User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

What if a COVID-19 test is negative?

In a physician WhatsApp group, a doctor posted he had fever of 101 °F and muscle ache, gently confessing that it felt like his typical “man flu” which heals with rest and scotch. Nevertheless, he worried that he had coronavirus. When the reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) for the virus on his nasal swab came back negative, he jubilantly announced his relief.

Like Twitter, in WhatsApp emotions quickly outstrip facts. After he received a flurry of cheerful emojis, I ruined the party, advising that, despite the negative test, he assume he’s infected and quarantine for 2 weeks, with a bottle of scotch.

It’s conventional wisdom that the secret sauce to fighting the pandemic is testing for the virus. To gauge the breadth of the response against the pandemic we must know who and how many are infected. The depth of the response will be different if 25% of the population is infected than 1%. Testing is the third way, rejecting the false choice between death and economic depression. Without testing, strategy is faith based.

Our reliance on testing has clinical precedence – scarcely any decision in medicine is made without laboratory tests or imaging. Testing is as ingrained in medicine as the GPS is in driving. We use it even when we know our way home. But tests impose a question – what’ll you do differently if the test is negative?

That depends on the test’s performance and the consequences of being wrong. Though coronavirus damages the lungs with reckless abandon, it’s oddly a shy virus. In many patients, it takes 3-4 swabs to get a positive RT-PCR. The Chinese ophthalmologist, Li Wenliang, who originally sounded the alarm about coronavirus, had several negative tests. He died from the infection.

In one Chinese study, the sensitivity of RT-PCR – that’s the proportion of the infected who test positive – was around 70%. To put this in perspective, of 1,000 people infected with coronavirus, 700 will test positive but 300 will test negative.

Is this good enough?

Three hundred “false-negative” people may believe they’re not contagious because they got a clean chit and could infect others. False negatives could undo the hard work of containment.

Surely, better an imperfect test than no test. Isn’t flying with partially accurate weather information safer than no information? Here, aviation analogies aren’t helpful. Better to think of a forest fire.

Imagine only 80% of a burning forest is doused because it’s mistakenly believed that 20% of the forest isn’t burning because we can’t see it burning. It must be extinguished before it relights the whole forest, but to douse it you must know it’s burning – a Catch-22. That “20% of the forest” is a false negative – it’s burning but you think it’s not burning.

Because coronavirus isn’t planning to leave in a hurry and long-term lockdown has grave economic consequences, testing may enable precision quarantining of people, communities, and cities. Rather than applying a one-size-fits-all lockdown on the whole nation, testing could tell us who can work and who should stay home. Why should Austin, if it has a low prevalence of infection, shut shop just because of New York City’s high prevalence?

Testing enables us to think globally but act locally. But it’s the asymptomatic people who drive the epidemic. To emphasize – asymptomatics are yet to have symptoms such as cough and fever. They’re feeling well and don’t know they’ve been colonized by the virus. Theoretically, if we test en masse we can find asymptomatics. If only those who test positive are quarantined, the rest can have some breathing space. Will this approach work?

RT-PCR’s sensitivity, which is low in early illness, is even lower in asymptomatics, likely because of lower viral load, which means even more false negatives. The virus’s average incubation time of 5 days is enough time for false negative asymptomatics – remember they resemble the uninfected – to visit Disney World and infect another four.

Whether false negatives behave like tinder or a controllable fire will determine the testing strategy’s success. The net contagiousness of false negatives depends how many there are, which depends on how many are infected. To know how many are infected we need to test. Or, to know whether to believe a negative test in any person we must test widely – another Catch-22.

Maybe we need a bigger test.

Chest CT is an alternative. It’s rapid – takes less than an hour whereas RT-PCR can take over a day to report. In one study CT had a sensitivity of 97% in symptomatic patients and was often positive before RT-PCR. But there are caveats.

The real sensitivity of CT is likely much lower than 97% because the study has biases which inflate performance. CT, like RT-PCR, has a low sensitivity in early illness and even lower sensitivity in asymptomatic carriers for the same reason – lower viral load. Furthermore, CT has to be disinfected to prevent spread, which limits its access for other patients.

Coronavirus’s signature on CT – white patches in lungs, known as ground glass opacities – doesn’t have the uniqueness of the Mark of Zorro, and looks like lung injury from other rogue actors, which means we can mistake other serious conditions for coronavirus. Imagine hyenas in wolf’s clothing.

No test is perfect. We still use imaging despite its imperfections. But, let’s ask: What would you do differently if the test is negative and you have mild symptoms of cough and fever? Should you not self-isolate? What if you’re falsely negative and still contagious? If the advice dispensed whether the test is positive or negative is the same – i.e. quarantine for 2 weeks – what’s the test’s value?

Perhaps people will more likely comply with voluntary quarantine if they know they’re infected. Information can nudge behavior. But the logical corollary is that to comply with social distancing you need to be tested. People flocking to CT scans to affirm they’re not infected could infect those hitherto uninfected. A pandemic is no time to test nudge theories.

Does that mean testing has no value? Testing is valuable in managing populations. To individuals, the results must be framed wisely, such as by advising those who test positive to quarantine because “you’re infected” and those who test negative to keep social distancing because “you could still be infected.”

Even when policy goals are uniform, messaging can be oppositional. “Get yourself tested now” contradicts “you must hunker down now.” When messages contradict, one must choose which message to amplify.

The calculus of testing can change with new tests such as antibodies. The value of testing depends also on what isolation entails. A couple of weeks watching Netflix on your couch isn’t a big ask. If quarantine means being detained in an isolation center fenced by barbed wires, the cost of frivolous quarantining is higher and testing becomes more valuable.

I knew the doctor with the negative RT-PCR well. He’s heroically nonchalant about his wellbeing, an endearing quality that’s a liability in a contagion. In no time he’d be back in the hospital; or helping his elderly parents with grocery. Not all false negatives are equal. False-negative doctors could infect not just their patients but their colleagues, leaving fewer firefighters to fight fires.

It is better to mistake the man flu for coronavirus than coronavirus for the man flu. All he has to do is hunker down, which is what we should all be doing as much as we can.

Dr. Jha is a contributing editor to The Health Care Blog, where this article first appeared. He can be reached @RogueRad.

This article appeared on Medscape.com.

In a physician WhatsApp group, a doctor posted he had fever of 101 °F and muscle ache, gently confessing that it felt like his typical “man flu” which heals with rest and scotch. Nevertheless, he worried that he had coronavirus. When the reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) for the virus on his nasal swab came back negative, he jubilantly announced his relief.

Like Twitter, in WhatsApp emotions quickly outstrip facts. After he received a flurry of cheerful emojis, I ruined the party, advising that, despite the negative test, he assume he’s infected and quarantine for 2 weeks, with a bottle of scotch.

It’s conventional wisdom that the secret sauce to fighting the pandemic is testing for the virus. To gauge the breadth of the response against the pandemic we must know who and how many are infected. The depth of the response will be different if 25% of the population is infected than 1%. Testing is the third way, rejecting the false choice between death and economic depression. Without testing, strategy is faith based.

Our reliance on testing has clinical precedence – scarcely any decision in medicine is made without laboratory tests or imaging. Testing is as ingrained in medicine as the GPS is in driving. We use it even when we know our way home. But tests impose a question – what’ll you do differently if the test is negative?

That depends on the test’s performance and the consequences of being wrong. Though coronavirus damages the lungs with reckless abandon, it’s oddly a shy virus. In many patients, it takes 3-4 swabs to get a positive RT-PCR. The Chinese ophthalmologist, Li Wenliang, who originally sounded the alarm about coronavirus, had several negative tests. He died from the infection.

In one Chinese study, the sensitivity of RT-PCR – that’s the proportion of the infected who test positive – was around 70%. To put this in perspective, of 1,000 people infected with coronavirus, 700 will test positive but 300 will test negative.

Is this good enough?

Three hundred “false-negative” people may believe they’re not contagious because they got a clean chit and could infect others. False negatives could undo the hard work of containment.

Surely, better an imperfect test than no test. Isn’t flying with partially accurate weather information safer than no information? Here, aviation analogies aren’t helpful. Better to think of a forest fire.

Imagine only 80% of a burning forest is doused because it’s mistakenly believed that 20% of the forest isn’t burning because we can’t see it burning. It must be extinguished before it relights the whole forest, but to douse it you must know it’s burning – a Catch-22. That “20% of the forest” is a false negative – it’s burning but you think it’s not burning.

Because coronavirus isn’t planning to leave in a hurry and long-term lockdown has grave economic consequences, testing may enable precision quarantining of people, communities, and cities. Rather than applying a one-size-fits-all lockdown on the whole nation, testing could tell us who can work and who should stay home. Why should Austin, if it has a low prevalence of infection, shut shop just because of New York City’s high prevalence?

Testing enables us to think globally but act locally. But it’s the asymptomatic people who drive the epidemic. To emphasize – asymptomatics are yet to have symptoms such as cough and fever. They’re feeling well and don’t know they’ve been colonized by the virus. Theoretically, if we test en masse we can find asymptomatics. If only those who test positive are quarantined, the rest can have some breathing space. Will this approach work?

