User login

Official news magazine of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Copyright by Society of Hospital Medicine or related companies. All rights reserved. ISSN 1553-085X

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-hospitalist')]

SARS serum neutralizing antibodies may inform the treatment of COVID-19

The immune responses of specific antibodies were maintained in more than 90% of recovered SARS-CoV patients for 2 years, raising the likelihood that the similarly behaving SARS-CoV-2 might provoke the same response, according to an online communication published in the Journal of Microbiology, Immunology and Infection.

The authors cited a cohort study of convalescent SARS-CoV patients (56 cases, from the Beijing hospital of the Armed Forces Police, China) that showed that specific IgG antibodies and neutralizing antibodies were highly correlated, peaking at month 4 after the onset of disease and decreasing gradually thereafter.

This and other studies suggest that the immune responses of specific antibodies were maintained in more than 90% of recovered SARS-CoV patients for 2 years, according to the authors.

However, of particular concern is the fact that only 11.8% of patients acquire specific SARS-CoV Abs in the early period after recovery at day 7, not reaching 100% until day 90, which highlights the importance of the detection of antibody titers for convalescent COVID-19 patients, according to the authors. “Otherwise, these patients with low titers of antibodies may not be efficient for the clearance of SARS-CoV-2.”

The authors also cited a recent study that showed how neutralizing antibody from a convalescent SARS patient could block the SARS-CoV-2 from entering into target cells in vitro, and suggested that previous experimental SARS-CoV vaccines and neutralizing antibodies could provide novel preventive and therapeutic options for COVID-19.

“These experiences from SARS-CoV are expected to have some implications for the treatment, management and surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 patients,” the authors concluded.

SOURCE: Lin Q et al. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2020 Mar 25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmii.2020.03.015.

The immune responses of specific antibodies were maintained in more than 90% of recovered SARS-CoV patients for 2 years, raising the likelihood that the similarly behaving SARS-CoV-2 might provoke the same response, according to an online communication published in the Journal of Microbiology, Immunology and Infection.

The authors cited a cohort study of convalescent SARS-CoV patients (56 cases, from the Beijing hospital of the Armed Forces Police, China) that showed that specific IgG antibodies and neutralizing antibodies were highly correlated, peaking at month 4 after the onset of disease and decreasing gradually thereafter.

This and other studies suggest that the immune responses of specific antibodies were maintained in more than 90% of recovered SARS-CoV patients for 2 years, according to the authors.

However, of particular concern is the fact that only 11.8% of patients acquire specific SARS-CoV Abs in the early period after recovery at day 7, not reaching 100% until day 90, which highlights the importance of the detection of antibody titers for convalescent COVID-19 patients, according to the authors. “Otherwise, these patients with low titers of antibodies may not be efficient for the clearance of SARS-CoV-2.”

The authors also cited a recent study that showed how neutralizing antibody from a convalescent SARS patient could block the SARS-CoV-2 from entering into target cells in vitro, and suggested that previous experimental SARS-CoV vaccines and neutralizing antibodies could provide novel preventive and therapeutic options for COVID-19.

“These experiences from SARS-CoV are expected to have some implications for the treatment, management and surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 patients,” the authors concluded.

SOURCE: Lin Q et al. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2020 Mar 25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmii.2020.03.015.

The immune responses of specific antibodies were maintained in more than 90% of recovered SARS-CoV patients for 2 years, raising the likelihood that the similarly behaving SARS-CoV-2 might provoke the same response, according to an online communication published in the Journal of Microbiology, Immunology and Infection.

The authors cited a cohort study of convalescent SARS-CoV patients (56 cases, from the Beijing hospital of the Armed Forces Police, China) that showed that specific IgG antibodies and neutralizing antibodies were highly correlated, peaking at month 4 after the onset of disease and decreasing gradually thereafter.

This and other studies suggest that the immune responses of specific antibodies were maintained in more than 90% of recovered SARS-CoV patients for 2 years, according to the authors.

However, of particular concern is the fact that only 11.8% of patients acquire specific SARS-CoV Abs in the early period after recovery at day 7, not reaching 100% until day 90, which highlights the importance of the detection of antibody titers for convalescent COVID-19 patients, according to the authors. “Otherwise, these patients with low titers of antibodies may not be efficient for the clearance of SARS-CoV-2.”

The authors also cited a recent study that showed how neutralizing antibody from a convalescent SARS patient could block the SARS-CoV-2 from entering into target cells in vitro, and suggested that previous experimental SARS-CoV vaccines and neutralizing antibodies could provide novel preventive and therapeutic options for COVID-19.

“These experiences from SARS-CoV are expected to have some implications for the treatment, management and surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 patients,” the authors concluded.

SOURCE: Lin Q et al. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2020 Mar 25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmii.2020.03.015.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF MICROBIOLOGY, IMMUNOLOGY AND INFECTION

Which tube placement is best for a patient requiring enteral nutrition?

Comparative advantages of EN tubes

Case

A 68-year-old diabetic nonverbal female presents to the ED because of “seizure” 1 hour ago. On exam, her blood glucose is 200. She is unable to speak and has dysphagia because of a stroke she sustained last month. The patient’s husband adds that she hasn’t been eating and drinking sufficiently in the past couple of days. Imaging was negative for any acute intracranial bleeds or lesions. Labs showed a serum sodium level of 150 milliequivalents/L. D5W is started, and the following day, the patient has a sodium level of 154 milliequivalents/L.

Brief overview

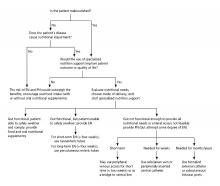

Many hospitalized patients are unable to maintain hydration and/or nutritional status by mouth and will need enteral nutrition. Variables such as past medical history, swallowing ability, history of aspiration, prognosis, and functional capacity of each gastrointestinal segment will determine the best option for enteral nutrition for each patient. Each type of enteral tube feeding has advantages, disadvantages, and complications.

Overview of the data

Enteral nutrition should be started within 24-48 hours in a critically ill patient who is unable to maintain intake according to the American Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition.1 This can be provided through a nasogastric (NG) tube, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube, PEG tube with jejunal extension (PEG-J), or a percutaneous endoscopic jejunal (PEJ) tube.1

NG tubes are often the first method deployed because of their low cost and convenience. They are also suitable for the patient who requires this type of feeding for less than 4 weeks. However, NG tubes do require some patient cooperation (to place and maintain)and are contraindicated in some patients with orofacial trauma, upper GI tumors, inadequate lower esophageal sphincter tone, and gastroparesis.2

Another option is a PEG tube, which is a good alternative for patients who are sedated; ventilated; or have neurodegenerative processes, stroke with dysphagia, or head and neck cancers. These are typically recommended when enteral nutrition will be needed for more than 4 weeks. Disadvantages of PEG tubes include tube obstruction or displacement, gastroesophageal reflux, and leakage of gastric content around the percutaneous site or into the peritoneum.

PEG-J tubes, PEJ tubes, or jejunostomy tubes are best suited for patients with GI dysmotility, patients who have unsuccessfully undergone the aforementioned methods, patients with histories of partial gastrectomies, or patients with gastric or pancreatic cancers/multiple traumas. The PEG-J tube extends into the distal duodenum; because it is longer and more narrow, it is more likely to coil and occlude the flow of nutrients during feedings.2,3 Jejunal feeding methods incorporate a continuous pump controlled infusion; if set too rapidly, this could cause dumping syndrome. A benefit of jejunal nutrition is a lower risk of aspiration, compared with other enteral tubes.4

It is best to appraise the selected method for its efficacy and patient preference. The American College of Gastroenterology recommends starting with orogastric or nasogastric feeds, and switching to postpyloric or jejunal feeds for those intolerant to or at high risk for aspiration.5 The most important aspect is early enteral nutrition in hospitalized patients unable to maintain oral nutrition.

