User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Mycosis Fungoides: Measured Approach Key to Treatment

HUNTINGTON BEACH, CALIFORNIA — When patients of Aaron Mangold, MD, first learn they have mycosis fungoides (MF), the most common form of primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), some are concerned about whether the diagnosis means a shortened life expectancy.

Dr. Mangold, codirector of the multidisciplinary cutaneous lymphoma clinic at Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Arizona, said at the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association. “For early-stage disease, I think of it more like diabetes; this is really a chronic disease” that unlikely will be fatal but may be associated with increased morbidity as the disease progresses, and “the overall goal of therapy should be disease control to increase quality of life.”

Patient- and lymphoma-specific factors drive the choice of therapy. The focus for patients with early-stage disease, Dr. Mangold said, is to treat comorbidities and symptoms, such as itch or skin pain, maximize their quality of life, and consider the potential for associated toxicities of therapy as the disease progresses. Start with the least toxic, targeted, nonimmunosuppressive therapy, “then work toward more toxic immunosuppressive therapies,” he advised. “Use toxic agents just long enough to control the disease, then transition to a maintenance regimen with less toxic immunosuppressive agents.”

When Close Follow-Up Is Advised

According to unpublished data from PROCLIPI (the Prospective Cutaneous Lymphoma International Prognostic Index) study presented at the fifth World Congress of Cutaneous Lymphomas earlier in 2024, the following factors warrant consideration for close follow-up and more aggressive treatment: Nodal enlargement greater than 15 mm, age over 60 years, presence of plaques, and large-cell transformation in skin. “These are some of the stigmata in early disease that might guide you toward referring” a patient to a CTCL expert, Dr. Mangold said. (Consensus-based recommendations on the management of MF in children were published in August of 2024.)

According to Dr. Mangold, topical/skin-directed therapies are best for early-stage disease or in combination with systemic therapies in advanced disease. For early-stage disease, one of his preferred options is daily application of a skin moisturizer plus a topical corticosteroid such as clobetasol, halobetasol, or augmented betamethasone, then evaluating the response at 3 months. “This is a cheap option, and we see response rates as high as 90%,” he said. “I don’t often see steroid atrophy when treating patients with active MF. There’s a tendency to think, ‘I don’t want to overtreat.’ I think you can be aggressive. If you look in the literature, people typically pulse twice daily for a couple of weeks with a 1-week break.”

Mechlorethamine, a topical alkylating gel approved in 2013 for the treatment of early-stage MF, is an option when patients fail to respond to topical steroids, prefer to avoid steroids, or have thick, plaque-like disease. With mechlorethamine, it is important to “start slow and be patient,” Dr. Mangold said. “Real-world data shows that it takes 12-18 months to get a good response. Counsel patients that they are likely to get a rash, and that the risk of rash is dose dependent.”

Other treatment options to consider include imiquimod, which can be used for single refractory spots. He typically recommends application 5 days per week with titration up to daily if tolerated for up to 3 months. “Treat until you get a brisk immune response,” he said. “We’ve seen patients with durable, long-term responses.”

UVB Phototherapy Effective

For patients with stage IB disease, topical therapies are less practical and may be focused on refractory areas of disease. Narrow-band UVB phototherapy is the most practical and cost-effective treatment, Dr. Mangold said. Earlier-stage patch disease responds to phototherapy in up to 80% of cases, while plaque-stage disease responds in up to half of cases. “More frequent use of phototherapy may decrease time to clearance, but overall response is similar.”

Dr. Mangold recommends phototherapy 2-3 days per week, titrating up to a maximal response dose, and maintaining that dose for about 3 months. Maintenance involves tapering the phototherapy dose to a minimal dose with continued response. “The goal is to prevent relapse,” he said.

For patients with MF of stage IIB and higher, he considers total skin electron beam therapy, an oral retinoid with phototherapy, systemic agents, and focal radiation with systemic treatment. One of his go-to systemic options is bexarotene, which he uses for early-stage disease refractory to treatment or for less aggressive advanced disease. “We typically use a low dose ... and about half of patients respond,” Dr. Mangold said. The time to response is about 6 months. Bexarotene causes elevated lipids and low thyroid function, so he initiates patients on fenofibrate and levothyroxine at baseline.

Another systemic option is brentuximab vedotin, a monoclonal antibody that targets cells with CD30 expression, which is typically administered in a specialty center every 3 weeks for up to 16 cycles. “In practice, we often use six to eight cycles to avoid neuropathy,” he said. “It’s a good debulking agent, the time to response is 6-9 weeks, and it has a sustained response of 60%.” Neuropathy can occur with treatment, but improves over time.

Other systemic options for MF include romidepsin, mogamulizumab, and extracorporeal photopheresis used in erythrodermic disease.

Radiation An Option in Some Cases

Dr. Mangold noted that low doses of radiation therapy can effectively treat MF lesions in as little as one dose. “We can use it as a cure for a single spot or to temporarily treat the disease while other therapies are being started,” he said. Long-term side effects need to be considered when using radiation. “The more radiation, the more side effects.”

Dr. Mangold disclosed that he is an investigator for Sun Pharmaceutical, Solagenix, Elorac, miRagen, Kyowa Kirin, the National Clinical Trials Network, and CRISPR Therapeutics. He has also received consulting fees/honoraria from Kirin and Solagenix.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

HUNTINGTON BEACH, CALIFORNIA — When patients of Aaron Mangold, MD, first learn they have mycosis fungoides (MF), the most common form of primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), some are concerned about whether the diagnosis means a shortened life expectancy.

Dr. Mangold, codirector of the multidisciplinary cutaneous lymphoma clinic at Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Arizona, said at the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association. “For early-stage disease, I think of it more like diabetes; this is really a chronic disease” that unlikely will be fatal but may be associated with increased morbidity as the disease progresses, and “the overall goal of therapy should be disease control to increase quality of life.”

Patient- and lymphoma-specific factors drive the choice of therapy. The focus for patients with early-stage disease, Dr. Mangold said, is to treat comorbidities and symptoms, such as itch or skin pain, maximize their quality of life, and consider the potential for associated toxicities of therapy as the disease progresses. Start with the least toxic, targeted, nonimmunosuppressive therapy, “then work toward more toxic immunosuppressive therapies,” he advised. “Use toxic agents just long enough to control the disease, then transition to a maintenance regimen with less toxic immunosuppressive agents.”

When Close Follow-Up Is Advised

According to unpublished data from PROCLIPI (the Prospective Cutaneous Lymphoma International Prognostic Index) study presented at the fifth World Congress of Cutaneous Lymphomas earlier in 2024, the following factors warrant consideration for close follow-up and more aggressive treatment: Nodal enlargement greater than 15 mm, age over 60 years, presence of plaques, and large-cell transformation in skin. “These are some of the stigmata in early disease that might guide you toward referring” a patient to a CTCL expert, Dr. Mangold said. (Consensus-based recommendations on the management of MF in children were published in August of 2024.)

According to Dr. Mangold, topical/skin-directed therapies are best for early-stage disease or in combination with systemic therapies in advanced disease. For early-stage disease, one of his preferred options is daily application of a skin moisturizer plus a topical corticosteroid such as clobetasol, halobetasol, or augmented betamethasone, then evaluating the response at 3 months. “This is a cheap option, and we see response rates as high as 90%,” he said. “I don’t often see steroid atrophy when treating patients with active MF. There’s a tendency to think, ‘I don’t want to overtreat.’ I think you can be aggressive. If you look in the literature, people typically pulse twice daily for a couple of weeks with a 1-week break.”

Mechlorethamine, a topical alkylating gel approved in 2013 for the treatment of early-stage MF, is an option when patients fail to respond to topical steroids, prefer to avoid steroids, or have thick, plaque-like disease. With mechlorethamine, it is important to “start slow and be patient,” Dr. Mangold said. “Real-world data shows that it takes 12-18 months to get a good response. Counsel patients that they are likely to get a rash, and that the risk of rash is dose dependent.”

Other treatment options to consider include imiquimod, which can be used for single refractory spots. He typically recommends application 5 days per week with titration up to daily if tolerated for up to 3 months. “Treat until you get a brisk immune response,” he said. “We’ve seen patients with durable, long-term responses.”

UVB Phototherapy Effective

For patients with stage IB disease, topical therapies are less practical and may be focused on refractory areas of disease. Narrow-band UVB phototherapy is the most practical and cost-effective treatment, Dr. Mangold said. Earlier-stage patch disease responds to phototherapy in up to 80% of cases, while plaque-stage disease responds in up to half of cases. “More frequent use of phototherapy may decrease time to clearance, but overall response is similar.”

Dr. Mangold recommends phototherapy 2-3 days per week, titrating up to a maximal response dose, and maintaining that dose for about 3 months. Maintenance involves tapering the phototherapy dose to a minimal dose with continued response. “The goal is to prevent relapse,” he said.

For patients with MF of stage IIB and higher, he considers total skin electron beam therapy, an oral retinoid with phototherapy, systemic agents, and focal radiation with systemic treatment. One of his go-to systemic options is bexarotene, which he uses for early-stage disease refractory to treatment or for less aggressive advanced disease. “We typically use a low dose ... and about half of patients respond,” Dr. Mangold said. The time to response is about 6 months. Bexarotene causes elevated lipids and low thyroid function, so he initiates patients on fenofibrate and levothyroxine at baseline.

Another systemic option is brentuximab vedotin, a monoclonal antibody that targets cells with CD30 expression, which is typically administered in a specialty center every 3 weeks for up to 16 cycles. “In practice, we often use six to eight cycles to avoid neuropathy,” he said. “It’s a good debulking agent, the time to response is 6-9 weeks, and it has a sustained response of 60%.” Neuropathy can occur with treatment, but improves over time.

Other systemic options for MF include romidepsin, mogamulizumab, and extracorporeal photopheresis used in erythrodermic disease.

