User login

Association Between Psoriasis and Obesity Among US Adults in the 2009-2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

To the Editor:

Psoriasis is an immune-mediated dermatologic condition that is associated with various comorbidities, including obesity.1 The underlying pathophysiology of psoriasis has been extensively studied, and recent research has discussed the role of obesity in IL-17 secretion.2 The relationship between being overweight/obese and having psoriasis has been documented in the literature.1,2 However, this association in a recent population is lacking. We sought to investigate the association between psoriasis and obesity utilizing a representative US population of adults—the 2009-2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data,3 which contains the most recent psoriasis data.

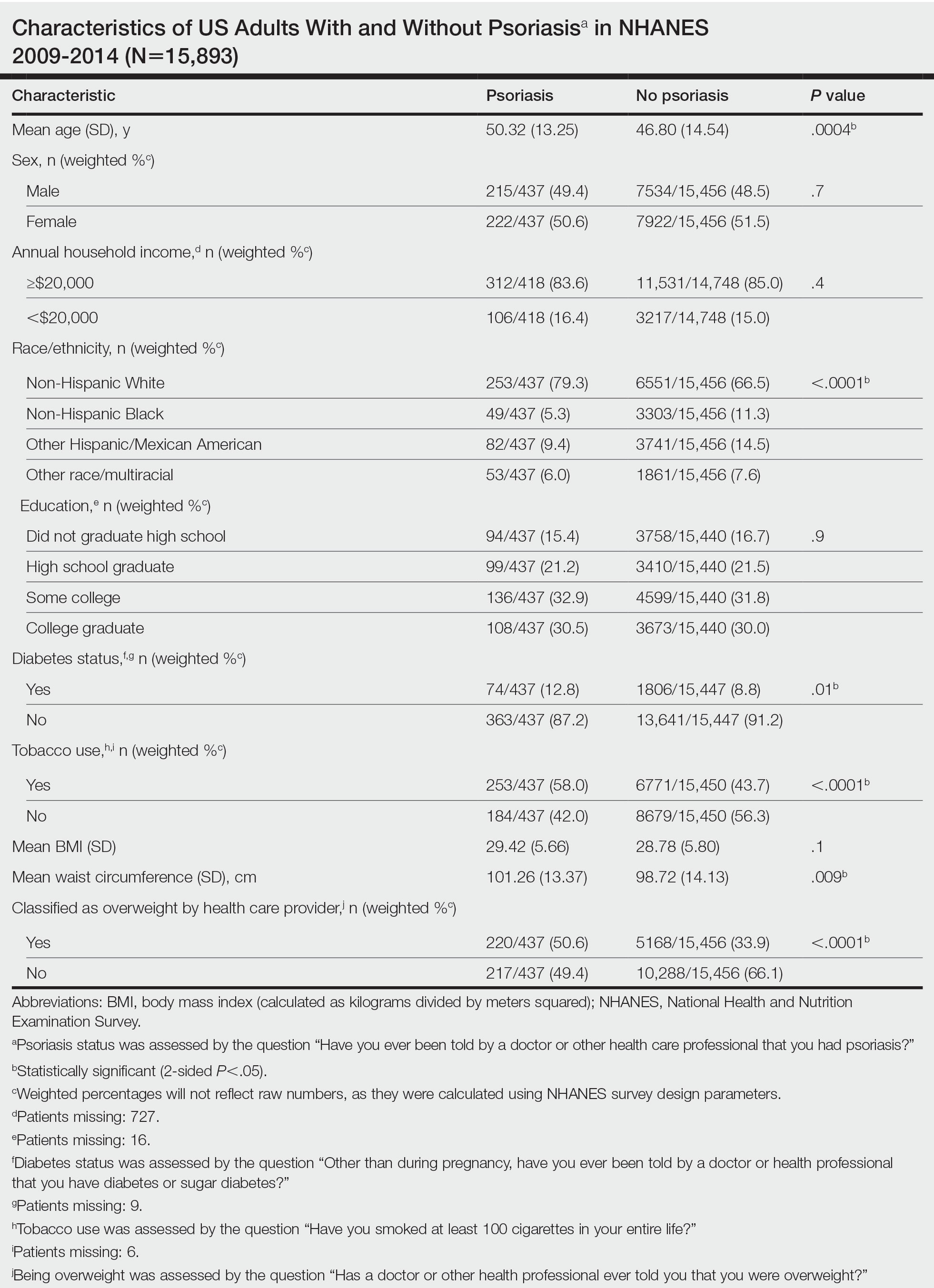

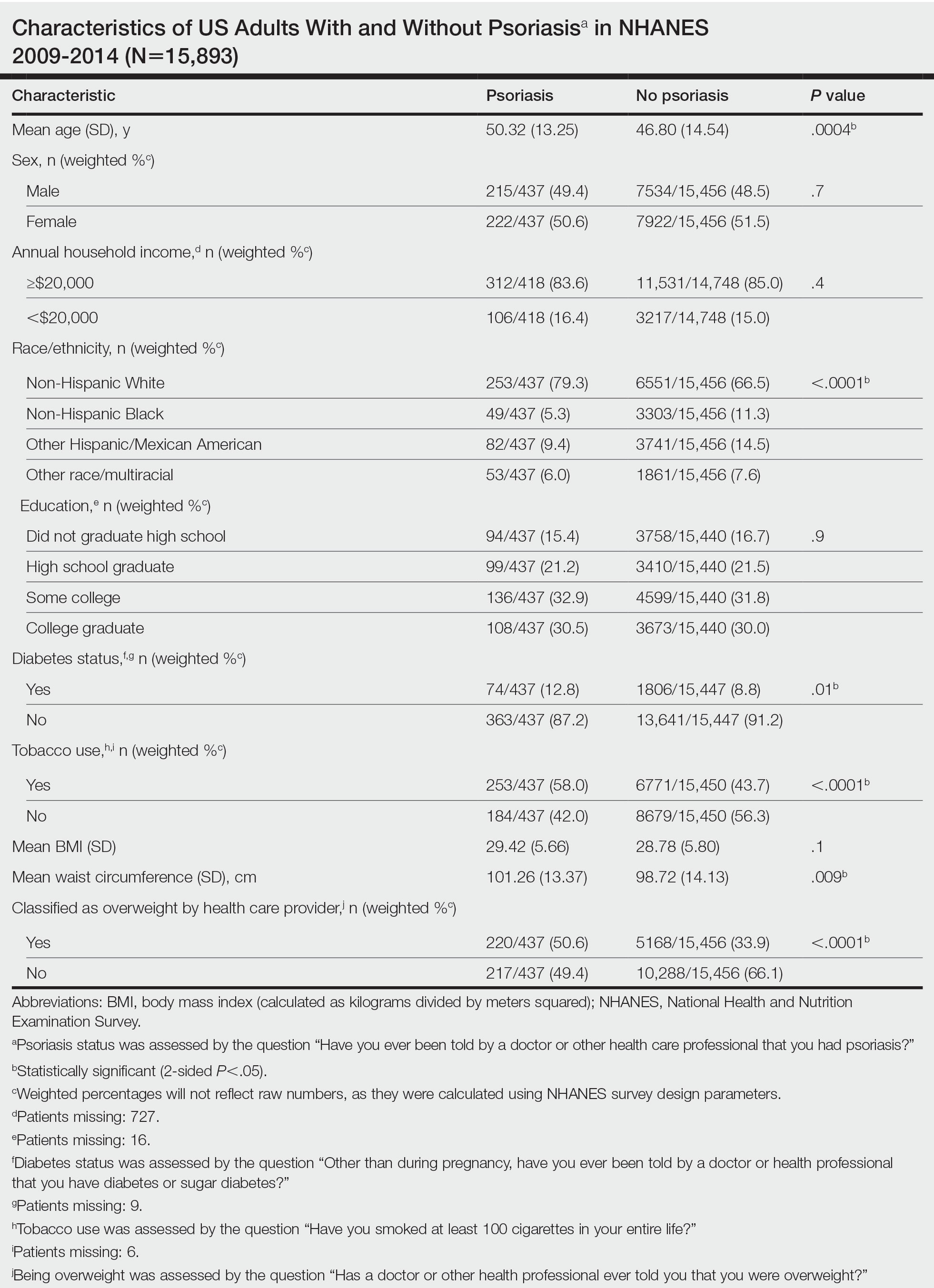

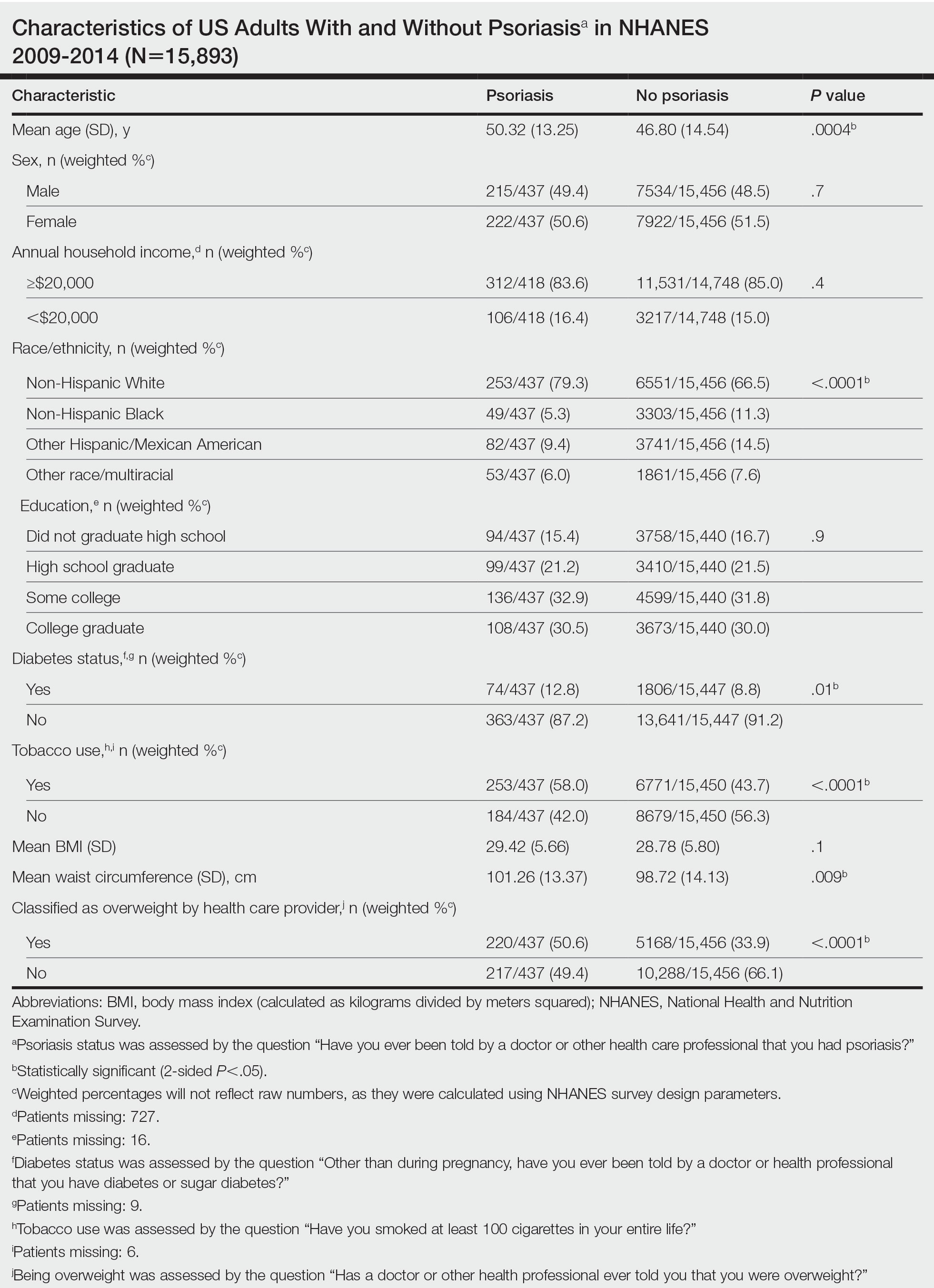

We conducted a population-based, cross-sectional study focused on patients 20 years and older with psoriasis from the 2009-2014 NHANES database. Three 2-year cycles of NHANES data were combined to create our 2009 to 2014 dataset. In the Table, numerous variables including age, sex, household income, race/ethnicity, education, diabetes status, tobacco use, body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, and being called overweight by a health care provider were analyzed using χ2 or t test analyses to evaluate for differences among those with and without psoriasis. Diabetes status was assessed by the question “Other than during pregnancy, have you ever been told by a doctor or health professional that you have diabetes or sugar diabetes?” Tobacco use was assessed by the question “Have you smoked at least 100 cigarettes in your entire life?” Psoriasis status was assessed by a self-reported response to the question “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health care professional that you had psoriasis?” Three different outcome variables were used to determine if patients were overweight or obese: BMI, waist circumference, and response to the question “Has a doctor or other health professional ever told you that you were overweight?” Obesity was defined as having a BMI of 30 or higher or waist circumference of 102 cm or more in males and 88 cm or more in females.4 Being overweight was defined as having a BMI of 25 to 29.99 or response of Yes to “Has a doctor or other health professional ever told you that you were overweight?”

