User login

Formerly Skin & Allergy News

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')]

The leading independent newspaper covering dermatology news and commentary.

Financial incentives affect the adoption of biosimilars

during the same time period in 2015-2019, according to an analysis published in Arthritis and Rheumatology.

The use of the biosimilars also was associated with cost savings at the VAMC, but not at the academic medical center, which illustrates that insufficient financial incentives can delay the adoption of biosimilars and the health care system’s realization of cost savings, according to the authors.

Medicare, which is not allowed to negotiate drug prices, is one of the largest payers for infused therapies. Medicare reimbursement for infused therapies is based on the latter’s average selling price (ASP) during the previous quarter. Institutions may negotiate purchase prices with drug manufacturers and receive Medicare reimbursement. Biosimilars generally have lower ASPs than their corresponding reference therapies, and biosimilar manufacturers may have less room to negotiate prices than reference therapy manufacturers. Consequently, a given institution might have a greater incentive to use reference products than to use biosimilars.

An examination of pharmacy data

The VA negotiates drug prices for all of its medical centers and has mandated that clinicians prefer biosimilars to their corresponding reference therapies, so Joshua F. Baker, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania and the Corporal Michael J. Crescenz VAMC, both in Philadelphia, and his colleagues hypothesized that the adoption of biosimilars had proceeded more quickly at a VAMC than at a nearby academic medical center.

The investigators examined pharmacy data from the University of Pennsylvania Health System (UPHS) electronic medical record and the Corporal Michael J. Crescenz VAMC to compare the frequency of prescribing biosimilars at these sites between Jan. 1, 2015, and May 31, 2019. Dr. Baker and his associates focused specifically on reference infliximab (Remicade) and the reference noninfusion therapies filgrastim (Neupogen) and pegfilgrastim (Neulasta) and on biosimilars of these therapies (infliximab-dyyb [Inflectra], infliximab-abda [Renflexis], filgrastim-sndz [Zarxio], and pegfilgrastim-jmdb [Fulphila]).

Because Medicare was the predominant payer, the researchers estimated reimbursement for reference and biosimilar infliximabs according to the Medicare Part B reimbursement policy. They defined an institution’s incentive to use a given therapy as the difference between the reimbursement and acquisition cost for that therapy. Dr. Baker and colleagues compared the incentives for UPHS with those for the VAMC.

VAMC saved 81% of reference product cost

The researchers identified 15,761 infusions of infliximab at UPHS and 446 at the VAMC during the study period. The proportion of infusions that used the reference product was 99% at UPHS and 62% at the VAMC. ASPs for biosimilar infliximab have been consistently lower than those for the reference product since July 2017. In December 2017, the VAMC switched to the biosimilar infliximab.

Institutional incentives based on Medicare Part B reimbursement and acquisitions costs for reference and biosimilar infliximab have been similar since 2018. In 2019, the institutional incentive favored the reference product by $49-$64 per 100-mg vial. But at the VAMC, the cost per 100-mg vial was $623.48 for the reference product and $115.58 for the biosimilar Renflexis. Purchasing the biosimilar thus yielded a savings of 81%. The current costs for the therapies are $546 and $116, respectively.

In addition, Dr. Baker and colleagues identified 46,683 orders for filgrastim or pegfilgrastim at UPHS. Approximately 90% of the orders were for either of the two reference products despite the ASP of biosimilar filgrastim being approximately 40% lower than that of its reference product. At the VAMC, about 88% of orders were for the reference products. Biosimilars became available in 2016. UPHS began using them at a modest rate, but their adoption was greater at the VAMC, which designated them as preferred products.

Tendering and a nationwide policy mandating use of biosimilars have resulted in financial savings for the VAMC, wrote Dr. Baker and colleagues. “These data suggest that, with current Medicare Part B reimbursement policy, the absence of financial incentives to encourage use of infliximab biosimilars has resulted in slower uptake of biosimilar use at institutions outside of the VA system. The implications of this are a slower reduction in costs to the health care system, since decreases in ASP over time are predicated on negotiations at the institutional level, which have been gradual and stepwise. ...

“Although some of our results may not be applicable to other geographical regions of the U.S., the comparison of two affiliated institutions in geographical proximity and with shared health care providers is a strength,” they continued. “Our findings should be replicated using national VAMC data or data from other health care systems.”

The researchers said that their findings may not apply to noninfused therapies, which are not covered under Medicare Part B, and they did not directly study the impact of pharmacy benefit managers. However, they noted that their data on filgrastim and pegfilgrastim support the hypothesis that pharmacy benefit managers receive “incentives that continue to promote the use of reference products that have higher manufacturer’s list prices, which likely will limit the uptake of both infused and injectable biosimilar therapies over time.” They said that “this finding has important implications for when noninfused biosimilars (e.g. etanercept and adalimumab) are eventually introduced to the U.S. market.”

European governments incentivize use of biosimilars

Government and institutional incentives have increased the adoption of biosimilars in Europe, wrote Guro Lovik Goll, MD, and Tore Kristian Kvien, MD, of the department of rheumatology at Diakonhjemmet Hospital in Oslo, in an accompanying editorial. Norway and Denmark have annual national tender systems in which biosimilars and reference products compete. The price of infliximab biosimilar was 39% lower than the reference product in 2014 and 69% lower in 2015. “Competition has caused dramatically lower prices both for biosimilars and also for the originator drugs competing with them,” wrote the authors.

In 2015, the government of Denmark mandated that patients on infliximab be switched to a biosimilar, and patients in Norway also have been switched to biosimilars. The use of etanercept in Norway increased by 40% from 2016 to 2019, and the use of infliximab has increased by more than threefold since 2015. “In Norway, the consequence of competition, national tenders, and availability of biosimilars have led to better access to therapy for more people in need of biologic drugs, while at the same time showing a total cost reduction of biologics for use in rheumatology, gastroenterology, and dermatology,” wrote the authors.

Health care costs $10,000 per capita in the United States, compared with $5,300 for other wealthy countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Low life expectancy and high infant mortality in the U.S. indicate that high costs are not associated with better outcomes. “As Americans seem to lose out on the cost-cutting potential of biosimilars, this missed opportunity is set to get even more expensive,” the authors concluded.

The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, the National Institutes of Health, and the American Diabetes Association contributed funding for the study. Dr. Baker reported receiving consulting fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb and Gilead, and another author reported receiving research support paid to his institution by Pfizer and UCB, as well as receiving consulting fees from nine pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Goll and Dr. Kvien both reported receiving fees for speaking and/or consulting from numerous pharmaceutical companies, including Pfizer.

SOURCES: Baker JF et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020 Apr 6. doi: 10.1002/art.41277.

during the same time period in 2015-2019, according to an analysis published in Arthritis and Rheumatology.

The use of the biosimilars also was associated with cost savings at the VAMC, but not at the academic medical center, which illustrates that insufficient financial incentives can delay the adoption of biosimilars and the health care system’s realization of cost savings, according to the authors.

Medicare, which is not allowed to negotiate drug prices, is one of the largest payers for infused therapies. Medicare reimbursement for infused therapies is based on the latter’s average selling price (ASP) during the previous quarter. Institutions may negotiate purchase prices with drug manufacturers and receive Medicare reimbursement. Biosimilars generally have lower ASPs than their corresponding reference therapies, and biosimilar manufacturers may have less room to negotiate prices than reference therapy manufacturers. Consequently, a given institution might have a greater incentive to use reference products than to use biosimilars.

An examination of pharmacy data

The VA negotiates drug prices for all of its medical centers and has mandated that clinicians prefer biosimilars to their corresponding reference therapies, so Joshua F. Baker, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania and the Corporal Michael J. Crescenz VAMC, both in Philadelphia, and his colleagues hypothesized that the adoption of biosimilars had proceeded more quickly at a VAMC than at a nearby academic medical center.

