User login

Official news magazine of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Copyright by Society of Hospital Medicine or related companies. All rights reserved. ISSN 1553-085X

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-hospitalist')]

Pediatric hospitalist and researcher: Dr. Samir Shah

Stoking collaboration between adult and pediatric clinicians

Samir S. Shah, MD, MSCE, director of the division of hospital medicine at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, believes that pediatric and adult hospitalists have much to learn from each other. And he aims to promote that mutual education in his new role as editor in chief of the Journal of Hospital Medicine.

Dr. Shah is the first pediatric hospitalist to hold this position for JHM, the official journal of the Society of Hospital Medicine. He says his new position, which became effective Jan. 1, is primed for fostering interaction between pediatric and adult hospitalists. “Pediatric hospital medicine is such a vibrant community of its own. There are many opportunities for partnership and collaboration between adult and pediatric hospitalists,” he said.

The field of pediatric hospital medicine has started down the path toward becoming recognized as a board-certified subspecialty.1 “That will place a greater emphasis on our role in fellowship training, which is important to ensure that pediatric hospitalists have a clearly defined skill set,” Dr. Shah said. “So much of what we learn in medical school is oriented to the medical care of adults. If you go into pediatrics, you’ve already had a fair amount of grounding in the healthy physiology and common diseases of adults. Pediatric hospital medicine fellowships offer an opportunity to refine clinical skill sets, as well as develop new skills in domains such as research and leadership.”

An emphasis on diversity

Although he has praised the innovative work of his predecessors, Mark Williams, MD, MHM, and Andrew Auerbach, MD, MPH, MHM, in shepherding the journal to its current strong position, Dr. Shah brings ideas for new features and directions.

“We as a field really benefit from a diversity of skill sets and perspectives. I’m excited to create processes to ensure equity and diversity in everything we do, starting with adding more women and more pediatric hospitalists to the journal’s leadership team, as well as purposefully developing a diverse leadership pipeline for the journal and for the field,” he said.

“We are intentionally reaching out to pediatricians to emphasize the extent to which JHM is invested in their field. For example, we have increased by seven the number of pediatricians as part of the JHM leadership team.” But pediatric hospitalists have always seen JHM as a home for their work, and Dr. Shah himself has published a couple dozen research papers in the journal. “It has always felt to me like a welcoming place,” he said.

“The great thing for me is that I’m not doing this alone. We have a marvelous crew of senior deputy editors, deputy editors, associate editors, and advisors. The opportunity I have is to leverage the phenomenal expertise and enthusiasm of this exceptional team.”

The journal under Dr. Auerbach’s lead created an editorial fellowship program offering opportunities for 1-year mentored exposure to the publication of academic scholarship and to different aspects of how a medical journal works. “We’re excited to continue investing in this program and included an editorial about it and an application form in the January 2019 issue of the Journal,” Dr. Shah said. He encourages editorial fellowship applications from physicians who historically have been underrepresented in academic medicine leadership.

“We’re also creating a column on leadership and professional development so that leaders in different fields can share their perspective and wisdom with our readers. We’ll be presenting a new, shorter review format; distilling clinical practice guidelines; and working on redesigning the journal’s web presence. We believe that our readers interact with the journal differently than they did five years ago, and increasingly are leveraging social media,” he said.

“I’m eager to broaden the scope of the journal. In the past, we focused on quality, value in health care and transitions of care in and out of the hospital, which are important topics. But I’m also excited about the adoption of new technologies, how to evaluate them and incorporate them into medical practice – things like Apple Watch for measuring heart rhythm,” Dr. Shah.

He wants to explore other technology-related topics like alarm fatigue and the use of monitors. Another big subject is the management of health of populations under new, emerging, risk-based payment models, with their pressures on health systems to take greater responsibility for risk. JHM is a medical journal and an official society journal, Dr. Shah said. “But our readership and submitters are not limited to hospitalists. As editor in chief, I’m here to make sure the journal is relevant to our members and to our other constituencies.”

Dr. Shah joined JHM’s editorial leadership team in 2009, then he became its deputy editor in 2012 and its senior deputy editor in 2015. A founding associate editor of the Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society, he has also served on the editorial board of JAMA Pediatrics. He is editor or coeditor of 12 books in the fields of pediatrics and infectious diseases, including coauthoring “The Philadelphia Guide: Inpatient Pediatrics for McGraw-Hill Education” while still a fellow in academic general pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) and, more recently, “Pediatric Infectious Diseases: Essentials for Practice,” a textbook for the pediatric generalist.

Broad scope of activities

Dr. Shah started practicing pediatric hospital medicine in 2001 during his fellowship training. He joined the faculty at CHOP and the University of Pennsylvania, also in Philadelphia, in 2005. In 2011 he arrived at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, a facility with more than 600 beds that’s affiliated with the University of Cincinnati, where he is professor in the department of pediatrics and holds the James M. Ewell Endowed Chair, to lead a newly created division of hospital medicine. That division now includes more than 55 physician faculty members, 10 nurse practitioners, and nine 3-year fellows.

Collectively the staff represent a broad scope of clinical and research activities along with consulting and surgical comanagement roles and a unique service staffed by med/peds hospitalists for adult patients who have been followed at the hospital since they were children. “Years ago, those patients would not have survived beyond childhood, but with medical advances, they have. Although they continue to benefit from pediatric expertise, these adults also require internal medicine expertise for their adult health needs,” he explained. Examples include patients with neurologic impairments, dependence on medical technology, or congenital heart defects.

Dr. Shah’s own schedule is 28% clinical. He also serves as the hospital’s chief metrics officer, and his research interests include serious infectious diseases, such as pneumonia and meningitis. He is studying the comparative effectiveness of different antibiotic treatments for community-acquired pneumonia and how to improve outcomes for hospital-acquired pneumonia.

Dr. Shah has tried to be deliberate in leading efforts to grow researchers within the field, both nationally and locally. He serves as the chair of the National Childhood Pneumonia Guidelines Committee of the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society, and he also is vice chair of the Pediatric Research in Inpatient Settings (PRIS) Network, which facilitates multicenter cost-effectiveness studies among its 120 hospital members. For example, a series of studies funded by the Patient- Centered Outcomes Research Institute has demonstrated the comparable effectiveness of oral and intravenous antibiotics for osteomyelitis and complicated pneumonia.

Sustainable positions

When he was asked whether he felt pediatric hospitalists face particular challenges in trying to take their place in the burgeoning field of hospital medicine, Dr. Shah said he and his colleagues don’t really think of it in those terms. “Hospital medicine is such a dynamic field. For example, pediatric hospital medicine has charted its own course by pursuing subspecialty certification and fellowship training. Yet support from the field broadly has been quite strong, and SHM has embraced pediatricians, who serve on its board of directors and on numerous committees.”

SHM’s commitment to supporting pediatric hospital medicine practice and research includes its cosponsorship, with the Academic Pediatric Association and the American Academy of Pediatrics, an annual pediatric hospital medicine educational and research conference, which will next be held July 25-28, 2019, in Seattle. “In my recent meetings with society leaders I have seen exceptional enthusiasm for increasing the presence of pediatric hospitalists in the society’s work. Many pediatric hospitalists already attend SHM’s annual meeting and submit their research, but we all recognize that a strong pediatric presence is important for the society.”

Dr. Shah credits Cincinnati Children’s Hospital for supporting a sustainable work schedule for its hospitalists and for a team-oriented culture that emphasizes both professional and personal development and encourages a diversity of skill sets and perspectives, skills development, and additional training. “Individuals are recognized for their achievements within and beyond the confines of the hospital. The mentorship structure we set up here is incredible. Each faculty member has a primary mentor, a peer mentor, and access to a career development committee. Additionally, there is broad participation in clinical operations, educational scholarship, research, and quality improvement.”

Dr. Shah’s professional interests in academics, research, and infectious diseases trace back in part to a thesis project he did on neonatal infections while in medical school at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. “I was working with basic sciences in a hematology lab under the direction of the neonatologist Dr. Patrick Gallagher, whose research focused on pediatric blood cell membrane disorders.” Dr. Gallagher, who directs the Yale Center for Blood Disorders, had a keen interest in infections in infants, Dr. Shah recalled.

