User login

Official news magazine of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Copyright by Society of Hospital Medicine or related companies. All rights reserved. ISSN 1553-085X

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-hospitalist')]

Becoming a high-value care physician

‘Culture shift’ comes from collective efforts

It’s Monday morning, and Mrs. Jones still has abdominal pain. Your ward team decides to order a CT. On chart review you notice she’s had three other abdominal CTs for the same indication this year. How did this happen? What should you do?

High-value care has been defined by the Institute of Medicine as “the best care for the patient, with the optimal result for the circumstances, delivered at the right price.”1 With an estimated $700 billion dollars – 30% of medical expenditures – spent on wasted care, there are rising calls for a transformational shift.2

You are now asked to consider not just everything you can do for a patient, but also the benefits, harms, and costs associated with those choices. But where to start? We recommend that trainees integrate these tips for high-value care into their routine practice.

1. Use evidence-based resources that highlight value

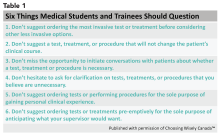

A great place to begin is the “Six Things Medical Students and Trainees Should Question,” originally published in Academic Medicine and created by Choosing Wisely Canada™. Recommendations range from avoiding tests or treatments that will not change a patient’s clinical course to holding off on ordering tests solely based on what you assume your preceptor will want (see the full list in Table 1).3

Other ways to avoid low-value care include following the United States Choosing Wisely™ campaign, which has collected more than 500 specialty society recommendations. Likewise, the American College of Radiology Appropriateness Criteria are designed to assist providers with ordering the appropriate imaging tests (for a more extensive list see Table 2).

2. Express your clinical reasoning

One driver of health care expenditures that is especially prevalent in academia is the pressure to demonstrate knowledge by recommending extensive testing. While these tests may rule out obscure diagnoses, they often do not change management.

You can still demonstrate a mastery of your patients’ care by expressing your thought process overtly. For instance, “I considered secondary causes of the patient’s severe hypertension but felt it was most reasonable to first treat her pain and restart her home medications before pursuing a larger work-up. If the patient’s blood pressure remains elevated and she is hypokalemic, we could consider testing for hyperaldosteronism.” If you explain why you think a diagnosis is less likely and order tests accordingly, others will be encouraged to consider value in their own medical decision making.

3. Hone your communication skills

One of the most cited reasons for providing unnecessary care is the time required to discuss treatment plans with patients – it’s much faster to just order the test than to explain why it isn’t needed. Research, however, shows that these cost conversations take 68 seconds on average.4 Costs of Care (see Table 2) has an excellent video series that highlights how effective communication allows for shared decision making, which promotes both patient engagement and helps avoid wasteful care.

Physicians’ first instincts are often defensive when a patient asks for care we perceive as unnecessary. However, exploring what the patient hopes to gain from said test or treatment frequently reveals concern for a specific, missed diagnosis or complication. Addressing this underlying fear, rather than defending your ordering patterns, can create improved rapport and may serve to provide more reassurance than a test ever could.5

As a physician-in-training, try to observe others having these conversations and take every opportunity to practice. By focusing on this key skill set, you will increase your comfort with in-depth discussions on the value of care.

4. Get involved in a project related to high-value care

While you are developing your own practice patterns, you may be inspired to tackle areas of overuse and underuse at a more systemwide level. If your hospital does not have a committee for high-value care, perhaps a quality improvement leader can support your ideas to launch a project or participate in an ongoing initiative. Physicians-in-training have been identified as crucial to these projects’ success – your frontline insight can highlight potential problems and the nuances of workflow that are key to effective solutions.6

5. Embrace lifelong learning and reflection

The process of becoming a physician and of practicing high-value care is not a sprint but a marathon. Multiple barriers to high-value care exist, and you may feel these pressures differently at various points in your career. These include malpractice concerns, addressing patient expectations, and the desire to take action “just to be safe.”6

Interestingly, fear of malpractice does not seem to dissipate in areas where tort reform has provided stronger provider protections.7 Practitioners may also inaccurately assume a patient’s desire for additional work-up or treatment.8 Furthermore, be aware of the role of “commission bias” by which a provider regrets not doing something that could have helped a previous patient. This regret can prove to be a stronger motivator than the potential harm related to unnecessary diagnostic tests or treatments.9

While these barriers cannot be removed easily, learners and providers can practice active reflection by examining their own fears, biases, and motivations before and after they order additional testing or treatment.

As a physician-in-training, you may feel that your decisions do not have a major impact on the health care system as a whole. However, the culture shift needed to “bend the cost curve” will come from the collective efforts of individuals like you. Practicing high-value care is not just a matter of ordering fewer tests – appropriate ordering of an expensive test that expedites a diagnosis may be more cost-effective and enhance the quality of care provided. Increasing your own awareness of both necessary and unnecessary practices is a major step toward realizing system change. Your efforts to resist and reform the medical culture that propagates low value care will encourage your colleagues to follow suit.

Dr. Lacy is assistant professor and associate clerkship director at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, as well as division director of high-value care for the division of hospital medicine. Dr. Goetz is assistant professor at Rush University Medical Center, Chicago. They met as 2015 Copello Fellows at the National Physician Alliance. Both have been involved in numerous high-value care initiatives, curricular development, and medical education at their respective institutions.

References

1. Committee on the Learning Health Care System in America, Institute of Medicine. “Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America.” Edited by Smith M, Saunders R, Stuckhardt L, and McGinnis JM. (Washington: National Academies Press, 2013). http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK207225/.

2. Berwick DM, Hackbarth AD. Eliminating waste in US health care. JAMA. 2012;307(14):1513-6.

3. Lakhani A et al. Choosing Wisely for Medical Education: Six things medical students and trainees should question. Acad Med. 2016 Oct;91(10):1374-8.

4. Hunter WG et al. Patient-physician discussions about costs: Definitions and impact on cost conversation incidence estimates. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:108.

5. van Ravesteijn H et al. The reassuring value of diagnostic tests: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86(1):3-8.

6. Moriates C, Wong BM. High-value care programmes from the bottom-up… and the top-down. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(11):821-3.

7. Snyder Sulmasy L, Weinberger SE. Better care is the best defense: High-value clinical practice vs. defensive medicine. Cleve Clin J Med. 2014;81(8):464-7.

8. Mulley AG, Trimble C, Elwyn G. Stop the silent misdiagnosis: Patients’ preferences matter. BMJ. 2012;345:e6572.

9. Scott IA. Cognitive challenges to minimising low value care. Intern Med J. 2017;47(9):1079-1083.

‘Culture shift’ comes from collective efforts

‘Culture shift’ comes from collective efforts

It’s Monday morning, and Mrs. Jones still has abdominal pain. Your ward team decides to order a CT. On chart review you notice she’s had three other abdominal CTs for the same indication this year. How did this happen? What should you do?

High-value care has been defined by the Institute of Medicine as “the best care for the patient, with the optimal result for the circumstances, delivered at the right price.”1 With an estimated $700 billion dollars – 30% of medical expenditures – spent on wasted care, there are rising calls for a transformational shift.2

You are now asked to consider not just everything you can do for a patient, but also the benefits, harms, and costs associated with those choices. But where to start? We recommend that trainees integrate these tips for high-value care into their routine practice.

1. Use evidence-based resources that highlight value

A great place to begin is the “Six Things Medical Students and Trainees Should Question,” originally published in Academic Medicine and created by Choosing Wisely Canada™. Recommendations range from avoiding tests or treatments that will not change a patient’s clinical course to holding off on ordering tests solely based on what you assume your preceptor will want (see the full list in Table 1).3

Other ways to avoid low-value care include following the United States Choosing Wisely™ campaign, which has collected more than 500 specialty society recommendations. Likewise, the American College of Radiology Appropriateness Criteria are designed to assist providers with ordering the appropriate imaging tests (for a more extensive list see Table 2).

2. Express your clinical reasoning

One driver of health care expenditures that is especially prevalent in academia is the pressure to demonstrate knowledge by recommending extensive testing. While these tests may rule out obscure diagnoses, they often do not change management.

