User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Some, not all, ultraprocessed foods linked to type 2 diabetes

High total intake of ultraprocessed food (UPF) is associated with an increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes, suggests a large-scale analysis that nevertheless revealed that the risk applies only to certain such foods.

The research was recently published in Diabetes Care by Zhangling Chen, PhD, Erasmus MC Rotterdam, Netherlands, and colleagues.

Examining almost 200,000 participants in three U.S. studies, yielding more than 5 million person-years of follow-up, the scientists found that high intake of UPF was associated with a 28% increased risk of type 2 diabetes, after statistical adjustments.

However, the increased risk was restricted to certain UPFs, including ready meals, refined breads, sweetened beverages, and sauces and condiments, with other foods considered UPFs, such as cereals, dark- and whole grain breads, and packaged sweet and savory snacks, among others, associated with a reduced risk of diabetes.

Senior author Jean-Philippe Drouin-Chartier, PhD, Nutrition Center, Laval University, Quebec City, told this news organization: “While whole grain breads can be considered as ultraprocessed foods, their consumption should not be discouraged. In our study, we observed that whole grain breads consumption is inversely associated with type 2 diabetes risk. This is supported by many studies linking dietary fiber consumption to better cardiometabolic health.”

Ultraprocessed food intake higher in the U.S. than in Europe

The researchers note that a handful of European studies have also reported an association between UPF consumption and increased type 2 diabetes risk, with the effect ranging from 15% to 53%, depending on the level of intake and the cohort of patients studied.

They note, however, that total UPF intake in the U.S. is “much higher than in Europe,” particularly in the case of ultraprocessed breads and cereals and artificially or sugar-sweetened beverages.

In the current study, they examined data on 71,781 women from the Nurses’ Health Study, 87,918 women from the NHS II, and 38,847 men from the Health Professional Follow-up Study, none of whom had cardiovascular disease, cancer, or diabetes at baseline.

In all three studies, questionnaires were administered every 2 years to collect demographic, lifestyle, and medical information, and a validated food frequency questionnaire was used every 2-4 years to assess participants’ diets over 30 years of follow-up.

Using the NOVA Food Classification system, the items on the food frequency questionnaire were categorized into one of four groups: unprocessed or minimally processed foods; processed culinary ingredients; processed foods; or UPFs, which were subdivided into nine mutually exclusive subgroups.

Servings per day were then used to determine individual UPF intake.

Higher total UPF intake was associated with a greater total energy intake, body mass index, and prevalence of hypercholesterolemia and/or hypertension, as well as lower healthy eating scores and physical activity.

The researchers calculated that, over 5,187,678 person-years of follow-up, there were 19,503 cases of type 2 diabetes across the three study cohorts.

Multivariate analysis taking into consideration a range of potential risk factors, including BMI, revealed that, across the three study cohorts, the highest quintile of UPF intake was associated with a significantly increased risk of type 2 diabetes.

Compared with the lowest quintile of UPF intake, the hazard ratio for incident type 2 diabetes was 1.28 (P < .0001), with an increase in risk per additional serving per day of 3%.

The UPFs associated with a higher type 2 diabetes risk were as previously described and also included animal-based products and ready-to-eat mixed dishes.

In contrast, intake of UPFs including cereals, dark and whole grain breads, packaged sweet and savory snacks, fruit-based products, and yogurt and dairy-based desserts were linked to a reduced risk of type 2 diabetes.

Then to further validate their findings, the researchers conducted a meta-analysis of their own and four additional studies, comprising 415,554 participants and 21,932 events, with a follow-up of 3.4-32.0 years.

They determined that the pooled relative risk of type 2 diabetes with the highest versus lowest levels of UPF consumption was 1.40, with each 10% increase in total UPF intake associated with a 12% increase in diabetes risk.

Ideal is to have access to minimally processed foods

The NOVA food classification system states that UPFs are industrial formulations “made mostly or entirely with substances extracted from foods, often chemically modified, with additives and with little, if any, whole foods added.”

A recent study questioned the value of the NOVA classification after finding that it had “low consistency” when assigning foods.

Previous studies have nevertheless revealed that UPFs and their constituents negatively affect the gut microbiota and can cause systemic inflammation, insulin resistance, and increased body weight.

Dr. Drouin-Chartier concluded: “There is a need to facilitate ... access to minimally processed foods. This encompasses [appropriate] pricing and physical access [to such foods], that is, addressing the issue of food deserts.”

The NHS I and II and HPFS studies are supported by National Institutes of Health. Dr. Drouin-Chartier has reported a relationship with the Dairy Farmers of Canada. No other financial relationships were declared.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

High total intake of ultraprocessed food (UPF) is associated with an increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes, suggests a large-scale analysis that nevertheless revealed that the risk applies only to certain such foods.

The research was recently published in Diabetes Care by Zhangling Chen, PhD, Erasmus MC Rotterdam, Netherlands, and colleagues.

Examining almost 200,000 participants in three U.S. studies, yielding more than 5 million person-years of follow-up, the scientists found that high intake of UPF was associated with a 28% increased risk of type 2 diabetes, after statistical adjustments.

However, the increased risk was restricted to certain UPFs, including ready meals, refined breads, sweetened beverages, and sauces and condiments, with other foods considered UPFs, such as cereals, dark- and whole grain breads, and packaged sweet and savory snacks, among others, associated with a reduced risk of diabetes.

Senior author Jean-Philippe Drouin-Chartier, PhD, Nutrition Center, Laval University, Quebec City, told this news organization: “While whole grain breads can be considered as ultraprocessed foods, their consumption should not be discouraged. In our study, we observed that whole grain breads consumption is inversely associated with type 2 diabetes risk. This is supported by many studies linking dietary fiber consumption to better cardiometabolic health.”

Ultraprocessed food intake higher in the U.S. than in Europe

The researchers note that a handful of European studies have also reported an association between UPF consumption and increased type 2 diabetes risk, with the effect ranging from 15% to 53%, depending on the level of intake and the cohort of patients studied.

They note, however, that total UPF intake in the U.S. is “much higher than in Europe,” particularly in the case of ultraprocessed breads and cereals and artificially or sugar-sweetened beverages.

In the current study, they examined data on 71,781 women from the Nurses’ Health Study, 87,918 women from the NHS II, and 38,847 men from the Health Professional Follow-up Study, none of whom had cardiovascular disease, cancer, or diabetes at baseline.

In all three studies, questionnaires were administered every 2 years to collect demographic, lifestyle, and medical information, and a validated food frequency questionnaire was used every 2-4 years to assess participants’ diets over 30 years of follow-up.

Using the NOVA Food Classification system, the items on the food frequency questionnaire were categorized into one of four groups: unprocessed or minimally processed foods; processed culinary ingredients; processed foods; or UPFs, which were subdivided into nine mutually exclusive subgroups.

Servings per day were then used to determine individual UPF intake.

Higher total UPF intake was associated with a greater total energy intake, body mass index, and prevalence of hypercholesterolemia and/or hypertension, as well as lower healthy eating scores and physical activity.

The researchers calculated that, over 5,187,678 person-years of follow-up, there were 19,503 cases of type 2 diabetes across the three study cohorts.

Multivariate analysis taking into consideration a range of potential risk factors, including BMI, revealed that, across the three study cohorts, the highest quintile of UPF intake was associated with a significantly increased risk of type 2 diabetes.

Compared with the lowest quintile of UPF intake, the hazard ratio for incident type 2 diabetes was 1.28 (P < .0001), with an increase in risk per additional serving per day of 3%.

The UPFs associated with a higher type 2 diabetes risk were as previously described and also included animal-based products and ready-to-eat mixed dishes.

In contrast, intake of UPFs including cereals, dark and whole grain breads, packaged sweet and savory snacks, fruit-based products, and yogurt and dairy-based desserts were linked to a reduced risk of type 2 diabetes.

Then to further validate their findings, the researchers conducted a meta-analysis of their own and four additional studies, comprising 415,554 participants and 21,932 events, with a follow-up of 3.4-32.0 years.

They determined that the pooled relative risk of type 2 diabetes with the highest versus lowest levels of UPF consumption was 1.40, with each 10% increase in total UPF intake associated with a 12% increase in diabetes risk.

Ideal is to have access to minimally processed foods

The NOVA food classification system states that UPFs are industrial formulations “made mostly or entirely with substances extracted from foods, often chemically modified, with additives and with little, if any, whole foods added.”

A recent study questioned the value of the NOVA classification after finding that it had “low consistency” when assigning foods.

Previous studies have nevertheless revealed that UPFs and their constituents negatively affect the gut microbiota and can cause systemic inflammation, insulin resistance, and increased body weight.