The investigators examined pharmacy data from the University of Pennsylvania Health System (UPHS) electronic medical record and the Corporal Michael J. Crescenz VAMC to compare the frequency of prescribing biosimilars at these sites between Jan. 1, 2015, and May 31, 2019. Dr. Baker and his associates focused specifically on reference infliximab (Remicade) and the reference noninfusion therapies filgrastim (Neupogen) and pegfilgrastim (Neulasta) and on biosimilars of these therapies (infliximab-dyyb [Inflectra], infliximab-abda [Renflexis], filgrastim-sndz [Zarxio], and pegfilgrastim-jmdb [Fulphila]).

Because Medicare was the predominant payer, the researchers estimated reimbursement for reference and biosimilar infliximabs according to the Medicare Part B reimbursement policy. They defined an institution’s incentive to use a given therapy as the difference between the reimbursement and acquisition cost for that therapy. Dr. Baker and colleagues compared the incentives for UPHS with those for the VAMC.

VAMC saved 81% of reference product cost

The researchers identified 15,761 infusions of infliximab at UPHS and 446 at the VAMC during the study period. The proportion of infusions that used the reference product was 99% at UPHS and 62% at the VAMC. ASPs for biosimilar infliximab have been consistently lower than those for the reference product since July 2017. In December 2017, the VAMC switched to the biosimilar infliximab.

Institutional incentives based on Medicare Part B reimbursement and acquisitions costs for reference and biosimilar infliximab have been similar since 2018. In 2019, the institutional incentive favored the reference product by $49-$64 per 100-mg vial. But at the VAMC, the cost per 100-mg vial was $623.48 for the reference product and $115.58 for the biosimilar Renflexis. Purchasing the biosimilar thus yielded a savings of 81%. The current costs for the therapies are $546 and $116, respectively.

In addition, Dr. Baker and colleagues identified 46,683 orders for filgrastim or pegfilgrastim at UPHS. Approximately 90% of the orders were for either of the two reference products despite the ASP of biosimilar filgrastim being approximately 40% lower than that of its reference product. At the VAMC, about 88% of orders were for the reference products. Biosimilars became available in 2016. UPHS began using them at a modest rate, but their adoption was greater at the VAMC, which designated them as preferred products.

Tendering and a nationwide policy mandating use of biosimilars have resulted in financial savings for the VAMC, wrote Dr. Baker and colleagues. “These data suggest that, with current Medicare Part B reimbursement policy, the absence of financial incentives to encourage use of infliximab biosimilars has resulted in slower uptake of biosimilar use at institutions outside of the VA system. The implications of this are a slower reduction in costs to the health care system, since decreases in ASP over time are predicated on negotiations at the institutional level, which have been gradual and stepwise. ...

“Although some of our results may not be applicable to other geographical regions of the U.S., the comparison of two affiliated institutions in geographical proximity and with shared health care providers is a strength,” they continued. “Our findings should be replicated using national VAMC data or data from other health care systems.”

The researchers said that their findings may not apply to noninfused therapies, which are not covered under Medicare Part B, and they did not directly study the impact of pharmacy benefit managers. However, they noted that their data on filgrastim and pegfilgrastim support the hypothesis that pharmacy benefit managers receive “incentives that continue to promote the use of reference products that have higher manufacturer’s list prices, which likely will limit the uptake of both infused and injectable biosimilar therapies over time.” They said that “this finding has important implications for when noninfused biosimilars (e.g. etanercept and adalimumab) are eventually introduced to the U.S. market.”

European governments incentivize use of biosimilars

Government and institutional incentives have increased the adoption of biosimilars in Europe, wrote Guro Lovik Goll, MD, and Tore Kristian Kvien, MD, of the department of rheumatology at Diakonhjemmet Hospital in Oslo, in an accompanying editorial. Norway and Denmark have annual national tender systems in which biosimilars and reference products compete. The price of infliximab biosimilar was 39% lower than the reference product in 2014 and 69% lower in 2015. “Competition has caused dramatically lower prices both for biosimilars and also for the originator drugs competing with them,” wrote the authors.

In 2015, the government of Denmark mandated that patients on infliximab be switched to a biosimilar, and patients in Norway also have been switched to biosimilars. The use of etanercept in Norway increased by 40% from 2016 to 2019, and the use of infliximab has increased by more than threefold since 2015. “In Norway, the consequence of competition, national tenders, and availability of biosimilars have led to better access to therapy for more people in need of biologic drugs, while at the same time showing a total cost reduction of biologics for use in rheumatology, gastroenterology, and dermatology,” wrote the authors.

Health care costs $10,000 per capita in the United States, compared with $5,300 for other wealthy countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Low life expectancy and high infant mortality in the U.S. indicate that high costs are not associated with better outcomes. “As Americans seem to lose out on the cost-cutting potential of biosimilars, this missed opportunity is set to get even more expensive,” the authors concluded.

The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, the National Institutes of Health, and the American Diabetes Association contributed funding for the study. Dr. Baker reported receiving consulting fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb and Gilead, and another author reported receiving research support paid to his institution by Pfizer and UCB, as well as receiving consulting fees from nine pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Goll and Dr. Kvien both reported receiving fees for speaking and/or consulting from numerous pharmaceutical companies, including Pfizer.

SOURCES: Baker JF et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020 Apr 6. doi: 10.1002/art.41277.

during the same time period in 2015-2019, according to an analysis published in Arthritis and Rheumatology.

The use of the biosimilars also was associated with cost savings at the VAMC, but not at the academic medical center, which illustrates that insufficient financial incentives can delay the adoption of biosimilars and the health care system’s realization of cost savings, according to the authors.

Medicare, which is not allowed to negotiate drug prices, is one of the largest payers for infused therapies. Medicare reimbursement for infused therapies is based on the latter’s average selling price (ASP) during the previous quarter. Institutions may negotiate purchase prices with drug manufacturers and receive Medicare reimbursement. Biosimilars generally have lower ASPs than their corresponding reference therapies, and biosimilar manufacturers may have less room to negotiate prices than reference therapy manufacturers. Consequently, a given institution might have a greater incentive to use reference products than to use biosimilars.

An examination of pharmacy data

The VA negotiates drug prices for all of its medical centers and has mandated that clinicians prefer biosimilars to their corresponding reference therapies, so Joshua F. Baker, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania and the Corporal Michael J. Crescenz VAMC, both in Philadelphia, and his colleagues hypothesized that the adoption of biosimilars had proceeded more quickly at a VAMC than at a nearby academic medical center.

The investigators examined pharmacy data from the University of Pennsylvania Health System (UPHS) electronic medical record and the Corporal Michael J. Crescenz VAMC to compare the frequency of prescribing biosimilars at these sites between Jan. 1, 2015, and May 31, 2019. Dr. Baker and his associates focused specifically on reference infliximab (Remicade) and the reference noninfusion therapies filgrastim (Neupogen) and pegfilgrastim (Neulasta) and on biosimilars of these therapies (infliximab-dyyb [Inflectra], infliximab-abda [Renflexis], filgrastim-sndz [Zarxio], and pegfilgrastim-jmdb [Fulphila]).

Because Medicare was the predominant payer, the researchers estimated reimbursement for reference and biosimilar infliximabs according to the Medicare Part B reimbursement policy. They defined an institution’s incentive to use a given therapy as the difference between the reimbursement and acquisition cost for that therapy. Dr. Baker and colleagues compared the incentives for UPHS with those for the VAMC.

VAMC saved 81% of reference product cost

The researchers identified 15,761 infusions of infliximab at UPHS and 446 at the VAMC during the study period. The proportion of infusions that used the reference product was 99% at UPHS and 62% at the VAMC. ASPs for biosimilar infliximab have been consistently lower than those for the reference product since July 2017. In December 2017, the VAMC switched to the biosimilar infliximab.

Institutional incentives based on Medicare Part B reimbursement and acquisitions costs for reference and biosimilar infliximab have been similar since 2018. In 2019, the institutional incentive favored the reference product by $49-$64 per 100-mg vial. But at the VAMC, the cost per 100-mg vial was $623.48 for the reference product and $115.58 for the biosimilar Renflexis. Purchasing the biosimilar thus yielded a savings of 81%. The current costs for the therapies are $546 and $116, respectively.