Application of the data to the original case

This is a severely hypernatremic diabetic patient unable to swallow. On day 2 of her hospitalization, the clinical team provided the patient with an NG tube for increased free-water intake to gradually decrease her serum sodium. By hospital day 4, the patient’s sodium had normalized. Considering the patient’s long-term prognosis and dysphagia, discussions were held with the patient and husband for PEG tube placement. The patient received a PEG tube and was subsequently discharged 2 days later.

Bottom line

Enteral nutrition is a common need among hospitalized patients. Modality of enteral nutrition will depend on the patient’s past medical history, anticipated duration, and preferences.

Dr. Basnet is the hospitalist program director for Apogee Physicians Group at Eastern New Mexico Medical Center in Roswell. Ms. Tayes is a third-year medical student at Burrell College of Osteopathic Medicine in Las Cruces, N.M., with interests in surgery, internal medicine, and emergency medicine. Ms. Gallivan is a third-year medical student at Burrell College of Osteopathic Medicine, with interests in cardiothoracic surgery, general surgery, and internal medicine.

References

1. Boullata JI et al. ASPEN Safe Practices for Enteral Nutrition Therapy. J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2016;1-89.

2. Kirby DF et al. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on tube feeding for enteral nutrition. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:1282.

3. Lazarus BA et al. Aspiration associated with long-term gastric versus jejunal feeding: A critical analysis of the literature. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1990;71:46.

4. Alkhawaja S et al. Postpyloric versus gastric tube feeding for preventing pneumonia and improving nutritional outcomes in critically ill adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Aug 4;(8):CD008875.

5. McCalve SA et al. ACG Clinical Guideline: Nutrition therapy in the hospitalized patient. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:315-34. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2016.28.

Additional reading

Bellini LM. Nutrition Support in Advanced Lung Disease. UptoDate. https://www-uptodate-com.ezproxy.ad.bcomnm.org/contents/nutritional-support-in-advanced-lung-disease?. Published April 20, 2018.

Commercial Formulas for the Feeding Tube. The Oral Cancer Foundation. https://oralcancerfoundation.org/nutrition/commercial-formulas-feeding-tube/. Published June 5, 2018.

Marik Z. Immunonutrition in critically ill patients: A systematic review and analysis of the literature. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34(11). doi: 10.1007/s00134-008-1213-6.

Wischmeyer PE. Enteral nutrition can be given to patients on vasopressors. Crit Care Med. 2020;48(1):122-5. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003965.

Comparative advantages of EN tubes

Comparative advantages of EN tubes

Case

A 68-year-old diabetic nonverbal female presents to the ED because of “seizure” 1 hour ago. On exam, her blood glucose is 200. She is unable to speak and has dysphagia because of a stroke she sustained last month. The patient’s husband adds that she hasn’t been eating and drinking sufficiently in the past couple of days. Imaging was negative for any acute intracranial bleeds or lesions. Labs showed a serum sodium level of 150 milliequivalents/L. D5W is started, and the following day, the patient has a sodium level of 154 milliequivalents/L.

Brief overview

Many hospitalized patients are unable to maintain hydration and/or nutritional status by mouth and will need enteral nutrition. Variables such as past medical history, swallowing ability, history of aspiration, prognosis, and functional capacity of each gastrointestinal segment will determine the best option for enteral nutrition for each patient. Each type of enteral tube feeding has advantages, disadvantages, and complications.

Overview of the data

Enteral nutrition should be started within 24-48 hours in a critically ill patient who is unable to maintain intake according to the American Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition.1 This can be provided through a nasogastric (NG) tube, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube, PEG tube with jejunal extension (PEG-J), or a percutaneous endoscopic jejunal (PEJ) tube.1

NG tubes are often the first method deployed because of their low cost and convenience. They are also suitable for the patient who requires this type of feeding for less than 4 weeks. However, NG tubes do require some patient cooperation (to place and maintain)and are contraindicated in some patients with orofacial trauma, upper GI tumors, inadequate lower esophageal sphincter tone, and gastroparesis.2

Another option is a PEG tube, which is a good alternative for patients who are sedated; ventilated; or have neurodegenerative processes, stroke with dysphagia, or head and neck cancers. These are typically recommended when enteral nutrition will be needed for more than 4 weeks. Disadvantages of PEG tubes include tube obstruction or displacement, gastroesophageal reflux, and leakage of gastric content around the percutaneous site or into the peritoneum.

PEG-J tubes, PEJ tubes, or jejunostomy tubes are best suited for patients with GI dysmotility, patients who have unsuccessfully undergone the aforementioned methods, patients with histories of partial gastrectomies, or patients with gastric or pancreatic cancers/multiple traumas. The PEG-J tube extends into the distal duodenum; because it is longer and more narrow, it is more likely to coil and occlude the flow of nutrients during feedings.2,3 Jejunal feeding methods incorporate a continuous pump controlled infusion; if set too rapidly, this could cause dumping syndrome. A benefit of jejunal nutrition is a lower risk of aspiration, compared with other enteral tubes.4

It is best to appraise the selected method for its efficacy and patient preference. The American College of Gastroenterology recommends starting with orogastric or nasogastric feeds, and switching to postpyloric or jejunal feeds for those intolerant to or at high risk for aspiration.5 The most important aspect is early enteral nutrition in hospitalized patients unable to maintain oral nutrition.

Application of the data to the original case

This is a severely hypernatremic diabetic patient unable to swallow. On day 2 of her hospitalization, the clinical team provided the patient with an NG tube for increased free-water intake to gradually decrease her serum sodium. By hospital day 4, the patient’s sodium had normalized. Considering the patient’s long-term prognosis and dysphagia, discussions were held with the patient and husband for PEG tube placement. The patient received a PEG tube and was subsequently discharged 2 days later.

Bottom line

Enteral nutrition is a common need among hospitalized patients. Modality of enteral nutrition will depend on the patient’s past medical history, anticipated duration, and preferences.

Dr. Basnet is the hospitalist program director for Apogee Physicians Group at Eastern New Mexico Medical Center in Roswell. Ms. Tayes is a third-year medical student at Burrell College of Osteopathic Medicine in Las Cruces, N.M., with interests in surgery, internal medicine, and emergency medicine. Ms. Gallivan is a third-year medical student at Burrell College of Osteopathic Medicine, with interests in cardiothoracic surgery, general surgery, and internal medicine.

References

1. Boullata JI et al. ASPEN Safe Practices for Enteral Nutrition Therapy. J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2016;1-89.

2. Kirby DF et al. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on tube feeding for enteral nutrition. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:1282.

3. Lazarus BA et al. Aspiration associated with long-term gastric versus jejunal feeding: A critical analysis of the literature. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1990;71:46.

4. Alkhawaja S et al. Postpyloric versus gastric tube feeding for preventing pneumonia and improving nutritional outcomes in critically ill adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Aug 4;(8):CD008875.

5. McCalve SA et al. ACG Clinical Guideline: Nutrition therapy in the hospitalized patient. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:315-34. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2016.28.

Additional reading

Bellini LM. Nutrition Support in Advanced Lung Disease. UptoDate. https://www-uptodate-com.ezproxy.ad.bcomnm.org/contents/nutritional-support-in-advanced-lung-disease?. Published April 20, 2018.

Commercial Formulas for the Feeding Tube. The Oral Cancer Foundation. https://oralcancerfoundation.org/nutrition/commercial-formulas-feeding-tube/. Published June 5, 2018.

Marik Z. Immunonutrition in critically ill patients: A systematic review and analysis of the literature. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34(11). doi: 10.1007/s00134-008-1213-6.

Wischmeyer PE. Enteral nutrition can be given to patients on vasopressors. Crit Care Med. 2020;48(1):122-5. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003965.

