User login

Nonblanchable Violaceous Macules of the Periorbital Skin

The Diagnosis: Primary AL Amyloidosis

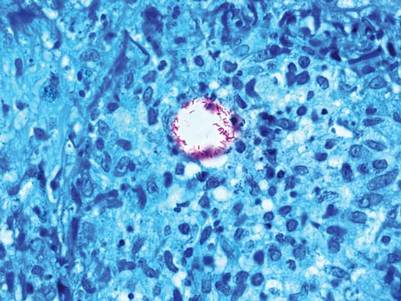

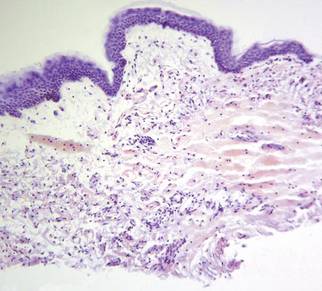

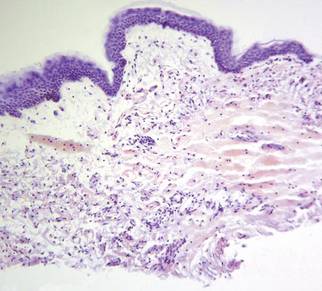

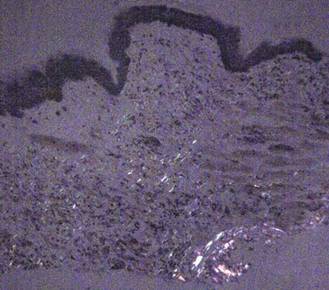

The patient initially presented with bruising around the eyes. She noted characteristic “easy bruising” after minor trauma. Serum protein electrophoresis demonstrated an elevated IgG κ level of 1.4 g/dL (reference range, 0.61–1.04 g/dL) with normal IgA and IgM. Skin biopsy revealed focal amyloid deposition in the dermis (Figures 1 and 2). Liquid chromatography tandem-mass spectrometry performed on peptides extracted from Congo red–positive areas of paraffin-embedded specimen identified peptides representing immunoglobulin κ light chain variable region 1, favoring AL κ-type amyloid deposition.

|  |

A bone marrow biopsy revealed plasma cell dyscrasia with 15% plasma cells but was negative for amyloid. A fine-needle fat-pad biopsy also was negative for amyloid. Systemic amyloid involvement was evaluated with a 24-hour urine collection but was negative for light chain proteinuria and albuminuria. A complete osseous survey was negative for focal lytic or sclerotic lesions, ruling out multiple myeloma. Echocardiogram and liver function tests were normal. We concluded that this patient exhibited a rare case of primary AL amyloidosis due to plasma cell dyscrasia with only cutaneous involvement. The patient was not a candidate for stem cell therapy because she was older than 70 years. She was initiated on several cycles of melphalan with dexamethasone by a collaborating oncology team.

The amyloidoses are a group of diseases that result from the extracellular deposition of insoluble fibrils in various organs. Amyloidosis can occur primarily from a plasma cell proliferative process or secondarily from a chronic inflammatory process. Light chain (AL) amyloidosis is the most commonform of primary systemic amyloidosis. In AL amyloidosis, an immunoglobulin light chain or a fragment of a light chain is produced by a clonal proliferation of plasma cells, with plasma cell dyscrasia typically ranging from 5% to 10%.1 Rarely, amyloidoses may present primarily as cutaneous lesions, as in this patient, which would warrant an evaluation for systemic involvement.

Skin biopsy was the key to diagnosis, as prior biopsy of bone marrow and fat-pad failed to demonstrate amyloid protein. Further analysis with mass spectrometry was used in conjunction with Congo red staining to increase the sensitivity and specificity of detecting overexpressed light chains. Recognition of the limited differential diagnosis of pinch purpura and appropriate processing of the biopsy specimen allowed diagnosis. The patient improved with cycles of combination melphalan and dexamethasone, which was shown to have similar outcome to those treated with melphalan and autologous stem cell rescue.2 Overall, this case highlights the extensive search for systemic involvement that should be undertaken with cutaneous presentations of amyloidosis and the importance of an interdisciplinary approach to treatment.

1. Kyle RA, Gertz MA. Primary systemic amyloidosis: clinical and laboratory features in 474 cases. Semin Hematol. 1995;32:45-49.

2. Jaccard A, Moreau P, Leblond V, et al. High-dose melphalan versus melphalan plus dexamethasone for AL amyloidosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:11.

The Diagnosis: Primary AL Amyloidosis

The patient initially presented with bruising around the eyes. She noted characteristic “easy bruising” after minor trauma. Serum protein electrophoresis demonstrated an elevated IgG κ level of 1.4 g/dL (reference range, 0.61–1.04 g/dL) with normal IgA and IgM. Skin biopsy revealed focal amyloid deposition in the dermis (Figures 1 and 2). Liquid chromatography tandem-mass spectrometry performed on peptides extracted from Congo red–positive areas of paraffin-embedded specimen identified peptides representing immunoglobulin κ light chain variable region 1, favoring AL κ-type amyloid deposition.

|  |

A bone marrow biopsy revealed plasma cell dyscrasia with 15% plasma cells but was negative for amyloid. A fine-needle fat-pad biopsy also was negative for amyloid. Systemic amyloid involvement was evaluated with a 24-hour urine collection but was negative for light chain proteinuria and albuminuria. A complete osseous survey was negative for focal lytic or sclerotic lesions, ruling out multiple myeloma. Echocardiogram and liver function tests were normal. We concluded that this patient exhibited a rare case of primary AL amyloidosis due to plasma cell dyscrasia with only cutaneous involvement. The patient was not a candidate for stem cell therapy because she was older than 70 years. She was initiated on several cycles of melphalan with dexamethasone by a collaborating oncology team.

The amyloidoses are a group of diseases that result from the extracellular deposition of insoluble fibrils in various organs. Amyloidosis can occur primarily from a plasma cell proliferative process or secondarily from a chronic inflammatory process. Light chain (AL) amyloidosis is the most commonform of primary systemic amyloidosis. In AL amyloidosis, an immunoglobulin light chain or a fragment of a light chain is produced by a clonal proliferation of plasma cells, with plasma cell dyscrasia typically ranging from 5% to 10%.1 Rarely, amyloidoses may present primarily as cutaneous lesions, as in this patient, which would warrant an evaluation for systemic involvement.

Skin biopsy was the key to diagnosis, as prior biopsy of bone marrow and fat-pad failed to demonstrate amyloid protein. Further analysis with mass spectrometry was used in conjunction with Congo red staining to increase the sensitivity and specificity of detecting overexpressed light chains. Recognition of the limited differential diagnosis of pinch purpura and appropriate processing of the biopsy specimen allowed diagnosis. The patient improved with cycles of combination melphalan and dexamethasone, which was shown to have similar outcome to those treated with melphalan and autologous stem cell rescue.2 Overall, this case highlights the extensive search for systemic involvement that should be undertaken with cutaneous presentations of amyloidosis and the importance of an interdisciplinary approach to treatment.

The Diagnosis: Primary AL Amyloidosis

The patient initially presented with bruising around the eyes. She noted characteristic “easy bruising” after minor trauma. Serum protein electrophoresis demonstrated an elevated IgG κ level of 1.4 g/dL (reference range, 0.61–1.04 g/dL) with normal IgA and IgM. Skin biopsy revealed focal amyloid deposition in the dermis (Figures 1 and 2). Liquid chromatography tandem-mass spectrometry performed on peptides extracted from Congo red–positive areas of paraffin-embedded specimen identified peptides representing immunoglobulin κ light chain variable region 1, favoring AL κ-type amyloid deposition.

|  |

A bone marrow biopsy revealed plasma cell dyscrasia with 15% plasma cells but was negative for amyloid. A fine-needle fat-pad biopsy also was negative for amyloid. Systemic amyloid involvement was evaluated with a 24-hour urine collection but was negative for light chain proteinuria and albuminuria. A complete osseous survey was negative for focal lytic or sclerotic lesions, ruling out multiple myeloma. Echocardiogram and liver function tests were normal. We concluded that this patient exhibited a rare case of primary AL amyloidosis due to plasma cell dyscrasia with only cutaneous involvement. The patient was not a candidate for stem cell therapy because she was older than 70 years. She was initiated on several cycles of melphalan with dexamethasone by a collaborating oncology team.

The amyloidoses are a group of diseases that result from the extracellular deposition of insoluble fibrils in various organs. Amyloidosis can occur primarily from a plasma cell proliferative process or secondarily from a chronic inflammatory process. Light chain (AL) amyloidosis is the most commonform of primary systemic amyloidosis. In AL amyloidosis, an immunoglobulin light chain or a fragment of a light chain is produced by a clonal proliferation of plasma cells, with plasma cell dyscrasia typically ranging from 5% to 10%.1 Rarely, amyloidoses may present primarily as cutaneous lesions, as in this patient, which would warrant an evaluation for systemic involvement.

Skin biopsy was the key to diagnosis, as prior biopsy of bone marrow and fat-pad failed to demonstrate amyloid protein. Further analysis with mass spectrometry was used in conjunction with Congo red staining to increase the sensitivity and specificity of detecting overexpressed light chains. Recognition of the limited differential diagnosis of pinch purpura and appropriate processing of the biopsy specimen allowed diagnosis. The patient improved with cycles of combination melphalan and dexamethasone, which was shown to have similar outcome to those treated with melphalan and autologous stem cell rescue.2 Overall, this case highlights the extensive search for systemic involvement that should be undertaken with cutaneous presentations of amyloidosis and the importance of an interdisciplinary approach to treatment.

1. Kyle RA, Gertz MA. Primary systemic amyloidosis: clinical and laboratory features in 474 cases. Semin Hematol. 1995;32:45-49.