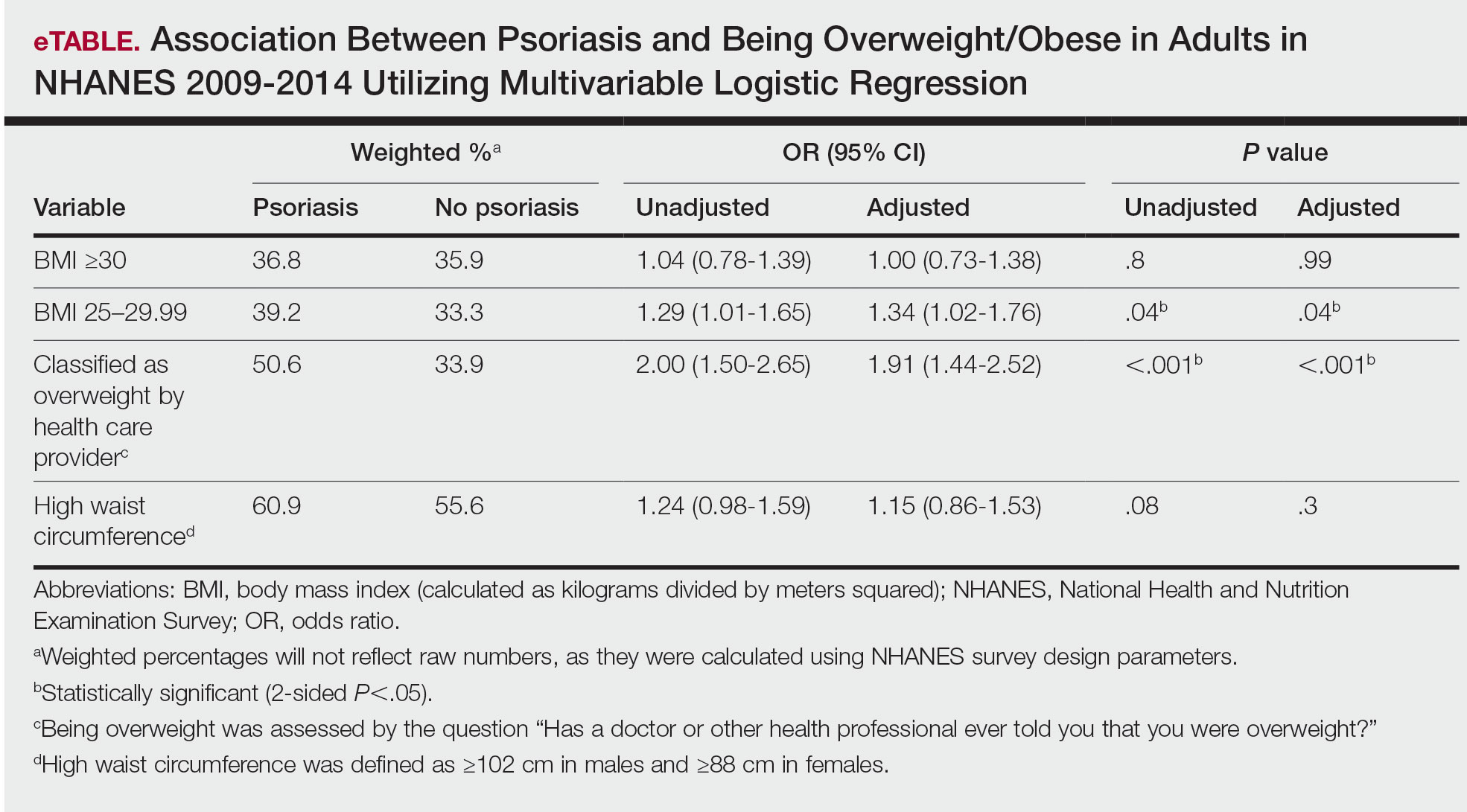

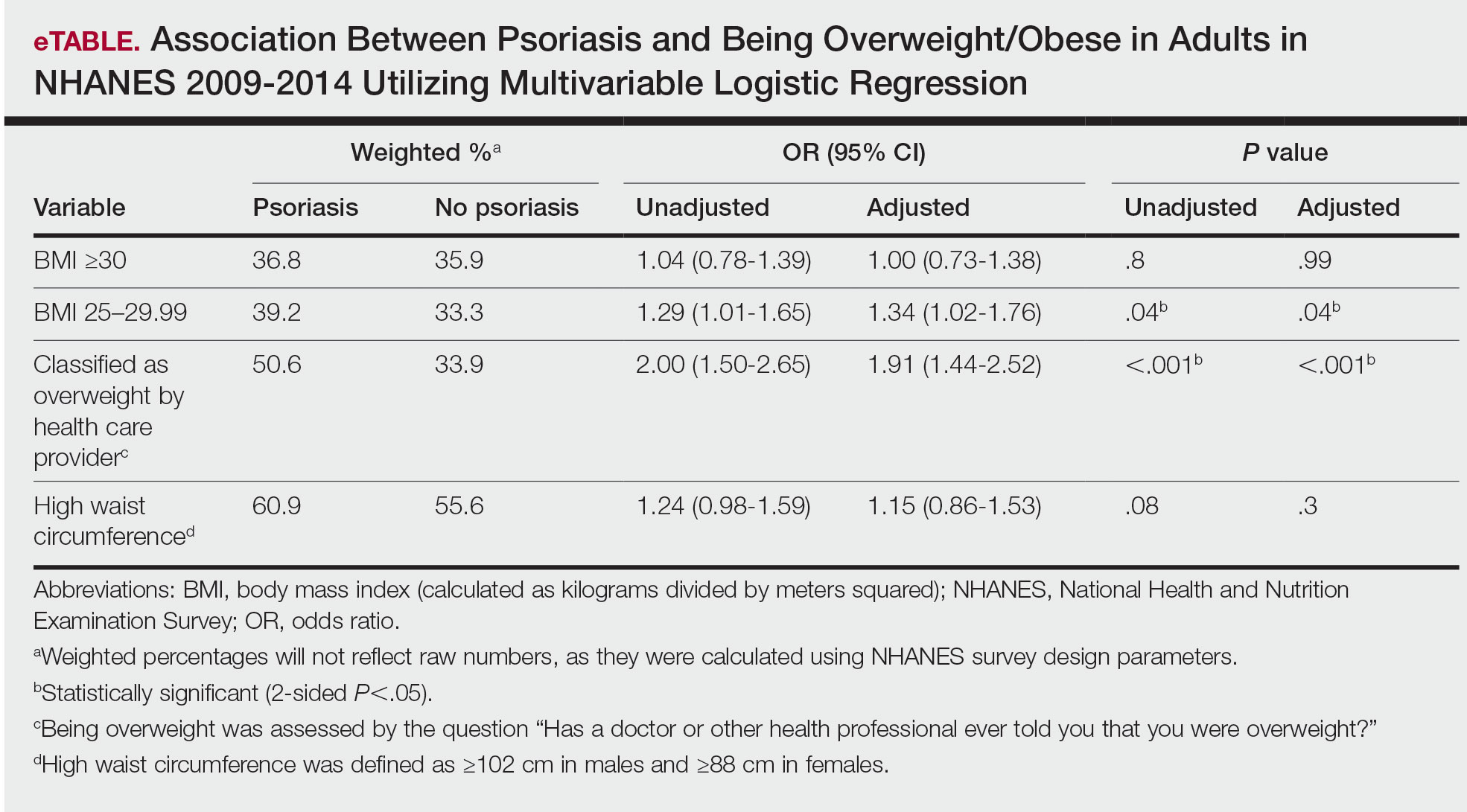

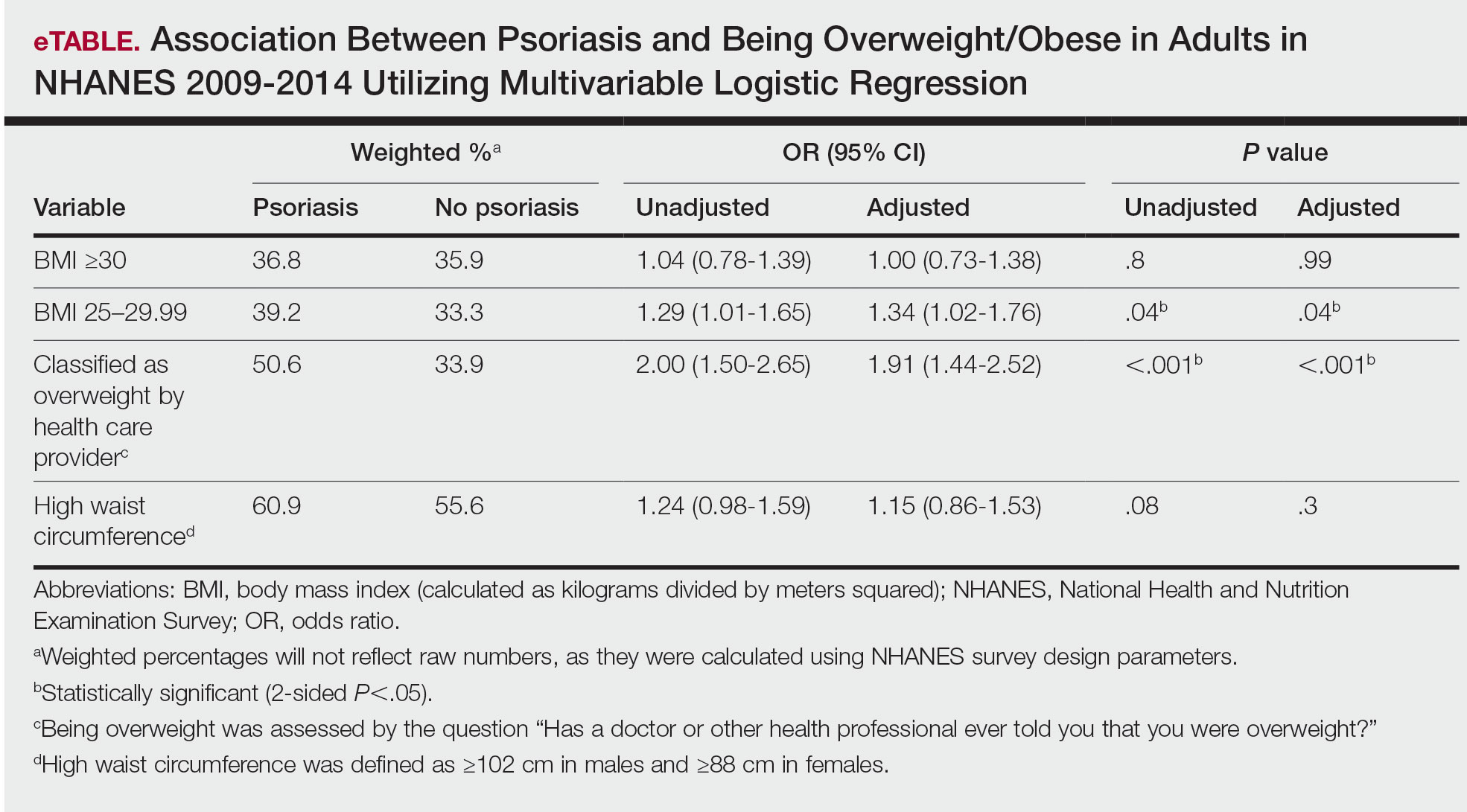

Initially, there were 17,547 participants 20 years and older from 2009 to 2014, but 1654 participants were excluded because of missing data for obesity or psoriasis; therefore, 15,893 patients were included in our analysis. Multivariable logistic regressions were utilized to examine the association between psoriasis and being overweight/obese (eTable). Additionally, the models were adjusted based on age, sex, household income, race/ethnicity, diabetes status, and tobacco use. All data processing and analysis were performed in Stata/MP 17 (StataCorp LLC). P<.05 was considered statistically significant.

The Table shows characteristics of US adults with and without psoriasis in NHANES 2009-2014. We found that the variables of interest evaluating body weight that were significantly different on analysis between patients with and without psoriasis included waist circumference—patients with psoriasis had a significantly higher waist circumference (P=.009)—and being told by a health care provider that they are overweight (P<.0001), which supports the findings by Love et al,5 who reported abdominal obesity was the most common feature of metabolic syndrome exhibited among patients with psoriasis.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis (eTable) revealed that there was a significant association between psoriasis and BMI of 25 to 29.99 (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.34; 95% CI, 1.02-1.76; P=.04) and being told by a health care provider that they are overweight (AOR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.44-2.52; P<.001). After adjusting for confounding variables, there was no significant association between psoriasis and a BMI of 30 or higher (AOR, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.73-1.38; P=.99) or a waist circumference of 102 cm or more in males and 88 cm or more in females (AOR, 1.15; 95% CI, 0.86-1.53; P=.3).

Our findings suggest that a few variables indicative of being overweight or obese are associated with psoriasis. This relationship most likely is due to increased adipokine, including resistin, levels in overweight individuals, resulting in a proinflammatory state.6 It has been suggested that BMI alone is not a definitive marker for measuring fat storage levels in individuals. People can have a normal or slightly elevated BMI but possess excessive adiposity, resulting in chronic inflammation.6 Therefore, our findings of a significant association between psoriasis and being told by a health care provider that they are overweight might be a stronger measurement for possessing excessive fat, as this is likely due to clinical judgment rather than BMI measurement.

Moreover, it should be noted that the potential reason for the lack of association between BMI of 30 or higher and psoriasis in our analysis may be a result of BMI serving as a poor measurement for adiposity. Additionally, Armstrong and colleagues7 discussed that the association between BMI and psoriasis was stronger for patients with moderate to severe psoriasis. Our study consisted of NHANES data for self-reported psoriasis diagnoses without a psoriasis severity index, making it difficult to extrapolate which individuals had mild or moderate to severe psoriasis, which may have contributed to our finding of no association between BMI of 30 or higher and psoriasis.

