User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Study Evaluates Safety of Benzoyl Peroxide Products for Acne

according to results from an analysis that used gas chromatography–mass spectrometry and other methods.

The analysis, which was published in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology and expands on a similar study released more than 6 months ago, also found that encapsulated BPO products break down into benzene at room temperature but that refrigerating them may mitigate this effect.

“Our research provides the first experimental evidence that cold storage can help reduce the rate of benzoyl peroxide breakdown into benzene,” said one of the study authors, Christopher G. Bunick, MD, PhD, associate professor of dermatology at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. “Therefore, cold storage throughout the entire supply chain — from manufacturing to patient use — is a reasonable and proportional measure at this time for those continuing to use benzoyl peroxide medicine.” One acne product, the newer prescription triple-combination therapy (adapalene-clindamycin-BPO) “already has a cold shipping process in place; the patient just needs to continue that at home,” he noted.

For the study — which was funded by an independent lab, Valisure — researchers led by Valisure CEO and founder David Light, used gas chromatography-mass spectrometry to detect benzene levels in 111 BPO drug products from major US retailers and selected ion flow tube mass-spectrometry to quantify the release of benzene in real time. Benzene levels ranged from 0.16 ppm to 35.30 ppm, and 38 of the products (34%) had levels above the FDA limit of 2 ppm for drug products. “The results of the products sampled in this study suggest that formulation is likely the strongest contributor to benzene concentrations in BPO drug products that are commercially available, since the magnitude of benzene detected correlates most closely with specific brands or product types within certain brands,” the study authors wrote.

When the researchers tested the stability of a prescription encapsulated BPO drug product at cold (2 °C) and elevated temperature (50 °C), no apparent benzene formation was observed at 2 °C, whereas high levels of benzene formed at 50 °C, “suggesting that encapsulation technology may not stabilize BPO drug products, but cold storage may greatly reduce benzene formation,” they wrote.

In another component of the study, researchers exposed a BP drug product to a UVA/UVB lamp for 2 hours and found detectable benzene through evaporation and substantial benzene formation when exposed to UV light at levels below peak sunlight. The experiment “strongly justifies the package label warnings to avoid sun exposure when using BPO drug products,” the authors wrote. “Further evaluation to determine the influence of sun exposure on BPO drug product degradation and benzene formation is warranted.”

In an interview, John Barbieri, MD, MBA, assistant professor of dermatology at Harvard Medical School and director of the Advanced Acne Therapeutics Clinic at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts characterized the findings as “an important issue that we should take seriously.” However, “we also must not overreact.”

BPO is a foundational acne treatment without any clear alternative, he said, pointing out that no evidence currently exists “to support that routine use of benzoyl peroxide–containing products for acne is associated with a meaningful risk of benzene in the blood or an increased risk of cancer.”

And although it is prudent to minimize benzene exposure as much as possible, Barbieri continued, “it is not clear that these levels are a clinically meaningful incremental risk in the setting of an acne cream or wash. There is minimal cutaneous absorption of benzene, and it is uncertain how much benzene aerosolizes with routine use, particularly for washes which are not left on the skin.”

Bunick said that the combined data from this and the study published in March 2024 affected which BPO products he recommends for patients with acne. “I am using exclusively the triple combination therapy (adapalene-clindamycin-benzoyl peroxide) because I know it has the necessary cold supply chain in place to protect the product’s stability. I further encourage patients to place all their benzoyl peroxide–containing products in the refrigerator at home to reduce benzene formation and exposure.”

Bunick reported having served as an investigator and/or a consultant/speaker for many pharmaceutical companies, including as a consultant for Ortho-Dermatologics; but none related to this study. Barbieri reported having no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

according to results from an analysis that used gas chromatography–mass spectrometry and other methods.

The analysis, which was published in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology and expands on a similar study released more than 6 months ago, also found that encapsulated BPO products break down into benzene at room temperature but that refrigerating them may mitigate this effect.

“Our research provides the first experimental evidence that cold storage can help reduce the rate of benzoyl peroxide breakdown into benzene,” said one of the study authors, Christopher G. Bunick, MD, PhD, associate professor of dermatology at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. “Therefore, cold storage throughout the entire supply chain — from manufacturing to patient use — is a reasonable and proportional measure at this time for those continuing to use benzoyl peroxide medicine.” One acne product, the newer prescription triple-combination therapy (adapalene-clindamycin-BPO) “already has a cold shipping process in place; the patient just needs to continue that at home,” he noted.

For the study — which was funded by an independent lab, Valisure — researchers led by Valisure CEO and founder David Light, used gas chromatography-mass spectrometry to detect benzene levels in 111 BPO drug products from major US retailers and selected ion flow tube mass-spectrometry to quantify the release of benzene in real time. Benzene levels ranged from 0.16 ppm to 35.30 ppm, and 38 of the products (34%) had levels above the FDA limit of 2 ppm for drug products. “The results of the products sampled in this study suggest that formulation is likely the strongest contributor to benzene concentrations in BPO drug products that are commercially available, since the magnitude of benzene detected correlates most closely with specific brands or product types within certain brands,” the study authors wrote.

When the researchers tested the stability of a prescription encapsulated BPO drug product at cold (2 °C) and elevated temperature (50 °C), no apparent benzene formation was observed at 2 °C, whereas high levels of benzene formed at 50 °C, “suggesting that encapsulation technology may not stabilize BPO drug products, but cold storage may greatly reduce benzene formation,” they wrote.

In another component of the study, researchers exposed a BP drug product to a UVA/UVB lamp for 2 hours and found detectable benzene through evaporation and substantial benzene formation when exposed to UV light at levels below peak sunlight. The experiment “strongly justifies the package label warnings to avoid sun exposure when using BPO drug products,” the authors wrote. “Further evaluation to determine the influence of sun exposure on BPO drug product degradation and benzene formation is warranted.”

In an interview, John Barbieri, MD, MBA, assistant professor of dermatology at Harvard Medical School and director of the Advanced Acne Therapeutics Clinic at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts characterized the findings as “an important issue that we should take seriously.” However, “we also must not overreact.”

BPO is a foundational acne treatment without any clear alternative, he said, pointing out that no evidence currently exists “to support that routine use of benzoyl peroxide–containing products for acne is associated with a meaningful risk of benzene in the blood or an increased risk of cancer.”

And although it is prudent to minimize benzene exposure as much as possible, Barbieri continued, “it is not clear that these levels are a clinically meaningful incremental risk in the setting of an acne cream or wash. There is minimal cutaneous absorption of benzene, and it is uncertain how much benzene aerosolizes with routine use, particularly for washes which are not left on the skin.”

Bunick said that the combined data from this and the study published in March 2024 affected which BPO products he recommends for patients with acne. “I am using exclusively the triple combination therapy (adapalene-clindamycin-benzoyl peroxide) because I know it has the necessary cold supply chain in place to protect the product’s stability. I further encourage patients to place all their benzoyl peroxide–containing products in the refrigerator at home to reduce benzene formation and exposure.”

Bunick reported having served as an investigator and/or a consultant/speaker for many pharmaceutical companies, including as a consultant for Ortho-Dermatologics; but none related to this study. Barbieri reported having no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

according to results from an analysis that used gas chromatography–mass spectrometry and other methods.

The analysis, which was published in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology and expands on a similar study released more than 6 months ago, also found that encapsulated BPO products break down into benzene at room temperature but that refrigerating them may mitigate this effect.

“Our research provides the first experimental evidence that cold storage can help reduce the rate of benzoyl peroxide breakdown into benzene,” said one of the study authors, Christopher G. Bunick, MD, PhD, associate professor of dermatology at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. “Therefore, cold storage throughout the entire supply chain — from manufacturing to patient use — is a reasonable and proportional measure at this time for those continuing to use benzoyl peroxide medicine.” One acne product, the newer prescription triple-combination therapy (adapalene-clindamycin-BPO) “already has a cold shipping process in place; the patient just needs to continue that at home,” he noted.

For the study — which was funded by an independent lab, Valisure — researchers led by Valisure CEO and founder David Light, used gas chromatography-mass spectrometry to detect benzene levels in 111 BPO drug products from major US retailers and selected ion flow tube mass-spectrometry to quantify the release of benzene in real time. Benzene levels ranged from 0.16 ppm to 35.30 ppm, and 38 of the products (34%) had levels above the FDA limit of 2 ppm for drug products. “The results of the products sampled in this study suggest that formulation is likely the strongest contributor to benzene concentrations in BPO drug products that are commercially available, since the magnitude of benzene detected correlates most closely with specific brands or product types within certain brands,” the study authors wrote.

When the researchers tested the stability of a prescription encapsulated BPO drug product at cold (2 °C) and elevated temperature (50 °C), no apparent benzene formation was observed at 2 °C, whereas high levels of benzene formed at 50 °C, “suggesting that encapsulation technology may not stabilize BPO drug products, but cold storage may greatly reduce benzene formation,” they wrote.

In another component of the study, researchers exposed a BP drug product to a UVA/UVB lamp for 2 hours and found detectable benzene through evaporation and substantial benzene formation when exposed to UV light at levels below peak sunlight. The experiment “strongly justifies the package label warnings to avoid sun exposure when using BPO drug products,” the authors wrote. “Further evaluation to determine the influence of sun exposure on BPO drug product degradation and benzene formation is warranted.”

In an interview, John Barbieri, MD, MBA, assistant professor of dermatology at Harvard Medical School and director of the Advanced Acne Therapeutics Clinic at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts characterized the findings as “an important issue that we should take seriously.” However, “we also must not overreact.”

BPO is a foundational acne treatment without any clear alternative, he said, pointing out that no evidence currently exists “to support that routine use of benzoyl peroxide–containing products for acne is associated with a meaningful risk of benzene in the blood or an increased risk of cancer.”

And although it is prudent to minimize benzene exposure as much as possible, Barbieri continued, “it is not clear that these levels are a clinically meaningful incremental risk in the setting of an acne cream or wash. There is minimal cutaneous absorption of benzene, and it is uncertain how much benzene aerosolizes with routine use, particularly for washes which are not left on the skin.”

Bunick said that the combined data from this and the study published in March 2024 affected which BPO products he recommends for patients with acne. “I am using exclusively the triple combination therapy (adapalene-clindamycin-benzoyl peroxide) because I know it has the necessary cold supply chain in place to protect the product’s stability. I further encourage patients to place all their benzoyl peroxide–containing products in the refrigerator at home to reduce benzene formation and exposure.”

Bunick reported having served as an investigator and/or a consultant/speaker for many pharmaceutical companies, including as a consultant for Ortho-Dermatologics; but none related to this study. Barbieri reported having no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF INVESTIGATIVE DERMATOLOGY

Utilization, Cost, and Prescription Trends of Antipsychotics Prescribed by Dermatologists for Medicare Patients

To the Editor:

Patients with primary psychiatric disorders with dermatologic manifestations often seek treatment from dermatologists instead of psychiatrists.1 For example, patients with delusions of parasitosis may lack insight into the underlying etiology of their disease and instead fixate on establishing an organic cause for their symptoms. As a result, it is an increasingly common practice for dermatologists to diagnose and treat psychiatric conditions.1 The goal of this study was to evaluate trends for the top 5 antipsychotics most frequently prescribed by dermatologists in the Medicare Part D database.

