be encouraged by interventions like this which, to be honest, ask very little of us as individuals. Maybe it’s time we accept the things, or people, that we cannot change.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. He reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

When it comes to the public health fight against respiratory viruses – COVID, flu, RSV, and so on – it has always struck me as strange how staunchly basically any intervention is opposed. Masking was, of course, the prototypical entrenched warfare of opposing ideologies, with advocates pointing to studies suggesting the efficacy of masking to prevent transmission and advocating for broad masking recommendations, and detractors citing studies that suggested masks were ineffective and characterizing masking policies as fascist overreach. I’ll admit that I was always perplexed by this a bit, as that particular intervention seemed so benign – a bit annoying, I guess, but not crazy.

I have come to appreciate what I call status quo bias, which is the tendency to reject any policy, advice, or intervention that would force you, as an individual, to change your usual behavior. We just don’t like to do that. It has made me think that the most successful public health interventions might be the ones that take the individual out of the loop. And air quality control seems an ideal fit here. Here is a potential intervention where you, the individual, have to do precisely nothing. The status quo is preserved. We just, you know, have cleaner indoor air.

But even the suggestion of air treatment systems as a bulwark against respiratory virus transmission has been met with not just skepticism but cynicism, and perhaps even defeatism. It seems that there are those out there who think there really is nothing we can do. Sickness is interpreted in a Calvinistic framework: You become ill because it is your pre-destiny. But maybe air treatment could actually work. It seems like it might, if a new paper from PLOS One is to be believed.

What we’re talking about is a study titled “Bipolar Ionization Rapidly Inactivates Real-World, Airborne Concentrations of Infective Respiratory Viruses” – a highly controlled, laboratory-based analysis of a bipolar ionization system which seems to rapidly reduce viral counts in the air.

The proposed mechanism of action is pretty simple. The ionization system – which, don’t worry, has been shown not to produce ozone – spits out positively and negatively charged particles, which float around the test chamber, designed to look like a pretty standard room that you might find in an office or a school.

Virus is then injected into the chamber through an aerosolization machine, to achieve concentrations on the order of what you might get standing within 6 feet or so of someone actively infected with COVID while they are breathing and talking.

The idea is that those ions stick to the virus particles, similar to how a balloon sticks to the wall after you rub it on your hair, and that tends to cause them to clump together and settle on surfaces more rapidly, and thus get farther away from their ports of entry to the human system: nose, mouth, and eyes. But the ions may also interfere with viruses’ ability to bind to cellular receptors, even in the air.

To quantify viral infectivity, the researchers used a biological system. Basically, you take air samples and expose a petri dish of cells to them and see how many cells die. Fewer cells dying, less infective. Under control conditions, you can see that virus infectivity does decrease over time. Time zero here is the end of a SARS-CoV-2 aerosolization.

This may simply reflect the fact that virus particles settle out of the air. But As you can see, within about an hour, you have almost no infective virus detectable. That’s fairly impressive.

Now, I’m not saying that this is a panacea, but it is certainly worth considering the use of technologies like these if we are going to revamp the infrastructure of our offices and schools. And, of course, it would be nice to see this tested in a rigorous clinical trial with actual infected people, not cells, as the outcome. But I continue to be encouraged by interventions like this which, to be honest, ask very little of us as individuals. Maybe it’s time we accept the things, or people, that we cannot change.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. He reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

When it comes to the public health fight against respiratory viruses – COVID, flu, RSV, and so on – it has always struck me as strange how staunchly basically any intervention is opposed. Masking was, of course, the prototypical entrenched warfare of opposing ideologies, with advocates pointing to studies suggesting the efficacy of masking to prevent transmission and advocating for broad masking recommendations, and detractors citing studies that suggested masks were ineffective and characterizing masking policies as fascist overreach. I’ll admit that I was always perplexed by this a bit, as that particular intervention seemed so benign – a bit annoying, I guess, but not crazy.