The self-reported nature of the survey questions and lack of questions regarding psoriasis severity serve as limitations to the study. Both obesity and psoriasis can have various systemic consequences, such as cardiovascular disease, due to the development of an inflammatory state.8 Future studies may explore other body measurements that indicate being overweight or obese and the potential synergistic relationship of obesity and psoriasis severity, optimizing the development of effective treatment plans.

- Jensen P, Skov L. Psoriasis and obesity. Dermatology. 2016;232:633-639.

- Xu C, Ji J, Su T, et al. The association of psoriasis and obesity: focusing on IL-17A-related immunological mechanisms. Int J Dermatol Venereol. 2021;4:116-121.

- National Center for Health Statistics. NHANES questionnaires, datasets, and related documentation. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://wwwn.cdc.govnchs/nhanes/Default.aspx

- Ross R, Neeland IJ, Yamashita S, et al. Waist circumference as a vital sign in clinical practice: a Consensus Statement from the IAS and ICCR Working Group on Visceral Obesity. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020;16:177-189.

- Love TJ, Qureshi AA, Karlson EW, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in psoriasis: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003-2006. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:419-424.

- Paroutoglou K, Papadavid E, Christodoulatos GS, et al. Deciphering the association between psoriasis and obesity: current evidence and treatment considerations. Curr Obes Rep. 2020;9:165-178.

- Armstrong AW, Harskamp CT, Armstrong EJ. The association between psoriasis and obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutr Diabetes. 2012;2:E54.

- Hamminga EA, van der Lely AJ, Neumann HAM, et al. Chronic inflammation in psoriasis and obesity: implications for therapy. Med Hypotheses. 2006;67:768-773.

To the Editor:

Psoriasis is an immune-mediated dermatologic condition that is associated with various comorbidities, including obesity.1 The underlying pathophysiology of psoriasis has been extensively studied, and recent research has discussed the role of obesity in IL-17 secretion.2 The relationship between being overweight/obese and having psoriasis has been documented in the literature.1,2 However, this association in a recent population is lacking. We sought to investigate the association between psoriasis and obesity utilizing a representative US population of adults—the 2009-2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data,3 which contains the most recent psoriasis data.

We conducted a population-based, cross-sectional study focused on patients 20 years and older with psoriasis from the 2009-2014 NHANES database. Three 2-year cycles of NHANES data were combined to create our 2009 to 2014 dataset. In the Table, numerous variables including age, sex, household income, race/ethnicity, education, diabetes status, tobacco use, body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, and being called overweight by a health care provider were analyzed using χ2 or t test analyses to evaluate for differences among those with and without psoriasis. Diabetes status was assessed by the question “Other than during pregnancy, have you ever been told by a doctor or health professional that you have diabetes or sugar diabetes?” Tobacco use was assessed by the question “Have you smoked at least 100 cigarettes in your entire life?” Psoriasis status was assessed by a self-reported response to the question “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health care professional that you had psoriasis?” Three different outcome variables were used to determine if patients were overweight or obese: BMI, waist circumference, and response to the question “Has a doctor or other health professional ever told you that you were overweight?” Obesity was defined as having a BMI of 30 or higher or waist circumference of 102 cm or more in males and 88 cm or more in females.4 Being overweight was defined as having a BMI of 25 to 29.99 or response of Yes to “Has a doctor or other health professional ever told you that you were overweight?”

Initially, there were 17,547 participants 20 years and older from 2009 to 2014, but 1654 participants were excluded because of missing data for obesity or psoriasis; therefore, 15,893 patients were included in our analysis. Multivariable logistic regressions were utilized to examine the association between psoriasis and being overweight/obese (eTable). Additionally, the models were adjusted based on age, sex, household income, race/ethnicity, diabetes status, and tobacco use. All data processing and analysis were performed in Stata/MP 17 (StataCorp LLC). P<.05 was considered statistically significant.

The Table shows characteristics of US adults with and without psoriasis in NHANES 2009-2014. We found that the variables of interest evaluating body weight that were significantly different on analysis between patients with and without psoriasis included waist circumference—patients with psoriasis had a significantly higher waist circumference (P=.009)—and being told by a health care provider that they are overweight (P<.0001), which supports the findings by Love et al,5 who reported abdominal obesity was the most common feature of metabolic syndrome exhibited among patients with psoriasis.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis (eTable) revealed that there was a significant association between psoriasis and BMI of 25 to 29.99 (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.34; 95% CI, 1.02-1.76; P=.04) and being told by a health care provider that they are overweight (AOR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.44-2.52; P<.001). After adjusting for confounding variables, there was no significant association between psoriasis and a BMI of 30 or higher (AOR, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.73-1.38; P=.99) or a waist circumference of 102 cm or more in males and 88 cm or more in females (AOR, 1.15; 95% CI, 0.86-1.53; P=.3).

Our findings suggest that a few variables indicative of being overweight or obese are associated with psoriasis. This relationship most likely is due to increased adipokine, including resistin, levels in overweight individuals, resulting in a proinflammatory state.6 It has been suggested that BMI alone is not a definitive marker for measuring fat storage levels in individuals. People can have a normal or slightly elevated BMI but possess excessive adiposity, resulting in chronic inflammation.6 Therefore, our findings of a significant association between psoriasis and being told by a health care provider that they are overweight might be a stronger measurement for possessing excessive fat, as this is likely due to clinical judgment rather than BMI measurement.

Moreover, it should be noted that the potential reason for the lack of association between BMI of 30 or higher and psoriasis in our analysis may be a result of BMI serving as a poor measurement for adiposity. Additionally, Armstrong and colleagues7 discussed that the association between BMI and psoriasis was stronger for patients with moderate to severe psoriasis. Our study consisted of NHANES data for self-reported psoriasis diagnoses without a psoriasis severity index, making it difficult to extrapolate which individuals had mild or moderate to severe psoriasis, which may have contributed to our finding of no association between BMI of 30 or higher and psoriasis.

The self-reported nature of the survey questions and lack of questions regarding psoriasis severity serve as limitations to the study. Both obesity and psoriasis can have various systemic consequences, such as cardiovascular disease, due to the development of an inflammatory state.8 Future studies may explore other body measurements that indicate being overweight or obese and the potential synergistic relationship of obesity and psoriasis severity, optimizing the development of effective treatment plans.

To the Editor:

Psoriasis is an immune-mediated dermatologic condition that is associated with various comorbidities, including obesity.1 The underlying pathophysiology of psoriasis has been extensively studied, and recent research has discussed the role of obesity in IL-17 secretion.2 The relationship between being overweight/obese and having psoriasis has been documented in the literature.1,2 However, this association in a recent population is lacking. We sought to investigate the association between psoriasis and obesity utilizing a representative US population of adults—the 2009-2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data,3 which contains the most recent psoriasis data.

We conducted a population-based, cross-sectional study focused on patients 20 years and older with psoriasis from the 2009-2014 NHANES database. Three 2-year cycles of NHANES data were combined to create our 2009 to 2014 dataset. In the Table, numerous variables including age, sex, household income, race/ethnicity, education, diabetes status, tobacco use, body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, and being called overweight by a health care provider were analyzed using χ2 or t test analyses to evaluate for differences among those with and without psoriasis. Diabetes status was assessed by the question “Other than during pregnancy, have you ever been told by a doctor or health professional that you have diabetes or sugar diabetes?” Tobacco use was assessed by the question “Have you smoked at least 100 cigarettes in your entire life?” Psoriasis status was assessed by a self-reported response to the question “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health care professional that you had psoriasis?” Three different outcome variables were used to determine if patients were overweight or obese: BMI, waist circumference, and response to the question “Has a doctor or other health professional ever told you that you were overweight?” Obesity was defined as having a BMI of 30 or higher or waist circumference of 102 cm or more in males and 88 cm or more in females.4 Being overweight was defined as having a BMI of 25 to 29.99 or response of Yes to “Has a doctor or other health professional ever told you that you were overweight?”

Initially, there were 17,547 participants 20 years and older from 2009 to 2014, but 1654 participants were excluded because of missing data for obesity or psoriasis; therefore, 15,893 patients were included in our analysis. Multivariable logistic regressions were utilized to examine the association between psoriasis and being overweight/obese (eTable). Additionally, the models were adjusted based on age, sex, household income, race/ethnicity, diabetes status, and tobacco use. All data processing and analysis were performed in Stata/MP 17 (StataCorp LLC). P<.05 was considered statistically significant.

The Table shows characteristics of US adults with and without psoriasis in NHANES 2009-2014. We found that the variables of interest evaluating body weight that were significantly different on analysis between patients with and without psoriasis included waist circumference—patients with psoriasis had a significantly higher waist circumference (P=.009)—and being told by a health care provider that they are overweight (P<.0001), which supports the findings by Love et al,5 who reported abdominal obesity was the most common feature of metabolic syndrome exhibited among patients with psoriasis.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis (eTable) revealed that there was a significant association between psoriasis and BMI of 25 to 29.99 (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.34; 95% CI, 1.02-1.76; P=.04) and being told by a health care provider that they are overweight (AOR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.44-2.52; P<.001). After adjusting for confounding variables, there was no significant association between psoriasis and a BMI of 30 or higher (AOR, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.73-1.38; P=.99) or a waist circumference of 102 cm or more in males and 88 cm or more in females (AOR, 1.15; 95% CI, 0.86-1.53; P=.3).

Our findings suggest that a few variables indicative of being overweight or obese are associated with psoriasis. This relationship most likely is due to increased adipokine, including resistin, levels in overweight individuals, resulting in a proinflammatory state.6 It has been suggested that BMI alone is not a definitive marker for measuring fat storage levels in individuals. People can have a normal or slightly elevated BMI but possess excessive adiposity, resulting in chronic inflammation.6 Therefore, our findings of a significant association between psoriasis and being told by a health care provider that they are overweight might be a stronger measurement for possessing excessive fat, as this is likely due to clinical judgment rather than BMI measurement.

Moreover, it should be noted that the potential reason for the lack of association between BMI of 30 or higher and psoriasis in our analysis may be a result of BMI serving as a poor measurement for adiposity. Additionally, Armstrong and colleagues7 discussed that the association between BMI and psoriasis was stronger for patients with moderate to severe psoriasis. Our study consisted of NHANES data for self-reported psoriasis diagnoses without a psoriasis severity index, making it difficult to extrapolate which individuals had mild or moderate to severe psoriasis, which may have contributed to our finding of no association between BMI of 30 or higher and psoriasis.

The self-reported nature of the survey questions and lack of questions regarding psoriasis severity serve as limitations to the study. Both obesity and psoriasis can have various systemic consequences, such as cardiovascular disease, due to the development of an inflammatory state.8 Future studies may explore other body measurements that indicate being overweight or obese and the potential synergistic relationship of obesity and psoriasis severity, optimizing the development of effective treatment plans.

- Jensen P, Skov L. Psoriasis and obesity. Dermatology. 2016;232:633-639.

- Xu C, Ji J, Su T, et al. The association of psoriasis and obesity: focusing on IL-17A-related immunological mechanisms. Int J Dermatol Venereol. 2021;4:116-121.

- National Center for Health Statistics. NHANES questionnaires, datasets, and related documentation. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://wwwn.cdc.govnchs/nhanes/Default.aspx

- Ross R, Neeland IJ, Yamashita S, et al. Waist circumference as a vital sign in clinical practice: a Consensus Statement from the IAS and ICCR Working Group on Visceral Obesity. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020;16:177-189.

- Love TJ, Qureshi AA, Karlson EW, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in psoriasis: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003-2006. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:419-424.

- Paroutoglou K, Papadavid E, Christodoulatos GS, et al. Deciphering the association between psoriasis and obesity: current evidence and treatment considerations. Curr Obes Rep. 2020;9:165-178.

- Armstrong AW, Harskamp CT, Armstrong EJ. The association between psoriasis and obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutr Diabetes. 2012;2:E54.

- Hamminga EA, van der Lely AJ, Neumann HAM, et al. Chronic inflammation in psoriasis and obesity: implications for therapy. Med Hypotheses. 2006;67:768-773.

- Jensen P, Skov L. Psoriasis and obesity. Dermatology. 2016;232:633-639.

- Xu C, Ji J, Su T, et al. The association of psoriasis and obesity: focusing on IL-17A-related immunological mechanisms. Int J Dermatol Venereol. 2021;4:116-121.

- National Center for Health Statistics. NHANES questionnaires, datasets, and related documentation. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://wwwn.cdc.govnchs/nhanes/Default.aspx

- Ross R, Neeland IJ, Yamashita S, et al. Waist circumference as a vital sign in clinical practice: a Consensus Statement from the IAS and ICCR Working Group on Visceral Obesity. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020;16:177-189.

- Love TJ, Qureshi AA, Karlson EW, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in psoriasis: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003-2006. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:419-424.

- Paroutoglou K, Papadavid E, Christodoulatos GS, et al. Deciphering the association between psoriasis and obesity: current evidence and treatment considerations. Curr Obes Rep. 2020;9:165-178.

- Armstrong AW, Harskamp CT, Armstrong EJ. The association between psoriasis and obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutr Diabetes. 2012;2:E54.

- Hamminga EA, van der Lely AJ, Neumann HAM, et al. Chronic inflammation in psoriasis and obesity: implications for therapy. Med Hypotheses. 2006;67:768-773.

Practice Points

- There are many comorbidities that are associated with psoriasis, making it crucial to evaluate for these diseases in patients with psoriasis.

- Obesity may be a contributing factor to psoriasis development due to the role of IL-17 secretion.