RT-PCR’s sensitivity, which is low in early illness, is even lower in asymptomatics, likely because of lower viral load, which means even more false negatives. The virus’s average incubation time of 5 days is enough time for false negative asymptomatics – remember they resemble the uninfected – to visit Disney World and infect another four.

Whether false negatives behave like tinder or a controllable fire will determine the testing strategy’s success. The net contagiousness of false negatives depends how many there are, which depends on how many are infected. To know how many are infected we need to test. Or, to know whether to believe a negative test in any person we must test widely – another Catch-22.

Maybe we need a bigger test.

Chest CT is an alternative. It’s rapid – takes less than an hour whereas RT-PCR can take over a day to report. In one study CT had a sensitivity of 97% in symptomatic patients and was often positive before RT-PCR. But there are caveats.

The real sensitivity of CT is likely much lower than 97% because the study has biases which inflate performance. CT, like RT-PCR, has a low sensitivity in early illness and even lower sensitivity in asymptomatic carriers for the same reason – lower viral load. Furthermore, CT has to be disinfected to prevent spread, which limits its access for other patients.

Coronavirus’s signature on CT – white patches in lungs, known as ground glass opacities – doesn’t have the uniqueness of the Mark of Zorro, and looks like lung injury from other rogue actors, which means we can mistake other serious conditions for coronavirus. Imagine hyenas in wolf’s clothing.

No test is perfect. We still use imaging despite its imperfections. But, let’s ask: What would you do differently if the test is negative and you have mild symptoms of cough and fever? Should you not self-isolate? What if you’re falsely negative and still contagious? If the advice dispensed whether the test is positive or negative is the same – i.e. quarantine for 2 weeks – what’s the test’s value?

Perhaps people will more likely comply with voluntary quarantine if they know they’re infected. Information can nudge behavior. But the logical corollary is that to comply with social distancing you need to be tested. People flocking to CT scans to affirm they’re not infected could infect those hitherto uninfected. A pandemic is no time to test nudge theories.

Does that mean testing has no value? Testing is valuable in managing populations. To individuals, the results must be framed wisely, such as by advising those who test positive to quarantine because “you’re infected” and those who test negative to keep social distancing because “you could still be infected.”

Even when policy goals are uniform, messaging can be oppositional. “Get yourself tested now” contradicts “you must hunker down now.” When messages contradict, one must choose which message to amplify.

The calculus of testing can change with new tests such as antibodies. The value of testing depends also on what isolation entails. A couple of weeks watching Netflix on your couch isn’t a big ask. If quarantine means being detained in an isolation center fenced by barbed wires, the cost of frivolous quarantining is higher and testing becomes more valuable.

I knew the doctor with the negative RT-PCR well. He’s heroically nonchalant about his wellbeing, an endearing quality that’s a liability in a contagion. In no time he’d be back in the hospital; or helping his elderly parents with grocery. Not all false negatives are equal. False-negative doctors could infect not just their patients but their colleagues, leaving fewer firefighters to fight fires.

It is better to mistake the man flu for coronavirus than coronavirus for the man flu. All he has to do is hunker down, which is what we should all be doing as much as we can.

Dr. Jha is a contributing editor to The Health Care Blog, where this article first appeared. He can be reached @RogueRad.

This article appeared on Medscape.com.

In a physician WhatsApp group, a doctor posted he had fever of 101 °F and muscle ache, gently confessing that it felt like his typical “man flu” which heals with rest and scotch. Nevertheless, he worried that he had coronavirus. When the reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) for the virus on his nasal swab came back negative, he jubilantly announced his relief.

Like Twitter, in WhatsApp emotions quickly outstrip facts. After he received a flurry of cheerful emojis, I ruined the party, advising that, despite the negative test, he assume he’s infected and quarantine for 2 weeks, with a bottle of scotch.

It’s conventional wisdom that the secret sauce to fighting the pandemic is testing for the virus. To gauge the breadth of the response against the pandemic we must know who and how many are infected. The depth of the response will be different if 25% of the population is infected than 1%. Testing is the third way, rejecting the false choice between death and economic depression. Without testing, strategy is faith based.

Our reliance on testing has clinical precedence – scarcely any decision in medicine is made without laboratory tests or imaging. Testing is as ingrained in medicine as the GPS is in driving. We use it even when we know our way home. But tests impose a question – what’ll you do differently if the test is negative?

That depends on the test’s performance and the consequences of being wrong. Though coronavirus damages the lungs with reckless abandon, it’s oddly a shy virus. In many patients, it takes 3-4 swabs to get a positive RT-PCR. The Chinese ophthalmologist, Li Wenliang, who originally sounded the alarm about coronavirus, had several negative tests. He died from the infection.

In one Chinese study, the sensitivity of RT-PCR – that’s the proportion of the infected who test positive – was around 70%. To put this in perspective, of 1,000 people infected with coronavirus, 700 will test positive but 300 will test negative.

Is this good enough?

Three hundred “false-negative” people may believe they’re not contagious because they got a clean chit and could infect others. False negatives could undo the hard work of containment.

Surely, better an imperfect test than no test. Isn’t flying with partially accurate weather information safer than no information? Here, aviation analogies aren’t helpful. Better to think of a forest fire.

Imagine only 80% of a burning forest is doused because it’s mistakenly believed that 20% of the forest isn’t burning because we can’t see it burning. It must be extinguished before it relights the whole forest, but to douse it you must know it’s burning – a Catch-22. That “20% of the forest” is a false negative – it’s burning but you think it’s not burning.

Because coronavirus isn’t planning to leave in a hurry and long-term lockdown has grave economic consequences, testing may enable precision quarantining of people, communities, and cities. Rather than applying a one-size-fits-all lockdown on the whole nation, testing could tell us who can work and who should stay home. Why should Austin, if it has a low prevalence of infection, shut shop just because of New York City’s high prevalence?

Testing enables us to think globally but act locally. But it’s the asymptomatic people who drive the epidemic. To emphasize – asymptomatics are yet to have symptoms such as cough and fever. They’re feeling well and don’t know they’ve been colonized by the virus. Theoretically, if we test en masse we can find asymptomatics. If only those who test positive are quarantined, the rest can have some breathing space. Will this approach work?

RT-PCR’s sensitivity, which is low in early illness, is even lower in asymptomatics, likely because of lower viral load, which means even more false negatives. The virus’s average incubation time of 5 days is enough time for false negative asymptomatics – remember they resemble the uninfected – to visit Disney World and infect another four.

Whether false negatives behave like tinder or a controllable fire will determine the testing strategy’s success. The net contagiousness of false negatives depends how many there are, which depends on how many are infected. To know how many are infected we need to test. Or, to know whether to believe a negative test in any person we must test widely – another Catch-22.

Maybe we need a bigger test.

Chest CT is an alternative. It’s rapid – takes less than an hour whereas RT-PCR can take over a day to report. In one study CT had a sensitivity of 97% in symptomatic patients and was often positive before RT-PCR. But there are caveats.

The real sensitivity of CT is likely much lower than 97% because the study has biases which inflate performance. CT, like RT-PCR, has a low sensitivity in early illness and even lower sensitivity in asymptomatic carriers for the same reason – lower viral load. Furthermore, CT has to be disinfected to prevent spread, which limits its access for other patients.

Coronavirus’s signature on CT – white patches in lungs, known as ground glass opacities – doesn’t have the uniqueness of the Mark of Zorro, and looks like lung injury from other rogue actors, which means we can mistake other serious conditions for coronavirus. Imagine hyenas in wolf’s clothing.

No test is perfect. We still use imaging despite its imperfections. But, let’s ask: What would you do differently if the test is negative and you have mild symptoms of cough and fever? Should you not self-isolate? What if you’re falsely negative and still contagious? If the advice dispensed whether the test is positive or negative is the same – i.e. quarantine for 2 weeks – what’s the test’s value?

Perhaps people will more likely comply with voluntary quarantine if they know they’re infected. Information can nudge behavior. But the logical corollary is that to comply with social distancing you need to be tested. People flocking to CT scans to affirm they’re not infected could infect those hitherto uninfected. A pandemic is no time to test nudge theories.

Does that mean testing has no value? Testing is valuable in managing populations. To individuals, the results must be framed wisely, such as by advising those who test positive to quarantine because “you’re infected” and those who test negative to keep social distancing because “you could still be infected.”

Even when policy goals are uniform, messaging can be oppositional. “Get yourself tested now” contradicts “you must hunker down now.” When messages contradict, one must choose which message to amplify.

The calculus of testing can change with new tests such as antibodies. The value of testing depends also on what isolation entails. A couple of weeks watching Netflix on your couch isn’t a big ask. If quarantine means being detained in an isolation center fenced by barbed wires, the cost of frivolous quarantining is higher and testing becomes more valuable.

