User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

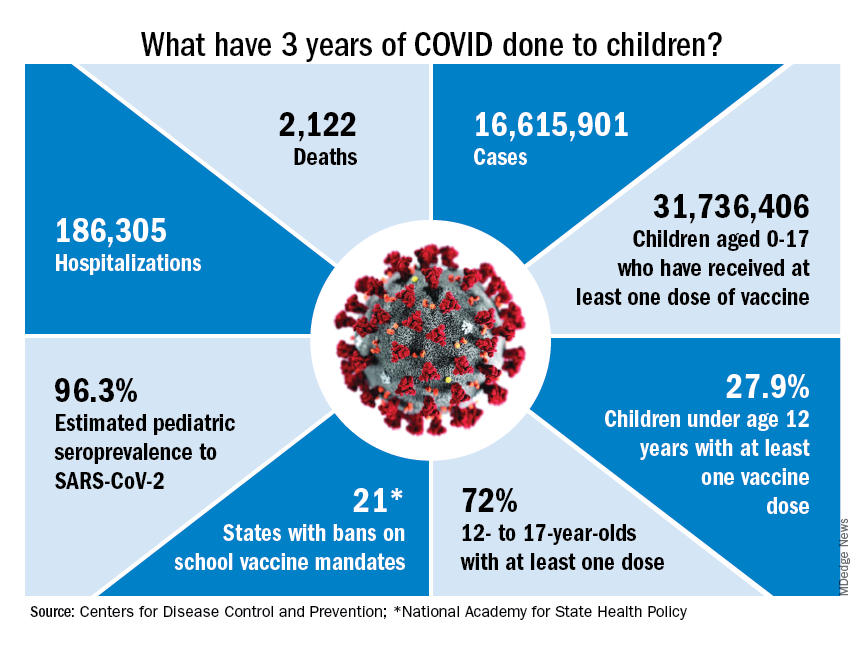

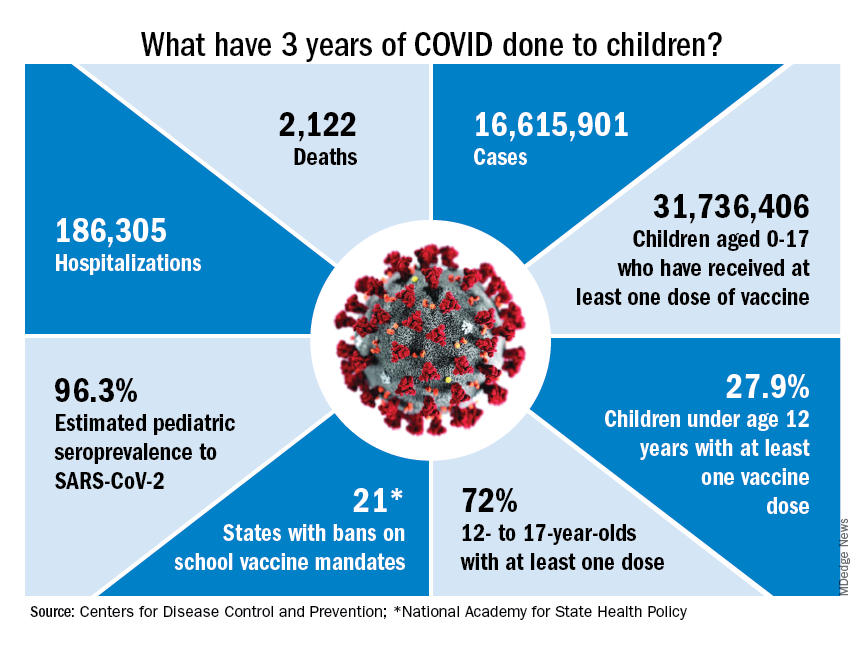

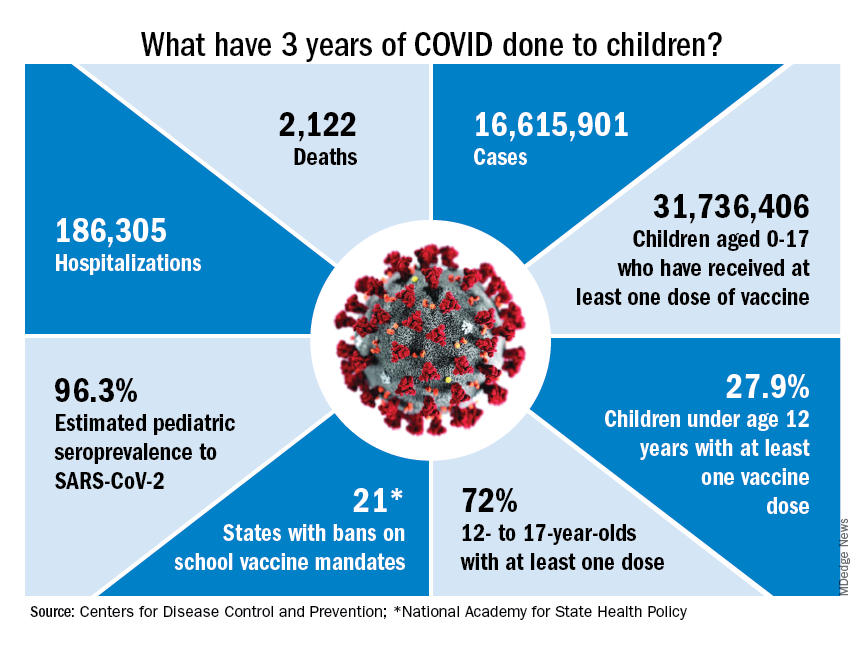

COVID-19 vaccinations lag in youngest children

Case: A 3-year-old girl presented to the emergency department after a brief seizure at home. She looked well on physical exam except for a fever of 103° F and thick rhinorrhea.

The intern on duty methodically worked through the standard list of questions. “Immunizations up to date?” she asked.

“Absolutely,” the child’s mom responded. “She’s had everything that’s recommended.”

“Including COVID-19 vaccine?” the intern prompted.

“No.” The mom responded with a shake of her head. “We don’t do that vaccine.”

That mom is not alone.

COVID-19 vaccines for children as young as 6 months were given emergency-use authorization by the Food and Drug Administration in June 2022 and in February 2023, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices included COVID-19 vaccine on the routine childhood immunization schedule.

COVID-19 vaccines are safe in young children, and they prevent the most severe outcomes associated with infection, including hospitalization. Newly released data confirm that the COVID-19 vaccines produced by Moderna and Pfizer also provide protection against symptomatic infection for at least 4 months after completion of the monovalent primary series.

In a Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report released on Feb. 17, 2023, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported the results of a test-negative design case-control study that enrolled symptomatic children tested for SARS-CoV-2 infection through Feb. 5, 2023, as part of the Increasing Community Access to Testing (ICATT) program.1 ICATT provides SARS-CoV-2 testing to persons aged at least 3 years at pharmacy and community-based testing sites nationwide.

Two doses of monovalent Moderna vaccine (complete primary series) was 60% effective against symptomatic infection (95% confidence interval, 49%-68%) 2 weeks to 2 months after receipt of the second dose. Vaccine effectiveness dropped to 36% (95% CI, 15%-52%) 3-4 months after the second dose. Three doses of monovalent Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine (complete primary series) was 31% effective (95% CI, 7%-49%) at preventing symptomatic infection 2 weeks to 4 months after receipt of the third dose. A bivalent vaccine dose for eligible children is expected to provide more protection against currently circulating SARS-CoV-2 variants.

Despite evidence of vaccine efficacy, very few parents are opting to protect their young children with the COVID-19 vaccine. The CDC reports that, as of March 1, 2023, only 8% of children under 2 years and 10.5% of children aged 2-4 years have initiated a COVID vaccine series. The American Academy of Pediatrics has emphasized that 15.0 million children between the ages of 6 months and 4 years have not yet received their first COVID-19 vaccine dose.

While the reasons underlying low COVID-19 vaccination rates in young children are complex, themes emerge. Socioeconomic disparities contributing to low vaccination rates in young children were highlighted in another recent MMWR article.2 Through Dec. 1, 2022, vaccination coverage was lower in rural counties (3.4%) than in urban counties (10.5%). Rates were lower in Black and Hispanic children than in White and Asian children.