In addition, Dr. Baker and colleagues identified 46,683 orders for filgrastim or pegfilgrastim at UPHS. Approximately 90% of the orders were for either of the two reference products despite the ASP of biosimilar filgrastim being approximately 40% lower than that of its reference product. At the VAMC, about 88% of orders were for the reference products. Biosimilars became available in 2016. UPHS began using them at a modest rate, but their adoption was greater at the VAMC, which designated them as preferred products.

Tendering and a nationwide policy mandating use of biosimilars have resulted in financial savings for the VAMC, wrote Dr. Baker and colleagues. “These data suggest that, with current Medicare Part B reimbursement policy, the absence of financial incentives to encourage use of infliximab biosimilars has resulted in slower uptake of biosimilar use at institutions outside of the VA system. The implications of this are a slower reduction in costs to the health care system, since decreases in ASP over time are predicated on negotiations at the institutional level, which have been gradual and stepwise. ...

“Although some of our results may not be applicable to other geographical regions of the U.S., the comparison of two affiliated institutions in geographical proximity and with shared health care providers is a strength,” they continued. “Our findings should be replicated using national VAMC data or data from other health care systems.”

The researchers said that their findings may not apply to noninfused therapies, which are not covered under Medicare Part B, and they did not directly study the impact of pharmacy benefit managers. However, they noted that their data on filgrastim and pegfilgrastim support the hypothesis that pharmacy benefit managers receive “incentives that continue to promote the use of reference products that have higher manufacturer’s list prices, which likely will limit the uptake of both infused and injectable biosimilar therapies over time.” They said that “this finding has important implications for when noninfused biosimilars (e.g. etanercept and adalimumab) are eventually introduced to the U.S. market.”

European governments incentivize use of biosimilars

Government and institutional incentives have increased the adoption of biosimilars in Europe, wrote Guro Lovik Goll, MD, and Tore Kristian Kvien, MD, of the department of rheumatology at Diakonhjemmet Hospital in Oslo, in an accompanying editorial. Norway and Denmark have annual national tender systems in which biosimilars and reference products compete. The price of infliximab biosimilar was 39% lower than the reference product in 2014 and 69% lower in 2015. “Competition has caused dramatically lower prices both for biosimilars and also for the originator drugs competing with them,” wrote the authors.

In 2015, the government of Denmark mandated that patients on infliximab be switched to a biosimilar, and patients in Norway also have been switched to biosimilars. The use of etanercept in Norway increased by 40% from 2016 to 2019, and the use of infliximab has increased by more than threefold since 2015. “In Norway, the consequence of competition, national tenders, and availability of biosimilars have led to better access to therapy for more people in need of biologic drugs, while at the same time showing a total cost reduction of biologics for use in rheumatology, gastroenterology, and dermatology,” wrote the authors.

Health care costs $10,000 per capita in the United States, compared with $5,300 for other wealthy countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Low life expectancy and high infant mortality in the U.S. indicate that high costs are not associated with better outcomes. “As Americans seem to lose out on the cost-cutting potential of biosimilars, this missed opportunity is set to get even more expensive,” the authors concluded.

The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, the National Institutes of Health, and the American Diabetes Association contributed funding for the study. Dr. Baker reported receiving consulting fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb and Gilead, and another author reported receiving research support paid to his institution by Pfizer and UCB, as well as receiving consulting fees from nine pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Goll and Dr. Kvien both reported receiving fees for speaking and/or consulting from numerous pharmaceutical companies, including Pfizer.

SOURCES: Baker JF et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020 Apr 6. doi: 10.1002/art.41277.

FROM ARTHRITIS & RHEUMATOLOGY

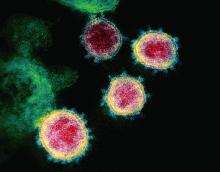

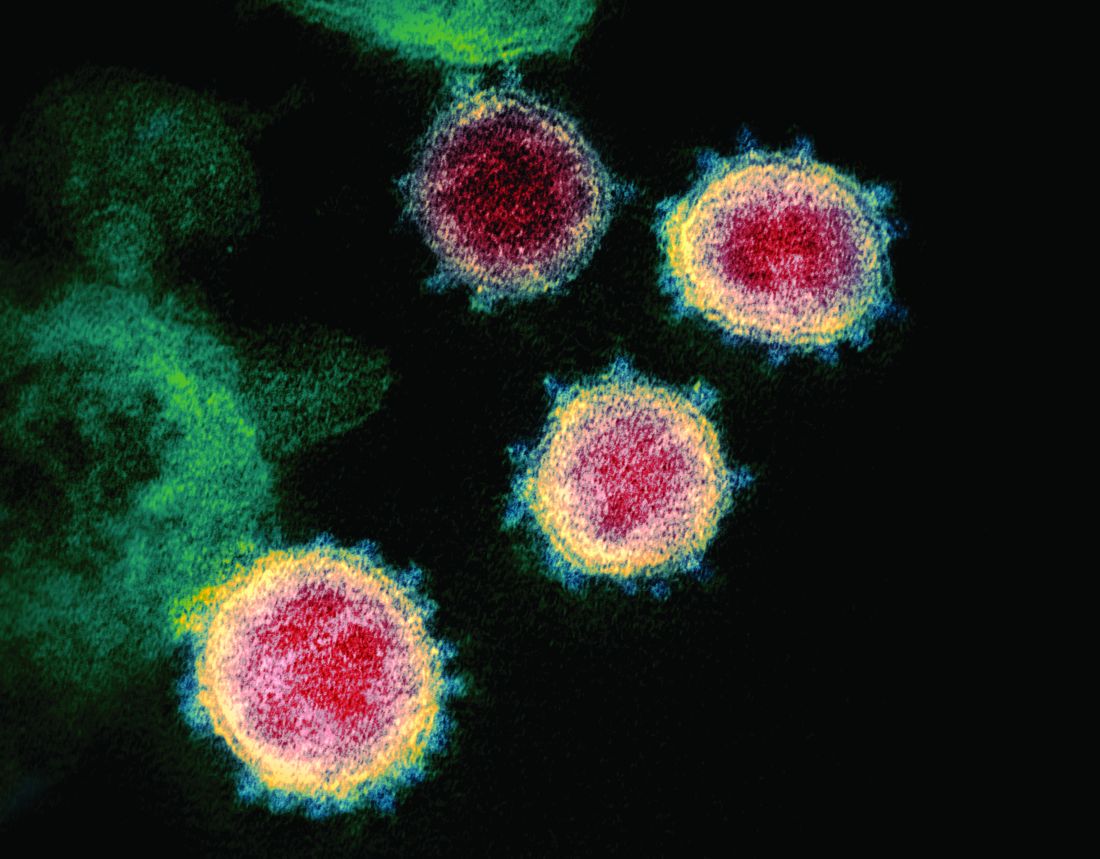

COVID-19 and its impact on the pediatric patient

Coronavirus disease of 2019, more commonly referred to as COVID-19, is caused by a novel coronavirus. At press time in April, its diagnosis had been confirmed in more than 2 million individuals in 185 countries and territories since first isolated in January 2020. Daily updates are provided in terms of the number of new cases, the evolving strategies to mitigate additional spread, testing, potential drug trials, and vaccine development. Risk groups for development of severe disease also have been widely publicized. Limited information has been provided about COVID-19 in children.

Terminology

Endemic. The condition is present at a stable predictable rate in a community. The number observed is what is expected.

Outbreak. The number of cases is greater than what is expected in the area.

Epidemic. An outbreak that spreads over a larger geographical area.

Pandemic. An outbreak that has spread to multiple countries and /or continents.