Radiation An Option in Some Cases

Dr. Mangold noted that low doses of radiation therapy can effectively treat MF lesions in as little as one dose. “We can use it as a cure for a single spot or to temporarily treat the disease while other therapies are being started,” he said. Long-term side effects need to be considered when using radiation. “The more radiation, the more side effects.”

Dr. Mangold disclosed that he is an investigator for Sun Pharmaceutical, Solagenix, Elorac, miRagen, Kyowa Kirin, the National Clinical Trials Network, and CRISPR Therapeutics. He has also received consulting fees/honoraria from Kirin and Solagenix.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

HUNTINGTON BEACH, CALIFORNIA — When patients of Aaron Mangold, MD, first learn they have mycosis fungoides (MF), the most common form of primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), some are concerned about whether the diagnosis means a shortened life expectancy.

Dr. Mangold, codirector of the multidisciplinary cutaneous lymphoma clinic at Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Arizona, said at the annual meeting of the Pacific Dermatologic Association. “For early-stage disease, I think of it more like diabetes; this is really a chronic disease” that unlikely will be fatal but may be associated with increased morbidity as the disease progresses, and “the overall goal of therapy should be disease control to increase quality of life.”

Patient- and lymphoma-specific factors drive the choice of therapy. The focus for patients with early-stage disease, Dr. Mangold said, is to treat comorbidities and symptoms, such as itch or skin pain, maximize their quality of life, and consider the potential for associated toxicities of therapy as the disease progresses. Start with the least toxic, targeted, nonimmunosuppressive therapy, “then work toward more toxic immunosuppressive therapies,” he advised. “Use toxic agents just long enough to control the disease, then transition to a maintenance regimen with less toxic immunosuppressive agents.”

When Close Follow-Up Is Advised

According to unpublished data from PROCLIPI (the Prospective Cutaneous Lymphoma International Prognostic Index) study presented at the fifth World Congress of Cutaneous Lymphomas earlier in 2024, the following factors warrant consideration for close follow-up and more aggressive treatment: Nodal enlargement greater than 15 mm, age over 60 years, presence of plaques, and large-cell transformation in skin. “These are some of the stigmata in early disease that might guide you toward referring” a patient to a CTCL expert, Dr. Mangold said. (Consensus-based recommendations on the management of MF in children were published in August of 2024.)

According to Dr. Mangold, topical/skin-directed therapies are best for early-stage disease or in combination with systemic therapies in advanced disease. For early-stage disease, one of his preferred options is daily application of a skin moisturizer plus a topical corticosteroid such as clobetasol, halobetasol, or augmented betamethasone, then evaluating the response at 3 months. “This is a cheap option, and we see response rates as high as 90%,” he said. “I don’t often see steroid atrophy when treating patients with active MF. There’s a tendency to think, ‘I don’t want to overtreat.’ I think you can be aggressive. If you look in the literature, people typically pulse twice daily for a couple of weeks with a 1-week break.”

Mechlorethamine, a topical alkylating gel approved in 2013 for the treatment of early-stage MF, is an option when patients fail to respond to topical steroids, prefer to avoid steroids, or have thick, plaque-like disease. With mechlorethamine, it is important to “start slow and be patient,” Dr. Mangold said. “Real-world data shows that it takes 12-18 months to get a good response. Counsel patients that they are likely to get a rash, and that the risk of rash is dose dependent.”

Other treatment options to consider include imiquimod, which can be used for single refractory spots. He typically recommends application 5 days per week with titration up to daily if tolerated for up to 3 months. “Treat until you get a brisk immune response,” he said. “We’ve seen patients with durable, long-term responses.”

UVB Phototherapy Effective

For patients with stage IB disease, topical therapies are less practical and may be focused on refractory areas of disease. Narrow-band UVB phototherapy is the most practical and cost-effective treatment, Dr. Mangold said. Earlier-stage patch disease responds to phototherapy in up to 80% of cases, while plaque-stage disease responds in up to half of cases. “More frequent use of phototherapy may decrease time to clearance, but overall response is similar.”

Dr. Mangold recommends phototherapy 2-3 days per week, titrating up to a maximal response dose, and maintaining that dose for about 3 months. Maintenance involves tapering the phototherapy dose to a minimal dose with continued response. “The goal is to prevent relapse,” he said.

For patients with MF of stage IIB and higher, he considers total skin electron beam therapy, an oral retinoid with phototherapy, systemic agents, and focal radiation with systemic treatment. One of his go-to systemic options is bexarotene, which he uses for early-stage disease refractory to treatment or for less aggressive advanced disease. “We typically use a low dose ... and about half of patients respond,” Dr. Mangold said. The time to response is about 6 months. Bexarotene causes elevated lipids and low thyroid function, so he initiates patients on fenofibrate and levothyroxine at baseline.

Another systemic option is brentuximab vedotin, a monoclonal antibody that targets cells with CD30 expression, which is typically administered in a specialty center every 3 weeks for up to 16 cycles. “In practice, we often use six to eight cycles to avoid neuropathy,” he said. “It’s a good debulking agent, the time to response is 6-9 weeks, and it has a sustained response of 60%.” Neuropathy can occur with treatment, but improves over time.

Other systemic options for MF include romidepsin, mogamulizumab, and extracorporeal photopheresis used in erythrodermic disease.

Radiation An Option in Some Cases

Dr. Mangold noted that low doses of radiation therapy can effectively treat MF lesions in as little as one dose. “We can use it as a cure for a single spot or to temporarily treat the disease while other therapies are being started,” he said. Long-term side effects need to be considered when using radiation. “The more radiation, the more side effects.”

Dr. Mangold disclosed that he is an investigator for Sun Pharmaceutical, Solagenix, Elorac, miRagen, Kyowa Kirin, the National Clinical Trials Network, and CRISPR Therapeutics. He has also received consulting fees/honoraria from Kirin and Solagenix.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM PDA 2024

Why Residents Are Joining Unions in Droves

Before the 350 residents finalized their union contract at the University of Vermont (UVM) Medical Center, Burlington, in 2022, Jesse Mostoller, DO, now a third-year pathology resident, recalls hearing about another resident at the hospital who resorted to moonlighting as an Uber driver to make ends meet.

“In Vermont, rent and childcare are expensive,” said Dr. Mostoller, adding that, thanks to union bargaining, first-year residents at UVM are now paid $71,000 per year instead of $61,000. In addition, residents now receive $1800 per year for food (up from $200-$300 annually) and a $1800 annual fund to help pay for board exams that can be carried over for 2 years. “When we were negotiating, the biggest item on our list of demands was to help alleviate the financial pressure residents have been facing for years.”

The UVM residents’ collective bargaining also includes a cap on working hours so that residents don’t work 80 hours a week, paid parental leave, affordable housing, and funds for education and wellness.

These are some of the most common challenges that are faced by residents all over the country, said A. Taylor Walker, MD, MPH, family medicine chief physician at Tufts University School of Medicine/Cambridge Health Alliance in Boston, Massachusetts, and national president of the Committee of Interns and Residents (CIR), which is part of the Service Employees International Union.

For these reasons, residents at Montefiore Medical Center, Stanford Health Care, George Washington University, and the University of Pennsylvania have recently voted to unionize, according to Dr. Walker.

And while there are several small local unions that have picked up residents at local hospitals, CIR is the largest union of physicians in the United States, with a total of 33,000 residents and fellows across the country (15% of the staff at more than 60 hospitals nationwide).

“We’ve doubled in size in the last 4 years,” said Dr. Walker. “The reason is that we’re in a national reckoning on the corporatization of American medicine and the way in which graduate medical education is rooted in a cycle of exploitation that doesn’t center on the health, well-being, or safety of our doctors and ultimately negatively affects our patients.”

Here’s what residents are fighting for — right now.

Adequate Parental Leave

Christopher Domanski, MD, a first-year resident in psychiatry at California Pacific Medical Center (CPMC) in San Francisco, is also a new dad to a 5-month-old son and is currently in the sixth week of parental leave. One goal of CPMC’s union, started a year and a half ago, is to expand parental leave to 8 weeks.

“I started as a resident here in mid-June, but the fight with CPMC leaders has been going on for a year and a half,” Dr. Domanski said. “It can feel very frustrating because many times there’s no budge in the conversations we want to have.”

Contract negotiations here continue to be slow — and arduous.

“It goes back and forth,” said Dr. Domanski, who makes about $75,000 a year. “Sometimes they listen to our proposals, but they deny the vast majority or make a paltry increase in salary or time off. It goes like this: We’ll have a negotiation; we’ll talk about it, and then they say, ‘we’re not comfortable doing this’ and it stalls again.”

If a resident hasn’t started a family yet, access to fertility benefits and reproductive healthcare is paramount because most residents are in their 20s and 30s, Dr. Walker said.

“Our reproductive futures are really hindered by what care we have access to and what care is covered,” she added. “We don’t make enough money to pay for reproductive care out of pocket.”

Fair Pay

In Boston, the residents at Mass General Brigham certified their union in June 2023, but they still don’t have a contract.

“When I applied for a residency in September 2023, I spoke to the folks here, and I was basically under the impression that we would have a contract by the time I matched,” said Madison Masters, MD, a resident in internal medicine. “We are not there.”

This timeline isn’t unusual — the 1400 Penn Medicine residents who unionized in 2023 only recently secured a tentative union contract at the end of September, and at Stanford, the process to ratify their first contract took 13 months.

Still, the salary issue remains frustrating as resident compensation doesn’t line up with the cost of living or the amount of work residents do, said Dr. Masters, who says starting salaries at Mass General Brigham are $78,500 plus a $10,000 stipend for housing.

“There’s been a long tradition of underpaying residents — we’re treated like trainees, but we’re also a primary labor force,” Dr. Masters said, adding that nurse practitioners and physician assistants are paid almost twice as much as residents — some make $120,000 per year or more, while the salary range for residents nationwide is $49,000-$65,000 per year.

