User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Risk factors in children linked to stroke as soon as 30s, 40s

In a case-control study, atherosclerotic risk factors were uncommon in childhood and did not appear to be associated with the pathogenesis of arterial ischemic stroke in children or in early young adulthood.

But by the fourth and fifth decades of life, these risk factors were strongly associated with a significant risk for stroke, heightening that risk almost tenfold.

“While strokes in childhood and very early adulthood are not likely caused by atherosclerotic risk factors, it does look like these risk factors increase throughout early and young adulthood and become significant risk factors for stroke in the 30s and 40s,” lead author Sharon N. Poisson, MD, MAS, associate professor of neurology at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, said in an interview.

The findings were published online in JAMA Neurology.

In this study, the researchers focused on arterial ischemic stroke, not hemorrhagic stroke. “We know that high blood pressure, diabetes, smoking, obesity, all of these are risk factors for ischemic stroke, but what we didn’t know is at what age do those atherosclerotic risk factors actually start to cause stroke,” Dr. Poisson said.

To find out more, she and her team did a case control study of data in the Kaiser Permanente Northern California system, which had been accumulating relevant data over a period of 14 years, from Jan. 1, 2000, through Dec. 31, 2014.

The analysis included 141 children and 455 young adults with arterial ischemic stroke and 1,382 age-matched controls.

The children were divided into two age categories: ages 29 days to 9 years and ages 10-19 years.

In the younger group, there were 69 cases of arterial ischemic stroke. In the older age group, there were 72 cases.

Young adults were divided into three age categories: 20-29 years (n = 71 cases), 30-39 years (144 cases), and 40-49 years (240 cases).

Among pediatric controls, 168 children aged 29 days to 9 years (46.5%) and 196 children aged 10-19 years (53.8%) developed arterial ischemic stroke.

There were 121 cases of ischemic stroke among young adult controls aged 20-29 years, 298 cases among controls aged 30-39 years, and 599 cases in those aged 40-49 years.

Both childhood cases and controls had a low prevalence of documented diagnoses of atherosclerotic risk factors (ARFs). The odds ratio of having any ARFs on arterial ischemic stroke was 1.87 for ages 0-9 years, and 1.00 for ages 10-19.

However, cases rose with age.

The OR was 2.3 for age range 20-29 years, 3.57 for age range 30-39 years, and 4.91 for age range 40-49 years.

The analysis also showed that the OR associated with multiple ARFs was 5.29 for age range 0-9 years, 2.75 for age range 10-19 years, 7.33 for age range 20-29 years, 9.86 for age range 30-39 years, and 9.35 for age range 40-49 years.

Multiple risk factors were rare in children but became more prevalent with each decade of young adult life.

The presumed cause of arterial ischemic stroke was atherosclerosis. Evidence of atherosclerosis was present in 1.4% of those aged 10-19 years, 8.5% of those aged 20-29 years, 21.5% of those aged 30-39 years, and 42.5% of those aged 40-49 years.

“This study tells us that, while stroke in adolescence and very early adulthood may not be caused by atherosclerotic risk factors, starting to accumulate those risk factors early in life clearly increases the risk of stroke in the 30s and 40s. I hope we can get this message across, because the sooner we can treat the risk factors, the better the outcome,” Dr. Poisson said.

Prevention starts in childhood

Prevention of cardiovascular disease begins in childhood, which is a paradigm shift from the way cardiovascular disease was thought of a couple of decades ago, noted pediatric cardiologist Guilherme Baptista de Faia, MD, from the Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital in Chicago.

“Our guidelines for risk factor reduction in children aim to address how or when do we screen for these risk factors, how or when do we intervene, and do these interventions impact cardiovascular outcomes later in life? This article is part of the mounting research that aims to understand the relationship between childhood cardiovascular risk factors and early cardiovascular disease,” Dr. Baptista de Faia said.

“There has been an interesting progression in our understanding of the impact of CV risk factors early in life. Large cohorts such as Bogalusa Heart Study, Risk in Young Finns Study, Muscatine Study, the Childhood Determinants of Adult Health, CARDIA, and the International Childhood Cardiovascular Cohorts (i3C) have been instrumental in evaluating this question,” he said.

The knowledge that atherosclerotic risk factors in children can lead to acceleration of atherosclerosis in later life opens the door to preventive medicine, said Dr. Baptista de Faia, who was not part of the study.

“This is where preventive medicine comes in. If we can identify the children at increased risk, can we intervene to improve outcomes later in life?” he said. Familial hypercholesterolemia is “a great example of this. We can screen children early in life, there is an effective treatment, and we know from populations studies that early treatment significantly decreases the risk for cardiovascular disease later in life.”

Dr. Poisson reported that she received grants from the National Institutes of Health during the conduct of this study, which was supported by the NIH.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a case-control study, atherosclerotic risk factors were uncommon in childhood and did not appear to be associated with the pathogenesis of arterial ischemic stroke in children or in early young adulthood.

But by the fourth and fifth decades of life, these risk factors were strongly associated with a significant risk for stroke, heightening that risk almost tenfold.

“While strokes in childhood and very early adulthood are not likely caused by atherosclerotic risk factors, it does look like these risk factors increase throughout early and young adulthood and become significant risk factors for stroke in the 30s and 40s,” lead author Sharon N. Poisson, MD, MAS, associate professor of neurology at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, said in an interview.

The findings were published online in JAMA Neurology.

In this study, the researchers focused on arterial ischemic stroke, not hemorrhagic stroke. “We know that high blood pressure, diabetes, smoking, obesity, all of these are risk factors for ischemic stroke, but what we didn’t know is at what age do those atherosclerotic risk factors actually start to cause stroke,” Dr. Poisson said.

To find out more, she and her team did a case control study of data in the Kaiser Permanente Northern California system, which had been accumulating relevant data over a period of 14 years, from Jan. 1, 2000, through Dec. 31, 2014.

The analysis included 141 children and 455 young adults with arterial ischemic stroke and 1,382 age-matched controls.

The children were divided into two age categories: ages 29 days to 9 years and ages 10-19 years.

In the younger group, there were 69 cases of arterial ischemic stroke. In the older age group, there were 72 cases.

Young adults were divided into three age categories: 20-29 years (n = 71 cases), 30-39 years (144 cases), and 40-49 years (240 cases).

Among pediatric controls, 168 children aged 29 days to 9 years (46.5%) and 196 children aged 10-19 years (53.8%) developed arterial ischemic stroke.

There were 121 cases of ischemic stroke among young adult controls aged 20-29 years, 298 cases among controls aged 30-39 years, and 599 cases in those aged 40-49 years.

Both childhood cases and controls had a low prevalence of documented diagnoses of atherosclerotic risk factors (ARFs). The odds ratio of having any ARFs on arterial ischemic stroke was 1.87 for ages 0-9 years, and 1.00 for ages 10-19.

However, cases rose with age.

The OR was 2.3 for age range 20-29 years, 3.57 for age range 30-39 years, and 4.91 for age range 40-49 years.

The analysis also showed that the OR associated with multiple ARFs was 5.29 for age range 0-9 years, 2.75 for age range 10-19 years, 7.33 for age range 20-29 years, 9.86 for age range 30-39 years, and 9.35 for age range 40-49 years.

Multiple risk factors were rare in children but became more prevalent with each decade of young adult life.

The presumed cause of arterial ischemic stroke was atherosclerosis. Evidence of atherosclerosis was present in 1.4% of those aged 10-19 years, 8.5% of those aged 20-29 years, 21.5% of those aged 30-39 years, and 42.5% of those aged 40-49 years.

“This study tells us that, while stroke in adolescence and very early adulthood may not be caused by atherosclerotic risk factors, starting to accumulate those risk factors early in life clearly increases the risk of stroke in the 30s and 40s. I hope we can get this message across, because the sooner we can treat the risk factors, the better the outcome,” Dr. Poisson said.

Prevention starts in childhood

Prevention of cardiovascular disease begins in childhood, which is a paradigm shift from the way cardiovascular disease was thought of a couple of decades ago, noted pediatric cardiologist Guilherme Baptista de Faia, MD, from the Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital in Chicago.

“Our guidelines for risk factor reduction in children aim to address how or when do we screen for these risk factors, how or when do we intervene, and do these interventions impact cardiovascular outcomes later in life? This article is part of the mounting research that aims to understand the relationship between childhood cardiovascular risk factors and early cardiovascular disease,” Dr. Baptista de Faia said.

