User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Is another COVID-19 booster really needed?

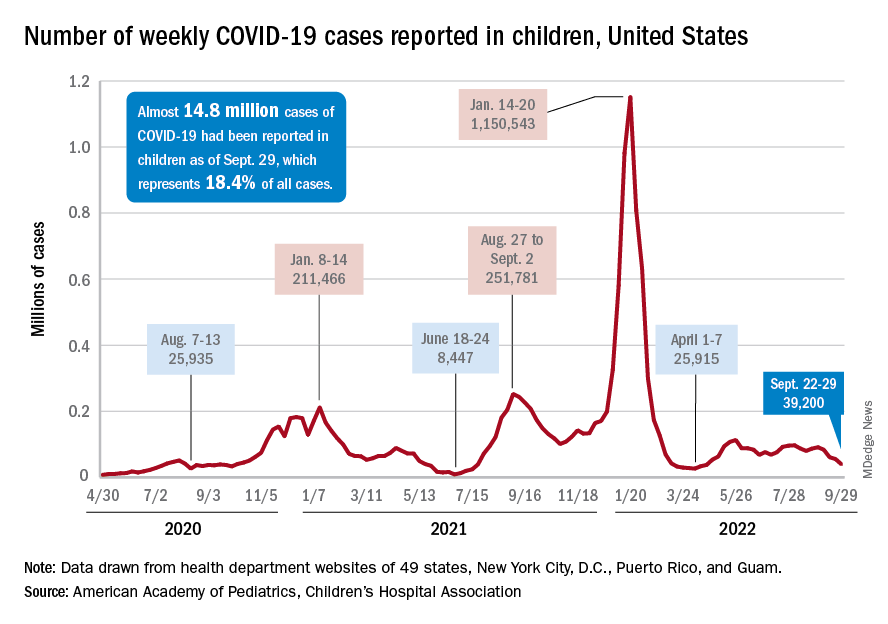

Many countries around the globe are starting to roll out another booster of the COVID-19 vaccine but, with public interest waning and a sense of normalcy firmly installed in our minds, this may prove an ill-fated effort, unless authorities can provide a coherent answer to the question “Is another jab really needed?” (The short answer is a firm “yes,” of course.)

In what we could call the “chronic” phase of the pandemic, most countries have now settled for a certain number of daily cases and a (relatively low) number of complications and deaths. It’s the vaccines that have afforded us this peace of mind, lest we forget. But they are different to other vaccines that we are more familiar with, such as the MMR that we get as kids and then forget about for the rest of our lives. As good as the different COVID-19 vaccines are, they never came with the promise of generating lifelong antibodies. We knew early on that the immunity they provide slowly wanes with time. That doesn’t mean that those who have their vaccination records up to date (which included a booster probably earlier in 2022) are suddenly exposed. Data suggest that although people several months past their last booster would now be more prone to getting reinfected, the protection against severe disease still hangs around 85%. In other words, their chances of ending up in the hospital are low.

Why worry, then, about further boosting the immune system? The same studies show that an additional jab would increase this percentage up to 99%. Is this roughly 10% improvement really worth another worldwide vaccination campaign? Well, this is a numbers game, after all. The current form of the virus is extremely infectious, and the Northern Hemisphere is heading toward the cold months of the year, which we have seen in past years increases COVID-19 contagions, as you would expect from any airborne virus. Thus, it’s easy to expect a new peak in the number of cases, especially considering that we are not going to apply any of the usual restrictions to prevent this. In these conditions, extending the safety net to a further 10% of the population would substantially reduce the total number of victims. It seems like a good investment of resources.

We can be more surgical about it and direct this new vaccination campaign to the population most likely to end up in the hospital. People with concomitant pathologies are at the top of the list, but it’s also an age issue. On the basis of different studies of the most common ages of admission, the cutoff point for the booster varies from country to country, with the lowest being 50 and in other cases hovering around 65 years of age. Given the safety of these vaccines, if we can afford it, the wider we cast the net, the better, but at least we should make every effort to fully vaccinate the higher age brackets.

The final question is which vaccine to give. There are confounding studies about the importance of switching to Omicron-specific jabs, which are finally available. Although this seems like a good idea, since Omicron infections elicit a more effective range of antibodies and new variants seem to better escape our defenses, recent studies suggest that there actually may not be so much difference with the old formula.

The conclusion? This regimen of yearly boosters for some may be the scenario for the upcoming years, similar to what we already do for the flu, so we should get used to it.

Dr. Macip is associate professor, department of molecular and cellular biology, University of Leicester (England). He reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

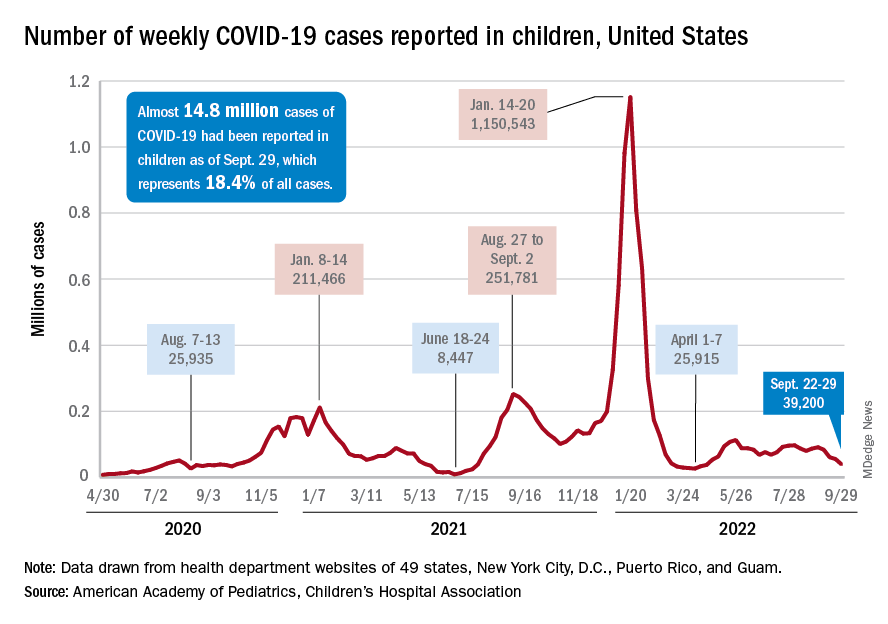

Many countries around the globe are starting to roll out another booster of the COVID-19 vaccine but, with public interest waning and a sense of normalcy firmly installed in our minds, this may prove an ill-fated effort, unless authorities can provide a coherent answer to the question “Is another jab really needed?” (The short answer is a firm “yes,” of course.)

In what we could call the “chronic” phase of the pandemic, most countries have now settled for a certain number of daily cases and a (relatively low) number of complications and deaths. It’s the vaccines that have afforded us this peace of mind, lest we forget. But they are different to other vaccines that we are more familiar with, such as the MMR that we get as kids and then forget about for the rest of our lives. As good as the different COVID-19 vaccines are, they never came with the promise of generating lifelong antibodies. We knew early on that the immunity they provide slowly wanes with time. That doesn’t mean that those who have their vaccination records up to date (which included a booster probably earlier in 2022) are suddenly exposed. Data suggest that although people several months past their last booster would now be more prone to getting reinfected, the protection against severe disease still hangs around 85%. In other words, their chances of ending up in the hospital are low.

Why worry, then, about further boosting the immune system? The same studies show that an additional jab would increase this percentage up to 99%. Is this roughly 10% improvement really worth another worldwide vaccination campaign? Well, this is a numbers game, after all. The current form of the virus is extremely infectious, and the Northern Hemisphere is heading toward the cold months of the year, which we have seen in past years increases COVID-19 contagions, as you would expect from any airborne virus. Thus, it’s easy to expect a new peak in the number of cases, especially considering that we are not going to apply any of the usual restrictions to prevent this. In these conditions, extending the safety net to a further 10% of the population would substantially reduce the total number of victims. It seems like a good investment of resources.

We can be more surgical about it and direct this new vaccination campaign to the population most likely to end up in the hospital. People with concomitant pathologies are at the top of the list, but it’s also an age issue. On the basis of different studies of the most common ages of admission, the cutoff point for the booster varies from country to country, with the lowest being 50 and in other cases hovering around 65 years of age. Given the safety of these vaccines, if we can afford it, the wider we cast the net, the better, but at least we should make every effort to fully vaccinate the higher age brackets.