“Every time we discuss the contract and talk about a financial package, they offer a 1.5% raise for the next 3 years while we had asked for closer to 8%,” Dr. Masters said. “Then, when they come back for the next bargaining session, they go up a quarter of a percent each time. Recently, they said we will need to go to a mediator to try and resolve this.”

Adequate Healthcare

The biggest — and perhaps the most shocking — ask is for robust health insurance coverage.

“At my hospital, they’re telling us to get Amazon One Medical for health insurance,” Dr. Masters said. “They’re saying it’s hard for anyone to get primary care coverage here.”

Inadequate health insurance is a big issue, as burnout among residents and fellows remains a problem. At UVM, a $10,000 annual wellness stipend has helped address some of these issues. Even so, union members at UVM are planning to return to the table within 18 months to continue their collective bargaining.

The ability to access mental health services anywhere you want is also critical for residents, Dr. Walker said.

“If you can only go to a therapist at your own institution, there is a hesitation to utilize that specialist if that’s even offered,” Dr. Walker said. “Do you want to go to therapy with a colleague? Probably not.”

Ultimately, the residents we spoke to are committed to fighting for their workplace rights — no matter how time-consuming or difficult this has been.

“No administration wants us to have to have a union, but it’s necessary,” Dr. Mostoller said. “As an individual, you don’t have leverage to get a seat at the table, but now we have a seat at the table. We have a wonderful contract, but we’re going to keep fighting to make it even better.”

Paving the way for future residents is a key motivator, too.

“There’s this idea of leaving the campsite cleaner than you found it,” Dr. Mostoller told this news organization. “It’s the same thing here — we’re trying to fix this so that the next generation of residents won’t have to.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Before the 350 residents finalized their union contract at the University of Vermont (UVM) Medical Center, Burlington, in 2022, Jesse Mostoller, DO, now a third-year pathology resident, recalls hearing about another resident at the hospital who resorted to moonlighting as an Uber driver to make ends meet.

“In Vermont, rent and childcare are expensive,” said Dr. Mostoller, adding that, thanks to union bargaining, first-year residents at UVM are now paid $71,000 per year instead of $61,000. In addition, residents now receive $1800 per year for food (up from $200-$300 annually) and a $1800 annual fund to help pay for board exams that can be carried over for 2 years. “When we were negotiating, the biggest item on our list of demands was to help alleviate the financial pressure residents have been facing for years.”

The UVM residents’ collective bargaining also includes a cap on working hours so that residents don’t work 80 hours a week, paid parental leave, affordable housing, and funds for education and wellness.

These are some of the most common challenges that are faced by residents all over the country, said A. Taylor Walker, MD, MPH, family medicine chief physician at Tufts University School of Medicine/Cambridge Health Alliance in Boston, Massachusetts, and national president of the Committee of Interns and Residents (CIR), which is part of the Service Employees International Union.

For these reasons, residents at Montefiore Medical Center, Stanford Health Care, George Washington University, and the University of Pennsylvania have recently voted to unionize, according to Dr. Walker.

And while there are several small local unions that have picked up residents at local hospitals, CIR is the largest union of physicians in the United States, with a total of 33,000 residents and fellows across the country (15% of the staff at more than 60 hospitals nationwide).

“We’ve doubled in size in the last 4 years,” said Dr. Walker. “The reason is that we’re in a national reckoning on the corporatization of American medicine and the way in which graduate medical education is rooted in a cycle of exploitation that doesn’t center on the health, well-being, or safety of our doctors and ultimately negatively affects our patients.”

Here’s what residents are fighting for — right now.

Adequate Parental Leave

Christopher Domanski, MD, a first-year resident in psychiatry at California Pacific Medical Center (CPMC) in San Francisco, is also a new dad to a 5-month-old son and is currently in the sixth week of parental leave. One goal of CPMC’s union, started a year and a half ago, is to expand parental leave to 8 weeks.

“I started as a resident here in mid-June, but the fight with CPMC leaders has been going on for a year and a half,” Dr. Domanski said. “It can feel very frustrating because many times there’s no budge in the conversations we want to have.”

Contract negotiations here continue to be slow — and arduous.

“It goes back and forth,” said Dr. Domanski, who makes about $75,000 a year. “Sometimes they listen to our proposals, but they deny the vast majority or make a paltry increase in salary or time off. It goes like this: We’ll have a negotiation; we’ll talk about it, and then they say, ‘we’re not comfortable doing this’ and it stalls again.”

If a resident hasn’t started a family yet, access to fertility benefits and reproductive healthcare is paramount because most residents are in their 20s and 30s, Dr. Walker said.

“Our reproductive futures are really hindered by what care we have access to and what care is covered,” she added. “We don’t make enough money to pay for reproductive care out of pocket.”

Fair Pay

In Boston, the residents at Mass General Brigham certified their union in June 2023, but they still don’t have a contract.

“When I applied for a residency in September 2023, I spoke to the folks here, and I was basically under the impression that we would have a contract by the time I matched,” said Madison Masters, MD, a resident in internal medicine. “We are not there.”

This timeline isn’t unusual — the 1400 Penn Medicine residents who unionized in 2023 only recently secured a tentative union contract at the end of September, and at Stanford, the process to ratify their first contract took 13 months.

Still, the salary issue remains frustrating as resident compensation doesn’t line up with the cost of living or the amount of work residents do, said Dr. Masters, who says starting salaries at Mass General Brigham are $78,500 plus a $10,000 stipend for housing.

“There’s been a long tradition of underpaying residents — we’re treated like trainees, but we’re also a primary labor force,” Dr. Masters said, adding that nurse practitioners and physician assistants are paid almost twice as much as residents — some make $120,000 per year or more, while the salary range for residents nationwide is $49,000-$65,000 per year.

“Every time we discuss the contract and talk about a financial package, they offer a 1.5% raise for the next 3 years while we had asked for closer to 8%,” Dr. Masters said. “Then, when they come back for the next bargaining session, they go up a quarter of a percent each time. Recently, they said we will need to go to a mediator to try and resolve this.”

Adequate Healthcare

The biggest — and perhaps the most shocking — ask is for robust health insurance coverage.

“At my hospital, they’re telling us to get Amazon One Medical for health insurance,” Dr. Masters said. “They’re saying it’s hard for anyone to get primary care coverage here.”

Inadequate health insurance is a big issue, as burnout among residents and fellows remains a problem. At UVM, a $10,000 annual wellness stipend has helped address some of these issues. Even so, union members at UVM are planning to return to the table within 18 months to continue their collective bargaining.

The ability to access mental health services anywhere you want is also critical for residents, Dr. Walker said.

“If you can only go to a therapist at your own institution, there is a hesitation to utilize that specialist if that’s even offered,” Dr. Walker said. “Do you want to go to therapy with a colleague? Probably not.”

Ultimately, the residents we spoke to are committed to fighting for their workplace rights — no matter how time-consuming or difficult this has been.

“No administration wants us to have to have a union, but it’s necessary,” Dr. Mostoller said. “As an individual, you don’t have leverage to get a seat at the table, but now we have a seat at the table. We have a wonderful contract, but we’re going to keep fighting to make it even better.”

Paving the way for future residents is a key motivator, too.

“There’s this idea of leaving the campsite cleaner than you found it,” Dr. Mostoller told this news organization. “It’s the same thing here — we’re trying to fix this so that the next generation of residents won’t have to.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Before the 350 residents finalized their union contract at the University of Vermont (UVM) Medical Center, Burlington, in 2022, Jesse Mostoller, DO, now a third-year pathology resident, recalls hearing about another resident at the hospital who resorted to moonlighting as an Uber driver to make ends meet.

“In Vermont, rent and childcare are expensive,” said Dr. Mostoller, adding that, thanks to union bargaining, first-year residents at UVM are now paid $71,000 per year instead of $61,000. In addition, residents now receive $1800 per year for food (up from $200-$300 annually) and a $1800 annual fund to help pay for board exams that can be carried over for 2 years. “When we were negotiating, the biggest item on our list of demands was to help alleviate the financial pressure residents have been facing for years.”

The UVM residents’ collective bargaining also includes a cap on working hours so that residents don’t work 80 hours a week, paid parental leave, affordable housing, and funds for education and wellness.

These are some of the most common challenges that are faced by residents all over the country, said A. Taylor Walker, MD, MPH, family medicine chief physician at Tufts University School of Medicine/Cambridge Health Alliance in Boston, Massachusetts, and national president of the Committee of Interns and Residents (CIR), which is part of the Service Employees International Union.

For these reasons, residents at Montefiore Medical Center, Stanford Health Care, George Washington University, and the University of Pennsylvania have recently voted to unionize, according to Dr. Walker.

And while there are several small local unions that have picked up residents at local hospitals, CIR is the largest union of physicians in the United States, with a total of 33,000 residents and fellows across the country (15% of the staff at more than 60 hospitals nationwide).

“We’ve doubled in size in the last 4 years,” said Dr. Walker. “The reason is that we’re in a national reckoning on the corporatization of American medicine and the way in which graduate medical education is rooted in a cycle of exploitation that doesn’t center on the health, well-being, or safety of our doctors and ultimately negatively affects our patients.”

Here’s what residents are fighting for — right now.

Adequate Parental Leave

Christopher Domanski, MD, a first-year resident in psychiatry at California Pacific Medical Center (CPMC) in San Francisco, is also a new dad to a 5-month-old son and is currently in the sixth week of parental leave. One goal of CPMC’s union, started a year and a half ago, is to expand parental leave to 8 weeks.

“I started as a resident here in mid-June, but the fight with CPMC leaders has been going on for a year and a half,” Dr. Domanski said. “It can feel very frustrating because many times there’s no budge in the conversations we want to have.”

Contract negotiations here continue to be slow — and arduous.

