User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Are the people we serve ‘patients’ or ‘customers’?

Dear Dr. Mossman,

At the multispecialty hospital where I work, administrators refer to patients as “customers” and tell us that, by improving “the customer experience,” we can reduce complaints and avoid malpractice suits. This business lingo offends me. Doesn’t providing good care do more to prevent malpractice claims than calling sick patients “customers”?

Submitted by “Dr. H”

“All words are pegs to hang ideas on.” As was true when Reverend Henry Ward Beecher uttered this phrase in the 19th century,1 names affect how we relate to and feel about people. Many doctors don’t think of themselves as “selling” services, and they find calling patients “customers” distasteful.

But for at least 4 decades, mental health professionals themselves have used a “customer approach” to think about certain aspects of psychiatrist–patient encounters.2 More pertinent to Dr. H’s questions, many attorneys who advise physicians are convinced that giving patients a satisfying “customer experience” is a sound strategy for reducing the risk of malpractice litigation.3

If the attorneys are right, taking a customer service perspective can lower the likelihood that psychiatrists will be sued. To understand why, this article looks at:

• terms for referring to health care recipients

• the feelings those terms generate

• how the “customer service” perspective has become a malpractice prevention

strategy.

Off-putting connotations

All the currently used ways of referring to persons served by doctors have off-putting features.

The word “patient” dates back to the 14th century and comes from Latin present

participles of pati, “to suffer.” Although Alpha Omega Alpha’s motto—“be worthy

to serve the suffering”4—expresses doctors’ commitment to help others, “patient”

carries emotional baggage. A “patient” is “a sick individual” who seeks treatment

from a physician,5 a circumstance that most people (including doctors) find unpleasant and hope is only temporary. The adjective “patient” means “bearing pains or trials calmly or without complaint” and “manifesting forbearance under provocation or strain,”5 phrases associated with passivity, deference, and a long wait to see the doctor.

Because “patient” evokes notions of helplessness and need for direction, non-medical psychotherapists often use “client” to designate care recipients. “Client” has the same Latin root as “to lean” and refers to someone “under the protection of another.” More pertinent to discussions of mental health care, a “client” also is “a person who pays a professional person or organization for services” or “a customer.”5 The latter definition explains what makes “client” feel wrong to medical practitioners, who regard those they treat as deserving more compassion and sacrifice than someone who simply purchases professional services.

“Consumer,” a word of French origin derived from the Latin consumere (“to take

up”), refers to “a person who buys goods and services.”5 If “consumers” are buyers, then those from whom they make purchases are merchants or sellers. Western marketplace concepts often regard consumers as sovereign judges of their needs, and the role of commodity producers is to try to satisfy those needs.6

The problem with viewing health care recipients this way is that sellers don’t caution customers about buying things when only principles of supply-and-demand govern exchange relationships.7 Quite the contrary: producers sometimes promote their products through “advertising [that] distorts reality and creates artificial needs to make profit for a firm.”8 If physicians behave this way, however, they get criticism and deserve it.

A “customer” in 15th-century Middle English was a tax collector, but in modern

usage, a customer is someone who, like a consumer, “purchases some commodity or service.”5 By the early 20th century, “customer” became associated with notions of empowerment embodied in the merchants’ credo, “The customer is always right.”9 Chronic illnesses often require self-management and collaboration with those labeled the “givers” and “recipients” of medical care. Research shows that “patients are more trusting of, and committed to, physicians who adopt an empowering communication style with them,” which suggests “that empowering

patients presents a means to improve the patient–physician relationship.”10

Feelings about names

People have strong feelings about what they are called. In opposing calling patients “consumers,” Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Krugman explains: “Medical care is an area in which crucial decisions—life and death decisions—must be made; yet making those decisions intelligently requires a vast amount of specialized knowledge; and often those decisions must also be made under conditions in which the patient …needs action immediately, with no time for discussion, let alone comparison shopping. …That’s why doctors have traditionally…been expected to behave according to higher standards than the average professional…The idea that all this can be reduced to money—that doctors are just people selling services to consumers of health care—is, well, sickening.”11

Less famous recipients of nonpsychiatric medical services also prefer being called

“patients” over “clients” or “consumers.”12-14 Recipients of mental health services have a different view, however. In some surveys, “patient” gets a plurality or majority of service recipients’ votes,15,16 but in others, recipients prefer to be called “clients” or other terms.17,18 Of note, people who prefer being called “patients” tend to strongly dislike being called “clients.”19 On the professional

side, psychiatrists—along with other physicians—prefer to speak of treating “patients” and to criticize letting economic phrases infect medical discourse.20-22

Names: A practical difference?

Does what psychiatrists call those they serve make any practical difference? Perhaps not, but evidence suggests that the attitudes that doctors take toward patients affects economic success and malpractice risk.

When they have choices about where they can seek health care, medical patients value physicians’ competence, but they also consider nonclinical factors such as family members’ opinions and convenience.23 Knowing this, the federal government’s Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services publishes results from its Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems to “create incentives for hospitals to improve their quality of care.”24

Nonclinical factors play a big part in patients’ decisions about suing their doctors, too. Many malpractice claims turn out to be groundless in the sense that they do not involve medical errors,25 and most errors that result in injury do not lead to malpractice suits.26

What explains this disparity? Often when a lawsuit is filed, whatever injury may have occurred is coupled with an aggravating factor, such as a communication gaffe,27 a physician’s domineering tone of voice,28 or failure to acknowledge error.29 The lower a physician’s patient satisfaction ratings, the higher the physician’s likelihood of receiving complaints and getting sued for malpractice.30,31

These kinds of considerations probably lie behind the recommendation of one hospital manager to doctors: “Continue to call them patients but treat them like

customers.”32 More insights into this view come from responses solicited from Yale

students, staff members, and alumni about whether it seems preferable to be a “patient” or a “customer” (Box).33

Bottom Line

When patients get injured during medical care, evidence suggests that how they feel about their doctors makes a big difference in whether they decide to file suit. If you’re like most psychiatrists, you prefer to call persons whom you treat “patients.” But watching and improving the things that affect your patients’ “customer experience” may help you avoid malpractice litigation.

Related Resource

• Goldhill D. To fix healthcare, turn patients into customers. Bloomberg Personal Finance. www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-01-03/to-fix-health-care-turn-patients-intocustomers.html.

Disclosure

Dr. Mossman reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Beecher HW, Drysdale W. Proverbs from Plymouth pulpit. New York, NY: D. Appleton & Co.;1887.

2. Lazare A, Eisenthal S, Wasserman L. The customer approach to patienthood: attending to patient requests in a walk-in clinic. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1975;32:553-558.

3. Schleiter KE. Difficult patient-physician relationships and the risk of medical malpractice litigation. Virtual Mentor. 2009;11:242-246.

4. Alpha Omega Alpha Honor Medical Society. Alpha Omega Alpha constitution. http://www.alphaomegaalpha.org/constitution.html. Accessed December 13, 2013. Accessed December 13, 2013.

5. Merriam-Webster. Dictionary. http://www.merriamwebster.com. Accessed December 9, 2013.

6. Kotler P, Burton S, Deans K, et al. Marketing, 9th ed. Frenchs Forest, Australia: Pearson Education Australia; 2013.

7. Deber RB. Getting what we pay for: myths and realities about financing Canada’s health care system. Health Law Can. 2000;21(2):9-56.

8. Takala T, Uusitalo O. An alternative view of relationship marketing: a framework for ethical analysis. Eur J Mark. 1996;30:45-60.

9. Van Vuren FS. The Yankee who taught Britishers that ‘the customer is always right.’ Milwaukee Journal. http://www.wisconsinhistory.org/wlhba/articleView.

asp?pg=1&id=11176. Published September 9, 1932. Accessed December 20, 2013.