The final question is which vaccine to give. There are confounding studies about the importance of switching to Omicron-specific jabs, which are finally available. Although this seems like a good idea, since Omicron infections elicit a more effective range of antibodies and new variants seem to better escape our defenses, recent studies suggest that there actually may not be so much difference with the old formula.

The conclusion? This regimen of yearly boosters for some may be the scenario for the upcoming years, similar to what we already do for the flu, so we should get used to it.

Dr. Macip is associate professor, department of molecular and cellular biology, University of Leicester (England). He reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

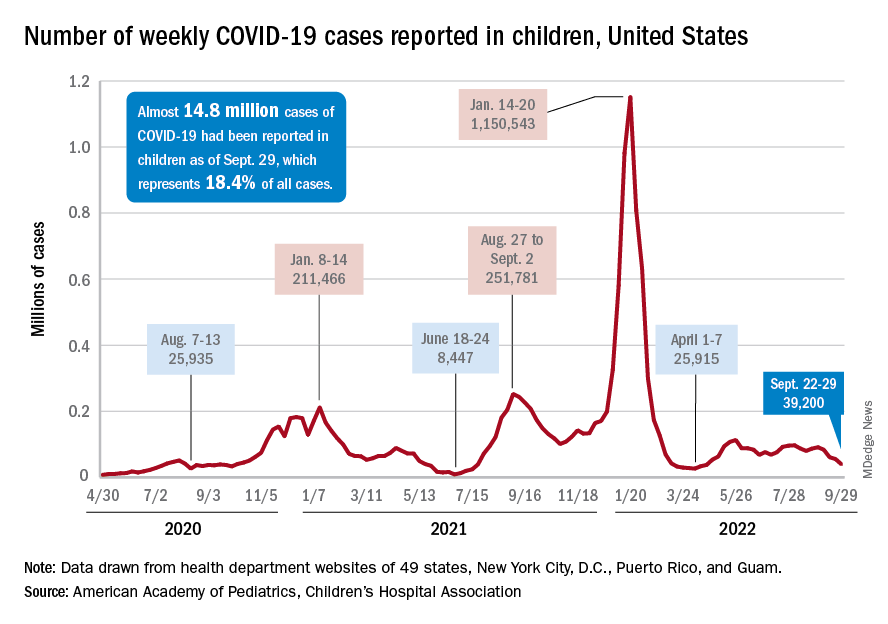

Many countries around the globe are starting to roll out another booster of the COVID-19 vaccine but, with public interest waning and a sense of normalcy firmly installed in our minds, this may prove an ill-fated effort, unless authorities can provide a coherent answer to the question “Is another jab really needed?” (The short answer is a firm “yes,” of course.)

In what we could call the “chronic” phase of the pandemic, most countries have now settled for a certain number of daily cases and a (relatively low) number of complications and deaths. It’s the vaccines that have afforded us this peace of mind, lest we forget. But they are different to other vaccines that we are more familiar with, such as the MMR that we get as kids and then forget about for the rest of our lives. As good as the different COVID-19 vaccines are, they never came with the promise of generating lifelong antibodies. We knew early on that the immunity they provide slowly wanes with time. That doesn’t mean that those who have their vaccination records up to date (which included a booster probably earlier in 2022) are suddenly exposed. Data suggest that although people several months past their last booster would now be more prone to getting reinfected, the protection against severe disease still hangs around 85%. In other words, their chances of ending up in the hospital are low.

Why worry, then, about further boosting the immune system? The same studies show that an additional jab would increase this percentage up to 99%. Is this roughly 10% improvement really worth another worldwide vaccination campaign? Well, this is a numbers game, after all. The current form of the virus is extremely infectious, and the Northern Hemisphere is heading toward the cold months of the year, which we have seen in past years increases COVID-19 contagions, as you would expect from any airborne virus. Thus, it’s easy to expect a new peak in the number of cases, especially considering that we are not going to apply any of the usual restrictions to prevent this. In these conditions, extending the safety net to a further 10% of the population would substantially reduce the total number of victims. It seems like a good investment of resources.

We can be more surgical about it and direct this new vaccination campaign to the population most likely to end up in the hospital. People with concomitant pathologies are at the top of the list, but it’s also an age issue. On the basis of different studies of the most common ages of admission, the cutoff point for the booster varies from country to country, with the lowest being 50 and in other cases hovering around 65 years of age. Given the safety of these vaccines, if we can afford it, the wider we cast the net, the better, but at least we should make every effort to fully vaccinate the higher age brackets.

The final question is which vaccine to give. There are confounding studies about the importance of switching to Omicron-specific jabs, which are finally available. Although this seems like a good idea, since Omicron infections elicit a more effective range of antibodies and new variants seem to better escape our defenses, recent studies suggest that there actually may not be so much difference with the old formula.

The conclusion? This regimen of yearly boosters for some may be the scenario for the upcoming years, similar to what we already do for the flu, so we should get used to it.

Dr. Macip is associate professor, department of molecular and cellular biology, University of Leicester (England). He reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Salt pills for patients with acute decompensated heart failure?

Restriction of dietary salt to alleviate or prevent volume overload in patients with acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF) is common hospital practice, but without a solid evidence base. A trial testing whether taking salt pills might have benefits for patients with ADHF undergoing intensive diuresis, therefore, may seem a bit counterintuitive.

In just such a randomized, placebo-controlled trial, the approach made no difference to weight loss on diuresis, a proxy for volume reduction, or to serum creatinine levels in ADHF patients receiving high-dose intravenous diuretic therapy.

The patients consumed the extra salt during their intravenous therapy in the form of tablets providing 6 g sodium chloride daily on top of their hospital-provided, low-sodium meals.

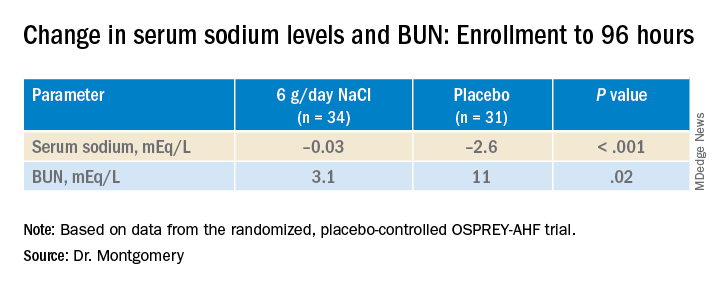

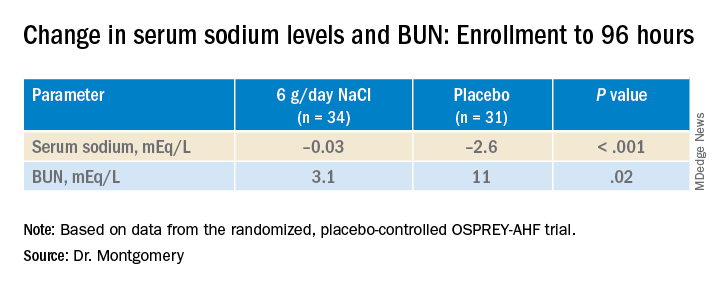

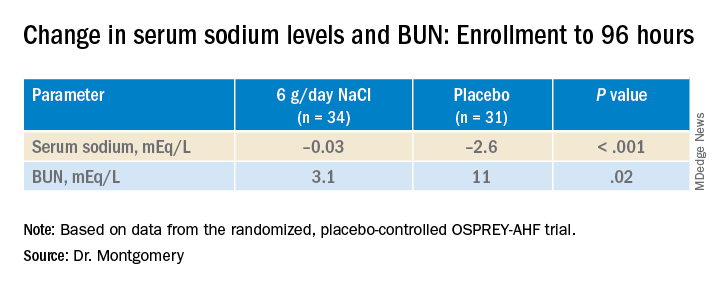

During that time, serum sodium levels remained stable for the 34 patients assigned to the salt tablets but dropped significantly in the 31 given placebo pills.

They lost about the same weight, averages of 4 kg and 4.6 kg (8.8-10 lb), respectively, and their urine output was also similar. Patients who took the salt tablets showed less of an increase in blood urea nitrogen (BUN) at both 96 hours and at discharge.

The findings “challenge the routine practice of sodium chloride restriction in acute heart failure, something done thousands of times a day, millions of times a year,” Robert A. Montgomery, MD, Cleveland Clinic, said when presenting the study at the annual scientific meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America.

The trial, called OSPREY-AHF (Oral Sodium to Preserve Renal Efficiency in Acute Heart Failure), also may encourage a shift in ADHF management from a preoccupation with salt restriction to focus more on fighting fluid retention.

OSPREY-HF took on “an established practice that doesn’t have much high-quality evidentiary support,” one guided primarily by consensus and observational data, Montgomery said in an interview.