“It goes back and forth,” said Dr. Domanski, who makes about $75,000 a year. “Sometimes they listen to our proposals, but they deny the vast majority or make a paltry increase in salary or time off. It goes like this: We’ll have a negotiation; we’ll talk about it, and then they say, ‘we’re not comfortable doing this’ and it stalls again.”

If a resident hasn’t started a family yet, access to fertility benefits and reproductive healthcare is paramount because most residents are in their 20s and 30s, Dr. Walker said.

“Our reproductive futures are really hindered by what care we have access to and what care is covered,” she added. “We don’t make enough money to pay for reproductive care out of pocket.”

Fair Pay

In Boston, the residents at Mass General Brigham certified their union in June 2023, but they still don’t have a contract.

“When I applied for a residency in September 2023, I spoke to the folks here, and I was basically under the impression that we would have a contract by the time I matched,” said Madison Masters, MD, a resident in internal medicine. “We are not there.”

This timeline isn’t unusual — the 1400 Penn Medicine residents who unionized in 2023 only recently secured a tentative union contract at the end of September, and at Stanford, the process to ratify their first contract took 13 months.

Still, the salary issue remains frustrating as resident compensation doesn’t line up with the cost of living or the amount of work residents do, said Dr. Masters, who says starting salaries at Mass General Brigham are $78,500 plus a $10,000 stipend for housing.

“There’s been a long tradition of underpaying residents — we’re treated like trainees, but we’re also a primary labor force,” Dr. Masters said, adding that nurse practitioners and physician assistants are paid almost twice as much as residents — some make $120,000 per year or more, while the salary range for residents nationwide is $49,000-$65,000 per year.

“Every time we discuss the contract and talk about a financial package, they offer a 1.5% raise for the next 3 years while we had asked for closer to 8%,” Dr. Masters said. “Then, when they come back for the next bargaining session, they go up a quarter of a percent each time. Recently, they said we will need to go to a mediator to try and resolve this.”

Adequate Healthcare

The biggest — and perhaps the most shocking — ask is for robust health insurance coverage.

“At my hospital, they’re telling us to get Amazon One Medical for health insurance,” Dr. Masters said. “They’re saying it’s hard for anyone to get primary care coverage here.”

Inadequate health insurance is a big issue, as burnout among residents and fellows remains a problem. At UVM, a $10,000 annual wellness stipend has helped address some of these issues. Even so, union members at UVM are planning to return to the table within 18 months to continue their collective bargaining.

The ability to access mental health services anywhere you want is also critical for residents, Dr. Walker said.

“If you can only go to a therapist at your own institution, there is a hesitation to utilize that specialist if that’s even offered,” Dr. Walker said. “Do you want to go to therapy with a colleague? Probably not.”

Ultimately, the residents we spoke to are committed to fighting for their workplace rights — no matter how time-consuming or difficult this has been.

“No administration wants us to have to have a union, but it’s necessary,” Dr. Mostoller said. “As an individual, you don’t have leverage to get a seat at the table, but now we have a seat at the table. We have a wonderful contract, but we’re going to keep fighting to make it even better.”

Paving the way for future residents is a key motivator, too.

“There’s this idea of leaving the campsite cleaner than you found it,” Dr. Mostoller told this news organization. “It’s the same thing here — we’re trying to fix this so that the next generation of residents won’t have to.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Crisugabalin Alleviates Postherpetic Neuralgia Symptoms in Phase 3 Study

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a phase 3 multicenter, double-blind study involving 366 patients in China (median age, 63 years; 52.7% men) with PHN with an average daily pain score (ADPS) of 4 or greater on the numeric pain rating scale who were randomly assigned to receive either crisugabalin 40 mg/d (n = 121), 80 mg/d (n = 121), or placebo (n = 124) for 12 weeks.

- Patients who did not experience any serious toxic effects in these 12 weeks entered a 14-week open-label extension phase and received crisugabalin 40 mg twice daily.

- The primary efficacy endpoint was the change in ADPS from baseline at week 12.

- Secondary efficacy endpoints included the proportion of patients achieving at least 30% and 50% reduction in ADPS at week 12; changes in the Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ), Visual Analog Scale, and Average Daily Sleep Interference Scale scores at week 12; and change in the SF-MPQ Present Pain Intensity scores at weeks 12 and 26.

TAKEAWAY:

- At week 12, among those on crisugabalin 40 mg/d and 80 mg/d, there were significant reductions in ADPS compared with placebo (least squares mean [LSM] change from baseline, −2.2 and −2.6 vs −1.1, respectively; P < .001).

- A greater proportion of patients on crisugabalin 40 mg/d (61.2%) and 80 mg/d (54.5%) achieved 30% or greater reduction in ADPS (P < .001) than patients who received placebo (35.5%). Similarly, a 50% or greater reduction in ADPS was achieved by 37.2% of patients on crisugabalin 40 mg/d (P = .002) and 38% on 80 mg/d (P < .001), compared with 20.2% for placebo.

- Crisugabalin 40 mg/d and crisugabalin 80 mg/d were associated with greater reductions in the pain intensity at week 12 than placebo (LSM, −1.0 and −1.2 vs −0.5, respectively; P < .001). Similar patterns were noted for other pain-related measures at weeks 12 and 26.

- Serious treatment-emergent adverse events occurred in four patients in each group; only 2.4% of those on 40 mg/d and 1.6% on 80 mg/d discontinued treatment because of side effects.

IN PRACTICE:

“Crisugabalin 40 mg/d or crisugabalin 80 mg/d was well-tolerated and significantly improved ADPS compared to placebo,” the authors wrote, adding that “crisugabalin can be flexibly selected depending on individual patient response and tolerability at 40 mg/d or 80 mg/d.”

SOURCE:

The study was led by Daying Zhang, PhD, of the Department of Pain Medicine at The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University, Nanchang, China. It was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The findings may not be generalizable to the global population as the study population was limited to Chinese patients. The study only provided short-term efficacy and safety data on crisugabalin, lacked an active comparator, and did not reflect the standard of care observed in the United States or Europe, where oral tricyclic antidepressants, pregabalin, and the lidocaine patch are recommended as first-line therapies.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was sponsored and funded by Haisco Pharmaceutical. Dr. Zhang and another author reported receiving support from Haisco. Two authors are company employees.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a phase 3 multicenter, double-blind study involving 366 patients in China (median age, 63 years; 52.7% men) with PHN with an average daily pain score (ADPS) of 4 or greater on the numeric pain rating scale who were randomly assigned to receive either crisugabalin 40 mg/d (n = 121), 80 mg/d (n = 121), or placebo (n = 124) for 12 weeks.

- Patients who did not experience any serious toxic effects in these 12 weeks entered a 14-week open-label extension phase and received crisugabalin 40 mg twice daily.

- The primary efficacy endpoint was the change in ADPS from baseline at week 12.

- Secondary efficacy endpoints included the proportion of patients achieving at least 30% and 50% reduction in ADPS at week 12; changes in the Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ), Visual Analog Scale, and Average Daily Sleep Interference Scale scores at week 12; and change in the SF-MPQ Present Pain Intensity scores at weeks 12 and 26.

TAKEAWAY:

- At week 12, among those on crisugabalin 40 mg/d and 80 mg/d, there were significant reductions in ADPS compared with placebo (least squares mean [LSM] change from baseline, −2.2 and −2.6 vs −1.1, respectively; P < .001).

- A greater proportion of patients on crisugabalin 40 mg/d (61.2%) and 80 mg/d (54.5%) achieved 30% or greater reduction in ADPS (P < .001) than patients who received placebo (35.5%). Similarly, a 50% or greater reduction in ADPS was achieved by 37.2% of patients on crisugabalin 40 mg/d (P = .002) and 38% on 80 mg/d (P < .001), compared with 20.2% for placebo.

- Crisugabalin 40 mg/d and crisugabalin 80 mg/d were associated with greater reductions in the pain intensity at week 12 than placebo (LSM, −1.0 and −1.2 vs −0.5, respectively; P < .001). Similar patterns were noted for other pain-related measures at weeks 12 and 26.

- Serious treatment-emergent adverse events occurred in four patients in each group; only 2.4% of those on 40 mg/d and 1.6% on 80 mg/d discontinued treatment because of side effects.

IN PRACTICE:

“Crisugabalin 40 mg/d or crisugabalin 80 mg/d was well-tolerated and significantly improved ADPS compared to placebo,” the authors wrote, adding that “crisugabalin can be flexibly selected depending on individual patient response and tolerability at 40 mg/d or 80 mg/d.”

SOURCE:

The study was led by Daying Zhang, PhD, of the Department of Pain Medicine at The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University, Nanchang, China. It was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The findings may not be generalizable to the global population as the study population was limited to Chinese patients. The study only provided short-term efficacy and safety data on crisugabalin, lacked an active comparator, and did not reflect the standard of care observed in the United States or Europe, where oral tricyclic antidepressants, pregabalin, and the lidocaine patch are recommended as first-line therapies.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was sponsored and funded by Haisco Pharmaceutical. Dr. Zhang and another author reported receiving support from Haisco. Two authors are company employees.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a phase 3 multicenter, double-blind study involving 366 patients in China (median age, 63 years; 52.7% men) with PHN with an average daily pain score (ADPS) of 4 or greater on the numeric pain rating scale who were randomly assigned to receive either crisugabalin 40 mg/d (n = 121), 80 mg/d (n = 121), or placebo (n = 124) for 12 weeks.

- Patients who did not experience any serious toxic effects in these 12 weeks entered a 14-week open-label extension phase and received crisugabalin 40 mg twice daily.

- The primary efficacy endpoint was the change in ADPS from baseline at week 12.

- Secondary efficacy endpoints included the proportion of patients achieving at least 30% and 50% reduction in ADPS at week 12; changes in the Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ), Visual Analog Scale, and Average Daily Sleep Interference Scale scores at week 12; and change in the SF-MPQ Present Pain Intensity scores at weeks 12 and 26.