2. Jaccard A, Moreau P, Leblond V, et al. High-dose melphalan versus melphalan plus dexamethasone for AL amyloidosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:11.

1. Kyle RA, Gertz MA. Primary systemic amyloidosis: clinical and laboratory features in 474 cases. Semin Hematol. 1995;32:45-49.

2. Jaccard A, Moreau P, Leblond V, et al. High-dose melphalan versus melphalan plus dexamethasone for AL amyloidosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:11.

A 71-year-old white woman presented with nonblanchable, violaceous, monomorphic macules involving the bilateral periorbital skin, upper chest, upper arms, and dorsal forearms of 1 year’s duration. Skin and bone marrow biopsies were performed.

Driver Partially Ejected From Vehicle

ANSWER

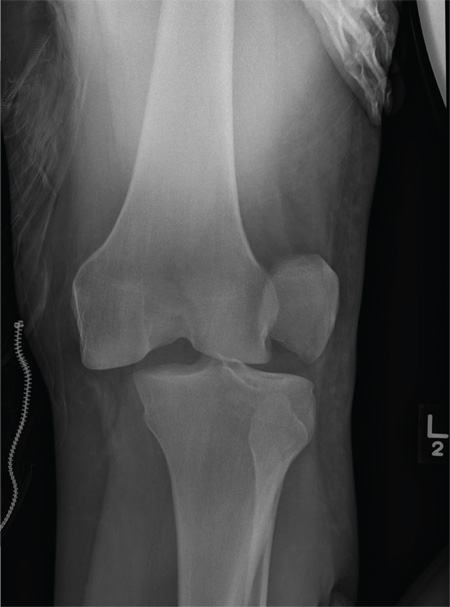

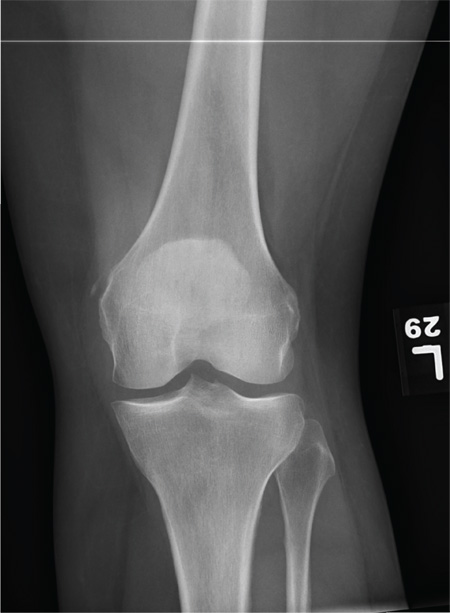

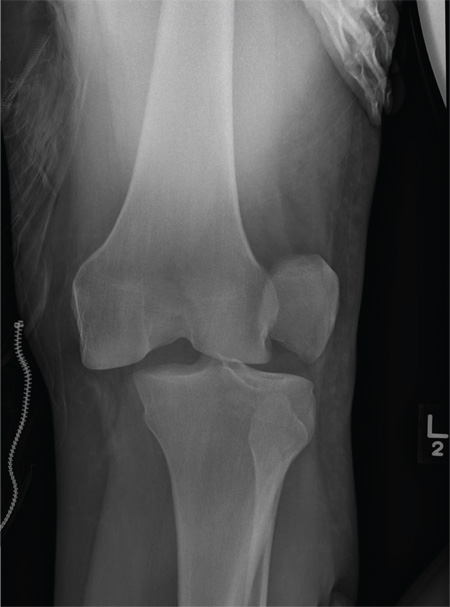

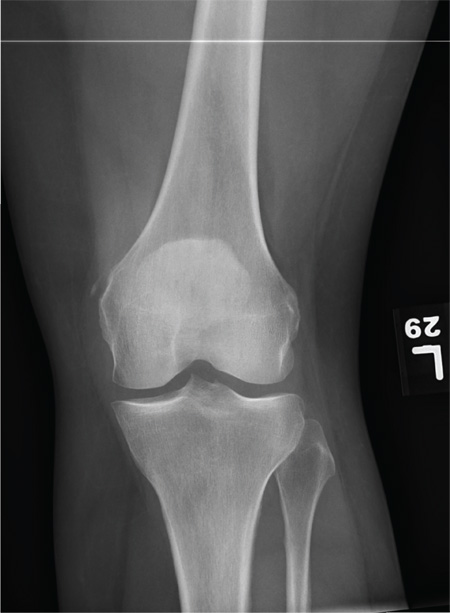

The radiograph shows that the distal femur is medially dislocated relative to the tibial plateau. In addition, the patella is laterally dislocated. No obvious fractures are evident.

Such injuries are typically associated with significant ligament injuries, especially of the medial collateral ligament (MCL), lateral collateral ligament (LCL), and anterior cruciate ligament (ACL). Orthopedics was consulted for reduction of the dislocation, as well as further workup (including MRI of the knee).

ANSWER

The radiograph shows that the distal femur is medially dislocated relative to the tibial plateau. In addition, the patella is laterally dislocated. No obvious fractures are evident.

Such injuries are typically associated with significant ligament injuries, especially of the medial collateral ligament (MCL), lateral collateral ligament (LCL), and anterior cruciate ligament (ACL). Orthopedics was consulted for reduction of the dislocation, as well as further workup (including MRI of the knee).

ANSWER

The radiograph shows that the distal femur is medially dislocated relative to the tibial plateau. In addition, the patella is laterally dislocated. No obvious fractures are evident.

Such injuries are typically associated with significant ligament injuries, especially of the medial collateral ligament (MCL), lateral collateral ligament (LCL), and anterior cruciate ligament (ACL). Orthopedics was consulted for reduction of the dislocation, as well as further workup (including MRI of the knee).

A 28-year-old man is brought to your facility by EMS for evaluation status post a motor vehicle accident. The patient was an unrestrained driver in a truck that went off the road into a ditch. The paramedics state that he was partially ejected, with his left leg caught in the window. There was brief loss of consciousness. Upon arrival, he is awake and alert, with a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 15. His primary complaints are of back and left leg pain. His medical history is unremarkable, and vital signs are stable. Primary survey shows no obvious injury. Secondary survey reveals moderate swelling and decreased range of motion in the left knee. Good distal pulses are present. As part of your orders, you request a portable radiograph of the left knee. What is your impression?

Woman Blacks Out Repeatedly, Doesn’t Remember Doing So

ANSWER

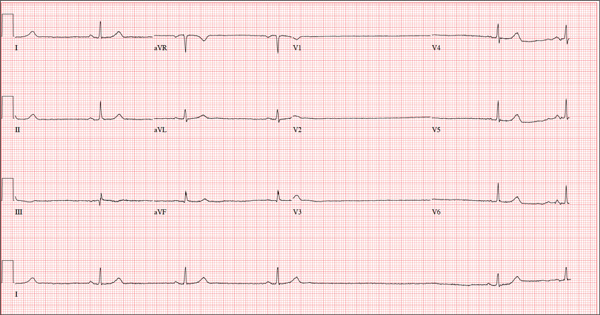

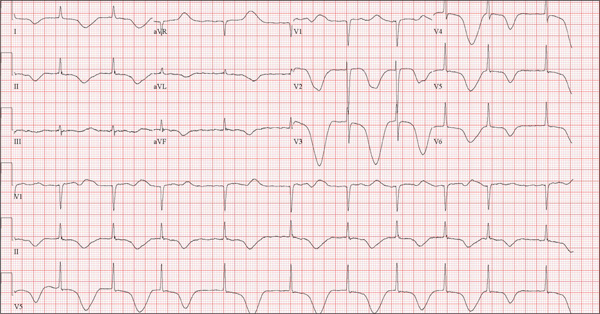

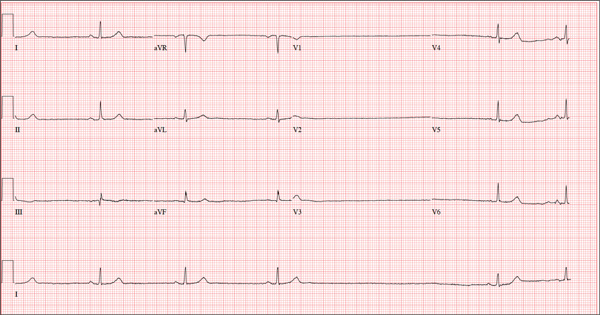

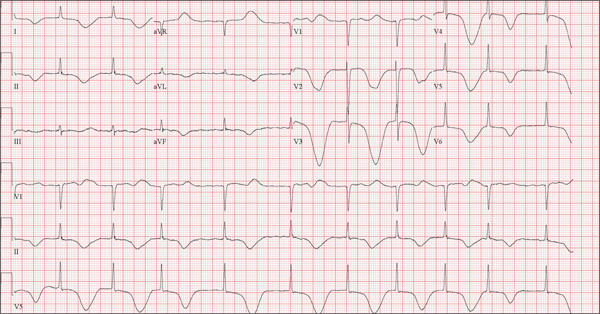

The ECG shows marked sinus bradycardia with a four-second pause consistent with sinus arrest. This may be due to conduction disease within the sinus node and may be exacerbated by use of β-blockers or calcium-channel blockers, or by hypothyroidism.

The patient’s episodes of near-syncope coincided with sinus arrest on telemetry monitoring. She underwent implantation of a dual-chamber permanent pacemaker and resumed all previous activities without issue.

ANSWER

The ECG shows marked sinus bradycardia with a four-second pause consistent with sinus arrest. This may be due to conduction disease within the sinus node and may be exacerbated by use of β-blockers or calcium-channel blockers, or by hypothyroidism.

The patient’s episodes of near-syncope coincided with sinus arrest on telemetry monitoring. She underwent implantation of a dual-chamber permanent pacemaker and resumed all previous activities without issue.

