User login

New PDT therapy for CTCL to be reviewed by FDA

based on phase 3 findings published in JAMA Dermatology.

The treatment employs an ointment formulation of synthetic hypericin (HyBryte), a photosensitizer, that is preferentially absorbed into malignant cells and activated with visible light – rather than ultraviolet light – approximately 24 hours later. Investigators saw significant clinical responses in both patch and plaque type lesions and across races during the 24-week placebo-controlled, double-blinded, phase 3, randomized clinical trial.

“Traditional phototherapy, ultraviolet B phototherapy, has a limited depth of penetration, so patients with thicker plaque lesions don’t respond as well ... and UVB phototherapy typically is less effective in penetrating pigmented skin,” Ellen J. Kim, MD, lead author of the FLASH phase 3 trial, said in an interview.

Visible light in the yellow-red spectrum (500-650 nm) “penetrates deeper into the skin” and is nonmutagenic in vitro, so “theoretically it should have a much more favorable long-term safety profile,” said Dr. Kim, a dermatologist at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Currently, she said, the risk of secondary malignancies inherent with UV PDT, including melanoma, is a deterrent for some patients, especially “patients with really fair skin and a history of skin cancer.”

Hypericin PDT also seems well suited for use with an at-home light unit. “In our field, it’s not about which therapy is [universally] better or best, but a matter of what works best for each patient at that moment in time, depending on the side-effect profile and other issues such as access,” Dr. Kim said. “It will be great to have another option for an incurable disease that requires chronic management.”

Mycosis fungoides (MF)/CTCL is considered an orphan disease, and the treatment has received orphan drug and fast track designations from the FDA, and orphan designation from the European Medicines Agency, according to a press release from its developer, Soligenix. The company is anticipating potential approval in the second half of 2023 and is targeting early 2024 for a U.S. launch, the statement said.

Phase 3 results

The pivotal trial involved 169 patients at 39 academic and community-based U.S. medical centers and consisted of several 6-week cycles of twice-weekly treatment punctuated by 2-week breaks. In cycle 1, patients were randomized 2:1 to receive hypericin or placebo treatment of three index lesions. Cycle 2 involved the crossover of placebo patients to active treatment of index lesions, and cycle 3 (optional) involved open-label treatment of all desired lesions (index and nonindex).

The trial defined the primary endpoint in phase 1 as 50% or greater improvement in the modified Composite Assessment of Index Lesion Severity score – a tool that’s endorsed by U.S. and international MF/CTCL specialty group consensus guidelines. For cycles 2 and 3, open-label response rates were secondary endpoints. Responses were assessed after 2-week rest periods to allow for treatment-induced skin reactions to subside.

After one cycle of treatment, topical hypericin PDT was more effective than placebo (an index lesion response rate of 16% vs. 4%; P =.04). The index lesion response rate with treatment increased to 40% after two cycles and 49% after three cycles. All were statistically significant changes.

Response rates were similar in patch and plaque-type lesions and regardless of age, sex, race, stage IA versus IB, time since diagnosis, and number of prior therapies. Adverse events were primarily mild application-site skin reactions. No serious drug-related adverse events occurred, Dr. Kim said, and “we had a low drop-out rate overall.”

Into the real world

The 24-week phase 3 trial duration is short, considering that “typically, phototherapy takes between 4 to 24 months [to achieve] full responses in CTCL,” Dr. Kim said in the interview.

So with real-world application, she said, “we’ll want to see where the overall response peaks with longer treatment, what the effects are of continuous treatment without any built-in breaks, and whether we will indeed see less skin cancer development in patients who are at higher risk of developing skin cancers from light treatment.”

Such questions will be explored as part of a new 4-year, 50-patient, open-label, multicenter study with the primary aim of investigating home-based hypericin PDT therapy in a supervised setting, said Dr. Kim, principal investigator of this study. Patients who are doing well after 6 weeks of twice-weekly therapy will be given at-home light units to continue therapy and achieve 1 year of treatment with no breaks. They will be monitored with video-based telemedicine.

“Long term, having a home unit should really improve patient access and compliance and hopefully effectiveness,” Dr. Kim said. Based on the phase 3 experience, “we think that continuous treatment will be well tolerated and that we may see greater responses.”

On Dec. 19, Soligenix announced that enrollment had begun in a phase 2a study of synthetic hypericin for treating patients with mild to moderate psoriasis.

Dr. Kim reported to JAMA Dermatology grants from Innate Pharma and Galderma; consulting/advisory fees from Almirall, Galderma, and Helsinn; and honoraria from Ology and UptoDate.

based on phase 3 findings published in JAMA Dermatology.

The treatment employs an ointment formulation of synthetic hypericin (HyBryte), a photosensitizer, that is preferentially absorbed into malignant cells and activated with visible light – rather than ultraviolet light – approximately 24 hours later. Investigators saw significant clinical responses in both patch and plaque type lesions and across races during the 24-week placebo-controlled, double-blinded, phase 3, randomized clinical trial.

“Traditional phototherapy, ultraviolet B phototherapy, has a limited depth of penetration, so patients with thicker plaque lesions don’t respond as well ... and UVB phototherapy typically is less effective in penetrating pigmented skin,” Ellen J. Kim, MD, lead author of the FLASH phase 3 trial, said in an interview.

Visible light in the yellow-red spectrum (500-650 nm) “penetrates deeper into the skin” and is nonmutagenic in vitro, so “theoretically it should have a much more favorable long-term safety profile,” said Dr. Kim, a dermatologist at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Currently, she said, the risk of secondary malignancies inherent with UV PDT, including melanoma, is a deterrent for some patients, especially “patients with really fair skin and a history of skin cancer.”

Hypericin PDT also seems well suited for use with an at-home light unit. “In our field, it’s not about which therapy is [universally] better or best, but a matter of what works best for each patient at that moment in time, depending on the side-effect profile and other issues such as access,” Dr. Kim said. “It will be great to have another option for an incurable disease that requires chronic management.”

Mycosis fungoides (MF)/CTCL is considered an orphan disease, and the treatment has received orphan drug and fast track designations from the FDA, and orphan designation from the European Medicines Agency, according to a press release from its developer, Soligenix. The company is anticipating potential approval in the second half of 2023 and is targeting early 2024 for a U.S. launch, the statement said.

Phase 3 results

The pivotal trial involved 169 patients at 39 academic and community-based U.S. medical centers and consisted of several 6-week cycles of twice-weekly treatment punctuated by 2-week breaks. In cycle 1, patients were randomized 2:1 to receive hypericin or placebo treatment of three index lesions. Cycle 2 involved the crossover of placebo patients to active treatment of index lesions, and cycle 3 (optional) involved open-label treatment of all desired lesions (index and nonindex).

The trial defined the primary endpoint in phase 1 as 50% or greater improvement in the modified Composite Assessment of Index Lesion Severity score – a tool that’s endorsed by U.S. and international MF/CTCL specialty group consensus guidelines. For cycles 2 and 3, open-label response rates were secondary endpoints. Responses were assessed after 2-week rest periods to allow for treatment-induced skin reactions to subside.

After one cycle of treatment, topical hypericin PDT was more effective than placebo (an index lesion response rate of 16% vs. 4%; P =.04). The index lesion response rate with treatment increased to 40% after two cycles and 49% after three cycles. All were statistically significant changes.

Response rates were similar in patch and plaque-type lesions and regardless of age, sex, race, stage IA versus IB, time since diagnosis, and number of prior therapies. Adverse events were primarily mild application-site skin reactions. No serious drug-related adverse events occurred, Dr. Kim said, and “we had a low drop-out rate overall.”

Into the real world

The 24-week phase 3 trial duration is short, considering that “typically, phototherapy takes between 4 to 24 months [to achieve] full responses in CTCL,” Dr. Kim said in the interview.

So with real-world application, she said, “we’ll want to see where the overall response peaks with longer treatment, what the effects are of continuous treatment without any built-in breaks, and whether we will indeed see less skin cancer development in patients who are at higher risk of developing skin cancers from light treatment.”

Such questions will be explored as part of a new 4-year, 50-patient, open-label, multicenter study with the primary aim of investigating home-based hypericin PDT therapy in a supervised setting, said Dr. Kim, principal investigator of this study. Patients who are doing well after 6 weeks of twice-weekly therapy will be given at-home light units to continue therapy and achieve 1 year of treatment with no breaks. They will be monitored with video-based telemedicine.

“Long term, having a home unit should really improve patient access and compliance and hopefully effectiveness,” Dr. Kim said. Based on the phase 3 experience, “we think that continuous treatment will be well tolerated and that we may see greater responses.”

On Dec. 19, Soligenix announced that enrollment had begun in a phase 2a study of synthetic hypericin for treating patients with mild to moderate psoriasis.