According to the CDC, high rates of poverty in Black and Hispanic communities may affect vaccination coverage by affecting caregivers’ access to vaccination sites or ability to leave work to take their child to be vaccinated. Pediatric care providers have repeatedly been identified by parents as a source of trusted vaccine information and a strong provider recommendation is associated with vaccination, but not all families are receiving vaccine advice. In a 2022 Kaiser Family Foundation survey, parents of young children with annual household incomes above $90,000 were more likely to talk to their pediatrician about a COVID-19 vaccine than families with lower incomes.3Vaccine hesitancy, fueled by general confusion and skepticism, is another factor contributing to low vaccination rates. Admittedly, the recommendations are complex and on March 14, 2023, the FDA again revised the emergency-use authorization for young children. Some caregivers continue to express concerns about vaccine side effects as well as the belief that the vaccine won’t prevent their child from getting sick.

Kendall Purcell, MD, a pediatrician with Norton Children’s Medical Group in Louisville, Ky., recommends COVID-19 vaccination for her patients because it reduces the risk of severe disease. That factored into her own decision to vaccinate her 4-year-old son and 1-year-old daughter, but she hasn’t been able to convince the parents of all her patients. “Some feel that COVID-19 is not as severe for children, so the risks don’t outweigh the benefits when it comes to vaccinating their children.” Back to our case: In the ED the intern reviewed the laboratory testing she had ordered. She then sat down with the mother of the 3-year-old girl to discuss the diagnosis: febrile seizure associated with COVID-19 infection. Febrile seizures are a well-recognized but uncommon complication of COVID-19 in children. In a retrospective cohort study using electronic health record data, febrile seizures occurred in 0.5% of 8,854 children aged 0-5 years with COVID-19 infection.4 About 9% of these children required critical care services. In another cohort of hospitalized children, neurologic complications occurred in 7% of children hospitalized with COVID-19.5 Febrile and nonfebrile seizures were most commonly observed.

“I really thought COVID-19 was no big deal in young kids,” the mom said. “Parents need the facts.”

The facts are these: Through Dec. 2, 2022, more than 3 million cases of COVID-19 have been reported in children aged younger than 5 years. While COVID is generally less severe in young children than older adults, it is difficult to predict which children will become seriously ill. When children are hospitalized, one in four requires intensive care. COVID-19 is now a vaccine-preventable disease, but too many children remain unprotected.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Norton Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. She is a member of the AAP’s Committee on Infectious Diseases and one of the lead authors of the AAP’s Recommendations for Prevention and Control of Influenza in Children, 2022-2023. The opinions expressed in this article are her own. Dr. Bryant discloses that she has served as an investigator on clinical trials funded by Pfizer, Enanta, and Gilead. Email her at [email protected]. Ms. Ezell is a recent graduate from Indiana University Southeast with a Bachelor of Arts in English. They have no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Fleming-Dutra KE et al. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72:177-182.

2. Murthy BP et al. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72:183-9.

3. Lopes L et al. KFF COVID-19 vaccine monitor: July 2022. San Francisco: Kaiser Family Foundation, 2022.

4. Cadet K et al. J Child Neurol. 2022 Apr;37(5):410-5.

5. Antoon JW et al. Pediatrics. 2022 Nov 1;150(5):e2022058167.

Case: A 3-year-old girl presented to the emergency department after a brief seizure at home. She looked well on physical exam except for a fever of 103° F and thick rhinorrhea.

The intern on duty methodically worked through the standard list of questions. “Immunizations up to date?” she asked.

“Absolutely,” the child’s mom responded. “She’s had everything that’s recommended.”

“Including COVID-19 vaccine?” the intern prompted.

“No.” The mom responded with a shake of her head. “We don’t do that vaccine.”

That mom is not alone.

COVID-19 vaccines for children as young as 6 months were given emergency-use authorization by the Food and Drug Administration in June 2022 and in February 2023, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices included COVID-19 vaccine on the routine childhood immunization schedule.

COVID-19 vaccines are safe in young children, and they prevent the most severe outcomes associated with infection, including hospitalization. Newly released data confirm that the COVID-19 vaccines produced by Moderna and Pfizer also provide protection against symptomatic infection for at least 4 months after completion of the monovalent primary series.

In a Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report released on Feb. 17, 2023, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported the results of a test-negative design case-control study that enrolled symptomatic children tested for SARS-CoV-2 infection through Feb. 5, 2023, as part of the Increasing Community Access to Testing (ICATT) program.1 ICATT provides SARS-CoV-2 testing to persons aged at least 3 years at pharmacy and community-based testing sites nationwide.

Two doses of monovalent Moderna vaccine (complete primary series) was 60% effective against symptomatic infection (95% confidence interval, 49%-68%) 2 weeks to 2 months after receipt of the second dose. Vaccine effectiveness dropped to 36% (95% CI, 15%-52%) 3-4 months after the second dose. Three doses of monovalent Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine (complete primary series) was 31% effective (95% CI, 7%-49%) at preventing symptomatic infection 2 weeks to 4 months after receipt of the third dose. A bivalent vaccine dose for eligible children is expected to provide more protection against currently circulating SARS-CoV-2 variants.

Despite evidence of vaccine efficacy, very few parents are opting to protect their young children with the COVID-19 vaccine. The CDC reports that, as of March 1, 2023, only 8% of children under 2 years and 10.5% of children aged 2-4 years have initiated a COVID vaccine series. The American Academy of Pediatrics has emphasized that 15.0 million children between the ages of 6 months and 4 years have not yet received their first COVID-19 vaccine dose.

While the reasons underlying low COVID-19 vaccination rates in young children are complex, themes emerge. Socioeconomic disparities contributing to low vaccination rates in young children were highlighted in another recent MMWR article.2 Through Dec. 1, 2022, vaccination coverage was lower in rural counties (3.4%) than in urban counties (10.5%). Rates were lower in Black and Hispanic children than in White and Asian children.

According to the CDC, high rates of poverty in Black and Hispanic communities may affect vaccination coverage by affecting caregivers’ access to vaccination sites or ability to leave work to take their child to be vaccinated. Pediatric care providers have repeatedly been identified by parents as a source of trusted vaccine information and a strong provider recommendation is associated with vaccination, but not all families are receiving vaccine advice. In a 2022 Kaiser Family Foundation survey, parents of young children with annual household incomes above $90,000 were more likely to talk to their pediatrician about a COVID-19 vaccine than families with lower incomes.3Vaccine hesitancy, fueled by general confusion and skepticism, is another factor contributing to low vaccination rates. Admittedly, the recommendations are complex and on March 14, 2023, the FDA again revised the emergency-use authorization for young children. Some caregivers continue to express concerns about vaccine side effects as well as the belief that the vaccine won’t prevent their child from getting sick.

Kendall Purcell, MD, a pediatrician with Norton Children’s Medical Group in Louisville, Ky., recommends COVID-19 vaccination for her patients because it reduces the risk of severe disease. That factored into her own decision to vaccinate her 4-year-old son and 1-year-old daughter, but she hasn’t been able to convince the parents of all her patients. “Some feel that COVID-19 is not as severe for children, so the risks don’t outweigh the benefits when it comes to vaccinating their children.” Back to our case: In the ED the intern reviewed the laboratory testing she had ordered. She then sat down with the mother of the 3-year-old girl to discuss the diagnosis: febrile seizure associated with COVID-19 infection. Febrile seizures are a well-recognized but uncommon complication of COVID-19 in children. In a retrospective cohort study using electronic health record data, febrile seizures occurred in 0.5% of 8,854 children aged 0-5 years with COVID-19 infection.4 About 9% of these children required critical care services. In another cohort of hospitalized children, neurologic complications occurred in 7% of children hospitalized with COVID-19.5 Febrile and nonfebrile seizures were most commonly observed.

“I really thought COVID-19 was no big deal in young kids,” the mom said. “Parents need the facts.”

The facts are these: Through Dec. 2, 2022, more than 3 million cases of COVID-19 have been reported in children aged younger than 5 years. While COVID is generally less severe in young children than older adults, it is difficult to predict which children will become seriously ill. When children are hospitalized, one in four requires intensive care. COVID-19 is now a vaccine-preventable disease, but too many children remain unprotected.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Norton Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. She is a member of the AAP’s Committee on Infectious Diseases and one of the lead authors of the AAP’s Recommendations for Prevention and Control of Influenza in Children, 2022-2023. The opinions expressed in this article are her own. Dr. Bryant discloses that she has served as an investigator on clinical trials funded by Pfizer, Enanta, and Gilead. Email her at [email protected]. Ms. Ezell is a recent graduate from Indiana University Southeast with a Bachelor of Arts in English. They have no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Fleming-Dutra KE et al. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72:177-182.

