User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Cautions when prescribing lithium

I was astonished that Dr. Melvin G. McInnis’ article on using lithium to treat bipolar disorder (BD) (Current Psychiatry, June 2014, p. 38-44; [http://bit.ly/1sszAUr]) did not address all the potential hazards of the medication. He discussed side effects, but only how to manage them so that patients will adhere to treatment.

I have used lithium for patients with BD, and often it is efficacious, although hazardous in overdose. Lithium toxicity can cause cardiac arrhythmias, and must be monitored closely. In addition, the effects of hydration and exercise on the lithium level, especially during summer, often are ignored.

Two of my patients, an adolescent and an adult, were well-maintained on lithium, adhered to treatment, and had no concurrent medical problems, but developed significant toxicity for no reason that I could determine. The adult had a lithium level of 2.0 mEq/L in the emergency room; the adolescent had a lithium level of 1.8 mEq/L. Levels this high are considered potentially lethal, and because it happened without warning and without a cause that I could determine, I consider lithium to be one of the riskier mood stabilizers. I still prescribe it, but with great caution.

Dr. McInnis also did not mention the possibility of lithium-induced diabetes insipidus, a condition in which the kidneys are no longer able to concentrate urine and that is marked by excessive urination, concomitant water intake, and low urine specific gravity. It is uncommon, but I have seen it 3 times in 30 years, in a practice that specializes in psychotherapy and does not see a high percentage of patients with BD. I consider it a condition that must be kept in mind as we follow our patients in long-term treatment.

Mary Davis, MD

Lancaster, Pennsylvania

Dr. McInnis responds

Dr. Davis raises the issue of lithium toxicity and provides examples of 2 patients who developed levels of 2.0 mEq/L and 1.8 mEq/L. These levels clearly are well beyond the toxicity threshold of 1.3 mEq/L, and the patients wisely sought urgent care. These scenarios exemplify the need for regular monitoring of the lithium level—in particular, when there is any change in physical or mental health status. Development of significant toxicity generally has some lead-time with emerging short-term side effects (outlined in Table 2 of my article), which underscores the importance of discussing the nature of emerging side effects with your patient.

Dr. Davis is correct in noting that the practitioner must be aware of long-term side effects of lithium. I find it helpful to discuss these effects with the patient in the context of short-term (days or weeks), intermediate (weeks or months), and long-term (months or years) time frames (Table 2). Diabetes insipidus is listed as an intermediate side effect.

I am grateful to Dr. Davis for raising the issue of hydration and summer heat, a concern among parents and coaches when student athletes practice strenuously for extended hours.1 Miller et al2 found that the concentration of lithium was between 1.2- and 4.6-fold in forearm sweat compared with serum levels, with the implication that heat-induced sweating may lower lithium levels. Jefferson et al3 studied 4 athletes after a 20-km race and found that all had become dehydrated but had a decrease in the serum lithium level. This is contrary to the widely held belief that excessive sweating predisposes to lithium toxicity.

BD is among the more lethal psychiatric disorders, and lithium is among the few medications shown to mitigate suicidal behavior.4 As with any medication, lithium is not without risk, and there is a clear need for informed medical management. Any notable change in health status or physical activity in a patient taking lithium is worthy of review, with recommendations based on knowledge of the patient and medical science.

1. Reardon CL, Factor RM. Sport psychiatry: a systematic review of diagnosis and medical treatment of mental illness in athletes. Sports Med. 2010;40:961-980.

2. Miller EB, Pain RW, Skripal PJ. Sweat lithium in manic-depression. Br J Psychiatry. 1978;133:477-478.

3. Jefferson JW, Greist JH, Clagnaz PJ, et al. Effect of strenuous exercise on serum lithium level in man. Am J Psychiatry. 1982;139(12):1593-1595.

4. Goodwin FK, Fireman B, Simon GE, et al. Suicide risk in bipolar disorder during treatment with lithium and divalproex. JAMA. 2003;290(11):1467-1473.

I was astonished that Dr. Melvin G. McInnis’ article on using lithium to treat bipolar disorder (BD) (Current Psychiatry, June 2014, p. 38-44; [http://bit.ly/1sszAUr]) did not address all the potential hazards of the medication. He discussed side effects, but only how to manage them so that patients will adhere to treatment.

I have used lithium for patients with BD, and often it is efficacious, although hazardous in overdose. Lithium toxicity can cause cardiac arrhythmias, and must be monitored closely. In addition, the effects of hydration and exercise on the lithium level, especially during summer, often are ignored.

Two of my patients, an adolescent and an adult, were well-maintained on lithium, adhered to treatment, and had no concurrent medical problems, but developed significant toxicity for no reason that I could determine. The adult had a lithium level of 2.0 mEq/L in the emergency room; the adolescent had a lithium level of 1.8 mEq/L. Levels this high are considered potentially lethal, and because it happened without warning and without a cause that I could determine, I consider lithium to be one of the riskier mood stabilizers. I still prescribe it, but with great caution.

Dr. McInnis also did not mention the possibility of lithium-induced diabetes insipidus, a condition in which the kidneys are no longer able to concentrate urine and that is marked by excessive urination, concomitant water intake, and low urine specific gravity. It is uncommon, but I have seen it 3 times in 30 years, in a practice that specializes in psychotherapy and does not see a high percentage of patients with BD. I consider it a condition that must be kept in mind as we follow our patients in long-term treatment.

Mary Davis, MD

Lancaster, Pennsylvania

Dr. McInnis responds

Dr. Davis raises the issue of lithium toxicity and provides examples of 2 patients who developed levels of 2.0 mEq/L and 1.8 mEq/L. These levels clearly are well beyond the toxicity threshold of 1.3 mEq/L, and the patients wisely sought urgent care. These scenarios exemplify the need for regular monitoring of the lithium level—in particular, when there is any change in physical or mental health status. Development of significant toxicity generally has some lead-time with emerging short-term side effects (outlined in Table 2 of my article), which underscores the importance of discussing the nature of emerging side effects with your patient.

Dr. Davis is correct in noting that the practitioner must be aware of long-term side effects of lithium. I find it helpful to discuss these effects with the patient in the context of short-term (days or weeks), intermediate (weeks or months), and long-term (months or years) time frames (Table 2). Diabetes insipidus is listed as an intermediate side effect.

I am grateful to Dr. Davis for raising the issue of hydration and summer heat, a concern among parents and coaches when student athletes practice strenuously for extended hours.1 Miller et al2 found that the concentration of lithium was between 1.2- and 4.6-fold in forearm sweat compared with serum levels, with the implication that heat-induced sweating may lower lithium levels. Jefferson et al3 studied 4 athletes after a 20-km race and found that all had become dehydrated but had a decrease in the serum lithium level. This is contrary to the widely held belief that excessive sweating predisposes to lithium toxicity.

BD is among the more lethal psychiatric disorders, and lithium is among the few medications shown to mitigate suicidal behavior.4 As with any medication, lithium is not without risk, and there is a clear need for informed medical management. Any notable change in health status or physical activity in a patient taking lithium is worthy of review, with recommendations based on knowledge of the patient and medical science.

I was astonished that Dr. Melvin G. McInnis’ article on using lithium to treat bipolar disorder (BD) (Current Psychiatry, June 2014, p. 38-44; [http://bit.ly/1sszAUr]) did not address all the potential hazards of the medication. He discussed side effects, but only how to manage them so that patients will adhere to treatment.

I have used lithium for patients with BD, and often it is efficacious, although hazardous in overdose. Lithium toxicity can cause cardiac arrhythmias, and must be monitored closely. In addition, the effects of hydration and exercise on the lithium level, especially during summer, often are ignored.

Two of my patients, an adolescent and an adult, were well-maintained on lithium, adhered to treatment, and had no concurrent medical problems, but developed significant toxicity for no reason that I could determine. The adult had a lithium level of 2.0 mEq/L in the emergency room; the adolescent had a lithium level of 1.8 mEq/L. Levels this high are considered potentially lethal, and because it happened without warning and without a cause that I could determine, I consider lithium to be one of the riskier mood stabilizers. I still prescribe it, but with great caution.

