User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

Dermatologic changes with COVID-19: What we know and don’t know

The dermatologic manifestations associated with SARS-CoV-2 are many and varied, with new information virtually daily. Graeme Lipper, MD, a member of the Medscape Dermatology advisory board, discussed what we know and what is still to be learned with Lindy Fox, MD, a professor of dermatology at University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) and a member of the American Academy of Dermatology’s COVID-19 Registry task force.

Graeme M. Lipper, MD

Earlier this spring, before there was any real talk about skin manifestations of COVID, my partner called me in to see an unusual case. His patient was a healthy 20-year-old who had just come back from college and had tender, purple discoloration and swelling on his toes. I shrugged and said “looks like chilblains,” but there was something weird about the case. It seemed more severe, with areas of blistering and erosions, and the discomfort was unusual for run-of-the-mill pernio. This young man had experienced a cough and shortness of breath a few weeks earlier but those symptoms had resolved when we saw him.

That evening, I was on a derm social media site and saw a series of pictures from Italy that blew me away. All of these pictures looked just like this kid’s toes. That’s the first I heard of “COVID toes,” but now they seem to be everywhere. How would you describe this presentation, and how does it differ from typical chilblains?

Lindy P. Fox, MD

I am so proud of dermatologists around the world who have really jumped into action to examine the pathophysiology and immunology behind these findings.

Your experience matches mine. Like you, I first heard about these pernio- or chilblains-like lesions when Europe was experiencing its surge in cases. And while it does indeed look like chilblains, I think the reality is that it is more severe and symptomatic than we would expect. I think your observation is exactly right. There are certainly clinicians who do not believe that this is an association with COVID-19 because the testing is often negative. But to my mind, there are just too many cases at the wrong time of year, all happening concomitantly, and simultaneous with a new virus for me to accept that they are not somehow related.

Dr. Lipper: Some have referred to this as “quarantine toes,” the result of more people at home and walking around barefoot. That doesn’t seem to make a whole lot of sense because it’s happening in both warm and cold climates.

Others have speculated that there is another, unrelated circulating virus causing these pernio cases, but that seems far-fetched.

But the idea of a reporting bias – more patients paying attention to these lesions because they’ve read something in the mass media or seen a report on television and are concerned, and thus present with mild lesions they might otherwise have ignored – may be contributing somewhat. But even that cannot be the sole reason behind the increase.

Dr. Fox: Agree.

Evaluation of the patient with chilblains – then and now

Dr. Lipper: In the past, how did you perform a workup for someone with chilblains?

Dr. Fox: Pre-COVID – and I think we all have divided our world into pre- and post-COVID – the most common thing that I’d be looking for would be a clotting disorder or an autoimmune disease, typically lupus. So I take a good history, review of systems, and look at the skin for signs of lupus or other autoimmune connective tissue diseases. My lab workup is probably limited to an antinuclear antibody (ANA). If the findings are severe and recurrent, I might check for hypercoagulability with an antiphospholipid antibody panel. But that was usually it unless there was something in the history or physical exam that would lead me to look for something less common – for example, cryoglobulins or an underlying hematologic disease that would lead to a predominance of lesions in acral sites.

My approach was the same. In New England, where I practice, I also always look at environmental factors. We would sometimes see chilblains in someone from a warmer climate who came home to the Northeast to ski.

Dr. Lipper: Now, in the post-COVID world, how do you assess these patients? What has changed?

Dr. Fox: That’s a great question. To be frank, our focus now is on not missing a secondary consequence of COVID infection that we might not have picked up before. I’m the first to admit that the workup that we have been doing at UCSF is extremely comprehensive. We may be ordering tests that don’t need to be done. But until we know better what might and might not be affected by COVID, we don’t actually have a sense of whether they’re worth looking for or not.

Right now, my workup includes nasal swab polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for COVID, as well as IgG and IgM serology if available. We have IgG easily available to us. IgM needs approval; at UCSF, it is primarily done in neonates as of now. I also do a workup for autoimmunity and cold-associated disease, which includes an ANA, rheumatoid factor, cryoglobulin, and cold agglutinins.

Because of reported concerns about hypercoagulability in COVID patients, particularly in those who are doing poorly in the hospital, we look for elevations in d-dimers and fibrinogen. We check antiphospholipid antibodies, anticardiolipin antibodies, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein. That is probably too much of a workup for the healthy young person, but as of yet, we are just unable to say that those things are universally normal.

There has also been concern that complement may be involved in patients who do poorly and tend to clot a lot. So we are also checking C3, C4, and CH50.

To date, in my patients who have had this workup, I have found one with a positive ANA that was significant (1:320) who also had low complements.

There have been a couple of patients at my institution, not my own patients, who are otherwise fine but have some slight elevation in d-dimers.

Dr. Lipper: Is COVID toes more than one condition?

Some of the initial reports of finger/toe cyanosis out of China were very alarming, with many patients developing skin necrosis or even gangrene. These were critically ill adults with pneumonia and blood markers of disseminated intravascular coagulation, and five out of seven died. In contrast, the cases of pseudo-pernio reported in Europe, and now the United States, seem to be much milder, usually occurring late in the illness or in asymptomatic young people. Do you think these are two different conditions?

Dr. Fox: I believe you have hit the nail on the head. I think it is really important that we don’t confuse those two things. In the inpatient setting, we are clearly seeing patients with a prothrombotic state with associated retiform purpura. For nondermatologists, that usually means star-like, stellate-like, or even lacy purpuric changes with potential for necrosis of the skin. In hospitalized patients, the fingers and toes are usually affected but, interestingly, also the buttocks. When these lesions are biopsied, as has been done by our colleague at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, Joanna Harp, MD, we tend to find thrombosis.

A study of endothelial cell function in patients with COVID-19, published in the Lancet tried to determine whether viral particles could be found in endothelial cells. And the investigators did indeed find these particles. So it appears that the virus is endothelially active, and this might provide some insight into the thromboses seen in hospitalized patients. These patients can develop purple necrotic toes that may progress to gangrene. But that is completely different from what we’re seeing when we say pernio-like or chilblains-like lesions.

The chilblains-like lesions come in several forms. They may be purple, red bumps, often involving the tops of the toes and sometimes the bottom of the feet. Some have been described as target-like or erythema multiforme–like. In others, there may not be individual discrete lesions but rather a redness or bluish, purplish discoloration accompanied by edema of the entire toe or several toes.

Biopsies that I am aware of have identified features consistent with an inflammatory process, all of which can be seen in a typical biopsy of pernio. You can sometimes see lymphocytes surrounding a vessel (called lymphocytic vasculitis) that may damage a vessel and cause a small clot, but the primary process is an inflammatory rather than thrombotic one. You may get a clot in a little tiny vessel secondary to inflammation, and that may lead to some blisters or little areas of necrosis. But you’re not going to see digital necrosis and gangrene. I think that’s an important distinction.

The patients who get the pernio-like lesions are typically children or young adults and are otherwise healthy. Half of them didn’t even have COVID symptoms. If they did have COVID symptoms they were typically mild. So we think the pernio-like lesions are most often occurring in the late stage of the disease and now represent a secondary inflammatory response.

Managing COVID toes

Dr. Lipper: One question I’ve been struggling with is, what do we tell these otherwise healthy patients with purple toes, especially those with no other symptoms? Many of them are testing SARS-CoV-2 negative, both with viral swabs and serologies. Some have suggestive histories like known COVID exposure, recent cough, or travel to high-risk areas. Do we tell them they’re at risk of transmitting the virus? Should they self-quarantine, and for how long? Is there any consensus emerging?

Dr. Fox: This is a good opportunity to plug the American Academy of Dermatology’s COVID-19 Registry, which is run by Esther Freeman, MD, at Massachusetts General Hospital. She has done a phenomenal job in helping us figure out the answers to these exact questions.