There are also potential downsides to dietary sodium restriction, including some that may complicate or block ADHF therapies.

“Low-sodium diets can be associated with decreased caloric intake and nutritional quality,” Dr. Montgomery observed. And observational studies suggest that “patients who are on a low sodium diet can develop increased neurohormonal activation. The kidney is not sensing salt, and so starts ramping up the hormones,” which promotes diuretic resistance.

But emerging evidence also suggests “that giving sodium chloride in the form of hypertonic saline can help patients who are diuretic resistant.” The intervention, which appears to attenuate the neurohormonal activation associated with high-dose intravenous diuretics, Dr. Montgomery noted, helped inspire the design of OSPREY-AHF.

Edema consists of “a gallon of water and a pinch of salt, so we really should stop being so salt-centric and think much more about water as the problem in decompensated heart failure,” said John G.F. Cleland, MD, PhD, during the question-and-answer period after Montgomery’s presentation. Dr. Cleland, of the University of Glasgow Institute of Health and Wellbeing, is not connected to OSPREY-AHF.

“I think that maybe we overinterpret how important salt is” as a focus of volume management in ADHF, offered David Lanfear, MD, Henry Ford Health System, Detroit, who is also not part of the study.

OSPREY-AHF was well conducted but applies to a “very specific” clinical setting, Dr. Lanfear said in an interview. “These people are getting aggressive diuresis, a big dose and continuous infusion. It’s not everybody that has heart failure.”

Although the study was small, “I think it will fuel interest in this area and, probably, further investigation,” he said. The trial on its own won’t change practice, “but it will raise some eyebrows.”

The trial included patients with ADHF who have been “admitted to a cardiovascular medicine floor, not the intensive care unit” and were receiving at least 10 mg per hour of furosemide. It excluded any who were “hypernatremic or severely hyponatremic,” said Dr. Montgomery when presenting the study. They were required to have an initial estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of at least 15 mL/min per 1.73 m2.

The patients were randomly assigned double blind at a single center to receive tablets providing 2 g sodium chloride or placebo pills – 34 and 31 patients, respectively – three times daily during intravenous diuresis.

At 96 hours, the two groups showed no difference in change in creatinine levels or change in weight, both primary endpoints. Nor did they differ in urine output or change in eGFR. But serum sodium levels fell further, and BUN levels went up more in those given placebo.

The two groups showed no differences in hospital length of stay, use of renal replacement therapy at 90 days, ICU time during the index hospitalization, 30-day readmission, or 90-day mortality – although the trial wasn’t powered for clinical outcomes, Dr. Montgomery reported.

"We have patients who complain about their sodium-restricted diet, we have patients that have cachexia, who have a lot of complaints about provider-ordered meals and recommendations,” Dr. Montgomery explained in an interview.

Clinicians provide education and invest a lot of effort into getting patients with heart failure to start and maintain a low-sodium diet, he said. “But a low-sodium diet, in prior studies – and our study adds to this – is not a lever that actually seems to positively or adversely affect patients.”

Dr. Montgomery pointed to the recently published SODIUM-HF trial comparing low-sodium and unrestricted-sodium diets in outpatients with heart failure. It saw no clinical benefit from the low-sodium intervention.

Until studies show, potentially, that sodium restriction in hospitalized patients with heart failure makes a clinical difference, Dr. Montgomery said, “I’d say we should invest our time in things that we know are the most helpful, like getting them on guideline-directed medical therapy, when instead we spend an enormous amount of time counseling on and enforcing dietary restriction.”

Support for this study was provided by Cleveland Clinic Heart Vascular and Thoracic Institute’s Wilson Grant and Kaufman Center for Heart Failure Treatment and Recovery Grant. Dr. Lanfear disclosed research support from SomaLogic and Lilly; consulting for Abbott Laboratories, AstraZeneca, Janssen, Martin Pharmaceuticals, and Amgen; and serving on advisory panels for Illumina and Cytokinetics. Dr. Montgomery and Dr. Cleland disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Restriction of dietary salt to alleviate or prevent volume overload in patients with acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF) is common hospital practice, but without a solid evidence base. A trial testing whether taking salt pills might have benefits for patients with ADHF undergoing intensive diuresis, therefore, may seem a bit counterintuitive.

In just such a randomized, placebo-controlled trial, the approach made no difference to weight loss on diuresis, a proxy for volume reduction, or to serum creatinine levels in ADHF patients receiving high-dose intravenous diuretic therapy.

The patients consumed the extra salt during their intravenous therapy in the form of tablets providing 6 g sodium chloride daily on top of their hospital-provided, low-sodium meals.

During that time, serum sodium levels remained stable for the 34 patients assigned to the salt tablets but dropped significantly in the 31 given placebo pills.

They lost about the same weight, averages of 4 kg and 4.6 kg (8.8-10 lb), respectively, and their urine output was also similar. Patients who took the salt tablets showed less of an increase in blood urea nitrogen (BUN) at both 96 hours and at discharge.

The findings “challenge the routine practice of sodium chloride restriction in acute heart failure, something done thousands of times a day, millions of times a year,” Robert A. Montgomery, MD, Cleveland Clinic, said when presenting the study at the annual scientific meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America.

The trial, called OSPREY-AHF (Oral Sodium to Preserve Renal Efficiency in Acute Heart Failure), also may encourage a shift in ADHF management from a preoccupation with salt restriction to focus more on fighting fluid retention.

OSPREY-HF took on “an established practice that doesn’t have much high-quality evidentiary support,” one guided primarily by consensus and observational data, Montgomery said in an interview.

There are also potential downsides to dietary sodium restriction, including some that may complicate or block ADHF therapies.

“Low-sodium diets can be associated with decreased caloric intake and nutritional quality,” Dr. Montgomery observed. And observational studies suggest that “patients who are on a low sodium diet can develop increased neurohormonal activation. The kidney is not sensing salt, and so starts ramping up the hormones,” which promotes diuretic resistance.

But emerging evidence also suggests “that giving sodium chloride in the form of hypertonic saline can help patients who are diuretic resistant.” The intervention, which appears to attenuate the neurohormonal activation associated with high-dose intravenous diuretics, Dr. Montgomery noted, helped inspire the design of OSPREY-AHF.

Edema consists of “a gallon of water and a pinch of salt, so we really should stop being so salt-centric and think much more about water as the problem in decompensated heart failure,” said John G.F. Cleland, MD, PhD, during the question-and-answer period after Montgomery’s presentation. Dr. Cleland, of the University of Glasgow Institute of Health and Wellbeing, is not connected to OSPREY-AHF.

“I think that maybe we overinterpret how important salt is” as a focus of volume management in ADHF, offered David Lanfear, MD, Henry Ford Health System, Detroit, who is also not part of the study.

OSPREY-AHF was well conducted but applies to a “very specific” clinical setting, Dr. Lanfear said in an interview. “These people are getting aggressive diuresis, a big dose and continuous infusion. It’s not everybody that has heart failure.”

Although the study was small, “I think it will fuel interest in this area and, probably, further investigation,” he said. The trial on its own won’t change practice, “but it will raise some eyebrows.”

The trial included patients with ADHF who have been “admitted to a cardiovascular medicine floor, not the intensive care unit” and were receiving at least 10 mg per hour of furosemide. It excluded any who were “hypernatremic or severely hyponatremic,” said Dr. Montgomery when presenting the study. They were required to have an initial estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of at least 15 mL/min per 1.73 m2.

The patients were randomly assigned double blind at a single center to receive tablets providing 2 g sodium chloride or placebo pills – 34 and 31 patients, respectively – three times daily during intravenous diuresis.

At 96 hours, the two groups showed no difference in change in creatinine levels or change in weight, both primary endpoints. Nor did they differ in urine output or change in eGFR. But serum sodium levels fell further, and BUN levels went up more in those given placebo.

The two groups showed no differences in hospital length of stay, use of renal replacement therapy at 90 days, ICU time during the index hospitalization, 30-day readmission, or 90-day mortality – although the trial wasn’t powered for clinical outcomes, Dr. Montgomery reported.

"We have patients who complain about their sodium-restricted diet, we have patients that have cachexia, who have a lot of complaints about provider-ordered meals and recommendations,” Dr. Montgomery explained in an interview.

Clinicians provide education and invest a lot of effort into getting patients with heart failure to start and maintain a low-sodium diet, he said. “But a low-sodium diet, in prior studies – and our study adds to this – is not a lever that actually seems to positively or adversely affect patients.”