Adverse Effects of the COVID-19 Vaccine in Patients With Psoriasis

To the Editor:

Because the SARS-CoV-2 virus is constantly changing, routine vaccination to prevent COVID-19 infection is recommended. The messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines from Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna as well as the Ad26.COV2.S (Johnson & Johnson) and NVX-CoV2373 (Novavax) vaccines are the most commonly used COVID-19 vaccines in the United States. Adverse effects following vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 are well documented; recent studies report a small incidence of adverse effects in the general population, with most being minor (eg, headache, fever, muscle pain).1,2 Interestingly, reports of exacerbation of psoriasis and new-onset psoriasis following COVID-19 vaccination suggest a potential association.3,4 However, the literature investigating the vaccine adverse effect profile in this demographic is scarce. We examined the incidence of adverse effects from SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in patients with psoriasis.

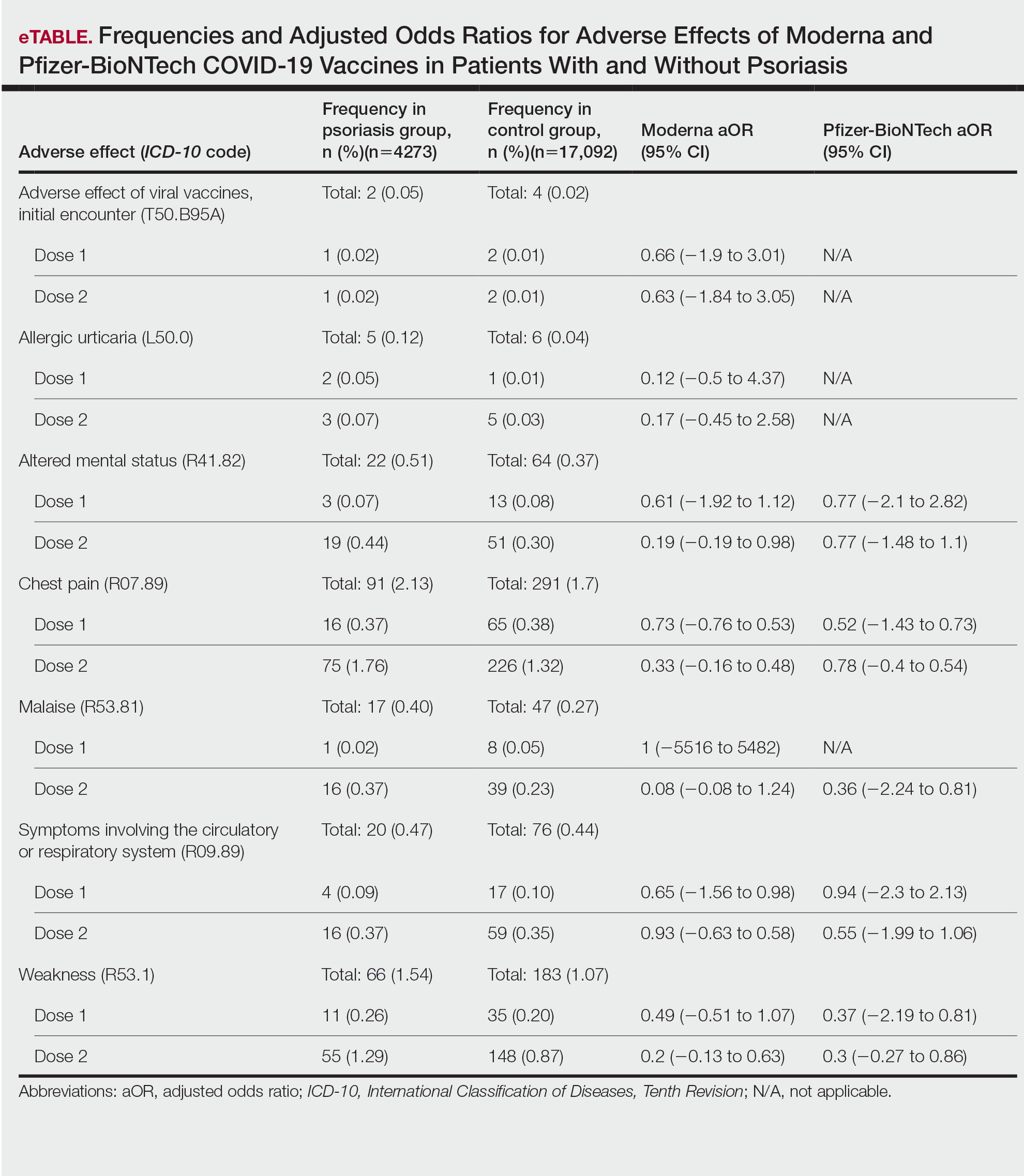

This retrospective cohort study used the COVID-19 Research Database (https://covid19researchdatabase.org/) to examine the adverse effects following the first and second doses of the mRNA vaccines in patients with and without psoriasis. The sample size for the Ad26.COV2.S vaccine was too small to analyze.

Claims were evaluated from August to October 2021 for 2 diagnoses of psoriasis prior to January 1, 2020, using the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) code L40.9 to increase the positive predictive value and ensure that the diagnosis preceded the COVID-19 pandemic. Patients younger than 18 years and those who did not receive 2 doses of a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine were excluded. Controls who did not have a diagnosis of psoriasis were matched for age, sex, and hypertension at a 4:1 ratio. Hypertension represented the most common comorbidity that could feasibly be controlled for in this study population. Other comorbidities recorded included obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic ischemic heart disease, rhinitis, and chronic kidney disease.

Common adverse effects as long as 30 days after vaccination were identified using ICD-10 codes. Adverse effects of interest were anaphylactic reaction, initial encounter of adverse effect of viral vaccines, fever, allergic urticaria, weakness, altered mental status, malaise, allergic reaction, chest pain, symptoms involving circulatory or respiratory systems, localized rash, axillary lymphadenopathy, infection, and myocarditis.5 Poisson regression was performed using Stata 17 analytical software.

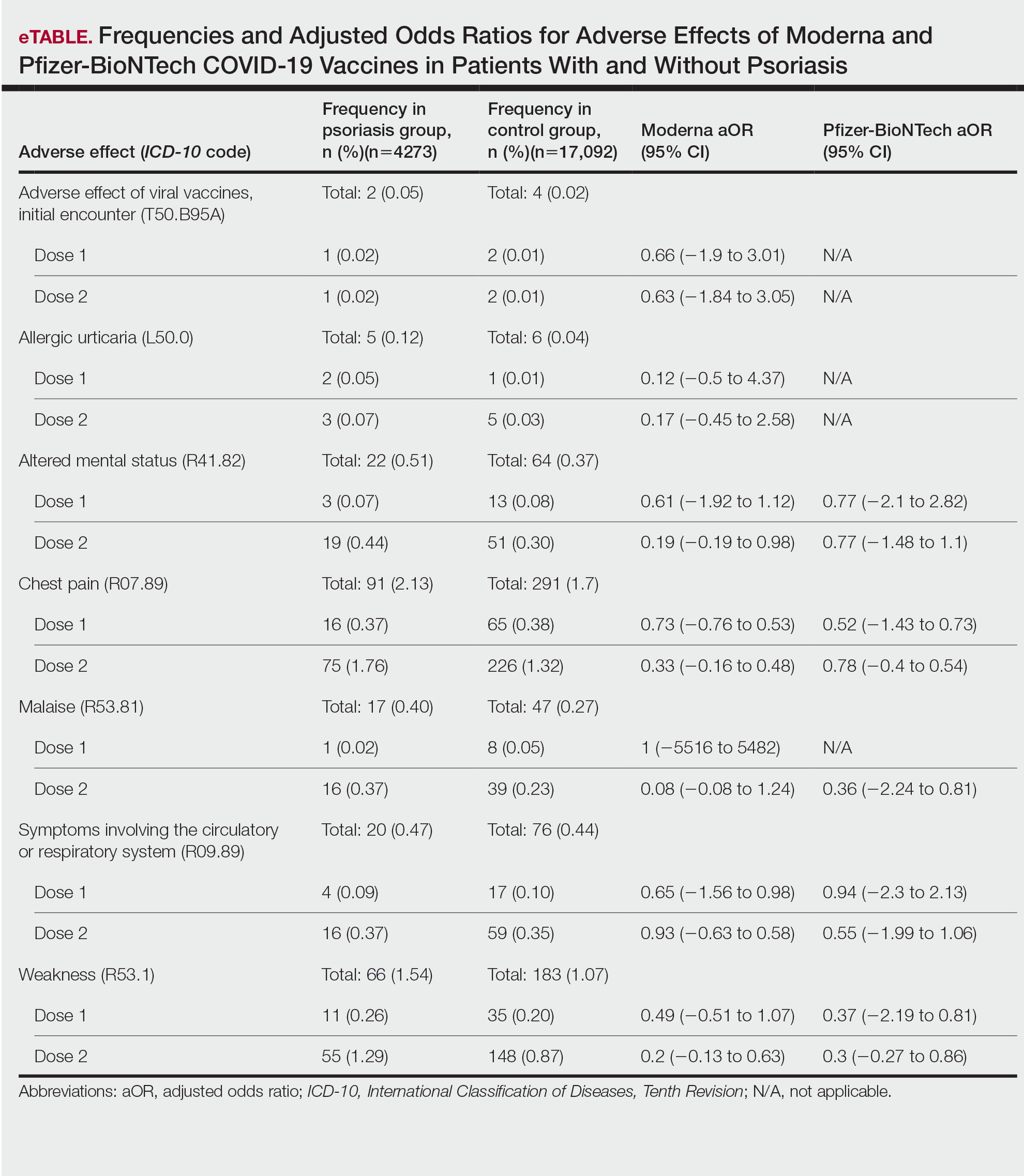

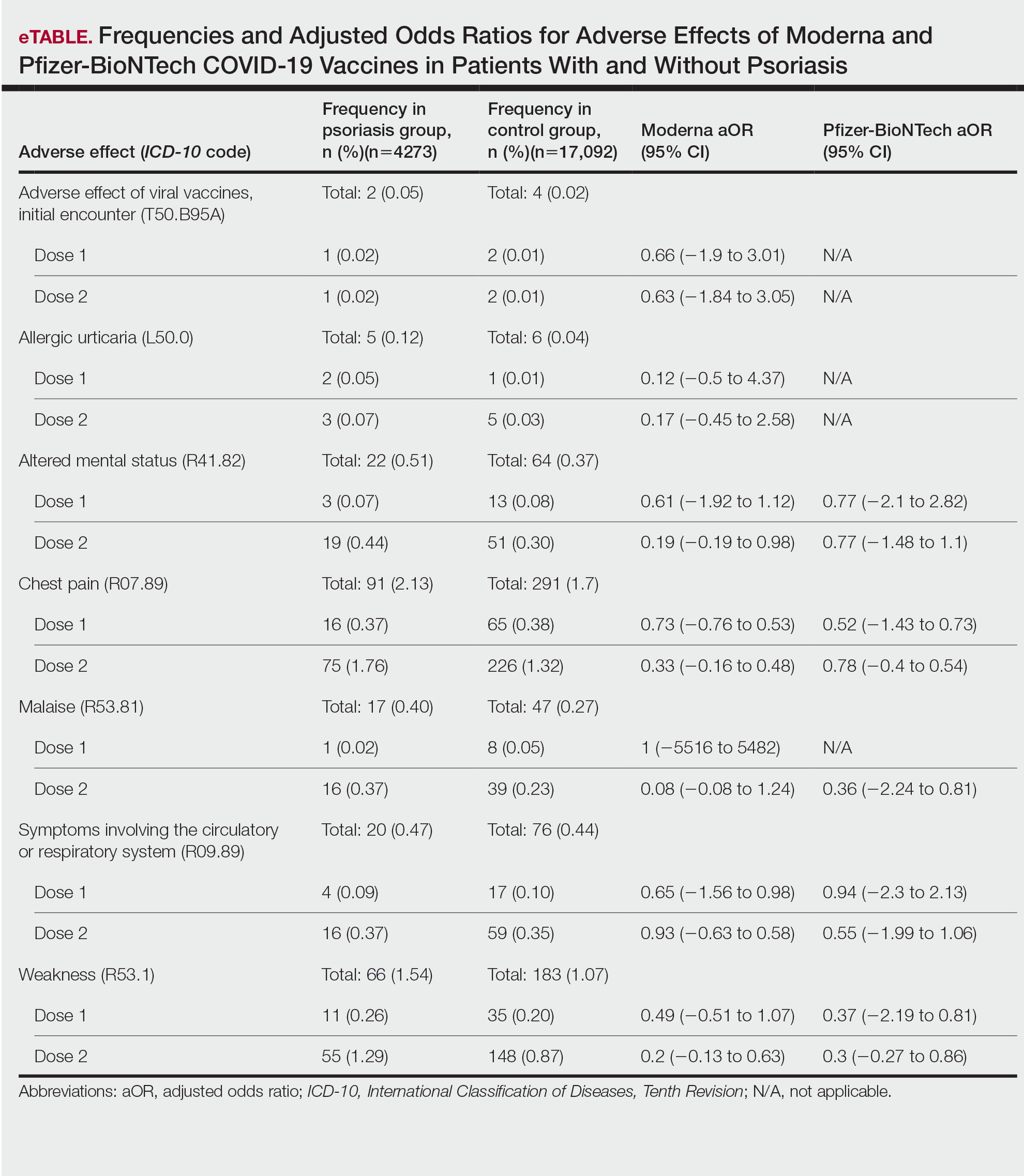

We identified 4273 patients with psoriasis and 17,092 controls who received mRNA COVID-19 vaccines (Table). Adjusted odds ratios (aORs) for doses 1 and 2 were calculated for each vaccine (eTable). Adverse effects with sufficient data to generate an aOR included weakness, altered mental status, malaise, chest pain, and symptoms involving the circulatory or respiratory system. The aORs for allergic urticaria and initial encounter of adverse effect of viral vaccines were only calculated for the Moderna mRNA vaccine due to low sample size.