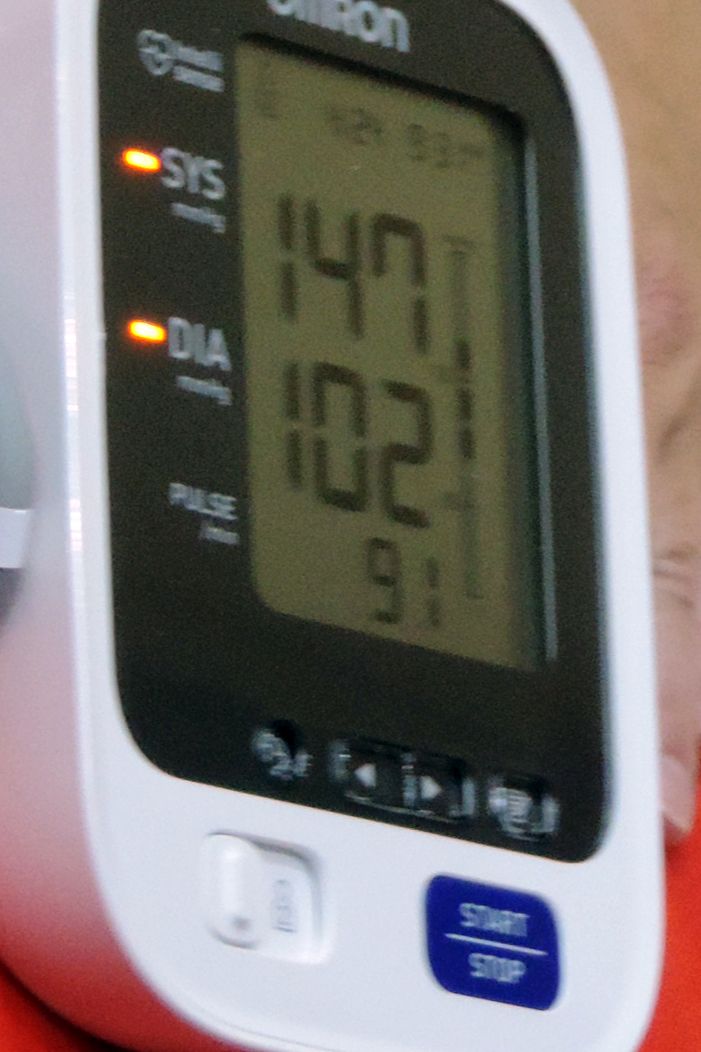

You can still demonstrate a mastery of your patients’ care by expressing your thought process overtly. For instance, “I considered secondary causes of the patient’s severe hypertension but felt it was most reasonable to first treat her pain and restart her home medications before pursuing a larger work-up. If the patient’s blood pressure remains elevated and she is hypokalemic, we could consider testing for hyperaldosteronism.” If you explain why you think a diagnosis is less likely and order tests accordingly, others will be encouraged to consider value in their own medical decision making.

3. Hone your communication skills

One of the most cited reasons for providing unnecessary care is the time required to discuss treatment plans with patients – it’s much faster to just order the test than to explain why it isn’t needed. Research, however, shows that these cost conversations take 68 seconds on average.4 Costs of Care (see Table 2) has an excellent video series that highlights how effective communication allows for shared decision making, which promotes both patient engagement and helps avoid wasteful care.

Physicians’ first instincts are often defensive when a patient asks for care we perceive as unnecessary. However, exploring what the patient hopes to gain from said test or treatment frequently reveals concern for a specific, missed diagnosis or complication. Addressing this underlying fear, rather than defending your ordering patterns, can create improved rapport and may serve to provide more reassurance than a test ever could.5

As a physician-in-training, try to observe others having these conversations and take every opportunity to practice. By focusing on this key skill set, you will increase your comfort with in-depth discussions on the value of care.

4. Get involved in a project related to high-value care

While you are developing your own practice patterns, you may be inspired to tackle areas of overuse and underuse at a more systemwide level. If your hospital does not have a committee for high-value care, perhaps a quality improvement leader can support your ideas to launch a project or participate in an ongoing initiative. Physicians-in-training have been identified as crucial to these projects’ success – your frontline insight can highlight potential problems and the nuances of workflow that are key to effective solutions.6

5. Embrace lifelong learning and reflection

The process of becoming a physician and of practicing high-value care is not a sprint but a marathon. Multiple barriers to high-value care exist, and you may feel these pressures differently at various points in your career. These include malpractice concerns, addressing patient expectations, and the desire to take action “just to be safe.”6

Interestingly, fear of malpractice does not seem to dissipate in areas where tort reform has provided stronger provider protections.7 Practitioners may also inaccurately assume a patient’s desire for additional work-up or treatment.8 Furthermore, be aware of the role of “commission bias” by which a provider regrets not doing something that could have helped a previous patient. This regret can prove to be a stronger motivator than the potential harm related to unnecessary diagnostic tests or treatments.9

While these barriers cannot be removed easily, learners and providers can practice active reflection by examining their own fears, biases, and motivations before and after they order additional testing or treatment.

As a physician-in-training, you may feel that your decisions do not have a major impact on the health care system as a whole. However, the culture shift needed to “bend the cost curve” will come from the collective efforts of individuals like you. Practicing high-value care is not just a matter of ordering fewer tests – appropriate ordering of an expensive test that expedites a diagnosis may be more cost-effective and enhance the quality of care provided. Increasing your own awareness of both necessary and unnecessary practices is a major step toward realizing system change. Your efforts to resist and reform the medical culture that propagates low value care will encourage your colleagues to follow suit.

Dr. Lacy is assistant professor and associate clerkship director at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, as well as division director of high-value care for the division of hospital medicine. Dr. Goetz is assistant professor at Rush University Medical Center, Chicago. They met as 2015 Copello Fellows at the National Physician Alliance. Both have been involved in numerous high-value care initiatives, curricular development, and medical education at their respective institutions.

References

1. Committee on the Learning Health Care System in America, Institute of Medicine. “Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America.” Edited by Smith M, Saunders R, Stuckhardt L, and McGinnis JM. (Washington: National Academies Press, 2013). http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK207225/.

2. Berwick DM, Hackbarth AD. Eliminating waste in US health care. JAMA. 2012;307(14):1513-6.

3. Lakhani A et al. Choosing Wisely for Medical Education: Six things medical students and trainees should question. Acad Med. 2016 Oct;91(10):1374-8.

4. Hunter WG et al. Patient-physician discussions about costs: Definitions and impact on cost conversation incidence estimates. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:108.

5. van Ravesteijn H et al. The reassuring value of diagnostic tests: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86(1):3-8.

6. Moriates C, Wong BM. High-value care programmes from the bottom-up… and the top-down. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(11):821-3.

7. Snyder Sulmasy L, Weinberger SE. Better care is the best defense: High-value clinical practice vs. defensive medicine. Cleve Clin J Med. 2014;81(8):464-7.

8. Mulley AG, Trimble C, Elwyn G. Stop the silent misdiagnosis: Patients’ preferences matter. BMJ. 2012;345:e6572.

9. Scott IA. Cognitive challenges to minimising low value care. Intern Med J. 2017;47(9):1079-1083.

It’s Monday morning, and Mrs. Jones still has abdominal pain. Your ward team decides to order a CT. On chart review you notice she’s had three other abdominal CTs for the same indication this year. How did this happen? What should you do?

High-value care has been defined by the Institute of Medicine as “the best care for the patient, with the optimal result for the circumstances, delivered at the right price.”1 With an estimated $700 billion dollars – 30% of medical expenditures – spent on wasted care, there are rising calls for a transformational shift.2

You are now asked to consider not just everything you can do for a patient, but also the benefits, harms, and costs associated with those choices. But where to start? We recommend that trainees integrate these tips for high-value care into their routine practice.

1. Use evidence-based resources that highlight value

A great place to begin is the “Six Things Medical Students and Trainees Should Question,” originally published in Academic Medicine and created by Choosing Wisely Canada™. Recommendations range from avoiding tests or treatments that will not change a patient’s clinical course to holding off on ordering tests solely based on what you assume your preceptor will want (see the full list in Table 1).3

Other ways to avoid low-value care include following the United States Choosing Wisely™ campaign, which has collected more than 500 specialty society recommendations. Likewise, the American College of Radiology Appropriateness Criteria are designed to assist providers with ordering the appropriate imaging tests (for a more extensive list see Table 2).