I’d encourage any clinicians who have a suspected COVID patient with a skin finding, whether or not infection is confirmed with testing, to enter information about that patient into the registry. That is the only way we will figure out evidence-based answers to a lot of the questions that we’re talking about today.

Based on working with the registry, we know that, rarely, patients who develop pernio-like changes will do so before they get COVID symptoms or at the same time as more typical symptoms. Some patients with these findings are PCR positive, and it is therefore theoretically possible that you could be shedding virus while you’re having the pernio toes. However, more commonly – and this is the experience of most of my colleagues and what we’re seeing at UCSF – pernio is a later finding and most patients are no longer shedding the virus. It appears that pseudo-pernio is an immune reaction and most people are not actively infectious at that point.

The only way to know for sure is to send patients for both PCR testing and antibody testing. If the PCR is negative, the most likely interpretation is that the person is no longer shedding virus, though there can be some false negatives. Therefore, these patients do not need to isolate outside of what I call their COVID pod – family or roommates who have probably been with them the whole time. Any transmission likely would have already occurred.

I tell people who call me concerned about their toes that I do think they should be given a workup for COVID. However, I reassure them that it is usually a good prognostic sign.

What is puzzling is that even in patients with pseudo-chilblains who have a clinical history consistent with COVID or exposure to a COVID-positive family member, antibody testing is often – in fact, most often – negative. There are many hypotheses as to why this is. Maybe the tests just aren’t good. Maybe people with mild disease don’t generate enough antibodies to be detected, Maybe we’re testing at the wrong time. Those are all things that we’re trying to figure out.

But currently, I tell patients that they do not need to strictly isolate. They should still practice social distancing, wear a mask, practice good hand hygiene, and do all of the careful things that we should all be doing. However, they can live within their home environment and be reassured that most likely they are in the convalescent stage.

Dr. Lipper: I find the antibody issue both fascinating and confusing.

In my practice, we’ve noticed a range of symptoms associated with pseudo-pernio. Some people barely realize it’s there and only called because they saw a headline in the news. Others complain of severe burning, throbbing, or itching that keeps them up at night and can sometimes last for weeks. Are there any treatments that seem to help?

Dr. Fox: We can start by saying, as you note, that a lot of patients don’t need interventions. They want reassurance that their toes aren’t going to fall off, that nothing terrible is going to happen to them, and often that’s enough. So far, many patients have contacted us just because they heard about the link between what they were seeing on their feet and COVID. They were likely toward the end of any other symptoms they may have had. But moving forward, I think we’re going to be seeing patients at the more active stage as the public is more aware of this finding.

Most of the time we can manage with clobetasol ointment and low-dose aspirin. I wouldn’t give aspirin to a young child with a high fever, but otherwise I think aspirin is not harmful. A paper published in Mayo Clinic Proceedings in 2014, before COVID, by Jonathan Cappel, MD, and David Wetter, MD, provides a nice therapeutic algorithm. Assuming that the findings we are seeing now are inflammatory, then I think that algorithm should apply. Nifedipine 20-60 mg/day is an option. Hydroxychloroquine, a maximum of 5 mg/kg per day, is an option. I have used hydroxychloroquine most commonly, pre-COVID, in patients who have symptomatic pernio.

I also use pentoxifylline 400 mg three times a day, which has a slight anti-inflammatory effect, when I think a blood vessel is incidentally involved or the patient has a predisposition to clotting. Nicotinamide 500 mg three times a day can be used, though I have not used it.

Some topical options are nitroglycerin, tacrolimus, and minoxidil.

However, during this post-COVID period, I have not come across many with pseudo-pernio who needed anything more than a topical steroid and some aspirin. But I do know of other physicians who have been taking care of patients with much more symptomatic disease.

Dr. Lipper: That is a comprehensive list. You’ve mentioned some options that I’ve wondered about, especially pentoxifylline, which I have found to be very helpful for livedoid vasculopathy. I should note that these are all off-label uses.

Let’s talk about some other suspected skin manifestations of COVID. A prospective nationwide study in Spain of 375 patients reported on a number of different skin manifestations of COVID.

You’re part of a team doing critically important work with the American Academy of Dermatology COVID-19 Dermatology Registry. I know it’s early going, but what are some of the other common skin presentations you’re finding?

Dr. Fox: I’m glad you brought up that paper out of Spain. I think it is really good and does highlight the difference in acute versus convalescent cutaneous manifestations and prognosis. It confirms what we’re seeing. Retiform purpura is an early finding associated with ill patients in the hospital. Pseudo pernio-like lesions tend to be later-stage and in younger, healthier patients.

Interestingly, the vesicular eruption that those investigators describe – monomorphic vesicles on the trunk and extremity – can occur in the more acute phase. That’s fascinating to me because widespread vesicular eruptions are not a thing that we commonly see. If it is not an autoimmune blistering disease, and not a drug-induced blistering process, then you’re really left with viral. Rickettsialpox can do that, as can primary varicella, disseminated herpes, disseminated zoster, and now COVID. So that’s intriguing.

I got called to see a patient yesterday who had symptoms of COVID about a month ago. She was not PCR tested at the time but she is now negative. She has a widespread eruption of tiny vesicles on an erythematous base. An IgG for COVID is positive. How do we decide whether her skin lesions have active virus in them?

The many dermatologic manifestations of COVID-19

Dr. Lipper: In the series in Spain, almost 1 out of 10 patients were found to have a widespread vesicular rash. And just under half had maculopapular exanthems. The information arising from the AAD registry will be of great interest and build on this paper.

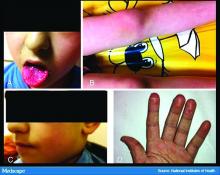

In England, the National Health Service and the Paediatric Intensive Care Society recently put out a warning about an alarming number of children with COVID-19 who developed symptoms mimicking Kawasaki disease (high fever, abdominal pain, rash, swollen lymph nodes, mucositis, and conjunctivitis). These kids have systemic inflammation and vasculitis and are critically ill. That was followed by an alert from the New York City Health Department about cases there, which as of May 6 numbered 64. Another 25 children with similar findings have been identified in France.

This is such a scary development, especially because children were supposed to be relatively “safe” from this virus. Any thoughts on who is at risk or why?

Dr. Fox: It’s very alarming. It appears that these cases look just like Kawasaki disease.

It was once hypothesized that Coronaviridae was the cause of Kawasaki disease. Then that got debunked. But these cases now raise the question of whether Kawasaki disease may be virally mediated. Is it an immune reaction to an infectious trigger? Is it actually Coronaviridae that triggers it?

As with these pernio cases, I think we’re going to learn about the pathophysiology of these diseases that we currently look at as secondary responses or immune reactions to unknown triggers. We’re going to learn a lot about them and about the immune system because of how this virus is acting on the immune system.

Dr. Lipper: As is the case with patients with pernio-like lesions, some of these children with Kawasaki-like disease are PCR negative for SARS-CoV-2. It will be interesting to see what happens with antibody testing in this population.

Dr. Fox: Agree. While some of the manufacturers of serology tests have claimed that they have very high sensitivity and specificity, that has not been my experience.

Dr. Lipper: I’ve had a number of patients with a clinical picture that strongly suggests COVID whose serology tests have been negative.

Dr. Fox: As have I. While this could be the result of faulty tests, my biggest worry is that it means that people with mild disease do not mount an antibody response. And if people who have disease can’t make antibodies, then there’s no herd immunity. If there’s no herd immunity, we’re stuck in lockdown until there’s a vaccine.

Dr. Lipper: That is a scary but real possibility. We need evidence – evidence like that provided by the AAD registry.

Dr. Fox: Agree. I look forward to sharing those results with you when we have them.

Dr. Lipper is a clinical assistant professor at the University of Vermont, Burlington, and a partner at Advanced DermCare in Danbury, Conn.