What we know about coronaviruses: They are host-specific RNA viruses widespread in bats, but found in many other species including humans. Previously, six species caused disease in humans. Four species: 229E, NL63, OC43, and HKU1 usually cause the common cold. Symptoms are generally self-limited and peak 3-4 days after onset. Infection rarely can be manifested as otitis media or a lower respiratory tract disease.

In February 2003, SARS-CoV, a novel coronavirus, was identified as the causative agent for an outbreak of a severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) which began in Guangdong, China. It became a pandemic that occurred between November 2002 and July 2003. More than 8,000 individuals from 26 countries were infected, and there were 774 deaths, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. No cases have been reported since April 2004. This virus most often infected adults, and the mortality rate was 10%. No pediatric deaths were reported. The virus was considered to have evolved from a bat CoV with civet cats as an intermediate host.

In September 2012, MERS-CoV (Middle East respiratory syndrome), another novel coronavirus also manifesting as a severe respiratory illness, was identified in Saudi Arabia. Current data suggests it evolved from a bat CoV using dromedary camels as an intermediate host. To date, more than 2,400 cases have been reported with a case fatality rate of approximately 35% (Emerg Infect Dis. 2020 Feb; 26[2]:191-8). Disease in children has been mild. Most cases have been identified in adult males with comorbidities and have been reported from Saudi Arabia (85%). To date, no sustained human-to-human transmission has been documented. However, limited nonsustained human-to-human transmission has occurred in health care settings.

Preliminary COVID-19 pediatric data

Multiple case reports and studies with limited numbers of patients have been quickly published, but limited data about children have been available. A large study by Wu et al. was released. Epidemiologic data were available for 72,314 cases (62% confirmed 22% suspected,15% diagnosed based on clinical symptoms). Only 965 (1.3%) cases occurred in persons under 19 years of age. There were no deaths reported in anyone younger than 9 years old. The authors indicated that 889 patients (1%) were asymptomatic, but the exact number of children in that group was not provided.1

Dong Y et al. reported on the epidemiologic characteristics of 2,135 children under 18 years who resided in or near an epidemic center. Data were obtained retrospectively; 34% (728) of the cases were confirmed and 66% (1,407) were suspected. In summary, 94 (4%) of all patients were asymptomatic, 1,088 (51%) had mild symptoms, and 826 (39%) had moderate symptoms at the time of diagnosis. The remaining 6% of patients (125) had severe/critical disease manifested by dyspnea and hypoxemia. Interestingly, more severe/critical cases were in the suspected group. Could another pathogen be the true etiology? Severity of illness was greatest for infants (11%). As of Feb. 8, 2020, only one child had died; he was 14 years old. This study supports the claim that COVID-19 disease in children is less severe than in adults.2

Data in U.S. children are now available. Between Feb. 12, 2020, and April 2, 2020, there were 149,770 cases of laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 reported to the CDC. Age was documented in 149,082 cases and 2, 572 (1.7%) were in persons younger than 18 years. New York had the highest percentage of reported pediatric cases at 33% from New York City, and 23% from the remainder of New York state; an additional 15% were from New Jersey and the remaining 29% of cases were from other areas. The median age was 11 years. Cases by age were 32% in teens aged 15-17 years; 27% in children aged 10-14 years; 15% in children aged 5-9 years; 11% in children aged 1-4 years; and 15% in children aged less than 1 year.

Exposure history was documented in 184 cases, of which 91% were household /community. Information regarding signs and symptoms were limited but not absent. Based on available data, 73% of children had fever, cough, or shortness of breath. When looked at independently, each of these symptoms occurred less frequently than in adults: 56% of children reported fever, 54% reported cough, and 13% reported shortness of breath, compared with 71%, 80%, and 43% of adults, respectively. Also reported less frequently were myalgia, headache, sore throat, and diarrhea.

Hospitalization status was available for 745 children, with 20% being hospitalized and 2% being admitted to the ICU. Children under 1 year accounted for most of the hospitalizations. Limited information about underlying conditions was provided. Among 345 cases, 23% had at least one underlying medical condition; the most common conditions were chronic lung disease including asthma (50%), cardiovascular disease (31%), and immunosuppression (8%). Three deaths were reported in this cohort of 2,135 children; however, the final cause of death is still under review.3

There are limitations to the data. Many of the answers needed to perform adequate analysis regarding symptoms, their duration and severity, risk factors, etc., were not available. Routine testing is not currently recommended, and current practices may influence the outcomes.

What have we learned? The data suggest that most ill children may not have cough, fever, or shortness of breath; symptoms which parents will be looking for prior to even seeking medical attention. These are the individuals who may likely play a continued role with disease transmission. The need for hospitalization and the severity of illness appears to be lower than in adults but not absent. Strategies to mitigate additional spread such as social distancing, wearing facial masks, and hand washing still are important and should be encouraged.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She has no relevant financial disclosures. Email Dr. Word at [email protected].

References

1. JAMA. 2020;323(13):1239-42.

2. Pediatrics. 2020:145(6): e20200702.

3. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020 Apr 10;69:422-6.

Coronavirus disease of 2019, more commonly referred to as COVID-19, is caused by a novel coronavirus. At press time in April, its diagnosis had been confirmed in more than 2 million individuals in 185 countries and territories since first isolated in January 2020. Daily updates are provided in terms of the number of new cases, the evolving strategies to mitigate additional spread, testing, potential drug trials, and vaccine development. Risk groups for development of severe disease also have been widely publicized. Limited information has been provided about COVID-19 in children.

Terminology

Endemic. The condition is present at a stable predictable rate in a community. The number observed is what is expected.

Outbreak. The number of cases is greater than what is expected in the area.

Epidemic. An outbreak that spreads over a larger geographical area.

Pandemic. An outbreak that has spread to multiple countries and /or continents.

What we know about coronaviruses: They are host-specific RNA viruses widespread in bats, but found in many other species including humans. Previously, six species caused disease in humans. Four species: 229E, NL63, OC43, and HKU1 usually cause the common cold. Symptoms are generally self-limited and peak 3-4 days after onset. Infection rarely can be manifested as otitis media or a lower respiratory tract disease.

In February 2003, SARS-CoV, a novel coronavirus, was identified as the causative agent for an outbreak of a severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) which began in Guangdong, China. It became a pandemic that occurred between November 2002 and July 2003. More than 8,000 individuals from 26 countries were infected, and there were 774 deaths, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. No cases have been reported since April 2004. This virus most often infected adults, and the mortality rate was 10%. No pediatric deaths were reported. The virus was considered to have evolved from a bat CoV with civet cats as an intermediate host.

In September 2012, MERS-CoV (Middle East respiratory syndrome), another novel coronavirus also manifesting as a severe respiratory illness, was identified in Saudi Arabia. Current data suggests it evolved from a bat CoV using dromedary camels as an intermediate host. To date, more than 2,400 cases have been reported with a case fatality rate of approximately 35% (Emerg Infect Dis. 2020 Feb; 26[2]:191-8). Disease in children has been mild. Most cases have been identified in adult males with comorbidities and have been reported from Saudi Arabia (85%). To date, no sustained human-to-human transmission has been documented. However, limited nonsustained human-to-human transmission has occurred in health care settings.