“There has been an interesting progression in our understanding of the impact of CV risk factors early in life. Large cohorts such as Bogalusa Heart Study, Risk in Young Finns Study, Muscatine Study, the Childhood Determinants of Adult Health, CARDIA, and the International Childhood Cardiovascular Cohorts (i3C) have been instrumental in evaluating this question,” he said.

The knowledge that atherosclerotic risk factors in children can lead to acceleration of atherosclerosis in later life opens the door to preventive medicine, said Dr. Baptista de Faia, who was not part of the study.

“This is where preventive medicine comes in. If we can identify the children at increased risk, can we intervene to improve outcomes later in life?” he said. Familial hypercholesterolemia is “a great example of this. We can screen children early in life, there is an effective treatment, and we know from populations studies that early treatment significantly decreases the risk for cardiovascular disease later in life.”

Dr. Poisson reported that she received grants from the National Institutes of Health during the conduct of this study, which was supported by the NIH.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a case-control study, atherosclerotic risk factors were uncommon in childhood and did not appear to be associated with the pathogenesis of arterial ischemic stroke in children or in early young adulthood.

But by the fourth and fifth decades of life, these risk factors were strongly associated with a significant risk for stroke, heightening that risk almost tenfold.

“While strokes in childhood and very early adulthood are not likely caused by atherosclerotic risk factors, it does look like these risk factors increase throughout early and young adulthood and become significant risk factors for stroke in the 30s and 40s,” lead author Sharon N. Poisson, MD, MAS, associate professor of neurology at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, said in an interview.

The findings were published online in JAMA Neurology.

In this study, the researchers focused on arterial ischemic stroke, not hemorrhagic stroke. “We know that high blood pressure, diabetes, smoking, obesity, all of these are risk factors for ischemic stroke, but what we didn’t know is at what age do those atherosclerotic risk factors actually start to cause stroke,” Dr. Poisson said.

To find out more, she and her team did a case control study of data in the Kaiser Permanente Northern California system, which had been accumulating relevant data over a period of 14 years, from Jan. 1, 2000, through Dec. 31, 2014.

The analysis included 141 children and 455 young adults with arterial ischemic stroke and 1,382 age-matched controls.

The children were divided into two age categories: ages 29 days to 9 years and ages 10-19 years.

In the younger group, there were 69 cases of arterial ischemic stroke. In the older age group, there were 72 cases.

Young adults were divided into three age categories: 20-29 years (n = 71 cases), 30-39 years (144 cases), and 40-49 years (240 cases).

Among pediatric controls, 168 children aged 29 days to 9 years (46.5%) and 196 children aged 10-19 years (53.8%) developed arterial ischemic stroke.

There were 121 cases of ischemic stroke among young adult controls aged 20-29 years, 298 cases among controls aged 30-39 years, and 599 cases in those aged 40-49 years.

Both childhood cases and controls had a low prevalence of documented diagnoses of atherosclerotic risk factors (ARFs). The odds ratio of having any ARFs on arterial ischemic stroke was 1.87 for ages 0-9 years, and 1.00 for ages 10-19.

However, cases rose with age.

The OR was 2.3 for age range 20-29 years, 3.57 for age range 30-39 years, and 4.91 for age range 40-49 years.

The analysis also showed that the OR associated with multiple ARFs was 5.29 for age range 0-9 years, 2.75 for age range 10-19 years, 7.33 for age range 20-29 years, 9.86 for age range 30-39 years, and 9.35 for age range 40-49 years.

Multiple risk factors were rare in children but became more prevalent with each decade of young adult life.

The presumed cause of arterial ischemic stroke was atherosclerosis. Evidence of atherosclerosis was present in 1.4% of those aged 10-19 years, 8.5% of those aged 20-29 years, 21.5% of those aged 30-39 years, and 42.5% of those aged 40-49 years.

“This study tells us that, while stroke in adolescence and very early adulthood may not be caused by atherosclerotic risk factors, starting to accumulate those risk factors early in life clearly increases the risk of stroke in the 30s and 40s. I hope we can get this message across, because the sooner we can treat the risk factors, the better the outcome,” Dr. Poisson said.

Prevention starts in childhood

Prevention of cardiovascular disease begins in childhood, which is a paradigm shift from the way cardiovascular disease was thought of a couple of decades ago, noted pediatric cardiologist Guilherme Baptista de Faia, MD, from the Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital in Chicago.

“Our guidelines for risk factor reduction in children aim to address how or when do we screen for these risk factors, how or when do we intervene, and do these interventions impact cardiovascular outcomes later in life? This article is part of the mounting research that aims to understand the relationship between childhood cardiovascular risk factors and early cardiovascular disease,” Dr. Baptista de Faia said.

“There has been an interesting progression in our understanding of the impact of CV risk factors early in life. Large cohorts such as Bogalusa Heart Study, Risk in Young Finns Study, Muscatine Study, the Childhood Determinants of Adult Health, CARDIA, and the International Childhood Cardiovascular Cohorts (i3C) have been instrumental in evaluating this question,” he said.

The knowledge that atherosclerotic risk factors in children can lead to acceleration of atherosclerosis in later life opens the door to preventive medicine, said Dr. Baptista de Faia, who was not part of the study.

“This is where preventive medicine comes in. If we can identify the children at increased risk, can we intervene to improve outcomes later in life?” he said. Familial hypercholesterolemia is “a great example of this. We can screen children early in life, there is an effective treatment, and we know from populations studies that early treatment significantly decreases the risk for cardiovascular disease later in life.”

Dr. Poisson reported that she received grants from the National Institutes of Health during the conduct of this study, which was supported by the NIH.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA NEUROLOGY

Acute otitis media pneumococcal disease burden in children due to serotypes not included in vaccines

My group in Rochester, N.Y., examined the current pneumococcal serotypes causing AOM in children. From our data, we can determine the PCV13 vaccine types that escape prevention and cause AOM and understand what effect to expect from the new pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCVs) that will be coming soon. There are limited data from middle ear fluid (MEF) cultures on which to base such analyses. Tympanocentesis is the preferred method for securing MEF for culture and our group is unique in providing such data to the Centers for Disease Control and publishing our results on a periodic basis to inform clinicians.

Pneumococci are the second most common cause of acute otitis media (AOM) since the introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCVs) more than 2 decades ago.1,2 Pneumococcal AOM causes more severe acute disease and more often causes suppurative complications than Haemophilus influenzae, which is the most common cause of AOM. Prevention of pneumococcal AOM will be a highly relevant contributor to cost-effectiveness analyses for the anticipated introduction of PCV15 (Merck) and PCV20 (Pfizer). Both PCV15 and PCV20 have been licensed for adult use; PCV15 licensure for infants and children occurred in June 2022 for invasive pneumococcal disease and is anticipated in the near future for PCV20. They are improvements over PCV13 because they add serotypes that cause invasive pneumococcal diseases, although less so for prevention of AOM, on the basis of our data.

Nasopharyngeal colonization is a necessary pathogenic step in progression to pneumococcal disease. However, not all strains of pneumococci expressing different capsular serotypes are equally virulent and likely to cause disease. In PCV-vaccinated populations, vaccine pressure and antibiotic resistance drive PCV serotype replacement with nonvaccine serotypes (NVTs), gradually reducing the net effectiveness of the vaccines. Therefore, knowledge of prevalent NVTs colonizing the nasopharynx identifies future pneumococcal serotypes most likely to emerge as pathogenic.

We published an effectiveness study of PCV13.3 A relative reduction of 86% in AOM caused by strains expressing PCV13 serotypes was observed in the first few years after PCV13 introduction. The greatest reduction in MEF samples was in serotype 19A, with a relative reduction of 91%. However, over time the vaccine type efficacy of PCV13 against MEF-positive pneumococcal AOM has eroded. There was no clear efficacy against serotype 3, and we still observed cases of serotype 19A and 19F. PCV13 vaccine failures have been even more frequent in Europe (nearly 30% of pneumococcal AOM in Europe is caused by vaccine serotypes) than our data indicate, where about 10% of AOM is caused by PCV13 serotypes.

In our most recent publication covering 2015-2019, we described results from 589 children, aged 6-36 months, from whom we collected 2,042 nasopharyngeal samples.2,4 During AOM, 495 MEF samples from 319 AOM-infected children were collected (during bilateral infections, tympanocentesis was performed in both ears). Whether bacteria were isolated was based per AOM case, not per tap. The average age of children with AOM was 15 months (range 6-31 months). The three most prevalent nasopharyngeal pneumococcal serotypes were 35B, 23B, and 15B/C. Serotype 35B was the most common at AOM visits in both the nasopharynx and MEF samples followed by serotype 15B/C. Nonsusceptibility among pneumococci to penicillin, azithromycin, and multiple other antibiotics was high. Increasing resistance to ceftriaxone was also observed.