“He would share with me interesting cases from his practice. What particularly captured my attention was realizing how the research I could do might have a direct impact on patients and families.” Thus inspired to do an additional year of medical school training at Yale before graduating in 1998, Dr. Shah used that year to focus on research, including a placement at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to investigate infectious disease outbreaks, which offered real-world mysteries to solve.

“When I was a resident, pediatric hospital medicine had not yet been recognized as a specialty. But during my fellowships, most of my work was focused on the inpatient side of medicine,” he said. That made hospital medicine a natural career path.

Dr. Shah describes himself as a devoted soccer fan with season tickets for himself, his wife, and their three children to the Major League Soccer team FC Cincinnati. He’s also a movie buff and a former avid bicyclist who’s now trying to get back into cycling. He encourages readers of The Hospitalist to contact him with input on any aspect of the Journal of Hospital Medicine. Email him at [email protected] and follow him on Twitter: @samirshahmd.

Reference

1. Barrett DJ et al. Pediatric hospital medicine: A proposed new subspecialty. Pediatrics. 2017 March;139(3):e20161823.

Stoking collaboration between adult and pediatric clinicians

Stoking collaboration between adult and pediatric clinicians

Samir S. Shah, MD, MSCE, director of the division of hospital medicine at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, believes that pediatric and adult hospitalists have much to learn from each other. And he aims to promote that mutual education in his new role as editor in chief of the Journal of Hospital Medicine.

Dr. Shah is the first pediatric hospitalist to hold this position for JHM, the official journal of the Society of Hospital Medicine. He says his new position, which became effective Jan. 1, is primed for fostering interaction between pediatric and adult hospitalists. “Pediatric hospital medicine is such a vibrant community of its own. There are many opportunities for partnership and collaboration between adult and pediatric hospitalists,” he said.

The field of pediatric hospital medicine has started down the path toward becoming recognized as a board-certified subspecialty.1 “That will place a greater emphasis on our role in fellowship training, which is important to ensure that pediatric hospitalists have a clearly defined skill set,” Dr. Shah said. “So much of what we learn in medical school is oriented to the medical care of adults. If you go into pediatrics, you’ve already had a fair amount of grounding in the healthy physiology and common diseases of adults. Pediatric hospital medicine fellowships offer an opportunity to refine clinical skill sets, as well as develop new skills in domains such as research and leadership.”

An emphasis on diversity

Although he has praised the innovative work of his predecessors, Mark Williams, MD, MHM, and Andrew Auerbach, MD, MPH, MHM, in shepherding the journal to its current strong position, Dr. Shah brings ideas for new features and directions.

“We as a field really benefit from a diversity of skill sets and perspectives. I’m excited to create processes to ensure equity and diversity in everything we do, starting with adding more women and more pediatric hospitalists to the journal’s leadership team, as well as purposefully developing a diverse leadership pipeline for the journal and for the field,” he said.

“We are intentionally reaching out to pediatricians to emphasize the extent to which JHM is invested in their field. For example, we have increased by seven the number of pediatricians as part of the JHM leadership team.” But pediatric hospitalists have always seen JHM as a home for their work, and Dr. Shah himself has published a couple dozen research papers in the journal. “It has always felt to me like a welcoming place,” he said.

“The great thing for me is that I’m not doing this alone. We have a marvelous crew of senior deputy editors, deputy editors, associate editors, and advisors. The opportunity I have is to leverage the phenomenal expertise and enthusiasm of this exceptional team.”

The journal under Dr. Auerbach’s lead created an editorial fellowship program offering opportunities for 1-year mentored exposure to the publication of academic scholarship and to different aspects of how a medical journal works. “We’re excited to continue investing in this program and included an editorial about it and an application form in the January 2019 issue of the Journal,” Dr. Shah said. He encourages editorial fellowship applications from physicians who historically have been underrepresented in academic medicine leadership.

“We’re also creating a column on leadership and professional development so that leaders in different fields can share their perspective and wisdom with our readers. We’ll be presenting a new, shorter review format; distilling clinical practice guidelines; and working on redesigning the journal’s web presence. We believe that our readers interact with the journal differently than they did five years ago, and increasingly are leveraging social media,” he said.

“I’m eager to broaden the scope of the journal. In the past, we focused on quality, value in health care and transitions of care in and out of the hospital, which are important topics. But I’m also excited about the adoption of new technologies, how to evaluate them and incorporate them into medical practice – things like Apple Watch for measuring heart rhythm,” Dr. Shah.

He wants to explore other technology-related topics like alarm fatigue and the use of monitors. Another big subject is the management of health of populations under new, emerging, risk-based payment models, with their pressures on health systems to take greater responsibility for risk. JHM is a medical journal and an official society journal, Dr. Shah said. “But our readership and submitters are not limited to hospitalists. As editor in chief, I’m here to make sure the journal is relevant to our members and to our other constituencies.”

Dr. Shah joined JHM’s editorial leadership team in 2009, then he became its deputy editor in 2012 and its senior deputy editor in 2015. A founding associate editor of the Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society, he has also served on the editorial board of JAMA Pediatrics. He is editor or coeditor of 12 books in the fields of pediatrics and infectious diseases, including coauthoring “The Philadelphia Guide: Inpatient Pediatrics for McGraw-Hill Education” while still a fellow in academic general pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) and, more recently, “Pediatric Infectious Diseases: Essentials for Practice,” a textbook for the pediatric generalist.

Broad scope of activities

Dr. Shah started practicing pediatric hospital medicine in 2001 during his fellowship training. He joined the faculty at CHOP and the University of Pennsylvania, also in Philadelphia, in 2005. In 2011 he arrived at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, a facility with more than 600 beds that’s affiliated with the University of Cincinnati, where he is professor in the department of pediatrics and holds the James M. Ewell Endowed Chair, to lead a newly created division of hospital medicine. That division now includes more than 55 physician faculty members, 10 nurse practitioners, and nine 3-year fellows.

Collectively the staff represent a broad scope of clinical and research activities along with consulting and surgical comanagement roles and a unique service staffed by med/peds hospitalists for adult patients who have been followed at the hospital since they were children. “Years ago, those patients would not have survived beyond childhood, but with medical advances, they have. Although they continue to benefit from pediatric expertise, these adults also require internal medicine expertise for their adult health needs,” he explained. Examples include patients with neurologic impairments, dependence on medical technology, or congenital heart defects.

Dr. Shah’s own schedule is 28% clinical. He also serves as the hospital’s chief metrics officer, and his research interests include serious infectious diseases, such as pneumonia and meningitis. He is studying the comparative effectiveness of different antibiotic treatments for community-acquired pneumonia and how to improve outcomes for hospital-acquired pneumonia.

Dr. Shah has tried to be deliberate in leading efforts to grow researchers within the field, both nationally and locally. He serves as the chair of the National Childhood Pneumonia Guidelines Committee of the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society, and he also is vice chair of the Pediatric Research in Inpatient Settings (PRIS) Network, which facilitates multicenter cost-effectiveness studies among its 120 hospital members. For example, a series of studies funded by the Patient- Centered Outcomes Research Institute has demonstrated the comparable effectiveness of oral and intravenous antibiotics for osteomyelitis and complicated pneumonia.

Sustainable positions

When he was asked whether he felt pediatric hospitalists face particular challenges in trying to take their place in the burgeoning field of hospital medicine, Dr. Shah said he and his colleagues don’t really think of it in those terms. “Hospital medicine is such a dynamic field. For example, pediatric hospital medicine has charted its own course by pursuing subspecialty certification and fellowship training. Yet support from the field broadly has been quite strong, and SHM has embraced pediatricians, who serve on its board of directors and on numerous committees.”

SHM’s commitment to supporting pediatric hospital medicine practice and research includes its cosponsorship, with the Academic Pediatric Association and the American Academy of Pediatrics, an annual pediatric hospital medicine educational and research conference, which will next be held July 25-28, 2019, in Seattle. “In my recent meetings with society leaders I have seen exceptional enthusiasm for increasing the presence of pediatric hospitalists in the society’s work. Many pediatric hospitalists already attend SHM’s annual meeting and submit their research, but we all recognize that a strong pediatric presence is important for the society.”