2. Murthy BP et al. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72:183-9.

3. Lopes L et al. KFF COVID-19 vaccine monitor: July 2022. San Francisco: Kaiser Family Foundation, 2022.

4. Cadet K et al. J Child Neurol. 2022 Apr;37(5):410-5.

5. Antoon JW et al. Pediatrics. 2022 Nov 1;150(5):e2022058167.

Case: A 3-year-old girl presented to the emergency department after a brief seizure at home. She looked well on physical exam except for a fever of 103° F and thick rhinorrhea.

The intern on duty methodically worked through the standard list of questions. “Immunizations up to date?” she asked.

“Absolutely,” the child’s mom responded. “She’s had everything that’s recommended.”

“Including COVID-19 vaccine?” the intern prompted.

“No.” The mom responded with a shake of her head. “We don’t do that vaccine.”

That mom is not alone.

COVID-19 vaccines for children as young as 6 months were given emergency-use authorization by the Food and Drug Administration in June 2022 and in February 2023, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices included COVID-19 vaccine on the routine childhood immunization schedule.

COVID-19 vaccines are safe in young children, and they prevent the most severe outcomes associated with infection, including hospitalization. Newly released data confirm that the COVID-19 vaccines produced by Moderna and Pfizer also provide protection against symptomatic infection for at least 4 months after completion of the monovalent primary series.

In a Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report released on Feb. 17, 2023, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported the results of a test-negative design case-control study that enrolled symptomatic children tested for SARS-CoV-2 infection through Feb. 5, 2023, as part of the Increasing Community Access to Testing (ICATT) program.1 ICATT provides SARS-CoV-2 testing to persons aged at least 3 years at pharmacy and community-based testing sites nationwide.

Two doses of monovalent Moderna vaccine (complete primary series) was 60% effective against symptomatic infection (95% confidence interval, 49%-68%) 2 weeks to 2 months after receipt of the second dose. Vaccine effectiveness dropped to 36% (95% CI, 15%-52%) 3-4 months after the second dose. Three doses of monovalent Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine (complete primary series) was 31% effective (95% CI, 7%-49%) at preventing symptomatic infection 2 weeks to 4 months after receipt of the third dose. A bivalent vaccine dose for eligible children is expected to provide more protection against currently circulating SARS-CoV-2 variants.

Despite evidence of vaccine efficacy, very few parents are opting to protect their young children with the COVID-19 vaccine. The CDC reports that, as of March 1, 2023, only 8% of children under 2 years and 10.5% of children aged 2-4 years have initiated a COVID vaccine series. The American Academy of Pediatrics has emphasized that 15.0 million children between the ages of 6 months and 4 years have not yet received their first COVID-19 vaccine dose.

While the reasons underlying low COVID-19 vaccination rates in young children are complex, themes emerge. Socioeconomic disparities contributing to low vaccination rates in young children were highlighted in another recent MMWR article.2 Through Dec. 1, 2022, vaccination coverage was lower in rural counties (3.4%) than in urban counties (10.5%). Rates were lower in Black and Hispanic children than in White and Asian children.

According to the CDC, high rates of poverty in Black and Hispanic communities may affect vaccination coverage by affecting caregivers’ access to vaccination sites or ability to leave work to take their child to be vaccinated. Pediatric care providers have repeatedly been identified by parents as a source of trusted vaccine information and a strong provider recommendation is associated with vaccination, but not all families are receiving vaccine advice. In a 2022 Kaiser Family Foundation survey, parents of young children with annual household incomes above $90,000 were more likely to talk to their pediatrician about a COVID-19 vaccine than families with lower incomes.3Vaccine hesitancy, fueled by general confusion and skepticism, is another factor contributing to low vaccination rates. Admittedly, the recommendations are complex and on March 14, 2023, the FDA again revised the emergency-use authorization for young children. Some caregivers continue to express concerns about vaccine side effects as well as the belief that the vaccine won’t prevent their child from getting sick.

Kendall Purcell, MD, a pediatrician with Norton Children’s Medical Group in Louisville, Ky., recommends COVID-19 vaccination for her patients because it reduces the risk of severe disease. That factored into her own decision to vaccinate her 4-year-old son and 1-year-old daughter, but she hasn’t been able to convince the parents of all her patients. “Some feel that COVID-19 is not as severe for children, so the risks don’t outweigh the benefits when it comes to vaccinating their children.” Back to our case: In the ED the intern reviewed the laboratory testing she had ordered. She then sat down with the mother of the 3-year-old girl to discuss the diagnosis: febrile seizure associated with COVID-19 infection. Febrile seizures are a well-recognized but uncommon complication of COVID-19 in children. In a retrospective cohort study using electronic health record data, febrile seizures occurred in 0.5% of 8,854 children aged 0-5 years with COVID-19 infection.4 About 9% of these children required critical care services. In another cohort of hospitalized children, neurologic complications occurred in 7% of children hospitalized with COVID-19.5 Febrile and nonfebrile seizures were most commonly observed.

“I really thought COVID-19 was no big deal in young kids,” the mom said. “Parents need the facts.”

The facts are these: Through Dec. 2, 2022, more than 3 million cases of COVID-19 have been reported in children aged younger than 5 years. While COVID is generally less severe in young children than older adults, it is difficult to predict which children will become seriously ill. When children are hospitalized, one in four requires intensive care. COVID-19 is now a vaccine-preventable disease, but too many children remain unprotected.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Norton Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. She is a member of the AAP’s Committee on Infectious Diseases and one of the lead authors of the AAP’s Recommendations for Prevention and Control of Influenza in Children, 2022-2023. The opinions expressed in this article are her own. Dr. Bryant discloses that she has served as an investigator on clinical trials funded by Pfizer, Enanta, and Gilead. Email her at [email protected]. Ms. Ezell is a recent graduate from Indiana University Southeast with a Bachelor of Arts in English. They have no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Fleming-Dutra KE et al. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72:177-182.

2. Murthy BP et al. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72:183-9.

3. Lopes L et al. KFF COVID-19 vaccine monitor: July 2022. San Francisco: Kaiser Family Foundation, 2022.

4. Cadet K et al. J Child Neurol. 2022 Apr;37(5):410-5.

5. Antoon JW et al. Pediatrics. 2022 Nov 1;150(5):e2022058167.

Older men more at risk as dangerous falls rise for all seniors

When Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) fell recently at a dinner event in Washington, he unfortunately joined a large group of his senior citizen peers.

This wasn’t the first tumble the 81-year-old has taken. In 2019, he fell in his home, fracturing his shoulder. This time, he got a concussion and was recently released to an in-patient rehabilitation facility. While Sen. McConnell didn’t fracture his skull, in falling and hitting his head, he became part of an emerging statistic: One that reveals falls are more dangerous for senior men than senior women.

This new research, which appeared in the American Journal of Emergency Medicine, came as a surprise to lead researcher Scott Alter, MD, associate professor of emergency medicine at the Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton.

“We always hear about lower bone density rates among females, so we didn’t expect to see males with more skull fractures,” he said.

Dr. Alter said that as a clinician in a southern Florida facility, his emergency department was the perfect study grounds to evaluate incoming geriatric patients due to falls. Older “patients are at higher risk of skull fractures and intercranial bleeding, and we wanted to look at any patient presenting with a head injury. Some 80% were fall related, however.”

The statistics bear out the fact that falls of all types are common among the elderly: Some 800,000 seniors wind up in the hospital each year because of falls.

The numbers show death rates from falls are on the rise in the senior citizen age group, too, up 30% from 2007 to 2016. Falls account for 70% of accidental deaths in people 75 and older. They are the leading cause of injury-related visits to emergency departments in the country, too.

Jennifer Stevens, MD, a gerontologist and executive director at Florida-based Abbey Delray South, is aware of the dire numbers and sees their consequences regularly. “The reasons seniors are at a high fall risk are many,” she said. “They include balance issues, declining strength, diseases like Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s, side effects of their medications, and more.”

In addition, many seniors live in spaces that are not necessarily equipped for their limitations, and hazards exist all over their homes. Put together, and the risks for falls are everywhere. But there are steps seniors, their families, and even middle-aged people can take to mitigate and hopefully prevent dangerous falls.