I knew the doctor with the negative RT-PCR well. He’s heroically nonchalant about his wellbeing, an endearing quality that’s a liability in a contagion. In no time he’d be back in the hospital; or helping his elderly parents with grocery. Not all false negatives are equal. False-negative doctors could infect not just their patients but their colleagues, leaving fewer firefighters to fight fires.

It is better to mistake the man flu for coronavirus than coronavirus for the man flu. All he has to do is hunker down, which is what we should all be doing as much as we can.

Dr. Jha is a contributing editor to The Health Care Blog, where this article first appeared. He can be reached @RogueRad.

This article appeared on Medscape.com.

San Diego County CMO vigorously leads COVID-19 response team

SAN DIEGO – On the days family physician Nick Yphantides, MD, announces updates on the COVID-19 epidemic to San Diego County residents, he can’t help but think about his late father.

In June of 2009, 75-year-old George Yphantides, a Steinway-trained piano technician who lived in Escondido, Calif., became the third person in the United States to die from complications of the pandemic H1N1 swine flu – just days before a vaccine became available.

“I loved my dad,” Dr. Yphantides, who has been San Diego County’s Chief Medical Officer since the year of his father’s death, said in an interview. “So, when you take a step back and take into consideration my sense of purpose in serving the 3.3 million residents of San Diego County, my passion based on my personal Christian faith, and my activation in terms of what happened to my dad, I have such a storm of internal sense of urgency right now.”

San Diego County and public health officials got experience with COVID-19 in advance of the country’s widely documented cases of community-based transmission. Around 9 pm on Jan. 31, 2020 – the Friday of Super Bowl weekend – Dr. Yphantides answered a phone call from Eric C. McDonald, MD, the county’s medical director of epidemiology. Dr. McDonald informed him that in a few days, a plane full of American citizens traveling from Wuhan, China, would be landing at Marine Corp Air Station Miramar in San Diego for a 2-week quarantine and that the task of providing medical support to any affected individuals fell on county officials.

“I will never forget that phone call,” he said. “We did have two positive cases. What we experienced with those evacuees was amazing surge preparation, and without exaggeration, I have worked 18-20 hours a day since that day.”

Fast forward to March 31, 2020, the county’s confirmed COVID-19 caseload had grown to 734, up 131 from the day before. As of the final day of March, nine people have died, with an age range between 25 and 87 years. Of confirmed cases, 61% are between the ages of 20 and 49, 43% are female, 19% have required hospitalization, 7% have required admission to intensive care, and the mortality rate has been 1.2%. Data currently show optimal proactive hospital capacity.

In the opinion of Dr. Yphantides, the 734 COVID-19 cases represent a tip of the iceberg. “How big is that iceberg? I can’t tell you yet,” he said.

"I see this as the Super Bowl of public health,” he exclaimed.

At least some of Dr. Yphantides’ vigor seems to be fueled by his pride in his team of professionals who have been helping him respond to the surge of COVID-19 cases.

As the county’s CMO, Dr. Yphantides serves as the liaison for the entire Emergency Medical System, the entire local health care delivery system, the entire physician and medical society network, the payor system, and the proportion of the area population using Medi-Cal.

Dr. Yphantides, who attended medical school at the University of California, San Diego, said that, compared with other regions of the country, San Diego County has made “tremendous progress” in overcoming many chronic lifestyle illnesses. For example, cardiovascular disease is no longer the number one cause of death in the county; it’s bookended by cancer and Alzheimer’s disease.

“In the context of the COVID-19 response, [the county’s health care team established] an entire incident command system in our emergency operations center. Our emergency operations center is activated to the top level,” he said.

Dr. Yphantides shares public communication efforts with Dr. McDonald and Wilma J. Wooten, MD, the county’s public health officer. The San Diego County CMO also engages with policymakers, including the board of supervisors, local mayors, state legislators, and national legislators.

“Because of the relational trust capital that I have in this community, I get pulled into unexpected rooms of discussion,” he said. This included meeting with top executives from the San Diego Padres in early March, putting them on notice that the 2020 Major League Baseball season would likely be postponed. (This was officially announced on March 16.)

“We have made some decisions that have devastated some people economically. Talk about flipping the switch. We are living and making history every day. It is unbelievable,” he said.

“San Diego is a more aged population compared to many other parts of the country. ... [Part] of the reason why I’m so frantically doing everything I can to prepare, to batten down the hatches, and to optimize our health care delivery system is because we have a population that collectively is more at risk [for more serious complications from COVID-19]. A lot of what drives me is advocacy,” Dr. Yphantides noted.

A colleague’s perspective

Kristi L. Koenig, MD, medical director of emergency medical services for the County of San Diego, characterized Dr. Yphantides’ management style as collaborative. “Under his leadership, we have the perspective of ‘just focus on patient care, get it done, be creative, work together as a team,’ ” said Dr. Koenig, who coedited the textbook, “Koenig and Schultz’s Disaster Medicine: Comprehensive Principles and Practices” (Cambridge University Press, 2016). “He’s decisive and he’s responsive. You don’t have to wait a long time to get a decision, which is very important right now because this is so fast moving.”

Dr. Koenig, who has worked with Dr. Yphantides for 3 years, said that she routinely feeds him information that might help the team navigate its response to COVID-19. “For example, if I see an idea for how to get more [personal protective equipment] and feed it to him, he might have a contact somewhere in a factory that could make the PPE,” she said. “We work together by my reminding him to keep it within the incident command system structure, so that we can coordinate all the resources and not duplicate efforts.”

He uses his personal connections in a way to implement ideas that are beneficial to the overall goal of decreasing morbidity and mortality,” Dr. Koenig added.

Predictions for San Diego County

Dr. Yphantides said he considers San Diego to still be in the calm before the storm and that he is working hard to “board up his community.” The county CMO is also trying to prepare the health care delivery system to optimize its capacity, of doing interventions with hopes of lowering the curve and enhancing the capacity, he said.

When the storm hits, “it’s going be brutal, because we’re going to lose life,” Dr. Yphantides said.

“I am praying that maybe by some of our efforts, instead of a Category 5 storm, it’ll be a Category 3 storm,” he remarked.

The future of health care

Dr. Yphantides views the COVID-19 pandemic as “an absolute game-changer” in terms of what the future of health care delivery will look like in the United States. “Whether the right word is the ‘Amazonification’ of health care, or the ‘Uberization’ of health care, I don’t know, but the essence of how we deliver care is radically being transformed literally before our eyes,” he said. “I would encourage my colleagues to embrace that” and take care of their people by doing whatever it takes under this unprecedented paradigm.

Meanwhile, Dr. Yphantides braces for a potential surge of COVID-19 cases in San Diego County in the coming weeks. He honors the memory of his dad, and he expresses thanks for his mom, who cares for his two teenaged daughters while he helps steward the region’s response to the pandemic.

“Without my mom I could not function in the way that I’m currently functioning,” he said. “So, when you add all of those factors up, and wrap it with a bowtie of sincere love and passion for my community, there’s a fire that’s burning inside of me right now.”

SAN DIEGO – On the days family physician Nick Yphantides, MD, announces updates on the COVID-19 epidemic to San Diego County residents, he can’t help but think about his late father.

In June of 2009, 75-year-old George Yphantides, a Steinway-trained piano technician who lived in Escondido, Calif., became the third person in the United States to die from complications of the pandemic H1N1 swine flu – just days before a vaccine became available.

“I loved my dad,” Dr. Yphantides, who has been San Diego County’s Chief Medical Officer since the year of his father’s death, said in an interview. “So, when you take a step back and take into consideration my sense of purpose in serving the 3.3 million residents of San Diego County, my passion based on my personal Christian faith, and my activation in terms of what happened to my dad, I have such a storm of internal sense of urgency right now.”

San Diego County and public health officials got experience with COVID-19 in advance of the country’s widely documented cases of community-based transmission. Around 9 pm on Jan. 31, 2020 – the Friday of Super Bowl weekend – Dr. Yphantides answered a phone call from Eric C. McDonald, MD, the county’s medical director of epidemiology. Dr. McDonald informed him that in a few days, a plane full of American citizens traveling from Wuhan, China, would be landing at Marine Corp Air Station Miramar in San Diego for a 2-week quarantine and that the task of providing medical support to any affected individuals fell on county officials.

“I will never forget that phone call,” he said. “We did have two positive cases. What we experienced with those evacuees was amazing surge preparation, and without exaggeration, I have worked 18-20 hours a day since that day.”

Fast forward to March 31, 2020, the county’s confirmed COVID-19 caseload had grown to 734, up 131 from the day before. As of the final day of March, nine people have died, with an age range between 25 and 87 years. Of confirmed cases, 61% are between the ages of 20 and 49, 43% are female, 19% have required hospitalization, 7% have required admission to intensive care, and the mortality rate has been 1.2%. Data currently show optimal proactive hospital capacity.

In the opinion of Dr. Yphantides, the 734 COVID-19 cases represent a tip of the iceberg. “How big is that iceberg? I can’t tell you yet,” he said.

"I see this as the Super Bowl of public health,” he exclaimed.