TAKEAWAY:

- At week 12, among those on crisugabalin 40 mg/d and 80 mg/d, there were significant reductions in ADPS compared with placebo (least squares mean [LSM] change from baseline, −2.2 and −2.6 vs −1.1, respectively; P < .001).

- A greater proportion of patients on crisugabalin 40 mg/d (61.2%) and 80 mg/d (54.5%) achieved 30% or greater reduction in ADPS (P < .001) than patients who received placebo (35.5%). Similarly, a 50% or greater reduction in ADPS was achieved by 37.2% of patients on crisugabalin 40 mg/d (P = .002) and 38% on 80 mg/d (P < .001), compared with 20.2% for placebo.

- Crisugabalin 40 mg/d and crisugabalin 80 mg/d were associated with greater reductions in the pain intensity at week 12 than placebo (LSM, −1.0 and −1.2 vs −0.5, respectively; P < .001). Similar patterns were noted for other pain-related measures at weeks 12 and 26.

- Serious treatment-emergent adverse events occurred in four patients in each group; only 2.4% of those on 40 mg/d and 1.6% on 80 mg/d discontinued treatment because of side effects.

IN PRACTICE:

“Crisugabalin 40 mg/d or crisugabalin 80 mg/d was well-tolerated and significantly improved ADPS compared to placebo,” the authors wrote, adding that “crisugabalin can be flexibly selected depending on individual patient response and tolerability at 40 mg/d or 80 mg/d.”

SOURCE:

The study was led by Daying Zhang, PhD, of the Department of Pain Medicine at The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University, Nanchang, China. It was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The findings may not be generalizable to the global population as the study population was limited to Chinese patients. The study only provided short-term efficacy and safety data on crisugabalin, lacked an active comparator, and did not reflect the standard of care observed in the United States or Europe, where oral tricyclic antidepressants, pregabalin, and the lidocaine patch are recommended as first-line therapies.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was sponsored and funded by Haisco Pharmaceutical. Dr. Zhang and another author reported receiving support from Haisco. Two authors are company employees.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Surgical Center Wins $421 Million Verdict Against Blue Cross

Insurance specialists told this news organization that the September 20 verdict is unusual. If upheld on appeal, one said, it could give out-of-network providers more power to decide how much insurers must pay them.

The case, which the St. Charles Surgical Hospital and Center for Restorative Breast Surgery first filed in 2017 in Louisiana state court, will be appealed and could ultimately land in federal court. The center has seen mixed results from a similar case it filed in federal court, legal documents show. Physicians from the center declined comment.

At issue: Did Blue Cross fail to fully pay the surgery center for about 7000 out-of-network procedures that it authorized?

The lawsuit claimed that the insurer’s online system confirmed that claims would be paid and noted the percentage of patient bills that would be reimbursed.

However, “Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Louisiana either slow-paid, low-paid, or no-paid all their bills over an eight-year period, hoping to pressure the doctors and hospital to either come into the network or fail and close down,” the surgery center’s attorney, James Williams, said in a statement.

Blue Cross denied that it acted fraudulently, “arguing that because the hospital is not a member of its provider network, it had no contractual obligation to pay anything,” the Times-Picayune newspaper reported. Authorization of a procedure doesn’t guarantee payment, the insurer argued in court.

In a statement to the media, Blue Cross said it disagrees with the verdict and will appeal.

Out-of-Network Free For All

Paul B. Ginsburg, PhD, professor of the Practice of Health Policy at the Price School of Public Policy, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, said out-of-network care doesn’t come with a contractual relationship.

Without a contract, he said, “providers can charge whatever they want, and the insurers will pay them whatever they want, and then it’s up to the provider to see how much additional balance bill they can collect from the patients.” (Some states and the federal government have laws partly protecting patients from balance billing when doctors and insurers conflict over payment.)

He added that “if insurance companies were on the hook to pay whatever any provider charges, nobody would ever belong to a network, and rates would be sky high. Many fewer people would buy insurance. Providers would [then] charge as much as they think they can get from the patients.”

What about the insurer’s apparent authorization of the out-of-network procedures? “They’re authorizing them because they believe the procedures are medically warranted,” Dr. Ginsburg said. “That’s totally separate from how much they’ll pay.”

Dr. Ginsburg added that juries in the South are known for imposing high penalties against companies. “They often come up with crazy verdicts.”

Mark V. Pauly, PhD, MA, professor emeritus of health care management at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, questioned why the clinic kept accepting Blue Cross patients.

“Once it became apparent that Blue Cross wasn’t going to pay them well or would give them a lot of grief,” Dr. Pauly said, “the simplest thing would have been to tell patients that we’re going to go back to the old-fashioned way of doing things: You pay us up front, or assure us that you’re going to pay.”

Lawton Robert Burns, PhD, MBA, professor of health care management at the Wharton School, said the case and the verdict are unusual. He noted that insurer contracts with employers often state that out-of-network care will be covered at a specific rate, such as 70% of “reasonable charges.”

A 2020 analysis found that initial breast reconstruction surgeries in the United States cost a median of $24,600-$38,000 from 2009 to 2016. According to the Times-Picayune, the New Orleans clinic billed Blue Cross for $506.7 million, averaging more than $72,385 per procedure.

Dr. Ginsburg, Dr. Pauly, and Dr. Burns had no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Insurance specialists told this news organization that the September 20 verdict is unusual. If upheld on appeal, one said, it could give out-of-network providers more power to decide how much insurers must pay them.

The case, which the St. Charles Surgical Hospital and Center for Restorative Breast Surgery first filed in 2017 in Louisiana state court, will be appealed and could ultimately land in federal court. The center has seen mixed results from a similar case it filed in federal court, legal documents show. Physicians from the center declined comment.

At issue: Did Blue Cross fail to fully pay the surgery center for about 7000 out-of-network procedures that it authorized?

The lawsuit claimed that the insurer’s online system confirmed that claims would be paid and noted the percentage of patient bills that would be reimbursed.

However, “Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Louisiana either slow-paid, low-paid, or no-paid all their bills over an eight-year period, hoping to pressure the doctors and hospital to either come into the network or fail and close down,” the surgery center’s attorney, James Williams, said in a statement.

Blue Cross denied that it acted fraudulently, “arguing that because the hospital is not a member of its provider network, it had no contractual obligation to pay anything,” the Times-Picayune newspaper reported. Authorization of a procedure doesn’t guarantee payment, the insurer argued in court.

In a statement to the media, Blue Cross said it disagrees with the verdict and will appeal.

Out-of-Network Free For All

Paul B. Ginsburg, PhD, professor of the Practice of Health Policy at the Price School of Public Policy, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, said out-of-network care doesn’t come with a contractual relationship.

Without a contract, he said, “providers can charge whatever they want, and the insurers will pay them whatever they want, and then it’s up to the provider to see how much additional balance bill they can collect from the patients.” (Some states and the federal government have laws partly protecting patients from balance billing when doctors and insurers conflict over payment.)

He added that “if insurance companies were on the hook to pay whatever any provider charges, nobody would ever belong to a network, and rates would be sky high. Many fewer people would buy insurance. Providers would [then] charge as much as they think they can get from the patients.”

What about the insurer’s apparent authorization of the out-of-network procedures? “They’re authorizing them because they believe the procedures are medically warranted,” Dr. Ginsburg said. “That’s totally separate from how much they’ll pay.”

Dr. Ginsburg added that juries in the South are known for imposing high penalties against companies. “They often come up with crazy verdicts.”

Mark V. Pauly, PhD, MA, professor emeritus of health care management at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, questioned why the clinic kept accepting Blue Cross patients.

“Once it became apparent that Blue Cross wasn’t going to pay them well or would give them a lot of grief,” Dr. Pauly said, “the simplest thing would have been to tell patients that we’re going to go back to the old-fashioned way of doing things: You pay us up front, or assure us that you’re going to pay.”

Lawton Robert Burns, PhD, MBA, professor of health care management at the Wharton School, said the case and the verdict are unusual. He noted that insurer contracts with employers often state that out-of-network care will be covered at a specific rate, such as 70% of “reasonable charges.”

A 2020 analysis found that initial breast reconstruction surgeries in the United States cost a median of $24,600-$38,000 from 2009 to 2016. According to the Times-Picayune, the New Orleans clinic billed Blue Cross for $506.7 million, averaging more than $72,385 per procedure.

Dr. Ginsburg, Dr. Pauly, and Dr. Burns had no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Insurance specialists told this news organization that the September 20 verdict is unusual. If upheld on appeal, one said, it could give out-of-network providers more power to decide how much insurers must pay them.

The case, which the St. Charles Surgical Hospital and Center for Restorative Breast Surgery first filed in 2017 in Louisiana state court, will be appealed and could ultimately land in federal court. The center has seen mixed results from a similar case it filed in federal court, legal documents show. Physicians from the center declined comment.

At issue: Did Blue Cross fail to fully pay the surgery center for about 7000 out-of-network procedures that it authorized?

The lawsuit claimed that the insurer’s online system confirmed that claims would be paid and noted the percentage of patient bills that would be reimbursed.

However, “Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Louisiana either slow-paid, low-paid, or no-paid all their bills over an eight-year period, hoping to pressure the doctors and hospital to either come into the network or fail and close down,” the surgery center’s attorney, James Williams, said in a statement.

Blue Cross denied that it acted fraudulently, “arguing that because the hospital is not a member of its provider network, it had no contractual obligation to pay anything,” the Times-Picayune newspaper reported. Authorization of a procedure doesn’t guarantee payment, the insurer argued in court.

In a statement to the media, Blue Cross said it disagrees with the verdict and will appeal.

Out-of-Network Free For All

Paul B. Ginsburg, PhD, professor of the Practice of Health Policy at the Price School of Public Policy, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, said out-of-network care doesn’t come with a contractual relationship.