Dr. Shah credits Cincinnati Children’s Hospital for supporting a sustainable work schedule for its hospitalists and for a team-oriented culture that emphasizes both professional and personal development and encourages a diversity of skill sets and perspectives, skills development, and additional training. “Individuals are recognized for their achievements within and beyond the confines of the hospital. The mentorship structure we set up here is incredible. Each faculty member has a primary mentor, a peer mentor, and access to a career development committee. Additionally, there is broad participation in clinical operations, educational scholarship, research, and quality improvement.”

Dr. Shah’s professional interests in academics, research, and infectious diseases trace back in part to a thesis project he did on neonatal infections while in medical school at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. “I was working with basic sciences in a hematology lab under the direction of the neonatologist Dr. Patrick Gallagher, whose research focused on pediatric blood cell membrane disorders.” Dr. Gallagher, who directs the Yale Center for Blood Disorders, had a keen interest in infections in infants, Dr. Shah recalled.

“He would share with me interesting cases from his practice. What particularly captured my attention was realizing how the research I could do might have a direct impact on patients and families.” Thus inspired to do an additional year of medical school training at Yale before graduating in 1998, Dr. Shah used that year to focus on research, including a placement at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to investigate infectious disease outbreaks, which offered real-world mysteries to solve.

“When I was a resident, pediatric hospital medicine had not yet been recognized as a specialty. But during my fellowships, most of my work was focused on the inpatient side of medicine,” he said. That made hospital medicine a natural career path.

Dr. Shah describes himself as a devoted soccer fan with season tickets for himself, his wife, and their three children to the Major League Soccer team FC Cincinnati. He’s also a movie buff and a former avid bicyclist who’s now trying to get back into cycling. He encourages readers of The Hospitalist to contact him with input on any aspect of the Journal of Hospital Medicine. Email him at [email protected] and follow him on Twitter: @samirshahmd.

Reference

1. Barrett DJ et al. Pediatric hospital medicine: A proposed new subspecialty. Pediatrics. 2017 March;139(3):e20161823.

Samir S. Shah, MD, MSCE, director of the division of hospital medicine at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, believes that pediatric and adult hospitalists have much to learn from each other. And he aims to promote that mutual education in his new role as editor in chief of the Journal of Hospital Medicine.

Dr. Shah is the first pediatric hospitalist to hold this position for JHM, the official journal of the Society of Hospital Medicine. He says his new position, which became effective Jan. 1, is primed for fostering interaction between pediatric and adult hospitalists. “Pediatric hospital medicine is such a vibrant community of its own. There are many opportunities for partnership and collaboration between adult and pediatric hospitalists,” he said.

The field of pediatric hospital medicine has started down the path toward becoming recognized as a board-certified subspecialty.1 “That will place a greater emphasis on our role in fellowship training, which is important to ensure that pediatric hospitalists have a clearly defined skill set,” Dr. Shah said. “So much of what we learn in medical school is oriented to the medical care of adults. If you go into pediatrics, you’ve already had a fair amount of grounding in the healthy physiology and common diseases of adults. Pediatric hospital medicine fellowships offer an opportunity to refine clinical skill sets, as well as develop new skills in domains such as research and leadership.”

An emphasis on diversity

Although he has praised the innovative work of his predecessors, Mark Williams, MD, MHM, and Andrew Auerbach, MD, MPH, MHM, in shepherding the journal to its current strong position, Dr. Shah brings ideas for new features and directions.

“We as a field really benefit from a diversity of skill sets and perspectives. I’m excited to create processes to ensure equity and diversity in everything we do, starting with adding more women and more pediatric hospitalists to the journal’s leadership team, as well as purposefully developing a diverse leadership pipeline for the journal and for the field,” he said.

“We are intentionally reaching out to pediatricians to emphasize the extent to which JHM is invested in their field. For example, we have increased by seven the number of pediatricians as part of the JHM leadership team.” But pediatric hospitalists have always seen JHM as a home for their work, and Dr. Shah himself has published a couple dozen research papers in the journal. “It has always felt to me like a welcoming place,” he said.

“The great thing for me is that I’m not doing this alone. We have a marvelous crew of senior deputy editors, deputy editors, associate editors, and advisors. The opportunity I have is to leverage the phenomenal expertise and enthusiasm of this exceptional team.”

The journal under Dr. Auerbach’s lead created an editorial fellowship program offering opportunities for 1-year mentored exposure to the publication of academic scholarship and to different aspects of how a medical journal works. “We’re excited to continue investing in this program and included an editorial about it and an application form in the January 2019 issue of the Journal,” Dr. Shah said. He encourages editorial fellowship applications from physicians who historically have been underrepresented in academic medicine leadership.

“We’re also creating a column on leadership and professional development so that leaders in different fields can share their perspective and wisdom with our readers. We’ll be presenting a new, shorter review format; distilling clinical practice guidelines; and working on redesigning the journal’s web presence. We believe that our readers interact with the journal differently than they did five years ago, and increasingly are leveraging social media,” he said.

“I’m eager to broaden the scope of the journal. In the past, we focused on quality, value in health care and transitions of care in and out of the hospital, which are important topics. But I’m also excited about the adoption of new technologies, how to evaluate them and incorporate them into medical practice – things like Apple Watch for measuring heart rhythm,” Dr. Shah.

He wants to explore other technology-related topics like alarm fatigue and the use of monitors. Another big subject is the management of health of populations under new, emerging, risk-based payment models, with their pressures on health systems to take greater responsibility for risk. JHM is a medical journal and an official society journal, Dr. Shah said. “But our readership and submitters are not limited to hospitalists. As editor in chief, I’m here to make sure the journal is relevant to our members and to our other constituencies.”

Dr. Shah joined JHM’s editorial leadership team in 2009, then he became its deputy editor in 2012 and its senior deputy editor in 2015. A founding associate editor of the Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society, he has also served on the editorial board of JAMA Pediatrics. He is editor or coeditor of 12 books in the fields of pediatrics and infectious diseases, including coauthoring “The Philadelphia Guide: Inpatient Pediatrics for McGraw-Hill Education” while still a fellow in academic general pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) and, more recently, “Pediatric Infectious Diseases: Essentials for Practice,” a textbook for the pediatric generalist.

Broad scope of activities

Dr. Shah started practicing pediatric hospital medicine in 2001 during his fellowship training. He joined the faculty at CHOP and the University of Pennsylvania, also in Philadelphia, in 2005. In 2011 he arrived at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, a facility with more than 600 beds that’s affiliated with the University of Cincinnati, where he is professor in the department of pediatrics and holds the James M. Ewell Endowed Chair, to lead a newly created division of hospital medicine. That division now includes more than 55 physician faculty members, 10 nurse practitioners, and nine 3-year fellows.

Collectively the staff represent a broad scope of clinical and research activities along with consulting and surgical comanagement roles and a unique service staffed by med/peds hospitalists for adult patients who have been followed at the hospital since they were children. “Years ago, those patients would not have survived beyond childhood, but with medical advances, they have. Although they continue to benefit from pediatric expertise, these adults also require internal medicine expertise for their adult health needs,” he explained. Examples include patients with neurologic impairments, dependence on medical technology, or congenital heart defects.

Dr. Shah’s own schedule is 28% clinical. He also serves as the hospital’s chief metrics officer, and his research interests include serious infectious diseases, such as pneumonia and meningitis. He is studying the comparative effectiveness of different antibiotic treatments for community-acquired pneumonia and how to improve outcomes for hospital-acquired pneumonia.

Dr. Shah has tried to be deliberate in leading efforts to grow researchers within the field, both nationally and locally. He serves as the chair of the National Childhood Pneumonia Guidelines Committee of the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society, and he also is vice chair of the Pediatric Research in Inpatient Settings (PRIS) Network, which facilitates multicenter cost-effectiveness studies among its 120 hospital members. For example, a series of studies funded by the Patient- Centered Outcomes Research Institute has demonstrated the comparable effectiveness of oral and intravenous antibiotics for osteomyelitis and complicated pneumonia.