2. Express your clinical reasoning

One driver of health care expenditures that is especially prevalent in academia is the pressure to demonstrate knowledge by recommending extensive testing. While these tests may rule out obscure diagnoses, they often do not change management.

You can still demonstrate a mastery of your patients’ care by expressing your thought process overtly. For instance, “I considered secondary causes of the patient’s severe hypertension but felt it was most reasonable to first treat her pain and restart her home medications before pursuing a larger work-up. If the patient’s blood pressure remains elevated and she is hypokalemic, we could consider testing for hyperaldosteronism.” If you explain why you think a diagnosis is less likely and order tests accordingly, others will be encouraged to consider value in their own medical decision making.

3. Hone your communication skills

One of the most cited reasons for providing unnecessary care is the time required to discuss treatment plans with patients – it’s much faster to just order the test than to explain why it isn’t needed. Research, however, shows that these cost conversations take 68 seconds on average.4 Costs of Care (see Table 2) has an excellent video series that highlights how effective communication allows for shared decision making, which promotes both patient engagement and helps avoid wasteful care.

Physicians’ first instincts are often defensive when a patient asks for care we perceive as unnecessary. However, exploring what the patient hopes to gain from said test or treatment frequently reveals concern for a specific, missed diagnosis or complication. Addressing this underlying fear, rather than defending your ordering patterns, can create improved rapport and may serve to provide more reassurance than a test ever could.5

As a physician-in-training, try to observe others having these conversations and take every opportunity to practice. By focusing on this key skill set, you will increase your comfort with in-depth discussions on the value of care.

4. Get involved in a project related to high-value care

While you are developing your own practice patterns, you may be inspired to tackle areas of overuse and underuse at a more systemwide level. If your hospital does not have a committee for high-value care, perhaps a quality improvement leader can support your ideas to launch a project or participate in an ongoing initiative. Physicians-in-training have been identified as crucial to these projects’ success – your frontline insight can highlight potential problems and the nuances of workflow that are key to effective solutions.6

5. Embrace lifelong learning and reflection

The process of becoming a physician and of practicing high-value care is not a sprint but a marathon. Multiple barriers to high-value care exist, and you may feel these pressures differently at various points in your career. These include malpractice concerns, addressing patient expectations, and the desire to take action “just to be safe.”6

Interestingly, fear of malpractice does not seem to dissipate in areas where tort reform has provided stronger provider protections.7 Practitioners may also inaccurately assume a patient’s desire for additional work-up or treatment.8 Furthermore, be aware of the role of “commission bias” by which a provider regrets not doing something that could have helped a previous patient. This regret can prove to be a stronger motivator than the potential harm related to unnecessary diagnostic tests or treatments.9

While these barriers cannot be removed easily, learners and providers can practice active reflection by examining their own fears, biases, and motivations before and after they order additional testing or treatment.

As a physician-in-training, you may feel that your decisions do not have a major impact on the health care system as a whole. However, the culture shift needed to “bend the cost curve” will come from the collective efforts of individuals like you. Practicing high-value care is not just a matter of ordering fewer tests – appropriate ordering of an expensive test that expedites a diagnosis may be more cost-effective and enhance the quality of care provided. Increasing your own awareness of both necessary and unnecessary practices is a major step toward realizing system change. Your efforts to resist and reform the medical culture that propagates low value care will encourage your colleagues to follow suit.

Dr. Lacy is assistant professor and associate clerkship director at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, as well as division director of high-value care for the division of hospital medicine. Dr. Goetz is assistant professor at Rush University Medical Center, Chicago. They met as 2015 Copello Fellows at the National Physician Alliance. Both have been involved in numerous high-value care initiatives, curricular development, and medical education at their respective institutions.

References

1. Committee on the Learning Health Care System in America, Institute of Medicine. “Best Care at Lower Cost: The Path to Continuously Learning Health Care in America.” Edited by Smith M, Saunders R, Stuckhardt L, and McGinnis JM. (Washington: National Academies Press, 2013). http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK207225/.

2. Berwick DM, Hackbarth AD. Eliminating waste in US health care. JAMA. 2012;307(14):1513-6.

3. Lakhani A et al. Choosing Wisely for Medical Education: Six things medical students and trainees should question. Acad Med. 2016 Oct;91(10):1374-8.

4. Hunter WG et al. Patient-physician discussions about costs: Definitions and impact on cost conversation incidence estimates. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:108.

5. van Ravesteijn H et al. The reassuring value of diagnostic tests: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86(1):3-8.

6. Moriates C, Wong BM. High-value care programmes from the bottom-up… and the top-down. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(11):821-3.

7. Snyder Sulmasy L, Weinberger SE. Better care is the best defense: High-value clinical practice vs. defensive medicine. Cleve Clin J Med. 2014;81(8):464-7.

8. Mulley AG, Trimble C, Elwyn G. Stop the silent misdiagnosis: Patients’ preferences matter. BMJ. 2012;345:e6572.

9. Scott IA. Cognitive challenges to minimising low value care. Intern Med J. 2017;47(9):1079-1083.

MedPAC to Congress: End “incident-to” billing

Incident-to billing occurs when an advanced practicing registered nurse (APRN) or a physician assistant (PA) performs a service but bills Medicare under the physician’s national provider number and receives full physician fee schedule payment, as opposed to 85% of the fee under their own number.

“Medicare beneficiaries increasingly use APRNs and PAs for both primary and specialty care,” according to MedPAC’s June report. “APRNs are furnishing a larger share and a greater variety of services for Medicare beneficiaries than they did in the past. Despite this growing reliance, Medicare does not have a full accounting of the services delivered and beneficiaries treated.”

Currently, identical coding requirements obscure whether the physician or the APRN/PA is providing the service, making it difficult to track volume and quality.

MedPAC estimated that, in 2016, 17% of all nurse practitioners billed all their services as incident to, as that was the number of nurse practitioners who never appeared in the performing provider field for reimbursement but ordered services/drugs or at least one Medicare fee-for-service beneficiary.

Another 34% billed some of their services as incident to as their name appeared at least once in the performing provider they ordered services/drugs for, but ordered more services/drugs for patients where they were not listed as the performing provider.

That leaves just about half (49%) who did not billing their services as incident to.

Requiring APRNs and PAs to bill directly for all of their services provided would update Medicare’s payment policies to better reflect current clinical practice, according to the MedPAC report. “In addition to improving policy makers’ foundational knowledge of who provides care for Medicare beneficiaries, direct billing could create substantial benefits for the Medicare program, beneficiaries, clinicians, and researchers that range from improving the accuracy of the physician fee schedule, reducing expenditures, enhancing program integrity, and allowing for better comparisons between cost and quality of care provided by physicians and APRNs/PAs.”

At their October 2018 meeting, MedPAC commissioners discussed how to appropriately compensate APRNs and PAs, should incident-to billing be eliminated; they ultimately recommended maintaining the 85% rate.

The American Academy of Family Practitioners spoke out against the idea of eliminating incident-to billing.

However, lowering all APRN/PA payments to 85% of what physicians make would impact doctors in a negative way, according to AAFP President Michael Munger, MD.

Dr. Munger described primary care as a team sport, and “this is certainly going to be felt in terms of the overall mission of delivering quality care.”

Access to care also could be reduced along with the reduced payment level.

“You have to make business decisions at the end of the day,” he said in an interview. “You need to make sure that you can have adequate revenue to offset expenses, and if you are going to take a 15% cut in your revenue in, you have to look at where your expenses are, and obviously salary is your No. 1 expense. If you are not able to count on this revenue and you can’t afford to have NPs and PAs as part of the team, it is going to become an access issue for patients.”

The MedPAC commissioner saw it differently.

“Most of these clinicians are already paid at this lower rate, and yet the supply of these clinicians has increased dramatically over the last several years,” the report states, adding that the salary differential between these clinicians and physicians “is large enough that employing them likely would remain attractive even if all of their services were paid at 85% of physician fee schedule rates.”