Dr. McInnis also did not mention the possibility of lithium-induced diabetes insipidus, a condition in which the kidneys are no longer able to concentrate urine and that is marked by excessive urination, concomitant water intake, and low urine specific gravity. It is uncommon, but I have seen it 3 times in 30 years, in a practice that specializes in psychotherapy and does not see a high percentage of patients with BD. I consider it a condition that must be kept in mind as we follow our patients in long-term treatment.

Mary Davis, MD

Lancaster, Pennsylvania

Dr. McInnis responds

Dr. Davis raises the issue of lithium toxicity and provides examples of 2 patients who developed levels of 2.0 mEq/L and 1.8 mEq/L. These levels clearly are well beyond the toxicity threshold of 1.3 mEq/L, and the patients wisely sought urgent care. These scenarios exemplify the need for regular monitoring of the lithium level—in particular, when there is any change in physical or mental health status. Development of significant toxicity generally has some lead-time with emerging short-term side effects (outlined in Table 2 of my article), which underscores the importance of discussing the nature of emerging side effects with your patient.

Dr. Davis is correct in noting that the practitioner must be aware of long-term side effects of lithium. I find it helpful to discuss these effects with the patient in the context of short-term (days or weeks), intermediate (weeks or months), and long-term (months or years) time frames (Table 2). Diabetes insipidus is listed as an intermediate side effect.

I am grateful to Dr. Davis for raising the issue of hydration and summer heat, a concern among parents and coaches when student athletes practice strenuously for extended hours.1 Miller et al2 found that the concentration of lithium was between 1.2- and 4.6-fold in forearm sweat compared with serum levels, with the implication that heat-induced sweating may lower lithium levels. Jefferson et al3 studied 4 athletes after a 20-km race and found that all had become dehydrated but had a decrease in the serum lithium level. This is contrary to the widely held belief that excessive sweating predisposes to lithium toxicity.

BD is among the more lethal psychiatric disorders, and lithium is among the few medications shown to mitigate suicidal behavior.4 As with any medication, lithium is not without risk, and there is a clear need for informed medical management. Any notable change in health status or physical activity in a patient taking lithium is worthy of review, with recommendations based on knowledge of the patient and medical science.

1. Reardon CL, Factor RM. Sport psychiatry: a systematic review of diagnosis and medical treatment of mental illness in athletes. Sports Med. 2010;40:961-980.

2. Miller EB, Pain RW, Skripal PJ. Sweat lithium in manic-depression. Br J Psychiatry. 1978;133:477-478.

3. Jefferson JW, Greist JH, Clagnaz PJ, et al. Effect of strenuous exercise on serum lithium level in man. Am J Psychiatry. 1982;139(12):1593-1595.

4. Goodwin FK, Fireman B, Simon GE, et al. Suicide risk in bipolar disorder during treatment with lithium and divalproex. JAMA. 2003;290(11):1467-1473.

1. Reardon CL, Factor RM. Sport psychiatry: a systematic review of diagnosis and medical treatment of mental illness in athletes. Sports Med. 2010;40:961-980.

2. Miller EB, Pain RW, Skripal PJ. Sweat lithium in manic-depression. Br J Psychiatry. 1978;133:477-478.

3. Jefferson JW, Greist JH, Clagnaz PJ, et al. Effect of strenuous exercise on serum lithium level in man. Am J Psychiatry. 1982;139(12):1593-1595.

4. Goodwin FK, Fireman B, Simon GE, et al. Suicide risk in bipolar disorder during treatment with lithium and divalproex. JAMA. 2003;290(11):1467-1473.

What makes you responsible during a screening call?

Help your patient with hoarding disorder move the clutter to the curb

Hoarding disorder (HD), categorized in DSM-5 under obsessive-compulsive and related disorders, is defined as the “persistent difficulty discarding or parting with possessions, regardless of their actual value.”1 Hoarders feel that they need to save items, and experience distress when discarding them. Prevalence of HD among the general population is 2% to 5%.

Compulsive hoarders usually keep old items in their home that they do not intend to use. In severe cases, the clutter is so great that areas of the home cannot be used or entered. Hoarders tend to isolate themselves and usually do not invite people home, perhaps because they are embarrassed about the clutter or anxious that someone might try to clean the house. Hoarders may travel long distances to collect items others have discarded.

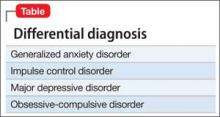

Hoarding can lead to psychiatric disorders and social problems. Hoarders tend to not develop attachment with people because they are more attached to their possessions. They may avoid social interactions; in turn, others avoid them. This isolation can lead to depression, anxiety, and substance abuse. Hoarders may be evicted from their home if the clutter makes the house dangerous or unfit to live in it. Compulsive hoarding is detrimental to the hoarder and the health and well-being of family members. Hoarding can coexist or can be result of other psychiatric disorders (Table).

Neural mechanism in hoarding

Hoarders may start to accumulate and store large quantities of items because of a cognitive deficit, such as trouble making decisions or poor recognition or acknowledgement of the situation, or maladaptive thoughts. Tolin et al1 found the anterior cingulate cortex and insula was stimulus-dependent in patients with HD. Functional MRI showed when patients with HD were shown an item that was their possession, they exhibited an abnormal brain activity, compared with low activity when the items shown were not theirs.

Interventions

Choice of treatment depends on the age of the patient and severity of illness: behavioral, medical, or a combination of both. For an uncomplicated case, management can begin with behavioral modification.

Behavioral modifications. HD can stem from any of several variables, including greater response latency for decision-making about possessions and maladaptive beliefs about, and emotional attachment to, possessions, which can lead to intense emotional experiences about the prospect of losing those possessions.2 Cognitive-behavioral therapy has shown promising results for treating HD by addressing the aforementioned factors. A step-by-step approach usually is feasible and convenient for the therapist and patient. It involves gradual mental detachment from items to accommodate the patient’s pace.2

Pharmacotherapy. There is no clear evidence for treating HD with any particular drug. Hoarders are less likely to use psychotropics, possibly because of poor insight (eg, they do not realize the potentially dangerous living conditions hoarding creates).3 Because HD is related to obsessive-compulsive disorder, it is intuitive to consider a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

There is still a need for more research on management of HD.

Disclosure

Dr. Silman reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Tolin DF, Stevens MC, Villavicencio AL, et al. Neural mechanism of decision making in hoarding disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(8):832-841.

2. Tolin DF, Frost RO, Steketee G. An open trial of cognitivebehavioral therapy for compulsive hoarding. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45(7):1461-1470.

3. Brakoulias V, Starcevic V, Berle D, et al. The use of psychotropic agents for the symptoms of obsessivecompulsive disorder. Australas Psychiatry. 2013;21(2): 117-121.

Hoarding disorder (HD), categorized in DSM-5 under obsessive-compulsive and related disorders, is defined as the “persistent difficulty discarding or parting with possessions, regardless of their actual value.”1 Hoarders feel that they need to save items, and experience distress when discarding them. Prevalence of HD among the general population is 2% to 5%.

Compulsive hoarders usually keep old items in their home that they do not intend to use. In severe cases, the clutter is so great that areas of the home cannot be used or entered. Hoarders tend to isolate themselves and usually do not invite people home, perhaps because they are embarrassed about the clutter or anxious that someone might try to clean the house. Hoarders may travel long distances to collect items others have discarded.

Hoarding can lead to psychiatric disorders and social problems. Hoarders tend to not develop attachment with people because they are more attached to their possessions. They may avoid social interactions; in turn, others avoid them. This isolation can lead to depression, anxiety, and substance abuse. Hoarders may be evicted from their home if the clutter makes the house dangerous or unfit to live in it. Compulsive hoarding is detrimental to the hoarder and the health and well-being of family members. Hoarding can coexist or can be result of other psychiatric disorders (Table).