Starting early

While in many cases the journey to lessen fall risks begins after a fall, the time to begin addressing the issue is long before you hit your senior years. Mary Therese Cole, a physical therapist and certified dementia practitioner at Manual Edge Physical Therapy in Colorado Springs, Colo., says that age 50 is a good time to start paying attention and addressing physical declines.

“This is an age where your vision might begin deteriorating,” she said. “It’s a big reason why elderly people trip and fall.”

As our brains begin to age in our middle years, the neural pathways from brain to extremities start to decline, too. The result is that many people stop picking up their feet as well as they used to do, making them more likely to trip.

“You’re not elderly yet, but you’re not a spring chicken, either,” Ms. Cole said. “Any issues you have now will only get worse if you’re not working on them.”

A good starting point in middle age, then, is to work on both strength training and balance exercises. A certified personal trainer or physical therapist can help get you on a program to ward off many of these declines.

If you’ve reached your later years, however, and are experiencing physical declines, it’s smart to check in with your primary care doctor for an assessment. “He or she can get your started on regular PT to evaluate any shortcomings and then address them,” Ms. Cole said.

She noted that when she’s working with senior patients, she’ll test their strength getting into and out of a chair, do a manual strength test to check on lower extremities, check their walking stride, and ask about conditions such as diabetes, former surgeries, and other conditions.

From there, Ms. Cole said she can write up a plan for the patient. Likewise, Dr. Stevens uses a program called Be Active that allows her to test seniors on a variety of measurements, including flexibility, balance, hand strength, and more.

“Then we match them with classes to address their shortcomings,” she said. “It’s critical that seniors have the ability to recover and not fall if they get knocked off balance.”

Beyond working on your physical limitations, taking a good look at your home is essential, too. “You can have an occupational therapist come to your home and do an evaluation,” Dr. Stevens said. “They can help you rearrange and reorganize for a safer environment.”

Big, common household fall hazards include throw rugs, lack of nightlights for middle-of-the-night visits to the bathroom, a lack of grab bars in the shower/bathtub, and furniture that blocks pathways.

For his part, Dr. Alter likes to point seniors and their doctors to the CDC’s STEADI program, which is aimed at stopping elderly accidents, deaths, and injuries.

“It includes screening for fall risk, assessing factors you can modify or improve, and more tools,” he said.

Dr. Alter also recommended seniors talk to their doctors about medications, particularly blood thinners.

“At a certain point, you need to weigh the benefits of disease prevention with the risk of injury if you fall,” he said. “The bleeding risk might be too high if the patient is at a high risk of falls.”

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMD.com.

When Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) fell recently at a dinner event in Washington, he unfortunately joined a large group of his senior citizen peers.

This wasn’t the first tumble the 81-year-old has taken. In 2019, he fell in his home, fracturing his shoulder. This time, he got a concussion and was recently released to an in-patient rehabilitation facility. While Sen. McConnell didn’t fracture his skull, in falling and hitting his head, he became part of an emerging statistic: One that reveals falls are more dangerous for senior men than senior women.

This new research, which appeared in the American Journal of Emergency Medicine, came as a surprise to lead researcher Scott Alter, MD, associate professor of emergency medicine at the Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton.

“We always hear about lower bone density rates among females, so we didn’t expect to see males with more skull fractures,” he said.

Dr. Alter said that as a clinician in a southern Florida facility, his emergency department was the perfect study grounds to evaluate incoming geriatric patients due to falls. Older “patients are at higher risk of skull fractures and intercranial bleeding, and we wanted to look at any patient presenting with a head injury. Some 80% were fall related, however.”

The statistics bear out the fact that falls of all types are common among the elderly: Some 800,000 seniors wind up in the hospital each year because of falls.

The numbers show death rates from falls are on the rise in the senior citizen age group, too, up 30% from 2007 to 2016. Falls account for 70% of accidental deaths in people 75 and older. They are the leading cause of injury-related visits to emergency departments in the country, too.

Jennifer Stevens, MD, a gerontologist and executive director at Florida-based Abbey Delray South, is aware of the dire numbers and sees their consequences regularly. “The reasons seniors are at a high fall risk are many,” she said. “They include balance issues, declining strength, diseases like Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s, side effects of their medications, and more.”

In addition, many seniors live in spaces that are not necessarily equipped for their limitations, and hazards exist all over their homes. Put together, and the risks for falls are everywhere. But there are steps seniors, their families, and even middle-aged people can take to mitigate and hopefully prevent dangerous falls.

Starting early

While in many cases the journey to lessen fall risks begins after a fall, the time to begin addressing the issue is long before you hit your senior years. Mary Therese Cole, a physical therapist and certified dementia practitioner at Manual Edge Physical Therapy in Colorado Springs, Colo., says that age 50 is a good time to start paying attention and addressing physical declines.

“This is an age where your vision might begin deteriorating,” she said. “It’s a big reason why elderly people trip and fall.”

As our brains begin to age in our middle years, the neural pathways from brain to extremities start to decline, too. The result is that many people stop picking up their feet as well as they used to do, making them more likely to trip.

“You’re not elderly yet, but you’re not a spring chicken, either,” Ms. Cole said. “Any issues you have now will only get worse if you’re not working on them.”

A good starting point in middle age, then, is to work on both strength training and balance exercises. A certified personal trainer or physical therapist can help get you on a program to ward off many of these declines.

If you’ve reached your later years, however, and are experiencing physical declines, it’s smart to check in with your primary care doctor for an assessment. “He or she can get your started on regular PT to evaluate any shortcomings and then address them,” Ms. Cole said.

She noted that when she’s working with senior patients, she’ll test their strength getting into and out of a chair, do a manual strength test to check on lower extremities, check their walking stride, and ask about conditions such as diabetes, former surgeries, and other conditions.

From there, Ms. Cole said she can write up a plan for the patient. Likewise, Dr. Stevens uses a program called Be Active that allows her to test seniors on a variety of measurements, including flexibility, balance, hand strength, and more.

“Then we match them with classes to address their shortcomings,” she said. “It’s critical that seniors have the ability to recover and not fall if they get knocked off balance.”

Beyond working on your physical limitations, taking a good look at your home is essential, too. “You can have an occupational therapist come to your home and do an evaluation,” Dr. Stevens said. “They can help you rearrange and reorganize for a safer environment.”

Big, common household fall hazards include throw rugs, lack of nightlights for middle-of-the-night visits to the bathroom, a lack of grab bars in the shower/bathtub, and furniture that blocks pathways.

For his part, Dr. Alter likes to point seniors and their doctors to the CDC’s STEADI program, which is aimed at stopping elderly accidents, deaths, and injuries.

“It includes screening for fall risk, assessing factors you can modify or improve, and more tools,” he said.

Dr. Alter also recommended seniors talk to their doctors about medications, particularly blood thinners.

“At a certain point, you need to weigh the benefits of disease prevention with the risk of injury if you fall,” he said. “The bleeding risk might be too high if the patient is at a high risk of falls.”

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMD.com.

When Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) fell recently at a dinner event in Washington, he unfortunately joined a large group of his senior citizen peers.

This wasn’t the first tumble the 81-year-old has taken. In 2019, he fell in his home, fracturing his shoulder. This time, he got a concussion and was recently released to an in-patient rehabilitation facility. While Sen. McConnell didn’t fracture his skull, in falling and hitting his head, he became part of an emerging statistic: One that reveals falls are more dangerous for senior men than senior women.

This new research, which appeared in the American Journal of Emergency Medicine, came as a surprise to lead researcher Scott Alter, MD, associate professor of emergency medicine at the Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton.

“We always hear about lower bone density rates among females, so we didn’t expect to see males with more skull fractures,” he said.

Dr. Alter said that as a clinician in a southern Florida facility, his emergency department was the perfect study grounds to evaluate incoming geriatric patients due to falls. Older “patients are at higher risk of skull fractures and intercranial bleeding, and we wanted to look at any patient presenting with a head injury. Some 80% were fall related, however.”

The statistics bear out the fact that falls of all types are common among the elderly: Some 800,000 seniors wind up in the hospital each year because of falls.

The numbers show death rates from falls are on the rise in the senior citizen age group, too, up 30% from 2007 to 2016. Falls account for 70% of accidental deaths in people 75 and older. They are the leading cause of injury-related visits to emergency departments in the country, too.

Jennifer Stevens, MD, a gerontologist and executive director at Florida-based Abbey Delray South, is aware of the dire numbers and sees their consequences regularly. “The reasons seniors are at a high fall risk are many,” she said. “They include balance issues, declining strength, diseases like Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s, side effects of their medications, and more.”