Dr. Drouin-Chartier concluded: “There is a need to facilitate ... access to minimally processed foods. This encompasses [appropriate] pricing and physical access [to such foods], that is, addressing the issue of food deserts.”

The NHS I and II and HPFS studies are supported by National Institutes of Health. Dr. Drouin-Chartier has reported a relationship with the Dairy Farmers of Canada. No other financial relationships were declared.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

High total intake of ultraprocessed food (UPF) is associated with an increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes, suggests a large-scale analysis that nevertheless revealed that the risk applies only to certain such foods.

The research was recently published in Diabetes Care by Zhangling Chen, PhD, Erasmus MC Rotterdam, Netherlands, and colleagues.

Examining almost 200,000 participants in three U.S. studies, yielding more than 5 million person-years of follow-up, the scientists found that high intake of UPF was associated with a 28% increased risk of type 2 diabetes, after statistical adjustments.

However, the increased risk was restricted to certain UPFs, including ready meals, refined breads, sweetened beverages, and sauces and condiments, with other foods considered UPFs, such as cereals, dark- and whole grain breads, and packaged sweet and savory snacks, among others, associated with a reduced risk of diabetes.

Senior author Jean-Philippe Drouin-Chartier, PhD, Nutrition Center, Laval University, Quebec City, told this news organization: “While whole grain breads can be considered as ultraprocessed foods, their consumption should not be discouraged. In our study, we observed that whole grain breads consumption is inversely associated with type 2 diabetes risk. This is supported by many studies linking dietary fiber consumption to better cardiometabolic health.”

Ultraprocessed food intake higher in the U.S. than in Europe

The researchers note that a handful of European studies have also reported an association between UPF consumption and increased type 2 diabetes risk, with the effect ranging from 15% to 53%, depending on the level of intake and the cohort of patients studied.

They note, however, that total UPF intake in the U.S. is “much higher than in Europe,” particularly in the case of ultraprocessed breads and cereals and artificially or sugar-sweetened beverages.

In the current study, they examined data on 71,781 women from the Nurses’ Health Study, 87,918 women from the NHS II, and 38,847 men from the Health Professional Follow-up Study, none of whom had cardiovascular disease, cancer, or diabetes at baseline.

In all three studies, questionnaires were administered every 2 years to collect demographic, lifestyle, and medical information, and a validated food frequency questionnaire was used every 2-4 years to assess participants’ diets over 30 years of follow-up.

Using the NOVA Food Classification system, the items on the food frequency questionnaire were categorized into one of four groups: unprocessed or minimally processed foods; processed culinary ingredients; processed foods; or UPFs, which were subdivided into nine mutually exclusive subgroups.

Servings per day were then used to determine individual UPF intake.

Higher total UPF intake was associated with a greater total energy intake, body mass index, and prevalence of hypercholesterolemia and/or hypertension, as well as lower healthy eating scores and physical activity.

The researchers calculated that, over 5,187,678 person-years of follow-up, there were 19,503 cases of type 2 diabetes across the three study cohorts.

Multivariate analysis taking into consideration a range of potential risk factors, including BMI, revealed that, across the three study cohorts, the highest quintile of UPF intake was associated with a significantly increased risk of type 2 diabetes.

Compared with the lowest quintile of UPF intake, the hazard ratio for incident type 2 diabetes was 1.28 (P < .0001), with an increase in risk per additional serving per day of 3%.

The UPFs associated with a higher type 2 diabetes risk were as previously described and also included animal-based products and ready-to-eat mixed dishes.

In contrast, intake of UPFs including cereals, dark and whole grain breads, packaged sweet and savory snacks, fruit-based products, and yogurt and dairy-based desserts were linked to a reduced risk of type 2 diabetes.

Then to further validate their findings, the researchers conducted a meta-analysis of their own and four additional studies, comprising 415,554 participants and 21,932 events, with a follow-up of 3.4-32.0 years.

They determined that the pooled relative risk of type 2 diabetes with the highest versus lowest levels of UPF consumption was 1.40, with each 10% increase in total UPF intake associated with a 12% increase in diabetes risk.

Ideal is to have access to minimally processed foods

The NOVA food classification system states that UPFs are industrial formulations “made mostly or entirely with substances extracted from foods, often chemically modified, with additives and with little, if any, whole foods added.”

A recent study questioned the value of the NOVA classification after finding that it had “low consistency” when assigning foods.

Previous studies have nevertheless revealed that UPFs and their constituents negatively affect the gut microbiota and can cause systemic inflammation, insulin resistance, and increased body weight.

Dr. Drouin-Chartier concluded: “There is a need to facilitate ... access to minimally processed foods. This encompasses [appropriate] pricing and physical access [to such foods], that is, addressing the issue of food deserts.”

The NHS I and II and HPFS studies are supported by National Institutes of Health. Dr. Drouin-Chartier has reported a relationship with the Dairy Farmers of Canada. No other financial relationships were declared.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM DIABETES CARE

Spironolactone: an ‘inexpensive, effective’ option for acne in women

HONOLULU – In the clinical experience of Julie C. Harper, MD, an increasing number of women with acne are turning to off-label, long-term treatment with spironolactone.

“Spironolactone is fairly accessible, inexpensive, and effective for our patients,” Dr. Harper, a dermatologist who practices in Birmingham, Ala., said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by MedscapeLIVE!

An aldosterone receptor antagonist commonly used to treat high blood pressure and heart failure, spironolactone also has antiandrogenic properties with a proven track record for treating acne and hirsutism. It reduces androgen production, inhibits 5-alpha reductase, and increases sex hormone binding globulin. The dosing range for treating acne is 25 mg to 200 mg per day, but Dr. Harper prefers a maximum dose of 100 mg per day.

According to a systematic review of its use for acne in adult women, the most common side effect is menstrual irregularity, while other common side effects include breast tenderness/swelling, fatigue, and headaches.

“The higher the dose, the higher the rate of side effects,” she said. Concomitant use of an oral contraceptive lessens menstrual irregularities and prevents pregnancies, to avoid exposure during pregnancy and the hypothetical risk of feminization of the male fetus with exposure late in the first trimester. “Early in my career, I used to say if you’re going to be on spironolactone you’re also going to be on an oral contraceptive. But the longer I’ve practiced, I’ve learned that women who have a contraindication to birth control pills or who don’t want to take it can still benefit from an oral antiandrogen by being on spironolactone.”

A large retrospective analysis of 14-year data concluded that routine potassium monitoring is unnecessary for healthy women taking spironolactone for acne. “If you’re between the ages of 18 and 45, healthy, and not taking other medications where I’m worried about potassium levels, I’m not checking those levels at all,” Dr. Harper said.

Spironolactone labeling includes a boxed warning regarding the potential for tumorigenicity based on rat studies, but the dosages used in those studies were 25-250 times higher than the exposure dose in humans, Dr. Harper said.

Results from a systematic review and meta-analysis of seven studies in the medical literature found no evidence of an increased risk of breast cancer in women with exposure to spironolactone. “However, the certainty of the evidence was low and future studies are needed, including among diverse populations such as younger individuals and those with acne or hirsutism,” the study authors wrote.

In a separate study, researchers drew from patients in the Humana Insurance database from 2005 to 2017 to address whether spironolactone is associated with an increased risk of recurrence of breast cancer. Recurrent breast cancer was examined in 29,146 women with continuous health insurance for 2 years after a diagnosis of breast cancer. Of these, 746 were prescribed spironolactone, and the remainder were not. The researchers found that 123 women (16.5%) who were prescribed spironolactone had a breast cancer recurrence, compared with 3,649 women (12.8%) with a breast cancer recurrence who had not been prescribed spironolactone (P = .004). Adjusted Cox regression analysis following propensity matching showed no association between spironolactone and increased breast cancer recurrence (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.966; P = .953).

According to Dr. Harper, spironolactone may take about 3 months to kick in. “Likely this is a long-term treatment, and most of the time we’re going to be using it in combination with other acne treatments such as topical retinoids or topical benzoyl peroxide, oral antibiotics, or even isotretinoin.”

A study of long-term spironolactone use in 403 women found that the most common dose prescribed was 100 mg/day, and 68% of the women were concurrently prescribed a topical retinoid, 2.2% an oral antibiotic, and 40.7% an oral contraceptive.

The study population included 32 patients with a history of polycystic ovarian syndrome, 1 with a history of breast cancer, and 5 were hypercoagulable. Patients took the drug for a mean of 471 days. “As opposed to our antibiotics, where the course for patients is generally 3-4 months, when you start someone on spironolactone, they may end up staying on it,” Dr. Harper said.