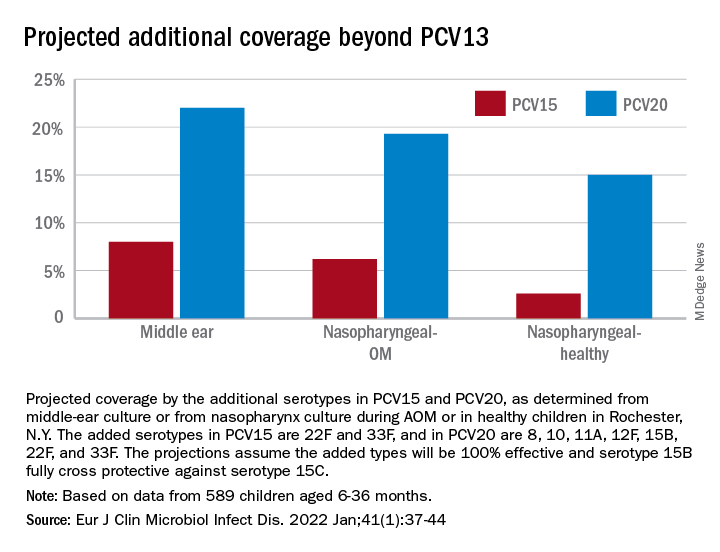

Based on our results, if PCV15 (PCV13 + 22F and 33F) effectiveness is identical to PCV13 for the included serotypes and 100% efficacy for the added serotypes is presumed, PCV15 will reduce pneumococcal AOMs by 8%, pneumococcal nasopharyngeal colonization events at onset of AOM by 6%, and pneumococcal nasopharyngeal colonization events during health by 3%. As for the projected reductions brought about by PCV20 (PCV15 + 8, 10A, 11A, 12F, and 15B), presuming serotype 15B is efficacious against serotype 15C and 100% efficacy for the added serotypes, PCV20 will reduce pneumococcal AOMs by 22%, pneumococcal nasopharyngeal colonization events at onset of AOM by 20%, and pneumococcal nasopharyngeal colonization events during health by 3% (Figure).

The CDC estimated that, in 2004, pneumococcal disease in the United States caused 4 million illness episodes, 22,000 deaths, 445,000 hospitalizations, 774,000 emergency department visits, 5 million outpatient visits, and 4.1 million outpatient antibiotic prescriptions. Direct medical costs totaled $3.5 billion. Pneumonia (866,000 cases) accounted for 22% of all cases and 72% of pneumococcal costs. AOM and sinusitis (1.5 million cases each) composed 75% of cases and 16% of direct medical costs.5 However, if indirect costs are taken into account, such as work loss by parents of young children, the cost of pneumococcal disease caused by AOM alone may exceed $6 billion annually6 and become dominant in the cost-effectiveness analysis in high-income countries.

Despite widespread use of PCV13, Pneumococcus has shown its resilience under vaccine pressure such that the organism remains a very common AOM pathogen. All-cause AOM has declined modestly and pneumococcal AOM caused by the specific serotypes in PCVs has declined dramatically since the introduction of PCVs. However, the burden of pneumococcal AOM disease is still considerable.

The notion that strains expressing serotypes that were not included in PCV7 were less virulent was proven wrong within a few years after introduction of PCV7, with the emergence of strains expressing serotype 19A, and others. The same cycle occurred after introduction of PCV13. It appears to take about 4 years after introduction of a PCV before peak effectiveness is achieved – which then begins to erode with emergence of NVTs. First, the NVTs are observed to colonize the nasopharynx as commensals and then from among those strains new disease-causing strains emerge.

At the most recent meeting of the International Society of Pneumococci and Pneumococcal Diseases in Toronto in June, many presentations focused on the fact that PCVs elicit highly effective protective serotype-specific antibodies to the capsular polysaccharides of included types. However, 100 serotypes are known. The limitations of PCVs are becoming increasingly apparent. They are costly and consume a large portion of the Vaccines for Children budget. Children in the developing world remain largely unvaccinated because of the high cost. NVTs that have emerged to cause disease vary by country, vary by adult vs. pediatric populations, and are dynamically changing year to year. Forthcoming PCVs of 15 and 20 serotypes will be even more costly than PCV13, will not include many newly emerged serotypes, and will probably likewise encounter “serotype replacement” because of high immune evasion by pneumococci.

When Merck and Pfizer made their decisions on serotype composition for PCV15 and PCV20, respectively, they were based on available data at the time regarding predominant serotypes causing invasive pneumococcal disease in countries that had the best data and would be the market for their products. However, from the time of the decision to licensure of vaccine is many years, and during that time the pneumococcal serotypes have changed, more so for AOM, and I predict more change will occur in the future.

In the past 3 years, Dr. Pichichero has received honoraria from Merck to attend 1-day consulting meetings and his institution has received investigator-initiated research grants to study aspects of PCV15. In the past 3 years, he was reimbursed for expenses to attend the ISPPD meeting in Toronto to present a poster on potential efficacy of PCV20 to prevent complicated AOM.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, Center for Infectious Diseases and Immunology, and director of the Research Institute, at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital.

References

1. Kaur R et al. Pediatrics. 2017;140(3).

2. Kaur R et al. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2021;41:37-44..

3. Pichichero M et al. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2018;2(8):561-8.

4. Zhou F et al. Pediatrics. 2008;121(2):253-60.

5. Huang SS et al. Vaccine. 2011;29(18):3398-412.

6. Casey JR and Pichichero ME. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2014;53(9):865-73. .

My group in Rochester, N.Y., examined the current pneumococcal serotypes causing AOM in children. From our data, we can determine the PCV13 vaccine types that escape prevention and cause AOM and understand what effect to expect from the new pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCVs) that will be coming soon. There are limited data from middle ear fluid (MEF) cultures on which to base such analyses. Tympanocentesis is the preferred method for securing MEF for culture and our group is unique in providing such data to the Centers for Disease Control and publishing our results on a periodic basis to inform clinicians.

Pneumococci are the second most common cause of acute otitis media (AOM) since the introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCVs) more than 2 decades ago.1,2 Pneumococcal AOM causes more severe acute disease and more often causes suppurative complications than Haemophilus influenzae, which is the most common cause of AOM. Prevention of pneumococcal AOM will be a highly relevant contributor to cost-effectiveness analyses for the anticipated introduction of PCV15 (Merck) and PCV20 (Pfizer). Both PCV15 and PCV20 have been licensed for adult use; PCV15 licensure for infants and children occurred in June 2022 for invasive pneumococcal disease and is anticipated in the near future for PCV20. They are improvements over PCV13 because they add serotypes that cause invasive pneumococcal diseases, although less so for prevention of AOM, on the basis of our data.

Nasopharyngeal colonization is a necessary pathogenic step in progression to pneumococcal disease. However, not all strains of pneumococci expressing different capsular serotypes are equally virulent and likely to cause disease. In PCV-vaccinated populations, vaccine pressure and antibiotic resistance drive PCV serotype replacement with nonvaccine serotypes (NVTs), gradually reducing the net effectiveness of the vaccines. Therefore, knowledge of prevalent NVTs colonizing the nasopharynx identifies future pneumococcal serotypes most likely to emerge as pathogenic.

We published an effectiveness study of PCV13.3 A relative reduction of 86% in AOM caused by strains expressing PCV13 serotypes was observed in the first few years after PCV13 introduction. The greatest reduction in MEF samples was in serotype 19A, with a relative reduction of 91%. However, over time the vaccine type efficacy of PCV13 against MEF-positive pneumococcal AOM has eroded. There was no clear efficacy against serotype 3, and we still observed cases of serotype 19A and 19F. PCV13 vaccine failures have been even more frequent in Europe (nearly 30% of pneumococcal AOM in Europe is caused by vaccine serotypes) than our data indicate, where about 10% of AOM is caused by PCV13 serotypes.

In our most recent publication covering 2015-2019, we described results from 589 children, aged 6-36 months, from whom we collected 2,042 nasopharyngeal samples.2,4 During AOM, 495 MEF samples from 319 AOM-infected children were collected (during bilateral infections, tympanocentesis was performed in both ears). Whether bacteria were isolated was based per AOM case, not per tap. The average age of children with AOM was 15 months (range 6-31 months). The three most prevalent nasopharyngeal pneumococcal serotypes were 35B, 23B, and 15B/C. Serotype 35B was the most common at AOM visits in both the nasopharynx and MEF samples followed by serotype 15B/C. Nonsusceptibility among pneumococci to penicillin, azithromycin, and multiple other antibiotics was high. Increasing resistance to ceftriaxone was also observed.