Without a contract, he said, “providers can charge whatever they want, and the insurers will pay them whatever they want, and then it’s up to the provider to see how much additional balance bill they can collect from the patients.” (Some states and the federal government have laws partly protecting patients from balance billing when doctors and insurers conflict over payment.)

He added that “if insurance companies were on the hook to pay whatever any provider charges, nobody would ever belong to a network, and rates would be sky high. Many fewer people would buy insurance. Providers would [then] charge as much as they think they can get from the patients.”

What about the insurer’s apparent authorization of the out-of-network procedures? “They’re authorizing them because they believe the procedures are medically warranted,” Dr. Ginsburg said. “That’s totally separate from how much they’ll pay.”

Dr. Ginsburg added that juries in the South are known for imposing high penalties against companies. “They often come up with crazy verdicts.”

Mark V. Pauly, PhD, MA, professor emeritus of health care management at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, questioned why the clinic kept accepting Blue Cross patients.

“Once it became apparent that Blue Cross wasn’t going to pay them well or would give them a lot of grief,” Dr. Pauly said, “the simplest thing would have been to tell patients that we’re going to go back to the old-fashioned way of doing things: You pay us up front, or assure us that you’re going to pay.”

Lawton Robert Burns, PhD, MBA, professor of health care management at the Wharton School, said the case and the verdict are unusual. He noted that insurer contracts with employers often state that out-of-network care will be covered at a specific rate, such as 70% of “reasonable charges.”

A 2020 analysis found that initial breast reconstruction surgeries in the United States cost a median of $24,600-$38,000 from 2009 to 2016. According to the Times-Picayune, the New Orleans clinic billed Blue Cross for $506.7 million, averaging more than $72,385 per procedure.

Dr. Ginsburg, Dr. Pauly, and Dr. Burns had no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Down Syndrome: Several Cutaneous Conditions Common, Study Finds

TOPLINE:

(DS) in a 10-year retrospective study.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a multicenter retrospective study of 1529 patients with DS from eight outpatient dermatology clinics in the United States and Canada between 2011 and 2021.

- In total, 50.8% of patients were children (0-12 years), 25.2% were adolescents (13-17 years), and 24% were adults (≥ 18 years).

- The researchers evaluated skin conditions in the patients.

TAKEAWAY:

- Eczematous dermatitis was the most common diagnosis, affecting 26% of patients, followed by folliculitis (19.3%) and seborrheic dermatitis (15.6%). Dermatophyte infections were diagnosed in 13%.

- Alopecia areata was the most common autoimmune skin condition, diagnosed in 178 patients (11.6%); 135 (75.8%) were children. Vitiligo was diagnosed in 66 patients (4.3%).

- The most common cutaneous infections were onychomycosis (5.9%), tinea pedis (5%), and verruca vulgaris/other viral warts (5%).

- High-risk medication use was reported in 4.3% of patients; acne vulgaris, hidradenitis suppurativa, and eczematous dermatitis were the most common associated conditions with such medications.

IN PRACTICE:

“Children, adolescents, and adults with DS are most often found to have eczematous, adnexal, and autoimmune skin conditions at outpatient dermatology visits,” the authors wrote. Their findings, they added, “offer valuable insights for clinicians and researchers, aiding in the improved prioritization of screening, diagnosis, and management, as well as facilitating both basic science and clinical research into prevalent skin conditions in individuals with DS.”

SOURCE:

The study was led by Tasya Rakasiwi, of the Department of Dermatology, Dartmouth Health, Manchester, New Hampshire, and was published online in Pediatric Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

Over 50% of the patients were children, potentially resulting in bias toward pediatric diagnoses and younger ages of presentation. Race, ethnicity, and sociodemographic factors were not captured, limiting the generalizability of the findings. Medical codes often do not capture disease phenotype or severity, and the manual conversion of International Classification of Diseases (ICD) 9 to ICD-10 codes may introduce potential conversion errors.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance. The authors declared no competing interests.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

(DS) in a 10-year retrospective study.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a multicenter retrospective study of 1529 patients with DS from eight outpatient dermatology clinics in the United States and Canada between 2011 and 2021.

- In total, 50.8% of patients were children (0-12 years), 25.2% were adolescents (13-17 years), and 24% were adults (≥ 18 years).

- The researchers evaluated skin conditions in the patients.

TAKEAWAY:

- Eczematous dermatitis was the most common diagnosis, affecting 26% of patients, followed by folliculitis (19.3%) and seborrheic dermatitis (15.6%). Dermatophyte infections were diagnosed in 13%.

- Alopecia areata was the most common autoimmune skin condition, diagnosed in 178 patients (11.6%); 135 (75.8%) were children. Vitiligo was diagnosed in 66 patients (4.3%).

- The most common cutaneous infections were onychomycosis (5.9%), tinea pedis (5%), and verruca vulgaris/other viral warts (5%).

- High-risk medication use was reported in 4.3% of patients; acne vulgaris, hidradenitis suppurativa, and eczematous dermatitis were the most common associated conditions with such medications.

IN PRACTICE:

“Children, adolescents, and adults with DS are most often found to have eczematous, adnexal, and autoimmune skin conditions at outpatient dermatology visits,” the authors wrote. Their findings, they added, “offer valuable insights for clinicians and researchers, aiding in the improved prioritization of screening, diagnosis, and management, as well as facilitating both basic science and clinical research into prevalent skin conditions in individuals with DS.”

SOURCE:

The study was led by Tasya Rakasiwi, of the Department of Dermatology, Dartmouth Health, Manchester, New Hampshire, and was published online in Pediatric Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

Over 50% of the patients were children, potentially resulting in bias toward pediatric diagnoses and younger ages of presentation. Race, ethnicity, and sociodemographic factors were not captured, limiting the generalizability of the findings. Medical codes often do not capture disease phenotype or severity, and the manual conversion of International Classification of Diseases (ICD) 9 to ICD-10 codes may introduce potential conversion errors.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance. The authors declared no competing interests.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

(DS) in a 10-year retrospective study.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a multicenter retrospective study of 1529 patients with DS from eight outpatient dermatology clinics in the United States and Canada between 2011 and 2021.

- In total, 50.8% of patients were children (0-12 years), 25.2% were adolescents (13-17 years), and 24% were adults (≥ 18 years).

- The researchers evaluated skin conditions in the patients.

TAKEAWAY:

- Eczematous dermatitis was the most common diagnosis, affecting 26% of patients, followed by folliculitis (19.3%) and seborrheic dermatitis (15.6%). Dermatophyte infections were diagnosed in 13%.

- Alopecia areata was the most common autoimmune skin condition, diagnosed in 178 patients (11.6%); 135 (75.8%) were children. Vitiligo was diagnosed in 66 patients (4.3%).

- The most common cutaneous infections were onychomycosis (5.9%), tinea pedis (5%), and verruca vulgaris/other viral warts (5%).

- High-risk medication use was reported in 4.3% of patients; acne vulgaris, hidradenitis suppurativa, and eczematous dermatitis were the most common associated conditions with such medications.

IN PRACTICE:

“Children, adolescents, and adults with DS are most often found to have eczematous, adnexal, and autoimmune skin conditions at outpatient dermatology visits,” the authors wrote. Their findings, they added, “offer valuable insights for clinicians and researchers, aiding in the improved prioritization of screening, diagnosis, and management, as well as facilitating both basic science and clinical research into prevalent skin conditions in individuals with DS.”

SOURCE:

The study was led by Tasya Rakasiwi, of the Department of Dermatology, Dartmouth Health, Manchester, New Hampshire, and was published online in Pediatric Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

Over 50% of the patients were children, potentially resulting in bias toward pediatric diagnoses and younger ages of presentation. Race, ethnicity, and sociodemographic factors were not captured, limiting the generalizability of the findings. Medical codes often do not capture disease phenotype or severity, and the manual conversion of International Classification of Diseases (ICD) 9 to ICD-10 codes may introduce potential conversion errors.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance. The authors declared no competing interests.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Disseminated Gonococcal Infection of Pharyngeal Origin: Test All Anatomic Sites

To the Editor:

Gonococcal infections, which are caused by the sexually transmitted, gram-negative diplococcus Neisseria gonorrhoeae, are a current and increasing threat to public health. Between 2012 and 2021, the rate of gonococcal infection in the United States increased 137.8% in men and 64.9% in women,1 with an estimated 1.5 million new gonococcal infections occurring each year in the United States as of 2021.2 Neisseria gonorrhoeae is the second most common bacterial sexually transmitted infection (STI), and patients with gonococcal infection frequently are coinfected with Chlamydia trachomatis, which is the most common bacterial STI. Uncomplicated gonococcal infection (also known as gonorrhea) most commonly causes asymptomatic cervicovaginal infection in women and symptomatic urethral infection in men.2 Other uncomplicated manifestations include rectal infection, which can be asymptomatic or manifest with anal pruritus, anal discharge, or tenesmus, and oropharyngeal infection, which can be asymptomatic or manifest with throat pain. If uncomplicated gonococcal infections are left untreated or are incompletely treated, serious complications including septic arthritis, myositis, osteomyelitis, myocarditis, endocarditis, and meningitis might occur.2-5 Ascending, locally invasive infections can cause epididymitis or pelvic inflammatory disease, which is an important cause of infertility in women.2,3 Gonococcal conjunctivitis also can occur, particularly when neonates are exposed to bacteria during vaginal delivery. Although rare, gonococcal bacteria can disseminate widely, with an estimated 0.5% to 3% of uncomplicated gonococcal infections progressing to disseminated gonococcal infection (DGI).3-6 Because DGI can mimic other systemic conditions, including a variety of bacterial and viral infections as well as inflammatory conditions, it can be difficult to diagnose without a high index of clinical suspicion. We present a case of DGI diagnosed based on dermatologic expertise and pharyngeal molecular testing.