This study demonstrated that patients with psoriasis do not appear to have a significantly increased risk of adverse effects from mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. Although the ORs in this study were not significant, most recorded adverse effects demonstrated an aOR less than 1, suggesting that there might be a lower risk of certain adverse effects in psoriasis patients. This could be explained by the immunomodulatory effects of certain systemic psoriasis treatments that might influence the adverse effect presentation.

The study is limited by the lack of treatment data, small sample size, and the fact that it did not assess flares or worsening of psoriasis with the vaccines. Underreporting of adverse effects by patients and underdiagnosis of adverse effects secondary to SARS-CoV-2 vaccines due to its novel nature, incompletely understood consequences, and limited ICD-10 codes associated with adverse effects all contributed to the small sample size.

Our findings suggest that the risk for immediate adverse effects from the mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccines is not increased among psoriasis patients. However, the impact of immunomodulatory agents on vaccine efficacy and expected adverse effects should be investigated. As more individuals receive the COVID-19 vaccine, the adverse effect profile in patients with psoriasis is an important area of investigation.

- Singh A, Khillan R, Mishra Y, et al. The safety profile of COVID-19 vaccinations in the United States. Am J Infect Control. 2022;50:15-19. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2021.10.015

- Beatty AL, Peyser ND, Butcher XE, et al. Analysis of COVID-19 vaccine type and adverse effects following vaccination. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e2140364. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.40364

- Bellinato F, Maurelli M, Gisondi P, et al. Cutaneous adverse reactions associated with SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. J Clin Med. 2021;10:5344. doi:10.3390/jcm10225344

- Elamin S, Hinds F, Tolland J. De novo generalized pustular psoriasis following Oxford-AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47:153-155. doi:10.1111/ced.14895

- Remer EE. Coding COVID-19 vaccination. ICD10monitor. Published March 2, 2021. Updated October 18, 2022. Accessed January 17, 2023. https://icd10monitor.medlearn.com/coding-covid-19-vaccination/

To the Editor:

Because the SARS-CoV-2 virus is constantly changing, routine vaccination to prevent COVID-19 infection is recommended. The messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines from Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna as well as the Ad26.COV2.S (Johnson & Johnson) and NVX-CoV2373 (Novavax) vaccines are the most commonly used COVID-19 vaccines in the United States. Adverse effects following vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 are well documented; recent studies report a small incidence of adverse effects in the general population, with most being minor (eg, headache, fever, muscle pain).1,2 Interestingly, reports of exacerbation of psoriasis and new-onset psoriasis following COVID-19 vaccination suggest a potential association.3,4 However, the literature investigating the vaccine adverse effect profile in this demographic is scarce. We examined the incidence of adverse effects from SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in patients with psoriasis.

This retrospective cohort study used the COVID-19 Research Database (https://covid19researchdatabase.org/) to examine the adverse effects following the first and second doses of the mRNA vaccines in patients with and without psoriasis. The sample size for the Ad26.COV2.S vaccine was too small to analyze.

Claims were evaluated from August to October 2021 for 2 diagnoses of psoriasis prior to January 1, 2020, using the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) code L40.9 to increase the positive predictive value and ensure that the diagnosis preceded the COVID-19 pandemic. Patients younger than 18 years and those who did not receive 2 doses of a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine were excluded. Controls who did not have a diagnosis of psoriasis were matched for age, sex, and hypertension at a 4:1 ratio. Hypertension represented the most common comorbidity that could feasibly be controlled for in this study population. Other comorbidities recorded included obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic ischemic heart disease, rhinitis, and chronic kidney disease.

Common adverse effects as long as 30 days after vaccination were identified using ICD-10 codes. Adverse effects of interest were anaphylactic reaction, initial encounter of adverse effect of viral vaccines, fever, allergic urticaria, weakness, altered mental status, malaise, allergic reaction, chest pain, symptoms involving circulatory or respiratory systems, localized rash, axillary lymphadenopathy, infection, and myocarditis.5 Poisson regression was performed using Stata 17 analytical software.

We identified 4273 patients with psoriasis and 17,092 controls who received mRNA COVID-19 vaccines (Table). Adjusted odds ratios (aORs) for doses 1 and 2 were calculated for each vaccine (eTable). Adverse effects with sufficient data to generate an aOR included weakness, altered mental status, malaise, chest pain, and symptoms involving the circulatory or respiratory system. The aORs for allergic urticaria and initial encounter of adverse effect of viral vaccines were only calculated for the Moderna mRNA vaccine due to low sample size.

This study demonstrated that patients with psoriasis do not appear to have a significantly increased risk of adverse effects from mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. Although the ORs in this study were not significant, most recorded adverse effects demonstrated an aOR less than 1, suggesting that there might be a lower risk of certain adverse effects in psoriasis patients. This could be explained by the immunomodulatory effects of certain systemic psoriasis treatments that might influence the adverse effect presentation.

The study is limited by the lack of treatment data, small sample size, and the fact that it did not assess flares or worsening of psoriasis with the vaccines. Underreporting of adverse effects by patients and underdiagnosis of adverse effects secondary to SARS-CoV-2 vaccines due to its novel nature, incompletely understood consequences, and limited ICD-10 codes associated with adverse effects all contributed to the small sample size.

Our findings suggest that the risk for immediate adverse effects from the mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccines is not increased among psoriasis patients. However, the impact of immunomodulatory agents on vaccine efficacy and expected adverse effects should be investigated. As more individuals receive the COVID-19 vaccine, the adverse effect profile in patients with psoriasis is an important area of investigation.

To the Editor:

Because the SARS-CoV-2 virus is constantly changing, routine vaccination to prevent COVID-19 infection is recommended. The messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines from Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna as well as the Ad26.COV2.S (Johnson & Johnson) and NVX-CoV2373 (Novavax) vaccines are the most commonly used COVID-19 vaccines in the United States. Adverse effects following vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 are well documented; recent studies report a small incidence of adverse effects in the general population, with most being minor (eg, headache, fever, muscle pain).1,2 Interestingly, reports of exacerbation of psoriasis and new-onset psoriasis following COVID-19 vaccination suggest a potential association.3,4 However, the literature investigating the vaccine adverse effect profile in this demographic is scarce. We examined the incidence of adverse effects from SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in patients with psoriasis.

This retrospective cohort study used the COVID-19 Research Database (https://covid19researchdatabase.org/) to examine the adverse effects following the first and second doses of the mRNA vaccines in patients with and without psoriasis. The sample size for the Ad26.COV2.S vaccine was too small to analyze.

Claims were evaluated from August to October 2021 for 2 diagnoses of psoriasis prior to January 1, 2020, using the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) code L40.9 to increase the positive predictive value and ensure that the diagnosis preceded the COVID-19 pandemic. Patients younger than 18 years and those who did not receive 2 doses of a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine were excluded. Controls who did not have a diagnosis of psoriasis were matched for age, sex, and hypertension at a 4:1 ratio. Hypertension represented the most common comorbidity that could feasibly be controlled for in this study population. Other comorbidities recorded included obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic ischemic heart disease, rhinitis, and chronic kidney disease.

Common adverse effects as long as 30 days after vaccination were identified using ICD-10 codes. Adverse effects of interest were anaphylactic reaction, initial encounter of adverse effect of viral vaccines, fever, allergic urticaria, weakness, altered mental status, malaise, allergic reaction, chest pain, symptoms involving circulatory or respiratory systems, localized rash, axillary lymphadenopathy, infection, and myocarditis.5 Poisson regression was performed using Stata 17 analytical software.

We identified 4273 patients with psoriasis and 17,092 controls who received mRNA COVID-19 vaccines (Table). Adjusted odds ratios (aORs) for doses 1 and 2 were calculated for each vaccine (eTable). Adverse effects with sufficient data to generate an aOR included weakness, altered mental status, malaise, chest pain, and symptoms involving the circulatory or respiratory system. The aORs for allergic urticaria and initial encounter of adverse effect of viral vaccines were only calculated for the Moderna mRNA vaccine due to low sample size.

This study demonstrated that patients with psoriasis do not appear to have a significantly increased risk of adverse effects from mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. Although the ORs in this study were not significant, most recorded adverse effects demonstrated an aOR less than 1, suggesting that there might be a lower risk of certain adverse effects in psoriasis patients. This could be explained by the immunomodulatory effects of certain systemic psoriasis treatments that might influence the adverse effect presentation.

The study is limited by the lack of treatment data, small sample size, and the fact that it did not assess flares or worsening of psoriasis with the vaccines. Underreporting of adverse effects by patients and underdiagnosis of adverse effects secondary to SARS-CoV-2 vaccines due to its novel nature, incompletely understood consequences, and limited ICD-10 codes associated with adverse effects all contributed to the small sample size.

Our findings suggest that the risk for immediate adverse effects from the mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccines is not increased among psoriasis patients. However, the impact of immunomodulatory agents on vaccine efficacy and expected adverse effects should be investigated. As more individuals receive the COVID-19 vaccine, the adverse effect profile in patients with psoriasis is an important area of investigation.

- Singh A, Khillan R, Mishra Y, et al. The safety profile of COVID-19 vaccinations in the United States. Am J Infect Control. 2022;50:15-19. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2021.10.015

- Beatty AL, Peyser ND, Butcher XE, et al. Analysis of COVID-19 vaccine type and adverse effects following vaccination. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e2140364. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.40364

- Bellinato F, Maurelli M, Gisondi P, et al. Cutaneous adverse reactions associated with SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. J Clin Med. 2021;10:5344. doi:10.3390/jcm10225344

- Elamin S, Hinds F, Tolland J. De novo generalized pustular psoriasis following Oxford-AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47:153-155. doi:10.1111/ced.14895

- Remer EE. Coding COVID-19 vaccination. ICD10monitor. Published March 2, 2021. Updated October 18, 2022. Accessed January 17, 2023. https://icd10monitor.medlearn.com/coding-covid-19-vaccination/

- Singh A, Khillan R, Mishra Y, et al. The safety profile of COVID-19 vaccinations in the United States. Am J Infect Control. 2022;50:15-19. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2021.10.015

- Beatty AL, Peyser ND, Butcher XE, et al. Analysis of COVID-19 vaccine type and adverse effects following vaccination. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e2140364. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.40364

- Bellinato F, Maurelli M, Gisondi P, et al. Cutaneous adverse reactions associated with SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. J Clin Med. 2021;10:5344. doi:10.3390/jcm10225344

- Elamin S, Hinds F, Tolland J. De novo generalized pustular psoriasis following Oxford-AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47:153-155. doi:10.1111/ced.14895

- Remer EE. Coding COVID-19 vaccination. ICD10monitor. Published March 2, 2021. Updated October 18, 2022. Accessed January 17, 2023. https://icd10monitor.medlearn.com/coding-covid-19-vaccination/

PRACTICE POINTS

- Patients who have psoriasis do not appear to have an increased incidence of adverse effects from messenger RNA COVID-19 vaccines.

- Clinicians can safely recommend COVID-19 vaccines to patients who have psoriasis.

New Treatments for Psoriasis: An Update on a Therapeutic Frontier

The landscape of psoriasis treatments has undergone rapid change within the last decade, and the dizzying speed of drug development has not slowed, with 4 notable entries into the psoriasis treatment armamentarium within the last year: tapinarof, roflumilast, deucravacitinib, and spesolimab. Several others are in late-stage development, and these therapies represent new mechanisms, pathways, and delivery systems that will meaningfully broaden the spectrum of treatment choices for our patients. However, it can be quite difficult to keep track of all of the medication options. This review aims to present the mechanisms and data on both newly available therapeutics for psoriasis and products in the pipeline that may have a major impact on our treatment paradigm for psoriasis in the near future.

Topical Treatments

Tapinarof—Tapinarof is a topical aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR)–modulating agent derived from a secondary metabolite produced by a bacterial symbiont of entomopathogenic nematodes.1 Tapinarof binds and activates AhR, inducing a signaling cascade that suppresses the expression of helper T cells TH17 and TH22, upregulates skin barrier protein expression, and reduces epidermal oxidative stress.2 This is a familiar mechanism, as AhR agonism is one of the pathways modulated by coal tar. Tapinarof’s overall effects on immune function, skin barrier integrity, and antioxidant activity show great promise for the treatment of plaque psoriasis.

Two phase 3 trials (N=1025) evaluated the efficacy and safety of once-daily tapinarof cream 1% for plaque psoriasis.3 A physician global assessment (PGA) score of 0/1 occurred in 35.4% to 40.2% of patients in the tapinarof group and in 6.0% of patients in the vehicle group. At week 12, 36.1% to 47.6% of patients treated with daily applications of tapinarof cream achieved a 75% reduction in their baseline psoriasis area and severity index (PASI 75) score compared with 6.9% to 10.2% in the vehicle group.3 In a long-term extension study, a substantial remittive effect of at least 4 months off tapinarof therapy was observed in patients who achieved complete clearance (PGA=0).4 Use of tapinarof cream was associated with folliculitis in up to 23.5% of patients.3,4

Roflumilast—

Topical roflumilast is a selective, highly potent PDE-4 inhibitor with greater affinity for PDE-4 compared to crisaborole and apremilast.8 Two phase 3 trials (N=881) evaluated the efficacy and safety profile of roflumilast cream for plaque psoriasis, with a particular interest in its use for intertriginous areas.9 At week 8, 37.5% to 42.4% of roflumilast-treated patients achieved investigator global assessment (IGA) success compared with 6.1% to 6.9% of vehicle-treated patients. Intertriginous IGA success was observed in 68.1% to 71.2% of patients treated with roflumilast cream compared with 13.8% to 18.5% of vehicle-treated patients. At 8-week follow-up, 39.0% to 41.6% of roflumilast-treated patients achieved PASI 75 vs 5.3% to 7.6% of patients in the vehicle group. Few stinging, burning, or application-site reactions were reported with roflumilast, along with rare instances of gastrointestinal AEs (<4%).9

Oral Therapy

Deucravacitinib—Tyrosine kinase 2 (TYK2) mediates the intracellular signaling of the TH17 and TH1 inflammatory cytokines IL-12/IL-23 and type I interferons, respectively, the former of which are critical in the development of psoriasis via the Janus kinase (JAK) signal transducer and activator of transcription pathway.10 Deucravacitinib is an oral selective TYK2 allosteric inhibitor that binds to the regulatory domain of the enzyme rather than the active catalytic domain, where other TYK2 and JAK1, JAK2, and JAK3 inhibitors bind.11 This unique inhibitory mechanism accounts for the high functional selectivity of deucravacitinib for TYK2 vs the closely related JAK1, JAK2, and JAK3 kinases, thus avoiding the pitfall of prior JAK inhibitors that were associated with major AEs, including an increased risk for serious infections, malignancies, and thrombosis.12 The selective suppression of the inflammatory TYK2 pathway has the potential to shift future therapeutic targets to a narrower range of receptors that may contribute to favorable benefit-risk profiles.

