User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Exercising to lose weight is not for every ‘body’

Exercising to lose weight is not for every ‘body’

This first item comes from the “You’ve got to be kidding” section of LOTME’s supersecret topics-of-interest file.

Investigators at the Shenzhen Institute of Advanced Technology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and the University of Roehampton noticed that some people who enrolled in exercise programs to lose weight did just the opposite: they gained weight.

Being scientists, they decided to look at the effects of energy expenditure and how those effects varied among individuals. The likely culprit in this case, they determined, is something called compensatory mechanisms. One such mechanism involves eating more food because exercise stimulates appetite, and another might reduce energy expenditure on other components like resting metabolism so that the exercise is, in effect, less costly.

A look at the numbers shows how compensatory mechanisms worked in the study population of 1,750 adults. Among individuals with the highest BMI, 51% of the calories burned during activity translated into calories burned at the end of the day. For those with normal BMI, however, 72% of calories burned during activity were reflected in total expenditure.

“People living with obesity cut back their resting metabolism when they are more active. The result is that for every calorie they spend on exercise they save about half a calorie on resting,” the investigators explained.

In other words, some bodies will, unconsciously, work against the conscious effort of exercising to lose weight. Thank you very much, compensatory mechanisms, for the boundarylessness exhibited in exceeding your job description.

When it comes to the mix, walnuts go nuts

When it comes to mixed nuts, walnuts get no love. But we may be able to give you a reason to not pick them out: Your arteries.

Participants in a recent study who ate about a half-cup of walnuts every day for 2 years saw a drop in their low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol. The number and quality of LDL particles in healthy older adults also improved. How? Good ol’ omega-3 fatty acids.

Omega-3 is found in many foods linked to lower risks of heart disease, lower cholesterol levels, and lower blood sugar levels, but the one thing that makes the walnut a front runner for Miss Super Food 2021 is their ability to improve the quality of LDL particles.

“LDL particles come in various sizes [and] research has shown that small, dense LDL particles are more often associated with atherosclerosis, the plaque or fatty deposits that build up in the arteries,” Emilio Ros, MD, PhD, of the Hospital Clínic of Barcelona and the study’s senior investigator, said in a written statement.

The 708 participants, aged 63-79 years and mostly women, were divided into two groups: One received the walnut diet and the other did not. After 2 years, the walnut group had lower LDL levels by an average of 4.3 mg/dL. Total cholesterol was reduced by an average of 8.5 mg/dL. Also, their total LDL particle count was 4.3% lower and small LDL particles were down by 6.1%.

So instead of picking the walnuts out of the mix, try to find it in your heart to appreciate them. Your body already does.

Begun, the clone war has

Well, not quite yet, Master Yoda, but perhaps one day soon, if a study from Japan into the uncanny valley of the usage of cloned humanlike faces in robotics and artificial intelligence, published in PLOS One, is to be believed.

The study consisted of a number of six smaller experiments in which participants judged a series of images based on subjective eeriness, emotional valence, and realism. The images included people with the same cloned face; people with different faces; dogs; identical twins, triplets, quadruplets, etc.; and cloned animated characters. In the sixth experiment, the photos were the same as in the second (six cloned faces, six different faces, and a single face) but participants also answered the Disgust Scale–Revised to accurately analyze disgust sensitivity.

The results of all these experiments were quite clear: People found the cloned faces far creepier than the varied or single face, an effect the researchers called clone devaluation. Notably, this effect only applied to realistic human faces; most people didn’t find the cloned dogs or cloned animated characters creepy. However, those who did were more likely to find the human clones eerie on the Disgust Scale.

The authors noted that future robotics technology needs to be carefully considered to avoid the uncanny valley and this clone devaluation effect, which is a very good point. The last thing we need is a few million robots with identical faces getting angry at us and pulling a Terminator/Order 66 combo. We’re already in a viral apocalypse; we don’t need a robot one on top of that.

Congratulations to our new favorite reader

The winner of last week’s inaugural Pandemic Pandemonium comes to us from Tiffanie Roe. By getting her entry in first, just ahead of the flood of responses we received – and by flood we mean a very slow and very quickly repaired drip – Ms. Roe puts the gold medal for COVID-related insanity around the necks of Australian magpies, who may start attacking people wearing face masks during “swooping season” because the birds don’t recognize them.

Exercising to lose weight is not for every ‘body’

This first item comes from the “You’ve got to be kidding” section of LOTME’s supersecret topics-of-interest file.

Investigators at the Shenzhen Institute of Advanced Technology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and the University of Roehampton noticed that some people who enrolled in exercise programs to lose weight did just the opposite: they gained weight.

Being scientists, they decided to look at the effects of energy expenditure and how those effects varied among individuals. The likely culprit in this case, they determined, is something called compensatory mechanisms. One such mechanism involves eating more food because exercise stimulates appetite, and another might reduce energy expenditure on other components like resting metabolism so that the exercise is, in effect, less costly.

A look at the numbers shows how compensatory mechanisms worked in the study population of 1,750 adults. Among individuals with the highest BMI, 51% of the calories burned during activity translated into calories burned at the end of the day. For those with normal BMI, however, 72% of calories burned during activity were reflected in total expenditure.

“People living with obesity cut back their resting metabolism when they are more active. The result is that for every calorie they spend on exercise they save about half a calorie on resting,” the investigators explained.

In other words, some bodies will, unconsciously, work against the conscious effort of exercising to lose weight. Thank you very much, compensatory mechanisms, for the boundarylessness exhibited in exceeding your job description.

When it comes to the mix, walnuts go nuts

When it comes to mixed nuts, walnuts get no love. But we may be able to give you a reason to not pick them out: Your arteries.

Participants in a recent study who ate about a half-cup of walnuts every day for 2 years saw a drop in their low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol. The number and quality of LDL particles in healthy older adults also improved. How? Good ol’ omega-3 fatty acids.

Omega-3 is found in many foods linked to lower risks of heart disease, lower cholesterol levels, and lower blood sugar levels, but the one thing that makes the walnut a front runner for Miss Super Food 2021 is their ability to improve the quality of LDL particles.

“LDL particles come in various sizes [and] research has shown that small, dense LDL particles are more often associated with atherosclerosis, the plaque or fatty deposits that build up in the arteries,” Emilio Ros, MD, PhD, of the Hospital Clínic of Barcelona and the study’s senior investigator, said in a written statement.

The 708 participants, aged 63-79 years and mostly women, were divided into two groups: One received the walnut diet and the other did not. After 2 years, the walnut group had lower LDL levels by an average of 4.3 mg/dL. Total cholesterol was reduced by an average of 8.5 mg/dL. Also, their total LDL particle count was 4.3% lower and small LDL particles were down by 6.1%.

So instead of picking the walnuts out of the mix, try to find it in your heart to appreciate them. Your body already does.

Begun, the clone war has

Well, not quite yet, Master Yoda, but perhaps one day soon, if a study from Japan into the uncanny valley of the usage of cloned humanlike faces in robotics and artificial intelligence, published in PLOS One, is to be believed.

The study consisted of a number of six smaller experiments in which participants judged a series of images based on subjective eeriness, emotional valence, and realism. The images included people with the same cloned face; people with different faces; dogs; identical twins, triplets, quadruplets, etc.; and cloned animated characters. In the sixth experiment, the photos were the same as in the second (six cloned faces, six different faces, and a single face) but participants also answered the Disgust Scale–Revised to accurately analyze disgust sensitivity.

The results of all these experiments were quite clear: People found the cloned faces far creepier than the varied or single face, an effect the researchers called clone devaluation. Notably, this effect only applied to realistic human faces; most people didn’t find the cloned dogs or cloned animated characters creepy. However, those who did were more likely to find the human clones eerie on the Disgust Scale.

The authors noted that future robotics technology needs to be carefully considered to avoid the uncanny valley and this clone devaluation effect, which is a very good point. The last thing we need is a few million robots with identical faces getting angry at us and pulling a Terminator/Order 66 combo. We’re already in a viral apocalypse; we don’t need a robot one on top of that.

Congratulations to our new favorite reader

The winner of last week’s inaugural Pandemic Pandemonium comes to us from Tiffanie Roe. By getting her entry in first, just ahead of the flood of responses we received – and by flood we mean a very slow and very quickly repaired drip – Ms. Roe puts the gold medal for COVID-related insanity around the necks of Australian magpies, who may start attacking people wearing face masks during “swooping season” because the birds don’t recognize them.

Exercising to lose weight is not for every ‘body’

This first item comes from the “You’ve got to be kidding” section of LOTME’s supersecret topics-of-interest file.

Investigators at the Shenzhen Institute of Advanced Technology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and the University of Roehampton noticed that some people who enrolled in exercise programs to lose weight did just the opposite: they gained weight.

Being scientists, they decided to look at the effects of energy expenditure and how those effects varied among individuals. The likely culprit in this case, they determined, is something called compensatory mechanisms. One such mechanism involves eating more food because exercise stimulates appetite, and another might reduce energy expenditure on other components like resting metabolism so that the exercise is, in effect, less costly.

A look at the numbers shows how compensatory mechanisms worked in the study population of 1,750 adults. Among individuals with the highest BMI, 51% of the calories burned during activity translated into calories burned at the end of the day. For those with normal BMI, however, 72% of calories burned during activity were reflected in total expenditure.

“People living with obesity cut back their resting metabolism when they are more active. The result is that for every calorie they spend on exercise they save about half a calorie on resting,” the investigators explained.

In other words, some bodies will, unconsciously, work against the conscious effort of exercising to lose weight. Thank you very much, compensatory mechanisms, for the boundarylessness exhibited in exceeding your job description.

When it comes to the mix, walnuts go nuts

When it comes to mixed nuts, walnuts get no love. But we may be able to give you a reason to not pick them out: Your arteries.

Participants in a recent study who ate about a half-cup of walnuts every day for 2 years saw a drop in their low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol. The number and quality of LDL particles in healthy older adults also improved. How? Good ol’ omega-3 fatty acids.

Omega-3 is found in many foods linked to lower risks of heart disease, lower cholesterol levels, and lower blood sugar levels, but the one thing that makes the walnut a front runner for Miss Super Food 2021 is their ability to improve the quality of LDL particles.

“LDL particles come in various sizes [and] research has shown that small, dense LDL particles are more often associated with atherosclerosis, the plaque or fatty deposits that build up in the arteries,” Emilio Ros, MD, PhD, of the Hospital Clínic of Barcelona and the study’s senior investigator, said in a written statement.

The 708 participants, aged 63-79 years and mostly women, were divided into two groups: One received the walnut diet and the other did not. After 2 years, the walnut group had lower LDL levels by an average of 4.3 mg/dL. Total cholesterol was reduced by an average of 8.5 mg/dL. Also, their total LDL particle count was 4.3% lower and small LDL particles were down by 6.1%.

So instead of picking the walnuts out of the mix, try to find it in your heart to appreciate them. Your body already does.

Begun, the clone war has

Well, not quite yet, Master Yoda, but perhaps one day soon, if a study from Japan into the uncanny valley of the usage of cloned humanlike faces in robotics and artificial intelligence, published in PLOS One, is to be believed.

The study consisted of a number of six smaller experiments in which participants judged a series of images based on subjective eeriness, emotional valence, and realism. The images included people with the same cloned face; people with different faces; dogs; identical twins, triplets, quadruplets, etc.; and cloned animated characters. In the sixth experiment, the photos were the same as in the second (six cloned faces, six different faces, and a single face) but participants also answered the Disgust Scale–Revised to accurately analyze disgust sensitivity.

The results of all these experiments were quite clear: People found the cloned faces far creepier than the varied or single face, an effect the researchers called clone devaluation. Notably, this effect only applied to realistic human faces; most people didn’t find the cloned dogs or cloned animated characters creepy. However, those who did were more likely to find the human clones eerie on the Disgust Scale.

The authors noted that future robotics technology needs to be carefully considered to avoid the uncanny valley and this clone devaluation effect, which is a very good point. The last thing we need is a few million robots with identical faces getting angry at us and pulling a Terminator/Order 66 combo. We’re already in a viral apocalypse; we don’t need a robot one on top of that.

Congratulations to our new favorite reader

The winner of last week’s inaugural Pandemic Pandemonium comes to us from Tiffanie Roe. By getting her entry in first, just ahead of the flood of responses we received – and by flood we mean a very slow and very quickly repaired drip – Ms. Roe puts the gold medal for COVID-related insanity around the necks of Australian magpies, who may start attacking people wearing face masks during “swooping season” because the birds don’t recognize them.

Even highly allergic adults unlikely to react to COVID-19 vaccine

published Aug. 31, 2021, in JAMA Network Open. Symptoms resolved in a few hours with medication, and no patients required hospitalization.

Risk for allergic reaction has been one of several obstacles in global vaccination efforts, the authors, led by Nancy Agmon-Levin, MD, of the Sheba Medical Center, Ramat Gan, Israel, wrote. Clinical trials for the Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccines excluded individuals with allergies to any component of the vaccine or with previous allergies to other vaccines. Early reports of anaphylaxis in reaction to the vaccines caused concern among patients and practitioners. Soon after, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and other authorities released guidance on preparing for allergic reactions. “Despite these recommendations, uncertainty remains, particularly among patients with a history of anaphylaxis and/or multiple allergies,” the authors added.

In response to early concerns, the Sheba Medical Center opened a COVID-19 referral center to address safety questions and to conduct assessments of allergy risk for the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine, the first COVID-19 vaccine approved in Israel. From Dec. 27, 2020, to Feb. 22, 2021, the referral center assessed 8,102 patients with allergies. Those who were not clearly at low risk filled out a questionnaire about prior allergic or anaphylactic reactions to drugs or vaccines, other allergies, and other relevant medical history. Patients were considered to be at high risk for allergic reactions if they met at least one of the following criteria: previous anaphylactic reaction to any drug or vaccine, multiple drug allergies, multiple other allergies, and mast cell disorders. Individuals were also classified as high risk if their health care practitioner deferred vaccination because of allergy concerns.

Nearly 95% of the cohort (7,668 individuals) were classified as low risk and received both Pfizer vaccine doses at standard immunization sites and underwent 30 minutes of observation after immunization. Although the study did not follow these lower-risk patients, “no serious allergic reactions were reported back to our referral center by patients or their general practitioner after immunization in the regular settings,” the authors wrote.

Five patients were considered ineligible for immunization because of known sensitivity to polyethylene glycol or multiple anaphylactic reactions to different injectable drugs, following recommendations from the Ministry of Health of Israel at the time. The remaining 429 individuals were deemed high risk and underwent observation for 2 hours from a dedicated allergy team after immunization. For these high-risk patients, both vaccine doses were administered in the same setting. Patients also reported any adverse reactions in the 21 days between the first and second dose.