Preliminary COVID-19 pediatric data

Multiple case reports and studies with limited numbers of patients have been quickly published, but limited data about children have been available. A large study by Wu et al. was released. Epidemiologic data were available for 72,314 cases (62% confirmed 22% suspected,15% diagnosed based on clinical symptoms). Only 965 (1.3%) cases occurred in persons under 19 years of age. There were no deaths reported in anyone younger than 9 years old. The authors indicated that 889 patients (1%) were asymptomatic, but the exact number of children in that group was not provided.1

Dong Y et al. reported on the epidemiologic characteristics of 2,135 children under 18 years who resided in or near an epidemic center. Data were obtained retrospectively; 34% (728) of the cases were confirmed and 66% (1,407) were suspected. In summary, 94 (4%) of all patients were asymptomatic, 1,088 (51%) had mild symptoms, and 826 (39%) had moderate symptoms at the time of diagnosis. The remaining 6% of patients (125) had severe/critical disease manifested by dyspnea and hypoxemia. Interestingly, more severe/critical cases were in the suspected group. Could another pathogen be the true etiology? Severity of illness was greatest for infants (11%). As of Feb. 8, 2020, only one child had died; he was 14 years old. This study supports the claim that COVID-19 disease in children is less severe than in adults.2

Data in U.S. children are now available. Between Feb. 12, 2020, and April 2, 2020, there were 149,770 cases of laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 reported to the CDC. Age was documented in 149,082 cases and 2, 572 (1.7%) were in persons younger than 18 years. New York had the highest percentage of reported pediatric cases at 33% from New York City, and 23% from the remainder of New York state; an additional 15% were from New Jersey and the remaining 29% of cases were from other areas. The median age was 11 years. Cases by age were 32% in teens aged 15-17 years; 27% in children aged 10-14 years; 15% in children aged 5-9 years; 11% in children aged 1-4 years; and 15% in children aged less than 1 year.

Exposure history was documented in 184 cases, of which 91% were household /community. Information regarding signs and symptoms were limited but not absent. Based on available data, 73% of children had fever, cough, or shortness of breath. When looked at independently, each of these symptoms occurred less frequently than in adults: 56% of children reported fever, 54% reported cough, and 13% reported shortness of breath, compared with 71%, 80%, and 43% of adults, respectively. Also reported less frequently were myalgia, headache, sore throat, and diarrhea.

Hospitalization status was available for 745 children, with 20% being hospitalized and 2% being admitted to the ICU. Children under 1 year accounted for most of the hospitalizations. Limited information about underlying conditions was provided. Among 345 cases, 23% had at least one underlying medical condition; the most common conditions were chronic lung disease including asthma (50%), cardiovascular disease (31%), and immunosuppression (8%). Three deaths were reported in this cohort of 2,135 children; however, the final cause of death is still under review.3

There are limitations to the data. Many of the answers needed to perform adequate analysis regarding symptoms, their duration and severity, risk factors, etc., were not available. Routine testing is not currently recommended, and current practices may influence the outcomes.

What have we learned? The data suggest that most ill children may not have cough, fever, or shortness of breath; symptoms which parents will be looking for prior to even seeking medical attention. These are the individuals who may likely play a continued role with disease transmission. The need for hospitalization and the severity of illness appears to be lower than in adults but not absent. Strategies to mitigate additional spread such as social distancing, wearing facial masks, and hand washing still are important and should be encouraged.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She has no relevant financial disclosures. Email Dr. Word at [email protected].

References

1. JAMA. 2020;323(13):1239-42.

2. Pediatrics. 2020:145(6): e20200702.

3. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020 Apr 10;69:422-6.

Coronavirus disease of 2019, more commonly referred to as COVID-19, is caused by a novel coronavirus. At press time in April, its diagnosis had been confirmed in more than 2 million individuals in 185 countries and territories since first isolated in January 2020. Daily updates are provided in terms of the number of new cases, the evolving strategies to mitigate additional spread, testing, potential drug trials, and vaccine development. Risk groups for development of severe disease also have been widely publicized. Limited information has been provided about COVID-19 in children.

Terminology

Endemic. The condition is present at a stable predictable rate in a community. The number observed is what is expected.

Outbreak. The number of cases is greater than what is expected in the area.

Epidemic. An outbreak that spreads over a larger geographical area.

Pandemic. An outbreak that has spread to multiple countries and /or continents.

What we know about coronaviruses: They are host-specific RNA viruses widespread in bats, but found in many other species including humans. Previously, six species caused disease in humans. Four species: 229E, NL63, OC43, and HKU1 usually cause the common cold. Symptoms are generally self-limited and peak 3-4 days after onset. Infection rarely can be manifested as otitis media or a lower respiratory tract disease.

In February 2003, SARS-CoV, a novel coronavirus, was identified as the causative agent for an outbreak of a severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) which began in Guangdong, China. It became a pandemic that occurred between November 2002 and July 2003. More than 8,000 individuals from 26 countries were infected, and there were 774 deaths, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. No cases have been reported since April 2004. This virus most often infected adults, and the mortality rate was 10%. No pediatric deaths were reported. The virus was considered to have evolved from a bat CoV with civet cats as an intermediate host.

In September 2012, MERS-CoV (Middle East respiratory syndrome), another novel coronavirus also manifesting as a severe respiratory illness, was identified in Saudi Arabia. Current data suggests it evolved from a bat CoV using dromedary camels as an intermediate host. To date, more than 2,400 cases have been reported with a case fatality rate of approximately 35% (Emerg Infect Dis. 2020 Feb; 26[2]:191-8). Disease in children has been mild. Most cases have been identified in adult males with comorbidities and have been reported from Saudi Arabia (85%). To date, no sustained human-to-human transmission has been documented. However, limited nonsustained human-to-human transmission has occurred in health care settings.

Preliminary COVID-19 pediatric data

Multiple case reports and studies with limited numbers of patients have been quickly published, but limited data about children have been available. A large study by Wu et al. was released. Epidemiologic data were available for 72,314 cases (62% confirmed 22% suspected,15% diagnosed based on clinical symptoms). Only 965 (1.3%) cases occurred in persons under 19 years of age. There were no deaths reported in anyone younger than 9 years old. The authors indicated that 889 patients (1%) were asymptomatic, but the exact number of children in that group was not provided.1

Dong Y et al. reported on the epidemiologic characteristics of 2,135 children under 18 years who resided in or near an epidemic center. Data were obtained retrospectively; 34% (728) of the cases were confirmed and 66% (1,407) were suspected. In summary, 94 (4%) of all patients were asymptomatic, 1,088 (51%) had mild symptoms, and 826 (39%) had moderate symptoms at the time of diagnosis. The remaining 6% of patients (125) had severe/critical disease manifested by dyspnea and hypoxemia. Interestingly, more severe/critical cases were in the suspected group. Could another pathogen be the true etiology? Severity of illness was greatest for infants (11%). As of Feb. 8, 2020, only one child had died; he was 14 years old. This study supports the claim that COVID-19 disease in children is less severe than in adults.2

Data in U.S. children are now available. Between Feb. 12, 2020, and April 2, 2020, there were 149,770 cases of laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 reported to the CDC. Age was documented in 149,082 cases and 2, 572 (1.7%) were in persons younger than 18 years. New York had the highest percentage of reported pediatric cases at 33% from New York City, and 23% from the remainder of New York state; an additional 15% were from New Jersey and the remaining 29% of cases were from other areas. The median age was 11 years. Cases by age were 32% in teens aged 15-17 years; 27% in children aged 10-14 years; 15% in children aged 5-9 years; 11% in children aged 1-4 years; and 15% in children aged less than 1 year.

Exposure history was documented in 184 cases, of which 91% were household /community. Information regarding signs and symptoms were limited but not absent. Based on available data, 73% of children had fever, cough, or shortness of breath. When looked at independently, each of these symptoms occurred less frequently than in adults: 56% of children reported fever, 54% reported cough, and 13% reported shortness of breath, compared with 71%, 80%, and 43% of adults, respectively. Also reported less frequently were myalgia, headache, sore throat, and diarrhea.

Hospitalization status was available for 745 children, with 20% being hospitalized and 2% being admitted to the ICU. Children under 1 year accounted for most of the hospitalizations. Limited information about underlying conditions was provided. Among 345 cases, 23% had at least one underlying medical condition; the most common conditions were chronic lung disease including asthma (50%), cardiovascular disease (31%), and immunosuppression (8%). Three deaths were reported in this cohort of 2,135 children; however, the final cause of death is still under review.3

There are limitations to the data. Many of the answers needed to perform adequate analysis regarding symptoms, their duration and severity, risk factors, etc., were not available. Routine testing is not currently recommended, and current practices may influence the outcomes.