MedPAC, as an advisory body to Congress, makes no disclosures.

Incident-to billing occurs when an advanced practicing registered nurse (APRN) or a physician assistant (PA) performs a service but bills Medicare under the physician’s national provider number and receives full physician fee schedule payment, as opposed to 85% of the fee under their own number.

“Medicare beneficiaries increasingly use APRNs and PAs for both primary and specialty care,” according to MedPAC’s June report. “APRNs are furnishing a larger share and a greater variety of services for Medicare beneficiaries than they did in the past. Despite this growing reliance, Medicare does not have a full accounting of the services delivered and beneficiaries treated.”

Currently, identical coding requirements obscure whether the physician or the APRN/PA is providing the service, making it difficult to track volume and quality.

MedPAC estimated that, in 2016, 17% of all nurse practitioners billed all their services as incident to, as that was the number of nurse practitioners who never appeared in the performing provider field for reimbursement but ordered services/drugs or at least one Medicare fee-for-service beneficiary.

Another 34% billed some of their services as incident to as their name appeared at least once in the performing provider they ordered services/drugs for, but ordered more services/drugs for patients where they were not listed as the performing provider.

That leaves just about half (49%) who did not billing their services as incident to.

Requiring APRNs and PAs to bill directly for all of their services provided would update Medicare’s payment policies to better reflect current clinical practice, according to the MedPAC report. “In addition to improving policy makers’ foundational knowledge of who provides care for Medicare beneficiaries, direct billing could create substantial benefits for the Medicare program, beneficiaries, clinicians, and researchers that range from improving the accuracy of the physician fee schedule, reducing expenditures, enhancing program integrity, and allowing for better comparisons between cost and quality of care provided by physicians and APRNs/PAs.”

At their October 2018 meeting, MedPAC commissioners discussed how to appropriately compensate APRNs and PAs, should incident-to billing be eliminated; they ultimately recommended maintaining the 85% rate.

The American Academy of Family Practitioners spoke out against the idea of eliminating incident-to billing.

However, lowering all APRN/PA payments to 85% of what physicians make would impact doctors in a negative way, according to AAFP President Michael Munger, MD.

Dr. Munger described primary care as a team sport, and “this is certainly going to be felt in terms of the overall mission of delivering quality care.”

Access to care also could be reduced along with the reduced payment level.

“You have to make business decisions at the end of the day,” he said in an interview. “You need to make sure that you can have adequate revenue to offset expenses, and if you are going to take a 15% cut in your revenue in, you have to look at where your expenses are, and obviously salary is your No. 1 expense. If you are not able to count on this revenue and you can’t afford to have NPs and PAs as part of the team, it is going to become an access issue for patients.”

The MedPAC commissioner saw it differently.

“Most of these clinicians are already paid at this lower rate, and yet the supply of these clinicians has increased dramatically over the last several years,” the report states, adding that the salary differential between these clinicians and physicians “is large enough that employing them likely would remain attractive even if all of their services were paid at 85% of physician fee schedule rates.”

MedPAC, as an advisory body to Congress, makes no disclosures.

Incident-to billing occurs when an advanced practicing registered nurse (APRN) or a physician assistant (PA) performs a service but bills Medicare under the physician’s national provider number and receives full physician fee schedule payment, as opposed to 85% of the fee under their own number.

“Medicare beneficiaries increasingly use APRNs and PAs for both primary and specialty care,” according to MedPAC’s June report. “APRNs are furnishing a larger share and a greater variety of services for Medicare beneficiaries than they did in the past. Despite this growing reliance, Medicare does not have a full accounting of the services delivered and beneficiaries treated.”

Currently, identical coding requirements obscure whether the physician or the APRN/PA is providing the service, making it difficult to track volume and quality.

MedPAC estimated that, in 2016, 17% of all nurse practitioners billed all their services as incident to, as that was the number of nurse practitioners who never appeared in the performing provider field for reimbursement but ordered services/drugs or at least one Medicare fee-for-service beneficiary.

Another 34% billed some of their services as incident to as their name appeared at least once in the performing provider they ordered services/drugs for, but ordered more services/drugs for patients where they were not listed as the performing provider.

That leaves just about half (49%) who did not billing their services as incident to.

Requiring APRNs and PAs to bill directly for all of their services provided would update Medicare’s payment policies to better reflect current clinical practice, according to the MedPAC report. “In addition to improving policy makers’ foundational knowledge of who provides care for Medicare beneficiaries, direct billing could create substantial benefits for the Medicare program, beneficiaries, clinicians, and researchers that range from improving the accuracy of the physician fee schedule, reducing expenditures, enhancing program integrity, and allowing for better comparisons between cost and quality of care provided by physicians and APRNs/PAs.”

At their October 2018 meeting, MedPAC commissioners discussed how to appropriately compensate APRNs and PAs, should incident-to billing be eliminated; they ultimately recommended maintaining the 85% rate.

The American Academy of Family Practitioners spoke out against the idea of eliminating incident-to billing.

However, lowering all APRN/PA payments to 85% of what physicians make would impact doctors in a negative way, according to AAFP President Michael Munger, MD.

Dr. Munger described primary care as a team sport, and “this is certainly going to be felt in terms of the overall mission of delivering quality care.”

Access to care also could be reduced along with the reduced payment level.

“You have to make business decisions at the end of the day,” he said in an interview. “You need to make sure that you can have adequate revenue to offset expenses, and if you are going to take a 15% cut in your revenue in, you have to look at where your expenses are, and obviously salary is your No. 1 expense. If you are not able to count on this revenue and you can’t afford to have NPs and PAs as part of the team, it is going to become an access issue for patients.”

The MedPAC commissioner saw it differently.

“Most of these clinicians are already paid at this lower rate, and yet the supply of these clinicians has increased dramatically over the last several years,” the report states, adding that the salary differential between these clinicians and physicians “is large enough that employing them likely would remain attractive even if all of their services were paid at 85% of physician fee schedule rates.”

MedPAC, as an advisory body to Congress, makes no disclosures.

What’s new in pediatric sepsis

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – The dogma of the “Golden Hour” for the immediate management of pediatric sepsis has been oversold and actually is based upon weak evidence, Luregn J. Schlapbach, MD, asserted at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

The true Golden Hour – that is, the time frame within which it’s imperative to administer the sepsis bundle comprised of appropriate antibiotics, fluids, and inotropes – is probably more like 3 hours.

“The evidence suggests that up to 3 hours you don’t really have a big difference in outcomes for sepsis. If you recognize shock there’s no question: You should not even wait 1 hour. But if you’re not certain, it may be better to give up to 3 hours to work up the child and get the senior clinician involved before you make decisions about treatment. So I’m not advocating to delay anything, said Dr. Schlapbach, a pediatric intensivist at the Child Health Research Center at the University of Queensland in South Brisbane, Australia.

The problem with a 1-hour mandate for delivery of the sepsis bundle, as recommended in guidelines by the Surviving Sepsis Campaign and the American College of Critical Care Medicine, and endorsed in quality improvement initiatives, is that the time pressure pushes physicians to overprescribe antibiotics to children who don’t actually have a serious bacterial infection. And that, he noted, contributes to the growing problem of antimicrobial resistance.

“You may have a child where you’re not too sure. Usually you would have done a urine culture because UTI [urinary tract infection] is quite a common cause of these infections, and many of these kids aren’t necessarily septic. But if people tell you that within 1 hour you need to treat, are you going to take the time to do the urine culture, or are you just going to decide to treat?” he asked rhetorically.

Dr. Schlapbach is a world-renowned pediatric sepsis researcher. He is far from alone in his reservations about the Golden Hour mandate.

“This is one of the reasons why IDSA [the Infectious Diseases Society of America] has not endorsed the Surviving Sepsis Campaign,” according to the physician, who noted that, in a position statement, IDSA officials have declared that discrimination of sepsis from noninfectious conditions remains a challenge, and that a 60-minute time to antibiotics may jeopardize patient reassessment (Clin Infect Dis. 2018 May 15;66[10]:1631-5).