Dr. Montgomery pointed to the recently published SODIUM-HF trial comparing low-sodium and unrestricted-sodium diets in outpatients with heart failure. It saw no clinical benefit from the low-sodium intervention.

Until studies show, potentially, that sodium restriction in hospitalized patients with heart failure makes a clinical difference, Dr. Montgomery said, “I’d say we should invest our time in things that we know are the most helpful, like getting them on guideline-directed medical therapy, when instead we spend an enormous amount of time counseling on and enforcing dietary restriction.”

Support for this study was provided by Cleveland Clinic Heart Vascular and Thoracic Institute’s Wilson Grant and Kaufman Center for Heart Failure Treatment and Recovery Grant. Dr. Lanfear disclosed research support from SomaLogic and Lilly; consulting for Abbott Laboratories, AstraZeneca, Janssen, Martin Pharmaceuticals, and Amgen; and serving on advisory panels for Illumina and Cytokinetics. Dr. Montgomery and Dr. Cleland disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Restriction of dietary salt to alleviate or prevent volume overload in patients with acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF) is common hospital practice, but without a solid evidence base. A trial testing whether taking salt pills might have benefits for patients with ADHF undergoing intensive diuresis, therefore, may seem a bit counterintuitive.

In just such a randomized, placebo-controlled trial, the approach made no difference to weight loss on diuresis, a proxy for volume reduction, or to serum creatinine levels in ADHF patients receiving high-dose intravenous diuretic therapy.

The patients consumed the extra salt during their intravenous therapy in the form of tablets providing 6 g sodium chloride daily on top of their hospital-provided, low-sodium meals.

During that time, serum sodium levels remained stable for the 34 patients assigned to the salt tablets but dropped significantly in the 31 given placebo pills.

They lost about the same weight, averages of 4 kg and 4.6 kg (8.8-10 lb), respectively, and their urine output was also similar. Patients who took the salt tablets showed less of an increase in blood urea nitrogen (BUN) at both 96 hours and at discharge.

The findings “challenge the routine practice of sodium chloride restriction in acute heart failure, something done thousands of times a day, millions of times a year,” Robert A. Montgomery, MD, Cleveland Clinic, said when presenting the study at the annual scientific meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America.

The trial, called OSPREY-AHF (Oral Sodium to Preserve Renal Efficiency in Acute Heart Failure), also may encourage a shift in ADHF management from a preoccupation with salt restriction to focus more on fighting fluid retention.

OSPREY-HF took on “an established practice that doesn’t have much high-quality evidentiary support,” one guided primarily by consensus and observational data, Montgomery said in an interview.

There are also potential downsides to dietary sodium restriction, including some that may complicate or block ADHF therapies.

“Low-sodium diets can be associated with decreased caloric intake and nutritional quality,” Dr. Montgomery observed. And observational studies suggest that “patients who are on a low sodium diet can develop increased neurohormonal activation. The kidney is not sensing salt, and so starts ramping up the hormones,” which promotes diuretic resistance.

But emerging evidence also suggests “that giving sodium chloride in the form of hypertonic saline can help patients who are diuretic resistant.” The intervention, which appears to attenuate the neurohormonal activation associated with high-dose intravenous diuretics, Dr. Montgomery noted, helped inspire the design of OSPREY-AHF.

Edema consists of “a gallon of water and a pinch of salt, so we really should stop being so salt-centric and think much more about water as the problem in decompensated heart failure,” said John G.F. Cleland, MD, PhD, during the question-and-answer period after Montgomery’s presentation. Dr. Cleland, of the University of Glasgow Institute of Health and Wellbeing, is not connected to OSPREY-AHF.

“I think that maybe we overinterpret how important salt is” as a focus of volume management in ADHF, offered David Lanfear, MD, Henry Ford Health System, Detroit, who is also not part of the study.

OSPREY-AHF was well conducted but applies to a “very specific” clinical setting, Dr. Lanfear said in an interview. “These people are getting aggressive diuresis, a big dose and continuous infusion. It’s not everybody that has heart failure.”

Although the study was small, “I think it will fuel interest in this area and, probably, further investigation,” he said. The trial on its own won’t change practice, “but it will raise some eyebrows.”

The trial included patients with ADHF who have been “admitted to a cardiovascular medicine floor, not the intensive care unit” and were receiving at least 10 mg per hour of furosemide. It excluded any who were “hypernatremic or severely hyponatremic,” said Dr. Montgomery when presenting the study. They were required to have an initial estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of at least 15 mL/min per 1.73 m2.

The patients were randomly assigned double blind at a single center to receive tablets providing 2 g sodium chloride or placebo pills – 34 and 31 patients, respectively – three times daily during intravenous diuresis.

At 96 hours, the two groups showed no difference in change in creatinine levels or change in weight, both primary endpoints. Nor did they differ in urine output or change in eGFR. But serum sodium levels fell further, and BUN levels went up more in those given placebo.

The two groups showed no differences in hospital length of stay, use of renal replacement therapy at 90 days, ICU time during the index hospitalization, 30-day readmission, or 90-day mortality – although the trial wasn’t powered for clinical outcomes, Dr. Montgomery reported.

"We have patients who complain about their sodium-restricted diet, we have patients that have cachexia, who have a lot of complaints about provider-ordered meals and recommendations,” Dr. Montgomery explained in an interview.

Clinicians provide education and invest a lot of effort into getting patients with heart failure to start and maintain a low-sodium diet, he said. “But a low-sodium diet, in prior studies – and our study adds to this – is not a lever that actually seems to positively or adversely affect patients.”

Dr. Montgomery pointed to the recently published SODIUM-HF trial comparing low-sodium and unrestricted-sodium diets in outpatients with heart failure. It saw no clinical benefit from the low-sodium intervention.

Until studies show, potentially, that sodium restriction in hospitalized patients with heart failure makes a clinical difference, Dr. Montgomery said, “I’d say we should invest our time in things that we know are the most helpful, like getting them on guideline-directed medical therapy, when instead we spend an enormous amount of time counseling on and enforcing dietary restriction.”

Support for this study was provided by Cleveland Clinic Heart Vascular and Thoracic Institute’s Wilson Grant and Kaufman Center for Heart Failure Treatment and Recovery Grant. Dr. Lanfear disclosed research support from SomaLogic and Lilly; consulting for Abbott Laboratories, AstraZeneca, Janssen, Martin Pharmaceuticals, and Amgen; and serving on advisory panels for Illumina and Cytokinetics. Dr. Montgomery and Dr. Cleland disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM HFSA 2022

Analysis of PsA guidelines reveals much room for improvement on conflicts of interest

, according to a retrospective analysis of all authors on the most recent guidelines issued by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and the Japanese Dermatological Association (JDA).

In addition to finding that the majority of the authors of psoriatic arthritis (PsA) clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) issued by the JDA and ACR received substantial personal payments from pharmaceutical companies before and during CPG development, researchers led by Hanano Mamada and Anju Murayama of the Medical Governance Research Institute, Tokyo, wrote in Arthritis Care & Research that “several CPG authors self-cited their articles without the disclosure of NFCOI [nonfinancial conflicts of interest], and most of the recommendations were based on low or very low quality of evidence. Although the COI policies used by JDA and ACR are clearly inadequate, no significant revisions have been made for the last 3 years.”

Based on their findings, which were made using payment data from major Japanese pharmaceutical companies and the U.S. Open Payments Database from 2016 to 2018, the researchers suggested that the medical societies should:

- Adopt global standard COI policies from organizations such as the National Academy of Medicine and Guidelines International Network, including a 3-year lookback period for COI declaration.

- Consider a comprehensive definition and rigorous management with full disclosure of NFCOI.

- Publish a list of authors making each recommendation to grasp the implications of COI in clinical practice guidelines.

- Mention the detailed date of the COI disclosure, which should be close to the publication date as much as possible.

Financial conflicts of interest

The researchers used payment data published between 2016 and 2018 for all 83 companies belonging to the Japan Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association, focusing on personal payments (for lecturing, writing, and consultancy) and excluding research payments, “since in Japan, the name, institution, and position of the author or researcher who received the research payment is not disclosed, which makes assessing research payments difficult.” To evaluate authors’ FCOI in the ACR’s CPG, the researchers analyzed the U.S. Open Payments Database “for all categories of general payments such as speaking, consulting, meals, and travel expenses 3 years from before the guideline’s first online publication on November 30, 2018.”