Neural mechanism in hoarding

Hoarders may start to accumulate and store large quantities of items because of a cognitive deficit, such as trouble making decisions or poor recognition or acknowledgement of the situation, or maladaptive thoughts. Tolin et al1 found the anterior cingulate cortex and insula was stimulus-dependent in patients with HD. Functional MRI showed when patients with HD were shown an item that was their possession, they exhibited an abnormal brain activity, compared with low activity when the items shown were not theirs.

Interventions

Choice of treatment depends on the age of the patient and severity of illness: behavioral, medical, or a combination of both. For an uncomplicated case, management can begin with behavioral modification.

Behavioral modifications. HD can stem from any of several variables, including greater response latency for decision-making about possessions and maladaptive beliefs about, and emotional attachment to, possessions, which can lead to intense emotional experiences about the prospect of losing those possessions.2 Cognitive-behavioral therapy has shown promising results for treating HD by addressing the aforementioned factors. A step-by-step approach usually is feasible and convenient for the therapist and patient. It involves gradual mental detachment from items to accommodate the patient’s pace.2

Pharmacotherapy. There is no clear evidence for treating HD with any particular drug. Hoarders are less likely to use psychotropics, possibly because of poor insight (eg, they do not realize the potentially dangerous living conditions hoarding creates).3 Because HD is related to obsessive-compulsive disorder, it is intuitive to consider a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

There is still a need for more research on management of HD.

Disclosure

Dr. Silman reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Hoarding disorder (HD), categorized in DSM-5 under obsessive-compulsive and related disorders, is defined as the “persistent difficulty discarding or parting with possessions, regardless of their actual value.”1 Hoarders feel that they need to save items, and experience distress when discarding them. Prevalence of HD among the general population is 2% to 5%.

Compulsive hoarders usually keep old items in their home that they do not intend to use. In severe cases, the clutter is so great that areas of the home cannot be used or entered. Hoarders tend to isolate themselves and usually do not invite people home, perhaps because they are embarrassed about the clutter or anxious that someone might try to clean the house. Hoarders may travel long distances to collect items others have discarded.

Hoarding can lead to psychiatric disorders and social problems. Hoarders tend to not develop attachment with people because they are more attached to their possessions. They may avoid social interactions; in turn, others avoid them. This isolation can lead to depression, anxiety, and substance abuse. Hoarders may be evicted from their home if the clutter makes the house dangerous or unfit to live in it. Compulsive hoarding is detrimental to the hoarder and the health and well-being of family members. Hoarding can coexist or can be result of other psychiatric disorders (Table).

Neural mechanism in hoarding

Hoarders may start to accumulate and store large quantities of items because of a cognitive deficit, such as trouble making decisions or poor recognition or acknowledgement of the situation, or maladaptive thoughts. Tolin et al1 found the anterior cingulate cortex and insula was stimulus-dependent in patients with HD. Functional MRI showed when patients with HD were shown an item that was their possession, they exhibited an abnormal brain activity, compared with low activity when the items shown were not theirs.

Interventions

Choice of treatment depends on the age of the patient and severity of illness: behavioral, medical, or a combination of both. For an uncomplicated case, management can begin with behavioral modification.

Behavioral modifications. HD can stem from any of several variables, including greater response latency for decision-making about possessions and maladaptive beliefs about, and emotional attachment to, possessions, which can lead to intense emotional experiences about the prospect of losing those possessions.2 Cognitive-behavioral therapy has shown promising results for treating HD by addressing the aforementioned factors. A step-by-step approach usually is feasible and convenient for the therapist and patient. It involves gradual mental detachment from items to accommodate the patient’s pace.2

Pharmacotherapy. There is no clear evidence for treating HD with any particular drug. Hoarders are less likely to use psychotropics, possibly because of poor insight (eg, they do not realize the potentially dangerous living conditions hoarding creates).3 Because HD is related to obsessive-compulsive disorder, it is intuitive to consider a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

There is still a need for more research on management of HD.

Disclosure

Dr. Silman reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Tolin DF, Stevens MC, Villavicencio AL, et al. Neural mechanism of decision making in hoarding disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(8):832-841.

2. Tolin DF, Frost RO, Steketee G. An open trial of cognitivebehavioral therapy for compulsive hoarding. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45(7):1461-1470.

3. Brakoulias V, Starcevic V, Berle D, et al. The use of psychotropic agents for the symptoms of obsessivecompulsive disorder. Australas Psychiatry. 2013;21(2): 117-121.

1. Tolin DF, Stevens MC, Villavicencio AL, et al. Neural mechanism of decision making in hoarding disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(8):832-841.

2. Tolin DF, Frost RO, Steketee G. An open trial of cognitivebehavioral therapy for compulsive hoarding. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45(7):1461-1470.

3. Brakoulias V, Starcevic V, Berle D, et al. The use of psychotropic agents for the symptoms of obsessivecompulsive disorder. Australas Psychiatry. 2013;21(2): 117-121.

8 tests rolled into a mnemonic to detect weakness in suspected conversion disorder

DSM-5 criteria for conversion disorder (or functional neurological symptom disorder) requires findings that are incompatible with recognized neurologic or medical conditions.1 Knowledge of signs specific to conversion disorder may help you diagnose the illness with confidence.

We review signs suggestive of conversion disorder. These can be remembered using the mnemonic How About Finding Some Conversion Weakness [in an otherwise] Strong Guy/Gal? (Table2).

Inconsistencies in motor function can be observed on examination. Signs may be consciously or unconsciously produced. Although most of the tests mentioned have high positive and negative predictive values (noted in the Table2) they have limited sensitivity and specificity,3 and the presence of a positive sign does not exclude the possibility of comorbid disease.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Stone J, LaFrance WC Jr, Levenson JL, et al. Issues for DSM- 5: conversion disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(6):626-627.

2. Daum C, Hubschmid M, Aybek S. The value of ‘positive’ clinical signs for weakness, sensory and gait disorders in conversion disorder: a systematic and narrative review. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2014;85(2):180-190.

3. Stone J, Carson A, Sharpe M. Functional symptoms and signs in neurology: assessment and diagnosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76(suppl 1):i2-i12.

DSM-5 criteria for conversion disorder (or functional neurological symptom disorder) requires findings that are incompatible with recognized neurologic or medical conditions.1 Knowledge of signs specific to conversion disorder may help you diagnose the illness with confidence.

We review signs suggestive of conversion disorder. These can be remembered using the mnemonic How About Finding Some Conversion Weakness [in an otherwise] Strong Guy/Gal? (Table2).

Inconsistencies in motor function can be observed on examination. Signs may be consciously or unconsciously produced. Although most of the tests mentioned have high positive and negative predictive values (noted in the Table2) they have limited sensitivity and specificity,3 and the presence of a positive sign does not exclude the possibility of comorbid disease.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

DSM-5 criteria for conversion disorder (or functional neurological symptom disorder) requires findings that are incompatible with recognized neurologic or medical conditions.1 Knowledge of signs specific to conversion disorder may help you diagnose the illness with confidence.

We review signs suggestive of conversion disorder. These can be remembered using the mnemonic How About Finding Some Conversion Weakness [in an otherwise] Strong Guy/Gal? (Table2).

Inconsistencies in motor function can be observed on examination. Signs may be consciously or unconsciously produced. Although most of the tests mentioned have high positive and negative predictive values (noted in the Table2) they have limited sensitivity and specificity,3 and the presence of a positive sign does not exclude the possibility of comorbid disease.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Stone J, LaFrance WC Jr, Levenson JL, et al. Issues for DSM- 5: conversion disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(6):626-627.

2. Daum C, Hubschmid M, Aybek S. The value of ‘positive’ clinical signs for weakness, sensory and gait disorders in conversion disorder: a systematic and narrative review. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2014;85(2):180-190.

3. Stone J, Carson A, Sharpe M. Functional symptoms and signs in neurology: assessment and diagnosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76(suppl 1):i2-i12.