Dr. Fox is a professor in the department of dermatology at the University of California, San Francisco. She is a hospital-based dermatologist who specializes in the care of patients with complex skin conditions. She is immediate past president of the Medical Dermatology Society and current president of the Society of Dermatology Hospitalists.

This article was first published on Medscape.com.

The dermatologic manifestations associated with SARS-CoV-2 are many and varied, with new information virtually daily. Graeme Lipper, MD, a member of the Medscape Dermatology advisory board, discussed what we know and what is still to be learned with Lindy Fox, MD, a professor of dermatology at University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) and a member of the American Academy of Dermatology’s COVID-19 Registry task force.

Graeme M. Lipper, MD

Earlier this spring, before there was any real talk about skin manifestations of COVID, my partner called me in to see an unusual case. His patient was a healthy 20-year-old who had just come back from college and had tender, purple discoloration and swelling on his toes. I shrugged and said “looks like chilblains,” but there was something weird about the case. It seemed more severe, with areas of blistering and erosions, and the discomfort was unusual for run-of-the-mill pernio. This young man had experienced a cough and shortness of breath a few weeks earlier but those symptoms had resolved when we saw him.

That evening, I was on a derm social media site and saw a series of pictures from Italy that blew me away. All of these pictures looked just like this kid’s toes. That’s the first I heard of “COVID toes,” but now they seem to be everywhere. How would you describe this presentation, and how does it differ from typical chilblains?

Lindy P. Fox, MD

I am so proud of dermatologists around the world who have really jumped into action to examine the pathophysiology and immunology behind these findings.

Your experience matches mine. Like you, I first heard about these pernio- or chilblains-like lesions when Europe was experiencing its surge in cases. And while it does indeed look like chilblains, I think the reality is that it is more severe and symptomatic than we would expect. I think your observation is exactly right. There are certainly clinicians who do not believe that this is an association with COVID-19 because the testing is often negative. But to my mind, there are just too many cases at the wrong time of year, all happening concomitantly, and simultaneous with a new virus for me to accept that they are not somehow related.

Dr. Lipper: Some have referred to this as “quarantine toes,” the result of more people at home and walking around barefoot. That doesn’t seem to make a whole lot of sense because it’s happening in both warm and cold climates.

Others have speculated that there is another, unrelated circulating virus causing these pernio cases, but that seems far-fetched.

But the idea of a reporting bias – more patients paying attention to these lesions because they’ve read something in the mass media or seen a report on television and are concerned, and thus present with mild lesions they might otherwise have ignored – may be contributing somewhat. But even that cannot be the sole reason behind the increase.

Dr. Fox: Agree.

Evaluation of the patient with chilblains – then and now

Dr. Lipper: In the past, how did you perform a workup for someone with chilblains?

Dr. Fox: Pre-COVID – and I think we all have divided our world into pre- and post-COVID – the most common thing that I’d be looking for would be a clotting disorder or an autoimmune disease, typically lupus. So I take a good history, review of systems, and look at the skin for signs of lupus or other autoimmune connective tissue diseases. My lab workup is probably limited to an antinuclear antibody (ANA). If the findings are severe and recurrent, I might check for hypercoagulability with an antiphospholipid antibody panel. But that was usually it unless there was something in the history or physical exam that would lead me to look for something less common – for example, cryoglobulins or an underlying hematologic disease that would lead to a predominance of lesions in acral sites.

My approach was the same. In New England, where I practice, I also always look at environmental factors. We would sometimes see chilblains in someone from a warmer climate who came home to the Northeast to ski.

Dr. Lipper: Now, in the post-COVID world, how do you assess these patients? What has changed?

Dr. Fox: That’s a great question. To be frank, our focus now is on not missing a secondary consequence of COVID infection that we might not have picked up before. I’m the first to admit that the workup that we have been doing at UCSF is extremely comprehensive. We may be ordering tests that don’t need to be done. But until we know better what might and might not be affected by COVID, we don’t actually have a sense of whether they’re worth looking for or not.

Right now, my workup includes nasal swab polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for COVID, as well as IgG and IgM serology if available. We have IgG easily available to us. IgM needs approval; at UCSF, it is primarily done in neonates as of now. I also do a workup for autoimmunity and cold-associated disease, which includes an ANA, rheumatoid factor, cryoglobulin, and cold agglutinins.

Because of reported concerns about hypercoagulability in COVID patients, particularly in those who are doing poorly in the hospital, we look for elevations in d-dimers and fibrinogen. We check antiphospholipid antibodies, anticardiolipin antibodies, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein. That is probably too much of a workup for the healthy young person, but as of yet, we are just unable to say that those things are universally normal.

There has also been concern that complement may be involved in patients who do poorly and tend to clot a lot. So we are also checking C3, C4, and CH50.

To date, in my patients who have had this workup, I have found one with a positive ANA that was significant (1:320) who also had low complements.

There have been a couple of patients at my institution, not my own patients, who are otherwise fine but have some slight elevation in d-dimers.

Dr. Lipper: Is COVID toes more than one condition?

Some of the initial reports of finger/toe cyanosis out of China were very alarming, with many patients developing skin necrosis or even gangrene. These were critically ill adults with pneumonia and blood markers of disseminated intravascular coagulation, and five out of seven died. In contrast, the cases of pseudo-pernio reported in Europe, and now the United States, seem to be much milder, usually occurring late in the illness or in asymptomatic young people. Do you think these are two different conditions?

Dr. Fox: I believe you have hit the nail on the head. I think it is really important that we don’t confuse those two things. In the inpatient setting, we are clearly seeing patients with a prothrombotic state with associated retiform purpura. For nondermatologists, that usually means star-like, stellate-like, or even lacy purpuric changes with potential for necrosis of the skin. In hospitalized patients, the fingers and toes are usually affected but, interestingly, also the buttocks. When these lesions are biopsied, as has been done by our colleague at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, Joanna Harp, MD, we tend to find thrombosis.

A study of endothelial cell function in patients with COVID-19, published in the Lancet tried to determine whether viral particles could be found in endothelial cells. And the investigators did indeed find these particles. So it appears that the virus is endothelially active, and this might provide some insight into the thromboses seen in hospitalized patients. These patients can develop purple necrotic toes that may progress to gangrene. But that is completely different from what we’re seeing when we say pernio-like or chilblains-like lesions.

The chilblains-like lesions come in several forms. They may be purple, red bumps, often involving the tops of the toes and sometimes the bottom of the feet. Some have been described as target-like or erythema multiforme–like. In others, there may not be individual discrete lesions but rather a redness or bluish, purplish discoloration accompanied by edema of the entire toe or several toes.

Biopsies that I am aware of have identified features consistent with an inflammatory process, all of which can be seen in a typical biopsy of pernio. You can sometimes see lymphocytes surrounding a vessel (called lymphocytic vasculitis) that may damage a vessel and cause a small clot, but the primary process is an inflammatory rather than thrombotic one. You may get a clot in a little tiny vessel secondary to inflammation, and that may lead to some blisters or little areas of necrosis. But you’re not going to see digital necrosis and gangrene. I think that’s an important distinction.

The patients who get the pernio-like lesions are typically children or young adults and are otherwise healthy. Half of them didn’t even have COVID symptoms. If they did have COVID symptoms they were typically mild. So we think the pernio-like lesions are most often occurring in the late stage of the disease and now represent a secondary inflammatory response.

Managing COVID toes

Dr. Lipper: One question I’ve been struggling with is, what do we tell these otherwise healthy patients with purple toes, especially those with no other symptoms? Many of them are testing SARS-CoV-2 negative, both with viral swabs and serologies. Some have suggestive histories like known COVID exposure, recent cough, or travel to high-risk areas. Do we tell them they’re at risk of transmitting the virus? Should they self-quarantine, and for how long? Is there any consensus emerging?