Dr. Harper disclosed that she serves as an advisor or consultant for Almirall, Cassiopeia, Cutera, EPI, Galderma, L’Oreal, Ortho Dermatologics, Sol Gel, and Vyne. She also serves as a speaker or member of a speaker’s bureau for Almirall, Cassiopeia, Cutera, EPI, Galderma, Journey Almirall, L’Oreal, Ortho Dermatologics, Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, and Vyne.

Medscape and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

HONOLULU – In the clinical experience of Julie C. Harper, MD, an increasing number of women with acne are turning to off-label, long-term treatment with spironolactone.

“Spironolactone is fairly accessible, inexpensive, and effective for our patients,” Dr. Harper, a dermatologist who practices in Birmingham, Ala., said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by MedscapeLIVE!

An aldosterone receptor antagonist commonly used to treat high blood pressure and heart failure, spironolactone also has antiandrogenic properties with a proven track record for treating acne and hirsutism. It reduces androgen production, inhibits 5-alpha reductase, and increases sex hormone binding globulin. The dosing range for treating acne is 25 mg to 200 mg per day, but Dr. Harper prefers a maximum dose of 100 mg per day.

According to a systematic review of its use for acne in adult women, the most common side effect is menstrual irregularity, while other common side effects include breast tenderness/swelling, fatigue, and headaches.

“The higher the dose, the higher the rate of side effects,” she said. Concomitant use of an oral contraceptive lessens menstrual irregularities and prevents pregnancies, to avoid exposure during pregnancy and the hypothetical risk of feminization of the male fetus with exposure late in the first trimester. “Early in my career, I used to say if you’re going to be on spironolactone you’re also going to be on an oral contraceptive. But the longer I’ve practiced, I’ve learned that women who have a contraindication to birth control pills or who don’t want to take it can still benefit from an oral antiandrogen by being on spironolactone.”

A large retrospective analysis of 14-year data concluded that routine potassium monitoring is unnecessary for healthy women taking spironolactone for acne. “If you’re between the ages of 18 and 45, healthy, and not taking other medications where I’m worried about potassium levels, I’m not checking those levels at all,” Dr. Harper said.

Spironolactone labeling includes a boxed warning regarding the potential for tumorigenicity based on rat studies, but the dosages used in those studies were 25-250 times higher than the exposure dose in humans, Dr. Harper said.

Results from a systematic review and meta-analysis of seven studies in the medical literature found no evidence of an increased risk of breast cancer in women with exposure to spironolactone. “However, the certainty of the evidence was low and future studies are needed, including among diverse populations such as younger individuals and those with acne or hirsutism,” the study authors wrote.

In a separate study, researchers drew from patients in the Humana Insurance database from 2005 to 2017 to address whether spironolactone is associated with an increased risk of recurrence of breast cancer. Recurrent breast cancer was examined in 29,146 women with continuous health insurance for 2 years after a diagnosis of breast cancer. Of these, 746 were prescribed spironolactone, and the remainder were not. The researchers found that 123 women (16.5%) who were prescribed spironolactone had a breast cancer recurrence, compared with 3,649 women (12.8%) with a breast cancer recurrence who had not been prescribed spironolactone (P = .004). Adjusted Cox regression analysis following propensity matching showed no association between spironolactone and increased breast cancer recurrence (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.966; P = .953).

According to Dr. Harper, spironolactone may take about 3 months to kick in. “Likely this is a long-term treatment, and most of the time we’re going to be using it in combination with other acne treatments such as topical retinoids or topical benzoyl peroxide, oral antibiotics, or even isotretinoin.”

A study of long-term spironolactone use in 403 women found that the most common dose prescribed was 100 mg/day, and 68% of the women were concurrently prescribed a topical retinoid, 2.2% an oral antibiotic, and 40.7% an oral contraceptive.

The study population included 32 patients with a history of polycystic ovarian syndrome, 1 with a history of breast cancer, and 5 were hypercoagulable. Patients took the drug for a mean of 471 days. “As opposed to our antibiotics, where the course for patients is generally 3-4 months, when you start someone on spironolactone, they may end up staying on it,” Dr. Harper said.

Dr. Harper disclosed that she serves as an advisor or consultant for Almirall, Cassiopeia, Cutera, EPI, Galderma, L’Oreal, Ortho Dermatologics, Sol Gel, and Vyne. She also serves as a speaker or member of a speaker’s bureau for Almirall, Cassiopeia, Cutera, EPI, Galderma, Journey Almirall, L’Oreal, Ortho Dermatologics, Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, and Vyne.

Medscape and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

HONOLULU – In the clinical experience of Julie C. Harper, MD, an increasing number of women with acne are turning to off-label, long-term treatment with spironolactone.

“Spironolactone is fairly accessible, inexpensive, and effective for our patients,” Dr. Harper, a dermatologist who practices in Birmingham, Ala., said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by MedscapeLIVE!

An aldosterone receptor antagonist commonly used to treat high blood pressure and heart failure, spironolactone also has antiandrogenic properties with a proven track record for treating acne and hirsutism. It reduces androgen production, inhibits 5-alpha reductase, and increases sex hormone binding globulin. The dosing range for treating acne is 25 mg to 200 mg per day, but Dr. Harper prefers a maximum dose of 100 mg per day.

According to a systematic review of its use for acne in adult women, the most common side effect is menstrual irregularity, while other common side effects include breast tenderness/swelling, fatigue, and headaches.

“The higher the dose, the higher the rate of side effects,” she said. Concomitant use of an oral contraceptive lessens menstrual irregularities and prevents pregnancies, to avoid exposure during pregnancy and the hypothetical risk of feminization of the male fetus with exposure late in the first trimester. “Early in my career, I used to say if you’re going to be on spironolactone you’re also going to be on an oral contraceptive. But the longer I’ve practiced, I’ve learned that women who have a contraindication to birth control pills or who don’t want to take it can still benefit from an oral antiandrogen by being on spironolactone.”

A large retrospective analysis of 14-year data concluded that routine potassium monitoring is unnecessary for healthy women taking spironolactone for acne. “If you’re between the ages of 18 and 45, healthy, and not taking other medications where I’m worried about potassium levels, I’m not checking those levels at all,” Dr. Harper said.

Spironolactone labeling includes a boxed warning regarding the potential for tumorigenicity based on rat studies, but the dosages used in those studies were 25-250 times higher than the exposure dose in humans, Dr. Harper said.

Results from a systematic review and meta-analysis of seven studies in the medical literature found no evidence of an increased risk of breast cancer in women with exposure to spironolactone. “However, the certainty of the evidence was low and future studies are needed, including among diverse populations such as younger individuals and those with acne or hirsutism,” the study authors wrote.

In a separate study, researchers drew from patients in the Humana Insurance database from 2005 to 2017 to address whether spironolactone is associated with an increased risk of recurrence of breast cancer. Recurrent breast cancer was examined in 29,146 women with continuous health insurance for 2 years after a diagnosis of breast cancer. Of these, 746 were prescribed spironolactone, and the remainder were not. The researchers found that 123 women (16.5%) who were prescribed spironolactone had a breast cancer recurrence, compared with 3,649 women (12.8%) with a breast cancer recurrence who had not been prescribed spironolactone (P = .004). Adjusted Cox regression analysis following propensity matching showed no association between spironolactone and increased breast cancer recurrence (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.966; P = .953).

According to Dr. Harper, spironolactone may take about 3 months to kick in. “Likely this is a long-term treatment, and most of the time we’re going to be using it in combination with other acne treatments such as topical retinoids or topical benzoyl peroxide, oral antibiotics, or even isotretinoin.”

A study of long-term spironolactone use in 403 women found that the most common dose prescribed was 100 mg/day, and 68% of the women were concurrently prescribed a topical retinoid, 2.2% an oral antibiotic, and 40.7% an oral contraceptive.

The study population included 32 patients with a history of polycystic ovarian syndrome, 1 with a history of breast cancer, and 5 were hypercoagulable. Patients took the drug for a mean of 471 days. “As opposed to our antibiotics, where the course for patients is generally 3-4 months, when you start someone on spironolactone, they may end up staying on it,” Dr. Harper said.

Dr. Harper disclosed that she serves as an advisor or consultant for Almirall, Cassiopeia, Cutera, EPI, Galderma, L’Oreal, Ortho Dermatologics, Sol Gel, and Vyne. She also serves as a speaker or member of a speaker’s bureau for Almirall, Cassiopeia, Cutera, EPI, Galderma, Journey Almirall, L’Oreal, Ortho Dermatologics, Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, and Vyne.

Medscape and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

AT THE MEDSCAPELIVE! HAWAII DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

TikTok’s fave weight loss drugs: Link to thyroid cancer?