Women made up most of the high-risk cohort (70.9%). The average age of participants was 52 years. Of the high-risk individuals, 63.2% reported prior anaphylaxis, 32.9% had multiple drug allergies, and 30.3% had multiple other allergies.

During the first 2 hours following immunization, nine individuals (2.1%), all women, experienced allergic reactions. Six individuals (1.4%) experienced minor reactions, including skin flushing, tongue or uvula swelling, or a cough that resolved with antihistamine treatment during the observation period. Three patients (0.7%) had anaphylactic reactions that occurred 10 to 20 minutes after injection. All three patients experienced significant bronchospasm, skin eruption, itching, and shortness of breath. Two patients experienced angioedema, and one patient had gastrointestinal symptoms. They were treated with adrenaline, antihistamines, and an inhaled bronchodilator. All symptoms resolved within 2-6 hours, and no patient required hospitalization.

In the days following vaccination, patients commonly reported pain at the injection site, fatigue, muscle pain, and headache; 14.7% of patients reported skin eruption, itching, or urticaria.

As of Feb. 22, 2021, 218 patients from this highly allergic cohort received their second dose of the vaccine. Four patients (1.8%) had mild allergic reactions. All four developed flushing, and one patient also developed a cough that resolved with antihistamine treatment. Three of these patients had experienced mild allergic reactions to the first dose and were premedicated for the second dose. One patient only reacted to the second dose.

The findings should be “very reassuring” to individuals hesitant to receive the vaccine, Elizabeth Phillips, MD, the director of the Center for Drug Safety and Immunology at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., said in an interview. She was not involved with the research and wrote an invited commentary on the study. “The rates of anaphylaxis and allergic reactions are truly quite low,” she said. Although about 2% of the high-risk group developed allergic reactions to immunization, the overall percentage for the entire cohort would be much lower.

The study did not investigate specific risk factors for and mechanisms of allergic reactions to COVID-19 vaccines, Dr. Phillips said, which is a study limitation that the authors also acknowledge. The National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases is currently trying to answer some of these questions with a multisite, randomized, double-blinded study. The study is intended to help understand why people have these allergic reactions, Dr. Phillips added. Vanderbilt is one of the sites for the study.

While researchers continue to hunt for answers, the algorithm developed by the authors provides “a great strategy to get people that are at higher risk vaccinated in a monitored setting,” she said. The results show that “people should not be avoiding vaccination because of a history of anaphylaxis.”

Dr. Phillips has received institutional grants from the National Institutes of Health and the National Health and Medical Research Council; royalties from UpToDate and Lexicomp; and consulting fees from Janssen, Vertex, Biocryst, and Regeneron.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

published Aug. 31, 2021, in JAMA Network Open. Symptoms resolved in a few hours with medication, and no patients required hospitalization.

Risk for allergic reaction has been one of several obstacles in global vaccination efforts, the authors, led by Nancy Agmon-Levin, MD, of the Sheba Medical Center, Ramat Gan, Israel, wrote. Clinical trials for the Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccines excluded individuals with allergies to any component of the vaccine or with previous allergies to other vaccines. Early reports of anaphylaxis in reaction to the vaccines caused concern among patients and practitioners. Soon after, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and other authorities released guidance on preparing for allergic reactions. “Despite these recommendations, uncertainty remains, particularly among patients with a history of anaphylaxis and/or multiple allergies,” the authors added.

In response to early concerns, the Sheba Medical Center opened a COVID-19 referral center to address safety questions and to conduct assessments of allergy risk for the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine, the first COVID-19 vaccine approved in Israel. From Dec. 27, 2020, to Feb. 22, 2021, the referral center assessed 8,102 patients with allergies. Those who were not clearly at low risk filled out a questionnaire about prior allergic or anaphylactic reactions to drugs or vaccines, other allergies, and other relevant medical history. Patients were considered to be at high risk for allergic reactions if they met at least one of the following criteria: previous anaphylactic reaction to any drug or vaccine, multiple drug allergies, multiple other allergies, and mast cell disorders. Individuals were also classified as high risk if their health care practitioner deferred vaccination because of allergy concerns.

Nearly 95% of the cohort (7,668 individuals) were classified as low risk and received both Pfizer vaccine doses at standard immunization sites and underwent 30 minutes of observation after immunization. Although the study did not follow these lower-risk patients, “no serious allergic reactions were reported back to our referral center by patients or their general practitioner after immunization in the regular settings,” the authors wrote.

Five patients were considered ineligible for immunization because of known sensitivity to polyethylene glycol or multiple anaphylactic reactions to different injectable drugs, following recommendations from the Ministry of Health of Israel at the time. The remaining 429 individuals were deemed high risk and underwent observation for 2 hours from a dedicated allergy team after immunization. For these high-risk patients, both vaccine doses were administered in the same setting. Patients also reported any adverse reactions in the 21 days between the first and second dose.

Women made up most of the high-risk cohort (70.9%). The average age of participants was 52 years. Of the high-risk individuals, 63.2% reported prior anaphylaxis, 32.9% had multiple drug allergies, and 30.3% had multiple other allergies.

During the first 2 hours following immunization, nine individuals (2.1%), all women, experienced allergic reactions. Six individuals (1.4%) experienced minor reactions, including skin flushing, tongue or uvula swelling, or a cough that resolved with antihistamine treatment during the observation period. Three patients (0.7%) had anaphylactic reactions that occurred 10 to 20 minutes after injection. All three patients experienced significant bronchospasm, skin eruption, itching, and shortness of breath. Two patients experienced angioedema, and one patient had gastrointestinal symptoms. They were treated with adrenaline, antihistamines, and an inhaled bronchodilator. All symptoms resolved within 2-6 hours, and no patient required hospitalization.

In the days following vaccination, patients commonly reported pain at the injection site, fatigue, muscle pain, and headache; 14.7% of patients reported skin eruption, itching, or urticaria.

As of Feb. 22, 2021, 218 patients from this highly allergic cohort received their second dose of the vaccine. Four patients (1.8%) had mild allergic reactions. All four developed flushing, and one patient also developed a cough that resolved with antihistamine treatment. Three of these patients had experienced mild allergic reactions to the first dose and were premedicated for the second dose. One patient only reacted to the second dose.

The findings should be “very reassuring” to individuals hesitant to receive the vaccine, Elizabeth Phillips, MD, the director of the Center for Drug Safety and Immunology at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., said in an interview. She was not involved with the research and wrote an invited commentary on the study. “The rates of anaphylaxis and allergic reactions are truly quite low,” she said. Although about 2% of the high-risk group developed allergic reactions to immunization, the overall percentage for the entire cohort would be much lower.

The study did not investigate specific risk factors for and mechanisms of allergic reactions to COVID-19 vaccines, Dr. Phillips said, which is a study limitation that the authors also acknowledge. The National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases is currently trying to answer some of these questions with a multisite, randomized, double-blinded study. The study is intended to help understand why people have these allergic reactions, Dr. Phillips added. Vanderbilt is one of the sites for the study.

While researchers continue to hunt for answers, the algorithm developed by the authors provides “a great strategy to get people that are at higher risk vaccinated in a monitored setting,” she said. The results show that “people should not be avoiding vaccination because of a history of anaphylaxis.”

Dr. Phillips has received institutional grants from the National Institutes of Health and the National Health and Medical Research Council; royalties from UpToDate and Lexicomp; and consulting fees from Janssen, Vertex, Biocryst, and Regeneron.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

published Aug. 31, 2021, in JAMA Network Open. Symptoms resolved in a few hours with medication, and no patients required hospitalization.

Risk for allergic reaction has been one of several obstacles in global vaccination efforts, the authors, led by Nancy Agmon-Levin, MD, of the Sheba Medical Center, Ramat Gan, Israel, wrote. Clinical trials for the Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccines excluded individuals with allergies to any component of the vaccine or with previous allergies to other vaccines. Early reports of anaphylaxis in reaction to the vaccines caused concern among patients and practitioners. Soon after, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and other authorities released guidance on preparing for allergic reactions. “Despite these recommendations, uncertainty remains, particularly among patients with a history of anaphylaxis and/or multiple allergies,” the authors added.

In response to early concerns, the Sheba Medical Center opened a COVID-19 referral center to address safety questions and to conduct assessments of allergy risk for the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine, the first COVID-19 vaccine approved in Israel. From Dec. 27, 2020, to Feb. 22, 2021, the referral center assessed 8,102 patients with allergies. Those who were not clearly at low risk filled out a questionnaire about prior allergic or anaphylactic reactions to drugs or vaccines, other allergies, and other relevant medical history. Patients were considered to be at high risk for allergic reactions if they met at least one of the following criteria: previous anaphylactic reaction to any drug or vaccine, multiple drug allergies, multiple other allergies, and mast cell disorders. Individuals were also classified as high risk if their health care practitioner deferred vaccination because of allergy concerns.

Nearly 95% of the cohort (7,668 individuals) were classified as low risk and received both Pfizer vaccine doses at standard immunization sites and underwent 30 minutes of observation after immunization. Although the study did not follow these lower-risk patients, “no serious allergic reactions were reported back to our referral center by patients or their general practitioner after immunization in the regular settings,” the authors wrote.

Five patients were considered ineligible for immunization because of known sensitivity to polyethylene glycol or multiple anaphylactic reactions to different injectable drugs, following recommendations from the Ministry of Health of Israel at the time. The remaining 429 individuals were deemed high risk and underwent observation for 2 hours from a dedicated allergy team after immunization. For these high-risk patients, both vaccine doses were administered in the same setting. Patients also reported any adverse reactions in the 21 days between the first and second dose.

Women made up most of the high-risk cohort (70.9%). The average age of participants was 52 years. Of the high-risk individuals, 63.2% reported prior anaphylaxis, 32.9% had multiple drug allergies, and 30.3% had multiple other allergies.

During the first 2 hours following immunization, nine individuals (2.1%), all women, experienced allergic reactions. Six individuals (1.4%) experienced minor reactions, including skin flushing, tongue or uvula swelling, or a cough that resolved with antihistamine treatment during the observation period. Three patients (0.7%) had anaphylactic reactions that occurred 10 to 20 minutes after injection. All three patients experienced significant bronchospasm, skin eruption, itching, and shortness of breath. Two patients experienced angioedema, and one patient had gastrointestinal symptoms. They were treated with adrenaline, antihistamines, and an inhaled bronchodilator. All symptoms resolved within 2-6 hours, and no patient required hospitalization.

In the days following vaccination, patients commonly reported pain at the injection site, fatigue, muscle pain, and headache; 14.7% of patients reported skin eruption, itching, or urticaria.

As of Feb. 22, 2021, 218 patients from this highly allergic cohort received their second dose of the vaccine. Four patients (1.8%) had mild allergic reactions. All four developed flushing, and one patient also developed a cough that resolved with antihistamine treatment. Three of these patients had experienced mild allergic reactions to the first dose and were premedicated for the second dose. One patient only reacted to the second dose.

The findings should be “very reassuring” to individuals hesitant to receive the vaccine, Elizabeth Phillips, MD, the director of the Center for Drug Safety and Immunology at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., said in an interview. She was not involved with the research and wrote an invited commentary on the study. “The rates of anaphylaxis and allergic reactions are truly quite low,” she said. Although about 2% of the high-risk group developed allergic reactions to immunization, the overall percentage for the entire cohort would be much lower.

The study did not investigate specific risk factors for and mechanisms of allergic reactions to COVID-19 vaccines, Dr. Phillips said, which is a study limitation that the authors also acknowledge. The National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases is currently trying to answer some of these questions with a multisite, randomized, double-blinded study. The study is intended to help understand why people have these allergic reactions, Dr. Phillips added. Vanderbilt is one of the sites for the study.

While researchers continue to hunt for answers, the algorithm developed by the authors provides “a great strategy to get people that are at higher risk vaccinated in a monitored setting,” she said. The results show that “people should not be avoiding vaccination because of a history of anaphylaxis.”

Dr. Phillips has received institutional grants from the National Institutes of Health and the National Health and Medical Research Council; royalties from UpToDate and Lexicomp; and consulting fees from Janssen, Vertex, Biocryst, and Regeneron.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID-clogged ICUs ‘terrify’ those with chronic or emergency illness

Jessica Gosnell, MD, 41, from Portland, Oregon, lives daily with the knowledge that her rare disease — a form of hereditary angioedema — could cause a sudden, severe swelling in her throat that could require quick intubation and land her in an intensive care unit (ICU) for days.

“I’ve been hospitalized for throat swells three times in the last year,” she said in an interview.

Dr. Gosnell no longer practices medicine because of a combination of illnesses, but lives with her husband, Andrew, and two young children, and said they are all “terrified” she will have to go to the hospital amid a COVID-19 surge that had shrunk the number of available ICU beds to 152 from 780 in Oregon as of Aug. 30. Thirty percent of the beds are in use for patients with COVID-19.

She said her life depends on being near hospitals that have ICUs and having access to highly specialized medications, one of which can cost up to $50,000 for the rescue dose.

Her fear has her “literally living bedbound.” In addition to hereditary angioedema, she has Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, which weakens connective tissue. She wears a cervical collar 24/7 to keep from tearing tissues, as any tissue injury can trigger a swell.

Patients worry there won’t be room

As ICU beds in most states are filling with COVID-19 patients as the Delta variant spreads, fears are rising among people like Dr. Gosnell, who have chronic conditions and diseases with unpredictable emergency visits, who worry that if they need emergency care there won’t be room.

As of Aug. 30, in the United States, 79% of ICU beds nationally were in use, 30% of them for COVID-19 patients, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

In individual states, the picture is dire. Alabama has fewer than 10% of its ICU beds open across the entire state. In Florida, 93% of ICU beds are filled, 53% of them with COVID patients. In Louisiana, 87% of beds were already in use, 45% of them with COVID patients, just as category 4 hurricane Ida smashed into the coastline on Aug. 29.

News reports have told of people transported and airlifted as hospitals reach capacity.

In Bellville, Tex., U.S. Army veteran Daniel Wilkinson needed advanced care for gallstone pancreatitis that normally would take 30 minutes to treat, his Bellville doctor, Hasan Kakli, MD, told CBS News.

Mr. Wilkinson’s house was three doors from Bellville Hospital, but the hospital was not equipped to treat the condition. Calls to other hospitals found the same answer: no empty ICU beds. After a 7-hour wait on a stretcher, he was airlifted to a Veterans Affairs hospital in Houston, but it was too late. He died on August 22 at age 46.

Dr. Kakli said, “I’ve never lost a patient with this diagnosis. Ever. I’m scared that the next patient I see is someone that I can’t get to where they need to get to. We are playing musical chairs with 100 people and 10 chairs. When the music stops, what happens?”