The 2018 ACR/National Psoriasis Foundation Guideline for the Treatment of Psoriatic Arthritis had 36 authors and the JDA’s Clinical Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Psoriatic Arthritis 2019 had 23. Overall, 61% of JDA authors and half of ACR authors voluntarily declared FCOI with pharmaceutical companies; 25 of the ACR authors were U.S. physicians and could be included in the Open Payments Database search.

A total of 21 (91.3%) JDA authors and 21 (84.0%) ACR authors received at least one payment, with the combined total of $3,335,413 and $4,081,629 payments, respectively, over the 3 years. The average and median personal payments were $145,018 and $123,876 for JDA authors and $162,825 and $58,826 for ACR authors. When the payments to ACR authors were limited to lecturing, writing, and consulting fees that are required under the ACR’s COI policy, the mean was $130,102 and median was $39,375. The corresponding payments for JDA authors were $123,876 and $8,170, respectively,

The researchers found undisclosed payments for more than three-quarters of physician authors of the Japanese guideline, and nearly half of the doctors authoring the American guideline had undisclosed payments. These added up to $474,000 for the JDA, which amounted to 38% of the total for personal payments that must be reported to the JDA based on its COI policy for clinical practice guidelines, and $218,000 for the ACR, amounting to 18% of the total for personal payments that must be reported to the society based on its COI policy.

Of the 11 ACR authors who were not eligible for the U.S. Open Payments Database search, 5 declared FCOI with pharmaceutical companies in the guideline, meaning that 26 (72%) of the 36 authors had FCOI with pharmaceutical companies.

The ACR only required authors to declare FCOI covering 1 year before and during guideline development, and although the JDA required authors to declare their FCOI for the past 3 years of guideline development, the study authors noted that the JDA guideline disclosed them for only 2 years (between Jan. 1, 2017, and Dec. 31, 2018).

“It is true that influential doctors such as clinical practice guideline authors tend to receive various types of payments from pharmaceutical companies and that it is difficult to conduct research without funding from pharmaceutical companies. However, our current research mainly focuses on personal payments from pharmaceutical companies such as lecture fees and consulting fees. These payments are recognized as pocket money and are not used for research. Thus, it is questionable that the observed relationships are something evitable,” the researchers wrote.

Nonfinancial conflicts of interest

Many authors of the ACR’s CPG and the JDA’s CPG also had NFCOI, defined objectively in this study as self-citation rate. NFCOI have been more broadly defined by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) as “conflicts, such as personal relationships or rivalries, academic competition, and intellectual beliefs”; the ICMJE recommends reporting NFCOI on its COI form.

The JDA guideline included self-citations by 78% of its authors, compared with 32% of the ACR guideline authors, but this weighed differently among the two guidelines in that only 12 of the 354 (3.4%) citations in the JDA guideline were self-cited, compared with 46 of 137 (34%) citations in the ACR guideline.

The researchers noted that while the self-citation rates between JDA and ACR authors “differed remarkably,” the impact of ACR authors on CPG recommendations was much more direct. Three-quarters of JDA authors’ self-cited articles were about observational studies, whereas 52% of the ACR authors’ self-cited articles were clinical trials, most of which were randomized, controlled studies, and these NFCOI were not disclosed in the guideline.

Half of the strong recommendations in the JDA guideline were based on low or very low quality of evidence, whereas the ACR guideline had no strong recommendations based on low or very low quality of evidence.

This study was supported by the nonprofit Medical Governance Research Institute, which receives donations from Ain Pharmacies Inc., other organizations, and private individuals. The study also received support from the Tansa (formerly known as the Waseda Chronicle), an independent nonprofit news organization dedicated to investigative journalism. Three authors reported receiving personal fees from several pharmaceutical companies for work outside of the scope of this study.

, according to a retrospective analysis of all authors on the most recent guidelines issued by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and the Japanese Dermatological Association (JDA).

In addition to finding that the majority of the authors of psoriatic arthritis (PsA) clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) issued by the JDA and ACR received substantial personal payments from pharmaceutical companies before and during CPG development, researchers led by Hanano Mamada and Anju Murayama of the Medical Governance Research Institute, Tokyo, wrote in Arthritis Care & Research that “several CPG authors self-cited their articles without the disclosure of NFCOI [nonfinancial conflicts of interest], and most of the recommendations were based on low or very low quality of evidence. Although the COI policies used by JDA and ACR are clearly inadequate, no significant revisions have been made for the last 3 years.”

Based on their findings, which were made using payment data from major Japanese pharmaceutical companies and the U.S. Open Payments Database from 2016 to 2018, the researchers suggested that the medical societies should:

- Adopt global standard COI policies from organizations such as the National Academy of Medicine and Guidelines International Network, including a 3-year lookback period for COI declaration.

- Consider a comprehensive definition and rigorous management with full disclosure of NFCOI.

- Publish a list of authors making each recommendation to grasp the implications of COI in clinical practice guidelines.

- Mention the detailed date of the COI disclosure, which should be close to the publication date as much as possible.

Financial conflicts of interest

The researchers used payment data published between 2016 and 2018 for all 83 companies belonging to the Japan Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association, focusing on personal payments (for lecturing, writing, and consultancy) and excluding research payments, “since in Japan, the name, institution, and position of the author or researcher who received the research payment is not disclosed, which makes assessing research payments difficult.” To evaluate authors’ FCOI in the ACR’s CPG, the researchers analyzed the U.S. Open Payments Database “for all categories of general payments such as speaking, consulting, meals, and travel expenses 3 years from before the guideline’s first online publication on November 30, 2018.”

The 2018 ACR/National Psoriasis Foundation Guideline for the Treatment of Psoriatic Arthritis had 36 authors and the JDA’s Clinical Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Psoriatic Arthritis 2019 had 23. Overall, 61% of JDA authors and half of ACR authors voluntarily declared FCOI with pharmaceutical companies; 25 of the ACR authors were U.S. physicians and could be included in the Open Payments Database search.

A total of 21 (91.3%) JDA authors and 21 (84.0%) ACR authors received at least one payment, with the combined total of $3,335,413 and $4,081,629 payments, respectively, over the 3 years. The average and median personal payments were $145,018 and $123,876 for JDA authors and $162,825 and $58,826 for ACR authors. When the payments to ACR authors were limited to lecturing, writing, and consulting fees that are required under the ACR’s COI policy, the mean was $130,102 and median was $39,375. The corresponding payments for JDA authors were $123,876 and $8,170, respectively,

The researchers found undisclosed payments for more than three-quarters of physician authors of the Japanese guideline, and nearly half of the doctors authoring the American guideline had undisclosed payments. These added up to $474,000 for the JDA, which amounted to 38% of the total for personal payments that must be reported to the JDA based on its COI policy for clinical practice guidelines, and $218,000 for the ACR, amounting to 18% of the total for personal payments that must be reported to the society based on its COI policy.

Of the 11 ACR authors who were not eligible for the U.S. Open Payments Database search, 5 declared FCOI with pharmaceutical companies in the guideline, meaning that 26 (72%) of the 36 authors had FCOI with pharmaceutical companies.

The ACR only required authors to declare FCOI covering 1 year before and during guideline development, and although the JDA required authors to declare their FCOI for the past 3 years of guideline development, the study authors noted that the JDA guideline disclosed them for only 2 years (between Jan. 1, 2017, and Dec. 31, 2018).

“It is true that influential doctors such as clinical practice guideline authors tend to receive various types of payments from pharmaceutical companies and that it is difficult to conduct research without funding from pharmaceutical companies. However, our current research mainly focuses on personal payments from pharmaceutical companies such as lecture fees and consulting fees. These payments are recognized as pocket money and are not used for research. Thus, it is questionable that the observed relationships are something evitable,” the researchers wrote.

Nonfinancial conflicts of interest

Many authors of the ACR’s CPG and the JDA’s CPG also had NFCOI, defined objectively in this study as self-citation rate. NFCOI have been more broadly defined by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) as “conflicts, such as personal relationships or rivalries, academic competition, and intellectual beliefs”; the ICMJE recommends reporting NFCOI on its COI form.

The JDA guideline included self-citations by 78% of its authors, compared with 32% of the ACR guideline authors, but this weighed differently among the two guidelines in that only 12 of the 354 (3.4%) citations in the JDA guideline were self-cited, compared with 46 of 137 (34%) citations in the ACR guideline.

The researchers noted that while the self-citation rates between JDA and ACR authors “differed remarkably,” the impact of ACR authors on CPG recommendations was much more direct. Three-quarters of JDA authors’ self-cited articles were about observational studies, whereas 52% of the ACR authors’ self-cited articles were clinical trials, most of which were randomized, controlled studies, and these NFCOI were not disclosed in the guideline.