10. Ouschan T, Sweeney J, Johnson L. Customer empowerment and relationship outcomes in healthcare consultations. Eur J Mark. 2006;40:1068-1086.

11. Krugman P. Patients are not consumers. The New York Times. http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/04/20/patients-are-not-consumers. Published April 20, 2011. Accessed December 13, 2013.

12. Nair BR. Patient, client or customer? Med J Aust. 1998;169:593.

13. Wing PC. Patient or client? If in doubt, ask. CMAJ. 1997;157:287-289.

14. Deber RB, Kraetschmer N, Urowitz S, et al. Patient, consumer, client, or customer: what do people want to be called? Health Expect. 2005;8(4):345-351.

15. Sharma V, Whitney D, Kazarian SS, et al. Preferred terms for users of mental health services among service providers and recipients. Psychiatr Serv. 2000;51(2): 203-209.

16. Simmons P, Hawley CJ, Gale TM, et al. Service user, patient, client, user or survivor: describing recipients of mental health services. Psychiatrist. 2010;34:20-23.

17. Lloyd C, King R, Bassett H, et al. Patient, client or consumer? A survey of preferred terms. Australas Psychiatry. 2001; 9(4):321-324.

18. Covell NH, McCorkle BH, Weissman EM, et al. What’s in a name? Terms preferred by service recipients. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2007;34(5):443-447.

19. Ritchie CW, Hayes D, Ames DJ. Patient or client? The opinions of people attending a psychiatric clinic. Psychiatrist. 2000;24(12):447-450.

20. Andreasen NC. Clients, consumers, providers, and products: where will it all end? Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:1107-1109.

21. Editorial. What’s in a name? Lancet. 2000;356(9248):2111.

22. Torrey EF. Patients, clients, consumers, survivors et al: what’s in a name? Schizophr Bull. 2011;37(3):466-468.

23. Wilson CT, Woloshin S, Schwartz L. Choosing where to have major surgery: who makes the decision? Arch Surg. 2007;142(3):242-246.

24. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Hospital consumer assessment of healthcare providers and systems. http://www.hcahpsonline.org. Accessed

January 26, 2014.

25. Studdert DM, Mello MM, Gawande AA, et al. Claims, errors, and compensation payments in medical malpractice litigation. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2024-2033.

26. Localio AR, Lawthers AG, Brennan TA, et al. Relation between malpractice claims and adverse events due to negligence—results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study III. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:245-251.

27. Huntington B, Kuhn N. Communication gaffes: a root cause of malpractice claims. Bayl Univ Med Cent. 2003;16(2):157-161.

28. Ambady N, Laplante D, Nguyen T, et al. Surgeons’ tone of voice: a clue to malpractice history. Surgery. 2002;132(1):5-9.

29. Witman AB, Park DM, Hardin SB. How do patients want physicians to handle mistakes? A survey of internal medicine patients in an academic setting. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156(22):2565-2569.

30. Stelfox HT, Gandhi TK, Orav EJ, et al. The relation of patient satisfaction with complaints against physicians and malpractice lawsuits. Am J Med. 2005;118(10):

1126-1133.

31. Hickson GB, Federspiel CF, Pichert JW, et al. Patient complaints and malpractice risk. JAMA. 2002;287(22):2951-2957.

32. Bain W. Do we need a new word for patients? Continue to call them patients but treat them like customers. BMJ. 1999;319(7222):1436.

33. Johnson R, Moskowitz E, Thomas J, et al. Would you rather be treated as a patient or a customer? Yale Insights. http://insights.som.yale.edu/insights/would-you-rather-betreated-patient-or-customer. Accessed December 13, 2013.

Dear Dr. Mossman,

At the multispecialty hospital where I work, administrators refer to patients as “customers” and tell us that, by improving “the customer experience,” we can reduce complaints and avoid malpractice suits. This business lingo offends me. Doesn’t providing good care do more to prevent malpractice claims than calling sick patients “customers”?

Submitted by “Dr. H”

“All words are pegs to hang ideas on.” As was true when Reverend Henry Ward Beecher uttered this phrase in the 19th century,1 names affect how we relate to and feel about people. Many doctors don’t think of themselves as “selling” services, and they find calling patients “customers” distasteful.

But for at least 4 decades, mental health professionals themselves have used a “customer approach” to think about certain aspects of psychiatrist–patient encounters.2 More pertinent to Dr. H’s questions, many attorneys who advise physicians are convinced that giving patients a satisfying “customer experience” is a sound strategy for reducing the risk of malpractice litigation.3

If the attorneys are right, taking a customer service perspective can lower the likelihood that psychiatrists will be sued. To understand why, this article looks at:

• terms for referring to health care recipients

• the feelings those terms generate

• how the “customer service” perspective has become a malpractice prevention

strategy.

Off-putting connotations

All the currently used ways of referring to persons served by doctors have off-putting features.

The word “patient” dates back to the 14th century and comes from Latin present

participles of pati, “to suffer.” Although Alpha Omega Alpha’s motto—“be worthy

to serve the suffering”4—expresses doctors’ commitment to help others, “patient”

carries emotional baggage. A “patient” is “a sick individual” who seeks treatment

from a physician,5 a circumstance that most people (including doctors) find unpleasant and hope is only temporary. The adjective “patient” means “bearing pains or trials calmly or without complaint” and “manifesting forbearance under provocation or strain,”5 phrases associated with passivity, deference, and a long wait to see the doctor.

Because “patient” evokes notions of helplessness and need for direction, non-medical psychotherapists often use “client” to designate care recipients. “Client” has the same Latin root as “to lean” and refers to someone “under the protection of another.” More pertinent to discussions of mental health care, a “client” also is “a person who pays a professional person or organization for services” or “a customer.”5 The latter definition explains what makes “client” feel wrong to medical practitioners, who regard those they treat as deserving more compassion and sacrifice than someone who simply purchases professional services.

“Consumer,” a word of French origin derived from the Latin consumere (“to take

up”), refers to “a person who buys goods and services.”5 If “consumers” are buyers, then those from whom they make purchases are merchants or sellers. Western marketplace concepts often regard consumers as sovereign judges of their needs, and the role of commodity producers is to try to satisfy those needs.6

The problem with viewing health care recipients this way is that sellers don’t caution customers about buying things when only principles of supply-and-demand govern exchange relationships.7 Quite the contrary: producers sometimes promote their products through “advertising [that] distorts reality and creates artificial needs to make profit for a firm.”8 If physicians behave this way, however, they get criticism and deserve it.

A “customer” in 15th-century Middle English was a tax collector, but in modern

usage, a customer is someone who, like a consumer, “purchases some commodity or service.”5 By the early 20th century, “customer” became associated with notions of empowerment embodied in the merchants’ credo, “The customer is always right.”9 Chronic illnesses often require self-management and collaboration with those labeled the “givers” and “recipients” of medical care. Research shows that “patients are more trusting of, and committed to, physicians who adopt an empowering communication style with them,” which suggests “that empowering

patients presents a means to improve the patient–physician relationship.”10

Feelings about names

People have strong feelings about what they are called. In opposing calling patients “consumers,” Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Krugman explains: “Medical care is an area in which crucial decisions—life and death decisions—must be made; yet making those decisions intelligently requires a vast amount of specialized knowledge; and often those decisions must also be made under conditions in which the patient …needs action immediately, with no time for discussion, let alone comparison shopping. …That’s why doctors have traditionally…been expected to behave according to higher standards than the average professional…The idea that all this can be reduced to money—that doctors are just people selling services to consumers of health care—is, well, sickening.”11

Less famous recipients of nonpsychiatric medical services also prefer being called

“patients” over “clients” or “consumers.”12-14 Recipients of mental health services have a different view, however. In some surveys, “patient” gets a plurality or majority of service recipients’ votes,15,16 but in others, recipients prefer to be called “clients” or other terms.17,18 Of note, people who prefer being called “patients” tend to strongly dislike being called “clients.”19 On the professional

side, psychiatrists—along with other physicians—prefer to speak of treating “patients” and to criticize letting economic phrases infect medical discourse.20-22

Names: A practical difference?