Dr. Schlapbach highlighted other recent developments in pediatric sepsis.

The definition of adult sepsis has changed, and the pediatric version needs to as well

The revised definition of sepsis, known as Sepsis-3, issued by the International Sepsis Definition Task Force in 2016 notably dropped systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), as a requirement for sepsis (JAMA. 2016;315[8]:801-10). The revised definition characterizes sepsis as a dysregulated host response to infection resulting in life-threatening organ dysfunction. But Sepsis-3 is based entirely on adult data and is not considered applicable to children.

The current Pediatric Sepsis Consensus Conference definition dates back to 2005. A comprehensive revision is getting underway. It, too, is likely to drop SIRS into the wastebasket, Dr. Schlapbach said.

“It is probably time to abandon the old view of sepsis disease progression, which proposes a progression from infection to SIRS to severe sepsis with organ dysfunction to septic shock, because most children with infection do manifest signs of SIRS, such as tachycardia, tachypnea, and fever, and these probably should be considered as more of an adaptive rather than a maladaptive response,” he explained.

The goal of the pediatric sepsis redefinition project is to come up with something more useful for clinicians than the Sepsis-3 definition. While the Sepsis-3 concept of a dysregulated host response to infection sounds nice, he explained, “we don’t actually know what it is.

“One of the challenges that you all know as pediatricians is that children who develop sepsis get sick very, very quickly. We all have memories of children who we saw and may have discharged, and they were dead 12 hours later,” he noted.

Indeed, he and others have shown in multiple studies that up to 50% of pediatric deaths caused by sepsis happen within 24 hours of presentation.

“So whatever happens, it happens very quickly. The true question for us is actually how and why do children progress from no organ dysfunction, where the mortality is close to zero, to organ dysfunction, where all of a sudden mortality jumps up dramatically. It’s this progression that we don’t understand at all,” according to Dr. Schlapbach.

The genetic contribution to fulminant sepsis in children may be substantial

One-third of pediatric sepsis deaths in high-income countries happen in previously healthy children. In a proof-of-concept study, Dr. Schlapbach and coinvestigators in the Swiss Pediatric Sepsis Study Group conducted exome-sequencing genetic studies in eight previously healthy children with no family history of immunodeficiency who died of severe sepsis because of community-acquired Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Two of the eight had rare loss-of-function mutations in genes known to cause primary immunodeficiencies. The investigators proposed that unusually severe sepsis in previously healthy children warrants exome sequencing to look for underlying previously undetected primary immunodeficiencies. That’s important information for survivors and/or affected families to have, they argued (Front Immunol. 2016 Sep 20;7:357. eCollection 2016).

“There are some indications that the genetic contribution in children with sepsis may be larger than previously assumed,” he said.

The longstanding practice of fluid bolus therapy for resuscitation in pediatric sepsis is being reexamined

The FEAST (Fluid Expansion As Supportive Therapy) study, a randomized trial of more than 3,000 children with severe febrile illness and impaired perfusion in sub-Saharan Africa, turned heads with its finding that fluid boluses significantly increased 48-hour mortality (BMC Med. 2013 Mar 14;11:67).

Indeed, the FEAST findings, supported by mechanistic animal studies, were sufficiently compelling that the use of fluid boluses in both pediatric and adult septic shock is now under scrutiny in two major randomized trials: RIFTS (the Restrictive IV Fluid Trial in Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock), and CLOVERS (Crystalloid Liberal or Vasopressors Early Resuscitation in Sepsis). Stay tuned.

Dr. Schlapbach reported having no financial conflicts regarding his presentation.

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – The dogma of the “Golden Hour” for the immediate management of pediatric sepsis has been oversold and actually is based upon weak evidence, Luregn J. Schlapbach, MD, asserted at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

The true Golden Hour – that is, the time frame within which it’s imperative to administer the sepsis bundle comprised of appropriate antibiotics, fluids, and inotropes – is probably more like 3 hours.

“The evidence suggests that up to 3 hours you don’t really have a big difference in outcomes for sepsis. If you recognize shock there’s no question: You should not even wait 1 hour. But if you’re not certain, it may be better to give up to 3 hours to work up the child and get the senior clinician involved before you make decisions about treatment. So I’m not advocating to delay anything, said Dr. Schlapbach, a pediatric intensivist at the Child Health Research Center at the University of Queensland in South Brisbane, Australia.

The problem with a 1-hour mandate for delivery of the sepsis bundle, as recommended in guidelines by the Surviving Sepsis Campaign and the American College of Critical Care Medicine, and endorsed in quality improvement initiatives, is that the time pressure pushes physicians to overprescribe antibiotics to children who don’t actually have a serious bacterial infection. And that, he noted, contributes to the growing problem of antimicrobial resistance.

“You may have a child where you’re not too sure. Usually you would have done a urine culture because UTI [urinary tract infection] is quite a common cause of these infections, and many of these kids aren’t necessarily septic. But if people tell you that within 1 hour you need to treat, are you going to take the time to do the urine culture, or are you just going to decide to treat?” he asked rhetorically.

Dr. Schlapbach is a world-renowned pediatric sepsis researcher. He is far from alone in his reservations about the Golden Hour mandate.

“This is one of the reasons why IDSA [the Infectious Diseases Society of America] has not endorsed the Surviving Sepsis Campaign,” according to the physician, who noted that, in a position statement, IDSA officials have declared that discrimination of sepsis from noninfectious conditions remains a challenge, and that a 60-minute time to antibiotics may jeopardize patient reassessment (Clin Infect Dis. 2018 May 15;66[10]:1631-5).

Dr. Schlapbach highlighted other recent developments in pediatric sepsis.

The definition of adult sepsis has changed, and the pediatric version needs to as well

The revised definition of sepsis, known as Sepsis-3, issued by the International Sepsis Definition Task Force in 2016 notably dropped systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), as a requirement for sepsis (JAMA. 2016;315[8]:801-10). The revised definition characterizes sepsis as a dysregulated host response to infection resulting in life-threatening organ dysfunction. But Sepsis-3 is based entirely on adult data and is not considered applicable to children.

The current Pediatric Sepsis Consensus Conference definition dates back to 2005. A comprehensive revision is getting underway. It, too, is likely to drop SIRS into the wastebasket, Dr. Schlapbach said.

“It is probably time to abandon the old view of sepsis disease progression, which proposes a progression from infection to SIRS to severe sepsis with organ dysfunction to septic shock, because most children with infection do manifest signs of SIRS, such as tachycardia, tachypnea, and fever, and these probably should be considered as more of an adaptive rather than a maladaptive response,” he explained.

The goal of the pediatric sepsis redefinition project is to come up with something more useful for clinicians than the Sepsis-3 definition. While the Sepsis-3 concept of a dysregulated host response to infection sounds nice, he explained, “we don’t actually know what it is.

“One of the challenges that you all know as pediatricians is that children who develop sepsis get sick very, very quickly. We all have memories of children who we saw and may have discharged, and they were dead 12 hours later,” he noted.

Indeed, he and others have shown in multiple studies that up to 50% of pediatric deaths caused by sepsis happen within 24 hours of presentation.

“So whatever happens, it happens very quickly. The true question for us is actually how and why do children progress from no organ dysfunction, where the mortality is close to zero, to organ dysfunction, where all of a sudden mortality jumps up dramatically. It’s this progression that we don’t understand at all,” according to Dr. Schlapbach.

The genetic contribution to fulminant sepsis in children may be substantial

One-third of pediatric sepsis deaths in high-income countries happen in previously healthy children. In a proof-of-concept study, Dr. Schlapbach and coinvestigators in the Swiss Pediatric Sepsis Study Group conducted exome-sequencing genetic studies in eight previously healthy children with no family history of immunodeficiency who died of severe sepsis because of community-acquired Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Two of the eight had rare loss-of-function mutations in genes known to cause primary immunodeficiencies. The investigators proposed that unusually severe sepsis in previously healthy children warrants exome sequencing to look for underlying previously undetected primary immunodeficiencies. That’s important information for survivors and/or affected families to have, they argued (Front Immunol. 2016 Sep 20;7:357. eCollection 2016).