Case

A 68-year-old diabetic nonverbal female presents to the ED because of “seizure” 1 hour ago. On exam, her blood glucose is 200. She is unable to speak and has dysphagia because of a stroke she sustained last month. The patient’s husband adds that she hasn’t been eating and drinking sufficiently in the past couple of days. Imaging was negative for any acute intracranial bleeds or lesions. Labs showed a serum sodium level of 150 milliequivalents/L. D5W is started, and the following day, the patient has a sodium level of 154 milliequivalents/L.

Brief overview

Many hospitalized patients are unable to maintain hydration and/or nutritional status by mouth and will need enteral nutrition. Variables such as past medical history, swallowing ability, history of aspiration, prognosis, and functional capacity of each gastrointestinal segment will determine the best option for enteral nutrition for each patient. Each type of enteral tube feeding has advantages, disadvantages, and complications.

Overview of the data

Enteral nutrition should be started within 24-48 hours in a critically ill patient who is unable to maintain intake according to the American Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition.1 This can be provided through a nasogastric (NG) tube, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube, PEG tube with jejunal extension (PEG-J), or a percutaneous endoscopic jejunal (PEJ) tube.1

NG tubes are often the first method deployed because of their low cost and convenience. They are also suitable for the patient who requires this type of feeding for less than 4 weeks. However, NG tubes do require some patient cooperation (to place and maintain)and are contraindicated in some patients with orofacial trauma, upper GI tumors, inadequate lower esophageal sphincter tone, and gastroparesis.2

Another option is a PEG tube, which is a good alternative for patients who are sedated; ventilated; or have neurodegenerative processes, stroke with dysphagia, or head and neck cancers. These are typically recommended when enteral nutrition will be needed for more than 4 weeks. Disadvantages of PEG tubes include tube obstruction or displacement, gastroesophageal reflux, and leakage of gastric content around the percutaneous site or into the peritoneum.

PEG-J tubes, PEJ tubes, or jejunostomy tubes are best suited for patients with GI dysmotility, patients who have unsuccessfully undergone the aforementioned methods, patients with histories of partial gastrectomies, or patients with gastric or pancreatic cancers/multiple traumas. The PEG-J tube extends into the distal duodenum; because it is longer and more narrow, it is more likely to coil and occlude the flow of nutrients during feedings.2,3 Jejunal feeding methods incorporate a continuous pump controlled infusion; if set too rapidly, this could cause dumping syndrome. A benefit of jejunal nutrition is a lower risk of aspiration, compared with other enteral tubes.4

It is best to appraise the selected method for its efficacy and patient preference. The American College of Gastroenterology recommends starting with orogastric or nasogastric feeds, and switching to postpyloric or jejunal feeds for those intolerant to or at high risk for aspiration.5 The most important aspect is early enteral nutrition in hospitalized patients unable to maintain oral nutrition.

Application of the data to the original case

This is a severely hypernatremic diabetic patient unable to swallow. On day 2 of her hospitalization, the clinical team provided the patient with an NG tube for increased free-water intake to gradually decrease her serum sodium. By hospital day 4, the patient’s sodium had normalized. Considering the patient’s long-term prognosis and dysphagia, discussions were held with the patient and husband for PEG tube placement. The patient received a PEG tube and was subsequently discharged 2 days later.

Bottom line

Enteral nutrition is a common need among hospitalized patients. Modality of enteral nutrition will depend on the patient’s past medical history, anticipated duration, and preferences.

Dr. Basnet is the hospitalist program director for Apogee Physicians Group at Eastern New Mexico Medical Center in Roswell. Ms. Tayes is a third-year medical student at Burrell College of Osteopathic Medicine in Las Cruces, N.M., with interests in surgery, internal medicine, and emergency medicine. Ms. Gallivan is a third-year medical student at Burrell College of Osteopathic Medicine, with interests in cardiothoracic surgery, general surgery, and internal medicine.

References

1. Boullata JI et al. ASPEN Safe Practices for Enteral Nutrition Therapy. J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2016;1-89.

2. Kirby DF et al. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on tube feeding for enteral nutrition. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:1282.

3. Lazarus BA et al. Aspiration associated with long-term gastric versus jejunal feeding: A critical analysis of the literature. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1990;71:46.

4. Alkhawaja S et al. Postpyloric versus gastric tube feeding for preventing pneumonia and improving nutritional outcomes in critically ill adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Aug 4;(8):CD008875.

5. McCalve SA et al. ACG Clinical Guideline: Nutrition therapy in the hospitalized patient. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:315-34. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2016.28.

Additional reading

Bellini LM. Nutrition Support in Advanced Lung Disease. UptoDate. https://www-uptodate-com.ezproxy.ad.bcomnm.org/contents/nutritional-support-in-advanced-lung-disease?. Published April 20, 2018.

Commercial Formulas for the Feeding Tube. The Oral Cancer Foundation. https://oralcancerfoundation.org/nutrition/commercial-formulas-feeding-tube/. Published June 5, 2018.

Marik Z. Immunonutrition in critically ill patients: A systematic review and analysis of the literature. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34(11). doi: 10.1007/s00134-008-1213-6.

Wischmeyer PE. Enteral nutrition can be given to patients on vasopressors. Crit Care Med. 2020;48(1):122-5. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003965.

COVID-19: More hydroxychloroquine data from France, more questions

A controversial study led by Didier Raoult, MD, PhD, on the combination of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin in patients with COVID-19 was published March 20. The latest results from the same Marseille team, which involve 80 patients, were reported on March 27.

The investigators report a significant reduction in the viral load (83% patients had negative results on quantitative polymerase chain reaction testing at day 7, and 93% had negative results on day 8). There was a “clinical improvement compared to the natural progression.” One death occurred, and three patients were transferred to intensive care units.

If the data seem encouraging, the lack of a control arm in the study leaves clinicians perplexed, however.

Benjamin Davido, MD, an infectious disease specialist at Raymond-Poincaré Hospital in Garches, Paris, spoke in an interview about the implications of these new results.

What do you think about the new results presented by Prof. Raoult’s team? Do they confirm the effectiveness of hydroxychloroquine?

These results are complementary [to the original results] but don’t offer any new information or new statistical evidence. They are absolutely superimposable and say overall that, between 5 and 7 days [of treatment], very few patients shed the virus. But that is not the question that everyone is asking.

Even if we don’t necessarily have to conduct a randomized study, we should at least compare the treatment, either against another therapy – which could be hydroxychloroquine monotherapy, or just standard of care. It needed an authentic control arm.

To recruit 80 patients so quickly, the researchers probably took people with essentially ambulatory forms of the disease (there was a call for screening in the south of France) – therefore, by definition, less severe cases.

But to describe such a population of patients as going home and saying, “There were very few hospitalizations and it is going well,” does not in any way prove that the treatment reduces hospitalizations.

The argument for not having a control arm in this study was that it would be unethical. What do you think?

I agree with this argument when it comes to patients presenting with risk factors or who are starting to develop pneumonia.

But I don’t think this is the case at the beginning of the illness. Of course, you don’t want to wait to have severe disease or for the patient to be in intensive care to start treatment. In these cases, it is indeed very difficult to find a control arm.

In the ongoing Discovery trial, which involves more than 3,000 patients in Europe, including 800 in France, the patients have severe disease, and there are five treatment arms. Moreover, hydroxychloroquine is given without azithromycin. What do you think of this?

I think it’s a mistake. It will not answer the question of the effectiveness of hydroxychloroquine in COVID-19, especially as they’re not studying azithromycin in a situation where the compound seems necessary for the effectiveness of the treatment.

In addition, Discovery reinforces the notion of studying Kaletra [lopinavir/ritonavir, AbbVie] again, while Chinese researchers have shown that it does not work, the argument being that Kaletra was given too late (N Engl J Med. 2020 Mar 18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001282). Therefore, if we make the same mistakes from a methodological point of view, we will end up with negative results.

What should have been done in the Marseille study?

The question is: Are there more or fewer hospitalizations when we treat a homogeneous population straight away?