Does what psychiatrists call those they serve make any practical difference? Perhaps not, but evidence suggests that the attitudes that doctors take toward patients affects economic success and malpractice risk.

When they have choices about where they can seek health care, medical patients value physicians’ competence, but they also consider nonclinical factors such as family members’ opinions and convenience.23 Knowing this, the federal government’s Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services publishes results from its Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems to “create incentives for hospitals to improve their quality of care.”24

Nonclinical factors play a big part in patients’ decisions about suing their doctors, too. Many malpractice claims turn out to be groundless in the sense that they do not involve medical errors,25 and most errors that result in injury do not lead to malpractice suits.26

What explains this disparity? Often when a lawsuit is filed, whatever injury may have occurred is coupled with an aggravating factor, such as a communication gaffe,27 a physician’s domineering tone of voice,28 or failure to acknowledge error.29 The lower a physician’s patient satisfaction ratings, the higher the physician’s likelihood of receiving complaints and getting sued for malpractice.30,31

These kinds of considerations probably lie behind the recommendation of one hospital manager to doctors: “Continue to call them patients but treat them like

customers.”32 More insights into this view come from responses solicited from Yale

students, staff members, and alumni about whether it seems preferable to be a “patient” or a “customer” (Box).33

Bottom Line

When patients get injured during medical care, evidence suggests that how they feel about their doctors makes a big difference in whether they decide to file suit. If you’re like most psychiatrists, you prefer to call persons whom you treat “patients.” But watching and improving the things that affect your patients’ “customer experience” may help you avoid malpractice litigation.

Related Resource

• Goldhill D. To fix healthcare, turn patients into customers. Bloomberg Personal Finance. www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-01-03/to-fix-health-care-turn-patients-intocustomers.html.

Disclosure

Dr. Mossman reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dear Dr. Mossman,

At the multispecialty hospital where I work, administrators refer to patients as “customers” and tell us that, by improving “the customer experience,” we can reduce complaints and avoid malpractice suits. This business lingo offends me. Doesn’t providing good care do more to prevent malpractice claims than calling sick patients “customers”?

Submitted by “Dr. H”

“All words are pegs to hang ideas on.” As was true when Reverend Henry Ward Beecher uttered this phrase in the 19th century,1 names affect how we relate to and feel about people. Many doctors don’t think of themselves as “selling” services, and they find calling patients “customers” distasteful.

But for at least 4 decades, mental health professionals themselves have used a “customer approach” to think about certain aspects of psychiatrist–patient encounters.2 More pertinent to Dr. H’s questions, many attorneys who advise physicians are convinced that giving patients a satisfying “customer experience” is a sound strategy for reducing the risk of malpractice litigation.3

If the attorneys are right, taking a customer service perspective can lower the likelihood that psychiatrists will be sued. To understand why, this article looks at:

• terms for referring to health care recipients

• the feelings those terms generate

• how the “customer service” perspective has become a malpractice prevention

strategy.

Off-putting connotations

All the currently used ways of referring to persons served by doctors have off-putting features.

The word “patient” dates back to the 14th century and comes from Latin present

participles of pati, “to suffer.” Although Alpha Omega Alpha’s motto—“be worthy

to serve the suffering”4—expresses doctors’ commitment to help others, “patient”

carries emotional baggage. A “patient” is “a sick individual” who seeks treatment

from a physician,5 a circumstance that most people (including doctors) find unpleasant and hope is only temporary. The adjective “patient” means “bearing pains or trials calmly or without complaint” and “manifesting forbearance under provocation or strain,”5 phrases associated with passivity, deference, and a long wait to see the doctor.

Because “patient” evokes notions of helplessness and need for direction, non-medical psychotherapists often use “client” to designate care recipients. “Client” has the same Latin root as “to lean” and refers to someone “under the protection of another.” More pertinent to discussions of mental health care, a “client” also is “a person who pays a professional person or organization for services” or “a customer.”5 The latter definition explains what makes “client” feel wrong to medical practitioners, who regard those they treat as deserving more compassion and sacrifice than someone who simply purchases professional services.

“Consumer,” a word of French origin derived from the Latin consumere (“to take

up”), refers to “a person who buys goods and services.”5 If “consumers” are buyers, then those from whom they make purchases are merchants or sellers. Western marketplace concepts often regard consumers as sovereign judges of their needs, and the role of commodity producers is to try to satisfy those needs.6

The problem with viewing health care recipients this way is that sellers don’t caution customers about buying things when only principles of supply-and-demand govern exchange relationships.7 Quite the contrary: producers sometimes promote their products through “advertising [that] distorts reality and creates artificial needs to make profit for a firm.”8 If physicians behave this way, however, they get criticism and deserve it.

A “customer” in 15th-century Middle English was a tax collector, but in modern

usage, a customer is someone who, like a consumer, “purchases some commodity or service.”5 By the early 20th century, “customer” became associated with notions of empowerment embodied in the merchants’ credo, “The customer is always right.”9 Chronic illnesses often require self-management and collaboration with those labeled the “givers” and “recipients” of medical care. Research shows that “patients are more trusting of, and committed to, physicians who adopt an empowering communication style with them,” which suggests “that empowering

patients presents a means to improve the patient–physician relationship.”10

Feelings about names

People have strong feelings about what they are called. In opposing calling patients “consumers,” Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Krugman explains: “Medical care is an area in which crucial decisions—life and death decisions—must be made; yet making those decisions intelligently requires a vast amount of specialized knowledge; and often those decisions must also be made under conditions in which the patient …needs action immediately, with no time for discussion, let alone comparison shopping. …That’s why doctors have traditionally…been expected to behave according to higher standards than the average professional…The idea that all this can be reduced to money—that doctors are just people selling services to consumers of health care—is, well, sickening.”11

Less famous recipients of nonpsychiatric medical services also prefer being called

“patients” over “clients” or “consumers.”12-14 Recipients of mental health services have a different view, however. In some surveys, “patient” gets a plurality or majority of service recipients’ votes,15,16 but in others, recipients prefer to be called “clients” or other terms.17,18 Of note, people who prefer being called “patients” tend to strongly dislike being called “clients.”19 On the professional

side, psychiatrists—along with other physicians—prefer to speak of treating “patients” and to criticize letting economic phrases infect medical discourse.20-22

Names: A practical difference?

Does what psychiatrists call those they serve make any practical difference? Perhaps not, but evidence suggests that the attitudes that doctors take toward patients affects economic success and malpractice risk.

When they have choices about where they can seek health care, medical patients value physicians’ competence, but they also consider nonclinical factors such as family members’ opinions and convenience.23 Knowing this, the federal government’s Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services publishes results from its Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems to “create incentives for hospitals to improve their quality of care.”24

Nonclinical factors play a big part in patients’ decisions about suing their doctors, too. Many malpractice claims turn out to be groundless in the sense that they do not involve medical errors,25 and most errors that result in injury do not lead to malpractice suits.26

What explains this disparity? Often when a lawsuit is filed, whatever injury may have occurred is coupled with an aggravating factor, such as a communication gaffe,27 a physician’s domineering tone of voice,28 or failure to acknowledge error.29 The lower a physician’s patient satisfaction ratings, the higher the physician’s likelihood of receiving complaints and getting sued for malpractice.30,31

These kinds of considerations probably lie behind the recommendation of one hospital manager to doctors: “Continue to call them patients but treat them like

customers.”32 More insights into this view come from responses solicited from Yale

students, staff members, and alumni about whether it seems preferable to be a “patient” or a “customer” (Box).33

Bottom Line

When patients get injured during medical care, evidence suggests that how they feel about their doctors makes a big difference in whether they decide to file suit. If you’re like most psychiatrists, you prefer to call persons whom you treat “patients.” But watching and improving the things that affect your patients’ “customer experience” may help you avoid malpractice litigation.