“There are some indications that the genetic contribution in children with sepsis may be larger than previously assumed,” he said.

The longstanding practice of fluid bolus therapy for resuscitation in pediatric sepsis is being reexamined

The FEAST (Fluid Expansion As Supportive Therapy) study, a randomized trial of more than 3,000 children with severe febrile illness and impaired perfusion in sub-Saharan Africa, turned heads with its finding that fluid boluses significantly increased 48-hour mortality (BMC Med. 2013 Mar 14;11:67).

Indeed, the FEAST findings, supported by mechanistic animal studies, were sufficiently compelling that the use of fluid boluses in both pediatric and adult septic shock is now under scrutiny in two major randomized trials: RIFTS (the Restrictive IV Fluid Trial in Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock), and CLOVERS (Crystalloid Liberal or Vasopressors Early Resuscitation in Sepsis). Stay tuned.

Dr. Schlapbach reported having no financial conflicts regarding his presentation.

LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA – The dogma of the “Golden Hour” for the immediate management of pediatric sepsis has been oversold and actually is based upon weak evidence, Luregn J. Schlapbach, MD, asserted at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

The true Golden Hour – that is, the time frame within which it’s imperative to administer the sepsis bundle comprised of appropriate antibiotics, fluids, and inotropes – is probably more like 3 hours.

“The evidence suggests that up to 3 hours you don’t really have a big difference in outcomes for sepsis. If you recognize shock there’s no question: You should not even wait 1 hour. But if you’re not certain, it may be better to give up to 3 hours to work up the child and get the senior clinician involved before you make decisions about treatment. So I’m not advocating to delay anything, said Dr. Schlapbach, a pediatric intensivist at the Child Health Research Center at the University of Queensland in South Brisbane, Australia.

The problem with a 1-hour mandate for delivery of the sepsis bundle, as recommended in guidelines by the Surviving Sepsis Campaign and the American College of Critical Care Medicine, and endorsed in quality improvement initiatives, is that the time pressure pushes physicians to overprescribe antibiotics to children who don’t actually have a serious bacterial infection. And that, he noted, contributes to the growing problem of antimicrobial resistance.

“You may have a child where you’re not too sure. Usually you would have done a urine culture because UTI [urinary tract infection] is quite a common cause of these infections, and many of these kids aren’t necessarily septic. But if people tell you that within 1 hour you need to treat, are you going to take the time to do the urine culture, or are you just going to decide to treat?” he asked rhetorically.

Dr. Schlapbach is a world-renowned pediatric sepsis researcher. He is far from alone in his reservations about the Golden Hour mandate.

“This is one of the reasons why IDSA [the Infectious Diseases Society of America] has not endorsed the Surviving Sepsis Campaign,” according to the physician, who noted that, in a position statement, IDSA officials have declared that discrimination of sepsis from noninfectious conditions remains a challenge, and that a 60-minute time to antibiotics may jeopardize patient reassessment (Clin Infect Dis. 2018 May 15;66[10]:1631-5).

Dr. Schlapbach highlighted other recent developments in pediatric sepsis.

The definition of adult sepsis has changed, and the pediatric version needs to as well

The revised definition of sepsis, known as Sepsis-3, issued by the International Sepsis Definition Task Force in 2016 notably dropped systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), as a requirement for sepsis (JAMA. 2016;315[8]:801-10). The revised definition characterizes sepsis as a dysregulated host response to infection resulting in life-threatening organ dysfunction. But Sepsis-3 is based entirely on adult data and is not considered applicable to children.

The current Pediatric Sepsis Consensus Conference definition dates back to 2005. A comprehensive revision is getting underway. It, too, is likely to drop SIRS into the wastebasket, Dr. Schlapbach said.

“It is probably time to abandon the old view of sepsis disease progression, which proposes a progression from infection to SIRS to severe sepsis with organ dysfunction to septic shock, because most children with infection do manifest signs of SIRS, such as tachycardia, tachypnea, and fever, and these probably should be considered as more of an adaptive rather than a maladaptive response,” he explained.

The goal of the pediatric sepsis redefinition project is to come up with something more useful for clinicians than the Sepsis-3 definition. While the Sepsis-3 concept of a dysregulated host response to infection sounds nice, he explained, “we don’t actually know what it is.

“One of the challenges that you all know as pediatricians is that children who develop sepsis get sick very, very quickly. We all have memories of children who we saw and may have discharged, and they were dead 12 hours later,” he noted.

Indeed, he and others have shown in multiple studies that up to 50% of pediatric deaths caused by sepsis happen within 24 hours of presentation.

“So whatever happens, it happens very quickly. The true question for us is actually how and why do children progress from no organ dysfunction, where the mortality is close to zero, to organ dysfunction, where all of a sudden mortality jumps up dramatically. It’s this progression that we don’t understand at all,” according to Dr. Schlapbach.

The genetic contribution to fulminant sepsis in children may be substantial

One-third of pediatric sepsis deaths in high-income countries happen in previously healthy children. In a proof-of-concept study, Dr. Schlapbach and coinvestigators in the Swiss Pediatric Sepsis Study Group conducted exome-sequencing genetic studies in eight previously healthy children with no family history of immunodeficiency who died of severe sepsis because of community-acquired Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Two of the eight had rare loss-of-function mutations in genes known to cause primary immunodeficiencies. The investigators proposed that unusually severe sepsis in previously healthy children warrants exome sequencing to look for underlying previously undetected primary immunodeficiencies. That’s important information for survivors and/or affected families to have, they argued (Front Immunol. 2016 Sep 20;7:357. eCollection 2016).

“There are some indications that the genetic contribution in children with sepsis may be larger than previously assumed,” he said.

The longstanding practice of fluid bolus therapy for resuscitation in pediatric sepsis is being reexamined

The FEAST (Fluid Expansion As Supportive Therapy) study, a randomized trial of more than 3,000 children with severe febrile illness and impaired perfusion in sub-Saharan Africa, turned heads with its finding that fluid boluses significantly increased 48-hour mortality (BMC Med. 2013 Mar 14;11:67).

Indeed, the FEAST findings, supported by mechanistic animal studies, were sufficiently compelling that the use of fluid boluses in both pediatric and adult septic shock is now under scrutiny in two major randomized trials: RIFTS (the Restrictive IV Fluid Trial in Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock), and CLOVERS (Crystalloid Liberal or Vasopressors Early Resuscitation in Sepsis). Stay tuned.

Dr. Schlapbach reported having no financial conflicts regarding his presentation.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM ESPID 2019

Repeated qSOFA measurements better predict in-hospital mortality from sepsis

Clinical question: Do repeated quick Sepsis-Related Organ Failure Assessment (qSOFA) measurements improve predictive validity for sepsis using in-hospital mortality, compared with a single qSOFA measurement at the time a clinician first suspects infection?

Background: Sepsis in hospitalized patients is associated with poor outcomes, but it is not clear how to best identify patients at risk. For non-ICU patients, the qSOFA score (made up of three simple clinical variables: respiratory rate greater than or equal to 22 breaths/minute, systolic blood pressure less than or equal to 100 mm Hg, and Glasgow Coma Scale score less than 15) has predictive validity for important outcomes including in-hospital mortality. qSOFA is relatively new in clinical practice, and the optimal utilization of the score has not yet been defined.

Study design: Retrospective Cohort Study.

Setting: All adult medical and surgical encounters in the ED, hospital ward, postanesthesia care unit (PACU), and ICU at 12 hospitals in Pennsylvania in 2012.

Synopsis: Kievlan et al. studied whether repeated qSOFA scores improved prediction of in-hospital mortality and allowed identification of specific clinical trajectories. The study included approximately 37,600 encounters. Authors abstracted demographic data, vital signs, laboratory results, and antibiotic/culture orders. An infection cohort was identified by a combination of orders for body fluid culture and antibiotics. The qSOFA scores were gathered at 6-hour intervals from the culture/antibiotic event (suspected sepsis). Scores were low (0), moderate (1), or high (greater than or equal to 2). Mean initial qSOFA scores were greater for patients who died, and remained higher during the 48-hours after suspected infection. Mortality was less than 2% in patients with an initial low qSOFA. 25% of patients with an initial moderate qSOFA had subsequent higher qSOFAs, and they had higher mortality, compared with patients with subsequent low qSOFA scores (16% vs. 4%).