ANSWER

The ECG shows marked sinus bradycardia with a four-second pause consistent with sinus arrest. This may be due to conduction disease within the sinus node and may be exacerbated by use of β-blockers or calcium-channel blockers, or by hypothyroidism.

The patient’s episodes of near-syncope coincided with sinus arrest on telemetry monitoring. She underwent implantation of a dual-chamber permanent pacemaker and resumed all previous activities without issue.

A 74-year-old woman is transferred from a skilled nursing facility (SNF) for evaluation following three episodes of near-syncope in the past week. Each episode occurred while the patient was “at rest,” sitting at a table playing cards with her fellow residents. The most recent episode, witnessed by a nurse’s aide, occurred this morning. The aide called the nursing supervisor to explain that the patient had been engaged in conversation and then slumped over in her chair for approximately three to four minutes. When her companions shook her, she promptly woke up and continued playing cards as if nothing had happened. Upon questioning, the patient denied experiencing shortness of breath, palpitations, or chest pain. Her statement that “this has never happened before” was promptly corrected by her companions. The patient’s medical history is positive for hypertension, hypothyroidism, cholecystitis, and diverticulitis. There is a remote history of pneumonia. Surgical history is positive for cholecystectomy, hysterectomy, and multiple colonoscopies. The patient’s regular medications include amlodipine, atorvastatin, levothyroxine, and baby aspirin. She is allergic to sulfa. A widow for 11 years, the patient has resided in the SNF for three years and has two sons who visit weekly. She is quite active, serving as chairwoman for many of the facility’s events. She has never smoked but says she “enjoys” a nightly glass of brandy before bed. Review of systems is positive for loose stools and occasional blood secondary to her diverticulitis. She denies palpitations, arrhythmias, tachycardia, or other cardiac symptoms. She wears corrective lenses and hearing aids. Vital signs include a blood pressure of 148/98 mm Hg; pulse, 50 beats/min; respiratory rate, 14 breaths/min; and temperature, 98.8°F. Her weight is 146.3 lb and her height, 58 in. Physical examination reveals a keenly alert, oriented (x 3), and well-nourished woman. Her hearing is intact with her hearing aids in place. There are no indications of carotid bruit, jugular venous distention, or thyromegaly. The lungs are clear in all fields. The cardiac exam is remarkable for a rate of 50 beats/min; the rhythm is regular. There is a grade II/VI systolic murmur over the left sternal border. The abdominal exam reveals well-healed surgical scars. Her abdomen is nontender, and there are no palpable masses. Peripheral pulses are strong and regular in all extremities, and there are minimal signs of osteoarthritis in her hands and fingers. The neurologic exam is intact and unremarkable. As you leave the patient’s room, you ask your new technician to obtain a 12-lead ECG. Shortly thereafter, the tech opens the exam room door, shouting for help. By the time you enter the room, the patient is lying comfortably on the exam table, wondering what is wrong. The tech hands you the ECG, which shows a ventricular rate of 29 beats/min; PR interval, 176 ms; QRS duration, 76 ms; QT/QTc interval, 474/329 ms; P axis, 30°; R axis, 42°; and T axis, 20°. What is your interpretation of this ECG?

Foot Rash + Gnarly Toenails = Man in Need of a Diagnosis

ANSWER

The correct answer is to perform a KOH examination (choice “b”), which takes just five minutes and offers the chance to establish the fungal origin of the rash. Although the patient’s skin is quite dry, the use of a moisturizer (choice “a”) is unlikely to address the overall problem. A punch biopsy (choice “c”) would be a logical choice if the KOH failed to solve the mystery. The use of combination creams (choice “d”) that contain a steroid (triamcinolone) and an antifungal (nystatin) is essentially an admission of the lack of a definitive diagnosis. For reasons discussed below, this strategy has almost no chance of helping.

DISCUSSION

In this case, the KOH prep showed numerous hyphal elements, confirming suspicions of a fungal origin. One potential source of these organisms was the patient’s feet, where fungal infection had been present for years (“more than 30,” questioning revealed).

A common scenario is one in which the patient applies a steroid cream to a bit of dry skin just above the feet, which allows the fungi to gain a “foothold” from which to spread upward onto the leg; this progress is assisted through scratching and additional steroid application. If no firm diagnosis is ever established, definitive treatment cannot be undertaken and the problem never resolves.

In my opinion, there is never a reason to prescribe a product containing nystatin. In 1950, when it was discovered by researchers working in New York State laboratories (after which it was named), its efficacy against Candida species represented a notable advance, given the limited drug choices available for that purpose. But it has little, if any, activity against the dermatophytes causing our patient’s problems. And the steroid (triamcinolone) in this combination product, far from adding any therapeutic benefit, effectively diminishes any natural immune response.

The other reason to refrain from prescribing nystatin is that, since its discovery, at least three generations of products that treat both fungi and yeast (the azoles, such as clotrimazole, econazole, and fluconazole) have become available and have been found to be very effective.

The more important issue in this case, however, is finally having an accurate diagnosis: tinea corporis, probably caused by the most common dermatophyte, Trichophyton rubrum. The patient’s body is obviously a very happy home for this ubiquitous organism, to the extent that our chances of eliminating it are quite small. But we can at least make the patient more comfortable.

Treatment entailed ketoconazole foam (applied bid to his legs) and a two-month course of oral terbinafine (250 mg/d), which cleared up most of the skin problem. For his overgrown toenails, the patient was advised to establish care with a podiatrist for regular trimming.

In terms of a differential, this patient might have had psoriasis or eczema—and may still have one or both, since there’s no law against having more than one condition in the same location. In time, we may have to reconsider our solitary diagnosis.

ANSWER

The correct answer is to perform a KOH examination (choice “b”), which takes just five minutes and offers the chance to establish the fungal origin of the rash. Although the patient’s skin is quite dry, the use of a moisturizer (choice “a”) is unlikely to address the overall problem. A punch biopsy (choice “c”) would be a logical choice if the KOH failed to solve the mystery. The use of combination creams (choice “d”) that contain a steroid (triamcinolone) and an antifungal (nystatin) is essentially an admission of the lack of a definitive diagnosis. For reasons discussed below, this strategy has almost no chance of helping.

DISCUSSION

In this case, the KOH prep showed numerous hyphal elements, confirming suspicions of a fungal origin. One potential source of these organisms was the patient’s feet, where fungal infection had been present for years (“more than 30,” questioning revealed).

A common scenario is one in which the patient applies a steroid cream to a bit of dry skin just above the feet, which allows the fungi to gain a “foothold” from which to spread upward onto the leg; this progress is assisted through scratching and additional steroid application. If no firm diagnosis is ever established, definitive treatment cannot be undertaken and the problem never resolves.

In my opinion, there is never a reason to prescribe a product containing nystatin. In 1950, when it was discovered by researchers working in New York State laboratories (after which it was named), its efficacy against Candida species represented a notable advance, given the limited drug choices available for that purpose. But it has little, if any, activity against the dermatophytes causing our patient’s problems. And the steroid (triamcinolone) in this combination product, far from adding any therapeutic benefit, effectively diminishes any natural immune response.

The other reason to refrain from prescribing nystatin is that, since its discovery, at least three generations of products that treat both fungi and yeast (the azoles, such as clotrimazole, econazole, and fluconazole) have become available and have been found to be very effective.

The more important issue in this case, however, is finally having an accurate diagnosis: tinea corporis, probably caused by the most common dermatophyte, Trichophyton rubrum. The patient’s body is obviously a very happy home for this ubiquitous organism, to the extent that our chances of eliminating it are quite small. But we can at least make the patient more comfortable.

Treatment entailed ketoconazole foam (applied bid to his legs) and a two-month course of oral terbinafine (250 mg/d), which cleared up most of the skin problem. For his overgrown toenails, the patient was advised to establish care with a podiatrist for regular trimming.

In terms of a differential, this patient might have had psoriasis or eczema—and may still have one or both, since there’s no law against having more than one condition in the same location. In time, we may have to reconsider our solitary diagnosis.

ANSWER

The correct answer is to perform a KOH examination (choice “b”), which takes just five minutes and offers the chance to establish the fungal origin of the rash. Although the patient’s skin is quite dry, the use of a moisturizer (choice “a”) is unlikely to address the overall problem. A punch biopsy (choice “c”) would be a logical choice if the KOH failed to solve the mystery. The use of combination creams (choice “d”) that contain a steroid (triamcinolone) and an antifungal (nystatin) is essentially an admission of the lack of a definitive diagnosis. For reasons discussed below, this strategy has almost no chance of helping.

DISCUSSION

In this case, the KOH prep showed numerous hyphal elements, confirming suspicions of a fungal origin. One potential source of these organisms was the patient’s feet, where fungal infection had been present for years (“more than 30,” questioning revealed).

A common scenario is one in which the patient applies a steroid cream to a bit of dry skin just above the feet, which allows the fungi to gain a “foothold” from which to spread upward onto the leg; this progress is assisted through scratching and additional steroid application. If no firm diagnosis is ever established, definitive treatment cannot be undertaken and the problem never resolves.

In my opinion, there is never a reason to prescribe a product containing nystatin. In 1950, when it was discovered by researchers working in New York State laboratories (after which it was named), its efficacy against Candida species represented a notable advance, given the limited drug choices available for that purpose. But it has little, if any, activity against the dermatophytes causing our patient’s problems. And the steroid (triamcinolone) in this combination product, far from adding any therapeutic benefit, effectively diminishes any natural immune response.

The other reason to refrain from prescribing nystatin is that, since its discovery, at least three generations of products that treat both fungi and yeast (the azoles, such as clotrimazole, econazole, and fluconazole) have become available and have been found to be very effective.