What have we learned? The data suggest that most ill children may not have cough, fever, or shortness of breath; symptoms which parents will be looking for prior to even seeking medical attention. These are the individuals who may likely play a continued role with disease transmission. The need for hospitalization and the severity of illness appears to be lower than in adults but not absent. Strategies to mitigate additional spread such as social distancing, wearing facial masks, and hand washing still are important and should be encouraged.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She has no relevant financial disclosures. Email Dr. Word at [email protected].

References

1. JAMA. 2020;323(13):1239-42.

2. Pediatrics. 2020:145(6): e20200702.

3. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020 Apr 10;69:422-6.

COVID-19: Mental illness the ‘inevitable’ next pandemic?

Social distancing is slowing the spread of COVID-19, but it will undoubtedly have negative consequences for mental health and well-being in both the short- and long-term, public health experts say.

In an article published online April 10 in JAMA Internal Medicine on the mental health consequences of COVID-19, the authors warn of a “pandemic” of behavioral problems and mental illness.

“COVID-19 is a traumatic event that we are all experiencing. We can well expect there to be a rise in mental illness nationwide,” first author Sandro Galea, MD, dean of the School of Public Health at Boston University, said in an interview.

“Education about this, screening for those with symptoms, and availability of treatment are all important to mitigate the mental health consequences of COVID-19,” Dr. Galea added.

Anxiety, depression, child abuse

The COVID-19 pandemic will likely result in “substantial” increases in anxiety and depression, substance use, loneliness, and domestic violence. In addition, with school closures, the possibility of an epidemic of child abuse is “very real,” the authors noted.

As reported online, a recent national survey by the American Psychiatric Association showed COVID-19 is seriously affecting Americans’ mental health, with half of U.S. adults reporting high levels of anxiety.

from the pandemic.

The first step is to plan for the inevitability of loneliness and its sequelae as populations physically and socially isolate and to find ways to intervene.

To prepare, the authors suggest the use of digital technologies to mitigate the impact of social distancing, even while physical distancing. They also encourage places of worship, gyms, yoga studios, and other places people normally gather to offer regularly scheduled online activities.

Employers also can help by offering virtual technologies that enable employees to work from home, and schools should develop and implement online learning for children.

“Even with all of these measures, there will still be segments of the population that are lonely and isolated. This suggests the need for remote approaches for outreach and screening for loneliness and associated mental health conditions so that social support can be provided,” the authors noted.

Need for creative thinking

The authors noted the second “critical” step is to have mechanisms in place for surveillance, reporting, and intervention, particularly when it comes to domestic violence and child abuse.

“Individuals at risk for abuse may have limited opportunities to report or seek help when shelter-in-place requirements demand prolonged cohabitation at home and limit travel outside of the home,” they wrote.

“Systems will need to balance the need for social distancing with the availability of safe places to be for people who are at risk, and social services systems will need to be creative in their approaches to following up on reports of problems,” they noted.

Finally, the authors note that now is the time to bolster the U.S. mental health system in preparation for the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Scaling up treatment in the midst of crisis will take creative thinking. Communities and organizations could consider training nontraditional groups to provide psychological first aid, helping teach the lay public to check in with one another and provide support,” they wrote.

“This difficult moment in time nonetheless offers the opportunity to advance our understanding of how to provide prevention-focused, population-level, and indeed national-level psychological first aid and mental health care, and to emerge from this pandemic with new ways of doing so.”

Invaluable advice

Reached for comment, Lloyd I. Sederer, MD, psychiatrist and adjunct professor at Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health in New York, described the article as “invaluable” noting that it “clearly and concisely describes the mental health consequences we can expect in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic – and what can (and needs) to be done to mitigate them.”

Dr. Sederer added that Dr. Galea has “studied and been part of the mental health responses to previous disasters, and is a leader in public health, including public mental health. His voice truly is worth listening to (and acting upon).”

Dr. Sederer offers additional suggestions on addressing mental health after disasters in a recent perspective article

Dr. Galea and Dr. Sederer have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Social distancing is slowing the spread of COVID-19, but it will undoubtedly have negative consequences for mental health and well-being in both the short- and long-term, public health experts say.

In an article published online April 10 in JAMA Internal Medicine on the mental health consequences of COVID-19, the authors warn of a “pandemic” of behavioral problems and mental illness.

“COVID-19 is a traumatic event that we are all experiencing. We can well expect there to be a rise in mental illness nationwide,” first author Sandro Galea, MD, dean of the School of Public Health at Boston University, said in an interview.

“Education about this, screening for those with symptoms, and availability of treatment are all important to mitigate the mental health consequences of COVID-19,” Dr. Galea added.

Anxiety, depression, child abuse

The COVID-19 pandemic will likely result in “substantial” increases in anxiety and depression, substance use, loneliness, and domestic violence. In addition, with school closures, the possibility of an epidemic of child abuse is “very real,” the authors noted.

As reported online, a recent national survey by the American Psychiatric Association showed COVID-19 is seriously affecting Americans’ mental health, with half of U.S. adults reporting high levels of anxiety.

from the pandemic.

The first step is to plan for the inevitability of loneliness and its sequelae as populations physically and socially isolate and to find ways to intervene.

To prepare, the authors suggest the use of digital technologies to mitigate the impact of social distancing, even while physical distancing. They also encourage places of worship, gyms, yoga studios, and other places people normally gather to offer regularly scheduled online activities.

Employers also can help by offering virtual technologies that enable employees to work from home, and schools should develop and implement online learning for children.

“Even with all of these measures, there will still be segments of the population that are lonely and isolated. This suggests the need for remote approaches for outreach and screening for loneliness and associated mental health conditions so that social support can be provided,” the authors noted.

Need for creative thinking

The authors noted the second “critical” step is to have mechanisms in place for surveillance, reporting, and intervention, particularly when it comes to domestic violence and child abuse.

“Individuals at risk for abuse may have limited opportunities to report or seek help when shelter-in-place requirements demand prolonged cohabitation at home and limit travel outside of the home,” they wrote.

“Systems will need to balance the need for social distancing with the availability of safe places to be for people who are at risk, and social services systems will need to be creative in their approaches to following up on reports of problems,” they noted.

Finally, the authors note that now is the time to bolster the U.S. mental health system in preparation for the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Scaling up treatment in the midst of crisis will take creative thinking. Communities and organizations could consider training nontraditional groups to provide psychological first aid, helping teach the lay public to check in with one another and provide support,” they wrote.

“This difficult moment in time nonetheless offers the opportunity to advance our understanding of how to provide prevention-focused, population-level, and indeed national-level psychological first aid and mental health care, and to emerge from this pandemic with new ways of doing so.”

Invaluable advice

Reached for comment, Lloyd I. Sederer, MD, psychiatrist and adjunct professor at Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health in New York, described the article as “invaluable” noting that it “clearly and concisely describes the mental health consequences we can expect in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic – and what can (and needs) to be done to mitigate them.”

Dr. Sederer added that Dr. Galea has “studied and been part of the mental health responses to previous disasters, and is a leader in public health, including public mental health. His voice truly is worth listening to (and acting upon).”

Dr. Sederer offers additional suggestions on addressing mental health after disasters in a recent perspective article

Dr. Galea and Dr. Sederer have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Social distancing is slowing the spread of COVID-19, but it will undoubtedly have negative consequences for mental health and well-being in both the short- and long-term, public health experts say.

In an article published online April 10 in JAMA Internal Medicine on the mental health consequences of COVID-19, the authors warn of a “pandemic” of behavioral problems and mental illness.

“COVID-19 is a traumatic event that we are all experiencing. We can well expect there to be a rise in mental illness nationwide,” first author Sandro Galea, MD, dean of the School of Public Health at Boston University, said in an interview.

“Education about this, screening for those with symptoms, and availability of treatment are all important to mitigate the mental health consequences of COVID-19,” Dr. Galea added.

Anxiety, depression, child abuse

The COVID-19 pandemic will likely result in “substantial” increases in anxiety and depression, substance use, loneliness, and domestic violence. In addition, with school closures, the possibility of an epidemic of child abuse is “very real,” the authors noted.