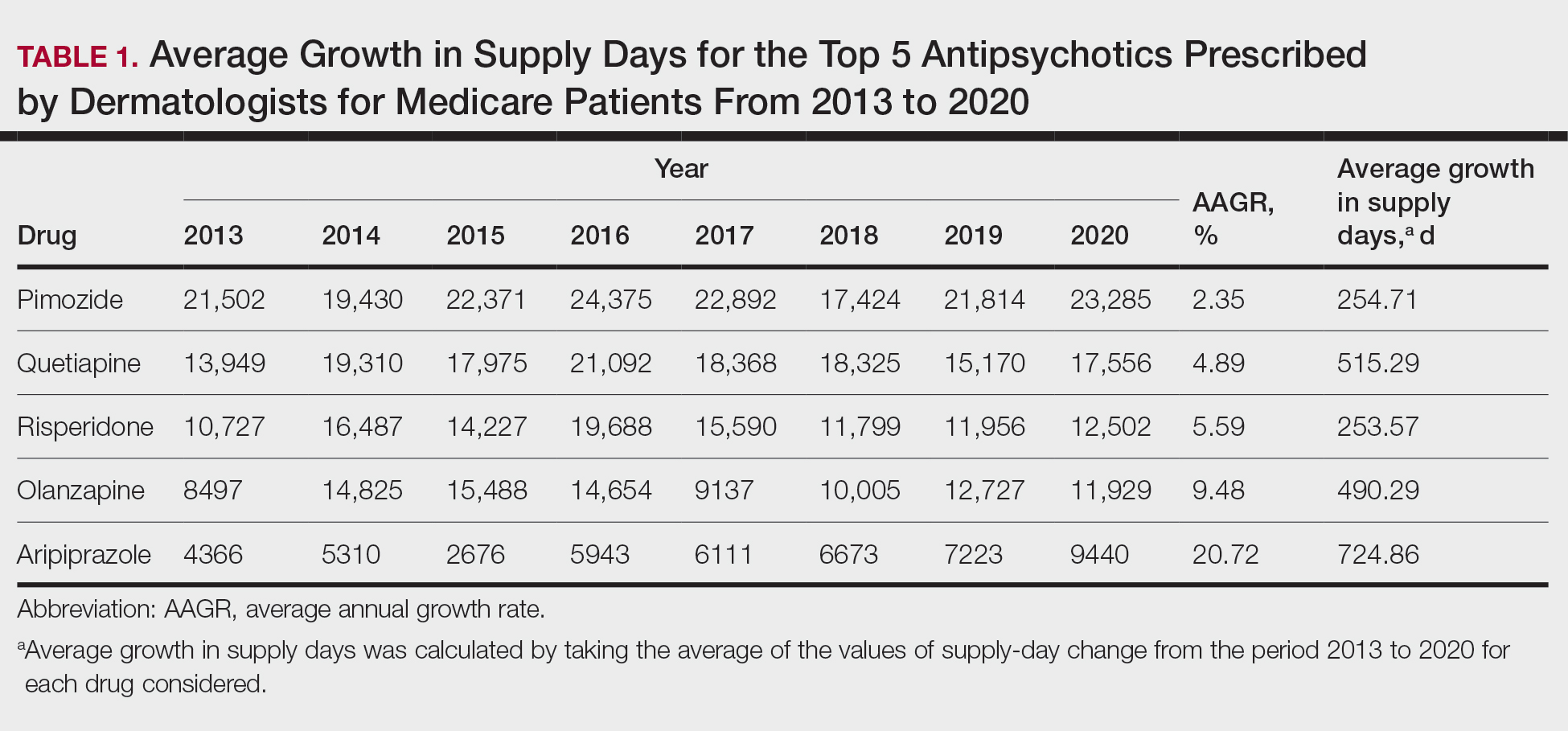

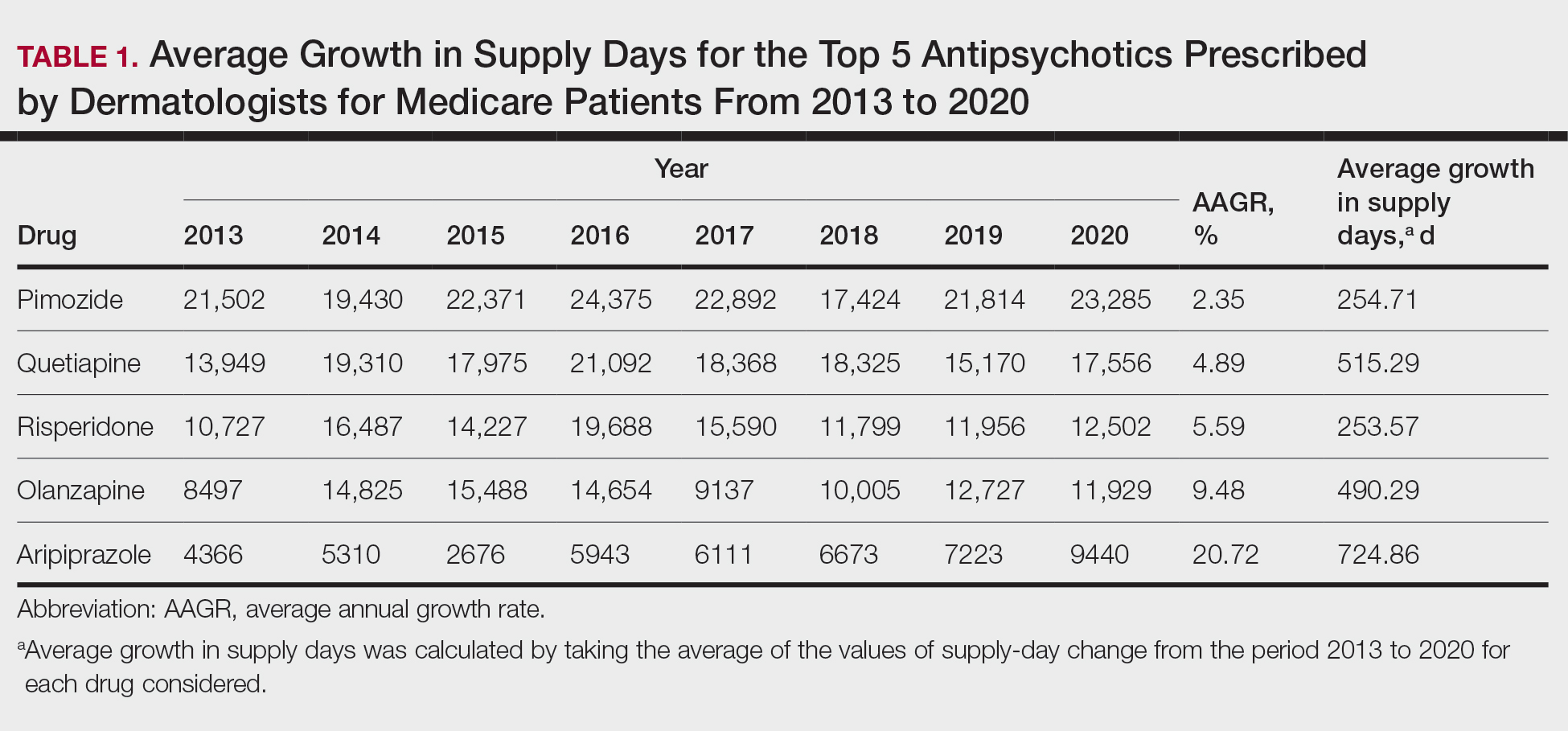

In this retrospective analysis, we consulted the Medicare Provider Utilization and Payment Data for January 2013 through December 2020, which is provided to the public by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.2 Only prescribing data from dermatologists were included in this study by using the built-in filter on the website to select “dermatology” as the prescriber type. All other provider types were excluded. We chose the top 5 most prescribed antipsychotics based on the number of supply days reported. Supply days—defined by Medicare as the number of days’ worth of medication that is prescribed—were used as a metric for utilization; therefore, each drug’s total supply days prescribed by dermatologists were calculated using this combined filter of drug name and total supply days using the database.

To analyze utilization over time, the annual average growth rate (AAGR) was calculated by determining the growth rate in total supply days annually from 2013 to 2020 and then averaging those rates to determine the overall AAGR. For greater clinical relevance, we calculated the average growth in supply days for the entire study period by determining the difference in the number of supply days for each year and then averaging these values. This was done to consider overall trends across dermatology rather than individual dermatologist prescribing patterns.