Related Resource

• Goldhill D. To fix healthcare, turn patients into customers. Bloomberg Personal Finance. www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-01-03/to-fix-health-care-turn-patients-intocustomers.html.

Disclosure

Dr. Mossman reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Beecher HW, Drysdale W. Proverbs from Plymouth pulpit. New York, NY: D. Appleton & Co.;1887.

2. Lazare A, Eisenthal S, Wasserman L. The customer approach to patienthood: attending to patient requests in a walk-in clinic. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1975;32:553-558.

3. Schleiter KE. Difficult patient-physician relationships and the risk of medical malpractice litigation. Virtual Mentor. 2009;11:242-246.

4. Alpha Omega Alpha Honor Medical Society. Alpha Omega Alpha constitution. http://www.alphaomegaalpha.org/constitution.html. Accessed December 13, 2013. Accessed December 13, 2013.

5. Merriam-Webster. Dictionary. http://www.merriamwebster.com. Accessed December 9, 2013.

6. Kotler P, Burton S, Deans K, et al. Marketing, 9th ed. Frenchs Forest, Australia: Pearson Education Australia; 2013.

7. Deber RB. Getting what we pay for: myths and realities about financing Canada’s health care system. Health Law Can. 2000;21(2):9-56.

8. Takala T, Uusitalo O. An alternative view of relationship marketing: a framework for ethical analysis. Eur J Mark. 1996;30:45-60.

9. Van Vuren FS. The Yankee who taught Britishers that ‘the customer is always right.’ Milwaukee Journal. http://www.wisconsinhistory.org/wlhba/articleView.

asp?pg=1&id=11176. Published September 9, 1932. Accessed December 20, 2013.

10. Ouschan T, Sweeney J, Johnson L. Customer empowerment and relationship outcomes in healthcare consultations. Eur J Mark. 2006;40:1068-1086.

11. Krugman P. Patients are not consumers. The New York Times. http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/04/20/patients-are-not-consumers. Published April 20, 2011. Accessed December 13, 2013.

12. Nair BR. Patient, client or customer? Med J Aust. 1998;169:593.

13. Wing PC. Patient or client? If in doubt, ask. CMAJ. 1997;157:287-289.

14. Deber RB, Kraetschmer N, Urowitz S, et al. Patient, consumer, client, or customer: what do people want to be called? Health Expect. 2005;8(4):345-351.

15. Sharma V, Whitney D, Kazarian SS, et al. Preferred terms for users of mental health services among service providers and recipients. Psychiatr Serv. 2000;51(2): 203-209.

16. Simmons P, Hawley CJ, Gale TM, et al. Service user, patient, client, user or survivor: describing recipients of mental health services. Psychiatrist. 2010;34:20-23.

17. Lloyd C, King R, Bassett H, et al. Patient, client or consumer? A survey of preferred terms. Australas Psychiatry. 2001; 9(4):321-324.

18. Covell NH, McCorkle BH, Weissman EM, et al. What’s in a name? Terms preferred by service recipients. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2007;34(5):443-447.

19. Ritchie CW, Hayes D, Ames DJ. Patient or client? The opinions of people attending a psychiatric clinic. Psychiatrist. 2000;24(12):447-450.

20. Andreasen NC. Clients, consumers, providers, and products: where will it all end? Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:1107-1109.

21. Editorial. What’s in a name? Lancet. 2000;356(9248):2111.

22. Torrey EF. Patients, clients, consumers, survivors et al: what’s in a name? Schizophr Bull. 2011;37(3):466-468.

23. Wilson CT, Woloshin S, Schwartz L. Choosing where to have major surgery: who makes the decision? Arch Surg. 2007;142(3):242-246.

24. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Hospital consumer assessment of healthcare providers and systems. http://www.hcahpsonline.org. Accessed

January 26, 2014.

25. Studdert DM, Mello MM, Gawande AA, et al. Claims, errors, and compensation payments in medical malpractice litigation. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2024-2033.

26. Localio AR, Lawthers AG, Brennan TA, et al. Relation between malpractice claims and adverse events due to negligence—results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study III. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:245-251.

27. Huntington B, Kuhn N. Communication gaffes: a root cause of malpractice claims. Bayl Univ Med Cent. 2003;16(2):157-161.

28. Ambady N, Laplante D, Nguyen T, et al. Surgeons’ tone of voice: a clue to malpractice history. Surgery. 2002;132(1):5-9.

29. Witman AB, Park DM, Hardin SB. How do patients want physicians to handle mistakes? A survey of internal medicine patients in an academic setting. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156(22):2565-2569.

30. Stelfox HT, Gandhi TK, Orav EJ, et al. The relation of patient satisfaction with complaints against physicians and malpractice lawsuits. Am J Med. 2005;118(10):

1126-1133.

31. Hickson GB, Federspiel CF, Pichert JW, et al. Patient complaints and malpractice risk. JAMA. 2002;287(22):2951-2957.

32. Bain W. Do we need a new word for patients? Continue to call them patients but treat them like customers. BMJ. 1999;319(7222):1436.

33. Johnson R, Moskowitz E, Thomas J, et al. Would you rather be treated as a patient or a customer? Yale Insights. http://insights.som.yale.edu/insights/would-you-rather-betreated-patient-or-customer. Accessed December 13, 2013.

1. Beecher HW, Drysdale W. Proverbs from Plymouth pulpit. New York, NY: D. Appleton & Co.;1887.

2. Lazare A, Eisenthal S, Wasserman L. The customer approach to patienthood: attending to patient requests in a walk-in clinic. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1975;32:553-558.

3. Schleiter KE. Difficult patient-physician relationships and the risk of medical malpractice litigation. Virtual Mentor. 2009;11:242-246.

4. Alpha Omega Alpha Honor Medical Society. Alpha Omega Alpha constitution. http://www.alphaomegaalpha.org/constitution.html. Accessed December 13, 2013. Accessed December 13, 2013.

5. Merriam-Webster. Dictionary. http://www.merriamwebster.com. Accessed December 9, 2013.

6. Kotler P, Burton S, Deans K, et al. Marketing, 9th ed. Frenchs Forest, Australia: Pearson Education Australia; 2013.

7. Deber RB. Getting what we pay for: myths and realities about financing Canada’s health care system. Health Law Can. 2000;21(2):9-56.

8. Takala T, Uusitalo O. An alternative view of relationship marketing: a framework for ethical analysis. Eur J Mark. 1996;30:45-60.

9. Van Vuren FS. The Yankee who taught Britishers that ‘the customer is always right.’ Milwaukee Journal. http://www.wisconsinhistory.org/wlhba/articleView.

asp?pg=1&id=11176. Published September 9, 1932. Accessed December 20, 2013.

10. Ouschan T, Sweeney J, Johnson L. Customer empowerment and relationship outcomes in healthcare consultations. Eur J Mark. 2006;40:1068-1086.

11. Krugman P. Patients are not consumers. The New York Times. http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/04/20/patients-are-not-consumers. Published April 20, 2011. Accessed December 13, 2013.

12. Nair BR. Patient, client or customer? Med J Aust. 1998;169:593.

13. Wing PC. Patient or client? If in doubt, ask. CMAJ. 1997;157:287-289.

14. Deber RB, Kraetschmer N, Urowitz S, et al. Patient, consumer, client, or customer: what do people want to be called? Health Expect. 2005;8(4):345-351.