The more important issue in this case, however, is finally having an accurate diagnosis: tinea corporis, probably caused by the most common dermatophyte, Trichophyton rubrum. The patient’s body is obviously a very happy home for this ubiquitous organism, to the extent that our chances of eliminating it are quite small. But we can at least make the patient more comfortable.

Treatment entailed ketoconazole foam (applied bid to his legs) and a two-month course of oral terbinafine (250 mg/d), which cleared up most of the skin problem. For his overgrown toenails, the patient was advised to establish care with a podiatrist for regular trimming.

In terms of a differential, this patient might have had psoriasis or eczema—and may still have one or both, since there’s no law against having more than one condition in the same location. In time, we may have to reconsider our solitary diagnosis.

For several years, a 66-year-old man has had an itchy rash on his right leg; recently, it has become more bothersome. In general, he has noticed that when cold weather arrives, the rash improves slightly, but it inevitably worsens again as winter progresses. Over the years, the providers he has consulted have prescribed a number of topical products—among them, antifungal and steroid creams. Each of these products seems to help for a short period, then stops; at that point, the patient switches to a different product, with similar mixed results. The patient says he doesn’t have any other skin problems. Examination reveals patches of dry skin scattered from the knee to the top of the patient’s foot. Most have a faintly erythematous surface and arciform borders. These patches blend into a similar rash that covers the sides of both feet. All 10 toenails are grossly dystrophic, yellowed, and overgrown. The skin on the patient’s other leg is somewhat dry but otherwise unaffected.

Cystic Nodule on the Palm

The Diagnosis: Nodular Hidradenoma

Nodular hidradenomas (NHs) are rare benign cutaneous adnexal neoplasms first described in 1949 as clear cell papillary carcinomas.1 Since then, various terms have been used to describe this entity, such as eccrine acrospiroma, solid-cystic hidradenoma, and clear cell hidradenoma.2 Review of the literature revealed a female predominance (2:1 ratio) and a mean age at presentation of 37.2 years.3,4 Nodular hidradenoma presents as an asymptomatic, solitary, mobile, firm nodule with intact overlying skin. Rarely, multiple nodules may occur.3 Some tumors display ulceration and serous fluid leakage.5 They occur most commonly on the scalp, face, and upper extremities with an average size of 2 cm.3 Rapid growth of the tumor may signal a malignant change.6

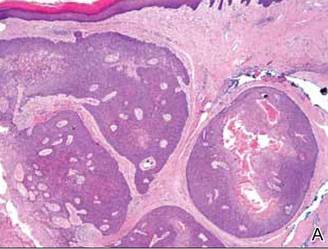

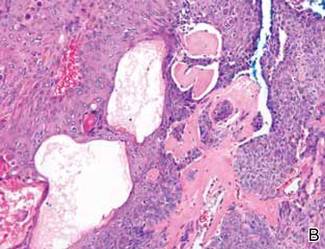

Histopathology reveals a lobulated, circumscribed, symmetrical tumor with dermal nests of epithelial cells that are polygonal with eosinophilic cytoplasm forming ductlike spaces (Figure). However, clear cell changes and squamous differentiation may be prominent features. Cystic spaces may result from tumor cell degeneration. Most tumors are encased by collagenous fibrous tissue and rarely have epidermal attachments.3

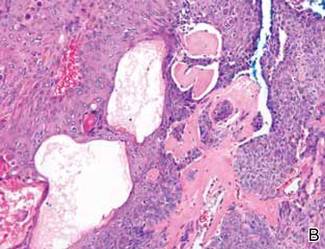

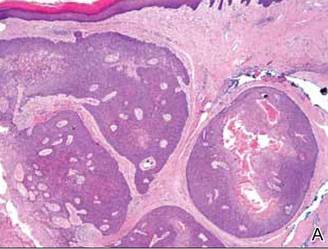

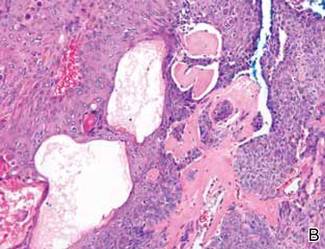

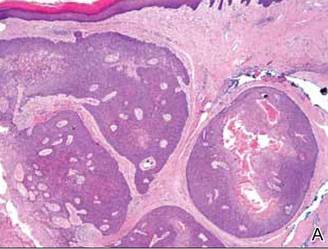

Anastomosing aggregates of squamous cells forming ductlike spaces were viewed on low-power magnification (A)(H&E, original magnification ×10). On higher power there were ductlike spaces and eosinophilic hyalinized stroma entrapped by the bland-appearing squamous proliferation (B)(H&E, original magnification ×20). |

Nodular hidradenoma traditionally has been considered to be of eccrine origin, but more recent literature indicates that the majority of NHs are of apocrine origin. Histologically, apocrine tumors display eosinophilic secretion, mucinous epithelium, squamous or sebaceous differentiation, and decapitation secretion, whereas eccrine tumors are identified by their lack of specific features.3

Nodular hidradenoma may recur after excision. Malignant transformation is rare. In one review, 6.7% (6/89) of NHs were malignant, characterized by abnormal mitoses, nuclear atypia, and necrosis.4 Malignant NH or nodular hidradenocarcinoma behaves aggressively with up to an 86% local recurrence and 60% rate of metastasis within 2 years.6 Survival time is inversely proportional to the size of the tumor and is generally poor, with a 5-year disease-free survival of less than 30%.6,7

Treatment of NH is achieved through primary excision or Mohs micrographic surgery; however, treatment of nodular hidradenocarcinoma is controversial and typically begins with wide local excision but may involve lymph node dissection if necessary. Use of adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation therapy for metastases warrants more clinical studies, as it is a rare occurrence.6 Our patient planned to undergo a total excision of the benign nodule once she healed from the biopsy; however, she was lost to follow-up, as she moved out of state.

1. Lui Y. The histogenesis of clear cell papillary carcinoma of the skin. Am J Pathol. 1949;25:93-103.

2. Obaidat NA, Khaled OA, Ghazarian D. Skin adnexal neoplasms–part 2: an approach to tumours of cutaneous sweat glands. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60:145-159.

3. Nandeesh BN, Rajalakshmi T. A study of histopathologic spectrum of nodular hidradenoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:461-470.

4. Hernández-Pérez E, Cestoni-Parducci R. Nodular hidradenoma and hidradenocarcinoma: a 10-year review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12:15-20.

5. Sirinoglu H, Celebiler O. Benign nodular hidradenoma of the face. J Craniofac Surg. 2011;22:750-751.

6. Souvatzidis P, Sbano P, Mandato F, et al. Malignant nodular hidradenoma of the skin: report of seven cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:549-554.

7. Ko CJ, Cochran AJ, Eng W, et al. Hidradenocarcinoma: a histological and immunohistochemical study. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:726-730.

The Diagnosis: Nodular Hidradenoma

Nodular hidradenomas (NHs) are rare benign cutaneous adnexal neoplasms first described in 1949 as clear cell papillary carcinomas.1 Since then, various terms have been used to describe this entity, such as eccrine acrospiroma, solid-cystic hidradenoma, and clear cell hidradenoma.2 Review of the literature revealed a female predominance (2:1 ratio) and a mean age at presentation of 37.2 years.3,4 Nodular hidradenoma presents as an asymptomatic, solitary, mobile, firm nodule with intact overlying skin. Rarely, multiple nodules may occur.3 Some tumors display ulceration and serous fluid leakage.5 They occur most commonly on the scalp, face, and upper extremities with an average size of 2 cm.3 Rapid growth of the tumor may signal a malignant change.6

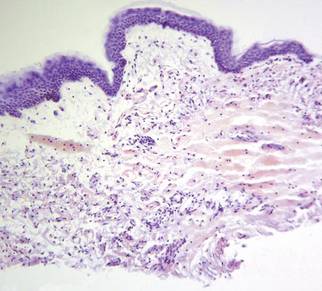

Histopathology reveals a lobulated, circumscribed, symmetrical tumor with dermal nests of epithelial cells that are polygonal with eosinophilic cytoplasm forming ductlike spaces (Figure). However, clear cell changes and squamous differentiation may be prominent features. Cystic spaces may result from tumor cell degeneration. Most tumors are encased by collagenous fibrous tissue and rarely have epidermal attachments.3

Anastomosing aggregates of squamous cells forming ductlike spaces were viewed on low-power magnification (A)(H&E, original magnification ×10). On higher power there were ductlike spaces and eosinophilic hyalinized stroma entrapped by the bland-appearing squamous proliferation (B)(H&E, original magnification ×20). |

Nodular hidradenoma traditionally has been considered to be of eccrine origin, but more recent literature indicates that the majority of NHs are of apocrine origin. Histologically, apocrine tumors display eosinophilic secretion, mucinous epithelium, squamous or sebaceous differentiation, and decapitation secretion, whereas eccrine tumors are identified by their lack of specific features.3

Nodular hidradenoma may recur after excision. Malignant transformation is rare. In one review, 6.7% (6/89) of NHs were malignant, characterized by abnormal mitoses, nuclear atypia, and necrosis.4 Malignant NH or nodular hidradenocarcinoma behaves aggressively with up to an 86% local recurrence and 60% rate of metastasis within 2 years.6 Survival time is inversely proportional to the size of the tumor and is generally poor, with a 5-year disease-free survival of less than 30%.6,7

Treatment of NH is achieved through primary excision or Mohs micrographic surgery; however, treatment of nodular hidradenocarcinoma is controversial and typically begins with wide local excision but may involve lymph node dissection if necessary. Use of adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation therapy for metastases warrants more clinical studies, as it is a rare occurrence.6 Our patient planned to undergo a total excision of the benign nodule once she healed from the biopsy; however, she was lost to follow-up, as she moved out of state.