At least some of Dr. Yphantides’ vigor seems to be fueled by his pride in his team of professionals who have been helping him respond to the surge of COVID-19 cases.

As the county’s CMO, Dr. Yphantides serves as the liaison for the entire Emergency Medical System, the entire local health care delivery system, the entire physician and medical society network, the payor system, and the proportion of the area population using Medi-Cal.

Dr. Yphantides, who attended medical school at the University of California, San Diego, said that, compared with other regions of the country, San Diego County has made “tremendous progress” in overcoming many chronic lifestyle illnesses. For example, cardiovascular disease is no longer the number one cause of death in the county; it’s bookended by cancer and Alzheimer’s disease.

“In the context of the COVID-19 response, [the county’s health care team established] an entire incident command system in our emergency operations center. Our emergency operations center is activated to the top level,” he said.

Dr. Yphantides shares public communication efforts with Dr. McDonald and Wilma J. Wooten, MD, the county’s public health officer. The San Diego County CMO also engages with policymakers, including the board of supervisors, local mayors, state legislators, and national legislators.

“Because of the relational trust capital that I have in this community, I get pulled into unexpected rooms of discussion,” he said. This included meeting with top executives from the San Diego Padres in early March, putting them on notice that the 2020 Major League Baseball season would likely be postponed. (This was officially announced on March 16.)

“We have made some decisions that have devastated some people economically. Talk about flipping the switch. We are living and making history every day. It is unbelievable,” he said.

“San Diego is a more aged population compared to many other parts of the country. ... [Part] of the reason why I’m so frantically doing everything I can to prepare, to batten down the hatches, and to optimize our health care delivery system is because we have a population that collectively is more at risk [for more serious complications from COVID-19]. A lot of what drives me is advocacy,” Dr. Yphantides noted.

A colleague’s perspective

Kristi L. Koenig, MD, medical director of emergency medical services for the County of San Diego, characterized Dr. Yphantides’ management style as collaborative. “Under his leadership, we have the perspective of ‘just focus on patient care, get it done, be creative, work together as a team,’ ” said Dr. Koenig, who coedited the textbook, “Koenig and Schultz’s Disaster Medicine: Comprehensive Principles and Practices” (Cambridge University Press, 2016). “He’s decisive and he’s responsive. You don’t have to wait a long time to get a decision, which is very important right now because this is so fast moving.”

Dr. Koenig, who has worked with Dr. Yphantides for 3 years, said that she routinely feeds him information that might help the team navigate its response to COVID-19. “For example, if I see an idea for how to get more [personal protective equipment] and feed it to him, he might have a contact somewhere in a factory that could make the PPE,” she said. “We work together by my reminding him to keep it within the incident command system structure, so that we can coordinate all the resources and not duplicate efforts.”

He uses his personal connections in a way to implement ideas that are beneficial to the overall goal of decreasing morbidity and mortality,” Dr. Koenig added.

Predictions for San Diego County

Dr. Yphantides said he considers San Diego to still be in the calm before the storm and that he is working hard to “board up his community.” The county CMO is also trying to prepare the health care delivery system to optimize its capacity, of doing interventions with hopes of lowering the curve and enhancing the capacity, he said.

When the storm hits, “it’s going be brutal, because we’re going to lose life,” Dr. Yphantides said.

“I am praying that maybe by some of our efforts, instead of a Category 5 storm, it’ll be a Category 3 storm,” he remarked.

The future of health care

Dr. Yphantides views the COVID-19 pandemic as “an absolute game-changer” in terms of what the future of health care delivery will look like in the United States. “Whether the right word is the ‘Amazonification’ of health care, or the ‘Uberization’ of health care, I don’t know, but the essence of how we deliver care is radically being transformed literally before our eyes,” he said. “I would encourage my colleagues to embrace that” and take care of their people by doing whatever it takes under this unprecedented paradigm.

Meanwhile, Dr. Yphantides braces for a potential surge of COVID-19 cases in San Diego County in the coming weeks. He honors the memory of his dad, and he expresses thanks for his mom, who cares for his two teenaged daughters while he helps steward the region’s response to the pandemic.

“Without my mom I could not function in the way that I’m currently functioning,” he said. “So, when you add all of those factors up, and wrap it with a bowtie of sincere love and passion for my community, there’s a fire that’s burning inside of me right now.”

SAN DIEGO – On the days family physician Nick Yphantides, MD, announces updates on the COVID-19 epidemic to San Diego County residents, he can’t help but think about his late father.

In June of 2009, 75-year-old George Yphantides, a Steinway-trained piano technician who lived in Escondido, Calif., became the third person in the United States to die from complications of the pandemic H1N1 swine flu – just days before a vaccine became available.

“I loved my dad,” Dr. Yphantides, who has been San Diego County’s Chief Medical Officer since the year of his father’s death, said in an interview. “So, when you take a step back and take into consideration my sense of purpose in serving the 3.3 million residents of San Diego County, my passion based on my personal Christian faith, and my activation in terms of what happened to my dad, I have such a storm of internal sense of urgency right now.”

San Diego County and public health officials got experience with COVID-19 in advance of the country’s widely documented cases of community-based transmission. Around 9 pm on Jan. 31, 2020 – the Friday of Super Bowl weekend – Dr. Yphantides answered a phone call from Eric C. McDonald, MD, the county’s medical director of epidemiology. Dr. McDonald informed him that in a few days, a plane full of American citizens traveling from Wuhan, China, would be landing at Marine Corp Air Station Miramar in San Diego for a 2-week quarantine and that the task of providing medical support to any affected individuals fell on county officials.

“I will never forget that phone call,” he said. “We did have two positive cases. What we experienced with those evacuees was amazing surge preparation, and without exaggeration, I have worked 18-20 hours a day since that day.”

Fast forward to March 31, 2020, the county’s confirmed COVID-19 caseload had grown to 734, up 131 from the day before. As of the final day of March, nine people have died, with an age range between 25 and 87 years. Of confirmed cases, 61% are between the ages of 20 and 49, 43% are female, 19% have required hospitalization, 7% have required admission to intensive care, and the mortality rate has been 1.2%. Data currently show optimal proactive hospital capacity.

In the opinion of Dr. Yphantides, the 734 COVID-19 cases represent a tip of the iceberg. “How big is that iceberg? I can’t tell you yet,” he said.

"I see this as the Super Bowl of public health,” he exclaimed.

At least some of Dr. Yphantides’ vigor seems to be fueled by his pride in his team of professionals who have been helping him respond to the surge of COVID-19 cases.

As the county’s CMO, Dr. Yphantides serves as the liaison for the entire Emergency Medical System, the entire local health care delivery system, the entire physician and medical society network, the payor system, and the proportion of the area population using Medi-Cal.

Dr. Yphantides, who attended medical school at the University of California, San Diego, said that, compared with other regions of the country, San Diego County has made “tremendous progress” in overcoming many chronic lifestyle illnesses. For example, cardiovascular disease is no longer the number one cause of death in the county; it’s bookended by cancer and Alzheimer’s disease.

“In the context of the COVID-19 response, [the county’s health care team established] an entire incident command system in our emergency operations center. Our emergency operations center is activated to the top level,” he said.

Dr. Yphantides shares public communication efforts with Dr. McDonald and Wilma J. Wooten, MD, the county’s public health officer. The San Diego County CMO also engages with policymakers, including the board of supervisors, local mayors, state legislators, and national legislators.

“Because of the relational trust capital that I have in this community, I get pulled into unexpected rooms of discussion,” he said. This included meeting with top executives from the San Diego Padres in early March, putting them on notice that the 2020 Major League Baseball season would likely be postponed. (This was officially announced on March 16.)

“We have made some decisions that have devastated some people economically. Talk about flipping the switch. We are living and making history every day. It is unbelievable,” he said.

“San Diego is a more aged population compared to many other parts of the country. ... [Part] of the reason why I’m so frantically doing everything I can to prepare, to batten down the hatches, and to optimize our health care delivery system is because we have a population that collectively is more at risk [for more serious complications from COVID-19]. A lot of what drives me is advocacy,” Dr. Yphantides noted.

A colleague’s perspective

Kristi L. Koenig, MD, medical director of emergency medical services for the County of San Diego, characterized Dr. Yphantides’ management style as collaborative. “Under his leadership, we have the perspective of ‘just focus on patient care, get it done, be creative, work together as a team,’ ” said Dr. Koenig, who coedited the textbook, “Koenig and Schultz’s Disaster Medicine: Comprehensive Principles and Practices” (Cambridge University Press, 2016). “He’s decisive and he’s responsive. You don’t have to wait a long time to get a decision, which is very important right now because this is so fast moving.”

Dr. Koenig, who has worked with Dr. Yphantides for 3 years, said that she routinely feeds him information that might help the team navigate its response to COVID-19. “For example, if I see an idea for how to get more [personal protective equipment] and feed it to him, he might have a contact somewhere in a factory that could make the PPE,” she said. “We work together by my reminding him to keep it within the incident command system structure, so that we can coordinate all the resources and not duplicate efforts.”