With #Ozempic and #ozempicweightloss continuing to trend on social media, along with the mainstream media focusing on celebrities who rely on Ozempic (semaglutide) for weight loss, the daily requests for this new medication have been increasing.

Accompanying these requests are concerns and questions about potential risks, including this most recent message from one of my patients: “Dr. P – I saw the warnings. Is this medication going to make me get thyroid cancer? Please let me know!”

Let’s look at what we know to date, including recent studies, and how to advise our patients on this very hot topic.

Using GLP-1 receptor agonists for obesity

We have extensive prior experience with glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, such as semaglutide, for treating type 2 diabetes and now recently as agents for weight loss.

Large clinical trials have documented the benefits of this medication class not only for weight reduction but also for cardiovascular and renal benefits in patients with diabetes. The subcutaneously injectable medications work by promoting insulin secretion, slowing gastric emptying, and suppressing glucagon secretion, with a low risk for hypoglycemia.

The Food and Drug Administration approved daily-injection GLP-1 agonist liraglutide for weight loss in 2014, and weekly-injection semaglutide for chronic weight management in 2021, in patients with a body mass index ≥ 27 with at least one weight-related condition or a BMI ≥ 30.

The brand name for semaglutide approved for weight loss is Wegovy, and the dose is slightly higher (maximum 2.4 mg/wk) than that of Ozempic (maximum 2.0 mg/wk), which is semaglutide approved for type 2 diabetes.

In trials for weight loss, data showed a mean change in body weight of almost 15% in the semaglutide group at week 68 compared with placebo, which is very impressive, particularly compared with other FDA-approved oral long-term weight loss medications.

The newest synthetic dual-acting agent is tirzepatide, which targets GLP-1 but is also a glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) agonist. The weekly subcutaneous injection was approved in May 2022 as Mounjaro for treating type 2 diabetes and produced even greater weight loss than semaglutide in clinical trials. Tirzepatide is now in trials for obesity and is under expedited review by the FDA for weight loss.

Why the concern about thyroid cancer?

Early on with the FDA approvals of GLP-1 agonists, a warning accompanied the products’ labels to not use this class of medications in patients with medullary thyroid cancer, a family history of medullary thyroid cancer, or multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 2. This warning was based on data from animal studies.

Human pancreatic cells aren’t the only cells that express GLP-1 receptors. These receptors are also expressed by parafollicular cells (C cells) of the thyroid, which secrete calcitonin and are the cells involved in medullary thyroid cancer. A dose-related and duration-dependent increase in thyroid C-cell tumor incidence was noted in rodents. The same relationship was not demonstrated in monkeys. Humans have far fewer C cells than rats, and human C cells have very low expression of the GLP-1 receptor.

Over a decade ago, a study examining the FDA’s database of reported adverse events found an increased risk for thyroid cancer in patients treated with exenatide, another GLP-1 agonist. The reporting system wasn’t designed to distinguish thyroid cancer subtypes.

Numerous subsequent studies didn’t confirm this relationship. The LEADER trial looked at liraglutide in patients with type 2 diabetes and showed no effect of GLP-1 receptor activation on human serum calcitonin levels, C-cell proliferation, or C-cell malignancy. Similarly, a large meta-analysis in patients with type 2 diabetes didn’t find a statistically increased risk for thyroid cancer with liraglutide, and no thyroid malignancies were reported with exenatide.

Two U.S. administrative databases from commercial health plans (a retrospective cohort study and a nested case-control study) compared type 2 diabetes patients who were taking exenatide vs. other antidiabetic drugs and found that exenatide was not significantly associated with an increased risk for thyroid cancer.

And a recent meta-analysis of 45 trials showed no significant effects on the occurrence of thyroid cancer with GLP-1 receptor agonists. Of note, it did find an increased risk for overall thyroid disorders, although there was no clear statistically significant finding pointing to a specific thyroid disorder.

Differing from prior studies, a recent nationwide French health care system study provided newer data suggesting a moderate increased risk for thyroid cancer in a cohort of patients with type 2 diabetes who were taking GLP-1 agonists. The increase in relative risk was noted for all types of thyroid cancer in patients using GLP-1 receptor agonists for 1-3 years.

An accompanying commentary by Caroline A. Thompson, PhD, and Til Stürmer, MD, provides perspective on this study’s potential limitations. These include detection bias, as the study results focused only on the statistically significant data. Also discussed were limitations to the case-control design, issues with claims-based tumor type classification (unavailability of surgical pathology), and an inability to adjust for family history and obesity, which is a risk factor alone for thyroid cancer. There was also no adjustment for exposure to head/neck radiation.

While this study has important findings to consider, it deserves further investigation, with future studies linking data to tumor registry data before a change is made in clinical practice.

No clear relationship has been drawn between GLP-1 receptor agonists and thyroid cancer in humans. Numerous confounding factors limit the data. Studies generally don’t specify the type of thyroid cancer, and they lump medullary thyroid cancer, the rarest form, with papillary thyroid cancer.

Is a detection bias present where weight loss makes nodules more visible on the neck among those treated with GLP-1 agonists? And/or are patients treated with GLP-1 agonists being screened more stringently for thyroid nodules and/or cancer?

How to advise our patients and respond to the EMR messages

The TikTok videos may continue, the celebrity chatter may increase, and we, as physicians, will continue to look to real-world data with randomized controlled trials to tailor our decision-making and guide our patients.

Thyroid cancer remains a rare outcome, and GLP-1 receptor agonists remain a very important and beneficial treatment option for the right patient.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

With #Ozempic and #ozempicweightloss continuing to trend on social media, along with the mainstream media focusing on celebrities who rely on Ozempic (semaglutide) for weight loss, the daily requests for this new medication have been increasing.

Accompanying these requests are concerns and questions about potential risks, including this most recent message from one of my patients: “Dr. P – I saw the warnings. Is this medication going to make me get thyroid cancer? Please let me know!”

Let’s look at what we know to date, including recent studies, and how to advise our patients on this very hot topic.

Using GLP-1 receptor agonists for obesity

We have extensive prior experience with glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, such as semaglutide, for treating type 2 diabetes and now recently as agents for weight loss.

Large clinical trials have documented the benefits of this medication class not only for weight reduction but also for cardiovascular and renal benefits in patients with diabetes. The subcutaneously injectable medications work by promoting insulin secretion, slowing gastric emptying, and suppressing glucagon secretion, with a low risk for hypoglycemia.

The Food and Drug Administration approved daily-injection GLP-1 agonist liraglutide for weight loss in 2014, and weekly-injection semaglutide for chronic weight management in 2021, in patients with a body mass index ≥ 27 with at least one weight-related condition or a BMI ≥ 30.

The brand name for semaglutide approved for weight loss is Wegovy, and the dose is slightly higher (maximum 2.4 mg/wk) than that of Ozempic (maximum 2.0 mg/wk), which is semaglutide approved for type 2 diabetes.

In trials for weight loss, data showed a mean change in body weight of almost 15% in the semaglutide group at week 68 compared with placebo, which is very impressive, particularly compared with other FDA-approved oral long-term weight loss medications.

The newest synthetic dual-acting agent is tirzepatide, which targets GLP-1 but is also a glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) agonist. The weekly subcutaneous injection was approved in May 2022 as Mounjaro for treating type 2 diabetes and produced even greater weight loss than semaglutide in clinical trials. Tirzepatide is now in trials for obesity and is under expedited review by the FDA for weight loss.

Why the concern about thyroid cancer?

Early on with the FDA approvals of GLP-1 agonists, a warning accompanied the products’ labels to not use this class of medications in patients with medullary thyroid cancer, a family history of medullary thyroid cancer, or multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 2. This warning was based on data from animal studies.

Human pancreatic cells aren’t the only cells that express GLP-1 receptors. These receptors are also expressed by parafollicular cells (C cells) of the thyroid, which secrete calcitonin and are the cells involved in medullary thyroid cancer. A dose-related and duration-dependent increase in thyroid C-cell tumor incidence was noted in rodents. The same relationship was not demonstrated in monkeys. Humans have far fewer C cells than rats, and human C cells have very low expression of the GLP-1 receptor.

Over a decade ago, a study examining the FDA’s database of reported adverse events found an increased risk for thyroid cancer in patients treated with exenatide, another GLP-1 agonist. The reporting system wasn’t designed to distinguish thyroid cancer subtypes.