In addition, many seniors live in spaces that are not necessarily equipped for their limitations, and hazards exist all over their homes. Put together, and the risks for falls are everywhere. But there are steps seniors, their families, and even middle-aged people can take to mitigate and hopefully prevent dangerous falls.

Starting early

While in many cases the journey to lessen fall risks begins after a fall, the time to begin addressing the issue is long before you hit your senior years. Mary Therese Cole, a physical therapist and certified dementia practitioner at Manual Edge Physical Therapy in Colorado Springs, Colo., says that age 50 is a good time to start paying attention and addressing physical declines.

“This is an age where your vision might begin deteriorating,” she said. “It’s a big reason why elderly people trip and fall.”

As our brains begin to age in our middle years, the neural pathways from brain to extremities start to decline, too. The result is that many people stop picking up their feet as well as they used to do, making them more likely to trip.

“You’re not elderly yet, but you’re not a spring chicken, either,” Ms. Cole said. “Any issues you have now will only get worse if you’re not working on them.”

A good starting point in middle age, then, is to work on both strength training and balance exercises. A certified personal trainer or physical therapist can help get you on a program to ward off many of these declines.

If you’ve reached your later years, however, and are experiencing physical declines, it’s smart to check in with your primary care doctor for an assessment. “He or she can get your started on regular PT to evaluate any shortcomings and then address them,” Ms. Cole said.

She noted that when she’s working with senior patients, she’ll test their strength getting into and out of a chair, do a manual strength test to check on lower extremities, check their walking stride, and ask about conditions such as diabetes, former surgeries, and other conditions.

From there, Ms. Cole said she can write up a plan for the patient. Likewise, Dr. Stevens uses a program called Be Active that allows her to test seniors on a variety of measurements, including flexibility, balance, hand strength, and more.

“Then we match them with classes to address their shortcomings,” she said. “It’s critical that seniors have the ability to recover and not fall if they get knocked off balance.”

Beyond working on your physical limitations, taking a good look at your home is essential, too. “You can have an occupational therapist come to your home and do an evaluation,” Dr. Stevens said. “They can help you rearrange and reorganize for a safer environment.”

Big, common household fall hazards include throw rugs, lack of nightlights for middle-of-the-night visits to the bathroom, a lack of grab bars in the shower/bathtub, and furniture that blocks pathways.

For his part, Dr. Alter likes to point seniors and their doctors to the CDC’s STEADI program, which is aimed at stopping elderly accidents, deaths, and injuries.

“It includes screening for fall risk, assessing factors you can modify or improve, and more tools,” he said.

Dr. Alter also recommended seniors talk to their doctors about medications, particularly blood thinners.

“At a certain point, you need to weigh the benefits of disease prevention with the risk of injury if you fall,” he said. “The bleeding risk might be too high if the patient is at a high risk of falls.”

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMD.com.

The human-looking robot therapist will coach your well-being now

Do android therapists dream of electric employees?

Robots. It can be tough to remember that, when they’re not dooming humanity to apocalypse or just telling you that you’re doomed, robots have real-world uses. There are actual robots in the world, and they can do things beyond bend girders, sing about science, or run the navy.

Look, we’ll stop with the pop-culture references when pop culture runs out of robots to reference. It may take a while.

Robots are indelibly rooted in the public consciousness, and that plays into our expectations when we encounter a real-life robot. This leads us into a recent study conducted by researchers at the University of Cambridge, who developed a robot-led mental well-being program that a tech company utilized for 4 weeks. Why choose a robot? Well, why spring for a qualified therapist who requires a salary when you could simply get a robot to do the job for free? Get with the capitalist agenda here. Surely it won’t backfire.

The 26 people enrolled in the study received coaching from one of two robots, both programmed identically to act like mental health coaches, based on interviews with human therapists. Both acted identically and had identical expressions. The only difference between the two was their appearance. QTRobot was nearly a meter tall and looked like a human child; Misty II was much smaller and looked like a toy.

People who received coaching from Misty II were better able to connect and had a better experience than those who received coaching from QTRobot. According to those in the QTRobot group, their expectations didn’t match reality. The robots are good coaches, but they don’t act human. This wasn’t a problem for Misty II, since it doesn’t look human, but for QTRobot, the participants were expecting “to hell with our orders,” but received “Daisy, Daisy, give me your answer do.” When you’ve been programmed to think of robots as metal humans, it can be off-putting to see them act as, well, robots.

That said, all participants found the exercises helpful and were open to receiving more robot-led therapy in the future. And while we’re sure the technology will advance to make robot therapists more empathetic and more human, hopefully scientists won’t go too far. We don’t need depressed robots.

Birthing experience is all in the mindset

Alexa, play Peer Gynt Suite No. 1, Op. 46 - I. Morning Mood.

Birth.

Giving birth is a common experience for many, if not most, female mammals, but wanting it to be a pleasurable one seems distinctly human. There are many methods and practices that may make giving birth an easier and enjoyable experience for the mother, but a new study suggests that the key could be in her mind.

The mindset of the expectant mother during pregnancy, it seems, has some effect on how smooth or intervention-filled delivery is. If the mothers saw their experience as a natural process, they were less likely to need pain medication or a C-section, but mothers who viewed the experience as more of a “medical procedure” were more likely to require more medical supervision and intervention, according to investigators from the University of Bonn (Germany).

Now, the researchers wanted to be super clear in saying that there’s no right or wrong mindset to have. They just focused on the outcomes of those mindsets and whether they actually do have some effect on occurrences.

Apparently, yes.

“Mindsets can be understood as a kind of mental lense that guide our perception of the world around us and can influence our behavior,” Dr. Lisa Hoffmann said in a statement from the university. “The study highlights the importance of psychological factors in childbirth.”

The researchers surveyed 300 women with an online tool before and after delivery and found the effects of the natural process mindset lingered even after giving birth. They had lower rates of depression and posttraumatic stress, which may have a snowballing effect on mother-child bonding after childbirth.

Preparation for the big day, then, should be about more than gathering diapers and shopping for car seats. Women should prepare their minds as well. If it’s going to make giving birth better, why not?

Becoming a parent is going to create a psychological shift, no matter how you slice it.

Giant inflatable colon reported in Utah

Do not be alarmed! Yes, there is a giant inflatable colon currently at large in the Beehive State, but it will not harm you. The giant inflatable colon is in Utah as part of Intermountain Health’s “Let’s get to the bottom of colon cancer tour” and he only wants to help you.

The giant inflatable colon, whose name happens to be Collin, is 12 feet long and weighs 113 pounds. March is Colon Cancer Awareness Month, so Collin is traveling around Utah and Idaho to raise awareness about colon cancer and the various screening options. He is not going to change local weather patterns, eat small children, or take over local governments and raise your taxes.

Instead, Collin is planning to display “portions of a healthy colon, polyps or bumps on the colon, malignant polyps which look more vascular and have more redness, cancerous cells, advanced cancer cells, and Crohn’s disease,” KSL.com said.

Collin the colon is on loan to Intermountain Health from medical device manufacturer Boston Scientific and will be traveling to Spanish Fork, Provo, and Ogden, among other locations in Utah, as well as Burley and Meridian, Idaho, in the coming days.

Collin the colon’s participation in the tour has created some serious buzz in the Colin/Collin community:

- Colin Powell (four-star general and Secretary of State): “Back then, the second-most important topic among the Joint Chiefs of Staff was colon cancer screening. And the Navy guy – I can’t remember his name – was a huge fan of giant inflatable organs.”

- Colin Jost (comedian and Saturday Night Live “Weekend Update” cohost): “He’s funnier than Tucker Carlson and Pete Davidson combined.”

Do android therapists dream of electric employees?

Robots. It can be tough to remember that, when they’re not dooming humanity to apocalypse or just telling you that you’re doomed, robots have real-world uses. There are actual robots in the world, and they can do things beyond bend girders, sing about science, or run the navy.

Look, we’ll stop with the pop-culture references when pop culture runs out of robots to reference. It may take a while.

Robots are indelibly rooted in the public consciousness, and that plays into our expectations when we encounter a real-life robot. This leads us into a recent study conducted by researchers at the University of Cambridge, who developed a robot-led mental well-being program that a tech company utilized for 4 weeks. Why choose a robot? Well, why spring for a qualified therapist who requires a salary when you could simply get a robot to do the job for free? Get with the capitalist agenda here. Surely it won’t backfire.