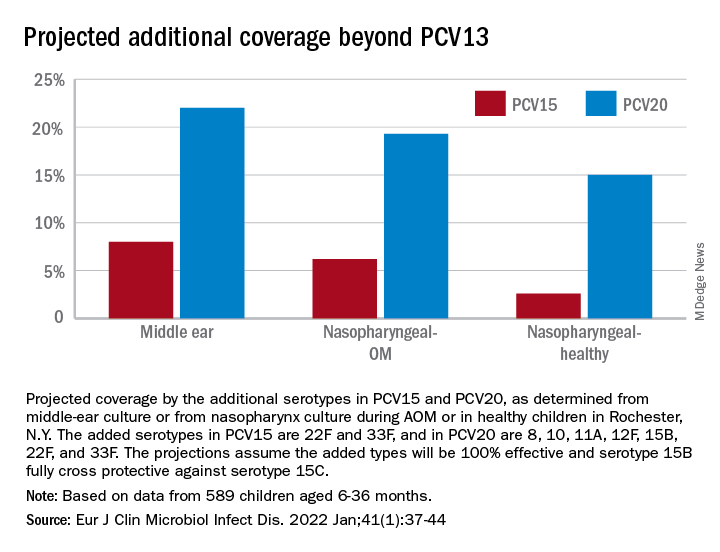

Based on our results, if PCV15 (PCV13 + 22F and 33F) effectiveness is identical to PCV13 for the included serotypes and 100% efficacy for the added serotypes is presumed, PCV15 will reduce pneumococcal AOMs by 8%, pneumococcal nasopharyngeal colonization events at onset of AOM by 6%, and pneumococcal nasopharyngeal colonization events during health by 3%. As for the projected reductions brought about by PCV20 (PCV15 + 8, 10A, 11A, 12F, and 15B), presuming serotype 15B is efficacious against serotype 15C and 100% efficacy for the added serotypes, PCV20 will reduce pneumococcal AOMs by 22%, pneumococcal nasopharyngeal colonization events at onset of AOM by 20%, and pneumococcal nasopharyngeal colonization events during health by 3% (Figure).

The CDC estimated that, in 2004, pneumococcal disease in the United States caused 4 million illness episodes, 22,000 deaths, 445,000 hospitalizations, 774,000 emergency department visits, 5 million outpatient visits, and 4.1 million outpatient antibiotic prescriptions. Direct medical costs totaled $3.5 billion. Pneumonia (866,000 cases) accounted for 22% of all cases and 72% of pneumococcal costs. AOM and sinusitis (1.5 million cases each) composed 75% of cases and 16% of direct medical costs.5 However, if indirect costs are taken into account, such as work loss by parents of young children, the cost of pneumococcal disease caused by AOM alone may exceed $6 billion annually6 and become dominant in the cost-effectiveness analysis in high-income countries.

Despite widespread use of PCV13, Pneumococcus has shown its resilience under vaccine pressure such that the organism remains a very common AOM pathogen. All-cause AOM has declined modestly and pneumococcal AOM caused by the specific serotypes in PCVs has declined dramatically since the introduction of PCVs. However, the burden of pneumococcal AOM disease is still considerable.

The notion that strains expressing serotypes that were not included in PCV7 were less virulent was proven wrong within a few years after introduction of PCV7, with the emergence of strains expressing serotype 19A, and others. The same cycle occurred after introduction of PCV13. It appears to take about 4 years after introduction of a PCV before peak effectiveness is achieved – which then begins to erode with emergence of NVTs. First, the NVTs are observed to colonize the nasopharynx as commensals and then from among those strains new disease-causing strains emerge.

At the most recent meeting of the International Society of Pneumococci and Pneumococcal Diseases in Toronto in June, many presentations focused on the fact that PCVs elicit highly effective protective serotype-specific antibodies to the capsular polysaccharides of included types. However, 100 serotypes are known. The limitations of PCVs are becoming increasingly apparent. They are costly and consume a large portion of the Vaccines for Children budget. Children in the developing world remain largely unvaccinated because of the high cost. NVTs that have emerged to cause disease vary by country, vary by adult vs. pediatric populations, and are dynamically changing year to year. Forthcoming PCVs of 15 and 20 serotypes will be even more costly than PCV13, will not include many newly emerged serotypes, and will probably likewise encounter “serotype replacement” because of high immune evasion by pneumococci.

When Merck and Pfizer made their decisions on serotype composition for PCV15 and PCV20, respectively, they were based on available data at the time regarding predominant serotypes causing invasive pneumococcal disease in countries that had the best data and would be the market for their products. However, from the time of the decision to licensure of vaccine is many years, and during that time the pneumococcal serotypes have changed, more so for AOM, and I predict more change will occur in the future.

In the past 3 years, Dr. Pichichero has received honoraria from Merck to attend 1-day consulting meetings and his institution has received investigator-initiated research grants to study aspects of PCV15. In the past 3 years, he was reimbursed for expenses to attend the ISPPD meeting in Toronto to present a poster on potential efficacy of PCV20 to prevent complicated AOM.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, Center for Infectious Diseases and Immunology, and director of the Research Institute, at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital.

References

1. Kaur R et al. Pediatrics. 2017;140(3).

2. Kaur R et al. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2021;41:37-44..

3. Pichichero M et al. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2018;2(8):561-8.

4. Zhou F et al. Pediatrics. 2008;121(2):253-60.

5. Huang SS et al. Vaccine. 2011;29(18):3398-412.

6. Casey JR and Pichichero ME. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2014;53(9):865-73. .

My group in Rochester, N.Y., examined the current pneumococcal serotypes causing AOM in children. From our data, we can determine the PCV13 vaccine types that escape prevention and cause AOM and understand what effect to expect from the new pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCVs) that will be coming soon. There are limited data from middle ear fluid (MEF) cultures on which to base such analyses. Tympanocentesis is the preferred method for securing MEF for culture and our group is unique in providing such data to the Centers for Disease Control and publishing our results on a periodic basis to inform clinicians.

Pneumococci are the second most common cause of acute otitis media (AOM) since the introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCVs) more than 2 decades ago.1,2 Pneumococcal AOM causes more severe acute disease and more often causes suppurative complications than Haemophilus influenzae, which is the most common cause of AOM. Prevention of pneumococcal AOM will be a highly relevant contributor to cost-effectiveness analyses for the anticipated introduction of PCV15 (Merck) and PCV20 (Pfizer). Both PCV15 and PCV20 have been licensed for adult use; PCV15 licensure for infants and children occurred in June 2022 for invasive pneumococcal disease and is anticipated in the near future for PCV20. They are improvements over PCV13 because they add serotypes that cause invasive pneumococcal diseases, although less so for prevention of AOM, on the basis of our data.

Nasopharyngeal colonization is a necessary pathogenic step in progression to pneumococcal disease. However, not all strains of pneumococci expressing different capsular serotypes are equally virulent and likely to cause disease. In PCV-vaccinated populations, vaccine pressure and antibiotic resistance drive PCV serotype replacement with nonvaccine serotypes (NVTs), gradually reducing the net effectiveness of the vaccines. Therefore, knowledge of prevalent NVTs colonizing the nasopharynx identifies future pneumococcal serotypes most likely to emerge as pathogenic.

We published an effectiveness study of PCV13.3 A relative reduction of 86% in AOM caused by strains expressing PCV13 serotypes was observed in the first few years after PCV13 introduction. The greatest reduction in MEF samples was in serotype 19A, with a relative reduction of 91%. However, over time the vaccine type efficacy of PCV13 against MEF-positive pneumococcal AOM has eroded. There was no clear efficacy against serotype 3, and we still observed cases of serotype 19A and 19F. PCV13 vaccine failures have been even more frequent in Europe (nearly 30% of pneumococcal AOM in Europe is caused by vaccine serotypes) than our data indicate, where about 10% of AOM is caused by PCV13 serotypes.