Dr. Kim reported to JAMA Dermatology grants from Innate Pharma and Galderma; consulting/advisory fees from Almirall, Galderma, and Helsinn; and honoraria from Ology and UptoDate.

based on phase 3 findings published in JAMA Dermatology.

The treatment employs an ointment formulation of synthetic hypericin (HyBryte), a photosensitizer, that is preferentially absorbed into malignant cells and activated with visible light – rather than ultraviolet light – approximately 24 hours later. Investigators saw significant clinical responses in both patch and plaque type lesions and across races during the 24-week placebo-controlled, double-blinded, phase 3, randomized clinical trial.

“Traditional phototherapy, ultraviolet B phototherapy, has a limited depth of penetration, so patients with thicker plaque lesions don’t respond as well ... and UVB phototherapy typically is less effective in penetrating pigmented skin,” Ellen J. Kim, MD, lead author of the FLASH phase 3 trial, said in an interview.

Visible light in the yellow-red spectrum (500-650 nm) “penetrates deeper into the skin” and is nonmutagenic in vitro, so “theoretically it should have a much more favorable long-term safety profile,” said Dr. Kim, a dermatologist at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Currently, she said, the risk of secondary malignancies inherent with UV PDT, including melanoma, is a deterrent for some patients, especially “patients with really fair skin and a history of skin cancer.”

Hypericin PDT also seems well suited for use with an at-home light unit. “In our field, it’s not about which therapy is [universally] better or best, but a matter of what works best for each patient at that moment in time, depending on the side-effect profile and other issues such as access,” Dr. Kim said. “It will be great to have another option for an incurable disease that requires chronic management.”

Mycosis fungoides (MF)/CTCL is considered an orphan disease, and the treatment has received orphan drug and fast track designations from the FDA, and orphan designation from the European Medicines Agency, according to a press release from its developer, Soligenix. The company is anticipating potential approval in the second half of 2023 and is targeting early 2024 for a U.S. launch, the statement said.

Phase 3 results

The pivotal trial involved 169 patients at 39 academic and community-based U.S. medical centers and consisted of several 6-week cycles of twice-weekly treatment punctuated by 2-week breaks. In cycle 1, patients were randomized 2:1 to receive hypericin or placebo treatment of three index lesions. Cycle 2 involved the crossover of placebo patients to active treatment of index lesions, and cycle 3 (optional) involved open-label treatment of all desired lesions (index and nonindex).

The trial defined the primary endpoint in phase 1 as 50% or greater improvement in the modified Composite Assessment of Index Lesion Severity score – a tool that’s endorsed by U.S. and international MF/CTCL specialty group consensus guidelines. For cycles 2 and 3, open-label response rates were secondary endpoints. Responses were assessed after 2-week rest periods to allow for treatment-induced skin reactions to subside.

After one cycle of treatment, topical hypericin PDT was more effective than placebo (an index lesion response rate of 16% vs. 4%; P =.04). The index lesion response rate with treatment increased to 40% after two cycles and 49% after three cycles. All were statistically significant changes.

Response rates were similar in patch and plaque-type lesions and regardless of age, sex, race, stage IA versus IB, time since diagnosis, and number of prior therapies. Adverse events were primarily mild application-site skin reactions. No serious drug-related adverse events occurred, Dr. Kim said, and “we had a low drop-out rate overall.”

Into the real world

The 24-week phase 3 trial duration is short, considering that “typically, phototherapy takes between 4 to 24 months [to achieve] full responses in CTCL,” Dr. Kim said in the interview.

So with real-world application, she said, “we’ll want to see where the overall response peaks with longer treatment, what the effects are of continuous treatment without any built-in breaks, and whether we will indeed see less skin cancer development in patients who are at higher risk of developing skin cancers from light treatment.”

Such questions will be explored as part of a new 4-year, 50-patient, open-label, multicenter study with the primary aim of investigating home-based hypericin PDT therapy in a supervised setting, said Dr. Kim, principal investigator of this study. Patients who are doing well after 6 weeks of twice-weekly therapy will be given at-home light units to continue therapy and achieve 1 year of treatment with no breaks. They will be monitored with video-based telemedicine.

“Long term, having a home unit should really improve patient access and compliance and hopefully effectiveness,” Dr. Kim said. Based on the phase 3 experience, “we think that continuous treatment will be well tolerated and that we may see greater responses.”

On Dec. 19, Soligenix announced that enrollment had begun in a phase 2a study of synthetic hypericin for treating patients with mild to moderate psoriasis.

Dr. Kim reported to JAMA Dermatology grants from Innate Pharma and Galderma; consulting/advisory fees from Almirall, Galderma, and Helsinn; and honoraria from Ology and UptoDate.

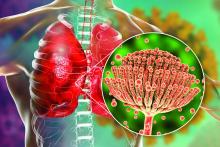

Rise of the fungi: Pandemic tied to increasing fungal infections

COVID-19 has lifted the lid on the risks of secondary pulmonary fungal infections in patients with severe respiratory viral illness – even previously immunocompetent individuals – and highlighted the importance of vigilant investigation to achieve early diagnoses, leading experts say.

Most fungi are not under surveillance in the United States, leaving experts without a national picture of the true burden of infection through the pandemic. However, a collection of published case series, cohort studies, and reviews from Europe, the United States, and throughout the world – mainly pre-Omicron – show that fungal disease has affected a significant portion of critically ill patients with COVID-19, with concerning excess mortality, these experts say.

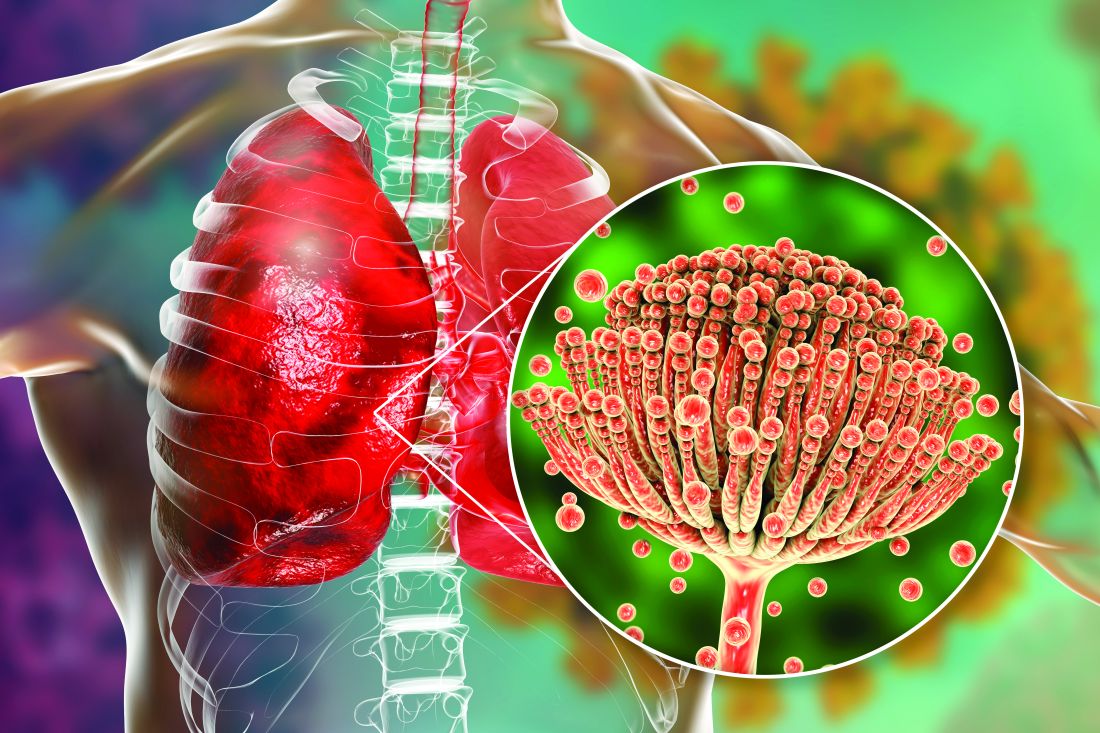

COVID-associated pulmonary aspergillosis (CAPA) has been the predominant fungal coinfection in the United States and internationally. But COVID-associated mucormycosis (CAM) – the infection that surged in India in early 2021 – has also affected some patients in the United States, published data show. So have Pneumocystitis pneumonia, cryptococcosis, histoplasmosis, and Candida infections (which mainly affect the bloodstream and abdomen), say the experts who were interviewed.

“We had predicted [a rise in] aspergillosis, but we saw more than we thought we’d see. Most fungal infections became more common with COVID-19,” said George Thompson, MD, professor of clinical medicine at the University of California, Davis, and cochair of the University of Alabama–based Mycoses Study Group Education Committee, a group of experts in medical mycology. Pneumocystitis, for instance, “has historically been associated with AIDS or different types of leukemia or lymphoma, and is not an infection we’ve typically seen in our otherwise healthy ICU patients,” he noted. “But we did see more of it [with COVID-19].”