Dr. Fox: This is a good opportunity to plug the American Academy of Dermatology’s COVID-19 Registry, which is run by Esther Freeman, MD, at Massachusetts General Hospital. She has done a phenomenal job in helping us figure out the answers to these exact questions.

I’d encourage any clinicians who have a suspected COVID patient with a skin finding, whether or not infection is confirmed with testing, to enter information about that patient into the registry. That is the only way we will figure out evidence-based answers to a lot of the questions that we’re talking about today.

Based on working with the registry, we know that, rarely, patients who develop pernio-like changes will do so before they get COVID symptoms or at the same time as more typical symptoms. Some patients with these findings are PCR positive, and it is therefore theoretically possible that you could be shedding virus while you’re having the pernio toes. However, more commonly – and this is the experience of most of my colleagues and what we’re seeing at UCSF – pernio is a later finding and most patients are no longer shedding the virus. It appears that pseudo-pernio is an immune reaction and most people are not actively infectious at that point.

The only way to know for sure is to send patients for both PCR testing and antibody testing. If the PCR is negative, the most likely interpretation is that the person is no longer shedding virus, though there can be some false negatives. Therefore, these patients do not need to isolate outside of what I call their COVID pod – family or roommates who have probably been with them the whole time. Any transmission likely would have already occurred.

I tell people who call me concerned about their toes that I do think they should be given a workup for COVID. However, I reassure them that it is usually a good prognostic sign.

What is puzzling is that even in patients with pseudo-chilblains who have a clinical history consistent with COVID or exposure to a COVID-positive family member, antibody testing is often – in fact, most often – negative. There are many hypotheses as to why this is. Maybe the tests just aren’t good. Maybe people with mild disease don’t generate enough antibodies to be detected, Maybe we’re testing at the wrong time. Those are all things that we’re trying to figure out.

But currently, I tell patients that they do not need to strictly isolate. They should still practice social distancing, wear a mask, practice good hand hygiene, and do all of the careful things that we should all be doing. However, they can live within their home environment and be reassured that most likely they are in the convalescent stage.

Dr. Lipper: I find the antibody issue both fascinating and confusing.

In my practice, we’ve noticed a range of symptoms associated with pseudo-pernio. Some people barely realize it’s there and only called because they saw a headline in the news. Others complain of severe burning, throbbing, or itching that keeps them up at night and can sometimes last for weeks. Are there any treatments that seem to help?

Dr. Fox: We can start by saying, as you note, that a lot of patients don’t need interventions. They want reassurance that their toes aren’t going to fall off, that nothing terrible is going to happen to them, and often that’s enough. So far, many patients have contacted us just because they heard about the link between what they were seeing on their feet and COVID. They were likely toward the end of any other symptoms they may have had. But moving forward, I think we’re going to be seeing patients at the more active stage as the public is more aware of this finding.

Most of the time we can manage with clobetasol ointment and low-dose aspirin. I wouldn’t give aspirin to a young child with a high fever, but otherwise I think aspirin is not harmful. A paper published in Mayo Clinic Proceedings in 2014, before COVID, by Jonathan Cappel, MD, and David Wetter, MD, provides a nice therapeutic algorithm. Assuming that the findings we are seeing now are inflammatory, then I think that algorithm should apply. Nifedipine 20-60 mg/day is an option. Hydroxychloroquine, a maximum of 5 mg/kg per day, is an option. I have used hydroxychloroquine most commonly, pre-COVID, in patients who have symptomatic pernio.

I also use pentoxifylline 400 mg three times a day, which has a slight anti-inflammatory effect, when I think a blood vessel is incidentally involved or the patient has a predisposition to clotting. Nicotinamide 500 mg three times a day can be used, though I have not used it.

Some topical options are nitroglycerin, tacrolimus, and minoxidil.

However, during this post-COVID period, I have not come across many with pseudo-pernio who needed anything more than a topical steroid and some aspirin. But I do know of other physicians who have been taking care of patients with much more symptomatic disease.

Dr. Lipper: That is a comprehensive list. You’ve mentioned some options that I’ve wondered about, especially pentoxifylline, which I have found to be very helpful for livedoid vasculopathy. I should note that these are all off-label uses.

Let’s talk about some other suspected skin manifestations of COVID. A prospective nationwide study in Spain of 375 patients reported on a number of different skin manifestations of COVID.

You’re part of a team doing critically important work with the American Academy of Dermatology COVID-19 Dermatology Registry. I know it’s early going, but what are some of the other common skin presentations you’re finding?

Dr. Fox: I’m glad you brought up that paper out of Spain. I think it is really good and does highlight the difference in acute versus convalescent cutaneous manifestations and prognosis. It confirms what we’re seeing. Retiform purpura is an early finding associated with ill patients in the hospital. Pseudo pernio-like lesions tend to be later-stage and in younger, healthier patients.

Interestingly, the vesicular eruption that those investigators describe – monomorphic vesicles on the trunk and extremity – can occur in the more acute phase. That’s fascinating to me because widespread vesicular eruptions are not a thing that we commonly see. If it is not an autoimmune blistering disease, and not a drug-induced blistering process, then you’re really left with viral. Rickettsialpox can do that, as can primary varicella, disseminated herpes, disseminated zoster, and now COVID. So that’s intriguing.

I got called to see a patient yesterday who had symptoms of COVID about a month ago. She was not PCR tested at the time but she is now negative. She has a widespread eruption of tiny vesicles on an erythematous base. An IgG for COVID is positive. How do we decide whether her skin lesions have active virus in them?

The many dermatologic manifestations of COVID-19

Dr. Lipper: In the series in Spain, almost 1 out of 10 patients were found to have a widespread vesicular rash. And just under half had maculopapular exanthems. The information arising from the AAD registry will be of great interest and build on this paper.

In England, the National Health Service and the Paediatric Intensive Care Society recently put out a warning about an alarming number of children with COVID-19 who developed symptoms mimicking Kawasaki disease (high fever, abdominal pain, rash, swollen lymph nodes, mucositis, and conjunctivitis). These kids have systemic inflammation and vasculitis and are critically ill. That was followed by an alert from the New York City Health Department about cases there, which as of May 6 numbered 64. Another 25 children with similar findings have been identified in France.

This is such a scary development, especially because children were supposed to be relatively “safe” from this virus. Any thoughts on who is at risk or why?

Dr. Fox: It’s very alarming. It appears that these cases look just like Kawasaki disease.

It was once hypothesized that Coronaviridae was the cause of Kawasaki disease. Then that got debunked. But these cases now raise the question of whether Kawasaki disease may be virally mediated. Is it an immune reaction to an infectious trigger? Is it actually Coronaviridae that triggers it?

As with these pernio cases, I think we’re going to learn about the pathophysiology of these diseases that we currently look at as secondary responses or immune reactions to unknown triggers. We’re going to learn a lot about them and about the immune system because of how this virus is acting on the immune system.

Dr. Lipper: As is the case with patients with pernio-like lesions, some of these children with Kawasaki-like disease are PCR negative for SARS-CoV-2. It will be interesting to see what happens with antibody testing in this population.

Dr. Fox: Agree. While some of the manufacturers of serology tests have claimed that they have very high sensitivity and specificity, that has not been my experience.

Dr. Lipper: I’ve had a number of patients with a clinical picture that strongly suggests COVID whose serology tests have been negative.

Dr. Fox: As have I. While this could be the result of faulty tests, my biggest worry is that it means that people with mild disease do not mount an antibody response. And if people who have disease can’t make antibodies, then there’s no herd immunity. If there’s no herd immunity, we’re stuck in lockdown until there’s a vaccine.

Dr. Lipper: That is a scary but real possibility. We need evidence – evidence like that provided by the AAD registry.