In our most recent publication covering 2015-2019, we described results from 589 children, aged 6-36 months, from whom we collected 2,042 nasopharyngeal samples.2,4 During AOM, 495 MEF samples from 319 AOM-infected children were collected (during bilateral infections, tympanocentesis was performed in both ears). Whether bacteria were isolated was based per AOM case, not per tap. The average age of children with AOM was 15 months (range 6-31 months). The three most prevalent nasopharyngeal pneumococcal serotypes were 35B, 23B, and 15B/C. Serotype 35B was the most common at AOM visits in both the nasopharynx and MEF samples followed by serotype 15B/C. Nonsusceptibility among pneumococci to penicillin, azithromycin, and multiple other antibiotics was high. Increasing resistance to ceftriaxone was also observed.

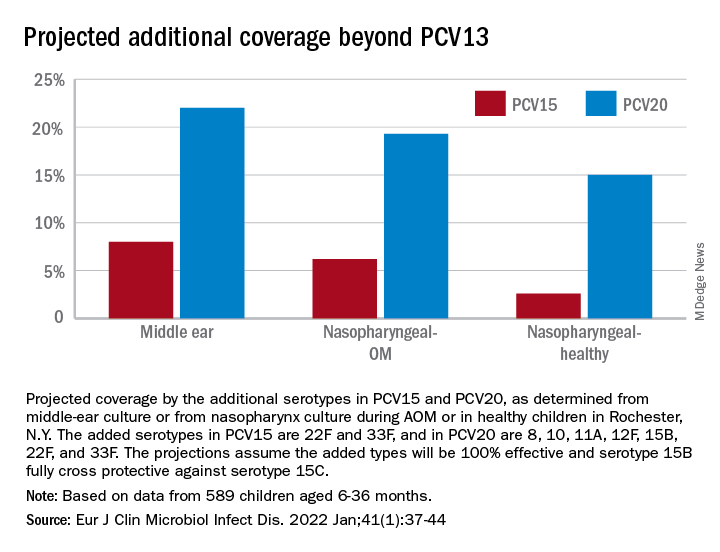

Based on our results, if PCV15 (PCV13 + 22F and 33F) effectiveness is identical to PCV13 for the included serotypes and 100% efficacy for the added serotypes is presumed, PCV15 will reduce pneumococcal AOMs by 8%, pneumococcal nasopharyngeal colonization events at onset of AOM by 6%, and pneumococcal nasopharyngeal colonization events during health by 3%. As for the projected reductions brought about by PCV20 (PCV15 + 8, 10A, 11A, 12F, and 15B), presuming serotype 15B is efficacious against serotype 15C and 100% efficacy for the added serotypes, PCV20 will reduce pneumococcal AOMs by 22%, pneumococcal nasopharyngeal colonization events at onset of AOM by 20%, and pneumococcal nasopharyngeal colonization events during health by 3% (Figure).

The CDC estimated that, in 2004, pneumococcal disease in the United States caused 4 million illness episodes, 22,000 deaths, 445,000 hospitalizations, 774,000 emergency department visits, 5 million outpatient visits, and 4.1 million outpatient antibiotic prescriptions. Direct medical costs totaled $3.5 billion. Pneumonia (866,000 cases) accounted for 22% of all cases and 72% of pneumococcal costs. AOM and sinusitis (1.5 million cases each) composed 75% of cases and 16% of direct medical costs.5 However, if indirect costs are taken into account, such as work loss by parents of young children, the cost of pneumococcal disease caused by AOM alone may exceed $6 billion annually6 and become dominant in the cost-effectiveness analysis in high-income countries.

Despite widespread use of PCV13, Pneumococcus has shown its resilience under vaccine pressure such that the organism remains a very common AOM pathogen. All-cause AOM has declined modestly and pneumococcal AOM caused by the specific serotypes in PCVs has declined dramatically since the introduction of PCVs. However, the burden of pneumococcal AOM disease is still considerable.

The notion that strains expressing serotypes that were not included in PCV7 were less virulent was proven wrong within a few years after introduction of PCV7, with the emergence of strains expressing serotype 19A, and others. The same cycle occurred after introduction of PCV13. It appears to take about 4 years after introduction of a PCV before peak effectiveness is achieved – which then begins to erode with emergence of NVTs. First, the NVTs are observed to colonize the nasopharynx as commensals and then from among those strains new disease-causing strains emerge.

At the most recent meeting of the International Society of Pneumococci and Pneumococcal Diseases in Toronto in June, many presentations focused on the fact that PCVs elicit highly effective protective serotype-specific antibodies to the capsular polysaccharides of included types. However, 100 serotypes are known. The limitations of PCVs are becoming increasingly apparent. They are costly and consume a large portion of the Vaccines for Children budget. Children in the developing world remain largely unvaccinated because of the high cost. NVTs that have emerged to cause disease vary by country, vary by adult vs. pediatric populations, and are dynamically changing year to year. Forthcoming PCVs of 15 and 20 serotypes will be even more costly than PCV13, will not include many newly emerged serotypes, and will probably likewise encounter “serotype replacement” because of high immune evasion by pneumococci.

When Merck and Pfizer made their decisions on serotype composition for PCV15 and PCV20, respectively, they were based on available data at the time regarding predominant serotypes causing invasive pneumococcal disease in countries that had the best data and would be the market for their products. However, from the time of the decision to licensure of vaccine is many years, and during that time the pneumococcal serotypes have changed, more so for AOM, and I predict more change will occur in the future.

In the past 3 years, Dr. Pichichero has received honoraria from Merck to attend 1-day consulting meetings and his institution has received investigator-initiated research grants to study aspects of PCV15. In the past 3 years, he was reimbursed for expenses to attend the ISPPD meeting in Toronto to present a poster on potential efficacy of PCV20 to prevent complicated AOM.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, Center for Infectious Diseases and Immunology, and director of the Research Institute, at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital.

References

1. Kaur R et al. Pediatrics. 2017;140(3).

2. Kaur R et al. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2021;41:37-44..

3. Pichichero M et al. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2018;2(8):561-8.

4. Zhou F et al. Pediatrics. 2008;121(2):253-60.

5. Huang SS et al. Vaccine. 2011;29(18):3398-412.

6. Casey JR and Pichichero ME. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2014;53(9):865-73. .

Biosimilar-to-biosimilar switches deemed safe and effective, systematic review reveals

Switching from one biosimilar medication to another is safe and effective, a new systematic review indicates, even though this clinical practice is not governed by current health authority regulations or guidance.

“No reduction in effectiveness or increase in adverse events was detected in biosimilar-to-biosimilar switching studies conducted to date,” the review’s authors noted in their study, published online in BioDrugs.

“The possibility of multiple switches between biosimilars of the same reference biologic is already a reality, and these types of switches are expected to become more common in the future. ... Although it is not covered by current health authority regulations or guidance,” added the authors, led by Hillel P. Cohen, PhD, executive director of scientific affairs at Sandoz, a division of Novartis.

The researchers searched electronic databases through December 2021 and found 23 observational studies that met their search criteria, of which 13 were published in peer-reviewed journals; the remainder appeared in abstract form. The studies totaled 3,657 patients. The researchers did not identify any randomized clinical trials.

“The studies were heterogeneous in size, design, and endpoints, providing data on safety, effectiveness, immunogenicity, pharmacokinetics, patient retention, patient and physician perceptions, and drug-use patterns,” the authors wrote.

The authors found that the majority of studies evaluated switches between biosimilars of infliximab, but they also identified switches between biosimilars of adalimumab, etanercept, and rituximab.

“Some health care providers are hesitant to switch patients from one biosimilar to another biosimilar because of a perceived lack of clinical data on such switches,” Dr. Cohen said in an interview.

The review’s findings – that there were no clinically relevant differences when switching patients from one biosimilar to another – are consistent with the science, Dr. Cohen said. “Physicians should have confidence that the data demonstrate that safety and effectiveness are not impacted if patients switch from one biosimilar to another biosimilar of the same reference biologic,” he said.

Currently, the published data include biosimilars to only four reference biologics. “However, I anticipate additional biosimilar-to-biosimilar switching data will become available in the future,” Dr. Cohen said. “In fact, several new studies have been published in recent months, after the cut-off date for inclusion in our systematic review.”

Switching common in rheumatology, dermatology, and gastroenterology

Biosimilar-to-biosimilar switching was observed most commonly in rheumatology practice, but also was seen in the specialties of dermatology and gastroenterology.

Jeffrey Weinberg, MD, clinical professor of dermatology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York City, said in an interview that the study is among the best to date showing that switching biosimilars does not compromise efficacy or safety.

“I would hypothesize that the interchangeability would apply to psoriasis patients,” Dr. Weinberg said. However, “over the next few years, we will have an increasing number of biosimilars for an increasing number of different molecules. We will need to be vigilant to observe if similar behavior is observed with the biosimilars yet to come.”