Also in Texas in August, Joe Valdez, who was shot six times as an unlucky bystander in a domestic dispute, waited for more than a week for surgery at Ben Taub Hospital in Houston, which was over capacity with COVID patients, the Washington Post reported.

Others with chronic diseases fear needing emergency services or even entering a hospital for regular care with the COVID surge.

Nicole Seefeldt, 44, from Easton, Penn., who had a double-lung transplant in 2016, said that she hasn’t been able to see her lung transplant specialists in Philadelphia — an hour-and-a-half drive — for almost 2 years because of fear of contracting COVID. Before the pandemic, she made the trip almost weekly.

“I protect my lungs like they’re children,” she said.

She relies on her local hospital for care, but has put off some needed care, such as a colonoscopy, and has relied on telemedicine because she wants to limit her hospital exposure.

Ms. Seefeldt now faces an eventual kidney transplant, as her kidney function has been reduced to 20%. In the meantime, she worries she will need emergency care for either her lungs or kidneys.

“For those of us who are chronically ill or disabled, what if we have an emergency that is not COVID-related? Are we going to be able to get a bed? Are we going to be able to get treatment? It’s not just COVID patients who come to the [emergency room],” she said.

A pandemic problem

Paul E. Casey, MD, MBA, chief medical officer at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago, said that high vaccination rates in Chicago have helped Rush continue to accommodate both non-COVID and COVID patients in the emergency department.

Though the hospital treated a large volume of COVID patients, “The vast majority of people we see and did see through the pandemic were non-COVID patents,” he said.

Dr. Casey said that in the first wave the hospital noticed a concerning drop in patients coming in for strokes and heart attacks — “things we knew hadn’t gone away.”

And the data backs it up. Over the course of the pandemic, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Health Interview Survey found that the percentage of Americans who reported seeing a doctor or health professional fell from 85% at the end of 2019 to about 80% in the first three months of 2021. The survey did not differentiate between in-person visits and telehealth appointments.

Medical practices and patients themselves postponed elective procedures and delayed routine visits during the early months of the crisis.

Patients also reported staying away from hospitals’ emergency departments throughout the pandemic. At the end of 2019, 22% of respondents reported visiting an emergency department in the past year. That dropped to 17% by the end of 2020, and was at 17.7% in the first 3 months of 2021.

Dr. Casey said that, in his hospital’s case, clear messaging became very important to assure patients it was safe to come back. And the message is still critical.

“We want to be loud and clear that patients should continue to seek care for those conditions,” Dr. Casey said. “Deferring healthcare only comes with the long-term sequelae of disease left untreated so we want people to be as proactive in seeking care as they always would be.”

In some cases, fears of entering emergency rooms because of excess patients and risk for infection are keeping some patients from seeking necessary care for minor injuries.

Jim Rickert, MD, an orthopedic surgeon with Indiana University Health in Bloomington, said that some of his patients have expressed fears of coming into the hospital for fractures.

Some patients, particularly elderly patients, he said, are having falls and fractures and wearing slings or braces at home rather than going into the hospital for injuries that need immediate attention.

Bones start healing incorrectly, Dr. Rickert said, and the correction becomes much more difficult.

Plea for vaccinations

Dr. Gosnell made a plea posted on her neighborhood news forum for people to get COVID vaccinations.

“It seems to me it’s easy for other people who are not in bodies like mine to take health for granted,” she said. “But there are a lot of us who live in very fragile bodies and our entire life is at the intersection of us and getting healthcare treatment. Small complications to getting treatment can be life altering.”

Dr. Gosnell, Ms. Seefeldt, Dr. Casey, and Dr. Rickert reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Jessica Gosnell, MD, 41, from Portland, Oregon, lives daily with the knowledge that her rare disease — a form of hereditary angioedema — could cause a sudden, severe swelling in her throat that could require quick intubation and land her in an intensive care unit (ICU) for days.

“I’ve been hospitalized for throat swells three times in the last year,” she said in an interview.

Dr. Gosnell no longer practices medicine because of a combination of illnesses, but lives with her husband, Andrew, and two young children, and said they are all “terrified” she will have to go to the hospital amid a COVID-19 surge that had shrunk the number of available ICU beds to 152 from 780 in Oregon as of Aug. 30. Thirty percent of the beds are in use for patients with COVID-19.

She said her life depends on being near hospitals that have ICUs and having access to highly specialized medications, one of which can cost up to $50,000 for the rescue dose.

Her fear has her “literally living bedbound.” In addition to hereditary angioedema, she has Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, which weakens connective tissue. She wears a cervical collar 24/7 to keep from tearing tissues, as any tissue injury can trigger a swell.

Patients worry there won’t be room

As ICU beds in most states are filling with COVID-19 patients as the Delta variant spreads, fears are rising among people like Dr. Gosnell, who have chronic conditions and diseases with unpredictable emergency visits, who worry that if they need emergency care there won’t be room.

As of Aug. 30, in the United States, 79% of ICU beds nationally were in use, 30% of them for COVID-19 patients, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

In individual states, the picture is dire. Alabama has fewer than 10% of its ICU beds open across the entire state. In Florida, 93% of ICU beds are filled, 53% of them with COVID patients. In Louisiana, 87% of beds were already in use, 45% of them with COVID patients, just as category 4 hurricane Ida smashed into the coastline on Aug. 29.

News reports have told of people transported and airlifted as hospitals reach capacity.

In Bellville, Tex., U.S. Army veteran Daniel Wilkinson needed advanced care for gallstone pancreatitis that normally would take 30 minutes to treat, his Bellville doctor, Hasan Kakli, MD, told CBS News.

Mr. Wilkinson’s house was three doors from Bellville Hospital, but the hospital was not equipped to treat the condition. Calls to other hospitals found the same answer: no empty ICU beds. After a 7-hour wait on a stretcher, he was airlifted to a Veterans Affairs hospital in Houston, but it was too late. He died on August 22 at age 46.

Dr. Kakli said, “I’ve never lost a patient with this diagnosis. Ever. I’m scared that the next patient I see is someone that I can’t get to where they need to get to. We are playing musical chairs with 100 people and 10 chairs. When the music stops, what happens?”

Also in Texas in August, Joe Valdez, who was shot six times as an unlucky bystander in a domestic dispute, waited for more than a week for surgery at Ben Taub Hospital in Houston, which was over capacity with COVID patients, the Washington Post reported.

Others with chronic diseases fear needing emergency services or even entering a hospital for regular care with the COVID surge.

Nicole Seefeldt, 44, from Easton, Penn., who had a double-lung transplant in 2016, said that she hasn’t been able to see her lung transplant specialists in Philadelphia — an hour-and-a-half drive — for almost 2 years because of fear of contracting COVID. Before the pandemic, she made the trip almost weekly.

“I protect my lungs like they’re children,” she said.

She relies on her local hospital for care, but has put off some needed care, such as a colonoscopy, and has relied on telemedicine because she wants to limit her hospital exposure.

Ms. Seefeldt now faces an eventual kidney transplant, as her kidney function has been reduced to 20%. In the meantime, she worries she will need emergency care for either her lungs or kidneys.

“For those of us who are chronically ill or disabled, what if we have an emergency that is not COVID-related? Are we going to be able to get a bed? Are we going to be able to get treatment? It’s not just COVID patients who come to the [emergency room],” she said.

A pandemic problem

Paul E. Casey, MD, MBA, chief medical officer at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago, said that high vaccination rates in Chicago have helped Rush continue to accommodate both non-COVID and COVID patients in the emergency department.

Though the hospital treated a large volume of COVID patients, “The vast majority of people we see and did see through the pandemic were non-COVID patents,” he said.

Dr. Casey said that in the first wave the hospital noticed a concerning drop in patients coming in for strokes and heart attacks — “things we knew hadn’t gone away.”

And the data backs it up. Over the course of the pandemic, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Health Interview Survey found that the percentage of Americans who reported seeing a doctor or health professional fell from 85% at the end of 2019 to about 80% in the first three months of 2021. The survey did not differentiate between in-person visits and telehealth appointments.

Medical practices and patients themselves postponed elective procedures and delayed routine visits during the early months of the crisis.

Patients also reported staying away from hospitals’ emergency departments throughout the pandemic. At the end of 2019, 22% of respondents reported visiting an emergency department in the past year. That dropped to 17% by the end of 2020, and was at 17.7% in the first 3 months of 2021.

Dr. Casey said that, in his hospital’s case, clear messaging became very important to assure patients it was safe to come back. And the message is still critical.

“We want to be loud and clear that patients should continue to seek care for those conditions,” Dr. Casey said. “Deferring healthcare only comes with the long-term sequelae of disease left untreated so we want people to be as proactive in seeking care as they always would be.”

In some cases, fears of entering emergency rooms because of excess patients and risk for infection are keeping some patients from seeking necessary care for minor injuries.

Jim Rickert, MD, an orthopedic surgeon with Indiana University Health in Bloomington, said that some of his patients have expressed fears of coming into the hospital for fractures.

Some patients, particularly elderly patients, he said, are having falls and fractures and wearing slings or braces at home rather than going into the hospital for injuries that need immediate attention.

Bones start healing incorrectly, Dr. Rickert said, and the correction becomes much more difficult.

Plea for vaccinations

Dr. Gosnell made a plea posted on her neighborhood news forum for people to get COVID vaccinations.

“It seems to me it’s easy for other people who are not in bodies like mine to take health for granted,” she said. “But there are a lot of us who live in very fragile bodies and our entire life is at the intersection of us and getting healthcare treatment. Small complications to getting treatment can be life altering.”

Dr. Gosnell, Ms. Seefeldt, Dr. Casey, and Dr. Rickert reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Jessica Gosnell, MD, 41, from Portland, Oregon, lives daily with the knowledge that her rare disease — a form of hereditary angioedema — could cause a sudden, severe swelling in her throat that could require quick intubation and land her in an intensive care unit (ICU) for days.

“I’ve been hospitalized for throat swells three times in the last year,” she said in an interview.

Dr. Gosnell no longer practices medicine because of a combination of illnesses, but lives with her husband, Andrew, and two young children, and said they are all “terrified” she will have to go to the hospital amid a COVID-19 surge that had shrunk the number of available ICU beds to 152 from 780 in Oregon as of Aug. 30. Thirty percent of the beds are in use for patients with COVID-19.

She said her life depends on being near hospitals that have ICUs and having access to highly specialized medications, one of which can cost up to $50,000 for the rescue dose.

Her fear has her “literally living bedbound.” In addition to hereditary angioedema, she has Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, which weakens connective tissue. She wears a cervical collar 24/7 to keep from tearing tissues, as any tissue injury can trigger a swell.

Patients worry there won’t be room

As ICU beds in most states are filling with COVID-19 patients as the Delta variant spreads, fears are rising among people like Dr. Gosnell, who have chronic conditions and diseases with unpredictable emergency visits, who worry that if they need emergency care there won’t be room.

As of Aug. 30, in the United States, 79% of ICU beds nationally were in use, 30% of them for COVID-19 patients, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

In individual states, the picture is dire. Alabama has fewer than 10% of its ICU beds open across the entire state. In Florida, 93% of ICU beds are filled, 53% of them with COVID patients. In Louisiana, 87% of beds were already in use, 45% of them with COVID patients, just as category 4 hurricane Ida smashed into the coastline on Aug. 29.

News reports have told of people transported and airlifted as hospitals reach capacity.

In Bellville, Tex., U.S. Army veteran Daniel Wilkinson needed advanced care for gallstone pancreatitis that normally would take 30 minutes to treat, his Bellville doctor, Hasan Kakli, MD, told CBS News.

Mr. Wilkinson’s house was three doors from Bellville Hospital, but the hospital was not equipped to treat the condition. Calls to other hospitals found the same answer: no empty ICU beds. After a 7-hour wait on a stretcher, he was airlifted to a Veterans Affairs hospital in Houston, but it was too late. He died on August 22 at age 46.

Dr. Kakli said, “I’ve never lost a patient with this diagnosis. Ever. I’m scared that the next patient I see is someone that I can’t get to where they need to get to. We are playing musical chairs with 100 people and 10 chairs. When the music stops, what happens?”

Also in Texas in August, Joe Valdez, who was shot six times as an unlucky bystander in a domestic dispute, waited for more than a week for surgery at Ben Taub Hospital in Houston, which was over capacity with COVID patients, the Washington Post reported.

Others with chronic diseases fear needing emergency services or even entering a hospital for regular care with the COVID surge.

Nicole Seefeldt, 44, from Easton, Penn., who had a double-lung transplant in 2016, said that she hasn’t been able to see her lung transplant specialists in Philadelphia — an hour-and-a-half drive — for almost 2 years because of fear of contracting COVID. Before the pandemic, she made the trip almost weekly.

“I protect my lungs like they’re children,” she said.

She relies on her local hospital for care, but has put off some needed care, such as a colonoscopy, and has relied on telemedicine because she wants to limit her hospital exposure.

Ms. Seefeldt now faces an eventual kidney transplant, as her kidney function has been reduced to 20%. In the meantime, she worries she will need emergency care for either her lungs or kidneys.

“For those of us who are chronically ill or disabled, what if we have an emergency that is not COVID-related? Are we going to be able to get a bed? Are we going to be able to get treatment? It’s not just COVID patients who come to the [emergency room],” she said.

A pandemic problem

Paul E. Casey, MD, MBA, chief medical officer at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago, said that high vaccination rates in Chicago have helped Rush continue to accommodate both non-COVID and COVID patients in the emergency department.

Though the hospital treated a large volume of COVID patients, “The vast majority of people we see and did see through the pandemic were non-COVID patents,” he said.

Dr. Casey said that in the first wave the hospital noticed a concerning drop in patients coming in for strokes and heart attacks — “things we knew hadn’t gone away.”

And the data backs it up. Over the course of the pandemic, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Health Interview Survey found that the percentage of Americans who reported seeing a doctor or health professional fell from 85% at the end of 2019 to about 80% in the first three months of 2021. The survey did not differentiate between in-person visits and telehealth appointments.

Medical practices and patients themselves postponed elective procedures and delayed routine visits during the early months of the crisis.

Patients also reported staying away from hospitals’ emergency departments throughout the pandemic. At the end of 2019, 22% of respondents reported visiting an emergency department in the past year. That dropped to 17% by the end of 2020, and was at 17.7% in the first 3 months of 2021.

Dr. Casey said that, in his hospital’s case, clear messaging became very important to assure patients it was safe to come back. And the message is still critical.

“We want to be loud and clear that patients should continue to seek care for those conditions,” Dr. Casey said. “Deferring healthcare only comes with the long-term sequelae of disease left untreated so we want people to be as proactive in seeking care as they always would be.”