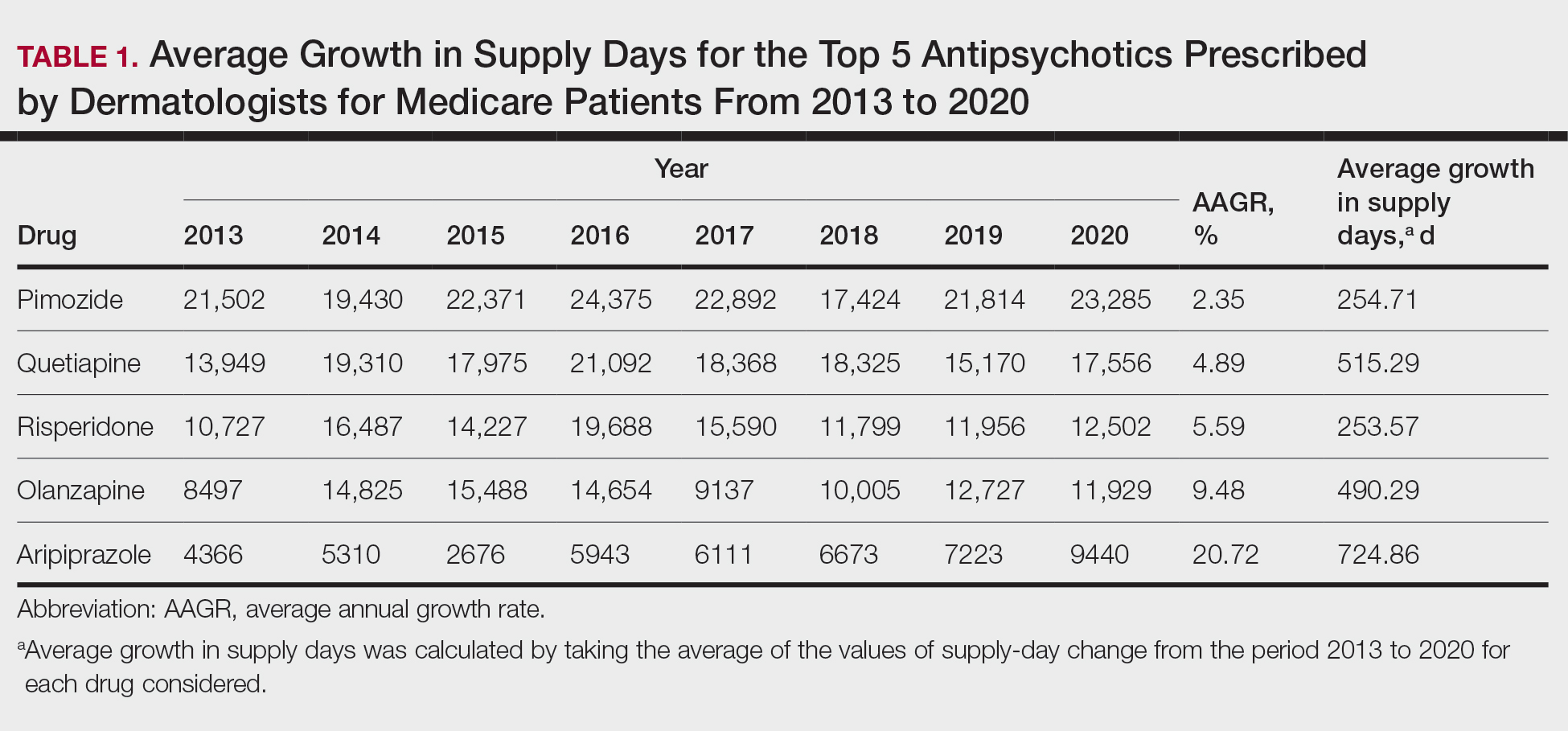

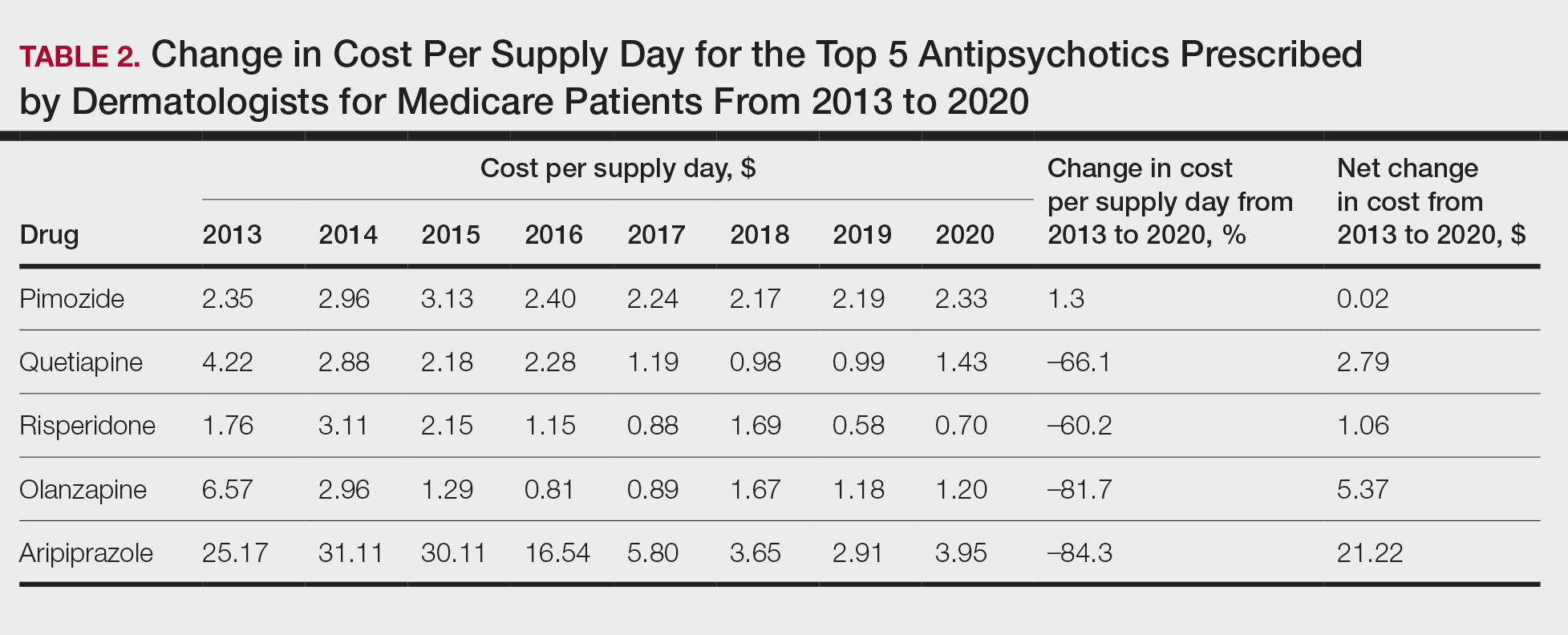

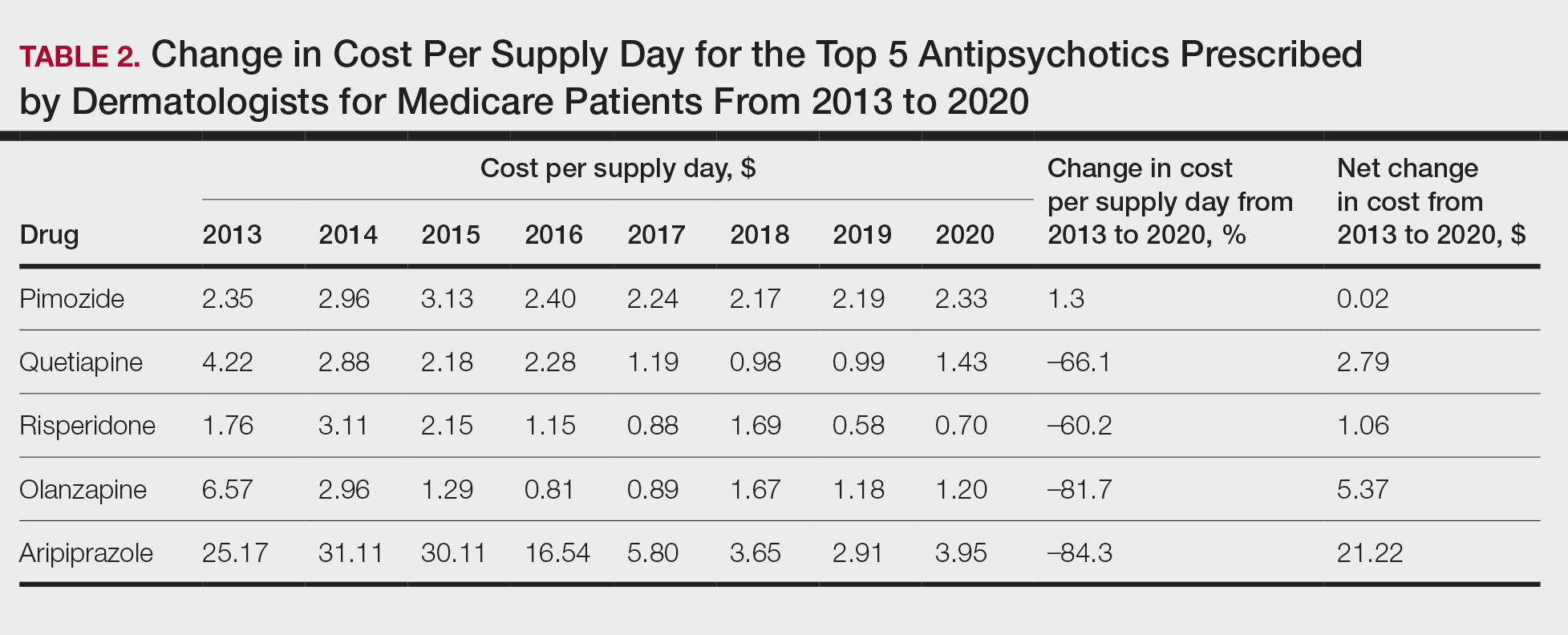

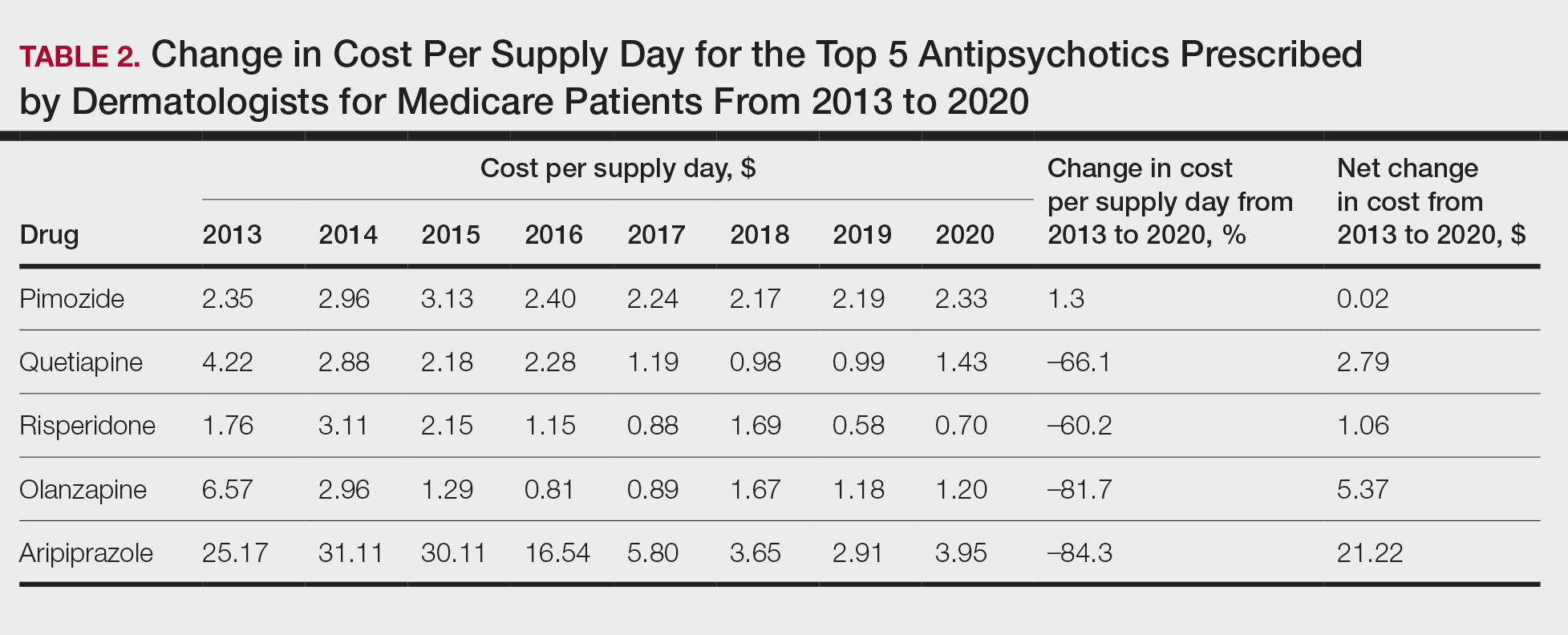

Based on our analysis, the antipsychotics most frequently prescribed by dermatologists for Medicare patients from January 2013 to December 2020 were pimozide, quetiapine, risperidone, olanzapine, and aripiprazole. The AAGR for each drug was 2.35%, 4.89%, 5.59%, 9.48%, and 20.72%, respectively, which is consistent with increased utilization over the study period for all 5 drugs (Table 1). The change in cost per supply day for the same period was 1.3%, –66.1%, –60.2%, –81.7%, and –84.3%, respectively. The net difference in cost per supply day over this entire period was $0.02, –$2.79, –$1.06, –$5.37, and –$21.22, respectively (Table 2).