Half of the strong recommendations in the JDA guideline were based on low or very low quality of evidence, whereas the ACR guideline had no strong recommendations based on low or very low quality of evidence.

This study was supported by the nonprofit Medical Governance Research Institute, which receives donations from Ain Pharmacies Inc., other organizations, and private individuals. The study also received support from the Tansa (formerly known as the Waseda Chronicle), an independent nonprofit news organization dedicated to investigative journalism. Three authors reported receiving personal fees from several pharmaceutical companies for work outside of the scope of this study.

, according to a retrospective analysis of all authors on the most recent guidelines issued by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and the Japanese Dermatological Association (JDA).

In addition to finding that the majority of the authors of psoriatic arthritis (PsA) clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) issued by the JDA and ACR received substantial personal payments from pharmaceutical companies before and during CPG development, researchers led by Hanano Mamada and Anju Murayama of the Medical Governance Research Institute, Tokyo, wrote in Arthritis Care & Research that “several CPG authors self-cited their articles without the disclosure of NFCOI [nonfinancial conflicts of interest], and most of the recommendations were based on low or very low quality of evidence. Although the COI policies used by JDA and ACR are clearly inadequate, no significant revisions have been made for the last 3 years.”

Based on their findings, which were made using payment data from major Japanese pharmaceutical companies and the U.S. Open Payments Database from 2016 to 2018, the researchers suggested that the medical societies should:

- Adopt global standard COI policies from organizations such as the National Academy of Medicine and Guidelines International Network, including a 3-year lookback period for COI declaration.

- Consider a comprehensive definition and rigorous management with full disclosure of NFCOI.

- Publish a list of authors making each recommendation to grasp the implications of COI in clinical practice guidelines.

- Mention the detailed date of the COI disclosure, which should be close to the publication date as much as possible.

Financial conflicts of interest

The researchers used payment data published between 2016 and 2018 for all 83 companies belonging to the Japan Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association, focusing on personal payments (for lecturing, writing, and consultancy) and excluding research payments, “since in Japan, the name, institution, and position of the author or researcher who received the research payment is not disclosed, which makes assessing research payments difficult.” To evaluate authors’ FCOI in the ACR’s CPG, the researchers analyzed the U.S. Open Payments Database “for all categories of general payments such as speaking, consulting, meals, and travel expenses 3 years from before the guideline’s first online publication on November 30, 2018.”

The 2018 ACR/National Psoriasis Foundation Guideline for the Treatment of Psoriatic Arthritis had 36 authors and the JDA’s Clinical Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Psoriatic Arthritis 2019 had 23. Overall, 61% of JDA authors and half of ACR authors voluntarily declared FCOI with pharmaceutical companies; 25 of the ACR authors were U.S. physicians and could be included in the Open Payments Database search.

A total of 21 (91.3%) JDA authors and 21 (84.0%) ACR authors received at least one payment, with the combined total of $3,335,413 and $4,081,629 payments, respectively, over the 3 years. The average and median personal payments were $145,018 and $123,876 for JDA authors and $162,825 and $58,826 for ACR authors. When the payments to ACR authors were limited to lecturing, writing, and consulting fees that are required under the ACR’s COI policy, the mean was $130,102 and median was $39,375. The corresponding payments for JDA authors were $123,876 and $8,170, respectively,

The researchers found undisclosed payments for more than three-quarters of physician authors of the Japanese guideline, and nearly half of the doctors authoring the American guideline had undisclosed payments. These added up to $474,000 for the JDA, which amounted to 38% of the total for personal payments that must be reported to the JDA based on its COI policy for clinical practice guidelines, and $218,000 for the ACR, amounting to 18% of the total for personal payments that must be reported to the society based on its COI policy.

Of the 11 ACR authors who were not eligible for the U.S. Open Payments Database search, 5 declared FCOI with pharmaceutical companies in the guideline, meaning that 26 (72%) of the 36 authors had FCOI with pharmaceutical companies.

The ACR only required authors to declare FCOI covering 1 year before and during guideline development, and although the JDA required authors to declare their FCOI for the past 3 years of guideline development, the study authors noted that the JDA guideline disclosed them for only 2 years (between Jan. 1, 2017, and Dec. 31, 2018).

“It is true that influential doctors such as clinical practice guideline authors tend to receive various types of payments from pharmaceutical companies and that it is difficult to conduct research without funding from pharmaceutical companies. However, our current research mainly focuses on personal payments from pharmaceutical companies such as lecture fees and consulting fees. These payments are recognized as pocket money and are not used for research. Thus, it is questionable that the observed relationships are something evitable,” the researchers wrote.

Nonfinancial conflicts of interest

Many authors of the ACR’s CPG and the JDA’s CPG also had NFCOI, defined objectively in this study as self-citation rate. NFCOI have been more broadly defined by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) as “conflicts, such as personal relationships or rivalries, academic competition, and intellectual beliefs”; the ICMJE recommends reporting NFCOI on its COI form.

The JDA guideline included self-citations by 78% of its authors, compared with 32% of the ACR guideline authors, but this weighed differently among the two guidelines in that only 12 of the 354 (3.4%) citations in the JDA guideline were self-cited, compared with 46 of 137 (34%) citations in the ACR guideline.

The researchers noted that while the self-citation rates between JDA and ACR authors “differed remarkably,” the impact of ACR authors on CPG recommendations was much more direct. Three-quarters of JDA authors’ self-cited articles were about observational studies, whereas 52% of the ACR authors’ self-cited articles were clinical trials, most of which were randomized, controlled studies, and these NFCOI were not disclosed in the guideline.

Half of the strong recommendations in the JDA guideline were based on low or very low quality of evidence, whereas the ACR guideline had no strong recommendations based on low or very low quality of evidence.

This study was supported by the nonprofit Medical Governance Research Institute, which receives donations from Ain Pharmacies Inc., other organizations, and private individuals. The study also received support from the Tansa (formerly known as the Waseda Chronicle), an independent nonprofit news organization dedicated to investigative journalism. Three authors reported receiving personal fees from several pharmaceutical companies for work outside of the scope of this study.

FROM ARTHRITIS CARE & RESEARCH

Newer drugs not cost effective for first-line diabetes therapy

To be cost effective, compared with metformin, for initial therapy for type 2 diabetes, prices for a sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitor or a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonist would have to fall by at least 70% and at least 90%, respectively, according to estimates.

The study, modeled on U.S. patients, by Jin G. Choi, MD, and colleagues, was published online Oct. 3 in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

The researchers simulated the lifetime incidence, prevalence, mortality, and costs associated with three different first-line treatment strategies – metformin, an SGLT2 inhibitor, or a GLP-1 agonist – in U.S. patients with untreated type 2 diabetes.

Compared with patients who received initial treatment with metformin, those who received one of the newer drugs had 4.4% to 5.2% lower lifetime rates of congestive heart failure, ischemic heart disease, myocardial infarction, and stroke.

However, to be cost-effective at under $150,000 per quality-adjusted life-years (QALY), SGLT2 inhibitors would need to cost less than $5 a day ($1,800 a year), and GLP-1 agonists would have to cost less than $6 a day ($2,100 a year), a lot less than now.

Knowing how expensive these drugs are, “I am not surprised” that the model predicts that the price would have to drop so much to make them cost-effective, compared with first-line treatment with metformin, senior author Neda Laiteerapong, MD, said in an interview.

“But I am disappointed,” she said, because these drugs are very effective, and if the prices were lower, more people could benefit.

“In the interest of improving access to high-quality care in the United States, our study results indicate the need to reduce SGLT2 inhibitor and GLP-1 receptor agonist medication costs substantially for patients with type 2 [diabetes] to improve health outcomes and prevent exacerbating diabetes health disparities,” the researchers conclude.

One way that the newer drugs might be more widely affordable is if the government became involved, possibly by passing a law similar to the Affordable Insulin Now Act, speculated Dr. Laiteerapong, who is associate director at the Center for Chronic Disease Research and Policy, University of Chicago.

‘Current prices too high to encourage first-line adoption’

Guidelines recommend the use of SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 agonists as second-line therapies for patients with type 2 diabetes, but it has not been clear if clinical benefits would outweigh costs for use as first-line therapies.

“Although clinical trials have demonstrated the clinical effectiveness of these newer drugs, they are hundreds of times more expensive than other ... diabetes drugs,” the researchers note.

On the other hand, costs may fall in the coming years when these new drugs come off-patent.

The current study was designed to help inform future clinical guidelines.

The researchers created a population simulation model based on the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study, Outcomes Model version 2 (UKPDS OM2) for diabetes-related complications and mortality, with added information about hypoglycemic events, quality of life, and U.S. costs.