1. Stone J, LaFrance WC Jr, Levenson JL, et al. Issues for DSM- 5: conversion disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(6):626-627.

2. Daum C, Hubschmid M, Aybek S. The value of ‘positive’ clinical signs for weakness, sensory and gait disorders in conversion disorder: a systematic and narrative review. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2014;85(2):180-190.

3. Stone J, Carson A, Sharpe M. Functional symptoms and signs in neurology: assessment and diagnosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76(suppl 1):i2-i12.

What are your responsibilities after a screening call?

Dear Dr. Mossman,

When I take a call from a treatment-seeker at our outpatient clinic, I ask brief screening questions to determine whether our services would be appropriate. Shortly after I screened one caller, Ms. C, she called back requesting a medication refill and asking about her diagnosis.

What obligation do I have to Ms. C? Is she my patient? Would I be liable if I didn’t help her out and something bad happened to her?

Submitted by “Dr. S”

Office and hospital Web sites, LinkedIn profiles, and Facebook pages are just a few of the ways that people find physicians and learn about their services. But most 21st century doctor-patient relationships still start with 19th century technology: a telephone call.

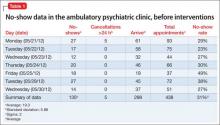

Talking with prospective patients before setting up an appointment makes sense. A short conversation can clarify whether you offer the services that a caller needs and increases the show-up rate for initial appointments.1

But if you ask for some personal history and information about symptoms in a screening interview, does that make the caller your patient? Ms. C seemed to have thought so. To find out whether Ms. C was right and to learn how Dr. S should handle initial telephone calls, we’ll look at:

• the rationale for screening callers before initiating treatment

• features of screening that can create a doctor-patient relationship

• how to fulfill duties that result from screening.

Why screen prospective patients?

Mental health treatment has become more diversified and specialized over the past 30 years. No psychiatrist nowadays has all the therapeutic skills that all potential patients might need.

Before speaking to you, a treatment-seeker often won’t know whether your practice style will fit his (her) needs. You might prefer not to provide medication management for another clinician’s psychotherapy patient or, if you’re like most psychiatrists, you might not offer psychotherapy.

In the absence of prior obligation (eg, agreeing to provide coverage for an emergency room), physicians may structure their practices and contract for their services as they see fit2—but this leaves you with some obligation to screen potential patients for appropriate mutual fit. In years past, some psychiatrists saw potential patients for an in-office evaluation to decide whether to provide treatment—a practicethat remains acceptable if the person is told, when the appointment is made, that the first meeting is “to meet each other and see if you want to establish a treatment relationship.”3

Good treatment plans take into account patients’ temperament, emotional state, cognitive capacity, culture, family circumstances, substance use, and medical history.4 Common mental conditions often can be identified in a telephone call.5,6 Although the diagnostic accuracy of such efforts is uncertain,7 such calls can help practitioners determine whether they offer the right services for callers. Good decisions about initiating care always take financial pressures and constraints into account,8 and a pre-appointment telephone call can address those issues, too.

For all these reasons, talking to a prospective patient before he comes to see you makes sense. Screening lets you decide:

• whether you’re the right clinician for his needs

• who the right clinician is if you are not

• whether he should seek emergency evaluation when the situation sounds urgent.

Do phone calls start treatment?

As Dr. S’s questions show, telephone screenings might leave some callers thinking that treatment has started, even before their first office appointment. Having a treatment relationship is a prerequisite to malpractice liability,9 and courts have concluded that, under the right circumstances, telephone assessments do create physician-patient relationships.

Creating a physician-patient relationship

How or when might telephone screening make someone your patient? This question doesn’t have a precise answer, but how courts decided similar questions has depended on the questions the physician asked and whether the physician offered what sounded like medical advice.10,11 A physician-patient relationship forms when the physician takes some implied or affirmative action to treat, see, examine, care for, or offer a diagnosis to the patient,9,12,13 such as:

• knowingly accepting someone as a patient14

• explicitly agreeing to treat a person

• “acting in some other way such that the patient might reasonably be led to assume a doctor-patient relationship has been established.”15

Also, the “fact that a physician does not deal directly with a patient does not necessarily preclude the existence of a physician-patient relationship,”12 so a telephone conversation can create such a relationship if it contains the right elements. Table 116 highlights actions that, during the course of screening, might constitute initiation of a physician-patient relationship. Table 2 offers suggestions for managing initial telephone contacts to reduce the chance of inadvertently creating a physician-patient relationship.

In the eyes of the law, whether a physician-patient relationship was formed depends on specific facts of the situation and may be decided by a jury.13,14 In the case of Ms. C, Dr. S might avoid premature creation of a physician-patient relationship by refraining from offering a diagnosis at the conclusion of the screening call.17

Prescribing

Although features of the original screening interview indicated that Ms. C was not yet Dr. S’s patient, prescribing certainly would commence a physician-patient relationship.18 But even if the screening had made Ms. C a patient, refilling her prescription now probably is a bad idea.

Assuming that a physician-patient relationship exists, it is unlikely that a short telephone interview gave Dr. S enough information about Ms. C’s medical history and present mental status to ensure that his diagnostic reasoning would not be faulty. It also is unlikely that telephone screening allowed Dr. S to meet the standard of care for prescribing—a process that involves choosing medications suitable to the patient’s clinical needs, checking the results of any necessary lab tests, and obtaining appropriate informed consent.19

Satisfying duties

Outpatient facilities can instruct telephone screeners to conduct interviews in ways that reduce inadvertent establishment of a treatment relationship, but establishing such a relationship cannot be avoided in all cases. If a caller is distraught or in crisis, for example, compassion dictates helping him, and some callers (eg, Ms. C) may feel they have a firmer treatment relationship than actually exists.

Once you have created a physician-patient relationship, you must continue that relationship until you end it appropriately.3 That does not mean you have to provide definitive treatment; you simply need to exercise “reasonable care according to the standards of the profession.”16,20 If a caller telephones in an emergency situation, for example, the screening clinician should take appropriate steps to ensure safety, which might include calling law enforcement or facilitating hospitalization.3

One way to fulfill the duties of a physician-patient relationship inadvertently established during initial screening is through explicit discharge (if medically appropriate) or transfer of care to another physician.15 A prudent clinic or practitioner will describe other mental health resources in the community and sometimes assist with referral if the inquiring potential patient needs services that the provider does not offer.

In many communities, finding appropriate mental health resources is difficult. Creative approaches to this problem include transitional psychiatry or crisis support clinics that serve as a “bridge” to longer-term services,21,22 preliminary process groups,23 and telepsychiatry transitional clinics.24 When a clinic does not accept a person as a patient, the clinic should clearly document 1) key features of the contact and 2) the rationale for that decision

Bottom Line

You have a right and a responsibility to screen prospective patients for good fit to your treatment services. In doing so, however, you might inadvertently create a physician-patient relationship. If this happens, you should fulfill your clinical responsibilities, as you would for any patient, by helping the patient get appropriate care from you or another provider.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Shoffner J, Staudt M, Marcus S, et al. Using telephone reminders to increase attendance at psychiatric appointments: findings of a pilot study in rural Appalachia. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58(6):872-875.

2. Hiser v Randolph, 1980 617 P2d 774 (Ariz App).

3. American Psychiatric Association. Practice management for early career psychiatrists: a reference guide, 6th edition. http://www.psych.org/practice/managing-a-practice/ starting-a-practice. Published October 16, 2006. Accessed July 8, 2014.

4. Delgado SV, Strawn JR. Difficult psychiatric consultations: an integrated approach. New York, NY: Springer; 2014.

5. Aziz MA, Kenford S. Comparability of telephone and face-to-face interviews in assessing patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Psychiatric Pract. 2004;10(5): 307-313.

6. Michel C, Schimmelmann BG, Kupferschmid S, et al. Reliability of telephone assessments of at-risk criteria of psychosis: a comparison to face-to-face interviews. Schizophr Res. 2014;153(1-3):251-253.