Numerous subsequent studies didn’t confirm this relationship. The LEADER trial looked at liraglutide in patients with type 2 diabetes and showed no effect of GLP-1 receptor activation on human serum calcitonin levels, C-cell proliferation, or C-cell malignancy. Similarly, a large meta-analysis in patients with type 2 diabetes didn’t find a statistically increased risk for thyroid cancer with liraglutide, and no thyroid malignancies were reported with exenatide.

Two U.S. administrative databases from commercial health plans (a retrospective cohort study and a nested case-control study) compared type 2 diabetes patients who were taking exenatide vs. other antidiabetic drugs and found that exenatide was not significantly associated with an increased risk for thyroid cancer.

And a recent meta-analysis of 45 trials showed no significant effects on the occurrence of thyroid cancer with GLP-1 receptor agonists. Of note, it did find an increased risk for overall thyroid disorders, although there was no clear statistically significant finding pointing to a specific thyroid disorder.

Differing from prior studies, a recent nationwide French health care system study provided newer data suggesting a moderate increased risk for thyroid cancer in a cohort of patients with type 2 diabetes who were taking GLP-1 agonists. The increase in relative risk was noted for all types of thyroid cancer in patients using GLP-1 receptor agonists for 1-3 years.

An accompanying commentary by Caroline A. Thompson, PhD, and Til Stürmer, MD, provides perspective on this study’s potential limitations. These include detection bias, as the study results focused only on the statistically significant data. Also discussed were limitations to the case-control design, issues with claims-based tumor type classification (unavailability of surgical pathology), and an inability to adjust for family history and obesity, which is a risk factor alone for thyroid cancer. There was also no adjustment for exposure to head/neck radiation.

While this study has important findings to consider, it deserves further investigation, with future studies linking data to tumor registry data before a change is made in clinical practice.

No clear relationship has been drawn between GLP-1 receptor agonists and thyroid cancer in humans. Numerous confounding factors limit the data. Studies generally don’t specify the type of thyroid cancer, and they lump medullary thyroid cancer, the rarest form, with papillary thyroid cancer.

Is a detection bias present where weight loss makes nodules more visible on the neck among those treated with GLP-1 agonists? And/or are patients treated with GLP-1 agonists being screened more stringently for thyroid nodules and/or cancer?

How to advise our patients and respond to the EMR messages

The TikTok videos may continue, the celebrity chatter may increase, and we, as physicians, will continue to look to real-world data with randomized controlled trials to tailor our decision-making and guide our patients.

Thyroid cancer remains a rare outcome, and GLP-1 receptor agonists remain a very important and beneficial treatment option for the right patient.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

With #Ozempic and #ozempicweightloss continuing to trend on social media, along with the mainstream media focusing on celebrities who rely on Ozempic (semaglutide) for weight loss, the daily requests for this new medication have been increasing.

Accompanying these requests are concerns and questions about potential risks, including this most recent message from one of my patients: “Dr. P – I saw the warnings. Is this medication going to make me get thyroid cancer? Please let me know!”

Let’s look at what we know to date, including recent studies, and how to advise our patients on this very hot topic.

Using GLP-1 receptor agonists for obesity

We have extensive prior experience with glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, such as semaglutide, for treating type 2 diabetes and now recently as agents for weight loss.

Large clinical trials have documented the benefits of this medication class not only for weight reduction but also for cardiovascular and renal benefits in patients with diabetes. The subcutaneously injectable medications work by promoting insulin secretion, slowing gastric emptying, and suppressing glucagon secretion, with a low risk for hypoglycemia.

The Food and Drug Administration approved daily-injection GLP-1 agonist liraglutide for weight loss in 2014, and weekly-injection semaglutide for chronic weight management in 2021, in patients with a body mass index ≥ 27 with at least one weight-related condition or a BMI ≥ 30.

The brand name for semaglutide approved for weight loss is Wegovy, and the dose is slightly higher (maximum 2.4 mg/wk) than that of Ozempic (maximum 2.0 mg/wk), which is semaglutide approved for type 2 diabetes.

In trials for weight loss, data showed a mean change in body weight of almost 15% in the semaglutide group at week 68 compared with placebo, which is very impressive, particularly compared with other FDA-approved oral long-term weight loss medications.

The newest synthetic dual-acting agent is tirzepatide, which targets GLP-1 but is also a glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) agonist. The weekly subcutaneous injection was approved in May 2022 as Mounjaro for treating type 2 diabetes and produced even greater weight loss than semaglutide in clinical trials. Tirzepatide is now in trials for obesity and is under expedited review by the FDA for weight loss.

Why the concern about thyroid cancer?

Early on with the FDA approvals of GLP-1 agonists, a warning accompanied the products’ labels to not use this class of medications in patients with medullary thyroid cancer, a family history of medullary thyroid cancer, or multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 2. This warning was based on data from animal studies.

Human pancreatic cells aren’t the only cells that express GLP-1 receptors. These receptors are also expressed by parafollicular cells (C cells) of the thyroid, which secrete calcitonin and are the cells involved in medullary thyroid cancer. A dose-related and duration-dependent increase in thyroid C-cell tumor incidence was noted in rodents. The same relationship was not demonstrated in monkeys. Humans have far fewer C cells than rats, and human C cells have very low expression of the GLP-1 receptor.

Over a decade ago, a study examining the FDA’s database of reported adverse events found an increased risk for thyroid cancer in patients treated with exenatide, another GLP-1 agonist. The reporting system wasn’t designed to distinguish thyroid cancer subtypes.

Numerous subsequent studies didn’t confirm this relationship. The LEADER trial looked at liraglutide in patients with type 2 diabetes and showed no effect of GLP-1 receptor activation on human serum calcitonin levels, C-cell proliferation, or C-cell malignancy. Similarly, a large meta-analysis in patients with type 2 diabetes didn’t find a statistically increased risk for thyroid cancer with liraglutide, and no thyroid malignancies were reported with exenatide.

Two U.S. administrative databases from commercial health plans (a retrospective cohort study and a nested case-control study) compared type 2 diabetes patients who were taking exenatide vs. other antidiabetic drugs and found that exenatide was not significantly associated with an increased risk for thyroid cancer.

And a recent meta-analysis of 45 trials showed no significant effects on the occurrence of thyroid cancer with GLP-1 receptor agonists. Of note, it did find an increased risk for overall thyroid disorders, although there was no clear statistically significant finding pointing to a specific thyroid disorder.

Differing from prior studies, a recent nationwide French health care system study provided newer data suggesting a moderate increased risk for thyroid cancer in a cohort of patients with type 2 diabetes who were taking GLP-1 agonists. The increase in relative risk was noted for all types of thyroid cancer in patients using GLP-1 receptor agonists for 1-3 years.

An accompanying commentary by Caroline A. Thompson, PhD, and Til Stürmer, MD, provides perspective on this study’s potential limitations. These include detection bias, as the study results focused only on the statistically significant data. Also discussed were limitations to the case-control design, issues with claims-based tumor type classification (unavailability of surgical pathology), and an inability to adjust for family history and obesity, which is a risk factor alone for thyroid cancer. There was also no adjustment for exposure to head/neck radiation.

While this study has important findings to consider, it deserves further investigation, with future studies linking data to tumor registry data before a change is made in clinical practice.

No clear relationship has been drawn between GLP-1 receptor agonists and thyroid cancer in humans. Numerous confounding factors limit the data. Studies generally don’t specify the type of thyroid cancer, and they lump medullary thyroid cancer, the rarest form, with papillary thyroid cancer.

Is a detection bias present where weight loss makes nodules more visible on the neck among those treated with GLP-1 agonists? And/or are patients treated with GLP-1 agonists being screened more stringently for thyroid nodules and/or cancer?

How to advise our patients and respond to the EMR messages

The TikTok videos may continue, the celebrity chatter may increase, and we, as physicians, will continue to look to real-world data with randomized controlled trials to tailor our decision-making and guide our patients.

Thyroid cancer remains a rare outcome, and GLP-1 receptor agonists remain a very important and beneficial treatment option for the right patient.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

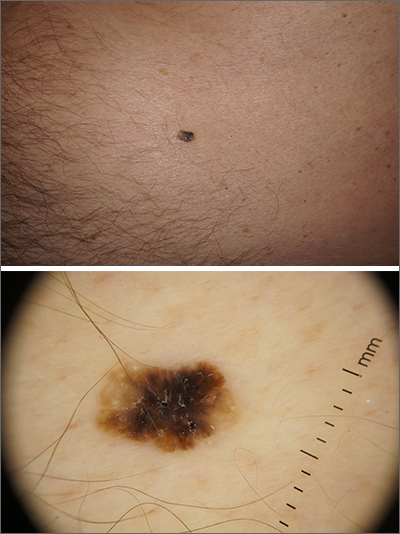

Solitary abdominal papule

Dermoscopy revealed an 8-mm scaly brown-black papule that lacked melanocytic features (pigment network, globules, streaks, or homogeneous blue or brown color) but had milia-like cysts and so-called “fat fingers” (short, straight to curved radial projections1). These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of seborrheic keratosis (SK).