The answer could be very clear, as a control already exists! They are the patients that flow into our hospitals every day – ironically, these 80 patients [in the latest results, presented March 27] could be among the 80% who had a form similar to nasopharyngitis and resolved.

In this illness, we know that there are 80% spontaneous recoveries and 20% so-called severe forms. Therefore, with 80 patients, we are very underpowered. The cohort is too small for a disease in which 80% of the evolution is benign.

It would take 1,000 patients, and then, even without a control arm, we would have an answer.

On March 26, Didier Raoult’s team also announced having already treated 700 patients with hydroxychloroquine, with only one death. Therefore, if this cohort increases significantly in Marseille and we see that, on the map, there are fewer issues with patient flow and saturation in Marseille and that there are fewer patients in intensive care, you will have to wonder about the effect of hydroxychloroquine.

We will find out very quickly. If it really works, and they treat all the patients presenting at Timone Hospital, we will soon have the answer. It will be a real-life study.

What are the other studies on hydroxychloroquine that could give us answers?

There was a Chinese study that did not show a difference in effectiveness between hydroxychloroquine and placebo, but that was, again, conducted in only around 20 patients (J Zhejiang Univ (Med Sci). 2020. doi: 10.3785/j.issn.1008-9292.2020.03.03). This cohort is too small and tells us nothing; it cannot show anything. We must wait for the results of larger trials being conducted in China.

It surprises me that, today, we still do not have Italian data on the use of chloroquine-type drugs ... perhaps because they have a care pathway that means there is no outpatient treatment and that they arrive already with severe disease. The Italian recommendations nevertheless indicate the use of hydroxychloroquine.

I also wonder about the lack of studies of cohorts where, in retrospect, we could have followed people previously treated with hydroxychloroquine for chronic diseases (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, etc.). Or we could identify all those patients on the health insurance system who had prescriptions.

That is how we discovered the AIDS epidemic in San Francisco: There was an increase in the number of prescriptions for trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim) that corresponded to a population subtype (homosexual), and we realized that it was for a disease that resembled pneumocystosis. We discovered that via the drug!

If hydroxychloroquine is effective, it is enough to look at people who took it before the epidemic and see how they fared. And there, we do not need a control arm. This could give us some direction. The March 26 decree of the new Véran Law states that community pharmacies can dispense to patients with a previous prescription, so we can find these individuals.

Do you think that the lack of, or difficulty in setting up, studies on hydroxychloroquine in France is linked to decisions that are more political than scientific?

Perhaps the contaminated blood scandal still casts a shadow in France, and there is a great deal of anxiety over the fact that we are already in a crisis, and we do not want a second one. I can understand that.

However, just a week ago, access to this drug (and others with market approval that have been on the market for several years) was blocked in hospital central pharmacies, while we are the medical specialists with the authorization! It was unacceptable.

It was sorted out 48 hours ago: hydroxychloroquine is now available in the hospital, and to my knowledge, we no longer have a problem obtaining it.

It took time to alleviate doubts over the major health risks with this drug. [Officials] seemed almost like amateurs in their hesitation; I think they lacked foresight. We have forgotten that the treatment advocated by Prof. Didier Raoult is not chloroquine but rather hydroxychloroquine, and we know that the adverse effects are less [with hydroxychloroquine] than with chloroquine.

You yourself have treated patients with chloroquine, despite the risk for toxicity highlighted by some.

Initially, when we first started treating patients, we thought of chloroquine because we did not have data on hydroxychloroquine, only Chinese data with chloroquine. We therefore prescribed chloroquine several days before prescribing hydroxychloroquine.

The question of the toxicity of chloroquine was not unjustified, but I think we took far too much time to decide on the toxicity of hydroxychloroquine. Is [the latter] political? I don’t know. It was widely publicized, which amazes me for a drug that is already available.

On the other hand, everyone was talking at the same time about the toxicity of NSAIDs. ... One has the impression it was to create a diversion. I think there were double standards at play and a scapegoat was needed to gain some time and ask questions.

What is sure is that it is probably not for financial reasons, as hydroxychloroquine costs nothing. That’s to say there were probably pharmaceutical issues at stake for possible competitors of hydroxychloroquine; I do not want to get into this debate, and it doesn’t matter, as long as we have an answer.

Today, the only thing we have advanced on is the “safety” of hydroxychloroquine, the low risk to the general population. ... On the other hand, we have still not made any progress on the evidence of efficacy, compared with other treatments.

Personally, I really believe in hydroxychloroquine. It would nevertheless be a shame to think we had found the fountain of youth and realize, in 4 weeks, that we have the same number of deaths. That is the problem. I hope that we will soon have solid data so we do not waste time focusing solely on hydroxychloroquine.

What are the other avenues of research that grab your attention?

The Discovery trial will probably give an answer on remdesivir [GS-5734, Gilead], which is a direct antiviral and could be interesting. But there are other studies being conducted currently in China.

There is also favipiravir [T-705, Avigan, Toyama Chemical], which is an anti-influenza drug used in Japan, which could explain, in part, the control of the epidemic in that country. There are effects in vitro on coronavirus. But it is not at all studied in France at the moment. Therefore, we should not focus exclusively on hydroxychloroquine; we must keep a close eye on other molecules, in particular the “old” drugs, like this antiviral.

The study was supported by the Institut Hospitalo-Universitaire (IHU) Méditerranée Infection, the National Research Agency, under the Investissements d’avenir program, Région Provence Alpes Côte d’Azur, and European funding FEDER PRIMI. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A controversial study led by Didier Raoult, MD, PhD, on the combination of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin in patients with COVID-19 was published March 20. The latest results from the same Marseille team, which involve 80 patients, were reported on March 27.

The investigators report a significant reduction in the viral load (83% patients had negative results on quantitative polymerase chain reaction testing at day 7, and 93% had negative results on day 8). There was a “clinical improvement compared to the natural progression.” One death occurred, and three patients were transferred to intensive care units.

If the data seem encouraging, the lack of a control arm in the study leaves clinicians perplexed, however.

Benjamin Davido, MD, an infectious disease specialist at Raymond-Poincaré Hospital in Garches, Paris, spoke in an interview about the implications of these new results.

What do you think about the new results presented by Prof. Raoult’s team? Do they confirm the effectiveness of hydroxychloroquine?

These results are complementary [to the original results] but don’t offer any new information or new statistical evidence. They are absolutely superimposable and say overall that, between 5 and 7 days [of treatment], very few patients shed the virus. But that is not the question that everyone is asking.

Even if we don’t necessarily have to conduct a randomized study, we should at least compare the treatment, either against another therapy – which could be hydroxychloroquine monotherapy, or just standard of care. It needed an authentic control arm.

To recruit 80 patients so quickly, the researchers probably took people with essentially ambulatory forms of the disease (there was a call for screening in the south of France) – therefore, by definition, less severe cases.

But to describe such a population of patients as going home and saying, “There were very few hospitalizations and it is going well,” does not in any way prove that the treatment reduces hospitalizations.

The argument for not having a control arm in this study was that it would be unethical. What do you think?

I agree with this argument when it comes to patients presenting with risk factors or who are starting to develop pneumonia.

But I don’t think this is the case at the beginning of the illness. Of course, you don’t want to wait to have severe disease or for the patient to be in intensive care to start treatment. In these cases, it is indeed very difficult to find a control arm.

In the ongoing Discovery trial, which involves more than 3,000 patients in Europe, including 800 in France, the patients have severe disease, and there are five treatment arms. Moreover, hydroxychloroquine is given without azithromycin. What do you think of this?

I think it’s a mistake. It will not answer the question of the effectiveness of hydroxychloroquine in COVID-19, especially as they’re not studying azithromycin in a situation where the compound seems necessary for the effectiveness of the treatment.