As reported online, a recent national survey by the American Psychiatric Association showed COVID-19 is seriously affecting Americans’ mental health, with half of U.S. adults reporting high levels of anxiety.

from the pandemic.

The first step is to plan for the inevitability of loneliness and its sequelae as populations physically and socially isolate and to find ways to intervene.

To prepare, the authors suggest the use of digital technologies to mitigate the impact of social distancing, even while physical distancing. They also encourage places of worship, gyms, yoga studios, and other places people normally gather to offer regularly scheduled online activities.

Employers also can help by offering virtual technologies that enable employees to work from home, and schools should develop and implement online learning for children.

“Even with all of these measures, there will still be segments of the population that are lonely and isolated. This suggests the need for remote approaches for outreach and screening for loneliness and associated mental health conditions so that social support can be provided,” the authors noted.

Need for creative thinking

The authors noted the second “critical” step is to have mechanisms in place for surveillance, reporting, and intervention, particularly when it comes to domestic violence and child abuse.

“Individuals at risk for abuse may have limited opportunities to report or seek help when shelter-in-place requirements demand prolonged cohabitation at home and limit travel outside of the home,” they wrote.

“Systems will need to balance the need for social distancing with the availability of safe places to be for people who are at risk, and social services systems will need to be creative in their approaches to following up on reports of problems,” they noted.

Finally, the authors note that now is the time to bolster the U.S. mental health system in preparation for the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Scaling up treatment in the midst of crisis will take creative thinking. Communities and organizations could consider training nontraditional groups to provide psychological first aid, helping teach the lay public to check in with one another and provide support,” they wrote.

“This difficult moment in time nonetheless offers the opportunity to advance our understanding of how to provide prevention-focused, population-level, and indeed national-level psychological first aid and mental health care, and to emerge from this pandemic with new ways of doing so.”

Invaluable advice

Reached for comment, Lloyd I. Sederer, MD, psychiatrist and adjunct professor at Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health in New York, described the article as “invaluable” noting that it “clearly and concisely describes the mental health consequences we can expect in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic – and what can (and needs) to be done to mitigate them.”

Dr. Sederer added that Dr. Galea has “studied and been part of the mental health responses to previous disasters, and is a leader in public health, including public mental health. His voice truly is worth listening to (and acting upon).”

Dr. Sederer offers additional suggestions on addressing mental health after disasters in a recent perspective article

Dr. Galea and Dr. Sederer have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Life in jail, made worse during COVID-19

An interview with correctional psychiatrist Elizabeth Ford

Jails provide ideal conditions for the spread of COVID-19, as made clear by the distressing stories coming out of New York City. Beyond the very substantial risks posed by the virus itself, practitioners tasked with attending to the large proportion of inmates with mental illness now face additional challenges.

Medscape Psychiatry editorial director Bret Stetka, MD, spoke with Elizabeth Ford, MD, former chief of psychiatry for NYC Health + Hospitals/Correctional Health Services and current chief medical officer for the Center for Alternative Sentencing and Employment Services (CASES), a community organization focused on the needs of people touched by the criminal justice system, to find out how COVID-19 may be reshaping the mental health care of incarcerated patients. As noted by Ford, who authored the 2017 memoir Sometimes Amazing Things Happen: Heartbreak and Hope on the Bellevue Hospital Psychiatric Prison Ward, the unique vulnerabilities of this population were evident well before the coronavirus pandemic’s arrival on our shores.

What are the unique health and mental health challenges that can arise in correctional facilities during crises like this, in particular, infectious crises? Or are we still learning this as COVID-19 spreads?

I think it’s important to say that they are still learning it, and I don’t want to speak for them. I left Correctional Health Services on Feb. 14, and we weren’t aware of [all the risks posed by COVID-19] at that point.

I worked in the jail proper for five and a half years. Prior to that I spent a decade at Bellevue Hospital, where I took care of the same patients, who were still incarcerated but also hospitalized. In those years, the closest I ever came to managing something like this was Superstorm Sandy, which obviously had much different health implications.

All of the things that the community is struggling with in terms of the virus also apply in jails and prisons: identifying people who are sick, keeping healthy people from getting sick, preventing sick people from getting worse, separating populations, treatment options, testing options, making sure people follow the appropriate hygiene recommendations. It’s just amplified immensely because these are closed systems that tend to be poorly sanitized, crowded, and frequently forgotten or minimized in public health and political conversations.

A really important distinction is that individuals who are incarcerated do not have control over their behavior in the way that they would in the outside world. They may want to wash their hands frequently and to stay six feet away from everybody, but they can’t because the environment doesn’t allow for that. I know that everyone – correctional officers, health staff, incarcerated individuals, the city – is trying to figure out how to do those things in the jail. The primary challenge is that you don’t have the ability to do the things that you know are right to prevent the spread of the infection.

I know you can’t speak to what’s going on at specific jails at the moment, but what sort of psychiatric measures would a jail system put forth in a time like this?

It’s a good question, because like everybody, they’re having to balance the safety of the staff and the patients.

I expect that the jails are trying to stratify patients based on severity, both physical and psychological, although increasingly it’s likely harder to separate those who are sick from those who aren’t. In areas where patients are sick, I think the mental health staff are likely doing as much intervention as they can safely, including remote work like telehealth. Telehealth actually got its start in prisons, because they couldn’t get enough providers to come in and do the work in person.

I’ve read a lot of the criticism around this, specifically at Rikers Island, where inmates are still closely seated at dining tables, with no possibility of social distancing. [Editor’s note: At the time of this writing, Rikers Island experienced its first inmate death due to COVID-19.] But I see the other side of it. What are jails supposed to do when limited to such a confined space?

That’s correct. I think it is hard for someone who has not lived or worked intensely in these settings to understand how difficult it can be to implement even the most basic hygiene precautions. There are all sorts of efforts happening to create more space, to reduce admissions coming into the jail, to try to expedite discharges out, to offer a lot more sanitation options. I think they may have opened up a jail that was empty to allow for more space.

In a recent Medscape commentary, Jeffrey Lieberman, MD, from Columbia University detailed how a crisis like this may affect those in different tiers of mental illness. Interestingly, there are data showing that those with serious mental illness – schizophrenia, severe mania – often aren’t panicked by disasters. I assume that a sizable percentage of the jail population has severe mental illness, so I was curious about what your experience is, about how they may handle it psychologically.

The rate of serious mental illness in jail is roughly 16% or so, which is three or four times higher than the general population.

Although I don’t know if these kinds of crises differentially affect people with serious mental illness, I do believe very strongly that situations like this, for those who are and who are not incarcerated, can exacerbate or cause symptoms like anxiety, depression, and elevated levels of fear – fear about the unknown, fear of illness or death, fear of isolation.

For people who are incarcerated and who understandably may struggle with trusting the system that is supposed to be keeping them safe, I am concerned that this kind of situation will make that lack of trust worse. I worry that when they get out of jail they will be less inclined to seek help. I imagine that the staff in the jails are doing as much as they can to support the patients, but the staff are also likely experiencing some version of the abandonment and frustration that the patients may feel.

I’ve also seen – not in a crisis of this magnitude but in other crisis situations – that a community really develops among everybody in incarcerated settings. A shared crisis forces everybody to work together in ways that they may not have before. That includes more tolerance for behaviors, more understanding of differences, including mental illness and developmental delay. More compassion.

Do you mean between prisoners and staff? Among everybody?

Everybody. In all of the different relationships you can imagine.

That speaks to the vulnerability and good nature in all of us. It’s encouraging.

It is, although it’s devastating to me that it happens because they collectively feel so neglected and forgotten. Shared trauma can bind people together very closely.

What psychiatric conditions did you typically see in New York City jails?

For the many people with serious mental illness, it’s generally schizophrenia-spectrum illnesses and bipolar disorder – really severe illnesses that do not do well in confinement settings. There’s a lot of anxiety and depression, some that rises to the level of serious illness. There is near universal substance use among the population.