He uses his personal connections in a way to implement ideas that are beneficial to the overall goal of decreasing morbidity and mortality,” Dr. Koenig added.

Predictions for San Diego County

Dr. Yphantides said he considers San Diego to still be in the calm before the storm and that he is working hard to “board up his community.” The county CMO is also trying to prepare the health care delivery system to optimize its capacity, of doing interventions with hopes of lowering the curve and enhancing the capacity, he said.

When the storm hits, “it’s going be brutal, because we’re going to lose life,” Dr. Yphantides said.

“I am praying that maybe by some of our efforts, instead of a Category 5 storm, it’ll be a Category 3 storm,” he remarked.

The future of health care

Dr. Yphantides views the COVID-19 pandemic as “an absolute game-changer” in terms of what the future of health care delivery will look like in the United States. “Whether the right word is the ‘Amazonification’ of health care, or the ‘Uberization’ of health care, I don’t know, but the essence of how we deliver care is radically being transformed literally before our eyes,” he said. “I would encourage my colleagues to embrace that” and take care of their people by doing whatever it takes under this unprecedented paradigm.

Meanwhile, Dr. Yphantides braces for a potential surge of COVID-19 cases in San Diego County in the coming weeks. He honors the memory of his dad, and he expresses thanks for his mom, who cares for his two teenaged daughters while he helps steward the region’s response to the pandemic.

“Without my mom I could not function in the way that I’m currently functioning,” he said. “So, when you add all of those factors up, and wrap it with a bowtie of sincere love and passion for my community, there’s a fire that’s burning inside of me right now.”

Case fatality rate for COVID-19 near 1.4%, increases with age

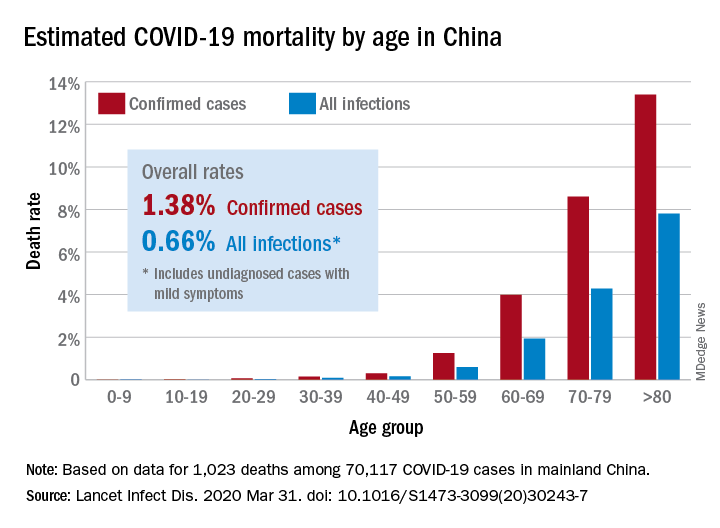

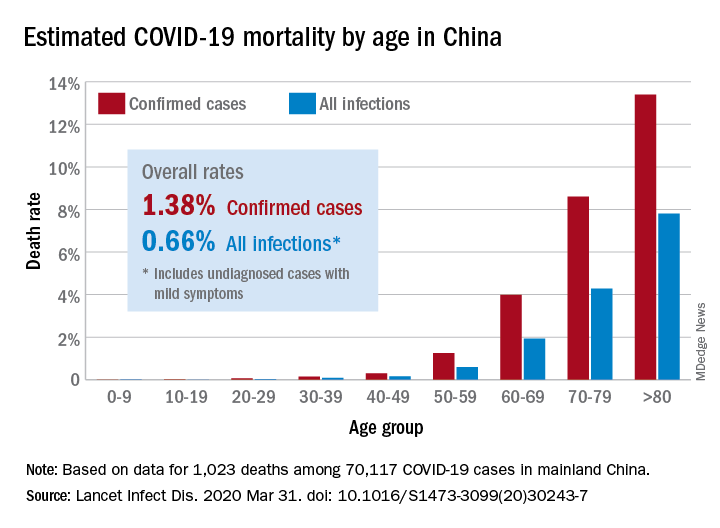

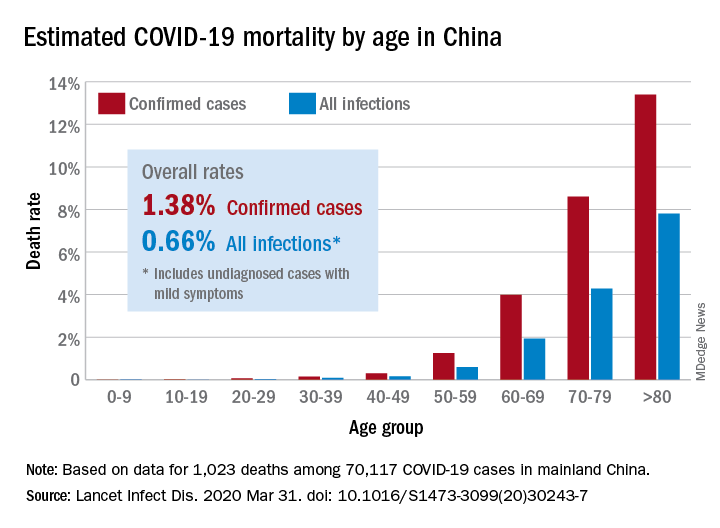

The risk for death from COVID-19 is 1.38% overall, according to a new study. However, the fatality rate rises with age, from well below 1% among children aged 9 years or younger to nearly 8% for seniors aged 80 years or older, the latest statistics show.

“These early estimates give an indication of the fatality ratio across the spectrum of COVID-19 disease and show a strong age gradient in risk of death,” Robert Verity, PhD, of University College London, and colleagues, wrote in a study published online in the Lancet Infectious Diseases.