Sustainable positions

When he was asked whether he felt pediatric hospitalists face particular challenges in trying to take their place in the burgeoning field of hospital medicine, Dr. Shah said he and his colleagues don’t really think of it in those terms. “Hospital medicine is such a dynamic field. For example, pediatric hospital medicine has charted its own course by pursuing subspecialty certification and fellowship training. Yet support from the field broadly has been quite strong, and SHM has embraced pediatricians, who serve on its board of directors and on numerous committees.”

SHM’s commitment to supporting pediatric hospital medicine practice and research includes its cosponsorship, with the Academic Pediatric Association and the American Academy of Pediatrics, an annual pediatric hospital medicine educational and research conference, which will next be held July 25-28, 2019, in Seattle. “In my recent meetings with society leaders I have seen exceptional enthusiasm for increasing the presence of pediatric hospitalists in the society’s work. Many pediatric hospitalists already attend SHM’s annual meeting and submit their research, but we all recognize that a strong pediatric presence is important for the society.”

Dr. Shah credits Cincinnati Children’s Hospital for supporting a sustainable work schedule for its hospitalists and for a team-oriented culture that emphasizes both professional and personal development and encourages a diversity of skill sets and perspectives, skills development, and additional training. “Individuals are recognized for their achievements within and beyond the confines of the hospital. The mentorship structure we set up here is incredible. Each faculty member has a primary mentor, a peer mentor, and access to a career development committee. Additionally, there is broad participation in clinical operations, educational scholarship, research, and quality improvement.”

Dr. Shah’s professional interests in academics, research, and infectious diseases trace back in part to a thesis project he did on neonatal infections while in medical school at Yale University, New Haven, Conn. “I was working with basic sciences in a hematology lab under the direction of the neonatologist Dr. Patrick Gallagher, whose research focused on pediatric blood cell membrane disorders.” Dr. Gallagher, who directs the Yale Center for Blood Disorders, had a keen interest in infections in infants, Dr. Shah recalled.

“He would share with me interesting cases from his practice. What particularly captured my attention was realizing how the research I could do might have a direct impact on patients and families.” Thus inspired to do an additional year of medical school training at Yale before graduating in 1998, Dr. Shah used that year to focus on research, including a placement at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to investigate infectious disease outbreaks, which offered real-world mysteries to solve.

“When I was a resident, pediatric hospital medicine had not yet been recognized as a specialty. But during my fellowships, most of my work was focused on the inpatient side of medicine,” he said. That made hospital medicine a natural career path.

Dr. Shah describes himself as a devoted soccer fan with season tickets for himself, his wife, and their three children to the Major League Soccer team FC Cincinnati. He’s also a movie buff and a former avid bicyclist who’s now trying to get back into cycling. He encourages readers of The Hospitalist to contact him with input on any aspect of the Journal of Hospital Medicine. Email him at [email protected] and follow him on Twitter: @samirshahmd.

Reference

1. Barrett DJ et al. Pediatric hospital medicine: A proposed new subspecialty. Pediatrics. 2017 March;139(3):e20161823.

Benefit of thrombectomy may be universal

The location of the arterial occlusive lesion and the imaging technique used to select patients for the procedure also do not influence the therapy’s benefits, the researchers said. Although the proportional benefit of thrombectomy plus medical management is uniform across subgroups, compared with medical management alone, patients may have different amounts of absolute benefit.

The results of the DEFUSE 3 (Endovascular Therapy Following Imaging Evaluation for Ischemic Stroke) trial, which were published in 2018, indicated that endovascular thrombectomy provided clinical benefits for patients with acute ischemic stroke if administered at 6-16 hours after stroke onset. As part of the trial’s prespecified analyses, Maarten G. Lansberg, MD, PhD, associate professor of neurology and neurological sciences at Stanford (Calif.) University Medical Center in California, and his colleagues sought to determine whether thrombectomy had uniform benefit among various patient subgroups (e.g., elderly people, patients with mild symptoms, and those who present late after onset).

A total of 296 patients were enrolled in the randomized, open-label, blinded-endpoint DEFUSE 3 trial at 38 sites in the United States. Eligible participants had acute ischemic stroke resulting from an occlusion of the internal carotid artery or middle cerebral artery and evidence of salvageable tissue on perfusion CT or MRI. In all, 182 patients met these criteria and were randomized and included in the intention-to-treat analysis. The researchers stopped DEFUSE 3 early because of efficacy.

The study’s primary endpoint was functional outcome at day 90, as measured with the modified Rankin Scale. Dr. Lansberg and his colleagues performed multivariate ordinal logistic regression to calculate the adjusted proportional association between endovascular treatment and clinical outcome among participants of various ages, baseline stroke severities, periods between onset and treatment, locations of the arterial occlusion, and imaging modalities, such as CT or MRI, used to identify salvageable tissue.

The population’s median age was 70 years, and 51% of participants were women. The median National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score was 16. When the researchers considered the whole sample, they found that younger age, lower baseline NIHSS score, and lower serum glucose level independently predicted better functional outcome. The common odds ratio for improved functional outcome with endovascular therapy, adjusted for these variables, was 3.1. Age, NIHSS score, time to randomization, imaging modality, and location of the arterial occlusion did not interact significantly with treatment effect.

“Our results indicate that advanced age, up to 90 years, should not be considered a contraindication to thrombectomy, provided that the patient is fully independent prior to stroke onset,” said the researchers. “Although age did not modify the treatment effect, it was a strong independent predictor of 90-day disability, which is consistent with prior studies of both tissue plasminogen activator and endovascular therapy.”

The trial’s small sample size may have allowed small differences between groups to pass unnoticed, said the reseachers. Other trials of late-window thrombectomy will be required to validate these results, they concluded.

The National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke supported the study through grants. Several investigators received consulting fees from and hold shares in iSchemaView, which manufactures the software that the investigators used for postprocessing of CT and MRI perfusion studies. Other authors received consulting fees from various pharmaceutical and medical device companies, including Genentech, Medtronic, Pfizer, and Stryker Neurovascular.

SOURCE: Lansberg MG et al. JAMA Neurol. 2019 Jan 28. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.4587.

The location of the arterial occlusive lesion and the imaging technique used to select patients for the procedure also do not influence the therapy’s benefits, the researchers said. Although the proportional benefit of thrombectomy plus medical management is uniform across subgroups, compared with medical management alone, patients may have different amounts of absolute benefit.

The results of the DEFUSE 3 (Endovascular Therapy Following Imaging Evaluation for Ischemic Stroke) trial, which were published in 2018, indicated that endovascular thrombectomy provided clinical benefits for patients with acute ischemic stroke if administered at 6-16 hours after stroke onset. As part of the trial’s prespecified analyses, Maarten G. Lansberg, MD, PhD, associate professor of neurology and neurological sciences at Stanford (Calif.) University Medical Center in California, and his colleagues sought to determine whether thrombectomy had uniform benefit among various patient subgroups (e.g., elderly people, patients with mild symptoms, and those who present late after onset).

A total of 296 patients were enrolled in the randomized, open-label, blinded-endpoint DEFUSE 3 trial at 38 sites in the United States. Eligible participants had acute ischemic stroke resulting from an occlusion of the internal carotid artery or middle cerebral artery and evidence of salvageable tissue on perfusion CT or MRI. In all, 182 patients met these criteria and were randomized and included in the intention-to-treat analysis. The researchers stopped DEFUSE 3 early because of efficacy.

The study’s primary endpoint was functional outcome at day 90, as measured with the modified Rankin Scale. Dr. Lansberg and his colleagues performed multivariate ordinal logistic regression to calculate the adjusted proportional association between endovascular treatment and clinical outcome among participants of various ages, baseline stroke severities, periods between onset and treatment, locations of the arterial occlusion, and imaging modalities, such as CT or MRI, used to identify salvageable tissue.

The population’s median age was 70 years, and 51% of participants were women. The median National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score was 16. When the researchers considered the whole sample, they found that younger age, lower baseline NIHSS score, and lower serum glucose level independently predicted better functional outcome. The common odds ratio for improved functional outcome with endovascular therapy, adjusted for these variables, was 3.1. Age, NIHSS score, time to randomization, imaging modality, and location of the arterial occlusion did not interact significantly with treatment effect.