In addition, Discovery reinforces the notion of studying Kaletra [lopinavir/ritonavir, AbbVie] again, while Chinese researchers have shown that it does not work, the argument being that Kaletra was given too late (N Engl J Med. 2020 Mar 18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001282). Therefore, if we make the same mistakes from a methodological point of view, we will end up with negative results.

What should have been done in the Marseille study?

The question is: Are there more or fewer hospitalizations when we treat a homogeneous population straight away?

The answer could be very clear, as a control already exists! They are the patients that flow into our hospitals every day – ironically, these 80 patients [in the latest results, presented March 27] could be among the 80% who had a form similar to nasopharyngitis and resolved.

In this illness, we know that there are 80% spontaneous recoveries and 20% so-called severe forms. Therefore, with 80 patients, we are very underpowered. The cohort is too small for a disease in which 80% of the evolution is benign.

It would take 1,000 patients, and then, even without a control arm, we would have an answer.

On March 26, Didier Raoult’s team also announced having already treated 700 patients with hydroxychloroquine, with only one death. Therefore, if this cohort increases significantly in Marseille and we see that, on the map, there are fewer issues with patient flow and saturation in Marseille and that there are fewer patients in intensive care, you will have to wonder about the effect of hydroxychloroquine.

We will find out very quickly. If it really works, and they treat all the patients presenting at Timone Hospital, we will soon have the answer. It will be a real-life study.

What are the other studies on hydroxychloroquine that could give us answers?

There was a Chinese study that did not show a difference in effectiveness between hydroxychloroquine and placebo, but that was, again, conducted in only around 20 patients (J Zhejiang Univ (Med Sci). 2020. doi: 10.3785/j.issn.1008-9292.2020.03.03). This cohort is too small and tells us nothing; it cannot show anything. We must wait for the results of larger trials being conducted in China.

It surprises me that, today, we still do not have Italian data on the use of chloroquine-type drugs ... perhaps because they have a care pathway that means there is no outpatient treatment and that they arrive already with severe disease. The Italian recommendations nevertheless indicate the use of hydroxychloroquine.

I also wonder about the lack of studies of cohorts where, in retrospect, we could have followed people previously treated with hydroxychloroquine for chronic diseases (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, etc.). Or we could identify all those patients on the health insurance system who had prescriptions.

That is how we discovered the AIDS epidemic in San Francisco: There was an increase in the number of prescriptions for trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim) that corresponded to a population subtype (homosexual), and we realized that it was for a disease that resembled pneumocystosis. We discovered that via the drug!

If hydroxychloroquine is effective, it is enough to look at people who took it before the epidemic and see how they fared. And there, we do not need a control arm. This could give us some direction. The March 26 decree of the new Véran Law states that community pharmacies can dispense to patients with a previous prescription, so we can find these individuals.

Do you think that the lack of, or difficulty in setting up, studies on hydroxychloroquine in France is linked to decisions that are more political than scientific?

Perhaps the contaminated blood scandal still casts a shadow in France, and there is a great deal of anxiety over the fact that we are already in a crisis, and we do not want a second one. I can understand that.

However, just a week ago, access to this drug (and others with market approval that have been on the market for several years) was blocked in hospital central pharmacies, while we are the medical specialists with the authorization! It was unacceptable.

It was sorted out 48 hours ago: hydroxychloroquine is now available in the hospital, and to my knowledge, we no longer have a problem obtaining it.

It took time to alleviate doubts over the major health risks with this drug. [Officials] seemed almost like amateurs in their hesitation; I think they lacked foresight. We have forgotten that the treatment advocated by Prof. Didier Raoult is not chloroquine but rather hydroxychloroquine, and we know that the adverse effects are less [with hydroxychloroquine] than with chloroquine.

You yourself have treated patients with chloroquine, despite the risk for toxicity highlighted by some.

Initially, when we first started treating patients, we thought of chloroquine because we did not have data on hydroxychloroquine, only Chinese data with chloroquine. We therefore prescribed chloroquine several days before prescribing hydroxychloroquine.

The question of the toxicity of chloroquine was not unjustified, but I think we took far too much time to decide on the toxicity of hydroxychloroquine. Is [the latter] political? I don’t know. It was widely publicized, which amazes me for a drug that is already available.

On the other hand, everyone was talking at the same time about the toxicity of NSAIDs. ... One has the impression it was to create a diversion. I think there were double standards at play and a scapegoat was needed to gain some time and ask questions.

What is sure is that it is probably not for financial reasons, as hydroxychloroquine costs nothing. That’s to say there were probably pharmaceutical issues at stake for possible competitors of hydroxychloroquine; I do not want to get into this debate, and it doesn’t matter, as long as we have an answer.

Today, the only thing we have advanced on is the “safety” of hydroxychloroquine, the low risk to the general population. ... On the other hand, we have still not made any progress on the evidence of efficacy, compared with other treatments.

Personally, I really believe in hydroxychloroquine. It would nevertheless be a shame to think we had found the fountain of youth and realize, in 4 weeks, that we have the same number of deaths. That is the problem. I hope that we will soon have solid data so we do not waste time focusing solely on hydroxychloroquine.

What are the other avenues of research that grab your attention?

The Discovery trial will probably give an answer on remdesivir [GS-5734, Gilead], which is a direct antiviral and could be interesting. But there are other studies being conducted currently in China.

There is also favipiravir [T-705, Avigan, Toyama Chemical], which is an anti-influenza drug used in Japan, which could explain, in part, the control of the epidemic in that country. There are effects in vitro on coronavirus. But it is not at all studied in France at the moment. Therefore, we should not focus exclusively on hydroxychloroquine; we must keep a close eye on other molecules, in particular the “old” drugs, like this antiviral.

The study was supported by the Institut Hospitalo-Universitaire (IHU) Méditerranée Infection, the National Research Agency, under the Investissements d’avenir program, Région Provence Alpes Côte d’Azur, and European funding FEDER PRIMI. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A controversial study led by Didier Raoult, MD, PhD, on the combination of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin in patients with COVID-19 was published March 20. The latest results from the same Marseille team, which involve 80 patients, were reported on March 27.

The investigators report a significant reduction in the viral load (83% patients had negative results on quantitative polymerase chain reaction testing at day 7, and 93% had negative results on day 8). There was a “clinical improvement compared to the natural progression.” One death occurred, and three patients were transferred to intensive care units.

If the data seem encouraging, the lack of a control arm in the study leaves clinicians perplexed, however.

Benjamin Davido, MD, an infectious disease specialist at Raymond-Poincaré Hospital in Garches, Paris, spoke in an interview about the implications of these new results.

What do you think about the new results presented by Prof. Raoult’s team? Do they confirm the effectiveness of hydroxychloroquine?

These results are complementary [to the original results] but don’t offer any new information or new statistical evidence. They are absolutely superimposable and say overall that, between 5 and 7 days [of treatment], very few patients shed the virus. But that is not the question that everyone is asking.

Even if we don’t necessarily have to conduct a randomized study, we should at least compare the treatment, either against another therapy – which could be hydroxychloroquine monotherapy, or just standard of care. It needed an authentic control arm.

To recruit 80 patients so quickly, the researchers probably took people with essentially ambulatory forms of the disease (there was a call for screening in the south of France) – therefore, by definition, less severe cases.

But to describe such a population of patients as going home and saying, “There were very few hospitalizations and it is going well,” does not in any way prove that the treatment reduces hospitalizations.

The argument for not having a control arm in this study was that it would be unethical. What do you think?

I agree with this argument when it comes to patients presenting with risk factors or who are starting to develop pneumonia.

But I don’t think this is the case at the beginning of the illness. Of course, you don’t want to wait to have severe disease or for the patient to be in intensive care to start treatment. In these cases, it is indeed very difficult to find a control arm.

In the ongoing Discovery trial, which involves more than 3,000 patients in Europe, including 800 in France, the patients have severe disease, and there are five treatment arms. Moreover, hydroxychloroquine is given without azithromycin. What do you think of this?