The Diagnosis: Nodular Hidradenoma

Nodular hidradenomas (NHs) are rare benign cutaneous adnexal neoplasms first described in 1949 as clear cell papillary carcinomas.1 Since then, various terms have been used to describe this entity, such as eccrine acrospiroma, solid-cystic hidradenoma, and clear cell hidradenoma.2 Review of the literature revealed a female predominance (2:1 ratio) and a mean age at presentation of 37.2 years.3,4 Nodular hidradenoma presents as an asymptomatic, solitary, mobile, firm nodule with intact overlying skin. Rarely, multiple nodules may occur.3 Some tumors display ulceration and serous fluid leakage.5 They occur most commonly on the scalp, face, and upper extremities with an average size of 2 cm.3 Rapid growth of the tumor may signal a malignant change.6

Histopathology reveals a lobulated, circumscribed, symmetrical tumor with dermal nests of epithelial cells that are polygonal with eosinophilic cytoplasm forming ductlike spaces (Figure). However, clear cell changes and squamous differentiation may be prominent features. Cystic spaces may result from tumor cell degeneration. Most tumors are encased by collagenous fibrous tissue and rarely have epidermal attachments.3

Anastomosing aggregates of squamous cells forming ductlike spaces were viewed on low-power magnification (A)(H&E, original magnification ×10). On higher power there were ductlike spaces and eosinophilic hyalinized stroma entrapped by the bland-appearing squamous proliferation (B)(H&E, original magnification ×20). |

Nodular hidradenoma traditionally has been considered to be of eccrine origin, but more recent literature indicates that the majority of NHs are of apocrine origin. Histologically, apocrine tumors display eosinophilic secretion, mucinous epithelium, squamous or sebaceous differentiation, and decapitation secretion, whereas eccrine tumors are identified by their lack of specific features.3

Nodular hidradenoma may recur after excision. Malignant transformation is rare. In one review, 6.7% (6/89) of NHs were malignant, characterized by abnormal mitoses, nuclear atypia, and necrosis.4 Malignant NH or nodular hidradenocarcinoma behaves aggressively with up to an 86% local recurrence and 60% rate of metastasis within 2 years.6 Survival time is inversely proportional to the size of the tumor and is generally poor, with a 5-year disease-free survival of less than 30%.6,7

Treatment of NH is achieved through primary excision or Mohs micrographic surgery; however, treatment of nodular hidradenocarcinoma is controversial and typically begins with wide local excision but may involve lymph node dissection if necessary. Use of adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation therapy for metastases warrants more clinical studies, as it is a rare occurrence.6 Our patient planned to undergo a total excision of the benign nodule once she healed from the biopsy; however, she was lost to follow-up, as she moved out of state.

1. Lui Y. The histogenesis of clear cell papillary carcinoma of the skin. Am J Pathol. 1949;25:93-103.

2. Obaidat NA, Khaled OA, Ghazarian D. Skin adnexal neoplasms–part 2: an approach to tumours of cutaneous sweat glands. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60:145-159.

3. Nandeesh BN, Rajalakshmi T. A study of histopathologic spectrum of nodular hidradenoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:461-470.

4. Hernández-Pérez E, Cestoni-Parducci R. Nodular hidradenoma and hidradenocarcinoma: a 10-year review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12:15-20.

5. Sirinoglu H, Celebiler O. Benign nodular hidradenoma of the face. J Craniofac Surg. 2011;22:750-751.

6. Souvatzidis P, Sbano P, Mandato F, et al. Malignant nodular hidradenoma of the skin: report of seven cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:549-554.

7. Ko CJ, Cochran AJ, Eng W, et al. Hidradenocarcinoma: a histological and immunohistochemical study. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:726-730.

1. Lui Y. The histogenesis of clear cell papillary carcinoma of the skin. Am J Pathol. 1949;25:93-103.

2. Obaidat NA, Khaled OA, Ghazarian D. Skin adnexal neoplasms–part 2: an approach to tumours of cutaneous sweat glands. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60:145-159.

3. Nandeesh BN, Rajalakshmi T. A study of histopathologic spectrum of nodular hidradenoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:461-470.

4. Hernández-Pérez E, Cestoni-Parducci R. Nodular hidradenoma and hidradenocarcinoma: a 10-year review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12:15-20.

5. Sirinoglu H, Celebiler O. Benign nodular hidradenoma of the face. J Craniofac Surg. 2011;22:750-751.

6. Souvatzidis P, Sbano P, Mandato F, et al. Malignant nodular hidradenoma of the skin: report of seven cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:549-554.

7. Ko CJ, Cochran AJ, Eng W, et al. Hidradenocarcinoma: a histological and immunohistochemical study. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:726-730.

A 73-year-old woman with a history of multiple strokes with residual left-sided motor deficits and resultant left-hand contracture, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and a remote history of treated colon cancer and breast cancer presented with hypertensive urgency and neck pain. Upon admission, the nursing staff found an “unusual growth” on the patient’s left hand. Dermatology was consulted and a 2×1.5×1.5-cm multilobulated, malodorous, slightly tender, nonfluctuant, gelatinous, mobile, cystic nodule overlying the fourth metacarpal palmar head was examined. The patient reported the lesion was present for more than a year. Imaging was pursued, but radiography, ultrasonography, and magnetic resonance imaging could not be performed adequately due to the patient’s severe contracture. Given the extensive differential diagnoses, an orthopedic hand surgeon performed a large incisional biopsy to obtain tissue diagnosis.

Firm Plaques and Nodules Over the Body

The Diagnosis: Pancreatic Panniculitis

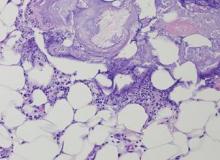

The biopsy specimen revealed necrosis of the panniculus with “ghost” cells (Figure). Calcification was encountered. Changes of vasculitis were not identified and fungal organisms were not noted. The histopathologic findings supported a diagnosis of pancreatic panniculitis.

Pancreatic panniculitis has been associated with pancreatitis, pancreatic carcinoma, pancreatic pseudocysts, congenital abnormalities of the pancreas, and drug-induced pancreatitis.1 Skin lesions may herald a diagnosis of pancreatic disease in an outpatient and should prompt thorough clinical evaluation when encountered in an outpatient setting. Our patient first developed tender nodules on the left shin 2 to 3 weeks prior to presentation. She reported that her initial nodules were flesh colored but then became erythematous and tender over 1 week’s time. The patient’s history was remarkable for ovarian cancer. She had been hospitalized 2 weeks prior to presentation for abdominal pain and ascites. Imaging studies revealed a cystic lesion in the head of the pancreas. The pancreas was traumatized during a peritoneal tap. Her nodules developed shortly thereafter and were distributed on the arms, legs, back, and abdomen.

Pancreatic tumors or inflammation are thought to trigger pancreatic panniculitis by releasing enzymes. Pancreatic enzymes such as lipase are thought to play a role in the development of pancreatic panniculitis by entering the vascular system and leading to fat necrosis.2,3 Biopsy reveals necrosis of adipocytes in the center of fat lobules.4 Ghost cells result from hydrolytic activity of enzymes on the fat cells followed by calcium deposition. A report indicates that fungal infection or gout also can cause changes that mimic pancreatic panniculitis.5

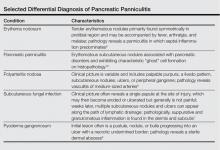

Other entities in the differential diagnosis can be excluded by biopsy. Polyarteritis nodosa is a vasculitis. Although panniculitis may be seen in polyarteritis as a secondary phenomenon, lesions are centered around blood vessels and often eventuate in ulceration.6 Subcutaneous fungal infection typically reveals organisms on periodic acid–Schiff stain.7 Pyoderma gangrenosum is associated with ulceration and a neutrophilic infiltrate that is often centered around a central pilosebaceous unit in developing lesions.8 Erythema nodosum is a panniculitis in which septal inflammation predominates.9 These differential diagnoses of pancreatic panniculitis are summarized in the Table.

Pancreatic panniculitis can be associated with acute arthritis and inflammation of periarticular fat.10 Treatment of pancreatic panniculitis is usually focused on the underlying pancreatic disease.11,12 Our patient benefited from analgesic therapy and her lesions improved on follow-up. Clinicians encountering a patient with new tender nodules should be prompted to perform a biopsy. When histopathologic evaluation reveals ghosted adipocytes, pancreatic panniculitis should be suspected and clinical evaluation undertaken.

1. Garcia-Romero D, Vanaclocha F. Pancreatic panniculitis. Dermatol Clin. 2008;26:465-470.

2. Berman B, Conteas C, Smith B, et al. Fatal pancreatitis presenting with subcutaneous fat necrosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:359-364.

3. Dhawan SS, Jimenez-Acosta F, Poppiti RJ Jr, et al. Subcutaneous fat necrosis associated with pancreatitis: histochemical and electron microscopic findings. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990;85:1025-1028.

4. Cannon JR, Pitha JV, Everett MA. Subcutaneous fat necrosis in pancreatitis. J Cutan Pathol. 1979;6:501-506.

5. Requena L, Sitthinamsuwan P, Santonja C, et al. Cutaneous and mucosal mucormycosis mimicking pancreatic panniculitis and gouty panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:975-984.

6. Grattan CEH. Polyarteritis nodosa. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. Vol 1. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:405-407.

7. Millett CR, Halpern AV, Heymann WR. Subcutaneous mycoses. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:1266-1273.

8. Moschella SL, Davis MDP. Pyoderma gangrenosum. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. Vol 1. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:427-431.

9. Patterson JW. Erythema nodosum. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:1641-1645.

10. Patterson JW. Pancreatic panniculitis. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:1649-1650.

11. Requena L, Sanchez Yus E. Panniculitis. part II. mostly lobular panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:325-361.