SKs go by many names and are often confused with nevi. Some patients might know them by such names as “age spots” or “liver spots.” Patients often have many SKs on their body; the back and skin folds are common locations. Patients may be unhappy about the way they look and may describe occasional discomfort when the SKs rub against clothes and inflammation that occurs spontaneously or with trauma.

Classic SKs have a well-demarcated border and waxy, stuck-on appearance. There are times when it is difficult to distinguish between an SK and a melanocytic lesion. Thus, a biopsy may be necessary. In addition, SKs are so common that collision lesions may occur. (Collision lesions result when 2 histologically distinct neoplasms occur adjacent to each other and cause an unusual clinical appearance with features of each lesion.) The atypical clinical features in a collision lesion may prompt a biopsy to exclude malignancy.

Dermoscopic features of SKs include well-demarcated borders, milia-like cysts (white circular inclusions), comedo-like openings (brown/black circular inclusions), fissures and ridges, hairpin vessels, and fat fingers.

Cryotherapy is a quick and efficient treatment when a patient would like the lesions removed. Curettage or light electrodessication may be less likely to cause post-inflammatory hypopigmentation in patients with darker skin types. These various destructive therapies are often considered cosmetic and are unlikely to be covered by insurance unless there is documentation of significant inflammation or discomfort. In this case, the lesion was not treated.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Wang S, Rabinovitz H, Oliviero M, et al. Solar lentigines, seborrheic keratoses, and lichen planus-like keratoses. In: Marghoob A, Malvehy J, Braun, R, eds. Atlas of Dermoscopy. 2nd ed. Informa Healthcare; 2012: 58-69.

Dermoscopy revealed an 8-mm scaly brown-black papule that lacked melanocytic features (pigment network, globules, streaks, or homogeneous blue or brown color) but had milia-like cysts and so-called “fat fingers” (short, straight to curved radial projections1). These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of seborrheic keratosis (SK).

SKs go by many names and are often confused with nevi. Some patients might know them by such names as “age spots” or “liver spots.” Patients often have many SKs on their body; the back and skin folds are common locations. Patients may be unhappy about the way they look and may describe occasional discomfort when the SKs rub against clothes and inflammation that occurs spontaneously or with trauma.

Classic SKs have a well-demarcated border and waxy, stuck-on appearance. There are times when it is difficult to distinguish between an SK and a melanocytic lesion. Thus, a biopsy may be necessary. In addition, SKs are so common that collision lesions may occur. (Collision lesions result when 2 histologically distinct neoplasms occur adjacent to each other and cause an unusual clinical appearance with features of each lesion.) The atypical clinical features in a collision lesion may prompt a biopsy to exclude malignancy.

Dermoscopic features of SKs include well-demarcated borders, milia-like cysts (white circular inclusions), comedo-like openings (brown/black circular inclusions), fissures and ridges, hairpin vessels, and fat fingers.

Cryotherapy is a quick and efficient treatment when a patient would like the lesions removed. Curettage or light electrodessication may be less likely to cause post-inflammatory hypopigmentation in patients with darker skin types. These various destructive therapies are often considered cosmetic and are unlikely to be covered by insurance unless there is documentation of significant inflammation or discomfort. In this case, the lesion was not treated.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

Dermoscopy revealed an 8-mm scaly brown-black papule that lacked melanocytic features (pigment network, globules, streaks, or homogeneous blue or brown color) but had milia-like cysts and so-called “fat fingers” (short, straight to curved radial projections1). These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of seborrheic keratosis (SK).

SKs go by many names and are often confused with nevi. Some patients might know them by such names as “age spots” or “liver spots.” Patients often have many SKs on their body; the back and skin folds are common locations. Patients may be unhappy about the way they look and may describe occasional discomfort when the SKs rub against clothes and inflammation that occurs spontaneously or with trauma.

Classic SKs have a well-demarcated border and waxy, stuck-on appearance. There are times when it is difficult to distinguish between an SK and a melanocytic lesion. Thus, a biopsy may be necessary. In addition, SKs are so common that collision lesions may occur. (Collision lesions result when 2 histologically distinct neoplasms occur adjacent to each other and cause an unusual clinical appearance with features of each lesion.) The atypical clinical features in a collision lesion may prompt a biopsy to exclude malignancy.

Dermoscopic features of SKs include well-demarcated borders, milia-like cysts (white circular inclusions), comedo-like openings (brown/black circular inclusions), fissures and ridges, hairpin vessels, and fat fingers.

Cryotherapy is a quick and efficient treatment when a patient would like the lesions removed. Curettage or light electrodessication may be less likely to cause post-inflammatory hypopigmentation in patients with darker skin types. These various destructive therapies are often considered cosmetic and are unlikely to be covered by insurance unless there is documentation of significant inflammation or discomfort. In this case, the lesion was not treated.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Wang S, Rabinovitz H, Oliviero M, et al. Solar lentigines, seborrheic keratoses, and lichen planus-like keratoses. In: Marghoob A, Malvehy J, Braun, R, eds. Atlas of Dermoscopy. 2nd ed. Informa Healthcare; 2012: 58-69.

1. Wang S, Rabinovitz H, Oliviero M, et al. Solar lentigines, seborrheic keratoses, and lichen planus-like keratoses. In: Marghoob A, Malvehy J, Braun, R, eds. Atlas of Dermoscopy. 2nd ed. Informa Healthcare; 2012: 58-69.

High caffeine levels may lower body fat, type 2 diabetes risks

the results of a new study suggest.

Explaining that caffeine has thermogenic effects, the researchers note that previous short-term studies have linked caffeine intake with reductions in weight and fat mass. And observational data have shown associations between coffee consumption and lower risks of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

In an effort to isolate the effects of caffeine from those of other food and drink components, Susanna C. Larsson, PhD, of the Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, and colleagues used data from studies of mainly European populations to examine two specific genetic mutations that have been linked to a slower speed of caffeine metabolism.

The two gene variants resulted in “genetically predicted, lifelong, higher plasma caffeine concentrations,” the researchers note “and were associated with lower body mass index and fat mass, as well as a lower risk of type 2 diabetes.”

Approximately half of the effect of caffeine on type 2 diabetes was estimated to be mediated through body mass index (BMI) reduction.

The work was published online March 14 in BMJ Medicine.

“This publication supports existing studies suggesting a link between caffeine consumption and increased fat burn,” notes Stephen Lawrence, MBChB, Warwick (England) University. “The big leap of faith that the authors have made is to assume that the weight loss brought about by increased caffeine consumption is sufficient to reduce the risk of developing type 2 diabetes,” he told the UK Science Media Centre.

“It does not, however, prove cause and effect.”

The researchers agree, noting: “Further clinical study is warranted to investigate the translational potential of these findings towards reducing the burden of metabolic disease.”

Katarina Kos, MD, PhD, a senior lecturer in diabetes and obesity at the University of Exeter (England), emphasized that this genetic study “shows links and potential health benefits for people with certain genes attributed to a faster [caffeine] metabolism as a hereditary trait and potentially a better metabolism.”

“It does not study or recommend drinking more coffee, which was not the purpose of this research,” she told the UK Science Media Centre.

Using Mendelian randomization, Dr. Larsson and colleagues examined data that came from a genomewide association meta-analysis of 9,876 individuals of European ancestry from six population-based studies.

Genetically predicted higher plasma caffeine concentrations in those carrying the two gene variants were associated with a lower BMI, with one standard deviation increase in predicted plasma caffeine equaling about 4.8 kg/m2 in BMI (P < .001).

For whole-body fat mass, one standard deviation increase in plasma caffeine equaled a reduction of about 9.5 kg (P < .001). However, there was no significant association with fat-free body mass (P = .17).

Genetically predicted higher plasma caffeine concentrations were also associated with a lower risk for type 2 diabetes in the FinnGen study (odds ratio, 0.77 per standard deviation increase; P < .001) and the DIAMANTE consortia (0.84, P < .001).

Combined, the odds ratio of type 2 diabetes per standard deviation of plasma caffeine increase was 0.81 (P < .001).

Dr. Larsson and colleagues calculated that approximately 43% of the protective effect of plasma caffeine on type 2 diabetes was mediated through BMI.

They did not find any strong associations between genetically predicted plasma caffeine concentrations and risk of any of the studied cardiovascular disease outcomes (ischemic heart disease, atrial fibrillation, heart failure, and stroke).