Dr. Fox: Agree. I look forward to sharing those results with you when we have them.

Dr. Lipper is a clinical assistant professor at the University of Vermont, Burlington, and a partner at Advanced DermCare in Danbury, Conn.

Dr. Fox is a professor in the department of dermatology at the University of California, San Francisco. She is a hospital-based dermatologist who specializes in the care of patients with complex skin conditions. She is immediate past president of the Medical Dermatology Society and current president of the Society of Dermatology Hospitalists.

This article was first published on Medscape.com.

The dermatologic manifestations associated with SARS-CoV-2 are many and varied, with new information virtually daily. Graeme Lipper, MD, a member of the Medscape Dermatology advisory board, discussed what we know and what is still to be learned with Lindy Fox, MD, a professor of dermatology at University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) and a member of the American Academy of Dermatology’s COVID-19 Registry task force.

Graeme M. Lipper, MD

Earlier this spring, before there was any real talk about skin manifestations of COVID, my partner called me in to see an unusual case. His patient was a healthy 20-year-old who had just come back from college and had tender, purple discoloration and swelling on his toes. I shrugged and said “looks like chilblains,” but there was something weird about the case. It seemed more severe, with areas of blistering and erosions, and the discomfort was unusual for run-of-the-mill pernio. This young man had experienced a cough and shortness of breath a few weeks earlier but those symptoms had resolved when we saw him.

That evening, I was on a derm social media site and saw a series of pictures from Italy that blew me away. All of these pictures looked just like this kid’s toes. That’s the first I heard of “COVID toes,” but now they seem to be everywhere. How would you describe this presentation, and how does it differ from typical chilblains?

Lindy P. Fox, MD

I am so proud of dermatologists around the world who have really jumped into action to examine the pathophysiology and immunology behind these findings.

Your experience matches mine. Like you, I first heard about these pernio- or chilblains-like lesions when Europe was experiencing its surge in cases. And while it does indeed look like chilblains, I think the reality is that it is more severe and symptomatic than we would expect. I think your observation is exactly right. There are certainly clinicians who do not believe that this is an association with COVID-19 because the testing is often negative. But to my mind, there are just too many cases at the wrong time of year, all happening concomitantly, and simultaneous with a new virus for me to accept that they are not somehow related.

Dr. Lipper: Some have referred to this as “quarantine toes,” the result of more people at home and walking around barefoot. That doesn’t seem to make a whole lot of sense because it’s happening in both warm and cold climates.

Others have speculated that there is another, unrelated circulating virus causing these pernio cases, but that seems far-fetched.

But the idea of a reporting bias – more patients paying attention to these lesions because they’ve read something in the mass media or seen a report on television and are concerned, and thus present with mild lesions they might otherwise have ignored – may be contributing somewhat. But even that cannot be the sole reason behind the increase.

Dr. Fox: Agree.

Evaluation of the patient with chilblains – then and now

Dr. Lipper: In the past, how did you perform a workup for someone with chilblains?

Dr. Fox: Pre-COVID – and I think we all have divided our world into pre- and post-COVID – the most common thing that I’d be looking for would be a clotting disorder or an autoimmune disease, typically lupus. So I take a good history, review of systems, and look at the skin for signs of lupus or other autoimmune connective tissue diseases. My lab workup is probably limited to an antinuclear antibody (ANA). If the findings are severe and recurrent, I might check for hypercoagulability with an antiphospholipid antibody panel. But that was usually it unless there was something in the history or physical exam that would lead me to look for something less common – for example, cryoglobulins or an underlying hematologic disease that would lead to a predominance of lesions in acral sites.

My approach was the same. In New England, where I practice, I also always look at environmental factors. We would sometimes see chilblains in someone from a warmer climate who came home to the Northeast to ski.

Dr. Lipper: Now, in the post-COVID world, how do you assess these patients? What has changed?

Dr. Fox: That’s a great question. To be frank, our focus now is on not missing a secondary consequence of COVID infection that we might not have picked up before. I’m the first to admit that the workup that we have been doing at UCSF is extremely comprehensive. We may be ordering tests that don’t need to be done. But until we know better what might and might not be affected by COVID, we don’t actually have a sense of whether they’re worth looking for or not.

Right now, my workup includes nasal swab polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for COVID, as well as IgG and IgM serology if available. We have IgG easily available to us. IgM needs approval; at UCSF, it is primarily done in neonates as of now. I also do a workup for autoimmunity and cold-associated disease, which includes an ANA, rheumatoid factor, cryoglobulin, and cold agglutinins.

Because of reported concerns about hypercoagulability in COVID patients, particularly in those who are doing poorly in the hospital, we look for elevations in d-dimers and fibrinogen. We check antiphospholipid antibodies, anticardiolipin antibodies, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein. That is probably too much of a workup for the healthy young person, but as of yet, we are just unable to say that those things are universally normal.

There has also been concern that complement may be involved in patients who do poorly and tend to clot a lot. So we are also checking C3, C4, and CH50.

To date, in my patients who have had this workup, I have found one with a positive ANA that was significant (1:320) who also had low complements.

There have been a couple of patients at my institution, not my own patients, who are otherwise fine but have some slight elevation in d-dimers.

Dr. Lipper: Is COVID toes more than one condition?

Some of the initial reports of finger/toe cyanosis out of China were very alarming, with many patients developing skin necrosis or even gangrene. These were critically ill adults with pneumonia and blood markers of disseminated intravascular coagulation, and five out of seven died. In contrast, the cases of pseudo-pernio reported in Europe, and now the United States, seem to be much milder, usually occurring late in the illness or in asymptomatic young people. Do you think these are two different conditions?

Dr. Fox: I believe you have hit the nail on the head. I think it is really important that we don’t confuse those two things. In the inpatient setting, we are clearly seeing patients with a prothrombotic state with associated retiform purpura. For nondermatologists, that usually means star-like, stellate-like, or even lacy purpuric changes with potential for necrosis of the skin. In hospitalized patients, the fingers and toes are usually affected but, interestingly, also the buttocks. When these lesions are biopsied, as has been done by our colleague at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, Joanna Harp, MD, we tend to find thrombosis.

A study of endothelial cell function in patients with COVID-19, published in the Lancet tried to determine whether viral particles could be found in endothelial cells. And the investigators did indeed find these particles. So it appears that the virus is endothelially active, and this might provide some insight into the thromboses seen in hospitalized patients. These patients can develop purple necrotic toes that may progress to gangrene. But that is completely different from what we’re seeing when we say pernio-like or chilblains-like lesions.

The chilblains-like lesions come in several forms. They may be purple, red bumps, often involving the tops of the toes and sometimes the bottom of the feet. Some have been described as target-like or erythema multiforme–like. In others, there may not be individual discrete lesions but rather a redness or bluish, purplish discoloration accompanied by edema of the entire toe or several toes.

Biopsies that I am aware of have identified features consistent with an inflammatory process, all of which can be seen in a typical biopsy of pernio. You can sometimes see lymphocytes surrounding a vessel (called lymphocytic vasculitis) that may damage a vessel and cause a small clot, but the primary process is an inflammatory rather than thrombotic one. You may get a clot in a little tiny vessel secondary to inflammation, and that may lead to some blisters or little areas of necrosis. But you’re not going to see digital necrosis and gangrene. I think that’s an important distinction.

The patients who get the pernio-like lesions are typically children or young adults and are otherwise healthy. Half of them didn’t even have COVID symptoms. If they did have COVID symptoms they were typically mild. So we think the pernio-like lesions are most often occurring in the late stage of the disease and now represent a secondary inflammatory response.

Managing COVID toes

Dr. Lipper: One question I’ve been struggling with is, what do we tell these otherwise healthy patients with purple toes, especially those with no other symptoms? Many of them are testing SARS-CoV-2 negative, both with viral swabs and serologies. Some have suggestive histories like known COVID exposure, recent cough, or travel to high-risk areas. Do we tell them they’re at risk of transmitting the virus? Should they self-quarantine, and for how long? Is there any consensus emerging?