Only those patients with initial qSOFA scores at the time of suspected infection were included, and missing data was common. The results may not be applicable to hospitals with a different sepsis case mix from the those of study institutions.

Bottom line: Repeated qSOFA measurements improve predictive validity for in-hospital mortality for patients with sepsis. Patients with low initial qSOFA scores have a low chance (less than 2%) of in-hospital mortality. Further studies are needed to determine how repeat qSOFA measurements can be used to improve management of patients with sepsis.

Citation: Kievlan DR et al. Evaluation of repeated quick sepsis-related organ failure assessment measurements among patients with suspected infection. Crit Care Med. 2018. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003360.

Dr. Linker is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York.

Clinical question: Do repeated quick Sepsis-Related Organ Failure Assessment (qSOFA) measurements improve predictive validity for sepsis using in-hospital mortality, compared with a single qSOFA measurement at the time a clinician first suspects infection?

Background: Sepsis in hospitalized patients is associated with poor outcomes, but it is not clear how to best identify patients at risk. For non-ICU patients, the qSOFA score (made up of three simple clinical variables: respiratory rate greater than or equal to 22 breaths/minute, systolic blood pressure less than or equal to 100 mm Hg, and Glasgow Coma Scale score less than 15) has predictive validity for important outcomes including in-hospital mortality. qSOFA is relatively new in clinical practice, and the optimal utilization of the score has not yet been defined.

Study design: Retrospective Cohort Study.

Setting: All adult medical and surgical encounters in the ED, hospital ward, postanesthesia care unit (PACU), and ICU at 12 hospitals in Pennsylvania in 2012.

Synopsis: Kievlan et al. studied whether repeated qSOFA scores improved prediction of in-hospital mortality and allowed identification of specific clinical trajectories. The study included approximately 37,600 encounters. Authors abstracted demographic data, vital signs, laboratory results, and antibiotic/culture orders. An infection cohort was identified by a combination of orders for body fluid culture and antibiotics. The qSOFA scores were gathered at 6-hour intervals from the culture/antibiotic event (suspected sepsis). Scores were low (0), moderate (1), or high (greater than or equal to 2). Mean initial qSOFA scores were greater for patients who died, and remained higher during the 48-hours after suspected infection. Mortality was less than 2% in patients with an initial low qSOFA. 25% of patients with an initial moderate qSOFA had subsequent higher qSOFAs, and they had higher mortality, compared with patients with subsequent low qSOFA scores (16% vs. 4%).

Only those patients with initial qSOFA scores at the time of suspected infection were included, and missing data was common. The results may not be applicable to hospitals with a different sepsis case mix from the those of study institutions.

Bottom line: Repeated qSOFA measurements improve predictive validity for in-hospital mortality for patients with sepsis. Patients with low initial qSOFA scores have a low chance (less than 2%) of in-hospital mortality. Further studies are needed to determine how repeat qSOFA measurements can be used to improve management of patients with sepsis.

Citation: Kievlan DR et al. Evaluation of repeated quick sepsis-related organ failure assessment measurements among patients with suspected infection. Crit Care Med. 2018. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003360.

Dr. Linker is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York.

Clinical question: Do repeated quick Sepsis-Related Organ Failure Assessment (qSOFA) measurements improve predictive validity for sepsis using in-hospital mortality, compared with a single qSOFA measurement at the time a clinician first suspects infection?

Background: Sepsis in hospitalized patients is associated with poor outcomes, but it is not clear how to best identify patients at risk. For non-ICU patients, the qSOFA score (made up of three simple clinical variables: respiratory rate greater than or equal to 22 breaths/minute, systolic blood pressure less than or equal to 100 mm Hg, and Glasgow Coma Scale score less than 15) has predictive validity for important outcomes including in-hospital mortality. qSOFA is relatively new in clinical practice, and the optimal utilization of the score has not yet been defined.

Study design: Retrospective Cohort Study.

Setting: All adult medical and surgical encounters in the ED, hospital ward, postanesthesia care unit (PACU), and ICU at 12 hospitals in Pennsylvania in 2012.

Synopsis: Kievlan et al. studied whether repeated qSOFA scores improved prediction of in-hospital mortality and allowed identification of specific clinical trajectories. The study included approximately 37,600 encounters. Authors abstracted demographic data, vital signs, laboratory results, and antibiotic/culture orders. An infection cohort was identified by a combination of orders for body fluid culture and antibiotics. The qSOFA scores were gathered at 6-hour intervals from the culture/antibiotic event (suspected sepsis). Scores were low (0), moderate (1), or high (greater than or equal to 2). Mean initial qSOFA scores were greater for patients who died, and remained higher during the 48-hours after suspected infection. Mortality was less than 2% in patients with an initial low qSOFA. 25% of patients with an initial moderate qSOFA had subsequent higher qSOFAs, and they had higher mortality, compared with patients with subsequent low qSOFA scores (16% vs. 4%).

Only those patients with initial qSOFA scores at the time of suspected infection were included, and missing data was common. The results may not be applicable to hospitals with a different sepsis case mix from the those of study institutions.

Bottom line: Repeated qSOFA measurements improve predictive validity for in-hospital mortality for patients with sepsis. Patients with low initial qSOFA scores have a low chance (less than 2%) of in-hospital mortality. Further studies are needed to determine how repeat qSOFA measurements can be used to improve management of patients with sepsis.

Citation: Kievlan DR et al. Evaluation of repeated quick sepsis-related organ failure assessment measurements among patients with suspected infection. Crit Care Med. 2018. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003360.

Dr. Linker is an assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital, New York.

Medicare may best Medicare Advantage at reducing readmissions

Although earlier research may suggest otherwise, traditional new research suggests.

Researchers used what they described as “a novel data linkage” comparing 30-day readmission rates after hospitalization for three major conditions in the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program for patients using traditional Medicare versus Medicare Advantage. Those conditions included acute MI, heart failure, and pneumonia.

“Our results contrast with those of previous studies that have reported lower or statistically similar readmission rates for Medicare Advantage beneficiaries,” Orestis A. Panagiotou, MD, of Brown University, Providence, R.I., and colleagues wrote in a research report published in Annals of Internal Medicine.

In this retrospective cohort study, the researchers linked data from 2011 to 2014 from the Medicare Provider Analysis and Review (MedPAR) file to the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS).

The novel linkage found that HEDIS data underreported hospital admissions for acute MI, heart failure, and pneumonia, the researchers stated. “Plans incorrectly excluded hospitalizations that should have qualified for the readmission measure, and readmission rates were substantially higher among incorrectly excluded hospitalizations.”

Despite this, in analyses using the linkage of HEDIS and MedPAR, “Medicare Advantage beneficiaries had higher 30-day risk-adjusted readmission rates after [acute MI, heart failure, and pneumonia] than did traditional Medicare beneficiaries,” the investigators noted.

Patients in Medicare Advantage had lower unadjusted readmission rates compared with those in traditional Medicare (16.6% vs. 17.1% for acute MI; 21.4% vs. 21.7% for heart failure; and 16.3% vs. 16.4% for pneumonia). After standardization, Medicare Advantage patients had higher readmission rates, compared with those in traditional Medicare (17.2% vs. 16.9% for acute MI; 21.7% vs. 21.4% for heart failure; and 16.5% vs. 16.0% for pneumonia).

The study authors added that, while unadjusted readmission rates were higher for traditional Medicare beneficiaries, “the direction of the difference reversed after standardization. This occurred because Medicare Advantage beneficiaries have, on average, a lower expected readmission risk [that is, they are ‘healthier’].” Prior studies have documented that Medicare Advantage plans enroll beneficiaries with fewer comorbid conditions and that high-cost beneficiaries switch out of Medicare Advantage and into traditional Medicare.

The researchers suggested four reasons for the differences between the results in this study versus others that compared patients using Medicare with those using Medicare Advantage. These were that the new study included a more comprehensive data set, analyses with comorbid conditions “from a well-validated model applied by CMS [Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services],” national data focused on three conditions included in the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, and patients discharged to places other than skilled nursing facilities and inpatient rehabilitation facilities.