12. Dahl PR, Su WP, Cullimore KC, et al. Pancreatic panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:413-417.

The Diagnosis: Pancreatic Panniculitis

The biopsy specimen revealed necrosis of the panniculus with “ghost” cells (Figure). Calcification was encountered. Changes of vasculitis were not identified and fungal organisms were not noted. The histopathologic findings supported a diagnosis of pancreatic panniculitis.

Pancreatic panniculitis has been associated with pancreatitis, pancreatic carcinoma, pancreatic pseudocysts, congenital abnormalities of the pancreas, and drug-induced pancreatitis.1 Skin lesions may herald a diagnosis of pancreatic disease in an outpatient and should prompt thorough clinical evaluation when encountered in an outpatient setting. Our patient first developed tender nodules on the left shin 2 to 3 weeks prior to presentation. She reported that her initial nodules were flesh colored but then became erythematous and tender over 1 week’s time. The patient’s history was remarkable for ovarian cancer. She had been hospitalized 2 weeks prior to presentation for abdominal pain and ascites. Imaging studies revealed a cystic lesion in the head of the pancreas. The pancreas was traumatized during a peritoneal tap. Her nodules developed shortly thereafter and were distributed on the arms, legs, back, and abdomen.

Pancreatic tumors or inflammation are thought to trigger pancreatic panniculitis by releasing enzymes. Pancreatic enzymes such as lipase are thought to play a role in the development of pancreatic panniculitis by entering the vascular system and leading to fat necrosis.2,3 Biopsy reveals necrosis of adipocytes in the center of fat lobules.4 Ghost cells result from hydrolytic activity of enzymes on the fat cells followed by calcium deposition. A report indicates that fungal infection or gout also can cause changes that mimic pancreatic panniculitis.5

Other entities in the differential diagnosis can be excluded by biopsy. Polyarteritis nodosa is a vasculitis. Although panniculitis may be seen in polyarteritis as a secondary phenomenon, lesions are centered around blood vessels and often eventuate in ulceration.6 Subcutaneous fungal infection typically reveals organisms on periodic acid–Schiff stain.7 Pyoderma gangrenosum is associated with ulceration and a neutrophilic infiltrate that is often centered around a central pilosebaceous unit in developing lesions.8 Erythema nodosum is a panniculitis in which septal inflammation predominates.9 These differential diagnoses of pancreatic panniculitis are summarized in the Table.

Pancreatic panniculitis can be associated with acute arthritis and inflammation of periarticular fat.10 Treatment of pancreatic panniculitis is usually focused on the underlying pancreatic disease.11,12 Our patient benefited from analgesic therapy and her lesions improved on follow-up. Clinicians encountering a patient with new tender nodules should be prompted to perform a biopsy. When histopathologic evaluation reveals ghosted adipocytes, pancreatic panniculitis should be suspected and clinical evaluation undertaken.

The Diagnosis: Pancreatic Panniculitis

The biopsy specimen revealed necrosis of the panniculus with “ghost” cells (Figure). Calcification was encountered. Changes of vasculitis were not identified and fungal organisms were not noted. The histopathologic findings supported a diagnosis of pancreatic panniculitis.

Pancreatic panniculitis has been associated with pancreatitis, pancreatic carcinoma, pancreatic pseudocysts, congenital abnormalities of the pancreas, and drug-induced pancreatitis.1 Skin lesions may herald a diagnosis of pancreatic disease in an outpatient and should prompt thorough clinical evaluation when encountered in an outpatient setting. Our patient first developed tender nodules on the left shin 2 to 3 weeks prior to presentation. She reported that her initial nodules were flesh colored but then became erythematous and tender over 1 week’s time. The patient’s history was remarkable for ovarian cancer. She had been hospitalized 2 weeks prior to presentation for abdominal pain and ascites. Imaging studies revealed a cystic lesion in the head of the pancreas. The pancreas was traumatized during a peritoneal tap. Her nodules developed shortly thereafter and were distributed on the arms, legs, back, and abdomen.

Pancreatic tumors or inflammation are thought to trigger pancreatic panniculitis by releasing enzymes. Pancreatic enzymes such as lipase are thought to play a role in the development of pancreatic panniculitis by entering the vascular system and leading to fat necrosis.2,3 Biopsy reveals necrosis of adipocytes in the center of fat lobules.4 Ghost cells result from hydrolytic activity of enzymes on the fat cells followed by calcium deposition. A report indicates that fungal infection or gout also can cause changes that mimic pancreatic panniculitis.5

Other entities in the differential diagnosis can be excluded by biopsy. Polyarteritis nodosa is a vasculitis. Although panniculitis may be seen in polyarteritis as a secondary phenomenon, lesions are centered around blood vessels and often eventuate in ulceration.6 Subcutaneous fungal infection typically reveals organisms on periodic acid–Schiff stain.7 Pyoderma gangrenosum is associated with ulceration and a neutrophilic infiltrate that is often centered around a central pilosebaceous unit in developing lesions.8 Erythema nodosum is a panniculitis in which septal inflammation predominates.9 These differential diagnoses of pancreatic panniculitis are summarized in the Table.

Pancreatic panniculitis can be associated with acute arthritis and inflammation of periarticular fat.10 Treatment of pancreatic panniculitis is usually focused on the underlying pancreatic disease.11,12 Our patient benefited from analgesic therapy and her lesions improved on follow-up. Clinicians encountering a patient with new tender nodules should be prompted to perform a biopsy. When histopathologic evaluation reveals ghosted adipocytes, pancreatic panniculitis should be suspected and clinical evaluation undertaken.

1. Garcia-Romero D, Vanaclocha F. Pancreatic panniculitis. Dermatol Clin. 2008;26:465-470.

2. Berman B, Conteas C, Smith B, et al. Fatal pancreatitis presenting with subcutaneous fat necrosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:359-364.

3. Dhawan SS, Jimenez-Acosta F, Poppiti RJ Jr, et al. Subcutaneous fat necrosis associated with pancreatitis: histochemical and electron microscopic findings. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990;85:1025-1028.

4. Cannon JR, Pitha JV, Everett MA. Subcutaneous fat necrosis in pancreatitis. J Cutan Pathol. 1979;6:501-506.

5. Requena L, Sitthinamsuwan P, Santonja C, et al. Cutaneous and mucosal mucormycosis mimicking pancreatic panniculitis and gouty panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:975-984.

6. Grattan CEH. Polyarteritis nodosa. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. Vol 1. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:405-407.

7. Millett CR, Halpern AV, Heymann WR. Subcutaneous mycoses. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:1266-1273.

8. Moschella SL, Davis MDP. Pyoderma gangrenosum. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. Vol 1. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:427-431.

9. Patterson JW. Erythema nodosum. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:1641-1645.

10. Patterson JW. Pancreatic panniculitis. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:1649-1650.

11. Requena L, Sanchez Yus E. Panniculitis. part II. mostly lobular panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:325-361.

12. Dahl PR, Su WP, Cullimore KC, et al. Pancreatic panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:413-417.

1. Garcia-Romero D, Vanaclocha F. Pancreatic panniculitis. Dermatol Clin. 2008;26:465-470.

2. Berman B, Conteas C, Smith B, et al. Fatal pancreatitis presenting with subcutaneous fat necrosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:359-364.

3. Dhawan SS, Jimenez-Acosta F, Poppiti RJ Jr, et al. Subcutaneous fat necrosis associated with pancreatitis: histochemical and electron microscopic findings. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990;85:1025-1028.

4. Cannon JR, Pitha JV, Everett MA. Subcutaneous fat necrosis in pancreatitis. J Cutan Pathol. 1979;6:501-506.

5. Requena L, Sitthinamsuwan P, Santonja C, et al. Cutaneous and mucosal mucormycosis mimicking pancreatic panniculitis and gouty panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:975-984.

6. Grattan CEH. Polyarteritis nodosa. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. Vol 1. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:405-407.

7. Millett CR, Halpern AV, Heymann WR. Subcutaneous mycoses. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:1266-1273.

8. Moschella SL, Davis MDP. Pyoderma gangrenosum. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. Vol 1. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:427-431.

9. Patterson JW. Erythema nodosum. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:1641-1645.

10. Patterson JW. Pancreatic panniculitis. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. Vol 2. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:1649-1650.

11. Requena L, Sanchez Yus E. Panniculitis. part II. mostly lobular panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:325-361.

12. Dahl PR, Su WP, Cullimore KC, et al. Pancreatic panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:413-417.

A 52-year-old woman presented with painful erythematous nodules of 2 weeks’ duration that began as a single lesion on the left shin and spread rapidly to involve the trunk, arms, and legs. A punch biopsy was performed. Pertinent history included a recent hospitalization for drainage of malignant ascites secondary to metastatic ovarian cancer. The lesions did not drain and were not pruritic. The patient did not have a history of fever, night sweats, nausea, headache, neurologic change, muscle aching, or recent weight loss.