7. Muskens EM, Lucassen P, Groenleer W, et al. Psychiatric diagnosis by telephone: is it an opportunity [published online March 15, 2014]? Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. doi: 10.1007/s00127-014-0861-9.

8. Cassel CK, Guest JA. Choosing wisely: helping physicians and patients make smart decisions about their care. JAMA. 2012;307(17):1801-1802.

9. Roberts v Sankey, 2004 813 NE2d 1195 (Ind App).

10. O’Neill v Montefiore Hospital, 1960 202 NYS 2d 436 (NY App).

11. McKinney v Schlatter, 1997 692 NE2d 1045 (Ohio App).

12. Dehn v Edgecombe, 865 A2d 603 (Md 2005).

13. Kelley v Middle Tennessee Emergency Physicians, 133 SW3d 587 (Tenn 2004).

14. Oliver v Brock, 342 So2d 1 (Ala 1976).

15. Appelbaum PS, Gutheil TG. Malpractice and other forms of liability. In: Appelbaum PS, Gutheil TG, eds. Clinical Handbook of Psychiatry and the Law, 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2007:115-116.

16. Simon RI, Shuman DW. The doctor-patient relationship. Focus. 2007;5(4):423-431.

17. Torres A, Wagner R. Establishing the physician-patient relationship. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1993;19(2):147-149.

18. Aboff BM, Collier VU, Farber NJ, et al. Residents’ prescription writing for nonpatients. JAMA. 2002;288(3):381-385.

19. Edersheim JG, Stern TA. Liability associated with prescribing medications. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;11(3):115-119.

20. Brown v Koulizakis, 331 SE2d 440 (Va 1985).

21. University of Michigan Department of Psychiatry. Crisis support clinic. http://www.psych.med.umich.edu/patient-care/crisis-support-clinic. Accessed July 9, 2014.

22. UAB Department of Psychiatry. http://www.uab.edu/ medicine/psychiatry. Accessed July 9, 2014.

23. Stone WN, Klein EB. The waiting-list group. Int J Group Psychother. 1999;49(4):417-428.

24. Detweiler MB, Arif S, Candelario J, et al. A telepsychiatry transition clinic: the first 12 months experience. J Telemed Telecare. 2011;17(6):293-297.

Dear Dr. Mossman,

When I take a call from a treatment-seeker at our outpatient clinic, I ask brief screening questions to determine whether our services would be appropriate. Shortly after I screened one caller, Ms. C, she called back requesting a medication refill and asking about her diagnosis.

What obligation do I have to Ms. C? Is she my patient? Would I be liable if I didn’t help her out and something bad happened to her?

Submitted by “Dr. S”

Office and hospital Web sites, LinkedIn profiles, and Facebook pages are just a few of the ways that people find physicians and learn about their services. But most 21st century doctor-patient relationships still start with 19th century technology: a telephone call.

Talking with prospective patients before setting up an appointment makes sense. A short conversation can clarify whether you offer the services that a caller needs and increases the show-up rate for initial appointments.1

But if you ask for some personal history and information about symptoms in a screening interview, does that make the caller your patient? Ms. C seemed to have thought so. To find out whether Ms. C was right and to learn how Dr. S should handle initial telephone calls, we’ll look at:

• the rationale for screening callers before initiating treatment

• features of screening that can create a doctor-patient relationship

• how to fulfill duties that result from screening.

Why screen prospective patients?

Mental health treatment has become more diversified and specialized over the past 30 years. No psychiatrist nowadays has all the therapeutic skills that all potential patients might need.

Before speaking to you, a treatment-seeker often won’t know whether your practice style will fit his (her) needs. You might prefer not to provide medication management for another clinician’s psychotherapy patient or, if you’re like most psychiatrists, you might not offer psychotherapy.

In the absence of prior obligation (eg, agreeing to provide coverage for an emergency room), physicians may structure their practices and contract for their services as they see fit2—but this leaves you with some obligation to screen potential patients for appropriate mutual fit. In years past, some psychiatrists saw potential patients for an in-office evaluation to decide whether to provide treatment—a practicethat remains acceptable if the person is told, when the appointment is made, that the first meeting is “to meet each other and see if you want to establish a treatment relationship.”3

Good treatment plans take into account patients’ temperament, emotional state, cognitive capacity, culture, family circumstances, substance use, and medical history.4 Common mental conditions often can be identified in a telephone call.5,6 Although the diagnostic accuracy of such efforts is uncertain,7 such calls can help practitioners determine whether they offer the right services for callers. Good decisions about initiating care always take financial pressures and constraints into account,8 and a pre-appointment telephone call can address those issues, too.

For all these reasons, talking to a prospective patient before he comes to see you makes sense. Screening lets you decide:

• whether you’re the right clinician for his needs

• who the right clinician is if you are not

• whether he should seek emergency evaluation when the situation sounds urgent.

Do phone calls start treatment?

As Dr. S’s questions show, telephone screenings might leave some callers thinking that treatment has started, even before their first office appointment. Having a treatment relationship is a prerequisite to malpractice liability,9 and courts have concluded that, under the right circumstances, telephone assessments do create physician-patient relationships.

Creating a physician-patient relationship

How or when might telephone screening make someone your patient? This question doesn’t have a precise answer, but how courts decided similar questions has depended on the questions the physician asked and whether the physician offered what sounded like medical advice.10,11 A physician-patient relationship forms when the physician takes some implied or affirmative action to treat, see, examine, care for, or offer a diagnosis to the patient,9,12,13 such as:

• knowingly accepting someone as a patient14

• explicitly agreeing to treat a person

• “acting in some other way such that the patient might reasonably be led to assume a doctor-patient relationship has been established.”15

Also, the “fact that a physician does not deal directly with a patient does not necessarily preclude the existence of a physician-patient relationship,”12 so a telephone conversation can create such a relationship if it contains the right elements. Table 116 highlights actions that, during the course of screening, might constitute initiation of a physician-patient relationship. Table 2 offers suggestions for managing initial telephone contacts to reduce the chance of inadvertently creating a physician-patient relationship.

In the eyes of the law, whether a physician-patient relationship was formed depends on specific facts of the situation and may be decided by a jury.13,14 In the case of Ms. C, Dr. S might avoid premature creation of a physician-patient relationship by refraining from offering a diagnosis at the conclusion of the screening call.17

Prescribing

Although features of the original screening interview indicated that Ms. C was not yet Dr. S’s patient, prescribing certainly would commence a physician-patient relationship.18 But even if the screening had made Ms. C a patient, refilling her prescription now probably is a bad idea.

Assuming that a physician-patient relationship exists, it is unlikely that a short telephone interview gave Dr. S enough information about Ms. C’s medical history and present mental status to ensure that his diagnostic reasoning would not be faulty. It also is unlikely that telephone screening allowed Dr. S to meet the standard of care for prescribing—a process that involves choosing medications suitable to the patient’s clinical needs, checking the results of any necessary lab tests, and obtaining appropriate informed consent.19

Satisfying duties

Outpatient facilities can instruct telephone screeners to conduct interviews in ways that reduce inadvertent establishment of a treatment relationship, but establishing such a relationship cannot be avoided in all cases. If a caller is distraught or in crisis, for example, compassion dictates helping him, and some callers (eg, Ms. C) may feel they have a firmer treatment relationship than actually exists.

Once you have created a physician-patient relationship, you must continue that relationship until you end it appropriately.3 That does not mean you have to provide definitive treatment; you simply need to exercise “reasonable care according to the standards of the profession.”16,20 If a caller telephones in an emergency situation, for example, the screening clinician should take appropriate steps to ensure safety, which might include calling law enforcement or facilitating hospitalization.3

One way to fulfill the duties of a physician-patient relationship inadvertently established during initial screening is through explicit discharge (if medically appropriate) or transfer of care to another physician.15 A prudent clinic or practitioner will describe other mental health resources in the community and sometimes assist with referral if the inquiring potential patient needs services that the provider does not offer.