More recently, with fewer patients during the Omicron phase in intensive care units with acute respiratory failure, the profile of fungal disease secondary to COVID-19 has changed. Increasing proportions of patients have traditional risk factors for aspergillosis, such as hematologic malignancies and longer-term, pre-COVID use of systemic corticosteroids – a change that makes the contribution of the viral illness harder to distinguish.

Moving forward, the lessons of the COVID era – the fungal risks to patients with serious viral infections and the persistence needed to diagnose aspergillosis and other pulmonary fungal infections using bronchoscopy and imperfect noninvasive tests – should be taken to heart, experts say.

“Fungal diseases are not rare. They’re just not diagnosed because no one thinks to look for them,” said Dr. Thompson, a contributor to a recently released World Health Organization report naming a “fungal priority pathogens” list.

“We’re going to continue to see [secondary fungal infections] with other respiratory viruses,” he said. And overall, given environmental and other changes, “we’re going to see more and more fungal disease in the patients we take care of.”

CAPA not a surprise

CAPA is “not an unfamiliar story” in the world of fungal disease, given a history of influenza-associated pulmonary aspergillosis (IAPA), said Kieren A. Marr, MD, MBA, adjunct professor of medicine and past director of the transplant and oncology infectious diseases program at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, who has long researched invasive fungal disease.

European researchers, she said, have led the way in describing a high incidence of IAPA in patients admitted to ICUs with influenza. In a retrospective multicenter cohort study reported in 2018 by the Dutch-Belgian Mycosis Study group, for instance, almost 20% of 432 influenza patients admitted to the ICU, including patients who were otherwise healthy and not immunocompromised, had the diagnosis a median of 3 days after ICU admission. (Across other cohort studies, rates of IAPA have ranged from 7% to 30%.)

Mortality was significant: 51% of patients with influenza and invasive pulmonary aspergillosis died within 90 days, compared with 28% of patients with influenza and no invasive pulmonary aspergillosis.

Reports from Europe early in the pandemic indicated that CAPA was a similarly serious problem, prompting establishment at Johns Hopkins University of an aggressive screening program utilizing biomarker-based testing of blood and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid. Of 396 mechanically ventilated COVID-19 patients admitted to Johns Hopkins University hospitals between March and August 2020, 39 met the institution’s criteria for CAPA, Dr. Marr and her colleagues reported this year in what might be the largest U.S. cohort study of CAPA published to date.

“We now know definitively that people with severe influenza and with severe COVID also have high risks for both invasive and airway disease caused by airborne fungi, most commonly aspergilliosis,” Dr. Marr said.

More recent unpublished analyses of patients from the start of the pandemic to June 2021 show persistent risk, said Nitipong Permpalung, MD, MPH, assistant professor in transplant and oncology infectious diseases at Johns Hopkins University and lead author of the cohort study. Among 832 patients with COVID-19 who were mechanically ventilated in Johns Hopkins University hospitals, 11.8% had CAPA, he said. (Also, 3.2% had invasive candidiasis, and 1.1% had other invasive fungal infections.)

Other sources said in interviews that these CAPA prevalence rates generally mirror reports from Europe, though some investigators in Europe have reported CAPA rates more toward 15%.

(The Mycoses Study Group recently collected data from its consortium of U.S. medical centers on the prevalence of CAPA, with funding support from the CDC, but at press time the data had not yet been released. Dr. Thompson said he suspected the prevalence will be lower than earlier papers have suggested, “but still will reflect a significant burden of disease.”)

Patients in the published Johns Hopkins University study who had CAPA were more likely than those with COVID-19 but no CAPA to have underlying pulmonary disease, liver disease, coagulopathy, solid tumors, multiple myeloma, and COVID-19–directed corticosteroids. And they had uniformly worse outcomes with regards to severity of illness and length of intubation.

How much of CAPA is driven by the SARS-CoV-2 virus itself and how much is a consequence of COVID-19 treatments is a topic of active discussion and research. Martin Hoenigl, MD, of the University of Graz, Austria, a leading researcher in medical mycology, said research shows corticosteroids and anti–IL-6 treatments, such as tocilizumab, used to treat COVID-19–driven acute respiratory failure clearly have contributed to CAPA. But he contends that “a number of other mechanisms” are involved as well.

“The immunologic mechanisms are definitely different in these patients with viral illness than in other ICU patients [who develop aspergilliosis]. It’s not just the corticosteroids. The more we learn, we see the virus plays a role as well, suppressing the interferon pathway,” for example, said Dr. Hoenigl, associate professor in the division of infectious diseases and the European Confederation of Medical Mycology (ECMM) Center of Excellence at the university. The earliest reports of CAPA came “when ICUs weren’t using dexamethasone or tocilizumab,” he noted.

In a paper published recently in Lancet Respiratory Medicine that Dr. Hoenigl and others point to, Belgian researchers reported a “three-level breach” in innate antifungal immunity in both IAPA and CAPA, affecting the integrity of the epithelial barrier, the capacity to phagocytose and kill Aspergillus spores, and the ability to destroy Aspergillus hyphae, which is mainly mediated by neutrophils.

The researchers ran a host of genetic and protein analyses on lung samples (most collected via BAL) of 169 patients with influenza or COVID-19, with and without aspergillosis. They found that patients with CAPA had significantly lower neutrophil cell fractions than patients with COVID-19 only, and patients with IAPA or CAPA had reduced type II IFN signaling and increased concentrations of fibrosis-associated growth factors in the lower respiratory tracts (Lancet Respir Med. 2022 Aug 24).

Tom Chiller, MD, MPH, chief of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s Mycotic Disease Branch, said he’s watching such research with interest. For now, he said, it’s important to also consider that “data on COVID show that almost all patients going into the ICUs with pneumonia and COVID are getting broad-spectrum antibiotics” in addition to corticosteroids.

By wiping out good bacteria, the antibiotics could be “creating a perfect niche for fungi to grow,” he said.

Diagnostic challenges

Aspergillus that has invaded the lung tissue in patients with COVID-19 appears to grow there for some time – around 8-10 days, much longer than in IAPA – before becoming angioinvasive, said Dr. Hoenigl. Such a pathophysiology “implicates that we should try to diagnose it while it’s in the lung tissue, using the BAL fluid, and not yet in the blood,” he said.

Some multicenter studies, including one from Europe on Aspergillus test profiles in critically ill COVID-19 patients, have shown mortality rates of close to 90% in patients with CAPA who have positive serum biomarkers, despite appropriate antifungal therapy. “If diagnosed while confined to the lung, however, mortality rates are more like 40%-50% with antifungal therapy,” Dr. Hoenigl said. (Cohort studies published thus far have fairly consistently reported mortality rates in patients with CAPA greater than 40%, he said.)

Bronchoscopy isn’t always pragmatic or possible, however, and is variably used. Some patients with severe COVID-19 may be too unstable for any invasive procedure, said Dr. Permpalung.

Dr. Permpalung looks for CAPA using serum (1-3) beta-D-glucan (BDG, a generic fungal test not specific to Aspergillus), serum galactomannan (GM, specific for Aspergillus), and respiratory cultures (sputum or endotracheal aspirate if intubated) as initial screening tests in the ICU. If there are concerns for CAPA – based on these tests and/or the clinical picture – “a thoughtful risk-benefit discussion is required to determine if patients would benefit from a bronchoscopy or if we should just start them on empiric antifungal therapy.”

Unfortunately, the sensitivity of serum GM is relatively low in CAPA – lower than with classic invasive aspergillosis in the nonviral setting, sources said. BDG, on the other hand, can be falsely positive in the setting of antimicrobials and within the ICU. And the utility of imaging for CAPA is limited. Both the clinical picture and radiological findings of CAPA have resembled those of severe COVID – with the caveat of cavitary lung lesions visible on imaging.

“Cavities or nodules are a highly suspicious finding that could indicate possible fungal infection,” said pulmonologist Amir A. Zeki, MD, MAS, professor of medicine at the University of California, Davis, and codirector of the UC Davis Asthma Network Clinic, who has cared for patients with CAPA.

Cavitation has been described in only a proportion of patients with CAPA, however. So in patients not doing well, “your suspicion has to be raised if you’re not seeing cavities,” he said.

Early in the pandemic, when patients worsened or failed to progress on mechanical ventilation, clinicians at the University of California, Davis, quickly learned not to pin blame too quickly on COVID-19 alone. This remains good advice today, Dr. Zeki said.

“If you have a patient who’s not doing well on a ventilator, not getting better [over weeks], has to be reintubated, has infiltrates or lung nodules that are evolving, or certainly, if they have a cavity, you have to suspect fungal infection,” said Dr. Zeki, who also practices at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in San Diego. “Think about it for those patients who just aren’t moving forward and are continuing to struggle. Have a high index of suspicion, and consult with your infectious disease colleagues.”