Indurated Erythematous Papules and Plaques on the Forearm

The Diagnosis: Mycobacterium chelonae Arising Within a Tattoo

A 3-mm punch biopsy specimen was obtained from one of the plaques. Histopathology revealed an unremarkable epidermis with granulomatous collections of epithelioid histiocytes in association with neutrophils and lymphocytes in the dermis (Figure 1). Periodic acid–Schiff stain was negative for fungal organisms. Gram stain was negative for bacteria. Fite stain was positive for acid-fast bacilli (Figure 2). Clinical and histopathologic findings led to the initial diagnosis of a mycobacterial infection within the tattoo. The patient was empirically started on oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily and oral clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily with mild improvement of the lesions over the next month. After 6 weeks the mycobacterial cultures were persistently negative and high-performance liquid chromatography was performed verifying the presence of Mycobacterium chelonae. Clarithromycin was continued and the doxycycline was replaced with oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (double strength) twice daily due to resistance. The patient was referred to an infectious disease specialist who concurred with the treatment regimen for a duration of 6 months to a year. A chest radiograph also was performed to rule out disseminated disease. Several months later the patient’s close friend presented with a similar infection that was acquired on the same day as our patient at the same tattoo parlor. The New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene was notified about these cases and informed us of other cases in New York State linked to contaminated tattoo ink.

|

Mycobacterium chelonae is a rapidly growing nontuberculous mycobacteria (Runyon group IV) that is found in nature and contaminated sources such as soil, lakes, sewage, and tap water.1 Inoculation ofM chelonae through contaminated instruments leads to the formation of painful lesions, abscesses, fistulas, and granulomas that are extremely difficult to treat.2 In our patient, M chelonae was most likely transmitted via contaminated tap water that was used to dilute the black tattoo ink to yield a gray color. Alternative sources are the ink itself or the container used to mix the ink.3Mycobacterium chelonae can cause infections in the skin, lungs, joints, bones, and eyes.4 With the exception of lung disease, trauma is the usual inciting factor. Disseminated infections are almost exclusively found in immunosuppressed individuals. Mycobacterium chelonae is typically found to grow on culture within 7 days. However, in our case there was no growth after 6 weeks of incubation. High-performance liquid chromatography analysis of mycolic acid is an alternative method of identifying mycobacteria. This technique verified the presence of M chelonae in our case when cultures were persistently negative.5

Mycobacterium chelonae is difficult to treat. The most common antibiotics used for treatment are clarithromycin, azithromycin, doxycycline, and linezolid.6 Studies of various antibiotics have shown that clarithromycin is the most effective macrolide against M chelonae.7 Tetracyclines also were studied in their effectiveness at treating nontuberculous mycobacteria infections but were found to have increased resistance to M chelonae.8 Although treatment regimens vary, the highest success rates are achieved with a minimum of 6 months of therapy using at least 2 drugs. Longer treatment is recommended for immunocompromised individuals.9

The case we present is important from a public health perspective. The tattoo industry and ink manufacturers should bemade aware of the risks of various infections from nonsterile techniques. Tattoo parlor employees should be advised of the risks of using nonsterile water for ink dilution and cleaning tattoo equipment. They also should be continuously educated on aseptic techniques.

1. Lee RP, Cheung KW, Chiu KH, et al. Mycobacterium chelonae infection after total knee arthroplasty: a case report. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2012;20:134-136.

2. Camargo D, Saad C, Ruiz F, et al. latrogenic outbreak of M. chelonae skin abscesses. Epidemiol Infect. 1996;117:113-119.

3. Rodríguez-Blanco I, Fernández LC, Suárez-Peñaranda JM, et al. Mycobacterium chelonae infection associated with tattoos. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011;91:61-62.

4. Karak K, Bhattacharyya S, Majumdar S, et al. Pulmonary infections caused by mycobacteria other than M. tuberculosis in and around Calcutta. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 1996;39:131-134.

5. Butler WR, Floyd MM, Silcox V, et al. Standardized Method for HPLC Identification of Mycobacteria. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services; 1996.

6. Brown-Elliot BA, Wallace RJ Jr, Blinkhorn R, et al. Successful treatment of disseminated Mycobacterium chelonae infection with linezolid. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:1433-1434.

7. Brown BA, Wallace RJ Jr, Onyi GO, et al. Activities of four macrolides, including clarithromycin, against Mycobacterium fortuitum, Mycobacterium chelonae, and Mycobacterium chelonae-like organisms. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:180-184.

8. Swenson JM, Wallace RJ Jr, Silcox VA, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility of five subgroups of Mycobacterium fortuitum and Mycobacterium chelonae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1985;28:807-811.

9. Leung YY, Choi KW, Ho KM, et al. Disseminated cutaneous infection with Mycobacterium chelonae mimicking panniculitis in a patient with dermatomyositis. Hong Kong Med J. 2005;11:515-519.

The Diagnosis: Mycobacterium chelonae Arising Within a Tattoo

A 3-mm punch biopsy specimen was obtained from one of the plaques. Histopathology revealed an unremarkable epidermis with granulomatous collections of epithelioid histiocytes in association with neutrophils and lymphocytes in the dermis (Figure 1). Periodic acid–Schiff stain was negative for fungal organisms. Gram stain was negative for bacteria. Fite stain was positive for acid-fast bacilli (Figure 2). Clinical and histopathologic findings led to the initial diagnosis of a mycobacterial infection within the tattoo. The patient was empirically started on oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily and oral clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily with mild improvement of the lesions over the next month. After 6 weeks the mycobacterial cultures were persistently negative and high-performance liquid chromatography was performed verifying the presence of Mycobacterium chelonae. Clarithromycin was continued and the doxycycline was replaced with oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (double strength) twice daily due to resistance. The patient was referred to an infectious disease specialist who concurred with the treatment regimen for a duration of 6 months to a year. A chest radiograph also was performed to rule out disseminated disease. Several months later the patient’s close friend presented with a similar infection that was acquired on the same day as our patient at the same tattoo parlor. The New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene was notified about these cases and informed us of other cases in New York State linked to contaminated tattoo ink.

|

Mycobacterium chelonae is a rapidly growing nontuberculous mycobacteria (Runyon group IV) that is found in nature and contaminated sources such as soil, lakes, sewage, and tap water.1 Inoculation ofM chelonae through contaminated instruments leads to the formation of painful lesions, abscesses, fistulas, and granulomas that are extremely difficult to treat.2 In our patient, M chelonae was most likely transmitted via contaminated tap water that was used to dilute the black tattoo ink to yield a gray color. Alternative sources are the ink itself or the container used to mix the ink.3Mycobacterium chelonae can cause infections in the skin, lungs, joints, bones, and eyes.4 With the exception of lung disease, trauma is the usual inciting factor. Disseminated infections are almost exclusively found in immunosuppressed individuals. Mycobacterium chelonae is typically found to grow on culture within 7 days. However, in our case there was no growth after 6 weeks of incubation. High-performance liquid chromatography analysis of mycolic acid is an alternative method of identifying mycobacteria. This technique verified the presence of M chelonae in our case when cultures were persistently negative.5

Mycobacterium chelonae is difficult to treat. The most common antibiotics used for treatment are clarithromycin, azithromycin, doxycycline, and linezolid.6 Studies of various antibiotics have shown that clarithromycin is the most effective macrolide against M chelonae.7 Tetracyclines also were studied in their effectiveness at treating nontuberculous mycobacteria infections but were found to have increased resistance to M chelonae.8 Although treatment regimens vary, the highest success rates are achieved with a minimum of 6 months of therapy using at least 2 drugs. Longer treatment is recommended for immunocompromised individuals.9

The case we present is important from a public health perspective. The tattoo industry and ink manufacturers should bemade aware of the risks of various infections from nonsterile techniques. Tattoo parlor employees should be advised of the risks of using nonsterile water for ink dilution and cleaning tattoo equipment. They also should be continuously educated on aseptic techniques.

The Diagnosis: Mycobacterium chelonae Arising Within a Tattoo

A 3-mm punch biopsy specimen was obtained from one of the plaques. Histopathology revealed an unremarkable epidermis with granulomatous collections of epithelioid histiocytes in association with neutrophils and lymphocytes in the dermis (Figure 1). Periodic acid–Schiff stain was negative for fungal organisms. Gram stain was negative for bacteria. Fite stain was positive for acid-fast bacilli (Figure 2). Clinical and histopathologic findings led to the initial diagnosis of a mycobacterial infection within the tattoo. The patient was empirically started on oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily and oral clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily with mild improvement of the lesions over the next month. After 6 weeks the mycobacterial cultures were persistently negative and high-performance liquid chromatography was performed verifying the presence of Mycobacterium chelonae. Clarithromycin was continued and the doxycycline was replaced with oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (double strength) twice daily due to resistance. The patient was referred to an infectious disease specialist who concurred with the treatment regimen for a duration of 6 months to a year. A chest radiograph also was performed to rule out disseminated disease. Several months later the patient’s close friend presented with a similar infection that was acquired on the same day as our patient at the same tattoo parlor. The New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene was notified about these cases and informed us of other cases in New York State linked to contaminated tattoo ink.

|

Mycobacterium chelonae is a rapidly growing nontuberculous mycobacteria (Runyon group IV) that is found in nature and contaminated sources such as soil, lakes, sewage, and tap water.1 Inoculation ofM chelonae through contaminated instruments leads to the formation of painful lesions, abscesses, fistulas, and granulomas that are extremely difficult to treat.2 In our patient, M chelonae was most likely transmitted via contaminated tap water that was used to dilute the black tattoo ink to yield a gray color. Alternative sources are the ink itself or the container used to mix the ink.3Mycobacterium chelonae can cause infections in the skin, lungs, joints, bones, and eyes.4 With the exception of lung disease, trauma is the usual inciting factor. Disseminated infections are almost exclusively found in immunosuppressed individuals. Mycobacterium chelonae is typically found to grow on culture within 7 days. However, in our case there was no growth after 6 weeks of incubation. High-performance liquid chromatography analysis of mycolic acid is an alternative method of identifying mycobacteria. This technique verified the presence of M chelonae in our case when cultures were persistently negative.5

Mycobacterium chelonae is difficult to treat. The most common antibiotics used for treatment are clarithromycin, azithromycin, doxycycline, and linezolid.6 Studies of various antibiotics have shown that clarithromycin is the most effective macrolide against M chelonae.7 Tetracyclines also were studied in their effectiveness at treating nontuberculous mycobacteria infections but were found to have increased resistance to M chelonae.8 Although treatment regimens vary, the highest success rates are achieved with a minimum of 6 months of therapy using at least 2 drugs. Longer treatment is recommended for immunocompromised individuals.9

The case we present is important from a public health perspective. The tattoo industry and ink manufacturers should bemade aware of the risks of various infections from nonsterile techniques. Tattoo parlor employees should be advised of the risks of using nonsterile water for ink dilution and cleaning tattoo equipment. They also should be continuously educated on aseptic techniques.