There were several limitations to our study. Our analysis was limited to the Medicare population. Uninsured patients and those with Medicare Advantage or private health insurance plans were not included. In the Medicare database, only prescribers who prescribed a medication 10 times or more were recorded; therefore, some prescribers were not captured.

Although there was an increase in the dermatologic use of all 5 drugs in this study, perhaps the most marked growth was exhibited by aripiprazole, which had an AAGR of 20.72% (Table 1). Affordability may have been a factor, as the most marked reduction in price per supply day was noted for aripiprazole during the study period. Pimozide, which traditionally has been the first-line therapy for delusions of parasitosis, is the only first-generation antipsychotic drug among the 5 most frequently prescribed antipsychotics.3 Interestingly, pimozide had the lowest AAGR compared with the 4 second-generation antipsychotics. This finding also is corroborated by the average growth in supply days. While pimozide is a first-generation antipsychotic and had the lowest AAGR, pimozide still was the most prescribed antipsychotic in this study. Considering the average growth in Medicare beneficiaries during the study period was 2.70% per year,2 the AAGR of the 4 other drugs excluding pimozide shows that this growth was larger than what can be attributed to an increase in population size.

The most common conditions for which dermatologists prescribe antipsychotics are primary delusional infestation disorders as well as a range of self-inflicted dermatologic manifestations of dermatitis artefacta.4 Particularly, dermatologist-prescribed antipsychotics are first-line for these conditions in which perception of a persistent disease state is present.4 Importantly, dermatologists must differentiate between other dermatology-related psychiatric conditions such as trichotillomania and body dysmorphic disorder, which tend to respond better to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.4 Our data suggest that dermatologists are increasing their utilization of second-generation antipsychotics at a higher rate than first-generation antipsychotics, likely due to the lower risk of extrapyramidal symptoms. Patients are more willing to initiate a trial of psychiatric medication when it is prescribed by a dermatologist vs a psychiatrist due to lack of perceived stigma, which can lead to greater treatment compliance rates.5 As mentioned previously, as part of the differential, dermatologists also can effectively prescribe medications such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for symptoms including anxiety, trichotillomania, body dysmorphic disorder, or secondary psychiatric disorders as a result of the burden of skin disease.5

In many cases, a dermatologist may be the first and only specialist to evaluate patients with conditions that overlap within the jurisdiction of dermatology and psychiatry. It is imperative that dermatologists feel comfortable treating this vulnerable patient population. As demonstrated by Medicare prescription data, the increasing utilization of antipsychotics in our specialty demands that dermatologists possess an adequate working knowledge of psychopharmacology, which may be accomplished during residency training through several directives, including focused didactic sessions, elective rotations in psychiatry, increased exposure to psychocutaneous lectures at national conferences, and finally through the establishment of joint dermatology-psychiatry clinics with interdepartmental collaboration.

- Weber MB, Recuero JK, Almeida CS. Use of psychiatric drugs in dermatology. An Bras Dermatol. 2020;95:133-143. doi:10.1016/j.abd.2019.12.002

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare provider utilization and payment data: part D prescriber. Updated September 10, 2024. Accessed October 7, 2024. https://www.cms.gov/data -research/statistics-trends-and-reports/medicare-provider-utilization-payment-data/part-d-prescriber

- Bolognia J, Schaffe JV, Lorenzo C. Dermatology. In: Duncan KO, Koo JYM, eds. Psychocutaneous Diseases. Elsevier; 2017:128-136.

- Gupta MA, Vujcic B, Pur DR, et al. Use of antipsychotic drugs in dermatology. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36:765-773. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2018.08.006

- Jafferany M, Stamu-O’Brien C, Mkhoyan R, et al. Psychotropic drugs in dermatology: a dermatologist’s approach and choice of medications. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E13385. doi:10.1111/dth.13385

To the Editor:

Patients with primary psychiatric disorders with dermatologic manifestations often seek treatment from dermatologists instead of psychiatrists.1 For example, patients with delusions of parasitosis may lack insight into the underlying etiology of their disease and instead fixate on establishing an organic cause for their symptoms. As a result, it is an increasingly common practice for dermatologists to diagnose and treat psychiatric conditions.1 The goal of this study was to evaluate trends for the top 5 antipsychotics most frequently prescribed by dermatologists in the Medicare Part D database.

In this retrospective analysis, we consulted the Medicare Provider Utilization and Payment Data for January 2013 through December 2020, which is provided to the public by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.2 Only prescribing data from dermatologists were included in this study by using the built-in filter on the website to select “dermatology” as the prescriber type. All other provider types were excluded. We chose the top 5 most prescribed antipsychotics based on the number of supply days reported. Supply days—defined by Medicare as the number of days’ worth of medication that is prescribed—were used as a metric for utilization; therefore, each drug’s total supply days prescribed by dermatologists were calculated using this combined filter of drug name and total supply days using the database.

To analyze utilization over time, the annual average growth rate (AAGR) was calculated by determining the growth rate in total supply days annually from 2013 to 2020 and then averaging those rates to determine the overall AAGR. For greater clinical relevance, we calculated the average growth in supply days for the entire study period by determining the difference in the number of supply days for each year and then averaging these values. This was done to consider overall trends across dermatology rather than individual dermatologist prescribing patterns.

Based on our analysis, the antipsychotics most frequently prescribed by dermatologists for Medicare patients from January 2013 to December 2020 were pimozide, quetiapine, risperidone, olanzapine, and aripiprazole. The AAGR for each drug was 2.35%, 4.89%, 5.59%, 9.48%, and 20.72%, respectively, which is consistent with increased utilization over the study period for all 5 drugs (Table 1). The change in cost per supply day for the same period was 1.3%, –66.1%, –60.2%, –81.7%, and –84.3%, respectively. The net difference in cost per supply day over this entire period was $0.02, –$2.79, –$1.06, –$5.37, and –$21.22, respectively (Table 2).

There were several limitations to our study. Our analysis was limited to the Medicare population. Uninsured patients and those with Medicare Advantage or private health insurance plans were not included. In the Medicare database, only prescribers who prescribed a medication 10 times or more were recorded; therefore, some prescribers were not captured.

Although there was an increase in the dermatologic use of all 5 drugs in this study, perhaps the most marked growth was exhibited by aripiprazole, which had an AAGR of 20.72% (Table 1). Affordability may have been a factor, as the most marked reduction in price per supply day was noted for aripiprazole during the study period. Pimozide, which traditionally has been the first-line therapy for delusions of parasitosis, is the only first-generation antipsychotic drug among the 5 most frequently prescribed antipsychotics.3 Interestingly, pimozide had the lowest AAGR compared with the 4 second-generation antipsychotics. This finding also is corroborated by the average growth in supply days. While pimozide is a first-generation antipsychotic and had the lowest AAGR, pimozide still was the most prescribed antipsychotic in this study. Considering the average growth in Medicare beneficiaries during the study period was 2.70% per year,2 the AAGR of the 4 other drugs excluding pimozide shows that this growth was larger than what can be attributed to an increase in population size.

The most common conditions for which dermatologists prescribe antipsychotics are primary delusional infestation disorders as well as a range of self-inflicted dermatologic manifestations of dermatitis artefacta.4 Particularly, dermatologist-prescribed antipsychotics are first-line for these conditions in which perception of a persistent disease state is present.4 Importantly, dermatologists must differentiate between other dermatology-related psychiatric conditions such as trichotillomania and body dysmorphic disorder, which tend to respond better to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.4 Our data suggest that dermatologists are increasing their utilization of second-generation antipsychotics at a higher rate than first-generation antipsychotics, likely due to the lower risk of extrapyramidal symptoms. Patients are more willing to initiate a trial of psychiatric medication when it is prescribed by a dermatologist vs a psychiatrist due to lack of perceived stigma, which can lead to greater treatment compliance rates.5 As mentioned previously, as part of the differential, dermatologists also can effectively prescribe medications such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for symptoms including anxiety, trichotillomania, body dysmorphic disorder, or secondary psychiatric disorders as a result of the burden of skin disease.5

In many cases, a dermatologist may be the first and only specialist to evaluate patients with conditions that overlap within the jurisdiction of dermatology and psychiatry. It is imperative that dermatologists feel comfortable treating this vulnerable patient population. As demonstrated by Medicare prescription data, the increasing utilization of antipsychotics in our specialty demands that dermatologists possess an adequate working knowledge of psychopharmacology, which may be accomplished during residency training through several directives, including focused didactic sessions, elective rotations in psychiatry, increased exposure to psychocutaneous lectures at national conferences, and finally through the establishment of joint dermatology-psychiatry clinics with interdepartmental collaboration.

To the Editor:

Patients with primary psychiatric disorders with dermatologic manifestations often seek treatment from dermatologists instead of psychiatrists.1 For example, patients with delusions of parasitosis may lack insight into the underlying etiology of their disease and instead fixate on establishing an organic cause for their symptoms. As a result, it is an increasingly common practice for dermatologists to diagnose and treat psychiatric conditions.1 The goal of this study was to evaluate trends for the top 5 antipsychotics most frequently prescribed by dermatologists in the Medicare Part D database.

In this retrospective analysis, we consulted the Medicare Provider Utilization and Payment Data for January 2013 through December 2020, which is provided to the public by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.2 Only prescribing data from dermatologists were included in this study by using the built-in filter on the website to select “dermatology” as the prescriber type. All other provider types were excluded. We chose the top 5 most prescribed antipsychotics based on the number of supply days reported. Supply days—defined by Medicare as the number of days’ worth of medication that is prescribed—were used as a metric for utilization; therefore, each drug’s total supply days prescribed by dermatologists were calculated using this combined filter of drug name and total supply days using the database.

To analyze utilization over time, the annual average growth rate (AAGR) was calculated by determining the growth rate in total supply days annually from 2013 to 2020 and then averaging those rates to determine the overall AAGR. For greater clinical relevance, we calculated the average growth in supply days for the entire study period by determining the difference in the number of supply days for each year and then averaging these values. This was done to consider overall trends across dermatology rather than individual dermatologist prescribing patterns.