I have come to appreciate what I call status quo bias, which is the tendency to reject any policy, advice, or intervention that would force you, as an individual, to change your usual behavior. We just don’t like to do that. It has made me think that the most successful public health interventions might be the ones that take the individual out of the loop. And air quality control seems an ideal fit here. Here is a potential intervention where you, the individual, have to do precisely nothing. The status quo is preserved. We just, you know, have cleaner indoor air.

But even the suggestion of air treatment systems as a bulwark against respiratory virus transmission has been met with not just skepticism but cynicism, and perhaps even defeatism. It seems that there are those out there who think there really is nothing we can do. Sickness is interpreted in a Calvinistic framework: You become ill because it is your pre-destiny. But maybe air treatment could actually work. It seems like it might, if a new paper from PLOS One is to be believed.

What we’re talking about is a study titled “Bipolar Ionization Rapidly Inactivates Real-World, Airborne Concentrations of Infective Respiratory Viruses” – a highly controlled, laboratory-based analysis of a bipolar ionization system which seems to rapidly reduce viral counts in the air.

The proposed mechanism of action is pretty simple. The ionization system – which, don’t worry, has been shown not to produce ozone – spits out positively and negatively charged particles, which float around the test chamber, designed to look like a pretty standard room that you might find in an office or a school.

Virus is then injected into the chamber through an aerosolization machine, to achieve concentrations on the order of what you might get standing within 6 feet or so of someone actively infected with COVID while they are breathing and talking.

The idea is that those ions stick to the virus particles, similar to how a balloon sticks to the wall after you rub it on your hair, and that tends to cause them to clump together and settle on surfaces more rapidly, and thus get farther away from their ports of entry to the human system: nose, mouth, and eyes. But the ions may also interfere with viruses’ ability to bind to cellular receptors, even in the air.

To quantify viral infectivity, the researchers used a biological system. Basically, you take air samples and expose a petri dish of cells to them and see how many cells die. Fewer cells dying, less infective. Under control conditions, you can see that virus infectivity does decrease over time. Time zero here is the end of a SARS-CoV-2 aerosolization.

This may simply reflect the fact that virus particles settle out of the air. But As you can see, within about an hour, you have almost no infective virus detectable. That’s fairly impressive.

Now, I’m not saying that this is a panacea, but it is certainly worth considering the use of technologies like these if we are going to revamp the infrastructure of our offices and schools. And, of course, it would be nice to see this tested in a rigorous clinical trial with actual infected people, not cells, as the outcome. But I continue to be encouraged by interventions like this which, to be honest, ask very little of us as individuals. Maybe it’s time we accept the things, or people, that we cannot change.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. He reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Physicians: Don’t ignore sexuality in your dying patients

I have a long history of being interested in conversations that others avoid. In medical school, I felt that we didn’t talk enough about death, so I organized a lecture series on end-of-life care for my fellow students. Now, as a sexual medicine specialist, I have other conversations from which many medical providers shy away. So, buckle up!

A key question in palliative care is: How do you want to live the life you have left? And where does the wide range of human pleasures fit in? In her book The Pleasure Zone, sex therapist Stella Resnick describes eight kinds of pleasure:

- pain relief

- play, humor, movement, and sound

- mental

- emotional

- sensual

- spiritual

- primal (just being)

- sexual

At the end of life, both medically and culturally, we pay attention to many of these pleasures. But sexuality is often ignored.

Sexuality – which can be defined as the experience of oneself as a sexual being – may include how sex is experienced in relationships or with oneself, sexual orientation, body image, gender expression and identity, as well as sexual satisfaction and pleasure. People may have different priorities at different times regarding their sexuality, but sexuality is a key aspect of feeling fully alive and human across the lifespan. At the end of life, sexuality, sexual expression, and physical connection may play even more important roles than previously.

‘I just want to be able to have sex with my husband again’

Z was a 75-year-old woman who came to me for help with vaginal stenosis. Her cancer treatments were not going well. I asked her one of my typical questions: “What does sex mean to you?”

Sexual pleasure was “glue” – a critical way for her to connect with her sense of self and with her husband, a man of few words. She described transcendent experiences with partnered sex during her life. Finally, she explained, she was saddened by the idea of not experiencing that again before she died.