Two phase 3 trials (N=1686) compared the efficacy and safety of deucravacitinib vs placebo and apremilast in adults with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis.13,14 At week 16, 53.0% to 58.4% of deucravacitinib-treated patients achieved PASI 75 compared with 35.1% to 39.8% of apremilast-treated patients. At 16-week follow-up, static PGA response was observed in 49.5% to 53.6% of patients in the deucravacitinib group and 32.1% to 33.9% of the apremilast group. The most frequent AEs associated with deucravacitinib therapy were nasopharyngitis and upper respiratory tract infection, whereas headache, diarrhea, and nausea were more common with apremilast. Treatment with deucravacitinib caused no meaningful changes in laboratory parameters, which are known to change with JAK1, JAK2, and JAK3 inhibitors.13,14 A long-term extension study demonstrated that deucravacitinib had persistent efficacy and consistent safety for up to 2 years.15

Other TYK2 Inhibitors in the Pipeline

Novel oral allosteric TYK2 inhibitors—VTX958 and NDI-034858—and the competitive TYK2 inhibitor PF-06826647 are being developed. Theoretically, these new allosteric inhibitors possess unique structural properties to provide greater TYK2 suppression while bypassing JAK1, JAK2, and JAK3 pathways that may contribute to improved efficacy and safety profiles compared with other TYK2 inhibitors such as deucravacitinib. The results of a phase 1b trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT04999839) showed a dose-dependent reduction of disease severity associated with NDI-034858 treatment for patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, albeit in only 26 patients. At week 4, PASI 50 was achieved in 13%, 57%, and 40% of patients in the 5-, 10-, and 30-mg groups, respectively, compared with 0% in the placebo group.16 In a phase 2 trial of 179 patients, 46.5% and 33.0% of patients treated with 400 and 200 mg of PF-06826647, respectively, achieved PASI 90 at week 16. Conversely, dose-dependent laboratory abnormalities were observed with PF-06826647, including anemia, neutropenia, and increases in creatine phosphokinase.17 At high concentrations, PF-06826647 may disrupt JAK signaling pathways involved in hematopoiesis and renal functions owing to its mode of action as a competitive inhibitor. Overall, these agents are much farther from market, and long-term studies with larger diverse patient cohorts are required to adequately assess the efficacy and safety data of these novel oral TYK2 inhibitors for patients with psoriasis.

EDP1815—EDP1815 is an oral preparation of a single strain of Prevotella histicola being developed for the treatment of inflammatory diseases, including psoriasis. EDP1815 interacts with host intestinal immune cells through the small intestinal axis (SINTAX) to suppress systemic inflammation across the TH1, TH2, and TH17 pathways. Therapy triggers broad immunomodulatory effects without causing systemic absorption, colonic colonization, or modification of the gut microbiome.18 In a phase 2 study (NCT04603027), the primary end point analysis, mean percentage change in PASI between treatment and placebo, demonstrated that at week 16, EDP1815 was superior to placebo with 80% to 90% probability across each cohort. At week 16, 25% to 32% of patients across the 3 cohorts treated with EDP1815 achieved PASI 50 compared with 12% of patients receiving placebo. Gastrointestinal AEs were comparable between treatment and placebo groups. These results suggest that SINTAX-targeted therapies may provide efficacious and safe immunomodulatory effects for patients with mild to moderate psoriasis, who often have limited treatment options. Although improvements may be mild, SINTAX-targeted therapies can be seen as a particularly attractive adjunctive treatment for patients with severe psoriasis taking other medications or as part of a treatment approach for a patient with milder psoriasis.

Biologics

Bimekizumab—Bimekizumab is a monoclonal IgG1 antibody that selectively inhibits IL-17A and IL-17F. Although IL-17A is a more potent cytokine, IL-17F may be more highly expressed in psoriatic lesional skin and independently contribute to the activation of proinflammatory signaling pathways implicated in the pathophysiology of psoriasis.19 Evidence suggests that dual inhibition of IL-17A and IL-17F may provide more complete suppression of inflammation and improved clinical responses than IL-17A inhibition alone.20

Prior bimekizumab phase 3 clinical studies have shown both rapid and durable clinical improvements in skin clearance compared with placebo.21 Three phase 3 trials—BE VIVID (N=567),22 BE SURE (N=478),23 and BE RADIANT (N=743)24—assessed the efficacy and safety of bimekizumab vs the IL-12/IL-23 inhibitor ustekinumab, the tumor necrosis factor inhibitor adalimumab, and the selective IL-17A inhibitor secukinumab, respectively. At week 4, significantly more patients treated with bimekizumab (71%–77%) achieved PASI 75 than patients treated with ustekinumab (15%; P<.0001), adalimumab (31.4%; P<.001), or secukinumab (47.3%; P<.001).22-24 After 16 weeks of treatment, PASI 90 was achieved by 85% to 86.2%, 50%, and 47.2% of patients treated with bimekizumab, ustekinumab, and adalimumab, respectively.22,23 At week 16, PASI 100 was observed in 59% to 61.7%, 21%, 23.9%, and 48.9% of patients treated with bimekizumab, ustekinumab, adalimumab, and secukinumab, respectively. An IGA response (score of 0/1) at week 16 was achieved by 84% to 85.5%, 53%, 57.2%, and 78.6% of patients receiving bimekizumab, ustekinumab, adalimumab, and secukinumab, respectively.22-24

The most common AEs in bimekizumab-treated patients were nasopharyngitis, oral candidiasis, and upper respiratory tract infection.22-24 The dual inhibition of IL-17A and IL-17F suppresses host defenses against Candida at the oral mucosa, increasing the incidence of bimekizumab-associated oral candidiasis.25 Despite the increased risk of Candida infections, these data suggest that inhibition of both IL-17A and IL-17F with bimekizumab may provide faster and greater clinical benefit for patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis than inhibition of IL-17A alone and other biologic therapies, as the PASI 100 clearance rates across the multiple comparator trials and the placebo-controlled pivotal trial are consistently the highest among any biologic for the treatment of psoriasis.

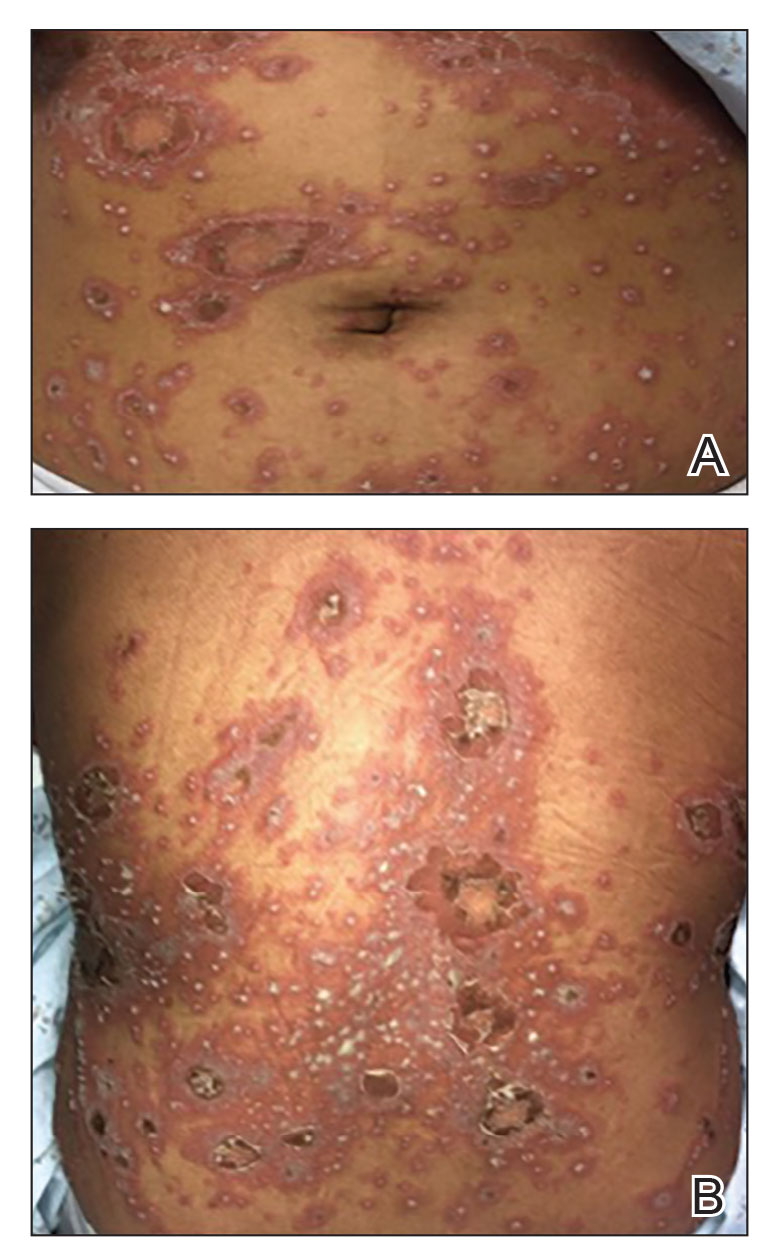

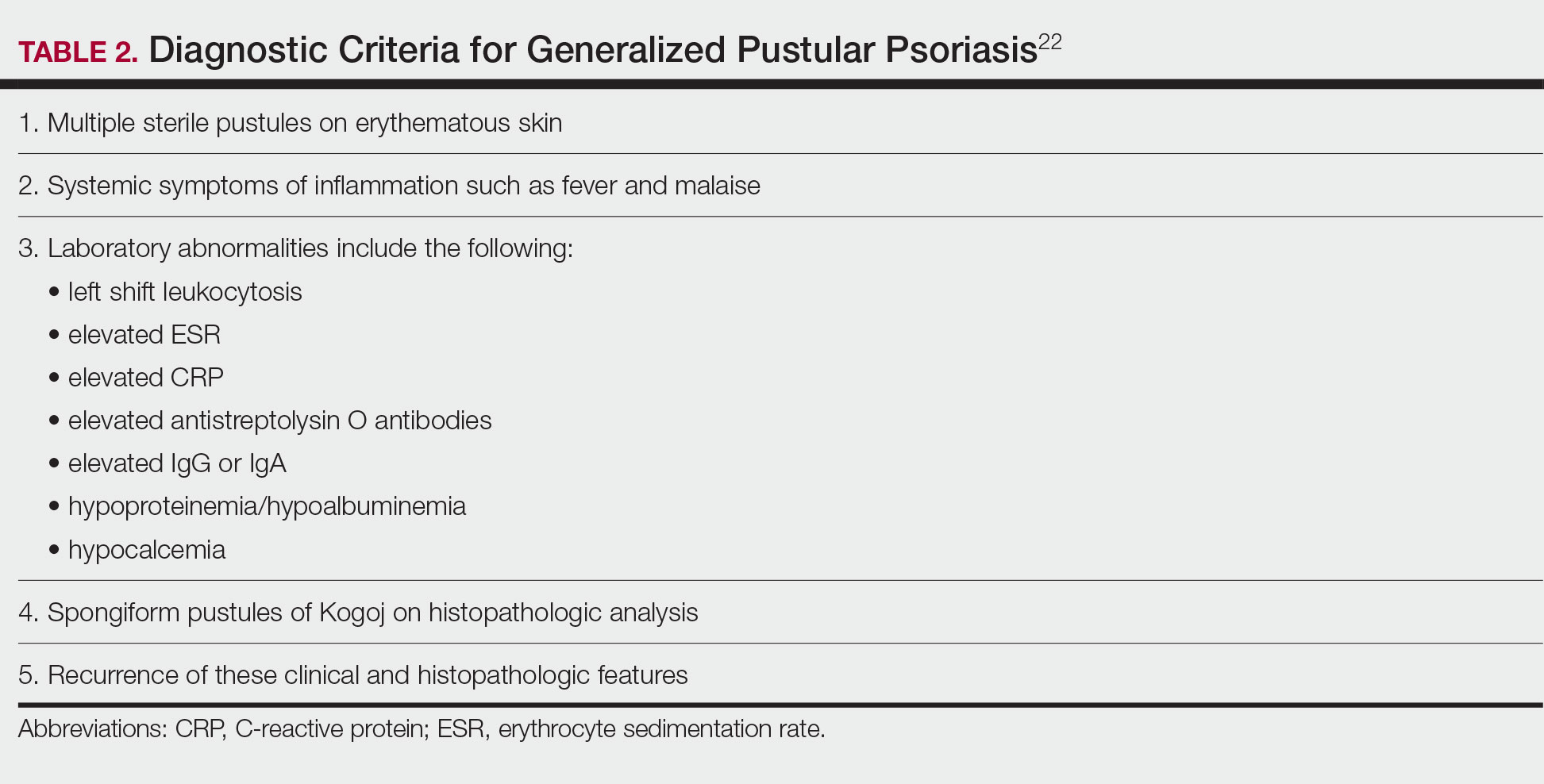

Spesolimab—The IL-36 pathway and IL-36 receptor genes have been linked to the pathogenesis of generalized pustular psoriasis.26 In a phase 2 trial, 19 of 35 patients (54%) receiving an intravenous dose of spesolimab, an IL-36 receptor inhibitor, had a generalized pustular psoriasis PGA pustulation subscore of 0 (no visible pustules) at the end of week 1 vs 6% of patients in the placebo group.27 A generalized pustular psoriasis PGA total score of 0 or 1 was observed in 43% (15/35) of spesolimab-treated patients compared with 11% (2/18) of patients in the placebo group. The most common AEs in patients treated with spesolimab were minor infections.27 Two open-label phase 3 trials—NCT05200247 and NCT05239039—are underway to determine the long-term efficacy and safety of spesolimab in patients with generalized pustular psoriasis.