15. Sharma V, Whitney D, Kazarian SS, et al. Preferred terms for users of mental health services among service providers and recipients. Psychiatr Serv. 2000;51(2): 203-209.

16. Simmons P, Hawley CJ, Gale TM, et al. Service user, patient, client, user or survivor: describing recipients of mental health services. Psychiatrist. 2010;34:20-23.

17. Lloyd C, King R, Bassett H, et al. Patient, client or consumer? A survey of preferred terms. Australas Psychiatry. 2001; 9(4):321-324.

18. Covell NH, McCorkle BH, Weissman EM, et al. What’s in a name? Terms preferred by service recipients. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2007;34(5):443-447.

19. Ritchie CW, Hayes D, Ames DJ. Patient or client? The opinions of people attending a psychiatric clinic. Psychiatrist. 2000;24(12):447-450.

20. Andreasen NC. Clients, consumers, providers, and products: where will it all end? Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:1107-1109.

21. Editorial. What’s in a name? Lancet. 2000;356(9248):2111.

22. Torrey EF. Patients, clients, consumers, survivors et al: what’s in a name? Schizophr Bull. 2011;37(3):466-468.

23. Wilson CT, Woloshin S, Schwartz L. Choosing where to have major surgery: who makes the decision? Arch Surg. 2007;142(3):242-246.

24. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Hospital consumer assessment of healthcare providers and systems. http://www.hcahpsonline.org. Accessed

January 26, 2014.

25. Studdert DM, Mello MM, Gawande AA, et al. Claims, errors, and compensation payments in medical malpractice litigation. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2024-2033.

26. Localio AR, Lawthers AG, Brennan TA, et al. Relation between malpractice claims and adverse events due to negligence—results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study III. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:245-251.

27. Huntington B, Kuhn N. Communication gaffes: a root cause of malpractice claims. Bayl Univ Med Cent. 2003;16(2):157-161.

28. Ambady N, Laplante D, Nguyen T, et al. Surgeons’ tone of voice: a clue to malpractice history. Surgery. 2002;132(1):5-9.

29. Witman AB, Park DM, Hardin SB. How do patients want physicians to handle mistakes? A survey of internal medicine patients in an academic setting. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156(22):2565-2569.

30. Stelfox HT, Gandhi TK, Orav EJ, et al. The relation of patient satisfaction with complaints against physicians and malpractice lawsuits. Am J Med. 2005;118(10):

1126-1133.

31. Hickson GB, Federspiel CF, Pichert JW, et al. Patient complaints and malpractice risk. JAMA. 2002;287(22):2951-2957.

32. Bain W. Do we need a new word for patients? Continue to call them patients but treat them like customers. BMJ. 1999;319(7222):1436.

33. Johnson R, Moskowitz E, Thomas J, et al. Would you rather be treated as a patient or a customer? Yale Insights. http://insights.som.yale.edu/insights/would-you-rather-betreated-patient-or-customer. Accessed December 13, 2013.

Answers to 7 questions about using neuropsychological testing in your practice

Neuropsychological evaluation, consisting of a thorough examination of cognitive and behavioral functioning, can make an invaluable contribution to the care of psychiatric patients. Through the vehicle of standardized measures of abilities, patients’ cognitive strengths and weaknesses can be elucidated—revealing potential areas for further interventions or to explain impediments to treatment. A licensed clinical psychologist provides this service.

You, as a consumer of reported findings, can use the results to inform your diagnosis and treatment plan. Recommendations from the neuropsychologist often address dispositional planning, cognitive intervention, psychiatric intervention, and work and school accommodations.

Probing the brain−behavior relationship

Neuropsychology is a subspecialty of clinical psychology that is focused on understanding the brain–behavior relationship. Drawing information from multiple disciplines, including psychiatry and neurology, neuropsychology seeks to uncover the cognitive, behavioral, and emotional difficulties that can result from known or suspected brain dysfunction. Increasingly, to protect the public and referral sources, clinical psychologists who perform neuropsychological testing demonstrate their competence through board certification (eg, the American Board of Clinical Neuropsychology).

How is testing conducted? Evaluations comprise measures that are standardized, scored objectively, and have established psychometric properties. Testing can performed on an outpatient or inpatient basis; the duration of testing depends on the question for which the referring practitioner seeks an answer.

Measures typically are administered by paper and pencil, although computer-based

assessments are increasingly being employed. Because of the influence of demographic variables (age, sex, years of education, race), scores are compared with normative samples that resemble those of the patient’s background as closely as possible.

A thorough clinical interview with the patient, a collateral interview with caregivers

and family, and review of relevant medical records are crucial parts of the assessment. Multiple areas of cognition are assessed:

• intelligence

• academic functioning

• attention

• working memory

• speed of processing

• learning and memory

• visual spatial skills

• fine motor skills

• executive functioning.

Essentially, the evaluation speaks to a patient’s neurocognitive functioning and cerebral integrity.

How are results scored? Interpretation of test scores is contingent on expectations of how a patient should perform in the absence of neurologic or psychiatric illness (ie, based on normative data and performancebased estimates of premorbid functioning).1 The overall pattern of intact scores and deficit scores can be used to form specific impressions about a diagnosis, cognitive strengths and weaknesses, and strategies for intervention.

Personality testing. In addition to the cognitive aspect of the evaluation, personality measures are incorporated when relevant to the referral question or presenting concern.

Personality tests can be broadly divided into objective and projective measures.

Objective personality measures, such as the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality

Inventory-Second Edition, require the examinee to respond to a set of items as

true or false or on a Likert-type scale from strongly agree to disagree. Responses are then scored in standardized fashion, making comparisons to normative data, which are then analyzed to determine the extent to which the examinee experiences psychiatric symptoms.

As part of testing, patients’ responses to ambiguous or unstructured standard

stimuli—such as a series of drawings, abstract patterns, or incomplete sentences—

are analyzed to determine underlying personality traits, feelings, and attitudes.

Classic examples of these measures include the Rorschach Test and the Thematic

Apperception Test.

Personality measures and psychiatric testing are designed to answer questions

related to patients’ emotional status. These measures assess psychiatric symptoms and diagnoses, whereas neuropsychological measures provide an understanding of patients’ cognitive assets and limitations.

7 Common questions about neuropsychological testing

1 Will my patient’s insurance cover these assessments? The question is common from practitioners who are considering requesting an assessment for a patient. The short answer is “Yes.”

Most payers follow Medicare guidelines for reimbursement of neuropsychological

testing; if testing is determined to be medically necessary, insurance companies often cover the assessment. Medicaid also pays for psychometric testing services. Neuropsychologists who have a hospital-based practice typically include patients

with all types of insurance coverage. For example, 40% of patients seen in a hospital are covered by Medicare or Medicaid.2

A caveat: Local intermediaries interpret policies and procedures in different ways,

so there is variability in coverage by geographic region. That is why it is crucial

for neuropsychologists to obtain preauthorization, as would be the case with other medical procedures and services sought by referral.

Last, insurance companies do not pay for assessment of a learning disability. The

rationale typically offered for this lack of coverage? The assessment is for academic, not medical, purposes. In such a situation, patients and their families are offered a private-pay option.

2 What are the indications for neuropsychological assessment? Psychiatric practitioners are one of the top medical specialties that refer their patients for neuropsychological testing.3 This is because many patients with a psychiatric or

neurologic disorder experience changes in cognition, mood, and personality. Such

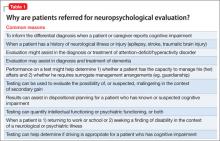

changes can range in severity from subtle to dramatic, and might reflect an underlying disease state or a side effect of medication or other treatment. Whatever the nature of a patient’s problem, careful assessment might help elucidate specific areas with which he (she) is struggling—so that you can better target your interventions. Table 1 lists common reasons for referring a patient for neuropsychological evaluation. Throughout this discussion, we describe examples of clinical situations in which neuropsychological testing is useful for establishing a differential diagnosis and dispositional planning.