Dr. Fox: This is a good opportunity to plug the American Academy of Dermatology’s COVID-19 Registry, which is run by Esther Freeman, MD, at Massachusetts General Hospital. She has done a phenomenal job in helping us figure out the answers to these exact questions.

I’d encourage any clinicians who have a suspected COVID patient with a skin finding, whether or not infection is confirmed with testing, to enter information about that patient into the registry. That is the only way we will figure out evidence-based answers to a lot of the questions that we’re talking about today.

Based on working with the registry, we know that, rarely, patients who develop pernio-like changes will do so before they get COVID symptoms or at the same time as more typical symptoms. Some patients with these findings are PCR positive, and it is therefore theoretically possible that you could be shedding virus while you’re having the pernio toes. However, more commonly – and this is the experience of most of my colleagues and what we’re seeing at UCSF – pernio is a later finding and most patients are no longer shedding the virus. It appears that pseudo-pernio is an immune reaction and most people are not actively infectious at that point.

The only way to know for sure is to send patients for both PCR testing and antibody testing. If the PCR is negative, the most likely interpretation is that the person is no longer shedding virus, though there can be some false negatives. Therefore, these patients do not need to isolate outside of what I call their COVID pod – family or roommates who have probably been with them the whole time. Any transmission likely would have already occurred.

I tell people who call me concerned about their toes that I do think they should be given a workup for COVID. However, I reassure them that it is usually a good prognostic sign.

What is puzzling is that even in patients with pseudo-chilblains who have a clinical history consistent with COVID or exposure to a COVID-positive family member, antibody testing is often – in fact, most often – negative. There are many hypotheses as to why this is. Maybe the tests just aren’t good. Maybe people with mild disease don’t generate enough antibodies to be detected, Maybe we’re testing at the wrong time. Those are all things that we’re trying to figure out.

But currently, I tell patients that they do not need to strictly isolate. They should still practice social distancing, wear a mask, practice good hand hygiene, and do all of the careful things that we should all be doing. However, they can live within their home environment and be reassured that most likely they are in the convalescent stage.

Dr. Lipper: I find the antibody issue both fascinating and confusing.

In my practice, we’ve noticed a range of symptoms associated with pseudo-pernio. Some people barely realize it’s there and only called because they saw a headline in the news. Others complain of severe burning, throbbing, or itching that keeps them up at night and can sometimes last for weeks. Are there any treatments that seem to help?

Dr. Fox: We can start by saying, as you note, that a lot of patients don’t need interventions. They want reassurance that their toes aren’t going to fall off, that nothing terrible is going to happen to them, and often that’s enough. So far, many patients have contacted us just because they heard about the link between what they were seeing on their feet and COVID. They were likely toward the end of any other symptoms they may have had. But moving forward, I think we’re going to be seeing patients at the more active stage as the public is more aware of this finding.

Most of the time we can manage with clobetasol ointment and low-dose aspirin. I wouldn’t give aspirin to a young child with a high fever, but otherwise I think aspirin is not harmful. A paper published in Mayo Clinic Proceedings in 2014, before COVID, by Jonathan Cappel, MD, and David Wetter, MD, provides a nice therapeutic algorithm. Assuming that the findings we are seeing now are inflammatory, then I think that algorithm should apply. Nifedipine 20-60 mg/day is an option. Hydroxychloroquine, a maximum of 5 mg/kg per day, is an option. I have used hydroxychloroquine most commonly, pre-COVID, in patients who have symptomatic pernio.

I also use pentoxifylline 400 mg three times a day, which has a slight anti-inflammatory effect, when I think a blood vessel is incidentally involved or the patient has a predisposition to clotting. Nicotinamide 500 mg three times a day can be used, though I have not used it.

Some topical options are nitroglycerin, tacrolimus, and minoxidil.

However, during this post-COVID period, I have not come across many with pseudo-pernio who needed anything more than a topical steroid and some aspirin. But I do know of other physicians who have been taking care of patients with much more symptomatic disease.

Dr. Lipper: That is a comprehensive list. You’ve mentioned some options that I’ve wondered about, especially pentoxifylline, which I have found to be very helpful for livedoid vasculopathy. I should note that these are all off-label uses.

Let’s talk about some other suspected skin manifestations of COVID. A prospective nationwide study in Spain of 375 patients reported on a number of different skin manifestations of COVID.

You’re part of a team doing critically important work with the American Academy of Dermatology COVID-19 Dermatology Registry. I know it’s early going, but what are some of the other common skin presentations you’re finding?

Dr. Fox: I’m glad you brought up that paper out of Spain. I think it is really good and does highlight the difference in acute versus convalescent cutaneous manifestations and prognosis. It confirms what we’re seeing. Retiform purpura is an early finding associated with ill patients in the hospital. Pseudo pernio-like lesions tend to be later-stage and in younger, healthier patients.

Interestingly, the vesicular eruption that those investigators describe – monomorphic vesicles on the trunk and extremity – can occur in the more acute phase. That’s fascinating to me because widespread vesicular eruptions are not a thing that we commonly see. If it is not an autoimmune blistering disease, and not a drug-induced blistering process, then you’re really left with viral. Rickettsialpox can do that, as can primary varicella, disseminated herpes, disseminated zoster, and now COVID. So that’s intriguing.

I got called to see a patient yesterday who had symptoms of COVID about a month ago. She was not PCR tested at the time but she is now negative. She has a widespread eruption of tiny vesicles on an erythematous base. An IgG for COVID is positive. How do we decide whether her skin lesions have active virus in them?

The many dermatologic manifestations of COVID-19

Dr. Lipper: In the series in Spain, almost 1 out of 10 patients were found to have a widespread vesicular rash. And just under half had maculopapular exanthems. The information arising from the AAD registry will be of great interest and build on this paper.

In England, the National Health Service and the Paediatric Intensive Care Society recently put out a warning about an alarming number of children with COVID-19 who developed symptoms mimicking Kawasaki disease (high fever, abdominal pain, rash, swollen lymph nodes, mucositis, and conjunctivitis). These kids have systemic inflammation and vasculitis and are critically ill. That was followed by an alert from the New York City Health Department about cases there, which as of May 6 numbered 64. Another 25 children with similar findings have been identified in France.

This is such a scary development, especially because children were supposed to be relatively “safe” from this virus. Any thoughts on who is at risk or why?

Dr. Fox: It’s very alarming. It appears that these cases look just like Kawasaki disease.

It was once hypothesized that Coronaviridae was the cause of Kawasaki disease. Then that got debunked. But these cases now raise the question of whether Kawasaki disease may be virally mediated. Is it an immune reaction to an infectious trigger? Is it actually Coronaviridae that triggers it?

As with these pernio cases, I think we’re going to learn about the pathophysiology of these diseases that we currently look at as secondary responses or immune reactions to unknown triggers. We’re going to learn a lot about them and about the immune system because of how this virus is acting on the immune system.

Dr. Lipper: As is the case with patients with pernio-like lesions, some of these children with Kawasaki-like disease are PCR negative for SARS-CoV-2. It will be interesting to see what happens with antibody testing in this population.

Dr. Fox: Agree. While some of the manufacturers of serology tests have claimed that they have very high sensitivity and specificity, that has not been my experience.

Dr. Lipper: I’ve had a number of patients with a clinical picture that strongly suggests COVID whose serology tests have been negative.

Dr. Fox: As have I. While this could be the result of faulty tests, my biggest worry is that it means that people with mild disease do not mount an antibody response. And if people who have disease can’t make antibodies, then there’s no herd immunity. If there’s no herd immunity, we’re stuck in lockdown until there’s a vaccine.