Empiric treatment is warranted in some cases if a patient is doing poorly and suspicion for fungal infection is high based on clinical, radiographic, and/or laboratory evidence, he said.

The CDC’s Dr. Chiller said that screening and diagnostic algorithms currently vary from institution to institution, and that diagnostic challenges likely dissuade clinicians from thinking about fungi. “Clinicians often don’t want to deal with fungi – they’re difficult to diagnose, the treatments are limited and can be toxic. But fungi get pushed back until it’s too late,” he said.

“Fungal diagnostics is an area we all need a lot more help with,” and new diagnostics are in the pipeline, he said. In the meantime, he said, “there are tools out there, and we just need to use them more, and improve how they’re used.”

While reported CAPA thus far has typically occurred in the setting of ICU care and mechanical ventilation, it’s not always the case, Dr. Permpalung said. Lung and other solid organ transplant (SOT) recipients with COVID-19 are developing CAPA and other invasive secondary invasive fungal infections despite not being intubated, he said.

Of 276 SOT recipients with COVID-19 who required inpatient treatment at Johns Hopkins University hospitals from the beginning of the pandemic to March 2022, 23 patients developed invasive fungal infections (13 CAPA). Only a fraction – 38 of the 276 – had been intubated, he said.

Mucormycosis resistance

After CAPA, candidiasis and COVID-19-associated mucormycosis (CAM) – most frequently, rhino-orbital-cerebral disease or pulmonary disease – have been the leading reported fungal coinfections in COVID-19, said Dr. Hoenigl, who described the incidence, timeline, risk factors, and pathogenesis of these infections in a review published this year in Nature Microbiology. .

In India, where there has long been high exposure to Mucorales spores and a greater burden of invasive fungal disease, the rate of mucormycosis doubled in 2021, with rhino-orbital-cerebral disease reported almost exclusively, he said. Pulmonary disease has occurred almost exclusively in the ICU setting and has been present in about 50% of cases outside of India, including Europe and the United States.

A preprint meta-analysis of CAM cases posted by the Lancet in July 2022, in which investigators analyzed individual data of 556 reported cases of COVID-19–associated CAM, shows diabetes and history of corticosteroid use present in most patients, and an overall mortality rate of 44.4%, most of which stems from cases of pulmonary or disseminated disease. Thirteen of the 556 reported cases were from the United States.

An important take-away from the analysis, Dr. Hoenigl said, is that Aspergillus coinfection was seen in 7% of patients and was associated with higher mortality. “It’s important to consider that coinfections [of Aspergillus and Mucorales] can exist,” Dr. Hoenigl said, noting that like CAPA, pulmonary CAM is likely underdiagnosed and underreported.

As with CAPA, the clinical and radiological features of pulmonary CAM largely overlap with those associated with COVID-19, and bronchoscopy plays a central role in definitive diagnosis. In the United States, a Mucorales PCR test for blood and BAL fluid is commercially available and used at some centers, Dr. Hoenigl said.

“Mucormycosis is always difficult to treat ... a lot of the treatments don’t work particularly well,” said Dr. Thompson. “With aspergillosis, we have better treatment options.”

Dr. Thompson worries, however, about treatment resistance becoming widespread. Resistance to azole antifungal agents “is already pretty widespread in northern Europe, particularly in the Netherlands and part of the U.K.” because of injudicious use of antifungals in agriculture, he said. “We’ve started to see a few cases [of azole-resistant aspergillosis in the United States] and know it will be more widespread soon.”

Treatment resistance is a focus of the new WHO fungal priority pathogens list – the first such report from the organization. Of the 19 fungi on the list, 4 were ranked as critical: Cryptococcus neoformans, Candida auris, Aspergillus fumigatus, and Candida albicans. Like Dr. Thompson, Dr. Hoenigl contributed to the WHO report.

Dr. Hoenigl reported grant/research support from Astellas, Merck, F2G, Gilread, Pfizer, and Scynexis. Dr. Marr disclosed employment and equity in Pearl Diagnostics and Sfunga Therapeutics. Dr. Thompson, Dr. Permpalung, and Dr. Zeki reported that they have no relevant financial disclosures.

COVID-19 has lifted the lid on the risks of secondary pulmonary fungal infections in patients with severe respiratory viral illness – even previously immunocompetent individuals – and highlighted the importance of vigilant investigation to achieve early diagnoses, leading experts say.

Most fungi are not under surveillance in the United States, leaving experts without a national picture of the true burden of infection through the pandemic. However, a collection of published case series, cohort studies, and reviews from Europe, the United States, and throughout the world – mainly pre-Omicron – show that fungal disease has affected a significant portion of critically ill patients with COVID-19, with concerning excess mortality, these experts say.

COVID-associated pulmonary aspergillosis (CAPA) has been the predominant fungal coinfection in the United States and internationally. But COVID-associated mucormycosis (CAM) – the infection that surged in India in early 2021 – has also affected some patients in the United States, published data show. So have Pneumocystitis pneumonia, cryptococcosis, histoplasmosis, and Candida infections (which mainly affect the bloodstream and abdomen), say the experts who were interviewed.

“We had predicted [a rise in] aspergillosis, but we saw more than we thought we’d see. Most fungal infections became more common with COVID-19,” said George Thompson, MD, professor of clinical medicine at the University of California, Davis, and cochair of the University of Alabama–based Mycoses Study Group Education Committee, a group of experts in medical mycology. Pneumocystitis, for instance, “has historically been associated with AIDS or different types of leukemia or lymphoma, and is not an infection we’ve typically seen in our otherwise healthy ICU patients,” he noted. “But we did see more of it [with COVID-19].”

More recently, with fewer patients during the Omicron phase in intensive care units with acute respiratory failure, the profile of fungal disease secondary to COVID-19 has changed. Increasing proportions of patients have traditional risk factors for aspergillosis, such as hematologic malignancies and longer-term, pre-COVID use of systemic corticosteroids – a change that makes the contribution of the viral illness harder to distinguish.

Moving forward, the lessons of the COVID era – the fungal risks to patients with serious viral infections and the persistence needed to diagnose aspergillosis and other pulmonary fungal infections using bronchoscopy and imperfect noninvasive tests – should be taken to heart, experts say.

“Fungal diseases are not rare. They’re just not diagnosed because no one thinks to look for them,” said Dr. Thompson, a contributor to a recently released World Health Organization report naming a “fungal priority pathogens” list.

“We’re going to continue to see [secondary fungal infections] with other respiratory viruses,” he said. And overall, given environmental and other changes, “we’re going to see more and more fungal disease in the patients we take care of.”

CAPA not a surprise

CAPA is “not an unfamiliar story” in the world of fungal disease, given a history of influenza-associated pulmonary aspergillosis (IAPA), said Kieren A. Marr, MD, MBA, adjunct professor of medicine and past director of the transplant and oncology infectious diseases program at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, who has long researched invasive fungal disease.

European researchers, she said, have led the way in describing a high incidence of IAPA in patients admitted to ICUs with influenza. In a retrospective multicenter cohort study reported in 2018 by the Dutch-Belgian Mycosis Study group, for instance, almost 20% of 432 influenza patients admitted to the ICU, including patients who were otherwise healthy and not immunocompromised, had the diagnosis a median of 3 days after ICU admission. (Across other cohort studies, rates of IAPA have ranged from 7% to 30%.)

Mortality was significant: 51% of patients with influenza and invasive pulmonary aspergillosis died within 90 days, compared with 28% of patients with influenza and no invasive pulmonary aspergillosis.

Reports from Europe early in the pandemic indicated that CAPA was a similarly serious problem, prompting establishment at Johns Hopkins University of an aggressive screening program utilizing biomarker-based testing of blood and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid. Of 396 mechanically ventilated COVID-19 patients admitted to Johns Hopkins University hospitals between March and August 2020, 39 met the institution’s criteria for CAPA, Dr. Marr and her colleagues reported this year in what might be the largest U.S. cohort study of CAPA published to date.

“We now know definitively that people with severe influenza and with severe COVID also have high risks for both invasive and airway disease caused by airborne fungi, most commonly aspergilliosis,” Dr. Marr said.

More recent unpublished analyses of patients from the start of the pandemic to June 2021 show persistent risk, said Nitipong Permpalung, MD, MPH, assistant professor in transplant and oncology infectious diseases at Johns Hopkins University and lead author of the cohort study. Among 832 patients with COVID-19 who were mechanically ventilated in Johns Hopkins University hospitals, 11.8% had CAPA, he said. (Also, 3.2% had invasive candidiasis, and 1.1% had other invasive fungal infections.)