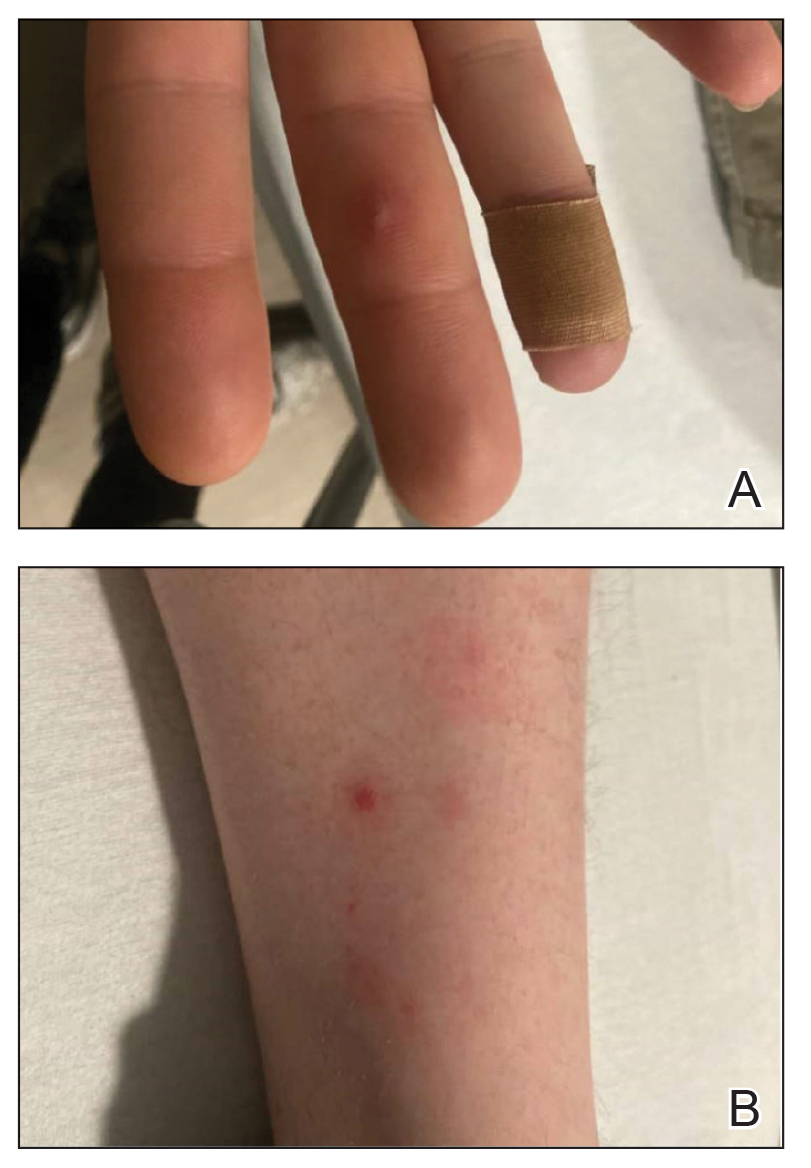

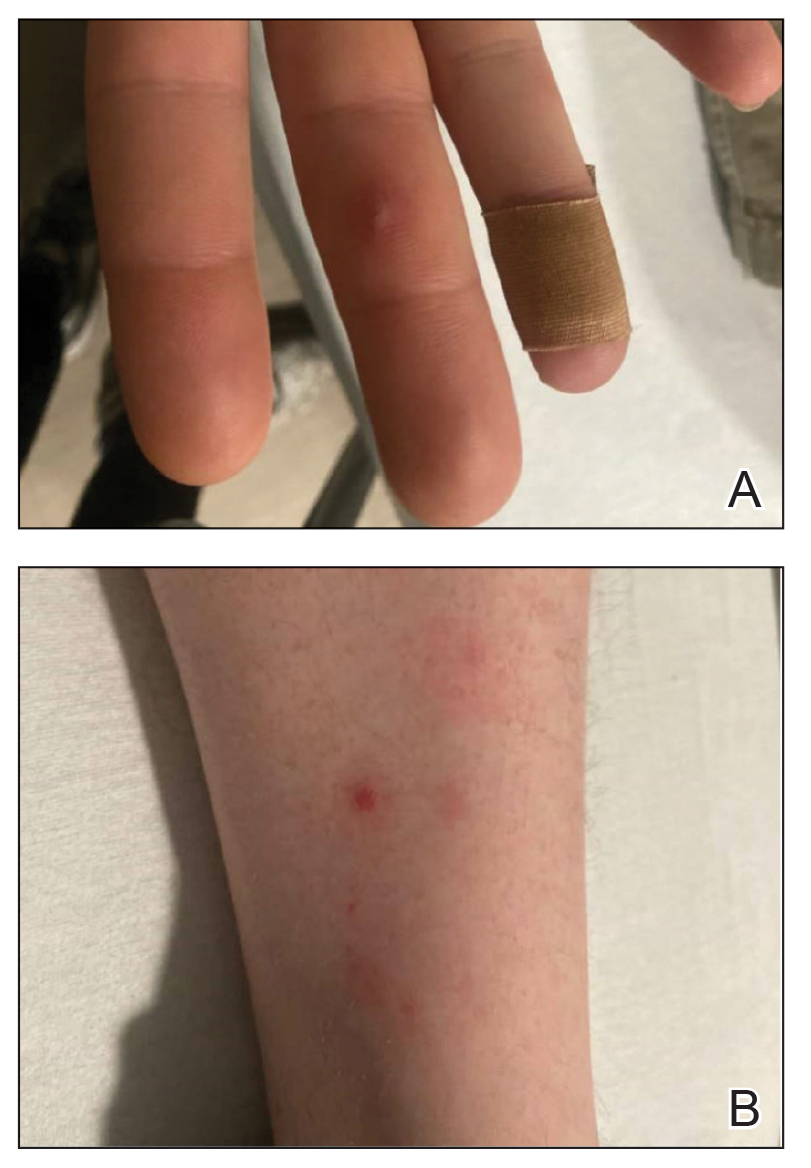

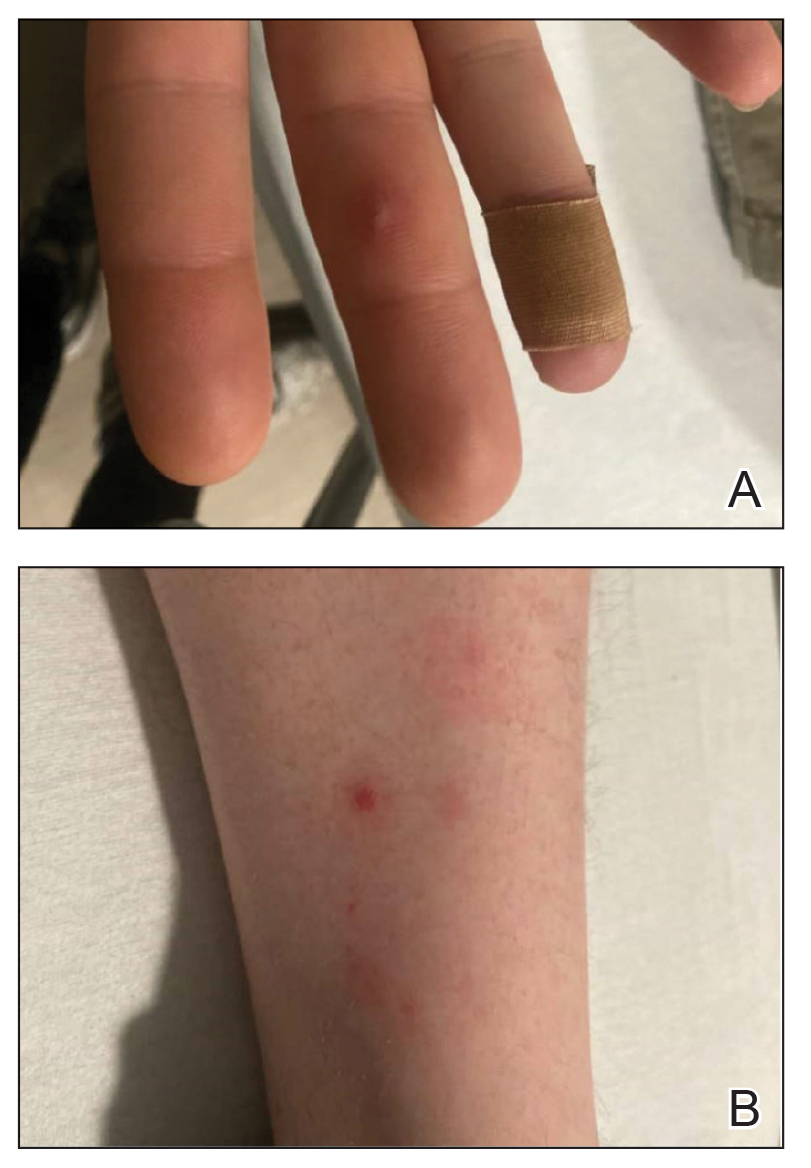

A 30-year-old man presented to the emergency department with a rash on the extremeities as well as emesis, fever, sore throat, and severe arthralgia in the wrists, hands, knees, and feet of 2 days’ duration. The patient also had experienced several months of dysuria. He reported daily use of the recreational drug ketamine, multiple new male sexual partners, and unprotected oral and receptive anal sex in recent months. He denied any history of STIs. Physical examination demonstrated tender edematous wrists and fingers, papulovesicles on erythematous bases on the palms, and purpuric macules scattered on the legs (Figure 1). The patient also had tonsillar edema with notable white tonsillar exudate.