I think it’s a mistake. It will not answer the question of the effectiveness of hydroxychloroquine in COVID-19, especially as they’re not studying azithromycin in a situation where the compound seems necessary for the effectiveness of the treatment.

In addition, Discovery reinforces the notion of studying Kaletra [lopinavir/ritonavir, AbbVie] again, while Chinese researchers have shown that it does not work, the argument being that Kaletra was given too late (N Engl J Med. 2020 Mar 18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001282). Therefore, if we make the same mistakes from a methodological point of view, we will end up with negative results.

What should have been done in the Marseille study?

The question is: Are there more or fewer hospitalizations when we treat a homogeneous population straight away?

The answer could be very clear, as a control already exists! They are the patients that flow into our hospitals every day – ironically, these 80 patients [in the latest results, presented March 27] could be among the 80% who had a form similar to nasopharyngitis and resolved.

In this illness, we know that there are 80% spontaneous recoveries and 20% so-called severe forms. Therefore, with 80 patients, we are very underpowered. The cohort is too small for a disease in which 80% of the evolution is benign.

It would take 1,000 patients, and then, even without a control arm, we would have an answer.

On March 26, Didier Raoult’s team also announced having already treated 700 patients with hydroxychloroquine, with only one death. Therefore, if this cohort increases significantly in Marseille and we see that, on the map, there are fewer issues with patient flow and saturation in Marseille and that there are fewer patients in intensive care, you will have to wonder about the effect of hydroxychloroquine.

We will find out very quickly. If it really works, and they treat all the patients presenting at Timone Hospital, we will soon have the answer. It will be a real-life study.

What are the other studies on hydroxychloroquine that could give us answers?

There was a Chinese study that did not show a difference in effectiveness between hydroxychloroquine and placebo, but that was, again, conducted in only around 20 patients (J Zhejiang Univ (Med Sci). 2020. doi: 10.3785/j.issn.1008-9292.2020.03.03). This cohort is too small and tells us nothing; it cannot show anything. We must wait for the results of larger trials being conducted in China.

It surprises me that, today, we still do not have Italian data on the use of chloroquine-type drugs ... perhaps because they have a care pathway that means there is no outpatient treatment and that they arrive already with severe disease. The Italian recommendations nevertheless indicate the use of hydroxychloroquine.

I also wonder about the lack of studies of cohorts where, in retrospect, we could have followed people previously treated with hydroxychloroquine for chronic diseases (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, etc.). Or we could identify all those patients on the health insurance system who had prescriptions.

That is how we discovered the AIDS epidemic in San Francisco: There was an increase in the number of prescriptions for trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim) that corresponded to a population subtype (homosexual), and we realized that it was for a disease that resembled pneumocystosis. We discovered that via the drug!

If hydroxychloroquine is effective, it is enough to look at people who took it before the epidemic and see how they fared. And there, we do not need a control arm. This could give us some direction. The March 26 decree of the new Véran Law states that community pharmacies can dispense to patients with a previous prescription, so we can find these individuals.

Do you think that the lack of, or difficulty in setting up, studies on hydroxychloroquine in France is linked to decisions that are more political than scientific?

Perhaps the contaminated blood scandal still casts a shadow in France, and there is a great deal of anxiety over the fact that we are already in a crisis, and we do not want a second one. I can understand that.

However, just a week ago, access to this drug (and others with market approval that have been on the market for several years) was blocked in hospital central pharmacies, while we are the medical specialists with the authorization! It was unacceptable.

It was sorted out 48 hours ago: hydroxychloroquine is now available in the hospital, and to my knowledge, we no longer have a problem obtaining it.

It took time to alleviate doubts over the major health risks with this drug. [Officials] seemed almost like amateurs in their hesitation; I think they lacked foresight. We have forgotten that the treatment advocated by Prof. Didier Raoult is not chloroquine but rather hydroxychloroquine, and we know that the adverse effects are less [with hydroxychloroquine] than with chloroquine.

You yourself have treated patients with chloroquine, despite the risk for toxicity highlighted by some.

Initially, when we first started treating patients, we thought of chloroquine because we did not have data on hydroxychloroquine, only Chinese data with chloroquine. We therefore prescribed chloroquine several days before prescribing hydroxychloroquine.

The question of the toxicity of chloroquine was not unjustified, but I think we took far too much time to decide on the toxicity of hydroxychloroquine. Is [the latter] political? I don’t know. It was widely publicized, which amazes me for a drug that is already available.

On the other hand, everyone was talking at the same time about the toxicity of NSAIDs. ... One has the impression it was to create a diversion. I think there were double standards at play and a scapegoat was needed to gain some time and ask questions.

What is sure is that it is probably not for financial reasons, as hydroxychloroquine costs nothing. That’s to say there were probably pharmaceutical issues at stake for possible competitors of hydroxychloroquine; I do not want to get into this debate, and it doesn’t matter, as long as we have an answer.

Today, the only thing we have advanced on is the “safety” of hydroxychloroquine, the low risk to the general population. ... On the other hand, we have still not made any progress on the evidence of efficacy, compared with other treatments.

Personally, I really believe in hydroxychloroquine. It would nevertheless be a shame to think we had found the fountain of youth and realize, in 4 weeks, that we have the same number of deaths. That is the problem. I hope that we will soon have solid data so we do not waste time focusing solely on hydroxychloroquine.

What are the other avenues of research that grab your attention?

The Discovery trial will probably give an answer on remdesivir [GS-5734, Gilead], which is a direct antiviral and could be interesting. But there are other studies being conducted currently in China.

There is also favipiravir [T-705, Avigan, Toyama Chemical], which is an anti-influenza drug used in Japan, which could explain, in part, the control of the epidemic in that country. There are effects in vitro on coronavirus. But it is not at all studied in France at the moment. Therefore, we should not focus exclusively on hydroxychloroquine; we must keep a close eye on other molecules, in particular the “old” drugs, like this antiviral.

The study was supported by the Institut Hospitalo-Universitaire (IHU) Méditerranée Infection, the National Research Agency, under the Investissements d’avenir program, Région Provence Alpes Côte d’Azur, and European funding FEDER PRIMI. The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

What if a COVID-19 test is negative?

In a physician WhatsApp group, a doctor posted he had fever of 101 °F and muscle ache, gently confessing that it felt like his typical “man flu” which heals with rest and scotch. Nevertheless, he worried that he had coronavirus. When the reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) for the virus on his nasal swab came back negative, he jubilantly announced his relief.

Like Twitter, in WhatsApp emotions quickly outstrip facts. After he received a flurry of cheerful emojis, I ruined the party, advising that, despite the negative test, he assume he’s infected and quarantine for 2 weeks, with a bottle of scotch.

It’s conventional wisdom that the secret sauce to fighting the pandemic is testing for the virus. To gauge the breadth of the response against the pandemic we must know who and how many are infected. The depth of the response will be different if 25% of the population is infected than 1%. Testing is the third way, rejecting the false choice between death and economic depression. Without testing, strategy is faith based.

Our reliance on testing has clinical precedence – scarcely any decision in medicine is made without laboratory tests or imaging. Testing is as ingrained in medicine as the GPS is in driving. We use it even when we know our way home. But tests impose a question – what’ll you do differently if the test is negative?

That depends on the test’s performance and the consequences of being wrong. Though coronavirus damages the lungs with reckless abandon, it’s oddly a shy virus. In many patients, it takes 3-4 swabs to get a positive RT-PCR. The Chinese ophthalmologist, Li Wenliang, who originally sounded the alarm about coronavirus, had several negative tests. He died from the infection.

In one Chinese study, the sensitivity of RT-PCR – that’s the proportion of the infected who test positive – was around 70%. To put this in perspective, of 1,000 people infected with coronavirus, 700 will test positive but 300 will test negative.

Is this good enough?

Three hundred “false-negative” people may believe they’re not contagious because they got a clean chit and could infect others. False negatives could undo the hard work of containment.