Authors of an accompanying editorial called for caution to be used in interpreting Medicare Advantage enrollment as causing an increased readmission risk.

“[The] results are sensitive to adjustment for case mix,” wrote Peter Huckfeldt, PhD, of the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and Neeraj Sood, PhD, of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, in the editorial published in Annals of Internal Medicine (2019 June 25. doi:10.7326/M19-1599) “Using diagnosis codes on hospital claims for case-mix adjustments may be increasingly perilous. ... To our knowledge, there is no recent evidence comparing the intensity of diagnostic coding between clinically similar [traditional Medicare] and [Medicare Advantage] hospital admissions, but if [traditional Medicare] enrollees were coded more intensively than [Medicare Advantage] enrollees, this could lead to [traditional Medicare] enrollees having lower risk-adjusted readmission rares due to coding practices.”

The editorialists added that using a cross-sectional comparison of Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare patients is concerning because a “key challenge in estimating the effect of [Medicare Advantage] is that enrollment is voluntary,” which can lead to a number of analytical concerns.

The researchers concluded that their findings “are concerning because CMS uses HEDIS performance to construct composite quality ratings and assign payment bonuses to Medicare Advantage plans.

“Our study suggests a need for improved monitoring of the accuracy of HEDIS data,” they noted.

The National Institute on Aging provided the primary funding for this study. A number of the authors received grants from the National Institutes of Health during the conduct of the study. No other relevant disclosures were reported.

SOURCE: Panagiotou OA et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Jun 25. doi: 10.7326/M18-1795.

Although earlier research may suggest otherwise, traditional new research suggests.

Researchers used what they described as “a novel data linkage” comparing 30-day readmission rates after hospitalization for three major conditions in the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program for patients using traditional Medicare versus Medicare Advantage. Those conditions included acute MI, heart failure, and pneumonia.

“Our results contrast with those of previous studies that have reported lower or statistically similar readmission rates for Medicare Advantage beneficiaries,” Orestis A. Panagiotou, MD, of Brown University, Providence, R.I., and colleagues wrote in a research report published in Annals of Internal Medicine.

In this retrospective cohort study, the researchers linked data from 2011 to 2014 from the Medicare Provider Analysis and Review (MedPAR) file to the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS).

The novel linkage found that HEDIS data underreported hospital admissions for acute MI, heart failure, and pneumonia, the researchers stated. “Plans incorrectly excluded hospitalizations that should have qualified for the readmission measure, and readmission rates were substantially higher among incorrectly excluded hospitalizations.”

Despite this, in analyses using the linkage of HEDIS and MedPAR, “Medicare Advantage beneficiaries had higher 30-day risk-adjusted readmission rates after [acute MI, heart failure, and pneumonia] than did traditional Medicare beneficiaries,” the investigators noted.

Patients in Medicare Advantage had lower unadjusted readmission rates compared with those in traditional Medicare (16.6% vs. 17.1% for acute MI; 21.4% vs. 21.7% for heart failure; and 16.3% vs. 16.4% for pneumonia). After standardization, Medicare Advantage patients had higher readmission rates, compared with those in traditional Medicare (17.2% vs. 16.9% for acute MI; 21.7% vs. 21.4% for heart failure; and 16.5% vs. 16.0% for pneumonia).

The study authors added that, while unadjusted readmission rates were higher for traditional Medicare beneficiaries, “the direction of the difference reversed after standardization. This occurred because Medicare Advantage beneficiaries have, on average, a lower expected readmission risk [that is, they are ‘healthier’].” Prior studies have documented that Medicare Advantage plans enroll beneficiaries with fewer comorbid conditions and that high-cost beneficiaries switch out of Medicare Advantage and into traditional Medicare.

The researchers suggested four reasons for the differences between the results in this study versus others that compared patients using Medicare with those using Medicare Advantage. These were that the new study included a more comprehensive data set, analyses with comorbid conditions “from a well-validated model applied by CMS [Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services],” national data focused on three conditions included in the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, and patients discharged to places other than skilled nursing facilities and inpatient rehabilitation facilities.

Authors of an accompanying editorial called for caution to be used in interpreting Medicare Advantage enrollment as causing an increased readmission risk.

“[The] results are sensitive to adjustment for case mix,” wrote Peter Huckfeldt, PhD, of the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and Neeraj Sood, PhD, of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, in the editorial published in Annals of Internal Medicine (2019 June 25. doi:10.7326/M19-1599) “Using diagnosis codes on hospital claims for case-mix adjustments may be increasingly perilous. ... To our knowledge, there is no recent evidence comparing the intensity of diagnostic coding between clinically similar [traditional Medicare] and [Medicare Advantage] hospital admissions, but if [traditional Medicare] enrollees were coded more intensively than [Medicare Advantage] enrollees, this could lead to [traditional Medicare] enrollees having lower risk-adjusted readmission rares due to coding practices.”

The editorialists added that using a cross-sectional comparison of Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare patients is concerning because a “key challenge in estimating the effect of [Medicare Advantage] is that enrollment is voluntary,” which can lead to a number of analytical concerns.

The researchers concluded that their findings “are concerning because CMS uses HEDIS performance to construct composite quality ratings and assign payment bonuses to Medicare Advantage plans.

“Our study suggests a need for improved monitoring of the accuracy of HEDIS data,” they noted.

The National Institute on Aging provided the primary funding for this study. A number of the authors received grants from the National Institutes of Health during the conduct of the study. No other relevant disclosures were reported.

SOURCE: Panagiotou OA et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Jun 25. doi: 10.7326/M18-1795.

Although earlier research may suggest otherwise, traditional new research suggests.

Researchers used what they described as “a novel data linkage” comparing 30-day readmission rates after hospitalization for three major conditions in the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program for patients using traditional Medicare versus Medicare Advantage. Those conditions included acute MI, heart failure, and pneumonia.

“Our results contrast with those of previous studies that have reported lower or statistically similar readmission rates for Medicare Advantage beneficiaries,” Orestis A. Panagiotou, MD, of Brown University, Providence, R.I., and colleagues wrote in a research report published in Annals of Internal Medicine.

In this retrospective cohort study, the researchers linked data from 2011 to 2014 from the Medicare Provider Analysis and Review (MedPAR) file to the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS).

The novel linkage found that HEDIS data underreported hospital admissions for acute MI, heart failure, and pneumonia, the researchers stated. “Plans incorrectly excluded hospitalizations that should have qualified for the readmission measure, and readmission rates were substantially higher among incorrectly excluded hospitalizations.”

Despite this, in analyses using the linkage of HEDIS and MedPAR, “Medicare Advantage beneficiaries had higher 30-day risk-adjusted readmission rates after [acute MI, heart failure, and pneumonia] than did traditional Medicare beneficiaries,” the investigators noted.

Patients in Medicare Advantage had lower unadjusted readmission rates compared with those in traditional Medicare (16.6% vs. 17.1% for acute MI; 21.4% vs. 21.7% for heart failure; and 16.3% vs. 16.4% for pneumonia). After standardization, Medicare Advantage patients had higher readmission rates, compared with those in traditional Medicare (17.2% vs. 16.9% for acute MI; 21.7% vs. 21.4% for heart failure; and 16.5% vs. 16.0% for pneumonia).

The study authors added that, while unadjusted readmission rates were higher for traditional Medicare beneficiaries, “the direction of the difference reversed after standardization. This occurred because Medicare Advantage beneficiaries have, on average, a lower expected readmission risk [that is, they are ‘healthier’].” Prior studies have documented that Medicare Advantage plans enroll beneficiaries with fewer comorbid conditions and that high-cost beneficiaries switch out of Medicare Advantage and into traditional Medicare.

The researchers suggested four reasons for the differences between the results in this study versus others that compared patients using Medicare with those using Medicare Advantage. These were that the new study included a more comprehensive data set, analyses with comorbid conditions “from a well-validated model applied by CMS [Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services],” national data focused on three conditions included in the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, and patients discharged to places other than skilled nursing facilities and inpatient rehabilitation facilities.