3 How does neuropsychological testing help with the differential diagnosis? As an example, one area in which cognitive testing can be beneficial is in geriatric psychiatry.Dementia. Aging often is accompanied by a normal decline in memory and other cognitive functions. But because subtle changes in memory and cognition also canbe the sign of a progressive cognitive disorder, differentiating normal aging from early dementia is essential. Table 2 summarizes typical changes in cognition with aging.

Neuropsychologists, through knowledge of psychometric testing and the brain−behavior relationship, can help you detect dementia and plan treatment early. To determine if cognitive changes are progressive, patients might undergo re-evaluation—typically, every 6 to 12 months—to ascertain if changes have occurred. Mood disorders. Neuropsychological evaluation can be useful in building a differential diagnosis when determining whether cognitive symptoms are attributable to a mood disorder or a medical illness. Cognitive deficits associated with an affective disturbance generally include impairments in attention, memory, and executive functioning.4 The severity of deficits has been linked to severity of illness. When patients with a mood disorder demonstrate localizing impairments or those of greater severity than expected, suspicion arises that another cause likely better explains those deficits, and further medical testing then is often recommended. Medical procedures. Increasingly, neuropsychological assessment is used to assist in determining the appropriateness of medical procedures. For example, neurosurgical patients being considered for deep brain stimulation, brain tumor resectioning, and epilepsy surgery often are referred for preoperative and postoperative testing. Treating clinicians need an understanding of current cognitive status, localization of functioning, and psychological status to make appropriate decisions about a patient’s candidacy for one of these procedures,and to understand associated risk.

4 How is neuropsychological testing used for dispositional planning? The

results of cognitive and psychological testing have implications for dispositional

planning for patients who are receiving psychiatric care. The primary issue often is

to determine the patient’s level of independence and ability to make decisions about his affairs.5

Neuropsychological testing can help determine if cognitive deficits limit aspects of functional independence—for example, can the patient live alone, or must he live with family or in a residential care facility? Generally, the greater the cognitive impairment, the more supervision and assistance are required. This relationship between cognitive ability and independence in activities of daily living has been demonstrated in many groups of psychiatric patients, including older adults with dementia,6 patients with schizophrenia,7 and those with bipolar disorder.8

Specific recommendations can be made regarding management of finances, administering medications, and driving. To formulate an appropriate dispositional plan, the referring psychiatrist might integrate recommendations from the neuropsychological assessment with findings of other evaluations and with information that has been collected about the patient.

5 Can neuropsychological testing be used to refer a patient for neurological and cognitive rehabilitation? Yes. The neuropsychologist is singularly qualified to make recommendations about a range of interventions for cognitive deficits that have been identified on formal testing.

Typically, recommendations for addressing cognitive deficits involve rehabilitation

focused on development and use of compensatory strategies and modification to promote brain health.9,10 Rehabilitation therapy typically is aimed at increasing functioning independence and reducing physical and cognitive deficits associated

with illness (eg, traumatic brain injury [TBI], stroke, orthopedic injury, debility).

Patients who have a TBI or who have had a stroke often have comorbid psychiatric problems, including mood and anxiety disorders, that can exacerbate deficits and impede engagement in rehabilitation. The neuropsychological evaluation can determine if this is the case and if psychiatric consultation is warranted to assist with managing symptoms.

Premorbid psychiatric illness can affect rehabilitation. Formal neuropsychological testing can assist with parsing out deficits associated with new-onset illness compared with premorbid psychiatric problems. The evaluation of a patient before he begins rehabilitation also can be compared with evaluations made during treatment and after discharge to 1) assess for changes and 2) update recommendations about management.

Recommendations about cognitive interventions might include specific compensatory strategies to address areas of weakness and capitalize on strengths. Such strategies can include using internal mnemonics, such as visual imagery (ie, using a visual image to help encode verbal information) or semantic elaboration (using semantic cues to aid in encoding and recall of information). Methods can help train patients to capitalize on areas of stronger cognitive functioning in compensating for their weaknesses; an example is the spaced-retrieval technique, which relies on repetition of information that is to be learned over time.11

Perhaps the most practical strategies for addressing areas of weakness are nonmnemonic-based external memory aids, such as diaries, notebooks, calendars, alarms, and lists.12 For example, for a patient with a TBI who has impaired memory, recommendations might include using written notes or a calendar system; using a pillbox for medication management; and using labels to promote structure and consistency in the home. These strategies are meant to promote increased independence and to minimize the effect of cognitive deficits on daily functioning.

Recommended strategies can include lifestyle changes to promote improved cognitive functioning and overall health, such as:

• sleep hygiene, to reduce the effects of fatigue

• encouraging the patient to adhere to a diet, take prescribed medications, and follow up with his health care providers

• developing cognitive and physical exercise routines.

In addition, a patient who has had a stroke or who have a TBI might benefit from psychotherapy or referral to a group program or community resources to help cope with the effects of illness.13

6 How does neuropsychological testing help determine the appropriate psychiatric intervention for a patient? Results of neuropsychological testing can help determine appropriate interventions for a psychiatric condition that might be the principal factor affecting the patient’s functioning.

Concerning psychoactive medications, consider the following:

Mood and anxiety disorders. Neuropsychological measures can help substantiate the need for pharmacotherapy in a comorbid mood or anxiety disorder in a patient who has a neurologic illness, such as stroke or TBI.

ADHD. In a patient who has attentiondeficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), results of cognitive testing might help determine if attention issues undermine daily functioning. Testing provides information beyond rating scale scores to justify diagnosis and psychopharmacotherapy.14

Dementia. Geriatric patients who have dementia often have coexisting behavioral and mood changes that, once evaluated, might improve with pharmacotherapy.

Other areas. Cognitive side effects of medications can be monitored by conducting testing before and after medication is started. The evaluation can address the patient’s ability to engage in psychotherapeutic interventions. Patients who have severe cognitive deficits might have greater difficulty engaging in psychotherapy, compared with patients who have less severe, or no, cognitive

impairment.15

7 Does neuropsychological testing help patients make return-to-work

and return-to-school decisions? Yes. Cognitive and psychiatric functioning have

implications for decisions about occupational and academic pursuits.

Patients who have severe cognitive or psychiatric symptoms might be or might not be able to maintain gainful employment or participate in school. Testing can help 1) document and justify disability and 2) establish recommendations about disability status. Those whose cognitive impairments or psychiatric symptoms are less severe might benefit from neuropsychological testing so that recommendations can be made regarding accommodations at work or in school, such as:

• reduced work or school schedule

• reduced level of occupational or academic demand

• change in supervision or evaluation procedures by employer or school.

Cognitive strengths and weaknesses can be used to help a patient devise and implement compensatory strategies at work or school, such as:

• note-taking

• audio recording of meetings and lectures

• using a calendar.

Patients sometimes benefit from formal vocational rehabilitation services to facilitate finding appropriate employment, returning to employment, and implementing workplace accommodations.

In conclusion

Neuropsychological evaluation, typically covered by health insurance, provides the

referring clinician with objective information about patients’ cognitive assets and limitations. In turn, this information can help you make a diagnosis and plan

treatment.

Unlike psychological testing, in which the patient is assessed for psychiatric

symptoms and conditions, neuropsychological measures offer insight into such

abilities as attention, memory, and reasoning. Neuropsychological evaluations also

can add insight to your determination of the cause of symptoms, thereby influencing decisions about medical therapy.