Based on our analysis, the antipsychotics most frequently prescribed by dermatologists for Medicare patients from January 2013 to December 2020 were pimozide, quetiapine, risperidone, olanzapine, and aripiprazole. The AAGR for each drug was 2.35%, 4.89%, 5.59%, 9.48%, and 20.72%, respectively, which is consistent with increased utilization over the study period for all 5 drugs (Table 1). The change in cost per supply day for the same period was 1.3%, –66.1%, –60.2%, –81.7%, and –84.3%, respectively. The net difference in cost per supply day over this entire period was $0.02, –$2.79, –$1.06, –$5.37, and –$21.22, respectively (Table 2).

There were several limitations to our study. Our analysis was limited to the Medicare population. Uninsured patients and those with Medicare Advantage or private health insurance plans were not included. In the Medicare database, only prescribers who prescribed a medication 10 times or more were recorded; therefore, some prescribers were not captured.

Although there was an increase in the dermatologic use of all 5 drugs in this study, perhaps the most marked growth was exhibited by aripiprazole, which had an AAGR of 20.72% (Table 1). Affordability may have been a factor, as the most marked reduction in price per supply day was noted for aripiprazole during the study period. Pimozide, which traditionally has been the first-line therapy for delusions of parasitosis, is the only first-generation antipsychotic drug among the 5 most frequently prescribed antipsychotics.3 Interestingly, pimozide had the lowest AAGR compared with the 4 second-generation antipsychotics. This finding also is corroborated by the average growth in supply days. While pimozide is a first-generation antipsychotic and had the lowest AAGR, pimozide still was the most prescribed antipsychotic in this study. Considering the average growth in Medicare beneficiaries during the study period was 2.70% per year,2 the AAGR of the 4 other drugs excluding pimozide shows that this growth was larger than what can be attributed to an increase in population size.

The most common conditions for which dermatologists prescribe antipsychotics are primary delusional infestation disorders as well as a range of self-inflicted dermatologic manifestations of dermatitis artefacta.4 Particularly, dermatologist-prescribed antipsychotics are first-line for these conditions in which perception of a persistent disease state is present.4 Importantly, dermatologists must differentiate between other dermatology-related psychiatric conditions such as trichotillomania and body dysmorphic disorder, which tend to respond better to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.4 Our data suggest that dermatologists are increasing their utilization of second-generation antipsychotics at a higher rate than first-generation antipsychotics, likely due to the lower risk of extrapyramidal symptoms. Patients are more willing to initiate a trial of psychiatric medication when it is prescribed by a dermatologist vs a psychiatrist due to lack of perceived stigma, which can lead to greater treatment compliance rates.5 As mentioned previously, as part of the differential, dermatologists also can effectively prescribe medications such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for symptoms including anxiety, trichotillomania, body dysmorphic disorder, or secondary psychiatric disorders as a result of the burden of skin disease.5

In many cases, a dermatologist may be the first and only specialist to evaluate patients with conditions that overlap within the jurisdiction of dermatology and psychiatry. It is imperative that dermatologists feel comfortable treating this vulnerable patient population. As demonstrated by Medicare prescription data, the increasing utilization of antipsychotics in our specialty demands that dermatologists possess an adequate working knowledge of psychopharmacology, which may be accomplished during residency training through several directives, including focused didactic sessions, elective rotations in psychiatry, increased exposure to psychocutaneous lectures at national conferences, and finally through the establishment of joint dermatology-psychiatry clinics with interdepartmental collaboration.

- Weber MB, Recuero JK, Almeida CS. Use of psychiatric drugs in dermatology. An Bras Dermatol. 2020;95:133-143. doi:10.1016/j.abd.2019.12.002

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare provider utilization and payment data: part D prescriber. Updated September 10, 2024. Accessed October 7, 2024. https://www.cms.gov/data -research/statistics-trends-and-reports/medicare-provider-utilization-payment-data/part-d-prescriber

- Bolognia J, Schaffe JV, Lorenzo C. Dermatology. In: Duncan KO, Koo JYM, eds. Psychocutaneous Diseases. Elsevier; 2017:128-136.

- Gupta MA, Vujcic B, Pur DR, et al. Use of antipsychotic drugs in dermatology. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36:765-773. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2018.08.006

- Jafferany M, Stamu-O’Brien C, Mkhoyan R, et al. Psychotropic drugs in dermatology: a dermatologist’s approach and choice of medications. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E13385. doi:10.1111/dth.13385

- Weber MB, Recuero JK, Almeida CS. Use of psychiatric drugs in dermatology. An Bras Dermatol. 2020;95:133-143. doi:10.1016/j.abd.2019.12.002

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare provider utilization and payment data: part D prescriber. Updated September 10, 2024. Accessed October 7, 2024. https://www.cms.gov/data -research/statistics-trends-and-reports/medicare-provider-utilization-payment-data/part-d-prescriber

- Bolognia J, Schaffe JV, Lorenzo C. Dermatology. In: Duncan KO, Koo JYM, eds. Psychocutaneous Diseases. Elsevier; 2017:128-136.

- Gupta MA, Vujcic B, Pur DR, et al. Use of antipsychotic drugs in dermatology. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36:765-773. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2018.08.006

- Jafferany M, Stamu-O’Brien C, Mkhoyan R, et al. Psychotropic drugs in dermatology: a dermatologist’s approach and choice of medications. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E13385. doi:10.1111/dth.13385

Practice Points

- Dermatologists are frontline medical providers who can be useful in screening for primary psychiatric disorders in patients with dermatologic manifestations.

- Second-generation antipsychotics are effective for treating many psychiatric disorders.

A 7-Year-Old Boy Presents With Dark Spots on His Scalp and Areas of Poor Hair Growth

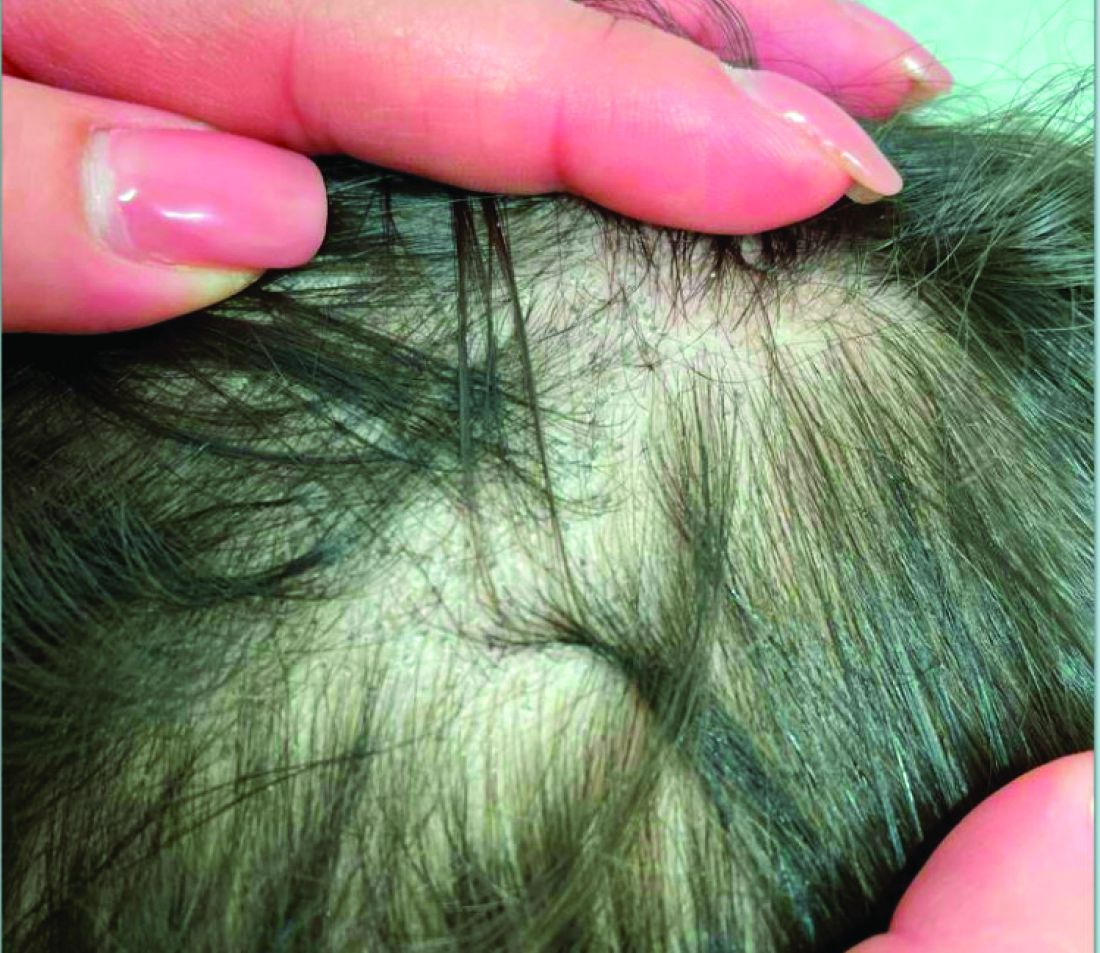

Given the trichoscopic findings, scrapings from the scaly areas were taken and revealed hyphae, confirming the diagnosis of tinea capitis. A fungal culture identified Trichophyton tonsurans as the causative organism.

Tinea capitis is the most common dermatophyte infection in children. Risk factors include participation in close-contact sports like wrestling or jiu-jitsu, attendance at daycare for younger children, African American hair care practices, pet ownership (particularly cats and rodents), and living in overcrowded conditions.

Diagnosis of tinea capitis requires a thorough clinical history to identify potential risk factors. On physical examination, patchy hair loss with associated scaling should raise suspicion for tinea capitis. Inflammatory signs, such as pustules and swelling, may suggest the presence of a kerion, further supporting the diagnosis. Although some practitioners use Wood’s lamp to help with diagnosis, its utility is limited. It detects fluorescence in Microsporum species (exothrix infections) but not in Trichophyton species (endothrix infections).

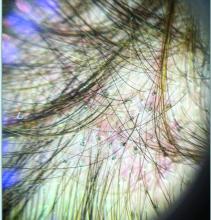

Trichoscopy can be a valuable tool when inflammation is minimal, and only hair loss and scaling are observed. Trichoscopic findings suggestive of tinea capitis include comma hairs, corkscrew hairs (as seen in this patient), Morse code-like hairs, zigzag hairs, bent hairs, block hairs, and i-hairs. Other common, though not characteristic, findings include broken hairs, black dots, perifollicular scaling, and diffuse scaling.

KOH (potassium hydroxide) analysis is another useful method for detecting fungal elements, though it does not identify the specific fungus and may not be available in all clinical settings. Mycologic culture remains the gold standard for diagnosing tinea capitis, though results can take 3-4 weeks. Newer diagnostic techniques, such as PCR analysis and MALDI-TOF/MS, offer more rapid identification of the causative organism.

The differential diagnosis includes:

- Seborrheic dermatitis, which presents with greasy, yellowish scales and itching, with trichoscopy showing twisted, coiled hairs and yellowish scaling.