The researchers also identified a nationally representative sample of people who would be eligible to start first-line diabetes therapy when their A1c reached 7% for the model.

Using National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data (2013-2016), the researchers identified about 7.3 million U.S. adults aged 18 and older with self-reported diabetes or an A1c greater than 6.5% with no reported use of diabetes medications.

Patients were an average age of 55, and 55% were women. They had had diabetes for an average of 4.2 years, and 36% had a history of diabetes complications.

The model projected that patients would have an improved life expectancy of 3.0 and 3.4 months from first-line SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 agonists, respectively, compared with initial therapy with metformin due to reduced rates of macrovascular disease.

“However, the current drug costs would be too high to encourage their adoption as first-line for usual clinical practice,” the researchers report.

‘Disparities could remain for decades’

Generic SGLT2 inhibitors could enter the marketplace shortly, because one of two dapagliflozin patents expired in October 2020 and approval for generic alternatives has been sought from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Dr. Choi and colleagues note.

However, it could still take decades for medication prices to drop low enough to become affordable, the group cautions. For example, a generic GLP-1 agonist became available in 2017, but costs remain high.

“Without external incentives,” the group writes, “limited access to these drug classes will likely persist (for example, due to higher copays or requirements for prior authorizations), as will further diabetes disparities – for decades into the future – because of differential access to care due to insurance (for example, private vs. public), which often tracks race and ethnicity.”

The study was supported by the American Diabetes Association. Dr. Choi was supported by a National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Aging grant. Dr. Laiteerapong and other co-authors are members of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Chicago Center for Diabetes Translation Research at the University of Chicago. Dr. Choi and Dr. Laiteerapong have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

To be cost effective, compared with metformin, for initial therapy for type 2 diabetes, prices for a sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitor or a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonist would have to fall by at least 70% and at least 90%, respectively, according to estimates.

The study, modeled on U.S. patients, by Jin G. Choi, MD, and colleagues, was published online Oct. 3 in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

The researchers simulated the lifetime incidence, prevalence, mortality, and costs associated with three different first-line treatment strategies – metformin, an SGLT2 inhibitor, or a GLP-1 agonist – in U.S. patients with untreated type 2 diabetes.

Compared with patients who received initial treatment with metformin, those who received one of the newer drugs had 4.4% to 5.2% lower lifetime rates of congestive heart failure, ischemic heart disease, myocardial infarction, and stroke.

However, to be cost-effective at under $150,000 per quality-adjusted life-years (QALY), SGLT2 inhibitors would need to cost less than $5 a day ($1,800 a year), and GLP-1 agonists would have to cost less than $6 a day ($2,100 a year), a lot less than now.

Knowing how expensive these drugs are, “I am not surprised” that the model predicts that the price would have to drop so much to make them cost-effective, compared with first-line treatment with metformin, senior author Neda Laiteerapong, MD, said in an interview.

“But I am disappointed,” she said, because these drugs are very effective, and if the prices were lower, more people could benefit.

“In the interest of improving access to high-quality care in the United States, our study results indicate the need to reduce SGLT2 inhibitor and GLP-1 receptor agonist medication costs substantially for patients with type 2 [diabetes] to improve health outcomes and prevent exacerbating diabetes health disparities,” the researchers conclude.

One way that the newer drugs might be more widely affordable is if the government became involved, possibly by passing a law similar to the Affordable Insulin Now Act, speculated Dr. Laiteerapong, who is associate director at the Center for Chronic Disease Research and Policy, University of Chicago.

‘Current prices too high to encourage first-line adoption’

Guidelines recommend the use of SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 agonists as second-line therapies for patients with type 2 diabetes, but it has not been clear if clinical benefits would outweigh costs for use as first-line therapies.

“Although clinical trials have demonstrated the clinical effectiveness of these newer drugs, they are hundreds of times more expensive than other ... diabetes drugs,” the researchers note.

On the other hand, costs may fall in the coming years when these new drugs come off-patent.

The current study was designed to help inform future clinical guidelines.

The researchers created a population simulation model based on the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study, Outcomes Model version 2 (UKPDS OM2) for diabetes-related complications and mortality, with added information about hypoglycemic events, quality of life, and U.S. costs.

The researchers also identified a nationally representative sample of people who would be eligible to start first-line diabetes therapy when their A1c reached 7% for the model.

Using National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data (2013-2016), the researchers identified about 7.3 million U.S. adults aged 18 and older with self-reported diabetes or an A1c greater than 6.5% with no reported use of diabetes medications.

Patients were an average age of 55, and 55% were women. They had had diabetes for an average of 4.2 years, and 36% had a history of diabetes complications.

The model projected that patients would have an improved life expectancy of 3.0 and 3.4 months from first-line SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 agonists, respectively, compared with initial therapy with metformin due to reduced rates of macrovascular disease.

“However, the current drug costs would be too high to encourage their adoption as first-line for usual clinical practice,” the researchers report.

‘Disparities could remain for decades’

Generic SGLT2 inhibitors could enter the marketplace shortly, because one of two dapagliflozin patents expired in October 2020 and approval for generic alternatives has been sought from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Dr. Choi and colleagues note.

However, it could still take decades for medication prices to drop low enough to become affordable, the group cautions. For example, a generic GLP-1 agonist became available in 2017, but costs remain high.

“Without external incentives,” the group writes, “limited access to these drug classes will likely persist (for example, due to higher copays or requirements for prior authorizations), as will further diabetes disparities – for decades into the future – because of differential access to care due to insurance (for example, private vs. public), which often tracks race and ethnicity.”

The study was supported by the American Diabetes Association. Dr. Choi was supported by a National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Aging grant. Dr. Laiteerapong and other co-authors are members of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Chicago Center for Diabetes Translation Research at the University of Chicago. Dr. Choi and Dr. Laiteerapong have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

To be cost effective, compared with metformin, for initial therapy for type 2 diabetes, prices for a sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitor or a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonist would have to fall by at least 70% and at least 90%, respectively, according to estimates.

The study, modeled on U.S. patients, by Jin G. Choi, MD, and colleagues, was published online Oct. 3 in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

The researchers simulated the lifetime incidence, prevalence, mortality, and costs associated with three different first-line treatment strategies – metformin, an SGLT2 inhibitor, or a GLP-1 agonist – in U.S. patients with untreated type 2 diabetes.

Compared with patients who received initial treatment with metformin, those who received one of the newer drugs had 4.4% to 5.2% lower lifetime rates of congestive heart failure, ischemic heart disease, myocardial infarction, and stroke.

However, to be cost-effective at under $150,000 per quality-adjusted life-years (QALY), SGLT2 inhibitors would need to cost less than $5 a day ($1,800 a year), and GLP-1 agonists would have to cost less than $6 a day ($2,100 a year), a lot less than now.

Knowing how expensive these drugs are, “I am not surprised” that the model predicts that the price would have to drop so much to make them cost-effective, compared with first-line treatment with metformin, senior author Neda Laiteerapong, MD, said in an interview.

“But I am disappointed,” she said, because these drugs are very effective, and if the prices were lower, more people could benefit.

“In the interest of improving access to high-quality care in the United States, our study results indicate the need to reduce SGLT2 inhibitor and GLP-1 receptor agonist medication costs substantially for patients with type 2 [diabetes] to improve health outcomes and prevent exacerbating diabetes health disparities,” the researchers conclude.

One way that the newer drugs might be more widely affordable is if the government became involved, possibly by passing a law similar to the Affordable Insulin Now Act, speculated Dr. Laiteerapong, who is associate director at the Center for Chronic Disease Research and Policy, University of Chicago.

‘Current prices too high to encourage first-line adoption’

Guidelines recommend the use of SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 agonists as second-line therapies for patients with type 2 diabetes, but it has not been clear if clinical benefits would outweigh costs for use as first-line therapies.

“Although clinical trials have demonstrated the clinical effectiveness of these newer drugs, they are hundreds of times more expensive than other ... diabetes drugs,” the researchers note.

On the other hand, costs may fall in the coming years when these new drugs come off-patent.

The current study was designed to help inform future clinical guidelines.

The researchers created a population simulation model based on the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study, Outcomes Model version 2 (UKPDS OM2) for diabetes-related complications and mortality, with added information about hypoglycemic events, quality of life, and U.S. costs.

The researchers also identified a nationally representative sample of people who would be eligible to start first-line diabetes therapy when their A1c reached 7% for the model.

Using National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data (2013-2016), the researchers identified about 7.3 million U.S. adults aged 18 and older with self-reported diabetes or an A1c greater than 6.5% with no reported use of diabetes medications.