As medical providers, we don’t all need to be sex experts, but our patients should be able to have open and shame-free conversations with us about these issues at all stages of life. Up to 86% of palliative care patients want the chance to discuss their sexual concerns with a skilled clinician, and many consider this issue important to their psychological well-being. And yet, 91% reported that sexuality had not been addressed in their care.

In a Canadian study of 10 palliative care patients (and their partners), all but one felt that their medical providers should initiate conversations about sexuality and the effect of illness on sexual experience. They felt that this communication should be an integral component of care. The one person who disagreed said it was appropriate for clinicians to ask patients whether they wanted to talk about sexuality.

Before this study, sexuality had been discussed with only one participant. Here’s the magic part: Several of the patients reported that the study itself was therapeutic. This is my clinical experience as well. More often than not, open and shame-free clinical discussions about sexuality led to patients reflecting: “I’ve never been able to say this to another person, and now I feel so much better.”

One study of palliative care nurses found that while the nurses acknowledged the importance of addressing sexuality, their way of addressing sexuality followed cultural myths and norms or relied on their own experience rather than knowledge-based guidelines. Why? One explanation could be that clinicians raised and educated in North America probably did not get adequate training on this topic. We need to do better.

Second, cultural concepts that equate sexuality with healthy and able bodies who are partnered, young, cisgender, and heterosexual make it hard to conceive of how to relate sexuality to other bodies. We’ve been steeped in the biases of our culture.

Some medical providers avoid the topic because they feel vulnerable, fearful that a conversation about sexuality with a patient will reveal something about themselves. Others may simply deny the possibility that sexual function changes in the face of serious illness or that this could be a priority for their patients. Of course, we have a million other things to talk about – I get it.

Views on sex and sexuality affect how clinicians approach these conversations as well. A study of palliative care professionals described themes among those who did and did not address the topic. The professionals who did not discuss sexuality endorsed a narrow definition of sex based on genital sexual acts between two partners, usually heterosexual. Among these clinicians, when the issue came up, patients had raised the topic. They talked about sex using jokes and euphemisms (“are you still enjoying ‘good moments’ with your partner?”), perhaps to ease their own discomfort.

On the other hand, professionals who more frequently discussed sexuality with their patients endorsed a more holistic concept of sexuality: including genital and nongenital contact as well as nonphysical components like verbal communication and emotions. These clinicians found sexuality applicable to all individuals across the lifespan. They were more likely to initiate discussions about the effect of medications or illness on sexual function and address the need for equipment, such as a larger hospital bed.

I’m hoping that you might one day find yourself in the second group. Our patients at the end of life need our help in accessing the full range of pleasure in their lives. We need better medical education on how to help with sexual concerns when they arise (an article for another day), but we can start right now by simply initiating open, shame-free sexual health conversations. This is often the most important therapeutic intervention.

Dr. Kranz, Clinical Assistant Professor of Obstetrics/Gynecology and Family Medicine, University of Rochester (N.Y.) Medical Center, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

I have a long history of being interested in conversations that others avoid. In medical school, I felt that we didn’t talk enough about death, so I organized a lecture series on end-of-life care for my fellow students. Now, as a sexual medicine specialist, I have other conversations from which many medical providers shy away. So, buckle up!

A key question in palliative care is: How do you want to live the life you have left? And where does the wide range of human pleasures fit in? In her book The Pleasure Zone, sex therapist Stella Resnick describes eight kinds of pleasure:

- pain relief

- play, humor, movement, and sound

- mental

- emotional

- sensual

- spiritual

- primal (just being)

- sexual

At the end of life, both medically and culturally, we pay attention to many of these pleasures. But sexuality is often ignored.

Sexuality – which can be defined as the experience of oneself as a sexual being – may include how sex is experienced in relationships or with oneself, sexual orientation, body image, gender expression and identity, as well as sexual satisfaction and pleasure. People may have different priorities at different times regarding their sexuality, but sexuality is a key aspect of feeling fully alive and human across the lifespan. At the end of life, sexuality, sexual expression, and physical connection may play even more important roles than previously.