Other sources said in interviews that these CAPA prevalence rates generally mirror reports from Europe, though some investigators in Europe have reported CAPA rates more toward 15%.

(The Mycoses Study Group recently collected data from its consortium of U.S. medical centers on the prevalence of CAPA, with funding support from the CDC, but at press time the data had not yet been released. Dr. Thompson said he suspected the prevalence will be lower than earlier papers have suggested, “but still will reflect a significant burden of disease.”)

Patients in the published Johns Hopkins University study who had CAPA were more likely than those with COVID-19 but no CAPA to have underlying pulmonary disease, liver disease, coagulopathy, solid tumors, multiple myeloma, and COVID-19–directed corticosteroids. And they had uniformly worse outcomes with regards to severity of illness and length of intubation.

How much of CAPA is driven by the SARS-CoV-2 virus itself and how much is a consequence of COVID-19 treatments is a topic of active discussion and research. Martin Hoenigl, MD, of the University of Graz, Austria, a leading researcher in medical mycology, said research shows corticosteroids and anti–IL-6 treatments, such as tocilizumab, used to treat COVID-19–driven acute respiratory failure clearly have contributed to CAPA. But he contends that “a number of other mechanisms” are involved as well.

“The immunologic mechanisms are definitely different in these patients with viral illness than in other ICU patients [who develop aspergilliosis]. It’s not just the corticosteroids. The more we learn, we see the virus plays a role as well, suppressing the interferon pathway,” for example, said Dr. Hoenigl, associate professor in the division of infectious diseases and the European Confederation of Medical Mycology (ECMM) Center of Excellence at the university. The earliest reports of CAPA came “when ICUs weren’t using dexamethasone or tocilizumab,” he noted.

In a paper published recently in Lancet Respiratory Medicine that Dr. Hoenigl and others point to, Belgian researchers reported a “three-level breach” in innate antifungal immunity in both IAPA and CAPA, affecting the integrity of the epithelial barrier, the capacity to phagocytose and kill Aspergillus spores, and the ability to destroy Aspergillus hyphae, which is mainly mediated by neutrophils.

The researchers ran a host of genetic and protein analyses on lung samples (most collected via BAL) of 169 patients with influenza or COVID-19, with and without aspergillosis. They found that patients with CAPA had significantly lower neutrophil cell fractions than patients with COVID-19 only, and patients with IAPA or CAPA had reduced type II IFN signaling and increased concentrations of fibrosis-associated growth factors in the lower respiratory tracts (Lancet Respir Med. 2022 Aug 24).

Tom Chiller, MD, MPH, chief of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s Mycotic Disease Branch, said he’s watching such research with interest. For now, he said, it’s important to also consider that “data on COVID show that almost all patients going into the ICUs with pneumonia and COVID are getting broad-spectrum antibiotics” in addition to corticosteroids.

By wiping out good bacteria, the antibiotics could be “creating a perfect niche for fungi to grow,” he said.

Diagnostic challenges

Aspergillus that has invaded the lung tissue in patients with COVID-19 appears to grow there for some time – around 8-10 days, much longer than in IAPA – before becoming angioinvasive, said Dr. Hoenigl. Such a pathophysiology “implicates that we should try to diagnose it while it’s in the lung tissue, using the BAL fluid, and not yet in the blood,” he said.

Some multicenter studies, including one from Europe on Aspergillus test profiles in critically ill COVID-19 patients, have shown mortality rates of close to 90% in patients with CAPA who have positive serum biomarkers, despite appropriate antifungal therapy. “If diagnosed while confined to the lung, however, mortality rates are more like 40%-50% with antifungal therapy,” Dr. Hoenigl said. (Cohort studies published thus far have fairly consistently reported mortality rates in patients with CAPA greater than 40%, he said.)

Bronchoscopy isn’t always pragmatic or possible, however, and is variably used. Some patients with severe COVID-19 may be too unstable for any invasive procedure, said Dr. Permpalung.

Dr. Permpalung looks for CAPA using serum (1-3) beta-D-glucan (BDG, a generic fungal test not specific to Aspergillus), serum galactomannan (GM, specific for Aspergillus), and respiratory cultures (sputum or endotracheal aspirate if intubated) as initial screening tests in the ICU. If there are concerns for CAPA – based on these tests and/or the clinical picture – “a thoughtful risk-benefit discussion is required to determine if patients would benefit from a bronchoscopy or if we should just start them on empiric antifungal therapy.”

Unfortunately, the sensitivity of serum GM is relatively low in CAPA – lower than with classic invasive aspergillosis in the nonviral setting, sources said. BDG, on the other hand, can be falsely positive in the setting of antimicrobials and within the ICU. And the utility of imaging for CAPA is limited. Both the clinical picture and radiological findings of CAPA have resembled those of severe COVID – with the caveat of cavitary lung lesions visible on imaging.

“Cavities or nodules are a highly suspicious finding that could indicate possible fungal infection,” said pulmonologist Amir A. Zeki, MD, MAS, professor of medicine at the University of California, Davis, and codirector of the UC Davis Asthma Network Clinic, who has cared for patients with CAPA.

Cavitation has been described in only a proportion of patients with CAPA, however. So in patients not doing well, “your suspicion has to be raised if you’re not seeing cavities,” he said.

Early in the pandemic, when patients worsened or failed to progress on mechanical ventilation, clinicians at the University of California, Davis, quickly learned not to pin blame too quickly on COVID-19 alone. This remains good advice today, Dr. Zeki said.

“If you have a patient who’s not doing well on a ventilator, not getting better [over weeks], has to be reintubated, has infiltrates or lung nodules that are evolving, or certainly, if they have a cavity, you have to suspect fungal infection,” said Dr. Zeki, who also practices at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in San Diego. “Think about it for those patients who just aren’t moving forward and are continuing to struggle. Have a high index of suspicion, and consult with your infectious disease colleagues.”

Empiric treatment is warranted in some cases if a patient is doing poorly and suspicion for fungal infection is high based on clinical, radiographic, and/or laboratory evidence, he said.

The CDC’s Dr. Chiller said that screening and diagnostic algorithms currently vary from institution to institution, and that diagnostic challenges likely dissuade clinicians from thinking about fungi. “Clinicians often don’t want to deal with fungi – they’re difficult to diagnose, the treatments are limited and can be toxic. But fungi get pushed back until it’s too late,” he said.

“Fungal diagnostics is an area we all need a lot more help with,” and new diagnostics are in the pipeline, he said. In the meantime, he said, “there are tools out there, and we just need to use them more, and improve how they’re used.”

While reported CAPA thus far has typically occurred in the setting of ICU care and mechanical ventilation, it’s not always the case, Dr. Permpalung said. Lung and other solid organ transplant (SOT) recipients with COVID-19 are developing CAPA and other invasive secondary invasive fungal infections despite not being intubated, he said.

Of 276 SOT recipients with COVID-19 who required inpatient treatment at Johns Hopkins University hospitals from the beginning of the pandemic to March 2022, 23 patients developed invasive fungal infections (13 CAPA). Only a fraction – 38 of the 276 – had been intubated, he said.

Mucormycosis resistance

After CAPA, candidiasis and COVID-19-associated mucormycosis (CAM) – most frequently, rhino-orbital-cerebral disease or pulmonary disease – have been the leading reported fungal coinfections in COVID-19, said Dr. Hoenigl, who described the incidence, timeline, risk factors, and pathogenesis of these infections in a review published this year in Nature Microbiology. .

In India, where there has long been high exposure to Mucorales spores and a greater burden of invasive fungal disease, the rate of mucormycosis doubled in 2021, with rhino-orbital-cerebral disease reported almost exclusively, he said. Pulmonary disease has occurred almost exclusively in the ICU setting and has been present in about 50% of cases outside of India, including Europe and the United States.

A preprint meta-analysis of CAM cases posted by the Lancet in July 2022, in which investigators analyzed individual data of 556 reported cases of COVID-19–associated CAM, shows diabetes and history of corticosteroid use present in most patients, and an overall mortality rate of 44.4%, most of which stems from cases of pulmonary or disseminated disease. Thirteen of the 556 reported cases were from the United States.

An important take-away from the analysis, Dr. Hoenigl said, is that Aspergillus coinfection was seen in 7% of patients and was associated with higher mortality. “It’s important to consider that coinfections [of Aspergillus and Mucorales] can exist,” Dr. Hoenigl said, noting that like CAPA, pulmonary CAM is likely underdiagnosed and underreported.

As with CAPA, the clinical and radiological features of pulmonary CAM largely overlap with those associated with COVID-19, and bronchoscopy plays a central role in definitive diagnosis. In the United States, a Mucorales PCR test for blood and BAL fluid is commercially available and used at some centers, Dr. Hoenigl said.

“Mucormycosis is always difficult to treat ... a lot of the treatments don’t work particularly well,” said Dr. Thompson. “With aspergillosis, we have better treatment options.”