Surely, better an imperfect test than no test. Isn’t flying with partially accurate weather information safer than no information? Here, aviation analogies aren’t helpful. Better to think of a forest fire.

Imagine only 80% of a burning forest is doused because it’s mistakenly believed that 20% of the forest isn’t burning because we can’t see it burning. It must be extinguished before it relights the whole forest, but to douse it you must know it’s burning – a Catch-22. That “20% of the forest” is a false negative – it’s burning but you think it’s not burning.

Because coronavirus isn’t planning to leave in a hurry and long-term lockdown has grave economic consequences, testing may enable precision quarantining of people, communities, and cities. Rather than applying a one-size-fits-all lockdown on the whole nation, testing could tell us who can work and who should stay home. Why should Austin, if it has a low prevalence of infection, shut shop just because of New York City’s high prevalence?

Testing enables us to think globally but act locally. But it’s the asymptomatic people who drive the epidemic. To emphasize – asymptomatics are yet to have symptoms such as cough and fever. They’re feeling well and don’t know they’ve been colonized by the virus. Theoretically, if we test en masse we can find asymptomatics. If only those who test positive are quarantined, the rest can have some breathing space. Will this approach work?

RT-PCR’s sensitivity, which is low in early illness, is even lower in asymptomatics, likely because of lower viral load, which means even more false negatives. The virus’s average incubation time of 5 days is enough time for false negative asymptomatics – remember they resemble the uninfected – to visit Disney World and infect another four.

Whether false negatives behave like tinder or a controllable fire will determine the testing strategy’s success. The net contagiousness of false negatives depends how many there are, which depends on how many are infected. To know how many are infected we need to test. Or, to know whether to believe a negative test in any person we must test widely – another Catch-22.

Maybe we need a bigger test.

Chest CT is an alternative. It’s rapid – takes less than an hour whereas RT-PCR can take over a day to report. In one study CT had a sensitivity of 97% in symptomatic patients and was often positive before RT-PCR. But there are caveats.

The real sensitivity of CT is likely much lower than 97% because the study has biases which inflate performance. CT, like RT-PCR, has a low sensitivity in early illness and even lower sensitivity in asymptomatic carriers for the same reason – lower viral load. Furthermore, CT has to be disinfected to prevent spread, which limits its access for other patients.

Coronavirus’s signature on CT – white patches in lungs, known as ground glass opacities – doesn’t have the uniqueness of the Mark of Zorro, and looks like lung injury from other rogue actors, which means we can mistake other serious conditions for coronavirus. Imagine hyenas in wolf’s clothing.

No test is perfect. We still use imaging despite its imperfections. But, let’s ask: What would you do differently if the test is negative and you have mild symptoms of cough and fever? Should you not self-isolate? What if you’re falsely negative and still contagious? If the advice dispensed whether the test is positive or negative is the same – i.e. quarantine for 2 weeks – what’s the test’s value?

Perhaps people will more likely comply with voluntary quarantine if they know they’re infected. Information can nudge behavior. But the logical corollary is that to comply with social distancing you need to be tested. People flocking to CT scans to affirm they’re not infected could infect those hitherto uninfected. A pandemic is no time to test nudge theories.

Does that mean testing has no value? Testing is valuable in managing populations. To individuals, the results must be framed wisely, such as by advising those who test positive to quarantine because “you’re infected” and those who test negative to keep social distancing because “you could still be infected.”

Even when policy goals are uniform, messaging can be oppositional. “Get yourself tested now” contradicts “you must hunker down now.” When messages contradict, one must choose which message to amplify.

The calculus of testing can change with new tests such as antibodies. The value of testing depends also on what isolation entails. A couple of weeks watching Netflix on your couch isn’t a big ask. If quarantine means being detained in an isolation center fenced by barbed wires, the cost of frivolous quarantining is higher and testing becomes more valuable.

I knew the doctor with the negative RT-PCR well. He’s heroically nonchalant about his wellbeing, an endearing quality that’s a liability in a contagion. In no time he’d be back in the hospital; or helping his elderly parents with grocery. Not all false negatives are equal. False-negative doctors could infect not just their patients but their colleagues, leaving fewer firefighters to fight fires.

It is better to mistake the man flu for coronavirus than coronavirus for the man flu. All he has to do is hunker down, which is what we should all be doing as much as we can.

Dr. Jha is a contributing editor to The Health Care Blog, where this article first appeared. He can be reached @RogueRad.

This article appeared on Medscape.com.

In a physician WhatsApp group, a doctor posted he had fever of 101 °F and muscle ache, gently confessing that it felt like his typical “man flu” which heals with rest and scotch. Nevertheless, he worried that he had coronavirus. When the reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) for the virus on his nasal swab came back negative, he jubilantly announced his relief.

Like Twitter, in WhatsApp emotions quickly outstrip facts. After he received a flurry of cheerful emojis, I ruined the party, advising that, despite the negative test, he assume he’s infected and quarantine for 2 weeks, with a bottle of scotch.

It’s conventional wisdom that the secret sauce to fighting the pandemic is testing for the virus. To gauge the breadth of the response against the pandemic we must know who and how many are infected. The depth of the response will be different if 25% of the population is infected than 1%. Testing is the third way, rejecting the false choice between death and economic depression. Without testing, strategy is faith based.

Our reliance on testing has clinical precedence – scarcely any decision in medicine is made without laboratory tests or imaging. Testing is as ingrained in medicine as the GPS is in driving. We use it even when we know our way home. But tests impose a question – what’ll you do differently if the test is negative?

That depends on the test’s performance and the consequences of being wrong. Though coronavirus damages the lungs with reckless abandon, it’s oddly a shy virus. In many patients, it takes 3-4 swabs to get a positive RT-PCR. The Chinese ophthalmologist, Li Wenliang, who originally sounded the alarm about coronavirus, had several negative tests. He died from the infection.

In one Chinese study, the sensitivity of RT-PCR – that’s the proportion of the infected who test positive – was around 70%. To put this in perspective, of 1,000 people infected with coronavirus, 700 will test positive but 300 will test negative.

Is this good enough?

Three hundred “false-negative” people may believe they’re not contagious because they got a clean chit and could infect others. False negatives could undo the hard work of containment.

Surely, better an imperfect test than no test. Isn’t flying with partially accurate weather information safer than no information? Here, aviation analogies aren’t helpful. Better to think of a forest fire.

Imagine only 80% of a burning forest is doused because it’s mistakenly believed that 20% of the forest isn’t burning because we can’t see it burning. It must be extinguished before it relights the whole forest, but to douse it you must know it’s burning – a Catch-22. That “20% of the forest” is a false negative – it’s burning but you think it’s not burning.

Because coronavirus isn’t planning to leave in a hurry and long-term lockdown has grave economic consequences, testing may enable precision quarantining of people, communities, and cities. Rather than applying a one-size-fits-all lockdown on the whole nation, testing could tell us who can work and who should stay home. Why should Austin, if it has a low prevalence of infection, shut shop just because of New York City’s high prevalence?

Testing enables us to think globally but act locally. But it’s the asymptomatic people who drive the epidemic. To emphasize – asymptomatics are yet to have symptoms such as cough and fever. They’re feeling well and don’t know they’ve been colonized by the virus. Theoretically, if we test en masse we can find asymptomatics. If only those who test positive are quarantined, the rest can have some breathing space. Will this approach work?

RT-PCR’s sensitivity, which is low in early illness, is even lower in asymptomatics, likely because of lower viral load, which means even more false negatives. The virus’s average incubation time of 5 days is enough time for false negative asymptomatics – remember they resemble the uninfected – to visit Disney World and infect another four.

Whether false negatives behave like tinder or a controllable fire will determine the testing strategy’s success. The net contagiousness of false negatives depends how many there are, which depends on how many are infected. To know how many are infected we need to test. Or, to know whether to believe a negative test in any person we must test widely – another Catch-22.