“Our results indicate that advanced age, up to 90 years, should not be considered a contraindication to thrombectomy, provided that the patient is fully independent prior to stroke onset,” said the researchers. “Although age did not modify the treatment effect, it was a strong independent predictor of 90-day disability, which is consistent with prior studies of both tissue plasminogen activator and endovascular therapy.”

The trial’s small sample size may have allowed small differences between groups to pass unnoticed, said the reseachers. Other trials of late-window thrombectomy will be required to validate these results, they concluded.

The National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke supported the study through grants. Several investigators received consulting fees from and hold shares in iSchemaView, which manufactures the software that the investigators used for postprocessing of CT and MRI perfusion studies. Other authors received consulting fees from various pharmaceutical and medical device companies, including Genentech, Medtronic, Pfizer, and Stryker Neurovascular.

SOURCE: Lansberg MG et al. JAMA Neurol. 2019 Jan 28. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.4587.

The location of the arterial occlusive lesion and the imaging technique used to select patients for the procedure also do not influence the therapy’s benefits, the researchers said. Although the proportional benefit of thrombectomy plus medical management is uniform across subgroups, compared with medical management alone, patients may have different amounts of absolute benefit.

The results of the DEFUSE 3 (Endovascular Therapy Following Imaging Evaluation for Ischemic Stroke) trial, which were published in 2018, indicated that endovascular thrombectomy provided clinical benefits for patients with acute ischemic stroke if administered at 6-16 hours after stroke onset. As part of the trial’s prespecified analyses, Maarten G. Lansberg, MD, PhD, associate professor of neurology and neurological sciences at Stanford (Calif.) University Medical Center in California, and his colleagues sought to determine whether thrombectomy had uniform benefit among various patient subgroups (e.g., elderly people, patients with mild symptoms, and those who present late after onset).

A total of 296 patients were enrolled in the randomized, open-label, blinded-endpoint DEFUSE 3 trial at 38 sites in the United States. Eligible participants had acute ischemic stroke resulting from an occlusion of the internal carotid artery or middle cerebral artery and evidence of salvageable tissue on perfusion CT or MRI. In all, 182 patients met these criteria and were randomized and included in the intention-to-treat analysis. The researchers stopped DEFUSE 3 early because of efficacy.

The study’s primary endpoint was functional outcome at day 90, as measured with the modified Rankin Scale. Dr. Lansberg and his colleagues performed multivariate ordinal logistic regression to calculate the adjusted proportional association between endovascular treatment and clinical outcome among participants of various ages, baseline stroke severities, periods between onset and treatment, locations of the arterial occlusion, and imaging modalities, such as CT or MRI, used to identify salvageable tissue.

The population’s median age was 70 years, and 51% of participants were women. The median National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score was 16. When the researchers considered the whole sample, they found that younger age, lower baseline NIHSS score, and lower serum glucose level independently predicted better functional outcome. The common odds ratio for improved functional outcome with endovascular therapy, adjusted for these variables, was 3.1. Age, NIHSS score, time to randomization, imaging modality, and location of the arterial occlusion did not interact significantly with treatment effect.

“Our results indicate that advanced age, up to 90 years, should not be considered a contraindication to thrombectomy, provided that the patient is fully independent prior to stroke onset,” said the researchers. “Although age did not modify the treatment effect, it was a strong independent predictor of 90-day disability, which is consistent with prior studies of both tissue plasminogen activator and endovascular therapy.”

The trial’s small sample size may have allowed small differences between groups to pass unnoticed, said the reseachers. Other trials of late-window thrombectomy will be required to validate these results, they concluded.

The National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke supported the study through grants. Several investigators received consulting fees from and hold shares in iSchemaView, which manufactures the software that the investigators used for postprocessing of CT and MRI perfusion studies. Other authors received consulting fees from various pharmaceutical and medical device companies, including Genentech, Medtronic, Pfizer, and Stryker Neurovascular.

SOURCE: Lansberg MG et al. JAMA Neurol. 2019 Jan 28. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.4587.

FROM JAMA NEUROLOGY

Key clinical point: Age, symptom severity, and serum glucose do not influence the benefit of thrombectomy for acute ischemic stroke.

Major finding: The adjusted common odds ratio for improved functional outcome with endovascular therapy was 3.1.

Study details: The randomized, open-label, blinded-end-point DEFUSE 3 trial included 182 patients.

Disclosures: The National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke funded the study through grants.

Source: Lansberg MG et al. JAMA Neurol. 2019 Jan 28. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.4587.

Anxiety, depression, burnout higher in physician mothers caring for others at home

Physicians who are also mothers have a higher risk of burnout and mood and anxiety disorders if they are also caring for someone with a serious illness or disability outside of work, according to a cross-sectional survey reported in a letter in JAMA Internal Medicine.

“Our findings highlight the additional caregiving responsibilities of some women physicians and the potential consequences of these additional responsibilities for their behavioral health and careers,” wrote Veronica Yank, MD, of the department of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, and her colleagues.

“To reduce burnout and improve workforce retention, health care systems should develop new approaches to identify and address the needs of these physician mothers,” they wrote.

The researchers used data from a June-July 2016 online survey of respondents from the Physicians Moms Group online community. Approximately 16,059 members saw the posting for the survey, and 5,613 United States–based mothers participated.

Among the questions was one on non–work related caregiving responsibilities that asked whether the respondent provided “regular care or assistance to a friend or family member with a serious health problem, long-term illness or disability” during the last year. Other questions assessed alcohol and drug use, history of a mood or anxiety disorder, career satisfaction and burnout.

Among the 16.4% of respondents who had additional caregiving responsibilities outside of work for someone chronically or seriously ill or disabled, nearly half (48.3%) said they cared for ill parents, 16.9% for children or infants, 7.7% for a partner, and 28.6% for another relative. In addition, 16.7% of respondents had such caregiving responsibilities for more than one person.

The women with these extra caregiving responsibilities were 21% more likely to have a mood or anxiety disorder (adjusted relative risk, 1.21; P = .02) and 25% more likely to report burnout (aRR, 1.25; P = .007), compared with those who did not have such extra responsibilities.

There were no significant differences, however, on rates of career satisfaction, risky drinking behaviors, or substance abuse between physician mothers who did have additional caregiving responsibilities and those who did not.

Among the study’s limitations were its cross-sectional nature, use of a convenience sample that may not be generalizable or representative, and lack of data on fathers or non-parent physicians for comparison.

SOURCE: Yank V et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Jan 28. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6411.

Physicians who are also mothers have a higher risk of burnout and mood and anxiety disorders if they are also caring for someone with a serious illness or disability outside of work, according to a cross-sectional survey reported in a letter in JAMA Internal Medicine.

“Our findings highlight the additional caregiving responsibilities of some women physicians and the potential consequences of these additional responsibilities for their behavioral health and careers,” wrote Veronica Yank, MD, of the department of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, and her colleagues.

“To reduce burnout and improve workforce retention, health care systems should develop new approaches to identify and address the needs of these physician mothers,” they wrote.

The researchers used data from a June-July 2016 online survey of respondents from the Physicians Moms Group online community. Approximately 16,059 members saw the posting for the survey, and 5,613 United States–based mothers participated.

Among the questions was one on non–work related caregiving responsibilities that asked whether the respondent provided “regular care or assistance to a friend or family member with a serious health problem, long-term illness or disability” during the last year. Other questions assessed alcohol and drug use, history of a mood or anxiety disorder, career satisfaction and burnout.

Among the 16.4% of respondents who had additional caregiving responsibilities outside of work for someone chronically or seriously ill or disabled, nearly half (48.3%) said they cared for ill parents, 16.9% for children or infants, 7.7% for a partner, and 28.6% for another relative. In addition, 16.7% of respondents had such caregiving responsibilities for more than one person.

The women with these extra caregiving responsibilities were 21% more likely to have a mood or anxiety disorder (adjusted relative risk, 1.21; P = .02) and 25% more likely to report burnout (aRR, 1.25; P = .007), compared with those who did not have such extra responsibilities.