The 26 people enrolled in the study received coaching from one of two robots, both programmed identically to act like mental health coaches, based on interviews with human therapists. Both acted identically and had identical expressions. The only difference between the two was their appearance. QTRobot was nearly a meter tall and looked like a human child; Misty II was much smaller and looked like a toy.

People who received coaching from Misty II were better able to connect and had a better experience than those who received coaching from QTRobot. According to those in the QTRobot group, their expectations didn’t match reality. The robots are good coaches, but they don’t act human. This wasn’t a problem for Misty II, since it doesn’t look human, but for QTRobot, the participants were expecting “to hell with our orders,” but received “Daisy, Daisy, give me your answer do.” When you’ve been programmed to think of robots as metal humans, it can be off-putting to see them act as, well, robots.

That said, all participants found the exercises helpful and were open to receiving more robot-led therapy in the future. And while we’re sure the technology will advance to make robot therapists more empathetic and more human, hopefully scientists won’t go too far. We don’t need depressed robots.

Birthing experience is all in the mindset

Alexa, play Peer Gynt Suite No. 1, Op. 46 - I. Morning Mood.

Birth.

Giving birth is a common experience for many, if not most, female mammals, but wanting it to be a pleasurable one seems distinctly human. There are many methods and practices that may make giving birth an easier and enjoyable experience for the mother, but a new study suggests that the key could be in her mind.

The mindset of the expectant mother during pregnancy, it seems, has some effect on how smooth or intervention-filled delivery is. If the mothers saw their experience as a natural process, they were less likely to need pain medication or a C-section, but mothers who viewed the experience as more of a “medical procedure” were more likely to require more medical supervision and intervention, according to investigators from the University of Bonn (Germany).

Now, the researchers wanted to be super clear in saying that there’s no right or wrong mindset to have. They just focused on the outcomes of those mindsets and whether they actually do have some effect on occurrences.

Apparently, yes.

“Mindsets can be understood as a kind of mental lense that guide our perception of the world around us and can influence our behavior,” Dr. Lisa Hoffmann said in a statement from the university. “The study highlights the importance of psychological factors in childbirth.”

The researchers surveyed 300 women with an online tool before and after delivery and found the effects of the natural process mindset lingered even after giving birth. They had lower rates of depression and posttraumatic stress, which may have a snowballing effect on mother-child bonding after childbirth.

Preparation for the big day, then, should be about more than gathering diapers and shopping for car seats. Women should prepare their minds as well. If it’s going to make giving birth better, why not?

Becoming a parent is going to create a psychological shift, no matter how you slice it.

Giant inflatable colon reported in Utah

Do not be alarmed! Yes, there is a giant inflatable colon currently at large in the Beehive State, but it will not harm you. The giant inflatable colon is in Utah as part of Intermountain Health’s “Let’s get to the bottom of colon cancer tour” and he only wants to help you.

The giant inflatable colon, whose name happens to be Collin, is 12 feet long and weighs 113 pounds. March is Colon Cancer Awareness Month, so Collin is traveling around Utah and Idaho to raise awareness about colon cancer and the various screening options. He is not going to change local weather patterns, eat small children, or take over local governments and raise your taxes.

Instead, Collin is planning to display “portions of a healthy colon, polyps or bumps on the colon, malignant polyps which look more vascular and have more redness, cancerous cells, advanced cancer cells, and Crohn’s disease,” KSL.com said.

Collin the colon is on loan to Intermountain Health from medical device manufacturer Boston Scientific and will be traveling to Spanish Fork, Provo, and Ogden, among other locations in Utah, as well as Burley and Meridian, Idaho, in the coming days.

Collin the colon’s participation in the tour has created some serious buzz in the Colin/Collin community:

- Colin Powell (four-star general and Secretary of State): “Back then, the second-most important topic among the Joint Chiefs of Staff was colon cancer screening. And the Navy guy – I can’t remember his name – was a huge fan of giant inflatable organs.”

- Colin Jost (comedian and Saturday Night Live “Weekend Update” cohost): “He’s funnier than Tucker Carlson and Pete Davidson combined.”

Do android therapists dream of electric employees?

Robots. It can be tough to remember that, when they’re not dooming humanity to apocalypse or just telling you that you’re doomed, robots have real-world uses. There are actual robots in the world, and they can do things beyond bend girders, sing about science, or run the navy.

Look, we’ll stop with the pop-culture references when pop culture runs out of robots to reference. It may take a while.

Robots are indelibly rooted in the public consciousness, and that plays into our expectations when we encounter a real-life robot. This leads us into a recent study conducted by researchers at the University of Cambridge, who developed a robot-led mental well-being program that a tech company utilized for 4 weeks. Why choose a robot? Well, why spring for a qualified therapist who requires a salary when you could simply get a robot to do the job for free? Get with the capitalist agenda here. Surely it won’t backfire.

The 26 people enrolled in the study received coaching from one of two robots, both programmed identically to act like mental health coaches, based on interviews with human therapists. Both acted identically and had identical expressions. The only difference between the two was their appearance. QTRobot was nearly a meter tall and looked like a human child; Misty II was much smaller and looked like a toy.

People who received coaching from Misty II were better able to connect and had a better experience than those who received coaching from QTRobot. According to those in the QTRobot group, their expectations didn’t match reality. The robots are good coaches, but they don’t act human. This wasn’t a problem for Misty II, since it doesn’t look human, but for QTRobot, the participants were expecting “to hell with our orders,” but received “Daisy, Daisy, give me your answer do.” When you’ve been programmed to think of robots as metal humans, it can be off-putting to see them act as, well, robots.

That said, all participants found the exercises helpful and were open to receiving more robot-led therapy in the future. And while we’re sure the technology will advance to make robot therapists more empathetic and more human, hopefully scientists won’t go too far. We don’t need depressed robots.

Birthing experience is all in the mindset

Alexa, play Peer Gynt Suite No. 1, Op. 46 - I. Morning Mood.

Birth.

Giving birth is a common experience for many, if not most, female mammals, but wanting it to be a pleasurable one seems distinctly human. There are many methods and practices that may make giving birth an easier and enjoyable experience for the mother, but a new study suggests that the key could be in her mind.

The mindset of the expectant mother during pregnancy, it seems, has some effect on how smooth or intervention-filled delivery is. If the mothers saw their experience as a natural process, they were less likely to need pain medication or a C-section, but mothers who viewed the experience as more of a “medical procedure” were more likely to require more medical supervision and intervention, according to investigators from the University of Bonn (Germany).

Now, the researchers wanted to be super clear in saying that there’s no right or wrong mindset to have. They just focused on the outcomes of those mindsets and whether they actually do have some effect on occurrences.

Apparently, yes.

“Mindsets can be understood as a kind of mental lense that guide our perception of the world around us and can influence our behavior,” Dr. Lisa Hoffmann said in a statement from the university. “The study highlights the importance of psychological factors in childbirth.”

The researchers surveyed 300 women with an online tool before and after delivery and found the effects of the natural process mindset lingered even after giving birth. They had lower rates of depression and posttraumatic stress, which may have a snowballing effect on mother-child bonding after childbirth.

Preparation for the big day, then, should be about more than gathering diapers and shopping for car seats. Women should prepare their minds as well. If it’s going to make giving birth better, why not?

Becoming a parent is going to create a psychological shift, no matter how you slice it.

Giant inflatable colon reported in Utah

Do not be alarmed! Yes, there is a giant inflatable colon currently at large in the Beehive State, but it will not harm you. The giant inflatable colon is in Utah as part of Intermountain Health’s “Let’s get to the bottom of colon cancer tour” and he only wants to help you.

The giant inflatable colon, whose name happens to be Collin, is 12 feet long and weighs 113 pounds. March is Colon Cancer Awareness Month, so Collin is traveling around Utah and Idaho to raise awareness about colon cancer and the various screening options. He is not going to change local weather patterns, eat small children, or take over local governments and raise your taxes.

Instead, Collin is planning to display “portions of a healthy colon, polyps or bumps on the colon, malignant polyps which look more vascular and have more redness, cancerous cells, advanced cancer cells, and Crohn’s disease,” KSL.com said.

Collin the colon is on loan to Intermountain Health from medical device manufacturer Boston Scientific and will be traveling to Spanish Fork, Provo, and Ogden, among other locations in Utah, as well as Burley and Meridian, Idaho, in the coming days.