- Psoriasis, which can mimic tinea capitis but presents with well-demarcated red plaques and silvery-white scales. Trichoscopy shows red dots and uniform scaling.

- Alopecia areata, which causes patchy hair loss without inflammation or scaling, with trichoscopic findings of exclamation mark hairs, black dots, and yellow dots.

- Trichotillomania, a hair-pulling disorder, which results in irregular patches of hair loss. Trichoscopy shows broken hairs of varying lengths, V-sign hairs, and flame-shaped residues at follicular openings.

Treatment of tinea capitis requires systemic antifungals and topical agents to prevent fungal spore spread. Several treatment guidelines are available from different institutions. Griseofulvin (FDA-approved for patients > 2 years of age) has been widely used, particularly for Microsporum canis infections. However, due to limited availability in many countries, terbinafine (FDA-approved for patients > 4 years of age) is now commonly used as first-line therapy, especially for Trichophyton species. Treatment typically lasts 4-6 weeks, and post-treatment cultures may be recommended to confirm mycologic cure.

Concerns about drug resistance have emerged, particularly for terbinafine-resistant dermatophytes linked to mutations in the squalene epoxidase enzyme. Resistance may be driven by limited antifungal availability and poor adherence to prolonged treatment regimens. While fluconazole and itraconazole are used off-label, growing evidence supports their effectiveness, although one large trial showed suboptimal cure rates with fluconazole.

Though systemic antifungals are generally safe, hepatotoxicity remains a concern, especially in patients with hepatic conditions or other comorbidities. Lab monitoring is advised for patients on prolonged or multiple therapies, or for those with coexisting conditions. The decision to conduct lab monitoring should be discussed with parents, balancing the very low risk of hepatotoxicity in healthy children against their comfort level.

An alternative to systemic therapy is photodynamic therapy (PDT), which has been reported as successful in treating tinea capitis infections, particularly in cases of T. mentagrophytes and M. canis. However, large-scale trials are needed to confirm PDT’s efficacy and safety.

In conclusion, children presenting with hair loss, scaling, and associated dark spots on the scalp should be evaluated for fungal infection. While trichoscopy can aid in diagnosis, fungal culture remains the gold standard for confirmation.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego.

References

Rudnicka L et al. Hair shafts in trichoscopy: clues for diagnosis of hair and scalp diseases. Dermatol Clin. 2013 Oct;31(4):695-708, x. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2013.06.007.

Gupta AK et al. An update on tinea capitis in children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2024 Aug 7. doi: 10.1111/pde.15708.

Anna Waskiel-Burnat et al. Trichoscopy of tinea capitis: A systematic review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2020 Feb;10(1):43-52. doi: 10.1007/s13555-019-00350-1.

Given the trichoscopic findings, scrapings from the scaly areas were taken and revealed hyphae, confirming the diagnosis of tinea capitis. A fungal culture identified Trichophyton tonsurans as the causative organism.

Tinea capitis is the most common dermatophyte infection in children. Risk factors include participation in close-contact sports like wrestling or jiu-jitsu, attendance at daycare for younger children, African American hair care practices, pet ownership (particularly cats and rodents), and living in overcrowded conditions.

Diagnosis of tinea capitis requires a thorough clinical history to identify potential risk factors. On physical examination, patchy hair loss with associated scaling should raise suspicion for tinea capitis. Inflammatory signs, such as pustules and swelling, may suggest the presence of a kerion, further supporting the diagnosis. Although some practitioners use Wood’s lamp to help with diagnosis, its utility is limited. It detects fluorescence in Microsporum species (exothrix infections) but not in Trichophyton species (endothrix infections).

Trichoscopy can be a valuable tool when inflammation is minimal, and only hair loss and scaling are observed. Trichoscopic findings suggestive of tinea capitis include comma hairs, corkscrew hairs (as seen in this patient), Morse code-like hairs, zigzag hairs, bent hairs, block hairs, and i-hairs. Other common, though not characteristic, findings include broken hairs, black dots, perifollicular scaling, and diffuse scaling.

KOH (potassium hydroxide) analysis is another useful method for detecting fungal elements, though it does not identify the specific fungus and may not be available in all clinical settings. Mycologic culture remains the gold standard for diagnosing tinea capitis, though results can take 3-4 weeks. Newer diagnostic techniques, such as PCR analysis and MALDI-TOF/MS, offer more rapid identification of the causative organism.

The differential diagnosis includes:

- Seborrheic dermatitis, which presents with greasy, yellowish scales and itching, with trichoscopy showing twisted, coiled hairs and yellowish scaling.

- Psoriasis, which can mimic tinea capitis but presents with well-demarcated red plaques and silvery-white scales. Trichoscopy shows red dots and uniform scaling.

- Alopecia areata, which causes patchy hair loss without inflammation or scaling, with trichoscopic findings of exclamation mark hairs, black dots, and yellow dots.

- Trichotillomania, a hair-pulling disorder, which results in irregular patches of hair loss. Trichoscopy shows broken hairs of varying lengths, V-sign hairs, and flame-shaped residues at follicular openings.

Treatment of tinea capitis requires systemic antifungals and topical agents to prevent fungal spore spread. Several treatment guidelines are available from different institutions. Griseofulvin (FDA-approved for patients > 2 years of age) has been widely used, particularly for Microsporum canis infections. However, due to limited availability in many countries, terbinafine (FDA-approved for patients > 4 years of age) is now commonly used as first-line therapy, especially for Trichophyton species. Treatment typically lasts 4-6 weeks, and post-treatment cultures may be recommended to confirm mycologic cure.

Concerns about drug resistance have emerged, particularly for terbinafine-resistant dermatophytes linked to mutations in the squalene epoxidase enzyme. Resistance may be driven by limited antifungal availability and poor adherence to prolonged treatment regimens. While fluconazole and itraconazole are used off-label, growing evidence supports their effectiveness, although one large trial showed suboptimal cure rates with fluconazole.

Though systemic antifungals are generally safe, hepatotoxicity remains a concern, especially in patients with hepatic conditions or other comorbidities. Lab monitoring is advised for patients on prolonged or multiple therapies, or for those with coexisting conditions. The decision to conduct lab monitoring should be discussed with parents, balancing the very low risk of hepatotoxicity in healthy children against their comfort level.

An alternative to systemic therapy is photodynamic therapy (PDT), which has been reported as successful in treating tinea capitis infections, particularly in cases of T. mentagrophytes and M. canis. However, large-scale trials are needed to confirm PDT’s efficacy and safety.

In conclusion, children presenting with hair loss, scaling, and associated dark spots on the scalp should be evaluated for fungal infection. While trichoscopy can aid in diagnosis, fungal culture remains the gold standard for confirmation.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego.

References

Rudnicka L et al. Hair shafts in trichoscopy: clues for diagnosis of hair and scalp diseases. Dermatol Clin. 2013 Oct;31(4):695-708, x. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2013.06.007.

Gupta AK et al. An update on tinea capitis in children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2024 Aug 7. doi: 10.1111/pde.15708.

Anna Waskiel-Burnat et al. Trichoscopy of tinea capitis: A systematic review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2020 Feb;10(1):43-52. doi: 10.1007/s13555-019-00350-1.

Given the trichoscopic findings, scrapings from the scaly areas were taken and revealed hyphae, confirming the diagnosis of tinea capitis. A fungal culture identified Trichophyton tonsurans as the causative organism.

Tinea capitis is the most common dermatophyte infection in children. Risk factors include participation in close-contact sports like wrestling or jiu-jitsu, attendance at daycare for younger children, African American hair care practices, pet ownership (particularly cats and rodents), and living in overcrowded conditions.

Diagnosis of tinea capitis requires a thorough clinical history to identify potential risk factors. On physical examination, patchy hair loss with associated scaling should raise suspicion for tinea capitis. Inflammatory signs, such as pustules and swelling, may suggest the presence of a kerion, further supporting the diagnosis. Although some practitioners use Wood’s lamp to help with diagnosis, its utility is limited. It detects fluorescence in Microsporum species (exothrix infections) but not in Trichophyton species (endothrix infections).

Trichoscopy can be a valuable tool when inflammation is minimal, and only hair loss and scaling are observed. Trichoscopic findings suggestive of tinea capitis include comma hairs, corkscrew hairs (as seen in this patient), Morse code-like hairs, zigzag hairs, bent hairs, block hairs, and i-hairs. Other common, though not characteristic, findings include broken hairs, black dots, perifollicular scaling, and diffuse scaling.

KOH (potassium hydroxide) analysis is another useful method for detecting fungal elements, though it does not identify the specific fungus and may not be available in all clinical settings. Mycologic culture remains the gold standard for diagnosing tinea capitis, though results can take 3-4 weeks. Newer diagnostic techniques, such as PCR analysis and MALDI-TOF/MS, offer more rapid identification of the causative organism.

The differential diagnosis includes:

- Seborrheic dermatitis, which presents with greasy, yellowish scales and itching, with trichoscopy showing twisted, coiled hairs and yellowish scaling.

- Psoriasis, which can mimic tinea capitis but presents with well-demarcated red plaques and silvery-white scales. Trichoscopy shows red dots and uniform scaling.

- Alopecia areata, which causes patchy hair loss without inflammation or scaling, with trichoscopic findings of exclamation mark hairs, black dots, and yellow dots.

- Trichotillomania, a hair-pulling disorder, which results in irregular patches of hair loss. Trichoscopy shows broken hairs of varying lengths, V-sign hairs, and flame-shaped residues at follicular openings.

Treatment of tinea capitis requires systemic antifungals and topical agents to prevent fungal spore spread. Several treatment guidelines are available from different institutions. Griseofulvin (FDA-approved for patients > 2 years of age) has been widely used, particularly for Microsporum canis infections. However, due to limited availability in many countries, terbinafine (FDA-approved for patients > 4 years of age) is now commonly used as first-line therapy, especially for Trichophyton species. Treatment typically lasts 4-6 weeks, and post-treatment cultures may be recommended to confirm mycologic cure.

Concerns about drug resistance have emerged, particularly for terbinafine-resistant dermatophytes linked to mutations in the squalene epoxidase enzyme. Resistance may be driven by limited antifungal availability and poor adherence to prolonged treatment regimens. While fluconazole and itraconazole are used off-label, growing evidence supports their effectiveness, although one large trial showed suboptimal cure rates with fluconazole.

Though systemic antifungals are generally safe, hepatotoxicity remains a concern, especially in patients with hepatic conditions or other comorbidities. Lab monitoring is advised for patients on prolonged or multiple therapies, or for those with coexisting conditions. The decision to conduct lab monitoring should be discussed with parents, balancing the very low risk of hepatotoxicity in healthy children against their comfort level.

An alternative to systemic therapy is photodynamic therapy (PDT), which has been reported as successful in treating tinea capitis infections, particularly in cases of T. mentagrophytes and M. canis. However, large-scale trials are needed to confirm PDT’s efficacy and safety.

In conclusion, children presenting with hair loss, scaling, and associated dark spots on the scalp should be evaluated for fungal infection. While trichoscopy can aid in diagnosis, fungal culture remains the gold standard for confirmation.