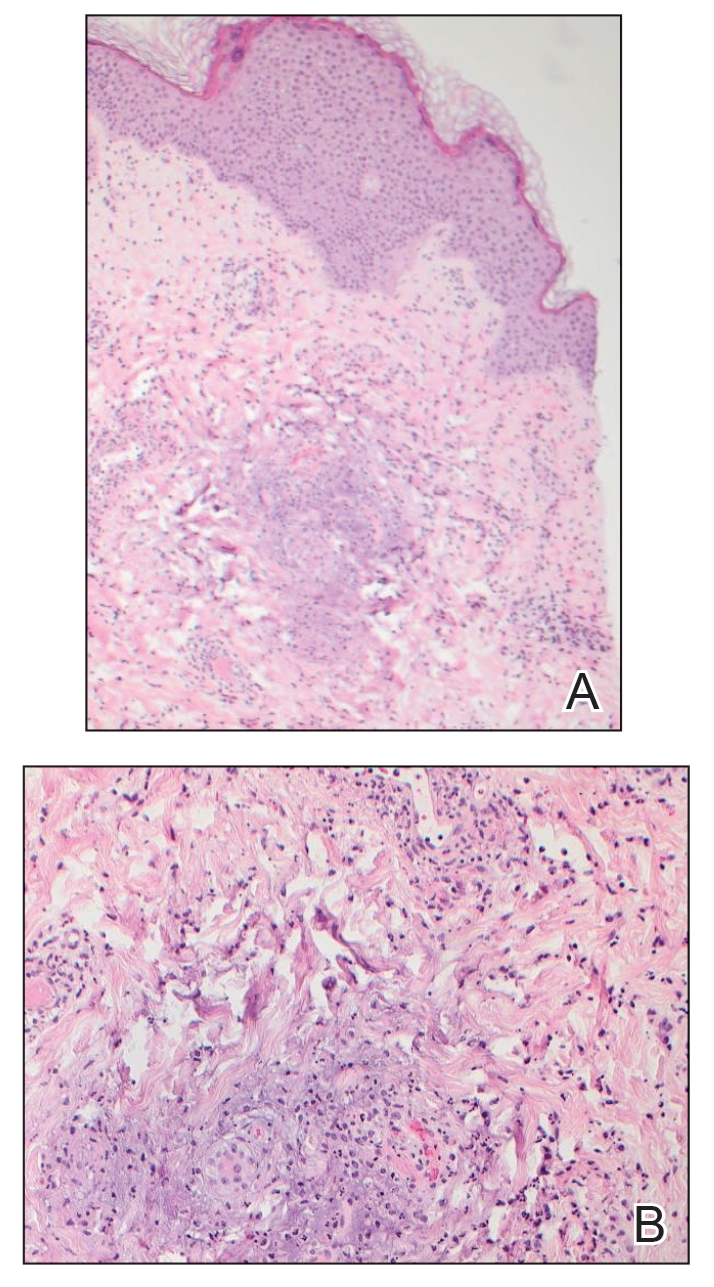

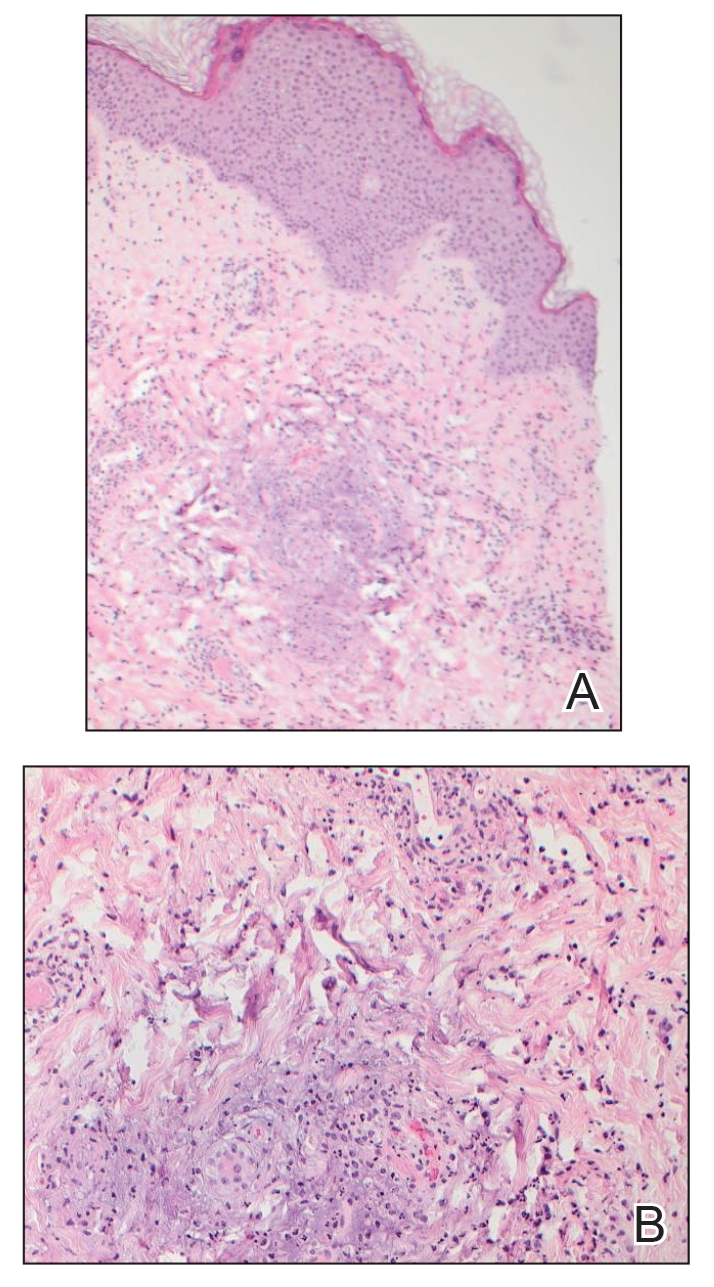

A shave biopsy performed on a papulovesicular lesion on the right thigh showed an intact epidermis with minimal spongiosis and no viral cytopathic changes. There was dermal edema with a moderate superficial and deep neutrophilic infiltrate, mild karyorrhexis, and focal dermal necrosis (Figure 2). Rare acute vasculitis with intravascular fibrin was seen. Periodic acid-Schiff stain for fungi, Gram stain for bacteria, and immunostains for human herpesviruses 1 and 2 were negative.

Laboratory studies revealed neutrophil-predominant leukocytosis (white blood cell count, 13.89×109/L [reference range, 4.5–11.0×109/L] with 78.2% neutrophils [reference range, 40.0%–70.0%]) as well as an elevated C-reactive protein level and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (19.98 mg/dL [reference range, <0.05 mg/dL] and 38 mm/h [reference range, 0–15 mm/h], respectively). His liver enzymes, kidney function, prothrombin time, and international normalized ratio were all normal. Urinalysis showed trace amounts of blood and protein, and urine culture was negative for pathogenic bacteria. A rapid plasma reagin test and a fifth-generation HIV antibody test were nonreactive, and bacterial blood cultures were negative for other infectious diseases. Nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) performed on a swab from a papulovesicular lesion was negative for human herpesviruses 1 and 2, varicella-zoster virus, orthopoxvirus, and mpox (monkeypox) virus. Based on recommendations from dermatology, NAATs for C trachomatis and N gonorrhoeae were performed on urine and on swabs from the patient’s rectum and pharynx; N gonorrhoeae was detected at the pharynx, but the other sites were negative for both bacteria. A diagnosis of DGI was made based on these results as well as the patient’s clinical presentation of fever, arthralgia, and papulovesicular skin lesions. The patient was treated with 1 g of intravenous ceftriaxone while in the hospital, but unfortunately, he was lost to follow-up and did not complete the full 1-week treatment course.

Disseminated gonococcal infection (also known as arthritis-dermatitis syndrome) is characterized by the abrupt onset of fever, skin lesions, and arthralgia in a symmetric and migratory distribution. Tenosynovitis involving the extensor tendons of the wrists, fingers, knees, and ankles (particularly the Achilles tendon) is characteristic. Skin manifestations usually include hemorrhagic vesicles and papulovesicles limited to the extremities, often with an acral distribution,2-5 though other cutaneous lesions have been described in DGI, including macules, purpura, periurethral abscesses, multifocal cellulitis, and necrotizing fasciitis.7 It is important to consider DGI in a patient who presents with acute systemic symptoms and any of these cutaneous manifestations, even in the absence of joint pain.

Diagnosis of DGI can be difficult, and surveillance is limited in the United States; therefore, the risk factors are somewhat unclear and might be changing. Traditional risk factors for DGI have included immunosuppression due to terminal complement deficiency, female sex, recent menstruation, and pregnancy, but recent data have shown that male sex, HIV infection, use of methamphetamines and other drugs, and use of the monoclonal antibody eculizumab for treatment of complement disorders have been associated with DGI.2,6-8 In the past decade, uncomplicated gonococcal infections have disproportionately affected Black patients, men who have sex with men, adults aged 20 to 25 years, and individuals living in the southern United States.1 It is unclear if the changing demographics of patients with DGI represent true risk factors for dissemination or simply reflect the changing demographics of patients at risk for uncomplicated gonococcal infection.6

Dermatologic expertise in the recognition of cutaneous manifestations of DGI is particularly important due to the limitations of diagnostic tools. The organism is fastidious and difficult to grow in vitro, thus cultures for N gonorrhoeae are not sensitive and require specialized media (eg, Thayer-Martin, modified New York City, or chocolate agar medium with additional antimicrobial agents).3 Molecular assays such as NAATs are more sensitive and specific than culture but are not 100% accurate.2,3,5 Finally, sterile sites such as joints, blood, or cerebrospinal fluid can be difficult to access, and specimens are not always available for specific microbial diagnosis; therefore, even when a gonococcal infection is identified at a mucosal source, physicians must use their clinical judgment to determine whether the mucosal infection is the cause of DGI or if the patient has a separate additional illness.