1. Lee RP, Cheung KW, Chiu KH, et al. Mycobacterium chelonae infection after total knee arthroplasty: a case report. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2012;20:134-136.

2. Camargo D, Saad C, Ruiz F, et al. latrogenic outbreak of M. chelonae skin abscesses. Epidemiol Infect. 1996;117:113-119.

3. Rodríguez-Blanco I, Fernández LC, Suárez-Peñaranda JM, et al. Mycobacterium chelonae infection associated with tattoos. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011;91:61-62.

4. Karak K, Bhattacharyya S, Majumdar S, et al. Pulmonary infections caused by mycobacteria other than M. tuberculosis in and around Calcutta. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 1996;39:131-134.

5. Butler WR, Floyd MM, Silcox V, et al. Standardized Method for HPLC Identification of Mycobacteria. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services; 1996.

6. Brown-Elliot BA, Wallace RJ Jr, Blinkhorn R, et al. Successful treatment of disseminated Mycobacterium chelonae infection with linezolid. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:1433-1434.

7. Brown BA, Wallace RJ Jr, Onyi GO, et al. Activities of four macrolides, including clarithromycin, against Mycobacterium fortuitum, Mycobacterium chelonae, and Mycobacterium chelonae-like organisms. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:180-184.

8. Swenson JM, Wallace RJ Jr, Silcox VA, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility of five subgroups of Mycobacterium fortuitum and Mycobacterium chelonae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1985;28:807-811.

9. Leung YY, Choi KW, Ho KM, et al. Disseminated cutaneous infection with Mycobacterium chelonae mimicking panniculitis in a patient with dermatomyositis. Hong Kong Med J. 2005;11:515-519.

1. Lee RP, Cheung KW, Chiu KH, et al. Mycobacterium chelonae infection after total knee arthroplasty: a case report. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2012;20:134-136.

2. Camargo D, Saad C, Ruiz F, et al. latrogenic outbreak of M. chelonae skin abscesses. Epidemiol Infect. 1996;117:113-119.

3. Rodríguez-Blanco I, Fernández LC, Suárez-Peñaranda JM, et al. Mycobacterium chelonae infection associated with tattoos. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011;91:61-62.

4. Karak K, Bhattacharyya S, Majumdar S, et al. Pulmonary infections caused by mycobacteria other than M. tuberculosis in and around Calcutta. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 1996;39:131-134.

5. Butler WR, Floyd MM, Silcox V, et al. Standardized Method for HPLC Identification of Mycobacteria. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services; 1996.

6. Brown-Elliot BA, Wallace RJ Jr, Blinkhorn R, et al. Successful treatment of disseminated Mycobacterium chelonae infection with linezolid. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:1433-1434.

7. Brown BA, Wallace RJ Jr, Onyi GO, et al. Activities of four macrolides, including clarithromycin, against Mycobacterium fortuitum, Mycobacterium chelonae, and Mycobacterium chelonae-like organisms. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:180-184.

8. Swenson JM, Wallace RJ Jr, Silcox VA, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility of five subgroups of Mycobacterium fortuitum and Mycobacterium chelonae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1985;28:807-811.

9. Leung YY, Choi KW, Ho KM, et al. Disseminated cutaneous infection with Mycobacterium chelonae mimicking panniculitis in a patient with dermatomyositis. Hong Kong Med J. 2005;11:515-519.

A 21-year-old man presented with growing, mildly pruritic, cutaneous papules and plaques on the right extensor forearm of 3 weeks’ duration. The lesions appeared 1 week after receiving a tattoo on the arm. One year prior the patient had a similar tattoo placed on another section of the right arm without any complications. The patient was afebrile and denied a history of sarcoidosis. Physical examination revealed indurated erythematous papules and plaques on the right extensor forearm that were most prominent in the gray-colored areas of the tattoo.

Hole in Jaw Has Drained Fluid for 20 Years

ANSWER

The correct answer is all of the above (choice “d”). The patient’s actual diagnosis, sinus tract of odontogenic origin (choice “a”), will be discussed further.

Branchial cleft cyst (choice “b”) is always in the differential for neck masses, and squamous cell carcinoma (choice “c”) should always be considered in cases of nonhealing lesions—although 20 years is an unlikely timeframe for that diagnosis! Additional differential possibilities include thyroglossal duct cyst and pyogenic granuloma.

DISCUSSION

Sinus tracts of odontogenic origin, also called dentocutaneous sinus tracts, are primarily caused by periapical abscesses. As the purulent material accumulates in the confined space around the apical area, pressure increases; this sets in motion a tunneling process that terminates in an outlet, often inside the mouth but also (often enough) on the skin.

In the latter instance, known as extraoral sinus, the opening forms along the chin or submental area. In 80% of cases, the source is the mandibular teeth.

Dermocutaneous sinuses of maxillary origin, though not unknown, are decidedly unusual. They can drain anywhere on the maxilla, including around the nose. In edentulous patients, retained tooth fragments or segments of apical abscesses can act as the nidus for this process.

When a draining sinus manifests more acutely or occurs in a patient from a high-risk area (eg, Mexico or Central America), other diagnoses must be considered. These include scrofula, in which regional nymph nodes, infected by Mycobacterium tuberculosis or atypical mycobacterial organism, break down and drain. The indolent nature and chronicity of this patient’s problem effectively ruled out this diagnosis.

Culture of the fluid draining from the abscess would reveal a number of organisms (mostly of the strep family) but would not show the actual causative bacteria, since they are typically anaerobic. Biopsy of the surrounding tissue is occasionally necessary, when squamous cell carcinoma or other neoplastic process is suspected.

TREATMENT

The patient was advised to see a dentist, who will likely obtain a panoramic radiograph of her teeth, with particular attention to the affected area.

If an abscess is identified, as expected, treatment would entail root canal or extraction. The sinus tract would then heal rather quickly.

Antibiotics would be of limited use without elimination of the pocket. However, when patients complain of discomfort or outright pain, antibiotics (eg, penicillin V potassium or amoxicillin/clavulanate) can help to reduce the inflammation and offer some relief.

ANSWER

The correct answer is all of the above (choice “d”). The patient’s actual diagnosis, sinus tract of odontogenic origin (choice “a”), will be discussed further.

Branchial cleft cyst (choice “b”) is always in the differential for neck masses, and squamous cell carcinoma (choice “c”) should always be considered in cases of nonhealing lesions—although 20 years is an unlikely timeframe for that diagnosis! Additional differential possibilities include thyroglossal duct cyst and pyogenic granuloma.

DISCUSSION

Sinus tracts of odontogenic origin, also called dentocutaneous sinus tracts, are primarily caused by periapical abscesses. As the purulent material accumulates in the confined space around the apical area, pressure increases; this sets in motion a tunneling process that terminates in an outlet, often inside the mouth but also (often enough) on the skin.

In the latter instance, known as extraoral sinus, the opening forms along the chin or submental area. In 80% of cases, the source is the mandibular teeth.

Dermocutaneous sinuses of maxillary origin, though not unknown, are decidedly unusual. They can drain anywhere on the maxilla, including around the nose. In edentulous patients, retained tooth fragments or segments of apical abscesses can act as the nidus for this process.

When a draining sinus manifests more acutely or occurs in a patient from a high-risk area (eg, Mexico or Central America), other diagnoses must be considered. These include scrofula, in which regional nymph nodes, infected by Mycobacterium tuberculosis or atypical mycobacterial organism, break down and drain. The indolent nature and chronicity of this patient’s problem effectively ruled out this diagnosis.

Culture of the fluid draining from the abscess would reveal a number of organisms (mostly of the strep family) but would not show the actual causative bacteria, since they are typically anaerobic. Biopsy of the surrounding tissue is occasionally necessary, when squamous cell carcinoma or other neoplastic process is suspected.

TREATMENT

The patient was advised to see a dentist, who will likely obtain a panoramic radiograph of her teeth, with particular attention to the affected area.

If an abscess is identified, as expected, treatment would entail root canal or extraction. The sinus tract would then heal rather quickly.

Antibiotics would be of limited use without elimination of the pocket. However, when patients complain of discomfort or outright pain, antibiotics (eg, penicillin V potassium or amoxicillin/clavulanate) can help to reduce the inflammation and offer some relief.

ANSWER

The correct answer is all of the above (choice “d”). The patient’s actual diagnosis, sinus tract of odontogenic origin (choice “a”), will be discussed further.

Branchial cleft cyst (choice “b”) is always in the differential for neck masses, and squamous cell carcinoma (choice “c”) should always be considered in cases of nonhealing lesions—although 20 years is an unlikely timeframe for that diagnosis! Additional differential possibilities include thyroglossal duct cyst and pyogenic granuloma.

DISCUSSION

Sinus tracts of odontogenic origin, also called dentocutaneous sinus tracts, are primarily caused by periapical abscesses. As the purulent material accumulates in the confined space around the apical area, pressure increases; this sets in motion a tunneling process that terminates in an outlet, often inside the mouth but also (often enough) on the skin.

In the latter instance, known as extraoral sinus, the opening forms along the chin or submental area. In 80% of cases, the source is the mandibular teeth.

Dermocutaneous sinuses of maxillary origin, though not unknown, are decidedly unusual. They can drain anywhere on the maxilla, including around the nose. In edentulous patients, retained tooth fragments or segments of apical abscesses can act as the nidus for this process.

When a draining sinus manifests more acutely or occurs in a patient from a high-risk area (eg, Mexico or Central America), other diagnoses must be considered. These include scrofula, in which regional nymph nodes, infected by Mycobacterium tuberculosis or atypical mycobacterial organism, break down and drain. The indolent nature and chronicity of this patient’s problem effectively ruled out this diagnosis.