The thermogenic response to caffeine has been previously quantified as an approximate 100 kcal increase in energy expenditure per 100 mg daily caffeine intake, an amount that could result in reduced obesity risk. Another possible mechanism is enhanced satiety and suppressed energy intake with higher caffeine levels, the researchers say.

“Long-term clinical studies investigating the effect of caffeine intake on fat mass and type 2 diabetes risk are warranted,” they note. “Randomized controlled trials are warranted to assess whether noncaloric caffeine-containing beverages might play a role in reducing the risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes.”

The study was supported by the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare, Swedish Heart Lung Foundation, and Swedish Research Council. Dr. Larsson, Dr. Lawrence, and Dr. Kos have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

the results of a new study suggest.

Explaining that caffeine has thermogenic effects, the researchers note that previous short-term studies have linked caffeine intake with reductions in weight and fat mass. And observational data have shown associations between coffee consumption and lower risks of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

In an effort to isolate the effects of caffeine from those of other food and drink components, Susanna C. Larsson, PhD, of the Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, and colleagues used data from studies of mainly European populations to examine two specific genetic mutations that have been linked to a slower speed of caffeine metabolism.

The two gene variants resulted in “genetically predicted, lifelong, higher plasma caffeine concentrations,” the researchers note “and were associated with lower body mass index and fat mass, as well as a lower risk of type 2 diabetes.”

Approximately half of the effect of caffeine on type 2 diabetes was estimated to be mediated through body mass index (BMI) reduction.

The work was published online March 14 in BMJ Medicine.

“This publication supports existing studies suggesting a link between caffeine consumption and increased fat burn,” notes Stephen Lawrence, MBChB, Warwick (England) University. “The big leap of faith that the authors have made is to assume that the weight loss brought about by increased caffeine consumption is sufficient to reduce the risk of developing type 2 diabetes,” he told the UK Science Media Centre.

“It does not, however, prove cause and effect.”

The researchers agree, noting: “Further clinical study is warranted to investigate the translational potential of these findings towards reducing the burden of metabolic disease.”

Katarina Kos, MD, PhD, a senior lecturer in diabetes and obesity at the University of Exeter (England), emphasized that this genetic study “shows links and potential health benefits for people with certain genes attributed to a faster [caffeine] metabolism as a hereditary trait and potentially a better metabolism.”

“It does not study or recommend drinking more coffee, which was not the purpose of this research,” she told the UK Science Media Centre.

Using Mendelian randomization, Dr. Larsson and colleagues examined data that came from a genomewide association meta-analysis of 9,876 individuals of European ancestry from six population-based studies.

Genetically predicted higher plasma caffeine concentrations in those carrying the two gene variants were associated with a lower BMI, with one standard deviation increase in predicted plasma caffeine equaling about 4.8 kg/m2 in BMI (P < .001).

For whole-body fat mass, one standard deviation increase in plasma caffeine equaled a reduction of about 9.5 kg (P < .001). However, there was no significant association with fat-free body mass (P = .17).

Genetically predicted higher plasma caffeine concentrations were also associated with a lower risk for type 2 diabetes in the FinnGen study (odds ratio, 0.77 per standard deviation increase; P < .001) and the DIAMANTE consortia (0.84, P < .001).

Combined, the odds ratio of type 2 diabetes per standard deviation of plasma caffeine increase was 0.81 (P < .001).

Dr. Larsson and colleagues calculated that approximately 43% of the protective effect of plasma caffeine on type 2 diabetes was mediated through BMI.

They did not find any strong associations between genetically predicted plasma caffeine concentrations and risk of any of the studied cardiovascular disease outcomes (ischemic heart disease, atrial fibrillation, heart failure, and stroke).

The thermogenic response to caffeine has been previously quantified as an approximate 100 kcal increase in energy expenditure per 100 mg daily caffeine intake, an amount that could result in reduced obesity risk. Another possible mechanism is enhanced satiety and suppressed energy intake with higher caffeine levels, the researchers say.

“Long-term clinical studies investigating the effect of caffeine intake on fat mass and type 2 diabetes risk are warranted,” they note. “Randomized controlled trials are warranted to assess whether noncaloric caffeine-containing beverages might play a role in reducing the risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes.”

The study was supported by the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare, Swedish Heart Lung Foundation, and Swedish Research Council. Dr. Larsson, Dr. Lawrence, and Dr. Kos have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

the results of a new study suggest.

Explaining that caffeine has thermogenic effects, the researchers note that previous short-term studies have linked caffeine intake with reductions in weight and fat mass. And observational data have shown associations between coffee consumption and lower risks of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

In an effort to isolate the effects of caffeine from those of other food and drink components, Susanna C. Larsson, PhD, of the Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, and colleagues used data from studies of mainly European populations to examine two specific genetic mutations that have been linked to a slower speed of caffeine metabolism.

The two gene variants resulted in “genetically predicted, lifelong, higher plasma caffeine concentrations,” the researchers note “and were associated with lower body mass index and fat mass, as well as a lower risk of type 2 diabetes.”

Approximately half of the effect of caffeine on type 2 diabetes was estimated to be mediated through body mass index (BMI) reduction.

The work was published online March 14 in BMJ Medicine.

“This publication supports existing studies suggesting a link between caffeine consumption and increased fat burn,” notes Stephen Lawrence, MBChB, Warwick (England) University. “The big leap of faith that the authors have made is to assume that the weight loss brought about by increased caffeine consumption is sufficient to reduce the risk of developing type 2 diabetes,” he told the UK Science Media Centre.

“It does not, however, prove cause and effect.”

The researchers agree, noting: “Further clinical study is warranted to investigate the translational potential of these findings towards reducing the burden of metabolic disease.”

Katarina Kos, MD, PhD, a senior lecturer in diabetes and obesity at the University of Exeter (England), emphasized that this genetic study “shows links and potential health benefits for people with certain genes attributed to a faster [caffeine] metabolism as a hereditary trait and potentially a better metabolism.”

“It does not study or recommend drinking more coffee, which was not the purpose of this research,” she told the UK Science Media Centre.

Using Mendelian randomization, Dr. Larsson and colleagues examined data that came from a genomewide association meta-analysis of 9,876 individuals of European ancestry from six population-based studies.

Genetically predicted higher plasma caffeine concentrations in those carrying the two gene variants were associated with a lower BMI, with one standard deviation increase in predicted plasma caffeine equaling about 4.8 kg/m2 in BMI (P < .001).

For whole-body fat mass, one standard deviation increase in plasma caffeine equaled a reduction of about 9.5 kg (P < .001). However, there was no significant association with fat-free body mass (P = .17).

Genetically predicted higher plasma caffeine concentrations were also associated with a lower risk for type 2 diabetes in the FinnGen study (odds ratio, 0.77 per standard deviation increase; P < .001) and the DIAMANTE consortia (0.84, P < .001).

Combined, the odds ratio of type 2 diabetes per standard deviation of plasma caffeine increase was 0.81 (P < .001).

Dr. Larsson and colleagues calculated that approximately 43% of the protective effect of plasma caffeine on type 2 diabetes was mediated through BMI.

They did not find any strong associations between genetically predicted plasma caffeine concentrations and risk of any of the studied cardiovascular disease outcomes (ischemic heart disease, atrial fibrillation, heart failure, and stroke).

The thermogenic response to caffeine has been previously quantified as an approximate 100 kcal increase in energy expenditure per 100 mg daily caffeine intake, an amount that could result in reduced obesity risk. Another possible mechanism is enhanced satiety and suppressed energy intake with higher caffeine levels, the researchers say.

“Long-term clinical studies investigating the effect of caffeine intake on fat mass and type 2 diabetes risk are warranted,” they note. “Randomized controlled trials are warranted to assess whether noncaloric caffeine-containing beverages might play a role in reducing the risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes.”