In many communities, finding appropriate mental health resources is difficult. Creative approaches to this problem include transitional psychiatry or crisis support clinics that serve as a “bridge” to longer-term services,21,22 preliminary process groups,23 and telepsychiatry transitional clinics.24 When a clinic does not accept a person as a patient, the clinic should clearly document 1) key features of the contact and 2) the rationale for that decision

Bottom Line

You have a right and a responsibility to screen prospective patients for good fit to your treatment services. In doing so, however, you might inadvertently create a physician-patient relationship. If this happens, you should fulfill your clinical responsibilities, as you would for any patient, by helping the patient get appropriate care from you or another provider.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dear Dr. Mossman,

When I take a call from a treatment-seeker at our outpatient clinic, I ask brief screening questions to determine whether our services would be appropriate. Shortly after I screened one caller, Ms. C, she called back requesting a medication refill and asking about her diagnosis.

What obligation do I have to Ms. C? Is she my patient? Would I be liable if I didn’t help her out and something bad happened to her?

Submitted by “Dr. S”

Office and hospital Web sites, LinkedIn profiles, and Facebook pages are just a few of the ways that people find physicians and learn about their services. But most 21st century doctor-patient relationships still start with 19th century technology: a telephone call.

Talking with prospective patients before setting up an appointment makes sense. A short conversation can clarify whether you offer the services that a caller needs and increases the show-up rate for initial appointments.1

But if you ask for some personal history and information about symptoms in a screening interview, does that make the caller your patient? Ms. C seemed to have thought so. To find out whether Ms. C was right and to learn how Dr. S should handle initial telephone calls, we’ll look at:

• the rationale for screening callers before initiating treatment

• features of screening that can create a doctor-patient relationship

• how to fulfill duties that result from screening.

Why screen prospective patients?

Mental health treatment has become more diversified and specialized over the past 30 years. No psychiatrist nowadays has all the therapeutic skills that all potential patients might need.

Before speaking to you, a treatment-seeker often won’t know whether your practice style will fit his (her) needs. You might prefer not to provide medication management for another clinician’s psychotherapy patient or, if you’re like most psychiatrists, you might not offer psychotherapy.

In the absence of prior obligation (eg, agreeing to provide coverage for an emergency room), physicians may structure their practices and contract for their services as they see fit2—but this leaves you with some obligation to screen potential patients for appropriate mutual fit. In years past, some psychiatrists saw potential patients for an in-office evaluation to decide whether to provide treatment—a practicethat remains acceptable if the person is told, when the appointment is made, that the first meeting is “to meet each other and see if you want to establish a treatment relationship.”3

Good treatment plans take into account patients’ temperament, emotional state, cognitive capacity, culture, family circumstances, substance use, and medical history.4 Common mental conditions often can be identified in a telephone call.5,6 Although the diagnostic accuracy of such efforts is uncertain,7 such calls can help practitioners determine whether they offer the right services for callers. Good decisions about initiating care always take financial pressures and constraints into account,8 and a pre-appointment telephone call can address those issues, too.

For all these reasons, talking to a prospective patient before he comes to see you makes sense. Screening lets you decide:

• whether you’re the right clinician for his needs

• who the right clinician is if you are not

• whether he should seek emergency evaluation when the situation sounds urgent.

Do phone calls start treatment?

As Dr. S’s questions show, telephone screenings might leave some callers thinking that treatment has started, even before their first office appointment. Having a treatment relationship is a prerequisite to malpractice liability,9 and courts have concluded that, under the right circumstances, telephone assessments do create physician-patient relationships.

Creating a physician-patient relationship

How or when might telephone screening make someone your patient? This question doesn’t have a precise answer, but how courts decided similar questions has depended on the questions the physician asked and whether the physician offered what sounded like medical advice.10,11 A physician-patient relationship forms when the physician takes some implied or affirmative action to treat, see, examine, care for, or offer a diagnosis to the patient,9,12,13 such as:

• knowingly accepting someone as a patient14

• explicitly agreeing to treat a person

• “acting in some other way such that the patient might reasonably be led to assume a doctor-patient relationship has been established.”15

Also, the “fact that a physician does not deal directly with a patient does not necessarily preclude the existence of a physician-patient relationship,”12 so a telephone conversation can create such a relationship if it contains the right elements. Table 116 highlights actions that, during the course of screening, might constitute initiation of a physician-patient relationship. Table 2 offers suggestions for managing initial telephone contacts to reduce the chance of inadvertently creating a physician-patient relationship.

In the eyes of the law, whether a physician-patient relationship was formed depends on specific facts of the situation and may be decided by a jury.13,14 In the case of Ms. C, Dr. S might avoid premature creation of a physician-patient relationship by refraining from offering a diagnosis at the conclusion of the screening call.17

Prescribing

Although features of the original screening interview indicated that Ms. C was not yet Dr. S’s patient, prescribing certainly would commence a physician-patient relationship.18 But even if the screening had made Ms. C a patient, refilling her prescription now probably is a bad idea.

Assuming that a physician-patient relationship exists, it is unlikely that a short telephone interview gave Dr. S enough information about Ms. C’s medical history and present mental status to ensure that his diagnostic reasoning would not be faulty. It also is unlikely that telephone screening allowed Dr. S to meet the standard of care for prescribing—a process that involves choosing medications suitable to the patient’s clinical needs, checking the results of any necessary lab tests, and obtaining appropriate informed consent.19

Satisfying duties

Outpatient facilities can instruct telephone screeners to conduct interviews in ways that reduce inadvertent establishment of a treatment relationship, but establishing such a relationship cannot be avoided in all cases. If a caller is distraught or in crisis, for example, compassion dictates helping him, and some callers (eg, Ms. C) may feel they have a firmer treatment relationship than actually exists.

Once you have created a physician-patient relationship, you must continue that relationship until you end it appropriately.3 That does not mean you have to provide definitive treatment; you simply need to exercise “reasonable care according to the standards of the profession.”16,20 If a caller telephones in an emergency situation, for example, the screening clinician should take appropriate steps to ensure safety, which might include calling law enforcement or facilitating hospitalization.3

One way to fulfill the duties of a physician-patient relationship inadvertently established during initial screening is through explicit discharge (if medically appropriate) or transfer of care to another physician.15 A prudent clinic or practitioner will describe other mental health resources in the community and sometimes assist with referral if the inquiring potential patient needs services that the provider does not offer.

In many communities, finding appropriate mental health resources is difficult. Creative approaches to this problem include transitional psychiatry or crisis support clinics that serve as a “bridge” to longer-term services,21,22 preliminary process groups,23 and telepsychiatry transitional clinics.24 When a clinic does not accept a person as a patient, the clinic should clearly document 1) key features of the contact and 2) the rationale for that decision

Bottom Line

You have a right and a responsibility to screen prospective patients for good fit to your treatment services. In doing so, however, you might inadvertently create a physician-patient relationship. If this happens, you should fulfill your clinical responsibilities, as you would for any patient, by helping the patient get appropriate care from you or another provider.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Shoffner J, Staudt M, Marcus S, et al. Using telephone reminders to increase attendance at psychiatric appointments: findings of a pilot study in rural Appalachia. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58(6):872-875.

2. Hiser v Randolph, 1980 617 P2d 774 (Ariz App).

3. American Psychiatric Association. Practice management for early career psychiatrists: a reference guide, 6th edition. http://www.psych.org/practice/managing-a-practice/ starting-a-practice. Published October 16, 2006. Accessed July 8, 2014.

4. Delgado SV, Strawn JR. Difficult psychiatric consultations: an integrated approach. New York, NY: Springer; 2014.

5. Aziz MA, Kenford S. Comparability of telephone and face-to-face interviews in assessing patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Psychiatric Pract. 2004;10(5): 307-313.

6. Michel C, Schimmelmann BG, Kupferschmid S, et al. Reliability of telephone assessments of at-risk criteria of psychosis: a comparison to face-to-face interviews. Schizophr Res. 2014;153(1-3):251-253.