Dr. Matiz is a pediatric dermatologist at Southern California Permanente Medical Group, San Diego.

References

Rudnicka L et al. Hair shafts in trichoscopy: clues for diagnosis of hair and scalp diseases. Dermatol Clin. 2013 Oct;31(4):695-708, x. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2013.06.007.

Gupta AK et al. An update on tinea capitis in children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2024 Aug 7. doi: 10.1111/pde.15708.

Anna Waskiel-Burnat et al. Trichoscopy of tinea capitis: A systematic review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2020 Feb;10(1):43-52. doi: 10.1007/s13555-019-00350-1.

Pulsed Dye Laser a “Go-To Device” Option for Acne Treatment When Access to 1726-nm Lasers Is Limited

CARLSBAD, CALIF. — Lasers and energy-based treatments alone or in combination with medical therapy may improve outcomes for patients with moderate to severe acne, according to Arielle Kauvar, MD.

At the Controversies and Conversations in Laser and Cosmetic Surgery annual symposium, Kauvar, director of New York Laser & Skin Care, New York City, highlighted several reasons why using lasers for acne is beneficial. “First, we know that topical therapy alone is often ineffective, and antibiotic treatment does not address the cause of acne and can alter the skin and gut microbiome,” she said. “Isotretinoin is highly effective, but there’s an increasing reluctance to use it. Lasers and energy devices are effective in treating acne and may also treat the post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation and scarring associated with it.”

The pathogenesis of acne is multifactorial, she continued, including a disruption of sebaceous gland activity, with overproduction and alteration of sebum and abnormal follicular keratinization. Acne also causes an imbalance of the skin microbiome, local inflammation, and activation of both innate and adaptive immunity.

“Many studies point to the fact that inflammation and immune system activation may actually be the primary event” of acne formation, said Kauvar, who is also a clinical professor of dermatology at New York University, New York City. “This persistent immune activation is also associated with scarring,” she noted. “So, are we off the mark in terms of trying to kill sebaceous glands? Should we be concentrating on anti-inflammatory approaches?”

AviClear became the first 1726-nm laser cleared by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of mild to severe acne vulgaris in 2022, followed a few months later with the FDA clearance of another 1726-nm laser, the Accure Acne Laser System in November 2022. These lasers cause selective photothermolysis of sebaceous glands, but according to Kauvar, “access to these devices is somewhat limited at this time.”

What is available includes her go-to device, the pulsed dye laser (PDL), which has been widely studied and shown in a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies to be effective for acne. The PDL “targets dermal blood vessels facilitating inflammation, upregulates TGF-beta, and inhibits CD4+ T cell-mediated inflammation,” she said. “It can also treat PIH [post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation] and may be helpful in scar prevention.”

In an abstract presented at The American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery (ASLMS) 2024 annual meeting, Kauvar and colleagues conducted a real-world study of PDL therapy in 15 adult women with recalcitrant acne who were maintained on their medical treatment regimen. Their mean age was 27 years, and they had skin types II-IV; they underwent four monthly PDL treatments with follow-up at 1 and 3 months. At each visit, the researchers took digital photographs and counted inflammatory acne lesions, non-inflammatory acne lesions, and post-inflammatory pigment alteration (PIPA) lesions.

The main outcomes of interest were the investigator global assessment (IGA) scores at the 1- and 3-month follow-up visits. Kauvar and colleagues observed a significant improvement in IGA scores at the 1- and 3-month follow-up visits (P < .05), with an average decrease of 1.8 and 1.6 points in the acne severity scale, respectively, from a baseline score of 3.4. By the 3-month follow-up visits, counts of inflammatory and non-inflammatory lesions decreased significantly (P < .05), and 61% of study participants showed a decrease in the PIPA count. No adverse events occurred.

Kauvar disclosed that she has conducted research for Candela, Lumenis, and Sofwave, and is an adviser to Acclaro.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

CARLSBAD, CALIF. — Lasers and energy-based treatments alone or in combination with medical therapy may improve outcomes for patients with moderate to severe acne, according to Arielle Kauvar, MD.

At the Controversies and Conversations in Laser and Cosmetic Surgery annual symposium, Kauvar, director of New York Laser & Skin Care, New York City, highlighted several reasons why using lasers for acne is beneficial. “First, we know that topical therapy alone is often ineffective, and antibiotic treatment does not address the cause of acne and can alter the skin and gut microbiome,” she said. “Isotretinoin is highly effective, but there’s an increasing reluctance to use it. Lasers and energy devices are effective in treating acne and may also treat the post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation and scarring associated with it.”

The pathogenesis of acne is multifactorial, she continued, including a disruption of sebaceous gland activity, with overproduction and alteration of sebum and abnormal follicular keratinization. Acne also causes an imbalance of the skin microbiome, local inflammation, and activation of both innate and adaptive immunity.

“Many studies point to the fact that inflammation and immune system activation may actually be the primary event” of acne formation, said Kauvar, who is also a clinical professor of dermatology at New York University, New York City. “This persistent immune activation is also associated with scarring,” she noted. “So, are we off the mark in terms of trying to kill sebaceous glands? Should we be concentrating on anti-inflammatory approaches?”

AviClear became the first 1726-nm laser cleared by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of mild to severe acne vulgaris in 2022, followed a few months later with the FDA clearance of another 1726-nm laser, the Accure Acne Laser System in November 2022. These lasers cause selective photothermolysis of sebaceous glands, but according to Kauvar, “access to these devices is somewhat limited at this time.”

What is available includes her go-to device, the pulsed dye laser (PDL), which has been widely studied and shown in a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies to be effective for acne. The PDL “targets dermal blood vessels facilitating inflammation, upregulates TGF-beta, and inhibits CD4+ T cell-mediated inflammation,” she said. “It can also treat PIH [post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation] and may be helpful in scar prevention.”

In an abstract presented at The American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery (ASLMS) 2024 annual meeting, Kauvar and colleagues conducted a real-world study of PDL therapy in 15 adult women with recalcitrant acne who were maintained on their medical treatment regimen. Their mean age was 27 years, and they had skin types II-IV; they underwent four monthly PDL treatments with follow-up at 1 and 3 months. At each visit, the researchers took digital photographs and counted inflammatory acne lesions, non-inflammatory acne lesions, and post-inflammatory pigment alteration (PIPA) lesions.

The main outcomes of interest were the investigator global assessment (IGA) scores at the 1- and 3-month follow-up visits. Kauvar and colleagues observed a significant improvement in IGA scores at the 1- and 3-month follow-up visits (P < .05), with an average decrease of 1.8 and 1.6 points in the acne severity scale, respectively, from a baseline score of 3.4. By the 3-month follow-up visits, counts of inflammatory and non-inflammatory lesions decreased significantly (P < .05), and 61% of study participants showed a decrease in the PIPA count. No adverse events occurred.

Kauvar disclosed that she has conducted research for Candela, Lumenis, and Sofwave, and is an adviser to Acclaro.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

CARLSBAD, CALIF. — Lasers and energy-based treatments alone or in combination with medical therapy may improve outcomes for patients with moderate to severe acne, according to Arielle Kauvar, MD.

At the Controversies and Conversations in Laser and Cosmetic Surgery annual symposium, Kauvar, director of New York Laser & Skin Care, New York City, highlighted several reasons why using lasers for acne is beneficial. “First, we know that topical therapy alone is often ineffective, and antibiotic treatment does not address the cause of acne and can alter the skin and gut microbiome,” she said. “Isotretinoin is highly effective, but there’s an increasing reluctance to use it. Lasers and energy devices are effective in treating acne and may also treat the post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation and scarring associated with it.”

The pathogenesis of acne is multifactorial, she continued, including a disruption of sebaceous gland activity, with overproduction and alteration of sebum and abnormal follicular keratinization. Acne also causes an imbalance of the skin microbiome, local inflammation, and activation of both innate and adaptive immunity.

“Many studies point to the fact that inflammation and immune system activation may actually be the primary event” of acne formation, said Kauvar, who is also a clinical professor of dermatology at New York University, New York City. “This persistent immune activation is also associated with scarring,” she noted. “So, are we off the mark in terms of trying to kill sebaceous glands? Should we be concentrating on anti-inflammatory approaches?”

AviClear became the first 1726-nm laser cleared by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of mild to severe acne vulgaris in 2022, followed a few months later with the FDA clearance of another 1726-nm laser, the Accure Acne Laser System in November 2022. These lasers cause selective photothermolysis of sebaceous glands, but according to Kauvar, “access to these devices is somewhat limited at this time.”

What is available includes her go-to device, the pulsed dye laser (PDL), which has been widely studied and shown in a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies to be effective for acne. The PDL “targets dermal blood vessels facilitating inflammation, upregulates TGF-beta, and inhibits CD4+ T cell-mediated inflammation,” she said. “It can also treat PIH [post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation] and may be helpful in scar prevention.”

In an abstract presented at The American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery (ASLMS) 2024 annual meeting, Kauvar and colleagues conducted a real-world study of PDL therapy in 15 adult women with recalcitrant acne who were maintained on their medical treatment regimen. Their mean age was 27 years, and they had skin types II-IV; they underwent four monthly PDL treatments with follow-up at 1 and 3 months. At each visit, the researchers took digital photographs and counted inflammatory acne lesions, non-inflammatory acne lesions, and post-inflammatory pigment alteration (PIPA) lesions.

The main outcomes of interest were the investigator global assessment (IGA) scores at the 1- and 3-month follow-up visits. Kauvar and colleagues observed a significant improvement in IGA scores at the 1- and 3-month follow-up visits (P < .05), with an average decrease of 1.8 and 1.6 points in the acne severity scale, respectively, from a baseline score of 3.4. By the 3-month follow-up visits, counts of inflammatory and non-inflammatory lesions decreased significantly (P < .05), and 61% of study participants showed a decrease in the PIPA count. No adverse events occurred.

Kauvar disclosed that she has conducted research for Candela, Lumenis, and Sofwave, and is an adviser to Acclaro.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A Hard Look at Toxic Workplace Culture in Medicine

While Kellie Lease Stecher, MD, was working as an ob.gyn. in Minneapolis, Minnesota, a patient confided in her a sexual assault allegation about one of Stecher’s male colleagues. Stecher shared the allegation with her supervisor, who told Stecher not to file a report and chose not to address the issue with the patient. Stecher weighed how to do the right thing: Should she speak up? What were the ethical and legal implications of speaking up vs staying silent?

After seeking advice from her mentors, Stecher felt it was her moral and legal duty to report the allegation to the Minnesota Medical Board. Once she did, her supervisor chastised her repeatedly for reporting the allegation. Stecher soon found herself in a hostile work environment where she was regularly singled out and silenced by her supervisor and colleagues.