There were no significant differences, however, on rates of career satisfaction, risky drinking behaviors, or substance abuse between physician mothers who did have additional caregiving responsibilities and those who did not.

Among the study’s limitations were its cross-sectional nature, use of a convenience sample that may not be generalizable or representative, and lack of data on fathers or non-parent physicians for comparison.

SOURCE: Yank V et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Jan 28. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6411.

Physicians who are also mothers have a higher risk of burnout and mood and anxiety disorders if they are also caring for someone with a serious illness or disability outside of work, according to a cross-sectional survey reported in a letter in JAMA Internal Medicine.

“Our findings highlight the additional caregiving responsibilities of some women physicians and the potential consequences of these additional responsibilities for their behavioral health and careers,” wrote Veronica Yank, MD, of the department of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, and her colleagues.

“To reduce burnout and improve workforce retention, health care systems should develop new approaches to identify and address the needs of these physician mothers,” they wrote.

The researchers used data from a June-July 2016 online survey of respondents from the Physicians Moms Group online community. Approximately 16,059 members saw the posting for the survey, and 5,613 United States–based mothers participated.

Among the questions was one on non–work related caregiving responsibilities that asked whether the respondent provided “regular care or assistance to a friend or family member with a serious health problem, long-term illness or disability” during the last year. Other questions assessed alcohol and drug use, history of a mood or anxiety disorder, career satisfaction and burnout.

Among the 16.4% of respondents who had additional caregiving responsibilities outside of work for someone chronically or seriously ill or disabled, nearly half (48.3%) said they cared for ill parents, 16.9% for children or infants, 7.7% for a partner, and 28.6% for another relative. In addition, 16.7% of respondents had such caregiving responsibilities for more than one person.

The women with these extra caregiving responsibilities were 21% more likely to have a mood or anxiety disorder (adjusted relative risk, 1.21; P = .02) and 25% more likely to report burnout (aRR, 1.25; P = .007), compared with those who did not have such extra responsibilities.

There were no significant differences, however, on rates of career satisfaction, risky drinking behaviors, or substance abuse between physician mothers who did have additional caregiving responsibilities and those who did not.

Among the study’s limitations were its cross-sectional nature, use of a convenience sample that may not be generalizable or representative, and lack of data on fathers or non-parent physicians for comparison.

SOURCE: Yank V et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Jan 28. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6411.

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Risk of anxiety and mood disorders is 21% higher and burnout is 25% higher among physician mothers with extra caregiving at home.

Study details: The findings are based on an online cross-sectional survey of 5,613 United States–based physician mothers conducted from June to July 2016.

Disclosures: No single entity directly funded the study, but the authors were supported by a variety of grants from foundations and the National Institutes of Health at the time it was completed. One coauthor is founder of Equity Quotient, a company that provides gender equity culture analytics for institutions, and another has consulted for Amgen and Vizient and receives stock options as an Equity Quotient advisory board member.

Source: Yank V et al. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2018 Jan 28. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6411.

Tamsulosin not effective in promoting stone expulsion in symptomatic patients

Clinical question: Does tamsulosin provide benefit in ureteral stone expulsion for patients who present with a symptomatic stone less than 9 mm?

Background: Treatment of urinary stone disease often includes the use of alpha-blockers such as tamsulosin to promote stone passage, and between 15% and 55% of patients presenting to EDs for renal colic are prescribed alpha-blockers. Current treatment guidelines support the use of tamsulosin, with recent evidence suggesting that this treatment is more effective for larger stones (5-10 mm). However, other prospective trials have called these guidelines into question.

Study design: Double-blind, placebo-controlled study.

Setting: Six emergency departments at U.S. tertiary-care hospitals.

Synopsis: 512 participants with symptomatic ureteral stones were randomized to either tamsulosin or placebo. At the end of a 28-day treatment period, the rate of urinary stone passage was 49.6% in the tamsulosin group vs. 47.3% in the placebo group (95.8% confidence interval, 0.87-1.27; P = .60). The time to stone passage also was not different between treatment groups (P = .92). A second phase of the trial also evaluated stone passage by CT scan at 28 days, with stone passage rates of 83.6% in the tamsulosin group and 77.6% in the placebo group (95% CI, 0.95-1.22; P = .24). This study is the largest of its kind in the United States, with findings similar to those of two recent international multisite trials, increasing the evidence that tamsulosin is not beneficial for larger stone passage.

Bottom line: For patients presenting to the ED for renal colic from ureteral stones smaller than 9 mm, tamsulosin does not appear to promote stone passage.

Citation: Meltzer AC et al. Effect of tamsulosin on passage of symptomatic ureteral stones: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(8):1051-7. Published online June 18, 2018.

Dr. Breviu is assistant professor of medicine and an academic hospitalist, University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

Clinical question: Does tamsulosin provide benefit in ureteral stone expulsion for patients who present with a symptomatic stone less than 9 mm?

Background: Treatment of urinary stone disease often includes the use of alpha-blockers such as tamsulosin to promote stone passage, and between 15% and 55% of patients presenting to EDs for renal colic are prescribed alpha-blockers. Current treatment guidelines support the use of tamsulosin, with recent evidence suggesting that this treatment is more effective for larger stones (5-10 mm). However, other prospective trials have called these guidelines into question.

Study design: Double-blind, placebo-controlled study.

Setting: Six emergency departments at U.S. tertiary-care hospitals.

Synopsis: 512 participants with symptomatic ureteral stones were randomized to either tamsulosin or placebo. At the end of a 28-day treatment period, the rate of urinary stone passage was 49.6% in the tamsulosin group vs. 47.3% in the placebo group (95.8% confidence interval, 0.87-1.27; P = .60). The time to stone passage also was not different between treatment groups (P = .92). A second phase of the trial also evaluated stone passage by CT scan at 28 days, with stone passage rates of 83.6% in the tamsulosin group and 77.6% in the placebo group (95% CI, 0.95-1.22; P = .24). This study is the largest of its kind in the United States, with findings similar to those of two recent international multisite trials, increasing the evidence that tamsulosin is not beneficial for larger stone passage.

Bottom line: For patients presenting to the ED for renal colic from ureteral stones smaller than 9 mm, tamsulosin does not appear to promote stone passage.

Citation: Meltzer AC et al. Effect of tamsulosin on passage of symptomatic ureteral stones: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(8):1051-7. Published online June 18, 2018.

Dr. Breviu is assistant professor of medicine and an academic hospitalist, University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

Clinical question: Does tamsulosin provide benefit in ureteral stone expulsion for patients who present with a symptomatic stone less than 9 mm?

Background: Treatment of urinary stone disease often includes the use of alpha-blockers such as tamsulosin to promote stone passage, and between 15% and 55% of patients presenting to EDs for renal colic are prescribed alpha-blockers. Current treatment guidelines support the use of tamsulosin, with recent evidence suggesting that this treatment is more effective for larger stones (5-10 mm). However, other prospective trials have called these guidelines into question.

Study design: Double-blind, placebo-controlled study.

Setting: Six emergency departments at U.S. tertiary-care hospitals.

Synopsis: 512 participants with symptomatic ureteral stones were randomized to either tamsulosin or placebo. At the end of a 28-day treatment period, the rate of urinary stone passage was 49.6% in the tamsulosin group vs. 47.3% in the placebo group (95.8% confidence interval, 0.87-1.27; P = .60). The time to stone passage also was not different between treatment groups (P = .92). A second phase of the trial also evaluated stone passage by CT scan at 28 days, with stone passage rates of 83.6% in the tamsulosin group and 77.6% in the placebo group (95% CI, 0.95-1.22; P = .24). This study is the largest of its kind in the United States, with findings similar to those of two recent international multisite trials, increasing the evidence that tamsulosin is not beneficial for larger stone passage.

Bottom line: For patients presenting to the ED for renal colic from ureteral stones smaller than 9 mm, tamsulosin does not appear to promote stone passage.

Citation: Meltzer AC et al. Effect of tamsulosin on passage of symptomatic ureteral stones: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(8):1051-7. Published online June 18, 2018.

Dr. Breviu is assistant professor of medicine and an academic hospitalist, University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

Mortality risk remains high for survivors of opioid overdose

Clinical question: What are the causes and risks of mortality in the first year after nonfatal opioid overdose?