In some cases, fears of entering emergency rooms because of excess patients and risk for infection are keeping some patients from seeking necessary care for minor injuries.

Jim Rickert, MD, an orthopedic surgeon with Indiana University Health in Bloomington, said that some of his patients have expressed fears of coming into the hospital for fractures.

Some patients, particularly elderly patients, he said, are having falls and fractures and wearing slings or braces at home rather than going into the hospital for injuries that need immediate attention.

Bones start healing incorrectly, Dr. Rickert said, and the correction becomes much more difficult.

Plea for vaccinations

Dr. Gosnell made a plea posted on her neighborhood news forum for people to get COVID vaccinations.

“It seems to me it’s easy for other people who are not in bodies like mine to take health for granted,” she said. “But there are a lot of us who live in very fragile bodies and our entire life is at the intersection of us and getting healthcare treatment. Small complications to getting treatment can be life altering.”

Dr. Gosnell, Ms. Seefeldt, Dr. Casey, and Dr. Rickert reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A Severe Presentation of Plasma Cell Cheilitis

Plasma cell cheilitis (PCC), also known as plasmocytosis circumorificialis and plasmocytosis mucosae,1 is a poorly understood, uncommon inflammatory condition characterized by dense infiltration of mature plasma cells in the mucosal dermis of the lip.2-5 The etiology of PCC is unknown but is thought to be a reactive immune process triggered by infection, mechanical friction, trauma, or solar damage.1,5,6

The most common presentation of PCC is a slowly evolving, red-brown patch or plaque on the lower lip in older individuals.2,3,5,7 Secondary changes with disease progression can include erosion, ulceration, fissures, edema, bleeding, or crusting.5 The diagnosis of PCC is challenging because it can mimic neoplastic, infectious, and inflammatory conditions.8,9

Treatment strategies for PCC described in the literature vary, as does therapeutic response. Resolution of PCC has been documented after systemic steroids, intralesional steroids, systemic griseofulvin, and topical calcineurin inhibitors, among other agents.6,7,10-16

We present the case of a patient with a lip lesion who ultimately was diagnosed with PCC after it progressed to an advanced necrotic stage.

Case Report

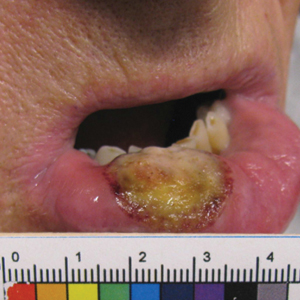

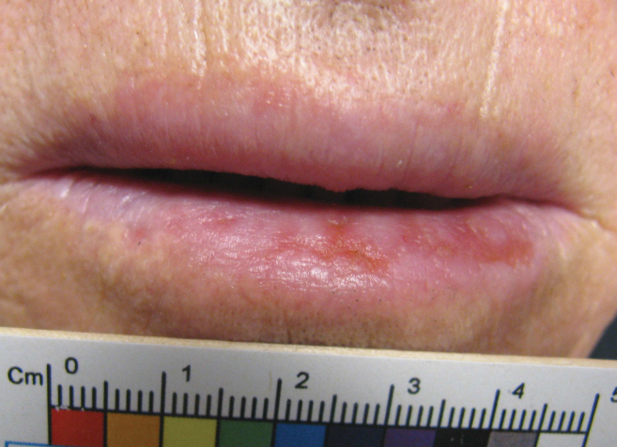

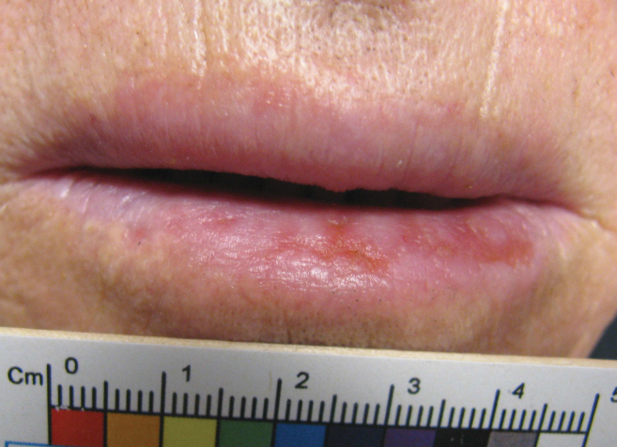

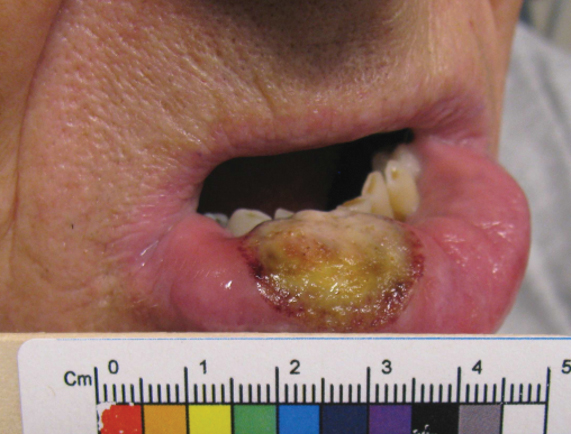

An 80-year-old male veteran of the Armed Services initially presented to our institution via teledermatology with redness and crusting of the lower lip (Figure 1). He had a history of myelodysplastic syndrome and anemia requiring iron transfusion. The process appeared to be consistent with actinic cheilitis vs squamous cell carcinoma. In-person dermatology consultation was recommended; however, the patient did not follow through with that appointment.

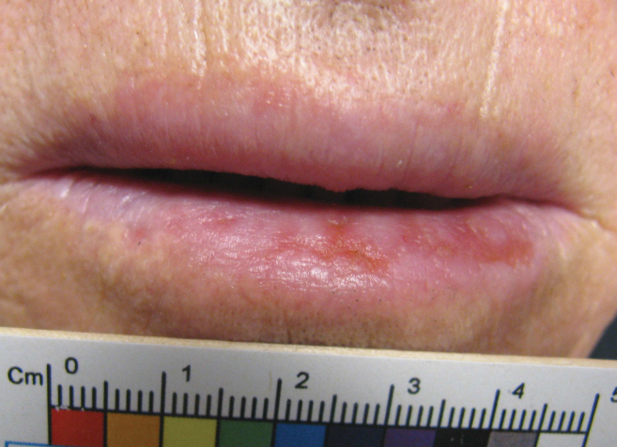

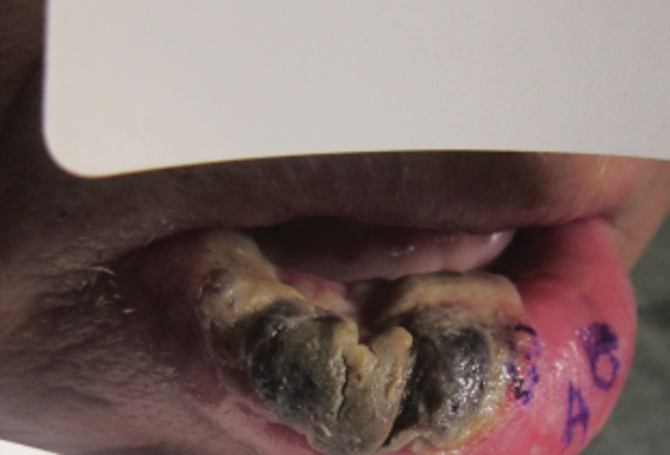

Five months later, additional photographs of the lesion were taken by the patient's primary care physician and sent through teledermatology, revealing progression to an erythematous, yellow-crusted erosion (Figure 2). The medical record indicated that a punch biopsy performed by the patient’s primary care physician showed hyperkeratosis and fungal organisms on periodic acid–Schiff staining. He subsequently applied ketoconazole and terbinafine cream to the lower lip without improvement. Prompt in-person evaluation by dermatology was again recommended.

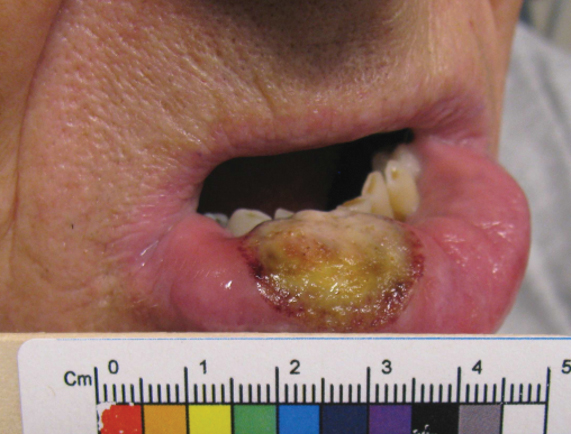

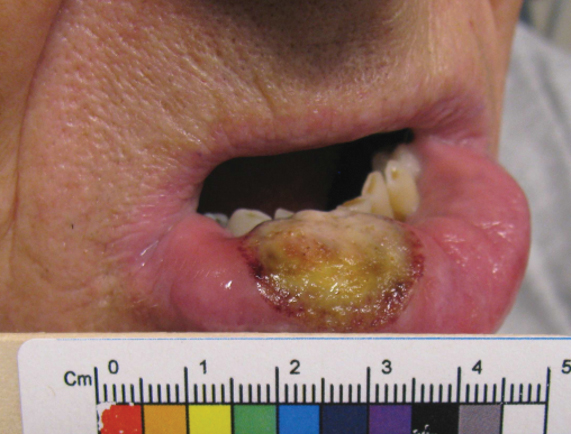

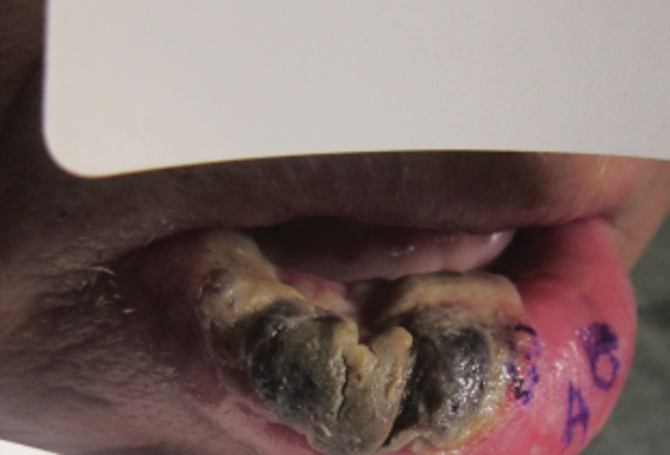

Ten days later, the patient was seen in our dermatology clinic, at which point his condition had rapidly progressed. The lower lip displayed a 3.0×2.5-cm, yellow and black, crusted, ulcerated plaque (Figure 3). He reported severe burning and pain of the lip as well as spontaneous bleeding. He had lost approximately 10 pounds over the last month due to poor oral intake. A second punch biopsy showed benign mucosa with extensive ulceration and formation of full-thickness granulation tissue. No fungi or bacteria were identified.