Last, these evaluations can aid with decision-making about dispositional planning

and whether adjunctive services, such as rehabilitation, would be of benefit.

Bottom Line

Neuropsychological assessments are a useful consultation to consider for patients

in a psychiatric setting. These evaluations can aid you in building and narrowing the differential diagnosis; identifying patients’ strengths and weakness; and making informed recommendations about functional independence.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Donders J. A survey of report writing by neuropsychologists, I: general characteristics and content. Clin Neuropsychol. 2001;15(2):137-149.

2. Lamberty GT, Courtney JC, Heilbronner RC. The practice of clinical neuropsychology: a survey of practices and settings. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis; 2005.

3. Sweet JJ, Meyer DG, Nelson NW, et al. The TCN/AACN 2010 “salary survey”: professional practices, beliefs, and incomes of U.S. neuropsychologists. Clin Neuropsychol. 2011;25(1):12-61.

4. Marvel CL, Paradiso S. Cognitive and neurologic impairment in mood disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2004;27(1):19-36,vii-viii.

5. Moberg PJ, Rick JH. Decision-making capacity and competency in the elderly: a clinical and neuropsychological perspective. NeuroRehabilitation. 2008;23(5):

403-413.

6. Bradshaw LE, Goldberg SE, Lewis SA, et al. Six-month outcomes following an emergency hospital admission for older adults with co-morbid mental health problems indicate complexity of care needs. Age Ageing. 2013; 42(5):582-588.

7. Medalia A, Lim RW. Self-awareness of cognitive functioning in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2004;71(2-3):331-338.

8. Andreou C, Bozikas VP. The predictive significance of neurocognitive factors for functional outcome in bipolar disorder. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2013;26(1):54-59.

9. Stuss DT, Winocur G, Robertson IH, eds. Cognitive neurorehabilitation: evidence and application. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2008.

10. Raskin SA, ed. Neuroplasticity and rehabilitation. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2011.

11. Glisky EL, Glisky ML. Memory rehabilitation in older adults. In: Stuss DT, Winocur G, Robertson IH. Cognitive neurorehabilitation. 1st ed. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2008.

12. Kapur N, Glisky EL, Wilson BA. External memory aids and computers in memory rehabilitation. In: Baddeley AD, Kopelman MD, Wilson BA. Handbook of memory disorders. Chichester, United Kingdom: Wiley; 2002:757-784.

13. Stalder-Luthy F, Messerli-Burgy N, Hofer H, et al. Effect of psychological interventions on depressive symptoms in long-term rehabilitation after an acquired brain injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil.

2013;94(7):1386-1397.

14. Hale JB, Reddy LA, Semrud-Clikeman M, et al. Executive impairment determines ADHD medication response: implications for academic achievement. J Learn Disabil. 2011;44(2):196-212.

15. Medalia A, Lim R. Treatment of cognitive dysfunction in psychiatric disorders. J Psychiatr Pract. 2004;10(1):17-25.

Neuropsychological evaluation, consisting of a thorough examination of cognitive and behavioral functioning, can make an invaluable contribution to the care of psychiatric patients. Through the vehicle of standardized measures of abilities, patients’ cognitive strengths and weaknesses can be elucidated—revealing potential areas for further interventions or to explain impediments to treatment. A licensed clinical psychologist provides this service.

You, as a consumer of reported findings, can use the results to inform your diagnosis and treatment plan. Recommendations from the neuropsychologist often address dispositional planning, cognitive intervention, psychiatric intervention, and work and school accommodations.

Probing the brain−behavior relationship

Neuropsychology is a subspecialty of clinical psychology that is focused on understanding the brain–behavior relationship. Drawing information from multiple disciplines, including psychiatry and neurology, neuropsychology seeks to uncover the cognitive, behavioral, and emotional difficulties that can result from known or suspected brain dysfunction. Increasingly, to protect the public and referral sources, clinical psychologists who perform neuropsychological testing demonstrate their competence through board certification (eg, the American Board of Clinical Neuropsychology).

How is testing conducted? Evaluations comprise measures that are standardized, scored objectively, and have established psychometric properties. Testing can performed on an outpatient or inpatient basis; the duration of testing depends on the question for which the referring practitioner seeks an answer.

Measures typically are administered by paper and pencil, although computer-based

assessments are increasingly being employed. Because of the influence of demographic variables (age, sex, years of education, race), scores are compared with normative samples that resemble those of the patient’s background as closely as possible.

A thorough clinical interview with the patient, a collateral interview with caregivers

and family, and review of relevant medical records are crucial parts of the assessment. Multiple areas of cognition are assessed:

• intelligence

• academic functioning

• attention

• working memory

• speed of processing

• learning and memory

• visual spatial skills

• fine motor skills

• executive functioning.

Essentially, the evaluation speaks to a patient’s neurocognitive functioning and cerebral integrity.

How are results scored? Interpretation of test scores is contingent on expectations of how a patient should perform in the absence of neurologic or psychiatric illness (ie, based on normative data and performancebased estimates of premorbid functioning).1 The overall pattern of intact scores and deficit scores can be used to form specific impressions about a diagnosis, cognitive strengths and weaknesses, and strategies for intervention.

Personality testing. In addition to the cognitive aspect of the evaluation, personality measures are incorporated when relevant to the referral question or presenting concern.

Personality tests can be broadly divided into objective and projective measures.

Objective personality measures, such as the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality

Inventory-Second Edition, require the examinee to respond to a set of items as

true or false or on a Likert-type scale from strongly agree to disagree. Responses are then scored in standardized fashion, making comparisons to normative data, which are then analyzed to determine the extent to which the examinee experiences psychiatric symptoms.

As part of testing, patients’ responses to ambiguous or unstructured standard

stimuli—such as a series of drawings, abstract patterns, or incomplete sentences—

are analyzed to determine underlying personality traits, feelings, and attitudes.

Classic examples of these measures include the Rorschach Test and the Thematic

Apperception Test.

Personality measures and psychiatric testing are designed to answer questions

related to patients’ emotional status. These measures assess psychiatric symptoms and diagnoses, whereas neuropsychological measures provide an understanding of patients’ cognitive assets and limitations.

7 Common questions about neuropsychological testing

1 Will my patient’s insurance cover these assessments? The question is common from practitioners who are considering requesting an assessment for a patient. The short answer is “Yes.”

Most payers follow Medicare guidelines for reimbursement of neuropsychological

testing; if testing is determined to be medically necessary, insurance companies often cover the assessment. Medicaid also pays for psychometric testing services. Neuropsychologists who have a hospital-based practice typically include patients

with all types of insurance coverage. For example, 40% of patients seen in a hospital are covered by Medicare or Medicaid.2

A caveat: Local intermediaries interpret policies and procedures in different ways,

so there is variability in coverage by geographic region. That is why it is crucial

for neuropsychologists to obtain preauthorization, as would be the case with other medical procedures and services sought by referral.

Last, insurance companies do not pay for assessment of a learning disability. The

rationale typically offered for this lack of coverage? The assessment is for academic, not medical, purposes. In such a situation, patients and their families are offered a private-pay option.

2 What are the indications for neuropsychological assessment? Psychiatric practitioners are one of the top medical specialties that refer their patients for neuropsychological testing.3 This is because many patients with a psychiatric or

neurologic disorder experience changes in cognition, mood, and personality. Such

changes can range in severity from subtle to dramatic, and might reflect an underlying disease state or a side effect of medication or other treatment. Whatever the nature of a patient’s problem, careful assessment might help elucidate specific areas with which he (she) is struggling—so that you can better target your interventions. Table 1 lists common reasons for referring a patient for neuropsychological evaluation. Throughout this discussion, we describe examples of clinical situations in which neuropsychological testing is useful for establishing a differential diagnosis and dispositional planning.

3 How does neuropsychological testing help with the differential diagnosis? As an example, one area in which cognitive testing can be beneficial is in geriatric psychiatry.Dementia. Aging often is accompanied by a normal decline in memory and other cognitive functions. But because subtle changes in memory and cognition also canbe the sign of a progressive cognitive disorder, differentiating normal aging from early dementia is essential. Table 2 summarizes typical changes in cognition with aging.

Neuropsychologists, through knowledge of psychometric testing and the brain−behavior relationship, can help you detect dementia and plan treatment early. To determine if cognitive changes are progressive, patients might undergo re-evaluation—typically, every 6 to 12 months—to ascertain if changes have occurred. Mood disorders. Neuropsychological evaluation can be useful in building a differential diagnosis when determining whether cognitive symptoms are attributable to a mood disorder or a medical illness. Cognitive deficits associated with an affective disturbance generally include impairments in attention, memory, and executive functioning.4 The severity of deficits has been linked to severity of illness. When patients with a mood disorder demonstrate localizing impairments or those of greater severity than expected, suspicion arises that another cause likely better explains those deficits, and further medical testing then is often recommended. Medical procedures. Increasingly, neuropsychological assessment is used to assist in determining the appropriateness of medical procedures. For example, neurosurgical patients being considered for deep brain stimulation, brain tumor resectioning, and epilepsy surgery often are referred for preoperative and postoperative testing. Treating clinicians need an understanding of current cognitive status, localization of functioning, and psychological status to make appropriate decisions about a patient’s candidacy for one of these procedures,and to understand associated risk.

4 How is neuropsychological testing used for dispositional planning? The

results of cognitive and psychological testing have implications for dispositional

planning for patients who are receiving psychiatric care. The primary issue often is

to determine the patient’s level of independence and ability to make decisions about his affairs.5

Neuropsychological testing can help determine if cognitive deficits limit aspects of functional independence—for example, can the patient live alone, or must he live with family or in a residential care facility? Generally, the greater the cognitive impairment, the more supervision and assistance are required. This relationship between cognitive ability and independence in activities of daily living has been demonstrated in many groups of psychiatric patients, including older adults with dementia,6 patients with schizophrenia,7 and those with bipolar disorder.8

Specific recommendations can be made regarding management of finances, administering medications, and driving. To formulate an appropriate dispositional plan, the referring psychiatrist might integrate recommendations from the neuropsychological assessment with findings of other evaluations and with information that has been collected about the patient.

5 Can neuropsychological testing be used to refer a patient for neurological and cognitive rehabilitation? Yes. The neuropsychologist is singularly qualified to make recommendations about a range of interventions for cognitive deficits that have been identified on formal testing.

Typically, recommendations for addressing cognitive deficits involve rehabilitation

focused on development and use of compensatory strategies and modification to promote brain health.9,10 Rehabilitation therapy typically is aimed at increasing functioning independence and reducing physical and cognitive deficits associated

with illness (eg, traumatic brain injury [TBI], stroke, orthopedic injury, debility).

Patients who have a TBI or who have had a stroke often have comorbid psychiatric problems, including mood and anxiety disorders, that can exacerbate deficits and impede engagement in rehabilitation. The neuropsychological evaluation can determine if this is the case and if psychiatric consultation is warranted to assist with managing symptoms.

Premorbid psychiatric illness can affect rehabilitation. Formal neuropsychological testing can assist with parsing out deficits associated with new-onset illness compared with premorbid psychiatric problems. The evaluation of a patient before he begins rehabilitation also can be compared with evaluations made during treatment and after discharge to 1) assess for changes and 2) update recommendations about management.

Recommendations about cognitive interventions might include specific compensatory strategies to address areas of weakness and capitalize on strengths. Such strategies can include using internal mnemonics, such as visual imagery (ie, using a visual image to help encode verbal information) or semantic elaboration (using semantic cues to aid in encoding and recall of information). Methods can help train patients to capitalize on areas of stronger cognitive functioning in compensating for their weaknesses; an example is the spaced-retrieval technique, which relies on repetition of information that is to be learned over time.11

Perhaps the most practical strategies for addressing areas of weakness are nonmnemonic-based external memory aids, such as diaries, notebooks, calendars, alarms, and lists.12 For example, for a patient with a TBI who has impaired memory, recommendations might include using written notes or a calendar system; using a pillbox for medication management; and using labels to promote structure and consistency in the home. These strategies are meant to promote increased independence and to minimize the effect of cognitive deficits on daily functioning.

Recommended strategies can include lifestyle changes to promote improved cognitive functioning and overall health, such as:

• sleep hygiene, to reduce the effects of fatigue

• encouraging the patient to adhere to a diet, take prescribed medications, and follow up with his health care providers

• developing cognitive and physical exercise routines.

In addition, a patient who has had a stroke or who have a TBI might benefit from psychotherapy or referral to a group program or community resources to help cope with the effects of illness.13

6 How does neuropsychological testing help determine the appropriate psychiatric intervention for a patient? Results of neuropsychological testing can help determine appropriate interventions for a psychiatric condition that might be the principal factor affecting the patient’s functioning.

Concerning psychoactive medications, consider the following:

Mood and anxiety disorders. Neuropsychological measures can help substantiate the need for pharmacotherapy in a comorbid mood or anxiety disorder in a patient who has a neurologic illness, such as stroke or TBI.

ADHD. In a patient who has attentiondeficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), results of cognitive testing might help determine if attention issues undermine daily functioning. Testing provides information beyond rating scale scores to justify diagnosis and psychopharmacotherapy.14

Dementia. Geriatric patients who have dementia often have coexisting behavioral and mood changes that, once evaluated, might improve with pharmacotherapy.

Other areas. Cognitive side effects of medications can be monitored by conducting testing before and after medication is started. The evaluation can address the patient’s ability to engage in psychotherapeutic interventions. Patients who have severe cognitive deficits might have greater difficulty engaging in psychotherapy, compared with patients who have less severe, or no, cognitive

impairment.15

7 Does neuropsychological testing help patients make return-to-work

and return-to-school decisions? Yes. Cognitive and psychiatric functioning have

implications for decisions about occupational and academic pursuits.

Patients who have severe cognitive or psychiatric symptoms might be or might not be able to maintain gainful employment or participate in school. Testing can help 1) document and justify disability and 2) establish recommendations about disability status. Those whose cognitive impairments or psychiatric symptoms are less severe might benefit from neuropsychological testing so that recommendations can be made regarding accommodations at work or in school, such as:

• reduced work or school schedule

• reduced level of occupational or academic demand

• change in supervision or evaluation procedures by employer or school.

Cognitive strengths and weaknesses can be used to help a patient devise and implement compensatory strategies at work or school, such as:

• note-taking

• audio recording of meetings and lectures

• using a calendar.

Patients sometimes benefit from formal vocational rehabilitation services to facilitate finding appropriate employment, returning to employment, and implementing workplace accommodations.

In conclusion

Neuropsychological evaluation, typically covered by health insurance, provides the

referring clinician with objective information about patients’ cognitive assets and limitations. In turn, this information can help you make a diagnosis and plan

treatment.

Unlike psychological testing, in which the patient is assessed for psychiatric

symptoms and conditions, neuropsychological measures offer insight into such

abilities as attention, memory, and reasoning. Neuropsychological evaluations also

can add insight to your determination of the cause of symptoms, thereby influencing decisions about medical therapy.

Last, these evaluations can aid with decision-making about dispositional planning

and whether adjunctive services, such as rehabilitation, would be of benefit.

Bottom Line

Neuropsychological assessments are a useful consultation to consider for patients