7. Muskens EM, Lucassen P, Groenleer W, et al. Psychiatric diagnosis by telephone: is it an opportunity [published online March 15, 2014]? Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. doi: 10.1007/s00127-014-0861-9.

8. Cassel CK, Guest JA. Choosing wisely: helping physicians and patients make smart decisions about their care. JAMA. 2012;307(17):1801-1802.

9. Roberts v Sankey, 2004 813 NE2d 1195 (Ind App).

10. O’Neill v Montefiore Hospital, 1960 202 NYS 2d 436 (NY App).

11. McKinney v Schlatter, 1997 692 NE2d 1045 (Ohio App).

12. Dehn v Edgecombe, 865 A2d 603 (Md 2005).

13. Kelley v Middle Tennessee Emergency Physicians, 133 SW3d 587 (Tenn 2004).

14. Oliver v Brock, 342 So2d 1 (Ala 1976).

15. Appelbaum PS, Gutheil TG. Malpractice and other forms of liability. In: Appelbaum PS, Gutheil TG, eds. Clinical Handbook of Psychiatry and the Law, 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2007:115-116.

16. Simon RI, Shuman DW. The doctor-patient relationship. Focus. 2007;5(4):423-431.

17. Torres A, Wagner R. Establishing the physician-patient relationship. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1993;19(2):147-149.

18. Aboff BM, Collier VU, Farber NJ, et al. Residents’ prescription writing for nonpatients. JAMA. 2002;288(3):381-385.

19. Edersheim JG, Stern TA. Liability associated with prescribing medications. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;11(3):115-119.

20. Brown v Koulizakis, 331 SE2d 440 (Va 1985).

21. University of Michigan Department of Psychiatry. Crisis support clinic. http://www.psych.med.umich.edu/patient-care/crisis-support-clinic. Accessed July 9, 2014.

22. UAB Department of Psychiatry. http://www.uab.edu/ medicine/psychiatry. Accessed July 9, 2014.

23. Stone WN, Klein EB. The waiting-list group. Int J Group Psychother. 1999;49(4):417-428.

24. Detweiler MB, Arif S, Candelario J, et al. A telepsychiatry transition clinic: the first 12 months experience. J Telemed Telecare. 2011;17(6):293-297.

1. Shoffner J, Staudt M, Marcus S, et al. Using telephone reminders to increase attendance at psychiatric appointments: findings of a pilot study in rural Appalachia. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58(6):872-875.

2. Hiser v Randolph, 1980 617 P2d 774 (Ariz App).

3. American Psychiatric Association. Practice management for early career psychiatrists: a reference guide, 6th edition. http://www.psych.org/practice/managing-a-practice/ starting-a-practice. Published October 16, 2006. Accessed July 8, 2014.

4. Delgado SV, Strawn JR. Difficult psychiatric consultations: an integrated approach. New York, NY: Springer; 2014.

5. Aziz MA, Kenford S. Comparability of telephone and face-to-face interviews in assessing patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Psychiatric Pract. 2004;10(5): 307-313.

6. Michel C, Schimmelmann BG, Kupferschmid S, et al. Reliability of telephone assessments of at-risk criteria of psychosis: a comparison to face-to-face interviews. Schizophr Res. 2014;153(1-3):251-253.

7. Muskens EM, Lucassen P, Groenleer W, et al. Psychiatric diagnosis by telephone: is it an opportunity [published online March 15, 2014]? Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. doi: 10.1007/s00127-014-0861-9.

8. Cassel CK, Guest JA. Choosing wisely: helping physicians and patients make smart decisions about their care. JAMA. 2012;307(17):1801-1802.

9. Roberts v Sankey, 2004 813 NE2d 1195 (Ind App).

10. O’Neill v Montefiore Hospital, 1960 202 NYS 2d 436 (NY App).

11. McKinney v Schlatter, 1997 692 NE2d 1045 (Ohio App).

12. Dehn v Edgecombe, 865 A2d 603 (Md 2005).

13. Kelley v Middle Tennessee Emergency Physicians, 133 SW3d 587 (Tenn 2004).

14. Oliver v Brock, 342 So2d 1 (Ala 1976).

15. Appelbaum PS, Gutheil TG. Malpractice and other forms of liability. In: Appelbaum PS, Gutheil TG, eds. Clinical Handbook of Psychiatry and the Law, 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2007:115-116.

16. Simon RI, Shuman DW. The doctor-patient relationship. Focus. 2007;5(4):423-431.

17. Torres A, Wagner R. Establishing the physician-patient relationship. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1993;19(2):147-149.

18. Aboff BM, Collier VU, Farber NJ, et al. Residents’ prescription writing for nonpatients. JAMA. 2002;288(3):381-385.

19. Edersheim JG, Stern TA. Liability associated with prescribing medications. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;11(3):115-119.

20. Brown v Koulizakis, 331 SE2d 440 (Va 1985).

21. University of Michigan Department of Psychiatry. Crisis support clinic. http://www.psych.med.umich.edu/patient-care/crisis-support-clinic. Accessed July 9, 2014.

22. UAB Department of Psychiatry. http://www.uab.edu/ medicine/psychiatry. Accessed July 9, 2014.

23. Stone WN, Klein EB. The waiting-list group. Int J Group Psychother. 1999;49(4):417-428.

24. Detweiler MB, Arif S, Candelario J, et al. A telepsychiatry transition clinic: the first 12 months experience. J Telemed Telecare. 2011;17(6):293-297.

A young man with psychosis whose heart is racing

Case Agitated and violent

Mr. C, age 19, presents with anxiety, agitation, isolation, social withdrawal, and paranoia. He is admitted to the inpatient unit after attempting to punch his father and place him in a headlock. Mr. C has no history of mental illness, no significant medical history, and no significant family history of mental illness.

The treatment team determines that this is Mr. C’s first psychotic break. He is given a diagnosis of psychosis, not otherwise specified and started on risperidone, titrated to 2 mg/d, later discontinued secondary to tachycardia. He is then started on haloperidol, 5 mg/d titrated to 10 mg/d, and psychotic symptoms abate. Mr. C is discharged with a plan to receive follow-up care at an outpatient mental health center.

One year later, Mr. C is readmitted with a similar presentation: paranoia, agitation, anxiety, and isolation. After discharge, he starts an intensive outpatient program (IOP) for long-term treatment of adults who have a diagnosis of a schizophrenia spectrum disorder.

Several medication trials ensue, including risperidone, escitalopram, citalopram, fluphenazine, lorazepam, quetiapine, and haloperidol. Despite these trials over the course of 2 years, Mr. C continues to display paranoia and agitation, and is unable to resume academic and community activities. Within the IOP, Mr. C is placed in a vocational training program and struggles to remain stable enough to continue his job at a small greenhouse.

Concurrently, Mr. C is noted to be abusing alcohol. After the IOP treatment team expresses concern about his abuse, he reduces alcohol intake and he and his parents are educated on the impact of alcohol use on schizophrenia.

Which treatment option would you choose next?

a) initiate a trial of clozapine

b) try a long-acting injectable antipsychotic

c) recommend inpatient treatment

The authors’ observations

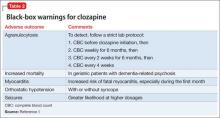

Clozapine is an atypical antipsychotic that is FDA-approved for treatment-resistant schizophrenia; it also helps reduce recurrent suicidal behavior in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder.

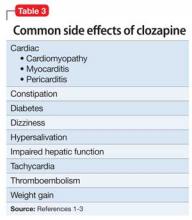

Clozapine works by blocking D2 receptors, thereby reducing positive symptoms. It also blocks serotonin 2A receptors, which enhances dopamine release in certain brain regions, thereby reducing motor side effects. Interactions at 5-HT2C and 5-HT1A receptors may address cognitive and affective symptoms. Clozapine can help relieve negative symptoms and can decrease aggression. Because it has a low risk of tardive dyskinesia, clozapine is useful when treating patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia.1-3

Treatment Quick heart rate

Mr. C’s IOP treatment team considers a clozapine trial because previous medication trials failed. All paperwork for the registry and screening labs are completed and Mr. C is started on clozapine.