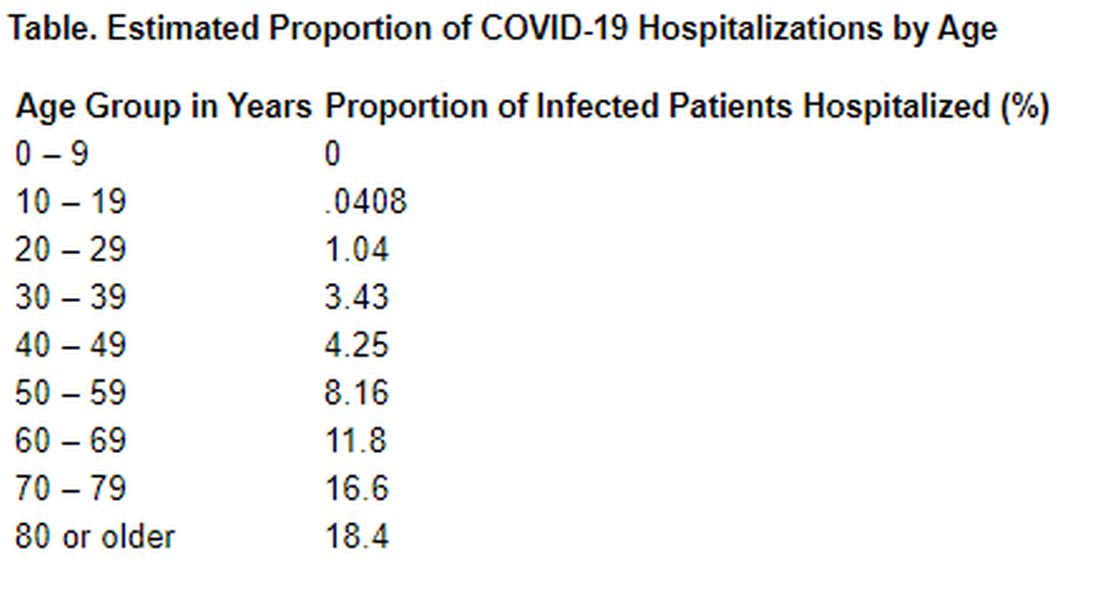

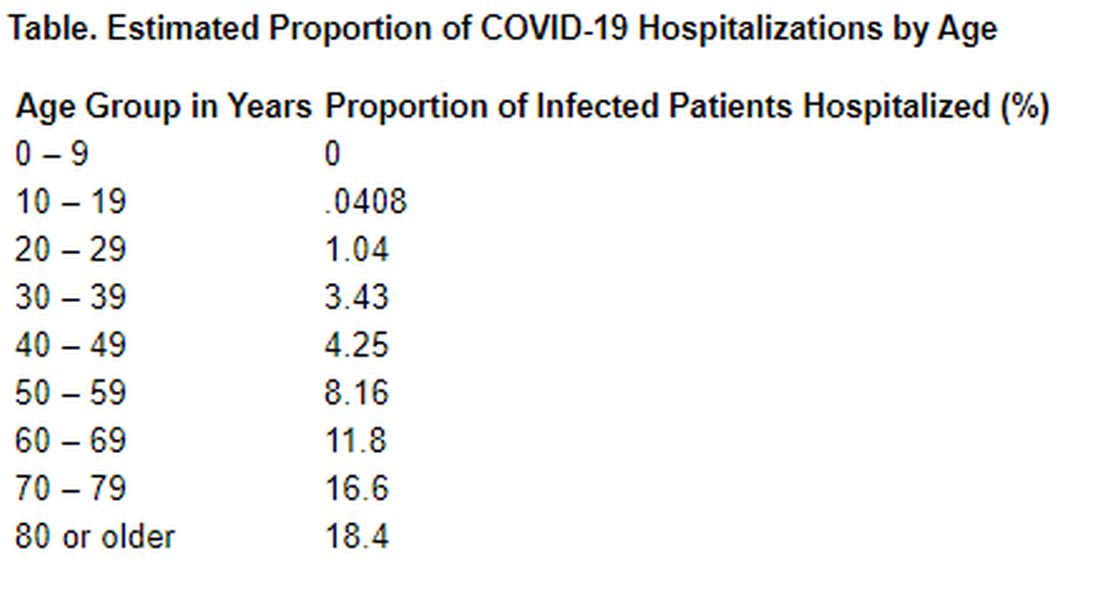

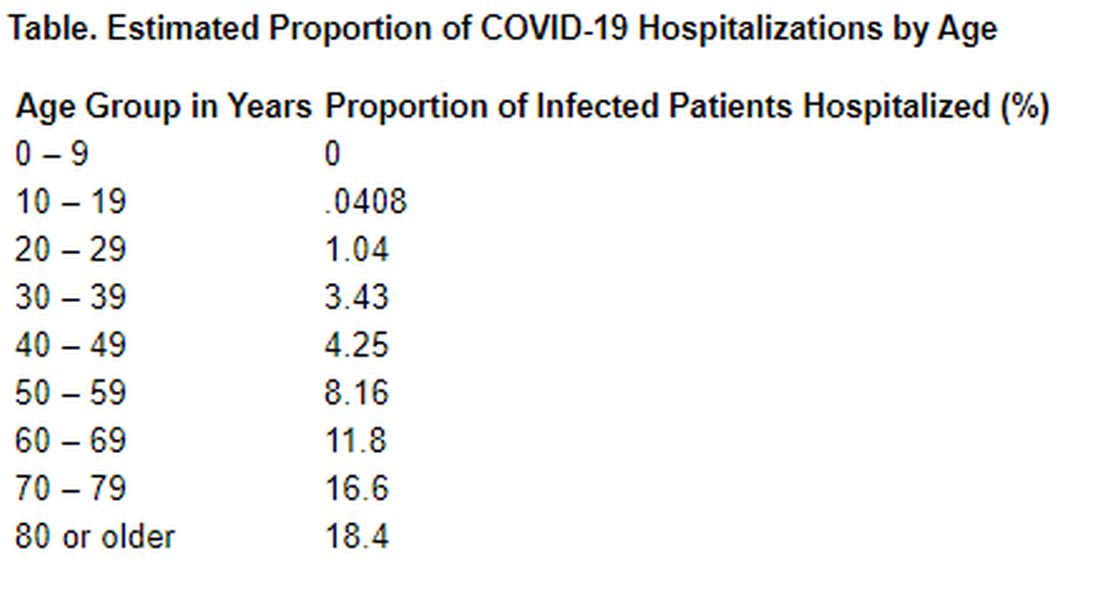

Among those infected with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, the risk for hospitalization also increases with age. Specifically, 11.8% of people in their 60s require admission, as do 16.6% of people in their 70s and 18.4% for those in their 80s or older.

The case fatality estimates are based on data regarding individual patients who died from COVID-19 in Hubei, China, through Feb. 8, as well as those who died in Hong Kong, Macau, and 37 countries outside China through Feb. 25.

“It is clear from the data that have emerged from China that case fatality ratio increases substantially with age. Our results suggest a very low fatality ratio in those under the age of 20 years. As there are very few cases in this age group, it remains unclear whether this reflects a low risk of death or a difference in susceptibility, although early results indicate young people are not at lower risk of infection than adults,” Dr. Verity and colleagues wrote.

The authors emphasized that serologic testing of adolescents and children will be vital to understanding how individuals younger than 20 years may be driving viral transmission.

In an accompanying editorial Shigui Ruan, PhD, of the department of mathematics at the University of Miami in Coral Gables, Fla., wrote that early detection, diagnosis, isolation, and treatment, as practiced in China, may help to prevent more deaths

“Even though the fatality rate is low for younger people, it is very clear that any suggestion of COVID-19 being just like influenza is false: Even for those aged 20-29 years, once infected with SARS-CoV-2, the mortality rate is 33 times higher than that from seasonal influenza,” he noted.

Dr. Ruan, who uses applied mathematics to model disease transmission, noted that otherwise healthy people stand a good chance – approximately 95% – of surviving COVID-19, but the odds of survival for people with comorbidities will be “considerably decreased.”

Time to death or discharge

Dr. Verity and colleagues first used data on deaths of 24 patients in mainland China and on 165 persons who recovered from infection outside of China to estimate the time between onset of symptoms and either death or discharge from the hospital. They estimated that the mean duration from symptom onset to death is 17.8 days, and the mean duration to discharge is 24.7 days.

They then estimated age-stratified case fatality ratios among all clinically diagnosed and laboratory-confirmed cases in mainland China to the end of the study period (70,117 cases).

The estimated crude case fatality ratio, adjusted for censoring, was 3.67%. With further adjustment for demographic characteristics and under-ascertainment, the authors’ best estimate of a case fatality ratio in China is 1.38%.

The following figure shows adjusted fatality infection rates by age group.

The investigators noted that the case fatality estimate is lower than the estimates for severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) outbreaks, both caused by coronaviruses, but “is substantially higher than estimates from the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic.”

Earlier reports suggested that the overall fatality rate in China through Feb. 11 was 2.3%. The rate in Hubei province, which is believed to be where the infection started, was 2.9%.

Hospitalizations rise with age

The investigators also estimated the proportion of infected patients who require hospitalization. Their estimation was based on data from a subset of cases reported in mainland China. The hospitalization estimates range from zero among the youngest patients to 18% among the oldest.

“Although China has succeeded in containing the disease spread for 2 months, such containment is unlikely to be achievable in most countries. Thus, much of the world will experience very large community epidemics of COVID-19 over the coming weeks and months. Our estimates of the underlying infection fatality ratio of this virus will inform assessments of health effects likely to be experienced in different countries, and thus decisions around appropriate mitigation policies to be adopted,” Dr. Verity and colleagues concluded.

In his editorial, Dr. Ruan agreed with that assessment. “Although China seems to be out of the woods now, many other countries are facing tremendous pressure from the COVID-19 pandemic,” he wrote. “The strategies of early detection, early diagnosis, early isolation, and early treatment that were practiced in China are likely to be not only useful in controlling the outbreak but also contribute to decreasing the case fatality ratio of the disease.”

The study was supported by the UK Medical Research Council. Dr. Verity and Dr. Ruan have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The risk for death from COVID-19 is 1.38% overall, according to a new study. However, the fatality rate rises with age, from well below 1% among children aged 9 years or younger to nearly 8% for seniors aged 80 years or older, the latest statistics show.

“These early estimates give an indication of the fatality ratio across the spectrum of COVID-19 disease and show a strong age gradient in risk of death,” Robert Verity, PhD, of University College London, and colleagues, wrote in a study published online in the Lancet Infectious Diseases.

Among those infected with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, the risk for hospitalization also increases with age. Specifically, 11.8% of people in their 60s require admission, as do 16.6% of people in their 70s and 18.4% for those in their 80s or older.

The case fatality estimates are based on data regarding individual patients who died from COVID-19 in Hubei, China, through Feb. 8, as well as those who died in Hong Kong, Macau, and 37 countries outside China through Feb. 25.

“It is clear from the data that have emerged from China that case fatality ratio increases substantially with age. Our results suggest a very low fatality ratio in those under the age of 20 years. As there are very few cases in this age group, it remains unclear whether this reflects a low risk of death or a difference in susceptibility, although early results indicate young people are not at lower risk of infection than adults,” Dr. Verity and colleagues wrote.

The authors emphasized that serologic testing of adolescents and children will be vital to understanding how individuals younger than 20 years may be driving viral transmission.

In an accompanying editorial Shigui Ruan, PhD, of the department of mathematics at the University of Miami in Coral Gables, Fla., wrote that early detection, diagnosis, isolation, and treatment, as practiced in China, may help to prevent more deaths

“Even though the fatality rate is low for younger people, it is very clear that any suggestion of COVID-19 being just like influenza is false: Even for those aged 20-29 years, once infected with SARS-CoV-2, the mortality rate is 33 times higher than that from seasonal influenza,” he noted.

Dr. Ruan, who uses applied mathematics to model disease transmission, noted that otherwise healthy people stand a good chance – approximately 95% – of surviving COVID-19, but the odds of survival for people with comorbidities will be “considerably decreased.”