Consultation and Histologic Analysis

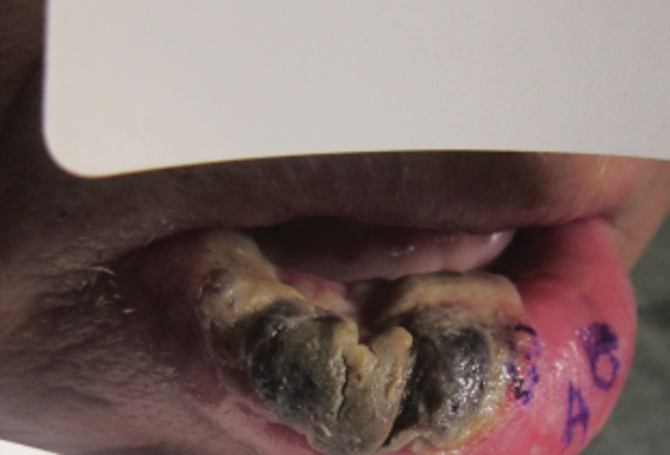

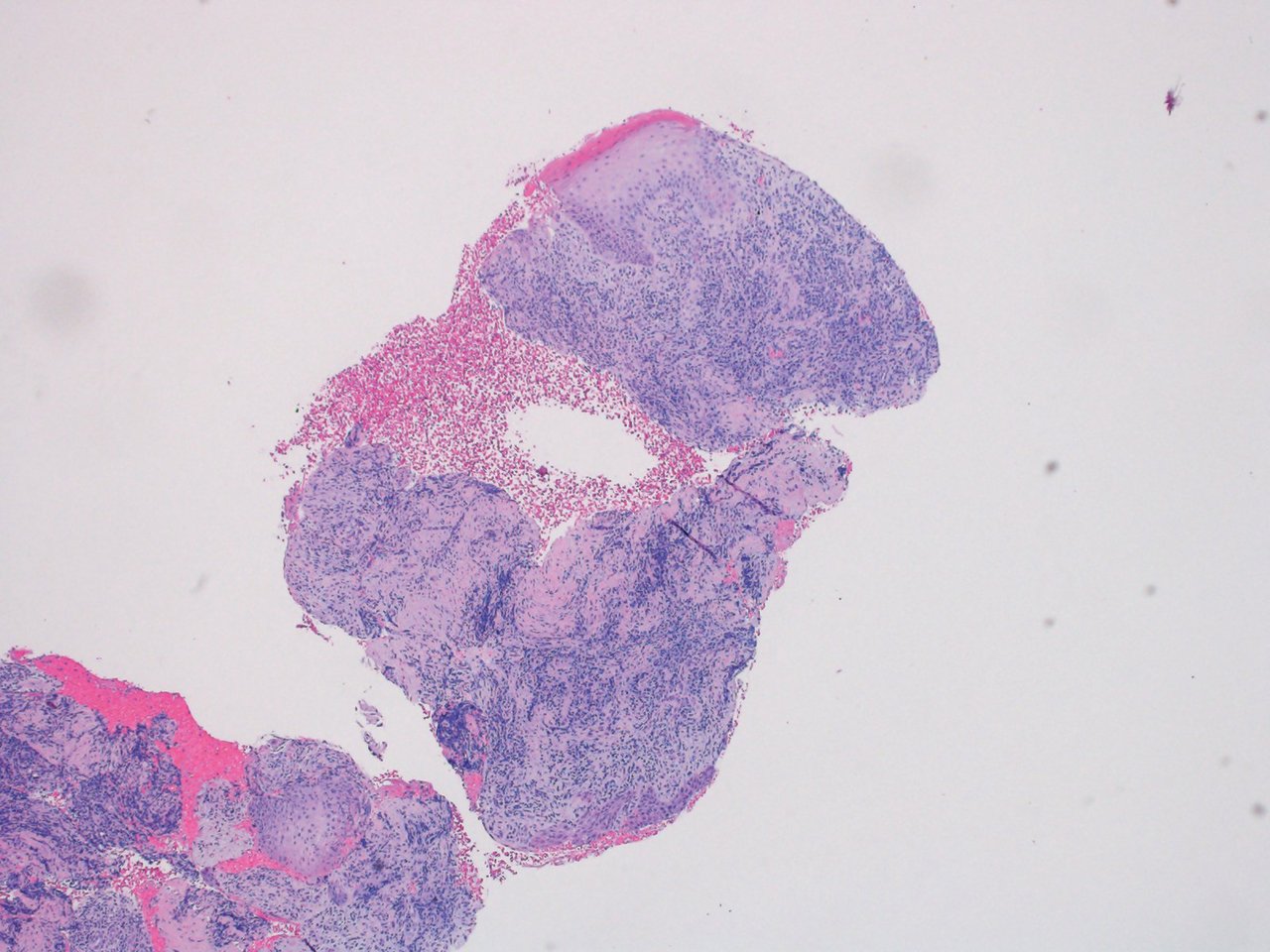

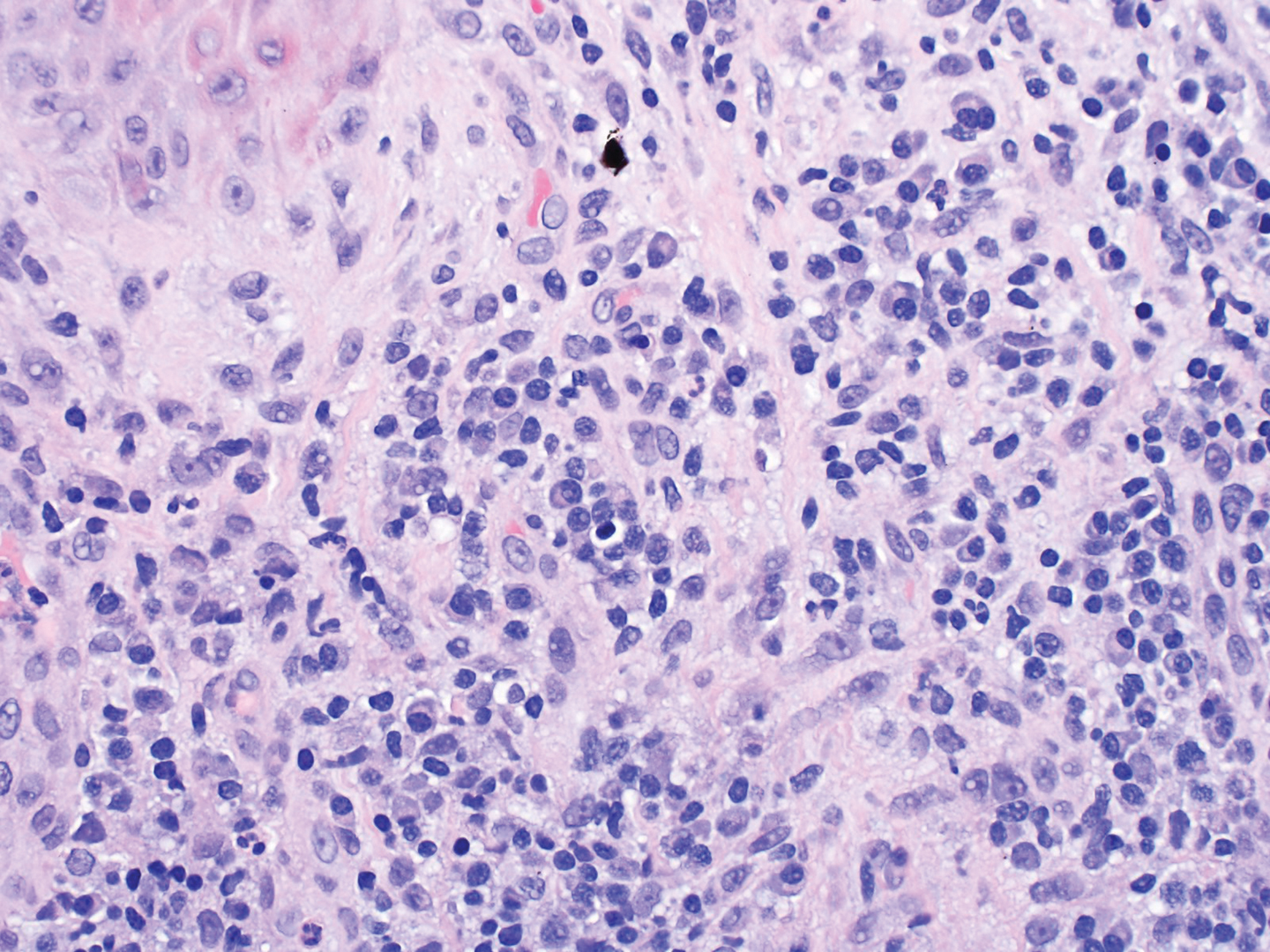

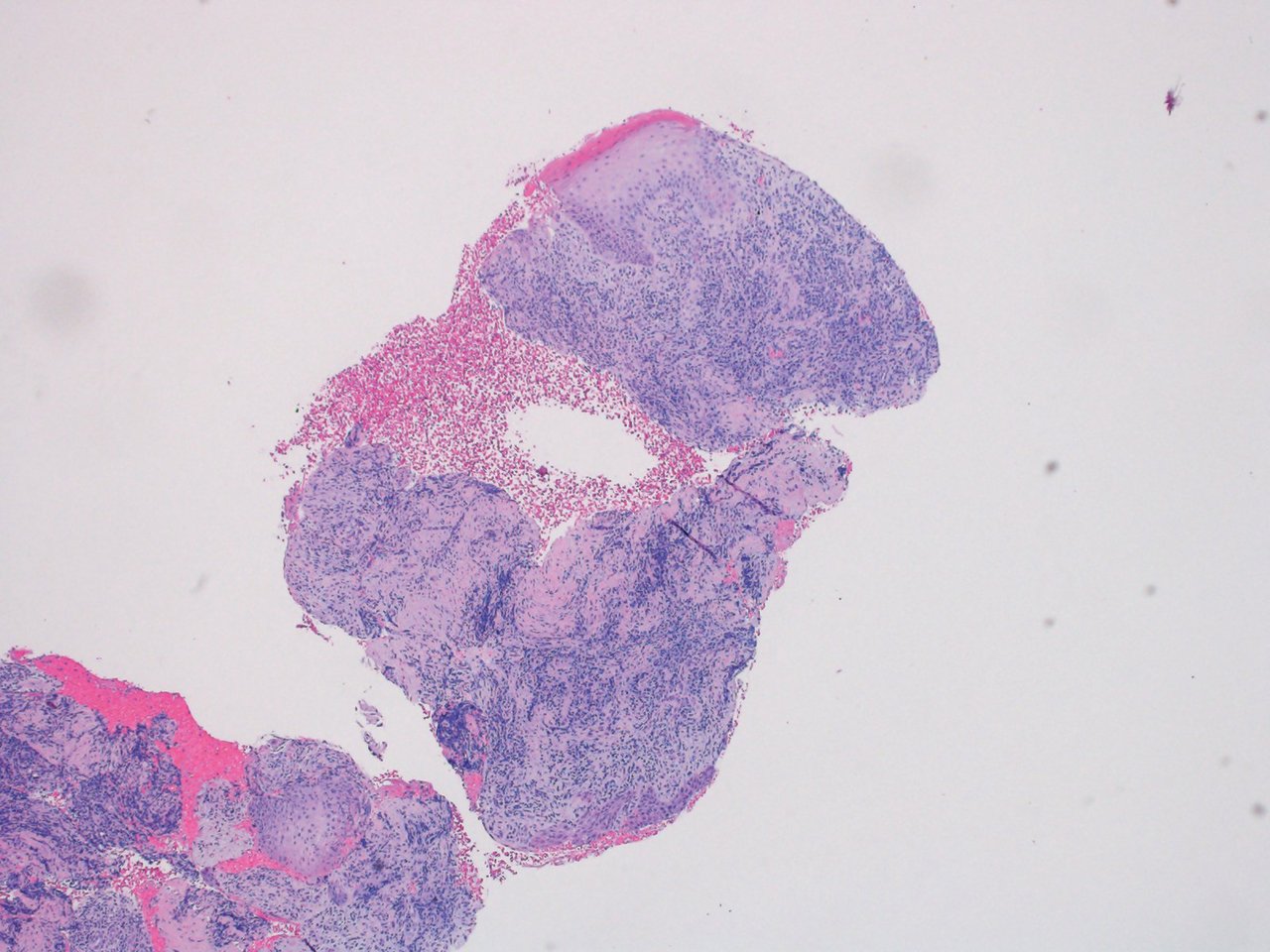

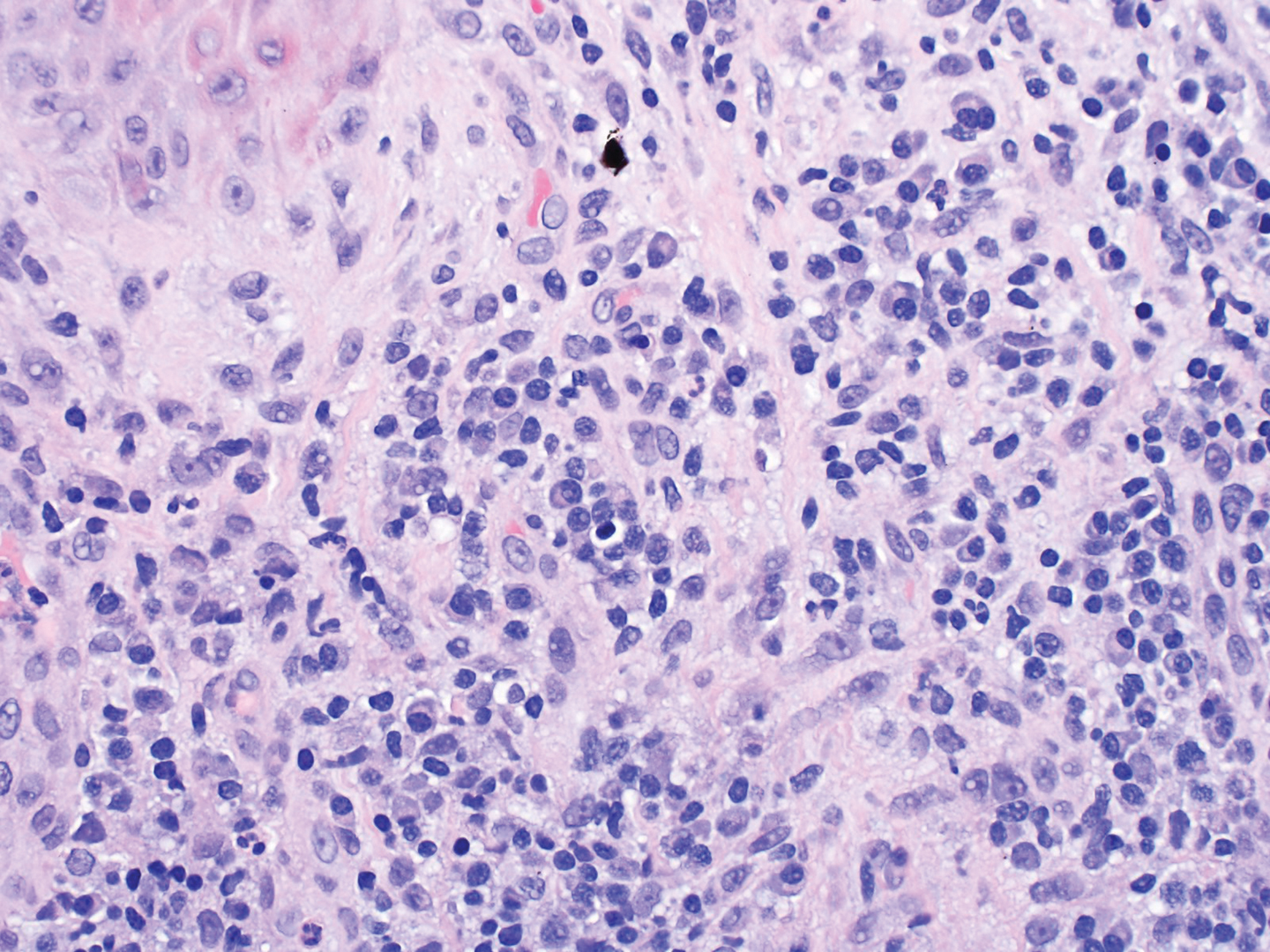

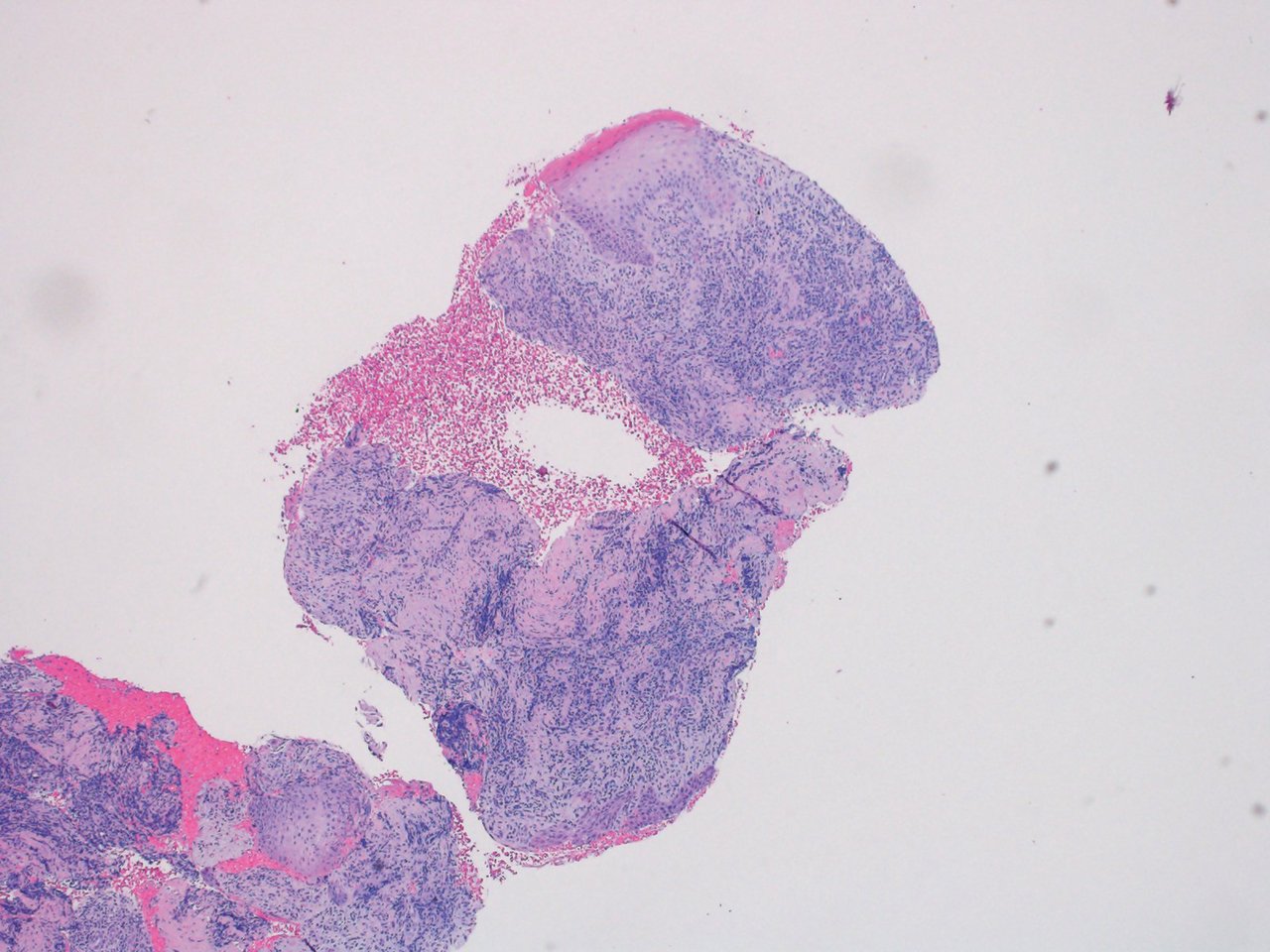

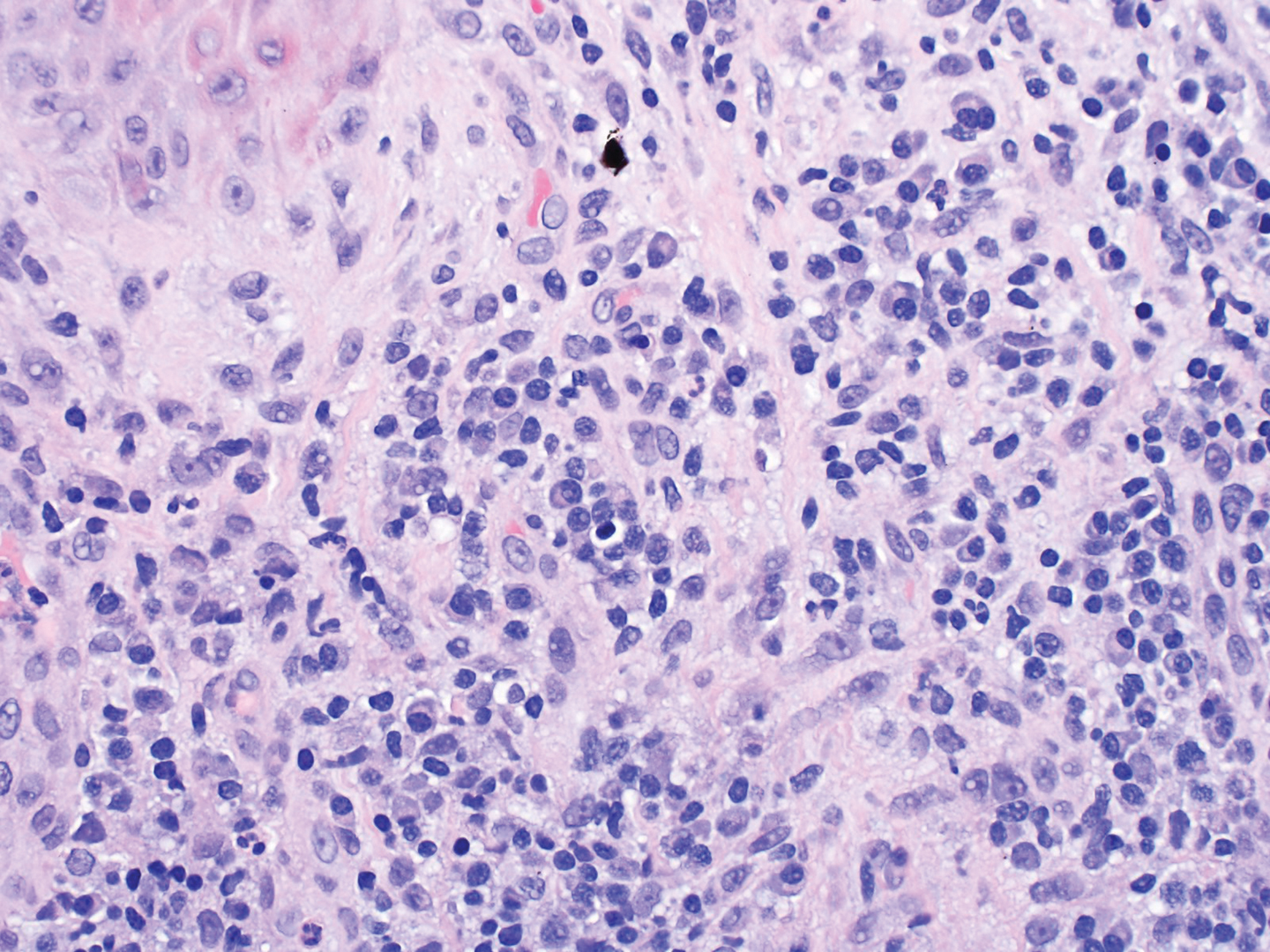

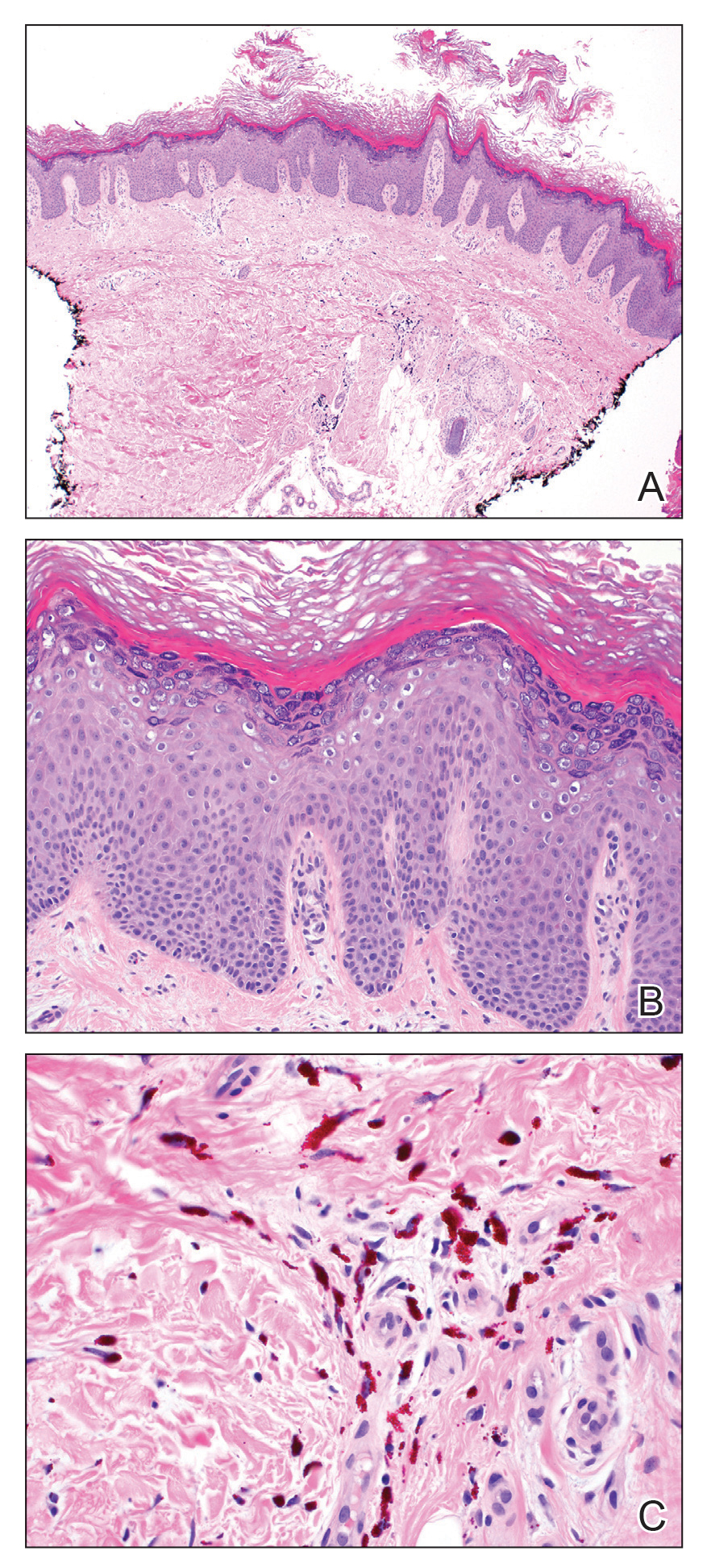

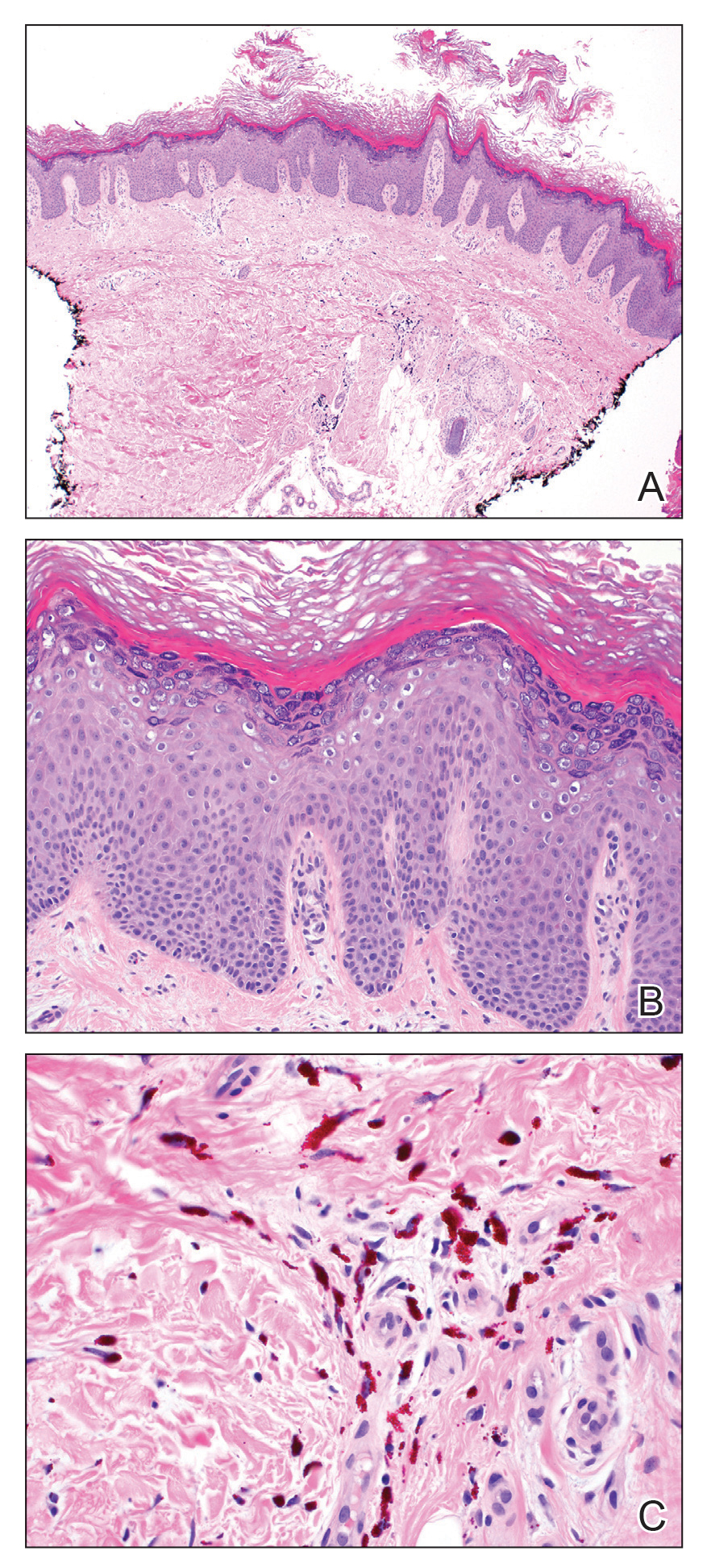

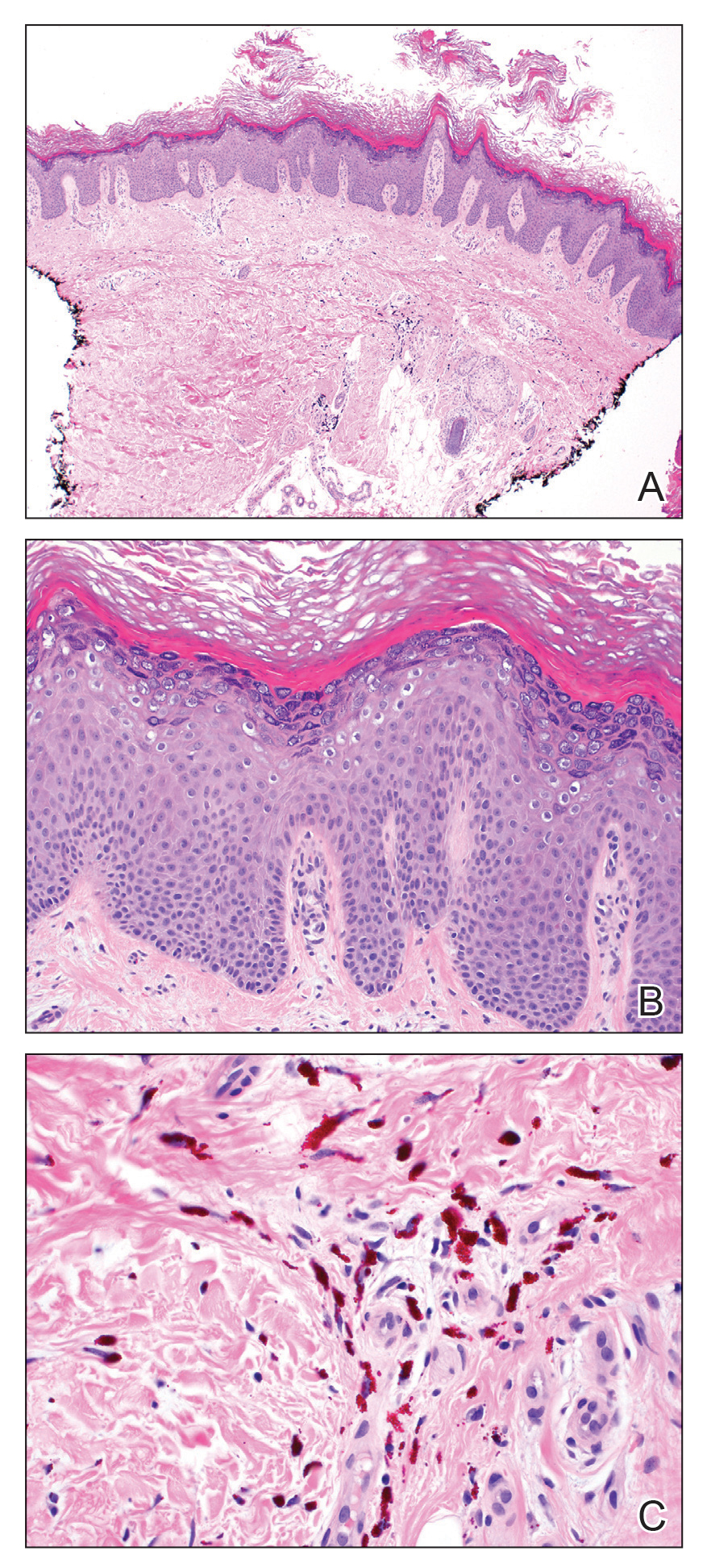

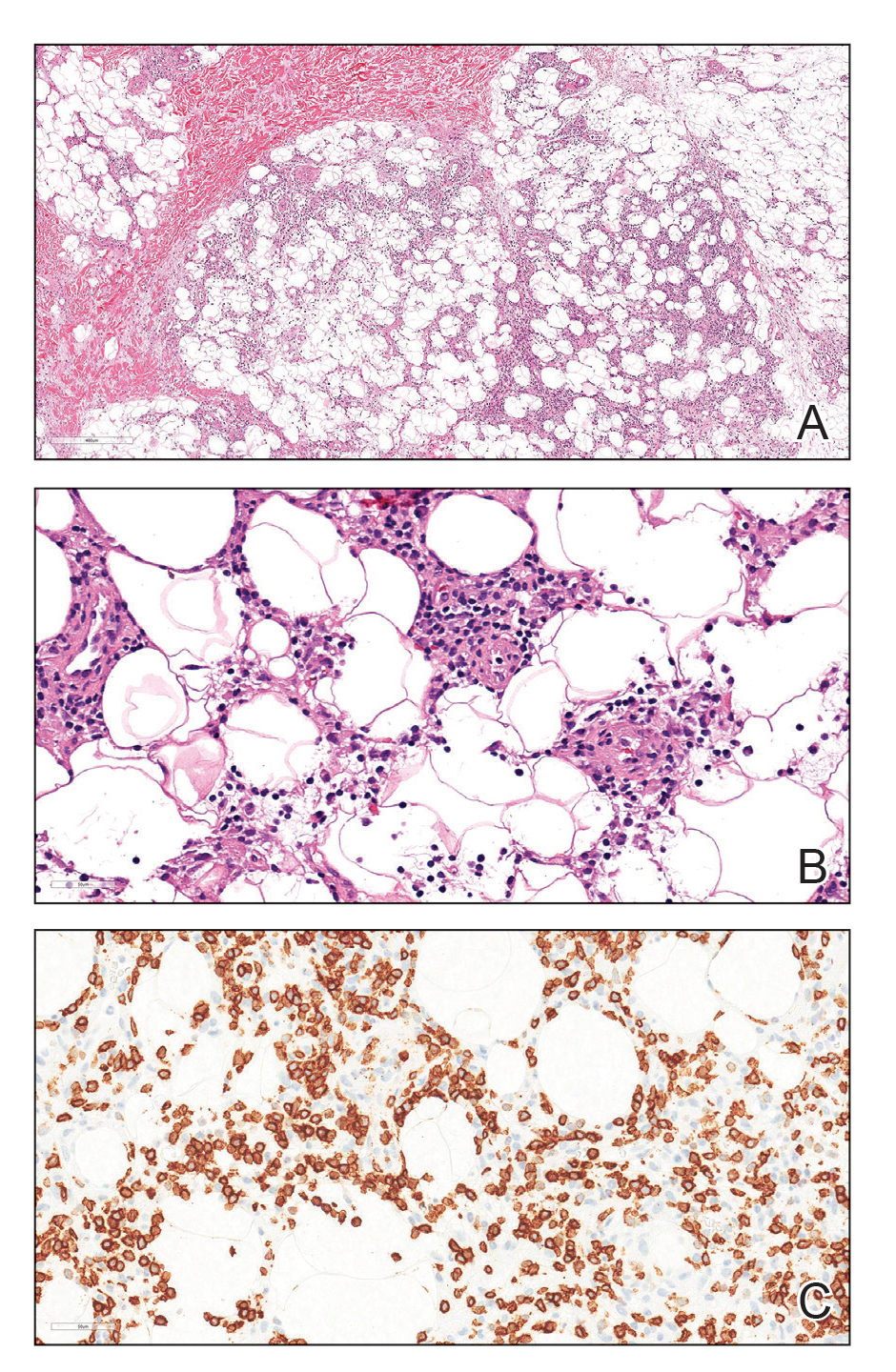

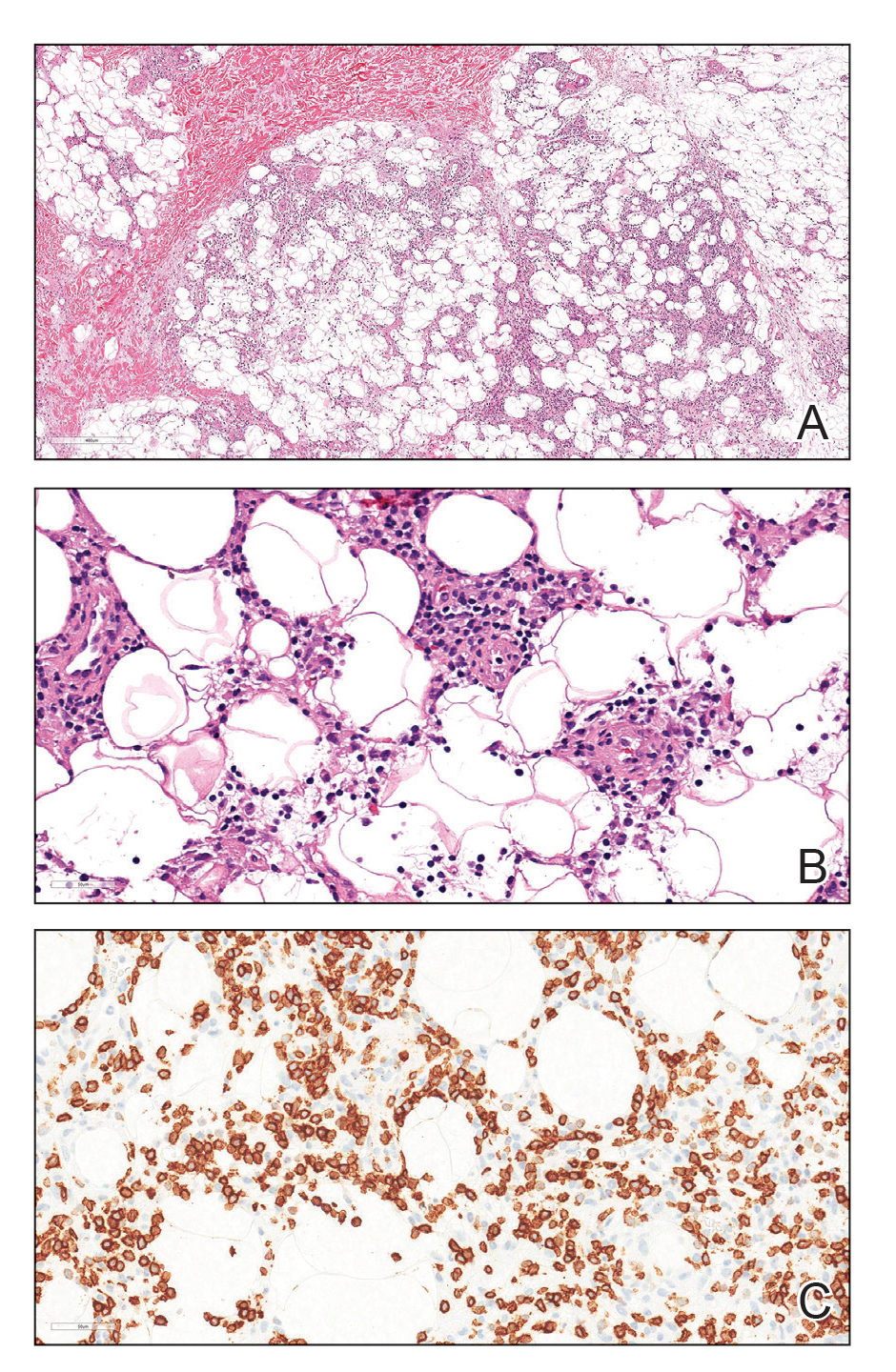

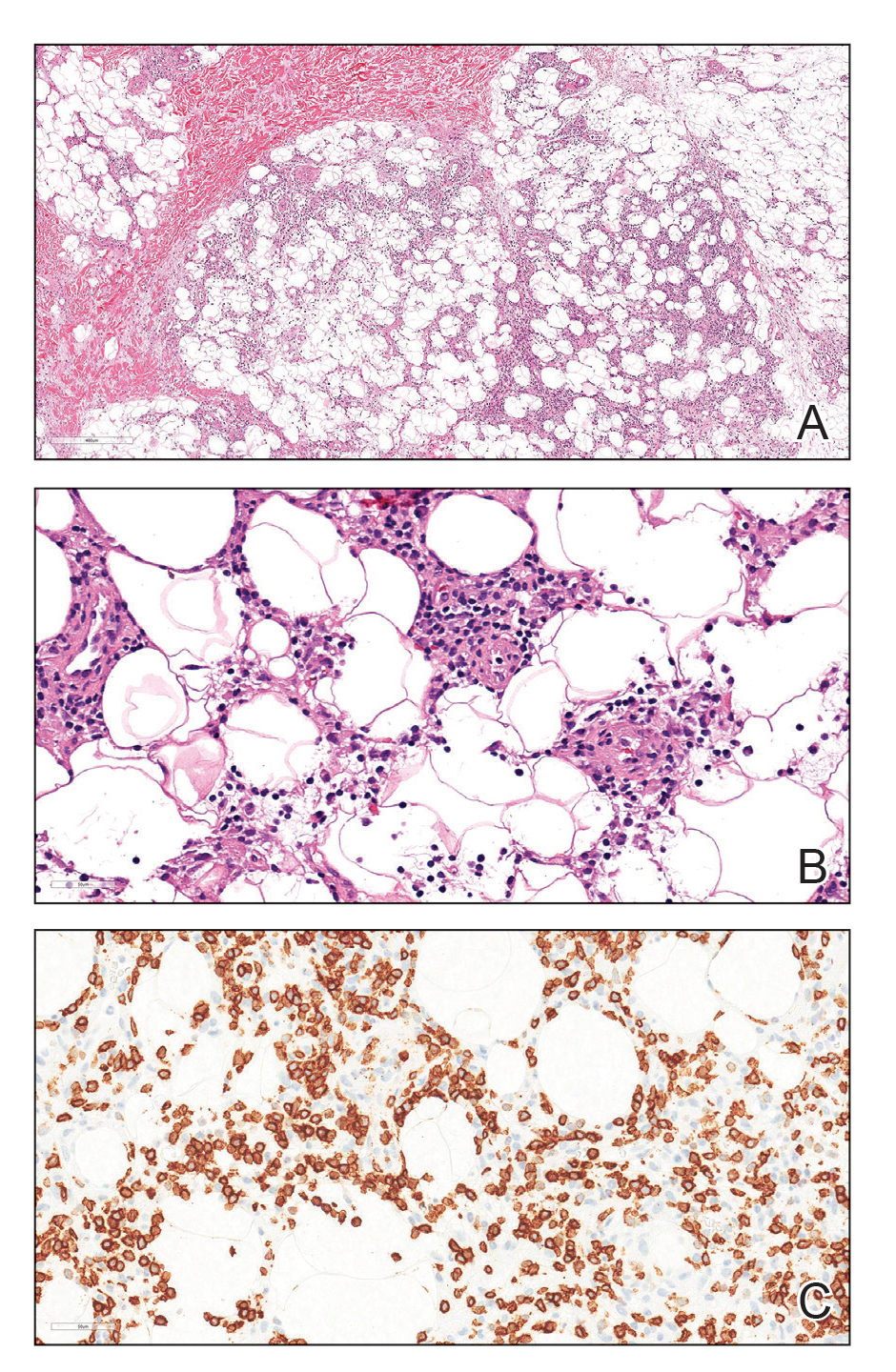

Dermatopathology was consulted and recommended a third punch biopsy for additional testing. A repeat biopsy demonstrated ulceration with lateral elements of retained epidermis and a dense submucosal chronic inflammatory infiltrate comprising plasma cells and lymphocytes (Figures 4 and 5). Immunohistochemical staining demonstrated a mixed inflammatory infiltrate with CD3+ T cells and CD20+ B cells. In situ hybridization studies demonstrated numerous lambda-positive and kappa-positive plasma cells without chain restriction. Periodic acid–Schiff with diastase and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver staining demonstrated no fungi. Findings were interpreted to be most consistent with a diagnosis of PCC.

Treatment and Follow-up

The patient was treated with clobetasol ointment 0.05% twice daily for 6 weeks and topical lidocaine as needed for pain. At 6-week follow-up, he displayed substantial improvement, with normal-appearing lips and complete resolution of symptoms.

Comment

The diagnosis and management of PCC is difficult because the condition is uncommon (though its true incidence is unknown) and the presentation is nonspecific, invoking a wide differential diagnosis. In the literature, PCC presents as a slowly progressive, red-brown patch or plaque on the lower lip in older individuals.2,3,5,7 The lesion can progress to become eroded, ulcerated, fissured, or edematous.5

Differential Diagnosis

The clinical differential diagnosis of PCC is broad and includes inflammatory, infectious, and neoplastic causes, such as actinic cheilitis, allergic contact cheilitis, exfoliative cheilitis, granulomatous cheilitis, lichen planus, candidiasis, syphilis, and squamous cell carcinoma of the lip.7,9 The histologic differential diagnosis includes allergic contact cheilitis, secondary syphilis, actinic cheilitis, squamous cell carcinoma, cheilitis granulomatosa, and plasmacytoma.17-19

Histopathology

On biopsy, PCC usually is characterized by plasma cells in a bandlike pattern in the upper submucosa or even more diffusely throughout the submucosa.20 In earlier studies, polyclonality of plasma cells with kappa and lambda light chains has been demonstrated5; in this case, such polyclonality militated against a plasma cell dyscrasia. There have been reports of a various number of eosinophils in PCC,5,20 but eosinophils were not a prominent feature in our case.