Conclusion

Although we have seen a renaissance in psoriasis therapies with the advent of biologics in the last 20 years, recent evidence shows that more innovation is underway. Just in the last year, 2 new mechanisms for treating psoriasis topically without steroids have come to fruition, and there have not been truly novel mechanisms for treating psoriasis topically since approvals for tazarotene and calcipotriene in the 1990s. An entirely new class—TYK2 inhibitors—was developed and landed in psoriasis first, greatly improving the efficacy measures attained with oral medications in general. Finally, an orphan diagnosis got its due with an ambitiously designed study looking at a previously unheard-of 1-week end point, but it comes for one of the few true dermatologic emergencies we encounter, generalized pustular psoriasis. We are fortunate to have so many meaningful new treatments available to us, and it is invigorating to see that even more efficacious biologics and treatments are coming, along with novel concepts such as a treatment affecting the microbiome. Now, we just need to make sure that our patients have the access they deserve to the wide array of available treatments.

- Bissonnette R, Stein Gold L, Rubenstein DS, et al. Tapinarof in the treatment of psoriasis: a review of the unique mechanism of action of a novel therapeutic aryl hydrocarbon receptor-modulating agent. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1059-1067.

- Smith SH, Jayawickreme C, Rickard DJ, et al. Tapinarof is a natural AhR agonist that resolves skin inflammation in mice and humans. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137:2110-2119.

- Lebwohl MG, Stein Gold L, Strober B, et al. Phase 3 trials of tapinarof cream for plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2219-2229.

- Strober B, Stein Gold L, Bissonnette R, et al. One-year safety and efficacy of tapinarof cream for the treatment of plaque psoriasis: results from the PSOARING 3 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:800-806.

- Card GL, England BP, Suzuki Y, et al. Structural basis for the activity of drugs that inhibit phosphodiesterases. Structure. 2004;12:2233-2247.

- Milakovic M, Gooderham MJ. Phosphodiesterase-4 inhibition in psoriasis. Psoriasis (Auckl). 2021;11:21-29.

- Papp K, Reich K, Leonardi CL, et al. Apremilast, an oral phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor, in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: results of a phase III, randomized, controlled trial (Efficacy and Safety Trial Evaluating the Effects of Apremilast in Psoriasis [ESTEEM] 1). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:37-49.

- Dong C, Virtucio C, Zemska O, et al. Treatment of skin inflammation with benzoxaborole phosphodiesterase inhibitors: selectivity, cellular activity, and effect on cytokines associated with skin inflammation and skin architecture changes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2016;358:413-422.

- Lebwohl MG, Kircik LH, Moore AY, et al. Effect of roflumilast cream vs vehicle cream on chronic plaque psoriasis: the DERMIS-1 and DERMIS-2 randomized clinical trials. JAMA. 2022;328:1073-1084.

- Nogueira M, Puig L, Torres T. JAK inhibitors for treatment of psoriasis: focus on selective tyk2 inhibitors. Drugs. 2020;80:341-352.

- Wrobleski ST, Moslin R, Lin S, et al. Highly selective inhibition of tyrosine kinase 2 (TYK2) for the treatment of autoimmune diseases: discovery of the allosteric inhibitor BMS-986165. J Med Chem. 2019;62:8973-8995.

- Chimalakonda A, Burke J, Cheng L, et al. Selectivity profile of the tyrosine kinase 2 inhibitor deucravacitinib compared with janus kinase 1/2/3 inhibitors. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021;11:1763-1776.

- Strober B, Thaçi D, Sofen H, et al. Deucravacitinib versus placebo and apremilast in moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: efficacy and safety results from the 52-week, randomized, double-blinded, phase 3 Program for Evaluation of TYK2 inhibitor psoriasis second trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:40-51.

- Armstrong AW, Gooderham M, Warren RB, et al. Deucravacitinib versus placebo and apremilast in moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: efficacy and safety results from the 52-week, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled phase 3 POETYK PSO-1 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:29-39.

- Warren RB, Sofen H, Imafuku S, et al. POS1046 deucravacitinib long-term efficacy and safety in plaque psoriasis: 2-year results from the phase 3 POETYK PSO program [abstract]. Ann Rheum Dis. 2022;81(suppl 1):841.

- McElwee JJ, Garcet S, Li X, et al. Analysis of histologic, molecular and clinical improvement in moderate-to-severe psoriasis: results from a Phase 1b trial of the novel allosteric TYK2 inhibitor NDI-034858. Poster presented at: American Academy of Dermatology Annual Meeting; March 25, 2022; Boston, MA.

- Tehlirian C, Singh RSP, Pradhan V, et al. Oral tyrosine kinase 2 inhibitor PF-06826647 demonstrates efficacy and an acceptable safety profile in participants with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis in a phase 2b, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:333-342.

- Hilliard-Barth K, Cormack T, Ramani K, et al. Immune mechanisms of the systemic effects of EDP1815: an orally delivered, gut-restricted microbial drug candidate for the treatment of inflammatory diseases. Poster presented at: Society for Mucosal Immunology Virtual Congress; July 20-22, 2021, Cambridge, MA.

- Glatt S, Baeten D, Baker T, et al. Dual IL-17A and IL-17F neutralisation by bimekizumab in psoriatic arthritis: evidence from preclinical experiments and a randomised placebo-controlled clinical trial that IL-17F contributes to human chronic tissue inflammation. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77:523-532.

- Adams R, Maroof A, Baker T, et al. Bimekizumab, a novel humanized IgG1 antibody that neutralizes both IL-17A and IL-17F. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1894.

- Gordon KB, Foley P, Krueger JG, et al. Bimekizumab efficacy and safety in moderate to severe plaque psoriasis (BE READY): a multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised withdrawal phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;397:475-486.

- Reich K, Papp KA, Blauvelt A, et al. Bimekizumab versus ustekinumab for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis (BE VIVID): efficacy and safety from a 52-week, multicentre, double-blind, active comparator and placebo controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;397:487-498.

- Warren RB, Blauvelt A, Bagel J, et al. Bimekizumab versus adalimumab in plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:130-141.

- Reich K, Warren RB, Lebwohl M, et al. Bimekizumab versus secukinumab in plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:142-152.

- Blauvelt A, Lebwohl MG, Bissonnette R. IL-23/IL-17A dysfunction phenotypes inform possible clinical effects from anti-IL-17A therapies. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:1946-1953.

- Marrakchi S, Guigue P, Renshaw BR, et al. Interleukin-36-receptor antagonist deficiency and generalized pustular psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:620-628.

- Bachelez H, Choon SE, Marrakchi S, et al. Trial of spesolimab for generalized pustular psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2431-2440.

The landscape of psoriasis treatments has undergone rapid change within the last decade, and the dizzying speed of drug development has not slowed, with 4 notable entries into the psoriasis treatment armamentarium within the last year: tapinarof, roflumilast, deucravacitinib, and spesolimab. Several others are in late-stage development, and these therapies represent new mechanisms, pathways, and delivery systems that will meaningfully broaden the spectrum of treatment choices for our patients. However, it can be quite difficult to keep track of all of the medication options. This review aims to present the mechanisms and data on both newly available therapeutics for psoriasis and products in the pipeline that may have a major impact on our treatment paradigm for psoriasis in the near future.

Topical Treatments

Tapinarof—Tapinarof is a topical aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR)–modulating agent derived from a secondary metabolite produced by a bacterial symbiont of entomopathogenic nematodes.1 Tapinarof binds and activates AhR, inducing a signaling cascade that suppresses the expression of helper T cells TH17 and TH22, upregulates skin barrier protein expression, and reduces epidermal oxidative stress.2 This is a familiar mechanism, as AhR agonism is one of the pathways modulated by coal tar. Tapinarof’s overall effects on immune function, skin barrier integrity, and antioxidant activity show great promise for the treatment of plaque psoriasis.

Two phase 3 trials (N=1025) evaluated the efficacy and safety of once-daily tapinarof cream 1% for plaque psoriasis.3 A physician global assessment (PGA) score of 0/1 occurred in 35.4% to 40.2% of patients in the tapinarof group and in 6.0% of patients in the vehicle group. At week 12, 36.1% to 47.6% of patients treated with daily applications of tapinarof cream achieved a 75% reduction in their baseline psoriasis area and severity index (PASI 75) score compared with 6.9% to 10.2% in the vehicle group.3 In a long-term extension study, a substantial remittive effect of at least 4 months off tapinarof therapy was observed in patients who achieved complete clearance (PGA=0).4 Use of tapinarof cream was associated with folliculitis in up to 23.5% of patients.3,4

Roflumilast—

Topical roflumilast is a selective, highly potent PDE-4 inhibitor with greater affinity for PDE-4 compared to crisaborole and apremilast.8 Two phase 3 trials (N=881) evaluated the efficacy and safety profile of roflumilast cream for plaque psoriasis, with a particular interest in its use for intertriginous areas.9 At week 8, 37.5% to 42.4% of roflumilast-treated patients achieved investigator global assessment (IGA) success compared with 6.1% to 6.9% of vehicle-treated patients. Intertriginous IGA success was observed in 68.1% to 71.2% of patients treated with roflumilast cream compared with 13.8% to 18.5% of vehicle-treated patients. At 8-week follow-up, 39.0% to 41.6% of roflumilast-treated patients achieved PASI 75 vs 5.3% to 7.6% of patients in the vehicle group. Few stinging, burning, or application-site reactions were reported with roflumilast, along with rare instances of gastrointestinal AEs (<4%).9

Oral Therapy

Deucravacitinib—Tyrosine kinase 2 (TYK2) mediates the intracellular signaling of the TH17 and TH1 inflammatory cytokines IL-12/IL-23 and type I interferons, respectively, the former of which are critical in the development of psoriasis via the Janus kinase (JAK) signal transducer and activator of transcription pathway.10 Deucravacitinib is an oral selective TYK2 allosteric inhibitor that binds to the regulatory domain of the enzyme rather than the active catalytic domain, where other TYK2 and JAK1, JAK2, and JAK3 inhibitors bind.11 This unique inhibitory mechanism accounts for the high functional selectivity of deucravacitinib for TYK2 vs the closely related JAK1, JAK2, and JAK3 kinases, thus avoiding the pitfall of prior JAK inhibitors that were associated with major AEs, including an increased risk for serious infections, malignancies, and thrombosis.12 The selective suppression of the inflammatory TYK2 pathway has the potential to shift future therapeutic targets to a narrower range of receptors that may contribute to favorable benefit-risk profiles.

Two phase 3 trials (N=1686) compared the efficacy and safety of deucravacitinib vs placebo and apremilast in adults with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis.13,14 At week 16, 53.0% to 58.4% of deucravacitinib-treated patients achieved PASI 75 compared with 35.1% to 39.8% of apremilast-treated patients. At 16-week follow-up, static PGA response was observed in 49.5% to 53.6% of patients in the deucravacitinib group and 32.1% to 33.9% of the apremilast group. The most frequent AEs associated with deucravacitinib therapy were nasopharyngitis and upper respiratory tract infection, whereas headache, diarrhea, and nausea were more common with apremilast. Treatment with deucravacitinib caused no meaningful changes in laboratory parameters, which are known to change with JAK1, JAK2, and JAK3 inhibitors.13,14 A long-term extension study demonstrated that deucravacitinib had persistent efficacy and consistent safety for up to 2 years.15

Other TYK2 Inhibitors in the Pipeline

Novel oral allosteric TYK2 inhibitors—VTX958 and NDI-034858—and the competitive TYK2 inhibitor PF-06826647 are being developed. Theoretically, these new allosteric inhibitors possess unique structural properties to provide greater TYK2 suppression while bypassing JAK1, JAK2, and JAK3 pathways that may contribute to improved efficacy and safety profiles compared with other TYK2 inhibitors such as deucravacitinib. The results of a phase 1b trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT04999839) showed a dose-dependent reduction of disease severity associated with NDI-034858 treatment for patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, albeit in only 26 patients. At week 4, PASI 50 was achieved in 13%, 57%, and 40% of patients in the 5-, 10-, and 30-mg groups, respectively, compared with 0% in the placebo group.16 In a phase 2 trial of 179 patients, 46.5% and 33.0% of patients treated with 400 and 200 mg of PF-06826647, respectively, achieved PASI 90 at week 16. Conversely, dose-dependent laboratory abnormalities were observed with PF-06826647, including anemia, neutropenia, and increases in creatine phosphokinase.17 At high concentrations, PF-06826647 may disrupt JAK signaling pathways involved in hematopoiesis and renal functions owing to its mode of action as a competitive inhibitor. Overall, these agents are much farther from market, and long-term studies with larger diverse patient cohorts are required to adequately assess the efficacy and safety data of these novel oral TYK2 inhibitors for patients with psoriasis.