Dr. Lipper: That is a scary but real possibility. We need evidence – evidence like that provided by the AAD registry.

Dr. Fox: Agree. I look forward to sharing those results with you when we have them.

Dr. Lipper is a clinical assistant professor at the University of Vermont, Burlington, and a partner at Advanced DermCare in Danbury, Conn.

Dr. Fox is a professor in the department of dermatology at the University of California, San Francisco. She is a hospital-based dermatologist who specializes in the care of patients with complex skin conditions. She is immediate past president of the Medical Dermatology Society and current president of the Society of Dermatology Hospitalists.

This article was first published on Medscape.com.

Planning for a psychiatric COVID-19–positive unit

Identifying key decision points is critical

Reports have emerged about the unique vulnerability of psychiatric hospitals to the ravages of COVID-19.

In a South Korea psychiatric hospital, 101 of 103 patients contracted SARS-CoV-2 during an outbreak; 7 eventually died.1,2 This report, among a few others, have led to the development of psychiatric COVID-19–positive units (PCU). However, it remains highly unclear how many are currently open, where they are located, or what their operations are like.

We knew that we could not allow a medically asymptomatic “covertly” COVID-19–positive patient to be introduced to the social community of our inpatient units because of the risks of transmission to other patients and staff.

In coordination with our health system infection prevention experts, we have therefore required a confirmed negative COVID-19 polymerase chain reaction nasal swab performed no more than 48 hours prior to the time/date of acute psychiatric inpatient admission. Furthermore, as part of the broad health system response and surge planning, we were asked by our respective incident command centers to begin planning for a Psychiatric COVID-19–positive Unit (PCU) that might allow us to safely care for a cohort of patients needing such hospitalization.

It is worth emphasizing that the typical patient who is a candidate for a PCU is so acutely psychiatrically ill that they cannot be managed in a less restrictive environment than an inpatient psychiatric unit and, at the same time, is likely to not be medically ill enough to warrant admission to an internal medicine service in a general acute care hospital.

We have identified eight principles and critical decision points that can help inpatient units plan for the safe care of COVID-19–positive patients on a PCU.

1. Triage: Patients admitted to a PCU should be medically stable, particularly with regard to COVID-19 and respiratory symptomatology. PCUs should establish clear criteria for admission and discharge (or medical transfer). Examples of potential exclusionary criteria to a PCU include:

- Respiratory distress, shortness of breath, hypoxia, requirement for supplemental oxygen, or requirement for respiratory therapy breathing treatments.

- Fever, or signs of sepsis, or systemic inflammatory response syndrome.

- Medical frailty, significant medical comorbidities, delirium, or altered mental status;

- Requirements for continuous vital sign monitoring or of a monitoring frequency beyond the capacity of the PCU.

Discharge criteria may also include a symptom-based strategy because emerging evidence suggests that patients may be less infectious by day 10-14 of the disease course,3 and viral lab testing is very sensitive and will be positive for periods of time after individuals are no longer infectious. The symptom-based strategy allows for patients to not require retesting prior to discharge. However, some receiving facilities (for example residential or skilled nursing facilities) may necessitate testing, in which case a testing-based strategy can be used. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention provides guidelines for both types of strategies.4

2. Infection control and personal protective equipment: PCUs require modifications or departures from the typical inpatient free-ranging environment in which common areas are provided for patients to engage in a community of care, including group therapy (such as occupational, recreational, Alcoholics Anonymous, and social work groups).

- Isolation: PCUs must consider whether they will require patients to isolate to their rooms or to allow modified or limited access to “public” or “community” areas. While there do not appear to be standard recommendations from the CDC or other public health entities regarding negative pressure or any specific room ventilation requirements, it is prudent to work with local infectious disease experts on protocols. Important considerations include spatial planning for infection control areas to don and doff appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) and appropriate workspace to prevent contamination of non–COVID-19 work areas. Approaches can include establishing clearly identified and visually demarcated infection control “zones” (often referred to as “hot, warm, and cold zones”) that correspond to specific PPE requirements for staff. In addition, individuals should eat in their own rooms or designated areas because use of common areas for meals can potentially lead to aerosolized spread of the virus.

- Cohorting: Generally, PCUs should consider admitting only COVID-19–positive patients to a PCU to avoid exposure to other patients. Hospitals and health systems should determine protocols and locations for testing and managing “patients under investigation” for COVID-19, which should precede admission to the PCU.

- PPE: It is important to clearly establish and communicate PPE requirements and procedures for direct physical contact versus no physical contact (for example, visual safety checks). Identify clear supply chains for PPE and hand sanitizer.

3. Medical management and consultation: PCUs should establish clear pathways for accessing consultation from medical consultants. It may be ideal, in addition to standard daily psychiatric physician rounding, to have daily internal medicine rounding and/or medical nursing staff working on the unit. Given the potential of COVID-19–positive patients to rapidly devolve from asymptomatic to acutely ill, it is necessary to establish protocols for the provision of urgent medical care 24/7 and streamlined processes for transfer to a medical unit.

Clear protocols should be established to address any potential signs of decompensation in the respiratory status of a PCU unit, including administration of oxygen and restrictions (or appropriate precautions) related to aerosolizing treatment such as nebulizers or positive airway pressure.

4. Code blue protocol: Any emergent medical issues, including acute respiratory decompensation, should trigger a Code Blue response that has been specifically designed for COVID-19–positive patients, including considerations for proper PPE during resuscitation efforts.

5. Psychiatric staffing and workflows: When possible, it may be preferable to engage volunteer medical and nursing staff for the PCU, as opposed to mandating participation. Take into consideration support needs, including education and training about safe PPE practices, processes for testing health care workers, return-to-work guidance, and potential alternate housing.

- Telehealth: Clinicians (such as physicians, social workers, occupational therapists) should leverage and maximize the use of telemedicine to minimize direct or prolonged exposure to infectious disease risks.

- Nursing: It is important to establish appropriate ratios of nursing and support staff for a COVID-19–positive psychiatry unit given the unique work flows related to isolation precautions and to ensure patient and staff safety. These ratios may take into account patient-specific needs, including the need for additional staff to perform constant observation for high-risk patients, management of agitated patients, and sufficient staff to allow for relief and break-time from PPE. Admission and routine care processes should be adapted in order to limit equipment entering the room, such as computer workstations on wheels.

- Medication administration procedures: Develop work flows related to PPE and infection control when retrieving and administering medications.

- Workspace: Designate appropriate workspace for PCU clinicians to access computers and documents and to minimize use of non–COVID-19 unit work areas.

6. Restraints and management of agitated patients: PCUs should develop plans for addressing agitated patients, including contingency plans for whether seclusion or restraints should be administered in the patient’s individual room or in a dedicated restraint room in the PCU. Staff training should include protocols specifically designed for managing agitated patients in the PCU.

7. Discharge processes: If patients remain medically well and clear their COVID-19 PCR tests, it is conceivable that they might be transferred to a non–COVID-19 psychiatric unit if sufficient isolation time has passed and the infectious disease consultants deem it appropriate. It is also possible that patients would be discharged from a PCU to home or other residential setting. Such patients should be assessed for ability to comply with continued self-quarantine if necessary. Discharge planning must take into consideration follow-up plans for COVID-19 illness and primary care appointments, as well as needed psychiatric follow-up.

8. Patients’ rights: The apparently highly infectious and transmissible nature of SARS-CoV-2 creates novel tensions between a wide range of individual rights and the rights of others. In addition to manifesting in our general society, there are potentially unique tensions in acute inpatient psychiatric settings. Certain patients’ rights may require modification in a PCU (for example, access to outdoor space, personal belongings, visitors, and possibly civil commitment judicial hearings). These discussions may require input from hospital compliance officers, ethics committees, risk managers, and the local department of mental health and also may be partly solved by using video communication platforms.