‘I just want to be able to have sex with my husband again’

Z was a 75-year-old woman who came to me for help with vaginal stenosis. Her cancer treatments were not going well. I asked her one of my typical questions: “What does sex mean to you?”

Sexual pleasure was “glue” – a critical way for her to connect with her sense of self and with her husband, a man of few words. She described transcendent experiences with partnered sex during her life. Finally, she explained, she was saddened by the idea of not experiencing that again before she died.

As medical providers, we don’t all need to be sex experts, but our patients should be able to have open and shame-free conversations with us about these issues at all stages of life. Up to 86% of palliative care patients want the chance to discuss their sexual concerns with a skilled clinician, and many consider this issue important to their psychological well-being. And yet, 91% reported that sexuality had not been addressed in their care.

In a Canadian study of 10 palliative care patients (and their partners), all but one felt that their medical providers should initiate conversations about sexuality and the effect of illness on sexual experience. They felt that this communication should be an integral component of care. The one person who disagreed said it was appropriate for clinicians to ask patients whether they wanted to talk about sexuality.

Before this study, sexuality had been discussed with only one participant. Here’s the magic part: Several of the patients reported that the study itself was therapeutic. This is my clinical experience as well. More often than not, open and shame-free clinical discussions about sexuality led to patients reflecting: “I’ve never been able to say this to another person, and now I feel so much better.”

One study of palliative care nurses found that while the nurses acknowledged the importance of addressing sexuality, their way of addressing sexuality followed cultural myths and norms or relied on their own experience rather than knowledge-based guidelines. Why? One explanation could be that clinicians raised and educated in North America probably did not get adequate training on this topic. We need to do better.

Second, cultural concepts that equate sexuality with healthy and able bodies who are partnered, young, cisgender, and heterosexual make it hard to conceive of how to relate sexuality to other bodies. We’ve been steeped in the biases of our culture.

Some medical providers avoid the topic because they feel vulnerable, fearful that a conversation about sexuality with a patient will reveal something about themselves. Others may simply deny the possibility that sexual function changes in the face of serious illness or that this could be a priority for their patients. Of course, we have a million other things to talk about – I get it.

Views on sex and sexuality affect how clinicians approach these conversations as well. A study of palliative care professionals described themes among those who did and did not address the topic. The professionals who did not discuss sexuality endorsed a narrow definition of sex based on genital sexual acts between two partners, usually heterosexual. Among these clinicians, when the issue came up, patients had raised the topic. They talked about sex using jokes and euphemisms (“are you still enjoying ‘good moments’ with your partner?”), perhaps to ease their own discomfort.

On the other hand, professionals who more frequently discussed sexuality with their patients endorsed a more holistic concept of sexuality: including genital and nongenital contact as well as nonphysical components like verbal communication and emotions. These clinicians found sexuality applicable to all individuals across the lifespan. They were more likely to initiate discussions about the effect of medications or illness on sexual function and address the need for equipment, such as a larger hospital bed.

I’m hoping that you might one day find yourself in the second group. Our patients at the end of life need our help in accessing the full range of pleasure in their lives. We need better medical education on how to help with sexual concerns when they arise (an article for another day), but we can start right now by simply initiating open, shame-free sexual health conversations. This is often the most important therapeutic intervention.

Dr. Kranz, Clinical Assistant Professor of Obstetrics/Gynecology and Family Medicine, University of Rochester (N.Y.) Medical Center, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

I have a long history of being interested in conversations that others avoid. In medical school, I felt that we didn’t talk enough about death, so I organized a lecture series on end-of-life care for my fellow students. Now, as a sexual medicine specialist, I have other conversations from which many medical providers shy away. So, buckle up!

A key question in palliative care is: How do you want to live the life you have left? And where does the wide range of human pleasures fit in? In her book The Pleasure Zone, sex therapist Stella Resnick describes eight kinds of pleasure:

- pain relief

- play, humor, movement, and sound

- mental

- emotional

- sensual

- spiritual

- primal (just being)

- sexual

At the end of life, both medically and culturally, we pay attention to many of these pleasures. But sexuality is often ignored.