Background: The current opioid epidemic has led to increasing hospitalizations and ED presentations for nonfatal opioid overdose. Despite this, little is known about the subsequent causes of mortality in these patients. Additional information could suggest potential interventions to decrease subsequent risk of death.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: U.S. national cohort of Medicaid beneficiaries, aged 18-64 years, during 2001-2007.

Synopsis: This cohort included 76,325 adults with nonfatal opioid overdose with 66,736 person-years of follow-up. In the first year after overdose, there were 5,194 deaths, and the crude death rate was 778.3 per 10,000 person-years. Compared with a demographically matched general population, the standardized mortality rate ratios (SMRs) for this cohort were 24.2 times higher for all-cause mortality and 132.1 times higher for drug use–associated disease. The SMRs also were elevated for conditions including HIV (45.9), chronic respiratory disease (41.1), viral hepatitis (30.6), and suicide (25.9). Though limited to billing data from Medicaid beneficiaries during 2001-2007, this study is important in identifying a relatively young population at high risk of preventable death and suggests that additional resources and interventions may be important in this population.

Bottom line: Adults surviving opioid overdose remain at high risk of death over the following year and may benefit from multidisciplinary interventions targeted at coordinating medical care and treatment of mental health and substance use disorders following hospitalization and emergency department presentations.

Citation: Olfson M et al. Causes of death after nonfatal opioid overdose. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018 Aug 1;75(8):820-7. Published online June 20, 2018.

Dr. Breviu is assistant professor of medicine and an academic hospitalist, University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

Clinical question: What are the causes and risks of mortality in the first year after nonfatal opioid overdose?

Background: The current opioid epidemic has led to increasing hospitalizations and ED presentations for nonfatal opioid overdose. Despite this, little is known about the subsequent causes of mortality in these patients. Additional information could suggest potential interventions to decrease subsequent risk of death.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: U.S. national cohort of Medicaid beneficiaries, aged 18-64 years, during 2001-2007.

Synopsis: This cohort included 76,325 adults with nonfatal opioid overdose with 66,736 person-years of follow-up. In the first year after overdose, there were 5,194 deaths, and the crude death rate was 778.3 per 10,000 person-years. Compared with a demographically matched general population, the standardized mortality rate ratios (SMRs) for this cohort were 24.2 times higher for all-cause mortality and 132.1 times higher for drug use–associated disease. The SMRs also were elevated for conditions including HIV (45.9), chronic respiratory disease (41.1), viral hepatitis (30.6), and suicide (25.9). Though limited to billing data from Medicaid beneficiaries during 2001-2007, this study is important in identifying a relatively young population at high risk of preventable death and suggests that additional resources and interventions may be important in this population.

Bottom line: Adults surviving opioid overdose remain at high risk of death over the following year and may benefit from multidisciplinary interventions targeted at coordinating medical care and treatment of mental health and substance use disorders following hospitalization and emergency department presentations.

Citation: Olfson M et al. Causes of death after nonfatal opioid overdose. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018 Aug 1;75(8):820-7. Published online June 20, 2018.

Dr. Breviu is assistant professor of medicine and an academic hospitalist, University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

Clinical question: What are the causes and risks of mortality in the first year after nonfatal opioid overdose?

Background: The current opioid epidemic has led to increasing hospitalizations and ED presentations for nonfatal opioid overdose. Despite this, little is known about the subsequent causes of mortality in these patients. Additional information could suggest potential interventions to decrease subsequent risk of death.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: U.S. national cohort of Medicaid beneficiaries, aged 18-64 years, during 2001-2007.

Synopsis: This cohort included 76,325 adults with nonfatal opioid overdose with 66,736 person-years of follow-up. In the first year after overdose, there were 5,194 deaths, and the crude death rate was 778.3 per 10,000 person-years. Compared with a demographically matched general population, the standardized mortality rate ratios (SMRs) for this cohort were 24.2 times higher for all-cause mortality and 132.1 times higher for drug use–associated disease. The SMRs also were elevated for conditions including HIV (45.9), chronic respiratory disease (41.1), viral hepatitis (30.6), and suicide (25.9). Though limited to billing data from Medicaid beneficiaries during 2001-2007, this study is important in identifying a relatively young population at high risk of preventable death and suggests that additional resources and interventions may be important in this population.

Bottom line: Adults surviving opioid overdose remain at high risk of death over the following year and may benefit from multidisciplinary interventions targeted at coordinating medical care and treatment of mental health and substance use disorders following hospitalization and emergency department presentations.

Citation: Olfson M et al. Causes of death after nonfatal opioid overdose. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018 Aug 1;75(8):820-7. Published online June 20, 2018.

Dr. Breviu is assistant professor of medicine and an academic hospitalist, University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

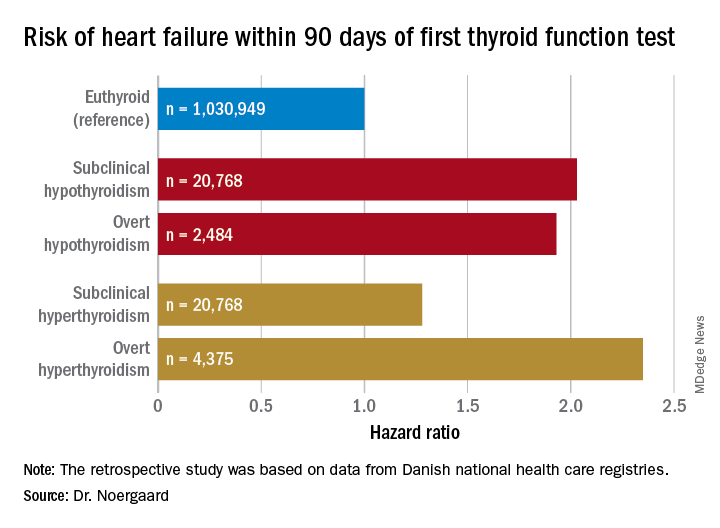

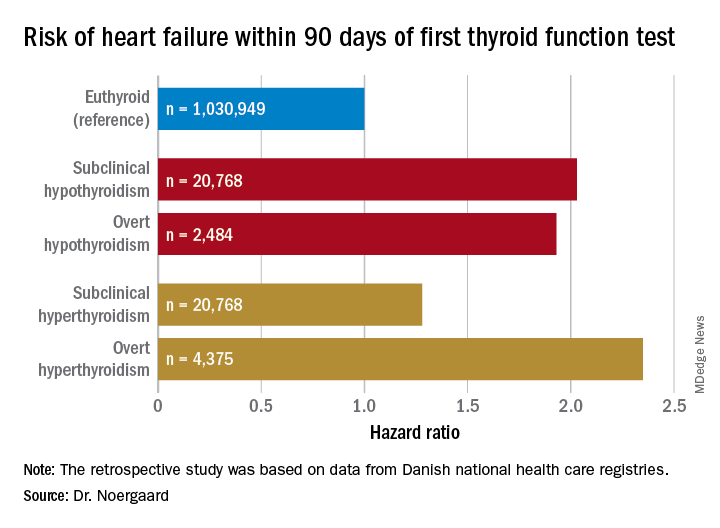

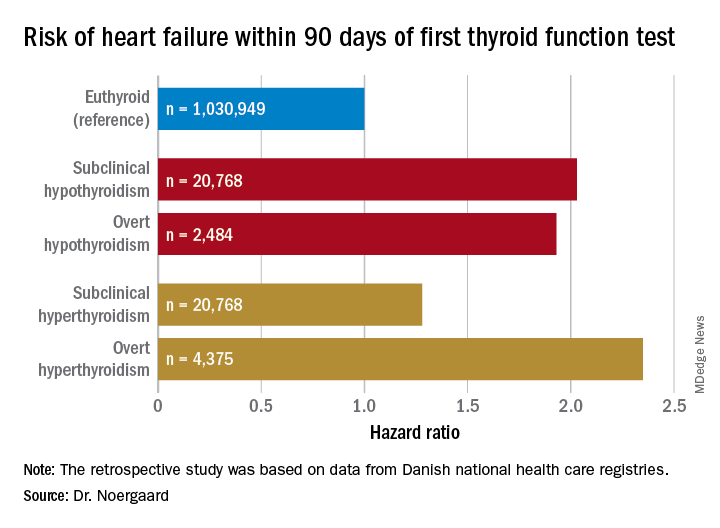

Subclinical hypothyroidism boosts immediate risk of heart failure

CHICAGO – The short-term risk of developing heart failure in patients with newly identified hypothyroidism, be it overt or subclinical, is double that of euthyroid individuals, Caroline H. Noergaard, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“This is really important clinically. The association with heart failure has previously been shown in both overt and subclinical hyperthyroidism, but it’s actually new knowledge that hypothyroidism is associated with immediate risk of heart failure. And a lot of people have subclinical hypothyroidism,” said Dr. Noergaard, a PhD student in epidemiology at Aalborg (Denmark) University.