Keith Choate, MD, PhD, professor of dermatology, pathology, and genetics, and associate dean for physician-scientist development at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said that biosimilars have comparable efficacy to the branded medication they replace. “If response is lost to an individual agent, we would not typically then switch to a biosimilar, but would favor another class of therapy or a distinct therapeutic which targets the same pathway.”

When physicians prescribe a biosimilar for rheumatoid arthritis or psoriatic arthritis, in 9 out 10 people, “it’s going to work as well, and it’s not going to cause any more side effects,” said Stanford Shoor, MD, clinical professor of medicine and rheumatology, Stanford (Calif.) University.

The systematic review, even within its limitations, reinforces confidence in the antitumor necrosis factor biosimilars, said Jean-Frederic Colombel, MD, codirector of the Feinstein Inflammatory Bowel Disease Clinical Center at Mount Sinai, New York, and professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

“Still, studies with longer follow-up are needed,” Dr. Colombel said, adding that the remaining questions relate to the efficacy and safety of switching multiple times, which will likely occur in the near future. There will be a “need to provide information to the patient regarding what originator or biosimilar(s) he has been exposed to during the course of his disease.”

Switching will increasingly become the norm, said Miguel Regueiro, MD, chair of the Digestive Disease & Surgery Institute, Cleveland Clinic. In his clinical practice, he has the most experience with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, and biosimilar-to-biosimilar infliximab switches. “Unless there are data that emerge, I have no concerns with this.”

He added that it’s an “interesting study that affirms my findings in clinical practice – that one can switch from a biosimilar to biosimilar (of the same reference product).”

The review’s results also make sense from an economic standpoint, said Rajat Bhatt, MD, owner of Prime Rheumatology in Richmond, Tex., and an adjunct faculty member at Caribbean Medical University, Willemstad, Curaçao. “Switching to biosimilars will result in cost savings for the health care system.” Patients on certain insurances also will save by switching to a biosimilar with a lower copay.

However, the review is limited by a relatively small number of studies that have provided primary data on this topic, and most of these were switching from infliximab to a biosimilar for inflammatory bowel disease, said Alfred Kim, MD, PhD, an adult rheumatologist at Barnes-Jewish Hospital, St. Louis, and assistant professor of medicine at Washington University in St. Louis.

As with any meta-analysis evaluating a small number of studies, “broad applicability to all conditions and reference/biosimilar pair can only be assumed. Also, many of the studies used for this meta-analysis are observational, which can introduce a variety of biases that can be difficult to adjust for,” Dr. Kim said. “Nevertheless, these analyses are an important first step in validating the [Food and Drug Administration’s] approach to evaluating biosimilars, as the clinical outcomes are consistent between different biosimilars.”

This systematic review is not enough to prove that all patients will do fine when switching from one biosimilar to another, said Florence Aslinia, MD, a gastroenterologist at the University of Kansas Health System in Kansas City. It’s possible that some patients may not do as well, she said, noting that, in one study of patients with inflammatory bowel disease, 10% of patients on a biosimilar infliximab needed to switch back to the originator infliximab (Remicade, Janssen) because of side effects attributed to the biosimilar. The same thing may or may not happen with biosimilar-to-biosimilar switching, and it requires further study.

The authors did not receive any funding for writing this review. Dr. Cohen is an employee of Sandoz, a division of Novartis. He may own stock in Novartis. Two coauthors are also employees of Sandoz. The other three coauthors reported having financial relationships with numerous pharmaceutical companies, including Sandoz and/or Novartis. Dr. Colombel reported financial relationships with many pharmaceutical companies, including Novartis and other manufacturers of biosimilars. Dr. Regueiro reports financial relationships with numerous pharmaceutical companies, including some manufacturers of biosimilars. Dr. Weinberg reported financial relationships with Celgene, AbbVie, Eli Lilly, and Novartis. Kim reports financial relationships with GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, and AstraZeneca. Dr. Aslinia, Dr. Shoor, Dr. Choate, and Dr. Bhatt reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Switching from one biosimilar medication to another is safe and effective, a new systematic review indicates, even though this clinical practice is not governed by current health authority regulations or guidance.

“No reduction in effectiveness or increase in adverse events was detected in biosimilar-to-biosimilar switching studies conducted to date,” the review’s authors noted in their study, published online in BioDrugs.

“The possibility of multiple switches between biosimilars of the same reference biologic is already a reality, and these types of switches are expected to become more common in the future. ... Although it is not covered by current health authority regulations or guidance,” added the authors, led by Hillel P. Cohen, PhD, executive director of scientific affairs at Sandoz, a division of Novartis.

The researchers searched electronic databases through December 2021 and found 23 observational studies that met their search criteria, of which 13 were published in peer-reviewed journals; the remainder appeared in abstract form. The studies totaled 3,657 patients. The researchers did not identify any randomized clinical trials.

“The studies were heterogeneous in size, design, and endpoints, providing data on safety, effectiveness, immunogenicity, pharmacokinetics, patient retention, patient and physician perceptions, and drug-use patterns,” the authors wrote.

The authors found that the majority of studies evaluated switches between biosimilars of infliximab, but they also identified switches between biosimilars of adalimumab, etanercept, and rituximab.

“Some health care providers are hesitant to switch patients from one biosimilar to another biosimilar because of a perceived lack of clinical data on such switches,” Dr. Cohen said in an interview.

The review’s findings – that there were no clinically relevant differences when switching patients from one biosimilar to another – are consistent with the science, Dr. Cohen said. “Physicians should have confidence that the data demonstrate that safety and effectiveness are not impacted if patients switch from one biosimilar to another biosimilar of the same reference biologic,” he said.

Currently, the published data include biosimilars to only four reference biologics. “However, I anticipate additional biosimilar-to-biosimilar switching data will become available in the future,” Dr. Cohen said. “In fact, several new studies have been published in recent months, after the cut-off date for inclusion in our systematic review.”

Switching common in rheumatology, dermatology, and gastroenterology

Biosimilar-to-biosimilar switching was observed most commonly in rheumatology practice, but also was seen in the specialties of dermatology and gastroenterology.

Jeffrey Weinberg, MD, clinical professor of dermatology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York City, said in an interview that the study is among the best to date showing that switching biosimilars does not compromise efficacy or safety.

“I would hypothesize that the interchangeability would apply to psoriasis patients,” Dr. Weinberg said. However, “over the next few years, we will have an increasing number of biosimilars for an increasing number of different molecules. We will need to be vigilant to observe if similar behavior is observed with the biosimilars yet to come.”

Keith Choate, MD, PhD, professor of dermatology, pathology, and genetics, and associate dean for physician-scientist development at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said that biosimilars have comparable efficacy to the branded medication they replace. “If response is lost to an individual agent, we would not typically then switch to a biosimilar, but would favor another class of therapy or a distinct therapeutic which targets the same pathway.”

When physicians prescribe a biosimilar for rheumatoid arthritis or psoriatic arthritis, in 9 out 10 people, “it’s going to work as well, and it’s not going to cause any more side effects,” said Stanford Shoor, MD, clinical professor of medicine and rheumatology, Stanford (Calif.) University.

The systematic review, even within its limitations, reinforces confidence in the antitumor necrosis factor biosimilars, said Jean-Frederic Colombel, MD, codirector of the Feinstein Inflammatory Bowel Disease Clinical Center at Mount Sinai, New York, and professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

“Still, studies with longer follow-up are needed,” Dr. Colombel said, adding that the remaining questions relate to the efficacy and safety of switching multiple times, which will likely occur in the near future. There will be a “need to provide information to the patient regarding what originator or biosimilar(s) he has been exposed to during the course of his disease.”

Switching will increasingly become the norm, said Miguel Regueiro, MD, chair of the Digestive Disease & Surgery Institute, Cleveland Clinic. In his clinical practice, he has the most experience with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, and biosimilar-to-biosimilar infliximab switches. “Unless there are data that emerge, I have no concerns with this.”

He added that it’s an “interesting study that affirms my findings in clinical practice – that one can switch from a biosimilar to biosimilar (of the same reference product).”

The review’s results also make sense from an economic standpoint, said Rajat Bhatt, MD, owner of Prime Rheumatology in Richmond, Tex., and an adjunct faculty member at Caribbean Medical University, Willemstad, Curaçao. “Switching to biosimilars will result in cost savings for the health care system.” Patients on certain insurances also will save by switching to a biosimilar with a lower copay.