Collin the colon’s participation in the tour has created some serious buzz in the Colin/Collin community:

- Colin Powell (four-star general and Secretary of State): “Back then, the second-most important topic among the Joint Chiefs of Staff was colon cancer screening. And the Navy guy – I can’t remember his name – was a huge fan of giant inflatable organs.”

- Colin Jost (comedian and Saturday Night Live “Weekend Update” cohost): “He’s funnier than Tucker Carlson and Pete Davidson combined.”

High school athletes sustaining worse injuries

High school students are injuring themselves more severely even as overall injury rates have declined, according to a new study presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons.

The study compared injuries from a 4-year period ending in 2019 to data from 2005 and 2006. The overall rate of injuries dropped 9%, from 2.51 injuries per 1,000 athletic games or practices to 2.29 per 1,000; injuries requiring less than 1 week of recovery time fell by 13%. But, the number of head and neck injuries increased by 10%, injuries requiring surgery increased by 1%, and injuries leading to medical disqualification jumped by 11%.

“It’s wonderful that the injury rate is declining,” said Jordan Neoma Pizzarro, a medical student at George Washington University, Washington, who led the study. “But the data does suggest that the injuries that are happening are worse.”

The increases may also reflect increased education and awareness of how to detect concussions and other injuries that need medical attention, said Micah Lissy, MD, MS, an orthopedic surgeon specializing in sports medicine at Michigan State University, East Lansing. Dr. Lissy cautioned against physicians and others taking the data at face value.

“We need to be implementing preventive measures wherever possible, but I think we can also consider that there may be some confounding factors in the data,” Dr. Lissy told this news organization.

Ms. Pizzarro and her team analyzed data collected from athletic trainers at 100 high schools across the country for the ongoing National Health School Sports-Related Injury Surveillance Study.

Athletes participating in sports such as football, soccer, basketball, volleyball, and softball were included in the analysis. Trainers report the number of injuries for every competition and practice, also known as “athletic exposures.”

Boys’ football carried the highest injury rate, with 3.96 injuries per 1,000 AEs, amounting to 44% of all injuries reported. Girls’ soccer and boys’ wrestling followed, with injury rates of 2.65 and 1.56, respectively.

Sprains and strains accounted for 37% of injuries, followed by concussions (21.6%). The head and/or face was the most injured body site, followed by the ankles and/or knees. Most injuries took place during competitions rather than in practices (relative risk, 3.39; 95% confidence interval, 3.28-3.49; P < .05).

Ms. Pizzarro said that an overall increase in intensity, physical contact, and collisions may account for the spike in more severe injuries.

“Kids are encouraged to specialize in one sport early on and stick with it year-round,” she said. “They’re probably becoming more agile and better athletes, but they’re probably also getting more competitive.”

Dr. Lissy, who has worked with high school athletes as a surgeon, physical therapist, athletic trainer, and coach, said that some of the increases in severity of injuries may reflect trends in sports over the past two decades: Student athletes have become stronger and faster and have put on more muscle mass.

“When you have something that’s much larger, moving much faster and with more force, you’re going to have more force when you bump into things,” he said. “This can lead to more significant injuries.”

The study was independently supported. Study authors report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

High school students are injuring themselves more severely even as overall injury rates have declined, according to a new study presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons.

The study compared injuries from a 4-year period ending in 2019 to data from 2005 and 2006. The overall rate of injuries dropped 9%, from 2.51 injuries per 1,000 athletic games or practices to 2.29 per 1,000; injuries requiring less than 1 week of recovery time fell by 13%. But, the number of head and neck injuries increased by 10%, injuries requiring surgery increased by 1%, and injuries leading to medical disqualification jumped by 11%.

“It’s wonderful that the injury rate is declining,” said Jordan Neoma Pizzarro, a medical student at George Washington University, Washington, who led the study. “But the data does suggest that the injuries that are happening are worse.”

The increases may also reflect increased education and awareness of how to detect concussions and other injuries that need medical attention, said Micah Lissy, MD, MS, an orthopedic surgeon specializing in sports medicine at Michigan State University, East Lansing. Dr. Lissy cautioned against physicians and others taking the data at face value.

“We need to be implementing preventive measures wherever possible, but I think we can also consider that there may be some confounding factors in the data,” Dr. Lissy told this news organization.

Ms. Pizzarro and her team analyzed data collected from athletic trainers at 100 high schools across the country for the ongoing National Health School Sports-Related Injury Surveillance Study.

Athletes participating in sports such as football, soccer, basketball, volleyball, and softball were included in the analysis. Trainers report the number of injuries for every competition and practice, also known as “athletic exposures.”

Boys’ football carried the highest injury rate, with 3.96 injuries per 1,000 AEs, amounting to 44% of all injuries reported. Girls’ soccer and boys’ wrestling followed, with injury rates of 2.65 and 1.56, respectively.

Sprains and strains accounted for 37% of injuries, followed by concussions (21.6%). The head and/or face was the most injured body site, followed by the ankles and/or knees. Most injuries took place during competitions rather than in practices (relative risk, 3.39; 95% confidence interval, 3.28-3.49; P < .05).

Ms. Pizzarro said that an overall increase in intensity, physical contact, and collisions may account for the spike in more severe injuries.

“Kids are encouraged to specialize in one sport early on and stick with it year-round,” she said. “They’re probably becoming more agile and better athletes, but they’re probably also getting more competitive.”

Dr. Lissy, who has worked with high school athletes as a surgeon, physical therapist, athletic trainer, and coach, said that some of the increases in severity of injuries may reflect trends in sports over the past two decades: Student athletes have become stronger and faster and have put on more muscle mass.

“When you have something that’s much larger, moving much faster and with more force, you’re going to have more force when you bump into things,” he said. “This can lead to more significant injuries.”

The study was independently supported. Study authors report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

High school students are injuring themselves more severely even as overall injury rates have declined, according to a new study presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons.

The study compared injuries from a 4-year period ending in 2019 to data from 2005 and 2006. The overall rate of injuries dropped 9%, from 2.51 injuries per 1,000 athletic games or practices to 2.29 per 1,000; injuries requiring less than 1 week of recovery time fell by 13%. But, the number of head and neck injuries increased by 10%, injuries requiring surgery increased by 1%, and injuries leading to medical disqualification jumped by 11%.

“It’s wonderful that the injury rate is declining,” said Jordan Neoma Pizzarro, a medical student at George Washington University, Washington, who led the study. “But the data does suggest that the injuries that are happening are worse.”

The increases may also reflect increased education and awareness of how to detect concussions and other injuries that need medical attention, said Micah Lissy, MD, MS, an orthopedic surgeon specializing in sports medicine at Michigan State University, East Lansing. Dr. Lissy cautioned against physicians and others taking the data at face value.

“We need to be implementing preventive measures wherever possible, but I think we can also consider that there may be some confounding factors in the data,” Dr. Lissy told this news organization.

Ms. Pizzarro and her team analyzed data collected from athletic trainers at 100 high schools across the country for the ongoing National Health School Sports-Related Injury Surveillance Study.

Athletes participating in sports such as football, soccer, basketball, volleyball, and softball were included in the analysis. Trainers report the number of injuries for every competition and practice, also known as “athletic exposures.”

Boys’ football carried the highest injury rate, with 3.96 injuries per 1,000 AEs, amounting to 44% of all injuries reported. Girls’ soccer and boys’ wrestling followed, with injury rates of 2.65 and 1.56, respectively.

Sprains and strains accounted for 37% of injuries, followed by concussions (21.6%). The head and/or face was the most injured body site, followed by the ankles and/or knees. Most injuries took place during competitions rather than in practices (relative risk, 3.39; 95% confidence interval, 3.28-3.49; P < .05).

Ms. Pizzarro said that an overall increase in intensity, physical contact, and collisions may account for the spike in more severe injuries.

“Kids are encouraged to specialize in one sport early on and stick with it year-round,” she said. “They’re probably becoming more agile and better athletes, but they’re probably also getting more competitive.”

Dr. Lissy, who has worked with high school athletes as a surgeon, physical therapist, athletic trainer, and coach, said that some of the increases in severity of injuries may reflect trends in sports over the past two decades: Student athletes have become stronger and faster and have put on more muscle mass.

“When you have something that’s much larger, moving much faster and with more force, you’re going to have more force when you bump into things,” he said. “This can lead to more significant injuries.”

The study was independently supported. Study authors report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

What do I have? How to tell patients you’re not sure

Physicians often struggle with telling patients when they are unsure about a diagnosis. In the absence of clarity, doctors may fear losing a patient’s trust by appearing unsure.