Dr. Thompson worries, however, about treatment resistance becoming widespread. Resistance to azole antifungal agents “is already pretty widespread in northern Europe, particularly in the Netherlands and part of the U.K.” because of injudicious use of antifungals in agriculture, he said. “We’ve started to see a few cases [of azole-resistant aspergillosis in the United States] and know it will be more widespread soon.”

Treatment resistance is a focus of the new WHO fungal priority pathogens list – the first such report from the organization. Of the 19 fungi on the list, 4 were ranked as critical: Cryptococcus neoformans, Candida auris, Aspergillus fumigatus, and Candida albicans. Like Dr. Thompson, Dr. Hoenigl contributed to the WHO report.

Dr. Hoenigl reported grant/research support from Astellas, Merck, F2G, Gilread, Pfizer, and Scynexis. Dr. Marr disclosed employment and equity in Pearl Diagnostics and Sfunga Therapeutics. Dr. Thompson, Dr. Permpalung, and Dr. Zeki reported that they have no relevant financial disclosures.

COVID-19 has lifted the lid on the risks of secondary pulmonary fungal infections in patients with severe respiratory viral illness – even previously immunocompetent individuals – and highlighted the importance of vigilant investigation to achieve early diagnoses, leading experts say.

Most fungi are not under surveillance in the United States, leaving experts without a national picture of the true burden of infection through the pandemic. However, a collection of published case series, cohort studies, and reviews from Europe, the United States, and throughout the world – mainly pre-Omicron – show that fungal disease has affected a significant portion of critically ill patients with COVID-19, with concerning excess mortality, these experts say.

COVID-associated pulmonary aspergillosis (CAPA) has been the predominant fungal coinfection in the United States and internationally. But COVID-associated mucormycosis (CAM) – the infection that surged in India in early 2021 – has also affected some patients in the United States, published data show. So have Pneumocystitis pneumonia, cryptococcosis, histoplasmosis, and Candida infections (which mainly affect the bloodstream and abdomen), say the experts who were interviewed.

“We had predicted [a rise in] aspergillosis, but we saw more than we thought we’d see. Most fungal infections became more common with COVID-19,” said George Thompson, MD, professor of clinical medicine at the University of California, Davis, and cochair of the University of Alabama–based Mycoses Study Group Education Committee, a group of experts in medical mycology. Pneumocystitis, for instance, “has historically been associated with AIDS or different types of leukemia or lymphoma, and is not an infection we’ve typically seen in our otherwise healthy ICU patients,” he noted. “But we did see more of it [with COVID-19].”

More recently, with fewer patients during the Omicron phase in intensive care units with acute respiratory failure, the profile of fungal disease secondary to COVID-19 has changed. Increasing proportions of patients have traditional risk factors for aspergillosis, such as hematologic malignancies and longer-term, pre-COVID use of systemic corticosteroids – a change that makes the contribution of the viral illness harder to distinguish.

Moving forward, the lessons of the COVID era – the fungal risks to patients with serious viral infections and the persistence needed to diagnose aspergillosis and other pulmonary fungal infections using bronchoscopy and imperfect noninvasive tests – should be taken to heart, experts say.

“Fungal diseases are not rare. They’re just not diagnosed because no one thinks to look for them,” said Dr. Thompson, a contributor to a recently released World Health Organization report naming a “fungal priority pathogens” list.

“We’re going to continue to see [secondary fungal infections] with other respiratory viruses,” he said. And overall, given environmental and other changes, “we’re going to see more and more fungal disease in the patients we take care of.”

CAPA not a surprise

CAPA is “not an unfamiliar story” in the world of fungal disease, given a history of influenza-associated pulmonary aspergillosis (IAPA), said Kieren A. Marr, MD, MBA, adjunct professor of medicine and past director of the transplant and oncology infectious diseases program at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, who has long researched invasive fungal disease.

European researchers, she said, have led the way in describing a high incidence of IAPA in patients admitted to ICUs with influenza. In a retrospective multicenter cohort study reported in 2018 by the Dutch-Belgian Mycosis Study group, for instance, almost 20% of 432 influenza patients admitted to the ICU, including patients who were otherwise healthy and not immunocompromised, had the diagnosis a median of 3 days after ICU admission. (Across other cohort studies, rates of IAPA have ranged from 7% to 30%.)

Mortality was significant: 51% of patients with influenza and invasive pulmonary aspergillosis died within 90 days, compared with 28% of patients with influenza and no invasive pulmonary aspergillosis.

Reports from Europe early in the pandemic indicated that CAPA was a similarly serious problem, prompting establishment at Johns Hopkins University of an aggressive screening program utilizing biomarker-based testing of blood and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid. Of 396 mechanically ventilated COVID-19 patients admitted to Johns Hopkins University hospitals between March and August 2020, 39 met the institution’s criteria for CAPA, Dr. Marr and her colleagues reported this year in what might be the largest U.S. cohort study of CAPA published to date.

“We now know definitively that people with severe influenza and with severe COVID also have high risks for both invasive and airway disease caused by airborne fungi, most commonly aspergilliosis,” Dr. Marr said.

More recent unpublished analyses of patients from the start of the pandemic to June 2021 show persistent risk, said Nitipong Permpalung, MD, MPH, assistant professor in transplant and oncology infectious diseases at Johns Hopkins University and lead author of the cohort study. Among 832 patients with COVID-19 who were mechanically ventilated in Johns Hopkins University hospitals, 11.8% had CAPA, he said. (Also, 3.2% had invasive candidiasis, and 1.1% had other invasive fungal infections.)

Other sources said in interviews that these CAPA prevalence rates generally mirror reports from Europe, though some investigators in Europe have reported CAPA rates more toward 15%.

(The Mycoses Study Group recently collected data from its consortium of U.S. medical centers on the prevalence of CAPA, with funding support from the CDC, but at press time the data had not yet been released. Dr. Thompson said he suspected the prevalence will be lower than earlier papers have suggested, “but still will reflect a significant burden of disease.”)

Patients in the published Johns Hopkins University study who had CAPA were more likely than those with COVID-19 but no CAPA to have underlying pulmonary disease, liver disease, coagulopathy, solid tumors, multiple myeloma, and COVID-19–directed corticosteroids. And they had uniformly worse outcomes with regards to severity of illness and length of intubation.

How much of CAPA is driven by the SARS-CoV-2 virus itself and how much is a consequence of COVID-19 treatments is a topic of active discussion and research. Martin Hoenigl, MD, of the University of Graz, Austria, a leading researcher in medical mycology, said research shows corticosteroids and anti–IL-6 treatments, such as tocilizumab, used to treat COVID-19–driven acute respiratory failure clearly have contributed to CAPA. But he contends that “a number of other mechanisms” are involved as well.

“The immunologic mechanisms are definitely different in these patients with viral illness than in other ICU patients [who develop aspergilliosis]. It’s not just the corticosteroids. The more we learn, we see the virus plays a role as well, suppressing the interferon pathway,” for example, said Dr. Hoenigl, associate professor in the division of infectious diseases and the European Confederation of Medical Mycology (ECMM) Center of Excellence at the university. The earliest reports of CAPA came “when ICUs weren’t using dexamethasone or tocilizumab,” he noted.

In a paper published recently in Lancet Respiratory Medicine that Dr. Hoenigl and others point to, Belgian researchers reported a “three-level breach” in innate antifungal immunity in both IAPA and CAPA, affecting the integrity of the epithelial barrier, the capacity to phagocytose and kill Aspergillus spores, and the ability to destroy Aspergillus hyphae, which is mainly mediated by neutrophils.

The researchers ran a host of genetic and protein analyses on lung samples (most collected via BAL) of 169 patients with influenza or COVID-19, with and without aspergillosis. They found that patients with CAPA had significantly lower neutrophil cell fractions than patients with COVID-19 only, and patients with IAPA or CAPA had reduced type II IFN signaling and increased concentrations of fibrosis-associated growth factors in the lower respiratory tracts (Lancet Respir Med. 2022 Aug 24).

Tom Chiller, MD, MPH, chief of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s Mycotic Disease Branch, said he’s watching such research with interest. For now, he said, it’s important to also consider that “data on COVID show that almost all patients going into the ICUs with pneumonia and COVID are getting broad-spectrum antibiotics” in addition to corticosteroids.

By wiping out good bacteria, the antibiotics could be “creating a perfect niche for fungi to grow,” he said.

Diagnostic challenges

Aspergillus that has invaded the lung tissue in patients with COVID-19 appears to grow there for some time – around 8-10 days, much longer than in IAPA – before becoming angioinvasive, said Dr. Hoenigl. Such a pathophysiology “implicates that we should try to diagnose it while it’s in the lung tissue, using the BAL fluid, and not yet in the blood,” he said.