Mr. C’s clozapine dosages are:

• Days 1 to 9: 25 mg/d

• Days 10 to 16: 50 mg/d

• Days 17 to 23: 75 mg/d

• Days 24 to 32: 100 mg/d

• Days 33 to 37: 125 mg/d

• Day 38: 150 mg/d.

On Day 45 of the clozapine trial, Mr. C is increasingly paranoid toward his father and thinks that his father is controlling his thoughts. Mr. C tells the attending psychiatrist that he ingested a handful of clonazepam and considered putting a bag over his head with the intent to commit suicide. Mr. C is admitted to the inpatient unit.

Admission vitals recorded a heart rate of 72 beats per minute but, later that day, the rate was recorded in the vital sign book as 137 beats per minute. The treatment team considers dehydration, anxiety, and staff error; Mr. C is observed carefully. Over the next 2 days, heart rate remains between 102 and 119 beats per minute.

Because of persistent tachycardia, the team orders lab studies, a medical consult, and an electrocardiogram (ECG). Thyroid panel, electrolytes, and clozapine level are within normal limits; ECG is unremarkable.

Although tachycardia is a known side effect of clozapine,3,4 we order an echocardiogram because of Mr. C’s young age and non-diagnostic laboratory workup. The echo study demonstrates reduced left-ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 45%. Tests for HIV infection and Lyme disease are negative. The cardiology team diagnoses cardiomyopathy of unknown origin.

Although Mr. C has a history of alcohol abuse, the cardiology team believes that alcohol consumption does not adequately explain the cardiomyopathy, given his young age and the limited number of lifetime drinking-years (approximately 4 or 5); the team determines that clozapine is causing secondary cardiomyopathy and tachycardia, leading to reduced LVEF. Clozapine is stopped because the recommended treatment for toxic secondary cardiomyopathy is to remove the offending agent. At this point, the clozapine dosage is 250 mg/d.

At the medical team’s recommendation, Mr. C is started on metoprolol, a beta blocker, at 25 mg/d.

The etiology of secondary cardiomyopathy includes all of the following except:

a) tachycardia-induced

b) autoimmune

c) radiation-induced

d) infiltrative

e) endomyocardial

The authors’ observations

Cardiomyopathies are diseases of the heart muscle causing mechanical and electrical dysfunction. This group of diseases has a range of symptoms, causes, and treatments. Disease manifests typically as arrhythmia, systolic dysfunction, or diastolic dysfunction. Classification systems are based on origin, anatomy, physiology, primary treatments, method of diagnosis, biopsy, histopathology, and symptomatic state.

The American Heart Association Scientific Statement5 distinguishes cardiomyopathies by degree of organ involvement. Diseases confined to the heart are defined as primary cardiomyopathy, which may have a genetic, acquired, or mixed cause. Acquired causes include inflammatory (myocarditis), stress (Takotsubo), peripartum, and tachycardia. Cardiomyopathies that are part of generalized systemic disorders are defined as secondary cardiomyopathy (Table 1).

Secondary cardiomyopathies have many causes. These include toxicity (medications or alcohol), cancer therapy, infiltrative, storage disease, and endomyocardial, inflammatory, autoimmune, endocrine, and neurologic diseases.5

Evaluation of suspected cardiomyopathy begins with a history and physical focused on identifying causative factors. Selective testing, based on pretest probabilities, might include lab testing, ECG, and echocardiography, and can narrow the differential diagnosis. When toxin-induced cardiomyopathy is suspected, withdrawing the toxin and monitoring for improvement is recommended. The treatment and prognosis for cardiomyopathies vary, based on the cause.6

Review of the literature

After 23 cases of fatal and non-fatal myocarditis were found in a study of 8,000 patients starting clozapine,7 manufacturers in Australia introduced clinical guidelines. Before initiating clozapine, they recommended, clinicians should:

• screen for cardiac symptoms

• screen for a family history of heart disease

• obtain baseline ECG

• obtain baseline markers of myocardial damage (troponin assay and serum creatinine)

• obtain baseline echocardiogram

• repeat cardiac monitoring after the first and second week and then repeat in 6 months

• maintain a high degree of vigilance for signs and symptoms of cardiac toxicity throughout clozapine treatment.8,9

After studying 38 cases of clozapine-induced myocarditis—3 fatal— Ronaldson et al10 listed primary diagnostic features as:

• tachycardia (heart rate >100 beats per minute)

• heart rate >120 beats per minute

• temperature >37°C

• chest pain

• troponin I/T level >2 ng/mL

• C-reactive protein (CRP) > 100 mg/L

• erythrocyte sedimentation rate >50 mm/h.

Among non-fatal cases, symptoms abated after clozapine was discontinued. In 36 of the 38 cases, symptoms emerged 14 to 22 days after clozapine was started. For tachycardia to be considered a diagnostic feature, it must persist for at least 24 hours; if the heart rate is ≥120 beats per minute, however, persistence is not a criterion. It was thought that elevated CRP might herald disease onset; the authors suggest that CRP >50 mg/L should warrant increased monitoring with daily ECG and troponin levels.

Authors’ recommendations include:

• measuring troponin and CRP and order an ECG at baseline and at 7, 14, 21, and 28 days

• examining patient for signs and symptoms of illness at these same intervals

• considering chest pain or fever as an indicator of cardiomyopathy

• asking patients to report any illness during this 4-week period

• if ECG is abnormal or troponin elevated, decreasing clozapine pending further investigation.10

When medications fail

We had to discontinue Mr. C’s clozapine, which meant that the therapeutic relationship established between him and the psychology fellow became an important and, at times, the only bond between him and the medical team while olanzapine was initiated. The alliance between patient and clinician is an important factor for positive prognosis in mental health treatment.11-13 Priebe and McCabe14 asked if the therapeutic relationship in psychiatry is “the basis of therapy or therapy itself?” In a review of studies that used an operationalized measurement of the therapeutic relationship in treating severe mental illness, the authors concluded that the therapeutic relationship is a reliable predictor of outcome.15

In Mr. C’s case, the psychology fellow, who also works with the Partial Hospitalization Program/Intensive Outpatient Program (PHP/IOP), joined the treatment team on the inpatient unit a few days into hospitalization. Eleven meetings, including a discharge session, were held between the psychology fellow and the patient during the inpatient hospitalization. Mr. C also participated in a daily group session, facilitated by the psychology fellow.

Maintaining recognition of the boundary disturbance that characterizes schizophrenic psychoses was important for Mr. C. As Auerhahn and Moskowitz16 wrote, the inpatient therapist can be transformed by the schizophrenia patient into the all-knowing, all-powerful early mother, which could contribute to substantial improvement in the patient’s functioning and report of symptoms, only to have the patient’s symptoms return after discharge.

In an effort to evaluate the duration, frequency, and intensity of Mr. C’s symptom experience, a goal of Mr. C’s hospitalization was to attach words to his internal states, including mood and intensity of paranoid ideation. We showed Mr. C directly and indirectly that reporting intensification of symptoms and decreased functioning would not result in abandonment or punishment, and worked to demonstrate through our actions that the treatment team differs from Mr. C’s view of the world as dangerous and others as hostile and omnipotent.

Treatment Developing language

Initially, Mr. C gives a number (from 1 to 10) to describe his mood, 10 being the happiest he has ever felt and 1 being the most depressed. The treatment team discusses how important it is that Mr. C know his feelings and be able to convey to others how he feels.

Over time, Mr. C is encouraged to attach a feeling word to the number, and by discharge, he stops using numbers and responds to inquiries about his feelings with a mood word. This practice has been reinforced with the patient in the IOP program, allowing him to continue practicing linking his internal state with feeling words.