Yet diagnostic uncertainty is an inevitable part of medicine.

“It’s often uncertain what is really going on. People have lots of unspecific symptoms,” said Gordon D. Schiff, MD, a patient safety researcher at Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

By one estimate, more than one-third of patients are discharged from an emergency department without a clear diagnosis. Physicians may order more tests to try to resolve uncertainty, but this method is not foolproof and may lead to increased health care costs. Physicians can use an uncertain diagnosis as an opportunity to improve conversations with patients, Dr. Schiff said.

“How do you talk to patients about that? How do you convey that?” Dr. Schiff asked.

To begin to answer these questions, The scenarios included an enlarged lymph node in a patient in remission for lymphoma, which could suggest recurrence of the disease but not necessarily; a patient with a new-onset headache; and another patient with an unexplained fever and a respiratory tract infection.

For each vignette, the researchers also asked patient advocates – many of whom had experienced receiving an incorrect diagnosis – for their thoughts on how the conversation should go.

Almost 70 people were consulted (24 primary care physicians, 40 patients, and five experts in informatics and quality and safety). Dr. Schiff and his colleagues produced six standardized elements that should be part of a conversation whenever a diagnosis is unclear.

- The most likely diagnosis, along with any alternatives if this isn’t certain, with phrases such as, “Sometimes we don’t have the answers, but we will keep trying to figure out what is going on.”

- Next steps – lab tests, return visits, etc.

- Expected time frame for patient’s improvement and recovery.

- Full disclosure of the limitations of the physical examination or any lab tests.

- Ways to contact the physician going forward.

- Patient insights on their experience and reaction to what they just heard.

The researchers, who published their findings in JAMA Network Open, recommend that the conversation be transcribed in real time using voice recognition software and a microphone, and then printed for the patient to take home. The physician should make eye contact with the patient during the conversation, they suggested.

“Patients felt it was a conversation, that they actually understood what was said. Most patients felt like they were partners during the encounter,” said Maram Khazen, PhD, a coauthor of the paper, who studies communication dynamics. Dr. Khazen was a visiting postdoctoral fellow with Dr. Schiff during the study, and is now a lecturer at the Max Stern Yezreel Valley College in Israel.

Hardeep Singh, MD, MPH, a patient safety researcher at the Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center and Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, called the new work “a great start,” but said that the complexity of the field warrants more research into the tool. Dr. Singh was not involved in the study.

Dr. Singh pointed out that many of the patient voices came from spokespeople for advocacy groups, and that these participants are not necessarily representative of actual people with unclear diagnoses.

“The choice of words really matters,” said Dr. Singh, who led a 2018 study that showed that people reacted more negatively when physicians bluntly acknowledged uncertainty than when they walked patients through different possible diagnoses. Dr. Schiff and Dr. Khazen’s framework offers good principles for discussing uncertainty, he added, but further research is needed on the optimal language to use during conversations.

“It’s really encouraging that we’re seeing high-quality research like this, that leverages patient engagement principles,” said Dimitrios Papanagnou, MD, MPH, an emergency medicine physician and vice dean of medicine at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia.

Dr. Papanagnou, who was not part of the study, called for diverse patients to be part of conversations about diagnostic uncertainty.

“Are we having patients from diverse experiences, from underrepresented groups, participate in this kind of work?” Dr. Papanagnou asked. Dr. Schiff and Dr. Khazen said they agree that the tool needs to be tested in larger samples of diverse patients.

Some common themes about how to communicate diagnostic uncertainty are emerging in multiple areas of medicine. Dr. Papanagnou helped develop an uncertainty communication checklist for discharging patients from an emergency department to home, with principles similar to those that Dr. Schiff and Dr. Khazen recommend for primary care providers.

The study was funded by Harvard Hospitals’ malpractice insurer, the Controlled Risk Insurance Company. The authors disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Physicians often struggle with telling patients when they are unsure about a diagnosis. In the absence of clarity, doctors may fear losing a patient’s trust by appearing unsure.

Yet diagnostic uncertainty is an inevitable part of medicine.

“It’s often uncertain what is really going on. People have lots of unspecific symptoms,” said Gordon D. Schiff, MD, a patient safety researcher at Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

By one estimate, more than one-third of patients are discharged from an emergency department without a clear diagnosis. Physicians may order more tests to try to resolve uncertainty, but this method is not foolproof and may lead to increased health care costs. Physicians can use an uncertain diagnosis as an opportunity to improve conversations with patients, Dr. Schiff said.

“How do you talk to patients about that? How do you convey that?” Dr. Schiff asked.

To begin to answer these questions, The scenarios included an enlarged lymph node in a patient in remission for lymphoma, which could suggest recurrence of the disease but not necessarily; a patient with a new-onset headache; and another patient with an unexplained fever and a respiratory tract infection.

For each vignette, the researchers also asked patient advocates – many of whom had experienced receiving an incorrect diagnosis – for their thoughts on how the conversation should go.

Almost 70 people were consulted (24 primary care physicians, 40 patients, and five experts in informatics and quality and safety). Dr. Schiff and his colleagues produced six standardized elements that should be part of a conversation whenever a diagnosis is unclear.

- The most likely diagnosis, along with any alternatives if this isn’t certain, with phrases such as, “Sometimes we don’t have the answers, but we will keep trying to figure out what is going on.”

- Next steps – lab tests, return visits, etc.

- Expected time frame for patient’s improvement and recovery.

- Full disclosure of the limitations of the physical examination or any lab tests.

- Ways to contact the physician going forward.

- Patient insights on their experience and reaction to what they just heard.

The researchers, who published their findings in JAMA Network Open, recommend that the conversation be transcribed in real time using voice recognition software and a microphone, and then printed for the patient to take home. The physician should make eye contact with the patient during the conversation, they suggested.

“Patients felt it was a conversation, that they actually understood what was said. Most patients felt like they were partners during the encounter,” said Maram Khazen, PhD, a coauthor of the paper, who studies communication dynamics. Dr. Khazen was a visiting postdoctoral fellow with Dr. Schiff during the study, and is now a lecturer at the Max Stern Yezreel Valley College in Israel.

Hardeep Singh, MD, MPH, a patient safety researcher at the Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center and Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, called the new work “a great start,” but said that the complexity of the field warrants more research into the tool. Dr. Singh was not involved in the study.

Dr. Singh pointed out that many of the patient voices came from spokespeople for advocacy groups, and that these participants are not necessarily representative of actual people with unclear diagnoses.

“The choice of words really matters,” said Dr. Singh, who led a 2018 study that showed that people reacted more negatively when physicians bluntly acknowledged uncertainty than when they walked patients through different possible diagnoses. Dr. Schiff and Dr. Khazen’s framework offers good principles for discussing uncertainty, he added, but further research is needed on the optimal language to use during conversations.

“It’s really encouraging that we’re seeing high-quality research like this, that leverages patient engagement principles,” said Dimitrios Papanagnou, MD, MPH, an emergency medicine physician and vice dean of medicine at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia.

Dr. Papanagnou, who was not part of the study, called for diverse patients to be part of conversations about diagnostic uncertainty.

“Are we having patients from diverse experiences, from underrepresented groups, participate in this kind of work?” Dr. Papanagnou asked. Dr. Schiff and Dr. Khazen said they agree that the tool needs to be tested in larger samples of diverse patients.

Some common themes about how to communicate diagnostic uncertainty are emerging in multiple areas of medicine. Dr. Papanagnou helped develop an uncertainty communication checklist for discharging patients from an emergency department to home, with principles similar to those that Dr. Schiff and Dr. Khazen recommend for primary care providers.

The study was funded by Harvard Hospitals’ malpractice insurer, the Controlled Risk Insurance Company. The authors disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Physicians often struggle with telling patients when they are unsure about a diagnosis. In the absence of clarity, doctors may fear losing a patient’s trust by appearing unsure.

Yet diagnostic uncertainty is an inevitable part of medicine.

“It’s often uncertain what is really going on. People have lots of unspecific symptoms,” said Gordon D. Schiff, MD, a patient safety researcher at Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

By one estimate, more than one-third of patients are discharged from an emergency department without a clear diagnosis. Physicians may order more tests to try to resolve uncertainty, but this method is not foolproof and may lead to increased health care costs. Physicians can use an uncertain diagnosis as an opportunity to improve conversations with patients, Dr. Schiff said.

“How do you talk to patients about that? How do you convey that?” Dr. Schiff asked.