Some multicenter studies, including one from Europe on Aspergillus test profiles in critically ill COVID-19 patients, have shown mortality rates of close to 90% in patients with CAPA who have positive serum biomarkers, despite appropriate antifungal therapy. “If diagnosed while confined to the lung, however, mortality rates are more like 40%-50% with antifungal therapy,” Dr. Hoenigl said. (Cohort studies published thus far have fairly consistently reported mortality rates in patients with CAPA greater than 40%, he said.)

Bronchoscopy isn’t always pragmatic or possible, however, and is variably used. Some patients with severe COVID-19 may be too unstable for any invasive procedure, said Dr. Permpalung.

Dr. Permpalung looks for CAPA using serum (1-3) beta-D-glucan (BDG, a generic fungal test not specific to Aspergillus), serum galactomannan (GM, specific for Aspergillus), and respiratory cultures (sputum or endotracheal aspirate if intubated) as initial screening tests in the ICU. If there are concerns for CAPA – based on these tests and/or the clinical picture – “a thoughtful risk-benefit discussion is required to determine if patients would benefit from a bronchoscopy or if we should just start them on empiric antifungal therapy.”

Unfortunately, the sensitivity of serum GM is relatively low in CAPA – lower than with classic invasive aspergillosis in the nonviral setting, sources said. BDG, on the other hand, can be falsely positive in the setting of antimicrobials and within the ICU. And the utility of imaging for CAPA is limited. Both the clinical picture and radiological findings of CAPA have resembled those of severe COVID – with the caveat of cavitary lung lesions visible on imaging.

“Cavities or nodules are a highly suspicious finding that could indicate possible fungal infection,” said pulmonologist Amir A. Zeki, MD, MAS, professor of medicine at the University of California, Davis, and codirector of the UC Davis Asthma Network Clinic, who has cared for patients with CAPA.

Cavitation has been described in only a proportion of patients with CAPA, however. So in patients not doing well, “your suspicion has to be raised if you’re not seeing cavities,” he said.

Early in the pandemic, when patients worsened or failed to progress on mechanical ventilation, clinicians at the University of California, Davis, quickly learned not to pin blame too quickly on COVID-19 alone. This remains good advice today, Dr. Zeki said.

“If you have a patient who’s not doing well on a ventilator, not getting better [over weeks], has to be reintubated, has infiltrates or lung nodules that are evolving, or certainly, if they have a cavity, you have to suspect fungal infection,” said Dr. Zeki, who also practices at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in San Diego. “Think about it for those patients who just aren’t moving forward and are continuing to struggle. Have a high index of suspicion, and consult with your infectious disease colleagues.”

Empiric treatment is warranted in some cases if a patient is doing poorly and suspicion for fungal infection is high based on clinical, radiographic, and/or laboratory evidence, he said.

The CDC’s Dr. Chiller said that screening and diagnostic algorithms currently vary from institution to institution, and that diagnostic challenges likely dissuade clinicians from thinking about fungi. “Clinicians often don’t want to deal with fungi – they’re difficult to diagnose, the treatments are limited and can be toxic. But fungi get pushed back until it’s too late,” he said.

“Fungal diagnostics is an area we all need a lot more help with,” and new diagnostics are in the pipeline, he said. In the meantime, he said, “there are tools out there, and we just need to use them more, and improve how they’re used.”

While reported CAPA thus far has typically occurred in the setting of ICU care and mechanical ventilation, it’s not always the case, Dr. Permpalung said. Lung and other solid organ transplant (SOT) recipients with COVID-19 are developing CAPA and other invasive secondary invasive fungal infections despite not being intubated, he said.

Of 276 SOT recipients with COVID-19 who required inpatient treatment at Johns Hopkins University hospitals from the beginning of the pandemic to March 2022, 23 patients developed invasive fungal infections (13 CAPA). Only a fraction – 38 of the 276 – had been intubated, he said.

Mucormycosis resistance

After CAPA, candidiasis and COVID-19-associated mucormycosis (CAM) – most frequently, rhino-orbital-cerebral disease or pulmonary disease – have been the leading reported fungal coinfections in COVID-19, said Dr. Hoenigl, who described the incidence, timeline, risk factors, and pathogenesis of these infections in a review published this year in Nature Microbiology. .

In India, where there has long been high exposure to Mucorales spores and a greater burden of invasive fungal disease, the rate of mucormycosis doubled in 2021, with rhino-orbital-cerebral disease reported almost exclusively, he said. Pulmonary disease has occurred almost exclusively in the ICU setting and has been present in about 50% of cases outside of India, including Europe and the United States.

A preprint meta-analysis of CAM cases posted by the Lancet in July 2022, in which investigators analyzed individual data of 556 reported cases of COVID-19–associated CAM, shows diabetes and history of corticosteroid use present in most patients, and an overall mortality rate of 44.4%, most of which stems from cases of pulmonary or disseminated disease. Thirteen of the 556 reported cases were from the United States.

An important take-away from the analysis, Dr. Hoenigl said, is that Aspergillus coinfection was seen in 7% of patients and was associated with higher mortality. “It’s important to consider that coinfections [of Aspergillus and Mucorales] can exist,” Dr. Hoenigl said, noting that like CAPA, pulmonary CAM is likely underdiagnosed and underreported.

As with CAPA, the clinical and radiological features of pulmonary CAM largely overlap with those associated with COVID-19, and bronchoscopy plays a central role in definitive diagnosis. In the United States, a Mucorales PCR test for blood and BAL fluid is commercially available and used at some centers, Dr. Hoenigl said.

“Mucormycosis is always difficult to treat ... a lot of the treatments don’t work particularly well,” said Dr. Thompson. “With aspergillosis, we have better treatment options.”

Dr. Thompson worries, however, about treatment resistance becoming widespread. Resistance to azole antifungal agents “is already pretty widespread in northern Europe, particularly in the Netherlands and part of the U.K.” because of injudicious use of antifungals in agriculture, he said. “We’ve started to see a few cases [of azole-resistant aspergillosis in the United States] and know it will be more widespread soon.”

Treatment resistance is a focus of the new WHO fungal priority pathogens list – the first such report from the organization. Of the 19 fungi on the list, 4 were ranked as critical: Cryptococcus neoformans, Candida auris, Aspergillus fumigatus, and Candida albicans. Like Dr. Thompson, Dr. Hoenigl contributed to the WHO report.

Dr. Hoenigl reported grant/research support from Astellas, Merck, F2G, Gilread, Pfizer, and Scynexis. Dr. Marr disclosed employment and equity in Pearl Diagnostics and Sfunga Therapeutics. Dr. Thompson, Dr. Permpalung, and Dr. Zeki reported that they have no relevant financial disclosures.

Rosacea and the gut: Looking into SIBO

, according to speakers at the annual Integrative Dermatology Symposium.

“SIBO is definitely something we test for and treat,” Raja Sivamani, MD, said in an interview after the meeting. Dr. Sivamani practices as an integrative dermatologist at the Pacific Skin Institute in Sacramento and is the director of clinical research at the institute’s research unit, Integrative Skin Science and Research. He led a panel discussion on rosacea and acne at the meeting.

Associations between SIBO and several dermatologic conditions, including systemic sclerosis, have been reported, but the strongest evidence to date involves rosacea. “There’s associative epidemiological evidence showing higher rates of SIBO among those with rosacea, and there are prospective studies” showing clearance of rosacea in patients treated for SIBO, said Dr. Sivamani, also adjunct associate professor of clinical dermatology at the University of California, Davis.

Studies are small, but are “well done and well-designed,” he said in the interview. “Do we need more studies? Absolutely. But what we have now is compelling [enough] for us to take a look at it.”

Findings of rosacea clearance

SIBO’s believed contribution to the pathophysiology of rosacea is part of the increasingly described gut microbiome-skin axis. SIBO has been recognized as a medical phenomenon for many decades and has been defined as an excessive bacterial load in the small bowel that causes gastrointestinal symptoms, according to the 2020 American College of Gastroenterology clinical guideline on SIBO.

Symptoms commonly associated with SIBO overlap with the cardinal symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS): abdominal pain; diarrhea, constipation, or both; bloating; and flatulence. SIBO can be diagnosed with several validated carbohydrate substrate (glucose or lactulose)–based breath tests that measure hydrogen and/or methane.

Hydrogen-positive breath tests suggest bacterial overgrowth, and methane-positive breath tests suggest small intestinal methanogen overgrowth. Methane is increasingly important and recognized, the AGA guideline says, though it creates a “nomenclature problem in the SIBO framework” because methanogens are not bacteria, the authors note.

In conventional practice, SIBO is typically treated with antibiotics such as rifaximin, and often with short-term dietary modification as well. Integrative medicine typically considers the use of supplements and botanicals in addition to or instead of antibiotics, as well as dietary change and increasingly, a close look at SIBO risk factors to prevent recurrence, Dr. Sivamani said. (His research unit is currently studying the use of herbal protocols as an alternative to antibiotics in patients with SIBO and dermatologic conditions.)