However, the review is limited by a relatively small number of studies that have provided primary data on this topic, and most of these were switching from infliximab to a biosimilar for inflammatory bowel disease, said Alfred Kim, MD, PhD, an adult rheumatologist at Barnes-Jewish Hospital, St. Louis, and assistant professor of medicine at Washington University in St. Louis.

As with any meta-analysis evaluating a small number of studies, “broad applicability to all conditions and reference/biosimilar pair can only be assumed. Also, many of the studies used for this meta-analysis are observational, which can introduce a variety of biases that can be difficult to adjust for,” Dr. Kim said. “Nevertheless, these analyses are an important first step in validating the [Food and Drug Administration’s] approach to evaluating biosimilars, as the clinical outcomes are consistent between different biosimilars.”

This systematic review is not enough to prove that all patients will do fine when switching from one biosimilar to another, said Florence Aslinia, MD, a gastroenterologist at the University of Kansas Health System in Kansas City. It’s possible that some patients may not do as well, she said, noting that, in one study of patients with inflammatory bowel disease, 10% of patients on a biosimilar infliximab needed to switch back to the originator infliximab (Remicade, Janssen) because of side effects attributed to the biosimilar. The same thing may or may not happen with biosimilar-to-biosimilar switching, and it requires further study.

The authors did not receive any funding for writing this review. Dr. Cohen is an employee of Sandoz, a division of Novartis. He may own stock in Novartis. Two coauthors are also employees of Sandoz. The other three coauthors reported having financial relationships with numerous pharmaceutical companies, including Sandoz and/or Novartis. Dr. Colombel reported financial relationships with many pharmaceutical companies, including Novartis and other manufacturers of biosimilars. Dr. Regueiro reports financial relationships with numerous pharmaceutical companies, including some manufacturers of biosimilars. Dr. Weinberg reported financial relationships with Celgene, AbbVie, Eli Lilly, and Novartis. Kim reports financial relationships with GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, and AstraZeneca. Dr. Aslinia, Dr. Shoor, Dr. Choate, and Dr. Bhatt reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Switching from one biosimilar medication to another is safe and effective, a new systematic review indicates, even though this clinical practice is not governed by current health authority regulations or guidance.

“No reduction in effectiveness or increase in adverse events was detected in biosimilar-to-biosimilar switching studies conducted to date,” the review’s authors noted in their study, published online in BioDrugs.

“The possibility of multiple switches between biosimilars of the same reference biologic is already a reality, and these types of switches are expected to become more common in the future. ... Although it is not covered by current health authority regulations or guidance,” added the authors, led by Hillel P. Cohen, PhD, executive director of scientific affairs at Sandoz, a division of Novartis.

The researchers searched electronic databases through December 2021 and found 23 observational studies that met their search criteria, of which 13 were published in peer-reviewed journals; the remainder appeared in abstract form. The studies totaled 3,657 patients. The researchers did not identify any randomized clinical trials.

“The studies were heterogeneous in size, design, and endpoints, providing data on safety, effectiveness, immunogenicity, pharmacokinetics, patient retention, patient and physician perceptions, and drug-use patterns,” the authors wrote.

The authors found that the majority of studies evaluated switches between biosimilars of infliximab, but they also identified switches between biosimilars of adalimumab, etanercept, and rituximab.

“Some health care providers are hesitant to switch patients from one biosimilar to another biosimilar because of a perceived lack of clinical data on such switches,” Dr. Cohen said in an interview.

The review’s findings – that there were no clinically relevant differences when switching patients from one biosimilar to another – are consistent with the science, Dr. Cohen said. “Physicians should have confidence that the data demonstrate that safety and effectiveness are not impacted if patients switch from one biosimilar to another biosimilar of the same reference biologic,” he said.

Currently, the published data include biosimilars to only four reference biologics. “However, I anticipate additional biosimilar-to-biosimilar switching data will become available in the future,” Dr. Cohen said. “In fact, several new studies have been published in recent months, after the cut-off date for inclusion in our systematic review.”

Switching common in rheumatology, dermatology, and gastroenterology

Biosimilar-to-biosimilar switching was observed most commonly in rheumatology practice, but also was seen in the specialties of dermatology and gastroenterology.

Jeffrey Weinberg, MD, clinical professor of dermatology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York City, said in an interview that the study is among the best to date showing that switching biosimilars does not compromise efficacy or safety.

“I would hypothesize that the interchangeability would apply to psoriasis patients,” Dr. Weinberg said. However, “over the next few years, we will have an increasing number of biosimilars for an increasing number of different molecules. We will need to be vigilant to observe if similar behavior is observed with the biosimilars yet to come.”

Keith Choate, MD, PhD, professor of dermatology, pathology, and genetics, and associate dean for physician-scientist development at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said that biosimilars have comparable efficacy to the branded medication they replace. “If response is lost to an individual agent, we would not typically then switch to a biosimilar, but would favor another class of therapy or a distinct therapeutic which targets the same pathway.”

When physicians prescribe a biosimilar for rheumatoid arthritis or psoriatic arthritis, in 9 out 10 people, “it’s going to work as well, and it’s not going to cause any more side effects,” said Stanford Shoor, MD, clinical professor of medicine and rheumatology, Stanford (Calif.) University.

The systematic review, even within its limitations, reinforces confidence in the antitumor necrosis factor biosimilars, said Jean-Frederic Colombel, MD, codirector of the Feinstein Inflammatory Bowel Disease Clinical Center at Mount Sinai, New York, and professor of medicine, division of gastroenterology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

“Still, studies with longer follow-up are needed,” Dr. Colombel said, adding that the remaining questions relate to the efficacy and safety of switching multiple times, which will likely occur in the near future. There will be a “need to provide information to the patient regarding what originator or biosimilar(s) he has been exposed to during the course of his disease.”

Switching will increasingly become the norm, said Miguel Regueiro, MD, chair of the Digestive Disease & Surgery Institute, Cleveland Clinic. In his clinical practice, he has the most experience with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, and biosimilar-to-biosimilar infliximab switches. “Unless there are data that emerge, I have no concerns with this.”

He added that it’s an “interesting study that affirms my findings in clinical practice – that one can switch from a biosimilar to biosimilar (of the same reference product).”

The review’s results also make sense from an economic standpoint, said Rajat Bhatt, MD, owner of Prime Rheumatology in Richmond, Tex., and an adjunct faculty member at Caribbean Medical University, Willemstad, Curaçao. “Switching to biosimilars will result in cost savings for the health care system.” Patients on certain insurances also will save by switching to a biosimilar with a lower copay.

However, the review is limited by a relatively small number of studies that have provided primary data on this topic, and most of these were switching from infliximab to a biosimilar for inflammatory bowel disease, said Alfred Kim, MD, PhD, an adult rheumatologist at Barnes-Jewish Hospital, St. Louis, and assistant professor of medicine at Washington University in St. Louis.

As with any meta-analysis evaluating a small number of studies, “broad applicability to all conditions and reference/biosimilar pair can only be assumed. Also, many of the studies used for this meta-analysis are observational, which can introduce a variety of biases that can be difficult to adjust for,” Dr. Kim said. “Nevertheless, these analyses are an important first step in validating the [Food and Drug Administration’s] approach to evaluating biosimilars, as the clinical outcomes are consistent between different biosimilars.”

This systematic review is not enough to prove that all patients will do fine when switching from one biosimilar to another, said Florence Aslinia, MD, a gastroenterologist at the University of Kansas Health System in Kansas City. It’s possible that some patients may not do as well, she said, noting that, in one study of patients with inflammatory bowel disease, 10% of patients on a biosimilar infliximab needed to switch back to the originator infliximab (Remicade, Janssen) because of side effects attributed to the biosimilar. The same thing may or may not happen with biosimilar-to-biosimilar switching, and it requires further study.

The authors did not receive any funding for writing this review. Dr. Cohen is an employee of Sandoz, a division of Novartis. He may own stock in Novartis. Two coauthors are also employees of Sandoz. The other three coauthors reported having financial relationships with numerous pharmaceutical companies, including Sandoz and/or Novartis. Dr. Colombel reported financial relationships with many pharmaceutical companies, including Novartis and other manufacturers of biosimilars. Dr. Regueiro reports financial relationships with numerous pharmaceutical companies, including some manufacturers of biosimilars. Dr. Weinberg reported financial relationships with Celgene, AbbVie, Eli Lilly, and Novartis. Kim reports financial relationships with GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, and AstraZeneca. Dr. Aslinia, Dr. Shoor, Dr. Choate, and Dr. Bhatt reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM BIODRUGS

How nonadherence complicates cardiology, in two trials

Each study adds new twist

Two very different sets of clinical evidence have offered new twists on how nonadherence to cardiovascular medicines not only leads to suboptimal outcomes, but also complicates the data from clinical studies.