The study was supported by the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare, Swedish Heart Lung Foundation, and Swedish Research Council. Dr. Larsson, Dr. Lawrence, and Dr. Kos have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM BMJ MEDICINE

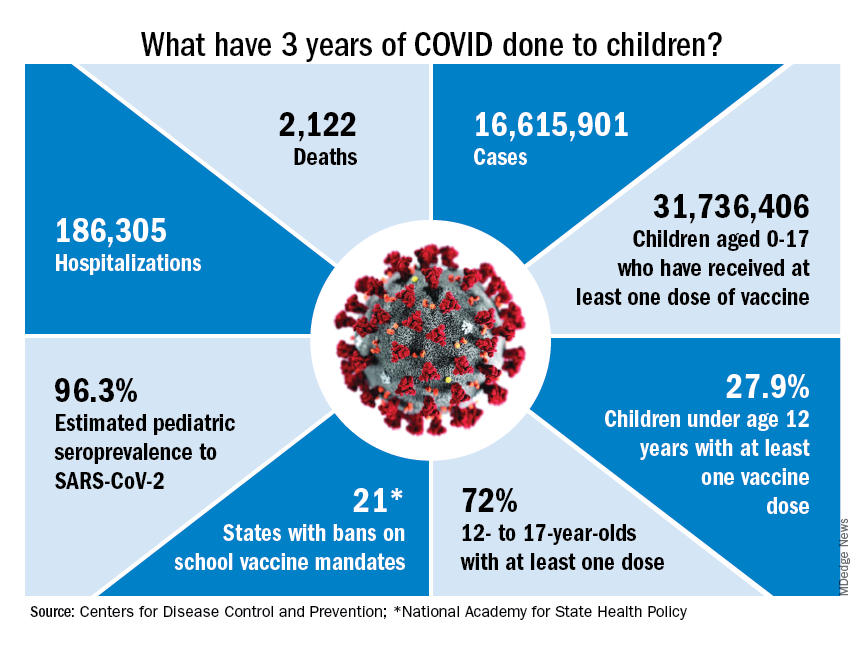

Pandemic hit Black children harder, study shows

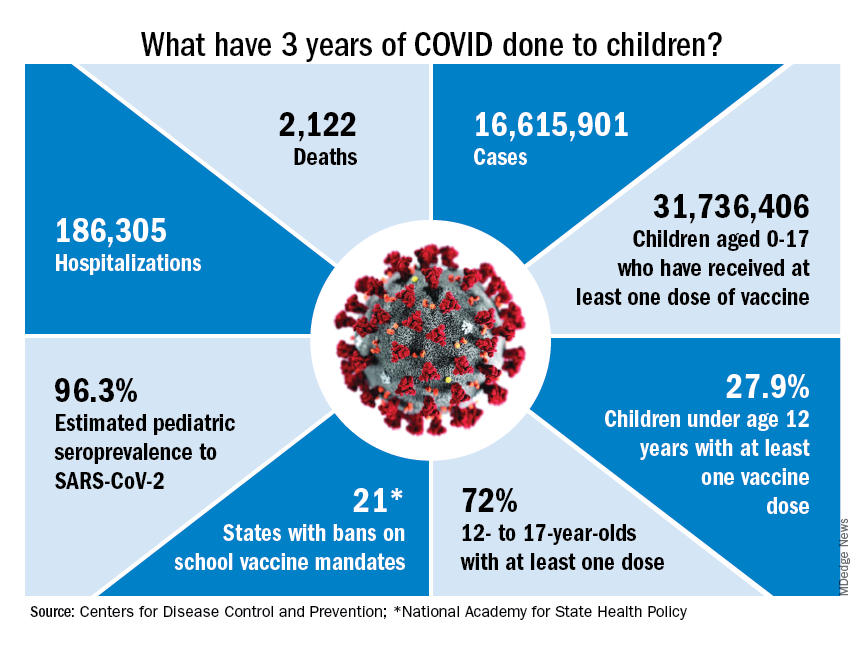

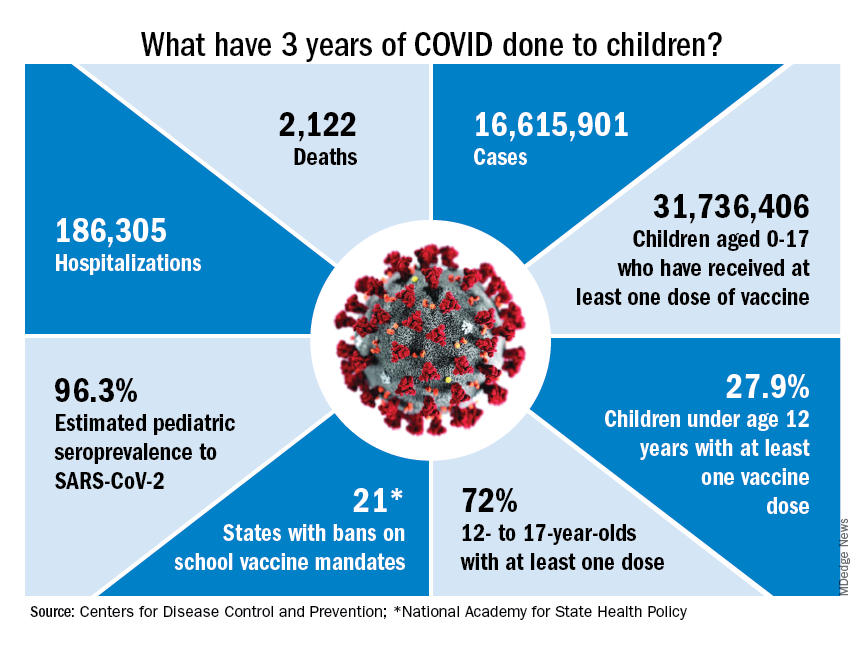

Black children had almost three times as many COVID-related deaths as White children and about twice as many hospitalizations, according to a new study.

The study said that 1,556 children have died from the start of the pandemic until Nov. 30, 2022, with 593 of those children being 4 and under. Black children died of COVID-related causes 2.7 times more often than White children and were hospitalized 2.2 times more often than White children, the study said.

Lower vaccination rates for Black people may be a factor. The study said 43.6% of White children have received two or more vaccinations, compared with 40.2% of Black children.

“First and foremost, this study repudiates the misunderstanding that COVID-19 has not been of consequence to children who have had more than 15.5 million reported cases, representing 18 percent of all cases in the United States,” Reed Tuckson, MD, a member of the Black Coalition Against COVID board of directors and former District of Columbia public health commissioner, said in a news release.

“And second, our research shows that like their adult counterparts, Black and other children of color have shouldered more of the burden of COVID-19 than the White population.”

The study was commissioned by BCAC and conducted by the Satcher Health Leadership Institute of the Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta. It’s based on studies conducted by other agencies over 2 years.

Black and Hispanic children also had more severe COVID cases, the study said. Among 281 pediatric patients in New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut, 23.3% of severe cases were Black and 51% of severe cases were Hispanic.

The study says 1 in 310 Black children lost a parent or caregiver to COVID between April 2020 and June 2012, compared with 1 in 738 White children.

Economic and health-related hardships were experienced by 31% of Black households, 29% of Latino households, and 16% of White households, the study said.

“Children with COVID-19 in communities of color were sicker, [were] hospitalized and died at higher rates than White children,” Sandra Harris-Hooker, the interim executive director at the Satcher Health Leadership Institute of Morehouse School, said in the release. “We can now fully understand the devastating impact the virus had on communities of color across generations.”

The study recommends several changes, such as modifying eligibility requirements for the Children’s Health Insurance Program to help more children who fall into coverage gaps and expanding the Child Tax Credit.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Black children had almost three times as many COVID-related deaths as White children and about twice as many hospitalizations, according to a new study.

The study said that 1,556 children have died from the start of the pandemic until Nov. 30, 2022, with 593 of those children being 4 and under. Black children died of COVID-related causes 2.7 times more often than White children and were hospitalized 2.2 times more often than White children, the study said.

Lower vaccination rates for Black people may be a factor. The study said 43.6% of White children have received two or more vaccinations, compared with 40.2% of Black children.

“First and foremost, this study repudiates the misunderstanding that COVID-19 has not been of consequence to children who have had more than 15.5 million reported cases, representing 18 percent of all cases in the United States,” Reed Tuckson, MD, a member of the Black Coalition Against COVID board of directors and former District of Columbia public health commissioner, said in a news release.

“And second, our research shows that like their adult counterparts, Black and other children of color have shouldered more of the burden of COVID-19 than the White population.”

The study was commissioned by BCAC and conducted by the Satcher Health Leadership Institute of the Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta. It’s based on studies conducted by other agencies over 2 years.

Black and Hispanic children also had more severe COVID cases, the study said. Among 281 pediatric patients in New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut, 23.3% of severe cases were Black and 51% of severe cases were Hispanic.

The study says 1 in 310 Black children lost a parent or caregiver to COVID between April 2020 and June 2012, compared with 1 in 738 White children.

Economic and health-related hardships were experienced by 31% of Black households, 29% of Latino households, and 16% of White households, the study said.

“Children with COVID-19 in communities of color were sicker, [were] hospitalized and died at higher rates than White children,” Sandra Harris-Hooker, the interim executive director at the Satcher Health Leadership Institute of Morehouse School, said in the release. “We can now fully understand the devastating impact the virus had on communities of color across generations.”