A few other “pearls” may be of value: Psychiatric hospitals that are colocated with a general acute care hospital or ED might be better situated to develop protocols to safely care for COVID-19–positive psychiatric patients, by virtue of the close proximity of full-spectrum acute general hospital services. Direct engagement by a command center and hospital or health system senior leadership also seems crucial as a means for assuring authorization to proceed with planning what may be a frightening or controversial (but necessary) adaptation of inpatient psychiatric unit(s) to the exigencies of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The resources of a robust community hospital or academic health system (including infection prevention leaders who engage in continuous liaison with local, county, state, and federal public health expertise) are crucial to the “learning health system” model, which requires flexibility, rapid adaptation to new knowledge, and accessibility to infectious disease and other consultation for special situations. Frequent and open communication with all professional stakeholders (through town halls, Q&A sessions, group discussions, and so on) is important in the planning process to socialize the principles and concepts that are critical for providing care in a PCU, reducing anxiety, and bolstering collegiality and staff morale.

References

1. Kim MJ. “ ‘It was a medical disaster’: The psychiatric ward that saw 100 patients with new coronavirus.” Independent. 2020 Mar 1.

2. Korean Society of Infectious Diseases et al. J Korean Med Sci. 2020 Mar 16;35(10):e112.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Symptom-based strategy to discontinue isolation for persons with COVID-19. Decision Memo. 2020 May 3.

4. He X et al. Nature Medicine. 2020. 26:672-5.

Dr. Cheung is associate medical director and chief quality officer at the Stewart and Lynda Resnick Neuropsychiatric Hospital at the University of California, Los Angeles. He has no conflicts of interest. Dr. Strouse is medical director, UCLA Stewart and Lynda Resnick Neuropsychiatric Hospital and Maddie Katz Professor at the UCLA department of psychiatry/Semel Institute. He has no conflicts of interest. Dr. Li is associate medical director of quality improvement at Yale-New Haven Psychiatric Hospital in Connecticut. She also serves as medical director of clinical operations at the Yale-New Haven Health System. Dr. Li is a 2019-2020 Health and Aging Policy Fellow and receives funding support from the program.

Identifying key decision points is critical

Identifying key decision points is critical

Reports have emerged about the unique vulnerability of psychiatric hospitals to the ravages of COVID-19.

In a South Korea psychiatric hospital, 101 of 103 patients contracted SARS-CoV-2 during an outbreak; 7 eventually died.1,2 This report, among a few others, have led to the development of psychiatric COVID-19–positive units (PCU). However, it remains highly unclear how many are currently open, where they are located, or what their operations are like.

We knew that we could not allow a medically asymptomatic “covertly” COVID-19–positive patient to be introduced to the social community of our inpatient units because of the risks of transmission to other patients and staff.

In coordination with our health system infection prevention experts, we have therefore required a confirmed negative COVID-19 polymerase chain reaction nasal swab performed no more than 48 hours prior to the time/date of acute psychiatric inpatient admission. Furthermore, as part of the broad health system response and surge planning, we were asked by our respective incident command centers to begin planning for a Psychiatric COVID-19–positive Unit (PCU) that might allow us to safely care for a cohort of patients needing such hospitalization.

It is worth emphasizing that the typical patient who is a candidate for a PCU is so acutely psychiatrically ill that they cannot be managed in a less restrictive environment than an inpatient psychiatric unit and, at the same time, is likely to not be medically ill enough to warrant admission to an internal medicine service in a general acute care hospital.

We have identified eight principles and critical decision points that can help inpatient units plan for the safe care of COVID-19–positive patients on a PCU.

1. Triage: Patients admitted to a PCU should be medically stable, particularly with regard to COVID-19 and respiratory symptomatology. PCUs should establish clear criteria for admission and discharge (or medical transfer). Examples of potential exclusionary criteria to a PCU include:

- Respiratory distress, shortness of breath, hypoxia, requirement for supplemental oxygen, or requirement for respiratory therapy breathing treatments.

- Fever, or signs of sepsis, or systemic inflammatory response syndrome.

- Medical frailty, significant medical comorbidities, delirium, or altered mental status;

- Requirements for continuous vital sign monitoring or of a monitoring frequency beyond the capacity of the PCU.

Discharge criteria may also include a symptom-based strategy because emerging evidence suggests that patients may be less infectious by day 10-14 of the disease course,3 and viral lab testing is very sensitive and will be positive for periods of time after individuals are no longer infectious. The symptom-based strategy allows for patients to not require retesting prior to discharge. However, some receiving facilities (for example residential or skilled nursing facilities) may necessitate testing, in which case a testing-based strategy can be used. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention provides guidelines for both types of strategies.4

2. Infection control and personal protective equipment: PCUs require modifications or departures from the typical inpatient free-ranging environment in which common areas are provided for patients to engage in a community of care, including group therapy (such as occupational, recreational, Alcoholics Anonymous, and social work groups).

- Isolation: PCUs must consider whether they will require patients to isolate to their rooms or to allow modified or limited access to “public” or “community” areas. While there do not appear to be standard recommendations from the CDC or other public health entities regarding negative pressure or any specific room ventilation requirements, it is prudent to work with local infectious disease experts on protocols. Important considerations include spatial planning for infection control areas to don and doff appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) and appropriate workspace to prevent contamination of non–COVID-19 work areas. Approaches can include establishing clearly identified and visually demarcated infection control “zones” (often referred to as “hot, warm, and cold zones”) that correspond to specific PPE requirements for staff. In addition, individuals should eat in their own rooms or designated areas because use of common areas for meals can potentially lead to aerosolized spread of the virus.

- Cohorting: Generally, PCUs should consider admitting only COVID-19–positive patients to a PCU to avoid exposure to other patients. Hospitals and health systems should determine protocols and locations for testing and managing “patients under investigation” for COVID-19, which should precede admission to the PCU.

- PPE: It is important to clearly establish and communicate PPE requirements and procedures for direct physical contact versus no physical contact (for example, visual safety checks). Identify clear supply chains for PPE and hand sanitizer.

3. Medical management and consultation: PCUs should establish clear pathways for accessing consultation from medical consultants. It may be ideal, in addition to standard daily psychiatric physician rounding, to have daily internal medicine rounding and/or medical nursing staff working on the unit. Given the potential of COVID-19–positive patients to rapidly devolve from asymptomatic to acutely ill, it is necessary to establish protocols for the provision of urgent medical care 24/7 and streamlined processes for transfer to a medical unit.

Clear protocols should be established to address any potential signs of decompensation in the respiratory status of a PCU unit, including administration of oxygen and restrictions (or appropriate precautions) related to aerosolizing treatment such as nebulizers or positive airway pressure.

4. Code blue protocol: Any emergent medical issues, including acute respiratory decompensation, should trigger a Code Blue response that has been specifically designed for COVID-19–positive patients, including considerations for proper PPE during resuscitation efforts.

5. Psychiatric staffing and workflows: When possible, it may be preferable to engage volunteer medical and nursing staff for the PCU, as opposed to mandating participation. Take into consideration support needs, including education and training about safe PPE practices, processes for testing health care workers, return-to-work guidance, and potential alternate housing.

- Telehealth: Clinicians (such as physicians, social workers, occupational therapists) should leverage and maximize the use of telemedicine to minimize direct or prolonged exposure to infectious disease risks.

- Nursing: It is important to establish appropriate ratios of nursing and support staff for a COVID-19–positive psychiatry unit given the unique work flows related to isolation precautions and to ensure patient and staff safety. These ratios may take into account patient-specific needs, including the need for additional staff to perform constant observation for high-risk patients, management of agitated patients, and sufficient staff to allow for relief and break-time from PPE. Admission and routine care processes should be adapted in order to limit equipment entering the room, such as computer workstations on wheels.