One study, a subanalysis of a major trial, outlined how taking more than the assigned therapy – that is, nonadherence by taking too much rather than too little – skewed results. The other was a trial demonstrating that early use of an invasive procedure is not a strategy to compensate for nonadherence to guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT).

“Both studies provide a fresh reminder that nonadherence is a significant problem in cardiology overall, but also in the trial setting when we are trying to interpret study results,” explained Usam Baber, MD, director of interventional cardiology, University of Oklahoma Health, Oklahoma City, coauthor of an editorial accompanying the two published studies.

Dr. Baber was the first author of a unifying editorial that addressed the issues raised by each. In an interview, Dr. Baber said the studies had unique take-home messages but together highlight important issues of nonadherence.

MASTER DAPT: Too much medicine

The subanalysis was performed on data generated by MASTER DAPT, a study evaluating whether a relatively short course of dual-antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) in patients at high risk of bleeding could preserve protection against major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) while reducing risk of adverse events. The problem was that nonadherence muddied the primary message.

In MASTER DAPT, 1 month of DAPT was compared with a standard therapy of at least 2 additional months of DAPT following revascularization and placement of a biodegradable polymer stent. Enrollment in the study was restricted to those with a high risk of bleeding, the report of the primary results showed.

The major message of MASTER DAPT was that the abbreviated course of DAPT was noninferior for preventing MACE but resulted in lower rates of clinically relevant bleeding in those patients without an indication for oral anticoagulation (OAC). In the subgroup with an indication for OAC, there was no bleeding benefit.

However, when the results were reexamined in the context of adherence, the benefit of the shorter course was found to be underestimated. Relative to 9.4% in the standard-therapy arm, the nonadherence rate in the experimental arm was 20.2%, most of whom did not stop therapy at 1 month. They instead remained on the antiplatelet therapy, failing to adhere to the study protocol.

This form of nonadherence, taking more DAPT than assigned, was particularly common in the group with an indication for oral anticoagulation (OAC). In this group, nearly 25% assigned to an abbreviated course remained on DAPT for more than 6 months.

In the intention-to-treat analysis, there was no difference between abbreviated and standard DAPT for MACE whether or not patients had an indication for OAC. In other words, the new analysis showed a reduced risk of bleeding among all patients, whether taking OAC or not after controlling for nonadherence.

In addition, this MASTER DAPT analysis found that a high proportion of patients taking OAC did not discontinue their single-antiplatelet therapy (SAPT) after 6 months as specified.

When correcting for this failure to adhere to the MASTER DAPT protocol in a patient population at high bleeding risk, the new analysis “suggests for the first time that discontinuation of SAPT at 6 months after percutaneous intervention is associated with less bleeding without an increase in ischemic events,” Marco Valgimigli, MD, PhD, director of clinical research, Inselspital University Hospital, Bern, Switzerland, reported in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

The findings “reinforce the importance of accounting and correcting for nonadherence” in order to reduce bias in the assessment of treatment effects, according to Dr. Valgimigli, principal investigator of MASTER DAPT and this substudy.

“The first interesting message from this study is that clinicians are reluctant to stop SAPT in these patients even in the setting of a randomized controlled trial,” Dr. Valgimigli said in an interview.

In addition, this substudy, which was prespecified in the MASTER DAPT protocol and employed “a very sophisticated methodology” to control for the effect of adherence, extends the value of a conservative approach to those who are candidates for OAC.

“The main clinical message is that SAPT needs to be discontinued after 6 months in OAC patients, and clinicians need to stop being reluctant to do so,” Dr. Valgimigli said. The data show “prolongation of SAPT increases bleeding risk without decreasing ischemic risk.”

In evaluating trial relevance, regulators prefer ITT analyses, but Dr. Baber pointed out that these can obscure the evidence of risk or benefit of a per-protocol analysis when patients take their medicine as prescribed.

“The technical message is that, when we are trying to apply results of a clinical trial to daily practice, we must understand nonadherence,” Dr. Baber said.

Dr. Baber pointed out that the lack of adherence in the case of MASTER DAPT appears to relate more to clinicians managing the patients than to the patients themselves, but it still speaks to the importance of understanding the effects of treatment in the context of the medicine rather than adherence to the medicine.

ISCHEMIA: Reconsidering adherence

In the ISCHEMIA trial, the goal was to evaluate whether an early invasive intervention might compensate to at least some degree for the persistent problem of nonadherence.

“If you are managing a patient that you know is at high risk of noncompliance, many clinicians are tempted to perform early revascularization. This was my bias. The thinking is that by offering an invasive therapy we are at least doing something to control their disease,” John A. Spertus, MD, clinical director of outcomes research, St. Luke’s Mid America Heart Institute, Kansas City, Mo., explained in an interview.

The study did not support the hypothesis. Patients with chronic coronary disease were randomized to a strategy of angiography and, if indicated, revascularization, or to receive GDMT alone. The health status was followed with the Seattle Angina Questionnaire (SAQ-7).

At 12 months, patients who were adherent to GDMT had better SAQ-7 scores than those who were nonadherent, regardless of the arm to which they were randomized. Conversely, there was no difference in SAQ-7 scores between the two groups when the nonadherent subgroups in each arm were compared.

“I think these data suggest that an interventional therapy does not absolve clinicians from the responsibility of educating patients about the importance of adhering to GDMT,” Dr. Spertus said.

In ISCHEMIA, 4,480 patients were randomized. At baseline assessment 27.8% were nonadherent to GDMT. The baselines SAQ-7 scores were worse in these patients relative to those who were adherent. At 12 months, nonadherence still correlated with worse SAQ-7 scores.

“These data dispel the belief that we might be benefiting nonadherent patients by moving more quickly to invasive procedures,” Dr. Spertus said.

In cardiovascular disease, particularly heart failure, adherence to GDMT has been associated numerous times with improved quality of life, according to Dr. Baber. However, he said, the ability of invasive procedures to modify the adverse impact of poor adherence to GDMT has not been well studied. This ISCHEMIA subanalysis only reinforces the message that GDMT adherence is a meaningful predictor of improved quality of life.

However, urging clinicians to work with patients to improve adherence is not a novel idea, according to Dr. Baber. The unmet need is effective and reliable strategies.

“There are so many different reasons that patients are nonadherent, so there are limited gains by focusing on just one of the issues,” Dr. Baber said. “I think the answer is a patient-centric approach in which clinicians deal with the specific issues facing the patient in front of them. I think there are data go suggest this yields better results.”

These two very different studies also show that poor adherence is an insidious issue. While the MASTER DAPT data reveal how nonadherence confuse trial data, the ISCHEMIA trial shows that some assumptions about circumventing the effects of nonadherence might not be accurate.

According to Dr. Baber, effective strategies to reduce nonadherence are available, but the problem deserves to be addressed more proactively in clinical trials and in patient care.

Dr. Baber reported financial relationships with AstraZeneca and Amgen. Dr. Spertus has financial relationships with Abbott, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Corvia, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer and Terumo. Dr. Valgimigli has financial relationships with more than 15 pharmaceutical companies, including Terumo, which provided funding for the MASTER DAPT trial.

Each study adds new twist

Each study adds new twist

Two very different sets of clinical evidence have offered new twists on how nonadherence to cardiovascular medicines not only leads to suboptimal outcomes, but also complicates the data from clinical studies.

One study, a subanalysis of a major trial, outlined how taking more than the assigned therapy – that is, nonadherence by taking too much rather than too little – skewed results. The other was a trial demonstrating that early use of an invasive procedure is not a strategy to compensate for nonadherence to guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT).

“Both studies provide a fresh reminder that nonadherence is a significant problem in cardiology overall, but also in the trial setting when we are trying to interpret study results,” explained Usam Baber, MD, director of interventional cardiology, University of Oklahoma Health, Oklahoma City, coauthor of an editorial accompanying the two published studies.

Dr. Baber was the first author of a unifying editorial that addressed the issues raised by each. In an interview, Dr. Baber said the studies had unique take-home messages but together highlight important issues of nonadherence.

MASTER DAPT: Too much medicine

The subanalysis was performed on data generated by MASTER DAPT, a study evaluating whether a relatively short course of dual-antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) in patients at high risk of bleeding could preserve protection against major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) while reducing risk of adverse events. The problem was that nonadherence muddied the primary message.