There is also almost universal trauma exposure, whether early-childhood experiences or the ongoing trauma of incarceration. Not everyone has PTSD, but almost everyone behaves in a traumatized way. As you know, in the United States, incarceration is very racially and socioeconomically biased; the trauma of poverty can be incredibly harsh.

What I didn’t see were lots of people with antisocial personality disorder or diagnoses of malingering. That may surprise people. There’s an idea that everybody in jail is a liar and lacks empathy. I didn’t experience that. People in jail are doing whatever they can to survive.

What treatments are offered to these patients?

In New York City, all of the typical treatments that you would imagine for people with serious mental illness are offered in the jails: individual and group psychotherapy, medication management, substance use treatment, social work services, even creative art therapy. Many other jails are not able to do even a fraction of that.

In many jails there also has to be a lot of supportive therapy. This involves trying to help people get through a very anxiety-provoking and difficult time, when they frequently don’t know when they are going to be able to leave. I felt the same way as many of the correction officers – that the best thing for these patients is to be out of the jail, to be out of that toxic environment.

We have heard for years that the jail system and prison system is the new psych ward. Can you speak to how this occurred and the influence of deinstitutionalization?

When deinstitutionalization happened, there were not enough community agencies available that were equipped to take care of patients who were previously in hospitals. But I think a larger contributor to the overpopulation of people with mental illness in jails and prisons was the war on drugs. It disproportionately affected people who were poor, of color, and who had mental illness. Mental illness and substance use frequently occur together.

At the same time as deinstitutionalization and the war on drugs, there was also a tightening up of the laws relating to admission to psychiatric hospitals. The civil rights movement helped define the requirements that someone had to be dangerous and mentally ill in order to get admitted against their will. While this was an important protection against more indiscriminate admissions of the past, it made it harder to get into hospitals; the state hospitals were closed but the hospitals that were open were now harder to get into.

You mentioned that prisoners are undergoing trauma every day. Is this inherent to punitive confinement, or is it something that can be improved upon in the United States?

It’s important that you said “in the United States” as part of that question. Our approach to incarceration in the U.S. is heavily punishment based.

Compared to somewhere like Scandinavia, where inmates and prisoners are given a lot more support?

Or England or Canada. The challenge with comparing the United States to Scandinavia is that we are socioeconomically, demographically, and politically so different. But yes, my understanding about the Scandinavian systems are that they have a much more rehabilitative approach to incarceration. Until the U.S. can reframe the goals of incarceration to focus on helping individuals behave in a socially acceptable way, rather than destroy their sense of self-worth, we will continue to see the impact of trauma on generations of lives.

Now, that doesn’t mean that every jail and prison in this country is abusive. But taking away autonomy and freedom, applying inconsistent rules, using solitary confinement, and getting limited to no access to people you love all really destroy a person’s ability to behave in a way that society has deemed acceptable.

Assuming that mental health professionals such as yourself have a more compassionate understanding of what’s going on psychologically with the inmates, are you often at odds with law enforcement in the philosophy behind incarceration?

That’s an interesting question. When I moved from the hospital to the jail, I thought that I would run into a lot of resistance from the correction officer staff. I just thought, we’re coming at this from a totally different perspective: I’m trying to help these people and see if there’s a way to safely get them out, and you guys want to punish them.

It turns out that I was very misguided in that view, because it seemed to me that everybody wanted to do what was right for the patient. My perspective about what’s right involved respectful care, building self-esteem, treating illness. The correction officer’s perspective seemed to be keeping them safe, making sure that they can get through the system as quickly as possible, not having them get into fights. Our perspectives may have been different, but the goals were the same. I want all that stuff that the officers want as well.

It’s important to remember that the people who work inside jails and prisons are usually not the ones who are making the policies about who goes in. I haven’t had a lot of exposure working directly with many policymakers. I imagine that my opinions might differ from theirs in some regards.

For those working in the U.S. psychiatric healthcare system, what do you want them to know about mental health care in the correctional setting?

Patients in correctional settings are mostly the same patients seen in the public mental health system setting. The vast majority of people who spend time in jail or prison return to the community. But there’s a difference in how patients are perceived by many mental health professionals, including psychiatrists, depending on whether they have criminal justice experience or not.

I would encourage everybody to try to keep an open mind and remember that these patients are cycling through a very difficult system, for many reasons that are at least rooted in community trauma and poverty, and that it doesn’t change the nature of who they are. It doesn’t change that they’re still human beings and they still deserve care and support and treatment.

In this country, patients with mental illness and incarceration histories are so vulnerable and are often black, brown, and poor. It’s an incredible and disturbing representation of American society. But I feel like you can help a lot by getting involved in the frequently dysfunctional criminal justice system. Psychiatrists and other providers have an opportunity to fix things from the inside out.

What’s your new role at CASES?

I’m the chief medical officer at CASES [Center for Alternative Sentencing and Employment Services]. It’s a large community organization that provides mental health treatment, case management, employment and education services, alternatives to incarceration, and general support for people who have experienced criminal justice involvement. CASES began operating in the 1960s, and around 2000 it began developing programs specifically addressing the connection between serious mental illness and criminal justice system involvement. For example, we take care of the patients who are coming out of the jails or prisons, or managing patients that the courts have said should go to treatment instead of incarceration.

I took the job because as conditions for individuals with serious mental illness started to improve in the jails, I started to hear more frequently from patients that they were getting better treatment in the jail than out in the community. That did not sit well with me and seemed to be almost the opposite of how it should be.

I also have never been an outpatient public psychiatrist. Most of the patients I treat live most of their lives outside of a jail or a hospital. It felt really important for me to understand the lives of these patients and to see if all of the resistance that I’ve heard from community psychiatrists about taking care of people who have been in jail is really true or not.

It was a logical transition for me. I’m following the patients and basically deinstitutionalizing [them] myself.

This article was first published on Medscape.com.

An interview with correctional psychiatrist Elizabeth Ford

An interview with correctional psychiatrist Elizabeth Ford

Jails provide ideal conditions for the spread of COVID-19, as made clear by the distressing stories coming out of New York City. Beyond the very substantial risks posed by the virus itself, practitioners tasked with attending to the large proportion of inmates with mental illness now face additional challenges.

Medscape Psychiatry editorial director Bret Stetka, MD, spoke with Elizabeth Ford, MD, former chief of psychiatry for NYC Health + Hospitals/Correctional Health Services and current chief medical officer for the Center for Alternative Sentencing and Employment Services (CASES), a community organization focused on the needs of people touched by the criminal justice system, to find out how COVID-19 may be reshaping the mental health care of incarcerated patients. As noted by Ford, who authored the 2017 memoir Sometimes Amazing Things Happen: Heartbreak and Hope on the Bellevue Hospital Psychiatric Prison Ward, the unique vulnerabilities of this population were evident well before the coronavirus pandemic’s arrival on our shores.

What are the unique health and mental health challenges that can arise in correctional facilities during crises like this, in particular, infectious crises? Or are we still learning this as COVID-19 spreads?

I think it’s important to say that they are still learning it, and I don’t want to speak for them. I left Correctional Health Services on Feb. 14, and we weren’t aware of [all the risks posed by COVID-19] at that point.

I worked in the jail proper for five and a half years. Prior to that I spent a decade at Bellevue Hospital, where I took care of the same patients, who were still incarcerated but also hospitalized. In those years, the closest I ever came to managing something like this was Superstorm Sandy, which obviously had much different health implications.

All of the things that the community is struggling with in terms of the virus also apply in jails and prisons: identifying people who are sick, keeping healthy people from getting sick, preventing sick people from getting worse, separating populations, treatment options, testing options, making sure people follow the appropriate hygiene recommendations. It’s just amplified immensely because these are closed systems that tend to be poorly sanitized, crowded, and frequently forgotten or minimized in public health and political conversations.