Maybe we need a bigger test.

Chest CT is an alternative. It’s rapid – takes less than an hour whereas RT-PCR can take over a day to report. In one study CT had a sensitivity of 97% in symptomatic patients and was often positive before RT-PCR. But there are caveats.

The real sensitivity of CT is likely much lower than 97% because the study has biases which inflate performance. CT, like RT-PCR, has a low sensitivity in early illness and even lower sensitivity in asymptomatic carriers for the same reason – lower viral load. Furthermore, CT has to be disinfected to prevent spread, which limits its access for other patients.

Coronavirus’s signature on CT – white patches in lungs, known as ground glass opacities – doesn’t have the uniqueness of the Mark of Zorro, and looks like lung injury from other rogue actors, which means we can mistake other serious conditions for coronavirus. Imagine hyenas in wolf’s clothing.

No test is perfect. We still use imaging despite its imperfections. But, let’s ask: What would you do differently if the test is negative and you have mild symptoms of cough and fever? Should you not self-isolate? What if you’re falsely negative and still contagious? If the advice dispensed whether the test is positive or negative is the same – i.e. quarantine for 2 weeks – what’s the test’s value?

Perhaps people will more likely comply with voluntary quarantine if they know they’re infected. Information can nudge behavior. But the logical corollary is that to comply with social distancing you need to be tested. People flocking to CT scans to affirm they’re not infected could infect those hitherto uninfected. A pandemic is no time to test nudge theories.

Does that mean testing has no value? Testing is valuable in managing populations. To individuals, the results must be framed wisely, such as by advising those who test positive to quarantine because “you’re infected” and those who test negative to keep social distancing because “you could still be infected.”

Even when policy goals are uniform, messaging can be oppositional. “Get yourself tested now” contradicts “you must hunker down now.” When messages contradict, one must choose which message to amplify.

The calculus of testing can change with new tests such as antibodies. The value of testing depends also on what isolation entails. A couple of weeks watching Netflix on your couch isn’t a big ask. If quarantine means being detained in an isolation center fenced by barbed wires, the cost of frivolous quarantining is higher and testing becomes more valuable.

I knew the doctor with the negative RT-PCR well. He’s heroically nonchalant about his wellbeing, an endearing quality that’s a liability in a contagion. In no time he’d be back in the hospital; or helping his elderly parents with grocery. Not all false negatives are equal. False-negative doctors could infect not just their patients but their colleagues, leaving fewer firefighters to fight fires.

It is better to mistake the man flu for coronavirus than coronavirus for the man flu. All he has to do is hunker down, which is what we should all be doing as much as we can.

Dr. Jha is a contributing editor to The Health Care Blog, where this article first appeared. He can be reached @RogueRad.

This article appeared on Medscape.com.

In a physician WhatsApp group, a doctor posted he had fever of 101 °F and muscle ache, gently confessing that it felt like his typical “man flu” which heals with rest and scotch. Nevertheless, he worried that he had coronavirus. When the reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) for the virus on his nasal swab came back negative, he jubilantly announced his relief.

Like Twitter, in WhatsApp emotions quickly outstrip facts. After he received a flurry of cheerful emojis, I ruined the party, advising that, despite the negative test, he assume he’s infected and quarantine for 2 weeks, with a bottle of scotch.

It’s conventional wisdom that the secret sauce to fighting the pandemic is testing for the virus. To gauge the breadth of the response against the pandemic we must know who and how many are infected. The depth of the response will be different if 25% of the population is infected than 1%. Testing is the third way, rejecting the false choice between death and economic depression. Without testing, strategy is faith based.

Our reliance on testing has clinical precedence – scarcely any decision in medicine is made without laboratory tests or imaging. Testing is as ingrained in medicine as the GPS is in driving. We use it even when we know our way home. But tests impose a question – what’ll you do differently if the test is negative?

That depends on the test’s performance and the consequences of being wrong. Though coronavirus damages the lungs with reckless abandon, it’s oddly a shy virus. In many patients, it takes 3-4 swabs to get a positive RT-PCR. The Chinese ophthalmologist, Li Wenliang, who originally sounded the alarm about coronavirus, had several negative tests. He died from the infection.

In one Chinese study, the sensitivity of RT-PCR – that’s the proportion of the infected who test positive – was around 70%. To put this in perspective, of 1,000 people infected with coronavirus, 700 will test positive but 300 will test negative.

Is this good enough?

Three hundred “false-negative” people may believe they’re not contagious because they got a clean chit and could infect others. False negatives could undo the hard work of containment.

Surely, better an imperfect test than no test. Isn’t flying with partially accurate weather information safer than no information? Here, aviation analogies aren’t helpful. Better to think of a forest fire.

Imagine only 80% of a burning forest is doused because it’s mistakenly believed that 20% of the forest isn’t burning because we can’t see it burning. It must be extinguished before it relights the whole forest, but to douse it you must know it’s burning – a Catch-22. That “20% of the forest” is a false negative – it’s burning but you think it’s not burning.

Because coronavirus isn’t planning to leave in a hurry and long-term lockdown has grave economic consequences, testing may enable precision quarantining of people, communities, and cities. Rather than applying a one-size-fits-all lockdown on the whole nation, testing could tell us who can work and who should stay home. Why should Austin, if it has a low prevalence of infection, shut shop just because of New York City’s high prevalence?

Testing enables us to think globally but act locally. But it’s the asymptomatic people who drive the epidemic. To emphasize – asymptomatics are yet to have symptoms such as cough and fever. They’re feeling well and don’t know they’ve been colonized by the virus. Theoretically, if we test en masse we can find asymptomatics. If only those who test positive are quarantined, the rest can have some breathing space. Will this approach work?

RT-PCR’s sensitivity, which is low in early illness, is even lower in asymptomatics, likely because of lower viral load, which means even more false negatives. The virus’s average incubation time of 5 days is enough time for false negative asymptomatics – remember they resemble the uninfected – to visit Disney World and infect another four.

Whether false negatives behave like tinder or a controllable fire will determine the testing strategy’s success. The net contagiousness of false negatives depends how many there are, which depends on how many are infected. To know how many are infected we need to test. Or, to know whether to believe a negative test in any person we must test widely – another Catch-22.

Maybe we need a bigger test.

Chest CT is an alternative. It’s rapid – takes less than an hour whereas RT-PCR can take over a day to report. In one study CT had a sensitivity of 97% in symptomatic patients and was often positive before RT-PCR. But there are caveats.

The real sensitivity of CT is likely much lower than 97% because the study has biases which inflate performance. CT, like RT-PCR, has a low sensitivity in early illness and even lower sensitivity in asymptomatic carriers for the same reason – lower viral load. Furthermore, CT has to be disinfected to prevent spread, which limits its access for other patients.

Coronavirus’s signature on CT – white patches in lungs, known as ground glass opacities – doesn’t have the uniqueness of the Mark of Zorro, and looks like lung injury from other rogue actors, which means we can mistake other serious conditions for coronavirus. Imagine hyenas in wolf’s clothing.

No test is perfect. We still use imaging despite its imperfections. But, let’s ask: What would you do differently if the test is negative and you have mild symptoms of cough and fever? Should you not self-isolate? What if you’re falsely negative and still contagious? If the advice dispensed whether the test is positive or negative is the same – i.e. quarantine for 2 weeks – what’s the test’s value?

Perhaps people will more likely comply with voluntary quarantine if they know they’re infected. Information can nudge behavior. But the logical corollary is that to comply with social distancing you need to be tested. People flocking to CT scans to affirm they’re not infected could infect those hitherto uninfected. A pandemic is no time to test nudge theories.

Does that mean testing has no value? Testing is valuable in managing populations. To individuals, the results must be framed wisely, such as by advising those who test positive to quarantine because “you’re infected” and those who test negative to keep social distancing because “you could still be infected.”