Also at the meeting, Jeffrey L. Anderson, MD, reported that free thyroxine levels within the normal reference range were associated in graded fashion with an increased prevalence and incidence of atrial fibrillation in a large Utah study, a finding that provides independent confirmation of an earlier report by investigators from the population-based Rotterdam Study.

“These findings validate those of the Rotterdam Study in a much larger dataset and may have important clinical implications, including a redefinition of the reference range and the target-free T4 levels for thyroxine replacement therapy,” observed Dr. Anderson, professor of internal medicine at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, and a research cardiologist at the Intermountain Medical Center Heart Institute.

Hypothyroidism and heart failure

Dr. Noergaard presented a retrospective study of over 1 million Copenhagen-area adults (mean age, 50 years) with no history of heart failure, who had their first thyroid function test. She and her coinvestigators turned to comprehensive Danish national health care registries to determine how many of these individuals were diagnosed with new-onset heart failure within 90 days after their thyroid function test.

Subclinical hypothyroidism was defined by a thyroid-stimulating hormone level greater than 5 mIU/L and a free T4 of 9-22 pmol/L. Overt hypothyroidism required a TSH greater than 5 mIU/L with a free T4 less than 9 pmol/L.

Free T4 predicts atrial fibrillation risk

Dr. Anderson presented a retrospective analysis of 174,914 adult patients in the Intermountain Healthcare EMR database, none of whom were on thyroid replacement at entry. The patients, who were a mean age of 64 years and 65% women, were followed for an average of 6.3 years. Of these, 88.4% had a free T4 within the normal reference range of 0.75-1.5 ng/dL, 7.4% had a value below the cutoff for normal, and 4.2% had a free T4 above the reference range.

Upon dividing the patients within the normal range into quartiles based upon their free T4 level, he and his coinvestigators found that the baseline prevalence of atrial fibrillation was 8.7% in those in quartile 1, 9.3% in quartile 2, 10.5% in quartile 3, and 12.6% in quartile 4. In a multivariate analysis adjusted for potential confounders, the risk of prevalent atrial fibrillation was increased by 11% for patients in quartile 2, compared with those in the first quartile, by 22% in quartile 3, and by 40% in quartile 4.

The incidence of new-onset atrial fibrillation during 3 years of follow-up was 4.1% in patients in normal-range quartile 1, 4.3% in quartile 2, 4.5% in quartile 3, and 5.2% in the top normal-range quartile. The odds of developing atrial fibrillation were increased by 8% and 16% in quartiles 3 and 4, compared with quartile 1.

Serum TSH and free T3 levels showed no consistent relationship with atrial fibrillation.

The Utah findings confirm in a large U.S. population the earlier report from the Rotterdam Study (J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015 Oct;100(10):3718-24).

Dr. Noergaard and Dr. Anderson reported having no financial conflicts regarding their studies, which were carried out free of commercial support.

CHICAGO – The short-term risk of developing heart failure in patients with newly identified hypothyroidism, be it overt or subclinical, is double that of euthyroid individuals, Caroline H. Noergaard, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“This is really important clinically. The association with heart failure has previously been shown in both overt and subclinical hyperthyroidism, but it’s actually new knowledge that hypothyroidism is associated with immediate risk of heart failure. And a lot of people have subclinical hypothyroidism,” said Dr. Noergaard, a PhD student in epidemiology at Aalborg (Denmark) University.

Also at the meeting, Jeffrey L. Anderson, MD, reported that free thyroxine levels within the normal reference range were associated in graded fashion with an increased prevalence and incidence of atrial fibrillation in a large Utah study, a finding that provides independent confirmation of an earlier report by investigators from the population-based Rotterdam Study.

“These findings validate those of the Rotterdam Study in a much larger dataset and may have important clinical implications, including a redefinition of the reference range and the target-free T4 levels for thyroxine replacement therapy,” observed Dr. Anderson, professor of internal medicine at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, and a research cardiologist at the Intermountain Medical Center Heart Institute.

Hypothyroidism and heart failure

Dr. Noergaard presented a retrospective study of over 1 million Copenhagen-area adults (mean age, 50 years) with no history of heart failure, who had their first thyroid function test. She and her coinvestigators turned to comprehensive Danish national health care registries to determine how many of these individuals were diagnosed with new-onset heart failure within 90 days after their thyroid function test.

Subclinical hypothyroidism was defined by a thyroid-stimulating hormone level greater than 5 mIU/L and a free T4 of 9-22 pmol/L. Overt hypothyroidism required a TSH greater than 5 mIU/L with a free T4 less than 9 pmol/L.

Free T4 predicts atrial fibrillation risk

Dr. Anderson presented a retrospective analysis of 174,914 adult patients in the Intermountain Healthcare EMR database, none of whom were on thyroid replacement at entry. The patients, who were a mean age of 64 years and 65% women, were followed for an average of 6.3 years. Of these, 88.4% had a free T4 within the normal reference range of 0.75-1.5 ng/dL, 7.4% had a value below the cutoff for normal, and 4.2% had a free T4 above the reference range.

Upon dividing the patients within the normal range into quartiles based upon their free T4 level, he and his coinvestigators found that the baseline prevalence of atrial fibrillation was 8.7% in those in quartile 1, 9.3% in quartile 2, 10.5% in quartile 3, and 12.6% in quartile 4. In a multivariate analysis adjusted for potential confounders, the risk of prevalent atrial fibrillation was increased by 11% for patients in quartile 2, compared with those in the first quartile, by 22% in quartile 3, and by 40% in quartile 4.

The incidence of new-onset atrial fibrillation during 3 years of follow-up was 4.1% in patients in normal-range quartile 1, 4.3% in quartile 2, 4.5% in quartile 3, and 5.2% in the top normal-range quartile. The odds of developing atrial fibrillation were increased by 8% and 16% in quartiles 3 and 4, compared with quartile 1.

Serum TSH and free T3 levels showed no consistent relationship with atrial fibrillation.

The Utah findings confirm in a large U.S. population the earlier report from the Rotterdam Study (J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015 Oct;100(10):3718-24).

Dr. Noergaard and Dr. Anderson reported having no financial conflicts regarding their studies, which were carried out free of commercial support.

CHICAGO – The short-term risk of developing heart failure in patients with newly identified hypothyroidism, be it overt or subclinical, is double that of euthyroid individuals, Caroline H. Noergaard, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“This is really important clinically. The association with heart failure has previously been shown in both overt and subclinical hyperthyroidism, but it’s actually new knowledge that hypothyroidism is associated with immediate risk of heart failure. And a lot of people have subclinical hypothyroidism,” said Dr. Noergaard, a PhD student in epidemiology at Aalborg (Denmark) University.

Also at the meeting, Jeffrey L. Anderson, MD, reported that free thyroxine levels within the normal reference range were associated in graded fashion with an increased prevalence and incidence of atrial fibrillation in a large Utah study, a finding that provides independent confirmation of an earlier report by investigators from the population-based Rotterdam Study.

“These findings validate those of the Rotterdam Study in a much larger dataset and may have important clinical implications, including a redefinition of the reference range and the target-free T4 levels for thyroxine replacement therapy,” observed Dr. Anderson, professor of internal medicine at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, and a research cardiologist at the Intermountain Medical Center Heart Institute.

Hypothyroidism and heart failure