Sexuality – which can be defined as the experience of oneself as a sexual being – may include how sex is experienced in relationships or with oneself, sexual orientation, body image, gender expression and identity, as well as sexual satisfaction and pleasure. People may have different priorities at different times regarding their sexuality, but sexuality is a key aspect of feeling fully alive and human across the lifespan. At the end of life, sexuality, sexual expression, and physical connection may play even more important roles than previously.

‘I just want to be able to have sex with my husband again’

Z was a 75-year-old woman who came to me for help with vaginal stenosis. Her cancer treatments were not going well. I asked her one of my typical questions: “What does sex mean to you?”

Sexual pleasure was “glue” – a critical way for her to connect with her sense of self and with her husband, a man of few words. She described transcendent experiences with partnered sex during her life. Finally, she explained, she was saddened by the idea of not experiencing that again before she died.

As medical providers, we don’t all need to be sex experts, but our patients should be able to have open and shame-free conversations with us about these issues at all stages of life. Up to 86% of palliative care patients want the chance to discuss their sexual concerns with a skilled clinician, and many consider this issue important to their psychological well-being. And yet, 91% reported that sexuality had not been addressed in their care.

In a Canadian study of 10 palliative care patients (and their partners), all but one felt that their medical providers should initiate conversations about sexuality and the effect of illness on sexual experience. They felt that this communication should be an integral component of care. The one person who disagreed said it was appropriate for clinicians to ask patients whether they wanted to talk about sexuality.

Before this study, sexuality had been discussed with only one participant. Here’s the magic part: Several of the patients reported that the study itself was therapeutic. This is my clinical experience as well. More often than not, open and shame-free clinical discussions about sexuality led to patients reflecting: “I’ve never been able to say this to another person, and now I feel so much better.”

One study of palliative care nurses found that while the nurses acknowledged the importance of addressing sexuality, their way of addressing sexuality followed cultural myths and norms or relied on their own experience rather than knowledge-based guidelines. Why? One explanation could be that clinicians raised and educated in North America probably did not get adequate training on this topic. We need to do better.

Second, cultural concepts that equate sexuality with healthy and able bodies who are partnered, young, cisgender, and heterosexual make it hard to conceive of how to relate sexuality to other bodies. We’ve been steeped in the biases of our culture.

Some medical providers avoid the topic because they feel vulnerable, fearful that a conversation about sexuality with a patient will reveal something about themselves. Others may simply deny the possibility that sexual function changes in the face of serious illness or that this could be a priority for their patients. Of course, we have a million other things to talk about – I get it.

Views on sex and sexuality affect how clinicians approach these conversations as well. A study of palliative care professionals described themes among those who did and did not address the topic. The professionals who did not discuss sexuality endorsed a narrow definition of sex based on genital sexual acts between two partners, usually heterosexual. Among these clinicians, when the issue came up, patients had raised the topic. They talked about sex using jokes and euphemisms (“are you still enjoying ‘good moments’ with your partner?”), perhaps to ease their own discomfort.

On the other hand, professionals who more frequently discussed sexuality with their patients endorsed a more holistic concept of sexuality: including genital and nongenital contact as well as nonphysical components like verbal communication and emotions. These clinicians found sexuality applicable to all individuals across the lifespan. They were more likely to initiate discussions about the effect of medications or illness on sexual function and address the need for equipment, such as a larger hospital bed.

I’m hoping that you might one day find yourself in the second group. Our patients at the end of life need our help in accessing the full range of pleasure in their lives. We need better medical education on how to help with sexual concerns when they arise (an article for another day), but we can start right now by simply initiating open, shame-free sexual health conversations. This is often the most important therapeutic intervention.

Dr. Kranz, Clinical Assistant Professor of Obstetrics/Gynecology and Family Medicine, University of Rochester (N.Y.) Medical Center, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Is metabolically healthy obesity an ‘illusion’?