During a presentation on rosacea at the meeting, Neal Bhatia, MD, director of clinical dermatology at Therapeutics Clinical Research, a dermatology treatment and research center in San Diego, said that currently available breath tests for SIBO “are very interesting tools for understanding what may be happening in the gut” and that the “rifaximin data are good.”

He referred to a study reported in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology showing that patients with rosacea were significantly more likely to have SIBO (41.7% of 48 patients vs. 5.0% of 40 controls; P < .001), and that 64.5% of rosacea patients who completed treatment with rifaximin had remission of rosacea at a 3-year follow-up.

An earlier crossover study is also notable, he said. This study enrolled 113 consecutive patients with rosacea and 60 age- and sex-matched controls, and randomized those with SIBO (52 of the 113 with rosacea vs. 3 of the 60 controls) to rifaximin or placebo. Rosacea cleared in 20 of the 28 patients in the rifaximin group and greatly improved in 6 of the 28. Of 20 patients in the placebo group, rosacea remained unchanged in 18 and worsened in 2. When patients in the placebo group were switched to rifaximin, SIBO was eradicated in 17 of the 20, and rosacea completely resolved in 15 of those patients, Dr. Bhatia said.

In his view, it will take more time, greater awareness of the rosacea-SIBO link, and a willingness “to take chances” for more dermatologists to consider SIBO during rosacea care. “Breath tests are not something used in the [typical dermatology] clinic right now, but they may make their way in,” he said at the meeting.

In a follow-up interview, Dr. Bhatia emphasized that “it’s really a question of uptake, which always takes a while” and of willingness to “think through the disease from another angle ... especially in patients who are recalcitrant.”

Treatment

Dr. Sivamani said in the interview that a third type of SIBO – hydrogen sulfide–dominant SIBO – is now documented and worth considering when glucose and lactulose breath tests are negative in patients with rosacea who have gastrointestinal symptoms.

The use of breath tests to objectively diagnose SIBO is always best, Dr. Sivamani said, but he will consider empiric therapy in some patients. “I always tell patients [about] the benefits of testing, but if they can’t get the test covered or are unable to pay for the test, and they have symptoms consistent with SIBO, I’m okay doing a trial with therapy,” he said.

Rifaximin, one of the suggested antibiotics listed in the AGA guideline, is a nonabsorbable antibiotic that is FDA-approved for IBS with diarrhea (IBS-D); it has been shown to not negatively affect the growth of beneficial bacteria in the colon.

However, herbals are also an attractive option – alone or in combination with rifaximin or other antibiotics – speakers at the meeting said. In a multicenter retrospective chart review led by investigators at the Johns Hopkins Hospital, herbal therapies were at least as effective as rifaximin for treating SIBO, with similar safety profiles. The response rate for normalizing breath hydrogen testing in patients with SIBO was 46% for herbal therapies and 34% for rifaximin.

Dietary change is also part of treatment, with the reduction of fermentable carbohydrates – often through the Low FODMAP Diet and Specific Carbohydrate Diet – being the dominant theme in dietary intervention for SIBO, according to the AGA guideline.

“There are definitely some food choices you can shift,” said Dr. Sivamani. “I’ll work with patients on FODMAP, though it’s hard to sustain over the long-term and can induce psychological issues. You have to provide other options.”

Dr. Sivamani works with patients on using “a restrictive diet for a short amount of time, with the gradual reintroduction of foods to see [what] foods are and aren’t [causing] flares.” He also works to identify and eliminate risk factors and predisposing factors for SIBO so that recurrence will be less likely.

“SIBO is definitely an entity that is not on the fringes anymore ... it adds to inflammation in the body ... and if you have an inflamed gut, there’s a domino effect that will lead to inflammation elsewhere,” Dr. Sivamani said.

“You want to know, do your patients have SIBO? What subset do they have? Do they have risk factors you can eliminate?” he said. “And then what therapies will you use – pharmaceuticals, supplements and botanicals, or a combination? And finally, what will you do with diet?”

Dr. Bhatia disclosed he has affiliations with Abbvie, Almirall, Arcutis, Arena, Biofrontera, BMS, BI, Brickell, Dermavant, EPI Health, Ferndale, Galderma, Genentech, InCyte, ISDIN, Johnson & Johnson, LaRoche-Posay, Leo, Lilly, Novartis, Ortho, Pfizer, Proctor & Gamble, Regeneron, Sanofi, Stemline, SunPharma, and Verrica. Dr. Sivamani did not provide a disclosure statement.

, according to speakers at the annual Integrative Dermatology Symposium.

“SIBO is definitely something we test for and treat,” Raja Sivamani, MD, said in an interview after the meeting. Dr. Sivamani practices as an integrative dermatologist at the Pacific Skin Institute in Sacramento and is the director of clinical research at the institute’s research unit, Integrative Skin Science and Research. He led a panel discussion on rosacea and acne at the meeting.

Associations between SIBO and several dermatologic conditions, including systemic sclerosis, have been reported, but the strongest evidence to date involves rosacea. “There’s associative epidemiological evidence showing higher rates of SIBO among those with rosacea, and there are prospective studies” showing clearance of rosacea in patients treated for SIBO, said Dr. Sivamani, also adjunct associate professor of clinical dermatology at the University of California, Davis.

Studies are small, but are “well done and well-designed,” he said in the interview. “Do we need more studies? Absolutely. But what we have now is compelling [enough] for us to take a look at it.”

Findings of rosacea clearance

SIBO’s believed contribution to the pathophysiology of rosacea is part of the increasingly described gut microbiome-skin axis. SIBO has been recognized as a medical phenomenon for many decades and has been defined as an excessive bacterial load in the small bowel that causes gastrointestinal symptoms, according to the 2020 American College of Gastroenterology clinical guideline on SIBO.

Symptoms commonly associated with SIBO overlap with the cardinal symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS): abdominal pain; diarrhea, constipation, or both; bloating; and flatulence. SIBO can be diagnosed with several validated carbohydrate substrate (glucose or lactulose)–based breath tests that measure hydrogen and/or methane.

Hydrogen-positive breath tests suggest bacterial overgrowth, and methane-positive breath tests suggest small intestinal methanogen overgrowth. Methane is increasingly important and recognized, the AGA guideline says, though it creates a “nomenclature problem in the SIBO framework” because methanogens are not bacteria, the authors note.

In conventional practice, SIBO is typically treated with antibiotics such as rifaximin, and often with short-term dietary modification as well. Integrative medicine typically considers the use of supplements and botanicals in addition to or instead of antibiotics, as well as dietary change and increasingly, a close look at SIBO risk factors to prevent recurrence, Dr. Sivamani said. (His research unit is currently studying the use of herbal protocols as an alternative to antibiotics in patients with SIBO and dermatologic conditions.)

During a presentation on rosacea at the meeting, Neal Bhatia, MD, director of clinical dermatology at Therapeutics Clinical Research, a dermatology treatment and research center in San Diego, said that currently available breath tests for SIBO “are very interesting tools for understanding what may be happening in the gut” and that the “rifaximin data are good.”

He referred to a study reported in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology showing that patients with rosacea were significantly more likely to have SIBO (41.7% of 48 patients vs. 5.0% of 40 controls; P < .001), and that 64.5% of rosacea patients who completed treatment with rifaximin had remission of rosacea at a 3-year follow-up.

An earlier crossover study is also notable, he said. This study enrolled 113 consecutive patients with rosacea and 60 age- and sex-matched controls, and randomized those with SIBO (52 of the 113 with rosacea vs. 3 of the 60 controls) to rifaximin or placebo. Rosacea cleared in 20 of the 28 patients in the rifaximin group and greatly improved in 6 of the 28. Of 20 patients in the placebo group, rosacea remained unchanged in 18 and worsened in 2. When patients in the placebo group were switched to rifaximin, SIBO was eradicated in 17 of the 20, and rosacea completely resolved in 15 of those patients, Dr. Bhatia said.

In his view, it will take more time, greater awareness of the rosacea-SIBO link, and a willingness “to take chances” for more dermatologists to consider SIBO during rosacea care. “Breath tests are not something used in the [typical dermatology] clinic right now, but they may make their way in,” he said at the meeting.

In a follow-up interview, Dr. Bhatia emphasized that “it’s really a question of uptake, which always takes a while” and of willingness to “think through the disease from another angle ... especially in patients who are recalcitrant.”

Treatment

Dr. Sivamani said in the interview that a third type of SIBO – hydrogen sulfide–dominant SIBO – is now documented and worth considering when glucose and lactulose breath tests are negative in patients with rosacea who have gastrointestinal symptoms.