“I got to a point where I felt like I couldn’t say anything at any meetings without somehow being targeted after the meeting. There was an individual who was even allowed to fat-shame me with no consequences,” Stecher said. “[Being bullied at work is] a struggle because you have no voice, you have no opportunities, and there’s someone who is intentionally making your life uncomfortable.”

Stecher’s experience is not unusual. Mistreatment is a common issue among healthcare workers, ranging from rudeness to bullying and harassment and permeating every level and specialty of the medical profession. A 2019 research review estimated that 26.3% of healthcare workers had experienced bullying and found bullying in healthcare to be associated with mental health problems such as burnout and depression, physical health problems such as insomnia and headaches, and physicians taking more sick leave.

The Medscape Physician Workplace Culture Report 2024 found similarly bleak results:

- 38% said workplace culture is declining.

- 70% don’t see a big commitment from employers for positive culture.

- 48% said staff isn’t committed to positive culture.

The irony, of course, is that most physicians enter the field to care for people. As individuals go from medical school to residency and on with the rest of their careers, they often experience a rude awakening.

It’s Everywhere

Noticing the prevalence of workplace bullying in the medical field, endocrinologist Farah Khan, MD, at UW Medicine in Seattle, Washington, decided to conduct a survey on the issue.

Khan collected 122 responses from colleagues, friends, and acquaintances in the field. When asked if they had ever been bullied in medicine, 68% of respondents said yes. But here’s the fascinating part: She tried to pinpoint one particular area or source of toxicity in the progression of a physician’s career — and couldn’t because it existed at all levels.

More than one third of respondents said their worst bullying experiences occurred in residency, while 30% said mistreatment was worst in medical school, and 24% indicated their worst experience had occurred once they became an attending.

The litany of experiences included being belittled, excluded, yelled at, criticized, shamed, unfairly blamed, threatened, sexually harassed, subjected to bigotry and slurs, and humiliated.

“What surprised me the most was how widespread this problem is and the many different layers of healthcare it permeates through, from operating room staff to medical students to hospital HR to residents and attendings,” Khan said of her findings.

Who Cares for the Caregivers?

When hematologist Mikkael Sekeres, MD, was in medical school, he seriously considered a career as a surgeon. Following success in his surgical rotations, he scrubbed in with a cardiothoracic surgeon who was well known for both his status as a surgeon and his fiery temper. Sekeres witnessed the surgeon yelling at whoever was nearby: Medical students, fellows, residents, operating room nurses.

“At the end of that experience, any passing thoughts I had of going into cardiothoracic surgery were gone,” Sekeres said. “Some of the people I met in surgery were truly wonderful. Some were unhappy people.”

He has clear ideas why. Mental health struggles that are all too common among physicians can be caused or exacerbated by mistreatment and can also lead a physician to mistreat others.

“People bully when they themselves are hurting,” Sekeres said. “It begs the question, why are people hurting? What’s driving them to be bullies? I think part of the reason is that they’re working really hard and they’re tired, and nobody’s caring for them. It’s hard to care for others when you feel as if you’re hurting more than they are.”

Gail Gazelle, MD, experienced something like this. In her case, the pressure to please and to be a perfect professional and mother affected how she interacted with those around her. While working as a hospice medical director and an academician and clinician at Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, she found herself feeling exhausted and burnt out but simultaneously guilty for not doing enough at work or at home.

Guess what happened? She became irritable, lashing out at her son and not putting her best foot forward with coworkers or patients.

After trying traditional therapy and self-help through books and podcasts, Gazelle found her solution in life coaching. “I realized just how harsh I was being on myself and found ways to reverse that pattern,” she said. “I learned ways of regulating myself emotionally that I definitely didn’t learn in my training.”

Today, Gazelle works as a life coach herself, guiding physicians through common challenges of the profession — particularly bullying, which she sees often. She remembers one client, an oncologist, who was being targeted by a nurse practitioner she was training. The nurse practitioner began talking back to the oncologist, as well as gossiping and bad-mouthing her to the nurses in the practice. The nurses then began excluding the oncologist from their cafeteria table at lunchtime, which felt blatant in such a small practice.

A core component of Gazelle’s coaching strategy was helping the client reclaim her self-esteem by focusing on her strengths. She instructed the client to write down what went well that day each night rather than lying in bed ruminating. Such self-care strategies can not only help bullied physicians but also prevent some of the challenges that might cause a physician to bully or lash out at another in the first place.

Such strategies, along with the recent influx of wellness programs available in healthcare facilities, can help physicians cope with the mental health impacts of bullying and the job in general. But even life coaches like Gazelle acknowledge that they are often band-aids on the system’s deeper wounds. Bullying in healthcare is not an individual issue; at its core, it’s an institutional one.

Negative Hierarchies in Healthcare

When Stecher’s contract expired, she was fired by the supervisor who had been bullying her. Stecher has since filed a lawsuit, claiming sexual discrimination, defamation, and wrongful termination.

The medical field has a long history of hierarchy, and while this rigidity has softened over time, negative hierarchical dynamics are often perpetuated by leaders. Phenomena like cronyism and cliques and behaviors like petty gossip, lunchroom exclusion (which in the worst cases can mimic high school dynamics), and targeting can be at play in the healthcare workplace.

The classic examples, Stecher said, can usually be spotted: “If you threaten the status quo or offer different ideas, you are seen as a threat. Cronyism ... strict hierarchies ... people who elevate individuals in their social arena into leadership positions. Physicians don’t get the leadership training that they really need; they are often just dumped into roles with no previous experience because they’re someone’s golfing buddy.”

The question is how to get workplace culture momentum moving in a positive direction. When Gazelle’s clients are hesitant to voice concerns, she emphasizes doing so can and should benefit leadership, as well as patients and the wider healthcare system.

“The win-win is that you have a healthy culture of respect and dignity and civility rather than the opposite,” she said. “The leader will actually have more staff retention, which everybody’s concerned about, given the shortage of healthcare workers.”

And that’s a key incentive that may not be discussed as much: Talent drain from toxicity. The Medscape Workplace Culture Report asked about culture as it applies to physicians looking to join up. Notably, 93% of doctors say culture is important when mulling a job offer, 70% said culture is equal to money, and 18% ranked it as more important than money, and 46% say a positive atmosphere is the top priority.

Ultimately, it comes down to who is willing to step in and stand up. Respondents to Khan’s survey counted anonymous reporting systems, more supportive administration teams, and zero-tolerance policies as potential remedies. Gazelle, Sekeres, and Stecher all emphasize the need for zero-tolerance policies for bullying and mistreatment.

“We can’t afford to have things going on like this that just destroy the fabric of the healthcare endeavor,” Gazelle said. “They come out sideways eventually. They come out in terms of poor patient care because there are greater errors. There’s a lack of respect for patients. There’s anger and irritability and so much spillover. We have to have zero-tolerance policies from the top down.”

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

While Kellie Lease Stecher, MD, was working as an ob.gyn. in Minneapolis, Minnesota, a patient confided in her a sexual assault allegation about one of Stecher’s male colleagues. Stecher shared the allegation with her supervisor, who told Stecher not to file a report and chose not to address the issue with the patient. Stecher weighed how to do the right thing: Should she speak up? What were the ethical and legal implications of speaking up vs staying silent?

After seeking advice from her mentors, Stecher felt it was her moral and legal duty to report the allegation to the Minnesota Medical Board. Once she did, her supervisor chastised her repeatedly for reporting the allegation. Stecher soon found herself in a hostile work environment where she was regularly singled out and silenced by her supervisor and colleagues.

“I got to a point where I felt like I couldn’t say anything at any meetings without somehow being targeted after the meeting. There was an individual who was even allowed to fat-shame me with no consequences,” Stecher said. “[Being bullied at work is] a struggle because you have no voice, you have no opportunities, and there’s someone who is intentionally making your life uncomfortable.”

Stecher’s experience is not unusual. Mistreatment is a common issue among healthcare workers, ranging from rudeness to bullying and harassment and permeating every level and specialty of the medical profession. A 2019 research review estimated that 26.3% of healthcare workers had experienced bullying and found bullying in healthcare to be associated with mental health problems such as burnout and depression, physical health problems such as insomnia and headaches, and physicians taking more sick leave.

The Medscape Physician Workplace Culture Report 2024 found similarly bleak results:

- 38% said workplace culture is declining.

- 70% don’t see a big commitment from employers for positive culture.

- 48% said staff isn’t committed to positive culture.

The irony, of course, is that most physicians enter the field to care for people. As individuals go from medical school to residency and on with the rest of their careers, they often experience a rude awakening.

It’s Everywhere

Noticing the prevalence of workplace bullying in the medical field, endocrinologist Farah Khan, MD, at UW Medicine in Seattle, Washington, decided to conduct a survey on the issue.

Khan collected 122 responses from colleagues, friends, and acquaintances in the field. When asked if they had ever been bullied in medicine, 68% of respondents said yes. But here’s the fascinating part: She tried to pinpoint one particular area or source of toxicity in the progression of a physician’s career — and couldn’t because it existed at all levels.

More than one third of respondents said their worst bullying experiences occurred in residency, while 30% said mistreatment was worst in medical school, and 24% indicated their worst experience had occurred once they became an attending.

The litany of experiences included being belittled, excluded, yelled at, criticized, shamed, unfairly blamed, threatened, sexually harassed, subjected to bigotry and slurs, and humiliated.

“What surprised me the most was how widespread this problem is and the many different layers of healthcare it permeates through, from operating room staff to medical students to hospital HR to residents and attendings,” Khan said of her findings.

Who Cares for the Caregivers?

When hematologist Mikkael Sekeres, MD, was in medical school, he seriously considered a career as a surgeon. Following success in his surgical rotations, he scrubbed in with a cardiothoracic surgeon who was well known for both his status as a surgeon and his fiery temper. Sekeres witnessed the surgeon yelling at whoever was nearby: Medical students, fellows, residents, operating room nurses.

“At the end of that experience, any passing thoughts I had of going into cardiothoracic surgery were gone,” Sekeres said. “Some of the people I met in surgery were truly wonderful. Some were unhappy people.”

He has clear ideas why. Mental health struggles that are all too common among physicians can be caused or exacerbated by mistreatment and can also lead a physician to mistreat others.

“People bully when they themselves are hurting,” Sekeres said. “It begs the question, why are people hurting? What’s driving them to be bullies? I think part of the reason is that they’re working really hard and they’re tired, and nobody’s caring for them. It’s hard to care for others when you feel as if you’re hurting more than they are.”

Gail Gazelle, MD, experienced something like this. In her case, the pressure to please and to be a perfect professional and mother affected how she interacted with those around her. While working as a hospice medical director and an academician and clinician at Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, she found herself feeling exhausted and burnt out but simultaneously guilty for not doing enough at work or at home.

Guess what happened? She became irritable, lashing out at her son and not putting her best foot forward with coworkers or patients.

After trying traditional therapy and self-help through books and podcasts, Gazelle found her solution in life coaching. “I realized just how harsh I was being on myself and found ways to reverse that pattern,” she said. “I learned ways of regulating myself emotionally that I definitely didn’t learn in my training.”