Patients were an average age of 55, and 55% were women. They had had diabetes for an average of 4.2 years, and 36% had a history of diabetes complications.

The model projected that patients would have an improved life expectancy of 3.0 and 3.4 months from first-line SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 agonists, respectively, compared with initial therapy with metformin due to reduced rates of macrovascular disease.

“However, the current drug costs would be too high to encourage their adoption as first-line for usual clinical practice,” the researchers report.

‘Disparities could remain for decades’

Generic SGLT2 inhibitors could enter the marketplace shortly, because one of two dapagliflozin patents expired in October 2020 and approval for generic alternatives has been sought from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Dr. Choi and colleagues note.

However, it could still take decades for medication prices to drop low enough to become affordable, the group cautions. For example, a generic GLP-1 agonist became available in 2017, but costs remain high.

“Without external incentives,” the group writes, “limited access to these drug classes will likely persist (for example, due to higher copays or requirements for prior authorizations), as will further diabetes disparities – for decades into the future – because of differential access to care due to insurance (for example, private vs. public), which often tracks race and ethnicity.”

The study was supported by the American Diabetes Association. Dr. Choi was supported by a National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Aging grant. Dr. Laiteerapong and other co-authors are members of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Chicago Center for Diabetes Translation Research at the University of Chicago. Dr. Choi and Dr. Laiteerapong have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Death of son reinforces flu vaccination message

“It was what the CDC [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] would call classic influenza-like illness,” Dr. Teichman said. “It was too late to start antivirals, so I gave him advice on symptomatic treatment. We texted the next day, and I was glad to hear that his fever was trending down and that he was feeling a little bit better.”

Two days later, his son called again.

“He said he was having trouble breathing, and over the phone I could hear him hyperventilating.” The retired pediatrician and health care executive told his son to seek medical care.

“Then I got the call that no parent wants to get.”

Brent’s cousin Jake called saying he couldn’t wake Brent up.

“I called Jake back a few minutes later and asked him to hold up the phone,” Dr. Teichman said. “I listened to EMS working on my son, calling for round after round of many medications. He was in arrest and they couldn’t revive him.”

“To this day when I close my eyes at night, I still hear the beeping of those monitors.”

Brent had no health conditions to put him at higher risk for complications of the flu. “Brent was a wonderful son, brother, uncle, and friend. He had a passion for everything he did, and that included his chosen calling of the culinary arts but also included University of Kentucky sports,” Dr. Teichman said.

Brent planned to get a flu vaccine but had not done it yet. “In his obituary, we requested that, in lieu of flowers or donations, people go get their flu shot,” Dr. Teichman said.

“I’m here today to put a face on influenza,” Dr. Teichman said at a news briefing Oct. 4 on preventing the flu and pneumococcal disease, sponsored by the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases.

New survey numbers ‘alarming’

The NFID commissioned a national survey of more than 1,000 U.S. adults to better understand their knowledge and attitudes about the flu, pneumococcal disease, vaccines, and the impact of COVID-19.

“We were alarmed to learn that only 49% of U.S. adults plan to get their flu vaccine this season,” said Patricia A. “Patsy” Stinchfield, a registered nurse, NFID president, and moderator of the news briefing. “That is not good enough.”

In addition, 22% of people at higher risk for flu-related complications do not plan to get vaccinated this season. “That’s a dangerous risk to take,” Ms. Stinchfield said.

An encouraging finding, she said, is that 69% of adults surveyed recognize that an annual flu vaccination is the best way to prevent flu-related hospitalizations and death.

“So, most people know what to do. We just need to do it,” she said.

The top reason for not getting a flu shot in 2022 mentioned by 41% of people surveyed, is they do not think vaccines work very well. Another 39% are concerned about vaccine side effects, and 28% skip the vaccine because they “never get the flu.”

The experts on the panel emphasized the recommendation that all Americans 6 months or older get the flu vaccine, preferably by the end of October. Vaccination is especially important for those at higher risk of complications from the flu, including children under 5, pregnant women, people with one or more health conditions, the immunocompromised, and Americans 65 years and older.

Ms. Stinchfield acknowledged that the effectiveness of the flu vaccine varies season to season, but even if the vaccine does not completely match the circulating viruses, it can help prevent serious outcomes like hospitalization and death. One of the serious potential complications is pneumonia or “pneumococcal disease.”

“Our survey shows that only 29% of those at risk have been advised to receive a pneumococcal vaccine,” Ms. Stinchfield said. “The good news is that, among those who were advised to get the vaccine, 74% did receive their pneumococcal vaccine,” she said. “This underscores a key point to you, my fellow clinicians: As health professionals, our recommendations matter.”

Higher doses for 65+ Americans

The CDC updated recommendations this flu season for adults 65 and older to receive one of three preferentially recommended flu vaccines, said CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, MD. The CDC is recommending higher-dose, stronger vaccines for older Americans “based on a review of the available studies, which suggested that in this age group, these vaccines are potentially more effective than standard-dose ... vaccines.”

During most seasons, people 65 and older bear the greatest burden of severe flu disease, accounting for most flu-related hospitalizations and deaths.

“They are the largest vulnerable segment of our society,” Dr. Walensky said.

What will this flu season be like?

Health officials in the flu vaccine business also tend to be in the flu season prediction business. That includes Dr. Walensky.

“While we will never exactly know what each flu season will hold, we do know that every year, the best way you can protect yourself and those around you is to get your annual flu vaccine,” she said while taking part remotely in the briefing.

How severe will the flu season be in 2022-23? William Schaffner, MD, said he gets that question a lot. “Don’t think about that. Just focus on the fact that flu will be with us each year.

“We were a little bit spoiled. We’ve had two mild influenza seasons,” said Dr. Schaffner, medical director of NFID and a professor of infectious diseases and preventive medicine at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn. “I think with all the interest in COVID, people have rather forgotten about influenza. I’ve had to remind them that this is yet another serious winter respiratory virus.

“As I like to say, flu is fickle. It’s difficult to predict how serious this next outbreak of influenza this season is going to be. We could look at what happened in the Southern Hemisphere,” he said.

For example, Australia had the worst influenza season in the past 5 years, Schaffner said. “If you want a hint of what might happen here and you want yet another reason to be vaccinated, there it is.”

What we do know, Dr. Walensky said, is that the timing and severity of the past two flu seasons in the U.S. have been different than typical flu seasons. “And this is likely due to the COVID mitigation measures and other changes in circulating respiratory viruses.” Also, although last flu season was “relatively mild,” there was more flu activity than in the prior, 2020-21 season.

Also, Dr. Walensky said, last season’s flu cases began to increase in November and remained elevated until mid-June, “making it the latest season on record.”

The official cause of Brent Teichman’s death was multilobar pneumonia, cause undetermined. “But after 30-plus years as a pediatrician ... I know influenza when I see it,” Dr. Teichman said.

“There’s a hole in our hearts that will never heal. Loss of a child is devastating,” he said. The flu “can take the life of a healthy young person, as it did to my son.

“And for all those listening to my story who are vaccine hesitant, do it for those who love you. So that they won’t walk the path that we and many other families in this country have walked.”

To prove their point, Dr. Teichman and Ms. Stinchfield raised their sleeves and received flu shots during the news briefing.

“This one is for Brent,” Dr. Teichman said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

“It was what the CDC [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] would call classic influenza-like illness,” Dr. Teichman said. “It was too late to start antivirals, so I gave him advice on symptomatic treatment. We texted the next day, and I was glad to hear that his fever was trending down and that he was feeling a little bit better.”

Two days later, his son called again.

“He said he was having trouble breathing, and over the phone I could hear him hyperventilating.” The retired pediatrician and health care executive told his son to seek medical care.

“Then I got the call that no parent wants to get.”

Brent’s cousin Jake called saying he couldn’t wake Brent up.

“I called Jake back a few minutes later and asked him to hold up the phone,” Dr. Teichman said. “I listened to EMS working on my son, calling for round after round of many medications. He was in arrest and they couldn’t revive him.”

“To this day when I close my eyes at night, I still hear the beeping of those monitors.”

Brent had no health conditions to put him at higher risk for complications of the flu. “Brent was a wonderful son, brother, uncle, and friend. He had a passion for everything he did, and that included his chosen calling of the culinary arts but also included University of Kentucky sports,” Dr. Teichman said.

Brent planned to get a flu vaccine but had not done it yet. “In his obituary, we requested that, in lieu of flowers or donations, people go get their flu shot,” Dr. Teichman said.