Time to death or discharge

Dr. Verity and colleagues first used data on deaths of 24 patients in mainland China and on 165 persons who recovered from infection outside of China to estimate the time between onset of symptoms and either death or discharge from the hospital. They estimated that the mean duration from symptom onset to death is 17.8 days, and the mean duration to discharge is 24.7 days.

They then estimated age-stratified case fatality ratios among all clinically diagnosed and laboratory-confirmed cases in mainland China to the end of the study period (70,117 cases).

The estimated crude case fatality ratio, adjusted for censoring, was 3.67%. With further adjustment for demographic characteristics and under-ascertainment, the authors’ best estimate of a case fatality ratio in China is 1.38%.

The following figure shows adjusted fatality infection rates by age group.

The investigators noted that the case fatality estimate is lower than the estimates for severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) outbreaks, both caused by coronaviruses, but “is substantially higher than estimates from the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic.”

Earlier reports suggested that the overall fatality rate in China through Feb. 11 was 2.3%. The rate in Hubei province, which is believed to be where the infection started, was 2.9%.

Hospitalizations rise with age

The investigators also estimated the proportion of infected patients who require hospitalization. Their estimation was based on data from a subset of cases reported in mainland China. The hospitalization estimates range from zero among the youngest patients to 18% among the oldest.

“Although China has succeeded in containing the disease spread for 2 months, such containment is unlikely to be achievable in most countries. Thus, much of the world will experience very large community epidemics of COVID-19 over the coming weeks and months. Our estimates of the underlying infection fatality ratio of this virus will inform assessments of health effects likely to be experienced in different countries, and thus decisions around appropriate mitigation policies to be adopted,” Dr. Verity and colleagues concluded.

In his editorial, Dr. Ruan agreed with that assessment. “Although China seems to be out of the woods now, many other countries are facing tremendous pressure from the COVID-19 pandemic,” he wrote. “The strategies of early detection, early diagnosis, early isolation, and early treatment that were practiced in China are likely to be not only useful in controlling the outbreak but also contribute to decreasing the case fatality ratio of the disease.”

The study was supported by the UK Medical Research Council. Dr. Verity and Dr. Ruan have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The risk for death from COVID-19 is 1.38% overall, according to a new study. However, the fatality rate rises with age, from well below 1% among children aged 9 years or younger to nearly 8% for seniors aged 80 years or older, the latest statistics show.

“These early estimates give an indication of the fatality ratio across the spectrum of COVID-19 disease and show a strong age gradient in risk of death,” Robert Verity, PhD, of University College London, and colleagues, wrote in a study published online in the Lancet Infectious Diseases.

Among those infected with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, the risk for hospitalization also increases with age. Specifically, 11.8% of people in their 60s require admission, as do 16.6% of people in their 70s and 18.4% for those in their 80s or older.

The case fatality estimates are based on data regarding individual patients who died from COVID-19 in Hubei, China, through Feb. 8, as well as those who died in Hong Kong, Macau, and 37 countries outside China through Feb. 25.

“It is clear from the data that have emerged from China that case fatality ratio increases substantially with age. Our results suggest a very low fatality ratio in those under the age of 20 years. As there are very few cases in this age group, it remains unclear whether this reflects a low risk of death or a difference in susceptibility, although early results indicate young people are not at lower risk of infection than adults,” Dr. Verity and colleagues wrote.

The authors emphasized that serologic testing of adolescents and children will be vital to understanding how individuals younger than 20 years may be driving viral transmission.

In an accompanying editorial Shigui Ruan, PhD, of the department of mathematics at the University of Miami in Coral Gables, Fla., wrote that early detection, diagnosis, isolation, and treatment, as practiced in China, may help to prevent more deaths

“Even though the fatality rate is low for younger people, it is very clear that any suggestion of COVID-19 being just like influenza is false: Even for those aged 20-29 years, once infected with SARS-CoV-2, the mortality rate is 33 times higher than that from seasonal influenza,” he noted.

Dr. Ruan, who uses applied mathematics to model disease transmission, noted that otherwise healthy people stand a good chance – approximately 95% – of surviving COVID-19, but the odds of survival for people with comorbidities will be “considerably decreased.”

Time to death or discharge

Dr. Verity and colleagues first used data on deaths of 24 patients in mainland China and on 165 persons who recovered from infection outside of China to estimate the time between onset of symptoms and either death or discharge from the hospital. They estimated that the mean duration from symptom onset to death is 17.8 days, and the mean duration to discharge is 24.7 days.

They then estimated age-stratified case fatality ratios among all clinically diagnosed and laboratory-confirmed cases in mainland China to the end of the study period (70,117 cases).

The estimated crude case fatality ratio, adjusted for censoring, was 3.67%. With further adjustment for demographic characteristics and under-ascertainment, the authors’ best estimate of a case fatality ratio in China is 1.38%.

The following figure shows adjusted fatality infection rates by age group.

The investigators noted that the case fatality estimate is lower than the estimates for severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) outbreaks, both caused by coronaviruses, but “is substantially higher than estimates from the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic.”

Earlier reports suggested that the overall fatality rate in China through Feb. 11 was 2.3%. The rate in Hubei province, which is believed to be where the infection started, was 2.9%.

Hospitalizations rise with age

The investigators also estimated the proportion of infected patients who require hospitalization. Their estimation was based on data from a subset of cases reported in mainland China. The hospitalization estimates range from zero among the youngest patients to 18% among the oldest.

“Although China has succeeded in containing the disease spread for 2 months, such containment is unlikely to be achievable in most countries. Thus, much of the world will experience very large community epidemics of COVID-19 over the coming weeks and months. Our estimates of the underlying infection fatality ratio of this virus will inform assessments of health effects likely to be experienced in different countries, and thus decisions around appropriate mitigation policies to be adopted,” Dr. Verity and colleagues concluded.

In his editorial, Dr. Ruan agreed with that assessment. “Although China seems to be out of the woods now, many other countries are facing tremendous pressure from the COVID-19 pandemic,” he wrote. “The strategies of early detection, early diagnosis, early isolation, and early treatment that were practiced in China are likely to be not only useful in controlling the outbreak but also contribute to decreasing the case fatality ratio of the disease.”

The study was supported by the UK Medical Research Council. Dr. Verity and Dr. Ruan have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID-19 experiences from the ob.gyn. front line

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to spread across the United States, several members of the Ob.Gyn. News Editorial Advisory Board shared their experiences.

Catherine Cansino, MD, MPH, who is an associate clinical professor in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of California, Davis, discussed the changes COVID-19 has had on local and regional practice in Sacramento and northern California.

There has been a dramatic increase in telehealth, using video, phone, and apps such as Zoom. Although ob.gyns. at the university are limiting outpatient appointments to essential visits only, we are continuing to offer telehealth to a few nonessential visits. This will be readdressed when the COVID-19 cases peak, Dr. Cansino said.

All patients admitted to labor & delivery undergo COVID-19 testing regardless of symptoms. For patients in the clinic who are expected to be induced or scheduled for cesarean delivery, we are screening them within 72 hours before admission.

In gynecology, only essential or urgent surgeries at UC Davis are being performed and include indications such as cancer, serious benign conditions unresponsive to conservative treatment (e.g., tubo-ovarian abscess, large symptomatic adnexal mass), and pregnancy termination. We are preserving access to abortion and reproductive health services since these are essential services.

We limit the number of providers involved in direct contact with inpatients to one or two, including a physician, nurse, and/or resident, Dr. Cansino said in an interview. Based on recent Liaison Committee on Medical Education policies related to concerns about educational experience during the pandemic, no medical students are allowed at the hospital at present. We also severely restrict the number of visitors in the inpatient and outpatient settings, including only two attendants (partner, doula, and such) during labor and delivery, and consider the impact on patients’ well-being when we restrict their visitors.

We are following University of California guidelines regarding face mask use, which have been in evolution over the last month. Face masks are used for patients and the health care providers primarily when patients either have known COVID-19 infection or are considered as patients under investigation or if the employee had a high-risk exposure. The use of face masks is becoming more permissive, rather than mandatory, to conserve personal protective equipment (PPE) for when the surge arrives.

Education is ongoing about caring for our families and ourselves if we get infected and need to isolate within our own homes. The department and health system is trying to balance the challenges of urgent patient care needs against the wellness concerns for the faculty, staff, and residents. Many physicians are also struggling with childcare problems, which add to our personal stress. There is anxiety among many physicians about exposure to asymptomatic carriers, including themselves, patients, and their families, Dr. Cansino said.

David Forstein, DO, dean and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Touro College of Osteopathic Medicine, New York, said in an interview that the COVID-19 pandemic has “totally disrupted medical education. At almost all medical schools, didactics have moved completely online – ZOOM sessions abound, but labs become demonstrations, if at all, during the preclinical years. The clinical years have been put on hold, as well as student rotations suspended, out of caution for the students because hospitals needed to conserve PPE for the essential personnel and because administrators knew there would be less time for teaching. After initially requesting a pause, many hospitals now are asking students to come back because so many physicians, nurses, and residents have become ill with COVID-19 and either are quarantined or are patients in the hospital themselves.