EDP1815—EDP1815 is an oral preparation of a single strain of Prevotella histicola being developed for the treatment of inflammatory diseases, including psoriasis. EDP1815 interacts with host intestinal immune cells through the small intestinal axis (SINTAX) to suppress systemic inflammation across the TH1, TH2, and TH17 pathways. Therapy triggers broad immunomodulatory effects without causing systemic absorption, colonic colonization, or modification of the gut microbiome.18 In a phase 2 study (NCT04603027), the primary end point analysis, mean percentage change in PASI between treatment and placebo, demonstrated that at week 16, EDP1815 was superior to placebo with 80% to 90% probability across each cohort. At week 16, 25% to 32% of patients across the 3 cohorts treated with EDP1815 achieved PASI 50 compared with 12% of patients receiving placebo. Gastrointestinal AEs were comparable between treatment and placebo groups. These results suggest that SINTAX-targeted therapies may provide efficacious and safe immunomodulatory effects for patients with mild to moderate psoriasis, who often have limited treatment options. Although improvements may be mild, SINTAX-targeted therapies can be seen as a particularly attractive adjunctive treatment for patients with severe psoriasis taking other medications or as part of a treatment approach for a patient with milder psoriasis.

Biologics

Bimekizumab—Bimekizumab is a monoclonal IgG1 antibody that selectively inhibits IL-17A and IL-17F. Although IL-17A is a more potent cytokine, IL-17F may be more highly expressed in psoriatic lesional skin and independently contribute to the activation of proinflammatory signaling pathways implicated in the pathophysiology of psoriasis.19 Evidence suggests that dual inhibition of IL-17A and IL-17F may provide more complete suppression of inflammation and improved clinical responses than IL-17A inhibition alone.20

Prior bimekizumab phase 3 clinical studies have shown both rapid and durable clinical improvements in skin clearance compared with placebo.21 Three phase 3 trials—BE VIVID (N=567),22 BE SURE (N=478),23 and BE RADIANT (N=743)24—assessed the efficacy and safety of bimekizumab vs the IL-12/IL-23 inhibitor ustekinumab, the tumor necrosis factor inhibitor adalimumab, and the selective IL-17A inhibitor secukinumab, respectively. At week 4, significantly more patients treated with bimekizumab (71%–77%) achieved PASI 75 than patients treated with ustekinumab (15%; P<.0001), adalimumab (31.4%; P<.001), or secukinumab (47.3%; P<.001).22-24 After 16 weeks of treatment, PASI 90 was achieved by 85% to 86.2%, 50%, and 47.2% of patients treated with bimekizumab, ustekinumab, and adalimumab, respectively.22,23 At week 16, PASI 100 was observed in 59% to 61.7%, 21%, 23.9%, and 48.9% of patients treated with bimekizumab, ustekinumab, adalimumab, and secukinumab, respectively. An IGA response (score of 0/1) at week 16 was achieved by 84% to 85.5%, 53%, 57.2%, and 78.6% of patients receiving bimekizumab, ustekinumab, adalimumab, and secukinumab, respectively.22-24

The most common AEs in bimekizumab-treated patients were nasopharyngitis, oral candidiasis, and upper respiratory tract infection.22-24 The dual inhibition of IL-17A and IL-17F suppresses host defenses against Candida at the oral mucosa, increasing the incidence of bimekizumab-associated oral candidiasis.25 Despite the increased risk of Candida infections, these data suggest that inhibition of both IL-17A and IL-17F with bimekizumab may provide faster and greater clinical benefit for patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis than inhibition of IL-17A alone and other biologic therapies, as the PASI 100 clearance rates across the multiple comparator trials and the placebo-controlled pivotal trial are consistently the highest among any biologic for the treatment of psoriasis.

Spesolimab—The IL-36 pathway and IL-36 receptor genes have been linked to the pathogenesis of generalized pustular psoriasis.26 In a phase 2 trial, 19 of 35 patients (54%) receiving an intravenous dose of spesolimab, an IL-36 receptor inhibitor, had a generalized pustular psoriasis PGA pustulation subscore of 0 (no visible pustules) at the end of week 1 vs 6% of patients in the placebo group.27 A generalized pustular psoriasis PGA total score of 0 or 1 was observed in 43% (15/35) of spesolimab-treated patients compared with 11% (2/18) of patients in the placebo group. The most common AEs in patients treated with spesolimab were minor infections.27 Two open-label phase 3 trials—NCT05200247 and NCT05239039—are underway to determine the long-term efficacy and safety of spesolimab in patients with generalized pustular psoriasis.

Conclusion

Although we have seen a renaissance in psoriasis therapies with the advent of biologics in the last 20 years, recent evidence shows that more innovation is underway. Just in the last year, 2 new mechanisms for treating psoriasis topically without steroids have come to fruition, and there have not been truly novel mechanisms for treating psoriasis topically since approvals for tazarotene and calcipotriene in the 1990s. An entirely new class—TYK2 inhibitors—was developed and landed in psoriasis first, greatly improving the efficacy measures attained with oral medications in general. Finally, an orphan diagnosis got its due with an ambitiously designed study looking at a previously unheard-of 1-week end point, but it comes for one of the few true dermatologic emergencies we encounter, generalized pustular psoriasis. We are fortunate to have so many meaningful new treatments available to us, and it is invigorating to see that even more efficacious biologics and treatments are coming, along with novel concepts such as a treatment affecting the microbiome. Now, we just need to make sure that our patients have the access they deserve to the wide array of available treatments.

The landscape of psoriasis treatments has undergone rapid change within the last decade, and the dizzying speed of drug development has not slowed, with 4 notable entries into the psoriasis treatment armamentarium within the last year: tapinarof, roflumilast, deucravacitinib, and spesolimab. Several others are in late-stage development, and these therapies represent new mechanisms, pathways, and delivery systems that will meaningfully broaden the spectrum of treatment choices for our patients. However, it can be quite difficult to keep track of all of the medication options. This review aims to present the mechanisms and data on both newly available therapeutics for psoriasis and products in the pipeline that may have a major impact on our treatment paradigm for psoriasis in the near future.

Topical Treatments

Tapinarof—Tapinarof is a topical aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR)–modulating agent derived from a secondary metabolite produced by a bacterial symbiont of entomopathogenic nematodes.1 Tapinarof binds and activates AhR, inducing a signaling cascade that suppresses the expression of helper T cells TH17 and TH22, upregulates skin barrier protein expression, and reduces epidermal oxidative stress.2 This is a familiar mechanism, as AhR agonism is one of the pathways modulated by coal tar. Tapinarof’s overall effects on immune function, skin barrier integrity, and antioxidant activity show great promise for the treatment of plaque psoriasis.

Two phase 3 trials (N=1025) evaluated the efficacy and safety of once-daily tapinarof cream 1% for plaque psoriasis.3 A physician global assessment (PGA) score of 0/1 occurred in 35.4% to 40.2% of patients in the tapinarof group and in 6.0% of patients in the vehicle group. At week 12, 36.1% to 47.6% of patients treated with daily applications of tapinarof cream achieved a 75% reduction in their baseline psoriasis area and severity index (PASI 75) score compared with 6.9% to 10.2% in the vehicle group.3 In a long-term extension study, a substantial remittive effect of at least 4 months off tapinarof therapy was observed in patients who achieved complete clearance (PGA=0).4 Use of tapinarof cream was associated with folliculitis in up to 23.5% of patients.3,4

Roflumilast—

Topical roflumilast is a selective, highly potent PDE-4 inhibitor with greater affinity for PDE-4 compared to crisaborole and apremilast.8 Two phase 3 trials (N=881) evaluated the efficacy and safety profile of roflumilast cream for plaque psoriasis, with a particular interest in its use for intertriginous areas.9 At week 8, 37.5% to 42.4% of roflumilast-treated patients achieved investigator global assessment (IGA) success compared with 6.1% to 6.9% of vehicle-treated patients. Intertriginous IGA success was observed in 68.1% to 71.2% of patients treated with roflumilast cream compared with 13.8% to 18.5% of vehicle-treated patients. At 8-week follow-up, 39.0% to 41.6% of roflumilast-treated patients achieved PASI 75 vs 5.3% to 7.6% of patients in the vehicle group. Few stinging, burning, or application-site reactions were reported with roflumilast, along with rare instances of gastrointestinal AEs (<4%).9

Oral Therapy

Deucravacitinib—Tyrosine kinase 2 (TYK2) mediates the intracellular signaling of the TH17 and TH1 inflammatory cytokines IL-12/IL-23 and type I interferons, respectively, the former of which are critical in the development of psoriasis via the Janus kinase (JAK) signal transducer and activator of transcription pathway.10 Deucravacitinib is an oral selective TYK2 allosteric inhibitor that binds to the regulatory domain of the enzyme rather than the active catalytic domain, where other TYK2 and JAK1, JAK2, and JAK3 inhibitors bind.11 This unique inhibitory mechanism accounts for the high functional selectivity of deucravacitinib for TYK2 vs the closely related JAK1, JAK2, and JAK3 kinases, thus avoiding the pitfall of prior JAK inhibitors that were associated with major AEs, including an increased risk for serious infections, malignancies, and thrombosis.12 The selective suppression of the inflammatory TYK2 pathway has the potential to shift future therapeutic targets to a narrower range of receptors that may contribute to favorable benefit-risk profiles.

Two phase 3 trials (N=1686) compared the efficacy and safety of deucravacitinib vs placebo and apremilast in adults with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis.13,14 At week 16, 53.0% to 58.4% of deucravacitinib-treated patients achieved PASI 75 compared with 35.1% to 39.8% of apremilast-treated patients. At 16-week follow-up, static PGA response was observed in 49.5% to 53.6% of patients in the deucravacitinib group and 32.1% to 33.9% of the apremilast group. The most frequent AEs associated with deucravacitinib therapy were nasopharyngitis and upper respiratory tract infection, whereas headache, diarrhea, and nausea were more common with apremilast. Treatment with deucravacitinib caused no meaningful changes in laboratory parameters, which are known to change with JAK1, JAK2, and JAK3 inhibitors.13,14 A long-term extension study demonstrated that deucravacitinib had persistent efficacy and consistent safety for up to 2 years.15

Other TYK2 Inhibitors in the Pipeline

Novel oral allosteric TYK2 inhibitors—VTX958 and NDI-034858—and the competitive TYK2 inhibitor PF-06826647 are being developed. Theoretically, these new allosteric inhibitors possess unique structural properties to provide greater TYK2 suppression while bypassing JAK1, JAK2, and JAK3 pathways that may contribute to improved efficacy and safety profiles compared with other TYK2 inhibitors such as deucravacitinib. The results of a phase 1b trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT04999839) showed a dose-dependent reduction of disease severity associated with NDI-034858 treatment for patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, albeit in only 26 patients. At week 4, PASI 50 was achieved in 13%, 57%, and 40% of patients in the 5-, 10-, and 30-mg groups, respectively, compared with 0% in the placebo group.16 In a phase 2 trial of 179 patients, 46.5% and 33.0% of patients treated with 400 and 200 mg of PF-06826647, respectively, achieved PASI 90 at week 16. Conversely, dose-dependent laboratory abnormalities were observed with PF-06826647, including anemia, neutropenia, and increases in creatine phosphokinase.17 At high concentrations, PF-06826647 may disrupt JAK signaling pathways involved in hematopoiesis and renal functions owing to its mode of action as a competitive inhibitor. Overall, these agents are much farther from market, and long-term studies with larger diverse patient cohorts are required to adequately assess the efficacy and safety data of these novel oral TYK2 inhibitors for patients with psoriasis.

EDP1815—EDP1815 is an oral preparation of a single strain of Prevotella histicola being developed for the treatment of inflammatory diseases, including psoriasis. EDP1815 interacts with host intestinal immune cells through the small intestinal axis (SINTAX) to suppress systemic inflammation across the TH1, TH2, and TH17 pathways. Therapy triggers broad immunomodulatory effects without causing systemic absorption, colonic colonization, or modification of the gut microbiome.18 In a phase 2 study (NCT04603027), the primary end point analysis, mean percentage change in PASI between treatment and placebo, demonstrated that at week 16, EDP1815 was superior to placebo with 80% to 90% probability across each cohort. At week 16, 25% to 32% of patients across the 3 cohorts treated with EDP1815 achieved PASI 50 compared with 12% of patients receiving placebo. Gastrointestinal AEs were comparable between treatment and placebo groups. These results suggest that SINTAX-targeted therapies may provide efficacious and safe immunomodulatory effects for patients with mild to moderate psoriasis, who often have limited treatment options. Although improvements may be mild, SINTAX-targeted therapies can be seen as a particularly attractive adjunctive treatment for patients with severe psoriasis taking other medications or as part of a treatment approach for a patient with milder psoriasis.

Biologics

Bimekizumab—Bimekizumab is a monoclonal IgG1 antibody that selectively inhibits IL-17A and IL-17F. Although IL-17A is a more potent cytokine, IL-17F may be more highly expressed in psoriatic lesional skin and independently contribute to the activation of proinflammatory signaling pathways implicated in the pathophysiology of psoriasis.19 Evidence suggests that dual inhibition of IL-17A and IL-17F may provide more complete suppression of inflammation and improved clinical responses than IL-17A inhibition alone.20