Treatment

As reported in the literature, treatment of PCC has been attempted using a broad range of strategies; however, the optimal regimen has yet to be elucidated.15 Numerous therapies, including excision, radiation, electrocauterization, cryotherapy, steroids, systemic griseofulvin, topical fusidic acid, and topical calcineurin inhibitors, have yielded variable success.6,7,10-16

The success of topical corticosteroids, as demonstrated in our case, has been unpredictable; the reported response has ranged from complete resolution to failure.9 This variability is thought to be related to epithelial width and the degree of acanthosis, with ulcerative lesions demonstrating a superior response to topical corticosteroids.9

Conclusion

Our case highlights the challenges of diagnosing and managing PCC, especially through teledermatology. Initial photographs of the lesion (Figure 1) that were submitted demonstrated a nonspecific erosion, which was concerning for any of several infectious, inflammatory, and malignant causes. Prompt in-person evaluation was warranted; regrettably, the patient’s condition worsened rapidly in the 10 days it took for him to be seen in-person by dermatology.

Furthermore, this case necessitated 3 separate biopsies because the pathology on the first 2 biopsies initially was equivocal, demonstrating ulceration and granulation tissue. The diagnosis was finally made after a third biopsy was recommended by a dermatopathologist, who eventually identified a bandlike distribution of polyclonal plasma cells in the upper submucosa, consistent with a diagnosis of PCC. Our patient’s final disease presentation (Figure 3) was exuberant and may represent the end point of untreated PCC.

- Senol M, Ozcan A, Aydin NE, et al. Intertriginous plasmacytosis with plasmoacanthoma: report of a typical case and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:265-268. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2008.03385.x

- Rocha N, Mota F, Horta M, et al. Plasma cell cheilitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:96-98. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2004.00791.x

- Farrier JN, Perkins CS. Plasma cell cheilitis. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;46:679-680. doi:10.1016/j.bjoms.2008.03.009

- Baughman RD, Berger P, Pringle WM. Plasma cell cheilitis. Arch Dermatol. 1974;110:725-726.

- Lee JY, Kim KH, Hahm JE, et al. Plasma cell cheilitis: a clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of 13 cases. Ann Dermatol. 2017;29:536-542. doi:10.5021/ad.2017.29.5.536

- da Cunha Filho RR, Tochetto LB, Tochetto BB, et al. “Angular” plasma cell cheilitis. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:doj_21759.

- Yang JH, Lee UH, Jang SJ, et al. Plasma cell cheilitis treated with intralesional injection of corticosteroids. J Dermatol. 2005;32:987-990. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2005.tb00887.x

- Solomon LW, Wein RO, Rosenwald I, et al. Plasma cell mucositis of the oral cavity: report of a case and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;106:853-860. doi:10.1016/j.tripleo.2008.08.016

- Dos Santos HT, Cunha JLS, Santana LAM, et al. Plasma cell cheilitis: the diagnosis of a disorder mimicking lip cancer. Autops Case Rep. 2019;9:e2018075. doi:10.4322/acr.2018.075

- Fujimura T, Furudate S, Ishibashi M, et al. Successful treatment of plasmacytosis circumorificialis with topical tacrolimus: two case reports and an immunohistochemical study. Case Rep Dermatol. 2013;5:79-83. doi:10.1159/000350184

- Tamaki K, Osada A, Tsukamoto K, et al. Treatment of plasma cell cheilitis with griseofulvin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:789-790. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(08)81515-0

- Choi JW, Choi M, Cho KH. Successful treatment of plasma cell cheilitis with topical calcineurin inhibitors. J Dermatol. 2009;36:669-671. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2009.00733.x

- Hanami Y, Motoki Y, Yamamoto T. Successful treatment of plasma cell cheilitis with topical tacrolimus: report of two cases. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:6.

- Jin SP, Cho KH, Huh CH. Plasma cell cheilitis, successfully treated with topical 0.03% tacrolimus ointment. J Dermatolog Treat. 2010;21:130-132. doi:10.1080/09546630903200620

- Tseng JT-P, Cheng C-J, Lee W-R, et al. Plasma-cell cheilitis: successful treatment with intralesional injections of corticosteroids. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:174-177. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2008.02765.x

- Yoshimura K, Nakano S, Tsuruta D, et al. Successful treatment with 308-nm monochromatic excimer light and subsequent tacrolimus 0.03% ointment in refractory plasma cell cheilitis. J Dermatol. 2013;40:471-474. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.12152

- Fujimura Y, Natsuga K, Abe R, et al. Plasma cell cheilitis extending beyond vermillion border. J Dermatol. 2015;42:935-936. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.12985

- White JW Jr, Olsen KD, Banks PM. Plasma cell orificial mucositis. report of a case and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 1986;122:1321-1324. doi:10.1001/archderm.122.11.1321

- Román CC, Yuste CM, Gonzalez MA, et al. Plasma cell gingivitis. Cutis. 2002;69:41-45.

- Choe HC, Park HJ, Oh ST, et al. Clinicopathologic study of 8 patients with plasma cell cheilitis. Korean J Dermatol. 2003;41:174-178.

Plasma cell cheilitis (PCC), also known as plasmocytosis circumorificialis and plasmocytosis mucosae,1 is a poorly understood, uncommon inflammatory condition characterized by dense infiltration of mature plasma cells in the mucosal dermis of the lip.2-5 The etiology of PCC is unknown but is thought to be a reactive immune process triggered by infection, mechanical friction, trauma, or solar damage.1,5,6

The most common presentation of PCC is a slowly evolving, red-brown patch or plaque on the lower lip in older individuals.2,3,5,7 Secondary changes with disease progression can include erosion, ulceration, fissures, edema, bleeding, or crusting.5 The diagnosis of PCC is challenging because it can mimic neoplastic, infectious, and inflammatory conditions.8,9

Treatment strategies for PCC described in the literature vary, as does therapeutic response. Resolution of PCC has been documented after systemic steroids, intralesional steroids, systemic griseofulvin, and topical calcineurin inhibitors, among other agents.6,7,10-16

We present the case of a patient with a lip lesion who ultimately was diagnosed with PCC after it progressed to an advanced necrotic stage.

Case Report

An 80-year-old male veteran of the Armed Services initially presented to our institution via teledermatology with redness and crusting of the lower lip (Figure 1). He had a history of myelodysplastic syndrome and anemia requiring iron transfusion. The process appeared to be consistent with actinic cheilitis vs squamous cell carcinoma. In-person dermatology consultation was recommended; however, the patient did not follow through with that appointment.

Five months later, additional photographs of the lesion were taken by the patient's primary care physician and sent through teledermatology, revealing progression to an erythematous, yellow-crusted erosion (Figure 2). The medical record indicated that a punch biopsy performed by the patient’s primary care physician showed hyperkeratosis and fungal organisms on periodic acid–Schiff staining. He subsequently applied ketoconazole and terbinafine cream to the lower lip without improvement. Prompt in-person evaluation by dermatology was again recommended.

Ten days later, the patient was seen in our dermatology clinic, at which point his condition had rapidly progressed. The lower lip displayed a 3.0×2.5-cm, yellow and black, crusted, ulcerated plaque (Figure 3). He reported severe burning and pain of the lip as well as spontaneous bleeding. He had lost approximately 10 pounds over the last month due to poor oral intake. A second punch biopsy showed benign mucosa with extensive ulceration and formation of full-thickness granulation tissue. No fungi or bacteria were identified.

Consultation and Histologic Analysis

Dermatopathology was consulted and recommended a third punch biopsy for additional testing. A repeat biopsy demonstrated ulceration with lateral elements of retained epidermis and a dense submucosal chronic inflammatory infiltrate comprising plasma cells and lymphocytes (Figures 4 and 5). Immunohistochemical staining demonstrated a mixed inflammatory infiltrate with CD3+ T cells and CD20+ B cells. In situ hybridization studies demonstrated numerous lambda-positive and kappa-positive plasma cells without chain restriction. Periodic acid–Schiff with diastase and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver staining demonstrated no fungi. Findings were interpreted to be most consistent with a diagnosis of PCC.

Treatment and Follow-up

The patient was treated with clobetasol ointment 0.05% twice daily for 6 weeks and topical lidocaine as needed for pain. At 6-week follow-up, he displayed substantial improvement, with normal-appearing lips and complete resolution of symptoms.

Comment

The diagnosis and management of PCC is difficult because the condition is uncommon (though its true incidence is unknown) and the presentation is nonspecific, invoking a wide differential diagnosis. In the literature, PCC presents as a slowly progressive, red-brown patch or plaque on the lower lip in older individuals.2,3,5,7 The lesion can progress to become eroded, ulcerated, fissured, or edematous.5

Differential Diagnosis

The clinical differential diagnosis of PCC is broad and includes inflammatory, infectious, and neoplastic causes, such as actinic cheilitis, allergic contact cheilitis, exfoliative cheilitis, granulomatous cheilitis, lichen planus, candidiasis, syphilis, and squamous cell carcinoma of the lip.7,9 The histologic differential diagnosis includes allergic contact cheilitis, secondary syphilis, actinic cheilitis, squamous cell carcinoma, cheilitis granulomatosa, and plasmacytoma.17-19

Histopathology

On biopsy, PCC usually is characterized by plasma cells in a bandlike pattern in the upper submucosa or even more diffusely throughout the submucosa.20 In earlier studies, polyclonality of plasma cells with kappa and lambda light chains has been demonstrated5; in this case, such polyclonality militated against a plasma cell dyscrasia. There have been reports of a various number of eosinophils in PCC,5,20 but eosinophils were not a prominent feature in our case.

Treatment

As reported in the literature, treatment of PCC has been attempted using a broad range of strategies; however, the optimal regimen has yet to be elucidated.15 Numerous therapies, including excision, radiation, electrocauterization, cryotherapy, steroids, systemic griseofulvin, topical fusidic acid, and topical calcineurin inhibitors, have yielded variable success.6,7,10-16

The success of topical corticosteroids, as demonstrated in our case, has been unpredictable; the reported response has ranged from complete resolution to failure.9 This variability is thought to be related to epithelial width and the degree of acanthosis, with ulcerative lesions demonstrating a superior response to topical corticosteroids.9

Conclusion

Our case highlights the challenges of diagnosing and managing PCC, especially through teledermatology. Initial photographs of the lesion (Figure 1) that were submitted demonstrated a nonspecific erosion, which was concerning for any of several infectious, inflammatory, and malignant causes. Prompt in-person evaluation was warranted; regrettably, the patient’s condition worsened rapidly in the 10 days it took for him to be seen in-person by dermatology.

Furthermore, this case necessitated 3 separate biopsies because the pathology on the first 2 biopsies initially was equivocal, demonstrating ulceration and granulation tissue. The diagnosis was finally made after a third biopsy was recommended by a dermatopathologist, who eventually identified a bandlike distribution of polyclonal plasma cells in the upper submucosa, consistent with a diagnosis of PCC. Our patient’s final disease presentation (Figure 3) was exuberant and may represent the end point of untreated PCC.

Plasma cell cheilitis (PCC), also known as plasmocytosis circumorificialis and plasmocytosis mucosae,1 is a poorly understood, uncommon inflammatory condition characterized by dense infiltration of mature plasma cells in the mucosal dermis of the lip.2-5 The etiology of PCC is unknown but is thought to be a reactive immune process triggered by infection, mechanical friction, trauma, or solar damage.1,5,6

The most common presentation of PCC is a slowly evolving, red-brown patch or plaque on the lower lip in older individuals.2,3,5,7 Secondary changes with disease progression can include erosion, ulceration, fissures, edema, bleeding, or crusting.5 The diagnosis of PCC is challenging because it can mimic neoplastic, infectious, and inflammatory conditions.8,9

Treatment strategies for PCC described in the literature vary, as does therapeutic response. Resolution of PCC has been documented after systemic steroids, intralesional steroids, systemic griseofulvin, and topical calcineurin inhibitors, among other agents.6,7,10-16

We present the case of a patient with a lip lesion who ultimately was diagnosed with PCC after it progressed to an advanced necrotic stage.

Case Report

An 80-year-old male veteran of the Armed Services initially presented to our institution via teledermatology with redness and crusting of the lower lip (Figure 1). He had a history of myelodysplastic syndrome and anemia requiring iron transfusion. The process appeared to be consistent with actinic cheilitis vs squamous cell carcinoma. In-person dermatology consultation was recommended; however, the patient did not follow through with that appointment.

Five months later, additional photographs of the lesion were taken by the patient's primary care physician and sent through teledermatology, revealing progression to an erythematous, yellow-crusted erosion (Figure 2). The medical record indicated that a punch biopsy performed by the patient’s primary care physician showed hyperkeratosis and fungal organisms on periodic acid–Schiff staining. He subsequently applied ketoconazole and terbinafine cream to the lower lip without improvement. Prompt in-person evaluation by dermatology was again recommended.

Ten days later, the patient was seen in our dermatology clinic, at which point his condition had rapidly progressed. The lower lip displayed a 3.0×2.5-cm, yellow and black, crusted, ulcerated plaque (Figure 3). He reported severe burning and pain of the lip as well as spontaneous bleeding. He had lost approximately 10 pounds over the last month due to poor oral intake. A second punch biopsy showed benign mucosa with extensive ulceration and formation of full-thickness granulation tissue. No fungi or bacteria were identified.

Consultation and Histologic Analysis

Dermatopathology was consulted and recommended a third punch biopsy for additional testing. A repeat biopsy demonstrated ulceration with lateral elements of retained epidermis and a dense submucosal chronic inflammatory infiltrate comprising plasma cells and lymphocytes (Figures 4 and 5). Immunohistochemical staining demonstrated a mixed inflammatory infiltrate with CD3+ T cells and CD20+ B cells. In situ hybridization studies demonstrated numerous lambda-positive and kappa-positive plasma cells without chain restriction. Periodic acid–Schiff with diastase and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver staining demonstrated no fungi. Findings were interpreted to be most consistent with a diagnosis of PCC.

Treatment and Follow-up

The patient was treated with clobetasol ointment 0.05% twice daily for 6 weeks and topical lidocaine as needed for pain. At 6-week follow-up, he displayed substantial improvement, with normal-appearing lips and complete resolution of symptoms.

Comment