“There has been a state-by-state call to consider graduating health professions students early, and press them into service, before their residencies actually begin. Some locations are looking for these new graduates to volunteer; some are willing to pay them a resident’s salary level. Medical schools are auditing their student records now to see which students would qualify to graduate early,” Dr. Forstein noted.

David M. Jaspan, DO, chairman of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the Einstein Health Care Network in Philadelphia, described in an email interview how COVID-19 has changed practice.

To minimize the number of providers on the front line, we have developed a Monday to Friday rotating schedule of three teams of five members, he explained. There will be a hospital-based team, an office-based team, and a telehealth-based team who will provide their services from home. On-call responsibilities remain the same.

The hospital team, working 7 a.m. to 5 p.m., will rotate through assignments each day:

- One person will cover labor and delivery.

- One person will cover triage and help on labor and delivery.

- One person will be assigned to the resident office.

- One person will be assigned to cover the team of the post call attending (Sunday through Thursday call).

- One person will be assigned to gynecology coverage, consults, and postpartum rounds.

To further minimize the patient interactions, when possible, each patient should be seen by the attending physician with the resident. This is a change from usual practice, where the patient is first seen by the resident, who reports back to the attending, and then both physicians see the patient together.

The network’s offices now open from 9 a.m. (many offices had been offering early-morning hours starting at 7 a.m.), and the physicians and advanced practice providers will work through the last scheduled patient appointment, Dr. Jaspan explained. “The office-based team will preferentially see in-person visits.”

Several offices have been closed so that ob.gyns. and staff can be reassigned to telehealth. The remaining five offices generally have one attending physician and one advanced practice provider.

The remaining team of ob.gyns. provides telehealth with the help of staff members. This involves an initial call to the patient by staff letting them know the doctor will be calling, checking them in, verifying insurance, and collecting payment, followed by the actual telehealth visit. If follow-up is needed, the staff member schedules the follow-up.

Dr. Jaspan called the new approach to prenatal care because of COVID-19 a “cataclysmic change in how we care for our patients. We have decided to further limit our obstetrical in-person visits. It is our feeling that these changes will enable patients to remain outside of the office and in the safety of their homes, provide appropriate social distancing, and diminish potential exposures to the office staff providers and patients.”

In-person visits will occur at: the initial visit, between 24 and 28 weeks, at 32 weeks, and at 36 or 37 weeks; if the patient at 36/37 has a blood pressure cuff, they will not have additional scheduled in-patient visits. We have partnered with the insurance companies to provide more than 88% of obstetrical patients with home blood pressure cuffs.

Obstetrical visits via telehealth will continue at our standard intervals: monthly until 26 weeks; twice monthly during 26-36 weeks; and weekly from 37 weeks to delivery. These visits should use a video component such as Zoom, Doxy.me, or FaceTime.

“If the patient has concerns or problems, we will see them at any time. However, the new standard will be telehealth visits and the exception will be the in-person visit,” Dr. Jaspan said.

In addition, we have worked our division of maternal-fetal medicine to adjust the antenatal testing schedules, and we have curtailed the frequency of ultrasound, he noted.

He emphasized the importance of documenting telehealth interactions with obstetrical patients, in addition to “providing adequate teaching and education for patients regarding kick counts to ensure fetal well-being.” It also is key to “properly document conversations with patients regarding bleeding, rupture of membranes, fetal movement, headache, visual changes, fevers, cough, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, fatigue, muscle aches, etc.”

The residents’ schedule also has been modified to diminish their exposure. Within our new paradigm, we have scheduled video conferences to enable our program to maintain our commitment to academics.

It is imperative that we keep our patients safe, and it is critical to protect our staff members. Those who provide women’s health cannot be replaced by other nurses or physicians.

Mark P. Trolice, MD, is director of Fertility CARE: the IVF Center in Winter Park, Fla., and professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Central Florida, Orlando. He related in an email interview that, on March 17, 2020, the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) released “Patient Management and Clinical Recommendations During the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic.” This document serves as guidance on fertility care during the current crisis. Specifically, the recommendations include the following:

- Suspend initiation of new treatment cycles, including ovulation induction, intrauterine inseminations, in vitro fertilization including retrievals and frozen embryo transfers, and nonurgent gamete cryopreservation.

- Strongly consider cancellation of all embryo transfers, whether fresh or frozen.

- Continue to care for patients who are currently “in cycle” or who require urgent stimulation and cryopreservation.

- Suspend elective surgeries and nonurgent diagnostic procedures.

- Minimize in-person interactions and increase utilization of telehealth.

As a member of ASRM for more than 2 decades and a participant of several of their committees, my practice immediately ceased treatment cycles to comply with this guidance.

Then on March 20, 2020, the Florida governor’s executive order 20-72 was released, stating, “All hospitals, ambulatory surgical centers, office surgery centers, dental, orthodontic and endodontic offices, and other health care practitioners’ offices in the State of Florida are prohibited from providing any medically unnecessary, nonurgent or nonemergency procedure or surgery which, if delayed, does not place a patient’s immediate health, safety, or well-being at risk, or will, if delayed, not contribute to the worsening of a serious or life-threatening medical condition.”

As a result, my practice has been limited to telemedicine consultations. While the ASRM guidance and the gubernatorial executive order pose a significant financial hardship on my center and all applicable medical clinics in my state, resulting in expected layoffs, salary reductions, and requests for government stimulus loans, the greater good takes priority and we pray for all the victims of this devastating pandemic.

The governor’s current executive order is set to expire on May 9, 2020, unless it is extended.

ASRM released an update of their guidance on March 30, 2020, offering no change from their prior recommendations. The organization plans to reevaluate the guidance at 2-week intervals.

Sangeeta Sinha, MD, an ob.gyn. in private practice at Stone Springs Hospital Center, Dulles, Va. said in an interview, “COVID 19 has put fear in all aspects of our daily activities which we are attempting to cope with.”

She related several changes made to her office and hospital environments. “In our office, we are now wearing a mask at all times, gloves to examine every patient. We have staggered physicians in the office to take televisits and in-office patients. We are screening all new patients on the phone to determine if they are sick, have traveled to high-risk, hot spot areas of the country, or have had contact with someone who tested positive for COVID-19. We are only seeing our pregnant women and have also pushed out their return appointments to 4 weeks if possible. There are several staff who are not working due to fear or are in self quarantine so we have shortage of staff in the office. At the hospital as well we are wearing a mask at all times, using personal protective equipment for deliveries and C-sections.

“We have had several scares, including a new transfer of an 18-year-old pregnant patient at 30 weeks with cough and sore throat, who later reported that her roommate is very sick and he works with someone who has tested positive for COVID-19. Thankfully she is healthy and well. We learned several lessons from this one.”

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to spread across the United States, several members of the Ob.Gyn. News Editorial Advisory Board shared their experiences.

Catherine Cansino, MD, MPH, who is an associate clinical professor in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of California, Davis, discussed the changes COVID-19 has had on local and regional practice in Sacramento and northern California.

There has been a dramatic increase in telehealth, using video, phone, and apps such as Zoom. Although ob.gyns. at the university are limiting outpatient appointments to essential visits only, we are continuing to offer telehealth to a few nonessential visits. This will be readdressed when the COVID-19 cases peak, Dr. Cansino said.

All patients admitted to labor & delivery undergo COVID-19 testing regardless of symptoms. For patients in the clinic who are expected to be induced or scheduled for cesarean delivery, we are screening them within 72 hours before admission.

In gynecology, only essential or urgent surgeries at UC Davis are being performed and include indications such as cancer, serious benign conditions unresponsive to conservative treatment (e.g., tubo-ovarian abscess, large symptomatic adnexal mass), and pregnancy termination. We are preserving access to abortion and reproductive health services since these are essential services.

We limit the number of providers involved in direct contact with inpatients to one or two, including a physician, nurse, and/or resident, Dr. Cansino said in an interview. Based on recent Liaison Committee on Medical Education policies related to concerns about educational experience during the pandemic, no medical students are allowed at the hospital at present. We also severely restrict the number of visitors in the inpatient and outpatient settings, including only two attendants (partner, doula, and such) during labor and delivery, and consider the impact on patients’ well-being when we restrict their visitors.

We are following University of California guidelines regarding face mask use, which have been in evolution over the last month. Face masks are used for patients and the health care providers primarily when patients either have known COVID-19 infection or are considered as patients under investigation or if the employee had a high-risk exposure. The use of face masks is becoming more permissive, rather than mandatory, to conserve personal protective equipment (PPE) for when the surge arrives.

Education is ongoing about caring for our families and ourselves if we get infected and need to isolate within our own homes. The department and health system is trying to balance the challenges of urgent patient care needs against the wellness concerns for the faculty, staff, and residents. Many physicians are also struggling with childcare problems, which add to our personal stress. There is anxiety among many physicians about exposure to asymptomatic carriers, including themselves, patients, and their families, Dr. Cansino said.